INDIGENT DEFENSE

COURSE DIRECTORS: Lynn Pride Richardson & Rick Wardroup

February 17, 2023 • Dallas, TX

Date Friday, February 17, 2023

Location Aloft Dallas Downtown 1033 Young St., Dallas, Texas 75202

Course Director Lynn Pride Richardson and Rick Wardroup

Total CLE Hours 6.0 Ethics: 1.0

Friday, February 17, 2023

Time Topic Speaker 8:15 am Registration & Continental Breakfast 8:45 am Opening Remarks Lynn Pride-Richardson and Rick Wardroup

9:00 am 1.0 Mitigation in the Non-Capital Case Liz Harvey

10:00 am 1.0 Defending the Blood Test DWI Case Chad Hughes 11:00 am Break 11:15 am 1.0 Evidence Refresher Impeachment and Objecting/Responding to Objections Eric Porterfield

12:15 pm Lunch Line

Presentation: Lawyer Wellness Rick Wardroup

pm Break

pm 1.0 General Forensic Pathology and How it Applies to the Fallacy of the Shaken Baby Syndrome Katherine Judson 2:45 pm 1.0

Caseload Standards for Indigent Defenders

Malia Brink

3:45 pm Adjourn

INDIGENT DEFENSE SEMINAR INFORMATION

:: 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

TCDLA

1.0 ETHICS

1:30

12:30 pm

Lunch

1:45

Criminal Defense Lawyers Project

speakers topic

Mitigation: Telling Your Client’s Story

Liz Harvey

Chad Hughes Defending the DWI Blood Case

Eric Porterfield Impeaching Witnesses in Federal and Texas Criminal Cases

Katherine Judson

Cognitive Bias in Forensic Pathology Decisions & Ending Manner-of-Death Testimony and Other Opinion Determinations of Crime

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Indigent Defense Table of Contents

Criminal Defense Lawyers Project

Indigent Defense

February 17, 2023

Aloft Dallas Downtown 1033 Young St, Dallas, Texas 75202

Topic:

Mitigation: Telling Your Client’s Story

Speaker: Liz Harvey

Harvey Sentencing Consulting

P.O. Box 30175 Austin, TX 78703

512.762.933 Phone

512.253.4238 Fax

liz@harveymitigation.com Email

Co-Authors: Mairead Burke, LMSW

Burke Mitigation and Consulting, LLC

P.O. Box 8313 Silber Spring, MD 20907 858.705.0338 Phone

mairead@burkemitigation.com Email www.burkemitigation.com Website

Clay B. Steadman

Jesko & Steadman

612 Earl Garrett St. Kerrville, TX 78028 830.257.5005 Phone

CSteadman612@hotmail.com Email

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

USE OF MITIGATION EVIDENCE

MAIREAD BURKE, LMSW, Austin Mitigation Specialist

Burke Mitigation and Consulting, LLC

CLAY B. STEADMAN, Kerrville

Law Offices of Jesko & Steadman

State Bar of Texas

SEX, DRUGS, & SURVEILLANCE

April 19, 2017

Austin

CHAPTER 9

This paper provides the nuts and bolts of what a lawyer needs to get a mitigation specialist on board, what a lawyer can expect a mitigation specialist to provide, and how to integrate mitigation information into every stage of the case to tell your client’s story.

MAIREAD BURKE, LMSW

P.O. Box 11543 ∙ Austin, TX 78711-1543

858-705-0338 ∙

mairead@burkemitigation.com ∙ Fax 512-842-7098

EDUCATION

University of Chicago

Master of Arts, School of Social Service Administration

Concentration: Clinical Social Work

Santa Clara University

Bachelor of Arts

Major: Communication

Minor: Women’s and Gender Studies

LICENSURE AND MEMBERSHIPS

Chicago, IL- 2013

Santa Clara, CA- 2007

Licensed Master Social Worker with the Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners since July 2014.

License #: 59512

National Association of Social Workers

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

EXPERIENCE

Mitigation Specialist and Case Consultant

Burke Mitigation and Consulting, LLC

Contractor

Austin, TX

October 2014- Present Independent

January 2014- October 2014

Emergency Department Social Worker Austin, TX

St. David’s Medical Center

Adult Case Manager

Howard Brown Health Center

Graduate Social Work Intern: Therapist

Jewish Child and Family Services

Graduate Social Work Intern

December 2014- Present

Chicago, IL

June 2013- April 2014

Chicago, IL

September 2012- May 2013

Chicago, IL

ACCESS Community Health Network Clinic at Sullivan High School

Mitigation Specialist and Forensic Investigator

NOLA Investigates

Jesuit Volunteer Corps Intern

NOLA Investigates

October 2011- June 2012

New Orleans, LA

August 2008- September 2011

New Orleans, LA

August 2007- August 2008

Clay B. Steadman

Is a partner in the Law Offices of Jesko & Steadman, in Kerrville, Texas. He has had a general law practice with his wife, Elizabeth, in Kerrville since 1995. His primary focus is litigation, with an emphasis on criminal defense.

As an active member of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association since 1995, he served on TCDLA’s Board of Directors from 2009 – 2015. Currently, he is a co-chair of the TCDLA Rural Practice Committee, and is a member of the Criminal Defense Lawyers Project Committee. Clay is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Educational Institute, and currently serves as the Vice-Chair of TCDLEI. He is a TCDLEI Super Fellow. Clay was appointed to serve on the faculty of the 41st Annual Texas Criminal Trial College for 2017.

As a charter member of the Hill Country Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, he has served on the Board of Directors since 2013. He is member of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the National Child Abuse Defense & Resource Center. Clay is also a member of the Kerr County Bar Association, and has been since 1995. In the past, within the Kerr County Bar Association, he has served in various leadership roles as President and Secretary. He is also a member of The College of the State Bar of Texas, and a member of the Texas State Bar Computer and Technology, Construction Law, and Consumer and Commercial Law Sections.

An active speaker, he has presented and spoken at over 20 continuing legal education seminars, served as course director, and authored numerous articles on various criminal defense legal topics.

Participating and being active in many local organizations throughout Kerrville and the surrounding area remains an important part of Clay’s fabric as a general law practitioner, in what is a predominately rural area. He remains actively involved with the Kerrville Tivy High School Mock Trial Team, and has been an attorney advisor with the team since 2001. In 2005, as an attorney advisor, the Kerrville Tivy High School Mock Trial Team won the Texas High School Mock Trial Competition, and competed in the National High School Mock Trial Competition in Charlotte, North Carolina. Locally, Clay has also served on the board of directors for the Hill Country Crisis Council, the Norman Turner Rehab House and the Riverhill Country Club.

Clay received his B.B.A. in Finance from the University of Texas at Austin in 1989, and his J.D. from St. Mary’s Law School in 1992.

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Applicable Standards and Case Law for Mitigation and Investigation ........................................................... 2 1. American Bar Association Standard on Criminal Justice [Section 4-4.1 (a)] 2 2. State Bar of Texas Performance Guidelines for Non-Capital Criminal Defense Representation [Guideline 4.1: Investigation – Generally] 2 3. Duty to Investigate Mitigation and Punishment Evidence 2 B. Mitigation: Where Do I Start 3 1. Case Law to Justify the Use of a Mitigation Specialist 3 2. First Steps for Retained Counsel 4 3. First Steps for Court Appointed Counsel 4 4. Retaining Your Mitigation Specialist 5 C. What You Can Expect from a Mitigation Specialist 6 D. Collecting Records for the Mitigation Investigation 6 1. Types of Records 6 2. Getting Records with a Signed Release 7 3. Use of Subpoenas and Motions/Court Orders to Obtain Records 7 4. Texas Public Information Act 10 5. 56.36 Crime Victim Act Provisions 11 6. Issues and Areas of Concern in Collecting Information 11 E. Using Mitigation Evidence ............................................................................................................................ 13 1. Use of Mitigation During Punishment ................................................................................................... 13 2. Case Law ............................................................................................................................................... 13 3. Incorporating Mitigation Evidence Into Guilt/Innocence ...................................................................... 14 4. Additional Factors to Consider .............................................................................................................. 15 5. Telling Your Client’s Story to the Jury ................................................................................................. 16 6. Demonstrative Exhibits ......................................................................................................................... 17 7. Accommodations for Trial..................................................................................................................... 18 F. Problems encountered by the lawyer ............................................................................................................. 18 1. Getting Mitigation Evidence Admitted ................................................................................................. 18 2. Most Common Mistakes ........................................................................................................................ 19 II. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................................................................... 19 APPENDIX ................................................................................................................................................................... 20

USE OF MITIGATION EVIDENCE

I. INTRODUCTION

Mitigation has been generally defined as the action of reducing the severity, seriousness, or painfulness of something. Mitigation can be used as a verb or a noun. In a practical sense when referenced, it can generally be seen as a manner of risk reduction. When an attorney collects, and uses mitigation evidence, it is a means by which to tell your client’s story and offer an explanation of their action(s), which require consideration by the trier of fact.

