Whose halfbaked idea was this?

What’s a Spider-Man …without his Amazing Friends?

what’s-a-happening?

Whose halfbaked idea was this?

What’s a Spider-Man …without his Amazing Friends?

what’s-a-happening?

BY ANDY MANGELS

Welcome back to Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning, your constant guide to the shows that thrilled us from yesteryear, exciting our imaginations and capturing our memories. Grab some milk and cereal, sit cross-legged leaning against the couch and dig in to Saturday Morning! This issue, we’ll take the first of a three-part dive into Marvel Productions’ heroic animation of 1981-1983, beginning with Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends

DOES WHATEVER A SPIDER CAN

Marvel’s most recognizable super-hero would premiere on ABC television in 1967 with a jazzy theme song intro that began with: “Spider-Man, Spider-Man, does whatever a spider can. Spins a web any size, catches thieves just like flies. Look out, here’s comes the Spider-Man.” The half-hour animated series by Grantray-Lawrence was an answer to Filmation’s popular The Superman/Aquaman Hour of Adventure, based on National Periodical Publications’ (now known as DC Comics) heroes of the air and seas [For more, be sure to check out RetroFan #3 & 25 –RetroEd]. It was also a companion piece to Hanna-Barbera’s other Marvel

(ABOVE) Spider-Man swings in this animation cel from Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends (1981). © Marvel.

series, The Fantastic Four, also on ABC [covered in RetroFan #33 –RetroEd] and Grantray-Lawrence’s syndicated Marvel Super-Heroes weekday show.

The new Spiderman series (without the official hyphen) was based on the creation of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, debuting in Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962). In the lore, when high school student and science nerd Peter Parker was bitten by a radioactive spider, he developed superstrength, enhanced senses, and the ability to stick to any substance like a spider. Using his science knowledge, Parker developed a synthetic web that he could shoot from wrist launchers, which enabled him to swing around New York City. Initially a reluctant hero, he eventually learned that “with great power comes great responsibility,” and began to use his new abilities to fight crime, now garbed in a red-and-blue skintight suit and calling himself Spider-Man.

The Marvel hero—nicknamed “Spidey,” “wall-crawler,” or “web-slinger”—next appeared on television as a guest-star during the 1974–1977 seasons of the Children’s Television Workshop public television series called The Electric Company. Unlike his comic counterpart, this Spidey was silent, with no quips or snappy comebacks.

Stan Lee sold CBS on a new primetime live-action Amazing Spider-Man show in 1977. Produced by Charles Fries, it starred Nicholas Hammond as Peter Parker and the wallcrawler. Although the pilot did well in the ratings, the

network failed to green-light a regular series, instead airing 12 further episodes over the next two years.

Overseas, Japanese audiences got a far better deal. The famous Toei Company produced 41 live-action episodes of Spider-Man (pronounced “Soupaidaman”) which aired on TV Tokyo from May 7, 1978 through March 14, 1979. With alien foes, giant robots, kaiju fights, and a flying Spider-car, this Spider-Man remained a mystery in the US until the late 1980s when bootleg videos began to show up in collectors’ circles. But it was animation that held Spidey in its web for the future. The hero guest-starred in episodes of ABC’s SpiderWoman series during the 1979–1980 season. The series was itself based on a female spinoff of Spidey that Marvel Comics had created for trademark purposes. The show was animated by DePatie-Freleng, who would soon have a closer working relationship with both Marvel and Spider-Man…

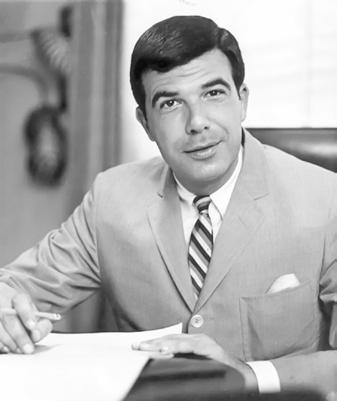

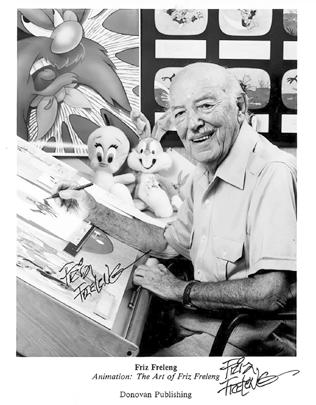

The full name of Spider-Woman’s production company was DePatie-Freleng Enterprises (also known as DFE). The studio had been founded in 1963 following the shut-down of Warner Bros.’ Burbank-based animation department. The studio’s two principals were David DePatie and Friz Freleng. DePatie, a production executive, had worked at Warner his whole career to that point. Freleng was a popular director who had introduced or developed most of Warner’s biggest animated stars.

DePatie-Freleng had a long resumé, but its biggest project ever was creating the animated adventures of the Pink Panther. This character had debuted in 1963 in the opening credits of a film—also titled The Pink Panther—about a bumbling detective. The company developed

(LEFT) David DePatie. (CENTER) Friz Freleng in a signed promotional photo for Animation: The Art of Friz Freleng. Courtesy of Donovan Publishing. (RIGHT) Logo of the DePatie-Freleng Films Marvel period.

animated shorts to play prior to feature films in theatres, television cartoons on NBC, and advertising. They also developed the animated title sequence for I Dream of Jeannie and the lightsaber animation for the first Star Wars film!

By 1980, however, Freleng was ready to move on. The pair sold their company and its assets to Marvel Comics on June 19, 1980. Freleng returned to Warner Bros., and DePatie became the new CEO and President of Marvel Productions. He retained some of his DFE staff, including, significantly, Lee Gunther, who became Vice President in Charge of Production. Other initial hires were producer/ writer Al Brodax (the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine) as Director of Program Development/Special Projects, and Jerry Eisenberg as Senior Producer.

When Marvel announced the studio’s formation, it already had some work lined up, including commercials for Oscar Mayer and Owens-Corning, and Pink Panther and Dr. Seuss prime-time specials to deliver for ABC. In their company announcement of Marvel productions in Hollywood Reporter, Marvel promised, “twenty developmental presentations for Saturday morning, cartoons, primetime specials,

and pilots.” Their budget from until the end of 1980 was only $100,000.

Marvel Productions was a subsidiary of the New Yorkbased Marvel Entertainment Group—itself a subsidiary of Cadence Industries—which was the publisher and licensor of Marvel Comics and its characters. By owning their own animation studio, Marvel hoped to be able to successfully break into Hollywood in a big way; until that time, nothing they had done had lasted more than one season except for CBS’s live-action The Incredible Hulk.

While Marvel president James Galton and editor-inchief Jim Shooter remained in New York to run the comics division, company figurehead and past publisher Stan Lee, who had the ebullient personality and skills of a carnival huckster, moved to Los Angeles specifically to pitch Marvel shows. Lee and his family moved into a high-rise condo in Westwood, near Beverly Hills.

By day, Lee went to Marvel Productions’ new office in Van Nuys, where as “Vice President, Creative Affairs,” his main responsibilities were to get films and TV series going based on both existing Marvel characters and any new characters Marvel Productions created. He generally didn’t write or offer stories to any of the projects. His office was full of mementos of his career. On display there was a sculpted bust of his wife, Joanie, by an old friend, Stanley Sawyer. A nearby storeroom had videocassettes and recordings of lectures, speeches, conventions, and TV appearances Lee had made over the years.

or glass walls looking into the outdoor area. “I enjoyed sitting outdoors and reading scripts in that great area and then discussing all our projects with David DePatie,” Lee would write in his 2002 semi-autobiography Excelsior: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. The initial employee count at Marvel Productions was around 18, including Lee, DePatie, Gunther, Brodax, and Eisenberg. It was a small shop.

Marvel Productions’ office was a one-story building at 4610 Van Nuys Boulevard in Sherman Oaks. It was a rather modest building with a sunny atrium in its center; all the offices had windows

James Galton talked about the role of Marvel Productions in Comics Scene #1, (January 1981) saying, “The intent of the animation house is to make money. The intent of the animation house is to make films and television programs using the popularity of our established characters. Despite the fact that television has taken away our readership, I think the

two things can be mutually beneficial. It’s something I always thought was right for the company—we should have our feet in both camps and whether or not people stop reading, there’s a big market out there for programming and we should be a part of it.”

