BY WILL MURRAY

More than sixty years ago, a futuristic cartoon predicted Zoom calls, flat-screen TVs, telemedicine, remote office work, online classes, FaceTime, household cleaning robots and a host of other innovations that didn’t materialize until well into the 21st-century.

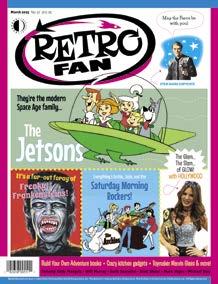

That show was ABC’s The Jetsons, and it was the second Hanna-Barbera Productions cartoon to be telecast in prime time. The Flintstones had debuted two years before as the first ever animated sitcom, and was a solid hit for ABC.

Joe Barbera recalled, “Somebody said, ‘What’s next?’ And we went from the rock era into the future.”

“It was very simple,” explained partner Bill Hanna. “We just thought, “Let’s do the flip side of The Flintstones and go into the future.”

The Jetsons premiered Sunday night, September 23, 1962, in the 7:30 time-slot.

One of the staff artists who worked on the project, Iwao Takamoto, remembered how it all began:

“One day Joe called a group of us in and said, ‘There’s going to be a new series about a family in the future,’ and that was the beginning of The Jetsons. It was to be similar to The Flintstones in the respect that the episodes were built on gimmickry and gags, only this time the gags are all futuristic spoofs on everyday life instead of stoneage ones.”

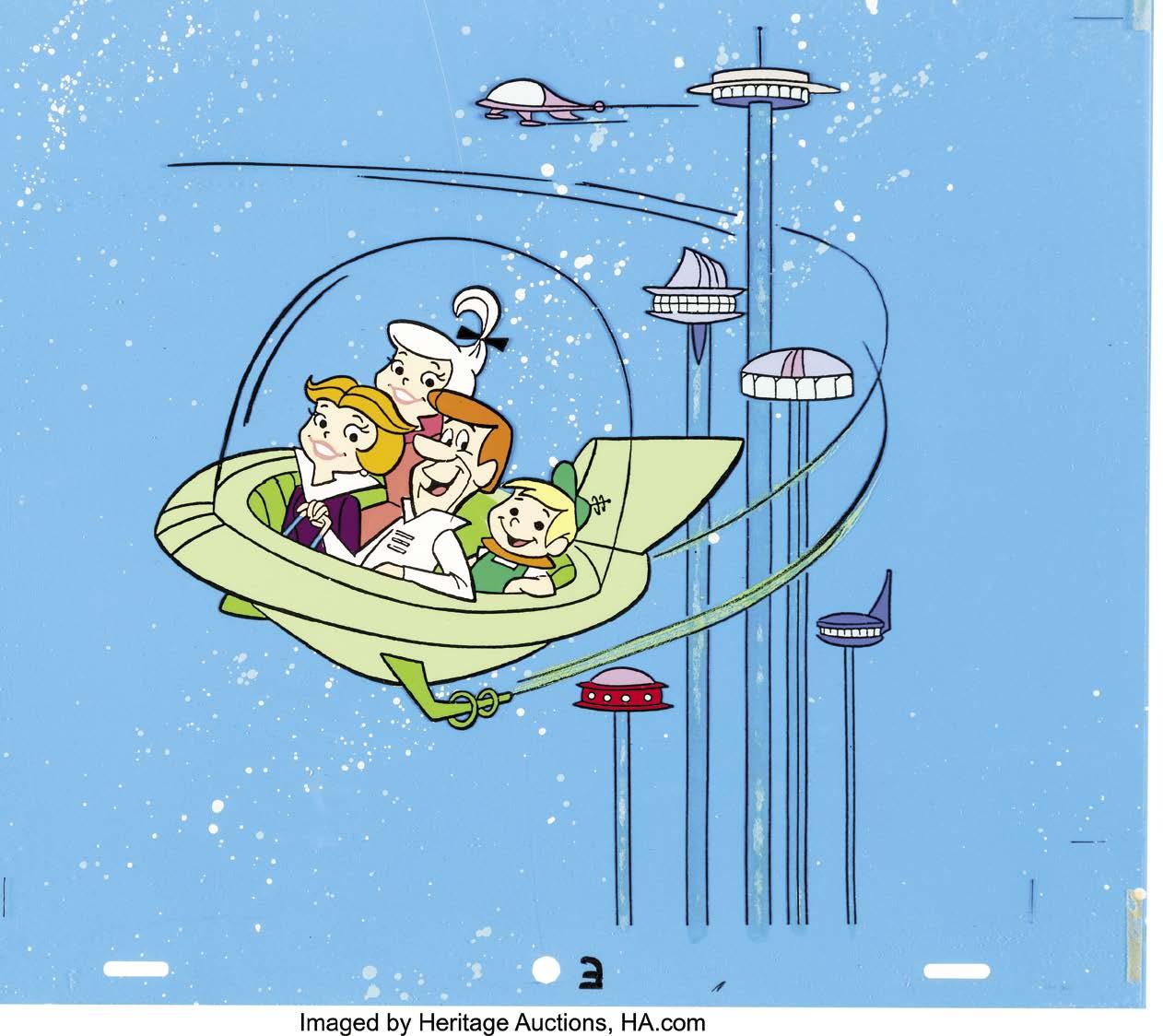

The Jetsons crowd into the family’s flying car in this promotional cel circa 1980s. © Warner Bros. Entertainment. Courtesy of Heritage.

The Flintstones was consciously modeled after Jackie Gleason’s Honeymooners sitcom, which was then out of production. Hanna-Barbera took their inspiration for The Jetsons from an entirely different medium.

“The inspiration for this show was the old Blondie movie series,” revealed Takamoto, “which also had a husband dealing with both his family at home and a demanding boss at work. Whereas the stories in The Flintstones were often driven by Fred’s bombastic over-enthusiasm about one thing or another, The Jetsons was structured in a more farcical way, with misunderstandings between the characters often driving the plots.”

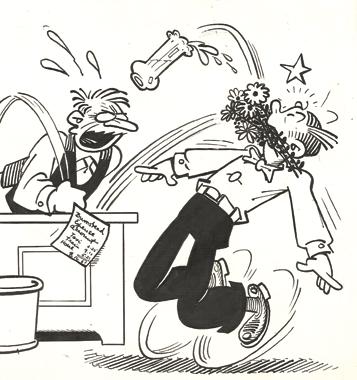

No question that The Jetsons borrowed the template originated by artist Chic Young in his long-lived comic strip, Blondie. George Jetson was Dagwood Bumstead, and his wife Jane stood in for Blondie. The futuristic couple had two children, a young boy named Elroy and a daughter, Janet. The Bumsteads had Alexander and Cookie. George was often at odds with his boss, Cosmo G. Spacely of Spacely Space Sprockets, just as Dagwood struggled to please his boss, Mr. Dithers.

Blondie, the vintage movie series, served as the inspiration for The Jetsons. © King Features Syndicate, Inc.

The task of designing the cast fell to several artists, but it’s unclear who deserves credit for whom.

H-B staffer Jerry Eisenberg recalled, “I remember trying to design the main characters, actually. Sometimes, it would be a blend. I know Iwao designed Astro the dog. And I think one or two of the other characters might have been ultimately designed by Bick [Dick Bickenbach]. Or maybe Ed Benedict was involved.”

Bickenback is believed to have been responsible for the final designs. Willie Ito and Gene Hazelton were also among H-B’s chief designers at that time, and presumably contributed to designing some Jetson family members.

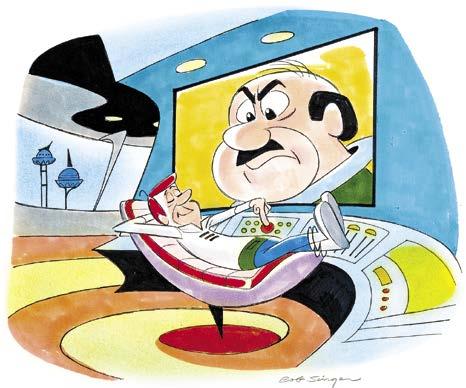

(LEFT) Where’s HR when you need them? Dagwood and his boss, Mr. Dithers. Cover art to Chic Young’s Dagwood Comics #89 (Harvey, 1958) attributed to Paul Fung, Jr. ©King Features Syndicate, Inc. (RIGHT) Cosmo G. Spacely was modeled after Mr. Dithers, Dagwood’s boss, seen here in a illustration by Bob Singer circa 2000s. (BELOW) Early Elroy Jetson design by Jerry Eisenberg (1962). © Warner Bros. Studios. Images courtesy of Heritage.

Preliminary concepts depicted a beefier George Jetson who resembled Fred Flintstone’s distant descendant. He was streamlined and modeled after actor Alan Young, then starring in Mr. Ed. Jane Jetson evolved from a short-haired blonde housewife to a saucy redhead. Children were not part of the original family unit. At first, Judy was much younger than teen-age. Even Astro was an entirely different breed of canine. Eventually, the familiar Jetson family took final form.

In one of those false starts that often plagued Hanna-Barbera during this time, they hired comedians Morey Amsterdam and Pat Carroll as George and Jane Jetson. After recording one episode, the duo were summarily fired, supposedly due to sponsor conflicts since the pair were also cast members of popular live-action TV shows. They sued for breach of contract, but lost. Amsterdam and Carroll were replaced by George O’Hanlon and Penny Singleton, who ironically had played the titular lead in numerous Blondie radio shows and movie features. This cemented the identification with their inspiration.

