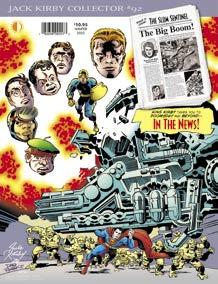

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR

the Sailor Man

KIRBY OBSCURA 19

Archie’s dynamic duo

THE CLIP JOINT 22 newspaper clippings about Kirby

JACK FAQs 26

Mark Evanier’s 2024 Kirby Tribute Panel, featuring Patrick McDonnell, Henry W. Holmes, and Kirbys!

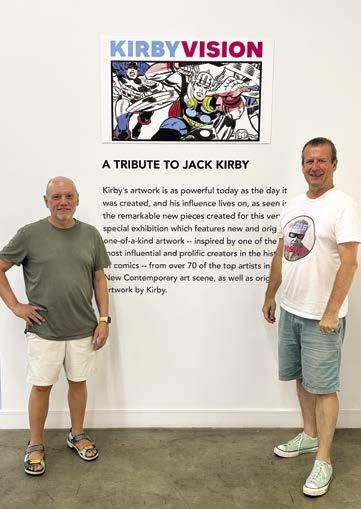

ARTVIEWS 36 the LA Kirbyvision exhibition

FOUNDATIONS 39

Johnny Reb & Billy Yank

INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY 48 DC gets an Edge

GALLERY 49

Superman’s pal and the newsboys

STRIPPER: MIKE MANLEY 56

FOUNDATIONS 59 man steals train!

STRIPPER: DAVID REDDICK 69

KIRBY KINETICS 71

Johnny Storm, rebel with a cause CLUBBING 75 the Boys Brotherhood Republic COLLECTOR COMMENTS ........78

Cover inks: DAVID REDDICK Cover color: GLENN WHITMORE

COPYRIGHTS: Batman, Big Barda, Clark Kent, Deadman, DNAliens, Dubbilex, Forever People, Green Arrow, Guardian, Jimmy Olsen, Mister Miracle, Mokkari, Morgan Edge, New Gods, Newsboy Legion, Simyan, Spectre, Superman, Terry Dean TM & © DC Comics • Blondie, Flash Gordon, Popeye, The Phantom TM & © King Features • Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four, Galactus, Giant-Man, Hulk, Inhumans, Iron Man, Lockjaw, Spider-Man, Sub-Mariner, Thor, Wasp, Watcher, X-Men TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.

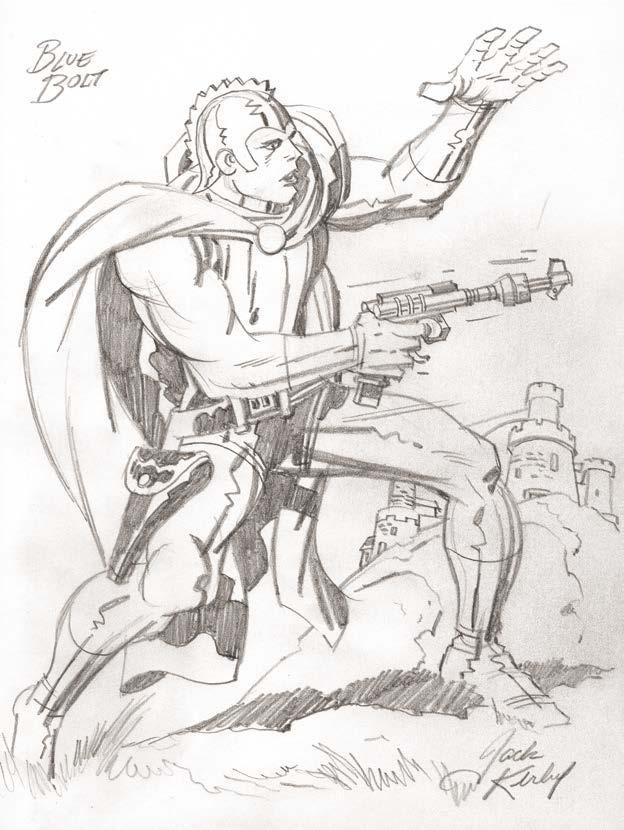

• Animal Hospital TM & © Ruby-Spears Productions • The Man Who Stole A Train TM & © Joe Simon and Jack Kirby Estates • Captain Victory, Jupiter Plaque, Montrose, Sky Masters TM & © Jack Kirby Estate • Destroyer Duck TM & © Steve Gerber and Jack Kirby Estates • Abdul Jones, Black Buccaneer, Blue Bolt, Captain 3-D, Cyclone Burke, Dash Dixon, Detective Riley, Facts You Never Knew!, Healthy, Wealthy and Wise!, Johnny Reb & Billy Yank, Lone Rider, Master Jeremy, Romance of Money, Socko the Seadog TM & © the respective rights holders • Black Hole

The

North American Syndicate, Inc.

Kirby’s earliest comic strip work for H.T. Elmo explored by Richard Kolkman

n the early 20th century, newspapers were the binding force of urban society. Before radio and television, the comic strip pages provided both a welcome respite from the day’s news, and a springboard for the imaginations of a generation of youth that absorbed the comics, and wanted more. Some dedicated their lives to cartooning as they propelled this new art form forward. As Joe Kubert remembered in 1994: “…every Sunday

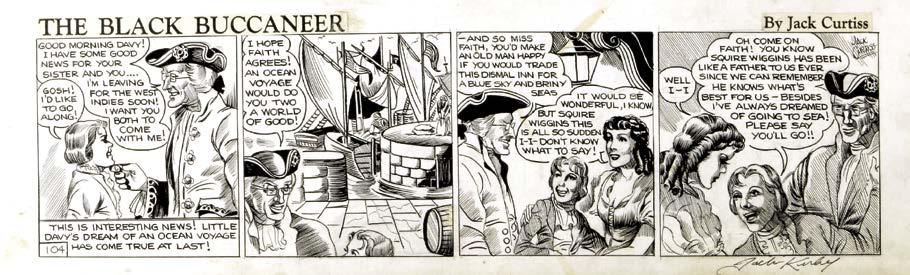

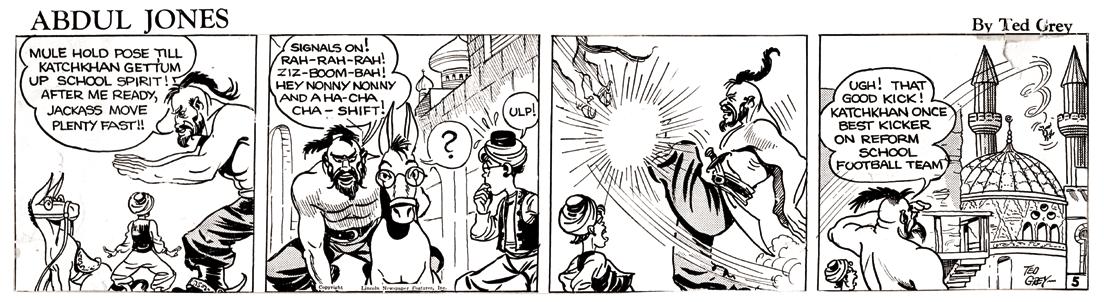

[this page] Here are two of Jack Kirby’s earliest professional jobs. The Black Buccaneer hails from 1937, when Jack was a mere 20 years old. Amazingly, this original art is still in existence. Jack’s mother Rose saved clippings from newspapers her son’s work appeared in, and many of those are the source material for images in this issue. Below is a previously unpublished Abdul Jones strip, drawn at the tail end of 1937, for release to papers in early 1938.

when the color comic strips came out, I’d lay on the floor and just kind of wrap them around me, around my head.” That was the world the boy cartoonists lived in.

Kirby described his influences to biographer Greg Theakston: “I admired the newspaper strips of my childhood… we had a lot of daily and Sunday papers in New York—The Daily News, The Herald Tribune, The Journal American… I followed Tailspin Tommy, Smitty, Toots and Casper, Moon Mullins, Dick Tracy, and Buck Rogers—and they were all as near as the corner ash can. I thought, ‘I could do this!’”

At age 12, Kurtzberg joined the legion of newsboys hawking newspapers in New York’s Lower East Side, while drawing crude comic strips for The Boys’ Brotherhood Republic Reporter. He rapidly improved his art and storytelling as he developed multiple strip concepts: untitled samples featuring family humor, space Vikings in spaceships, and nautical intrigue of pirates and plunder. At the end of 1935, while contemplating his departure from Max Fleischer’s animation factory, Jacob eventually landed (he likely answered an ad) at the doorstep of H.T. Elmo’s Lincoln Newspaper

Features. Elmo most likely saw promise in Jacob’s earnest sample strips, and hired the young cartoonist who signed his work “Jack Curtiss” among a host of other pen names. H.T. Elmo [above] was born Arazio Theodore Elmo on April 3, 1903—the sixth of Joseph and Josephine Elmo’s seven children, in Manhattan. Elmo’s early art training is unknown, but his earliest known strip is Little Otto (1926), a daily for Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. He is rumored to have done some amateur pages in Judge magazine. By 1926, Elmo went by the name “Horace T. Elmo” or H.T. Elmo, now a lifetime resident of the Bronx.

Elmo opened the doors of Lincoln Newspaper Features at

130 West 46th Street in New York City. Lincoln found a successful niche by servicing hundreds of small newspapers across the country. Ambitious and nimble, Elmo went where the major syndicates didn’t. It’s unknown if Elmo had sales agents or even how far his features reached, but John Morrow’s own research found that Socko the Seadog (usually accompanied by other Elmo features) got some decent geographical coverage with these now-defunct papers:

• The Rutherford Courier (Smyrna, Tennessee)

• The Dixie Democrat (Murfreesboro, Tennessee)

• Scottsbluff Farm Journal (Scottsbluff, Nebraska)

• The Fillmore Chronicle (Fairmont, Nebraska) — the first Kirby Socko (#136) ran Sept. 14, 1939

• The Indiana Democrat (Indiana, Pennsylvania)

• Indiana Weekly Messenger (Indiana, Pennsylvania) — Socko ran Jan. 2–Nov. 20, 1941

• National Road Traveler (Lewisville, Indiana; population 531 in 1940—now that’s a small paper!)

