Maria Khozina

Master of Architecture

Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

September 2021 - April 2023

Mentor: Marc Schoonderbeek

Committee:

Rick ten Doeschate, Michelle Provoost, Arna Mačkić

Maria Khozina

Master of Architecture

Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

September 2021 - April 2023

Mentor: Marc Schoonderbeek

Committee:

Rick ten Doeschate, Michelle Provoost, Arna Mačkić

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

John Donne“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Viktor E. FranklIn memory of my father, who always encouraged me to think broadly.

This project is an investigation into the role of an architect and language of architecture in an authoritarian state.

How architects can use their skills and knowledge to contribute to social change, and what role can archtecture play in the political agenda?

While “Average place” is a political issue, it is also one that has personal consequences and implications. It is about grief, the feeling of home and belonging lost. It is about a loss of understanding of one’s role as a citizen and as an architect within their homeland.

Through this project, the architect wants to explore how they can engender positive change by using their craft and professional role.

The project demonstrates how architecture can be a tool for expressing feelings and spreading ideas in order to create positive change in people’s lives.

Grief can be a powerful motivator, and through this project I was reminded of the importance of the community and the power of creative expression to make a difference.

While the specific definitions may vary, they all generally refer to the use of communication and manipulation to influence public opinion and behaviour in favour of a particular cause, group, or ideology.

Propaganda of the Russian State does not carry the function of causing an issue. It doesn’t expect you to act, it loves unconditionally. Propaganda wields a subtler influence than we may imagine. It speaks not to the mind but to the heart, seducing it with unbridled love. Its power lies not in provoking action, but in shaping perception.

In the 1930s, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis identified a variety of propaganda techniques that were commonly used in newspapers and on the radio, mass media of that period. Name-calling is a spell that smears ill repute on individuals or groups, seeking to discredit and incite fear. Glittering generalities, on the other hand, weave a web of positive words and ideas, creating a beguiling image of a

product, an idea, or an individual. Bandwagon, harnesses our need for belonging, presenting a popular idea as the norm to entice us to follow. It doesn’t demand action, but conformity. Then there is card-stacking, a game of manipulation, where only one side of an argument is laid out, omitting any contradicting facts. This creates a lopsided view and subtly nudges opinion in one direction, without necessarily requiring action. Propaganda gives you a sense of belonging without participation.

I see a great problem of Russian society in this very unwillingness to question, to reason, to think critically.

Throughout its history, Russia has experienced periods of authoritarian rule and political oppression, which may have led to a culture of conformity and distrust of authority. The Russian government has been known to tightly control media and limit access to information, which limits the exposure of Russian citizens to diverse perspectives and ideas. The Russian education system has been criticized for being overly rote and focused on mem-

This legacy may contribute to a reluctance to question authority or challenge the status quo, and a preference for conformism over individualism. A poor familiarity with alternative viewpoints, and a lack of ability or willingness to question authority, can lead to a deficiency in critical thinking skills.

Art, on contrary to propaganda, encourages a person to think. Art allows a person to remain human, to think about something, to make some decisions, including in politics.

Art has the power to encourage critical thinking and inspire reflection, and it can be a powerful tool for individual expression and political dissent. However, it is also true that art has been co-opted by governments and other entities as a form of propaganda but despite that fact, it remains an important form of individual expression and a means of promoting critical thinking and reflection.

Architecture is a political art.

Architecture can be seen as an expression of power and control, as it often involves large financial investments and decisions about the use and allocation of physical space. Buildings can also be seen as tools of exclusion and inclusion, as they define physical space and determine who has access to it. Design can either promote social inclusion and accessibility or perpetuate social exclusion and inequality. Architects and designers may be dependent on clients who have specific political agendas, such as governments or corporations. This can influence the design of buildings and public spaces and can have implications for the use and allocation of physical space.

As a citizen of Russia, as an architect from Russia, I find myself in time of great need for the new reference points and vision for the future. It is imperative that we find ways to connect with one both as individuals and as society. Through the art of spatial practices, we can begin to

establish new points of reference for solidarity and encourage the free coexistence of our communities.

I consider it, to look for new in architecture, to change the perception of the acting forces in the profession, to broaden the spectrum of influence of architecture. The impossibility of compromise today gives us a unique opportunity to look differently at established practices and re-evaluate them.

To achieve this, we must look beyond the traditional bounds of architecture and explore new horizons. Only by broadening the spectrum of architectural influence and strengthening cross-disciplinary collaboration can we truly make a meaningful impact. While challenges we face today may seem insurmountable, they also present us with an unique opportunity to chart a new path forward.

Language describes reality. It is one of the tools of architecture. And although a word can be forbid-

den, in architecture it can take on a new meaning. The right word is like the right proportion of a window.

I, as an architect, am the catalyst of doubt myself. My doubt provides for the search for the correct words, the same as a search for the best proportion or detail of a building.

The architecture of the project is expressed in design principles. The elements that appeared or were implemented by the architect to create these principles (conversation, letter, sketch, critique, scheme, word, etc.) are equal parts of the project as they allow to define necessary actions in the principals and their order.

The design principles allow a project to go from the verbalization of a problem to its formalization. The design of an architectural machine should be based on the parameters created by the architect; they are intended to be a universal language for creating any type of political machine.

By integrating into one system the elements of the plastic arts, the utilitarian nature of architecture, and the constraints in which the architect’s work is carried out, I produce - the Architectural Machine.

Machines are one of the fundamental elements in architecture. Vitruvius, saw machines as tools to aid in the construction of buildings. Aureli, believed that machines should be integrated into the very fabric of a building itself. Leonardo da Vinci was an architect who believed in the potential of machines to revolutionize the field of architecture. He saw machines as means of exploring new forms and structures. Francesco Colonna, the author of Poliphili Hypnerotomachia, described a fantastical machine that could create entire buildings out of thin air. In the 18th century, Giovanni Battista Piranesi created intricate etchings of imaginary machines and structures that blurred the line between architecture and engineering.

In the early 20th century, architects

like Auguste Perret and Le Corbusier embraced the potential of machines to streamline construction and create efficient, functional buildings.

In my case, the machine is the formal embodiment of a social issue of concern to the architect. I, as the playwright of my work, can choose which machine to design by me. I create, a Machine of Political.

Machines address the relationship between architecture and power. There are no definitive answers to that question, only attempts to try to explore that relationship. Building in ambiguities will only ‘trigger’ one’s desire to be involved in the workings of the machines. A certain curiosity is to be brought forward in the architecture to ensure in this participatory act. It is therefore also a play with conventions and cliché, though these would never be fully confirmed.

Me as an architect

What is the role of the architect in the authoritarian state?

Does architecture have an agency in an authoritarian state?

My name is Masha and I am from Russia. I have lived in Moscow all my life. I adore my home. I like my country, but unfortunately not the people who run it. I don’t agree with either the foreign or domestic policy of the ruling parties. Despite living a fulfilling and exciting life in the fast-paced metropolis of Moscow, I have always been haunted by a lingering sense of apprehension for my future and the future of my country

I think when you live in a country like Russia, you have to have a backup plan in case something happens that is a red line for you. For me, studying at the Academy was that plan. It allowed me to hone my skills as an architect while also providing a safety net in the event of a crisis. Unfortunately, my red line and that very ‘eventuality’ happened in February 2022.

I didn’t believe a full scale war was possible. I didn’t believe and neither did most of my acquaintances, people whose opinion I listened to, experts from journalists to political scientists, I didn’t want to believe, we didn’t want to believe.

In February 22, I was in the middle of working on my final project at the Academy, I was going to do a project in Moscow, exploring the potential of architecture for latent protest. The beginning of the invasion made me rethink some aspects of my work. I had new, different questions. Russians, who have been in opposition to Putin and his government since the beginning of the war, have several basic feelings: shame, pain, frustration, and rage. And while Ukraine has gained a new sense of statehood, Russia’s future is now under great question. In seeking answers to at least some of my questions, I turned to my professional spectrum. I didn’t understand what I, as an architect, a person who creates, can do in a country which destroys. What could be the role of architecture in an authoritarian state?

This work is not about traditional design methods, it’s about finding a different language of architecture, a language that can be used to explore the role of architecture and power, and to define my role as an architect.

In 1991, the collapse of the Soviet Union brought a wave of hope and optimism to Russia. The new government was committed to building a democratic society, with free elections, independent media, and a market economy. Boris Yeltsin was elected as Russia’s first president in 1991, and under his leadership, the country took important steps towards democratization. New laws were enacted to protect human rights, and private businesses were allowed to flourish.

