Edited by

PETER NORMANTON

Edited by

PETER NORMANTON

IT CREPT FROM THE TOMB is published by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC, 27614. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Website: www.twomorrows. com. Editor: Peter Normanton, Publisher: John Morrow, Proofreader: Scott Peters. All characters are TM & © their respective companies unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter © the respective authors. Editorial package is © 2018 Peter Normanton and TwoMorrows Publishing. All rights reserved. All illustrations contained herein are copyrighted by their respective copyright holders and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. No material from this book may be reproduced in any form, including print and digital, without the express permission of the publisher.

TwoMorrows Publishing 10407 Bedfordtown Drive Raleigh, NC, 27614 www.twomorrows.com email: store@twomorrows.com

First printing, January 2018 Printed in the USA ISBN: 978-1-60549-081-6

The Avengers, Captain America, Fantastic Four, Ghost Rider, Human Torch, Journey into Mystery, Manthing, Son of Satan, Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish, Thor, Tomb of Dracula, Werewolf by Night, X-Men TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. • Action Comics, Adventure Comics, Batman, Detective Comics, The Flash, House of Mystery, House of Secrets, Jimmy Olsen, Lois Lane, My Greatest Adventure, Mystery in Space, Showcase, Strange Adventures, Superboy, Superman, Tales of the Unexpected, Wonder Woman TM & © DC Comics • Tales from the Crypt, Haunt of Fear, Vault of Horror, Shock Suspenstories, Weird Fantasy, Weird Science © Wm. M Gaines Agent • Black Magic TM & © Joe Simon and Jack Kirby Estates • Creepy and Eerie TM & © Warren Publications. All other characters and properties TM & © the respective owners.

For over four decades the Cold War held the world to ransom. While the super powers stockpiled an everexpanding arsenal of atomic weaponry, the comic book publishers flourished just as they had during the Golden Age. In one way or another most of us will have memories of these years, some having experienced the duck and cover drills under the guidance of Bert the Turtle, whereas the less fortunate would have endured active combat in south-east Asia. For those of my generation it was the CND demonstrations united in their rallying call to ban the bomb and with it the annihilatory strategies of `First Strike Capacity’, `Pre-emptive Nuclear Strikes’, `Counterforce’ and the seemingly inescapable `Mutually Assured Destruction’. The threat posed by the bomb would transform into the politics of a chilling pragmatism, casting a portentous shadow over our lives and ultimately influencing the content of the comics flowing onto the newsstands. It was these comic books, so many of them consigned to the waste bin by well-meaning parents, that would one day return to shape the dreams of the Cold War Kid.

As to when the Cold War actually started is still the subject of considerable debate, but there is no doubt with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 the western world finally breathed a sigh of relief. Almost half a century earlier, the Allies and the Soviets had been united in their quest to destroy the Nazis, but their alliance was never truly stable. When the United States delivered their nuclear payload over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, relations became even more fraught. The Soviets, recognising they could now face a similar fate, set out to acquire this deadly technology in the hope of restoring the balance of power.

The duplicitous means by which they set out to pursue their nuclear aspirations would inevitably come to light and have far reaching consequences. With this in mind, the Cold War may well have stemmed from a series of events which occurred in Canada during 1946, culminating on the evening of September 5th, when a

member of the Russian embassy, located in the city of Ottawa, slipped away with 109 highly classified documents. These files were to reveal the lengths to which the Soviet Union had gone to infiltrate the most senior echelons of the Canadian government, all the while adding to their knowledge of the western powers’ global operations. When he first became aware of his government’s designs on America’s fledgling nuclear programme, Lieutenant Igor Sergeyevich Gouzenko of the GRU (Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye), Soviet Military Intelligence, began to compile a dossier he kept hidden from his colleagues. His testimony would ensure his family safe haven in the United States, but more significantly exposed the underhand nature of the Soviet Union.

This episode and those that followed, inadvertently bolstered a weary comic book industry, desperately in need of a new lease of life. Sales of the morale-boosting superhero comics championed throughout the war years had fallen steadily, with Captain America and his valiant ilk, who had once confronted Hitler’s elite, now reduced to battling petty criminals. The glory which had reigned over the Golden Age of the comic book was now looking appreciably dispirited.

The industry wasn’t entirely without hope, a range of crime and romance titles were to ensure its immediate survival. Occasionally they would capture the uncertainty of the day, most notably in the pages of Quality Comics’ Love Secrets #32, the Charles Sultan-illustrated “I Fell for a Commie” in the August of 1953. However, when the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear device on 29 August 1949, this survival and everything else with it was suddenly thrown into jeopardy. Panic spread across the free world, but the American press gave their readers an assurance the United States was still well ahead of the game. For all of their bravado, it was impossible to deny, the Soviets were now ascendant, plunging the super powers into an unimaginable arms race, the scale of which could have wiped out everything on Earth.

Worse was to come for the citizens of America. It was discovered certain members of the Manhattan Project had been giving Soviet scientists access to their work; amongst them Theodore Hall

Saucers” and Ozzie’s “Look—Flying Saucers!” respectively. Murphy Anderson’s rendering for the cover to Mystery in Space #15, while being an absorbing piece of flying saucer memorabilia, hints at a technology way beyond its time. We would one day come to know it as the Star Wars weaponry or Strategic Defence Initiative of the 1980s, a proposed defence system that was to prove paramount in the latter stages of the Cold War. EC and Atlas would make the flying saucer their domain, with tales of such incredible creativity they would leave their readership looking to the skies, once, of course, their outlandish content had been thoroughly digested. Only recently there have been suggestions it was Stalin himself who was behind the happening at Roswell. It’s safe to say, that if the Soviets had developed a flying saucer, the West would have been held over a rather precarious precipice.

One way or another the saucers could be dealt with, but when the Korean People’s Army surprised the world with a full-scale offensive, which saw them cross the 38th parallel into South Korea in the hours before sunrise on 25th June 1950, the United Nations were presented with a more serious problem. This incursion would begin a most acrimonious campaign, one which was to rage for the next three years, leaving 2.5 million people dead, most of them innocent civilians. As the conflict escalated, a new comic book phenomenon emerged: The Korean War comic. These titles enjoyed considerable popularity, thriving upon a war which the United Nations could have brought to an end as early as 1951 when the communists were forced back to the 38th parallel. However, there was a determination to drive these brainwashed aggressors from the Korean Peninsula, little realising the Chinese, still recovering from Civil War, would never accept the enemy encamped on their border. World War III loomed, as MIG fighters piloted by the Soviets and Chinese spiralled across the skies, dogfighting with American jet fighters. Such imagery roused the comic publishers; Exciting War promised `Blazing Korean Battle Action’, while Atlas’s Battlefield pledged `War Tales from Front Lines.’ These tales were indeed exciting, but even amid the excess of the pre-Code comic, the atrocities committed on the killing fields could never be fully

Like most old codgers (I turned 60 a few years back, fourth of July), my appreciation of comic books sits squarely in the past—1959-60 to be precise, which is when these wonderful creations first really hit the big time with British kids.

The first ones were dated November and December 1959, though a few Octobers and even, as I recall, one September wormed their way into the metal racks of newsagent shops up and down the country . . . not least Guest’s Greeting Cards emporium in Leeds Market which, in those halcyon days, smelled of fruit and flowers, frying bacon and cigarette smoke. The store itself was run by Alice, a wonderful woman with a mouth of stained teeth which could really be described only as ‘hit and miss’ (thus it became known in our house as Alice’s) and she and the proprietor, Mr. Guest, allowed me to ‘save’ a wad of comics and buy them in twos, threes and fours over the two weeks leading up to the next delivery. Sometimes it stretched to even six comics, if mum or dad were feeling flush—I mean, wow! Four shillings and sixpence (that’s 22.5 pence to most of you reading this).

I was a hardened DC fan, a preference already cemented by a solid collection of one shilling (1/-) black-and-white comics (Big 68 Pages—Don’t Take Less) such as the 13-issue run of Mystery In Space, five

Once Upon A Time

Little has been written about the comic book artist Lou Morales. I only discovered him by accident! The key was the cover he created for Hot Rods and Racing Cars #8 (July 1952), which I spotted in Ernest Gerber’s essential Photo Journal Guide to Comic Books, while scanning the covers with my trusty 2x magnifying glass. His art, while seemingly crude, had an undeniable energy, quite suited to the covers of these pre-Code years, particularly those reared in the Charlton stable.

