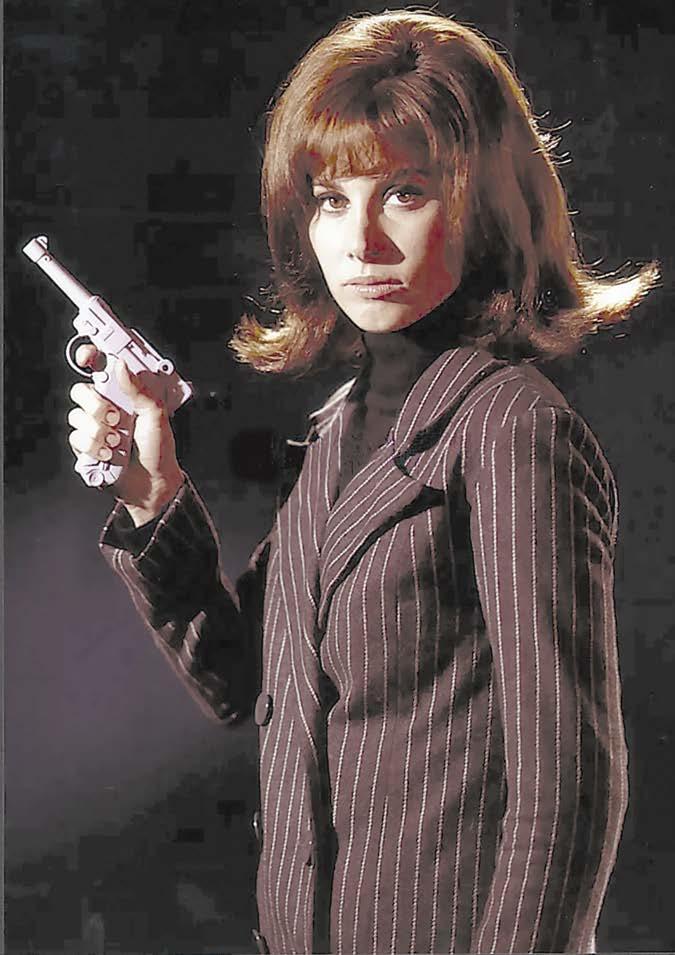

STEFANIE POWERS

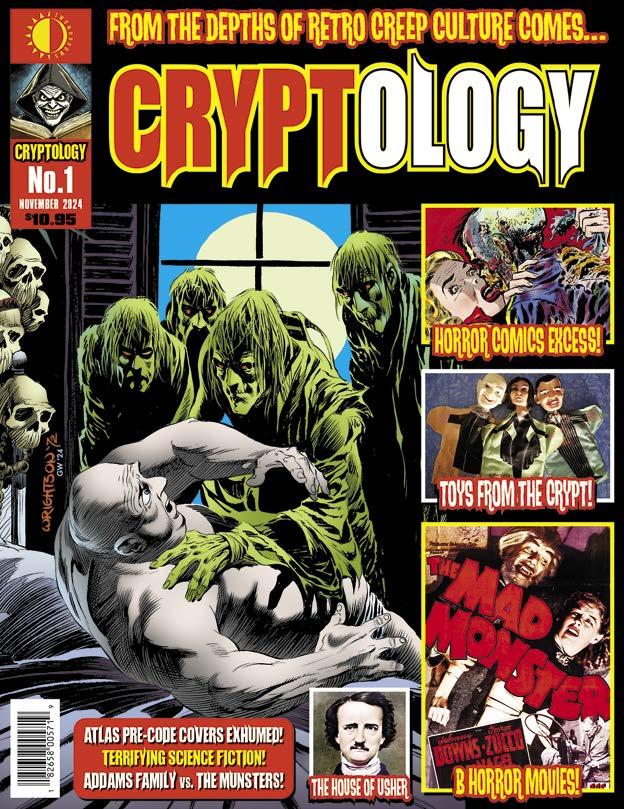

“Greetings, creep culturists! For my debut issue, I, the CRYPTOLOGIST (with the help of FROM THE TOMB editor PETER NORMANTON), have exhumed the worst Horror Comics excesses of the 1950s, Killer “B” movies to die for, and the creepiest, kookiest toys that crossed your boney little fingers as a child! But wait... do you dare enter the House of Usher, or choose sides in the skirmish between the Addams Family and The Munsters?! Can you stand to gaze at Warren magazine frontispieces by this issue’s cover artist BERNIE WRIGHTSON, or spend some Hammer Time with that studio’s most frightening films? And if Atlas pre-Code covers or terrifying science-fiction are more than you can take, stay away! All this, and more, is lurching toward you in TwoMorrows Publishing’s latest, and most decrepit, magazine—just for retro horror fans, and featuring my henchmen WILL MURRAY, MARK VOGER, BARRY FORSHAW, TIM LEESE, PETE VON SHOLLY, and STEVE and MICHAEL KRONENBERG!”

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 #1 is Now Shipping!

The Cryptologist and his ghastly little band have cooked up more grisly morsels, including: ROGER HILL’s conversation with our diabolical cover artist DON HECK, severed hand films, pre-Code comic book terrors, the otherworldly horrors of Hammer’s Quatermass, another Killer “B” movie classic, plus spooky old radio shows, and the horror-inspired covers of the Shadow’s own comic book. Start the ghoul-year with retro-horror done right by FORSHAW, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, RICHARD HAND, VON SHOLLY, and editor PETER NORMANTON

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95

(Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships January 2025

This third wretched issue inflicts the dread of MARS ATTACKS upon you—the banned cards, the model kits, the despicable comics, and a few words from the film’s deranged storyboard artist PETE VON SHOLLY! The chilling poster art of REYNOLD BROWN gets brought up from the Cryptologist’s vault, along with a host of terrifying puppets from film, and more comic books they’d prefer you forget! Plus, more Hammer Time, JUSTIN MARRIOT on obscure ’70s fear-filled paperbacks, another Killer “B” film, and more to satiate your sinister side!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships April 2025

Our fourth putrid tome treats you to ALEX ROSS’ gory lowdown on his Universal Monsters paintings! Hammer Time brings you face-to-face with the “Brides of Dracula”, and the Cryptologist resurrects 3-D horror movies and comics of the 1950s! Learn the origins of slasher films, and chill to the pre-Code artwork of Atlas’ BILL EVERETT and ACG’s 3-D maestro HARRY LAZARUS. Plus, another Killer “B” movie and more awaits retro horror fans, by NORMANTON, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, VOGER, and VON SHOLLY!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships

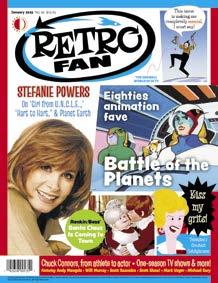

Voger’s Vault of Vintage Varieties Stefanie Powers

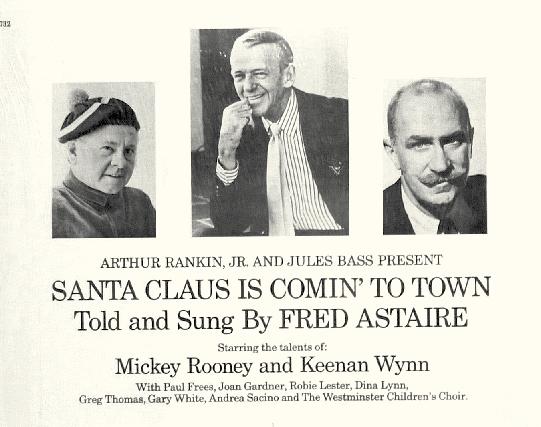

Retro Animation Rankin/Bass’ Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town

Will Murray’s 20th Century Panopticon One-Season TV Wonders

Retro Sci-Fi Battle of the Planets

Retro Sports The Rifleman’s Chuck Connors

Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning TV Comic Ads

Oddball World of Scott Shaw! SCTV

Scott Saavedra’s Secret Sanctum TV Catch Phrases

RetroFan™ issue 36, January 2025 (ISSN 2576-7224) is published bi-monthly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to RetroFan, c/o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614.

Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. Ed Catto, Associate Editor. John

retroed@twomorrows.com.

Stefanie Powers attained TV icon status as the title secret agent and fashionplate in the 1966–1967 spin-off series The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. © Stefanie Powers.

BY MARK VOGER

Once they make a doll out of you, or star you in a comic book, you will never be forgotten by a certain strain of fan—the unerringly loyal, hopelessly devoted genre fan.

Devotees of the super-spy genre of the swinging Sixties—which yielded Dr. No, Goldfinger, Secret Agent, Get Smart, and The Man From U.N.C.L.E.—will always remember Stefanie Powers for her 1966 –1967 spin-off series The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. ( TGFU ). Powers starred as April Dancer, the glamorous and resourceful secret agent who karate-chopped her way into our hearts while wearing the latest groovy fashions.

“I was under contract at Columbia at the time,” Powers told me of being cast as April, when we

“They had done a pilot of the show with Mary Ann Mobley playing the girl from U.N.C.L.E. and Norman Fell, the comedian, playing her assistant. But they [the studio] didn’ t like the

“I was in England working when I got the message that my contract had been sold; MGM bought me out of my contract to do The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. Because I was in England—with the ‘mods ’ and ‘rockers ’ and Carnaby Street and all of that swinging Sixties ’ stuff happening—I thought it would be interesting to bring that into it.”

Born in 1942 in Los Angeles, Powers has had many career milestones apart from The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. She worked with such movie icons as Tallulah

Bankhead, Helen Hayes, and John Wayne; she was a two-time Disney heroine; and she co-starred with Robert Wagner in the long-running romantic mystery series Hart to Hart.

Powers felt fortunate to have been among the last wave of contract players signed to a studio at the tail end of Hollywood’s so-called “star system.” Powers was young but, she maintained, experienced.

Recalled the actress: “I had been in a ballet company; I worked for [choreographer] Jerome Robbins. I had worked in a couple of movies when I was put under contract to Columbia. But I was a teenager. And I was a real teenager, not an overly sophisticated teenager. And certainly not a teenager the likes of which we have today.

“So you might say I was wide-eyed by comparison to the teenagers today, who are exposed to so much more, and who begin a ‘physical’ life—even though they’re not emotionally stimulated—much earlier than we did in those days.”

Powers paid her dues in small film roles and episodic television. A breakthrough came when she was fourth-billed as Rebecca, the daughter of John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, no less, in Andrew V. McLaglen’s Western comedy McLintock! (1963). Rebecca’s separated parents bicker over where “Becky” should stay once she returns home from an Eastern school. Should she live with father in the rollicking town of McLintock (named after Wayne’s wealthy cattle baron)? Or with mother in stuffy Newport?

Few characters get the buildup, or the entrance, that Powers’ Rebecca receives in this movie. The whole town is on hand, complete with a marching band, beneath a “Welcome home Rebecca McLintock” banner, as her train chugs in. The movie even gives Powers a dramatic moment in a thoughtfully written heartto-heart with Wayne.

Was Wayne a teddy bear toward Powers?

“I would never call him a teddy bear,” she said with a laugh. “Everybody on that set was part of the John Ford/John Wayne extended family. It was very much a familial feeling on that set.”

McLintock! led to larger roles in such films as Die! Die! My Darling! (1965), “hagsploitation” horror opposite Bankhead, and Stagecoach (1966), an all-star remake of the classic 1939 John Ford Western that made Wayne a household name.

(LEFT) In an early attention-getting role, Powers played Rebecca, the modern-thinking debutante daughter of John Wayne’s wealthy cattle baron in the Western comedy McLintock! (1963). © Batjac Productions. © United Artists. (BELOW) Powers, as the glamorous, resourceful superspy April Dancer in The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

(OPPOSITE PAGE) From left: Yootha Joyce, Powers, and Tallulah Bankhead in a intense scene from the “hagsploitation” horror film Die! Die! My Darling! (1965). © Columbia Pictures.

several issues of a Girl From U.N.C.L.E. magazine that presented fiction (stories and “complete novels”) and often featured painted cover illustrations.

April gave Ideal’s costume-changing super-hero toy Captain Action a run for its money with the costume changes and accessories that came with her Marx action figure. Promised the box-cover type: “Complete with over 30 pieces of personal attire, disguises and weapons.” Within the box, children found a radio purse, hat box, clutch purse, shoulder bag, garter holster, assorted “ wigs” (in plastic, not doll “hair ”), grenade bracelet, opera glasses, sword umbrella, revolver, and derringer. Whew!

The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. lasted for one season; the final episode aired on April 11, 1967. The Man From U.N.C.L.E. was cancelled the following year.

Following TGFU, Powers starred in a pair of Disney features, The Boatniks (1970) and Herbie Rides Again (1974), the latter co-starring Hayes. Powers maintained a high profile on TV with guest shots on just about any series you can remember from the period: Banacek, Mod Squad, The Sixth Sense, Barnaby Jones, McCloud, Marcus Welby, Medical Center, Cannon, Kung Fu, Petrocelli, Harry O, The Streets of San Francisco, McMillan and Wife, and The Bionic Woman.

It all paid off when Powers landed her second hour-long series, Hart to Hart (1979 –1984), in which she co-starred with Robert Wagner. For fans of Sixties TV, Hart to Hart was a bit of deja vu, with the stars of It Takes a Thief and The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. joining forces, looking more or less like their old selves. (Only the hairstyles had changed.)

(LEFT) Leo Margulies Corp. published the fiction-packed The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. Magazine. © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (RIGHT) Powers and co-stars in caricature form in a detail from the movie poster for Walt Disney’s The Boatniks (1970). © Walt Disney Productions. (BELOW) Robert Wagner and Powers starred as married jet-setters Jonathan and Jennifer Hart, who traded droll banter while solving crimes. © American Broadcasting Co. © Spelling-Goldberg Productions.

BY RICK GOLD s CHMIDT

In 1970, Rankin/Bass Productions was in its lucky seventh year of making classic holiday specials, and they really hit the jackpot with Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town. It defined the magic in their trademark Animagic stop-motion animation. Until this point, Santa Claus was a character that was primarily used to sell Coca-Cola and cigarettes—a jolly, round, and lovable character, but the public didn’t know much about him. This special aired on ABC-TV December 14, 1970, and changed all of that for generations to come.

Originally sponsored by Milton Bradley and Playschool, Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town made it into the Nielsen Top 10 with its debut and with subsequent airings. A big part of its success was the star talent that producers Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass secured for this one. Film dancing super-star Fred Astaire was a Hollywood

legend by 1970, and is still considered one of the greatest dancers in the world. At 1970’s Academy Awards ceremony, which was preceded by Rankin/Bass’ Mad, Mad, Mad Comedians (their highest-rated special), Fred Astaire was called up to the microphone by Bob Hope. Astaire jokingly said he didn’t do much dancing anymore, and then launched into a wonderful dance routine.

Fred was still amazing in 1970, and a wonderful host for this special as North Pole mailman S. D. Kluger. He explained in an open air interview for Rankin/Bass Productions, “Well, Kluger is like all the other characters in Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town. He’s an Animagic puppet, that’s actually what they call them. He’s carved and painted and dressed and then placed on the set, and then a technician is in charge of each movement he makes, and each separate motion is photographed and

(TOP) Promotional art by Paul Coker, Jr. (digitally enhanced and edited) featuring caricatures of (LEFT TO RIGHT) Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass. (ABOVE) Rankin, Jr. and Bass, circa 1970s. (LEFT) Santa and Mrs. Claus stand at the center of this promotional photograph. Unless otherwise noted, all images accompanying this article are courtesy of Rick Goldschmidt. © 2012 Miser Bros Press/Rick Goldschmidt archives.

then, it’s sort of like an animated cartoon, you know, only these are actual figures, then they are put together to make a movie out of it. The final effect is really very life-like and it is quite delightful!”

