STUDENTS SAY THE COST OF AN AMBULANCE IS PREVENTING THEM FROM SEEKING NECESSARY EMERGENCY CARE.

IS YALE PAYING ATTENTION?

Volume 55, Issue 3 January 2023 The Magazine About Yale and New Haven

THE COST TO RIDE BY JESSE GOODMAN

Dear readers,

We’d like to greet you with a goodbye. Specifically, take care. Take care is a promise willed to the departing. It means keep yourself safe and pay attention. Volume 55, Issue 3 of The New Journal follows people and communities who intimately understand what it means to fulfill this promise, and when a promise isn’t enough. Formal systems of support can fail to help individuals, so informal systems—from personal networks to strangers who want to help—step up to take care when those established channels fall short. In this issue, communities take the wheel, literally.

“Reintegration Roadblocks” follows an organization that supports people reintegrating post-incarceration to overcome the innumerable hurdles on the road to getting a driver’s license; while, in “Scrap Cycling,” a writer cycles after the man behind Peels on Wheels—a start-up filling in for New Haven’s landfill-dependency by collecting neighborhood food scraps on his bike. In our cover story, students make the game-time decision for their friends in alcohol-induced emergencies: either call 9-1-1—sinking their friends into the debt induced by an uninsured ambulance trip—or hang up to take care of the emergency themselves. “It’s not right,” Chief Perez says when our Executive Editor Jesse Goodman speaks to him. “We’re supposed to take care of each other.”

It doesn’t stop there. In one story, we see a woman spend decades fighting to build public memory of Lucretia, an enslaved woman who is believed to be the first Black resident of New Haven. In another, the crowds brought together by the Elm City Express come back to life, with wins shared both among the players and the city alike. In “This Tattoo Is Permanent,” clients’ queer identities and permanent ink collide as modes of rebellion, thanks to the work of a queer tattoo artist. And, in the endnote, a man tends to the pianos in the School of Music one string at a time, the quiet enabler of the thrum of the ivories at hundreds of concerts.

We’d like to thank the writers, editors, copy editors, designers, Photography Head Lukas Flippo, and Creative Director Kevin Chen for the tremendous amount of care they put into this issue. Our collective promise is this issue, which we now depart, and leave to you.

Take care,

The Managing Board

Thank you to our donors.

Neela Banerjee*

Anson M. Beard

James Carney

Andrew Court

Romy Drucker

Jeffrey Foster

David Gerber

David Greenberg*

* Donated twice. Thank you!

Matthew Hamel

Makiko Harunari

James Lowe

Chaitanya Mehra

Ben Mueller

Sarah Nutman

Peter Phleger

Jeffrey Pollock

Adriane Quinlan

Elizabeth Sledge

Gabriel Snyder

Fred Strebeigh

Arya Sundaram

Stuart Weinzimer

Steven Weisman

Suzanne Wittebort

Editors-in-Chief Nicole Dirks

Dereen Shirnekhi

Executive Editor Jesse Goodman

Managing Editor J.D. Wright

Associate Editors

Amal Biskin Abbey Kim

Meg Buzbee Yosef Malka

Jabez Choi Cleo Maloney

Lazo Gitchos Paola Santos

Ella Goldblum Kylie Volavongsa

Yonatan Greenberg

Senior Editors

Beasie Goddu Madison Hahamy

Alexandra Galloway Zachary Groz

Copy Editors

Marie Bong Edie Lipsey

Adrian Elizalde Lukas Trelease

Rafaela Kottou Yingying Zhao

Creative Director Kevin Chen

Design Editors

Meg Buzbee Charlotte Rica

Camille Chang Karela Palazio

Etai Smotrich-Barr

Photography Lukas Flippo

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Peter Cooper • Jonathan Dach • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred Strebeigh

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley •

Susan Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Andy Court • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff •

Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • Susan Dominus

• David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura

Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren

Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya

Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark

Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard •

Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper

• Haley Cohen • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey

Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka

Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen

• Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer

Pitts • R. Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie

Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley

• Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth Sledge •

Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder • Elizabeth Steig

• Aliyya Swaby • John Jeremiah Sullivan • Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita

Whiteleather • Blake Townsend Wilson • Daniel

Yergin • William Yuen

2 TheNewJournal

thenewjournalatyale.com

Letter from the Editors

points of departure

snapshots

Coin-Gate: Who Stole Yale’s Doubloon?

Seventy years ago, five burglars stole nearly one million dollars worth of coins from the Yale Numismatics collection. We still don’t know who they were.

By Lara Yellin

The Rise and Fall of the Elm City Express

For a glorious two years, New Haven had a soccer team.

By Maggie Grether

critical angle

Lucretia’s Corner

Nearly four hundred years after the earliest known enslaved African was brought to New Haven, a local researcher has found a small way to remember her.

By Johnny Phan

cover story

Students say the high cost of an ambulance is preventing them from seeking emergency care. Is Yale paying attention?

By Jesse Goodman

By Jesse Goodman

The Cost To Ride Reintegration Roadblocks

Previously incarcerated Connecticut residents face complicated barriers to receiving their licenses, making it difficult to get to work.

By Ángela S. Pérez Aguilar

When Yale Harbored a Nazi, Part 2: The Open Secret

Years after one Nazi was exposed at Yale, another remained on the faculty of the Slavic Languages and Literatures department.

By Zachary Groz

This Tattoo is Permanent

Art and queerness at the Broken Crystal Tattoo Studio in Milford, Connecticut.

By Eileen Huang

endnote

Piano Man

In the School of Music, piano technician William Harold has been attending the 130 Steinways for the last twenty-five years.

By Cora Hagens

poems

Theseus’ Ship

By Amanda Budejen

all else

Gilgamesh to Enkidu

By Edie Lipsey

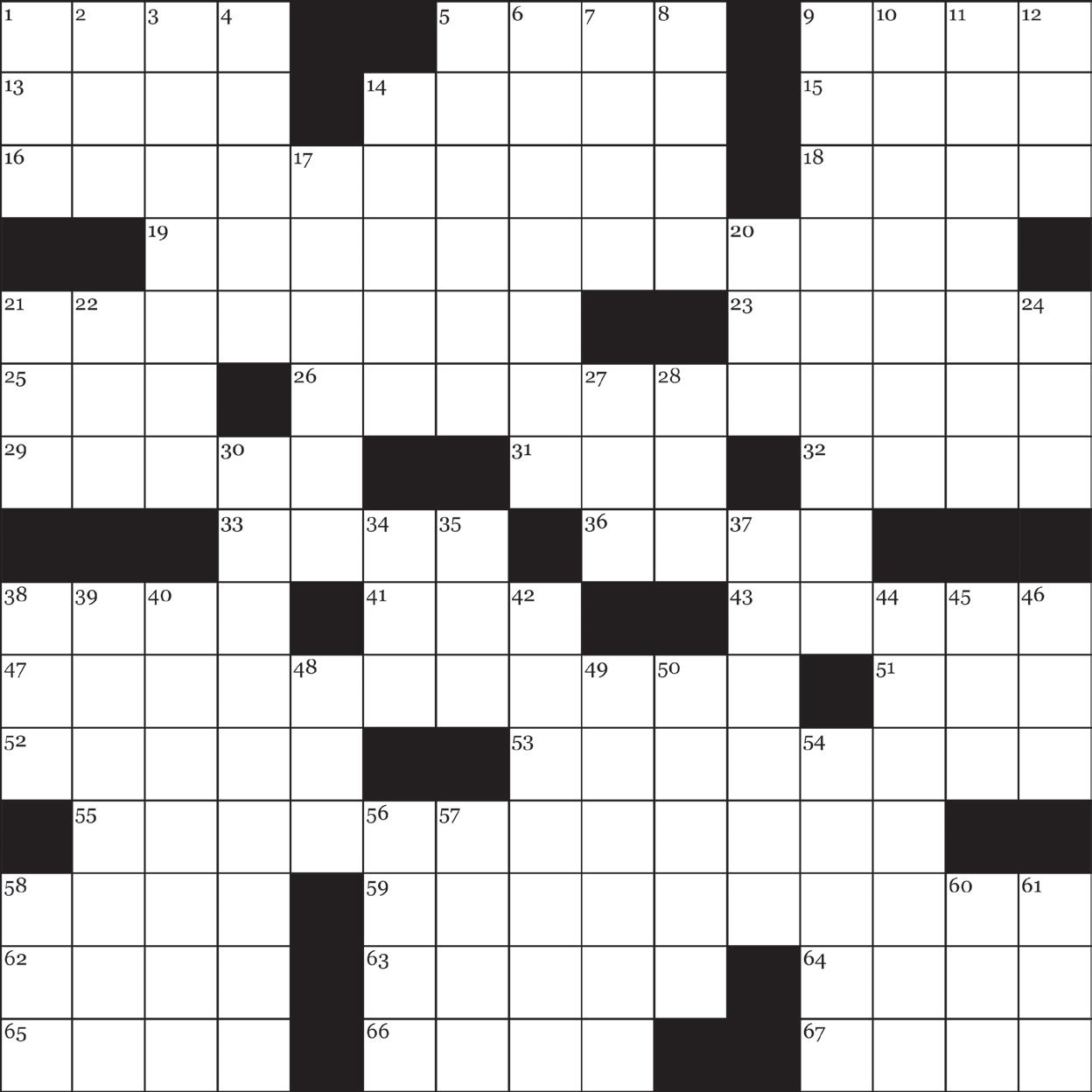

On my good friend, Reese Jacobs, essay , by Lana Perice, page 43. Diamond Cave, photo essay , by Rachel Shin, page 50. Animal Crossing, crossword , by Jesse Goodman, page 55.

3 profile

January 2023 Contents 14 22 36 4 46 6 10 42 54 52 38

Sadie Bograd joins Domingo Medina as he picks up your leftovers on his bike.

image credits: lukas flippo; TSA.gov; igor petrov

Scrap Cycling

Domingo Medina, owner and founder of Peels & Wheels Composting, surveys the heap of food waste before him. Over a thousand pounds of rejected leftovers are spread in a neat rectangle at his feet, the sweet smell of decay punching through the winter chill. His son, Noah, shoos his dog away from a banana peel. One employee scours the pile for still-edible melons and potatoes to take home. Another wades into the garbage, picking out stray pieces of plastic and compost bin liners.

Medina grabs a shovel to start turning the pile as he tells me about his composting setup.

“It’s all human-scale,” he says. “It doesn’t require any machinery, just labor force.”

Medina is the brains and one-sixth of the brawn behind Peels & Wheels, New Haven’s bike-based composting service. For $7.50 per pickup, Medina and his five employees will collect your food scraps and pedal them to a small facility by the Mill River where orange rinds and eggshells slowly turn back into soil for local farms and gardens. Since its founding in 2014, Peels & Wheels has diverted over one hundred and ninety thousand pounds of food waste.

I joined Medina for his Monday pickup route on a blustery morning in December. It took a while for him to confirm our meeting point: “My references are trees, doors, corners, not numbers,” he told me.

