Countdown to Studio Zero

When Starlin, Brunner, Weiss, Englehart, and Orzechowski almost made it into RollingStone

by JON B. COOKE

In late 2001, over dinner, in between regaling yours truly about the story behind an unpublished Warlock tale he penciled, Alan Weiss told me about an intriguing moment in the lives of some of the most popular comics creators working at Marvel in the mid-’70s. After explaining that Jim Starlin (who was with us there at the Manhattan restaurant, along with Allen Milgrom) and he wanted to work together upon a move to California, they then collaborated on an inventory issue starring Adam Warlock.

“So that was it; it was very simple,” Weiss said. “Starlin, [Frank] Brunner, and I shared a basement studio at the time called Studio Zero, in Oakland, so that was penciled during that brief period when we were all working together. It was quite a nice thing. There was a very amiable easy-going atmosphere. It was just fun! That was the idea! Jim had an idea, in the context of the black-&-whites…”

Weiss then turned to Starlin in that Italian eatery — Casa di Meglio, on West 48th Street — and asked, “Do you remember Dark Fantasy? You were going to edit a black-&-white book for Marvel that was more adult-oriented, with creator-owned characters, out of California…? You asked me to create a character for it, because I was going to do ‘Hotspur and the Darklings’ for you. I remember it clearly. It never happened. This was almost the same period, actually a little later than that period when we — the California contingent — went up to do the insert for Rolling Stone.”

Weiss continued, “Jim, [Steve] Englehart, Mike Friedrich, Brunner, and myself, and we went up there, and thought Rolling Stone really wanted to get these new comics from the new guys and, of course, they just wanted glitter rock super-heroes.”

In that Big Apple eatery, I was likely too mesmerized by the fact an issue intended to be Warlock #16 had been drawn by one of my favorite artists (never mind a proposed mag called Dark Fantasy helmed by Jim effin’ Starlin!) to suitably focus on the existence of Studio Zero and the Rolling Stone super-hero saga. But, in a more recent chat with Weiss, where we talked about his ol’ pal, “Screens,” writer Mary Skrenes, he reminded me about the Oakland studio.

WISH THEY ALL COULD BE CALIFORNIA BOYS

First of the Marvel Bullpenners to move to the West Coast was Steve Englehart, who was then at the height of his fame scribing The Avengers, Captain America, and (with artist Brunner) Doctor Strange. The writer shared, “I wanted to go and the rest of ’em thought it sounded cool, so I moved out, got a house, Frank and Jan Brunner came out to share it, and then all the rest of those guys came out and just sort of crashed there for a while.”

His pad was in San Anselmo. “I had a girlfriend at the time who had a sister in San Francisco,” he said, “and so we came out, it was

my birthday, and I said, ‘Oh, I’ll take you to San Francisco, because I’m making money now doing comics.’ And we went out and I really liked San Francisco. I just thought, ‘This is a cool place.’ And Kirby had already moved to California, so I knew it was possible to do, so I did. And I mean, I was telling people and the Brunners said they wanted to come out, too, and then the other guys came after that. Personally, if I had to choose between living in California and New York, I would have no question about California.”

“In New York,” Frank Brunner recalled, “I was living like a vampire. I would work all night and sleep during the day, because New York was so noisy, at least for me, and it was so quiet at night, comparatively, so I came out to California for a visit, and really liked what I saw, and I moved out… and I switched to working during the day!”

Brunner emphasized the creators were actually not moving on from the House of Ideas. “Oh, no, we weren’t leaving Marvel,” he professed. “I remember, while I was driving to California, I was trying to get some [Doctor Strange #1, June ’74] layouts done!”

Weiss, who had initially come East from Las Vegas in 1970, but had become disillusioned with the mainstream comics realm, had already returned to Sin City to reevaluate things. “Well, I’d headed back out West to back off from the comics for a while, to refresh and re-prioritize, so to speak. You know, there are some elements of the business end of the comics business that can tend to really grind down your original love and youthful enthusiasm for the medium. So, while I was out there, I spent a little less time doing comics and a lot more time exploring, researching, and experiencing…you know, real ‘meaning of life’ stuff.”

As for the artists’ San Francisco nightlife, “Marvel

Above: Courtesy of the estate of photographer/comix historian/ mentor Clay Geerdes, a photo of the “Marvel West” gang circa 1974. From left is Alan Weiss, Jim Starlin, Frank and Jan Brunner, Steve Englehart, Mike Friedrich (kneeling), and Tom Orzechowski. Below: During the days of Studio Zero, Alan Weiss penciled an inventory issue of Warlock that ultimately was never finished.

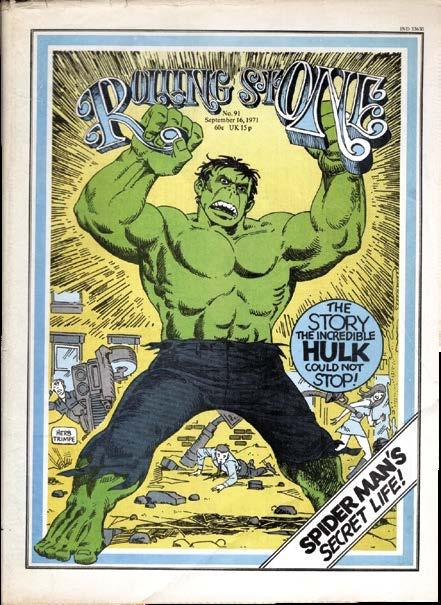

Above: Rolling Stone’s Marvel Bullpen ish [#91, Sept. 16, ’71] (cover: Herb Trimpe), A History of Underground Comics [’74] (cover: Rand Holmes), and the Straight Arrow Books mascot. Below: I Am Coyote [’84] (cover: Marshall Rogers) and Coyote #1 [Apr. ’83] (cover: Steve Leialoha).

West” associate Steve Leialoha said, with a laugh, “Despite rumors you may have heard, there wasn’t that much partying. Except in the case of Alan Weiss, who lived in a house with stewardesses and God knows what went on there. I used to wonder why he did so little work and then I saw where he lived.” Still, the collective was actively looking for outlets to use their talents outside Marvel.

GATHERING NO MOSS

If Rolling Stone was not distinctly an underground publication when the magazine was launched as a bi-weekly in 1967, it certainly took advantage of the iconoclastic realm from whence it was born, San Francisco. “Despite being founded in the counterculture center of the United States,” Jessica Hyman wrote, “the magazine failed to embrace many of the norms of that community, which is precisely what allowed it to become so successful.”

Still, from Rolling Stone’s logo designed by ZAP Comix collective member Rick Griffin, the periodical strove to at least appear radical, whatever its commitment to mainstream popularity. And, embracing the Baby Boomers’ love of comics, an aspect of that endeavor gave focus to funnybooks. To name but two, in 1971, there was onetime Marvel employee Robin Green’s “exposé” of Stan Lee and the Bullpen in a lengthy piece behind a Herb Trimpe cover, and 1973’s A History of Underground Comics, by Mark James Estren, an ambitious if terribly flawed survey of the comix scene, published by R.S.’s publishing imprint, Straight Arrow Books.

So, with the crew newly arrived in the Bay Area, Englehart initiated a meeting with the increasingly popular Boomer rock ’n’ roll magazine. “I just thought, ‘Rolling Stone is cool, but they don’t have a comic section. And here we are, we could do a comic section for them, so let’s go ask ’em.’ I think we just called ’em up… It’s just like, ‘It’s Rolling Stone and they’re right over there in San Francisco. Let’s just go talk to ‘em.’ And they talked to us.”