In defending someone accused of a criminal act, there are three basic premises of your client’s responsibility and their acceptance of same: (1) I didn’t do it, (2) I did it but I had a good reason, and (3) I did it and I am sorry. Generally, when collecting and using mitigation evidence we would be focusing on (3) I did it, and I am sorry, but (2) could become relevant in a situation where the accused may have an insanity or diminished capacity defense, and same is argued during the guilt/innocence phase of the trial. However, in most cases the use of mitigation evidence will be implemented during the punishment phase of a trial. Indeed, if you are offering evidence to reduce the severity, seriousness or painfulness of an act, it is by its very definition punishment evidence, and it is unlikely to have any relevance during the guilt/innocence phase of the trial. However, its limited relevance in the guilt/innocence phase, should not deter you from attempting to offer same at the outset of trial, if the premise of your defensive strategy is “I did it, and I am sorry”.

Mitigation can be an art-form to be perfected throughout the trial, that allows us to tell our client’s story from a compassionate point of view, which resonates acceptance of responsibility. The court or jury does not want to hear your client’s excuse(s) for their behavior, but they will listen to your explanation. The use of mitigation can allow you to explain how your client finds himself in his current situation (alleged criminal act), and offer their explanation of what precipitated and led to the manner in which he acted. Mitigation can illustrate to those charged with making a decision regarding your client’s criminal culpability, a rational understanding of your client’s perception of the event(s) which have led to this very time in his life. It is a time of your client’s reckoning and judgment, which if presented and argued successfully, allows the decision maker to consider a fuller explanation of your client’s behavior, and not solely focus on the result.

William Shakespeare often incorporated themes of mercy and forgiveness throughout his literary works. In the Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare offers the following quote from his character Portia, who is then presently disguised as the attorney Balthazar, who pleads for mercy from Shylock before the Venetian Court of Justice:

The quality of mercy is not strain'd,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath: it is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:

'Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomes

The throned monarch better than his crown;

His sceptre shows the force of temporal power, The attribute to awe and majesty, Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings; But mercy is above this sceptred sway; It is enthroned in the hearts of kings, It is an attribute to God himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God's When mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew, Though justice be thy plea, consider this, That, in the course of justice, none of us

Should see salvation: we do pray for mercy;

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render The deeds of mercy. I have spoke thus much

To mitigate the justice of thy plea; Which if thou follow, this strict court of Venice

Must needs give sentence 'gainst the merchant there.

The Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene

This quote is an example of the high esteem that Shakespeare held for those who had compassion and showed mercy. Specifically, this is an example of how Shakespeare presented mercy as a quality which was most valuable to

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 1

those individuals in positions of power, influence and standing within society. See Generally, Bloody Constraint: War and Chivalry in Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. Theodor Meron. (1998) Page 133. ISBN 0195123832.

A. Applicable Standards and Case Law for Mitigation and Investigation

As attorneys and zealous advocates, we are required to properly investigate and prepare our client’s defense, and to ensure that this effort and manner of preparation continues through trial, if necessary. Child abuse and child death cases are particularly difficult because of the complexity of the subject matter, and the horrendous facts that are generally involved. However, as difficult as it is to defend these types of cases, we cannot “mail it in”, so to speak. At all times, you need to be diligent and thorough in your efforts of investigating the facts of your client’s case, as well as preparing same for trial.

1. American Bar Association Standard on Criminal Justice [Section 4-4.1 (a)]

Defense counsel should explore all avenues leading to facts relevant to the merits of the case and the penalty in the event of conviction. The investigation should include efforts to secure information in the possession of the prosecution and law enforcement authorities. The duty to investigate exists regardless of the accused’s admissions or statements to defense counsel of facts constituting guilt or the accused stated desire to plead guilty. In other words, we must investigate the case facts despite our client’s best efforts to handcuff our ability to effectively defend their case

2. State Bar of Texas Performance Guidelines for Non-Capital Criminal Defense Representation [Guideline 4.1: Investigation – Generally]

You are required to complete an independent review of the case as promptly as possible. This is a good reason for getting an investigator involved as soon as possible. Verify that the charge(s) are legally and factually correct. Verify and investigate both areas of the client’s case, specifically being those facts pertaining to guilt/innocence and punishment. Ex Parte Niswanger, 335 S.W.3d 611 (Tex. Crim. App. 2011) [Citing Strickland v. Washington]

Counsel’s function is to make the adversarial testing process work in the particular case. Accordingly, competent advice requires that an attorney conduct an independent legal and factual investigation sufficient to enable him to have a firm command of the case and relationship between the facts and each element of the offense.

3. Duty to Investigate Mitigation and Punishment Evidence

The standard by which the appellate court’s review ineffective assistance of counsel, is the same for both the guilt/innocence and punishment phases of a defendant’s trial. See Hernandez v. State, 988 S.W.2d 770 (Tex. Crim. App 1999). Further, in 2006, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals expanded this rationale in holding that a defense counsel’s failure to investigate the basis of his client’s mitigation defense can amount to ineffective assistance of counsel. Ex Parte Gonzales, 204 S.W.3d 391 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006).

Moreover, the United States Supreme Court had previously adopted this standard, as espoused in Ex Parte Gonzales, in non-capital cases. See Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510 (2003). Both the First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeals in Houston, Texas, have found that defense counsel can be ineffective in a non-capital case, for failure to present available character evidence when the record shows that the witnesses would have been able to offer mitigating testimony. See Milburn v. State, 15 S.W.3d 267 (Tex. App. – Houston [14th Dist.] 2000, pet. ref’d); See also, Shanklin v. State 190 S.W.3d 154 (Tex. App. – Houston [1st] 2005), pet. dism’d 211 S.W.3d 315 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007).

I know what you are thinking, great I am now paranoid about how I am defending my client’s case. That is not the intended purpose of this article, as I am always uncomfortable in the ethics portion of any CLE seminar, because it is human nature to second guess your decisions. You are not alone, as any good trial attorney will have those same anxieties during trial preparation. The purpose of providing you the applicable case law and standards is to help you identify what is required to be investigated for mitigation purposes, and seek the trial court’s assistance, if necessary, in providing effective assistance of counsel in the punishment phase of your client’s trial

We must remind ourselves that we have a duty not only to investigate those facts pertaining to the guilt or innocence of our client, but to also thoroughly investigate any and all facts pertaining to the punishment of our client. In a punishment type case, facing an impossible set of facts, you can sometimes feel overwhelmed or that there is nothing you can do to assist and/or defend your client. However, you must persist, and continue to investigate thoroughly any pertinent mitigation and/or punishment evidence, because the failure to do so may result in a finding of ineffective assistance of counsel

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 2

B. Mitigation: Where Do I Start

In the recent movie, “The Martian”, starring Matt Damon, there is a great line at the end of the movie where Damon’s character, who survived alone on Mars for 543 days before being rescued, tells a group of astronaut candidates, “You just begin. You do the math. You solve one problem …. and you solve the next one…and then the next. And if you solve enough problems, you get to come home.” As an attorney, I can identify with this statement, as we are often put in what appears to be an impossible situation, and asked to fix it, make it right. It can be an overwhelming sensation, that may intimidate us into a position of taking no action at all. I would argue that this not a solution or a strategy, but is a form of resignation. No pun intended, but it is not rocket science, as you should be able to readily recognize when you are retained or appointed on a case, if the collection and use of mitigation evidence will assist you in representing your client effectively. So, what do I need to do? You begin, by recognizing the need to investigate, collect and use all mitigation information and evidence concerning your client, his background, his family, and what circumstances have delivered him to you for advice and guidance.

