The Urban Grid

The urban block is the crossroad of architecture, urban design and master planning. It embodies adaptability and resilience which is today becoming one of the core pillars of city development. In a city plan, the urban block becomes a semi-private entity that emerges and informs the shape and character of the surrounding urban spaces. Consequently, the relationship between private and public realms becomes crucial for the future of urbanism; it is through the design of the urban block that the relationship between private and public is established as they become key elements for the organisation of civic and social life. 4They offer a platform for design creativity at a high level without excess individualism, as Rem Koolhaas wrote in Delirious New York. 5

Urban blocks can be identified and studied as the very ‘products’ of grid subdivision and accommodation. For a long time, the grid has been seen as a spatial mechanism through which land had been appropriated – first through subdivision and then through tabulation 6. From prehistoric changes - from round to rectangular house structures - comes a revolutionary change mirrored in the practice of dividing space using straight lines 7 This transition, as archaeologist Mario Liverani suggests, was driven by the imperative of quantifying economic transactions and assigning concrete value to commodities, labor, time, and land.

4 Christopher M, Pizzi, “Dimensions of Urbanism: Urban Blocks,” Academy of Art University, June 24, 2022, https://www.acsa-arch.org/proceedings-index/, 1.

5 Eamonn Canniffe, “Rem Koolhaas: Delirious New York : A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (1978),” architectureandurbanism, January 1, 2010, https://architectureandurbanism.blogspot.com/2012/02/rem-koolhaasdelirious-new-york1978.html#:~:text=’%20What%20the%20five%20different%20’blocks,glorified%20Manhattan%20in%20order%20 for.

6 Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Appropriation, Subdivision, Abstraction,” JSTOR, 2018, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26588516.

7 Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson, “A Theoretical Approach to the Study of House Form,” For theory building in archaeology, April 22, 2014, https://www.academia.edu/821517/A_theoretical_approach_to_the_study_of_house_form.

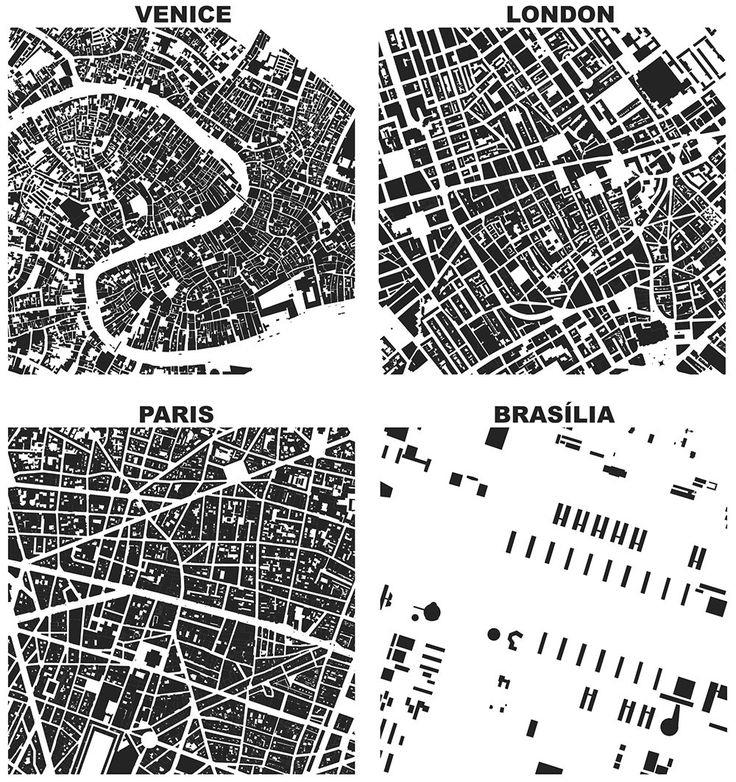

In the context of urbanization, the grid took on a new symbolic meaning in industrialising cities of the 19th century, where the grid became a significant symbol of uncontrolled urban expansion 8 . Since medieval cities had been built on the land available to them inside the city walls, the rapid growth in the population led to severe housing shortages, which were solved by an extension of city sprawl, beyond the original city walls. As cities swelled during the industrial revolution, they faced problems of poor sanitation, inadequate water supply, pollution from industry, a rise in diseases and a further entrenchment of poverty. To handle filling and rehousing the population, planners turned again to gridiron planning 9 (figure 1) This rational approach and the need for efficient solutions, led to the creation of regular, strictly organized cities with almost equal blocks 10 .

