Editor-in-Chief

Anastasia Fedosova

Deputy Editor

General Assistant Editor

Art Editor

Adrianna Rokita

Aisling Doherty-Madrigal

Jack Smyth

Language Editors

Alessandra Aspromonte

Jade Brunton

Cúán de Búrca

Eoghan Conway

Caroline Loughlin

Felix Vanden Borre

Alexander Payne

Layout

Adrianna Rokita & Jack Smyth & Anastasia Fedosova

Faculty Advisor

Dr Peter Arnds

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road, Healthy, free, the world before me, The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

In his essay “The Viae: The Roman Roads in Britain”, the British poet and painter David Jones speaks of the importance of roads from a historical and archaeological perspective, observing how they record and layer up the lives and experiences of generation after generation, so that “[w]hen we look down the street we are apt to make a recalling of the people, living and dead, of that street.”

By choosing “Roads” as an editorial theme for this issue, I wanted to encourage a kind of archeological view of translation, as a process in which the translator’s voice, experience, and history are layered unto that of the author, as if the translator walked the path laid down by the author years, decades, centuries ago.

So many literary roads, routes, paths, tracks, journeys, vehicles, and escapes are presented in the pages to come. The variety of languages is as astonishing as ever: Turkish, Chinese, Norwegian, Middle English, Yiddish, Hebrew, Gorani, Hindi, Latin… We are delighted to have included an Irish-Polish and a German-Irish translations. Amongst the authors translated are Eavan Boland, Italo Calvino, Patrick Kavanagh, Paul Éluard, Antonio Machado, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Robert Frost.

The notion of “Roads” reflects the variety of choices — of paths — the translator can take in their work. The techniques and methods of literary translation are endless, providing a range of opportunities to interpret and adjust the original. In this issue, you will find the sound of a Portuguese “Trem de Ferro” domesticated for Irish culture, and a sense of Parisian nostalgia relocated to Dublin. You will also find a translation of Dante that preserves the original syntax and rhythm.

Serendipitously, I received two translations of Mikhail Lermontov’s “Выхожу один я на дорогу…”, a poem that was certainly at the back of my mind when I chose the theme. It thus seems right to begin and conclude this issue with two different versions of the same text, each of high value and an achievement of its own, that also showcase two alternate routes taken by the two translators, routes that start together, but lead to very distinct destinations.

My journey as the Editor-in-Chief of JoLT is coming to an end. It was a wonderful year, and there aren’t enough words to express my gratitude for all the things I’ve learnt and the friendships I’ve made. My sincerest thank you is to my editorial team: Adrianna, Aisling, Alessandra, Jade, Cúán, Eoghan, Caroline, Alexander, Felix, and Jack. I am once again grateful for your enthusiasm, hard work, and love of languages. It has been a pleasure working with you. Together, we’ve travelled from the dreamland into reality. Yet, I know that with this path ending, many more are opening up in front of us.

This issue is for everyone who is currently on the road. Whether you are reaching your destination or have just stepped on a path untrodden, whether you feel there is no light at the end of the tunnel or have every hope and confidence in the success of your journey, your courage to have started and to keep going is to be admired. One step at a time, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.

‘I set out alone along the road… ’ trans. by Ailbhe Cannon

When I saw that the theme of this issue of JoLT was “Roads”, this poem by Lermontov immediately came to mind. While the opening line is directly related to the theme, the poet is clearly setting out on a journey of self-discovery and introspection, which can be considered part of the metaphorical road that is life.

‘A Blind Cosmos’s Blinded Roads’ trans. by Alok Debnath

This poem (originally a song) is from the 1953 Indian movie Patita, which follows the story of an impoverished young woman who meets someone who loves her and asks her to take charge of her own destiny. It plays at the movie's tragic climax as the woman's love interest laments his now-wife's unfortunate past, its impact on his social standing, and the future of his married life.

‘Woods and Clearings’ trans. by Greta Chies

The poet walks the winding paths of the ancient Cansiglio forest, deeper and deeper, seeking his own primordial roots. He uses the local archaic dialect, as wild and thick as the forest; the only language which still allows him to find the “lost path [...] that won’t yield to translation”.

‘Dr. Happy’ trans. by Oisín Thomas Morrin

“Roads – in their many forms – appear to unite us; yet, they simultaneously act as the divider between us. This excerpt explores the nature of the boundaries of the links between us.

‘Return Song’ trans. by Ana Olivares Muñoz Ledo

Sagu Palm’s Song by Japanese songwriter Ichiko Aoba is mysterious and magical. I decided to translate this song as Return Song because it invites the listener to wonder where we are going, the origin of life in a seashell or how the road of the dragon looks from space. Who is the dragon? Maybe that is what the song wants us to wonder about.

‘Prázdniny s Tátou Během Rozvodu’ trans. by Michaela Králová

Jessica Traynor’s 2022 collection, Pit Lullabies, contains visceral and intimate poems about motherhood, violence, and in ‘Holidaying With Dad During the Divorce’, about the anxieties which follow us throughout life. The title mirrors the ‘high-road’ taken by the narrator, as well as the literal road travelled with her father.

‘Sessizlikte’ trans. by Mert Moralı

I have always had a deep affinity for being on the road and a peaceful sense of strangeness it wakes up in me. In Gerry Murphy’s “In the Quiet”, I experience this “peaceful strangeness” in a very similar manner. Now, I share this feeling with my translation.

‘An Bóthar Síoraí’ trans. by Seathrún Sardina

The poem, sung by Bilbo Baggins at the end of The Hobbit, represents the completion of his journey and arrival, at least, to a place where he is safe. At both the literal level of travelling on a road, and the allegorical one of the paths his life took,it represents an end of a journey and a return to peace.

‘Spojrzenie na morze’ trans. by Kinga Jurkiewicz

This poem urges the addressee to choose a path on the crossroads of life. It employs ample seafaring metaphors and imagery, and is permeated with a sense of urgency.

‘No Trem ’ trans. by Isabela Facci Torezan

In this short story Lydia Davis describes part of a train journey, but we can also read it as a metaphor to the common journey, the common road of life, that we are all on. We may be very different people, or have just a few similarities, but we are heading towards the same direction.

‘Horse’ trans. by Adrianna Rokita

Paul Éluard's poem alludes to the expectations and pressures that our environments place on us in terms of the paths we take in life. Remaining true to ourselves while accepting the responsibilities that come with each new journey is one of life's greatest challenges.

‘En Calle Raglan’ trans. by Eoghan Conway

Kavanagh’s poem charts the course of a love affair from its inception to its ultimate acknowledged resignation. The physical streets of Dublin and the journey they facilitate depicts the pursuit of love from its fruition to failure.

‘Road or life on foot’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

Some roads require slow going with patience and reflection, because they cross bumps, a tough country or state of mind. Mental and physical migration can take years or a lifetime.

‘Whole words’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

Taking courage, roads may be chosen, or we’re dragged along despite ourselves, trying to find a purpose or destiny as we go.

‘Beyond the bridge’ trans. by Ilaria Lico

Calvino is striving to narrate through a fictional young lady the events, feelings, and emotions shared by those Italians who, like him, fought against the Nazi fascists during the Second World War. The author describes the tortuous path that leads “beyond the bridge”, metaphorically the long-desired “fair, free, and cheerful world”.

‘The Migration Road’ trans. by Aysel K. Basci

“The Migration Roads” is a poem I translated from the Turkish. It is written by the renowned, contemporary Turkish poet and author, Murathan Mungan about the plight of the involuntary immigrants in the Middle East and elsewhere, most notably, the Syrians. The relationship between the poem and the ROADS theme is quite direct and obvious.

‘Wunderblume’ trans. by Maeve Carolan

This text comes from an anthology of folk stories about a mountain in Thuringia. All describe the road leading to and from the mountain, as the characters undergo dramatic change in their lives. Here, a shepherd takes his usual road, unaware that his life is about to change forever.

‘

‘Vision from the Afterlife’ trans. by Octavio Pérez Sánchez

Charon embodies multiple aspects of roads. We come to him at the end of life's road, but it is also through him that souls find their way to peace. He is the guide that leads across the rivers of the underworld, but, as arbiter and toll collector, Charon is also the obstacle that disallows passage. A disallowance that, as is hinted at in Perelló's "Visión de Ultratumba", can lead to a new, terrible road: that of a restless spirit.

‘Rut. Nam. I, 183-194, 197-204 ’ trans. by Alessandro Bonvini

The passage marks Rutilius’ farewell to his beloved Rome. He has to come back to his native land, Gaul, hit by the Vandals. From the harbor he looks back at the Urbs. Among the shimmering seven hills and people’s noise, Rutilius hears the voice of his familiar place: dream or reality?

‘墙与窗’ trans. by Chaomei Chen

Such themes as “roads” and “travelling” remind me of Walls and Windows, a play about the Irish Travellers, a traditionally peripatetic indigenous ethno-cultural group. Representing the sufferings of contemporary Travellers, literally living “on the road”, on a trailer or a caravan, Rosaleen McDonagh confronts social issues like racism and ableism.

The four stanzas given here make that first part of every story where everything is perfect as it is - that moment just before a magical green entity crashes your banquet and challenges you to go on a perilous journey, by the end of which you will find who you truly are and have been all along.

‘A Lad on the Road’ trans. by Denis

It is a folk song or a poem (pesne means both) from the Gorani people, a South Slavic Muslim ethnic group in Kosovo and the surroundings. It belongs to the subgenre of migrant worker songs. Men worked abroad while their wives waited at home. The longing and anxiety are palpable.

This is a verse from a song by the French singer Barbara in which she alludes to the streets of Paris. Similar to many of the singer’s songs, the verse laments a lost love. I chose to be quite liberal with my translation. I strayed away from the exact vocabulary in the original text in order to keep the lyrical value of the piece. I also decided to experiment with the method of domestication.