• The Lathrop Optimist (Lathrop, Missouri)

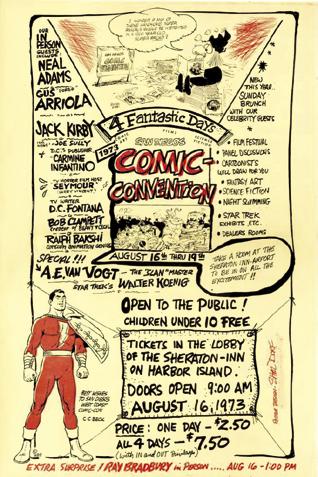

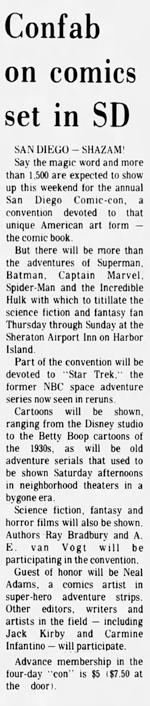

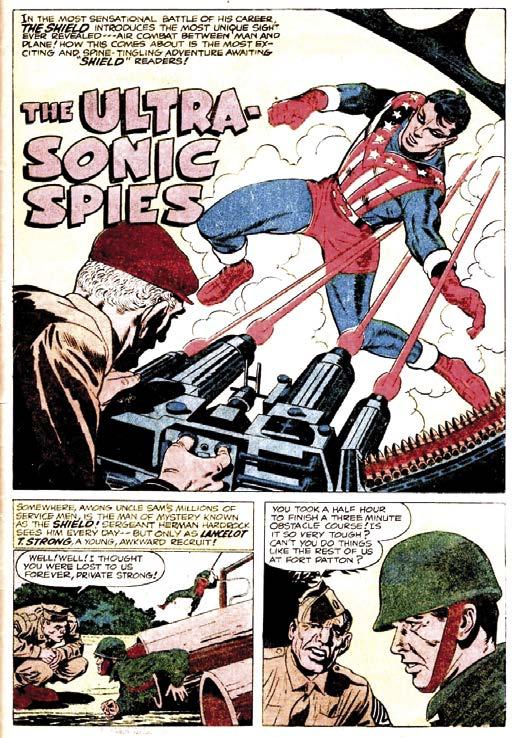

[The following excerpts are likely from August 16, 1973. This was the first year the convention was officially called the San Diego Comic-Con, and it opened with keynote addresses by Guest of Honor Neal Adams, Carmine Infantino, and Mike Friedrich. At this first panel, comic strip artists were well represented, with both Kirby and Adams having produced syndicated strips. The discussion focused on production, and specifically coloring:]

GUS ARRIOLA (creator of the comic strip Gordo): I send in an indication of what I want. I have a black-&-white photostat made of the Sunday page, and then I color that in exactly the way I want it to appear—and plus that, they’ve given me a chart of the screens and the numbers, so there’s no mistake. So I not only color it, but I put the number of the color screen that I want, according to that chart, and it comes out very close. You wanted to know what medium I use to color that indication—it’s colored India inks.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Neal and Jack, do you both use colored India inks to do indications before you send in an issue?

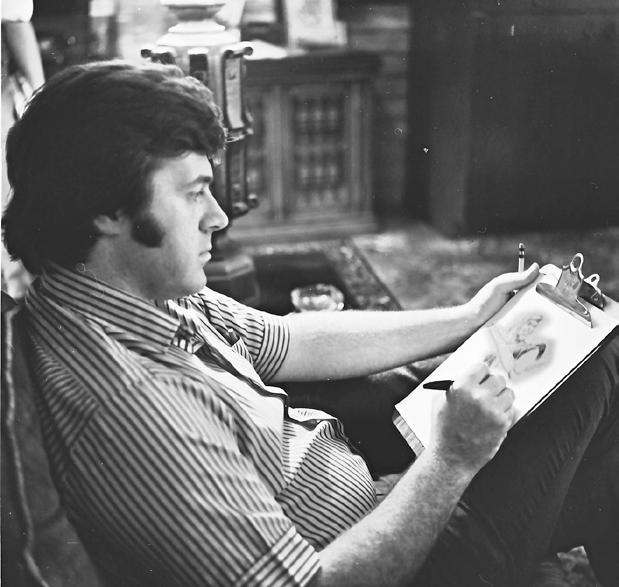

JACK KIRBY: Mike Royer [left, photographed at this 1973 con] works on my strips before I send them back to New York. As far as color goes, DC’s equipped to do that job, and has very competent people to do that job, and I rely on them in that respect, and I’m quite satisfied in what they do.

NEAL ADAMS: I try to get to color my own stuff, and a couple of artists do, because possibly you can be very personal about it, and possibly they think there are things they want to get. I like to do my stuff with Dr. Martin’s Dyes. Some people do it with watercolors. Some people do it with India ink. The problem is, comic book reproduction has, at its fingertips, only 64 colors to work with. Now, that sounds like a lot of colors, but it’s really not a lot of colors. What that means is that, comics books have in the red family, three values of red to use: 100% of red, 50% of red, and 25% of red. They have those same values in other colors, yellow and blue, as we all know, right? Printing colors are made of red, yellow, and blue. Those are the only three colors that are used, and all the other colors are made by combinations of those colors. And unfortunately, you only have three values to work with. If you multiply those colors together—in other words, 25% of red and 25% of blue and 25% of yellow, you get gray. 100% of yellow and 50% of red, and you get a nice bright orange. These are the limitations of the comic book reproduction method. They’re very grave limitations, and the people who do color the comic books have to operate within these limits. Just to clarify; what happens to the color guides is, they’re taken to—in the case of most comic book companies— Chemical Colorplate in Connecticut. Ladies in the area, and one or two gentlemen, work on a freelance piecework basis, and what they do is, they take photographs of all the pages, and with this red paint, they paint out all the

areas that are not to have a particular color, on acetate prints of the pages. And they have to do about nine of these acetates prints. And they photograph these onto a plate through a screen. The screen may be a 50%, or a 25%, or a solid. This way, they put together 50%, 25% of each of the colors on separate plates. It’s a very, very crude method. It’s called “fake separation” because that’s exactly what it is. Maybe one day we’ll get out of that, and get into really good color separation.

At National Comics for a while, we were doing reprints of old ’40s material, which we did not have black-&-whites of. We photographed the color, and washed the color out. And what we do is, photographically, they would aim for the highest contrast of black-&-white, and then they would hire someone to sit down with white paint and go over and try and wash out all the registering of the other colors that came up in black-&-white. Red would always show up on a black-&-white, and so we’d have to go over and take white paint over all the values of red that would come through. We had problems with lettering on that too. If there was lettering on balloons—this was a slow, painful process, and there isn’t really any better way to do it at this point, at least economically. Shel has something to say about that.

SHEL DORF (co-founder of the San Diego Comic-Con, and one-time letterer of Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon newspaper strip): Jerry Bails asked me to do some of the work on his strips, for Who’s Who in American Comic Books... I told him that I’d been playing around with trying to drop reds. As you know, when you photograph red, it turns black. So you’ll see these pictures of people’s faces, and it looks like they’ve got some disease. They have all these little black marks on them. One of the methods I discovered is, if you use panchromatic film and a red filter, it drops it out, it becomes invisible. All the reds drop out. The only problem with that is, all the blues turn black. [laughter] So when we’re shooting for Batman, this was the hardest one. [He] has a pink face, and a blue and black costume. You shoot for red, and all the blues turn black. You shoot for the blue, the blues drop out white, and the red turns black. So what we did, we shot two negatives; one dropping the blues, one dropping the red. We made a sandwich, we made one print, and all of them dropped out together. It takes a little bit of experimentation, but they came out. But it’s very expensive.

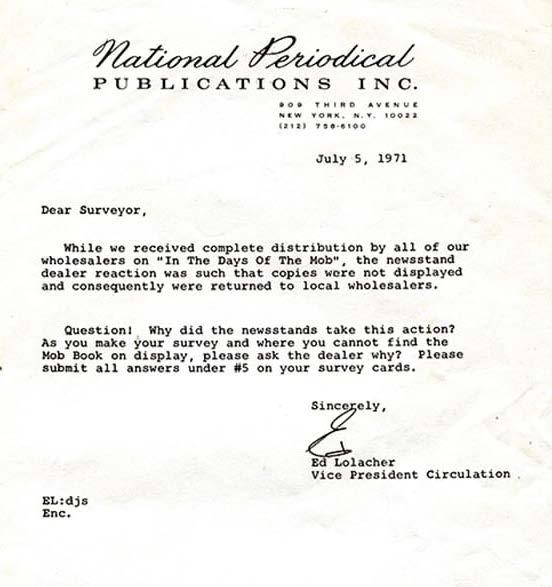

ADAMS: National Periodicals has a pseudogenius production department, outside of the fact that sometimes we think it’s part of their job to mess up our artwork. [laughter] The fact is that there are people in there

that have more ideas than I ever heard of, having to do with reproduction. And Jack Adler, who is one of the heads of the production department at National Periodicals, has developed a method of combining filters so that they drop out the red. Now remember, we’re talking about photographing a printed comic book page, and just trying to get the black in the photograph. All that color’s got to go away. So they put on a filter that kind of eases out the yellow, and a filter that eases out the red, and a filter to kind of ease out the blue, and they shoot it. All that stuff also eases out a lot of the black, so they have to shoot it very strong, and very carefully, so that they pull up the black and stop it before the other color comes out. And they’ve worked out a method to do this; all those reprints you see in National Periodicals are done this way. What happens is, some of the black does come out, and they have to have guys to touch it up, so there are freelance artists who, at the beginning of their careers, will be able to say that they touched up all those old comic books, because that’s what they did to earn some extra dough, until they became professionals.

[on syndicated newspaper strips—Adams speaks as a veteran of the field,

due to his Ben Casey strip work from 1962–1966]

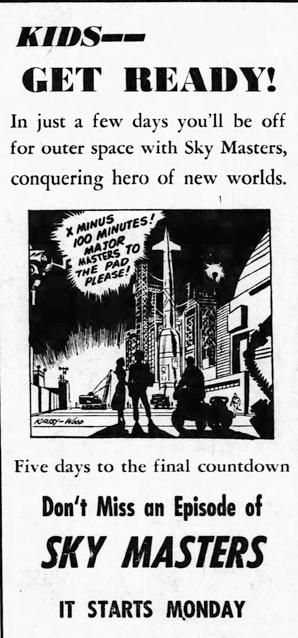

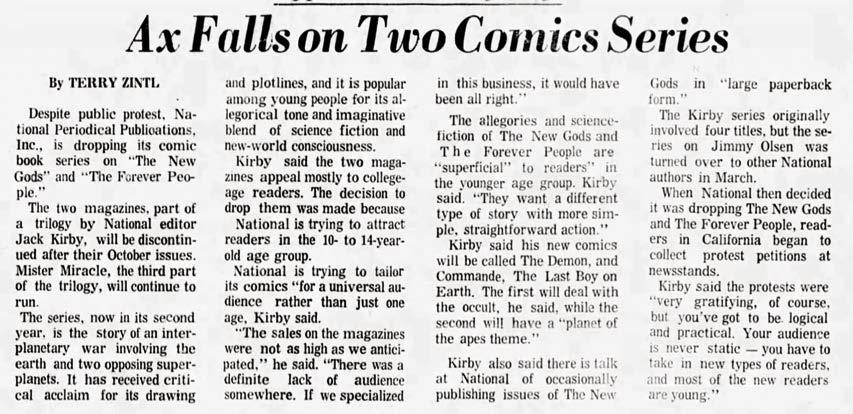

The Times-Advocate (Escondido, CA) from Aug. 14, 1973.