In Excelsior!, Lee described his first meeting with a network executive to pitch animation. “Since it was our first meeting, she acted as though she really wanted to get to know me, to learn how I felt about Saturday morning cartoons. I was generally pleased when she asked for my opinion of the cartoons appearing on network TV at the time.” He suggested to her that most animation dialogue didn’t sound very intelligent, and that better writing could

Will Meugniot is one of those who’s done it it all—writing, directing, storyboarding, and comics—fueled by his authentic passion for comics and pop culture. Among his many accomplishments is his work on the animated shows in the ’80s, ’90s, and beyond. We recently caught up with Will to learn more about his efforts on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends in particular.

RETROFAN: You’ve worked on so many animated shows. Where does your work on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends fit in with your career?

WILL MEUGNIOT: I started working on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends in 1981. That was my fourth year in the animation business and about six years after my first professional comic book

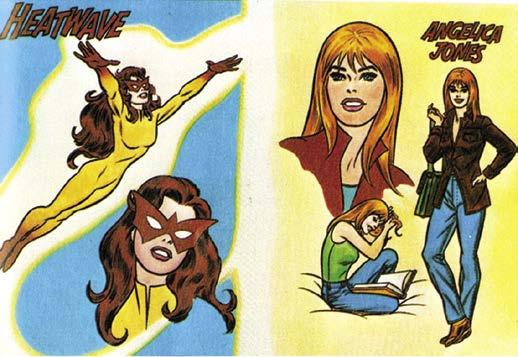

(THIS PAGE) Firestar displays her powers. Art by Will Meugniot.

(OPPOSITE PAGE) Meugniot storyboard detail featuring Firestar and Spider-Man. © Marvel. Art courtesy Will Meugniot.

work in Marvel Chillers #3. By then, I’d done a few Tarzan and Korak stories for Edgar Rice Burroughs and a couple of fill in issues for Marvel Comics, but animation had become the main thrust of my work with storyboards for Godzilla, Jana of the Jungle, Scooby-Doo, Popeye, Super Friends, The Thing, Flash Gordon, Sport Billy, The Lone Ranger, Zorro, Blackstar and a few others. My work on the Flash Gordon animated series and the first animated Lone Ranger episode led to a two-year stint as a storyboard supervisor for Filmation’s action adventure cartoons [We covered Filmation’s Flash Gordon in RetroFan #23 –RetroEd].

Just as I was getting burned out by Filmation’s restrictive use of stock animation, I got a call from my friend, Larry Houston, who told me that Marvel Productions needed a new storyboard artist, and quickly. I hustled over, had an interview with my old Super Friends boss, Don Jurwich, and got hired on the spot. I started on Spidey two weeks later, after living out my two weeks’ notice at Filmation.

RF: As a long-time comics fan, what did you like best about working on this show?

WM: Several things: It was the first Marvel animated show that tried to present a form of the Marvel Universe with cameos by many of the other Marvel Heroes. It used comic book writers for some of the stories, most notably Christie Marx and Don Glut. Stan Lee was in the Marvel Production offices and it was a rare day that he didn’t come by for at least a quick hello. But the best thing about the experience was sharing the art bullpen with Rick Hoberg, Larry Houston, Russ Heath, and Dick Sebast. We all got along so well, and had a common vision of trying to do more ambitious animation than had been the norm at the time. We bonded so strongly that Rick and Larry are my dearest friends to this day.

RF: Conversely, as a long-time comics fan, were there things about this show you did not like?

WM: Obviously, Ms. Lion, the “funny” dog character was something that none of us liked. And occasionally there’d be something “off” in the scripts, like the Hiawatha Smith character. But, just two years earlier, the only Marvel show in production was Hanna Barbera’s comedic Thing cartoon, for which I did many storyboards, so the SpiderFriends (as we who worked on it called the show) was a huge step up!

Also, the show suffered a bit from a “generation gap”. Most of the directors were old school and had come up through the ranks at Art Center and Disney. They’d been taught “rules” which applied well to traditional animation, but didn’t always work well for super-heroes.

As an example, in the first episode of the ’80s Marvel animated Hulk series, I did a shot of the Hulk trying to break out of his Bruce Banner-designed prison cell, pulling his fist straight back away from camera, holding a beat, then snapping it forward, filling the scene, essentially giving motion to a powerful Kirby pose. The animation director was very proud of how he’d “improved” the action by having the Hulk comically twirl his fist around before launching the punch. It destroyed the shot, but the guy really thought he’d made it better.

RF: You had many collaborators on this show. Who were they and how did you all work together?

WM: I’ve already mentioned working in the bullpen with Rick, Larry, and Dick. The four of us were always trying to “top” each other with inventive action and direct references to the Marvel Comics upon which the show was based. Also, Larry and I would sometimes sneak in cameos by anime characters in the backgrounds, especially in the episodes we knew Toei

BY WILL MURRAY

The counterculture of the 1960s was slow to creep into dramatic primetime network programming. Pop music, of course, faced no such barriers. Musical variety shows like Hootenanny and Shindig were among the first to bring the new sound to prime time. The Monkees was a rare Rock ’n’ Roll sitcom.

On traditional shows, the odd hippie might pop up as comic relief or a bad guy. The people who programmed the networks, and those who wrote the scripts, belonged to an earlier generation, and didn’t know what to make of the rebellious youth wave sweeping the world. Attempts to cash in on the counterculture like Coronet Blue came and went.

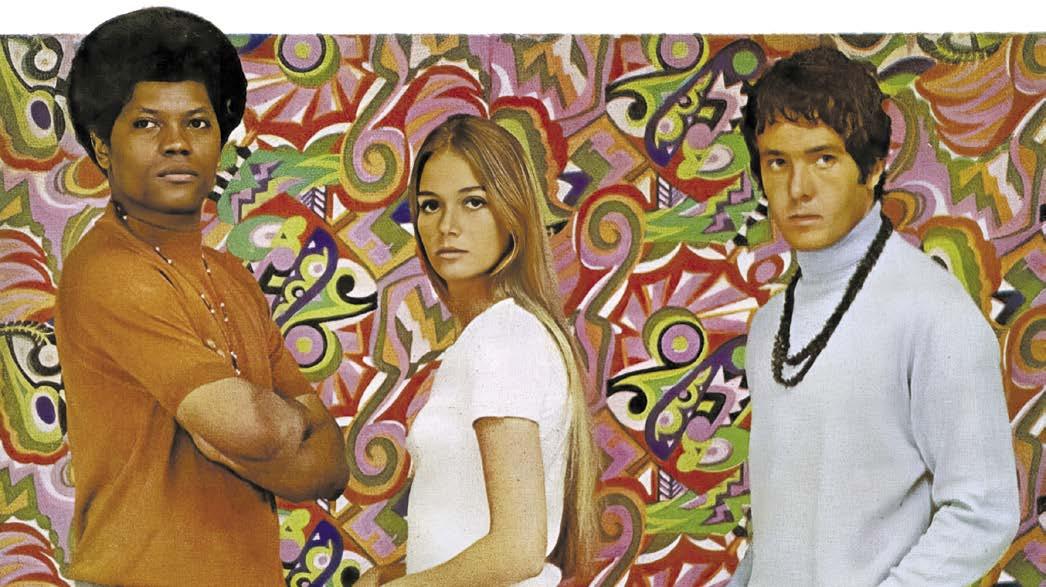

The Mod Squad, which premiered on September 24, 1968, in a 90-minute episode called “The Teeth of the Barracuda,” was the first dramatic program to embrace the counterculture on its own terms.

It starred Michael Cole as Pete Cochran, Peggy Lipton as Julie Barnes, and Clarence Williams III as Lincoln Hayes. Kicked out of his parent’s Beverly Hills home for being an anti-establishment dropout, Pete was arrested for stealing a car. Linc was picked up during the Watts riots. Julie had run away from home. Her mother was a streetwalker, and Julie was arrested for vagrancy. All three were branded as juvenile delinquents, but Police Captain Adam Greer saw in them a different potential. He also had a problem.