‘Carbon compounds’ trans. by Vilde Bjerke Torset and Harry Man

Jon Ståle Ritland is an ophthalmologist and being close to a laser, inscribing corrections into the lens of the eye, and carbon as something that acts as a universal point of connection between all life on earth. It’s both the basis for all life and its greatest adversary. Here the poem moves between its conception as lines appearing on the white, electric document, to the physical action of reading and meaning forming a new connection, a new route between the poet in one time period in the past and the reader in the present.

‘Black holes’ trans. by Vilde Bjerke Torset and Harry Man

Here the black hole is both the pupil of the eye and cave-mouth at the entrance to a mine. The poem acts stereoscopically, finding a way to work both down and across the page, reflecting the subject in the experience.

‘Runnin' Train’ trans. by Julia Álvares

This 1936 poem is meant to be read aloud. It mimics the sound of a train, its engines picking up speed, the whistles. A passenger reminisces as the train cuts through a rural landscape. My translation sets the train and the passenger in the countryside of Ireland.

‘Il Sentiero Della Carestia’ trans. by Liam Frabetti

In this poem, Boland makes an analogy between the tone her doctor uses to announce her infertility and the tone of 19th century British officials discussing the Great Irish Famine. His condescending and dispassionate tone leads her to feel that her infertile body is as pointless as a famine road.

‘A Day ’ trans. by Reyzl Grace

In much American writing, the road means (middle-class) freedom. Veprinski, who grew up poor in Ukraine and worked in New York sweatshops, sharply boundaries earth and sky and forces our attention to those who have not been birds – those for whom the road has been the symbol of things unreachable.

‘An bóthar, nár tógadh’ trans. by Gráinne Caulfield

Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken was written as a joke for a friend as they could never pick a trail when out for their walks. Frost is quoted as saying about this poem, “I’m never more serious than when joking.”

‘Cisa’s Highway’ trans. by Elena Poletto

The poem, from Stella variabile, Vittorio Sereni (1979), addresses the enigma of death and the impalpable (but real) presence of emptiness.The highway in the background is dazzling and flourishing, full of mythological figures and omens, however they only represent a cruel hope in the void of existence, on the road-life that lead to death...

‘The First Girls’ trans. by Lucile Brenon

I chose the first excerpt, “Les premières filles” (“The First Girls”) in relation to this issue's theme because it depicts two women having a conversation about their teenage days. They are looking back on the roads they have already traveled.

‘I Go by Dreaming Roads’ trans. by Ana Orbegozo

Antonio Machado (1875-1939) is best known for his lyrics about countryside roads in Castille. But his observations about ‘the road’ are really meditations on the nature of life. This poem focuses on a traveller who cannot see where his road goes and yet seems to be reaching the end of his journey.

‘Féile Chorp Chríost i “Máirseáil Radetzky’’’ trans. by Aoibh Ní Chroimín

On a literal level, the extract depicts roads as places of public gatherings and pageantry. On a more metaphorical level, the novel traces the paths of Lieutenant Trotta, his family, and the Empire in which he lives in the lead up to the First World War.

‘My Destination’ trans. by Breno Moura Motta

In this poem Cora Coralina depicts life as a journey along a road, and her loved one as a companion that she stumbles upon unintentionally. The “white stone from a fish’s head” is a reference to otoliths, stones that grow in the heads of all fish.

‘Inferno, Canto I, 1 - 60.’ trans. by Martha Giambanco

The Divine Comedy is the allegorical tale of the journey all men must undertake on earth to achieve truth and salvation, forfeiting the road of sin. In his path of atonement and moral purification, Dante is antagonised by three beasts, symbolising lust, pride and avarice. Thus, having reached the middle of his life, Dante now finds himself at the ultimate crossroad.

‘Trans-European Express ’ trans. by Greta Chies

Trieste is a crossroads of languages and cultures, a border-town suspended between East and West, “a wonderful rift between worlds”. Standing on its pier, one can imagine endless roads leading far away. The author, a travel writer, knows this well: Trieste is the shore where he has “dreamt every departure”.

‘The Farewell’ trans. by Rachele Faggiani

We pass through several roads, when proceeding in life. Should we go back or move forward? The poem expresses the feeling of having to literally retrace our steps and decide what’s the next path we’re going to take.

‘I go out on the road alone… ’ trans. by Cian Dunne

Lermontov’s use of trochaic pentameter in this longer-line, lyric poem was unusual, therefore more commonly associated with short-line folk poetry and song. Work by later poets written in similar metrical and stanza form was subsequently assumed to be in dialogue with Lermontov’s precedent. Thus, this romantic, meditative poem, as well as outlining the onset of its speaker’s journey, sets a poetic path for Lermontov’s imitators to follow.

Выхожу один я на дорогу;

Сквозь туман кремнистый путь блестит;

Ночь тиха. Пустыня внемлет богу,

И звезда с звездою говорит.

В

небесах торжественно и чудно!

Спит земля в сиянье голубом…

Что же мне так больно и так трудно?

Жду ль чего? Жалею ли о чем?

Уж не жду от жизни ничего я,

И не жаль мне прошлого ничуть;

Я ищу свободы и покоя!

Я б хотел забыться и заснуть!

Но не тем холодным сном могилы…

Я б желал навеки так заснуть,

Чтоб в груди дремали жизни силы, Чтоб дыша вздымалась тихо грудь;

Чтоб всю ночь, весь день мой слух лелея, Про любовь мне сладкий голос пел, Надо мной чтоб вечно зеленея

Темный дуб склонялся и шумел.

I set out alone along the road, A stony path shines through the fog, In the quiet night, the wilds listen to God, And the stars are speaking to each other.

The heavens are full of wonder and glory! The earth sleeps bathed in blue light, But why is it all so hard for me? What am I waiting for? What do I regret?

I don’t expect all that much from life, And the past I don’t regret in the least, I’m merely searching for freedom and peace, And I’d like to forget myself and sleep.

But not that cold sleep of the dead. I’d like to sleep forever with, My life force dosing in my chest, Rippling with soft and quiet breaths.

All day and night, I’d treasure the sound, Of a sweet voice singing to me of love, And above me, growing endlessly, A dark oak murmurs and bows to me.

Translated by Ailbhe CannonShailendra (Music by: Shankar-Jaikishan, Performed by: Talat Mahmood)

अंधे रास्ते

तो जाएं कहाँ

आग़ाज़ के दिन तेरा

तय हो चुका

जलते रहें हैं जलते

A blind cosmos’s blinded roads, I wonder where they lead. This world, and you, are both the Other, Where does that leave me?

The want to live is no more, Death brings no solace either. This shore has tears, the other sighs, And my heart speaks neither.

A blind cosmos’s blinded roads, I wonder where they go.

Is there no one to call us anymore, To wait lovingly at our door?

Oh, those plagued by grief, know, Our destination is death alone.

The blinded roads of a blind cosmos, I wonder where they go.

Having started your Day, Marks the end of mine, That which was ablaze stays afire, Like this earth and sky.

A blind cosmos’s blinded roads, I wonder where they lead. The world, now you, are both the Other, Where does that leave me?

Tu ti va incontra al doman co la léngua đe jeri, no stà bađar le ṣlenguaẑone đe incόi, a le femenete che le cava le piantine đa la léngua đei bòce par semenar garnèi ẑènẑa đolor - đal bosch se inpara pura co la boca, al basta mastegar na foja, o ‘n ramet, par saver l’àrbol e ‘l tènp che ‘l lo mof –, no stà assar crésser nte i lavri al fenìscol a cuèrđer ògne paròla salvàrega, tu savarà nò sol de le rađis e đe le ponte, ma anca đe ‘n troi par al bosch che no ‘l vol farse trađur.

No sò se me perđarò, viẑa mea, quan alti i to faghèr!, no se pol véđer gnanca na s’cianta đe cel, e che ođor bòn de vita đeversa!, vae revès par scansar le vartore, a mi te voe tuta atorno, a missiarme al sangue, a méter i pas a l’anda đel cor, e la voẑe ingalivađa al fià đe foje, al tremar đe unbrìe, la mènt qua no la se confonde, la sa đe ‘n logo điṣest Parađiṣe, là ghe n’è na fontana ndove i bef i oṣèi strachi romài đe la đornađa, nte i so òci l’è tut al sol che no veđe.

Ciare cussì le matine đe agost: al vènt al ṣgorla ẑime indormenẑađe i valon i par lame đe bombaṣo al bosch al se impinẑa đe cant a còro le se cuẑa le unbrìe fin a stuṣarse là su le va e vien s’ciapađe đe ṣbir squaṣi i volesse pontar ṣbrach de nèole, l’è pròpio questa l’ora muneṣina đe perđerse đrìo i orivi đe le viẑe ndove le ṣlùṣega le franbolère, tut descolẑ par i troi del Maẑarόl fa ‘n bocia che l’à ocet de panegassa a ẑupar đa ògne foja la guaẑ de vita.

You head towards tomorrow with the language of yesterday. Don’t listen to the slanderers of today, the women rooting out seedlings from children’s tongues to sow there painless grains. The forest is a teacher to the mouth, you need only taste a twig, a leaf, to know the tree and the time which moves it –, don’t let the moss grow between your lips, burying every last wild word; then you will know about roots and fronds, and about a lost path through the woods that won’t yield to translation.

I don’t know, forest mine, if I will lose my way, how tall are your beech trees! Not a scrap of sky can I see, how nice the scent of mingled life! I walk the wrong way, elude the clearings, I want you to be all around me, stirring my blood, tuning my steps to the heart’s rhythm, my voice to the leaves’ breath, the shivering shadows. The mind will not go astray here, it knows of a place called Paradise; there I’ll find a spring where birds go seeking water, weary of the day. All the sun I cannot see is in their eyes.