Attending the meeting among the Marvel freelancers was Englehart, Brunner, Weiss, and Starlin. Weiss offered there was the slimmest chance Frank’s then-wife, Jan Brunner, was with them. “I don’t think she was, but she very well could have been. She was always welcome to hang with the guys, even if she was sometimes/often the only gal. She was always game, like Mary

[Skrenes]. But Mary wasn’t on the West Coast with what I’ve come to call ‘The Wild Bunch.’ I loved that rowdy little gal. She’s been split from Frank for a long time now, but she’d have some fun stories.”

Englehart, who speculated that Orz may have been at the meeting, believes the pitch was to produce a modest-sized insert into the mag. “Like an eight-page thing, I think… [nothing] longer than that, although that would’ve meant each of our stories was two pages at best or something… Maybe we were offering 16 pages or 32 pages. I’m not real sure at this point, but I know I wanted to do Coyote and Jim had whatever he was doing.”

COYOTES ON PEYOTE

Born of a psychedelic trip Englehart and Weiss experienced while wandering around the Las Vegas desert, when the writer dropped by to visit the artist for a month in the summer of 1973, Coyote was a character who eventually debuted in a serialized story in Eclipse, The Magazine [#1–7, May ’81–Jan. ’83] — collected in I Am Coyote [Eclipse, Oct. ’84] — and the Epic Comics’ series, Coyote #1–16 [Apr. ’83–Jan. ’86]. In a text page in #1, Englehart wrote, “Al and I envisioned the Hulk leaping over those sands… then turned to a new character, a young guy ‘raised by coyotes on peyote.” In brief, the essence of the story’s overall theme was decidedly anti-corporate.

To the Rolling Stone reps, Englehart explained, “I pitched Coyote and they said, ‘Well, who would the villains be?’ And I said, ‘Well, corporations.’ And they said, ‘Well, we’re a corporation. Thanks anyway.’ Which was my introduction to, ‘Oh, yeah, Rolling Stone: not what you think it is.’ And then later, at the end of Firestarter, Stephen King had a [scene] where they needed to go to some reliable media place, and they thought about the New York Times, but they said, ‘No, no, no, let’s go to Rolling Stone.’ And I laughed because, you know, corporations were bad guys then and they’re bad guys now in many ways.” In Starlin’s recollection, “All our ideas were anti-corporate, and they said, ‘You can’t do this, because we’re corporate ourselves!’”*

Weiss explained their respective concepts were in the spirit of the underground comix ethos of retaining rights to one’s own work. “We got to know a lot of those [comix] guys. We were interested in owning our own creations like they all did. At one point, we were approached by Rolling Stone to produce a comics insert feature, all creator-owned characters. We were really excited about it! Wow! A chance to do something outside of any editorial policy or censorship — but the whole thing turned sour fast. Rolling Stone wasn’t really interested in any innovative concepts. They wanted super-heroes in glitter bands! So that thing never happened — and, of course, there were the many dead-end adventures with various hippie entrepreneurs who were all going to create the newest, most futuristic, hip, creator-friendly comics company… but ended up blowing any capital on announcement party favors.”

Englehart recalled, “I know we didn’t sit around and go, ‘Hey, gang, let’s all do an anti-corporate thing. But that was certainly where I wanted to go and I guess it was where [Starlin] wanted to go, but I don’t think they were all, I don’t think that was the one theme that everybody was playing off of. Other people were offering whatever they wanted to offer.”

A WORD OR TWO FROM FONG-TORRES

Reached for comment, former Rolling Stone senior editor and writer Ben Fong-Torres said, “Your best bet is to talk with [R.S. founder] Jann Wenner, who would’ve been the person who would have met with the artists.… The art director might have had a hand in the decision, and so might [had] the business department.”

* More recently, Starlin shared, “I remember [my proposal] was anti-corporate but, at this point, it was something I never did any work on again, so I don’t recall what it was. It didn’t stick with me. It’s not like a Breed or Dreadstar or any of the things that I did more than a page on. I don’t think it was anything that developed into anything else other than that one-shot [pitch].”

McCarthy’s in Like Errol

The first portion of our profile of the eclectic CARtoons , Mattel, and underground comix artist

