Italiana La Metallurgia

International Journal of the Italian Association for Metallurgy

n. 02 febbraio 2025

Organo ufficiale dell’Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia. Rivista fondata nel 1909

International Journal of the Italian Association for Metallurgy

n. 02 febbraio 2025

Organo ufficiale dell’Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia. Rivista fondata nel 1909

International Journal of the Italian Association for Metallurgy

Organo ufficiale dell’Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia. HouseorganofAIMItalianAssociationforMetallurgy. Rivista fondata nel 1909

Direttore responsabile/Chiefeditor: Mario Cusolito

Direttore vicario/Deputydirector: Gianangelo Camona

Comitato scientifico/Editorialpanel: Marco Actis Grande, Silvia Barella, Paola Bassani, Christian Bernhard, Massimiliano Bestetti, Wolfgang Bleck, Franco Bonollo, Irene Calliari, Mariano Enrique Castrodeza, Emanuela Cerri, Vlatislav Deev, Andrea Di Schino, Donato Firrao, Bernd Kleimt, Carlo Mapelli, Denis Jean Mithieux, Roberto Montanari, Marco Ormellese, Mariapia Pedeferri, Massimo Pellizzari, Barbara Previtali, Evgeny S. Prusov, Dario Ripamonti, Dieter Senk

Segreteria di redazione/Editorialsecretary: Marta Verderi

Comitato di redazione/Editorialcommittee: Federica Bassani, Gianangelo Camona, Mario Cusolito, Carlo Mapelli, Federico Mazzolari, Marta Verderi, Silvano Panza

Direzione e redazione/Editorialandexecutiveoffice: AIM - Via F. Turati 8 - 20121 Milano tel. 02 76 02 11 32 - fax 02 76 02 05 51 met@aimnet.it - www.aimnet.it

Reg. Trib. Milano n. 499 del 18/9/1948. Sped. in abb. Post. - D.L.353/2003 (conv. L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB UD

Immagine in copertina: Shutterstock

Gestione editoriale e pubblicità Publisher and marketing office: siderweb spa sb Via Don Milani, 5 - 25020 Flero (BS) tel. 030 25 400 06 commerciale@siderweb.com - www.siderweb.com

La riproduzione degli articoli e delle illustrazioni è permessa solo citando la fonte e previa autorizzazione della Direzione della rivista. Reproduction in whole or in part of articles and images is permitted only upon receipt of required permission and provided that the source is cited.

siderweb spa sb è iscritta al Roc con il num. 26116

n. 02 febbraio 2025 Anno 116 - ISSN 0026-0843

Editoriale / Editorial a

Memorie scientifiche / Scientific papers Corrosione / Corrosion

Corrosion behaviour in acidic environments of alloy 625 produced by Material Extrusion: effect of the process-generated microstructure and defects

T. Persico, S. Lorenzi, M. Cabrini, L. Nani, T. Pastore, G. Barbieri, F. Cognini ....................................................... pag.08

Monitoraggio tramite emissione acustica dei meccanismi di cracking assistiti da idrogeno durante prove di trazione a bassa velocità di deformazione in atmosfera di idrogeno puro e miscelato

S. Rahimi, G. Scionti, E. Piperopoulos, M. F. Milazzo, E. Proverbio ...................................................................... pag.16

Effect of natural inhibitors on the corrosion properties of titanium and magnesium alloys

M. Faraji, L. Pezzato, A. Yazdanpanah, I. Calliari, M. Esmailzadeh ........................................................... pag.27

La valutazione della velocità di corrosione nei cavi post-tesi delle strutture in calcestruzzo armato precompresso

E. Proverbio, M. Giglio, A. Gennari Santori ................................................................................... pag.36

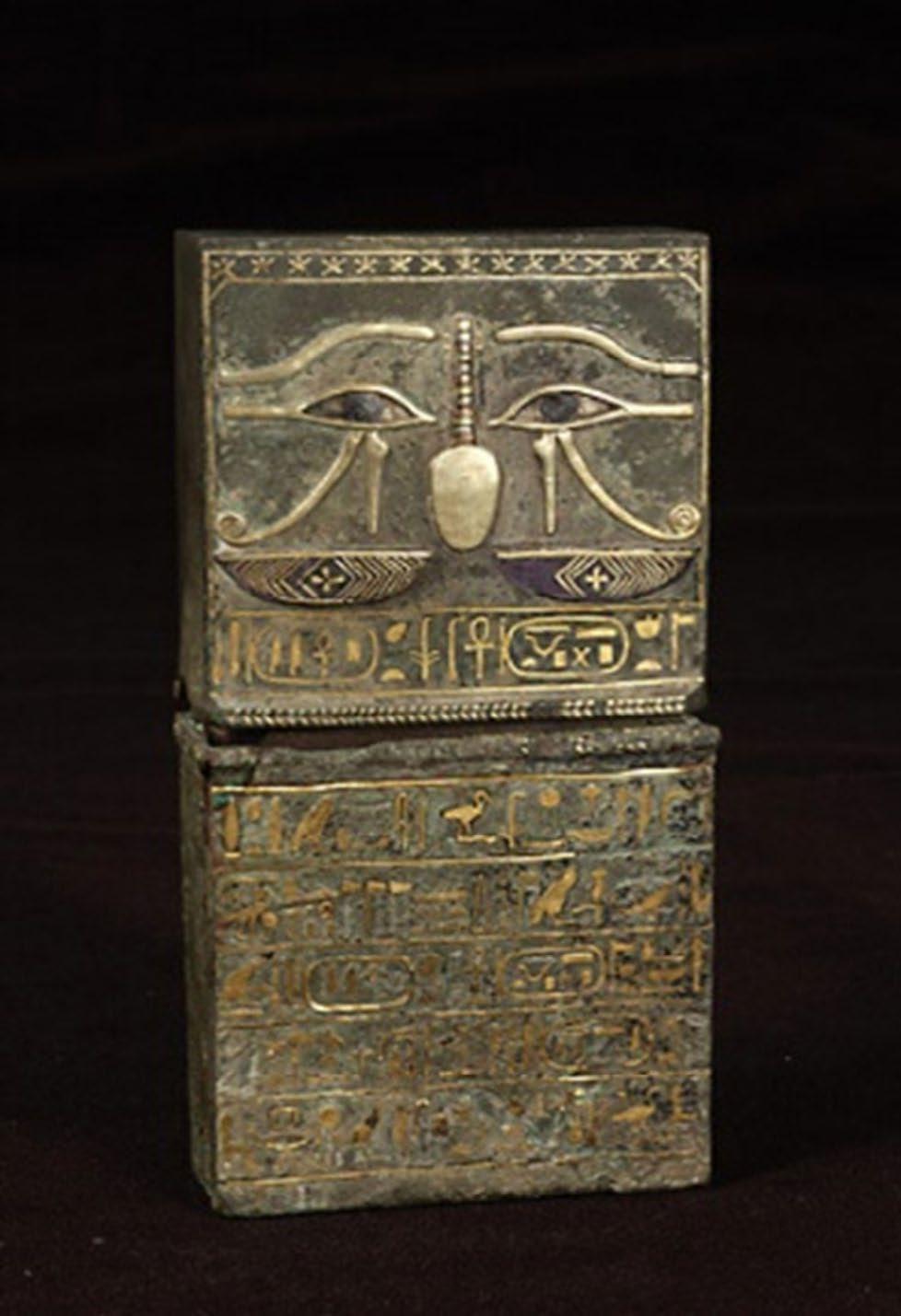

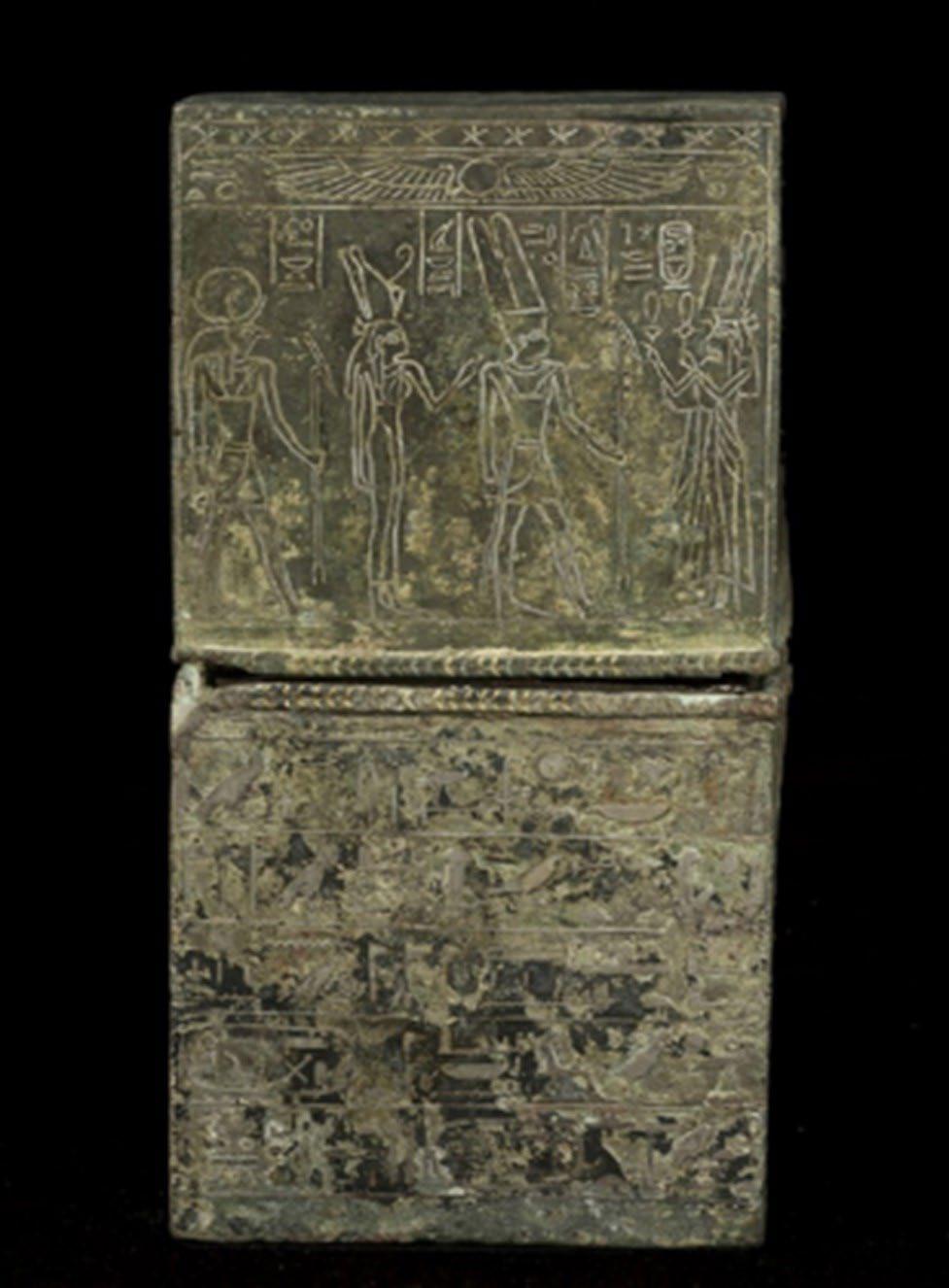

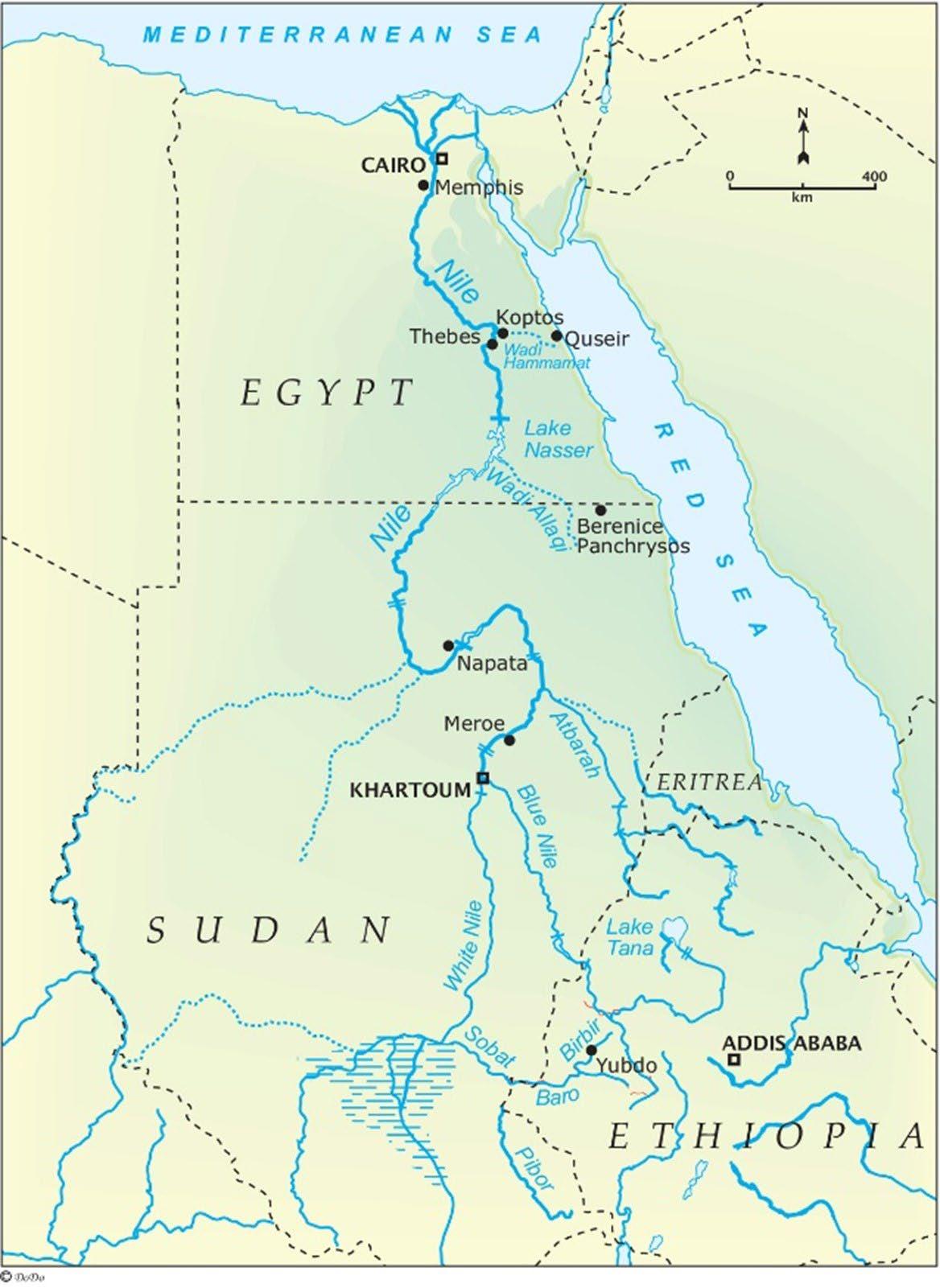

Attualità industriale / Industry news Celestial and earthly origins of platinum edited by: A. Cremona ......................................................................................................... pag.42

Atti e notizie / AIM news Concorso “Metallurgia a fumetti” pag.51 Eventi AIM / AIM

The knowledge and the development of the new ideas enhance progress. With the 7th European Steel Technology and Application Days 2025 (7th ESTAD 2025) AIM offers attendants and visitors the opportunity to meet, exchange their ideas, perform fruitful discussion and create new professional relationships involving technology providers, suppliers, producers and customers.

