TRINITY

VOLUME 9

ISSUE I

J OURNAL OF L ITERARY T RANSLATION

Volume 9 Issue I: “Prophecy”

T

he desire to know one’s destiny is common to all men, in every age and every corner of the planet, and perhaps it is even more so now during these uncertain and extraordinary times (I am afraid I needed to insert a reference to the COVID-19 pandemic at some point, hence better sooner than later!). The oracular practice, that is, the custom of seeking answers from the higher powers as regards to one’s fate, is as old as time, dating to an almost mythical past. In Greek and Roman civilizations, prophecies exerted a prominent influence, to the point that, in both the private and the public sphere, no extraordinary decision was made unless the divine’s message was undoubtedly one of approval. And this is where trouble first occurs. In antiquity, communication between gods and mortals needed to be mediated by the Sibyl, the high priestess who, mystically possessed by the divine spirit, translated the deities’ will to the besecheers. It sounds easy, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, the oracles were always offered in rather obscure and ambiguous terms, thus needing further interpretation. This is just additional proof of a very important lesson: the act of translation is never straightforward. Significantly, Umberto Eco affirmed that

2

Evelyn De Morgan, Cassandra, (1898)

'translation is the Art of Failure', in the sense that, since it is the peculiarity of language that every language is a carrier of culture and identity in its own way, it follows that the translator's job is not merely that of capturing the essential literary meaning of the source text, but most importantly that of 'making intelligible a whole culture', to borrow another iconic definition by Anthony Burgess. Our cover art pays tribute to Apollo, god of prophecy (among other things), with bleeding, hollow eyes, in Oedipus-like fashion, to remark this ineffability of vision. Nevertheless, we like to think that we have provided a good response, and indeed, in this volume you will find the theme of Prophecy as it has been portrayed across time and space through the lens of different languages and, by extension, of different societies. I want to conclude by thanking my editorial team for their precious work, as well as all contributors who have made this issue so special: we would not be here without you. The response to our call for submissions around this editorial theme has been positively overwhelming, we have received a massive input of high-quality material which has made the selection process quite challenging. That said, I could not be prouder to officially introduce you to the winter's issue of the Trinity Journal of Literary Translation.

Martina Giambanco

Editorial Staff 2020/21 Editor-in-Chief Martina Giambanco Deputy Editor Margherita Galli Art Editor Liadan RuaidhrĂ Stockman

Assistant Editors Cameron Hill Constance Quinlan Cian Dunne Faculty Advisor Dr Peter Arnds

3

Table of Contents The Harbinger photograph by Alexander Fay

5

Cassandra is dreaming artwork by Aifric Doherty

6

Divination photograph by Alexander Fay

7

Finding my way photograph by Alexander Fay

7

Agamemnon (1214-1241) Ancient Greek-English translation by Matthew Wainwright 8 Cassandra POV Edvard Munch artwork by Aifric Doherty

10

Zeno’s Conscience Italian-English translation by Francesca Corsetti

12

I Will Be a Sky photograph by Alexander Fay

15

The Second Coming English-Irish translation by Áine Mills Aphorisms on Futurism English-Mandarin translation by Bowen Wang Jacques the Fatalist and his Master French-English translation by Holly Ronayne The Prophetess (Fragments) Czech-English translation by Štěpán Krejčí

4

16

18

24

26

Reverie artwork by Evvie Kyrozi

30

Fear and Loathing under lockdown (Ralph Steadman knew) artwork by Aifric Doherty

31

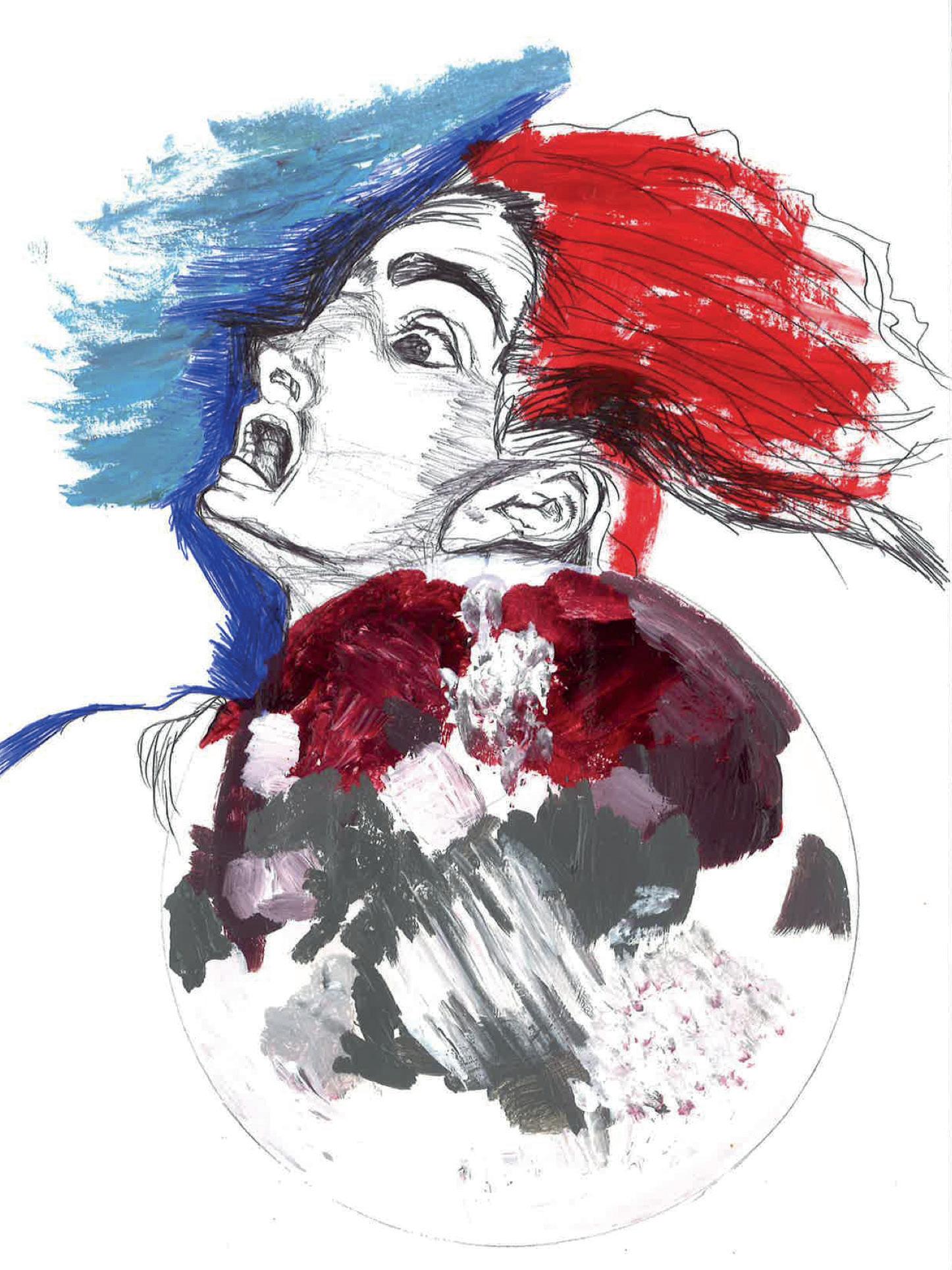

Witchspay (35-45) Old Norse-English translation by Ioannis Stavroulakis Mirror, Mirror English-Arabic translation by Maeve Lane and Dr. Tylor Brand Pen-Soeur artwork by Penny Stuart Autumn Song Spanish-English translation by Christian Cowper Cassandra is screaming artwork by Aifric Doherty The Old Tortoise’s Parable Portuguese-English translation by Michael McCaffrey As a Tense Image Italian-English translation by Andrea Bergantino The Amber Spyglass English-Irish translation by Aislinn Ní Dhomhnaill Prophecy French-English translation by Rebecca Notari

32

36 37

38 40 42

46

48

54

El Porvenir artwork by Andres Murillo

56

Molly's Window artwork by Penny Stuart

57

Laurus Russian-English translation by Dana Bagirova

58

It Can’t Happen Here English-Irish translation by Tadhg McTiernan

64

Le Cannet's Head artwork by Penny Stuart Before the Storm English-Polish translation by Magdalena Kleszczewska

Nightmare prophecy in white artwork by Ellecia Vaughan

68

Nightmare prophecy in red artwork by Ellecia Vaughan

69

Notes on Contributors

70

66 68

Alexander Fay, The Harbinger 5

Aifric Doherty, Cassandra is dreaming

6

Alexander Fay, Finding my way

Alexander Fay, Divination

7

ANCIENT GREEK

Aγαμέμνων (1214-1241) by Aeschylus

This passage is from Agamemnon, the first play in the Oresteia trilogy. Here, Cassandra predicts Agamemnon’s death by Clytemnestra and Ægisthus. Cassandra, a Trojan princess and

Κασάνδρα ἰοὺ ἰού, ὢ ὢ κακά. ὑπ’ αὖ με δεινὸς ὀρθομαντείας πόνος στροβεῖ ταράσσων φροιμίοις ..... ὁρᾶτε τούσδε τοὺς δόμοις ἐφημένους νέους, ὀνείρων προσφερεῖς μορφώμασιν; παῖδες θανόντες ὡσπερεὶ πρὸς τῶν φίλων, χεῖρας κρεῶν πλήθοντες οἰκείας βορᾶς· σὺν ἐντέροις τε σπλάγχν’, ἐποίκτιστον γέμος, πρέπουσ’ ἔχοντες, ὧν πατὴρ ἐγεύσατο. ἐκ τῶνδε ποινάς φημι βουλεύειν τινά, λέοντ’ ἄναλκιν, ἐν λέχει στρωφώμενον οἰκουρόν, οἴμοι, τῷ μολόντι δεσπότῃ— ἐμῷ· φέρειν γὰρ χρὴ τὸ δούλιον ζυγόν· νεῶν τ’ ἄπαρχος Ἰλίου τ’ ἀναστάτης οὐκ οἶδεν οἵα γλῶσσα, μισητῆς κυνὸς λείξασα κἀκτείνασα φαιδρὸν οὖς δίκην, ἄτης λαθραίου τεύξεται κακῇ τύχῃ.

