Resilience Between Rivers

Updates to the “Land Use” and “Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources” Chapters of Sustainable Greenfield, Greenfield’s 2014 Master Plan

Prepared for the City of Greenfield

Aaron Dell, Jessica Ladin, and Annie Mellick

The Conway School Winter 2024

Resilience Between Rivers

Updates to the “Land Use” and “Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources” Chapters of Sustainable Greenfield, Greenfield’s 2014 Master Plan

Prepared for the City of Greenfield

The Conway School, 2024

Aaron Dell, Jessica Ladin, Annie Mellick

Acknowledgments

The Conway Team would like to acknowledge the extensive and valuable assistance provided by our partners from the Sustainable Greenfield Implementation Committee (SGIC):

Mary Chicoine, SGIC Chair

Nancy Hazard, SGIC Public Member

Jonah Keane, SGIC Public Member

Eric Twarog, City of Greenfield Planning & Development Department Director

We would also like to thank everyone who took the time to speak with us about the issues facing Greenfield and what makes it a great place to live.

Contents Executive Summary������������������������������������������� 5 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������ 7 Land Use Introduction ����������������������������������������������������13 Climate Change �����������������������������������������������20 Downtown �������������������������������������������������������22 Housing 24 Water and Infrastructure ��������������������������������27 Solar Energy 32 Conclusion �������������������������������������������������������33 Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources Introduction ����������������������������������������������������35 Geology, Aquifers, and Soils 36 Forested Greenfield ���������������������������������������38 Water Resources ���������������������������������������������44 Connectivity Planning & Conservation 53 Threats to Wildlife�������������������������������������������59 Recreation 60 Agriculture �����������������������������������������������������64 Historic Resources ������������������������������������������67 Cultural Resources ������������������������������������������73 Conclusion �������������������������������������������������������79 Recommendations 80 Map Data���������������������������������������������������������87 Works Cited 88

Executive Summary

This update to the “Land Use” and “Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources” chapters of Greenfield’s 2014 Master Plan, Sustainable Greenfield, is the outcome of a partnership between the Conway School and the City of Greenfield. A team of three students from the Conway School reviewed the progress made by the Sustainable Greenfield Implementation Committee (SGIC) in implementing the Master Plan since 2014 as well as more recent planning documents to understand the city’s goals and its progress toward achieving them. The Conway team also conducted two community engagement sessions, the first to refine the scope of the project and the second to gather feedback about specific recommendations. This final report incorporates the information gathered from the community engagement events, spatial analyses, additional research, and input from individual citizens and experts to make recommendations about how Greenfield can improve its residents’ quality of life while conserving its historical and cultural heritage and restoring and protecting its natural environment.

Sustainable Greenfield established the complementary land use goals of encouraging infill development and conserving open space, and this update carries those goals forward. By focusing development in already-built areas, the city can minimize the costs associated with new development; while, by protecting open spaces, it can ensure the continued existence of finite resources such as forests and farmland. Since 2014, the price of housing has risen dramatically, and so the need to densify downtown has grown acute. This update recommends zoning reforms that would make it easier to build more housing downtown such as allowing multifamily dwellings by right in more areas, raising the maximum allowable number of units in new multifamily dwellings, and updating dimensional standards to allow row houses. It also stresses that affordability and accessibility to people of all ages and abilities must be a priority in efforts to expand the city’s housing stock.

The goal of infill development can also be understood as part of a broader ongoing effort to revitalize the downtown area. Measures that encourage the renovation and creative reuse of urban spaces (including underutilized parking lots) remain needed as Greenfield, like many other cities and towns across the United States, struggles to understand what a Main Street can or should look like after the proliferation of online retail. Part of the answer, as suggested by community engagement participants, may include expanding and caring for community spaces and green spaces, perhaps with the coordinated aid of volunteers. It may also include maintaining and strengthening the city’s focus on inclusion of non-vehicular traffic.

Climate change has and will continue to intensify some of the problems facing Greenfield while also posing new challenges. The city’s already-pressing need for housing will only grow should there be in-migration from coastal areas due to storms and sea-level rise; but, as more housing is constructed, infrastructure must also be able to support a greater population. Currently, Greenfield’s sewer and storm-water systems are aging and over-capacity, frequently stressed by heavy rains. The city is seeking, and should continue to seek, opportunities to overhaul these systems, and it should do so in ways that promote the well-being of the broader natural environment whenever possible. The same goes for its efforts to grow solar; participants at the second community engagement meeting were nearly unanimous in asserting that the city should prioritize new solar on rooftops or already-disturbed areas, not forests or farmland.

Greenfield’s waterways, wetlands, and forests are remnants of a once continuous natural landscape that has only relatively recently been fragmented by human uses. At the community engagement events facilitated by the Conway team, many participants voiced their desire to conserve and restore remaining natural landscapes, which not only provide recreation opportunities and ecosystem services such as floodwater storage and carbon sequestration but also contribute to the city’s unique character. This report identifies continuous “habitat corridors” where Greenfield should focus its conservation efforts, notably along waterways and north-south ridgelines. It proposes adopting a River Corridor Zone along the Green River that would recognize erosion hazards and respect the river’s natural meander, and it also discusses the strategy of creating “patches” in the urban landscape with street trees, pollinator habitat, rain gardens, and other features that may function as “stepping stones” for birds, pollinators, and other wildlife.

The report also recommends that, along with protecting priority natural landscapes, Greenfield continues its efforts to conserve agricultural lands. Soils suitable for agriculture may be permanently displaced or degraded by development, and so it is important to the region’s food security that farmlands on prime agricultural soils remain in agricultural use whenever possible (this is especially critical given the possibility of disruption to food systems due to climate change). Greenfield’s agricultural lands also contribute to its identity as a “food hub,” and this report recommends that the city further develop its food production, processing, and distribution ecosystem by seeking additional complementary industries (space for which remains available in the city’s industrial park).

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 5

Greenfield’s natural and working landscapes are keys to its identity as a community; so are its recorded history, the physical traces of that history, and its ongoing cultural traditions. Many participants in the community engagement events facilitated by the Conway team expressed a strong desire for a sense of local history and identity that includes but not limited to the era following European colonization, and this report recommends that the city continue and deepen its efforts to recognize the long tenure and continued existence of Indigenous people here wherever possible. The plan emphasizes the intrinsic value of Greenfield’s natural beauty, historical sites, and cultural richness, recognizing them as vital elements of the city’s identity and community well-being. It also poses questions about how the city might develop a positive vision for its future while holding on to what is most important in its past.

By integrating sustainable development practices, environmental care, and efforts to protect heritage, Greenfield aims to create a future where its assets can continue to flourish for generations. The plan’s recommendations provide a roadmap to guide the city toward this shared vision of sustainability and resilience.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 6

Introduction

Deep Roots, Turbulent Forecast

This update of the “Land Use” (LU) and “Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources” (NHC) chapters of Sustainable Greenfield, Greenfield’s 2014 master plan, is the outcome of a partnership between the City of Greenfield and the Conway School.

Our goal was to identify strategies to build resilience in the face of climate change and the loss of biodiversity while enhancing the quality of life of the people who live in Greenfield. In order to achieve this, three graduate students from the Conway School reviewed the progress made in implementing Sustainable Greenfield since 2014. They also reviewed more recent planning documents, including the 2021 Open Space and Recreation Plan and the 2023 Downtown Revitalization Plan and, in coordination with a four-person team representing the Sustainable Greenfield Implementation Committee, engaged the community in two meetings to learn about what people in Greenfield value and their hopes for the future.

This document reflects those efforts as well as the latest predictions about how climate change may affect Greenfield and Franklin County. It offers analyses of issues facing the city that fall under the general topics of Land Use and Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources (two of the seven required chapters of a comprehensive plan under M.G.L. Ch. 41 § 81D), and it recommends measures the city can take to address those issues through mechanisms such as zoning, policy, coordination with other organizations, communication and outreach, further planning efforts and boots-on-the-ground projects. Where appropriate, it acknowledges issues that relate to Land Use and Natural, Historic, and Cultural resources but that may be addressed in more detail in other chapters of the comprehensive plan.