I had heard his name in connection with the now notorious “severed tongues” cover, which had graced (or was it disgraced?) Lawbreakers Suspense Stories #11. I then recalled I had an early issue of Hot Rods and Racing Cars, so I hastily dug it out to discover it was issue #9. This, too, led with a Lou Morales

One-hit wonders, one-shots, call them what you will, these are the comic books that have thwarted even the most ardent collectors since their first publication. None more so than this pairing; published by Hillman, when the craze for horror comics was nearing its zenith. Carrying a cover date of October 1952, their impact echoes the zeitgeist of this rapidly expanding comic book industry, each tempting with a typically maleficent intent. While these ignominious depictions blended with the macabre spectacle plaguing the American newsstands, they were in truth the siblings of an almost redundant breed, the crime comic. Hillman never joined the clamour for these four-colour tomes of terror. Monster Crime Comic deigned to chill with “Another Hallowe’en” and “The Canvas Tomb,” but neither could be ascribed to the loathsome lore that was corrupting the youth of America.

Alex L. Hillman’s tenure as a comic book publisher can be traced to the Golden Age, debuting in February 1940 with the short-lived Miracle Comics, followed a month later by Rocket Comics, both under the Hillman-Curl imprint. The origins of this minor publishing house go back a few years before to September 1936, when Hillman, the then president of Godwin and Arcadia House, and Samuel Curl, the firm’s sales manager, joined together to embark on a new venture. In less than twelve months, their Clue Club Mystery line of crime and mystery books began to reap the benefit of extensive circulation across the whole of North America.

This fledgling company soon followed with a series of digest-sized publications, led by Mystery Novel of the Month, prior to the appearance of Western Novel Classic, which promptly spawned an array of gun-slinging offshoots, before Thriller Novel Classic emerged from the shadows to ply its unwholesome trade.

Hillman’s reputation was further enhanced by a string of highly successful true confession magazines coupled with a similarly popular series on true crime, each of which debuted prior to the launch of the general interest journal, Pageant. On the newsstands, Airboy Comics was an unassailable triumph, with two of its characters in particular garnering an

He may be better known these days for his books on crime fiction and films, but as a short-trousered schoolboy in the north of England, Barry Forshaw’s real enthusiasm was for American comics—everything from Superman to Mystery in Space (always in the black-and-white UK reprints which were all that were available in that distant day). But then a taunting school friend’s conversation opened his eyes to an exhilarating new genre in the comics field—a genre which (unbeknownst to him) had already been banned in the UK: reprinted American horror comics....

Superadventure

Decades (many decades) later, I still remember it well. As a reading-obsessed boy in Liverpool in the 1960s (just before the advent of The Beatles), I had an ironclad weekly ritual that I looked forward to with keenness of anticipation. It involved walking past the towering walls of Walton jail (always wondering about the unseen miscreants behind that forbidding brickwork—as I still do when I revisit the city from London) and making my way to a small corner shop where I had a weekly standing order for a variety of comics. The plump, motherly ladies who ran the shop knew me well and handed over with a smile the latest Superman, Batman or Superadventure (the latter the awkward UK/Australian retitling of DC’s World’s Finest, which featured both superheroes), and accepted my carefully saved (and meagre) pocket money in

exchange for these 32-page treasures. Who cared that these black-and-white reprints hardly matched the multicolour splendour of the American originals? They still comfortably fed a fantasy-hungry boy in a gray era well before videos (or, in my case, even TV; my family didn’t own one). And there was another local shop which supplied even heftier doses of this fantastic American escapism than the slim sixpenny books mentioned above: chunky shilling reprints of inventive and imaginative American magazines such as Adventures into the Unknown and even a short-lived reprint series of an elegantly drawn superhero dressed all in scarlet, The Flash. All were, of course, excellent—if unthreatening— fare, post-Comics Code, as I later learned, with censorship firmly in place. But intriguing shadows beckoned. I had intimations that there was another forbidden genre of comics that occasionally surfaced and which had already been banned after a government decree in 1955: horror comics—gruesome and lurid tales of murder and monsters. As Liverpool was still a functioning port city, the occasional pre-censorship book would sneak in from the US as ship’s ballast—such as something invitingly called Adventures into Weird Worlds, which dealt with everything from vampires rapacious for blood to killer robots, with illustrations far more grotesque and unsettling than the post-code material that was my usual fare. But even these rare horror titles paled into insignificance after one playground encounter—the repercussions of which are still (thankfully) with me in middle age.

Tempting talk

In the schoolyard of St. John’s Primary School (now as overgrown and derelict as any gloomy setting in any of the horror comics), there was one boy—not really a friend—who enjoyed taunting me with deeply desirable-sounding comics that were simply beyond my reach. With a broad malicious smile, he told me that he had bought some Superman and Superboy comics in full colour—British reprints, what’s more, not the American originals. I didn’t believe him until he produced them: short runs of these books which were haphazardly coloured in this country, before the blackand-white reprints once again took over. But such books were tantalisingly dangled under my nose, never lent or (God forbid!) given—his greatest enjoyment came from teasing. Don’t we all learn about cruelty in the schoolyard? Preliminary tauntings over, he then came up with a dilly. With a wide grin, he produced a 68-page shilling title that bore the immensely tempting legend ‘Not suitable for children’ (what could be more intriguing?) and showed a scantily dressed young woman at a circus looking in horror as an axe thrown by a fellow performer is aimed straight at her head while onlookers gawp open-mouthed. The book was called Tales from the Crypt—and not only did it promise more gruesome material than anything I’d seen before, but it looked nothing like the other horror comics that had come my way—my tormentor flicked through the pages and I saw that it was much better drawn than most books I’d seen (I was already an aficionado of comics illustrators, having trained myself to

The chilling sight of leathern wings across moonlit skies was in evidence when the comic book was still in its nascence. From these skies, they would swoop down into the streets below, assuming human form, before stealing from the shadows with malice aforethought. In the years preceding the sanctions of the Comics Code, the vampire’s kiss was never a prelude to romance, rather it was borne of evil, with a sole desire to satiate its lust for human blood, and in so doing spread its malfeasance from the graveyards into the avenues beyond.

Long before horror comics became all the rage, the first of the vampire legion stole into four single page instalments in the contents of New Fun, starting with #6, in the October of 1935, when supernatural hero Dr. Occult set out to thwart the machinations of the villainous Vampire Master. Written by Superman’s creator Jerry Seigel and ably assisted by the man of steel’s artist Joe Shuster, whose

exquisite style embodied this halcyon epoch, this was the beginning of the vampire’s reign in the comic book. Dr. Occult would eventually vanquish his nemesis, but was unable to stem this unholy tide, as the undead returned to leave their indelible mark on the newsstands of North America.

As the 1930s gave way to a new decade, the comic book flourished, just as the world once again prepared for war. With the democracies of the free world engaged against the slaughter of the Axis powers, the superhero ascended to become the champion of the comic book publishers and the youth of America alike. Shortly after his debut in Detective Comics #27 (May 1939), Batman was bound for Paris in a two part tale, introduced in #31 (September 1939). Initially he was assailed by the unscrupulous Monk,

before venturing on, in the next issue, across Europe into Hungary, where the vampire Dala waited in the shadows. The curtain would fall on their treacherous ways when Batman eventually traced their coffins. Maybe if they had chanced upon Bob Kane’s iconic cover to Detective Comics #31, they would have been a little more wary of Bruce Wayne’s alter ego. Alas, for them it wasn’t to be; they were destined to fall before the caped crusader.

This episode went to press as the Nazis conspired to subjugate Europe in its entirety. It didn’t take long for the vampire horde to enter into a pact with this evil force. When Captain America Comics #24 (March 1943) hit the stands, Cap was thrown into a confrontation with Count Vernis on Vampire Mountain, in the tale `The Vampire Strikes.’ It was a nail biting encounter, revealing this heinous breed at its most lethal. The Count wouldn’t be the only supernatural villain to conspire with the Nazi abomination, zombielike creatures together with demonic entities would follow suit, to gift the comic book its finest moment. These vampires weren’t the misunderstood

victims martyred in the literature of the latter twentieth century; far from it, they were baneful manifestations, impelled solely by their rapacious appetence.

During the 1940s, only one comic book character used the name “Vampire”. She made her one and only appearance in Gem Comics #16, an Australian anthology title published by Frank Johnson in 1948. This issue has become something of an enigma, with collectors finding it almost impossible to locate this long forgotten heroine’s solitary adventure. Apparently her skinhugging outfit, the creation of Pete Chapman, met with an appreciable amount of disapproval amongst the parents of those children who, in this instance, were unusually eager to hand over their pocket money. It has since proved one of the hidden gems of the hobby.

