The Great Mid-1950s Super-Hero Revival

From TV’s Superman To The Silver Age Flash

by Mark Carlson-Ghost

Four-Color Heroes From The Age Of Eisenhower

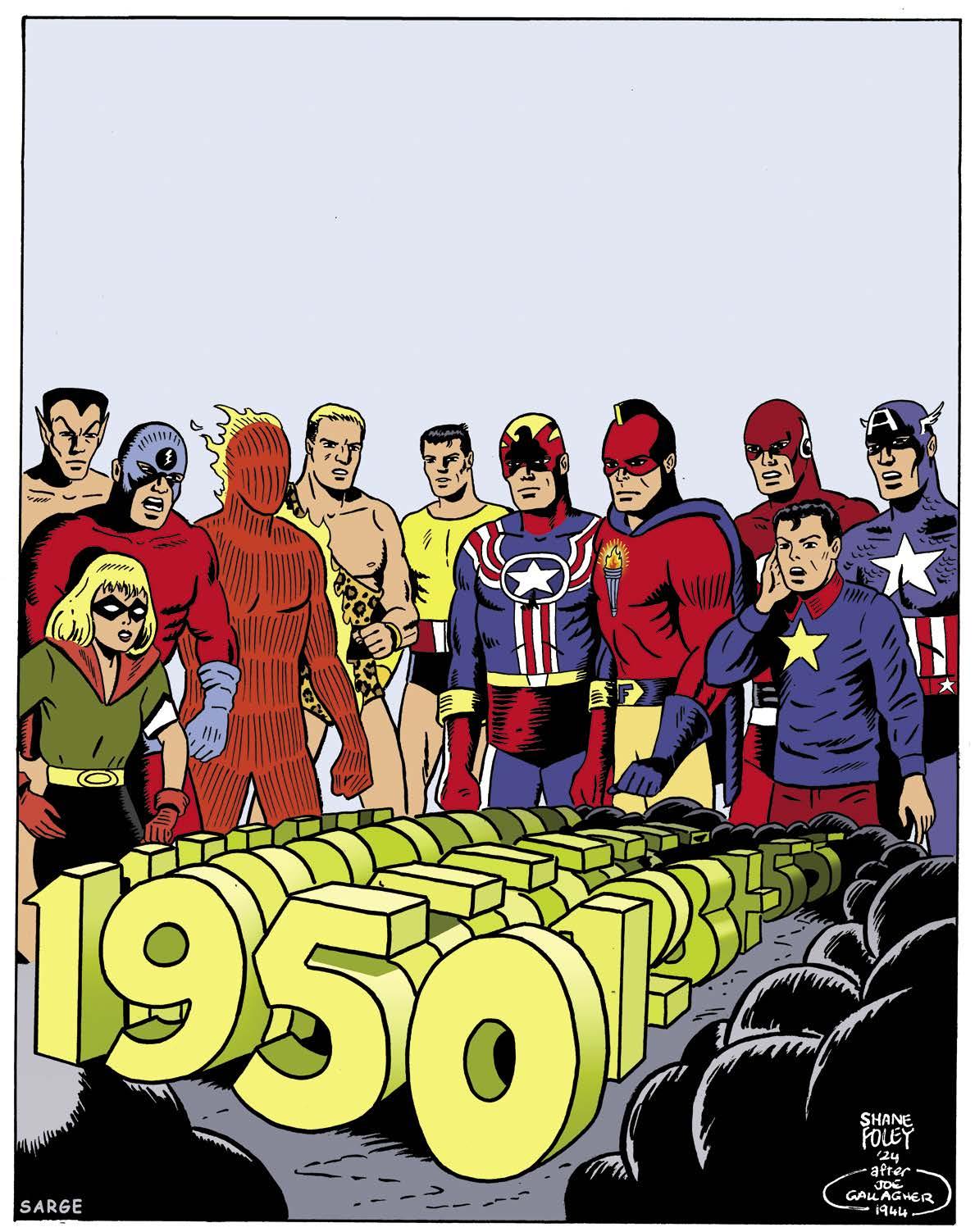

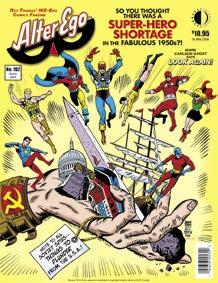

This frontispiece was drawn by Shane Foley and colored by Randy Sargent as an homage to Joe Gallagher’s cover and matching splash page for All-Star Comics #21 (Summer 1944). (L. to r.:) Sub-Mariner, Captain Flash, Tomboy, Human Torch, Strongman, Nature Boy, Fighting American, The Flame, Wonder Boy, The Avenger, Captain America. Thanks, guys! [Sub-Mariner, Human Torch, & Captain America TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.; Fighting American TM & © Estates of Joe Simon & Jack Kirby; other heroes TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Dwight D. Eisenhower President of the United States, 1953-1961