As Executive Producer Aaron Spelling explained it, “This is the story of three lonely young kids who have been in trouble with the police. They are on probation, and the police say to them: ‘We don’t understand you and we know you don’t understand us, but [we] want you to help us bridge the generation gap.’ After Vietnam and civil rights, that’s our biggest problem today, in my opinion.”

Reluctantly, the trio agree to go undercover for one case. But only one. The tagline was “Cops. One White. One Blonde. One Black.”

The Mod Squad had its origins in a law-enforcement program that dated back to the 1950s. The Los Angeles Police Department had recruited some young kids to go undercover into the drug scene as it existed then. But the show’s originator, Buddy Ruskin, couldn’t sell the concept for nearly a decade.

Spelling became intrigued with Ruskin, who had lost his undercover police job because he got too old to pass as a youth. “He had been a member of the young narcotics squad in Los Angeles, roaming Sunset Strip and working in high schools to find out who was selling drugs to kids, and who was getting them involved in drug-related crimes,” related Spelling.

By the late 1960s, the drug scene was a very different reality. Teenagers were also quite different. In New York City, Mayor Lindsay had formed a “Hippie Squad” to tackle the problem there.

Producer Aaron Spelling took the idea and updated it for 1968. Originally, it was going to be called The Young Detectives. Spelling renamed it The Mod Squad. At that time, Mod meant Carnaby Street fashions, but in this case, it was short for modern.

The first Mod Squad cast member was Michael Cole. Spelling had seen him in an episode of Gunsmoke. When Cole read the pilot script, he told the producer he hoped the show would never air.

“Michael came to my office and hated the whole idea of the show because he thought it was a story of three hippie kids playing cops,” Spelling recounted. “He thought it was The Monkees, without music. But when he read the script and saw what we were trying to do, he wanted to do it.”

“It sounded to me as if kids were being sent out to squeal on other kids,” Cole recalled.

As the oldest actor cast, Williams provided the gravitas for the group. His big break came when Bill Cosby saw him in the New York play, Slow Dance on the Killing Ground. Three months later, Spelling called him to the coast to do a guest shot on The Danny Thomas Hour, playing a getaway driver. After crashing the car, Williams admitted he never learned to drive.

“And what it was, unbeknownst to me, until after I got out to Hollywood,” revealed Williams, “they said, this is a screen test for a series we’re going to do called The Mod Squad. And you were recommended to us by Bill Cosby, and that’s how that happened.”

Contentedly living a bohemian lifestyle, Lipton also initially wasn’t interested until she read the script. Told to report for a Friday audition, she begged off, saying that she was off to Haight-Asbury for the weekend. Obligingly, the producers agreed to wait until Monday.

“There I was,” she later reminisced, “in my blue jeans, T-shirt and beads, reading away. They knew and I knew that this would be my trip.”

Lipton’s brother, Robert, had unsuccessfully auditioned for the part of Pete Cochran.

Veteran actor Tige Andrews was cast as Captain Greer, the show’s resident father figure. After playing a cop on Robert Taylor’s The Detectives, the last thing he wanted was to play another. “When the casting office called me about the series, they didn’t mention anything about the police,” he related. “I got the impression I was to be the father of three kids, and I thought the title meant something like ‘The Jones Crowd.’”

Meeting Clarence Williams in the production office instantly dispelled that misconception. “This show is like no other,” Spelling assured him.

The producer struggled to find a young actress to fit his vision of Julie Barnes. “Peggy Lipton was a little different,” Spelling explained. “We had tested 16 girls and none was quite right. I’d remembered seeing Peggy at the Daisy a number of times and I was always impressed by a sort of lonely look. She always looked to me like a canary with a broken wing, and that’s exactly the character we had in mind.”

Peggy Lipton (Julie), Michael Cole (Pete), and Clarence Williams III (Linc). Tige Andrews (Captain Adam Greer) sure looks out of place in a suit. © Paramount Home Entertainment.

“I must admit,” Andrews confessed, “I balked. I figured the role would be the usual cliché of the tough guy in short sleeves, married to the job. I had done that already. I discussed it at length with Aaron Spelling, the executive producer, and a kind of biography of Captain Adam Greer emerged. Adam Greer doesn’t run around complaining

BY MARK VOGER

hungover—a not altogether unfamiliar state for Ol’ Duke.

For a long stretch of cinematic history, movies about Jesus were deferentially reverent. There was no, to borrow a phrase, separation of church and state here.

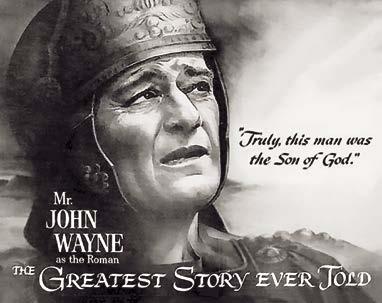

From two epics of the silent era, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927), through films like The Robe (1953), Day of Triumph (1954), Ben Hur (1959), Nicholas Ray’s remake King of Kings (1961) and the aforementioned Greatest Story Ever Told, you’d swear the Vatican itself signed off on these releases.

Which is why, when the double-album Jesus Christ Superstar hit record shops on October 27, 1970, it was an instant magnet for controversy. At first, the brou-ha-ha was triggered by the title alone, which to many (but not all) religious folks sounded like a violation of the Third Commandment: “Thou shalt not take the Lord’s name in vain.”

If you weren’t alive at the time—as many of us older RetroFans were—you can’t imagine the ruckus this album kicked up. Christian religious leaders called it sacrilege. Jewish religious leaders called it anti-Semitic. It was banned by the BBC.

But money talked. Within a month, Superstar was certified gold,

and it topped the Billboard charts as the #1 album of 1971. (Ironically, that initial blast of controversy helped nudge the album to success.)

Superstar grew into an entertainment behemoth. There was a Broadway adaptation (1971–73) that was nominated for five Tonys, a Broadway cast album, Norman Jewison’s 1973 theatrical film, a touring production, three Broadway revivals (including one in 2012 with two Tony wins), and many performances in the realm of local theater. NBC’s live simulcast of JCS on Easter 2018, which starred John Legend as Jesus and Sara Bareilles as Mary Magdalene, provided further proof that a work once deemed profane was now a bona fide institution.

Meanwhile, back in 1970, the old guard was irked by another unexpected development in Christ culture. Whether

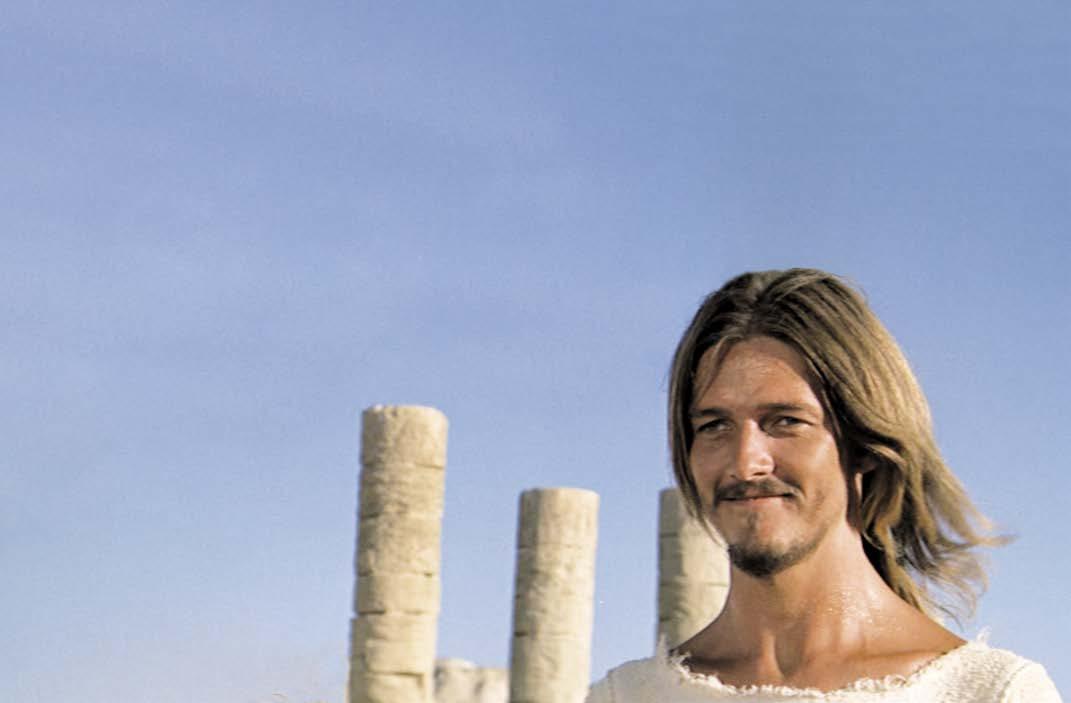

(ABOVE) Ted Neeley played the title role in Norman Jewison’s movie adaptation of Jesus Christ Superstar (1971).

