TRANSIT-ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT COLLABORATION STUDY

Page intentionally left blank.

Page intentionally left blank.

PLAN

Process

Cross-cutting

Stream: Restoration and Stream

Analysis

Vulnerability Assessment of the Waipahu Rail Corridor

Land-Use and Effects on Native Hawaiian Cultural

Community Engagement

Flood Impact on Vulnerable

Pouhala Marsh

the Use of Pouhala Marsh

Special thanks to Leo Asuncion of the Hawaiʻi Office of Planning, Harrison Rue of the City and County of Honolulu, Ryan Tam of HART, and Dean Sakamoto of SHADE.

PLAN 620, Fall 2017 Class: Wesley Bradshaw, Trevor Fitzpatrick, Sameer Saraswat, Malachi Krishok, Courtney Payne and Cody Winchester, Erin “Bear” Braich, Imelda Carlos, Matt Fernandez, Umeyo Momotaro, Aarthi Padmanabhan, Brandon Soo, Kialoa Mossman, Daesza Tomas, & Sky Uyehara, Lara, Mukai, and Nishioka, Britta Johnson, Marc Malate, Grace Wolff, Emily Odell, Mio Shimada, and Navin Tagore-Erwin.

PLAN 678, Fall 2017 Class: Aida Arik, Bear Braich, Laura Mo, Amanda Rothschild, Brandon Soo, Grace Wolff, Britta Johnson, Cody Winchester, Luke Sarvis, Malachi Krishok, Miles Nishioka, Sameer Saraswat, Trevor Fitzpatrick, Marc Malate, Umeyo Momotaro, Wesley Bradshaw, Matthew Fernandez, and Rocco Tramontano.

PLAN 642, Spring 2018 Class: John Canner, Elizabeth Dionne, Matthew Fernandez, Miles Nishio ka, Silvia Sulis, Rafaela De Melo Barros, Kishor Bhatta, Wesley Bradshaw, Mintu Miah, Brandon Soo.

Graduate Assistants: Imelda Carlos, Sara Doermann, and Yusraa Tadj

The University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center (UHCDC) and the University of Hawai‘i Department of Urban and Regional Planning (UH DURP) entered into an agreement in Fall 2017 to provide proof of concept research, planning, and design as part of a University collaborative effort focusing on the Waipahu Transit Oriented Development (TOD). The project deliverables were broken down into two parts: part one involved three DURP graduate level classes and part two involving the public policy center. This inter im report includes DURP’s contribution to this agreement, part one.

DURP officially entered into an agreement with UHCDC to complete work on Waipahu TOD on March 19, 2018. The primary goal of this collaboration was to study TOD interagency communication, community, engagement, research, planning, design, and funding process as well as complete in-depth, multi-scalar, and multi-disciplinary study of the Waipahu TOD area, specifically to use the Waipahu TOD area as a pilot region to establish an applied research and design framework that supports a macro to micro level systems-based approach that better informs the funding of capital improvement projects in the future. DURP, tasked with specific deliverables, distributed them amongst three courses: PLAN 620, PLAN 678, and PLAN 642. Following includes details on how each course met their deliverables, their process, and how they collaborated.

DURP, three courses, each with their own deliverables:

PLAN 620: Environmental Planning: Fall 2017

• Past, present, and future Hazards Assessment

• Ecological Conditions Assessment

PLAN 678: Site Planning: Fall 2017

• Conceptual site planning

• Site visits, analysis, and Interviews

• Past and future Conditions Assessment

• Project Overview

• Stakeholder Interviews

• Housing Needs Assessment

PLAN 642: Planning Urban Infrastructure: Spring 2018

• Infrastructure Capacity Analysis

PLAN 620 Environmental Planning’s, main focus was in helping students accumulate knowledge on the natural and built environment. Specifically, this course targets urbanization’s effect on the natural landscape through land use, hydrology, climate change, urban forestry, and biodiversity. While learning about these subjects, students learned different planning strategies and policy tools to minimize environmental impact.

This course’s deliverables included; Hazards assessment, Ecological Conditions Assessment & overarching hazards assessment. These deliverables were completed in the form of final papers through a process described in the following sections:

• Weekly Waipahu blog

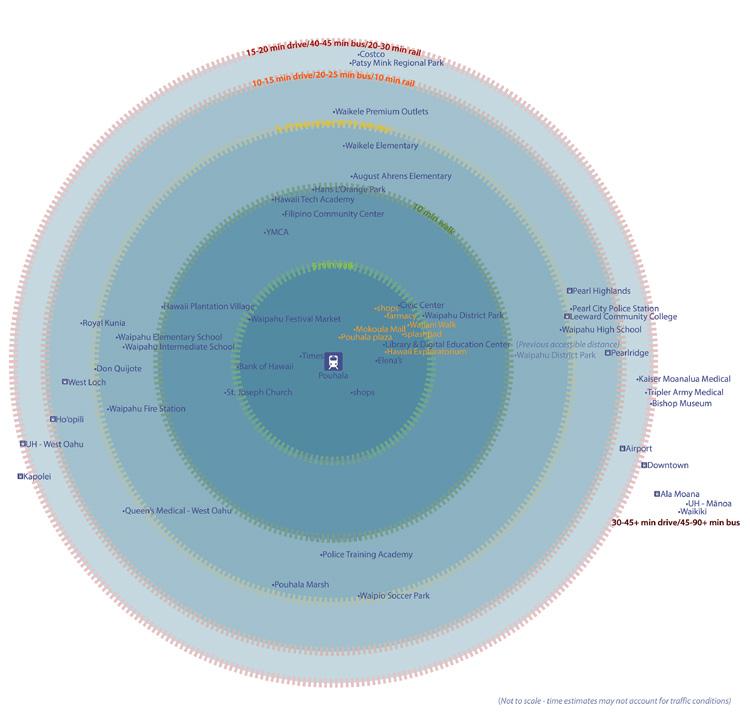

• September 23, 2017: Site visit, guided tour where students learned a brief histor y of the neighborhood, demographics, what was within a quarter-mile and half-mile radius, and existing conditions at the proposed Waipahu Transit Center.

• October 31, 2017: Midterm presentations, in collaboration with PLAN 678 students presented their findings with community reviewers present

• December 12, 2017: Final presentations and paper with community reviewers

The class was broken into seven teams, each with their own specific topic related to Waipahu TOD. Presented below are brief summaries from each team report describing concerns of the area and detailing solutions that can be implemented in Waipahu.

Situated at the base of the Waipio, Waiawa, and Waikele watersheds, the low lying coastal area of Waipahu is highly prone to rain-induced flooding and sea level rise (SLR). The frequency of flood events will increase with climate change that has been fueled by greenhouse gas emissions1. While addressing flooding has been identified in the City and County and State’s TOD plans, they have not formally included the potential for SLR to affect the development Pouhala station and Waipahu area. Current TOD Zoning and Land Use regulations call for increases in building and population density, and placement of buildings close to the street with building facades that have transparent windows and entrances at the ground level to foster active streets and spaces2. Without setting buildings further back and elevating sidewalks and other important infrastructure, these zoning and land use regulations will increase the potential damage caused by rain induced flooding and SLR.

Increases in building and population density are also associated with decreases in green space and an expansion of impervious surfaces. The replacement of green space with impervious surfaces can exacerbate flooding issues due to channelization and pluvial and stormwater runoff that can overload infrastructure as well as existing watersheds3. Since much of the TOD around Pouhala station will depend on creative cost-effective public and private partnerships and affect

large portions of vulnerable populations in Waipahu, policies should be implemented to leverage existing or proposed assets and provide resources to stakeholders that encourages adaptation and mitigation measures to the effects of flooding in a manner that increases the capacity of the social and built environment4

$1,004,050,900 of land and building value, 54,882.32 ft of roads, and approximately 18,011 Waipahu residents could be affected by a 100-yr flood5. The aim of this policy brief is to provide the state of Hawaiʻi and City and County of Honolulu with flood-related adaptation measures that should be implemented in Waipahu as the various stakeholders continue to construct the Pouhala station and redevelop the surrounding area in accordance with Transit Oriented Development (TOD) and its principles. A large section of Honolulu’s rail transit and its proposed TODs are located in high risk flood zones6. This includes the Pouhala station. The state’s Office of Planning and the Department of Planning and Permitting for the City and County of Honolulu have already identified flooding as an issue that needs to be addressed in the Waipahu area, but have yet to account for the expected 3-6 feet of sea level rise (SLR) by 2100. Failure to account for six feet of SLR could potentially affect $347,868,400 of land and building assets, 16,233.43 ft of roads, and 8,478 people in Waipahu through groundwater inundation and permanent flooding. Additionally, much of the flood affected areas of Waipahu contain high percentages of foreign born, elderly, and impoverished populations7. A variety of adaptation measures will need to be implemented in Waipahu to reduce the risk and vulnerability to both physical assets and human populations.

After evaluation of flood risks for Waipahu and careful consideration of Waipahu’s topography, soil composition, social and cultural dynamics and impacts of transit, this report recommends a few adaptation measures that could be implemented in Waipahu as well as a framework that could be useful as a statewide approach to TOD planning.

1. Green infrastructure: Green infrastructure at both household and neighborhood scales can be very effective in capacity building for flood adaptation as well as reducing pollution and protecting property by reducing and treating stormwater at these sources. Studies have shown it is capable of reducing public spending on infrastructure8. a. The State and City and County of Honolulu should strongly consider implementing an incentivized green infrastructure policy and approach to water management.

2. Infrastructure and design based solutions: The fact that a large section of proposed high density TOD zone falls in high flood risk area calls for adaptive capacity building in these areas. In this specific case, it is found that infrastructure and design based solutions might be more effective than ecosystem based approaches. This report proposes measures such as elevated streets, sidewalks, sacrificial street levels, elevated structures and temporary urbanism as possible ways to achieve increased adaptive capacity.

3. Land swap/land buyback: Land swaps, which are effectively swapping privately

1 UCS, 2017

City and County of Honolulu: Proposed Development Standards in the TOD Special District (Adopted October 2017)

Siekmann & Siekmann, 2015

State of Hawaiʻi, 2017

See GIS Group’s report.

See Figure 2

See maps in Figure 2 and the Social Dynamics Groups report.

Bloomberg, 2006; Bloomberg & Holloway 2010

owned land for public land, and Land buybacks are some of the more expensive adaptation measures. Although land swaps and buybacks are typically used post disaster in most cases, it is argued that these measures should be used in anticipator y ways before disaster rather than in a traditional reactionary manner. The most vulnerable areas in Waipahu which have relatively lower land value might be a good candidate for this program.

a. State and City and County permitting departments should work with local realtors to monitor the sale and development of vulnerable parcels and to find aid in providing the funding to purchase these lands proactively as part of the Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program9

1. Adaptation strategies will generally benefit from combining design based mitigation, social capacity building, and policy based mitigation approaches.

2. While a general hazard mitigation framework can be employed in planning statewide TOD, due to the combined fact that adaptation and mitigation measures have trade-offs and the fact that each location has unique opportunities and constraints, specific adaptive measures should be consider on a place-based approach. There might not be an effective one-size-fits-all adaptive measure. For example, while coastal hybridization may protect some districts from marine based flooding resulting from sea level rise, other locations may still become inundated by rising groundwater

3. New construction and site planning should be anticipatory, rather than reactionary, regarding hazard mitigation. Even though the most severe impacts of climate change may seem far off in the future, the city and county should work now with a sense of urgency to prepare for it.

Kapakahi stream is a degraded environment within Waipahu that empties into Pouhala Marsh and the west loch of Pearl Harbor. The Waipahu TOD Plan proposes stream restoration and creating a stream walk to connect the Farrington/Mokuola neighborhoods. Recommendations for each section are created through field observations and an analysis of similarly conditioned case studies. The following actions are recommended for specific portions of the stream (see appendix figure 3): removing culvert pipes, widening the stream, daylighting (physically uncovering stream), lining stream bottom with rocks and stream plants, increasing permeable surface buffer zones, address pollution, invasive species removal and native outplanting. These recommendations serve to regain ecological function (i.e. increase water retention, groundwater recharge and bank stabilization) rather than aim for an unattainable pre-western contact state.