Such are clear August mornings: the wind shakes sleeping fronds, the glens resemble ponds of cotton-wool, a choir of calls illuminates the woods, the shadows crouch and slowly fade; above, flocks of swallows come and go as if trying to stitch up tears in the clouds. This tender hour is the time to go astray at the edges of woods where raspberry bushes glimmer, barefoot along the paths of fairies, like a sparrow-eyed child sucking from each leaf the dew of life.

Translated by Greta Chies- Inniu. Breathnaímis ar phictiúr. Tírdhreach.

Chuala mé clic sa dorchadas. Chuala mé comhla sa bhos thíos uaim ag sleamhnú isteach agus ansin ag preabadh amach arís. Léim pictiúr lán de dhathanna éagsúla – buí, oráiste agus dearg – suas ar an tsíleáil. Ní fhéadfainn é a dhéanamh amach.

- Cuirfidh mé é sin i bhfócas duit anois.

D'éirigh an pictiúr níos cruinne go mór agus paistí áille bánghlasa agus iliomad línte tanaí dúghorma ag lúbarnaíl trí dhathanna ómra, agus paistí beaga ilghnéitheacha eile - glas, bándearg, corcra, dubh, liath - chomh maith le línte beaga gléineacha dearga trasna na línte beaga gorma.

- Rorschach de mo chuid féin é seo. Bhuel ní liomsa é dáiríre. 'Paranóia' atá air. Is le healaíontóir Dúitseach é. Emil Van Roon. Tá mé an-bhródúil as. Anois, inis dom cad a fheiceann tú ann.

Lig mé liom féin oiread na fríde, agus tharla rud aisteach. Bhí sé mar a bheinn ar ais arís sa ghairdín sin a raibh mé ann agus mé ag léamh an scéil úd in Comhar os cionn seachtaine roimhe sin. Mhothaigh mé an t-aiteas céanna orm arís, iarracht den ghliondar agus den sceon. Ansin mhothaigh mé ciontach, damnaithe, aonarach, ar bhealach gránna. Ba bheag nár aithin mé an tinneas a bhí orm.

- Ha, arsa Áthas, feiceann tú rud éigin ann.

Shíl mé gur cheart dom cur síos a dhéanamh ar a bhfaca mé. Ba sheo é an saol, agus bhí mé ag breathnú aníos air ó tholg an amhrais.

- Today. Let’s look at a picture. A landscape.

I heard a click in the darkness. I heard a shutter being slid across and bouncing back again. A kaleidoscope of colour – yellow, oranges and red –jumped out onto the ceiling. I couldn’t make it out.

- I will put it into focus for you now.

The image became much clearer; pretty pale-green patches and a multitude of thin navy lines wriggled between shades of amber, and other small patches – greens, pinks, purples, blacks and greys – along with small bright red lines that crossed over the thin blue ones.

- A Rorschach painting of my own. Well, it’s not really mine. It’s called “Paranoia”. It is by a Dutch artist by the name of Emil Van Roon. I’m very proud of it. Now, tell me what you see.

I relaxed myself, and something strange happened. It was as if I was in the garden again reading that story in Comhar over a week ago. I felt the same happiness again, the sense of joy and the satisfaction I had. Then, I felt guilty, damned, alone, in an awful way. I came close to recognising the illness I had.

- Ha, said Áthas, you see something.

I thought I should describe what I saw. For life was a play and I was now looking down on it from the gallery of suspicion.

- Feicim, a dúirt mé go trialach, go bhfuil an saol seo briste suas ina phaistí, ina chodanna éagsúla, is d'fhéadfá a rá go bhfuil a dhath féin ar gach paiste, agus a chruth is a dhéanamh féin. Is tá na paistí gormghlasa ann ar nós uisce a Meánmhara maidin earraigh, is tá na paistí maotha ómra mar a bheadh coilearnach beithe tráthnóna fómhair. Agus tá oiread sin paistí idir gach paiste gur dócha go bhféadfá a rá nach gairdín atá ann ach cathair - cathair ghríobháin. Ach go samhlaítear dom anois nach sráideanna atá idir na paistí ach srutháin, canálacha domhaine dúghorma. Feictear dom gurb í seo cathair na Veinéise. Seo iad dathanna San Marco. Agus feicim droichid bheaga dearga anseo is ansiúd thar na canálacha sa chaoi is gur féidir leat dul áit ar bith is maith leat sa chathair seo.

- An-deas. Molaim do shamhlaíocht. Canálacha agus droichid. Cá dtéann na droichid sin? ...

- Droichid shóisialta iad. Úsáideann daoine iad. Is ar an gcaoi sin a dhéanann paiste amháin teagmháil le paiste eile. Agus is bealaí sóisialta eile iad na canálacha. Ach ní teagmháil dhíreach í; ar na canálacha. Agus tá na canálacha ar fad ceangailte le chéile. Ach ní mar sin do na droichid. Bíonn na droichid ceangailte le paistí daite. Agus is aisteach an chaoi gurb iad na rudaí a scarann na paistí ó chéile, gurb iad sin na rudaí a chuireann i dteagmháil lena chéile iad.

- I see, I said warily, that this life is broken up into patches, in their various parts, and you could say that each one has its own colour and shape as it deems itself. And the pale-green patches are like the water of the Mediterranean on a spring morning, and the amber ones like a birch grove on an autumn afternoon. And the multitude of patches between them… it’s more like they are a city, no, a maze. But now it seems to me that there aren’t roads between the patches, but instead streams: navy-blue deep streams. It looks like the City of Venice. It’s the colours of San Marco. And I see little red bridges here and there over the canals in a way that allows you to go wherever you want in this chair.

- Very interesting… What an interesting interpretation. Canals and bridges. Where do these bridges go?

…

- These are bridges that link society. The people use them. It’s in this way that one patch can connect with another patch. And the canals are another means. But they’re not a direct means – the canals, I mean. And the canals are all interconnected; but, it’s not so with the bridges. The bridges are connected by the coloured patches. And isn’t it strange how the things that divide the patches from each other are the things that bring them together.

何処へゆくのか 嵐の中で 水鏡に映る 隣合う世界

私が跳ねれば 空に波紋が 風は交わり 狭間に龍の道が 見えるだろう

満ち引きを見ている原生の茂り 丘の上で星を見る子ども 風が吹いている

夜光貝 触れる指 命の振り分け 光に 消える神さま

かえるのうたが きこえてくるよ

In the centre of the storm, the water reflects neighbouring worlds. Where are you going?

If I jump, the sky will ripple with the wind. From space, the road of the dragon looks like this.

The movement of the tides grows strong. Over the hill, children view the stars.

The wind is blowing. Touch a seashell with a finger and understand that the force of life is like a ray, a disappearing god.

Return song, I hear you.

His car is a nervous breakdown, scattering chrome along the motorway. He gasps through panic attacks in tunnels and medieval towers. The falconry display goes on regardless and eejits in velour have a crack at each other with plywood lances. I'm in fugue state, headphones glued to me as mum calls to accuse him of kidnapping. Come for a drink, he says. No. Retreat to the Travelodge, dry my one pair of decent flares rancid from days of rain, in the mysterious trouser press. My anger flits and shifts like a clot of starlings. He presses into my hands some Gunter Grass, and Sylvia Plath –time-capsule messages in a language we don't share, and the evening heaves with the bellow of cows taken from their calves.

Jeho auto je nervové zhroucení, rozhazující chrom po dálnici.

Lapá po dechu v záchvatech paniky v tunelech a středověkých věžích.

Sokolnická přehlídka pokračuje tak jako tak, a debilové ve veluru se navzájem zkoušejí s překližkovými kopími.

Dočasně jsem ztratila identitu, sluchátka přilepená k uším, když volá máma, aby ho obvinila z únosu.

Přijď na skleničku, říká.

Ne. Najdi ústratí v Travelodge, usuš si své jediné slušné zvonáče

žluklé od několikadenního deště, v záhadném lisu na kalhoty.

Můj hněv poletuje a mění se jako houf špačků.

Tiskne mi do dlaní

něco od Guntera Grasse, a Sylvie Plath –vzkazy v časových kapslích v jazyce, který nesdílíme, a večer se vzdouvá bučením krav, odebraných od svých telat.

The wind dies down after all, the rain stops, the night expands to include the farthest ice-cold galaxies. you sit out silently on the beach at Lagos and fancy you could hear a micro-chip drop anywhere between the Cape and Cairo, or, drifting across the darkened curve of the South Atlantic, the sound of early evening traffic snarling up in Rio De Janeiro

Rüzgâr diniyor

nihayet, duruyor yağmur, buz tutmuş galaksileri

içine almak için

genişliyor gece.

Sessizce oturuyorsun

Lagos’daki kumsalda ve ne hoş bir his

Ümit Burnu ile Kahire arasında bir yerde düşen bir mikroçipin sesini duymak, yahut, sürüklenmek

Güney Atlantik’in kararan kıvrımında, akşamüstü trafiğinin

keşmekeşinde

Rio De Janeiro’da

Roads go ever ever on, Over rock and under tree, By caves where never sun has shone, By streams that never find the sea; Over snow by winter sown, And through the merry flowers of June, Over grass and over stone, And under mountains in the moon.

Roads go ever ever on Under cloud and under star, Yet feet that wandering have gone Turn at last to home afar. Eyes that fire and sword have seen And horror in the halls of stone Look at last on meadows green And trees and hills they long have known.