8

ENGLISH priestess of Apollo, had the curse that she could give true prophecies which would never be believed: a natural choice for the theme of prophecy.

Agamemnon (1214-1241) translated by Matthew Wainwright

Cassandra Agh! Agh! What evils! Once again the terrible pain of accurate prophecy Spins me about, troubling me with its...introductions. Do you see them there, sitting in their homes, Youthful, like dreams in their appearance? Like children slaughtered by loved ones, Hands full of the homely food – their flesh, Clearly holding their entrails and innards, A most pitiful burden that their father savoured. For that deed, I tell you, a lion plots his revenge, Impotent, lying in his bed, A housebound coward – Oh no! – for the returning master: My master, since I must bear the yoke of slavery. The Leader of men and Troy’s Bane, He does not know what will come to evil fruition By the hateful bitch, whose tongue licked his hand, Who stretched her ears in gladness, in the manner of Skulking Ruin.

9

ANCIENT GREEK

τοιάδε τόλμα· θῆλυς ἄρσενος φονεύς· ἔστιν—τί νιν καλοῦσα δυσφιλὲς δάκος τύχοιμ’ ἄν; ἀμφίσβαιναν, ἢ Σκύλλαν τινὰ οἰκοῦσαν ἐν πέτραισι, ναυτίλων βλάβην, 1235 † θύουσαν Ἅιδου μητέρ’ † ἄσπονδόν τ’ Ἄρη φίλοις πνέουσαν; ὡς δ’ ἐπωλολύξατο ἡ παντότολμος, ὥσπερ ἐν μάχης τροπῇ. δοκεῖ δὲ χαίρειν νοστίμῳ σωτηρίᾳ. καὶ τῶνδ’ ὅμοιον εἴ τι μὴ πείθω· τί γάρ; 1240 τὸ μέλλον ἥξει. καὶ σύ μ’ ἐν τάχει παρὼν ἄγαν γ’ ἀληθόμαντιν οἰκτίρας ἐρεῖς.

Aifric Doherty, Cassandra POV Edvard Munch 10

ENGLISH Such courage she has as a woman, to be the murderer Of a man! What dreadful monster should I call Her? A serpent? Or some Scylla Residing among the rocks, a menace for sailors, Seething mother of Hades, blowing relentless War At her husband? How the utterly shameless woman Shouted for joy, like at the turn of battle, And seems to rejoice at his returning safety. It matters not whether I can persuade him: What’s the point? What will come will come. Soon you here now Shall also pity me and call me the Oracle of Truth.

11

ITALIAN

La coscienza di Zeno by Italo Svevo

La Coscienza di Zeno, published in 1923, is a novel about the main character Zeno’s ineptitude. Here, Zeno concludes that life itself is the real disease, and his pessimism reaches its climax with the

La vita somiglia un poco alla malattia come procede per crisi e lisi ed ha i giornalieri miglioramenti e peggioramenti. A differenza delle altre malattie la vita è sempre mortale. Non sopporta cure. Sarebbe come voler turare i buchi che abbiamo nel corpo credendoli delle ferite. Morremmo strangolati non appena curati. La vita attuale è inquinata alle radici. L’uomo s’è messo al posto degli alberi e delle bestie ed ha inquinata l’aria, ha impedito il libero spazio. Può avvenire di peggio. Il triste e attivo animale potrebbe scoprire e mettere al proprio servizio delle altre forze. V’è una minaccia di questo genere in aria. Ne seguirà una grande ricchezza...nel numero degli uomini. Ogni metro quadrato sarà occupato da un uomo. Chi ci guarirà dalla mancanza di aria e di spazio? Solamente al pensarci soffoco! Ma non è questo, non è questo soltanto. Qualunque sforzo di darci la salute è vano. Questa non può appartenere che alla bestia che conosce un solo progresso, quello del proprio organismo. Allorché la rondinella comprese che per essa non c’era altra possibile vita fuori dell’emigrazione, essa ingrossò il muscolo che muove le sue ali e che divenne la parte più considerevole del suo organismo. La talpa s’interrò e tutto il suo corpo si conformò al suo bisogno. Il cavallo s’ingrandì e trasformò il suo piede. Di alcuni animali non sappiamo il progresso, ma ci sarà stato e non avrà mai leso la loro salute. Ma l’occhialuto uomo, invece, inventa gli ordigni fuori del suo corpo e se c’è stata salute e nobiltà in chi li inventò, quasi sempre manca in chi li usa. Gli ordigni si comperano, si vendono e si rubano e l’uomo diventa sempre più furbo e più debole. 12

ENGLISH dramatic solution he proposes. The catastrophic ending of the novel might also be defined prophetic, as it foretells the invention of the atomic weapon, or the more dystopian doomsday device.

Zeno’s Conscience translated by Francesca Corsetti

Life looks like sickness as it proceeds by crises and lysis, and has daily improvements and worsenings. Unlike other diseases, life is always fatal. It cannot bear treatments. It would be like filling the holes we have in the body, believing them to be wounds. We would die strangled the moment we are healed. The present life is corrupt from its roots. Man has put himself in place of trees and beasts and has polluted the air, and impeded free space. Worse it might be. The wretched but active animal might discover other forces and put them at his own service. There is a threat of this kind in the air. A great wealth will follow‌in the number of men. Each square metre will be filled by men. Who will heal us from the lack of air and space? The mere thought makes me suffocate! But it is not this, not merely this. Any effort to give us health is vain. This cannot belong but to the beast that knows only one progress: the one of its organism. Once the swallow realised that there was no other way out than migration, it developed the muscle that moves its wings, and which became the most sizable part of its body. The mole buried itself, and the whole of its body adapted to its need. The horse enlarged itself and modified its foot. Some animals’ progress is unknown, but there must have been one which has not damaged their health. Yet, the bespectacled man devises contraptions out of his body and if there was any health or nobleness in those who invented them, it is almost always missing in those who use them. Those devices can be bought, sold, and stolen, and man becomes increasingly cunning and weak. Actually, you can tell that their shrewdness grows proportionately to their weakness.

13

ITALIAN I primi suoi ordigni parevano prolungazioni del suo braccio e non potevano essere efficaci che per la forza dello stesso, ma, oramai, l’ordigno non ha più alcuna relazione con l’arto. Ed è l’ordigno che crea la malattia con l’abbandono della legge che fu su tutta la terra la creatrice. La legge del più forte sparì e perdemmo la selezione salutare. Altro che psico-analisi ci vorrebbe: sotto la legge del possessore del maggior numero di ordigni prospereranno malattie e ammalati. Forse traverso una catastrofe inaudita prodotta dagli ordigni ritorneremo alla salute. Quando i gas velenosi non basteranno più, un uomo fatto come tutti gli altri, nel segreto di una stanza di questo mondo, inventerà un esplosivo incomparabile, in confronto al quale gli esplosivi attualmente esistenti saranno considerati quali innocui giocattoli. Ed un altro uomo fatto anche lui come tutti gli altri, ma degli altri un po’ più ammalato, ruberà tale esplosivo e s’arrampicherà al centro della terra per porlo nel punto ove il suo effetto potrà essere il massimo. Ci sarà un’esplosione enorme che nessuno udrà e la terra ritornata alla forma di nebulosa errerà nei cieli priva di parassiti e di malattie.

14

ENGLISH His first contraptions appeared as extensions of his arm and could not be efficient but for its own strength; yet, at this stage, the device has no connection with the limb. And it is the same contraption that creates the disease, abandoning the law that created all the Earth. The survival of the fittest disappeared, and we lost natural selection. Far more than psychoanalysis would be necessary: diseases and patients will flourish under the law of the possessor of the highest number of contraptions. Perhaps, through an inconceivable catastrophe generated by these devices we would restore our health. When poison gases would suffice no longer, a man just like any other, in the secrecy of a room of this world, will invent an unequalled explosive, compared to which all the explosives available nowadays will be considered as innocuous toys. And another man, just like any other as well, but even sicker than the others, will steal that explosive and climb up to the centre of the world to place it where its outcome may be maximum. There will be a colossal explosion which no one will hear, and the Earth, once back to its state of nebula, will wander in the skies deprived of parasites and diseases.

Alexander Fay, I Will Be a Sky 15

ENGLISH

The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats

One hundred years on from its first appearance in print, Yeats’ poem reminds us of the cyclical nature of chaos. Things fall apart.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. Surely some revelation is at hand; Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

16

IRISH

Anarchy reigns. We anxiously await the dawn of an impending and as-of-yet somewhat ambiguous new era as it lumbers towards us.

An tAteacht translated by Áine Mills

Ag casadh ’s ag casadh sa ghirfeacht leathnaithe Ní féidir leis an seabhac an seabhcóir a chloisteáil; Titeann rudaí as a chéile; ní sheasann an lár; Scaoiltear an ainrialtacht lom leis an domhan, Scaoiltear an taoide doiléirithe ag an bhfuil, agus chuile áit Báitear searmanas na soineantachta; Easpa diongbháilteachta sa chuid is fearr, agus an chuid is measa Lán den dúdhiongbháilteacht. Ní féidir é ach go bhfuil nochtadh éigin chugainn; Ní féidir é ach go bhfuil an tAteacht chugainn. An tAteacht! Ar éigean na focail sin amuigh Sula ngoilleann ollíomhá as Spiritus Mundi Ar mo radharc: áit éigin i ngaineamh an fhásaigh Cruth ar a bhfuil corp leoin agus ceann fir, Stánadh chomh folamh agus míthrócaireach leis an ngrian, A chuid leasracha malla á mbogadh aige, agus mórthimpeall air Scáileanna éin dhiomúcha an fhásaigh ag rothlú. Titeann an dorchadas an athuair; ach tá a fhios agam anois Gur chorraigh cliabhán ag luascadh Fiche céad de chodladh gan chorraí ina thromluí, Agus cén t-onchú, a ionú aige faoi dheireadh, A thagann go malltriallach go Beithil lena bhreith?

