The Comic Book Man

The finale of a three-part interview celebrating of the 100 th birthday of the late

Who is Arnold Drake?

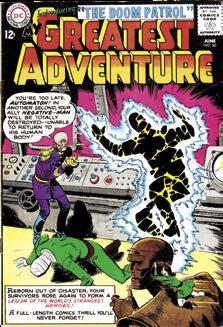

For those who missed parts one and two: the Manhattan native, recipient of the very first Bill Finger Award, is celebrated as co-creator of The Doom Patrol, Deadman, and The Guardians of the Galaxy, as well as co-author of the graphic novel widely considered the first of its kind, It Rhymes with Lust [1950].

In his extensive career, Arnold [1924–2007] worked for just about every major comic book publisher in innumerable genres. — JBC.

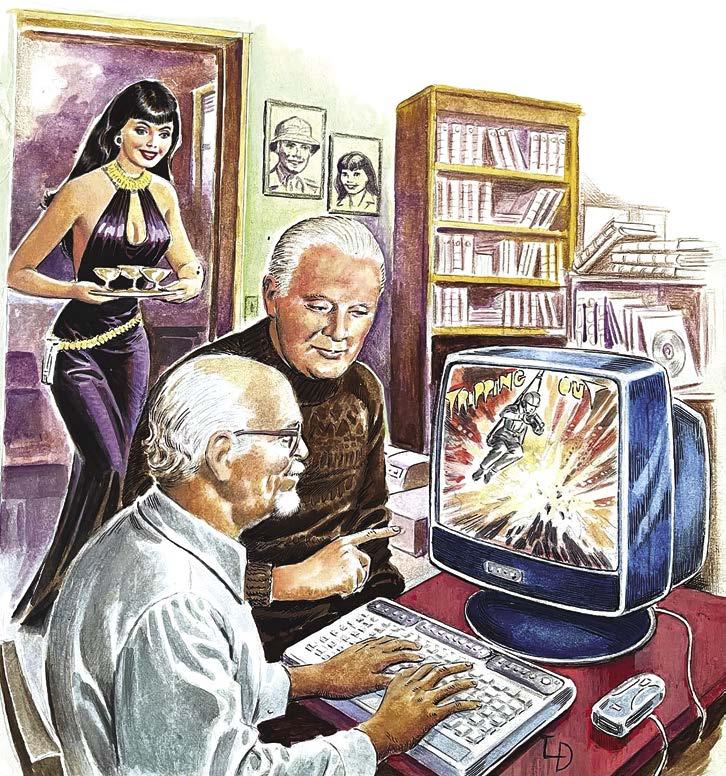

Below: Luis Dominguez depicts A.D. and he working on their 2002 Heavy Metal story, “Tripping Out.” Who’s that lady serving drinks…?

Conducted by JON B. COOKE

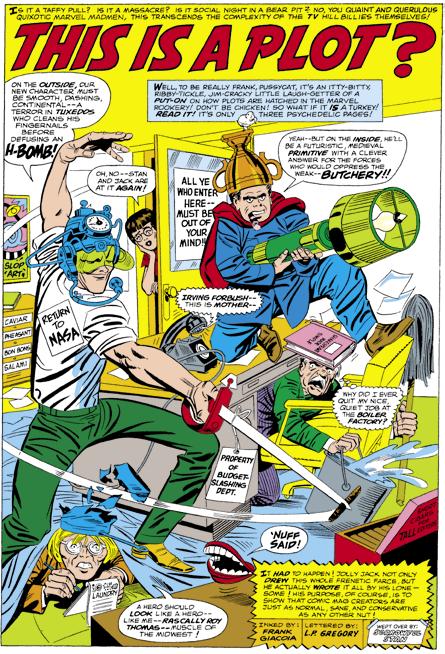

[Editor's Note: When last we left the conversation, Arnold was discussing an increasingly nasty atmosphere in the late ’60s at DC Comics — arguably publisher of his best comics work — and his decision to jump over to Marvel for an (albeit short-lived) stay. That portion showcased his large body of humor work, which included notable scripts for The Adventures of Jerry Lewis and Stanley and His Monster. We pick up the interview to cover some other DC-related subjects, including what was a labororganizing effort among the writers . Note that footnotes are courtesy of Drake fan/friend Marc Svensson, who refers to his interview with A.D. in Alter Ego Vol. 3, #17 [Sept. ’02] . — Y.E.]

Comic Book Creator: Was there, in fact, a writer’s strike at DC?

Arnold Drake: There was never a writer’s strike. A bunch of the writers, led by Bob Haney and myself, got together. That would have been about eight of us, seven, eight, something like that. We wanted to be dealt with as a group rather than individuals, because the house was playing us off against each other. We had some real gripes. Everybody says that the “strike” was about health insurance. The strike was not about health insurance. What it was about was recognition, which is a lot more basic than health insurance. It’s about [DC Comics president Jack] Liebowitz being willing to say, “I will talk with one or two of you guys who will represent all the writers.” Well, the writers wanted to do it, but the artists

Arnold Drake

were not interested. The artists, almost to a man, said, “We’re not workers, we’re artists. Unions are for workers!” And when I said, “Look, I’ve been a member of the Screenwriter’s Guild for quite a while, and screenwriters who consider themselves both writers and artists are workers, or they wouldn’t have bought the guild.” That didn’t cut any ice. They were not interested in that kind of talk. I think they were just also kind of scared.

CBC: They were just rationalizing.

Arnold: Yeah, and I think they were convinced that, if they did that, they’d all be fired.

CBC: Did you help lead this? This was you and Bob?

Arnold: Yeah. Essentially it was Haney and myself, with a lot of back-up from John Broome. Unfortunately, John was out of the country most of the time, so we didn’t get all of the strength from him that we might have, but he was solidly behind us. [Bill] Finger was behind us, [Gardner] Fox was behind us, the Woods — Dave, in particular, was. Otto Binder was strongly behind us.*

CBC: Edmund Hamilton?

Arnold: No, he wasn’t.

CBC: Who was Leo Dorfman?

Arnold: One of the writers. I believe Leo was with us. I didn’t really get to know Leo very well. The only artist who went along with it was [Kurt] Schaffenberger.**

CBC: Did George Kashdan play into this at all?

Arnold: Well, he was an editor there and he was sympathetic. And I think that’s one of the reasons that they got rid of him. CBC: Was he the only sympathetic editor?

Arnold: Oh, no. [Jack] Schiff was. But Schiff kept clear of us, even though he was very sympathetic to what we were doing. Kashdan did not keep clear of us, and made it evident that he thought that they ought to negotiate. I think he tried to make the point that I made in Liebowitz’s office, which is, “If you do this, you will bring great honor to the field. The field right now is looked down upon. If you recognize a guild like this, you will improve conditions and raise the image for everybody, including the publishers.” That was one of the seven points I tried to make. I think Liebowitz saw nothing but, “Unions, unions!”

Years later, Infantino told me that the moment we left the room, Leibowitz called his Friday-morning-golfing-buddy, [Marvel president] Martin Goodman to say, “The writers are forming a union!”

* The list of people involved in the failed attempt to unionize is consistent with my original interview and subsequent conversations over the years, with the exception of “Wood brothers.” There were three Wood Brothers: Bob, Dick and Dave. Bob, artist and publisher at Lev Gleason comics, was convicted of killing his girlfriend and was killed in a car accident shortly after his release in 1966 and most assuredly had nothing to do with the DC writers. Dick Wood is the unmentioned brother, although I suspect his involvement was minor.