© Universal Studios. (LEFT) John Wayne appeared as “the Roman” in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), at a time when Hollywood movies about Jesus were deferentially reverent.

© United Artists.

you called this phenomenon the “Jesus movement,” the “Jesus people,” or the “Jesus freaks,” it seemed odd that certain hippies—who many mainstream Americans viewed as unemployed, unshowered pot smokers—were claiming Jesus as their figurehead.

Was the world going crazy?

Picture, if you will, a dude wearing long hair, a beard and sandals, preaching a message of peace and love.

That would either be a Woodstock refugee or Jesus, right?

Which is why so many long-hairs seized upon redundancies between hippie philosophy and the teachings of Christ.

From 1968 through the early ’70s, Jesus was, you might say, “rebranded” as a hippie figurehead. Some “cults” or “sects” popped up that took the idea very seriously—so much so, that Time magazine devoted a cover story to “The Jesus Revolution” in its June 21, 1971 issue. (The gorgeous pop-art cover was created by Polish graphic artist Stanislaw Zagorski.) The cover of the June 30, 1972 edition of Life touted the “Great Jesus Rally in Dallas.”

Besides Jesus Christ Superstar, there was Godspell, a “musical based on the gospel according to St. Matthew.”

So-called “folk masses” were held at Catholic churches, during which guitars, rather than organs, accompanied hymns, adding a wisp of grooviness to the staid ritual.

At times, Jesus made improbable showings on the

(LEFT) The double-album Jesus Christ Superstar achieved gold record status within two months of its release on Oct. 2, 1970. © Decca Records. (CENTER) The cover of the album Godspell (1971), a “musical based on the gospel according to St. Matthew.” © Bell Records. (RIGHT) On the Rolling Stone’s “Sympathy for the Devil,” Mick Jagger sang the lyric, “I was around when Jesus Christ / had his moments of doubt and pain.” © London Records.

pop charts. In 1968, Mick Jagger evoked Christ with a lyric in the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil”: “I was around when Jesus Christ / had his moments of doubt and pain.” On the 1969 hit “Sweet Cherry Wine” (#7), Tommy James of the Shondells sang “He gave us sweet cherry wine,” which James later acknowledged was a reference to his Christian faith, albeit a candy-coated one.

In 1969, Norman Greenbaum’s trippy hit “Spirit in the Sky” (#3) pulled no punches: “Prepare yourself / you know it’s a must / Gotta have a friend in Jesus / so you know that when you die / he’s gonna recommend you / to the spirit in the sky ...”

Likewise, Ocean’s 1970 hit “Put Your Hand in the Hand” (#2) was anything but cryptic, inviting listeners to put their hand in the hand of the man who “stilled the water” and “calmed the sea,” the man “from Galilee.”

Jesus Christ Superstar yielded two songs which charted in 1971: “Superstar” (#14) and

(LEFT) The “Jesus Revolution” was examined by Time magazine in 1971, with cover art of a psychedelic Jesus by Polish graphic artist Stanislaw Zagorski. © Time. (RIGHT) The Way was a Bible for cool kids augmented by contemporary lingo and photographs. © Tyndale House Publishers.

BY DON VAUGHAN

Beverly Washburn was 12 years old when she landed the role of Lisbeth Searcy in the Walt Disney production of Old Yeller. She was a Hollywood veteran by that point, having appeared in her first film, The Killer That Stalked New York, when she was 6 years old.

Old Yeller was a seminal film for Beverly, and among the handful of films that her fans most often ask about when they meet her at autograph shows. But her memories are a bit more melancholic these days because Beverly holds the sad distinction of being the last living cast member of Old Yeller, following the passing of Tommy Kirk on September 28, 2021 at age 79.

I was introduced to Beverly through my good friend Kenny Miller, an actor whose credits include I Was a Teenage

Werewolf, Attack of the Puppet People, and A Touch of Evil, directed by Orson Welles. I had collaborated with Kenny on his memoir, Kenny Miller: Surviving Teenage Werewolves, Puppet People and Hollywood (McFarland), and he directed Beverly to me when she expressed interest in writing her life story.

The experience was revelatory. Beverly’s filmography includes numerous motion pictures of note (Shane, The Greatest Show on Earth, Spider Baby) and dozens of classic television shows (Leave It to Beaver, Thriller, Star Trek). Hearing Beverly talk about her film and television career was tremendous fun, and I quickly learned how she had gained the reputation as one of the sweetest people in show business. Our friendship was set from our very first conversation.

(ABOVE) The young stars of Old Yeller, Tommy Kirk and Beverly Washburn. © Disney. (LEFT) Beverly Washburn appears as Arlene Galway in a 1967 Star Trek episode “The Deadly Years.” She’s had this far off stare (FAR LEFT) since she was a kid! © Paramount Global. Photos courtesy of IMDb.

Beverly’s memories of Old Yeller remain vivid, despite the passing of 66 years. She recalls her first meeting with the film’s director, Robert Stevenson, and the casting director, and being asked to read a few scenes from the film, known in the industry as sides. The screenplay was written by William Tunberg, whose credits include the film Garden of Evil and numerous television shows, and Fred Gipson, author of the source novel.

“This was at Disney Studios, and Walt Disney was also in attendance during my reading,” Beverly tells RetroFan. “They told me the reading was for a film called Old Yeller, which was about a boy and his new dog. Well, they only had to mention that I would be working with a dog and I got very excited.”

(LEFT) Kirk as Travis Coates and Washburn as Lisbeth Searcy in a promotional photo for Old Yeller. (RIGHT) Little Kevin Corcoran as Arliss Coates astride the mongrel. (INSET) The first publication of Old Yeller (HarperCollins, 1956), given the Newbery honor a year later. Old Yeller movie © Disney.

As for Disney’s presence, Beverly says he was quiet and offered little comment. “He didn’t have a lot to say, he basically just sat there,” she recalls. “Once we started filming, he would come on set every day and watch, but he never told anyone how to do their job. He would just kind of stand back and watch us film a scene, then smile and leave. We didn’t have a lot of interaction with him, but he gave us his stamp of approval.”

Beverly was one of several young actresses vying for the role of Lisbeth, and she didn’t think she would get the part. “Looking back, any Mouseketeer could have had the role and been wonderful in it,” she notes, “but they were all busy with The Mickey Mouse Club, so the studio looked outside for an actress to play Lisbeth. I had earlier worked with director Robert Stevenson on a television show. He remembered me,

and I believe he was instrumental in me getting the role.”

The film was based on the children’s novel by Fred Gipson, published in 1956 and winner of the 1957 John Newbery Medal. It tells the story of the Coates, a Texas ranch family consisting of father Jim (Disney stalwart Fess Parker), mother Katie (Dorothy McGuire), younger son Arliss (Kevin Cocoran), and older son Travis (Tommy Kirk). Jim must leave his family to go on a cattle drive, leaving Travis in charge. Shortly after, a stray dog causes a ruckus while Travis is working the corn field, angering the boy. Arliss loves the dog, however, so Katie brings it into the family in the hope that the dog will protect her youngest son.

Travis does his best to drive the dog away, but ultimately changes his mind when Yeller defends Arliss against an angry bear. The dog serves and protects the family in numerous other ways, ingratiating itself into everyone’s hearts. During a hunt for wild pigs, Yeller saves Travis from a boar attack, but is severely wounded in the fight. Travis leaves Yeller in a cave. Travis limps home, and returns later with Katie, who dresses both Travis’ and Yeller’s wounds.

Neighbor Bud Searcy (Jeff York) and his daughter, Lisbeth, pay a visit. Yeller had impregnated their family dog, so Lisbeth offers Travis one of the puppies, but Travis rejects it. Bud notifies Katie of a rabies epidemic in the region, giving Katie momentary cause for concern that Travis might have been infected during his run-in with the boar. Bud leaves, but Lisbeth stays to help with Travis’ recovery.