Across the Pacific Ocean, with the war now thankfully at an end, sales of superhero comics suddenly plummeted; it seemed the youngsters of the United States were no longer in need of a costumed daredevil to save the day. The comic book publishing houses, mainly based in New York, were going to have to look elsewhere for inspiration. Initially, romance and crime comics came to the fore, then without warning the horror comic crept onto the newsstands. Eerie Comics was the first, with an unsettling Nosferatu-styled cover, which continues to capture the imagination of the modern day horror comic reader. Visually, on its release, it made quite an impact, but it wasn’t enough for its publishers, Avon, to commit

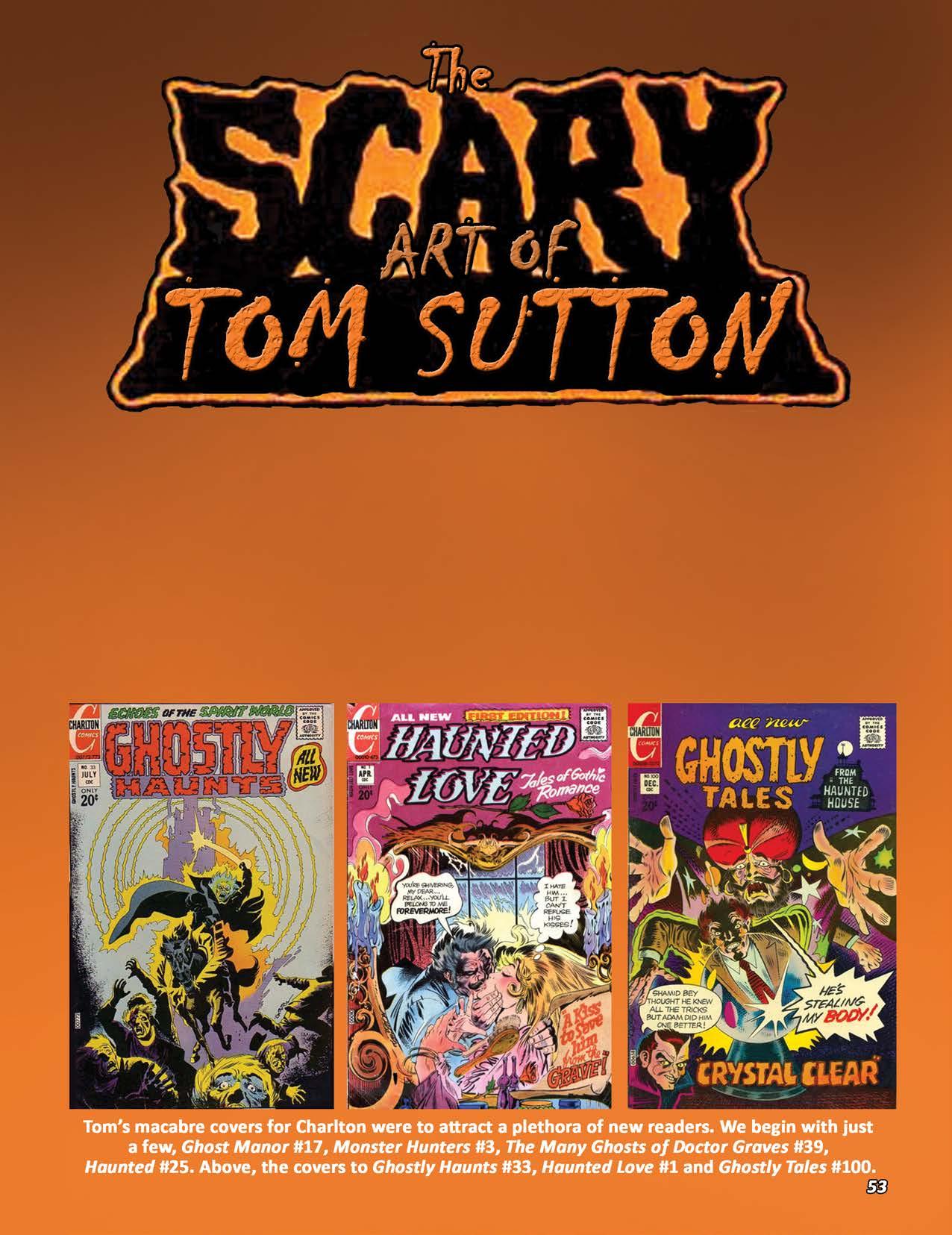

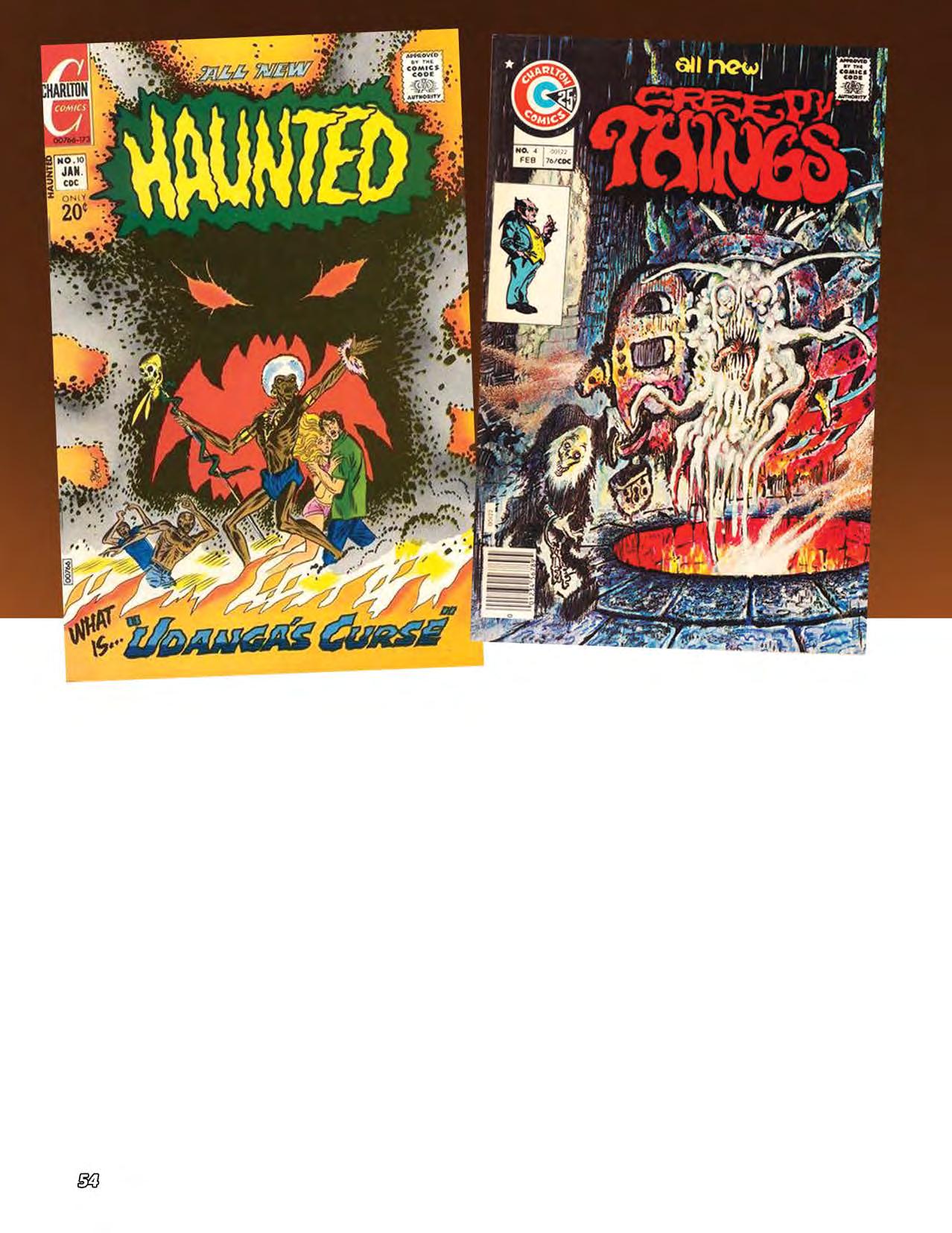

Charlton were never high on my wants list when I first started reading comic books; I was a dyed in the wool Marvelite. How I would like to say those garish looking comics grabbed me when I first saw them; but it never happened that way. I can’t have been alone in my misgivings, because, God bless them, those Charltons always seemed to be the last to leave the racks, if they ever did. When there was nothing else to be had I would give one of their titles a go, but the result was invariably the same, leaving me feeling short-changed as they failed to stir my craving for the macabre.

The very appearance of a Charlton comic, during the 1970s, was tawdry when compared to their illustrious

competitors. The quality of the print quality suggested their product was destined for a short life, as it seeped into your pores. E-Man did hit a chord, albeit in the strangest of ways and every once in a while one of their weird tales did induce a degree of other worldliness, but for the most part Charlton’s appeal was lost on me.

Now let’s turn the clock forward to 1991, when I chanced upon a bunch of Charltons for almost next to nothing. The war books I confess were of little interest and a fair amount of the mystery stories weren’t worth the paper they were printed on. However, amongst this bunch was a number of tales which did pique my curiosity, this was owing to the penmanship of Rudy Palais, Pete

Morisi, Pat Boyette, Steve Ditko, Wayne Howard, Joe Staton and most significantly Tom Sutton. Having spent some time with these stories, I finally realised how the company had kept on going. While their mode of production may have been cheap, they did have at their behest a highly talented team, each of whom had a varying approach to his style of storytelling. The more I saw of Tom’s work in these titles, the more I wondered how I could have ever missed this phase in his career. If I had come upon these issues back in the day, I just might have been more inclined to have sought them out and place them alongside my treasured Skywalds. I had previously encountered Tom’s work in issues #9-11 of Werewolf by Night, but the pages he produced for Charlton revealed a darker, almost manic, vision. This enigmatic display should have dignified Charlton a place amongst the loftiest echelons of the comic book macabre, but too much of their output fell short of Tom’s genius.

