COMIC BOOK

THE 1940S 1945-1949

Edited by KEITH DALLAS and JOHN WELLS

THE 1940S 1945-1949

Edited by KEITH DALLAS and JOHN WELLS

THE 1940S 1945-1949

Edited by KEITH DALLAS and JOHN WELLS

To our recently departed comic book historian colleagues: Bob Beerbohm, Roger Hill, Bill Schelly, Jim Vadeboncouer, and Mike Voiles.

Editors:

Contributing Writers:

Logo Design:

Layout/Design:

Proofreading:

Cover Design:

Publisher:

Keith Dallas and John Wells

Kurt Mitchell and Richard Arndt

(from an outline provided by Bill Schelly)

Bill Walko

David Paul Greenawalt

Kevin Sharp

Jon B. Cooke

John Morrow

Publisher’s Note: Some of the images in this book are of varying quality, since many vintage pages are available only from less-than-ideal microfiche reproductions. In every instance, we used the best images available to us.

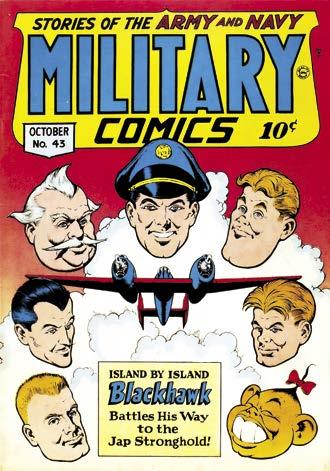

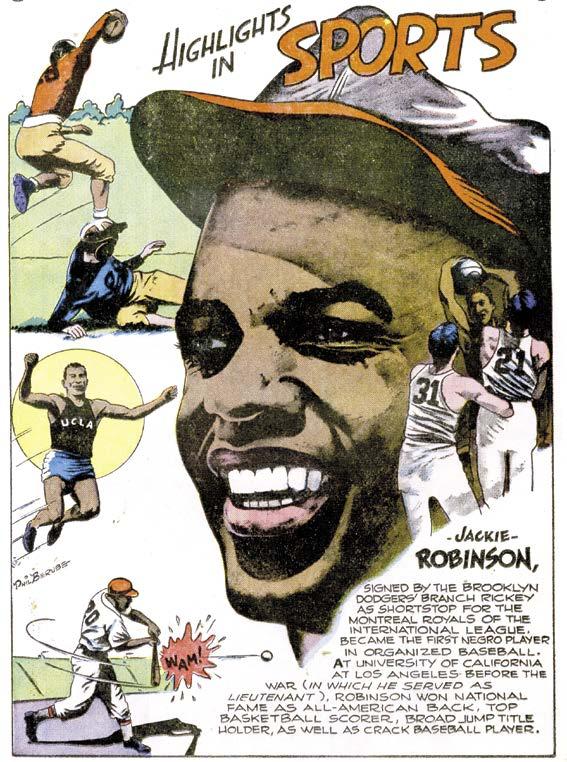

Also, some of the comics covered here depict ethnic and racial stereotypes and slurs that were commonplace in the 1940s, but are offensive by today’s standards. In the interest of an accurate documentation of comics history, they are not being censored, so we ask for your understanding, and to keep this context in mind, when viewing them.

TwoMorrows Publishing 10407 Bedfordtown Drive Raleigh, North Carolina 27614 www.twomorrows.com • 919-449-0344 email: twomorrow@aol.com

First Printing • August 2024 • Printed in China ISBN 978-1-60549-099-1

American Comic Book Chronicles: 1945-1949 is published by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, North Carolina, 27614, USA. 919-449-0344. Keith Dallas, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. All characters depicted herein are TM and © their respective owners, as noted where they appear. All textual material in this book is © 2024 TwoMorrows Publishing.