The meeting will be focused on the technological advances, changes of the supply chain involving the raw materials and energy sources, transformation of the production processes and plants to accomplish the twin transition (ecological and digital) and the new perspective of steel applications.

Scientific international experts in all fields of iron and steelmaking processes, steel materials and steel application will review the proposed papers.

IRONMAKING

STEELMAKING

ROLLING OF FLAT AND LONG PRODUCTS, FORGING

STEEL MATERIALS AND THEIR APPLICATION, ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING, SURFACE TECHNOLOGIES

HYDROGEN-BASED STEELMAKING, CO2-MITIGATION, TRANSFORMATION ENVIRONMENT /ENERGY

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION

All paper proposals must be submitted online. Please visit: www.aimnet.it/estad2025 and go to the Call for Papers section. Your abstract can be a maximum of 300 words.

To submit an abstract, please proceed as follows:

1) Write your abstract (max. 300 words)

2) Submit your abstract online at: www.aimnet.it/estad2025/ > Call for Papers section

3) Papers must be submitted in English

4) All papers must focus on best practices

Please submit your abstracts by 28 February 2025. All abstracts will be refereed by the scientific international experts. In the case of too many submissions, abstracts of equal quality will be accepted on a first come, first serve basis.

Via Filippo Turati 8 | 20121 Milano MI | Italy

Email: estad2025@aimnet.it

Phone: +39 02 76021132 www.aimnet.it/estad2025 Sisters societies

“"L’utilizzo di nuovi materiali e di nuove tecnologie di produzione, così come la necessaria transizione ecologica, pongono continue sfide nel campo della corrosione con la necessità di comprendere l’affidabilità e le caratteristiche chimico/ fisiche dei nuovi materiali/ prodotti."

“The use of new materials and new production technologies,aswellas thenecessaryecological transition, pose continuous challengesinthefieldof corrosion with the need to understandthereliability andchemical/physical propertiesofnewmaterials/ products.”

In questo numero de “La Metallurgia Italiana” vengono proposti alcuni articoli presentati nella sessione di “Corrosione” della 40° edizione del Convegno Nazionale dell’Associazione Italiana di Metallurgia, tenutosi a Napoli dall’11 al 13 Settembre 2024.

L’utilizzo di nuovi materiali e di nuove tecnologie di produzione, così come la necessaria transizione ecologica, pongono continue sfide nel campo della corrosione con la necessità di comprendere l’affidabilità e le caratteristiche chimico/fisiche dei nuovi materiali/ prodotti.

In questo numero sono stati selezionati interessanti studi relativi all’utilizzo di Inconel, acciai inossidabili e di nuova generazione, titanio e leghe di magnesio, per diversi campi di applicazione: energia, Oil&Gas, costruzioni marine e automotive.

Grazie alla capacità di produrre parti complesse e di

Annalisa Acquesta Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

This issue of “La Metallurgia Italiana” features some of the papers presented in the “Corrosion” session of the 40th National Conference of the Italian Metallurgical Association, held in Naples from 11 to 13 September 2024.

The use of new materials and new production technologies, as well as the necessary ecological transition, pose continuous challenges in the field of corrosion with the need to understand the reliability and chemical/physical properties of new materials/ products.

In this issue, we have selected interesting studies on the use of Inconel, stainless and new-generation steels, titanium and magnesium alloys for various application fields: energy, Oil&Gas, marine construction and automotive sectors.

Thanks to its ability to produce complex, close-to-

forma prossima a quella finale di componenti metallici, la produzione additiva o additive manufacturing (AM), nota anche come stampa 3D, ha suscitato un crescente interesse in un'ampia gamma di settori industriali e di ricerca, specialmente nei casi in cui la lavorazione del metallo richieda elevati costi, come nel caso delle leghe a base di Nichel. Tuttavia, è noto che la microstruttura prodotta dalle tecnologie AM è completamente differente da quella ottenuta quando vengono utilizzate tecnologie convenzionali, e questo può avere ripercussioni sulle proprietà meccaniche e di resistenza alla corrosione. Piccole variazioni nei parametri di processo possono alterare notevolmente la microstruttura. Persico e colleghi hanno confrontato il comportamento a corrosione della lega 625 prodotta mediante la più recente tecnologia additiva, Material Extrusion (MEX), con quello mostrato da una tecnologia convenzionale. La MEX, pur mostrando vantaggi rispetto alle altre tecniche AM, tra cui l’elevata velocità di deposizione e la semplicità nella gestione della materia prima, presenta numerose macro-porosità endogene che possono influire sulla resistenza alla corrosione. I risultati mostrati pongono le basi per ulteriori approfondimenti volti allo studio della relazione fra microstruttura e comportamento a corrosione della lega 625 prodotta mediante altre tecnologie AM.

L’adozione dell’idrogeno come vettore energetico per la transizione ecologica pone numerosi problemi da affrontare e risolvere, come lo stoccaggio in grandi quantità, il trasporto su lunghe distanze a costi contenuti, nonché il possibile utilizzo di infrastrutture esistenti. Pertanto, vi è un crescente interesse nello studio dei meccanismi di corrosione che possono generarsi a seguito della reazione dell’idrogeno con i componenti metallici con cui verrà a contatto, in particolare degli acciai usati per la rete gas. Importanti diventeranno anche le tecniche con cui tali problematiche potranno essere evidenziate, come mostrato dallo studio di Proverbio e colleghi, che mostrano la possibilità di distinguere, me-

final-shaped parts of metal components, additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has attracted growing interest in a wide range of industries and research sectors, especially in cases where metal processing requires high costs, as in the case of nickel-based alloys. However, it is known that the microstructure produced by AM technologies is completely different from that obtained when conventional technologies are used, and this can affect the mechanical and corrosion resistance properties. Small variations in process parameters can significantly alter the microstructure. Persico and colleagues compared the corrosion behaviour of alloy 625 produced by the latest additive technology, Material Extrusion (MEX), with that exhibited by conventional technology. Although MEX shows advantages over other AM techniques, including high deposition speed and simplicity in raw material handling, it has numerous endogenous macro-porosities that can affect corrosion resistance. The results shown lay the groundwork for further investigations to study the relationship between microstructure and corrosion behaviour of Alloy 625 produced by other AM technologies.

The adoption of hydrogen as an energy carrier for the ecological transition poses numerous problems that need to be addressed and resolved, such as storage in large quantities, cost-effective transport over long distances,andthepossibleuseofexistinginfrastructure. Therefore, there is growing interest in the study of the corrosion mechanisms that can be generated as a result of the reaction of hydrogen with the metal components with which it will come into contact, particularly the steels used for the gas network. Also important will be thetechniquesbywhichtheseissuescanbehighlighted, as shown by the study by Proverbio and colleagues, who demonstrate the possibility of distinguishing, by means of acoustic emission techniques, the different hydrogen-assisted cracking mechanisms of a new generation API 5L X65Q steel.

diante tecniche di emissione acustica, i diversi meccanismi di cracking assistiti dall'idrogeno di un acciaio API 5L X65Q di nuova generazione.

Gli acciai inossidabili duplex combinano molte delle caratteristiche ottimali degli acciai inossidabili ferritici e austenitici. Tuttavia, l'alterazione termica derivante dai processi di saldatura di questi acciai è la causa di potenziali precipitazioni di fase indesiderate e della mancanza di equilibrio microstrutturale tra i due principali componenti strutturali: ferrite e austenite. Pigato e colleghi hanno dimostrato che l'aggiunta di cobalto, mediante trattamento di elettrodeposizione, è un metodo efficace per ottenere l'equilibrio di fase nelle saldature di testa, una volta ottimizzato lo spessore della placcatura.

L'integrazione degli inibitori green, come materiali eco-compatibili, nelle strategie di prevenzione della corrosione dei metalli è auspicata come un approccio responsabile, economico ed ecologico. Farij e colleghi hanno mostrano gli effetti di alcuni inibitori naturali, a base di succo di melograno e pomodoro ed estratto di alghe, sulla resistenza alla corrosione del titanio (grado 2) e della lega di magnesio AZ31.

Duplex stainless steels combine many of the optimal characteristics of ferritic and austenitic stainless steels. However, thermal alteration resulting from the welding processes of these steels is the cause of potential unwanted phase precipitation and lack of microstructural balance between the two main structural components: ferrite and austenite. Pigato and colleagues demonstrated that the addition of cobalt, by means of electrodeposition treatment, is an effective method to achieve phase balance in butt welds, once the plating thickness has been optimised.

The integration of green inhibitors, as eco-friendly materials, into metal corrosion prevention strategies is advocated as a responsible, economic and ecological approach. Farij and colleagues showed the effects of some natural inhibitors, based on pomegranate and tomato juice and algae extract, on the corrosion resistance of titanium (grade 2) and AZ31 magnesium alloy.

T. Persico, S.

Lorenzi, M. Cabrini, L. Nani, T. Pastore, G. Barbieri, F. Cognini

Additive manufacturing (AM) is gaining increasing interest in various strategic industrial sectors such as Oil & Gas, aerospace, and chemical industries. This group of technologies includes both innovative yet well-established techniques and more recent methods like Material Extrusion (MEX). This technique shows several advantages over other AM techniques, including high deposition rates and simplicity in feedstock material handling; however, it presents numerous endogenous macro-defects that can affect the corrosion resistance. The relationship between the defects of this technology and its corrosion behaviour still needs to be thoroughly investigated. This work studies the relationship between microstructure, internal defects, and corrosion behaviour in reducing acidic environments of alloy 625 obtained through MEX, compared to the same alloy obtained with traditional technology. The results lay the groundwork for further studies aimed to study the relationship between microstructure and corrosion behaviour of alloy 625 obtained with other AM technologies.

KEYWORDS: ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING, CORROSION, NICKEL SUPERALLOY, MICROSTRUCTURE, DEFECTS

Alloy 625 (UNS N06625) is a highly alloyed nickel-base alloy that presents good mechanical strength, high corrosion resistance in several environments, creep resistance and weldability. Because of this attractive combination of properties, alloy 625 has found widespread applications in sectors such as nuclear, Oil&Gas, energy, chemical and aerospace [1], [2], [3]. The high levels of Cr, Mo and Nb provide good corrosion resistance, especially for localized corrosion, increasing the pitting resistance equivalent number (PREN) [4]. Furthermore, Nb reduces the deleterious effect of Mo and Cr precipitates at the grain boundary on the resistance to intergranular corrosion [5]. The Al and Ti additions are primarily for refining purposes, while Fe provides further solid solution strengthening [3]. Alloy 625 is typically used for the production of fluid-dynamic parts and valves components for the energy and Oil&Gas sectors and is commonly manufactured by plastic deformation processes and subsequent machining. Concerning the machinability, alloy 625 usually leads to excessive tool wear and high material removal rates. Consequently, the

T. Persico, S. Lorenzi, M. Cabrini, L. Nani, T. Pastore

Department of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Università degli studi di Bergamo, Italy

G. Barbieri, F. Cognini

Department for Sustainability - Research Centre of Casaccia, ENEA, Rome, Italy

cost of the manufactured part can significantly increase with the complexity of the final geometry. [6], [7].

Additive Manufacturing (AM) technologies can be successful for nickel alloys because they achieve high material utilization efficiencies, do not cause tool wear and can manufacture complex geometries without a substantial increase of the cost [8], [9].

Additive manufacturing is a family of technologies that deposits materials layer by layer to create geometric 3D components. The most common technologies utilize metal powder or wire as feedstock. These techniques melt the metallic material in the printing process, so the product is ready for the usage [1], [10]. The high cooling speed provides completely different microstructures with respect the traditional worked alloys, generally with higher mechanical properties. Despite, the main disadvantages of AM technologies are speed and production costs. To overcome these difficulties, new techniques have been developed to require a much simpler and cheaper printing equipment with much higher production speeds [11]. This is achieved by using an auxiliary polymer as in material extrusion (MEX) technology. The printing process involves the deposition of a polymer filament filled with metal powders. Conversely traditional additive technologies, there is not the melting of the metal powder during the deposition. Post-deposition treatments are mandatory: debinding to remove the polymer and sintering to consolidate the metal powders [12], [13]. Previous studies have shown that MEX technology

presents elongated and interconnected macro-defects with periodic distribution within the material, depending on the adopted deposition strategy [13]. The aim of this work is to investigate the relationship between corrosion behaviour, microstructure and defects of an alloy 625 obtained by MEX and to compare it with the results obtained by the same alloy produced by hot working (HW) by means of corrosion tests in sulfuric acid at different temperatures.

