9 minute read

Douglas Fir Plywood A MODERN \TOODEN

MIRACLE _ HO\r IT IS MADE. .I t

Frequently in our editorials this journal has referred to plywood as the finest step forward the lumber industry has rnade in generations-perhaps ever. The lumber and building industry the country over has come to know plywood and its uses more and better all the time, until now the big, bright, clear panels of various sizes and thicknesses, manufactured and sold for a thousand practical uses, are a fixture in every retail lumber yard. Yet even now, as he looks at the great sheets of wood piled high in his shed, the retail lumber dealer generally has little if any knowledge of just how they manufacture this modern miracle of wood. This story, therefore, is told to give a terse but understandable picture of the process of plywood manufacture and preparation for market. In this story we are using the case of Douglas Fir plywood, because this is the plywood giant, whose

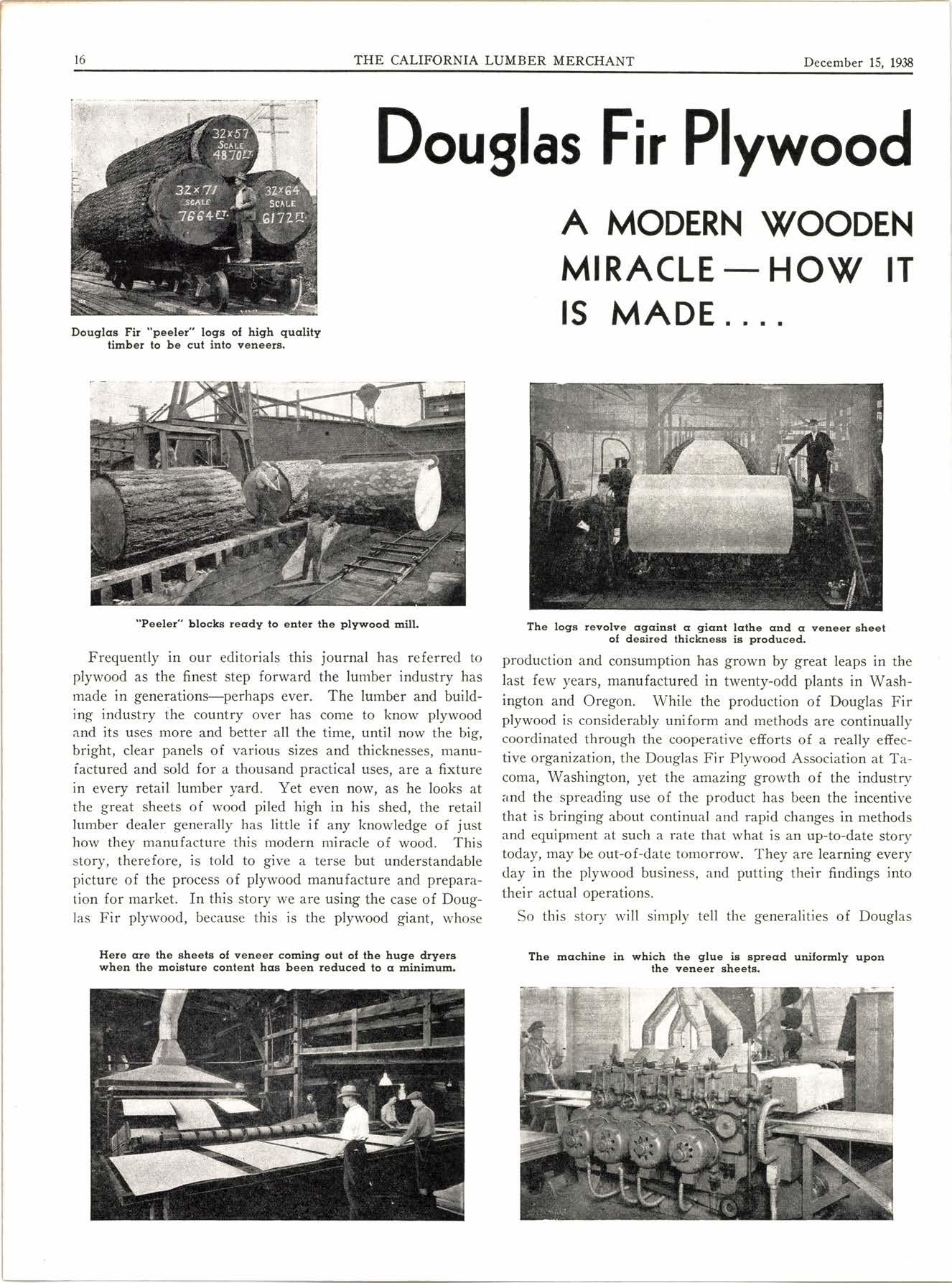

Here cre the sheets ol veneer coming out ol the hugre dryere when the moigture content hcg been reduced to c minimum.