**Interestingly other than here, I have never heard Arnold, Bob Haney, or anyone else bring up Leo Dorfman in reference to the failed union. Leo Dorfman wrote some of the zaniest stories printed in Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen and some of the other Superman titles. He was incredibly prolific in the Mort Weisinger stable.

Illustration © the estate of Luis Domiguez.

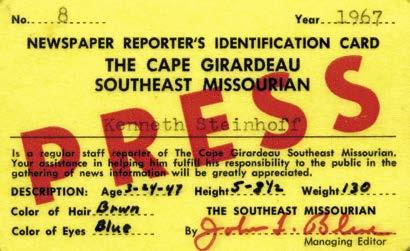

Courtesy of Marc Svensson.

Incidentally, at a private meeting, Leibowitz unconsciously insulted me by saying, “When I was your age, I was a socialist, too.” But when he was 40, nearly every first- or second-generation Jew was a socialist. So were lots of Germans, Italians, and Irish. Now [referring to the George W. Bush administration] Washington is in the hands of a thousand Christian fascists and corporate capos.

CBC: Was that talk between Leibowitz and Goodman the reason you and Stan Lee (Goodman’s cousin) didn’t hit it off well?

Arnold: Probably. Plus Stan’s unacknowledged guilt about stealing my Doom Patrol and calling it, “The X-Men.” To say nothing about switching my “Brotherhood of Evil” into his “Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.”

CBC: Let’s talk about The Doom Patrol. What kind of guy was Bruno Premiani?

Arnold: Very intelligent. He was a dedicated anti-fascist. He was forced to leave Italy because of Mussolini and then, some years later, he was forced to leave Argentina because of Peron. He had started as a political cartoonist in Italy when he was about 17 years old. And Mussolini didn’t like his cartoons.*

CBC: Do you know roughly what year he was born? Was he your age?

Arnold: Yes. He was about 10 years older than I am. My guess is he was born somewhere between 1912 and 1913, something like that. [Wikipedia states January 4, 1907.]

CBC: And did you guys talk politics at all?

Arnold: Oh, yeah. He came to my house one night for dinner and he started talking about McCarthyism, which was prevalent at that time. And he said, “You know, it’s like fascism. It could be the road to fascism.” And I said to him, “Bruno, you were chased out of Italy, you were chased out of Argentina. Don’t get chased out of this country, because you may have no other place to run to.”

Bruno was a very different experience, I think, for all the editors at DC. They had never quite seen what he had brought, which was a great deal of intelligence and understanding of his time and place, a great respect for the work itself, and dedication to it. The wonderful thing about Bruno is that he had learned to get along. I don’t know how hard it was for him to learn that, but he had learned it, which means that… Well, when he had a disagreement, when [Murray] Boltinoff would say to him, “Bruno, would you do this?” Or “Would you do that, instead of what you’ve done here?” Bruno would look at it for a moment and then nod his head, and say [affects an Italian accent] “I will do it, Murray, but it will be very poor.” So he had learned to get along.

* Arnold told this story to me a bunch of times, and I never got tired of hearing it. It is abbreviated for this interview and, please keep in mind, I am retelling an Arnold Drake story that he told in his own entertaining way. It is a story as telling of Arnold as it is of Bruno Premiani. Arnold’s long version went something like this, with the exception of my comment in the parenthesis: When Bruno was young and Mussolini was coming to power Premiani’s political cartoons were pointing out the true nature of Mussolini and his Fascist party. (I would like to quickly point out Premiani was there for the birth of the word “fascist” and contributed to our understanding of its broader definition. He was not just a “dedicated anti-Fascist”; he was the original anti-Fascist.) When the warrants for his arrest were issued, he had to flee, and flee he did. He next wound up in Spain. Premiani was soon in the same situation he was in Italy after criticizing Franco. He was also still too close to Italy and Mussolini, who were still

I worked closely — and still do — after 40 years, I’m still working with Luis Dominguez, who was probably the artist closest to Bruno in style and personality and friendship. They came up here six months apart, from Buenos Aires, where they had worked together on the Argentinian version of Classic Comics, and things like that. And Bruno, as I said, learned to get along, through various (probably nasty) experiences. But Luis has never learned that in all these years. Luis will still blow his top and walk away from a job because it isn’t exactly the way he would like to do it. For the last 10 years, I’ve been his agent and he’s turned down more than one assignment that I’ve gotten for him, simply because… Well, for example, I got him an assignment to do some Christmas cards and they had religious themes. He didn’t object to that. (I mean, he did object, but he didn’t make a big noise about it.) But when I got him an as-

interested in his affairs, so Bruno fled to Argentina. When he was in Argentina, he became an outspoken critic of Juan Peron, because Bruno was Bruno. He had to leave for another country, and Bruno soon found himself in the United States. Eventually Bruno felt he had to flee the United States and return to Argentina with the situation improved there. When asked why he had to “flee,” Bruno cited the rise of Ronald Reagan, stating, “I know a fascist when I see one!”

Above: Comic book great Arnold Drake on the balcony of his Manhattan apartment, circa 1999. The photographer is unknown.

Below: The Doom Patrol, an Arnold Drake creation, debuted in My Greatest Adventure #80 [June ’63]. Art by Bruno Premiani.

known that, he would have been with us in a shot. And I’m told that Gil tried to do it, himself, about 10 years later.

So I think I was a pretty sh*tty organizer. [Jon laughs] So that didn’t help too much. And I offer as an explanation, in part, the fact that both my parents died within about six months of each other at that time. My wife was inordinately fond of my mother, because my wife’s own relationship with her mother was not good, and she found in my mother the mother that she wished she had. So, when both my folks died within six months of each other, it had quite an impact on us. So I said, “Screw this. Let’s pack our bags and go someplace for a while and try to get this out of our system.” So we did that. We went to London and lived there.

CBC: Is it in the late ’60s?

Arnold: Nineteen sixty-seven, yeah.

CBC: And this was after the… Arnold: After the meeting. There were two meetings. Everything changes that… As a result of our discussions, which I guess I led… I don’t think there’s any question I did… as a result of that, Liebowitz came to respect me. I don’t think he trusted me. There was no reason why he should. But he respected me, and he would open questions with me that I don’t think he discussed with anybody except maybe his top editors. At one point, he said to me, “I don’t have a real editor-in-chief. I have these two men, Weisinger and Schiff, but I don’t have an editor-in-chief because, if I appoint one, the other one will leave.”

So he said, “I have no answer for that problem and it’s gone unanswered for a number of years.” So I said, “I think there is

a fairly simple answer.” And he said, “What’s that?” And I said, “Bring in an editor-in-chief from outside the organization. Bring in somebody who will impress the hell out of both Schiff and Weisinger.” And he said, “Who would that be?” And I said, “Offhand, I don’t know, Mr. Liebowitz, but I would try to hire a top vice president at Time magazine, for example.” And he said, “Are you crazy? You think that there’s an editor at Time who would want to go to the comics business?” And I said, “Yes, if you offer him double what they’re paying him.” So he said, “No, no, no, no.” Which was a part of the “we’re really a whorehouse, why would anybody want to do business with us?”

And another time he told me proudly how Mort had brought him a marvelous proposition. There was a guy who I think was from Boston, but was now living out on the island where Mort lived, and they used to come in on a train together, and they would talk together, and this guy was fully prepared to bankroll a pilot for a Superman television cartoon for TV, a Superman TV cartoon. And Mort brought it in, and Liebowitz was kind of excited about it. The guy’s willing to put up his own money and so on, and so forth. So he told me about it, and my reaction was, “I don’t understand why you don’t form your own studio and do Superman here, and use your artists to do storyboards, and then get some professional animators.” He said, “What do I know about the animation business?” And I said, “What did you know about the comic book business in 1937?” But, see, that’s the other aspect of him that I spoke of, the non-risk-taking Liebowitz.