Materials

MEX-processed specimens were made with a MetalXMarkforged System using commercial alloy 625 powder-filled polymer filament of approximately 1.8 mm in diameter as feedstock material. Following the sintering process, the material has a composition reported in Tab. 1. The specimens consist of 5 mm x Ø 15 mm cylinders composed of two zones with different scanning strategies. The outer area, named contour, is filled with 4 stripe-thick with parallel direction between successive layers. The core, defined as the inner zone, is realized with layers with deposition directions alternately oriented at +45° and -45°. The HW material consisted in hot-rolled bar with a diameter of 16 mm (chemical composition reported in Table 1) that was heat treated and then mechanically cut to get 5 mm thick specimens. The performed heat treatment is a "Grade 1" following ASTM B446: solubilization at 980 °C for 32 minutes and quenching in water.

Microstructural investigation and defects

characterization

The specimens were analyzed after grinding with silicon carbide emery papers up to 4000 grit and subsequently polishing with 1 µm diamond suspension. The specimens have been investigated with a digital-optical microscope

(OM) Keyence VHX-7100 and a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) Zeiss Sigma 300 equipped with an Oxford x-Act probe for energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). For metallographic analysis, the etching solution 15-10-10 (HCl, HNO3, CH3COOH) was used.

Corrosion immersion test in sulfuric acid

Immersion corrosion tests were carried out according to ASTM G31 in a 50% (wt.%) H2SO4 solution at 50°C, 80°C and boiling temperature. The specimens were placed in a 1 L Erlenmeyer flask with a reflux condenser to avoid the evaporation of the test solution. At the bottom of the flask, a thin layer of boiling chips was spread in order to promote the boiling and avoid the contact between the specimens and the flask background. The cell was heated by a thermostatic bath and the test solution temperature was monitored by internal thermometer. Before the tests, all the specimens underwent mechanically grinding using SiC emery papers up to 4000 grit and then polishing with 1 µm diamond suspension. Then, they were weighted 3 times before the immersion. After 24 hours of immersion,

the specimens were extracted from the solution, washed with distilled water and rinsed in acetone, then weighted again to establish the weight loss. All the corroded specimens were further analysed (OM/SEM/EDS).

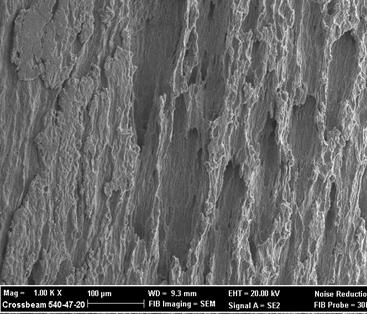

Microstructural investigation and defects characterization

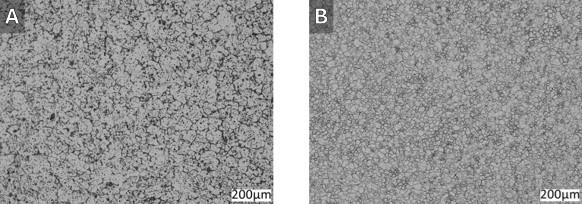

The MEX-fabricated specimens showed a microstructure with equiaxed austenitic grains and several precipitates, as visible in Figure 1A. Moreover, typical macro-defects of MEX technology were also visible under digital optical microscope. Hot worked specimens were characterized as well by austenitic equiaxed grains with characteristic twins as shown in Fig. 1B, with finer grains with respect to MEX specimens.

EDS analysis detected carbides of Ni e Mo in alloy 625 manufactured via MEX, as shown in Fig. 2A. It is focal to specify that such carbides are homogeneously arranged and in block shapes in the core, while they are elongated and primarily arranged along the grain boundaries in the contour. Furthermore, inclusions of oxides rich in Al, Si, and Cr and surrounded by a secondary phase were discovered (Fig. 2B). In literature, it has been proposed that oxides and carbides form during debinding and

sintering by the capture of impurities [14], [15]. The reference HW material is characterised by the presence of carbides, both in blocks and elongated along the grain boundary forming semi-continuous chains, as visible in Fig. C. Second phases rich of titanium were also detected in HW specimens.

Corrosion tests in sulfuric acid

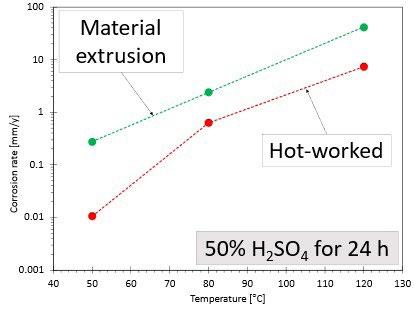

The weight losses in 50% sulfuric acid solution showed an exponential trend depending on the temperature of the solution, as seen in Fig. 3. At higher temperatures, there is an increase of the movement of ions and reduction of oxygen concentration all contributing to higher corrosion rates [16], [17].

Fig.3 - Velocità di corrosione della lega 625 in 50% H2SO4 in funzione della temperatura della soluzione / Corrosion rates vs solution temperature of alloy 625 in 50% H2SO4

The corrosion rate of alloy 625 HW is comparable with the values already reported in the literature [18], [19].

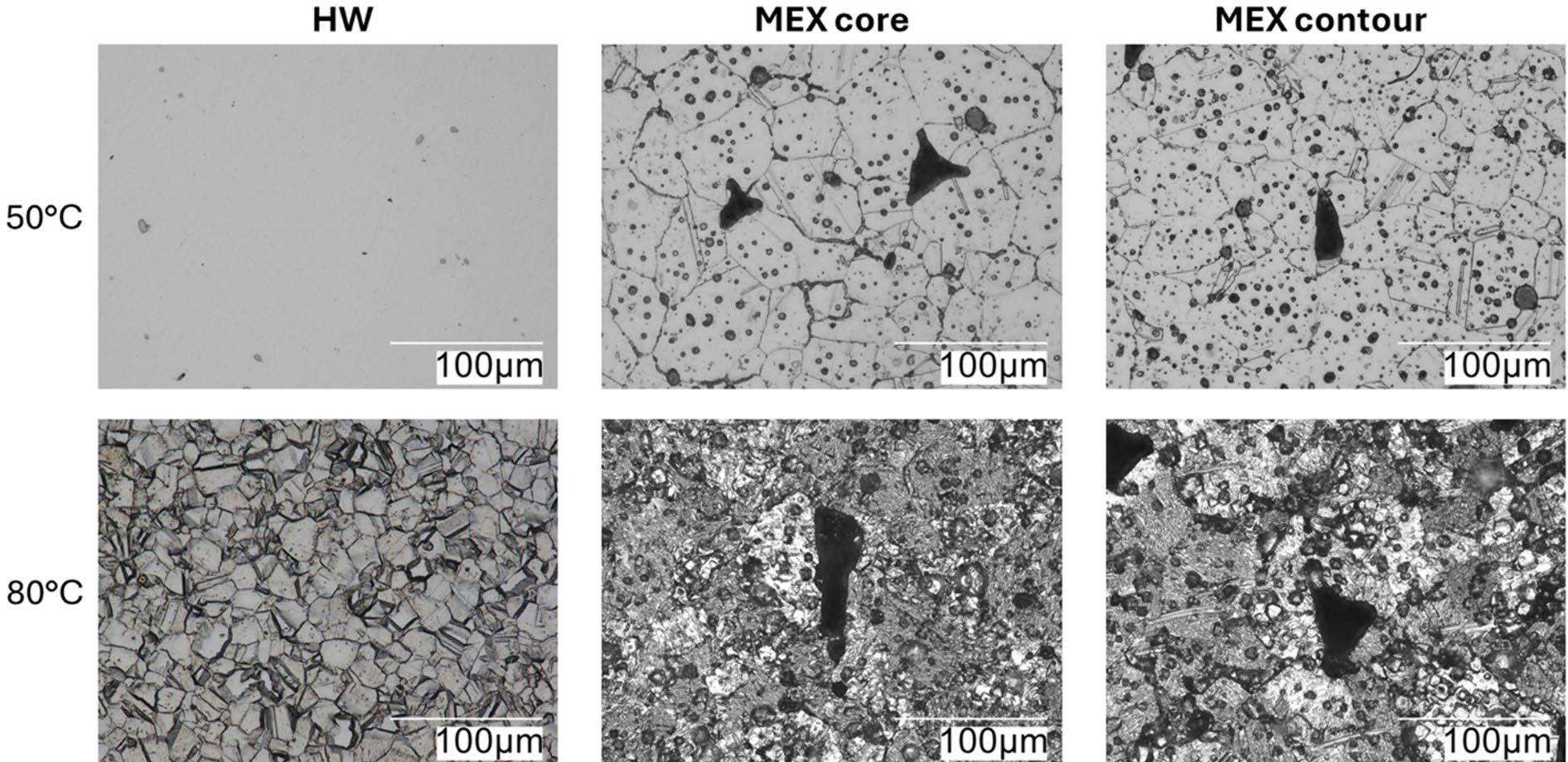

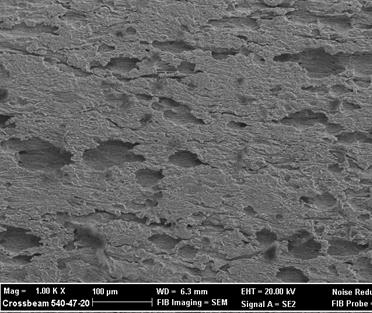

Conversely, MEX exhibited corrosion rates an order of magnitude higher than those of the alloy obtained through traditional technology. Furthermore, MEX showed high corrosion rates already at 50 ºC, while HW displayed significantly lower corrosion rates at that temperature. Digital optical microscope analysis of the exposed surfaces proved that the corrosion attacks morphology

in both MEX and HW preferentially follows the grain boundaries, as shown in Fig. 4.

EDS of alloy 625 after the immersion test demonstrated that the interface between carbides/Ni-grain and oxides/ Ni-grain is the predominant site where the corrosion occurs (Fig. 5). Therefore, it is plausible that the intergranular corrosion behaviour of Alloy 625 in both HW and MEX is highly affected by the presence of carbides with adjacent Ni and Cr depleted zones, distributed along the grain boundaries [20].

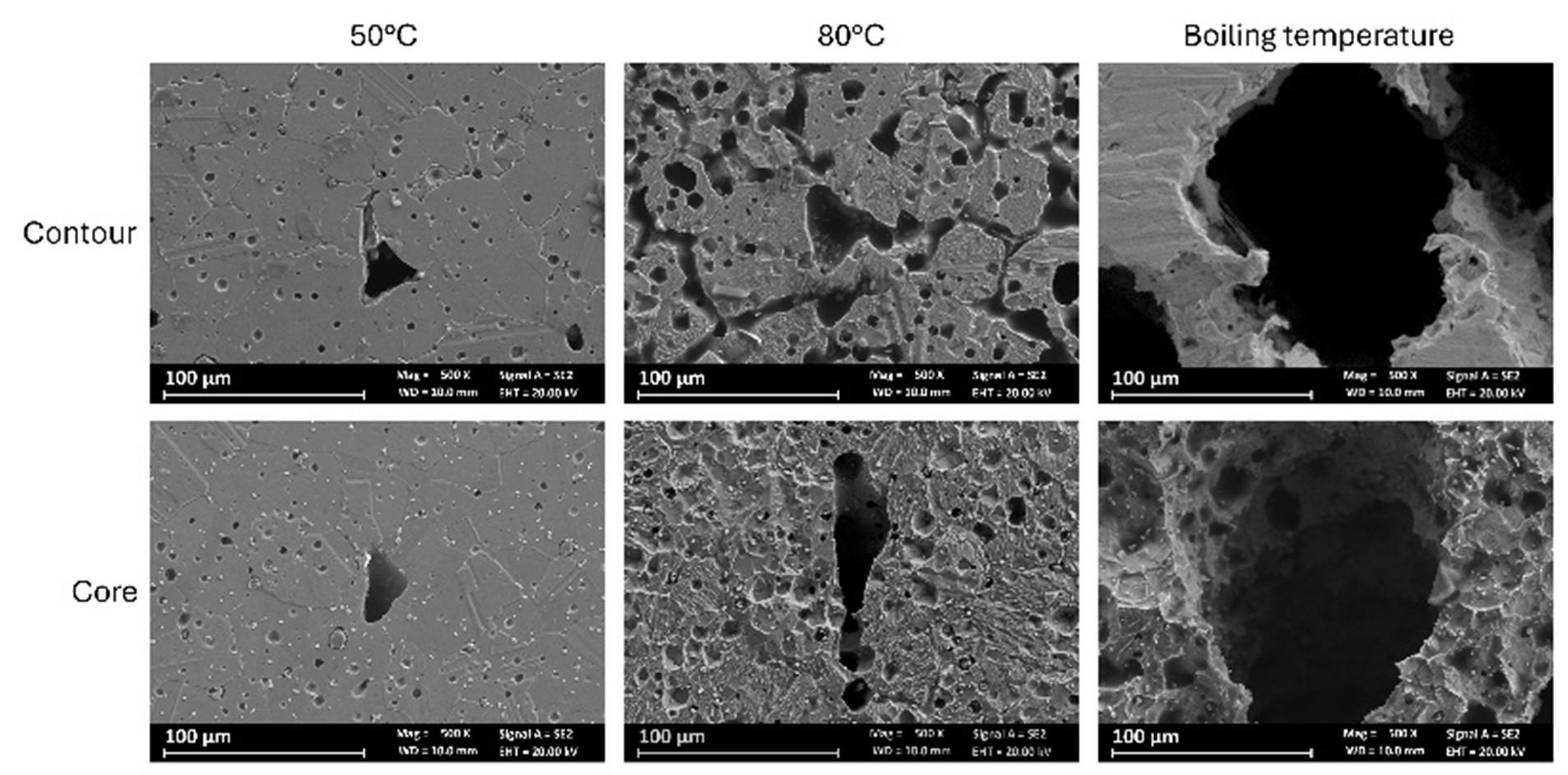

During immersion test, macro-defects of alloy 625 MEX increased in size because of severe corrosion occurring. The defect size increased greatly with the aggressiveness of the solution, as visible in Fig. 6. The enlargement of defects leads to an expansion of surface exposed to the corrosive environment, contributing to the higher corrosion rates observed in MEX specimens if compared to the HW benchmark.

