Roshanpura

PREFACE

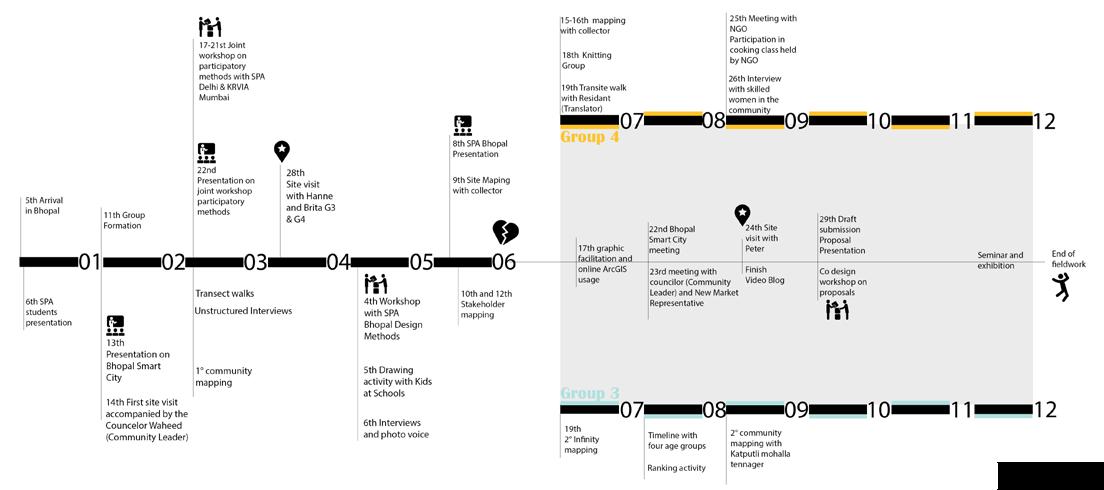

This report is the outcome of a one-semester fieldwork in Bhopal, India, conducted by students at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in collaboration with the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) Bhopal and SPA Delhi. The fieldwork was part of a research project “Smart Sustainable City Regions in India” (SSCRI) financed by the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU). The one-semester fieldwork is an integral part of the 2-year International Master of Science Program in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) at NTNU. Previous fieldtrips have been undertaken in Nepal, Uganda and India.

As is tradition, the diverse backgrounds and nationalities of students participating in the UEP fieldwork ensures a multi-perspective view. This year’s 21 fieldwork participants are architects, social workers, engineers, landscape architects and planners, coming from Albania, Bangladesh, Canada, China, France, Germany, Honduras, India, Lithuania, Morocco, Mexico, Norway, Tunisia and the USA.

This first semester fieldwork gives students a real life practice of the so-called ‘UEP approach’, which focuses on an integrated area-based situation analysis followed by strategic proposals.

Through daily interactions with local communities and relevant stakeholders, students became acquainted with the community and discovered the complex realities of these areas, with their specific assets and challenges. By using a design thinking and participatory methods, this exercise gives the community a voice by making them active participants.

The main topic studied was informality in all its forms, and particular attention has been given to public space, gender, heritage, land and urban transformation. Students were also asked to put their areas and proposals in the perspective of the Smart Cities Mission, which is the largest urban development fund and initiative currently implemented by the Government of India.

The semester started with two intensive weeks of preparation with a number of lectures at the home campus of NTNU in Trondheim. The first weeks of our stay in Bhopal, the students became familiar with the city while staying at the SPA Bhopal campus, through a number of lectures and presentations from students and staff from SPA Bhopal and a heritage walk through the old city. By the end of these first weeks, students were divided in six groups and assigned an area.

Through a joint workshop with SPA Bhopal, SPA Delhi and Krvia Mumbai on participatory methods familiarized themselves with their communities and participatory methods, which helped them to build trust with the residents. They continued using these methods and design thinking methods to conduct a situational analysis involving different stakeholders. A joint workshop with the design students from SPA Bhopal on co-design followed by a number of community workshops integrated the design thinking approach that helped to co-design a series of proposals.

Students prepared four situational reports with proposals. This reports sums up the work done by group 3 and 4 in Roshanpura.

Hanne Vrebos, Rolee Aranya, Brita Fladvad Nielsen and Peter Andreas Gotsch, fieldwork supervisors, NTNU, Department of Architecture and Planning

ACKNOWLEDGMENT ABSTRACT

We are extremely grateful to the people and organizations for whom successful completion of the fieldwork would not have been possible. Without their constant support and motivation, the whole process would not have been achievable in such a limited time. We express immense gratitude to Professor N. Sridharan, Director of the School of Planning and Architecture, Bhopal and other SPA Bhopal faculty and staff for sharing their knowledge with us and for hospitably hosting us during our stay in Bhopal.

Additionally, we would like to thank the students of Master of Urban Design SPA Delhi, KRVIA Mumbai, and Master of Design SPA Bhopal for sharing their thoughts and methodologies during collaborative studio workshops. Their collaboration provided us with language assistance, cultural context, and methodology support. We are especially grateful to our professors, Professor Dr. Peter Andreas Gotsch, Director of Urban Environmental Program, Professor Rolee Aranya, Vice Dean for Education, Brita Fladvad Nielsen and Hanne Vrebos from NTNU, Trondheim for their guidance and assistance throughout the fieldwork. Without their support and passion, we would have never made it to India or acquired so many Post-It notes. Thanks is also due to Lau Ying Tung (Crystal) for bringing light, laughter, and new perspectives to our group in the first weeks.

Last but not the least, we are enormously thankful to the people in Roshanpura, especially the formal and informal representatives and local translators for taking an interest and participating in the activities, being available to answer our queries and show us around, and enrich us with vast amount of information. And to all the residents of Roshanpura, thank you for opening your home and community to us. We are forever grateful.

As low income countries strive to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations, the persistent problem of poverty and its solutions repeatedly surface amongst reports of human rights abuses towards the poor and marginalized. Slums represent a physical manifestation of poverty, and, of the low income countries, India is particularly notorious for its slum populations. In 2015, with its announcement of the Smart Cities Mission, the Government of India set out to eradicate slums through its Slum Free Cities initiative. However, this usually results in slum inhabitants being forced out onto increasingly marginalized land. The current research asks whether urban planning can be used as a tool to address poverty?

A group of Masters in Urban Ecological Planning students at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) set out to answer this question during a three month fieldwork exercise in Bhopal, the capital of the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. A group of six students worked in Roshanpura slum, dividing the area along the main street the slum developed out of. Both groups employed participatory methods to study the area through the lens of the Livelihoods Framework and informality. The aim of the fieldwork was to develop strategic interventions that facilitate the

residents of Roshanpura to engage with each other, institutions, and available resources to improve their livelihoods. The two proposals offered at the end of the fieldwork sought to build on what the residents already had, respectively, cultural heritage and the women’s marketable skills. While purely educational, the research serves as a case study for urban planners working with slum dwellers.

