STRATEGIC VISION

for Taiwan Security

The Belt and Road in Africa

Weighing the Pros and Cons

Letsiwe Portia Magongo & Ruei-Lin Yu

2020: Year of Cross-Strait Tension

Shao-cheng Sun

Clash in Eastern Ladakh

Amrita Jash

Proposal: Taiwan Tripwire Force

Kitsch Liao

ROC’s Evolving Defensive Posture

Ying-yu Lin

Volume 10, Issue 48 w February, 2021 w ISSN 2227-3646

STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan Security

Contents

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision. Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for reprints should be made with the editor. The editors are responsible for the selection and acceptance of articles; responsibility for opinions expressed and accuracy of facts in articles published rests solely with individual authors. The editors are not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; unaccepted manuscripts will be returned if accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. Strategic Vision remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Cover photograph of a Niger Armed Forces soldier clearing a room during a training exercise with the 409th Expeditionary Security Forces Squadron air advisors at the FAN compound on Nigerien Air Base 201 in Agadez, Niger, July 10, 2019, is courtesy of Devin Boyer.

....................................4 .................................... 10 ............................. 16 ............................ 22 ......................... 28

w February,

Volume 10, Issue 48

2021

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Associate Editor

Dean Karalekas

Editorial Board

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Richard Hu, NCCU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Lipin Tien, NDU

Hon-Min Yau, NDU

Ruei-lin Yu, NDU

Li-Chung Yuan, NDU

From The Editor

We here at Strategic Vision are honored to embark upon our tenth year in publication, and are glad to have you join us as we continue to analyze the events and trends in cross-strait and Asia-Pacific security as they reshape our world. In addition, it is our fervent hope that you had a wonderful Lunar New Year, and that the Year of the Ox has something good in store for all our readers.

The Indo-Pacific Region remains as dynamic and complex as ever, and we wish to keep our readers abreast of recent developments. To that end we offer our latest issue.

We launch our tenth year with an exciting issue, beginning with Dr. Ruei-Lin Yu, a professor at the ROC National Defense University, and Letsiwe Portia Magongo, a student at the ROC National Defense University, who examine some of the benefits and challenges of China’s infrastructure projects in East Africa.

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security

(ISSN 2227-3646) Volume 10, Number 48, February, 2021, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Taiwan Center for Security Studies. No. 64, Wan Shou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Executive Editor directly via email at: dkarale.kas@gmail.com. Or by telephone at: +886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: www.csstw.org

© Copyright 2021 by the Taiwan Center for Security Studies.

Next, Dr. Shao-cheng Sun, a visiting professor at the Citadel in the United States, examines China’s increased diplomatic and military pressure on Taiwan. This is followed by an analysis of the recent border tensions between China and India by Dr. Amrita Jash, a research fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies in New Delhi, India.

Kitsch Liao, an independent defense analyst based in Taipei, offers a thought-provoking strategic proposal for discussion, that of the establishment of a US tripwire force in Taiwan that, if deployed covertly, could aid in deterrence.

Finally, Dr. Ying-yu Lin, an adjunct assistant professor at the Institute of Strategic and International Affairs at National Chung Cheng University in Chiayi, Taiwan, argues that Taiwan’s defense strategy must continue to evolve as the US-China relationship also continues to evolve and change.

Once again, we are extremely proud to continue providing the very best in coverage and analysis of the military, security, and political changes that affect our region, and are glad to play a part in keeping our readers up to date with the information they need.

All our best wishes for the Year of the Ox.

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor Strategic Vision

All articles in this periodical represent the personal views of the authors, and not necessarily their institutions, the TCSS, NDU, or the editors

Strategic Vision vol. 10, no. 48 (February, 2021)

Balancing Growth

Weighing the pros and cons of Chinese BRI infrastructure projects in Africa

East African countries have an important strategic importance for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Kenya, Somalia, and Tanzania lie at the western edge of the Indian Ocean and provide China with crucial access to Africa, whereas Djibouti and Egypt are full-fledged BRI partners in close proximity to the Mediterranean Sea, and therefore help connect China to Europe. Given the recent expansion of Beijing’s influence in

this region, it is necessary to develop a clear-eyed view of the beneficial, as well as detrimental, impacts of China’s BRI on the countries of East Africa.

The progress of the BRI in East Africa is evident from the ambitious infrastructure projects undertaken in its name. Chinese companies have launched a range of construction projects on harbors, highways, and railways. In Kenya, the main BRI development projects are the construction of a modern port at

4 b

Letsiwe Portia Magongo is a student at the ROC National Defense University. Dr. Ruei-Lin Yu is a professor at the ROC National Defense University.

Letsiwe Portia Magongo & Ruei-Lin Yu

photo: Joe Harwood

Sailors with the People’s Liberation Army Navy march in a military parade in Djibouti City celebrating the country’s 40th annual Independence Day.

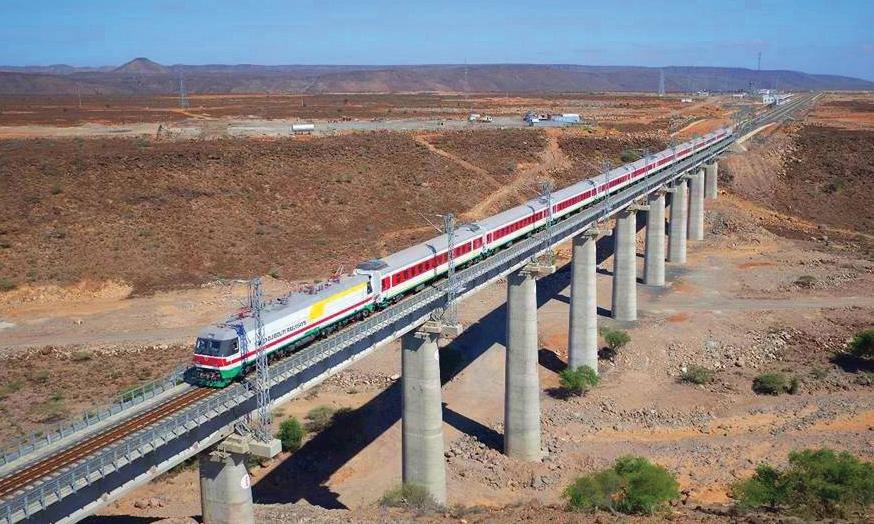

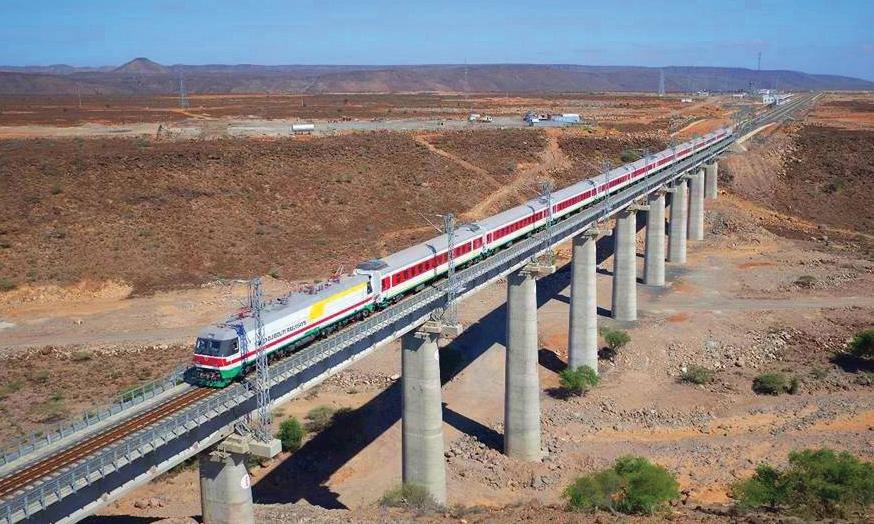

Lamu, the improvement of the Mombasa port, and the construction of the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, a 480 km-long line that connects the port city with the capital, replacing the narrow-gauge Uganda Railway built in 1901 by British colonial authorities. In Djibouti, which is strategically located at the confluence of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, China has completed the construction of a fully electrified cross-border railway line running from Addis Ababa to the Red Sea port of Djibouti, and is funding a US$300 million water pipeline system to transport drinking water from Ethiopia to Djibouti. The modernization of the 752 kilometer-long EthiopiaDjibouti Railway cost US$4 billion, 70 percent of which was financed by China’s Exim Bank.

