The Evolution of Beirut Souks

From Tradition to Consumerism

Urban Form

Housing and Urbanism, M.A.

Architectural Association, School of Architecture

March 25, 2024

I. Abstract II. Introduction: Beirut: History, Civil War, Solidaire

III. Solidaire Competition Brief and Project Entries

V. The transition from a Market to a Mall

VI. Conclusion VII. References

Abstract

By analyzing the changes in the Beirut Souks over time, from an old market to a modern commercial area, it is evident that these transformations are influenced by a wider phenomenon like globalization and urbanization. The traditional souks used to be divided into distinct sections such as a gold and spices market. In contrast, today's modern souks, which form a shopping center, have been redesigned, and each section distinctively represents the most profitable and well-known shops.

Reconstructing Beirut Souks with a ‘mix of modern elements and historic touches’ by the same company restoring Beirut –publicly launched with an open international competition in 1994 – envisioned a navigable series of stalls and passages that fitted traditional forms to contemporary retail. In total, this competition garnered more than 300 entries that diverged widely; however the jury did not declare a clear winner. Instead, the masterplan was drawn by the Lebanese architect Jad Tabet. He in turn commissioned the individual pods that filled it to individual architects. Thus, Moneo reconstructed the southern souk. Though ‘restorers’ tried to replicate the physical layout and forms of the old souks with modern techniques, the familial and communal links that permeated them shriveled as globalized supply chains and branded retail channels rolled deep into the Middle East and elsewhere. They transformed construction practices and the ways that people interacted in

them: they made the souks bigger, more commercial and more cosmopolitan, looking less like the product of local history and more like a giant shopping mall.

This essay looks at the socio-cultural consequences of this transition, analyzing Solidere’s effort to reconstruct Beirut in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War. Two main points are considered: the architectural project of Rafael Moneo and the historical background of the souks in order to understand the impact that the urban redevelopment carried for the cultural identity of Beirut.

Introduction: Beirut: History, Civil War, Solidaire

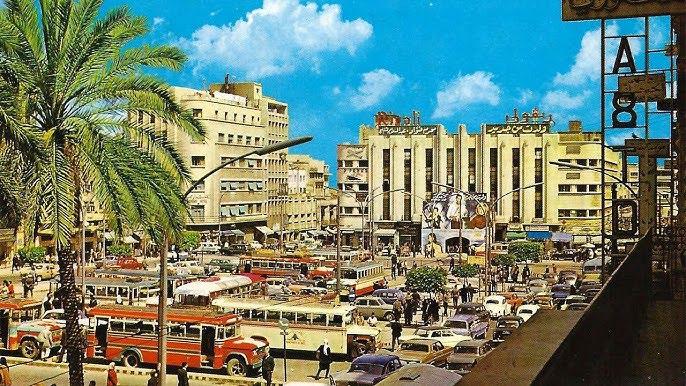

–What is this city? (Figure 1)

I looked up at him.

–What city, Elie?

–This one Mom!

He pointed to a photograph album that he had taken from the drawer.

–That’s Beirut, Elie!

–Beirut?!

He gasped surprisingly:

–We live in Beirut. I’ve never seen these streets and buildings in my life!

I smiled. He was born after the war. I didn’t know how to explain to him that this was ‘Beirut.’ 1

In 1975, the civil war in Lebanon started. It was a complex conflict driven by political parties, militias, and foreign powers, each with their own ‘agendas’. The war lasted for 15 years, and it resulted in significant loss of life, displacement of populations, and extensive damage to infrastructure. The center of Beirut was a core area for militia fighting, as there was a ‘green line’ that split Beirut’s west from its east.

After the war ended in 1982, and in an attempt to ‘reconstruct’ the city center, a private company called ‘Solidare’ was initiated by the Lebanese Prime Minister at that time, Rafic Al Hariri. A series of laws were passed, and others were issued that allowed them to work freely. 2

The souks (markets) of the city center persisted through the civil war. Indeed, the demolition of the souks started in 1982, and lasted to 1992, as part of the reconstruction plan. The story of ‘Elie and his mom’ is merely the opposite of what Solidare was promoting. It promised to preserve the cultural identity where indeed it cleared the old city and prepared it to be built with new standards clear from its traditional impurities.

