“Greetings, creep culturists! For my debut issue, I, the CRYPTOLOGIST (with the help of FROM THE TOMB editor PETER NORMANTON), have exhumed the worst Horror Comics excesses of the 1950s, Killer “B” movies to die for, and the creepiest, kookiest toys that crossed your boney little fingers as a child! But wait... do you dare enter the House of Usher, or choose sides in the skirmish between the Addams Family and The Munsters?! Can you stand to gaze at Warren magazine frontispieces by this issue’s cover artist BERNIE WRIGHTSON, or spend some Hammer Time with that studio’s most frightening films? And if Atlas pre-Code covers or terrifying science-fiction are more than you can take, stay away! All this, and more, is lurching toward you in TwoMorrows Publishing’s latest, and most decrepit, magazine—just for retro horror fans, and featuring my henchmen WILL MURRAY, MARK VOGER, BARRY FORSHAW, TIM LEESE, PETE VON SHOLLY, and STEVE and MICHAEL KRONENBERG!”

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 Now Shipping!

CRYPTOLOGY #2

The Cryptologist and his ghastly little band have cooked up more grisly morsels, including: ROGER HILL’s conversation with our diabolical cover artist DON HECK, severed hand films, pre-Code comic book terrors, the otherworldly horrors of Hammer’s Quatermass, another Killer “B” movie classic, plus spooky old radio shows, and the horror-inspired covers of the Shadow’s own comic book. Start the ghoul-year with retro-horror done right by FORSHAW, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, RICHARD HAND, VON SHOLLY, and editor PETER NORMANTON

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95

(Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships January 2025

CRYPTOLOGY #3

This third wretched issue inflicts the dread of MARS ATTACKS upon you—the banned cards, the model kits, the despicable comics, and a few words from the film’s deranged storyboard artist PETE VON SHOLLY! The chilling poster art of REYNOLD BROWN gets brought up from the Cryptologist’s vault, along with a host of terrifying puppets from film, and more comic books they’d prefer you forget! Plus, more Hammer Time, JUSTIN MARRIOT on obscure ’70s fear-filled paperbacks, another Killer “B” film, and more to satiate your sinister side!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships April 2025

CRYPTOLOGY #4

Our fourth putrid tome treats you to ALEX ROSS’ gory lowdown on his Universal Monsters paintings! Hammer Time brings you face-to-face with the “Brides of Dracula”, and the Cryptologist resurrects 3-D horror movies and comics of the 1950s! Learn the origins of slasher films, and chill to the pre-Code artwork of Atlas’ BILL EVERETT and ACG’s 3-D maestro HARRY LAZARUS. Plus, another Killer “B” movie and more awaits retro horror fans, by NORMANTON, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, VOGER, and VON SHOLLY!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships

Volume 1, Number 155

October 2024

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Michael Eury

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Roger Ash

PUBLISHER

John Morrow

DESIGNER

Rich J. Fowlks

COVER ARTISTS

José Luis García-López and Bernie Wrightson

(Alternate, unused cover for DC Comics’

The House of Mystery #251. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions.)

COVER COLORIST

Glenn Whitmore

COVER DESIGNER

Michael Kronenberg

PROOFREADER

Kevin Sharp

SPECIAL THANKS

Mike Baron

Mike W. Barr

Jonathan Brown

Gary Cohn

DC Comics

Tom DeFalco

J. M. DeMatteis

Jim Fern

Jack C. Harris

Heritage Auctions

Dan Johnson

Tom King

Michael Kronenberg

Steve Kronenberg

Paul Kupperberg

Rod Labbe

James

Ed Lute

Ralph

Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond!

BEYOND CAPES: DC’s Other Houses of Mystery

Gothic-inspired line expansions opened the door for the mysterious Mister E

OFF MY CHEST: The Haunted Tank: Being At War with Our Past

A pastor/comic fan considers the problematic Confederate heritage behind DC’s enduring war feature

WHAT THE—?!: My Brief Love Affair with Eerie Publications .

A personal discovery of Eerie Publications’ gore-drenched comic mags

FLASHBACK: Do You Dare Enter… The Tower of Shadows? .

Marvel’s ill-fated attempts at Bronze Age horror anthologies

BEYOND CAPES: The Unexpected

Steady your nerves for a sizzling survey of one of DC’s most sinister anthologies

FLASHBACK: Elvira’s House of Mystery

Move over, Cain—the Mistress of the Dark is moving in!

BACKSTAGE PASS: House II: The Second Story 73

Tom DeFalco and Ralph Macchio were surprised to be asked about this little-known adaptation

BACK TALK: Reader Reactions

BACK ISSUE™ issue 155, October 2024 (ISSN 1932-6904) is published monthly (except Jan., March, May, and Nov.) by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Back Issue, c/o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614

Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. Roger Ash, Associate Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: BACK ISSUE, c/o Roger Ash, Associate Editor, 2715 Birchwood Pass, Apt. 7, Cross Plains, WI 53528. Email: rogerash@hotmail.com. Eight-issue subscriptions: $97 Economy US, $147 International, $39 Digital. Please send subscription orders and funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial office. Cover artwork by José Luis García-López and Bernie Wrightson, originally produced as the cover of House of Mystery #251 but unpublished. All characters depicted are TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. All editorial matter © 2024 TwoMorrows and Michael Eury. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING

by John Wells

It wasn’t the oldest house on the block, but it had seen better days. Touring the property, Joe Orlando saw a real fixer-upper and he was already envisioning candidates who could bring it back to life. In the right hands, the House of Mystery could be a trendsetter.

The “House of Mystery” name had been employed for years in such projects as a 1930 newspaper serial by Austin J. Small, a 1934 movie starring Ed Lowry and Verna Hillie, and a kid-friendly, award-winning radio series from 1945 to 1950 where Roger Elliot (played by John Briggs) told spooky stories to youngsters. With the radio show out of the picture, DC launched a House of Mystery comic book in October 1951 (inset). Edited by Jack Schiff, it was a vehicle for DC to establish a foothold in the horror genre without actually getting those feet dirty. Unlike the often-graphic excesses of other publishers, DC took its younger audience into account and kept things clean, often explaining away seemingly supernatural situations with rational explanations. By the time a companion House of Secrets title debuted in September 1956, the winds were shifting, and both residences found fantasy and science fiction sweeping away the last vestiges of horror-lite. The new approach stuck around into the 1960s, with superheroes and costumed characters moving in. “Eclipso” and “Prince Ra-Man” were on a double-bill when The House of Secrets was shuttered in July 1966. House of Mystery fared better, its own dual features—“Dial H For Hero” and “Manhunter From Mars”—carrying on through 1967.

Do You Dare Enter…?