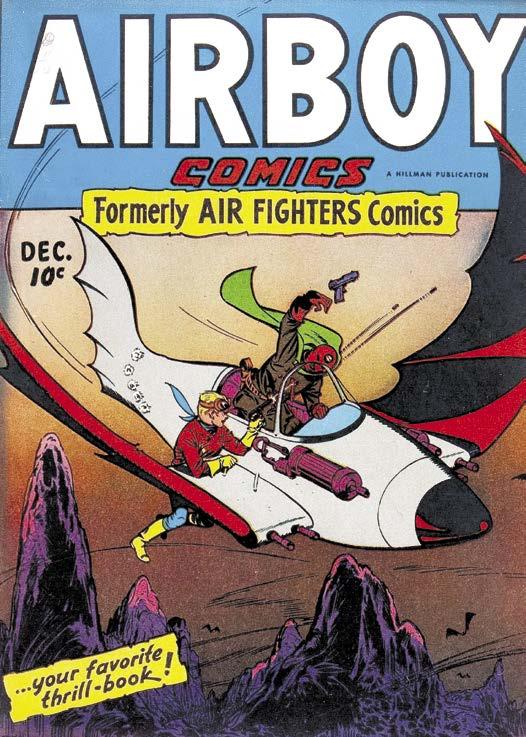

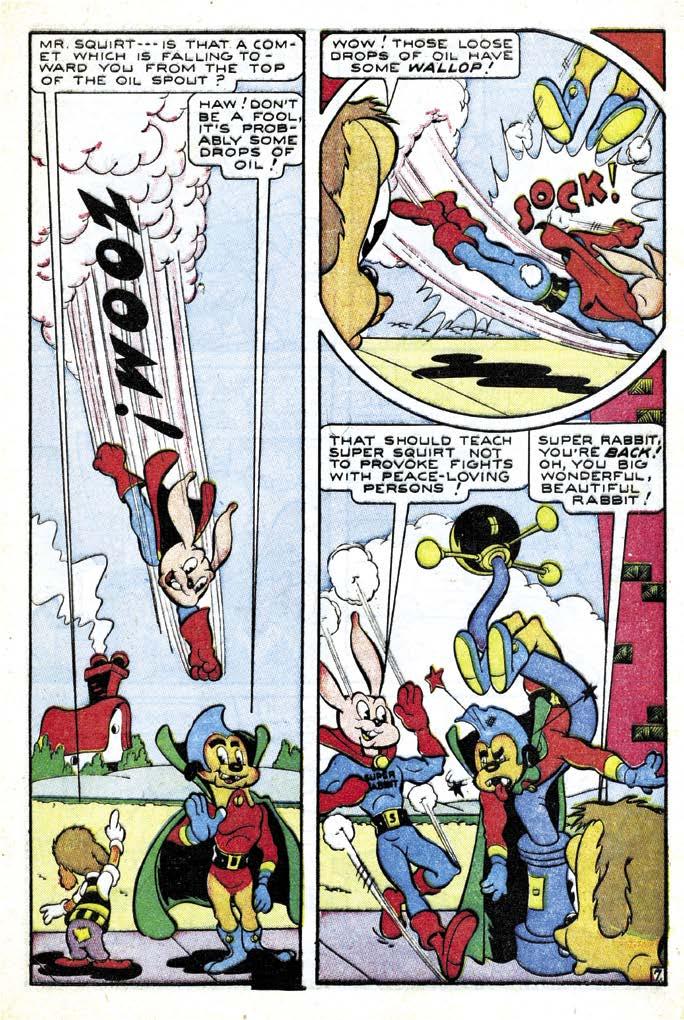

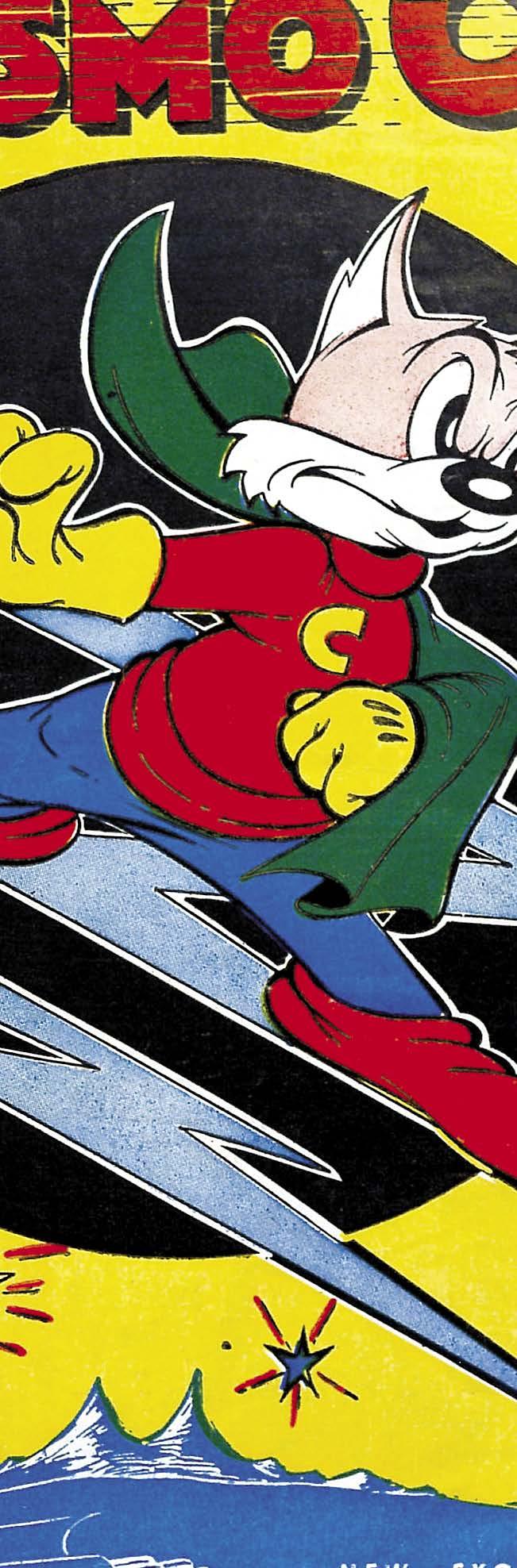

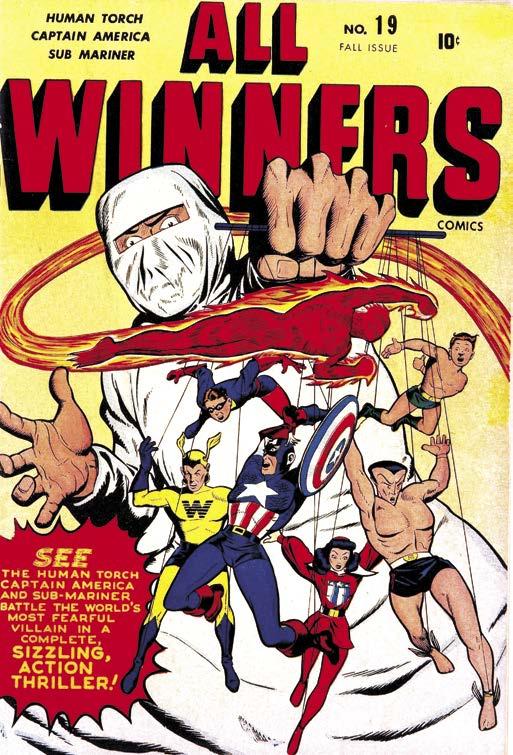

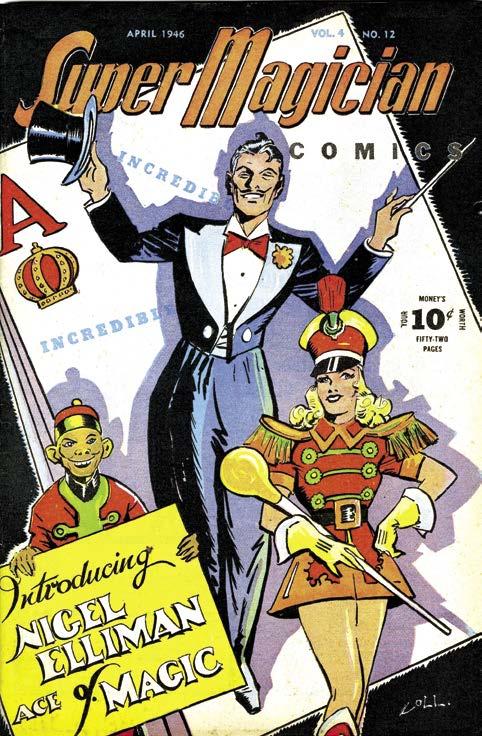

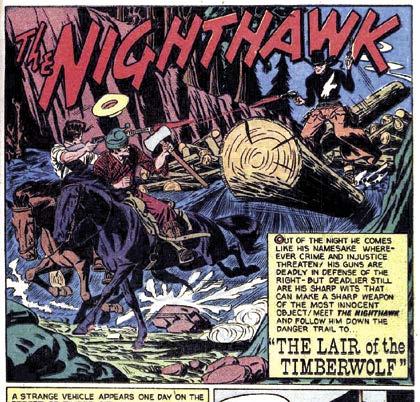

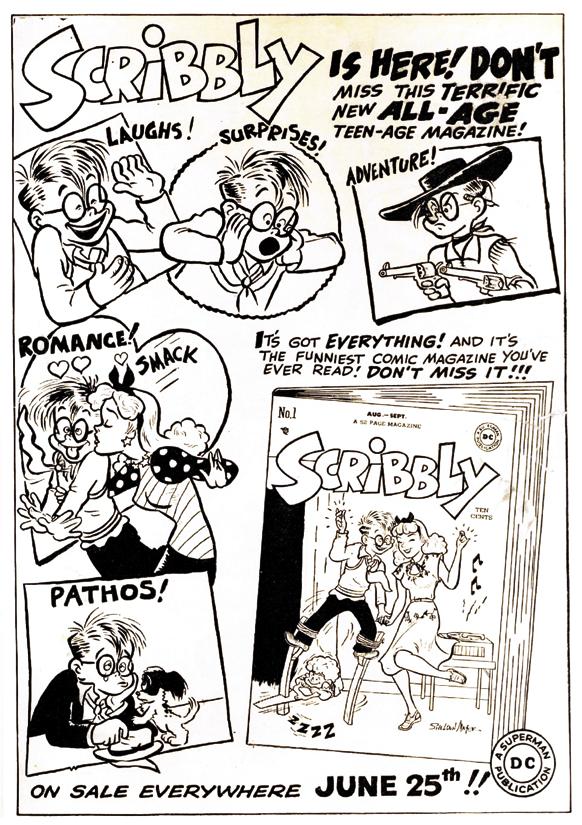

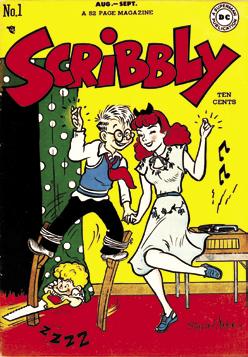

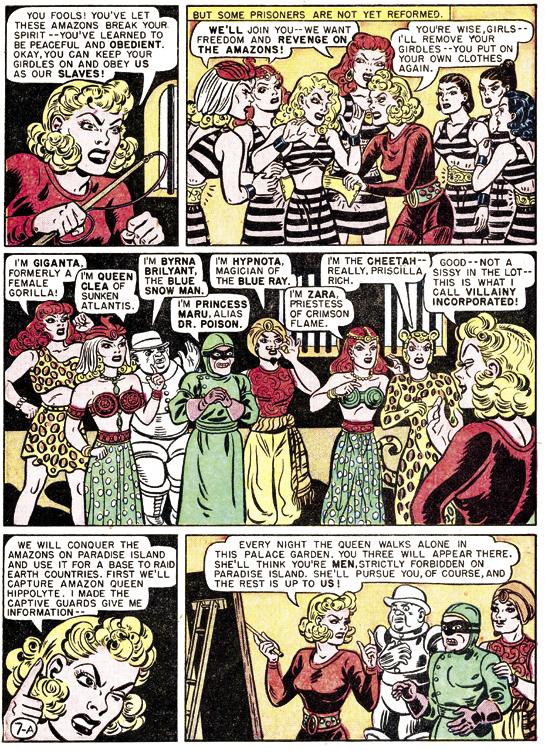

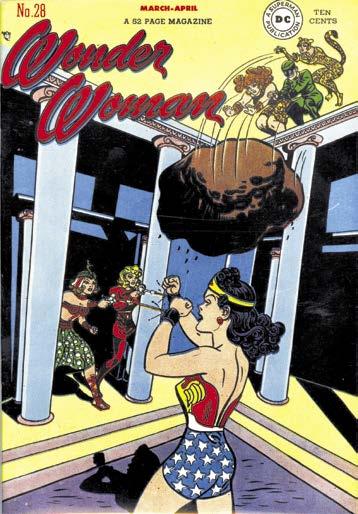

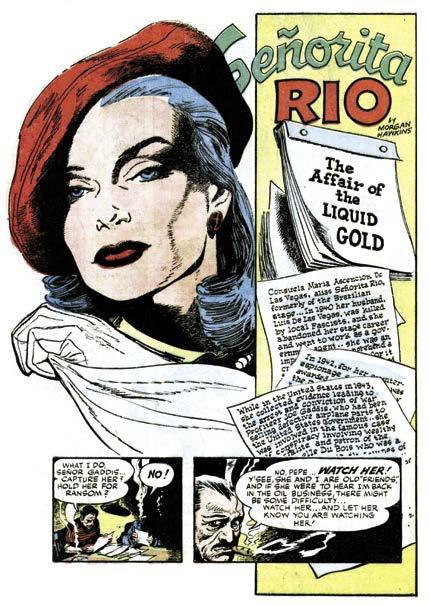

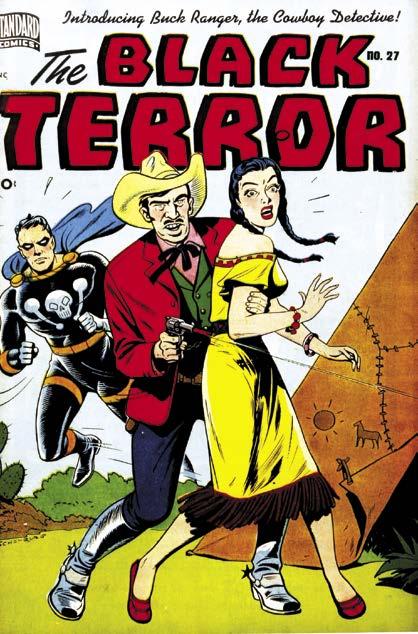

Steve Canyon TM and © Estate of Esther Parsons Caniff. Archie, Jughead, Katy Keene, John Goldwater, Suzie TM and © Archie Comic Publications, Inc. Li’l Abner TM and © Capp Enterprises Inc. The Shadow TM and © Condé Nast. Mighty Mouse TM and © CBS Operations, Inc. Baby Huey, Little Lulu, The Lone Ranger TM and © Classic Media, LLC. Little Orphan Annie TM and © Content Agency, LLC. The Atom, Batman, Binky, Black Canary, Blackhawk, Blue Lama, Crime Smasher, Doll Man, Dover and Clover, Flash, Fox and the Crow, Green Arrow, Green Lantern, Harlequin, Hawkman, Huntress, Icicle, Johnny Thunder, Jor-El, Justice Society of America, Lois Lane, Nighthawk, Per Degaton, Phantom Lady, Riddler, Robin, Rodeo Rick, Sargon the Sorcerer, Scribbly, Shazam Heroes, Solomon Grundy, Streak the Wonder Dog, Superboy, Superman, Thorn, Tomahawk, Tommy Tomorrow, Vigilante, Wildcat, The Wizard, Wonder Woman, Wyoming Kid TM and © DC Comics. Bambi, Donald Duck, Dumbo, Mickey Mouse, Pinocchio, Uncle Scrooge McDuck TM and © Disney Enterprises Inc. Tarzan TM and © ERB, Inc. Sheena TM and © Galaxy Publishing and Valdoro Entertainment. Blondie, Rip Kirby © King Features Syndicate, Inc., LLC. All Winners Squad, Black Rider, Blonde Phantom, Bucky, Captain America, Ghost Rider, Hedy De Vine, Human Torch, Kid Colt, Millie the Model, Namora, Nellie the Nurse, Sub-Martiner, Sun Girl, Toro, Two-Gun Kid, Venus, Wilbur TM and © Marvel Characters, Inc. Pogo TM and © Okefenokee Glee & Perloo Inc. Peanuts TM and © Peanuts Worldwide LLC. Sad Sack TM and © Sad Sack, Inc. Terry and the Pirates TM and © Tribune Media Services, Inc. Dick Tracy TM and © Tribune Content Agency. Abbie an’ Slats TM and © United Feature Syndicate, Inc. Andy Panda, Oswald the Rabbit, Woody Woodpecker TM and © Walter Lantz Productions, Inc. Bugs Bunny TM and © Warner Bros. Commissioner Dolan, Gerhard Schnobble, P’Gell, Plaster of Paris, Powder Pouf, Saree, Silk Satin, The Spirit, Thorne Strand TM and © Will Eisner Studios Inc. Airboy, Atoman, Atomic Man, Black Cat, Black Diamond, Black Terror, Black Dwarf, Boy Explorers, Bronze Man, Candy, Captain Wings, Challenger, The Claw, Cosmo Cat, Crime Does Not Pay, Dr. Desmond Drew, Dynamic Man, El Kuraan, Firehair, Frankenstein, Gabby Hayes, The Golem, Green Lama, Green Mask, Gunsmoke, The Heap, Hopalong Cassidy, Intellectual Amos, Little Max, Marmaduke Mouse, Monte Hale, Mopsy, Mortie Mouse, Nigel Elliman-Ace of Magic, Ozzie Turner, Raggedy Ann and Andy, Señorita Rio, Sky Girl, Skyman, South

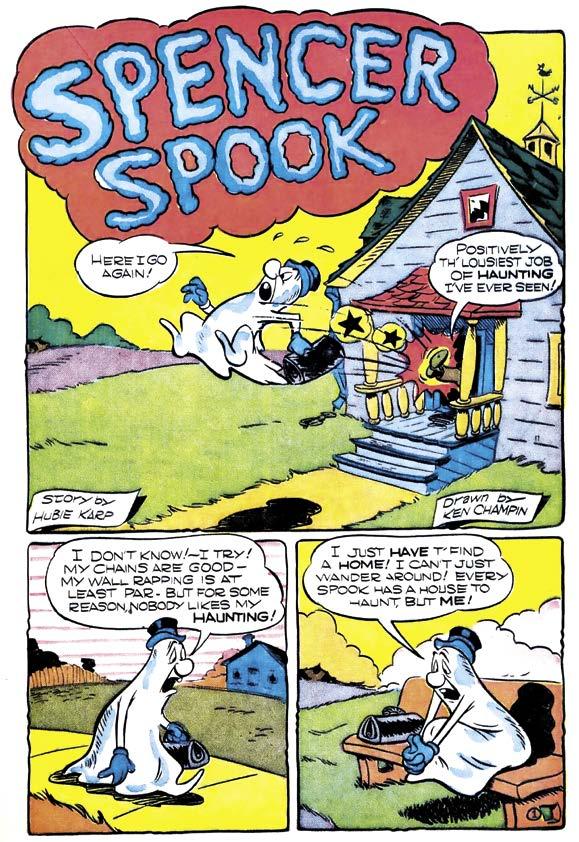

Spencer Spook, Stuntman, Supermouse, Tom Mix, Torchy Todd, Upan Atom, Volto TM and © respective copyright owners.

By Keith Dallas, with the assistance of Ray Botorff, Jr.

The monthly date that appears on a comic book cover doesn’t usually indicate the exact month the comic book arrived at the newsstand or at the comic book store. Since their inception, American periodical publishers—including but not limited to comic book publishers—postdated their issues in order to let vendors know when they should remove unsold copies from their stores. In the 1930s, the discrepancy between a comic book’s cover date and the actual month it reached the newsstand was one month. For instance, Detective Comics #1 is cover dated March 1937 but actually went on sale one month earlier in February. Starting in 1940, comic book publishers hoped to increase each issue’s shelf life by widening the discrepancy between cover date and release date to two months. In 1973, the discrepancy was widened again to three months. The expansion of the Direct Market in the 1980s, though, turned

the cover date system on its head as many Direct Market-exclusive publishers chose not to put cover dates on their comic books while some put cover dates that matched the issue’s release date.

This all creates a perplexing challenge for comic book historians as they consider whether to chronologize comic book history via cover date or release date. The predominant comic book history tradition has been to chronologize via cover date, and American Comic Book Chronicles is following that tradition. This means though that some comic books that were released in the final months of one year won’t be dealt with until the chapter covering the following year. Each chapter, however, will include a yearly timeline that uses a comic book’s release date to position it appropriately among other significant historical, cultural and political events of that year.

Determining the exact number of copies a comic book title sold on the newsstand is problematic. The best that one can hope to learn is a close approximation of a comic book’s total sales. This is because the methods used to report sales figures were (and still are) fundamentally flawed. Beginning in 1960, periodical publishers that sold through the mail—which included comic book companies—were required to print circulation data (which eventually included a comic book title’s average print run, average paid circulation, and average returns from the newsstand) in their annual statements of “Ownership, Management and Circulation” in one issue of each of their titles. Prior to 1960, however, circulation data was information conveyed privately from the distributors to the publishers and subsequently reported by some publishers to the Audit Bureau of Circulations for advertisers’ use. Advertisers wanted to know the potential reach one of their ads would have in a comic book, but often the Audit Bureau didn’t break down sales data by individual title, only by individual publisher.

Throughout the 1950s, comic book sales data was printed in distributor newsletters like Box Score of Magazine Sales and resources for advertisers like the N.W. Ayer and Sons guides. Occasionally, though, sales figures would end up in media kits and publisher press statements. And then there was the U. S. Senate Subcommittee, which published a report in 1950 that focused on juvenile delinquency. It included sales figures of individual comic book titles from 1949 (and sometimes from several prior years) that were provided by the comic book publishers themselves. The problem is that since the publishers self-reported this data, its reliability can certainly be questioned. American Comic Book Chronicles then recognizes the flawed nature of newsstand circulation data but is resigned to the fact that it is also the only data available and will consider it a close approximation of a comic book’s total sales numbers.

By John Wells

“Attention! If you desire to know any information of any comic magazines ever published, someone in this house will tell you what to know at a price of five cents per question. I will pay you five cents if I cannot answer your question within a month.”

Posted on a residential porch in Washington, D.C. in July 1946, the flyer bearing those words didn’t generate much profit for David Pace Wigransky, who had turned thirteen the month before. Bright and articulate for his age, the teenager gave his few clients—generally boys who often asked “foolish questions”—their money’s worth. His collection boasted a precise 1,240 comic books in mid-1946, a number that had swelled to 5,212 two years later.

That was a lot of comic books. In a bit over a decade, the familiar four-color periodicals had taken the publishing world by storm. The lowbrow offspring of more respectable newspaper strips were coming into their own, playing with layouts and storytelling in ways that the restrictive strip format didn’t allow. Comic books also produced an essentially new genre, cornering the market on the fantastic adventures of costumed superheroes. The exploits of men (and the occasional women) in tights sent sales soaring for participating publishers during World War II.

As this volume details, when the war ended in 1945, the comic book industry faced a steep learning curve ahead. With wartime restrictions of paper supply lifted, publishers—both established and newcomers hoping to make a quick buck—began ramping up production. Growth came with its own set of challenges, not the least of which was the fact that the postwar audience had shifted.