ABBREVIATIONS

LIST OF FIGURES

Livelihoods Framework = LF

Urban Ecological Planning = UEP

Norwegian University of Science and Technology = NTNU

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs = MoHUA

Area Based Development = ABD

Bhopal Smart City Development Corporation Limited = BSCDCL

Madhya Pradesh Urban Development Company Limited = MPUDCL

Bhopal Municipal Corporation = BMC Government of India = GOI

Directorate of Town and Country Planning = DTCP

Bus Rapid Transit System = BRTS

Ground floor plus additional floor = G+1

Ground floor plus two additional floors = G+2

Bhopal Municipal Corporation = BMC

Women’s Community Center = WCC

Introduction

1.1

Roshanpura Square 12

1.2 The Golden Gate- The gate of the Taj Maha 14

1.3. Smart City Bhopal / Area Based Development Project Proposal 17

1.4. Evolution of Bhopal and Roshanpura 18

1.4. Map of proposed metro line in Bhopal 20

1.4. Map of Roshanpura, New Market and Area Based Development situation 21

Situational Analysis

2.1.1 Land Use Map 26

2.1.2 Typology of structures in Northern Lower Area 28

2.1.3 Typology of structures in Southern Upper Area 29

2.1.4 Example of open spaces in Roshanpura 30

2.1.5 Types of streets and alleyways 31

2.1.6 Evolution of Services through Roshanpura 32

2.1.7 Tank used for water collection 33

2.1.8 Pipeline of Water Supply 33

2.1.9 Electric wiring in the Main Street 34

2.1.10 Public Toilet 35

2.1.11 Roshanpura And Main Transport Hubs 36

2.1.12 Bhopal Transportation and Connectivity 37

2.2.1. Political Structure 39

2.2.2 Informal leader 40

2.2.3. Rajasthani Woman 41

2.2.4. Muslim Women 41

2.2.5 Katputli Women 41

2.2.6 Rajasthani Women and Muslim Girl from Hyderabad 41

2.2.7 Map of neighbourhoods / communities in Roshanpura 43

2.2.8 Pottery 44

2.2.9 Clay Idols 44

2.2.10 Lace Making 44

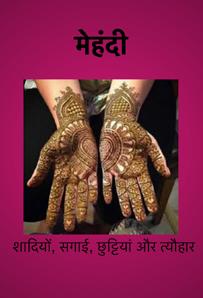

2.2.11 Mehendi 44

2.2.12 Cultural heritage in Roshanpura 45

2.2.13 Map of religious institutions 46

2.2.14 Shree Durga Temple

2.2.15 Mosque

2.2.16 Calendar of religious festivities

2.2.17 Kali Goddess

2.3.1 Gender Labor Displacement

2.3.2 Store inside Roshanpura

2.3.3 Flow of Skilled/Unskilled Labor

2.3.4 Microfinance Scheme Self-Help groups

2.3.5 Microfinance Scheme Bank program

2.3.6 Types of stores in the Commercial Area

2.3.7 Commercial Area in Rajbhaven Road

2.4.1 Map of Roshanpura’s Schools and Health Centers

2.4.2 Spiritual Health Center

2.5.1 Street in the lower area

2.5.2 Surface sewage / Lower area

2.5.3 Low quality structures /Lower area

2.5.4 Two store structures / Upper area

2.5.5 Two store structures / Upper area

2.5.6 Section of the slope in Roshanpura

Roshanpura South

3.1.2 A senior puppeteer in the sidewalk by his house 77

3.1.3 Transect walk 77

3.1.4 Open ended interviews 78

3.1.5 Open ended interviews 79

3.1.6 Drawing activity with kids in public school 80

3.1.7 Affinity mapping following livelihoods framework approach 82

3.1.8 Inhabitants filling out ranking activity form

3.1.9 Community discussions with women of Roshanpura

3.1.11 Instances from co-design workshop

3.1.12 Kids in front of the window grill they colored in co-design workshop

3.2.1 Upper one: plastic drums used for storing water

3.2.2 Lower one: unstable built protrusions

3.2.3 Alleys used by vendors to sell vegetables

3.2.4 Sign board stating about the puppeteers’ society

3.2.5 A niche used for storing and displaying puppets 92

3.2.6 Craftsmen of Katputli Mohalla creating models with paper mache 93

3.2.7 The identified marginalized group 94

3.2.8 Meera, a Rajasthani woman from Katputli Mohalla sitting at the entrance of her 97

3.3.1 Upper one: Women of Kathputli Colony House 98

3.3.2 Lower one: members of local self-help groups 98

3.3.3 Inhabitants of Kathputli Mohalla 99

3.3.4 Formal representative of Roshanpura 100

3.3.5 Women of Roshnapura engaged in small enterprises

3.3.6 Stakeholder Mapping

3.4.1 Flow diagram explaining justification

3.4.2 Dimensions of the proposal

3.4.3 Existing entrance to the street

3.4.4

Proposed element at the entrance 109

3.4.5 Graphical illustration of the proposed entrance 110

3.4.6 Upper one: Proposed scheme of Wall art 111

3.4.7 Concept diagram of action proposal 112

3.4.8 Delineating activities in the proposed street market 115

3.4.9 Graphical illustration of the proposed street market 116

3.4.10 Graphical illustration of the proposed wall art and entrance element 117

3.4.11 Concept diagram of action proposal III 121

Roshanpura North

4.1.1

Meeting with the representative of New Market 127

4.1.2 Picture with the NGO working with women trainings 127

4.1.3 Interview with inhabitants of the North East area of Roshanpura 128

4.1.4 First Stakeholder Analysis 131

4.1.5 Mobile Collector from ArcGIS 132

4.1.6 Transect Walks 132

4.1.7 Selfie Voice 134

4.1.8 Knitting Lady and Neighbours 134

4.1.9 The place the knitting lady liked the most 134

4.1.10 Photo Voice 2nd Attempt 135

4.1.11 Activity with the kids at school 137

4.1.12 Knitting Activity 139

4.1.13 Roshanpura Hospitality 139

4.1.14 Cooking class 139

4.1.15 Info Board Mock Up 141

4.1.16 Tell us your skills Board 142

4.1.17 Puppeteers Show during co-design workshop 144

4.2.1 Interview with women 147

4.2.2 Former Police Officer in Roshanpura with his niece 147

4.2.3 Before and After of an open space in the Northern Area 149

4.2.4 Woman not happy to live there, even if relocated 150

4.2.5 Interview with women 151

4.2.6 Whatching sari being made 152

4.2.7 Stakeholder Analysis 154

4.2.8 Stakeholder mapping 155

4.3.1 Possible places to put the Information Board 159

4.3.2 Main Information Board 161

4.3.3

Render : Implementation of the information board 163

4.3.4 Indian Cooperative Credit Society Limited 166

4.3.5 Scheme of the cooperative organization 170

4.3.6 Steps to open the cooperative 171

4.3.8 Plan of the Women Cooperation Center 172

4.3.7 Area organization of the WCC 172

4.3.9 Section of the WCC 173

4.3.10 WCC 173

4.3.11 Render of the WCC 174

5.1 Group picture with a family 176

* Unless otherwise indicated all pictures and graphics were produced by the authors.

Introduction

Step out of the rickshaw at Roshanpura Square and one is immediately overwhelmed by the noise and bustle. Horns honk as two-wheelers, cars, and rickshaws zip around the roundabout in the middle of the square. Shops, informal stands and street hawkers line the roads, barely allowing pedestrians to pass along the sidewalks. This is the New Market, the commercial heart of the city of Bhopal. However, from the plaza head down Roshanpura Road towards the Raj bhavan and, turning in at one of the many food stands along the road, you enter another world. A hidden labyrinth of narrow alleyways that open onto private courtyard, pleasantly situated in the shade of a few trees, and closely built houses of varying qualities and colorful exteriors, greets you. Residents washing their laundry or dishes smile and wave as you navigate, looking at playing children, goats, and parked motorbikes. The smell of cooking from one house drifts along the narrow passageway to mingle with the stench of garbage and animals emanating from another. This residential oasis, while a relief from

the commercial exterior, is an onslaught of colors, people, smells, and sounds. This is Roshanpura: a multifaceted, historical community peacefully comprising the many faces and faiths of India. For two months, a group of masters students in Urban Ecological Planning (UEP) from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) conducted fieldwork in Roshanpura, attempting to understand the community and the dynamic urban landscape. The ultimate goal is to put people at the center of urban planning. The following report, after describing the context, provides a situational analysis of Roshanpura, followed by a discussion of methods, the researchers’ findings from the fieldwork, finally their recommendations for strategic community interventions, and ending with the students’ reflections. Throughout the fieldwork, the students followed the principles of UEP, which include, among others, acting as facilitators rather than providers; working from the bottomtop rather than from top-down or bottom-up; working on a smaller, area-based scale on a formalinformal continuum; and developing proposals that are both contextual and views the city as an organism (Sliwa et al, 2018, 8). While the proposals developed through this approach are smaller in both size and the number of people impacted, it sets off a chain reaction of innovations that empower the people under the planner’s purview.