In 2016, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) established a military base in Djibouti near existing American, Japanese and French military bases. The purpose of the PLA facility is to secure the BRI route and to facilitate multilateral operations. As a result, China’s navy has played a significant role in anti-piracy operations off the Somalia coast and peacekeeping missions in South Sudan.

Furthermore, the military base serves the purpose of quick response in case of emergencies requiring Chinese troops in South Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East. Hence, the port is a mixture of both a commercial and military venture, and a symbol of China’s expanding interests.

Barriers to trade

Africa is home to 54 independent states, most of which are landlocked countries without direct access to ports. As a consequence, transporting commodities between these countries has been a barrier to intra-continental and international trade. Due to inefficient transport routes with inadequate infrastructure, it costs nearly 50 to 75 percent more to transport goods in this region than in other parts of the world. Such a situation hinders regional and international trade, and leads the African continent to further isolation from global value chains. Hence, investment in highway and railway infrastructure and power generation is essential to the alleviation of integration bottlenecks.

BRI in Africa b 5

The Mombasa sea port has a centuries-old history as a harbour city and serves as an important gateway to East Africa.

photo: Erasmus Kamugisha

VISION

It is important to note that China’s Maritime Silk Road is expected to reach Africa through the Mombasa Port in Kenya, and extend inland along the Mombasa-Nairobi railway line. The plan also includes the Djibouti-Addis Railway and the NairobiMombasa Railway. Travel time on the 759 kilometer Djibouti-Addis line has been reduced from three days to 12 hours. The Port of Djibouti plays a key role in Ethiopia’s export and imports to and from Asia, Europe, and Africa. The railway has eased the logistical challenges in the African region by providing wider export market access to manufactured goods in Ethiopia.

Unlocking trade opportunities

Nairobi has been a focal point for the BRI and has benefited from Chinese-funded road and railway infrastructure projects that connect cities in Kenya and extend to other regions in Africa. The completion of the Kenyan railway will help link Kenya with Uganda,

Burundi, Ethiopia, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda. This link will unlock international and intra-continental trade opportunities. In June 2017, the Nairobi-Mombasa railway was opened at an estimated cost of US$3.2 billion. This railway line could replace the estimated 4,000 trucks that use the road on a daily basis.

With regard to the energy sector, China’s banks have been actively funding hydro power projects with an estimated US$5.3 billion in investments. In Ethiopia, the Exim bank of China has invested in construction of hydraulic dams like Tekeze and Gibe III. The World Bank has projected that energy projects funded by China in Africa will have a power-generation capacity of over 6,000 megawatts. This is more than one-third of Africa’s current hydropower generation capacity.

These examples illustrate how the diversification of Africa’s infrastructure has been a major goal of the Chinese BRI. First, improved infrastructure can raise a country’s profile by promoting and attracting more investments from different economic sectors. Second,

6 b

STRATEGIC

The Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway is a critical link between landlocked Ethiopia and the east coast of Africa.

photo: Skilla 1st

with improved infrastructure connectivity, economic capacity may increase, thus increasing domestic productivity and foreign investment. This will further reduce the cost of doing business. Unfortunately, there are a number of pitfalls that stand in the way of such progress.

China’s role as a substitute source of funding came at a time when African countries were scouting for alternative sources of capital for their development. It is therefore important that African countries create a strategy to guide their engagement with China to advance and protect Africa’s own developmental goals. Regardless of the positive impact expected from

the BRI development in African infrastructure, there are unavoidable challenges that cannot be ignored. Beijing leaders proclaim a policy of non-interference in foreign countries, but their actions often fail to live up to this standard, and are—at the very least—less than transparent. Most BRI investments target developing countries where corruption is already prevalent in the form of autocratic regimes and weak governing institutions that easily succumb to corrupt practices.

The high cost of BRI infrastructure projects in African countries in particular is an unfortunate reality interwoven with the problem of corruption. In that light, a number of countries have reconsidered

BRI in Africa b 7

Graphic: US Government

their BRI projects. In 2018, the government of Sierra Leone cancelled a China-funded airport project at a cost of US$318 million, citing debt concerns. The exposure of systematic corruption, paired with a lack of accountability, has generated a great deal of public criticism. This is particularly true in Kenya.

In 2014, Kenyan activist Okiya Omtatah and the Law Society of Kenya launched a lawsuit to halt construction on the aforementioned US$3.2 billion railway link project between Kenya and China. The plaintiffs alleged that the contract was “single sourced” and not put out to tender. The Kenyan High Court had earlier dismissed the case, ruling in favor of the respondents, the China Road Bridge Corporation (CRBC) and the Kenyan state-run railway. The appellate court reversed this decision, however, finding in favor of the plaintiff. The court ruled that the contract between the Kenyan Government and the CRBC failed to comply with Kenyan law in the procurement of the Standard Gauge Railway, which is a critical part of China’s BRI in East Africa.

This court case in Kenya demonstrates the potential

consequences of China’s failure to engage in open and transparent conduct. Kenya’s unmanageable debt, which resulted in part from the aforementioned railway, was well beyond the government’s budget. The situation is marked by implausible expectations, opaque contracts, and a closed bidding process. In order to minimize unnecessary corruption costs, it is important for both China and African states involved in the BRI to increase transparency and scrutinize the terms of their contracts. Furthermore, both sides need to raise their level of commitment to engaging in a competitive bidding process.

In sum, participation in the BRI will not guarantee that Africa will reap benefits. Economic and policy barriers present challenges in Africa, as well as in developing countries in other regions. These challenges are evident from cross-border delays, and from burdensome procedures in customs and foreign direct investment (FDI) restrictions. World Bank data indicates that while it takes approximately ten days for imports in G-7 countries, it takes an average of 21 days to import goods into Africa. Moreover, in

8 b STRATEGIC VISION

Boatmen ply their trade in Zanzibar. Loans from the Chinese government funded a new harbor, expansion of Karume airport, and other projects.

photo: Carlos Casados

terms of foreign-firm start-ups, industrial land access, commercial dispute arbitration, and FDI policies, BRI economies are more cumbersome and have more restrictions than Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies. For example, in Kenya and other developing countries in Africa, establishing a business requires complicated procedures for documentation, extensive transaction periods, overlapping title deeds, and other onerous procedures.

In view of the challenges discussed above, it would be beneficial for African states to implement policy reforms to counter the low, or negative, BRI infrastructure investment returns. The World Bank concludes that the BRI could increase trade among participating countries by 4.1 percent. These impacts could be tripled on average if reforms in trade matched advancements in the transportation infra-

structure. Therefore, it is critical for African states to implement economic and trade policy reforms that support their development path and BRI infrastructure development. Moreover, it is important to carefully analyze the project’s returns in order to set realistic economic goals, thereby avoiding the risks of overestimating benefits from projects. Overestimating the economic benefits to be derived from BRI infrastructure projects may result in inadequate use or exploitation of infrastructure.