17

ENGLISH

Aphorisms on Futurism by Mina Loy

Painter-poet Mina Loy published this futurist manifesto in photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work. Here, her clairvoyant writing not only addresses the visions

DIE in the Past Live in the Future. THE velocity of velocities arrives in starting. IN pressing the material to derive its essence, matter becomes deformed. AND form hurtling against itself is thrown beyond the synopsis of vision. THE straight line and the circle are the parents of design, form the basis of art; there is no limit to their coherent variability. LOVE the hideous in order to find the sublime core of it. OPEN your arms to the dilapidated; rehabilitate them. YOU prefer to observe the past on which your eyes are already opened. BUT the Future is only dark from outside. Leap into it—and it EXPLODES with Light. FORGET that you live in houses, that you may live in yourself— FOR the smallest people live in the greatest houses.

18

MANDARIN

of Dada/Feminism and Futurism, but conceives of a future predicted in a futurist manner, and conceptualises an epistemology for the chaos and disorder of a postwar world.

未来主义格言

translated by Bowen Wang

死于过去, 生向未来。

速度已开始加速。

在挤压材料以获取其本质时,物质将发生变形。 且形式冲破自身, 超越了视觉的界限。

那直线和圆是设计的“父母” ,是艺术的基石; 它们的协调可变性永不 受限。 喜欢丑陋之物,去发现它的崇高内核。

张开双臂向失意者敞开怀抱; 修复他们的身心。 你偏爱观察过去, 目光止于当下。

但未来只是外表漆黑, 纵身跃入——它将迎着光芒爆发。

忘却你所居的房子吧, 忘却栖身于内的自己—— 因为最小的人住在最大的房子里。

19

ENGLISH BUT the smallest person, potentially, is as great as the Universe. WHAT can you know of expansion, who limit yourselves to compromise? HITHERTO the great man has achieved greatness by keeping the people small. BUT in the Future, by inspiring the people to expand to their fullest capacity, the great man proportionately must be tremendous—a God. LOVE of others is the appreciation of oneself. MAY your egotism be so gigantic that you comprise mankind in your self-sympathy. THE Future is limitless—the past a trail of insidious reactions. LIFE is only limited by our prejudices. Destroy them, and you cease to be at the mercy of yourself. TIME is the dispersion of intensiveness. THE Futurist can live a thousand years in one poem. HE can compress every aesthetic principle in one line. THE mind is a magician bound by assimilations; let him loose and the smallest idea conceived in freedom will suffice to negate the wisdom of all forefathers. LOOKING on the past you arrive at “Yes,” but before you can act upon it you have already arrived at “No.”

20

但是最小的人也可以像宇宙一样浩瀚无垠。

MANDARIN

何为扩张,你知几许?谁又在迫使你去妥协? 迄今为止,当权者皆以人民的渺小来实现自己的霸业。 但在未来,只有激励民众实现自身的最大价值,才能成就上帝般的 伟业。 爱及他者,是对自己的欣赏。

愿你的中心自我强大异常,以至在自我同情中包容人类。 未来是无限的——而过去只是一串不良反应。

生命只会受限于我们的偏见。打破它,你将不会再受自我摆布。 时间是分散了的力量。

未来主义者可以在诗歌中活至千年。

他可以将所有的美学原理化为一句诗。

思维是受同化束缚的魔法师;让它放松些,在自由中创造出的最微 小的想法也足以胜过所有前人的智慧。 留恋过去,你会止于自我“肯定”的成就。但未付诸实践之前,你永 远 一“无”所有。

21

ENGLISH THE Futurist must leap from affirmative to affirmative, ignoring intermittent negations—must spring from stepping-stone to stone of creative exploration; without slipping back into the turbid stream of accepted facts. THERE are no excrescences on the absolute, to which man may pin his faith. TODAY is the crisis in consciousness. CONSCIOUSNESS cannot spontaneously accept or reject new forms, as offered by creative genius; it is the new form, for however great a period of time it may remain a mere irritant—that molds consciousness to the necessary amplitude for holding it. CONSCIOUSNESS has no climax. LET the Universe flow into your consciousness, there is no limit to its capacity, nothing that it shall not re-create. UNSCREW your capability of absorption and grasp the elements of Life—Whole. MISERY is in the disintegration of Joy; Intellect, of Intuition; Acceptance, of Inspiration. CEASE to build up your personality with the ejections of irrelevant minds. NOT to be a cipher in your ambient, But to color your ambient with your preferences. NOT to accept experience at its face value.

22

MANDARIN

未来主义者必须从一个明确的立场跳到另一个,忽略不断的否 定——必须从垫脚石站上创造性探索的基石,而避免身陷既定事实 的乱流。 在这里,人不可将自己的信念寄托在绝对之上。 今天是意识的危机。

意识不能自发地接受或拒绝那些天才般创造的新形式;无论多长时 间内,新形式只能作为一种刺激物,使意识获得进行反应时所需的 能量。 意识没有高潮。

让宇宙流入你的意识中,它无穷无尽,可以重现一切。 释放你的吸收能力并把握住整个生命的要素。 痛苦是快乐的解体; 智性是直觉的解体; 认同是启蒙的解体。

停下用无关的思维去构建自己的个性。 不要随波逐流, 而是成为周遭的主宰。

不要单凭其表面价值吸收经验。

23

FRENCH

Jacques le Fataliste et son maître

The following is an excerpt from a late 18th century philosophical novel regarding the philosophy of determinism or fatalism - the idea that what the future holds is

by Denis Diderot Jacques ne connaissait ni le nom de vice, ni le nom de vertu ; il prétendait qu’on était heureusement ou malheureusement né. Quand il entendait prononcer les mots récompenses ou châtiments, il haussait les épaules. Selon lui la récompense était l’encouragement des bons ; le châtiment, l’effroi des méchants. « Qu’est-ce autre chose, disait-il, s’il n’y a point de liberté, et que notre destinée soit écrite là-haut ? » Il croyait qu’un homme s’acheminait aussi nécessairement à la gloire ou à l’ignominie, qu’une boule qui aurait la conscience d’elle-même suit la pente d’une montagne ; et que, si l’enchaînement des causes et des effets qui forment la vie d’un homme depuis le premier instant de sa naissance jusqu’à son dernier soupir nous était connu, nous resterions convaincus qu’il n’a fait que ce qu’il était nécessaire de faire. Je l’ai plusieurs fois contredit, mais sans avantage et sans fruit. En effet, que répliquer à celui qui vous dit : « Quelle que soit la somme des éléments dont je suis composé, je suis un ; or, une cause n’a qu’un effet ; j’ai toujours été une cause une ; je n’ai donc jamais eu qu’un effet à produire ; ma durée n’est donc qu’une suite d’effets nécessaires. » C’est ainsi que Jacques raisonnait d’après son capitaine. La distinction d’un monde physique et d’un monde moral lui semblait vide de sens. Son capitaine lui avait fourré dans la tête toutes ces opinions qu’il avait puisées, lui, dans son Spinoza qu’il savait par cœur. D’après ce système, on pourrait imaginer que Jacques ne se réjouissait, ne s’affligeait de rien ; cela n’était pourtant pas vrai. Il se conduisait à peu près comme vous et moi. Il remerciait son bienfaiteur, pour qu’il lui fît encore du bien. Il se mettait en colère contre I’homme injuste ; et quand on lui objectait qu’il ressemblait alors au chien qui mord la pierre qui l’a frappé : « Nenni, disait-il, la pierre mordue par le chien ne se corrige pas ; l’homme injuste est modifié par le bâton. » Souvent il était inconséquent comme vous et moi, et sujet à oublier ses principes, excepté dans quelques circonstances où sa philosophie le dominait évidemment ; c’était alors qu’il disait : « Il fallait que cela, car cela était écrit là-haut. »

24

ENGLISH predetermined and due to sequences of cause and effect. The novel has been likened to Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy for its meandering and comic narration style.

Jacques the Fatalist and his Master translated by Holly Ronayne

Jacques knew neither the name of vice nor of virtue; he claimed that a person was fortunately or unfortunately born. Upon hearing spoken the words reward or retribution, he shrugged his shoulders. According to him, reward was the encouragement of the good; retribution, the wrath of the wicked. “Moreover”, he would say, “our destiny is written in the heavens, and so we have no freedom”. He believed that, by necessity, a man was brought to glory or disgrace, just as a self-aware ball follows the slope of a mountain; and that, if one knew of the link of cause and effect that shapes man’s life from birth to final breath, one would remain convinced that he did simply what was necessary to do. I have contradicted it many times before, but to no avail. Indeed, what to reply to he who tells you: “regardless of the sum of my parts, I am an individual being. However, each cause has but one effect. I have always been but one cause, hence I have never had but one effect to produce; my life therefore is simply a series of necessary effects.” It is in this manner that Jacques reasoned with his captain. The distinction between a physical world and a moral world seemed senseless to him. It was his captain that had filled his head with all these opinions that he had drawn from the Spinoza that he knew by heart. Following this system, one can imagine that Jacques neither rejoiced nor despaired of anything; not so. He behaved rather like you and I. He thanked his benefactor, so that he would still do good. He became angered at the iniquitous man; and when slighted he became like the dog that bites the stone that struck him: “Nay”, said he, “the stone bitten by the dog cannot be corrected; the unjust man is corrected by the baton”. Like anyone, he was often inconsistent, and inclined to forget his principles, except in certain circumstances when his philosophy evidently dominated him; it was then that he would say: “It had to be, for it was written in the heavens.” 25

CZECH

Věštkyně (úlomky) by Karel Jaromír Erben Když oko vaše slzou se zaleje, když na vás těžký padne čas, tehda přináším větvici naděje, tu se můj věští ozve hlas. Nechtějte vážiti lehce řeči mojí, z nebeť přichází věští duch; zákon nezbytný ve všem světě stojí a vše tu svůj zaplatí dluh. Řeka si hledá konce svého v moři, plamen se k nebi temeni; co země stvoří, sama zase zboří: avšak nic nejde v zmaření. Jisté a pevné jsou osudu kroky, co má se státi, stane se; a co den jeden v své pochová toky, druhý zas na svět vynese. — Viděla jsem muže na Bělině vodě, praotce slavných vojvodů, an za svým pluhem po dědině chodě, vzdělával země úrodu. Tu přišli poslové od valného sněmu, a knížetem jest oráč zván, oblekli oděv zlatoskvoucí jemu, a nedoorán zůstal lán. 26

“Prophetess” is the last poem in K.J. Erben’s collection Kytice (The Bouquet) published in 1853.