CBC: The accountant.

Arnold: Yeah. He saved the business, and then it couldn’t bloom, it couldn’t blossom, because of him.

CBC: Now, if you look at it with the sheer change of the writing, all of a sudden the medium age of writers, between 1966 and ’68, dropped to basically teenage level. Marv Wolfman, Len Wein, Mike Friedrich, any number of very young, green writers who were comic book fans coming in, while the old guard literally disappeared overnight, except for Weisinger’s books, and even then, even Julie Schwartz, he didn’t have Gardner Fox or John Broome anymore. Leo Dorfman was gone in short order and replaced by Cary Bates… And I don’t know if I told you this before, but I interviewed Joe Orlando before he passed away, and he told me a story about you sitting in Liebowitz’s office, that was disparaging. He basically portrayed you as being a very arrogant writer, as being somebody who was just very arrogant. And he said that, I’m paraphrasing, but, “Little did Arnold know that the artists were in charge now.”

Arnold: Well, I knew that.

CBC: And then you weren’t there anymore. All of a sudden your credits started appearing over at Marvel. You didn’t do “Deadman” anymore. You were gone.

Arnold: They didn’t throw me out. I walked out.

CBC: Was it a hostile environment that made you walk out?

Arnold: I made a deal with Irwin Donenfeld and he had reneged. I went into his office and I said, “Irwin, you know the climate in the business has changed, and your answer is Carmine Infantino.” I said, “That’s a very good answer, but that’s only half of the formula. What you have is a Jack Kirby. You need a Stan Lee.” And I said, “I’m offering myself.” So he said, “Well, that’s interesting, but you’ll have to give me time to think about it.” So I said, “Well, how much time do you want?” And he said, “Six months.” So I understood that he was saying, “You’re a schmuck.” So I said, “Oh, okay. Well, I’m agreed that you want six months to decide, but in the meantime, I want a 30 percent raise in my rate.”

CBC: Might as well go for broke, right? [laughs]

This page: Above refers to Arnold’s last Doom Patrol issue, #121 [Oct. ’68]. Below is cast of the Doom Patrol [2019–23] TV show.

Interview Conducted by Jon B. Cooke

Comic Book Creator: You were born April 22nd, 1947, and your middle name is Kerfoot…? What’s that from?

Steve Englehart: We’re not exactly sure. It’s a family name, but not recognizably any language. So, you know, it just is.

CBC: That’s kind of a cool name. Did you continue it?

Steve: No, we did not continue it. We did find a town in Wales once named Kerfot, with just one O, but nobody there understood how that might connect to me, so I got no explanation.

CBC: What’s your ethnic background?

Steve: Well, I have the German name, but DNA stuff says I’m like 60% British Isles, you know… Central European whatever.

CBC: Your father worked for the Louisville CourierJournal and the Dayton Daily News, right?

Steve: Yeah, he was a journalist, starting out at the Dayton Daily News, and I lived in Dayton from age one to three. Then he got the job at the Louisville Courier-Journal, so I lived in Louisville from three to 13. Then they made him the Indiana bureau chief, because Louisville is right on the river between Kentucky and Indiana. And so we moved up to Indianapolis, where I lived from 13–18. Then I went to college back east.

CBC: Do you have brothers and sisters?

Steve: One each, yes. I’m the oldest.

CBC: Were you a bookish child?

Steve: There are actual books that I handmade, where I would type a story and figured out the pagination — you know, if you cut the pages and folded them together into a booklet, so that you read it in the right order, and so forth. So I was not only interested in stories, but also in the process, the actual physicality of a book. I will jump to comics at this point: I was really fascinated about how the four-color process worked. And, you know, how they did all that stuff in addition to liking the stories.

can’t draw any overall conclusion from that, other than I like to see behind the scenes, here they were in 1930 doing something, and here they are doing it in the ‘50s…

CBC: Those little booklets that you made…? What were they?

Steve: A couple of them were Hardy Boys books and they still exist. My mom kept them. I would have to figure out what pages, how the pages would line up, and then I would type on the pages. To this day, I’m a two-finger typist, even though I’m a professional writer. I would type to the end of that page, and then I’d figure out where the next page would appear, and then I’d go continue the story on that. It was the process that was interesting.

CBC: That’s interesting. To what do you attribute that to? I mean, to be actually into the construction, to create signatures of a booklet and all that?

Steve: I don’t know, it’s just something that fascinated me. Growing up in the ’50s, there was Superman, Batman, and whatever, but there was also the Dick Tracy reprints. And I loved them and still love Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy. I noticed as, as they did the reprints, that there was content that had been in the newspaper and then, in the Harvey reprints, when they reprinted the comic strips — this was after the Comics Code [was established] — they took out the violent stuff, but they only took the violent image out of the black plate. So there would be guys holding the shape of a gun that was colored blue, shooting a red blast, but there was no actual gun. You know what I’m saying? The black plate had been edited, but not the other plates. That was one of the intricacies, the secrets of the business… people think that because I write comics, I should be into science fiction, but I’m much more into mysteries and wanting to know the secret. I can’t say why I feel that way; it’s just what I like.

CBC: Were you a precocious child? Did you start reading early?

Steve: Yeah, I think so. I read The Hardy Boys, which my father had from when he was a kid. So I had Hardy Boys from the ’30s and had Hardy Boys from the ’50s. It was interesting how they had changed them over time, you know. I

Did you borrow your dad’s typewriter or have your own?

Steve: I don’t remember. I can’t believe I had my own. On the other hand, I can’t believe that my dad could loan me a typewriter because he was working on it, you know? So I guess we must have had a second one.

CBC: What did you aspire to at that young age? Did you want to write? Did you want to be Franklin W. Dixon?

Steve: I was interested. The thing that caught me into comics as printed was the art. Part of that is there weren’t groundbreaking stories in the ’50s. It was all pretty, pretty bland and, you know, Comics Code approved. But you did have Dick Sprang doing Batman art and that was fascinating… I only wrote because I was asked to write something, at the start of my career. I enjoyed the writing and they liked what I wrote. And so we went on from there. But no, at the time before that, I was pointed in an artistic direction.

CBC: Did you visit your dad at the newspaper? Steve: Sometimes, yeah, sure.

Did you like it? Did you get the sense of a bullpen?

Steve: When he was in Louisville, he was the night city editor for a while. I don’t know if it was the whole time, but I remember going to see him at night, after my mom and my sister and I had been someplace, we stopped in, but he was busy being the night city editor. So we didn’t hang around or poke around or whatever. I’ve seen newspaper offices, but I don’t think it made much of an impression, one way or the other.

CBC: Were you distant from your dad or able to bond with him?

Steve: He was sort of a distant guy. I mean, we weren’t far apart, but we weren’t, you know, close either. So somewhere in the middle.

CBC: Was he an FDR Democrat or Dewey Republican…?

Steve: This is when newspapers were probably at their height, in the ’50s. He had his personal politics, but he never got into politics. I remember politicians would send him gifts at Christmas time and he would send them back, that kind of thing. I mean, he was he was very apolitical in his job. Politics were a personal matter. I think he was a Democrat, but he never slanted the news.

I look back on that as the golden age of journalism, where Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite… when journalism was an honorable profession, trying to present the news accurately without fear or favor. I liken that a lot to the golden age of comics and, in my case, the bronze age. But things have deteriorated in both of those professions from when they were at their best.