HISTORY OF BHOPAL

efficient administration, set up a judicial system, and supported women’s education (Ibid., 34-35).

The city of Bhopal lies atop the eleventh-century city Bhojapal, founded by Raja Bhoj. Legend has it that Raja Bhoj suffered from an incurable disease, and a sage advised him to bathe daily in a lake fed by 365 springs. Thus, Raja Bhoj’s engineers built two large dams, creating the Upper Lake of Bhopal (Fortun, 2001, 159). Later, the smaller, Lower Lake, was built, giving Bhopal the name the “City of Lakes.”

The modern city of Bhopal was established in 1709 by the Afghan chief Dost Mohammed Khan, carving out a Muslim kingdom that would continue until Independence (Ibid., 160). The kingdom’s strong rulers contributed to its survival, but in 1818 it gained additional protection when the ruler of Bhopal signed a treaty of alliance with the British Governor-General, Lord Hastings (Sultaan, 1980, 32).

Most notable about Bhopal is its more than one hundred years history of women rulers. The “Century of Women’s Rule” began in 1819 by Qudisa Begum. After the assassination of her husband, Nazar, she declared her daughter, Sikandar, Nazar’s rightful successor, successfully persuading her and her husband’s family to sign allegiance to her daughter (Ibid.). The “Century of Women’s Rule” lasted until 1926 when Sultan Jahan abdicated in favor of her son. During the century, the begums improved Bhopal’s infrastructure, created an

India gained Independence in 1947, and Bhopal was one of the last princely states to join the Union Government, signing the agreement in 1949 (Census of India, 2011, 13). After Independence, Bhopal became a center for migration, welcoming Hindu refugees from Pakistan and later Muslims from across India, who migrated to Bhopal in large numbers seeking security in the largest Muslim state after Hyderabad. As a result, in 1961, half of the residents of Bhopal were immigrants (Fortun, 2001, 160).

Despite a rich history, today Bhopal is most well known for the Union Carbide Gas Tragedy. On December 3, 1984, the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal released 40 tons of toxic gas. The death toll in the first few days after the disaster ranges from two to 15 thousand. Best estimates place the death toll at ten thousand (Ibid, xiii). Union Carbide is a multinational chemical company based in the United States. They originally came to India as part of the Green Revolution, the U.S.’s attempt to eradicate hunger through technological advances and the “westernization” of agriculture around the world. Union Carbide built a plant in Bhopal since the Government of India identified the area as “backward” and targeted it for industrial development. Bhopal was also centrally located and well connected by roads, rail, and air to other parts of India (Ibid., xiv). At first, the plant provided much needed jobs and improved agricultural output, but soon the plant began to suffer from mismanagement and neglected safety regulations. At the time of the disaster, the plant was only operating at a quarter of its capacity, but they had hugh stocks of chemicals stored in tanks ready for direct sale (Ibid.).

The poor were the hardest hit. Those living in slums adjacent to the plant had no warning or means of seeking protection. The railway station and surrounding area were also hit hard, with those sleeping on the platforms and waiting for trains asphyxiating (Ibid., xv). In the aftermath of the tragedy, victims came forward demanding compensation for their losses, and activists called for the CEO of Union Carbide to be charged with homicide. Anger and controversy swirled as the government developed criteria for determining if a victim’s claim was “gas-related” or classed as “temporary.” Then, in 1991, Union Carbide settled outside of court (Ibid., xviii). Commentators of the tragedy have framed the disaster as a side effect of globalization, while activists argue that the disaster demonstrates how the lives of those in poor countries are worth less than those in wealthier countries. Bhopal continues to deal with the aftermath of the tragedy, as the gas caused severe, long term health effects and the plant contaminated the soil and water in the immediate vicinity. While activists continue to fight for government compensation, many residents of Bhopal and government officials wish to put the tragedy behind them.

Bhopal is dependent on agriculture, followed by the service sector and civil service. The literacy rate in Bhopal, 73.4%, is lower than the district, 80.4%, and only 35.1% of the population is working. Of those employed, only 16.3% of the female population are employed, compared to 19.6% female employment in the district (Ibid., 15 and 28). While Bhopal falls behind in the district in terms of literacy and female employment, Hindu and Mughal influences and subsequent waves of migrants make the city a historically and culturally rich melting pot of traditions and multiculturalism. .

smart city mission Bhopal

BHOPAL

Today, Bhopal is the capital city of Madhya Pradesh, the central and largest state in India by area. As of the 2011 Census, the City of Bhopal’s population numbered 1,798,218 with an area of 285.88 square kilometers (Census of India, 26). Economically,

In 2015, the Government of India launched the Smart Cities Mission. Over the next five years, a total of 100 cities would be chosen, and Bhopal became one of the first 20 “lighthouse” cities (Chakrabarty, 2018, 2). While the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) offers no clear definition of what a “smart city” is, the objective of the Smart Cities Mission is “to promote cities that provide core infrastructure and give a decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of ‘smart solutions’(MoUD, 2015, 5)” while emphasizing inclusion, sustainability, and replicability. The strategy for achieving this is through retrofitting, redevelopment, and greenfield development. As such, each city chosen develops an Area Based Development (ABD) plan and a PanCity Development plan. (Ibid., 8).

Bhopal’s Smart City development is being implemented by the Bhopal Smart City Development Corporation Limited (BSCDCL), a semi-public company jointly owned by the Government of Madhya Pradesh and incorporated solely for the implementation of the Smart City Project in Bhopal. BSCDCL is equally managed by Madhya Pradesh Urban Development Company Limited (MPUDCL) and Bhopal Municipal Corporation (BMC). The BSCDCL “envisions transforming the City of Lakes, tradition and heritage into a leading destination for smart, connected and ecofriendly communities focused on education, research, entrepreneurship and tourism (BSCDCL, 2018).” In accordance with the national level Smart Cities Mission, Bhopal has developed an ABD plan and a Pan-City Development plan. The ABD development plan has identified a site in Tatya Tope (TT) Nagar on 342 acres of government land. The Pan-City Development plan incorporates the city-wide improvements related to infrastructure, citizen engagement, transit, and citizen well-being. Projects include a Bhopal Smart App, smart poles, a Control and Command Centre and Incubator Centre, smart streets, heritage conservation, designated bike lanes and bike sharing, smart transit, Housing for All, and the Bhopal Metro Rail Project (Ibid.) The focus is on improving connectivity, efficiency in service provision, and government transparency and citizen engagement.

HISTORY OF ROSHANPURA

The history of Roshanpura is closely intertwined with the history of India and, more specifically, the history of Bhopal. During the British era, the land where Roshanpura stands was a forested area named Lalkothi. After Independence in 1947, the land transferred to the Government of India, and people from surrounding states and other parts of Madhya Pradesh settled and began developing the land. The first communities to settle in Roshanpura were the Gwallah (milkmen). A main street in the middle of Roshanpura served as the origin point of the settlement, with subsequent waves of migrants building out from this central point. At its inception, Roshanpura marked the border of the city of Bhopal, but later developed into a central business district. The New Market began being built in the 1961, generating a massive amount of economic activity in the area. In 1984, the Government of Madhya Pradesh awarded the residents of Roshanpura documents of Patta (lease of land) for the next 30 years, providing residents with a sense of tenure security.

Like much of Bhopal, the 1984 Union Carbide Gas Tragedy impacted the lives of the residents of Roshanpura. The disaster occured 12 to 15 kilometers from Roshanpura, and inhabitants suffered from diseases associated with exposure to the lethal chemicals released by the plant. For years after the tragedy, the residents sought compensation for the damages done to their health and the loss of loved ones from the tragedy. Several residents who received compensation invested it in their homes in Roshanpura.

Bhopal

roshanpura

Today Roshanpura is approximately 80,000 m², located adjacent to the Raj Bhavan, the Governor’s house, the Jansampark Bhavan, public library, and across from the New Market. While there are no official statistics for the community, the population is estimated to be between ten to twelve thousand with approximately 1,600 households. With 5,038 registered voters, two political parties have set up offices near Roshanpura in order to take advantage of its sizable vote bank. Houses, connected by narrow alleyways, fight for space, with household activities spilling into the streets, and homes climbing up to accommodate new family members.