This examples discussed above illustrate the need to take a long-term perspective on BRI investment in Africa in terms of the amount of capital invested, and the extent to which BRI projects can stimulate the local economy. These risks and challenges need to be addressed by both Chinese and African stakeholders to ensure that BRI investment in Africa is productive for Africans as well as for China. n

BRI in Africa b 9

Children in Malawi pose for a photograph. Malawi remains one of the few nations in Africa that has yet to sign an MoU with China on the BRI.

photo: Dean Karalekas

Hindsight 2020

Over the past year, Beijing leaders have turned up the heat in Taiwan Strait

Shao-cheng Sun

Cross strait relations have become extremely tense in 2020. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) blamed Taiwan for having a one-sided policy and becoming too close to the administration of US President Donald Trump, with Beijing lashing out over the prospect of high-ranking US officials being allowed to visit Taiwan and meet with Republic of China (ROC) leaders. The Trump administration also approved several advanced weapons sales to Taiwan. China responded to these highprofile visits and arms sales by threatening military

action. According to the PRC Foreign Ministry, these activities have encouraged Taiwan independence, and China will make the necessary response.

Taiwan is being threatened with invasion by voices within the Chinese state-run media, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) announced it would defeat Taiwan independence at all cost. Since 2020, the PLA has been flexing its military muscle more frequently by flying aircraft and sending warships close to Taiwan proper. In September, PLA aircraft repeatedly breached the median line in the Taiwan Strait.

10 b Strategic Vision vol. 10, no. 48 (February, 2021)

Dr. Shao-cheng Sun is an assistant professor at The Citadel specializing in China’s security, East Asian affairs, and cross-strait relations. He can be reached for comment at ssun@citadel.edu

A photograph of the Taiwan Strait taken during the Gemini X mission in 1966 shows Taiwan’s proximity to China.

photo: NASA

Even though China has done this in the past whenever cross-strait relations take a turn for the worse, the frequency of these incursions has been much greater in 2020. In response to China’s mounting military threat, the ROC government has taken steps to try and de-escalate the rising tensions. Foreign Minister Joseph Wu stated that Taiwan did not seek to establish a diplomatic relationship with the United States, while ROC President Tsai Ing-wen expressed a willingness to hold bilateral talks with Beijing. PRC leaders ignored Taiwan’s goodwill gestures, however, with Chinese official media releasing a video of an amphibious military attack on an island very much like Taiwan. According to China’s Taiwan Affairs Office, the reason for the rise in tensions is that ROC leaders refuse to accept the “one-China” principle, and they continue in their collusion with the United States. While China’s perception of current rising tensions across the Taiwan Strait seem to deviate from reality, it is important to understand their perspective on the issue, and why they continue to escalate the military threat.

The 1992 Consensus

The Chinese government asserts that the mounting cross-strait tensions can be attributed to increased US-Taiwan “collusion,” but mostly to President Tsai’s refusal to accept the 1992 Consensus—a term that refers to an agreement by negotiators at a 1992 meeting who found a way to sidestep Beijing’s longstanding precondition that, before talks could begin, both sides must verbally declare that there is only one China. These negotiators decided to agree to disagree, in that each had—in his mind and in his heart while making the affirmation—a different interpretation of what that “China” is: for the Taiwan delegates, this was the Republic of China, whereas the Chinese delegates had in their minds the People’s Republic. Additionally, Chinese leaders have observed that the

ROC government is moving toward de-Sinicization by removing Chinese history from Taiwanese textbooks and portraying the Chinese government as an enemy. They think that if the trend does not cease, the Tsai administration will eventually move toward de jure independence.

The Chinese government and media have repeatedly accused the Tsai administration of promoting de-Sinicization, claiming that Taiwan has moved toward the path of separatism by severing its connection with China, moving toward independence,

and allying itself with the United States. The Chinese 2019 Defense White Paper claimed that Taiwan separatist forces and their actions remain the gravest threat to peace in the Taiwan Strait and the biggest barrier to a peaceful unification. Indeed, the percentage of ROC citizens who identify as Taiwanese rose to historic heights, according to a 2020 survey conducted by the Taiwan Think Tank, with only 2.0 percent of respondents saying they self-identified as Chinese, compared to 62.6 percent self-identifying as Taiwanese. The trend of a rising Taiwanese identity, and a continued drift away from a Chinese identity, has frustrated PRC authorities who would prefer not to have to use force to annex the island.

The Chinese government has increased its diplomatic pressure on Taiwan, frustrating Taiwan’s efforts to participate in intergovernmental organizations such as the World Health Organization, the International Civil Aviation Organization, and the International Criminal Police Organization. Taipei has earnestly sought international recognition, but there are only 15 countries that still recognize the ROC as a sovereign state, and most intergovernmen-

Cross-Strait Tensions b 11

“Taiwan’smedicaldiplomacyandits exemplaryhandlingoftheCOVID-19 pandemic has garnered positive coverageintheinternationalpress.”

tal organizations bar Taiwan’s participation at China’s behest. During the Coronavirus pandemic, Taiwan donated millions of masks and medical supplies to its diplomatic allies and friendly countries around the world, including the United States and several European countries. Taiwan’s medical diplomacy and its exemplary handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has garnered positive coverage in the international press, whereas China’s image has suffered due to PRC intervention in Hong Kong, its culpability for the spread of Coronavirus worldwide, and its aggressive territorial expansion in the South China Sea, among other behaviors. Taiwan’s active pursuit of international recognition has been interpreted by the Chinese government as an attempt to disrupt the status quo of cross-strait relations.

Support for Taiwan

The Trump administration has publicly ratcheted up support for Taiwan. First, it did this by sending high-ranking cabinet members on visits to the island. In August and October 2020, Trump dispatched Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar

and Under Secretary of State Keith Krach to Taipei, the highest-level American officials to visit Taiwan since Washington severed diplomatic ties with Taipei in 1979. The arrival of US officials enraged Chinese leaders, who view the move as a violation of China’s internal affairs. Second, the US Congress has shown strong bipartisan support to Taiwan. In March 2020, President Trump signed the bipartisan TAIPEI Act, subsequently passed by the US Congress, which commits the US government to help Taiwan improve its international standing. Third, some government officials have proposed that the United States should adopt a position of strategic clarity on Taiwan and send a clear message to Beijing that it would defend the island should the PLA attempt an invasion. Fourth, US arms sales to Taiwan have increased. Between May and October 2020, Washington approved almost US$5 billion in arms sales to Taipei, including submarine-launched wire-guided torpedoes, high-mobility artillery rocket launchers, and Harpoon Coastal Defense Systems, among others.

The PRC government has perceived Taiwan’s deSinicization, Taipei’s international recognition seeking, and the aforementioned US support as a threat

12 b STRATEGIC VISION

ROC President Tsai Ing-wen poses for a group photograph with ROC air defense troops. Taiwan’s air defense units are on the front lines of Taiwan’s defense.

photo: ROC Presidential Office

to the very survival of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime. Thus, Beijing has employed a host of methods in response, including coercive rhetoric, aggressive diplomacy, and even more worrying, belligerent military posturing against the Tsai administration.

Promulgated in 2005, China’s Anti-Secession Law is ambiguous about what actions it would consider a casus belli. The law gives Beijing legal cover for the use of military force to respond to any attempted Taiwanese secession from China, as well as if Chinese leaders perceive “major incidents entailing secession,” or if all possibilities for peaceful unification are exhausted. In a desire to bolster his legacy, PRC President Xi Jinping may take aggressive actions in response to the rise of Taiwan’s independence movement coupled with soured US-China relations. According to the legislation, the tripwires for China’s use of force include a declaration of Taiwan independence or indefinite delay of cross-strait dialogue on unification. With this law in place, China’s current saber rattling poses a grave threat to Taiwan’s security.

In 2020, Chinese leaders used strong rhetoric

against Taiwan, with Xi claiming that China reserves the right to use all necessary measures against the island. On May 22, 2020, PRC Premier Li Keqiang delivered a speech at the National People’s Congress in which he reiterated his country’s desire to unify with Taiwan, though he left out the word “peaceful.” On September 21, after PLA warplanes made sorties over the Taiwan Strait, PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesman Wang Wenbin denied the very existence of a median line in the Taiwan Strait, opining that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of Chinese territory; there is no socalled median line of the strait.” The PLA ramped up this rhetoric, with Defense Ministry spokesman Ren Guoqiang telling reporters, on the Taiwan issue, that “those who play with fire are bound to get burned.” Moreover, throughout 2020, the Chinese mouthpiece media was constantly threatening Taiwan with invasion.