This section of the stream is relatively narrow and has a low flow rate. Widening the stream at this location is advised. The stream flows into a series of culverts as it transitions into Transect Section 2. These culverts cause the water to stagnate as it “bottlenecks” into the pipes. Removal of the culvert pipes will decrease the water level and increase flow

9 Grannis, 2011

10 Please refer to Appendix I, Table 1.

This portion of the Kapakahi stream near the Plantation Village provides many opportunities. Hawaiʻi’s Plantation Village is an outdoor museum of historical homes and gardens that tell the story of the different cultures that make up modern Hawaiʻi through guided tours and storytelling. Hawaiian people and non-Hawaiian settlers have historically used streams for a variety of cultural and cultivation practices. This segment would be an ideal location for aggressive habitat restoration as well as educational or historical showcases of traditional, postcontact and plantation era stream cultivation. Native stream ecology will contribute to a living museum concept.

This portion of the stream suffers from the effects of burial as it is funneled into culverts below a concrete parking lot. Storm drains in the parking drains oils and various other contaminants down into the waters below. This study recommends daylighting of this portion of stream to bring the Kapakahi back to the surface. This is a major construction job in one of the primary commercial areas of Waipahu. It its important to acknowledge that parking is a major concern for the Waipahu community. The long term benefits of stream restoration, flood mitigation, and providing public space will long outweigh the short term inconvenience of daylighting. It will be critical to engage and work with the surrounding business owners and accommodate their concerns.

This portion of the Kapakahi Stream suffers from high levels of pollution and invasive species. Restoration efforts should focus on the softening of the hard engineered edges of this stream and remove of the invasive Ipomoea aquatica weed. A source point of pollution can be pinpointed near the Waipahu “Drop-off Convenience Center for Refuse and Recycling” located near the end of Waipahu Depot Street. One of the largest forms of litter at this location are plastic bottle caps. Several shopping carts that had been upended into the stream can also be observed. The Drop-off Convenience Center for Refuse and Recycling is not a compatible land use for this area. This study recommends the relocation of the center to a more urban industrial area that has more compatible land use. An alternative solution could be to leave the center and force them to develop a plan to address the issue.

The Waipahu Depot Street, which runs parallel to the Kapakahi stream, has 2-way traffic lanes as well as lanes for street parking on both sides. It is recommended that removal of street parking take place in this location as well as consolidating the traffic flow into the two easternmost lanes. This extra space would allow for the steam to be widened and develop a riparian zone at the stream’s perimeter. The pedestrian greenway could then be expanded along this transect to provide pedestrian access to the Pouhala Marsh.

This is the most natural area of the entire stream. Efforts in this area should include the continued conservation and restoration efforts being undertaken as well as encourage greater public use. Currently the Pouhala Marsh is closed off to the public. This pristine area is a great community asset and will be a great source of education and recreation for the community once opened. Community organizations could be invited to help out with removing garbage, invasive species, planting native trees and habitat building.

Stakeholders:

Stream restoration offers an alternative solution to past engineering and construction practices. By harnessing environmental and design expertise the process of daylighting streams rejuvenates waterways and supports both ecosystem and community health. Similar

to streams, restoration efforts cannot be viewed in a vacuum but rather as the culmination of various processes and actions moving downstream. Before beginning in a stream restoration or daylighting process, project leaders must think about how to engage community. In order to have successful and sustainable restoration projects, communication between numerous stakeholders including the broader community must be included as a central part of any process

Past programs show that with necessary funding and policy support, involving both “grassroots” and “grasstops” stakeholder input from the visioning to implementation to maintenance can lead to greater sustainability. Building relationships and including protocol that allows regular access and guidelines for educational and/or volunteer groups to help with maintaining and monitoring the project area is a practice that has been proven successful. Volunteer stewardship allows for active interaction with the ecosystem and new learning opportunities. In addition, in-kind donations such as volunteering, partnerships with local institution and foundations is also key to securing funding and ongoing support. On-going research and data collection are crucial for monitoring needs and maximizing the results of a stream restoration project. Streams offer spaces to build relationships with university researchers and school programs where the restoration can be studied and used as a learning laboratory. Including government stakeholders early on can pay dividends and speed up the implementation of a the restoration project down the road. Specific areas where government partnerships may be especially beneficial are: understanding and completing the required permitting; gaining insight and doing due diligence tied to historic preservation and archeological surveys; and understanding, establishing, and building in protocols and coordination with regulatory agencies. See Appendix I, Table 2, for list of possible community stakeholders.

Possible constraints to implementing recommendations include businesses that utilize parking area above the stream in daylighting sections, residents who use street parking in the stream widening sections and overall funding. It is suggested that a bottoms-up approach be used in any restoration project involving Kapakahi Stream, where funding sources and key stakeholders are addressed and included throughout the process. Engaging the community is essential to the long term success of stream restoration projects. Development of the Kapakahi stream walk provides an opportunity to reduce flooding issues, improve habitat quality, increase community recreational and connections with the natural environment.

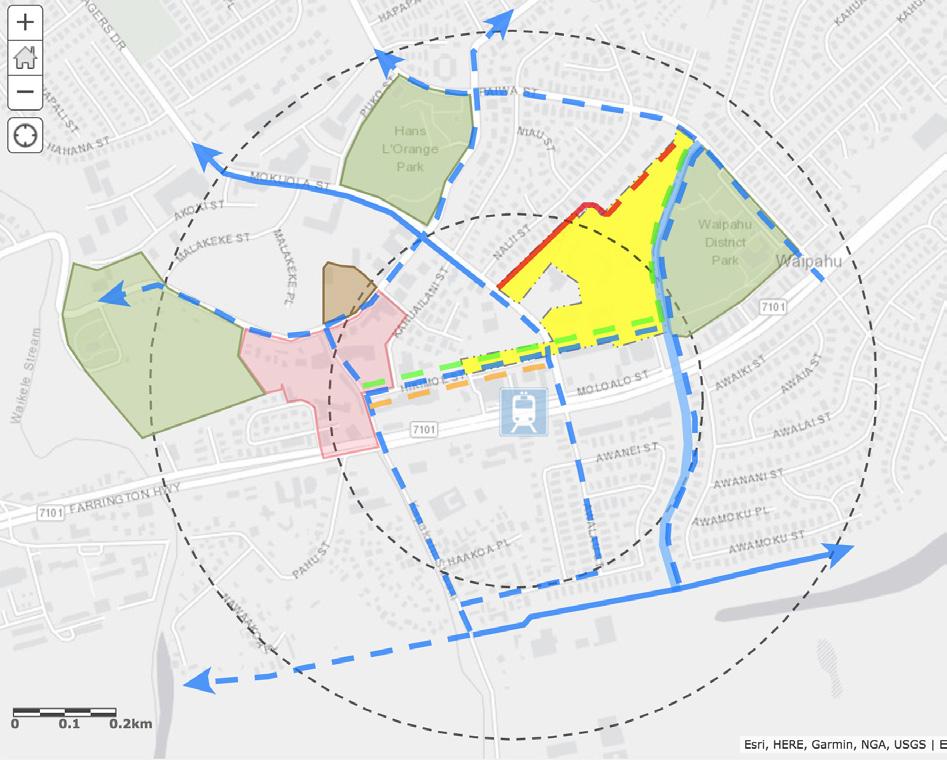

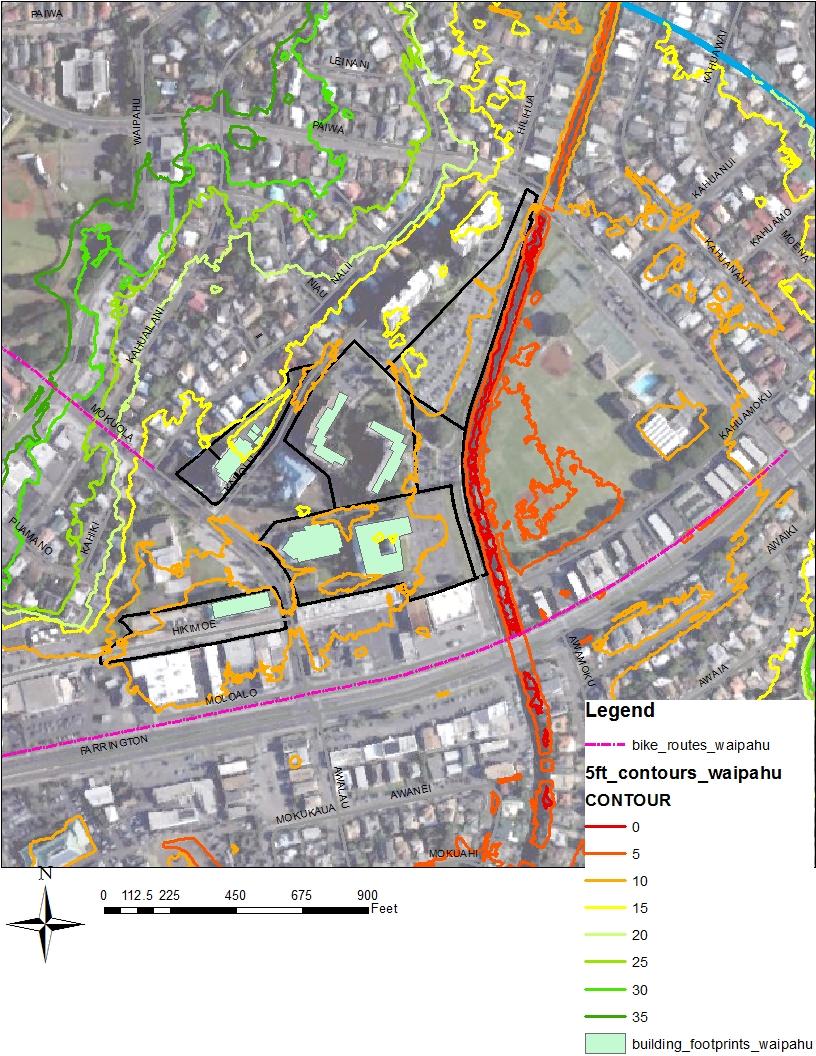

This study investigated the complex relationship between environmental risks and social, physical, and economic vulnerability in a case study carried out in Waipahu Rail Corridor, focusing on flood vulnerability. Waipahu is receiving a massive infrastructure investment by being the only town along the rail line that will be have two of the rail stations, Pouhala and Hō‘ae‘ae. Waipahu means, “bursting waters” in Hawaiian and has a history of flooding, so with the rail’s proximity to surface hydrology and the shoreline, flooding vulnerability need to be assessed.

To best understand the flooding vulnerability of the Waipahu Rail Corridor a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) based approach was utilized. The area was assessed based on different social, physical, and economic factors and then put through four different flooding scenarios: (1) storm surge based on a category 4 hurricane, (2) tsunami from the FEMA tsunami zones, (3) 100 year riverine flooding, and (4) 6 feet of sea level rise (see appendix figure 1). The

analysis showed that areas south of the rail line in Waipahu is the most vulnerable to flooding in the corridor. The area’s dense population, aging infrastructure, and low annual income illustrates that the impacts felt from flooding event would be felt the greatest here. With the City of Honolulu and State of Hawaiʻi investing heavily in the rail line, assessment of the impacts a flooding event has on the surround areas needs to be a key component in future planning processes.

The rail corridor of Waipahu is the ½ mile radius around Pouhala and Hō‘ae‘ae Rail Stations including the ½ mile connecting the two stations. The HART Rail Line runs through Waipahu on top of Farrington Highway giving residents of Waipahu the amenity of using rail or a highway to connect to the rest of Oʻahu. Waipahu and the Hō‘ae‘ae Rail Stations are located in central Oʻahu along the West Loch of Pearl Harbor (see appendix figure 4).

TOD projects impact social aspects in terms of homeownership, household size, and number of units particularly in the heavily populated areas. Given the current social vulnerability assessment (see appendix figure 2), future plans and policies around TOD, TOD should consider the hazard impacts on social within the lower portion of Farrington Hwy near coastline and proximity to Waikele and Kapakahi Streams. Also areas within Mokuola, Hikimoe, Leowahine, Pupukahi, Pupupuhi and Leokane.

The vulnerability assessment on physical infrastructure showed that there are clusters of considerably old sewage mains and laterals surrounding the Pouhala Rail Station. The install dates of the pipes give an idea of what materials the pipes are made out of. Pipes installed before 1950 which made the area considered very vulnerable to disruptions such as pipe breaks and blockages before flooding scenarios were added. The assessment also showed that the stormwater infrastructure south of Farrington Highway is older and has less capacity than the rest of the Waipahu Rail Corridor. This infrastructure needs to have the highest capacity in the corridor due to its proximity to the shoreline. Upgrading and installing more stormwater infrastructure in this area will not only immediately decrease the flood risk of these block groups, but the block groups located just north of Farrington Highway as well.

