LAND, STORIES, AND KIN

Growing from Memory at Wainer Woods Farm

The Conway School Spring 2024

The Conway School Spring 2024

Our thanks go out to the core team that has supported us in the building of this project, including: Merri Cyr and Mark Walker for their generosity in supplying us with photos for this project; foresters Rupert Grantham and Jim Rassman for laying the solid groundwork for our site analysis; Robin Winters, David Cole, and Betty Slade for their depth and breadth of knowledge of Westport's history; Robert Cox and Cousin Denny for their connection to family and the land; as well as Nate Erwin and Michelle Nikfarjam from the Pocasset-Pokanoket Land Trust for their wisdom and resourcefulness; Chief Rob’s uncles, for their time and care to hold knowledge of the plant and animal communities and family history on the land; and deep gratitude to our client, Chief Rob, who, with kindness and unending support, has entrusted us to help him tell his family’s stories. It has been an honor.

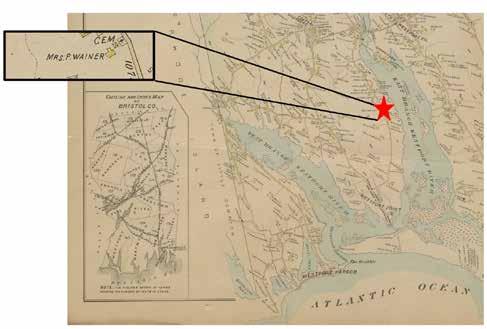

Chief Two Running Elk's family's roots in what is now known as Westport, Massachusetts, go back thousands of years. His family's story weaves together the historical accounts of the Royal family of the Pocasset-Pokanoket Wampanoag, the Mayflower settlers, Cape Cod's whaling industry, the abolitionist and back-to-Africa movements, and the history of African American wealth, farming, and homesteading in the 19th and 20th centuries. Fortunately, this incredible story remains legible today in the landscape of the family's ancestral home: the historic Wainer Woods Farm.

Today the descendants of Michael Wainer and a team of scientists, artists, and activists, led by Pocasset Wampanoag of Pokanoket Nation Chief Nij-Pajikwat-Mo'z (Chief Two Running Elk; Chief Robert Cox; Chief Rob), are developing plans to revitalize this historic property and share it with those interested in learning more about Native American and African American history in Westport.

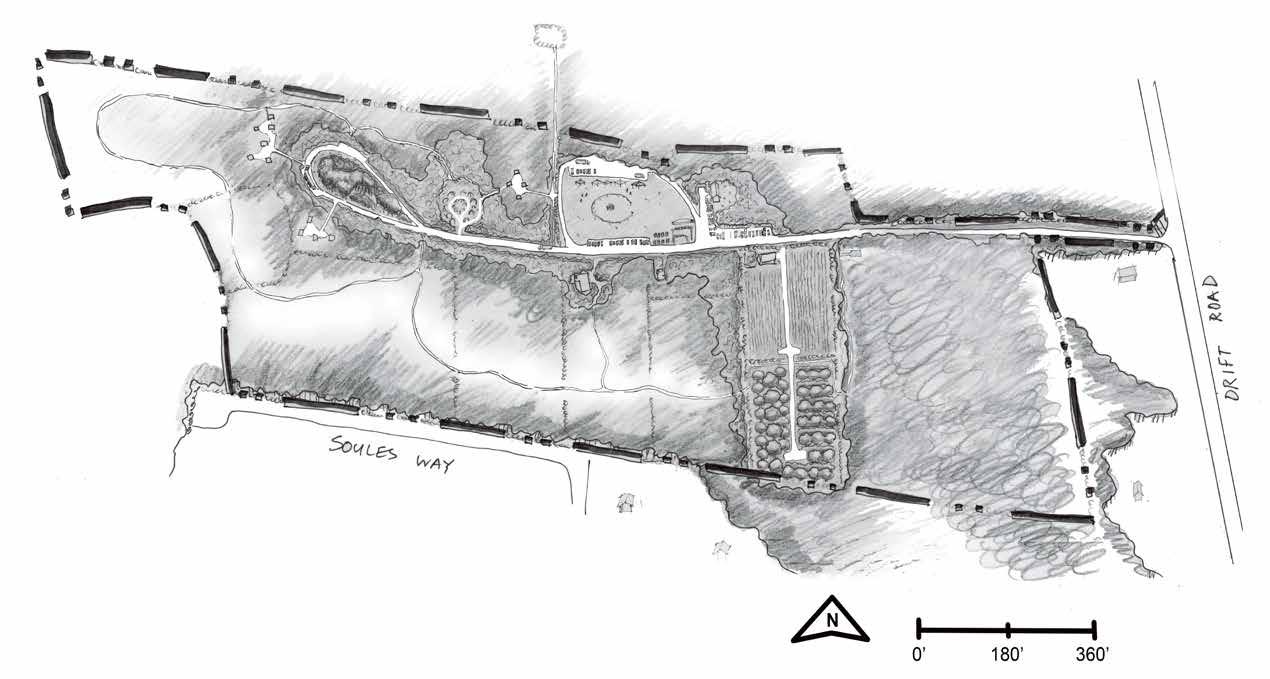

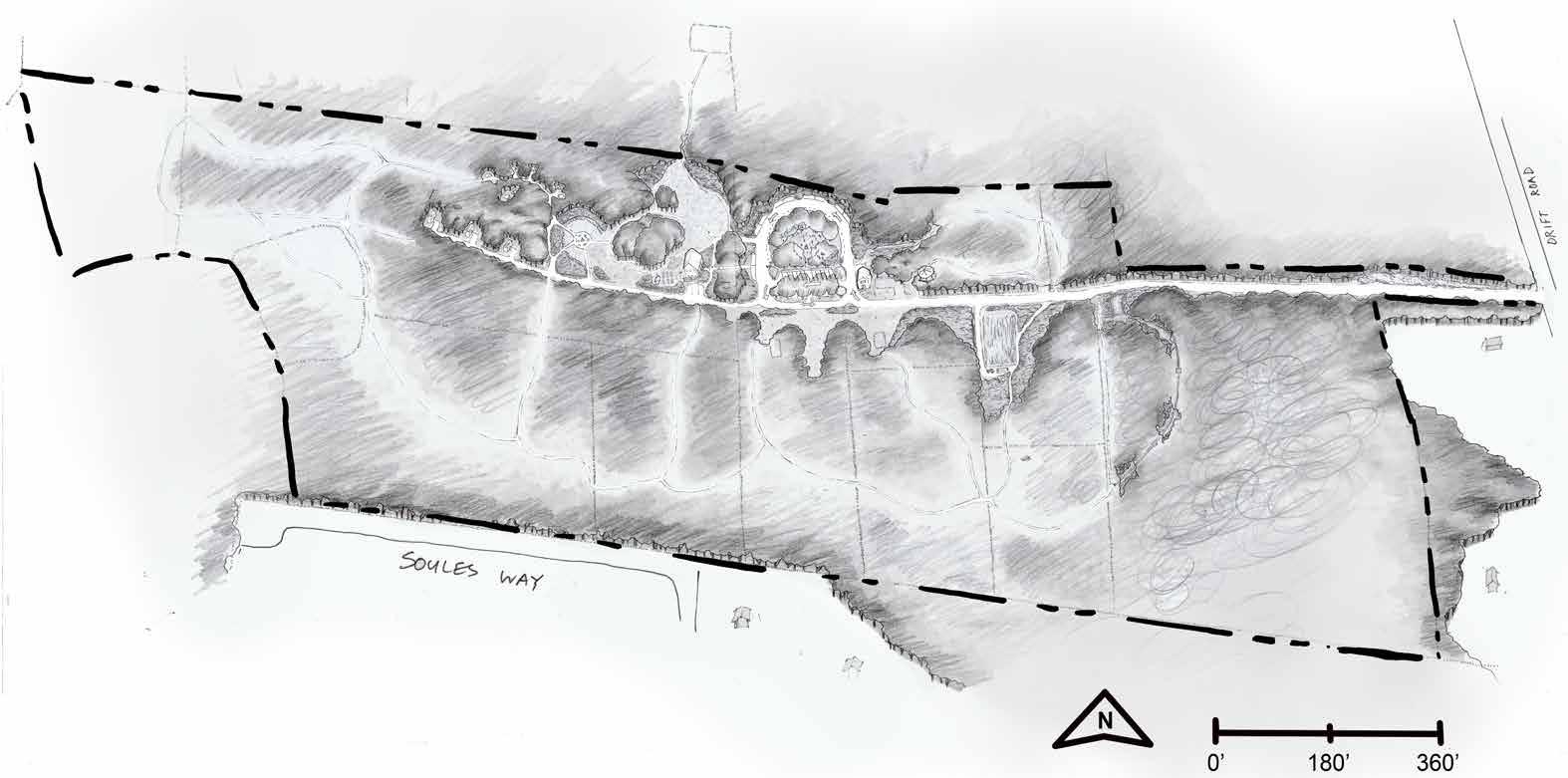

This site plan prepared by Conway School graduate students for the Wainer Woods family farm includes the programmatic elements described by Chief Nij-Pajikwat-Mo’z and by the forestry management plan prepared by Walden Forest Conservation in September 2023. The Conway team’s designs place elements on both of the site’s parcels, as outlined in the forestry plan.

The 43 acres that this site comprises amount to the largest private landholding by an individual Pocasset tribal member remaining today. Though notions of land ownership did not exist, or were at least substantively different, within the Pocasset and many other indigenous North American tribes, the territory managed with deep expertise by the Pocasset once encompassed present-day Tiverton, Rhode Island, and large swaths of Southeastern Massachusetts including Fall River, Freetown, Dartmouth, Fairhaven, Westport, Swansea and Middleboro. The Pocassets were one of the largest and most powerful tribes in the Pokanoket federation, and were among the first to interact with the Mayflower passengers, with their Chief Corbitant being among the signers of the 1621 Treaty at Plymouth (Ferreira et al.). The tribe’s numbers had already been greatly reduced by rodent-borne diseases carried to North America by English ships before the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620, after which thousands of indigenous lives were ended in King Philip’s War. The Pocassets were further fragmented by the creation of the South Pond Reservation in 1707, which divided the tribe by forcibly situating them on two small, separate parcels of land. The Pocassets successfully petitioned to move to a contiguous group of lots at Watuppa Reservation in 1707, but this was taken by the State of Massachusetts in 1907 so that the pond could be used as a regional water source (Conforti). Unlike the nearby Mashpee tribe, the Pocasset tribe has not been federally recognized, preventing it from gaining federal support and funding access. The Pocasset people have been consistently fractured and disinvested in for over four centuries, with private land holdings by tribal members becoming ever more rare. The contemporary beach tourism economy of this coastal part of Massachusetts has driven up property taxes astronomically, further increasing the financial pressure on landowning tribal members to sell off their remaining tribal territory to real estate developers.