Since early September 2020, China has been conducting a show of force in the Taiwan Strait, with PLA warplanes flying increased patrols around Taiwan to prepare for the future military invasion and test Taiwan’s response time. PLA warplanes and naval

Cross-Strait Tensions b 13

The US Navy Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS John Finn conducts underway replenishment in the Indo-Pacific area of operations.

photo: Chris Cavagnaro

ships have roamed the strait almost daily, many breaching the median line, bilateral acknowledgment of which has helped keep the peace through several previous generations of Chinese leaders.

Nor is Taiwan the only intended victim of these thinly veiled military threats. In September, the PLA released a video of Chinese H-6 bombers making a

simulated strike on a runway that bore an uncanny resemblance to Anderson Air Force Base on Guam. On October 10, to mark the ROC’s National Day, the PLA staged a large-scale island-invasion military exercise, and broadcast the drill. It was the first time this decade that the Chinese media ran full coverage of the entire exercise of a staged military landing on Taiwan, stoking nationalistic sentiment. Thanks to Beijing ramping up military pressure against Taiwan this way, tensions have risen to levels not seen in decades.

The PLA could conduct a campaign designed to force Taiwan into unification. According to the US

Department of Defense’s 2020 Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, the PLA could initiate the following options, individually or in combination: an air and maritime blockade, a limited force or coercive options, an air and missile campaign, or a military invasion of Taiwan. China’s State broadcaster CCTV warned that “the first battle would be the last battle.” It is very likely that if China attacks Taiwan, it would be an invasion. The Taipei Bureau Chief of Bloomberg News, Samson Ellis, also believes that a PLA attack against Taiwan prior to a military invasion would utilize cyber and electronic forces to target Taiwan’s key infrastructure. Airstrikes would target Taiwan’s top leaders in a decapitation attack, and an invasion would follow, with PLA warships and submarines traversing the Taiwan Strait.

In the face of the mounting threat from China, the ROC military said its armed forces have the right to self-defense and counterattack amid “harassment and threats,” though it vowed to follow a guideline of no escalation of conflict, and no triggering incidents. Taiwan has also taken steps to prepare for future military conflict. Taiwan will enhance its asymmetric capabilities which include offensive

14 b STRATEGIC VISION

An F-16DJ approaches a barrier cable at Yokota Air Base, Japan, with Mount Fuji visible in the background.

photo: Jan David De Luna Mercado

“Thedownsideofstrategicambiguityis that Washington is not able to send a clear,consistentmessageofdeterrence toleadersinBeijing.”

and defensive information and electronic warfare, shore-based mobile missiles, fast mine-laying, minesweeping, and drones.

In the past 40 years, the United States government has adhered to a policy of strategic ambiguity to govern its approach to cross-strait relations. However, the downside of strategic ambiguity is that Washington is not able to send a clear, consistent message of deterrence to leaders in Beijing. Most Chinese people think that if a military conflict were to occur across the Taiwan Strait, the chances that the United States would deploy military forces to defend Taiwan are slim. This perception has encouraged the Chinese government to become more aggressive. Thus, some scholars and US government officials have recently floated the idea of strategic clarity; that Washington should send a clear message of US military support to defend Taiwan against any Chinese military action. In general, the United States opposes unilateral actions aimed at altering the cross-strait status quo. If China attacks Taiwan, the US reaction would likely be to

mobilize the international community and put sanctions on China. In the face of China’s mounting military threat against Taiwan, the US security policy has come to a critical juncture. Some American security strategists have suggested that Washington abandon its policy of strategic ambiguity. Trump’s former national security adviser, John Bolton, asked the administration to come to Taiwan’s defense. Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, argued that the United States should unequivocally state it would intervene to deter China and reassure US allies. Writing in Foreign Affairs, Haass declared that the time had come “for the United States to introduce a policy of strategic clarity: one that makes explicit that the United States would respond to any Chinese use of force against Taiwan.” To prevent China from launching a military invasion, the ROC government should encourage the United States to adopt such a policy of strategic clarity: this would go a long way toward making China think twice before launching any military attacks against Taiwan. n

Cross-Strait Tensions b 15

A US Navy ensign prepares a surface contact report while navigating the USS Barry during underway operations in the Taiwan Strait.

photo: Samuel Hardgrove

Strategic Vision vol. 10, no. 48 (February, 2021)

Locking Horns

Chinese, Indian troops clash as border tensions flare up in Eastern Ladakh

Amrita Jash

Border tensions between India and China that have troubled the region since May 2020 took a violent turn when troops of the Indian Army and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) clashed in the Galwan Valley on June 15 in Eastern Ladakh, resulting in the most serious military casualties seen in 45 years. Up to this point, border frictions had been characterized by a lack of weapons fire, but the recent spate of casualties threw a spanner into the works. While the Galwan clash occurred in

Indian territory, Beijing put the blame on New Delhi: The PLA’s move was “a response to India’s actions;” specifically, what the Chinese leadership consider “illegal construction of defense facilities across the border into Chinese territory in the Galwan Valley region,” according to Beijing’s state-run media outlet, the Global Times.

This has resulted in troop buildups and high alert on both sides of the contested border given the ongoing face-off at two points: the Galwan River (which

16 b

Dr. Amrita Jash is a research fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) in New Delhi, India. She holds a PhD in Chinese Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University.

The Shyok River (The River of Death) flows through northern Ladakh in India and the Ghangche District of Gilgit–Baltistan of Pakistan.

photo: Eatcha

last witnessed tensions in 1962) and Pangong Lake in Eastern Ladakh. In addition, the eight rounds of talks between the two militaries have fallen into a deadlock, signaling a potential breaking point in the fragile peace.

The US factor

Adding to the intensity at the border is the US factor. Taking a stand against China, US Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Alice Wells issued a strong statement suggesting that Chinese aggression is not “rhetorical,” given that India on “a very regular basis has to experience the pinpricks of the Chinese military.” Furthermore, on the Galwan clash, the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in its 2020 Annual Report to Congress stated that, “some evidence suggested the Chinese government had planned the incident, potentially including the pos-

sibility for fatalities.”

India-China tensions will also feel the heat of stronger Indo-US ties. Under such dynamics, the big question remains: How sustainable is peace given the changing circumstances, and how long can any form of confrontation be avoided?

The critical importance of the unresolved border issue can be argued in a three-fold perspective. First, 22 rounds of Special Representative (SR) Talks (last held in December 2019) have failed to reach any resolution. The SR mechanism—one of the key confidence-building measures between India and China—was established in 2003 to resolve the boundary issue. Second, increasing incidents of friction in areas along the de facto Line of Actual Control (LAC), which is disputed in three sectors: the eastern sector in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh; the central sector in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand; and the western sector in Aksai Chin. Third, the increasing military build-up is having a spiraling security-di-

India-China

b 17

Border Clash

US and Indian soldiers take part in the closing ceremonies for exercise Yudh Abhyas 14.

photo: Arctic Wolves

lemma effect, prompting the action-reaction behavior witnessed between India and China.

In this context, the impetus to the ongoing stand-off in Eastern Ladakh was provided by the twin incidents of border clashes along the LAC. On May 5, around 250 Indian and Chinese troops clashed at Finger 5; one of the spurs that descend to Pangong Lake along its northern bank. This was followed by an incident near Naku La Pass in the Sikkim sector. On May 17, Indian intelligence agencies reported incursions into India’s air space by PLA helicopters in the LAC in North Sikkim. Adopting a guarded reaction, China responded by saying its “troops there are committed to uphold peace and stability.” Indian Army Chief General Manoj Mukund Naravane announced that Indian troops were maintaining their posture along the border with China, and that infrastructure development in the areas was also on track. What caused the setback was the Galwan Valley incident in June.

