13 minute read

Dr. Marvin Altner

Language of Sound and Sound Images

Notes on Stephan von Huene’s Lexichaos

Dr. Marvin Altner

Who has never experienced the ambivalent feelings and thoughts caused by the sight of the dizzying abyss of a mountain valley or the depth of horizon of the sea’s surface? Immanuel Kant described this ambivalence as Angst-Lust (lustful fear) in his analysis of the sublime, as a sense of threat to one’s own existence induced by visual perception, without actually posing a physical threat to the observer.¹ At the Barenboim-Said Akademie’s Pierre Boulez Saal, amidst Stephan von Huene’s Lexichaos, the relationship between work and observer, at first glance, does not appear as an existential questioning of humanity and the world. And yet one basic constant of the aesthetic of the sublime is found here as well: the broadened view of the panorama-like oval of curving wall segments that enclose the observer. The uniform wood panels measuring 100 cm in height and 70 cm in breadth² that are affixed to the walls at regular intervals show black letters on a white background, decreasing in size from top to bottom, but set with irregular spacing and differing font size within the lines. Martin Warnke justly compares the lettering to an“ophthalmological chart,”³ emphasizing the painted letters, their font weights and positioning on the surfaces. We will return to this aspect. First, however, let us recapitulate the position of the subject in an eyesight test. It is a delicate matter: for young people, this may be one of the first moments in life in which they recognize that seeing (which also means recognizing and understanding) are not “natural,” automatic functions. Subjective perception (which is taken for granted) and biophysical functioning of perception are dissociated, thereby becoming problematic. Even later, for example

when consulting an optician as age-related farsightedness sets in, looking at the letter panels can cause mixed feelings: what and how much can I still read? The functioning of our eyes is central to our orientation within the world. When the forms start to dissolve and the subject begins—increasingly distressed—to guess at the letters, hoping to perhaps decipher them correctly by chance, this demonstrates the predicament of our limited perception. The distress here is not existential, as the subject knows that ground lenses will later solve the problem of adjusting one’s gaze anew and to the familiar acuity.

At the optician’s, we do not expect a combination of letters that would bridge the gaps in reading and aid recognition. Confronted with von Huene’s panels, the observer will initially be optimistic about getting to the bottom of these linguistic images. But there is no word, no meaning; panel after panel presents the same absence of content and significance. Invariably, von Huene shows only the forms, relying on formal aspects and leaving the observer to the individualization of the graphemes. They transform language into an abstract graph, driving anyone seeking out the meaning of words within to desperation.

If the aesthetics of the sublime as exemplified by the sea and the mountaintops are abysmal and can cause distress due to the relation of size (humans vs. nature), Stephan von Huene’s Lexichaos plumbs the depths of a loss of meaning whose representation via the panels recalls the fundamental insecurity of linguistic meaning. At the same time, it illustrates the limitations of visual faculty: if one “reads” the panels from top to bottom, the legibility and thus identifiability of the letters decreases to the point where they become almost illegible from a certain distance. The panels illustrate the disappearance of signifiers. By comparison, in Andy Warhol’s serial death and disaster serigraphs⁴ from the 1960s, the gradual decrease or increase of black printing ink from the upper to the lower border means that the visibility of the depicted objects is reduced to such a degree that ultimately, we see almost monochrome color surfaces. Amidst this emptiness, figures, objects, and events die a visual death. In Lexichaos, the letters’ isolation and their lack of context prevent conventional “reading” and “understanding,” and our impulse to decipher and interpret withers as we continue to observe. Neither one, however, stops at the negation of the visible (Warhol) and of meaning (von Huene). In Warhol’s case, it is the almost monochrome color surfaces, the colorful parts of the images that keep them alive,

even where the structures of the printing screen dissolve. Yet how could a—different—meaning be discerned from the alphabet on the panels and towers of Lexichaos? A look at the genealogy of graphemes in von Huene’s oeuvre shall lay the groundwork for an answer through the use of four examples.⁵

