“Revisiting Gurna” How successful has this project been, and to what sense vernacular architecture can still be relevant?

Yasmina Arafat Housing Form

MA Housing and Urbanism – Term 1 January 12, 2024

Abstract

Constructed close to seven decades past, New Gurna stands as a monumental testament to Fathy's innovative approach which challenged established norms. A thorough examination of its enduring existence unfolds a narrative that transcends beyond basic architectural planning into the fundamental principles of safeguarding historical heritage intertwined with community-centered design initiatives.

Fathy's vision recognized the imperative for ecologically conscious methods, offering useful insights into how vernacular architecture could combat contemporary sustainability issues. Consequently, Gurna transformed into a global standard-exemplar for environmental harmony and durability, demonstrating that vernacular building concepts can contribute significantly to solving present-day ecological stability dilemmas.

The societal significance of Gurna is as profound as its architectural prominence. Fathy's blueprint was fundamentally grounded in a comprehensive attention of communal necessities, preserving cultural heritage whilst providing pragmatic housing solutions. This essay examines the conditions contributing to the negative

perception surrounding Gurna; it interrogates if the deficit originated from design flaws, imperfect execution or external factors.

This essay goes beyond a mere critique, recognizing the complex interplay of success and failure inherent in New Gurna's context. Despite not fully achieving its original goals, it has sustained an enormous impact and played a crucial role in framing contemporary architectural discourse; this points to an unconventional form of success. This essay is thus deeply rooted in Fathy's principles that highlight efficiency, functionality together with profound relation with individuals and their surroundings. The following essay delves in a nuanced approach arguing for the unique achievement embedded within New Gurna's enduring influence on architectural philosophy.

Introduction – About Hasan Fathy

“If you were given a million pounds, what would you do with them? A question they were always asking us when we were young, one that would start our imagination roaming and set us daydreaming. I had two possible answers: one, to buy a yacht, hire an orchestra, and sail round the world with my friends listening to Bach, Schumann, and Brahms; the other, to build a village where the fellaheen would follow the way of life that I would like them to.” 1

- Hasan Fathy

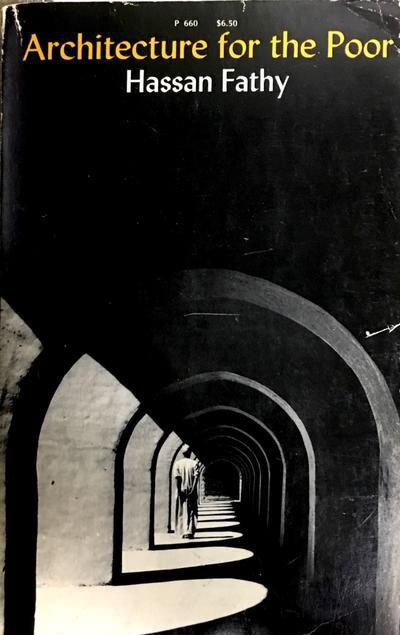

As he mentioned in the opening of his book, “The Architecture of the Poor”, Hasan Fathy, the modernist Egyptian architect, expressed his deep love for his homeland, where he ventured on a journey of transforming and reshaping the Egyptian peasants’ lives and revitalizing the Egyptian countryside. He thus believed that any significant change to be should be rooted in a close bond with the peasant / fellah, by living with them, sharing their struggles and dedicating his life to their on-ground

1 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.1

2 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.3

improvements. He thus examined various ways to uplift those peasants from their despairing life conditions. In his exploration, Fathy discovered the deep- rooted wisdom in the peasants’ use of mud bricks, where they have inherited this craft from their Nubian ancestors in Aswan, Egypt. The versatility and simplicity of this material held the key to sustainable and practical solutions for providing descent affordable housing. 2

Afterwards, his study was recognized, and then he was commissioned designing the New Gurna village project. Fathy’s work didn’t stop on designing the masterplan, as his passion for the project made him dedicate himself to the peasants’ wellbeing, involving them in the design, ensuring their participation and considering all their social and economic aspects. 3 Although this project failed in its reality, it later became a milestone in Fathy’s Legacy, challenging

3 Wakil, L., & Fathy, H. (2018). Hassan Fathy: An architectural life. The American University in Cairo Press. Pp. 10

conventional aspects of sustainability and proved that vernacular could yet be relevant.