Leanann bóithre ar bhóithre go síoraí

Thar chloch ‘s faoi chrann

Cois phluaiseanna dorcha gan ghrian

Cois uisce tréigthe i sruthán

Thar sneachta an gheimhridh go mín

Tríd na bláthanna Meithimh is aeraí

Thar fhéar agus thar chloch bhinn

Agus faoi shléibhte gealaí

Leanann bóithre ar bhóithre go síoraí

Faoi réaltaí ‘s faoi scamaill

Ach na cosa a bhí ar strae imí

Anois casta ar bhaile ar deireadh thall

Súile a bhí lán radhairc claímh ‘s tine lasta

‘S uafáis na dtollán cloiche lán-bhaoil

Anois dírí ar ar bhánta glasa atá

Agus ar chnoic ‘s ar chrainn a shaoil

Bernadette Nic an tSaoir

Ní fhanann muir

Ní bhíonn sí socair

A tráthanna féin aici

Don teacht is imeacht

Caitear chugat an bruth faoi thír

Dein do rogha rud leis

Go dtaga do charn arís chugat

Bí réidh ar an mbuille

Seachain tú féin idir long is lamairne

Nó fágfar tú ar gcúl

Mar chailleach na luaithe buí

Go dté do ghrian i bhfarraige

Woda nie czeka

Jest niespokojna

Sama decyduje

O przypływach i odpływach

Strzeż się okrętu poniewieranego przez fale

Ty sam musisz obrać kurs

Oby twój stos znów cię odnalazł

Bądź gotów na cios

Nie zostań pomiędzy

Statkiem a pomostem

Jak staruszka przy piecu

Aż słońce zatonie na dno

We are united, he and I, though strangers, against the two women in front of us talking so steadily and audibly across the aisle to each other. Bad manners.

Later in the journey I look over at him (across the aisle) and he is picking his nose. As for me, I am dripping tomato from my sandwich on to my newspaper. Bad habits.

I would not report this if I were the one picking my nose.

I look again and he is still at it.

As for the women, they are now sitting together side by side and quietly reading, clean and tidy, one a magazine, one a book. Blameless.

Estamos unidos, ele e eu, apesar de não nos conhecermos, contra as duas mulheres na nossa frente conversando alto ininterruptamente do outro lado do corredor. Mal educadas.

Mais para a frente no caminho eu olho para ele (do outro lado do corredor) e ele está cutucando o nariz. Quanto a mim, eu estou pingando tomate do meu sanduíche no meu jornal. Maus hábitos.

Eu não contaria isso se fosse eu que estivesse cutucando o nariz. Olho de novo e ele ainda está fazendo isso.

Quanto às mulheres, elas agora estão sentadas juntas lado a lado e lendo silenciosamente, limpas e arrumadas, uma lê uma revista, a outra um livro. Irrepreensíveis.

Cheval seul, cheval perdu, Malade de la pluie, vibrant d’insectes, Cheval seul, vieux cheval.

Aux fêtes du galop, Son élan serait vers la terre, Il se tuerait.

Et, fidèle aux cailloux, Cheval seul attend la nuit Pour n’être pas obligé De voir clair et de se sauver.

Lone horse, lost horse

Sick from the rain, spirited by insects, Lone horse, horse of years bygone

At galloping shows, His ardour would take him to the ground, He could die.

Yet, faithful to the pebbles, Lone horse waits for the night When he is not obliged To see clearly and save his own life.

Translated by Adrianna RokitaOn Raglan Road on an autumn day I met her first and knew That her dark hair would weave a snare that I might one day rue; I saw the danger, yet I walked along the enchanted way, And I said, let grief be a fallen leaf at the dawning of the day.

On Grafton Street in November we tripped lightly along the ledge Of the deep ravine where can be seen the worth of passion's pledge, The Queen of Hearts still making tarts and I not making hayO I loved too much and by such and such is happiness thrown away.

I gave her gifts of the mind I gave her the secret sign that's known To the artists who have known the true gods of sound and stone And word and tint. I did not stint for I gave her poems to say. With her own name there and her own dark hair like clouds over fields of May

On a quiet street where old ghosts meet I see her walking now Away from me so hurriedly my reason must allow That I had wooed not as I should a creature made of clayWhen the angel woos the clay he'd lose his wings at the dawn of day.

En la Calle Raglan un día de otoño la encontré por primera vez y supe que su pelo oscura tejería una trampa que algún día lamentaría; Vi el peligro, pero caminé, por el camino encantado, Y dije, que la pena sea una hoja caída al amanecer del día.

En la Calle Grafton en noviembre bailamos suavemente por el borde De un barranco hondo donde puede verse el valor de la promesa de pasión, La Reina de Corazones sigue haciendo tartas pero yo sin hacer henoAy amé demasiado, ¿así así es desechada tal felicidad?

Le di dones de la mente, le di la señal secreta que conocen los artistas que han conocido los verdaderos dioses de sonido y piedra Y de matiz y palabra. No escatimé pues le di poemas para recitar. Con su propio nombre allí y su propio pelo oscuro como nubes sobre campos de mayo.

En una calle silenciosa donde antiguos fantasmas se encuentran Ahora la veo alejarse de mí con tanta prisa, mi razón debe permitir Que yo había cortejado, pero no como debería, una criatura hecha de arcillaCuando el ángel corteja la arcilla, él perdería sus alas, al amanecer del día.

Zoek je de wereld en kleren doen zeer op de huid, ben je ziek, of de eelt komt van je ziel, en niemand weet dat je gaat.

Kiezel, rots, edelsteen: tekens op een heenweg waar de paden ontbreken. Water en brood in woorden: sporen ontstaan in het voortgaan.

Wie valt over een baksteen en een been breekt, gaat weken in het gips, blijft zo dicht bij zichzelf, maar als je verliefd wordt op een verboden gebied? Dan wacht je in een grot of greppel en hou de adem in, tot de laatste tijd voorbijgaat en iets compleet nieuws begint.

Searching the world and clothes are hurting on our skin, we can fall ill, or a shield comes off our soul, and no one knows that we’re going.

Pebbles, rocks, gems are signs on the way here, where the track seems gone; they’re bread and water in words, and the steps will be found as we tread.

If we trip over a brick and break a leg, we’ll wear a cast and stay close to ourselves, but when we love this land that is out of bounds? Then we’ll wait in a ditch or a cave and hold our breaths, until another time has passed and something brand new is at hand.

Hoe weet een gedicht nu dat het naar je toe moet komen: wanneer je hart een zwaar hoofd heeft?

Waar vind je discipline om te schrijven?

Nee, die heb ik nodig om te stoppen, voor schoonmaaktaken: het huis, mezelf, het leven.

Of het leven schrijft: ‘Sla een brede straat in, raap woorden op, jezelf, en geef me zin.’

Een straat aan poëzie bracht me naar zee, het leek of ik zelf werd aangespoeld: geen

zwembroek of pen, papier, niet recht of los van lijf en leden, maar een stevig en soepel gedicht mens.

Op het strand stond een publiek, ze staarden, schreeuwden en wezen alsof ik doof en dom was, of onleesbaar.

Toch niet omdat een uitstekend deel ontbrak?

How does a poem know to pave its way to you now: when the heart feels a heavy head?

Where do you find discipline to write? No, I need strictness to stop for jobs, cleaning the house or me and life.

Or life writes: “Turn into a wide street, pick up words and yourself, to feed me.”

A road of poetry took me to the sea; it felt like being washed ashore myself, no swim gear or notebook, no loose or firm limbs and skin, but a supple and sound human verse?

There was a crowd on the beach, gaping, shrieking and pointing at me as if I were deaf and dumb or unreadable!

Please, not because a significant part was missing?

O ragazza dalle guance di pesca o ragazza dalle guance d'aurora io spero che a narrarti riesca la mia vita all'età che tu hai ora.

Coprifuoco, la truppa tedesca la città dominava, siam pronti: chi non vuole chinare la testa con noi prenda la strada dei monti.

Avevamo vent'anni e oltre il ponte oltre il ponte ch'è in mano nemica vedevam l'altra riva, la vita tutto il bene del mondo oltre il ponte.

Tutto il male avevamo di fronte tutto il bene avevamo nel cuore a vent'anni la vita è oltre il ponte oltre il fuoco comincia l'amore.

Silenziosa sugli aghi di pino su spinosi ricci di castagna una squadra nel buio mattino discendeva l'oscura montagna.

La speranza era nostra compagna a assaltar caposaldi nemici conquistandoci l'armi in battaglia scalzi e laceri eppure felici.

Avevamo vent'anni...

Non è detto che fossimo santi l'eroismo non è sovrumano corri, abbassati, dai corri avanti! ogni passo che fai non è vano.

Vedevamo a portata di mano oltre il tronco il cespuglio il canneto l'avvenire di un giorno più umano e più giusto più libero e lieto.

Avevamo vent'anni...

Ormai tutti han famiglia hanno figli che non sanno la storia di ieri io son solo e passeggio fra i tigli con te cara che allora non c'eri.

E vorrei che quei nostri pensieri quelle nostre speranze di allora rivivessero in quel che tu speri o ragazza color dell'aurora.

Avevamo vent'anni...

Oh, rosy-cheeked lady, oh, bright-cheeked lady, I hope you will read from my mouth what the story of my life at your age was about.

Curfew: the German soldiers dominating the city, we are ready: those who won’t take off their hats will take with us the mountain path.

We were twenty and beyond the bridge, beyond the now-enemy bridge, the other bank, life, all the beauty of the world, beyond the bridge.

In front of us the devil but our hearts, of good, were plenty Life is beyond the bridge, Love is beyond war, when you are twenty.

On pine needles and chestnut burs, in the darkness of the morning, a troop was silently walking, descending the gloomy mountain

Assaulting our enemies with Comrade Hope by our side, barefoot, exhausted but still happy, we won the battle with pride.

I’m not saying we were superhumans, no need to be extraordinary to be fearless run, go down, come on, run! No step taken is worthless.

Beyond the tree trunk, the bush, the reed, we then stood watching the dawn of a cheerful and fairer world finally approaching.

Now everyone has a family and children who of the past are unaware, I am here, alone, walking among lindens with you, my dear, who are not there. Oh, dawn-colored lady, I would like that those wishes and thoughts may revive in what you now hope.

