for the CREATIVE and CURIOUS

59

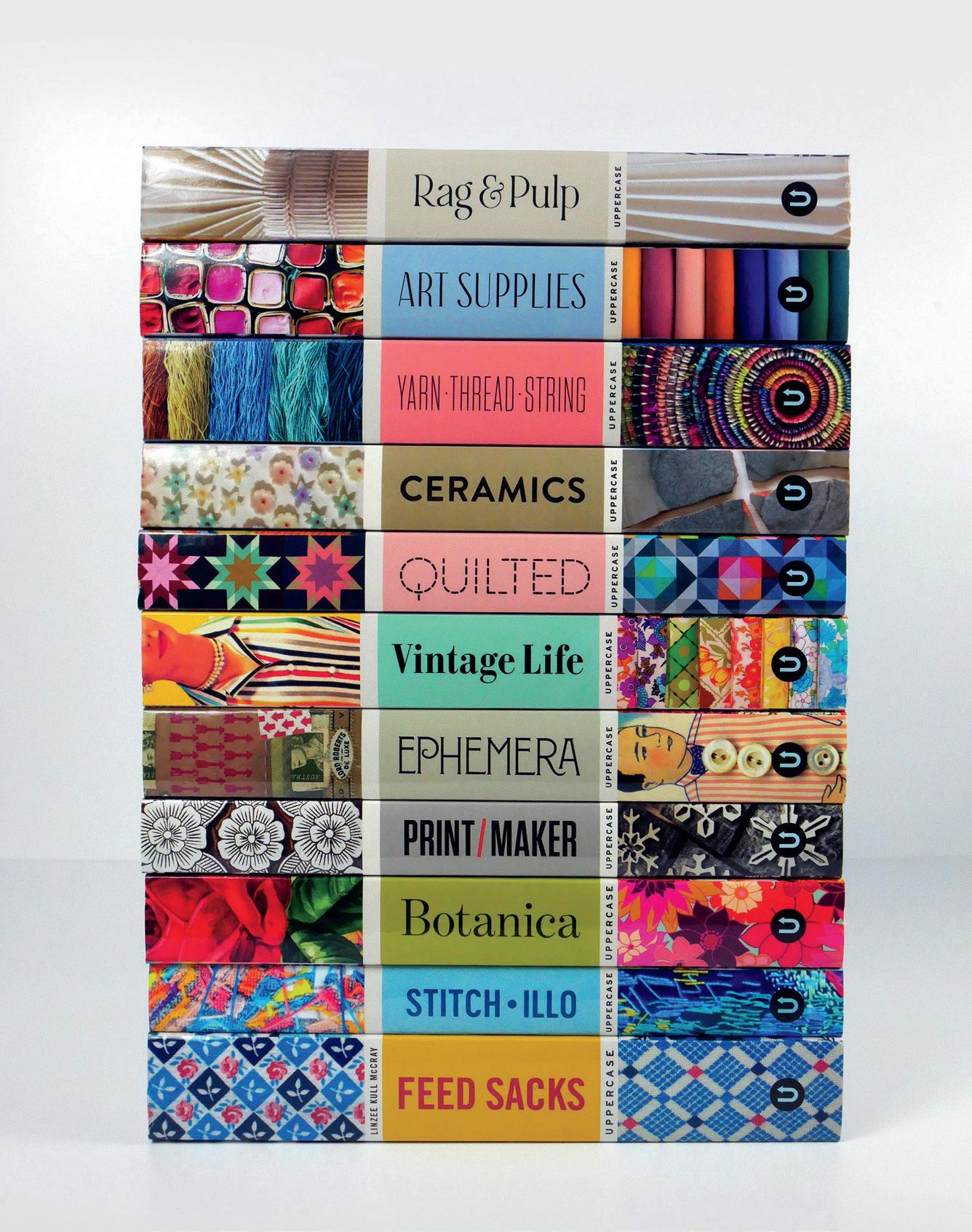

ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume N The UPPERCASE Encyclopedia of Inspiration encyclopediaofinspiration.com

FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

Dear Reader,

As creative people, we are driven by something that exists within us: a feeling we need to express, a thing we need to make, a perspective we need to share. It’s just part of who we are. Creating and making is our language of expression, our self-identity and, for those of us who make a living through art, our currency.

Although the bright glow of algorithmic social media might sway us from time to time, and the novelty of new artificial intelligence tools might grab at our attention, it is always worth remembering that how we use our creative time and talents is up to us. It is through mental exertion combined with physical effort that art and crafts are made. The marks that we make are uniquely ours, made real through our own hands.

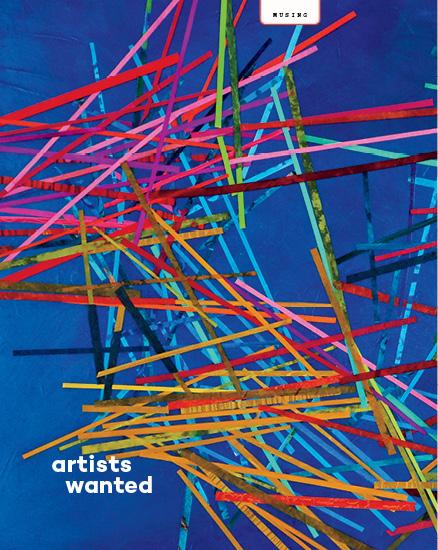

No artificial intelligence can replace what is unique to us as creative individuals. It’s what contributor Sharon VanderKaay calls “AH-HA”— authentic human-hand art—in her essay “Artists Wanted.” Authentic human-hand art is what we need now, more than ever.

So get your hands dirty. Eschew modern technologies. Mess around with mark making. Find yourself.

Janine Vangool PUBLISHER, EDITOR, DESIGNER

ENCYCLOPEDIA uppercasemagazine.com ||| 3

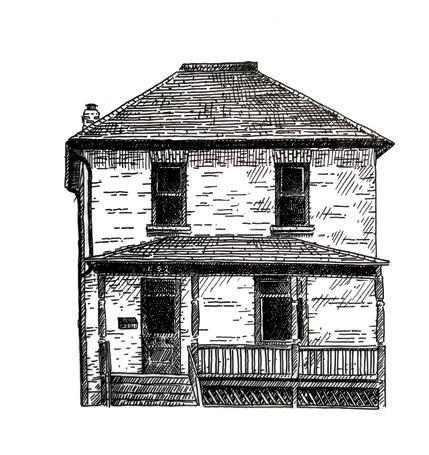

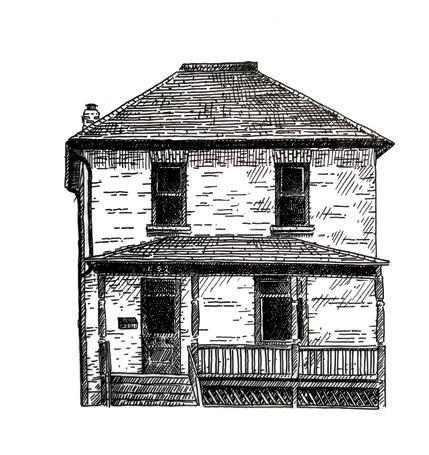

Sign up for my newsletter for free content and an introductory subscription offer: uppercasemagazine.com/free After 18 years of renting studio space, I’m thrilled to have moved into UPPERCASE’s forever home in a beautiful old home built in 1907.

OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER 2023 4 ||| UPPERCASE

Contents

Kathryn Davé is a writer living and working in beautiful Greenville, South Carolina. With experience in both advertising and journalism, she is driven by curiosity, narrative and instinct. Her editorial work is focused on art, travel, food and culture because she believes what we choose to make and share tells the story of who we are. Kathryn enjoys long runs, chasing her three little boys around, late afternoon sunlight and lazy dinners on the deck.

kathryndave.com

Welcome Editor’s Letter 3 Subscriptions 6 Snippets . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 BEING 10 A Season for Stitching by Meera Lee Patel FRESH . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 Malika Victor, Jody Rita, Rolla Elmeligi, Dayna Wilson

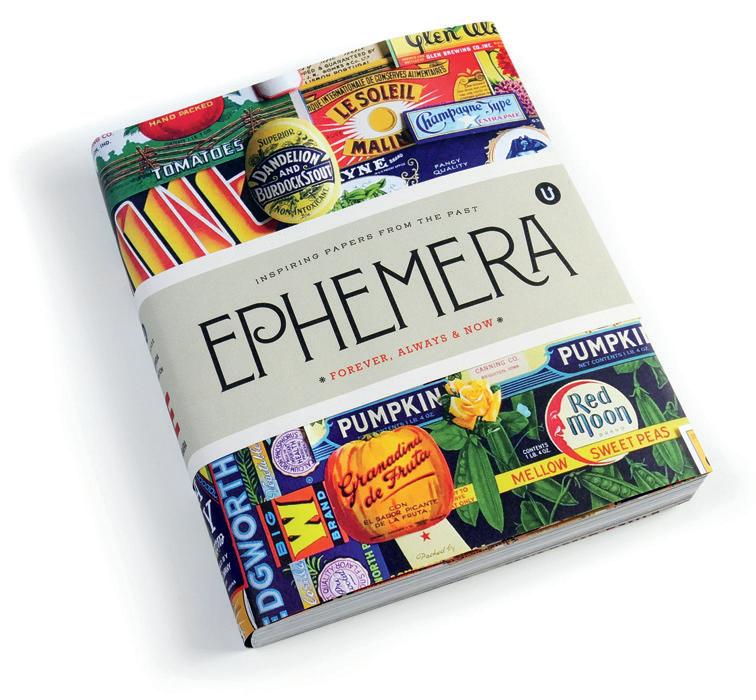

LIBRARY . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Recommended Reading CREATIVE CAREERS 16 Martina Sestakova BUSINESS 18 How to Get Started Selling Art & Handcrafts Online by Arianne Foulks illustration by Andrea D’Aquino ECO 20 Sustainability Initiatives EPHEMERA . . . . . . . . . . 22 by Mark E. Sackett and Melanie Roller

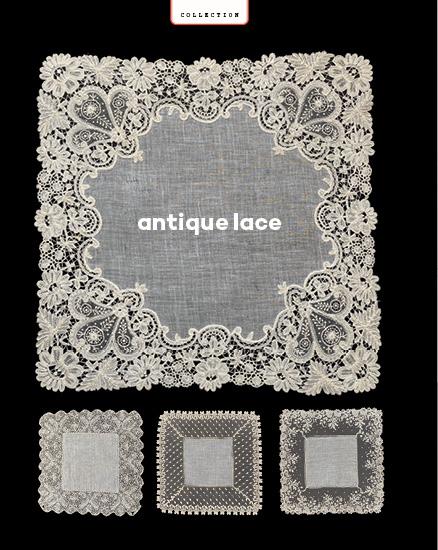

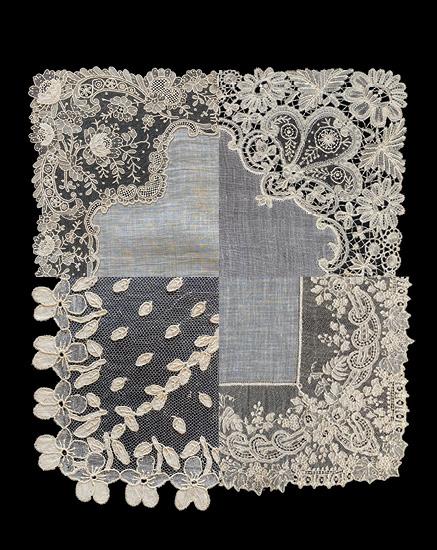

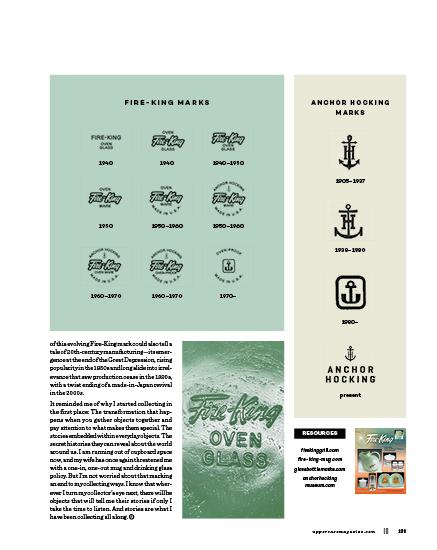

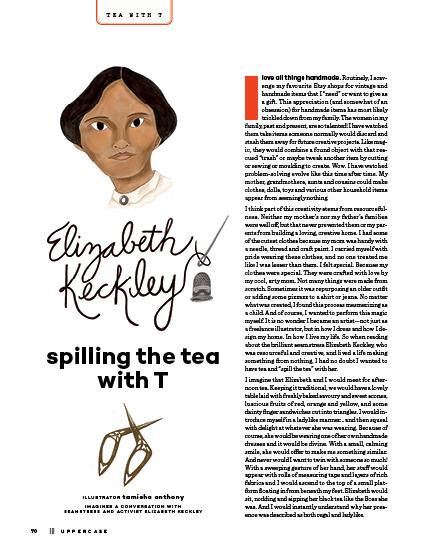

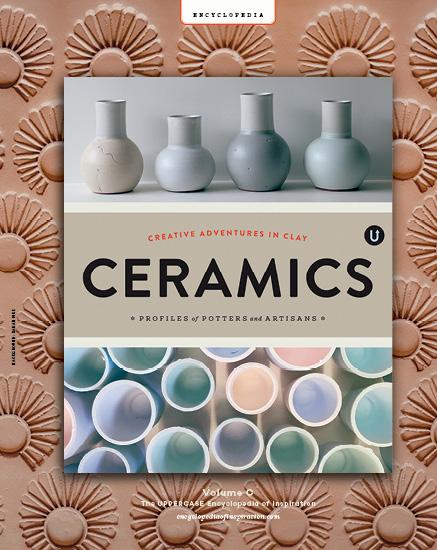

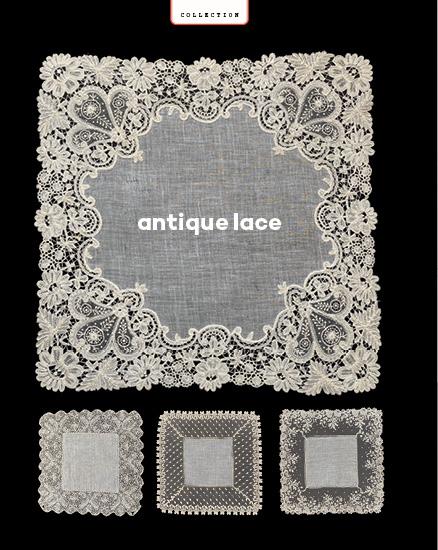

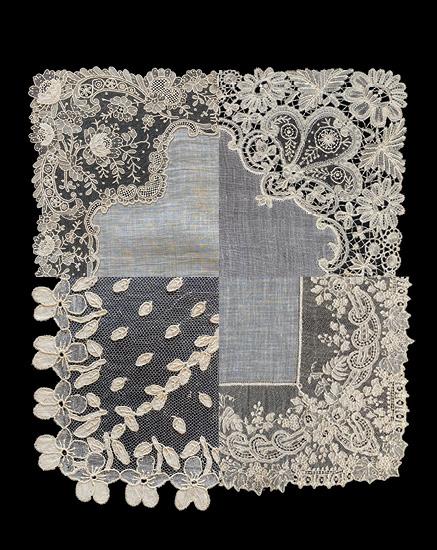

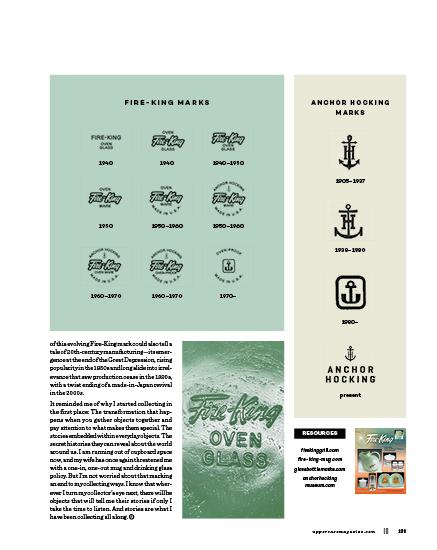

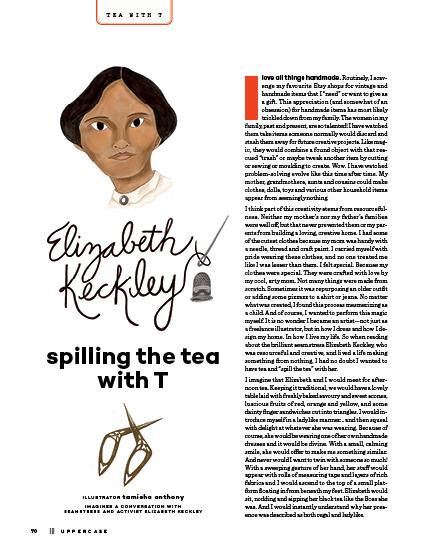

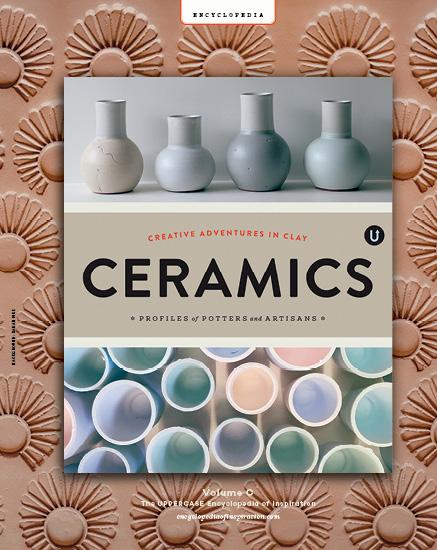

BEGINNINGS 28 Making it Slow: Alex Forby, Kent Ambler, Allison & Jamie Nadeau, Abena Motaboli and Julie Spako by Kathryn Davé ORIGIN 36 Maker’s Marks Featuring Florian Gadsby by Correy Baldwin ABECEDARY 42 Maker’s Marks by Lydie Raschka PROCESS 44 What Is the Artist Without the Mark? story by Helen Hallows photos by Holly Booth MUSING 48 Artists Wanted by Sharon VanderKaay PARTICIPATE 52 Making Marks TEA WITH T 70 Elizabeth Keckley by Tamisha Anthony TOGETHER . . . . . . . . . 74 The Calligraphic Marks and Textures of Yukimi Annand by Joy Vanides Deneen SKETCHBOOK 82 Healing Marks by Ana Buzzalino ASK LILLA 84 Slow Art to Find Your Style by Lilla Rogers Craft COVER ARTIST . . . . . . . 86 A Meandering Path to Minimalism: Catherine-Marie Longtin story by Leigh Metcalf photos by Tom Leighton GALLERY 96 Made by Hand CLAY 112 Wild Clay: Melissa Weiss by Claire Dibble CRAFT 118 Endangered Crafts story by Jane Audas illustrations by Dide Tengiz COLLECTION 120 Antique Lace by Maryline Collioud-Robert Misc. HOBBY 124 Object Stories by Brendan Harrison Subscriber Studios 126 Sarah Lalonde Looking Forward / Shares 128 COVET . . . . . . . . . . . . 130 In a Word by Andrea Jenkins uppercasemagazine.com ||| 5

catherinemarielongtin.com @catherinemarielongtin

Fine Print

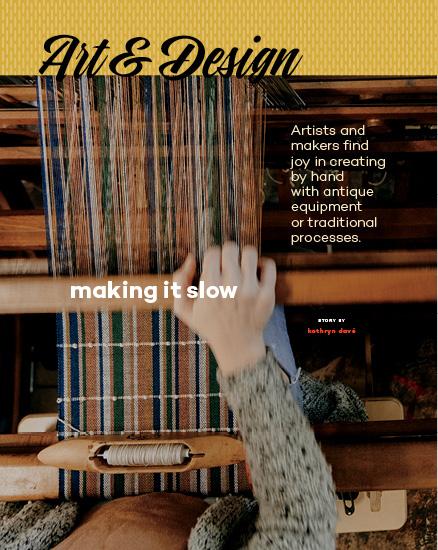

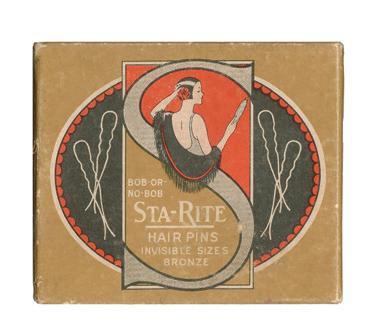

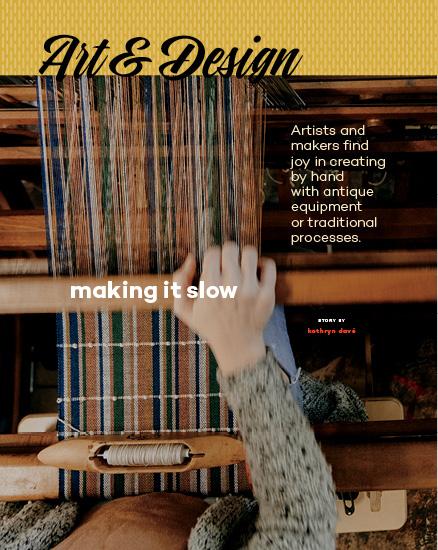

Art & Design

CONTRIBUTOR Catherine-Marie Longtin

UPPERCASE

1052 Memorial Dr NW Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 3E2

Janine Vangool

PUBLISHER, EDITOR, DESIGNER janine@uppercasemagazine.com

CUSTOMER SERVICE shop@uppercasemagazine.com

Correy Baldwin COPYEDITOR

Core Contributors

Tamisha Anthony

Jane Audas

Correy Baldwin

Andrea D’Aquino

Arianne Foulks

Joy Vanides Deneen

Brendan Harrison

Andrea Jenkins

Andrea Marván

Kerrie More

Meera Lee Patel

Leigh Metcalf

Lydie Raschka

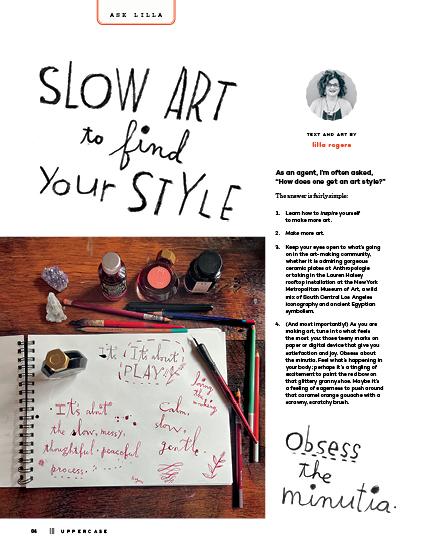

Lilla Rogers

Cedric Victor

PRINTED IN CANADA BY THE PROLIFIC GROUP.