In 1799, the client’s 5th great uncle, Captain Paul Cuffe, a man of Wampanoag and African descent who had made a fortune in merchant shipping and a name in abolitionist activism, bought land from descendants of Mayflower passengers that included the 43 acres upon which the client’s site is now located. This was part of the 70,000 acres of Pocasset lands that had been signed over to the Plymouth Colony settlers in the 17th century. He then sold the property, located on modern-day Drift Road, to his sister and her husband Mary and Michael Wainer, both indigenous; this land became the Wainer family farm (Westport Historical Society). In the tradition of the region, trees were cleared, fields turned and stone walls constructed for agriculture and the keeping of livestock. The property’s bounty of natural resources included (and includes today) species used for indigenous medicine, food, and ceremony, and over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries the Wainer family combined Pocasset farming, foraging, and forestry practices with what became standard agriculture methods in the New England region. During the 19th century, the Wainers may have provided asylum on their farm for black men, women, and children fleeing enslavement, while Paul Cuffe used his whaling ship to carry those wishing to return to Africa back to their homeland (Miles) (Grinde Jr.).

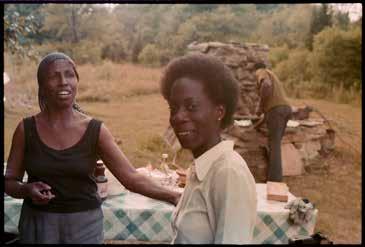

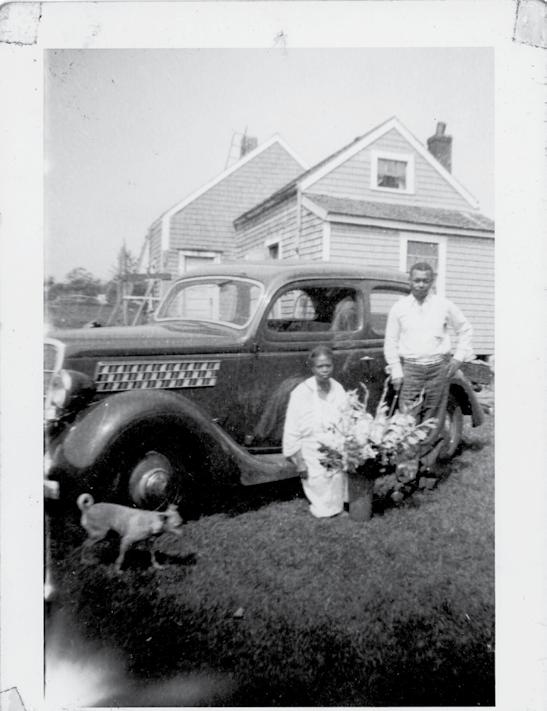

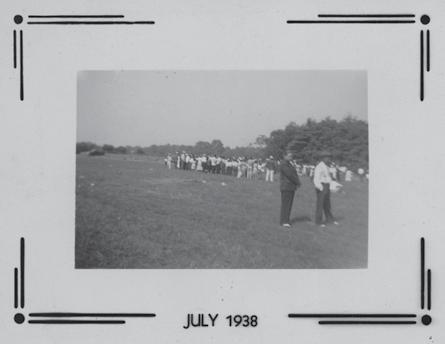

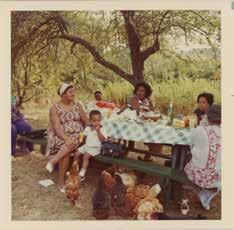

Over time, the Wainer farm became a community hub thanks to the family’s welcoming nature and hospitality. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Wainers hosted clambakes and other gatherings on the farm to which transportation was provided from offsite (Wortham). The Wainers enjoyed hosting and feeding the community, and the client hopes to host members of his family, his tribe, and his community much in the same way that his family did, using the site’s rich story to spread knowledge about the region’s littleacknowledged black and indigenous history. As the largest remaining landholding of a Pocasset tribal member in a region that experienced violent and strategic fragmentation over hundreds of years at the hands of imperialist forces, this site has the power to tell a unique but essential American story about abolition, intergenerational knowledge, the interconnectivity of living things, community building, and ongoing resistance to injustice.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

The Chief wants to be able to host friends, family, and the community on the site, grow food, tell the stories of his family history, and eventually retire there. To achieve these goals, certain requirements must be met.

including powwows, school groups, camping, educational workshops, clambakes/cookouts, and private family events.

• a powwow space meeting traditional standards for dimensions and access for various user groups

• parking for 60-100 cars and at least three RVs

• clear wayfinding for drivers: safe and sturdy access road into the site, turnaround for large vehicles (emergency, construction, forestry)

• clear wayfinding for self-guided visitors on foot: safe paths free of sharp brambles and poison ivy, effective signs

• waste management systems: septic, composting toilets, and/or PortaPotties

• campsites

• desirable relationships between public and private zones of use

Goal: Telling Ancestral Stories in the Landscape

including the stories of Paul Cuffe, indigenous life and practices, and the Wainer family’s farming history.

Requirements

• protection of the existing onsite features and natural resources that tell these stories (old structure foundations, walls and boundary stones, farm equipment)

• wayfinding guided by narrative that puts visitors in contact with historic elements and artworks

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

Goal: Farming & Teaching of TEK

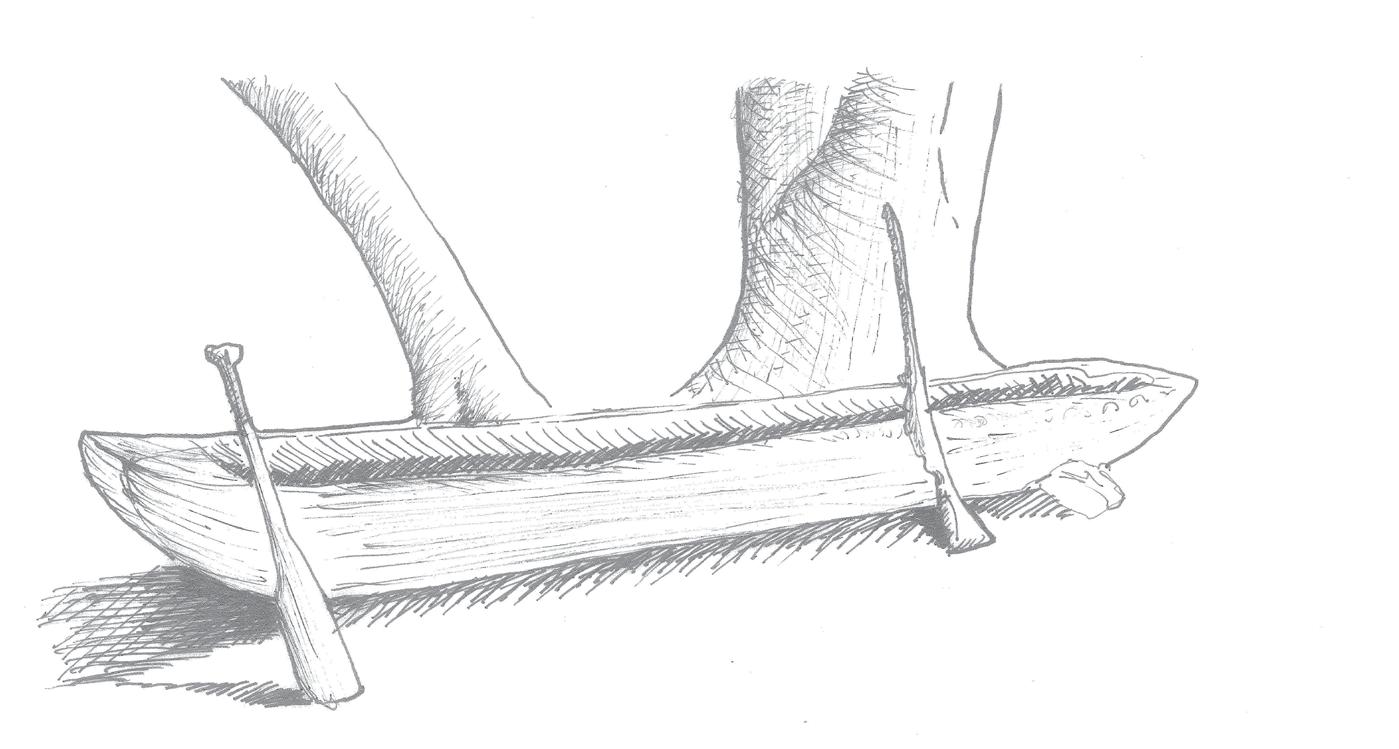

including practices of foraging, medicine making, farming, hunting and tanning, mishoon building, and being in relationship to local species.

• a covered outdoor classroom that doubles as a rain shelter

• areas cleared of forest and tilled for agricultural use

• a fire-safe area for building a mishoon, and a place to submerge it in winter

• protected diversity of plants and wildlife for foraging, observing, hunting, and making medicine

Goal: Siting a Permanent Residence for the Client

Requirements

• a building envelope that can accommodate an estimated house footprint and a possible septic leach field

• siting and plans for an efficient septic system or an alternative that has minimal negative impact on the wetland

• space for a kitchen garden adjacent to the home

• temporary large vehicle access for the construction process that protects natural resources from damage

• comfortable buffers between client's home and high-activity event zones

1615-1619

Diseases carried to North America by rodents on English ships kills all but a fraction of eastern Massachusetts's indigenous people.

1620

English settlers on the Mayflower land in Patuxet territory and form Plymouth colony just east of Westport.

1621

Beginning of period during which significant amount of tribal land was given over to colonists via Englishlanguage bill of sale signed by Royal Pokanoket King Massassoit.

Indigenous land encompassing modern-day Westport is signed over to Mayflower passenger, George Soule. 1621

1675-1676

King Philip's War: thousands killed. Colonists gain control of the region. Nearly all of the remaining indigenous population was either enslaved, publicly executed, or moved onto reservations.

Pokanoket cultural identity is criminalized, and colonial settlers begin referring to Pokanoket people as "Wampanoag."

Paul Cuffe, an ancestor of the client and an affluent PocassetPokanoket and AfricanAmerican businessman, whaler, and abolitionist, buys back traditional Pocasset-Pokanoket land, containing the project site on Drift Road, from Mayflower descendents.

Paul Cuffe sells the land to his brotherin-law and business partner, Michael Wainer, marking the origins of the Wainer Family Farm as it is known today. Work clearing agricultural fields and building stone walls commences, and the farm operates to varying degrees of intensity into the 20th century. Wainers provide sanctuary on the farm for African Americans fleeing enslavement.