We were twenty…

Söyleyin dağlara rüzgara

Yurdundan sürgün çocuklara

Düşmesin kimse yılgınlığa

Geçit vardır yarınlara

Göç yolları

Göründü bize

Görünür elbet

Göç yolları

Bir gün gelir

Döner tersine

Dönülür elbet

En büyük silah umut etmek

Yadigar kalsın size

Yol verin kanatlı atlara

Sürgünden dönen çocuklara

Ateşler yakın doruklarda

Geçit vardır yarınlara

Dağılsak da göç yollarında

Yarın bizim bütün dünya

Tell the mountains, the wind

And the children in exile

Not to despair

There are paths to tomorrow

Today, the migration roads

Appear before us

They certainly do

But a day will come

When those roads

Will change course

They certainly will

The best weapon is hope

It’s the only gift we can leave for you

Give way to the winged horses

And the children returning from exile

Set fire to the peaks

There are paths to tomorrow

Even if we disperse along these roads

Tomorrow, the whole world will be ours

Einst weidete ein Hirt aus dem nahen Sittendorf seine Heerde am Fuße des Kyffhäuferbergs. Er war ein braver; hübscher Mensch, und mit einem guten aber armen Mädchen verlobt; doch weder er noch sie hatte ein Hüttchen oder Geld, eine Wirtschaft einzurichten. In Gedanken über seine Lage versunken, ging er traurig den Burg hinan; aber je höher er stieg, desto mehr schwand ihm die Traurigkeit, denn mild und freundlich lachte die Sonne. Bald befand er sich auf der Höhe. Da schimmerte ihm eine wunderschöne Blume entgegen, dergleichen er auf seine Wanderungen im Gebirge noch nie gesehen hatte. Er pflückte sie und steckte sie an seinen Hut, um sie seiner Braut mitzunehmen. Auf der höchten Spiße des Kyffhäufers angelangt, bemerkte er unter den Trümmern ein Gewölbe, dessen Eingang halb verschüttet war. Er geht hinein, findet viele kleine glänzende Steine auf der Erde liegen, und steckt so viele derselben ein, als seine Taschen fassen können. Nun wollte er das Gewölbe wieder verlassen, da rief ihm eine dumpfe Stimme zu: „Vergiß das Beste nicht!“ Er aber wußte bei diesen Worten nicht, wie ihm geschah, und flüchtete so haftig aus dem Gewölbe, daß er selbst nicht wußte, wie er an das Tageslicht kam. Kaum sah er wieder die Sonne und feine Heerde, so schlug eine Thür, die er vorher gar nicht gesehen hatte, mit großem Geräusche hinter ihm zu. Er griff noch seinem Hute, doch die wunderschöne Blume, die er seiner Braut hatte geben wollen, war fort; sie war beim Stolpern in dem Gewölbe herabgefallen. Als er wehmüthig nach der Stelle seines Hutes blickte, an der sie befestigt gewesen war, stand er plötzlich ein Zwerg vor ihm und sprach: „Wo hast Du die Wunderblume, die Du fandest?“ – „Verloren“, sagte traurig der Hirt. „Dir war sie bestimmt“, erwiederte der Zwerg, „und sie ist mehr werth, als die ganze Rothenburg“. Traurig geht der Hirt am Abend zu seiner Braut, und erzählt ihr die Geschichte von der verlorene Wunderblume. Beide weinen, denn Hüttchen und Hochzeit waren nun wieder auf lange Zeit verschwunden. Endlich denkt der Hirt an die von ihm eingesteckten Steine. Wieder etwas heiterer gestimmt, wirft er dieselben seinem Mädchen in den Schooß, und siehe, es find lauter Goldstücke! Sie konnten sich nun ein Häuschen kaufen und ein Stück Acker dazu, und in einem Monat waren sie Mann und Frau. – Und die Wunderblume? Die ist verschwunden; Bergleute suchen sie bis auf heutigen Tag, und zwar nicht allein in den Gewölben des Kyffhäufers, sondern auch, da vorgebogene Schäße rücken, auf der Questenberg, und selbst auf der Nordseite des Harzes. Bis jeßt aber ist sie noch keinem wieder bestimmt gewesen. Einige glauben, die wunderblume blüht nur alle hundert Jahre einmal, und wer sie dann finde, gelange zu großen Reichthümern.

Once, a shepherd set his sheep out to pasture on the foot of the Kyffhäuser. He was a good, handsome man and engaged to a good, but poor, girl. Indeed, neither he nor she had a little cottage or enough money to set up an inn. Whilst lost in thought over his sad situation, he wistfully travelled up to the castle on the mountainside. But the higher he climbed, the more his sadness dwindled as the sun shone down, gently and pleasantly, on his face. Soon, he found himself at the top.

There, a beautiful flower, the likes of which he had never seen on his journeys before, glistened and shimmered in front of him. He picked the flower and placed it in his hat to bring to his bride. As he reached the highest peak of the Kyffhäuser, he noticed a dark, half-blocked entrance of a vault under the ruins. Approaching it, he found many small, glimmering stones laying on the ground. He filled his bag with as many of the stones as he could. And, as he left the ruins, a muffled voice called out to him “Don’t forget the best thing!” But he did not understand what had happened to him as he heard these words, and so he fled from the vault so quickly that he did not know how he had returned to daylight.

No sooner had he set eyes again on the sun and his fine herd than a door, which he had not seen at all, slammed shut behind him with a great noise. He reached for his hat, but the beautiful flower that he wanted to give to his bride was gone – it had fallen as he scrambled to get out of the vault. As he morosely gazed at the place on the hat where it had been fastened, a dwarf suddenly appeared before him and spoke; “Where do you have the magic flower that you found?” – “Gone,” said the shepherd forlornly. “It was meant for you,” replied the dwarf, “and it is worth more than all of Rothenburg castle.” That evening, the shepherd travelled sadly back to his bride and told her the story of the lost magic flower. They cried, as their hopes of their little cottage and their wedding had disappeared, with seemingly no future. Finally, the shepherd remembered the stones that he had pocketed earlier. With sudden glee, he threw the stones onto the girl’s lap, only to find they had turned to pieces of gold! Now, they could buy a cottage for themselves and even a piece of land to go with it, and within a month they were wed. And the magic flower? It disappeared. The people of the mountain still search for it today, not just in the Kyffhäuser vault, but also where arched beams on the Questenberg mountain move, and even on the north side of the Harz highlands. Some say that the magic flower only blooms once every hundred years, and whoever finds it will enjoy wealth beyond their wildest dreams.

El viejo Caronte, de faz angulosa, tendiome en la orilla su mano huesosa, con árido gesto y ademán salvaje buscando, impaciente, mi pobre bagaje.

Miré en la otra orilla la playa desierta, entre los fulgores de una luz incierta; sentí la nostalgia fugaz de la vida, en el triste instante de la despedida.

"Fui pobre en el mundo -le dije al ancianomi bolsa está exhausta, mirad, buen hermano". Y el viejo barquero, con la mano diestra, retiró la barca, se fue lentamente… En el panorama, tétrico, silente, fulguró en sus ojos una luz siniestra.

Old Charon, at the bank and gaunt of face, Stretched out his bony hand towards me, his count'nance stony and his gestures wild, he sought, impatient, for the purse I'd brought.

I eyed the empty beach on th'other shore; among the gleam of such uncertain light I felt the fleeting kiss of life's nostalgia within the sombre instant of good-bye.

"Poor I was in life," I told that grizzled figure, "My purse is empty, look, kind brother!" But the boatman, with his favoured hand, pushed against the pier, retreating slowly…

Of that dismal, silent image, this remains: Two eyes that flared with deep, sinister light.

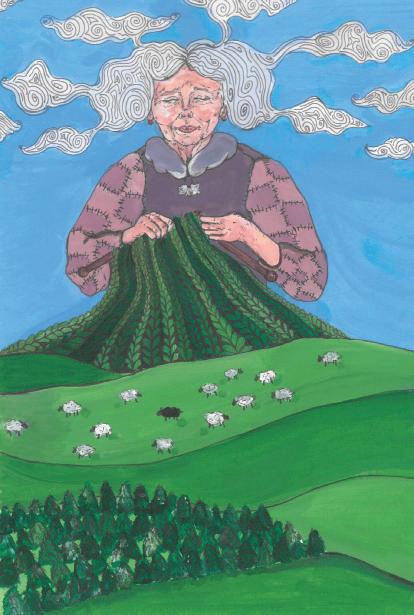

Orla Leyden - Road

Orla Leyden - Road

Ella Sloane - Forging Paths

Ella Sloane - Forging Paths

Katharina Ranefeld - Recalibrate

Katharina Ranefeld - Recalibrate

Naemi Dehde - Dublin

Naemi Dehde - Dublin

Et iam nocturnis spatium laxauerat horis

Phoebus Chelarum pallidiore polo.

Cunctamur temptare salum portuque sedemus, nec piget oppositis otia ferre moris, occidua infido dum saeuit gurgite Plias dumque procellosi temporis ira calet.

Respectare iuuat uicinam saepius urbem et montes uisu deficiente sequi, quaque duces oculi grata regione fruuntur, dum se, quod cupiunt, cernere posse putant. Nec locus ille mihi cognoscitur indice fumo, qui dominas arces et caput orbis habet

[…]

Sed caeli plaga candidior tractusque serenus signat septenis culmina clara iugis.

Illic perpetui soles atque ipse uidetur quem sibi Roma facit purior esse dies.

Saepius attonitae resonant Circensibus aures; nuntiat accensus plena theatra fauor:

Pulsato notae redduntur ab aethere uoces, uel quia perueniunt uel quia fingit amor.