Interior pages are printed on 100% post-consumer recycled Rolland Enviro 100.

Sustainability Initiatives

Through the Wren Trailblazer fund, UPPERCASE removes two tons of carbon each month with an additional two tons of carbon offset monthly. Please join fellow readers in the Wren Impact forest.

wren.co/groups/uppercase

SUBSCRIBE

SUBSCRIPTIONS

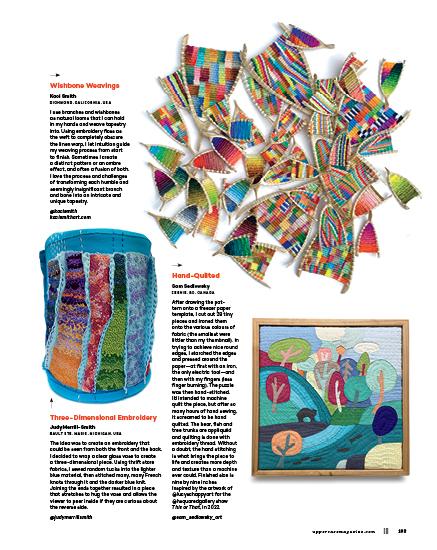

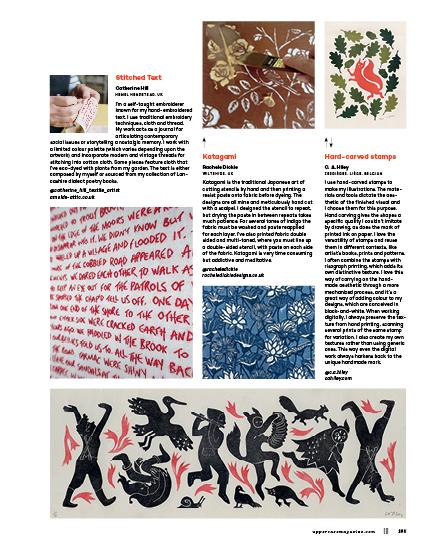

This quarterly magazine is released in January, April, July and October.

CANADA

CAD $ 96

UNITED STATES

USD $ 80

INTERNATIONAL

CAD $ 144

Our shop will do the currency conversion for you.

RENEWALS

You will receive a notice by email when it is time to renew. Renew online anytime to add issues to your current subscription.

GIFTS

Simply enter the recipient’s name and address in the shipping information and your name, email and billing address during checkout.

BACK ISSUES

Get them while you can! Once they’re gone, they’re gone. Back issues will not be reprinted. uppercasemagazine.com

STOCKISTS

To view our list of stockists or to carry UPPERCASE in your shop: uppercasemagazine.com/ stockists

QUESTIONS?

Have a question about your subscription or a change of address? Email us: shop@uppercasemagazine.com

Thank you to all of the talented writers, illustrators, creative collaborators and loyal readers who contributed their talents to this issue of UPPERCASE.

Thank you to everyone who submitted to the open calls for this issue. Even if you weren’t featured within these printed pages, your effort was noticed and appreciated!

SUBMISSIONS

UPPERCASE welcomes everyone and all identities, ages, talents and abilities. We share an inclusive, positive and community-minded point of view. Everyone is welcome to explore our creative challenges and submit to the magazine—you don’t have to be a professional artist or writer.

Please visit the Submissions page of our website for current open calls for submissions. The Fresh, Sketchbook, Creative Careers and Subscriber Studio columns are always open and submissions will be considered for print and for inclusion in All About YOU: the weekend UPPERCASE newsletter featuring creativity from readers around the world.

In the spirit of reconciliation, we acknowledge that we live, work and play on the traditional territories of the Blackfoot Confederacy (Siksika, Kainai, Piikani), the Tsuut’ina, the Îyâxe Nakoda Nations, the Métis Nation (Region 3) and all people who make their homes in the Treaty 7 region of Southern Alberta.

NEWSLETTER

Sign up for the newsletter to receive free content and behind-the-scenes peeks at the making of the magazine—plus a welcome discount on your subscription!

uppercasemagazine.com/free

You can also pitch your own work, propose an article about someone else or suggest a topic that you would like to research through the Open Pitch submisison form.

Please make sure that your submission is suitable for UPPERCASE magazine. Be familiar with the magazine and its writing and visual style.

uppercasemagazine.com/ participate

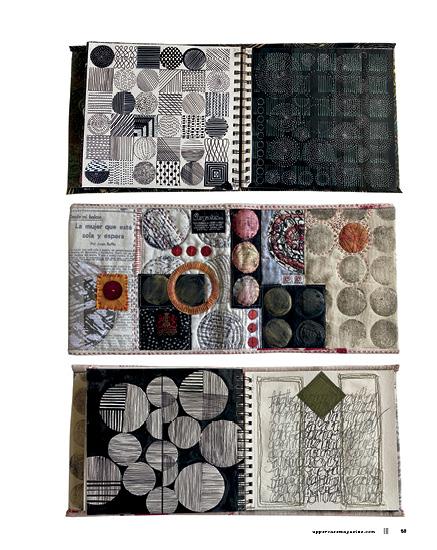

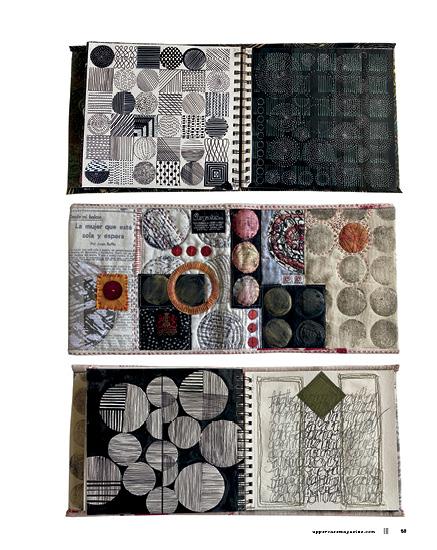

This independent magazine thrives because of you— its loyal subscribers! uppercasemagazine.com

6 ||| UPPERCASE

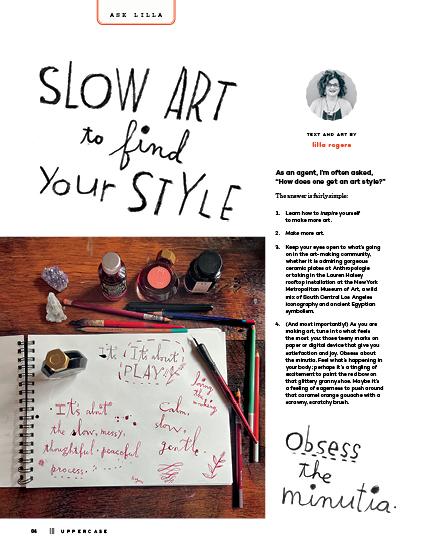

PUBLISHED INDEPENDENTLY SINCE 2009 for the CREATIVE and CURIOUS ™ ™

Subscribe!

Snippets

PORTRAITS

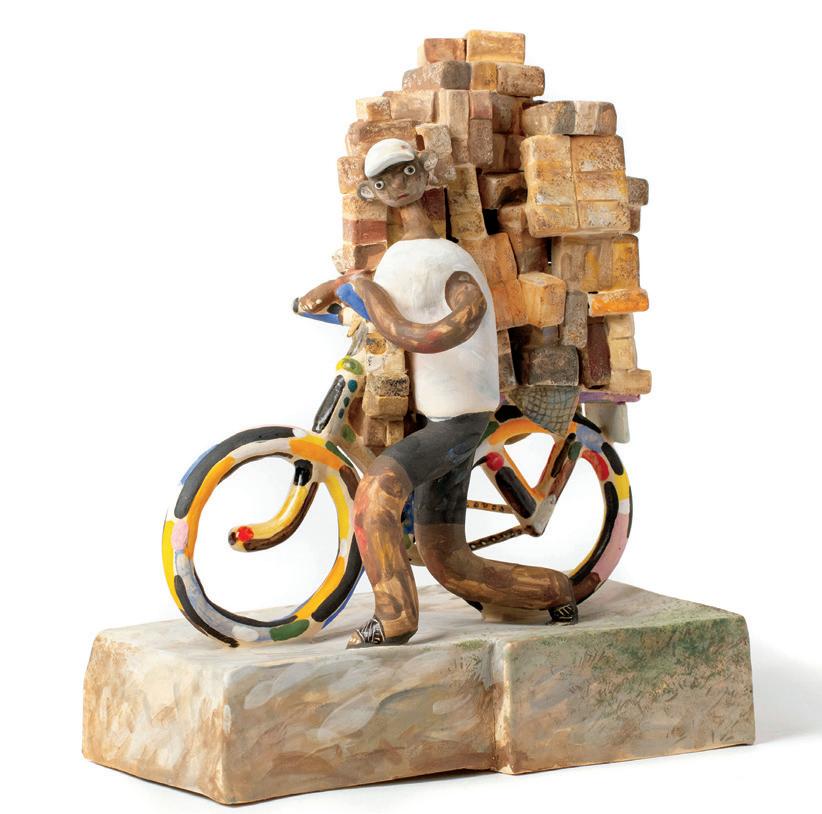

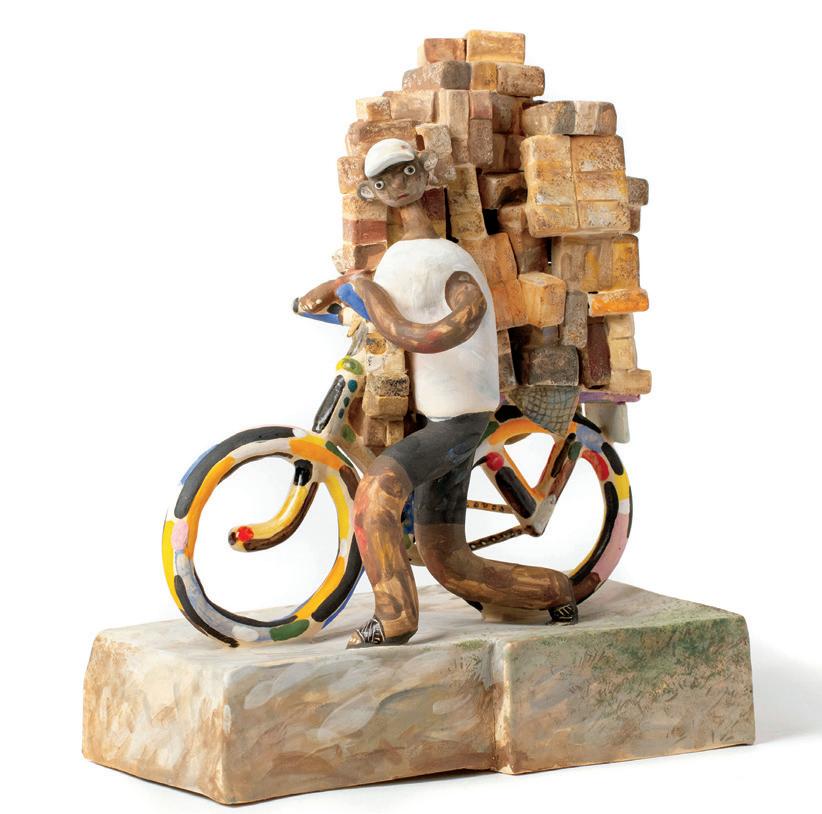

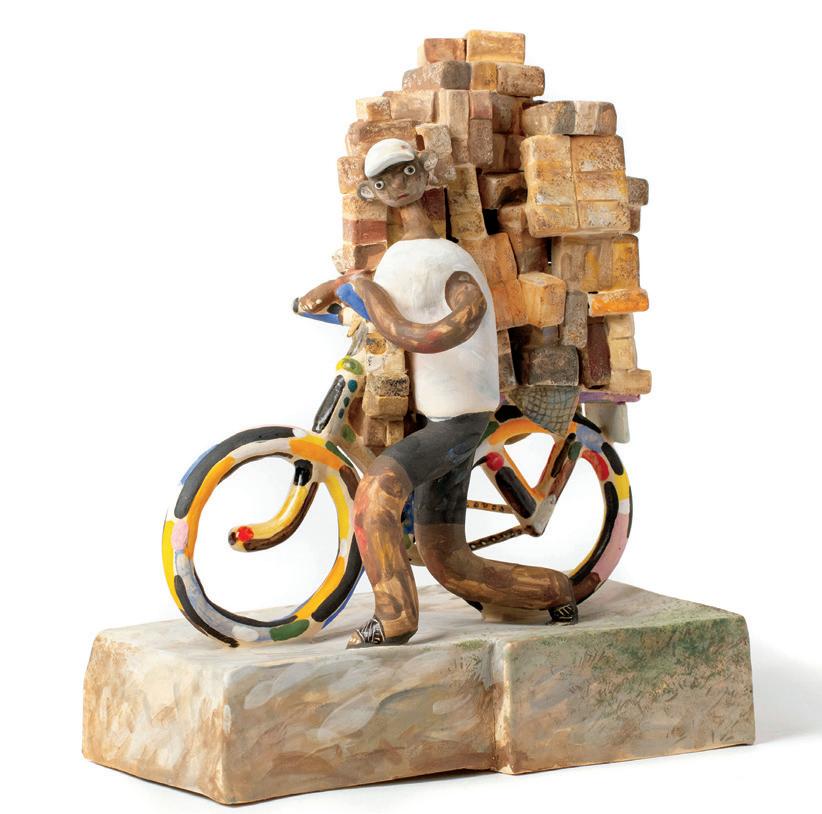

Bike Shop

Taili Wu

NEW YORK, NEW YORK, USA

Bike Shop is a series of sculptures inspired by people from all walks of life, whose bikes play an important role. The sculptures are hand-built ceramics with underglaze and spotted glaze on top. monstershaper.com

@tailiwu

8 ||| UPPERCASE

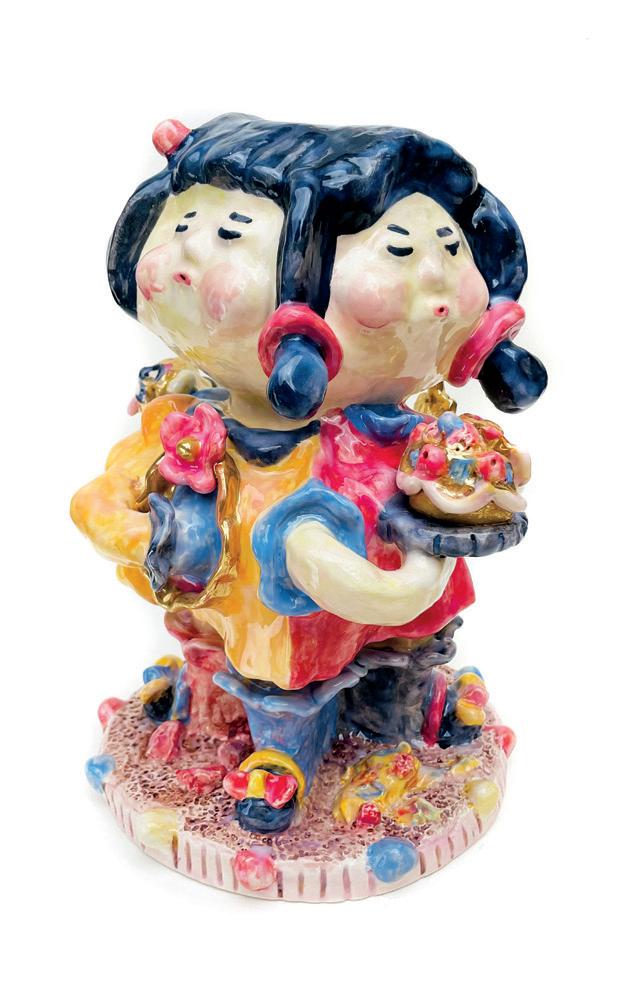

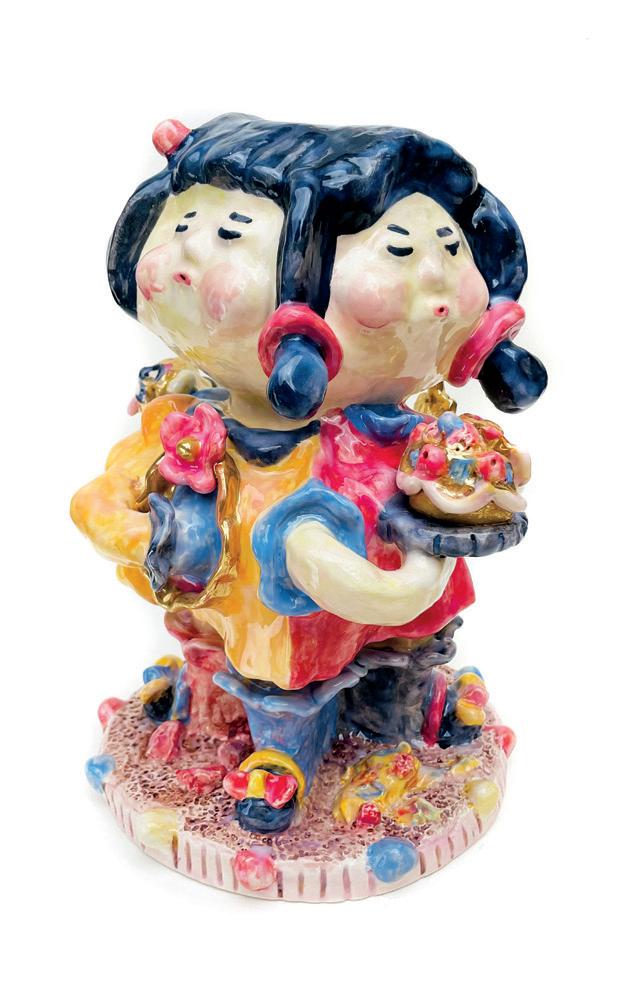

Hand-Built Ceramics

Nani Puspasari

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

As an artist, I begin by conceptualizing a storytelling narrative for my hand-built ceramic sculptures. Using clay and sculpting tools, I handly shape the clay, paying close attention to details and symbolic elements that enhance the narrative. After drying, the sculpture undergoes a bisque firing to remove moisture and make it durable. I then apply carefully chosen glazes or underglazes to add colour and texture. The sculpture is fired again at a higher temperature to fuse the glazes with the clay surface. Throughout the process, I remain focused on the nar rative, ensuring each decision contributes to its storytelling potential.

designani.com/art

@_designani

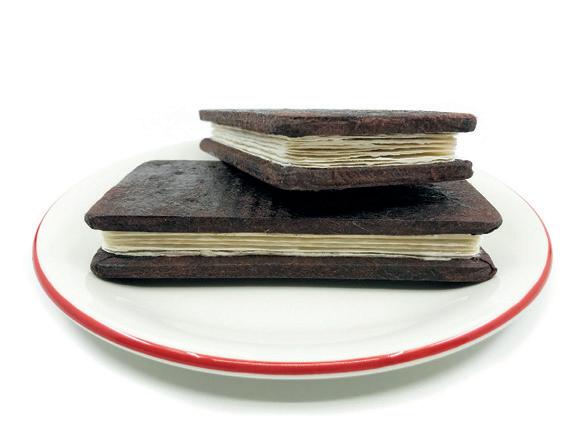

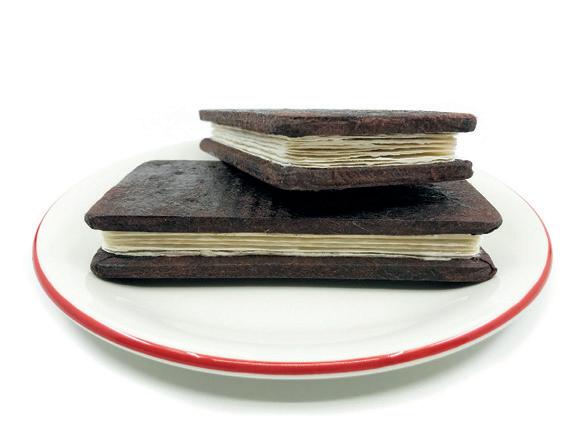

Ice Cream Sandwich Book

Laurie Coughlin

ARLINGTON, TEXAS, USA

The ice cream sandwich is my favourite frozen novelty! So much so that I have made it into a book object—a book not meant to be read but seen as sculptural art that brings me joy. This cool sweet treat is made using the accordion-fold book structure. Sometimes when I’m doing something, a tangential idea will pop into my head, like this book. I was looking at handmade paper, and it told me that it would make a great ice cream sandwich. Other times, I gather things intuitively until one day the pile changes from a random assortment to the shape of a story.