His process, though, he knows by heart. He coasts into each customer’s driveway, eyes peeled for the little green bin left on the porch or by the dumpster. He weighs the bucket with a portable scale, spins the top off with a practiced ease, and heaves its contents into one of the large black bins on his trailer, smacking the base to dislodge tenacious scraps. And then he bikes away to his next destination, his trailer fourteen or so pounds heavier.

Medina rides a beast of a bicycle:

bright orange with an electric assist, a heavy gray trailer, and tires as thick as my forearm. My gray road bike looks puny by comparison. Although Medina was dragging three hundred pounds of garbage, I found myself racing to keep up as I followed him up Canner and down Orange, stopping at three consecutive houses on Whitney Avenue.

Our route reflected the business’s limited clientele. Peels & Wheels only accepts customers in East Rock, Prospect Hill, Wooster Square, Downtown New Haven, and Westville, plus Spring Glen and Whitneyville in Hamden—an eight mile radius covering some of the wealthiest parts of the region. The collection area doesn’t include the lower-income neighborhoods of Fair Haven, although that’s where the compost is processed, or Newhallville, even though it’s next to Prospect Hill.

not willing to get into boards, and meeting every month, and trying to convince people. My time of convincing is done. For me, it’s about doing.”

Employee Austin Larkin takes a similar perspective. I chat with him while we hack discarded vegetables into pieces, increasing their surface area so they decompose faster. Larkin describes himself as a former “guerrilla composter” who used to bury his food waste in backyards and parks before he discovered Peels & Wheels.

“It felt very logical and also radical,” Larkin says as he jabs a hoe into a particularly sturdy carrot. “Obviously it’s not enough, but it’s also better than nothing. It’s what’s possible right now. And it’s not about finding an ideal, it’s about progress.”

Progress, though, might be difficult without more institutional support. Two years ago, New Haven’s Food System Policy Division received a $90,000 USDA grant, which it used to improve community garden compost systems and start community composting working groups. But due to bureaucratic challenges, the Division failed to find city-owned land where they could start another food waste diversion site. Instead, they used the money to expand Common Ground High School’s compost facility (which Medina helped establish).

Medina says he worries about these inequalities, but sees them as the inherent limitations of running a business. It’s not that he doesn’t want to serve more neighborhoods, but that there aren’t enough people requesting his services. Weekly collection costs $30 a month (although about twenty off-campus Yale students get subsidized pickups through the Yale Student Environmental Coalition). Peels & Wheels is funded by its customers, so its customers are mostly people with funds to spare.

“I needed to do something that could pay for itself. I worked a long, long time for not-for-profits,” he told me. “It required me to write grants and to chase the money, and I got tired of it…I’m just

In general, local efforts at food waste management are “a little fragmented” and limited by budgetary constraints, according to Deborah Greig, Common Ground’s Farm Director. There are a handful of independent initiatives: in addition to Peels & Wheels, many restaurants contract with the Hartford-based scrap collector Blue Earth Compost, while Yale sends its dining hall discards to an anaerobic digestion facility in Southington. But there’s no citywide compost infrastructure, and no organizations devoted to helping interested residents develop composting skills.

“You need to have municipal-level compost. It almost doesn’t matter that there’s micro-haulers out there,” Greig said. “I think it’s impossible to create equity and access in education and composting itself until there’s also a larger effort [by] the city.”

Medina agrees: he notes that Peels & Wheels is New Haven’s main home compost hauler, yet it only serves about five hundred households out of more than fifty thousand in the city. But he

4 January 2023 TheNewJournal Points of Departure

illustrations by meg buzbee

The Peels & Wheels compost pile in the parking lot of Pheonix Press near the Mill River.

Sadie Bograd / The New Journal

insists that a micro-scale approach can work on a municipal level. Most citywide compost systems, he says, rely on massive trucks and process food waste in a central hub. They treat food waste as a “nuisance” to whisk away rather than a valuable good to return to local residents. He would prefer a decentralized network of compost haulers and processors, with programs like Peels & Wheels closing the loop in every zip code.

“Everybody sees my business like something cute,” he said. “But it’s also a demonstration that things can be done differently.”

Although Medina swears his operation is scalable, he is struggling to make it last. Right now, Peels & Wheels operates rent-free from the parking lot of sustainable printing company Phoenix Press, sweeping stray bits of food from the asphalt at the end of each processing session. Local nonprofit New Haven Farms—which has since merged with the New Haven Land Trust to become Gather New Haven—grows crops in a small plot beneath the press’ wind turbines, and Medina founded Peels & Wheels so that they could have free compost processed on site. But Phoenix Press’ owners are selling, and Medina has yet to find a new location.

Medina is not a melancholy man— fist bumps are his preferred farewell gesture—but as he ponders this dilemma, he turns pensive. Expanding the city’s compost systems requires broader concern about food waste. But how do you get people to stop making their garbage someone else’s problem—to stop “pushing the wrinkle,” as Medina puts it?

He takes heart in the fact that he is providing a valuable service for his community. Peels & Wheels started, according to college freshman Noah, as “a notepad with five clients” and “a bunch of little containers all around the house.” Over the last nine years, his dad’s company has kept one hundred and ninety thousand pounds of food waste out of incinerators and created nearly sixteen thousand metric yards of soil-enriching compost.

And it doesn’t hurt that subscribers tend to be effusive in their gratitude.

“I tried [composting with] worms and unfortunately I filled my house with bugs and so Domingo’s service was a godsend when I learned about it,” Virginia Chapman, a Peels & Wheels customer and Director of Yale’s Office of Sustainability, said in an email. “I love the low carbon footprint (the wheels), the garden it was supporting,

and the compost I get back every year for my garden.”

Besides, the job stays interesting. Most of what ends up in the compost bins is fairly standard—chopped vegetables, stale bread, the accidental piece of silverware. But when I ask Medina about the strangest thing he’s seen in a compost bin, he has an answer prepared.

“I honestly thought there was a woman that was trying to compost her husband,” Medina said.

Strands of hair and fingernail clippings started showing up in her compost bin. Then shirts, then trousers.

Medina never saw any human limbs—and, as far as he knows, there were none to be disposed of. But if it weren’t aiding and abetting a murder, he says Peels & Wheels could have composted them.

“We’ll take anything that’s organic… animal or plant-based.” ∎

Points of Departure

Sadie Bograd is a sophomore in Davenport College.

285 Nicoll Street, New Haven CT 06511 203-936-9446 www.mactivity.com Fitness Center 5 TheNewJournal January 2023

Coin-Gate: Who Stole Yale’s Doubloon?

Seventy years ago, five burglars stole nearly one million dollars worth of coins from the Yale Numismatics collection. We still don’t know who they were.

By Lara Yellin

on the night of May 29th, 1965, five masked men broke into Sterling Memorial Library. The thieves hid among the stacks of old books before overtaking the night guards and breaking into the basement vaults. That night, they would carry out four thousand looted coins, weighing about sixty pounds, from the Yale Numismatics collection—one of the most decorated and valuable coin collections in the world. Among their loot, they took Yale’s famed Brasher Doubloon, the first gold coin produced in the United States following independence. Altogether, the stolen artifacts totaled a value of almost one million dollars at the time—the largest robbery New Haven had ever seen. The case remains unsolved.

“The theft was carried out with expert selectivity,” explained James Tanis, the University Librarian at the time, in a June 7, 1965, Yale University News Bureau press release. “Only a limited number of the stolen coins are unique and readily identifiable . . . In some instances, the thieves selected from individual trays only those coins combining high value and potential for undetected sale.”

Only a discerning eye can identify details that make coins more valuable, like their metallic composition and historic origin—the thieves had that eye. The press release also noted that the heist relied upon the “deactivation of burglar alarms and knowledge of the details of the safe keeping of

the collection,” both well-kept secrets of the University Library. The thieves knew what they were looking for, and they knew how to get it.

Complete records of the coins in Yale’s numismatics collection were never made, largely because of the inconsistent means used to acquire them. Yale’s collection was obtained through various donations and gifts made by life-long collectors affiliated with the University, growing to more than one hundred thousand coins over two hundred years. By the time of the heist, only those who routinely handled the collection or assisted with its curation knew its specific contents. The collection’s long-time curator, Theodore V. Buttrey, was one of the only people with the memory and experience required to be able to recount the collection. Just before the heist, however, Buttrey left his curatorial position to become a professor of Greek and Latin at the University of Michigan.

Following the break-in, Sterling Library administrators called Buttrey back to New Haven to identify the missing coins and provide an estimate of their cumulative value. The previously mentioned University press release also outlined these missing objects; the first page, titled “pieces easily identifiable,” contained the descriptions of only seventeen coins. To the untrained eye, the rest of the list read as disorganized and incomprehensible. To numismatists, however, attuned to the differences in composition and origin of the stolen coins, patterns appeared immediately—almost all

of the collection’s American and English gold coins, for example, were stolen. The absence of one particular coin was conspicuous: Yale’s Brasher Doubloon. A 1981 New York Times article described Brasher Doubloons as “known among coin collectors as well as a Rembrandt among art lovers.” Ephraim Brasher, a New York goldsmith, forged only seven of these valuable gold coins in 1787. Brasher’s doubloons were made in the pre-federal period, before the establishment of the Philadelphia mint. Prior to the federal production of money, different types of metals were used to form the same coins, creating disparities in what should have been consistent values. Brasher would assay the coin’s actual value by measuring its weight in gold to ensure a standardized value. Upon completion, he would stamp the coins with his hallmark ‘EB.’ In addition to the

6 January 2023 TheNewJournal

Snapshot

layout design by kevin chen

Only a discerning eye can identify details that make coins more valuable, like their metallic composition and historic origin the thieves had that eye.

coins’ pure composition and EB impression, the elaborate and unique designs covering each doubloon added to their historical and monetary value. The coins circulated in New York following their production, and in 1944, New York’s Holy Trinity Church donated one of the seven coins to Yale’s growing numismatics collection.

Yale’s famous coin was not missing for long. Two years after the 1965 break-in, Richard F. Andrews, an insurance agent specializing in the discovery of lost valuables, recovered the doubloon in Miami. According to a 1982 New York Times article, Andrews was working a different case in Florida when he “came across a trail” that led him to the Doubloon. The same article noted that Andrews “traced [the coin] through underworld figures to a coin collector in Chicago” but maintained that the coin was found in Miami. Andrews refused to provide further information about the coin’s recovery to the Times, adding only that “no money exchanged hands” in return for the doubloon. He only explained that the “investigation of the missing coins is still active—if I reveal any details, it will make the job much more difficult.’”

needed the extra income to help fund the construction of the new Mudd library, leveraging the coin for a $650,000 payout. Following its sale, Yale added that concerns over the security of the Doubloon contributed to the decision

The five men made it out with over seven thousand coins, exceeding a modern value of ten million dollars. Among the loot was one of the other seven existing Brasher Doubloons.