When Travis is almost fully recovered, the Coates’ cow, Rose, collapses. Travis recognizes the symptoms of rabies

BY SCOTT SHAW!

In the second half of the 1950s, when I was a kid yearning to become a professional cartoonist, I spent a lot of my time studying the various animated cartoons shows on TV. They were mainly old cartoons but with a sprinkling of new ones. The Fleischer Studio’s animated shorts featuring Popeye the Sailor and MGM’s Tom & Jerry shorts were my favorites, but I’d already memorized most of them. Things were getting a bit boring for my cartoon-lovin’ generation, until HannaBarbera’s The Ruff and Reddy Show and Jay Ward’s Rocky and His Friends began to appear on our parents’ TV sets.

Over the years, aside from Rocky and His Friends, Jay Ward Productions made three more animated series: Hoppity Hooper (1964–1967), The Dudley Do-Right Show (1964–1966), and George of the Jungle (1967). It was also responsible for creating hundreds of memorable animated cereal commercials for General Mills and the Quaker Oats Company. And it all came from a small studio on Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood. Although it had a team of top writers and cartoonists, Jay wasn’t interested in quantity over quality. A proud eccentric who also owned a successful real estate company in Berkeley, California, Jay Ward’s main goal was to make certain that everything that came out of his studio was funny. Unfortunately, many episodes of Rocky and His Friends were animated in Mexico and lacked quality, but the well-executed animation from Jay Ward Productions made a huge difference. After the production of Rocky and His Friends was done, Ward

still occasionally needed to sub-hire a few other small studios in Los Angeles to help him out. The results were much better than before... and funnier, too.

(ABOVE) Original art to The Flintstones #29 (Gold Key, 1965) by Harvey Eisenberg and Larry Meyer, two of the many talents who created Hanna-Barbera. © Warner Bros.

On the other hand, a few years before Rocky and His Friends, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera—who had been making Oscar-winning Tom & Jerry shorts for nearly two decades at MGM, with the most generous budgets for seven-minute cartoons during the Golden Age of Hollywood—were now trying to survive.

In 1940, Hanna and Barbera jointly directed Puss Gets the Boot, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Cartoon Short Subject. Their boss, MGM producer Fred Quimby, who had wanted to start a new animation unit, gave Hanna and Barbera permission to pursue their cat-and-mouse idea. The result was their most famous creation, Tom and Jerry. Over the next seventeen years, Hanna and Barbera worked almost exclusively on Tom and Jerry, directing more than 114 highly popular cartoon shorts. Tom and Jerry also made guest appearances in several of MGM’s live-action films, including Anchors Aweigh (1945) and Invitation to the Dance (1956) with Gene Kelly, and Dangerous When Wet (1953) with Esther Williams. Over the years, thirteen Tom and Jerry shorts were nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film and won seven of those nominations.

Fred Quimby accepted each Academy Award for Tom and Jerry without inviting Barbera and Hanna onstage. The cartoons were also released with Quimby listed as the sole producer, following the same practice for which he had condemned Ising. Quimby once delayed a promised raise to Barbera by six months. When Quimby retired in late 1955, Hanna and Barbera were placed in charge of MGM’s animation division. As MGM began to lose more revenue on animated cartoons due to television, the studio soon realized that re-releasing old cartoons was far more profitable than producing new ones. In 1957, MGM ordered Barbera and Hanna’s business manager to close the cartoon division and lay off everyone.

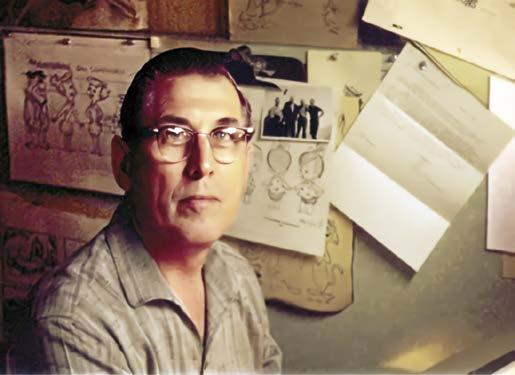

(TOP LEFT) Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera during the early days of their company, Hanna-Barbera. (TOP RIGHT) Poster for “Cue Ball Cat,” a Tom and Jerry animated short. Though directed by Hanna and Barbera, Fred Quimby (RIGHT) took the lion’s share of credit. Tom and Jerry © Warner Bros. Poster courtesy of Heritage. Fred Quimby photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Fortunately, Bill and Joe had been adjusting the production values of their Tom & Jerry shorts as MGM’s animation budgets had begun to dwindle. UPA’s more modern, strippeddown style was already an influence on the look of all the other studios, even Disney. Once they realized that they still had a year left on their contracts, they brazenly took advantage of it.

During that last year at MGM, Bill Hanna branched out into television, forming the short-lived company Shield Productions with fellow animator Jay Ward, who had

created the series Crusader Rabbit. Their partnership soon ended, and in 1957, Hanna re-teamed with Joseph Barbera, explaining the process of production on a low budget, quickly made “planned animation” TV series like...uh... Crusader Rabbit?

Every “crusade” of Crusader Rabbit consisted of a 19- or 24-minute cliffhanger episode that could be edited into a single story. The early episodes were barely animated, using cut-out flat figures that were filmed moving, thanks to an attached (but rarely seen) wooden stick, The show’s heroes, Crusader Rabbit (a smart and brave bunny) and Ragland T. Tiger a.k.a. “Rags” (a goofy, cowardly striped predator), were simply designed, with often repeating poses. An off-screen narrator was useful because no lips needed to be animated.

In 1957, Barbera re-teamed with his former partner Hanna to produce cartoon films for television and theatrical release. The two brought their different skills to the company as they had at MGM. Barbera was a skilled gag writer and sketch artist, while Hanna had a gift for timing, story construction, and recruiting top artists. Major business decisions would be made together, though each year, the title of president alternated between them. A coin toss determined that Hanna would have precedence in the naming of the new company, first called H-B Enterprises but soon changed to Hanna-Barbera Productions. (Speaking of coins, Bill and Joe invested $30,000 out-of-pocket to spark the venture.) Barbera and Hanna’s MGM colleague George Sidney, the director Model drawing of Crusader Rabbit and Rags circa 1950s. Artist uncredited. © 20th Century Fox. Courtesy of Heritage.

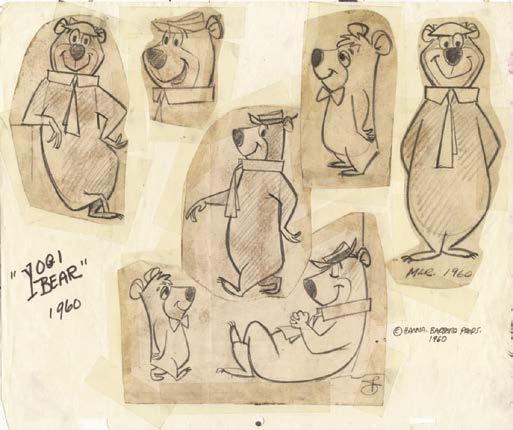

Bear model

by

that created Oswald.) Benedict briefly returned to Disney in the 1940s, receiving his only Disney credit on the animated film Make Mine Music. He then spent several years creating animation for television commercials for Paul Fennell’s Cartoon Films (the former Ub Iwerks Studio), the first notable example of Benedict using the modernized sleek character designs he would later employ. In 1952, Benedict was contacted by Tex Avery, who had worked with him at Universal. Avery invited Benedict to work on Avery’s animation unit at MGM. Benedict performed lead animation and layout duties for Avery, and later for Michael Lah’s prior to his departure from the studio. His work can be seen in Tex’s “Dixieland Droopy,” “The First Bad Man,” and “Deputy Droopy.” In the late 1950s, Benedict was recruited by former MGM directors William Hanna and Joseph Barbera to provide character designs for their new animated television series, The Ruff and Reddy Show. He eventually became the primary character designer at Hanna-Barbera, designing Yogi Bear, Huckleberry Hound, Quick Draw McGraw, the various characters on The Flintstones, and many others. Benedict left Hanna-Barbera in the late 1960s, but continued providing freelance work until his retirement in the early 1970s. Despite this, he later worked on H-B’s What A Cartoon! short and Johnny Bravo in 1997, specifically as a background consultant and layout artist. Ed Benedict died in his sleep at his home in Auburn, California.