Born on the 15 April 1937 in North Adams, Massachusetts, Tom came to work for Charlton in 1972, debuting in the ninth issue of Attack (December 1972). Here, he demonstrated a style reminiscent of the EC war comics produced by the legendary Harvey Kurtzman.

Very shortly, Tom would bring his love of EC to Charlton’s resurgent horror line.

As a youngster, his artistic endeavours were praised by Norman Rockwell. He quite rightly enjoyed the moment, but rather than resting on his laurels pushed himself further, inspired by the giants of the day, Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond and Hal Foster. Absorbing the finer detail of their flair, he garnered his style building on his technique. A few years hence Tales from the Crypt and its babbling acolytes would supplement his desire for the genre, to one day enhance the Charlton horror collective. His admiration for Johnny Craig would inspire the name of the hero he created for Stars and Stripes, although he later confessed it was a cheap imitation of Frank Robbins’ longstanding syndicated strip Johnny Hazard. The tales Tom crafted for Jim Warren reflect these early influences, but they were by no means copies of these past masters, it was already obvious he had his own unique style. His line exhibited a refined sense of creativity, honed while in the employ of several advertising agencies in Boston. This would be developed to even greater heights when he came to work in New York in the employ of Topps; but it was the comic book that was his true calling.

If yours is the wish to spend a few hours lost in a stack of your favourite horror comics, let’s just make sure you have combed your hair, washed behind your ears and polished your shoes and most importantly ensure your behaviour is absolutely impeccable. To be neglect in any of these details might draw the wrong kind of attention, which in turn may necessitate your beloved horror comics being removed pending a ban by Parliamentary statute. A bit of an overreaction you might think, but all it took, so it would appear, was one ill kept child to change the course of comics in what was then Great Britain. A few years hence, Americanstyled comics would fall under Parliamentary scrutiny, culminating in a mandate which remains on the statute books to this very day.

The war was almost twelve months over when George Pumphrey first considered the possibility of using children’s comics as a viable source of reading material. He was looking to develop the reading skills of the children in his charge at a time when reading material was in very short supply. Poor Mr Pumphrey, his noble intent would never have imagined the iniquity coursing through so many of these seemingly innocent publications. When he set out on this quite admirable quest, he would have been unaware of the disparaging views held by his contemporaries for this cartoon-styled mayhem. As the weeks followed, it became obvious a large amount of these comics fell short of the standard for which he had hoped. It would have been better for all if he had just forgotten his experiment; resigning himself to the fact comic books were little more than a youthful diversion. It wasn’t to be, for when young Ethel shared her choice of reading, his view was forever changed.

A Disgraceful Publication

Ethel was only nine years old, poorly dressed and a tad grubby. She demonstrated an incessant need for attention and as a result was inclined to being unusually naughty. Furthermore, her temper bordered on the uncontrollable, evincing a cruel streak she readily inflicted on her playmates. These flaws in character paled into insignificance when she handed over the comic in her possession. The Beano and the more gentle Every Girl’s Magazine were no longer her cup of tea, she favoured the tawdry contents of something going by the name Eerie. Given the timeline, there is a very good chance this was the original Avon edition dating back to 1947, as opposed to the later British reprint.

Now, if Ethel had been a quiet young lady, lovingly nurtured in the leafy suburbs of the English home-counties, with a disposition in keeping with the values espoused by the Great Britain of these years, would this offending copy of Eerie have been dismissed by Pumphrey? Probably not, I am quite certain this copy of Eerie would have still been a cause for grave concern, for the excess he uncovered in these pages was not in keeping with the accepted notion of a children’s comic.

The review of Wertham’s tome, which appeared eight years later in the Times Literary Supplement, would have further exacerbated Pumphrey’s anxiety, but as Martin Barker’s book A Haunt of Fears points out, by this time there were several other bodies driving the campaign to put an end to those American-styled comics, amongst them child protection groups, the

National Union of Teachers and the Communist Party. Prior to their involvement Pumphrey’s campaign had been a cry in the wilderness, although a public opinion poll of 1952 suggested 69% of parents were in accord with a wholesale ban on comics. The Government, however, maintained it was the duty of both parents and teachers to ensure the children in their care were not unduly exposed to harmful comics. Legislation at this juncture was not forthcoming.

The incensed Pumphrey put pen to paper, his consternation documented in his book Children’s Comics: A Guide for Parents and Teachers. As the book quickly unfolded, he mentioned a series of international gatherings condemning these damaging comic books. These meetings were to lead to the formation of several committees across Western Europe, each seeking to moderate the content of the comics so easily obtainable by young children, although his book overlooked naming these countries. At the same time, the conferences of several professional bodies and trade unions were also expressing their infuriation with these disreputable comics, with the teaching union raising the most serious cause for concern.

Unlike Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, Pumphrey’s short book itemised many of those offending comics which had come to his attention. However, there was one comic he didn’t name, a bound volume of these particularly objectionable comics, placed on sale next to the children’s annuals just before the Christmas of 1954. I wonder if this could have been the bumper 160 page Black Magic Album, one of the most highly prized treasures of the entire period. We’ll never know for sure, but all these years later his efforts have provided a crop of titles worthy of any collection; a veritable service if ever there was one, but not quite what George had intended.

All these years later those comics he considered favourable to the development of young children have failed to stir the interest of the enthusiast in quite the same way as the atrocities he was so eager to condemn. In criticising Wertham for his omitting to supplement his text with an index, he accidentally availed himself to the latter-day collector. The inclusion of an index to Seduction of the Innocent would have consequently avoided so much conjecture, but then maybe that was the point Wertham was trying to make. Regardless, Pumphrey wasn’t about to let Wertham off lightly, accusing him of making out images within the panels of a comic book few people would ever identify. His allusion to pictures within pictures immediately springs to mind, as does Batman’s homosexual affiliation with Robin, although Pumphrey mistakenly referred to Superman rather than Batman. Perhaps the use of the word Superman was to generalise our super powered brethren and their youthful assistants. The accusation, however, still defies belief.

Vile Corrupters of Innocents

Pumphrey was an educated man, but even he wasn’t averse to resorting to outrageous sensationalism, portraying the American comic book industry as a vile corrupter of innocents, whose product had ever so stealthily established a hold on its young readership. The imagery was indeed emotive, a feature which was to prove

When the family of Cleveland-born Alfred Richard Eadeh moved to Brooklyn, New York, they brought their son to a city that would one day yield him work as a commercial artist. Only a part of this lengthy career would be spent in the employ of the comic book industry, at what was one of the most fascinating periods in the history of this four-coloured mayhem. Al was to live to a ripe old age, but there is so little known about his time in comics, which amounted to a mere seven years. For all of the ingenuity he displayed at the drawing board, he would never distinguish himself as one of the luminaries of the medium. Only those with a passion for pre-Code horror would have ever truly appreciate his perturbing sense of design, the majority of which was picked up by Atlas for their infamous line of horror titles.

Having attended the Pratt Institute in New York during the 1930s, he found work as a commercial art, before

enrolling in the armed forces in Jamaica, New York on 7th March 1941. This was nine months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbour. His enlistment papers reveal he was a single man, employed as an artist. By the end of the war, Private Eadeh had been promoted to the rank of sergeant, while receiving commissions as a cartoonist from the incredibly popular serviceman’s journal, Yank Magazine

On his return to civilian life, Al’s story was very similar to that of many other young servicemen, in finding it difficult to acquire a steady flow of work. Positions in the city’s advertising agencies were few and far between, but there were a growing number of openings for freelance comic artists. This had the added bonus of allowing him to work from home, away the busy humdrum of the comic book publishing houses.

An opportunity arose in the studio owned by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, in which he spent quite some time,

I first came upon Richard Corben’s breathtaking artwork as a very impressionable fifteen-year-old, following the excitement of my first trip to London. It was supposedly a school outing to the London Science Museum, but I had one thing in mind, slipping off to the country’s premier comic shop of the day, Dark They Were and Golden Eyed, situated in St. Ann’s Court, just off Wardour Street slap bang in the middle of the capital’s Soho district. During the morning I did as was expected, traipsing around the science museum, which turned out to be a very enjoyable experience, but all the time I was hankering to get through the hustle and bustle of the city to make my way to Wardour Street. How on earth I managed to get there is beyond me; this was the summer of 1977, a long time before the advent of the internet and Google maps. When I think back, somebody up there must have been guiding me, for those who know me well enough, will tell you my sense of direction leaves much to be desired.