The Comics Code Authority grants you permission! DC’s Bronze Age horror craze actually started in the late Silver Age with this, the first retooled issue of The House of Mystery, #174 (May–June 1968). Cover by either Joe Orlando and George Roussos, or Mort Meskin, from a Carmine Infantino layout. (Unless otherwise noted, all art scans accompanying this article are courtesy of John Wells.)

JOE ORLANDO TAKES UP RESIDENCE

Besieged by Marvel Comics’ rising popularity and watching sales slip as the buzz from the Batman show wore off, to shake things up DC promoted artist Carmine Infantino to head its editorial department. Those changes included the recruitment of new editors and the exploration of genres unconnected to superheroes. Although the horror genre had been drastically curtailed by the mid-1950s’ institution of the Comics Code, it hadn’t gone away. Indeed, Warren’s black-and-white horror mags as well as four-color ghost books from Dell and Gold Key—all published without Code oversight—were thriving in the 1960s. Even with full Code approval, Charlton was doing a booming business with Ghostly Tales, whose successful 1966 launch led to companion titles Many

Ghosts of Dr. Graves and Strange Suspense Stories in 1967. It was time for DC to get a piece of the action, and Executive Vice President Irwin Donenfeld asked Infantino to make it happen.

“We did that,” Infantino noted in Comic Book Artist #1 (1998), “but we also did other things because we were also doing other things because we didn’t want to tip our hand to Marvel that were going to jump into the [genre].” In the pages of the On the Drawing Board ( OTDB ) fanzine, rumors flew. Dick Giordano would be editing a revival of ACG’s Adventures into the Unknown title, OTDB #65 declared, with a Steve Ditko–created “Dr. Strange–type” as its lead. Never mind, reported the next issue. “There is also talk from DC of reviving the Phantom Stranger as a possible co-feature in House of Mystery,” OTDB #64 mentioned in January 1968. This, too, did

COVER OF MYSTERY

House of Mystery #174’s cover—which opens our article—has become iconic, as well as replicated. Preceding its production was the alternate version shown here, attributed to longtime artist Mort Meskin.

Meskin made a name for himself on DC Golden Age features including “Johnny Quick” and “Wildcat” and in the Silver Age on House of Secrets ’ “Mark Merlin” series. He left comics for commercial art in 1965, but three years later purportedly inquired about new DC assignments.

“There was a reference in a 1968 Murray Boltinoff lettercol (probably Unexpected) to Meskin having returned to DC after at least three years of not being there, and of course, he seemingly never showed up anywhere,” according to Mike Tiefenbacher, former editor of The Comic Reader “I even asked Carmine specifically in 1971 when I interviewed him, and naturally, he had no answer for me. Jim Aparo included Meskin in his sneaks in that Aquaman story where he listed all of his DC contemporaries [during the Sea King’s visit to the trippy “City on the Edge of Nowhere” in Aquaman #50, artist Aparo drew DC creators’ surnames within the watery background of page 11, panel 1 ed.], as I recall the only guy who wasn’t obviously doing new work. [The unpublished HOM #174 cover art] looks to me like the proof that he had returned, and likely dropped in to see Murray while delivering his art, prompting the mention.”

Tiefenbacher adds that while he suspects Meskin worked from an Infantino layout—as Orlando also recalled regarding his version of the same cover— Meskin’s art “seems to have been refined, something that was likely to happen if he’d gone to an ad agency following his final Mark Merlin stories, and especially since he could finally take his time. But the inking looks like his to me, as do the poses, and those kids’ faces look like his style as well.

“Looking at the actual published cover, I would say it too is an Infantino/Meskin collaboration! Those kids’ faces are Meskin faces, and the inking is too sophisticated for Roussos—look at that lovely brickwork!—who’d collaborated with Meskin for years.”

he had published were ones that featured boys in danger,” Orlando recalled in CBA #1. “He got the idea from an illustration in Tom Sawyer where Tom was in a graveyard and witness to a murder. That concept, in many different ways, worked over and over again. Neal did the best covers for House of Mystery. Many times, he would walk in with a sketch he had come up with himself and I would get a story written for the sketch. It was a fun way to work—to have that kind of rapport with artists, writers, and creative director.”

House of Mystery #175 also expanded Sergio Aragonés’ presence in the book, not only continuing his “Page 13” feature but adding pages of horror-tinged sight gags with the umbrella title “Cain’s Game Room.” The logistical problems of also working around a fixed filler on page 13 was eventually too much for the former. It was retitled “Room 13” with issue #185 and Aragonés quit drawing it after issue #190, followed by two final pages by John Costanza (#194) and Lore Shoberg (#198). A different Aragonés filler—“Cain’s Gargoyles”—emerged to replace it, running intermittently between issues #188 and 239 (1970–1976), with a last Dave Manak page seen in issue #280 (1980).

“Cain’s Game Room” was the most enduring, though. Its final installment, also by Manak, ran in House of Mystery #297 (1981).

Aragonés was far from the only fresh talent to appear in House of Mystery. While Murray Boltinoff preferred established pros in Unexpected, Orlando saw great potential in the new generation of comic book fans that craved a place at the table. Having recently sold a Blackhawk script to Dick Giordano, a 22-year-old writer received an offer from Orlando. He’d “seen my horror fanzine Stories of Suspense,” Marv Wolfman recalled to Richard Arndt in Alter Ego #113 (2012), and “asked me to re-dialogue a horror story he’d bought from another writer.” That tale—HOM #176’s “Roots of Evil”—was soon followed by a Wolfman-scripted three-pager in issue #179.

The latter represented the first published artwork by Bernie (then Berni) Wrightson. The 19-year-old’s sample art at a convention had impressed Carmine Infantino and Dick Giordano enough for them to offer him their upcoming “Nightmaster” series. Performance anxiety got the best of the teenager, but Infantino was sympathetic. ‘We shouldn’t have given you a book right off the bat,’ Wrightson recalled him saying, in Comic Book Artist #5 (1999). ‘You’re intimidated and we’re going to take you off this. […] We’ll put you on the fillers for the mystery books to break you in.’

“I had an awful lot of help from Joe Orlando,” Wrightson told Cooke in CBA #5. “He was the best guy for me and any young artist. I learned so much

What’re You Laughing At?

House of Mystery not only raised goosebumps, it tickled funny bones with one-page humor features. Here, from issue #177 (Nov.–Dec. 1968), are an Orlando-drawn “Room 13” door hanger and a “Cain’s Game Room” gag page illo’ed by the one and only Sergio Aragonés.

TM & © DC Comics.