In City Planning according to Artistic Principles (1889), Camillo Sitte placed the city plan as a comprehensive work of art reflecting the community aspirations. Sitte in his book emphasized the role of the planner as the artist shaping the urban landscape. Yet this vision was challenged by the statistically organised city planning dominated by survey and zoning practices. Jane Jacobs later criticized both approaches to urban planning as they failed to engage with the realities of the urban life. She rejected the notion of the city as being a work of art and a result of surveys, arguing that planning is ‘artificial’ 11 .

This clash between ‘living processes’ (ie, organic growth) and ‘static systems’ (ie, planning systems) has long been criticized. Christopher Alexander posed the question: does a

8 Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Appropriation, Subdivision, Abstraction,” JSTOR, 2018, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26588516.

9 Maria Oikonomou, “The Transformation of the Urban Block in the European City,” Academia, January 15, 2018, https://www.academia.edu/10797196/The_transformation_of_the_urban_block_in_the_European_City.

10 Spiro Kostof, The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings through History (Boston: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 20.

11 Leslie Martin, “The Grid as Generator,” wordpress, 1972, https://lsproject2009.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/thegrid-as-generator- -urban-design-reade-feb-2007.pdf.

city possess a sense of the living, and is it a natural phenomenon of organic growth, or an artificial phenomenon with no life of its own? 12 Thus, his main argument is that the urban activities can’t be regulated by a single plan. Indeed this can overlook the potential for organic interactions and synergies.

Figure 1. Grid layout among different cities Retrieved from Geoff Boeing

12 Christopher Alexander, A City Is Not a Tree (New York: Architectural forum, 1965).

London’s Urban Planning Approach

Turning our focus to London, it becomes evident that the city grapples with its own set of urban challenges. The population in London was estimated at around 7 million in 1981, today it is around 9 million, and predicted to reach 15 million in 2035 13. This increased urban growth creates a pressing issue for housing affordability and availability. The urban grid was a solution to accommodate this increasing urban sprawl and the perimeter block has been favored due to its ability to maximize land use. The block becomes a result of connecting streets , with the block boundaries created by the buildings themselves.

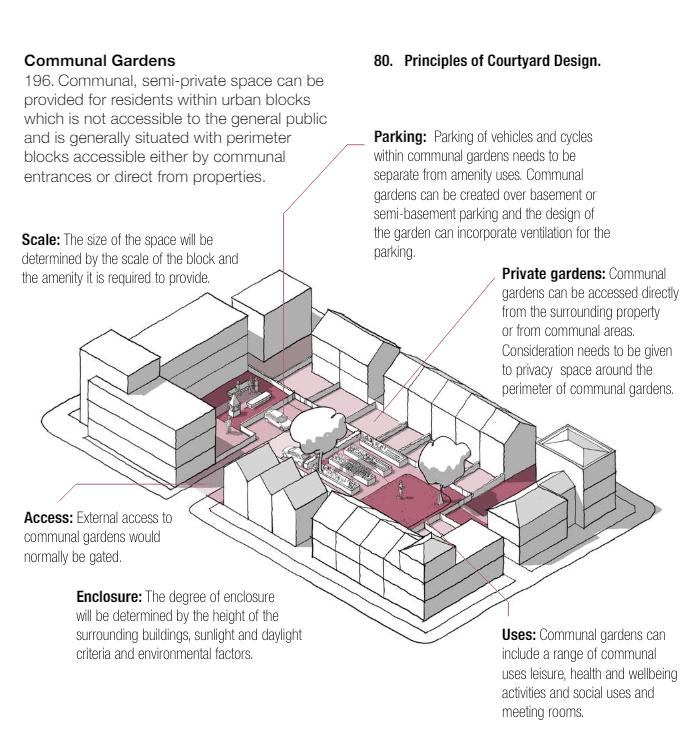

The London Plan 14, a strategic document that outlines the city’s development strategy, emphasizes the importance of block structures from a legal point of view. It claims that these blocks are integral elements to achieve a sustainable development and ensure efficient land use, in addition to creating inclusive communities. According to the plan, this approach in planning is crucial as it creates ‘active frontages’ that bound up the streets and public spaces, making them more safe and inclusive (figure 2).