The analysis on economic vulnerability showed that TOD projects impact the economic developments surrounding them. These impacts include the cost of living mainly for those people who are within the poverty class, whom have low household incomes, and no employment status. These impacts also include the affordability of properties and lands within a TOD area. TOD plans and policies such as that of the Pouhala and Hō‘ae‘ae rail transit stations that do not address flooding and the current equitable distribution of resources and land use will have very high economic impacts on the cost and quality of living in the TOD area, especially for those who are lower on the socioeconomic scale.

The Honolulu rail line and transit stations are massive investments in the infrastructure of Oʻahu. By 2030, nearly 70 percent of O‘ahu’s population and more than 80 percent of the island’s jobs will be located along the 20-mile rail corridor (HART, 2017). However, the location of some

of the rail stations such as the Pouhala and Hō‘ae‘ae stations in Waipahu are vulnerable to environmental risks such as riverine flooding, climate induced sea level rise, storm surges, and tsunamis. These environmental risks have the opportunity to heavily impact the social, physical, and economical aspects of the area. Some of these aspects may already be vulnerable either due to population demographics, the age or number of critical infrastructure, or even the socioeconomic capacity of those residents. Flooding has the potential to greatly increase these vulnerabilities. Therefore, rail lines, transit stations, and the surrounding infrastructure need to be assessed first for environmental risks based on whether they are in close proximity to the shoreline, located in a flood zone, or geographically have a histor y of flooding.

Over the past century, Waipahu has seen a massive decline in Native Hawaiian Cultural Resources (NHCRs) due to land-use change and urbanization. Although many people think the history of Waipahu began in the sugar cane plantation era, there are many stories and myths that offer insight into how life was lived in Waipahu prior to Hawaiʻi’s introduction to the western world. With the introduction of plantation companies came the first major shift in land-use and thus a change in livelihood for Hawaiians in Waipahu. O‘ahu’s rapidly growing population encouraged developers to create homes and neighborhoods in Waipahu, leading to another major shift in land-use and destruction of NHCRs. Today, the last remaining NHCR is being threatened by impending rising sea levels. A variety of groups, such as Honolulu Association for Rail Transit (HART), Kumu Pono Associates LLC, General Engineering Consultants, and Central Surveys Hawaiʻi Inc. collaborated to prepare a Traditional Cultural Properties (TCPs) study. This study included the analysis of historic maps and descriptions of historic places to develop information on the relationship of the Project’s transit alignment and associated transit facilities to natural geographic features, traditional land uses, native tenant residency practices, and traditionally named localities13. These groups found four cultural properties, several fishponds, and added the traditional course of the streams in the area. However, after reviewing the ethnographic study created by Kumu Pono Associates, the properties listed on the TCP map were vague and did not accurately represent the amount of NHCR that were in the Waipahu area. HART, along with the state, has not done enough to highlight native Hawaiian stories and resources, which remain to be the bases of its history. Loss of cultural resources can lead to a decline in Hawaiian pride and identity as Waipahu begins to lose its meaning. To combat the absence of NHCRs in Waipahu, we offer feasible, non-structural recommendations such as incorporating Hawaiian values and activities in parks and open spaces, establishing meaningful interpretive signage, planting native Hawaiian plants from the area in available green spaces. We also recommend bringing back loko i’a practices to combat the effects of sea level rise and its impacts to Waipahu.

Pouhala Marsh, also known as Pouhala fish and wildlife reserve has been an iconic resource for native Hawaiians. In many of the historical maps provided by DAGS, Pouhala is the largest feature at 70-acres in total area. However, after the housing boom in the 60’s and 70’s, Pouhala’s wetland ecosystem degraded with silt accumulation, water pollution and invasive species. Today, the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DOFAW) is managing the area and has created a draft restoration plan for wetland enhancement and water bird habitat development for four rare bird species14. Though Pouhala is heading towards the right directions, the cultural resources that remain in Pouhala are at high risk of being destroyed by sea level rise and frequent storms. Sea levels are projected to rise 3.2 ft by 2100 and all models show Pouhala Marsh under water by the

same time. If global patterns remain as projected, the last traditional NHCR will be lost, erasing the foundation set by Waipahu’s earliest ancestors. This goes against the Hawaiʻi’s TOD Key principle of engaging in equitable development.

Though Waipahu will remain a plantation town, this study offers to honor the pre-contact history by incorporating continued restoration of environment and loko i’a at Pouhala, planting native Hawaiian plants, originally from the area, in available green spaces in Waipahu, and by incorporating meaningful interpretive signage, Hawaiian values and activities. As stated above, DOFAW along with many collaborators such as DUCKS unlimited and Oceanit have come together to create a restoration plan for Pouhala Marsh. After speaking with Ati, the DOFAW manager for Pouhala, it became clear that there was little effort and money being put into the project. By bringing together different sectors to get familiar with the place and with each other much can be accomplished in restoration efforts within a few short years, protecting and re-emphasizing the importance of the last NHCR in Waipahu. By restoring the loko i’a it will provide an alternative to coastal armoring. Loko i’a, or fishponds are often built with an outer wall made of sand or rock. These walls are not so compact as to not let water in, instead just acts as a barrier for fish. Loko i’a then have the potential of slowing sea level rise in a specific area without damaging its surroundings. Planting native plants that were originally from the area allows people to connect to their environment as Hawaiians did, allowing community members to understand their environment on a deeper level. This level of interest enhances community engagement and connectivity. Incorporating meaningful interpretive signage will play a huge role in cultural revitalization as it serves to educate the community, brings the community together and brings back native Hawaiian Identity. From small signs of Hawaiian plants with its name and its uses to beautiful and intricate murals painted on the side of buildings, these signs will educate all citizens of every nation. By creating and engaging people of all ages from children to elders to help recreate the traditional stories of an area, those stories gain life. Stories such as Kaʻahupahau and her battle with Keliʻikauokaʻū or Makanieʻoe uncovering an underground spring will be highlighted in these murals. Lastly incorporating Hawaiian values and activities helps accomplish both state and city objectives of creating an equitable development, and understanding local knowledge through community collaboration and placemaking implementation. To go about this, it is recommend incorporating Hawaiian makahiki games like Konane, or Hawaiian checkers, moa paheʻe, and ʻulu maika. Due to Waipahu’s current identity of sports and recreation, this would be a great way to incorporate past identity with modern interest.

To summarize this study’s findings, another Hawaiian proverb is used, “I ka wā ma mua, ka wā mahope”, the era that pasts is our future. To use the mistakes of our past land-use to inform how land-use practice today, use past knowledge to revitalize the foundational characteristics of Waipahu and use past Hawaiian values and activities to connect Waipahu as a community.

The current approach at Pouhala Marsh in Waipahu has resulted in a situation of concern. Limited resources have allowed the natural environment to become overgrown and degraded. And, the physical appearance of the marsh has made itself invisible and unfriendly to community Fortunately, most of the land was designated as preservation and was placed under the management of the State’s Department of Land and Natural Resources. Unfortunately, interest in

restoration of this critical ecosystem has remained low in the community and the potential for a collaborative process has been absent.

In this briefing, policy change is recommended to be redirected toward a plan for long-term, re-establishment of people to nature through strategies that create visibility, educational opportunity, and recreational purpose. Through thoughtful consideration of protecting the environment, human engagement with Pouhala Marsh can be provided by: 1) guided walking trails, 2) construction of lookouts, 3) interpretive signage, 4) a more friendly street view from Waipahu Depot Road, 5) the addition of external signage, 6) provision of more shade, and 7) construction of a restroom, water fountain, and benches near the entr y point.

Through these, community engagement strategies, public interest and awareness will be developed. Through interest, awareness, and time, a community vision will be inspired. Through coordination of the stakeholders, a unified vision will be attained. And through the development of practical steps, the vision can be achieved.

Visibility of an open space is critical if attention by people is desired. When thinking about visibility, there are two forms that make a place known to the general public and the community: 1) the street view appearance and 2) external directional and advertising signage. Precedent shows that adequate visibility leads to more engagement with the open space, followed by more awareness of the natural environment.

Street view appearance should be as simple as regular maintenance of the grounds such as diligent efforts to maintain native species and the removal of invasive species. In addition, connectivity with the marsh to the rest of the surrounding area requires maintained sidewalks and roads which provide accessibility from other destinations in Waipahu. When appearance is not maintained on the parcel, connecting sidewalks, and roads, people’s interest is discouraged, and worse, illegal activities are instigated as people view the site as an unattended, isolated, and hidden space.

External signage is an additional strategy to make the public space more visible to the people. Directive signage with the name of the space and indicators on how to get there placed strategically on visible, permanent posts would be a feasible approach. Strategic locations for external signage would be along Farrington Hwy near Waipahu Depot Road and at the Pouhala HART Station.

Interpretive walks in areas with sensitive habitats is a popular method of allowing people to have interactions with these environment, while also protecting the habitat from harmful activities. Interpretive walks are designed on the premises of providing 1) guided walking trails, 2) lookout areas, and 3) educational signage.

The main component to an interpretive walk is the guided walking trail. These guided walking trails typically feature rails or ropes along a pathway that can be either one directional leading to a different destination or in a loop, where the visitors end where they began. The advantage that guided trails provide is structured human interaction with the environment, protecting the sensitive habitats from harmful interactions such as being walked upon.

A unique and fun feature that draws a lot of people’s attention on guided walking trails are

lookouts. Lookouts are recognizable in the form of covered decks that allow for shade and a unique view of the marsh.

One of the most educational and amusing components on a guided walking trail are the frequent informative signs throughout the pathway. Signs can be user friendly, with images and interesting facts. The size of these signs can vary from small/medium signs attached to posts, and large information boards which can be laid out either horizontally for easy viewing, or vertically to provide more information on both or several sides of the board(s). Interpretive texts can explain information pertaining to the geological and biological function of the habitat, wildlife and endangered species of flora and fauna, retelling of historical events and cultural practices taken place in the site.

Resting areas provide conveniences for visitors while reducing harmful effects on the sensitive habitat. Shade is one of the most relaxing, cheapest, and environmentally friendly strategies for the comfort of visitors of Pouhala Marsh. Strategically placed trees and overhead cover can provide shade to visitors along the guided walking trail. Where trees and built overhead cover are not possible, adequate signage could be provided to inform visitors to fill up on water, wear a hat that provides adequate protection, and the approximate amount of time it takes to complete the distance of the trail.

Potential for restrooms, water fountains, and benches in the area nearest the entr y point for Pouhala Marsh would be the most useful site for accommodating these amenities. The purpose of these amenities would be to provide a rest station for visitors before and after their visit. With this location furthest away from sensitive habitat and nearest to the existing infrastructure, i.e. sewer and water lines, this appears to be the most ideal location for a potential rest station.

The idea of community engagement is intended to be a long term plan that is beneficial to both the environment and the residents. An aware and involved community may require investment in resources and time, but the impacts discussed are worthy of the cause. Lastly, as the community takes stewardship over their land, management of natural resources and climate change mitigation becomes significantly easier on those involved.

Flooding poses a serious threat to life and property and its predicted impacts as a result of sea level rise (SLR) will become increasingly more severe over the years, especially in already flood-prone communities like Waipahu. It is important to consider vulnerable populations within a community and how flooding impacts them. Specifically in Waipahu, the most vulnerable populations include foreign-born individuals, those over age 65, and those experiencing poverty Due to the importance of ensuring flood-preparedness and adaptation, we framed our analysis of the planning opportunities around flooding in Waipahu through a framework of equity. While it is true that all persons living in a flood zone are at risk, some individuals will be much more vulnerable to the potential impacts than others based on factors they may not be able to control. It is essential to address the issues of flooding in Waipahu in the early stage of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) since the station area is directly in a flood-hazard zone. Though other stations may not exist in flood zones, the entire state of Hawaiʻi faces pressing challenges as a result of climate change and SLR. TOD presents an excellent opportunity for new development to carefully address the reality of climate change; however, it is vital that development around each

TOD station takes a unique approach that will most benefit the character of the different communities.

After an analysis of Waipahu, it was determined that the specific members of the community most likely to live in the flood-hazard zones within the TOD area include:

• Those who fall within 200% of the federal poverty line (Appendix B)

• Those who identify as foreign-born

• Those who are 65 years of age and older

These people face challenges for a variety of reasons. Those who face poverty do not have the same resources to survive a flood as would those of a higher socioeconomic status. Their livelihood is also much more likely to be disrupted if they lose a home or some other large asset that they do not have the resources to rebuild15

Immigrant communities across the country and in Hawaiʻi face many challenges. Specifically in Waipahu, the largest foreign born populations include Filipinos and those from the various Compact of Free Association (COFA) communities including the Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Palau. The COFA communities come to Hawaiʻi for services that the United States has promised them after bombing many of their islands for nuclear testing. In addition to the negative stigma that foreign-born residents can face, there are often a lack of services to meet their needs (i.e. translators, livelihoods, et cetera), exacerbated by the fact that they may need to learn and adjust to a new way of life16 .