These souks which were easily ‘wiped off’, had a major historic and cultural significance to the Lebanese (originally the Phoenicians). The oldest souk was ‘Souk Ayyas’ (figure 2) which had traditional architecture and featured Antabli fountain. ‘Souk al Jamil’ (Jamil means elegant in Arabic) (figure 4) featured well-

1 "Merip," Saree Makdisi, accessed March 24, 2024, https://merip.org/1997/06/reconstructing-history-in-central

2 Hadi Makarem, "Downtown Beirut between Amnesia and Nostalgia," LSE (2012), https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2012/10/17/downtownbeirut-between-amnesia-and-nostalgia

ordered retail shops. Souk al Sagha was a jewelry market, and others. 3

After the clearing of the site finished in 1994, a competition to rebuild the souks was organized by Solidaire. This completion was very important at that time as it was an open competition to redesign a city center. The competition had more than 300 international and local entries, from famous architects like Stan Allen, Aldo Rossi, and Zaha Hadid. However, the competition did not yield a clear winner, and after the competition the souk project was commissioned to Jad Tabet, followed by the subsequent commissioning of different parcels to individual architects including Rafael Moneo. The souk by Moneo was completed in 2009, and he described it as ‘not being a building but a living premise within the city that will revive Beirut’ 4

Yet, the question that arises is this: despite Moneo's sensitive approach to culture and context, why do the ‘Beirutis’ not feel like they belong to that place? Was Moneo's design truly able to revive the life and spirit of the souk, or did it merely transform it into a shopping mall shaped by market forces, real estate interests, and political agendas?

2. Souk Ayyas, c. 1982.

3 Elie Haddad “Projects for a competition: reconstructing the souks of Beirut (1994),” (2014) Urban Design International, 9, 153.

4 "B Beirut Souks," Rafael Moneo, accessed March 24, 2024, https://rafaelmoneo.com/en/projects/souks-in-beirut.

Solidaire Competition Brief and Project Entries

Solidere’s competition brief called on entrants to re-conceive the souks in terms of modern needs, while also respecting their historical importance. To underline this, the competition kit contained images of the pre-war souks and memories from old residents.

However, an important structural challenge stemmed from the need to accommodate new functions (a large underground parking lot, in particular) that compelled architects to substantially change the old street patterns. This, added to the guidelines for a department store, a two- and four-cinema complex, and the retention and preservation of the Majidiyeh Mosque (c1467) and the Ibn-Iraq mausoleum (c1187), as well as suggestions to retain the façades of buildings along the eastern edge and even to reconstruct the KhanAntoun Bey caravanserai (18th cent), had to contend with numerous contradictions. 5 Design-wise, the submitted projects ranged from the typological, to the dynamic, to the dialectic, to the orientalism to the grid layout approach.

For example, the scheme by Aldo Rossi (figure 5), which won a citation, made an explicit proposal to keep the old street pattern intact while providing new landmarks, the ‘ziggurat’, which relates to the buildings around it, like the mosque, in a reassuring yet different way, as an ‘object’. Further, Rossi pushed the boundaries beyond its historic shell and expanded the project into the new landfill area by establishing a network of piers extending into the water.

In contrast, Zaha Hadid’s scheme (figure 6) was pure ‘Hadid’, with her trademark flowing dynamic lines translated as horizontal strips running along the north-south axis. It is approached here as in all her other projects, with no direct reference to context, except in the northern bit of the site where more traditional buildings house the department store, and

here, by virtue of its linearity, dominant spatial arrangements start to get interesting.

The proposal by Stan Allen (figure 7) is the most intricate and interesting manifestation of a fuzzy boundary between the organic and the mechanical. Rather than a ‘classical conception of the city as a whole’, Allen instead offers ‘a system of operations’, where the ‘notion of place’ itself is called into question, with further dilutions of the basic distinction between physical and conceptual space.

Meanwhile, in another suite of entries, the historical dialectic found itself at the heart of the project, as it opened to future epochs in projections and juxtapositions. This is how Maurice Bonfils’ (Lebanese local) (figure 8) project developed a horizontal roof not so much as a space of identity, but a layered overlay on the public space above the horizontal mosaic of

5 Elie Haddad “Projects for a competition: reconstructing the souks of Beirut (1994),” (2014) Urban Design International, 9, 153.

elements that were assembled below. There, the dialogue opened a conversation between two fields of temporality: the minaret as a landmark from the past, asserting itself through the simple prism of nonconformity in the dominant space of the horizontal scale, and as a strong symbol of the continuous tie with the past amid the context of present times.

Several others similar to Le Corbusier’s proposal for Venice Hospital, were clearly proposing a grid system on an irregular site. Jean Paul Viguier proposed a ‘system of solids and voids’, that initially recalled a horizontal version of the oriental musharabiyah (the intricate screened window) which resulted in a play of light and shadows (figure 9). The enclosure formed by this means recreated more systematically the sensual effects of the setting of the more traditional market-places.