If you are retained, you will need to make sure that your client has paid you or has sufficient funds in reserve to hire a mitigation specialist, an investigator, and usually at least one psychological or psychiatric expert. Based upon my experience in this area of the law, you will normally need a minimum of $10,000.00, to initially retain the services of a mitigation specialist, an investigator, and a psychologist. This may vary from case to case, but it has been my experience that most retainers for these types of experts and investigators, depending upon the severity of the case, will range from $3,000.00 to $5,000.00. Further, it is likely that the initial retainer will not be sufficient to pay all expenses and fees for these types of experts through trial.

If you are court appointed, or if your client has hired you but is now out of available funds for these types of experts and investigators, you are required to seek assistance from the trial court, and request authorization for the funding for these types of experts and investigators.

1. Case Law to Justify the Use of a Mitigation Specialist

a. Ake

Established that an indigent defendant has a right to a court-appointed expert under certain circumstances. Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087 (1985). In Taylor v. State, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, in following the precedent established in Ake, held that the defendant is entitled to independent expert assistance, not one who is required to report to the State or the court. Taylor v. State, 939 S.W. 2d 148 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996).

As previously mentioned above, defense counsel’s failure to investigate available facts or a basis of the client’s mitigating evidence, can be held as ineffective assistance of counsel. Ex Parte Gonzales at 391. More specifically, the Court reasoned that in determining whether or not counsel conducted a reasonable investigation, the reviewing court must initially determine if a reasonable investigation would uncovered the available mitigation evidence. See Id.

b. Miller v. Dretke

United States 5th Circuit Opinion. Female Defendant was charged and convicted of deadly conduct and sentenced to 8 years in prison. The Court had determined that there was significant psychological evidence available regarding the Defendant’s mental and emotional state, due to injuries she suffered as a result of a car accident. Specifically, the court reasoned that defense counsel’s failure to pursue this type of mitigation investigation and present this evidence through the defendant’s physicians, was not a sound tactical or strategic decision. The Defendant’s case was reversed for ineffective assistance of counsel for purposes of punishment. See Generally, Miller vs. Dretke, 420 F.3d 356 (5th Cir. 2005)

Lair v. State

Texas First Court of Appeals Opinion. The Defendant was convicted of possession of a controlled substance of more than 200 grams but less than 400 grams. First degree felony, further enhanced on basis of Defendant’s prior felony conviction. The Defendant was sentenced to 70 years in prison. The appellate court found that there were over twenty witnesses, including the Defendant’s mother, relatives, and neighbors, who were ready and willing to testify, but were never contacted by defense counsel. The appellate court concluded that a reasonable probability existed that the Defendant’s prison sentence would have been less severe had the jury had the opportunity to balance the mitigating testimony, which was available from the additional witnesses, who were subsequently not called during punishment to testify. Therefore, in the instant case the appellate court concluded the Defendant was actually and substantially prejudiced by his defense counsel’s failure to seek out and present available mitigating character evidence from those additional witnesses. The Defendant’s case was reversed for purposes of punishment. See Lair v. State, 265 S.W.3d 580 (Tex. App. – Houston [1st Dist.] 2008).

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 3

c.

d. Lampkin v. State Texas Sixth Court of Appeals Opinion. The Defendant was convicted of felony driving while intoxicated, third or more. After finding the Defendant guilty of felony driving while intoxicated, he was enhanced based on two prior felony convictions, and sentenced to 99 years in prison. The appellate court found the defendant’s trial counsel did not know about the available mitigating evidence, because he did not investigate the matter. The appellate court concluded that it was beyond speculation or conjecture that a reasonable probability existed that the Defendant’s assessed prison sentence would have been less severe had the available mitigating evidence been presented at trial. Therefore, the Defendant’s case was reversed for purposes of punishment. See, Lampkin v. State, 470 S.W.3d 876 (Tex. App. –Texarkana 2014).

In applying this line of case precedent and rationale, it is clear that a criminal defense attorney is compelled to investigate all reasonably available mitigation evidence. Further, it is clear that if your client does not have adequate funds to hire the appropriate expert(s) and investigator(s), in order to investigate and present all relevant mitigating evidence, they must seek assistance and funds from court to do so.

2. First Steps for Retained Counsel

If retained, you will need to interview your client and make an initial determination if his background or circumstances have any connection to the situation surrounding the criminal accusation in question. I have found that in preparing a case for trial, which involves mitigating facts and evidence, you will generally need to employ and utilize least three (3) types of expert and investigative resources:

a. Fact Investigator

b. Mitigation Specialist/Investigator

c. Psychologist

Some cases, either based on the criminal conduct alleged or the background of the accused, may involve the employment and utilization of a specific type of expert for purposes of mitigation. By example in a sexual assault case, you may need to employ the services of a qualified psychologist to perform and complete a sexual assault risk assessment and evaluation. The same may be the case in a situation in which your client was an abused spouse and a victim of battered spousal syndrome. Your ability to find and employ a qualified expert, as same pertains to your case, is only limited by your creativity in defense strategy.

You may have to prepare for a potential Gatekeeper hearing under Texas Rules of Evidence 705. As a defense attorney, I have used this type of hearing to voir dire the State’s expert, and potentially exclude their testimony, as it is not relevant or probative in assisting the jury making a determination regarding guilt/innocence or punishment. However, the Gatekeeper hearing can be used by the State in this same capacity. Keep in mind that during the punishment phase of a trial, the court generally takes a much more liberal position on what it determines to be relevant and material. As such, it is usually easier to argue the relevancy and admissibility of mitigation evidence during punishment.

Make sure when you quote a fee for the case, that you have considered what if any expert or investigative resources you may need in preparing for trial. Moreover, you need to ensure that adequate resources are available to employ those types of expert and investigative resources. Based upon the case law discussed above, it is clear that defense counsel’s failure to employ the necessary mitigating resources, because the client is out of money, will expose defense counsel to post-judgment ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

In the event that your client has retained your legal services, but at some point, no longer has sufficient funds to retain and employ expert(s) and investigator(s) for any purpose, including a mitigation investigation, you must seek an authorization of funds for those types of resources from the trial court. This will be accomplished in the same manner as if you were a court appointed attorney. The only difference, is in the motion you would present to the court for authorization of funds, is that you would assert that your client was not initially indigent or that his family initially retained you as his counsel, but currently the defendant has no other resources available for fees, expenses or services, and is now indigent. I will sometimes provide the trial court an affidavit from my client to that effect, which is attached to the ex parte motion seeking funds.

3. First Steps for Court Appointed Counsel

You will still need to interview your client and his available family members, to determine if his background or family history has any connection to pending criminal accusation. Once you have determined the need to investigate potential mitigation evidence, you will need to request authorization of funds from the trial court, such that you can retain the appropriate resources.

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 4

a. Ex Parte Motion for Authorization to Expend Funds for Mitigation Specialist

b. Ex Parte Motion for Authorization to Expend Funds for Psychological Expert

c. Motion for Authorization to Expend Funds for Investigator

I do not usually file a motion for an investigator ex parte, because from a strategy standpoint I want the State to know that I am also investigating the facts surrounding the case.

4. Retaining Your Mitigation Specialist Getting Started:

a. Once you have reviewed the case facts and spoken to your client, make the necessary phone calls to available experts, investigators, or mitigation specialists, and determine their availability, hourly rate, and terms of employment.

b. Obtain the necessary funding required for the mitigation specialist or other experts. This is accomplished by getting a retainer for the mitigation specialist payable to them or your trust account, or getting an Order Authorizing Funding from the trial court. The funding order should specify the mitigation specialist’s and expert’s hour rate, the number of hours of work initially authorized, and the amount of funds initially authorized. The Order Authorizing Funding should also provide for the reimbursement of necessary travel and other miscellaneous expenses connected to the investigation.

c. Provide the mitigation specialist or other experts with a legal retention letter from your office, which outlines payment considerations and terms of employment. (A Copy is Included in the Document Appendix)

d. Deliver the retainer check or order authorizing funding and legal retention letter to the mitigation specialist or other experts.