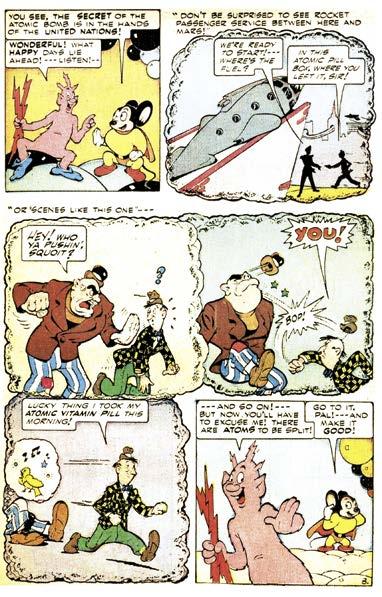

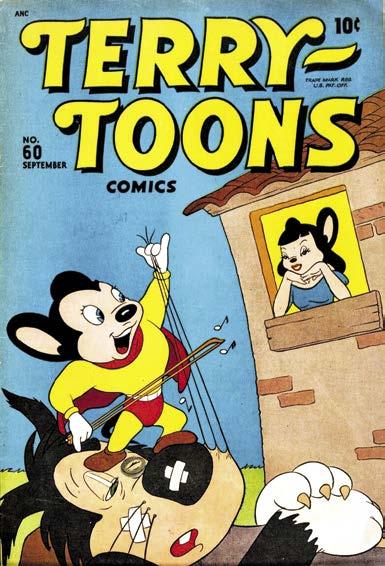

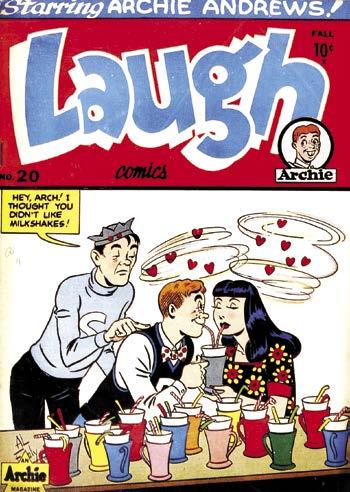

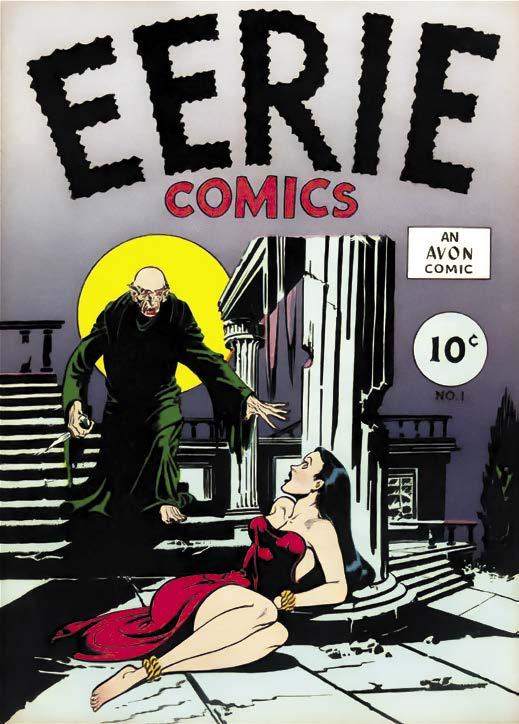

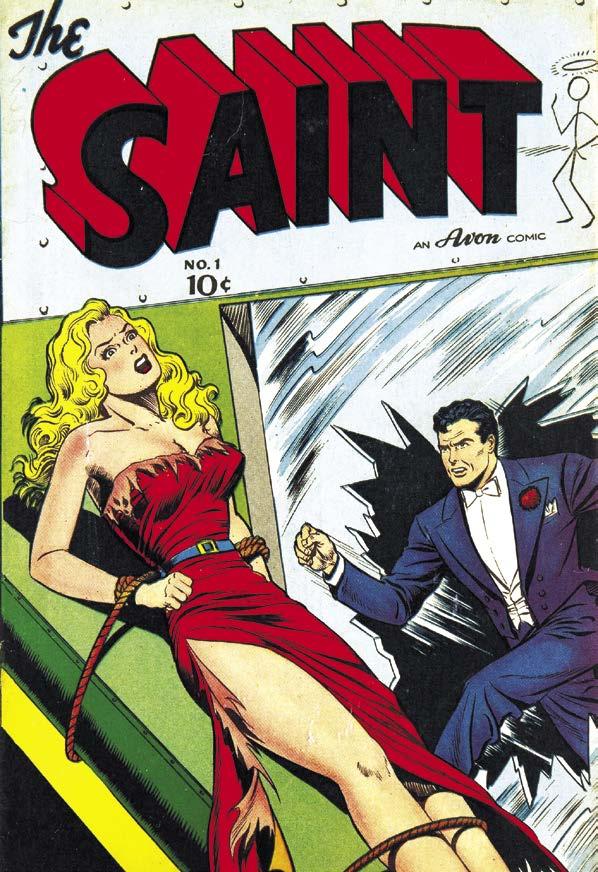

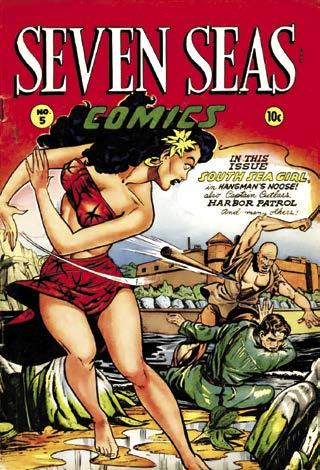

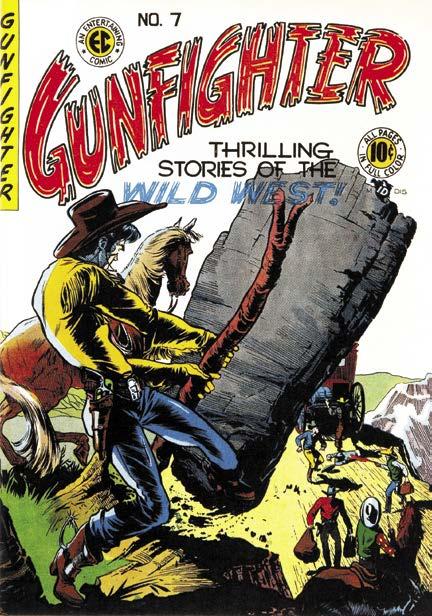

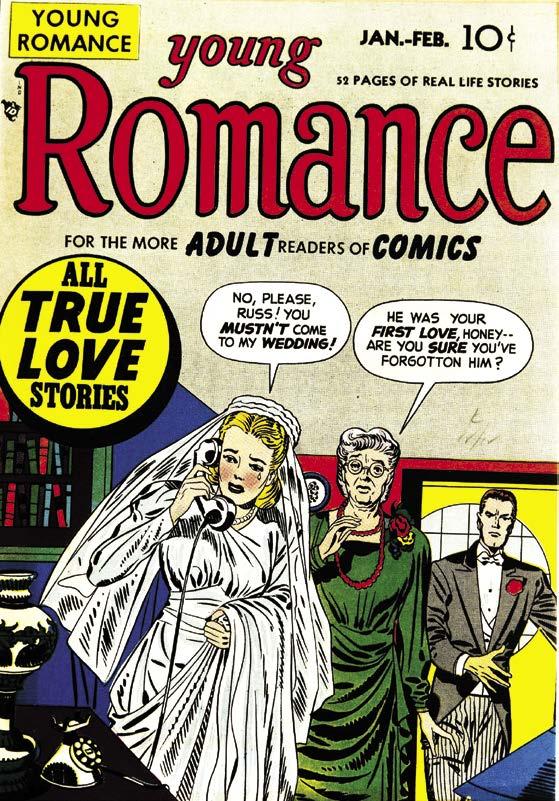

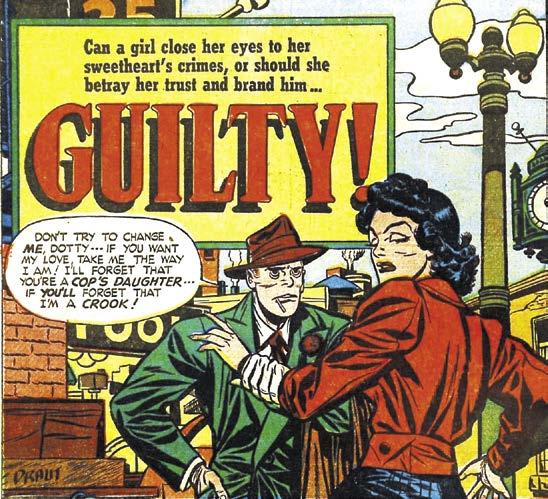

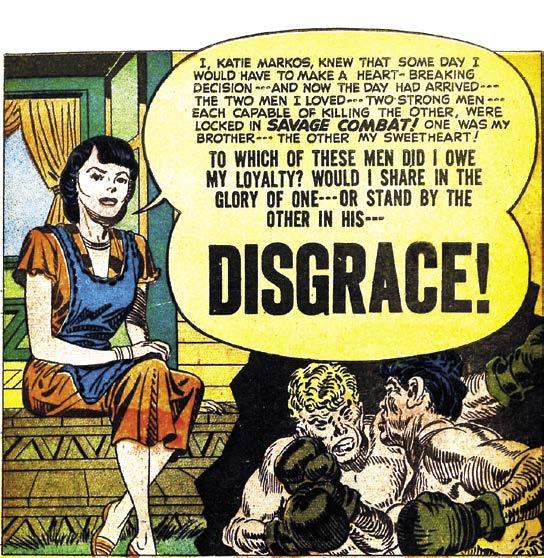

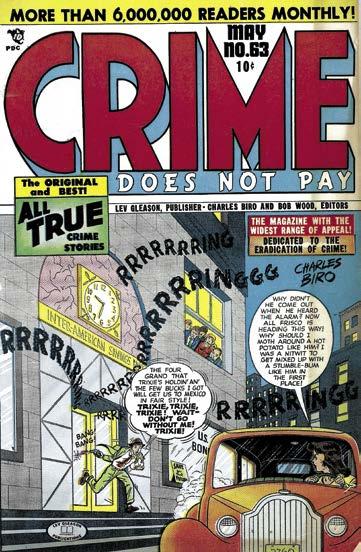

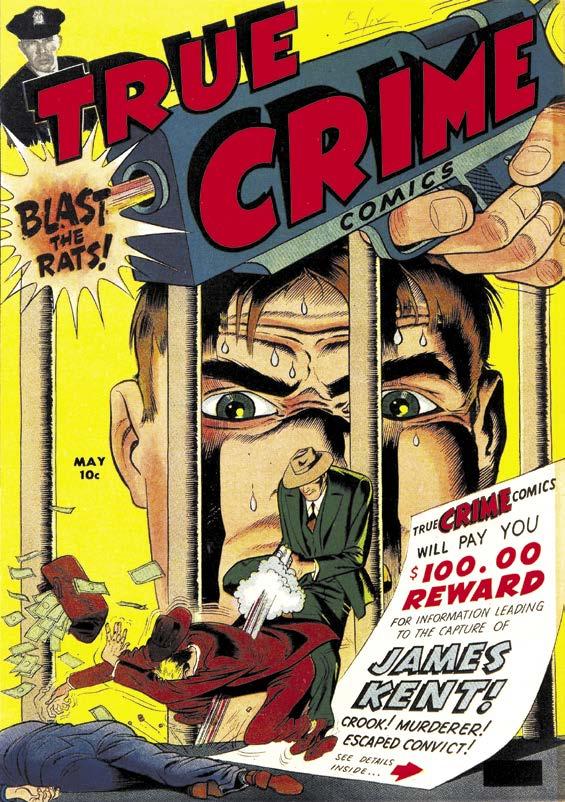

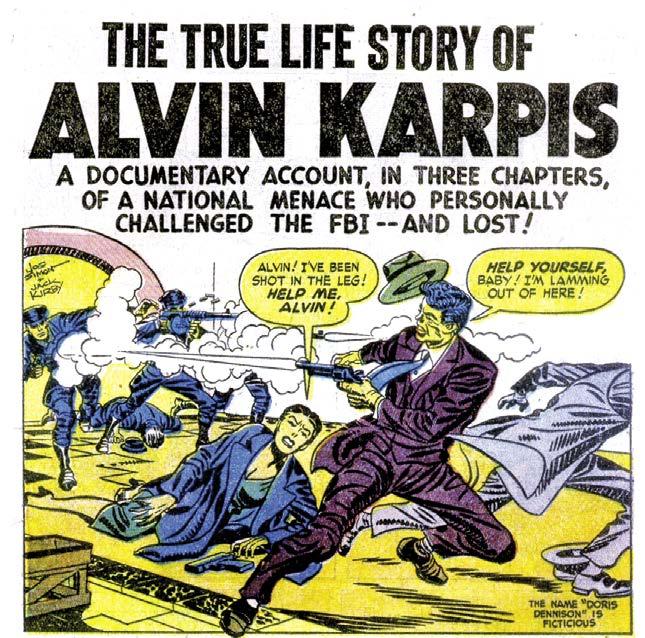

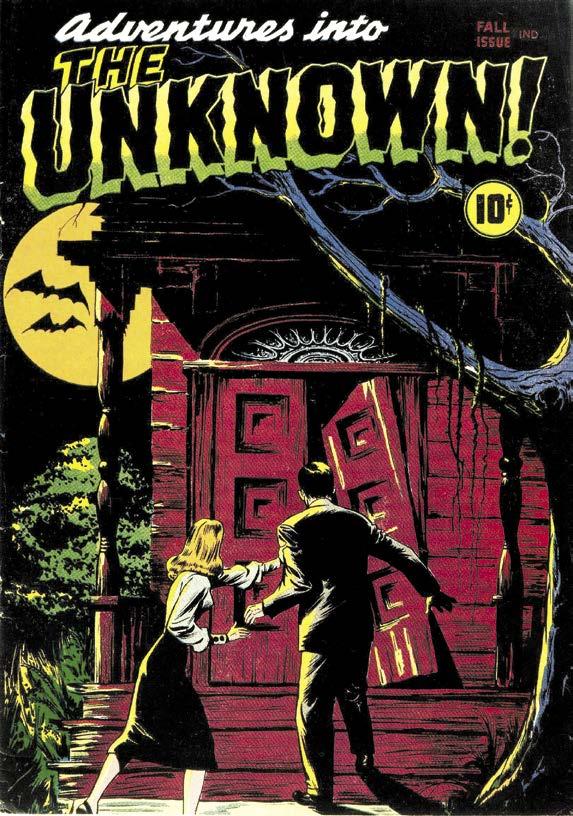

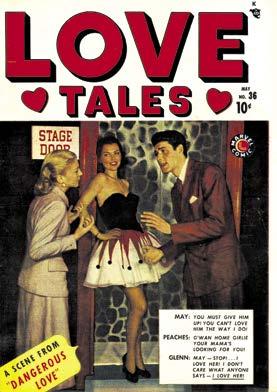

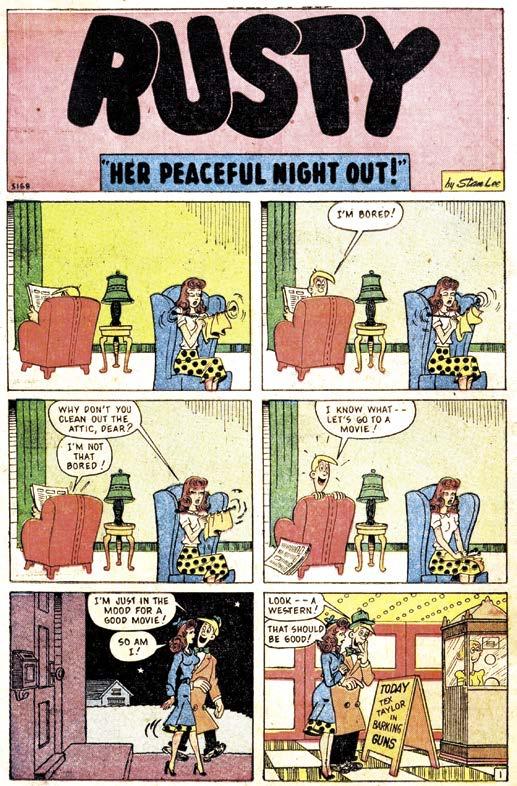

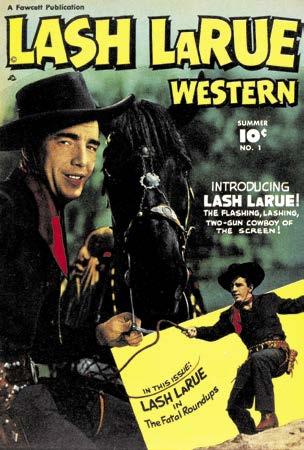

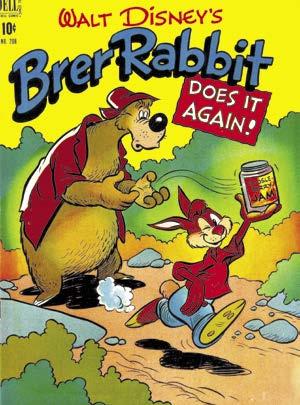

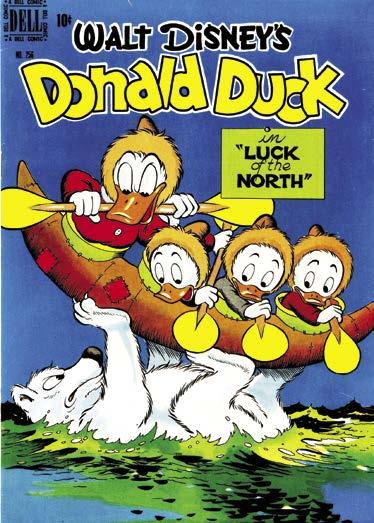

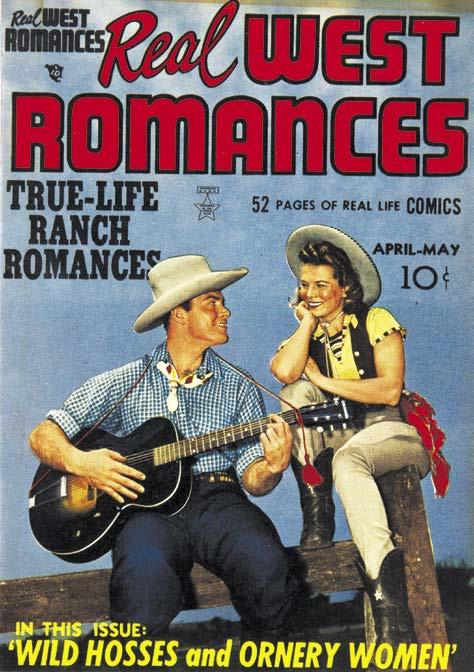

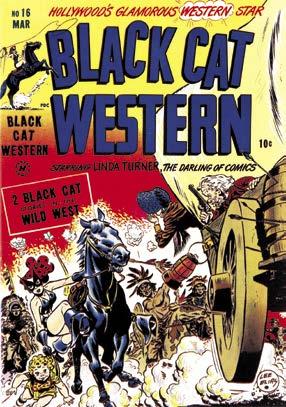

Those who placed their bets on superheroes soon discovered that they were no longer the cash cow they had once been. New genres were pushed to the forefront—funny animals, crime, Westerns, and teen humor were high on the list—while reliable innovators Joe Simon and Jack Kirby pioneered the romance comic and set into motion an eventual “love glut.”

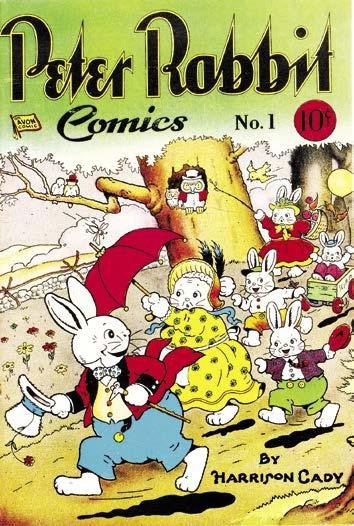

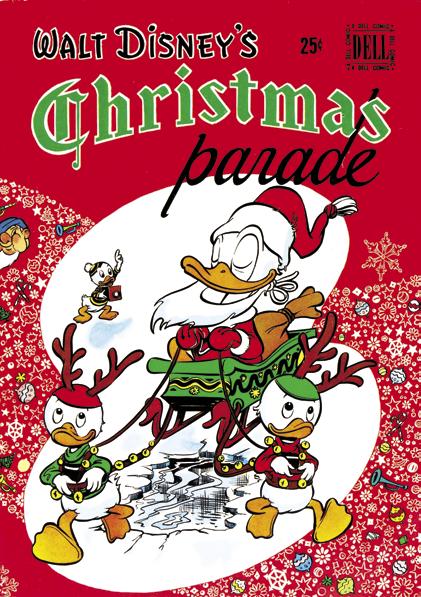

That’s not to say that there wasn’t still plenty of life in the old favorites. Dell’s prestigious line of licensed titles remained a trusted destination for children and parents alike. The publisher enhanced its reputation further in the late 1940s through Walt Kelly’s sublime Pogo, the elevation of Carl Barks’ Donald Duck stories into a brilliant series of longform adventures, and the emergence of John Stanley and Irving Tripp’s inspired comic book version of Little Lulu.

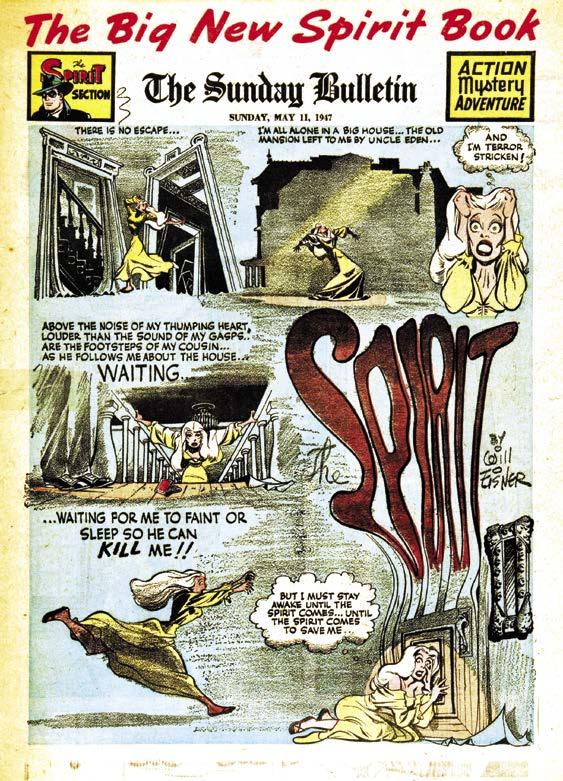

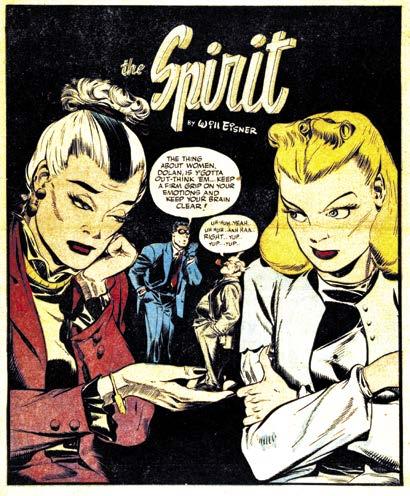

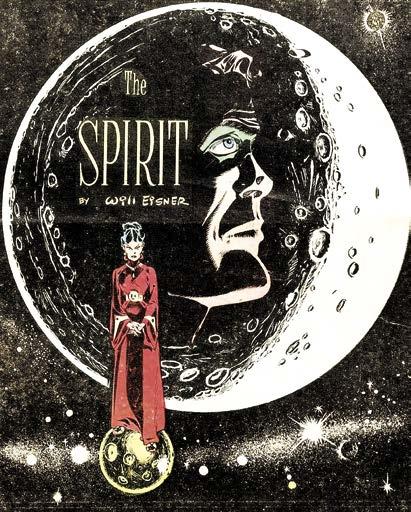

Returning from the Army in late 1945, Will Eisner resumed work on the Spirit section, not merely improving on the

wartime work of his substitutes but surpassing his early 1940s material. Moving on to the end of the 1940s, the feature became a weekly master class in cartooning.