When this happens, I’m ready to bring it to life. The process of determining materials, design, printing and binding is pretty methodical. Once the book is complete, I write instructions on

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 9

NOVELTY

STORYTELLING

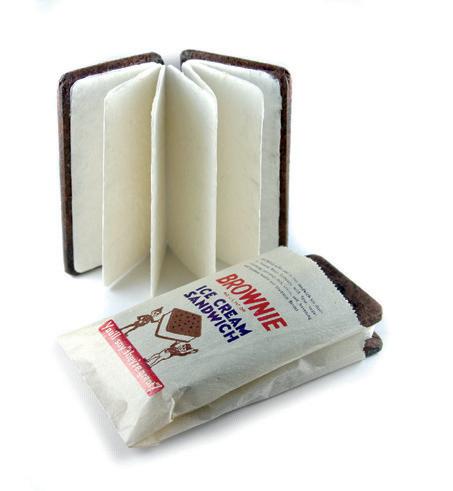

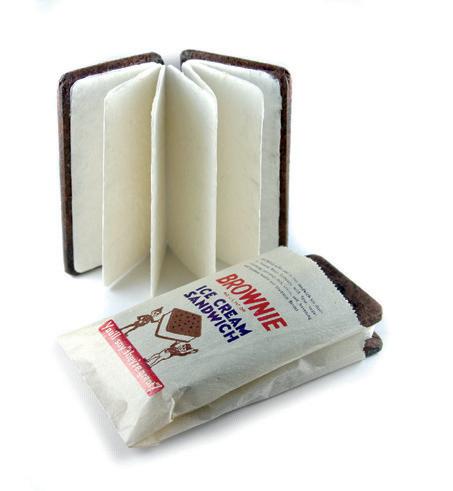

a season for stitching

ARTICLE AND ILLUSTRATION BY meera lee patel

It has been nearly three months since I became a mother of two young girls. I still wake multiple times a night to nurse the small child who shares my room before returning to sleep fitfully, hoping I will be able to close my eyes once again. I wake at 6:30 am, before the rest of my family stirs, and rub the tiredness from my eyes. It’s another day—another curious day, where anything could happen, but already it feels predictable. I make my toddler’s breakfast, pack her lunch and head to the basement to begin a load of laundry.

When I return upstairs, I look at the clock: 6:45 am. The perfect time for a change. I reach for my phone, and a few seconds later, Paul Simon’s voice radiates from the kitchen walls, following me around as I cook breakfast for my family. I move rhythmically now, cracking eggs and stirring oatmeal, the fatigue slowly lifting itself off my bones. I feel the pulse of creativity rattling inside me, unavoidable in the morning stillness. It wants to be heard. It wants to be captured, shot into the sky like a brilliant firework.

It’s been 11 weeks since I have stepped inside my studio—the little room that shoots off my bedroom, the one that I retreat to when I need to most feel like myself. I have missed myself for months now—or is it that I have mourned myself for months now?—because admittedly, I no longer know who I am. I am tangled; tired, and full of knots. I’ve been through this transition before, with the birth of my first child, and I had prepared myself for it. Don’t fight it this time, I tell myself. Let it be. Soon, you will become someone new But who?

I have 15 more minutes of quiet before small hands and morning cries chase these thoughts from me. I eagerly wait for the day I will again sit in front of a large, blank canvas with a large span of time stretched before me. I want to feel the roughness of paper against my hands, the stony scent of gouache against my skin, bristles

twisting between my fingers. On that day, I will feel more like myself. On that day, I will put paint to paper and see who reveals herself to me.

In her book Feel Something, Make Something, Caitlin Metz describes the act of art making as a form of release, a way to “examine the contents of your heart and mind from a fresh point of view.” “When I create from my feelings,” she writes, “the enigmatic becomes manifest; mark-making reverberates like an echo delineating the edges of my consciousness, a mirror reflecting the inconceivable. Something transcendent happens when we allow the swirling, fearsome tangle to tumble out onto paper, canvas, or clay or into poetry, song, or dance.”

I recognize that much of the frustration I feel these days comes from a lack of physically making. Caring for an infant (and toddler) leaves little space for much else, and on the days I do have a spare hour or two for myself, the minutes dissolve further into domesticity: a fresh dinner for my family or decluttering our living space. These are acts of love, and they are creative in their own right, but they don’t translate my emotions the way art making does. Like my home, my mind needs decluttering, and for the sake of self-preservation, I decide to prioritize it.

“Drawing—or mark-making—has been a space for me to explore concepts without committing—before language, there were images,” writes Caitlin. After a few months without drawing, I feel bewildered, unsure of how to begin. I decide to start small to avoid becoming overwhelmed, choosing a pencil and a Post-it Note as my tools. I draw a small line and then another. As I layer them on top of each other, I realize I am drawing my infant daughter in stitches, the way a needle does with thread. This is the first spark—a signal that I am on the right path. The tangible act of mark making unlocks inspiration the same way

somatic movement unravels anxiety: you must do to change how you feel. I decide to make an embroidered painting—a long-term project I will work on throughout my year-long maternity leave, to aid me in processing this particular season I’m in. I choose it deliberately for the tedious, meditative nature of the work involved, and for its tactility. I need to feel the thread and needle, the drape of the linen as it pours over my knees. I need to feel the rhythm of my days without letting the movements mindlessly wash through me. I need to feel the frustration and monotony—and the sweetness and joy, without minimizing the weight and value of either.

I choose a large sheet of paper, and I begin to make new marks. As I draw, I do the work I have been avoiding: I think about who I used to be and who I would like to be a year from now. I make a list of the things I no longer am: pregnant or a mother of one, a graduate student, a person who derives self-worth from serving others. I think about who I am becoming: a mother of two young girls, a children’s author-illustrator, a more patient person, an artist who is more certain of herself. I let myself be.

I am blurry, still, and will be for some time, but the scritch-scratch of pencil against paper brings me towards myself; a train slowly, steadily approaching its station. As I transfer my drawing to a large piece of linen, I consider all I would like to process: my postpartum identity loss, the months of sleeplessness, the mourning of who I once was, how I thought things would be. I think about what I want to remember most: a marriage that perseveres, the affection between two sisters, the tiny smile of an infant who only knows warmth from the world.

I begin to stitch, slowly. My fingers stumble in their unknowing. First one, then another. I move slowly and try not to rush. I want to remember these days. There is much to learn. There is much to love.

meeralee.com

10 ||| UPPERCASE

BEING

|||

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 11

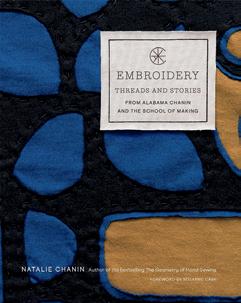

Malika Victor

BRONX, NEW YORK, USA

I am an aspiring artist and illustrator based in the Bronx. Black hair and the delicate characteristics of plants serve as key sources of inspiration for my artistic work. I attempt to include the finer aspects that I think to be beautiful in my illustrations. For many years, natural hair textures and styles have served as icons of a significant cultural heritage.

I am captivated by Black hair’s complexity, delicateness and tenacity. I want to emphasize its beauty and strength through my illustrations. Another important source of inspiration for my art is nature. I depict the spirit, diversity and beauty of the natural world in my works. My illustrations are continuously changing as I experiment with different methods

fresh talent

and aesthetics. My goal is to produce illustrations that are significant and thought provoking in addition to being aesthetically attractive. I want people to be inspired by my art and appreciate the variety of the natural world. I aspire to use my abilities as an illustrator to produce book covers that perfectly encapsulate the essence of the stories they represent. I aim to create immersive art by blending Black hair and natural components.

@malikavictor malikavictor.myportfolio.com/ illustration

Jody Rita

APPIGNANO, MACERATA, ITALY

I’m an Aussie Italian living in Italy. I have been working as a professional graphic designer for 20 years and have always put aside my art. So one day I said to my husband, well why don’t we just do what we love? You do your violin making and I’ll do my art. So we did just that. We’re still juggling work while working on our creative projects, but things are coming along. I hope to become a professional surface pattern designer and I think I’m “fresh,” probably because I’m new at it and for sure I’m still doing things wrong (but perhaps in a good way). Secondly, being here in Italy has a certain influence on my work; I’ve been adapting the wonderful bright colours used in traditional Sicilian folk art.

@dancingirldesigns dancingirldesigns.myportfolio.com

12 ||| UPPERCASE

FRESH

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY

QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

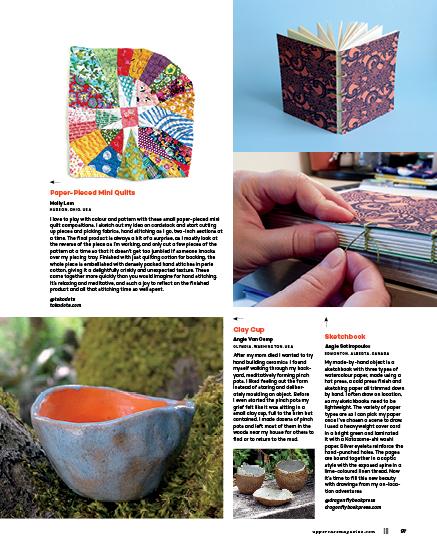

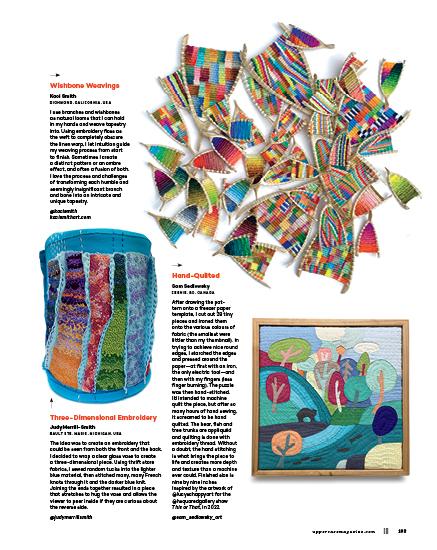

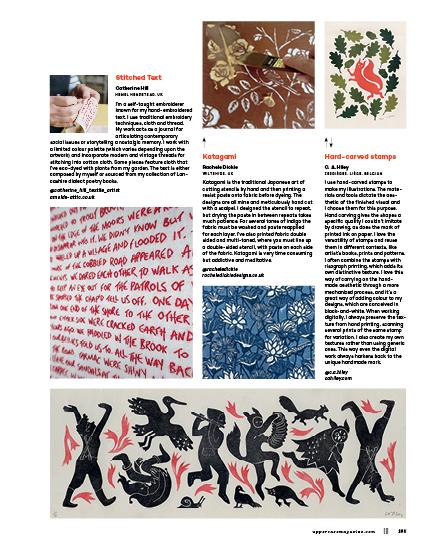

personal crafts

14 ||| UPPERCASE

RECOMMENDED READING BY janine vangool

HISTORICAL EMOTIONAL FASHIONABLE

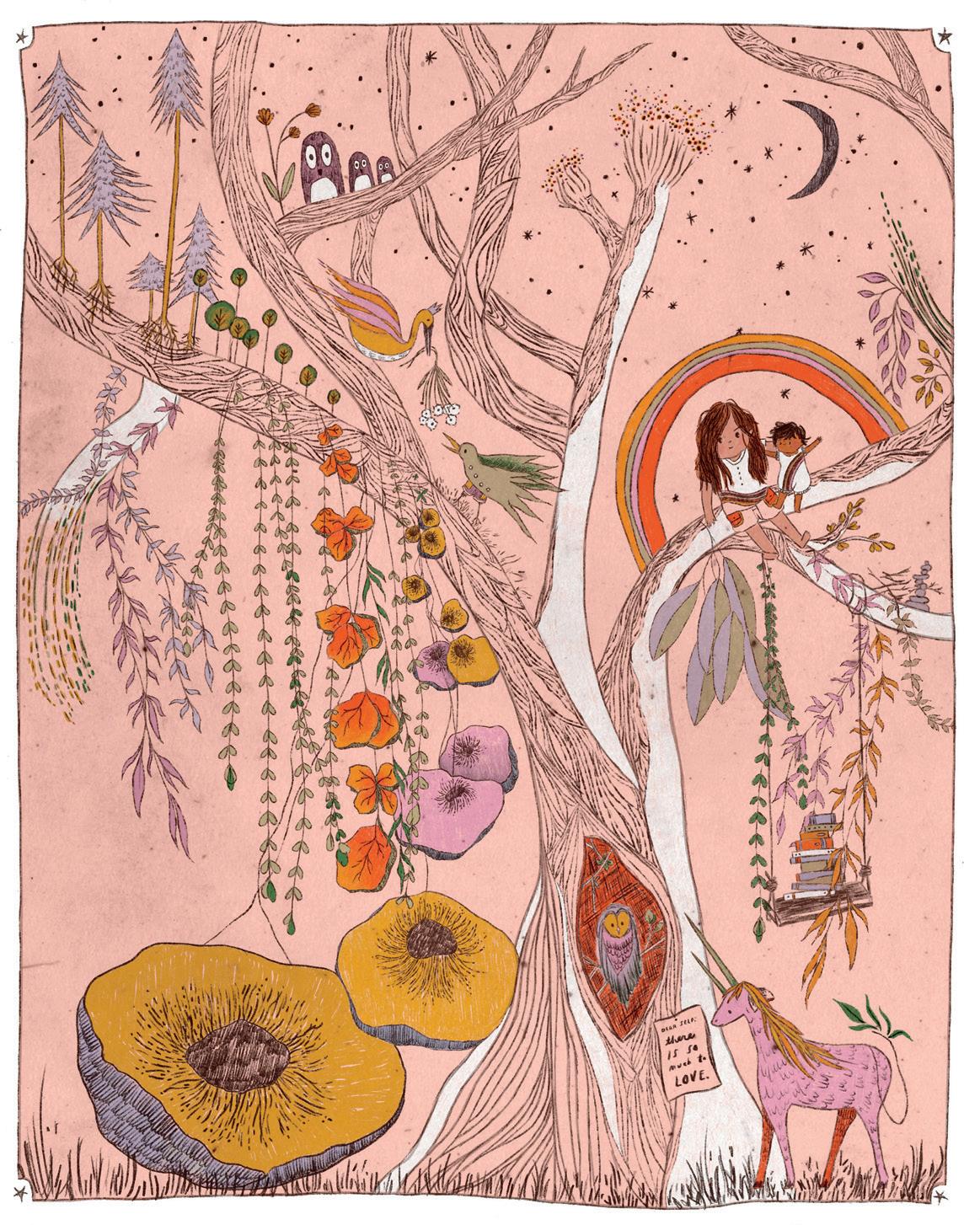

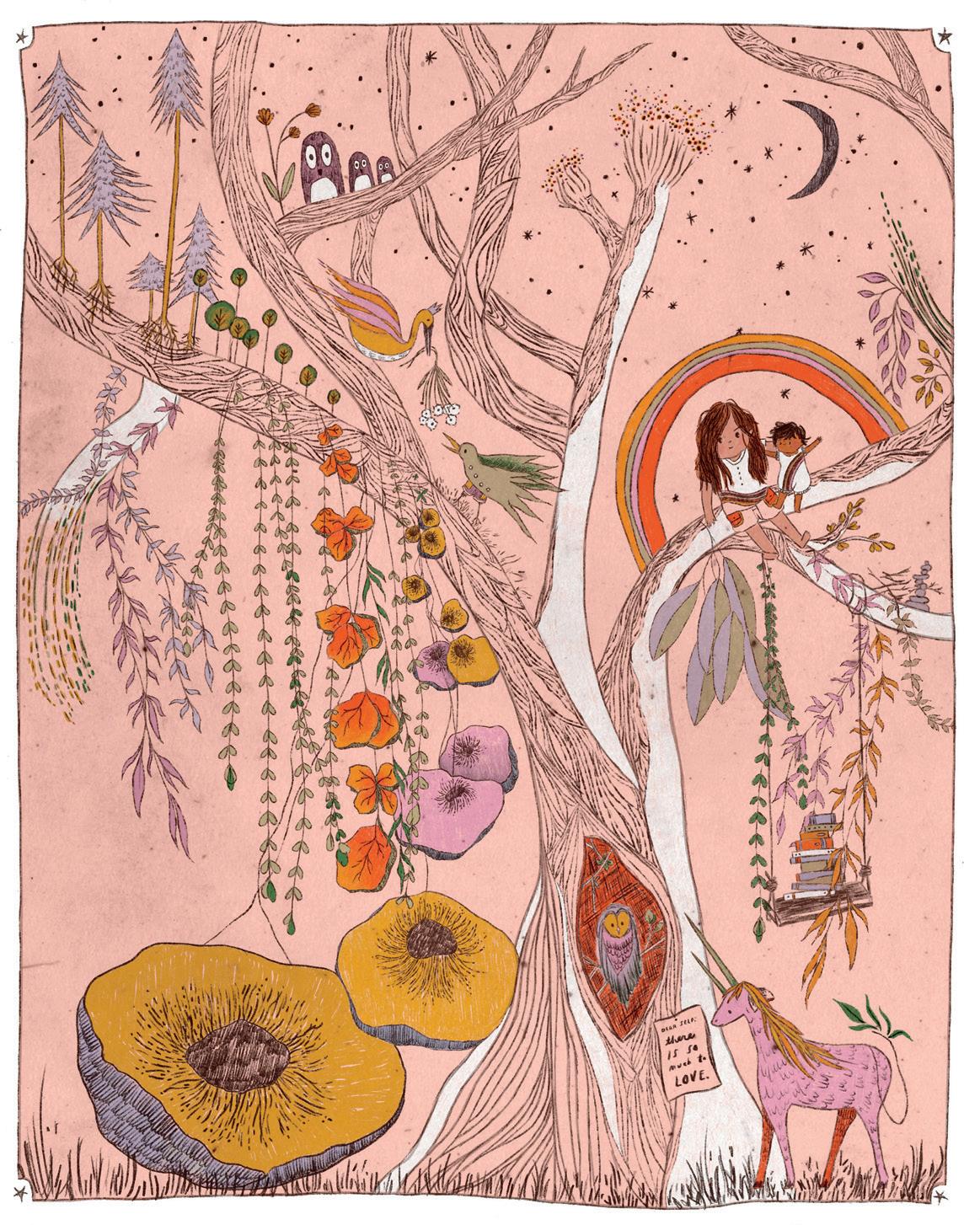

Embroidery:

Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and the School of Making

NATALIE CHANIN

“I’ve come to believe that craft, making, and creative endeavours toward producing sustainable products will create an enduring future for our community.”

