Philippe Daverio

Philippe Daverio

Philippe Daverio

Philippe Daverio

Spigoli di roccia, le mie forme

Kanten aus dem Felsen, meine Formen

Edges from the Rock, My Shapes

Copertina / Umschlagbild / Cover

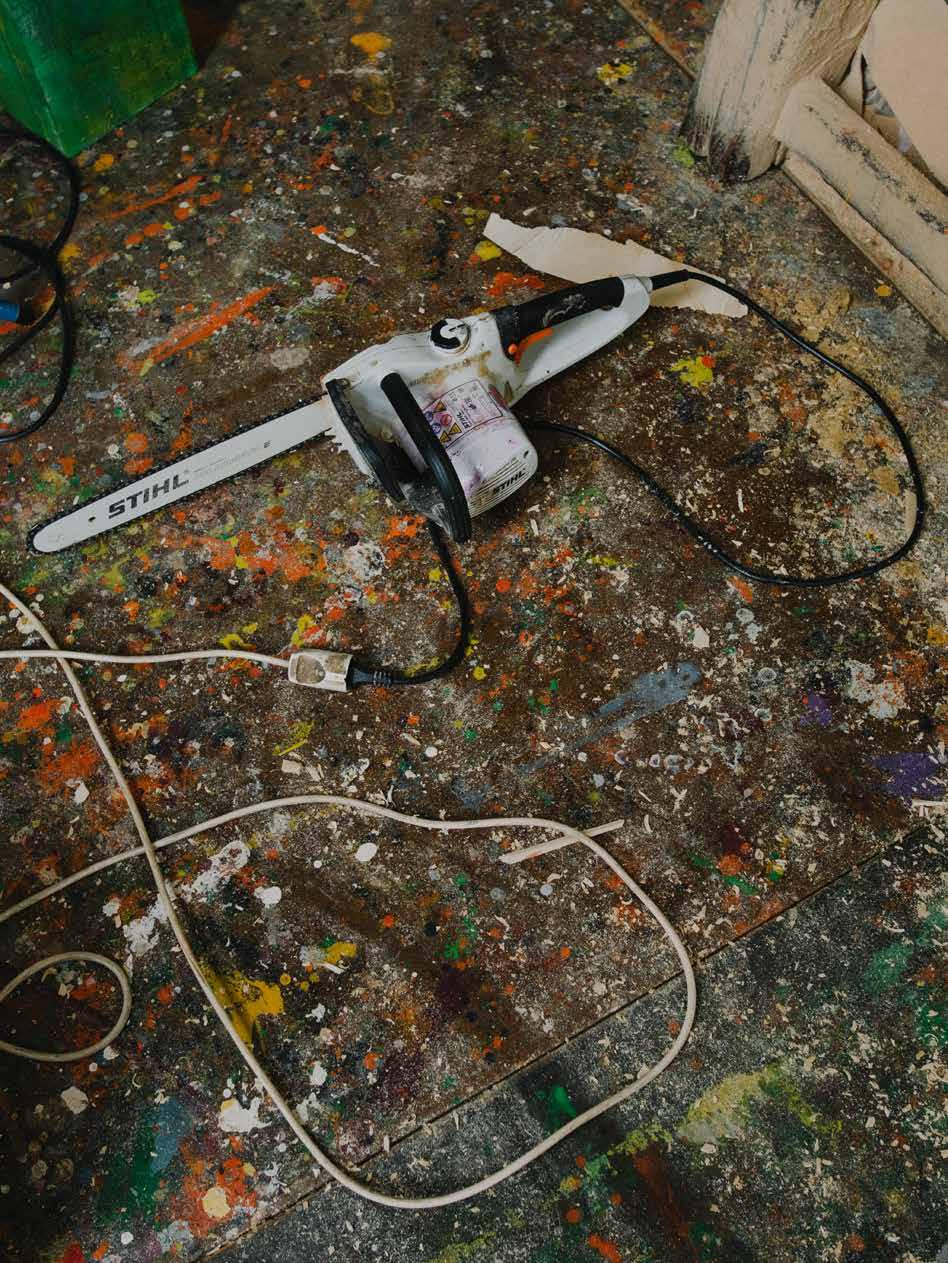

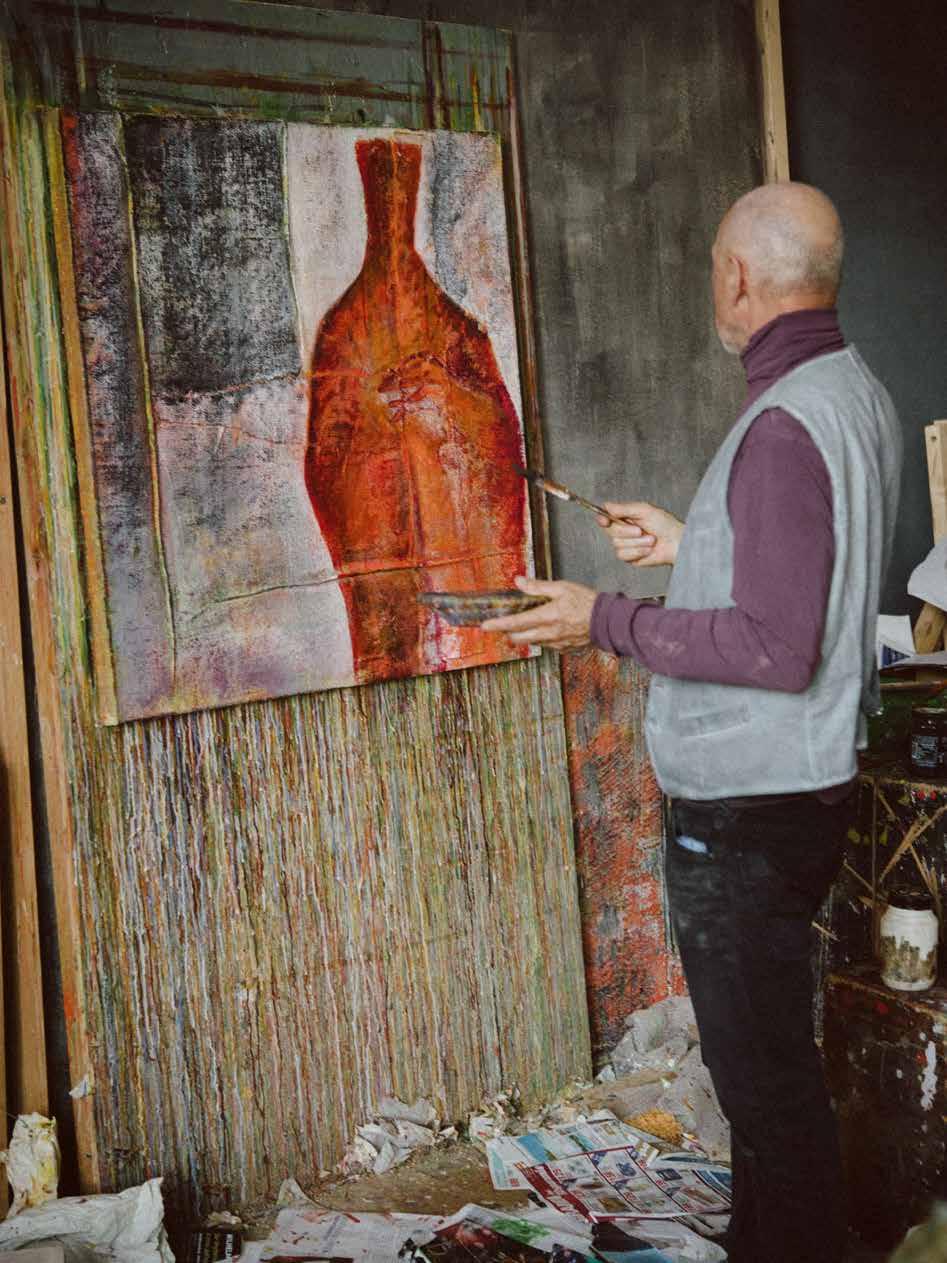

Atelier 2020

Progetto grafico / Graphische Gestaltung / Design

Luigi Fiore

Coordinamento redazionale / Redaktionelle Koordinierung / Editorial Coordination

Vincenza Russo

Redazione / Redaktion / Editing

Cristina Pradella

Impaginazione / Ausführung / Layout

Faycal Zaouali

Pubblicato in Italia da / Herausgegeben in Italien von / First published in Italy by Skira editore S.p.A. Palazzo Casati Stampa via Torino 61 20123 Milano Italy www.skira.net

© Gli autori per i loro testi / Die Schriftstellern für ihre Texte / The Authors for their texts © 2021 Skira editore, Milano Tutti i diritti riservati. Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere riprodotta o trasmessa in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo elettronico, meccanico o altro senza l’autorizzazione scritta dei proprietari dei diritti e dell’editore.

Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Buch darf weder im Ganzen noch teilweise reproduziert werden oder in irgendeiner Form mit elektronischen, mechanischen oder sonstigen Techniken veröffentlicht oder übertragen werden ohne die schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlegers oder der Inhaber der Urheberrechte.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-88-572-4691-8

Printed in Italy

Crediti fotografici / Bildrechte / Photo Credits

Oliver Helbig, pp. / SS. / pp.: 1-8, 30-147, 172-180

Sebastiano Daverio, p. / S. / p.: 12

Filippo Simonetti, pp. / SS. / pp.: 14, 18, 26, 148, 152, 154, 162, 163, 165

Donatella Simonetti, pp. / SS. / pp.: 150, 164, 166

Egon Dejori, pp. / SS. / pp.: 155, 156, 161, 164, 168, 170, 171, 192

Claudia Senoner, p. / S. / p.: 167, 169

Ringraziamenti / Dank / Acknowledgements

Per le traduzioni / Für die Übersetzungen / For the translations: Virginia Salviati

Per i testi / Für die Texte / For the texts

Per / Für / For Philippe Daverio, Elena Daverio

Mauro Passarin

Carmela Vargas

Leo Andergassen

Per il sostegno / Zur Unterstützung / For supporting:

Ripartizione 18 Amministrazione scuola cultura Ladina

Colui che colpisce l’immagine Der, der ein Bild haut He Who Hews Images

Segni del tempo

Zeichen der Zeit Signs of Time

Mauro Passarin

Parola alla forma Die Form spricht Giving Words to Shape

Carmela Vargas

Opere / Werke / Works 2004-2020

Elenco delle opere / Liste der Werke / List of Works

Esposizioni Ausstellungen

Philippe Daverio, Claudia e / und / and Wilhelm Senoner 02.02.2020 Milano / Mailand / Milan

Philippe Daverio

Philippe Daverio, Claudia e / und / and Wilhelm Senoner 02.02.2020 Milano / Mailand / Milan

Philippe Daverio

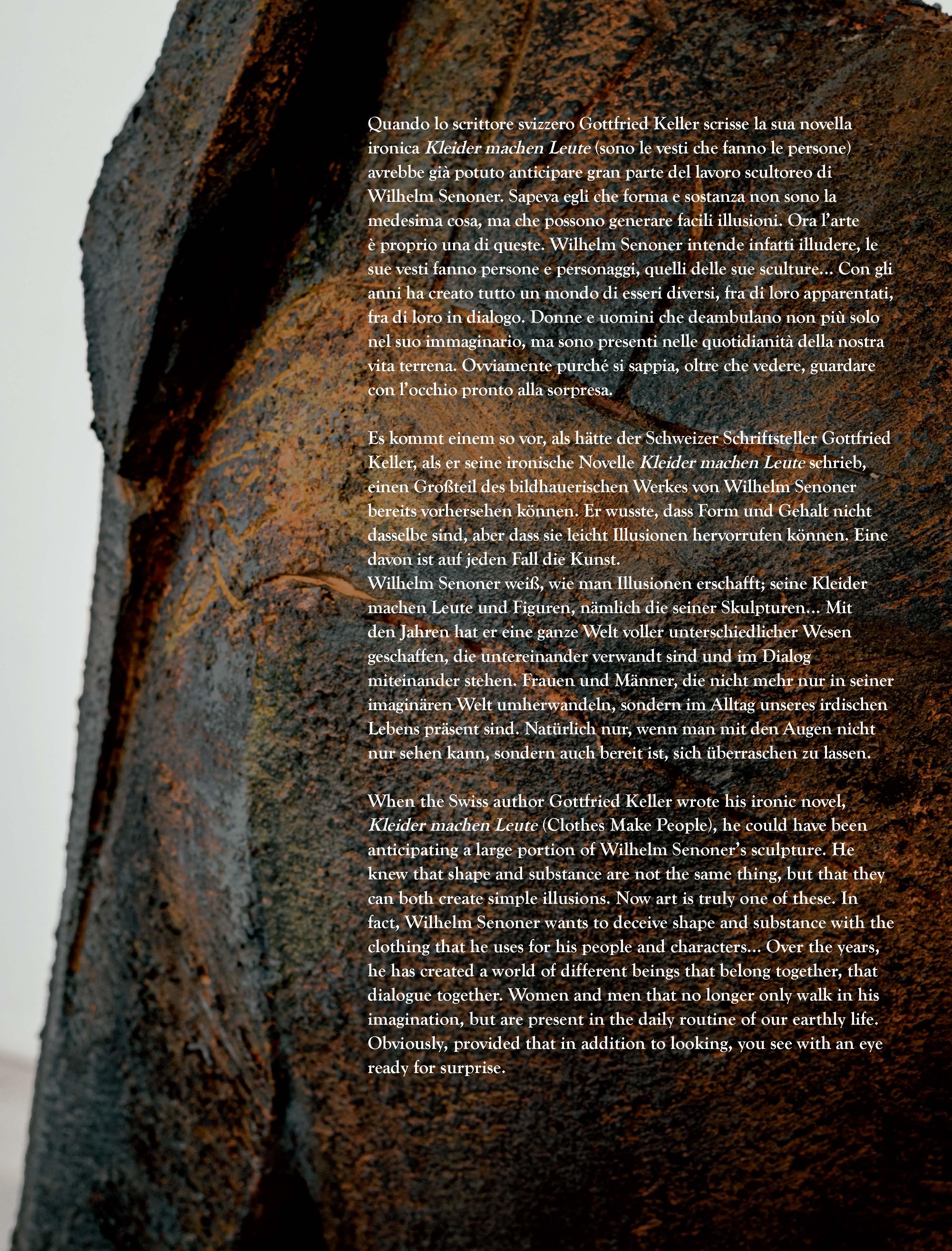

Quando lo scrittore svizzero Gottfried Keller scrisse la sua novella ironica Kleider machen Leute (sono le vesti che fanno le persone) avrebbe già potuto anticipare gran parte del lavoro scultoreo di Wilhelm Senoner. Sapeva egli che forma e sostanza non sono la medesima cosa, ma che possono generare facili illusioni. Ora l’arte è proprio una di queste.

Wilhelm Senoner intende infatti illudere, le sue vesti fanno persone e personaggi, quelli delle sue sculture. E queste vesti non sono necessariamente solo stoffe che cadono formando le linee delle opere, sono sostanza stessa di queste opere, al punto che per illudere ulteriormente riempiono le scavature delle superfici con colori densi che sono la vera trama del loro tessuto.

Le vesti servono a generare esaltazioni visive. Esattamente come nella grande stagione della cultura classica greca, quando il drappo dava lo spazio alla libertà del corpo, per Senoner, che di questa grecità è in tutti i sensi l’opposto, le vesti sono la chiave della narrazione. Danno il senso sonoro alle opere, la percezione del fruscio mentre i personaggi deambulano o si muovono sdraiati. Per “dare” anima alle sue creature, Senoner le muove, le anima nel senso più elementare della parola. Ne è il creatore dal soffio vitale.