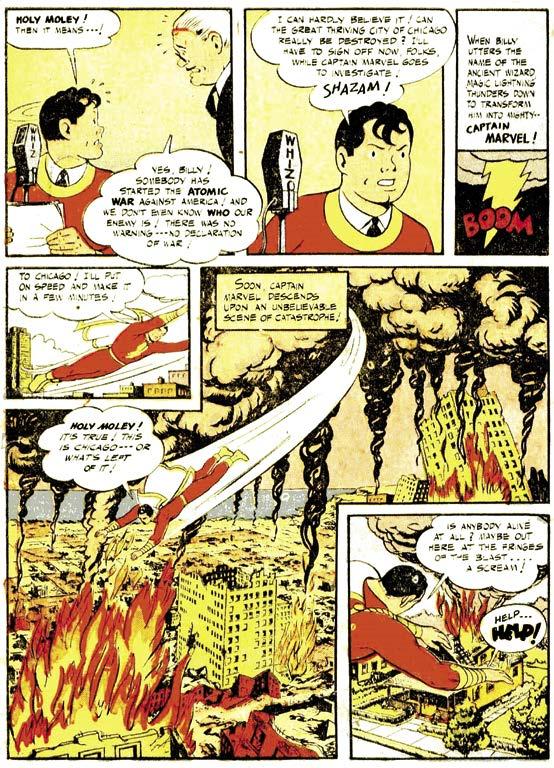

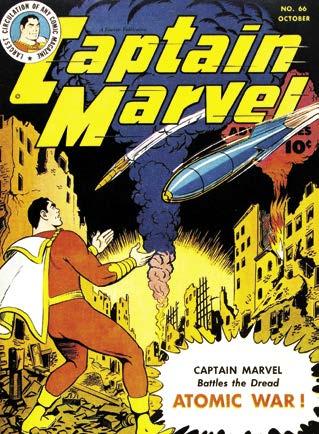

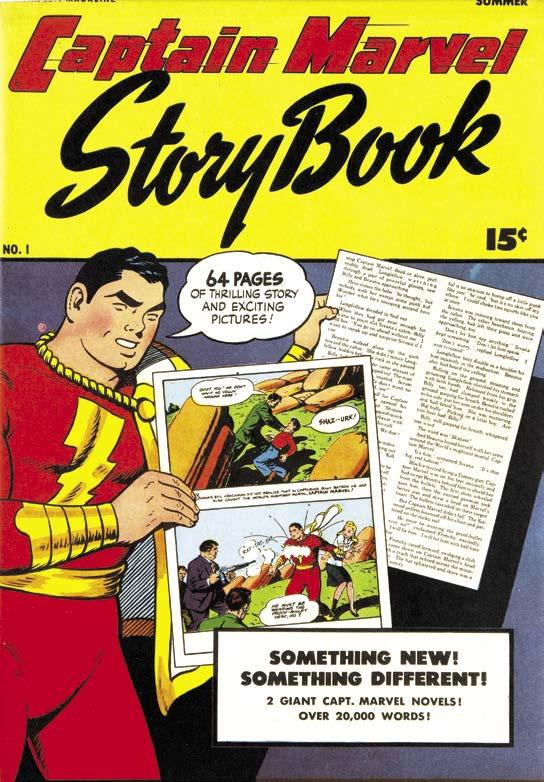

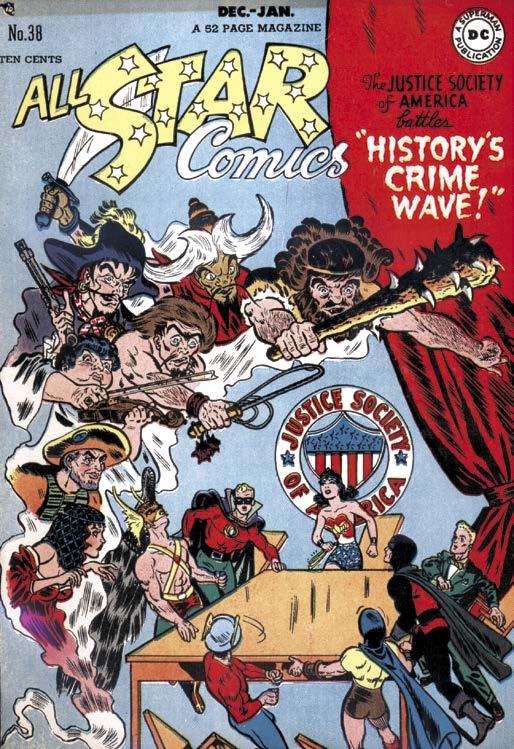

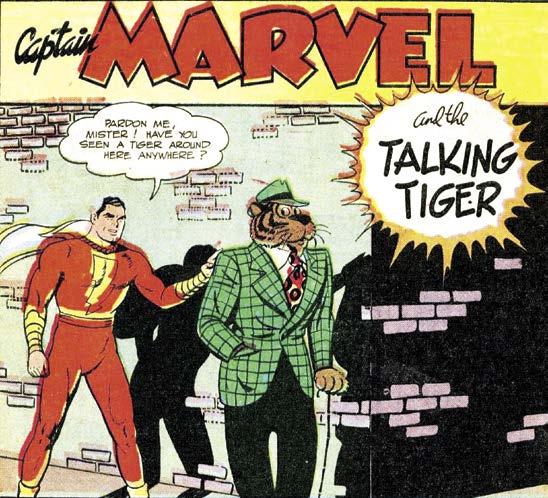

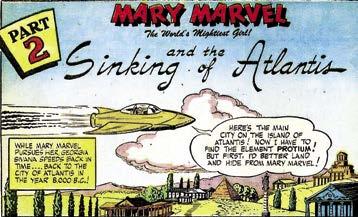

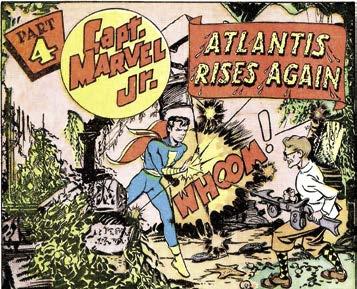

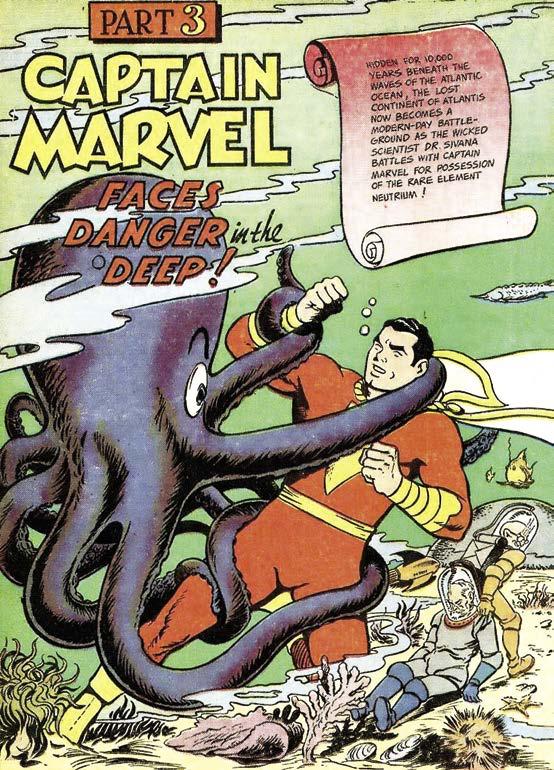

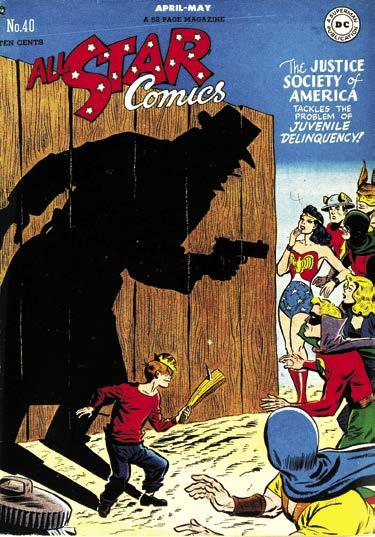

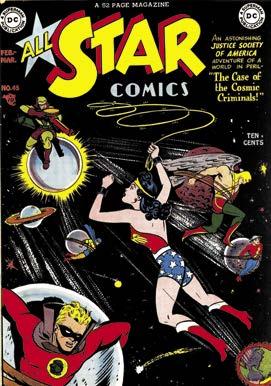

With the prolific writer Otto Binder at the helm (often with lead artist C.C. Beck), Fawcett’s adventures of Captain Marvel and his satellite Marvel Family shifted into their mostpolished period in the postwar years, still boasting strong sales even during a superhero slump. Major players like Superman and Batman notwithstanding, most other costumed characters weren’t as lucky. At National/ DC, it wasn’t for lack of trying. With new editor Julius Schwartz, the extant secondary superhero comics saw a burst of fresh characters and a series peak for the Justice Society of America in All-Star Comics.

Schwartz’s books benefited from contributions by still-raw artists like Carmine Infantino, Joe Kubert, and Alex Toth, all destined for stardom in the coming decades. Elsewhere, the comic book industry profited from a host of illustrators newly discharged from the Army, men like John Severin, Curt Swan, and Wallace Wood. Bringing up the rear were the young upstarts meant for big things. Al Williamson, a mere two years older than Dave Wigransky, was drawing comic books professionally by the age of 17 in 1948.

Wigransky, who also aspired to cartooning but was stylistically more

in tune with 1960s underground artists, also expressed—in a 1948 letter to Dell president George Delacorte— a desire to “write a book on the history of American Comic Magazines during the first half of the twentieth century.” Since Dave hadn’t just read most of them but corresponded with several extant creators, such a book would have been invaluable for future historians.

That tome never came to be, which is to everyone’s misfortune because the specific period covered in this volume—after the World War II explosion and before the seismic 1950s—has remained a spotty era in the vast library of comic book histories. That explains, in part, why this particular volume of American Comic Book Chronicles has been so long in coming.

The challenge of documenting the history of 1945-1949 is, of course, the fact that nearly all of its active players are gone. Therefore, we—and all who love comics—owe a very deep debt to all of the fans-turned-historians who have interviewed creators over the years, getting their irreplaceable stories on the record while they were still with us. Roy Thomas’ Alter Ego alone, with scores of archived interviews conducted by Jim Amash and many others, has been vital to the ongoing oral history of comic books.

Along with Roy, we also extend our greatest thanks to Mike Tiefenbacher, who graciously reviewed much of the manuscript and offered both great insight and fact-checking. Thanks as well to P.C. Hamerlinck, Ken Quattro, Wayne Smith, and Mark Waid for their own help in making this longawaited volume a reality. Regularly consulted as well were indispensable websites such as the Grand Comic Database, Mike’s Amazing World of Comics, Comic Book Plus, Newspapers.com, and the Internet Archive.

Although the volumes in this series have not been released chronologically, the publication of American Comic Book Chronicles 1945-1949 now allows the reader to follow a rich history spanning 1940 through 1999 in an unbroken line of books.

In the pages that follow, amidst the history of various series and publishers, you’ll also find an undercurrent of

opposition to the comic book industry and the emergence of a man who would become Public Enemy #1 to a generation of fans: Dr. Fredric Wertham. Dave Wigransky, as you’ll see on pages 159 and 160, was among the first—and most eloquent—to stand up to the anti-comic crusader but the fight was only beginning. That story continues in American Comic Book Chronicles The 1950s, by Bill Schelly.

Bill, by the way, was originally tapped to write this volume of American Comic Book Chronicles. The Eisner Award-winning historian, whose outstanding work includes biographies of Otto Binder, Joe Kubert, Harvey Kurtzman, and John Stanley, shaped an extensive outline for this five-year period of comic book history, even drawing on Otto Binder’s letters to Clifford Kornoelje (a.k.a. Jack Darrow) from his personal files. Tragically, Bill passed away in 2019 before he could truly begin writing this volume. Using Bill’s outline as a guide, Kurt Mitchell and Richard Arndt then drafted this book’s chapters before Keith Dallas and I ran the manuscript through its final paces, personally researching each section, adding considerable additional content (and context), and prioritizing the readability of the narrative (while ensuring it was aligned with American Comic Book Chronicles’ other volumes).

Throughout it all, we remained inspired by the passions of David Pace Wigransky, which, prior to his death in 1969, expanded in adulthood to encompass some 8,000 record albums and a vast collection devoted to his favorite performer, Al Jolson. His comic book scholarship, happily, remained intact. Writing about notorious publisher Victor Fox for 1962’s Xero #8, Richard Kyle was advised to reach out to Wigransky, who had read all the Fox comics and was able to cheerfully correct errors in the draft. There is no indication that he charged a nickel for the information.

Bibliographical information on David Pace Wigransky comes from The Washington Evening Star (July 19, 1946) and a thread by “sfcityduck” at the cgcomics.com message board.

World War Two, the most destructive conflict in human history, was finally winding down. The once-mighty coalition of Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and fascist Italy was fragmenting, as the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, China, and other members of the alliance known as the United Nations continued their assault on Axis territory. A desperate attempt to turn back the Allied invasion forces at the month-long Battle of the Bulge ended with the ignominious retreat of German troops from France in late January, while to the east the Red Army wrested Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania from Nazi control. In the Pacific theater, the Japanese were being slowly forced out of the occupied territories, sacrificing tens of thousands of fighting men in the Battles of Manila, Corregidor, and Iwo Jima. Allied air forces now ruled the skies, inflicting terrible destruction on military and civilian targets alike. The firebombing of Dresden in February claimed 25,000 lives. A similar attack on Tokyo a month later killed 100,000 and left over a million homeless. If the folks on the Home Front had any qualms about the severity of these raids, they put them aside as word began to leak out of the atrocities uncovered during the liberation of the concentration camps where the Nazis had come uncomfortably close to achieving their genocidal “Final Solution.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin met in Yalta on the Crimean peninsula in February to discuss the future, issuing a Declaration of Liberated Europe that promised “the earliest possible establishment through free elections of governments responsive to the will of the people.” Of critical importance to Roosevelt was a pledge obtained from Stalin that the USSR would enter the war against Japan as soon as Germany surrendered, a pledge conservative second-guessers later claimed Stalin used to manipulate the exhausted, fragile president into inadvertently greenlighting the Soviets’ postwar stranglehold on Eastern Europe.

One by one, the Axis dictators fell. On April 28, Benito Mussolini was summarily executed by Italian partisans as he tried to escape with his mistress to Switzerland. Il Duce’s corpse was hung upside down from a lamppost, his former subjects standing in line for a chance to jeer at and spit on the once-feared Fascist leader. Two days later, with Russian troops on the outskirts of Berlin, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in the underground bunker where the mad Führer had been hiding for weeks (though rumors of his survival and escape persisted for decades afterward). But Americans took little joy in the deaths of Mussolini and Hitler, for they were preoccupied with a catastrophic loss of their own.

On April 12, while vacationing at Warm Springs, Georgia, FDR suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. He died that evening. Though his doctors had long feared something like this would happen, it was a shock to the nation that had elected Roosevelt to an unprecedented fourth term just six months before. America had lost more than its head of state, more than its commander-in-chief. FDR redefined the relationship between the governing and the governed, ushering in a new era of federal paternalism through such radical innovations as Social Security and unemployment insurance. To many Americans, it was inconceivable that this political titan, the only president an entire generation had ever known, was gone, that they would never again hear his voice over their radios, that he would not see the country through to final victory. And no one was more shocked and dismayed at this turn of events than his successor, Harry S. Truman. Summoned to the White House without explanation, the new vice-president—Roosevelt’s third— had no idea of what awaited him:

“[T]he long black car turned off Pennsylvania [Avenue], through the northwest gate, and swept up the drive, stopping under the North Portico. The time was 5:25. Two ushers were waiting at the door. They took his hat and escorted him to a small, oak-paneled elevator... that ascended now very slowly to

the second floor. In the private quarters, ... in her dressing room, Mrs. Roosevelt was waiting. [She] stepped forward and gently put her arm on Truman’s shoulder. ‘Harry, the President is dead.’ Truman was unable to speak. ‘Is there anything I can do for you?’ he said at last. ‘Is there anything we can do for you,’ she said. ‘For you are the one in trouble now’” (McCullough 342).

The new president was nothing like the charismatic, patrician Roosevelt. The son of middle-class farm folk, a captain of artillery during the First World War, Truman had risen through the ranks of one of the most corrupt political machines in the U.S without being personally tainted by the association. As the junior senator from Missouri, he had quickly distinguished himself through hard work and uncompromising integrity. But nobody in the Democratic Party had expected him to actually become president, and few believed he was up to the task. Nonetheless, it was Truman who presided over the celebration of V-E Day in May, Truman who went toe-to-toe with Stalin and new British Prime Minister Anthony Eden at the final Allied conference in Potsdam two months later, and Truman who made the fateful decision to use a new weapon, the end product of the top-secret Manhattan Project, that would not only bring the war to an abrupt and dramatic end but make America the first global superpower. The war officially ended on September 2, 1945 (following the Japanese Empire’s surrender on August 14), but you’d never know it from America’s

comic books. The time lag between production and publication meant that comics cover-dated December went on sale in October and featured content created in July or August. Thus, few comics bearing a 1945 date acknowledged the war’s end. Indeed, many of these comics didn’t acknowledge Germany’s surrender on May 8 either and Nazi villains continued to prowl some lines’ pages for months afterward. It would be well into 1946 before WWII was finally in the comic book industry’s rear-view mirror.

The industry as of January 1, 1945 consisted of eight major publishing houses (those releasing 50 or more issues a year), 15 minor lines (12 to 49 issues), and a score of small companies, with 32 additional publishers joining them by year’s end. More than a thousand comic books were released this year, the raison d’etre of a complex skein of business, personal, and familial relationships among publishers, printers, distributors, and commercial art studios. Looking back from the 21st century, where comic books are a niche product available primarily in specialty stores, it can be difficult to fathom how popular— and profitable—they once were. By ’45, one out of every three periodicals sold in the U.S. was a comic book. Small wonder that so many newcomers were clamoring to jump onboard this gravy train.

As it had been from its birth in the mid-’30s, the industry was located primarily in the New York metropolitan area, with outliers in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, and elsewhere. This reality was obscured at times by publishers whose legal business

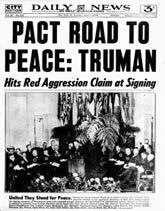

A compilation of the year’s notable comic book history events alongside some of the year’s most significant popular culture and historical events. (On sale dates are approximations.)

April

Pacific Theater of World War II.

April 12: President Roosevelt dies at the age of 63 of a cerebral hemorrhage while posing for a portrait at a resort in Warm Springs, Georgia. He is succeeded by the vice president, Harry S. Truman.

March 31: Tennessee Williams’ play The Glass Menagerie opens on Broadway after premiering in Chicago the previous year. The drama about a dysfunctional Southern family will win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best American Play of the year.

May 8: Victory in Europe Day (or V-E Day) is commemorated as the Allies officially accept Germany’s unconditional surrender. In a radio address President Truman announces that the war in Europe has ended.

July 20: Comic book creator Jack Kirby is honorably discharged from the U.S. Army, having earned a Bronze Star and Combat Infantryman Badge for his service during World War II. He reunites with his longtime creative partner, Joe Simon, once the latter is discharged from the United States Coast Guard.

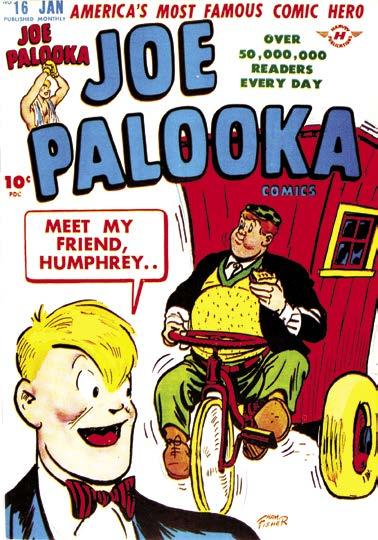

June 7: A backup story written and drawn by Bill Woggon in Archie Comics’ Wilbur Comics #5 introduces Katy Keene, “the Pin-Up Queen.” The object of affection of countless boys, Katy Keene will soon become Archie Comics’ second-most popular property. JANUARY

February 23: Four days after landing on the Japanese-occupied island of Iwo Jima, the U.S. Marines capture Mount Suribachi. A photograph of six Marines raising the U.S. flag on top of the mountain becomes one of the most iconic images of World War II.