Rummaging through the boxes I chanced upon a copy of the fourth issue of Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction, one of my favourite titles of the day. As with so many of the contributions to this magazine’s short-lived run, it was a mind blowing affair, which took me back to the elation I had felt on first reading the Damon Knight-edited science fiction anthologies Beyond Tomorrow and Worlds to Come. Richard’s only appearance in this title, “Encounter at War”, had previously seen publication in the fourth issue of underground title Anomaly, dating back to 1972. This was quite a bold move by Marvel Comics, daring to reprint material from a province considered by many to be utterly anarchic. There’s nothing unusual about violence in the pages of a comic book, but “Encounter at War” escalated the levels of mayhem, taking them to fever pitch. This was the first time I had ever seen an airbrush used in a comic book, having yet to behold Alex Schomburg’s covers for Wonder Comics and Startling Comics. These thirteen pages were a euphoric overload of the senses; surely this had to be comic book nirvana. The excess inundating this tale may have sprouted from the science fiction films of the 1950s and the social turmoil of 60s America. However, the inferno he witnessed as a child, which engulfed his parents’ farm house in Anderson, Missouri, would have left an infinitely more resounding impression.

An admirer of EC’s science fiction and horror titles, Richard insists he started drawing a long time before he was able to read and write, tracing the characters from his elder brother’s comic books, then fleshing them out into something new. In the field of comic books, Frank Frazetta, Wallace Wood, and Alex Toth would be his inspiration, but his interest in art would develop to encompass the masters, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Durer, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Parish and quite significantly Rodin, each of whom would play their part in ennobling his stylistic panache. Before being exposed to their genius, Richard completed his first comic book, Trail Comics; a joyous eight part narration recounting the escapades of the family’s pet dog, Trail.

Trail Comics was but the beginning. Alongside his love of art and comic books emerged a fascination for film making, having received his first cine camera as a teenager. The possibilities inherent in this medium would coalesce to expand his sense of creativity, later influencing his approach to comic book design. The flip page animations conceived in his school exercise books were already a thing of the past, replaced by experiments with clay-based animations. These would culminate in his 16mm film “NeverWhere,” completed while in the employ of a Kansas City industrial film company. Assisted by some of his colleagues, he spliced graphic animation with live-action to win a CINE Golden Eagle.

When he received his BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute, he was still pursuing his quest to develop ideas for science fiction films, which continued to place live action side by side with his elaborate modelling. These imaginative constructions were bringing a three-dimensional quality to the pages he was producing, with one of his futuristic spacecraft designs making it to the cover of the September 1968 Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Those who would have been poring over its pages in search of Jack London’s latest offering, may have overlooked the potential on show in this cover, one that a few years hence would overwhelm a new generation of fantasy and science fiction devotees.

It was around this time Richard was introduced to comic book fandom, through Dennis Cunningham’s Weirdom. Soon after the monthly Voice of Comicdom triumphed to become the first fanzine to publish his strips. The summer of 1968 would be terrorised with “Monsters Rule” and “Lure of the Tower” as Richard took his first steps into the world of comic books. These fledgling efforts very quickly gained an enthusiastic following, amongst them a young man who had plans to lure him into the underground.

Writer and editor, Dennis Cunningham wasted no time in collaborating with Richard on a tale set in the seventeenth century, chronicling an infestation of plague destined to see publication in Weirdom #13. The contents of this issue were later reprinted in 1971, with a few alterations as Tales from the Plague. Fifteen years later, Bill Leach released another reprint, this time with a new wraparound cover designed by Richard himself. Tales from the Plague was a sullen account, unrepentant in its depiction of human suffering, deserving of each reprint, owing in no small

part to Dennis Cunningham’s extensive research of this medieval scourge. The artwork, throughout, is dark, far darker than would be seen in many of the tales set to leave his studio, yet these pages are essential to any adherent of his bewitching artistry.

In no shape or form did any of this work produced between 1968 and 1969 lend itself to the mainstream, it would be another five or six yeas before an occasional illustration would make it to the early issues of Marvel’s Savage Sword of Conan. However, over in San Francisco, Gary Arlington recognised a prodigy in the making in the pieces submitted to Voice of Comicdom and Weirdom. For some time he had been toying with the idea of an underground horror comic styled on EC’s legendary line; the lavish abandon portrayed in these strips suited his vision perfectly. However, there were those amongst the underground who felt this finesse was not in keeping with the more subversive aspects of the movement. The philosophy of this band of creators was revolutionary, each with a desire to bring change (or was it havoc?) to the old world order. Gary Arlington ignored these mutterings; assured in his belief this virtually unknown artist from Kansas could bring his dream to life.

Richard lived up to expectation, delivering the EC-styled “Lame Lem’s Love,” to the pages of Skull #2 in 1970. Greg Irons and Jack Jaxon were quick to appreciate his talent, spurring him onto even greater heights. So came the bizarre love story “Horrible Harvey’s House,” under the pseudonym “Gore,” published in Skull #3, the antecedent to his interpretation of H.P. Lovecraft’s “Rats in the Walls” for issue #4, released almost two years later. Issue #6 would be Skull’s finale, an issue which would take advantage of Richard’s contribution to Tom Vietch’s “Gothic Tale.” His passion

Fresh from his run on Ka-Zar the Savage, one of Marvel’s first regular direct-sales comics titles, writer Bruce Jones established Bruce Jones Associates, along with his wife April Campbell, and began producing comic books for the independent publisher Pacific Comics. Among the titles was the science fiction anthology Alien Worlds, and that fan favourite is returning to the printed page courtesy of Raw Studios.

Bruce Jones has worked as an artist, writer, graphic designer and editor, bringing a fine sense of quality to the many works he has been involved in. He established his professional career in the 1970s, producing horror and science fiction material for black-and-white magazine publishers such as Skywald and Warren, where he would work with world famous artists such as Richard Corben, Russ Heath and Bernie Wrightson, people who he would continue to collaborate with in later years.

The ‘good-girl’ has a long and successful career upon which she can readily call. During the 1920s, our heroine appeared in the pulps of the period as louche, often en déshabillé and promiscuous. This good-girl was an object of unending desire, flirtatious, pliable and persuadable for extra-marital sexual trysts. These risqué titles were often referred to as bedsheets, owing, if for no other reason, to their large format. When it became clear that the carping censors and their noisome acolytes were displeased with her near constant state of undress and wanton tendencies, her role had to be reviewed.

Following this reappraisal, the good-girl was soon fit to be tied, passively awaiting a decidedly horrible fate. On numerous covers she could be seen clamped within all manner of elaborate devices, each designed to either impale, immolate, immerse or decapitate, at the hands of evil criminals, dwarves or Igor-like henchmen; who in turn were directed by deviously manipulative Machiavellian overseers. These iniquitous men saw the undressing a woman as a focus for humiliation, torture or her ultimate

destruction. On some of these covers, the hero could be seen arriving not a moment too soon, to relieve the luckless good-girl from her distress, whilst restoring offcamera some much-needed clothing. The good-girl’s second coming was initiated by publisher Henry Steeger, in a format which was to become known as ‘weird menace’ or ‘shudder pulp’ magazines. This change in emphasis began late 1933, with a revamped Dime Mystery, followed in 1934 by Steeger’s Horror Stories and Terror Tales. Whilst Steeger was both the progenitor and leader in the field, rival companies soon joined the fray

Rough Around the Edges

Americ an pulps of the 1930s were crude publications, printed on cheap quality, coarse woodpulp paper. They were designed to be enjoyed, maybe passed on a couple of times, and then discarded. The covers were flimsy affairs, although made of decent coated-stock, which was glued to the interior spine; with the whole left untrimmed. Any rough handling

caused tears or creasing to the cover, thus jeopardising their long term survivability. The cover illustrations however were bright, brash and colourful, designed specifically to titillate and induce an impulse purchase. Ignored at the time, many of these illustrators have since assumed iconic status. The stories inside were violent, often lustful, but always fast-paced and exciting, with an occasional spot illustration to cheer the proceedings. Their writers were habitually pseudonymous, though ably skilled in their disreputable practice. The point-of-sale copy (as opposed to a dedicated subscription copy) was another innovation; one which allowed the casual buyer to browse and make a chance purchase. This novelty, which seems so ordinary to us, now accustomed to our modern free market lifestyle, was made available by a highly significant group of behindthe-scenes distribution networks, which were seldom noticed by the casual bystander. These networks were able to speed said publications from printer to bindery and hence to the newsstands or other retailers dotted across the vast American continent. An ad-hoc distribution network had been in existence since the 1800s, which acquired an element of coherence during America’s Civil War (1861-1865), with the formation of the American News Company in 1864. Other rival distributors would follow, but ANC remained pre-eminent with an enviable worldwide network and a dedicated retail outlet (Union News) at US railways stations, until the US government enforced its complete dissolution due to unethical business practices, in 1957.