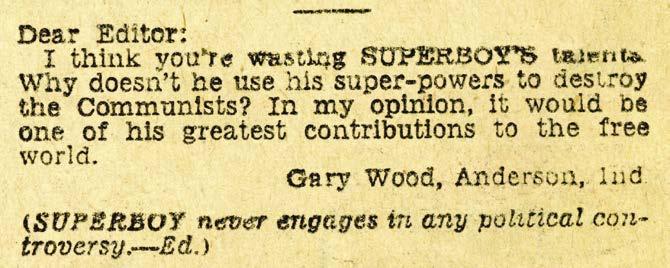

Previous spread: On left page are Steve and Terry Englehart from the 1980s. On the right is Kendal Whitehouse’s portrait of the writer, taken at San Diego Comic-Con in 2012. Above: Steve distinctly recalled being put off by comics for a time because of this lame response Superboy [#73, June ’59] editor Mort Weisinger gave to a reader’s question. Cover art by Curt Swan (pencils) and Stan Kaye (inks).

Below: Steve’s brother, Tom, is 10 years younger, and here’s a pic of the latter’s arrival at Casa Englehart, when Steve was… (Ye Ed checks his arithmetic)… 10 years old!

CBC: Were you an informed as a youngster? Did you read the news at all or were you…

Steve: Yeah. We subscribed to both Time and Newsweek, and I read them both cover to cover every week. Again, reality fascinates me, you know. What do people do? How does it all work? You know, that kind of thing… Every week I would plunk down — we had big, big windows in the living room that faced the sun — and I would lie in the sun and read Time and Newsweek and there were two newspapers a day back in those days. I read everything.

CBC: Coming into the 1960 election, what was that like at your age? You were about 12, 13 years old. Did it look like “the torch has been passed to a new generation,” so to speak? Was it an optimistic time?

Steve: Yes, absolutely. The ’60s… I have to jump sideways to comics again because the ‘60s felt like a time of just unlimited possibilities. I mean, it started with the young president who very quickly said, “We’re going to the moon before the decade was out.” And so, I think, that had a lot to do with Marvel Comics getting on their feet… it was the time you could wear a costume. There were the mods and the rockers, and just everybody sort of blossomed in the ’60s clothes-wise, comics-wise, music-wise, all that stuff. So, yeah, it was a cool time to be 13. And, of course, like everybody else who’s old enough to do it, I can remember when Kennedy got shot, which was a shock. But then, right after that, the Beatles appeared and we were off to a whole new thing.

CBC: I actually had a friend track down that Superboy letter column, there’s a letter that says exactly what you said in an interview, where the reader asks the editor why doesn’t Superboy fight the commies and Mort Weisinger answers, saying Superboy doesn’t get political. So that actually had an effect on you?

Steve: Well, I just explained that my dad never got political, but that was his job — not to be political — but, in terms of Superboy, any of those guys, it seemed like there were always obvious enemies in the world and it didn’t make any sense to me that the super-heroes would just ignore that. I thought that at the time (and I’m not sure when I gave that interview where I talked about that), but I can immediately connect that to the Captain America/Watergate stuff. So, when I had a chance to do something…

CBC: I think the timing would have been right around when the Cuban revolution had taken place. It was the June 1959 comic book and the Cuban revolution happened in January of 1959. Were Commies the bad guys when you were a kid?

Steve: Yes, they were, but I don’t know that I was ever right-wing, so I never thought of them as demons or anything. But they were just sort

of the guys that were posited as the bad guys in the world, you know? So, yeah, we didn’t like Communists particularly, but I don’t think it affected me very deeply being in Kentucky and Indiana… I wasn’t running into Communists, so I didn’t have to worry about it.

CBC: How old were you when you moved from Kentucky?

Steve: Thirteen.

CBC: That’s an impressionable age. Did it have an effect on you to be yanked out of Louisville?

Steve: Yes, to an extent. The Courier-Journal had a Washington bureau, so there was a guy permanently in D.C., but every year they would take one of their editors and send him to Washington to gain larger experience, whatever. So, in ’59, we moved to Washington for nine months, something like that. And so I was yanked out of fifth grade and went to sixth grade in Washington, which was interesting to add to my experience, but to be dropped into a whole other school system, new friends, all that good stuff, and then to be yanked out of it again after nine months… So I went back to Louisville and, for better or for worse… I was always a smart kid. And that year, in the seventh grade in Louisville, they instituted what I guess you would today call AP classes, where they took people they considered smart and put ’em in special classes. And so I was in with all the other people who were considered smart. And so we had our smart group dynamic going on.

Then I was yanked out of that in the eighth grade to go to Indianapolis, and I had started studying Spanish in the seventh grade, under a Cuban teacher who had fled Cuba. So I started studying Spanish in the seventh grade and, when I got to Indianapolis, they did not have any Spanish for the eighth grade. So I had to wait till the ninth grade to continue Spanish and then the teacher was not a good teacher. I knew more Spanish than she did…

So all that jumping around was disconcerting, in a sense. But, on the other hand, when you’re 13-years old, you just go where your dad goes. I mean, you don’t need to parse it particularly. My wife was an Army brat and she talks about moving every two years and so my situation wasn’t that terrible. But I was sorry, having been anointed as a smart kid and put in smart kid classes, it was weird to not have any access to that the following year. But you know, whatever… you do what you do.

CBC: When you were in Kentucky, did you have neighborhood kids that you hung around?

Steve: Sure. Yeah.

CBC: Did you maintain any of those friendships afterwards or were the friendships all done?

Steve: Yeah, they were all done. I mean, we had no internet. Once we moved, you know, unless I was going to write letters to people… Though I would do that, that was about my only option.

CBC: Were you close with your siblings?

Steve: Yes. My sister was born two years and two days after me. My brother was born ten years after me, so I was I was tight with my sister. And so, you know, by the time he was eight, I was gone away to college. So that was just a different relationship. But my sister and I obviously were close together…

CBC: So did you watch a lot of TV?

Steve: Yes, I did. Loved TV. Louisville, in those days, had no ABC station, so I would hear about things like 77 Sunset Strip and Maverick, and I couldn’t see them except when I went to Washington. We only had two network stations in Louisville, back in the day.

CBC: Were the schools you went to, were they all-white or were they integrated?

Superboy #73

clipping courtesy of Marc

Svensson.

Photo courtesy of Steve Englehart.

Above: Steve’s first scripting gig (plotted by Al Hewetson), in Monsters on the Prowl #15 [Feb. ’72], illustrated by Syd Shores. Below:

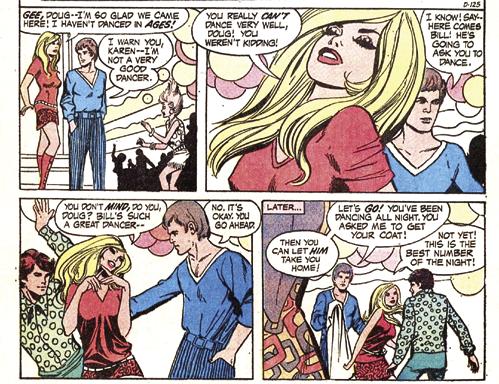

Steve art job for the “Do’s and Don’ts of Dating by Paige Peterson” one-pager, Young Romance #174 [Sept. ’71]. Inks by Vince Colletta.

tion, I said, “You know, when I get out of the Army, I would like to work with you.” I mean, what a ridiculous thing to say, right? But he said, “Well, can you come up every weekend?” And I said, “Yeah, but I’m in the Army.” And he said, “But just come up every weekend.” And so that’s what I did.