O’Hanlon, who had auditioned unsuccessfully for Fred Flintstone, once observed, “George Jetson is an average man. He has trouble with his boss, he has problems with his kids, and so on. The only difference is that he lives in the next century.”

“We’ve taken today’s family and moved them 100 years in the future,” noted Joe

Barbera. “Their problems are the same we find today, but their solutions are more complicated.”

The Jetsons lived in the Sky Pad Apartments in Orbit City, which consisted of buildings modeled after Seattle’s Space Needle. George worked only three days a week for three hours. His job, according to different sources, was either a “referential unisonic digititap indexer,” or a “digital control operator”—which means he’s office foreman for a factory so completely automated he’s the only employee.

“His job was simply to go in in the morning, sit down, and press one button,” explained Barbera. “Is anything easier than that?“

The Spacely Sprockets Company supplies materials to General Rotors. Many storylines hung on George’s frequent work travails, which went beyond routine push-button duty.

As Joe Barbera explained, “In reality, however, George is frequently required to do more than push a button, especially when he is caught between the demands of his family and those of Cosmo G. Spacely, who is engaged in an unending struggle with his business rival, Mr. Cogswell, chairman of Cogswell Cogs.”

(ABOVE) He was almost George! Morey Amsterdam from the Dick Van Dyke Show. © CBS. (LEFT) Publicity photo of a young Alan Young circa 1944.

The Jetsons focused on the traditional sitcom themes (home, family and work) that were also fodder for

Bill Hanna expressed confidence at the time, saying, “I know we’re opposite Disney this season, and it doesn’t really worry me, especially as we too shall be in color.”

Unfortunately for The Jetsons, color television sets were so uncommon in America that few saw the show as telecast, with its innovative pastels and metallic hues. This probably led to the ratings drop.

It did not help ratings that The Jetsons was up against Disney’s Wonderful World of Color on NBC and on CBS.

As Joe Barbera recalled in his 1994 autobiography, in Toons, “It is a testament to the fundamental strength of Jetsons that it wasn’t simply creamed by these shows. What did happen is that the Nielsen share split neatly into three virtually identical parts—something like a sixteen or seventeen share for each show. But doing relatively well like that is not good enough….”

The following season, ABC moved The Jetsons Saturday mornings in reruns, where they were more successful. Over the following two decades, the show appeared on the Saturday morning kids’ block of all three networks.

It simply refused to fade away.

“There are only 24 of them, but they kept the cult going for 25 years,“ Barbera reflected.

In 1974, Joe Barbera pitched a cartoon series focusing only on grown-up reporter Judy Jetson and teenager Elroy, but the network countered by asking for a different futuristic animated show that became Partridge Family, 2200 AD.

Astro popped up a few years later in a short-lived series called Space Stars, which included a segment called Space Mutts. Astro was one of three dogs who worked for Space Patrol Officer Space Ace. The Jetsons were supposed to appear in this series, but it was terminated after 11 installments.

When Jetsons reruns became popular with college kids in the 1980s, and Hoyt Curtin’s Jetsons theme unexpectedly charted in 1986, it created interest in

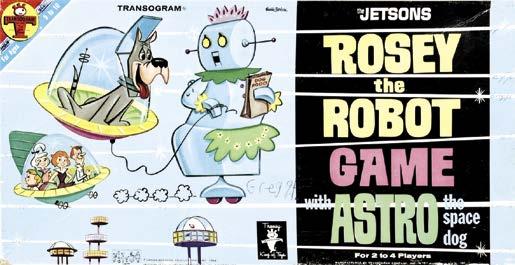

Jetsons merchandise (CLOCKWISE FROM THE TOP) Rosey the Robot Game (Transogram, 1962), Hot Wheels Premium Jetsons flying car (Mattel, 2022), George Jetson tin litho hopper toy (Marx, 1963), Jetson’s Space Copter (Transogram, 1962), Jetson’s Space Ball (Marx, 1962), Astro hand puppet (Knickerbocker Toys, c. 1962). © Warner Bros. Entertainment. Hot Wheels flying car courtesy of Worthpoint. All other toys courtesy of Heritage.

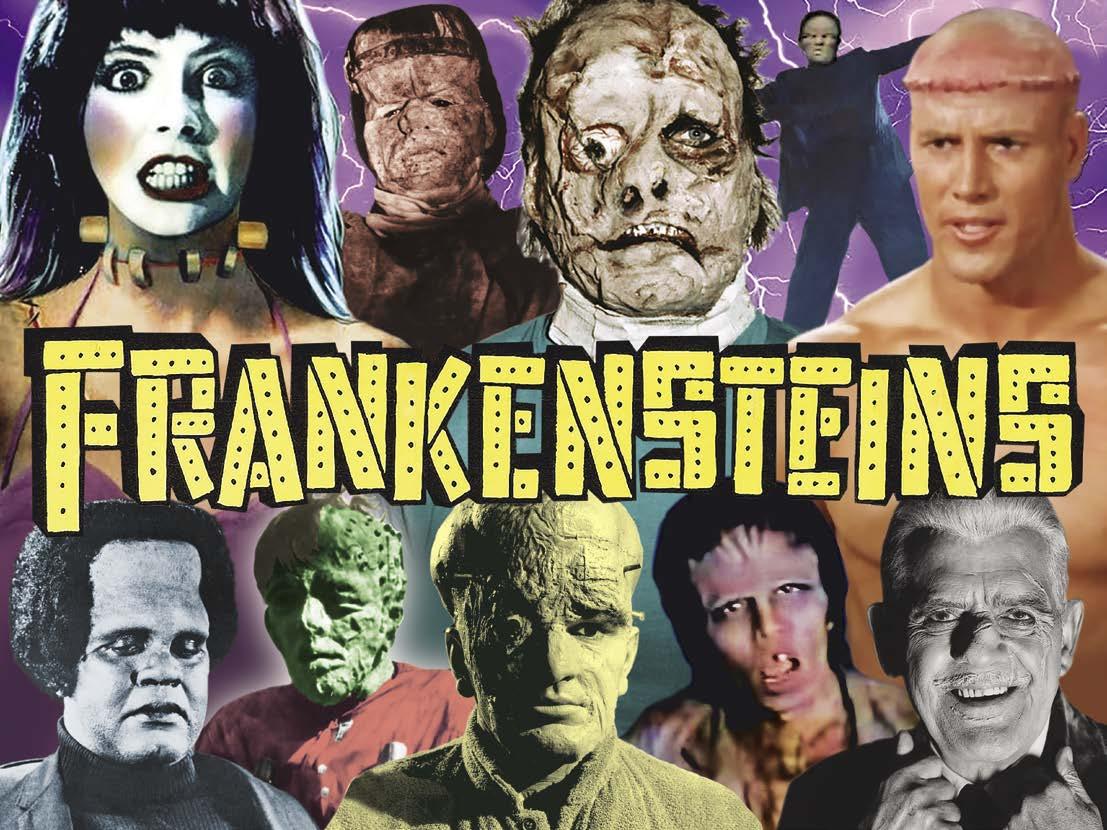

Forgive them, Mary Shelley, for taking your creation’s name in vain

BY MARK VOGER

In the Frankenstein films of the Thirties and Forties, there was much talk of the “Frankenstein family name”—how it was disgraced by the murderous monster, not to mention malicious gossipers and torch-wielding villagers.

But the true cause of Frankenstein’s fall from grace is the fact that Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel fell into the public domain. As a result, there have been many Frankenstein movies wherein the family name is exploited, if not downright disrespected.

Much as we revere Universal Studios’ canon, the series was the first to commit this crime against classic literature. Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man? Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein? Admit it: Universal took liberties.

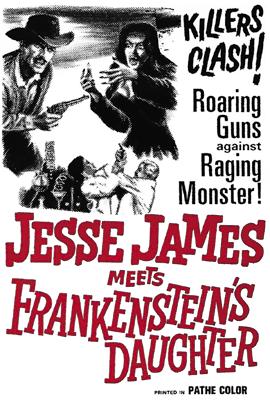

Subsequent film titles got even crazier, though they are catnip to shlock aficionados. Yes, there’s a movie titled Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter. Yes, there’s a Frankenstein Island. These have little to do with Shelley’s novel, even as they depict (alleged) descendants of her antihero Victor Frankenstein.

My Top 10 picks for the freakiest Frankenstein movies follow, plus a “dishonorable mention” list. So, tighten up those neck bolts ...

Whit Bissell as Professor Frankenstein—a first name is never given—is the real monster in this quickie follow-up to AIP’s surprise hit I Was a Teenage Werewolf.

He slaps and emotionally abuses his fiancé (Phyllis Coates). He coerces a colleague (Robert Burton) into becoming an unwilling accomplice in his mad experiments. He imprisons his creation, a weirdly buff teen monster (Gary Conway), in a darkened morgue.

Gary Conway in monster mode gets rough with Angela Austin in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. © American International Pictures.

And if that’s not enough, he maintains an alligator pit.

So, Herbert L. Strock’s film is less about the fate of the teenage Frankenstein than Bissell’s richly deserved comeuppance. I figured him for alligator food from the get-go.

Set-up: Professor Frankenstein is a visitor from England, though you’d never know it from Bissell’s non-accent. The Prof has been lecturing in America about his controversial theories in transplantation. (His infamous surname doesn’t seem to alarm his Yankee hosts.)

“I plan to assemble a human being using parts and organs from different cadavers,” he confides in his assistant Dr. Karlton.