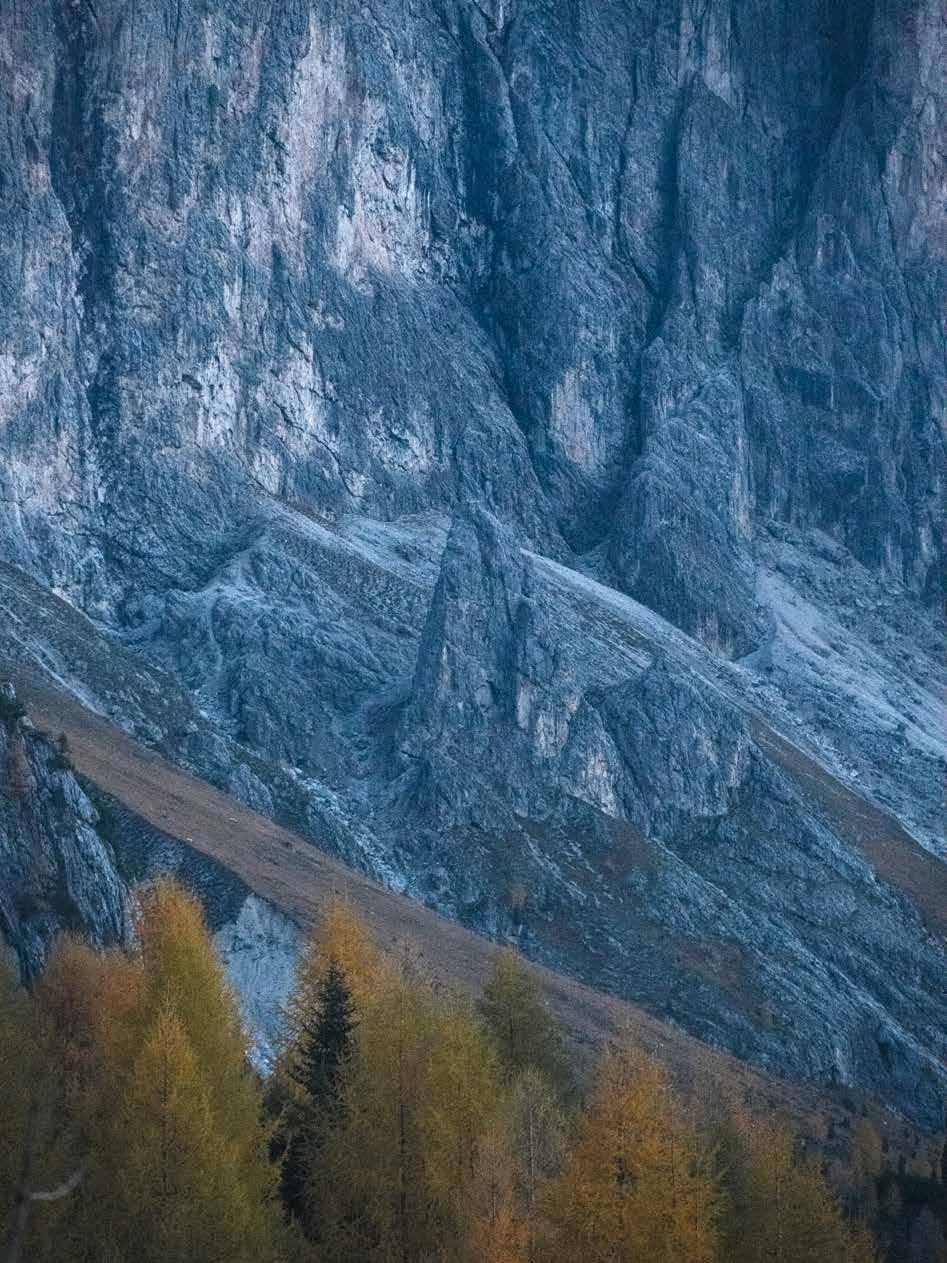

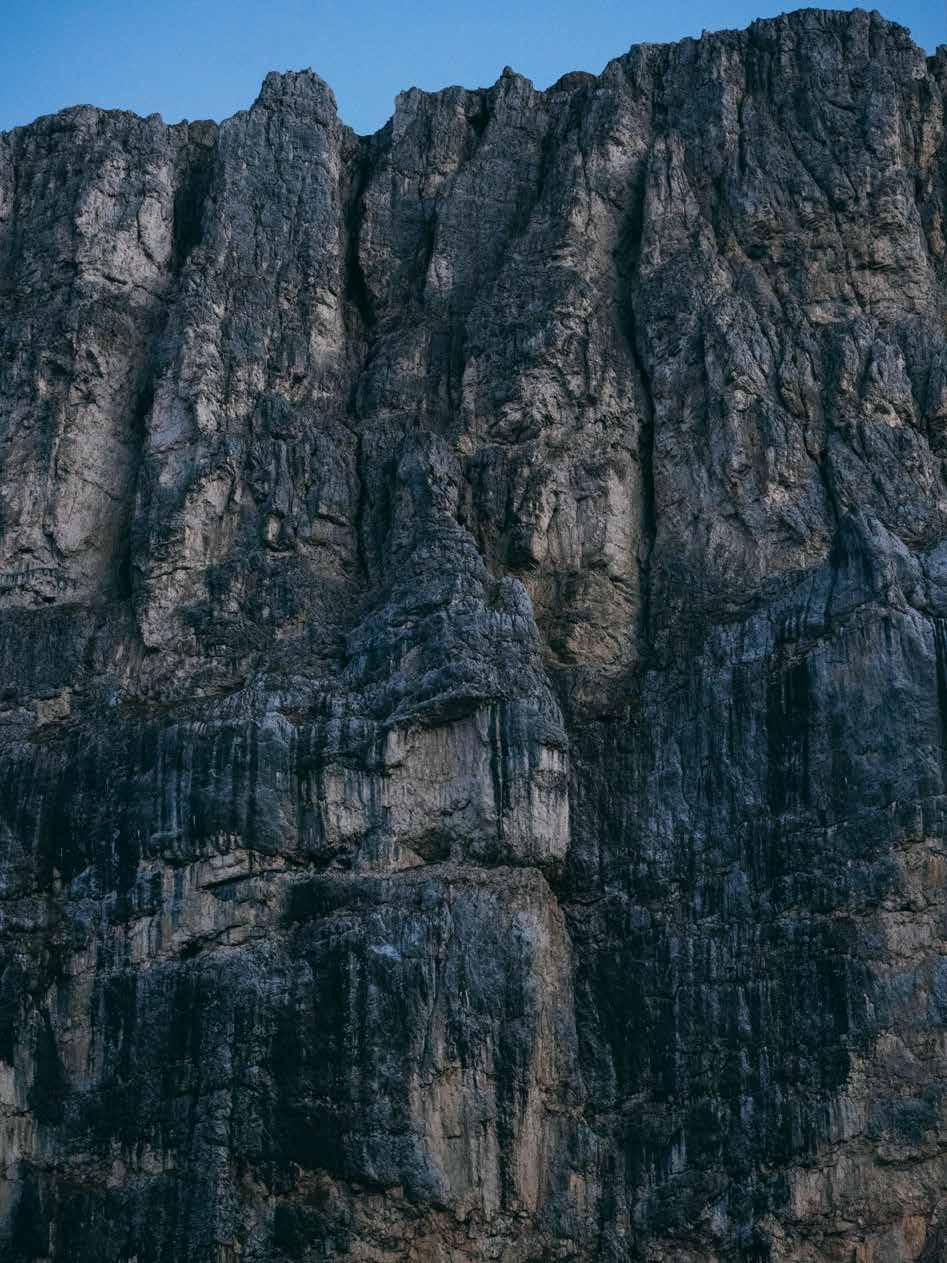

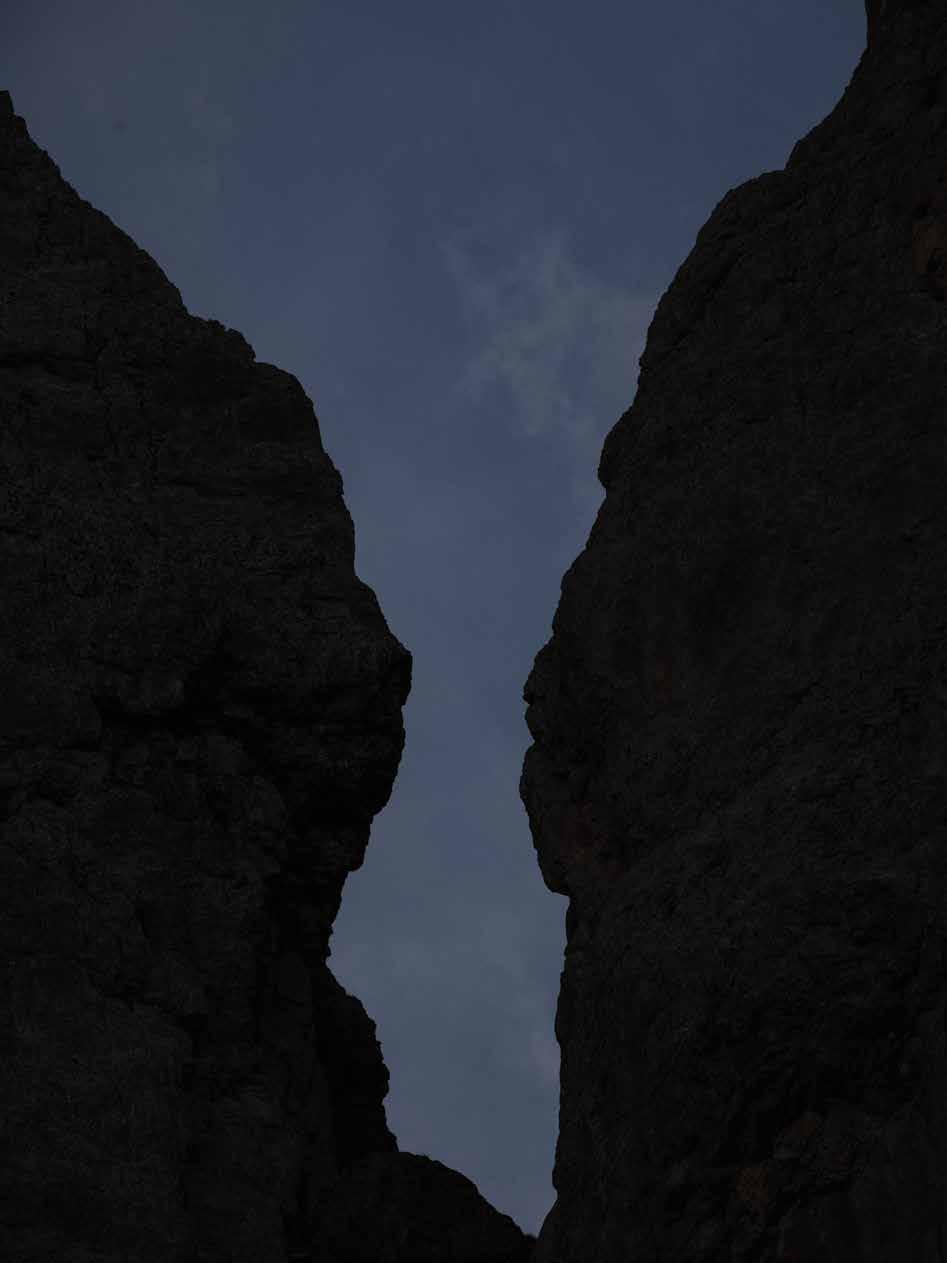

Mi sono chiesto più d’una volta da dove dovesse provenire questa sua volontà generativa, da dove venisse la sua voglia di intagliare il legno secco per dargli una vita nuova. È egli uomo di montagna; ma tutte le montagne non sono le stesse. Vi sono rilievi montani geologicamente antichi e resi tondi dagli infiniti cicli di erosione storica; ormai morbidi nelle loro apparenze lambiscono i cieli. Vi sono montagne giovani che si ergono sfacciate, graffiando i cieli con le loro rocce crude; sovvertono le stratificazioni geologiche piane e le proiettano sfacciate nella linea dei cieli. Ed è in quest’ultime che Senoner trova l’ispirazione al suo fare.

In tedesco lo scultore si chiama Bildhauer, colui che colpisce l’immagine: scolpire e colpire sono la medesima azione, anzi scolpire è ottenere la forma con il colpire ricavando il risultato dal togliere il superfluo; scolpire è scavare. Non è aleatoria questa visione poiché già Michelangelo distingueva le opere plastiche in due categorie ben distinte: quella del cavare contrapposta a quella del mettere, la scultura contrapposta alla pratica della cera che serve al procedimento della fusione in bronzo. La scultura è gesto platonico che va a rivelare l’idea che la materia cela già nel suo contenuto; la plastica è procedimento opposto, aristotelico si potrebbe sostenere, dove sono i sensi che vanno a plasmare l’immagine. L’Onnipotente Creatore del Cielo e della Terra quando delimita gli oceani si fa scultore, quando con la creta forma il primo uomo si fa plastico; e poi con il soffio gli dà la vita e lo rende simile a sé stesso. L’Uomo fu voluto a immagine e somiglianza di Dio e a sua volta diventò creatore. Ecco la teosofia arcana che dai primordi lontani stimola l’essere umano a creare sculture, sculture ovvero esseri che prima dell’intervento non esistevano.

Wilhelm Senoner si sente al contempo platonico e aristotelico. Cava dalla materia il superfluo per rivelarne la forma, per liberarne la forma già inclusa nella materia. Successivamente arricchisce l’opera con il gesto plastico del ricoprirla con una materia ulteriore, che è quella della pittura. In questa prassi, che ha curiosi richiami con le coloriture che già applicava Marino Marini, consiste la dialettica complessa del suo lavoro. Il colore è il soffio che dà all’opera il senso della vita.

Con gli anni ha creato tutto un mondo di esseri diversi, fra di loro apparentati, fra di loro in dialogo. Donne e uomini che deambulano non più solo nel suo immaginario, ma sono presenti nelle quotidianità della nostra vita terrena. Ovviamente purché si sappia, oltre che vedere, guardare con l’occhio pronto alla sorpresa.

Philippe Daverio

Philippe Daverio

Es kommt einem so vor, als hätte der Schweizer Schriftsteller Gottfried Keller, als er seine ironische Novelle Kleider machen Leute schrieb, einen Großteil des bildhauerischen Werkes von Wilhelm Senoner bereits vorhersehen können. Er wusste, dass Form und Gehalt nicht dasselbe sind, aber dass sie leicht Illusionen hervorrufen können. Eine davon ist auf jeden Fall die Kunst.

Wilhelm Senoner weiß, wie man Illusionen erschafft; seine Kleider machen Leute und Figuren, nämlich die seiner Skulpturen. Und dabei sind die Kleider nicht notwendigerweise nur Stoffe, die fallen und mit ihren Linien die Gestalt der Werke formen, vielmehr sind die Kleider selbst Gehalt dieser Werke, so dass sie, um die Illusion fortzusetzen, die Kerben in der Oberfläche mit reichen Farben füllen, welche den wahren Faden ihres Gewebes darstellen.

