REVITALIZING COOLEY BROOK IN BLISS AND LAUREL PARKS

Prepared for the Town of Longmeadow’s Department of Planning and Community Development

By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle The Conway School, Spring 2023

In lovIng memory of leon Waverly BaIley Jr.

September 21st 1936 - May 2nd 2023

Longmeadow Resident from 1963 - 2022

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the Longmeadow residents and the visitors of Laurel and Bliss Parks who generously gave us their time and feedback.

Thank you to our Core Team for your continued support and feedback throughout the project process:

Corrin Meise-Munns, Assistant Town Manager

Troy Barry, Geofluvial Morphologist, Tighe & Bond

Timothy Keane, Town Engineer, Department of Public Works

John Bresnahan, Conservation Commission Chair

Bari Jarvis, Director, Parks and Recreation

Kristin Carnahan, Resident Advisor

David Marinelli, Resident Advisor

Thank you to the Longmeadow Historical Society for sharing historical maps and photos of Longmeadow, the parks, and the Olmsted Brothers designs.

Thank you to the experts who advised us and shared their time:

Glenn Motzkin, Ecologist

Sebastian Gutwein, Principal Designer, Regenerative Design Group

Denise Burchsted, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Keene State College

Alex Krofta, Ecological Restoration Project Manager, Save the Sound

And to the faculty, staff, and students of the Conway School, without which we would not be here.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey. INDEX

Project Overview ................................................................ 1 Zones of Cooley Brook ....................................................... 2 Existing conditions ............................................................. 3 Timeline ................................................................................ 4 Stream infrastructure ....................................................... 5 Hydrology & hydraulics ..................................................... 6 Land Cover........................................................................... 7 Soils ..................................................................................... 8 Drainage .............................................................................. 9 Active River Area & Slopes ................................................ 10 Sediment Transport .......................................................... 11 Vegetation ......................................................................... 12 Habitat ............................................................................... 13 Circulation & Access ......................................................... 14 Park Functions & Users .................................................... 15 focus areas and themes .................................................... 16 Waterworks Summary ...................................................... 17 Supporting succession ..................................................... 18 design details 1 ................................................................. 19 PRESERVE THE PUMP ......................................................... 20 design details 2 ................................................................. 21 Laurel Pond Summary ...................................................... 22 The Escarpment ................................................................. 23 design details 3 ................................................................. 24 A nature-based dam .......................................................... 25 Design details 4 ................................................................. 26 Headwaters Summary ....................................................... 27 Spread the Wealth ............................................................ 28 Design details 5 ................................................................. 29 bridge the gap ................................................................... 30 design details 6 ................................................................. 31 bioengineering details ...................................................... 32 Regional Dam Removals ................................................... 33

PROJECT OVERVIEW

The Town of Longmeadow’s Department of Planning and Community Development contracted the Conway School to build upon the 2020 Conway Project Enhancing Ecology in the Heart of Longmeadow: Two Visions for Bliss and Laurel Parks. The 2020 Conway project took a broader look at the parks’ functions and human uses, and a main takeaway from the project was the need to improve the function and stability of the Cooley Brook stream system before changes could be made to the human-scale park functions. Based on that project as well as subsequent studies of the parks and brook, this document aims to explore possibilities for increasing ecological health in the brook and strengthening the human/stream experience, specifically through visualizing what the system could look like if the two dams on the brook were removed. This document considers the balance between natural systems and humanaltered systems in and around the Cooley Brook, and presents alternatives for the Longmeadow community to evaluate and refine.

Cooley Brook tells a tale of human intervention, serving many humandirected functions over the centuries. As the uses of the brook and two parks have shifted, so has the attention paid to different parts of the brook system. Today, the Town of Longmeadow recognizes the importance of Cooley Brook to address essential stormwater management needs and the opportunity to advance Longmeadow’s climate resilience goals by increasing the function and balance of the stream system. Prioritizing stormwater management also necessitates evaluating the ecological health of the system and human interactions with the brook in order to identify interventions to increase stability. These three visions of the Cooley Brook—providing functioning stormwater infrastructure and flood resiliency, being ecologically healthy, and providing a fulfilling human/stream connection—guide the clients’ goals for this project.

This document has been produced in conjunction with Longmeadow’s Department of Parks and Recreation, Department of Public Works, Conservation Commission, and the Longmeadow Planning Department. Tighe & Bond, an environmental engineering firm, produced a Hydrology & Hydraulics Study of Cooley Brook in Bliss and Laurel Parks and provided feedback and resources to inform conceptual designs.

ProJect goals

1. A resilient and safe-to-access stream channel

Develop conceptual designs for three locations along the stream to improve the function of the brook. Incorporate green stormwater infrastructure through bioengineering interventions to increase floodplain and riparian connectivity , and enhance the human/stream relationship.

2. Well-informed and engaged community and process

Communicate the scientific data to the community and get their feedback on conceptual designs focused on the human/stream interface.

3. A healthy and diverse ecosystem

Explore the opportunity to increase ecological health in this system.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 1/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

PROJECT OVERVIEW

Laurel Park

Laurel Park Bliss Park

Forest Park

River I-91

Turner Park

Connecticut

Longmeadow Street

Longmeadow Springfield Massachusetts Connecticut Cooley Brook

Bliss Park

Cooley Brook in relation to the town of Longmeadow, the Connecticut River, and neighboring public parks.

Aerial view of Bliss and Laurel Parks and the neighborhood.

Longmeadow Street Bliss Road Laurel Street

ZONES OF COOLEY BROOK

Cooley Brook flows west from its stormwater-pipe headwaters in Bliss Park for about 1.5 miles before it empties into the Connecticut River. The brook can roughly be broken into four character zones based on human land use, the boundaries of which are marked by stream-road crossings and stormwater infrastructure.

Zone 3: Private Property

In Zone 3, Cooley Brook flows through the backyards of private homes. The stream channel is heavily armored with rip-rap and rocks to maintain its location. After flowing under Elmwood Avenue through a culvert, the stream flows down a natural bedrock escarpment which forms a series of waterfalls in the brook for approximately 25 vertical feet.

Zone 1: Headwaters

Bliss Park marks the first zone, where two stormwater pipes empty into the stream channel at its headwaters. In this zone, the stream has steep banks and a deep, incised channel.

Zone 2: Ponds

In the second zone, Laurel Park, two human-made dams slow the movement of Cooley Brook and stop the transportation of sediment by the stream. The first dam (B) was designed by the Olmsted Brothers as an aesthetic part of the human experience of this landscape and the second dam is formed by infrastructure left over from when the brook was used as a water source for Longmeadow (C).

In the last zone, the brook flows through a 9-foot-wide culvert under I-91. The stream channel is heavily armored around I-91 to protect the highway infrastructure from a more dynamic stream channel, but closer to the Connecticut River the banks are no longer stabilized and the brook is able to form some natural meanders, though the banks are still extremely steep.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 2/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu ZONES OF COOLEY BROOK

N 500’ 0 Park Parcel Culvert Dam

A B A A C D E F G C B D E F G

Zone 4: I-91 to the Connecticut River

EXISTING CONDITIONS

Cooley Brook runs east to west through Bliss and Laurel Parks. The parks are a forested refuge in the heart of Longmeadow, offering woodland trails, a playground, and active recreation facilities including ball fields, tennis courts, and a swimming pool.

LaureL Park

• Laurel Park has two parking lots: a pull-off on Longmeadow Street on the park’s western extent and a long, gravel driveway leading from Laurel Street to a lot with undefined parking spaces and unclear boundaries.