“You don’t dare!” is Karlton’s reply.

“Don’t dare?” the Prof says. “I’m sure that someone spoke those same words, and hurled that same challenge, at that great ancestor of mine whose name I bear. The knowledge, the know-how, is in my blood. It’s my heritage. But where Baron Frankenstein created a monster, I shall bring forth a perfectly normal human being.”

Good luck with that.

IWATF doesn’t evoke the then-contemporary teen world like its predecessor. I Was a Teenage Werewolf was largely set at a high school; it depicted a teen party and presented a rock ’n’ roll song. In contrast, Teenage Frankenstein briefly visits a Lovers Lane. Otherwise, Bissell continually reiterates that the monster is made of teen parts, in a bid to justify that seductive title.

The climax is in color. The process is not exactly Technicolor… more like Techni-Magenta. Bissell should be commended for keeping a straight face while delivering the film’s most memorable line: “Speak! You’ve got a civil tongue in your head. I know you have, because I sewed it back myself.”

Released in 1958 but set in the far-off futuristic year of 1970, Howard W. Koch’s film brings back the O.G. himself—Boris Karloff—to show the small fry how it’s done. Karloff fails at this, unfortunately, but he’s hardly the sole culprit.

It’s a shame, because Frankenstein 1970 — as Marlon Brando once put it—could’a been a contender. The sometimes campy film updates the centuries old legend with a couple of then

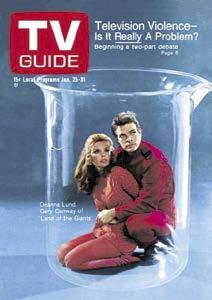

(LEFT) Whit Bissell as Professor Frankenstein takes Conway as the monster out for a little drive in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. (RIGHT) Viewers would get to see Gary Conway’s chiseled good looks in shows like Land of the Giants. Pictured here on the cover of TV Guide (January 25–31 1969) with Deanna Lund. (BELOW) An advertisement for I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. Teenage Frankenstein © American International Pictures. Land of the Giants © 20th Century Fox. Image courtesy of TV Guide Cover Archive.

contemporary themes: television and atomic power. All that’s missing is Bill Haley and the Comets.

The meta premise has the last surviving Baron Frankenstein (Karloff) allowing a TV crew to film a horror series in the original Frankenstein castle. The Baron needs the money, you see, to buy an atomic reactor for his lab so that he can (yawn) revive the original Frankenstein monster.

Tortured by the Nazis, the baron is disfigured with a droopy eye and nasty facial scars. The pompadour—another Fifties touch?—doesn’t help his appearance either. Adrift with a comicbook script and lackluster direction, Karloff is left with no choice

And someone at NASA opened the film vaults to this production. We see so much cleverly used stock footage of locales, vehicles, machinery and liftoffs that it’s gotta be an inside job. My guess? A near-retirement administrator indulging his aspiring-filmmaker grandson.

The campy performance by Lou Cutell as pointyeared alien Dr. Nadir alone is worth the price of admission. Cutell walks a fine line; he doesn’t wink at the camera, literally, but he does sometimes catch its gaze. His costume would be right at home in a leather bar.

For the record, those two songs are “To Have and to Hold” by the Distant Cousins and “That’s the Way It’s Got to Be” by the Poets, both real-life singles by real-life bands on the real-life label DinoVoX. The Poets, of Scotland, were managed by Andrew Loog Oldham, who also shepherded the early Rolling Stones. The Stones became superstars, while the Poets got a song on Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster. Life can be cruel.

Actually, it’s Frankenstein’s granddaughter who Jesse James meets, but that’s the least of the gaffes in this insane (but endearing) genre mashup.

There once was a prolific director of low-budget films who became known as William “One Shot” Beaudine, due to his propensity for settling on the first take while shooting a given scene. Beaudine had a history with horror, having directed Bela Lugosi in four films. In 1966, he filmed two back-to-back horror westerns as a double feature for the drive-in market.

(ABOVE) Rudolph Frankenstein (Steven Geray) and his sister Maria (Narda Onyx) work on their latest monster (Cal Border) in Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter. (LEFT) Movie poster for Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966). © Embassy Pictures.

The second feature was titled—it never gets old — Billy the Kid vs. Dracula.

For starters, Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter addresses the obvious question: How does a Frankenstein end up in the Old West? Siblings Maria Frankenstein (Narda Onyx) and her brother Rudolph (Steven Geray) have relocated from Vienna to the American West for two reasons. No. 1: The plentiful electrical storms. No. 2: They were wanted by the Viennese authorities for —what else—carrying on their grandfather’s unorthodox experiments.

Meanwhile, the outlaw Jesse James (John Lupton) and his musclebound sidekick Hank Tracy (Cal Bolder) are being pursued by a lawman (Jim Davis). Once Maria lays eyes on Hank, she knows she has found the perfect subject for a brain transplant. (Maria brought her prize possession all the way from Vienna: the final artificial brain made by her grandfather. Don’t question the logic, just enjoy the movie.) Soon Hank is lumbering around with a prominent surgical scar atop a shaved head. It’s not a terrific makeup job, but anyway, he’s a Frankensteinian monster.

Believe it or not, JJMFD has a connection to the movie that started it all, James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein. The laboratory scenes feature recognizable electrical props from Whale’s seminal horror film. These were loaned to Beaudine’s production by Ken Strickfaden, Hollywood’s electrical wizard who supplied the props and know-how for Frankenstein and its 1935 sequel, Bride of Frankenstein.

An outlaw-turned-monster (Cal Bolder) is egged on by his creator, Maria Frankenstein (Narda Onyx), in Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966). © Embassy Pictures.

“As contagious as chicken pox.”

That’s how New York Times correspondent Aljean Harmetz described a paperback book series she observed her daughter becoming obsessed with reading at the time—the time being the early 1980s and the series, Choose Your Own Adventure. In the years that followed, CYOA would become jaw-droppingly popular among eight- to 13-year-olds. It proved to become a children’s book phenomenon of epic proportions—is it a game? Is it a book? Is it a… gamebook? Put simply, the CYOA franchise totally blew the freakin’ minds of young readers, mainly Gen X middle-schoolers who feverishly bought copies during the late ’70s and through the ’80s in droves.

In that dawning age of Atari and Nintendo, the real miracle of CYOA was to divert, however fleetingly, the collective attention span of kids away from the allure of video games and to get girls and boys to read actual books. And, in retrospect, the CYOA publishing legacy is nothing less than staggering. CYOA was the fourth most successful kids book series of all time, which, by the

end of the 20th Century, would sell 250 million copies worldwide. Between 1979 and 1998, those millions, more than a few translated into as many as 40 languages, included 184 different titles in the primary series published in paperback by Bantam— not to mention (take a breath) 52 volumes in the Bantam Skylark CYOA series for readers 7–10; 12 CYOA Walt Disney books; a pair of Choose Your Own Super Adventures; six CYOA: Passport; and, perhaps inspired by the ’90s Goosebumps craze, 18 Choose Your Own Nightmare selections. There were also 18 Young Indiana Jones tie-ins; three Star Wars versions; a six-volume science fiction spin-off called Space Hawks; and even a kiddie series under the umbrella title, Choose Your Own First Adventure 1

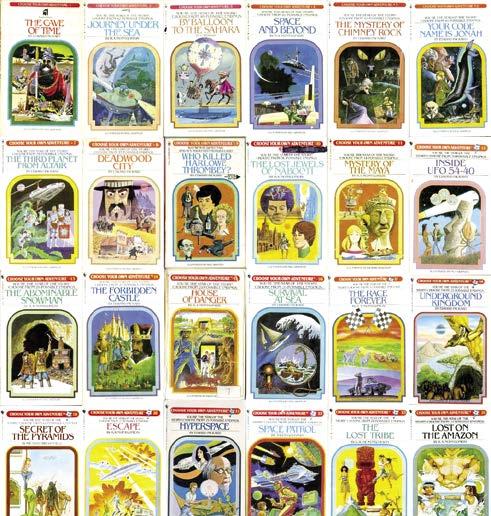

Can you find the unicorn? An amazing array of Choose Your Own Adventure covers. © Chooseco LLC.

1 Those listed here reflect only the Bantam catalog’s original CYOA trademarked series and their spin-offs, and none from subsequent publishers.

The origin saga of CYOA, an oft-told tale in the publishing realm, is the stuff of industry legend, a success boasting two fathers and numerous midwives (in the guise of agents, editors, and writers), a creation 12 years in the making that began with a stymied Manhattan antitrust/entertainment lawyer thinking up bedtime stories on the fly. One night in 1969, an exhausted Ed Packard was concocting a yarn for his two daughters, Caroline and Andrea. “I was tired from a long day at work,” he told the Marketplace website, “and I couldn’t think of what should happen next. So I asked them. I got two different answers. I could sense that this was an unusual approach. They could not just identify with the main character; they could be the main character.”

(ABOVE LEFT) Edward Packer, creator of the Choose Your Own Adventure series in 1984. (ABOVE RIGHT) A 1984 photo of editor Judy Gitenstein. (RIGHT) Publisher and writer, Ray Montgomery.