Furthermore, another entries could be defined by orientalism as the proposal of Mimar Group’s (figure 10) which tried to recreate domes, vaults and arches.

However, the competition did not yield a clear winner 6, indeed the master plan was commissioned to the Lebanese architect, Jad Tabet (the overall master plan was reviewed by the noted international design firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill). In this phase, an international team of designers under contract

developed sub-projects within the final master plan. The team included the international architects Rafael Moneo, Kevin Dash, Zaha Hadid and the French architect Olivier Vidal. The general program of works had four main components: a multiplex cinema, a department store, commercial spaces, and a large parking facility underground. Specifically, the restoration of historic monuments such as the Majidiyeh Mosque and the IbnIraq mausoleum was included as part of the overall scheme, along with a series of squares and public spaces. The aim was to blend modern infrastructure with the preservation of Lebanon’s architecture and history.

The rebuilding of the Souks had been a matter of dispute. The Lebanese architect, and the Dean of School of Architecture and Design at the Lebanese American University, Elie Haddad saw the Souks as belonging to an increasingly homogeneous territory of discrete, pan-Arab grid-yards, stitched together by an increasingly dominant real-estate logic of capture, production and conversion 7 . His perspective suggests that the reconstruction may have prioritized commercial concerns over the preservation of the unique character and authenticity of the original souks, potentially leading to a loss of cultural richness and depth in favor of commercial expediency.

6 Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere Critical Inquiry,” 1997 Critical Inquiry, 23 (3) Front Lines/Border Post (Spring), 680

7 7 Elie Haddad “Projects for a competition: reconstructing the souks of Beirut (1994),” (2014) Urban Design International, 9, 153.

Rafael Moneo’s Project for the Reconstruction of the South Souk

The New Beirut Souks project occupies a significant portion of land that has undergone a complete transformation, erasing its former fabric. Rafael Moneo, selected via an international competition to design Solidere’s new souks (Daniel Libeskind had served as a consultant), was commissioned the reconstruction of the southern side of the souk. 8 He viewed the vast emptiness as both a challenge and an opportunity for rapid development. For many Beirutis, however, the erasure of their historic downtown by Solidaire was more scaring than the war itself. In their eyes, Solidere’s work amounted to the systematic wiping out of historic Downtown.

Moneo's architectural approach aimed to blend the traditional character of a souk with contemporary retail settings, all within the city's new financial and commercial hub. This meant that pre-existing street patterns largely (though not wholly) determined the road layout of the new district, with most of the souks fully maintaining their earlier volumes and roles. The streets of the old souks provided the axes of the new souks, being recreated both in terms of the size of the programmatic element and in terms of the function performed. His intention was that the new souks, while aspiring to link with their context through the alignment of the roads, also reinterpreted function and form, in Moneo’s view of what ‘good’ contextual architecture would be. In this, as he wrote: ‘If the intention had not been to reconstruct anything but to do something which could be … seen like something inserted and inserted well within that schema [of the city]. It can’t be a reconstruction of something, but of something that is a volumetry that wraps itself within something else and integrates well with tradition and modernity. It is not a building but a premise that lives within the city’ 9

The new souk thus extended as a series of interlaid buildings, streets, and squares aiming for a certain permeability and openness. All accesses are from the outside. There are nine major and six minor sections organized along an open north-south axis. More than 150 retail units occupy the complex that includes the Jewellery Souk, a complex system of pavilions spread over two floors. All retail outlets are upmarket as the clientele is ‘high end’. However, it would be superficial to dismiss this as simply another transition to the ‘shopping mall’.

8 9"Beirut Souks," Rafael Moneo, accessed March 24, 2024, https://rafaelmoneo.com/en/projects/souks-in-beirut.

The transition from a Market to a Mall

Despite the urbanistic attempt to replicate the contextual architecture and create a ‘traditional’ fabric to connect the new buildings with the memory of the city, it could be argued that the conceptualization of the Souks comes at a considerable cost, casting heavy doubt on their ability to authentically reconstruct a sense of Beirut’s history and character.

In Moneo’s efforts to salvage history, memory and authenticity through the preservation of the physical layout and design, he kind of assumed that these elements in the reconstruction of the site ‘alone’ can uphold that.