Die Kleider dienen dazu, visuelle Exaltationen zu schaffen. Genau wie zur großartigen Zeit der klassischen griechischen Kultur, als das Gewand der Freiheit des Körpers Raum gab, sind für Senoner, der von diesem griechischen Wesen in allem das Gegenteil ist, die Kleider der Schlüssel zur Erzählung. Sie geben den Werken ihren Lautsinn, die Wahrnehmung des Rauschens, während die Figuren laufen oder sich im Liegen bewegen. Um seinen Kreaturen eine Seele zu „geben“, bewegt er sie und beseelt sie so im elementaren Sinne des Wortes. Er ist ihr Schöpfer, der ihnen Leben einhaucht.

Ich habe mich mehr als einmal gefragt, woher dieser Schöpfungswille von ihm stammt, woher seine Lust kommt, das trockene Holz zu schnitzen, um ihm neues Leben einzugeben. Er ist ein Mann der Berge; aber alle Berge sind nicht gleich. Es gibt geologisch alte Bergreliefs, die von unzähligen Erosionszyklen der Vergangenheit abgerundet wurden, so dass sie nun fast weich erscheinen und den Himmel sanft umspielen. Dann gibt es jüngere Berge, die übermütig herausstehen und mit ihren rauen Felsen am Himmel kratzen; sie durchbrechen die ebenen geologischen Schichten und richten sie kühn zum Himmel auf. Und gerade diese Berge sind es, die Senoner in seinem Schaffen Inspiration geben.

Wie der Begriff sagt, ist ein Bildhauer der, der ein Bild „haut“: Meißeln und Hauen ist derselbe Vorgang, dabei ist (Aus-)Meißeln das Erschaffen einer Form durch Hauen, indem durch Wegnehmen des Überflüssigen das Resultat herausgearbeitet wird; Meißeln heißt demnach Ausgraben. Diese Sichtweise ist nicht aleatorisch, denn schon Michelangelo unterschied plastische Arbeiten in zwei grundverschiedene Kategorien: das Wegnehmen im Gegensatz zum Auflegen, die Bildhauerei im Gegensatz zum Wachsverfahren, das für den Bronzeguss genutzt wird. Die Bildhauerei ist eine platonische Geste, die den im Inneren bereits vorhandenen, von der Materie verhüllten Gedanken freilegt; ein gegensätzliches, man könnte sagen aristotelisches Verfahren ist dagegen die Plastik, bei der das Bild durch die Sinne gestaltet wird. Der Allmächtige Schöpfer von Himmel und Erde wurde zum Bildhauer, als er das Meer begrenzte, er war Plastiker, als er mit der Schöpfung den ersten Menschen schuf; und dann hauchte er ihm Leben ein und machte ihn zu seinem Ebenbild. Der Mensch war von Gott nach seinem Bilde gewollt und wurde seinerseits zum Schöpfer. Das ist die geheimnisvolle Theosophie, die seit den fernen Anfängen den Menschen antreibt, Skulpturen zu schaffen – Skulpturen bzw. Wesen, die es vor dem Schöpfungsakt noch nicht gab.

Wilhelm Senoner sieht sich sowohl als Platoniker als auch als Aristoteliker. Er nimmt das Überflüssige der Materie weg, um ihre Form freizulegen, um aus der Materie, in der die Form eingeschlossen ist, diese zu befreien. Anschließend bereichert er das Werk durch eine plastische Geste, indem er es mit einer anderen Materie bedeckt – damit meine ich die Malerei. Dieses Verfahren, das interessante Verweise auf die Farbigkeit von Marino Marini enthält, stellt die komplexe Dialektik seines Schaffens dar. Die Farbe ist der Hauch, der dem Werk Leben verleiht. Mit den Jahren hat er eine ganze Welt voller unterschiedlicher Wesen geschaffen, die untereinander verwandt sind und im Dialog miteinander stehen. Frauen und Männer, die nicht mehr nur in seiner imaginären Welt umherwandeln, sondern im Alltag unseres irdischen Lebens präsent sind. Natürlich nur, wenn man mit den Augen nicht nur sehen kann, sondern auch bereit ist, sich überraschen zu lassen.

When the Swiss author Gottfried Keller wrote his ironic novel, Kleider machen Leute (Clothes Make People), he could have been anticipating a large portion of Wilhelm Senoner’s sculpture. He knew that shape and substance are not the same thing, but that they can both create simple illusions. Now art is truly one of these.

In fact, Wilhelm Senoner wants to deceive shape and substance with the clothing that he uses for his people and characters. And these clothing are not only the fabrics that fall, creating the lines of his works. They are simultaneously the substance of these works. And to deceive further, they fill in the surface grooves with dense colours that are the true weave of their fabric.

These clothes are used to generate visual celebration. Exactly like in the great season of classic Greek culture, where drape gave the body freedom of space, to Senoner clothing is the key to his story, precisely for the opposite reason. Clothing gives his works a sense of sound: the perception of rustling while the characters walk or move when lying down. To “give” his creatures a soul, Senoner moves them, he animates them in the most basic sense of the word. He is the creator of their breath of life.

I have asked myself more than once where his desire to generate, where his desire to carve dry wood to give it new life comes from. He is a mountain man; but not all mountains are the same. There are geologically ancient mountains, smoothed by the infinite cycles of historic erosion, which have become soft in their appearance as they brush the sky. There are young mountains that brashly rise up, scraping the sky with their rough rocks; subverting the flat geological stratifications and boldly projecting in the skyline. And it is in the latter that Senoner finds inspiration for his creativity.

In German, a sculptor is called a Bildhauer, or he who hews images: sculpting and striking with the same action; rather, sculpting is obtaining shape by striking, obtaining the result by removing the excess. Sculpting is excavating. This vision is not chance because already Michelangelo distinguished his sculptures in two well defined categories: the removing contrasting with the adding, sculpting contrasting with the wax work that serves for the bronze moulding procedure. Sculpture is a Platonic expression that reveals the idea that matter hides within; moulding is the opposite procedure, which could be seen as Aristotelian, where the senses mould the image. When the All-powerful Creator of the Sky and Earth defined the oceans, he became a sculptor; when he created the shape of the first man he made a mould; and then he blew his breath in it giving it life and make it similar to himself. Man was desired in the image and appearance of God and in turn became a creator. That is the arcane theosophy that from the far dawn of time stimulates man to create sculptures, sculptures or beings that before his action did not exist.

Wilhelm Senoner feels like both Plato and Aristotle. He removes extra material to reveal its shape, to free the shape already enveloped in the material. Then he enriches the work with moulding, covering it with another material, which is paint. This practice, which has curious references with the colours that Marino Marini applied, consists in the complex dialect of its work. The colour is the breath that gives the works their sense of life.

Over the years, he has created a world of different beings that belong together, that dialogue together. Women and men that no longer only walk in his imagination, but are present in the daily routine of our earthly life. Obviously, provided that in addition to looking, you see with an eye ready for surprise.

Mauro Passarin

Mauro Passarin

Wilhelm Senoner è uno di quei testimoni del genio umano che con sapienza plasmano la materia, la nutrono di colore e le danno forma.

Lo fa ripercorrendo i luoghi della sua infanzia, del suo vissuto, della sua fantasia, facendoci vivere un’esperienza sospesa tra ciò che è e ciò che dovrebbe essere.

Sospesa tra l‘amore per la montagna e la profondità dei suoi simboli, la ricerca artistica di Wilhelm Senoner intesse finemente rimandi, produce echi, coltiva silenzi.

Ed è in questo spazio fuori dal tempo, che insieme alle ombre penetra qualche sottile lama di luce che affida alle sue opere nuovi e antichi significati.

L’avventura artistica di Wilhelm Senoner è dunque inscindibile dai luoghi in cui pensa le sue sculture ed è commisurata, volta per volta, all’esigenza di calibrare gli equilibri ritmici in vibrazione, coinvolgendo lo spettatore come parte attiva del significato dell’opera.

Con le sue sculture ci comunica tutto ciò che ha colpito la sua sensibilità e, guardando alle sue opere, ognuno di noi prova l’emozione che ha sentito l’artista osservando l‘incanto delle montagne.

Non ci sono limiti nella natura e non ci sono nella scultura di Senoner. Con il suo lavoro, egli riesce a ottenere l’atmosfera che circonda la figura, il colore che la anima, la prospettiva che la colloca nello spazio, fino a sondare le energie cromatiche che si diffondono nella profondità del vuoto intorno.

Le plastiche di Wilhelm Senoner fungono da recipienti di spettacoli naturali e la loro forza espressiva riesce a trasformare l’arte in pensiero naturale.

Arriva dalla terra il legno che Wilhelm lavora, elemento da sempre custode delle impressionanti architetture rocciose delle Dolomiti, cresciuto forte e vigoroso, stagione dopo stagione, e ora parte di un’opera che ne ha prolungato all‘infinito l’esistenza.

I segni lasciati dalle sue mani sono i segni del tempo, segni che plasmano, formano, modificano lentamente, come lento è il suo modellare; forme leggere, le sue figure esprimono una delicatezza compositiva in equilibrata contrapposizione alla primigenia materia.

Wilhelm Senoner riesce, come pochi altri scultori, a elaborare il proprio discorso plastico radicandolo ben dentro la forza fisica e umana delle sue montagne, creando con le sue sculture un formidabile ponte tra la storia geologica degli spigoli delle rocce e l’aspirazione alla modernità.

Sembra quasi che l’artista ci indichi per la sua scultura e per la montagna che l’ha generata nuovi percorsi dello sguardo, inedite traiettorie spaziali, accompagnati da una lavorazione della materia capace di infondere sensazioni sempre più profonde.

Sensazioni che inducono a pensare che l’insieme delle superfici ruvide e delle linee irte di sporgenze dure e spigolose si sollevi quando si compie l’atto di osservare l’opera.

Ecco, le sculture di Senoner sono una sorta di omaggio all’eroismo della natura e delineano la grammatica di un linguaggio sicuro, diretto e privo di retorica.

La sua arte possiede una grazia indicibile che probabilmente scaturisce da una sua personale e misteriosa armonia terrena non priva di trascendenza.

Una personalità riflessiva quella di Senoner, abituata a veder chiaro, a costruire, passo dopo passo, la sua propria vicenda artistica.

Credo che il principio della creatività di Wilhelm vada cercato nella sua capacità di emozionarsi e nel riuscire a fermare quegli attimi che diventano impulso creativo, per dire ancora una volta che l’umano e lo spirituale si possono aggregare in un’unica raffigurazione.

Per Wilhelm Senoner l’arte non è dunque imitazione, ma illusione e contemplazione, è il piacere di uno spirito che penetra nel mistero della natura; è la più esaltante missione dell’uomo che cerca di capire l’universo e di farlo comprendere agli altri.

Wilhelm Senoner ist eine Manifestation des menschlichen Genies, der voller Weisheit die Materie gestaltet, sie mit Farbe nährt und ihr eine Form gibt.

Dazu kehrt er an Orten seiner Kindheit, seines Lebens und seiner Fantasie ein und ermöglicht uns schwebende Erlebnisse zwischen der realen Welt und der, wie sie sein sollte.

Schwebend zwischen der Liebe für die Berge und der Tiefe ihrer Symbole, verwebt die künstlerische Suche von Wilhelm Senoner auf feinste Art Bezüge, erzeugt Echos und pflegt das Schweigen.

In diesem zeitlosen Raum dringen neben den Schatten auch feine Lichtstrahlen ein, die seinen Werken neue und alte Bedeutungen geben.

Das künstlerische Geschick von Wilhelm Senoner ist demnach als untrennbar von den Orten anzusehen, in denen er seine Skulpturen erdenkt, und passt sich von Mal zu Mal der Notwendigkeit an, die vibrierenden, rhythmischen Balancen zu justieren, wobei der Betrachter als aktiver Bestandteil von Sinn und Bedeutung des Werkes einbezogen wird.

Mit seinem bildhauerischen Schaffen kommuniziert er uns alles, was seine Sinne berührt hat, und beim Betrachten seiner Werke kann jeder Einzelne von uns die Emotionen nachempfinden, die der Künstler beim Anblick der Herrlichkeit der Berge gespürt hat.

Die Natur kennt keine Grenzen und so sind auch in der Bildhauerei von Senoner keine zu finden. Mit seiner Arbeit erschafft er eine Atmosphäre um die Figur herum, Farbe, die sie mit Leben erfüllt, eine Perspektive, die sie im Raum positioniert, und ergründet dabei auch die Energie der Farben, die sich in den Tiefen der umgebenden Leere ausbreitet.

Die Plastiken von Wilhelm Senoner tragen ganze Naturschauspiele in sich, und ihre Expressivität ist in der Lage, Kunstwerke in Gedanken an die Natur zu verwandeln.

Das Holz, mit dem Senoner arbeitet, wächst aus der Erde und ist seit jeher ein Element, das die beeindruckende Felsenarchitektur der Dolomiten fest in sich trägt; über Jahre und Jahreszeiten hinweg ist das Holz kräftig und robust gewachsen, um jetzt Teil eines Kunstwerkes zu sein, welches seine Existenz bis ins Unendliche verlängert hat.

Die von seinen Händen hinterlassenen Zeichen sind Zeichen der Zeit; sie gestalten, formen, verändern langsam, so langsam wie sein Modellieren. Seine Figuren voller Leichtigkeit strahlen eine gestalterische Feinheit aus, die in einem ausgewogenen Kontrast zur urzeitlichen Materie steht.

Wilhelm Senoner gelingt es wie nur wenigen anderen Bildhauern, seinen plastischen Diskurs auszuarbeiten, indem er ihn fest in der physischen und menschlichen Kraft seiner Berge verwurzelt; auf diese Weise schafft er mit seinen Skulpturen eine wunderbare Brücke zwischen der geologischen Geschichte der Felskanten und der Aspiration nach Moderne.

Fast scheint es, als zeige uns der Künstler mit seinen Skulpturen und dem Gebirge, das sie inspiriert hat, neue, ungeahnte Wege der Betrachtung und der Durchquerung des Raumes, im Zusammenspiel mit einer Verarbeitung der Materie, die tiefste Empfindungen einzuflößen vermag.

Diese Empfindungen verleiten uns im Moment der Betrachtung des Werkes zu dem Gefühl, als würden sich die rauen Oberflächen und borstigen Linien harter, vorspringender Kanten abheben.

Die Skulpturen von Senoner sind eine Art Hommage an das Heldentum der Natur und zeigen die Grammatik einer selbstsicheren, direkten und rhetorikfreien Sprache.

Seine Kunst besitzt eine unbeschreibliche Anmut, die sehr wahrscheinlich seiner persönlichen, mysteriösen, leicht transzendenten irdischen Harmonie entspringt.

Die Persönlichkeit von Senoner ist reflektiert; er ist gewohnt, klar zu sehen und seinen künstlerischen Werdegang Schritt für Schritt aufzubauen.

Der Ursprung der Kreativität von Wilhelm ist, meine ich, in seiner Fähigkeit zu suchen, Gefühle zu entwickeln und diese Augenblicke erfolgreich festzuhalten, die dann zu einem kreativen Impuls werden, um noch einmal zu betonen, dass das Menschliche und das Geistige in einer einzigen Darstellung verschmelzen können.

Für Wilhelm Senoner ist die Kunst keine Imitation, sondern Illusion und Besinnung, ein Vergnügen des Geistes, der in das Geheimnis der Natur eindringt; sie ist die faszinierendste Mission eines Menschen, der versucht, das Universum zu verstehen und anderen verständlich zu machen.