Additionally, Hawaiʻi has a high rate of older adults, with 21.5% of the population aged 60 and over compared to 19.5% of the general population in the United States. In Honolulu County, the rate of older adults is 20.9% . The older adult population17 is vulnerable often due to a lack of services available for their specific needs. For example, there are only 1.7 geriatricians for every 10,000 older adults in this nation18

The three groups that were identified as being vulnerable within the Waipahu TOD station have important implications for future planning in Waipahu and elsewhere. The three main takeaways for the State and City and County to consider in TOD areas is 1) that it is better to plan for flooding on a local level, 2) that there is an importance to not just introduce structural approaches but also non-structural approaches when it comes to flood mitigation and adaptation and 3), social impacts should be considered community by community when addressing flood impacts in the future.

• Dealing with the issue of flooding on a local scale is the most beneficial for the residents and for long term sustainability of adaptation . Some local scale techniques include identifying the stakeholders, building relationships with them, working within the context of community institutions, and gaining their support. Each specific community will have its own needs, even if some of their circumstances are quite similar, so working within those contexts are very important.

• The TOD zone in Waipahu of course will involve many structural approaches to flood adaptation because of all the new development. There are structural ways to mitigate flooding issues that are helpful, but it is often more sustainable to take a non-structural approach which focuses on people and resiliency. Structural approaches include engineered barriers, infrastructure, and modifications to water sources, and they can be helpful in some

15 Few, 2003

16 Labrador, 2009

17 Yahirun and Zan, 2016

18 Bardach and Rowles, 2012

instances but ultimately their success has been mixed and their cost high. Non-structural approaches however tend to focus less on prevention and more on impact reduction. Some examples include having comprehensive warning systems and evacuation programs, helping reduce poverty, as well as educating the community on flooding and theimpacts of climate change induced SLR.

• Social factors should be considered when addressing flood impacts and planning for the future of Waipahu. As our findings illustrate, socio-economic status, age, and place born all impact people’s vulnerability to flooding in the Waipahu TOD area. There are many other vulnerable populations, however, that should be explored as the City and County develop in other communities along the rail. Some of these variables include: young children, disabled, homeless, and gender.

Waipahu, located in Central O‘ahu, is a highly ecologically vulnerable region when considering impacts from climate change induced sea level rise and chronic inundation. The Waikele Watershed, Kapakahi stream, and Pouhala Marsh have experienced heavy degradation from development,changing land uses over time, non-point source pollution from stormwater flow.

The Kapakahi Stream itself is deemed an impaired body of water per the Clean Water Act sec. 303(d). Addressing these issues takes a multidisciplinary approach as there are many identified stakeholders within the community with diverse vulnerabilities and needs. With the Waipahu Town Action Plan in motion to strategically prepare Waipahu for transit-oriented development (TOD) through different proposed projects, the impaired state of the Waikele and Kapakahi watersheds are certainly a subject of concern. This report emphasizes the importance of complete wetland restoration and targeted riparian area restoration.

Through this paper’s research and site assessments this study makes the following recommendations:

1. Limited (as feasible) restoration of riparian areas along the Kapakahi Stream

2. Enhance infrastructure/riparian restoration to decrease non-point-source pollution

3. Continue “citizen scientist” and community/school restoration projects

4. Encourage entire system restoration

a. Establish network of hybrid shoreline to provide flood risk management benefits b. Focus on complete marsh restoration

5. Consider Climate Change - SLR (can overwhelm restoration processes and capacities) a. Consider combined engineering solutions (levees or berms) with green infrastructure

6. Follow through with Waipahu Town Action Plan objective to establish interpretive signage at Pouhala Marsh.

a. Increasing awareness can lay the foundations for community stewardship.