Secrets ’ comeback was edited by Paul Levitz, who was now DC’s Editorial Coordinator. Joe Orlando, meanwhile, had become the publisher’s managing editor and he began relinquishing his old editorial assignments. Levitz took over House of Mystery with issue #255 (cover-dated Nov.–Dec. 1977, on sale in August) and House of Secrets with issue #149 (on sale in September with a Jan. 1978 cover date).

“I wasn’t the editor earlier, even unofficially,” Levitz emphasizes to BI. “I did usually pick stories out of the inventory, and I liked making extra bucks ($15 each) writing intro pages, so I probably aimed the page count combination to permit that. But Joe okayed the picks and worked with Carmine on covers. As an assistant I sometimes edited scripts, and usually got to suggest a preferred artist on the ones going to the Philippines but I never made art assignments to American artists or bought scripts.”

Among his first acts was exhuming a striking old Bernie Wrightson piece featuring a grotesque swamp creature. Originally seen in the 1971 fanzine Reality #2, it was revised by the artist for a prospective House of Mystery cover but never used beyond centerspread art in The Amazing World of DC Comics #2 (1974). Levitz was determined to change that, using it as the cover of HOM #255 and commissioning a matching story by newcomer Cary Burkett and artist Frank Redondo. Another Wrightson cover adorned HOM #256’s Halloween edition after which Joe Orlando was recruited to pencil the next three (with inks by Dick Giordano).

On Levitz’s watch, the lapsed practice of employing new creators on the mystery books made a welcome return. A humble one-pager in issue #255, for starters, was the first published work by penciler Alex Saviuk. In issue #257, Mark Bright essentially drew himself into his first comics story. Scripted by fellow newcomer Scott Edelman, the three-pager dealt with a budding artist willing to go to any lengths to replace an entrenched veteran cartoonist. Other creators early in their pro careers included writer Greg Potter (HOM #259), and artists Michael Golden (HOM #257, 259; HOS #148, 149, 151), and Bob McLeod (HOM #258).

Still a 32-page title, House of Secrets offered limited possibilities for experimentation, but Levitz quickly perked up its covers, with fine pieces by Michael Kaluta (HOS #149, 151, 154), Jim Starlin (HOS #150), Ernie Chan (#152), and Jim Aparo (#153). Issue #151 was bookended by experimental, visually strong stories by artists Arthur Suydam and Michael Golden (with respective scripters Cary Burkett and Roger McKenzie).

Levitz was also a fan of the Phantom Stranger—a character he’d written at the end of the hero’s run in 1975—and decided to return him to the spotlight twice in the fall of 1977. Following a team-up with Deadman in October’s DC Super-Stars #18, the Stranger joined Abel and his skeptic frenemy Dr. Thirteen for a full-length adventure in November’s House of Secrets #150. Gerry Conway wrote a direct sequel to a story of his from HOS #89 (1970) that had involved a Catholic priest and Jewish rabbi pooling their faiths to thwart an incursion by Satan. Don Heck drew the original and Gerry Talaoc the followup.

“I think Gerry had a gap in his schedule, and I wanted to do something out of the ordinary,” Levitz recalls. “I had fond memories of his early Phantom Stranger stories that had Dr. Thirteen connections.” In issue #153’s letters column, Levitz teased “that plans are in the works for some new Phantom Stranger stories by Len Wein and Jim Aparo to appear later [in 1978].”

Third Time’s a Charm (top) Bernie Wrightson’s swamp creature illo for the fanzine Reality #2 eventually (bottom) found its way into print in the fanzine The Amazing World of DC Comics #2 before (inset top) new HOM editor Paul Levitz had a story built around it for publication in issue #255 (Nov.–Dec. 1977).

No Secrets (with apologies to Carly Simon) (top) The final issue of House of Secrets, #154 (Oct.–Nov. 1978). Cover by Michael Wm. Kaluta. (inset) Kaluta’s giant-spider cover art intended for

Weird Mystery Tales #26 was (bottom) reappropriated for publication in House of Mystery #263.

PLOP GOES THE IMPLOSION

Like many of the publisher’s 1978 plans, it was not to be. June was the month that kicked off the DC Explosion, a companywide makeover that increased the page count of all of its standard books from 17 to 25 pages of story with an attendant price hike from 35¢ to 50¢ [see Keith Dallas and John Wells’ excellent book from TwoMorrows, Comic Book Implosion, for a deep dive into this topic—ed.]. Coinciding with the move, House of Mystery abandoned its Dollar Comic format with issue #260 in June. Had the package not sold as well as hoped? “I wouldn’t assume any particular logic behind the format shifts of that period,” Levitz cautions. “Lots of reactions and over-reactions.”

The reaction that mattered was that of Warner execs, who demanded that the initiative be halted immediately. DC’s bestsellers would continue on as 40¢ comics on a uniform monthly schedule with a smattering of bimonthly Dollar Comics. The weaker titles were culled from the line immediately. The cancellations included Secrets of Haunted House (for the second time), The Witching Hour, the recently launched Doorway to Nightmare (starring Madame Xanadu), and… House of Secrets , with July 1978’s issue #154. Seeking to salvage some of the material, DC upgraded The Unexpected to a Dollar Comic effective with issue #189 and effectively made it a triple-feature with the Three Witches and Abel each claiming a third of the book. Doorway to Nightmare stories also appeared in evennumbered issues. Jack C. Harris was named editor of the collective package.

A Romeo Tanghal–illustrated gag page in issue #190 found Abel slipping off to his new comic book, delighted to finally be free of his abusive old dwelling. His smile fell away once he opened a door at the DC offices that led right back to the House of Secrets. “We thought you knew,” his editor chortled. “The only rule of your new job is to expect the unexpected!” House of Mystery handled some of the spillover, too. The Michael Kaluta cover and related Jack Oleck/Bill Draut story meant for the canceled Weird Mystery Tales #26 ran in November 1978’s HOM #265 instead. For the mystery books, coordinating excess inventory was just a typical day at the office.

“The intro page count was downscaled to a single page beginning with HOM #260’s downscaling of page count,” Paul Kupperberg notes, “and I continued writing these horror tableaus through to #275. By the way and just FYI, I was simultaneously writing the HOM letters columns the whole time I was doing the intros.”

by Alissa Marmol-Cernat

DC Comics’ long-standing tradition of horror anthologies is well known among comic book enthusiasts of all ages, the genre having seen a sudden surge in popularity at the dawn of the Bronze Age, after surviving the troubled 1950s and the limitations imposed by the Comics Code Authority. Even now, yearly Halloween specials call back to the classics.

However, either through a multitude of adaptations featuring their hosts or mere longevity, it’s really only House of Mystery and House of Secrets that have breached the mainstream and may be considered—if you’ll excuse the pun—household names.

But what about all those other sinister houses and forbidden mansions counted among DC’s menagerie of horrors? It’s high time you, dear reader, joined BACK ISSUE in an exploration of these twisting hallways of the obscure.