The Nubian Influence

Architectural practices in Nubia, a region spanning southern Egypt and northern Sudan along the Nile River's course, have developed over several centuries into a distinctive and historically significant style. This architectural culture embodies both 4 Schijns, W., Kaper, O. E., & Kila, J. (2008). Vernacular mud brick architecture in the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt and the design of the Dakhleh Oasis Training

practicality and aesthetics influenced by local environmental factors as well as cultural nuances of the area.

The architectural style inherent within Nubian design displays a deep comprehension of exploiting regional resources effectively. In this context, the significance of mud bricks is paramount in Nubian building practices. The craft demonstrated by Nubian builders through their innovative use of these earth elements extends beyond mere wall formation into vaulted ceiling construction thus refuting any prejudiced perspectives regarding constrained usage possibilities for such materials. 4

A particular Nubian impact on Fathy's work pertains to the technique of constructing vaults without elaborate centering. The craftsmanship exhibited by Nubian masons demonstrate their expertise, reflecting a capacity to fabricate resilient and longlasting vaulted edifices without any dependence on complicated wooden structures typically employed in other regions. This innovative approach not only and Archaeological Conservation Centre. Oxford: Oxbow. Pp.12

streamlined the building procedure but also rendered it financially feasible for the working class who could utilize mud bricks - an abundant local resource - to form sturdy and visually appealing roofs.

The parabolic shape observed in the vaults, resonating with bending moment blueprints, illustrated a synchronization with the inherent qualities of mud bricks. The outcome was more than just being functional; it epitomized a balance between shape and utility where the material itself determined architectural organization, and each delineation adhered to the distribution of stresses.

Indeed, Nubian architecture introduced a new yet already existing vocabulary of design constituents that Fathy integrated into his work. Ranging from vaults and domes to pendentives, squinches, and arches; these architectural facets mirrored an affluent cultural heritage. The perpetually and interweaving of curved contours and the symmetrical transition between elements brought forth boundless aesthetic appeal. These architectural shapes were not merely ornamental; rather they evolved as integral

components of the structure itself, proffering a comprehensive and significant blueprint void of any additional adornment. 5

Fundamentally, the impact of Nubian inspiration transcended mere building methodologies; it incorporated a comprehensive perspective on architecture that took into account earth materials, cultural stylistic elements and structural integrity. Fathy's examination of Nubian architectural practices not only tackled present-day issues associated with rural accommodation but also established groundwork for an architectural ideology founded on simplicity, practicality and admiration for the innate elegance intrinsic to native design ideologies.

5 Schijns, W., Kaper, O. E., & Kila, J. (2008). Pp.30

The Two Villages

Located on the site of Noble Tombs in Aswan, and due to the residents’ expansion up to seven thousand peasants, all living around those tombs, were some are discovered by the Department of Antiquities and others not, the peasants economy became closely tied to tomb robbing and trading those found artifacts. 7

The vibrant colors and intricate designs adorning the Nubian architecture, characterized by dried mud bricks and vaulted roofs, are a response to the tribe's history of relocation and flooding, with the use of symbols, religious connotations, and vivid hues serving as a means to create protective and joyous envelopes against perceived evil forces. 6

Figure 3. The Nubian Village in Aswan Source: Archdaily

6 Yakubu, P. (2023). Motifs and Ornamentations: Inspirations Behind the Colors of African Traditional Architecture

The situation culminated, when an entire tomb artifact, constituting of a rock carving disappeared, which forced the Department of Antiquities to harshly address this issue. Their only solution back-then was to evacuate the land of Old Gurna and displace its residents. 8 However, executing their decision was another obstacle. Finding a proper land and designing a whole new village that could house seven thousand peasants with their crafts, possessed financial problems.