e. If your client is in custody, then you will need to prepare a letter to the county or state correctional facility in which he or she is being held, authorizing your mitigation specialist, investigator, or expert to have access to your client. You need to ensure that your mitigation specialist, investigator or expert when meeting with your client at the correctional facility is provided a secure and private meeting area, such that privilege is maintained. (A Copy is Included in the Document Appendix)

f. Make sure that you provide the mitigation specialist or other experts with all the discoverable information, witness interviews, and offense reports. I usually do this digitally, and provide all members of the defense team a flash drive with the discoverable information received from the State. Also, I would have your mitigation specialist meet with the client and start collecting information prior to having your psychologist or other expert evaluate your client. I normally proceed in this manner, such that you and your mitigation specialist can formulate a plan for exactly how and under what specific psychological criteria you want to have your client evaluated. As an example, in a murder case you may not want to have a complete psychological evaluation completed by your expert, because this type of evaluation, which includes an MMPI (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory), may indicate that your client is a sociopath or has sociopathic characteristics. This is because the MMPI is standardized psychometric test of adult personality and psychopathology. This type of testing can often open Pandora’s box, regarding your client and his propensity to break the law or for violence. In some cases, we do not want an initial psychological evaluation, however complete it may be, which may provide a differential diagnosis or could be used to determine a therapeutic assessment procedure. As the point of the spear, you and the mitigation specialist need to coordinate your efforts so that you can control the content and expected outcome of your client’s psychological evaluation.

g. One caveat I would offer pertains to a situation in which you are utilizing the services of a psychologist or psychiatrist or other therapeutic expert. While you should initially provide this type of expert all the information you receive from the State, you must be cautious in how you provide this type of expert any information you, your investigator, or mitigation specialist have obtained. If this expert is potentially going to testify, by proceeding cautiously, you can monitor and limit the dissemination of otherwise privileged or harmful information. Keep in mind, once you designate this witness as a testifying expert, any information they have reviewed in preparation of their testimony can be subpoenaed to trial. While it will be necessary to have this expert review some of the information, you, the investigator, or mitigation specialist have obtained, it should not just be forwarded to them for review, without taking any precautionary safeguards.

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 5

Attached Document Appendix:

See the

C. What You Can Expect from a Mitigation Specialist

A mitigation specialist will cultivate information through interviews, record collection and analysis, and research; and will assist the attorney in developing mitigation themes and strategies for the presentation of information to the trier of the fact.

Breaking that down step-by-step, first the mitigation specialist will meet with the client, go over their life history and gather pertinent information, and have the client sign HIPAA compliant releases. Then, the mitigation specialist will obtain the client’s records, analyze them, and interview additional witnesses, like the client’s family and friends. Next, the mitigation specialist will provide you with: interview summaries/testimony outlines, records with Business Records Affidavits that are suitable for introduction as exhibits, and a biopsychosocial history of the client.

This mitigation investigation will be the most in-depth assessment the client has ever undergone, and it’s expected that the mitigation investigation will uncover issues that have gone undiagnosed and untreated for myriad reasons. For that reason, it’s important that the mitigation specialist is qualified by training and experience to recognize signs and symptoms of possible psychiatric, psychological, medical, neurological, substance abuse, educational, and developmental issues that come up in interviews and records.

A mitigation specialist is not a testifying expert; they will assist in identifying issues that warrant expert assessment, identifying specific experts, and developing specific questions for the experts to evaluate and provide opinions about. Once you’ve chosen the expert, the mitigation can consult with them about their role in the case and provide relevant background information.

Next, the mitigation specialist will use the gathered information and expert opinions to assist you in preparing for plea negotiation. If the case is not resolved through a plea, they will assist in developing strategies for the presentation of lay and expert witnesses at trial.

In preparation for trial the mitigation specialist will provide a Punishment Phase Witness List, a memo that synthesizes pertinent mitigation information into a comprehensive mitigation guide. The memo includes mitigation themes, lay and expert witnesses to testify and an outline of their testimony, witnesses they anticipate the State may call and their anticipated testimony, and a recommendation with supportive reasoning for an appropriate sentence.

D. Collecting Records for the Mitigation Investigation

1. Types of Records

The following is a list of records a mitigation specialist will likely collect, depending on the specific needs of your case. The list is by no means exhaustive, but it gives an idea of the common records that are needed in a mitigation investigation:

a. Medical records

b. Psychological records

c. Psychiatric records

d. Educational and Special Educational records

e. Social Security Disability records

f. Employment records

g. Personnel records

h. Social Security Earnings records

i. Military records

j. Child Protective Services and other community agency records

k. Foster care and other placement records

l. Arrest, conviction, correctional, and probation records

m. Juvenile arrest, conviction, correctional, and probation records

n. Police Department calls for service records to client’s residences

The following records from discovery and/or the investigation of the crime, and really all records from discovery, are relevant to the mitigation investigation and should be provided to your mitigation specialist:

a. Client’s statement

b. Witness statements

c. Affidavits of Non-Prosecution (which is a type of statement)

d. Offense reports

e. I.R.S. records

f. Property records

g. Court records

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 6

h. Attorney General records and information

i. Texas Department of Criminal Justice Institutional Division

j. County Jail records

k. Police Department records of complaints

l. Video Cam surveillance records

m. Crime Lab records

n. Medical Examiner (autopsy) reports

o. Crime Stoppers records

p. Social Media in all forms

2. Getting Records with a Signed Release

A HIPAA compliant release with your client’s full name, date of birth, social security number if applicable, and signature is needed to obtain the following records. The mitigation specialist will collect these records with a Business Records Affidavit so they are suitable for introduction as exhibits (See Document Appendix).

a. Medical records

b. Psychological records

c. Psychiatric records

d. Educational and Special Educational records

e. Employment records

f. Personnel records

The following records require agency-specific signed releases.

a. Social Security Disability records require SSA-3288 (See Document Appendix)

b. Social Security Earnings records require SSA-7050-F4 (See Document Appendix)

c. Military records require Standard Form 180 (See Document Appendix)

I encourage you to request these records with a signed release rather than a subpoena so the records will come directly to you instead of being shared with the prosecution. If agencies refuse to provide records, then consider issuing a subpoena.

3. Use of Subpoenas and Motions/Court Orders to Obtain Records

When using a subpoena to obtain records you should first file a specific motion requesting the information in question, and get a court order requiring same be produced. After obtaining a court order requiring the production of the documents, issue a subpoena duces tecum and attach the court order as an exhibit. I will then either subpoena the documents using the duces tecum to a specific pre-trial court setting, or request that the documents be produced instanter. If I am attempting to subpoena information which I believe a party may deem sensitive, I will state in my motion for discovery and subsequent subpoena that the records may be produced to the court “in camera”. My general experience has been once the court signs and order requiring the documents to be produced, most entities will comply with an instanter request because they do not want to appear in court unnecessarily. However, this is not the case with Child Protective Services records as they will require the redacted records to be produced in conjunction with a signed agreed protective order covering same, or have the records redacted and produced “in camera”.

a. Child Protective Services

Use of subpoenas to obtain CPS records, which generally are subpoenaed “in camera”. Note: Provisions which generally necessitate an “in camera” inspection of CPS records:

(1) Tex. Fam. Code Section 261.201 Confidentiality and Disclosure of Information

(2) 40 Tex. Admin. Code Section 700.202 Definitions

(3) 40 Tex. Admin. Code Section 700.203 Access to Confidential Information Maintained by the Texas Department of Protective and Regulatory Services (TDPRS)

(4) 40 Tex. Admin. Code Section 700.204 Redaction of Records Prior to Release

(5) 40 Tex. Admin. Code Section 700.205 Procedures for Requesting Access to Confidential Information

(6) 40 Tex. Admin. Code Section 700.206 Videotapes, Audiotapes and Photographs

(7) 40 Tex. Admin Code Section 700.207 Charges for Copies of Records

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 7

Procedurally you can request and/or subpoena these records, and they will be subject to being redacted by the CPS legal/records department, and upon being “desensitized” they are produced “in camera” for inspection by the court. I sometimes receive the redacted records in hardcopy form, but lately have been receiving them in digital form on a CD or DVD. In reviewing these records if you discover a redacted portion which may contain material, relevant or potentially exculpatory information you should file a specific motion for discovery on that issue, and assert your rationale for requiring the court to order CPS to produce that information in an un-redacted form.

b. Juvenile Detention and Probation Records

I would file a motion specifically referencing and requesting that this type of information be produced by the State or in the alternative order that it be produced and file a subpoena duces tecum requesting same and attaching a copy of the Court’s order stating what must be produced. If the State files a Motion to Quash, I initially would agree to the documents being produced “in camera” to the Court, subject to review, and then produced to the Defendant. If the court refuses to produce the documents submitted “in camera”, request the court make a finding that you are not entitled to said documents, object to the court’s finding, and then have all the documents marked as an appellate exhibit, to be unsealed if an appeal is pursued.