• Hiking and informal mountain biking trails form several loops on either side of Cooley Brook, only a few of which come near the stream, and two bridges enable stream crossing.

• Cooley Brook runs through a culvert under Laurel Street into Laurel Park where it is obstructed twice, first by the Olmsted-designed dam forming Laurel Pond and second by the former waterworks impoundment forming the slow-moving, broad stream channel downstream of Laurel Pond.

BLiss Park

• Bliss Park has three parking lots; a driveway off Laurel Street closest to the pool and playground, a half gravel/half asphalt lot located centrally off Bliss Road, and a long gravel driveway off Bliss Road on the park’s east end.

• Stormwater pipes enter the site from Oakwood Drive and Bliss Road, carrying runoff into the incised stream channel in Bliss Park, the pipes’ outfalls forming the headwaters of the Cooley Brook.

• North of Cooley Brook, the wide, forested trails are a popular spot for dog-walkers. The trails follow the topography, where post-glacial windswept dune deposits form a small ridge.

• South of Cooley Brook, active recreation facilities provide programmed space for baseball, tennis, swimming, basketball, and the beloved “Mr. Potatohead” playground. The tennis courts and pool are closed for the time-being; the pool overflow was draining into Cooley Brook and the courts need maintenance.

• The trails in Bliss Park rarely approach the stream due to steeper, eroded slopes along the stream channel, limiting stream interaction and views.

communIty engagement In BlIss and laurel Parks

Community engagement is a critical component within the project scope. The Town of Longmeadow hopes to receive thoughtful feedback on concepts for revitalizing Cooley Brook to inform management decisions moving forward.

The Conway team spoke to twenty-six groups of park-goers while canvassing Bliss and Laurel Parks on a sunny Saturday afternoon in May 2023. Drawing on key findings from the Tighe & Bond Hydrology & Hydraulics study, the Conway team facilitated conversations with park-goers about their understanding of and relationship with Cooley Brook. The Conway team found that many people weren’t familiar with the stream, the role it played in the watershed, or the ecological and structural integrity of the system. Lack of access to the stream makes it a secondary feature within the parks. Park users said that the two parks serve very different functions. Laurel Park provides biking and hiking trails; people use the park to experience nature. Bliss Park is a programmed space with a playground, sport fields and courts, and nice dog walking trails north of the stream. Many park-goers were surprised to learn about the results of the Hydrology & Hydraulics Study (see sheet 6) and expressed the opinion that with this data, improving stream health should be a priority.

The Conway team designed and printed interpretive signs that were placed in strategic locations. The signs followed a historic, cultural, and ecological narrative through the parks and were used to generate interest in a community survey written by the Conway team. The survey had only three respondents prior to the installation of interpretive signs. The week following, the survey received thirty more responses, with more every day. The interpretive signs enabled another layer of storytelling and engagement with the community, and the survey will remain open through the next phase of the project.

clImate change ImPacts cooley Brook

Cooley Brook’s role as stormwater infrastructure necessitates forward-thinking around climate change.

Larger, more frequent storms and extended summer droughts affect the hydrologic processes of Cooley Brook and its watershed. A higher volume and velocity of stormwater entering the stream paired with limited opportunity for infiltration in the watershed cause problems of erosion and flooding. Droughts reduce stream flow in the summer months, creating an imbalance in nutrient transport associated with the base flow and seasonal flooding of Cooley Brook. This has implications for ecosystem health, water quality, and aquatic habitat, as well as human safety, recreation, and built infrastructure.

The Town of Longmeadow recognizes the Cooley Brook as a critical natural resource for managing stormwater and mitigating the impacts of flooding within its watershed. Revitalizing Cooley Brook to manage additional stormwater associated with climate change, increase ecosystem health, and improve wildlife habitat can help the Town of Longmeadow achieve greater resilience in the face of climate change.

Seasonal precipitation change in the Northeast shows wetter winters and drier summers, impacting natural resources and human communities in the region.

Source: Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios: The Northeast US (Kunkel et al. 2013)

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 3/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

EXISTING CONDITIONS

Laurel pond and dam

active recreation facilities

headwaters; stormwater pipe outfalls

waterworks reservoir and impoundment longmeadow st. entrance

laurel st. entrance

laurel st. entrance

bliss rd. east entrance bliss rd. central entrance

hiking/biking trails

Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

dog walking trails

THE STORY OF COOLEY BROOK IN BLISS AND LAUREL PARKS

The 1.5-mile stream has a long history of human use and modification, with both cultural and ecological implications of past land use on its modern-day functions and uses.

2020

enhancIng ecology In the heart of longmeadoW

Two Visions for Bliss and Laurel Parks

By Cara Montague and Shaine Meulmester

Longmeadow Citizens to Save Our Parks (LCSOP) contracted the Conway School in 2020 to develop design concepts with the goal of improving the ecological health and functioning of Bliss and Laurel Parks while meeting the recreational needs of park visitors.

2020 rePort summary

• Montague and Muelmester’s two design alternatives, Protect the Pond and Natural Processes, explored different approaches to the design and maintenance of the former waterworks and Laurel Pond.

Population growth spurs the construction of waterworks to supply drinking water

Olmsted Brothers design and construct Laurel Pond and dam

Numerous native groups share the Connecticut Valley, including Nonotucks, Agawams, Woronocos, and other indigenous tribes.

The Town purchases 81 acres from Scott Cooley to protect the health of the watershed surrounding the reservoir.

Longmeadow votes to join Springfield’s water system and the waterworks are abandoned and reservoir used as the town swim hole called “The Pump.”

Town stormwater system is completed, directing runoff from surrounding neighborhoods directly into Cooley Brook and eliminating the need for “The Pump”as a swim destination

• Protect the Pond explored preserving the pond while mitigating stormwater runoff and improving water quality through increased pond maintenance.

• Natural Processes explored allowing natural stream processes to shape the landscape. The pond slowly becomes marsh and the waterworks is revived as a recreational space.

• Neither design alternative explored dam removal.

• This document highlighted the need to continue research, community engagement, and planning to revitalize Cooley Brook.

TODAY

The needs and functions of Cooley Brook are once again changing.

This 2023 report is part of a series of projects that will study, assess, design, and apply bioengineering solutions to improve the Cooley Brook and its watershed as a stormwater management resource, natural stream system, and recreational resource.

2022-2023: The Town hires Tighe & Bond with Community Preservation Act (CPA) funding to complete a Hydraulics, Hydrology & Geomorphic Study on Cooley Brook.

2023: Tighe & Bond produces a 40% green stormwater infrastructure design (GSI) for Bliss Park and Blueberry Hill Elementary School funded through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

Fall 2023 - 2025: In 2023, the town applied for a Municipal Vulnerability Plan (MVP) grant and a Long Island Sound Futures Fund (LISFF) grant that, if awarded, will be implemented over the next few years.

• MVP will fund alternatives analysis and 60% design for restoration of Cooley Brook within the parks, advancement of GSI in the watershed to 60% design, identify watershed areas for GSI based on needs identified in modeling, and an H&H and reference reach study for the brook downstream of the parks.