Greenfield is a city of approximately 17,470 residents situated at the confluence of the Fall, Green, Deerfield, and Connecticut Rivers. It is also the meeting point of Route 2 and Interstate 91 and is often described as the “hub” of Franklin County, Massachusetts. The territory in and around Greenfield is the traditional homeland of Native peoples including the Pocumtuck. After its settlement by European colonists, Greenfield’s economy centered around agriculture and then transitioned into manufacturing, which grew thanks to river access and hydro-power. This growth lasted until the second half of the twentieth century when it was curtailed by economic globalization; however, synergy between the town’s agricultural and industrial elements has since helped to make Greenfield a center of food processing and distribution as well as precision manufacturing. Today, Greenfield remains a dynamic community with artistic and cultural resources concentrated in its southeastern urban core as well as an abundance of open space and farmland to the north and west.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 7

Regional Context

Franklin County is the northernmost of three Massachusetts counties along the Connecticut River (the other two being Hampshire and Hampden). Massachusetts county government was disbanded in 1997 (Massachusetts Acts of 1996, Ch. 151, §567), but coordination and planning among local governments continues under the Franklin Regional Council of Governments (FRCOG). Greenfield, formerly the county seat, is the most populous city or town within Franklin County, and its location at the intersection of major roads, rivers, and rail lines makes its description as a regional “hub” appropriate. The contrast between uplands and river valley is the most salient geographical feature of Franklin County as a whole, with Greenfield and its neighboring towns of Gill, Montague, and Deerfield occupying a low plain along the river as it descends from Northfield.

Green River

VERMONT

D e e r f i e l d R i v e r C o n n e c t i c u t R i v e r

NEW HAMPSHIRE MASSACHUSETTS

Community Engagement

So that these updated chapters of Greenfield’s comprehensive plan might reflect the perspectives and aspirations of those living in Greenfield, the Conway team facilitated two community engagement events: an in-person meeting on February 5, 2024 at the John Zon Community Center (followed by an online questionnaire for those who could not attend) and a follow-up meeting on Zoom on March 11, 2024. Participants included former and current city council members, former mayors, planning board members, teachers, climate activists, housing advocates and more.

About eighty people attended the first community engagement event, and forty-nine people completed the accompanying online survey. The first event was designed to elicit a broad spectrum of responses about Greenfield’s challenges and assets. It was organized around four focus areas: “Our Greenfield” (land use and development), “Wild Greenfield” (natural resources and biodiversity), “Food Hub” (the food web within Greenfield), and “Cultural Heritage” (Greenfield’s identity and history). The Conway team constructed stations for each focus area with questions and activities at each station that allowed community members to engage in conversation and voice their opinions.

Responses from this first meeting showed clear trends. On the topic of development, housing emerged as a primary theme. Both attendees of the meeting and respondents to the accompanying online survey emphasized a need for affordable housing and expressed concern about the recent rise in real-estate prices. Among sixty-eight responses to the question of what issue facing Greenfield was most important, twenty-one mentioned housing. One person wrote,

I’ve lived here my entire life and investors from out of town buy every house I can afford. I’m close to having to move out of the city I grew up in due to this.

When asked to choose three “development priorities,” a clear majority chose housing:

Another common theme was the city’s urban core. Many participants noted the diminishing presence of local retail in the downtown area and the presence of large stores west of downtown. Along with calling for a revitalized central district, respondents expressed an interest in enhancing the city’s infrastructure to include more pedestrian-friendly transportation options such as bike lanes and safer sidewalks as well as improvements in public transportation to ensure connectivity across different parts of the city and to landmarks like Poet’s Seat and the Green River. Part

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 9

Housing 86 Renewable energy 47 Culture 45 Retail 40 Industry 26 Outdoor recreation areas 26 Agriculture 23

of a community-created timeline of Greenfield’s history from February 5 event.

When it came to conservation, water emerged as the leading interest. In another pick-three exercise, seventy-nine respondents chose water (wetlands, rivers, and streams) as a “conservation priority” followed by street trees and pollinator habitat with fifty-three votes each. This pattern of response seemed to reflect residents’ awareness of the city’s unique geography, with three rivers flowing around and through the center of town and abundant wetlands and streams in the surrounding area. Discussions and comments delved into contentious topics such as dam removal, with some residents expressing a desire to keep the city’s historic Wiley & Russell Dam but a majority suggesting that it should be removed as part of an effort to restore the health of the watershed. Residents also voiced an appreciation for Greenfield’s locally sourced food and praised the city’s relationship with the nonprofit organization Just Roots to promote and support local agriculture.

When asked to describe the relationship between urban and rural Greenfield, responses were less consistent. Some respondents insisted that they were completely unified, while others used words like “disconnected,” “complicated,” and “invisible.” It wasn’t always clear whether these responses referred to physical or social relationships. Participants praised the aesthetic contrast between these two areas (“within minutes can transition from biking in a developed area to being among farms & forest”) while calling for better access for those without cars.

When residents reflected on what initially attracted them to Greenfield and what has kept them there, many cited a sense of community. One online survey respondent shared the following story about what drew them to Greenfield:

We liked the mix of people: the old-school long-time locals (some farmers, some townies), the hippies who came in the ‘60s and ‘70s and stayed, the influx of academic and college professional types and lesbian families that couldn’t afford the Northampton and Amherst of the ‘90s and beyond, the multiple immigrant communities that continue to arrive and establish themselves. We stay here because all of those groups continue to enrich and inform the evolving cultural ways of the community [and we] stay for the same reasons. We would like to feel safe enough to bike or walk with our children from our northern Greenfield home into town. Currently there is just no good way to do it.

Respondents also shared a desire to acknowledge and more fully recognize the history of Indigenous peoples in the region. Many insisted that the story of Greenfield did not begin with European colonists but rather with the Pocumtuck and others who inhabited the region for thousands of years prior to colonization. They praised efforts to make Indigenous history visible (such as a series of interpretive signs along a bike trail in nearby Turners Falls) and expressed a desire to include Indigenous stakeholders in decisions about land use.

Lets see downtown reach its full potential.

Conservation within Greenfield, especially of the city’s waters.

Greenfield’s history began long before colonial times!

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 10

The follow-up meeting on March 11 was designed to gather feedback about specific recommendations being considered for inclusion in the updated chapters. About thirty-six people attended via Zoom. The Conway team shared a slide presentation summarizing their work to-date, and participants were asked to respond to polls and chat prompts about proposed recommendations.

Major findings from the second meeting related to housing, solar energy, and recreation. Attendees generally agreed that new housing should not go just anywhere but were split as to whether it should be concentrated downtown (50%) or in the “missing middle” (45%); twelve out of twenty-six respondents voted for both of these options. Participants were more united on efforts to deploy more solar panels, stating that they should “maintain urgency, but prioritize roofs and parking lots” (92%) rather than seeking to build “as much as possible, anywhere” (8%). And, attendees showed consistency in their visions for beloved recreation areas. A majority said that the Green River Swimming and Recreation Area, which floods regularly, should be evaluated for more low-maintenance site design options (91%) rather than abandoned (9%); a similar majority thought that Highland Pond would benefit from efforts at ecological restoration (95%) rather than restoration for ice-skating (0%).

The chat room allowed free-form conversations to develop alongside the presentation, some of which attracted a high degree of interest. As presenters broached the topic of green infrastructure, one attendee noted,

Outside of downtown, we still have absurd parking requirements…So many cities have done away with parking requirements, why don’t we do the same? Maybe we can find ways to help encourage private lot owners to convert some of that parking back to rain gardens and other things like being proposed.

This comment attracted multiple “likes” and responses, suggesting one strategy for achieving the desired conservation goals that the Conway team had not considered up to that point.

The following two chapters revisit Greenfield’s master plan in light of the interests and concerns voiced at these community engagement events. This input, along with additional research and analysis, was used to generate the set of recommendations at the end of the document.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 11

Mary Chicoine

The February 5 community engagement event

Greenfield has achieved a high level of ecosystem health, recreational opportunities, and biodiversity through conservation, restoration, and stewardship of its open spaces and natural areas.

Agricultural land is preserved to ensure a vibrant local food supply, while increasing Greenfield’s role as a regional food hub including production, aggregation, processing, and distribution infrastructure.