c. Adult Probation

I would file a motion specifically referencing and requesting that this type of information be produced by the State or in the alternative order that it be produced and file a subpoena duces tecum requesting same and attaching a copy of the Court’s order stating what must be produced. If the State files a Motion to Quash, I initially would agree to the documents being produced “in camera” to the Court, subject to review, and then produced to the Defendant. If the court refuses to produce the documents submitted “in camera”, request the court make a finding that you are not entitled to said documents, object to the court’s finding, and then have all the documents marked as an appellate exhibit, to be unsealed if an appeal is pursued.

d. Jail

I would file a motion specifically referencing and requesting that this type of information be produced by the State or in the alternative order that it be produced and file a subpoena duces tecum requesting same and attaching a copy of the Court’s order stating what must be produced. If the State files a Motion to Quash, I initially would agree to the documents being produced “in camera” to the Court, subject to review, and then produced to the Defendant. If the court refuses to produce the documents submitted “in camera”, request the court make a finding that you are not entitled to said documents, object to the court’s finding, and then have all the documents marked as an appellate exhibit, to be unsealed if an appeal is pursued.

e. Prison

Most types of Prison Records are available to be subpoenaed, so long as you are willing to pay for the expense of copying and delivering the records to you, and you send the subpoena to the correct contact individual. In most instances, you will be attempting to get your client’s prison records, and as such, a release is the most expedient manner in which to request these records. I have listed below some of the addresses and contact information I have used in the past to request certain documents regarding T.D.C.J.I.D. records.

(1) Offender Visitor List

Attention: Custodian of Records

Texas Department of Criminal Justice T.D.C.J. Open Records Office and Pen Packets

Huntsville, Texas 77342-0099

Phone: (936) 437-8696

Fax: (936) 437-6227

(2) Disciplinary Records

Attention: Custodian of Records

Texas Department of Criminal Justice T.D.C.J. Open Records Office and Pen Packets

Huntsville, Texas 77342-0099

Phone: (936) 437-8696

Fax: (936) 437-6227

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 8

(3)

Inmate Grievance Records

Attention: Custodian of Inmate Grievance Records

901 Normal Park, Suite #101

Huntsville, Texas 77320

Phone: (936) 437-8024

(4)

Inmate Medical Records

Attention: Custodian of Medical Records Health Services Archives

262 FM 3478, Suite #B

Hunstville, Texas 77320

Phone: (936) 439-1345

You may also need to contact UTMB Managed Care to subpoena medical records and can get their contact information by calling their office at (936) 439-1345. As such, once you contact this office you can determine if you need to issue two separate subpoenas.

f. Medical and Mental Health

If these records cannot be obtained with a signed HIPAA compliant release, then consider using court action to collect them. When subpoenaing medical records, mental health records, or counseling and therapy records, you will need the individuals full name, date of birth, social security number if available, the dates and/or period of treatment specific to you case, and the name and address of the facility and/or care provider. These types of subpoenas are sometimes objected to by the facility or care provider under HIPAA. If this is the case, I would file a specific motion for discovery on this issue and address same with the court, specifically identifying why this information is necessary. If the court grants your discovery request, re-issue the subpoena with the attached order stating that the described information is to be delivered “in camera” to the Court for inspection, and within the subpoena itself identify a pretrial hearing date and time for which these records are to be produced.

g. Miscellaneous Records

I will also use a court order and subpoena duces tecum to request and obtain the following additional types of records:

(1) Employment Records

If these records cannot be obtained with a signed HIPAA compliant release, then consider using court action to collect them. I first file a specific motion for discovery requesting these specific type of records, identifying the employer name and address. Once I have obtained a court order regarding this type of information I will issue a subpoena duces tecum and attach the court order as an exhibit.

(2) School Records

If these records cannot be obtained with a signed HIPAA compliant release, then consider using court action to collect them. I first file a specific motion for discovery requesting these specific type of records, identifying the school district name and address or school name and address. Once I have obtained a court order regarding this type of information, I will issue a subpoena duces tecum and attach the court order as an exhibit. When subpoenaing education/school records, you will need to include the individual’s full name, date of birth, social security number if available, the dates and periods of records you are seeking, and the name and address of the specific educational entity you are requesting the records from.

(3) Crime Stoppers Records

The Defendant has a right to Crime Stoppers Information. As such you will need to file a discovery motion requesting this information and/or prepare a subpoena to the individual in possession of the applicable local crime stoppers information. This information can be subpoenaed and produced “in camera”. Under Thomas v. State, 837 S.W.2d 106 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992), the defendant has a constitutional right to the production of crime stoppers information in the possession of the local Crime Stoppers program, the Crime Stoppers Advisory Council or the District Attorney’s office. Further, what is more interesting, under Crawford v. State, 892 S.W.2d 1 (Tex. Crim. App. 1994), any exculpatory information contained within a crime stoppers report is “Brady” material, and as such, there is no burden on the defendant under the Fourteenth Amendment to specifically request this material. This presents an interesting twist to the newly enacted amendments to Article 39.14 (Michael Morton Act), as the State has a continuing obligation to produce “Brady” material, which could potentially include Crime Stoppers information and records. Because of the potential “Brady”

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 9

element involved, you may want to subpoena the requested information “in camera”, because at a minimum the court can then make a determination if the requested information contains “Brady” material. If the court denies you access to this information, I would request that it be sealed, and marked as an exhibit for appellate purposes. This way you can attempt to preserve error, and further insist that the court is now the gatekeeper of this information, and should it be deemed material at the time it is inspected or at any future stage of the trial, it must be released to the defendant for review. See Generally, Thomas v. State, 837 S.W.2d 106 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992). This presents an interesting dynamic at trial, because if the information is “Brady”, but initially withheld from the inspection of the defendant, I would argue that the release of this information during trial is a Brady violation, and request a mistrial, and subsequently argue that jeopardy has attached.

Once you have started gathering any of these types of records via subpoena, and you may want to use these records in any form at trial, you must meet the requirements under the Texas Rules of Evidence 803 (6) – Business Records Exception, and the authentication requirements under Texas Rules of Evidence 902 (10), you will need to have the necessary affidavit completed and the records filed with the required notice being sent to the State or any other opposing party, at least 14 days prior to the commencement of trial.

4. Texas Public Information Act

Prepare an Open Records Request pursuant to the Texas Public Information Act, Chapter 552, of the Texas Government Code, to any Police Departments or other law enforcement subdivisions you believe could have information regarding your client

a. Use of the Texas Public Information Act to obtain other possible incidents of unlawful conduct involving the alleged victim, the family of the victim, or any other fact or mitigation witnesses. At this stage an investigator’s services can be invaluable, because these types of witnesses are generally more receptive to speaking to an investigator than the defense attorney.

b. Use of Texas Public Information Act to make an open records request to Texas Commission on Law Enforcement regarding any law enforcement personnel involved, such that you can verify their education and training.

c. Generally, you can obtain Attorney General Records and/or documents by sending a written request to the Public Information Coordinator. Again, if this is not successful or you do not receive a response, file a specific motion for discovery and obtain a ruling, and attach the order to the subpoena, and request that said information be subpoenaed “in camera” to the Court on a specific date and time. At a minimum, it will force the Attorney General of Texas to respond.

d. Be aware of the requirements of Chapter 552 of the Texas Government Code, as these are the statutory guidelines for requesting information pursuant and under the Texas Public Information Act. Listed below are some of the pertinent sections of Texas Public Information Act, which I have referenced and used in obtaining certain public information and records.

(1) §552.002 –Definition of Public Information; Media Containing Public Information

(2) §552.003 – Definitions

(3) §552.004 – Preservation of Information

(4) §552.021 – Availability of Public Information

(5) §552.022

(6) §552.026

(7) §552.0055

Categories of Public Information; Examples

Education Records

Subpoena Duces Tecum or Discovery Request (A subpoena duces tecum or request for discovery that is issued in compliance with a statute or rule of civil or criminal procedure is not considered to be a request for information under this chapter) (ie: don’t refer to the information you may be requesting pursuant to a subpoena or your request for discovery as public information or records).