6 - Macro-difetti dei provini MEX post immersione in H2SO4 a differenti temperature / MEX macro-defects after immersion test in H2SO4 at different temperature.

At all test temperatures, there was a distinct difference of corrosion morphology between core and contour in the MEX samples. In both regions, it is evident that the corrosive attack initiates at the interface between the carbides and the base material. In the contour, the corrosion is strictly intergranular, while the core showed a more homogeneous morphology. This observation is consistent with the different carbide arrangements and shapes in the core and contour.

This study investigated the alloy 625 produced via Material Extrusion in terms of internal defects, microstructure and corrosion behaviour. The research aimed to understand how the material obtained through MEX may exhibit different corrosion behaviour compared to the same material produced traditionally. This work lays the foundation to characterize the corrosion behaviour of further additive manufacturing technologies. The main highlighted findings are as follows:

• Both technologies provide austenitic equiaxed grains. MEX specimens showed homogeneously distributed carbides with block shapes within the

core, while in the contour they were elongated and primarily aligned along grain boundaries. HW material is also characterised by carbides, both in blocks and elongated along the grain edge forming semicontinuous chains.

• Corrosion immersion tests in sulfuric acid demonstrated that Alloy 625 produced by MEX exhibited corrosion rates significantly higher than those produced by HW. Intergranular corrosion mechanism occurs in both HW and MEX specimens, predominantly in the contour region.

• During the corrosion test, the macro-defects widened significantly. This indicates that in areas where the material exhibits active behaviour, the macro-defects characteristic of MEX technology have a deleterious effect.

This research was funded by the European Union, NextGenerationEU program: MICS – Made in Italy circolare e sostenibile, spoke 6.04 Development of new alloys with improved properties and decreased environmental impact for AM powder production.

[1] M. Karmuhilan and S. Kumanan, “A Review on Additive Manufacturing Processes of Inconel 625,” J Mater Eng Perform, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 2583–2592, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1007/S11665-021-06427-3/TABLES/5.

[2] V. Shankar, K. Bhanu Sankara Rao, and S. L. Mannan, “Microstructure and mechanical properties of Inconel 625 superalloy,” Journal of Nuclear Materials, vol. 288, no. 2–3, pp. 222–232, Feb. 2001, doi: 10.1016/S0022-3115(00)00723-6.

[3] S. Floreen, G. E. Fuchs, and W. J. Yang, “The Metallurgy of Alloy 625,” Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivatives (1994), pp. 13–37, Aug. 1994, doi: 10.7449/1994/SUPERALLOYS_1994_13_37.

[4] E. L. Hibner, “CORROSION/86,” NACE International, vol. paper no. 181, 1986.

[5] GD. E. NC. Smith, “The effect of niobium on the corrosion resistance of nickel-base alloys,” Proc Int Symp Niobium High Temp Appl, 2004.

[6] Y. L. Hu, X. Lin, X. B. Yu, J. J. Xu, M. Lei, and W. D. Huang, “Effect of Ti addition on cracking and microhardness of Inconel 625 during the laser solid forming processing,” J Alloys Compd, vol. 711, pp. 267–277, Jul. 2017, doi: 10.1016/J.JALLCOM.2017.03.355.

[7] Y. AbouelNour and N. Gupta, “In-situ monitoring of sub-surface and internal defects in additive manufacturing: A review,” Mater Des, vol. 222, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.MATDES.2022.111063.

[8] G. Sander et al., “Corrosion of Additively Manufactured Alloys: A Review,” Corrosion, vol. 74, no. 12, pp. 1318–1350, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.5006/2926.

[9] W. E. Frazier, “Metal additive manufacturing: A review,” J Mater Eng Perform, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 1917–1928, Apr. 2014, doi: 10.1007/ S11665-014-0958-Z/FIGURES/9.

[10] M. Cabrini et al., “Stress corrosion cracking of additively manufactured alloy 625,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 20, p. 6115, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.3390/MA14206115/S1.

[11] J. M. Costa, E. W. Sequeiros, M. T. Vieira, and M. F. Vieira, “Additive Manufacturing: Material Extrusion of Metallic Parts,” U.Porto Journal of Engineering, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 53–69, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.24840/2183-6493_007.003_0005.

[12] Y. Thompson, J. Gonzalez-Gutierrez, C. Kukla, and P. Felfer, “Fused filament fabrication, debinding and sintering as a low cost additive manufacturing method of 316L stainless steel,” Addit Manuf, vol. 30, p. 100861, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1016/J.ADDMA.2019.100861.

[13] A. Carrozza et al., “A comparative analysis between material extrusion and other additive manufacturing techniques: Defects, microstructure and corrosion behavior in nickel alloy 625,” Mater Des, vol. 225, p. 111545, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1016/J. MATDES.2022.111545.

[14] K. Horke, A. Meyer, and R. F. Singer, “Metal injection molding (MIM) of nickel-base superalloys,” Handbook of Metal Injection Molding, pp. 575–608, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-102152-1.00028-3.

[15] Y. Thompson et al., “Metal fused filament fabrication of the nickel-base superalloy IN 718,” J Mater Sci, vol. 57, no. 21, pp. 9541–9555, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1007/S10853-022-06937-Y/FIGURES/8.

[16] A. Mishra, “Performance of corrosion-resistant alloys in concentrated acids,” Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters), vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 306–318, Apr. 2017, doi: 10.1007/S40195-017-0538-Y/TABLES/3.

[17] P. Pedeferri, “Uniform Corrosion in Acidic and Aerated Solutions,” Engineering Materials, pp. 145–167, 2018, doi: 10.1007/978-3-31997625-9_8.

[18] ASM, “ASM Handbook Volume 13: Corrosion,” ASM Metals Handbook, pp. 1–1135, 2003, Accessed: Jul. 20, 2023.

[19] “HAYNES® 625 alloy - Haynes International.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://haynesintl.com/en/datasheet/ haynes-625-alloy/#iso-corrosion-diagrams

[20] A. K. Jena and M. C. Chaturvedi, “The role of alloying elements in the design of nickel-base superalloys,” J Mater Sci, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 3121–3139, Oct. 1984, doi: 10.1007/BF00549796/METRICS.

La manifattura additiva (AM) sta acquistando sempre maggiore interesse in diversi settori industriali come quelli dell’Oil&Gas, aerospaziale e chimico. Questo gruppo di tecnologie comprende tecniche innovative ma ben consolidate, nonché metodi più recenti come la Material Extrusion (MEX). Questa tecnica mostra vantaggi rispetto alle altre tecniche AM, tra cui l’elevata velocità di deposizione e la semplicità nella gestione della materia prima; tuttavia, presenta numerose macro-porosità endogene che possono influenzare la resistenza alla corrosione. La relazione fra i difetti di questa tecnologia e il suo comportamento a corrosione è ancora da approfondire. Questo lavoro studia la relazione fra la microstruttura, i difetti interni e il comportamento a corrosione in ambiente acido riducente della lega 625 ottenuta tramite MEX, rispetto alla lega ottenuta con tecnologia tradizionale. I risultati pongono le basi per ulteriori approfondimenti volti allo studio della relazione fra microstruttura e comportamento a corrosione della lega 625 prodotta mediante altre tecnologie AM.

S.

Rahimi, G. Scionti, E. Piperopoulos, M. F. Milazzo, E. Proverbio

L’idrogeno sta diventando il vettore energetico più importante nel processo di transizione energetica in particolare per il trasporto e lo stoccaggio dell’energia. Vi è quindi un crescente interesse nell’utilizzo di miscele di idrogeno e gas naturale per ridurre le emissioni di carbonio. Comunque, il dibattito sulla compatibilità dell’attuale rete del gas naturale con l’idrogeno è ancora aperto e non esiste un’armonizzazione sul valore della concentrazione ammissibile di idrogeno nel gas naturale. In effetti le leggi nazionali e le direttive UE stabiliscono differenti limiti per l’iniezione di idrogeno nella rete gas. La tecnica dell'emissione acustica è stata utilizzata con successo per studiare i meccanismi di cracking assistiti dall'idrogeno nelle leghe metalliche. La tecnica è stata utilizzata in questo caso per monitorare i meccanismi di cracking durante prove di velocità a deformazione lenta su campioni tubolari di acciaio al carbonio pressurizzati con idrogeno puro e gas idrogeno miscelato con metano. L'analisi meccanica e morfologica delle superfici di frattura ha evidenziato l'influenza della pressione parziale sui meccanismi di fessurazione. L'emissione acustica (EA) ha consentito l'identificazione di diversi cluster di dati correlati alle specifiche modalità di cracking osservate.

INTRODUZIONE

La miscelazione dell'idrogeno nelle esistenti reti di gas naturale è uno degli approcci primari utili alla decarbonizzazione delle reti di distribuzione, alla riduzione delle emissioni di gas serra e alla promozione dello sviluppo di un'economia dell'idrogeno. Tale approccio è anche alla base della procedura Power-to-Gas (P2G) per prevede l’utilizzo dell'elettricità rinnovabile in eccesso per produrre idrogeno da iniettare nella rete gas. Utilizzare le infrastrutture esistenti per il gas naturale per passare all'uso dell'idrogeno verde può inoltre evitare investimenti significativi e ritardi temporali associati alla costruzione di una nuova rete di distribuzione per il trasporto dell'idrogeno. Questo approccio ha peraltro il potenziale di favorire l’incremento della produzione di impianti di energia rinnovabile, aumentare la quota di idrogeno verde nelle forniture energetiche e garantire i mezzi per la fornitura

Sina Rahimi, Giuseppe Scionti, Elpida Piperopoulos, Maria Francesca Milazzo, Edoardo Proverbio Università degli Studi di Messina

di idrogeno per applicazioni nel settore di produzione primaria di energia e dei trasporti [1].

L’impiego di idrogeno all'interno delle infrastrutture esistenti deve essere accompagnato da una attenta valutazione dell’eventuale impatto sull'integrità, sulla durata e la sicurezza dell'intera infrastruttura man mano che la percentuale di idrogeno nella miscela aumenta. Concentrazioni differenti di idrogeno possono avere implicazioni differenti sulle linee di trasmissione, distribuzione e servizio, sugli impianti di stoccaggio e sulle apparecchiature per l'uso finale [2]. Concentrazioni di idrogeno relativamente basse (1-5% in volume) sono considerate ammissibili senza che queste comportino un aumento significativo dei fattori di rischio nello stoccaggio, nella trasmissione e nell'utilizzo di miscele di idrogeno. Miscele di idrogeno fino al 20% sono in fase di valutazione, al momento senza la registrazione di incidenti significativi [3] [4]. È da evidenziare tuttavia che, ad oggi, si riscontra nei paesi europei una varietà di limiti per l’utilizzo di idrogeno in miscela con valori che vanno dallo 0,1% al 12% in volume e che caratterizzano il diverso approccio utilizzato in ogni paese [5]. Questa mancanza di armonia tra le normative indica lacune tuttora esistenti sulla conoscenza dell’interazione dell’idrogeno con i materiali e le strutture.

La concentrazione specifica nella miscela per una particolare rete gas deve essere studiata attentamente in funzione delle differenti tipologie di acciai utilizzati nelle condotte d'epoca, della composizione del gas naturale e delle condizioni operative specifiche di ciascuna sezione della rete di gas naturale (trasmissione, distribuzione, linee di servizio). L'iniezione e la miscelazione dell'idrogeno richiedono lo studio delle modifiche necessarie al monitoraggio, alla manutenzione e alla sostituzione delle reti di condotte esistenti, per mantenere la sicurezza e la consegna dei prodotti del gas agli utilizzatori finali.

In effetti la maggior preoccupazione resta la valutazione dell’effetto dell’idrogeno sul comportamento dei materiali ed in particolare degli acciai usati per la rete gas [6] [2]. È stato osservato che piccole quantità di idrogeno possono avere un effetto sostanziale sulla fatica e sulla frattura degli acciai [7]. Inoltre, la composizione e la microstruttura degli acciai hanno una notevole influenza sulla suscettibilità all’infragilimento da idrogeno. Gli acciai API 5L X52 sono stati utilizzati per il trasporto di gas naturale fin

dai primi anni '50, il contenuto di carbonio di tali acciai era circa quasi tre volte superiore a quello attualmente presente nei moderni acciai della stessa classe di resistenza. Nel processo di produzione moderni sono state inoltre introdotti trattamenti termici e processi termomeccanici che hanno modificato sostanzialmente la microstruttura e le proprietà degli acciai originali [6]. Lo scopo di questa ricerca è quello di valutare gli effetti della composizione dell’atmosfera di lavoro sul comportamento di un acciaio API 5L X65Q di nuova generazione durante prove a velocità deformazione lenta (SSR). Il contemporaneo utilizzo di tecniche di monitoraggio di Emissione Acustica (EA), come applicato anche in letteratura [8] e di tecniche di clustering [9] dei dati di EA ha permesso l'identificazione di diverse popolazioni di eventi di EA correlabili con le specifiche modalità di fratturazione osservate. Tuttavia, in letteratura sono stati riportati risultati contraddittori riguardo la correlazione tra infragilimento da idrogeno e segnali di EA in funzione della tipologia di materiale e delle condizioni sperimentali adottate. Sebbene esistano prove convincenti che segnali di EA di elevata energia ed ampiezza siano riconducibili all'avanzamento di cricche negli acciai infragiliti da idrogeno [8] [10], alcuni autori riportano l‘assenza di alterazioni dell'ampiezza e dell'attività di EA in acciai dopo la carica di idrogeno, nonostante la modalità di frattura sia cambiata da duttile a fragile con riduzione della duttilità [11].

Per le prove sono stati utilizzati dei provini cavi (diametro della sezione di misura 10 mm, diametro del foro interno 4 mm), appositamente disegnati [12] e ottenuti a partire da barre estratte da una tubazione senza saldatura da 12 pollici di diametro e 17 mm di spessore di parete in acciaio al carbonio API 5L X65Q (acciaio temprato e rinvenuto) fornita dalla Nippon Steel Corporation. La composizione dell’acciaio è riportata in Tab. 1

Tab. 1 - Composizione dell’acciaio utilizzato per la produzione del tubo API 5L X65Q, % in peso / Composition of steel used for the production of API 5L X65Q pipe, % by weight.