Our adaptable and resilient green infrastructure enhances and promotes compact development and redevelopment and offers ecological and social benefits.

Compact residential and commercial development and redevelopment that is focused in and around Greenfield’s historic downtown and other previously developed areas, incorporates increased density, mixed use development, and infrastructure reuse as the norm and supports our green, adaptable, and resilient infrastructure.

View from Rocky Ridge into Greenfield Matt Gregory

2014 Sustainable Greenfield Land Use Goals

Land Use

Learning from the Past, Envisioning a Future

We envision a balanced relationship between Greenfield’s lively urban core and its wild and working open spaces. We will strive for mindful patterns of development. This includes concentrating new development in already developed areas. Our goal is to recognize and cultivate the benefits provided by the natural environment to help create a comfortable, safe, and climate-resilient city.

Greenfield is located in the Connecticut River Valley: a mosaic of roads, farms, towns, ponds, rivers, and wetlands below the forests of the surrounding uplands. According to geologists, the conglomerate rock that underlies much of present-day Greenfield was formed millions of years ago under an inland sea. At the end of the last Ice Age, glacial lakes filled the Connecticut River Valley, and the sediments that flowed into those lakes became the parent material of the region’s rich soils.

Humans have chosen to live close to rivers throughout history, and this valley is no exception. Indigenous peoples densely settled the river valley for thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans. The people living in the place that is now called Greenfield when Europeans arrived included the Pocumtuck among others. The Pocumtuck told stories about a Great Beaver who was punished for his tyranny over the valley. Some of these stories identify the line of hills running from Pocumtuck Ridge (also called Rocky Mountain) to Mount Sugarloaf as the tail and body of this demigod (Bruchac).

While much knowledge about Indigenous land-use practices in this part of the continent has been lost or is not widely available, it is believed that the Pocumtuck and their neighbors fished, planted crops in the fertile lowlands, and hunted in the uplands. According to Jennifer Lee, a member of the Northern Narragansett tribe and an independent researcher, “Indigenous peoples from all around the Northeast gathered seasonally to fish and celebrate at Peskeompskut—now called Turners Falls” (42). The retreat of the glaciers was followed by cycles of flooding and sediment deposition, impoundment by beavers, and low-intensity human use which created the prime farmland that helped to attract the first European colonists to the area.

The coming of Europeans brought drastic changes. Colonial forestry and agriculture deforested from sixty to eighty percent of the landscape in the northeast (Harvard Forest). Roads dissected forests and valley bottoms. Beaver were trapped to near extinction, dams were built on many rivers, and other river channels were constrained within formerly expansive floodplains. Energy harnessed from rivers powered mills throughout the region, and Greenfield’s development as a prominent wealthy mill town and center of manufacturing set the stage for the diversity of land use practices we see today.

The geographical location and physical characteristics of Greenfield have shaped its past, inform its present, and will guide its future as a community. Today, its residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural zones of use remain enmeshed in a wider natural landscape. Climate change is likely to bring changes both expected and unexpected to that landscape and the people who rely on it.

Conservation planning seeks to balance human needs with a regard for the complexity and value of ecosystems by conserving and connecting remnant patches in the fragmented landscape and restoring disturbed areas. Following the example of previous master plans, this document aims to reflect community-held values and ideas about where and how growth should occur and what areas or resources should be conserved. The community has the ability to manage land use patterns through a variety of tools such as planning, zoning, regulations, incentives, and conservation restrictions, which can help Greenfield plan a future that is more sustainable over the long term.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 13

Development Patterns

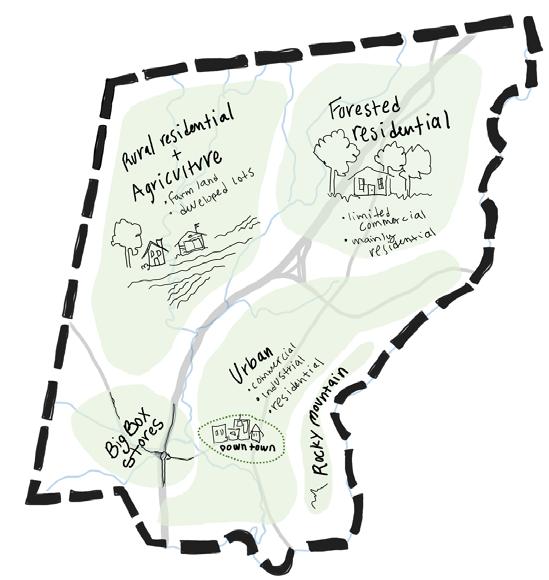

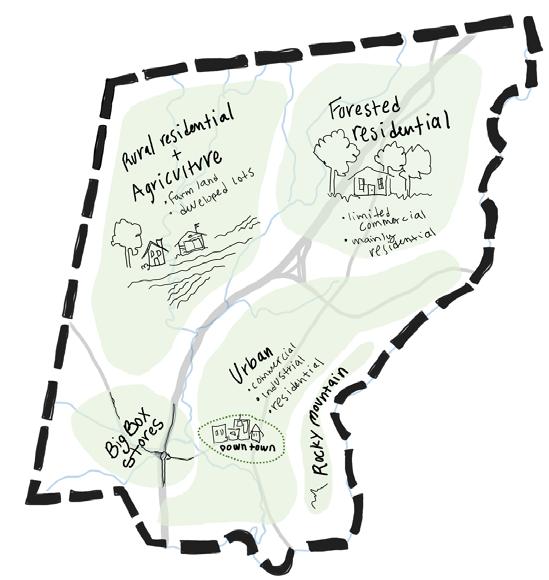

Greenfield covers approximately 22 square miles (14,020 acres) and is most densely developed south of Route 2 and east of Interstate 91 (see Land Cover map on facing page). Commercial corridors extend from the downtown area along Federal Street and Main Street, and a narrow industrial district follows the train tracks north of Arch Street (see Zoning map below). Residences surround the urban core. The average lot size for a single-, two-, or three-family home in this part of town is 13,806 square feet. Nearly 72% of residential lots in this Urban Residential zone are single-family homes, and 14% are two-family homes.

North and west of Interstate 91, lower-density neighborhoods, forests, and farms make up a landscape with a more rural character. Most of Greenfield’s agricultural lands are here, along the banks of the Green River. East of Interstate 91 and north of Route 2, houses and planned industry occupy a forested matrix. In these areas, the average lot size for a single-, two-, or three-family home is about 73,000 square feet.

An industrial park may be defined as “a defined area designed to accommodate industrial and manufacturing uses” (FRCOG, “Planned Industrial Park Inventory Update,” 1). The Interstate-91 Industrial Park in Greenfield is currently zoned over 268.3 acres and hosts twenty-two businesses. At present, it contains three parcels that are “ready for development” and three parcels that are developable “with constraints.” A recent inventory notes that “there is market interest for planned industrial park space in Franklin County” (8), and the development of planned (as opposed to unplanned) industry is a form of compromise between economic and environmental values. Industries that would add to or complement Greenfield’s already robust food processing sector could be especially valuable to the city.

Zoning

Central Commercial

General Commercial

General Industry

Health Service

Limited Commercial

Planned Industry Office

Urban Residential

Suburban Residential

Rural Residential

Semi-Residential

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 14

Land Cover

Based on 2016 data from MassGIS.

Land Use

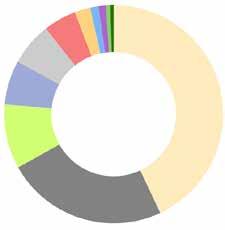

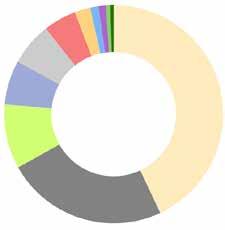

According to 2016 land use data provided by MassGIS and summarized in Greenfield’s 2021 Open Space and Recreation Plan, about 52%, or 7,285 acres, of the city is devoted to commercial, industrial, residential, or mixed use (see Land Use map on facing page). Among these use-areas, residential (multi-family and single family) land made up the largest portion with 4,323 acres (32%) and commercial the second-largest with 688 acres (5%). One can see at a glance the varied mosaic of uses in the downtown area, a legacy of the city's industrial past. The infographic below summarizes land use in Greenfield as defined by Property Tax Classification Codes.