So while not every Friday, for most of them I’d go hop on the train and go to New York. Neal liked the lightbox at DC that I guess he didn’t have at home (or maybe this was a better one, but he liked working on it). So he would, as a rule, hang around after 5:00 until midnight or 1:00 in the morning working. And I would work with him and then I would go to Columbia and would sleep on a couch, and then I would go out to his house in the Bronx, I believe, on Saturday and spend all day out there. Um, I would get fed and I would play with his kids, but it was there when I worked on this Vampirella [“The Soft, Sweet

Lips of Hell,” #10, Mar. ’71] job that he was doing, and he only worked on it on the weekends when I was there. I mean, he did his other stuff during the weekdays, but every week I’d come up and we’d do the Vampirella thing. And he insisted on having my name on the credits, which nobody did for their assistants, let alone a guy who’s just breaking in as an assistant. But he said, “This way, when you go onward, you’ll have a published credit.”

Neal was just the best guy ever in those days, and I’m fully aware that he changed over time. But, at that point, he was just the best guy ever. And when I applied for conscientious objector, I had to be interviewed by a shrink and a priest, because this was the ’60s. You had to be interviewed by an officer knowledgeable in matters pertaining to conscientious objection, and there aren’t any, because why would an officer know that? But they assigned me a W.A.C. Major, which I thought is about as bad as you could get, because to be a W.A.C, you had to want to be in the Army. And to be a major, you would have to re-enlist in the Army. But she was the one that I had to talk with to convince her that I was sincere. And Neal, on his own dime, came down to Maryland to testify about my character. That’s kind of guy he was… so: wow!

CBC: When you were working together, did you guys just talk about life in general?

Steve: We did. Neal was a very interesting guy. When I told him about the whole conscientious objector thing, that was fine with him. And, in fact, I’m sure that he thought that was a good idea, but he never pushed me. You know, he never was trying to convince me that I ought to do anything in particular. We would talk all weekend, and every Sunday, I’d go catch a train and go back to Maryland, to Aberdeen Proving Ground… You asked me if I’m a forthright kind of guy…? I guess I am, going to Neal Adams at the height of his popularity and say, “Hey, how about if you take me on?” But he did and so, when I got out of the Army, I did have a published credit. I knew people in the business and I was on the path to being a comic book artist, which was what I had still been shooting for.

CBC: Did you just volunteer? Were you were you doing this for free or did you get any reimbursement for it?

Steve: What…? For working with Neal? I got fed and that was enough, you know. No, he wasn’t paying me for that.

CBC: Did you work on any of the DC stuff?

Steve: Yes. I did some one-page mysteries for Murray Boltinoff. Filler things. I did backgrounds for Bob Oksner on “Supergirl” and Jimmy Olsen. I did some backgrounds for Dick Giordano on some Detective stuff. I mean, I was in the entering phase of things, doing the pickup stuff. Same as when I started writing, where I was doing romance books and things like that, where you start out small and hopefully work your way up.

CBC: You’ve previously mentioned you had done work with Dick’s brother-in-law, Sal Trapani, and the Bob Oksner stuff. How did you come upon that if you’re just coming up on weekends?

Did Neal have those pages for you?

Steve: No, this was with when I was in the Army. It was only with Neal. Right when I went to New York, then I’d do a thing for Murray Boltinoff and either he or somebody would say, “Well, Bob Oksner needs somebody to do backgrounds. And then I’d go to Bob, who lived in New Jersey, and I would go to his place. I didn’t spend the night there. I probably just went down on the Saturday and did it. I don’t think I was sleeping at Columbia when I was doing that, but I’m not exactly sure. But, at this point, I did go to Bob’s place and do backgrounds for him. And I’d go to Dick’s place and do backgrounds for him.

CBC: What was Bob like?

“Terror of the Pterodactyl”

Steve: Bob was a great guy, too. A really nice guy… most people in comics are. (I mean, not everybody, as you may be aware, Jon.) Bob was just a friendly guy and had a really nice art style, and he had cute daughters, as I recall, around my age. I took one of his daughters out once when I was down there, on a Saturday night. So I must have brought her back, but I didn’t pass out at his house. So I’m not real sure what I did on the Saturday nights when I was doing working for him, but I was keeping busy. I was doing the entry level stuff, but that’s what I was at the time: entry level.

CBC: Wow. For the Vampirella job you were working on, did you ever have any dealings with Warren editors or Jim himself?

Steve: I dealt with Jim later, when I was writing Vampirella. We would stop by, once I was in New York. In those days, you

had to be in New York City. I knew John Severin was out in Denver and Sal Buscema was in Washington, D.C., but otherwise, everybody was in New York. So, if you were in Warren’s neighborhood, you’d just drop by.

I mean, by that time, if you’re actually doing work for them, it’s not so weird to drop in. Jim took a bunch of us to dinner one night and then brought us back up to his apartment. I remember he had a bidet, and he was showing it off his bidet… none of this is to snark on anybody. I liked Jim.

When the Jules Feiffer book, The Great Comic Book Heroes, came out, I went to my bookstore at Wesleyan and had him order it for me. It had fascinating stories of what happened in the ’40s and I got to see these early characters and so forth. So, by the ’70s, I thought, “If you’re going to be in a business, you should know everything about it.” So I was fascinated and really paid attention to how comics done in the ’40s. Who did them… and about the ’50s, etc. So what I’m trying to lead up to here is that Wally Wood and Bill Everett were still around in New York, at that time. Will Eisner was around. I went to parties with Wally Wood and helped him when he was supremely drunk and got him on a subway and rode with him to his stop.

I mean, the stuff you do when you’re entering this magical world…!

CBC: You were the first of the “Crusty Bunkers”? Is that fair?

Steve: In retrospect, yes. When Neal took me on, he had never taken anybody on before, and there was no name for it. It was just assistant. But I guess he liked having assistants and so, you know, then he started getting more of them, they became the Crusty Bunkers. So, yeah, in retrospect, that’s fair to say.

CBC: You once told a story that Neal taught you not to believe companies’ sales reports. You saw evidence of numbers not matching what Neal had been told…?

Steve: Yes. Definitely. That’s endemic at DC. When Joe Staton and I did Green Lantern and then Green Lantern Corps, Dick did a column about how we had doubled the sales on Green Lantern, and yet we never saw any royalties… We’re in the jumping all the way to today. You may or may not know that Joe Staton and I don’t get a dime for Guy Gardner. We have never gotten royalties. We’ve never gotten credit for Guy Gardner.

CBC: Not even a gratuity like Marvel does?

Steve: Nope. DC’s official position is that there was a guy named Guy Gardner. Completely different guy, but because I said it was the same guy, then I didn’t create anything. You know, Joe didn’t create anything. We’ve been after them for 40 years about that, and Guy Gardner is about to be in the Superman movie, and I really don’t want to rain on James Gunn’s parade. I like James Gunn. I like the Guardians movies. I like the Suicide Squad movie. But whenever Guy Gardner comes up, people go, “Whoa, what do you think about that? And I go, well, they’ve been ripping us off for 40 years. So I’m hoping that we can resolve that, and feel free to tell your readers I would like them to resolve it. I would like them to give me and Joe what we should get. And so when people come around, I can say, “Yeah, I love Guy Gardner.” End of story. But I mean, that’s just DC’s thing. You’ve seen about

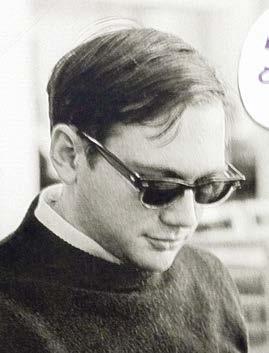

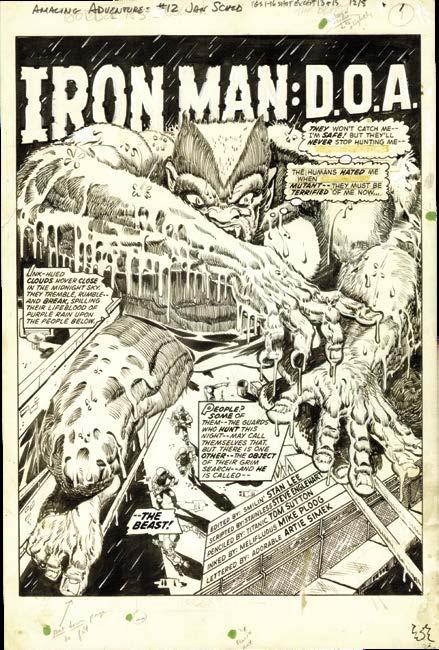

Above: Steve in 1973. He scribbled on the pic, “Note the glasses!” Inset left: Evocative Amazing Adventures #12 splash. Tom Sutton (pencils) and Mike Ploog (inks).