Indeed, rebuilding based on a nostalgic image of form, is not sufficient if the aim is to create urban artifacts and foster a forward-looking new, transformative reality of the city. Beyond the physical structure of the Souks, and understanding how that structure produced its specific operational dynamics including maintaining a certain character conferred to the Old souks, what matters more is a deep understanding of the operative functions of those structures.

The old souks were a result of the historical formation of Beirut’s ancient core as a port-city, and them maintaining their role as a marketplace where the mercantile population traded goods –first local and then imported – over centuries. Central to this trade was ‘familiality’, as particular trades were acquired (through inheritance) by particular families. Trades were

therefore diverse and the idea of ‘familiality’ was central to the way the souks formed their unique character representing the city. In the new souks, this familial aspect is missing, replaced with international and corporate brands that do not confer any individuality, character or local particularity. The new souks are not different from any other commercial area of the city, or any other city.

Furthermore, changes in the relationship between buyers and sellers highlight the shift from traditional souks to modern globalized retail arrangements. In traditional souks, the owner often acts as not only the producer and the importer but the trader and the main point of contact. In the new souks, retail now follows a globalized structure in which the buyer and merchant are increasingly decoupled through multiple intermediaries disrupting the traditional chain of transactions from production to sales.

The second is the larger scale of the new shops, more akin to a shopping mall than to its predecessor. Though the souk’s ancient volumes are preserved, key souks such as al-Tawileh, alJamil and al-Arwam have larger shops that conform to modern retail standards. Programmatically and organizationally, too, the new souks are akin to shopping malls: they accommodate the souk within the demands of a modern retail sphere (larger shops, department stores, supermarkets) and the accessibility of a modern car-centered city. Moneo himself speaks openly of

these inspirations, describing one of the main souk streets as ‘organized along the model of modern malls’, with ‘two big anchors’ – a supermarket and a store on the south end of the souk, and a department store on the north end. Therefore, the rebuilding of the Beirut Souks in the era of globalization appeared to have lost an identifiable cultural reference, nurturing rather consumerism.

Conclusion

An occupational guild provided the people with their means of livelihood, and likewise their cultural identity, bound up with shared traditions and authorities. Considering factors such as these, it is difficult to see how the transformation of the Beirut Souks, from a local, self-sufficient market to a modern hyper commercial complex, does anything other than undermine something of significant cultural value in Beirut.

Aside from their role as a marketplace, the Beirut Souks were central to many Beirutis’ understanding of the city’s sense of identity and character. Yet, Solidere’s reconstruction, though aiming to restore the dynamism of the city center after decades of trauma and war, has eroded the very features that made the souks special. While Rafael Moneo’s respect for culture and context came through in his design, it didn’t restore to them the pulsating heart that made the old souks unique. They became mere tools for commercial and urban development.

The shift from a souk to a shopping mall echoed broader processes of globalization, by which the cities of the world are being standardized through generic retail spaces and corporate commercial developments. The transition also meant the (partial) loss of Beirut’s distinctive character, and the entrenchment of a consumerist mindset that would perpetuate a profit-driven approach to the city’s historic heritage. Even more graphically, the new layout of bigger, more open-plan souks testified to urban space itself being commodified in the globalizing city.

Hence, while the architectural nod to tradition may be present in the form of preserved facades and street layouts, the underlying ethos of consumerism prevails, overshadowing any semblance of cultural heritage. The reconstruction plan of Solidaire, didn’t only relocate the Beirutis, it had also created a new ground that only fits with consumerist standards, devoid of any Beiruti’ traditions.

References

Beyhum, N. (1991) Reconstruire Beyrouth: Les Paris sur le Possible. Lyon: Maison de l'Orient.

Beyhum, N., Tabet, J.-and Salam, A. et al. (1991) I'mar Bayrout wal Fursa al Daiah (The Reconstruction of Beirut and the Lost Opportunity). Beirut: Maison de l'Orient.

Haddad, Elie. " Projects for a competition: reconstructing the souks of Beirut (1994)." (2014) Urban Design International, 9, 151-170.

Makarem, Hadi. "Downtown Beirut between Amnesia and Nostalgia," LSE (2012), https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2012/10/17/downtown-beirutbetween-amnesia-and-nostalgia

Makdisi, Saree. "Merip." Accessed March 24, 2024. https://merip.org/1997/06/reconstructing-history-in-central

Moneo, Rafael. "Beirut Souks." Accessed March 24, 2024. https://rafaelmoneo.com/en/projects/souks-in-beirut.

Moneo, Rafael (1998) in Rowe, P. and Sarkis, H. (eds.) Projecting Beirut, Episodes in the Construction and Reconstruction of a Modern City. NY: Prestel.