A line of shops and stalls ring Roshanpura, a final barrier to the multicultural, peaceful community that lives within. Inside, Muslims and Hindus live peacefully side by side, intermixed throughout the community, and residents boast of their family connections in other parts of Madhya Pradesh and other states in India. While there are a range of socioeconomic and education levels in Roshanpura, what connects them all is their pride in their home and sense of community.

smart city

mission in ROSHANPURA

Unlike other communities in Bhopal, Roshanpura is likely to be directly affected by the Smart City Mission in Bhopal. The ABD site is located in TT Nagar, adjacent to the New Market (see Figure 1). Furthermore, Roshanpura lies on the axes of the planned Bhopal Metro Rail Project, with three

planned metro stations within the New Market area (see Figure 2). While this will provide greater connectivity to the area, boosting its economic activity, it has the potential to severely disrupt the lives of those living in Roshanpura and to displace residents. Other planned Smart City projects related to the New Market include the creation of a smart road and designated bike lanes. Similarly, these changes will improve connectivity, relieve the traffic congestion, and boost economic activity, but it will require a shift in the commercial activities in the area.

Within this context, the researchers sought to conceptualize Roshanpura. Taking into account Roshanpura’s history, and the history of Bhopal as a whole, they developed a framework through which to study the area and its dynamics. Over the two months of fieldwork, the students devised and tested different research methods, attempted to geographically learn the area, and develop relationships with the residents. The proceeding section details the results of these efforts. Despite the section’s detail, the researchers recognize their inability to completely grasp all elements of Roshanpura due to their time constraint and their status as “outsiders.”

SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS

The following analysis of Roshanpura has been organized into the livelihoods framework proposed by Carole Rakodi (2002). The LF consists of five capitals: physical, social, financial, human, and natural. While the LF is a simplification of the study area, as it is unable to completely capture the complexity of its systems, its strength lies in its ability to allow researchers to better understand the multidimensional aspects of a community. As such, it proves useful for understanding household strengths, structures, and needs. Furthermore, unlike other tools, it also takes into account historical and cultural systems that shape societal mores, determine spheres of political influence, and marginalization. Most importantly, it takes a positive approach to studying vulnerable communities by focusing on what the community has rather than what it lacks.

Apart of the complexity that the LF does not reflect, is the concept of formality and informality. Within the capitals is a mix of informally and formally derived assets. According to the urban planner Uwe

Altrock, informality results from a mismatch between how the state theoretically should function and how it actually functions (172). There are two types of resulting informality: complementary informality occurs in a setting not covered by formal rules, contributing to the proper functioning of formal institutions and often preempting formalization; supplementary informality occurs when the formal institutions do not work properly, and therefore the informal institutions must step in to fulfill their role (Ibid., 175). Informality does not mean illegal, nor does it connotate a development context, but rather informality and formality manifests along a spectrum of formal-informal hybrids.

In Roshanpura, the formal-informal spectrum has dynamically shaped the area and continues to shape the residents’ LF. Overtime, as the community and the state simultaneously developed, assets once firmly situated within informal institutions have gradually become formalized. As a result, formality and informality are inseparable. In the following analysis, the LF helps to conceptualize and organize the community’s complexity, but in order to properly understand it, its assets must be placed along the formal-informal spectrum. For, while Roshanpura may be classed as an “informal” settlement, the reality is much more nuanced.

Physical Capital

Physical capital includes basic infrastructure (i.e. shelter, water, energy, transport, etc) as well as productive and household assets that enable people to pursue their livelihoods (Rakodi, 11). The assets found under physical capital are some of the most recognizable due to their material manifestations. Considering the dominant perception of informal settlements, Roshanpura’s physical capital is surprisingly strong. Roshanpura’s physical capital falls into four categories: land use, building typology, infrastructure, and connectivity.

Building typology

Definition of a Slum

According to Section 3 of the Slums Areas, Im provement and Clearance Act, 1956, the Gov ernment of India (GOI) defines slums as mainly those residential areas where dwellings are in any respect unfit for human habitation; or by reasons of dilapidation, overcrowding, faulty arrangements and designs of such buildings, narrowness or faulty arrangement of streets, lack of ventilation, light, sanitation facilities or any combination of these factors which are detrimental to safety, health and morals (Joshi, Saxena, 2015, p. 107).

Land Use

According to the Directorate of Town and Country Planning (DTCP) - Madhya Pradesh land use map of Bhopal Master Plan 2005, the entire settlement area is officially categorized as public/semi-public land (DTCP, M.P, 2013) . Reference to Roshanpura map of land use

The majority of the study area in Roshanpura can be characterized by highly dense residential use. Small shops and home-based enterprises dot the inner streets, and there is a significant commercial area concentrated on the southern edge of the area along Rajbhavan Road across from the New Market.

Religious spaces are evenly distributed, with thirteen Hindu temples and places of worship, two mosques and one Dargah (Muslim priest tomb). The main and wider streets are of mixed use: parking, playground, workspace, and community and festival space.

Census of India 2001 has adopted the definition of ‘Slum’ areas as:

- All areas notified as ‘Slum’ by State/Local Government and UT Administration under any Act; All areas recognized as ‘Slum’ by State/Local Government and UT Administration, which have not been formally notified as slum under any Act; A compact area of at least 300 populations or about 60-70 households of poorly built congested tenements, in unhygienic environment usually with inadequate infrastructure and lacking in proper sanitary and drinking water facilities (Ibid).

FInally, UN-Habitat defines a slum household as a group of individuals living under the same roof in an urban area who lack one or more of the following:

Durable housing of a permanent nature that protects against extreme climate conditions. Sufficient living space which means not more than three people sharing the same room. Easy access to safe water in sufficient amounts at an affordable price.

Access to adequate sanitation in the form of a private or public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people.

Security of tenure that prevents forced evictions. (UN-HABITAT, 2006)

Due to the older construction, size, density, and shared toilets facilities, some pockets and plots in Roshanpura could be categorized as slums. However, based on the quality of the structures observed, the majority of the houses and infrastructure in Roshanpura do not fit into the above definitions of a slum. Instead, Pucca houses (permanent), with a significant number of G+1 and some G+2 structures, rather than Kachha (temporary) houses are the predominant housing type. Residents build new buildings and additions to older constructions with bricks, cement, concrete blocks and metal roof.

Reference to picture

Of note is the shift in the predominant housing type from the southern end of Roshanpura to the northern end. Pucca houses dominate the southern end, and, as one moves north down the natural slope, Kacha houses begin to dominate. It is on the northern end where the majority of the pockets and plots that meet the above definitions of a “slum” reside. Reference to section

Regardless of house typology, the construction that takes place in Roshanpura occurs in the informal sector, bypassing building regulations and permits. New buildings, conversions of old buildings, and additions are done primarily by residents by themselves, with help from family and social connections. Residents want their homes to be more permanent structures and express a desire for the government to assist in covering the construction costs.

Land Tenure and The Patta Act

Perceptions of tenure security in Roshanpura are high due to the majority of residents possessing leaseholds obtained in 1984 through a state scheme commonly known as the Patta Act. The Patta Act in essence formalized the informal occupation and appropriation of government land, legitimizing and recognizing the community and imparting rights of tenure. According to the ward councilor’s office, 1,500 Pattas were given under this scheme, most of them expiring in 2014, with a five-year renewal after this date. Research indicates that residents with secure tenure rights have more incentives to invest in and upgrade land and housing. Additionally, secure tenure is a necessary condition to improve access to economic opportunity, including livelihoods, credit markets, and public and municipal services (Payne et al, 2014, 4). In Roshanpura, it is evident by the quality of housing, infrastructure, and the area’s status as one of the oldest settlements in Bhopal that the shelter quality has improved significantly since its establishment by the first dwellers in 1947. Thus, within Roshanpura there is a link between the quality of the structures and tenure status of the residents, which is further evidenced by the residents with the poor quality housing and infrastructure on the northern end experiencing greater tenure insecurity than those on the southern end.