Wainer family operates the farm during the summer season, hosting clambakes, community events, and frequent family gatherings. The family grows hay, row crops, and medicinal plants using traditional indigenous and other contemporary regional methods.

1980 s -2020 s

Remaining residence on property is deserted by family members, and unused agricultural fields become reforested.

2024

The Conway School team joins Chief Two Running Elk, the Pocasset-Pokanoket Land Trust, and others in developing a plan that will bring community back to the property while protecting its ecological integrity.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

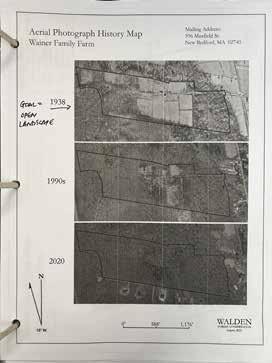

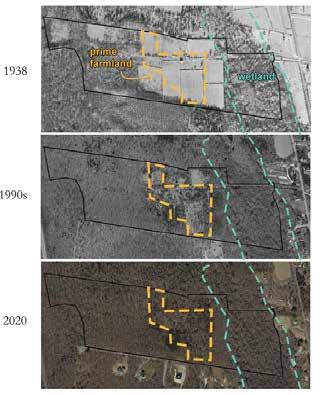

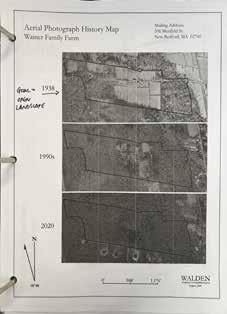

By the 1930s, around fifty percent of the site's forest had been cleared for agriculture. The land was used for hay, annual row crops, and livestock, as well as for parties and gatherings for the family and larger community, with the scale of these activities tapering off by the 1980s. The eastern third of the property, which contains the wetland, was never cleared for growing, and was used instead for foraging.

By the 1990s, the property was no longer an operational farm, and the client's grandparents had departed the onsite residence, which, though in an unlivable state of disrepair, is extant onsite today. The site had become largely reforested.

By the 2020s, the site had become completely reforested. Housing developments had begun to emerge on Soule's Way, adjacent to the southern property line.

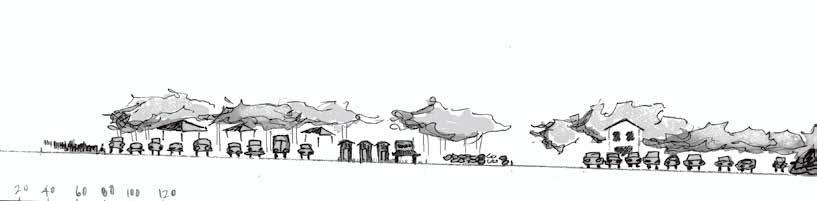

Only an hour from Boston, Westport is a coastal town with high development and tourism pressure coupled with a strong conservation movement. It is part of the region locally known as the "farm coast" in which towns have made an effort to support local farming, forestry, and fishing industries, and the events, artists, and small businesses associated with them.

The low-density residential neighborhood in which Wainer Woods sits is dominated by single-family homes, some of which are seasonal vacation homes. Neighborhood residents enjoy the views and recreation offered by the Westport River estuary that Drift Road parallels and the five-minute southern drive to the popular Horseneck Beach area.

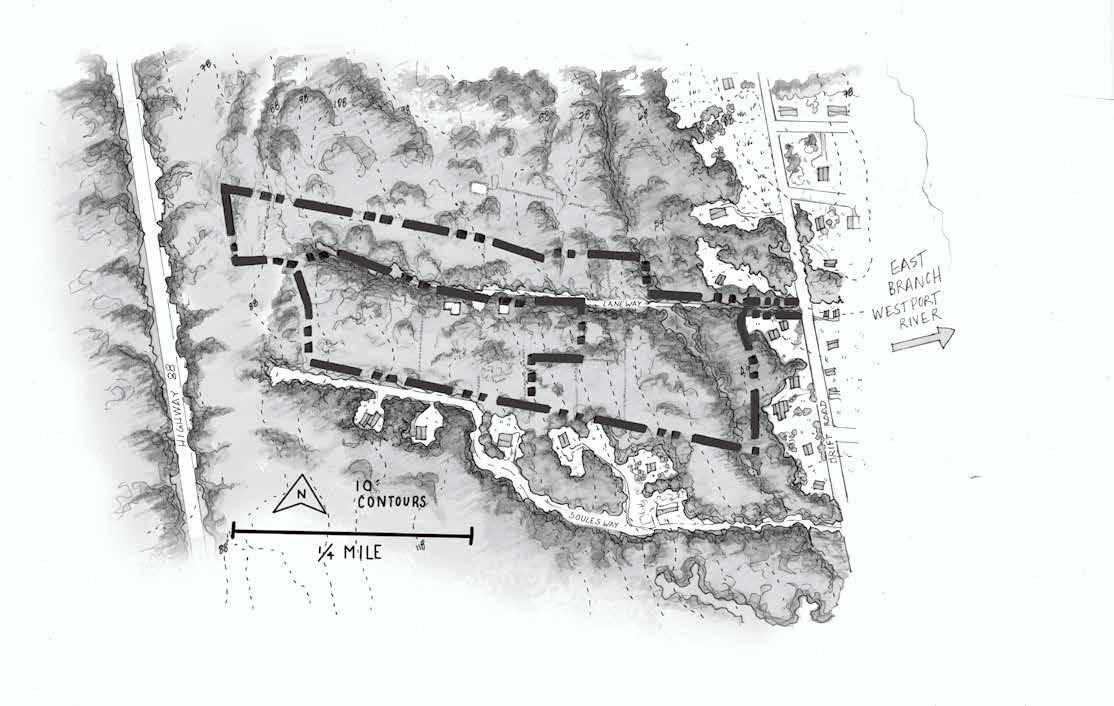

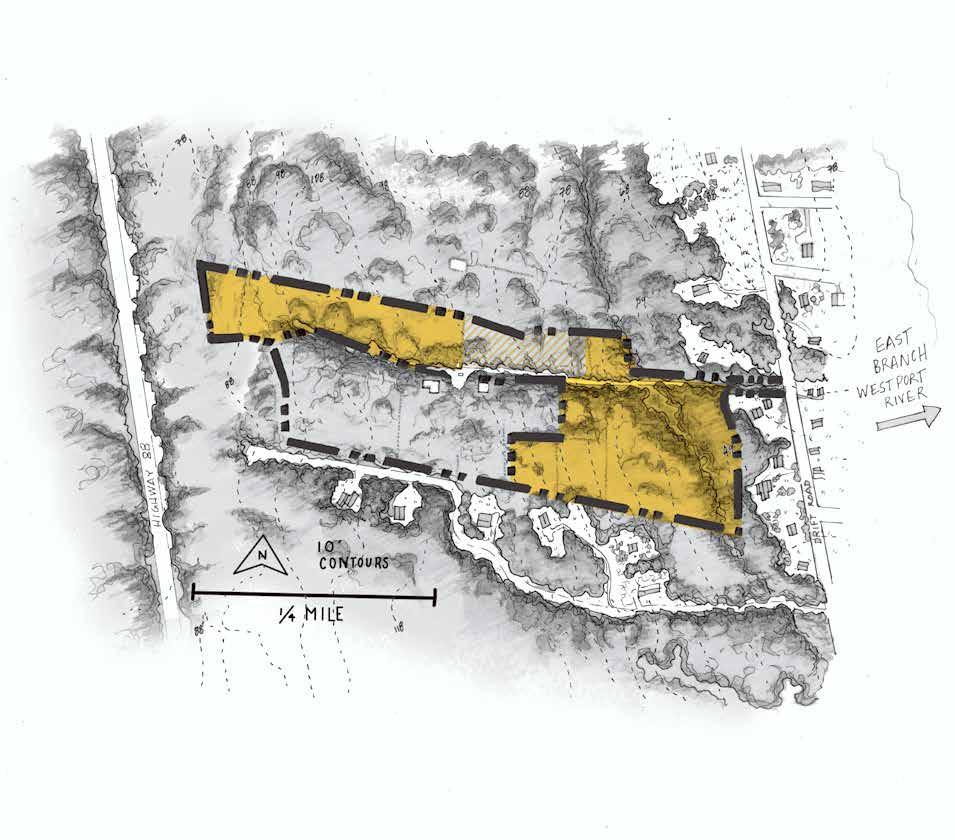

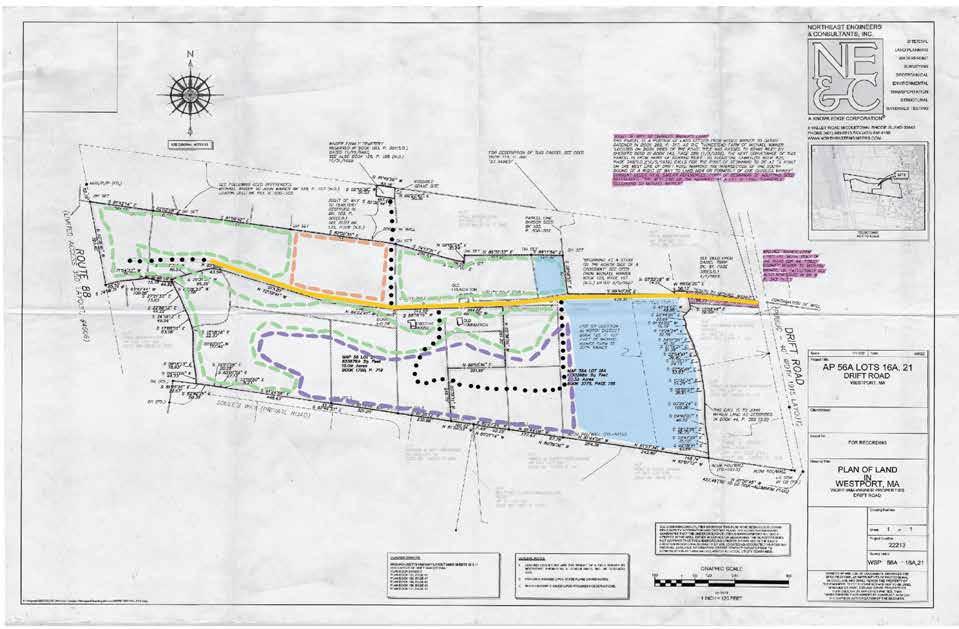

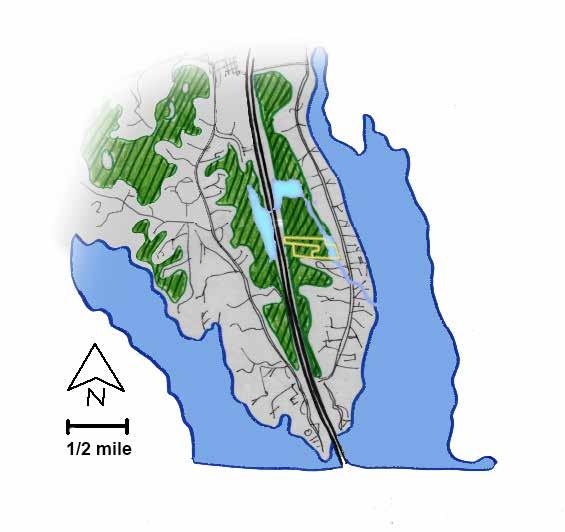

Wainer Woods comprises two adjacent parcels that together are a half mile from east to west, stretch 0.15 miles from north to south, and total 43 acres. The house and farm fields abandoned in the 1980s have become densely forested. In the spring of 2024 woody vegetation was cleared from the historic laneway to allow for vehicle access and parking for two cars towards the site center where three old stone foundations and a collapsing cabin remain. A shallow, hand dug stone well exists, but needs inspection and testing. No septic or other wastewater system are currently on site, and no sewer infrastructure is available for hookup.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

When talking about the two parcels that make up the family property, Chief Rob calls the northern parcel the Tomahawk and the southern parcel the Chopping Block. It is a family agreement that no infrastructure be sited on the Chopping Block parcel, and that it only contains low-impact design elements, such as trails.