(8) §552.225

(9) §552.228

(10) §552.231

Time for Examination

Providing Suitable Copy of Public Information Within Reasonable Time

Responding to Request for Information That Require Programming or Manipulation of Data

(11) §552.261

Charge for Providing Copies of Public Information

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 10

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

5. 56.36 Crime Victim Act Provisions

Under Article 56.36 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, an application for compensation must be verified, and contain among other things, the date upon which the criminally injurious conduct occurred, and a description of the nature and circumstances of the criminally injurious conduct. In my opinion this is a sworn statement of the alleged victim, which should be discoverable under Article 39.14.

Currently, I have taken the position that we should be able to discover and subpoena certain Crime Victim’s compensation records. Any individual who applies for and accepts compensation from the crime victim’s fund agrees to cooperate with and pursue the prosecution of the accused. I would argue that this is in some cases a financial motive for the alleged victim to pursue this case. Articles 56.311 through 56.54 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, basically establish the requirements of the application for, and the award and/or receipt of Crime Victims Funds from the Attorney General’s Office. There is not a specific prohibition of which I am aware that prohibits you from obtaining this information, and if there is a hearing conducted under Article 56.40 on an application for compensation, this hearing or pre-hearing conference is open to the public, unless the Attorney General or hearing officer determines it should not be public. I would argue that this issue merits further thought, because given the right set of circumstances we should at least file a specific motion for discovery and/or subpoena these records “in camera”.

Under Article 56.36 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, an application for compensation must be verified, and contain among other things, the date upon which the criminally injurious conduct occurred, and a description of the nature and circumstances of the criminally injurious conduct. In my opinion this is a sworn statement of the alleged victim, which should be discoverable under Article 39.14. If we can obtain this information it may be very useful in our investigation. I would suggest that you initially file a specific motion of discovery, requesting this information, and explaining why it is relevant, and necessary in the preparation of the client’s defense. The application itself and its required contents under Article 56.36 is a type of sworn fact statement, which should be discoverable. This will force the State, and perhaps the Attorney General’s office to respond and offer argument and authorities as to why this information is and should be protected. If you can obtain a ruling granting this discovery request, then you should subpoena the necessary records from the individual who has been designated in your county to be the Victim Assistance Coordinator. Attach a copy of the court’s order to your subpoena, and subpoena the records to the court on a designated pre-trial date. I would make sure that the Attorney General’s Office is given a courtesy copy of the subpoena. Obtaining an affidavit of non-prosecution, can be used as mitigation evidence, but if used in trial you would need to proffer same through the alleged victim, such that the jury is aware that the victim does not want to pursue the case.

6. Issues and Areas of Concern in Collecting Information

a. Affidavits of Non-Prosecution

(1) If you have an investigator, allow your investigator to make the initial contact with the alleged victim. You will need to monitor the content of how your investigator should communicate with the alleged victim. In my opinion, it is not wise to allow your investigator to get too involved in procuring the affidavit, because you do not want to sacrifice the credibility of your investigator, or jeopardize their continued involvement in the investigation process.

(2) In reaching out to the alleged victim for this purpose, you must understand that any information or resultant contact conveyed to the alleged victim for this purpose, depending upon the circumstances, may be turned over to the State or Law Enforcement.

(3) In contacting the alleged victim, you need to be familiar with said alleged victim’s rights of privacy, and of the very expansive list of rights they have under Chapter 56 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure (Rights of Crime Victims). In reviewing the articles contained in Chapter 56 these individuals are not referred to as an alleged victim, but in fact are assumed to be victims from the beginning of the legal proceedings. So much for the presumption of innocence.

(4) Initially, as a general rule I will not contact or have my investigator contact the alleged victim for purposes of signing an Affidavit of Non-Prosecution, unless we have received information that they desire to cooperate with our investigation and execute an affidavit of this nature.

(5) If the alleged victim desires to execute an Affidavit of Non-Prosecution, it can be accomplished for any specified reason as explained in the affidavit, but the basic rational rests on two premises; (1) the alleged victim no longer desires to pursue the prosecution of the defendant, and the interests of justice are served by a dismissal of the charges, and (2) the alleged victim recants their previous statement as being untrue, and as a result the defendant should not be prosecuted.

(6) You cannot give legal advice to the alleged victim. If I meet with the alleged victim to sign the affidavit, I will record the meeting with their consent, and explain to them that I cannot give them legal advice, and if

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 11

they have any questions regarding the substance of the affidavit itself, or how it may affect them from a legal perspective, they need to seek the advice of legal counsel.

(7) In the event that you are preparing an affidavit, based upon the fact that the alleged victim is now recanting their statement, if asked by the individual about the potential legal consequences of recanting and/or retracting their statement based upon it being a false statement, I will tell them they can potentially face charges ranging from false report to a peace officer (based upon an unsworn statement), to perjury (based upon a sworn statement), but I will not elaborate or offer legal advice. If this issue arises, you should tell the alleged victim not to sign the affidavit until they have had the opportunity to seek the advice of legal counsel.

(8) It is my experience that most Affidavits of Non-Prosecution are executed because the alleged victim no longer desires to pursue the investigation.

(9) You need to explain to your client and the alleged victim, that regardless of whether the Affidavit of NonProsecution is executed, the State still has the prerogative to pursue criminal charges.

(10) Based on my experience, other than notarizing the affidavit if necessary, your staff should not discuss or play any role in obtaining the Affidavit of Non-Prosecution.

b. Interviewing and Getting a Statement From the Alleged Victim

(1) It is always preferable to use an investigator to get a statement from the alleged victim.

(2) Other than notarizing the statement if it is sworn to or acknowledged, your staff should not discuss or play any role in obtaining a statement from the alleged victim.

(3) Again, know if the alleged victim is not cooperative with your investigative efforts any information they obtain from you or your investigator will certainly be turned over to the State. (ie: never tell an alleged victim, well my client is saying this is what happened) The alleged victim is just like any witness, they do not have to speak to you or your investigator.

(4) If an alleged victim will speak to me, and I am taking a statement from them, I will record the statement with their consent. If they will not consent to me recording the statement, that should be a red flag as to what may commence in that interview. If I cannot record the statement, and I continue the interview I may have just made myself a witness in the case as to a prior inconsistent statement to which I would have to testify in trial. In my opinion you should always avoid this situation as it is not worth the risk, and does not further your investigation.

(5) It is preferable for the reasons previously discussed to use an investigator to get a statement from an alleged victim. Often having an experienced investigator working on your defense team, when this type of situation arises, is the only thing that may allow you to use that prior inconsistent statement in trial.

(6) In contacting and getting a statement from an alleged victim, whether it is you or your investigator, be aware of Texas Penal Code Sections 36.05 (Tampering With Witness) and 36.06 (Obstruction or Retaliation).

(7) If family or friends are cooperating with your investigation, and they are assisting in contacting or getting a statement from an alleged victim, they need to be made aware of Texas Penal Code Sections 36.05 (Tampering With Witness) and 36.06 ( Obstruction or Retaliation).

(8) The purpose of mentioning these penal code statutes is based on my previous experience you may get a call from the State or law enforcement suggesting these lines have been crossed, and you need to be familiar with them, so you can respond appropriately.

c. Interviewing and Getting a Statement From a Witness

(1) Many of the same caveats and precautions, which apply in interviewing and obtaining a statement from an alleged victim, apply to witnesses as well. It is unusual to get a statement from a mitigation witness before trial, but these guidelines for interviewing are important to keep in mind with all witnesses.

(2) It is always preferable to use an investigator in obtaining a witness statement.

(3) Other than notarizing the statement if it is sworn to or acknowledged, your staff should not discuss or play any role in obtaining a statement from a witness.

(4) The witness does not have to speak to you or your investigator. If they choose not to speak to you or your investigator, that needs to be documented, such that you can confront them with the fact that they refused to speak to you. I will usually ask them why they refuse to speak to me or my investigator, because that information can be useful, depending on the answer.

(5) If I am the person conducting an interview of a witness, I will ask permission and get consent to record the interview. If possible, I will have another person with me when I speak to a witness, so there is no confusion as to what was being discussed. If the witness will not allow me to record the conversation, and I don’t have

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 12

a witness I will generally tread lightly, because the witness could turn on you, and again you become a witness to a prior inconsistent statement.