BAD ROMANCE

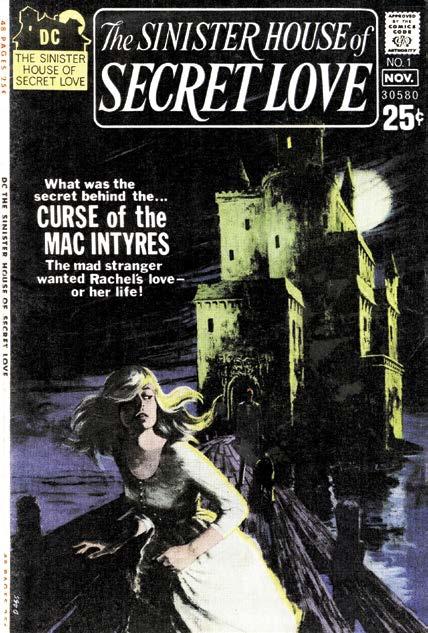

Haunted Hearts

Gothic romance cast its dark shadows upon these early Bronze Age DC titles: (left) Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love #1 (Sept.–Oct. 1971). Cover painting by George Ziel. (right) Sinister House of Secret Love #1 (Oct.–Nov. 1971). Cover painting by Victor Kalin.

Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love and Sinister House of Secret Love were DC’s proverbial other houses. Sister titles and effectively companion pieces to one another, they both initially showcased full-length tales of gothic romance before an abrupt rebranding to Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion and Secrets of Sinister House with their respective fifth issues in the summer of 1972.

According to American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1970s , the 1966 soap opera Dark Shadows served as the original inspiration for the books. While the similarities to the hit TV show are undeniable, the stories published within those first five issues most certainly hail from the gothic literary tradition made famous by the likes of Mary Shelley and Charlotte Brontë. In fact, virtually every staple of the

genre is present and the tales within invariably follow the same structure: an innocent heroine falls for a handsome stranger with a mysterious past, and must contend with supposedly supernatural, ultimately mundane forces that wish to do her harm before she can earn her happy ending.

If seemingly repetitive at a glance, these gothic romances were compelling, mature, often genuinely eerie, and altogether different from their more famous contemporaries. It comes as no surprise then that Dorothy Woolfolk, one of the first women in the industry, was the editor behind Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love , as well as the first issue of Sinister House of Secret Love , and both series showcased an astounding number of female protagonists never before

seen outside of general romance comics, the one other ostensibly “feminine” genre.

Every issue featured a painted cover by artists such as Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Victor Kalin, and Jerome Podwil, among others—all darkly atmospheric covers, more reminiscent of pulps than anything else, and undoubtedly visually striking on the stands. As the late Joe Orlando—later the editor on both titles—put it in an interview published in Comic Book Artist #1 (Spring 1998), “That’s because at that time, the Gothics in the paperback market were doing so well. I studied the covers on the paperbacks and they always had the woman in the foreground, a sinister guy pursuing them, and a house or castle in the background with always one window lit. So that was a formula I used.”

Forbidden Tales

Although the series’ title changed to (left) Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion with issue #5 (May–June 1972), its hypnotic Nick Cardy cover art still suggested the book’s gothic content. Before long, with a new logo, Dark Mansion was delivering standard DC horror fare—often buoyed by extraordinary artwork such as (right) Michael Wm. Kaluta’s macabre melting man on the cover of #13 (Oct.–Nov. 1973).

TM

THE REALM OF THE DARK MANSION

Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love #1 (Sept.–Oct. 1971), the first of the gothic line to hit the shelves, told the tale of Laura Chandler, an orphan set on investigating the death of her best friend after accepting the offer to work and live in the imposing Langfrey House—the site of her friend’s mysterious death, and her husband’s ancestral home. One of the most memorable sequences involves Laura’s late-night wanderings around the manor and her bizarre encounter with a ghostly looking young girl confined to a disused floor of the house; as the girl frightens Laura away with a sing-song chant of “Mommy locked me up… Mommy locked me u-up…,” it becomes immediately apparent that this is to be one of the most chilling stories of the bunch.

It was a fitting start for a new variety of horror comics, and this first issue even came with a real life mystery of its own. While the story is magnificently rendered by Tony DeZuniga, the unknown writer is only mentioned in the letters column of the second issue as “an Englishwoman who, for reasons of her own, wished to remain anonymous.”

The rest of the series follows the tone set by its debut, with Tony DeZuniga and Don Heck alternating as regular interior artists, and Jack Oleck and Dorothy Manning penning an issue each amongst a gaggle of uncredited writers. Most stories were period pieces, best exemplified by the Dracula -esque “Kiss of Death” in #3 and its strange tale of the enigmatic Baron Dravko and the beautiful nurse he’d summoned to his castle.

By issue #5 (May–June 1972), the book would become Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion but it would take another issue for its contents to fall in line with the more familiar—and no doubt commercially successful—type of horror anthologies DC was publishing at the time. This final issue centered around romance, entitled “They All Came to Die” and attributed to the creative team of Jack Oleck and Don Heck, evidently took its cues from Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None and saw six people trapped on an island with a killer intent on making each of them pay for their greatest secrets.

The following issue, which also marked the end of Dorothy Woolfolk’s tenure as editor, ushered in the classic anthology format with a double feature consisting of a high-stakes Jack Kirby tale about a crime-solving psychic and an unsettling story of one woman’s pursuit of riches by Mike Friedrich and Jose Delbo.

It wasn’t just the theme and format that would change for the former gothic romance title, though; issue #7 (Sept.–Oct. 1972)— the first published under Joe Orlando’s editorship—completed the transformation into something of a House of Mystery/Secrets replica by introducing a host for the first time in the book’s history. Unlike Cain and Abel’s humorous hijinks, the Witch of the Dark Mansion left a much more tonally appropriate impression—first seen in an eye-catching Michael Kaluta splash page, the Witch was a thin, purple-clad woman with a wild mane of dark hair raising a toast to “dark mansions!” against the sinister silhouette of one such house with a chained man kneeling at her feet. The Witch would continue appearing in every issue of the anthology, even once Denny O’Neil assumed editorial reins with #13 (Oct.–Nov. 1973), and right up until an untimely cancellation with issue #15 (Feb.–Mar. 1974).

Interestingly enough, if Forbidden Tales of Dark Mansion occupies the annals of the obscure, then at the very least it certainly hasn’t been forgotten altogether—its host would later resurface as a supporting

Urban Renewal

With its fourth and final issue (Apr.–May 1972) under its original Sinister House of Secret Love title (top), a change in logo occurred. Cover by Tony DeZuniga. The title was renamed Secrets of Sinister House with #5 and soon eschewed its gothic roots, featuring traditional DC horror material like (bottom) this eye-catching Nick Cardy cover on issue #16 (Jan.–Feb. 1974).