At that time Hasan Fathy was starting to get known for his exploration of affordable housing techniques using mud bricks, and thus he impressed the authorities who asked

7 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.8

8 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.8

him to work on this project. Upon his approval, he embarked on a monumental journey: building a new village for the displaced Gournis.

Choosing a site for the new village was carried out by a committee, which included representatives from the Department of Antiquities, Gourna’s Mayor, sheikhs from different hamlets (religious people), and Fathy himself. A plot of land close to the main road and railway was finally selected. 9 Fathy’s passion for vernacular housing techniques, made him fully committed towards improving the living conditions of those villagers whilst preserving their cultural heritage, through innovative and affordable building solutions.

9 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.11

Marked in Red is the Old Gourna, in Green the New Gourna, and in Yellow is where some tribes are now relocated.

5. Gourna Location Map Source: Archdaily

New Gurna Design Ideas

The New Gurna design was solely linked to the social and urban lives of the Gournis.

They constituted originally of five tribes, further organized into small groups called ‘badanas’. 10 Each tribe was allocated in a neighborhood within the newly proposed plan, while still preserving their social structure and customs.

Fathy wanted to engage the villagers in the design process. His strategy included interviewing them on site, and even involving them in the construction process, teaching them bricklaying and roof-building techniques. He also wanted to improve their wellbeing. Skilled masters were enlisted to teach the youner Gournis crafts like weaving

10 Mehrez, Samia. (2016). The literary life of Cairo: One Hundred Years in the heart of the city

Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. Pp.35

and pottery. 11 His vision was to transform the village into arts and crafts’ hub, supplying products to the city dwellers and tourists. He also incorporated existing monuments like the pigeon towers, maziara structures, and mosque designs from the old village into the new plan. The climate of upper Egypt was instrumental in his design decisions. Fathy, addressed the need for temperature control, emphasizing on the importance of materials like mud bricks which have low heat conductivity. However he acknowledged the challenge of retaining heat in these structures. To solve this, he included living unites on the lower floors, sheltered by thick walls, and transitioning to the rooftop during the night. Courtyards functioned as air reservoirs, promoting cooler temperatures during the nighttime. 12

Fathy also acknowledged the imoportance of air movement. He thus incorporated wind catches to ventilate buildings. The orientation of structures was determined by both sun and wind, with specific attention to shading strategies. Additionally, he included

traditional elements like mushrabiyas, providing secluded views for the residents.

Thus, this holistic approach including local traditions, climante response and community adaptability, reflected Fathy's commitment to creating a sustainable and culturally rich environment in New Gourna.

New Gourna Plan

The urban blueprint for New Gourna, shaped by the societal and metropolitan arrangement of Old Gourna, incorporated a vast marketplace functioning as the principal gateway to the community. Guests would traverse across the railway line, step into this market via an entrance portal before continuing through another arched access point on its far side to reach central village spaces. Around this plaza were various public edifices such as mosques, khans, village halls, theatres,and exhibition centres with permanent displays.

Further communal facilities like boys' elementary schools were sited at greater distances from these core areas while craft institutions were tactically positioned in proximity to commercial zones. The design

11 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.31

12 Sibahi, Abdurrahman. (2014). “Hassan Fathy and the New Gourna Experiment.” Medium.

objective was to divide the plan into four distinct sectors each housing one of significant clans

hailing from old gournas tranditions. The narrow lanes leading towards semi-private plazas had been intentionally conceived providing both shade and seclusion.