Wilhelm Senoner is an affirmation of the human genius that knowingly transforms matter, nurturing it with colour and giving it shape.

He does this by recalling the lands of his childhood, his life, and his imagination, taking us on a voyage suspended between what is and what could be.

Tethered in the heights of his love for mountains and the depth of its symbols, Wilhelm Senoner’s artistic research is interwoven with allusions, producing echoes and cultivating silence.

It is in this space, removed from the effects of time, that a thin blade of light penetrates the shadows, giving his works new and ancient significance.

There is no way to separate Wilhelm Senoner’s artistic adventure from the venues where his sculptures are envisioned. In each creation, its presence is commensurate with the need to calibrate the vibrating rhythmic balances, engaging the onlooker as an active participant in the meaning of the work.

His sculptures communicate everything that strikes his sensitivity. When viewing his works, the individual experiences the artist’s own emotions when beholding the enchantment of the mountains.

There are no limits to nature and there are none in Senoner’s sculpture. With his work, he creates an atmosphere that envelopes the figure, the colour that animates it, the perspective of its spatial location, while exploring the chromatic energy that spreads across the expanse of the vacuum around it.

Wilhelm Senoner’s sculptures act as containers for nature’s masterpieces and their expressive force transforms art into natural thought.

Wilhelm’s medium is nurtured by the earth: wood. It preserves a reflection of the surrounding nature, the spectacular limestone walls of the Dolomite Alps. It has grown strong and hardy, season after season, and has become integral to a work of art, extending its existence into eternity.

The signs left by his hands are the signs of time, signs that shape, mould, and slowly change, as slowly as his modelling is. Light shapes, his figures express an elegance of composition in balanced juxtaposition with the primordial matter.

As few other sculptors can, Wilhelm Senoner is able to process his sculptural language, rooting it deeply in the physical and human force of his mountains, creating with his sculptures a formidable bridge between the geological history of its sharp rocks and the aspiration for innovation.

It almost appears that the artist is showing us new visual paths for his sculpture and for the mountains that generated it, original spatial trajectories, while working materials able to infuse ever deeper sensations.

These are impressions that lead us into believing that the combination of rough surfaces and prickly lines of hard pointy protrusions lift up as we regard the work of art.

These are Senoner sculptures, like paying homage to the heroism of nature as they define the grammar of a strong, direct language without rhetoric.

His art possesses an indescribable grace that probably springs from his personal, mysterious, earthly harmony, not lacking in transcendence.

Senoner’s reflexive personality is used to seeing clearly, to building his artistic sequence step-by-step.

I believe that Wilhelm’s creative principle lies in his ability to be touched and able to solidify those instants that become a creative impulse to say again that man and spirit can blend in a single representation.

For Wilhelm Senoner, art is not imitation, rather it is illusion and contemplation. It is the pleasure of a spirit that penetrates into the mystery of nature. It is man’s most exciting mission as he attempts to understand the universe and makes others understand it.

Trovarsi ai piedi del Sasso Lungo, percorrere l’Alpe di Siusi, salire fino a Rasciesa, stare di fronte al Murfrëit è come entrare in un luogo dell’anima, avere di fronte qualcosa che senti di avere già dentro, qualunque sia il posto geografico dal quale provieni. Non è un’esperienza solamente visiva, è il contatto reale con scenari che scopri misteriosamente di avere già visto dentro di te, prima ancora di conoscerli geograficamente. È come entrare in contatto con un immaginario profondo sedimentato nelle tue più antiche sensazioni dello spazio, dell’aria, della forza della natura, del silenzio, della vastità. Sei messo a contatto con l’origine sensitiva di ciò che nel corso del tempo la razionalità adulta ti ha fatto organizzare in concetti e parole: un ritorno alla radice prima e nuda della tua stessa percezione razionale del mondo.

Un’esperienza forte e nello stesso tempo comune che stenta a trovare le parole per raccontarsi e si trasforma, più modestamente, nel diffuso piacere della montagna, nel gusto della passeggiata, nell’attrazione perfino turistica per quelle vette impervie. Il sentimento profondo si fa modesto e si incanala dentro modeste spiegazioni.

Non è un caso che la vera gente di montagna, quando pure si allontani da quelle valli, tanto spesso aspira a ritornarci e tante volte davvero ci ritorna, e non è un caso che quella stessa gente di montagna non sia mai ciarliera.

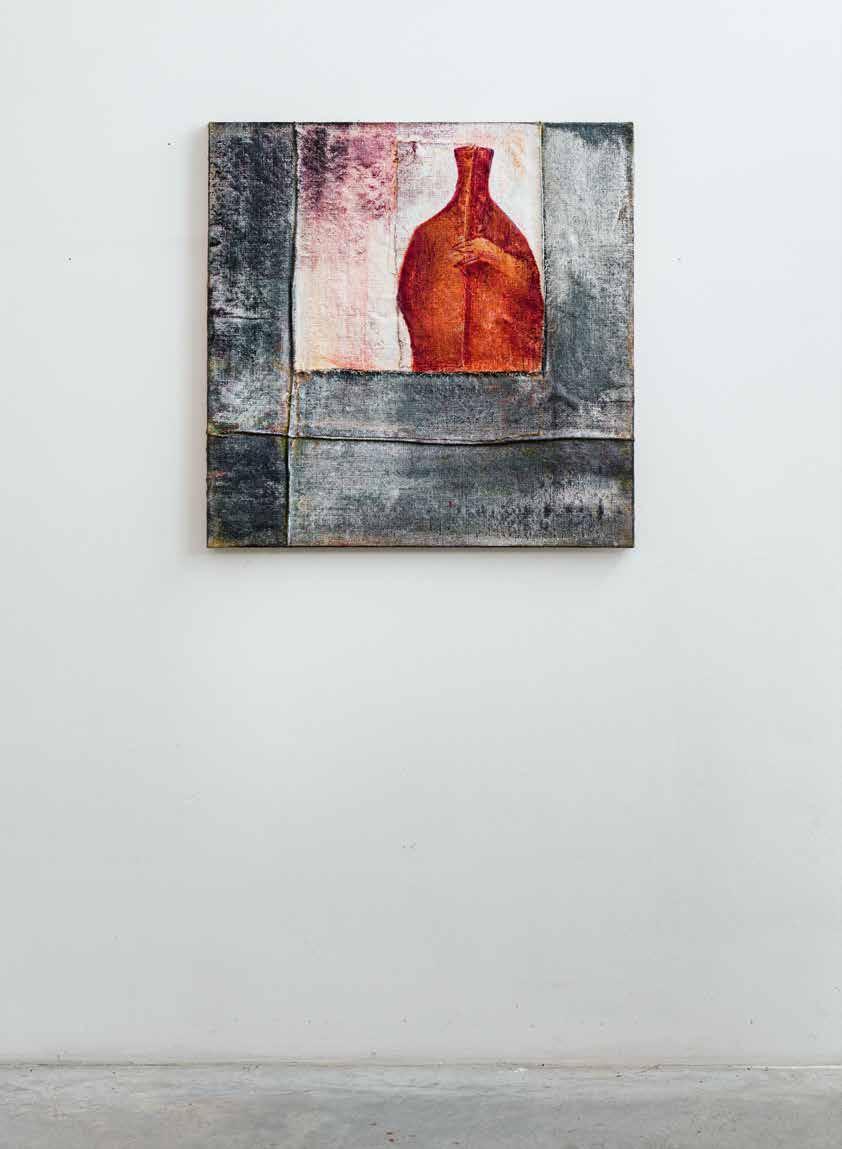

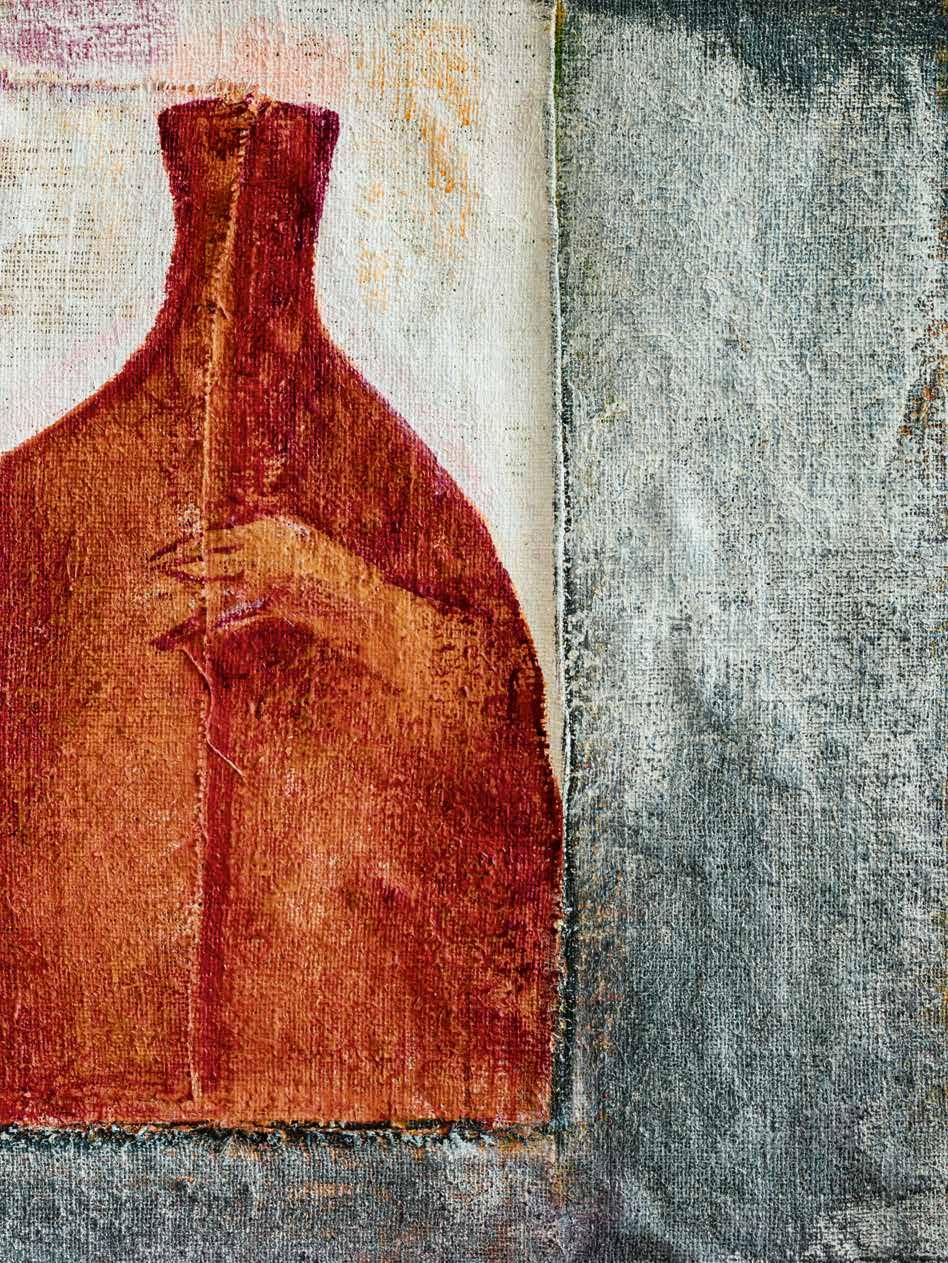

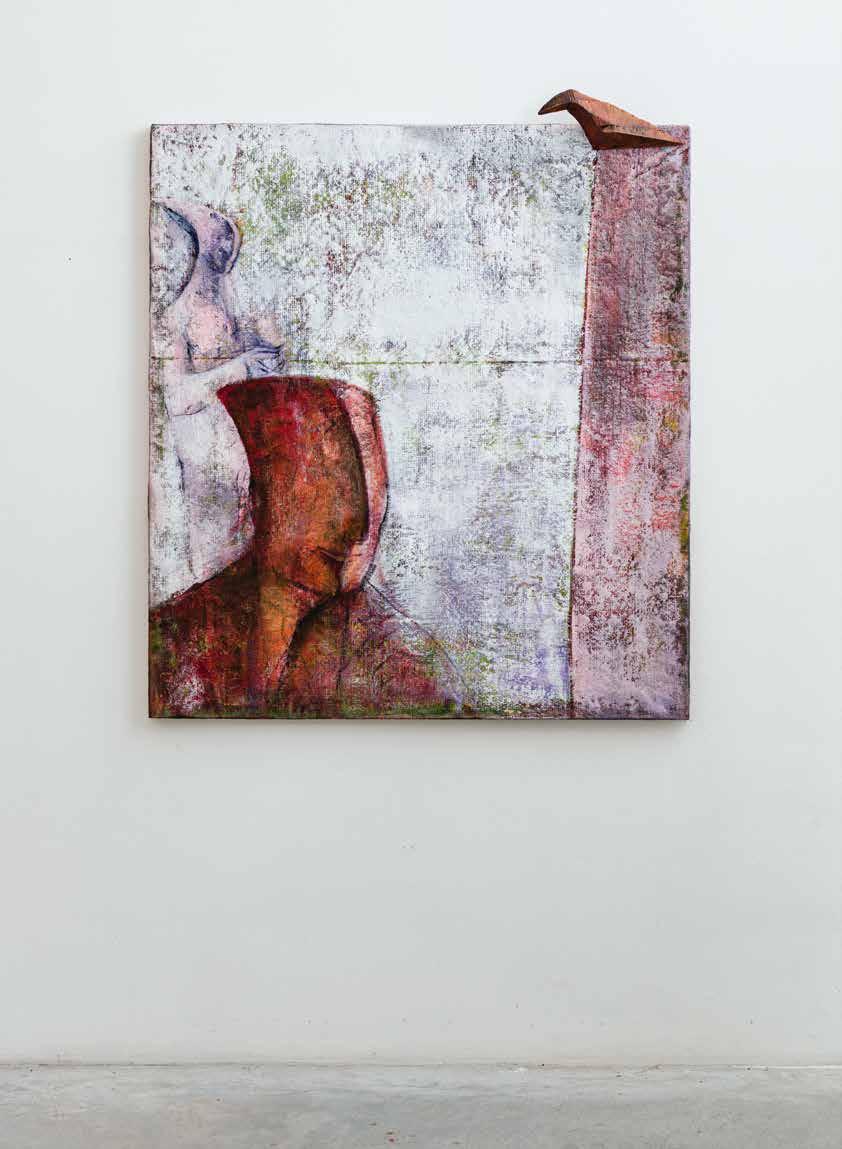

Così, quando entri nello spazio grande e luminoso dello studio di Wilhelm Senoner a Ortisei, non avverti una così grande differenza da quelle impressioni vissute all’aperto. La materia delle montagne, i colori della terra, finanche la percezione sensoriale dell’aria, del vento e del silenzio si rinnovano mentre ti aggiri tra i suoi giganti di legno, che sembra pietra, e di bronzo. Donne e uomini che accennano un passo (Donna sulla pedana, 2018), corpi che si abbracciano (Tensione simbiotica, 2017), madri che riflettono (Madre in meditazione, 2018), uomini che fumano (L’uomo col sigaro, 2016): tutti in dialogo con quei “guardiani delle montagne” (Philippe Daverio 2016) fantasticamente collocati fuori, sulle vette del Murfrëit, sotto il passo Gardena. E quand’anche lo sguardo si sposti sulle opere di pittura, non viene a mancare la medesima continuità con i colori e i materiali delle grandi statue.