TIn Like A Wildfire— Out Like A Thunderstorm

The mid-1950s “Indian summer” (or was it a “false spring”?) of comicbook super-heroes unofficially began with the autumn publication of Timely/ Atlas’ (future Marvel’s) Young Men #24 (Dec. 1953), behind Carl Burgos’ cover that spotlighted The Human Torch but also featured the Sub-Mariner (minus his hyphen) and Captain America—as colored, reportedly, by early-1960s Marvel colorist Stan Goldberg. That period ended, with a whimper not a bang, behind the Dick Giordano/ Vince Alascia cover of Charlton’s Nature Boy #5 (Feb. 1957)—actually the series’ third issue, which went on sale in late ’56, only a few months after DC’s Showcase #4 had introduced a brand new incarnation of The Flash. Thanks to the Grand Comics Database and Michael T. Gilbert, respectively, for these cover scans. [Young Men cover TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.; Nature Boy cover TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

he Golden Age of super-heroes was fading fast. In 1949 alone, the Sub-Mariner, Green Lantern, and The Human Torch all saw their solo comicbooks canceled. Former stalwarts like Black Terror, Skyman, and Phantom Lady had all disappeared earlier from newsstands. Nor did they leave the scene unescorted by most of their costumed colleagues.

And, unless you were a psychic, the heyday of the Silver Age that began haltingly in 1956 and reached its height in the 1960s was still a long way off—and probably unforeseen, even undreamed-of.

But, in between these two consequential eras, from 1953 to 1956 (or even, technically, into 1957), there was a resurgence of super-hero titles as exciting as it was short-lived. Captain America, Phantom Lady, and Blue Beetle sprang back into action. So did the Sub-Mariner and Human Torch. New heroes like Captain Flash, The Avenger, and Fighting American made promising beginnings.

And then, before you knew it, those colorful heroes disappeared. Again. What happened? What prompted a sudden influx of costumed heroes at a time when readers of comicbooks no longer seemed interested in their adventures? What contributed to their demise? This article attempts a fresh investigation into the 1950s super-hero revival and the cost-saving measures that all too often accompanied it. With the threat of unprecedented censorship lurking in the wings, very little in the industry was on solid footing.

A Bad Time For Super-Heroes

As a new decade dawned, readers of super-hero comicbooks had every reason to feel discouraged. 1949 had been a brutal year for costumed adventurers of every stripe. Companies across the industry were abandoning their costumed characters, some of them going out of business entirely.

Scattered cancellations had already begun the previous year. Fawcett Publications had dropped Mary Marvel, Wow Comics, and

Captain Midnight, but kept their other Marvel Family titles (five in all) going. But now heroic casualties were piling up at an alarming rate. Street & Smith, Novelty, and Columbia all shuttered their doors, meaning no more four-color adventures of The Shadow, Doc Savage, The Target and his Targeteers, or Skyman. Fox Publications and Standard soldiered on but ceased publication of Blue Beetle and Phantom Lady and Black Terror and Fighting Yank between them.

Several larger companies kept a few of their super-hero comics but dramatically cut back their line-ups. Over at Quality, Modern Comics, Police Comics, and Feature Comics, anthology titles that had cover-featured Blackhawk, Plastic Man, and Doll Man, were either canceled or radically altered their content in 1950. Doll Man’s solo title was axed three years later. (Plastic Man would stretch things out till autumn of 1956, when Quality sold out to DC, but the final two years’ worth of issues featured mostly reprints.)

At DC Comics, the situation was only marginally better. The publication of Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman continued uninterrupted, but Flash Comics and Green Lantern were both canceled in 1949. “Justice Society of America” stories in All-Star Comics provided some comfort to longtime fans until the turn of 1951, when they too were put out to pasture.

Comic scholars debate just when the Golden Age of comicbooks ended, but one thing is clear: If super-hero adventures weren’t entirely dead, they were in deep decline.

Early Television, Science Heroes, & Costumed Cowboys

Though there was no longer a strong market for super-hero comics, other genres like romance, Westerns, crime, and horror flourished. Not only that, with the burgeoning number of households who owned a television, boys and girls were increasingly discovering new heroes to follow, albeit in black&-white. Comicbook publishers were eager to jump on the

bandwagon. The first comicbook treatments of television space operas appeared in 1950: Space Patrol, Captain Video, and Tom Corbett, Space Cadet

But even as it provided fodder for comicbook adaptations, television was a genuine threat to the comics industry. Movie-like excitement (however cheesy early television special effects may have been) was now available in homes, and for free! A few sci-fi super-heroes inspired by the likes of these new video spacemen appeared in comicbooks in the very early 1950s, Timely’s Marvel Boy and DC’s “Captain Comet” chief among them.