A review of von Huene’s work⁶ shows: isolated letters or groups of letters are a leitmotif that is present even in the drawings from the first half of the 1960s, as his career was taking off in California.⁷ There, they accompany figures in images, taking on the appearance of names, sounds, or signals. They lend body postures and gestures of the figures the expression of restrained speech. The figures wish to express themselves; one almost feels that one can hear them breathe and their bodies expanding and deflating, filling with air and rendering sounds audible when it is expelled. (Pneumatic processes have frequently occupied von Huene in his works using organ pipes in his later sculptures, and the steles of the Lexichaos towers harken back to these forms and functions.) The letter sounds are closer to those emitted by animals than to human language; they convey the impression of primeval, pre-linguistic articulation. Simultaneously, in the interstice between figures and objects they take on compositional functions, allowing the linguistic image and the visual idiom to interact. The expectation of legibility is suggested, yet denounced at the same time.⁸ The letters invariably appear in the upper case, revealing the draftsman’s dynamic style.

The latter is absent from the literary elements of the so-called ZEIT-Collagen (1980). Their title points to the fact that they were created as part of a correspondence between Stephan von Huene and one of the editors of the weekly DIE ZEIT, Petra Kipphoff, who would later become his wife. In the ZEIT-Collagen, von Huene mixes drawings with newspaper clippings containing mainly printed portraits, body parts (mostly hands), and fragments of words. Unlike the drawings, language only appears in printed form. And unlike Lexichaos, some of the sources of the sequences of letters can still be adumbrated, for example in the two partial words “Ate” and “ause,”⁹ which are easily amalgamated into “Atempause” (breathing time). Especially because these collages are the result of a private correspondence, it is significant how consistently Stephan von Huene has taken images and text of DIE ZEIT apart, focusing our gaze on many details: glances and gestures, typographical issues and phonemes. For example, in “icht” the viewer/reader recognizes the “ich” (ego) in “Licht” (light),¹⁰ which he or she might never

have sighted before. Here a playful and lighthearted approach to language is apparent that may be imagined as an unfinishable journey of discovery, less about words but rather into the words. The more familiar the reader/viewer of the text is with the language in which the texts were written, the less likely he or she is to notice such separations of words, from which an infinite amount of new letter constellations can arise. A lack of understanding causes a more distanced gaze, sharpening our attention for subordinate, smaller units of form and sound.

In the collages, von Huene has created these units with a light touch and little effort, using scissors and adhesive tape on A4 sheets of paper; at the same time, however, they also correlate with the installations in which he implemented similar work on language on a large scale and with considerable technical effort. In one of them, Text Tones (1979), metal tubes fitted with microphones and mounted on six narrow cubic pedestals record sounds and noises made by visitors and replay them, modified by a computer. Observant viewers/ listeners can partially recognize the fragments of language/sound and consciously influence the output by speaking, singing, or clapping near the tubes—and then waiting until the apparatus has processed this sound material. Text Tones encourages the visitor to participate, both in the installation and in the social space, inasmuch as other visitors are also animated, and they can all communicate with one another. The more people assemble, the more cacophonous and therefore unpredictable the resulting sounds. The technology also functions toward alienation. The language reproduced is no longer quite one’s own, the acoustic mirror reflects a twisted sound, and the listener—depending on individual disposition—reacts with irritation or curiosity, astonishment or animation to the electronic rendition of his or her voice. Oscillating between comprehension and incomprehension, the familiar language usually taken for granted must be deciphered like a foreign one for which there is no dictionary.

Continuing and heightening von Huene’s language-based work on sculptures and installations, Text Tones was followed by an extreme case of linguistic fragmentation and reduction. Three years before constructing the Lexichaos towers, his kinetic sound sculpture Erweiterter Schwitters (1987) represents a continuation of the Ursonate (1923–32) by the Dadaist language and image artist Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters’s sound poem was a radical work to begin with, foregoing the meaning of words entirely, while the artist created allusions to