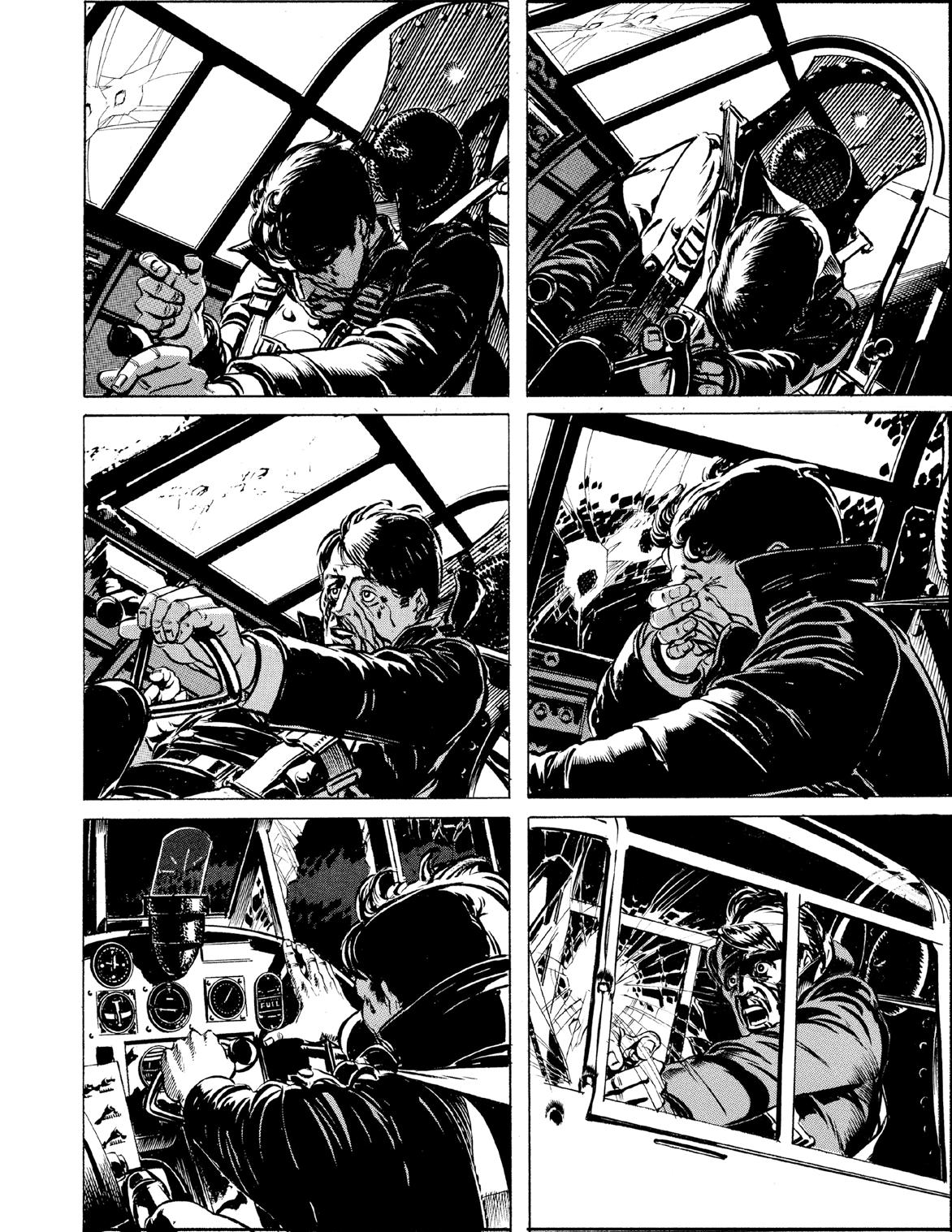

[Editor’s Note: Ever since encountering his lovingly rendered Blackhawks homage in Slow Death #7 [Winter ’76–77] — reprinted, with his generous permission, in full this issue — I’ve been dying to find out who was the artist of that fantastic, brilliantly drawn, and wordless story. In discovering it was a Los Angelesborn cartoonist named Errol McCarthy, way better recognized in the realm of He-Man, Master of the Universe fandom and by magazine, I just had to get to know him better, and to share as much as I could of his lushly inked work with readers! I’m happy to boast that the only comics short story I’ve ever scripted was visualized by Errol, in Slow Death so I’m pleased as punch to focus on the man, a friendly as hell, terrific guy, in this here mag. The following is derived from a phone interview conducted by me, autobiographical sketches, Y.E.]

Yeah, sure, the guy spent his formative years in the prairie hinterlands of Billings, Montana, from ages 11 to 22, but Errol Dean McCarthy, born in the City of Angels, on April 8, 1937, has always had Southern California coursing through the veins of his creativity (probably of a 20w viscosity!). In high school, we’d have probably called him a Motorhead but, in truth, the gent proves to be

Errol’s earliest years were not easy. He never knew his father and, as he told me, “My mother liked to be married a lot, so that we moved around a lot… It was kind of unstable, but I had loving grandparents and loving foster parents. So, overall, it was very

good. I also have a very fine sister, who lives now up in the state of Washington.”

Billings, he explained, “It was a very nice place. It’s the largest city in Montana. I think it’s got a population of 90,000 now, and it was 40–45,000 then. And it’s beautifully located… but the winters are like… forget it! Any place that gets to 40 below in the winter — no, thanks!” But, even before arriving in Big Sky Country, Errol was drawing. “When I was about nine or 10, it was just fun inventing my own stories and drawing them instead of doing schoolwork. And I still have most of the drawings, in fact. It was great.”

And, in the secure care of his “very old-fashioned, very wonderful” grandparents, Errol discovered a lifelong appreciation as a youngster. “I’d always got into comics. I mean, E.C. Comics and all that stuff… I always loved comic books… And it was the art. I mean, E.C. had the best artists and the best writers, I think, to this day. Wally Wood, Jack Davis, John Severin.” And the stories themselves? “Some of them are still shocking. I mean, what would you think if your kid came home with an E.C. comic book…?”

Did his grandparents catch sight of his favored comic books? “They were not interested in that stuff. In fact, the only negative experience I had was a friend of mine borrowed some of my E.C.s, and they were Jehovah’s Witnesses, and his mother took the comics out and burned them. And, looking back, I guess I don’t blame her. I was a little pissed off, but they were just comic books. They were a dime and I could get another one. So they didn’t really have any value, at that time. But they are still impressive, to this day, to look at that work. Especially Wally Wood… my God, he put a lot into that. And they all did. They really did.”

The fledgling artist enjoyed high school and, like so many males of his generation, he developed a love for things mechani-

This page: Clockwise from bottom is Mitzi and Errol McCarthy; He-Man art detail by E.M.; and his self-promotional art.

Photo courtesy of Errol McCarthy He-Man TM & © Mattel. Truly Amazing Art © Errol D. McCarthy.

cal. “As a teen, I developed an interest in anything with an engine. This included airplanes, sports cars, and motorcycles. My high school buddies had real hot rods, and many, many evenings were spent cruising and occasionally — actually! — picking up girls, American Graffiti-style!

“The closest thing to a real hot rod that I had was a bored-out ’48 Chevy coupe with a very loud muffler. Once, while writing a ticket, a cop said, ‘It was the loudest thing I’ve ever heard!’ Plans to install a ’50 Olds V-8 with a Lincoln Zephyr tranny remained just plans. Drawing was a different thing, since, if I can draw, I reasoned, I can create anything! I became the school cartoonist and study hall was all about drawing cars and airplanes.”

His aspirations during those years? “Young men are going in all directions,” he said. “I also wanted to be a Marine, which is really stupid, and a pilot. So I was an aviation cadet for a very short time and it finally occurred to me… I was in junior college, and one of my art instructor’s former students came in with some of his work, and he had gone to Art Center [College of Design], and this poor guy looked like he had just gotten out of a prison camp. He somehow that inspired me. ‘Oh, I want to do that!’ So I did.”

TO LIVE AND DRAW IN L.A.

Until it moved to Pasadena in 1976, the prestigious Art Center was located in downtown Los Angeles. “At the time,” Errol said, “it was the finest commercial art school there was. And I disappointed them because I turned out to be a cartoonist.”

He had, Errol confessed, became a mildly subversive influence at the institution. “There was a funny thing that happened at Art Center, which is kind of a lah-de-dah art school,” said he. “One day, we’re all out in the atrium having lunch, and another classmate and I started talking about comic books, and pretty soon there was a group around us. We felt conspiratorial because this was, like, 1965, and comics were so out of [favor] back then. But it was great, man. And comics stuck around and came back, didn’t they?”

And it was at Art Center where Errol would meet his future bride, Margaret May Hakes — Mitzi — who expressed a tolerance for his passions. “Our first date,” he explained, “was a hot rod show and a trip to a comic book stand. She passed the ‘test’ and we were married.” That “test,” he later elaborated, “Well, that she saw what I was really interested in and accepted me for what it was.” The two were wed on September 23, 1967. He proudly declared, “I married a very fine artist. I mean, she’s really terrific.”

In 1968, Errol graduated with a bachelor of fine arts degree, and he shared in a jocular biographical sketch he scribed, “My first art job out of school was as an illustrator at McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft. It was 1969 and the new three-engine DC-10 had just come out. I quickly found out that my real talent was as a cartoonist — not a lah-de-dah illustrator! After that, I did posters and funny stuff. I had failed Art Center School! Boo-hoo-hoo, etc.”

The artist continued, “My first freelance comic-book job came from answering a want ad in the [Los Angeles Times, in 1971]. It was a one-shot [magazine] entitled Car Nuts. It was published by Quentin Miller, who had been a CARtoons regular. That job, plus an underground comic story, led to Petersen Publishing, which had three comic books at the time: CARtoons, Hot Rod Cartoons, and Cycletoons. I soon had work in all three, plus my full-time job as an illustrator at McDonnell-Douglas.”

(Robert Petersen, who had launched Hot Rod magazine in 1948, spun off CARtoons in 1959, a comics/cartoon magazine started by Pete Millar and Carl Kohler, launching a genre. Millar later described CARtoons as dealing “mostly in humor (albeit often politically motivated or peppered with insider jabs).” CARtoons lasted 182 issues, plus specials, folding in 1991.)

CARtoons CARTOONIST

Around the end of summer 1973, The Daily Chronicle, of Centralia, Washington, later noted, “Errol McCarty and his artist-wife, Mitzi, retreated from the ‘rat race’ of California to the glory of Pacific Northwest living… They chose Centralia because Centralia College offered them an opportunity for supplemental employment.”