Sum of Shape_Area by USEGENNAME

Residential 32%

Right-of-way 10%

Open Land 17%

Mixed Use 16%

Tax Exempt 9%

Commercial 5%

Agriculture 8%

Water 1%

Industrial 1%

Recreation 1%

Forest 1%

Greenfield’s open spaces–land that has not been developed for commercial, industrial, or residential use–may be identified and mapped according to ownership and level of protection from development. Approximately 2,700 acres (20% of Greenfield’s land area) may be considered open space, of which 1,548 acres (11%) are privately owned, 855 acres (6%) are City-owned, 133 acres (1%) are owned by the state, and 63 acres are owned by conservation organizations or land trusts. About 16% (2,296 acres) of Greenfield’s total land area is permanently protected (see map on page 63, Protected Open Space).

The well-defined transition from the developed downtown area to the open spaces of the Green River Valley north and west of Interstate 91 can be seen in the graphic below.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 16

I-91

Rural to Urban Greenfield

Rocky Mountain

Residential 31.1% (17,515,729.2) Open Land 16.83% (9,483,290.1) Mixed Use 15.3% (8,623,734.2) Right-of-way 10.04% (5,657,910.7) Tax Exempt 8.5% (4,787,669.9) Agriculture 7.7% (4,338,262.5) Commercial

(2,784,869.3) Water 1.666% (938,593.3) Forest 1.562%

Recreation

Industrial 1.035% (583,206.0) Unknown 0.00000003083% (0.0)

4.94%

(879,880.1)

1.32% (743,654.1)

Land Use

Based on 2016 data from MassGIS.

Residential Land Use Trends

This map shows the increase in land area devoted to residenetial land use since 1971, most notably along corridors north and west of downtown. It combines hand-delineated land use data from 1971 and 2005 with land cover data from 2016 filtered by use.

2016 1971

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 18

Shelburne

Land Use Trends

Toward the end of the twentieth century, development trends in Greenfield favored new single-family homes on large lots. In 2014, Sustainable Greenfield noted that the amount of land devoted to low-density housing had increased in the town’s rural northern and western areas between 1971 and 2005. This increase occurred despite a decrease in the town’s population, and these homes were often built on forested or formerly agricultural lands. When construction on agricultural land occurs, it results in permanent loss of the land for agriculture; additionally, soil is often moved or destroyed.

Although the 2016 land use data is not directly commensurable with earlier data due to changes in data classification methodology, there is some evidence to suggest that this trend of development on farms and in forests continues (see map on previous page). The Conway team was able to identify at least one agricultural field that was converted into a housing subdivision between 2005 and 2016. The conversion of farmland to homes is driven by a statewide housing shortage as well as the economic needs of farmers, and zoning regulations help to determine what kinds of housing get built. While the need for housing is great, the need to address the financial security of farmers is also of paramount importance. We need farmers and farmland to ensure our food security as well as build climate resilience.

Recent Planning Efforts

Since its 2004 Community Development Plan, Greenfield has recognized and attempted to mitigate the loss of open space due to low-density residential development by favoring higher-density development in the downtown area (Sustainable Greenfield 35). That plan included a mix of housing types to suit a range of choices for both market rate and affordable units, which carried over to the city’s 2014 goals of preserving agricultural land and focusing residential and commercial development in previously developed areas.

Greenfield also completed a Downtown Master Plan in 2003 and an update, the Downtown Greenfield Revitalization Plan, in 2023. Updates to the plan related to land use include goals such as: addressing barriers to housing stock improvements, allowing multi-family development and accessory dwelling units (ADU) by right, enhancing the downtown experience through outdoor dining and cultural activities, revising zoning to encourage development through mixed-use permitting, and creating an adaptive reuse overlay district to encourage increased density and reuse of downtown space.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 19

Climate Change

Greenfield has seen extreme temperatures, increases in precipitation, periods of drought, and extreme weather events impact its natural resources, local economy, and health of residents. Recent major meteorological events include an extreme drought in 2022 during which the city was under an outdoor watering ban and at least two severe rain events in 2023 causing flooding, damage to farmland and crops, sewage discharges into rivers, and a declaration of a state of emergency.

Recognizing the need to protect natural resources and the built environment, the Conway team has made climate change a special focus area of this update. Improving the resilience of the community and its infrastructure, supporting local agriculture, mitigating the impacts of flooding, protecting water quality, and decreasing energy use and fossil fuel use are specific goals Greenfield can pursue in response to climate change. This section summarizes some of the climate-related issues that Greenfield is facing which are also referred to throughout the document.

Resilience Building

In 2019 Greenfield was awarded a Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) planning grant by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, and the city’s MVP Resiliency Plan was published in 2021. Greenfield, along with many other towns in Franklin County, has been certified as an MVP Community, qualifying the city to apply for and receive MVP Action Grants for projects to improve resilience to climate change.

Collaboration between the Greenfield Energy and Sustainability Department and the Franklin Regional Council of Governments to develop a Municipal Net-Zero Operations Plan further demonstrates the City’s commitment to achieve net-zero emissions in municipal operations and contribute to state and national emissions reductions targets such as the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2050 (“Greenfield Spotlights Energy Progress”).

Agriculture

Climate change is also affecting Greenfield’s farms and farmers. For example, Just Roots’ farm fields have been subjected to prolonged standing water due to heavy rains in the past few years, ruining crops or making fields unplantable altogether. Other farms in the region have seen crops and soils washed away by flooding, causing devastation to farmers and placing more pressure on the food system overall. Many farmers in Greenfield and the surrounding area have already adopted practices that are both sustainable and that enable them to better withstand climate-related stresses, and the city should support these efforts.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 20

Precipitation and Flooding

Parts of Greenfield experience flooding when the Green River overflows its banks or when the stormwater system is inundated by a heavy rain; more erratic and extreme patterns of precipitation due to climate change will likely make flooding more frequent. During periods of drought, heavy rainfall can lead to flooding when the dry ground is unable to absorb the sudden large quantities of water.

Flooding events have reshaped the city in lasting ways. In August 2005 Greenfield received 9 inches of rain, 3 times more than the monthly average the previous year, resulting in the overflow of the Green River and flooding that caused the displacement of 75 individuals in the Wedgewood Gardens Trailer Park (Department of Public Works). Two years later, the town secured a FEMA Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grant and a state Urban Self-Help grant (now known as the PARC grant) to acquire the property affected by the flooding. This funding enabled the town to acquire the land and remove the trailer park pads and utilities, effectively transforming the area into permanently protected open space, formally renamed Millers Meadow.

The presence of high groundwater levels also poses significant challenges, as many Greenfield residents experience wet basements. It is common in the more populated part of the city to see hoses running from basements and discharging water from sump pumps, and there is reason to believe that other pumps are connected directly to the sanitary sewer system. Greenfield’s wastewater treatment plant is not currently sized to accommodate the volumes of water that it receives during heavy rain events, meaning that on such occasions it must release raw sewage into the Green River. Moreover, the plant’s location in the 100-year floodplain of the Green and Deerfield Rivers presents a potential risk to public health and the environment should the plant itself flood, as it did during Hurricane Irene in 2011. Although the plant received upgrades to resist flooding in 2000 and 2014, workshop participants for the MVP Resiliency Plan “identified that this facility is still of concern and needs additional upgrades in order to build resiliency against future flooding events, and other updates are needed to reduce inflow and infiltration pressure and reduce the risk of combined waste water and storm water hazard events” (9) (see also “Water and infrastructure”).

Forests and Trees

Trees, both in an urban setting and in forests, can help to mitigate the effects of climate change while at the same time being vulnerable to those effects. Much of Greenfield is forested, and forests play an important role in sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as well as retaining water and providing valuable wildlife habitat (Harvard Forest). Some forests in Greenfield are logged, while others are at risk of being cleared for development. The City should do what it can to encourage sustainable forestry practices (see "Forested Greenfield").

Street trees (which tied for second with pollinator habitat as a “conservation priority” of community engagement participants) can also help to mitigate the effects of climate change by providing shade and lowering ground surface temperatures. They are most helpful as a climate mitigation strategy when planted in strategic locations such as by streets or parking lots. As they do in the forest, street trees can help to manage flooding and reduce runoff by aiding the infiltration of water into soil.