13 Super Density - Greater London Authority, accessed April 20, 2024, https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/rep-82-100001a_referred_to_in_matter_4_statement_superdensity_2015_download.pdf, 6.

14 “The London Plan 2021,” London City Hall, June 27, 2023, https://www.london.gov.uk/programmesstrategies/planning/london-plan/new-london-plan/london-plan-2021.

Figure 2. Design codes proposed by the London Plan Retrieved from Geoff Boeing

According to Allies and Morrison – one of the major urban planners in London – the perimeter block is a fundamental organising principle in the design of the residential components within the masterplan: it corresponds to the outer edge of a city block, clustering development along its frontages. They claim that one important consequence of this design choice is in the way it structures the relationship between privately owned plots, streets and public space. Moreover, the courtyard in a perimeter block will usually be left open to allow for sufficient sunlight to all parts

of the building. This area can be used for many different purposes: gardens or yards, but depending on the nature of the block these could be private or public, owned by individuals or a large collective of landlords. The perimeter block typology therefore enforces a continual separation between private, communal and public spheres in the city. Each side of the block should adapt to the adjacent street or space. Moreover, same standard urban grid can be used to accommodate different building uses, without necessarly resorting to tall buildings, as Leslie Martin notes in his 1972 essay on land use 15

But can we experience this sense of neighborhood in London as Allies and Morrison and other urbanists / developers are claiming?

I would argue that what it is producing is for sure the opposite. This approach to urbanism, carries certain costs: it can produce indeterminate, confusing street grids that fail to provide both legibility and variety. The final outcome is a neutral masterplan lacking any hierarchy, and this neutrality is a choice. These issues raise major questions: how flexibile are the streets in our city? And how could a street become an armature for event?

In ‘The Death and Life of the Great American Cities’ 16, Jane Jacobs advocated for more open and permeable mixed environments, where strangers, inhabitants and passers by would have a sense of ‘eyes on the street’. So, does placing housing on street levels, create successful streets? The problem is that those streets lack a ‘clear purpose’ opposite to what Haussman created in Paris, as Colin Rowe 17 would argue (figure 3).

15 Paul Eaton, “The Residential Perimeter Block: Principles, Problems and Particularities,” Allies and Morrison, accessed April 20, 2024, https://www.alliesandmorrison.com/research/the-residential-perimeter-block-principlesproblems-and-particularities.

16 Jane Jacobs and Jason Epstein, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York, NY: Modern Libray, 2011).

17 Colin Rowe, Fred Koetter, and Kenneth Hylton, Collage City (Gollion Suisse: Infolio, 2005).

from the Internet

Figure 3. Haussman’s plan for Paris Retrieved

In "Event Cities," Bernard Tschumi challenged conventional notions of architecture by emphasizing the integral relationship between space and event, arguing that architecture must not only consider physical form but also accommodate the activities and movements of its inhabitants 18 . He also stated in the Manhattan Transcripts the following: “I would like people in general, and not only architects, to understand that architecture is not only what it looks like, but also what happens in it”. 19

Both Bernard Tschumi's perspective on architecture and the Haussmann plan for urban redevelopment in Paris emphasize the importance of considering events and streets in architectural design and urban planning. In the context of the Haussmann plan, the arrangement of blocks was intricately influenced by the surrounding streets, adapting to their position and hierarchy within the city 20 . Haussmann's plan aimed to create a cohesive urban fabric aligned with the hierarchical structure of Paris's streets, demonstrating a strategic approach to urban planning and establishing a sense of order and continuity throughout Paris.