Below: AA #11 [Mar. ’72]. Art by Gil Kane (p) and Bill Everett (i).

me and the original Batman movie, where they ripped me off? I do not like them.

CBC: Did Marvel treat you any differently?

Steve: Yes! When they didn’t give Kirby credit on the Avengers movie, everybody gave Marvel sh*t. So somebody at Disney was smart enough to go, “Well, we can give these people credit and we can give them some money because we’re Disney and we have infinite amount of money.” (They did at the time.) So they went to people who had created stuff and, you know, me and everybody else and said, here’s a contract, we’re going to give you X-amount of money and we’ll give you a screen credit and so forth. And I’m sure part of it was, “Let’s buy their goodwill.”

I’ve been very clear because I bitched about Mantis… I love James Gunn, but that’s not my Mantis. And that’s my point. The movie was fine. I like Pom Klementieff. I like the Mantis that was on screen, but wasn’t my Mantis.

So I’m perfectly happy to say whatever’s on my mind. But fact is that when Mantis or Star-Lord or Shang-Chi or any of these characters show up, I get a screen credit and I get some residuals. And I was talking to Steve Epting about Winter Soldier. They took Bucky Barnes and turned it into Winter Soldier

and they get paid for that; whereas DC would go, “Nope, you didn’t create it.” So the two companies are very different in how they treat their talent.

CBC: Tell me about that epiphany that the artist’s life wasn’t for you.

Steve: It wasn’t so much an epiphany. I got on staff at Marvel, I took Gary Friedrich’s slot as the lowest ranking editorial person for six weeks.

CBC: How did you get that?

Steve: Well, that’s the story. Because I was in New York, I got to know pretty much everybody in comics, including Gary. We went to a couple bars together now and again, and somebody was murdered — a stewardess — in the apartment above Gary’s in New York and his wife said, “I want to get the f*ck out of here for a while. Let’s go back to Missouri, where you’re from.” So Gary got in touch and said, “They’re gonna need somebody to fill in for me while I’m gone for six weeks. Would you want to do that? I’ll talk to Roy.” And I said, “Yeah.” I was, at that time, living in Milford, Connecticut, which is a two-hour train ride out of the city. So I would have to take a two-hour train ride in and a two-hour train ride out every day. And so I wasn’t like leaping at this. But getting on staff at Marvel, that was a step forward that seemed like a good idea. So I went down, talked to Roy and again, in my forthright manner, I said, “Yeah, I’ll do this four days a week; I’m not coming for five.” And he said, “Okay, sure.” So I was on staff at Marvel.

At the end of six weeks, Gary had a six-page monster story and he was just so laid back out in Missouri, he didn’t want to write it. So he sent it back. Roy looked around the room and asks me, “Well, you want to write this thing?” And I said, “Sure, I’ll do that.” And I went home that night, wrote it, brought it back, and they liked what I wrote. So then they said, “Hey, you want to write some more stuff?” And I said, “Sure.”

And, pretty soon, I was not doing very much in the way of art, but I was writing and, in those days, they didn’t let you on the super-hero books until you served an apprenticeship writing romance and Westerns and monsters. So I wrote romance and Westerns and monsters, and did do art on a couple of romance books, too. I was still doing it, but I did like the writing. You know, it turns out writing is not hard for me. I like the process of the logical systems, as I said, about languages and so forth. It’s like, okay, you’ve got all these ideas now, how do you put them together in some sort of coherent narrative that has a big climax, has good visuals, and all those things you have to think about when you’re writing comics? I liked doing it. And so, I did a complete one issue of The Ringo Kid with Dick Ayers, which never got printed. I did several romance stories, writing and drawing. I did some monster stories, and then after X-number of months, they said, “Well, you want to write ‘The Beast’?”

CBC: What about art? Did art just fall by the wayside because you got too busy with writing?

Steve: Yes. I stayed on staff for a while, and I would go home at night. I eventually moved to Stamford, which was 45 minutes out of the city, not two hours. But I would be on staff by day, and then I would go home at night and I would write, and that took up my time. I didn’t have any time to do any art after that. Stopping with the couple of romance stories that I did, that was probably the last art that I did. And it’s been so long, when people now have me sign stuff and ask me to do a little sketch, I’m like, “Nope, I haven’t drawn anything for 50 years. I’m not not gonna do that.”

CBC: So what were you doing up in Milford? Why so far away? And what were you doing?

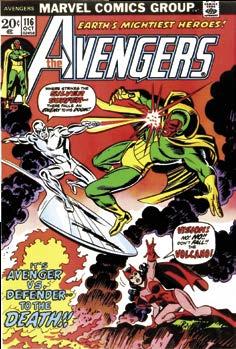

This spread: Wonderful spread by Dave Cockrum from Giant-Size Avengers #2 [Nov. ’74], featuring Mantis, and some time-travelin’ baddies.Below: The Avengers #116 [Oct. ’73]. Art by John Romita (pencils) and Mike Esposito (inks).

fighting Commies, but it wasn’t the same Commies. It was a different type of Communist. And racism certainly had nothing to do with Vietnam in that regard. Well, I mean, it was racism…

CBC: It was the rationalization for the war. I mean, flat out we were there to fight Communism. That was the big threat. The domino theory and all stuff like that…

Steve: But the thing was that, growing up in the ‘50s, there was a certain type of “We hate Commies,” right? That’s it. And I think it was that mindset that led to the war. But I don’t think a lot of people who were fighting the war were to… It moved on. I mean, this was a different sort. This wasn’t the evil Russian mastermind infiltrator, look-under-your-bed, kind of Communist. This was a bunch of guys across the ocean, and they might have been Communists. And that’s why we were fighting them, but I don’t think that the people who were actually doing the fighting thought in those terms.

CBC: Did you invent Roxxon?

Steve: Yes. Roxxon. Yes, I did.

CBC: That’s kind of daring, right? You were taking on Exxon?

Steve: Well, yeah, but I don’t think Exxon was going to come after me for it. I don’t know how daring it was…

[At this point, Steve regals the interviewer with an anecdote about “Studio Zero,” which we’re saving for next issue’s in-depth article on Englehart & Company almost getting in Rolling Stone magazine! — Y.E.]

CBC: Well, my brother and I, we instantly recognized the double X as being play on Exxon.

Steve: Oh yeah, sure.

CBC: Just a curious question: did you receive, way back in the ’70s, did you receive comp copies of every single thing that was published?

Steve: By Marvel and DC? Yes. I mean, not from Charlton or anything like that, but yes, we all got every book that both companies published.