And the Sun’s divine charioteer had already widened the hours of the night – paller, Libra welcomed him into her sky. We could not but hesitate. «Who dares to brave the swelling sea? ». Sitting in the harbour, we relish our tranquil time – unexpected the delay. Meanwhile, the declining Pleiad rages against the faithless stream and the boisterous season’s wrath is inflamed. It delights to look back, again and again, at the near city, to chase the hills with my ceasing sight. Wherever they lead me, my eyes savor those beloved lands, while they can see – so they think –what they are longing for. Nor does a wisp of smoke give me a trace of that place, which owns the sovereign hills, which owns the head of the world. […] But a more dazzling region of the sky, a placid tract reveals the bright summits on its seven ridges. «Look, sunlight is perpetual there. Terser –they say – is the day which Rome makes for herself». More than once in my dazed ears the Circus’ noise resonates, aroused acclamation reveals packed stands, familiar voices are given back from the air which echoes beat. «Are they reaching us? » «Perhaps it is Love who molds them».

They’re coming tomorrow. The key worker and social worker with their files, papers and pens. Trying to hide my hands. The shakes. In the last while, since John died … promising myself it would never come to this … Even with all their papers and pens, mobile phones, one of them brought a computer. Knowing more about their lives than they do about me … John used to say ‘we know more about settled people than they’ll ever know about us’. Waking up … my head sore … not fit for anything, my mind is pure clear. Knowing that women like me are just another piece of shite on someone’s shoes. They’ll tell me fine, no change on the housing list. To be honest as bad as this hotel room is, the idea of a hostel … Kaleigh is all loved up. Darren had his arms around her and offered me a can. They are full of pity for me. They have each other, they have a child. What do I have? Kaleigh going on about how they’re moving out on Friday, they got a place. A two-roomed apartment. He’s swearing he won’t take any more stuff. She’s saying that I can visit them. How her daughter Sophie has gotten really fond of me, close to me. [……]

Yesterday my mother-in-law, after sitting in the café for an hour, texts me saying she’d no way of bringing the boys to see me this week. That’s three weeks without seeing me children. When the kids were smaller, we showed them photographs of the grandparents living on the road. The photographs were a bribe. The pictures made everyone look happy. They don’t show the real hard life that my grandparents had living on the road. The guilt was in both of us. But it’s probably what took John in the end. We bought a small trailer and moved away from the site. From John’s family. His mother took over minding the kids. My own family, Mam and Dad are dead. Moving from trailer to trailer with different brothers and sisters, tension usually runs into an argument. A nuisance, a burden. Nobody said it but I felt it. Rendering myself homeless. My two children, the shelter couldn’t handle it. Social services put me on the priority list. This room, this life, it’s not living. Our boys loved the trailer. My mother, my brother and sisters, we thought those days were over. The kids for the first few days were excited. But then, in school, they were embarrassed saying they were living on the side of a road. The trailer, my eldest boy, the wheelchair, the school, things got hard to manage. John was always stressed. The landlord wanted money up front. For the first eight months. Not asking how, or where he got the extra money. My suspicions were unspoken. Then things got tight, the landlord got greedy. Men were coming to our door, looking for John. They’d push past me and the children. Calling the Guards would be bringing on more trouble. The landlord rather than asking us to leave, increased the rent. John sent me a text, it was two o’clock in the afternoon.

他们明天就要来了。社区工作者和专门对接我的人。他们会带着档案、文件和 笔。我得尽可能把手藏起来,别让他们看见我在颤抖。自从约翰死后,最后的 时刻……我告诉自己绝不能把事情变成这样……即使带了所有的文件和笔, 他们总有一个人还会拿着电脑。我了解这群人可比他们了解我要多……约翰 以前常说“我们了解居有定所的人可远比他们对我们的了解多”。我知道像我 这样的女人就像狗屎一样,什么也不是。他们会告诉我,不用担心,政府救济 房的名单不会变的。说实话,那房子比这酒店房间也好不到哪儿去,跟廉价招 待所差不多……卡雷非常兴奋,达伦双臂搂着她,给我递了一罐啤酒。他们非 常可怜我。他们有彼此,还有一个孩子,我有什么呢?接着卡雷说他们周五就 要搬走了,他们找了个新地方,一个两居室的套房。达伦发誓,有了这房子他 就不会再多奢求什么了。卡雷说我可以去他们家玩,她女儿可喜欢我了,跟我 亲近。(……)

昨天,我婆婆在咖啡馆坐了一小时,接着发短信说,我这礼拜别想见到我的两 个儿子。这样的话我就连着三个礼拜见不到孩子们了。他俩还小的时候,我和 约翰常给他们看爷爷奶奶住在大马路上的照片。现在看来那些照片简直像一 种贿赂,收买了所有人。照片里完全看不出我爷爷奶奶以前住在路边上的日 子有多么艰难,这事让我们都感到很愧疚。不过,这也可能是约翰最后选择那 样结束自己生命的原因。我们搬离了这个地方,买了一辆小拖车。我自己的 家人,我爸妈都已经死了。从小我和兄弟姐妹们一起从一辆拖车搬家到另一 辆拖车上,人与人之间的冲突经常演化成争吵,让人厌恶,心理负担加重。没 有人这么说过,但我能感觉到,这样的生活方式让我变成了无家可归的人。对 我两个孩子来说,像现在这样住在酒店里也无法让他们摆脱那种漂泊感。两 个儿子还是喜欢拖车。我妈妈,还有兄弟姐妹们,我们都以为那些日子早已结 束了。孩子们刚住进拖车时非常高兴。但是没过多久,在学校的时候,他们说 起自己住在马路边上,难免感到尴尬。拖车、大儿子、轮椅、学校……事情变得 越来越难以解决。约翰总是焦虑不已。房东把钱看得比什么都重。最开始八个 月,我没有问约翰他从哪儿搞到的那些钱,没有问他是怎么搞到手的。但我心 里充满疑问。接着事情变得难办,房东也越来越贪心。有人直接找上门,问约 翰在哪里,他们推开我和孩子挤进我们家门。报警只会招来更多麻烦。房东倒 是没直接叫我们搬走,却涨了房租。那是半夜两点钟,约翰给我发了条短信。

SIÞEN þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at Troye, Þe borȝ brittened and brent to brondeȝ and askez, Þe tulk þat þe trammes of tresoun þer wroȝt Watz tried for his tricherie, þe trewest on erthe: Hit watz Ennias þe athel, and his highe kynde, Þat siþen depreced prouinces, and patrounes bicome Welneȝe of al þe wele in þe west iles. Fro riche Romulus to Rome ricchis hym swyþe, With gret bobbaunce þat burȝe he biges vpon fyrst, And neuenes hit his aune nome, as hit now hat; Tirius to Tuskan and teldes bigynnes, Langaberde in Lumbardie lyftes vp homes, And fer ouer þe French flod Felix Brutus On mony bonkkes ful brode Bretayn he settez wyth wynne, Where werre and wrake and wonder Bi syþez hatz wont þerinne, And oft boþe blysse and blunder Ful skete hatz skyfted synne.

,היורט לע הפקתמו רוצמ ץקמ

,רפא דע הפרשנו הלפנש ריעה

םינומא תרפה שרח םשש םחולה

.לבתב היוזבה ותדיגב לע טפשנ

,ויחבושמו ליצאה סאיניא אוה

םינודא וכפהו ושבכ רבכ תוזוחמ זאמש .ברעמ ייא רשוע לכ לע טעמכ

.הרהמב אמור לא אב םרה סולומור

;רדהו דוה בורב ריעה םמור תישאר

.רתונש םשכ ,המשכ שמיש ומש

.םיבושיי בשיי הנקסוטב סויסיט

.םיתב הנב דרבוגנל הידרבמולב

סוטורב ,תפרצ ימימל רבעמו

תועבג יבחרמ לע הינטירב תא הנב

.ליגב

אלפו םיעגפ תוערפ

;וצרפ וז ץראב

הלא לבאו הרוא

.וצח םיתעה תא

Ande quen þis Bretayn watz bigged bi þis burn rych, Bolde bredden þerinne, baret þat lofden, In mony turned tyme tene þat wroȝten. Mo ferlyes on þis folde han fallen here oft Þen in any oþer þat I wot, syn þat ilk tyme. Bot of alle þat here bult, of Bretaygne kynges, Ay watz Arthur þe hendest, as I haf herde telle.

Forþi an aunter in erde I attle to schawe, Þat a selly in siȝt summe men hit holden, And an outtrage awenture of Arthurez wonderez.

If ȝe wyl lysten þis laye bot on littel quile, I schal telle hit as-tit, as I in toun herde, with tonge, As hit is stad and stoken In stori stif and stronge, With lel letteres loken, In londe so hatz ben longe.

,המקוה ליצא ןורב ידיב הינטירבשכ

,ברק תופדור ,תוזעונ תושפנ האלמנ

.םינמזה םרזב וערז סרהש וארנ הז ךלפב םיאלפ רתוי

.יתרכה ותוא רחא לכמ ,זאמ

,וטלש םשש הינטירב יכלממ ךא

.דבוכמ רתויב היה ,יתעמש ,רותרא

,ללוגל שקבא התרקש הקתפרה ןכל

,שממ המיהדמכ ואר םיברש

.רותרא תוישעמ ןיבמ ףא האלפומ

,םיעגר המכל ףא רישל ובישקת םא

לע ריעב יתעמשש יפכ ,דימ הנרפסא

,ןושל

,הובתכ רבכש יפכו

,הרובג ירופיסב

,הורזש תויתואב

.הרוגש הרתונ ךכו

Na gurbet je, na gurbet je, Ture son videlo. Ture son videlo.

Ka tîrnalo, ka tîrnalo Ture po putište, Ture po putište.

Konja vodi, konja vodi Ture samo hodi, Ture samo hodi.

Ljep vo torba, ljep vo torba Ture gladno hodi,

Ture gladno hodi.

Voda gazi, voda gazi Ture žedno hodi, Ture žedno hodi.

Ka pribljiži, ka pribljiži Ture ka pri selo, Ture ka pri selo.