ADAMS: The difference between syndicated strips and comic books... they’re multifarious. Jack knows the feeling of meeting that deadline every week. He had Sky Masters to work on, which is the one that stands out in my mind, but I think a lot of other ones, too. But Sky Masters is like, the glowing thing that I remember. You have all kinds of very strange problems in syndicated strips. You have the problem of “cut-off”. On some Sunday pages, they take off the first three panels in some papers. Sometimes they take off one of the three panels. You’ll do a large panel and two small ones, and they take off the little dinky one on the right, and somebody said something important there, and it goes. If you work for a particular syndicate, and you draw your page one way—in other words, if you draw it horizontally, and do deep panels, which you’d have to do if you draw it horizontally, then the bottoms of the panels get cut off. If you do dailies for the news syndicate, for example, you have to leave extra stuff on the bottom of the dailies that will get cropped off; that happens to you a lot. You also have to leave space in the upper lefthand corner, where you don’t necessarily put the logo of the strip on a daily strip, but some papers decide they’re going to put it in there, and they do it. You have to be prepared for papers not printing color very well. So there might’ve been some disadvantages. Your audience is different. You can’t tell as long a story. You can’t get as much into the soap opera quality of the story as you can with a strip. I found it a lot more comfortable and a lot more free and a lot more adventuresome in that—the syndicated strip business is not exactly what it was. Those with humor strips are surviving a lot better than those with realistic strips. They syndicates are not very receptive to realistic strips anyway. The comic book business is flowering like crazy. I’d like nothing better than have some of the comic book thinking go back into the comic strip world. I don’t know what’s gonna happen, but I am delighted in the comic book business, but again, there are difficulties. There are difficulties with the lack of control and the color.

KIRBY: Although the coloring is usually... from my own experience, I’ve seen the coloring done at the publishing house itself, by the particular people who—well, they’ve gathered up the experience in the field to handle that sort of thing, and actually, they do it very well. I rely on them all the time I’ve been in the business. Of course, the printers themselves can do it. The printer has the means to do it, and often does. It’s done on what we call silver prints. It’s something that evolved; it’s like a photostat that involves a quality of paper, and this paper takes color very well. The

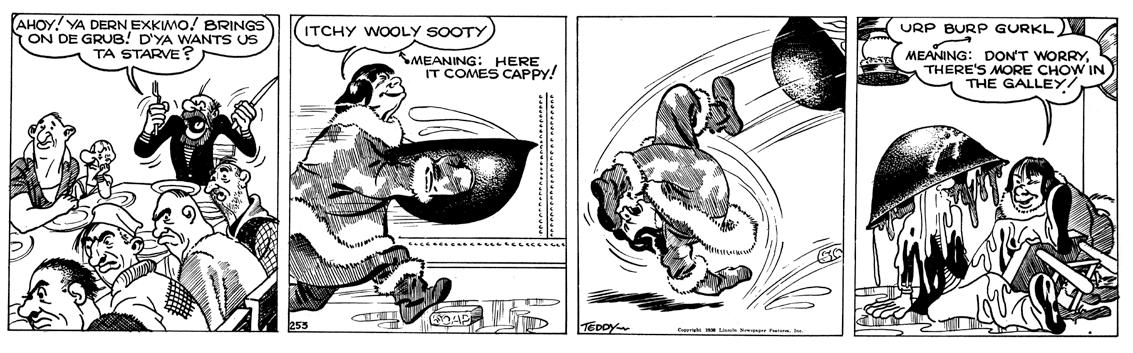

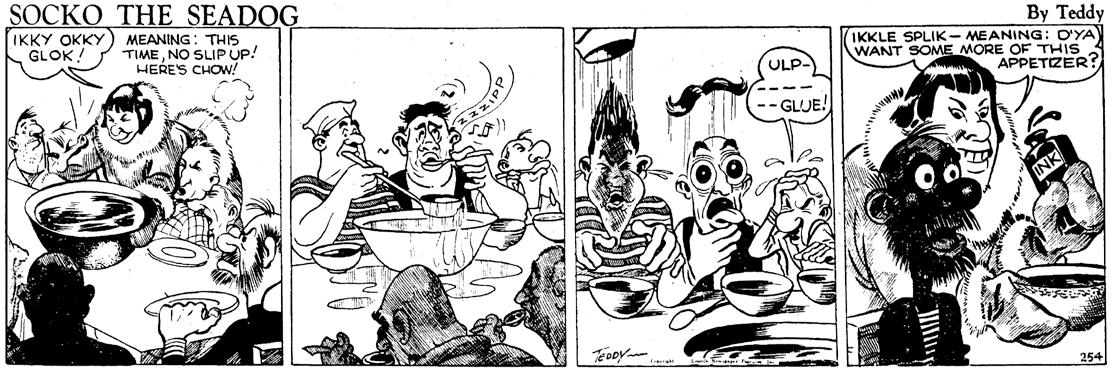

Kirby’s surviving continued Socko stories are:

#136–145 (at the gym, Polynesian islands)

#148–154 (in Baghdad)

#155–158 (sea battle)

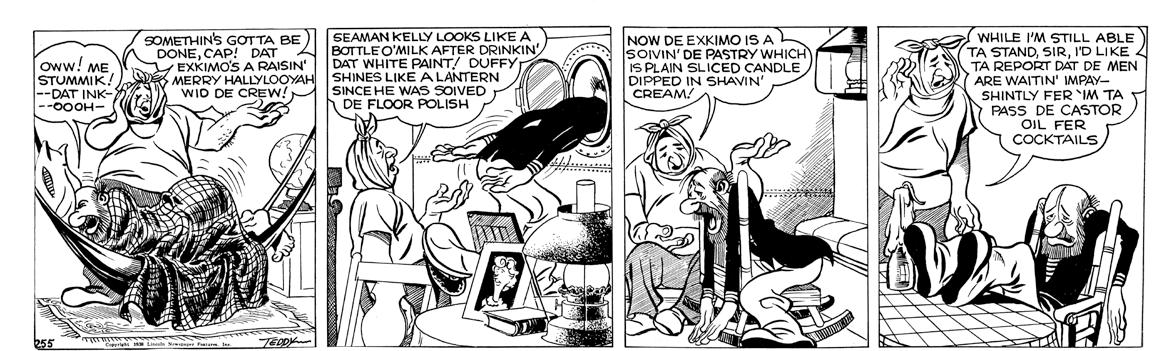

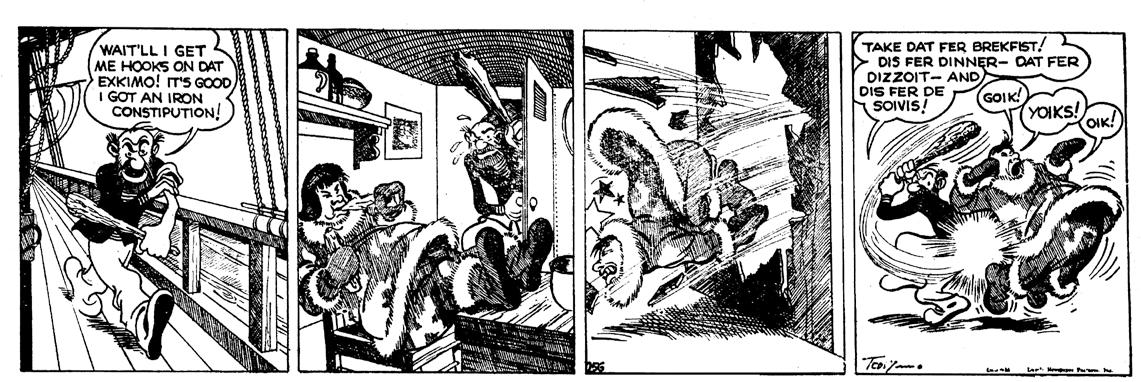

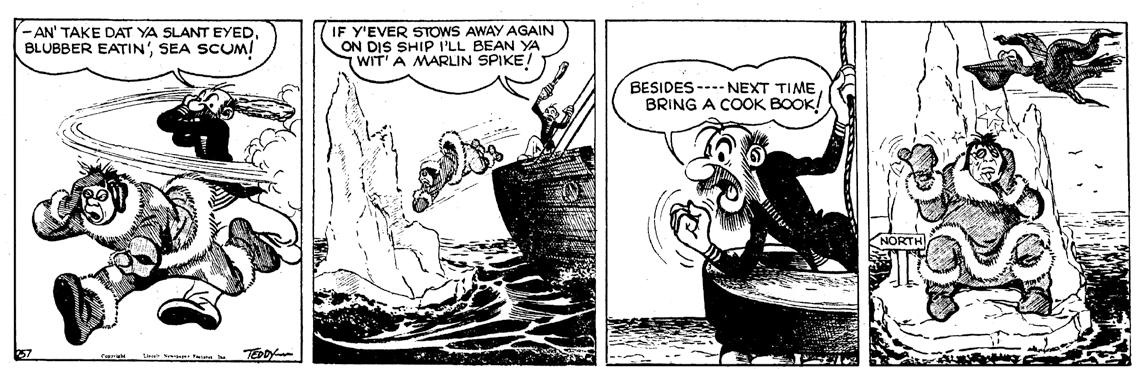

#253–260 (shown here)

#273a–285a (Max the mule, Mexico bullfight)

#269b–285b (starts at end of #285a’s bullfight with “El Falfa” the bull, then Blatwood Blotz tries to get Socko to pilot his submarine)

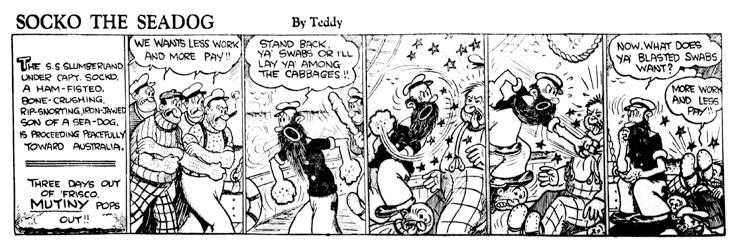

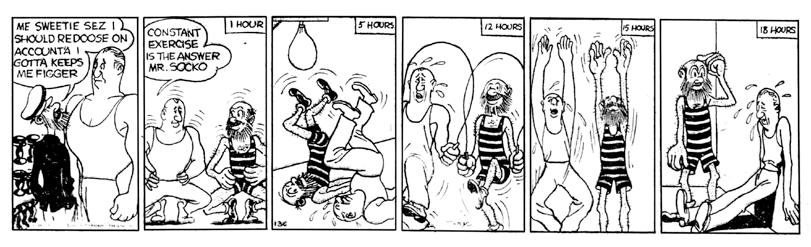

by John Morrow

ocko the Seadog is an obvious rip-off of Elzie Segar’s Popeye, but it’s not without merit—mainly, that it was an early training ground for Jack Kirby. Socko started its numbering with #100 and a 1936 copyright date, and strips through at least #107 were likely drawn by H.T. Elmo himself, using the pen name “Teddy” (from his middle name Theodore). Kirby joined Lincoln Features in 1936, and having experience working on Max Fleisher’s Popeye cartoons, took over Socko around strip #136 (sadly, no #108–135 examples exist).