Despite Andrews’ discretion, virtually no progress has been made on the case since 1967. Only one person has been convicted of a crime relating to the heist: John Reisen, an employee of the Chicago-based Columbia Stamp and Coin Company, was found storing sixty-nine of Yale’s missing coins in the company safe. The Yale Daily News reported on the event, emphasizing hope that Reisen’s arrest would lead to further discoveries relating to the heist. No further arrests have been made in the sixty-five years following.

Yale librarians and administration seem to want to leave this dramatic component of their numismatics career in the past. In 1981, Yale decided to sell their recovered Brasher Doubloon despite the energy and expenses invested in its recovery. The University reportedly

Yale’s numismatics collection has continued to grow in prestige and contents, despite its doubloon-less state. Perhaps the University’s eagerness to rid themselves of the Brasher Doubloon reflects their desire to move on from the embarrassment of the heist.

There is no shortage, however, of stories of other numismatic-related crimes. Contrary to the popular perception of coin-collecting as a hobby, drama is rampant in the numismatics community. Just two years after Yale’s break-in, millions of dollars’ worth of coins were stolen from the Miami mansion of Willis H. du Pont, the former Chief Executive Officer of General Motors and a famed numismatist. The mansion’s alarm system reportedly failed to turn on when five masked burglars entered in the night. Du Pont interpreted the thieves’ demand to give them “the money” too literally, and led them to his basement coin collection.

According to another article published by the Professional Coin Grading Service, one of the Miami thieves decided to keep a stolen coin for himself. He happened to select the Brasher Doubloon. For safekeeping, he taped it to his ankle. A few months later, he was admitted to the hospital following a severe beating by his mafioso father-in-law. The nurses attending to him found the doubloon still taped to his leg, recovering a coin worth nearly one million dollars.

Unlike the du Pont robbery, which is well-recorded and well known among coin collectors of varying degrees of seriousness, the infamous Yale Numismatics Collection heist is only infamous among those entrenched in mint madness—a small, but dedicated audience. This is despite the odd similarities in the cases. Even Yale’s undergraduate coin community was largely unaware of the dramatic

7 TheNewJournal January 2023

illustrations by Charlotte Rica From funtopics.com

From The New York Times

An aerial view of the Florida United Numismatics convention floor.

Yale heist, until after the inaugural meeting of the Yale Numismatics Club, formed in 2021 by undergraduate numismatists eager to work more closely with the famed collection.

“A lot of people imagine coin collectors as nerdy kids or really old men,” said Noah Savolainen ’25, a sophomore in Grace Hopper College and co-founder of the Numismatics Club. “And there are a lot of those. But many coin dealers are just successful finance guys or suave high school dealers who sell coins instead of drugs.” Like the Yale heist revealed, the coin world can be equally lucrative and deceptive—traders need insider knowledge and a reputation of integrity within the community.

“I’ve been involved with coin collecting for a very long time, and it’s become a social and professional element of my life, on top of it being a hobby,” said Savolainen. He’s not alone. A few days before Savolainen spoke with me, he had been in Florida at the Florida United Numismatists (FUN) show, which attracts hundreds of dealers and thousands of attendees.

“Coin collecting is a hobby for almost everybody who’s involved with it, and a business for the others,” Savolainen explained. At FUN, Savolainen attended an auction offering coins from the collection of Harry Bass—a millionaire financier and avid numismatist—with sales that totalled $24 million.

know it. Noah said, “The President of [Heritage Auctions] was on the phone speaking with anonymous buyers bidding through the phone. There is a lot of anonymity within the coin world.” He explained that security is a large issue that most collectors, buyers, and sellers often worry about.

the black market or liquified for its component assets, are often the subject of large robberies. What makes this heist so peculiar is its lack of closure.

The auction is a high-energy scene. Objects smaller than an iPhone can pack a room with people willing to spend millions on a single coin. Someone attending their first auction, or perhaps even their first coin show, could be seated next to someone with a world-renowned collection and never

Christian Hartch, a junior at Princeton University and fellow numismatist, reinforced this concern. He and Noah recently visited the New York International Numismatics Conference, where World Numismatics—a collection showing at the event—claimed to have around six figures worth of coins stolen from the show. Hartch said, “There’s always stuff going around, getting stolen.”

But despite this rather dramatic element of the coin world, it is not often talked about or highlighted as a large component of the community culture. In fact, Hartch, who created and runs one of the largest coin-oriented YouTube channels—Treasure Town Coins, with over one hundred thousand subscribers—had not even heard of the Yale heist until he learned of this article.

The heist that occurred at Yale seventy years ago was not rare in that valuable objects, easily used as collateral on

Today, Yale’s numismatics collection is alive and well. In 2001, the continuously growing collection boasting three hundred thousand coins moved into the bright, beautiful Bela Lyon Pratt Gallery of Numismatics in the Yale University Art Gallery. The gallery is composed of two adjacent wood-paneled rooms. The room on the right takes up the valuable real estate of a museum corner room with large, undisrupted windows looking down on Chapel Street. It houses just one large table that sits surrounded by a small library of worn books. The adjacent room of the gallery more resembles a maze of history, housing multiple floor-to-ceiling shelving units tightly packed with foam and leather padding. Despite the romantic and grand atmosphere of the gallery, unlike the glamorous drama of the fine arts community and their million-dollar mysteries, no one wants to talk about the successful collection’s mysterious past. Even the current curators of Yale’s collection—who hold the responsibility of elevating the collection’s profile—declined to comment on the crime. For now, things remain quiet and unsolved in the mystery of the missing coins. No one seems to want to dwell on it. Few even know about it. ∎

8 January 2023 TheNewJournal

Coin-gate: Who stole Yale’s doubloon?

Lara Yellin is a sophomore in Berkeley College.

From news.yale.edu

Like the Yale heist revealed, the coin world can be equally lucrative and deceptive— traders need insider knowledge and a reputation of integrity within the community.

Inside the new Bela Lyon Pratt Gallery of Numismatics.

Brasher doubloon photos courtesy of 2-clicks-coins.com.

“Forgotten Watershed: Writing Russia’s Great War into Modern Jewish Historiography”

Polly Zavadivker is Assistant Professor of History and director of the Program in Jewish Studies at the University of Delaware. She is completing a book project entitled “A Nation of Refugees: World War I and Russia’s Jews” (under contract with Oxford University Press). She is the editor and translator from Russian of The 1915 Diary of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Writer at the Eastern Front (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016). Her articles and essays have appeared in Jewish Social Studies, Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook, and the multi-volume series Russia’s Great War and Revolution. Her next project will be an attempt to place Soviet Jewish writer Vasily Grossman in the canon of European Holocaust writers.

She is completing a book project entitled “A Nation of Refugees: World War I and Russia’s Jews” (under contract with Oxford University Press). She is the editor and translator from Russian of The 1915 Diary of S. An -sky: A Russian Jewish Writer at the Eastern Front (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016). Her articles and essays have appeared in Jewish Social Studies, Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook, and the multi-volume series Russia ’s Great War and Revolution. Her next project will be an attempt to place Soviet Jewish writer Vasily Grossman in the canon of European Holocaust writers .

Judaic Studies Program Jewish History Colloquium presents Dr. Polly Zavadivker

Thursday, March 2, 2023 @ 12:00PM STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRAY JUDAICA COLLECTION READING ROOM (120 High Street, 3rd Floor, Room 335B) For additional information contact Renee Reed at renee.reed@yale.edu

Assistant Professor of History, University of Delaware

The Rise and Fall of the Elm City Express

For a glorious two years, New Haven had a soccer team.

10 Snapshot

TheNewJournal

By Maggie Grether

In the stands of Yale’s Reese Stadium, four drummers pounded out a roiling beat. Their heads bobbed in telepathic communion as the rhythm rolled through a crowd of over three thousand people.

It was August of 2017, and fans had gathered for the championship game of the semi-pro National Premier Soccer League, or NPSL. The final was a showdown between Texas’s Midland Odessa F.C. and the Elm City Express—New Haven’s fledgling team, which had remarkably risen to the league championship in its inaugural year.

The game’s first goal came when Tavoy “Bull” Morgan, Elm City’s fleetfooted top scorer, twisted past three defenders to slot the ball into the corner of the net. Minutes later, Morgan scored again: a mid-air volley with his right foot, which blasted the ball to an impossible space just between the crossbar and the keeper’s outstretched fingers. In celebration, the Bull rammed a defender to the ground and sprinted to the stands with his hands cupped behind his ears to hear the fan commotion. More goals followed—the final score: 5–0, Elm City Express.

The 2017 NPSL championship marked a high in New Haven sports. Over the past century, the city has seen a hockey team, a baseball team, and another soccer team come and go. And by 2019, Elm City had disbanded too, leaving New Haven, once again, without a professional sports team.

But during that 2017 season, a new team and an eager fan base briefly alchemized into something unstoppable. “We started in the cold of February, and we ended up winning it by August,” remembers former right winger Shaquille Saunchez over a phone call last December. “It’s a journey that probably we will never forget.”

An online search for Elm City Express leads you five thousand miles south to the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. The team was owned by the company K2 Soccer North America and its affiliate K2 Soccer South America, which also oversees a Brazilian soccer club. Both companies operate under the Brazilian-based investment outfit Baltoro Group. The reason why K2 Soccer landed in New Haven remains somewhat unknown—but when the company arrived, they found a rich history of soccer in the city.

Josh Nelkin was an Elm City fan and is a former player for the New York

Matches drew in die-hard soccer heads and people new to the game, young kids who dreamed of one day playing under an Elm City jersey and older fans Nelkin recognized from his pickup days, fans from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Even local Arsenal and Liverpool supporters quelled their rivalry to unite behind Elm City.

Ukrainians, an amateur soccer club. He remembers growing up in New Haven in the eighties and nineties among a vibrant and welcoming pickup soccer scene, rooted in the city’s European, Latin American, and African immigrant communities. Nelkin had always wished for a Connecticut soccer team. “A New Haven-based team seemed like a far, far, dream,” he tells me over the phone.

Nelkin’s dream became reality when Elm City arrived in 2017. The team built a roster based on local talent: in addition to a few loan players from K2 Soccer’s Brazilian club, management recruited heavily among soccer alumni from Post University, University of Connecticut, Quinnipiac University, Sacred Heart University, and other Connecticut schools.

“[Elm City] were the unifiers, all

barriers were broken,” Nelkin remembers. Matches drew in die-hard soccer heads and people new to the game, young kids who dreamed of one day playing under an Elm City jersey and older fans Nelkin recognized from his pickup days, fans from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Even local Arsenal and Liverpool supporters quelled their rivalry to unite behind Elm City.

Some of the team’s most loyal fans included participants of Elm City Internationals, a New Haven organization that offers academic and soccer programming to low-income youth, especially immigrants and refugees. Lauren Mednick, the organization’s founder, remembers her students collecting autographs and kicking the ball around with players after matches. Outside of games, a few Elm City players tutored and coached students during their summer academy. Mednick would take students to practically every match, even traveling out of state so kids wouldn’t miss a chance to see their favorite players. “It was really something that they looked forward to, especially our youngest kids at the time. They really idolized the players and got to know the players,” Mednick says, and even over our crackly phone call, I can hear the smile in her voice.