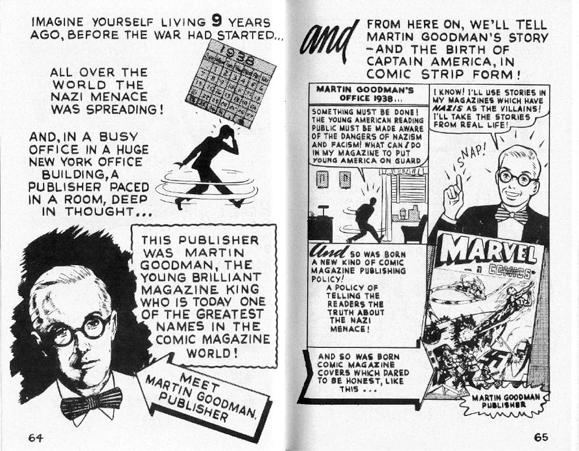

address was actually that of their out-of-state printer, a ploy designed to bypass New York City’s stringent tax code. MLJ, Family, Creston, Continental, Orbit, and Four Star, for example, all used 420 DeSoto Avenue in St. Louis, the home of World Color Press, as their legal address, though their executive and editorial offices were all in Manhattan. Another common practice was using different corporate identities for the comics in a publisher’s line to minimize taxes and ensure that the failure of one title couldn’t bring down the rest. Publisher Martin Goodman released 36 titles in 1945 under 31 different names (including one that wouldn’t become the company’s legal name until 1973: Marvel Comics). To compound the confusion, some players in the industry had their fingers in multiple pies, as in the case of Ben Sangor, who not only owned half-interest in Creston and his son-in-law Ned Pines’ Better/Standard/Nedor group but also owned the studio that pack-

aged their contents. Making sense of it all is not for the faint of heart.

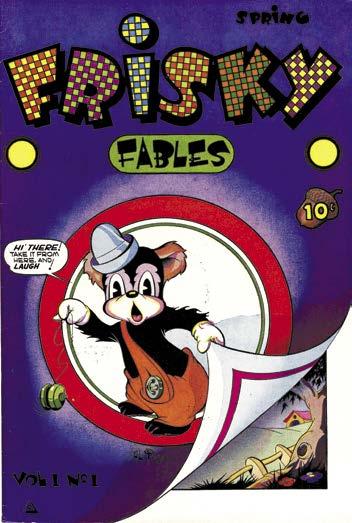

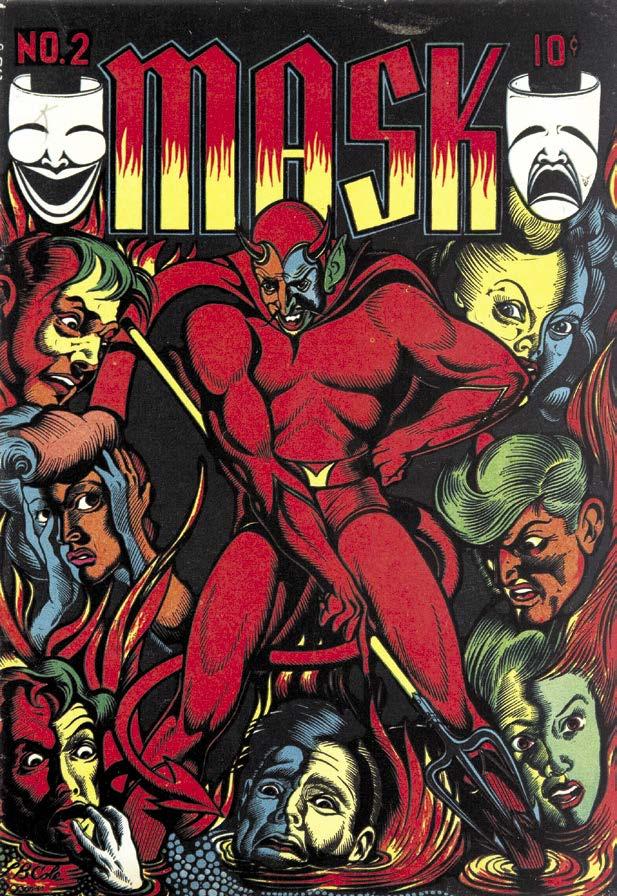

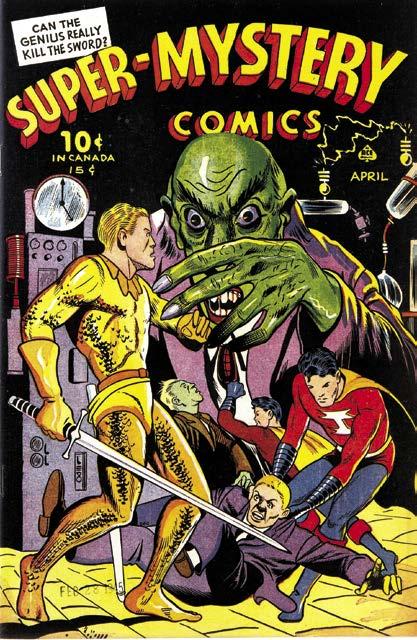

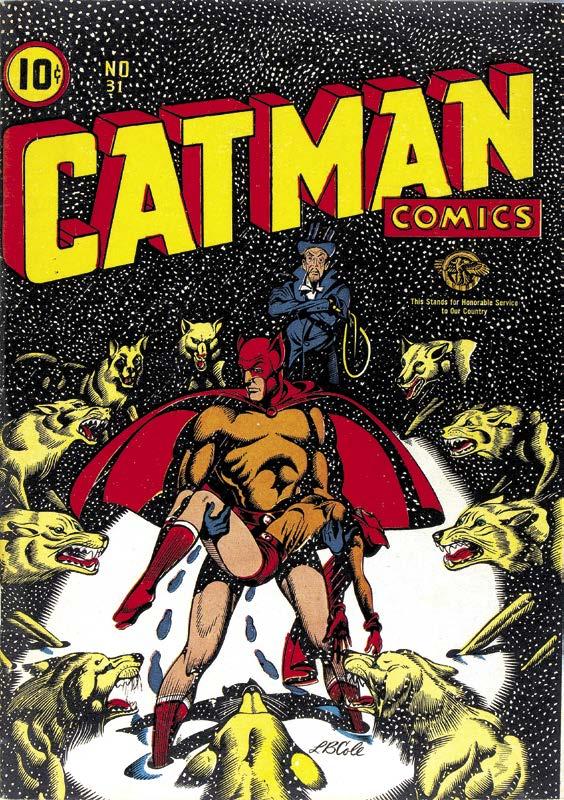

The larger publishing houses—Quality, DC, Timely, All-American, Dell— either maintained an “in-house” creative staff or dealt directly with freelance artists and writers. Others contracted with packaging services like Sangor’s to provide part or all of their content. Such art studios created features, fillers, covers, whatever a client needed, the quality of the work frequently dependent on what page rate the client was willing to pay. Sometimes it worked the other way around, with the studio selling small publishing firms on the idea of starting a line of comics. This practice reached its peak in 1945, as services like Funnies, Inc., the Bernard Baily and L.B. Cole studios, and newcomer Jason Comic Art lent their talents to some 30-odd first-time comics publishers, many of them managing to eke out only a single issue before

April 30: As Soviet troops surround Berlin, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler commits suicide by shooting himself in the head in his subterranean bunker. The previous day he had married his longtime companion Eva Braun who also kills herself by ingesting a cyanide capsule.

April 28: One day after being captured, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini is executed by Communist partisans.

to stay in business despite wartime restrictions, some shops were less than particular about who they did business with. It is hard to say if they knew the comics they were creating were printed on black market newsprint but they apparently had plausible deniability. When the federal government began cracking down on the shadiest publishers in February, those responsible for the content on display within those illicit pages escaped any legal consequences.

The temptation to violate the federal government’s Limitation Order L-244, which held existing publishers to 75% of their 1942 usage and denied paper altogether to any publisher not in business in ’42, was considerable. The demand for comic books outweighed the limited supply. As comics historian Will Murray notes in his seminal study “Black Market Comics of the Golden Age”:

“During World War II, comic books sold like never before or

August 2: U.S. President Harry Truman, Soviet Union Premier Josef Stalin and British Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee conclude their two week meeting in Potsdam, Germany to establish Europe’s postwar order. Among other things, the leaders agree to separate Germany into four occupied zones.

July 30: On its way back to the Philippines after delivering components of the first uranium bomb, the naval cruiser U.S.S. Indianapolis is

by a Japanese submarine. Of the 900 crewmen who jump into the shark-infested sea, only 317 survive after being adrift for four days. In the history of the U.S. Navy, it is the greatest loss of life at sea from a single ship.

August 6: The Enola Gay, a U.S. Air Force bomber, drops a uranium bomb (named “Little Boy”) over Hiroshima, Japan. The nuclear detonation destroys the city, killing approximately 140,000 soldiers and civilians.

August 9: Bockscar, a U.S. Air Force bomber, drops a plutonium bomb (named “Fat Man”) over Nagasaki, Japan. The nuclear detonation destroys most of the city, killing approximately 74,000 people, mostly civilians.

August 14: Victory over Japan Day (or V-J Day) is commemorated as President Truman announces that Japan has surrendered unconditionally.

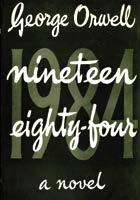

August 17: George Orwell’s novella Animal Farm is published in England. The political allegory satirizes the Soviet Union through a group of farm animals who rebel against their owner to create a free and equal society that turns out to be anything but.

September 2: World War II officially ends.

August 10: The creation of cartoonist Ruth Atkinson, aspiring model

series will become Marvel Comics’ longest-running humor title, lasting until 1973.

since. Kids loved them. Adults read them. Soldiers in battlefields from Europe to the Pacific devoured them. Both Superman and Batman peaked at over 1,600,000 copies [per issue] sold, with Captain Marvel not far behind at 1,300,000 per issue. It was a true Golden Age, for profit-hungry publishers as well as for readers. There was only one problem: Paper” (28).

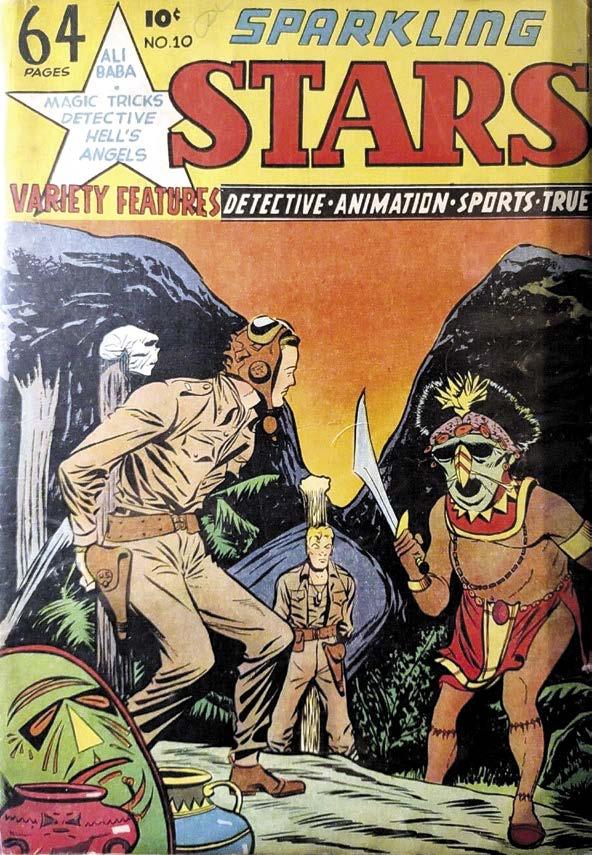

The availability of newsprint meant the difference between success and ruin for a comics line. The major players, and many of the minor ones, were either divisions of larger publishing houses or had ties to printing or distribution firms, assuring them a steady, albeit reduced, supply of newsprint. Other companies diverted paper meant for their pulp magazines—the popularity of paperback books had bled off a significant portion of the pulp audience— to their better-selling comics. Some turned to proxy publishers, who traded their name and excess paper for a cut of the proceeds. Still, accommodations had to be made. At the beginning of the decade, the standard comic book had been 68 pages (including covers) for a dime. By 1945, only one newsstand comic—Holyoke’s Sparkling Stars—

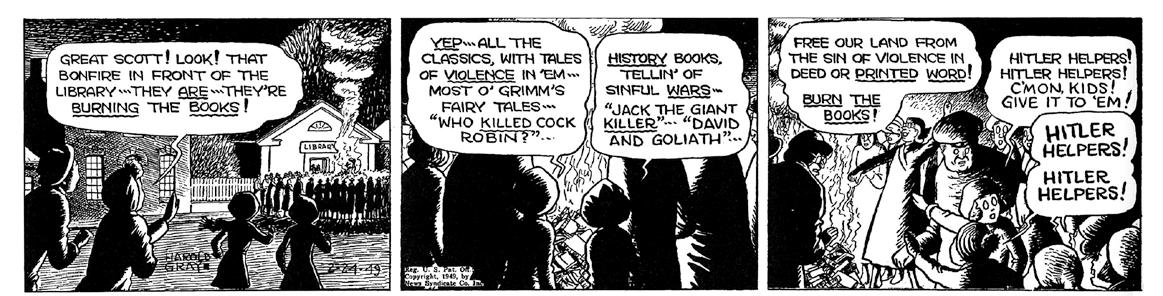

November: Students of Saints Peter and Paul School in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin perform a comic-book burning after a school-sponsored collection drive amassed over 1500 copies.

November 21: In a story written by Otto Binder and drawn by C.C. Beck and Pete Costanza, the first issue of Fawcett Comics’ The Marvel Family introduces Black Adam, an ancient Egyptian who was corrupted by the powers Shazam bestowed upon him.

December 21: General George Patton, who commanded the U.S. Third Army after the Allied invasion of Normandy, dies at the age of 60 in Heidelberg, Germany, of injuries from an automobile accident.

remained that size. Quality maintained its line at 60 pages, but most of the other houses had settled on 52 pages as the new industry standard. Timely’s monthlies were this standard size, but its quarterlies were a slim 36 pages. The Fawcett and Fox lines offered nothing but 36-pagers.

Precious as those pages were, many publishers willingly sacrificed them to make up some of the revenue lost to restricted print runs. While advertising had been common on the inside and back covers at the start of the decade, interior pages were entirely devoted to creative content

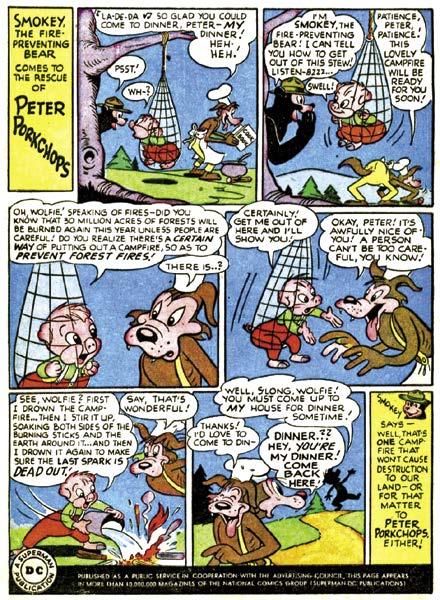

save for the occasional “house ad” touting the publisher’s other titles. Now, not only were ads becoming routine, many of them took the form of a comic strip. Joining “Captain Tootsie,” produced by the Beck-Costanza Studio for Tootsie Roll, on the newstands this year were “Volto from Mars” (Grape-Nuts cereal), “Adventures of ‘R.C.’ and Quickie” (Royal Crown Cola), and “Thom McAn” (Thom McAn shoes). More followed over the next few years. Promotional comic books like Western Printing’s Omar Book of Comics, a subscription-only premium for a chain of midwestern bakeries, were also becoming increasingly common, and would become more so once restrictions were lifted. Unfortunately, many of these esoteric titles have been casualties of paper drives and the passage of time so that, in some cases, not a single copy has survived down to the present day. Coverage of such ephemera in these pages must, of necessity, be incomplete.

As the war dragged on into the spring, restrictions were tightened once again. Dell, Fiction House, Eastern Color, United Feature, McKay, Ace, Family, and Chesler had no choice but to reduce their comics to 36 pages, while DC, Magazine House, Parents’ Magazine, All-American, Street & Smith, Novelty Press, MLJ, Rural Home, Hillman, and

Crestwood maintained their lines at 52. There was talk around the industry that some publishers were getting preferential treatment. Still, it was hard to complain when entire print runs were selling out regardless of content or quality.

In the beginning was Famous Funnies.

The first modern format comic book distributed through newsstands and other retail outlets, Famous Funnies was by 1945 the longest running title in America. Originally a “one-shot” jointly published in 1934 by Dell Publishing and the Eastern Color Printing Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, the subsequent ongoing series was produced without Dell’s participation. As it had from the beginning, Famous Funnies featured reprints of syndicated strips, notably Philip Nowlan and Richard Calkins’ space opera “Buck Rogers,” the aviation strip “Scorchy Smith,” Russell Stamm’s pseudo-superheroine “Invisible Scarlett O’Neil,” Coulton Waugh’s boys’ adventure series “Dickie Dare,” and a half-dozen others. When the title dropped from 52 to 36 pages with its July issue (#132), several lesser strips were dropped and remained gone when it returned to 52 pages at the end of the year.