The Tomahawk parcel is enrolled in the Massachusetts Chapter 61A program in an effort to reduce the tax burden and support the client's farming, forestry, and foraging goals, and as such is required to sell a minimum of $500 of agricultural products annually. The program encourages landowners to create or maintain farming and forestry land use instead of development, and in return offers significant tax relief for landowners for the ten years of enrollment. However, landowners can build a residence or any non-agricultural infrastructure within an exclusionary building envelope area delineated in the required forestry management plan enrolled with the state.

According to the forestry plan enrolled with the state for the site in 2023 by Walden Forest Conservation, a three-acre building envelope is set aside in the middle of the Tomahawk parcel. This envelope was created to hold Chief Rob's residence as well as all event-specific elements such as the powow and event field, parking, and associated waste management systems.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

Current access to the site is fairly limited. One access road with no turnaround areas dictates vehicular traffic as well as most foot traffic. Cars must find cleared areas to turn around wherever possible, and damage was recently done to historic stone walls when a large flatbed truck was unable to turn around easily after entering the site to drop off a shipping container. After the agricultural fields were abandoned, the site became reforested and overgrown in places with vegetation so dense that access is nearly impossible. In order to meet the client’s goals for the site, access for vehicles and people needs to be easier, safer, and more straightforward.

The site is bisected from east to west by a dirt road referred to as “the laneway,” which provides access from Drift Road and is wide enough for a single car until it reaches the westernmost portion of the property where it narrows into a walking path. It is bordered by stone walls roughly until it reaches the 61A exclusion envelope, where cars historically parked and turned around near the residence and farm buildings. This road has been the site’s largest artery of circulation for vehicles and pedestrians since its construction in the early days of the farm’s operation. Recently, the tires of a large flatbed truck delivering a shipping container to the property on a wet day created ruts in the laneway several feet deep. The laneway is slated to be repaired using NRCS funding. This funding may also cover the widening of a segment of the laneway, possibly to a width that would allow two cars to pass each other.

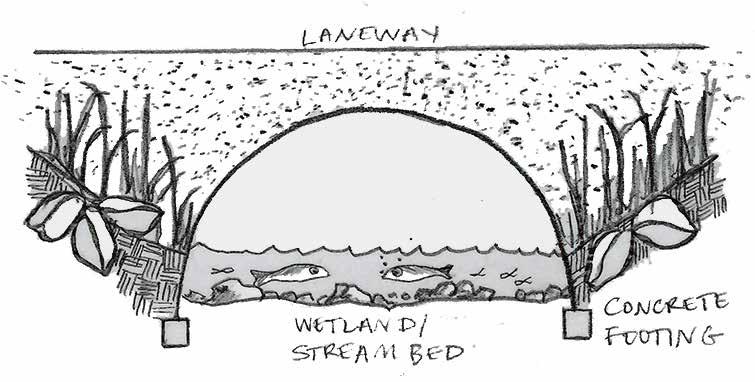

A handmade culvert allows the laneway to cross over the wetland. The details of the culvert’s construction and current weight-bearing capacity are unknown, but if large vehicles are to be expected on the property in the future, it may be necessary to rebuild and fortify the culvert to support heavier loads.

The wetland that makes up roughly the eastern third of the site is not easily traversable, and supports delicate wetland species that amount to a significant portion of the site’s biodiversity. The wetland has not experienced significant foot traffic for many decades, and its ecological health has benefited from a lack of disturbance. The client wishes to forage in and around the wetland and allow visitors to do the same, using new trails and/or a boardwalk system to keep foot traffic confined to certain areas while protecting others.

Poison ivy is nearly omnipresent on the site, but it is particularly concentrated in the southern half of the site in the open woodland in the southern and eastern parts of the site. It creates a significant constraint to getting around the property comfortably and safely on foot in areas where there are no clear footpaths. While its presence might be considered a problem, it could also help to keep most foot traffic to any future paths and out of sensitive habitat areas.

Stone field walls, built by the Wainer family in the late 19th-early 20th century, create a grid across the entire site and dictate access in a significant way. Most have an opening through which all traffic must pass; some have no openings at all. It would be possible to alter the locations of these openings in order to resituate access points, but as these walls are historic artifacts, minimal disturbance might be preferred and paths designed to pass through the existing points of entry.

Dense and often thorny vegetation (honeysuckle, greenbrier, multiflora rose) prevents easy access in these areas.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

Rocks as large as several feet in diameter cover the ground in this area, having been removed from the ground during field clearing and being no longer needed for the construction of stone walls. These rocks make the area tricky to navigate on foot. Some may need to be moved to add features requested by the client in the northwest portion of the site.

Existing footpaths have been created by human and wildlife use in the southern portion of the site. In the northern portion of the site, the client has cleared wider access paths with machinery. The client wants to expand this path network to include foraging trails and provide access to agriculture and agroforestry areas as well as features like an outdoor classroom, art pieces, and historical artifacts.

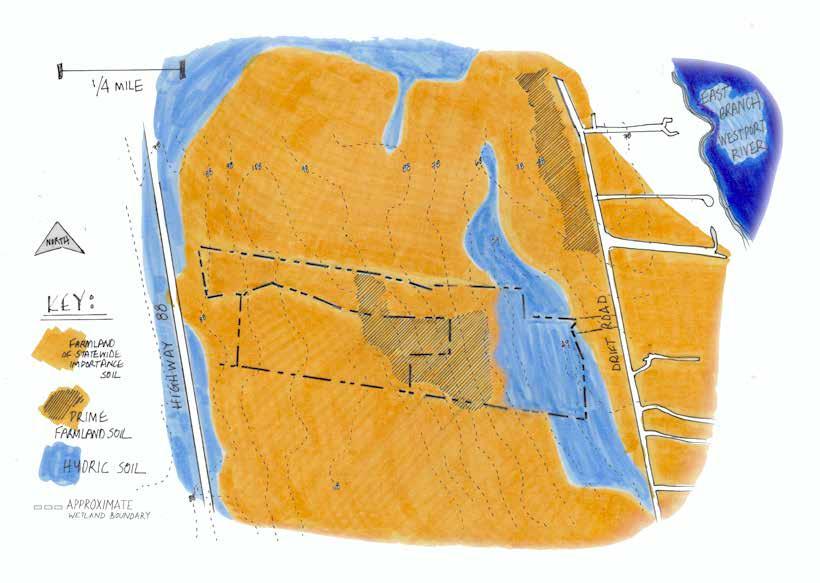

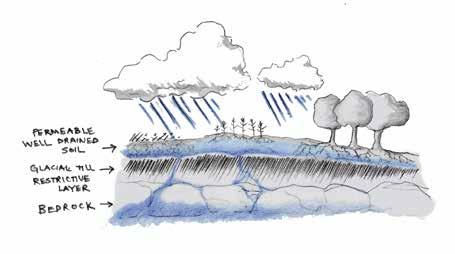

Over ten thousand years ago the glaciers of the last ice age dropped huge amounts of rocks and sand as they melted and receded northwards from the Massachusetts coastal lands that the Wainer family's ancestors inhabited. The agriculturally productive and wetland soils that have accumulated since the glacial retreat at Wainer Woods are strongly influenced by the patterns and characteristics of the glacially deposited material on which they have formed.

Over the milennia since the glaciers retreated and left ridges in the landscape of Westport, water and carbon rich organic matter (dropped leaves, dead wood, decaying organisms, etc.) have followed gravity downhill and collected into low spots. At Wainer Woods this flow has occurred from the hill just south of the property towards the low areas on the west and east sides of the property. This formed wetlands on the eastern edge of the Tomahawk parcel and to the west of the property along Highway 88.

The soils in these low spots are rich, wet, and mucky, make unproductive farmland, and are legally protected from alteration by the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act (310 CMR 10.00). The wetland's biodiversity has harbored valuable medicinals that the Wainer family has foraged for generations, and as such is a powerful community resource for Chief Rob's hope to share TEK with others.

The wetlands at Wainer Woods are also one of the property's greatest resources for the client's climate change mitigation and adaptation goals. In addition to providing a valuable forage and wildlife biodiversity hotspot, the site's wetlands are the most productive carbon sink and storage landscape type on the property. Though they make up a mere 3% of the world's surface, wetlands store 30 to 50% of the world’s carbon, which is twice as much as global forests (UN Environment).

The site's upland soils contain the well-draining coarse sands and rock particles that the glaciers deposited as they retreated many thousands of years ago, and have combined with organic particles from decaying life at the soil's surface ever since. The organic matter adds a spongelike quality that keeps the well draining soils moist, but not water logged. These conditions, combined with low erodability and flooding frequency, at least 40 inches of rooting depth, desirable pH balance, and other characteristics produce desirable qualities for conventional crop production.

The USDA has classified farm soils of national significance to conservation as Prime Farmland Soils, and state significant soils are Soils of Statewide Importance. Over 90% of the soils at Wainer Woods are are classified as Prime or of Statewide importance. This bodes well for the client's goals to grow locally adapted annual crops such as the three sisters.