CBC: They sent you packages when you were out in California? You received a weekly package?

Steve: Yes. So, as I said, I read everything on my way to becoming a professional. And then, after I got to be a professional, I got all the books for free, which was fine, you know, but I continued to read everything. I like to know what else is going on in, in whatever world I’m in.

CBC: When I was a kid, I was truly annoyed at this idea of using one page of art and turning it sideways and printing it as two pages of art because it was just so obvious by the thick ink line from being enlarged and you’re like the only guy who remembered it and you’ve mentioned it repeatedly. It just seems outrageous to do something like that and cheat the freelancers (and readers).

Steve: I’m totally with you on all of that. But you’re working for the company and they go, “This is what we’re going to do.” And you go, “Well, okay, then.” But I totally agree. You could tell that it was blown up. I think I would try to make it a double-page spread so that at least it could be one piece of art, but sometimes it was panels and you could see the panels were bigger and everything was bigger and all that. They didn’t do it for too long, but it was a dumb idea, but it was somebody in accounting somewhere going, “Well, look how much money we could save if we did this!”

CBC: But it was also ripping off you freelancers.

Steve: Yeah, but what are you going to do?

CBC: Steve, you certainly did something by ’76. You walked.

Steve: Well yes, you can do that. I have walked several times

over the years. But it’s not like I want to walk. “I think this would be really cool, let’s do that.” Somebody said to me once, “You think like a hero, which is why you write super-heroes” and, you know, whatever… But I do have a sort of sense of right and wrong, and making a page twice as big as it ought to be is wrong. But it’s not like “walkable” wrong. But there are things where I’ve said, “I can’t do that,” and then I leave. So I’m glad they didn’t keep doing that but, at the time, that wasn’t big enough for me to do anything drastic.

CBC: But things were starting to pile up on each other. As a reader, I recognized there was an exodus from comics that just went over to alternative comics. You went to Europe and became a novelist at the same time there was this great exodus coming from comics. And your career really tracks that. Did you feel like you were at the forefront of that exit or was it just you amongst the other guys? Do you think your actions, perhaps, could have encouraged others to do things to their own benefit?

Steve: I would say “perhaps.” I don’t know any specifically. When I did walk, there wasn’t a mass exodus behind me. So I don’t know that I encouraged anybody directly. Indirectly,

Above: Cover proof for Captain America #176 [Aug. ’74]. Art by John Romita. Below: Nomad by Sal Buscema.

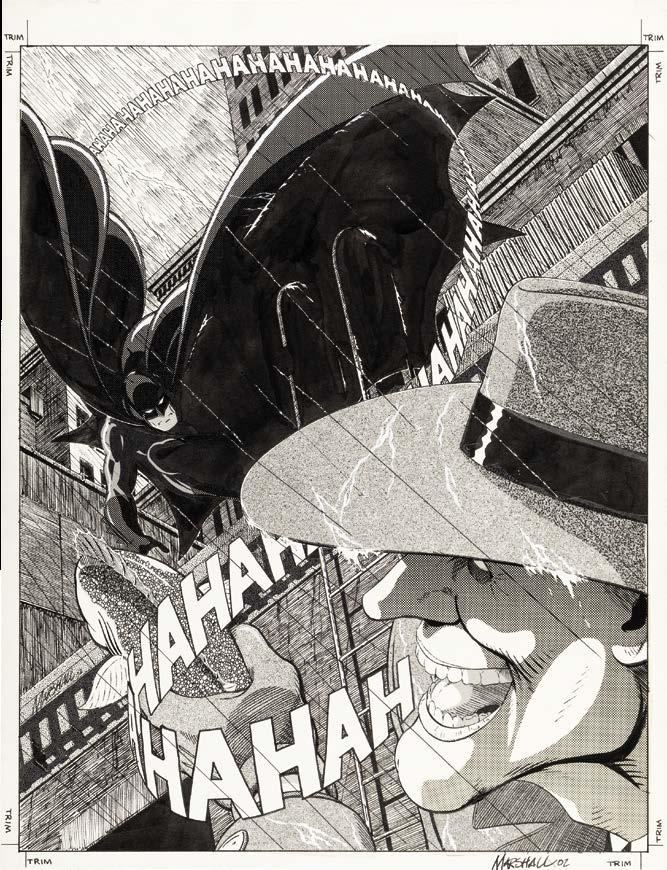

This page: Please don’t get snippy because virtually no attention was given in this interview to Steve and Marshall Rogers’ great Batman work in the ’70s. That extended conversation — which included a separate interview with the artist — took place in Comic Book Artist Collection, Vol. 3 [2002], available at the TwoMorrows website (in the CBA Special Edition #2 PDF). Here’s the wonderful original and printed artwork by the late, great Marshall Rogers for Ye Ed’s compilation.

on, too, so… The Red Skull has weird sh*t going on. I guess my comic-book view of things is that those guys are just cool characters, you know?

CBC: One thing I noticed too with the Mantis character: I think that’s really revealing that what you did is that you let the character grow on her own. You would repeatedly call her a “Saigon slut,” right? And, in the end, she was not anything like that. It seemed to be denigrating the plight of South Vietnamese women who were forced to work a life of prostitution during the Vietnam War and yet she shook that off.

Steve: She was supposed to be a femme fatale. I’m sure you’ve read this in other interviews, but she was supposed to come in and create tension in the Avengers by sort of coming on to all of them. And that was her goal. That was what I had in mind for her. Something to shake up the team.

But right after I introduced her, Roy said there weren’t going to be any annuals that summer, and I had really loved the annuals as a reader. So I said, “Well, I’m writing The Avengers and The Defenders. Can I do a summer-long thing where they fight each other?” And he said, “If you screw up one deadline, everything will fall apart.” And I said, “I won’t screw up any deadlines.” And he said, “Okay, then go for it.” That was the editorial thing.

So, all of a sudden, I had to do a story in which she participated and she had to be fighting on the Avengers side and doing stuff. And so the whole thing about her being a femme fatale later came back in a minor sense with her and the Vision

and Wanda, but she suddenly took a turn becoming like a real teammate and not a distraction. And I said, “Well, that’s interesting.” Now I’ve got her in the book, but she’s different from what I thought she was going to be.

I’ve told this story in analogy many times. You write, you come up with an idea, and the guy’s going to go to Chicago and then for whatever reason, he has to go to Cleveland, and you can force him to go to Chicago or you can say, “Okay, well, now that he’s in Cleveland, how does that change what I want to do?” And that was basically what I learned by doing her in each issue. I would do a story that moved the Avengers forward and concentrated on other Avengers and this and that and the other thing. But she was there and she’d have to do something. And last issue, she did this thing, so now she’s at this point. So now, in this issue, she’s going to move off of that point. She didn’t have to end at any point. It was not like, “Oh yeah, she’s eventually going to become the Celestial Madonna.” It was just, “Here’s a story and then here’s another story. And there’s a mystery about where she came from. And then there’s…” Every once in a while, I’ll read interviews with other writers and they’ll go, “My characters determine where the story goes.” And I go, “Yeah, then that’s the best way to do it, rather than try to force anything, try to make things happen, you know.” So that’s Mantis.

CBC: It seemed to me with Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Mantis is this sensual creature. Or at least, you know, this hyper-empathic character that seems to contain a germ of an idea from the original comics, and yet she was somehow transformed into this different character. Do you see any of your Mantis in the movie character?