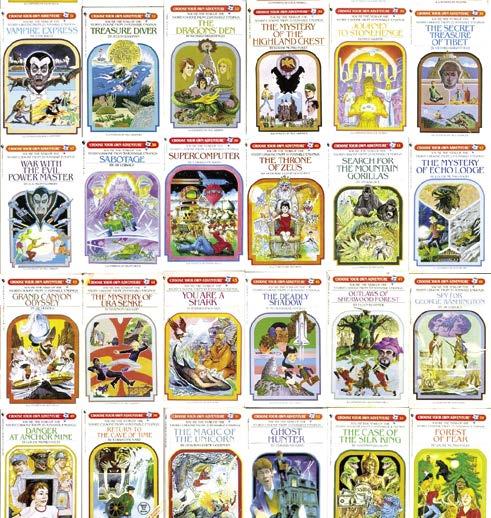

Struck by that experience and the notion of giving readers a choice of different endings, Packard wrote his first book, The Adventures of You: Sugarcane Island, during the train commute between his law office in the city and his suburban Connecticut home. Packard’s effort was then shopped around by an enthusiastic agent he enlisted, but the concept failed to catch any publisher interest, with one responding, “It’s hard enough to get children to read, and you’re just making it harder, with all these choices.” And so, the manuscript languished for five years until Packard, while on a ski getaway, picked up the Spring 1975 issue of Vermont Life. Therein, Packard found the perfect publishing team in Connie and Ray Montgomery of Waitsfield, Vermont. The magazine profile described the couple’s intention as Vermont Crossroads Press to “design, write, and create a series of children’s books, games, and activities that are specifically and exclusively for children.” To the attorney’s relief, the Montgomerys were sparked upon reading Sugarcane Island, immediately recognizing that the formula lurking within Packard’s fictional scenario was one rife with potential. It was also an excellent fit for their stated mission to bypass traditional purchasers of children’s books—the gatekeepers of parents, librarians, and teachers —and publish efforts that appealed directly to kids.

(LEFT) The Adventures of You Series: Sugarcane Island (Archway 1978). (BELOW LEFT) Which Way Books edition (Archway 1982). (BELOW RIGHT) Revised and expanded as Choose Your Own Adventure #62 (Bantam 1986). © Chooseco LLC.

In a recent interview, onetime Bantam series editor Judy Gitenstein mapped out the CYOA formula: “Choose Your Own Adventure is a series in which the main character is you, the reader. The books are told in the second person. The scene is set on page one. You are a deep-sea diver or detective, or any number of other things, setting off on an adventure. In the course of reading, you, the reader, come to a point in the story where you have to make a decision as to what you want to do. Depending on the choice, the story crosses and crisscrosses to its ending. You might come out okay or meet your end, and, in every case, you can dive back in to make another choice and live another ending. In each book, there could be hundreds of possible combinations of plotlines and about 40 possible endings.”

Sugarcane Island became a top seller for Vermont Crossroads, but the company was too small to alone capitalize on the vast promise offered by the “Adventures of You” premise, and (newly divorced) Ray Montgomery and Packard, who together owned stakes in the property, went on to separately peddle the idea of a series before the larger publishing houses. Packard’s pitch found a receptive audience with “upstart” editor Joëlle Delbourgo at Bantam Books, who immediately recognized the innovation’s potential. “My first

reaction was that it was a brilliant concept and, to make an impact, you had to publish it as a series with a unifying cover concept,” she told Harmetz in 1981, two years after rescuing Sugarcane Island from getting submerged in the publisher’s slush pile.

Delbourgo, who would soon leave Bantam and ultimately become a literary agent herself, shared in 2014 with Jake Rossen in a Mental Floss website piece, “I got really excited, I said [referring to Montgomery’s literary agent] ‘Amy [Berkower], this is revolutionary.’ This is pre-computer, remember. The idea of interactive fiction, choosing an ending, was fresh and novel. It tapped into something very fundamental.” As a result of Delbourgo’s lobbying with higher-ups, Bantam was sold on the idea and contracted for a half-dozen books. In her comprehensive New Yorker feature on CYOA titled “Now What?” (from the Sept. 19, 2022, issue), Leslie Jamison explained, “As Packard tells it, Bantam ‘wouldn’t sign the deal’ without Packard’s involvement; as Montgomery’s widow, Shannon Gilligan, tells it, Montgomery’s sense of fairness, as well as a feeling that six books in a year was too much for one writer, inspired him to get Packard involved. However it happened, they eventually split the deal.”

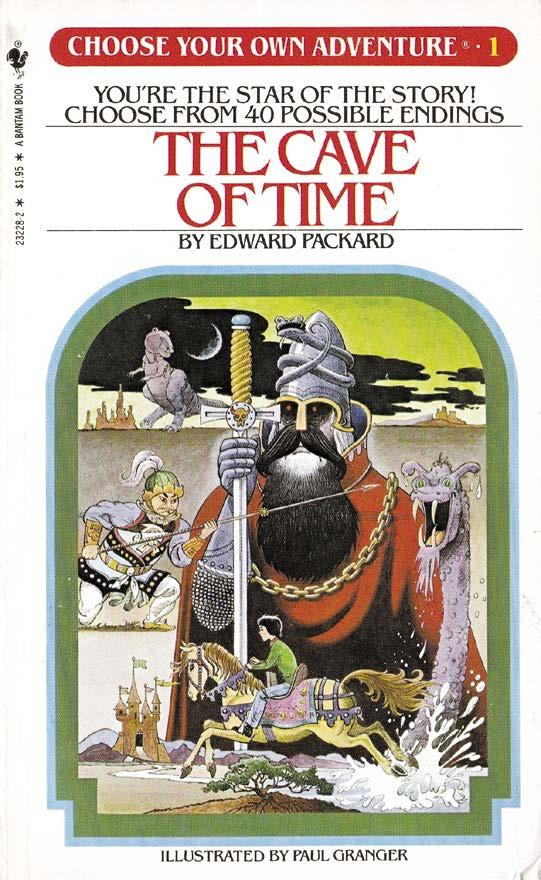

The first entry in the series was also among CYOA’s most fondly recalled, The Cave of Time [1979], a story involving time travel,

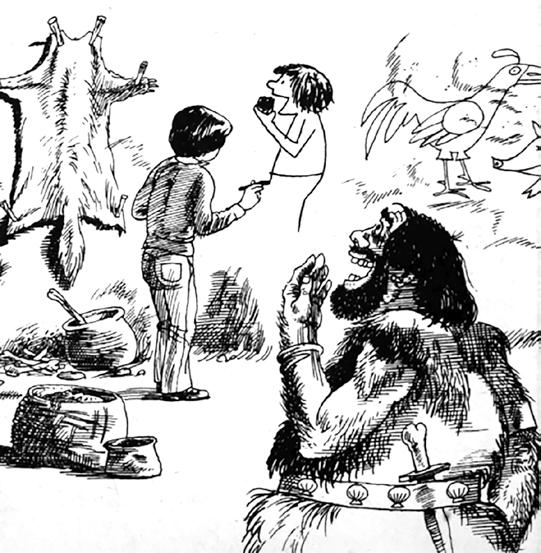

(LEFT) The first Choose Your Own Adventure title, The Cave of Time (Bantam, 1979). Cover and interior art by Don Hedin working as Paul Granger. A pre-historic human is delighted by those who can draw (and aren’t we all?).

© Chooseco LLC.

dinosaurs, and UFOs (and much more), which was initially conceived by Andrea Packard (she of the bedtime storytelling ten years prior). Jamison revealed that Packard’s daughter “had recently gone spelunking at summer camp, crawling into a small cave beneath the main cave, farther than anyone else, and felt torn between exploring more—had anyone ever seen these tunnels?—and returning to safety.” Her father, facing the daunting task of having to write six titles in a short timespan, shouted “Great idea! Get started!” With that, he chucked Andrea a legal pad to start scribbling. As one internet scholar mapped out, The Cave of Time contained 40 possible endings, 13 of which resulted in death, a few by cataclysm and a couple as the result of being eaten alive. (Packard’s daughter would receive credit in the book for the concept, title, and editorial assist, and, to this day, she collects a portion of the royalties for that debut volume, which had been reprinted by Bantam at least 32 times.)

Flush with confidence regarding the series, Bantam extravagantly promoted CYOA from the word go. Gitenstein revealed that an entire print-run was put aside for free distribution. Delbourgo told the Times, “We did absolutely nothing except give the books away. We gave thousands of the books to our salesmen and told them to give five to each bookseller and tell him to give them to the first five kids into his shop.” That remarkable gamble paid off. Word-of-mouth praise spread like a virus, and a true cultural phenomenon infected an entire generation. Summarizing its impact, Jamison reported, “The Choose franchise hit a generational sweet spot, alongside the rise of Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games. Back then, it was these text-based experiences

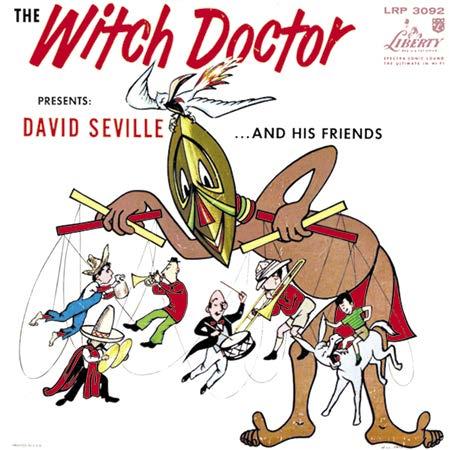

(LEFT) Please, Christmas, don’t be late! Alvin and the Chipmunks sing “The Christmas Song.” (BELOW) The proto-Alvin album: The Witch Doctor! © Bagdasarian Productions.

fabricated musical groups, who appeared in animation and live action, as studios and networks tried to grasp the tenuous ages when kids became tweens became teens. Our story will take us from 1960 to 1988, and will attempt to be a comprehensive look… although I will no doubt miss someone’s favorite!