After extensive searching through numerous newspaper archives, it’s clear that most papers running Socko were weeklies (or twice a week at best), and would often run strips out of order. After reassembling the

There is a running continuity within Kirby’s Socko, but not always with consecutive numbering. The more loosely rendered, unconnected gag-a-day strips are randomly interspersed within Jack’s continued storylines, so presumably Elmo had some daily clients who could run continued stories without confusing their readers. Why are there “a” and “b” versions in those above numbers? Because there were 17 final continuity strips that reused the numbers 269–285. That final sequence abruptly ends with a beautiful French reporter “Evonne Evonne” trying to trick Socko into piloting Blatwood Blotz’ submarine. So I’m calling those last continuity strips #269b–285b. They’re in the correct order on the pages that follow, so you’ll see what I mean.

Strip sources, in addition to Jack’s own files:

https://chronicling america.loc.gov/

https://nyshistoric newspapers.org

https://panewsarchive. psu.edu

https://libguides. njstatelib.org/ digitized-newspapers

https://newspaper archive.com

surviving strips numerically, there are numerous missing ones, including #108–135, 142–144, 171, 229–252, 270a–271a, 280a–282a, 281b, and #283b. Either those strips never existed, or more likely there’s no surviving examples due to their running in small town newspapers that are lost to time and World War II paper drives.

During my research, I discovered the Saybrook Gazette and Arrowsmith News (published in Saybrook, Illinois) was running Socko as late as 1950. So either Elmo was still making sales that late, or that paper was just reusing old proofs in their files (that newspaper first ran Socko from its non-Kirby beginnings withstrip #101 on Feb. 5, 1942; #100 never ran).

Despite some ethnic stereotypes that are looked upon unfavorably today, this strip shows Jack’s early skill at storytelling, and adding a maximum of impact in just a few panels. By the end of Kirby’s run, he was using a crosshatching technique in his inking, akin to what he used on the more serious Blue Beetle strip of the time. The evolution shown across these examples indicates just how quickly Kirby was improving during this era. H

KIRBY

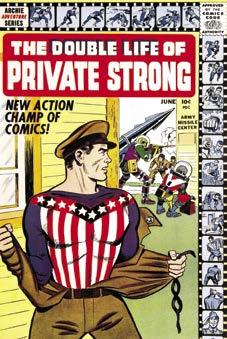

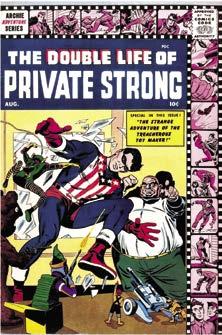

If you’ve been reading this column over the years, you’ll know that I’ve been pretty thorough in investigating all the work by Jack Kirby which belongs in the category described in the title—that’s to say, “Obscura,” rather than mainstream. If the truth be told, I’ll admit that I frequently moved into territory other than that reserved just for the cognoscenti. Are the Challengers of the Unknown obscure these days? They haven’t had their own book for quite a while and made only fitful appearances in the DC animated shows. The men living on borrowed time are, it has to be said, largely forgotten heroes, although I’d guess that readers of this magazine will have at least those first issues illustrated by The King (or collected in the handsome DC hardback edition, which I imagine isn’t cheap these days). So, yes, Obscura. But what about Private Strong, he of the “Double Life”? Or, if you prefer his superhero moniker, The Shield? As with so much of Kirby’s immensely creative work in the 1950s, this particular costumed character only had a couple of outings in The Double Life of Private Strong—just two comic books before a half-hearted revival later with other less accomplished artists. And his newsstand demise at the hands of Archie Comics’ John Goldwater was not due to faltering sales; there was hardly time to even register the requisite figures with only a measly

two books appearing. The standard story of the termination, disputed in several quarters, was that Goldwater had received a cease-and-desist order from DC Comics which obliged him to kill the book. The reason was similar to what did-in Captain Marvel earlier that decade: the character had aped the daddy of all superheroes, DC’s Superman. It’s been pointed out that while Captain Marvel was indeed a clone of The Man of Steel, there was some attempt to make The Shield more individual. Yes, he could fly, but his unusual dexterity in dodging bullets was stressed, as was the ability to generate crackling energy from his hands. However, of course, his costume was skintight blue Lycra with red trunks and boots; no cape, but still...! However, it might be pointed out that another superhero had been using that color combination for a while, and it could also be argued that Kirby was more inspired by his own creation with Joe Simon: Captain America—not to mention his newer version of that character, Fighting American, the latter a character whose reign stretched to a variety of successful issues. Whatever the reason, The Shield was a briefly glowing comet in the night sky, and after one spectacular first issue and a perhaps less impressive second issue, he was gone. That first issue has been discussed in this column before, but we haven’t turned the spotlight on issue #2—the final issue. It’s time…

The Double Life of Private Strong had hit the ground running with the first issue, featuring some of Kirby’s most energetic work in the period, and was as impressive as its equally short-lived companion title, Adventures of The Fly (although more modest talents were to produce subsequent issues of The Fly after Kirby said goodbye). The second issue once again features the memorable notion of a filmstrip across the top and down the righthand side of the cover showing The Shield in a lively little mini-adventure, kayo-ing spies before returning to his secret identity of a none-too-bright farmboy turned soldier—the Private Strong of the title. And those of us old enough to remember the appearance of this comic in the UK—where both issues were much seen (unlike such DC titles we were desperate to see, such as the early Showcase

Delaware), Feb. 23, 1972.

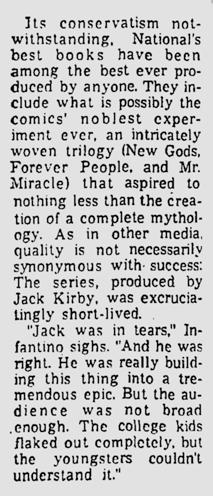

[below] Unpublished Master

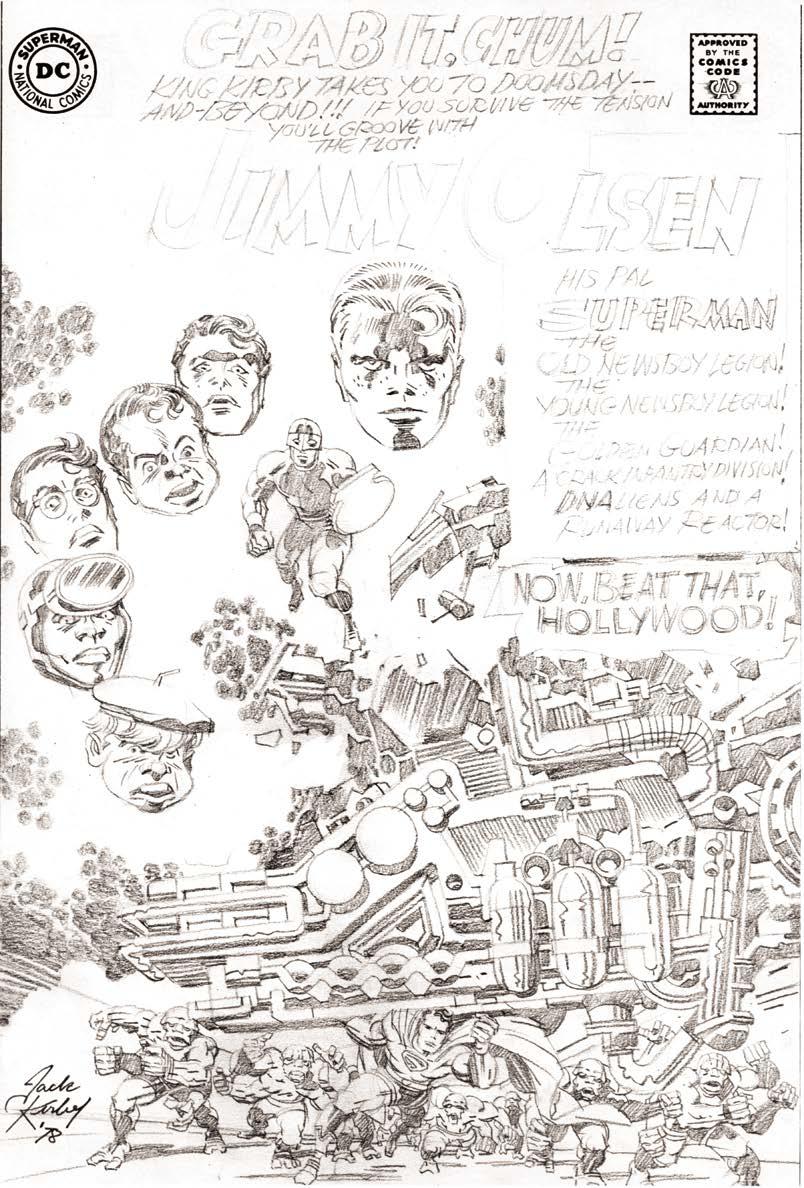

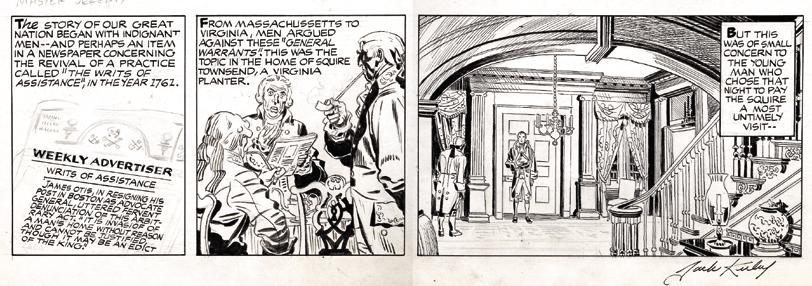

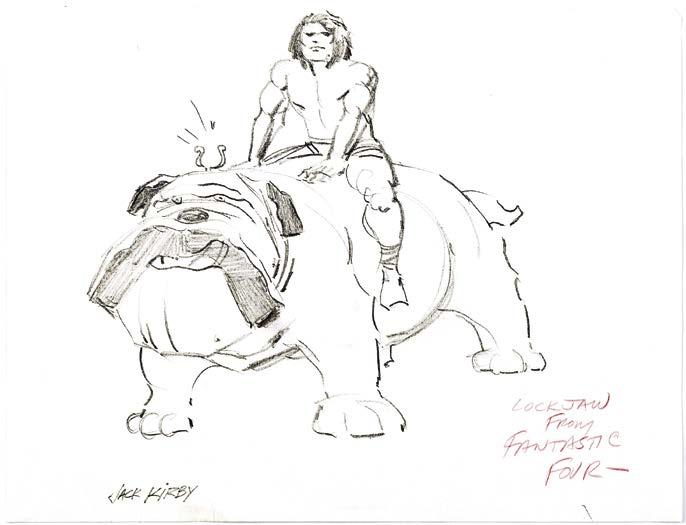

[next page, top] Editor John Morrow’s birthday is right around the time this issue is in your hands. If anyone out there owns this wonderful sketch and wants to gift it, you’d really make his day special—it’s even prognosticatedy personalized to him by Jack!