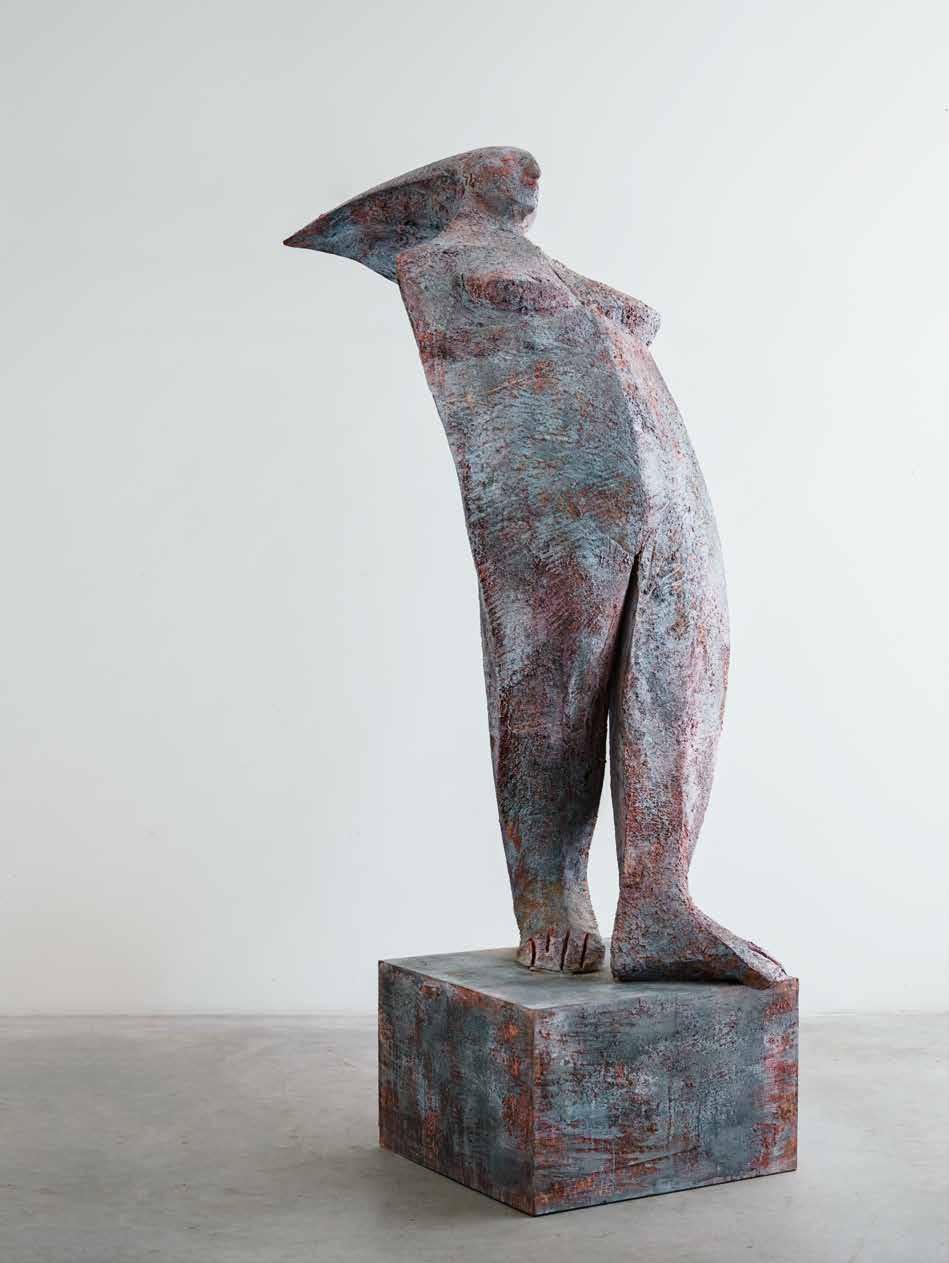

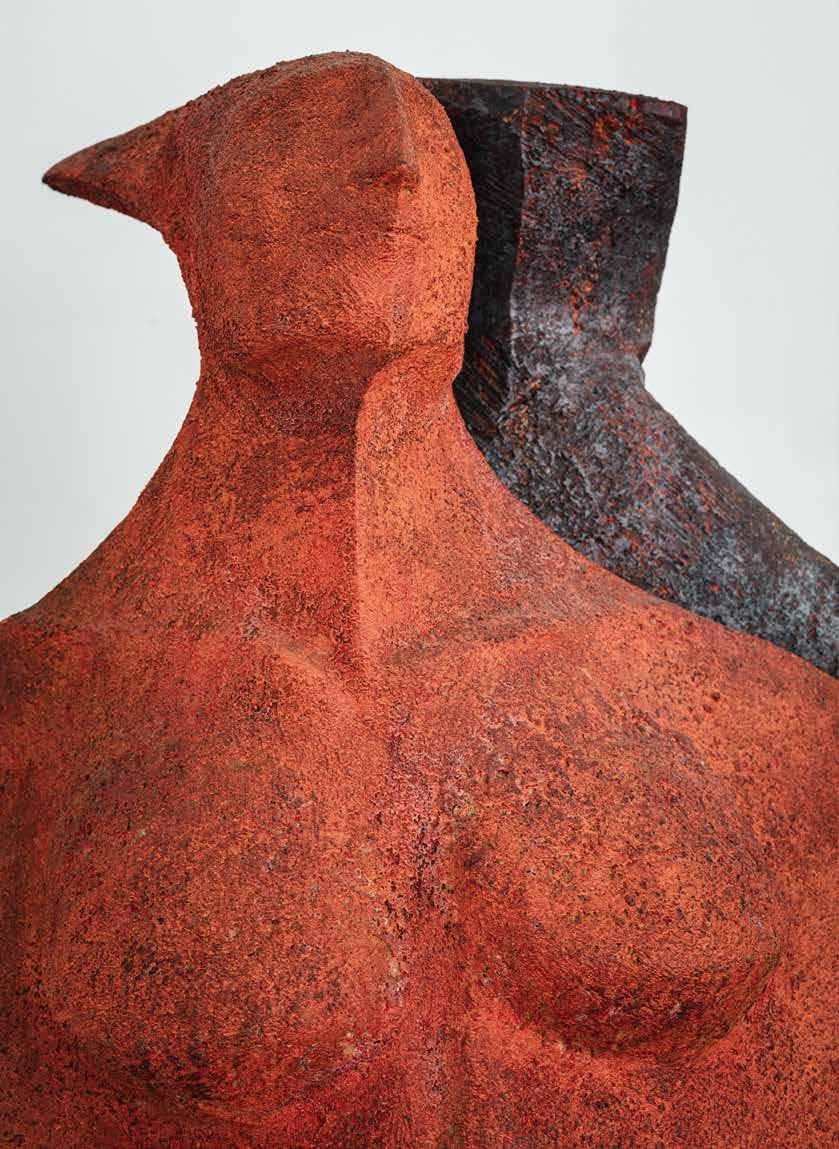

E si comincia a capire perché mai questo popolo di giganti, così potenti e materici, così riconoscibili come umani, ha tuttavia un particolare fisicamente anomalo: una testa che mai si circoscrive in forma naturalisticamente attendibile, bensì si appuntisce, svetta, si allunga come se trattenesse una folata di vento rappresa, come se cristallizzasse su di sé il soffio del vento di fuori.

In un momento viene capovolta ogni abitudine visiva cui la grande tradizione scultorea nordeuropea ha abituato il riguardante: la tradizione dei Veit Stoss, Hans Leinberger, Tilman Riemenschneider, tutti benissimo conosciuti da Wilhelm Senoner e da lui appassionatamente studiati e riprodotti in gioventù; da Baxandall in poi abbiamo imparato a guardarli come campioni della forma fratta, cercinata, incessantemente in tensione e movimento. Una scultura che, dal punto di vista di quella italiana, procede più per via di mettere che per via di levare. E invece qui, nella scultura di Senoner, la forma si ricompatta in massa plastica e attinge a una diversa espressività, non emotiva, non descrittiva, mai frammentaria. Una scultura che dà risposta profonda a richieste profonde: come parole senza suono queste statue finalmente rispondono, con voce arcana, a quelle ancestrali sensazioni che non sai dire. E capisci che per dirle, quelle sensazioni, ci vuole la lingua della forma, non quella delle parole. Il sentimento che non sapevi dire era il sentimento della forma.

Wenn man am Fuße des Langkofel steht, entlang der Seiser Alm wandert, bis zur Raschötz aufsteigt und vor dem Murfrëit steht, kommt es einem so vor, als erreiche man einen Ort der Seele. Man steht vor etwas, das man gefühlt bereits in sich trägt, ganz gleich aus welcher geografischen Ecke man stammt. Es ist nicht nur ein visuelles Erlebnis, es ist die reale Begegnung mit Landschaften, von denen man in geheimnisvoller Weise feststellt, sie in seinem Innern bereits gesehen zu haben, noch bevor man sie geografisch kennengelernt hat. Es ist, als käme man in Kontakt mit tiefgründigen imaginären Welten, die sich in den eigenen urältesten Empfindungen von Raum, Luft, Naturkraft, Stille, Größe abgelagert haben. Als entdecke man die Urgefühle dessen, was im Laufe der Zeit mit der Rationalität des Erwachsenseins in Begriffen und Worten geordnet wurde: eine Rückkehr zur ersten, nackten Wurzel der eigenen rationalen Wahrnehmung der Welt.

Dabei handelt es sich um ein kraftvolles und gleichzeitig gemeinsames Erlebnis, das sich nur schwer mit Worten beschreiben lässt und, etwas bescheidener werdend, sich in die weit verbreitete Freude an den Bergen verwandelt, in das Vergnügen eines Spaziergangs und in die sogar touristische Anziehungskraft der so unnahbaren Gipfel. Die tiefgründigen Gefühle werden bescheidener und ergießen sich in bescheidenen Erklärungen.

Es ist kein Zufall, dass das echte Bergvolk, umso mehr, je weiter es sich von den Tälern entfernt, sehr oft wünscht, in diese zurückzukehren, und viele Male dies auch tatsächlich tut; und es ist kein Zufall, dass genau dasselbe Bergvolk nie sehr gesprächig ist.

Wenn man dann in den großen, lichterfüllten Raum des Ateliers von Wilhelm Senoner in Ortisei eintritt, spürt man eigentlich keinen so großen Unterschied zu den Eindrücken der äußeren Umgebung. Die Gebirgslandschaft, die Farben des Erdbodens, ja sogar die sinnliche Wahrnehmung der Luft, des Windes und der Stille – alldem begegnet man erneut, während man zwischen den Riesen aus Holz, das wie Stein scheint, oder aus Bronze umherwandelt.

Frauen und Männer mit angedeutetem Schritt (Donna sulla pedana, 2018), sich umarmende Körper (Tensione simbiotica, 2017), nachdenkliche Mütter (Madre in meditazione, 2018), rauchende Männer (L’uomo col sigaro, 2016): Sie alle stehen im Dialog mit den „Hütern der Berge“ (Philippe Daverio 2016), die auf märchenhafte Weise da draußen, auf den Gipfeln des Murfrëit, unter dem Grödner Pass stehen. Und wenn der Blick dann auf die Gemälde fällt, ist auch dort dieselbe Kontinuität mit den Farben und Materialien der großen Statuen wiederzufinden.

Und so langsam versteht man, warum dieses Volk der Riesen, die so kraftvoll und von Materie durchdrungen, so erkennbar menschlich sind, dennoch eine auffällige körperliche Besonderheit haben: Der Kopf nimmt niemals eine naturalistische Form an, sondern läuft spitz zu, gipfelt, streckt sich lang, als trüge er darin einen anhaltenden Windstoß, als hätte sich der Wind draußen auf ihren Köpfen kristallisiert.

Im Handumdrehen wird jede visuelle Gewohnheit, an die der Betrachter durch die große nordeuropäische Bildhauertradition gewöhnt war, umgestoßen: die Tradition von Veit Stoss, Hans Leinberger, Tilman Riemenschneider. Allesamt sind Wilhelm Senoner wohl bekannt und

wurden von ihm in seiner Jugend mit viel Hingabe studiert und reproduziert. Seit Baxandall haben wir gelernt, Skulpturen als Muster einer zerklüfteten, gekerbten, ununterbrochen in Spannung und Bewegung befindlichen Form anzusehen, bei denen – aus Sicht der italienischen Bildhauerei – mehr durch Auflegen als durch Wegnehmen gearbeitet wird. Hier dagegen, in der Bildhauerei von Senoner, setzt sich die Form wieder zu einer plastischen Masse zusammen und schöpft aus einer anderen Ausdruckskraft, die nicht emotional, nicht beschreibend und niemals fragmentarisch ist. Seine Bildhauerei gibt eine tiefgründige Antwort auf tiefgehende

Anliegen: Wie Worte ohne Laute antworten diese Statuen endlich mit arkaner Stimme auf jene Urempfindungen, die sich nicht benennen lassen. Und so versteht man, dass jene Empfindungen nur mit der Sprache der Form und nicht mit der Sprache der Worte gesagt werden können. Das Gefühl, das sich nicht benennen ließ, war das Gefühl der Form.

Imagine standing at the foot of Langkofel, walking through the Seiser Alm, climbing up to Raschötz, and standing facing the Murfrëit. It is like entering a holy place. In front of you, you see your soul, regardless of where you are from geographically. Your experience is not just visual. You come into contact with real panoramas that, mysteriously, you discover you have known deep inside, even before you have seen them or know where they are located geographically. It is like touching a dreamscape buried deeply among your most primal feelings for space, air, forces of Nature, silence, and vastness. You are in touch with the sensory origin for what has over time allowed you to organize concepts and words under the influence of adult rationality: you return to the origin roots of your rational perception of the world.

It is a strong, yet common, experience that struggles to find the words for expression and is transformed, modestly, within the sprawling pleasure of the mountains, in the pleasure of hiking, even within the touristic attraction of those impervious peaks. It is a deep feeling that humbles and is channelled through simple explanations.

It is not by chance that true mountaineers, even when they are far from their valleys, often dream of returning home; and many times, they do. Nor is it by chance that these same mountain-reared people are never chatty.

So, when you enter the wide-open, luminous space that is Wilhelm Senoner’s studio in Ortisei, your feelings are similar to your experience out in the open. The raw materials from the mountains, the colours of the Earth, even the sensation of the air, the wind and the silence are with you as you wander among his wooden giants, which appear to be hewn from stone or cast in bronze. Women and men appear to walk (Donna sulla pedana, 2018), bodies that embrace themselves (Tensione simbiotica, 2017), meditative mothers (Madre in meditazione, 2018), and men smoking (L’Uomo col sigaro, 2016): they all speak to those “guardians of the mountains” (Philippe Daverio 2016) imaginatively arranged outdoors, on the peaks of the Murfrëit, below the Grödner Pass. As your eyes slide over his paintings, the continuity of colour and materials found in the large statues continues. You begin to understand why this population of giants, so powerful and material, so recognizably human, has a specific physical fault: their heads never have a naturalistically reliable shape; rather, they come to points, standing out, elongated as if caught in a blast of wind and set, crystallizing the puffs of the outdoors winds.