Richard “Bick” Frederick Bickenbach (August 9, 1907–June 28, 1994) was born in Indiana. In the mid-1930s he moved to Los Angeles, where he became an animator for Ub Iwerks’ studio, and then Walter Lantz Productions. Between 1939 and 1947, he worked as an animator and layout artist for Warner Bros., first in Bob Clampett’s and Friz Freleng’s crews, then in Arthur Davis’ and Bob McKimson’s. Bickenbach was a spot-on imitator of famous crooner Bing Crosby,

and voiced caricatures of the singer in various Looney Tunes shorts, among them Frank Tashlin’s “Swooner Crooner” (1944), Clampett’s “Book Revue” (1946), Freleng’s “Hollywood Daffy” (1946), McKimson’s “Hollywood Canine Canteen” (1946), “The Mouse-Merized Cat” (1946), and “What’s Up Doc?” (1950), and Arthur Davis’ “Catch As Cats Can” (1947). In 1947, Bickenbach joined MGM’s cartoon studio in 1946, to provide layouts for roughly eighty Tom and Jerry shorts during the decade he was there. After MGM closed down its animation department in 1957, Bickenbach became one of Bill and Joe’s longest-running employees, designing many of the studio’s early model sheets and character designs and layouts for several of their early animated series: The Huckleberry Hound Show, The Quick Draw McGraw Show, The

Richard “Bick” Frederick Bickenbach

Flintstones, The Yogi Bear Show, The Jetsons, Top Cat, Magilla Gorilla, Jonny Quest, The Herculoids, and Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! While working in Hanna-Barbera’s animation studio, “Bick” also moonlighted as an assistant to cartoonist Gene Hazelton on the Sunday pages of The Flintstones syndicated newspaper comic strip (1961–1965). Bickenbach

Production art of Huckleberry Hound by Dick Bickenbach (1957). © Warner Bros. Courtesy of Heritage.

BY LEE WEINSTEIN

Fall of 1964 saw the beginning of a television season for the bizarre. Four outré new sitcoms premiered, in addition to two science fiction shows starting their second season: My Favorite Martian and The Outer Limits. The four new sitcoms were The Addams, Family, The Munsters, Bewitched, and finally, My Living Doll. The most successful of these was Bewitched which went on to run for eight seasons. The Addams Family and The Munsters lasted only two seasons each, but went on to eternal syndication, and each spawned several movies and reboots. [See TwoMorrow’s new hit magazine Cryptology #1 for more on these two classics –RetroEd ] Pundits wondered in print about the sudden explosion on TV of science fiction, fantasy, and general weirdness.

My Living Doll was the last of the four to premiere. Viewers who tuned in to CBS on Sunday, September 27 at 9:00 p.m. saw a smiling Bob Cummings with an animated cartoon of a mechanical robot that transformed, piece by piece, into a winking, nightgown-clad Julie Newmar. The premise was

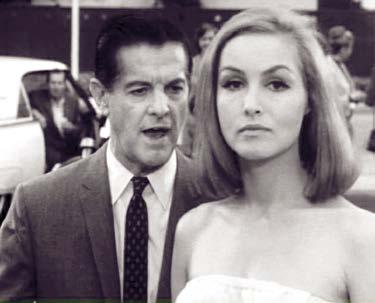

(ABOVE) Robert Cummings (LEFT) as Dr. Robert McDonald and Julie Newmar (RIGHT) as Rhoda Miller (a.k.a. AF-709) were the stars of My Living Doll (CBS, 1964–1965). © CBS Studios. © Jack and Florence Chertok.

that Miss Newmar’s character, the titular “doll,” although apparently a beautiful woman, was actually a robot. It was originally to be titled The Living Doll, but was re-titled at Cummings’ request. Newmar still refers to it by the original title.

It premiered to good reviews. The New York Times said it “...has the makings of a popular novelty hit...”. Philadelphia’s Evening Bulletin headlined the reviews of the day with “Living Doll Unveiled as Excellent Comedy.” The Philadelphia Inquirer described it as “an engrossing sci-fi serial.”

Produced by Jack Chertok, it followed in the footsteps of his successful sitcom, My Favorite Martian. But it didn’t fare well in the ratings and lasted only one season. Because there were too few episodes for a syndication package, the show sadly dropped into obscurity. To make matters worse, the archived episodes of the show were destroyed in the 1994 Northridge earthquake. A diligent search led by the late Peter J. Greenwood, worldwide licensing manager for Chertok Television, turned up eleven episodes from collectors. They were transferred from 16 mm film to a two DVD set, which he co-produced in 2012.

The series had a good pedigree. Chertok, in addition to My Favorite Martian, had produced such successful series as Sky King, The Lone Ranger, and Private Secretary. Bob Cummings, a one-time movie leading man, had starred in three previous popular sitcoms. All of the episodes, except

the first, were helmed by former radioactor-turned-director Ezra Stone, who also directed episodes of such classic sitcoms as The Munsters and Leave It to Beaver. The music was composed and conducted by George Greeley, who had also done the music for My Favorite Martian. Howard Leeds, a screenwriter and sometime producer, produced the entire series. But above all, My Living Doll was a showcase for the talents of Julie Newmar, whose portrayal of Rhoda the robot earned her a Golden Globe nomination in 1965 for best female TV star. She was chosen for the role by James Aubrey, then president of CBS. To her it was the part of a lifetime.

Like Bewitched, My Living Doll was about an ordinary man living with an extraordinary woman. But while Samantha and Darren were married, Dr. Robert MacDonald (Cummings) and Rhoda were not and could not be married. Samantha was a savvy witch with potent magical powers. Rhoda, although in some ways superhuman, was also quite childlike. She was perhaps more comparable to Jeannie in I Dream of Jeannie, which premiered a year later. She too was not married to the mortal man she lived with, and like Rhoda, didn’t completely understand the world she had come to live in. (See RetroFan #31 for more on Bewitched, and RetroFan #18 for more on I Dream of Jeannie –RetroEd.)

The idea of a robot in the form of a woman was not a new one—the 1925 film Metropolis features one. Another robot is the key figure in the 1959 Twilight Zone episode “The Lonely.” But this may have been the first attempt to explore its comic potential.

Leo Guild, who suggested the idea, wrote occasional screenplays, but was more known as a ghostwriter of paperback memoirs for movie stars. It was devel-

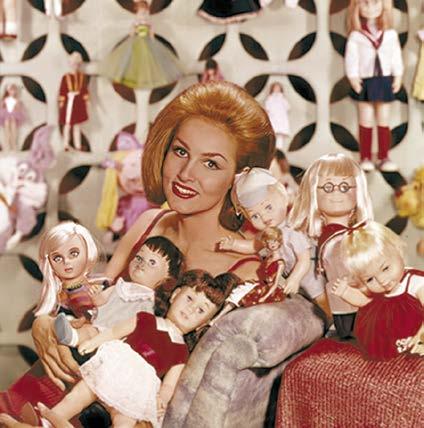

(FAR LEFT) Who needs an instruction manual? Bob Cummings and Julie Newmar get things started. (LEFT) Newmar as AF-709 stops traffic in the first episode of My Living Doll while wearing only a towel-like outfit. (BELOW) Newmar smiles with actual dolls in this promotional photo. © CBS Studios. © Jack and Florence Chertok.

oped into a series by Bill Kelsay and Al Martin who wrote the premiere episode, and, not coincidently, both had written for My Favorite Martian.

The producers wanted a young actor for the male lead to create sexual tension with Newmar. Ephraim Zimbalist Jr. was initially considered, but things didn’t work out. Cummings was already under contract to the network.