However, by the late 1990s, the situation began to change. Corruption was rampant, and the government seemed unable to address the country’s economic problems. In 1999, Yeltsin resigned, and Vladimir Putin, a former KGB agent, became the new president. Putin promised to restore order and stability to Russia, and at first, he was popular. He launched a crackdown on organized crime and terrorism, and the economy began to improve. But over time, his government became increasingly authoritarian.

Media outlets critical of the government were shut down, and journalists who dared to speak out against Putin were harassed or even killed. The opposition parties were either co-opted or banned. Putin’s government passed laws restricting civil liberties, and the courts became increasingly subservient to the executive branch.

In 2011 and 2012, the first large-scale protests erupted in Russia, fueled by accusations of electoral fraud in the parliamentary and presidential elections, against the backdrop of Putin’s presidential nomination after Medvedev’s term ends. Putin responded with a crackdown on civil society and the opposition, passing laws that restricted protests, NGOs, and online activity.

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, triggering a conflict with Ukraine. The annexation was followed by sanctions from the international community and a rise in nationalist sentiment within Russia.

From 2014 to 2018, the government launched a series of trials against opposition figures, including Alexei Navalny, who was sentenced to multiple prison terms on politically motivated charges, and Boris Nemtsov, who was shot in the back on a bridge 100 metres from the Kremlin.

In 2018, Putin was re-elected as the president in an election widely criticized as neither free nor fair. The government continued its crackdown on dissent, and there were reports of the widespread election fraud.

The peaceful assemblies continued to be suppressed, with mass detentions and criminal and administrative prosecution of organisers and participants. The dissemination of information about uncoordinated rallies is also restricted and the approval procedure remains unbalanced and disproportionately complicated

In 2019, the government introduced a remote electronic voting system for several regions of the country. This system severely limits observer control, increases the likelihood of data leakage, and, according to some experts, makes it easier for the authorities to falsify elections.

In 2020 and 2021, Russia passed new laws that further restricted free speech, political activity, and online privacy. The Russian constitution was amended in 2020, one of the main clauses of which, will allow Putin to be in power until 2036. These are the years of the first the poisoning and then the arrest of Alexei Navalny. The beginnings of the blossoming of the law on foreign agents and extremely violent detentions and arrests at protests against the regime, that were the years when the government used the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to impose new restrictions on public gatherings and protests.

Overall, the past decade has seen a steady erosion of democratic institutions and civil liberties in Russia, with the government consolidating power and suppressing dissent. While there are still some opposition voices and civil society organizations operating in the country, their ability to affect change is limited, and the prospects for a return to democracy in Russia remain uncertain.

2022 marks Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Everything before that moment

catastrophe. Nevertheless, especially now one can clearly see all the decisions the government has made over the last decade to stupefy citizens with the state propaganda.

Throughout 2022 about half a million Russians left they country; this year was a record for the number of new articles in the Russian Criminal Code; 20,467 detentions on political grounds were made; 10 organizations were declared extremist by Russian courts; at least 20 people were detained on suspicion of treason; 10-11 million people lost the right to be elected; 378 individuals, organizations and associations were recognized as “foreign agents”; 176 individuals and organizations were prosecuted for their anti-war position; 6 civil society organizations were liquidated; 22 obviously repressive new laws were adopted; 26 mass media outlets were fined for spreading fake news about the Russian military; for the sake of military censorship over 9000 websites were blocked, including all the media outlets which expressed different opinions from the official resources.

At the end of 2022, Russia was almost excluded from the global context. With nine sanctions packages imposed on it Russia became the leader in terms of imposed sanctions.

In just a few short decades, Russia has gone from a country with promising democratic prospects to an authoritarian state excluded from the global context.

Since the late 2000s, dissatisfaction with Russia’s ruling parties has been steadily growing. It reached a peak during the 2012 presidential election when Vladimir Putin’s was elected president again, after a one term break of his protégé, Dmitry Medvedev. This move was widely viewed as a spurious attempt to circumvent the country’s term limits.

In the years that followed, the Russian government steadily increased its control over the minds and actions of the population, restricting and dictating their opinions. Despite resistance attempts, the government’s intimidation tactics, including the deployment of Rosgvardeys (National Guard of Russia) and real prison sentences for expressing opinions, prevented protest movement from achieving its goals.

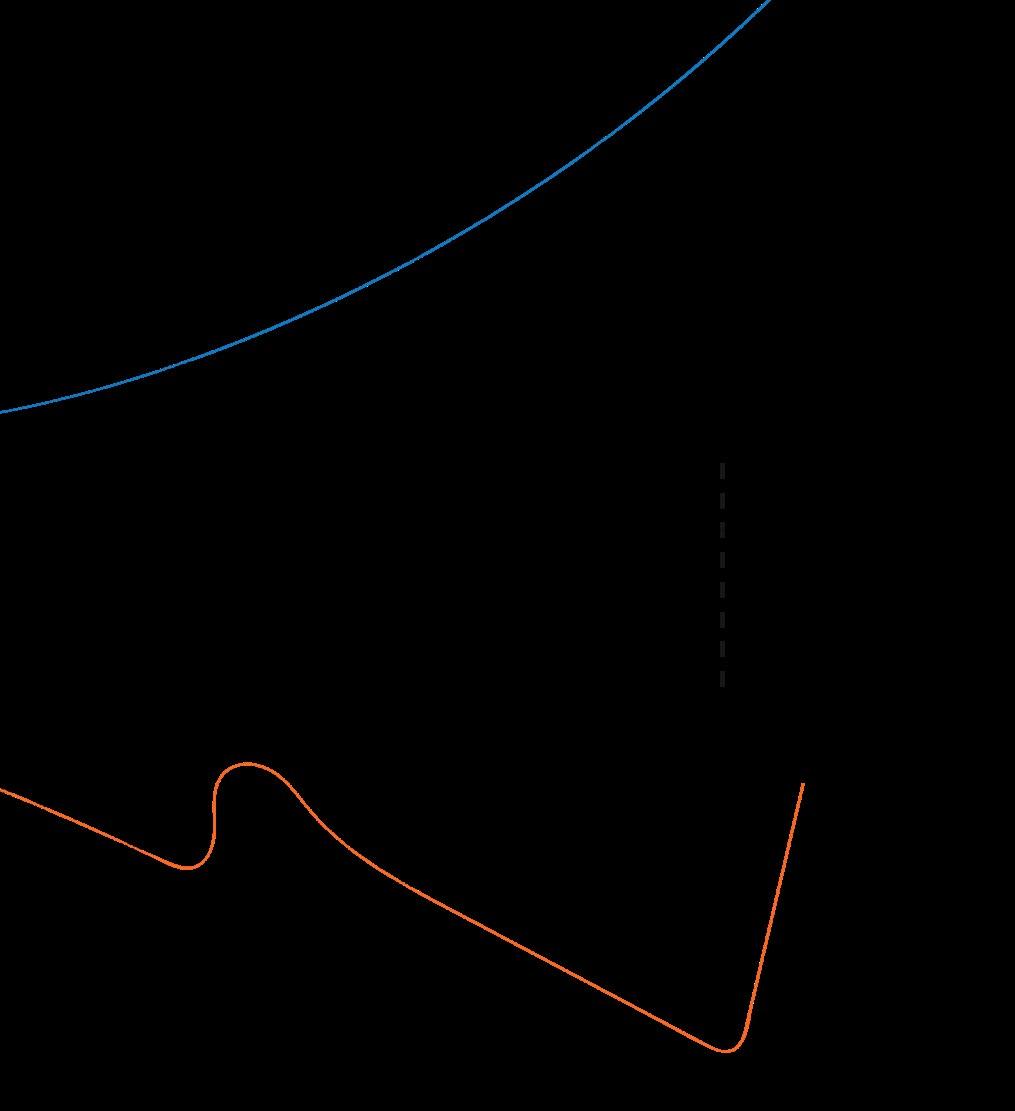

The development of state control, repression and the abolition of opposition, The Russian Federation

The timeline of protests in Russia over the past decade shows a clear increase in both the frequency and the size of demonstrations. However, the government’s repression of dissent has prevented these movements from gaining momentum and achieving real change.