All at once, the visual habits of the great northern European sculptors are overturned. Wilhelm Senoner knows the traditions of Veit Stoss, Hans Leinberger, and Tilman Riemenschneider very well. He studied them with dedication and reproduced their techniques in his youth. From Baxandall onwards, we have learned to look at them as shapes, girdled constantly under stress and in motion. Sculpture that, from the Italian viewpoint, is performed more often by way of addition than by way of removal. It is here, in Senoner’s sculpture, that shape is compacted into a plastic mass and taps into a new type of expression, not emotive, not descriptive, never fragmented. It is sculpture that provides a response to our deep-seated needs: like words without sound, in arcane voice, these statues respond to the ancestral sensations you cannot express. And you understand that, in order to express them, those feelings, you need a language of shape and not of words. The feelings you could not express were the feelings of the shape.

Uomo con Scudo/Aquilone, Spirito delle

Dolomiti

Mann mit Schild/Drachen, Dolomitengeist

Man with Shield/Kite, Dolomite Spirit

2010

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

225 × 70 × 58 cm (p. 80)

Donna con Palla di Neve

Frau mit Schneeball

Woman with Snowball

2017

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

228 × 64 × 64 cm (p. 82/83)

Uomo che Pensa e Uomo che Aspetta

Denkender Mann und Wartender Mann

Thinking Man and Man Waiting

2019/2020

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

170 × 35 × 32 cm

172 × 37 × 32 cm (p. 85)

La Donna del Vento

Die Frau des Windes

The Woman of the Wind

2013

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

228 × 64 × 64 cm (p. 88/89)

Donna che Pensa

Denkende Frau

Thinking Woman

2016

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

196 × 55 × 49 cm (p. 91)

Nudo Verde

Akt Grün

Act Green

2019

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

136 × 25 × 25 cm (p. 92)

Donna sulla Pedana

Frau auf dem Laufsteg Woman on the Catwalk

2018

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

237 × 208 × 88 cm (p. 94/95)

Donna con Marionetta

Frau mit Marionette Woman with Puppet

2017

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

207 × 60 × 60 cm (p. 96/97)

Uomo che Pensa

Denkender Mann

Thinking Man

2018

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

207 × 76 × 55 cm (p. 98/99)

Respiro Atem Breath

2015

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

190 × 65 × 63 cm

(p. 102/103)

Madonna Blu

Blaue Madonna

Blue Madonna

2017

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

200 × 65 × 55 cm

(p. 104)

Donna con Guanti Rossi

Frau mit Roten Handschuhen

Woman with Red Gloves

2015

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

190 × 56 × 40 cm

(p. 107)

Eva Eva Eve 2017

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

167 × 31 × 31 cm (p. 109)

Uomo con Gallo/Pietro

Mann mit Hahn/Petrus

Man with Cock/Peter

2019

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

207 × 73 × 45 cm (p. 110/111)

Donna Sdraiata/Venere

Liegende Frau/Venus

Woman Lying Down/Venus

2013

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

90 × 210 × 90 cm (p. 114/115)

Schiena contro Schiena

Rücken an Rücken

Back to back

2008

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

225 × 78 × 92 cm (p. 116)

Eva Eva Eve 2020

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

220 × 75 × 50 cm (p. 118)

Il Ritmo dell’essere Der Rhythmus des Seins

The Rhythm of Being

2013

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

158 × 180 × 95 cm (p. 119, 148, 162/163)

Uomo e Donna in Cammino

Mann und Frau im Gehen

Walking Man and Woman

2014

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

210 × 150 × 80 cm (p. 120)

Il Bacio

Der Kuss

The Kiss

2020

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

220 × 73 × 50 cm (p. 122)

Omaggio a Franz Kafka

Homage an Franz Kafka

Homage to Franz Kafka

2019

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

154 × 60 × 90 cm (pedana/Laufsteg/

catwalk 180 × 210 cm) (p. 123)

Donna con Guanti Rossi

Frau mit Roten Handschuhen

Woman with Red Gloves

Donna con Colomba

Frau mit Taube

Woman with Dove

2004/2005

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

207 × 60 × 51 cm

208 × 60 × 58 cm (p. 124/125)

Sorgere

Aufbrechen

Rise Up

2014

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

174 × 157 × 70 cm (p. 126)

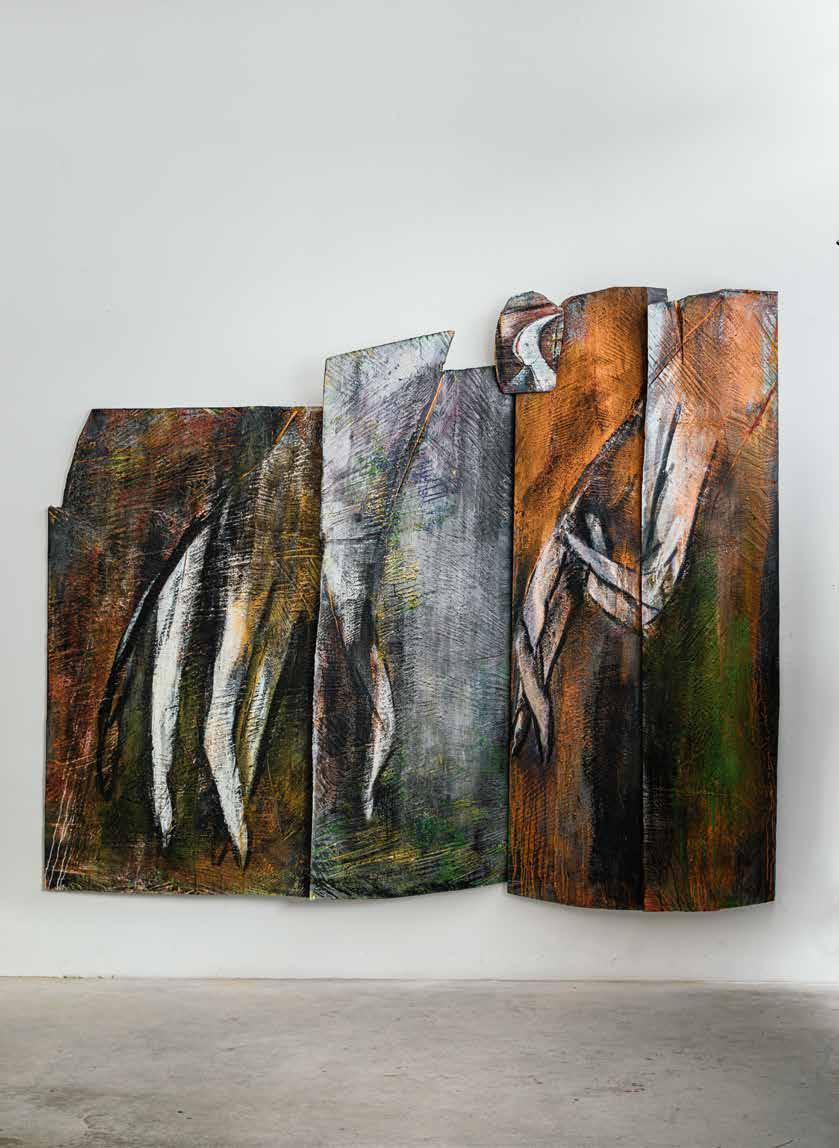

Sorgere Aufbrechen

Rise Up

2018

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

200 × 140 × 4 cm

(p. 127)

Paesaggio I

Landschaft I

Landscape I

2012

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

140 × 127 × 4 cm

(p. 128)

Paesaggio II

Landschaft II

Landscape II

2012

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

140 × 127 × 4 cm

(p. 129)

Il Bacio

Der Kuss

The Kiss

2018

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

180 × 80 × 4 cm (p. 130)

Pneuma-Ombre

Pneuma-Schatten

Pneuma-Shadow

2010

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

157 × 127 × 4 cm (p. 131)

Uomo in Rosso Mann in Rot

Man in Red

2019

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

100 × 100 × 4 cm (p. 132)

Uomo alla Finestra

Mann am Fenster Man at the Window

2019

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

90 × 90 × 4 cm (p. 133)

Uomo e Donna nel Paesaggio Mann und Frau in der Landschaft

Man and Woman in the Landscape

2019

Juta, acrilici, terre e colle

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

140 × 127 × 4 cm (p. 137)

Uomo in Cammino

Gehender Mann

Walking Man

2016

Juta, acrilici, terre, colle e tiglio

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden, Leime und Linde Jute, acrylics, earth pigments, glues and lime

127 × 140 × 4 cm (p. 138)

Donna alla Finestra

Frau am Fenster

Woman at the Window

2019

Juta, acrilici, terre, colle e tiglio

Jute, Acrylfarben, Erden, Leime und Linde

Jute, acrylics, earth pigments, glues and lime

90 × 90 × 4 cm (p. 139)

Paesaggio Tridimensionale

Dreidimensionale Landschaft

Three-dimensional Landscape

2017

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

197 × 105 × 96 cm (p. 140)

Murfrëit

Murfrëit

Murfrëit

2019

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

250 × 290 × 20 cm (p. 141)

Paesaggio

Landschaft

Landscape

2018

Tiglio, acrilici, terre e colle

Linde, Acrylfarben, Erden und Leime

Lime, acrylics, earth pigments and glues

195 × 100 × 8 cm (p. 143)

2020

Mostra Triennale delle Arti Visive a Roma, Palazzo Borghese, Roma (IT)

“Linguaggio Interiore”, Cris Contini Contemporary, Londra (GB)

2019

“Controtempo”, Typac Center, Ortisei –Val Gardena (IT)

2018

“Il Ritmo dell’Essere”, Typak Center, Ortisei – Val Gardena (IT) (p. 150)

“Le opere di Wilhelm Senoner sono ‘Denkbilder’ (creatrici di pensieri) e riescono a esprimere ciò che è difficilmente descrivibile attraverso le singole parole”, ha affermato la curatrice Elena Filippi nel 2018 all’inaugurazione della mostra “Il Ritmo dell’Essere”. L’esposizione è durata due mesi e l’artista ha presentato le sue opere in uno scenario davvero notevole, davanti al panorama di montagne visibili dal suo paese natio, Ortisei. Nel suo atelier Senoner ha esposto, oltre a numerose sculture già conosciute, l’ultima versione del suo lavoro intitolato Il Bacio. In esso si può percepire, come ha detto Elena Filippi, “L’andamento di quel ritmo stupendo del dare e ricevere gratuitamente: l’uno senza l’altro non avrebbe quel significato meraviglioso che invece ha.” “Come nell’antica Grecia si distingueva fra il ritmo più tranquillo che riprendeva il ritmo proprio della natura (arhythmòs) e quello dinamico, spesso imprevedibile degli eventi umani (rhythmòs), così le sculture di Senoner ci permettono di sperimentare ritmi diversi. Quiete e movimento, ripetizione continua come il muoversi verso ciò che è nuovo” afferma sempre Elena Filippi, la quale poi cita il critico d’arte Leo Andergassen: “Senoner percepisce l’arte come armonia ed equilibro formale. Anche se verosimilmente i movimenti simulano partenze e cambiamenti, questi non possono esistere senza la quiete”.

“Uomo con Scudo/Aquilone, Spirito delle Dolomiti”, Villa Imperiale, Bad Ischl (AT)

“Squarci”, Palazzo Fogazzaro, Schio (IT)

2017 “Elogio all’Ombra”, Biblioteca Daverio, Milano (IT)

Quando nel 2017 Philippe Daverio, l’antropologo della cultura, ha esposto

le opere di Wilhelm Senoner nella sua Galleria a Milano, nel discorso di apertura ha detto: “Wilhelm Senoner è uno sciamano d’oggi, uno che lavora per andare a scoprire i misteri arcani. Come gli sciamani cerca la sua ispirazione in fondo al bosco, fra le montagne, talvolta sulle cime tempestose. Esalta figure eroiche che provengono dagli strati profondi della sua coscienza e ne fa simboli d’una modernità alternativa”. Le forme nelle sculture di Senoner hanno un aspetto così fluido, come se lo scultore le avesse ottenute con un taglio netto di coltello. Nella mostra “Elogio all’ombra” sono stati esposti anche i dipinti di Senoner oltre alle famose sculture in legno di tiglio e in bronzo. Queste opere secondo Daverio sono “I custodi di una memoria collettiva”.

(p. 14, 152)

“Murfrëit”, Fondazione Manfred Sauer, Lobbach (DE)

2016

“Murfrëit”, Passo Gardena – Val Gardena (IT)

Per il suo settantesimo compleanno nel settembre 2016, Wilhelm Senoner ha allestito una mostra all’aperto, su un prato sotto il passo Gardena, dove ha esposto varie sue opere. Fin da quando era un giovane artista, Wilhelm veniva a disegnare in questi luoghi, dove ha sempre trovato le sue forme, ispirandosi alle rocciose pareti a picco del Murfrëit. “Ricollocando le sue sculture là sulle montagne, Senoner ha risposto al loro appello”, ha scritto il filosofo e storico Giovanni Gurisatti in occasione della mostra, affermando inoltre: “In questo ruvido altrove rispetto agli spazi espositivi dei musei dei palazzi e residenze, le sculture di Senoner sembrano finalmente a loro agio”.

Accanto alle sculture in bronzo, Senoner ha installato pareti in legno espressamente realizzate, che assomigliano talmente nel colore e nella forma alle pareti montuose del Murfrëit, da dare l’impressione che la roccia si rispecchi nel legno. L’antropologo della cultura

Philippe Daverio ha detto di Senoner: “Oltre a fare il Bild-hauer (scultore), gli sarebbe piaciuto fare il pittore e questa sua sensibilità pittorica conferisce alle superfici che Wilhelm lavora un effetto sorprendente, non dissimile ai colori che hanno le pietre delle montagne. A guardarle bene queste sculture sembra che abbiano una patina data dal tempo, dalla natura stessa”.

(p. 164/171)

2014

“Francis Bacon & Wilhelm Senoner”, 19° Art Innsbruck, Innsbruck (AT) Mystik Berg, International Mountain Summit, Bressanone (IT)

“Mito & Uomo & Montagna”, Castel Coira, Sluderno (IT)

“ie Iona”, Museo Civico, Chiusa (IT)

“ie Iona” così il Museo Civico di Chiusa ha intitolato la mostra delle sculture di Wilhelm Senoner allestita nella sua patria originaria, il Sud Tirolo; significa “Io, Giona”, il profeta del vecchio testamento, colui che non ha mai detto parole profetiche sagge e che Dio mette continuamente alla prova. Proprio come Giona, lo scultore gardenese condivide con il suo pubblico messaggi semplici. Le sue opere possono essere interpretate in molti modi, come i racconti biblici, e osservando ciò che le figure di Senoner ci mostrano, a qualsiasi interpretazione si arrivi ci viene svelato molto sull’umanità. Per lo storico dell’arte Leo Andergassen rappresentano “l’accettazione di ciò che è”. (p. 161)

2013

“Il Ritmo dell’Essere”, Complesso Monumentale di San Silvestro, Vicenza (IT) In occasione del IX Festival Biblico di Vicenza le sculture di Wilhelm Senoner sono state esposte per un mese, da metà maggio a metà giugno 2013, negli spazi del complesso monumentale di San Silvestro. La maggior parte delle sue figure umane sono state posizionate all’interno dell’antica chiesa romanica con le pareti in cotto a vista. Gli organizzatori dell’esposizione, tra cui la promotrice Enrica Volpi, hanno scritto: “La ricerca artistica di Wilhelm è vita, riflessione, ingegnosità, si oppone a tutto ciò che in senso classico significa statico, fisso e museale”.

(p. 148, 162/163)

2012

“Uno di noi”, Fondazione Minoprio, Como (IT)

Nella primavera del 2012, alla Fondazione Minoprio, a Como, l’Ing. Franco Gerosa e l’Arch. Andrea Gerosa hanno organizzato una mostra dove si sono potute apprezzare le opere di Wilhelm Senoner. Nella Villa Raimondi la Fondazione ha esposto le sculture di Senoner definendole “Uno di noi” e riconoscendole come “Archetipi dell’Umanità”.