Head coach Ted Haley remembers that the number of fans grew steadily with each game. “It was kind of like the new restaurant that people start to rave about,” Haley says. “We were lucky enough to catch fire.”

According to Haley, the team also had supporters’ groups, or fan clubs, including a group with a New Haven pizza theme. “My kids still sing the songs that they were singing,” he adds.

The pizza song, I discovered, was to the tune of “Seven Nation Army.” Its composers were members of an Elm City supporters’ group known as the Brick Oven Brigade.

I meet Ed Foley, one of the Brigade’s founding members, at The Cannon, a soccer bar on Dwight Street. The Cannon is styled like an English pub and home to the New Haven Gooners, a local fan base of the English Premier League team Arsenal F.C. Behind the bar, amidst a red collage of Arsenal memorabilia, hangs a blue Elm City scarf.

Foley, who is trim with a well-kept goatee, is a regular at The Cannon and a long-time member of the Gooners.

11 TheNewJournal January 2023

Layout design by Kevin Chen & camille chang

Left page, clockwise from top left: Youtube recap of the 2017 NPSL National Championship final match in Jess Dow Field; photo gallery of the match; Elm City Express scarf; once active Facebook supporter’s group, “The Yard Dogs”. Left page: YouTube; National Premier Soccer League; Camille Chang; Facebook

He spins stories expertly, never pausing or backtracking, and his speech is peppered with references to mythology and ancient history I have to look up after we talk. There’s a palpable excitement in his voice as he recalls stories about Elm City.

with the Brazilian management and a lack of enough funding to carry on past the 2018 season.

With fans dispersed among Jess Dow’s bleachers, the games lost their original intimacy.

Foley describes Elm City’s 2017 season as “the halcyon days,” and the games as the “the greatest open mic night in all of New Haven.” He and his friends would sit behind the goal and poke fun at the opposition’s keeper—giving them nicknames or calling them by celebrity look-alikes. He remembers once yelling at the opposing team as they lined up for a defensive corner kick until a defender stopped, turned around, and started laughing. “It was—how would I put it . . . not a hostile atmosphere, but an imposing atmosphere of just we’re gonna laugh at you for like ninety minutes and offer you a beer afterwards,” Foley says.

In the YouTube recap of the finals, after Elm City wins, players and fans melt onto the field in a screaming, jumping mass. Fans shake blue and white scarves while the silver cup gleams overhead.

The Brigade was born when Foley bought a $3.50 Italian flag emblazoned with the word “ PIZZA” off of Amazon. But he objects when I refer to him as a founder of Brick Oven Brigade. “It really wasn’t anything that formal,” he says, “we were just local dummies.”

While Foley has scrubbed Brick Oven Brigade socials off the internet, the now-inactive Facebook of a different supporters’ group lingers as a snapshot of that exciting time in Elm City Express history: The Yard Dogs, named after guard dogs that roam rail yards to protect trains. Their posts are just as aggressive as the group’s name suggests, tearing into their Connecticut rivals, especially Hartford F.C. , and reveling in Elm City’s dizzying rise.

For that 2017 season, Elm City Express had no brakes. They rolled through the regular season with a 9–2–1 record. In the postseason, they glided past their first four opponents, scoring eleven total goals and conceding only one. Suddenly, the team had reached the league championship.

In the YouTube recap of the finals, after Elm City wins, players and fans melt onto the field in a screaming, jumping mass. Fans shake blue and white scarves while the silver cup gleams overhead. Mednick remembers players hoisting one of her students up on their shoulders in the middle of the field. In the back, you can see Foley waving the PIZZA flag.

“It was like the epitome of local team wins,” says Foley. He went to Christy’s, a soccer pub at the time, and partied with players after the game. “It was just a real good night. One of those feelings that you only really get with a semi-professional team.”

Loose summer nights stiffened into a Northeastern autumn, and Elm City entered the off-season. When the team returned in 2018, Nelkin, Haley, Foley, and the players I talked to said the urgency and energy of the first season had dissipated.

First, Elm City lost their home turf. When Reese Stadium underwent renovations in 2018, the team moved to Jess Dow Field at Southern Connecticut State University. Dow Field was twice as large as Reese and less centrally located.

The roster changed, too. According to goalkeeper Matt Jones, nearly all players worked separate jobs to supplement their income, making it difficult to keep players longterm. In the background, rumors floated about conflict

The official announcement that Elm City would not participate in the 2019 season appeared on the team’s Instagram in January. It remains the last post on the account.

There’s no epic trainwreck to mark the end of Elm City Express: just a scattering of gently rusted remains. As I collected bits of the team’s story, I wandered through abandoned social media accounts, old YouTube clips, and corporate websites translated from Portuguese; I learned about the pickup soccer games that used to rule Yale fields and heard strange stories of hundreds of Elm City scarves spontaneously appearing at the local Savers. Slowly, an image began to emerge—one of a team so intimate, so tangible for fans that, for one summer, it became transcendent.

In one telling, the story of Elm City Express ends in a surprising tragedy: a source of joy for New Haveners vanishing with no satisfying explanation. In a different version, Elm City’s demise was inevitable. The very things that made the team special—its smallness, localness, its concentrated fanbase—made it difficult to pull in a wide group of casual viewers, creating a model too insular to survive long-term.

What I can say for sure, is that New Haven had a soccer team. A good one, too. They created something special at Reese stadium. But they’re not here anymore, and the craving for the energy, connection, and purpose Elm City generated for its fans remains. Nearly every fan I talked to expressed a hope that someday Elm City, or a local team like it, could return to the city.

12 January 2023 TheNewJournal

The Rise and Fall of the Elm City Express

From amazon.com

Since the disbandment, some players joined other teams or started coaching, while others moved on to different professions. The players most involved with Elm City Internationals are still in contact with the kids they mentored, usually through FaceTime. Ted Haley remains at Post University. Foley has directed much of his energy back to the New Haven Gooners. He still has the PIZZA flag, however, packed away at his parents’ house.

Foley remembers his time with Elm City as a “weird little bright spot” in his life while he worked a job he didn’t like. For one excellent summer, he slipped into a routine: meeting friends for drinks, going to the game, winning, and then bringing everyone back to the bar to celebrate.

“Knowing the way it ended and how disappointing it would be, I’d still take it,”

he says. “I wouldn’t even say bittersweet, just sweet memories.”

Nelkin hasn’t given up on his dream of a New Haven soccer team. He thinks the Elm City fan base lies dormant, ready to be resurrected at any moment. Yale’s renovated soccer field, set in front of the brick backdrop of Coxe Cage field house, reminds Nelkin of a small English stadium, and he believes that, if Elm City Express came back, they could consistently sell it out. Every time he passes the stadium, he peeks inside and imagines: the stands brimming with New Haven soccer heads, the pitch studded with players in navy shirts, the air filled with chanting, a shrill whistle, and the echo of drums. ∎

13 TheNewJournal January 2023

The Rise and Fall of the Elm City Express

Maggie Grether is a first-year in Ezra Stiles College.

Slowly, an image began to emerge one of a team so intimate, so tangible for fans that, for one summer, it became transcendent.

Top: The last post on the Elm City Express’s Instagram page announced that they would not be competing in the 2019 season of the NPSL. Facebook post and Facebook comment texts were taken from “The Yard Dogs” Facebook group.

Screenshot courtesy of @elmcityexpress on Instagram.

Previously incarcerated Connecticut residents face complicated barriers to receiving their licenses, making it difficult to get to work.

REINTEGRATION ROADBLOCKS

By Ángela S. Pérez Aguilar

14

TheNewJournal

immy Robinson is learning how to use the Uber app in Claire’s Corner Copia. Dressed in a newsboy cap, a pink jacket, and a plaid button-down, he looks at his phone skeptically. His friend Annie Nisenson managed to secure him a $100 voucher for the app, and she leans over his shoulder to show him how to navigate it. Apps like Uber are new to Robinson; in fact, most are new to him. Robinson was serving life without parole before an unexpected pardon culminated with his release in 2021. He recalls the length of his incarceration exactly: forty years, seven months and two hours.

Robinson is used to taking the bus to work each morning. His bus is supposed to come at ten minutes to six. Sometimes the bus comes early, sometimes late, Robinson says. But he tries to make it to the bus stop at a good time for him to arrive at work on time no matter what—he works at EMERGE, an organization that supports clients through a variety of reintegration programs post-incarceration, as a shop manager.

Instead of using tools like the CT Transit app to support him in navigating the bus system, he has learned by memorization and trial-and-error. He knows the phone number to call about bus status, and does so when necessary.

Robinson, however, will soon have no need for the Uber or CT Transit app. In October 2022, he was able to secure his learner’s permit. He’s preparing for his road test so he can finally receive his license.

His license will be a badge of honor, an accomplishment that many people in the process of reintegration struggle to acquire. Connecticut’s most recently available data from the National Institute of Corrections suggests that as of December 31, 2019, 36,475 residents are on probation and 3,651 are under parole. For most of these residents, transportation everything from navigating public transport to securing a license is a major barrier to reintegration.

When Andrew Ramsay began his sentence, it was 1991. When he came back home, it was 2021. Since returning, Ramsay has had to learn how to navigate public transportation in New Haven. Ramsay noted that his family has helped him, but that he initially depended on Uber so as not to “disrupt” their lives. He stopped using Uber because the app’s surge pricing left a dent in his paychecks. Currently, he switches between public transportation and having a friend drive him.

“Everything is all brand new, so it’s like I’m a baby. I’m starting all over again,” Ramsay says. He speaks eloquently about the difficult process of securing the required documents to acquire a license, emphasizing that he keeps faith and patience.

Like Robinson, he is employed at EMERGE, a self-described “self-sufficient social enterprise committed to assisting formerly incarcerated people successfully integrate back into their families and communities.” They have a variety of programs for formerly incarcerated people to get started, including a Transitional Employment Program, peerto-peer group meetings called Real Talk, and a Trauma Informed Men’s Group. In their Transitional Employment Program, participants earn at least $15 an hour, while working up to twenty-four hours a week in construction, landscaping, and property management. The other sixteen hours of the work week are reserved for support programs.

There are six supervisors at EMERGE, all of whom have been through EMERGE’s programs and have experience being formerly incarcerated. EMERGE Executive Director Alden Woodcock calls them “the heart and soul of the organization,” noting their roles teaching crewmembers, communicating with staff, operating equipment, and caring for the organization’s tools, vehicles, and equipment.

On top of the burden of finding a job is finding one accessible through public transportation. With no car and no flexible income to afford ride-share apps or taxis, formerly incarcerated people depend on buses, trains, bicycles, or walking to get to and from work.

In the mornings, participants arrive at EMERGE’s headquarters at 830 Grand Avenue—on a bus line—and from there they split up and drive to different worksites or work from the headquarters. EMERGE supports their participants throughout the process of securing documents, bus passes, and licenses. They helped Ramsay get a bus pass and Robinson secure his permit.