(6) In contacting and getting a statement from a witness, whether it is you or your investigator, be aware of Texas Penal Code Sections 36.05 (Tampering With Witness) and 36.06 (Obstruction or Retaliation).

(7) If family or friends are cooperating with your investigation, and they are assisting in contacting or getting a statement from a witness, they need to be made aware of Texas Penal Code Sections 36.05 (Tampering With Witness) and 36.06 ( Obstruction or Retaliation).

(8) The purpose of mentioning these statutes is based on my previous experience you may get a call from the State or law enforcement suggesting these lines have been crossed, and you need to be familiar with them, so you can respond appropriately.

E. Using Mitigation Evidence

The use of mitigation evidence during trial is not much different than the use of other factual evidence, however, mitigation evidence tells a different story than factual evidence. When using mitigation facts and evidence, the premise of the defense is:

1. I did it, but I had a reason or

2. I did it and I am sorry

Using mitigation evidence effectively allows you to offer the jury an explanation regarding your client’s behavior or action(s) that contributed to his pending set of circumstances. As discussed previously, a jury will be much more accepting of your client’s explanation versus an excuse. It is a hollow and meaningless apology for criminal behavior if your client’s only response to a criminal accusation is I am sorry. A sincere apology must offer context and an explanation of the behavior or the circumstances involved.

If a husband cheats on his wife, the husband’s action(s) are unforgivable. While no apology can comfort his wife, she will require an explanation, because that is human nature. I believe that before we can forgive, we must understand. Before, we can understand, we require information, and that information must be plausible. The jury must be able to understand and follow the mitigation information and evidence we give them to consider. If the jury understands your client’s explanation, they can sympathize with his story and are more likely to identify with his behavior. The successful combination of these story-telling elements, allows you to offer the jury a compelling mitigation defensive theory.

1. Use of Mitigation During Punishment

a. If at all relevant as to the circumstances of the commission of the offense, client’s background or psychological history I would attempt to admit the evidence.

b. You must lay the proper predicate, through the appropriate witness for the mitigation evidence.

c. You must convince the court of the relevance of the mitigation evidence.

d. If the State objects and the court sustains the objection to the mitigation evidence you need to argue the admissibility under the appropriate case law.

e. If the court does not allow you to admit the proposed mitigation evidence, you need to reiterate your objection to the court’s ruling and request a hearing outside of the presence of the jury, such that you can create a bill of exception which will preserve the mitigation evidence or testimony for appellate review, if necessary.

2. Case Law

a. Positive Legal Precedent Regarding Treatment of Admissibility of Mitigation Evidence

(1)

Draheim v. State

The focus of the punishment phase of trial is the personal responsibility and moral blameworthiness of the defendant for the crime with which he is charged. Moreover, evidence regarding the criminal offense charged or the defendant that tends to reduce a defendant’s moral blameworthiness may be received during the punishment phase of defendant’s trial as mitigating evidence. See Generally, Draheim v. State, 916 S.W. 2d 716 (Tex. App.

San Antonio 1996, pet ref’d).

(2)

Sanders v. State

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 13

–

Evidence may be offered during the punishment phase of the defendant’s trial which concerns the circumstances of the offense itself or to the defendant himself before, or during the time of the commission of the offense. See Sanders vs. State, 25 S.W.3d 854 (Tex. App. – Houston [14th Dist.] 200, no pet.).

b. Negative Legal Precedent Regarding Admissibility of Mitigation Evidence

(1) Stiehl v. State

Factors arising independently of the defendant or arising after the offense was committed are properly excluded as punishment evidence. This case dealt with the defendant attempting to enter into evidence certain conditions of the county jail in which defendant was being detained. See Stiehl v. State, 585 S.W.2d 716 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979).

(2) Miller v. State

The defendant is not permitted to present and admit evidence of their contrition through a third person, as this type of evidence is legally not admissible. Miller v. State, 770 S.W.2d 865 (Tex. App. – Austin, 1989, pet ref’d).

3. Incorporating Mitigation Evidence Into Guilt/Innocence

The prospect of using mitigation evidence in the guilt/innocence phase of your client’s trial is only limited by your creativity and your ability to overcome the State’s objection as to relevance. However, there are two distinct areas in which you can always use mitigation evidence in the guilt/innocence phase of a trial as follows:

a. Incompetency & Insanity

If you believe that your client may suffer from some type of mental illness or intellectual disability which renders them unable to proceed to trial, you are required to file a motion requesting a competency evaluation under Chapter 46B of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. However, if when having received the case you suspect that incompetency is a possibility you should seek to retain the services of your own independent psychologist to evaluate your client on this basis and test their intellectual functioning. You do not want to rely solely on the court appointed psychologist for this purpose, and you want to have the ability from a trial standpoint to get ahead of the State on this issue.

If you have given notice of the affirmative defense of insanity, under Chapter 46C of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, again you are going to have to retain your own independent psychological expert to assist you in this regard, prior to giving notice TCCP 46C, which then subjects your client to an evaluation by a psychologist appointed by the court.

Further, from a strategy perspective, even if your client is found to be competent to stand trial, but does suffer from some type of mental illness or intellectual disability, you can enter mitigation evidence during guilt/innocence for several relevant reasons. Moreover, if you are arguing not guilty by reason of insanity, you have an absolute right to put on this type of evidence. In these situations, even if not successful in arguing that your client is incompetent or that he is was insane at the time of the offense, you will be effectively front-loading your mitigation evidence for purposes of using same during punishment. If successful, this strategy can have a profound effect on the jury, because you have introduced them who your client is, and why his behavior can be explained.

b. Other Instances of Front-Loading Mitigation

This type of evidence should be admissible during guilt/innocence to the extent it demonstrates your client’s state of mind, his mental health history as same pertains to his home environment and family, and offers a plausible explanation for the circumstances surrounding the criminal act alleged to have been committed. Some examples would be:

(1) Challenging the indictment with information about the defendant’s state of mind

Some medical and psychiatric issues make a defendant incapable of acting in an intentional and knowingly manner.

• A person with certain intellectual disabilities doesn’t have the ability to form the mens rea to act intentionally and knowingly, as required under the Texas Penal Code for some criminal allegations. The pervasive nature of an intellectual disability can affect state of mind of an individual at all times.

• There are cognitive and rational processing issues associated with other mental illnesses, (ie: a person with paranoid schizophrenia will have decreased cognitive functioning)

Use of Mitigation Evidence Chapter 9 14

• The significance of and meaning of an intellectual disability or mental illness can offer the court, and ultimately the jury, an explanation of why the defendant behaved in a certain manner, within the context of the crime charged. By example, some individuals who suffer from an intellectual disability are often followers, and as function of their intellectual disability they are easily manipulated, and do not have the mental acuity to plan a criminal act or scheme.

(2) Challenging a Client’s Statement

Your client is slow and suffers from a learning disability or intellectual disability, but confesses to law enforcement. This confession may be the product of a false confession, and as such, while some of it may be true, the basis of the confession is false. This will allow you during guilt/innocence to offer an explanation of your client’s behavior and initial interaction with law enforcement.

Suppressing your client’s statement on this basis:

• Considering the client’s medical and psychiatric issues, was the defendant competent to understand Miranda and the waiver of his right to remain silent?

• Considering the client’s medical and psychiatric issues, did the defendant have the capacity to understand the warning at the beginning of jail phone call before making a recorded call which may amount to a confession?

(3) Examples of frontloading mitigation

• Your client evades law enforcement. If your client has paranoid schizophrenia, this information is valuable to a jury to understand how he reacted to law enforcement.

• If attempting to argue self-defense in a case where a woman has killed her husband, but she herself has been a repeated victim of abuse and suffers from battered spousal syndrome. It is relevant for the jury to understand her background and fear, so you can explain why her action(s) were reasonable.

• Your client is extremely high on methamphetamine and hurts or kills someone. The State will argue that voluntary intoxication is not a defense. This is true, and the jury cannot consider same as a defense to the actual crime committed. However, I would argue that your client’s state of mind is relevant as same concerns the circumstances under which the act was committed or how the act was committed. This could allow you to successfully argue that your client was criminally negligent, rather than reckless or committed an act intentionally and knowingly. I am not suggesting you will be successful in pursuing this defense, however, it should allow you to argue said evidence is relevant, such that it can be introduced during the guilt/innocence phase of the trial. This normally will not work in a case of intoxication assault or manslaughter. However, if your client suffers from obvious signs of mental illness and is intoxicated at the time of the offense, I would argue that evidence of your client’s mental health status is relevant during guilt/innocence, such that you cannot distinguish between the effects of the intoxication or mental illness, for purposes of trial. How many of our clients with mental illness self-medicate with alcohol or drugs? In my opinion that is relevant during any phase of a trial.