Here is a beautiful book commemorating the story of Natalie Chanin developing her clothing company, Alabama Chanin, two decades ago, and founding the School of Making 10 years later. Known for her 100% cotton garments handstitched with stencilled and cut layers of jersey, Natalie began her company with sustainable fashion at its core. The first collections were made of upcycled, found graphic T-shirts that were cut up, recombined, embellished and embroidered. Over time, her unique appliqué methods and commitment to sustainable sourcing of cotton materials near her community in Florence, Alabama, have led to international regard for her ethos and style. While finished clothing from Alabama Chanin has high-end pricing due to the incredible handwork required for each garment, Natalie makes her technique accessible through many previous publications and affordable patterns. This latest book is a coffee-table book of Natalie’s archive of work, with beautiful extreme close-up crops of many of her designs, allowing the reader to admire the workmanship, stitch by stitch.

alabamachanin.com

@alabamachanin

Feel

Something, Make Something: A Guide to Collaborating with Your Emotions

“I like to say ‘mark-making’ over ‘drawing’ because it softens the idea of drawing as a rigid, specific type of skill. Anyone can make a mark! Mark-making allows my body to speak about things for which there are no words.”

Caitlin Metz shares her personal practice of using drawing, documentation and mind mapping to examine her interior world. Rather than look away from feelings, trauma and fluid identity, she encourages us to collaborate with our emotions within the safe, private space of journaling and art making. “Expressive mark-making is like opening the release valve on your emotional instapot and letting the rush of steam release from your body,” she writes. Borrowing from the aesthetics of zine making, this softcover book is printed in two colours on a soft, uncoated paper, giving the reader a pleasing, even calming, sensory experience. Cover to cover, it’s a quick read. But if you actually take the time to do the exercises and converse with your emotions, it could take a lifetime.

caitlinmetz.com

@caitlinhasfeels

“Enter here to find thirteen oneof-a-kind stories inspired by fourteen one-of-a-kind objects… You are invited to realize and enjoy the usefulness and pleasure these handmade objects brought to people in the past, and to consider what you might try crafting with your hands in your own time.”

This children’s book presents various American-made object vignettes by author Carole Lexa Schaefer and paintings by Becca Stadtlander. Though the actual items can be viewed in museums and the photographs are shown in the back of the book, the author and illustrator bring context to them through narrative writing, poetry and illustration. It tells the story of James Wilson, a blacksmith from Bradford, Vermont, who in 1810 became the first handmade globemaker in the United States. It imagines a girl named Lucy using a salt-glazed stoneware butter churn decorated with cobalt blue horses in the 1860s. It wonders about the Ojibwe boy in the mid- to late 1800s who might have donned a bandolier bag adorned with thousands of glass beads. It is a pretty book to spark the imagination and conversation.

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

clschaefer.com

beccastadtlander.com

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 15 LIBRARY

CAITLIN METZ

Made By Hand: A Crafts Sampler

TEXT BY CAROLE LEXA SCHAEFER ILLUSTRATIONS BY BECCA STADTLANDER

PLEASE

SUBSCRIBE

sustainability initiatives

STORY BY janine vangool EDITOR / PUBLISHER / DESIGNER

STORY BY janine vangool EDITOR / PUBLISHER / DESIGNER

We all love print on paper— nothing can compare to the tactile pleasure of reading books and magazines!—but I also understand the environmental impact that producing products and selling items through e-commerce has on the environment. Here are the ways that UPPERCASE is reducing its footprint and trying to make change for the better.

Paper

The interior pages of UPPERCASE magazine and books are printed on Rolland Enviro® Satin, which is made of 100% post-consumer fibre. This means that the source material has already been used for its original intended purpose by individuals, households or commercial facilities, and has been reclaimed for recycling and processed chlorine-free. The paper is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. The covers of UPPERCASE magazine and books vary in paper stock but always contain as much recycled content as possible.

Printing

UPPERCASE is printed in Canada through the Prolific Group: “From our materials and manufacturing methods, to our transportation choices, Prolific’s commitment to the environment is an integral part of our business. We partner with our suppliers, employees and clients to achieve real, measurable environmental improvements. Prolific uses vegetable-based inks which contain 70% bio-renewable content and have low VOC emissions.”

Plastics-Free Packaging

Since 2019, UPPERCASE has been plastics free— we do not use poly bags or shrink wrap. (If you order some older back issues, those may still be protected in shrink wrapping.) Subscriptions sent from our printer are mailed in 100% recycled (50% post-consumer) and recyclable kraft mailers that are certified by the Sustainable Forestry Initiative and the Forest Stewardship Council. UPPERCASE also encourages subscribers to reuse and upcycle the kraft envelopes rather than simply recycle them.

20 ||| UPPERCASE ECO

|||

|||

|||

Mineralized CO2 from Climeworks’ direct air capture plant “Orca,” Iceland ©2022, Climeworks

Being climate-conscious is integral to UPPERCASE magazine

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY

QUARTERLY

PRINT MAGAZINE PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

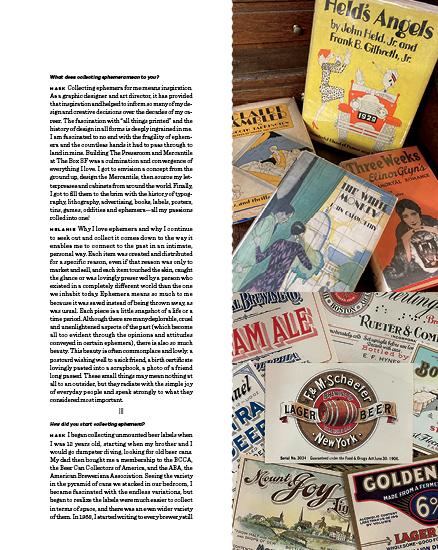

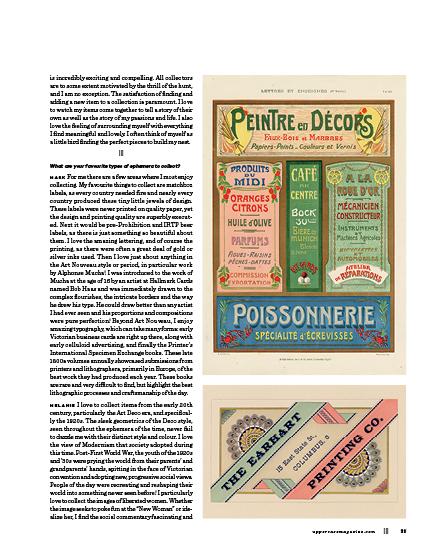

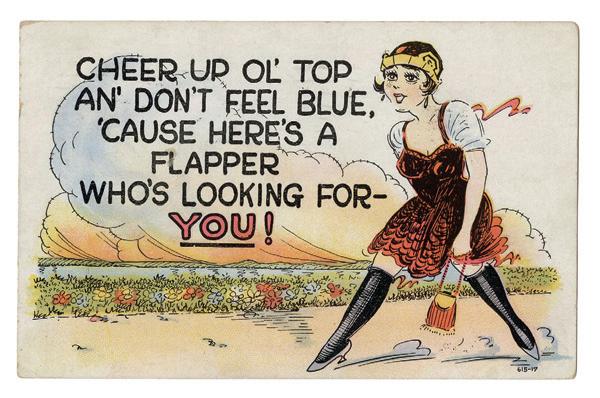

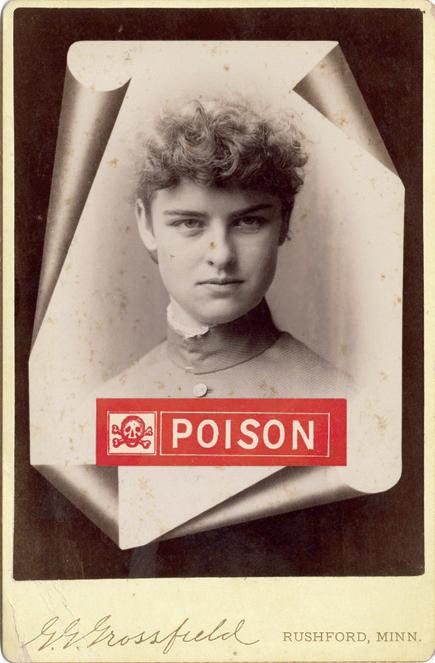

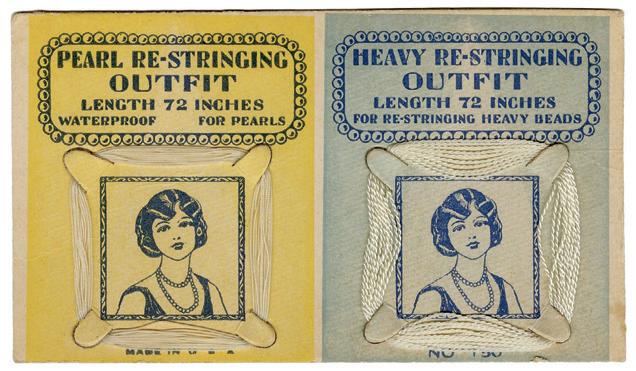

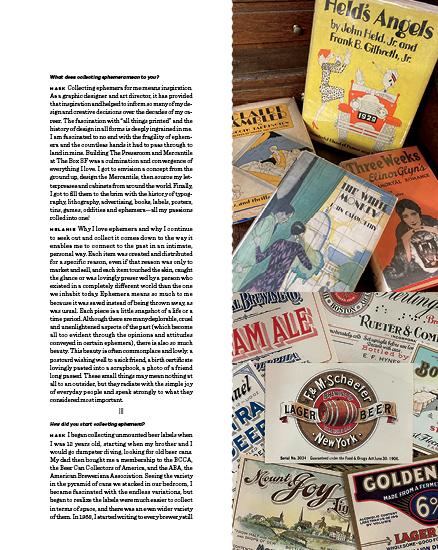

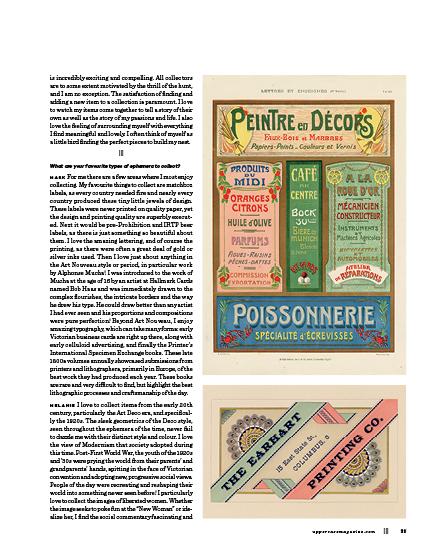

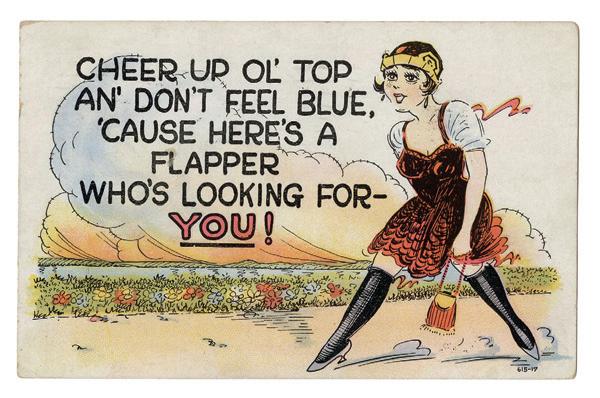

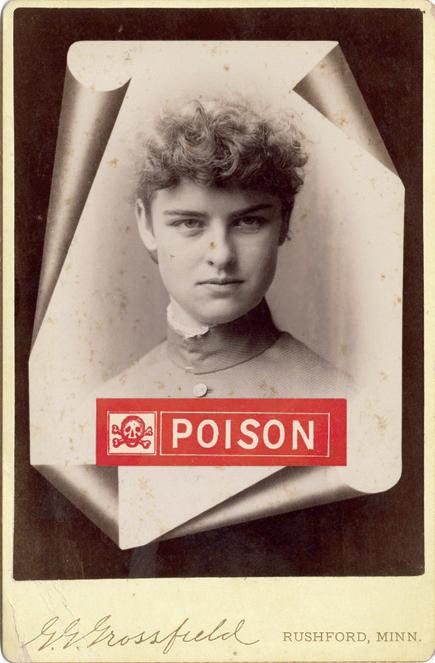

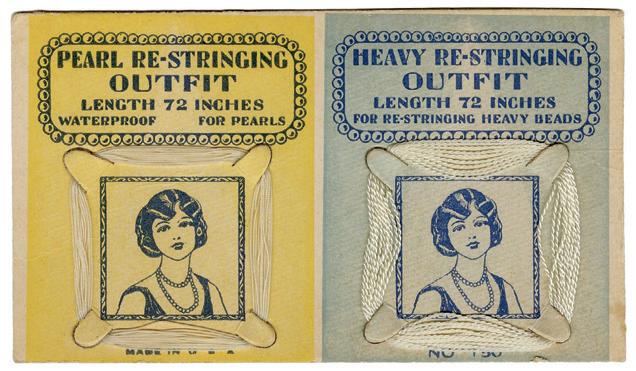

oddly fresh—even when viewing it from a time when women have advanced leaps and bounds. Some of my favourite pieces to search for and collect are magazines focused on film, fashion and culture; illustrated boxes and tins; sheet music; and anything with a distinct historical connection or “modern” perspective. I also love the cartoon aesthetic of the time and early illustrators such as Harriet Fish, Ethel Hays and John Held Jr.

How has being a collector altered or transformed your life?

MARK Being a collector has had numerous impacts on my creativity throughout my life. It has helped inform how I see and create as a designer. It has also helped me to learn and experience the importance of staying open to different approaches to a visual or production problem. It has taken me around the world, allowed me to meet people in over 50 countries and ultimately led to establishing friendships that have lasted years. I find it interesting that when you choose to live a creative life, and that creativity permeates every aspect of it, your work ceases to become work, your ideas become better and you are always learning and absorbing. In turn, your entire life and perspective is just different. To this day, my favourite morning is grabbing a hot tea, a pain au chocolat and a camera, and wandering an antique fair, collectors or paper show, enjoying “the thrill of the hunt”—knowing that if I scan properly, I might just find one of “my things” buried in that pile, or on that table! And that instant… that’s the best feeling there is for a collector!

MELANIE Being a collector of ephemera has helped develop my mind and connect me directly to my own place in the long narrative of human history. It has also deepened my understanding of humanity as a species: our biases, wants and essential needs. As the large majority of the ephemera that exists is a form of advertising, I find it fascinating to try and understand the goals and motives that prompted a certain piece to be produced. I find myself asking, “What did the advertiser want the consumer to experience when viewing this artwork?” Or, “what would compel someone to preserve this particular piece for decades upon decades?” Each piece of ephemera is itself a little riddle, with no concrete answers. I feel that when I am collecting or searching for collectibles, I am constantly growing as a person and I am constantly learning new and interesting things. Ephemera has never failed to introduce me to new topics to explore or lead me down unexpected rabbit holes.

26 ||| UPPERCASE

|||

|||

What advice would you share with someone just starting to collect ephemera?

MARK Pick something that you are passionate about and begin the hunt! Coming from a person who has built a whole store around many collections, recognize that you can’t buy or afford everything, but buy the things that speak to you.

MELANIE Do your research and learn everything you can about what you love to collect. This will give you a distinct advantage during your search. Most importantly, never stop being curious!

theboxsf.com

@theboxsfmercantile

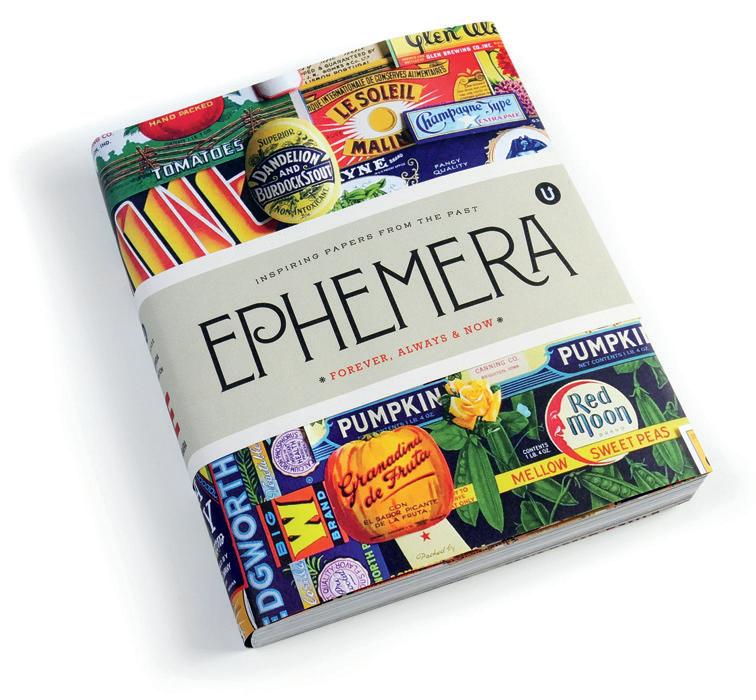

Ephemera, Volume E of the UPPERCASE Encyclopedia of Inspiration (featuring a profile of The Box SF) is being reprinted!

uppercasemagazine. com/ephemera

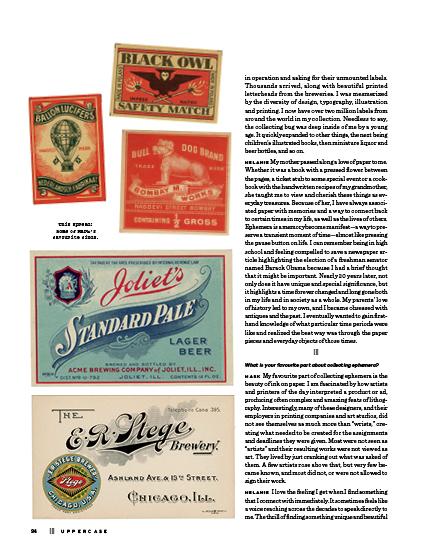

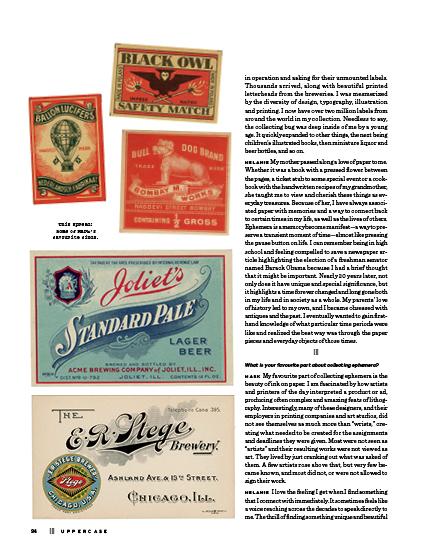

This spread: some of Melanie’s favourite finds.

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 27

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

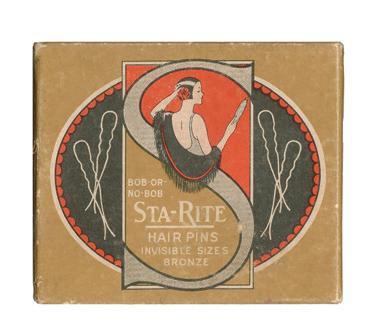

Alex Forby, who works primarily on an old 1970s loom and a 100-year-old Union rug loom, describes the act of weaving as “meditative.” The antique rug loom came to Alex dirty and in pieces, dust-covered from someone’s attic. She carefully cleaned and refurbished the loom for production, imagining the practical, personal goods that would have been made on her vintage looms over the years: a coverlet for someone’s bed, a wall tapestry, a baby blanket. Today, Alex is creating items with her Daughter Handwovens inventory in mind, but the actual weaving process on the loom remains unaltered by time. After sketching her pattern design and selecting her yarn colours, Alex then threads the loom—a long, painstaking phase—before settling into the zen-like rhythm of weaving. “I really have chosen it specifically for the slowness,” she says. “There are computerized looms available, and even that for me is almost too much like cheating. I want to weave the way they have always done it. The whole point is that it is handmade with a very human touch.”

For Abena Motaboli, a Chicago-based multidisciplinary artist, the traditional, laborious work of creating natural dyes and earth pigments grounded her in a sense of time and place. “Getting into natural dyes is something that really helped me slow down and learn how to notice and listen,” Abena says. Working with the rhythm of the seasons and her location, Abena gathers plants, flowers, bark and soil, including some from the garden she has planted and tended herself. She repurposes secondhand fabric and gives it new life by washing, soaking and dyeing it to become anything from tea towels to scarves to large-scale installations. Nature dictates the outcome: beautiful, subtle expressions of colour that vary according to season and geography.

Abena, who is from Lesotho in Southern Africa and came to the US to study fine art at Columbia College Chicago, began exploring plant and earth pigments when she started painting with tea and coffee. Years of creating with these “plant guides” inspired her to study natural dyes from traditions around the world and eventually begin creating her own, right in Chicago. “The more that I work with plants, the more that I feel in touch with what’s going on around me, more connected to the earth,” says Abena. The seasonality of her work has trained her eye to take in more of the natural world, a habit that creates what she calls “spaciousness” in her everyday life.