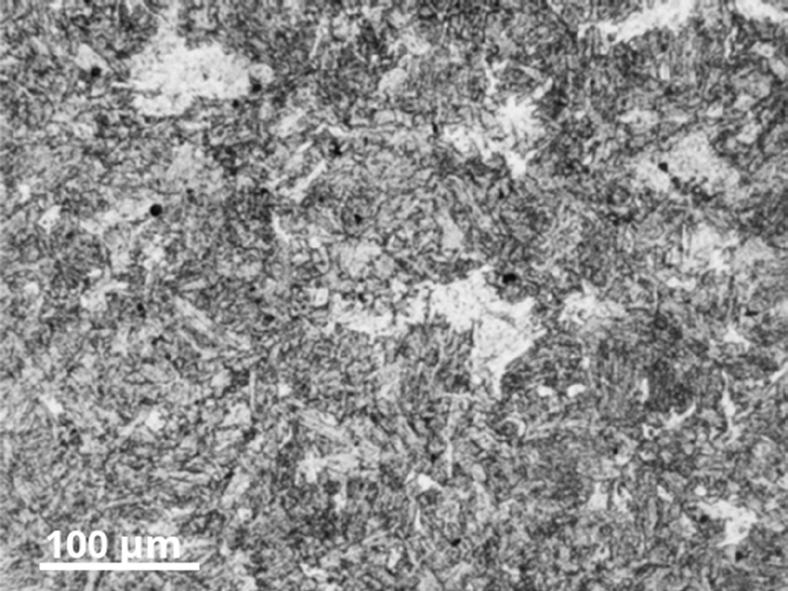

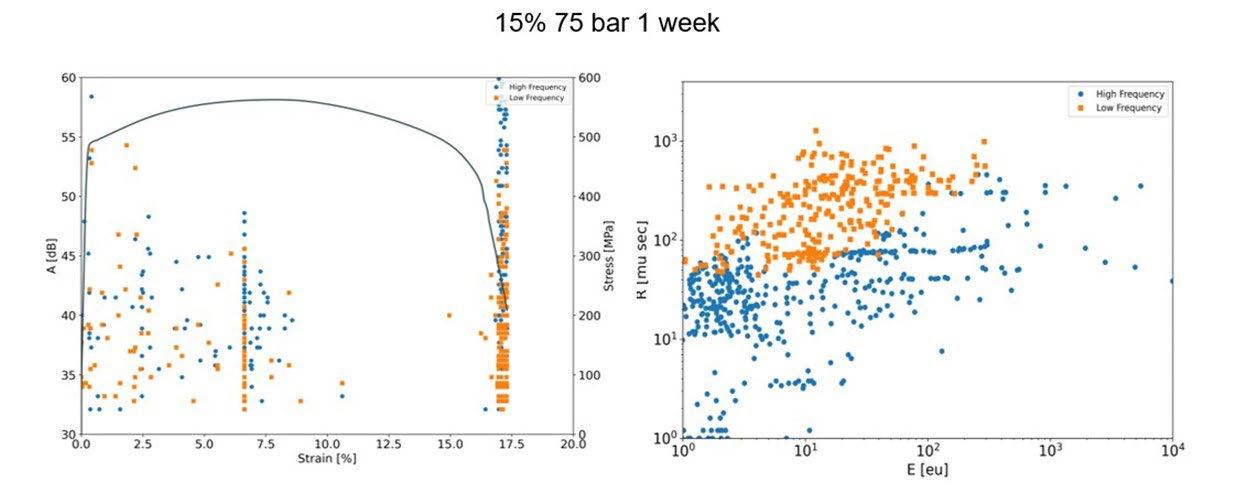

La tubazione è stata prodotta con processo di termo-formatura e trattamento di tempra e rinvenimento e la microstruttura risultate è costituita da ferrite (ferrite aciculare e poligonale) e bainite (Fig. 1). La caratterizzazione meccanica è stata effettuata con prove di trazione a velocità di deformazione lenta (SSR) con una velocità di deformazione (ϵ ˙) pari a 10-6 s-1. Le caratterizzazioni meccaniche eseguite come meglio descritto in [13] sono state eseguite pressurizzando il circuito di prova con gas idrogeno puro (purezza del gas 99,999%) a 10 MPa (100 bar) e 1 MPa (10 bar) o miscele di idrogeno – metano al 15% alle pressioni indicate nella Tabella 1. I test, condotti tutti in triplice ripetizione, sono stati eseguiti dopo un tempo prefissato di

“precarica” (mantenimento del sistema in pressione senza applicazione del carico), variabile da 24 h a una settimana. Le prove in atmosfera di idrogeno miscelato sono state condotte a 75 bar per avvicinarsi ad un valore compatibile con le massime pressioni di esercizio riscontrabili nelle condotte gas. La frazione di idrogeno impiegata è stata variata dal 5% al 15%. In questo lavoro sono riportati solo i risultati ottenuti al 15% di frazione molare. In queste condizioni la pressione parziale di idrogeno è di 11.25 bar prossima al valore di 10 bar utilizzato per i test in idrogeno puro a bassa pressione.

Fig.1 -Micrografia ottica dell’acciaio API 5L X65Q utilizzato per i test. Sezione longitudinale. Attacco Nital 2% / Optical micrography of API 5L X65Q steel used for test. Longitudinal cross section. Nital etching, 2%

Tab.2 - Condizioni di prova e identificazione dei campioni - Test conditions and sample identification.

Pressione

Due sensori piezoelettrici di EA a banda larga (Vallen VS 150-MS) sono stati fissati sia al supporto inferiore che al superiore dei campioni. Un terzo sensore, utilizzato come sensore di guardia, è stato posizionato vicino al dispositivo di serraggio superiore. La soglia per l'ampiezza (A) e il tempo di discriminazione della durata del segnale (DDT) è stata impostata rispettivamente a 30,2 dB e 0,4 ms. La rimozione del rumore tramite sensore di guardia e il filtraggio parametrico sono stati effettuati sui dati grezzi. Il filtraggio parametrico è stato basato sull’utilizzo dei conteggi (CNTS) e dei parametri durata (D) e frequenza media (AF), impiegati come indici utili alla discriminazione della modalità di propagazione delle cricche ad alta e bassa frequenza [14], gli eventi AE sono stati successivamente clusterizzati mediante un algoritmo di miscela gaussiana [15].

RISULTATI E DISCUSSIONE

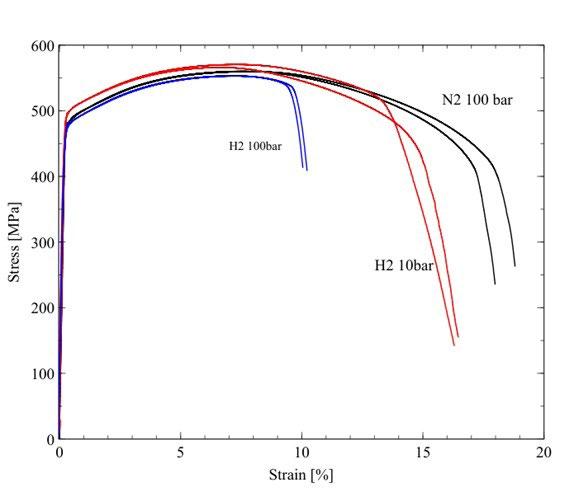

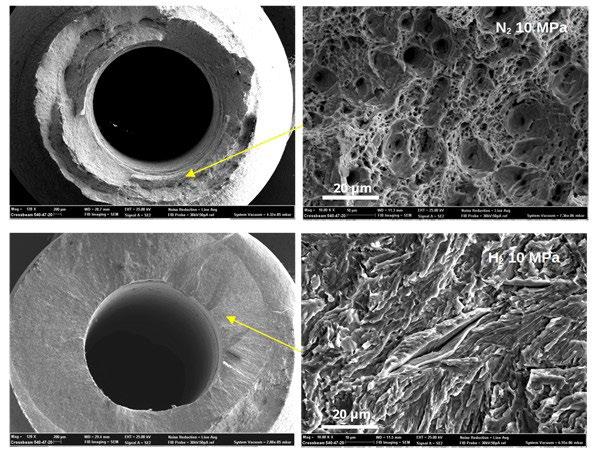

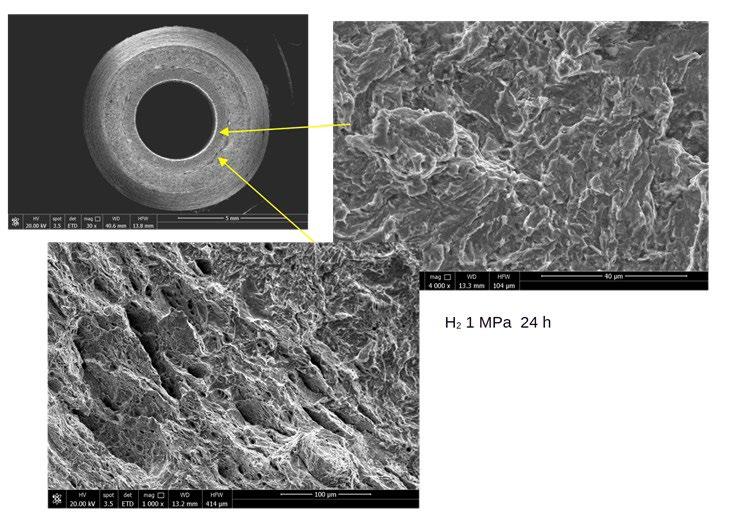

In assenza di idrogeno (test N100) il comportamento meccanico e la modalità di frattura dell’acciaio sono tipicamente duttili. Si tenga presente la forma tubolare influisce in parte sul comportamento del materiale soprattutto in termini di riduzione di sezione. La superficie di frattura è duttile con una morfologia fibrosa e caratterizzata da numerose porosità e dai tipici dimples. Si evidenza la presenza di numerose inclusioni non metalliche. Passando ad una atmosfera di idrogeno puro alla stessa pressione (test H100), il comportamento cambia drasticamente, anche se non si apprezza un’alterazione del carico di snervamento o del carico di rottura, la deformazione a rottura crolla significativamente passando da 17.7% ± 1.3 a 10.4% ± 1.7, rispettivamente (Fig. 2). La superficie di frattura è netta con una microstruttura tipica di un meccanismo di clivaggio o quasi-clivaggio evidenziata delle numerose faccette di clivaggio che interessano i grani bainitici e di ferrite aciculare che caratterizzano la microstruttura di questo acciaio. Notabile la presenza di cricche lenticolari ortogonali alla superficie e riconducibile a meccanismi di decoesione assistita da idrogeno (HEDE) a bordo grano [16]. Un comportamento a frattura duttile è individuabile solo in una porzione ridotta di superficie in prossimità del bordo esterno e riconducibile alla superficie di strappo (Fig. 3).

Nel caso dei test condotti a pressione ridotta (1 MPa [10 bar]), la superficie di frattura è caratterizzata da una su-

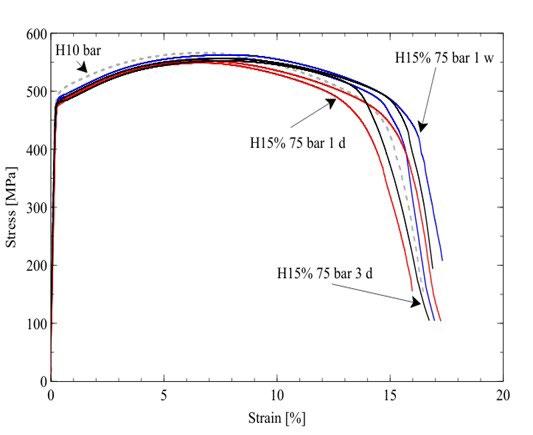

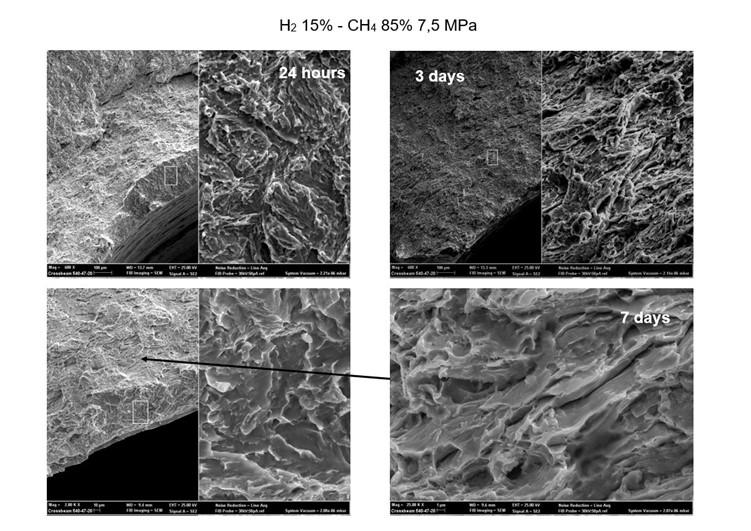

perficie anulare interna piana di circa 400-500 µ m di spessore con morfologia “fragile” e da una superficie a taglio orientata a circa 45° con progressiva transizione verso una frattura completamente duttile. La frattura per clivaggio o quasi-clivaggio è limitata a ridotte porzioni di superficie in prossimità della cavità interna. Sulla superficie a frattura “fragile”, ad alto ingrandimento, sono evidenti creste di strappo (tearing) e altre caratteristiche tipiche di un comportamento di micro-plasticità locale assistita da idrogeno [17] [8] (Fig. 4). Sorprendentemente passando dal test in idrogeno puro a 10 bar a quelli in miscela di idrogeno al 15% e 75 bar di pressione assoluta, benché le curve di sforzo-deformazione in condizioni di SSR si differenzino di poco e comunque in maniera non statisticamente significativa, è interessante notare che le superfici di frattura si distinguono in maniera abbastanza netta da quelle osservate in idrogeno puro a 10 bar.