As the government continues to tighten its grip, it remains to be seen how much longer the population will tolerate their actions. It is clear, however, that seeds of dissatisfaction with ruling parties have been sown and are unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Bolotnaya Square case, 2012

He Is Not Dimon to You, 2017

Ingush case, 2019

Moscow case, 2019

Vladikavkaz case, 2020

Palace case, 2021

Anti-war case, 2022

Anti-war case, 2022

Increase in the number of detainees at solitary pickets (data to 2020)

2020(january-june)

A solitary picket is the only form of public action that, according to Russian law, does not need to be notified in advance to the authorities. Nevertheless, detentions of participants of such actions are not uncommon, and in 2020 this problem has reached new proportions.

Detentions at solitary pickets in Moscow 2012-2020

number of detainees

number of detainees

In the 2000s, Russia experienced a promising era of growth and development, breaking away from the past characterized by oligarchs, side deals, and shady privatizations. This period saw the rise of massive IPOs and the growth of supermarket and telecom chains, resulting in the Russian economy’s impressive 10% annual growth.

At the same time, in August 1999, Russia launched the Second War in Chechnya, followed by a series of large explosions in Russian cities, including Moscow, resulting in deaths of over 300 people. Putin, who was the prime minister at the time, blamed Chechen terrorists for the attacks, although some suspected that the FSB may have been involved. Regardless, Putin’s response significantly boosted his popularity, and he was elected president less than a year late.

Timeline 2

Correlation between the growth of regressions and cultural and economic developments, The Russian Federation

In the mid-2000s, Russia experienced its wealthiest period. Moscow became a cool, modern European capital, and people had a chance to travel and even take weekend trips to European cities. However, this prosperity was matched by the Kremlin’s deception, as they appointed a fake president, Dmitry Medvedev, who seemed like a modernizer but was merely a puppet. The Kremlin’s trick was eventually revealed when in 2011 Medvedev announced that he was stepping down to make way for Putin’s return to power. This deceit angered the people, and in December of 2011, when the Kremlin brazenly rectified parliamentary elections, it sparked protests on the streets.

The key word during these protests was “Dignity,” as people demanded choices and a say in their government. The rallies grew from 5000 to 50000 to 100000 people, eventually moving to Bolotnaya Square, an island on the Moscow river, just across from the Kremlin. Despite the police presence, the atmosphere was not fearful

or violent. At that time it felt like the people were more powerful than the authorities because people controlled the narrative of the media, which was liberal and oppositional. However, the Kremlin was smarter than the liberals thought, waiting for the right moment to regain control.

In March 2012, Putin returned to the Kremlin as the president, and the people protested his return. This time, however, the protests turned violent, and the police responded with force. After Putin’s return to power, prosecutors went after the Bolotnaya Square protestors, putting people in jail for participating in the rallies. This was when the protests started to feel dangerous, and the hope began to fade, replaced by anger and a sense of loss.

The shooting of Boris Nemtsov, the main Russian opposition leader at the time, on February 27, 2015, on the bridge across the Kremlin, marked one of the turning points. It made people realize how well an authoritarian state could work. You, as a person, felt that you could do whatever, work, party, create a business but don’t bother yourself with politics.

Emigration from Russia by years

Figures below appear important to illustrate the scale of the phenomenon

Total

The estimate by the authors of the study based on data from the Federal State Statistics Service and the host states

By 2018, Moscow became a city of landscape parks, cycling lines, and public wi-fi, and it felt like the best place in the world to live. Cool districts, job opportunities, trendy places, express delivery and the best services from tech to beauty. It was possible to squeeze in a think “maybe it is not so bad”, but not for very long. In 2018, Putin was re-elected for the fourth term as thee president, but Bolotnaya Square remained quiet. However, the increased aggression from the riot police at protests, along with greater control and real consequences for speaking out, made people feel like the wall separating them from state repression was getting thinner and thinner.

On the morning of February 24, 2022, everything changed. Russia was plunged into a full-scale war, and the creative class that had once thrived in the country was suddenly deemed irrelevant. The wall that had once separated the people from state repression had crumbled, leaving many vulnerable to the whims of those in power.

Legislation on “foreign agents” Amendments and application practice in 2022 176 individuals, organizations and associations were recognized as “foreign agents” in 2022 Legal

Number and type of undesirable organizations by years

Breakdown of share consistency data, 2017-2019

agreed not agreed

Breakdown of data by topic, 2017-2019

Crimea migration legislation

Ukraine education against torture

LGBT healthcare

antifa

nationalist agenda

freedom of assembly ecology

dwelling urbanistic gender rights

freedom of speech

narrowly economic requirements foreign policy

other political prisoners

corruption against authority elections

On February 24th, Russia underwent a sudden shift towards authoritarianism, which had been a concern for many years. But suddenly, literally one night our worst fear became a reality. Work, that creative class had been doing these years to improve the country, became meaningless overnight. Even more, we questioned, whether we had unwittingly contributed to this system’s growth.

The nightmarish change left free-thinking Russians feeling like outsiders in their own country, which is precisely what the Kremlin wanted. Putin encouraging people to leave, resulted in the biggest brain drain from Russia since the Bolshevik revolution. Some people stayed to keep the bright hope of life in Russia alive.

The situation is too overwhelming to express solely through grief, so I decided to channel my emotions into something useful. As an architect, I believe that our field has the power to create meaning-

ful visualizations that can communicate complex emotions and ideas.

However, when a country is in a state of destruction, it can be difficult to know what is truly meaningful. How can we create something that speaks to the heart of a nation in turmoil? How can we use architecture to make a positive impact when so much has been lost?

As an architect, I have embarked on a project that delves into the complex relationship between architecture and power within authoritarian states.

While focus will be on the contemporary Russia, the project aims to offer valuable insights that can benefit architects in other authoritarian countries facing similar challenges. Although it does not provide definitive answers, it seeks to explore issues to highlight possible solutions.

To truly understand the profound and basic horrors of war and how Russian people react to it, I knew that I needed to delve deeply into the issue. I focused on investigating the reasons behind the acceptance of this destructive conflict and exploring the various reactions, attitudes, and dynamics of opinion that emerged in the first few months of the active invasion.

Through extensive analysis and personal experience of living through the catastrophic events unfolding in my country, I have come to form two major questions that continue to drive my research.

I wanted to investigate reasons behind acceptance of a destructive war by people whose memories of World War II are still fresh. What leads to this acceptance? Do all these people truly support the war, or are they indifferent to it? Are they fully aware of their decisions, or is something

else taking all the focus away from their lives? Are people genuinely supportive of the war, or is it indifference or lack of awareness that is leading to their acceptance?

Also, I reflect on my role as an architect in a country at war. What an architect, a person who creates and often works closely with state institutions, can do in a country that destroys? Is there any way to put professional knowledge to good use?

Architecture is a powerful medium that reflects the values, beliefs, and aspirations of a society. However, in authoritarian states where the government controls much of the media and public expression, can architecture become a hidden tool? If so, what type of reflection can we use it for?

In the beginning of the war, polls conducted by VTsIOM, the Russian government affiliate, and Levada Centre, an independent sociological research organisation, indicated that 70-80% of Russians were in favor of the war. However, it is important to look beyond these figures to understand the dynamics of what is happening.

To understand what is going on, one should follow the dynamics of what is happening, and it is possible to trace it back to situations that are already familiar, but war is not a predictable situation. We do not understand what public opinion is during a war. Therefore it is necessary to collect data to be able to make a complete assessment. Also, the way questions are phrased can significantly impact responses, often the question may contain the answer in itself or provoke you to choose the right option.

Support of the war, 2022-2023, % of respondents

Whether or not you personally support the actions of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine % of respondents

Further surveys by various sociologists reveal that 60-80% of Russians are clearly in favor of the war, while 20-40% are against it, with a high percentage of no answers. Here we should return to the question of dynamics. Researchers from the independent Chronicle Project who asked their respondents additional controlling questions about their attitude towards Russian aggression, succeeded in revealing that in addition to the “declarative majority” of support (60%), there is another majority - the “non-resistance majority” to the war (50-52%). The latter include both those who avoid answering the direct question about support for the war, and those who declare support, but who in other answers do not support the decisions and beliefs which are being held.

The “majority of non-resistance” is the most concerning group as they allows the pro-war minority (35-40%) to confidently dominate the public sphere, they appear unwilling or unaware that they have a choice.

Based on my personal experience, I believe that the social analysis of the Chronicle project provides an accurate reflection of public opinion in the country. While individuals who hold a clear pro-war stance have raised numerous inquiries to me, it is the cohort of skeptics that causes me greater concern and heightened questioning.