In seeking to understand Beijing’s behavior along the LAC, four key aspects must be highlighted: First, China intends to change the status quo at the bor-

der: compromise is not in China’s interests. Second, the Chinese transgression exemplifies a pattern that is continuous, cyclical, and violent in nature. Third, unlike past stand-offs, Eastern Ladakh brings forth a marked change in terms of simultaneous engagements at multiple points, as well as an increase in force posturing. Fourth, areas such as Sikkim and Himachal Pradesh, which remain comparatively less disputed, are also targets for China flexing its military muscle. Thus, the net effect is an erosion of the salience of the existing confidence-building measures and protocols between India and China.

Chinese adventurism

The question remains: what is the reason for Chinese adventurism in Eastern Ladakh in times of the COVID-19 crisis? For India, two reasons stand out for the Chinese trigger in Eastern Ladakh: First, China’s sensitivity to India’s abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in August 2019, which opened the door to the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization

18 b STRATEGIC VISION

A P-8A Poseidon, a militarized version of the Boeing 737 commercial aircraft, taxis down the flight line at Misawa Air Base, Japan.

photo: Jan David De Luna Mercado

Act. As a result, the former state of Jammu and Kashmir was reorganized as the new Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the new Union Territory of Ladakh. Beijing is opposed to this development, as it perceives it to have undermined China’s territorial sovereignty—Beijing considers Ladakh to be a Chinese territory in the western section of the ChinaIndia boundary. Thus, Eastern Ladakh can be seen as China’s reciprocal response to India’s action. Second, China is sensitive to India’s infrastructure development along the LAC. In this case, the trigger was the 255 kilometer-long Darbuk-Shyok- Daulat Beg Oldi road (completed in 2019 after 18 years of construction), which is a key strategic highway to the north of the Karakoram Pass. China also harbors resentment over India’s long-standing opposition to joining the Belt and Road Initiative: a position that is hindering China’s ability to press its interests in South Asia, particularly the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

What remains apparent is that, in the aftermath of the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the border dispute has not just become protracted, but is constantly witnessing new signs of unrest. Incidents of transgressions have also become rampant. This intensification runs counter to the “Wuhan Spirit” that called for a strengthening of military communication and building trust and mutual understanding, with the aim of enhancing predictability and effectiveness in the management of border affairs. Thus, the India-China border dispute is not just protracted but has become volatile, making it a potential hotspot in Asia.

Boosting India-US ties

The ongoing India-China crisis along the LAC in Eastern Ladakh has provided a boost to India-US ties. This is evident from the inking of the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA)

India-China Border Clash b 19

An Indian army paratrooper exits a CH-47 Chinook helicopter during a partnered airborne training exercise with US Army paratroopers at Fort Bragg.

photo: Michael J. MacLeod

on October 27, during the Third India-US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue. Arguably, it was the tensions with China that provided an impetus to the signing of BECA, completing the mandate of the four foundational agreements to enhance interoperability between the two militaries as well as promoting exchange of high-end military technology. The other three agreements include: the 2002 General Security of Military Information Agreement; the 2018 Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement; and the 2018 Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement. Two key aspects make BECA especially significant: first, the exchange of maps, nautical and aeronautical charts, and other unclassified geospatial information with the United States helps India to effectively track the Chinese footprint along the LAC and in the Indian Ocean. Second, the sharing of sensitive US satellite and sensor data will provide a significant boost to India’s military capabilities, especially, in striking targets with pinpoint accuracy. Thus, it remains clear that every step forward

in India-US ties will only be a challenge for China in its quest for great power status.

Change in mindset

With no breakthroughs despite eight rounds of commander-level talks, it is clear that India’s China policy needs a serious rethinking and a change in mindset. The old ways of assessing China need to be dismissed and replaced with a new paradigm, based on the following benchmarks: First, following the adage that there are no permanent friends or permanent enemies, but only permanent interests, India should always act from a position of strength when dealing with China. Second, there should be no doubt about Chinese intentions to change the status quo along the border in favor of Beijing. Third, the recurrent ingress is a sign of Beijing’s reluctance to resolve the boundary disputes with New Delhi, be it now or in the future. Fourth, China’s acts of transgression are no longer local or normal, but have become premedi-

20 b STRATEGIC VISION

An Indian soldier with 12 Madras looks down the sight of his rifle in a cordon and search training demonstration at Chaubattia Military Station, India.

photo: Samuel Northrup

tated and top-down in their approach, and used as a means to test India’s resolve. Fifth, China’s actions are guided by the salami slicing strategy, which is an incremental approach towards securing its claims. This was the strategy used so effectively by Beijing to take control over the South China Sea, and it is now being applied against India along the disputed border. Finally, deception is the most important tool of Chinese warfare, thus one must expect there to be a sharp difference between what is said and what is done by Beijing. Galwan was another example demonstrating Beijing’s strategy of keeping the LAC active, despite its calls for resolution through an early harvest. Thus, rather than being worried, India should be prepared.

Recent episodes further signify that the COVID-19 pandemic has failed to tone down behavior on the border. This also dampens the celebratory spirit for this year’s anniversary of 70 years of India-China ties, with 2020 having been designated “India-China

Cultural and People to People Exchanges” year. With the high stakes involved and no resolution in sight, the border dispute between the two countries remains far from settled. Furthermore, the pandemic has not made much of a difference in averting the risks of contingencies. Rather, if relations take a further downturn under the virus outbreak, like that between China and the United States, the border flare-ups will only become a routine display of power between New Delhi and Beijing. It is the lack of consensus between the two powers along the LAC that has increasingly contributed to the distrust of the other’s intentions. Hence, a timely check of perceptions can aid in avoiding misadventures which can arise when two actors assume the worst of each other. It is in the best interests of both New Delhi and Beijing to refrain from adding new issues to the old disputes, which only makes the case more complicated and further delays any potential boundary settlement, protracting the disputes. n

India-China Border Clash b 21

INS Rana of the Indian Navy’s Western Fleet leads a passing exercise formation behind the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan.

photo: Gary Prill

Tripwire Tricks

Examining covert deployment of tripwire force in Taiwan for de-escalation Kitsch

China’s unilateral escalation of tensions across the Taiwan Strait has intensified over the second half of 2020, with increased crossing of the midline by warplanes and incursions of the Republic of China (ROC) ADIZ on an almost daily basis. The United States has employed largely political measures in response, including high-level visits by US officials, an increase in arms sales, and public announcement of political and military dialogue, to signal its support for Taipei. Though important and welcomed by the government and people of Taiwan, such oblique measures would do little to deter an armed invasion by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and analysts have suggested various

measures to provide a more stable deterrence mechanism, one of which is the idea of placing a tripwire force on Taiwan.

An overt tripwire deployment represents a discrete, non-continuous level of escalation that might spur further escalation by Beijing, and increases the cost for all sides should any side choose to back down. Therefore a salami-slicing approach to covert US force deployment to Taiwan, buttressed by credible communication channels to China, such as Confidence Building Measures (CBMs), would constitute a superior option for eventual de-escalation.

A successful tripwire’s primary mechanism of deterring an invasion operates on the logic of deter-

22 b Strategic Vision vol. 10, no. 48 (February, 2021)

Kitsch Liao is an independent defense analyst who is currently based in Taipei, Taiwan. He can be reached for comment at kitschquixote@gmail.com

Liao

A US soldier in Baghdad, Iraq reconnects a simulated tripwire as part of a counter-improvised explosive device course in preparation for missions.

photo: Samantha Simmons

rence by denial; by directly making a PLA invasion of Taiwan unlikely to succeed instead of threatening punishment, such as retaliatory attacks against civilian infrastructure in Shanghai. The measure’s credibility relies on two components: the nationality threshold/audience cost and an established capacity to escalate (C2E). The nationality threshold refers to the effects of a country’s own uniformed military personnel dying at the hands of another country’s uniformed military, and the associated public outcry, that would force the government’s hand in honoring the commitment represented by the tripwire force. In the words of Thomas Schelling, the mission of a tripwire force is to “die heroically, dramatically, and in a manner that guarantees the action cannot stop there.” This is also referred to as a “tying-hands” signaling mechanism.