In addition to the monthly Famous Funnies, Eastern Color published two bi-monthlies nominally edited by Harold J. Moore but actually assembled under the supervision of art director Stephen A. Douglas. The elder of these titles was Heroic Comics. Originally divided almost equally between newspaper strip reprints and original material, Heroic was now down to only one reprinted strip, Russell Keaton’s “Flying Jenny.” It was dropped following issue #31 (July), a victim of the mandated reduction in pages. Also taking his last bow in that same issue was “Hydroman,” a mysteryman able to transform himself into various forms of water, who dated back to the book’s earliest days. Preceding him into comics limbo were the title’s other costumed crusaders, “Man o’ Metal” and “The Music Master.” They were replaced by two new strips that survived the switch to 36 pages. Charles A. “Chuck” Winter’s “Vitaman, the Boy with the B1 Complex” was a mildly funny farce about a dimwitted, vitamin-gulping, would-be superhero. The boxing strip “The Kid from Brooklyn” starred young artist Hal Every, who reluctantly took up prizefighting to pay for his ailing mother’s medical bills. It was the work of Woodrow “Woody” Gelman, a former animator who would go on to become a major player in the fields of advertising—he created the Popsicle Pete and Bazooka Joe characters—and, in the 1960s, publishing as the guiding spirit behind Nostalgia Press. In addition to such true war stories as “I Seen My Duty and Done It,” “Auf Weidersehn in Berlin,” “The Story of the Japanese G.I.,” and “504 Nazis at One Clip,” every issue of Heroic Comics included a featurette by Charles Bange called “What Do You Know About...?” covering such topics as parachutes, maps, weather forecasting, and the new jet airplanes.

Alternating with Heroic on newsstands, Jingle Jangle Comics was its antithesis in tone and style. Offering a variety of humor and fantasy strips aimed at young children and the adults who read to them, the book’s

greatest asset was the cartoonist whose feature, “Jingle Jangle Tales,” led off each issue. A veteran illustrator with an impressive resumé spanning three decades, George Carlson was a master of nonsense, filling his pages with quirky characters, bizarre sight gags, non-sequiturs, digressions, and inspired wordplay, all delineated in a style akin to his contemporary Dr. Seuss. Sci-fi legend and lifelong Carlson fan Harlan Ellison described the artist as “what Walt Disney started out to be and never quite made” and “one of the first cartoonists of the absurd” (241-242). Story titles like “The Polka-Dot King and the Cranberry-Plated Crown,” “The ExtraStylish Ostrich and the Sugar-Lined Neck-Tie,” and “The Very Horseless Jockey and the Steamed-Up Steam Engine” only hint at the delights within. Carlson’s other feature, “The Pie-Faced Prince of Pretzleburg,” went on a brief hiatus following the August issue (#16), as did “Hortense the Lovable Brat,” both in response to the drop in page count. Surviving the cut were Dave Tendlar’s “Chauncey Chirp and Johnny Jay,” feisty senior citizen “Aunty Spry,” and “Bingo and Glum in Fairytale Land” (alternately titled “Bingo’s Adventures” and “Bingo’s Frolics”), now drawn by Woody Gelman.

The success of Famous Funnies did not go unnoticed. Two of the largest syndication services decided to

launch their own comics lines featuring their comic strips, their initial offerings hitting newsstands simultaneously in early 1936. Both companies were still going strong in 1945, their sales driven by the proven appeal of the strips they collected.

United Feature Syndicate, Inc. counted among its properties such popular features as Burne Hogarth’s Rococo interpretation of “Tarzan,” Al Capp’s satiric hillbilly saga “Li’l Abner,” and Ernie Bushmiller’s deceptively simplistic kid strip “Nancy.” These characters were the stars of the company’s monthly anthologies, Tip Top Comics and Sparkler Comics, and the quarterly showcase title Comics on Parade, each issue entirely devoted to a single feature. As it had the previous year, United Feature skipped the May issues of Tip Top and Sparkler to stretch its paper supply,

but this proved inadequate after its allocation was once again cut back. Thus, the monthlies were reduced to 36 pages for their July through October issues, with CoP following suit with its September issue (#2, but actually #50).

UFS had begun commissioning original series for the monthlies in 1940, mostly starring superheroes. After Pearl Harbor, all but one of these characters—Bernard Dibble’s humorous “El Bombo,” a super-strong South American Indian—enlisted in the military, their features transitioning to straight war strips without costumes or powers. With the war winding down, this trend began to reverse itself. Tip Top’s “The Triple Terror,” starring comics’ only crimefighting triplets, and Sparkler’s “Spark Man,” both by the team of writer Fred Methot and artist Paul Bernadier, donned their costumes once more following their discharges, though Spark Man’s electrical powers were not restored. (Curiously enough, the

pre-war, super-powered version appeared in his own all-reprint 36-page one-shot courtesy of proxy publisher Francis M. McQueeny, a comic almost certainly in violation of Limitation Order L-244.) Tip Top’s other original series, Dibble’s “Bill Bumlin,” took the opposite tack, shucking its previous fantasy elements in favor of straight domestic comedy.

The Philadelphia-based David McKay Company was the licensed publisher of comic books featuring such enormously popular King Features Syndicate humor strips as Chic Young’s “Blondie,” Harold Knerr’s “The Katzenjammer Kids,” George McManus’ “Bringing Up Father” (with Maggie and Jiggs), Carl Anderson’s “Henry,” Billy DeBeck’s “Barney Google” (co-starring Snuffy Smith), and “Thimble Theater” featuring Popeye (a mere shadow of itself since the death of creator Elzie Segar), as well as such equally popular adventure series as Hal Foster’s “Prince Valiant,” Alex Raymond and Don Moore’s “Flash Gordon” and “Jungle Jim,” Roy Crane’s “Buz Sawyer,” Lee Falk’s “The Phantom” and “Mandrake the Magician” (drawn by Wilson McCoy and Phil Davis, respectively) and the comic strip incarnations of “The Lone Ranger” and Zane Grey’s “King of the Royal Mounted.” McKay’s three monthlies—King Comics, Ace Comics, and Magic Comics—had little difficulty adapting to their mandated reduction to 36 pages with their July-dated issues, either dropping their lesser features or, in the case of those strips appearing in more than one title, cutting them back to a single book. A fourth comic, the quarterly Feature Book, was a showcase title like United Feature’s Comics on Parade, its 1945 offerings including two issues devoted to Blondie and one each to Mandrake and the Katzies.

One of the earliest and most successful comic book lines was the offspring of a partnership between two publishing powerhouses. Dell Publishing, one of the earliest magazine companies to embrace the modern comic book format, and Whitman Publishing, a subsidiary of the Wisconsin-based Western Printing & Lithographing, first joined forces in 1938. Dell provided the financing and distribution, Whitman provided the content, and Western provided the printing. By 1945, their output included five monthly titles, three bi-monthlies, and the irregularly published omnibus title Four Color.

The comics were produced out of three separate editorial offices. Alice Neilsen Cobb edited Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories from Western’s Poughkeepsie printing facility, also overseeing those issues of Four Color that spotlighted Disney properties. Eleanor Packer, aided by the line’s art director Carl Buettner, managed Whitman’s Los Angeles offices, where moonlighting animators and story men crafted the contents of Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies, Our Gang Comics, and New Funnies, featuring characters from Disney rivals Warner Brothers, MGM, and Walter Lantz respectively. Coordinating their efforts from New York City was editor-in-chief Oskar Lebeck. His staff put together Animal Comics and the syndicated strip reprint titles Popular Comics, Super Comics, and Red Ryder Comics, as well as providing content for Cobb’s and Packer’s

books. Under the watchful eye of executive Helen Honig Meyer, the Dell comics line stood out from its competitors not only in the sheer volume of popular licensed characters it offered, but in the quality of the stories told and the clean, attractive art illustrating them. Unfortunately for those providing those stories and art, the company rarely allowed its content creators to sign their work, most often due to contractual obligations to licensors who insisted on that anonymity.

Helen Meyer had every reason to trust Oskar Lebeck’s judgment. A former theatrical designer who emigrated from Germany in 1930, Lebeck held himself and everyone who worked for him to high standards, yet he was neither a martinet nor micromanager. Artist Roger Armstrong said of the editor-in-chief:

“[Lebeck] was a fantastic guy, because he was the kind of editor who, when he came out [to Los Angeles], would look at your stuff and say he didn’t like this and he didn’t like that, ‘but we’ll run it. But next time...’ What Oskar would do was give you suggestions on how it could be improved, but he didn’t lay down rigid rules” (Barrier 55).

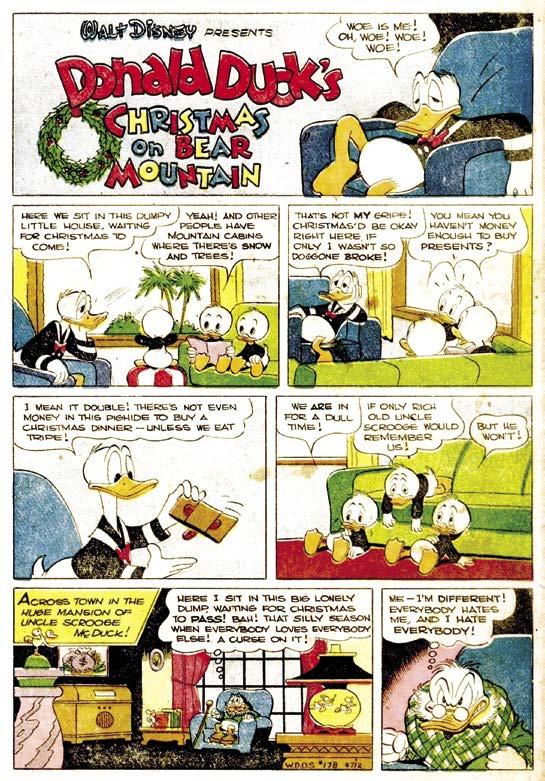

No title showcased these advantages more clearly than Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. Dell’s bestselling comic from its debut in the autumn of 1940, WDC&S originally served as a vehicle for reprints of the Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Silly Symphonies newspaper strips distributed by King Features Syndicate. While pages continued to be reserved for the first two, the book now emphasized new material. Each issue led off with a 10-page “Donald Duck” story written and drawn by Carl Barks. A veteran of the Disney Studio’s story department, Barks had a keen grasp of the mechanics of comics storytelling coupled with a vivid visual imagination. Though he tended to reserve his best ideas for the greater length available in Four Color, his stories for Walt Disney’s Comics were no less delightful in the eyes of the readers who knew him only as “the good duck artist.” Most stories revolved around Donald’s war of wills with nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie, but Barks occasionally sent the four off on an adventure, as when they bought a tramp steamer and sailed it to Mexico or encountered a tribe of prehistoric Indians while touring the Grand Canyon. High adventure was on hand in “Mickey Mouse” as well, at least in those strips from the ’30s, with situation comedy the focus of those sequences reprinted from more recent years. Joining “Bucky Bug,” now illustrated by Don Gunn, in the back pages of WDC&S as of the January issue (#52) was a series based on the Oscar-winning 1933 Silly Symphonies short “The Three Little Pigs.” Created by Carl Buettner and Wingate “Chase” Craig, a former animator whose credits included the short-lived Charlie McCarthy syndicated strip, “Li’l Bad Wolf” starred the sweet-natured offspring of the cartoon’s villain, Zeke “Big Bad” Wolf. Despite his father’s best attempts to rear him in his own predatory image, Li’l Wolf preferred playing with the other animals to eating them. The longest-running series in the title not starring a duck or a mouse, “Li’l Bad Wolf” has appeared in nearly every subsequent issue, running well into the 21st century. Disney’s big guns also made their annual appearance in the 1945 edition of Donald and

Mickey Merry Christmas, a giveaway available only at Firestone Tires dealerships.

Just behind Walt Disney’s Comics on Helen Meyer’s sales reports was Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies, featuring the animated characters appearing in theatrical cartoons produced for Warner Brothers by Leon Schlesinger. The comics did not attempt to duplicate the over-the-top slapstick and frenetic pacing of the cartoons, relying instead on the interplay between the characters’ personalities to provide the humor. “Bugs Bunny,” “Porky Pig,” and “Elmer Fudd” regularly guest-starred in each other’s series. (Bugs, in fact, popped up in every “Elmer” episode this year, and in all but three of “Porky.”) “Henery Hawk” also regularly featured guest stars, primarily Beaky Buzzard. Setting a different tone from the rest of the book, “Sniffles and Mary Jane” was a gentle series that sent its leads, a mouse and a little girl who could magically shrink to his size, to such seasonally apropos locales as the Land of Christmas Trees, Valentine Land, and Jack o’ Lantern Land and introduced them to Robin Hood, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, and the Sunset Elves, who guard the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. These flights of fancy came courtesy of writer Chase Craig and artist Roger Armstrong, with first George Weiss then Don Gunn stepping in after Armstrong was drafted. Other artists contributing to Looney Tunes this year were cover artist Daniel “Dan” Gormley, Carl Buettner, Vivian “Vivie” Risto, and Thomas “Tom” McKimson, whose long list of animation credits included the original design of Tweety Bird.

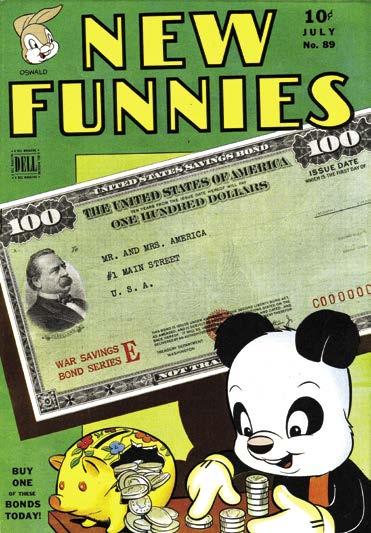

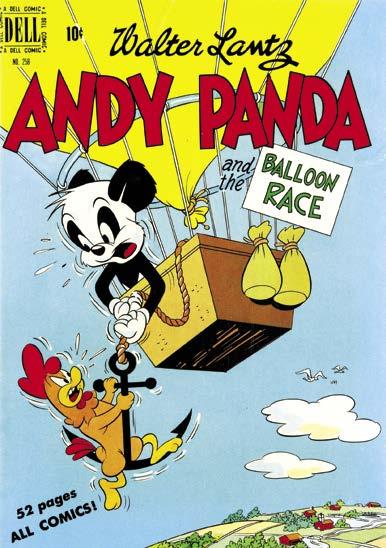

New Funnies, one of Dell’s longest-running titles, began life as a forum for reprinted syndicated strips but had since switched to a showcase for characters from cartoons produced by Walter Lantz. To this point, “Andy Panda” had been the book’s star. In theaters, by contrast, he found his cartoons eclipsed in popularity by those starring “Woody Woodpecker,” a reality reflected in the comics when Andy began sharing the cover with Woody as of the November

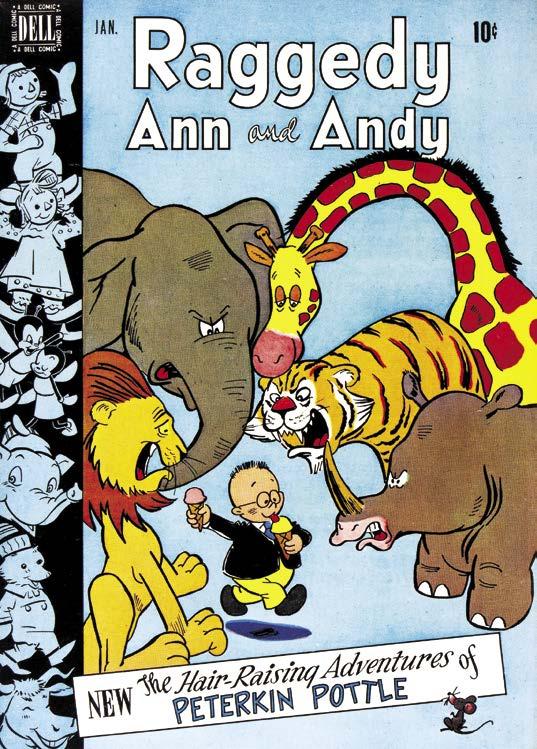

issue (#105). Andy still commanded the book’s lead-off spot. Artist Dan Gormley put him and housemate Charlie Chicken through their paces, illustrating scripts provided by, among others, John Stanley. A former animator and magazine cartoonist, Stanley both drew and wrote Woody’s series, as well as providing scripts for others. “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” was a rarity among Dell’s funny animal strips in telling its stories as a serial. This year found Oswald and his pal Toby befriending Timothy the Talking Dog, a vaudeville performer on the run from his abusive master, in a four-part tale (#95-98, January-April), then, after a pair of standalone episodes, moving to a new house in the country. Besieged by termites, they foiled their foes by converting their abode into a houseboat and sailing downriver to new adventures. Other Lantz stars with regular berths in New Funnies were “Homer Pigeon,” drawn by Vivie Risto, and “Li’l Eightball,” a series painful for modern sensibilities to endure due to its egregious use of racist caricatures. Two strips were not part of the Lantz stable. Franklyn “Frank” Thomas’ “Billy and Bonny Bee” fell victim to the title’s mandated reduction in pages, but “Raggedy Ann and Andy” kept its slot. Dell workhorse Gaylord DuBois and artist George Kerr superbly captured the look and tone of Johnny Gruelle’s classic book series, plunging the living rag dolls into perils they inevitably overcame through their unfailing courage and kindness. It provided a welcome break from the slapstick of its companion strips.