When Fred Astaire was asked to describe the animated special’s legends of Santa Claus, he exclaimed, “Well, first I’d like to say that the way the story of Santa Claus is handled here is what attracted me to the script, and led to my doing the narration for it. The explanations are imaginative without being too cute, you know, for instance, it tells why Santa Claus is sometimes called Kris Kringle. To explain this, there’s a foundling wearing a pendant with Claus engraved on it, and it is adopted and raised by a family of toymakers named Kringle. The story treats other legends in the same logical way. Like how Santa came to give out presents only on Christmas Eve, and his reindeer learned to fly, and that sort of thing.”

Arthur Rankin told me, “My favorite story about Fred was when [voice actor] Paul Frees walked into the studio. Paul was my dear friend and we used him in almost everything we did, and he had a great sense of humor. So, in the studio was Fred with his agent, Shep Fields. Before Shep became an agent, he had this ridiculous act called Shep Fields and His Rippling Rhythm, in front of an orchestra. He was known for the novelty of blowing into a champagne glass with music and making bubbles. When Paul walked into the studio to record, he walked right past Fred Astaire and said, ‘Not the Shep Fields!,’ I was on the floor laughing!”

For Kris Kringle/Santa Claus, they needed the perfect voice. Stan Francis, who voiced Santa in Rankin/Bass’ Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, had already passed away—during a performance on stage, actually—in 1966. Arthur wanted someone who could act, but bring a performance to the screen that would be good for animation, and Mickey Rooney fit that bill perfectly. Arthur explained to me, “Mickey was very, very good as an actor. When I gave him the script, he would crawl up my lapel very excited. He was perfect!” A friend of mine from FOX 32 in Chicago, Vic, later

(LEFT) Detail of the Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town album’s reverse side. Pictured are (LEFT TO RIGHT) Mickey Rooney as Kris Kringle, Fred Astaire as the Narrator, and Keenan Wynn as the Winter Warlock. (RIGHT) Robie Lester is all dressed up as Mrs. Claus in this lighthearted promotional image.

The Narrator was not just voiced by Fred Astaire but looked like him as well.

approached Mickey Rooney about this special, and had him sign his laser disc. Rooney told him that at first he didn’t want to do the special, but was very glad that he did. So many fans had told him how much it had meant to them, and he could see the magic in it.

Rankin/Bass Productions musical composer Maury Laws said, “My favorite things that we did had Mickey Rooney in them! We ended up using him again for The Year Without a Santa Claus and for the 1979 feature film Rudolph and Frosty’s Christmas in July.”

Keenan Wynn was another excellent and versatile character actor, whose voice was perfect for the character Winter Warlock and for animation in general! His father, Ed Wynn, appeared in Rankin/Bass’ The Daydreamer in 1966. I believe Keenan was approached by Arthur Rankin on the set of the film The Monitors in Chicago, during filming, sometime in 1968 or 1969. Actress Sherry Jackson told me she met Arthur and took pictures with him, and Jackie Vernon was there, signing up for his [voice-acting] role as Frosty. Keenan was one of the hardest-working men in show business and could handle most any kind of role. He brought personality to old Winter, and personality is the key to Animagic.

Robie Lester was the voice of Jessica, the future Mrs. Kris Kringle. She had great success in recording for various Walt Disney or Disneyland records over the years, and even appeared on Walt’s various TV shows. Before her passing, we formed a great

BY WILL MURRAY

When I think of my favorite television programs of the Sixties, I have a special place in my heart for a handful of shows that lasted only a single season. This is pure nostalgia, of course. But another part is the desire, now 60 years along, for more episodes of those short-lived series.

With that in mind, let’s look at two of my favorite one-season wonders.

Although it ran as a midseason replacement in 1967, Coronet Blue was initially filmed two years previously, for the 1965–1966 television series.

Starring Frank Converse, it debuted on May 29 with the episode titled “A Time to Be Born.” Arriving in New York City by passenger ship, the protagonist is called by the name “Gigot” by a fellow traveler, who tells him that Margaret wants to talk to him.

Up on deck, he meets with an extremely well-dressed woman, who tells him: “We know what you’re doing. You’re not really with us. You’ve been pretending all along. I’m surprised at you.”

One man pulls a silenced gun, but it’s knocked aside. Gigot is slugged unconscious and thrown overboard, but not before all identification has been stripped from him.

When he comes to at dock side, he can’t remember his name or anything except two words: coronet blue.

The nameless protagonist is taken to Alden General Hospital. Regaining consciousness, he has no idea who he is. He adopts the name Michael Alden, based on the hospital where he landed and the first name of his doctor. Against the supervising physician’s orders, he decides to strike out on his own. This despite having no money, home, or identity.

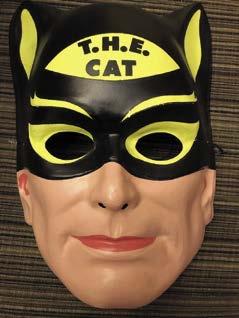

(LEFT) Are you curious yellow? Perplexingly, the series’ logo for Coronet Blue was yellow. (RIGHT) Cat got your tongue? A feline beast peers with silent menace over the T.H.E. Cat logo. © CBS Studios.

“I gotta find out what’s out there, doctor,” Alden explains. “I mean, what’s out there for me.”

Leaving the hospital, he gets a job washing dishes at the Screaming I coffee shop run by Max Spier, played by Joel Silver. While attempting to reassemble his life, Alden discovers he’s being followed. He also has recurring dreams of a woman he can’t identify.

The hunt for his real identity begins when Alden discovers a bar called the Blue Coronet, owned by a man who is obsessed with the coronet symbol. This leads Alden to a party and a young woman named Alix, who introduces him to his father, a dealer in boats.

While at work, he discovers that he speaks fluent Spanish. Where did he learn that language? It’s a mystery.

Alden and Alix fall in love and plan to run off together. But during a romantic picnic, a sniper attacks. Alix is shot dead by mistake while the shooter gets away.

The premiere episode ended with Michael Alden planning to go to San Francisco to find the owner of the Blue Coronet bar. Inexplicably, that continuity set-up was ignored in the second aired episode, in which he encountered a family who claimed to be his own. Of course, they weren’t. Otherwise, the quest might have ended right there.

Evidently, the producers rethought the idea that Michael Alden would be a man on the run like David Janssen in The Fugitive, journeying from state to state in his quest. Other than the odd episode that found him in another state, Alden stuck to New York City—a

dangerous choice, given the number of times he was ambushed by his original assailants.

Periodically, Alden stumbles upon possible clues that he thinks will point him toward his origins—a sapphire crown worn by a magician’s assistant, among others. Frequently–-at least in the early episodes—he is targeted for assassination by shadowy stalkers who are almost never individualized or identified by name or nationality.

After surviving one attempt to kill him, Alden regains consciousness in a monastery and sees a stained-glass window depicting Saint Anthony bearing his face—surrounded by demons. This episode, “A Dozen Demons,” introduced Brian Bedford as novitiate monk Brother Anthony, who appeared occasionally as one of the few recurring characters who helped Alden pursue his quest.

Coronet Blue was initially promoted as “a no-format format,” because Michael Alden was going to be the only regular cast member. Apparently, the producers also found this too difficult to sustain, and quickly abandoned this trajectory, along with the man-on-the-run approach.

During the development stage, series creator Larry Cohen stated, “Coronet Blue is about a man who is nearly murdered, and in each succeeding week’s episode he is chasing his would-be murderer.”

But according to executive producer Herbert Brodkin, Coronet Blue was an allegory for a “more abstract quest for identity to be explored in each episode.”