Their dissent and grievances are not represented in the public sphere. As a result, the opinion of about

38% of supporters of the war and 10% of its opponents is represented in this sphere. That is, the number of convinced supporters of the war is approximately four times greater than the number of its convinced opponents. This corresponds exactly to the widespread and superficial, though not incorrect, notion that 80% of Russians support the war.

Meanwhile, support for the war is the only officially acceptable position in Russia, while non-support is stigmatised and even criminalised if expressed publicly.

Do you personally support or not the actions of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine? in % respondents for each age group, December 2022

Do you personally support or not the actions of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine? in % respondents by information sources trusted by respondents, December 2022

“I can’t understand why people in Russia are silent!” - this scream could be read in hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian posts in the first weeks of the war. “Do they really support this? They don’t care?”

And while I could understand why people didn’t speak out and protest openly, I couldn’t understand how most Russians could support the war. It seemed to me that now everyone would be thinking about it.

From opinion polls, data analysis, interviews, and personal observations, I discovered groups of people whose attitudes, or lack thereof, interested me the most.

This is basically the “majority of non-resistance” which includes: people who find it difficult to form an opinion on the war, those who claim to support it but

subscribe to a “normative” discourse that mostly does not suit their preferences, those who claim to support it but are not inwardly sympathetic to it, and people who only speak in shorthand phrases imposed by the state propaganda.

Apart from that, I am interested in people who have chosen a position of complete obedience to the decisions of the state, and who often say “they know better at the top”, “we are small people” and other similar phrases. It is as if this group doesn’t feel they have the right to have their own opinion on such, as they say, “big issues”. Where dthis attitude comes from?

As can be seen in the timeline, both modern Russia and the Soviet Union cannot boast of frequent changes of power. And yet The constant turnover of power is important in any democratic society because it helps to prevent the consolidation of power in the hands of a few individuals or political parties. This turnover ensures that different perspectives and ideas are represented in government and that no one group becomes too powerful and entrenched.

When there is no turnover of power, it can lead to issues when leaders who remain in power for extended periods of time may become increasingly authoritarian and corrupt, seeking to maintain their power at all costs. Also, it can be difficult for new ideas and approaches to emerge. The same individuals or parties remain

Turnover of the government, The Soviet Union and The Russian Federation

in power, and there may be little incentive to innovate or make changes. This can lead to a lack of progress and development in society.

For the longest time, the Soviet Union was ruled by two men, Stalin and Brezhnev. Joseph Stalin established a totalitarian regime that suppressed all political opposition and dissent. Under Stalin’s rule, millions of people were killed, imprisoned, or sent to labor camps in the infamous Gulag system. The Soviet government also imposed strict censorship, control over media, and indoctrination through propaganda. The legacy of Stalin’s repressive regime had a lasting impact on the mentality of Soviet citizens, making them afraid to express their opinions openly and distrustful of the government.

Living under communism had a profound impact on the mentality of Soviet citizens. The lack of political freedom, censorship, and propaganda meant that people were unable to express their opinions openly or think critically about the government’s policies. The experience of living under Stalin’s repressive regime had a lasting impact on the mentality of Soviet citizens, making them fearful and distrustful of the government. Leonid Brezhnev, who succeeded Nikita Khrushchev as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was not a great politician, and he could hardly be called a leader at all. Brezhnev’s rule was characterized by stagnation and a lack of political and economic reforms, which led to a sense of apathy and resignation among Soviet citizens.

At the same time, Mikhail Gorbachev, who was in power from 1985 to 1991, attempted to reform the Soviet system through his policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). Gorbachev’s reforms led Timeline 4

The prevailing mood in the country, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation

to an increase in political freedom and a relaxation of censorship. However, they also led to social and economic instability, which contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Vladimir Putin, who came to power in 2000, has been criticized for his repressive policies and crackdowns on political opposition. Putin has also been accused of human rights abuses, including the persecution of journalists, activists, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Putin’s leadership has led to a sense of disillusionment among many Russians and a lack of trust in the government.Living under communism had a profound impact on the mentality of Soviet citizens. The lack of political freedom, censorship, and propaganda meant that people were unable to express their opinions openly or think critically about the government’s policies. The experience of living under Stalin’s repressive regime had a lasting impact on the mentality of Soviet citizens, making them fearful and distrustful of the government.

During the Soviet era, the government exerted tight control over the media, allowing only official news and propaganda to be broadcast to the public. The lack of access to alternative sources of information meant that many Soviet citizens were unable to challenge the government’s narrative. Any material critical of the Soviet system or its leaders was heavily censored.

International exchange was also limited, both in terms of travel and information, contributing to a sense of mistrust and suspicion among Soviet citizens towards the outside world.

In the 1980s, the Soviet government began to loosen its controls on the media, leading to a period of cultural and intellectual growth known as the “Thaw.” This period was marked by the emergence of new cultural figures and a greater openness to outside influences.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia experienced a period of greater openness, both in terms of access to information and international exchange. Borders were opened, and the media became more diverse, with new independent newspapers and television channels emerging. The internet also became more widely available, providing access to a wealth of information and alternative viewpoints.

However, the crisis in the 1990s, marked by hyperinflation and rapid changes in living standards, had a profound impact on the mentality of Russians. Many struggled to make ends meet and became disillusioned with the government’s ability to manage the economy. Corruption was rampant, and many people felt that the government was not working in their best interests.

The economic growth of the 2000s brought some relief to Russians, but it also led to increased corruption and inequality. Putin’s government has been accused of enriching a group of oligarchs at the expense of the rest of the population. The lack of political freedom and the government’s repression of political opposition have led to a sense of resignation and cynicism among many Russians.

Data 6

Press Freedom Index, 2021

Since the late 2000s, the Russian government has tightened its control over the media and limited access to information. Putin’s government has been accused of using censorship and propaganda to control the narrative and suppress dissent. The government has also restricted access to the internet and cracked down on social media platforms. Additionally, the government has limited international exchange, particularly in terms of political and cultural exchange, contributing to a sense of isolationism among many Russians.

Good Situation

Satisfactory situation

Noticeable problems

Difficult situation

Very serious situation

Not classified

After the analysis, we concluded that one of the fundamental, underlying problems of people raised up in Russia is a lack of critical thinking. It is a complex issue that can be attributed to several factors.

The systematic propaganda of the Russian government plays a significant role in shaping public opinion and limiting citizens’ perspectives. This propaganda promotes a particular narrative that reinforces the government’s power and suppresses alternative views. The Soviet era’s legacy of repression, coupled with communist and socialist ideologies, created a culture where conforming to the government’s directives without questioning them was expected.

The generation now making decisions has grown up with limited access to the global pool of information. The exchange of knowledge between countries during the Soviet times was tightly controlled and restricted, which could not positively influence the development of a broad outlook, which is one of the keys to having a healthy critical mind.

In Russia there is a deep-seated cultural belief in the importance of strong leadership and centralized decision-making. During the Soviet era, the government promoted the idea of a strong and unified state, and citizens were taught to prioritize the interests of the collective over their own individual interests.

In the post-Soviet era, the transition to democracy and market capitalism has been combined with political instability, economic turmoil and widespread corruption. This has led to a sense of frustration among the population and a belief that stability and strong leadership are more important than individual freedoms and rights. In many ways, Putin has won the love of the population by “pulling the country out” of that instability, which has only confirmed people’s view that “they know better at the top”.

These historical and contemporary factors have contributed to a culture in which many Russians view the government as the ultimate authority and are reluctant to question its decisions.

Architecture has always been more than just the design of buildings. It is a powerful medium that reflects the values, beliefs, and aspirations of a society. In authoritarian states, where the government controls much of the media and public expression, architecture can become a hidden tool for the expression of dissenting opinions.

I watch as my country flattens other people’s houses, destroys urban network, ruin lives. With the start of the full-scale invasion I have lost all sense of why and what I, as an architect, can create in a country that destroys.

There are many ways an architect can use his professional skills in opposition to the state. We can design buildings that subtly undermine official narratives or buildings that meet the needs of communities marginalised by the state, create public spaces that promote free expression and

debate and much more, but all this has lost all meaning for me when I look at Mariupol, a city the size of Milan, which my government has basically razed to the ground.

I wish that my profession would help me to create and feel somehow useful to those people of my country who are now grieving with me. I have many architect friends who stayed in Moscow, they want to do something useful. For myself, for them, and for all architects in similar circumstances, I decided to do this project.

I’m trying to figure out how architecture can be means of confrontation against the authoritarian state and the problems I care about. I would like to believe that we can make a difference and make a change, even if in very small, imperceptible, but important steps.