[next page, bottom] We’ve no idea why Lockjaw from the Inhumans has a barbarian-looking dude riding on his back. Maybe this was an animation idea Jack pitched?

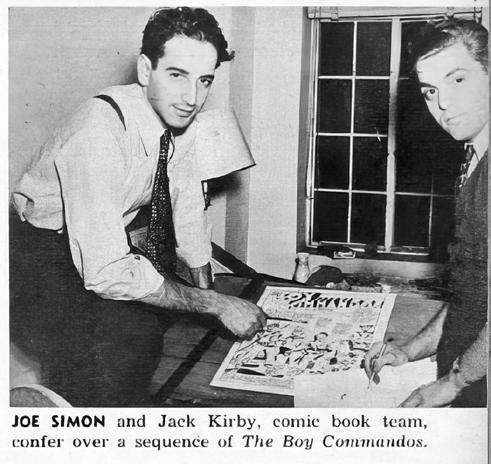

MARK EVANIER: We have a different panel than was advertised because two of our people are sick. We also have a friend of mine—Henry, come over here and sit next to me. I’ll tell you who this man is in a moment, but first I have to greet one of my dearest friends. [pause as Henry Holmes makes his way to the podium] You’re probably wondering who this man is. Over the years, there were a lot of people who fought for creators’ rights in comics. I have been in the industry long enough to have seen how bad it was. When I got into comics, there were problems with Work For Hire, and the way they treated people—you didn’t get to keep your originals, they would treat people very badly. When I met Jack Kirby, one of the things that stopped me from trying to make my career in comics was seeing how unhappy Jack was with the way they had treated him. And I thought, “If they could treat Jack Kirby that way, think what they’ll do to me.” So I never did comics full-time, but I was around for this struggle and watched the industry change, and this is one of the men who changed it a lot.

You may remember a comic book Jack worked on called Destroyer Duck. That was a benefit comic book to raise money, because Steve Gerber was locked in a

lawsuit with Marvel Comics over Howard the Duck—the ownership of it, and his firing from the company. We had to raise money, because Steve’s legal bills were getting to be astronomical, and Marvel was intentionally trying to drive them up. “We can outspend this guy. Maybe we can’t beat him in court, but we can beat him in his wallet.” So even with people chipping in, and people loaning him money that they never got back, it was still very financially ruinous. Steve fortunately had a very good attorney, who did wonderful things for him, got a great settlement out of it, and along the way helped open up the entire industry for creators to get much better deals. He negotiated some of the first creator-owned deals. That lawyer did the contract for my book called the DNAgents. He negotiated the contract when we took Groo to Marvel, and got the first real good creator deal ever out of Marvel. That lawyer’s name was Henry W. Holmes. This is Henry W. Holmes. [applause]

We’re going to talk about other things first, and then we’ll talk to Henry in the second half of the panel. I will tell you, Henry represented some of the biggest stars and executives in Hollywood. His client list was insane; I’ll go through it. I am the only client he ever had that I’ve never heard of. [laughter] It’s amazing.

In addition to Henry, we have some other wonderful people. Over the years I have been amazed at how Jack Kirby inspired so many other people in the creative arts. Obviously, he inspired a lot of people who wanted to draw big giant super-heroes beating up on each other. We understand that. But he inspired people who were poets and authors and musicians and dancers. I even got a fan letter one time after Jack passed away, from a guy who was a spot welder, who wanted to explain to me how Jack Kirby inspired him to be a better spot welder. I can’t figure that out to save

my life, but he did. [laughter]

If you’re familiar with a comic strip called Mutts, you know it’s a brilliant, clever, funny comic strip, that people love, with characters people love around the world. You’d never think that guy was inspired by Jack Kirby—well, he was. He’s Patrick McDonnell, sitting right here. [applause]

And what would a Kirby panel be without Kirbys? [laughter] Say hello to Jack’s grandkids: Tracy Kirby and Jeremy Kirby. [applause] Tracy, Jeremy, what news have you got for Kirby fans, about things that are going on in Jack’s world? Oh, and we have an announcement a little later about something special, but first, Tracy, tell us about what you’re working on.

TRACY KIRBY: Well, now that my children have been getting a little bit older, thank good ness, I’m able to dedicate more time to my own career. My creativity stems in landscape design; that’s about as good as I could get, with drawing circles on paper. stuck with that. But I’ve been really excited to start working with the wonderful guys who created this amazing nonprofit, the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center. Hopefully there will be, one day in the future, a brick and mortar [location], which would be amazing. The pop-up exhibits have been going great. If you are in the L.A. area, there’s two more weeks of the Kirbyvision exhibition at the Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles. It is amazing! The first time I stepped in, it was like, “Finally, a professional, amazing exhibit that is dedicated to Jack Kirby and his inspiration, instead of it always being Jack Kirby art as part of another exhibition.” So this is a really wonderful exhibition. If you have a chance

to get there, it closes on August 3rd. They’re hoping to work partnerships out with other galleries, to have this exhibit in other places, especially on the East Coast. So fingers crossed for that.

I also had the chance—there’s a gentleman named Ray Wyman who did the Art of Jack Kirby [biography] awhile back. He is going to be launching a very cool podcast starting next Spring, and he has been working on about forty hours of recorded conversations with Jack. It’s really awesome, because it’s just offthe-cuff, completely out-there conversations, just letting Jack talk about everything.

So I’ve been sitting and helping the guys at booth 1803, so come and say “Hi.” [spots the Kirby Museum guys in the audience] Oh, you’re right there! [laughter, applause] Jeremy?

JEREMY KIRBY: I’m just here to see you guys! [laughter] Thank you all for being here. I’m excited.

MARK: I’m always fascinated to ask Kirby relatives a question about this. I told this on another panel, but it belongs on this panel. As you may know, I broke my ankle earlier this year. It was a mess, a terrible situation, with agony—you’d never believe the pain I was in for a while. I broke it in the bathroom upstairs in my house. Four burly firemen, each one of whom should’ve had a superhero costume of his own, [laughter] showed up to carry me down the stairs. It should’ve taken a whole brigade. [laughter] They get me down the stairs, they put me on a gurney, they wheel the gurney out to the street, and they’ve got one of these fire rescue trucks out there—an ambulance, basically. And they put me in the back of the truck, and one of the guys is driving, and one is riding with me. I was almost screaming in pain, it was so excruciating. And I’m on this gurney, and he’s saying, “We’ll get you there, we’ll get you there...”, a very sympathetic person. And at one point he says, “Your house has a lot of comic books in it.” [laughter] And I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Did you ever hear of a guy named Jack Kirby?” [laughter] “Jack Kirby? Let me tell you...!” All the way there, I told him about Jack. I love telling people about Jack, I love the reactions I get. I think I’ve told this story too many times, about the kid in Costco who looked at me. I had a CD-Rom of Jack Kirby comics, and this kid was boxing things, and he says to me, “These comics are by Jack Kirby, the greatest comic book artist ever. Marvel f*cked him over.” [laughter]

You’d be surprised how many times in my career as a writer for TV shows and such, I’d walk into meetings and the people there say, “Never mind the thing you came to pitch. Tell us about Jack.” [laughter] What kind of reaction do you get these days, from people

used to, that’s for sure. The cool thing is that, over the most recent years, my kids have been getting a lot of reactions, and some of the teachers know who got a Kirby gene in her, for a much better artist she said, “Mom, this has been cool. They inspirational piece,”

Sydney is Jack Kirby’s great granddaughter kind of let it slip out to the class. [laughter] And Sydney said it was kind of weird; it was the first time a couple of the kids near her went “No way!” [laughter] So it’s kind of cool, because probably ten years ago, I would say “Jack Kirby” and people would say “Who?” or “Oh, isn’t that Stan Lee who created everything?” Not a lot of people knew, and now when I’m at work or people will see a movie and say, “Hey, I think I saw your grandfather’s name on the movie credits.” So it’s been nice. It’s been a long time coming... I definitely feel like we get a lot more people coming up. It’s cool letting people know who my grandfather is, and what he did. And of course, everyone will get on their phone and start googling it and go, “Oh my God, you’re right! Whoa!” [laughter]

JEREMY: I agree. [laughter] Absolutely. It’s a big change from years past. It used to be the opposite. I was never ashamed, but I would kind of hide it a little, cause you don’t know what reaction you’d get if you told them, “Yeah, my grandfather was instrumental in creating this character,” and their first thought was “the other guy.” And then you’d have to explain things, and after a while you just got sick of explaining it. I’d say, starting fifteen years ago or so, when credits started to finally go on some of the movies, and comic art started getting more popular, and people started deep-diving on the Internet—sometimes the Internet can be a good thing.

Now it pops up in the weirdest places. I run a software company; we work with digital forensics for the federal government, and state and local agencies. I was on the phone with the head of HSI [Homeland Security Investigations], their cyber division. We were talking, and he brought up my last name, and he’s like, “Y’know, Kirby’s an interesting name, blah, blah, blah,” and I brought up [my grandfather] was an artist, and he goes, “I was hoping you were related to that Kirby. He’s awesome.” [laughter] And a police chief, literally just two weeks ago, one of my guys that works for me was on a live Teams meeting with him, talking about our products. And he saw a bunch of comic book stuff in the back, and said, “I’m the biggest Jack Kirby fan there is.” And they obviously [bought] the software and everything else. [laughter] And I sent him one of my grandfather’s comics, and said, “Thank you so much for what you do.” [laughter] We’re seeing it in so many new places that we’d never have seen it in the past, and it’s awesome.

how Google works, and for a while, I couldn’t figure out why they kept showing me pictures of vacuum cleaners. [laughter] And I realized there were Kirby vacuum cleaners, and I was searching for Jack a lot. And now if you go in and type in “vacuum cleaner,” it’ll show you a picture of Jack Kirby. [laughter]

TRACY: That’s funny, I received that exact same reaction. When I would say my last name, I always got the joke: “Oh, are you related to the Kirby vacuums?” And honestly, for the last ten years, I have not received that joke. [laughter] It’s usually the opposite now.