TM & © DC Comics.

The South shall rise... from the dead. The ghost of the Confederate States of America has figuratively hung over the United States of America for generations. In the work we discuss in this essay, the ghost becomes literal. As a Southerner, the phantom of a bygone area has hung over my head and taunted me from the past. How do we relate to the time when an economic system built on the atrocities of slavery ripped our country apart, and teach that shameful history? Do we confront it head-on? Do we put our heads

under the sheets to hide from it and pretend it is not there?

Our country and culture have failed to answer these questions and to make any real amends for this ghoulish history. The complexities of this tortured relationship can be found in the pages of DC Comics’ war feature “The Haunted Tank,” which appeared in the series G.I. Combat This series weaves the complexity of the USA’s Civil War into battle action while peering into a multi-generational family dynamic that reflects the painful intricacies of the dynamic above.

by Jonathan R. Brown

In this article, we will examine how creators engaged the concept of war as an evolving concept through the eyes of the Stuart family that connected through war even after death. We will provide a character synopsis of General J.E.B. Stuart and how he related to the crew of a tank that bore his name. By doing these things we will hopefully gain an understanding of how “The Haunted Tank” was able to outlast other DC war features. Finally, we will conclude by looking at the 2008 Vertigo miniseries that confronted the racist and vile nature of the Confederacy head-on and how it forever tied these sins into the fabric of the Haunted Tank forever.

Haunted by History

(top left) The imposing figure of General J.E.B. Stuart, from the dust jacket painting of John W. Thomason, Jr.’s biography of the Confederate officer, New York: Scribner’s first edition, 1930. (main) In DC Comics’ long-running “Haunted Tank” feature in G.I. Combat, the ghost of General Stuart guided his descendent ad his tank mates through the perils of World War II. Undated specialty illo by longtime Haunted Tank artist Sam Glanzman. Both, courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com). (bottom left) In recent years, opposition to the glorification of the Confederacy has led to some communities’ removals of statues of Confederate heroes, like this monument to General Robert E. Lee, losing its berth at Lee Circle in New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 19, 2017. Photo courtesy of Infrogmation of New Orleans/Wikimedia Commons.

‘INTRODUCING THE HAUNTED TANK’

The Haunted Tank, the creation of writer Robert Kanigher and artist Russ Heath, was introduced in G.I. Combat #87 (Apr.–May 1961). Kanigher, the series’ mainstay, would be joined on the Haunted Tank by several legendary artists in addition to Heath including Joe Kubert, Sam Glanzman, and Dick Ayers. The serialized story would have one of the longest runs of any DC Comics war feature, ending in 1987 when G.I. Combat was canceled with issue #288 (Mar. 1987), the final story penned by series creator Kanigher and illustrated by Glanzman. Murray Boltinoff would serve as the series’ long-running editor starting with G.I. Combat #74 and staying with the crew until the demise of the book.

At the heart of the story is the crew of an M3 Stuart tank, a nimble, light machine that saw extensive use in the North African and European theaters during World War II. The series meticulously details the tank’s engagements in these harrowing battlegrounds, providing a visceral depiction of warfare.

However, it’d the Haunted Tank’s unique supernatural twist that sets it apart. The tank is haunted by the ghost of Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart, an audacious cavalry commander known for his daring maneuvers during the US Civil War. This spectral presence is not just any haunting; General Stuart is a distant relative of the tank’s commander, Lt. Jeb Stuart, creating a profound personal connection between the past and present. The ghost of General Stuart, visible exclusively to Jeb, assumes the role of a guardian angel to the

Ghostly Guardian

Lt. Stuart and crew christen “The Haunted Tank” in G.I. Combat #150 (Oct.–Nov. 1971).

Story by Bob Kanigher, art by Russ Heath. Original art to story page 14 courtesy of Heritage.

Comics.

crew. He does not merely linger as a silent specter; instead, he actively engages with Jeb, offering invaluable tactical advice drawn from his own combat experiences, imparting historical wisdom, and providing moral support during the crew’s most perilous moments.

This blend of historical military action with the supernatural element of a guiding spirit creates a rich, multi-layered narrative. General Stuart’s presence connects the valor and tactics of 19th-Century warfare with the mechanized combat of World War II. This dynamic between the ghostly advisor and the tank crew adds depth to the storyline, exploring themes of legacy, duty, and the enduring nature of courage across different eras of conflict. The “Haunted Tank” series stands out for its ability to weave these elements together, creating a compelling tale that resonates with both war history enthusiasts and fans of supernatural fiction.

The series’ introductory story in G.I. Combat #87 is aptly entitled “Introducing the Haunted Tank.” From the beginning, the reader finds themselves in the middle of World War II action. An M-3 Stuart tank is taking damage from an enemy Tiger tank. The crew has been incapacitated. All of a sudden the tank begins to move on its own and disables the other combatant. After escaping this encounter, the crew begins to come to. Briefly, we are introduced to Slim Stryker, Rick Rawlins, and Arch Asher, the crew of this particular M3 Stuart tank. In this first issue, we don’t get much of a sense of their personalities, for it is their commander Jeb Stuart who is the heart of this story. Just like the tank he commands, he is named after Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart. Present-day Jeb flashes back to his boyhood where he idolized the Southern cavalry leader. We see scenes of Jeb playing war imagining what he would have been like to be the CSA leader. He gives thanks to his father—he named him after the general—and it is revealed that Jeb is the blood descendant of the aforementioned warmonger. The depiction moves to Jeb visiting a memorial to his ancestor and being in awe of what he sees as a great man. The story takes an interesting turn as it is revealed Jeb has been able to hear the voice of his long-deceased family member, and has carried that with him into the present moment where he now finds himself to be a commander in his own theater of war.

In the second part of the story, we return to the present battle. Our weary and hurt crew is not out of the woods yet as more Tiger tanks are encroaching on their position. It is here the voice returns to Jeb and offers advice. Our Stuart takes the advice of the disembodied voice and delivers salvation to his crew. At the end of the story, the crew reflects on how miraculous their escape was. We are given an inner monologue where Jeb reveals he believes this voice to be that of his dead Civil War–fighting ancestor. He is thankful for his presence and hopes one day the voice will reveal itself to the crew.

This first issue does not offer much about the complexities of the relationship a US soldier has with a past family member who actively fought against the United States of America. That notion is practically omitted. What we do see is a glorified view of the Confederacy, its leaders, and the soldiers who fought for their cause. These figures are idolized by young boys. They are worthy of monuments. There is simply no sense that the Confederates were enemies of the country our tank crew now fights for. However, as the story continues, our protagonist’s relationship to the past will evolve, similarly to how mainstream culture’s understanding and presentation of the Civil War and its participants evolved.