Errol took the position of part-time commercial art instructor, teaching illustration, lettering, and photography, as well as giving a night course in painting. Mitzi taught evening craft instruction, including weaving, and, as if the couple wasn’t busy enough, in between those responsibilities and Errol meeting his freelance obligations for Petersen, husband and wife built a “picturesque home overlooking Offut Lake.”

Errol explained, “We were busy all the time. We were teaching school in a small town in western Washington, near Olympia, and building a house, which is crazy we were young and dumb. We were literally doing it ourselves! I still can’t believe how busy we were.”

Amidst all that exhausting labor, the cartoonist was also having a blast with his Petersen comics accounts. “My favorite work in CARtoons was probably the post ers, but I enjoyed it all and wrote nearly everything that I did. It was also wonderful working with the tal ented editors of the three books — Jack Bonestell, George (Pappy) Lemmons, and especially Dennis Ellefson (who later worked with me at Mattel.)”

The artist also said, “It was great fun and I can hardly believe I got paid for it! They even let me write some of it.”

Above: We’ll show more of Errol’s comic book cover pastiches like this one next ish! Below: Hogg Ryder and Tanya

Jon B. Cooke

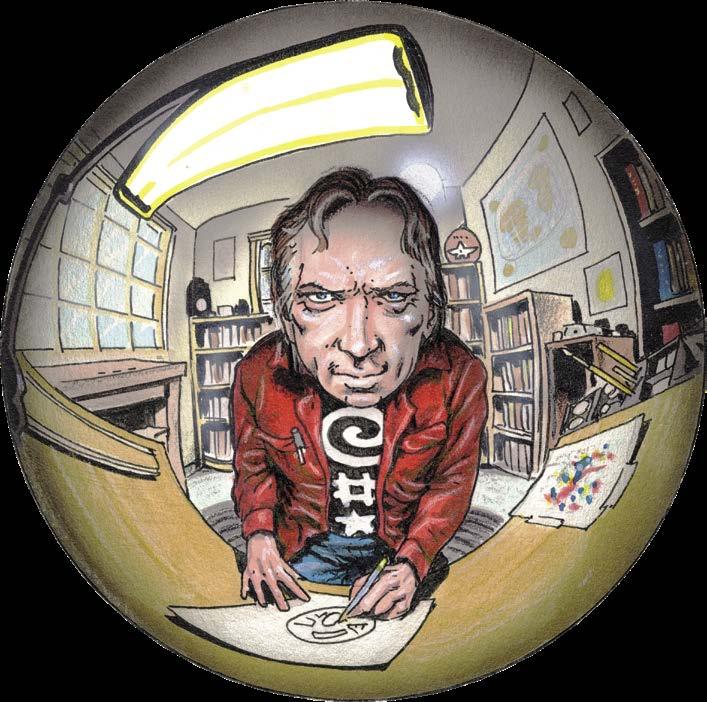

Previous spread: On left page is Rick Veitch’s “Self-Portrait in Six Dimensions,” which appeared as the cover of Arthur Magazine [#33, Jan. ’13], a California based “All Ages Counterculture” tabloid. The right page features 1995 self-portrait of Roarin’ Rick, this one inspired by artist Maurits Cornelis Escher.

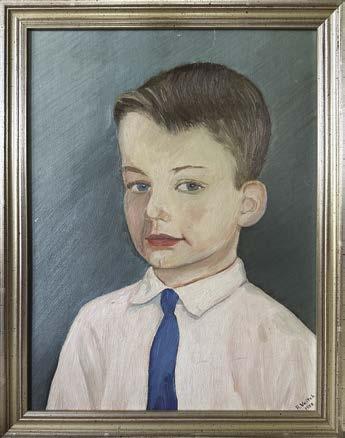

This page: Top and inset Ricky the Kid, circa 1955, and a 1958 portrait of the wee laddie by his Scottish-born father, Robert Veitch [1912–1970], below in a 1937 Columbia University class portrait.

out with beatniks in New York, writing poetry, and they were sending the poetry ’zines back home, so they’d be floating around our house.

CBC: He had a poetry ’zine with a title named after him, Tom Veitch Magazine

Rick: That came later. But in 1961, 1962, I was reading Joe Brainard and Frank O’Hara and Anne Waldman stuff. I couldn’t make sense of it, but it was just something I absorbed. Tom was part of the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, and he put us on the comp list, so we got everything they did. They published the first underground comic by Joe Brainard. It was called C Comics and it was like scratchy drawings of Henry and Nancy f*cking, but it predates ZAP by three or four years.

CBC: So your parents understood the content was beatnik?

Rick: Yeah. They sort of frowned on it and couldn’t relate to it.

CBC: But they let the ’zines…

Rick: Yeah, they’d float around the house.

CBC: Was there any pride about Tom and what he was doing?

Rick: No. He’d dropped out of Columbia and they saw his life as a poet as a failure.

CBC: Originally, what’d your father do?

Rick: My father was the sales manager for the Robertson Paper Company, in Bellow Falls, Vermont. It was an office job.

CBC: Middle class?

Rick: Yeah, we were middle class.

meeting my mother and settling. She was from Bellows Falls.

CBC: So he was going to school in Manhattan.

Rick: He was originally from Scotland and immigrated when he was 12. He lived in Queens, and he and his brothers all worked their way through Columbia.

CBC: Veitch is a Scottish name?

Rick: Yes.

CBC: Is there any meaning to it?

Rick: I believe it is a Norman word related to cattle herds.

CBC: About your other siblings: what did they end up doing?

Rick: Let’s go back to Tom first, because that’s really a key thing with the family. He was the oldest son, a brilliant guy, really talented. He got a full-boat scholarship to Columbia out of high school and he was born on my father’s birthday. So it was like he was “The Guy”: good-looking, smart, good with his hands, good with schoolwork. He just seemed to do everything well. But he got to New York, took acid, dropped out of Columbia, and started living the poet life, emulating Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg, and all those guys. And that was part of what knocked the blocks out from under my parents. Then Kennedy got assassinated. Everything got really hard for them and they never really pulled it together again.

The rest of the kids all had some sort of talent. My sister Wendy was an accomplished actress. My brother Michael is a singer/songwriter. Brother Peter builds houses. Brother Rob became a corporate consultant. We were a wild creative bunch! My dad, even though he worked at the paper mill, would bring home weekend art jobs doing logos and pen-&-ink illustrations for the wrapping papers they printed at the mill.

The thing is he didn’t even acknowledge that I was an artist. I was making art all the time, and his response was, “You can’t make a living at it.” That was his whole attitude, I guess. He hadn’t been able to make a living at it himself, so he was convinced that it was a waste. He had the tools I needed to learn, too — pen-&-ink and brush — but he never showed me how to use them.

CBC: How do you feel about that now?

Rick: Well, there’s a weird disconnect. What I did get out of it was observing him when he was working on art projects, and sensing that he was really happy doing art. And somehow, I think, that strengthened my resolve to follow through and do what I was born to do.

CBC: With [Rick’s youngest son] Kirby, do you share that with him? Has he been witness to that same joy?

CBC: White collar?

Rick: Yes, white collar. He was also intermediary. He worked with the workers, but he would go to paper mill conventions in New York City and stuff like that.

CBC: Could he work with his hands? Was he handy around the house?

Rick: Yeah, he was very handy around the house.

CBC: But he couldn’t comprehend the creative impulse…?