ENGLISH

The poem’s lines are spoken by the legendary Czech prophet “Libuše” and include motifs from Czech mythology.

The Prophetess (Fragments) translated by Štěpán Krejčí

When the tears start flowing to your eyes, when you’re hit by times severe, the one who then carries the hope is I, my prophesying voice sounds near. Be wary of taking my words lightly, a forecasting spirit descends on you; all the world’s governed by laws not altered lightly, everything finally pays its due. The river in the ocean is searching for its reason, heavenward climbs the burning flame, what earth has born she buries the next season: nought goes to waste nor stays the same. Firm and unfaltering is fortune’s every step, that which should happen, happen will: what sinks away with one day’s swathing ebb, returns in another’s flowing spill. — I saw a man where water meets the meadow, Noble dukes’ father in his toil, roaming the hamlet in his old plough’s shadow, reaping the fruit of our land’s soil. Now messengers came from council’s chamber, Addressing the ploughman as their prince, they dressed him in robes of gold and splendour, The field unfurrowed ever since. 27

CZECH Položil rádlo a propustil voly: „Odkud jste vyšli, jděte zpět!" a své bodadlo zarazil tu v poli, aby pučilo v list i květ. Pojala voly nedaleká hora podnes ji značí vody rmut; a suchá holi lískovice kora vydala trojí bujný prut. A pruty vzkvětly a ovoce nesly: leč dospěl jenom jich jeden; druhé dva zvadly a ze stromu klesly, nevzkřísivše se po ten den. Slyšte a vězte - nejsouť marné hlasy, vložte je pilně na paměť: nastane doba, přijdou zase časy, kdež obživne i mrtvá sněť. Obě ty větve v ušlechtilém květu vzmohou se šíře, široce a nenadále ku podivu světu přinesou blahé ovoce. Tu přijde kníže ve zlatě a nachu, aby zaplatil starý dluh, a vyndá na svět ze smetí a prachu Přemyslův zavržený pluh. A z duté hory ven povolá voly i zase k pluhu přiděje a zanedbanou doorá tu roli a zlatým zrnem zaseje. I vzejde setí, jaře bude kvésti, bujně se zaskví zlatý klas: a s ním i vzejde země této štěstí a stará sláva vstane zas. 28

ENGLISH He dropped the plough and set the oxen free: “From whence you came now depart!” and into the earth he thrust his chiseled beam so that a blossom may spring from its heart. The oxen were captured by a nearby mountain — until this day marked by water’s tears; the abandoned tool like nature’s grandest fountain spurted three twigs like three lush spears. And the twigs bloomed and bore fruitful crown: Yet only one reached adulthood’s reign; The others wilted and from the tree fell down, Never to spring again. Hear and believe - fruitless are not these voices, place them carefully in your trust: a time is coming, new age’s prognosis, that restores even the deadest rust. Both of those branches in the noblest of blooms will rise again as broad as can be and at once to the world’s wondering swoon Excellent fruit they will bring to thee. Then a prince will arrive dressed in lilac and gold, to repay the debt of past, from dust of the earth he’ll raise a thing old Přemysl’s plough which aside had been cast. And from the hollow mountain he’ll recall the ox to harness the beast in plough again the neglected field, he’ll rid of the rocks and plant it with his golden grain. The seeds will grow in the warm sun of spring, the golden crop will amply shine: and happiness to this land it lastly will bring, rise will the glory of fathers thine. 29

Evvie Kyrozi, Reverie 30

Aifric Doherty, Fear and Loathing under lockdown (Ralph Steadman knew) 31

OLD NORSE

VÖLUSPÁ (35-45) by Anonymous Hapt sá hon liggja undir hvera lundi lægjarnlíki Loka áþekkjan; þar sitr Sigyn þeygi um sínum ver vel glýjuð. Vituð ér enn eða hvat?

Sal sá hon standa sólu fjarri Náströndu á, norðr horfa dyrr; féllu eitrdropar inn um ljóra, sá er undinn salr orma hryggjum.

Á fellr austan um eitrdala söxum ok sverðum, Slíðr heitir sú.

Sá hon þar vaða þunga strauma menn meinsvara ok morðvarga ok þanns annars glepr eyrarúnu; þar saug Níðhöggr nái framgengna, sleit vargr vera. Vituð ér enn eða hvat?

Stóð fyr norðan á Niðavöllum salr ór gulli Sindra ættar; en annarr stóð á Ókólni, bjórsalr jötuns, en sá Brímir heitir.

32

Völuspá is part of the Poetic Edda, an anonymous collection of poems that form the principal text of Scandinavian -especially Icelandicmythology and poetry. Völuspá is the prophecy of the

ENGLISH magical seeress, that recounts key events in the history of everything: from the beginning when there was nothing, to the apocalyptic doom of the gods, and the subsequent rebirth of the world.

She saw a prisoner lying in Cauldron-grove similar to the appearance of Loki the fraud-yearning; Sigyn sits there, apropos her man ill-gleeful. wit ye more or what? A stream falls from the east across dales of atter, with scissors and swords: it’s called Grimness. To the north stood, at the Nomoon flats, a hall of gold of the dynasty of Dwarfs, another at Noncoldi stood, the beer-hall of the giant, that Surfy is called.

WITCHSPAY (35-45) translated by Ioannis Stavroulakis A hall she saw stand far from the sun on Corpsebeach, the doors face north; atter-drops fell from the louver, that hall’s wound with worm-spines. She saw there wading the heavy streams perjurers, murder-wolves one steals the girl of the other; there Hate-chop sucked corpses that’re gone, the wolf tore men. wit ye more or what?

33

OLD NORSE

34

Austr sat in aldna í Járnviði ok fœddi þar Fenris kindir; verðr af þeim öllum einna nökkurr tungls tjúgari í trolls hami.

Gól um ásum Gullinkambi, sá vekr hölða at Herjaföðrs; en annarr gelr fyr jörð neðan sótrauðr hani at sölum Heljar.

Fyllisk fjörvi feigra manna, rýðr ragna sjöt rauðum dreyra; svört verða sólskin um sumur eptir, veðr öll válynd. Vituð ér enn eða hvat?

Geyr Garmr mjök fyr Gnípahelli; festr man slitna, en freki renna. Fjöld veit hon frœða, fram sé ek lengra, um ragnarök römm sigtíva.

Sat þar á haugi ok sló hörpu gýgjar hirðir glaðr Egðir; gól um hánum í gaglviði fagrrauðr hani, sá er Fjalarr heitir.

Brœðr munu berjask ok at bönum verðask, munu systrungar sifjum spilla; hart er í heimi, hórdómr mikill, skeggjöld, skálmöld, skildir ’ru klofnir, vindöld, vargöld, áðr veröld steypisk; man engi maðr öðrum þyrma.

ENGLISH

In the east sat the old one in Iron-wood she raised there Fenrir’s brood; of all of these one becomes, with appearance of a troll, a moon-thief. He fills himself with the life-force of near-dead men, reddens the gods’ house with wound-blood red; sunshine becomes black the summer thereafter, and dangerous all storms become. wit ye more or what? There on the mound sat and struck the harp the Giantess-herder, glad Weapon-jack; and in the Geesewood above him the fair-reddish rooster crew, Fjalarr he’s called.

Above the gods Goldencomb crew, it wakes the healths at Host-father’s; also crows under the earth the catawba-red rooster, at Hell’s halls. Garm howls a great deal by Gnipcave; the fetters will break, and the wolf will run. plenty of lore does she know, I see longer, about the Divines’ strong doom, of the wargods. Brothers each other will fight and become banes, the children of sisters will kinship spoil; it’s tough in this world, much harlotry; halberd-age, seax-age, asunder are shields, wind-age, wolf-age, until the world falls;

35

ENGLISH

Mirror, Mirror By Spike Milligan

A young spring-tender girl combed her joyous hair ‘You are very ugly’ said the mirror. But, on her lips hung a smile of dove-secret loveliness, for only that morning had not the blind boy said, ‘You are beautiful’?

36

Milligan presents two different conceptions of beauty: aesthetic and inner beauty. The author suggests that while the young girl’s own reflection is not in her own eyes aesthetically

ARABIC beautiful, the prophetic declaration of a blind boy that she is beautiful is more important. Thus, Milligan implies that beauty is only skin-deep, and that inner beauty is what really matters.

مرآة،مرآة translated by maeve lane and dr. tylor brand مشطت فتا ٌة حنونة شعرهاً فرحان ِ .“قال إليها املرآة “انت بشعة ، و لكن علق عىل شفتها رس َة يف جاملتها ّ بسمة ِلنَ قال إليها الفتى املكفوف يف صباح اليوم ِ ”انت عيوين”؟

Penny Stuart, Pen - soeur 37

SPANISH

Canción Otoñal by Federico García Lorca

38

'Canción Otoñal' was first published in 1921's Book of Poems (Libro de Poemas), Federico García Lorca's second collection.

Hoy siento en el corazón un vago temblor de estrellas pero mi senda se pierde en el alma de la niebla. La luz me troncha las alas y el dolor de mi tristeza va mojando los recuerdos en la fuente de la idea.

¿Se deshelará la nieve cuando la muerte nos lleva? ¿O después habrá otra nieve y otras rosas más perfectas?

Todas las rosas son blancas, tan blancas como mi pena, y no son las rosas blancas que ha nevado sobre ellas. Antes tuvieron el iris. También sobre el alma nieva. La nieve del alma tiene copos de besos y escenas que se hundieron en la sombra o en la luz del que las piensa. la nieve cae de las rosas pero la del alma queda, y la garra de los años hace un sudario con ella.

¿Y si el amor nos engaña? ¿Quién la vida nos alienta si el crepúsculo nos hunde en la verdadera ciencia del Bien que quizá no exista y del Mal que late cerca? Si la esperanza se apaga y la Babel se comienza, ¿qué antorcha iluminará los caminos en la Tierra?

¿Será la paz con nosotros como Cristo nos enseña? ¿O nunca será posible la solución del problema?