Pa zagljeda, pa zagljeda jeno presno gropče, jeno presno gropče.

Pa zapraša, pa zapraša Ture ofčarčića, Ture ofčarčića.

Ćije lji je, ćije lji je ovja presno gropče, ovja presno gropče?

Ni umrela, ni umrela jena mlada žena, jena mlada žena.

Toga mi se, toga mi se Ture šubeljejsa, Ture šubeljejsa.

Ka mi vljeze, ka mi vljeze Ture vo dvoroji, Ture vo dvoroji.

Pa zagljeda, pa zagljeda jeden šaren ćiljim, jeden šaren ćiljim.

Pa zapraša, pa zapraša mila stara majka, mila stara majka.

Šo je ćiljim, šo je ćiljim što ste go opralje, šo ste go opralje?

Ni umrela, ni umrela Ture milj-Hamida Ture milj-Hamida.

Te čekala, te čekala duša nedavala, duša nedavala.

Ja da dojdem, ja da dojdem Hamida da viđam, jardîm da gi bidem.

Ka se skači, ka se skači gore vo odaja, gore vo odaja.

Pa zagljeda, pa zagljeda jeden muški ruljek, jeden muški ruljek. Toga mi se, toga mi se Ture raželalo, Ture raželalo.

Working abroad a lad had a dream

That he went along a road

The lad had a horse yet he was walking

The lad carried bread yet he was hungry

The lad trod a river yet he was thirsty

The lad came upon a village

Where he saw a wee fresh grave

Then the lad asked a shepherd boy

Whose is this wee fresh grave?

A young woman, our neighbour, has died

This dream greatly unsettled the lad

When the lad returned to his abode

He saw a many-coloured kilim

Then he asked his dear auld mother

Why did ye move this kilim?

Lad, our Hamida the fragrant has died

She was waiting for you, fighting death

Why didn’t you send word, mother

I could’ve come to see Hamida

I could’ve been of help

Then he ran upstairs to their chamber

Where he saw a boy wean in nappies

And the lad burst into tears.

Tu m’as dit

Cette fois c’est le dernier voyage

Pour nos cœurs déchirés c’est le dernier naufrage

Au printemps, tu verras, je serai de retour

Le printemps, c’est joli, pour se parler d’amour

Nous irons voir ensemble les jardins refleuris

Et déambulerons dans les rues de Paris.

This time, it’s the last time astray Our destroyed hearts No longer torn away. In Spring, you will see, I’ll have returned.

Spring, it’ll be perfect For the love we’ll have earned

You and I together, flowers blooming all around These Dublin streets will nurture This beautiful love we have found.

karbonforbindelsene

i berøringen mellom min hånd og plastikktastaturet, de speilvendte bokstavene beveger seg som rulletekst på øyebunnen når du leser dette, nervekoblingene

i Wernickes område som akkurat nå tolker ord og mening, i avstanden

mellom den jeg er når jeg skriver

og den du er når du leser avstand i tid, avstand i geografi, avstanden mellom atomene

før forbindelsene brytes noe av meg blir borte

når du blar om

the carbon compounds: where my hand touches the plastic keyboard, the inverted letters rise like closing credits over the retina as you read this, the synaptic connections in the Wernicke’s area decode this very moment word and meaning, bridge the distance between who I am as I write and who you are as you read the distance in time, in geography, the distance between atoms before the connection is broken something in me leaves when you turn the page

svarte hull i sannhetene gravd ut av gruvegangene i møtet med lyset for å frakte seg selv over havet på det hvite arket i kullet ligger konklusjonene og lengselen etter berøring i en sjakt av sammenpresset tid

black holes in truths dug out of mineshafts that encounter the light to ferry across the sea on the white page the coal, the conclusion and longing for touch a chute of compressed time

Manuel Bandeira

Café com pão Café com pão Café com pão

Virge Maria que foi isto maquinista?

Agora sim

Café com pão

Agora sim

Voa, fumaça

Corre, cerca

Ai seu foguista

Bota fogo

Na fornalha

Que eu preciso

Muita força

Muita força

Muita força

Ôo…

Foge, bicho

Foge, povo

Passa ponte

Passa poste

Passa pasto

Passa boi

Passa boiada

Passa galho

De ingazeira

Debruçada

No riacho

Que vontade

De cantar!

Ôo…

Quando me prendero

No canaviá

Cada pé de cana

Era um oficiá

Ôo…

Menina bonita

Do vestido verde

Me dá tua boca

Pra matá minha sede

Ôo…

Vou mimbora vou mimbora

Não gosto daqui

Nasci no sertão

Sou de Ouricuri

Ôo…

Vou depressa

Vou correndo

Vou na toda

Que só levo

Pouca gente

Pouca gente

Pouca gente

Bacon and cabbage

Bacon and cabbage

Bacon and cabbage

Sweet suffering Jaysus, what was that, engineer?

Now you’re at it

Bacon and cabbage

Now you’re at it

Flying smoke

Fly by fence

Mr. Stoker

Feed the fire

In the furnace

‘Cause I need

So much power!

So much power!

So much power!

Ooo

Run, beasts

Run, folks

Passing bridges

Passing posts

Passing fields

Passing yokes

Passing heards

Passing branches

Of the willow

That are pointing

To the stream

How it makes me

Want to sing!

Translated by Julia ÁlvaresOoo

When I was arrested

In the farm of that man

The sheep that I tended

Were all black and tan

Ooo

Pretty cailín

Pale blue eyes

Give me your lips’n’

Quench my desire

Ooo

I’m going away, I’m going away

I don’t like it here

I grew up in Inisheer

Was born in Ballyhea

Ooo

I’m rushing

I’m hasting

I’m shpeeding

‘Cause I carry

Just’ few folks

Just’ few folks

Just’ few folks

‘Idle as trout in light Colonel Jones these Irish, give them no coins at all; their bones need toil, their characters no less.’ Trevelyan’s seal blooded the deal table. The Relief Committee deliberated: Might it be safe, Colonel, to give them roads, roads to force From nowhere, going nowhere of course?

“One out of every ten and then another third of those again women - in a case like yours.”

Sick, directionless they worked; fork, stick were iron years away; after all could they not blood their knuckles on rock, suck April hailstones for water and for food? Why for that, cunning as housewives, each eyed –as if at a corner butcher - the other’s buttock.

“Anything may have caused it, spores a childhood accident; one sees day after day these mysteries.”

Dusk: they will work tomorrow without him. They know it and walk clear; he has become a typhoid pariah, his blood tainted, although he shares it with some there. No more than snow attends its own flakes where they settle and melt, will they pray by his death rattle.

“You never will, never you know but take it well woman, grow your garden, keep house, good-bye.”

‘Immobili come trote sotto luce Colonnello Jones questi Irlandesi, non diamo loro neanche uno spicciolo; le loro ossa necessitano fatica, il loro temperamento pure.’ Il timbro di Trevelyan insanguinò il tavolo degli affari. La Commissione Soccorsi deliberò: ‘Sarebbe prudente, Colonnello, dar loro dei sentieri, sentieri per sfinire dal nulla, verso il nulla ovviamente?’

"Una su dieci e poi un altro terzo di queste donne- in un caso come il suo"

Lavoravano, ammalati e senza scopo; forcone, bastone erano lontani anni ferro; dopotutto non potevano sbucciarsi le nocche sulla roccia, dissetarsi e saziarsi succhiando la grandine d’aprile? Di conseguenza, scaltri come casalinghe, ognuno adocchiavacome dal macellaio dietro casa- le natiche dell’altro.

"Impossibile saperne la causa, spore, un incidente da bambina; misteri come questi si presentano giorno dopo giorno."

Crepuscolo: domani lavoreranno senza di lui. Lo sanno e lo tengono a disparte; il tifo l’ha trasformato in reietto, il suo sangue sporco, anche se condiviso con alcuni. Proprio come la neve, che trascura dove vengono depositati e sciolti i suoi fiocchi, non pregheranno al suo rantolo della morte.

"Non ce la farà mai, mai le assicuro ma la prenda bene donna, coltivi il suo giardino, si occupi della casa, addio."

‘It has gone better than we expected, Lord Trevelyan, sedition, idleness, cured in one. From parish to parish, field to field; the wretches work till they are quite worn, then fester by their work; we march the corn to the ships in peace; this Tuesday I saw bones out of my carriage window, your servant Jones.

“Barren, never to know the load of his child in you, what is your body now if not a famine road?”

‘Ha superato le nostre aspettative, Lord Trevelyan, sedizione, ozio, tutto curato nello stesso tempo; di parrocchia in parrocchia, di campo in campo, i miserabili lavorano fino allo sfinimento, e marciscono sotto il loro lavoro; portiamo il mais alle barche in pace; questo martedì ho visto delle ossa dal finestrino della mia carrozza, il vostro servitore Jones.’

"Arida, non potrà mai conoscere il peso del bambino di suo marito nel ventre, cos'è il suo corpo adesso se non un sentiero della carestia?"

פּעק עפּמעט ,ערעווש — רעזייה

,למיה ןופ ךיובּ ןקירעדינ ןיא ןָא ןרַאפּש ךאילש ןפיוא עניילק ןשטנעמ

.למירד ןיא סיפ יד ןרעטנָאלפּ

,ואוו םורד ןעיצ לגיופ עניילק סעיַאטס

,לגילפ ןופ ףור רעייז טימ ץרַאה סָאד טינ ןגער ייז

,קירעיורט ןוא ןיילק זיא יז ;ןוז יד זיא טָא — ןוז יד

.לגיפּש־נשַאט ןיימ יוו ,קירעיורט ןוא ןיילק

Houses — dull, heavy heads lean into the low stomach of the sky. People, small on the road, tangle their feet in a nap.

Little flocks of birds fly south, where they will not rend the heart with the call of their wings. The sun — there is the sun; she is small and sad, small and sad, like my pocket mirror.