Perimeter blocks in London, created static streets, they were a result of block arrangments, opposite to Haussman’s plan. The streets became a tool for every institution to have its own identity and character, so this is indeed a creation of a ‘private-active frontage’. For the streets to become an armature for event, they need to have a common purpose rooted in collective decision making.

On the other hand, the renovation of the Third Street Promenade in Los Angeles, transformed it from a block street relationship lacking any sense of identity, into a pedestrian, car free street

18 Bernard Tschumi, Event Cities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000).

19 Bernard Tschumi, The Manhattan Transcripts (London: Academy Editions, 1981).

20 Philippe Panerai et al., Urban Forms: Death and Life of the Urban Block (Oxford England: Architectural Press, 2004).

having a sense of sequence and continuity and thus becoming a landmark 21. We can then capture a sense of collectiveness, where everyone is participating, having a sense of purpose, where there is a relationship between the form and the activity, creating an urban armature between the street, the buildings and the mall facing it.

Coming back to London, we see that the current housing paradigms are too prescriptive and restrictive, promoting a limited set of solutions (notably the perimeter block) in response to the changing demographics of the city. The appeal of trying to integrate a much more varied range of uses that would better accommodate community living demands, may question the perimeter block approach, especially given the complex and challenging nature of many of the UK’s urban settings.

The reimagination of Tottenham Hale (figure 4), by Allies and Morrison demonstrates the increasing emphasis of densification around transportation nodes. On closer inspection, however, it is also very apparent that there was a dominant emphasis on housing and retail as the main uses. This was not necessarily the outcome of a collaborative participatory process, but rather reflected the strategic interests of property developers to steer those processes in particular ways that met their needs. Moreover, typologically speaking, the workspaces exhibit a corporate character, lacking the flexibility and adaptability required to cater the dynamic character of the emerging industries.

21 Lawrence Barth, Event, Critical Urbanism Lecture (February 4, 2024).

Figure 4. Reimagination of Tottenham Hale Retrieved from the Allies and Morrison

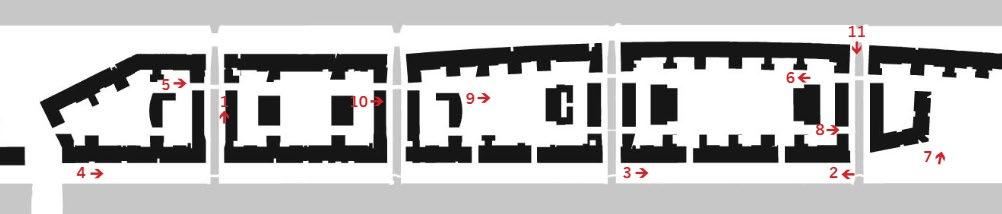

A similar approach can be seen in the renovation of the southern edge of Blackhorse Lane (figure 5). The site had an industrial heritage, however the masterplan was driven by a perimeter block approach. This approach disregarded its industrial character, and created housing environments that are inward looking, lacking any sense of community engagement. The streets are identical and rational, lacking any clear differentiation and hierarchy. There is no place that we can call a collective plaza, and no place that has a secondary relationship to a place that has a primary sense of grouping.

Through reliance on these standard planning models (figure 6), urbanists often miss the opportunity of innovative typologies which mix living and working, leading to vibrant inclusion, and not units, separated spatially and institutionalized into monotypes.

So, what if we relax the idea that everything should be street-based and we diversified the immediate associations with the buildings that we are going to deploy so that they can create courtyards, patios, plazas, alleyways and we start to give a sense of purpose to each of these things, where there is a conceivable chosen relationship amongst the actors in those locations?

Figure 5. Planning of the southern edge of Blackhorse Lane Diagram by the author

Figure 6. The urban grid along Blackhorse Lane Diagram by the author

Amsterdam Revisited

Good housing design should have a variety of scales, dealing with the building scale, the street, the neighborhood, and the individual. However, housing models in the UK, and specifically in London are too restrictive, based on a single solution – as discussed previously –the perimeter block. This model can’t accommodate to the changing needs of the growing population or to the changing ways of space accommodation 22 .