Mister Universe was a short-lived, four-issue title published in 1951 and ’52 by Media Publications, a.k.a. Stanley Morse, and mostly drawn by Ross Andru. The first-issue splash page hinted at Captain Marvel (or even Wonder Woman) territory: “Possessing the speed of a Mercury, the wisdom of a Zeus, the strength of a Hercules, and the looks of an Adonis, put them all together and you have… Mister Universe.” But former Marine Tommy Turner turned out to be just an exceptionally put-together young man who wins a Mister Universe contest held in Greece seeking to find the man who comes closest “to having all the qualities of the gods.” Turner promptly becomes a professional wrestler, sporting his new moniker, dispatching enemy agents and crooks as he encounters them. Text features educate the reader about the history of wrestling. By issue #4 Turner has rejoined the military, but it’s too little, too late, to save the title.

The Mystery Of The Vanishing Super-Heroes

If 1949 was the year by which the great majority of 1940s-born comicbook super-heroes had ended their four-color careers, 1950 was when the cancellation of the once-popular All-Star Comics, starring the seven-member Justice Society of America, put a line under that trend, discontinuing half of DC Comics’ remaining costumed heroes in one fell swoop after issue #57. Cover-dated Feb.-March 1951, it went on sale in late 1950. Pencils by Arthur Peddy; inks by Bernard Sachs. Courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © DC Comics.]

The Marvel & The Mutant Two outliers, released around the same time most other super-heroes were giving up the ghost, were the costumed star of Timely’s Marvel Boy #1 (Dec. 1950), with Russ Heath art—and “Captain Comet,” who debuted in DC’s Strange Adventures #9 (June ’51). To spotlight the latter character, we’ve depicted the cover of the very next month’s SA #10, by Carmine Infantino & Bernard Sachs, because we reprinted #9’s cover in A/E #188. Neither hero would ever attain true stardom, though Captain Comet—the first avowedly mutant comicbook super-hero ever—stuck around considerably longer. Courtesy of Michael T. Gilbert & the GCD, respectively. [TM & © DC Comics & Marvel Characters, Inc., respectively.]

The creators of super-hero comics seemed reluctant to entirely give up on the conventions of their former headliners. Or perhaps their new efforts fell under the maxim of “Old habits die hard.” In addition to the world of science-fiction, comicbook writers attempted to transplant super-hero conventions onto Western and (less often) horror comicbooks.

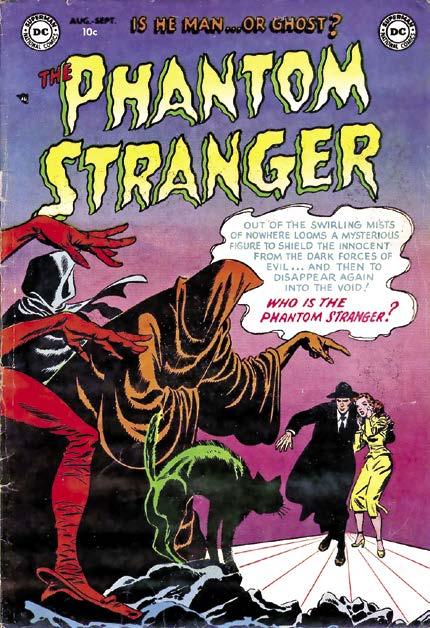

Toby’s Purple Claw was a rare horror super-hero, and the Hand of Fate and Phantom Stranger comicbooks featured supernatural story hosts who occasionally veered into active engagement. Masked cowboys were far more common.

Magazine Enterprises’ Ghost Rider, Red Mask, and Lemonade Kid were among the most conventionally “super-heroic” of the lot, complete with costumes, gimmicks, and colorful villains. Not surprisingly, veteran super-hero writer Gardner Fox penned many of these tales. The Lone Ranger and his horde of comicbook imitators, despite their masked identities, were more clearly traditional Westerns at their core.

Publishers were eager to latch on to any new craze that promised to boost sales. Harvey Publications, for one, bankrolled Simon & Kirby’s response to 1953’s 3-D craze. As the wildly creative pair told the story, 50,000 years ago two races vied for control of the Earth: the D people and the evil Cat People. A dying race, the D people instilled all of their hopes and dreams into The Book of D Millennia later (i.e., in 1953), teenaged Danny Davis opens the mysterious book

Lend A Hand—Or Even A Claw—Said The Stranger (Above & right:) Three mystery/horror titles of the early ’50s that featured continuing heroes:

The cover of DC’s The Phantom Stranger #1 (Aug.-Sept. ’52) is by Carmine Infantino & Sy Barry; the mysterious hero took part in all stories. [TM & © DC Comics.]