As with their predecessors, the weird menace pulp would also incur the wrath of the officialdom. In particular the National Organisation for Decent Literature (formed 1938), and subsequently by New York City’s serving Mayor, Fiorello Henry La Guardia (1882-1947), who vowed to rid the newsstands of their presence. The United States Postal Service/USPS was the authoriser of postal permits; essential for cheap transit from publisher to customer, and it too actively sought to remove items deemed unsuitable. In an attempt to mollify her detractors, the good-girl became less scantily clad; merely threatened, rather than enduring further acts of torture. Good-

girl covers featuring gun or knife-play, poisoning, or shadowy threatening figures became popular motifs. Due to censorious pressure, Trojan/Culture’s highly risqué Spicy lines (Spicy Adventure, Spicy Western, Spicy Detective) were cancelled in favour of Speed Adventure, Speed Western, and Speed Detective, launched 1943. When Trojan’s Dan Turner Hollywood Detective was targeted in 1943, it lopped off the hero’s name and continued as Hollywood Detective, until 1950.

Notwithstanding, the pulp lines shrivelled and failed due to several factors, amongst which were the demands of an increasingly sophisticated readership for more presentable publications. This precipitated the rise of the ‘true crime’ magazine, which initially adopted the painted cover style of the pulp, before switching to photographic-style portrayals but staged using actors or models; a style that remains popular to this very day. Within these publications, the good-girl could change guise to become the provocative femme-fatale, and a threat to any unwary male; as exemplified in the hardboiled crime and B-movie film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. America’s entry into World War II following the Japanese air-strike on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), also heralded the rise of the patriotically oriented flag-waver magazine. Here, the good-girl was adapted to stay-at-home factory worker (Rosie the Riveter et al), enlisted servicewoman or wholesome pinup girl. All of these titles favoured smoother, glossier stock to do the images justice. The text-heavy pulps evolved into the glossy magazine, handsomely illustrated inside, or the pocket-sized digest; edges now trimmed and altogether more attractive. These ran alongside its mutant twin the paperback (initially digest-sized), where the good-girl thrived as a beautiful, voluptuous, amoral, born on the wrong side of the tracks temptress (‘Swamp Girl,’ ‘Tramp Girl,’ ‘Trailer Girl’ et al).

Pin-Up

The 1940s styles pinup or ‘cheesecake’ magazine was led by publisher Robert ‘Bob’ Harrison, with such titles as Beauty Parade, Eyeful, Flirt, Giggles and Whisper; many of which featured the airbrushed cover illustrations of pinup specialist

Peter Driben. Harrison became notorious following the launch of his ground-breaking, but vicious, Hollywood celebrity-tattle magazine, Confidential in 1952, which culminated in the infamous Confidential Magazine Trial of 1957. In addition, the good-girl was represented via photos of numerous wannabe starlets, or occasionally the genuine Hollywood stars themselves. A staple of these titles was the photo feature of a seemingly plucky, optimistic but ultimately fallible femme. These hapless females were seen in a variety of improbable poses, photographed from all possible angles as they tried to accomplish a task that was plainly beyond their skills. Mostly, these were tasks that men would accomplish with ease; you get the idea... The conceit, she doesn’t realise what is being glimpsed while striving to remain upright, covered and decent. Equally presumptuous, the innocent reader has chanced inadvertently upon these candid photos or illustrations. More knowing, the would-be censors were not always convinced.

Another premise was the natural-history magazine, wherein the native tribe could be photographed in its natural habitat. This was usually accompanied by an obligatory shot or two, featuring bare-breasted tribeswomen. Here, the native innocence seemed real and hence the viewers’ voyeurism was probably guaranteed. During its formative period, the Hollywood fan magazine also used idealised painted illustrations before opting for the now traditional colour close-up but still ideal photograph. Post-war, the flag-waver would evolve into the adult humour digest, many featuring risqué pinup covers and thinly veiled double entendre. These proliferated from the

While horror comics became the scapegoat for the delinquency evinced amongst the youth of North America during the 1950s, attitudes in Brazil were appreciably different. Brazilian commentators take great pleasure in celebrating the legacy bequeathed by their country’s horror comics. As with the United States, the boom came at the dawn of the 1950s, but in this instance continued well into the 1960s, before receding in the face of the superhero early in the subsequent decade.

Comic books weren’t entirely without their critics, having been attacked by conservative groups in the country as far back as the 1930s. They were cited for being detrimental to children, with left wing groups questioning the role of the heroes in these tales, considering them distanced from reality. Pressure was also exerted by Brazilian creators, keen to limit the amount of comics entering the country from the United States. They had a need to ensure there was a bountiful supply of work lined up for their studios. Initially

Brazil’s approach to horror was heavily influenced by the comics coming in from the United States, but it wasn’t long before they developed a virtuosity inspired by the local folklore spiced with a dash of racy eroticism. The 1960s would be harrowed by an unsettled period of intense political turmoil, yet the horror publishers maintained their huge readership. While much of the country suffered at the hands of the oppressive military dictatorship which seized power in 1964, the comic book industry remained largely untouched.

Two years after the American Comics Group released Adventures into the Unknown, the fledgling publishing house Editora La Selva first experimented with a line of home-grown horror comics. It was the beginning of a twenty-year run, which would see their readers, who were supposedly adult, subjected to rivers of blood, as voodoo conspired with blighted bandits, cannibals gorged on the grisly contents of their cooking pots and

tortured lycanthropes prowled the darkened streets, while an untamed vampire breed sought out succulent flesh. This phenomenon would not wane in popularity until the 1970s, when it was consumed by the costumed heroes of the United States. However, such was the draw of the supernatural, the genre survived into the 1990s to witness the publication of seven issues of Cripto do Terror in 1991 by Editora Record. Cripto do Terror reprinted many of EC’s horror stories in a 100-page black-and-white magazine format, allegedly for an adult audience. Several of these covers were the work of the Rio de Janeiro-born artist Carlos Chagas, whose homage to Jack Davis, Johnny Craig and Al Feldstein has gone largely unrecognised. His inclusion on this title would have come as no surprise to Brazilian comic book fans, for as well as illustrating for newspapers and comic strips, his artistry

The Comics Code Authority was introduced Oct 1, 1954 by the newly-formed Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA), affecting all comics of contributing publishers dated February to April 1955 & thereafter. Faced with draconian measures now enforced by the newly appointed ‘Comics Czar’ Charles Murphy, which would severely restrict what could or could not be portrayed, publishers sought to maintain interest in different ways. Some companies opted for prizes (Prize Mystery, Win A Prize etc.), whilst others moved opted for games or puzzles comics.

Publisher Martin Goodman, whose Atlas comics always boasted striking covers, sought to tempt potential readers

with intrigue. However, such were the forces now mustered against comics, the December 1955 dated Spellbound #25 (a title only recently resurrected from pre-Comics Code period suspension, so effectively the second issue), was criticised by the New York State’s Joint Legislative Committee in their end of year report dated March 1956. Despite its Code-approved cover, the Committee considered the CMAA had suffered a lapse of judgement in approving it; as “the underlying theme of the cover in Exhibit 42 is terror despite the fact that the features of the man are not shown and the comic is not entitled either ‘horror’ or ‘terror’ ” and urged “constant vigilance” and “watchful waiting” (page 88). Exhibit 42 refers to an illustration of the offending cover, which appeared (in black & white) on page 91 of the Report.

As anything remotely evoking horror or terror was thought unsuitable, Atlas experimented with covers broken into three or four panels set in a solid colour surround. This effect was tried on all of their mystery titles except Adventure Into Mystery, Mystical Tales and the aforementioned Spellbound. Many of these panelled covers were drawn or at least drafted by Carl Burgos, each seeking to tempt the casual browser with several story teasers instead of one. This was a period when children would examine items prior to purchase, rather than buy regularly or on impulse; attracted by a high-impact cover. Each panelled cover was laid out individually to sustain interest, with the plain borders coloured attractively to catch the readers’ attention. Its origins go back to 1950, when some covers had a main panel, with three small panels running vertically down the left side. The war title Combat Kelly was the first to utilise the panelled

Rescued from the Ashes

Among aficionados of comic books, it is fairly well known that Editor Emeritus Stan Lee once lost a priceless collection of comics he had worked on due to a flooded basement. It’s a worrying notion that sometimes haunts my sleepless hours, when I hear a dripping sound in the eaves of my house. Might I suffer similarly distressing water damage to books acquired decades ago? (But water damage from above, rather than below as with Stan Lee?) My cherished comic collection is squirreled away securely in (thus far) drip-free cupboards, menaced only by condensation and a few undernourished moths—but who knows what the English climate has in store for my hundred-year-old, past-its-best house? And it isn’t only rain I have to worry about—what about the cigarette that slips from a sleepy neighbour’s lips in the house next door and results in both houses being consumed by fire? Apart from a wife and a pair of underpants for modesty, what will I grab from that blazing building in the wee small hours to rescue? What comics will I be clutching to my shivering chest as I watch the conflagration of the rest of my collection warm the London night? (And I’m not worried about that sleeping neighbour—he burnt my comics collection, didn’t he?)