These diverging points of view would not help the series as it went through its challenging production cycle.

Star Frank Converse was a six-feet, two-inch blond hunk, blue-eyed, 27, and virtually unknown. Originally an older actor was envisioned in the role, but the casting of Alden, whom the press dubbed as “soulful,” proved key to appealing the youth demographic of the Sixties. Michael Alden is supposed to be 19.

The Trials of O’Brian, which was in turn replaced by another show. This was typical network politics. Aubrey had not supported Slattery’s People.

Even though it had lost its Friday night slot on the CBS schedule, Coronet Blue began filming in the spring of 1965. After spending two million dollars to produce the series, CBS cut the episode order in half.

“Sure, I’m disappointed,” said Larry Cohen at the time, “but what the hell. They’re committed for 13 episodes, which are being filmed now, so I’ll make at least 20 grand, and who knows, maybe it will go in mid-season. Something on CBS is probably going to flop, and they’ll need it.”

CBS vice president of programming Michael Dann insisted, “We have enormous enthusiasm for Coronet Blue and expect it will be in our schedule in 1966.”

But neither happened. The show was not used as a mid-season replacement, nor did it air during the 1966–1967 schedule. Industry observers wondered why CBS would spend two million dollars on a show and not broadcast it. No one had a good answer to the question.

Twenty-two episodes were planned. This was cut to 13 after the show was temporarily shelved owing to a regime change at CBS.

When CBS President James Aubrey was ousted early in 1965, Executive Producer Herbert Brodkin got caught in the crossfire and lost several ongoing shows, including The Defenders and Coronet Blue, which never aired in its intended 10 p.m. Friday time slot during the 1965–1966 television season.

Instead, CBS reversed its cancellation of Slattery’s People, scheduling it at that time. The reprieved show didn’t last, and was replaced by

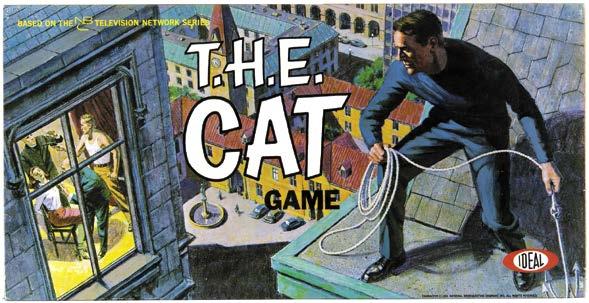

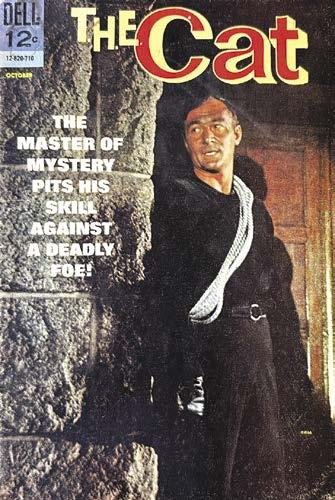

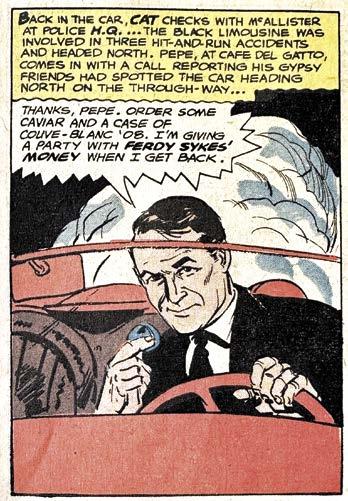

Every cat needs to get around town! Rare TV show merchandise including (LEFT) an AMT Model kit—for T.H.E. Cat. T.H.E. Cat © CBS Studios. Mask, gun, and game courtesy of Worthpoint.

like that. Every script is loaded with action. We take whatever the writers might say and embellish it, and actually choreograph the script. There’s a former stunt man who works out the action and we spend as much time on that as we do on the dramatic part.”

Loggia’s athletic background served him well. “I seem to have a flair for this kind of action,” he acknowledged. “They say Errol Flynn had a flair for the top of the stairs and Douglas Fairbanks had a flair at the bottom. I have a flair somewhere in the middle.”

The moody production managed to avoid criticism for its violence. “I think what gets us off the hook here is the bizarre quality of the show,” Loggia observed. “Also, the spirit of our violence is different. We don’t go in for slow-moving, bonecrunching stuff; instead, Cat is supposed to be not only deadly but beautiful to watch in action, and that’s the way it seems to be getting across. Women write in, not to complain about violence, but to ask if I took ballet lessons, because of the way I move.

“NBC-TV did pull one scene from an episode they considered too violent,” he revealed. “We will remake the scene. But it’s my feeling that if Cat moves like Doug Fairbanks did, it takes the curse of violence off the show. I don’t intend to play the character like Smilin’ Jack.”

Most of the stunt work was by Loggia himself. “This series is ultra-action, full tilt, and I do all my own stunts. I don’t have to, and maybe they’d rather I didn’t. But doing

T.H.E. Cat prowled the comic spinner racks in 1967 with a four-issue Dell series. T.H.E. Ca t #4’s photo cover of Robert Loggia, with interior artwork by Jack Sparling. T.H.E. Cat © CBS Studios.

it myself, I feel I own the part. And it helps the show. There’s an enormous difference when the camera comes in and it’s you.”

Well, not every stunt, as the actor admitted. “I’d never attempt the things T.H.E. Cat has to do as a matter of routine. In our pilot show, for instance, I used a double for the tightrope scene. And even the double didn’t want to do it. He had to walk about 50 feet across this rope, 100 feet above the ground. He was protected, not by a net, but by a pile of cardboard boxes about 25 feet high that would break his fall. Once he did start to fall, but caught himself.”

Loggia suffered his own scrapes. “I had to pass through a window in the pilot. I was spiked under the right eye when a grappling hook came loose.”

After shooting the first 16 episodes, production took a break in order to retool in the face of only average ratings.

It was September 1978 and the previous year’s theatrical release of Star Wars had created an unexpected renewed interest in science fiction/adventure stories.

Most television producers were caught off guard; there were no new programs in that genre being prepared to attract hungry viewers. The only existing science fiction series were well-worn reruns of things like The Twilight Zone (1959) or Star Trek (1966). Not many other shows in the genre survived long enough to make it as daily syndicated offerings. New programming was being sought out as quickly as possible, and only one company, Sandy Frank Entertainment, was ready by the 1978 series premiere season with their program, Battle of the Planets

It was a striking animated series that hit the ground running. Five days a week (in most markets), for 85 full episodes. Its rich, detailed animation, fantastic cosmos-soaring stories, quickpaced action, and rousing music were all immediately attractive to children. Each aspect set it apart from just about everything else on TV. The series became an instant ratings powerhouse that flattened competition across North America. It left a strong impression and achieved its goal of making rapt viewers of youngsters who wanted more outer space adventures.

BY JA s ON HO f IU s

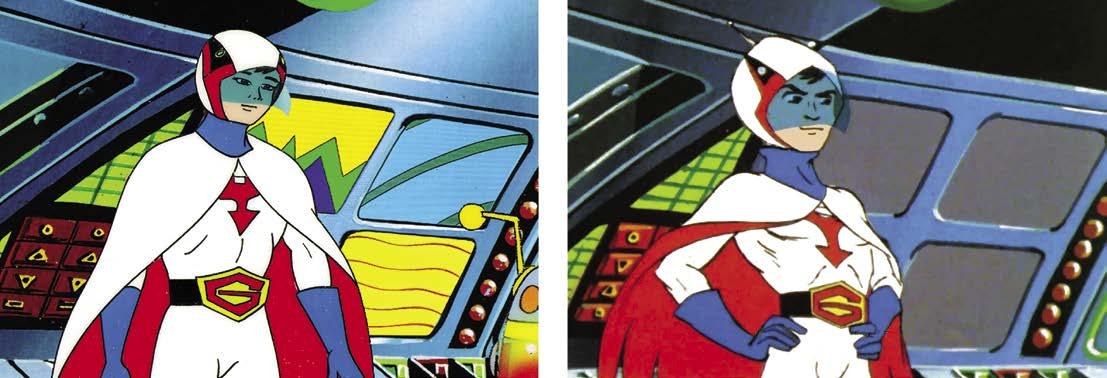

A Gatchaman promotional image. Artist unknown. Japan’s Gatchaman was the basis for Battle of the Planets. Photos accompanying this article are courtesy of Jason Hofius. Battle of the Planets © Tatsunoko Production Co., Ltd.