‘THE BATTLE ORIGIN OF THE HAUNTED TANK’

The first two years of the series tell the stories that follow the introductory comic. While we can see characters develop and the ghost of Stuart begins to materialize more and more, we still do not have much of a sense of how all of this began.

That would all change in G.I. Combat #114 (Oct.–Nov. 1965), with the story entitled “The

by Michael Kronenberg

Inspired by EC Comics’ acclaimed horror titles and their “Ghoulunatic” hosts the Old Witch, the Crypt Keeper, and the Vault Keeper, Warren Publications launched the blackand-white magazine Creepy in 1964, hosted by Uncle Creepy. Two years later, after the success of Creepy Warren launched the companion magazine Eerie, hosted by Cousin Eerie. In 1968, National Periodicals (DC Comics) shifted House of Mystery back to a horror anthology, hosted by Cain. In 1969, DC followed with the revival of House of Secrets as a horror anthology, hosted by Cain’s brother Abel. Both titles saw a jump in sales, thanks to former EC artist Joe Orlando taking the helm as editor. With superhero sales beginning to wane, Marvel Comics’ Stan Lee wanted to create his own horror titles that could compete with DC’s recent successes. In 1969, Marvel launched Tower of Shadows ( TOS ), followed the next month by Chamber of Darkness ( COD ). TOS was hosted by the ghoulish Digger and COD hosted by Headstone P. Gravely.

Mind-Blowing Mayhem

John Romita, Sr.’s covers to Marvel’s entries in the (burgeoning) Bronze Age horror anthology trend: (left) Tower of Shadows #1 (Sept. 1969), with its host Digger seen in the corner box; and Chamber of Darkness #1 (Oct. 1969), unveiling host Headstone P. Gravely in the corner box.

TM & © Marvel.

Tower of Shadows would last only nine issues and Chamber of Darkness would only survive for eight issues. Nearly forgotten now, both titles featured work by some of comics’ best writers and artists: Denny O’Neil, Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin, Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, John Buscema, Johnny Craig, Wally Wood, and Bernie Wrightson. TOS and COD were also fertile ground for new talent like Barry Smith, Gerry Conway, Len Wein, Gary Friedrich, and Marv Wolfman. But both series could not overcome poor sales, extremely uneven stories, and a lack of editorial identity. DC had Joe Orlando editing their horror titles, bringing his EC experience, but Stan Lee’s direction for TOS and COD was disjointed and distracted. As each series moved along during their brief tenure, they became more populated by reprints from Marvel’s stock of horror tales from the late ’50s/early ’60s. However, there were several excellent stories, two of which would help change comics history, and one story that would help push a legend away from Marvel and to DC.

Dark Shadows

A chilling entrance into Shadow House, rendered in cinematic glory by the unmatchable Jim Steranko. From Tower of Shadows #1’s “At the Stroke of Midnight.” Special thanks to Michael Kronenberg for this article’s interior page scans.

& © Marvel.

‘THE MONSTER’

Chamber of Darkness #4 (Apr. 1970) featured one of the last Marvel stories by Jack Kirby before he signed with DC Comics. In this seven-pager, a wealthy, ugly, and lonely man is believed to be a monster by the ignorant people of his village. A tragic story that echoes both The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Frankenstein

There are several reasons why 1970 would be the end of Kirby at Marvel. He’d failed to come to an agreement for a new contract with Marvel publisher Martin Goodman. Goodman didn’t recognize Kirby’s tremendous contributions to Marvel’s success for over 30 years. Instead, it was believed that Stan Lee had done it all and Kirby was just an artist who drew what Lee told him.

Lee decided to feature his most popular artists in TOS and COD’s debut issues: Steranko in TOS #1 and Kirby in COD #1. The COD story would be plotted and drawn by Kirby and scripted by Lee. A horror/supernatural story was familiar ground

for both from their Atlas/early Marvel days. Kirby dove into the story with relish, providing some of his best penciled work in a long while. (Kirby’s original penciled pages can be seen in The Jack Kirby Collector #13, 1996.)

Lee didn’t like the story or the art that Kirby had submitted. Kirby was contacted by the Marvel offices and told that the job was rejected and being sent back to him with many changes and corrections that Lee wanted done. This was an insult to Kirby, but as a true professional, he reworked his pages, including cutting and pasting panels to change the story to meet Lee’s requests. Lee then decided he did not want to write the script for the reworked pages, perhaps as a concession because he knew Kirby wanted to start writing his own material or because he still hated the revised pages. Kirby provided a script for the revised pages, but several parts of his script were altered before the final lettering; these final changes were most likely done by Lee.

Art changes were made to the story’s villain by the Marvel Bullpen and the story’s inker John Verpoorten. Some felt that the character too closely resembled the Fantastic Four villain Quasimodo (Kirby referred to the character as “Hunchy” in his border notes). Kirby’s script on the last page was completely discarded and a new ending was written, most likely by Lee, without Kirby’s knowledge. All of this resulted in “The Monster” not appearing in COD #1 as originally intended, but in COD #4. Whether this was the final straw that sent Kirby to DC is not known, but it certainly helped to push him out the door. The following issue of COD (#5, June 1970) would feature Kirby’s last story in the series titled “…And Fear Shall Follow.” In addition to the art (John Verpoorten inks), Kirby wrote the story about an American U-2 pilot who crashes his plane in China. He escapes from the wreckage, but a strange man pursues him relentlessly, even walking through walls. The pilot eventually realizes that he died in the crash and the man is going to escort him to the world beyond.

ENTER STARR THE SLAYER— ALIAS CONAN THE BARBARIAN

In the foreword to The Barry Windsor-Smith Conan Archives, Roy Thomas writes that in the late 1960s, readers began bombarding Marvel with letters demanding “sword and sorcery” comics. Paperback versions of Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter, Warlord of Mars, and in particular Robert E. Howard’s Conan with their quintessential Frank Frazetta covers had become incredibly popular. TOS already featured two excellent sword and sorcery stories written and illustrated by comics legend Wally Wood. Unexpectedly, the story “The Sword and the Sorcerers” by Roy Thomas and Barry Smith in Chamber of Darkness #4 would become a fortuitous preview for one of Marvel’s most heralded comics of all-time—Conan the Barbarian. The plot, loosely based on Conan creator and pulp author Robert E. Howard, is as follows: Novelist Len Carson plans to write one final story in his popular sword and sorcery series to kill off the protagonist, Starr the Slayer. But his creation comes to life and kills him in self-defense. This seemingly innocuous sto-