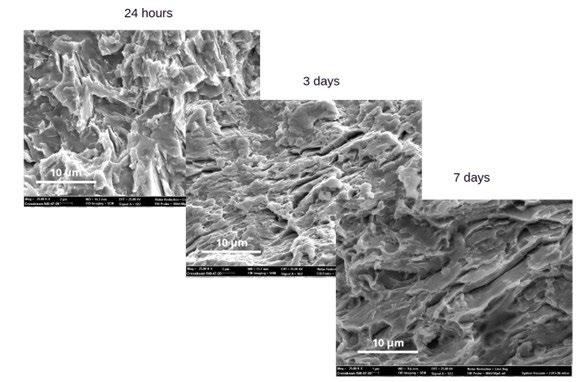

La superficie di frattura è in effetti più complessa. La porzione più interna (in prossima alla cavità centrale) per uno spessore di circa 600 - 800 µm mostra meccanismi di frattura misti con aree di clivaggio ridotte, frammiste a zone a comportamento parzialmente-duttile (non sono però presenti dimples) e caratterizzate da numerose fratture ortogonali alla superficie riconducibili a meccanismi di decoesione assistita da idrogeno. In prossimità della cavità interna sono individuabili limitate aree con frattura a clivaggio simili a quelle osservate per l’idrogeno puro ad alta pressione (Fig. 5). Nella superficie restante il meccanismo degrada verso l’esterno in una frattura prevalentemente duttile. È interessante notare che modificando il tempo di precarica, benché macroscopicamente la morfologia della superficie di fattura non si modifichi sostanzialmente, a livello microstrutturale si apprezzano alterazioni sia dell’estensione che della distanza delle cricche ortogonali alla superficie. Più fitte e di ridotta dimensione per tempi di precarica brevi (24 ore) più marcate ed estese per tempi di precarica lunghi (Fig. 6). Dati di letteratura e modelli di diffusione per l’idrogeno nell’acciaio X65 [18] [19] supportano l’ipotesi che i processi diffusivi e di cattura giochino un ruolo predominante durante la fase di precarica.

Fig.2 - Curve sforzo deformazione ottenute durante le prove di SSR nei diversi ambienti gassosi: a) gas puri, b) miscela di idrogeno-metano a 75 bar con tempi di pre-carica variabili - Stress-strain curves obtained during SSR tests in different gaseous environments: a) pure gases, b) hydrogen-methane mixture at 75 bar with variable precharging times. (a) (b)

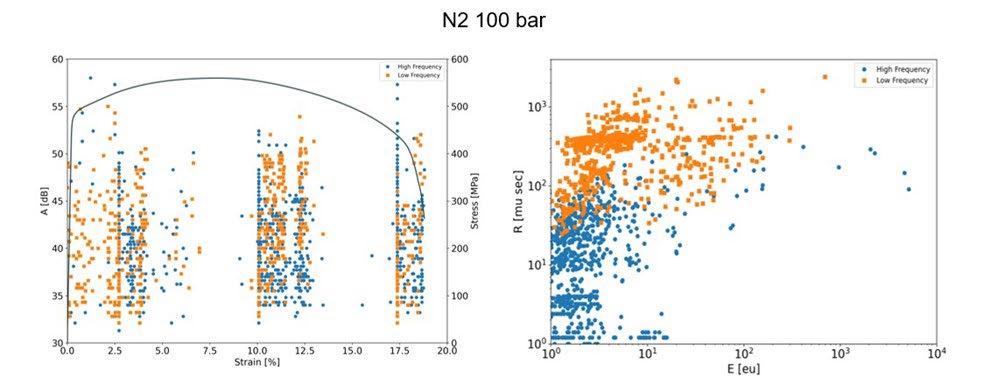

Il monitoraggio con tecniche di Emissione Acustica effettuato durante le prove di SSR ha permesso di mettere in evidenza i diversi comportamenti in campo plastico (zona di incrudimento) e in zona post-strizione prima della frattura finale dell’acciaio. Gli eventi di EA sono stati clusterizzati sulla base dei parametri di forma d’onda in

due popolazioni in cui un ruolo predominante è stato determinato dal rapporto tra il risetime (R, tempo di salita dell’impulso sino al valore massimo) e la frequenza media (AF, rapporto tra il numero di conteggi per impulso e la durata D dell’impulso stesso).

Fig.3 - Superficie di frattura dei provini testati in azoto e idrogeno puri a 10 MPa (100 bar). / Fracture surface of specimens tested in pure nitrogen and hydrogen at 10 MPa (100 bar).

Fig.4 - Superficie di frattura dei provini testati in idrogeno puro a 1 MPa (10 bar) / Fracture surface of specimens tested in pure hydrogen at 1 MPa (10 bar).

Fig.5 - Superficie di frattura dei provini testati in miscela di idrogeno-metano al 15% a 7.5 MPa (75 bar) per diversi tempi di pre-carica / Fracture surface of the specimens tested in 15% hydrogen-methane mixture at 7.5 MPa (75 bar) for different pre-charging times.

Fig.6 - Dettagli microstrutturali della superficie di frattura dei provini testati in miscela di idrogeno-metano al 15% a 7.5 MPa (75 bar) per diversi tempi di pre-carica / Microstructural details of the fracture surface of the specimens tested in 15% hydrogen-methane mixture at 7.5 MPa (75 bar) for different pre-charging times.

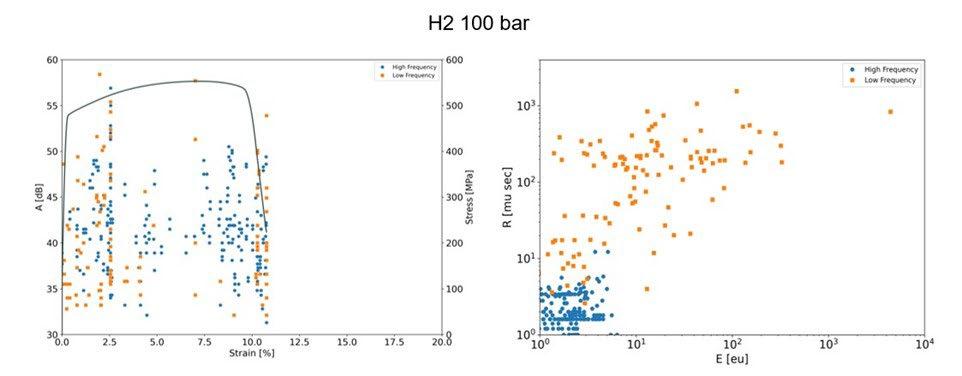

Fig.7 - Prove di trazione in atmosfera di gasi puri e ampiezza A [dB] degli eventi di EA durante le prove di SSR (curva superiore). Correlazione tra risetime (R) e Energia in eu (1 eu corresponde a 10-9 V s) degli impulsi di EA nelle due popolazioni di eventi (eventi ad alta frequenza, simboli blu, eventi a bassa frequenza simboli arancioni), curve inferiori / Tensile tests in pure gas atmosphere. Amplitude [dB] of EA events during SSR tests (upper curve). Correlation between risetime (R) and Energy [eu, 1 eu corresponds to 10-9 V s] of EA pulses in the two event populations (high frequency events, blue symbols, low frequency events orange symbols), lower curves.

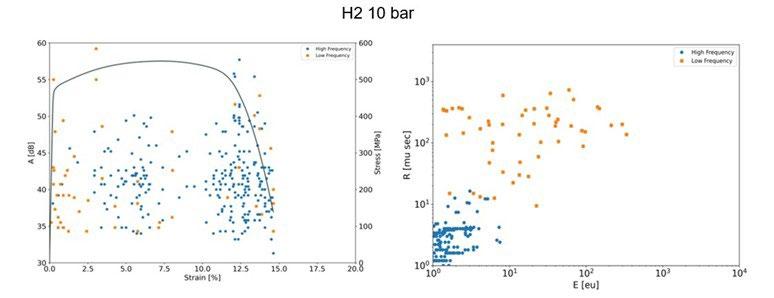

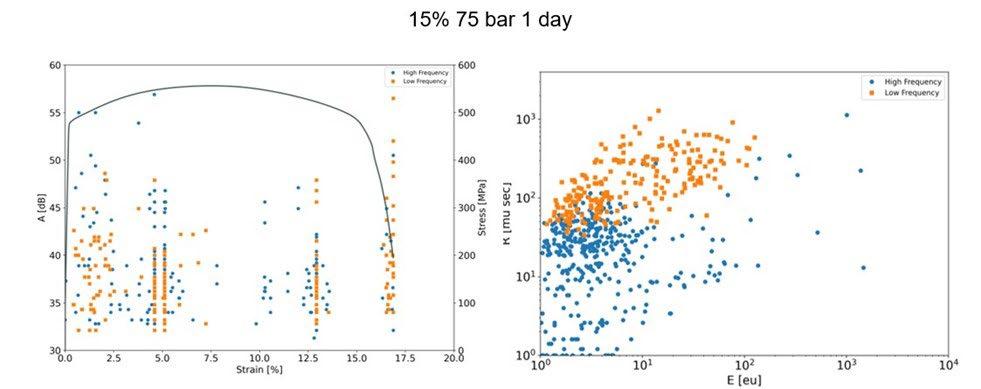

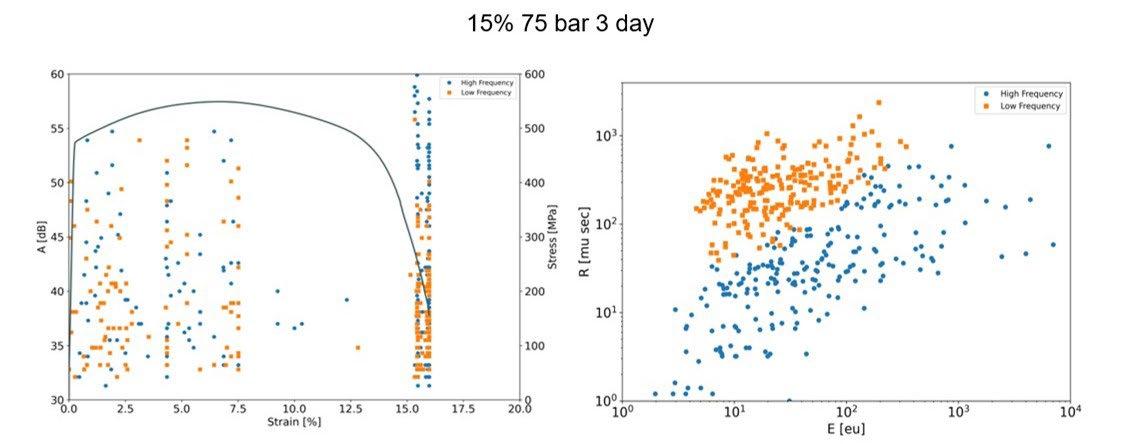

Fig.8 - Prove di trazione in idrogeno miscelato a differenti tempi di precarica. Ampiezza [dB] degli eventi di EA durante le prove di SSR (curva superiore). Correlazione tra risetime (R) e Energia [eu, 1 eu corresponde a 10-9 V s] degli impulsi di EA nelle due popolazioni di eventi (eventi ad alta frequenza, simboli blu, eventi a bassa frequenza simboli arancioni), curve inferiori / Tensile tests in blended hydrogen at different charging times. Amplitude [dB] of EA events during SSR tests (upper curve). Correlation between risetime (R) and Energy [eu, 1 eu corresponds to 10-9 V s] of EA pulses in the two event populations (high frequency events, blue symbols, low frequency events orange symbols), lower curves.

È importante ricordare che durante un test di deformazione meccanica le sorgenti di emissione acustica possono essere molteplici, dallo scorrimento delle dislocazioni, ai meccanismi di decoesione delle inclusioni, di nucleazione delle cricche, di coalescenza dei microvuoti, di frattura delle inclusioni non metalliche o delle lamelle di cementite, o di avanzamento delle cricche, etc. Il comportamento di AE durante le prove di trazione dei campioni testati in azoto è quello tipico degli acciai a basso tenore di carbonio (Fig. 7). Il tasso più elevato di emissione di eventi si osserva durante la fase di incrudimento con netta prevalenza di eventi a media energia ed elevata durata (simboli in arancio in figura). Successivamente l’emissione riprende subito dopo l’innesco della strizione con una popolazione mista di eventi, ad indicare l’insorgenza di meccanismi aggiuntivi con emissioni brevi e a ridotta energia. La fase successiva di riduzione della sezione diventa generalmente silente sino all’approssimarsi della frattura finale ove riscontriamo gli eventi più energetici. Secondo la letteratura l’evento energetico di EA impulsivo di tipo burst è spesso associato alla frattura di inclusioni non metalliche o lamelle di cementite [8]. Il comportamento dei provini in atmosfera di idrogeno puro è invece caratterizzato da una ridotta emissività e da una popolazione di eventi ad alta frequenza con risetime estremamente brevi e impulsi di ridotta energia. Questi eventi sono preponderanti nella fase di frattura finale, che si estende con gradualità a partire dal raggiungimento del carico massimo e associabili all’avanzamento delle cricche con meccanismi di strappo (tearing), cracking e fessurazione per clivaggio osservati sulla superficie di frattura. La popolazione di eventi a bassa frequenza è sostanzialmente limitata alla fase di incrudimento. Viceversa, la fase di frattura finale è ben limitata e distinta nei provini testati in miscela di idrogeno, con una significativa presenza di eventi ad alta energia e bassa frequenza riconducibili a meccanismi di lacerazione per scorrimento plastico (shearing). Contrariamente ai provini testati in idrogeno puro il cluster di eventi ad alta frequenza (simboli blu) include anche eventi ad alta energia (Fig. 8). Notabile l’assenza di eventi acustici nella fase di post strizione, se si esclude una ridotta emissività riscontrata solo per i provini pre-caricati per 24 ore. Sebbene la correlazione diretta sia difficile questa differenziazione funzione del tempo di pre-carica è supportata dalla differente

morfologia microstrutturale riscontrata sulle superficie di frattura (Fig. 6).