Ramsay found out about EMERGE at a job fair. There were construction hats lined up on a table and some people in discussion around it. He walked over and started up a conversation. “They heard my story and wanted to see better for me and I’ve been there ever since,” Ramsays says. “Everything that I need to really navigate in society EMERGE has helped me to get.”

Ramsay is now one of the supervisors at EMERGE , many of whom drive newer employees to their job assignments. Supervisors that cannot drive stay at the EMERGE building or support in other ways instead. Ramsay sometimes feels “discouraged” because he cannot help the team by driving.

Currently, Ramsay is working on securing his Social Security card in order to apply for a state identification card, and eventually a driver’s license.

Ramsay wakes up around 4 a.m. and starts his day with a prayer before getting ready for it. By 6 a.m., he’s off on the ten-minute walk from his West Haven home to the bus stop. He leaves the house early to give himself time in case the bus is early. Ramsay takes the 265 to the New Haven Green, a ten to fifteen minute ride, and then walks another thirteen minutes to EMERGE’s headquarters. He is a supervisor now, and makes sure to be there before 7 a.m. The total commute takes about forty-five minutes.

If Ramsay had a car, the commute would be about fifteen minutes. But in the year since he was

16 TheNewJournal

Reintegration Roadblocks

released from incarceration, he has been unable to secure a state identification, or a driver’s license.

It can be incredibly difficult to get a job post-incarceration, especially with the increase in national unemployment since the start of the COVID19 pandemic, not to mention the usual obstacles for formerly-incarcerated people—employer prejudice, lack of educational degrees, and a lack of the documentation necessary to be added to someone’s payroll, for example.

The court’s expectation for formerly incarcerated people is to integrate immediately, requiring weekly proof of job searches to be sent to their probation officers, noted Hannah Duncan, the Curtis-Liman fellow at Yale Law School’s Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law. This creates pressure to accept any offer at all—even if the job is far away or has odd hours. Duncan herself has managed clients who commute for hours to get to and from their job.

In the federal system, supervised release or probation can be part of a sentence, and those under these must still report to a probation officer. Violating conditions of their release from custody as part of their probation or supervised release can mean you get sent back to jail full-time employment is often a condition of release from custody, Duncan says. Full-time employment being a condition often leads to accepting the first job offer you get. On top of this, it is immensely frowned upon to reject offers in the face of so many job application rejections.

On top of the burden of finding a job is finding one accessible through public transportation. With no car and no flexible income to afford ride-share apps or taxis, formerly incarcerated people depend on buses, trains, bicycles, or walking to get to and from work.

The New Haven bus system is run by the Connecticut Department of Transportation, and is free to ride for now, as the state legislature recently extended a free bus policy until April. Ramsay describes the bus system as “O.K.” The buses can be inconsistent, so he opts for the walk from the New Haven Green to EMERGE.

Unless people get jobs on a bus line, they need a car. But, for the formerly incarcerated, getting a car is painfully difficult.

The majority of Connecticut residents— more than three fourths drive alone to work, but formerly incarcerated people struggle not only to secure a car, but also a permit, license, and registration.

Much of this struggle boils down to the same thing: applicants need documents that people who

have not been away from home for prolonged periods of time tend not to have. And they cost money to get.

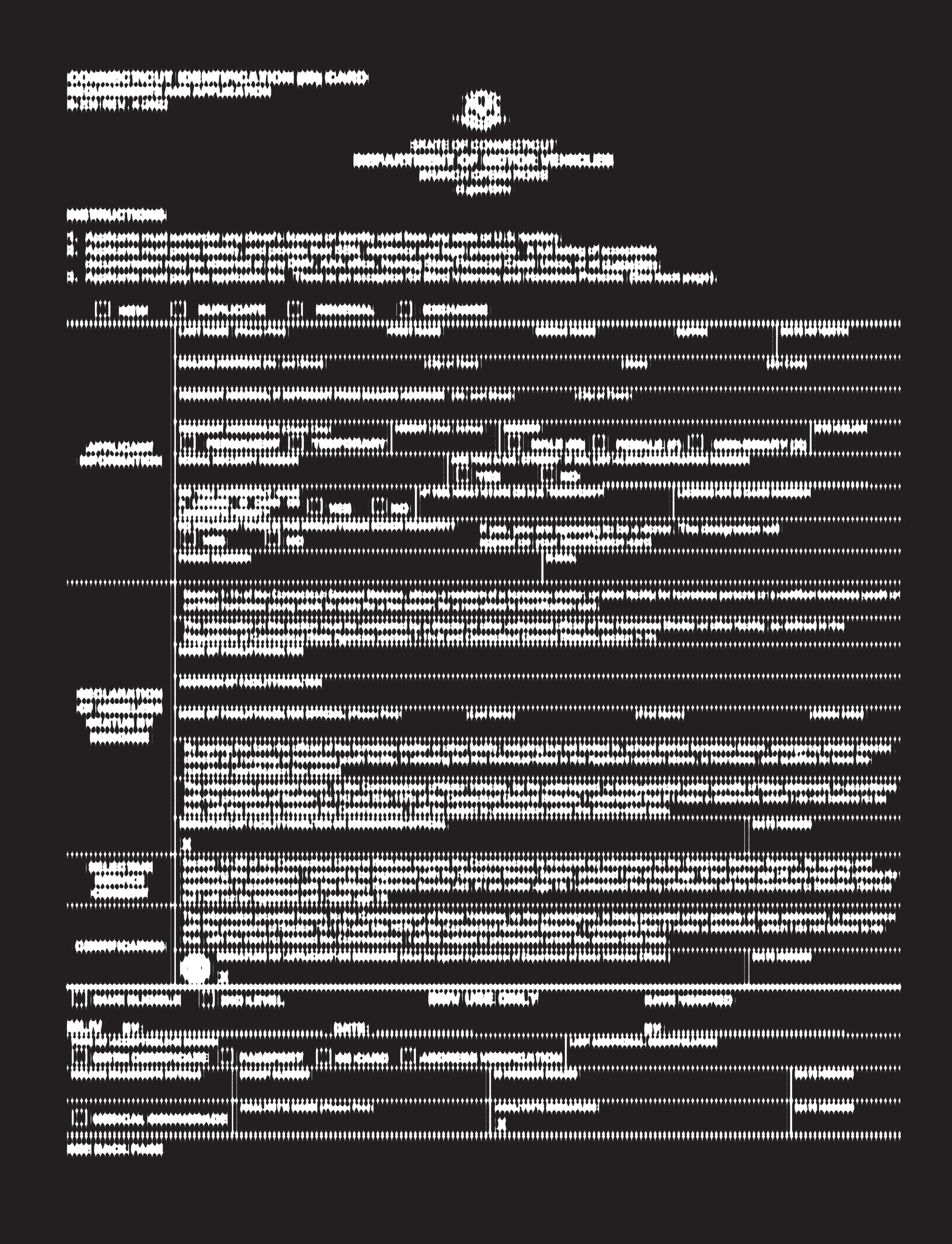

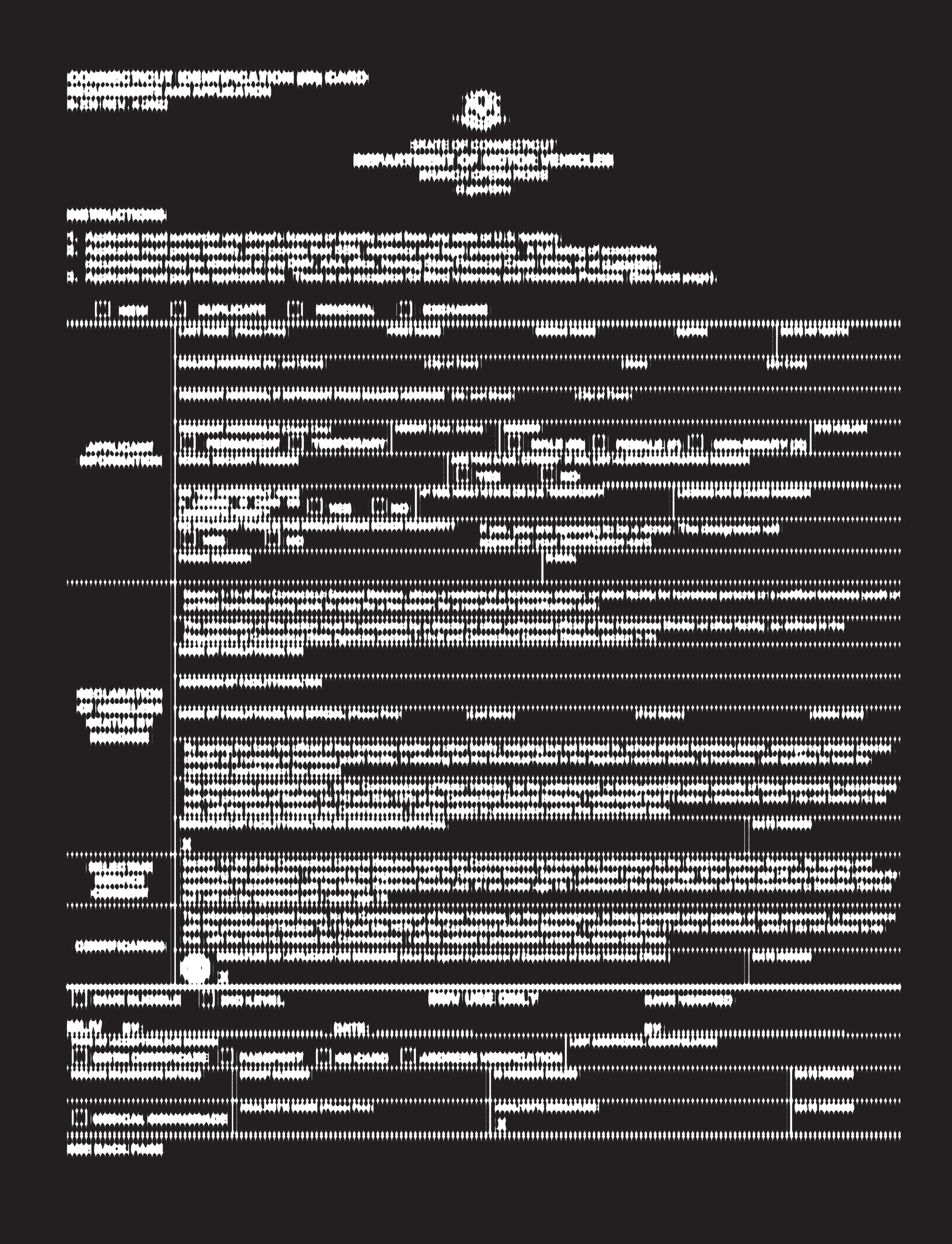

In order to secure an identification from the state of Connecticut, applicants must show three categories of documents: proof of identity, proof of a Social Security number, and proof of Connecticut residency.