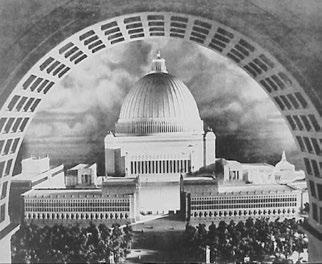

Architecture has been used as a tool of state power throughout history, serving as means to convey and legitimize political ideologies, project authority, and control public space. The use of architecture as means of vertical communication between the state and its citizens is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, reflecting the varied ways in which architecture can be used to project and reinforce political power.

The power of architecture lies in its ability to serve as a powerful symbol of a state’s identity, values, and power. Monuments, palaces, and government buildings are often designed to convey a sense of grandeur and power, reinforcing the legitimacy of the ruling regime. Such buildings often serve as a physical manifestation of the state’s power, projecting an image of strength and authority to both visitors and citizens. However, architecture can also be used to control and regulate public space, making it difficult or impossi-

Timeline 7

Architecture and Power, Worldwide

ble for citizens to engage in dissent or protest. Buildings and urban planning can be designed to restrict the movement of citizens, making it harder for them to navigate and escape. Architecture can also be used as a tool of propaganda, with the design of buildings and public spaces conveying specific messages or ideas.

Soviet-era architecture, for example, was often designed to communicate the ideals of communism and the power of the state.Finally, architecture can be used to promote economic development and infrastructure projects that benefit the state. Large-scale construction projects such as highways and airports can help to boost the economy and reinforce the power of the state. Soviet-era architecture, for example, was often designed to communicate the ideals of communism and the power of the state.Finally, architecture can be used to promote economic development and infrastructure projects that benefit the state. Large-scale construction projects such as highways and airports can help to boost the economy and reinforce the power of the state.

The architecture of resistance is a concept that refers to the use of architecture as a tool for political resistance against oppression, domination, or injustice. It involves designing buildings, spaces, and structures that express opposition to the status quo and promote social change.

The architecture of resistance can take many forms, from overtly political buildings that serve as symbols of resistance to more subtle design choices that challenge dominant ideologies. For example, a building’s design may incorporate symbols, imagery, or materials that represent a particular cause or movement. Alternatively, public spaces may be designed to encourage free expression and civic engagement, allowing people to gather and discuss issues that are important to them.

The architecture of resistance is often associated with social and political movements that seek to challenge power structures and promote social justice, such as anti-colonial, feminist, or environmental movements. It can also be a means of preserving cultural identity and heritage in the face of political and social repression.

There is no such thing as universal architecture of resistance. It is always particular, responding to the specifics of a place and time. The achitecture of resistance is impermanent, ephemeral, because situations change, and with them the very need for resistance.

Architecture can resist by being for something, so after resistance, it still will have a meaning.

Using architecture as a tool of resistance is a reflection of the power and potential of design to shape the world around us. Architects are able to create spaces that embody our deepest values and aspirations, and use these spaces as a means to resist authoritarianism and oppression.

Throughout history, architects have used their skills to challenge dominant power structures and resist oppressive regimes. From the ancient Greeks, who designed temples as a means of resistance against the Persians, to contemporary architects. During the civil rights movement in the US, architects designed community centres, churches and other public buildings that provided safe places for African American communities to organise and gather. Similarly, during the Occupy Wall Street movement, architects designed opening

structures and shelters to support protesters and maintain their occupation of public spaces. Another approach to architecture of resistance is to involve users in the design process. This participatory design approach is a powerful tool for empowering marginalised communities and creating spaces that reflect their values and aspirations.

The architecture of resistance offers a powerful way to rethink architecture as an emancipatory, inclusive and elitist practice accessible to only a few. This approach raises important questions about the role of the architect in society and whether architecture can truly be an insurgent practice where everyone has the potential to be an agent of design and construction.

The example of Moscow serves as a clear illustration of how the authorities appropriate all public space. Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the ‘right to the city’ is lost, as any opinions that diverge from state ideology are pushed to the physical or discursive periphery of the city, if not both.

Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin’s team employs the urban planning technique of initially saturating space with meaning. Thus, any space built, renovated or restored already has a label or functionality prescribed by the authorities. Scholars have pointed out that urban planners, who usually work for the authorities, tend to disregard the opinions of residents regarding certain urban spaces. In the interaction model between space and ideology, ideology tends to physically transform space.

Collection 3

City as unwilling participant, Russia

In the last decade, there has been a strong trend towards either endowing territories with meanings or depriving them of meanings. Cecil Clementin’s work highlights how empty spaces in the city are appropriated by the discourse of power. For instance, the empty square between the Borovitsky Gate and the Pashkov House was filled with a huge statue of Prince Vladimir, who is revered in Orthodoxy as Equal-to-the-Apostles, introducing the power discourse of ‘Orthodoxy as the spiritual pillar’ of the country. Meanwhile, the empty square that emerged after the demolition of the Rossiya Hotel, located just a hundred metres from the Kremlin walls, was stripped of its political status, and Zaryadye Park was established in its place.

The close relationship between architecture and urban planning professionals and the authorities in Russia has become increasingly apparent over the last decade. The ‘My Street’ program, a multi-year project aimed at improving the urban environment and landscaping of areas, has brought positive changes to public spaces in numerous Russian cities. However, concerns have been raised about the quality of work done, with some suggesting that the tiles used were intentionally low quality to create a case for more funding and possible corruption. Additionally, the program has been criticized for the use of CCTV footage to identify individuals who do not conform to the government’s wishes, as well as the excessive and sometimes contradictory functions assigned to public spaces that can limit people’s ability to reflect..

Another program launched two years later, the housing renovation program, aimed at replacing the housing stock of the 1950s to 1980s, mainly the so-called ‘Khrushchevs’. Despite being presented as a way to improve

residents’ quality of life and create a comfortable urban environment, it sparked much debate and controversy. The assessment of the cost of housing and social support for the inhabitants was considered unethical, and the state’s involvement in new construction and the relocation of residents from expensive to cheaper areas of the city was suspect.

The Russian state architectural bureau’s involvement in designing new residential buildings for the Ukrainian city of Mariupol during the ongoing conflict is a striking example of the interaction between architects and the authorities. Despite the city being destroyed by Russian bombs, a new master plan for the city, complete with bicycle lanes and recreational areas, was created and published by the Russian Ministry of Construction the same month as the annexation. Clips of happy residents of new residential complexes are continuously aired on state television, using architecture as a form of propaganda and bribery. This raises ethical concerns regarding the role of architects in advancing the interests of the state.

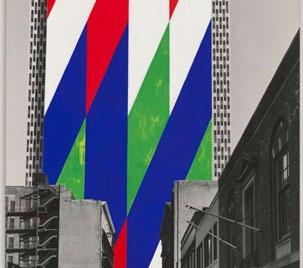

When it comes to art in the USSR, the usual associations arise: socialist realism, strict censorship, lack of creative freedom. But in addition to official art, there was also underground art, inaccessible to the mass viewer for ideological reasons. These were works that did not fit the criteria of conventional social realism.

During the 1960s, artists used images of spacecraft and cosmonauts in their works as a form of protest against government policies. These works hinted at human rights violations and social injustice, and stood in contrast to conceptualism by directly mocking the Soviet regime.

To avoid censorship, artists organized independent underground exhibitions that showcased works forbidden for public display. However, these activities put artists at risk of reprisals from state authorities. In the 1980s, many artists emigrated from the country, while those who stayed tried to establish constructive dialogue with the authorities. In Leningrad, artists formed the Association of Experimental Exhibitions,

Collection 5

Resistance through culture, Russia

which organized many exhibitions over the next decade. This allowed artists to showcase their works to the public and to engage with the government in a more constructive manner.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian culture, having found itself embedded in a global context, lost the right to be universal and define its own criteria. The artists were able to reflect on the experience of searching for a new national identity and language of representation. Their response was a radical gesture of exhibitionism, communicative violence and linguistic surrender.

It could be said that performances, installations and other gestures became the only artistic fact in contemporary Russian culture in which the relationship between man and power, economic catastrophe and the ambition of a new national ideology were reflexed.

Not Allowed

Russia

For now partly allowed

I am deeply interested in the properties of architecture that are necessary and significant for the projects and situations I am examining. I believe that architecture has the potential to be a powerful tool for subtle forms of resistance. Unlike more direct forms of resistance such as protests or texts, architecture’s impact is not always immediately apparent and may involve a range of diverse methods for engaging with people. This is because architecture doesn’t just present itself to individuals; it also shapes the spaces they occupy.