Rick: Well, I think that’s really the core of the problem: he was creative, he was a very good artist. He had worked his way through Columbia University and took a lot of graphic art courses, and I think he wanted to be an illustrator for advertising. But, somehow, he ended up in Vermont,

Rick: Yeah, I’ve tried to. I mean, he went to art school. He’s a classically trained water colorist and I brought him into coloring comics…but it’s not his thing. He’s good at it, he likes it when he’s doing it, but it’s not something he really wants to pursue.

CBC: What were the first comics you read?

Rick: Comics for me begin at three or four with my brothers reading Uncle Scrooge and Little Lulu to me. We got the Boston Globe and, on Sunday, they had this big, beautiful comic section that I’d just pore over. I became really fascinated with any form of graphics. So, at one point, I collected signs. In those days, some guy would silk screen signs like “The Circus is Coming to Town,” or “Fair Day,” or something, and they’d put ’em in the shop windows. And so I would go downtown, me and my friend, and we’d watch the dates and, when the sign was out of date, we’d ask for the sign. So we had this collection of silkscreen signs…

CBC: Those would actually have value today.

Rick: I lost them all, but the best one was the Hell Drivers.

CBC: The “Hell Drivers”?

Rick: There was these guys who would drive cars up and over

All

courtesy of Rick Veitch.

it, but he seemed content with comics. I liked the way his imagination was constantly flowing.

CBC: You’ve bought up Carl Jung before. I had read that you were going through a depression just out of your teenage years, picking up a volume of Jung. Does he remain important to you?

Rick: Oh yeah. I’ve got a complete set of his works and, while I haven’t read every single one, I’ve read a lot of ’em two or three times. What happened was, when I was 20, 21 years old I had been living crazy, and everything fell in on me. I got into this really bad depression, where I could hardly get out of bed. I started having these amazing dreams, really vivid mind-movies, that were just astounding.

CBC: Was this the beginning of them?

Rick: This was the beginning of me really paying attention to

dreams, to the point where I was writing them down in detail. I had these notebooks where I would record them in prose and pictures. And that’s when someone handed me a volume of The Portable Jung. At first read, I didn’t understand it, but, man, it was like, “Yeah! This is it!”

CBC: And what was “it”?

Rick: Well, that there is a meaning to our dreams. That, if we pay attention to them, they’ll guide us into finding who and what we really are. And that’s exactly what happened to me. Dreamwork pulled me right out of the

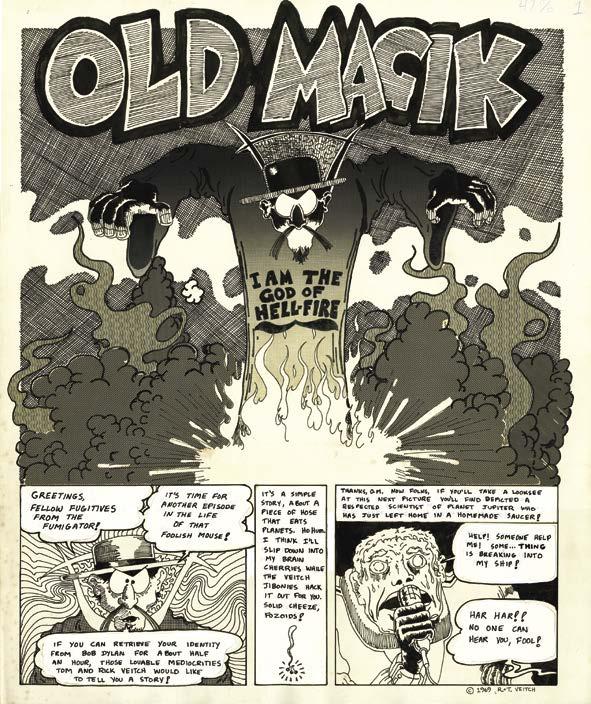

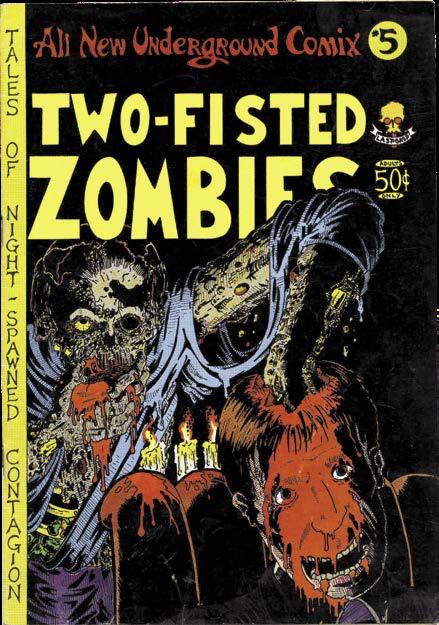

Above: Two examples of the Brothers Veitch’s underground comix work, scanned from the original art. Below: All New Underground Comix #5 [’73]

Bottom: Rick’s Jung library.

would buy recognizable comic books and throw ‘em in the back seat to keep us quiet. Dennis the Menace, I remember very well. Harvey Comics… Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen… Jimmy and Superman being Flamebird and Nightwing is one of the greatest comic-book memories I have of those days. How can a super-hero be the secret identity of a different super-hero…? The mind boggles! [laughs] What do you think made Weisinger so oddly wonderful for a six- or seven-year-old?

Rick: Well, that would be a good question for Alan because, like I say, he did intertwine his scripts with his magical practices, That run of Promethea he did with J.K. Williams, where she travels up the Kabbalah, puts a very esoteric way of thinking on a level a normal person can easily access. For my part, I had spent so much of my youth trying to draw Curt Swan panels, I was a good fit for his retro vision.

CBC: You and I definitely share a love of Jack Kirby, and I find him to be utterly transcendent. He appeals to me in a human way that is separate from comics, on a personal level. Do you that same feeling about him?

Rick: Absolutely. The arc of his life, is just amazing. I found it hard to swallow when Art Spiegelman and Will Eisner came down on Kirby for being a “fascist artist.” The guy was a patriot who picked up a gun and fought his way across Europe to defeat fascism. The New Gods is a brilliant evolving meditation

on the dangers of 20th century fascism. Jack Kirby is a really great model for a man who tapped into the primal imagination. What he did with it and what he had to go through culturally, politically and then creatively, has had a profound impact on all of us.

CBC: In spite of his being basically oppressed by Stan Lee and those who were exploiting him… Joe Simon and…

Rick: The whole businesses is designed like that and he was caught in it.

CBC: What did you learn from that?

Rick: The business side? I can’t say I learned anything other than to be outraged. And it feeds into that feeling we all shared in the ’80s: that comics needed to be reformed. I still feel that way, but the ’80s everybody, the creators, the readers, the retailers, the distributors, all the new publishers sprouting up understood we had this great art form entangled with a business culture that needed to be reformed. And it kind of happened there for about 10 years. Now, not so much.

CBC: The billions of dollars generated…

Rick: But, with Kirby, he was such a gift to us. Every single issue of every Kirby comic I saw as a kid fed my head with new concepts I hadn’t seen before.

CBC: Jimmy Olsen #133 completely destroyed me and built me back up again at 11 or 12…

Rick: The same for me with “The Tales of Asgard” in the back of Thor. And every two weeks, there’s a new Kirby comic at the grocery store, if not more. There might be three in a month! So it’s this constant presence, this constant cornucopia of fresh stuff. And, when he left Marvel, it was clear that Stan had nothing. Marvel Comics instantly became vacuous.