The family's land use history supports the data provided by the National Resource Conservation Services. Historical imagery show from the forestry plan shows that the last farmland areas abandoned were the prime farmland soils towards the site's center.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

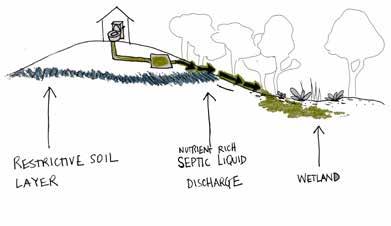

Although several distinct soil types exist on the site, one of the characteristics that both lowland-wetland and upland-farmland soils share is the presence of a dense layer of compacted rock that lies within 60 inches of the surface. Unlike the deep, water-wicking sand deposits found elsewhere in the Cape coastal region, the dense restrictive layer in the Wainer Woods soils prevents water from draining too far away from the surface, which keeps moist soils within reach of plant roots. As such, crops and natural vegetation are more resilient to droughty conditions (Cates 2020). However, in a heavy season of rain, even prime agricultural soils with a densic layer could remain too wet for annual crops to grow well.

A restrictive layer can provide hydration benefits in a drought, but can also function like a tractor hardpan and lead to drainage and soil quality problems if not handled with care. Use of heavy modern farming and forestry equipment while soils are wet could compact them to the point of making them unproductive for agriculture. Compaction can also exacerbate soil erosion, runoff, and sediment and nutrient accumulation in streams, and cause an overall decrease in water supply to plants (Bryant 2015). Climate change is likely to increase the risk of soil compaction, and not only because high intensity rainfall is a major compacting agent of bare agricultural fields. By 2050 the ten percent annual chance of a daily rainfall event (2.4 to 4 inches) could occur five times more frequently than it has historically (Massachusetts 2022 Climate Change Assessment Report for the Southern Coastal Region). More rain could mean that the soils at Wainer Woods are likely to remain wet for long periods, increasing the likelihood that they are wet when heavy machinery or lots of foot traffic are needed during harvest periods, or when large-scale events are held at the event field.

Although the property is unlikely to become flooded with sea level rise, even at a 4 foot rise projection (“Expansion Map: Potential Floodplain Expansion with Sea Level Rise in Buzzards Bay”). However, sea level rise could have a significant impact on well water supply on the property.

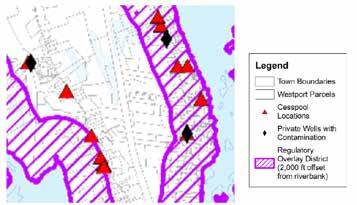

Increasing temperatures and sea level rise are projected to futher impact the availability of clean drinking water in Westport through saltwater intrusion and septic contamination of rising groundwater. Most of Westport's residents are on private wells, and many households and businesses have resorted to using bottled water for drinking and cooking. The number of contaminated wells are likely to continue increasing as nutrient and bacterial contamination loads continue to enter the watershed through existing and new development.

Traditional private septic system failure is a major contributor to the widespread eutrophication of water bodies across the coastal region, including Buzzard's Bay, the estuary habitat that Wainer Woods drains into. As of 2020 over two hundred private wells are reported as contaminated from bacteria and nitrates from failing septics in Westport, two of which lie within a half mile of the Wainer Woods property. Like many water bodies on the coast, the East Branch of the Westport River is impaired due to the presence of fecal coliform from the failure of private septics. Septic systems have a high failure potential in soils with a restrictive layer because of their water holding capacity. Wainer Woods's depth to water table is between twelve and twenty-four inches, so its soils are rated as "very limited" for septic (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service). Human waste management strategies at the site should take into account the high potential for septic failure, the proximity to wetlands and other sensitive habitat, as well as regional nutrient and bacterial pollution issues.

"Today, by far the largest source of nitrogen to most Buzzards Bay harbors and coves remains residential septic systems. Even new, properly functioning Title 5 septic systems do little to prevent nitrogen pollution."

-Buzzards Bay Coalition, 2022 "State of Buzzards Bay" Report

The first 200 feet of natural vegetation along water bodies is often cited as the most important landscape feature to protect water quality and habitat. The Chapter 61A building envelope registered with the state is adjacent to the property's wetland and overlaps the 100-foot buffer zone regulated by the Wetlands Protection Act and the 300-foot buffer recommended by local watershed activists and ecologists. Construction of a house and septic system within the buffer could not only contribute to the region's water contamination problems via nutrient and bacterial runoff, but also cause acute habitat degradation to the wetland on site.

All soils on site feature a restrictive layer that holds water within 60 inches of the soil's surface (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service).

Septic systems have a high failure potential in soils with a restrictive layer because these soils can remain saturated, preventing discharged sewage from proper treatment before it reaches nearby water bodies or groundwater. Nutrient and pathogen contamination from improperly managed human waste has caused large scale habitat degradation of the local and regional coastal watersheds, and contaminated thousands of people's drinking water.

Westport's 2020 Water Resource Management Plan recommends the establishment of a Regulatory Overlay district that would require all new septics installed within 2,000 feet from the Westport River to have a denitrification component. This zone would include the Wainer Woods property, but has not yet been adopted by the town. Although denitrification systems successfully reduce nitrogen output of septics and leach fields, they do not prevent other nutrient, chemical, or pathogen contamination that are problematic in the watershed.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

The soil's restrictive layer influences broad hydrologic patterns on site which affects patterns of life found on site. Wainer Woods's groundwater is prevented from draining far from the soil's surface and follows gravity along the restrictive layer from high to low points in the landscape, and sometimes pushes out of the sides of the gentle slopes to form natural cold-water springs. The Wainer Woods forestry plan made by Walden Conservation Group in 2023 maps three of these springs on the eastern side of the property, at the western edge of the wetland. Springs have not been mapped on the west side of the property that drains into a northern wetland, but given the geologic conditions their existence is possible.

As the springs drain from the forested uplands directly into the wetland and stream complex that they abut, they emit cold, clean, and oxygenated water that contributes to the health and species richness of the site and its broader regional habitat. As oxygenated groundwater emerges from the springs it stays cold under the shade of shrub and forest cover along the stream before draining into the warm saltwater estuary of the Westport River branches.

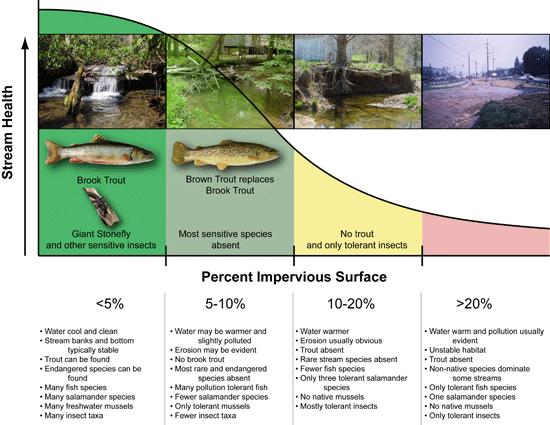

The combination of fresh and saltwater is the defining feature of estuaries that makes them some of the most biologically rich habitat on Earth (US National Park Service). Many of the local wildlife and plant beings that the Wainer family's Pocasset ancestors formed relationships with before colonization are specifically adapted to the combination of the cold, clean, nutrient-rich, oxygenated freshwater and the shallow, warm saltwater bays of the Westport River estuaries, including sea-run brook trout, river herring, white perch, stripers, American eel, sea lampreys, blue crabs, bay scallops, quahogs, eel grass, salt meadow grass, and many others. New England's estuaries have been degraded by large-scale deforestation and wetland destruction for housing development and agriculture, the damming of rivers and streams, and nutrient, chemical, and bacterial pollution over the last four hundred years, reducing once-abundant populations of estuary dependent species to the point of rarity or extinction. Today the Westport River-branch estuaries are designated as habitat that supports rare and endangered species by the Massachusetts Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program, and are under limited protection by the state's Rare and Endangered Species Act. However, the health of these habitats are ulitimately dependent on everyday decisions made by landowners within the watershed.

The removal of vegetation for impervious parking surface, coupled with building construction, and increases in vehicular traffic are likely to have a direct impact on the water quality entering the wetland via polluted stormwater runoff, sedimentation, and increasing water temperatures from lack of shaded forest canopy. The health of the wetland-stream-estuary habitat can be protected by keeping 200-300 feet of its vegetative buffer maximally covered by forest or shrubland, minimizing impervious surface area, infiltrating stormwater runoff, and concious fertilizer application practices. As an educational community hub Wainer Woods has a unique opportunity to showcase landscape stewardship practices that bolster the connection of land, water, and life.

point to the south, which causes rain and groundwater to flow east into the onsite wetland and west into the wetland just outside the property boundary along Highway 88.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

East Branch of Westport River Wainer Woods spring-fed wetland-stream complex forests, shrublands, grasslands

The site makes up the widest section of continuously natural vegetation uninterrupted by development on the east side of Highway 88, and possibly on the entire Westport peninsula. The forests and shrubland on the site are contributing to the ecological health of the entire region not only by providing high-quality habitat for plant and animal beings on land, but also by protecting the quality of water on which all local life depends through pollution filtration, erosion prevention, and the maintenance of the cool temperatures of freshwater streams.

The brook trout found in Westport break tradition with the rest of their species. Typically found only in freshwater, the brook trout along the eastern seaboard have behaviorally adapted to move between freshwater streams and saltwater estuaries. Although as a species they do not need saltwater to complete their life cycles, they do need their freshwater habitat to be cold and oxygenated. Brook trout generally return to the stream they spawned in, so each stream supports a genetically distinct group, and as development has significantly reduced their populations enough along the northeastern coasts that they are typically not genetically diverse enough to be self-sustaining north of the Mason-Dixon Line, although their historical range was through Maine.

According to the Buzzards Bay Coalition, Westport has enough of these clean, cold, oxygen-rich streams that it supports the northernmost self-sustaining population of sea-run brook trout on the eastern seaboard, and in 2023 documented them in the stream that flows through Wainer Woods. The trout, and many other animal and plant beings, depend on the site's clean groundwater springs, forested 300-foot buffers, and lack of contamination to thrive.