Dell’s other two monthlies, Popular Comics and Super Comics, were still largely devoted to newspaper strip reprints, as was the bi-monthly Red Ryder Comics. Popular featured “Terry and the Pirates,” “Gasoline Alley,” “Smilin’ Jack,” “Felix the Cat,” and “The Gumps; Super starred “Dick Tracy,” “Little Orphan Annie,” “Brenda Starr,” “Moon Mullins,” “Winnie Winkle,” and “Harold Teen;” and Red Ryder headlined the title cowboy plus “Captain Easy,” “Alley Oop,” “King of the Royal Mounted,” and “Freckles and His Friends.” Each book also included original material. “Gang

Busters,” adapting the radio crime drama, appeared in every issue of Popular. The fictional adventures of famed circus animal trainer “Clyde Beatty,” scripted by Gaylord DuBois, ran in Super Comics. DuBois also wrote the war strip “The Flying Yanks,” which was replaced as of Red Ryder #28 (November) by “Telecomics,” depicting the daily lives of a family living in the future. Sadly, no credits are available for this strange, amusing precursor of The Jetsons. Our Gang Comics, the bi-monthly spotlighting characters licensed from MGM, was triply blessed: it featured the work of Carl Barks, John Stanley, and Walter Crawford “Walt” Kelly, each a master of the medium. It was Kelly who wrote and drew the title strip based on the long-running series of short films, the last of which was released in 1944. He had never felt obliged to reproduce the lowbudget inner city vibe of the shorts, sending his cast on adventures around the world and introducing original characters for Buckwheat, Froggie, Janet, and Red to interact with. This year was no different. Kelly had the gang start their own detective agency, solve the “Indian Treasure Mystery,” and encounter boy scientist Baxter and washed-up vaudevillian Professor Hector Hannibal Horatio Gravy and his trained cats Lancelot the Lion and Tammany the Tiger (a prototype for the later Pogo character). Barks, meanwhile, was producing “Barney Bear and Benny Burro,” two standalone animated characters originally teamed up when the comic’s page count was cut from 68 to 52. Though lacking the subtle characterizations of his “Donald Duck” work, his stories here were no less imaginative or entertaining. Stanley was responsible for two strips, “Tom and Jerry” and “Johnny Mole,” writing and usually drawing both series, sometimes assisted by Dan Gormley. Carl Buettner provided the art for a new series debuting in issue #17 (May-June). “Wuff, the Prairie Dog,” tired of living on the ground, decided to become a squirrel with the usual catastrophically comical outcome. Thereafter, Wuff was consigned to the title’s requisite prose stories, a demotion necessitated by Our Gang’s reduction to 36 pages.

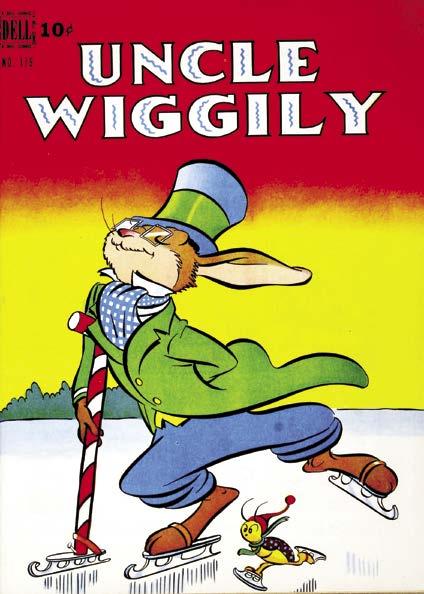

As good as Walt Kelly’s work on “Our Gang” was, it suffered by comparison to what he was doing in Animal Comics Here, he continued to develop the cast of swamp critters populating “Albert and Pogo,” introducing such mainstays of the later syndicated strip as turtle troubadour Churchy LaFemme, crackpot scientist Howland Owl, the perpetually dour Porkypine, and the bombastic hound dog later known as Beauregard Bugleboy, as well as one-shot characters like the skunk Downwind, and medicine show hustler Dr. Legerdemane Z. Presto. Equally prominent were the ongoing adventures of “Uncle Wiggily,” adapted by Gaylord DuBois and H.C. McBride from the popular children’s book series by Howard R. Garis, a surprisingly dark strip with predators not only trying to kill the characters but sometimes succeeding! Dubois was also at the typewriter for “Raggedy Animals,” a “Raggedy Ann” spin-off that was canceled mid-year. Both Kelly and John Stanley contributed to a trio of strips featuring cartoon stars from Famous Studios. Despite their best efforts, “Blackie,” “Cilly Goose,” and “Hector the Henpecked Rooster” were all dropped from the title following the October-November issue (#17), the result of Paramount, the parent company of Famous Studios, letting the license lapse.

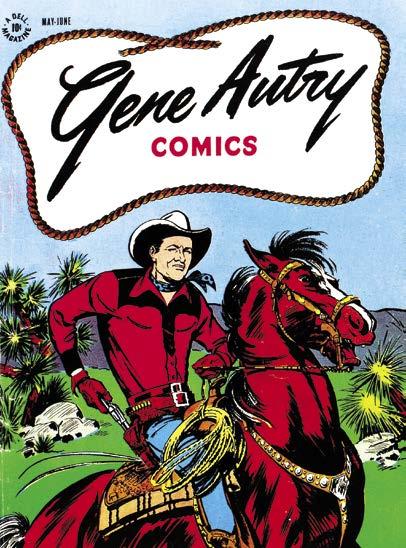

Dell released 30 issues of Four Color with a 1945 date, approximately one every 12 days. The anthology title had begun life collecting syndicated strip reprints from the monthlies, and eleven issues continued that tradition this year including issues devoted to “Smokey Stover” (#64), “Smitty” (#65), “The Gumps” (#73), “Little Orphan Annie” (#76), “Felix the Cat” (#77), “Smilin’ Jack” (#80), “Moon Mullins” (#81), “Tillie the Toiler” (#89), and three King Features strips usually found in David McKay titles: “Popeye” (#70), “The Lone Ranger” (#82), and “Flash Gordon” (#84). Movie cowboys Gene Autry and Roy Rogers fixed their brands on five issues, Autry in #66, 75, and 83, Rogers in #63 and 86. Both were scripted by Gaylord DuBois, with art by Tillman “Till” Gooden, Albert Micale, and former Disney animator Jesse Marsh, whose association with Western Publishing would continue until his death in 1966.

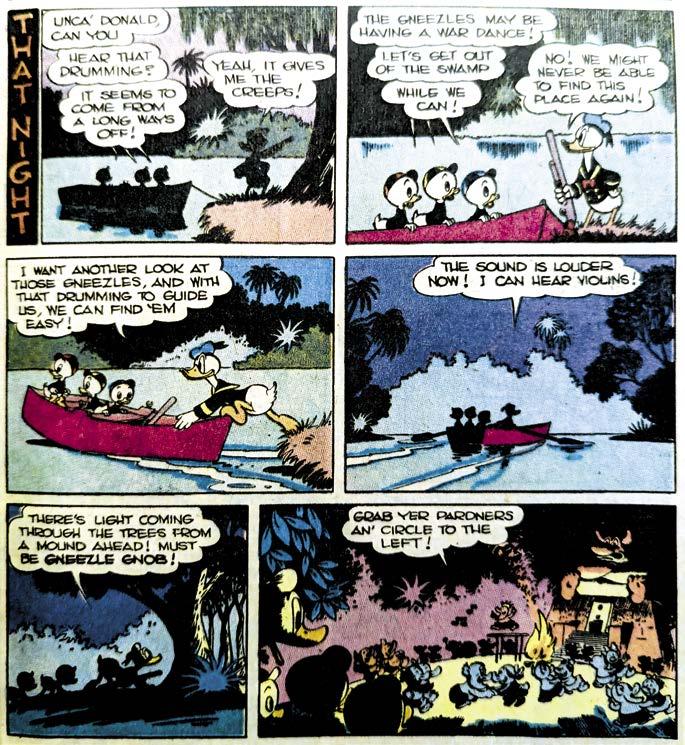

Solo appearances by characters from Walt Disney’s Comics, Looney Tunes, and New Funnies had become a staple of Four Color, a way for Helen Meyer to gauge which features might merit their own ongoing titles when wartime restrictions were lifted. Carl Barks contributed a wonderful blend of exotic setting, thrilling adventure, fantasy, and comedy in #62’s “Donald Duck Finds Frozen Gold,” wherein Donald and the boys volunteered to fly penicillin to a plague-stricken Alaskan village, unaware they were also carrying a map to a cache of gold stolen by Foxy Pete and his gang of cutthroats. In a second story, “Mystery of the Swamp,”

the gang encountered the Gneezles, gnomish little people living deep within the Everglades. Donald also co-starred in “Three Caballeros” (#71), a new adventure of the characters introduced in the feature film of the same name. In issue #79, Mickey Mouse and Goofy matched wits with a gang of jewel thieves and rescued a kidnapped heiress. Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig co-starred in each other’s solo outings in #66 and 78. In the former, Bugs and Porky volunteered to fly an experimental rocket to Saturn, where they were enslaved by the race of antennaed rabbits who live beneath its surface; in the latter, Porky encountered gangsters after being mistaken for a famous investigative reporter. John Stanley and Lloyd White crafted issue #67’s epic tale of Oswald the Rabbit spending a night in a witch’s castle to free the little people of a subterranean kingdom from a curse. Other New Funnies characters featured in their own issues of Four Color were “Raggedy Ann” (#72) and “Andy Panda” (#85).

The talents of Walt Kelly were front-and-center in a quintet of issues. He provided illustrations for “Mother Goose and Nursery Rhymes Comics” (#68), including an all-new composition, “The Mother Goose Birthday Party.” Two issues of “Fairy Tale Parade” (#69 and 87) included not only such familiar classics as “The Frog Prince” and “The Three Wishes” as interpreted by Arthur Jameson and George Kerr but a pair of Kelly originals, “Tiny Folk and the Giant” and “Tiny Folk and the Dragon.” His work could also be seen in the year’s final two issues (#90 and 91),

writing and drawing the entirety of “Christmas with Mother Goose” and contributing the charming story “Christmas Comes to the Wood Land” to the 1945 edition of “Santa Claus Funnies.” If Dell could be said to have a star artist, Walt Kelly was it... but he was not without stiff competition.

The single most important issue of Four Color released this year was #74, the debut of a character who would enhance the publisher’s bottom line for the next two decades. The creation of Marjorie Henderson Buell, who signed her work Marge, “Little Lulu” began life as a weekly panel cartoon in the back pages of The Saturday Evening Post. The character’s popularity soon led to a long-running ad campaign for Kleenex Tissues, and an ongoing series of animated cartoons from Famous Studios beginning in 1943. David McKay had released five cardboard-covered collections of the panel but this was Lulu’s first appearance in material created specifically for the comic book medium. Oskar Lebeck knew exactly who should handle the new property:

“John Stanley recalled, ‘Oskar handed me the assignment but I’m sure it was due to no special form of brilliance that he thought I’d lend to it. … I just happened to be available at the time,’ … Later Stanley acknowledged, ‘Somehow, it suited me. They insisted I do it.’ Not only was Stanley’s cartooning style right for Little Lulu, he was also one of Lebeck’s best writers. Indeed, Lulu would be more about story than art. Lebeck knew that Stanley’s hard-edged sense of humor and intellect were perfect for a feature coming out of a ‘class’ magazine” (Schelly 45).

Stanley hit the ground running with a trio of hilarious stories, as well as a number of one-page pantomime sequences, introducing the irrepressible Lulu Moppet, her best friend (and frequent nemesis)

Tubby Tompkins, and Alvin, the toddler with the rampant id she babysat. This first issue only hinted at the comedy gold to come, but it was a solid start for what has since been hailed as the perfect mar-

riage of character and creator and made “Little Lulu” a cultural touchstone for two generations of comic book readers.

For All-American Comics publisher Maxwell C. Gaines, 1945 represented a new beginning. Since first starting the line in 1939, Gaines—who had played a critical role in the birth of the modern comic book in his days at Eastern Color—had been beholden to other men, first Detective Comics head honcho Harry Donenfeld, who helped finance the start-up, then to DC partner Jacob “Jack” Liebowitz, who received Donenfeld’s share of AllAmerican as a gift. Gaines hadn’t gotten along with either man, so when the opportunity arose in late ’44 to buy out Liebowitz, he leaped at the chance.

Even sharp-eyed comics fans may have missed the clues revealing the break between All-American Comics and its sister company, Detective Comics. TM and © DC Comics.

“[Dr. Marston] wanted me writing as soon as possible. Before he hired me, he’d only been able to have men writers, many of whom didn’t have his background or understand his philosophy [a reference to Marston’s dissatisfaction with Gardner Fox’s handling of the character in All-Star] ... I was able to get that kind of psychology into my stories that reflected his philosophies and beliefs. We both had this huge imagination. We would laugh about the things we would think about when writing those stories. ... It was such a fascinating job” (Arndt 9).

Though his comics continued to be distributed by Independent News, jointly owned by Donenfeld and Paul Sampliner, Gaines was now the sole master of his company’s fate. He and his editor-in-chief Sheldon Mayer had good reason to feel confident. Even without its corporate ties to DC, All-American was still the sixth most prolific comic book publisher in America. It helped that the company’s line-up included three of the most popular superheroes. The newsprint shortage prevented AA from upgrading the bi-monthly anthologies All-American Comics and Flash Comics to the monthly schedule alongside Sensation Comics, but that compromise allowed Gaines and Mayer to keep the entire line at 52 pages save for the 84-page 15¢ Comic Cavalcade and the all-reprint quarterly Mutt & Jeff, which dropped to 44 pages with its Summer issue (#18).

Hummel’s first script appeared in the Spring issue (#12) of the Wonder Woman solo title, a story that pitted the Amazon princess against a cabal of arms dealers calling themselves the Third World War Promoters. Both Marston and Mayer were obviously pleased with her work: she wrote all four 1945 issues of the quarterly, three out of four Comic Cavalcade episodes, and a handful of stories for Sensation. Among the menaces she dreamed up that year were the suave Gentleman Killer, embittered botanist Creeper Jackson and his homicidal

With her series running in three different titles, her regular appearances alongside the Justice Society of America— comics’ first (and at this point only successful) superhero team—in All-Star Comics, and a daily syndicated strip, “Wonder Woman” was unquestionably All-American’s hottest property. One of the feature’s strengths was its consistency. Every Wonder Woman story published in 1945, in comic books and in newspapers, was illustrated by cartoonist Harry G. Peter, aided by his small studio staff. Cocreator William Moulton Marston, no longer able to work at full capacity since contracting polio in August of 1944, sought help with the writing duties for the comic books from his new assistant, a recent graduate of the Katherine Gibbs School to whom Marston had taken a shine while teaching a psychology course there. Originally hired simply to type scripts, 19-year-old Joye Hummel was soon crafting her own, albeit under her mentor’s close supervision. In a 2018 interview, Hummel recalled:

Octopus Plants, and the inhuman Seal Men, would-be conquerors of an idyllic matriarchal society hidden away in the Arctic. Hummel’s stories were indeed faithful to Marston’s vision, but she downplayed the scenes of bondage he indulged in and none of her scripts featured Axis villains. Marston made frequent use of such foes, as in Sensation #37 (January) where the German military attacked Paradise Island while its protective barrier was down for repairs. In a later issue, he introduced Countess Draska Nishi, leader of International Spies, Inc. Wonder Woman clashed with the slinky spy queen again in the June Sensation (#42), the first story outside the JSA series written by someone other than Marston or Hummel. Former Fox Publications scripter Robert Kanigher, freelancing once more after being discharged from the Army, wasn’t crazy about the character but he gave it a good try anyway, little suspecting that within three years the fate of the Amazing Amazon would be in his hands.

AA’s other super-stars, “The Flash” and “Green Lantern,” also appeared in an anthology, a solo title, and Comic Cavalcade. The duo were also back on active duty with the Justice Society as of All-Star Comics #24 (Spring). Original writer Gardner F. Fox continued to helm the Fastest Man Alive’s exploits throughout the year, scripting 23 out of 24 solo stories as well as his appearances with the JSA. Artist Everett E. Hibbard received a byline in every episode, whether it featured his art or those of his ghosts Jon Chester “Chet” Kozlak or Martin Naydel. Humor remained a staple of the Crimson Comet’s series, much of it in the form of his sidekicks, The Three Dimwits. Highlights for the year included the super-swift Jay Garrick’s first encounter with The Turtle, billed as “the slowest criminal alive,” and a trip through time to Robin Hood’s Sherwood Forest where Flash discovered he was the original Will Scarlet. Flash Comics #66 (October-November) featured the only comic book credit for Robert Bloch, the fantasy and horror writer best remembered today for the novel Psycho. AA story editor Julius Schwartz, who’d represented Bloch during Schwartz’s days as a literary agent, had suggested giving comics a go, pointing to Alfred Bester, Henry Kuttner, and Edmond Hamilton, other respected sci-fi and fantasy authors currently supplementing their incomes by writing for All-American. It was not to be. “[Bloch wrote] a hell of a good story,” the editor recalled in his memoir, “but when I tried to get him to write another, he simply grumbled ‘Once was enough,’ and I never brought it up again” (Schwartz 77). As for Green Lantern, Bester and his compatriots kept the master of the mighty power ring and Doiby Dickles, his cab-driving man Friday, busy against menaces like The Dandy, Blackbeard, The Backwards Man, The Lizard, psychic Albert Zero, the ghost of executed gangster King Shark, and a returning Solomon Grundy. Co-creator Martin “Mart” Nodell illustrated those episodes running in the Green Lantern quarterly, with Paul Reinman and utility player Chet Kozlak handling those running in AllAmerican Comics and Comic Cavalcade

The break with DC was most apparent in the pages of AllStar Comics. Where the “Justice Society of America” roster was once evenly split between AA and DC heroes, now it spotlighted only those characters to which All-American held the trademarks. The return of Flash and the Lantern

to active duty alongside chairman Hawkman, recording secretary Wonder Woman, Dr. Mid-Nite, Johnny Thunder, and The Atom (the JSA strip was the only place the Mighty Mite appeared in 1945) meant the end of the surreal bylaw that required JSAers with their own solo titles to assume honorary membership status. The change came abruptly enough that the art in All-Star #26 (Fall) had to be altered to substitute GL and Flash for DC super-doers Starman and The Spectre. The Justice Society’s greatest accomplishment for the year occurred an issue later. “A Place in the World” threw a spotlight on the rights of the handicapped. The story, in which Wildcat filled in for Atom, earned the series a mention in the World Book Encyclopedia, a feat of which scripter Gardner Fox was justifiably proud.