32 ||| UPPERCASE

Art as a response to nature is a timeless instinct. For artist Kent Ambler and ceramicist Julie Spako, the mediums that felt right to share their observations and memories of the natural world also happened to be some of the earliest forms of art: woodcut printmaking and hand-built pottery.

In the 1990s, when Kent was studying art in college, he took a printmaking class and instinctively understood the language of woodcuts. “It just clicked. Somehow I could visualize it in my head,” he says. Woodcuts are the oldest form of printmaking, and the tools required are very simple: a block of wood, various carving tools, ink, paper and some sort of tool to apply pressure for transferring the design—even a wooden spoon could work, Kent notes.

He went on to grow a successful career in art around woodcuts and paintings, working from “observation, intuition and memory.” His home on 12 acres in the woods of Upstate South Carolina informs his subject matter: birds, dogs, trees, town life. Often described as “painterly,” his woodcuts begin with an observational sketch before he carves a block of wood with quick, shallow cuts that he intentionally keeps loose. Each block is hand inked with its own colour and pressed in layers onto the paper. Kent limits his woodcuts to a run of 20 to 30 prints and does not make digital copies, finding a strange dissonance in a digital print of a handmade print. “If someone sees a woodcut of mine, they know I printed it myself from the block,” he explains. From start to finish, making one of his woodcut prints involves hours of his time. Such an investment of time imbues each print with meaning and value—a timeless part of art and craft’s appeal.

spakoclay.com

@spakoclay

34 ||| UPPERCASE

Julie Spako

Spako Clay

Austin ceramicist Julie Spako makes hand-built, hand-drawn and hand-painted pottery that marries simplicity of form with elegant, complex floral designs.

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

ORIGIN

FEATURING AN INTERVIEW WITH florian gadsby

maker’s marks STORY BY correy baldwin

Emily Carr: the questioning mark of an artist

For a brief period early in her career, around 1924 to 1930, the painter Emily Carr, who would become one of Canada’s most cherished artists, took up pottery. It was a difficult and precarious period for her: she was on the leading edge of modern art, but working in what was then a provincial town in a colonial territory far removed from artistic circles. Unable to sell her work or find students, Carr was forced to close her Vancouver studio and move back to her home in Victoria, where she proceeded to cobble together various desperate sources of income.

She set up and ran a boarding house (her “House of All Sorts”), bred Old English Sheepdogs and made pottery to sell to tourists, building her own wood-fired brick kiln (“a crude thing”) in her backyard. For 15 years she all but gave up on art, aside from the pottery, which, although she loved the material, brought her little pleasure: “Stacking, stoking, watching, testing, I made hundreds and hundreds of stupid objects, the kind that tourists pick up,” she later wrote.

As a painter, Carr used an impressionistic, modernist style to explore the significance of the Canadian wilderness, as well as her deep respect for the Indigenous communities along Canada’s West Coast. She continued exploring Indigenous imagery and iconography through her various ceramic pots and bowls. It was a creative outlet, but the commodification also crystallized her thoughts on appropriation: “I ornamented my pottery with Indian designs— that was why the tourists bought it. I hated myself for prostituting Indian Art.”

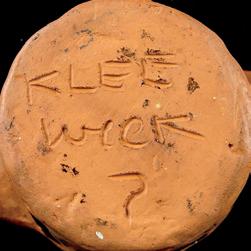

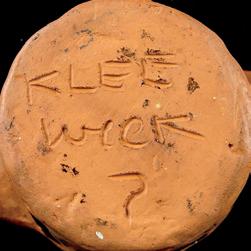

The Nuu-chah-nulth people, whom she had visited and come to know, had taken to calling her “Klee Wyck,” or “Laughing One.” It was this name, Klee Wyck, that she used to sign her pottery. It was, perhaps, an acknowledgement of her Indigenous sources; perhaps even a form of apology. Or perhaps it was an expression of a certain loss of identity: this was not the work of Emily Carr, the painter, as she knew herself. For she didn’t just sign her work “Klee Wyck,” she also added another symbol, her maker’s mark: a single, lonely question mark. “Is this me?” it seems to ask. “Am I still an artist?” As a mark and a gesture of doubt and uncertainty, I find it remarkable. It leaves me rather breathless.

florian gadsby

Florian Gadsby is a ceramicist working in North London whose craftsmanship and generous social media presence (including in-depth and informative YouTube videos) has gained him a large following and much respect in the world of contemporary ceramics.

His own maker’s mark is a simple, elegant and runelike “F,” which he sets into the base of his ceramics using his own handmade porcelain stamps. It is something that he actively encourages other ceramic artists to do as well, for the personal connection it creates with one’s work. Today’s ceramicists may be tempted to use plastic and metal 3D-printed stamps, easily purchased online. But Florian creates his own stamps, using the same care and craftsmanship that he brings to his ceramic pots. For him, these handmade tools are indispensable.

As a material, porcelain shrinks around 15% to 20% after drying and being fired in a kiln. This, Florian says, allows him to carve a slightly larger stamp that will then shrink down to a smaller, more discrete size. Porcelain is also strong and durable, and smooth, making it easier to carve finer details.

38 ||| UPPERCASE

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

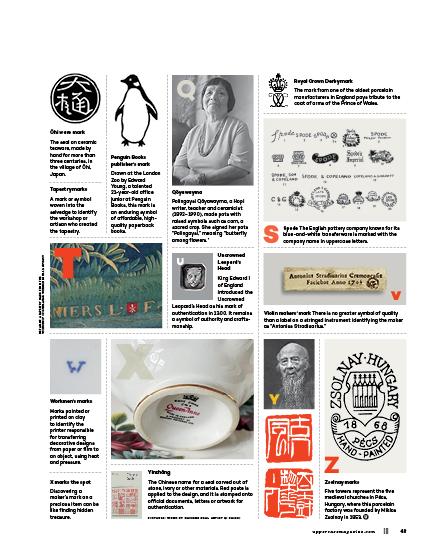

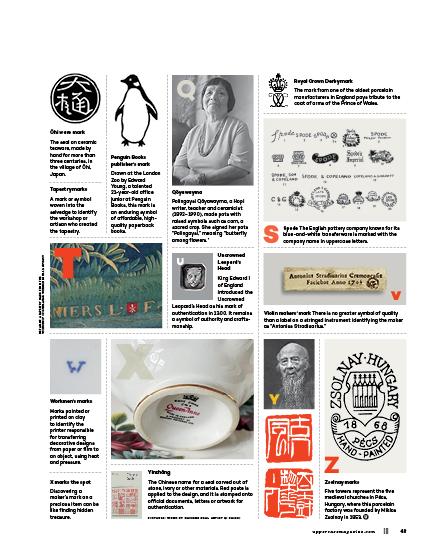

Assay office mark

A mark guaranteeing the authenticity of a metal object. Each testing office has its unique symbol. The Edinburgh Assay Office uses a castle symbol.

maker’s marks

COMPILED BY lydie raschka

Backstamp

A stamp on the back of porcelain or pottery that shows where the object was made. The willow pattern on tableware by Burgess and Leigh (Burleigh) in England uses willow branches.

Cipher

Date ciphers are symbols or codes used on ceramics and porcelain to indicate their manufacturing date.

HEATHCERAMICS.COM

Factory marks

Marks that identify a manufacturer’s products. The mark on Blue Mountain Pottery in Canada is a triangle of three trees.

Glazer’s mark

Used by the person who applies the glaze to pottery.

Hallmark

A stamp or series of stamps that indicate the place of origin, date of manufacture and metal content. A lotus flower or a cat denotes silver from Egypt.

Diamond registration marks

Used on ceramics to signify the registration and protection of the design.

Eames label Designers Charles and Ray Eames used paper or foil labels on their work, such as the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman, and the Eames Molded Plywood Chair.

Jugtown Pottery mark

Established in 1917 in North Carolina, Jugtown produces pitchers, vases, candlesticks and other items, in addition to jugs.

Kerr jar marks

Entrepreneur Alexander Kerr’s surname is embossed on his company’s wide-mouth quart, pint and half-pint home canning jars.

Limoges marks

Limoges, France, has been an important centre of porcelain production since the 18th century. The Latrille Freres (1899–1913) factory stood in an old abbey, as reflected in their mark.

Imperial Porcelain Factory mark

Founded in 1744, this factory-made porcelain for the ruling family of Russia included dishes, figurines, animals, vases and snuff boxes.

McKinley Tariff Act

This US law from 1890 raised taxes on foreign goods, requiring makers to include the country of origin in their marks for law enforcement and buyer information.

Navajo silver hallmarks

Symbols from the natural world are often found in Navajo silver marks. Jeweller Sadie Calvin used birds to mark her work.

42 ||| UPPERCASE ABECEDARY

MASONJARMERCHANT.COM

DETAIL OF A TAPESTRY MARK FROM THE WORKSHOP OF GUILLAUME WERNIER IN LILLE, NPS.GOV

STORY BY helen hallows

PHOTOS BY holly booth studio

PHOTOS BY holly booth studio

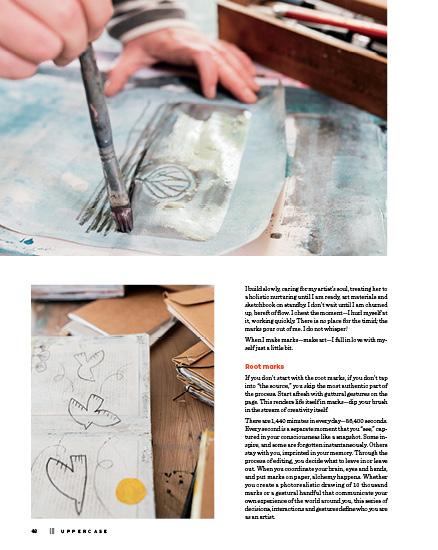

How do you touch the world? How do what you see, what you feel and the stories that you notice become tangible? Where does thought become mark—and become art? What processes create the transitions from thought to action? How can you prevent creative blocks to this flow and make authentic art with your own mark?

44 ||| UPPERCASE

what is the artist without the mark?

PROCESS

Giving birth to ideas

Conceptualizing art is part of the creative process. In our imagination, anything is possible: images dance and projects seem boundless. It is easy to dwell in this space, gathering ideas and fantasizing about outcomes. It is much harder to build a reality from those dreams. Making art is a raw attempt at grasping something from a world of infinite possibilities. Creativity is caught—and expressed—through our physical marks. There is nothing more sublime than feeling like a conduit for a thought, achieved by quieting the mind and embracing the active meditation of drawing or painting. Lean in to the inevitability of mistakes: you may feel vulnerable and a little hesitant. Have a love affair with the materials and trust them in their role in bringing out a new piece of art from within you. The resulting marks might not meet what was in your imagination but making art requires an acceptance of what is rather than a continuation of a fantasy. It is a brave soul who deals with the reality of art making.

Within your marks lies the spontaneity, the awkwardness and the clashes of materials that render the nub of a new idea. It is a suggestion of something to be built upon, to be revisited and repurposed. From the failings in one sketch, you may see the possibility for another. At this stage, there is a letting go of infinite possibilities and a focus on the next iteration of marks. Through editing and distillation, many ideas become one.

Look away, look within

In our connected, highly visual age, it is easy to jump on someone else’s bandwagon and take on their pursuit and wear it as our own. To go deeper—and to fully express oneself—we must turn away from the torrent of digital media. This takes discipline and requires vulnerability. Lovingly accept your shortcomings and embrace your processes. Let go of all you wish to be, and be who you uniquely are. Your unique voice exists. Despite all the noise of social media, there is still space for your marks, your successes, your failures and your art. Do not let yourself catch “fear-of-the-blank-page-itis” and stop yourself from wading into the river of creativity. You have to be in there, wholeheartedly splashing about, to find out who you are.

For me, the pulse of creativity very much comes with the ebb and flow of life. I know when I am not in a good place because I find it hard to show up at the page. My creativity is part of my wholeness and a part of my well-being. I have to give myself nourishment before I can create. When I am not able to accept myself, or I have given space to my inner (or outer) critics, I find it so hard to switch off my overthinking mode and just make marks!

Follow your intuition

Academic learning has given us tools to prioritize the analytical side of our brains, rather than to be bold, brave, inventive and inspirational. We learn that others have done it better than us and should receive our awe, and that we can only ever be a poor assimilation of those who have succeeded in the canons of art history. In contrast, as an intuitive artist, I try to bring my inner child to the page, to embrace the direct, joyful, playful wisdom of just doing!

Stay in the moment. Be bold, be brave. Show up at the page. Trust yourself to be you. Even if your marks are not what you expected, they are valuable—they represent your development, your conversation with the universe.

Let loose

Bringing what was in, out, can be hard! Fight against procrastination and just begin the unpolished business of creating. Frustration can grow if you don’t show up authentically, but there is such fulfillment in laying one’s soul bare on the page!

I take joy from the squelch of paint, the flow of ink, the push of a pencil on paper. It is a release, an empowerment, a rekindling memory of who I am, my purpose— when I can find myself in this secure space, a meditative nurturing space, when I can feel my way, not think my way forward. I feel more alive. My art becomes alive.

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 45

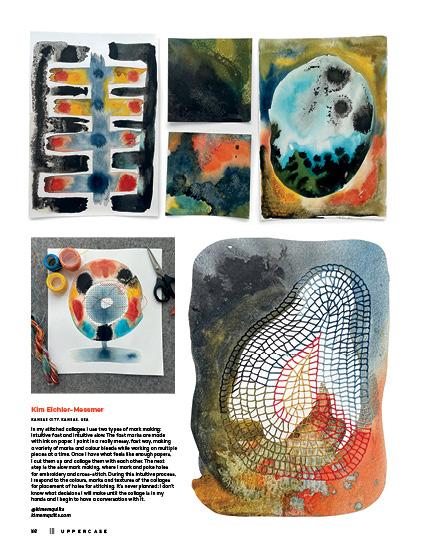

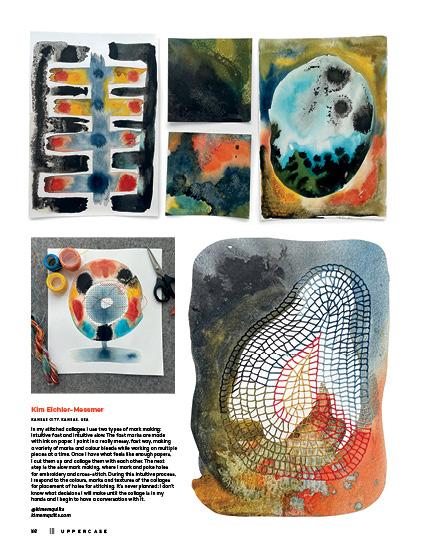

Clare Taylor

MANSFIELD, UK

Unfathomable calligraphy and joyful, accidental pattern making is my style. Working with ceramics and textiles, inevitably there is a crossover of the language of marks from one medium to another. Hand-stitched loops on paper are pressed into the beautifully responsive surface of clay. Subtle, stitched and imprinted textures tell the story of my own style of gestures. I use discarded items, such as pen lids and broken buttons, to breathe new life into them as mark-making tools. Curiosity and experimentation are key.

@curiousclaredesigns curiousclaredesigns. co.uk

Laura Croft

ILKLEY, WEST YORKSHIRE, UK

I use mark making in both illustrative and abstract work that is either screenprinted or printed digitally. Sometimes it may just be a bit of texture in an illustration and other times the print is purely textural. I love working in Indian ink using a variety of tools, including brushes, sponges, parts of plants or scraps of card. In this project, however, I explored some new processes, such as sequentially sanding layers of emulsion to create marks and working into a gelli plate with dried plants and then printing.

@letterandbrush

58 ||| UPPERCASE

NEW YORK, NEW YORK, USA

For most of my life I thought being an artist meant having a natural ability to draw something realistically. I never could and felt little inclination to learn, but in the last decade when I started painting intuitively I realized that scribbly marks were integral to my painting process. Each person’s scribble is unique to them, just like handwriting. I work intuitively, integrating marks with larger areas of paint and sometimes collaged paper. I use acrylic paint with different-sized brushes, graphite, acrylic markers or charcoal. I work in layers, creating depth. I often feel that if I were the size of a pinprick, I could crawl between those layers and marvel at my own fantasy land of colours and marks.

@laurasalzberg laurasalzberg.com

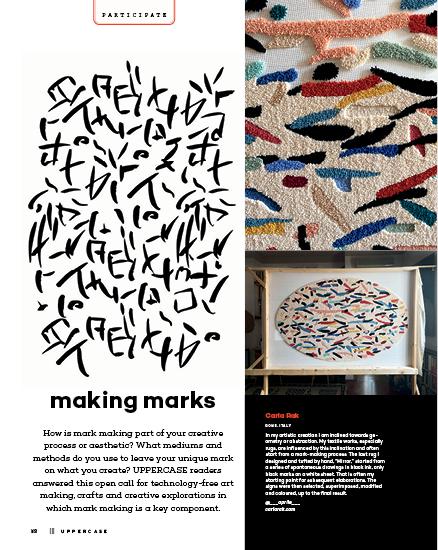

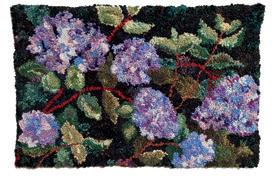

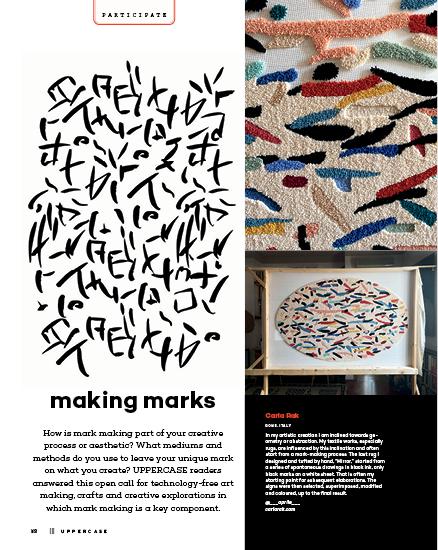

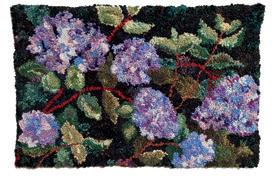

WAUSAU, WISCONSIN, USA

Hooking a rug is a steady process of pulling one loop of wool through an opening in linen, and then pulling up the next loop. Each loop is a mark that grows to become a pixelated shape of colour. These wonky shapes merge together and magically blend to form an image from my mind’s eye.

@lindaraetherdesigns lindaraetherdesigns.com

||| 59

Laura Salzberg

Linda Raether

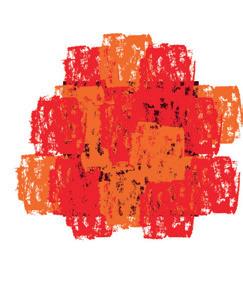

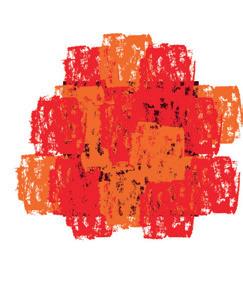

Melissa Gatti Conde

SÃO CARLOS, BRAZIL

I use different kinds of media such as watercolour and ink, and in this specific case I used dry pastels to make a couple of squares and create a texture. After that I vectorized them in Illustrator, making a pattern tile and recolouring it. I think it is very unique and has a cozy feeling—if it was made of wool and was on upholstery it would be grand!

@melissaconde_designs

Rekha Krishnamurthi

JERSEY CITY, NEW JERSEY, USA

Mark making is integral to my mixed-media collage art practice. Mark making is how I create texture and pattern, design and add elements of my South Asian culture to my artwork. My mark-making technique is very loose and flowy. I’m drawn to contrasting and bold colours. The main mediums I work with are acrylic paint, watercolour, brush markers, Sharpie markers, graphite, Posca paint pens, ink pads and gel pens. To make collage fodder, I use a variety of papers ranging from plain copy paper to tracing paper, brown paper bags, tissue paper, rice paper, deli paper, acetate and watercolour paper. My mark-making tools include a gelli plate, paintbrushes, brayers, masking fluid, stencils, stamps (including my own handcarved stamps), glass jars, jar lids, sponges and other household items. The end result is a colourful, eye-catching mixed-media art collage on stretched canvas or sulphite paper.

@divineny divineny.com

60 ||| UPPERCASE

Ruth Chapman

ARMONK, NEW YORK, USA

These compositions of birds and plants focus on renewal and the simple beauty of everyday life. My aim is to evoke a feeling of joy, connection and comfort—a sanctuary from the world outside.