What might be surprising to many are the origins of Battle of the Planets. Viewers didn’t know much about it at first, other than most of it looked nothing like the typical cartoon production they were familiar with. Children who grew up in North America knew a certain type of animation. A style from the most well-known and prolific cartoon studio, Hanna-Barbera Productions, had become standard. Some may also have noticed the phrase, “Produced in association with Tatsunoko Production Co., Ltd.” and the odd little seahorse logo in its end credits. In fans’ eyes, Battle of the Planets clearly wasn’t another Hanna-Barbera show. Or... was it?

The answer is a bit complicated. Battle of the Planets was the end result of a series created in both Japan and the United States. Many of the stateside personnel involved in its production did indeed have histories with Hanna-Barbera. Due to this, Battle of the Planets was actually steeped in the studio’s history. So much so that it could almost be considered as a project from them. But where did it come from and how did so many Hanna-Barbera veterans fit into the story of bringing it to air?

The basis for Battle of the Planets was a Japanese television show called Science Ninja Team Gatchaman Longtime American television syndicator Sandy Frank was looking to create his very first original syndicated series just as the Star Wars craze took hold. In 1977, he bought the licensing rights to Gatchaman and renamed it Battle of the Planets to capitalize on the trend. Gatchaman turned out to be far from the outer space adventure Frank had envisioned and had already been pre-selling to U.S. television program buyers. Its

stories took place strictly on Earth. Not only that, it also had a lot of hard-hitting action and violence that would never be permitted to air in North America. Frank had to reshape Gatchaman into what he wanted and he needed people familiar with television animation production to do it.

At the time, a number of studios were creating animation for American television, including Filmation, DePatie-Freleng, Rankin/Bass, the newly started Ruby-Spears, and a few others. But Hanna-Barbera reigned over them all in success and sheer number of series produced.

William Hanna and Joseph Barbera met in the Thirties at MGM’s animated theatrical shorts section. Both were involved in different areas of production; neither was an animator. While there, they worked on the some of the studio’s most popular cartoon series, including Tom & Jerry and Droopy. The duo eventually headed the animated shorts department. But when MGM closed their animation section, Hanna and Barbera struck out on their own, formed Hanna-Barbera Enterprises (soon to be Hanna-Barbera Productions), and expanded into television animation. Their simplified style cut animation tasks to the bare minimum, which allowed them to more easily create weekly TV

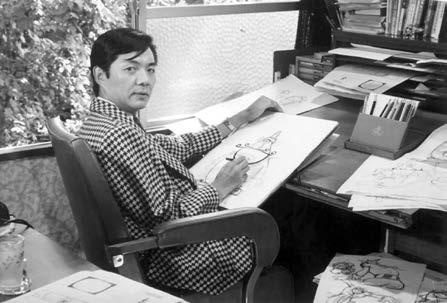

Creator of Gatchaman, Tatsuo Yoshida.

A Battle of the Planets promotional advertisement that listed contributors Alan Dinehart and Jameson Brewer and mentioned their work at Hanna-Barbera.

series. Their first was The Ruff and Reddy Show in late 1957, then The Huckleberry Hound Show (1958), and The Quick Draw McGraw Show (1959). Prime-time TV animation followed with The Flintstones in 1960, and Hanna-Barbera soon entered their busiest period.

The need for creators was at an all-time high. Hanna-Barbera employed scores of production personnel; anyone a normal production studio would need, with the addition of many types of visual artists. It remained that way through the late Eighties, when weekly animation slowed. But in 1977, things were going strong and the thriving studio was putting out about ten shows a week.

It was at that time Sandy Frank purchased Gatchaman. His main task was to find someone to translate the series for North American TV. When getting into something new, Frank always sought out guidance from the best sources he could. So, it was only natural that he looked toward Hanna-Barbera. A number of people involved in Battle of the Planets ’ creation, including Sandy Frank himself

stray ping-pong ball; Keyop played silly drum solos. These types of repeated gags filled time and give kids a familiar “base” to land on each time they were shown. They were examples of the HannaBarbera playbook, and never present in the original Japanese series.

Comic book artist and character designer extraordinaire, Alex Toth came up with the design for Battle of the Planets ’ original robot character, 7-Zark-7. Toth was deeply-rooted at Hanna-Barbera and provided character designs for most of their more serious adventure series, including Jonny Quest, Space Ghost and Dino Boy (1966), Birdman (1967), and Super Friends. He was a friend of Alan Dinehart and did the Zark design as a favor to him.

Graphic artist Thomas Wogatzke began his history at HannaBarbera in the early Seventies, where he developed the logos for shows like Super Friends and Scooby’s All Star Laff-A-Lympics (1977). He continued at the studio through the Nineties. While there, he worked closely with Alex Toth. It was Toth who suggested him to Alan Dinehart to work on Battle of the Planets. Wogatzke created several treatments for the design and ultimately developed its final logo.

Emil Carle was listed as Battle of the Planets ’ production manager, but he actually created much of the American-produced animation along with Harold Johns. Carle had a long association with Hanna-Barbera, going all the way back to the days of The Huckleberry Hound Show. He also worked on many of the studio’s most fondlyremembered productions, including The Flintstones and Wacky Races (1968). In the early Seventies, Carle went freelance. He then split much of his time between Filmation and Hanna-Barbera. He was no longer exclusive to the Hanna-Barbera studio, but still did a lot of work on their television programs and specials. Jameson Brewer himself even contributed to animation duties. His most noticeable work was in scenes where he redesigned Mark to look more detailed and heroic.

The writing staff of Battle of the Planets comprised highly experienced TV writers, most of whom were known by Brewer and Dinehart. Of the 11 writers on Battle of the Planets, only seven actually wrote scripts. Of those seven, four had previous experience at Hanna-Barbera.

Jameson Brewer was the head writer/story editor for the series. He only had credit as co-writer on one script (with Peter

Character designer Alex Toth’s 7-Zark-7 model sheet.

Germano), but he did major revisions and editing on each and every episode.

The primary writer for Battle of the Planets was Peter Germano. He was a magazine author, novelist, and television writer whose favorite genre was Westerns. Germano gained an interest in children’s television in the late Sixties, due to the frequent visits and viewing habits of his grandchildren. He came to Hanna-Barbera to write for Valley of the Dinosaurs (1974). Germano wrote 27 and a half scripts for Battle of the Planets, making him the largest contributor to the series by far.

Jameson Brewer brought another old friend and prolific scriptwriter, Sid Morse, on to Battle of the Planets. The two worked together on various projects through the years. They both landed at Hanna-Barbera around the same time, where they wrote scripts for The New Scooby-Doo Movies. Morse wrote for more of the studio’s series in 1972, including The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan. Later, he wrote episodes of the teenaged I Dream of Jeannie clone, Jeannie (1973), and was story editor on The Robonic Stooges (1977). He also wrote for their live-action/animated series, The Skatebirds (1977). Morse created nine Battle of the Planets scripts.

Television script writer Harry Winkler worked primarily in liveaction for decades, but also dipped occasionally into animation.