CBC: I would offer that, from the very beginning of Captain America Comics #1, having, on the cover, a revolutionary political statement of having a character punching out a real-life political leader (albeit fascist) in the jaw on the cover of a comic book is as brave as f*ck to do something like that.

Rick: Hear, hear!

CBC: And for his Jewish publisher to go along with, it was great. It transcended comics.

Rick: And Captain America is, today, a 21st century film icon. I’d like to see him punching more Nazis though.

CBC: I do see “The Glory Boat” [New Gods #6, Jan. ’72] as being important to you. That was one of the concepts for doing this cover was initially on that. What is that savagery of Orion and the lightness of Lightray and all that to you?

Rick: Jack caught the Zeitgeist at the time, and part of it is, like a true artist, he’s working on himself. He’s got PTSD from being in the war, and that’s Orion, this violent guy who loses it and turns into a monster who requires a Mother Box to put himself back together. Great, great concept! And impulsive angry Orion partners with Lightray, who’s a sweetheart and a total planner who’s always trying to quiet Orion down. It’s a perfect matching, and Jack holds the whole thing together with the Source, which is his greatest creation, I think. Its the same living spirit that Jung and the alchemists are talking about, but Jack gives it give a name: the Source! And in so doing he describes it not by any human terms, but by its living quality as the source of all reality.

And then he takes you on this sprawling saga in which all the characters have a sustaining relationship with the Source. No one turns it into a weapon, although, I guess, Darkseid probably was going to be moving in that direction. But then we see [George] Lucas stealing the concept for Star Wars, turning it into a weapon.

CBC: Is the Source the absence of ego? As you said, regarding

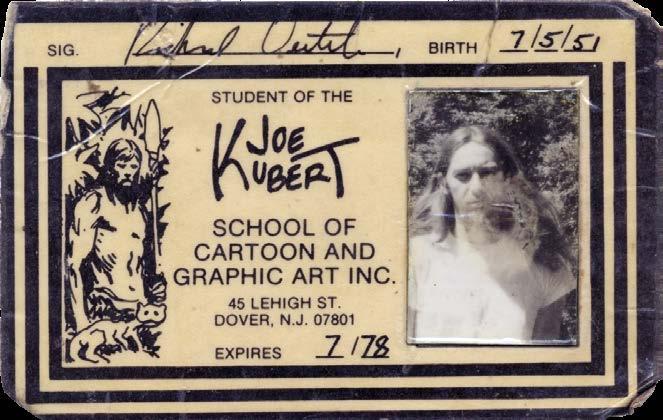

Above: Rick Veitch’s student ID from his days at the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art.

Below: The first building to house the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art was the Baker Mansion, located at 45 Lehigh Street, in the town of Dover.

connection.

CBC: This is the second time.

Rick: After he had joined the cult. What was great about working with Joe Kubert on a story is how it felt like creative play. Bissette and I had that, and I had that with Archie, as well. I ended up having it with Alan Moore, too. But Tom, I didn’t. It was like a weird push-pull thing with him. It just didn’t flow.

CBC: And what were you trying to do?

Rick: I had broken into Heavy Metal and was trying to pull a graphic novel together with him as writer. All we had was a title, The Planetary Route. I traveled out to California, where he was living in the town with the cult, and spent two weeks there trying to come up with ideas. But he kept wanting to turn it into a story about his guru. So it just didn’t fly.

CBC: Did you two have an estrangement thereafter?

Rick: We were estranged off and on because he was the type of guy, if he didn’t get his way, he would be really mad and hold grudges and stuff.

CBC: And how did his passing affect you?

Rick: Well, we were able to reconcile. The last year, he reached out and we had a couple of really great meetings and really great talks, and we just agreed not to talk about politics, and then we were fine.

CBC: So Two-Fisted Zombies was before you had the Jungian experience?

Rick: Yes, the TFZ deal happened around 1970. Tom was living on Stinson Beach [in Marin County, California], and Greg Irons lived right down the road. Greg had gone to Mexico. So, Tom said, “If you come out, you can crash in Greg’s barn.” I got a

couple of friends and we drove out West from Vermont.

CBC: When was this?

Rick: In 1970, probably late in the year. I spent the winter out there and I was still drawing comics but, by then, had figured out how Rapidographs worked and to draw on large paper. I did the first six or seven pages of Two-Fisted Zombies, with the axe murder opening, and I left the word balloons empty thinking Tom could write some wacky poetry or something. Tom showed the pages to Ron Turner at Last Gasp. Ron was doing this whole series, All New Underground Comics. He said, “You write it, Tom, and we’ll pay you to do it.” And so that’s how that all happened.

CBC: That must have been a thrill.

Rick: It was great, but I made the mistake of leaving Cali-

fornia and going back to Vermont and moving in with my old hippie buddies, who’re soon to become meth dealers. It was like this insane summer of my life, but I got the book done, and it came out. And then the whole underground comix business collapsed. So I thought I had it and didn’t have it.

It fell from my fingertips.

CBC: Did you go to conventions at all?

Rick: When I was out there, I went to one of the Berkeley Cons.

CBC: And what was Greg Irons like?

Rick: Greg, I didn’t really get to know him that well. He was always traveling when I was out there, but I did get to meet him a few times. He was kind, with a wry sense of humor, and he seemed to really go for the mad sh*t that Tom was spewing out. The crazier, the more violent, the more horror-oriented, he loved it, and he was really quick. He drew his comics small and really fast. He’d whip out a 20-page comic a week or something. Just unbelievable.

CBC: Nobody could do horror like him.

Rick: His characters, were people you’d seen on the street,

Above: Superhero Catalog page by Rick Veitch produced by the Kubert School for entrepreneur Ivan Snyder’s Superhero Enterprises/Heroes World.

Inset right: Ivan Snyder’s catalogs had a multitude of names, including The Heroes World Catalog [#1, ’79]. Cover art by Joe Kubert.

Below: Rick drew this illo for the inside cover of an Ivan Snyder catalog. It depicts the 60-foot super-hero mural the Kubert School created for the Livingston, N.J., mall store front.

Above: Ever an advocate for self-publishing and independent comics, Rick has compiled his creator-owned material into color collections to be sold on his website, including Abraxas and the Earthman, bringing together his nine-part Epic Illustrated serial from1982–83.

Below: The cartoonist has also partnered with IDW on occasion to create hardbound editions of earlier efforts, including The One [2018], collecting his 1985–86 six-issue mini-series for Epic Comics, edited by Archie Goodwin.

in that phone call, the name Comicon.com popped up, and we were in business.

CBC: How did it go?

Rick: The first couple of years were great. In the beginning, we were selling advertising and virtual booths and people were sending us checks. The concept was growing by leaps and bounds. People liked it. People wanted to have booths. What really kicked it off was when Marvel sued their freelancers. Do you remember all that?

CBC: I don’t remember them suing their freelancers.

Rick: Well, it was something that happened during the Marvel bankruptcy. One of the parties to the bankruptcy was suing the freelancers and ex-employees for their severance packages, and we got the story. We ran it on our little news site, the Splash, and it attracted all kinds of people to the site; so much so the she servers couldn’t keep up with it. We were able to build on that, build a readership, and also build a network of sources. Because, once that hit, I got contacted by people up and down and in and out of the industry, wanting to describe what was really going on behind the scenes at Marvel, DC, Diamond, and others. They were all pissed off that the once promising direct sales market had been hijacked by the greed heads.