HENRY W. HOLMES: Stan Lee didn’t have a vacuum cleaner named after him. [laughter]

MARK: Before we move off of Tracy and Jeremy here to get to our next guest, do you find that there are people who go, “Could you draw me a picture of Captain America?”

TRACY: I immediately tell people I did not get the gene. When I did archaeology, I used to get made fun of for not being able to draw pottery shards. I’m creative in other ways, but I’m definitely not the artiste. My daughter, though, is actually getting people to ask her to draw pictures. In fact, she got her first little commission by another artist at the Kirbyvision exhibition.

JEREMY: She’s amazing. You’ll definitely be seeing her in the future. She has the gift. Her ability to draw—it’s awesome.

MARK: In the early days of Google, I was searching for things, learning

MARK: One of the things I’ve tried to convince people of over the years, is that Jack was more than a guy who drew. Jack was more importantly a guy who thought, a guy with good ideas. Somebody on the Internet said, “Well, I like John Buscema’s Silver Surfer better than Jack Kirby’s.” That’s fine if they like John Buscema’s art, there’s nothing wrong with that at all. But I think sometimes they don’t get that John Buscema and Jack Kirby were not doing the same job. Drawing a comic book, drawing a character, is only a small piece of what Jack Kirby did. John Buscema did not approach his work as—and this is not a knock on John Buscema or any of those guys—“Okay, how do I revolutionize the business with this story? How do I create something new that will spin off into other avenues, and make the company more successful? How do I take comics to another level, moving in new directions?” One of the things that Jack was not that good at was looking backward. He really didn’t want to do the same characters over and over again. He wanted to come up with the next idea, the new idea, and his time at DC was very frustrating, because some people at DC didn’t want new ideas, especially from the guy who did those awful Marvel ideas. He was up against a bunch of people who, first of all, I think did

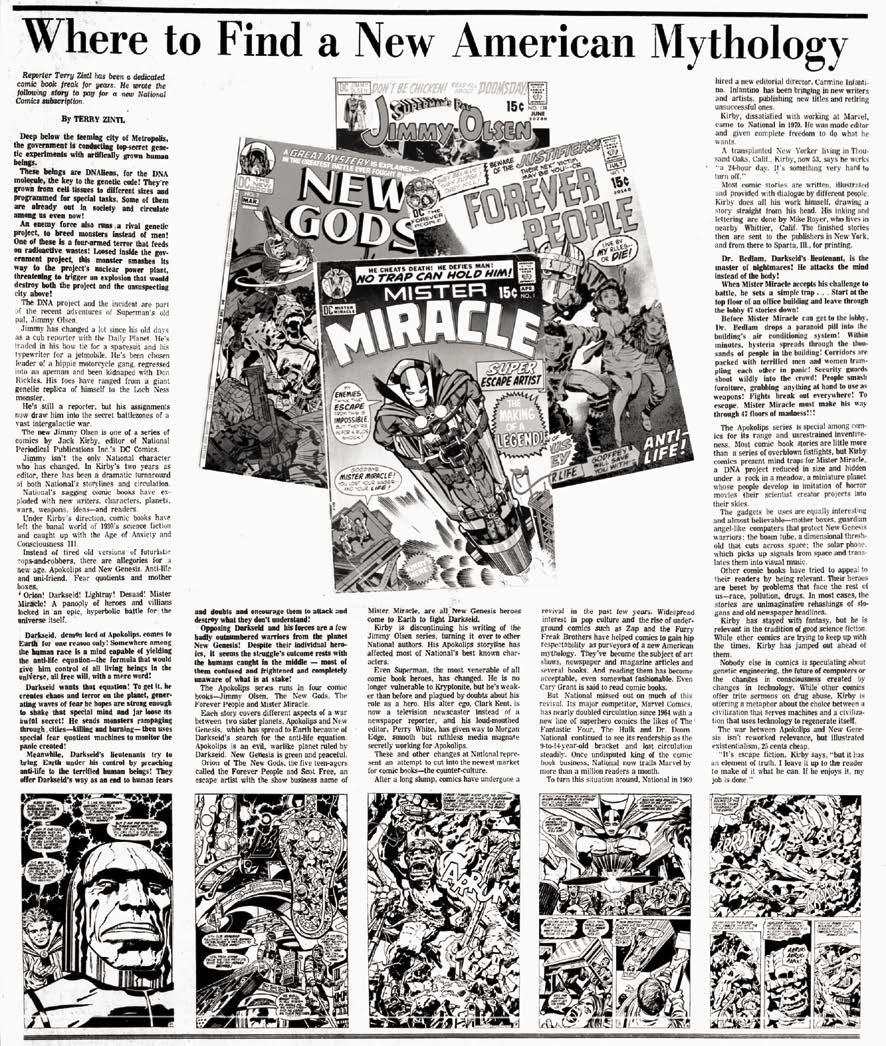

[Summer 2024 saw one of the largest exhi bitions of Jack Kirby original art ever put on in the United States. Kirbyvision took over Los Angeles’ Corey Helford Gallery from June 29–August 3, showcasing 50 pages of rare Kirby art alongside new work by over 70 artists from the New Contemporary scene, each providing their own unique interpretation of Kirby’s characters, concepts, and sensibilities. We present here a conversation with curators Randolph Hoppe and Tom Kraft of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center, as they reflect on what it took to be a part of such an ambitious event.]

THE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR: How did you end up working with the Corey Helford Gallery to bring Kirbyvision to life?

TOM KRAFT: I met [Corey Helford Gallery owner] Bruce Helford at an LA Comic Art Show around 2019. He collects Jack Kirby’s original art from Captain 3-D, a 1953 Harvey Publishing comic book that only ran for one issue. He told me his dream was to create the best Kirby exhibition ever. I mentioned that the Museum would love to bring something like the pop-up exhibitions we’ve done in New York City to Los Angeles. In July 2022, he suggested we contact [CHG director] Sherri Trahan. Sherri mentioned that the gallery was booked til 2025. So we waited. Then, in February 2024, we received word that the gallery had a cancellation, and the Kirby show was scheduled for July, leaving us less than five months to put it all together.

TJKC: Where did “Kirbyvision” come from?

TOM: I started brainstorming ideas for a thematic approach to the show. Sherri explained that the show wasn’t to be just an exhibition of original art, but also to showcase some of the 200 artists they represent, who would show new art that could be sold. So the combination of new artwork combined with Kirby original art, made “Kirbyvision” a perfect choice.

RANDOLPH HOPPE: We hosted a blog for a number of years called Kirby-Vision by Jason Garrattley. So when Tom mentioned that he thought “Kirbyvision” was a good idea, I thought so too, because we’d already been hosting it! I did reach out to Jason and let him know that we were using that name. It’s pretty important that we’re not only getting Kirby’s work out there, but also showing the world that he did have a vision for comics and storytelling. It’s also just a great name.

TJKC: How did the “Kirbyvision” concept shape the exhibition going forward? Where did the 3-D elements come from?

TOM: The idea of having 3-D elements was 100% Bruce Helford’s. So we centered the exhibit around his suggestion to enlarge three pages from Captain 3-D into four-foot wide panels to hang on the wall. He also wanted to display some of the original Captain 3-D art that he owns.

TJKC: Those huge 3-D panels, as well as the complete reprint of Captain 3-D you did at Treasury size, looked really spectacular. How did those come together, and how did you get the 3-D just right?

TOM: That took scanning in the comic at high resolution. The original comic had faded and browned, so color correction and restoration were needed. Eric Kurland from 3-D Space, a museum in Los Angeles dedicated