13 Precious Issues

That last-minute burning house rescue: a difficult one, isn’t it? But

(for me) it might have to be 13 precious issues (a complete run) of Mystery in Space—not the glossy original American 1950s editions in full colour (they can always be replaced), but the ones that I bought as a grubby-kneed schoolboy and have lovingly cherished over the years (despite some ill-advised, yellowing Sellotape repairs)—namely, the chunky, 68-page Strato/Thorpe & Porter shilling editions which reprinted material from what is probably the most inventive and ingenious period of DC’s definitive science fiction comic. And here I may differ from most admirers of this celebrated title by suggesting that the finest era for legendary editor Julius Schwartz and his creative team (including such stellar artists as a pre-Flash Carmine Infantino and a pre-Green Lantern Gil Kane—the latter Schwartz’s Mystery in Space cover artist of choice) produced their finest work; not in the space opera genre (with which the title’s run both began and ended); that is to say, not the continuing adventures of the Knights of the Galaxy who appeared in the inaugural issue and who commandeered the early issues of the comic (much as the proto-superhero Captain Future did similar service in the Schwartz’s companion SF book Strange Adventures), or in the run of the comic from issue #53, when galactic traveller Adam Strange’s adventures on the planet Rann began—and continued (slightly repetitively) for the rest of the run.

There are certain moments in your life that never leave you, such was a damp Friday evening in the mid November of 1979, when I was looking forward to getting home from an interview in North Wales. It was the first of my university evaluations, which possibly might account for this long-ago memory, but there was a little more to the tale. In the months that followed I would choose not to include Bangor on my shortlist, although I have since wished I had seriously reconsidered. But on that eve my thoughts were elsewhere, for in my lap was the latest issue of Heavy Metal, number 31, cover-dated October 1979.

In those days, Heavy Metal was an exceptional magazine, distanced from its contemporaries by virtue of its outlandish content. Its slant was wholly different in style, almost at odds with the fare to which I had so long been privy. The contributions for this particular edition had been selected with Halloween in mind, a time of year celebrated across the Atlantic, but back then largely ignored in the United Kingdom. While Heavy Metal was indeed a treat, this issue was even more so, for the entire issue had been dedicated to the legacy of H.P. Lovecraft. The brief editorial revealed a significant part of the content had been taken from the “Homage a Lovecraft” issue of Metal Hurlant, numbered 33bis, first seen just over 12 months before in September 1978. On this showing, the French edition had been extended to 150 pages, carrying an additional 50 pages when compared to the regular issues of the period. As the train coursed along the darkened coast, I learned of the “cult like veneration” the French lauded upon Lovecraft’s hideous vision. I could only wonder if his words assumed a more eldritch guise in their French translation; it has always been, and remains, a beguiling language.

H R Giger had been called upon to craft a typically disturbing cover for Metal Hurlant’s “Homage a Lovecraft,” at a time in his life he would have been working on Alien. The US edition dared to go that one step further, their cover presented Jeff Knight Potter’s photographic portrayal of the baroque prince himself. Jeff set the tone for that which would follow, only four years after his work had first graced the cover of Nils Hardin’s highly collectible Xenophile. The year 1979 would be one Jeff would also remember; Don Grant published his first illustrated book, reprinting H Warner Munn’s Tales of the Werewolf Clan, an omnibus of these stories originally presented in the pages of Weird Tales almost half a century before.

Cultural Attaché

Concluding his epic presentation to the House Un-American Activities Committee on March 26, 1947, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover likened Communism to a disease: “Communism, in reality, is not a political party. It is a way of life; an evil and malignant way of life. It reveals a condition akin to disease that spreads like an epidemic; and like an epidemic, a quarantine is necessary to keep it from infecting the Nation.” During World War II (1941-45 in U.S.A), The Soviet Union was considered America’s ally. Post War, however, the Communist ideology and imperial aims exemplified by Soviet leader Josef Stalin (1878-1953) were seen as an evil influence on World affairs. Allied fears were compounded when Russia (also as: The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics/U.S.S.R) detonated its own atomic bomb on September 24th, 1949. In the East, the ‘Hammer and Sickle’ symbolised the collective strength of Soviet farmer and industrial worker. It was first employed in 1922, following the Russian Revolution of 1917. To the West, the emblem was visual shorthand for evil; similar to the ‘Red Star’ favoured by the Communist Chinese. These symbols would adorn anything or anyone with a Communist taint. Into this fevered climate,

U.S. interest groups released numerous anti-Communist pamphlets, leaflets, articles etc. Many reflecting the tone and rhetoric of Hoover’s testimony. Among them were several comics from the Catechetical Guild Educational Society, based in St. Paul, Minnesota. A publisher founded in 1936 by Father Louis Gales, assisted by Fathers Paul Bussard and Edward Jennings. Catholic Digest premiered that November and remains in print to this day. From 1942, the Guild was the publisher of Topix (until 1952) and other religious comics.

Allthough recorded in Overstreet’s Comic Book Price Guide with nominal values, the Guild’s anti-Communist tracts were largely unseen, before copies materialised in 1979. This occurred, when a Priest attended a comic mart in Philadelphia; his briefcase bearing comics from the defunct publisher’s files. The Cleric was soon involved in intense discussions with three comic dealers, before departing the scene “with a fistful of thousand dollar bills.” (Overstreet #10 Market Report, 1980). The Guild’s anti-Communist titles include: Is This Tomorrow, 1947 (preceded by Confidential; an all-black-and-white pre-publication proof), Blood Is the Harvest, 1950 (uncommon; a black-and-white side-stapled prototype also exists), If the Devil Would Talk, 1950 (Roman Catholic Guild imprint) and The Red Iceberg, from1960. There was even a slim 64-page 1952 paperback condemning Communist China, Blueprint For Enslavement by Father James A. McCormick, with an evocative cover by artist Stanley Borack. Whilst, The Truth Behind the Trial of Cardinal Mindszenty (1949) was a religio-political comic (with a French-Canadian version from the Montreal-based Editions Fides; La Vérite Concernant Le Cardinal Mindszenty). József Mindszenty (1892-1975) had opposed Communism in his native Hungary, suffering torture, a criminal ‘show trial’ and imprisonment, before living in exile for his final years. The religious leader was also portrayed by actor Charles Bickford in the 1950 movie release, “Guilty of Treason,” based on Mindszenty’s memoirs. Unconquered was a giveaway from National Committee for A Free Europe, Inc, which described the show trial in Communist Czechoslovakia of Milada Horakova (1901—1950), with twelve co-defendants and her subsequent execution, despite pleas in the West for clemency. It is made more memorable by the artwork of Alexander Toth.

America Menaced!

Under an iconic holocaust cover, the Guild released Is This Tomorrow, America Under Communism!, in 1947. With alarming images, the 48-page 4colour story conjures the nightmare scenario how US Communist conspirators could suborn the American democratic system into a totalitarian state. Two priced (10c) and two unpriced versions are known. The former were distributed by Hearst’s International Circulation Company (ICC). The original unpriced edition can be identified by the flames in top right hand corner, whilst the later unpriced version has a telltale blank yellow circle. The original unpriced an at least one priced edition were released by the Guild, who also the copyright holder. It was also reprinted in three consecutive issues of the Guild’s Catholic Digest (July to September, v12#9 to v12#11). A later unpriced/undated edition was released by the Chicagobased National Research Bureau. More from them shortly. With an estimated 4-million copies all told, Is This Tomorrow remains common to this day. The chilling hypothesis was also restaged for foreign markets. It was adapted by author Neil Alexander McArthur, with new cover art and some interior

For those of you who may not be aware, I think it wise to prepare you for a sojourn into the most chilling of the pre-Code terrors. There were many creators who liberally conspired with the abject, but in the next few pages you will to come face to face with one of the genre’s most hideously inspired artists. Dark his work truly was, yet he had an uncanny knack for infusing his vision with a rather wry sense of humour. When I first wrote this piece some ten years ago, it was in essence a belated apology to one of comic books’ most energetic creators. Amongst his contemporaries his disposition and professionalism combined to make him one of the most admired artists of the day, the volume of invigorating work flowing from his studio combined with the number of regular assignments, surely bearing testimony to this. However, during the 1970s, I was one of those so called comic fans who sided with one aficionado, whose sarcasm alluded to Don Heck’s somewhat under-subscribed fan club. How little did I know of the rich history of the four colour comic book and more importantly how could I have forgotten the excitement of those early issues of The Avengers, which still rate amongst my favourite comic books. Thankfully, my impression of Don’s work was forever changed on Boxing Day 1992, while sprawled in front of the fire with Ernie Gerber’s Photo-Journal Guide to Comic Books. In those precious hours I came upon a couple of titles, of which until then I had only vaguely heard mention, and for the first time experienced the macabre magnificence of Don Heck’s work, at a time in his life when he was but a novice.