BY DAVID KRELL

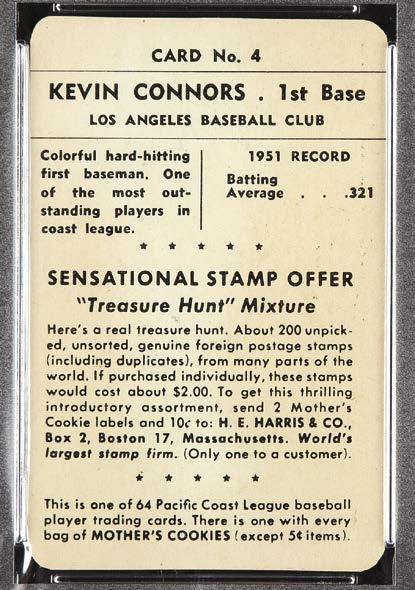

“Connors! He didn’t even play for the Padres! Connors was an Angel! Don’t you remember? The old Padres first baseman was Luke Easter!”

So begins “The Deuce,” a 1979 episode of The Rockford Files starring James Garner [see RetroFan #27 for our look at The Rockford Files]. Mills Watson, who later starred as Deputy Perkins in The Misadventures of Sheriff Lobo —a spin-off of B.J. and the Bear —offers the dialogue in a scene depicting his character betting a fellow bar patron that he can’t answer questions about the Pacific Coast League of the Forties. Their familiarity indicates that they’ve been through these types of conversations before.1

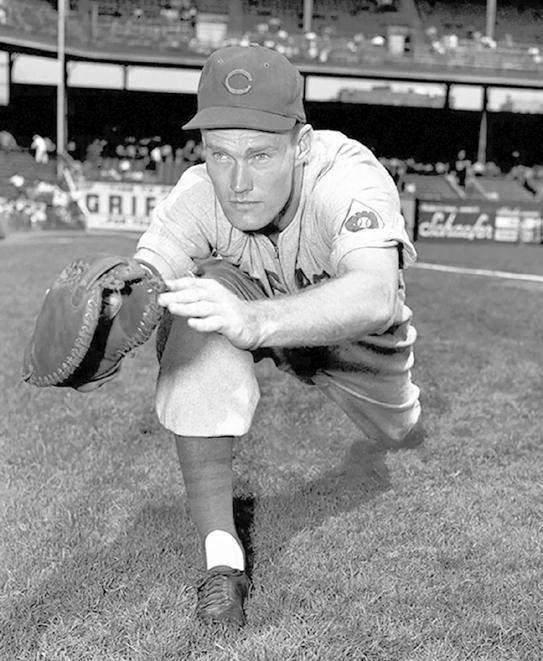

“Connors” refers to Chuck Connors. Yes, that Chuck Connors. Born on April 10, 1921, as Kevin Joseph Aloysius Connors, he graduated from Seton Hall University in northern New Jersey and played professional baseball before he found fame and success as an actor. The Brooklyn native signed with his hometown Dodgers, who sent him to their Newport club in the Class D Northeast Arkansas League in 1940. He notched one hit in four games for an anemic .091 average. His next stint happened in 1942. Playing for the Norfolk Tars in the Yankees organization, Connors fared much better against competition in the Class B Piedmont League. Across 72 games, he batted .264.

After the season ended, Connors enlisted in the U.S. Army and contributed to America’s World War II effort on the home front, where he became a tank training instructor. Semi-pro baseball and professional basketball in the American Basketball League were his athletic pursuits until after the war. In 1946, Connors returned to the Piedmont League and employment by the Dodgers. It was a productive year for the 6’5" first baseman, who played in 119 games and hit .293.

A jump to the double-A Mobile Bears in the Southern Association followed in 1947; he hit .255 in 145 games. Connors ascended to triple-A with the 1948 Montreal Royals of the International League and a roster of future Major Leaguers including Sam Jethroe, Don Newcombe, Al Gionfriddo, Duke Snider, and Clyde King. He stayed with the Royals for two seasons, batting .307 and .319.

Connors also played for the Boston Celtics in the Basketball Association of America from 1946 to 1948. The Dodgers front office called him to the Brooklyn club and he saw action in one game in

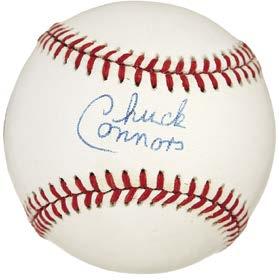

(LEFT) Chuck Connors on the set of The Rifleman in a signed publicity photo. (INSET) A Connors-signed baseball. © Levy-Gardner-Laven Productions. Both, courtesy of Heritage.

1949, pinch hitting for Carl Furillo on May 1 with one out and Gil Hodges on first base in the bottom of the ninth with the Dodgers trailing the Phillies 4-2. Connors hit a ground ball to the pitcher, Russ Meyer, who tossed it to shortstop Granny Hamner covering second base; Hamner fired to first baseman Eddie Waitkus to complete a double play.

Playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers fulfilled a forecast regarding his fate in the hands of Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey. “I told Mr. Rickey it was time he brought me up,” said the ballplayer in February. “I told him that as great as he is at picking men and moving them around, he has never come up with a first baseman, but that I’m his man if he’ll give me a chance in my own hometown.”2

While Rickey assessed Connors and other members of the Dodgers organization at the Major League and Minor League levels during 1949 spring training, a piece in the Brooklyn Eagle noted the first baseman’s gift for entertaining with a focus on an iconic baseball poem. “Like all great artists, he has a wide streak of sentiment in his make-up,” wrote Eagle columnist Harold C. Burr. “There’s pathos in ‘Casey at the Bat.’” Further, Burr revealed that Connors had a side gig and a unique niche regarding his boss. “He rents himself out as an entertainer at stags and smokers. He likes to kid Rickey, which can’t be said of any other ball player in the Dodger organization, and when he has cause to write to the club he always uses red ink.”3

Connors advanced his entertainment pursuits by printing up business cards highlighting his assets, including “reciting, ghostwriting, and magic shows.”4 There was a growing awareness of Connors’s passion for performing. An article from UPI recapped a game in which Connors hit two home runs in the first game of an International League double header against the Baltimore Orioles but added that “he would chuck the whole business for the legitimate stage.” Montreal lost the first game 5-3 and won the second game 7-2.5

Ultimately, Fondy went to the Cubs. Connors showcased his power on March 31 against the San Francisco Seals when he smashed three home runs for the Los Angeles Angels—Chicago’s team in the triple-A Pacific Coast League. Final score: 12-1.8 Nearly two months later, Connors went yard twice in another 12-1 victory against the Seals. He got called up to the Cubs after batting .328 with 22 homers. Fondy went to the Angels; he had batted .293 in the National League.9

Connors played in 66 games for the Cubs, tallying a .239 average. After the season, Chicago’s front office sent him back to the Angels. “Every time I look up, I’m either catching a train for

Returning to the Royals in 1950, Connors batted .290 in 121 games. Rickey jettisoned Connors to the Chicago Cubs organization after the season, reportedly getting $25,000 for his prospect. The Brooklyn Eagle described the first baseman as “overjoyed” because Gil Hodges had earned security at the position for the Dodgers, which left minimal opportunities for Connors to play the position. Previous attempts at persuading Rickey to part ways failed.6 Connors competed for a spot on the Cubs with Dee Fondy. With the Dodgers’ double-A Fort Worth Cats in the Texas League, Fondy’s prowess resulted in a .297 average and 141 games for the 1950 season. Fondy was five years younger, but Connors had an advantage—his mouth. Chicago Tribune reporter Edward Burns noted the complaints of Cubs manager Frankie Frisch regarding a quiet infield. “If Connors is elected that squawk definitely is solved. Chuck can be heard for miles.”7

(ABOVE) Batter up! Chuck Connors, with the Los Angeles Angels, via a 1952 Mother’s Cookies trading card. (RIGHT) Is the “C” for Chuck? Chuck Connors on the Chicago Cubs. Logo TM Chicago Cubs.