• LISFF will fund an EPA 9-Element Watershed Based Plan for the Cooley Brook drainage area; design and implement a resident outreach campaign concerning Low Impact Development (LID) and GSI in yards, prioritize up to 10 locations for GSI retrofits within municipal rights-of-way within the Cooley Brook watershed; and work with DPW to develop standardized design details for GSI systems that they are comfortable maintaining and implementing.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 4/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu

TIMELINE PRE-CONTACT <1600S 1895 1906 1924 1934 1970

Rendering of proposed pool in Laurel Park, 1934

“The Pump” cleared of vegetation, 1916

Flooding Laurel Pond after dam construction, 1936 Laurel Pond dam after construction, 1936

Waterworks shown on 1912 Atlas

Laurel Pond dam under construction, 1934

Olmsted Brothers’ design for Bliss and Laurel Parks, 1934

STREAM INFRASTRUCTURE

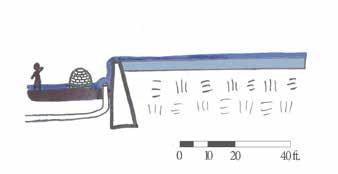

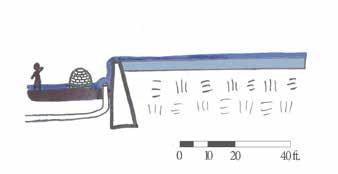

The human-made infrastructure in Laurel and Bliss Parks alters and partially defines the brook’s character. Traveling upstream, there is a culvert under Longmeadow Street, the old waterworks dam, Laurel Pond dam, the culvert under Laurel Street, and the stormwater pipes at the brook’s headwaters. Because of the infrastructure and nearby development, it is highly unlikely Cooley Brook’s flow patterns could be allowed to return to completely natural processes. Instead, the question is how to maximize ecological integrity within the stream system while still supporting human uses in the watershed. These sketches represent the scale of infrastructure alteration to the landscape, and are drawn to scale horizontally with a 2x exaggeration on the vertical scale.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 5/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

STREAM INFRASTRUCTURE E A B C D E

All drawings to scale horizontally with 2x vertical scale

Longmeadow Street

A Culvert under Longmeadow Street

Laurel Street

D Culvert under Laurel Street

Exposed manhole Dam Concrete channel and aboveground flow Buried clay pipe B Waterworks Dam Pedestrian bridge Dam Laurel Pond

Stormwater Pipes at Headwaters

C Laurel Pond Dam

2x vertical 2x vertical 2x vertical 2x vertical 2x vertical

stream Infrastructure locus maP

SUMMARY OF THE HYDROLOGY & HYDRAULICS STUDY

The Hydrology & Hydraulics study concluded that dam removal is feasible based on the stream dynamics, and that the dams do not contribute enough stormwater mitigation to protect the area from flooding. Additionally, the study illustrated the poor ecological health of the system, which should be addressed in the parks and upstream to restore ecological integrity.

The Environmental Engineering firm Tighe & Bond released a Hydrologic and Hydraulic Study of Bliss & Laurel Parks in April 2023. In this study, the authors created hydrologic (amounts of water) and hydraulic (how the water flows) models for existing conditions of Cooley Brook in Bliss and Laurel Parks, and created the same models for the system with both dams removed. Part of the study also assessed the erosion and bank failures along the brook, using existing erosion levels to predict how much of the banks could be eroded. The goal of this study was to understand the current conditions of Cooley Brook, how much the dams contribute to slowing stormwater, and what effect potential dam removal would have on the flow dynamics of the stream system. Below are the main findings of this report:

• Neither Laurel Dam nor the waterworks dam store significant quantities of floodwater. During normal conditions water flows over the dams, meaning that during storms, the reservoirs behind the dams have no volume for flood storage (Figure 1).

• With or without removal of the two dams, a 100-year storm (a storm with a recurrence interval of 100 years, which has a 1% chance of occurring on any given year) will overflow onto Laurel and Longmeadow Streets.

• The culverts under Laurel and Longmeadow Streets (combined with the landforms) do provide flood storage because they are undersized: they are too small for the amount of water flowing into them (Figure 2).

• Because they are undersized, the culverts are at risk of failure (Figure 2).

• The brook’s erosive power has the potential to remove 690 tons of sediment from the stream banks every year, and the dams then trap most of that sediment. That weight is roughly equivalent to the weight of ten blue whales being deposited behind the dams every year (Figure 3).

• Interventions such as green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) are needed in the watershed to slow and clean water before it enters the brook and to decrease the amount of water entering the culverts.

• Dam removal would improve the ecological health of the stream by increasing habitat connection. This would also increase floodplain connectivity which would help provide flood storage.

In conclusion, this study determined that the existing conditions contribute to poor ecological health and a large imbalance of sediment transport. The dams are currently not maintained, suggesting that a plan for moving forward with this system should include either routine maintenance (repairs to the dams and dredging of sediments putting pressure on the dams) or the dams should be removed. This study suggests that the second course of action is not only feasible but would contribute numerous benefits to the Cooley Brook system, including increasing the ecological integrity of the system, addressing the sediment transport imbalance, and allowing for floodplain reconnection that would increase flood storage potential.

This study also highlights the role of culverts in this system and the flood storage they help provide. Because the culverts are undersized for the amount of stream flow, when more water needs to get through the culvert than can fit, it backs up behind the culvert. However, though this backwater effect slows the movement of stormwater, it negatively impacts the health of the culvert. These effects can already be seen at the inlet and outlet of the Laurel Street culvert through localized erosion and scouring. If the culverts were to fail or blow out, according to the Tighe & Bond engineers, it could cause catastrophic damage to the streets and completely alter how the stream flows.

Longmeadow relies upon Cooley Brook for stormwater management due to the limited ability to slow and infiltrate stormwater in the developed watershed (see sheet 7), but since both dams currently have water flowing over them at all times, the dams have little ability to manage water. The study also showed that this system is experiencing a higher amount of sediment being added to the system than is healthy. The variability of stream flows contributes to the high levels of erosion. In order to manage the variability of stream flows, the large volume of stormwater entering the system, and the excessive amount of sediment being eroded, Tighe & Bond recognizes that interventions are needed higher up in the watershed, and have begun the research and design process for green stormwater infrastructure interventions (see sheet 4).

According to the Tighe & Bond engineers, removing the dams will not cause immediate negative impacts to the hydrology or hydraulics. Since stream systems are highly dynamic, Tighe & Bond recommends that if the dams are removed that they be replaced by bioengineering structures, to help provide grade control and floodplain connectivity in the system. In all, this Hydrology & Hydraulics study demonstrates the need for intervention to improve the stability and resiliency of the Cooley Brook system.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 6/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey. HYDROLOGY & HYDRAULICS

k t

Base flow at Laurel Dam

100-year flood event at Laurel Dam

Figure 1

Base flow at the Laurel Street culvert

Storm event at the Laurel Street culvert

Figure 2

Figure 3 x10

LAND COVER IN THE COOLEY BROOK WATERSHED

The high amount of developed land and impervious surface cover in the watershed increases the amount of runoff entering Cooley Brook and negatively affects its water quality.