ENGLISH

Like much of Lorca's work, it lives in the gap between poem and song, its meter highly rhythmic compared to contemporary poetry in English. Today I feel upon my heartstrings a vague trembling of stars but I find my way is lost in a soul of mist and fog. The light tramples on my wings and the pain I call my sadness makes wet and cold my mem’ries in a fountain of ideas. The roses all are white so white just like my sickness but the roses are not white from the snow that lies atop them. Before they wore a rainbow. Snow falls also on the soul. And the snow-white souls have flakes of kisses and have stages that have sunk into the shadows or the light of he who thought them. The snow falls from the roses but stays still where the soul dwells as the clawing of the years makes with it a veil.

Autumn Song translated by Christian Cowper Will the snow not melt and thaw when death’s hand comes to claim us? Or will there be more snowfall and other perfect roses? Will we find that peace be with us as Christ to us has promised? or will we never see the solution to the problem? And if our love deceives us? Whose life will be salvation if we sink into the twilight with the scientific knowledge That Good may not exist and that Evil beats close by it? If hope turns itself off and Babel then commences what torch will light the way through the roads we walk on earth?

39

SPANISH Si el azul es un ensueño, ¿qué será de la inocencia? ¿qué será del corazón si el Amor no tiene flechas? Y si muerte es la muerte, ¿qué será de las poetas y de las cosas dormidas que ya nadie las recuerda? ¡Oh sol de las esperanzas! iAgua Clara! iLuna nueva! ¡Corazones de los niños! ¡Almas rudas de las piedras! Hoy siento en el corazón un vago temblor de estrellas y todas las rosas son tan blancas como mi pena.

Aifric Doherty, Cassandra is screaming

40

ENGLISH If the blue is all a dream what becomes of innocence? what will become of hearts if Love has lost its arrows? And if death is only death what will become of poets And all the sleeping things that are already forgotten? Oh sun of all our hopes! Clear water! Bright new moon! The love in children’s hearts and rough souls of broken stones! Today I feel upon my heartstrings A vague trembling of stars and the roses all are white so white just like my sickness.

41

PORTUGUESE

Parábola do cágado velho Pepetela

In warring Angola, traditional and modern values are at odds with one another. And while the aged Ulume tries to stop the

Ulume, o homem, olha o seu mundo. Por vezes a terra lhe parece estranha. Fica num planalto sem fim, embora se saiba que tudo acaba no mar. Chanas e cursos de água por toda a parte. Junto dos rios tem florestas, nalguns pontos apenas muxitos, aquelas matitas em baixas húmidas. As elevações são pequenas, excepto a Munda que corta a terra no sentido norte-sul. Nunca se vê o cume da Munda, sempre encoberto por espessos nevoeiros. O seu kimbo fica colado ao pé da Munda, outra forma de dizer montanha, na base de um morro encimado por grandes rochedos cinzentos, por vezes azuis. De cima do morro sai um regato que acaba por se acoitar, muito à frente, num rio largo, o Kuanza de todas forças e maravilhas, quase fora do seu mundo. Desse regato tiram a água para as nakas, onde verdejam os legumes e o milho de bandeiras brancas. Nele também bebe o gado. Mesmo no tempo das piores secas a água do regato nunca falhou. No alto do morro ainda, existe a gruta de onde todos os dias sai um enorme cágado para ir beber a água da fonte. Palmeiras de folhas irrequietas rodeiam o kimbo, casando com mangueiras e bananeiras, pintando de verde-escuro os amarelos e verdes esbatidos do capim e do milho. Neste quadro familiar, algo faz a terra se afigurar de repente estranha. É um momento especial a meio da tarde em que tudo parece parar. O vento não agita as palmas, as aves suspendem seus cantos, o sol brilha num azul profundo sem fulgurações. Até o restolhar dos insectos deixa de ser ouvido. Como se a vida ficasse em suspenso, só, na luminosidade dum céu enxuto.

42

ENGLISH

passing of time and the changes that come with it, he realizes that just as the old tortoise has shown him, he cannot stop it.

The Old Tortoise’s Parable translated by Michael McCaffrey

Ulume, the man, looks out upon his world. At times, this land seems foreign to him. It sits upon an endless plateau— although it is well known that everything ends at the ocean. Savannahs and nullahs cover the land. Along the rivers are forests that thin to brush in the low humidity. The land is flat, except for the Munda which cuts through the earth from north to south. You can never see the top of the Munda as it is always concealed by thick fog. His village is located at the foot of the Munda—another word for mountain—situated at the base of a hill topped by grey and blue boulders. From the top of the hill flows a gentle stream that seeks refuge in a faraway and otherworldly river: the powerful and magnificent Kuanza. From this stream comes the water that brings life to the vegetables and white corn of the village’s gardens. The cattle, too, drink from this stream. Even in the worst of droughts, the stream never falters. At the top of the hill is a grotto from which an enormous tortoise emerges every morning to go and drink from the source. Palm trees with restless leaves border the village; mango and banana trees intertwine to paint dark green the yellows and faded greens of the grass and corn. In this familiar scene, something makes the land turn foreign all of a sudden. It is a singular moment in the middle of the afternoon in which everything seems to stop: the wind no longer disturbs the leaves, the birds pause their songs, the bright sun shines in a blue sky without a single flash. The buzzing of insects fades away into inaudibility. It is as if life itself has been put on hold, standing alone, in the light of a torrid sky. 43

PORTUGUESE Um instante apenas. E nem sempre acontece. O tempo precisa de estar limpo, de preferência depois de uma chuvada, a Lua tem de aparecer apesar do Sol, e no peito deve ter a angústia da espera. Todos os dias sobe ao morro mais próximo, senta nas pedras a fumar o cachimbo que ele próprio talhou em madeira dura, e espera. A passagem do cágado velho, mais velho que ele pois já lá estava quando nasceu, e o momento da paragem do tempo. É um momento doloroso, pelo medo do estranho. Apesar das décadas passadas desde a primeira vez. Mas também é um instante de beleza, pois vê o mundo parado a seus pés. Como se um gesto fosse importante, essencial, mudando a ordem das coisas. Odeia e ama esse instante e dele não pode escapar. Quando ainda muito jovem, falou disso aos outros. Ninguém notara, imaginação só dele. Também era o único que ia para o cimo do morro observar o vale e o mundo. Os amigos conheciam a existência do cágado velho, mas preferiam as cercanias do kimbo, onde brincavam e tentavam namorar as raparigas que iam ao regato. Assim, o cume do Mundo ficava só para ele. Nunca mais falou desse estranho instante, nem a Munakazi. Ela perguntou no princípio da vida comum, mas que hábito é esse de ires todos os dias para cima do morro à tarde? E ele respondeu é só um hábito desde criança. Tentou ligar essa sensação a coisas que lhe sucediam depois, como predição do que vai vir. Mas nada. Não havia ligação possível de adivinhar. As coisas iam e vinham, boas ou más, quer chegasse o instante quer não. Acontecia apenas. No seu rabo não parecia trazer o bem ou o mal, o desejado ou o temido. E continua a acontecer, de vez em quando. Talvez mais frequentemente agora. E Ulume fica apenas vazio, numa grande paz intranquila.

44

ENGLISH It lasts perhaps only an instant and is never guaranteed, for the weather must be clear, preferably right after it rains; the moon needs to be visible even with the sun out; and one’s chest has to be filled with the anguish of longing. Every day, Ulume goes up the closest hill, sits down on the stone, smokes the pipe that he made himself from strong wood, and waits. The passing of the old tortoise—who is much older than Ulume, for it was alive at the time of his birth—is the moment when time stops. It is a painful moment that evokes the fear of the unknown despite many decades having passed since it first occurred. But it is also a beautiful moment in which he can watch the world stop below him. It is as if this gesture was important, even essential, to change the order of things. He hates and loves this inescapable moment. While still in his youth, he described this moment to others. No one paid him any mind; it was just his imagination. But he was the only one that would make the climb to the top of the hill to look upon the valley and the land below. His friends knew of the existence of the old tortoise, but they preferred to concern themselves with matters closer to the village. They would play together and try to flirt with girls who were on their way to the stream. So, the top of the hill was left to Ulume. He never again spoke about this strange moment, not even to Munakazi. At the beginning of their shared life she had asked him what kind of habit it was to climb up the hill each afternoon? And his response was that it was merely a habit from his childhood. He had tried to link this feeling to things that had happened to him before, like a prediction of what is to come. But nothing. There was no connection to discover. Things come and go, good or bad, whether that moment comes or not. And it rarely does happen. Upon his tail, the tortoise brings neither the good nor the bad, the desired nor the feared. And it will continue to happen every once in a while. Maybe more frequently now. And Ulume becomes empty, in a great restless peace.

45

ITALIAN

Dall’immagine tesa Clemente Rebora Dall’immagine tesa vigilo l’istante con imminenza di attesa – E non aspetto nessuno: nell’ombra accesa spio il campanello che impercettibile spande un polline di suono – e non aspetto nessuno: fra quattro mura stupefatte di spazio più che un deserto non aspetto nessuno. Ma deve venire, verrà, se resisto a sbocciare non visto, verrà d’improvviso, quando meno l’avverto. Verrà quasi perdono di quanto fa morire, verrà a farmi certo del suo e mio tesoro, verrà come ristoro delle mie e sue pene, verrà, forse già viene il suo bisbiglio.

46

This poem was written by the Italian author Clemente Rebora in 1920. It is about the eager anticipation of the fulfilment of a prophecy, highlighted

ENGLISH

by the intensive use of verbs in the future tense. It is usually interpreted in a religious sense, but it may also be open to other interpretations, as prophecies are.

As a Tense Image translated by Andrea Bergantino

As a tense image I watch for the instant In the imminence of waiting – And I expect nothing: In the bright shadow I spy on the bell Which imperceptibly spreads A pollen of sound – And I expect nothing: Inside these four walls Astonished by space More than the desert I expect nothing. It must come though, It will, if I endure To bloom unseen, It will come all at once, When I feel it the least. It will come as forgiveness For how painful it is, It will come to make me sure Of its own and my bliss, It will come as relief Of mine and its suffering, It will come, perhaps it’s coming, Its whisper.