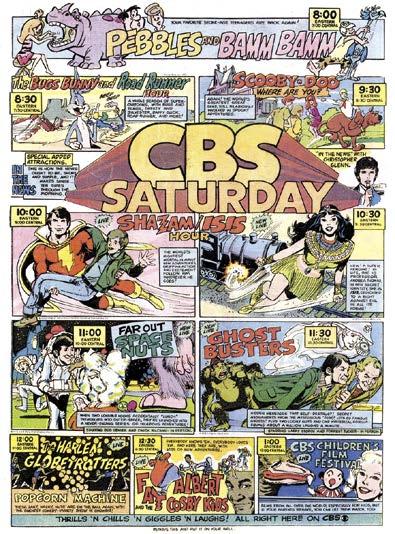

BY ANDY MANGEL s

Welcome back to Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning. Prepare for a visual feast! Saturday morning television was appointment viewing for anyone growing up from the Sixties to the Nineties. From 8 a.m. to noon, while their parents slept in from the workweek, kids could sit in front of the television and enjoy a time just for them. Cartoons—and later, live-action series— were produced by studios like Filmation Associates, DePatie-Freleng Enterprises, Total Television, Jay Ward Productions, Hanna-Barbera Productions, Sid and Marty Krofft, D’Angelo Productions, Marvel Productions, Sunbow Productions, Ruby-Spears, DIC, Film Roman, and others. But how could the networks best reach kids to let them know when the new shows would be airing? Enter the television ads that ran in the comics, touting new and exciting fall seasons! It made sense, since many shows were adapted from comic books! For most kids, those two-page spreads were their first looks at future TV favorites, but by the mid-Seventies, comic ads were dropping and plain TV Guide ads were sometimes the only promotions. In the third of a yearly series, we’re offering you a rare look at every Saturday ad we can find from 1975–1977!

(LEFT) This lackluster ad for ABC’s 1975 Saturday morning line-up season—beginning on September 7th— didn’t appear in any comic books; it only appeared in TV Guide! Artwork and photos are courtesy the collection of Andy Mangels.

The two-page color version of this ad for CBS’s 1975 season appeared in comic book centerfolds, and—as noted by text at the bottom—was meant to be a removed as a wall poster. (RIGHT) The black-and-white version for TV Guide was less busy. Art for both was by Neal Adams’ Continuity Associates, and as the artists were often working from black-and-white photos, the colors for some characters—especially Isis—were a bit off!

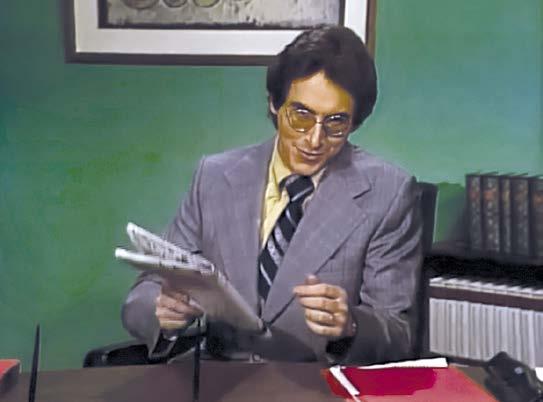

BY s COTT s HAW!

The first time I watched this show, it was called SCTV Network (a k a SCTV 90) in 1981, when the show was airing late on NBC. I really dug it, but at first, my mind couldn’t help but compare it to Saturday Night Live. There were parodies of celebrities, but also lots of characters who were new to me. Don’t get me wrong, I loved Second City Television (SCTV’s original title)—especially John Candy and Joe Flaherty—and the parodies of every aspect of television: TV series, TV commercials, newscasts on TV, films on TV, public service spots on TV, TV on TV, etc…

But where was this Melonville place, who were its unusual residents intended to be parodies of, and what did “Second City” mean? Finally, I realized that they were the weirdo “stars” of SCTV, each created by a cast member, not a corporate committee. Bingo!

I also possessed no thoughts of someday working with almost all of the cast of SCTV but to my delight, less than a decade later, it happened. (The exceptions were Harold Ramis, Robin Duke, and Tony Rosato.) I’ll get around to that later; first things first...

On December 16, 1959, the first revue show of “The Second City” premiered at 1842 North Wells Street in Chicago, Illinois. The small cabaret theater sarcastically based its name on a series of articles published in the New Yorker magazine in 1952. The string of snarky pieces—later collected as a book—considered Chicago to be inferior to New York City, thusly bearing the title “The Second City.” Rooted in the groundbreaking “Theater Games” of author/

(ABOVE, FROM LEFT TO RIGHT) Joe Flaherty as Guy Caballero, John Candy as Johnny LaRue, Catherine O’Hara as Lola Heatherton, Andrea Martin as Edith Prickley, Eugene Levy as Gus Gusstofferson, Martin Short as Ed Grimley, and behind Andrea Martin is Juul Haalmeyer, SCTV costume designer and “dancer.” (INSET) SCTV logo. (LEFT) When you’re No. 2, you try harder. The Second City at 1616 North Wells Street, Chicago, Illinois. Photographed August 15, 2015. Victor Grigas/Wikimedia Commons. © The Second City.

teacher/school owner Viola Spolin and co-founded by Bernard Sahlins (eventual owner and co-founder of the Second City), Howard Alk, and Spolin’s son Paul Sills, it grew to become an influential and prolific comedy empire, developing the art of improvisation and fostering generations of performers. In 1961, their Broadway musical revue, From the Second City, earned Tony Award nominations for ensemble members Severn Darden and Barbara Harris. The alumni of The Second City includes too many well-known talents to list here. But as always, Second City ’s comedy style has always leaned

toward improv satire and commentary regarding contemporary society, performing without scripts nor planning of any kind.

Andrew Alexander’s (b. 1947) a man who developed and produced live theater revues. He purchased the Canadian rights to the Second City of Toronto, which had opened in 1972... for one dollar. How did he get such a bargain? The truth was that the Second City of Toronto was in big trouble, financially speaking. Alexander took over its debts in exchange for the rights to operate the improv comedy troupe. Bernie Sahlins agreed, and in 1974, Alexander took control of it. Then he formed a partnership with Len Stuart to create the Second City Entertainment Company in 1976, a TV and film production company. Its initial project, a television production, was historic: Second City Television, a k a SCTV, that same year. He went on to co-develop and executive produce over 150 hours of television comedy for SCTV.

Alexander was born in London and moved with his family to Canada in 1951. After selling ads for a newspaper, editing Ski Magazine, and working for the ill-fated John Lennon Peace Festival in Toronto, Andrew was eventually hired by the Ivanhoe Theater in Chicago. There, he met Bernie Sahlins. In 1985, Andrew Alexander became co-owner of the Second City Chicago.

In 1974, Alexander called together the then-current cast of the stage show—including John Candy, Joe Flaherty, Dave Thomas, and Eugene Levy—to discuss a format for a Second City TV series. Also in attendance were Second City vets Harold Ramis, Sheldon Patinkin, and Del Close, along with business partner Bernie Sahlins. There is much dispute as to who actually created the SCTV series. The show itself bears no “created by” credit, although it gives “developed by” credits to Bernard Sahlins and Andrew Alexander

According to Dave Thomas’ account in his book SCTV: Behind the Scenes, various ideas were batted around, but SCTV was created by either or both Sheldon Patinkin and Del Close. No one involved agrees with each other on that “fact.”

However, the premise of a cheap, tiny, obscure TV station in a small town definitely came from Harold Ramis. The fictitious TV station (later network) would be located in the town of Melonville. (Unspecified, the earliest episodes imply the town is in Canada, but most later episodes place it in the U.S.) The cast immediately jumped on the idea as a workable model for presenting a virtually unlimited range of characters, sketches, and ideas, while still having a central premise that tied everything together. From there, the actual content of the show (the characters, the situations, the Melonville setting, etc.) was all the work of the cast, with contributions from Alexander and Sahlins. Alexander remained as a producer and executive producer throughout SCTV ’s run. Sahlins stayed for the first two seasons as a producer. Sheldon Patinkin was the first season’s writer/post-production supervisor, and was constantly irritating the cast by editing their skits, often losing their best lines and poses. By this time, Del Close had no further involvement with the series.