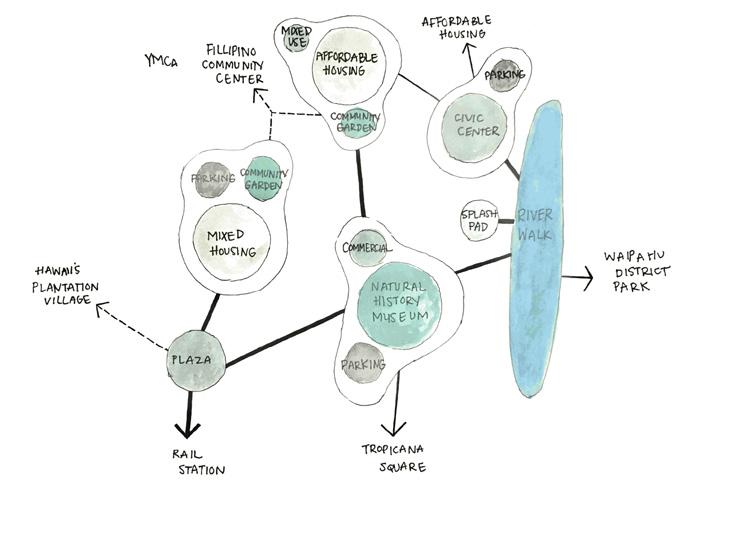

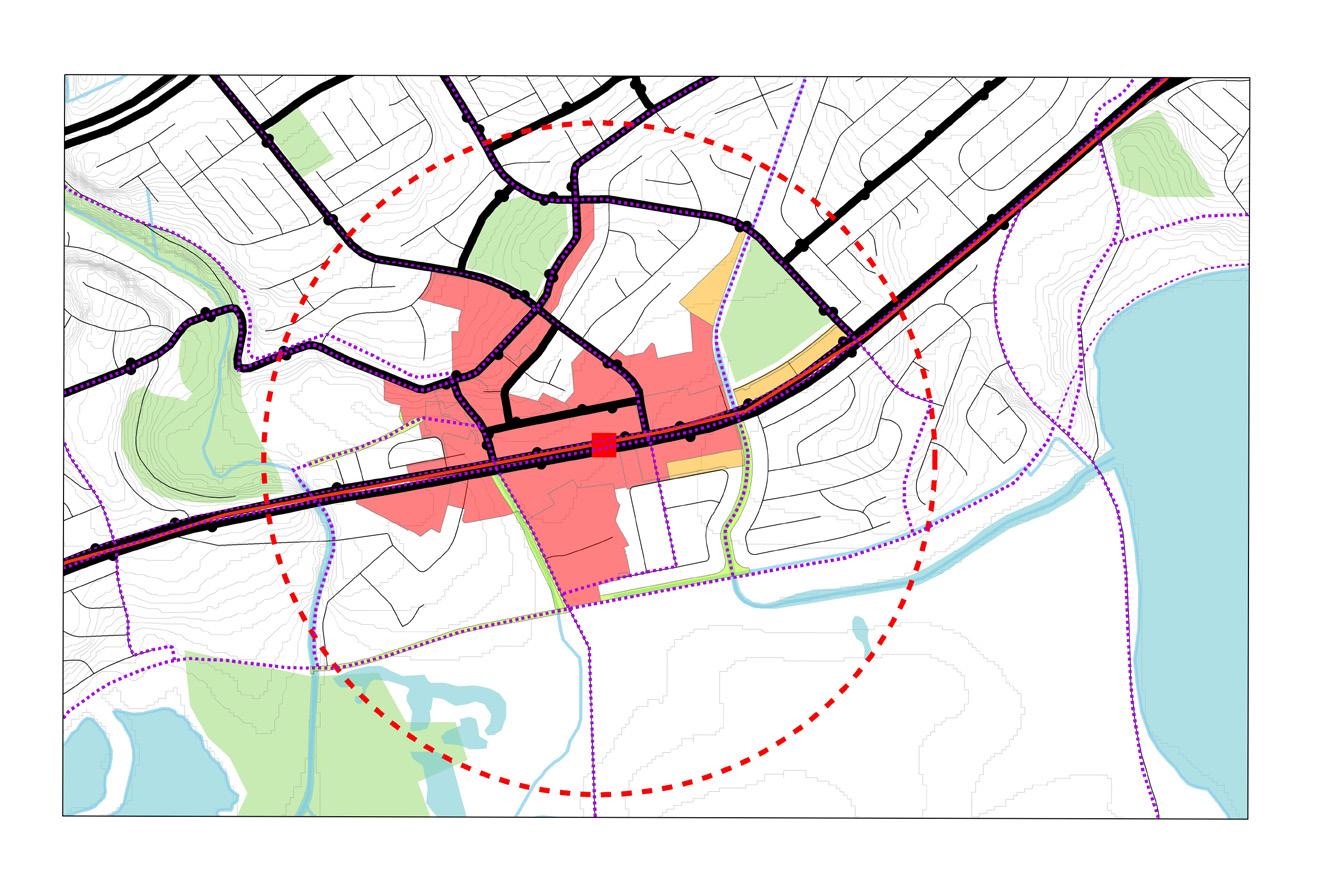

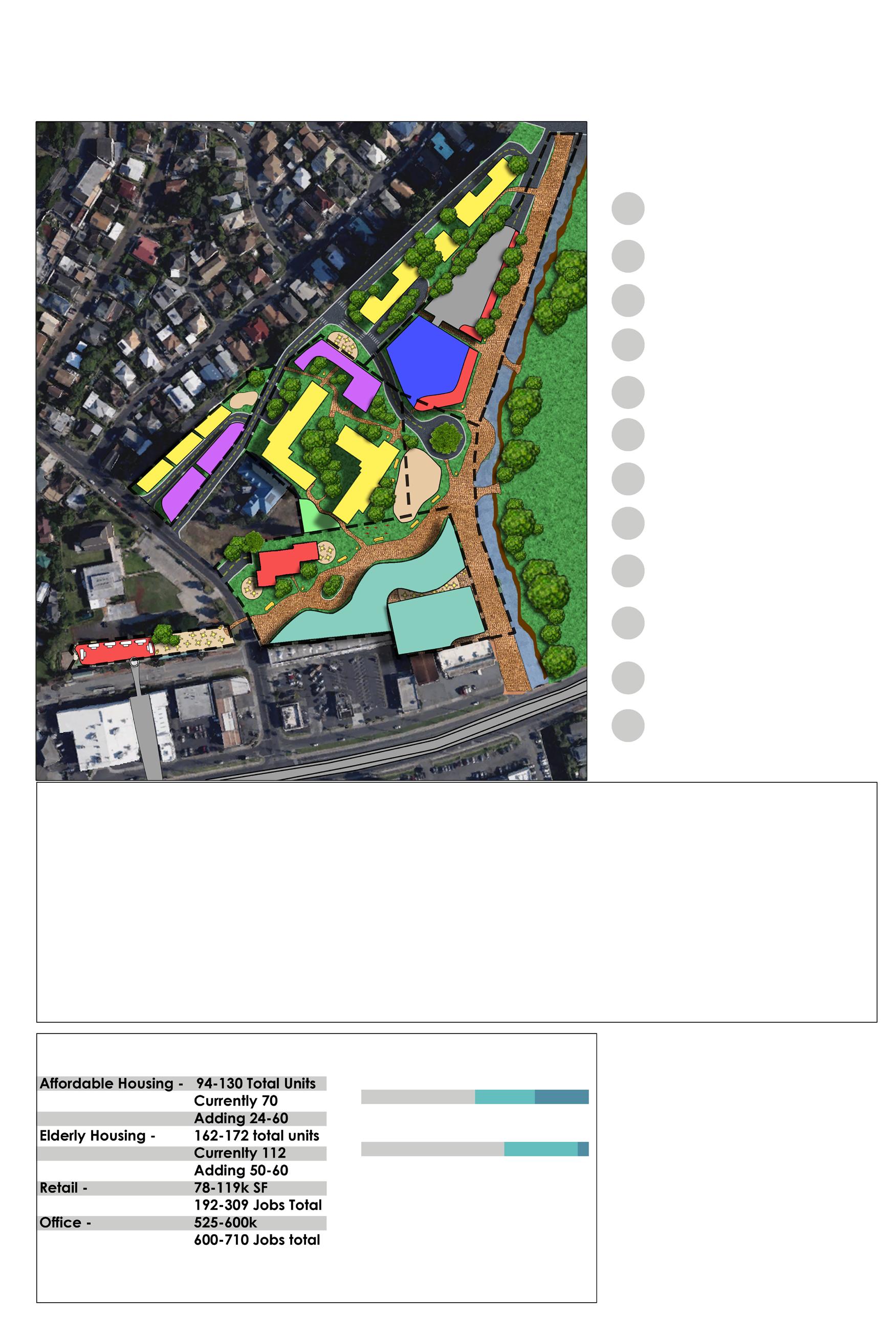

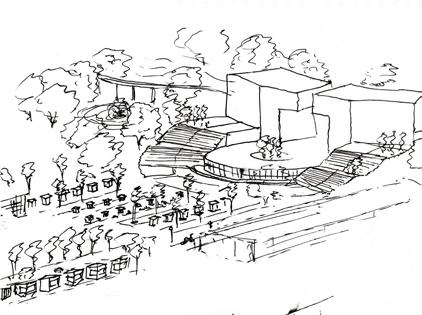

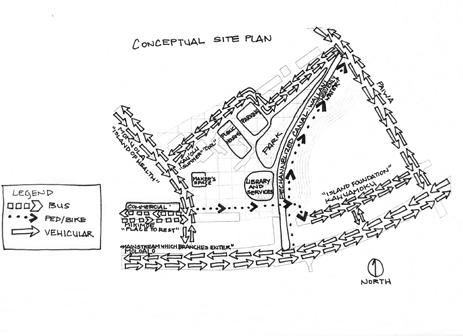

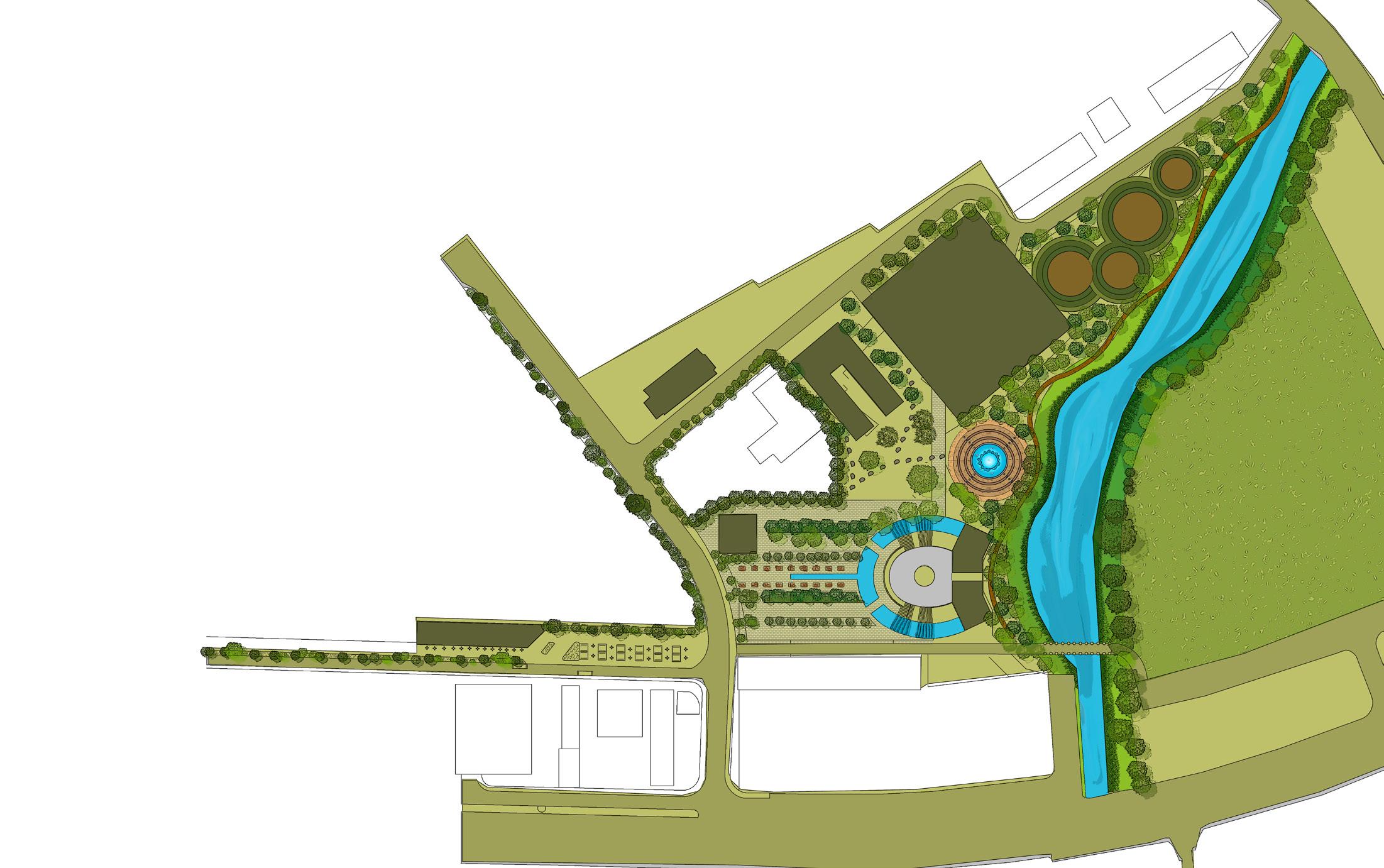

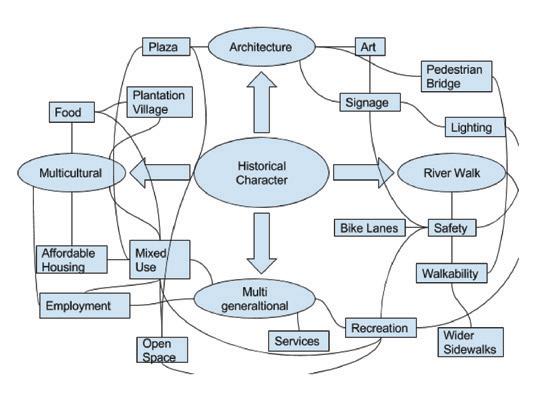

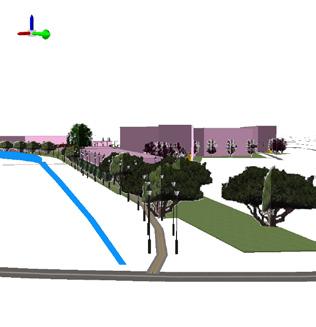

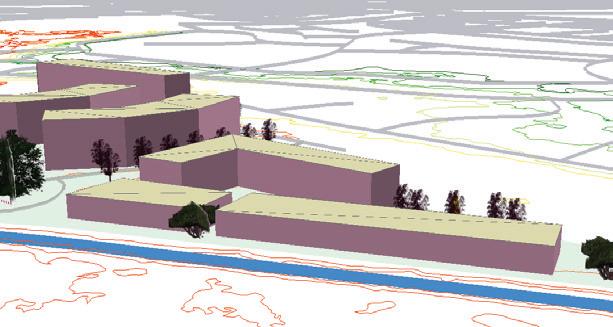

This course focused on three components including 1) how market and non-market forces interact in shaping the built environment 2) fundamental principles of site planning and 3) graphic communication for planners. Students learned to respond to a RFP through a handson program called Urban Plan (supported by the Urban Land Institute) and use visual media to communicate design alternatives before developing conceptual site plans for six state parcels adjacent to the Pouhala Transit Center Station. Course deliverables included: three conceptual site plans and stakeholder interviews. Students were expected to do multiple site visits, gather data, and analyze existing conditions and precedents to facilitate program and design development. The key research issues identified by the client included: potential use of the Waipahu Civic Center as an elementary school, alternatives for the relocation of social services housed in the Waipahu Civic Center, impact of flood zones on future development in the six parcels, and alignment of proposed land uses with the community’s cultural identity, history, and demographics.

• September 23, 2017: Site visit; guided tour with client; overview of neighborhood, socio-demographic characteristics, existing conditions within a quarter-mile and halfmile radius including the Pouhala Transit Center Station, and the City and County’s TOD plan for the area.

• October 17, 2017: Completed interviews with stakeholders, site analysis and precedent studies

• October 31, 2017: Midterm presentations in collaboration with PLAN 620 students; presented findings and received feedback from external reviewers including client representative

• November 7, 2017: Concept and program development

• November 14, 2017: Design development

• December 15, 2017: Final deliverables presented to the client and stakeholders

Student teams conducted stakeholder interviews to learn more about existing conditions on the six state parcels. These interviews with representatives of State agencies, community organizations, and small business owners informed site analysis and, consequently, conceptual site design. First, student teams investigated the six parcels through a site inventory, which entailed a thorough documentation (mapping, data collection) of the broader context within which the site was located. Second, they analyzed the site to identify on-site and off-site opportunities and challenges for implementing the proposed land use program. The six key site inventory and analysis themes included: regional context, history and social character, culture(s) and community values, built form, transportation, land use and environment. Finally, students formed three larger groups to develop conceptual site plans drawing on their analyses and interviews. They focused on the following questions:

i. Regional scale: How does the concept/big idea respond to the larger context? What are the key drivers (e.g. from site analysis, stakeholder interviews, and precedents) that

inform the concept?

Drawing should include a regional schematic context map/relationships with surrounding land uses (including the City and County’s TOD Neighborhood Plan); circulation (how do vehicular, pedestrian, bike circulation intersect with the proposed program? Indicate the levels of circulation using different line weights/colors for arrows, particularly among nodes at this scale); hydrology (how does this influence/ shape the concept?); network of open spaces (how can existing and proposed open spaces be connected and how would that leverage the use of these spaces?)

[Select an appropriate graphic scale for the final: e.g. 1”=500’]

ii. Site scale (focusing on the 6 parcels and adjacent areas – quarter-mile or half-mile radius): How does the concept transition into a program of uses? What mix of uses are appropriate for an “urban village”? How much of each use? Where? How does the proposed program respond to adjacent parcels, to the Pouhala Transit Center Station and other nodes (e.g. cultural, social) and site characteristics (e.g. environmental, codes, ordinances)?

Drawing should highlight concept and program (land uses/facilities), acreage/square footage for each use, relationships among different uses (transferring the conceptual bubble into actual buildings, parking, open space, and circulation – vehicular and pedestrian). Configure building footprints, particularly new ones so that they are placed appropriately on the parcels. Draw on site analysis findings for placement decisions and add details such as vegetation, streets, sidewalks, and so on. [Select an appropriate graphic scale for the final: e.g. 1”=200’]

iii. Block and street scale: What anchors the concept or ‘big idea’? What is the focal point or organizing element of the plan?

Drawing should provide a more detailed version of a focal point in your concept – what is the organizing element(s) that holds the plan together? This could be a street, green infrastructure, a gathering space, a building, and so on. Include urban design elements, supported with sections or sketches.

[Select an appropriate graphic scale for the final: e.g. 1”=100’ or 1”=50’]

Each of the three conceptual site plans developed a project program that responded to the client’s needs and priorities while considering community goals such as affordable housing, public health and safety, protecting natural and cultural resources, and enhancing local economic development. They leveraged intrinsic and extrinsic site factors that became apparent through site analysis.

This concept is based on the idea of flow and coalescence in the living environment: flow of water, people, culture, and history. It calls for the redevelopment of the six state parcels to support inter-generational connection through the removal of barriers (material and visual) between the parcels, allowing visitors and residents to coalesce around gathering places. The premise is that this will create a place with a sense of ownership.

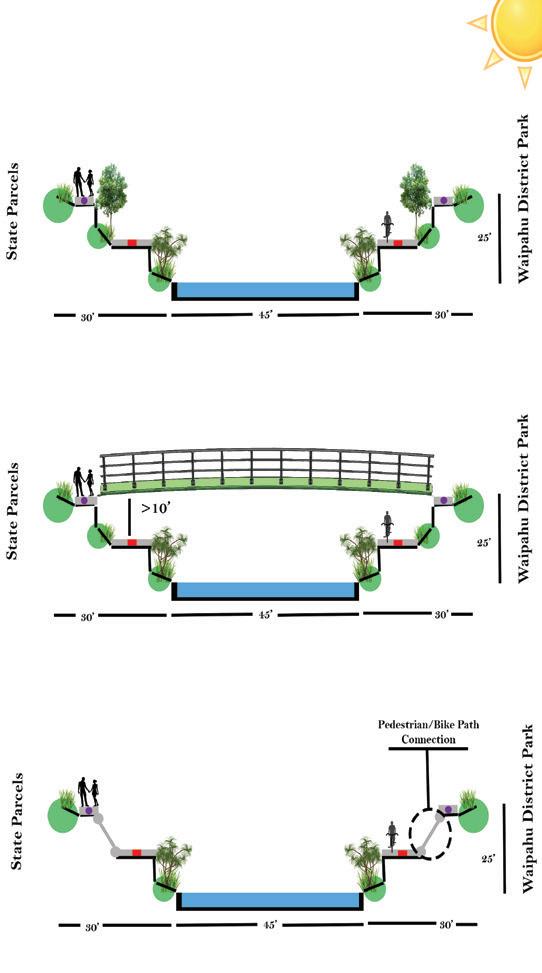

To enhance connectivity and encourage experiences in nature, the conceptual plan recommends creating a Hawai‘i Exploratorium, dechannelizing the Wailani canal, providing a promenade, and restoring native vegetation.