Infrastructure

Within the LF, infrastructure represents predom inantly a collective rather than individual resource, and it is important for household maintenance, livelihoods, health and social interaction. This con tributes to human and social capital and enables people to access income-generating activities (Ra kodi, 2002, 11). Within Roshanpura, infrastructure consists of the area’s streets; water, electricity, and sanitation services; and other shared amenities.

walking around the settlement, and, according to the residents, some of these spaces function as gathering places by the neighbors. See figure x.x

Each street typology has its own dynamic related to the available space. Though, due to the cramped nature of the area, all streets, regardless of size, represent an informal appropriation of space. Households appropriate the streets in front of their homes, turning them into an extension of the house, playgrounds, or workspace.

Streets

Most of the streets are paved with cement or concrete. Based on their condition and function, streets can be divided into three types, each one with its own dynamics related to available space:

1. Narrow alleys. The most common typology due to the high housing density, these streets are characterized by high levels of street level interactions, with frequent encounters between humans, motorbikes, animals, and sewage. Despite the limited space, residents with houses along these street still use them to conduct their daily activities and socializing. See figure x.x

2. Medium and large size streets. There are three streets of this scale within Roshanpura. These streets usually have the most diverse usage, from parking space for two wheelers, auto-rickshaws, and the rare car to playgrounds, festival celebrations, and workspace for women and craftsmen. See figure x.x

3. Open spaces in the middle of clusters of houses. These pockets can easily be found by

Water, Electricity, Sanitation and Other Amenities

Basic utilities were nonexistent when the first dwellings were established in 1947. Residents formed informal connections into the municipal grid or developed their own forms of infrastructure. However, overtimes the local government gradually begun to formalize these services, providing formal connections to the municipal grid. Thus, water, electricity, and sanitation represent the dynamic nature of formality, for, even today, there is an element of informality in the formal connections the residents of Roshanpura enjoy.

Water

A river located at the bottom of the slope on which the settlement was established initially served as the means of water collection. In 1984, as part of the implementation of the Patta Act and their changed land tenure status, the local government connected the area to the municipal grids for both water and electricity. Nevertheless, the services were not provided on a regular basis until recent years. Two years ago the local government built a water distribution system. The system has superficial lines in every house, and initially water distribution occurred once a week. However, since 2018 water distribution occurs for one hour each day. There are discrepancies in terms of the residents’ descriptions of the time and cost of water services, with reported times of distribution ranging from one hour to 15 minutes and costs ranging from free to a service charge.

Electricity

According to the residents, electricity became available permanently five years ago. Despite having official connections, exposed wiring and connections are common throughout the structures. Here again discrepancies among residents’ descriptions of service provision occur, with reported prices for electricity ranging from 1,500 rupees to 5,000 rupees. It appears the discrepancy stems partially from whether the houses have registered meters or not. Reference to picture

Sanitation

In recent years government policies promoting better sanitation have resulted in in-house toilets with septic tanks in most houses. However, while few in number, community toilets are still used by family or house clusters. One unit can be found on the north edge in precarious condition with no maintenance from the neighbors or the local authorities. Reference to picture

Additionally, a large number of sewage lines are still open, both on the sides and the center of the streets. However, during the fieldwork, several streets underwent improvements that put sewage lines under the streets. According to the ward councilors office, this work will cover all of Roshanpura.

Other Amenities

Private companies provide Internet connections and cable television coverage to the area. As a result, even for the poorer quality houses, there are a large number of antennas on the rooftops.

Location and Connectivity

Roshanpura is located in the heart of the city, near the intersection of the Old City and TT Nagar areas (figure 2.1.11), and two high traffic arteries: Roshanpura Road and the BRTS corridor. This provides its residents with good connectivity to the rest of the city, Madhya Pradesh, and neighboring states by all means of transportation, including BTRS, both the Bhopal Junction and Habibganj railway stations, and Raja Bhoj Airport (figure 2.1.12).

2.1.12 Bhopal

Social Capital

social capital consists of the social resources on which people can draw on when pursuing a livelihood. These resources include social networks, relationships of trust and reciprocity, and access to social institutions. Social resources become assets when they are persistent and give rise to stocks, of knowledge or trust, that people can draw from even if the social interaction is not permanent (Rakodi, 10). The social assets in Roshanpura can be described under three categories, political, social, and cultural.

infrastructure, town planning, waste management, education, public health, welfare, public safety, and developmental work. Presently Smt. Shabista Asif Zaki serves as the ward councillor for Roshanpura. She has held her post since 2014 after the last Indian General Elections with a four year term limit.

2.2.1. Political Structure

Political

India has three levels of government – local, state and national. At the national level, power is divided between three branches: the executive (president, prime minister, and council of ministers), legislative (parliament and legislative assembly), and judicial (supreme court) branch. Each state is represented by a Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) and a Member of Parliament (MP). On the state level, the Chief Minister serves as the head. The current Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh is Shivraj Singh Chauhan. The president also elects a governor for each state, but their role is largely ceremonial.

On the local level, the municipal government is divided into zones, which is further divided into wards. Hence, wards are the smallest administrative unit in India. In the municipal government of Bhopal, Roshanpura falls into zone five and ward 24. Each ward elects a municipal councillor to represent the their ward. The councillor is responsible for the civic issues in their ward, including roads,

Besides the formally elected government representatives, Roshanpura also has an informal form of representation. A formerly elected ward councillor, who was born and still lives in Roshanpura with his extended family, serves as the inhabitants first source for assistance and as their liaison with the formally elected authorities. Through his connections with the authorities, he is able to solve infrastructure issues and help the residents access government services and exercise their public rights.

He occupies an interesting situation in that he moved from a firmly formalized position of representation to a more informal hybrid along the formal-informal spectrum. While his positions within the community is largely unchanged, its shift to the informal sphere demonstrates how the formal-informal spectrum moves both directions.

As stated previously, the land of Roshanpura officially belongs to the GOI. However, the government of Madhya Pradesh formalized the inhabitants’ right to use the land with distribution of Pattas. Though the lease agreements expired in 2014, the majority of the people have neither paused in investing in their properties nor moved out of Roshanpura. Part of the reason for the government’s recognition of this informal settlement is due to Roshanpura’s significant vote bank. Thus, improvements to residents’ living conditions only occur during elections when candidates from all political parties offer promises of formalization in return for votes.

Social

Roshanpura is a vibrant society, with a variety of social interactions tying together the fabric of daily life. On a regular day, in the morning the children and men go to school and work, and the women organize themselves into groups to help with daily household chores, taking advantage of the hour of water service to clean laundry and dishes. In the afternoon, the women take a siesta or gossip while completing their daily chores, and the children come back from school and play in the streets. In the evenings, every street has a group of inhabitants socializing. Children are safe as long as they stay inside the settlement, where they roam about in groups, visit houses of friends and family, and use the streets as their playground.

Within the social fabric of Roshanpura, the residents have organized themselves into specific neighborhoods. These neighborhoods shape their identities around the predominant historical occupations and the state or city of origin of the original settlers of that neighborhood.

Through participatory mapping activities with the residents, the researchers identified the following neighborhoods: Gwallah Mohalla

The Gwallahs, or milkmen, were the first people to migrate to Roshanpura other parts of Madhya Pradesh, such as Gwalior and Sagar, and today they comprise the largest community in Roshanpura. These people keep cows and goats and historically practiced animal husbandry as their main occupation, producing and distributing milk and milk products. Today, while each household keeps several goats, the working members of each family have embraced alternative professions.

Khumhar Mohalla

The Khumhars, or the potters, work with clay and mud collected from the surrounding land to make, among other things, pots, vessels, idols, and earthen lamps. Several potter families prepare these items and sell them in the New Market. However, the potters’ advancing age and the younger generations’ lack of interest in taking up the craft has resulted in the big stone wheels used for making heavier clay items to go unused. Also, the replacement of clay vessels by steel and aluminum products have lessened the demand of clay goods. Some crafted clay items are shipped from Lucknow, painted, packed, and then sold in the market for higher prices. The items produced change throughout the year due to consumer demands changing with the festive seasons.