Pur risultando evidente che il quadro dei meccanismi di frattura sia abbastanza complesso, in funzione anche della microstruttura iniziale di questo acciaio, risulta parimenti chiaro che un approfondimento dei meccanismi emissivi supportato anche da indagini e osservazioni in condizioni di prova parziale (test interrotti a diversi valori di deformazione) potrebbe fornire informazioni interessanti sugli effetti dell’idrogeno in presenza ed in assenza di gas di miscela, anche ai fini di una eventuale applicazione per il monitoraggio in campo.

L’esecuzione di prove di trazione a bassa velocità di deformazione di provini cavi in acciaio API 5L X65Q in atmosfera di idrogeno e miscela di idrogeno-metano ha permesso di evidenziare come la presenza di idrogeno anche a bassa pressione o in frazione relativamente ridotta (15% in miscela di metano) possa influire in maniera significativa sul comportamento dell’acciaio.

L’utilizzo di idrogeno in miscela con il metano pur non modificando sostanzialmente l’allungamento a rottura rispetto a quello osservato in atmosfera di idrogeno puro a bassa pressione (10 bar) promuove l’evoluzione di meccanismi di frattura significativamente differenti. Gli effetti dell’idrogeno sul movimento delle dislocazioni e i relativi meccanismi di danno associati quali coalescenza dei microvuoti (MVC), plasticità localizzata favorita dall'idrogeno (HELP), emissione di dislocazioni indotta dall'adsorbimento (AIDE) e la nucleazione e coalescenza di nanovuoti indotta da vacanze (NVC), risultano qui preponderanti rispetto a meccanismi di frattura per clivaggio o quasi-clivaggio riscontrati in idrogeno puro.

L’utilizzo della tecnica di emissione acustica ha permesso di mettere in luce le differenze nelle modalità di frattura nelle diverse condizioni di prova sebbene un’analisi dei dati più approfondita sia necessaria per associare con certezza gli specifici meccanismi di danno con i cluster di eventi di EA e rimuovere eventuali eventi spuri. Notabile ad ogni modo il fatto che il cluster predominante in presenza di idrogeno puro è quello riconducibile ad eventi ad alta frequenza e ridotta energia (burst di ridotta durata),

di contro in presenza di idrogeno blended il contributo di eventi ad alta energia e lunga durata (meccanismi di

shearing) è significativo soprattutto nella fase finale della frattura.

[1] Topolski K, Reznicek EP, Erdener BC, San Marchi CW, Ronevich JA, Fring L, et al. Hydrogen Blending into Natural Gas Pipeline Infrastructure: Review of the State of Technology. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). 2022; (October). Available from: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy23osti/81704.pdf

[2] Somerday, B.P. & San Marchi, Chris, Effects of Hydrogen Gas on Steel Vessels and Pipelines. Materials for the Hydrogen Economy. 2007, Report n. SAND2006-1526P. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420006070.ch7

[3] Melaina MW, Antonia O, Penev M. Blending Hydrogen into Natural Gas Pipeline Networks: A Review of Key Issues [Internet]. Golden, CO (United States); 2013 Mar. Available from: http://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1068610/

[4] Krosch D, O’Shea B. Hydrogen in the Gas Distribution Networks. Clean Energy Transition - Department for Energy and Mining. 2020;149.

[5] Ronevich J, Marchi CS. Hydrogen Effects on Pipeline Steels and Blending into Natural Gas influence of stress in hydrogen environments Hydrogen Materials Mechanics. 2019;

[6] Belato Rosado D, De Waele W, Vanderschueren D, Hertelé S. Latest developments in mechanical properties and metallurgical features of high strength line pipe steels. International Journal Sustainable Construction & Design. 2013;4(1).

[7] Meng B, Gu C, Zhang L, Zhou C, Li X, Zhao Y, et al. Hydrogen effects on X80 pipeline steel in high-pressure natural gas/hydrogen mixtures. Int J Hydrogen Energy [Internet]. 2017;42(11):7404–12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.05.145

[8] Merson ED, Myagkikh PN, Klevtsov G V., Merson DL, Vinogradov A. Effect of fracture mode on acoustic emission behavior in the hydrogen embrittled low-alloy steel. Eng Fract Mech. 2019 Apr 1;210:342–57.

[9] Qiu F, Shen Z, Bai Y, Shan G, Qu D, Chen W. Hydrogen defect acoustic emission recognition by deep learning neural network. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024 Feb 7;54:878–93.

[10] Bhattacharya AK, Parida N, Gope PC. Monitoring hydrogen embrittlement cracking using acoustic emission technique. J Mater Sci [Internet]. 1992 Mar 1;27(6):1421–7. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00542897

[11] You Y, Teng Q, Zhang Z, Zhong Q. The effect of hydrogen on the deformation mechanisms of 2.25Cr–1Mo low alloy steel revealed by acoustic emission. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2016 Feb;655:277–82.

[12] Piperopoulos E, Milazzo MF, Rahimi S, Bruzzaniti P, Proverbio E. Definition of an Experimental Set-up for Studying the Safety of Hydrogen Transport Systems. Chem Eng Trans [Internet]. 2023;105:109–14. Available from: www.cetjournal.it

[13] Rahimi, S., Scionti, G., Piperopoulos, E., & Proverbio, E. (2024). Coupled slow strain rate and acoustic emission tests for gaseous hydrogen embrittlement assessment of API X65 pipeline steel. Materials Letters, 367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2024.136598

[14] Du K, Li X, Tao M, Wang S. Experimental study on acoustic emission (AE) characteristics and crack classification during rock fracture in several basic lab tests. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences. 2020 Sep 1;133:104411.

[15] Calabrese L, Galeano M, Proverbio E, Di Pietro D, Donato A, Cappuccini F. Advanced signal analysis of acoustic emission data to discrimination of different corrosion forms. International Journal of Microstructure and Materials Properties. 2017;12(3–4).

[16] Djukic MB, Bakic GM, Sijacki Zeravcic V, Sedmak A, Rajicic B. The synergistic action and interplay of hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms in steels and iron: Localized plasticity and decohesion. Vol. 216, Engineering Fracture Mechanics. Elsevier Ltd; 2019.

[17] Martin ML, Fenske JA, Liu GS, Sofronis P, Robertson IM. On the formation and nature of quasi-cleavage fracture surfaces in hydrogen embrittled steels. Acta Mater. 2011 Feb;59(4):1601–6.

[18] Fallahmohammadi, E., Bolzoni, F., Fumagalli, G., Re, G., Benassi, G. Lazzari, L., Hydrogen diffusion into three metallurgical microstructures of a C–Mn X65 and low alloy F22 sour service steel pipelines. 2014, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 39. 13300–13313. https://doi.org10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.122 .

[19] Jemblie L, Hagen AB, Hagen CHM, Nyhus B, Alvaro A, Wang D, et al. Safe pipelines for hydrogen transport. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.06.309

Hydrogen is becoming the most important energetic vector in the energetic transition process in particular energy transport and energy storage. There is therefore a growing interest in using hydrogen blends in natural gas to reduce carbon emissions. However, the debate on the compatibility of the current natural gas network with hydrogen gas is still open, and there is no harmonization of allowable hydrogen concentration in natural gas. Indeed, national laws and EU Directives set different limits for hydrogen injection into the Gas Grid.

The Acoustic Emission technique has been successfully used to study hydrogen-assisted cracking mechanisms in metal alloys. The technique was used here to monitor the cracking mechanisms during slow strain rate tests on tubular carbon steel specimens pressurized with pure hydrogen and methane blended hydrogen gas. Mechanical as well as morphological analysis of fracture surfaces evidenced the influence of partial pressure on cracking mechanisms. Acoustic Emission allowed the identification of different data clusters correlated with the specific observed cracking modes.

KEYWORDS: STEEL, HYDROGEN, HYDROGEN ASSISTED CRACKING, ACOUSTIC EMISSION

M.Faraji, L. Pezzato, A. Yazdanpanah, I. Calliari, M. Esmailzadeh

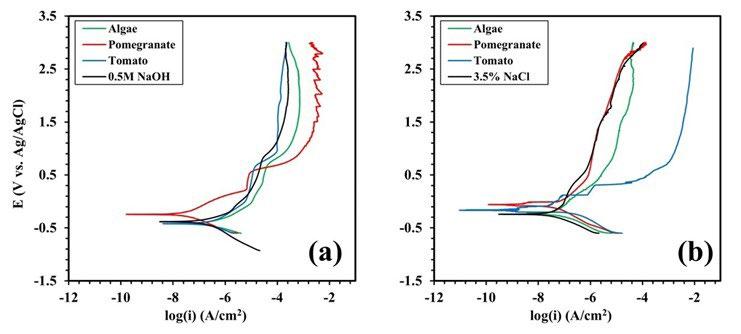

This study investigates the effects of natural inhibitors (pomegranate juice, algae extract and tomato juice) on the corrosion resistance of titanium (grade 2) and magnesium alloys (AZ31). After sample preparation, corrosion tests were conducted using a potentiostat, employing Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and Potentiodynamic Polarization (PDP) tests. Two electrolytes were tested: a solution 3.5% NaCl and a solution 0.5M NaOH. All the tests were performed with 5% of inhibitor and with the reference solution. Also, inhibition efficiency was calculated on the base of PDP tests. The study found that pomegranate juice can act as good corrosion inhibitor for titanium and magnesium alloys in aqueous solutions 0.5M NaOH. This was demonstrated by the increase in the corrosion potential and impedance modulus and decrease in the corrosion current density after the addition of pomegranate juice to the solution. However, in a 3.5% NaCl solution, the efficacy of pomegranate juice was less pronounced, probably due to the high aggressivity of the electrolyte. Tomato juice and algae extract have instead shown very low inhibition effect in all the tested conditions.

KEYWORDS: NATURAL INHIBITOR, CORROSION, POMEGRANATE JUICE, TITANIUM, MAGNESIUM

Corrosion is one of the most destructive phenomena that affects many industrial sectors, such as the marine construction, oil and gas and automotive. Numerous studies have been conducted via different inhibitors to prevent harmful effects of corrosive processes [14]. In particular the interest on green inhibitors as ecofriendly materials is currently grown to address corrosion problems [5]. In recent years, several research have been conducted on employing plant and fruit extracts as natural inhibitors, highlighting them as environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional inhibitors for preventing metal corrosion. The advantages of using these green inhibitors are manifold. Firstly, they effectively safeguard metals from corrosion while preserving ecological equilibrium. Secondly, being derived from renewable, biodegradable, and eco-friendly resources, they contribute to minimizing environmental contamination. Compared to traditional inhibitors, they are not only more economical but also several are capable of being recycled. Therefore, integrating green inhibitors into metal corrosion prevention strategies is advocated as a responsible, affordable, and eco-conscious approach [6-8]. The mature section of the pomegranate fruit is rich in

sugars, acids, vitamins, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and crucial nutrients [9]. It is recognized for its medicinal benefits, including antioxidant, antibacterial, and inhibitory effects, which are attributed to its content of anthocyanins like pelargonidin, delphinidin, and cyaniding, along with other phenolic compounds such as hydrolysable tannins including punicalin, punicalagin, gallagic, pedunculagin, ellagic acid and organic acids [10-17]. This paper aims to investigate how the use of pomegranate juice as a natural inhibitor influence the corrosion of Titanium (grade 2) and Magnesium (AZ31) alloys, tested in two different aqueous solutions: 3.5% NaCl and 0.5M NaOH. Also, other two natural inhibitors (tomato juice and algae extract) were preliminary tested but the results were not satisfactory.

An initial ingot of grade 2 titanium alloy and of AZ31 magnesium alloy was cut transversally with a disc cutter, under the jet of a cooling fluid, in order to avoid thermal alterations and lubricate the blade. As a result, square samples with a side of 15 mm and a thickness of no more than 3-4 mm were obtained. After cutting, the samples were grinded and polished using a series of silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive papers (160, 320, 800, 1000 and 1200 grit) to provide smooth surfaces. Then the samples were washed with ultrasound to obtain an optimal surface finish free of impurities. Both potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were

conducted using a Gamry Interface 1010E potentiostat in a three-electrode configuration using a Platinum electrode as counter electrode a calomel electrode as reference and the tested sample (1 cm2) as working electrode. PDP tests were conducted between -2V and +3V with a scan rate of 1 mV/s. EIS tests were conducted with a sinusoidal perturbation of 10 mV over the frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz. All the electrochemical tests were conducted after 30 min of OCP stabilization in two different electrolytes 0.5 M NaOH and 3.5% NaCl aqueous solutions. The tests were firstly conducted in the solution without the inhibitor, as reference, and after the addition of 5% of corrosion inhibitor (pomegranate juice, tomato juice and algae extract). Results of the EIS were after fitted with proper equivalent circuit using Z-View software and the equivalent circuit is presented in the section of the results. Corrosion potential and corrosion current density were graphically extrapolated from PDP tests using the Tafel law and then the data were employed to calculate the inhibition efficiency.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

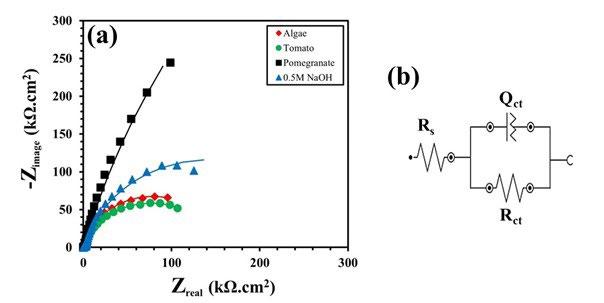

Fig. 1-2 show the Nyquist plots of the grade 2 titanium samples in 0.5 M NaOH and 3.5% NaCl solution with or without the natural inhibitors. In these figures, the experimental and fitting data can be observed by the scattered dots and straight line respectively.

Fig.1 - a) Nyquist plots of the Ti samples in 0.5M NaOH solution with/without inhibitors b) Schematic of the equivalent electrical circuit on the electrode surface / a) Diagramma di Nyquist relativo ai test su Ti grado 2 in soluzione 0.5M NaOH b) Circuito equivalente utilizzato per il fitting dei dati sperimentali

Tab.1 - EIS parameters of the equivalent circuit for grade 2 Ti in 0.5 M NaOH with/without inhibitor / Valori ottenuti dal fitting dei dati EIS sperimentali relativi ai test su campioni in Ti grado 2 in soluzione 0.5M NaOH con e senza inibitore.