• The Hawai‘i Exploratorium will create an interactive space for exploring Hawai‘i’s rich natural and built history while learning about anthropogenic forces shaping the islands’ future. It will also offer other community gathering spaces such as a library and digital education center, a child day care center, a public gathering space, and space for schools to use in the future.

• Dechannelizing the Wailani drainage canal will allow water to flow in a semi-natural state while providing space for the stream to swell during times of heavy rain. Benefits of such an intervention include enhancing wildlife habitat, decreasing water and air pollution, and increased flood protection.

• The Wailani promenade will facilitate a flow of people to promote coalescence across generations. It will provide a place for social interaction, and help improve residents’ physical and mental health by offering respite.

An interactive educational space for ex ploring Hawai`i’s rich natural and built his tory while learning about how anthropo genic forces are shaping the islands’ future. The Exploratorium building also offers com munity gathering space, including: Library and Digital Education Center

Child Day Care Center

Public stage and reservable space

Potential space for a school to meet future needs

Dechanneling Wailani Drainage Canal will allow water to flow in a semi-natural state, while providing space for the stream to swell during times of heavy rain. Benefits may include:

Enhanced habitat for wildlife and opportunity for native vegetation

Decreased water and air pollution

More aesthetically pleasing

Better flood protection and area for water overflow

Waipahu in Hawaiian translates to “bursting waters.” This walkway is provides flow be tween people and the natural environ ment, and allows people to coalesce across generations. The promenade pro vides the following benefits:

Increased physical and mental health Space for people to take respite

A place for happenstance, where users can connect between Waipahu District Park, Paiwa Street, and the Pearl Harbor Historic Bike Trail

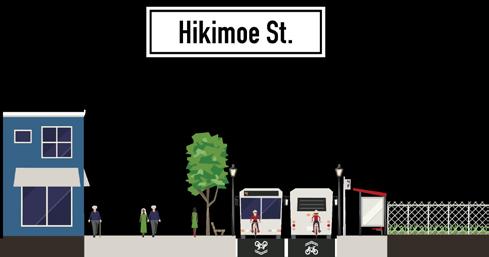

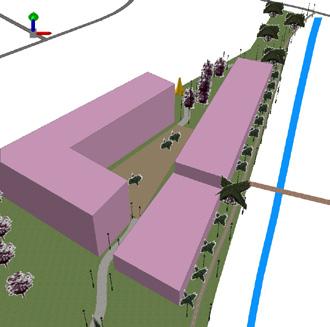

This design concept calls for the creation of Wailani Place, a free-flowing space to connect and rejuvenate the community, a space that celebrates the intertwining of water, history, and culture. The conceptual plan proposes increasing walkability, implementing infrastructure to adapt to climate change, and designing spaces that activate the public realm.

• Increasing walkability will present a seamless experience by connecting transit to community resources. The plan recommends adding 3,500 ft. of bicycle and pedestrian pathways, 100,000 sq.ft of street level marketplace, 350 housing units, and 230 jobs with easy access to public transit.

• Creating community resources designed to keep pace with changing neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics will support adaptability. A part of this plan will involve creating a green rooftop to accommodate 700 parking spots that will also serve as a community garden. Dechannelizing 1,584 ft. of Wailani canal and incorporating five floodable features along the Wailani canal walk will address flood mitigation.

• Connecting the community to its past through interactive spaces incorporating education and family recreation is important for its overall wellbeing. This can be accomplished by preserving 78% of the area as open space. The addition of a 20,000 sq.ft public library with high-speed Internet access will provide public service to the community. Incorporating 11,520 sq.ft. of makerspace and public markets will help to support farm to table initiatives, community gardens, classes, inter-generational activities, and trade skills.

Wailani Place celebrates the intertwining of water, history, and culture by

Waipahu

Waikele

Wailani

Pouhala

Hikimoe

Mokuola

Moloalo

Kau

Olu

Place to rest

Island of health

Main stream into which branches

Summer

Cool, refreshing,

Kaihualani

Site

3,500 feet of Bicycle and Pedestrian Pathways

100,000 square feet of Street Level Marketspace

350 Housing Units Accessible to Transit

230 Jobs Accessible to Transit

700 Parking Spots in Green Rooftop Parking Structure

5 Floodable Features Along Wailani Canal Walk

1,584 feet of Wailani Canal De-channelized for Flood Mitigation

20,000 square foot Public Library

90,000 square feet of Office Space for Service Providers

78% Open Space 11,520 square feet of Maker’s Space for Community Use

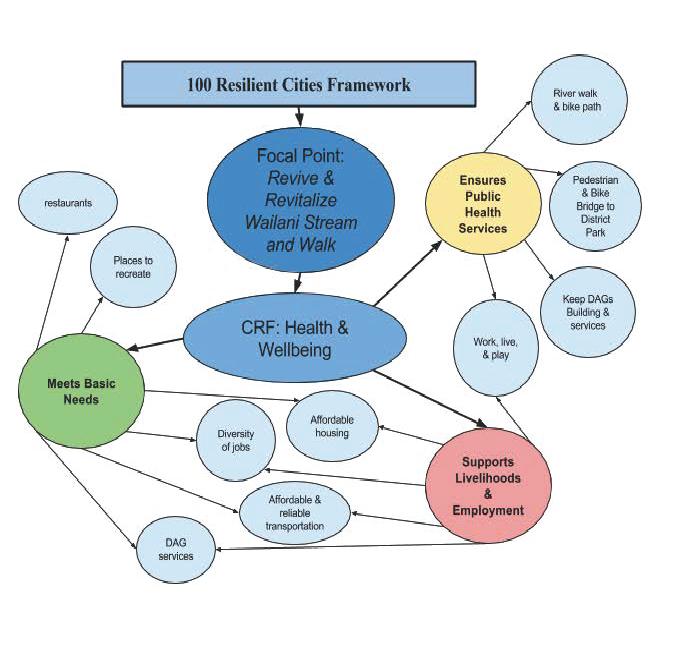

This design concept envisions the restoration of Wailani canal to showcase its importance as a life source and gathering place for Waipahu. It aligns future development on the six state held parcels with meeting basic needs, supporting livelihoods, and providing adequate public services. The concept calls for the provision of ample green space in Wailani to encourage an active lifestyle for Waipahu residents. The proposed parks and recreational facilities provide opportunities for physical activity accessible to a diverse group of community members. Four key recommendations in this plan are:

• At least 30% affordable housing in each housing block.

• A mix of affordable housing throughout the development to promote diversity and community interaction.

• Revision of parking requirements to promote TOD and alternative transportation.

• Creative use of savings from reduced transportation costs toward promoting housing affordability.

University of Hawaii at Manoa

Building #1 (4-Story Mixed-Use) - Department of Accounting and General Services (DAGS) - Library (1st Floor) - After School programs - Adult/Child Daycare

Building #2 (3-Story Mixed-Use) - Workout Gym - Yoga/Dance Studio - Boxing/MMA Gym

Building #3 (4-Story Mixed-Use) - Retail (1st Floor) - Bike/Skateboard Shop - Co ee Shop - Convenience Store (7/11, Deli) - Biki Stop - Studio Apartments (2nd - 4th Floors)

Building #5 (6-Story Mixed-Use)

- Corner Convenience Store (1st Floor) - O ce Space (1st Floor) - Bank - Insurance - Medical (1st Floor) - Pharmacy - Housing (2nd-6th Floor)

Building #6 (6-Story Mixed-Use) - Medical (1st Floor) - Pediatrician - Medical Clinic - Dentist -Diagnostic Lab - Urgent Care - Retail/Restaurants (1st Floor) - Dine-in/Take-out - Cafe - Vitamin Shop - Sports Shop - Housing (2nd -6th Floors)

Building #4 (4-Story Mixed-Use) - Small Business Retail Market (1st Floor) - E.G. South Shore Market - Cater to Residential Market - Pub/Sports Bar (2nd Floor) - O ce Space (2nd Floor) - Housing (3rd-4th Floors)

Building #7 ( 3 6-Story Mixed-Use) - Retail/Restaurants (1st Floor) - Co ee Shop - Ice Cream Parlor - Bakery - River Walk Restaurants - Housing (2nd-6th Floor)

University of Hawaii at Manoa Department of Urban and Regional Planning

This course focused on urban infrastructure, how to define it, how it’s planned and regulated. Students learned about limitations of existing infrastructure and green infrastructure practices. By end of semester they were able to connect the built environment, urban development, and multi-modal transportation access.

This course’s deliverable was completing an infrastructure capacity analysis. This deliverable was completed in the form of a final report through a process described in the following sections.

• In-Class Exercise 1 (1/31/2018) = Transportation Demand Analysis

• Field trip (2/28/2018) = Community Mapping Data Collection

• Assignment 3 (3/7/2018)= Interview a practitioner about the existing condition of infrastructure in the Waipahu TOD area

• In-Class Exercise 2 (3/14/2018) = Community Infrastructure Needs Survey

• Analysis = Survey on the field trip with analysis of the result of the survey to better understand infrastructure needs and desires from the local community

• Final Presentation (4/4/2018) = Capacity Analysis for Transportation and

• Green Infrastructure = Identify the capacity, constraints, and opportunities for infrastructure development in Waipahu TOD area.

In urban infrastructure planning, public participation and local knowledge synthesis are the keys to efficient infrastructure planning. The information input from residents can provide insights on, for example, what kinds of places and routes different groups of residents find pleasant, calming, inconvenient, unsafe, including sites where respondents experience flooding, which activities they appreciate, how the environment supports or hinders these activities and what kind of future the different demographic groups find worth striving for (Juhola et. al., 2013). However, planning and decision-making are complicated by competing arguments on whose benefits to prioritize (Bäcklund, and Mäntysalo, 2010). The subjective nature of residents’ input makes it special as compared to inputs arising from ecological and other professional or scientific types of knowl edge, as the latter may be regarded as objective’ and non-political (Delvaux, and Schoenaers, 2012). Nonetheless, the importance of community needs assessment can’t be undermined.

The assessment made by the students from Urban Infrastructure class at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP), for community needs in Waipahu, incorporate the questionnaire surveys. A total of 45 responses were collected for both transportation and green infrastructure surveys. Sets of questions were asked, eliciting community perspectives on issues related to transit-oriented development (TOD). Two questions were highlighted; 1) the severity of issues identified and 2) the desired improvements in Waipahu. The results of the survey indicated that over 50% of the respondents felt traffic congestion and safety were the biggest issues. Indicators used for determining safety include bicycle and pedestrian, street light, crime, and flooding. The second severe issue was insufficient parking and followed by limited

bus stops, bike lanes, sidewalks, and accessibility to existing facility such as green space. The desired improvements place an emphasis on the provision of parking and bus stops. We found some consistencies in the survey results conducted by DURP students and results from the department of planning and permitting (DPP), particularly on the physical safety. The DPP used randomly selected sample of 2,700 households within a half mile of the Waipahu and West Loch transit stations. The top two concerns were related to mobility; 60% of respondents wanted to see improved sidewalks, 45% wanted more car parking, and 36% wanted more walking paths and trails. However, there are differences in the sample sizes, length of the questionnaire, and the survey methods. The DPP survey provided a more complete and thorough explanation on community’s perspectives than DURP survey.