The artist of the cover of Ace’s The Hand of Fate #12 (Aug. ’52) is unknown. This is the first issue on which the spirit of Fate appears as a character, and his intercessions inside were intermittent. While the artist credits of the cover of Toby Press’ Purple Claw #1 (Aug. ’53) are uncertain, the most likely candidates are interior artists Ben Brown & Dave Gantz. All scans courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Personally, We’d Have Preferred To See Miss Universe

(Left:) Mister Universe, penciled by Ross Andru and inked by Mike Espositio for Stanley Morse, wasn’t a true super-hero title but assumed a few of its trappings, though Tommy Turner seldom wore the wrestlers’ togs shown on the cover. The series, whose first issue was dated July 1951, was probably inspired by a movie of the same name (and wrestling/bodybuilder theme) earlier that year and starring TV’s future Ben Casey, Vince Edwards. Andru may have inked the cover of #1. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

and discovers a pair of 3-D-like glasses. When he dons them, Captain 3-D, the heroic last survivor of the D people, leaps from the book. Alas, Captain 3-D was destined to be a one-shot.

As it happened, the biggest development in the world of superheroes in the early 1950s didn’t happen in comicbooks but rather on television. Adults of a certain age remember a series called The Adventures of Superman with an unmistakable fondness. The program had a huge impact. But, to better understand all of that, a little background is in order.

Two For The Show...?

(Above:) The covers of Simon & Kirby’s (and Harvey Comics’) Captain 3-D #1 (Nov. 1953) and Dell/Western’s stand-alone Green Hornet (a.k.a. Four Color #496. Sept. ‘53), the latter by an unidentified artist. It could be argued that one or both of these de facto one-shots were the start of the “mid-1950s super-hero revival,” since they came out shortly before Timely/Atlas’ Young Men #24. But the former surely owed its existence primarily to the 3-D craze launched by the 1953 film Bwana Devil... and it’s hard to say what Dell/Western had in mind with its Green Hornet singleton—which, incidentally, was drawn within by Frank Thorne and scripted by Paul S. Newman. [Captain 3-D TM & © Estates of Joe Simon & Jack Kirby; Green Hornet TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Superman’s Arrival On The Small Screen

As noted, the comics industry was clearly taking notice of television and movie franchises and moved to license kid-friendly properties to be featured in their own comicbooks. DC Comics, along with Dell and Fawcett, was at the forefront in taking advantage of such opportunities on an ongoing basis. In 1950, DC launched The Adventures of Bob Hope and in 1952 followed up with The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. And Dell and Fawcett had over a dozen screen-cowboy titles between them. That said, DC was perhaps the only publisher consistently working to translate their comicbook properties into other media. Indeed, they devoted one of their prime editorial staff to precisely that purpose.

Whitney Ellsworth was DC’s liaison with Hollywood and had been for over a decade. He had worked with Fleischer Studios as a consultant in producing the well-regarded Superman animated shorts in the early ’40s. Ellsworth served a similar role with Columbia Studios’ popular serials featuring Superman, Batman, Vigilante, and Congo Bill. But his most successful move was envisioning a television series for the Man of Steel.

Look! Up In The Sky!

Whitney Ellsworth

From overall editor of DC Comics for several years—to DC’s

Ellsworth helped conceive a clever gambit, producing a B-movie starring Superman and featuring actors who were available to star in a subsequent television series devoted to the hero. In essence, the movie served as a pilot to test the viability of the project. Not only that, but revenue from the movie could help offset the production costs of setting up the series.

Superman and the Mole Men debuted in theatres on November 23, 1951, starring George Reeves as Superman and Phyllis Coates as Lois Lane. It met with enough success to green-light the TV series, to be distributed through syndication rather than through affiliation with a specific network. While an exact date of the first televised episode is disputed, it aired in September of 1952 with Reeves and Coates reprising their roles. John Hamilton, playing Perry White, and Jack Larson as Jimmy Olsen joined the cast.

(Right:) A vintage poster for the 1951 movie Superman and the Mole Men, which introduced George Reeves as the Man of Steel. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Hollywood point man.

It took several months after filming to assess whether the program was significantly successful to justify moving forward with a second season. Long enough that Phyllis Coates had moved on to another project and was now unavailable. She was replaced by Noel Neill, who had co-starred with Kirk Alyn in the 1948 and 1950 Superman serials. Neill would play the role for the rest of the series.