Some critics were initially skeptical of using Newmar to portray an emotionless robot. They felt it would be a waste of her talents. But her background in dance and mime served her well in fleshing out Rhoda’s actions. Among other things, she had played the non-speaking part Stupifyin’ Jones, in the film Li’l Abner (1959) and eccentric roles, such as the free-spirited Vicki Russell, in two episodes of Route 66 (1961), and Miss Devlin (a.k.a. the Devil) in the hour-long 1963 Twilight Zone episode “Of Late I Think of Cliffordville.” As Rhoda, she was able to convey a very likable personality with a great sense of comic timing. A method actor, she had to immerse herself in the character for 13 weeks to fully internalize Rhoda’s movements and personality.

There was no official pilot, but the initial episode, “Boy Meets Girl”, set the stage for what was to follow. Rhoda, officially “sub-Project AF-709” developed by Dr. Carl Miller (Henry Beckman), wanders out of the Space Research Center. Bob MacDonald, the Center’s psychiatrist, finds her. A panicked Dr. Miller realizes he can’t bring his topsecret project back into the building past the security guards. Bob is obliged to take her home. Miller is then suddenly

Robot women had been onscreen for quite a while, starting with Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

BY SCOTT SAAVEDRA

Mr. Potato Head was the first toy I can recall lusting after. I would see his face (one of supposedly 1,001) staring at me from a reasonably colorful box perched atop a low shelving unit at the local Gilbert “five-and-dime”, and I really

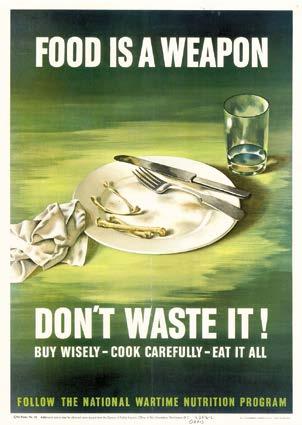

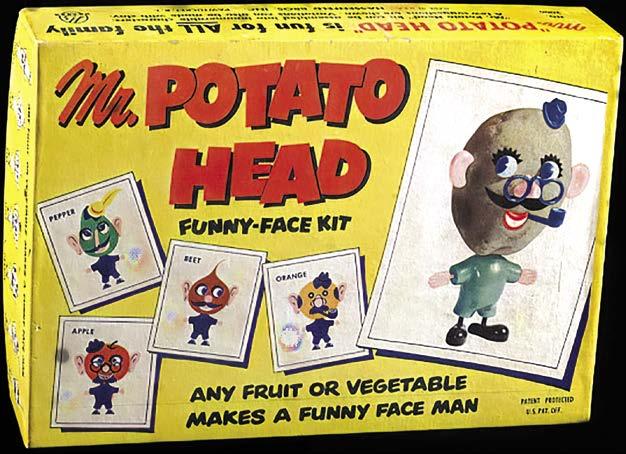

wanted the guy. I suspect that I was about six or seven years old. Eventually, I was added to the ranks of millions of other little boys and girls who owned this weirdly fascinating plaything. Circa 1967, Mr. Potato Head came with a plastic potato head on which you took plastic pieces resembling eyes, noses, mouths, body, shoes, hands, and, of course, a pipe; most with sharp points to better plunge them into the potato face. I have the vaguest memory of sticking the plastic pieces into an actual potato as was the original intention back when the toy was introduced in 1952. This may have happened at a friend’s house since I doubt my mom would have ever let me waste food that way. She grew up during the war years and lived with the rationing that was a way of life then. It was immoral to waste food… a sin, even. Anything really good you wanted to eat—be it sugar, coffee, wheat, or meat—was limited during World War II (and the first World War too). People were encouraged to grow their own vegetables and clean their plates. It was serious business. There was one item, however, that citizens were encouraged to eat plenty of: potatoes. Potatoes were easy to grow and weren’t seasonal. They could be enjoyed all year long as food or, as it turned out, with a face attached.

(ABOVE LEFT) Cooky the Cucumber with Her Friend

Mr. Potato Head box front minus digitally removed text. Courtesy of the Secret Sanctum Archives. © Hasbro. (ABOVE RIGHT) Due to rationing, citizens were encouraged to not waste food during World War II. Courtesy of the University of North Texas Digital Library. (LEFT) Detail of a World War I potato promotion. Courtesy of USDA.

Herman, Hillel, and Henry were the three Polish-Jewish brothers who began Hassenfeld Brothers in 1923. They sold fabric remnants (any piece of fabric 1.5 yards or less) eventually expanding into pencils, pencil cases, and other school supplies. By 1942 they had become mostly a toy company selling fairly nondescript doctor and nurse kits. It would be a decade before Hasbro had a toy hit with Mr. Potato Head (and more than a decade after that before they had another homerun with G.I. Joe, a story for another time).

So, Hasbro had this new, weird food-abusing toy. What do they do with it? Something quite new and unexpected. Hasbro put out television commercials for Mr. Potato Head aimed at children on—this is for real—the Jackie Gleason Show.

MR. POTATO HEAD, SUPERSTAR

The Jackie Gleason gambit worked, notably changing the way toys were advertised. Previously, adults with income were the targets of print ads. Kids watched a lot of television and saw a lot of commercials. Now, maybe kids couldn’t buy their own toys, but the little rascals could hound parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles until they got what they wanted. And what they wanted was Mr. Potato Head. Hasbro sold over one million sets that first year. The next year, aggressively taking advantage of the Mister’s popularity, Hasbro added a Mrs. Potato Head featuring an odd rope of “real” hair to give her that

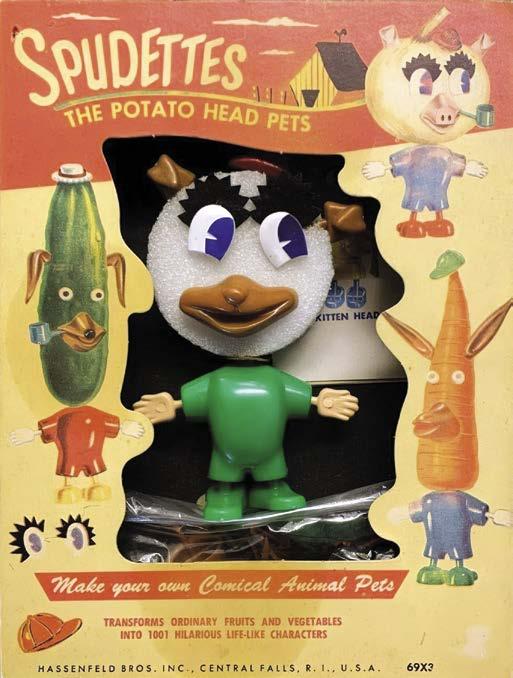

(LEFT) A frankly nightmarish screen capture from a very early Mr. Potato Head television commercial. Courtesy of Duke University Digital Collection. (RIGHT) Spud-ettes (sometimes spelled without the hyphen) were introduced as “potato head pets” but used the same fruits and vegetables that the “human” potato heads used. The pets—like Mr. Potato Head—were smokers. © Hasbro. Courtesy of Worthpoint.

(LEFT) Mr. Potato Head Funny-Face Kit was a huge hit for Hasbro (1952). Courtesy of National Museum of American History. © Hasbro.

“recently drunk” look. Two kids: Brother Spud and Sister Yam would follow. Spudettes (sometime hyphenated) were food-based pets. Then Mr. and Mrs. got a car, a boat, a kitchen set, and, in a real plot twist, a tiny human baby in a stroller. Not to put too fine a point on it (though I am), it