Commentary by John Morrow

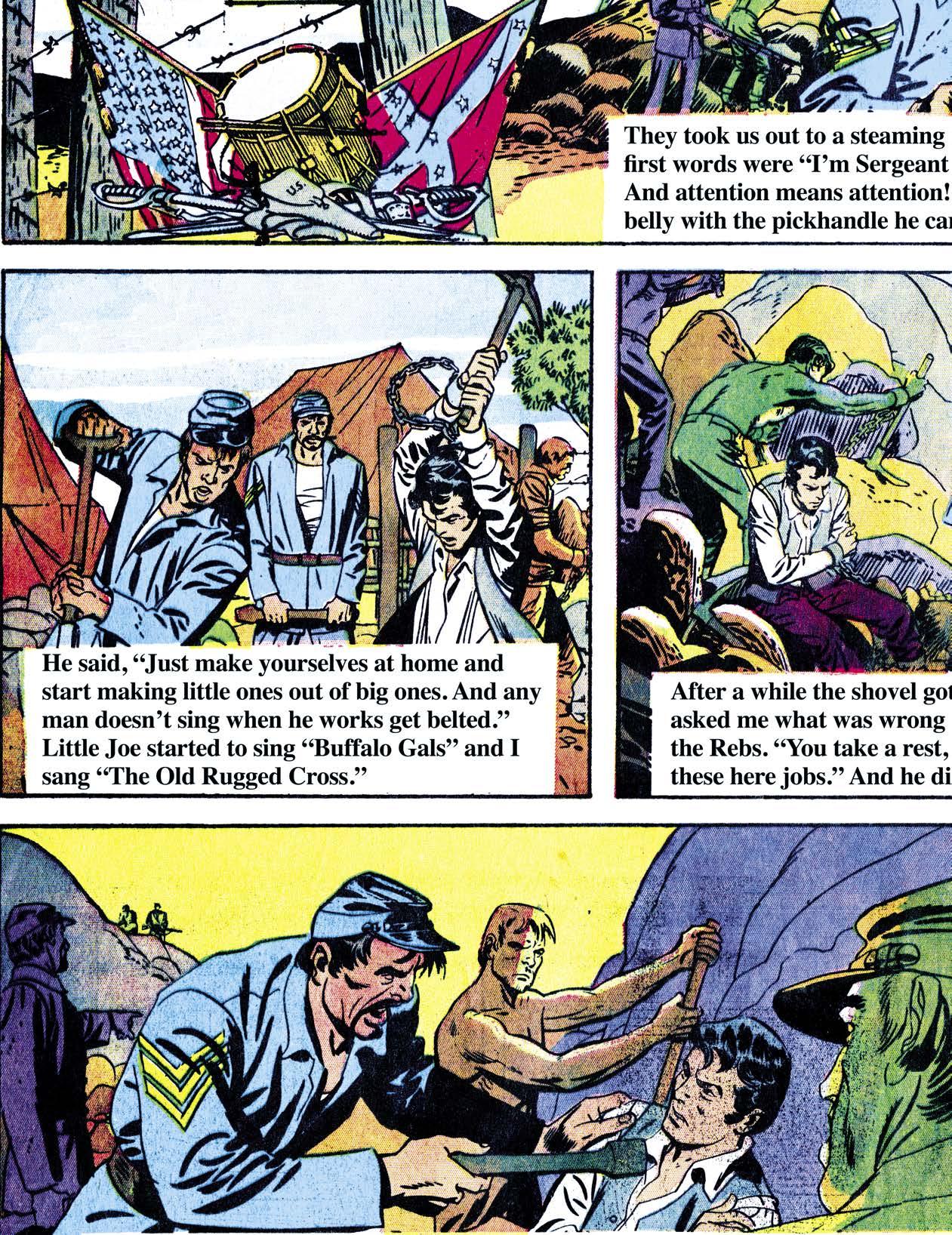

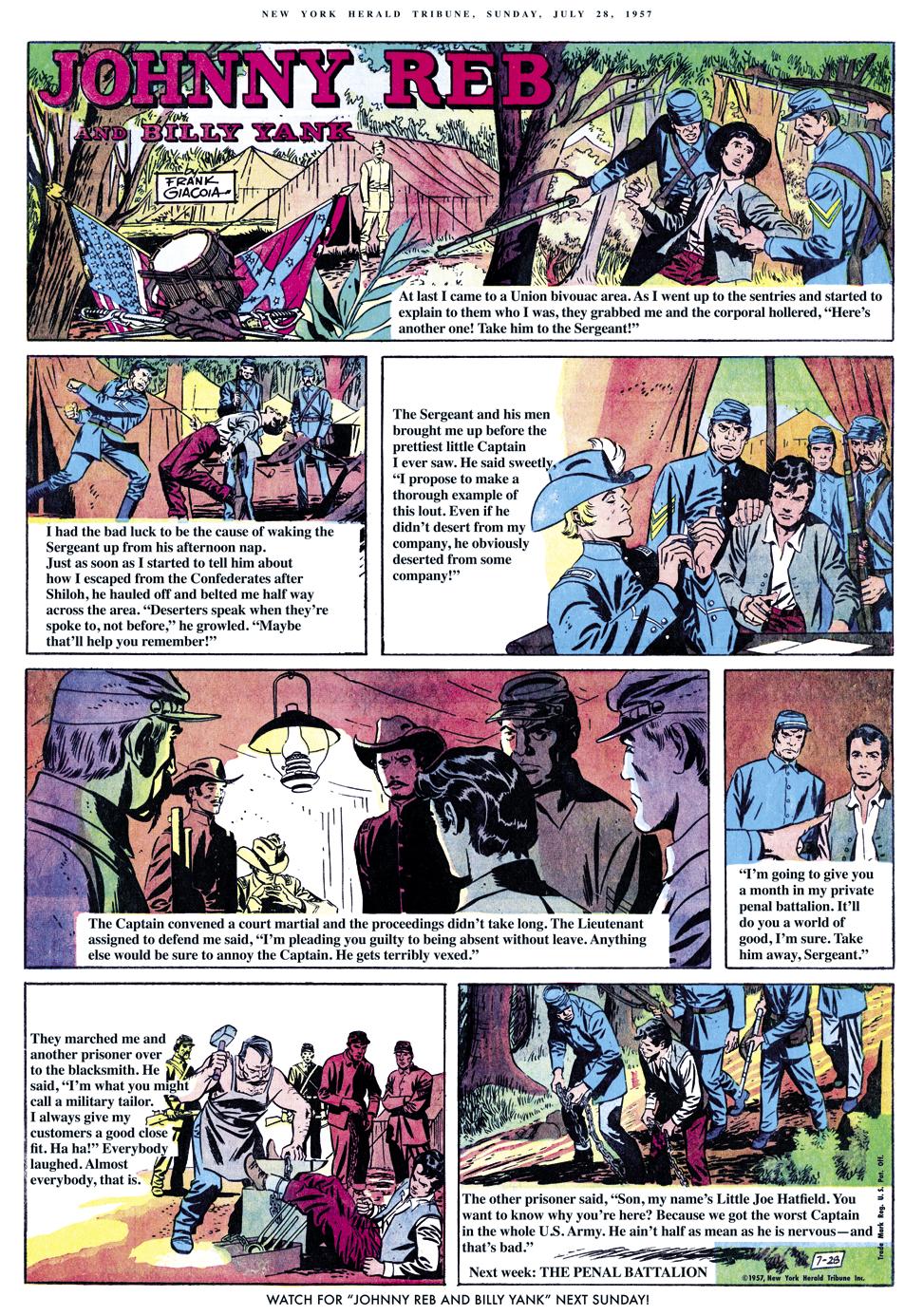

Johnny Reb and Billy Yank was a Sunday comic strip by Frank Giacoia which ran from November 18, 1956 to May 24, 1959. It told alternating stories of a Confederate and a Union solider during the American Civil War, and the title originated with the 1905 novel of the same name by Alexander Hunter, a Confederate soldier who kept diaries of his war service.

Giacoia regularly turned to friends to ghost the strip for him, including Mike Sekowsky, Joe Kubert, and good old Jack Kirby. Jack ghosted 28 Sundays, from his first on July 28, 1957, to his last on Feb. 2, 1958.

To give you an idea of the size these strips ran, take four pages of this issue (stacked two-and-two), and that’s about the size of the newsprint one Sunday filled when it first started publication in the New York Herald Tribune.

(The background image on this page is actual size!) Standard newspaper broadsheets were typically 15" x 22¾" in those days, but the last full page strip (the final one reprinted here) appeared on Sept. 22, 1957. After that, it went to a half-size horizontal format, and by December 8, 1957, it had eschewed typeset lettering for comic book-style handlettering.

For ease of reading, we’ve recreated the Times Roman and Futura typeset lettering in these examples to exactly match the original strips, staying true to the original line breaks and positioning.

Read all about Jack’s Jimmy Olsen pencil work, through commentary by

Shane Foley

[left] Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #144, page 6 (Dec. 1971)

Speaking of Morgan Edge (you have read the previous piece, have you not?), what better way to open a Kirby pencil gallery than with a page of his final depiction of Edge. And what a sinister, evocative image it is in panel 4—one of Kirby’s best of him, surely—and, as we can see if we compare this to the published version, far better in pencil than in ink. (I’m not one who hates all Vince Colletta’s inking—there were some very good jobs—but this book isn’t one of the best. The inking on panel 4 here loses much of what Kirby achieved in pencil form, while there are details omitted in panels 2 and 6, Edge’s hair is often simply blacked in over the detail, and the background in panel 2 has lost all life.)

[next page]

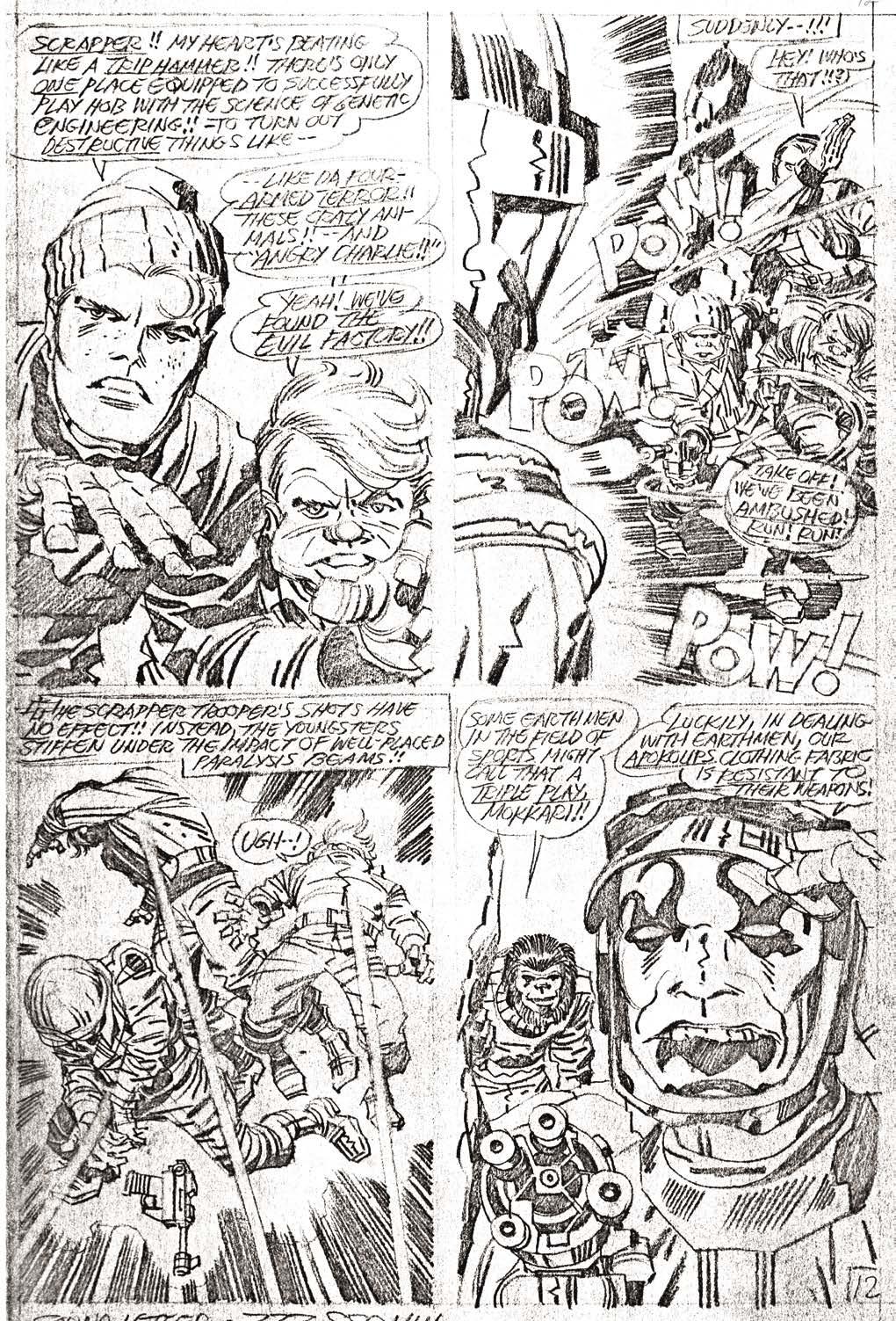

Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen #145, page 12 (Jan. 1972) EXTRA! The Evil Factory has been found (as seen in pencil form in TJKC #48) and this following page has the fallout. Two action panels showcase Kirby’s explosive action, then in panel 4 we get a stunningly powerful portrait of Mokkari. Here, he has finally been drawn more closely to his original appearance after some inconsistent previous appearances. The only downside is, in the inks (again), the detail in that gun in panel 4 is very sloppily changed. And of course, Olsen himself is inked by Murphy Anderson, making him far less Kirby-ish.