Using Longmeadow Street as the outflow location for the Hydrology & Hydraulics Study, Tighe & Bond calculated that 412 acres drain into Cooley Brook upstream of the Longmeadow Street culvert. Suburban housing developments cover most of the watershed, and were broadly completed by the 1970s (Montague & Meulmester, 2). The development led to alterations of the watershed’s soils, drainage patterns, and land cover. Today, impervious surfaces such as roofs, roads, and sidewalks cover 50.5% of the watershed (NOAA). Though forest is reported to cover the other half of the watershed, this reflects a limitation of the NOAA data set, which does not distinguish between one tree in a turf yard and a block of trees. Bliss and Laurel Parks contribute the most notable contiguous sections of forest in the watershed, with impervious cover limited to the active recreation areas of Bliss Park.

maJor land cover tyPes In the cooley Brook Watershed

Stream systems begin to experience degradation of habitat and water quality when their watersheds have 10% impervious surface cover, and when they exceed 25% impervious surface cover, the habitat and water quality of a stream system can be severely impaired, especially when runoff goes straight from impervious surfaces to a water body (New Hampshire Estuaries Project). Since water cannot infiltrate into the soil when impervious surfaces cover the ground, that water flows across the surface and concentrates in channels. This causes stream volumes to dramatically increase during storms and move through the system quickly, instead of water slowly being added to the base flow over a longer period of time. This fast-moving, higher volume of water has much more power to erode the stream banks. Also, water draining off impervious surfaces is much more likely to carry pollutants from roadways or built environments, in turn decreasing water quality and affecting aquatic health. These effects of high impervious surface cover in the watershed are evident in Cooley Brook with its steeply eroded banks, algal blooms, and poor aquatic habitat (Barry).

The same amount of water falling on a developed area will flash through the stream system much faster than a forested area, where the vegetation and non-compacted soils slow the movement of runoff and release it more slowly and at a more steady rate into the stream.

Highly manicured lawns that rely on frequent pesticide application are the norm in the neighborhood, but are not reflected in the NOAA Land Cover data set. Lawn does a poor job of infiltrating stormwater, and lawn fertilizers are common pollutants of streams.

Evergreen Forest

Deciduous Forest

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 7/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

LAND COVER

24.5% 23.7% 0.5% 0.7%

50.5%

Over half of the Cooley Brook Watershed (as defined by the Tighe & Bond Hydrology & Hydraulics study) is developed and covered by impervious surface, greatly affecting the water quality and quantity entering Cooley Brook.

Turf

Water

Developed

% Of Surface Cover for Cooley Brook’s Watershed

The high percentage of developed land reflects the highly altered nature of Cooley Brook’s watershed and implies severe stream health degradation.

SURFICIAL GEOLOGY AND SOILS

The soils of the watershed have little ability to infiltrate stormwater and shed it into Cooley Brook. Conversely, the soils of the parks have high infiltration capacity but are highly erodible.

The soils of Cooley Brook’s watershed also reflect the high level of development and alteration of the landscape. The entire watershed shares similar underlying geologic characteristics: Mesozoic sedimentary rock forms the bedrock, which is overlain by surficial deposits of well-sorted sand, associated with the shores of Glacial Lake Hitchcock, which covered the present-day Connecticut River valley. Though there are two types of surficial deposits listed by the USGS for the watershed (stream-terrace deposits and inland-dune deposits), both deposits are made up of well-sorted sand and tend to form similar soils.

Though the entire watershed has sandy surficial deposits, the soils overlying them mostly do not reflect those characteristics. Typically, water moves quickly through soils formed in sand deposits, making them well-draining and causing low runoff potential since runoff easily infiltrates. Because Laurel and Bliss parks have had legal protections since the early 1900s and have experienced little development, the soils of the parks reflect that sandy character. However, completely encircling the parks, the soil characteristics change, reflecting the level of impervious development in the surrounding area. Fill, or supplemental soil from a different location, is often brought in during the construction process. The urban fill complex used in most of the development of this area has high clay content, which creates soils that are poorly drained and when saturated have high runoff potential (MassGIS). Some of the urban fill has no drainage characteristic listed on the MassGIS soil map. Soils with high clay content have little ability to infiltrate runoff and instead runoff flows over the surface before entering a stream channel or storm drain. Since Cooley Brook’s watershed is 51% impervious, and the soils have high runoff potential outside of the parks, most of the stormwater cannot infiltrate and is carried into Cooley Brook. Before stormwater pipes directed more water into this system, the drainage area would have been much smaller and the soils would have been dominantly sandy. Development of the watershed forced Cooley Brook to accommodate much larger quantities of stormwater. Sand particles do not hold together as well as clay particles do, meaning sand is easier to erode than clay. Since Cooley Brook’s banks are made up of sand, this suggests that the Cooley Brook stream channel frequently shifts and experiences high levels of erosion. In other parts of the brook like zones 3 and 4 on sheet 2, riprap hardens the channel to stop it from naturally shifting. Compounding on the higher natural erosion potential of the soils, the alteration of the watershed also increases erosion potential by increasing the amount and speed of stormwater entering the brook.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 8/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey. SOILS

Sandy banks of Cooley Brook in Bliss Park

Sandy mineral soil is visible below the tree roots due to intense erosion in Bliss Park.

underlyIng surfIcIal dePosIts

soIls In the cooley Brook Watershed

DRAINAGE

A century of development has increased the quantity and velocity of water entering Cooley Brook, making watershed-scale interventions to capture, store and infiltrate stormwater necessary to balance the processes of erosion and deposition in the stream channel.

Completed in 1970, the Longmeadow municipal stormwater system collects water from 237 acres of impervious surfaces and carries it directly into Cooley Brook at nine storm drain outfalls. The development in effect increased the area of the brook’s watershed beyond what the natural topography produced. Development in the neighborhoods surrounding the parks has greatly altered the hydrology of the watershed. In its existing condition, water sheds off houses, lawns, driveways, and roads into 482 catch basins, then through just over 61,000 feet of drain lines. The storm drain system divides the watershed into ten subbasins on 465 acres (Longmeadow GIS).

Blueberry Hill Elementary School, though not part of the watershed, experiences regular flooding in its parking lots. Currently, the stormwater system servicing the school and several residential streets surrounding it daylight stormwater into an intermittent stream branch of Longmeadow Brook to the south. Due to the regular flooding of the school, the Town is considering

adding an overflow drain that would transport floodwater into Cooley Brook during heavy rain events. This would increase the quantity and velocity of water entering the brook only during intense rain events, which would put additional pressure on the already stressed system. Engineering a stormwater overflow at Blueberry Hill Elementary School would mean capturing water through an additional 59 catch basins and 8,276.5 linear feet of stormwater pipe over an additional 53.9 acres of land (Longmeadow GIS). If the quantity of water entering the stream were greatly reduced throughout the watershed, for example, by increasing infiltration in the heavily developed neighborhoods, the Blueberry Hill Elementary School overflow may be a reasonable solution to the flooding taking place. Otherwise, adding overflow drainage will perpetuate the problems of water quality and quantity in Cooley Brook. The municipal storm system creates a challenge to achieving a stable and resilient stream channel. Without watershed-scale planning for stormwater infiltration, the processes of erosion and sedimentation will remain out of balance and efforts to stabilize the stream channel may be jeopardized by intense storms and flooding. The Town is already pursuing design plans to alleviate stormwater infiltration and retention with the Resilient Stormwater

Project. Tighe & Bond is identifying green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) interventions in concert with stream restoration for Cooley Brook. This multiscalar approach has the goal of discovering the best solutions to handling hydromodifications in the watershed and achieving stability in Cooley Brook.

Flooding in Bliss Park

A two-inch rainstorm in May 2023 caused notable flooding in Bliss Park. The paths, basketball court, and playground were inundated with stormwater. Though there are several stormwater catch basins in the park, topographical low areas and compacted soil cause pooling that affects the most heavily-used spaces in the park.