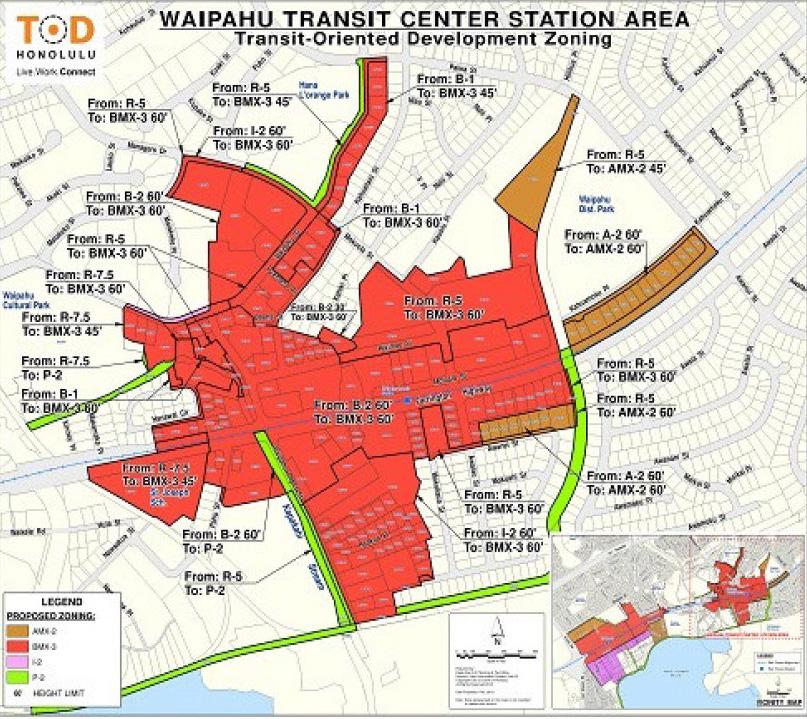

Accurate forecasting is vital for effective planning during the design and construction of infra structure projects. The purpose of the maximum build-out analysis is to determine if the current or any future infrastructure would suffice to support a maximum build-out. This scenario is based on the TOD special district zoning changes (see figure 1), however, also on assumptions that certain parcels would have better corresponding uses. Large floor area ratio (FAR) of 3.5 is used for the calculations for parcels zoned BMX-3 (community business mixed use), which would include bonuses granted if the development provides social benefits to the community such as public space and a high percentage of affordable units. FAR 1.9 is used for parcels zoned AMX-2 (medium-density apartment mixed use). Accurate forecasting is vital for effective plan ning during the design and construction of infrastructure projects. The purpose of the maximum build-out analysis is to determine if the current or any future infrastructure would suffice to support a maximum build out. This scenario is based on the TOD special district zoning changes (see figure 1), however, also on assumptions that certain parcels would have better correspond ing uses. Large floor area ratio (FAR) of 3.5 is used for the calculations for parcels zoned BMX-3 (community business mixed use), which would include bonuses granted if the development provides social benefits to the community such as public space and a high percentage of afford able units. FAR 1.9 is used for parcels zoned AMX-2 (medium-density apartment mixed use). The heights are set to the maximum for BMX-3 and AMX-2 with 60 feet and 45 feet respectively Maximum FAR and building heights are drawn from the recommendations on the TOD zoning. The 1,000-unit public housing project detailed in the State TOD Plans are given a value of 450 sqft based on an estimate of the average sizes of the existing units in Hoolulu and Kamalu. A val ue of 600 sqft is given to any other residential units that are not public housings, whereas 1000 sqft is given to both office and retail.

Overall, the results generated from the build-out scenario show a high development scale within BMX-3 parcels, with the total area ranges from 0.5 to 4.5 acres. Approximately 2,052,249 sqft of the area will be created, which translates into the generation of 1,374 dwelling units in the residential area, 676 office units, and 300 retail units. Similarly, a total of 251,473 sqft will be generated for AMX-2, which consists of an additional 329 dwelling units and 42 retail units. The assumption is that this scenario would likely to create more retail activity and the provisioning of office space, hence, resulting in a wide variety of job creation.

The result from the maximum build-out analysis is partially used to calculate other equally im portant factors in developing the surrounding TOD.

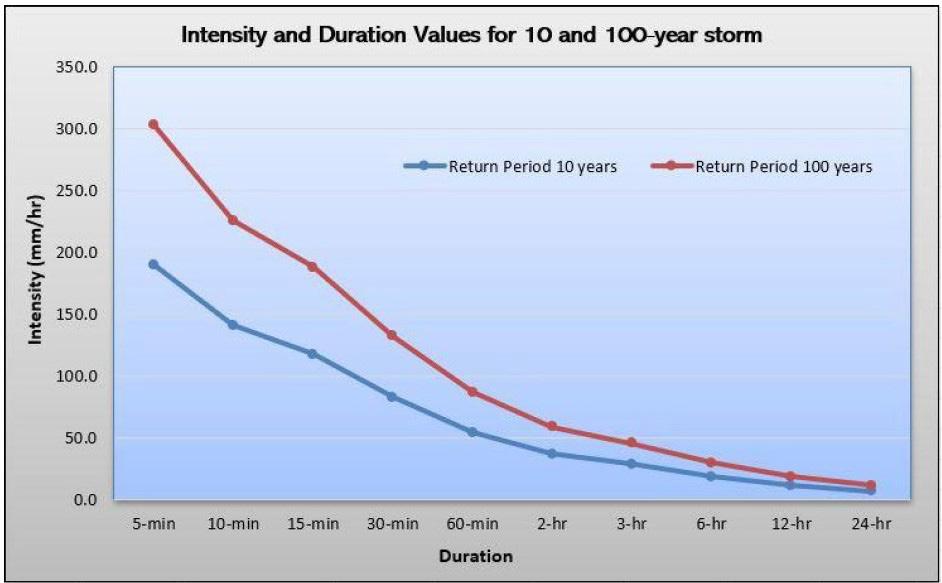

This section presents a rough assessment and estimation of surface runoff in a smaller portion of Waikele watershed. Great attention is paid to two focused areas; Waipahu and state parcels located adjacent to Waipahu transit station. Surface runoff is an important and significant factor affecting the development and progress of floods, soil erosion, and other hydrological hazards (Vojtek et al., 2016). For the analysis, the spatial interpretation of different land use categories incorporating the digital elevation model (DEM) is used, as well as the calculation of local precip itation of 10 and 100-year return period in order to estimate the time of concentration of surface runoff. The 10-year span indicates the common design standard used for stormwater facilities, and the 100-year is used for a case of extreme flooding.

Generally, the calculation of surface runoff is based on the potential retention in the catchment (Vojtek et al., 2016), and then calculated using the values of representative IDF curve numbers. However, this analysis uses a simplified approach using Rational Method Equation, which is the simplest method to determine peak discharge from drainage basin runoff, as well as the most common method used for sizing sewer systems: Q = 0.0028 CiA, with Q represents the peak runoff rate (m3/s), C is runoff coefficient, i is the rainfall intensity (mm/h), and A is the total area (ha).

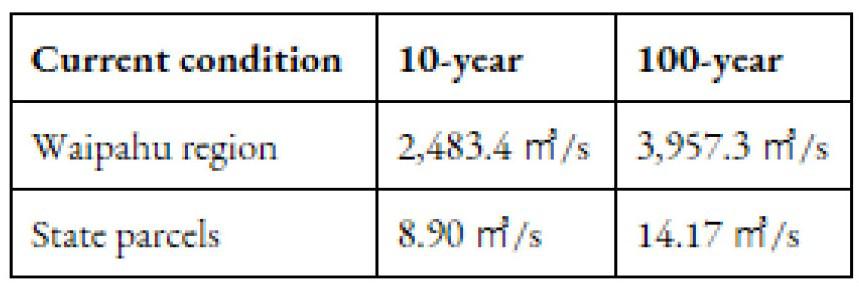

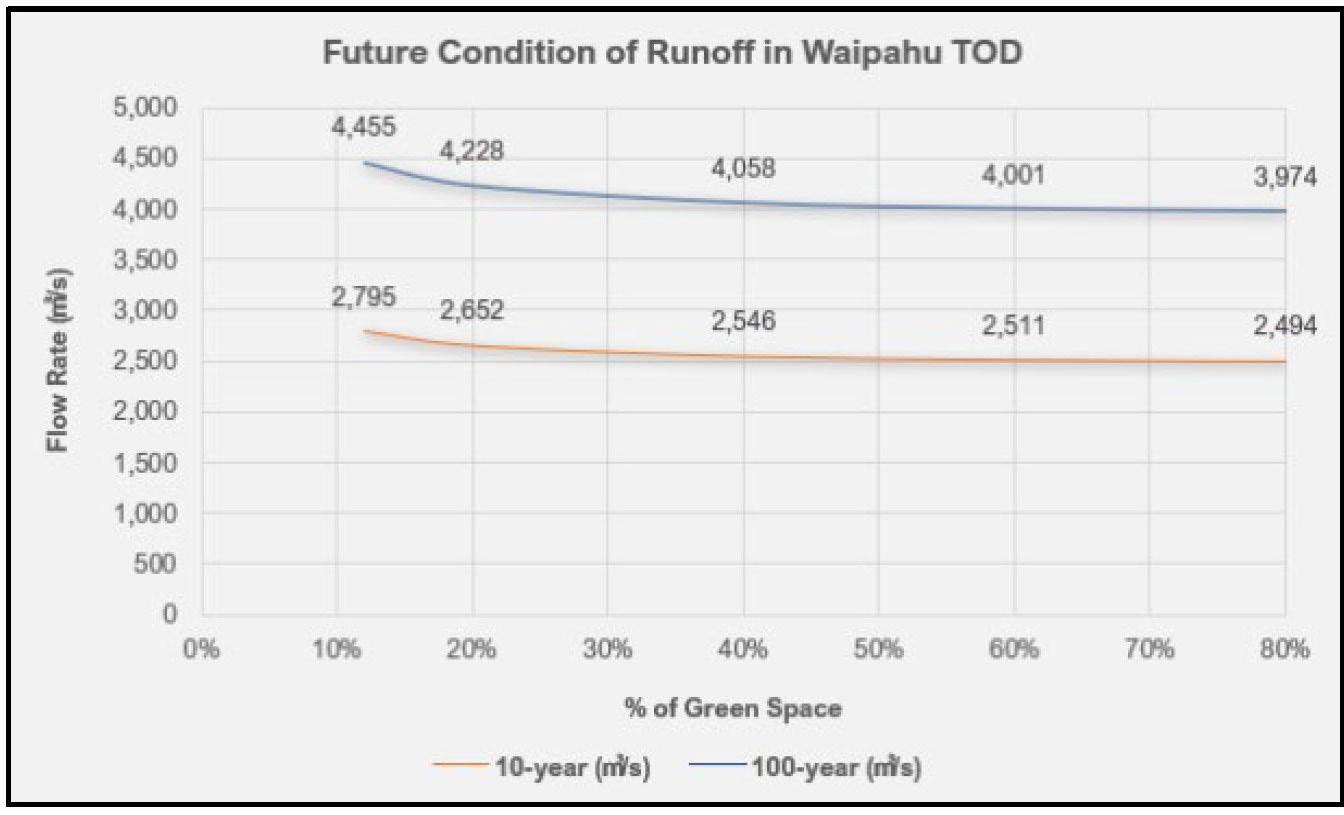

In the present condition (see table 1), the surface runoff has always been the case during rainfall. Farrington highway and streets in low-lying areas are prone to flooding. The increased amount of impervious surface, particularly in retail, residential and parking areas have over time contributed to the increase in flow rate in Waipahu region. The expansion of the green space is to mitigate

Intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curve combined for 10 and 100-year return

Figure

Figure 3. Run-off flow rate when combined with green space

Table 1. Future condition of surface runoff flow rate

the issue; if the 12% of green space is added to the current TOD zoning, approximately 2,795 m3/s is expected to be generated during the 10-year return period. In order to keep the flow rate at the current level, the future estimation encourages the zoning to set aside ≥ 80% of the devel opment as green space (see figure 3).