Simply having resolve is insufficient without concomitant capacity, however, and C2E is defined as the capability of the defender—in this case the United States—to project a second echelon force into the theater to continue the fight, since the tripwire force

was never expected to stop the enemy advance alone. This calls into question America’s capacity to project significant amount of force to Taiwan and its vicinity without prior preparation.

A multitude of issues

The employment of a tripwire force presents a multitude of issues that may instead exacerbate current tensions. Prime among these is that such a deployment could be misinterpreted as tacitly acknowledging Taiwan’s sovereignty. It could also be seen as a violation of the primary condition underlining the original Sino-US rapprochement, which included the withdrawal of US forces from Taiwan. A reintroduction of US forces permanently stationed on the island may very well unravel a process that took decades to achieve, and making de-escalation all but impossible.

Second, by making the possibility of American intervention more explicit, this strategy would sacrifice Washington’s flexibility of response. Third, it is hard to withdraw openly deployed forces without incur-

Covert Tripwire Force b 23

A Lockheed F-104A with the 83rd Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Taoyuan Air Base, Taiwan, on September 15, 1958, during the Quemoy Crisis.

photo: USAF

VISION

ring an audience cost, consequently endangering deterrence against Taiwan independence: Should there be a significant move toward de jure independence that requires the pulling of tripwire forces, the cost in reputation and domestic audience would both be great. Fourth, the Chinese may nonetheless doubt US resolve, both for enduring the shock of suffering severe losses within a short time frame, and for an extended confrontation.

A final issue with the tripwire strategy is its very nature: to effect a conventional escalation of hostilities should it fail to serve as a deterrent. The Chinese could choose to respond to a tripwire deployment in a like escalatory manner, such as by moving against one of Taiwan’s outlying islands, for example; a move that a small tripwire force on Taiwan proper would be powerless to deter.

Facing the dilemma posed by deteriorating credibility and the many negative implications of an overt tripwire force, recent studies on covert action could shed some light on an alternative strategy that seeks

to extract much of the benefit of a tripwire force, but which may alleviate many of the aforementioned negative consequences.

By its very nature, covert action reduces the external audience cost, the reputational cost, and the domestic stakes involved, thereby alleviating much of the cost for de-escalation on both sides. Additionally, covert action creates the illusion of a limited war that is helpful in avoiding further open escalation, specifically through the mechanism of plausible deniability. Much of the military relationship between the ROC and the United States is, if not covert, certainly under the radar.

Red line

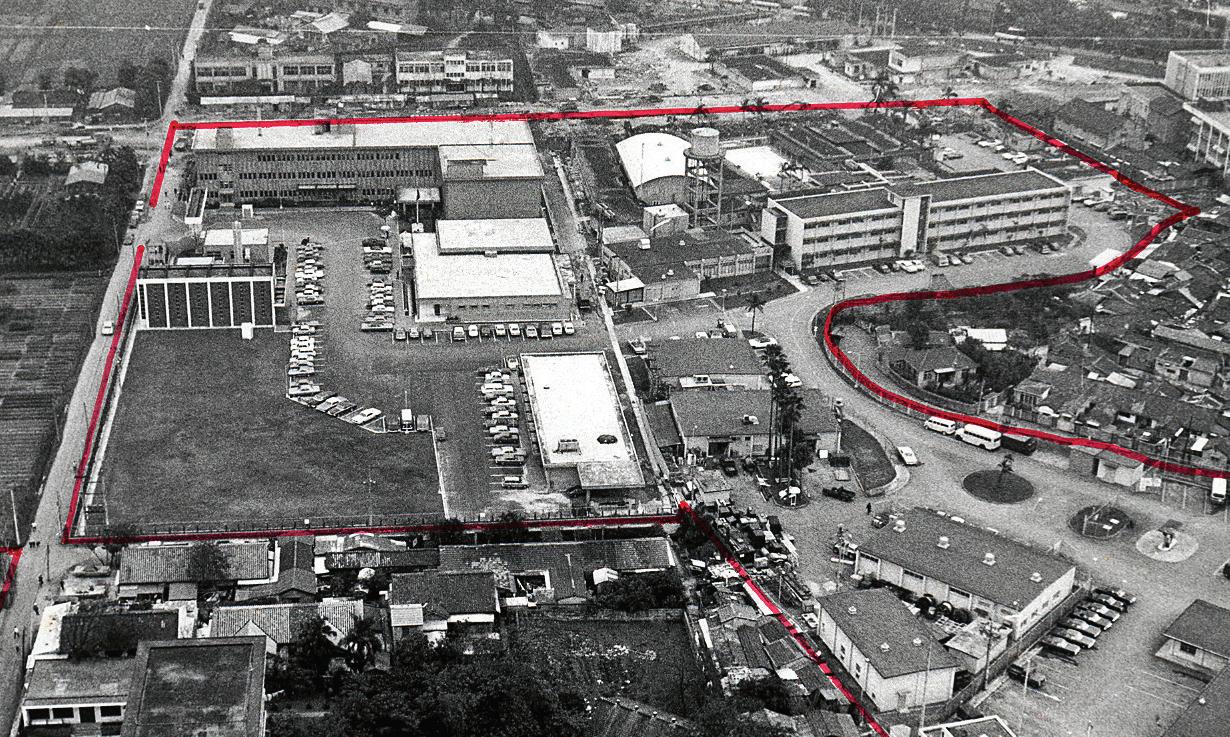

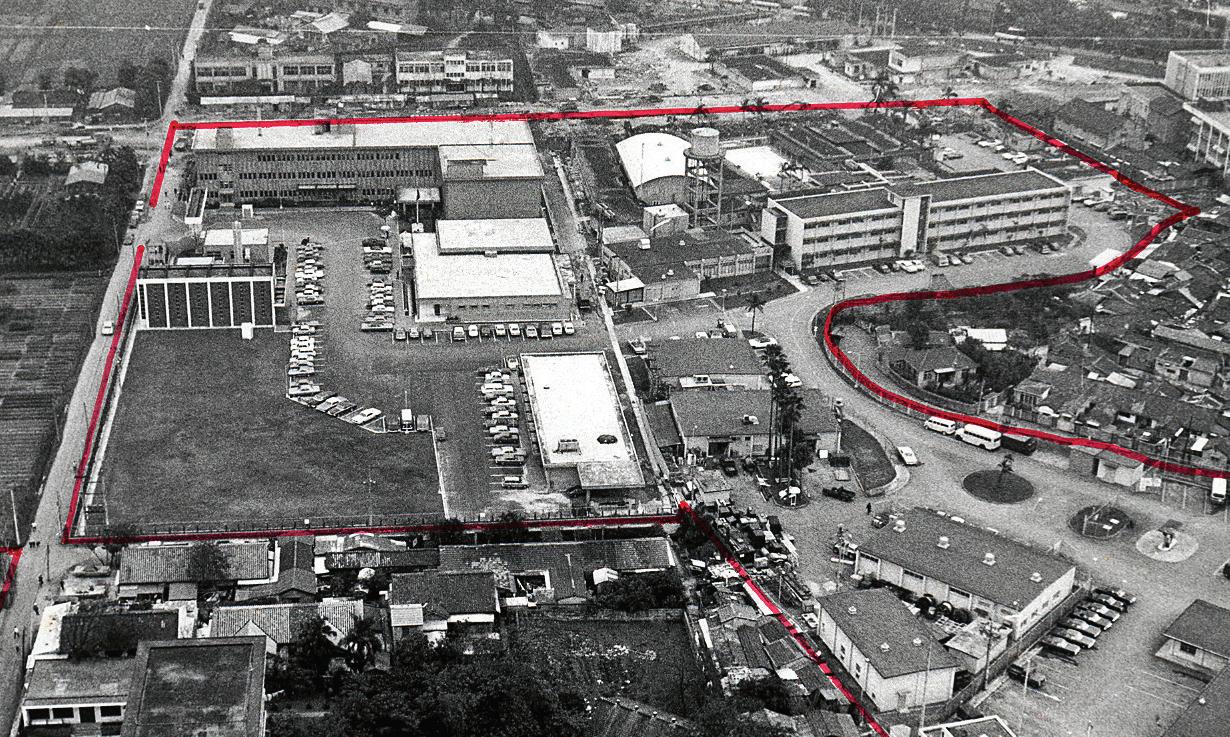

Basing US military personnel on Taiwan openly is equivalent to a red line that would force China’s hand into an invasion. Yet, since 1979, the US military presence in Taiwan has ranged from nonuniformed advisors as part of arm sales programs,