Improving stormwater conveyance and increasing infiltration of runoff will reduce the impact flooding has on park features and benefit Cooley Brook by reducing the quantity and velocity of runoff. Existing stormwater drains present an opportunity for siting infiltration basins with overflow drains connecting to existing infrastructure.

hydromodIfIcatIon In the cooley Brook Watershed

Hydromodification is the alteration of hydrological characteristics of a waterway or watershed (U.S. EPA, 2007). Changes in the timing and volume of runoff from a site are known as “hydrograph modification” or “hydromodification,” occurring when an area is developed; increased impervious surfaces, stream channelization and alteration, and dam construction are a few processes that alter the hydrological characteristics of a waterway. Hydromodification can cause the degradation of water resources, though the term is not reserved for negative outcomes. Threshold design—a traditional stream restoration strategy that uses erosion-resistant materials like rocks or grass liners to keep the stream within one rigid channel—can also be considered hydromodification.

From the development of the Longmeadow Waterworks in the late nineteenth century to the completion of the town storm sewer in the late twentieth century, the Cooley Brook and its watershed have experienced over a century of hydromodification at the hands of its human inhabitants to meet the needs of a growing community. The storm drain system increases the watershed area, and impervious surfaces increase the velocity and quantity of runoff entering Cooley Brook beyond what would occur in the watershed’s predeveloped, vegetated state, where the forests and sandy soils would slow and infiltrate stormwater before entering the stream.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 9/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

DRAINAGE

Blueberry Hill Elementary School

stormwater pipe flow

surficial drainage

surficial drainage

stormwater pipe flow

Stone reinforces Cooley Brook west of I-91

Stormwater is unable to infiltrate impervious surfaces on Farmington Ave.

Blueberry Hill Catchment Area

A small rainstorm causes significant flooding across the ADA walking path and playground in Bliss Park

lowarea

Bliss Park flooding

ACTIVE RIVER AREA & SLOPES

Planning for the future of the Cooley Brook system must include consideration of human activities that occur within the active river area and allow for potential changes to stream flow dynamics. The future of this stream system, without intervention, will include more erosion because of the steep slopes. One option for intervention is to harden the channel by reinforcing the slopes with rock or some other mechanism which would force the brook to maintain one flow regime. Hardening the channel and banks would decrease risk to humanbuilt structures, but would alter and potentially decrease ecological health. Rivers constitute more than just the area where water flows on any given day. All areas likely to flood during the 100-year flood event make up the active river area. This area includes the stream channel, stream banks, terraces, floodplains, and slopes providing sediment necessary for stream processes. The active river area also reflects stream channel migration: since rivers are dynamic and flow patterns change, rivers need to be able to modify where the stream channel flows on the landscape over time. Because stream channel migration typically happens over a long period of time and full inundation of the active river area happens infrequently, permanent structures are often built within the active river area and are at risk of damage.

Part of the active river area are the slopes that provide sediment for stream processes. Balanced river systems create terraces that fill up with increasingly large storm events. The slopes of Cooley Brook exhibit this terracing effect in some locations, namely the areas where forest has remained intact over the centuries and where dams have caused the slowing of water. However, slopes of the brook’s banks are excessively steep (compared to the broadly flat watershed) contributing to the loss of the terrace landform. Much of the brook’s excessively steep slopes are greater than the angle of repose, the slope that can be maintained based on gravity and the type of material. Having a slope steeper than the angle of repose suggests that this material is not stable and is easily mobilized by water, wind, or gravity itself. The steep slopes of the banks reflect the power of water in Cooley Brook to incise, or cut down, the stream channel. In stream systems with highly erodible banks, incised channels are common, but are not stable and are susceptible to mass wasting events like a bank collapsing into the brook. This reflects the highly dynamic nature of stream systems within their active river areas. Though this is a natural process, because this system is in a highly developed area, the brook has less ability to naturally rework its channel without impacting human uses.

stream channel bankfull (2-year flood event)

active river area (100-year flood event)

outside the active river area

1’ = 30’

2x vertical

sloPes of laurel & BlIss Parks sloPes greater than the angle of rePose

B’ B B’ B

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 10/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu

ACTIVE RIVER

AREA & SLOPES

A conceptual diagram of stable stream terraces shows the different levels of flood stages and associated habitat connectivity. The steep slopes and alterations of the vegetation types and flow patterns in the Cooley Brook system have led to the erasure of many terraces there.

Cooley Brook’s active river area includes many trails and two bridges. Three parking lots and the swimming pool border the active river area. This prompts the question of how much flood risk is acceptable for different human structures and uses.

A cross-section through Laurel Pond shows terraces on the forested side; terraces are absent on the grassy slope where the vegetation type has less ability to stabilize the slope. The loss of terraces changes how flood events affect this landscape.

A cross-section through Bliss Park’s ballfields and hiking trails shows the steep slopes proximate to the brook, shallow slopes in the active recreation areas, and moderate slopes that correspond with an underlying dune deposit and provide interesting topography for the hiking trails.

A’ A

the actIve rIver

area of cooley Brook

The neighborhood is flat. Moderate slopes in the park correspond to underlying dune deposits and provide topography for mountain biking and hiking trails. The steepest slopes occur on the banks of Cooley Brook.

Slopes greater than the angle of repose (>33%) border the brook, suggesting high levels of erosion.

Parking Paved path along the pool area cooley brook Forest and hiking trails

stormWater Increases the sedIment load

SEDIMENT TRANSPORT

Dams and stormwater pipes significantly alter the flow dynamics of Cooley Brook in different ways, affecting how sediment moves through the stream system. Erosion (sediment loss) and deposition (sediment gain) are natural stream processes that occur evenly along a stream profile in a stable stream system. Dams interrupt these natural processes, concentrating and separating erosion and deposition to different areas of the stream system.

The steep slopes of the Cooley Brook system do provide sediment for stream processes but the presence of dams in the system highly alters sediment transport processes. Minor changes in flow dynamics and stream channel conditions (like the presence of meanders or riffles) contribute to the variability of erosion and deposition across a small distance in a typical stream channel. Once a dam is introduced, it cuts off the transport of sediment beyond its structure and slows the movement of water. This creates a concentrated area of deposition on the upstream side of the dam. Because of the changes to flow dynamics and sediment transport, water moves more quickly farther upstream and immediately downstream of the dam, leading to high levels of erosion in those areas. This process is reflected in the Cooley Brook system, with much of the erosion being concentrated in Bliss Park and the deposition being concentrated behind the dams in Laurel Park. The Tighe & Bond geomorphic study predicted the potential for 690 tons of sediment to be eroded from the banks of Cooley Brook every year, which is roughly equivalent to the weight of ten blue whales.

Flow Direction

Erosion (sediment loss)

Deposition (sediment gain)

Unaltered Stream Channel Stream Channel with Dams

Stream sediment loads depend on the channel dimension, sediment size, and stream slope, and are always proportional to the stream discharge.

Phase 1: Before the addition of stormwater pipes in the Cooley Brook system, the processes of erosion and deposition are in balance and the sediment load carried by the water is proportional to the amount of water carried by the stream over time. In this system, the sediment size is coarse, reflecting the sandy soils, and the slopes are steep in response to the sediment characteristics.

Phase 2: After stormwater drains bring larger volumes of water into the stream, the system is thrown out of balance and high levels of erosion occur.

Phase 3: In order to return to balance, the amount of sediment carried by the stream must increase. Erosion and deposition once again balance each other out, but more sediment and more water now move through the system. Because of the presence of the dams, erosion and deposition are concentrated in different areas of the brook.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 11/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey. SEDIMENT TRANSPORT

Bliss Park

Laurel Park

Laurel Dam

Concrete Reservoir

Waterworks Dam

Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

dams dIsruPt sedIment transPort

(sediment loss)

(sediment gain) A A C B B C

Sediment deposition decreases water quality and habitat in the concrete reservoir.