To achieve this, I create collages from papers that I print in acrylic using a gel plate and other tools. I make marks on the gel plate and also directly on the papers with craft foam, found objects, carved vegetables, texture wedges and watercolour pencils. I love experimenting with interesting textures and patterns.

As I cut and assemble the collage, I apply more paint with brushes and sponges. I use mark making to loosely represent the veins of a petal, a bird’s speckled feathers, the mottled surface of a vase. The marks add a richness to the artwork as a whole, and it’s also satisfying to see the individual patterns and textures close up.

Liz Nania

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, USA

My artmaking is all about making marks. I open my sketchbook, dip my brush into ink or high-flow acrylic paint, and without a single plan, I put the brush to paper and begin making marks. As the ink dries, I may build several layers of marks. Or not. About every two months I’ll have filled each page of a thick handmade sketchbook with marks. I make large and small paintings, books and textile art, and spontaneous mark making is the core of all my work. It’s always a thrill!

@liz.b.n.art

liznania.com

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

@ruthchapman.art ruthchapmanart.com

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 61

Melissa Jander

CAMANO ISLAND, WASHINGTON, USA

I work in colourful oil paints using expressive brush marks to convey movement and light effects on my still life and landscape paintings. Through many years of painting I have developed my own unique calligraphy for applying colour to the canvas that helps communicate an emotional response to my subject.

@melissajander_art melissajander.com

Tracey English

LONDON, UK

I love to produce patterned papers in my illustrations. Most of my images start with a day of mark and texture making. I tend to use acrylic inks so that the colours don’t run or mix with the glue. Bits of corrugated card and children’s foam stamps are amongst my favourite tools. I always test out packaging in case it produces an interesting quality of mark. I never throw away brushes, as the older they get the better the marks they create! @traceyenglish tracey-english.co.uk

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 63

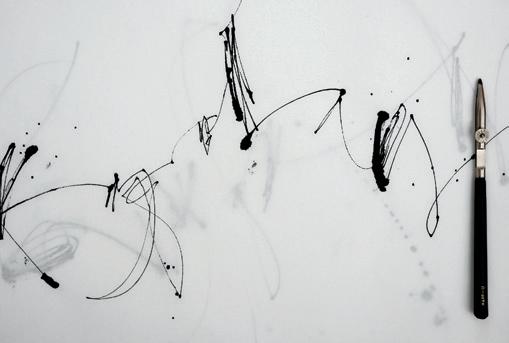

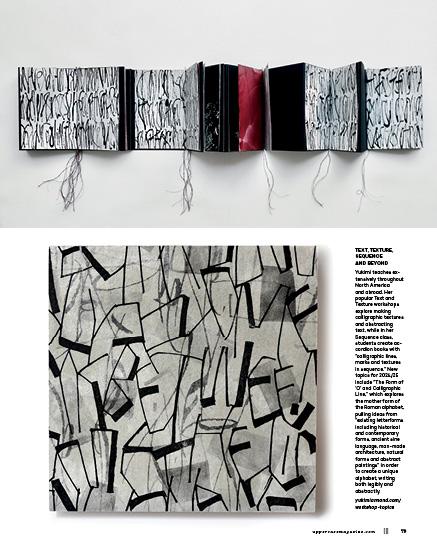

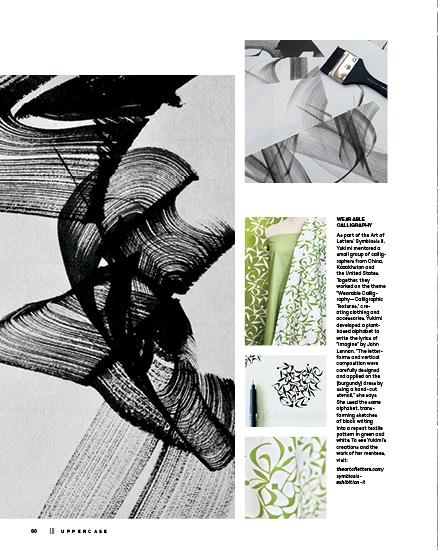

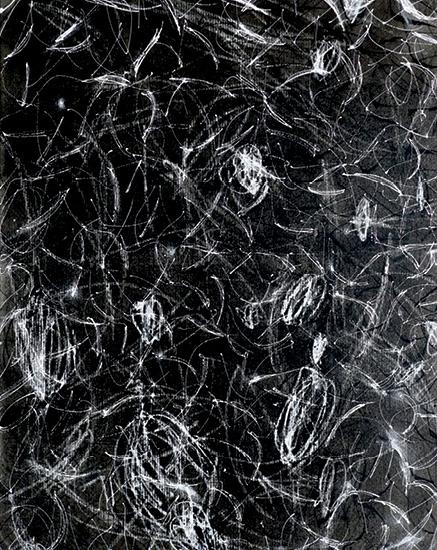

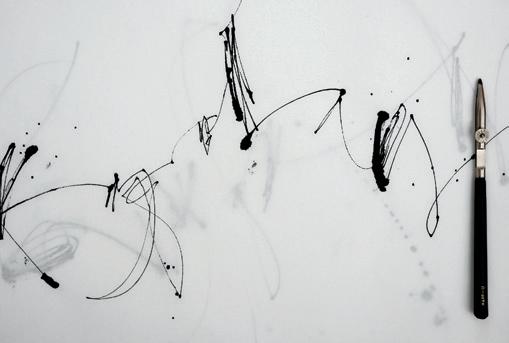

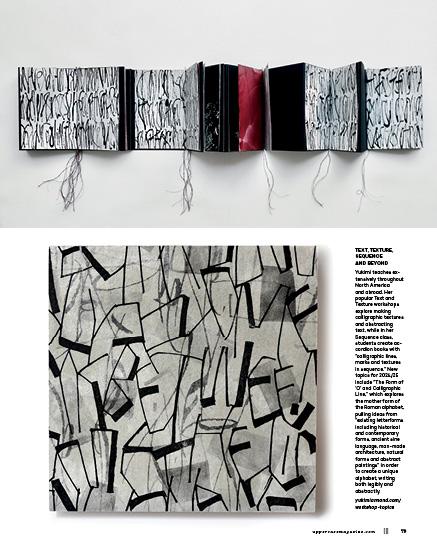

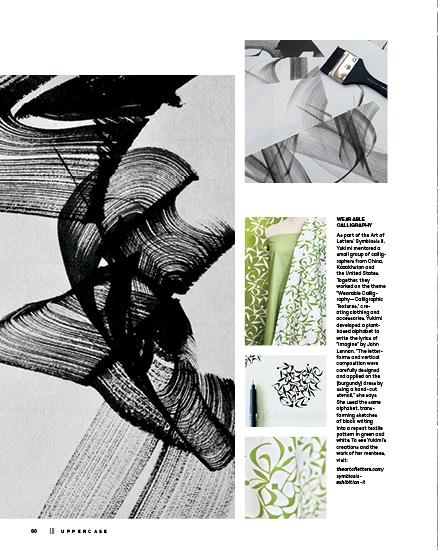

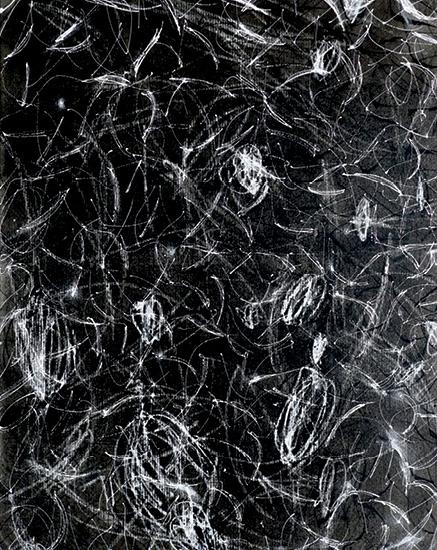

Yukimi went on to study visual communication design and spent “hours drawing both Japanese and Roman alphabets with pencils and brushes,” fascinated not just by the letters as tools of communication but by the beauty of the forms themselves. She worked as a graphic designer and director at Takenobu Igarashi Studio before moving to the United States in the early nineties. In 2000, she began to study traditional Western calligraphy at a local adult education centre, studying the traditional italic. As her studies continued, she wanted to find ways to express her emotions through her calligraphy. She was drawn to the work of lettering artists like Hans-Joachim Burgert, Thomas Ingmire and Denise Lach, as well as the American Abstract Expressionists like Mark Tobey, Lee Krasner, Conrad Marca-Relli and Willem de Kooning. And harkening back to her childhood by the ocean and hills, she has always been inspired by nature. “Nature has everything—line, form, contrast, colour, unity, harmony, equivalence,” Yukimi says. She began to experiment with capturing natural elements, incorporating those organic forms into her letters and texture development. She organizes inspiration images and photographs into extensive reference files. She often hangs photos on her studio wall, analyzing how she can interpret abstract works and natural textures, using her knowledge of calligraphy.

Her upstairs home studio is full of light and a diverse array of tools, from traditional calligraphy pens to handmade writing implements and objects found in nature. Her tools are categorized by type and also by shape. As she pulls out boxes and unfurls her fabric pen rolls, she points out the relationships between her tools. She notes that, for example, the soft curve of a thick pointed brush relates to the radius cut of a metal folded pen, allowing her to use the tools in a similar way. A balsa stick can inform the use of a wide flat brush (even a soft one) because both tools have a flat edge. A specific movement, therefore, can be explored with different tools, while harnessing one’s muscle memory. The movement is essentially the same, but the resulting mark will have different qualities and energy.

Depending on the scale of the piece, Yukimi will either work in a chair, standing over her table or sitting on the floor. While her studio is sunny and bright, she finds that her deepest moments of concentration occur between ten o’clock in the evening and two o’clock in the morning. When she works, she does not listen to music. “I always work with words and texts. They have their own sounds,” she explains. “I listen to the sound of words when I create.”

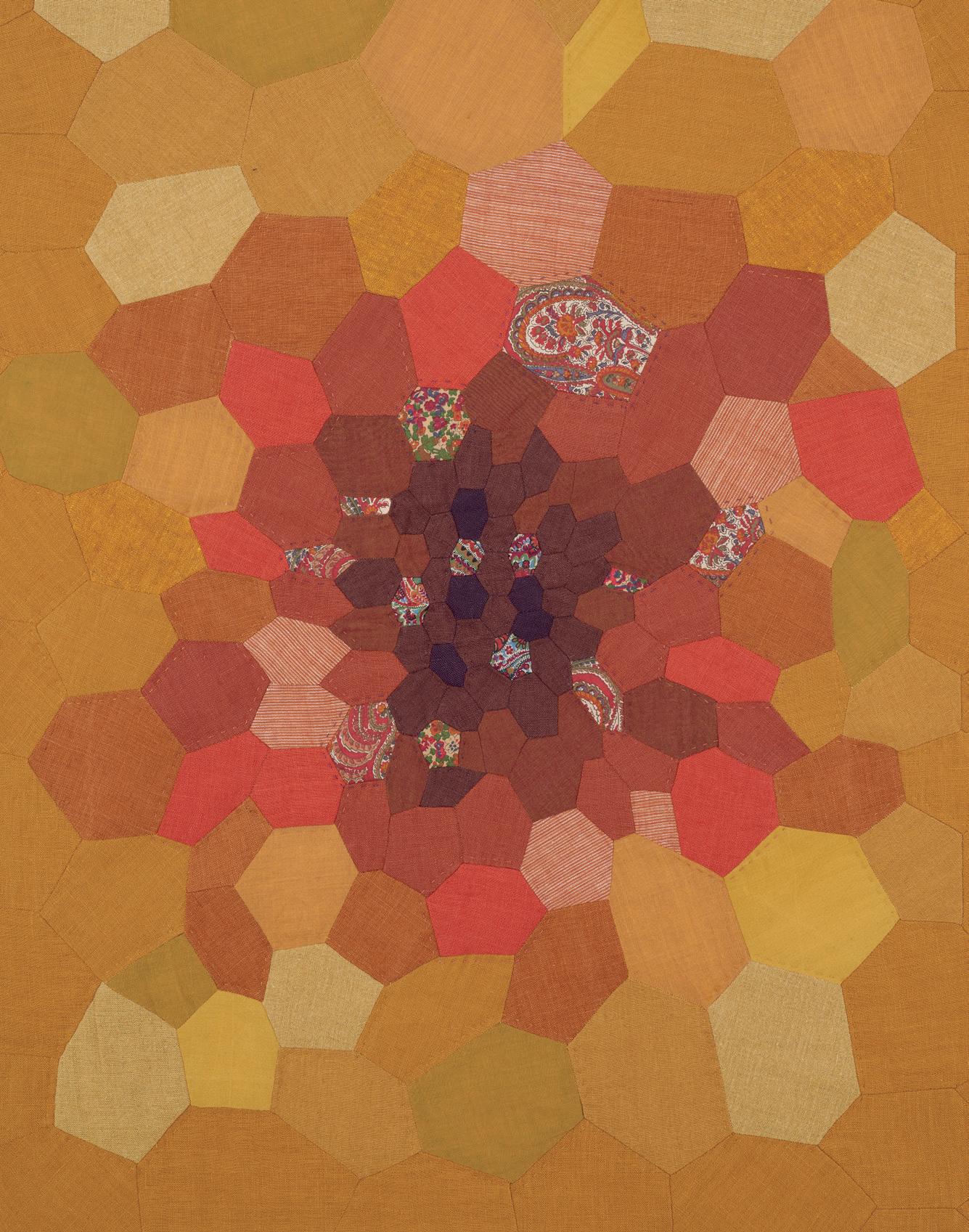

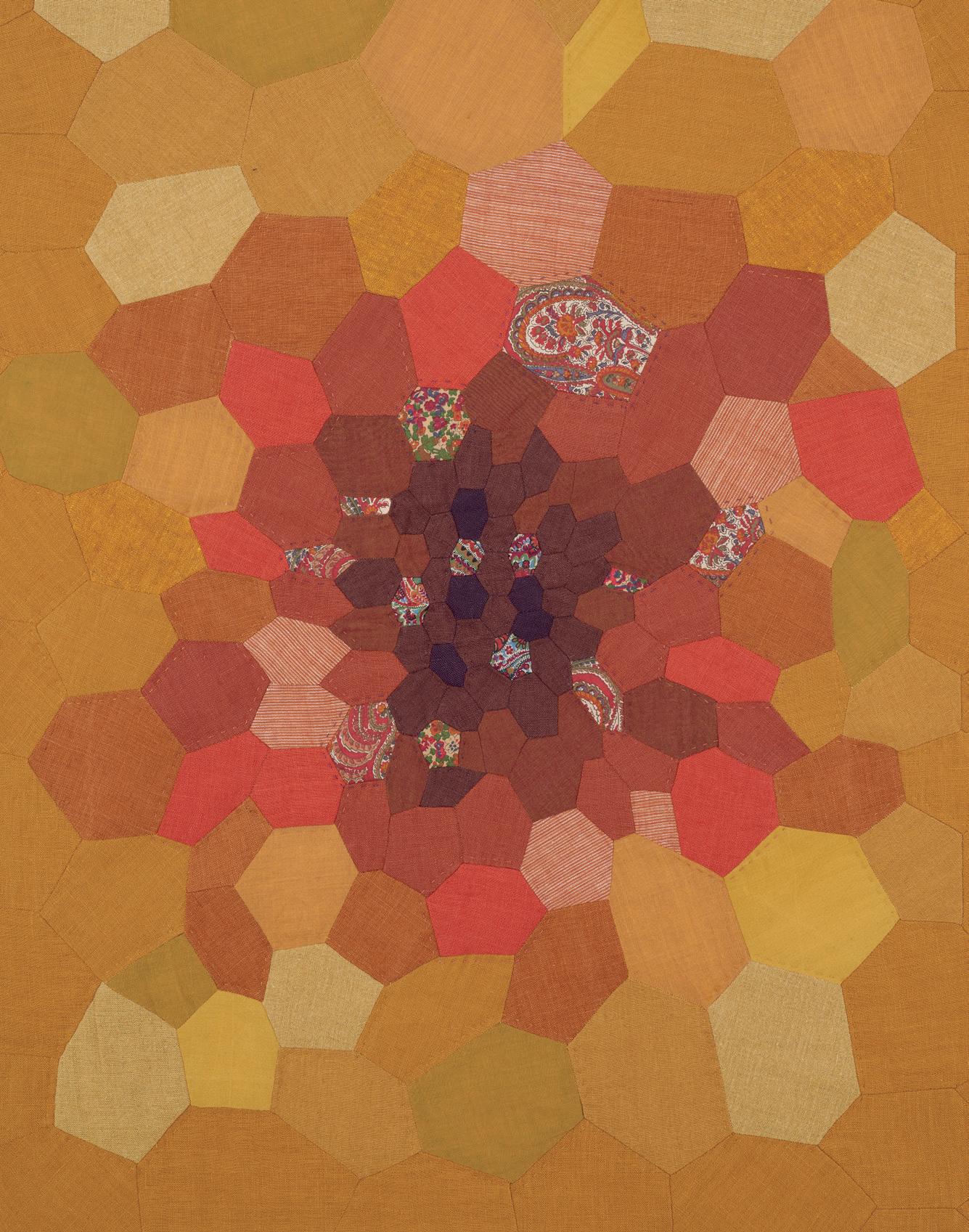

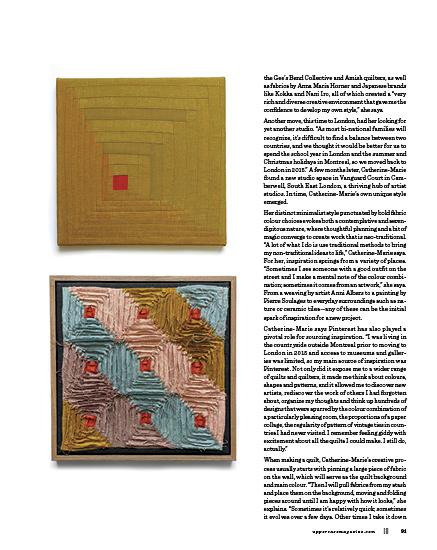

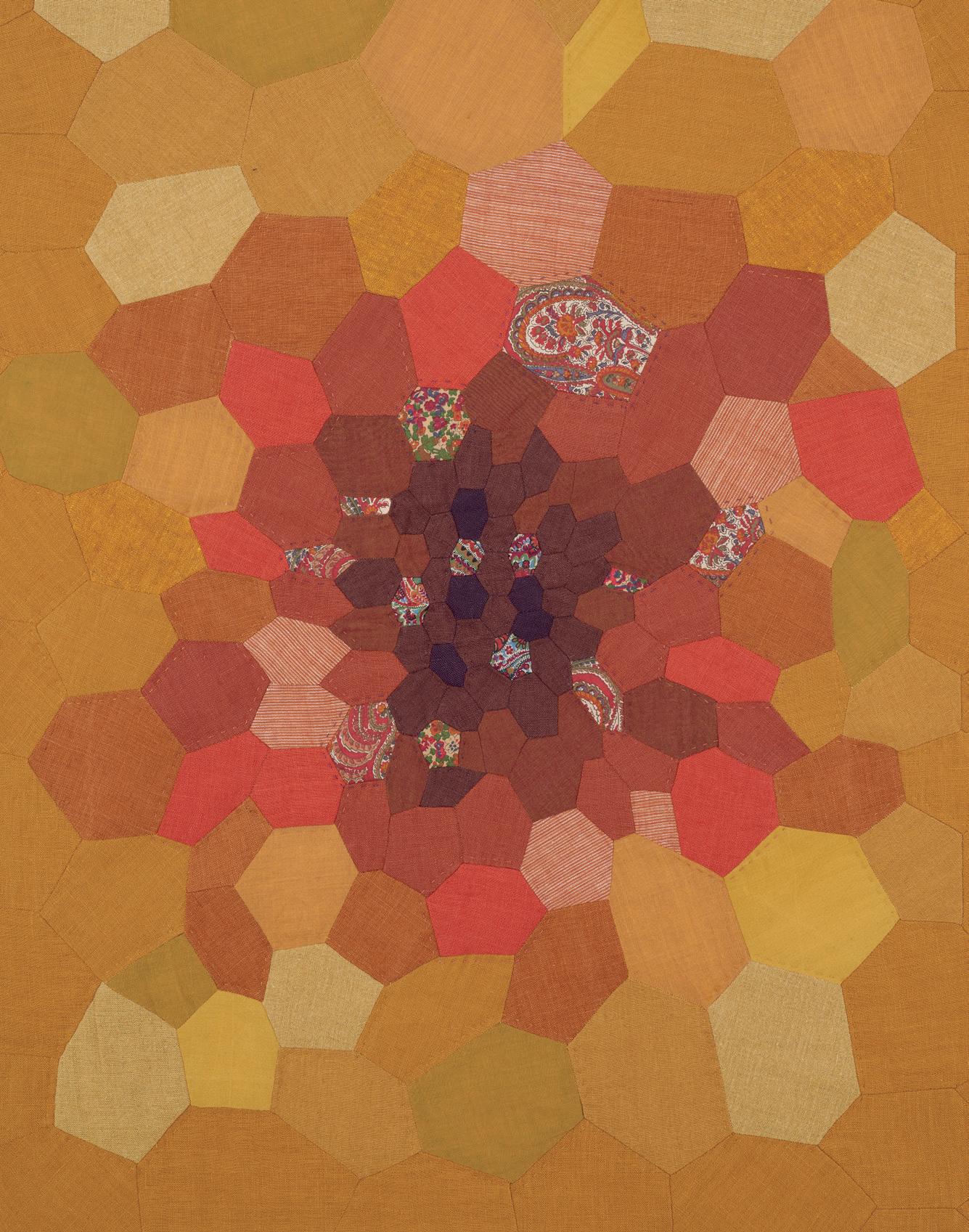

Her mom taught her to sew, and while Catherine-Marie adored browsing for fabrics with her mom, she was not particularly interested in making her own clothes as a teenager, preferring clothing in the shops instead. She didn’t want to bother with sewing patterns, fitting and unpicking stitches. While she had no trouble finding clothes she liked, she did struggle to find bed linens she liked. When she was 16 years old her father made her a wooden double bed to her specifications and she searched for months for a duvet cover she liked. She had plenty of inspiration from the interior decoration magazines that filled their house, such as French Elle Decor, which her mom bought every month.