Proof of identity should include at least one “primary document.” For U.S.-born citizens, “primary documents” must be a birth certificate or a passport.

Alden Woodcock, EMERGE’s Executive Director, notes that unless a family member saves your Social Security card and birth certificate for you while incarcerated, it is incredibly difficult to secure a state-issued identification card. According to Connecticut 211, a human and social services resource, personal documents obtained during intake or incarceration are stored in “a secure location” at each correctional facility.

Nonetheless, Robinson notes that there is a lot of “poor management” and that his Social Security card was lost during his incarceration.

pay my taxes. I’m working. I’m doing all these things. And to this day, I’m still struggling right now to get my documentation,” Ramsay says. This documentation is not just essential for transportation— identification is often required to apply for housing, banking, and healthcare.

Even if a family member is able to hold onto your documents, this might not be enough, depending on the length of the sentence. Illness, death, and other unprecedented factors can affect whether family or friends have been able to hold onto them the longer the sentence, the older parents and family members get and the more likely illness or death has affected them.

For Ramsay, who is a U.S. citizen but was born in Jamaica, the process of securing a birth certificate was even harder. His mother formerly had his documentation, but she passed away during his sentence and his documents were lost. Ramsay has been making lots of phone calls and sending lots of emails to gather the documents he needs to prove that he is a U.S. citizen.

“I pay my taxes. I’m working. I’m doing all these things. And to this day, I’m still struggling right now to get my documentation,” Ramsay says. This documentation is not just essential for transportation identification is often required to apply for housing, banking, and healthcare.

To request a birth certificate, applicants must go to the town vital records where they were born, the town of their mother’s residence at the time of birth, or the State Vital Records Office. In order to request it, they must fill out an application and mail it, along with a government-issued photo identification, and a payment of $30 per copy.

In Ramsay’s case, he had to contact the Jamaican government and pay for his birth certificate to be sent to Connecticut. So far, this is all he has been able to secure in order to demonstrate proof of identity and citizenship, but is still in need of his Social Security Card.

Alongside a birth certificate as primary documentation, you can show a passport at the DMV

17 January 2023

“I

Reintegration Roadblocks

18

Similar problems occur with this option passports, which expire ten years after being issued, are no longer valid for many leaving incarceration. And to apply for one, applicants must show a birth certificate, proof of identity, and pay the required fees (which consist of a $130 application fee and a $35 “execution fee”).

To get both these pieces of identification, you run into circularities and dead ends. If applicants want to recall a birth certificate, they need an identification. If they want an identification card, they need a birth certificate. But what are applicants meant to do when they are starting over?

The second category of documentation that applicants are required to show at the DMV is proof of Social Security. This can be in the form of a Social Security card, or specific tax forms. Tax forms, however, require consistent employment that not all formerly incarcerated people have. They are also usually given to employees in January to denote the payments of the year before; depending on when they begin work, this could leave applicants up to a year with no identification.

Ramsay still has his Social Security number, but this is not enough for the DMV—they want the physical card. This can be another dead end: in order to request a Social Security card replacement from the Social Security Administration, applicants are asked to show a driver’s license. It’s circular.

Ramsay has been unable to acquire his Social Security card so far. Robinson notes that the pandemic made it more difficult to secure his own card, as he had to make routine calls to explain his situation instead of going to the offices directly and receiving guidance.

For proof of residency, there must be two pieces of mail from two separate senders. This means that people experiencing housing insecurity face additional barriers.

Ramsay is still fighting to get his identification and Social Security card; he has depended on EMERGE’s assistance throughout the process. He gets little help from his probation officer. The State of Connecticut’s Judicial Branch defines the role of probation officers as responsible for providing “intake, assessment, referral, and supervision services to [the] sentenced individual.” This notably includes check-ins to ensure that probationers are making progress in their re-integration. Despite this, Ramsay’s probation officer has told Ramsay that securing his documentation is not within the scope of their work, emphasizing to Ramsay that the officer’s role is to come to Ramsay’s house or office, take

urinalyses, and make sure he has a job.

“It’s easy to say ‘You know what? Eff this.’ and go back to what we know,” Ramsay says. “And that’s where the problem comes in . . . You go through a lot of hurdles, but I just try to stay faithful.”

To secure a license, they have to navigate the plethora of documents and applications to secure their documentation, pay all the required costs, acclimate to life post-incarceration, abide by their probation officer’s requirements, and work towards financial stability in the process. If all of this sounds confusing, that’s because it is.

There are barriers for people post-incarceration who’ve held driver’s licenses in the past, too: incarceration usually implies driver’s license suspension. In order to retain the license, there is a required restoration fee of $175. If there are taxes owed on a vehicle under the applicant’s name, then the taxes or tickets must be paid off, too, before the driver’s license can be restored.

Once those are all paid, driving privileges are restored, meaning it becomes possible to apply for a learner’s permit. Even if someone has formerly held a license, they are required to re-acquire a permit, with the restriction that the holder can only drive when accompanied by someone twenty years or older who has held a license without suspension for more than four consecutive years. After ninety days with a permit, applications must pass a vision test and a twenty-fivequestion knowledge test, and take an eight-hour Safe Driving Practices Course. Failure of the vision or knowledge tests require applicants to reschedule the tests online and pay the fees once again. These include a $40 testing fee (that includes all the tests) and a $19 fee for the learner’s permit itself. The fee for a non-driver state identification is $28. This process can be long and expensive.

Not only are the abundance of fees a barrier to many, testees need to provide their own vehicle for the driver’s exam and potentially miss work for the permit test, Safe Driving Practices Course, and driver’s test. Availability for appointments range from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays, with some available slots on Saturdays.

Robinson had to wait almost a year to get his Social Security card. His documentation was lost during his sentence, although he is not sure why. Through work with the Parole Project in Louisiana, where he was incarcerated, and EMERGE in New Haven, he has managed to secure his Social Security card, birth certificate, and, as of October, his learner’s permit. Following his release, Robinson moved to New Haven to support his mother, with whom he currently lives. He notes that securing a Social Security card was particularly difficult as a result of the pandemic, since he could not go to the offices

19 January 2023

To get both these pieces of identification, you run into circularities and dead ends. If applicants want to recall a birth certificate, they need an identification. If they want an identification card, they need a birth certificate. But what are applicants meant to do when they are starting over?

Reintegration Roadblocks

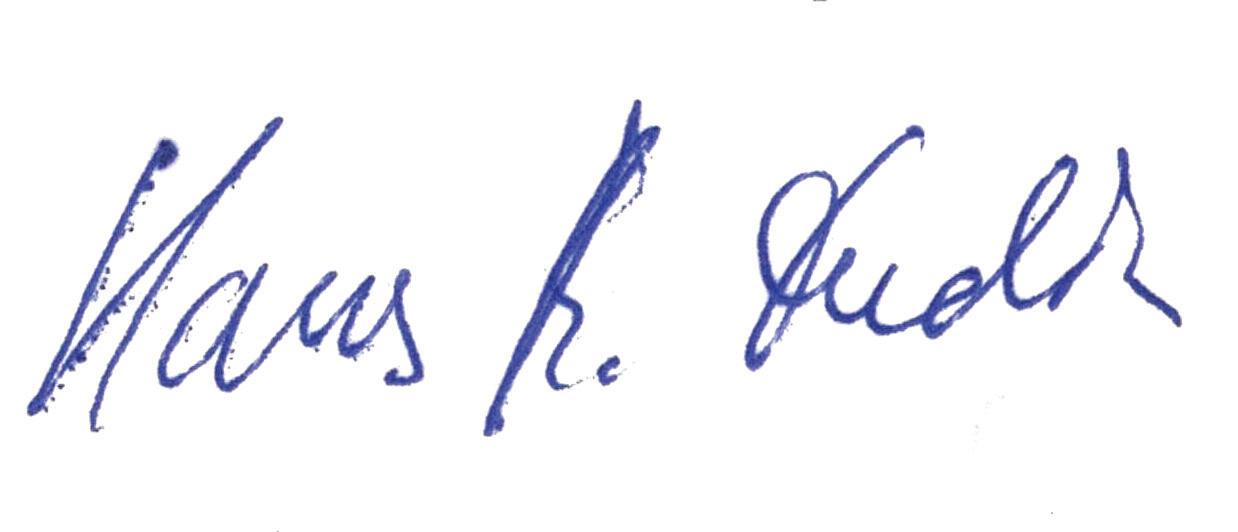

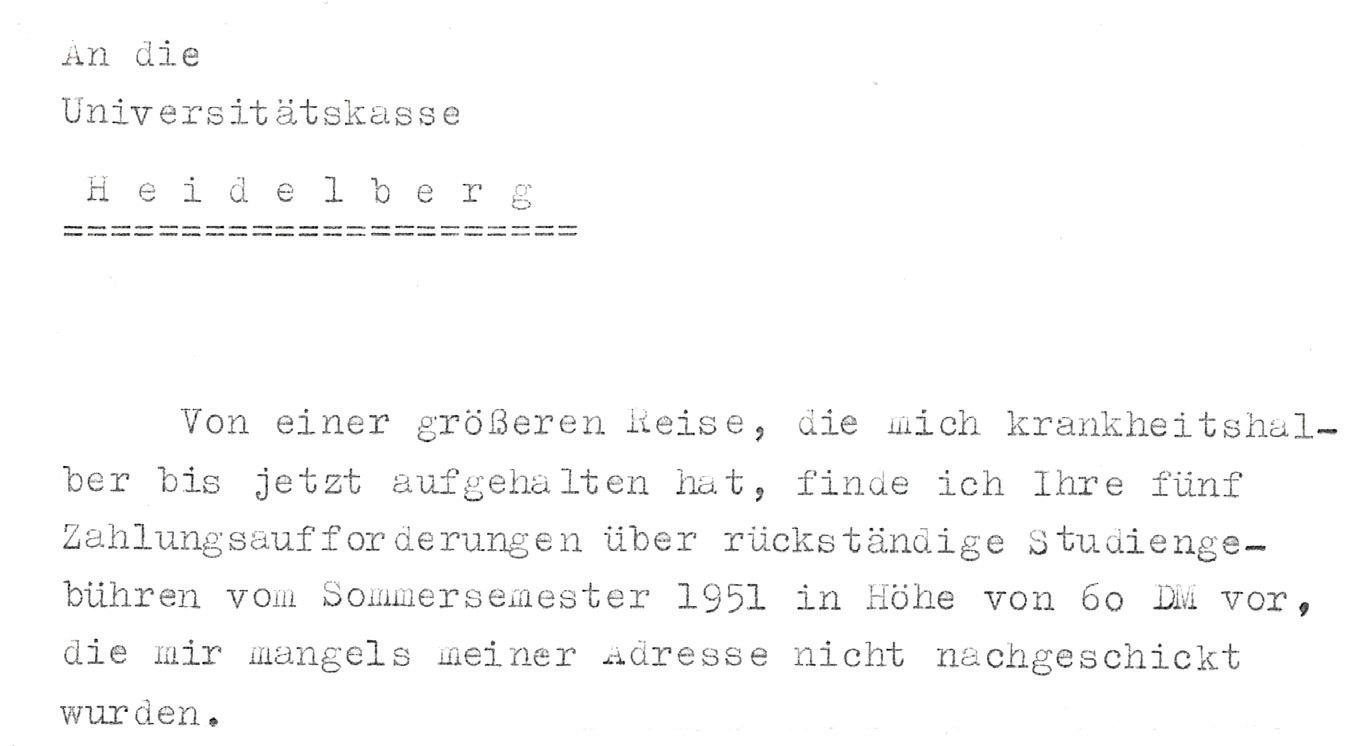

Cover: Connecticut ID application form B-230, courtesy of the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles. Left, top: Social Security card, courtesy of Illinois Wesleyan University; bottom: Connecticut driver’s license, courtesy of the Transportation Security Administration.

and work out what was necessary. Instead, he fielded calls and emails until he was able to secure it.