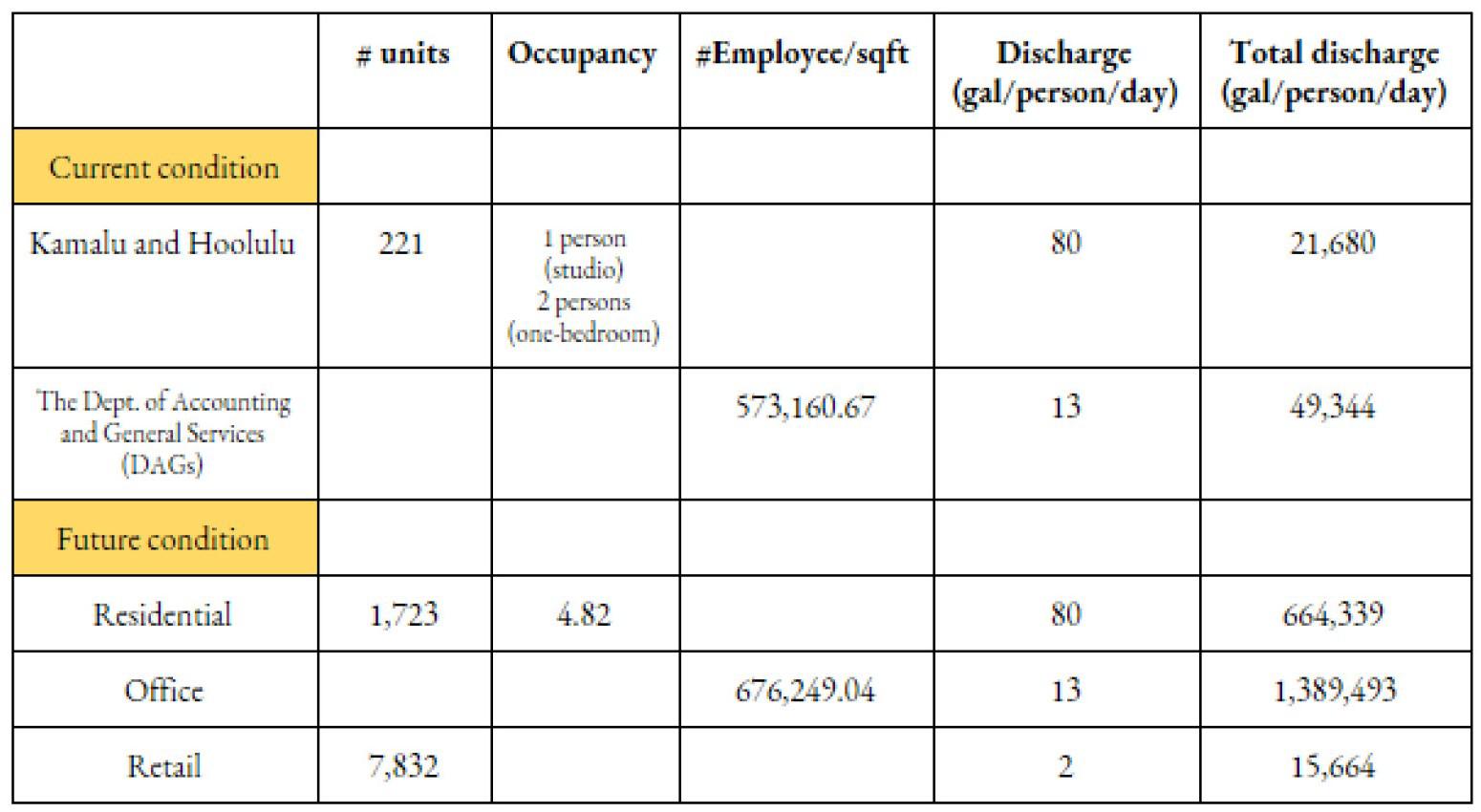

When planning for development in the region, it is important that population projection is taken into consideration. For the proposed TOD development, one of the objectives is to estimate the usage of sewer, water, and electricity need for the future, or the amount that will be produced once the development takes place. This section explores further the current situation in the state parcel development and the implications for future development.

The data obtained from the Department of Environmental Services indicates that the current per capita/sqft sewage treated is at an approximate of 80 gal/person/day. As more development is adopted, the population and overall density are projected to increase. In terms of designing the future sewer system, it is important that the current development follow the design guide lines and in accordance with the latest revision of the City and Country Standard Construction Specifications. Table 2 shows current and future sewer usage in the residential and office areas. For the future condition, the results from build-out analysis such as dwelling units, number of employees per square foot, and retail (see table 5 for estimated parking) are incorporated to create assumptions on the amount of wastewater produced. A simple calculation is applied for residential: #housing units X occupancy X discharge per person OR #dwelling units X HH size X discharge per person

Most of the wastewater that enters the system flow toward the Waipahu Wastewater Pump Station. According to the Environmental Assessment for the Waipahu Wastewater Pump Station

Modification (1995), the pump station can only accommodate flows up until the year 2020. Currently, the sewer system is adequate for a population of about 198,000 people within Central Oʻahu, and 28,000 of those customers are from Waipahu. Currently, in the state parcels, there are 16 sewer mains with diameter ranges from 8 to 24 inches, 2 sewer laterals with a diameter of 6 inches, and 13 sewer manholes. The volume for sewer mains is 16 times of the lateral, and suppose the laterals are not enough to accommodate current usage, then it is quite likely that the sewer mains could not meet the needs for future development. There are implications from the proposed development in Waipahu; it will likely to contribute to 28.8 times greater than the currently generated wastewater. The density changes in the TOD area are also expected to result in increased wastewater flows, which will necessitate needed upgrades to the pump station.

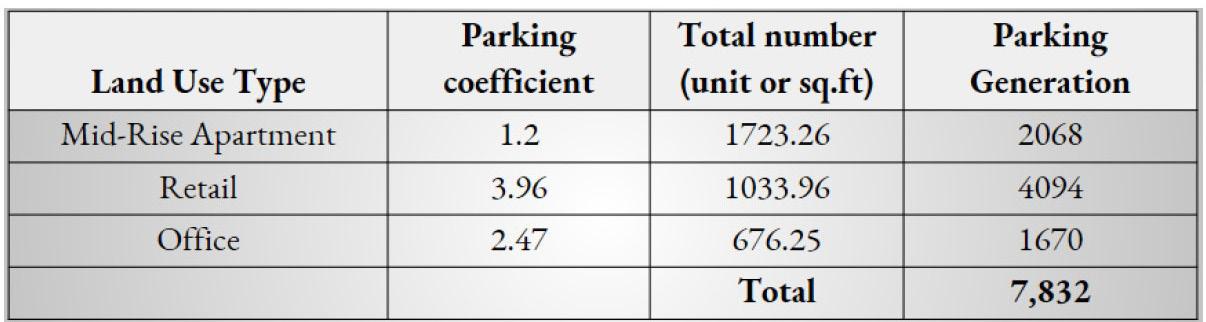

Parking generation estimates are calculated using the build-out scenario and are done using generation parking coefficients from the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Parking Generation Report, the 4th edition. The parking generation numbers would most likely be much lower in reality, especially in a TOD where the parking requirements are reduced if not eliminated. However, it is still relevant to get estimates of parking generation given a maximum build-out scenario. It is assumed that future apartment buildings would have mid-rise characteristics in an urban setting. This coefficient came out to be 1.2 parking stalls per dwelling unit. The shopping coefficient of 3.96 per 1000 sqft was used to calculate the parking generation of retail. This coefficient is likely much larger than what would be present in a TOD. However, for compar ative purposes and lack of data to a more accurate coefficient, 3.96 is still used for the parking generation calculations. The number of parking stalls generated in an urban office building is 2.47 stalls per 1000 sqft. For the elementary school in parcel 4, an estimate of the number of students in the school is based on how many students were in a school of similar size. Manoa elementary school, which contains about 550 students, was used in this case and generates 0.17 per student. Finally, the library generates 0.42 stalls per sqft in urban areas.

This section provides several recommendations that emerge from our analysis in Waipahu, as well as literature and community goals:

1. The survey from City and County of Honolulu and students at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) suggest a strong interest in walkability and the provision of recre ational facilities. The research relevant to green infrastructure planning also insists on the central challenge of flooding and stormwater runoff. Planners work with Waipahu TOD may choose to consider greenways, corridors, green spaces, which, if implemented properly, may better inte grate the need for reduced flooding and stormwater runoff while satisfying community needs.

2. Incorporate elements of green roofs and bioswales in the future state coordinated develop ment plans could become an importance in the face of rising tides and extreme weather events. Research suggests green roofs have the potential to retain a high percentage of rainfall, however, meeting targets during extreme weather events will be instrumental to successful implementa tion in Waipahu.

3. Consider using decentralized wastewater treatment that can reduce the overflow incidents from centralized system contributing to the surface water pollution. A decentralized sewer that put emphasis on wastewater treatment and recycling system can likewise reduce the demand on public water infrastructure and water resources.

4. Eliminate minimum parking requirements, and implement district level parking maximum, and

Table 2. Current and future condition of sewer

Table 3. Parking generation from build-out scenario

adopt regulations and incentives encouraging shared and adaptable parking. Mixing land use, as one objective of the TOD, is a catalyst for increasing parking efficiency and reducing the amount of parking needed in an area.

There are lists of best management practices (BMPs) for infrastructure planning that can be used to meet the established goals for the transit-oriented development (TOD) in Waipa hu, including to prepare for emerging trends in transportation. For example, the city of Marlbor ough in Massachusetts has taken steps to decrease the oversupply of parking through provisions for shared parking, compact car spaces, and temporary reserve parking. Particularly on the compact car regulation, it allows up to 33% of a site’s required parking spaces to be reduced by 1 foot in width and 2 feet in length, which reduces the footprint needed to hold the same number of cars. In Oak Bluffs, MA, both fees-in-lieu and a shared parking program have been utilized within its zoning ordinance. Although the shared parking is obtained through a Special Permit process, it allows developers to find an alternative to meeting the minimum parking requirements in cases where excessive pavement may detract from community character and reduce quality open space (oakbluffsma.gov). In terms of reducing the stormwater runoff, the city of New York provides a decent example by implementing the green roofs in Javits Center. The 7 acres green roofs beside providing habitat for wildlife, it could prevent approximately 6.8 million gallons of stormwater run-off. The soil and shrubs present in the roof actively absorb water from storms, while simultaneously reduce the energy consumption by 26% or equal to saving 3 million USD. The heating and cooling costs are also reduced by 25%.

Infrastructure plays a vital role in shaping the extent and location of growth and development in a city, and the first step of determining how infrastructure will be built is in the creation of an infrastructure plan (Baer, 1997). A good infrastructure plan must be multidimen sional and integrated with other aspects of infrastructure planning in a comprehensive manner, rather than as an isolated element of planning and development (Neuman, 2012). For example, transportation plans must not only consider transportation demand, congestion issues, and multi-modal opportunities, but it must also consider land use and an environmental assessment of potential threats such as flooding, climate change, and sea level rise, among other things. Therefore, it essential that transportation infrastructure planning is linked with other aspects of infrastructure planning, such as green infrastructure.

Discussion - goals/objectives - Joint Site visit and midterm PLAN 620 & 678 (Picture on G-drive from midterm), joint community talk

• September 23, 2017: Joint site visit to Waipahu with PLAN 620 & 678

• October 31, 2017: Joint midterm presentations of PLAN 620 & 678

• April 12, 2018: Waipahu Community Talk with PLAN 620, 642, & 678

620 & 678 cross-scale

620 watershed scale

678 community local scale

Classes were able to share information and perspective to give more holistic perspective to pursue concept design 620 emphasized climate change and climate change impacts, especially flooding -Informs concept designs for 678

Watershed > community > design

Analysis of climate change and implications for parcels. Developing concepts for Ask 642 and 678 if they have further to add for

1. UCS Report 2017

2. City and County of Honolulu: Proposed Development Standards in the TOD Special District (Adopted October 2017)

3. Siekmann, T., & Siekmann, M. (2015). Resilient urban drainage–Options of an optimized area-management. Urban Water Journal. 12(1), 44-51.

4. State of Hawaiʻi. (2017). Unified Approach for Development of State Lands: Key Principles for State Investment in TOD/TRD

8. Bloomberg, M. (2006). A Greener Greater New York. The City of New York. a. Bloomberg, M. R., & Holloway, C. (2010). NYC green infrastructure plan. A Sustain able Strategy for Green Waterways.

9. Grannis, J. (2011). Adaptation tool kit: sea-level rise and coastal land use. How gov ernments can use land-use practices to adapt to sea-level rise. Georgetown Climate Center, Washington.

13. SRI Foundation 2012

14. Oceanit. (2017). POUHALA MARSH WETLAND RESTORATION. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from http://www.oceanit.com/pouhala-marsh-wetland-resto ration

15. Few, R. (2003).Flooding,vulnerability and coping strategies: local responses to a global threat. Progressing Development Studies. 3(1).43-58.

16. Labrador, R.N. (2009). We Can Laugh at Ourselves. Beyond Yellow English. 288308. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327359.003.0017

17. Yahirun, J., & Zan, H. (2016). Hawaiʻi’s Older Adults: A Demographic Profile. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi, Center on the Family.

18. Bardach, S.H., & Rowels, G.D. (2010). Geriatric Education in the Health Profession: Are We Making Progress? The Gerontologist. 52(5), 607-618. doi:10.1093/ geront/gns006

Table 1: Suggested Action and Potential Benefits by Transect

The Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) entered into an agreement with Waipa hu Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Collaboration to research how transit projects affect communities. Specifically, they wanted an in-depth, multi-scalar, and multidisciplinary study completed on a specific TOD area, Waipahu. From this study, a practicum report was generated that focused on four main subjects; climate change, economic development, housing, placemak ing, and transportation. Below is a summary of this report that contains historical background, descriptions, and recommendations in regards to each section.