Dwellings varied in their dimensions based on footprints left by original structures they supplanted. They received individual attention during construction ensuring introduction of variety only when it served a meaningful purpose 13

The Peasant House

A peasant’s livelihood, different from an urban dweller, relies entirely on one or two cows with a piece of land to generate income. In the absence of formal protection mechanisms such as insurance or state assistance programs, any loss in livestock or crop failure could lead to extreme deprivation for the family. This reality reflects prominently within their homes, which need to cater to sizeable food storage needs along with accommodations for animals' sheltering requirements. Chickens often wander unrestricted amongst toddlers playing amidst dust while cows are occasionally observed sharing space inside human dwellings - more reminiscent of animal sheds than conventional households. Fathy thus recognized those challenges and he carefully incorporated their solutions within his design.

The architectural layout of the bedroom is reminiscent of historic Arab homes, featuring a cubed room with a domed ceiling reflecting the concept of ka'a. This design was conceived to be simple enough for replication by any villager across Egypt, even without technical expertise. The structure's resilience against varying weather patterns is ensured through its dome

spanning three meters, vault extending twoand-a-half meters and thickened walls flanking each side of iwans. Positioned in an isolated segment within the courtyard rests a baking oven; typically used every third day due to community preference for efficiency.

Fathy found inspiration from Austrian techniques when looking for efficient heating solutions - he adapted their Kachelofen principle using straightforward materials available locally. He also took into consideration traditional cooking practices at ground level conducted by rural women while designing his kitchen system; aiming to create permanent kitchens that would reduce smoke build-up in family rooms as part these efforts. 14

To address water supply issues, the structures were grouped to enable effective sewage drainage, and water was procured from sizable glass storage vessels placed atop buildings. Fathy took into account alternative mechanisms for fostering social

interactions like reinventing the concept of Turkish baths. The laundry facility's modern design featured a shallow cavity surrounded by brick enclosures where water would be funneled in through pipes connected to rooftop containers. In designing the waste disposal system, Fathy incorporated an innovative flushing mechanism that utilized one pipe with dual discharge points.

Fathy also addressed the challenge of stables for peasants' cattle in the village. He designed stalls with vaults, each accommodating two animals and featuring a manger. The resulting plan created a cohesive yet culturally sensitive village.

In his consideration of peasants and the research behind mud bricks, Fathy addressed both the social and technical facets of the project. However, a major question arises:

What led to the perceived failure of his project, and what enduring lessons we can learn from it that still make it relevant?

14 Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press. pp.48

The drawings show the wind movement inside the complexes

8. New Gourna drawings by Hasan Fathy

Source: Atlas

The Village Legacy Despite Failure

Hasan Fathy’s New Gourna project faced significant challenges leading to its perceived failure, mainly attributed to the local inhabitants' reluctance to cooperate.

The Gourni’s resisted Fathy's vision, attributing that to his use of domes in housing, where they associated it with funerary architecture. They also shared their need for larger, modern houses due to family expansions. The other failure was technical. The mudbrick in Gurna contained salt, something Fathy did not know, which made them subject to humidity. The village thus experienced collapses, structural damage, and deteriorating living conditions. Key structures like the Mosque, Khan, Theater, and Crafts Center faced various issues, from closure to repurposing, reflecting the project's struggles. 15

Regarding the question of whether the project failed, a nuanced perspective is essential. While New Gourna faced challenges and criticisms during its implementation, its enduring legacy and impact on architectural discourse argue against a simplistic notion of failure.

Instead, the project can be seen as a precursor to contemporary discussions on sustainable architecture and socially responsible design.

Globally, the construction industry contributes to approximately 8% of the world's carbon dioxide emissions. The considerable number is mainly due to the widespread application of construction materials, mainly concrete and steel. Consequently, this practice leads to resource depletion, global warming, and an overall decline in environmental quality. The impact of these constructions extends beyond environmental concerns and affects both human health and the architectural landscape.

Moreover, many modern buildings and constructions share a generic design, devoid of any unique characteristics that reflect the local environment. Whether influenced by industrialization or driven by a fast-paced market, this approach has eroded the sense of identity and belonging in our surroundings.