Erosion

Deposition

Intense erosion creates a deeply incised channel in Bliss Park.

Incision exposes tree roots.

areas of erosIon & dePosItIon

VEGETATION

The vegetation in Bliss and Laurel Parks reflects historical land use and is impacted by invasive species pressure from surrounding residential properties. An understanding of the site’s successional trajectory can inform decisions made to reduce invasive species, restore native vegetation, and manage ecosystem characteristics.

Bliss and Laurel Parks are a forested refuge within the highly developed town of Longmeadow. According to a 2023 community survey, residents feel the parks are a place to connect with nature and exchange suburban life for a more “wild” or “natural” experience. The site is characterized by transitional hardwood forests, with a diversity of plant communities influenced by the gradient of topography crossing the stream channel, by soil conditions, and by past land use.

laurel Park

In Laurel Park, early successional secondary growth is most abundant in the canopy, a result of historical clearing in the early twentieth century. Black locust, black birch, black cherry, red maple and white pine are most abundant with associated species of red oak, black oak, and white oak. Sugar maple and American beech are present, but less frequent. The topography creates a tapestry of soil conditions; low-lying flat areas along the stream host emergent marsh wetlands in saturated soils and the gullied, sandy slopes create mesic, or moderate moisture, conditions ideal for upland tree species. A dense understory of invasive species limits the view of and access to the stream. Chocolate vine and Asiatic bittersweet drape the branches and trunks of trees while burning bush, multiflora rose, and Japanese barberry create a nearly impenetrable shrub layer beneath.

BlIss Park

Bliss Park is characterized by more mature secondary growth. The canopy is abundant with larger diameter white pine, white oak, red oak, and American beech, suggesting Bliss Park experienced less intense forest clearing. The active recreation area is covered with turf punctuated by ornamental and introduced species like Bradford pear, Austrian pine, and Norway maple.

Transitional Hardwood/Introduced Spp. Early Successional Secondary Growth

Transitional Hardwood Early Successional Secondary Growth

aggressIve non-natIve sPecIes

The aggressive, introduced species are a challenge for the Town, given its limited maintenance capacity. Construction for stream rehabilitation may be an opportunity to remove invasive species, but disturbance can create an opening required for many of these species to recolonize in force. Efforts to alter the stream and eliminate invasive species should be paired with thoughtful planting decisions and active maintenance during establishment. Reducing mowing would cut down maintenance to help distribute efforts and resources for managing the invasive species. A thriving native forest could be sustained by planting competitive native shrub species, managing the spread of invasives after removal, and replicating a mid-successional forest type beyond the stream channel.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 12/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

A B C

invasive species core

VEGETATION

Open Turf / Black Oak

Ornamental Landscape Plants

Red Pine - White Pine Grove

Pine - Oak Forest Mature Secondary Growth

Marsh

Forested Wetland

Invasive species out-compete native species in the understory in Laurel Park

Mature secondary growth abundant with oak and white pine in Bliss Park

A B C

The emergent marsh on the east end of Laurel Pond

Turf

Forested Wetland

HABITAT

The parks are home to a diversity of wildlife; improvement to habitat should be species-specific and more research is necessary to determine what species will benefit most from habitat restoration.

BioMap3 identifies core habitat, critical natural landscape, and regional rare species habitat within the Connecticut River area; aquatic and wetland core habitat in Forest Park; and rare species habitat in Turner Park following the Longmeadow Brook. The mapped core habitat creeps up Cooley Brook from the Connecticut River but ends at Elmwood Avenue, where the stream flows through a more developed residential area, under a culvert, and cascades down a sandstone bedrock escarpment. The escarpment represents a significant change in elevation for the stream; the stream drops around 25 feet vertically over a 210-foot distance. The escarpment and culvert may make it harder for fish to travel upstream, though more research is required to make a conclusive determination.

Though not mapped by BioMap, the parks do host a diversity of wildlife habitat. Dace, a cold water fisheries species, were observed in the stream, painted turtles rest on downed trees in Laurel Pond, great blue heron fish the marsh on the pond’s east end, red-shouldered hawks soar overhead, and neighbors report regular sightings of coyote and fox.

While wildlife are visible within the parks, their habitat is impacted by the water quality in Cooley Brook, particularly for aquatic species. Sediment deposition behind the dams increases the turbidity of the water. This limits the amount of light available for photosynthesis by beneficial aquatic plants, in turn reducing dissolved oxygen levels in the system (Henley et al. 2008). Many fish and invertebrates rely on abundant dissolved oxygen in the water to sustain life. Additionally, sediment deposition behind the dams fills small gaps between the more coarse stream bed material. Many invertebrates rely on these small gaps, where the relatively still water at the stream bottom provides ideal habitat for species that have specialized to spend their larval stage here (Mass DEP, 2007). Removing the dams in Cooley Brook may increase habitat for certain species, and decrease it for others. If increasing habitat is a priority in this system, decisions should reflect a species-specific approach.

ConnectcutRiver

Forest Park

ecological disconnect at Elmwood Ave?

Laurel and Bliss Parks

local aquatic and wetland habitat along Pecousic Brook

Cooley Brook

Turner Park

local rare species habitat along Longmeadow Brook

Great Blue Heron

regional rare species, critical natural landscape, and core habitat in and adjacent to CT River

This charismatic bird can be seen flying beneath the forested canopy along Cooley Brook or hunting in the shallow, slow waters near the marsh. They have a highly variable diet, eating fish, frogs, salamanders, insects, rodents and birds (Audubon). The wetland and aquatic habitat of the emergent marsh supports a diversity of feeding options for the great blue heron.

Northern Redbellied Dace

This small minnow prefers sluggish waters in cool freshwater streams with ample vegetated cover, and tend to thrive in places with a history of beaver activity. They are found in Laurel Pond and the old reservoir feeding on plant material detritus, algae, and small invertebrates (New Hampshire Fish and Game). They are eaten by herons and predaceous insects. They rarely coexist with larger predaceous fish, implying that larger fish are likely not present in Cooley Brook or Laurel Pond.

Painted Turtle

Resting on downed logs in Laurel Pond and the old reservoir, painted turtles live in wetland areas with an abundance of vegetation and basking areas like slow-moving streams, shallow ponds, and marshes. They nest in sandy areas with open canopy. They are an exciting feature of the ecology along the stream.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 13/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey. HABITAT

Great blue heron - Source: Tom Franks Shutterstock

Northern redbellied dace - Source: The Innovation Center of St. Vrain Valley Schools Painted turtle - Source: Jay Ondreika Shutterstock

Stream channel food web shows the relationship between plants, invertebrates, and fish species.

Source: Science Direct “MicroHabitats”

CIRCULATION AND ACCESS

Steep slopes and dense understory vegetation constrain access to Cooley Brook and limit people’s interaction with the stream; lack of connection with the stream creates a gap in knowledge and understanding of the stream, its health, and what it means to steward the Cooley Brook.