47

ENGLISH

The Amber Spyglass by Philip Pullman

This extract from the third instalment of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials highlights the foundation of the series –

Chapter 6- Adamant Tower " Now, Fra Pavel," said the Inquirer of the Consistorial Court of Discipline, "I want you to recall exactly, if you can, the words you heard the witch speak on the ship." The twelve members of the Court looked through the dim afternoon light at the cleric on the stand, their last witness. He was a scholarly-looking priest whose daemon had the form of a frog. The Court had been hearing evidence in this case for eight days already, in the ancient high-towered College of St. Jerome. "I cannot call the witch's words exactly to mind," said Fra Pavel wearily. "I had not seen torture before, as I said to the Court yesterday, and I found it made me feel faint and sick. So exactly what she said I cannot tell you, but I remember the meaning of it. The witch said that the child Lyra had been recognized by the clans of the north as the subject of a prophecy they had long known. She was to have the power to make a fateful choice, on which the future of all the worlds depended. And furthermore, there was a name that would bring to mind a parallel case, and which would make the Church hate and fear her." "And did the witch reveal that name?" "No. Before she could utter it, another witch, who had been present under a spell of invisibility, managed to kill her and escape." "So on that occasion, the woman Coulter will not have heard the name?" 48

IRISH

the prophecy that the main character, Lyra, will be the person to either save or destroy every existing world.

An Fadradharcán Ómra translated by Aislinn Ní Dhomhnaill

Caibidil a 6 – An Túr Stuacach “Anois, Pavel,” a deir Cúistiúnaí na Cúirte Smachtúla, “Ba mhaith liom go ndéanfaidh tú cur síos ar na focail a chuala tú ón gChailleach ar bord na loinge. D’amharc an giúiré ar an chléireach ag seasamh i measc solas lag na gréine. Sagart a bhí ann, le cuma léannta air, agus sprid i gcruth frog in aice leis. Le hocht lá anuas a bhí An Chúirt ag éisteacht le fianaise faoin gcás, sa seancholáiste. “Ní cuimhin liom go díreach cad é a dúirt sí,” arsa Pavel agus é ag osnáil. “Ní raibh céastóireacht feicthe agam roimhe seo, mar a dúirt mé cheana, agus d’éirigh mé tinn dá bharr. Mar sin, níl a fhios agam go díreach cad a dúirt sí, ach is cuimhin liom an brí a bhí leis.Dúirt an Cailleach gur aithin clanna an Tuaiscirt an páiste Lyra mar ábhar tairngreachta a bhí ar eolas acu le fada. Beidh an chumhacht aici a rogha chinniúnach a dhéanamh, agus is ar sin a bhraithfeadh na domhain uilig. Agus bhí ainm ann, a thabharfadh chun cuimhne cás cosúil le seo,agus go mbeadh eagla ar an Eaglais roimpi.” “Agus ar inis an Chailleach an t-ainm sin duit?” “Níor inis. Sula raibh sí in ann é a rá, mharaigh chailleach eile dofheicthe í, agus d’éalaigh sí.” “Is cinnte nár chuala Mrs. Coulter an t-ainm?”

49

ENGLISH "That is so." "And shortly afterwards Mrs. Coulter left?" "Indeed." "What did you discover after that?" "I learned that the child had gone into that other world opened by Lord Asriel, and that there she has acquired the help of a boy who owns, or has got the use of, a knife of extraordinary powers," said Fra Pavel. Then he cleared his throat nervously and went on: "I may speak entirely freely in this court?" "With perfect freedom, Fra Pavel," came the harsh, clear tones of the President. "You will not be punished for telling us what you in turn have been told. Please continue." Reassured, the cleric went on: "The knife in the possession of this boy is able to make openings between worlds. Furthermore, it has a power greater than that--please, once again, I am afraid of what I am saying...It is capable of killing the most high angels, and what is higher than them. There is nothing this knife cannot destroy." He was sweating and trembling, and his frog daemon fell from the edge of the witness stand to the floor in her agitation. Fra Pavel gasped in pain and scooped her up swiftly, letting her sip at the water in the glass in front of him. "And did you ask further about the girl?" said the Inquirer. "Did you discover this name the witch spoke of?" "Yes, I did. Once again I crave the assurance of the court that--" "You have it," snapped the President. "Don't be afraid. You are not a heretic. Report what you have learned, and waste no more time."

50

IRISH “ ‘S ea.” “Agus d’imigh Mrs. Coulter go gairid ina dhiaidh sin?” “D’imigh.” “Cad a d’fhoghlaim tú ina dhiaidh sin?” “D’fhoghlaim mé gur imigh an páiste go dtí domhan eile a d’oscail an tUasal Asriel, agus go bhfuil cabhair faighte aici ó bhuachaill atá miodóg áirithe aige, agus go bhfuil cumhacht dochreidte ag an miodóg sin,” arsa Pavel. Ghlan sé a scornach go neirbhíseach agus lean sé ar aghaidh: “Tig liom labhairt go hionraic sa chúirt seo?” “Amach is amach, Pavel,” a deir an t-Uachtarán ina ghuth garbh, soiléir. “Ní bheidh píonós ar bith curtha ort mar gheall ar an tiomna seo. Lean ort.” “Tá cumas ag an miodóg sin bearna a chruthú idir domhan amháin agus domhan eile. Ar a bharr sin, tá cumas níos mó aige ná sin amháin—le bhur dtoil, tá eagla orm é seo a rá…d’fhéadfadh an miodóg na haingil is ardchéimiúla a mharú, agus cad atá níos airde ná iad. Níl rud ar bith narbh fhéidir leis a scriosadh.” Bhí sé ag cur allais agus ag croitheadh, agus thit a sprid ó chlár na mionn, chomh trína chéile is a bhí sí. Lig Pavel cnead leis an bpian, tharraing sé suas í, agus thug sé braon uisce di. “Agus ar cheistigh tú a thuilleadh í faoin gcailín?” a d’fhiafraigh an Cúistiúnaí. “Ar aimsigh tú an t-ainm seo a luaigh an Chailleach?” “D’aimsigh. Arís, teastaíonn gealltanas ón chúirt uaim go-” “Is agat atá sé,” arsa an t-Uachtarán go giorraisc. “Ná bíodh eagla ort. Abair linn cad a d’fhoghlaim tú agus ná bí ag cur amú ama.”

51

ENGLISH "I beg your pardon, truly. The child, then, is in the position of Eve, the wife of Adam, the mother of us all, and the cause of all sin." The stenographers taking down every word were nuns of the order of St. Philomel, sworn to silence; but at Fra Pavel's words there came a smothered gasp from one of them, and there was a flurry of hands as they crossed themselves. Fra Pavel twitched, and went on: "Please, remember--the alethiometer does not forecast ; it says, 'If certain things come about, then the consequences will be...,' and so on. And it says that if it comes about that the child is tempted, as Eve was, then she is likely to fall. On the outcome will depend...everything. And if this temptation does take place, and if the child gives in, then Dust and sin will triumph." There was silence in the courtroom. The pale sunlight that filtered in through the great leaded windows held in its slanted beams a million golden motes, but these were dust, not Dust--though more than one of the members of the Court had seen in them an image of that other invisible Dust that settled over every human being, no matter how dutifully they kept the laws. "Finally, Fra Pavel," said the Inquirer, "tell us what you know of the child's present whereabouts." "She is in the hands of Mrs. Coulter," said Fra Pavel. "And they are in the Himalaya. So far, that is all I have been able to tell. I shall go at once and ask for a more precise location, and as soon as I have it, I shall tell the Court; but..." He stopped, shrinking in fear, and held the glass to his lips with a trembling hand. "Yes, Fra Pavel?" said Father MacPhail. "Hold nothing back." "I believe, Father President, that the Society of the Work of the Holy Spirit knows more about this than I do." Fra Pavel's voice was so faint it was almost a whisper. 52

IRISH “Gabh mo leiscéal. Mar sin, is sa chinniúnt céanna le hÉabha, bean Ádhamh, ár máthair agus cúis peaca uile, atá an páiste, Lyra.” Ba mná rialta agus iad faoi mhóid chiúnais mar luathscríobhnóirí; ach ligeadh cnead astu nuair a chuala said focail Pavel, agus bhí mearbhall orthu ar feadh nóiméad agus comhartha na croise á dhéanamh acu. Bhuail baoth-thonn Pavel, agus lean sé ar aghaidh: “Le bhur dtoil- ná déan dearmaid, ní dhéanann an compás léitheoireachta réamhaisnéís;; deir sé ‘más rud é go dtarlaíonn rudaí áirithe, ansin na torthaí a bheidh ann ná…’ agus mar sin. Más rud é go meallfar an páiste, mar a mhealladh Éabha, seans mhaith go dtitfidh sí. Beidh… gach rud ag brait ar an toradh. Agus má tharlaíonn an cathú seo, agus má ghéilleann sí, beidh an bua ag an Damhna Dorcha agus ag an bpeaca.” Bhí ciúnas iomláin sa chúirt. Bhí na milliún damhna sa mheathsholas a chuir bhrat ar an tseomra, agus ba dhamhna é seo, seachas Damhna Dorcha, agus feictear iontu íomhá an Damhna eile sin a chur isteach ar achan duine, is cuma cé chomh umhal don dlí is atá siad. “Ceart go leor, Pavel,” arsa an Cúistiúnaí, “inis dúinn cá háit ina bhfuil an páiste anois, más féidir leat.” “Tá sí á choinneáil ag Mrs. Coulter,” a d’fhreagair Pavel. “Agus sna Himiléithe atá siad. Sin an t-aon rud atá ar eolas agam. Rachaidh mé láithreach agus gheobhaidh mé freagra níos cruinne duit. Chomh luath is atá a fhios agam, inseoidh mé leis an Chúirt, ach…” Stad sé, eagla air, agus d’ól sé beagán uisce, a lámh ag croitheadh. “Sin é, Pavel?” dúirt an tAthair MacPháil. “Inis gach rud dúinn.” “Creidim, a Athair, go bhfuil níos mó eolais ag Sochaí an Spiorad Naofa faoin ábhar seo ná atá agam féin.” Bhí guth Pavel chomh híseal le cogar.

53

FRENCH

Prophétie by Jules Supervielles

Un jour la Terre ne sera Qu'un aveugle espace qui tourne Confondant la nuit et le jour. Sous le ciel immense des Andes Elle n'aura plus de montagnes, Même pas un petit ravin.

Restées à l’état de vapeur Regarderont par la portière Pensant que Paris n’est pas loin Et ne sentiront que l’odeur Du ciel qui vous prend à la gorge.