The logs revolve cgcinst cr gicnt lcrthe <rnd c veneer sheet oI desired thickness is produced. production and consumption has grown by great leaps in the last few years, manufactured in twenty-odd plants in Washington and Oregon. While the production of Douglas Fir plywood is considerably uniform and methods are continually coordinated through the cooperative efforts of a really efiective organization, the Douglas Fir Plywood Association at Tacoma, Washington, yet the amazing growth of the industry and the spreading use of the product has been the incentive that is bringing about continual and rapid changes in methods and equipment at such a rate that what is an up-to-date story today, may be out-of-date tomorrow. They are learning every day in the plywood business, and putting their findings into their actual operations.

So this story will simply tell the generalities of Douglas

Fir plywood manufacture as they prevail today in a modern Northwestern plant.

The principle of wood veneering is NOT new. Excavators in the oldest tombs in Egypt have uncovered furniture built of veneered wood that are fully 3,500 years old, so we know that .the principle of plywood has been known to man since our earliest civilizations. But it was not until 1905 that modern plywood making began. About that date the methods rvhich have resulted in volume production were developed, and led to its present amazing growth. Even after the beginning of the present industry in 1905, it was many years before plywood meant anything but a decorative material to t925. . .t53,262,609

1926.. .t72,96tr,W

1927.. .206,2W,990

1928.. .275,7rt,204 t92g. .359,424,919

1930.. .305,000,000

1931. . .235,900,042

1932. . .200,709,354

1933. . .390,430,455

1934. . .383,769,327

1935 . .490,955,093 t936. .700,000,000

1937 (Estimated) ..725,000,000 square square square square square square square square square square square square square feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet feet lhe run the lqthe cnd move towqrd the be used for furniture, doors, or just fancy wall coverings. Its use as a general structural and building material whereever and whenever big, flat, clear sheets of powerful wood are desired, is entirely new. And the uses grow every day.

Visitors to the World's Fair now being completed at San Francisco will see plywood used as plywood was never used before, for literally thousands of important building purposes. They will see tremendous sheets of plywood D+ly thick being used in the Colonnade of States.

As evidence of the manner in which the production and use of Douglas Fir plywood has grown, witness this table of production:

The Douglas Fir plywood industry today employs 5,000 people in its own mills, and another 1,000 in the production of materials. The industry has 925,000,000 invested, and annual payrolls of $7,500,000. Raw materials and supplies cost the industry $7,500,000 annually.

Douglas Fir plywood is made from what are called "peeler" logs, which are the finest, clearest, softest, straightest of Douglas Fir logs. "Peeler" logs are selected strictly for their superior excellence. Plywood cannot be successfully manufactured from anything but that type of log. These logs must have a minimum diameter of 3 feet at the small end, and must be free from limb knots and other exterior defects.

They average between 5 and 6 feet in diameter. The end of the log must indicate that it contains a minimum of sap and a maximum of clear, soft, heartwood. The logs are sawed into lengths of 6, 8, 10, or 12 f.eet,'the length of the panels into which they are to be made. Then a power crane lifts the blocks to the proPer position on a giant lathe. This lathe rotates the block against a long keen-cutting blade, ancl a sheet of smooth veneer is cut or peeled (this is where the name "peeler" comes from) from the entire length of the block, in much the same way as unwinding a great roll of newsprint paper.

From the lathe the veneer is carried on conveyor lines across tables to the clippers, which cut the sheets of veneer into desired widths by a simple "guillotine" operation. From the clippers the pieces are conveyed to tables where they are sorted and graded as to quality. Then they go to the dryer. Large mechanical dryers of either the conveyor or roller type are used, 4 to 6lines high, which removes the moisture from the sheets in from 5 to 30 minutes depending on the thickness of the veneer. The drying process is highly scientific, and all sheets are dried to an exact moisture content.

Then long outfeed conveyors receive the veneer from the dryers and the material is again graded and sorted as to rvidth and grade. The lower grade stock goes to the core rooms where it is cut to required sizes for use as center sheets, cores, and cross bands of the panels, on which the better veneers form the outer coverings. Next comes the gluing operation. First, the face veneer is laid down, and then the crossbanding or core veneers' with glue on both sides, is laid upon it with the grain at right angles to that of the face. and other sheets follow according to the number of plies desired in the finished panel. Each veneer is placed in such a position that the grain of the succeeding panel is at a 90 degree angle to the previous one. Then the freshly glued panels are piled into stacks about 3 feet high, with heavy retaining boards above, below, and between the panels to insure uniformity of pressure, which stacks are placed in heavy hydraulic presses' where pressure ranging from 100 to 200 pounds per square inch is applied. The amount of pressure varies with the type of glue used. The pressure is maintained for a period of hours.