Let’s turn the clock back to the first half of the twentieth century, when Don came into this world on the 2nd of January 1929 in Jamaica, New York. As a child he was already demonstrating an artistic flair with a liking for Donald Duck. His was the desire to draw, nothing more, nothing less. His father

recognised his aptitude and as the dutiful parent attempted to guide his son into the respected tradition of architecture. Don, however, had other ideas. While still a teenager, he enrolled in several correspondence courses as well as classes at Woodrow Wilson Vocational High School in Jamaica. He would later continue his studies at Community College in Brooklyn.

These invaluable years of study provided an essential grounding for his eventual vocation. In 1949, the aspiring cartoon artist was recommended for a position in the production department at Harvey Comics. After an interview with Leon Harvey, late one Saturday afternoon, Don was offered his first paid work in comics. While in their employ he got to see the work of the artists he so admired, as he re-pasted newspaper comic strip photostats into a format compatible with a regular-sized comic book. His days would be spent with the page upon page of work by Jack Kirby, Lee Elias and a notable giant of the syndicated comic strip, Milton Caniff. There couldn’t have been a more suitable education for this young fellow whose aptitude for comic book art would soon elevate him beyond his wildest dreams.

Each and every day, Don was constantly absorbing so much about the comic book process, but his superiors were reluctant to encourage him in his calling, denying him the opportunity to assume that prized place at the drawing board. Their attitude wasn’t to put him off, together with his friend and fellow production artist, Pete Morisi, he parted company with Harvey Comics to pursue a career as a freelance comic book artist. Portfolio in hand, he went across town to meet the editors at Quality and Hillman.

These meetings would prove fruitful, resulting in a series of short mystery stories brought to life by his artwork. His patience was now rewarded. Almost immediately he secured a new client in the guise of Toby Press. They lined his artistry up for the pages of Billy the Kid. These assignments helped further his ambition, but not even this determined fellow could have anticipated that which was about to follow. An unknown publisher, by the name of Comic Media, was looking to acquire his skills. Allen Hardy’s Comic Media were not a household name, but once Don and Peter Morisi set to work, they would carve their own mark into these pre-Code years. Allen, it soon transpired, had also worked for Harvey in their circulation department.

When Weird Terror premiered in the summer months of 1952, it made quite an impression. Spectacular it surely was, with an air of dread seeping through its hideous dungeon scene, assaulting the senses so as not to divert the gaze of

I’d like to share a serendipitous and weird background story to a short comic strip of mine. Back in 1990, when producing art for Fantaco publishing, I was pretty much left to my own devices and could throw into the mix anything I wished. This freedom to choose was liberating; thankfully the response to my efforts was very enthusiastic. Coming up with the goodies wasn’t a problem; instead my dilemma was that being new to comic art, I didn’t feel I had a look or trademark style and found myself attempting differing styles and approaches. Due to various reasons, not everything I worked on back then saw the light of day, simply because I chose not to send it in. I preedited the choice if I felt the art was a little bit off or that I could improve on it.

Towards the later issues of Gore Shriek, I worked up one such strip. It was a starker-drawn story and had more solid blacks as opposed to the thin shading lines I used; the storyline featured a wraparound twist to it. I’m not entirely sure why I never sent it into the Fantaco publishing offices. It could have been because I wasn’t too keen on the way it looked, or it could be that this was the first time I experimented gluing printed lettering on and it didn’t suit as well as I expected—plus there was the fact that it had no monsters or actual gore in it. Whenever a misfire such as this happens, it’s simply classed as good exercise, so into one of my practice folders it went, settling near the bottom of the pile for a long, long time.

Here is quick and basic run through the storyline for the strip that I entitled DEJA-VU. It opens with a guy working alone in a convenience store. He’s the owner and busy stacking bottles of alcohol onto a shelf. Just over his shoulder in the background we can see at the unattended sales counter, a shadowy figure enter, being spotted rummaging around behind the counter. In outrage, the owner yells, startling the intruder who abruptly turns and flees.

The shop owner now realises he has just been robbed, and takes off in pursuit, discarding the bottle he was holding, which smashes on the floor. During this footchase, the shop owner decides to take a shortcut through the back alley and cut him

The fear of aliens descending from the skies to lay siege to our world— especially those hailing from Mars—was a common theme in the comic books of the early 1950s. The pleasure these tales derived from terrifying their readers with this threat from the red planet bordered on the insane, as did its denizens’ schemes to tear our world asunder. As mentioned earlier in these pages, the comic books of these years not only promulgated the Martian directive to subvert our species, they drew upon a paranoia quite particular to the United States of the early Cold War.

When Mars attacked, rarely did they come armed with the gargantuan array of atomic hardware evinced in Journey into Mystery #52’s (May 1959) “Menace

From Mars!” rendered by the legendary Jack Kirby. In the year 2306, a voyage of 34 million miles, maybe more depending on the orbit of the two planets, was about to touch down on alien soil. This was to be a momentous chapter in the history of mankind; first contact with the citizenry of Mars. The futuristic cityscape laid before our eyes would shape Jack’s vision of fabled Asgard a few years hence, but in his pages this revolutionary architecture harboured a species technologically far ahead of our own, yet marred by their enmity for our world. His fate of should have been sealed, but our intrepid space traveler would outwit this belligerent horde to lay bare their Achilles heel. His resilience in the face of such an unimaginable force

would bring comfort to many young readers, who may have had doubts as to their future at a time of such great uncertainty.

Space Western Comics was one of those curious hybrid titles, merging the contradictory frontiers of the wild west with those way beyond the fringe of Earth’s orbit. Issue #40 (Sept-Oct 1952) brought the “Saucer Men” from Mars down upon us. Only Spurs Jackson and his Space Vigilantes stood in the way of this bloodthirsty squadron, undaunted by the splash panel depicting four saucer-shaped objects glowing in the night sky. Again, it looked as if we were doomed, but the very air we breathe proved our saviour, keeping these Martian fiends at bay. If they were to have been exposed to our atmosphere they would have suffered an excruciating death. This ill-fated foray should have been over, but Spurs found himself captured, then escorted to Mars to stand before the Martian queen. Thula truly was a queen, but as with many before her, she fell victim to the charms of our Spurs, allowing him to safely return to Earth. The same could not be said for the EC staff at 225 Lafayette Street, when Weird Science #21 (September-October 1953) appeared on the newsstands. “EC Confidential” was brutal in its portrayal of these evil minions,

which had swarmed from Mars. EC have Messrs Feldstein and Wood to thank for what could have been the company’s early demise, which I am sure you will agree would have had the anticomics crusaders rubbing their hands in sheer delight.

Demon-like Ghosts

Head-on confrontations were all very well, but when Mars adopted a more surreptitious approach, their invasion plans proved all the more successful. Eerie #11’s (April 1953) “Robot Model L2—Failure!” documented how quickly their legions overran most of South America. Eltoo had been trained to terminate the Martian infiltrators, but when he killed one of their spies, he was also blamed for the deaths of his creator and his grand-daughter. This duping of ordinary men and women into the betrayal of their compatriots indicated a sinister development in the Martian stratagem, aligning their treachery with the machinations of the Soviets. This subterfuge became all the more pernicious in “Ghosts From Mars” when it was brought to light in the third issue of Dark Mysteries (October—November 1951) the Mars-Men were orchestrating the release of demon-like ghosts from their saucers circling the Earth as a harbinger to invasion.

The kid wanders into his local newsagents having dodged the local thugs. It’s early on a Sunday morning, so the lowlifes will still be wallowing in their pits and morning mass is but a distant memory. He pores through the magazine rack in the hope of finding something special, even though the horror magazines have been scarce of late, including his beloved Dracula Lives which has merged with his other favourite, Planet of the Apes. Poor kid, he is still looking for one of those deranged Skywalds. Maybe a copy of Nightmare or that really sick-sounding Psycho. Ah, but this is the autumn of 1976 and the Skywald Publication Corporation had bitten the dust more than twelve months ago, victims of the escalating cost of paper, which had precipitated the demise of this latest fad for the horror comic. The kid wasn’t to know; how could he?

The revolving rack did carry a rather pleasant surprise though, two issues of a magazine he hadn’t previously seen,

each evocative of the inveigling Skywald horrormood. The covers to these, the second and third issues of House of Hammer, insisted he dip into his pockets to secure the pair. However, there was a snag, an all too common one: The price tag. These magazines were thirty-five pence a go, and what was left of yesterday’s pocket money would only run to a single issue. He stumps up the pennies and five-penny pieces from his pocket in exchange for a copy of the second issue. If it hits the mark he will be back next week to pick up the one he has had to leave behind.

Hit the mark House of Hammer most certainly did, but that following week there was no sign of anything bearing its name on the revolving rack, now laden with more adult fare. It would be another twenty-five years before I tracked down that elusive third issue.