BY ANDY MANGELS

WELCOME BACK TO Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Morning, your constant guide to the shows that thrilled us from yesteryear, exciting our imaginations and capturing our memories. Grab some milk and cereal, sit cross-legged leaning against the couch, and dig in to Retro Saturday Morning! This issue, gimme a beat, as we’re taking a look and listen to the rock-and-roll world of Saturday mornings, with the fictional bands that used to dazzle you with their catchy songs and repetitive dance moves!

Two issues ago, I took a rare issue off, and Mark Arnold gave readers a look at the “real world” musicians who had made it onto Saturday morning. But this time, we’ll search instead for the first

(1960/1961)

In the world of music, novelty records were an interesting and unusual way to sell records; similar today to short Tik-Toks or joke memes. One of the most unusual of these came about due to a method that all kids with record players knew. Records rotated at 33 1/3 rpm (rotations per minute), but singles rotated at 78 rpm. If one played a regular record at 78 rpm, the voices were sped up and sounded silly and high-pitched. Armenian-American singer, songwriter, record producer, and actor Ross Bagdasarian (known onstage as David Seville) used this sped-up effect in 1958 on a novelty song called “Witch Doctor,” which hit #1 on the charts.

Bagdasarian was inspired to do more in the format, and created a trio called The Chipmunks, naming them Simon, Theodore, and Alvin after the three record producers who managed him at Liberty Records. His first song with them was “The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late),” released in November 1958. It hit the #1 spot by New Year’s Day. More Chipmunk songs followed, as well as toys and plans for an animated television series.

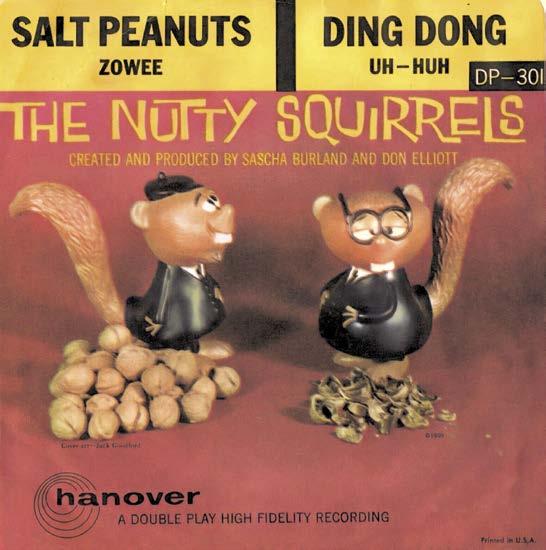

A rival for The Chipmunks was soon created by jazz musicians Don Elliott and Granville Alexander “Sascha” Burland, who titled their virtual band The Nutty Squirrels. They began releasing music that was similar to The Chipmunks, but had more scat singing and

bebop jazz elements. As the Squirrels rose in popularity, a race ensued to see who could get on television first. The Chipmunks were having troubles with their designs, so in September 1960, The Nutty Squirrels Present debuted on syndicated television stations all over the world. Filmed in color, the show was transferred into black-and-white for some countries. Thirty half-hour episodes were created, comprised of 150 six-minute shorts, with Elliott and Burland supplying their voices.

Although The Nutty Squirrels Present is the first animated series about a music band, it was not original to animation, nor was the second such series, The Alvin Show, the animated television series featuring Alvin and the Chipmunks that aired on CBS from October 4, 1961, to 1965. Each episode of The Alvin Show featured a sevenminute Chipmunks adventure, a seven-minute Clyde Crashup story, and one or two musical sequences of a Chipmunks song. Broadcast in black-and-white during its first season, The Alvin Show moved to color in 1962, when CBS moved it to Saturday morning broadcast.

(LEFT) This made it tough for their secret identities—the band was also called the Impossibles. (RIGHT) The Impossibles original production cel title card. © Warner Bros. Entertainment

(LEFT) Dig it, Daddy-O! The Nutty Squirrels on vinyl. © Transfilm-Wylde Productions. (BELOW) The Beagles, inspired by Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. © DreamWorks Classics/ DreamWorks Animation.

CBS decided to double down on musical cartoons in 1966, introducing two music-based shows to the nascent Saturday morning schedule. The Beagles was produced by Total Television, a company affiliated with the General Mills food corporation. Although the name would imply a Beatles pastiche, the show instead featured a duo inspired by Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, rather than a quartet. The Beagles ran for one year on CBS before cancellation; ABC picked it up for reruns from 1967–1968. None of the Beagles’ musical numbers made it to record shops.

The second music show on the CBS docket was Frankenstein Jr. and The Impossibles, which included a segment about a trio of super-heroes named The Impossibles—Coil-Man, Fluid-Man, and Multi-Man—who were also as a popular rock-and-roll group when

they weren’t out saving the world. The trio all played guitars from atop a bandstand that could secretly transform into the Impossimobile, the Impossi-jet, and other motorized vehicles! Each of the 18 episodes were only six minutes long, so the music that was played was often very short snippets of five total songs, and did not result in any ancillary records.

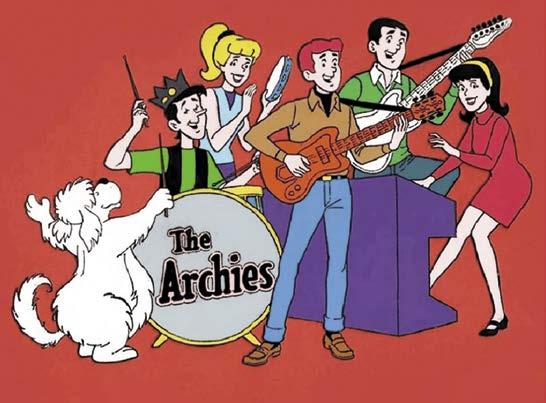

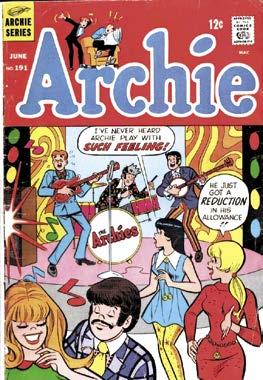

With their musical appetite whetted, CBS wasn’t about to quit. On September 14, 1968, Saturday morning television was given a seismic jolt when Filmation Studios’ The Archie Show debuted. Adapting the comic characters from Archie Comics Group, the animated series soon became one of the highest-rated TV shows on the air, with its combination of comedy, teenage players, music, and dancing. Not only were the kids from Riverdale obsessed with

The Archies are ready to rock! (BELOW) The Archies band were frequently in Archie Comics. © Archie Comic Publications. Comic courtesy of Heritage.

typical teen things, they also were all in a rock band together!

Music producer Don Kirshner created the musical sound of The Archies, utilizing singer Ron Dante, backed by Toni Wine. The Archie Show and its fictional band The Archies were soon everywhere—in magazines, comic books, toys, and even on cereal boxes!

The Archie Show featured two eight-minute stories, a threeminute musical segment, and other “how to dance” or short joke segments [see a full article on The Archies TV history in our sister magazine Back Issue #108 –Editor]. The musical segment would feature The Archies as a band, singing a pop song. Because that music wasn’t specific to any of the plots, Kirshner and his team could work on their own, independent of the animation or storytelling process. Kirschner had turned The Monkees into a hit,

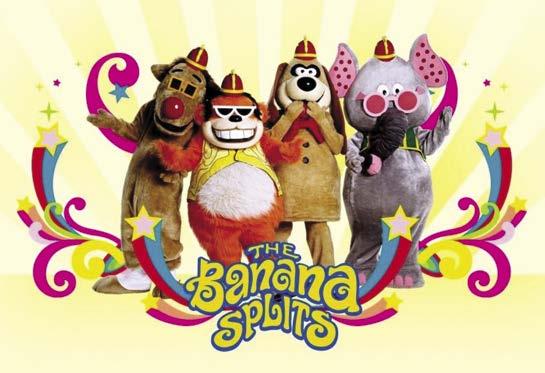

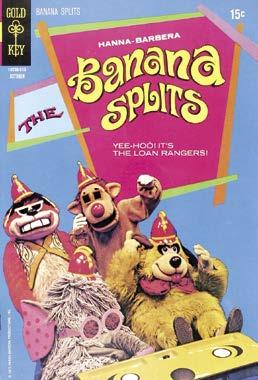

(ABOVE) Tra la la, la la la la… The Banana Splits! (BELOW) Making up a mess of fun! The Banana Splits #4 from Gold Key, Oct. 1970. © Warner Bros. Entertainment. Courtesy of Heritage.

and now, he was using his magic on a musical super-group that wouldn’t talk back… because they were animated.

“When it came to the songs, we’d tell Kirshner what we wanted to do, what the attitude should be, and what kind of stories we were doing, and then he would produce the songs and deliver them to us whole,” Filmation head Lou Scheimer said in interviews for the book Lou Scheimer: Creating the Filmation Generation [also from our publisher, TwoMorrows –Editor again]. As noted, the show needed three-minute catchy pop songs, as well as brief segments that would teach kids to dance. Scheimer recalled that the music scenes were, “kind of like early music videos. We’d show The Archies playing their guitars and drums and singing, and there would be groovy effects behind them. We also taught a ‘Dance of the Week’ which were some very weird dances put together by a bunch of animators who were not teenagers… and probably not dancers either.”