Looking into other approaches to block typologies, one can see how the European models, through their varied approaches emphasize on diversity and adaptability. Rather than placing housing on their ground floors, they diversify the functions and create different spaces and amenities, so instead to advocating for ‘active frontages’ they activate their ground floors enhancing living and working across all levels, and making the streets function as event armatures.

The buildings created by the perimeter block have to address from one side a street and another side a courtyard. Often, those courtyards are closed off. However, European models have a greater emphasize on providing communal outdoor spaces, moving away from the rigid approach. This dynamic design process will enhance the living and working environments at all scales, thus increasing the benefits of the locals, and makes the block, street and building work together as a whole entity, instead of putting clear boundaries between what is public and what is private.

In the Netherlands, the provision for housing lies mostly in the hands of the state, opposite to the case in the UK, where around 80% of the housing delivery lies in the hand of

22 Jonathan Woodroffe, “We Have a Lot to Learn from European Housing Design,” Building Design, March 1, 2023, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/we-have-a-lot-to-learn-from-european-housing-design/5121741.article.

developers 23. As a result, a great emphasize will be placed on the quality of living provided by and within these projects.

The Eastern Harbour District of Amsterdam which was built in 1900, was reclaimed for housing, and divided into 3 parts: KNSM Island, Java Island, and Borneo Spoorenburg 24 (figure 7).

Figure 7. The Eastern Harbour District of Amsterdam Retrieved from Amsterdam Arquitectura

Starting with Java Island (figure 8), this narrow peninsula underwent a significant transformation under the visionary plan by architect Sjoerd Soeters. The metaphoric concept of

23 Jonathan Woodroffe, “We Have a Lot to Learn from European Housing Design,” Building Design, March 1, 2023, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/we-have-a-lot-to-learn-from-european-housing-design/5121741.article.

24 Sjoerd Soeters, Java island Amsterdam Harbour Renovation, accessed April 22, 2024, https://pphp.nl/wpcontent/uploads/2017/05/JAVA-ISLAND.pdf.

the ‘ocean liner’ 25 proposed by the city planning department, was a main driver in the master plan. This concept envisioned a linear building type with multiple decks and amenities creating an extra layer of social dynamics. The architects here addressed also the issue of creating big, endless horizontal galleries (one of the problems of housing in London). These galleries, which are open to everybody, and when we have tens of them in a housing project, they don’t have any purpose other than leading people to their units. Thus, the elevator becomes the only meeting area, however, with this much of residents, it becomes hard to get to know people there. Thus, in sprawling, horizontally oriented developments, residents often will have a sense of anonymity and isolation. Thus, Soeters here proposed a vertical arrangement of units, focusing on creating different housing typologies, for different living styles.

By opening up the courtyards of Java Island, the architects have created different potentialities for the space. Rather than confining the space to a singular function – such as a traditional enclosed courtyard – the result of perimeter blocks – the open courtards created a sense of flexibility allowing for a range of creativity, recreation and collaboration to emerge.

Borneo Spoorenburg (figure 9) had a different architectural approach. The masterplan was carried out by West 8, and it influenced regeneration projects later on 26 Unlike Java Island, this development maintained a low-rise profile, mainly three stories high. To achieve the desired density of 100 dwellings per hectare, the houses were organized back-to-back, a reinterpretation of traditional Dutch housing. The diverse number of architects who contributed in the design created a varied streetscape, characterized by a harmonious scale, rhythm of openings, and

25 The concept of the ocean liner was not entirely new, it was proposed by Le Corbusier in le paquetbot ‘Flandre’ as a solution to housing in France, and the different possibilities linear buildings can offer.

26 Prewett Bizley, “Borneo Sporenburg Revisited,” Prewett Bizley Architects | Passivhaus | Retrofit, May 13, 2023, https://www.prewettbizley.com/graham-bizley-blog/borneo-sporenburg.

prevalent use of bricks. The pavements created are as well generous enough allowing for a varied pedestrian activity. The roads being single track, with parking limited to one side, show that the development had prioritized people over cars. Despite its density, it still offers a sense of neighborhood, with greenery adorning house facades, and residents reclaiming the pavement with tables, benches and plants. Here the streets are evidently functioning as urban armatures, and the whole development offers a sense of community and collectiveness.