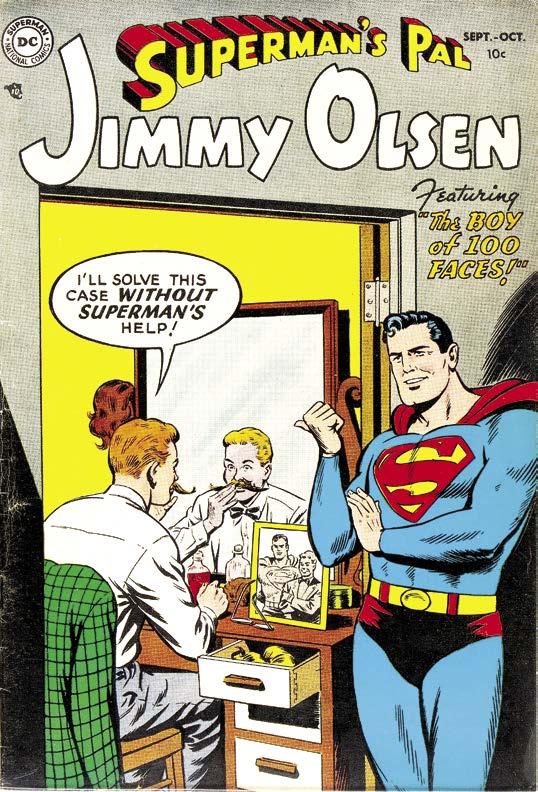

Overall, though, it would be safe to say that, by the summer of 1953, other comics publishers were aware of DC’s success with the series. And if there was an accompanying bump in sales for the Superman family of comicbooks, Irwin Donenfeld was known to boast. The fact that DC added a Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen comicbook in 1954, after Larson as the cub reporter had become a breakout star, suggests the comics were doing just fine.

Keep that summer of 1953 date in mind. Roy Thomas has long held a theory that it was the success of Adventures of Superman that led Martin Goodman, the publisher of Timely/Atlas/Marvel, to revive his line of super-heroes that same year. But it’s possible that one other, previously unheralded event may have contributed to that decision.

Captain America Returns (To Movie Theatres!)

The success of the Superman television series may have prompted a failing movie studio to try and milk a few additional dollars out of another super-hero property. Republic Pictures informed Martin Goodman of their intention to dust off their 1944 15-chapter Captain America serial, retitling it Return of Captain America. Youngsters might be forgiven for thinking the 1944 chapter-play was a new creation. The serial, featuring Dick Purcell as Cap, was not exactly a faithful rendition. This led film restoration expert Eric Stedman to wonder if an earlier version of the script had featured another character.

It is helpful to realize that, just as Columbia was the exclusive producer of movie serials featuring DC characters, Republic in the

early 1940s was the one that brought Fawcett heroes to life. In 1941, they released an Adventures of Captain Marvel serial, and the next year produced one starring Spy Smasher. But in 1944 they switched companies, releasing a Captain America chapter drama with a lead character who didn’t have much in common with the original other than his costume.

Republic’s Captain America carried a gun rather than a shield, operated without Bucky as a partner, and was secretly District Attorney Grant Gardner rather than loyal soldier Steve Rogers. Unlike Rogers, he also had an attractive secretary as a romantic interest. Stedman credibly speculates the original script may have featured another Fawcett hero, Mr. Scarlet, who also carried a gun at times and was secretly a special prosecutor. If so, Scarlet’s declining popularity may have necessitated the change of character.

“A Great Metropolitan Newspaper”

The main cast members of TV’s The Adventures of Superman. (L. to r.:) John Hamilton (Perry White)… George Reeves (Superman/Clark Kent)… Jack Larson (Jimmy Olsen)… Noel Neill (the second & major Lois Lane.) [Publicity shot TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Pal-ing Around

The Curt Swan/Stan Kaye cover of Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #1 (Sept.Oct. 1954). This comic title was the first DC result of the success of The Adventures of Superman on TV. [TM & © DC Comics.]

Curt Swan

Solo—So High!

[continued from p. 11]

“Look!” an anxious bystander exclaims. “He’s back from the dead!”

The gathered crowd is decidedly more fearful than celebratory. In very small panels at the bottom of the cover, potential readers were informed “Submariner [sic] and Captain America also in this issue,” accompanied by small images of those two heroes.

The hint of horror in the cover of that inaugural issue suggests some hedging on precisely what Atlas was trying to sell. But surging anti-comicbook sentiment quickly shifted editorial focus to straightforward super-hero action.

Alter Ego #35 goes into loving detail about the content of those super-hero-packed issues of Young Men. And those interested in reading the stories for themselves can peruse the first of three 2007-2008 hardcover Marvel Masterwork volumes featuring Atlas Era Heroes. It is interesting to note that in those stories Steve Rogers has resumed his post-war job as a high school teacher, rather than his more dynamic role as an Army private.