Although it had never been done before, The Archies’ music was planned for public release. Filmation contracted for two years with Kirshner for eight singles and two albums, to be distributed through RCA Records. The first release for record and 8-track cartridge tapes was simply to be called The Archies, and ads for the debut album appeared in TV Guide the same week as the show started on September 14, 1980. Both The Archie Show and The Archies album were monster hits. In a television first, The Archies became the first animated band to be featured on a late-night variety show, The Ed Sullivan Show!

While CBS had a surprise hit on their hands, NBC decided to finally arrive at the Saturday morning party, with a HannaBarbera-produced variety series called The Banana Splits. The costumed hosts of the show were Fleegle the beagle (on guitar and

BY SCOTT S h AW!

I’ve been lucky in many ways. One of those gifts—in my experience at least—was to be an “only child.” I didn’t have to compete with anyone but myself, and I was able to focus on my interests. I was a boy cartoonist/paleontologist/weirdo, armed with pencils, crayons, correctly-pronouncing-dinosaur-names, and Disney’s 200,000 Leagues Under the Sea introduced me to science fiction and the concept of world peace when I was three years old. Of course, I was a spoiled rotten kid.

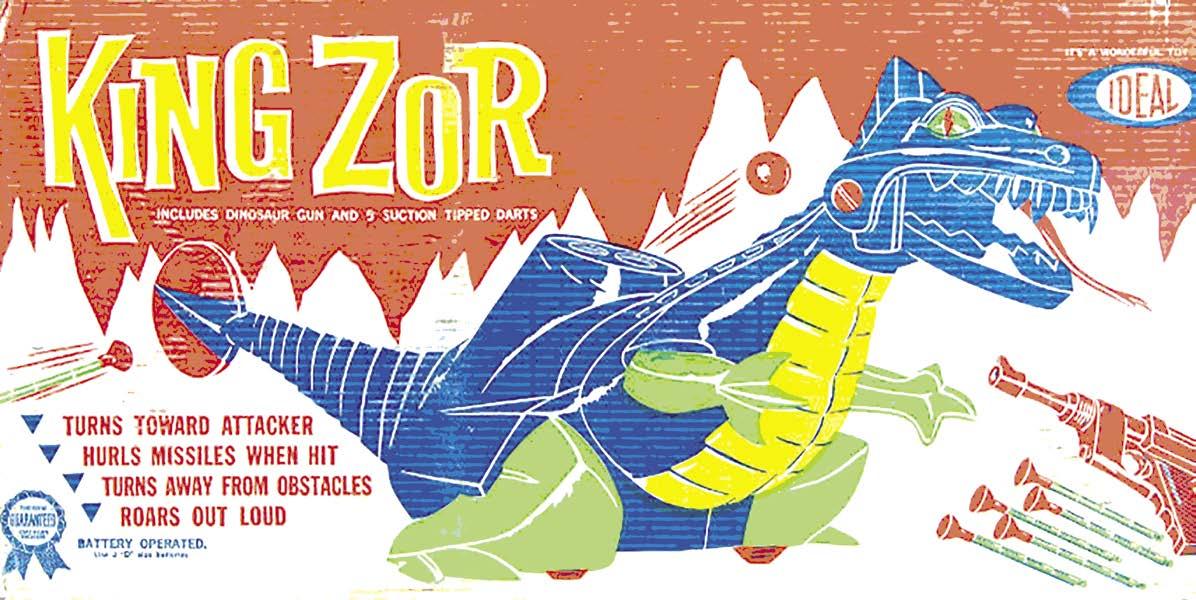

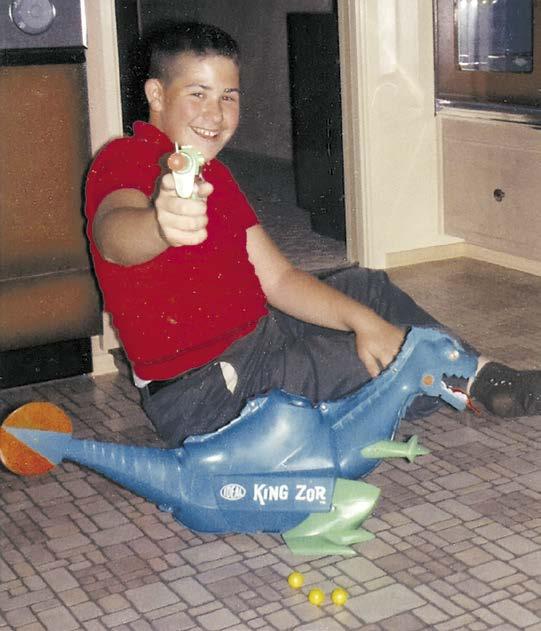

So it wasn’t any surprise that when Ideal Toys’ Mr. Machine was released to the world, I was immediately fascinated that he was a toy robot that I could take apart and reassemble. On September 4, 1960, I received him for my ninth birthday, one of the greatest toys I ever owned... until King Zor arrived on the scene.

Two years later, my Mr. Machine and all of his parts were still doing fine. King Zor, a massive robot dinosaur would turn 180 degrees if you hit him in the tail, then shoot balls at you. King Zor was the coolest, most aggressive dinosaur toy up to that point in time. I rebuilt my Mr. Machine and added cardboard parts to resemble King Zor. It was a great gimmick for campaigning the message to my parents that I really needed King Zor for Xmas. And here’s a photo to prove that it worked!

My nostalgia for these meaningful gifts led to researching their background. Both were produced by Ideal Toys—at the time, one of the industry’s better companies—and created and designed by Marvin Glass and Associates. The studio’s creative output definitely had an influence on my career when I was designing Hanna-Barbera and Simpsons figures for McFarlane Toys.

Marvin Glass and company created imaginative toys that made millions of kids happy for decades. Unfortunately, when the man behind the fun was a kid named Marvin I. Goldberg, he was anything but happy.

(ABOVE) King Zor box art. Digitally altered. (LEFT) Scott Shaw! and his majesty, King Zor. Photo courtesy of Scott Shaw!

To flee the anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia, Marvin’s paternal grandparents and their children—the middle child of six kids was Marvin’s father Louis—joined two million other Jews to flee to America. Arriving in the U.S. sometime between 1894 and 1897, they settled in Chicago, where Louis finished his schooling and focused on the garment industry. There, he met Rose Glass, his future wife and Marvin’s mother. Rose’s family—including her four brothers: Theodore, Jacob, Frances, and Harry—came from what is now

Western Ukraine. Harry eventually developed dementia and was committed to the Chicago State Hospital at the age of thirty-nine. On June 29, 1913, Louis Goldberg and Rose Glass were wed; the next year, on July 14, their son Marvin I. Goldberg was born.

Six years later, the family had moved to Bucktown and into a three-story brick apartment. Louis, now a garment salesman, was often on the road for days at a time, leaving Marvin alone with his mother. It’s unknown if or how Rose’s increasingly hostile mental issues were related to her brother Harry, but one thing was certain. One day, when Louis wasn’t at home, Rose attempted to murder her only child by trying to throw him out of an upper-story window. She was committed to the “insane hospital” outside of Chicago, Dunning Institution, where Rose remained for decades.

Rose’s sister Frances and her husband Louis Goldberg (no relation) took over the duty of raising Marvin. They lived in the Polish section of the Southside Chicago neighborhood known as the “Back of the Yards,” named for its location, west of the city’s Union Stock Yards. The stench of enormous slaughterhouses; miles of penned hogs, sheep, and cattle; fertilizer plants; rendering vats; garbage dumps accumulated alley trash; a few tanneries; and a fetid sewer known as “Bubbly Creek” made Marvin’s new life not much better than his old one. “Aunt Frances” and “Uncle Louis”, however, truly loved him. In

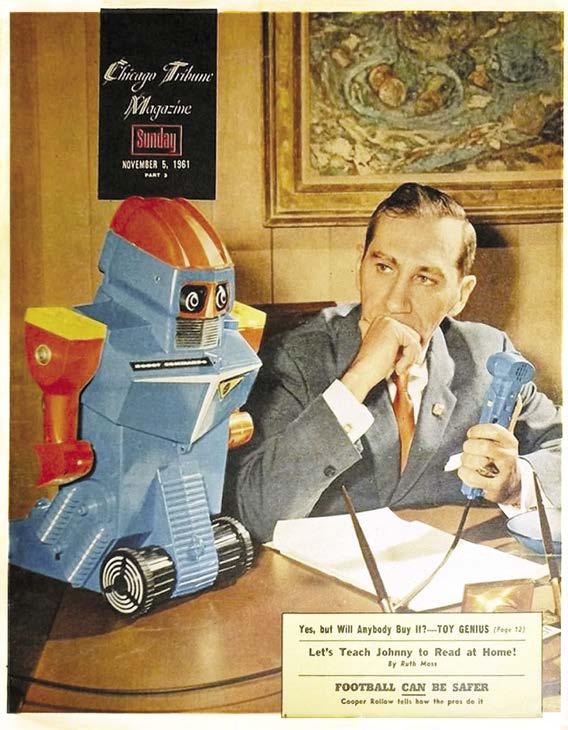

(LEFT) Toy legend Marvin Glass thoughtfully observes a Robot Commando toy robot on the cover of the Chicago Tribune Magazine for November 5, 1961. © Chicago Tribune.

reaction, young Marvin was very “unruly,” tossing ink on the drapes, stomping his feet, and having angry tantrums.