24 b STRATEGIC

Taipei Air Station in 1975. Taipei Air Station was located off Roosevelt Road, close to National Taiwan University, in Gongguan, southern Taipei, Taiwan.

photo: ROC Presidential Office

to uniformed servicemen on low-key training exercises. ROC forces also train in the continental United States, with the most visible example being an entire squadron of Taiwanese F-16s and pilots participating in US exercises and training in advanced beyond-visual-range tactics and air refueling techniques. This and other ongoing exchanges are an open secret, never officially acknowledged by Washington, thereby avoiding charges that the United States is supporting Taiwan sovereignty, and so therefore failing to solicit the usual blustery public condemnations from Beijing.

It seems likely, therefore, that in lieu of an overt deployment of a tripwire force, the adoption of a salami-slicing strategy on a US military deployment in the country could have a higher chance of success. Covert deployment of rotational forces could first be increased, with occasional, controlled leaks of information acting as probing and signaling mechanisms. Depending on the need for stronger deterrence toward China, or communication against de jure independence in Taiwan, the force deployment and level of cooperation can be adjusted without incurring an unwanted audience cost in Taiwan, China, or the United States.

Furthermore, depending on the circumstances and results of such covert action, further escalation into the pre-positioning of material, or logistics hubs enabling power projection, could be attempted. Such actions need not be military in nature: joint response teams for regional HA/DR operations of the type

proposed by retired USMC Lt. Col Grant Newsham can be attempted alongside US allies in the region. Such dual-use hardware and personnel could represent a form of further escalation that would remain below the level of overt military deployment, and may have the additional benefit of reassuring US allies in the region of US resolve in maintaining regional order.

These courses of action would provide a way to fine-tune signaling mechanisms and buttress US resolve, as well as having the potential to reinforce the US capability to escalate in a Taiwan-invasion scenario. Since the nature of the initial presence would be covert, or at least discrete, the audience cost can be avoided. In countering Beijing’s current intensification of cross-strait tensions, intentional leaks and subsequent action leading to just short of a full reveal can be manipulated to fine-

tune escalation, while eventual reveal can achieve the desired deterrence effect of a tripwire through the tying-hands and nationality-threshold mechanisms. Before the outbreak of a crisis and full revelation, plausible deniability of covert deployments and the non-military nature of overt activities would afford Washington continued flexibility to shift its deter-

Covert Tripwire Force b 25

“The deployment of a covert tripwire forcewouldcommunicateastrongsignal regarding US resolve in protecting Taiwanwithoutviolatingpre-established tacitunderstandingswithChina.”

Badge of the United States Taiwan Defense Command (1955-1979)

rence posture—flexibility that would otherwise be lacking with the public deployment of an overt tripwire force.

The salami-slicing approach however—marked by small steps, each too minor to constitute a casus belli—only constitutes half of the equation. Assurances must also be conveyed to the Beijing regime for there to be any hope of eventual de-escalation. To this end, re-establishment of hot-line and various confidence building measures is of paramount importance. Unfortunately, the Chinese tend to use the establishment and discontinuation of CBMs as a signaling mechanism, calling into question their utility in a crisis. This does not diminish the importance of establishing such a channel, but it does reinforce the urgency of reaching a consensus on its use and importance with China.

The exact sequence of the establishment of CBMs and covert deployments is beyond the scope of this article. However, once acknowledged in covert negotiations, the “facts on the ground” of deployed US forces would function as a bargaining chip in

negotiations to facilitate de-escalation, while a further escalation into full revelation would allow the force to function as a tripwire during a crisis. This would naturally rely heavily on an accurate reading of Chinese signaling and communication mechanisms. Consequently both the studies on Chinese signaling, as well as the establishment of reliable hot lines, are urgently required.

Urgent and severe challenge

China’s unilateral escalation of tensions across the Taiwan Strait, particularly in the past six months, presents an urgent and severe challenge to the continued efficacy of Washington’s strategy of dual deterrence through strategic ambiguity. Should the Chinese be successful in establishing this escalation as the new norm—essentially the method that won Beijing control over the South China Sea—China could then leverage the situation and inflict everincreasing coercive actions against Taiwan, damaging both US credibility and Taiwan security. The deploy-

26 b STRATEGIC VISION

ZTZ96 battle tanks are disgorged onto the enemy’s shore by a Zubr (Bison) class hovercraft purchased from Russia in a PLA amphibious landing exercise.

photo: PRC Gov

ment of a covert tripwire force would communicate a strong signal regarding US resolve in protecting Taiwan without violating pre-established tacit understandings with China since 1972. Depending on the method employed, this could also have the secondary effect of reinforcing America’s capability to escalate and therefore increase the credibility of its security commitment.

A salami-slicing approach to the deployment of a tripwire force, which grants finer control over escalation and de-escalation through a lower audience cost, with the option to escalate into non-military deployment or full revelation during a crisis, represents a potential strategy for credible yet reversible escalation while sidestepping the political fallout that would be associated with a sudden and overt force deployment. However, to get to de-escalation and restore the status quo ante, establishment of a clear channel of communication incorporating reliable CBMs need to be simultaneously pursued.

The ultimate goal of a successful deterrence strategy across the Taiwan Strait would be to prevent a military confrontation, and particularly one involving the United States, as well as preserving Taiwan’s freedom of self-determination. Accordingly, any use of force and escalation into a crisis would constitute a failure of general deterrence, necessitating a dangerous escalation into immediate deterrence. In the context of the proposed salami-slicing strategy, this would involve the public revelation of a uniformed US tripwire force stationed in Taiwan. Such an immediate deterrence usually puts both sides’ actions in the spotlight, and increases the audience cost of de-escalation and backing down. Consequently, the deployment of covert forces to Taiwan, and the communication to China through credible channels, must be accomplished in such a way that it avoids triggering the crisis it seeks to prevent. Covert deployment, as proposed herein, represents a possibility that is worthy of further discussion. n

Covert Tripwire Force b 27

The US Army deployed a tripwire force to Berlin in the Cold War to deter the Soviet Union, whose tanks are pictured here during the Berlin Crisis of 1961.

photo: USAMHI;

Strategic Vision vol. 10, no. 48 (February, 2021)

Keeping Pace

ROC defensive posture must continue to evolve as US-China rivalry grows Ying-yu Lin

Ongoing US-China tensions have covered areas of contention ranging from trade, foreign relations, technology protection, to military muscle-flexing. Although the militaries of the two sides show enough restraint to refrain from taking each other on, both sides have expanded their freedom of action in airspace and underwater management and other areas through military exercises and other provocative actions. In Taiwan, there is a widespread understanding of defense matters and a lack of a militant mindset among the population, and hence a strong consensus that Taiwan must not be the party that initiates a war. Nevertheless, Taiwan

has to guard against possible use of force by China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), since the PLA might opt to do so under domestic pressure. Despite the fact that China now mainly employs “gray zone” strategies in its approach to the Taiwan issue, Taiwan still cannot rule out the possibility of China’s use of force against the island. The PLA as we know it now is not what it was before the most recent military reform that kicked off in 2016. The PLA has been holding frequent military exercises in recent years to achieve intimidation in politics and foreign relations and also to support military reforms. These developments have become a serious threat to Taiwan.