And we were doing great getting that information out and selling ads. But then Google came through with their targeted advertising. So, instead of going to Comicon.com to find comic-book people, you go to Google. And that caused our income stream to vanish and it was all downhill from there. We kept it going for another 10 years until we finally sold it.

CBC: I remember being astonished in those first few years of connecting with any number of creators and the concept of it alone, it did feel like a comic convention. It lived up to its premise, a rare thing.

Rick: And I love working with Steve. He’s a sweetheart.

CBC: He’s a fine artist. Where did he, just quickly, where did he develop his chops?

Rick: I think he was like me. He was a kid doing comics, but he caught onto computers really early somehow. So he was like 12 or something when he got his first Mac. And so, by the time I met him, he was probably… well, actually, I had met him before we started Comicon.com. He had come to a couple of the Spirits of Independence* things, and so I got to know him a little bit there. But he was writing code while I was still learning to copy and paste.

*Spearheaded by alternative comics creator Dave Sim, the “Spirits of Independence” tour was a series of events at comic shops in North America in the mid-’90s celebrating the independent, creator-owned comics movement.

CBC: How was the income from that? Were there flush years?

Rick: They were. We’d probably bring in $7–8,000 a year, which was not huge, not enough to live on. I still had to work. But I was finding gigs directly through the site, selling sketches and books, and people finding me through Comicon.com, as well.

CBC: So you didn’t feel like you were not giving all to your work with the time spent on the website?

Rick: It was part of my work because we were looking for a new way to get our comics out. The door was being shut at Diamond and we all knew that. So it was time for a new form of distribution and that’s what we were hoping to build. We were a little ahead of the curve. I mean, there’s a lot more going on right now in terms of selling online and stuff but, in those days, there was no credit card online or PayPal. So it was all done by mail, but what we were hoping was that we could build a network of retailers and start soliciting books just like we did through Diamond, but we were never able to pull that together. It needed somebody else to focus on the logistics. Steve and I just weren’t able to do that.

CBC: Right. And you need to have a guaranteed income to be able to attract somebody like that…

Rick: Or someone could see the potential in it and just start a business by themselves. It was really what was needed and it never quite happened.

[After a break, talk resumes about how Marvel and DC deal respectively with on-screen credit and reprint fees.]

CBC: Marvel’s been good, I’ve heard. If they put a name on the screen, that person gets a check.

Rick: But it’s not a big check. For all the books that have been reprinted through DC, I get quarterly royalties.

CBC: Can you buy groceries with your four checks a year?

Rick: I probably pull in about $15,000 a year now, but depending on what’s released. When they released the Alan Moore/Rick Veitch Swamp Thing stuff, I made $25,000. But there are constant sales of the backlist and they’re really good about getting checks to freelancers.

CBC: And people are really good about buying them again!

Rick: Yeah! Everybody must have bought those Swamp Things a dozen times by now.

CBC: This independent streak of yours: where did this start developing?

Rick: It’s an extension of what I was doing as a kid; making my own home-brew comics. I wanted to make my own comics and tell my own stories. That was me from the beginning.

Even at Kubert School, I remember articulating to my lettering teacher, Hy Eisman, “I really want to learn lettering because I want to move back to Vermont and just do my own comics rather than stay in New York and become part of the machine.”

And so I took the time to learn lettering and doing that opened

That and everything else you learned, right? Coloring, production techniques of separations…

Yeah. The whole nine yards. , did you ever do press checks or anything like that? Or how deep could you go into production…? You couldn’t. I was doing fully painted comics, but these were gang-scanned on this giant drum scanner, so you never knew what you were going to get for color separations. And it was always about saving money, so it always looked like sh*t. But now, with desktop publishing and my own high-end scanner, I can get those painted pages to look just

Abraxas and the Earthman, The One TM & © Rick Veitch.

like I want them to.

CBC: So the IDW collections, for instance, all of that was re-scanned?

Rick: Anything I owned and knew I wanted to republish later, I kept, so I’ve got all that Epic art. Brat Pack was rescanned from the original art. The One was recolored by Kirby Veitch.

CBC: So you lived in Dover, right, and frequented New York City. What did you think of the city?

Rick: I was younger then and so I was really into the hustle and bustle of it. This was just at the beginning of hip hop, so you’d see that kind of music going on in the back of buses or on the street corners. And I found that really interesting. I was reading Henry Miller at the time, and so he’s got this thing about walking the streets cogitating about life and philosophy, and so I was into it on that level. But it was also that it was the center of comic book publishing at the time. And a very easy 30-minutes from Dover. and you’re into lower Manhattan…

CBC: So, from early on, at the Kubert School, you knew you were going to come back up to Vermont?

Rick: Well, it was my hope because I really love Vermont and I had a kid up here by my first wife, so I wanted to be a part of that.

CBC: When did you get married?

Rick: Nineteen seventy-three, maybe. Something like that.

CBC: This was after your epiphany?

Rick: Yeah. I had Ezra with her. But it didn’t work out for

us. And then, when I met Cindy, she was from New Jersey. I brought her back to show her Vermont, and she’s like, “We’re living here.” [laughs] So she helped kick my butt to get me back here.

CBC: So do you maintain contact with Ezra?

Rick: Oh, yeah. He lives a few towns over. We work on comics together, as well.

CBC: Cool. What does he do as a day job?

Rick: He’s an art teacher. He’s teaching comics at a local private school.

CBC: How are you as a dad?

Rick: Probably not as attentive as I should be, but I’m not overpowering either. I’m sure I fail on many, many levels. I try to be there. Now there’s a grandson, too, so that’s awesome.

CBC: What’s his name?

Rick: Jasper. He’s 12.

CBC: How’s it to be a grandfather?

Rick: Completely changes your life. You see your genetics carried on.

CBC: So you got divorced in what year, roughly?

Rick: Probably would’ve been… well, we separated while I was at Kubert School. So that would’ve been, like, ’77. And then it took a couple of years for the divorce to actually be finalized.

CBC: What was your reaction to the Steven Spielberg letter about Bissette and your work on the 1941 adaptation?*

Rick: We were too green to even understand what we had done. Heavy Metal gave us this job. We lit out for Vermont and just went crazy. We weren’t even thinking that this was a commercial gig and we needed to make sure the client’s happy. We just went with our underground instincts. And the production became such a beast between Steve and I. Trying to get him focused and working was a major, major problem.

CBC: Is that when you vowed not to work with him again?

*The comics adaptation of Spielberg’s movie was not appreciated by the director, who, despite calling the artists, “ruthlessly talented (though demented),” was disturbed by the “savage representation.“

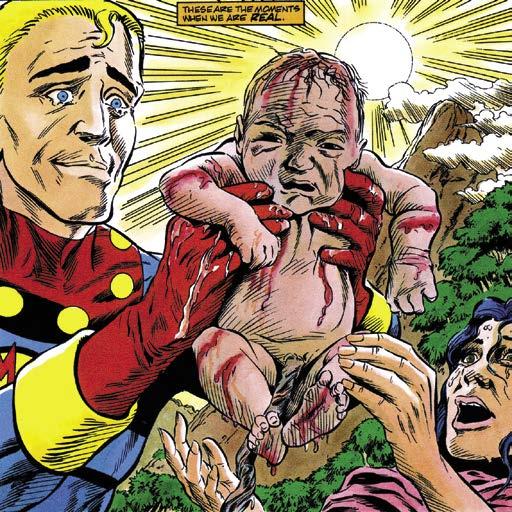

This page: After a period of animus between creator and corporation, Rick Veitch is now having his Swamp Thing stories collected by DC featuring his credit as author. Does that mean his unpublished Swamp Thing #88 will ever see the light of day? Stranger things have happened… Oh, and we include a panel from Miracleman #9 [July ’86] and a specialty drawing.