Again, you are only limited on the use of mitigation evidence during the guilt/innocence phase of your client’s trial, by your own creativity and being able to overcome the State’s relevancy objection(s).

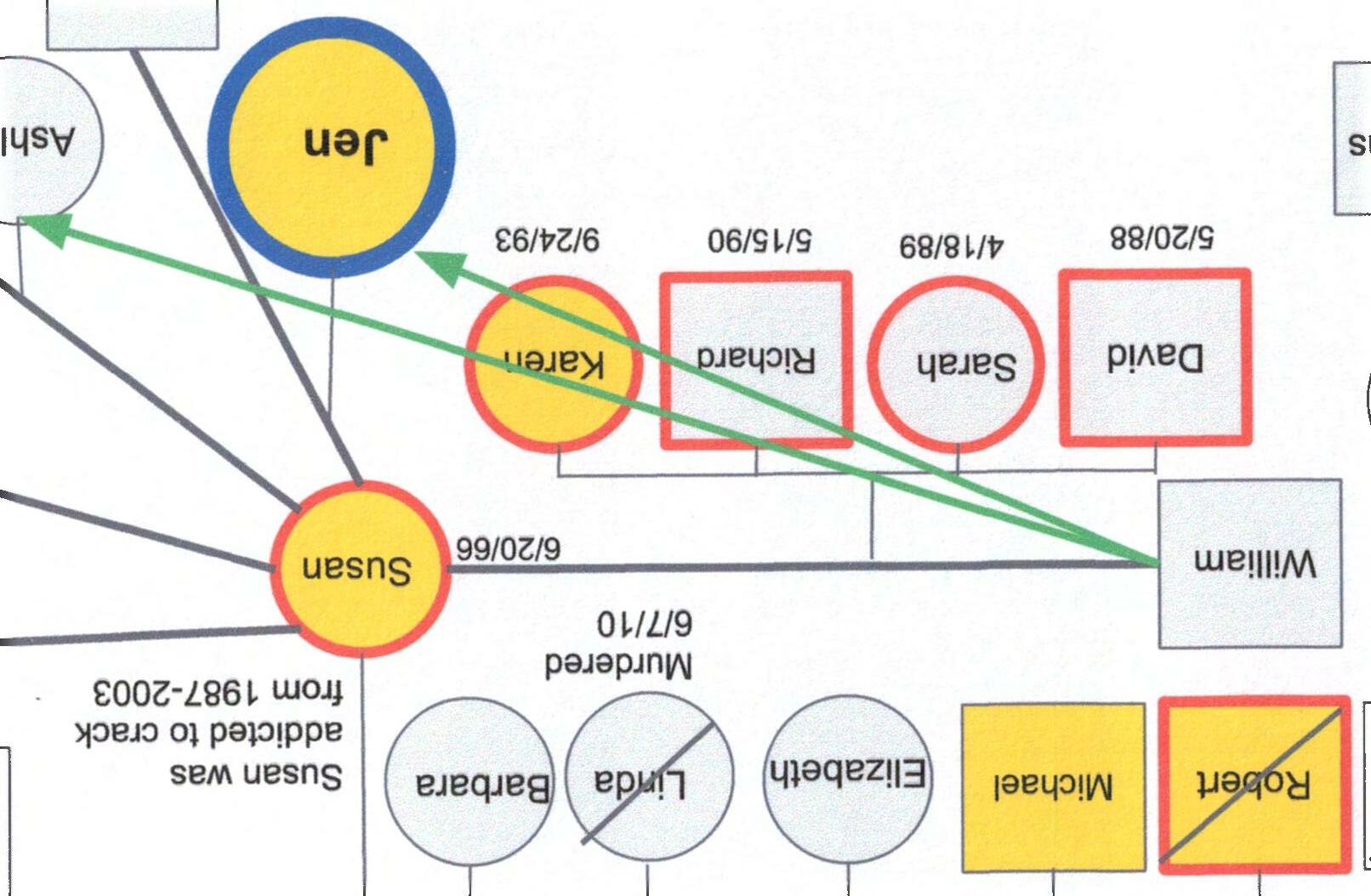

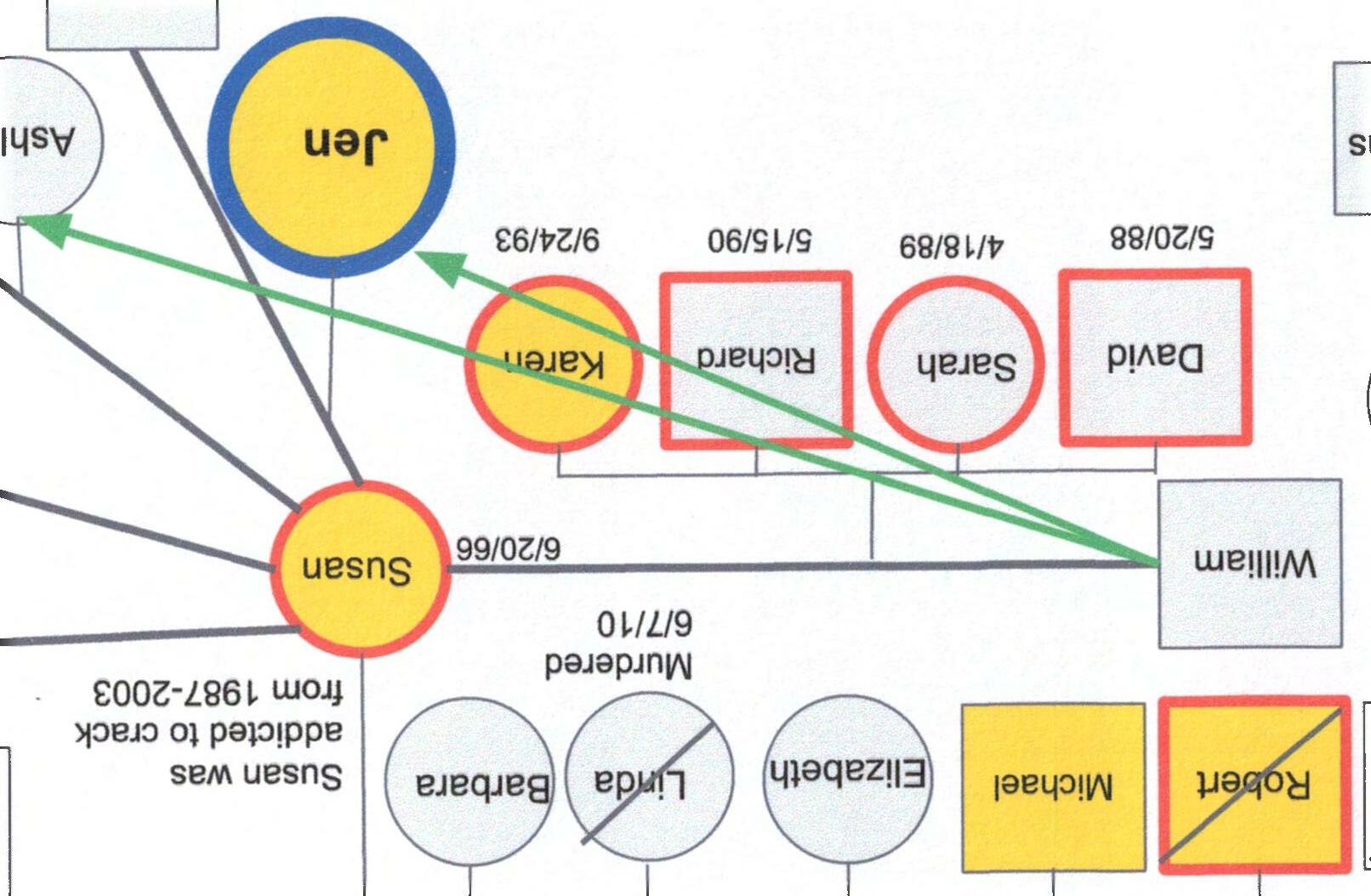

4. Additional Factors to Consider