Katputli Mohalla

The Katputli Mohalla, or puppeteers’ neighborhood, is located next to the BRTS Corridor on the border of the settlement. These people came to Roshanpura from Rajasthan in 1980. Their occupation involves performing puppet shows and traditional songs and stories. Historically they belonged to the caste of performers for the royal court of Rajasthan. In addition to being performers, they are experts in Rajasthani folk music, wooden puppet craft, and regional performance. Their sole source of income comes from their performances, even traveling abroad to perform. However, since the 1990s, when the television and other forms of western entertainment technology enter the Indian market, demand for their performances have gradually declined. Their general condition has deteriorated as the number of commissioned shows dried up, and today their poverty and marginalization reflects in their dismal living conditions. However, the

younger generation is still taught to perform with puppets, and they continue to pride themselves in their puppets and performing arts.

Bhoi Mohalla

The Bhoi Mohalla, or fishermen neighborhood, came to Roshanpura from Maharashtra. They are the smallest of the identified neighborhoods, occupying a single small alley in the middle of Roshanpura. Historically, these people used to be connected to fishing industry, but they currently pursue other occupations.

Chamar Mohalla

The Chamar Mohalla, or cobbler neighborhood, is located mostly in the eastern part of Roshanpura and is inhabited by people who have historically worked as cobblers, or shoemakers. These people have made significant advances in housing and education. However, due to the decreased demand for leather work and the rise of the commercial shoe industry, this community like others have also switched to contemporary professions.

Cultural

Inhabited by people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, the inhabitants of Roshanpura retain their traditions by means of tangible and intangible expressions. While they may share the same language, their attires, food preferences, dialects, gender relations, methods of carrying out daily chores, and willingness to communicate with outsiders demonstrates the wide range of variation among those who live in Roshanpura.

Residents express their local and regional cultures through the production of traditional handicrafts for profit and personal use. For example, women make garlands, laces, and embroidery and practice mehendi art, sometimes as the sole source of income for the household. Additionally, the potters produce clay items to sell in the New Market, and the puppeteers make wooden dolls to use in their shows and to sell in the New Market. In particular, as migrant cultural artists, the puppeteers, in both their craftsmanship and performance art, play an important role in Roshanpura’s cultural diversity.

Also, the different religious affiliations manifest in the form of the many temples and mosques within the 20 acre area. Despite the difference in religion and the historical animosity between Hindus and Muslims in India, Roshanpura’s residents take pride in their ability to live harmoniously side-by-side, celebrating the major festivals of both religions together. The festivals are mostly religious and take place near the temples and mosques. In preparation for festivals, typically men from the younger generation informally organize in groups to collect money to put up marquees and arrange for idols, worship offerings, food distribution, flowers, lights and other decorations for the festivals.

Ultimately, Roshanpura’s social capital lies in the pride they possess for their home. The people retain their historical and cultural connections through the establishment of cultural neighborhoods and the continuation of traditional handicraft and art production. However, the community operates as a cohesive whole through the common celebration of festivals. Despite the turmoil and riots experienced elsewhere in India, the community of Roshanpura, regardless of caste, creed, or religion, continue to live and celebrate together peacefully.

Financial Capital

In urban economies, financial capital is particularly important in a household’s ability to weather stresses and shocks to their livelihoods. Financial capital consists of financial resources, such as sources of monetary incomes, savings, credit, remittances, and pensions (Rokodi, 11). However, these resources are usually inaccessible for the urban poor. In Roshanpura, the residents’ financial capital takes the form of income generating occupations, microfinancing, and the community’s commercial sector.

Occupations

Occupations in Roshanpura are by the gendering of space. Within the city, there are certain spaces considered acceptable for women and others dominated solely by men. In general, men tend to work outside of the home and women stay inside the home or their neighborhood. Due to cultural prohibitions, the spaces women can occupy, and therefore the occupations they can pursue, are more limited compared to men. However, this varies based on the needs, religion, caste, education, and family dynamics within individual households. Thus, while all women work, most of them are limited to the work of a housewife and are prohibited from using their labor to make money.

Men’s Occupations

The occupations of the men in Roshanpura fall into four categories. First, one segment works with handicraft production. For example, a group of men, age 25 to 30 years old, have jobs in the Old City selling traditional Indian jewelry, such as bangles, brooches, and bracelets. Other men, especially those who belong to the Kathputli

Mohalla, make other traditional handicrafts, such as puppets, drums, and pottery, and sell them in the New Market and Old City. And finally, there are a few men who work at tailors, either from their own homes or in shops in the New Market.

Second, a large segment of the male population in Roshanpura work in the small business sector as street vendors, with stalls or stands, street hawkers, or shopkeepers. These entrepreneurs acquire fruits and vegetables, other food items for making fast foods such as eggs and dairy products, and finished products like craft products and clothes from wholesalers in the Old City. They then resell these items at fruit and vegetable or fast food stalls and stands or on the sidewalk as street hawkers in the Old City, Arera Colony area, or the New Market. Additionally, a few sell produce items from carts in the streets and alleyways of Roshanpura. It is difficult to distinguish between formal and informal business. The New Market in particular has a large informal business sector that has firmly established itself into the fabric of the commercial activity of the area. Informally established stalls and stands, appropriating the sidewalks next to the New Market, have become permanent fixtures, and the vendors have informally organized themselves, making the formal and informal vendors indistinguishable. Furthermore, the managers of the New Market’s formal institutions tolerate the informal vendors, as they contribute to bringing economic activity to the area.

Third, men who have completed higher levels of education work in the civil service. The presence of the governor’s house, government offices, and government housing next to Roshanpura provides opportunities for these men to find jobs working for the government. Many of these men have college

Labor Displacement

degrees in fields like engineering or urban planning and find an outlet for their skills through work for the municipality. Finally, a large portion of the men living in Roshanpura are occasionally employed as manual laborers in factories, construction, or dishwashers. These men have lower levels of education and are considered unskilled.

Women’s Occupations

Women have similar occupations as men, but they perform them in limited spheres and on a much more occasional bases. First, women also produce handicrafts, such as laces, jewelry, pottery, and saris, for sale, but they do this from their own homes and either have male relatives sell the finished product or hand over the finished product to a middleman, who then sells it in shops in the New Market. The price of each handicraft varies according the type, festival, and whether they are working for themselves or a middleman. Normally, the price ranges from 10 to 25 rupees per piece.

Second, similar to the men, the women also have small businesses, working as street vendors or hawkers. These women also acquire items from wholesalers, such as clothes, lingeries, jewelry, or fruits and vegetables, in the Old City and then sell them on the street as hawkers or at small stands in the New Market. These women are few in number though, gaining permission to run their own businesses by finishing household chores in the morning. More common is for women to run small snack stands inside Roshanpura, allowing them to make some money while staying in close proximity to their homes.

Third, the majority of the women seasonally during the wedding and festival season. Primarily,

these women work for local caterers as cooks or do mehendi in their homes during the wedding season. Additionally, women make decorations for festivals. For example, during Diwali, women pack the colorful powders used for making the rangoli decorative patterns in Indian households in small plastic bags, and their male relatives then sell them in the New Market. Fourth, there are a few women within Roshanpura who have completed higher levels of education, including a few with college degrees. While some of these women revert to roles as housewives, others work as teachers in the local schools, both in and outside Roshanpura.

Finally, due to their lack of education, skills, and age, older women, from 50 to 60 years old, find obs as domestic help. However, this occupation does not provide a regular income, and these women would like to be able to work from home. Much of their employment problems stems from historical caste distinctions. These women historically come from lower castes and experience social rejection and ostracizing, resulting in their inability to find gainful employment.