According to a 2023 community survey, 55% of respondents arrive at the parks on foot, 25% by car, and 20% by bike. This speaks to the locality of park users. Those who drive park at one of five parking areas, two in Laurel Park and three in Bliss Park. The primary parking in Laurel Park is located off Laurel Street, hidden from the road. This area is a “free-for-all” lot with no delineated or painted parking spaces and ambiguous boundaries. Rogue parking occurs on the surrounding turf and atop the roots of mature oaks and pines, potentially harming the trees. Respondents feel there is sufficient parking at the parks, though some expressed safety concerns for Laurel Street parking lot; offset

from the road, cars frequently idle in the lot at night and residents feel there is a limited ability to monitor what occurs there. A relocated and better defined parking area could decrease the impact on vegetation and increase public safety.

Access to the stream is constrained by steep slopes and dense understory vegetation in both parks. Direct interaction with the stream is limited to the two bridge crossings in Laurel Park, the trails around Laurel Pond, and a desire line through the woods behind the swimming pool in Bliss Park. The lack of safe and accessible circulation near the stream means that some people are hardly aware of its existence. Providing improved access to the stream may increase awareness of the stream, better residents’ understanding of the challenges it faces, and inspire park-goers to advocate for and steward Cooley Brook.

Active Recreation Circulation in Bliss Park

& ACCESS

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 14/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu

CIRCULATION

Rogue parking in the Laurel Pond lot Cars park on top of tree roots in the Laurel Pond lot

Asphalt/gravel Bliss Park lot from Bliss Road Trailhead parking on the shoulder of the driveway

A B D C F E A B C D E F Courts Playground Parking Pool Ball fields Lawn travel Car travel Pedestrian travel forest trails desire line to stream cooleybrook

Asphalt walking paths in Bliss Park meet ADA requirements Bliss Park trailhead at the east lot.

EXISTING PARK FUNCTIONS & USERS

Bliss and Laurel Parks serve distinct purposes and functions for a range of users. Though not an integral part of everyone’s park experience, Cooley Brook and its active river area affect what activities can occur where.

Laurel Park Bliss Park

Nature Experience

Mountain biking

Wildlife viewing

Interactions with the pond

Exploring nature

Nature solitude

Park users

Dog walking

Hiking Trails

Stormwater

infrastructure

Structured play

Playground

Physically accessible

Multi-use grass areas

Age- and abilityinclusive

Swimming pool

Ballfields

Tennis

Laurel Park provides mountain biking trails, a place for dog walking through the early successional woods, fishing and wildlife interactions at Laurel Pond, and the opportunity for quiet contemplation while resting next to the slowmoving water of the pond. Main users of Laurel Park are adults, teenagers, older kids, and animals including dogs, great blue herons, and painted turtles. Bliss Park can be separated into southern and northern portions, roughly bisected by Cooley Brook. Active recreation is concentrated in the southern portion, with a renowned Boundless Playground, baseball fields, basketball courts, a tennis court (currently closed) and a swimming pool (currently closed since it drained into the Cooley Brook). The playground and sports fields create a steady flow of families and park visitors, though these visitors usually limit their activities to these areas. When many of these visitors were interviewed, they were not aware of the presence of Cooley Brook just beyond the fields and swimming pool. Users of the active recreation areas are mostly families with young kids and toddlers, older folks, and sports teams. Lastly, the northern portion of Bliss Park is frequented by similar users as Laurel Park, with more dog walkers, but the upland and intact forest ecosystem provides a different landscape experience and more diverse wildlife habitat. Despite these distinct functions, the parks are unified by Cooley Brook, and the necessity to increase balance in the brook’s system so it can function as stormwater infrastructure for the town. The different parks and functions

must be addressed individually but also with attention to how they interact with each other and how Cooley Brook interacts with each. As part of the community engagement process for this project, the Conway team created a public survey asking park-goers about their experience in Laurel and Bliss Parks with an emphasis on their experience with Cooley

“I agree with efforts to sink and slow stormwater but worry about the expense. While history is important, the remnants of the old waterworks are a bit of an eyesore.”

“I have heard of dogs getting sick from going in the stream due to high bacteria levels so I avoid the stream.”

Laurel Pond (16)

FUNCTIONS & USERS

Informal Path (4)

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu

PARK

CONCEPTUAL DESIGN THEMES & FOCUS AREAS

The Town of Longmeadow contracted the Conway School to develop conceptual designs for three focus areas in Bliss and Laurel Parks. Focus areas were chosen in collaboration with the client, Tighe & Bond, and the Conway team and informed by the historical and ecological context of each area.

a. WaterWorks

The former waterworks and reservoir are key elements of the historical narrative in Laurel Park. This area represents over a century of human intervention in the landscape where the town of Longmeadow made land use decisions supported by community values and the infrastructure needs of a growing population. With century-old infrastructure abandoned in the stream, this area faces problems of neglected management, ecological degradation, and poor accessibility.

B. laurel Pond

Designed by the Olmsted Brothers, this area is a point of pride and rich cultural history in the Longmeadow community. As the needs and functions of Cooley Brook once again change, the open views and cherished history of Laurel Pond make it a logical location to design for the preservation of the beauty and peaceful serenity of the landscape while improving its ecological functioning and strengthening the human-stream connection.

c. headWaters

The headwaters face some of the most serious erosion problems and bank failures in the parks. The active recreation facilities see the most use of any location in the parks, yet the people who use them don’t often interact with the nearby stream. For this, the headwaters represents the loss of human connection with Cooley Brook. Stormwater infiltration, human-stream connection and ecosystem health could be improved in this area to increase the resilience of Cooley Brook in the face of climate change.

DESIGN THEMES

Design concepts are organized into two themes to help visualize alternatives and understand their trade-offs. Functional elements for a Regenerative and Healthy Ecosystem may coexist with elements from an Improved Human-Stream Experience. For the purposes of this document, the first concept for each focus area attempts to prioritize elements of a Regenerative and Healthy Ecosystem, while the second prioritizes elements for an Improved Human-Stream Experience.

Regenerative & Healthy Ecosystem

functional elements

Bioengineering strategies

• Erosion/bank stabilization

• Floodplain connectivity

• Stream habitat connectivity

Infiltration & bioretention

Riparian buffer vegetation

Selective stream access

Reduced turf

Conceptual Design Alternatives

Some elements may coexist, but others require trade-offs.

Improved Human-Stream Experience

Stream interaction

All-persons trails

Boardwalks & observation decks

Bridges

Interpretive signage and interactive elements

Picnic/rest areas

Natural play spaces

INTERVENTIONS

Each focus area is preceded by a site-specific summary analysis that includes pertinent analyses from the first part of this document. Design elements are organized into two categories to help characterize interventions and assess the trade-offs between ecological health, human-stream connection, and maintenance requirements of each design.

hydro-ecologIcal changes

Landscape interventions that change the stream, vegetation, and soils of the site; hydrology and hydraulics of the stream and watershed; and infiltration and stabilization in the stream and surrounding area.

the human element

Landscape interventions that change how people connect to their culture and history, the natural world and each other.

comParIson Bar

To quickly assess the trade-offs between ecological health, human stream connection, and maintenance requirements, each concept page uses a sliding comparison bar. This is used to compare the concepts to one another, and is not based on hard criteria. The comparison bars should provoke thought, conversation, and critical thinking. The thought process to support these decisions is described through Pros and Cons and discussion of installation and maintenance in the side bar of each design.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 16/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu

FOCUS AREAS AND THEMES

Human / Stream Connection Low High Maintenance Low High Ecological Health Low High a B c

WATERWORKS SUMMARY ANALYSIS

Highly altered stream flow dynamics caused by 120-year-old abandoned pipe and reservoir infrastructure and associated land use history create a complicated and highly variable active river area.