The ‘King’

of Monsters

(left) “The Monster” in Chamber of Darkness #4 (Apr. 1970) was one of the final stories produced for Marvel by Jack “King” Kirby before his historic and well-publicized leap to DC Comics, where he’d soon introduce his enduring Fourth World. Note that Kirby also penned the tale. Inks by John Verpoorten. (right) Marvel’s dynamic duo of Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith brought wizards and swordplay into Chamber of Darkness #4 by introducing Starr the Slayer, their prototypical version of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian.

work up a proposal to publisher Martin Goodman, which Goodman accepted. On a meager budget from Goodman’s office, Thomas wrote a letter to the Howard estate offering $200 per issue for the use of Conan as a Marvel hero. To Thomas’ surprise, they accepted. With that, Thomas began writing the first issue of Conan the Barbarian , but who would draw it? With $200 an issue going to the Howard estate, Marvel was not going to assign one of their high-paid, top-tier artists like John Buscema (who seemed to be the logical choice). In a 1998 interview for Comic Book Artist, Barry Smith said, “I believe that Stan wasn’t wholly behind the idea of a Conan comic and, if I recall, he was against putting an important artist on a book that was probably going to tank. Obviously, I was not considered an important artist at that period.” Thanks to his “trial run” in COD #4, the 22-yearold Barry Smith became Conan’s first Marvel artist, and the rest is comic book history.

On the letters page of Chamber of Darkness #6, editor Stan Lee responded to a letter about T & S’s story in issue #4, that the first issue of Conan would be released next month. A house ad for Conan the Barbarian #1’s debut appears opposite that letters page.

H . P. LOVECRAFT

Both TOS and COD adapted three H. P. Lovecraft stories. Considered one of the greatest writers of supernatural/horror fiction, Stephen King stated, “Lovecraft was the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale and was responsible for my own fascination with horror and the macabre. He’s the largest influence on my writing.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Lovecraft’s stories began gaining popularity with a new generation thanks to paperback reprints. Marvel arranged with Arkham House, who owned the rights to and published Lovecraft’s work, to adapt three stories. The first was “The Terrible Old Man” in Tower of Shadows #3 (Jan. 1970), written by Roy Thomas, with pencils by Barry Smith and inks by John Verpoorten and Dan Adkins. The story concerns a strange old man

In 1968, horror comics were poised to make a comeback at DC Comics. This move would open up a new market for the publisher and create a hit line for DC in the Bronze Age. The success of these books was due to a man who knew a thing or two about the genre, Joe Orlando. Orlando had been a part of the legendary EC Comics bullpen of the early 1950s, a pool of talent that included one of the greatest lineups of artists any publisher ever had. When it came to the company’s output, their crowning achievements were their horror comics: Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, and Haunt of Fear, featuring the work of a who’s who of artist greats that included Jack Davis, Johnny Craig, and Graham Ingels, as well as Orlando. Orlando had also had recent success helping to launch Warren’s black-and-white magazine, Creepy, in 1964.

DC’s decision to take a chance on horror comics was a bold venture at the time. After all, “horror” was still a dirty word in the business. It had been less than 15 years since the entire comic book industry came under intense scrutiny by parents, teachers, and other concerned citizens outraged at the violence and sex in comics. The pressure back then was so great to clean up the industry, the US Senate even held an inquiry to investigate the perceived harm comics were causing America’s youth. And it had been horror comics (as well as crime comics), just like the ones EC put out, that helped put the entire medium in the crosshairs.

DC hedged its bet on horror by rolling Orlando’s new line out under the preferred term, “mystery books.” But a monster hit by any other name is still a monster hit. As detailed in this issue’s opening article, Orlando took two old standbys, House of Mystery and House of Secrets, and led DC into scary new territory, with more mystery titles following from both Orlando and other editors.

by Dan Johnson

What you are about to read, however, is the history of a book in DC’s mystery line, one Orlando didn’t edit himself, even though he would have an impact on it in several ways. This is a story we think you will find most… Unexpected.

HISTORY FROM THE CRYPT

Before we dive into the comic book that Unexpected was destined to become, we must look at the comic book that it used to be and the events that helped reshape it.

Originally titled Tales of the Unexpected , the first issue of this series was cover-dated February–March 1956. Tales of the Unexpected launched less

Cheating Death

After a few years of format and logo changes, DC’s The Unexpected settled into its Bronze Age logo with issue #115 (Oct.–Nov. 1969).

Cover by Neal Adams.

than two years after the aforementioned US Senate Subcommittee hearings that investigated juvenile delinquency and the effect comic books had on this social problem.

There had been concerns over comic book content by the general public for years before this investigation took place. The main concern was over acts of sex, crime, and violence depicted in comic books and how they shaped the impressionable minds of children who read them. Slowly but surely, the heat was turned up on everyone associated with comics until it reached a boiling point in 1954. In that year, every publisher, including National Periodicals, later known as DC Comics, was in the soup. Eventually, after the Comics Code Authority was launched to help show the public that comics were cleaning up their act, the controversy subsided.

PLAYING IT SAFE

Part of the effort to rebuild trust between publishers and the parents of young readers was axing horror comics altogether. Even though the genre was off the table, anthologies were still popular, especially ones that focused on science fiction and fantasy. And by fantasy, that meant ghost stories and other tales with supernatural elements that skirted the line of horror without fear of parental outrage. Initially, these were the kind of stories featured in Tales of the Unexpected As time went on, the focus shifted more and more to science fiction stories. The book began life under editor Jack Schiff, a man who really had a fondness for aliens of all shapes and sizes. After all, he was the editor who had turned Batman into a science fiction hero in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He was also the first editor on House of Mystery and House of Secrets . When he was removed from the Batman titles in favor of the “New Look” under Julius Schwartz, Schiff took over Mystery in Space and Strange Adventures from Schwartz.

By the late 1950s, covers featuring aliens and other worlds became the norm for this title. Its fate as a science fiction comic book was sealed for certain when it got its own anchor feature. With issue #40 (Aug. 1959), the book became home for Space Ranger, a character that had tryouts in Showcase #15 (Aug. 1958) and 16 (Sept. 1958). Dubbed “Guardian of the Solar System,” Space Ranger was like a futuristic Batman, hiding his true identity to better fight the threats that loomed in outer space. Space Ranger took over the covers for Tales of the Unexpected starting with issue #43 (Nov. 1959) and remained the book’s cover feature until #82 (May 1964). Beginning with issue #83 (June–July 1964), the Green Glob, a creation of the Guardians of the Universe, was introduced, and it would be featured in stories where it interacted with various humans as it worked to better their lives in amazing ways.