During this, Marvin’s actual father, Louis Goldberg, continued to live in Chicago, remarrying the same year his son turned ten and bearing a daughter, Sonia, when Marvin was sixteen. Louis’ son reconnected with him and his new family.

Eventually, Marvin learned to ignore his situation by obsessing on the fantasy world of entertainment. His hero was the movie star and creative genius Charlie Chaplin, with whom the Chicago youngster greatly identified. They both struggled through troubled childhoods, had mothers with mental problems, and lived in poverty. He was also very interested in hypnotism. By the time he grew to be a pre-teen, Marvin had become an enterprising go-getter, selling encyclopedias at a furious rate.

“I didn’t have many toys as a child,” Marvin once said, “and I became very concerned about them. I guess I never stopped thinking about toys. In many ways I’ve remained a child.”

As an adult, Marvin avoided sharing information about his life or family with the public. He would alter their names, nationalities, locations, and beliefs, as well as his own history, such as schooling. He’s noted for attending many different colleges and universities, but there is no evidence that he was ever in college. He was so secretive that there is no accurate information regarding what Marvin was doing with his life during most of his twenties. It’s very possible that he was working for his biological father Louis, who by that time was involved with the liquor industry and gambling syndicate. Marvin contradicted himself in interviews so many times that he eventually became known as “The Troubled King of Toys.”

Marvin’s earliest semi-professional gig was working with a freelance graphic artist named Carl Sachs, working together on “some sort of paper items,” probably for Louis’ secret partner. Marvin also had an uncle in the art business, Theodore Glass, who had worked at an engraving company in Chicago. He had moved to California, and was also an inspiration

In 1942, while visiting his mother in the sanitarium, Marvin met Judd Reed, a commercial artist working for an advertising company, who was there to see his wife. While the two young men chatted, Judd introduced Marvin to the toy industry. Their chemistry and backgrounds were ideal; Judd was an industrial designer, artist, sculptor, and graphic designer, while Marvin was an outstanding salesman. The two of them would be business associates for decades. Their team expanded with the addition of artist/illustrator Eoina “Joe” Nudelman. According to Marvin, “For years, we lived and worked together in Nudelman’s studio, playing Gypsy music, drinking vodka,

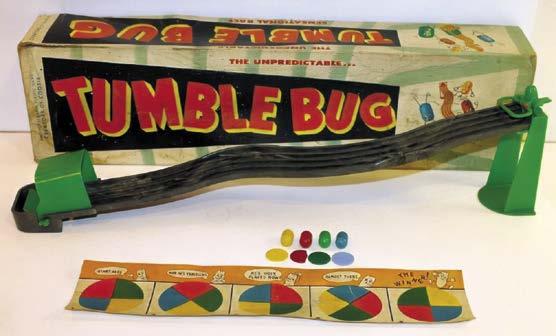

(LEFT) Tumble Bug (1954), an early much-needed success for Marvin Glass. (BELOW LEFT) Big Max and his Electronic Conveyor from Remco.

Meanwhile, Topic Toys was busy with a long line of goodies: Merry-Go-Sip, Mov A Toy Book, and themed spoon sets, toothbrush sets, and whistles (1949); Yank A Tooth, Dipsy Diver, Goosy Lucy, and Lazy Daisy (1950), Koo-Koo Clock, Tidy Teddy, Magic Cage, Blushing Sweethearts, Noah’s Nesting Ark, Jack in the Bank, and assorted whistles and flutes; and The Unimal, Moody Mutt, and Back Seat Driver (1951) and Bull’s Eye Bomber (1952.) Meanwhile, H. Fishlove and Co. handled Hi Pardner Pencil Pistol, Pin Up Pencil, Katy Kangaroo, Razzer Tie Clip Elephant (1951), and Razzer Tie Clip Donkey (1952.) Marvin Glass’ Endless Stream Fire Boat was a recurring theme, beginning with Amerline.

Unfortunately, those years’ efforts were mainly to survive. Goldfarb left the company in 1952 and Nudelman exited a few years later. And Topic Toys was no longer exclusive to Marvin Glass and Associates, who was still borrowing money to stay afloat. Fortunately, his outfit got back on track, with a new team of outstanding model makers who were familiar with then-contemporary technology, as well as many new manufacturers. The post-WWII baby boom brought a huge wave of toy-seeking children who watched the somewhat new media, television, complete with advertising. America’s culture and fads shifted to the young.

However, 1953 though 1955 were still rough for MGA, although Marvin acquired the rights to Hank Ketcham’s popular new comic panel series, Dennis the Menace, in 1954. But during this period, MGA had only one true success: 1954’s Tumble Bug, gelatin pill capsules with a weighted ball inside, a gimmick that had been around since the mid-1800s, but with the added appeal of games and races for the tumble bugs. Most of the other toys and novelties seemed more or less similar to the toys they started out with. Their Whoops (H. Fishlove and Co., 1959), a plastic slab of phony vomit, became a classic in the Halls of Practical Jokes. However, in the second half of the decade, MGA was starting to take advantage of current fads, especially science fiction, with Robo the Robot Dog (Wyandotte Toys, 1956), the magnetic robot Big Max (Remco, 1957), and Robot Hands and Mask (Kilgore, 1958.) These sci-fi toys led to MGA’s first massive breakout toy that put Marvin Glass and Associates on the map.

Machine box front. (RIGHT) Robot Commando. Mr. Machine courtesy of Worthpoint. Robot Commando courtesy of toytent.com

By this time, Marvin had expanded the number of rooms he rented at the Alexandria Hotel, with multiple locks on every one to insure security. He now had a team of a dozen designers and model makers. As Marvin described their process, “All the men in my shop have become necessary to each other by some process of symbiosis. One is a designer, one an engineer, one an artist; every man lets other man’s ideas seep in and enhance his own, sort of converging his own talents and abilities. The idea of the creative genius that could sit down and come up with a great toy, well, you

BY DAN MURP h Y

“We’re the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling

We’re all champions in the ring

We come from the streets

We come from the cities

We come from a world where there is no pity.”

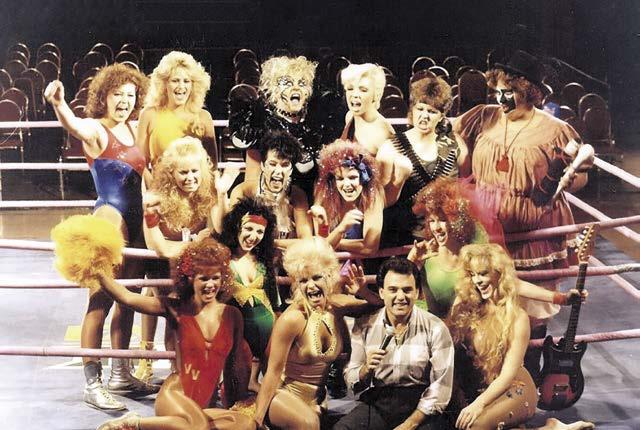

In September 1986, thousands of unsuspecting television viewers were greeted by two dozen scantily clad beauties (and one very awkward tuxedoed man) belting out this rap inside a pink-roped wrestling ring.

Yes, the rap needed work; it was somehow even hokier than the Chicago Bears’ “Super Bowl Shuffle” released ten months earlier. The hair was teased high, the Lycra was tight. The dancing ranged from hip-swiveling gyrations to arrhythmic swaying and handclapping. But the pure “what the hell is this?” hypnotic spectacle of it all was enough to give pause to the most jaded of channel surfers.

America had discovered GLOW. And America was captivated.

The Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling was the brainchild of David B. McLane, an aspiring television promoter (and the aforementioned awkward tuxedoed man) hailing from Indianapolis, Indiana. A professional wrestling fan since childhood, McLane had established

a fan club in honor of Indiana rasslin’ hero Dick the Bruiser as a teenager. Dick the Bruiser (real name William Afflis Jr.) was also co-owner of the World Wrestling Association, the regional wrestling promotion in the area. McLane’s passion, energy, and dedication caught Afflis’ attention and the grappler brought McLane onboard to help in the office and eventually become an on-air ring announcer and commentator.

But the era of small regional pro wrestling territories was coming to an end. In 1982, Vince McMahon Jr. took the reins of the World Wrestling Federation from his father. Unlike Vince Sr., Vince Jr. wanted to expand the WWF outside of its base in New York and the Northeast and grow it into a national wrestling company. Over the next few years, McMahon raided talent from other promotions, bought them out, or beat them down by competing head-to-head against them in their own market. Buoyed by stars like Hulk Hogan, Roddy Piper, Andre the Giant, and “Superfly” Jimmy Snuka—and agreements with NBC and MTV—McMahon’s WWF had garnered the lion’s share of the wrestling market.

While many territorial wrestling promoters groused about McMahon’s business practices and cartoonish and gimmick-heavy presentation of wrestling, McLane saw inspiration and opportunity.

Women’s wresting had been a novelty act since Mildred Burke started turning heads and kicking asses in the 1930s, but Afflis had been reluctant to push women’s matches in the WWA. The WWF had terrific success with Wendi Richter as women’s champion in 1984. Instead of having one female star, why not start a company full of them? McLane set out to establish an all-women’s pro wrestling promotion.

While searching for investors, McLane managed to connect with Meshulam Riklis, the multi-millionaire businessman and owner of the Riviera Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, and the then-husband of actress Pia Zadora. Riklis put McLane in touch with Matt Cimber, a producer, writer, and exploitation film director who had previously been married to Jayne Mansfield.

The Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling, ringside with David McLane in 1986. Courtesy of IMDb.

BY SCOTT SAAVEDRA

What if I told you that with this one amazing Secret Sanctum collection of vowels and consonants you could remove the ugly stains of boredom from your daily grind? Expand your mind? Improve your chances of having interesting conversations at cocktail parties? What would you pay for that? One million dollars? Twenty dollars? How about a mere ten U.S. dollars and a scant ninety-five cents for a curated prime selection of sentences carefully placed—by hand—into thoughtful paragraphs. That would be the most astounding bargain of all time! You know it. I know it. But wait, there’s more. If you read this installment of Secret Sanctum right now we will add punctuation and photographs at no extra charge! You can’t afford to pass up this incredible limited-time offer.

What if we made this an even better deal with no added cost to you, your family, or the people of your community? You’d be amazed, right? We will give, without any hidden fees or expectation of appreciation, eleven additional professional RetroFan features collected in a handsome magazine format fully in color and with a quality square binding once found only in the finest magazines of Europe. This is a once-in-a-two-month period offer than you simply can’t pass up.

Act now!

The kitchen has to be one of the top three rooms here at the Secret Sanctum mainly because that’s where the food and coffee comes from. Unsurprisingly, it’s where all the kitchen gadgets live. What exactly is a kitchen gadget then? It’s basically a tool that is electrical or mechanical and solves a genuine or perceived need in a novel way. Not everything here will exactly fit that description. The rules of logic are very fluid in the Sanctum. Mostly, they are devices that purport to fix a need that is, at best, useful-ish and, at worst, another darn thing cluttering up the place. Many kitchen gadgets are impulse buys that come and go without much of a

ripple. Far too many don’t live up to their promises. But what they aren’t are funny novelties. A corncob butter applicator is a novel gadget. A corncob holder in the shape of human ears is a novelty. Kitchen novelties are for office Secret Santas and something to give your mother when you’ve run out of good ideas for a gift.

A good kitchen gadget could really make a homemaker’s day (if you believe the advertising).

Some of the items were designated “As Seen on TV,” a term of salesmanship that could apply to any number of products featured in television commercials. Usually, it’s applied to gadgets demonstrated by very enthusiastic individuals. In the Sixties and Seventies, sellers of these gadgets relied on brief commercials to

(LEFT) The Automatic Corn Butterer is a novel gadget while the (RIGHT) human ear corn holders are a novelty item and therefore not a proper kitchen gadget.

make their pitch and snag the sale quickly by offering to ship before you even had to pay. (“Order now. Operators are standing by.”) The post office would collect on delivery. The rise of credit cards and a lack of desire on the part of the postal service to have delivery personnel stopping here and there to collect cash changed all that.

Fun credit fact: circa the mid-Seventies, housewives (adult women) needed a husband’s approval to get her own credit card.

There have been gadgets that have become kitchen necessities and considered important advances in homemaking tech. Among the top devices (and debut date) are the blender (1919), the toaster (1919), the ice cream scoop (1896), Mr. Coffee (1972), and the can opener (1858). This edition of the Secret Sanctum has nothing to do with anything like that.

Food processors are fairly common now, but that wasn’t the case when the Veg-O-Matic made its debut in 1963. The Veg-O-Matic was a non-electric device for preparing vegetables with greater ease, and it got home chefs (okay, housewives) interested. Take your potato (please) or canned meat product (Spam!), and the Veg-O-Matic can slice it and dice it quickly and cleanly.

The Veg-O-Matic was the creation of Samuel Joseph Popeil (1915–1984). Popeil was the CEO of Popeil Brothers Inc., makers of a number of gadgets including the Pocket Fisherman. Popeil got his start as a product salesman for the family business when he was 17. At first, he did not enjoy demonstrating vegetable peelers and the like in department stores to shoppers, but it eventually grew on him. He rose up the ranks of Popeil Brothers and became quite wealthy, so wealthy his estranged wife wanted to have him killed. The intended assassin was a man named… Peeler. Yep, yep, yep. It was Samuel’s son Ron whose salesmanship and inventiveness would take the Veg-O-Matic (and other home gadgets) into a whole new level of public awareness. Ron Martin Popeil (1935–2021) didn’t want to be poor and he didn’t want to live with his grandparents anymore (having been sent to them after his parents divorced when he was four). At 16 Ron moved to Chicago where Popeil Brothers made their products. He began selling Popeil’s housewares (which he bought from his father at wholesale) as a

The Popeil Brothers’ Chop-O-Matic chops nuts and other smaller food items. Unlike some of the kitchen gadgets here, this one is actually fun to use and a good stress-reducer. © Popeil Bros. Inc.

pitchman at swap meets and other locales. According to his autobiography The Salesman of the Century (Delacorte Press, 1995), he made more money than he’d ever seen before. However, Ron noticed that he used up lots of vegetables when demonstrating the Veg-O-Matic at fairs, department stores, and five-and-dimes and that made for a burdensome overhead. There had to be a better way to sell his wares, and there was: television.

His first two commercials were for the Ronco Spray Gun, his own invention, and the Popeil Brothers’ Chop-O-Matic. The ChopO-Matic has a hazy origin. In fact, according to But, Wait! There’s More! The Irrestible Appeal and Spiel of Ronco and Popeil by Timothy Samuelson (Rizzoli, 2002), getting solid intel on the history of these gadget sellers is difficult. It wasn’t history that the Popeil Brothers or Ronco were after. It was sales.

Then came the commercial for the Veg-O-Matic. That really made an impact. By 1968 Ronco had almost $9 million in revenue, and in the next year went public. Sales for the Veg-O-Matic dropped off once electric food processors took hold. Unmentioned in the Veg-O-Matic sales-pitch was the fact that you needed a bit of strength to use it. According to As Seen on TV by Lou Harry and Sam Stall (Quirk Books, 2002) Ron Popeil had a “vice-like grip”, so using this un-powered gadget was easier for him than it was for gentle moms in the kitchen.

(LEFT) The Veg-O-Matic was invented by Samuel J. Popeil circa 1963. It was one of the first products to have be touted as “Seen on TV.” (RIGHT) The Popeil Kitchen Magician does to vegetables what the Veg-O-Matic can’t. © Ronco. Veg-o-Matic courtesy of BitBytes/ Wikipedia. Kitchen Magician courtesy of Worthpoint.

A quick note: The “o-matic” suffix is what your smarter word scientists call a “back-formation.” Basically, it’s a slimming of “automatic” wherein an automatic vegetable cleaving device becomes a “Veg-o-matic.” The first use of the suffix appears to go back to the Twenties in the U.S. and was attached to a heating company product, the Oil-O-Matic. (RetroFan, come for the crazy, cool stuff, stay for the esoteric etymology.)

And speaking of words: Ron Popeil claims that he never said, “It slices, it dices”—which is very much associated with the Veg-OMatic—in any of the product’s commercials.

If you like to entertain, it all begins in the kitchen (or, to be fair, a bar or speakeasy if you have one at home). And if you want to serve up your drinks in a nice cold glass, be it lemonade or a classy martini, a quick, easy way to chill and frost drinkware might be nice. Ron Popeil has got you covered with the Ronco Glass Froster. Many other gadget makers produced similar items, like the Instant Icer, Chill Master, Jr., and Chiller Diller.

Basically, a pressurized spray can of, according to one company, “special formula liquid” was set in a container with a specially

Solutions for problems that we modern refrigerator owners no longer have: (TOP) An infrared defroster and (ABOVE) a defroster in a can.

(ABOVE) The Invento Chiller Diller circa 1960 and several other similar gadgets all basically used the same technology. © Hammacher Schlemmer.

designed lid. Place the open end of a glass in need of frosting down on the lid and zing! Frosted glass. It was probably fun to watch (the first time) and did the job.

But wait, there’s more.

In 1969 a report from the National Commission on Product Safety Hearings outlined two main issues with the pressurized spray cans and their contents. The main safety issue was the potential for frostbite, and it was recommended that the spray cans be kept away from children (“Sorry, Billy, no martini for you. So scram”). The other issue wasn’t about safety so much as customer satisfaction. The cans left a brief odor in the glass that could affect the taste of one’s drink. The recommendation here was to wait a moment before pouring the beverage.

And while we’re on the subject of cold. Anyone recall needing to thaw refrigerator freezers? There were cheap solutions designed to combat the frost, including an electric infrared defroster that claimed to work so quickly that frozen food won’t have time to thaw. Another ice-buster was Frost Free, an aerosol spray defroster that “doesn’t harm metal”. So that’s nice.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

Eggs are a versatile staple food. Some say it’s the perfect food. So why mess with success? But then again, why not? We are a nation of inventors after all.

The Egg Cuber is one of those “why did this happen?” type of inventions (and I am genuinely curious but have no answers). What the Egg Cuber does is, with a bit of effort, make a hard-boiled egg maintain a rounded square shape instead of a non-creepy egg shape. The only real excuse offered up by the makers is to prevent eggs from rolling away but putting them in a bowl would have the same effect. The process to square an egg takes several minutes per egg. You have better things to do.

Another puzzler is the Ronco In the Shell Egg Scrambler. This device fulfills no crushing need whatsoever. In theory, you can make a yellow hard-boiled egg, but recipes that call for that sort of thing are likely pretty rare. Additionally, once scrambled in the shell