Translated by Reyzl GraceTwo roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Because it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same, And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. Oh, I kept the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

Scar dhá bhóthar i gcoill bhuí, Agus brón orm, níor fhéad mé an dá cheann acu a thaisteal Agus mise i m’aonar, is fada a sheas mé Agus d’fhéach mé síos ceann acu, chomh fada is ab fhéidir liom Go dtí an áit ar lúb sé sa chasarnach

Ghabh mé an ceann eile ansin, chomh cothrom lena mhalairt, Agus an ceann is fearr agamsa, b’fhéidir, Toisc go raibh sé féarmhar is ag iarraidh caithimh; Ach ina ainneoin sin, Bhí siad caite nach mór mar an gcéanna,

Agus an mhaidin sin luigh an dá cheann acu, Mar a chéile ar dhuilleoga, gan rian dubh satailte orthu, Ó, choinnigh mé an chéad cheann i gcomhair lá eile!

Ach fós féin, leis an eolas ar conas a leanann bealaí bealaí eile, Bhí mé in amhras an dtiocfainn ar ais go deo na ndeor.

Beidh an scéal seo á insint agam le hosna Áit éigin tamall fada amach uainn: Scar dhá bhóthar i gcoill, agus ghabh mé–Ghabh mé an ceann ab annamh a thaistealaítí, Agus ba é sin a rinne an difríocht ar fad.

Tempo dieci anni, nemmeno prima che rimuoia in me mio padre (con malagrazia fu calato giù e un banco di nebbia ci divise per sempre).

Oggi a un chilometro dal passo una capelluta scarmigliata erinni agita un cencio dal ciglio di un dirupo, spegne un giorno già spento, e addio.

Sappi – disse ieri lasciandomi qualcuno –sappilo che non finisce qui, di momento in momento credici a quell’altra vita, di costa in costa aspettala e verrà come di là dal valico un ritorno d’estate.

Parla così la recidiva speranza, morde in un’anguria la polpa dell’estate, vede laggiù quegli alberi perpetuare ognuno in sé la sua ninfa e dietro la raggera degli echi e dei miraggi nella piana assetata il palpito di un lago fare di Mantova una Tenochtitlàn.

Di tunnel in tunnel di abbagliamento in cecità tendo una mano. Mi ritorna vuota. Allungo un braccio. Stringo una spalla d’aria.

Ancora non lo sai

– sibila nel frastuono delle volte la sibilla, quella che sempre più ha voglia di morire –non lo sospetti ancora che di tutti i colori il più forte il più indelebile

è il colore del vuoto?

Ten years - maybe lessbefore my father (re)dies in me (with carelessness he was lowered down and a fog bank divided us forever).

Today, a kilometre from the mountain pass, a dishevelled hairy Erinys waves a cloth from the edge of a cliff; extinguishes an already extinguished day, and farewell.

Know - said someone leaving me onceknow that it does not end here, from moment to moment, believe in that other life, from coast to coast, wait for it - it will come as a summer's return beyond the mountain pass.

Thus speaks the recidivist hope, bites the pulp of summer in a watermelon, sees out there those trees perpetuate each in itself its own nymph and behind the halo of echoes and vision in the thirsty valley the pulses of a lake making of Mantua a Tenochtitlàn.

From tunnel to tunnel from dazzle to blindness I stretch out a hand. It comes back to me empty. I extend an arm. I hold a shoulder of air.

You still do not know - hisses in the din of the vaults the Sibyl, the one that more and more wishes to dieDon’t you suspect that of all colours the strongest, the fastest is the colour of emptiness?

À l’heure de l’apéro après le boulot, coincées entre la cuisine et le bar, on se demande Comment tu as su toi, c’est un truc qu’on fait entre filles

Un truc qu’on veut savoir. Ensuite on se raconte. C’est parfois un bon souvenir, pas toujours.

Sara ferme les yeux elle se souvient J’étais en deuxième année donc. On faisait une fête avec les premières années et une fille m’a regardée toute la soirée avec un regard de désir que je n’avais jamais vu avant, un désir de femme, tu vois. Pas un désir d’homme, elle précise.

Moi je l’écoute et je vois la musique trop forte, je vois les pintes de bière pas bonne, l’odeur rance des chiottes carrelées trop éclairées tatouées au blanco, je vois Sara avec sa tête brouillée entre l’enfance l’adolescence et quelque chose de plus qui est ce qu’elle deviendra et que je connaîtrais un jour. Je vois les regards en coin, échangés l’air de rien devant les copains qui ne voient pas, qui ne peuvent même pas imaginer. Et cette fille, toujours là. Elle me regarde ? Elle me regarde encore. Elle voit que je la regarde et elle ne tourne pas les yeux.

Je vois le désir et la surprise aussi, et la chaleur dans le ventre et les regards encore, le vertige – je vois tout.

Sara attrape une cacahuète dans le petit bol chinois, puis elle reprend.

Ça m’a transpercé le ventre comme une lance ce désir de femme. Elle a fini par m’embrasser. Je pense que je me suis pris la décharge électrique de ma vie. J’étais pas prête. J’avais un mec et tout. Elle en avait rien à foutre. On se tait je dis Tu racontes bien elle a une façon de raconter qui est simple et claire et concise, et je l’aime encore plus d’avoir un jour été cette étudiante qui comprend qui elle est, elle si belle certainement contre la bouche de cette fille qui savait un peu mieux, qui l’avait vraiment vue.

Elle me dit Et toi ?

After work, with a glass of wine, trapped between the kitchen and the counter, we ask each other How did you know? That is something girls do. Something we want to know. And then, the story begins. It’s a good one, sometimes, not always.

Sara closes her eyes, she remembers. It was my second year of college. We were at a party with the firstyears and a girl stared at me the entire night with desire in her eyes like I’d never seen before, a woman’s desire, you know. Not a man’s, she adds.

As I listen, I feel the music playing too loudly, I see the pints of nasty, cheap beer, the foul smell of the toilets, floor white-tiled, walls tipp-ex tattooed. I see Sara with a face that doesn’t know if it is still a child, a teenager or already something more, someone more, that someone Sara will become and someone I will know, one day. I see the stares, exchanged casually in front of friends who do not see, who cannot even imagine. And that girl, still there. Is she looking at me? She is still looking at me. She knows that I stare and she does not look away.

I see desire, surprise, warmth spreading in stomachs and stares, still; giddiness – I see everything.

Sara grabs a peanut from the Chinese bowl and continues. It pierced my stomach like a spear, that woman’s desire. She ended up kissing me. I think it was the biggest electric shock I have ever felt in my life. I was not ready. I had a boyfriend and everything. She did not care.

We are silent and I say, You’re a good storyteller, she has this way of speaking which is simple, clear and concise, and I love her that much more for having been that student who understands who she is, pretty against the mouth of the girl who knew more, who really saw her. She asks, And you?

Et moi c’était l’été de mes quinze ans un été comme ça un été où il y avait eu des garçons évidemment, mais surtout il y avait eu Lola et ses longs cheveux bruns, Lola qui était parisienne et un peu scandaleuse, Lola qui fumait des clopes entre ses lèvres lourdes et son accent titi qui faisait traîner la fin des phrases. J’avais tout de suite voulu ne pas quitter Lola, mettre de la crème solaire sur son dos, aller avec elle à la rivière, l’écouter parler, être l’amie de Lola pour l’été. Je l’avais invitée Lola à dormir à la maison il ne s’était pas passé grand-chose et pourtant

Culottes tee-shirts sur le lit du grenier, elle portait un string qui lui faisait des hanches de femme et ça m’avait fait des nœuds au ventre

Elle s’était laissé regarder Elle m’avait dit Tu aimes bien non Ça n’était pas une question mais oui, j’aimais bien

J’avais dormi près de Lola qui savait mon désir

Après ça n’avait plus été exactement pareil, j’ai achevé en finissant mon verre.

Sara avait hoché la tête en retournant les brocolis au beurre blanc.

Blanc, c’est aussi la couleur de nos silences, qu’on peut laisser durer longtemps parce qu’il n’y a pas besoin d’en dire plus. On sait, je crois, la chance qu’on a d’avoir un jour croisé les premières filles.

And me, it was the summer I turned fifteen, a summer like that, a summer with boys, obviously, but above all, a summer with Lola and her long brown hair, Parisian Lola, scandalous Lola, Lola who smoked cigarettes between her heavy lips, Lola who elongated the end of her sentences the way Parisians do. I immediately wanted never to leave Lola, to apply sunscreen on her back, to go to the river with her, to listen to her speak, to be Lola’s friend for the summer. I had invited Lola to sleep at my house and nothing happened but still

Panties and t-shirts on the bed in the attic, she was wearing a thong that gave her hips like a woman and it twisted my stomach up in knots

She let herself be looked at She told me, You like it don’t you, it was not a question but yes, I did like it

I slept next to Lola who knew what I yearned for After that it was never really the same, I concluded, finishing my glass.

Sara nodded while turning over the broccoli in the white butter sauce.

White is also the colour of our silences, they can last a long time because there is no need to say more. We know, I believe, how lucky we were to have met the first girls.

Yo voy soñando caminos de la tarde. ¡Las colinas doradas, los verdes pinos, las polvorientas encinas!... ¿Adónde el camino irá?

Yo voy cantando, viajero a lo largo del sendero... -la tarde cayendo está-.

En el corazón tenía la espina de una pasión; logré arrancármela un día: ya no siento el corazón.

Y todo el campo un momento se queda, mudo y sombrío, meditando. Suena el viento en los álamos del río.

La tarde más se oscurece; y el camino que serpea y débilmente blanquea se enturbia y desaparece.

Mi cantar vuelve a plañir: Aguda espina dorada, quién te pudiera sentir en el corazón clavada.

I go by dreaming roads in the evening. The hills all golden, the green pines, the dust-covered holm oaks! … Where will the road go?