According to Fig. 1a, the impedance at lower frequencies serves as an indicative measure of both the polarization resistance and the corrosion resistance. Therefore, the corrosion resistance values of the specimens are in the order of pomegranate > 0.5 NaOH (reference) > tomato > Algae. Fig. 1b displays the equivalent electrical circuit employed to fit the experimental data obtained by EIS test. The circuit includes a solution resistance (Rs) in series with a parallel capacitive loop charge transfer resistance and constant phase element (CPE) of the oxide layer formed on the surface (Rct/Qct). The CPE is inserted into the circuit to serve as an alternative to the capacitor, aiming for a closer fitting under conditions where the frequency exponent is below 1.0. [18-20]. The charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the double layer is inversely proportional to the corrosion rate. According to Tab. 1, the Rct value of the Ti sample in 0.5 M NaOH solution without any inhibitors is 2.82 × 105 Ω .cm-2 By adding the pomegranate extract as an inhibitor, the Rct value was increased to 2.01 × 106 Ω .cm-2. In other cases, it

was observed that tomato juice and algae have a negative effect on the corrosion resistance of Ti samples in NaOH solution, so that the Rct values is decreased to 1.52 × 105 and 1.56 × 105 Ω .cm-2, respectively.

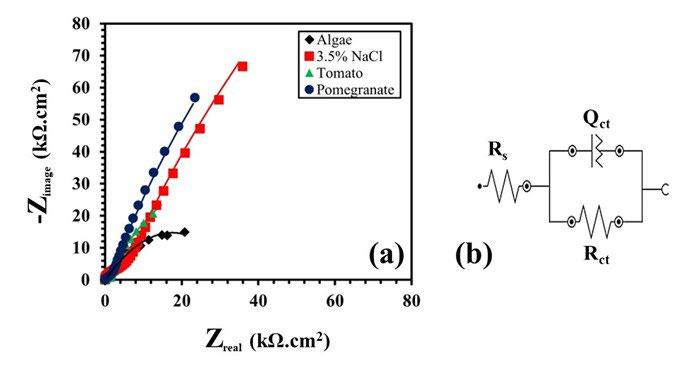

Fig. 2a displays the results of the EIS tests carried out on a grade 2 Ti sample in 3.5% NaCl solution. In this case it does not evidence a significant increase in corrosion resistance using natural inhibitors. It can be observed that the use of pomegranate juice produces only a slight inhibition effect, especially in comparison with the results obtained in 0.5 M NaOH solution. According to the equivalent electrical circuit (Fig. 2b) and EIS parameters given in Tab. 2, the Rct value of the Ti sample in 3.5% NaCl solution without any inhibitors, was increased from 8.14 × 105 Ω .cm-2 to 1.53 × 106 Ω .cm-2 by adding pomegranate juice. Inversely the addition of tomato and algae decreased the corrosion resistance of the Ti alloy, so that the value of Rct significantly decreased to 92413 and 39450 Ω .cm-2, respectively.

Fig.2 - a) Nyquist plots of the grade 2 Ti samples in 3.5% NaCl solution with different inhibitors. b) Schematic of the equivalent electrical circuit on the electrode surface / a) Diagramma di Nyquist relativo ai test su Ti grado 2 in soluzione 3.5% NaCl b) Circuito equivalente utilizzato per il fitting dei dati sperimentali

Tab.2 - EIS parameters of the equivalent circuit for grade 2 Ti in 3.5% NaCl solution with/without / Valori ottenuti dal fitting dei dati EIS sperimentali relativi ai test su campioni in Ti grado 2 in soluzione 3.5% NaCl con e senza inibitore inhibitor.

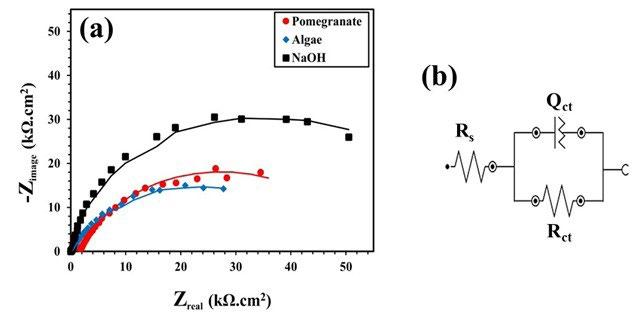

Fig. 3a reports the results of the EIS tests carried out on AZ31 samples in 0.5M NaOH solution. In the case of AZ31 alloy, it can be observed that the use of natural inhibitors does not change the impedance and corrosion resistance values; this means that the natural inhibitors studied in this work have no significant effects on the corrosion properties of magnesium in these conditions. Fig. 3b illustrates the equivalent electrical circuit employed to fit the experimental data obtained by EIS test. As shown in Tab. 3, by addition of pomegranate juice and algae into 0.5M NaOH solution, the Rct value of the AZ31 alloy sample was decreased from 70506 Ω .cm-2 to 50825 and 43920 Ω .cm-2, respectively, thus indicating negative effect of these natural compounds on the corrosion properties of AZ31 alloy.

Fig.3 - a) Nyquist plots of the AZ31 samples in 0.5M NaOH solution with different inhibitors b) Schematic of the equivalent electrical circuit on the electrode surface / a) Diagramma di Nyquist relative ai test su lega di magnesio AZ31 in soluzione 0.5M NaOH b) Circuito equivalente utilizzato per il fitting dei dati sperimentali

Tab.3 - EIS parameters of the equivalent circuit for AZ31 magnesium alloy in 0.5 M NaOH with/without inhibitor / Valori ottenuti dal fitting dei dati EIS sperimentali relativi ai test su lega di magnesio AZ31 in soluzione 0.5M NaOH con e senza inibitore

Potentiodynamic polarization (PDP)

Fig. 4 and 5 show the potentiodynamic polarization curves of grade 2 Ti and AZ31 samples in 2 different solutions (0.5 M NaOH and 3.5% NaCl). Corrosion parameters were determined by applying the Tafel extrapolation method. Linear regression was performed on the linear portions of both the anodic and cathodic branches of the

polarization curves [21, 22]. For active–passive materials such as titanium, careful selection of the linear region was essential to avoid the transition region where passive film formation or breakdown occurs. In instances where a sharp increase in current density was observed (indicative of passive film breakdown or localized corrosion initiation) those data points were excluded from the linear fit.

Fig.4 -PDP curves of the Ti samples in a) 0.5M NaOH and b) 3.5% NaCl solution with different inhibitors. / Risultati delle prove potenziodinamiche su Ti grado 2 in a) 0.5 M NaOH e b) 3.5% NaCl in soluzioni con diversi inibitori.

Fig. 4a shows the trends of the polarization curves in the case of titanium immersed in an aqueous solution 0.5M NaOH + natural inhibitors. By considering the graph, it can be observed that the only curve that deviates from the solution without inhibitors (reference solution) is the curve of the pomegranate juice. Tab. 6 shows the corrosion parameters of the grade 2 Ti samples graphically extrapolated from PDP curves in 0.5M NaOH, particularly the i corr and Ecorr. The presence of pomegranate juice obviously causes a shift in the E corr of NaOH from -384 to -244 mV. Also, a remarkable decrease in the icorr value of the sample tested in solution containing pomegranate juice can be observed, indicating high inhibition effect. According to the figure, the addition of pomegranate extract results in a pronounced increase in anodic current density at potentials above 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The anodic current for the pomegranate-treated sample is approximately one order of magnitude higher compared to the material in NaOH without inhibitors. This behavior suggests that rather than simply reducing the corrosion rate, pomegranate extract may be influencing the

passivation process, potentially modifying the stability of the surface oxide layer. The increased anodic current in this range indicates that the inhibitor may be facilitating localized dissolution or altering the electrochemical properties of the protective film. In contrast, the algae and tomato extracts in NaOH do not exhibit the same extent of anodic current enhancement, indicating a different mode of interaction with the oxide layer. The fact that the anodic current density increases significantly in the presence of pomegranate extract implies that a simple Tafel extrapolation approach would be insufficient to accurately determine the corrosion rate, as it does not account for changes in passivation and trans passive behavior at higher potentials.

Fig. 4b illustrates the behavior of a grade 2 Ti sample in 3.5% NaCl solution. From the graph it can be observed that the natural inhibitors under consideration do not significantly increase the resistance of the material as comparing the anodic branch of the different curves it is evident that there is no improvement. Considering the corrosion potential there is a slight increase in this

parameter in the presence of tomato juice and a more significant increase in the presence of pomegranate juice. Globally, however, it can be stated that from PDP tests the inhibitors do not produce significant positive effects to the corrosion properties 3.5% NaCl solution. Unlike the pomegranate extract in NaOH, the presence of tomato extract does not result in a significant overall improvement in corrosion resistance. The increased anodic current density suggests that the extract may be destabilizing the passive oxide film, potentially making the material more vulnerable to localized corrosion in chloride-rich environments. The algae and pomegranatetreated samples in NaCl exhibit relatively lower anodic current densities, suggesting that these extracts provide better surface protection under chloride exposure. Tab. 5 displays the corrosion parameters of the grade 2 Ti samples graphically extrapolated from PDP curves in 3.5% NaCl. The presence of pomegranate juice causes a shift in

the E corr of NaCl solution from -255 to -82 mV. The i corr value of pomegranate juice in NaCl solution is 9.67 × 10-7 mA/ mm2, which has the best corrosion resistance among the inhibitors, but the differences are very small in comparison to the other tested samples.

Finally, in Fig. 5 the trends of the polarization curves of the AZ31 in 0.5M of NaOH solution are shown. From this graph it is first noted that the only significant improvement is at the level of corrosion potential in the case of the solution with the addition of pomegranate juice, as the corrosion potential is significantly higher than the one in other curves. Looking at the anodic branch, however, we note that the pomegranate juice does not bring particular improvements to the resistance of the material.

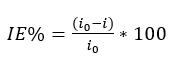

From the polarization curves it was possible to calculate the efficiency of the single inhibitors inserted in the different solutions. The efficiencies reported in Tables 3 to 5 have been calculated using the following formula:

where IE% is the inhibitors percentage efficiency, i0 is the current density in the case of the solution without inhibitors and i is the current density in the solution with the inhibitor of which the efficiency is to be calculated.

From the tables, it is possible to note that pomegranate juice has good efficiency in all three different tested solutions whereas the effect if tomato juice and algae extract is controversial and, in any case, lower than the one of pomegranate juice.

Fig.5 - PDP curves of the AZ31 alloy samples in 0.5M NaOH solution with different inhibitors / Risultati delle prove potenziodinamiche su lega AZ31 in 0.5 M NaOH con diversi inibitori.

Tab.4 - The corrosion parameters and IE% inhibitors of AZ31 alloy samples in 0.5M NaOH / Dati estrapolati dalle prove potenziodinamiche e efficienza di inibizione per i campioni di lega AZ31 in soluzione 0.5M NaO

Tab.5 - The corrosion parameters and IE% inhibitors of Ti samples in 3.5% NaCl / Dati estrapolati dalle prove potenziodinamiche e efficienza di inibizione per i campioni di Ti grado 2 in soluzione 3.5% NaCl

Tab.6 - The corrosion parameters and IE% inhibitors of grade 2 Ti samples in 0.5M NaOH / Dati estrapolati dalle prove potenziodinamiche e efficienza di inibizione per i campioni di titanio grado 2 in soluzione 0.5M NaOH

In this study the effect of 3 natural inhibitors (pomegranate and tomato juice and algae extract) on the corrosion behavior of grade 2 Ti and AZ31 Mg in two different environments (0.5M NaOH and 3.5% NaCl) was investigated. It was observed that the only substance that give significant effect in terms of corrosion inhibition is pomegranate juice. In fact, this substance has shown to produce a remarkable increase of the corrosion potential in the case of grade 2 titanium inserted in an aqueous solution with 0.5M of NaOH and a remarkable improvement of the corrosion potential also for AZ31 magnesium alloy inserted in the same solution. In the case of aqueous solution with 3.5% NaCl, however, the inhibitors were found to be less effective, even though, pomegranate juice is still the best of the three. In the EIS tests, pomegranate was found to produce a remarkable increase in the polarization resistance in the case of titanium inserted in aqueous solution with 0.5M of NaOH. Interestingly, pomegranate exhibits inhibitory effects; however, these effects are less pronounced under PD polarization. In conclusion, it is advisable to choose pomegranate juice as a possible natural inhibitor to conduct further investigations in order to clarify better the mechanism of corrosion inhibition. Algae and tomato juice instead did not give positive results in this study.

[1] O. Fayomi, I. Akande, S. Odigie, Economic impact of corrosion in oil sectors and prevention: An overview, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing, 2019, p. 022037.

[2] J. Panchal, D. Shah, R. Patel, S. Shah, M. Prajapati, M. Shah, Comprehensive review and critical data analysis on corrosion and emphasizing on green eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for oil and gas industries, Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion 7(3) (2021) 107.

[3] M. Faraji, S. Karimi, M. Esmailzadeh, L. Pezzato, I. Calliari, H. Eskandari, The electrochemical and microstructure effects of TiB2 and SiC addition to AA5052/Al2O3 surface composite coatings in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, Journal of Bio-and Tribo-Corrosion 8(4) (2022) 117.

[4] S. Karimi, N. Fakhar, M. Faraji, F. Fereshteh-Saniee, Simultaneous improvement of mechanical strength and corrosion resistance in aluminum alloy 5083 via severe plastic deformation, Materials Chemistry and Physics 313 (2024) 128755.

[5] N.O. Eddy, U.J. Ibok, R. Garg, R. Garg, A. Iqbal, M. Amin, F. Mustafa, M. Egilmez, A.M. Galal, A brief review on fruit and vegetable extracts as corrosion inhibitors in acidic environments, Molecules 27(9) (2022) 2991.

[6] N. Hossain, M. Asaduzzaman Chowdhury, M. Kchaou, An overview of green corrosion inhibitors for sustainable and environment friendly industrial development, Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 35(7) (2021) 673-690.