It also soon emerged that each of the three heroes was given a recurring arch-enemy. For Captain America, the return of The Red Skull was nearly inevitable, even if he was now a mere shadow of

The covers of Timely-Atlas’ first three solo hero issues of the revival: The Human Torch #36 (April ’54) by Burgos, Sub-Mariner #33 (April ’54) by Everett, and Captain America #76 (May ’54)—the latter cover probably (but not for sure) by Burgos. Courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

on two other occasions, but that’s it as far as flame-related powers. Curious.

Even more interesting is a narrative blurb in the hero’s third and final issue (May ’55). “Watch The Flame smoke out a crime czar and his motley crew!” the writer entices before adding, “Not with fire, but with fists…”

It was hardly a coincidence that this issue was also the first to sport the stamp of the new Comics Code Authority (CCA).

Did the reviewers of the CCA require that addition, worrying that some impulsive youth might have a flame-related mishap?

Some specifics regarding the Code’s beginnings will follow shortly. But first, the return of a heroine who would have given dedicated censors nightmares in her heyday.

Phantom Lady’s Not-So-Sexy Return

Farrell’s third super-hero revival seemed the most promising: the Phantom Lady! And unlike Black Cobra and The Flame, the

heroine had only disappeared from newsstands five years earlier.

Phantom Lady had appeared in comics published by two different publishers, but always written and drawn by members of the Eisner-Iger/Iger-Roche art shop. She first appeared as a rather conventional female heroine in Quality’s Police Comics from 1941 to 1943. Secretly Sandra Knight, the daughter of a U.S. Senator, Phantom Lady’s efforts at fighting enemies of America were bolstered by her black-light projector that could bathe her foes in incapacitating darkness.

A far bustier version of the heroine was featured in Victor Fox’s All-Top Comics, as well as in her own title from 1947 to 1949, this time often drawn by the inimitable Matt Baker, at other times by Jack Kamen. In the Fox version, Sandra Knight was often seen in lingerie and Phantom Lady frequently tied up.

Now, in the shadow of the impending imposition of the Comics Code, Farrell and Iger-Roche brought her back once again, this time for what would turn out to be a short run of only four issues. Her enemies were most often communist spies, and her costume more confining. The bare midriff and exposed cleavage

2013 in two

Phantom, Be A Lady Tonight!

(Left:) That crazy, mixed-up Ajax numbering again! The uncredited cover of Phantom Lady #5 (Dec. 1954-Jan. 1955), the first revival issue. (Right:) The most celebrated (or notorious, take your pick) of the Fox Comics Phantom Lady covers was that of #17 (April ’48), illustrated by the great Matt Baker. Both scans courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

The entire run of “Phantom Lady” stories, from the Quality group through Fox through Ajax-Farrell, was collected by PS Artbooks in

hardcover volumes titled Roy Thomas Presents Phantom Lady

Knight & Daze

In his second issue (March ’55), four months after the first, Captain Flash fought another baddie with a name that would resonate in the future—The Black Knight—with the usual exciting Sekowsky cover and interior art— —while yeoman artist Edvard Mortiz took over the “Tomboy” feature for its final three appearances. Scripters unknown. Thanks to Michael T. Gilbert for the scans. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

As for “Tomboy,” Captain Flash’s backup feature, she seems to have been thoughtfully conceived as well. Janie Jackson appears to be a girly girl, so her family never suspects she has adopted the action-oriented, masked persona of Tomboy. For all of her spunk and athletic ability, the heroine has no special powers. Despite the intended contrast between Janie and her Tomboy alter ego, Tomboy’s outfit is still pretty feminine in nature, comprised of a green short-sleeved blouse, black skirt and eye mask, and red boots, gloves, and cape.

While Tomboy’s origin is never provided, Janie was presumably inspired by the example of her police lieutenant father. But Janie is also spurred on by her older brother, who mocks Janie for her apparently meek demeanor. A bit of an odd dynamic is created when her brother begins to idolize Tomboy, enough that his blonde girlfriend goes so far as to pose as Tomboy to recapture his interest. Needless to say, this maneuver doesn’t go well and the real Tomboy needs to rescue her when she’s captured by crooks.

Tomboy also appears to be collecting a modest rogue’s gallery of her own. The Claw is described as Tomboy’s “most deadly enemy,” even though hero and villain only crossed paths once, in

Captain Flash #1. The Claw is a maniacal gang leader who sports a mustache, black cape and hat, and gray, animal-like paws complete with claws, hence his name. In her second appearance, Tomboy tangles with Sound Wave, a master of sonic manipulation. Despite a dynamic code name, his attire was nondescript.