The diversity of occupations within Roshanpura is a direct result of its proximity to the New Market. Due to their close proximity, there is a strong economic relationship between the inhabitants of Roshanpura and the New Market. In front of the main avenue of the New Market, people of Roshanpura have developed an active flux of financial assets, as the New Market serves as both a source of jobs and a major shopping area for the residents. This flux occurs along a continuum of formality and informality, for while the New Market is a formally designated commercial area it grew from the informal activity that developed in response to the presence of Roshanpura. Today, the informality

2.3.2 Store inside Roshanpura

in the area serves as a support for the formal institutions, drawing in customers, supplying labor, and in general imparting the area with a strong identity as the commercial heart of Bhopal.

However, despite the diversity of occupations for both men and women in Roshanpura, the residents still experience income insecurity due to the majority of residents’ education and skill levels qualifying them for low paying and irregular occupations. Additionally, some households only have one or two income earners for whole extended families. Yet, their household income varies from 500 to 600 rupees per day in the bad season.

Scheme Self-Help groups

2.3.5 Microfinance Scheme Bank program

Micro-finance

Self Help Groups or SHGs, regionally known as Sayang Sahayata Samuha, are one of the keystones in microfinance in India. The approach combines access to low-cost financial services, like loans and savings, with a process of self-management and development for the women who join a SHG. These groups come in multiple forms, from ones formed and run by individuals, those offered by private banks, and government sponsored schemes.

A few years ago, a few groups of women in Roshanpura attempted to form SHGs. Members

made small regular savings contributions over a few months until there was enough money to begin lending to members. However, these groups largely failed due to unavoidable issues regarding consistency of members contributing to savings and the inability of members in repaying loans.

Currently, a few groups of women in Roshanpura have entered into schemes with small private banks located in Madhya Pradesh and other states where they acquire credit by depositing their own savings and receiving it back in the form of micro-credit loans. These schemes fall under the SHG Bank Link Programme, which seeks to provide credit to women, the poor, and other segments of the population who are unable to access credit.

“The Self Help Group – Bank Linkage Programme (SHG-BLP) has now completed 21 years of its existence as an alternative mechanism for providing formal banking services to the unreached rural poor. Through a simple and informal savings-led and savings linked process, the thrust of the SHGBLP has been on provision of micro-credit to the poor for meeting their emergent credit needs to enabling them to take up livelihoods for combating poverty.” (Central Bank of India, 2018). The loans the women receive are primarily used for health related needs, house repairs or for setting up or extending small businesses. There are also government schemes that link SHGs with micro-finance services. However, the women of Roshanpura have not been able to tap into this source of funding.

Commercial string

The commercial area of Roshanpura is located on two sides of its outer border that faces the square. This string of commercial activity serves as a buffer for the inner residential area and a landmark for the community. The area has been there since the arrival of the first settlers, approximately 1947-1950, and has played an important role in the development of the settlement. Furthermore, it has a strategic location next to a busy main road in Bhopal. Along the string, formality and informality live side-by-side, as local chain restaurants with customer seating and regulated kitchens stand next to tiny tea stalls that are little more than a hot plate and kettle. The dynamic mix of informal and formal shops, stands, and stalls reflects the general evolution and gradual formalization of the community and the commercial character of the area.

Figure X shows the distribution of the stores and businesses that shape the commercial string. There are five categories of commercial activity identified along the commercial string: ten restaurants, fourteen eatery stalls, two pharmacies, 26 stores and nine services. The stores specialize in a variety of products and services, including, among other, hardware and clothes, bakeries, tea and tobacco, appliances, furniture, jewelry, and bookstores. It appears the shopkeepers of this area live in Roshanpura.

Human Capital

W

ithin the livelihoods framework, human capital consists of the quality and quantity of a household’s labor assets. A household’s ability to access its labor assets is facilitated or constrained by the levels of education and skills within the household, the health status of household members, and the number of members able to work (Rokodi, 10). The households in Roshanpura employ a diverse mix of strategies in the use of their labor resources, especially in terms of education and health.

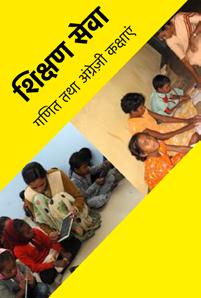

more than the public school, but they receive grants for providing scholarships to the children of families labeled “marginalized.” Previously, there was a craft school in Roshanpura, but it has since closed.

Education

Within Roshanpura there are five schools, three private, one public, and one Madrassa school (for Islamic education). Both the public and private schools cater primarily to the children who live in Roshanpura, with only a few coming from outside the community. There are typically two blocks of classes a day, one for the younger children and the other for the older children. However, there are notable differences between the public and private schools. The private schools have multiple rooms to separate grades and teach from kindergarten to the tenth standard. In comparison, the public school is a one room schoolhouse, and only teaches from the first to the fifth standard. Additionally, the private school teachers have lower qualifications than the public school teachers, but they live in Roshanpura while the public school teachers do not. Lunch at the public school is provided by an NGO, while students at the private school are required to bring their own meals. The private schools’ fees are also

The schools in Roshanpura have gone through a gradual process of formalization. The oldest school started approximately 30 years ago when a few residents recognized the need for the children of Roshanpura to receive an education. The school, like the other private schools in Roshanpura, arose informally through the efforts of an educated resident and a benefactor. Overtime the private schools have gained some form of formal recognition, receiving grants from the government and NGOs to fund students’ attendance and provide lunch. The educational facilities gained further formalization when in 2003 the public school was founded under the national government’s Education for All scheme started in 2001.

In addition to the schools in Roshanpura, several families send their children to schools located within the New Market. Mainly older children who want to pursue secondary education attend these school. Additionally, older children have the opportunity to attend the S. V. Polytechnic College located just north of Roshanpura by Polytechnic Square.

In terms of adult education and skills building, for two months a local NGO hosted a food processing cooking workshop for low income women. The NGO, funded by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, holds workshops in areas near high populations of low income women with the goal of empowering them to start their own businesses. The workshops offer both technical and business education, and, upon completion of the workshop,

the NGO provides special government small business loans and creates a support system to help the women start their own businesses. However, the workshops only last a few months, and the NGO changes locations.

A less temporary form of adult skills building is in the form of informal skills sharing from social and familial networks. Women learn skills from women in their social circles, such as stitching, embroidery, knitting, cooking, and mehendi. Men learn skills associated with the family business, or they learn technical skills related to manual labor from their social circle.

Health

The residents of Roshanpura have three viable options for health services. First is a private clinic located on the southern end of Roshanpura. However, for many residents this option is prohibitively expensive. Another option is a spiritual healing center. The center provides spiritual training to overcome addictions and natural medicines for free. However, it does not provide care for more severe illnesses or injuries. The final accessible option is the government hospital located on the edge of the New Market. For most residents, this is the most affordable option. However, in order to reach it, they must take a rickshaw.

Natural Capital

N

atural capital derives from the natural resources available for households to use towards their livelihoods. These include land, water, and other environmental resources (Rokodi, 2002, 11).

In urban area, depending how broadly or narrowly it is defined, natural capital is not as important as the other capitals. The researchers recognize that the residents of Roshanpura are indirectly dependent on natural resources for their basic needs, such as food, energy, and water. However, this analysis of their natural capital is limited to those found in Roshanpura, which consist of two main assets: topography and animals. Roshanpura is geographically defined by a natural slope that starts in the south at Rajbhaven Road and descends north to Banganga Road. Except for those who live at the bottom of the slope on the northern end of Roshanpura, the slope benefits the inhabitants with a natural flood control and drainage system. As such, inhabitants location along the slope reflects both their social status and tenure security. Those living in the southern, higher end of the slope have a greater perceived tenure security, which reflects in their higher level of investment in their homes. Meanwhile, those living on the northern, lower end of the slope have a weaker sense of tenure security. Another natural asset consists of the animals kept by the residents . Largely due to the presence of the Gwallahs, many residents keeps goats and cows, which unreservedly roam the streets and alleyways of Roshanpura. Residents raise them mostly for milk, both for household consumption and sale in the New Market by M.P. State Cooperative Dairy Federation Ltd.