Downstream 250 feet from the Laurel Pond dam, Cooley Brook enters an approximately 2,500-square-foot concrete-walled reservoir. The water then flows into a concrete channel where it is conveyed to a second dam. As the water flows over the dam, it enters a buried clay pipe and flows underground before resurfacing approximately 200 feet downstream. A secondary channel has also been formed by time and high flow, so along the entirety of these 500 feet of altered channel dynamics, there is both a natural channel and a constructed channel. The vegetation reveals the land’s history: this area was cleared for access when the reservoir was used as the town’s swimming hole called “The Pump” and then was subsequently abandoned once the pool in Bliss Park was constructed. Today the vegetation consists of a thick tangle of invasive species and early successional forest species, which blocks views of the leftover waterworks infrastructure and limits human interactions with the stream. The bridge crossing the river forms the main point of human/stream connection in this area.

Buried pipe resurfaces; end of infrastructure

Water enters concrete channel Dam; water enters buried clay pipe

100-year

Stormwater Infrastructure

Slopes >33%

Site of Intense Erosion (>1.9 tons/year)

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 17/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

WATERWORKS SUMMARY

Old Reservoir

Thick forest of nonnative and early successional species

Sunny Lawn

A A’ Exposed manhole Dam A’ A 0 20ft. 10 A B A C C B A D D D

Concrete channel meets the dam.

The bridge creates the most significant human/ stream connection.

Thick vegetation, mostly aggressive non-natives, blocks views of the water in most areas.

The slow-moving water in the reservoir shows signs of heavy sedimentation, which reduces aquatic habitat.

The concrete wall of the reservoir creates a hard border between aquatic and woodland habitats, not allowing for riparian or wetland connection between the two.

The waterworks dam is surrounded by potentially hazardous leftover infrastructure. The cross-section above shows the dam in profile.

Flood Event Trail

0 40ft. 20

Concrete channel and aboveground flow

Buried clay pipe Bridge

WATERWORKS : SUPPORTING SUCCESSION

How can construction for stream stability and ecosystem regeneration allow for stream succession and change over time? This design enables dynamic processes, giving space for the stream to succeed over time and elevating the human experience above the ecosystem with an all-persons boardwalk and observation deck.

hydro-ecologIcal changes

• The southern third of the lawn is seeded with tall meadow grass and forb species.

• Invasive species are removed and the area is planted with competitive native floodplain species such as alder, willow, and silky dogwood.

• The concrete channel and dam are removed and repurposed as lunkers, a structure that helps stabilize banks and increases fish habitat.

• Dredged sediment is reused to develop emergent marsh ecosystems along the banks to benefit water quality, and aquatic and wetland habitat.

• Bioengineering features such as step pools, live stakes, fabric-encapsulated soil lifts, lunkers, and root wads slow water, stabilize the bank, and establish the toe of the marsh. See sheet 32 for bioengineering details.

the human element

• A new bridge longer than bankfull width allows for more natural change in the stream channel.

• Existing trails to the south of the stream are rerouted to limit the degradation of the slope.

• An out-and-back all-persons boardwalk and trail leads to an overlook.

• An overlook observation deck allows park-goers to connect with the restored stream.

• A new trail connects the observation deck to the existing trails leading to the Laurel Pond area.

Pros

• Embraces the highly dynamic stream system, allowing ample space for stream succession and change.

• Increased aquatic and wetland habitat.

• Terraced marshes and riparian areas slow, capture, and infiltrate stormwater and increase floodplain access.

• All-persons boardwalk and observation deck allow people to connect with the stream while limiting human disturbance.

• Creating access for construction is an opportunity to remove invasive species and replant with competitive native species.

cons

• Will require significant disturbance during construction.

• Disturbance will encourage recolonization of invasive species and will require active management for at least five years.

InstallatIon / maIntenance

• Installation will require vast clearing, though this provides ample opportunities to remove invasive species and restore native riparian/ floodplain vegetation to increase floodplain access.

• Native plant revegetation will require intensive maintenance for the first five years, but reduce maintenance in the long-term.

• Helical piles may anchor the boardwalk, causing less disturbance to the wetland marsh than other methods.

• The bioengineering strategies like fabric-encapsulated soil lifts, step pools, live stakes, root wads, and lunkers, will require skilled technicians for installation.

• Mowing is reduced by a third. The mow-path follows the southern edge of the all-persons trail.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 18/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

SUPPORTING SUCCESSION B D A A B C C D E E F H G I H I J Human / Stream Connection Low High Maintenance Low High Ecological Health Low High concePtual desIgn 1 J F G

CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DETAILS 1

The stream cross-section shows the relationship between the human experience and the dynamic stream ecosystem. The stream profile shows the change in stream gradient, with step pools reducing flow velocity upon dam removal.

R evitalizing C ooley B R ook in B liss & l au R el P a R ks Longmeadow, MA Prepared for Town of Longmeadow By Savannah Bailey and Brett Towle Spring 2023 19/34 88 Village Hill Rd. Northampton, MA 01060 413-369-4044 www.csld.edu Not for construction. Part of a student project and not based on a legal survey.

DESIGN DETAILS 1 A A’ B’ B riparian/floodplain restoration step pools all-persons boardwalk observation deck connecting trail meadow mow line A A’ B’ B new bridge Rerouted EXISTING TRAILS all-persons boardwalk emergent marsh step pool forested slope and trails forested slope and trails stabilized bank emergent marsh bridge step pools boardwalk deck

WATERWORKS : PRESERVE THE PUMP

How much infrastructure is necessary to remove for stream health? When does the level of disturbance outweigh the benefits of a “natural” channel? In answering these questions, this design also strives to maximize human / stream connection in this location.

hydro-ecologIcal changes

• A native meadow is established in the turf area to increase habitat and decrease runoff, with a mown path providing a shortcut to the all-persons trail.

• The dam and buried clay pipe are removed, replaced with boulder step pools to make up for the elevation change.

• A notch is cut in the concrete reservoir wall to create a new stream channel and flow into the concrete channel is blocked off.

• Fabric-encapsulated soil lifts (FESL) stabilize the worst bank failure and a new trail with infiltration steps provide access to a cobblestone beach.

• Wetland areas are allowed to form naturally before and after the concrete reservoir, where the water slows.

the human element

• An all-persons trail loop is constructed, using a mix of boardwalks and stone dust to bring people right into the stream and encourage interaction.

• Shrub species are planted around the trail’s switchback to discourage cutthroughs and also to soften the transition from forest to meadow ecotype.

• The areas heavily disturbed by the infrastructure removal are replanted with native riparian vegetation, blocking views of the stream and creating a sense of mystery and discovery along the trail.

• An interactive pump activity allows visitors to reactivate the concrete channel when they use the pump, celebrating the waterworks history and recalling when this area was the town’s swimming hole called “The Pump.”

• A viewing platform creates a destination and a vista overlooking the reservoir area.

Pros

• Less disturbance to site than the first Waterworks design.

• Creates destinations and learning opportunities.

• Celebrates history of human interaction with the site.

• Increases wetland areas and reestablishes some floodplain access.

cons

• Concrete reservoir limits the connection between the aquatic, wetland, and riparian ecotypes.

• Would require lots of new trail construction.

• Amount of boardwalk increases cost.

InstallatIon / maIntenance

• Installation will require vast clearing, though this provides ample opportunities to replant with native vegetation to increase ecosystem function.

• Concrete channel and hand pump will likely require design, engineering, and maintenance.

• Meadow and shrubland will require little (yearly) maintenance once established.

• Step pools may require periodic maintenance.