Robinson had to return on three separate occasions to the DMV before they granted him a learner’s permit. Once, they refused him because the letter he showed did not have a date on it.

“You see so many people,” Robinson says. “They become heartbroken because they go to get their license and many fail time and time again. And it’s like it’s very next door to being impossible.”

In total, fees can amount to about $348, including testing, document copies, restoration fees, and the combined cost of securing both a permit and license. Applicants also have to pay the fees for each attempt if they fail, a burden for those with inconsistent or low-paying work.

“Those are barriers that you have to go through, but you got to go through them because you’re trying to dismiss catching the bus and being to work on time,” Robinson says. “You don’t have a lot of support. You don’t have a lot of help . . . Just trial and error, you know, that’s how you learn the system.”

Robinson finally secured his permit on October 10, 2022, about a year after his release.

“It’s wonderful,” Robinson says. “I’ve gotten a job and through EMERGE and been promoted from a crew member to a shop manager. Now I’m real close to getting my driver’s license . . . And I’m not the only one.”

As a result of this long and difficult process, many people reintegrating post-incarceration drive without a license, according to Liman Fellow and lawyer Hannah Duncan. Throughout her work in public interest law, she has been informed of cases where individuals violate parole, probation, or supervised release in order to drive out of necessity.

“It’s just so much easier,” Woodcock, EMERGE’s Executive Director, says. “Your chances of being pulled over are pretty slim, but if you do get pulled over without a license, and you’re on parole, you can get violated and sent back to jail. So that’s the risk that you run.”

The problem does not end once a license is secured. Now comes the process of buying and registering a car.

Getting a car alone is a costly process. In the last two years, used-car prices have increased dramatically used car prices are currently 43 percent higher nationally than the typical depreciation rates. Additionally, securing a loan to pay for a car is significantly harder for someone with both a criminal history and little to no credit history.

In order to register a car, identification in the form of a driver’s license or passport must be provided, along with proof of ownership in the form of a title or former owner registration. If the vehicle is

from another state, there are different requirements.

The DMV also requires proof of Connecticut car insurance and a Bill of Sale, a document with vehicle, buyer, and seller information, as well as the selling price and date of the vehicle. These can be drafted independently as long as they include all the necessary information. Car insurance in Connecticut can cost upwards of $800 per car, but drivers with a driving record or violation are charged more sometimes upwards of $2,000. Despite car insurance being mandatory in most states, companies can still deny applicants due to many factors, including credit history, type of vehicle, financial history and driving record.

The DMV charges fees for car registration, in addition to the insurance required for registration. To register a regular passenger car, the fees total $225.

Ramsay notes that a license may seem like “a small thing, but it’s a big thing at the end of the day.” He echoes that the difficulty of the process can be inhibiting to many who are trying to reintegrate.

“You see so many people,” Robinson says. “They become heartbroken because they go to get their license and many fail time and time again. And it’s like it’s very next door to being impossible.”

While only 10 percent of Connecticut residents are Black and 15 percent are Hispanic, 40 percent of incarcerated people in Connecticut are Black and 25 percent of them are Hispanic. As a result, these re-entry costs largely impact people of color disproportionately.

Things like state identifications and driver’s licenses are determined by state and federal requirements, meaning local government has little bearing on these requirements. New Haven’s main contribution to people reintegrating is through workarounds to getting a driver’s license: the public transit system and continued development of bike lanes. In summer of 2022, New Haven announced its Safe Routes for All Plan, which hopes to move away from a city transportation system that is based around cars, by enhancing the infrastructure of biking, walking, and public transit in the city.

Woodcock, EMERGE’s Executive Director, notes that most formerly incarcerated people he is aware of through EMERGE take public transportation or depend on others for car rides, while a smaller amount bike or walk.

Ramsay continues to gather the necessary documents to get his permit soon. Robinson will soon be scheduling his first attempt at his road test since passing the written test for a driver’s license.

“If you don’t have this documentation, [it’s easy to] go back to what you know,” Ramsay says. “But that wasn’t my case. I said, ‘You know what? I’m just gonna still take it one day at a time.’” ∎

20

TheNewJournal Reintegration Roadblocks

Ángela S. Pérez Aguilar is a junior in Berkeley College.

Dr. Ashley Walters

Romancing the Russian Revolution: Anna Strunsky, William English Walling, and the Red Wedding

Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies and Director of the Pearlstine/ Lipov Center for Southern Jewish Culture at the College of Charleston. Her research interests include American and East European Jewish history, Jews and American culture, the history of leftist political movements, and Jews in the American South. She is currently working on a book manuscript titled, Intimate Radicals: East European Jewish Women and Progressive American Desires. She is also co-editing and contributing to a volume titled, Reframing Jewish American Literary History through Women’s Writing.

21 january 2023 TheNewJournal

“

Colloquium

” Judaic Studies Program Jewish History

presents

April 12, 2023 @ 12:00PM STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRAY JUDAICA COLLECTION READING ROOM (120 High Street, 3rd Floor, Room

For additional information contact Renee Reed at renee.reed@yale.edu

Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies, College of Charleston

Wednesday,

335B)

Ashley Walters is an

2023001289 PRESORT PBPS004 <B>

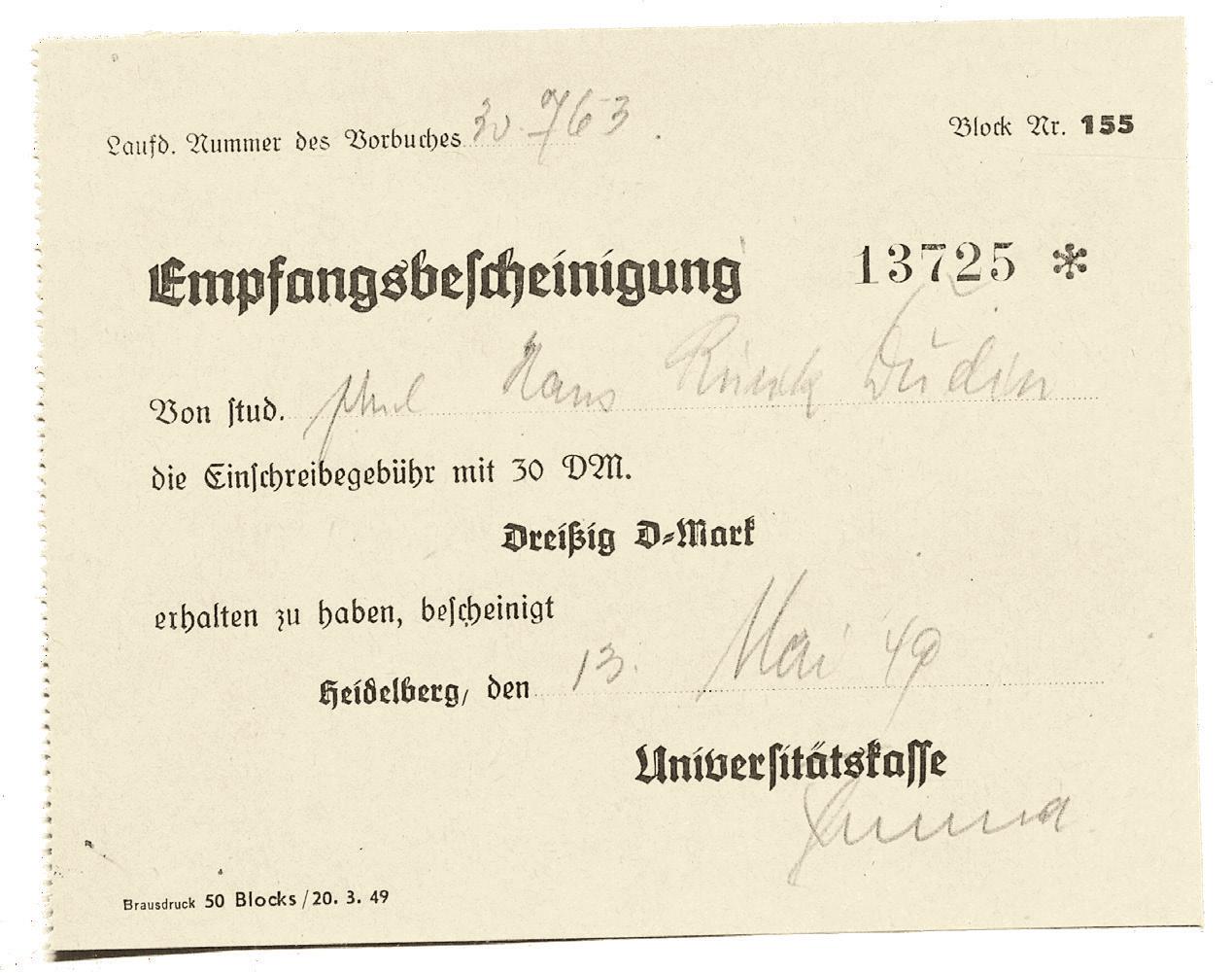

PATIENT NAME PLEASE DETACH AND RETURN THIS PORTION WITH YOUR PAYMENT OR PROVIDE INSURANCE INFORMATION ON THE REVERSE SIDE SEE REVERSE SIDE FOR INSURANCE INFORMATION OR FOR INSTRUCTIONS TO PAY YOUR BILL ONLINE. KEEP THIS PORTION FOR YOUR RECORDS Calls to and from our Customer Care Department may be monitored and recorded for training and quality assurance purposes. FEDERAL TAX ID: 58-1036407 FEDERAL TAX ID: 58-1036407 Page 23 of 56 ACCOUNT NO. TRIP NO. INVOICE DATE SERVICE TO SERVICE FROM DATE OF SERVICE PAY YOUR BILL ONLINE AT: www.myemsaccount.com The New Journal

Four students asked to be referred to by their first initial due to discomfort speaking publicly about their experiences consuming alcohol.

Will Caraccio ’25 was getting ready for bed one night in October, 2022, when he got a text that his friend and former roommate, Kyle Hovannesian ’25, was drunk. Really drunk.