While it is true that trees help mitigate climate change, they are also vulnerable to the warming climate. Warmer temperatures and drought conditions during the growing season can stress trees and slow growth (EPA). The MVP Resiliency Plan notes that as temperatures rise and growing seasons increase, habitat conditions for trees in Massachusetts are shifting further north to higher and cooler elevations. This means that the “typical New England forests” will look different over time as birch, maple and beech decline and oak and hickory continue to thrive.

In many cases, warmer temperatures are also favorable to tree pests. The emerald ash borer is currently killing the green ash trees (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) that populate streets and in parks (including Main Street) in Greenfield. Meanwhile, the hemlock wooly adelgid is threatening forest populations of Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). And non-native trees that were once popular in landscaping (such as the Norway maple and the Callery pear/ Bradford pear) are escaping into the wild. Clearly, the future forests of New England will look drastically different than those of centuries ago, but the policies adopted by Greenfield today will help to determine the degree and character of this difference.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 21

Downtown

Greenfield’s downtown combines historic charm with regional accessibility. It boasts walkability, a vibrant arts and culture scene, excellent restaurants, and an active business community. Its industrial past has moreover helped to establish a mosaic of distinct land uses and mixed-use settings that contribute to the city’s dynamism as a regional “food hub.” But like many cities across the United States, Greenfield faces the question of what a downtown area can or should be as changes wrought by online retail and other factors alter the composition of the traditional Main Street.

Despite its many assets, the downtown area currently contains a number of vacant and underused spaces that represent both challenges and opportunities. Since the publication of Sustainable Greenfield in 2014, the City has modernized its zoning use-schedules and eliminated parking minimums to promote infill development and redevelopment downtown. Further zoning reforms such as an infill development ordinance and/or adaptive reuse overlay district could make it easier to redevelop nonconforming lots, making downtown more attractive to builders while preserving its variegated character.

Another opportunity is presented by the amount of land area currently devoted to parking downtown. The 2023 Downtown Greenfield Parking Study found that there is “significant [parking] capacity available across the Downtown throughout the entire day” and that “the newer Olive Street Garage offering an updated and centralized public parking opportunity [is] far from achieving optimal utilization even during typical peak periods” (17). One online survey respondent enthusiastically echoed this idea, writing that “there is PLENTY of vacant parking lot space for new development” and continuing,

I would like to see the upper levels of downtown reused, adding residents, vibrancy, and safety to the community. With that huge parking garage I would think all the surface parking lots could be built on. The little street in front of City Hall could be greened over to make Court Square more usable and feel less like a tiny island in a sea of whizzing cars.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 22

The respondent’s comment about green space brings up another theme that was prevalent in discussions and comments about downtown during the community engagement process: participants’ appreciation of—and desire for more—public spaces and green spaces. During the second public discussion on Zoom, “liked” responses to the question “[w]hat is working or could work to enliven community gathering spaces in Greenfield?” included “[m] ore street trees, more parklets, more pedestrian areas” and “[m]ore places to hang between businesses but not for customer use only.” Respondents also recognized that such spaces require maintenance and that, while such maintenance should not be left to volunteers alone, work by designated volunteer coordinator might help to ease the burden of maintenance on other city departments.

In addition to questions of land use, issues of transportation and access arose frequently during discussions of downtown. One member of the community expressed a wish for “affordable rail access to Brattleboro, Boston, Hartford, and Berkshire East” and “safe bike paths everywhere.” Greenfield has developed and extended several bike lanes and pedestrian walking paths since 2014 as part of its Complete Streets initiative, and it continues to do so. It is also currently piloting weekend fixed-route bus service via the Franklin Regional Transit Authority (FRTA). At several points throughout the community engagement process, participants pointed to the city’s proximity to Interstate 91 and Route 2 as advantages but stressed the need for non-vehicular access across these routes. The themes of pedestrian and bicycle access are touched on in more detail in the “Recreation” section of the “Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources” chapter and will be treated more fully in an updated “Transportation” chapter of the comprehensive plan.

The 2023 Downtown Greenfield Revitalization Plan further addresses matters related to the downtown area.

Downtown Main Street Holiday Lights

Downtown Main Street Holiday Lights

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 23

City of Greenfield, 2022

Housing

The topic of housing will be treated fully in a separate updated chapter of the master plan. However, housing was identified as Greenfield’s number one “development priority” by community engagement participants, and decisions about land use (such as zoning) may affect the availability and accessibility of housing. Many residents said that Greenfield needs more affordable and accessible (barrier free) housing and that efforts to meet this need should also prioritize the conservation of natural resources and open space. As one person put it,

Safe & affordable housing is clearly an issue. I would like to see Greenfield address this in a way that still preserves our forests, pollinator habitats, farms, and our need for reduced greenhouse gases. Trying to create a healthy and resilient community/natural environment needs to be at the heart of any plans around housing.

Another community member stated that “Greenfield does not have enough affordable housing,” while a third noted the need for “[a]ccess to safe and affordable housing for unhoused, low income, and mobility limited people.” A recent article in The Recorder interviewed three seniors who are currently struggling to find housing in Greenfield. “Anybody who knows anything about housing knows it’s bad,” one of the individuals profiled in the article said; “[e]ven if you are wealthy, it’s a challenge to find the housing that you’re looking for, even if you’re able-bodied. If you have a disability, it’s extremely difficult to find housing that’s got even minimal accessibility” (qtd. in Bhat).

The need for housing in Greenfield reflects nationwide trends. According to the Federal Government Accountability Office, “land prices increased 60% from 2012-2019, and the cost of homes more than doubled from 1998 to 2021.” Rents also increased “about 24%” from 2020 to 2023. In the Pioneer Valley, home prices rose 6% between October 2022 and October 2023 to a median of $335,000. 608 homes were listed for sale in October 2023, down from 902 a year earlier (MacLean).

According to the Greenfield’s 2023-24 Community Preservation Plan,

An estimated 69% of Greenfield renters pay over 30% of their income on housing, and are considered cost-burdened. This is a much higher rate of cost-burden among renters than in the State, where an estimated 46% of renters pay too much for housing. Even more striking, an estimated 21% of renters are paying more than 50% of income on housing (considered severely cost-burdened). Greenfield’s percentage of cost-burdened homeowners is much less, at 29%, but is still higher than the State rate of 27% (32).

The Greenfield Housing Authority (GHA)

Established in 1946, the GHA offers a range of housing options for low-income individuals and families, senior citizens, and those with special needs. It developed 72 units of Veterans housing in 1949 and has since expanded its scope of operations. The Winslow Building, with 55 Single Room Occupancy (SRO) units, provides affordable and convenient living in proximity to downtown for individuals aged 18 and above, including those who are elderly, disabled, or working. The GHA also participates in revitalization programs for downtown properties such as SHARP, Core Focus, and 705 Moderate Rehab. It is currently developing five new affordable housing units at 300 Conway Street (Greenfield Housing Authority).

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 24

The Winslow Building

Since 2014, the city has sought to increase housing availability and density through zoning reforms. It has allowed attached Accessory Dwelling Units and two- and three-family dwellings by right in all residential districts, and it has taken measures to improve housing access for vulnerable populations. Multiple housing projects are currently underway, including the renovation of Wilson’s Department Store and 300 Conway Street. Non-profits have also stepped in to help fill gaps; in April 2023, the Zoning Board of Appeals issued a special permit for a 36-unit permanent supportive housing complex at 60 Wells Street, a partnership between Rural Development, Inc., and Clinical & Support Options, Inc (Rural Development, Inc.). While these measures represent progress, further opportunities exist to expand and diversify Greenfield’s housing stock through zoning policy changes.

To encourage more housing downtown, the City could consider more permissive regulations for multifamily units. Multifamily units are currently allowed by right only in the Central Commercial zone; elsewhere they require a special permit, which is a significant deterrent to developers. Greenfield could expand by-right (pending site plan review) development of multifamily units to the Semi-Residential zone, which adjoins the Central Commercial zone. Alternatively, or in addition to this measure, the current limit of 24 units in new multifamily dwellings could be raised. Measures to allow easier redevelopment of nonconforming lots could also provide opportunities for more housing. Strategies that focus on downtown have the virtue of encouraging new housing near existing infrastructure (such roads and utilities) and public services (such as schools, libraries, and hospitals). Within the Urban Residential (RA) zone, the city could look for ways to encourage single-family to two- or three-family conversions.