The Avenger & Strongman

The Avenger is sometimes described as Magazine Enterprise’s only costumed hero, though Jerry Siegel’s Funnyman (1947), Dick Ayers’ Ghost Rider (1949)—hey, nothing says the Old West can’t have super-heroes—Jet Powers, Captain of Science (1950), and The Lemonade Kid (1950) also seem deserving of the designation. But I digress.

As told in The Avenger #1 (cover-dated Feb.-March 1955), when millionaire scientist Roger Wright’s brother and sister-in-law are captured by communists, Roger is inspired by a child’s Ghost Rider mask to adopt the masked identity of The Avenger to rescue them. As The Avenger, Wright wears a red uniform and cowl, with white gloves, belt, and gun holster. He sports a large red “A” enclosed in a white circle on his chest.

As the origin story unfolds, it emerges that the communists hoped to use Roger’s relatives as bargaining chips to obtain the secret behind his atomic-powered Starjet. Wright defeats the communists, only then realizing they have already killed his kin. After educating the defeated Russian general that “it is the individual man and not the state that is most important,” The Avenger vows to “prevent future crime and oppression you plan to bring upon the innocent people of the Earth.”

Richard Wright proceeds to do just that, devoting his fortune, his scientific expertise, and his physical prowess to defeat communists in their seemingly endless schemes.

The creators of The Avenger appear to have been long-time comicbook writer Paul S. Newman and artist Dick Ayers, though Gardner Fox also wrote for the character from the start. Fox was already writing costumed characters in the Western genre for the company, such as Red Mask and the aforementioned Ghost Rider.

(Above:) An Aquaman and Aqualad commission, date uncertain, but likely drawn when Ramona was in her eighties or later. Outstanding! [Aquaman & Aqualad TM & © DC Comics]

TRINA, BECK, & FCA

A 2-Part Tribute To TRINA ROBBINS

by P. C. Hamerlinck

Trina Robbins was one of the many Golden Age comicbook-reading kids who wishfully shouted (or whispered) “Shazam!” and dreamed that the word would turn them into a super-hero. For many, Trina was a real-life super-hero… a trailblazer of the 1960s counterculture underground comix movement (before saying goodbye to them in 1977 because, as she put it, they had become “yucky”)… to a successful mainstream magazine illustrator and comicbook cartoonist before settling into the role of esteemed and well-respected scholar/historian.

I first got to know Trina during the 1980s through C.C. Beck’s “Critical Circle”—a small group of individuals that Beck had handpicked to comment and debate by mail on the various comic art essays he was writing at the time. Trina and I were two of its members right up until Beck disbanded the Circle on September 9, 1989, after suffering a stroke which paralyzed his entire left side.

Upon learning that Trina had passed away (on April 10, 2024), I took a moment to peruse the Beck file material bequeathed to me many years ago, which includes photocopies of correspondence he had with so many of us. I took out the folder containing letters he had written to Trina. Here are some excerpts from a few of Beck’s missives:

February 5, 1985:

I’m glad to know that your strip [Misty] is being handled by Marvel. How can any company named after the great Captain himself be anything but honest, upright, true, steadfast, and so on? I wish they had revived the Big Red Cheese instead of DC. I’ve met Jim Shooter and Stan Lee and like them both.

Trina’s passion for comics history was apparent in her ofteninquisitive letters to Beck. She asked the artist his inspiration for Billy Batson.

I based him on Chester Gump and Skeezix… typical boy heroes something like Tom Sawyer or Jim Hawkins, the boy in Treasure Island.

She also inquired if he knew Chad Grothkopf, artist of “Hoppy The Marvel Bunny.”

No, I don’t recall meeting Chad, although I may have. However, I do recall meeting Walt Disney. Fawcett art director Al Allard sent me to a reception for him. I knew only vaguely who he was at the time, and he had probably never heard of me. We looked at each other suspiciously and neither of us said a word.

March 17, 1986:

Your Misty stories are as cheerful and entertaining as can be. I’m amazed that you can present them without ever including fights with knives, dope, booze, pregnant teenagers, and all that stuff. And I’m more amazed that any publisher will even look at your material.

January 15, 1987:

I’m glad to hear that you are still full of vigor in spite of the way you’ve been treated in the industry. I could very easily imagine what Marvel could do to your Misty—turn her into a six-foot-tall, musclecovered monstrosity wearing pasties and a garter belt. Look at what DC did to Captain Marvel.

As for your starting a new character, don’t think they won’t try to stop you. Captain Marvel didn’t look anything like Superman, but DC still sued Fawcett as soon as he appeared. Now that they own the old boy they’re turning him into another monstrosity.

The comics field is in its baroque period now. Hype and overkill are in style; honesty and truth are signs of imbecility or, in my case, of senility.