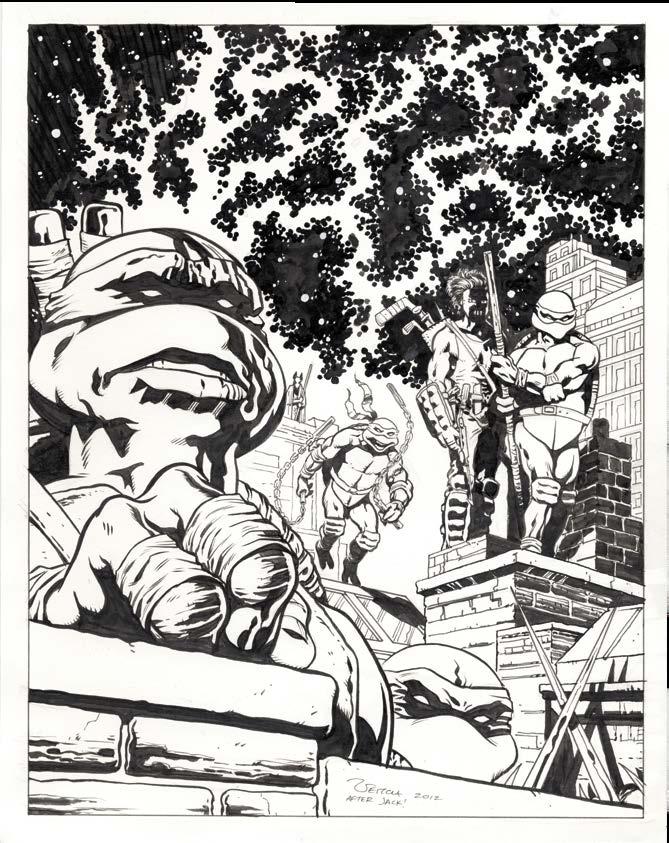

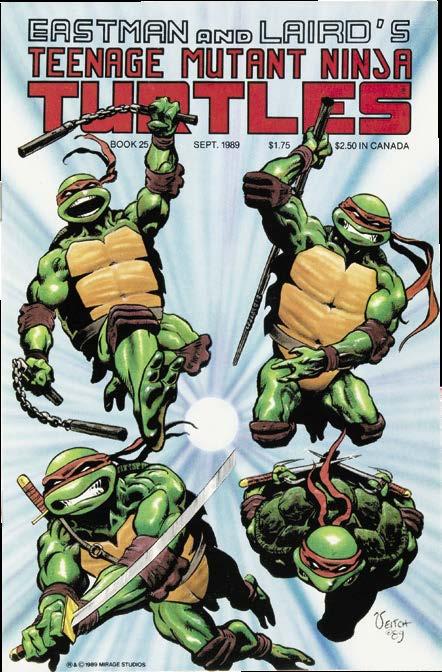

Inset right: Rick estimates he produced 200 or so pages of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles material for creators Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, including TMNT #25 [Sept. ’89].

Rick: Well, not to rely on him for a production job. I really loved working with him on the creative end, In fact, the way I got drawn into Swamp Thing was by ghosting pages for him; not for the money but just the pleasure of drawing comics together and working on Alan’s scripts.

TwoMorrows needs your help!

DIAMOND COMIC DISTRIBUTORS

CBC: To what do you attribute your pragmatism and keeping an eye on the ball?

Rick: I think it goes back to me doing this as a kid, For me there’s a certain element of play in making comics. And it’s still how I want to center my life, playing with this amazing art form every day. The way the industry is set up, you’re often overworked. But the way I’m set up now, it’s just perfect. I get up every morning and go, “Oh, boy. I get to draw comics.”

FILED FOR BANKRUPTCY IN JANUARY without paying for our December and January magazines and books, leaving us with enormous losses— and we still have to pay the expenses on those items, and keep producing new ones. Until payments from our new distributors begin in the Fall, we’re staying afloat with WEBSTORE SALES

Every new order (print or digital) and subscription will help TwoMorrows get through this, and emerge even stronger for 2026. Please download our NEW 74-PAGE 2025 CATALOG and order something if you can: https://shorturl.at/gA9Fv

And then I just spend as much time as feels right. And I’m not on the monthly grind anymore, but I’m turning out new Maximortal comics all the time, and Rare Bit Fiends and the Panel Vision series.

CBC: Are you the happiest man in comics?

Rick: I don’t know if I’m the happiest man, but I found my groove. In fact this is how I always imagined it would be as a kid . “Oh yes, I’ll live in the country, with a beautiful wife and kids, in a beautiful place, get stoned, and make comics.”

Also, ask your local comics shop to change their orders from Diamond to LUNAR DISTRIBUTION, our new distributor. We’ve had to adjust our release dates for the remainder of 2025 while we wait for orders from our new distributor, so you may see some products ship earlier or later than originally scheduled. We should be back to normal by end of Fall 2025; thanks for your patience!

Below: Rick Veitch is just too cool for school with this wild TMNT commission that’s a pastiche of Jack Kirby’s great final New Gods #1 [Mar. ’71] page, seen above. Kirby pencils, Vince Colletta inks.

CBC: Do you say, “I’m having my play, but I’m not going to hit miss my deadline.” That’s your gift to yourself or whatever?

Rick: Well, I was always good at doing production work, but I have to say that, over time, it would wear you down and the play aspect would dissipate. So it’s great to be free of the production aspects and let the creativity flow more naturally.

CBC: Typically, for a mainstream series, how long would that period last? You were cut short with Swamp Thing, right?

Rick: Yeah, but that was a good solid three years. I was either penciling, or writing and penciling, so that was an insane amount of work.

CBC: What is your limit, typically?

Rick: Swamp Thing should have been my limit, but also I was doing side jobs. I took on a couple issues of Miracleman I did a fill in on Nexus, “Munden’s Bar,” stuff like that. We’d bought this old house in need of work. So, if it was time to put a roof on it, and I needed five grand, I’d pencil an extra issue of something alongside Swamp Thing and not sleep for a couple of weeks.

CBC: So that part’s no fun.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

Rick: It wasn’t horrible. I take some perverse pride in being able to do it. I think Army@Love

CBC: How long did that last?

Rick: It was 18 issues, bi-monthly books. So that was about three years, too.

CBC: What years? Why am I blanking on that?

Rick: Launched in 2007. It was after

CBC: Was that working for Shelly Bond or…

Rick: No, that was Karen. Although, day-to-day, I worked with [associate editor] Pornsak Pichetshote. He was awesome.

CBC: What do you think of that whole Vertigo thing?

Rick: It was great. Karen had amazing instincts for finding audiences for stuff that was outside of what was considered the norm. I mean, she midwifed Sandman, which was unlike anything else at the time. She gave it all the power of a major label and built it into a giant franchise. That’s really an achievement.

CBC: They just let it go. Vertigo’s gone…

Rick: Yeah, but Sandman lives on. DC is a whole different organization now. Because of super-hero films they’ve been swallowed and digested by the corporate food chain.

CBC: It’s interesting that

COMIC BOOK CREATOR #38

RICK VEITCH discusses his career from undergrounds and the Kubert School; the ’80s with 1941, Epic Illustrated and