(p. 19, 26, 154)

2011

54° Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, Torino Esposizioni, Torino (IT)

“Nel profumo del vento”, Rasciesa, Parco Naturale UNESCO Puez-Odle (IT)

Con la mostra “Nel profumo del vento” Wilhelm Senoner è riuscito a esaudire uno dei suoi desideri. Nell’estate del 2011 un elicottero ha trasportato sette sculture in bronzo fino alla cima del Rasciesa, parco naturale del Puez-Odle, a 2300 m di altezza, dove sono state ancorate al suolo. Qui in cima ai monti, sulle Dolomiti divenute Patrimonio Mondiale Naturale dell’UNESCO, Senoner a suo tempo aveva trovato le forme per le sue figure umane. Lassù ha inserito nel paesaggio montano Donna nel Vento, Uomo in Cammino e altre cinque sculture, che in realtà, come tutte le sue opere, sono frutto di quell’ambiente, provengono da quei luoghi: le loro linee si ritrovano negli spigoli delle montagne, le superfici nelle rocce e le teste nelle pareti rocciose.

(p. 172/179)

2010 “Evoluzione”, Fraunhofer-Haus, Monaco di Baviera (DE)

Con la serie di mostre “Scienza e Arte in Dialogo”, la Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft invita entrambe le discipline a un discorso stimolante. L’obiettivo è quello di motivare ricercatori e artisti a lasciare percorsi familiari e ad avventurarsi in un cambiamento di prospettiva. “Fin dall’epoca romantica, si è tentato più volte di mettere in scena la scienza come antitesi dell’arte. Ma i processi creativi in entrambe le discipline sono simili.

Artisti e scienziati osservano, descrivono e sperimentano. Entrambi vogliono spiegare le connessioni. Ignorare le loro differenze in termini di metodi o risultati sarebbe sbagliato, perché è proprio questa tensione che rende il dialogo tra arte e scienza così produttivo ed emozionante”, ha affermato Dorothée Höfter, fondatrice e Responsabile di Progetto della serie di mostre Fraunhofer.

Nel 2010 la serie è stata dedicata alle sculture e ai dipinti di Wilhelm Senoner, che è anche scultore e scienziato dei materiali. Höfter ha spiegato: “Senoner è interessato alle relazioni interpersonali: a prima vista le sue figure sembrano molto simili, ma a ben guardare lo spettatore scopre in esse un’espressione molto individuale e unica. Lontano da ogni realismo superficiale, dà alle sue sculture qualcosa di magico”.

(p. 155)

2009

“Figure – Forme – Persone”, Museo Diocesano, Bressanone (IT)

Il Museo Diocesano nel Palazzo Vescovile di Bressanone, la cosiddetta Hofburg, espone soprattutto arte del Medioevo, del Rinascimento e del Barocco, come il tesoro del Duomo con i suoi paramenti sacri e busti reliquiari. Le mostre di opere moderne sono un bellissimo contrasto con i pezzi pregiati antichi. Nel 2009 il Museo ha esposto le opere di Wilhelm Senoner dedicandogli una mostra, perché gli organizzatori dell’installazione hanno visto le sue sculture in legno e bronzo come “un passaggio fra contemporaneo e antico”. L’artista Senoner, da giovane formatosi secondo la tradizione degli scultori gardenesi, ha realizzato pale

d’altare prima di trovare forme libere ed eterne per le sue figure umane. Nelle sue forme dinamiche e al contempo spigolose inserite nelle cantine medievali del Palazzo Vescovile, l’osservatore può ritrovare tutti e due gli aspetti del tempo: figure tramandate dalla mitologia greca e figure contemporanee, una Eva con Mela come una coppia al semaforo.

(p. 156/157)

2007

“Wilhelm Senoner, Sculture”, Abbazia di Certosa, Val Senales (IT) (p. 192)

“Scultura e Pittura”, Thomas & Bernadett Rüschen, Königstein (DE)

2006

“Scultura e Pittura”, Museo d’Arte Moderna Mario Rimoldi, Cortina d’Ampezzo (IT)

2005

“Sculture e Disegni,” Galleria Max-21, Iphofen (DE)

“Sculture in Bronzo”, Interart Beeldentuin & Galerie, Heeswijk Dinther (NL)

2004

“Wilhelm Senoner”, Galleria Altesse, Nendeln (LI)

2003

“Sculture e Disegni”, Galleria Kersten, Brunnthal (DE)

2020

Triennale der bildenden Kunst in Rom, Palazzo Borghese, Rom (IT)

Innere Stimme, Cris Contini Contemporary, London (GB)

2019

Controtempo, Typak Center, St. Ulrich –Gröden (IT)

2018

Der Rhythmus des Seins, Typak Center, St. Ulrich – Gröden (IT) (p. 150)

„Die Werke Wilhelm Senoners sind Denkbilder, denen es gelingt, das auszudrücken, was nur schwer in Worte zu fassen ist“, sagte die Kuratorin Elena Filippi, als sie 2018 die Ausstellung Der Rhythmus des Seins eröffnete. Vor dem Bergpanorama seiner Heimat St. Ulrich präsentierte der Künstler zwei Monate lang eine der umfangreichsten Schauen seines Werks. Neben zahlreichen bekannten Skulpturen zeigte Senoner in seinem Atelier auch erstmals eine neue Darstellung der Arbeit Der Kuss

An ihr könne man den „wundervollen Rhythmus vom selbstlosen Geben und Nehmen verstehen“, sagte Filippi: „Eines wäre sinnlos ohne das andere. Ähnlich wie im antiken Griechenland zwischen dem eher ruhigen, sich wiederholenden Rhythmus der Natur (arhythmòs) und dem dynamischen, oft unvorhersehbaren Rhythmus menschlicher Ereignisse (rhythmòs) unterschieden wurde, ließen sich anhand der Skulpturen Senoners unterschiedliche Rhythmen erfahren. Ruhe und Bewegung, Wiederholung genauso wie der Aufbruch zu Neuem“. Die Kuratorin zitierte den Kunstkritiker

Leo Andergassen: „Senoner erlebt Kunst in der Harmonie und im formalen Ausgleich. Wenn auch die Bewegungen vermeintlich Aufbruch und Veränderung simulieren, so gibt es diese nicht unter Preisgabe von Ruhe.“

Mann mit Schild/Drachen, Dolomitengeist, Kaiservilla, Bad Ischl (AT)

Passages, Palazzo Fogazzaro, Schio (IT)

2017

Lob im Schatten, Bibliothek Daverio, Mailand (IT)

Als Philippe Daverio in seiner Galerie in Mailand 2017 die Arbeiten Wilhelm Senoners zeigte, sagte

der Kulturanthropologe in seiner Eröffnungsrede: „Wilhelm Senoner ist ein Schamane der heutigen Zeit, einer, der sich daran macht, geheimnisvolle Rätsel aufzudecken. Wie die Schamanen sucht er seine Inspiration inmitten des Waldes, in den Bergen, auf stürmischen Höhen. Heraus hebt er heroische Figuren, die aus den tieferen Schichten seines Bewusstseins stammen, und macht sie zu Symbolen einer alternativen Moderne“. Die Formen von Senoners Skulpturen wirkten so flüssig, als habe der Bildhauer sie mit dem Schwung eines Messers ausgeschnitten. Die Ausstellung Lob im Schatten versammelte neben Senoners bekannten Lindenholz- und Bronzeskulpturen auch seine Gemälde. Zusammen bildet das Werk laut Daverio einen „Träger kollektiver Erinnerung“.

(p. 14, 152)

Murfrëit, Manfred Sauer Stiftung, Lobbach (DE)

2016

Murfrëit, Grödner Joch – Gröden (IT)

Zu seinem 70. Geburtstag im September

2016 installierte Wilhelm Senoner einige Skulpturen unter dem Grödner Joch. Hier am Murfrëit hatte er als junger Künstler gezeichnet und in den schroffen Felswänden seine Gestalten gefunden.

„Indem er die Skulpturen dort, auf dem Berg, aufgestellt hat, hat Senoner auf ihren Ruf reagiert“, schrieb der Geschichtsphilosoph Giovanni Gurisatti anlässlich der Freilichtausstellung. „In diesem rauen Anderswo im Vergleich zum glatten Ausstellungsraum scheinen die Figuren Senoners sich endlich wohl zu fühlen.“

Neben die Skulpturen aus Bronze stellte Senoner eigens gefertigte Holzwände, die in Farbe und Form den Gebirgswänden des Murfrëit dermaßen ähnelten, dass sich der Fels im Holz zu spiegeln schien. Der Kulturanthropologe Philippe

Daverio sagte über Senoner: „Außer ein Bild-hauer zu sein, wäre er auch gern Maler geworden: und diese malerische Einfühlsamkeit verleiht den Oberflächen von Wilhelm eine erstaunliche Wirkung, ähnlich den Farben der Gebirgssteine. Bei genauem Betrachten scheint es, dass die Natur selbst den Skulpturen mit der Zeit eine Patina verliehen hat.“

(p. 164/171)

2014

Mystik Berg, International Mountain Summit, Brixen (IT)

Mythos & Mensch & Berg, Churburg Schloss, Schluderns (IT)

ie Iona, Stadtmuseum, Klausen (IT)

„Ich, Jona“ nannte das Stadtmuseum Klausen die Ausstellung von Wilhelm Senoners Skulpturen in seiner Heimat Südtirol, nach Jona, dem Propheten aus dem Alten Testament, der keine weisen Prophetenworte hat und den Gott ständig aufs Neue prüft. Genauso wenig wie Jona teilt der Grödner Bildhauer mit seinem Publikum einfache Botschaften. Sein Werk lässt sich vielfältig interpretieren wie die biblische Geschichte, und zu welcher Deutung man kommt, verrät mindestens so viel über die Menschen, die schauen, wie über Senoners Menschenfiguren, die zur Schau stehen. Der Kunsthistoriker Leo Andergassen sah in ihrem Ausdruck „die Akzeptanz dessen, was ist“. (p. 161)

2013

Der Rhythmus des Seins, Denkmalkomplex San Silvestro, Vicenza (IT)

Wilhelm Senoners Skulpturen waren anlässlich des IX. Bibelfestival in Vicenza einen Monat lang, von Mitte Mai bis Mitte Juni 2013, in den Räumen des Denkmalkomplexes San Silvestro zu sehen; die meisten seiner menschlichen Figuren säumten die romanische Backsteinkirche. Die Ausstellungsmacherinnen, mit die Initiatorin Enrica Volpi schrieben: „Wilhelms künstlerische Suche ist Leben, Reflektion, Einfallsreichtum, sie stellt sich gegen alles, was im klassischen Sinn statisch, fest und museal ist“. (p. 148, 162/163)

2012

Einer von uns, Minoprio Stiftung, Como (IT)

Im Frühjahr 2012 haben Ing. Franco Gerosa und Arch. Andrea Gerosa eine dem Werk Wilhelm Senoners gewidmete Ausstellung in der Minoprio Stiftung im norditalienischen Como organisiert. Unter dem Titel Einer von uns zeigte die Stiftung in der Villa Raimondi die Skulpturen Senoners, in denen sie „Archetypen der Menschheit“ erkannte. (p. 19, 26, 154)

2011

54° Biennale von Venedig, Italienischer Pavillon, Torino Esposizioni, Turin (IT)

Im Duft des Windes, Raschötz, UNESCO Naturpark Puez-Geisler (IT)

Mit der Ausstellung Im Duft des Windes hat sich Wilhelm Senoner 2011 einen Wunsch erfüllt. Ein Helikopter brachte im Sommer die sieben Skulpturen aus Bronze einzeln zur Raschötzer Hochalm im Naturpark Puez-Geisler, wo sie auf 2300 Meter Höhe im Boden verankert wurden. Hier oben im Gebirge, im UNESCO-Weltnaturerbe der Dolomiten, hat Senoner einst die Formen für seine Menschenfiguren gefunden. So fügten sich die Frau im Wind, ein Gehender Mann und die anderen fünf Skulpturen natürlich in die Bergumgebung ein: Sie stammen von hier. Ihre Linien finden sich in den Gebirgszügen wieder, ihre Oberfläche im Gestein und ihre Gesichter in den Felswänden. (p. 172/179)

2010

Aufwind, Fraunhofer-Haus, München (DE)

Mit der Ausstellungsreihe Wissenschaft und Kunst im Dialog lädt die FraunhoferGesellschaft beide Disziplinen zu einem anregenden Diskurs ein. Sie will Forschende und Kunstschaffende motivieren, gewohnte Pfade zu verlassen und Perspektivwechsel zu wagen. „Seit der Romantik wird immer wieder versucht, die Wissenschaft als Gegenspielerin der Kunst zu inszenieren. Doch die kreativen Prozesse beider Disziplinen ähneln sich. Künstler und Wissenschaftler beobachten, beschreiben und experimentieren. Beide wollen Zusammenhänge erklären. Ihre Unterschiede im Hinblick auf Methoden

oder Ergebnisse zu ignorieren wäre aber falsch, macht doch gerade dieses Spannungsverhältnis den Dialog zwischen Kunst und Wissenschaft so produktiv und spannend“, sagte Dorothée Höfter, die Gründerin und Projektleiterin der Fraunhofer-Ausstellungsreihe.

2010 widmete sich die Reihe den Skulpturen und Bildern Wilhelm Senoners, der als Bildhauer auch Materialwissenschaftler ist. Höfter erklärte: „Senoner interessiert das Zwischenmenschliche, auf den ersten Blick wirken seine Figuren sehr ähnlich, und doch stellt der Betrachter bei genauerem Hinsehen in ihnen einen ganz individuellen und einzigartigen Ausdruck fest. Von jedem oberflächlichen Realismus distanziert, verleiht er seinen Skulpturen etwas Magisches“.