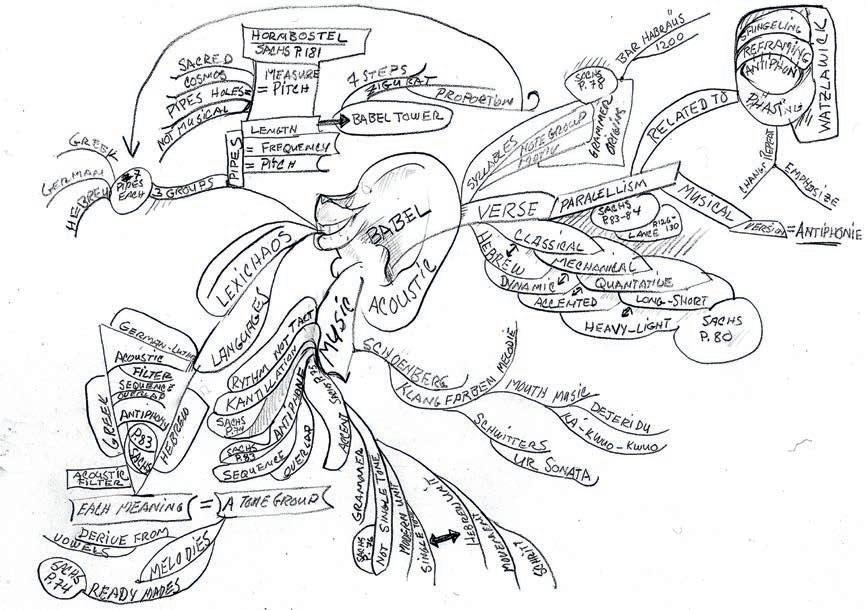

Stephan von Huene, mind map for Lexichaos, 1990, pencil on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm, Humboldt University Berlin, Hermann von Helmholtz Center for Cultural Techniques

the realities of daily life by pronouncing, for instance, written abbreviations of terms or extracts of words taken from advertisements as if they were complete words. Therein, the sound poem consisting of found word fragments is comparable to Schwitters’s image collages made from everyday materials. Taking the above-mentioned Pasadena Drawings with their close connection between letters and body shapes and sounds as a point of departure, it seems probable that von Huene’s particular esteem for Schwitters’s own performance of Ursonate was also based on the strongly accentuated lip, tongue, and guttural sounds Schwitters used to reinterpret the term “body language.” Inspired by the notion of an automatic Ursonate performer, von Huene created an electromechanical figure uttering sounds dictated by a random phoneme generator. In his commentary Erweiterter Schwitters. Eine Studie in experimenteller Realität (1989), he

explains: “My goal was to excavate the elements associating language experiences from the Ursonate, so that the sounds of the phonemes would be brought to the limits where timbre and the putative sound of language, divested of meaning, would merge.”¹¹ Reduced to timbre, to the idea of a language based on sound color, the elements that once pointed to words/sentences/text are now transformed into musical form. Were it to be notated, it would have to be in the form of a noise score or a language drawing.

Given this backdrop of remarks on the early body/noise drawings and the later kinetic sound sculptures and sound installations, the character and subject matter of Lexichaos. Vom Verstehen des Missverstehens zum Missverstehen des Verständlichen (“From Understanding Misunderstanding to Misunderstanding the Understandable“) becomes clearer. As music made up of sounds is performed in Erweiterter Schwitters, Lexichaos presents images formed out of letters. At first glance, it seems a rigid, repetitive arrangement, brought about by omitting the bodies animated by automation which were central to von Huene’s earlier works. One might miss the playful element of interaction that visitors could experience between the sound tubes of Text Tones.

Lexichaos has other traits: compared to earlier creations, von Huene formalizes (typographically precisely rendered letters, black on white), systematizes (the alphabet as the material of apparently infinite combinations), and represents (as a serially conceived exhibition) the shaping of his linguistic ciphers to a higher degree, abstracting from them and summarizing them in panels that he himself called an extension of concrete poetry, approaching the purely visual.¹² The ordered chaos of the letters is meant to seduce the viewer into actually pronouncing them, shaping the letters with their lips and making the forms resound with their breath.¹³ The moving bodies are those of the visitors who follow the example of Erweiterter Schwitters, transforming graphemes (as the silent protagonists of the exhibition) into speech and body movement. The eyesight test is also a test of speech and movement, with the bells built into the panels a possible signal to pay attention! After all, each letter contains an abyss of meaning whose depth remains unfathomable. At the Pierre Boulez Saal, where Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s Songs without Words might be heard on any other day, Stephan von Huene’s Lexichaos is performed: letters without words. But not without sound.

