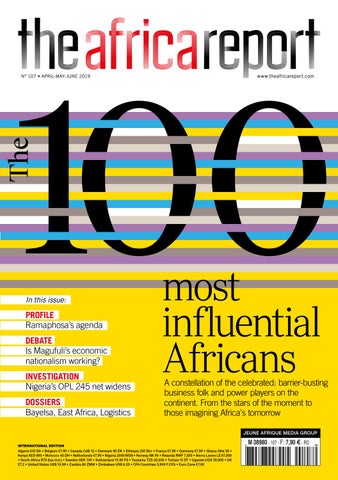

theafricareport

100 www.theafricareport.com

THE AFRICA REPORT

The

N° 107 • APRIL-MAY-JUNE 2019

In this issue:

PROFILE Ramaphosa’s agenda

QUARTERLY EDITION • N° 107 • APRIL - MAI - JUNE 2019

DEBATE Is Magufuli’s economic nationalism working? INVESTIGATION Nigeria’s OPL 245 net widens DOSSIERS Bayelsa, East Africa, Logistics

most influential Africans

A constellation of the celebrated: barrier-busting business folk and power players on the continent. From the stars of the moment to those imagining Africa’s tomorrow JEUNE AFRIQUE MEDIA GROUP

INTERNATIONAL EDITION

Algeria 610 DA • Belgium €7.90 • Canada CA$ 12 • Denmark 80 DK • Ethiopia 200 Birr • France €7.90 • Germany €7.90 • Ghana GH¢ 35 • Kenya KES 900 • Morocco 45 DH • Netherlands €7.90 • Nigeria 2000 NGN • Norway NK 95 • Rwanda RWF 7,500 • Sierra Leone LE 67,000 • South Africa R75 (tax incl.) • Sweden SEK 100 • Switzerland 10.90 FS • Tanzania TZS 20,000 • Tunisia 15 DT • Uganda UGX 30,000 • UK £7.2 • United States US$ 15.99 • Zambia 80 ZMW • Zimbabwe US$ 6.20 • CFA Countries 3,900 F.CFA • Euro Zone €7.90