My intention is to utilize architectural skills at the intersection of art. Unlike fine art, which more frequently provides users with an opportunity for observation and introspection, I aspire to involve the full spectrum of human senses and encourage interaction with the user.

My objective is not only to interact with visitors but also to connect with other architects who find themselves in similar circumstances or share my situation. By applying the principles of participatory

architecture, I aim to transfer these skills to interactions with other professionals and engage in collaborative work.

I seek to explore the potential and agency of architecture in the face of an authoritarian regime. Although I do not anticipate finding a clear-cut solution, I intend to utilize my profession as a medium for resistance. My hope is that through this work, I can inspire others to see the possibilities of architecture beyond its traditional role and to recognize the power it holds in shaping our world.

To raise doubts by encouraging people to participate with an architecture built on ambiguities

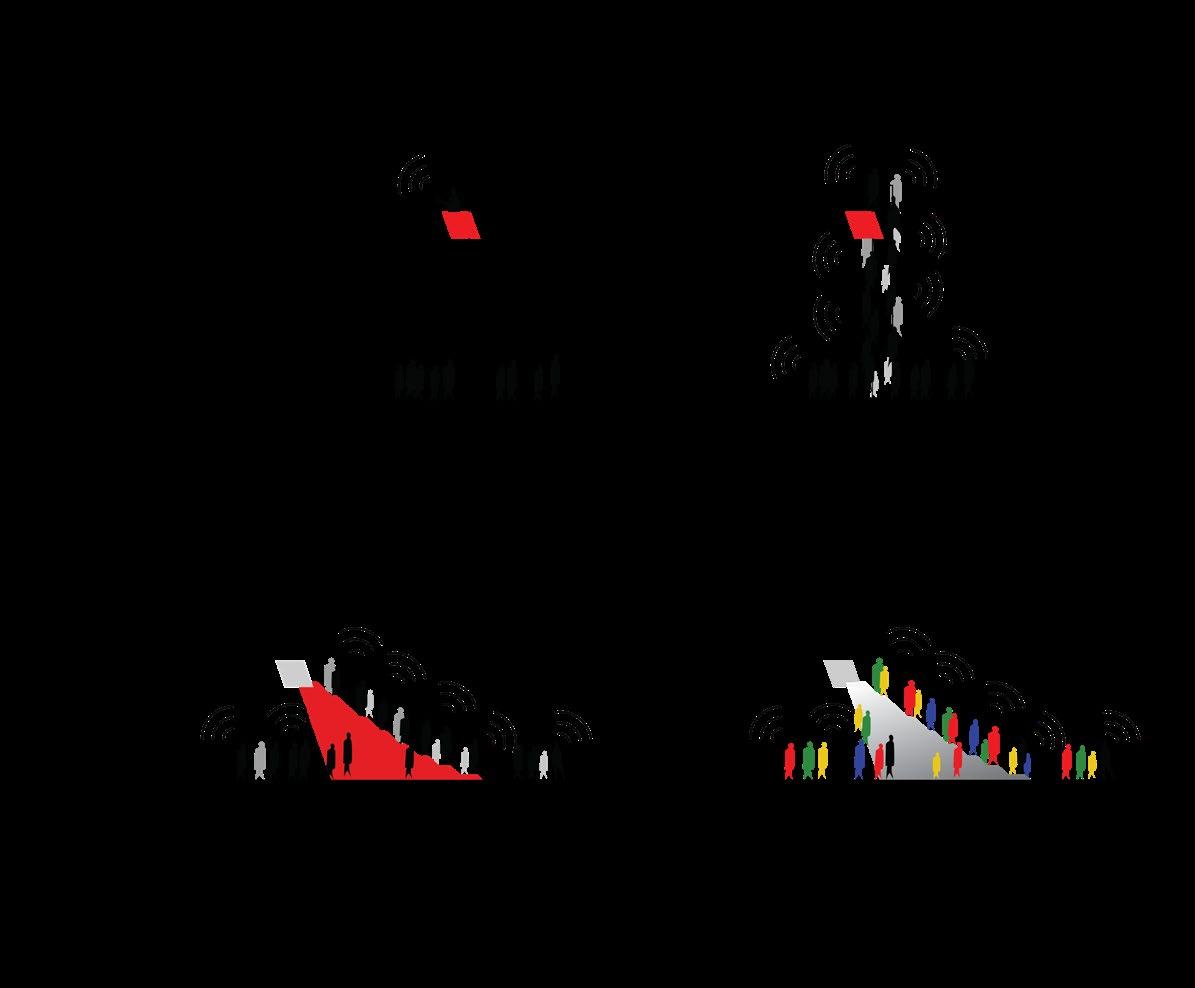

Architect as an activist Architecture and the knowledge of architects as a hidden tool in the conversation

Upon conducting an analysis of the categories of interest, two primary objectives for the project were identified.

The overarching goal is to explore the potential of architecture to interact with people, specifically examining how architectural tools can engage users in interaction and deepen the comprehension of their experience. This includes investigating whether architecture can operate on a subconscious level, evoking associations and prompting a thought process. Architecture shapes physical and symbolic boundaries, influencing individual and social trajectories. Therefore, we seek to assess the extent to which architecture affects individuals and whether it has enough agency to engage with them on a subconscious level, prompting reflection rather than delivering a concrete message.

It is my contention that the present circumstances in my country can be attributed to a lack of critical thinking skills among the populace. I believe this is a result of historical events, living condi-

tions, and types of regimes and authorities that have emphasized the immediate physical concerns necessary for survival, leaving little time for reflection. However, I maintain that the habit of reflection and the ability to think critically can be cultivated through a gradual and unobtrusive process. In light of the current limitations on active protest in Russia, the tools of spatial practices, as opposed to overt influence, are more suitable than ever.

My objective is to restore the social mission of architecture and architects in authoritarian countries, creating a tool that permits architects to serve the public good directly with their hands. It is worth noting that defining the public good may prove challenging. In this project, we do not seek to convey a particular message to the public; rather, we hope to establish a starting point for fostering reflection on what individuals require for a better life.

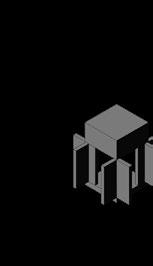

The term “architectural machines” was originally coined by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze to describe how architecture can be viewed as a dynamic system that generates and transforms subjectivity. In this sense, architectural machines are not just functional or aesthetic objects, but active and dynamic systems that both shape and are shaped by human experience and perception. By integrating the elements of plastic arts, the utilitarian nature of architecture, and the constraints in which architects work, I aim to create the Architectural Machine.

The machine is the formal embodiment of social issue that concerns the architect. As the playwright of my work, I can choose which machine to design, and in my case, I choose the Machine of Political. Machines address the relationship between architecture and power, and while there are no definitive answers, attempts can be made to explore this relationship.