The news was alarming, but not totally surprising. Will and Kyle had been roommates throughout their first year. Halloween night was the first time Kyle needed an ambulance. Will came home around one in the morning to find vomit all over the room, a third of a handle of vodka gone, and Kyle, nearly unresponsive, unable to walk by himself––all the warning signs of a potential overdose he was taught to look for in Yale’s safety training. “The first time I saw it, I was terrified. I was like, this kid is going to die,” Will said. “It’s kind of traumatizing.”

That night, Will followed protocol. He called 911, listened for sirens, and talked with the paramedics as they loaded Kyle into the back of the ambulance. Will passed it off as a typical “Welcome to Yale” moment, a rite of passage nearly all college first years experience. But the situation repeated itself; once, and then again. Will kept calling for help, listening for the ambulance to pull up outside the gates of Old Campus, watching the paramedics wheel his friend out on a gurney.

As harrowing as the ambulance trips and overnight hospitalizations may have been for Kyle, both he and Will remember the problems really starting after Kyle left the hospital. Kyle would get a bill from the ambulance company that promised to suck up all the money he’d been saving up from his student job at––of all places––Yale Health. It meant signing up for more shifts at work, calculating how much credit he could afford to spend, and cutting down on expenses, just to afford the following semester’s tuition. “I’m thinking, ‘there goes my entire savings,’” Kyle said. “[It] kind of starts a chain reaction that takes over my life.” Eventually, Kyle learned calling an ambulance was virtually out of the question.

“His life could be in jeopardy, or at least his health could be in jeopardy, whether or not it kills him. But at the same time he’s begging me, pleading with me not to call,” Will said. “So I don’t know what to do. I genuinely think if I were to call the ambulance every time he would have dropped out.”

So when Will got that text in October of 2022, he knew the drill. It turned out a scared friend who worried for Kyle’s safety had already called 911, and an ambulance was on the way. Will sprang into action. “What I did essentially was to say, ‘I know you don’t want to go in the ambulance.

You need to put on a really good performance for me,’” he said.

Will led Kyle to bed and turned off the lights. When the paramedics showed up, he lied and told them Kyle was fine; he was in bed, sleeping it off. When they demanded to see him anyway, Will told them to wait. He crept into the room and tried to prepare Kyle as best he could. He knew that the paramedics would ask Kyle some questions; he’d seen it enough times before to get the gist: Where are you? How old are you? How much money is seven quarters? Kyle, for his part, was terrified. He wouldn’t remember anything from that night, except this encounter with the paramedics. He knew if he failed to convince them he was okay, they would make him go to the hospital, and he’d get slammed with another bill. “I was telling myself, ‘O.K., sit up straight, speak slow, clear, annunciate’ It was very high pressure,” Kyle said. Both played their part well. With Will’s help, and the calming influence of the darkened room, they managed to persuade the paramedics to leave.

Representatives at Yale Health and the Yale Dean’s Office have told me they haven’t heard that ambulance bills present an obstacle to seeking medical attention, or have claimed outright that they do not. But students appear to disagree. Over the last six months, I spoke with twenty-one current and recently-graduated Yale students about experiences in which they personally hesitated to call for an ambulance, or witnessed someone hesitating to call one. Some of them had taken an ambulance trip at Yale already, and preferred to risk their health rather than experience it again. Others had heard what it would cost them or their friends, and figured it was safer to handle the situation on their own. These students spoke of other concerns that contributed to their hesitation, but one factor was far and away the most common and significant: the bill.

He knew if he failed to convince them he was okay, they would make him go to the hospital, and he’d get slammed with another bill. “I was telling myself, ‘O.K., sit up straight, speak slow, clear, annunciate’ . . . It was very high pressure,” Kyle said.

“I remember my friend was really drunk and really sick and was being wheeled out to the people that came with the stretchers,” said K. “And she was asking me, ‘Am I going to have to pay for this?’...That’s not something that you should be thinking about if you’re in that state.”

The dilemma of whether to call an ambulance during a true emergency, these students told me, is a threat to students’ mental and physical well-being, as well as their financial security. Many of these students claim that Yale has not meaningfully addressed or acknowledged the issue, leading them to doubt whether the University is upholding its fundamental responsibility to ensure the safety of its students.

DISCLAIMER SECTION 1

Page 24 of 56 THE COST TO RIDE

The New Journal

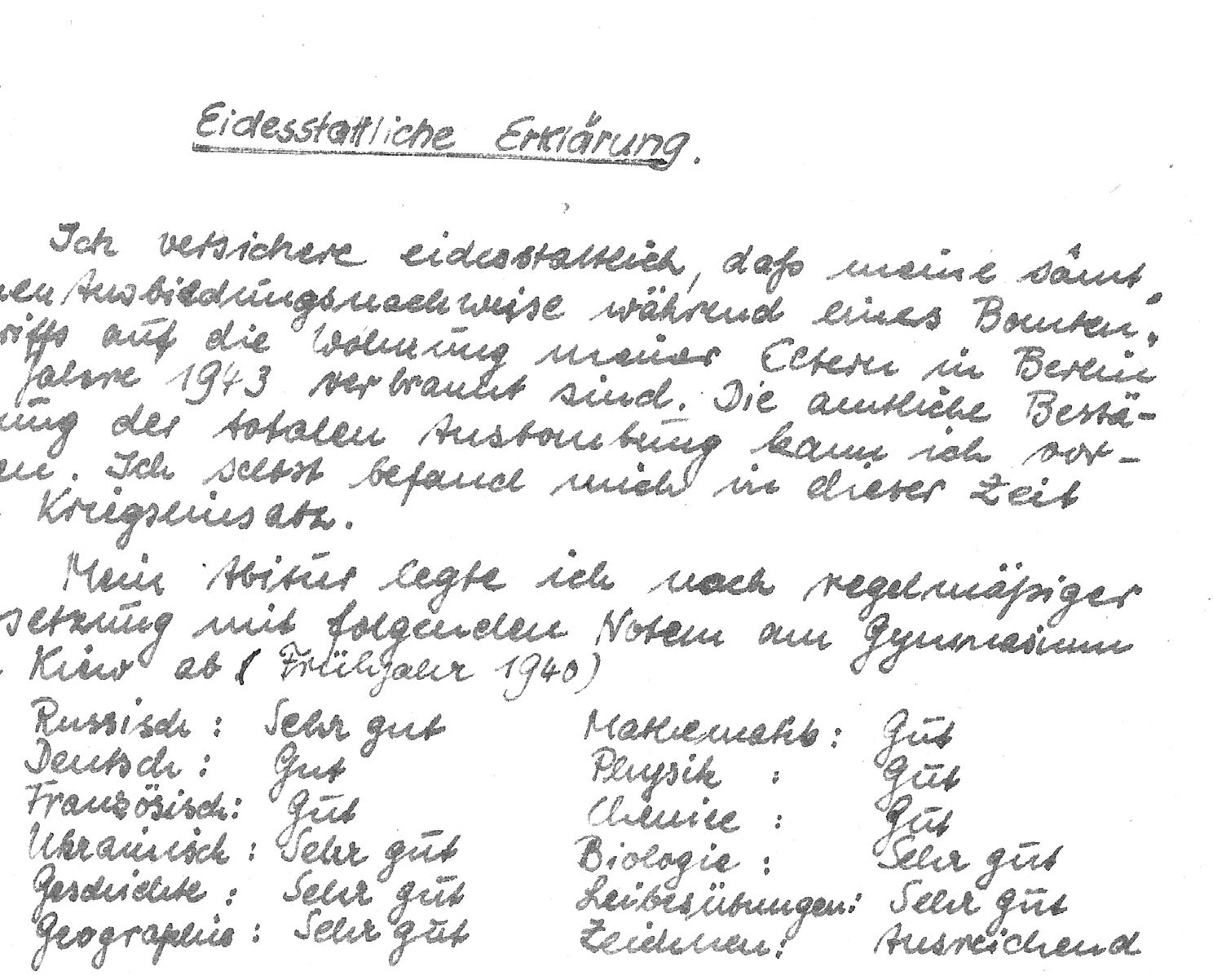

Anna Tender was biking by the Peabody museum on Whitney Street when she fell off her bike and broke her wrist. A passerby noticed Anna laying on the ground, her skin flush pale, her hand sticking out in entirely the wrong direction, and decided to call an ambulance. But Anna was a junior, and by that time she’d heard a lot of stories from people who’d had to go to the hospital for alcohol emergencies. She knew what she might have to pay for it. “While I was laying there with my wrist broken, I was like, ‘can you please not call 911?’” Anna said. “I just really did not want to pay for an ambulance ride.” When the ambulance showed up, Anna declined to get in, signing the refusal of service waiver with her nondominant hand. She took a seat by the Peabody, and waited fifteen minutes for a friend to come pick her up and drive her to the emergency room. “Thinking back on it, it’s wild that that was the thing that I was really worried about.”

Page 25 of 56 THE COST TO RIDE The New Journal

Outside the Yale New Haven Hospital emergency room.

“If you talk to any student, they’d agree that [ambulances] should be free,” Kyle told me. “And Yale knows it’s a problem, how could they not?...I’m sure they realize this is putting a financial burden on students. They’d just rather put the burden on me than pay for it themselves.

Most administrators I reached out to declined or did not respond to requests for comment regarding the problems these twenty-one students described. Of the few administrators from whom I was able to obtain statements, none expressed prior awareness of the full scope of the issue.

THE ADMINISTRATION

“I think there definitely is a hesitation to call ambulances around here because of the prohibitive cost . . . I would say that probably everyone at Yale, specifically people at Yale who tend to go to events with alcohol or parties, probably knows someone who’s had to pay for an ambulance.”

ANNA TENDER ’23

When I was a first year, I learned quickly from friends and upperclassmen not to call an ambulance unless the situation was seriously life-threatening. It was part of my informal induction process to Yale, alongside how to sneak into the dining hall, or cram for my L1 final. In my experience as an undergraduate, Yale students who don’t hear the warning at first hear it eventually, and students who don’t hear it early enough often learn through painful experience.

“I think that’s something that was drilled into me. Never call an ambulance because you will be charged like $1000 I think it’s just like common knowledge,” said R.

High-ranking administrators at Yale, however, appear not to know this unwritten rule among Yale students. Dr. Jennifer McCarthy, Chief Medical Officer of Yale Health, told me she’d never looked into it. “Until you reached out to me, I hadn’t really thought of [cost] as an issue that would preclude people from calling,” she told me.

Shaun Heffernon, a prominent member of the Board of Advisors for Yale Emergency Medical Services (YEMS), and EMT instructor at Yale, said that, to his knowledge, worry about ambulance fees has never put a student at physical risk, nor have there been any internal discussions at YEMS about the problem of ambulance billing.

I reached out to many members of the Dean’s Office, including all fourteen residential college deans, Dean of Yale College Pericles Lewis, and Marichal Gentry, former Dean of Student Affairs and one of the founders of Yale’s Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Initiative (AODHRI, pronounced “Audrey”). All either didn’t respond to requests for comment or