(p. 155)

2009

Figuren – Gestalten –Personen, Diözesanmuseum, Brixen (IT) Das Diözesanmuseum in der Hofburg Brixen zeigt hauptsächlich Kunst aus Mittelalter, Renaissance und Barock, wie den Domschatz mit seinen liturgischen Gewändern und Reliquienbüsten. Zu den Prunkstücken der Vergangenheit setzen Ausstellungen zeitgenössischer Werke einen Kontrast. 2009 widmete das Museum Wilhelm Senoner eine Schau, denn in seinen Plastiken in Holz und Bronze sahen die Ausstellungsmacher „einen Übergang zwischen zeitgenössisch und steinalt“. Gegründet auf die Tradition der Grödner Bildhauer gestaltete Senoner als junger Künstler Altarfiguren, bevor

er für seine Menschengestalten freie, zeitlose Formen fand. Wer hinschaute, konnte in seinen so dynamischen wie kantigen Gestalten, aufgereiht im mittelalterlichen Kellergewölbe der Hofburg, beides erkennen: überlieferte Figuren aus der griechischen Mythologie und Zeitgenossen von nebenan, eine Eva mit Apfel genauso wie ein Paar an einer Ampel. (p. 156/157)

2007 Wilhelm Senoner – Bildhauer, Kartause Allerengelberg, Schnals (IT) (p. 192)

Skulptur und Malerei, Thomas & Bernadett Rüschen, Königstein (DE)

2006

Skulpturen und Malereien, Museum für moderne Kunst Mario Rimoldi, Cortina d’Ampezzo (IT)

2005

Skulpturen und Zeichnungen, Galerie Max21, Iphofen (DE)

Skulpturen in Bronze, Interart Beeldentuin & Galerie, Heeswijk Dinther (NL)

2004 Wilhelm Senoner, Galerie Altesse, Nendeln (LI)

2003

Skulpturen und Zeichnungen, Galerie Kersten, Brunnthal (DE)

2020

Triennial Exhibition of Visual Arts in Rome, Palazzo Borghese, Rome (IT)

Inner Language, Cris Contini Contemporary, London (GB)

2019

Unaware, Typac Center, Ortisei – Val Gardena (IT)

2018

The Rhythm of Being, Typak Center, Ortisei – Val Gardena (IT) (p. 150)

“Wilhelm Senoner’s Works are ‘Denkbilder’ (thought creators) and express the most difficult concepts that are difficult to describe only with words,” said Elena Filippi, the curator, in 2018 at the inauguration of the show The Rhythm of Being. The show lasted two months and the artist presented his works against a truly magnificent background: his mountains, those in his native town of Ortisei. In his atelier, in addition to numerous sculptures that are already popular, Senoner exhibited the latest version of his work called The Kiss In this work, it is easy to understand, as Elena Filippi said, “The flow of that marvellous rhythm of the freedom of giving and receiving: one without the other would not have that amazing significance that it has. Like how in ancient Greece the quieter rhythm based on the rhythms of nature (aryhthmòs) was distinguished from the dynamic rhythm of man (rythmòs), so Senoner’s sculptures allow us to experience different rhythms. Quiet and movement, continuous repetition, like moving towards something new,” affirms Elena Filippi, who then cited the art critic Leo Andergassen: “In Senoner’s figurative world, what counts is the moulded existence, the moving figure. Everything is moving, panta rhei.”

Man with Shield/Kite, Dolomite Spirit, Kaiservilla, Bad Ischl (AT)

Passages, Palazzo Fogazzaro, Schio (IT)

2017 Acclaim for Shadow, Daverio Library, Milan (IT)

When in 2017 Philippe Daverio, the cultural anthropologist, showed Wilhelm Senoner’s works in his gallery in Milan, in the opening speech he said: “Senoner is a modern-day shaman, someone who

works to discover arcane mysteries. Like shamans, he looks for inspiration deep into the woods, among the mountains, at times on the stormy peaks. He lauds heroic figures that emerge from the deepest stratum of his awareness and makes them symbols of an alternative modernity.”

The shapes in Senoner’s sculptures are fluid, as if the sculptor attained them with a net cut of the knife. The show Acclaim for shadow exhibited Senoner’s paintings, as well as his famous lime wood and bronze sculptures. According to Daverio, these works are “a guardian of collective memory”.

(p. 14, 152)

Murfrëit, Manfred Sauer Foundation, Lobbach (DE)

2016

Murfrëit, Gardena Pass – Val Gardena (IT)

For his seventieth birthday in September 2016, Wilhelm Senoner presented an open-air show on the fields beneath the Gardena Pass, where he exhibited a number of his works. It is in these places that young Wilhelm came to draw and where he found his shapes, inspired by the shear rocky walls of the Murfrëit. “Placing his sculptures there, on the mountains, Senoner answered their call”, wrote the historic philosopher Giovanni Gurisatti about the open-air exhibition. He continued: “In this rough place, when compared to the exhibition spaces of museums, palaces, and residences, Senoner’s sculptures finally appear to be at ease”.

Next to his bronze sculptures, Senoner installed wood partitions, specially built, so similar in colour and shape to the mountainous walls of the Murfrëit, that the rock seems to be reflected in the wood. Cultural anthropologist Philippe Daverio said of Senoner: “In addition to being a Bild-hauer (sculptor), he would have loved to be a painter. It is this pictorial sensitivity that he confers to the surfaces he works, a surprising effect, very similar to the colours that rocks in the mountains have. Looking at them carefully, these sculptures appear with a patina of time, applied by Nature herself”.

(p. 164/171)

2014

Francis Bacon & Wilhelm Senoner, 19th Art Innsbruck, Innsbruck (AT)

Mystik Berg, International Mountain Summit, Bressanone (IT)

ie Iona, City Museum, Chiusa (IT)

“I, Ionah” is the name that the City Museum in Chiusa gave to the exhibition of sculpture by Wilhelm Senoner in his native lands of South Tyrol. Jonah is the Old Testament prophet who never said wise prophetic words and is continuously put to test by God. Just like Jonah, the sculptor from Val Gardena shares simple messages with his public. His works can be interpreted just like the bible story in many ways, and much about humanity is revealed observing everything Senoner’s figures represent, regardless of the interpretation. For Leo Andergassen, art historian, they represent “the acceptance of what it is”.

(p. 161)

2013

The Rhythm of Being, San Silvestro Monument Complex, Vicenza (IT)

On the occasion of Vicenza’s IX Biblical Festival, Wilhelm Senoner’s sculpture was exhibited for a month, from midMay to mid-June 2013, in the spaces of the San Silvestro monument complex. Most of his human figures were located inside the ancient Romanesque church with exposed brickwork. The exhibit organizers, including the promotor Enrica Volpi, wrote: “Wilhelm’s artistic research is life, reflection, ingenuity; he is opposed to anything that is in a classic sense static, fixed or museum-like”.

(p. 148, 162/163)

2012

One of Us, Minoprio Foundation, Como (IT)

During the spring of 2012, Ing. Franco Gerosa and Arch. Andrea Gerosa organized an exhibition showcasing Wilhelm Senoner’s artwork in Minoprio Foundation, Como (in northern Italy). The foundation showed Senoner’s sculptures in Villa Raimondi as One of Us, recognizing them as “Human Archetypes”.

(p. 19, 26, 154)

2011

54° The Venice Biennale, Italy Pavilion, Torino Esposizioni, Turin (IT)

On the Perfume of the Wind, Rasciesa, Puez-Odle Nature Park UNESCO Word Heritage Natural Site (IT)

With the exhibition On the Perfume of the Wind, Wilhelm Senoner fulfilled one

of his heart’s desires. In the summer of 2011, a helicopter moved seven of his bronze sculptures to the summit of Rasciesa, in the Puez-Odle nature park, at an altitude of 2300 m above sea level, where they were anchored to the ground. It was here, on top of the mountains, where the Dolomites became a UNESCO World Heritage Natural Site, that Senoner found the shape for his human figures. Up there, in the mountain landscape, he inserted Woman in the Wind, Walking Man and five other sculptures that are as all his works the product of those places. Their lines are visible in the mountain edges, their surfaces in the rock, and the heads in the rock walls.

(p. 172/179)

2010

Evolution, Fraunhofer-Haus, Munich (DE)

With the exhibition series Science and Art in Dialog, the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft invites both disciplines to a stimulating discourse. It aims to motivate researchers and artists to leave the familiar path and dare to change their perspective. “Since the Romantic period, attempts have been made time and again to stage science as the antithesis of art. But the creative processes of both disciplines are similar. Artists and scientists observe, describe and experiment. But to ignore their differences in terms of methods or results would be wrong, since it is precisely this tension that makes the dialogue

between art and science so productive and fascinating”, says Dorothée Höfter, founder and project manager of the Fraunhofer exhibition series.

In 2010, the series was dedicated to the sculptures and paintings of Wilhelm Senoner, who as a sculptor is also a materials scientist. Höfter explained: “Senoner is interested in human relationships; at first glance his figures seem very similar, but on closer inspection the viewer discovers a very individual and unique expression in them. Away from any superficial realism, he gives his sculptures something magical”.

(p. 155)

2009

Figures – Shapes – People, Diocesan Museum, Bressanone (IT)

The Bressanone Diocesan Museum in the Bishop’s Palace, named Hofburg Castle, primarily features Romanesque, Renaissance and Baroque art, like the Cathedral Treasure with its vestments and reliquary busts. The exhibits of modern works are a wonderful contrast with the valuable antiques. In 2009, the Museum dedicated an exhibit to Wilhelm Senoner’s works, as the organizers of the installation saw “a passage between contemporary and antique” in his sculptures. As a young artist, Senoner trained in the tradition of the Val Gardena sculptors. He made altarpieces even before he found the free and eternal

shapes of his human figures. With their dynamic shapes, with their sharp edges, when inserted in the vaulted-ceiling medieval basements of Hofburg Castle, the observer can see both the aspects of time: shapes passed on from Greek mythology and contemporary figures, an Eve with Apple as well as a couple at a traffic light.

(p. 156/157)

2007

Wilhelm Senoner – Sculptor, Allerengelberg Monastery, Val Senales (IT) (p. 192)

Sculpture and Painting, Thomas & Bernadett Rüschen, Königstein (DE)

2006

Sculpture and Paint, Modern Art Museum Mario Rimoldi, Cortina d’Ampezzo (IT)

2005

Sculptures and Drawings, Art Gallery Max21, Iphofen (DE)

Bronze Sculptures, Interart Beeldentuin & Galerie, Heeswijk Dinther (NL)

2004

Wilhelm Senoner, Altesse Gallery, Nendeln (LI)

2003

Sculptures and Drawings, Kersten Gallery, Brunnthal (DE)

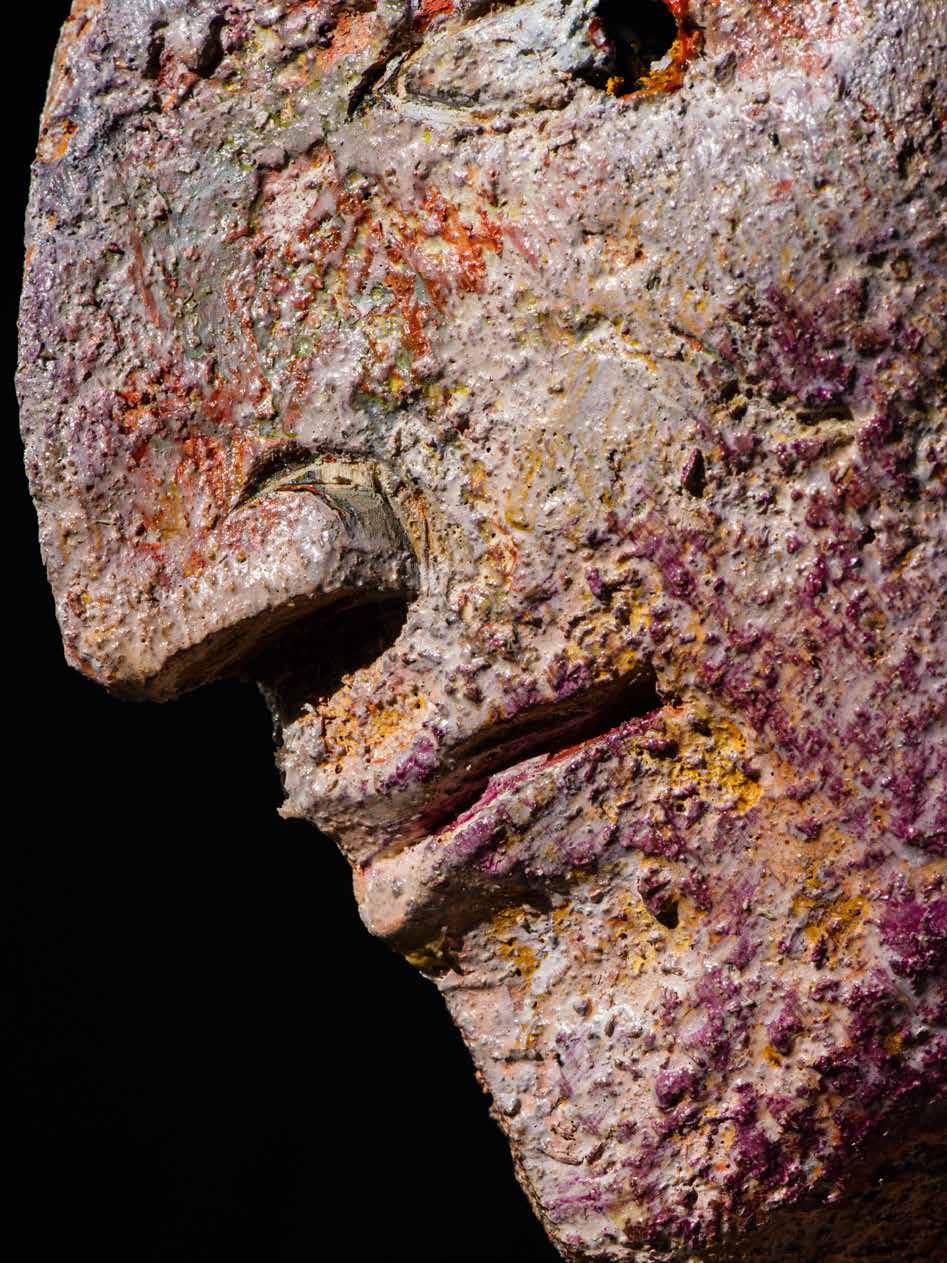

Wilhelm Senoner è uno scultore unico, nato a Ortisei in Val Gardena nel 1946, dove ha iniziato fin da piccolo a prendere confidenza con il mondo del legno e della scultura. Come tutti sanno, il legno è la “materia prima” di questa valle delle Dolomiti, diventata meta ambita dei turisti proprio per le sue sculture artistiche, attività sviluppatasi in una fase di povertà sociale. Senoner non è un artista accademico, non proviene dal mondo universitario dell’arte. Ciò che lui è, s’intuisce dall’empiria materializzatasi nelle sue opere. Il suo apprendistato con diversi scultori gardenesi è durato almeno dodici anni. All’inizio sono stati lunghi periodi di pratica presso i vecchi maestri, una fase questa completamente dedicata a esercizi sulle forme di stili storici. Si è cimentato magistralmente sul tardo gotico, misurandosi con artisti quali Hans Klocker e Michael Pacher. Nonostante ciò ha sempre mantenuto un’attenzione particolare per la natura, che resta sempre la materia di studio da lui preferita. Probabilmente la predilezione per il legno di tiglio deriva proprio dalla sua formazione incentrata sul periodo del tardo gotico tedesco. Tilman Riemenschneider riusciva a realizzare le sue forme naturalistiche proprio grazie alla morbidezza di questo materiale. Il cirmolo autoctono avrebbe permesso solamente proporzioni ben definite. L’incontro con la massa di grande formato così sagomata ci riporta a Senoner stesso, al suo modo di vedere la forma e di comunicare, al suo sguardo sugli uomini. L’uomo è e rimane il suo unico obiettivo. Soggetto e oggetto allo stesso tempo. Nel dialogo con il legno policromo talvolta regna una sensazione di assoluto silenzio. Nessun monologo fuoriesce dai blocchi. Domande e risposte restano uguali nella ripetizione del suo archetipo. Vengono rigettate al fruitore. Wilhelm Senoner è anche pittore. I suoi quadri a volte traggono spunto da ciò che prima è nato come scultura, mentre a volte nascono come bozzetto dal quale riprodurre la scultura stessa. Di conseguenza si può affermare che le sue sculture in legno siano caratterizzate da una superficie pittorica. L’effetto materico non nasce come una pelle incisa nel legno bensì il colore viene applicato come rivestimento, traendo spunto dalla tradizione lavorativa sulla composizione. Non vengono ripresi i metodi storici, classici, di lunga tradizione, ma l’artista sperimenta qualcosa di completamente nuovo. Miscela la segatura con la colla, che poi viene applicata come un “guscio