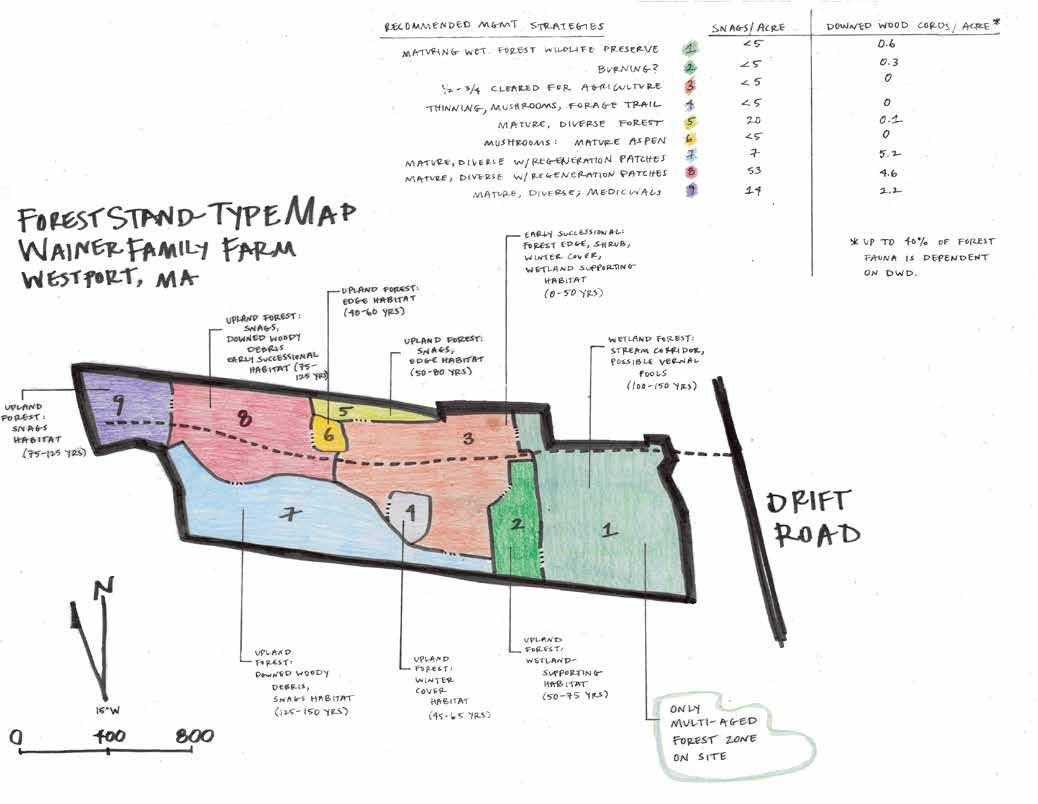

Though the entire site is now reforested, the specific reforestation patterns in species composition tell a story when examined carefully. Land that was previously cleared for agriculture is now mostly populated with young, even-aged forest, and the fields that were most recently abandoned (visible as partly reforested in the 1990s aerial view of the property) are populated with young trees and early-succession shrubby species, both native and invasive, that offer rich foraging opportunities for humans and wildlife.

A site analysis and forest management plan was completed by Walden Forest Conservation as a required component of the site’s successful entry into the Massachusetts 61A Program, through which the property tax burden on the client will be greatly reduced going forward provided that the site is managed to produce agricultural and forest products as laid out in the approved forest management plan. The analyses on this page are based on broad vegetation patterns described in the Walden Forest Management Plan, which themselves reflect the property’s land use history in highly tangible and legible ways. To the left, the character of each stand is described; below, recommended management strategies appear alongside a per-acre count of snags and downed woody debris, which provide critical habitat for birds and insects.

The wetland, having been largely uncleared for agricultural cultivation, has the oldest, only multi-aged forest onsite at 100-150 years old. It is high in species diversity and provides dense cover, nesting cavities, and all-season water access (including likely vernal pools) to mammals, amphibians, fish, birds, and insects.

An even-aged, mixed oak and maple stand on a former hayfield abandoned 5075 years ago that provides crucial canopy shade, stabilizes soil, and intercepts rainfall in areas upslope of the seeps and the wetland.

The area once occupied by agricultural fields, the family residence, and barns was These fields were the most recently abandoned, and shrubby, early succession vegetation dominates, providing crucial habitat and forage even in the case of invasive species. Large old-field trees are present, like the catalpa and numerous oaks. Shrub habitat removed here should be replaced elsewhere whenever possible.

A cedar stand with an understory of American holly and large highbush blueberry specimens provides winter habitat and berry forage in an otherwise largely deciduous site.

Abandoned much earlier than Stand 3, this stand is dominated by red maple and red oaks with black gum, sassafras, American holly, arrowwood viburnum, spicebush and greenbrier. Heavy spongy moth damage has created snags and downed woody debris that are valuable bird and insect habitat.

Stand 6 is an aspen grove uncommon to the region, likely 40-60 years old. Moderate regeneration, including holly, oak and black cherry, is present, with an understory of highbush blueberry and greenbrier. Aspen provides a valuable substrate for growing mushrooms, and stand shapes and extents can be managed by mowing suckers.

Stand 7 is even-aged primarily composed of maturing scarlet and black oaks, with a dense understory of sweet pepperbush, greenbrier and highbush blueberry. Downed woody debris is less prevalent here than in neighboring Stand 8, but still provides valuable habitat in this stand.

The decline of 50-60% of Stand 8's oaks due to spongy moths in the last 20 years has created bird and insect habitat and allowed in light for understory species, including sassafras and highbush blueberry. If dead trees are cut, they could be relocated to other areas of the property and retained as nurse logs rather than burned to preserve generations of beneficial insects and nesting opportunities for birds and small mammals.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

With fewer oaks than Stand 8, Stand 9 has been less affected by spongy moths. Red maple, red oak, yellow birch, and the increasingly rare American beech are prominent.

The site’s existing vegetation and water resources are invaluable for wildlife and for meeting the client’s goals of teaching Traditional Ecological Knowledge on the property. This page highlights a very small sampling of the species that live and grow on the site, the active preservation of which would further teaching and sustainability objectives.

Pennsylvania bittercress (Cardamine pensylvanica) provides early pollen for bees and butterflies, while skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) attracts beetles and flies, whose role as key pollinators is often overlooked.

Asiatic/Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) has beautiful, vivid red seeds that make it easy to understand why the plant is still sold in nurseries as an ornamental despite its extremely aggressive and damaging habit in the Northeastern region. Its vines can grow to sixty feet in length, and ten inches in diameter. Like Japanese Honeysuckle, its vines can strangle and smother valuable native plants and decrease plant and wildlife diversity.

Though often treated like an undesirable invasive, greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) is actually native to the eastern third of North America, and all of its parts are edible, with historical uses dating back many thousands of years to the Indigenous peoples of this region. Its soft, vining new shoots and leaves, which can be snapped off in spring before thorns harden, taste like asparagus, while its berries ripen in early fall and can be eaten raw or made into jams, jellies and syrups. Its starchy roots can be dried for flour or cooked down into a thickening agent. It has reported medicinal value for digestive health and reducing inflammation in the body. Many bird species benefit from greenbrier as well, eating its fruit in the fall and winter, while white-tailed deer take advangate of its high-protein vegetative parts and nest in its dense cover, which protects their young from predators.

Where frequent human traffic is not necessary or desired, Greenbrier could be left in place or selectively cut back to provide shrubby habitat doubling as a natural traffic barrier. Where clearing and footpaths are needed, a combination of digging out, cutting back, and harvesting for its edible shoots can be an effective management strategy.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), which produces an abundance of shoots in the early spring, can overtake delicate spring ephemeral plants, which the client may wish to cultivate as medicinals for foraging. Its strong vines can easily smother surrounding native trees and shrubs. It succeeds in both low and high light conditions, and generally appears first in areas with increased human activity before spreading more widely.

Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) was introduced to North America as an erosion control mechanism, and spreads where its own branches touch the ground and where animal droppings deposit seeds. Like other common invasives on the site, it moves into areas with increased traffic and disturbance, but also spreads in low-traffic meadows and wooded areas via seed dispersal. It provides significant wildlife forage and habitat, but can outcompete valuable native understory species.

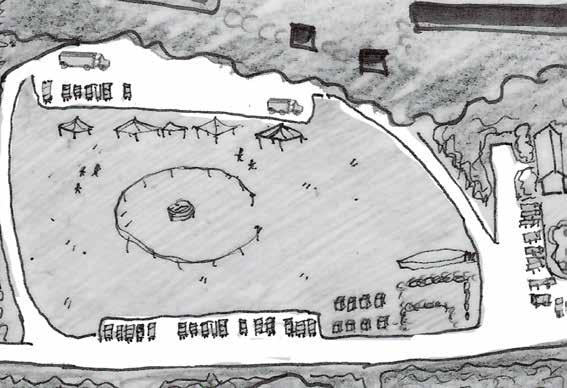

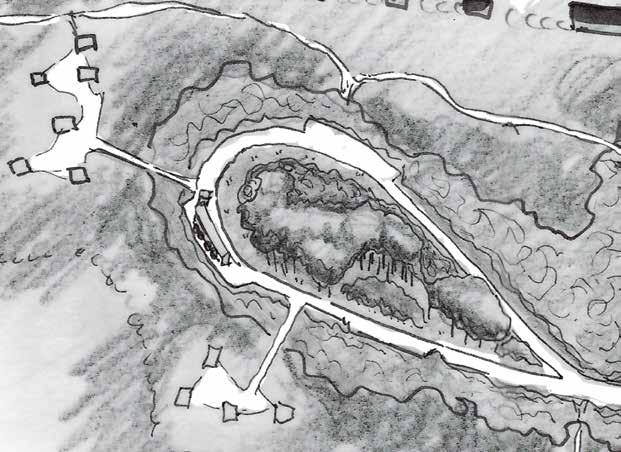

This design presents one possible configuration of elements that would allow the client to have large gatherings on the site, enabling a wide range of vehicle types including cars, RVs, large vendor trucks, service vehicles for utilities and waste management, and construction vehicles to be on the site simultaneously. Compared to the second design, Protecting a Legacy, this design has larger areas cleared for annual row crops and agroforestry, necessitating more farm labor. The Chief might find that “work parties” or workshops with volunteer groups are desirable, and this design’s 75+ parking spots would be able to accommodate such events as well as camping parties and cookouts of many sizes. The private residence closely abuts the event field, as The Chief has expressed a desire to be “right in the action.”

Cleared spaces for tents are carved into the quiet western woodland and accessible by trails rather than vehicles, lending them a private, retreat-like feeling. The 18-wheel turning loop doubles as a parking area for RVs.

To accommodate a number of large vehicles onsite simultaneously, two turnaround options are added to the laneway, including a turning loop for an 18-wheel truck, per The Chief's request. This design makes it possible for an 18-wheel truck to enter, turn around, and exit the site using either turning loop if one is blocked by other vehicles. The driving area around the event field includes parking bays that allow vehicles to circulate freely around the loop even when cars are parked there.

The powwow space is large and expansive in this design, prioritizing flexible, uninterrupted open space for vehicles, vendor tents, service vehicles, portable toilets and other event features over shade or vegetative screening.

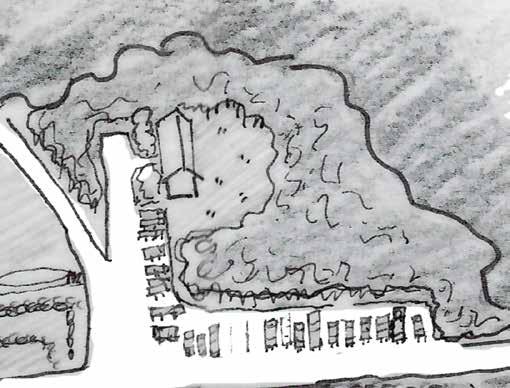

The home and small kitchen garden are sited directly adjacent to the event field, which would allow The Chief to feel immersed in the activities during events. Parking for the client, family and friends abuts the house. Shrubs and woodland hug the home and private yard to the east.