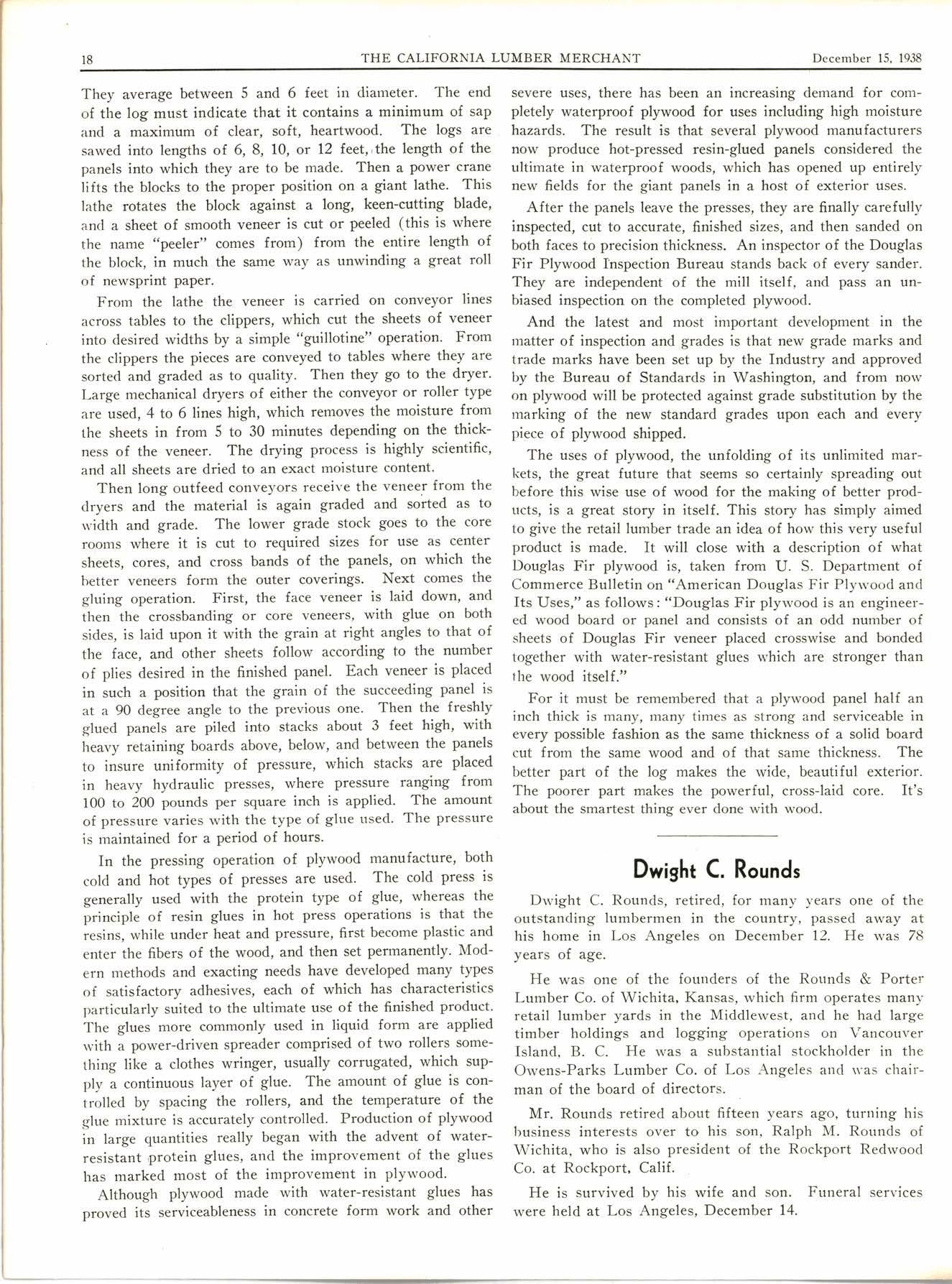

In the pressing operation of plywood manufacture, both cold and hot types of presses are used. The cold press is generally used with the protein type of glue, whereas the principle of resin glues in hot press operations is that the resins, while under heat and pressure, first become plastic and enter the fibers of the wood, and then set permanently. Modern methods and exacting needs have developed many types of satisfactory adhesives, each of which has characteristics particularly suited to the ultimate use of the finished product. The glues more commonly used in liquid form are applied with a power-driven spreader comprised of two rollers something like a clothes wringer, usually corrugated, which supply a continuous layer of glue' The amount of glue is controlled by spacing the rollers, and the temperature of the glue mixture is accurately controlled. Production of plywood in large quantities really began with the advent of waterresistant protein glues, and the improvement of the glues has marked most of the improvemeht in plywood.