KNSM Island (figure 10), was redeveloped based on a blueprint offered by Jo Coenen 27 . Considering the former industrial program of the site, the redevelopment plan was based on ‘super blocks’ to mimick the sizes of the warehouses which existed previously on site. KNSM was a result of extensive densification, through optimizing land use. Adaptive reuse strategies were employed in order to incorporate the industrial heritage of the site with the more contemporary urban fabric created. Similar to Borneo, the redevelopment of KNSM was done by more than 100 architects, and this reflects in the elevation. The streets also prioritize pedestrian accesss over cars and these streets open up to a variety of public spaces from plazas to parks to waterfront promenades, and this is what we can call ‘a primary space having a secondary relationship with another space’, what London is currentl y lacking.

27 Nino Schoonen, “Heritage and Architecture,” TUDelft, n.d., accessed April 23, 2024.

Figure 8. Java Island Retrieved from Sjoerd Soeters

Figure 9. Borneo Spoorenburg Retrieved from prewettbizley

Figure 10. KNSM Island Retrieved from Area-arch

Streets as Event Armatures

Urban plans like Java Island, Borneo Spoorenberg, and KNSM Island show a remarkable variation of different sorts of morphological starting points. These plans have a clear purpose, and create places that open up to a range of possibilities.

If we reimagine to visit them again after 30 years, one could tell that maybe everything around the areas will change its purpose and perhaps become denser. However, these fabrics could accommodate a completely different sort of life in the area, thus they can still retain their basic function. This is totally different from what we could configure by looking at plans like the Tottenham Hale and Blackhorse Lane, where the outdoor spaces are just an outcome of the plan, where there isn’t much to be done to those spaces. And this is the fundamental difference between the two plans.

Studio Woodroffe Papa in London, tried to demonstrate how such an approach to urban planning can be done in the UK, through their Dockley Apartments project, located in London 28.The project embraces a unique character of its surrounding characterized by food producers, artisans, traders and wholesalers. The ground floor thus incorporated such public functions in order to complement those of the adjacent railway. The galleries created are thought of to create a second layer of social interaction and connection. By offering varied housing options, and activating the ground floor, this project created an urban envornment where residents can work, live, and socialize.

28 “Dockley Apartments,” Dockley Apartments - Studio\Woodroffe\Papa Architects, accessed April 23, 2024, https://www.woodroffepapa.com/projects/dockleyapartments/#:~:text=The%20scheme%20comprises%201%2C%202,to%20the%20site’s%20surrounding%20context .

Conclusion

Through examining the different urban planning approaches between London and Amsterdam, it became evident that urban planning decisions play an important role in giving a purpose and character to our cities. While London has predominantly favored the perimeter blocks, Amsterdam has embraced a more diverse, flexible and adaptable model, as we experienced in Java Island, Borneo Spoorenburg and KNSM Island. London’s planners and developers advocated that the perimeter block as a solution to create active frontages and creates efficiency in landuse 29. However,this essay argued that the streets created by the urban grid, are rational, indeterminate and lack any diversity. As observed in developments around Tottenham Hale and Blackhorse Lane, these developments led to masterplans that lack any sense of purpose and identity, where the streets are serving as ‘conduits’ for individual institutions rather than fostering a collective sense of purpose.

In contrast, European models and in particular Amsterdam, prioritized diversity, adaptability and community engagement 30. The projects discussed in the essay demonstrated a more nuanced approach to urban design, and block design strategy, through incorporating varied typologies that in turn encourage social interaction, foster a sense of neighborhood and collective ownership among the residents.

29 “The London Plan 2021,” London City Hall, June 27, 2023, https://www.london.gov.uk/programmesstrategies/planning/london-plan/new-london-plan/london-plan-2021.

30 Jonathan Woodroffe, “We Have a Lot to Learn from European Housing Design,” Building Design, March 1, 2023, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/we-have-a-lot-to-learn-from-european-housing-design/5121741.article.

Unlike the rigid and hierarchical street layouts created by perimeter blocks in London, the streets in Amsterdam function as urban armatures, capable of accommodating a wide range of activities and events.