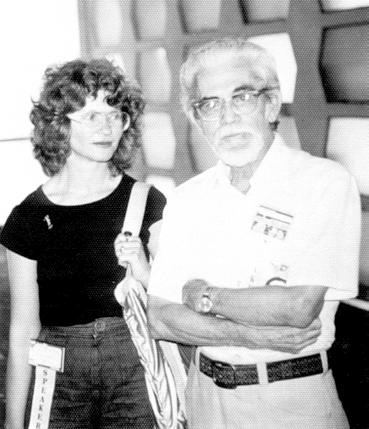

The Mary Marvel Marching Society (Left:) Trina Robbins and C.C. Beck at the San Diego Comic-Con, 1977—the year each of them received an Inkpot Award. Each drew illustrations of Fawcett’s Mary Marvel from time to time, too.

Photo scanned by P.C. Hamerlinck from Beck’s personal scrapbook.

(Right:) In fact, here’s Trina’s Mary Marvel cover art for P.C. Hamerlinck’s self-published FCA #56, Summer ’96. [Shazam heroine TM & © DC Comics.]

Play Misty For Me!

Trina’s “Super Misty”—from the sixth (and final) issue of her Marvel/Star Comics series Misty, dated Oct. 1986—was an obvious one-time homage to Mary Marvel. In an earlier story in that same issue, Misty is seen working on a skit at “Station WOW”—a small shout-out to Fawcett’s Wow Comics, which starred Mary Marvel for much of the 1940s. Coloring by Elaine Lee; lettering by Lois Buhalis; everything else by Trina Robbins. [Misty TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.]

March 3, 1989:

You’re right about our living in a country where we have a right to satire. My opinion is that what we have today is not satire but childish, tasteless, name-calling slander. The laughs we hear today are the laughs that were once heard from the mob every time a head was lopped off by the executioner. I’m not laughing, are you?

March 7, 1986:

I agree with you [about] a good artist’s being able to illustrate a poor story and make it acceptable because of their great artwork, as Howard Pyle and some of the great illustrators did with Robin Hood and other old stories. But how many great illustrators are ever around at any one time? Especially working in comic books? There were some terrible artists working on the Captain Marvel stories at times but the stories themselves, thanks to Fawcett editors and writers, were always so good that nobody could ruin them entirely. The same thing can be said of the early Superman and Batman comics; later the art got better, but the stories became worse.

Beck occasionally offered unsolicited drawing guidance to

Trina, as on July 7, 1988:

One of my beliefs is that illustrating stories takes a lot of the imaginative quality out of them rather than adding anything to them.

Never draw any more than necessary. If characters can be left out of a panel without hurting anything, leave them out. Show backgrounds once to establish them, then leave them out.

The purpose of illustrations is to show the actions and emotions of the characters, not the details of their costumes and anatomy. The characters must move, roll their eyes, shrug, wave their arms, frown, smile, laugh, cry. Any character who is not doing something should not be shown.

What is not seen is more intriguing than what is seen. Off-panel sounds and voices are more exciting than on-panel ones.

Lines around the outside of objects should be heavier than lines inside them. This is why I don’t like lots of shadows on figures as realistic artists use—they break up the figures.

You probably know all these things and won’t argue with me about them. Many artists did—and still do. The late Don Newton insisted on drawing Captain Marvel with shadows all over him. Some of today’s artists have called my work “stick-figure.”

Counterculture & Comix

(Above:) Trina strikes a patriotic pose in front of her East Village boutique, NYC circa 1967.

(Right:) In 1970 she produced the first all-woman comixbook, It Ain’t Me Babe, published by Last Gasp. Pictured are Olive Oyl, Wonder Woman, Mary Marvel, Little Lulu, Sheena, and Elsie the Cow. [Wonder Woman, Shazam heroine TM & © DC Comics; Sheena is a trademark of Galaxy Publishing, Inc., & Val D’Oro Entertainment, or successors in interest; other characters TM & © the respective copyright holders.]

December 12, 1988:

I’m really happy to hear from you. I thought that I might have offended you by expressing some views not in agreement with your more liberal opinions, and that perhaps you had written me off as a hopeless far-right conservative, which i am not. I have been in a fight with narrow-mindedness and bigotry all my life and still am.

We got to learn more about Trina after Critical Circle members were

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

ALTER EGO #192

MARK CARLSON-GHOST documents the mid-1950s super-hero revival featuring The Human Torch, Captain America, SubMariner, Fighting American, The Avenger, Phantom Lady, The Flame, Captain Flash, and others—with art by JOHN ROMITA, JOHN BUSCEMA, BILL EVERETT, SIMON & KIRBY, MIKE SEKOWSKY, MORT MESKIN, BOB POWELL, and other greats! Plus FCA, Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt, and more! (84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=133&products_id=1819