BY JOHN C. BRUENING

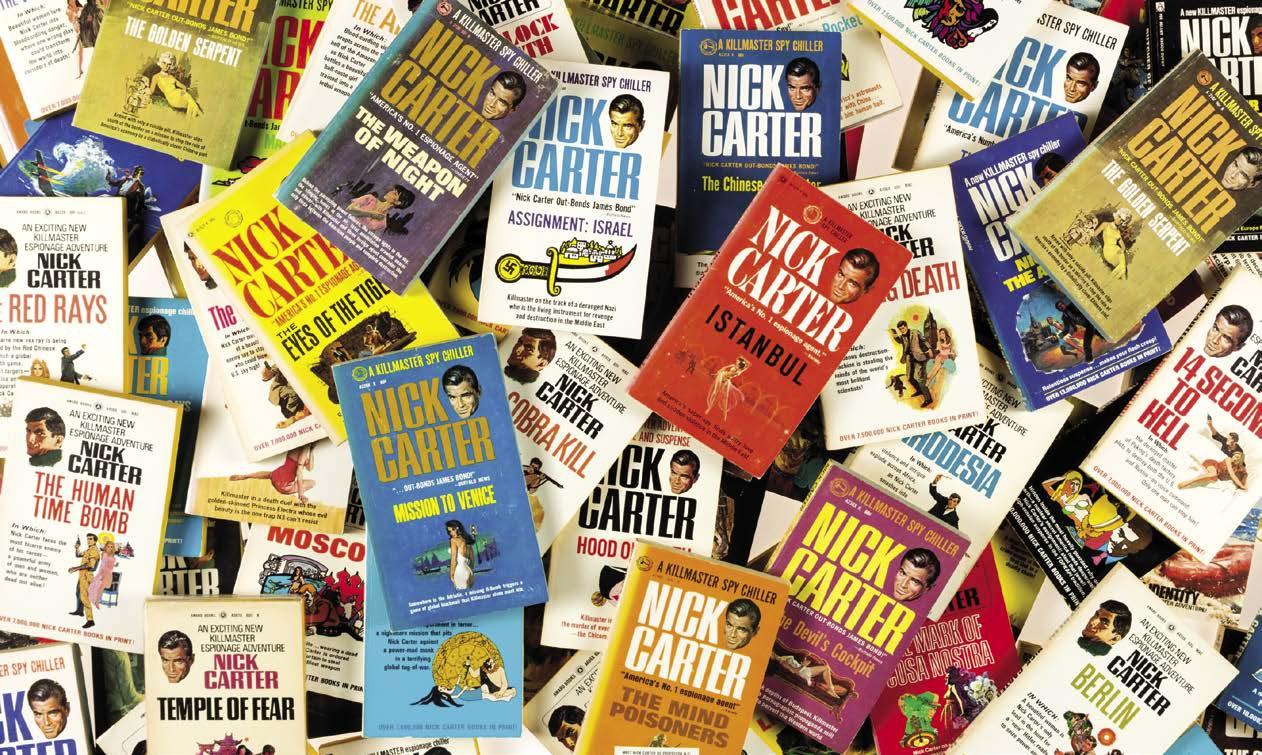

Beginning in the mid-’60s, at a time when eastern and western global superpowers were locked in a bitter and protracted Cold War, a fictional secret agent named Nick Carter—a.k.a. Killmaster—appeared in the pages of a series of paperback novels that maintained a consistent level of commercial success for more than two decades. Nick Carter was, in many respects, an American answer to Ian Fleming’s enormously popular Agent 007, the iconic James Bond. While Bond may have been more widely recognized among mainstream audiences, Carter actually had a 67-year head start on his British counterpart.

Indeed, for a character who had already been around for nearly eight decades by the time he made his first appearance in paperback in 1964, Nick Carter defied his advanced years and did a masterful job of confronting and neutralizing assassins, saboteurs, terrorists, and various other global threats. And he kept it up for an impressive run: 261 books over a span of 26 years.

Nick Carter’s first appearance in paperback in 1964 was by no means his debut in popular literature. The character’s origin actually reaches back to a time that no one living in the 21st century can even hope to remember firsthand.

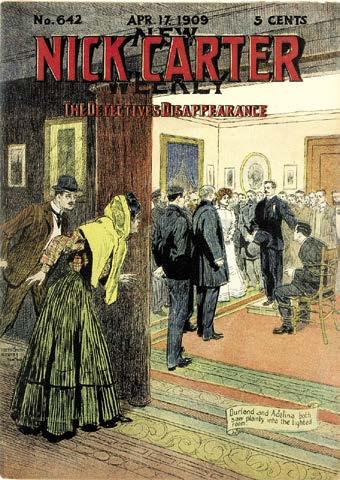

(ABOVE) A selection of Nick Carter paperbacks from 1967–1981. (LEFT) The New Nick Carter Weekly #642 (Apr. 17, 1909). © Condé Nast. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Heritage.

He was originally conceived as a street level private detective by John R. Coryell and Ormond G. Smith. Coryell was a prolific writer whose work appeared under various pen names for several different weekly story papers. These were periodicals published during the late 1800s that specialized in serialized fiction printed on cheap paper and were generally dismissed as low-brow entertainment. Smith was the son of Francis Smith, one of the co-founders of the New York-based Street & Smith Publications.

Carter solved his first case in a 13-week serial called “The Old Detective’s Pupil; or, The Mysterious Crime of Madison Square,” which ran in Street & Smith’s New York Weekly in the fall of 1886. The character eventually became popular enough for Street & Smith to feature him as the headliner of his own publication, Nick Carter Weekly. He appeared in hundreds of stories over the course of more than thirty years

DIAMOND COMIC DISTRIBUTORS

until Nick Carter Weekly ceased publication in 1915.

FILED FOR BANKRUPTCY IN JANUARY without paying for our December and January magazines and books, leaving us with enormous losses— and we still have to pay the expenses on those items, and keep producing new ones. Until payments from our new distributors begin in the Fall, we’re staying afloat with WEBSTORE SALES

Every new order (print or digital) and subscription will help TwoMorrows get through this, and emerge even stronger for 2026. Please download our NEW 74-PAGE 2025 CATALOG and order something if you can: https://shorturl.at/gA9Fv

Also, ask your local comics shop to change their orders from Diamond to LUNAR DISTRIBUTION, our new distributor. We’ve had to adjust our release dates for the remainder of 2025 while we wait for orders from our new distributor, so you may see some products ship earlier or later than originally scheduled. We should be back to normal by end of Fall 2025; thanks for your patience!

Carter’s further adventures were sporadic over the next couple of decades. As the story papers and dime novels of the late 1800s gave way to the burgeoning pulp magazine market of the 1920s, Street & Smith attempted to resurrect the young detective in a series of stories that ran in its monthly Detective Story Magazine in the mid-1920s, but the effort failed. Nearly a decade later, with the rise in popularity of the hardboiled detective—a crime fiction archetype created by writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler— Street & Smith tried again with Nick Carter Detective Magazine. This pulp recast the title character in the same mold as popular fictional private eyes like Sam Spade and Phillip Marlowe. It ran from 1933 to 1936.

Throughout these early years, Carter also made a successful transition to other media, including several films from the silent era to the late 1930s, and a popular radio crime drama called Nick Carter, Master Detective, which aired on the Mutual network from 1943 to 1955.

The decades after World War II set the stage for an entirely different kind of Nick Carter. By the early 1960s, America and her allies in the free world were knee-deep in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. International espionage, geopolitical intrigue, and a technological race with the Soviet space program defined the decade. The most popular fictional spy in the world was James Bond, who first appeared in author Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, originally published in 1953. Ten years after Casino Royale, Fleming was already a dozen books into his 007 series. Two of them had already been adapted to the big screen, and a third movie was in the works. In just a few years, Bond— James Bond—had become a household name on both sides of the Atlantic.

In an effort to get in on the action, American book and magazine publishing entrepreneur Lyle Kenyon Engel secured the licensing of the Nick Carter property from Street & Smith. Engel completely rebooted the

( LEFT) Nick Carter, Master Detective (MGM, 1939) one sheet . (BELOW) Nick Carter comic book splash page from Shadow Comics #3 (Street & Smith, May 1940).

© Condé Nast. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Heritage.

character as an American superspy: agent N3, a highly skilled operative for AXE, a fictional agency of the U.S. government. In February 1964, Award Books published Run, Spy, Run, the first installment in its Nick Carter—Killmaster series. No author was credited for this or any of the subsequent novels in the Killmaster series, but Run, Spy, Run was written by Michael Avallone, who at the time had been writing mystery fiction and film and television series novelizations for ten years. Run, Spy, Run laid out Nicholas J. Huntington Carter’s backstory in simple, straightforward terms: World War II veteran, followed by post-war work with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) before joining AXE. His physical description met the criteria for the standard action hero: tall, muscular and ruggedly handsome, with thick dark hair and steel-gray eyes. His skills were diverse. He was an excellent marksman and fighter; he practiced yoga daily to maintain strength, balance, and focus; and over the course of the series, we learned that he had a mastery of a dozen languages and a basic competence in several others.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER

OR

And in those brief interludes between neutralizing bad guys, he demonstrated a similar level of skill and prowess between the sheets. Like 007, whose persona as