“I loved leafing through the luscious interiors and seeing beautiful home textiles from chic Parisian shops, so it always felt like a bit of a letdown when I had to choose something from the shelves of department stores,” Catherine-Marie explains. Her mom eventually took her to a textile studio on Boulevard Saint-Laurent, where she commissioned someone to make a duvet cover and pillow cases for her. Catherine-Marie says the result was “simple yet luxurious and beautiful. The upgrade in fabrics, away from the ubiquitous polycotton of the times, made a huge difference [to me] and planted the seeds for more homemade duvet covers over the years.”

Although the initial spark of inspiration for her quilting career stems from the creative influences of her upbringing, she also did well in academics and completed

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

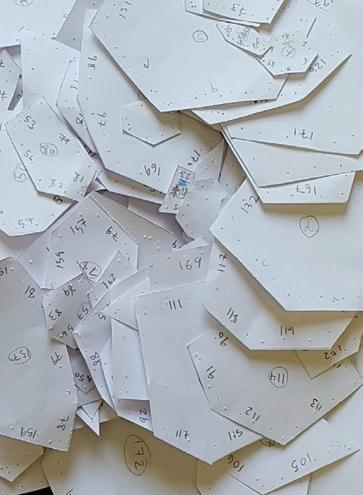

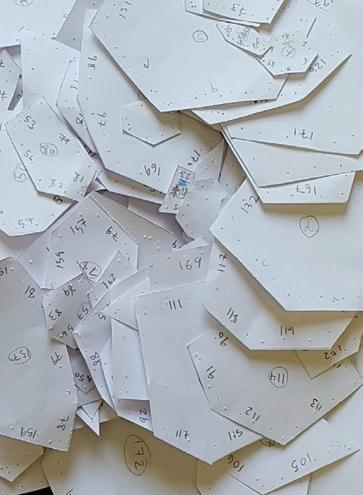

to work on something else until I can come up with a design I want to make into a quilt.”

Her process for English paper piecing is somewhat different. She enjoys playing with distorting traditional patterns like hexagons or squares. Then she will draw a pattern on a piece of light card stock, and then number each piece. Afterwards she cuts up the pattern, bastes fabric around each individual piece of card stock and stitches them back together. “It’s a bit like a jigsaw puzzle,” she says. “It provides amazing precision, as all the pieces will fit back together in the way you cut them up.” She adds that she doesn’t need to worry about seam allowance or precision sewing.

Her methodical and minimalist style also echoes some of the tools and supplies she uses, many of which are quite old. Catherine-Marie finds comfort in using sewing tools and supplies from her late grandmother’s sewing box, which she says “has a distinct smell of Roger and Gallet soap.” When she works with her grandmother’s tools or with fabrics such as antique silks and cottons, “there’s a sense of connection, and a reflection about the materiality of life—the things we leave behind—how objects can survive us and be used by someone else.” She also finds it humbling when someone who is recently bereaved contacts her to make a memory quilt out of the clothes of their loved one. “Every stain, tear, worn-out cuff or collar tells a story and I’m glad these clothes get to have another life and be cherished,” she says.

Not only does she find comfort in the tools she uses, and in memorializing materials for others, she also finds

92 ||| UPPERCASE

1 4 7 2 5 3 6

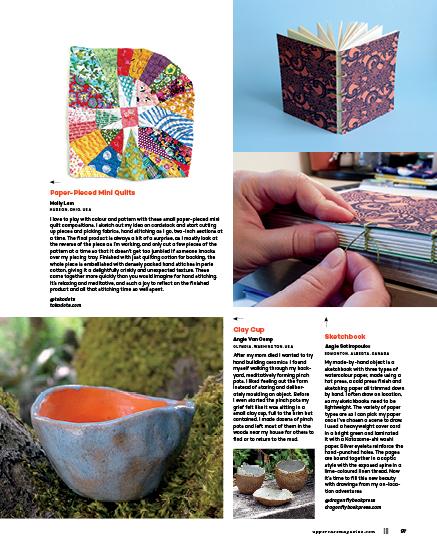

1 Knitted Welcome Blankets

Kristin Frentzel Regen

BETHESDA, MARYLAND, USA

I learned to knit in 2017 as part of the Welcome Blanket project, an initiative created to welcome new refugees and immigrants to the United States. Each blanket was accompanied by a personal note, and words of encouragement. I fell in love with this beautiful, meditative art and this means of creating a tangible welcome for others, and after creating several welcome blankets, I have knit several baby blankets to welcome new souls into the world. I find the simplicity of stripes to be soothing and simultaneously timeless and modern.

@regenkristin

2 Crocheted Flowers

Judy Ewing

GOLDEN VALLEY, MINNESOTA, USA

I crochet flower washcloths for girls at an orphanage in Kenya.

3

5 Hand-Dyed, Handspun Yarn

Rachel M. Post

CHERRY VALLEY, CA, USA

I make one-of-a-kind handdyed and handspun yarn. My creations are powered by my feet, my hands and my exploration of nature. I love the process of this heritage craft. I feel the presence of my ancestors when I am spinning.

@rachelmpost rachelmpost.com

6

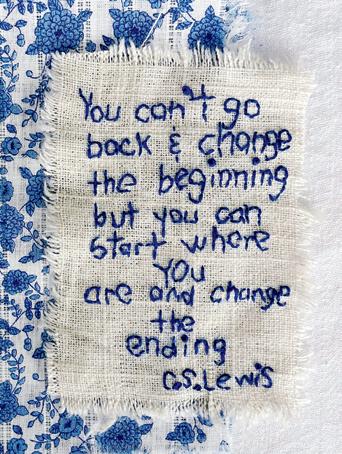

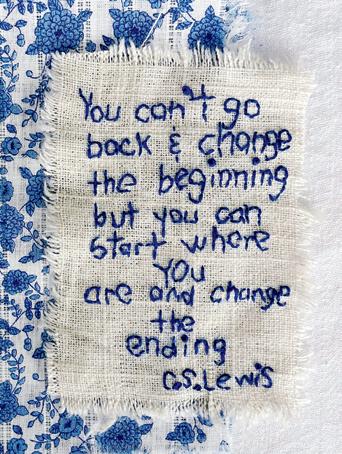

Slow Stitching

Dagmar Leuenberger-Swift

WEST KELOWNA, BC, CANADA

I love to slow stitch. The simple task of pushing the needle through the fabric is meditative and grounding. Stitching words and quotes gives the fabric a sense of purpose.

@cookie1949

7 Heirloom Knits

Mitsziko Mote

EDMOND, OKLAHOMA, USA

Air-Dry Clay

Caroline-Isabelle Caron

OTTAWA, ONTARIO, CANADA

I have tried my hands on every kind of clay in my life, even ceramics, and have failed every time. I am not made for it. Except about 30 years ago, there was some leftover air-dry clay that was going to be thrown out. I mindlessly played with it until I realized I had sculpted a baboon. My only clay art to ever come out. It lives on my desk.

4

I love creating heirloom pieces by processing through a variety of techniques. My favourite approach is by knitting an item, then embellishing it with a flat design in duplicate stitch (created from a vintage chart) and dimensional embroidery (stitched intuitively).

This has the delightful effect of modernizing old patterns yet maintaining their romantic identity. The meditative process of creating by hand is thus satisfied while allowing for enough variety to avoid it becoming tedious.

@studiomitsziko studiomitsziko.com

Stamping

Anick Globensky-Bromow

MONTREAL, QUEBEC, CANADA

I had an itch to try something new and I came across a handmade stamping kit. I had a blast! Such fun to create something by hand and use it in my journals. I want to try my hand at crochet next!

@nicky.bromow

8 Sashiko

Hope Coppinger

MORRISTOWN, NEW JERSEY, USA

This little pillow was purchased as a piece of fabric with a sashiko pattern printed on it, which I chose to practise my hand stitching. Using variegated thread, I enjoyed the way colours blended and collided with each other. My

teenage son saw me working on it and admired it (a rare feat from a teenager!), so I stitched his initials on the back to make it truly his.

@hopecoppinger

9 Bowls

Anne Buckingham

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA

These small, hand-stitched bowls are made from found and recycled materials, including tea bags, soft plastics and repurposed yarns. I enjoy the challenge that comes with using what is on hand and allowing the materials to define the outcome. As a registered art therapist I find that the slow process of making the bowls is a great reflective practice: the softness of materials coming together in a structure, the slow and repetitive stitching, and the acceptance of an unexpected outcome. Each bowl develops its own personality, which lends itself to being decorative or used in some way.

annebuckingham.com

10 Kilts

Robin Cassady-Cain

TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA

Traditional Scottish kilts are made using six to ten yards of 100% wool, usually, but not always, Scottish tartan. Each kilt is painstakingly stitched by hand using five to seven different types of stitches, and consists of nine different stages: constructing the front apron and under apron, setting up the pleats, measuring and stitching the pleats, debulking the pleats and steeking, stabilizing and sewing the canvas lining, attaching and stitching the waistband, lining the kilt, attaching the straps and buckles, and basting and pressing. Each kilt takes about 15 to 20 hours to stitch and is constructed to have room to grow—and when taken care of properly, is made to last more than a lifetime.

@hocassady_jewellery_ and_kilts houseofcassady.ca

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 107

8 9 10

Clay Sculpture

Sara Swink

WEST LINN, OREGON, USA

This is a Wally. It’s a small sculpture made of clay that hangs on the wall. I’ve made hundreds of these, each one unique. It starts with two pinch pots joined together to make a hollow body, then a third to make the head. I add coils formed into ears, arms and legs, then incise features with a wooden tool and an X-Acto knife. I cut a hole in the back for hanging. Now it’s ready for bisque firing, after which I’ll stain it to bring out the incised lines, brush on colourful glazes and fire it again.

@sara.swink.ceramics saraswink.com

Hand-Built Ceramics

Kirsten Schiel

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH, USA

This year, I decided to shift most of my ceramic work off the wheel and onto my workbench. Hand-built work is more time-consuming to make, and harder to sell. But to keep resisting the pivot felt like I was denying an artistic authenticity I needed to express. There is magic in creating something entirely by hand. I feel a heightened sense of connection that translates into deep reflection of my own life experiences while crafting these pieces.

My aim is never to trick the clay into behaving like a material it is not, but rather to collaborate with it. I create pieces that accentuate the organic texture, colour and movement of the clay body. There is a conscious surrender that I practise as the piece takes form. I begin the process with a loose idea, and let the clay guide the evolution to the finished product.

@sils.ceramic.studios

silsceramics.com

Friendly Creatures

Lauren Semark-Schmoll

NORTH VANCOUVER, BC, CANADA

Almost every creation you see here was made for a friend (I’m 15 years old). It’s what gave me the motivation to finish them in the span of four days. For each one, I started with some tinfoil from my kitchen drawer and used it to create the “bones” of the creature, essentially the sculpting before the sculpting. I then used Sculpey clay to build on top of the tinfoil until I was happy with how the character looked. Then, they went straight into the oven for about 15 minutes, and once they had cooled down I used acrylic paint to give them some colour. They were completed with a coating of Modge Podge to protect them. When they were done, I couldn’t help myself, and had photo shoots with them in nature, imagining how they would explore/interact with the world around them if they were actually alive.

110 ||| UPPERCASE

Linen Shirt-Dress

Kelsey Worth

BUFFALO, NEW YORK, USA

This is a linen shirt-dress that I hand sewed over three weeks of my summer vacation. I learned to sew when I was six years old, and I’ve always used a machine. This year, I wanted to slow down my making practice, and put as much care and intention into a garment as I possibly could. Hand stitching every seam was the best way I could think of to do that, and indeed, every stitch was made with joy and love. I am so proud of this dress, and of my 10 hand-stitched buttonholes. You can see the work of my two hands in every seam. It will be treasured for a long time, I hope.

@worthdrygoods worthdrygoods.substack.com

Rebuilt Threads

Kate Ritchie

CALGARY, ALBERTA, CANADA

These objects are generated through listening to the needs of the threads, and the process reflects this active listening. First, textile volunteers are solicited, listening to the objects to see who is up for the dance, allowing the objects their agency. Next, we fall apart, listening to the object— thread by thread, the object is taken apart. The act of removing the threads is slow and requires attention. To respect the original form, the threads removed are kept in order, placed between the pages of books, so their original order is maintained. Finally, these objects come together in a new context. Removed from their homes between the pages of a book, the threads are held in a new warp. This process of selecting, falling apart and coming together has proven to be infinite. There is no end to the number of times we can break apart and rebuild.