In more rural areas, Open Space/Cluster Developments (also called Conservation Subdivisions) represent a mechanism by which construction of housing may be paired with permanent conservation of open space. While Greenfield has an Open Space ordinance, the City could consider amendments that make open space developments more attractive to builders and/or more effective at conserving agricultural and forested lands. Such measures could include density bonuses for affordable housing and increased protection of open space, smaller lot sizes, or greater open space requirements in rural districts.

A final tool that the City could explore is a Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) program that would allow landowners to sell development rights from one area (often rural or sensitive land) to developers in another area where growth is encouraged. Such programs are designed to protect rural areas by directing development to more suitable locations. As a preliminary measure, the City could investigate whether there are zones within Greenfield that would benefit from such an arrangement.

Conventional Development Versus Cluster Development

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 25

Water Quality and Stormwater Infrastructure

Quality of Greenfield’s waterways as assessed in compliance with the Clean Water Act, municipal stormwater network, and 100-year flood zone.

BERNARDSTON ROAD

MOHAWKTRAIL

FEDERAL STREET

HIGHSTREET

MAIN STREET

GREENFIELDROAD

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 26

SOSTREE

FRENCHKING HIGHWAY 2A 5 5 2 5 5 5 2A 2A 2 91 91 91 Library High School Poet Seat Swim Area 0 1.5 3 0.75 Miles ¯

Water and Infrastructure

The waters that flow through Greenfield and the city’s water infrastructure make up an integrated system. The health of the city’s waterways (both their ability to support natural communities and their safety for human purposes such as fishing and swimming) depends in part on how its infrastructure functions, and this function depends in turn on “upstream” inputs such as rain. Factors to consider when making decisions about land use that relate to water and infrastructure include residents’ desire to conserve and restore the city’s waters (water was the most chosen “conservation priority” among community engagement participants) and the effects of climate change, notably the likelihood of more frequent heavy rains (Crimmins et. al.) and the possibility of migration from coastal areas (OSRP 3-13).

Another important factor is the state of the city’s infrastructure. As in many other cities and towns across the United States, elements of Greenfield’s sewer and stormwater networks are old and deteriorating. Some segments of the sewer were laid more than a century ago and have since shifted, making them vulnerable to inflow and infiltration. Illicit connections from residential sump pumps also burden the system. During heavy rain events, the volume of water in the system increases greatly, making it necessary to release sewage into the Green River. Not only this, but streets are frequently closed in Greenfield as the Department of Public Works responds to and repairs broken and collapsed pipes. To fully repair the sanitary sewer network would require lining many pipe segments and replacing others according to an official from the Department of Public Works.

The town’s stormwater system is also due for an overhaul. Many of its culverts are too small to accommodate peak discharges during heavy rain events, meaning that parts of the city experience localized flooding (Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Update Committee 35-6; MVP Resiliency Plan 9). It is common for streets such as Nash’s Mill Road and Arch Street to be closed due to flooding. Even when the stormwater system functions as intended, stormwater flows untreated from impervious surfaces into the Green River and other waterways carrying pollutants and sometimes heat, which degrade water quality. It is possible to mitigate these effects by incorporating “green infrastructure” into system upgrades when opportunities allow (see “Green Infrastructure” box).

The Clean Water Act

Under the Clean Water Act, states are required to monitor waterways with respect to their ability to support human uses and aquatic life. Waterways are assigned a Class that specifies the uses they must support as well as a Category based on their ability to support those uses. Class A waters must be able to supply drinking water, while Class B waters should allow recreation and ecosystem function but not necessarily be drinkable. All of the monitored waterways within Greenfield are Class B. The Categories are summarized by MassGIS as follows:

Category 1) Unimpaired and not threatened for all designated uses.

Category 2) Unimpaired for some uses and not assessed for others.

Category 3) Insufficient information to make assessments for any uses.

Category 4) Impaired for one or more uses, but not requiring the calculation of a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL).

Category 5) Impaired for one or more uses and requiring a restorative “action” plan, such as a TMDL or Alternative Restoration Plan (impairment due to pollutant(s) such as nutrients, metals, pesticides, solids, and pathogens).

(MassGIS Data: MassDEP 2022 Integrated List of Waters (305(b)/303(d)))

Waterways are reevaluated every few years. In 2022, the Green River south of Swimming Pool Dam was evaluated at Category 5; specific impairments of this stretch included E. Coli, Fecal Coliform, Lack of a Coldwater Assemblage, Temperature, and Turbidity. It should be noted that while the Green River above Pumping Station Dam/Eunice Williams Covered Bridge was also evaluated at Category 5, it is a Class A waterway and was considered impaired only because of temperature (Watershed Planning Program).

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 27

River Corridor

While rains are the primary driver of flooding downtown, flooding also occurs along the banks of the Green River. The Green River Swimming and Recreation Area flooded during Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 (MVP Resiliency Plan 44-6) and, according to members of the community, continues to experience significant flooding. Other low-lying areas along the river also flood regularly (35-6). The city currently plans to reduce flooding and erosion along the river through measures such as bank stabilization, planting native trees and shrubs, developing and implementing a knotweed eradication plan at Millers Meadow, and repairing the retaining wall at the Recreation Area. It also currently recognizes a Floodplain overlay district based on the “one percent annual chance flood” as defined by FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Maps from 1980—that is, the elevation that water is expected to reach in a 100-year flood; however, these maps underestimate the actual current frequency of flooding and do not take into account fluvial erosion hazards that are related to, but different from, flood hazards.

Fluvial erosion hazards—streambed and streambank erosion that can occur during flooding—are of particular concern in this part of New England. A history of land clearance and development along rivers, in connection with attempts to control flooding through techniques such as straightening the river channel and constructing berms, has led to “an escalating cycle of increasing flood damages and costly repairs” (FRCOG). A different approach to managing flood hazards is to recognize and accommodate a river’s natural movement within its “corridor”: “the area of land surrounding a river that provides for the meandering, floodplain, and the riparian functions necessary to restore and maintain the naturally stable or least erosive form of a river thereby minimizing erosion hazards over time” (UMass Amherst Extension). In 2019, the Franklin Regional Council of Governments prepared a corridor map of the Green River as well as a model River Corridor Protection Overlay District Zoning Bylaw; adopting a zoning overlay district based on this map and model bylaw could help Greenfield to better manage current erosion hazards and avoid such hazards in the future. Given that much of the riparian lands that are valuable to the community as flood storage are privately owned, this overlay district could work in tandem with efforts to mitigate flooding through River Corridor Easements (RCE) or Conservation Restrictions (CR) in particular areas.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 28

Shelburne Road Culvert Failure Greenfield DPW, 22 March 20224

Flooding on Arch Street City of Greenfield DPW

example river corridor map showing channel migration and flow paths (Not an official delineation, for illustration purposes only.)

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 29

The term “green infrastructure” originally referred to natural landscapes (forests, wetlands, etc.) that filter or absorb stormwater. Over time, it has grown to include engineered systems that supplement or replace traditional “gray infrastructure.” While gray infrastructure is designed to convey water away from the built environment as quickly as possible, green infrastructure is designed to slow and hold water in vegetated areas that mimic natural systems. The Water Infrastructure Improvement Act (2019) defines green infrastructure as “the range of measures that use plant or soil systems, permeable pavement or other permeable surfaces or substrates, or landscaping to store, infiltrate, or evapotranspirate stormwater and reduce flows to sewer systems or to surface waters” (EPA, “What is Green Infrastructure?”).

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

Green Roof

A green roof is a vegetative layer installed on a rooftop. A vegetated growing medium helps to slow the velocity of stormwater runoff and reduces the total amount of runoff. Other benefits of green roofs include natural air and water filtration, reducing temperature, and functioning as insulation. Green roofs can also attract beneficial insects and birds (EPA, “Using Green Roofs to Reduce Heat Islands”). Green roofs in densely developed urban environments are especially beneficial for mitigating the heat island effect and reducing runoff.