Situated on prime agricultural soils that the client's family historically used for agriculture, 3 total acres is designated for annual row crops and agroforestry. The design presents one possible placement of access points for farm vehicles, allowing The Chief to bring in large farming machinery to the center of these fields should he choose to. The list of crop and agroforestry species is being determined by the client in close consultation with Freed Seed Federation and a PhD student at the University of Vermont. For planting to succeed in these areas, invasive species will need to be strategically managed. These two adjoining fields encroach on the 100' wetland buffer, which could require permitting from the local Conservation Commission since the farm has not been in demonstrably continuious use since its beginnings. If permitted, precautions should be taken not to increase sedimentation or nutrient runoff into the wetlands by installing buffers like straw bales and avoiding the use of fertilizers on crops.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

The Home & Private Yard

Trees and shrubs provide some buffer between the house and the event field, and a smaller “family and friends” parking area abuts the house, lending the residence a bit of privacy from the main event space. A small kitchen garden adjacent to the house enables the client to harvest herbs and vegetables conveniently near the home. To the east of the house, low fruiting shrubs can be foraged near to the client’s kitchen, and replace some of the early successional insect and bird habitat lost to clearing for development.

This design sites the house between the wetland and the event field and traffic loop, in the interest of keeping cars, gravel particulate from parking areas, fuel and coolant spills, and compaction from frequent vehicle traffic outside the wetland buffer.

The house construction process and the installation of septic or another waste management system could still damage the health of the wetland, however. If The Chief sites the house as it appears in this design, it is important to wetland health that precautions be taken for managing waste responsibly. Further details on

The three-quarter-acre powwow space in this design is very open and unobstructed, allowing vehicles and people to move freely in the absence of much vegetation. The size of the inner dancing circle could expand or contract depending on the size of the event. This inner dancing circle is accessed on foot from the east, in the traditional Pocasset style. Spectators and vendors may form concentric rings around the center point. The old barn foundation and a whaling ship land art piece, to be designed and installed by Mark Walker, occupy the southeastern corner of the event space, providing visitors with historical context immediately upon their arrival to the event field.

Before water could be provided to the public from the well onsite its water quailty would need to be tested and permitted for public use. If the well is not permitted water could be provided on site in portable water storage tanks filled by a local potable water hauler (See page 12 on regional and local water quality issues).

The two-lane driving loop around the event field will allow drivers to enter, park, and exit the event space area from the eastern and western connection points to the laneway. Parking for one hundred can occur between two parking bays directly off the laneway. Larger trucks can enter the loop from either side to service the events, or proceed to the turning loop further west if need be. For 18-wheel trucks to access the laneway from the north on Drift Road, the laneway’s apron may need to be widened by at least fifty feet on the north side, requiring permitting.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

The client could use this fire pit between large events for burning brush generated from forest maintenance, or purely for enjoyment. Stones already present could be resituated and used to ring the burning area, or the burning area could be less rigidly defined and adjusted to fit the needs of the client and the event. The area could be cleared or mowed annually to prepare for events, with special care taken to mow early in the season to protect grass-nesting species, see page 23.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

This turning loop is sized to allow an 18-wheel truck to make a complete turn and reenter the laneway in the western part of the site. Due to space constraints within the 61A exclusion envelope, having a second turning loop necessitates one being sited outside the 61A exclusion envelope. 61A dictates that this turning loop must be used for agricultural purposes if it is sited outside the exclusion envelope. To minimize negative impact on the site’s woodland habitat, trees and downed woody debris should be allowed to remain to the greatest extent possible in the center of the turning loop. This will also create a more positive, retreat-like experience for RV campers using the loop for overnights during events. Stones cleared from this area could be relocated to create

Protecting a Legacy prioritizes the visitor's experience, habitat support, and educational space. To protect the wetland and habitat quality of the oak-hickory forests to the west, the Chapter 61A building envelope for the residence is shifted to the west, the truck loop is replaced with secluded shipping container cabins and campsites, and agroforestry takes priority over annual crop space. A two to three hundred foot buffer of natural vegetation bolsters the water and habitat quality of the wetland. Over forty parking spaces accommodate medium to large sized gatherings of 80 to 120 people, with designated private parking areas for cabins and the home.

To reduce the risk of pollution from septics, parking areas, and other human activities, the residence is placed in the uplands between the event field and cabin-campsite areas. The move provides a full 300-foot wetland buffer, and would require an amendment to the Chapter 61A forestry plan currently registered with the state. Instead of a well, the house is outfitted with a metal roof, water harvest and storage systems, and reverse-osmosis and UV filtration to provide drinking and greywater use.

The visitor's educational experience is focused in the art orchard. This area features a barn that doubles as event space, an agroforestry orchard, an outdoor classroom, and interactive artworks. Adjacent to parking and the event field, this space offers easy access and wayfinding upon arrival.

An Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) compliant wetland boardwalk offers an accessible experience through the wetland and increases foraging and stewardship access with minimal impact. A viewing platform overlooks a potential mishoon submersion area.

Guests staying overnight in the cabin and tent campsites enjoy the secluded woodland, have access to multiple trails, and are close to the meadow firepit area for gathering.

A robust network of trails invites visitors to explore the landscape from gathering and main event areas, and provides access across the site for land stewards.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

5,000 square feet of row crops serves as a demonstration garden. The small size reduces labor inputs and keeps agricultural activity outside of the minimum 200' wetland buffer zone. A shipping container and road provide equipment access and harvest storage.

The Chief's residence, situated between the event field and cabin-camping areas, sits in the center of the action while retaining a sense of private space. While the house has a direct view into the site's main parking area to the east, a sentry of high canopy trees over a stone wall draws a clear line between the highly public event field and the home. The laneway is narrowed to a single lane beyond the event field to limit vehicular traffic through the oak-hickory habitat, and three parking spots sit in front of the house.

A warm-season grassland with wildflowers to the north and west of the house offers early successional habitat that is increasingly hard to come by for the species that depend on it. The tall, narrow poplars that seeded in when this area was open earlier in the century are easily accessed for regular harvest for mushroom cultivation, and their suckering edges are kept in check by mown paths. Mown paths also edge foragable shrubland habitat that smooths the transition from forest to grassland. These paths lead from the main event field to the family cemetery to the north, the chief's private garden to the south, and the firepit gathering and cabin-camping areas to the west.

Finally, since the house is sited in the uplands, chemical, nutrient, and pathogenic contamination of the wetlands with septic and vehicular pollution is greatly reduced.

The event field provides ample room for powwows and other large events, while the Art Orchard accommodates smaller gatherings and provides a place for visitors to explore the history of the site. The event field's several trees provide cooling shade in the heat, and give the space an enclosed feel. Existing saplings could be selected and flagged for preservation during the invasives removal required for the lawn's establishment. As in the previous design, the dancing circle is expandable as needed and accessed from the east, and spectators and vendors are arranged around it.

To meet water needs for events see the Powow Space and Event Field section on page 17.

Similar to Dreaming Big, this design will enable a wide range of vehicle types including cars, RVs, vendor trucks, tractor trailers, service vehicles for utilities and waste management, and construction vehicles to be on site. All of these vehicle types are acommodated within the drive encircling the event field, however, for 18-wheel trucks to access the site from the north on Drift Road an easement from the northern neighbor would need to be secured in order to widen the laneway's apron.Attendees drive down the laneway, turn right just before the event field, and park in the designated parking area to the south of the event field. During a large event like a powwow, the action in the event field draws visitors in. Vendors proceed along the loop that encircles the event field and park along the innermost edge, while RVs park along the outer edge, and two lanes of traffic between allow for safe negotiation of space. During quieter events the visitor's curiosity is piqued on arrival by a bronze sculpture of the family's ancestor, Michael Wainer, that directs their attention to the welcome center and Art Orchard's educational space.

The event field area accommodates nearly 60 parking spaces in total. Twenty two spots for event attendees abut the laneway, space for 5-10 RVs or 15 cars encircles the outer edge of the loop, and 20 vendor cars or 15 small truck spaces line the field itself. When counted with the eight spaces from the residence and cabin-camping areas the total number of parking spaces on site reaches 65. This does not include the access lane along the small agricultural field to the southeast that could be used for parking overflow during the largest of events.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

Human waste management on this site is complicated by regional issues of drinking water contamination and widespread habitat degradation from nutrient and pathogenic pollution by septic systems (see page 12). No current waste management system exists on site, there is no sewer hookup option, and systems for both private use and large events will be required for to accommodate the project's program. Portable toilets (PortaPotties) are the likely short-term solution for both events and private use.

Regarding long term solutions, Wainer Woods has a unique opportunity to develop ecological waste management systems from the start, rather than having to retrofit older systems. Additionally, the project has potential to serve as a demonstration site for cutting edge technology of waste management for all those who visit.

Several local organizations have sprung into action around the issue, and are invested in helping property owners develop responsible waste management solutions, including The Green Center (Falmouth, MA), The Massachusetts Alternative Septic System Technology Center (Falmouth, MA), Buzzard's Bay Coalition (New Bedford, MA), and Rich Earth Institute (Brattleboro, VT). For well-researched reading on the topic, consider The Second Edition of the Humanure Handbook by Joseph Jenkins.

Systems

Solution Type Opportunities

Waterless, self-contained compost toilets + container (Loveable Loos, Toilets for People, SunMar)

Waterless, split-system compost toilets + 50%-sized septic (Clivus, Phoenix, Sun-Mar)

Septic system with a nitrogen filtering component (various types)

Urine diversion systems (various types)

Inexpensive ($20-1,000) and easy to install. Several options to choose from. May require only halfsized septic system for potential leachate to be compliant with state regulations.

Lower maintenance. Requires less-frequent removal of humus byproduct (1-3 years). Takes up less space in the bathroom than self-contained models. Requires only half-sized septic system for potential leachate to be compliant with state regulations.

Traditional flush toilet that many are accustomed to using. Effectively reduces nitrogen pollution.

Constraints

Higher maintenance. Generally requires frequent removal of humus byproduct (1-12 weeks). Some systems require electricity for fan operation. Requires a small space on site for humus burial to be compliant with state regulations.

Expensive ($8,000-20,000) and requires professional installation. Requires electricity for fan operation. Requires a small space on site for humus burial to be compliant with state regulations.

Most expensive option ($35k). The site will likely require a specialized system adapted to high water tables, which may drive up the cost further. Does not address phosphorous or pathogen contamination. A small step above business-as-usual.