28 b

Dr. Ying-yu Lin is an adjunct assistant professor at the Institute of Strategic and International Affairs at National Chung Cheng University in Chiayi, Taiwan. He can be reached at singfredrb@gmail.com

Ordinary Seaman Gordon Garner stands watch during sunset aboard HMCS Regina (FFH 334) during Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2020.

photo: Dan Bard

Judging by the PLA’s most recent exercises, it is evident that invading Taiwan will no longer be the job of any single theater command. It will be executed in the form of a joint attack from the “four seas,” namely the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, Taiwan Strait, and South China Sea. The Northern and Southern Theater Commands are most likely to be responsible for blocking access to the Taiwan Strait to carry out a strategy of blocking enemy reinforcements and encircling enemy positions. The Eastern Theater Command is still the main force to engage in an invasion of Taiwan. However, if the PLA wants to launch naval blockades in the East and South China seas, it will surely face the US military head-on. Whether an armed conflict will ensue is a political decision, and one that both sides must contemplate.

The PLA has adopted a new slogan: “First battle as decisive battle (or final battle)” for its upcoming campaign against Taiwan. If an armed conflict in the Taiwan Strait drags on too long, it will increase the odds of international intervention and produce negative variables for China’s domestic politics. Therefore, time is a key factor in the armed takeover of Taiwan. Dictums from Sun Tzu’s Art of War are applicable here, such as “subdue the enemy without fighting” and “the

highest form of war-fighting is to frustrate the enemy’s plans; the second best is to engage the enemy diplomatically; the next is to engage the enemy in the field; and the worst option is to besiege walled cities.” The best option for Beijing leaders is to unify Taiwan without having to resort to force. If the goal of “peaceful unification” cannot be achieved anytime soon, a possible option is to intimidate Taiwan through military strength but without deploying a large number of troops in the process. This may be the reason why the PLA now greatly relies on gray zone strategies in its intimidation against Taiwan, hoping to improve its battlefield management in the region and reduce Taiwan’s strategic response time. If the strategy of unifying through military force does not work, China might seek to raise tensions in the Taiwan Strait once again by launching simultaneous air and naval blockades. The PLA might even try to encircle Taiwan’s offshore islands or block access to them. The old tactic of encircling enemy positions and attacking their reinforcements might be used against Taiwan. If all the methods mentioned above fail to achieve their desired goals, the PLA will then likely opt to attack Taiwan proper.

Beijing would gather a sizable concentration of troops to intimidate Taiwan militarily, but it still

Keeping Pace With PLA b 29

A serviceman with the ROC military takes part in combat exercises in Taiwan. As the PLA evolves, the ROC military must adapt to new challenges.

photo: ROC MND

hopes that the goal of unifying Taiwan can be achieved through limited use of force. Whether this can be done depends greatly on the willpower of the Taiwan people. Do people in Taiwan have the strength of will it would take to support their military and help it defend against the PLA? This question helps explain why China has recently been using proxy methods such as misinformation, public-opinion warfare, and cognitive warfare against Taiwan’s public—to divide and conquer. The goal is to take advantage of a division of opinion among Taiwan’s people, and to prompt a call for surrender shortly after firing the first shot in the Taiwan Strait. These efforts also contribute to the attainment of the goal encapsulated in the aforementioned motto, in that the first battle must be a decisive battle.

Preventing the battle

Taiwan cannot pin its hopes for peace on the goodwill of China. Some people argue that if the first battle is indeed to be a decisive battle, then preventing that battle from ever happening is of critical importance. Maintaining peace in the Taiwan Strait is, of course, one way to achieve this goal, but if the Republic of China (ROC) military is greatly inferior to the PLA, or if the Taiwan people lack the will to fight, then this decisive battle will be lost before it begins. As Mao Zedong put it, “Fight no battle unprepared and fight no battle you are not sure of winning.”

Since war is always evolving and changing, adapting to new threats and technological advances and making self-improvements is critical. Taiwan should observe recent developments in the PLA (as well as the US military) and be mindful of the implications thereof, especially with respect to command mechanism changes of the post-reform PLA, wherein the PLA has made progress in improving its joint operations capabilities, and has adopted new war plans for use against Taiwan. Moreover, the US Indo-Pacific

strategy will surely be adjusted to keep up with new technological applications and international competition.

During the international maritime exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2020, for instance, the United States and its allies adopted a strategy that was markedly different from anything used the past. An important change was the absence of aircraft carriers from the exercise, a move indicating the US military’s seeming departure from the decades-old practice of counting on the aircraft carrier as the central focus of the strike group. Does this mean that the US and its allies have started to probe into the possibility of a carrier-free strategy against China? There is indeed that possibility, since the PLA has been focusing its efforts on the development of anti-access and area denial capabilities against US aircraft carriers since the Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1996.

Is it possible for the US military to win a battle without the use of carriers? The USS Essex (LHD-2) amphibious assault ship can also serve as a carrier and provide similar services to the United States and its allies. The focus of RIMPAC 2020 was on coalition cooperation operations and distributed lethality. So, will carriers play a feigning attack role, as US marines did in the Gulf War of 1991, to divert the attention of the PLA and achieve the effect of distributed lethality against the PLA through coalition cooperation with other friendly militaries? All these issues deserve further study.

Has Taiwan adjusted its defense strategy to effectively react to political and military changes in China and the United States? This is of critical importance to Taiwan’s national security. Support from Taiwan’s public will be a key determinant in whether Taiwan can survive as an independent country. The national defense education program that the ROC Ministry of National Defense has been promoting is intended to increase the general public’s understanding of national defense, which comes from a growing familiarity with defense issues

30 b STRATEGIC VISION

in general. However, quite a few people are still skeptical about what the military is doing, or has done. They even hold a negative view of their military.

These negative views provide a good opportunity for China to launch cognitive warfare operations against Taiwan. US arms sales to Taiwan has been one area where the public has been misinformed. A lot of misinformation, and information taken out of context, is being circulated on social media and in chat groups. Advances in digital technology contribute to the spread of such misinformation and the general public’s misunderstanding towards the government. Taiwan’s national defense has concentrated on building combat strength, but it has not reacted to the invisible war already being fought—a war that seeks to undermine the will and morale of the Taiwan people. In the near-term, Taipei must do more to defend against the challenges from Beijing’s cognitive warfare campaigns. The national defense education program must include a comprehensive plan to raise public awareness about these problems, and to provide accurate information to counter Chinese propaganda.

Taiwan can also play a larger international role in providing expertise and insight into the increasingly powerful PLA. Regardless of how cross-strait relations develop, PLA studies will always be a critical subject for Taiwan, and many other nations in the Indo-Pacific region. According to former US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, “PLA modernization is a trend the world must study and prepare for – much like the US and the West studied and addressed the Soviet armed forces in the 20th century.”

Esper also noted that the PLA does not serve the state; rather, it serves the Chinese Communist Party. They PLA is therefore different from most other militaries in the world. Interpreting developments in the PLA from a Western perspective can easily lead to misjudgment and error. Taiwan, and Taiwanese PLA scholars and experts, are well-positioned to help provide insight into the PLA because they share a common language with China, and have a long history of observing and analyzing China and the PLA. With its unique expertise on the PLA, Taiwan must assume a larger role in international academic and government forums on the PLA. n

Keeping Pace With PLA b 31

The Wasp-class amphibious assault ship USS Essex (LHD 2) transits the Pacific Ocean during Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2020.

photo: John McGovern

Visit our website: www.csstw.org/journal/1/1.htm