De toutes les maisons du monde Ne durera plus qu'un balcon Et de l'humaine mappemonde Une tristesse sans plafond De feu l'Océan Atlantique Un petit goût salé dans l'air, Un poisson volant et magique Qui ne saura rien de la mer.

Un chant d’oiseau s’élèvera

D'un coupé de mil-neuf-cent-cinq (Les quatre roues et nul chemin!) Trois jeunes filles de l'époque

54

As the title suggests, this is a prophecy, a very pessimistic one,

A la place de la forêt

Que nul ne pourra situer, Ni préférer, ni même entendre, Sauf Dieu qui, lui, l’écoutera Disant : «C’est un chardonneret »

ENGLISH

of what may become of the world.

One day the Earth will only Be a blank space that makes Obsolete day and night. Under the immense sky of the Andes She won’t have any more mountains, Not even a little ravine. Of all the houses in the world Only a balcony will stand And of the human world map A ceaseless sadness Of fire the Atlantic Ocean A little salty taste in the air, A flying and magical fish That will never know the sea. From a 1905 coupé (The four wheels and no road!) Three young girls of that time

Prophecy translated by rebecca notari Immortalized in steam Will look through the car door Thinking that Paris isn’t far away And they will only smell the odour Of the sky that takes you by the throat. Instead of the forest A bird’s song will rise Which no one will be able to locate, Or prefer, not even understand Except God, who, listening, will say: “It’s a goldfinch”.

55

Andres Murillo, El Porvenir

Penny Stuart, Molly's Window

RUSSIAN

Лавр by Eugene Vodolazkin

This is an excerpt from Vodolazkin’s award-winning novel set in the 15-16th century. It introduces an important

Амброджо Флеккиа родился в местечке Маньяно. На восток от Маньяно, в дне пути верхом, лежал Милан, город святого Амвросия. В честь святого назвали и мальчика. Амброджо. Так это звучало на языке его родителей. Напоминало, возможно, об амброзии, напитке бессмертных. Родители мальчика были виноделами. Помощь мальчика семейному делу пришла с неожиданной стороны. За пять дней до большого сбора винограда Амброджо сообщил, что виноград следует собирать немедленно. Он сказал, что утром, когда он открыл глаза, но по-настоящему еще как бы не проснулся, ему предстало видение грозы. Это была страшная гроза, и Амброджо описал ее в подробностях. В описании присутствовали внезапно сгустившийся мрак, завывание ветра и со свистом летящие градины величиной с куриное яйцо. Мальчик рассказывал, как спелые гроздья винограда бились мочалкой о стволы, как круглые льдинки на лету дырявили мечущиеся листья и добивали на земле упавшие ягоды. Вдобавок ко всему с небес спустился синий звенящий холод и место катастрофы укрылось тонким слоем снега. Такую грозу Флеккиа-старший видел лишь единожды в жизни, а мальчик не видел никогда. Однако все подробности рассказа в точности сходились с тем, что в свое время наблюдал отец. Не склонный к мистике, Флеккиа-старший после колебаний все же послушался Амброджо и приступил к сбору винограда. Он ничего не сказал соседям, потому что боялся осмеяния. Но после того как пять дней спустя над Маньяно действительно разразилась страшная гроза, Флеккиа оказались единственным семейством, собравшим в тот год урожай.Смуглого отрока посещали и другие видения. Они касались самых разных сфер жизни, но от виноделия были уже довольно далеки. Так, Амброджо предсказал войну, развернувшуюся в 1494 году на территории Пьемонта между французскими королями и Священной Римской империей. Сын винодела ясно видел, как с запада на восток мимо Маньяно промаршировали передовые французские части. 58

ENGLISH

character, a small-town Italian with a unique gift of foresight, who will later join the protagonist on a joint adventure.

Laurus translated by Dana Bagirova

Ambrogio Fleccia was born in a little place called Magnano, a two days’ ride from Milan, the city of St Ambrose. They named the boy in honour of Saint Ambrogio. That is what it sounded like in his parents’ tongue. Perhaps, it reminded them of ambrosia, the drink of the immortal. The boy’s parents were winemakers. The boy’s assistance to the family business came from an unexpected turn. Five days prior to a large harvest, Ambrogio announced that the grapes ought to be harvested immediately. He stated that in the morning, upon opening his eyes, half-awake, he had a vision of a storm. It was a terrible storm, and Ambrogio described it in detail. His account of it included a sudden, thick darkness, howling wind, and hailstones the size of a hen’s egg whizzing to the ground. The boy described ripe clusters of grapes being squashed against tree trunks, and round pieces of ice piercing the thrashing leaves before finishing off the fallen fruit on the ground. On top of everything, a tinkling blue frost descended from the heavens and the sight of the calamity was covered with a thin layer of snow. Fleccia-senior had seen such a storm once in his life, though the boy had never. And yet, all the details of the description were completely in line with what the father had seen in his days. Not having much taste for mysticism, Fleccia-senior, with much hesitation, eventually listened to Ambrogio and began the grape picking. He mentioned nothing of it to the neighbours, fearing ridicule. Even so, after a great storm engulfed Magnano five days later, the Fleccia were the only family with harvest crops that year. The olive-skinned boy would be visited by further visions. They were related to all kinds of different spheres of life, though by now were quite removed from winemaking. Thus, Ambrogio predicted the war which began in 1494 on Piedmont territory, between the French kings and the Holy Roman Empire. The vintner’s son could clearly see the French front lines marching Eastwards from the West past Magnano.

59

RUSSIAN Местное население французы почти не трогали, лишь отобрали для пополнения провианта мелкий скот да двадцать бочек пьемонтского вина, показавшегося им неплохим. Эта информация поступила к Флеккиа-старшему в 1457 году, то есть очень заранее, что, в сущности, и не позволило ему извлечь из нее возможную пользу. О предсказанных боевых действиях он забыл уже через неделю. Амброджо предсказал также открытие Христофором Колумбом Америки в 1492 году. Это событие тоже не привлекло внимания отца, поскольку на виноделие в Пьемонте существенного влияния не оказывало. Самого же мальчика видение привело в трепет, ибо сопровождалось зловещим свечением контуров всех трех Колумбовых каравелл. Нехорошим светом был тронут даже орлиный профиль первооткрывателя. Генуэзец Коломбо, перешедший в силу обстоятельств на испанскую службу, был, по сути, земляком Амброджо. Не хотелось думать, что 12 октября 1492 года такой человек занимался чем-то неподобающим, и оттого световые эффекты ребенок был склонен объяснять чрезмерной наэлектризованностью атлантической атмосферы. Когда Амброджо подрос, он выразил желание уехать во Флоренцию, чтобы учиться в тамошнем университете. Амброджо читал историков античных и средневековых. Читал анналы, хроники, хронографы, истории городов, земель и войн. Он узнавал, как создавались и рушились империи, происходили землетрясения, падали звезды и выходили из берегов реки. Особо отмечал исполнение пророчеств, а также появление и осуществление знамений. В таком преодолении времени ему виделось подтверждение неслучайности всего происходящего на земле. Люди сталкиваются друг с другом (думал Амброджо), они налетают друг на друга, как атомы. У них нет собственной траектории, и оттого их поступки случайны. Но в совокупности этих случайностей (думал Амброджо) есть своя закономерность, которая в каких-то частях может быть предвидима. Полностью же ее знает лишь Тот, Кто все создал. Однажды во Флоренцию пришел купец из Пскова. Купца звали Ферапонтом. На фоне местного населения он выделялся длинной, о двух хвостах бородой и огромным оспяным носом. Помимо связок соболиных шкур Ферапонт привез известие, что в 1492 году на Руси ждут конца света. К этим сведениям во Флоренции отнеслись в целом спокойно. Из всех живших во Флоренции сообщение купца Ферапонта показалось по-настоящему важным только одному человеку – Амброджо. 60

ENGLISH The French barely bothered the locals, apart from grabbing some small livestock in order to top up their provisions and some twenty barrels of Piedmont wine, which they discovered to be quite nice. This information came to Fleccia-senior in 1457, so prematurely that it prevented him from benefiting from it in any way. He forgot all about the foretold military action just a week later. Similarly, Ambrogio predicted Columbus discovering America in the year 1492. This event also failed to get the father’s attention as it bore no real impact on winemaking in Piedmont. The boy himself, however, was thrilled about the vision – accompanied by an evil glow which outlined all three of Columbus’s caravels. Even the discoverer’s eagle-like profile was touched by the ill light. Colombo of Genoa, who was now in service of Spain due to force of circumstances, was in effect Ambrogio’s countryman. It was rather unpleasant to think that on October 12, 1492, a man of his character would be up to something unseemly, and so the boy wrote off the strange light effects as being caused by the excessive electrification of the Atlantic atmosphere. When Ambrogio got older, he expressed a desire to move to Florence, to attend university there. Ambrogio read both antique and medieval historians. He read annals, chronicles, chronographs, histories of cities, lands and wars. He learned about empires being created and destroyed, earthquakes, stars falling and rivers overflowing their banks. He paid particular attention to fulfilments of prophecies, as well as the emergence and materialization of omens. In these triumphs over time, he saw a confirmation that everything on Earth happens for a reason. People cross paths with each other (Ambrogio would think), they crash into one another, like atoms. They have no trajectories of their own, and therefore their actions are accidental. Yet in the aggregate of these accidents (Ambrogio would think) there is a pattern which, in some aspects, can be foreseen. As for the full picture, it is only known by He, who created all things. One day, a merchant from Pskov arrived in Florence. The merchant’s name was Ferapont. Against the backdrop of the local population, he stood out with his long, two-tailed beard and a massive nose. Along with bundles of sable hide, Ferapont brought the news that over in Russia they were expecting the end of the world to come in 1492. The reaction in Florence was altogether quite calm. Of everyone living in Florence, there was only one person who found the message of Ferapont the merchant to be of significance – Ambrogio.