@kharvr kateharveyritchie.com

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 111

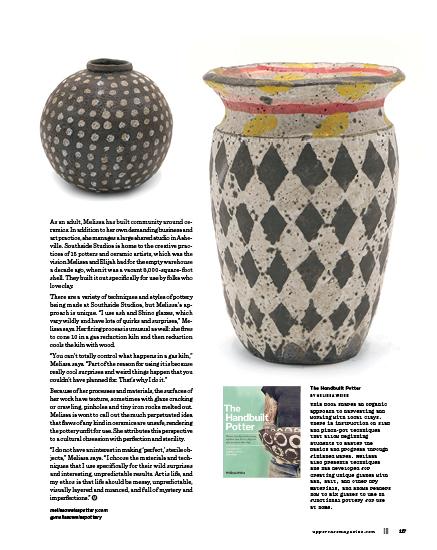

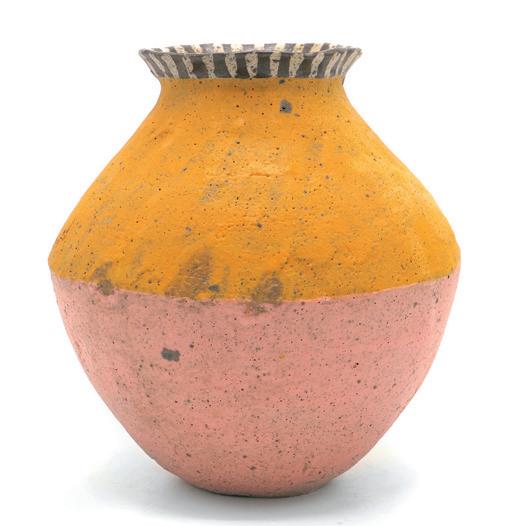

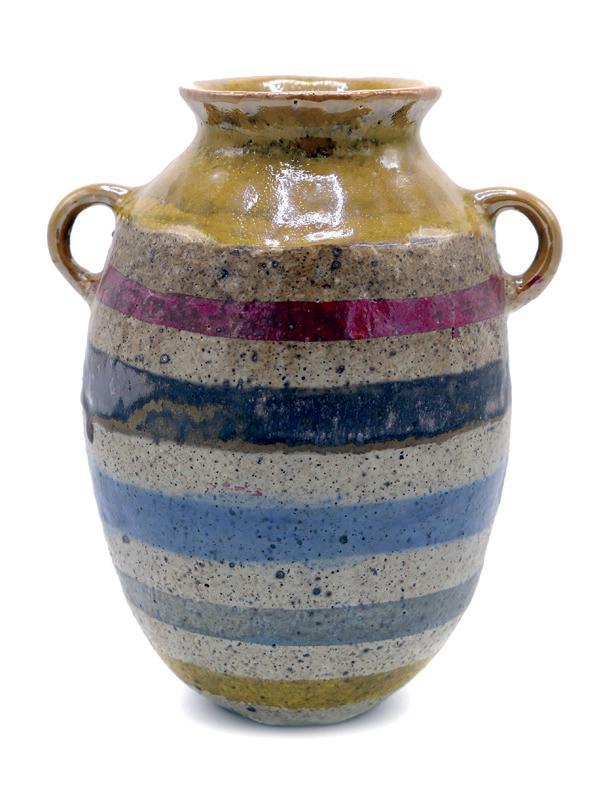

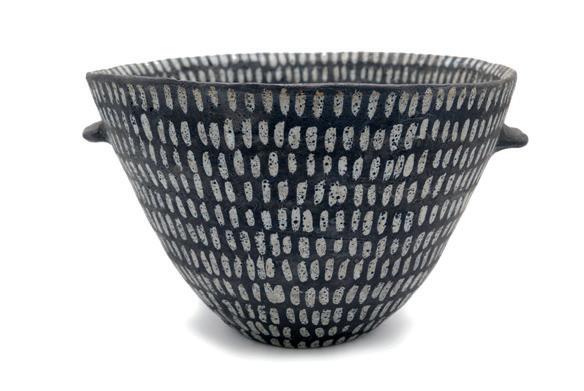

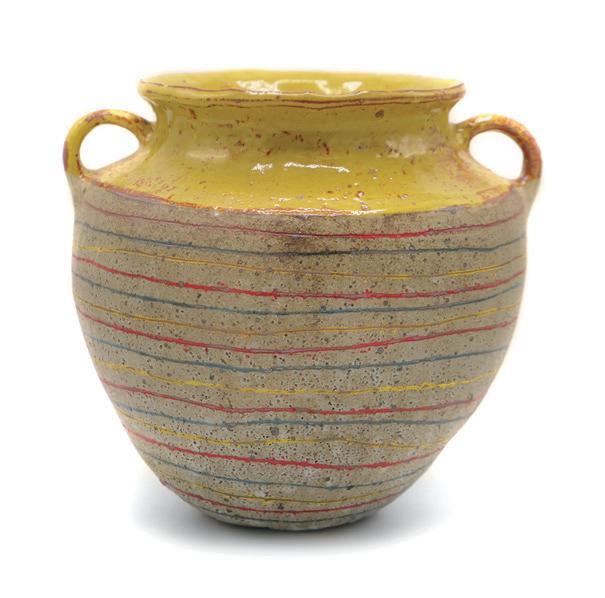

wild clay

COLOURFUL

COLOURFUL

HAND-BUILT CERAMICS

BY MELISSA WEISS

STORY BY claire dibble

BY MELISSA WEISS

STORY BY claire dibble

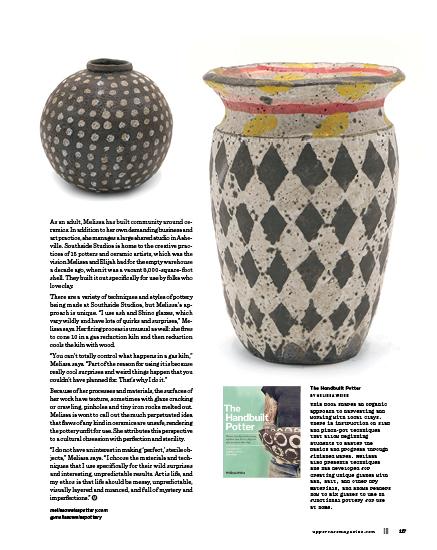

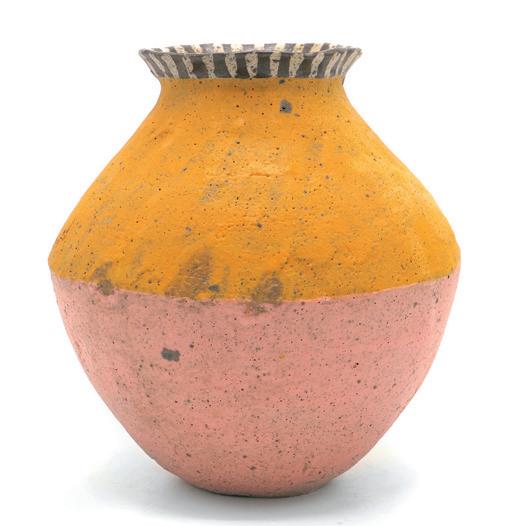

112 ||| UPPERCASE CLAY

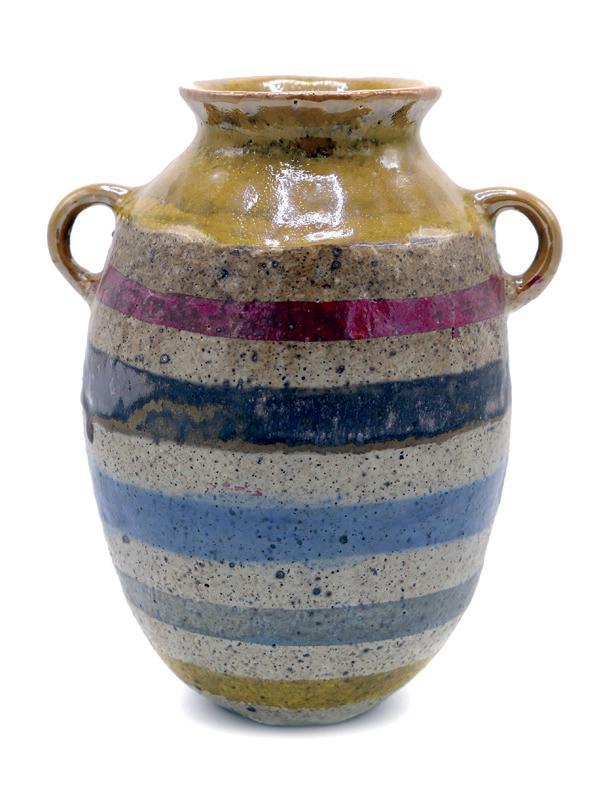

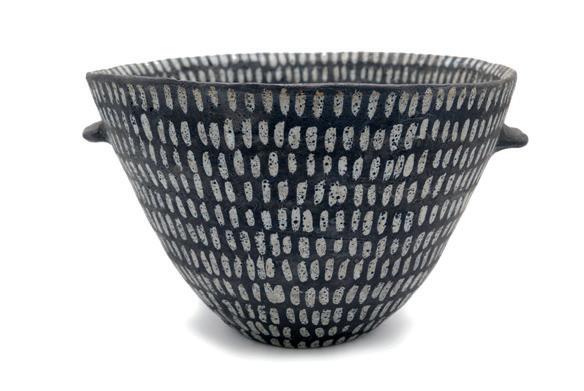

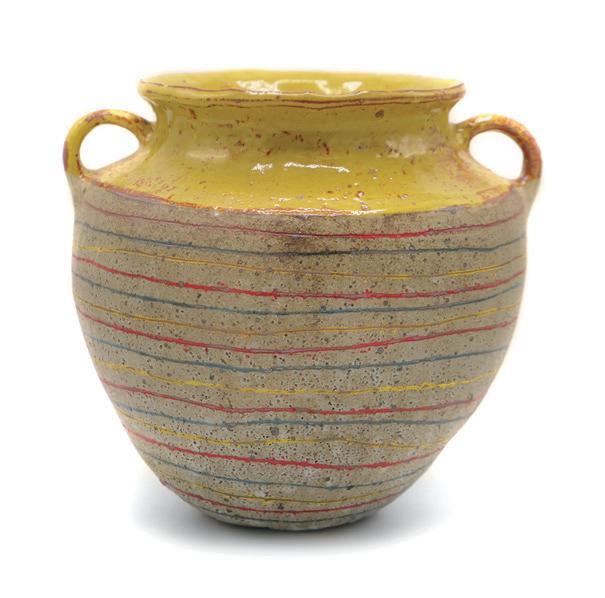

Melissa Weiss makes things with clay. She also makes the clay. The functional pieces that come into being through her hands are full of character and texture and— some might say—flaws. It is these imperfections that delight Melissa. It is the uncertainty in her process that keeps her engaged and excited and ready for the next surprise.

This openness to whatever may come is one part of a practice that also includes an incredible attention to detail, experimentation, testing and patience in finding methods that are reliable. It is a dichotomy that many an artist lives out by devoting considerable effort to hone a craft, while also maintaining flexibility when things go differently than expected.

Things went differently than expected for Melissa before she got into ceramics. She was living in a remote corner of Arkansas as a new mom, thinking life might be one sort of way. Things changed, and she found herself in another state, in a small city rather than down a long dirt road. That new situation, in Asheville, North Carolina, opened doors that Melissa could not have predicted, including a door to a pottery studio.

Back then, when she was newly immersed in the world of ceramics, Melissa was surprised to find an easily accessible layer of natural clay on the land that had been her home in Arkansas. During that visit, she filled a bucket and brought it home to Asheville.

“I spent weeks testing different variations of recipes, incorporating this wild clay, until I came up with a clay body that was workable, durable and aesthetically what I wanted,” Melissa says. That was 15 years ago, and she has been using this custom clay body ever since.

“We dig 2,000 pounds each year, which sounds like an incredible amount of clay, but it’s really just about 20 five-gallon buckets,” Melissa says. “The digging is kind of the easy part.” The harder part is the full process of making the clay in thousand-pound batches. Her husband, Elijah Ferguson, has taken on the substantial

task. “He’s the behind-the-scenes other half of my pottery business,” she says.

Elijah starts the process by soaking the Arkansas wild clay with water in a big metal drum and then using a drill to mix it into a slurry. Next he runs the slurry through a screen that is fine enough to catch potentially problematic large particles, but that still allows some of the finer bits through. These particles and the choice to include them in the clay are part of what gives Melissa’s work its distinctive look. Then Elijah adds the other ingredients—sand, feldspar, Georgia red clay and another ball clay—and pours this mixture into racks to drain and dry to the right consistency over several weeks. In the final step he runs the drained clay through a pug mill for one last round of mixing before Melissa shapes it into mugs and pots and other works.

“I love the digging part and going back to that land every year, but the land is bittersweet,” Melissa says. “It has as many tough associations as good ones; many of my most profound adult life experiences happened at that land, the happiest and the most brutal.”

uppercasemagazine.com ||| 113

These days, decorating her works is what brings Melissa the most joy. “Exploring colour and how much feeling and meaning it has, has been extraordinarily satisfying,” she says. Where once she adorned her pots and mugs with patterns in black-and-white, now there is yellow and pink and green. The colours are somehow both bold and earthy, bright but paradoxically subdued. “That’s partly because I’m using underglaze, which is bold and bright, but I’m also using stained Shino glazes, which are more subdued,” Melissa says.

Prior to this relatively recent deep dive into colour, Melissa’s work was held within the confines of commercial success. One of the pitfalls of selling a lot of work as a potter is that there is not a lot of free time left over for trying new things.

“I had wanted to try colour, it was on my radar, but I didn’t really have the time to devote to figuring out how,” Melissa says. “In ceramics it’s not like in other mediums where you just pick up colour; it’s a little more complicated because you have to formulate to ensure it works with your clay body and your firing.”

After some initial testing and experimenting, Melissa found methods for adding colour to her work in layers that still show the qualities of the clay underneath. It is the pairing of colours that is a real delight, for both Melissa and the folks who buy and use her pottery. Some of the works are about colour alone, while others have drawings carved into them with the aid of a wax resist. Cats, snakes, bananas and flowers are some of the motifs that Melissa has been drawing lately, purely for the joy of it.

Throughout her career, and especially in these recent years of colour play, Melissa has been setting aside the pieces that come out of the kiln with unexpected results. These become her favourites, and sometimes also prompt the next round of experimentation. She holds onto them as references so that she can attempt to recreate an odd effect. This, Melissa surmises, is contrary to what might be expected of a ceramicist.

“There is something that happens in ceramics that I think is a real detriment to people’s experimentation,” Melissa says. “Because so much can go wrong, we’re taught to be scared of trying things.”

Melissa was not and is not afraid to try new things. She lets the unpredictabilities of her materials and process guide her in new directions. This means that the moment of opening the kiln to reveal the successes— and sometimes the failures—of a hard-earned batch of pottery can be rather tense. Melissa jokes about watching the reveal through her fingers, eyes partially covered. Years of experience and a very steady practice help ensure that it is mostly successes that emerge from the kiln.

“I love this material and I love how endless it is,” Melissa says. “You can just change one little thing and it blows open the doors—like, I’ve changed my firing before and it made the work totally different.”

Though there is a great deal of experimenting in some aspects of Melissa’s work, she is quick to point out that her forms are simple. “I don’t make complicated, fussed-over ceramic forms,” she says. “I use very basic methods that people have used for tens of thousands of years.”

114 ||| UPPERCASE

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

THIS IS A LOW RES PREVIEW OF A HIGH QUALITY QUARTERLY PRINT MAGAZINE

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE

subscriber studios

Want to be featured?

Submit your studio story! uppercasemagazine.com/participate

Sarah Lalonde

CLINTON, NEW YORK, USA

We refer to my studio space as my “princess palace!” A few years after our children left the nest, we turned one of the bedrooms into an office, so I had a quiet space to work on my STEAM-based business. I started taking watercolour courses online, alcohol ink courses and acrylic lessons. I also learned about cutting stamps and printmaking. As the time I spent creating increased, so did the number of art supplies I had. Like most artists, I became obsessed with all things art! I love my studio space! It is bright and airy. I can look out the window and see the lush green field across the street. My husband and I installed shelving in the closet and on the wall, for storage. There is an electric fireplace that I turn on first thing when mornings are chilly, so I can be comfy right away. A rug and a yoga mat allow me to take a meaningful break from sitting.

lalondestudios.com

@lalondestudios

126 ||| UPPERCASE

STUDIO

ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume Y The UPPERCASE Encyclopedia of Inspiration encyclopediaofinspiration.com BACKGROUND: AMANDA MCCAVOUR

looking forward

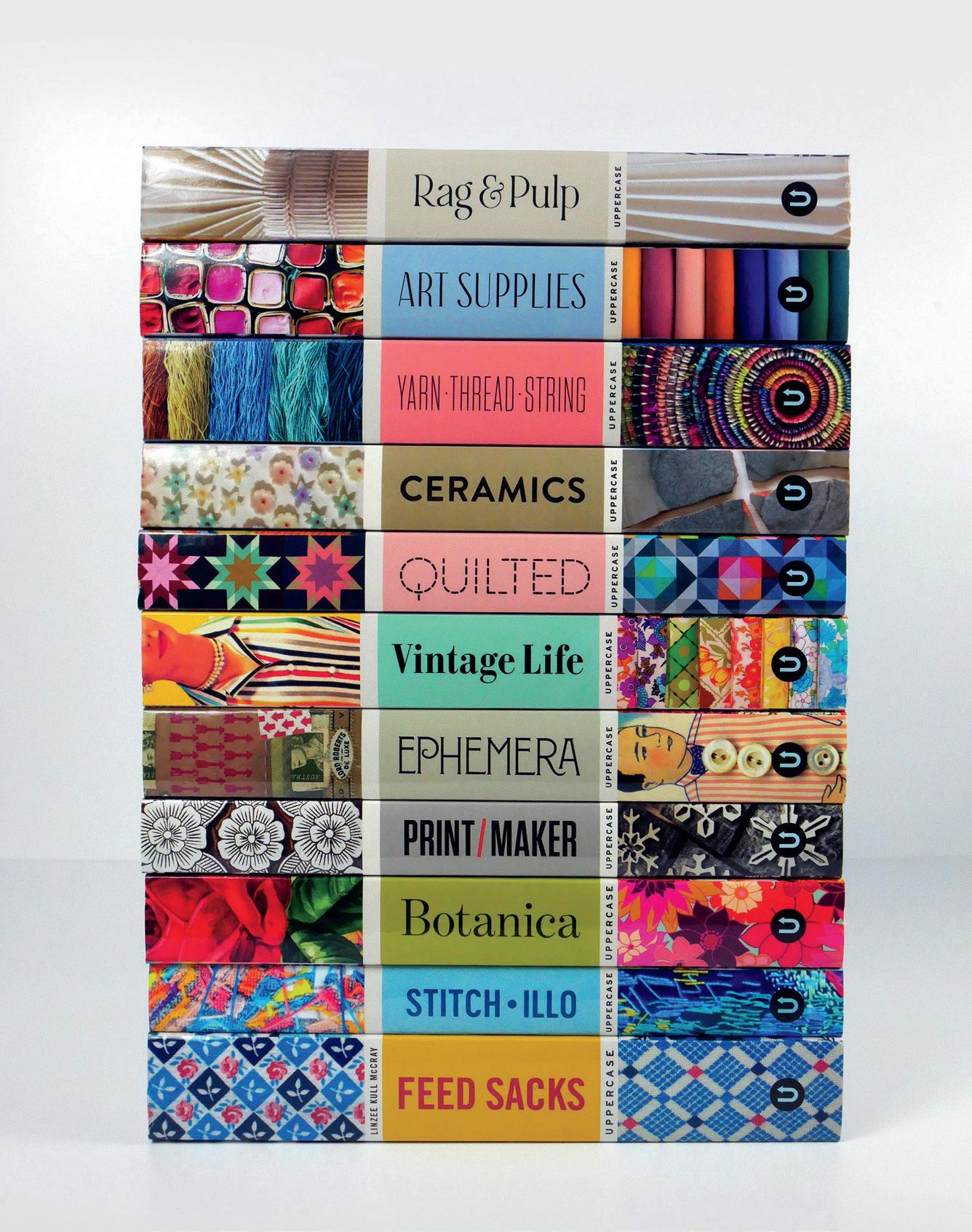

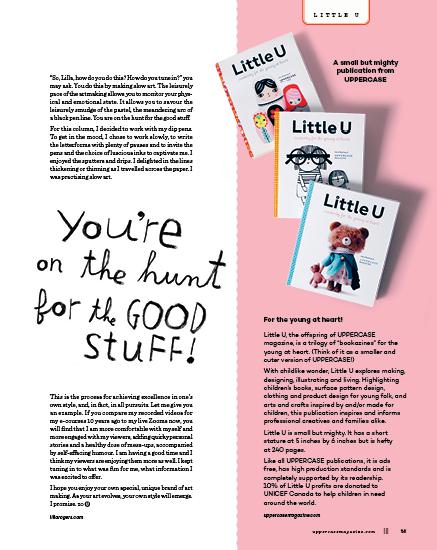

UPPERCASE Encyclopedia of Inspiration

Volume E: Ephemera Reprint coming November 2023

uppercasemagazine.com/ephemera

Volume N: Notions

Planned for release in early 2024 (date to be confirmed)

uppercasemagazine.com/volumeN

The next volumes in the UPPERCASE Encyclopedia of Inspiration will be announced soon!

Be sure to sign up for my weekly newsletter for behind-the-scenes updates and the latest on open calls for submissions for UPPERCASE books and magazines.

uppercasemagazine.com/free

UPPERCASE magazine

#60 January-February-March 2024

#61 April-May-June 2024

#62 July-August-September 2024

#63 October-November-December 2024

Pitch your article ideas and theme suggestions anytime!

uppercasemagazine.com/participate

Circle

Make connections, nurture your creative spirit and grow your business!

The UPPERCASE Circle is a vibrant community hub, one that is a valuable source of motivation, inspiration and encouragement for like-minded and kind-hearted creative people from around the world. Although the community is initially brought together by its support for and appreciation of UPPERCASE magazine, the Circle will enhance your experience of all things UPPERCASE while providing additional value to your creative life through conversation and the sharing of knowledge.

• Connect with members of the UPPERCASE community— both near and far—who share your interests.

• Share your work with your peers, mentors and potential customers.

• Find inspiration, motivation and new perspectives.

• Move your creative business forward with tips, tools and support from peers and guest experts.

• Live video conferences and video chats.

Access to this community is FREE when you subscribe to UPPERCASE magazine!

uppercasecircle.com

128 ||| UPPERCASE CIRCLE

Have you made something with the subscribers’ kraft envelope or reused the magazine or postcards in an interesting way?

Please share your pictures and stories of my books, magazines and fabric on Instagram @uppercasemag #uppercaselove.

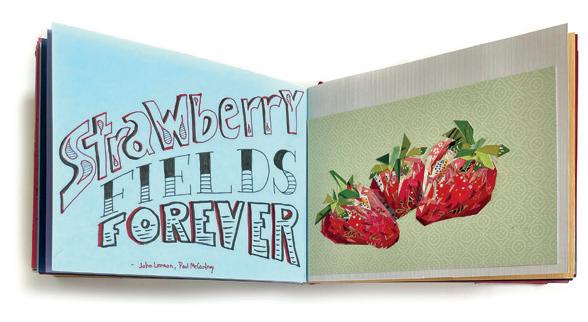

Judy Ormshaw

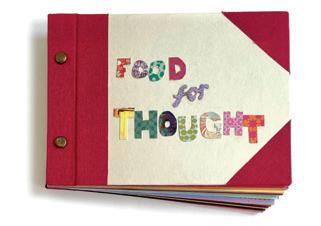

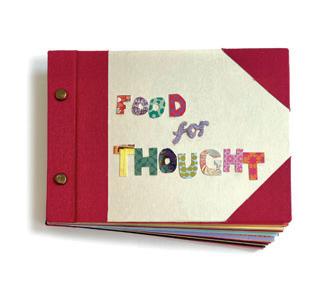

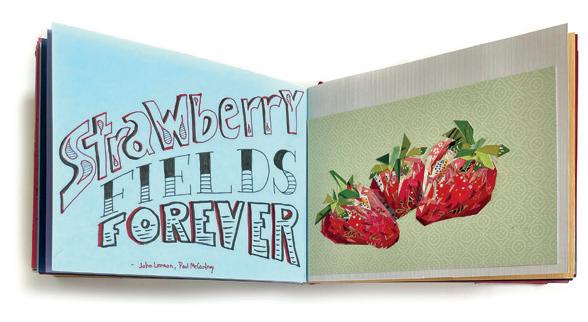

I wanted to try paper collage so one day I grabbed a little card from my stash and made an apple. I noticed other similar cards and used them to make more fruits, supplementing with other similar papers. Then I got a subscription to UPPERCASE magazine and all of a sudden I was getting more and more of the little subscription cards so that it turned into an actual project. The idea for assembly into a book came from being inspired to try hand lettering (UPPERCASE issue 43). The title was contributed by Marie Nahas from UPPERCASE Circle. I used more subscription cards to snip the letters for the title free form. I even used the confetti from the hole punch to do a fanciful back page. I don’t like wasting things. The whole thing is completely handmade using just scissors, glue and paper scraps.

Alexandra Snowdon

The fiddly linocut is done, I made a bookmark! Janine, the editor of @uppercasemag encourages subscribers to use the kraft envelope the mag comes in to make something creative so I did! @alexandrasnowdon

SHARES

STORY AND PHOTO BY andrea jenkins

in a word

When I see a sign that says “vintage,” I follow it. Even if I don’t have a cent on me, even if I’m running late. I spotted one such sign recently (while in a rush, of course) and stopped mid-stride, considered the time for a second before making a sharp turn in the arrow’s direction. At the end of a narrow corridor, I found a small, unmarked shop stacked from floor to ceiling with, as promised, vintage—racks of houndstooth blazers, old dresses dizzy with colour, piles of faded denim. I tried on floppy felt hats while the shop owner smoked outside and spoke with a few regulars in a melodious Italian. I emerged a good 15 minutes later, empty-handed but dopamine levels surging all the same, just for having looked, for having followed a sign with the word “vintage” on it.

Some words are more malleable than others. They begin with one meaning but then roll through the decades only to be shaped into something else. The dictionary definition of the word “vintage” refers to wine and/or wine making, but ask anyone today and you will invariably hear something different. In pondering the meaning myself, I went poking around (and by poking around, I mean asking everyone I know, plus a few strangers) and was not exactly surprised to find that when we talk about vintage, yes, sometimes we are talking about a bottle of wine but we are also (and more likely) talking about a pair of mom jeans from the nineties or a set of milky glass Pyrex bowls in a candy rainbow of mid-century colours. In other words, the term “vintage” refers to what has aged, and perhaps more importantly, what has aged well, whether we’re talking wine, cars, clothes, objects or otherwise. But there is more to it than that, I think. Discovering vintage as a teenager in the eighties felt like joining a secret club. My first real find was a stunner from the thirties, which I spotted while digging through an impossible mountain of musty old clothes at a Tennessee flea market. I paid exactly three dollars for a shell-pink satin nightgown with glamorous butterfly sleeves and impeccable stitching, and wasn’t sure what I loved more—the secret history I was convinced it held or the fact that nothing like it could ever be found at the mall. I never actually wore the gown but dreamt instead of all the ways I might. It hung on my bedroom wall like a promise.