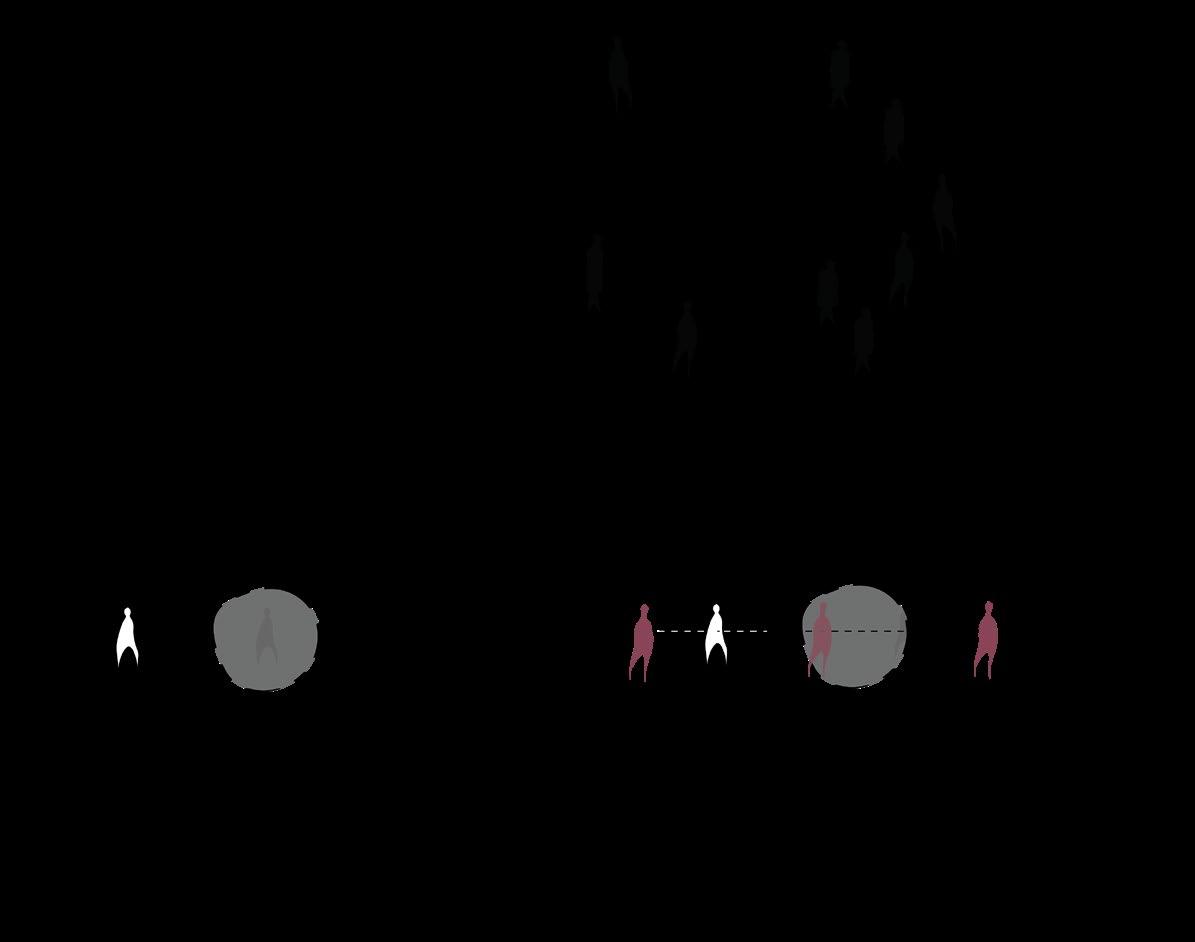

All machines have a certain set of features required to interact with people.

Building in ambiguities can trigger one’s desire to be involved in the workings of the machines. A certain curiosity needs to be elicited in the architecture to ensure this participatory act. I play with conventions and clichés, although they would never be fully confirmed. They will provide the user with the necessary information base even before the interaction begins and serve as the foundation for the development of doubts.

I aim to create a language that architects can use to create their own machines that speak the vernacular of their location and respond to their experiences. And since we cannot predict the outcomes of the interaction, this is just an attempt to set the stage for further reflection..

Machines deal with architecture in the form of participatory engagement with a people. We want to evolve the concept of participation to a more active engagement with the public. We see people as co-creators of the built environment, as opposed to passive recipients of design decisions. In our opinion, this should help users develop a personal relationship with the subject and provoke a personal opinion of it.

In this context, the machine can be seen as a metaphor for architecture, as both are complex systems made up of multiple parts that work together to achieve a common goal. The mechanism, then, refers to the way in which people interact with the built environment. Just as a machine cannot function without proper mechanisms, architecture cannot fulfill its purpose without the participation of people who inhabit it.

Participatory architecture is not only about involving the public in the design process but also about empowering them to take an active role in shaping their

surroundings. This can take many forms, from community workshops and public consultations to co-design processes and collaborative construction projects. The aim is to create a sense of ownership and belonging among people who use the space, which in turn can lead to a more sustainable and resilient community.

Another benefit of participatory architecture is that it can lead to a more meaningful and satisfying experience for the people who use the space. When people feel that they are capable to change something in the design of a building or a public space, they are more likely to feel sense of ownership and pride in the space. This can lead to a greater sense of community and social cohesion, which in turn can have positive impacts on health and wellbeing.

The mentioned projects share a common interest in creating immersive and interactive architectural experiences that engage the viewer’s senses and emotions. These works challenge traditional understanding of architecture as a static and functional entity, and instead propose more fluid and dynamic relationship between space, perception, and experience.

Despite the diversity of the approaches, these works share a common goal of creating spatial experiences that go beyond mere function or form, and instead aim to provoke more profound engagement with a space and its implications.

These pojects can be seen as “architectural machines” insofar as they use technology, mechanics, and sensory stimuli to create an interactive and transformative experience of space.

Architectural machines are interactive constructions that aim to instil doubt in the participant. Their design principles must abide by fundamental parameters, upon which various images can be superimposed. Embedding a sense of curiosity within the architecture of machines is imperative for facilitating human interaction with them. Ambiguity must also be present, as it “triggers” human desire to engage with these architectural machines.

We anticipate that this project will be useful for architects from any authoritarian country. They can utilize this concept to produce their own machines. As the objects interact with users through language and comprehensible symbols, it is crucial for these machines to fit the specific context of their location, making each machine unique and suitable only for particular zones.

To ease the process of designing machines by other architects, we have outlined the principles that guided us in creating our own machines.

The primary and fundamental parameter is the ability for human interaction with the machine, along with the presence of ambiguity within its design elements. The physical parameters and location recommendations are only advisory and depend mainly on the architects’ financial resources, the environment’s availability, and the state’s control over public spaces.

AMBIGUITY OF MACHINES

LOCATIONS FOR MACHINES

Architectural machines are the carriers of embedded metaphors. Only through interaction with machines users can reveal hidden meanings and experience them through different senses.

The machines are created for thoughtful and innumerable interactions that allow the exploration of symbols that are not what they seem at the first sight. Multiplication of complexity allows seeing the world in its diversity. It also creates various contradictions and paradoxes.

Proposed technical characteristics improve usability, assembly, and relocation of machines. 1 2 3 4

The creators are the ones who decide locations for their machines. Certain criteria of location are important to ensure that wide range of people get to interact with machines.

Through human-machine interaction, it is assumed that doubt is aroused

Recommendations on physical parameters are rather tentative and the degree of compliance depends almost solely on the capabilities of architects and/or machine builders.

We take as basic parameters a low budget for construction, installation and transportation of objects, as well as the ability to move objects in one ‘meaningful’ area.

However, there are some factors that have to be taken into account when designing architectural machines that aim to interact with visitors. The first parameter pertains to the autonomy of design, which permits the machine to engage visitors without the involvement of the author. The machine must be designed to facilitate interaction with visitors in a seamless manner, ensuring positive experience. Additionaly, vernacular materials are recommended, as they help visitors to build initial connection with the object as something familiar and recognizable, thereby easing the entry into the interaction.

Proposed technical characteristics improve usability, assembly, and relocation of machines.

- Modular structure enables easy assembly and relocation.

- Availability of professional equipment or skill can influence complicity of joints.

One or two creators with average construction skills can assemble the machine. The results may vary depending on the finances or skill.

- The maximum weight of detail is related to the amount of creators:

24 kg - one creator

33 kg - two creators

Design of machine ought to initiate an interaction with a user without participation of the creator.

- Autonomy of the machine is crucial as contact with the creator can greatly affect user-perception of the machine.

- All interactive mechanisms should be usser-friendly and intuitive.

- It’s essential to add a short description label for each machine.

In order to interact with wide amount of people it’s important to change locations. Hence, it’s crucial to create machines with future relocations in sight.

In order to have a wide range of possible locations, machines need to be designed within certain dimmensions - from minimal sizes of a doorway to the maximal sizes related to usability, safety and future relocations.

Local and easy-to-access materials will help machines to become more accessible in construction and to connect with people by using familiar materials in unfamiliar way.

- Wheels can be used in design of machine, but it’s crucial to choose appropriate wheel-type for the future relocations.

- Structure of machine needs to be flexible and sturdy for the repeated reassembly. Avoid fixed joints (welding) and joints that can damage material over time (self-tapping screws).

- The minimal dimensions are related to the size of doorway - 80x210cm (WxH)

- Beware of height limitations for usability and future relocations (height of bridges, tunnels, parking, etc.)

- Beware of size and requirements limitations for structures without building permit.

-Beware of dimension limitations for relocation with car or bicycle (width of roads and paths).

- Using local materials in the creation of machine can give a greater sense of connection with the surroundings.

- Easy-to-access materials are materials that widely available in any location. Using them in the creation of machines will reduce construction time and costs.

A concept of interaction between visitors and architectural machines plays a crucial role in revealing the metaphors embedded in these objects. In order to enhance visitors’ experience, it is recommended that multiple machines are endowed with the ability to interact with different senses and a varying number of people. This will allow visitors to fully perceive machines and meanings embedded in them.