Reduces nutrient loads by 80-90%. Compatible with most of the above systems. Allows for peecycling use on crops with the highest NPK needs. Inexpensive.

If used in combination with a traditional flush toilet system, a full-sized septic is still required, though this may change with pending legislation.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

In addition to global environmental impacts like air pollution and release of greenhouse gases, vehicles and the infrastructure built to accommodate them have measurable impacts at the site scale. One of the ways that roads affect wildlife is that animals appear much less likely to travel across roads than landscapes with unbroken natural vegetation, which makes it more difficult for them to travel to needed resources.

There is a documented link between impervious surface cover and ecosystem decline. In a naturally vegetated setting water slowly infiltrates into the ground, slowed by the leaves and filtered by the plant roots. However, to allow safe easy driving across the landscape, roads are built to be as flat and compacted as possible, making water infiltration impossible. Water that hits impervious surfaces during rain events typically collects chemicals and sediments, and heats up before draining with high velocity into nearby wetlands and streams. This process has a range of impacts on water bodies and the life that depends on them, including chemical and salt accumulation, excessive sedimentation that chokes plants and animals living in the waterways, and high water temperatures that many species adapted to freshwater streams, such as the brook trout, cannot tolerate.

To reduce the effects of impervious surfaces on the ecosystems at work at Wainer Woods, it is recommended to take the following actions:

→ Reduce impervious surfaces and vehicular traffic as much as is feasible on site. Consider bussing event attendees to and from the site.

→ Avoid actions that compact or erode the soil’s surface.

→ Prioritize green infrastructure in laneway renovation to infiltrate runoff from impervious surfaces.

→ Install an open-bottomed culvert to improve wetland connection and allow for aquatic species movement.

→ Avoid application of salt as a de-icing agent.

→ Educate visitors about the relationship between wetland health and vehicular and impervious surface impact.

Removal methods for invasive species include physical, chemical, and biological techniques, as well as the use of fire. Each method has advantages and disadvantages, and all have potentially negative environmental impacts. The effectiveness and potential ecological impacts of any of these strategies depends on their proper application by a knowledgeable, licensed professional. Factors such as the density of the target species, seasonal timing of application, inclement weather such as rain or wind, and intensity of use or strength of application can all influence the success rate of the method employed. A careful combination of multiple methods is generally considered most effective, especially when immediately followed by establishment of competitive desirable native species that shade the ground and prevent invasive seeds from germinating

Although mechanical or physical removal is often considered the low-impact option because it avoids the use of harmful chemicals, it has its own set of potential negative impacts. When the roots of established target species are dug out the soil becomes loose and prone to erosion and wash-outs, impacting nearby water quality and aquatic wetland habitat health through the accumulation of sediments in low spots. The use of heavy machinery such as excavators, mulchers, or bulldozers often leads to soil compaction, making prime agricultural soils unfarmable, and furthering stormwater runoff issues. Physical removal by cutting a plant repeatedly (sometimes upwards of five times in a season for several consecutive seasons) while leaving the root system intact can effectively kill the plant while reducing risks to soil erosion and adjacent habitat degradation. Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is a species can often be controlled with this method. However, repeated cutting often requires very high labor inputs for several years to be effective before a site is ready for plant installation. If timed and managed appropriately, biological removal by grazing animals such as goats can perform repeated cutting with great success.

Chemical removal involves selective or broadscale use of herbicides, and while their potential for negative environmental impacts are widely known, the potential need for responsible and selective application are not as well understood by the general public. Many invasive species do not respond to physical removal alone, such as Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) and Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica). Contamination risks to adjacent wetlands or desired native species are generally higher when applied by a broadcast foliar spray than by selective cutting of stems and immediate application with a dauber bottle.

Finally, invasive species management with low-intensity fire is a growing topic of interest in the Cape region that may be particularly relevant to the project goals of sharing and demonstrating TEK.

For successful removal of invasive species with minimal ecological risk it is recommended that a tailored invasive species management plan be made for the site. The plan should consider factors such as target species, desired species, site conditions, proximity to wetlands or other sensitive habitat, the desired landscape type after removal (e.g. meadow, shrubland, forest), and future uses of each space (powwow space, etc.). Additionally, regular on-site observations during both implementation and post-implementation phases of the work are strongly recommended.

Grassland birds are among the most imperiled in the nation due to the removal of grassland habitat for agriculture and development, as well as the natural succession of meadow habitat to forest. Migratory birds travel thousands of miles to lay their eggs in New England meadows annually, only to have their nestlings killed by mowing. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 made it illegal to kill the nestlings of migratory birds, by mowing or any other action. While it is unlikely that any of Massachusetts’ most endangered grassland-nesting bird species like the bobolink, vesper sparrow, and eastern meadowlark will nest on this site, as these species need more than 10 acres of uninterrupted meadow habitat to do so. The following practices support bird-benefitting insect species that are also crucial to the larger food web, to successful pollination and food production, and to turtles and other native wildlife.

In areas where meadow is meant to be partially mowed in advance of the event season, it would be safest for wildlife to follow the Audubon Society’s best practices for maintaining meadow habitat:

• Where mowing is needed, mow before May 15 and keep the area mown until the event season is over to intentionally make the site unusable for nesting.

• Attempt to maximize unmown areas wherever possible.

• Where mowing is not needed, keep disturbance, including foot and dog traffic, to an absolute minimum during the breeding season for many grassland nesting species (May 15 to August 15).

• Reduce the growth of forbs and woody vegetation in areas meant to remain meadow habitat, and reduce thatch by mowing every two to three years. Cutting or mowing for this purpose should be done from August 15 to September 15 to prevent woody vegetation from setting seed.

Grasshoppers like the American Bird Grasshopper are a preffered food of many bird species, sometimes making 30-90% of the diet that grassland birds consume. Somewhat unique from other grasshoppers, when this grasshopper is disturbed it often flies gracefully into nearby trees (Black).

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager

The Eastern Box Turtle depends on many habitat types to complete it's life cycle. They overwinter in upland forests, and can be found staying cool in wetland marshes during hot summer days. It's nesting habtitat, open meadows and other early successional landscapes, are increasingly difficult to come by as many of New England's open spaces have grown into forests and it's open spaces are disturbed by ATV and mowing of fields during the active season (Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program and Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife).

Association to Preserve Cape Cod. “State of the Waters Cape Cod 2023.” 2023. Atwood, J., et al. “Best Management Practices for Nesting Grassland Birds.” 2017. Black, Scott. “Protecting Grassland Ecosystems from Insecticides.” Xerces Society, 2 Sept. 2021, www.xerces.org/blog/protecting-grassland-ecosystems-from-insecticides. Bryant, Lara. “Organic Matter Can Improve Your Soil’s Water Holding Capacity.” NRDC, May 27, 2015. https://www.nrdc.org/bio/lara-bryant/organic-matter-can-improve-your-soils-water-holding-capacity. Cates, Anna. “The Connection between Soil Organic Matter and Soil Water.” Minnesota Crop News, March 24, 2020. https:// blog-crop-news.extension.umn.edu/2020/03/the-connection-be- tween-soil-organic.html.

Conforti, William. “Fall River’s Watuppa Reservation: A Brief Account of It’s Origin and Evolution Including a Profile of the Fall River Indian Reservation.” Mar. 1996. Cruz, Carl J., and New Bedford Historical Society. “Envisioning Paul Cuffe: Images from 811-2017.” Mar. 2018.

“Expansion Map: Potential Floodplain Expansion with Sea Level Rise in Buzzards Bay.” Climate.buzzardsbay.org, climate.buzzardsbay.org/floodplain-expansion-map.html. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Ferreira, Carl, et al. “Sowams Heritage Area History – Sowams Heritage Area.” Sowams Heritage Area, 6 Dec. 2017, sowamsheritagearea.org/wp/sowams-heritage-area-project/. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Grantham, Rupert, and Walden Forest Conservation Company. Forest Management Plan - Wainer Family Farm. Sept. 2023.

Grinde Jr., Donald. “Paul Cuffe Sr. (1759-1817) •.” Black Past, 18 Jan. 2007, www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/cuffe-paul-sr-1759-1817/.

Hayed, Ted. “Culture and History.” Pocasset Pokanoket Land Trust, East Bay RI Newsletter, 1 Mar. 2024, www.pocassetlandtrust.org/category/news/culture-and-history/. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Kopansky, Dianna. “Peatlands Store Twice as Much Carbon as All the World’s Forests.” UN Environment, 1 Feb. 2019, www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/peatlands-store-twice-much-carbon-all-worlds-forests.

Laurel, Schaider, et al. “Emerging Contaminants in Cape Cod Private Drinking Water Wells .” Nov. 2011.

Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division. “How Impervious Surface Impacts Stream Health.” MANTA Publication: 12-212007-187, July 2008.

Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. “2022 Massachusetts Climate Change Assessment Regional Reports Volume III.” Dec. 2022.

Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program, and Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. “Eastern Box Turtle Fact Sheet.” 2015.

Neal, Joseph C, et al. Weeds of the Northeast. Comstock Publishing Associates, 2023.

“Pocasset – the POCASSET WAMPANOAG TRIBE of the POKANOKET NATION.” Pocassetpokanoket.com, 2016, pocassetpokanoket.com/pocasset/. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Rasmussen, M., Jakuba, R.W., Costa, J.E., Lefebvre, P. (2022); 2022 State of Buzzards Bay. 12pp.

Richard, Tetek. “Timeline of 17th Century Events with Relevance to Sowams – Sowams Heritage Area.” Sowams Heritage Area, 17 May 2018, sowamsheritagearea.org/wp/timeline-of-17th-century-events/. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Miles, Tiya. “Native Americans and the Underground Railroad (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov, Dec. 2020, www.nps.gov/articles/000/native-americans-and-the-underground-railroad.htm.

Town of Westport Planning Board, et al. “Targeted-Integrated Water Resource Management Plan .” 17 Jan. 2017.

USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Web Soil Survey. NRCS Soil Survey Center Lincoln, NE, June 2020.

US National Parks Service. “Estuaries - Oceans, Coasts & Seashores (U.S. National Park Service).” Nps.gov, 2016, www.nps.gov/subjects/oceans/estuaries.htm.

Westport Historical Society. “A History of the Wainer Farm Property in Westport, Massachusetts.” Paul Cuffe, 6 Dec. 2022, paulcuffe.org/2022/12/06/a-history-of-the-wainer-farm-property-in-westport-massachusetts Accessed 22 June 2024.

Wortham, George Hugh Jr. “The Country, Memories of the Wainer Farm on Drift Road by George H. Wortham Jr.” Westport Historical Society, 9 Feb. 2021, wpthistory.org/2021/02/the-country-memories-of-the-wainerby-george-h-wortham-jr/. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Designed By: Leah Stanton and Isabella Yeager