Although plywood made with water-resistant glues has proved its serviceableness in concrete form work and other severe uses, there has been an increasing demand for completely waterproof plywood for uses including high moisture hazards. The result is that several plywood manufacturers now produce hot-pressed resin-glued panels considered the ultimate in waterproof woods, which has opened up entirely new fields for the giant panels in a host of exterior uses.

After the panels leave the presses, they are finally carefully inspected, cut to accurate, finished sizes, and then sanded on both faces to precision thickness. An inspector of the Douglas Fir Plywood I'nspection Bureau stands back of every sander. They are independent of the mill itself, and pass an unbiased inspection on the completed plywood.

And the latest and most important development in the rnatter of inspection and grades is that new grade marks and trade marks have been set up by the Industry and approved by the Bureau of Standards in Washington, and from now on plywood will be protected against grade substitution by the marking of the new standard grades upon each and every piece of plywood shipped.

The uses of plywood, the unfolding of its unlimited markets, the great future that seems so certainly spreading out before this wise use of wood for the making of better products, is a great story in itself. This story has simply aimed to give the retail lumber trade an idea of how this very useful product is made. It will close with a description of what Douglas Fir plywood is, taken from U. S. Department of Commerce Bulletin on "American Douglas Fir Plywood and Its lJses," as follows: "Douglas Fir plywood is an engineered wood board or panel and consists of an odd number of sheets of Douglas Fir veneer placed crosswise and bonded together with water-resistant glues which are stronger than the wood itself."

For it must be remembered that a plywood panel half an inch thick is many, many times as strong and serviceable in every possible fashion as the same thickness of a solid board cut from the same wood and of that same thickness. The better part of the log makes the wide, beautiful exterior. The poorer part makes the powerful, cross-laid core. It's about the smartest thing ever done with wood.

Dwight C. Rounds

Dwight C. Rounds, retired, for many years one of the outstanding lumbermen in the country, passed away at his home in Los Angeles on December 12. He was 78 years of age.

He was one of the founders of the Rounds & Porter Lumber Co. of Wichita, Kansas, which firm operates many retail lumber yards in the Middlewest, and he had large timber holdings and logging operations o.n Vancouver Island, B. C. He was a substantial stockholder in the Owens-Parks Lumber Co. of Los Angeles and lras chairman of the board of directors.

Mr. Rounds retired about fifteen years ago, turning his business interests over to his son, Ralph M. Rounds of Wichita, who is also president of the Rockport Redwood Co. at Rockport, Calif.

He is survived by his wife and son. Funeral services were held at Los Angeles, December 14.

Yield of Ponderosa Pina Stands Studied

Results of a studl' of the yield of Ponderosa pine in even-age'd stands have just been made available in a nern' technical bulletin published by the Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agri.culture.

The study was made by lValter H. Meyer, forrnerly silvicultrrrist of the Pacific Northwest Forest Experiment Station.

Ponderosa pine, he says, is one of the rnost importarrt trees of the western United States, grou'ing on more than 5O million acres in a rang'e extending fronr the western border of the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast ranges. The wood is commercially valuable throughout its range.

The maximum number of trees on an acre in yorlng even-aged Ponderosa rpine stands mav be t'ell over 10.000, probably near 20,000, Mr. Meyer says, but at maturity the number is neve'r more than a feu' hundrecl. This enormous re,duction in number of trees involves the loss of much volume that is seldom utilized under present forest practices. The loss of volume through normal mortality may be as much as 42 per cent of the live volume at 100 )'ears.

In his study, NIr. Ifeyer has prepared numerous tables, including increment tables, stand and stock tables from which predictions of future sizes of trees can be made, height curve graphs tlseful in calculating volume, grorvth and f ield, and volume tables in cubic and board feet. Copies of Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin No. 630. "Yield of Even-aged Stands of Ponderosa Pine." rnay be obtained for 15 cents frorn the Superintendent of I)ocuments. Washington, D. C.

Mn Ltnmbermaln,

Our Denseter is, of course, Philippine Mahogany, Furthertnore, it is some of the finest stock from the Islands.

The handsorne graining, the firm terture, and eeen color oJ this splendid wood make it especially suitable for trim and paneling.

Denseter Cabin Lining (3/8 r 6 A 3/8 * 8) ofrers a profitoble way to please your customers.

May we bring you a sample to show them what a beautilul paneling this good

P hilippine Mahogany makes?

E. I. STANTON & SON