61

RUSSIAN Юноша разыскал Ферапонта и спросил у него, на основании чего им было сделано заключение о конце света именно в 1492 году. Ферапонт отвечал, что это заключение делалось не им, но было услышано от компетентных людей в Пскове. Не будучи способен как-либо обосновать фатальную дату, Ферапонт в шутку предложил Амброджо отправиться за пояснениями в Псков. Амброджо не засмеялся. Он задумчиво кивнул, ибо такой возможности не исключал. К этому же времени относится знакомство Амброджо Флеккиа с будущим мореплавателем Америго Веспуччи. Амброджо обратил внимание Америго Веспуччи на странное сближенье предполагаемых событий 1492 года. С одной стороны – открытие нового континента, с другой – ожидавшийся на Руси конец света. Насколько (недоумение Амброджо) эти события связаны, и если связаны, то – как? Не может ли (догадка Амброджо) открытие нового континента быть началом растянувшегося во времени конца света? И если это так (Амброджо берет Америго за плечи и смотрит ему в глаза), то стоит ли такому континенту давать свое имя?Настал день, когда Амброджо понял, что готов отправиться на Русь. Последним, что от него услышали флорентийцы, оказалось предсказание страшного наводнения, которому суждено было обрушиться на город 4 ноября 1966 года. Призывая горожан к бдительности, Амброджо указал, что река Арно выйдет из берегов и на улицы хлынет масса воды объемом 350 000 000 куб. м. Впоследствии Флоренция забыла об этом предсказании, как забыла она и о самом предсказателе. Амброджо отправился в Маньяно и сообщил о своих планах отцу. Но ведь там предел обитаемого пространства, сказал Флеккиастарший. Зачем ты туда поедешь? На пределе пространства, ответил Амброджо, я, может быть, узнаю нечто о пределе времени.

62

ENGLISH The youth sought Ferapont out and asked him what the conclusion was based on, that the end of the world would specifically take place in 1492. Ferapont replied that this conclusion was not made by him, but instead heard from competent people in Pskov. Being unable to somehow justify the fatal date, Ferapont jokingly suggested Ambrogio set out to Pskov for the explanation. But Amrogio did not laugh. He nodded, contemplating, for he was open to that option. To this timeframe also belongs the meeting of Ambrogio Fleccia and the future voyager Amerigo Vespucci. From his eyes, Ambrogio effortlessly determined where Vespucci’s course lay. It was obvious that in the year of 1490, Amerigo would head to Seville, where, while working in the trading house of Gianotto Berardi, he would take part in financing Columbus’s expeditions. Ambrogio drew Amerigo Vespucci’s attention to the strange convergence of the events expected in 1492. On the one hand – discovery of a new continent, on the other – Russia's anticipated apocalypse. Just how related (Ambrogio’s wondered) are those events, and if they are, then in what way? Could (Ambrogio’s guess) the new continent’s discovery be the beginning of the end, stretched out over time? And if this was the case (Ambrogio takes Amerigo by his shoulders and looks him in the eyes), then is it worth naming such a continent after yourself?The day came when Ambrogio knew he was ready to set out to Russia. The last thing the Florentines heard from him was a prediction of a terrible flood, destined to descend upon the city on November 4, 1966. Calling for alertness amongst the civilians, Ambrogio indicated that the river Arno would overflow its banks and the streets would be flushed with a mass of water measuring 350,000,000 cubic metres in volume. Subsequently, Florence forgot this prediction just as it forgot its predictor. Ambrogio departed for Magnano and there informed his father of his plans. But there lies the boundary of inhabited space, said Fleccia-senior. Why would you go there? At the boundary of space, responded Ambrogio, I might learn something about the boundary of time.

63

ENGLISH

It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis

Sinclair Lewis’ clairvoyant 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here portends the rise of fascism in America under tactless president Buzz Windrip.

"Well, I've been—I didn't vote for Windrip, personally, but I begin to see where I was wrong. I can see now that he has not only great personal magnetism, but real constructive power—real sure-enough statesmanship. Some say it's Lee Sarason's doing, but don't you believe it for a minute. Look at all Buzz did back in his home state, before he ever teamed up with Sarason! And some say Windrip is crude. Well, so were Lincoln and Jackson. Now what I think of Windrip—" "The only thing you ought to think of Windrip is that his gangsters murdered your fine brother-in-law! And plenty of other men just as good. Do you condone such murders?" "No! Certainly not! How can you suggest such a thing, Dad! No one abhors violence more than I do. Still, you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs—" "Hell and damnation!" "Why, Pater!" "Don't call me 'Pater'! If I ever hear that 'can't make an omelet' phrase again, I'll start doing a little murder myself! It's used to justify every atrocity under every despotism, Fascist or Nazi or Communist or American labor war. Omelet! Eggs! By God, sir, men's souls and blood are not eggshells for tyrants to break!" "Oh, sorry, sir. I guess maybe the phrase is a little shopworn! I just mean to say—I'm just trying to figure this situation out realistically!" "'Realistically'! That's another buttered bun to excuse murder!"

64

IRISH

This extract shows the protagonist, dissenting journalist Doremus Jessup, arguing with his Windrip-sympathising son Philip.

Ní tharlódh a leithéid anseo translated by Tadhg Mc Tiernan

“Bhuel, Táim tar éis – Níor vótáil mise ar son Windrip, ach tuigim anois an fáth go raibh mé mícheart. Feicim anois nach amháin go bhfuil tarraingteacht phearsanta íontach aige, ach fíor-chumhacht fhiúntach – fíor státaireacht dáiríre. Deirtear go bhfuil Lee Sarason taobh thiar de, ach ná creid é sin in aon chor. Cuir san áireamh an méid a rinne Buzz ina cheantar baile féin, roimh dó dul riamh i bpáirt le Sarason! Agus deirtear go bhfuil Windrip garbh. Bhuel, sin mar a bhí Lincoln agus Jackson. Anois an tuairim atá agam maidir le Windrip – “ “Níor cheart go mbeadh ach tuairim amháin agat maidir le Windrip, - gur dhúnmharaigh seisean agus a chuid chaimiléirí do dheartháir céile uasal! Agus neart fear eile a bhí chomh uasal sin. An dtacaíonn tú le dúnmharuithe dá leithéid?” “Ní thacaím dár ndóigh! Cad é mar a thiocfadh leat rud mar sin a rá, a dhaid! Níl gráin níos láidre ag aon duine ar fhoréigean ná atá agamsa. Mar sin féin, ní fhaightear saill gan saothrú –“ “In ainm Dé!” “A thiarcais, a phatrarc!” “Ná glaoigh ‘patrarc’ orm! Má chloisim riamh an nath sin arís , “ní fhaightear saill”, rachaidh mé i mbun píosa dúnmharaithe a dhéanamh mé féin! Thugadh sé údarás do gach aon ainghníomh de gach aon fhorlámhas, faisistí nó Nazi nó cumannaí nó cogadh lucht oibre Mheiriceá. ‘Saill” atá I gceist! In ainm dé, tá níos mó in anamacha agus fuil na bhfear ná saill a dhéanamh ag tíoránaigh!” “Bhuel, gabh mo leithscéal. Is dócha gur ráiteas saghas seanchaite é! Níl mé ach ag iarraidh a rá – Nílim ach ag déanamh iarracht cúrsaí a dhéanamh amach go réadúil!” “’Go réadúil’! Ní hea sin ach seanleithscéal don dhúnmhairíocht!”

65

ENGLISH "But honestly, you know—horrible things do happen, thanks to the imperfection of human nature, but you can forgive the means if the end is a rejuvenated nation that—" "I can do nothing of the kind! I can never forgive evil and lying and cruel means, and still less can I forgive fanatics that use that for an excuse! If I may imitate Romain Rolland, a country that tolerates evil means—evil manners, standards of ethics—for a generation, will be so poisoned that it never will have any good end."

Penny Stuart, Le Cannet's Head. 66

IRISH “Ach i ndáiríre, tarlaíonn rudaí uafásacha, de bharr laige an duine, ach is féidir glacadh leis an mbealach ina bhaintear amach an cuspóir más tír í a bhfuil beocht inti arís –” “Ní féidir glacadh le rud dá laghad! Ní féidir liom glacadh riamh le bealaí olca bréagacha cruálacha, ní airím glacadh le fanaicigh a bhraitheann é sin mar leithscéal! Más féidir liom aithris a dhéanamh ar Romain Rolland, tír a ghlacann le bealaí olca – béasa olca, caighdeáin eitic – ar feadh glúine, beidh an tír chomh nimhithe sin nach mbainfidh sí amach riamh cuspóir maith.”

67

ENGLISH

Before the Storm by David Butler There is a moment, before the storm, when the winds hold their breath; the boughs stop moving; the cloud, backlit, is photograph-still; the lake’s meniscus reverent. A moment in suspense. An instant, when future imperfect appears to hang in the balance; when the dice have yet to fall, the first fat drops to explode in the dust-tormented earth.

Ellecia Vaughan, Nightmare prophecy in white 68

Prophecy in the poem is not a mere divination but a quiet scrutiny of seemingly peaceful nature. It is a moment captured in all its beauty and terror, put in emotional and

POLISH

poignant language which leaves no doubt that the “inspired declaration of divine will” is made not by the poet but by the “dusttormented” planet itself.

Przed burzą

translated by Magdalena Kleszczewska

Chwilę przed burzą wiatr wstrzymuje oddech, gałęzie nieruchomieją, a chmura – podświetlona – jest zatrzymanym kadrem; menisk jeziora – pełen nabożności. Chwila napięcia. Sekunda, w której przyszłość niedoskonała zdaje się wisieć na włosku, kości mają zostać rzucone, a pierwsze grube krople wybuchnąć na udręczonej pyłem ziemi.

Ellecia Vaughan, Nightmare prophecy in red

69

Notes on Contributors (in order of appearance) Alexander Fay is a proud native of Dublin’s North Inner City, and a JS physics student who came in through the Trinity Access Programmes (TAP). He is not a photographer, he just likes to take nice pictures. Aifric Doherty is a current Msc student at The London School of Economics and former assistant editor of the journal. She thinks Cassandra should scream more. Matthew Wainwright is a junior sophister studying single-honours Classics from Bath, England. He has a great love for all things old & quirky, all areas in which Classics excels. Francesca Corsetti is an undergraduate student of Foreign Languages and Literature at the University of Bologna, currently attending her last year at Trinity College Dublin. She is particularly interested in late-Victorian literature.

70

Jean A.D. Ingres, Oedipus Explaining the Enigma of the Sphinx, 1827.

Ă ine Mills is an alumna of TCD (BA (Mod.) English Literature and Modern Irish)