15 Senses Atlas. (2020).

In contrast, Hasan Fathy's architectural approach stands out. Rather than merely replicating past vernacular architecture, or modern architecture of his era, Fathy drew inspiration from vernacular to improve the living conditions of the local population. He actively involved the community in the design process, ensuring that structures were tailored to meet their specific needs. As contemporary concerns increasingly center around sustainability, studying Fathy's architecture underscores the relevance of the saying "old is gold." Despite their limited resources, vernacular architectures demonstrated innovative solutions that resonate with today's emphasis on environmental conservation and resource efficiency.

If Hasan Fathy's project had been taken more seriously and if architects of that era had acknowledged the pressing social and environmental issues, we might be living in a cleaner and more ecologically responsible world today. Fathy's forward-thinking approach serves as a reminder of the potential consequences of neglecting sustainability and the importance of integrating such considerations into architectural practices for a more harmonious relationship between built environments and nature.

Conclusion

My exploration into Hasan Fathy's intellectual realm via this essay has significantly heightened my esteem for his pioneering concepts. His book, "The Architecture of the Poor", reveals a story that transcends mere architectural constructs and ventures into areas promoting cultural conservation as well as community-focused design ethos. Fathy’s foresight discerned an impending necessity for ecologically considerate approaches long before they became recognized, thereby providing invaluable perspectives on how vernacular architecture could be harnessed to meet contemporary sustainability constraints.

Not only is New Gourna's architectural relevance notable, but its social implications are also equally pivotal. Fathy's blueprint stemmed from an in-depth recognition of communal necessities, safeguarding cultural legacy while offering a practical habitat.

Even though the initiative did not entirely succeed in achieving its initial objectives, it has however left an enduring imprint and acted as a determining force within modern architectural discussions - demonstrating success of another kind. Anchored on Fathy's core values including efficacy, practicality, along with deep ties to people

and their surrounding environment; this venture provides multi-dimensional insights. The pioneering attitude of Fathy continues to shape later architectural concepts by instilling prioritization towards sustainability measures alongside cultural awareness and active participation from communities.

In summary, Hassan Fathy's commitment to tackling housing difficulties in developing countries makes him an invaluable figure for those participating in rural advancement initiatives. His objective was to cultivate a native habitat at the least expense possible, resulting in improved economic status and quality of life within vernacular poor communities. Utilizing traditional design techniques and materials permitted him to integrate his profound knowledge of Egypt's agrarian economy with a wide comprehension of historic architectural practices.

Fathy enabled local inhabitants not only to manufacture their building materials but also construct their homes themselves. In making design choices, he took into account factors such as climate conditions, public health considerations along with conventional artisan skills. Hence, Hasan Fathy’s

progressive methodology helps emphasize that had there been early recognition towards sustainability issues concerning architecture could have conceivably led us toward creating built environments which are more environmentally respectful whilst being sensitive towards cultural norms.

The image shows that although economically cheap and the project wasn’t approached by an esthetic and design approach, social aspects can create inspiring architecture

Source:

References

Bertini, V. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.bdonline.co.uk/briefing/reappraising-hassanfathy-the-forgotten-modernist/5096731.article

Fathy, H. (1976). Architecture for the poor: An experiment in rural Egypt. University of Chicago Press.

Mehrez, S. (2016). The literary life of Cairo: One Hundred Years in the heart of the city. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Richards, J. M., Serageldin, I., Rastorfer, D, & Fathy, H. (1985). Hassan Fathy. Singapore: Concept Media u.a.

Schijns, W., Kaper, O. E., & Kila, J. (2008). Vernacular mud brick architecture in the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt and the design of the Dakhleh Oasis Training and Archaeological Conservation Centre. Oxford: Oxbow.

Sibahi, A. (2014). Hassan Fathy and the new Gourna experiment. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@asibahi/hassan-fathy-and-the-new-gourna-experiment5cbd0b286d2a

Wakil, L. el, & Fathy, H. (2018). Hassan Fathy: An architectural life. The American University in Cairo Press.