Steve: I’ve said for a long time the only thing those two have in common is they’re both female. All of the attributes of the comic book Mantis were jettisoned before you got the movie Mantis. But the empathy, the sensitivity? Yes, I can see that. I asked James Gunn why he brought in a character and then completely changed it. And he said, “Well, I needed a character like the one I had in the movie.” And, as a writer, I can understand that. You’re putting together a group and you need certain elements to kind of bounce off each other and so forth. I’ve been very vocal about the fact that I was disappointed. I spent a year-and-a-half creating this particular character and then it all got jettisoned. But, on the other hand, I’m not the kind of guy to go, “Well, James, you shouldn’t have done that.” He was making his movie. He needed what he needed. So, I like the Mantis on screen. I like those movies. I like Pom Klementieff as Mantis, etc. But it wasn’t my Mantis and I had spent a lot of time on Mantis, so I was naturally disappointed. The situation that exists with Disney and Marvel is, if they use Mantis, I get royalties, right? Even if it’s not my Mantis, which is kind of weird, but okay. I’m sure you’ve read those Hollywood interviews where they say, “What was it like working with that actor? Oh, that actor was great. I love that actor. Everything was fabulous all the time.” If I don’t think so, I’ll say so. But Disney doesn’t complain that I’m not totally on board all the time. So that’s cool, you know? So that’s the end of that.

CBC: To be precise, they’re not royalties, right? They are gratuities.

Steve: Yeah, I guess they probably are.

CBC: Because Marvel is the “creator” of all things Marvel, right?

Steve: But it wasn’t, “If we give you this, you have to kiss our asses all the time.”

CBC: Were you a nut for Watergate? Did you watch all the proceedings that were taking place on a daily basis on weekday

This page: Please don’t get snippy because virtually no attention was given in this interview to Steve and Marshall Rogers’ great Batman work in the ’70s. That extended conversation — which included a separate interview with the artist — took place in Comic Book Artist Collection, Vol. 3 [2002], available at the TwoMorrows website (in the CBA Special Edition #2 PDF). Here’s the wonderful original and printed artwork by the late, great Marshall Rogers for Ye Ed’s compilation.

on, too, so… The Red Skull has weird sh*t going on. I guess my comic-book view of things is that those guys are just cool characters, you know?

CBC: One thing I noticed too with the Mantis character: I think that’s really revealing that what you did is that you let the character grow on her own. You would repeatedly call her a “Saigon slut,” right? And, in the end, she was not anything like that. It seemed to be denigrating the plight of South Vietnamese women who were forced to work a life of prostitution during the Vietnam War and yet she shook that off.

Steve: She was supposed to be a femme fatale. I’m sure you’ve read this in other interviews, but she was supposed to come in and create tension in the Avengers by sort of coming on to all of them. And that was her goal. That was what I had in mind for her. Something to shake up the team.

But right after I introduced her, Roy said there weren’t going to be any annuals that summer, and I had really loved the annuals as a reader. So I said, “Well, I’m writing The Avengers and The Defenders. Can I do a summer-long thing where they fight each other?” And he said, “If you screw up one deadline, everything will fall apart.” And I said, “I won’t screw up any deadlines.” And he said, “Okay, then go for it.” That was the editorial thing.

So, all of a sudden, I had to do a story in which she participated and she had to be fighting on the Avengers side and doing stuff. And so the whole thing about her being a femme fatale later came back in a minor sense with her and the Vision

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL

and Wanda, but she suddenly took a turn becoming like a real teammate and not a distraction. And I said, “Well, that’s interesting.” Now I’ve got her in the book, but she’s different from what I thought she was going to be.

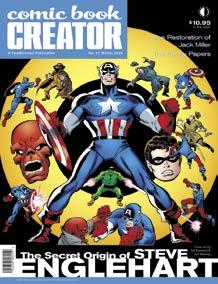

COMIC BOOK CREATOR #37

I’ve told this story in analogy many times. You write, you come up with an idea, and the guy’s going to go to Chicago and then for whatever reason, he has to go to Cleveland, and you can force him to go to Chicago or you can say, “Okay, well, now that he’s in Cleveland, how does that change what I want to do?” And that was basically what I learned by doing her in each issue. I would do a story that moved the Avengers forward and concentrated on other Avengers and this and that and the other thing. But she was there and she’d have to do something. And last issue, she did this thing, so now she’s at this point. So now, in this issue, she’s going to move off of that point. She didn’t have to end at any point. It was not like, “Oh yeah, she’s eventually going to become the Celestial Madonna.” It was just, “Here’s a story and then here’s another story. And there’s a mystery about where she came from. And then there’s…” Every once in a while, I’ll read interviews with other writers and they’ll go, “My characters determine where the story goes.” And I go, “Yeah, then that’s the best way to do it, rather than try to force anything, try to make things happen, you know.” So that’s Mantis.

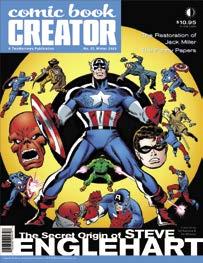

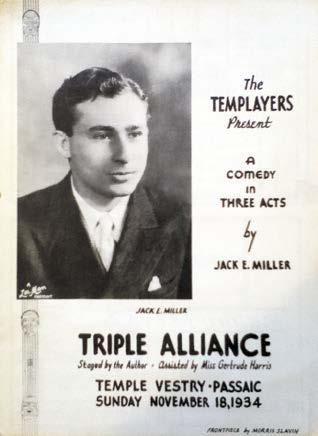

STEVE ENGLEHART is spotlighted in a career-spanning interview, former DC Comics’ romance editor BARBARA FRIEDLANDER redeems the late DC editor JACK MILLER, DAN DIDIO discusses going from DC exec to co-publisher, we conclude our 100th birthday celebration for ARNOLD DRAKE, take a look at the 1970s underground comix oddity THE FUNNY PAGES, and more, including HEMBECK! (84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_132&products_id=1800

CBC: It seemed to me with Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Mantis is this sensual creature. Or at least, you know, this hyper-empathic character that seems to contain a germ of an idea from the original comics, and yet she was somehow transformed into this different character. Do you see any of your Mantis in the movie character?

Steve: I’ve said for a long time the only thing those two have in common is they’re both female. All of the attributes of the comic book Mantis were jettisoned before you got the movie Mantis. But the empathy, the sensitivity? Yes, I can see that. I asked James Gunn why he brought in a character and then completely changed it. And he said, “Well, I needed a character like the one I had in the movie.” And, as a writer, I can understand that. You’re putting together a group and you need certain elements to kind of bounce off each other and so forth. I’ve been very vocal about the fact that I was disappointed. I spent a year-and-a-half creating this particular character and then it all got jettisoned. But, on the other hand, I’m not the kind of guy to go, “Well, James, you shouldn’t have done that.” He was making his movie. He needed what he needed. So, I like the Mantis on screen. I like those movies. I like Pom Klementieff as Mantis, etc. But it wasn’t my Mantis and I had spent a lot of time on Mantis, so I was naturally disappointed. The situation that exists with Disney and Marvel is, if they use Mantis, I get royalties, right? Even if it’s not my Mantis, which is kind of weird, but okay. I’m sure you’ve read those Hollywood interviews where they say, “What was it like working with that actor? Oh, that actor was great. I love that actor. Everything was fabulous all the time.” If I don’t think so, I’ll say so. But Disney doesn’t complain that I’m not totally on board all the time. So that’s cool, you know? So that’s the end of that.

CBC: To be precise, they’re not royalties, right? They are gratuities.

Steve: Yeah, I guess they probably are.

CBC: Because Marvel is the “creator” of all things Marvel, right?

Steve: But it wasn’t, “If we give you this, you have to kiss our asses all the time.”

CBC: Were you a nut for Watergate? Did you watch all the proceedings that were taking place on a daily basis on weekday