Rain Garden

Rain gardens, or vegetated basins, are designed to temporarily collect, store, and absorb surface water runoff from rooftops, driveways, sidewalks, parking lots, lawns, and other impermeable surfaces. A garden of deep-rooted shrubs, grasses, or flowers, planted in a small depression below a slope, builds soil structure while infiltrating and recharging groundwater (Groundwater Foundation). Rain gardens are ideal for private spaces such as lawns or public spaces such as parking lots. They may be constructed around existing storm drains. A rain garden planted with native plants not only provides an attractive alternative to a turf detention basin but also supports pollinators and other wildlife.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 30

Green infrastructure elements may be incorporated into a community at different scales. Site-scale examples could include a rain barrel, a rain garden, a green roof, or a permeable sidewalks or parking lot. Neighborhood-scale examples could include a row of trees or a bioswale along a street, a park, a constructed wetland, or stream daylighting (renovating existing infrastructure to restore ecosystem function). “When green infrastructure systems are installed throughout a community, city or across a regional watershed, they can provide cleaner air and water as well as significant value for the community with flood protection, diverse habitat, and beautiful green spaces” (EPA, “Green Infrastructure”).

Like traditional “gray infrastructure,” green infrastructure must be properly designed and maintained to fulfill its intended functions. For example, engineered wetlands often require a sediment-capture mechanism that must be emptied periodically. Maintenance may require the identification of, and care for, plants (especially if native plants are desired). When properly designed and maintained, green infrastructure will aid in the management of stormwater, improve water quality, offer habitat for wildlife, and provide shade and lush greenery for human enjoyment.

Pervious pavement

Pervious pavement may be installed in place of traditional asphalt or concrete parking lots, sidewalks, paths, or streets to infiltrate water rather than shedding it as runoff. Compared to traditional pavement, alternative materials allow rain and snowmelt to filter through layers of rock, gravel, and soil. Subsurface pipes may be installed to rout water to a storm sewer or natural channel. Permeable pavements could lower construction costs for some projects by reducing the need for conventional drainage features (EPA, “Soak Up the Rain).

Bioswale

Bioswales, or vegetated channels, are linear swales designed to slow and infiltrate surface water runoff from nearby impervious surfaces before it is routed into storm sewers, natural channels, or groundwater. Plants and soil microbes break down pollutants and improve water quality while reducing the volume of water entering drainage systems. Flexible siting requirements mean that bioswales may be integrated with medians and curbs, greening the streetscape while taking pressure off of existing infrastructure (NACTO, “Urban Street Design Guide”).

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 31

Solar Energy

Greenfield has made great strides in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and has ambitious goals in place to complete the transition to nearly carbon-free electric power by 2050. The city’s municipal operations have achieved significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions since 2008 (including a 39% reduction in emissions from electricity and a 96% reduction in emissions from heating oil, as detailed in the Net-Zero Operations Plan). In 2012, the City installed a 2 megawatt solar farm on its capped landfill. Since 2014, Greenfield has also seen 500 kilowatts of rooftop solar added to homes and businesses, construction of a 1.2 megawatt solar farm on the City’s wellfield in 2021, opening of the new zero-net-energy-ready library with a solar array, and a donation from a private resident to install a rooftop array on the DPW office in 2023. The John W. Olver Transit Center, built on a brownfield site in 2012, includes a ground-mounted photovoltaic array.

So far, Greenfield has avoided major sacrifices of its natural and working lands to solar installations. Not all places have been so fortunate. A 2023 report by MassAudubon and Harvard Forest, Growing Solar, Protecting Nature, reveals that “[s]ince 2010, ground-mount solar has displaced at least 1,800 acres of high biodiversity lands and nearly 1,300 acres of farmland” (Executive Summary 3). But as MassAudbon states on its web page for the report,

Every acre of forest destroyed is a huge loss for birds and other wildlife, clean air and water, natural beauty, and recreation. But most importantly, cutting forests and developing farmlands to build solar energy doesn’t make sense for the climate: natural ecosystems and farm soils absorb 10% of Massachusetts’ greenhouse gas emissions every year. Both nature conservation and solar energy must be treated as essential strategies in our response to the climate crisis.

During the second community engagement session facilitated by the Conway team, participants expressed their desire to grow solar and while also protecting open space. Participants were asked “[w]hich statement best expresses your attitude toward new solar?” and given the following three choices: “[a]s much as possible, anywhere”; “[m]aintain urgency, but prioritize roofs and parking lots”; and, “I don’t think we need more solar.” Twenty-four out of twenty-six respondents chose “[m]aintain urgency, but prioritize roofs and parking lots.”

Growing Solar, Protecting Nature identifies priority areas for solar energy development based on factors such as solar potential, land availability, and compatibility with conservation goals. By strategically siting solar installations on already disturbed or less ecologically sensitive lands, the report suggests ways to minimize the loss of forests and agricultural lands to solar development. Greenfield already restricts by-right development of commercial-scale solar arrays to the General Industry and Planned Industry zones. They are allowed by special permit in several other zones. By taking habitat and conservation values into account when deciding whether or not to grant a special permit, and by continuing its already-strong efforts to site solar on already-developed or disturbed environments, Greenfield can continue to be a leader in solar best practices.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 32

Solar on DPW offices

Paul Franz, 2023

Conclusion

Decisions about land use have shaped Greenfield's landscape today for better and worse. Planning a future that respects history while encouraging sustainable growth means taking seriously the missteps of the past and the challenges of the present, especially climate change.

This update’s vision for Greenfield is rooted in an appreciation of its natural and historical context, from ancient geological formations to the long tenure of Indigenous stewardship and more recent industrial uses. By acknowledging and learning from this heritage, the community can forge a path forward that respects the interconnectedness of human activity and the natural world.

Encouraging the concentration of development and redevelopment in already-developed areas and protecting wild and working open spaces are important measures to reduce environmental impacts and encourage the city’s resilience.

Through a coordinated effort guided by thoughtful planning, sustainable development practices, and a commitment to environmental stewardship, Greenfield can build upon its already considerable progress toward becoming a sustainable community, moving toward a future in which human well-being is further enhanced by wise use of natural abundance. The Recommendations section at the end of this document lists some strategies that may aid in this effort.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 33

2014 Sustainable Greenfield Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources Goals

Greenfield’s natural, historic, and cultural resources will be an integral part of the town’s identity with wider recognition and use.

Residents and visitors of all ages will enjoy various recreational opportunities as a vital contribution to their health and wellbeing.

Our natural world and the scenic, rural, and agricultural landscapes will be protected, preserved, and improved to support biodiversity and healthy living in Greenfield.

Greenfield’s cultural life will be encouraged, expanded, and better promoted, with more established town-wide events.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 34

Annual community supper

Kirsten Levitt, 2018

Natural, Historic, and Cultural Resources

Landscapes and Identities

Greenfield’s identity as a community is intimately tied to the land itself and the histories of the peoples who have lived here. We recognize that the first peoples of this land were Indigenous, and we seek to learn from their example in our care for, and stewardship of, the land. We seek to enrich, not degrade, the land’s soils, waters, and biodiversity in our work and recreation. We recognize the value of telling and retelling the stories of those who have lived here in order to understand and reconcile our kinship through the land. We also recognize the value of conserving historically significant places that we love.

Greenfield’s character as an Indigenous settlement or gathering place, its subsequent development by colonizers as an agricultural center and mill town, and its responses to the upheavals of globalization and e-commerce all reflect, to one degree or another, regional and even national experiences. Climate change may also bring disruption on a grand scale. But along with its experience of these broad trends, Greenfield is also defined by a particular landscape and the lives of those who have passed through it. Stories and events such as the tale of the Great Beaver, the killing of Eunice Williams for whom the Eunice Williams Bridge is named, construction of the first bridge over the Connecticut River to Montague, the Greenfield Recorder beginning its publication, the opening of the Greenfield Energy Park, and the January 2017 Women’s Rally contribute to a unique and distinct local history. Greenfield’s natural, historic, and cultural resources are not “resources” in a generic sense but rather those things that confer upon Greenfield its identity as a community.