1 Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft (1790/1793), in: idem, Werke, Darmstadt 1966,

Vol. V, pp. 233–620. Summarized in, among others: Christine Pries, Einleitung, in: idem (Ed.), Das Erhabene. Zwischen Grenzerfahrung und Größenwahn, Weinheim 1989, pp. 7–11. 2 In his lecture “Getty Talk,” Stephan von Huene half-jokingly compared their size to that of Moses’s Tablets of the Law. What was not a joke might have been the idea that the Ten

Commandments are just as fundamental in their meaning for humanity as graphemes and phonemes are as visual and acoustic preconditions for language and therefore linguistic communication. Cf. the reprint of the “Getty Talk” in: Alexis Ruccius, Klangkunst als

Embodiment. Die kinetischen Klangskulpturen Stephan von Huenes, Frankfurt am Main 2019, pp. 317–331, here: p. 329. Ruccius also refers to it in his notes on the Lexichaos installation, cf. p. 217. 3 Cf. the present publication, p. 62. 4 Ingrid Mössinger (Ed.), Andy Warhol. Death and Disaster. Exhibition catalogue of the

Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz 2014–2015, Bielefeld 2014. 5 More extensively on this subject: Petra Oelschlägel, Lettern ohne Wörter, Stimmen ohne

Text. Das Eigenleben der Buchstaben in den Zeichnungen Stephan von Huenes, in:

Hubertus Gaßner and Petra Kipphoff von Huene (Eds.), The Song of the Line – Stephan von Huene. Zeichnungen aus fünf Jahrzehnten, exhibition catalogue Ostfildern 2010, pp. 79–91. 6 The author has decided to forego comparative illustrations here. A representative selection of illustrations (and other materials) of Stephan von Huene’s works can be found at www.stephanvonhuene.de. 7 A depiction of all the letter sequences from the Pasadena Federzeichnungen of 1961 can also be found there, cf. p. 78. 8 Alexis Ruccius therefore described the letters in the early drawings as “self-referential”:

“They are signals referring to themselves, to their own form and their own sound.”

In: Ruccius 2019, p. 206. 9 Gaßner and Kipphoff von Huene (Eds.) 2010, p. 115, Ill. D 1980-58. 10 Ibid., p. 114, Ill. D 1980-17. 11 Cf. Stephan von Huene, Erweiterter Schwitters. Eine Studie in experimenteller Realität, in: Lucie Schauer (Ed.), MaschinenMenschen, exhibition catalogue Berlin 1989, pp. 111–113. Cf. also Jesús Muños Morcillo’s extensive analysis of von Huene’s work with phonemes in: idem, Elektronik als Schöpfungswerkzeug. Die Kunsttechniken des

Stephan von Huene (1932–2000), Bielefeld 2016, from p. 153 in the chapter Harmonie der Phoneme. This also sums up the literature on this topic. 12 “I thought of an extension of concrete poetry. Concrete poetry goes into the direction of the visual. And I made them totally visual, almost.” Stephan von Huene in: “Getty Talk,”

Ruccius 2019, p. 329. 13 “Well, one way I could be sure, that you would try to spell it out is to look it [sic] like an eye chart, which I did.” Stephan von Huene in: “Getty Talk,” ibid., p. 329.

Marvin Altner has curated exhibitions at the Hamburg Kunsthalle, the Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten (Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation) Berlin-Brandenburg, and the Max Liebermann Haus, among others. He was a research associate at Berlin’s Deutsches Historisches Museum and Gropius Bau and since 2012 has been on the faculty of the Kassel Kunsthochschule. He has published essays on 20th-century and contemporary art.

Stephan von Huene, Lexichaos, 1990 (detail), one of 27 wood panels, 100 x 70 x 4,7 cm