The above analysis of Roshanpura reveals that the community’s strengths lie in its physical, social, and financial capital. Furthermore, from formal economic exchanges with informal businesses to informal political leaders leveraging formal institutions on the community’s behalf, there is a constant interaction between formality and informality within Roshanpura’s LF. However, while the LF provides the researchers with a solid foundation on which to comprehend the complexity of the community, it does not capture the interconnections between the capitals. For example, land tenure can fall within the realm of physical, social, and natural capital. Through this recognition, it became apparent Roshanpura’s location is the overarching determinant of the area’s assets set and ultimately their available livelihood strategies. For instance, Roshanpura’s location puts it at the heart of major transport systems, connecting the residents to the rest of the city; being next to the governor’s house contributes to their political influence; its proximity to the commercial heart of the city provides residents with jobs; and the location’s topography benefits residents with a natural drainage system.

With the recognition of the locations complexity and importance, it became imperative for the location to be split between two research teams. Not having a natural break within the community’s cohesiveness, the researchers divided the site along the central main street from which Roshanpura first originated and developed out from. Group three focused their attention on the southern end of the site towards Roshanpura road where the ground is higher, while Group four focused on the northern end where the ground is lower. The following sections describe first Group three’s methods, findings, and strategic proposals, followed by Group four’s methods, findings, and strategic proposals.

Roshanpura

METHODS

METHODOLOGY

Throughout the fieldwork, the values of UEP defined the methodology. We had three objectives in developing our methodology. First, to emphasize on the Bottom-Top approach, we ventured into the field without any preconceived ideas as in how to bring about changes in the area if needed.The researchers also stressed letting the people of the area tell their own stories. The final objective was to develop and analyze Roshanpura’s livelihoods framework.

The researchers decided to use a participatory learning and action approach. This allows a better learning and engaging process with communities, which combines visual methods with natural interviewing techniques. It is intended to facilitate a process of collective analysis while enabling all community members, regardless of their age, ethnicity or literacy capabilities, to participate (Thomas, 2002, p.1).

In order to elaborate the situational analysis, we collaborated with the community to gather information. The researchers’ main goal of the fieldwork was to put their finger on the pulse of Roshanpura. The fieldwork went through three phases:

THE FIRST PHASE

The first three weeks represented a broader approach and revolved around understanding the prevailing scenario in Roshanpura, including, among other things, employment, education,

health, housing, and culture. One of the researchers’ objectives was to also be transparent with the community about who they are and their purpose for being there.

THE SECOND PHASE

The next and longest phase, involved the tactical use of methods to identify and analyze the major concerns in the area. The researchers devised a logical issue-based narrative approach to filtering through various perceptions.

The main aim of this phase was to identify the prevailing issues and align the methods accordingly. By this time, the members of the community were familiar with the researchers and were easier to approach. The key objectives during this phase were to identify the opportunities rather than just the challenges, and to identify and understand the informality the urban milieu has to offer. In particular, the researchers were interested in the appropriation of public open spaces inside the slum. Thus, the second phase started with the idea of working on open spaces, but through further investigation a new focus presented itself and carried into the third phase.

THE THIRD PHASE

The third and the final phase involved documentation, analysis of the results from the different methods, and most importantly development of a strategic proposal. The researchers realized that despite their transparency with the community, a few people still expected some form of financial assistance at the end of the fieldwork. Hence, it was necessary for the researchers to inform and show them their work and engage residents in the design process.

FIRST PHASE

OBSERVATION

As newcomers to Roshanpura, the first goal was to build rapport by making the people familiar with our presence. While walking through the site, observing, the researchers participated in reciprocal conversations with the community, equally sharing information about themselves and where they are from. No pictures or videos were taken in the first weeks. By using this method,the researchers were able to introduce themselves to the community and explain the purpose of the fieldwork.

TRANSECT WALKS

The researchers asked one of the informal leaders in Roshanpura to lead them on a walk through the area. He guided them around major and smaller streets and pointed out predominant neighbo rhoods, landmarks, shops, and introduced them to inhabitants. The walk allowed them to get a ge neral overview of the area, the built environment, and the people. Additionally, it helped to highlight the area’s density, both in terms of structures and population, and the natural slope. The researchers were able to observe how the neighborhoods grew around a temple or from people from the same caste settling in close proximity. Also, they obser ved the heterogeneous culture of different religions and traditions.

3.1.2 A senior puppeteer in the sidewalk by his house

3.1.3 Transect walk

3.1.2 A senior puppeteer in the sidewalk by his house

3.1.3 Transect walk

OPEN-ENDED INTERVIEWS

Next, the researchers conducted informal, open-en ded interviews. These encouraged the residents to choose the topic and elaborate on how they per ceived Roshanpura. By making the topic of the in terviews broad, the researchers were able to gather basic factual information about livelihoods, access to infrastructure, basic demography and Roshanpu ra’s development trends. This process proved help ful in developing a holistic image of the area. While there was a risk that people would be reluc tant to participate, due to the interruption of their daily lives this could represent, the majority of the community was open and responsive. One of the advantages of these interviews was the freedom they gave to residents to express their concerns and thoughts.

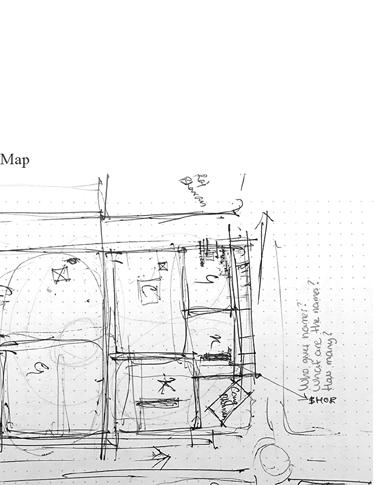

COMMUNITY MAPPING - PRELIMINARY

Community mapping is a powerful tool within the participatory approach, where the residents of Ro shanpura acted as the experts, sharing with the researchers their knowledge of the area. The first attempt was with a girl and her brother. Upon being asked to draw a map defining the extents of the neighborhoods, they were hesitant and not confi dent in their abilities to provide a map. However, after being provided with a base map and asked to show how the neighborhood structure works, they were able to provide a partially accurate neighbo rhood map. The activity showed how neighbo rhoods evolved out of the dominant traditional oc cupations of the people in the area.

After a couple of days, the researchers came up with a structure to fill in the general inquiries about Roshanpura.

The researchers tried to gather information about thve basic physical demographics (i.e. number of houses and households, schools, clinics, shops etc.); mentally map the area, orienting themselves around landmarks and open spaces, and delinea ting the invisible edges; know issues regarding ba sic infrastructure and livelihoods; and also identify the housing typology and social structure. The re searchers intended to find out potential stakehol ders and major concerns in informality. The flexibility of the methods resulted in new findings about other topics not previously consider, which widened their understanding of the area.

SECOND PHASE

COMMUNITY MAPPING

This tool was used in different occasions over this phase.The first was with the informal councilor at his house over cups of tea. The researchers and infor mal councilor together made a map of Roshanpura that depicted the different neighborhoods which divide and delineated the community. This map served as a means to further locate the researcher in the space.

DRAWING ACTIVITY WITH CHILDREN

As part of the participatory approach, we wanted to be inclusive with different age groups. The resear chers chose to engage with the children, as they had observed a large number playing in the streets. In order to connect with as many as possible, it was decided to work with the local schools. The resear chers believed drawing would be the best way for the children to express their ideas, so they organized two drawing activities in two of the schools in the area: Sunrise public school (private school run by a resident of Roshanpura) and the public school under the Government scheme of Sarva Shiksha Aviyan.

The researchers asked children from the elemen tary level to eighth standard in the private school, to draw their favorite places in and around their houses. Whereas, the kids in the public school were asked to draw any space they like inside Roshanpu ra where they do their outdoor activities.

The researchers hoped the briefs would help build the LF for Roshanpura and provide more informa tion on one of the most evident problems iden tified, the lack of open spaces. The researchers hoped to learn how residents use open spaces in micro and macro scale. Both Roshanpura North and SPA Bhopal students joined the researchers for this activity, so both schools could be covered at the same time. To communicate better with the children and to build trust, two of the researchers joined the children in the drawing activity.