Overall, Tales of the Unexpected was a fun read with some inventive stories and solid artwork across the board. But aliens and science fiction were becoming played out by the end of the 1960s. This book needed new life and a new direction. It was time for a new day, one that could only be found in the dead of night.

Beware of the Glob

Weird science fiction propelled the earliest issues of Tales of the Unexpected, starting with (top left) this trippy Bill Ely–drawn bird-man cover for issue #1 (Feb.–Mar. 1956). (top right) Space Ranger rocketed into the title beginning with #43 (Nov. 1959)—and check out the washtones on that snazzy Bob Brown cover! (bottom) It’s “The Green Glob,” a short-lived attempt at a recurring feature in Tales of the Unexpected. Excerpt from the “Green Glob” story in issue #83 (June–July 1964). Art by George Roussos.

Comics.

by James Heath Lantz

The decade of the 1980s gave those who grew up during the BACK ISSUE era numerous icons of every genre in every medium. The Terminator, Yoda, Freddy Krueger, and Charles Lee “Chucky” Ray are just a few examples of such characters.

Yet, few have crossed over in those genres and mediums like the Queen of Halloween herself, Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. BACK ISSUE will continue to tour the macabre haunted houses in comics with Elvira’s time in DC Comics’ House of Mystery. Think of it as Trick or Treat with Elvira providing the treats... of scary comic book stories.

THE HOUSE‘S NEW OCCUPANT

Cassandra Peterson was born in Manhattan, Kansas, on September 17, 1951. She spent her formative years fascinated by the horror genre while other girls her age were into dolls. Peterson began her show business career as a dancer in Las Vegas when she was a teenager, eventually acting in such movies as Diamonds Are Forever and Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie and in television shows like Happy Days and Fantasy Island .

Six years after the death of horror host Larry “Seymour” Vincent, producers wanted to bring the horror anthology Fright Night back to television in some form. Cassandra Peterson had created a character inspired by Kabuki makeup, the Ronettes, and a Valley Girl character she played in the improvisational troupe the Groundlings. Elvira, Mistress of the Dark debuted with the premiere of Movie Macabre on September 26, 1981. Elvira served as the host who introduced horror and science fiction films with her unique brand of humor during the show’s five-year run. [ Editor’s note: To learn more, check out the profile of Elvira in issue #2 of our sister magazine, RetroFan ; it’s still available in digital form at www.twomorrows.com .] Elvira proved to be so popular she was in film and television roles and appeared as a frequent Tonight Show guest. One such appearance even featured Tonight ’s guesthost Joan Rivers briefly showing the audience the first issue of the Elvira’s House of Mystery ( EHOM ) comic book.

House of Mystery , as detailed in this issue’s opening article, began during the heyday of Golden Age pre-Code horror comics with its first issue released on October 5, 1951. The terrifying abode closed its doors in 1983 with the caretaker Cain evicted and the house condemned in issue #321.

The Cain Scrutiny

Who’s that in the House (of Mystery)? Could it be… Satan? Naw… it’s the Mistress of the Dark, horror schlock queen Elvira! Cover to Elvira’s House of Mystery #1 (Jan. 1986) by Brian Bolland.

TM & © DC Comics.

From East to West

DC’s Elvira’s House of Mystery depicted its hostess in a variety of settings and scenarios—with the Mistress of the Dark’s sharp wit never wavering. Covers to issues #2 (Apr. 1986) and 3 both penciled by Denys Cowan; #2’s cover is inked by Rick Magyar and #3’s by Dick Giordano. TM &

DC Comics would revive the series with Elvira, the megapopular Hostess with the Mostess. Elvira proved to be as versatile as the comics medium. Her wit, charm, and overall personality verified that she was more than the Queen of Halloween while breaking the fourth wall at times. Whether she was perusing numerous DC Comics publications looking for Cain in Elvira’s House of Mystery #5, a cowgirl sheriff introducing the first story in #3, an astronaut, a time-traveler and a robot befuddling Adam Strange in #7, a tribute to the Statue of Liberty on the cover of #8, a teacher in #10, or a red-and-white clad Mistress of Christmas in a pinup by Paul Gulacy in Elvira’s House of Mystery Presents Elvira’s Haunted Holiday Special #1, Elvira proved she could do and be anything the visual medium of comic books demanded without the need a huge Hollywood budget.

One of the most important things about working on a comic book based on a film, television series, or celebrity is the artist’s renderings of the famous people portrayed within the pages. Elvira, Mistress of the Dark is perhaps one of the most brilliant examples of how good the images can look. Jim Fern, who inked several stories in six of the 11 issues of Elvira’s House of Mystery , took time out of his busy schedule to discuss his work on the series.

to quipping in the classic style she used in Movie Macabre , the Mistress of the Dark must find clues to Cain’s whereabouts hidden within the tales of terror recounted by the spirits within the eerie abode. Elvira’s job as narrator/host/ finder of lost Cains is not an easy one, as it sometimes has her bantering and verbally squabbling with the House of Mystery’s supernatural occupants.

To aid the Hostess with the Mostess in her quest, readers were asked in an essay contest to write about what happened to Cain. The winner was announced, and his writing published in the letters page of Elvira’s House of Mystery #11 (Jan. 1987). First prize champion David Annandale of Canada was unavailable for comment to BACK ISSUE . However, legend has it he spends his summers and holidays in both the House of Mystery and House of Secrets listening to the numerous tales of terror.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

“I will say one thing up front,” Fern tells BACK ISSUE’s readers. “I was asked by editor Ed Hannigan to redraw many of Elvira’s faces that the other artists did because likenesses are my forte. Cassandra Peterson liked what I was doing and wanted me to be the one who made sure all the faces were looking like her.”

Elvira’s time in the DC Universe begins in issue #1 (Jan. 1986), when she finds sanctuary from an angry mob in the empty House of Mystery. She must listen to stories of previous occupants while occupying the house. In addition

BACK ISSUE #155

For those of you wondering about Cain’s fate, all two of you needn’t worry. Wraparound host segments “Elvira’s Film Festival” (Nov. 1986’s Elvira’s House of Mystery #9) and “The Cain Mutiny” (#10) reveal the ex-caretaker is trapped in a projector roll. Once he’s liberated, Cain banters with Elvira, thereby smashing the aforementioned fourth wall to see who will introduce EHOM #10’s first story. The Mistress of the Dark is not amused when Cain upstages her. He eventually agrees to be her partner until he meets Elvira’s new assistant—Cain’s brother Abel, who aids Elvira in torturing Cain while the trio look at the Find Cain Contest entries in EHOM #11. In the meantime, the Hostess with the Mostess is welcomed with zombified open arms by Cain, Abel, and the Three Witches of The Witching Hour by the end of that issue, proving that Elvira is a force to be reckoned with, even in comic books.