Parameters related to interaction with sences are the most significant to consider in the design of architectural machines. Human perception of a space is determined by both visual and bodily sensations. Therefore, incorporating interaction with multiple senses can make the perception of machines more dynamic and memorable. This approach also provides authors with more opportunities to communicate with the user through the architectural language.

Architectural machines are the carriers of the embedded metaphors. Only through interaction with machines users can reveal hidden meanings and experience them through different senses.

Seemingly passive our bodies constantly receive information and analyze surroundings through though primary senses.

- Vision. Distant Stimulation

Vision is the quickest human sense of all. Sight enables quick spatial assessment, but designing primarily or exclusively for sight will prevent from creating an allrounded and in-depth experience. Sensations of shape & size, ratios of color, shade and shadow, space, and motion.

- Hearing. Distant Stimulation

Sound helps a person perceive space. Sound reaches a person, while sight shows what is in the distance. Sensations of localization, loudness, pitch, acoustically reflective or absorbing materials, shape/ size of a space, and amount of objects inside.

- Smell. Inhaled Stimulation

Smell is an important human sense that is closely connected to memory and emotions. People are able to remember a certain place or an event by a particular smell related to it.

- Skin-Sense of Air. Contact Stimulation

Skin is the biggest sensory organ of the human body. Even without active touch, it’s possible to sense changes in temperature or humidity. Air and wind can work as sensory material, giving the brain signals about the qualities of space. Sensations of air movement, environmental temperature, the warmth of the sun, and humidity in the air.

- Pressure and Tension through active touch

Actively exploring and interacting with the space through own sensations, enables new perspectives for the perception of the space.

Active touch stands for initiating and seeking information about an object or a surface through haptic senses. Further exploration of objects can evolve into applying more forcible touch, making it movable and experiencing new sensations like pressure or tension either in interaction with the objects or with one’s self.

- Haptic. Contact Stimulation

Tactile architecture promotes slowness and closeness, it engages and unifies. Tactile sensitivity replaces distancing visual cues with improved materiality, closeness, and intimacy. Sensations of surface temperature, roughness/hardness or softness, contour identity, and vibrations.

- Expansion/Compression of Space

It’s perceivable through different sensory experiences. Even being unable to see the space it’s possible to perceive changes in height due to the difference in acoustics.

- Kinesthesia. Position and movement in space

Kinesthesia is the perception of body movements through changes in body position and motion. It enables instead of just seeing the space or watching other people experience the space, to explore it through active interaction with the space.

- The mechanism needs to be user-friendly and intuitive.

An architectural machine is an architectural object with an interactive mechanism within. Through the interaction with the mechanism user can explore the imbedded symbolism and metaphore of the object.

- One user

- Two users (gender,age,nationality)

- Three to six users (amount of users allows comfortable simultaneous interaction)

User can experience different things by interacting with machine while being alone or with various people around. Creating machines for different amount of people allows wider range of experiences.

- One user vs others

We advocate for a multiplication of complexity, as oversimplified representations of the world lead to homogenization and the erasure of diversity. The incorporation of certain level curiosity in the design is essential in facilitating human interaction with machines, while the presence of ambiguities can stimulate human desire to engage with them.

Our approach assumes that establishing a basic understanding of an object can facilitate the formation of an opinion about it. Thus, it is important to create “base” symbols that are familiar to the user and to employ widely recognized archetypal forms.

In situations where expressing oneself through traditional means such as speech or writing is risky or prohibited, art and architecture can provide means of veiled expression. By utilizing the language of architectural harmonization, metaphors, and symbols, and working with different modes of perception, authors can convey messages to people in multiple dimensions, without having to express them directly.

The machines are created for thoughtful and innumerable interactions that allow the exploration of symbols that are not what they seem at the first sight. Multiplication of complexity allows seeing the world in its diversity. It also creates various contradictions and paradoxes.

In the world of post-truth, it is important to have an anchor, a foundation of sorts. Otherwise, anything can be questioned. This can cause excessive distrust, a lack of understanding of the essence of the machine, and doubt on even basic aspects of it. An understandable and familiar to the majority symbolism of the machine will enable average person to have a basic understanding of the machine even before interacting with it. And with the futrther exploration enable user to discover metaphor embedded with machines by the creators.

Clear symbolism will facilitate initial interaction with the machine. Unlike archetypes, which are perceived almost intuitively, symbols are intertwined with the culture. Therefore, the symbolism may differ from region to region and from country to country.

Archetypality

An archetype is a prototype, the original meaning of something. The “first” form or basic model is copied, imitated, or “merged” with other statements or objects but the fundamental characteristics are kept intact. In the creation of machines familiar and archetypical forms can be used to create an easily distingvished structure. For example, the tower archetype is a cylindrical shape elongated along the vertical axis.

In a situation where expressing one’s opinion in the usual way, trough writing or speaking, becomes dangerous or forbidden, architecture and the art can help to express one’s position in an indirect, veiled way. Using metaphors and symbols, working with different types of perception, transmitting information multidimensional, the creators can convey the desired message to the users without doing it in a prohibited manner. Even as authoritarian states are constantly improving the recognition of even metaphorical references, the art has no limitations in the symbolism of images.

Common element used in several machines creates coherent visual assembly for the user.

Combinations

When creating several machines, particular combinations can enhance users’ perception of the machines. The machines can be assembled together or placed at a distance from each other. In different locations, various combinations can be used - there are no limitations in quantity.

Architectural composition

Architecture can convey the embedded message by using harmonization tools. Perceived intuitively, they give aesthetic expressiveness to the machines, influence users’ perception of spaces, and reveal hidden meanings in a multidimensional way.

A metaphor embedded in the machines enables an alternative way of communication between the creator and the user. Through interaction with the machine embedded metaphors can arouse a doubt in the knowledge of the user and it can initiate a change in their perception. For example political metaphor can be used to explore different angles of present society.

- Theoretical human rights vs Actual human rights

- Architectural expression of the machines and qualities of the mechanisms within vs characteristics of propaganda

- Political statements of the regime influence various architectural characteristics of the machines.

- A-contextual

If machines are going to be frequently relocated to the different areas with various cultures and characteristics, it’s advisable to use universally known symbols.

- Recognizable

Even if the machine operates in a single specific place, the main symbol of the machine needs to be unmistakably recognizable to a wide range of people.

- Colors

The same color can be applied differently by using various tints, shades, or tones.

- Mono-materiality

Mono-materiality is the use of predominantly one material for esthetic and technical parts of machines. It can look especially impressive when using different processing techniques for the same material.

- Theme

Creating with the same symbolic theme can unite separate machines in one assembly. For example, it can be the simple geometrical shapes - cube, cone, pyramid, etc.

- Scale and Proportions

The same scale of objects helps a person to perceive them as part of an assembly. This applies both to the proportionality of linear dimensions (height, width), and to the similarity of areas and volumes.

-Repetition

Repeatedly applying specific elements in the creation of different machines can visually unite them and enable the user to see them as part of the same group

- Routing

Consider various user scenarios. Since the machines interact with different human senses, focus on different experiences through exploration.

- Common characteristics

Several machines don’t have to be positioned next to each other. Having common elements, keeping visual connection, and having the same theme of the site placement - machines with common distinct characteristics can be considered a group.

- Base Floor level, similar finishing materials, or one base structure for several objects can be used as a unifying factor.

- Various experiences

Grouped machines can help unveil and enhance the experiences that users get from interaction. Placing contrasting machines next to each other can influence the experience of exploration.

- Assembly

An assembly of machines can create a unifying metaphor that each machine will amplify. By changing the configuration of the assembly different scenarios can be created, and therefore cause a greater range of experiences for the users.

The concept of the project is that the choice of a specific location for each of the machines is left to the authors of objects. This approach allows machines to be situated in various countries and regions, thereby exposing people from diverse backgrounds to the interactive and participatory nature of machines. To optimize the number of individuals who can interact with the machines, we suggest several criteria to aid in the selection of appropriate sites.

The proposed criteria include accessibility, visibility, and the presence of public spaces. By considering these criteria, authors can increase the likelihood of machines being experienced by a diverse range of individuals.

Urban and rural areas require careful consideration of various traffic flows and population groups in choosing a site for the machines. Certain conditions are necessary for extensive interactions with the machines.

We reccomend use locations like:

- Gathering places

- Areas with stable people traffic

- Places in need of activation

The creators are the ones who decide locations for their machines. Certain criteria of location are important to ensure that wide range of people get to interact with machines.