There were problems, too. These SCTV episodes were made on a threadbare budget; the total amount for the first seven episodes was $35,000, a measly $5,000 per episode. Working with the then-regional Canadian network Global, they were aired one month at a time. Also, the cast’s salary varied with the member in

a “Favoured Nations” deceit with unequal pay. It made John Candy especially not trust Andrew Alexander one bit, and he was very open with that assessment.

According to Harold Ramis, “As far as a transition from Second City, we had this wonderful opportunity with SCTV to take all of the things we’d learned onstage and directly translate them into television without any network sponsors or producers in authority. We were the authorities. We got do what we wanted and operate the same way we did onstage, just in a different medium.”

Harold Allen Ramis (November 21, 1944–February 2 4, 2014) was born and raised in Chicago. After graduating from a St. Louis, Missouri, college in 1966, he worked in a mental institution. After

Brothers (a popular SCTV sketch which we’ll discuss in a moment) spin-off cartoon series Bob & Doug (2009 – 2011).

Every one of SCTV ’s cast also served as writers on the show, although Martin and O’Hara did not receive writing credits on the first four episodes. Ramis served as SCTV ’s original head writer, but only appeared on-screen as a regular during the first season (spread out over two years) and in a few select episodes in the second season before his “Moe Greene” character was written out. Ramis and Flaherty also served as associate producers. Sahlins produced the show; Global staffer Milad Bessada produced and directed the first 13 episodes, but he wasn’t a good fit for comedy. Therefore, George Bloomfield became the director as of Episode 14. Toward the end of the season, Brian Doyle-Murray was hired as a writer, due to his experience on the original Second City in its first stage show. The laugh track used in early episodes was recorded using audience reactions during live performances in the Second City theater.

With the exception of Ramis, every cast member of SCTV worked as a regular performer on another Canadian TV show concurrently with the first year of SCTV. Flaherty, Candy, Thomas, and Martin also worked together as regulars on The David Steinberg Show. It also featured future SCTV cast member Martin Short. Martin, Flaherty, and Levy were also cast members of the shortlived comedy/variety series The Sunshine Hour. In addition to his work on SCTV, Levy was also a cast member of the CBC sketch comedy series Stay Tuned, At the same time SCTV debuted, Candy and O’Hara became regular cast members of the CBC comedy series Coming Up Rosie This gave John Candy the distinction of appearing as a regular on three TV series simultaneously, on three different Canadian networks.

(ABOVE) Moranis as Gerry Todd, star of “The Gerry Todd Show.” (ABOVE RIGHT) Martin as Perini Scleroso, Candy as Dr. Tongue, (SITTING) Flaherty as Count Floyd, Martin Short as Ed Grimley, and Levy as Bruno. © The Second City.

Speaking of John, his stand-out character, “ Johnny LaRue,” a sleazy, dishonest, ladies’ man who behaves like a low-budget Hugh Hefner, was the first regular character to appear on SCTV Other iconic characters who premiered during SCTV ’s Season One included:

f Harold Ramis’ “Maurice ‘Moe’ Green,” an incompetent game/talk show host, actor, playwright, critic, licensed chiropractor, and eventually, SCTV’s station manager.

f Joe Flaherty’s “Guy Caballero,” the highly authoritative, brusque, and greedy head of SCTV Network, usually seen in a wheelchair to gain respect; and “Floyd Robertson,” the news anchor of the Melonville Nightly News and recovering alcoholic.

f Andrea Martin’s “Edith Prickley,” the SCTV Network’s boisterous station manager, as well as “Cheryl Kinsey”, uncomfortable sexologist, and “Pirini Scleroso,” nonspecific foreigner attempting to grasp English.

f Eugene Levy’s “Earl Camembert,” socially awkward news anchor on SCTV News, and “Bobby Bittman,” narcissistic, loud, egotistic, showy filmmaker, writer, comedian, and singer.

Other than its writers and performers, SCTV ’s make-up, hair, and wardrobe artists were absolutely the most valuable members of the show. It was a team that was only mentioned in the show’s credits, but SCTV wouldn’t have been remotely as entertaining

BY s COTT s AAVEDRA

The catch phrase, a few words of little or great import that take on a life of their own by virtue of vigorous vocal repetition, is older than you may expect. My assumption was that it was a construct of our mass communication age, but no. Politics have long driven catch phrases like “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” a popular campaign slogan and song in 1840 that promoted the presidential candidate William Henry Harrison, who still lost to Martin Van Buren (embarrassing!). Some of us are old enough (not me) to remember Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “I Like Ike” campaign slogan and song (“I like Ike, you like Ike, we all like Ike…”). He won in a landslide.

But it’s still available in independent bookstores, comic book shops, by mail order and subscription, and digitally! Don’t miss an issue— subscribe today!

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_ info&cPath=61&products_id=1375

Going back to ancient Greece (I like to do research), the catch phrase “resting on laurels” had a positive meaning in that it described a person of achievement. It eventually became a negative when it described a person (often an athlete or popular performer) who sadly relives days of past glories, recounting some long-ago accomplishment (like when I won so, so many trophies while on my high school’s speech team with an informational speech about Superman… I was on top of the world then). “Painting the town red” is another

still-in-use catch phrase all due, so the story goes, to one man and some of his friends. Henry de la Poer Beresford, the third Marquis of Waterford (also known as the Mad Marquis), was a drunk and known troublemaker. In 1837, he and his hooligans were completely sloshed and messed up the sweet little English town of Melton Mowbray (where fine Stilton cheese is made). As part of their wanton foolishness, they removed knockers from doors, broke windows, and painted a post office with red paint. A toll-keeper and a constable were painted red as well. There was more, but you get the idea. Brazen debauchery, to say the least.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

RETROFAN #36

Modern mass communication has allowed catch phrases to appear and quickly become part of daily conversation. Newspaper comic strips had them. Popeye said, “I am what I am.” Radio shows have faded in our cultural memory, but somebody somewhere is saying, “Say goodnight, Gracie.” Movie catch phrases are some of my favorite words to use in conversation, “Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!” But our focus today will be on television catch phrases, which are abundant. As you will soon see. The following is just a sampling though (I do have a life you know).

What is it about catch phrases that we seem to like? According to Christopher Peterson, Ph.D., writing for Psychology Today in 2012, it’s because they make us happy, especially when encountering others familiar with the phrase, and that’s good enough for me. Maybe some of the following catch phrases will make you happy, too.

Feel the G-Force of Eighties sci-fi toon BATTLE OF THE PLANETS! Plus: The Girl from U.N.C.L.E.’s STEFANIE POWERS, CHUCK CONNORS, The Oddball World of SCTV, Rankin/Bass’ stop-motion Santa Claus Is Coming to Town, TV’s Greatest Catchphrases, one-season TV shows, and more! With ANDY MANGELS, WILL MURRAY, SCOTT SAAVEDRA, SCOTT SHAW, MARK VOGER & MICHAEL EURY (84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_152&products_id=1776

Henry Winkler, who played Arthur “Fonz” Fonzarelli on Happy Days (1974–1984), had dyslexia, a learning disorder that made reading and learning his lines difficult. He decided to reduce his verbiage to expressive versions of “aaay!” The blog popculturereferences.com notes that Happy Days pushed for catch phrases to the show’s detriment. “Sit on it,” “Exactamundo” and its variants, Ralph Malph’s “I still got it!,” and Chachi’s mysterious “Wa, wa, wa” (before he became a show regular) were used, overused, and even discarded by later seasons.