In Event Cities, Bernard Tschumi highlighted the importance of streets not only as physical spaces, but also places to socialize and interact. Thus architecture is not only about the physical form but also the activities and experiences that occur within it.

To sum up, through comparing the two models, a fundamental debate arises: streets as circulation nodes versus streets as places for social interactive and community collaboration. We should acknowledge that streets are not passive elements, indeed they are able to foster community cohesion and cultural exchange. Thus, it is important to reimagine the streets as event structures, focusing on their role in shaping more inclusive, resilient and active urban spaces.

References:

The active city. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.urhahn.com/wp-content/uploads/TheActive-City-2017-10-10-lowres.pdf.

Alexander, Christopher. A city is not a tree. New York: Architectural forum, 1965.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. “Appropriation, Subdivision, Abstraction.” JSTOR, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26588516.

Bizley, Prewett. “Borneo Sporenburg Revisited.” Prewett Bizley Architects | Passivhaus | Retrofit, May 13, 2023. https://www.prewettbizley.com/graham-bizley-blog/borneosporenburg.

Canniffe, Eamonn. “Rem Koolhaas: Delirious New York : A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (1978).” architectureandurbanism, January 1, 2010. https://architectureandurbanism.blogspot.com/2012/02/rem-koolhaas-delirious-new- york1978.html#:~:text=’%20What%20the%20five%20different%20’blocks,glorified%20Manh attan%20in%20order%20for.

“Dockley Apartments.” Dockley Apartments - Studio\Woodroffe\Papa Architects. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.woodroffepapa.com/projects/dockleyapartments/#:~:text=The%20scheme%20comprises%201%2C%202,to%20the%20site’s%2 0surrounding%20context.

Eaton, Paul. “The Residential Perimeter Block: Principles, Problems and Particularities.” Allies and Morrison. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.alliesandmorrison.com/research/theresidential-perimeter-block-principles-problems-and-particularities.

Hunter-Anderson, Rosalind L. “A Theoretical Approach to the Study of House Form.” For theory building in archaeology, April 22, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/821517/A_theoretical_approach_to_the_study_of_house_form.

Jacobs, Jane, and Jason Epstein. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Modern Libray, 2011.

Kostof, Spiro. The city shaped: Urban patterns and meanings through history. Boston: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

“The London Plan 2021.” London City Hall, June 27, 2023. https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/planning/london-plan/new-londonplan/london-plan-2021.

Martin, Leslie. “The Grid as Generator.” wordpress, 1972. https://lsproject2009.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/the-grid-as-generator- -urban-designreade-feb-2007.pdf.

Oikonomou, Maria. “The Transformation of the Urban Block in the European City.” Academia, January 15, 2018. https://www.academia.edu/10797196/The_transformation_of_the_urban_block_in_the_Eu ropean_City.

Panerai, Philippe, Jean Castex, Jean-Charles Depaule, and Ivor Samuels. Urban forms: Death and Life of the Urban Block. Oxford England: Architectural Press, 2004.

Pizzi, Christopher M. “Dimensions of Urbanism: Urban Blocks.” Academy of Art University, June 24, 2022. https://www.acsa-arch.org/proceedings-index/.

Rowe, Colin, Fred Koetter, and Kenneth Hylton. Collage City. Gollion Suisse: Infolio, 2005.

Schoonen, Nino. “Heritage and Architecture.” TUDelft, n.d. Accessed April 23, 2024.

Soeters, Sjoerd. Java island Amsterdam Harbour Renovation. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://pphp.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/JAVA-ISLAND.pdf.

Super Density - Greater London Authority. Accessed April 20, 2024. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/rep-82-100001a_referred_to_in_matter_4_statement_superdensity_2015_download.pdf.

Tschumi, Bernard. Event Cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Tschumi, Bernard. The Manhattan Transcripts. London: Academy Editions, 1981.

Woodroffe, Jonathan. “We Have a Lot to Learn from European Housing Design.” Building Design, March 1, 2023. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/we-have-a-lot-to-learn-fromeuropean-housing-design/5121741.article.