The monthly Sensation Comics lost a series that had been with the title since the first issue. “The Gay Ghost” made his final bow in the February issue (#38). The swashbuckling “Black Pirate,” now drawn by Alfonso Greene, returned for a two-issue stand (#41-42) before taking a six-month sabbatical. His pages went first to the last hurrah of “The Whip,” followed by a new series, “Picture Stories from Mythology,” a companion to the “Picture Stories from American History” feature that ran in all three anthology books. An educator before entering the comics industry, Gaines scripted these strips himself, with Allen Simon illustrating the history segments and Donald “Don” Cameron the retellings of classical myths. The publisher’s niece Evelyn Gaines wrote two other Sensation strips, “Mr. Terrific” and “Little Boy Blue and the Blue Boys,” using the pen name Lynne Evans. Stan Josephs, nee Aschmeier, limned the exploits of the Man of a Thousand Talents, while Frank Harry drew those of the costumed kid gang. The most entertaining of the title’s back-ups was

“Wildcat.” Though the strip had lost some of its noir ambience after cartoonist Joe Gallagher took over the art, it made up for it with a sense of humor, much of it centered on the Feline Fury’s sidekick, gangly hillbilly Stretch Skinner, and his eccentric kinfolk.

Flash Comics’ other star character, “Hawkman,” lost longtime artist “Shelly” Moldoff to the draft. Replacing him was 18-year-old Joseph “Joe” Kubert, an industry veteran despite his youth. Sheldon Mayer, who could be brutal towards artists he felt weren’t doing their best work, was uncharacteristically gentle with Kubert:

“It’s a funny thing—I’ve seen Shelly Mayer verbally rip a guy apart. I’ve seen him take original pages and fling them right across the room because he felt the guy didn’t do a good, quality job. If Shelly wanted to make a point, that’s what he did. For some reason he never did that with me. ... [H]e was kind, and tolerated all this crap from me without any of that kind of abuse” (Schelly 66-67).

Kubert rewarded his editor’s tolerance by giving the Winged Wonder’s adventures an exciting new energy. Though not yet the draftsman Moldoff was, he was an instinctively visual storyteller with a dynamic compositional sense and lively brushwork that brought Gardner Fox’s scripts to electrifying life. In 1945, Hawkman and Hawkgirl faced off against old foe Simple Simon, a French optician turned super-criminal named The Monocle, and

a horde of Chinatown zombies. In the August-September Flash Comics (#66), the Flying Furies met Neptune Perkins, an oceanographer forced by a strange salt deficiency to live in the ocean, an obscure character who gained a new lease on life in the 1980s. Like “Wildcat,” the tongue-incheek adventures of John B. Wentworth and Stan Joseph’s “Johnny Thunder” turned to its hero’s family for its laughs this year, introducing Johnny’s snooty cousin and his bratty kids, as well as love interest Daisy Darling’s niece Angel, who was anything but. Despite the presence of Johnny’s magical servant, The Thunderbolt, the series was the title’s least appealing feature. Wentworth and Frank Harry’s “The Ghost Patrol,” starring a trio of spectral aviators, no longer used the European Theater as a backdrop as of issue #61 (January), but without the war as its focus the strip seemed to be flailing. Mayer put it on hiatus while the kinks were worked out, substituting extra episodes of All-American back-up “Hop Harrigan.”

Flagship title All-American Comics didn’t lose any features in 1945, but several got new looks of one kind or another. Jon L. Blummer’s “Hop Harrigan” diverged from the radio series based on the strip by having its boyish hero and best buddy Tank Tinker discharged from the U.S. Army Air Force and return to civilian life as employees of the All-American Aircraft Company (though episodes somehow ended up running out of order, the duo showing up as civilians, then back in uniform, then being mustered out). “Red, White and Blue,” the title’s longest-running series, found Hawkman co-creator Dennis Neville replacing Joe Gallagher at the drawing board mid-year. John Wentworth continued to script the adventures of the trio of military intelligence agents. The team of Joseph Greene and Stan Josephs produced every installment of “Dr. Mid-Nite,” siccing nogoodniks like The Banshee and The Walking Bomb on the blind mystery-man.

With Wonder Woman, The Flash, and Green Lantern headlining, the oversized Comic Cavalcade had no trouble attracting buyers. Gaines and Mayer counted on that built-in appeal to expose the title’s readers to more high-minded content like “Johnny Everyman,” a series by Jack Schiff and John Daly appearing simultaneously in DC’s World’s Finest Comics. The title character, a globetrotting troubleshooter, left the war zone behind as of the Autumn issue (#12), returning stateside to deliver a powerful message against racism. Issue #10 (Spring) featured “Tomorrow the World,” a tightly condensed adaptation of the Fredric March anti-Nazi movie of the same name, illustrated by E.E. Hibbard. The 10-page story was reprinted as a standalone giveaway distributed to schools and libraries, and promoted an essay contest judged by authors Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Paul Gallico, William Shirer, and Rex Stout offering $1000 in prizes.

That Sheldon Mayer, himself a top-notch cartoonist, was growing weary of his duties as editor and art director became evident when, seemingly on a whim, he both wrote and drew every feature in the Summer issue (#5) of Funny Stuff. Ronald Santi’s “The Three Mousketeers,” “Bulldog Drumhead,” and “Who’s Who in Zooville” and Martin Naydel’s “McSnurtle the Turtle,” starring funny animal super-speedster The Amazing Whatsit, were fine

strips in their own right but shone even brighter under Mayer, while Saul Kessler’s “Blackie Bear,” the book’s weakest link, never looked better. If these artists resented their boss commandeering their series for an issue, which meant a dip in their incomes, they kept it to themselves.

Mayer was not the only one growing restless. After just six months of going it alone, M.C. Gaines made a startling decision. Believing that the market for superheroes was on the decline and determined to use the medium to educate and uplift, Gaines sold the entire All-American line—and the rights to all its characters—to Donenfeld and Leibowitz for $500,000, retaining only his pet project, Picture Stories from the Bible Mayer, Schwartz, and the rest of the AA staff were given office space at DC’s Lexington Avenue headquarters, where they had settled by the time the December issues were coming off the presses. Seventy years later, it may look like Gaines got the short end of the stick but at the time it was

a smart decision. As his son, William M. “Bill” Gaines, told it:

“[W]hen [my father] had the AA group, he was all set. He had his distribution, he had his paper. During World War II, paper was very important, and paper was allocated on the basis of what you had used or a percentage of it. So when he sold his business to DC, what they were buying, largely, were his paper contracts. They were interested in Wonder Woman, and so forth and so on, but they were more interested in the paper. As luck had it, the war was over six months later... There was plenty of paper, and they didn’t make as good a deal as they could have if they’d waited six months. But that was his good luck and their bad luck” (Decker 56).

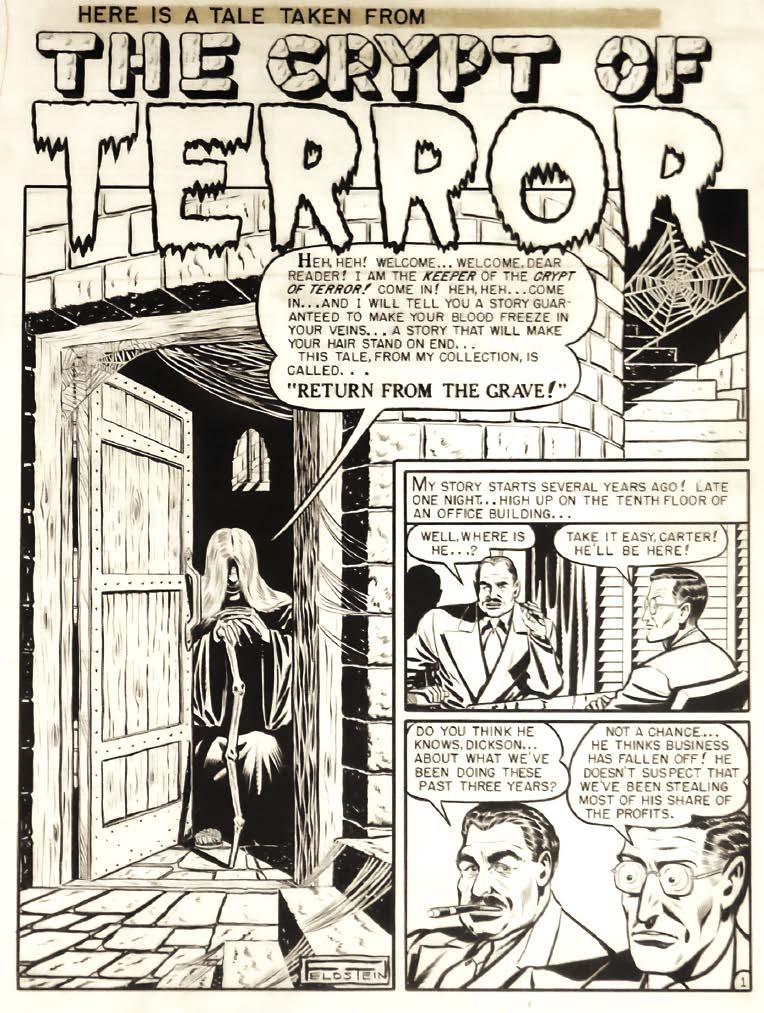

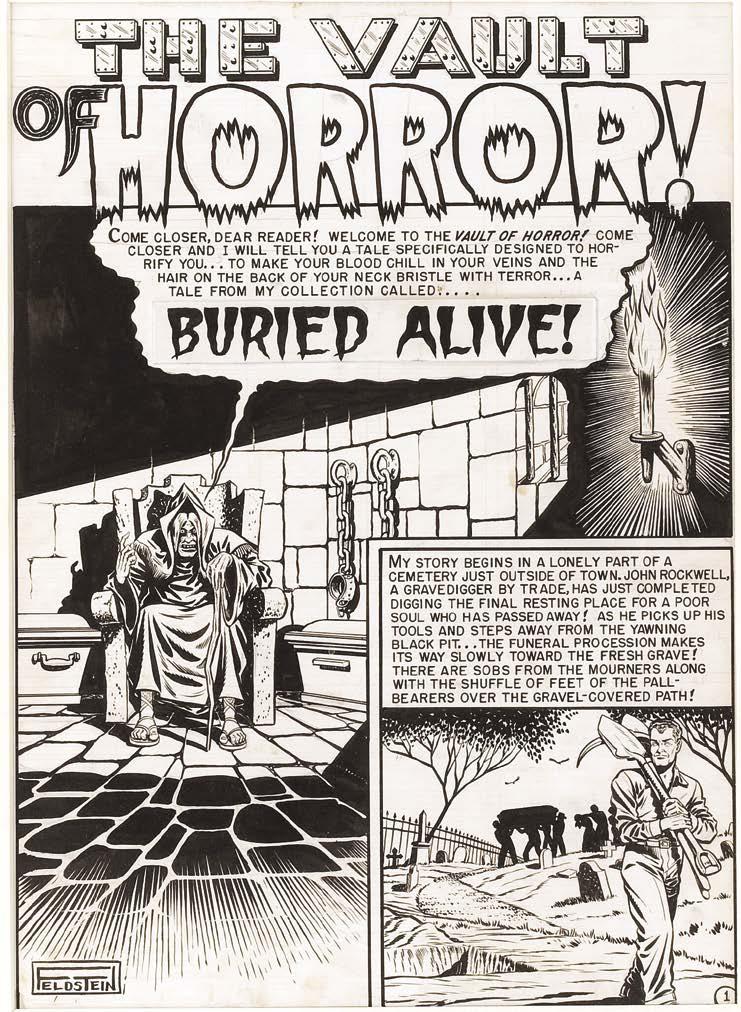

Gaines kept his office on Lafayette Street open, hired University of Pittsburgh history professor W.W.D. Sones as his editor, and devoted himself to his new Educational Comics line. Its first offerings were a second collected edition of Picture Stories from the Bible, this one reprinting the New Testament issues of the standardsized comic; the first issue of Picture Stories from American History, reprinting episodes of that series that originally ran in All-American, Flash Comics, Sensation, and Comic Cavalcade, and Desert Dawn, an American Museum of Natural History giveaway starring Bugs Bunny lookalike Johnny Jackrabbit. It was a modest but respectable start for the company that became both celebrated and vilified in the 1950s as the legendary E.C. Comics.

Even before adding the All-American titles to its roster, Detective Comics, Inc., was a dominant presence on America’s newsstands. With three monthlies, four bi-monthlies, and five quarterlies at the start of 1945, as well as ownership of all rights to

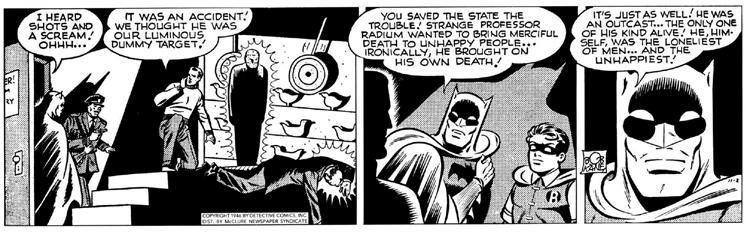

When it came to costumed superheroes, DC literally wrote the book. The popularity of Superman and Batman, and their exposure in other media, earned their corporate owners—but not their creators—a fortune.

Superman and Batman (both generating beaucoup bucks through merchandising and licensed appearances in other media), the publishing house that began in 1934 as Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s National Allied Publishing was successful beyond what co-publishers Jack Leibowitz and Harry Donenfeld could have imagined when they first launched their hostile takeover of Wheeler-Nicholson’s operation in ’37. DC—which also published comics this year under the corporate identities of Superman, Inc., World’s Best Comics Co., and Tilsu Publications, Inc.—had initiated the costumed mystery-man craze in 1938 with the Man of Tomorrow’s debut in Action Comics #1. They remained the foremost purveyors of superheroic fantasy with more than a score of such paragons featured across the line. The company’s Editorial Advisory Board of prominent educators, child psychologists, and sociologists kept the less wholesome aspects of the genre in check, ensuring a family-friendly brand of action characterized by bloodless violence, sexless romances, and moral certitude served up in easily digested 8- to 12-page “done-in-ones” under the supervision of editor-in-chief Whitney “Whit” Ellsworth and story editor and art director Jack Schiff. No longer content to let the caped-and-cowled set do all the work, the company had launched a small line of humor titles late in ’43 which doubled in size this year with the addition of two books devoted to animationstyle funny animals, one new, one converted from superhero material. Though never achieving the popularity of Dell’s line-up of ducks, mice, and wabbits, DC’s comic book critters would hold their own in the marketplace for over two decades.

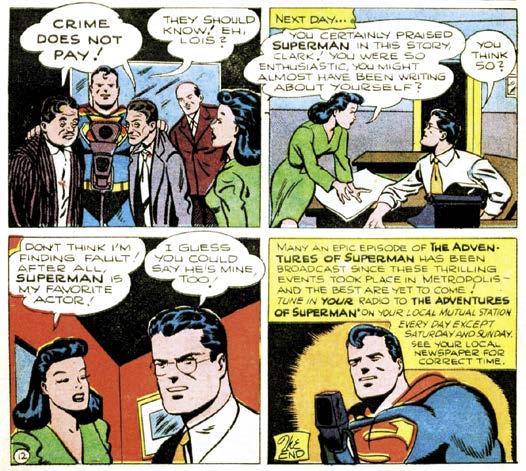

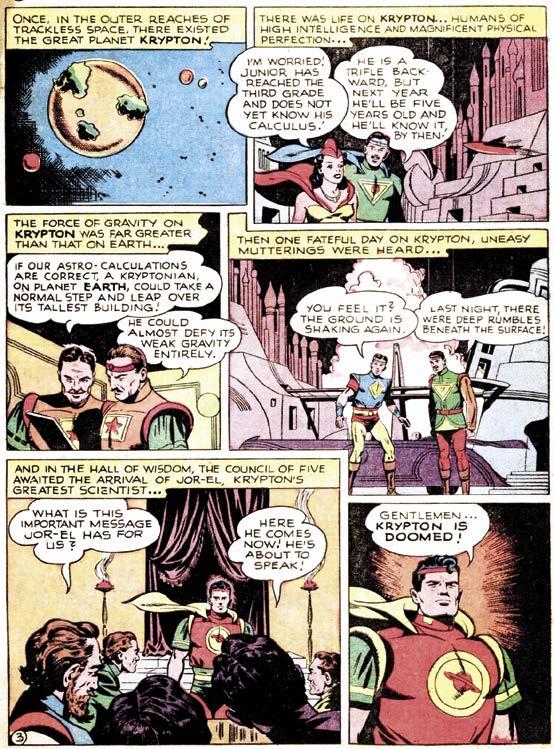

No DC character was more crucial to Harry and Jack’s bottom line than Superman. The Last Son of Krypton not only appeared in the monthly Action Comics, his bi-monthly solo title, the quarterly World’s Finest Comics, and the oneshot giveaway Superman’s Christmas Play Book but also starred in a newspaper strip distributed by the McClure Syndicate, a daily radio series over the Mutual Network, and animated cartoons produced by Famous Studios for Paramount Pictures. With co-creator and head writer Jerome “Jerry” Siegel serving in the Army, most of the scripting chores fell to Donald C. “Don” Cameron (no relation to the Picture Stories from the Bible illustrator of the same name), backed by Alvin Schwartz, Batman co-creator Milton “Bill” Finger, and Joseph Greene. Art for the series continued to be provided primarily by the studio of co-creator Joseph “Joe” Shuster, with contributions from staffers Sam Citron, John Sikela, Pete Riss, and Ira Yarbrough. Cameron’s stories tended to focus on returning villains like The Prankster, The Toyman, con man J. Wilbur Wolfingham, and the extradimensional trickster Mr. Mxyztplk, while occasionally trying out new opponents like The Wizard of Wokit, an immortal sorcerer terrorizing a Balkan town, and The Water Sprite, a corrupt construction contractor posing as the vengeful messenger of Neptune. One of Cameron’s scripts repurposed a Siegel storyline rejected by editorial in which the alien powerhouse was