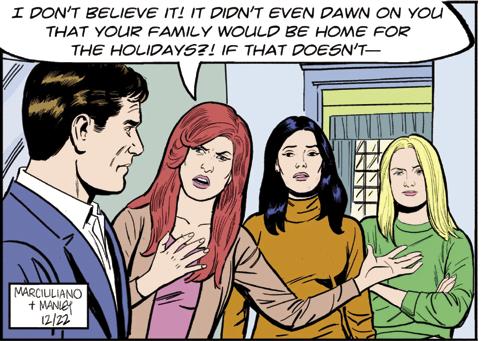

THE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR: Tell our readers how you got your start in comics and newspaper cartooning.

[right]

[below] Examples of Mike’s current work on the syndicated comic strips Judge Parker and The

[next page, bottom] Mike pays tribute to Kirby’s cover for Fantastic Four #97 (April 1970).

MIKE MANLEY: I’m 62, and probably 63 years old by the time this sees print. I guess I was always aware of newspaper comics, mostly because of the Sunday papers as a kid, and I remember them being pretty big, and liking Peanuts. I don’t remember a lot of the other strips, although I’m sure I looked at them. I was much more into comic books than newspapers as a kid, although my dad was a comic book and newspaper strip fan, and he used to tell me about certain comic books and characters that he liked as a kid, like Popeye and Dick Tracy and the Phantom. I remember him telling me about Eugene the Jeep, the little character from Popeye, which I found fascinating, because he was never in any of the Popeye cartoons that I saw as a kid.

I became a much bigger fan of comic strips in my teens because I really got into studying comic books, which led me back to comic strips and all the great classic comic strips, especially the adventure strips. So as a teenager, I was very aware of the history of the comic strip, and I had some reprints of Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon, especially. I also was aware that all of the comic book greats

like Neal Adams and Wally Wood and Joe Kubert, and all the artists I’d admired, also had a hand in doing comic strips, and greatly admired the classic comic strip artists who were giants. Then in the ’80s I got to know Al Williamson and befriended him, and shared his studio along with Bret Blevins. And of course, Al was one of the all-time greats, and had an amazing collection—not of his own work, but so many great Hal Fosters and Alex Raymonds, and so many classic comic strip pieces that he basically saved from being destroyed.

And of course, because he had all of that stuff, it was a great opportunity to study the originals of so many of the classic strip artists who were very influential on all of the comic book artists of that first Golden Age generation, especially people like Jack Kirby. You can see a lot of Milton Caniff, as well as Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, in Jack Kirby’s work if you know where to look. Their way of spotting blacks, especially, was very heavily influenced by Caniff.

I really got my start in comic strips through a chance job, again connected to Al Williamson. Around 2008–2009, King Features was doing some new work or new stories with Secret Agent Corrigan or Secret Agent X9, which was the strip that Al used to do, and there was a publisher named Egmont Scandinavia that was reprinting Al’s strips along with Modesty Blaze, and they wanted to do a new story or two. So Brendan Burford, who was the editor at King Features at the time, got my name,

THE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR: What’s your age, and your background in cartooning and newspapers?

This issue’s cover inker, interviewed by John Morrow via e-mail on September 16, 2024

worked my way into a full-time cartoonist/newsroom artist position at a daily newspaper for several years, and from there, Jim Davis hired me to write and draw for his Garfield comic strip. During my nearly 15 years at the Garfield studio, I also created a comic strip called “The Trek Life” for CBS/Paramount’s official Star Trek website around 2005, StarTrek.com, which blossomed into quite a variety of published work (featuring my own characters that I created for my comic strip there) in places such as IDW’s official Star Trek comic books, manga for TokyoPop, and comics and illustrations for the official Star Trek Magazine, to name a few. I also created two different comic strips for Roddenberry Entertainment, the company created by Gene Roddenberry (creator of Star Trek) and worked on several wonderfully fun side projects over the years, including Popeye and Flash Gordon, to name a few. The topper and dream-come-true to it all is that in 2017, Dean Young and King Features Syndicate asked me to join the Blondie comics team, which is my primary work, and I love it. We recently introduced a new regular character, a pastry chef named “Maya,” into the Blondie comics universe and it’s just so fun. That’s the name of the game… fun! And if you’re wondering if I ever make a Dagwood sandwich while working on Blondie comics, the answer would be yes

TJKC: What was your earliest exposure to Kirby’s work? And did you immediately take to it, or was it initially off-putting in any way?

[above] The closest Jack ever came to doing Flash Gordon was probably his work with Joe Simon on Blue Bolt in the 1940s. Here is that character from Roz Kirby’s 1970s sketchbook. Below is David’s more humorous take on Flash Gordon.

[next page] Examples of David’s work on Blondie and Popeye, and [center] one of Jack’s early in-betweening drawings from when he worked at the Max Fleischer studios in the mid1930s.

How’d you get your start, for instance?

DAVID REDDICK: I’m 53, but I keep telling myself I’m a Time Lord, so it’s really just a number, right?

I got my start in cartooning by sending single panel cartoons to my local small town newspaper for free back in my twenties, after I came out of the Navy. That grew into more small town newspapers at a small rate per cartoon, and grew from there. Eventually, I

REDDICK: My earliest exposure to Jack Kirby‘s work was actually in the 1970s when I was a little kid walking downtown in my city to a little bookstore that sold comic books on the spinner rack. I actually specifically remember the first Jack Kirby work that caught my attention and that was his Kamandi comic book. I was taken by the broad brush strokes, the powerful placement of black ink, and the really straightforward, dynamic way he set up his panels and pages. His drawing hit like a sledgehammer. You could practically hear it. Jack Kirby, to me, drew in such a solid, straightforward way, in the same way Johnny Cash sang songs in such a straightforward, solid way, down to the lyrics. That same kind of feeling. Raw. Honest. Solid. There was and is an accessibility to Jack Kirby‘s work that

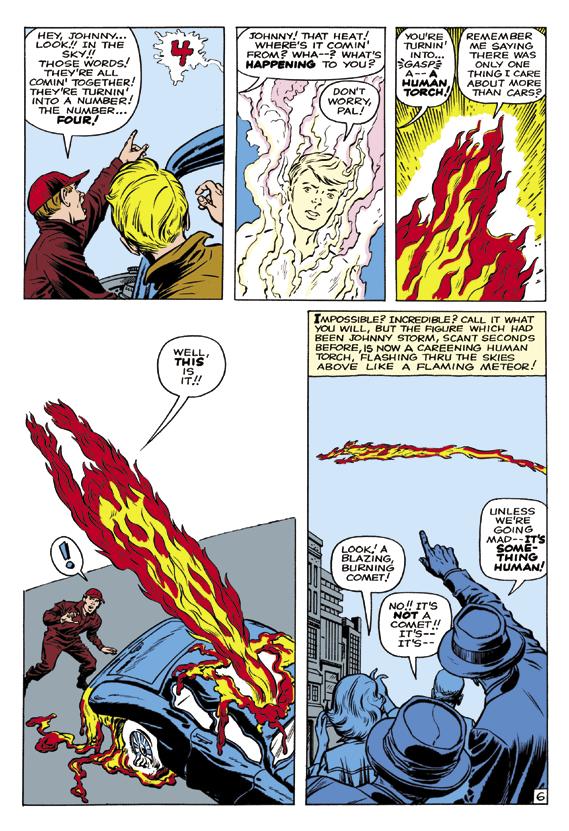

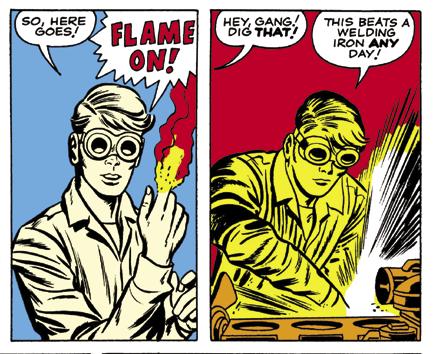

t can be argued that from a socio-economic perspective, the modern teenager was invented in the post-war era of the mid-1950s. James Dean was certainly the celluloid teenage role model, as Elvis was a musical Dean wannabe who made rock ’n’ roll the official teenage music. Comics followed suit with the teenage Legion of Super-Heroes in 1958 and the Justice League’s pseudo hipster teen mascot Snapper Carr in 1960. But it wasn’t until 1961 that Kirby and Lee’s Fantastic Four presented us with the most well rounded and actually cool teen comic book character in the form of Johnny Storm, a.k.a. the Human Torch. Johnny was temperamentally perfect to represent his generation. Dean would have been a perfect casting choice for the Torch, or perhaps Steve McQueen if we had caught him at 17 instead of seeing him pretend to be that age in The Blob.

As mentioned, Johnny Storm was cool, but like the truly cool, he smoldered inside. In fact, he burned, figuratively and literally with the passionate flame of youth. Several Kirby scholars, including Charles Hatfield, have spoken about the King’s use in his work of the semi-wild young blonde boy, comparing Kamandi to Angel from Boys’ Ranch and Serafin of the Forever People. In my opinion, Johnny Storm would also fall into this category. In Johnny’s case, his blonde hair was also a clear visual representation of his flame powers.

A re-imagining of the previous Golden Age Torch, Johnny Storm would represent the youth-oriented American future as the youngest member of the Fantastic Four. In the team’s first issue, Johnny is seen hanging out with his peers, tinkering with a hot rod (one of the quintessential ’50-’60s teen obsessions). When he sees the signal for the team to assemble, he bursts into flame, melting the car to slag as he flies off. 1

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

Johnny was hot-headed, impulsive, rebellious, and sometimes at odds with the other, older members of the group. Johnny often ran afoul of Ben Grimm, a.k.a. the Thing, who resented the boy’s youthful arrogance and literal flamboyance. From the outset, The Fantastic Four had been about relationships. They were clearly a surrogate family, with Reed and Sue as parental authority figures and Ben and Johnny as squabbling sibling rivals. Initially, with the Thing’s attraction for Sue, there was the potential for a pseudoOedipal conflict, but this thread was quickly abandoned and the focus was primarily on Ben’s resentment towards his deformity and his jealousy of Johnny. This would drive the Torch away from the group. Like his volatile flame, Johnny’s rebellious spirit would not be contained, and so he was the first to stray from the family.

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=133&products_id=1814

On page five of the fourth issue, Johnny is again seen in a garage with his buddies, this time welding his hot rod with his finger. 2 As the page unfolds, Ben’s seething rage has compelled him to track down the Torch, but Johnny escapes his brutal clutches and goes further underground. His need to escape his dysfunctional family drives him into the underbelly of the city, where he encounters his destiny. When he throws the amnesiac Prince Namor into