Experiences of the land itself are an especially important “resource” in this sense because they are one of the things that the land’s pre-colonial inhabitants and those who came after share. As stated in the city’s Open Space and Recreation Plan,

[T]he history of Greenfield—how people came to settle the land, use its resources, and enjoy its forests, streams, and bodies of water—can be seen in the landscapes that have retained a sense of the past. The unique environments in Greenfield play a very important role in providing residents with a sense of place. Brooks, mountains, wetlands, and City centers provide markers on the landscape within which we navigate our lives. (4-42)

Greenfield’s present-day inhabitants have come to recognize and value these natural markers. Groups such as Greening Greenfield and the Greenfield Tree Committee are working to cultivate reciprocity between Greenfield’s natural landscapes and human communities, while organizations such as the Nolumbeka Project are advancing public recognition of those who have been here the longest. These efforts deepen and contextualize the work that has already been done to preserve and celebrate Greenfield’s recent history by organizations such as the Greenfield Historical Society and the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage.

Along with its cultural “resources,” Greenfield also possesses resources in an economic sense. Positioned at a regional crossroads connecting New York to the south and Vermont to the north, and the Berkshires and Boston east and west, Greenfield functions as a commercial hub amidst valuable natural landscapes. Sustainable Greenfield describes the city as “a community with numerous and varied cultural amenities in a beautiful historic setting, with ready access to the rivers and fields, woods and hills of the Pioneer Valley and the recreational opportunities they provide” that “capitalize[s] on these assets to attract visitors and new residents, as well as retaining existing residents.” Indeed, Greenfield’s natural and cultural assets are boons to those who live here. The following analyses and recommendations aim to outline ways in which residents of Greenfield might further enrich, rather than diminish, these natural and cultural assets in their work and recreation, and so approach the goal of “sustainability” established in the 2014 plan and continued in this update.

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 35

Geology, Aquifers, and Soils

Greenfield occupies a low glacial outwash plain between the Connecticut River to the east and the Berkshire Highlands/Southern Green Mountains to the west. When Glacial Lake Hitchcock filled the Connecticut River Valley during the last Ice Age, all of present-day Greenfield was underwater. Streams flowing into Lake Hitchcock from the surrounding highlands carried stony debris that settled out as they entered the lake, forming deep sand deposits in northern Greenfield. Today, these sand deposits hold water and function as aquifers for Greenfield and surrounding towns. The process of sediment deposition was further modified by beavers and Indigenous land use practices, generating rich soils suitable for agriculture.

Bedrock

The deposition of glacial sediments took place between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago, but the bedrock under these deposits is much older. Greenfield’s bedrock (and the rock under much of the river valley to the south) can be classified as arkose, a type of sandstone. It formed over millions of years as the floor of an inland sea (Sustainable Greenfield 148). At some point, an outpouring of basalt lava covered some of this arkose to create Rocky Mountain, which rises abruptly between downtown Greenfield and the Connecticut River. Columns of basalt and rocky outcroppings of rose arkose can be seen most readily in Highland Park and along the Pocumtuck Ridge. The basalt continues under what is now called the Pocumtuck Range, which stretches from Rocky Mountain to Mount Sugarloaf in Deerfield, and which takes its name from the Pocumtuck people.

30' Contours

Surficial Geology

Sand and Gravel

Till or Bedrock

Fine-Grained Deposit

Floodplain Alluvium

Depth of Surficial Deposit

200'+

Aquifers

30' Contours

High yield

Medium yield

Surficial Geology

Sand and Gravel

Water Supplies

Till or Bedrock

Public well

Fine-Grained Deposit

Surface water supply

Floodplain Alluvium

Prime Soils

Depth of Surficial Deposit

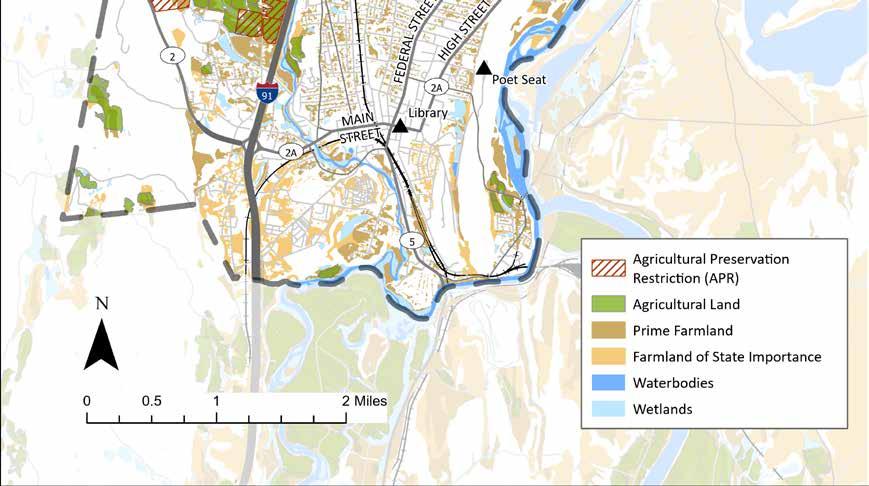

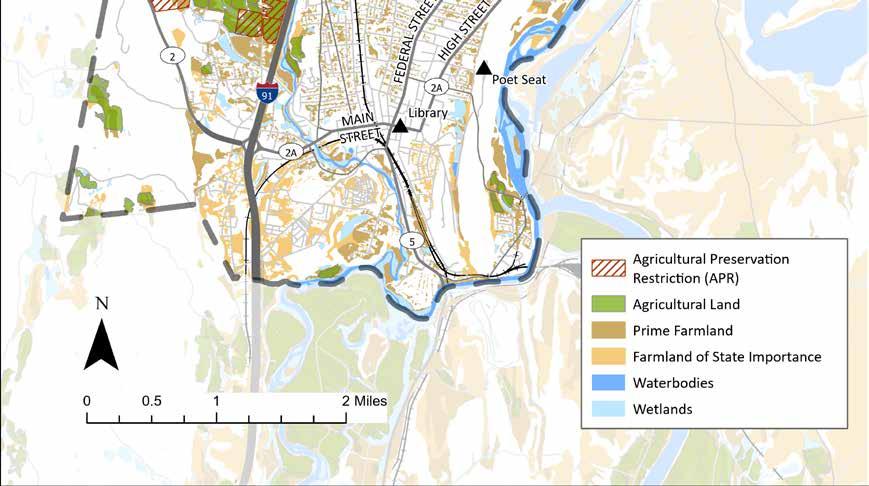

Topography, Surficial Geology, Aquifers, and Soils (facing page) Greenfield’s low position relative to the surrounding hills can be seen in the map on the top left. Sand and gravel carried by streams entering Lake Hitchcock settled into deep surficial deposits (top right), many of which now function as aquifers (bottom left). Greenfield’s prime soils are made up of even finer sediments deposited by floodwaters and trapped by beavers along the Green River and other waterways.

50'-100'

All areas are prime farmland

100'-200'

200'+

Farmland of statewide importance

Wetlands

Aquifers

High yield

Medium yield

Water Supplies

Public well

Surface water supply

Prime Soils

All areas are prime farmland

Farmland of statewide importance

Wetlands

Greenfield LU/NHC Update 36

100'-200'

50'-100'

¯ 0 1 0.5 Miles

Forested Greenfield

Forests and trees provide valuable wildlife habitat and ecosystem services. Conserving forests and greening the urban environment will help to ensure the long-term viability of Greenfield’s economy, the city’s comfort and attractiveness for its human residents, and biodiversity (see also “Connectivity Planning and Conservation”).

Forests

Massachusetts forests are home to diverse plant and animal species, including rare and endangered species, and forested watersheds in Massachusetts provide clean drinking water to millions of people. Forests also capture and store carbon in soils, trees, and associated organisms. In 2016, approximately 55% of Greenfield was “forested” according to land cover data, although the amount of contiguous forested habitat was significantly less—perhaps 33%. Most forested areas are located along Greenfield’s northern and western borders as well as on Rocky Mountain and in isolated patches between neighborhoods and farms.

Greenfield’s publicly-accessible forests, in addition to serving the above-mentioned ecological functions, are cherished for recreational activities such as walking, snowshoeing, and nature exploration. Highland Park, Temple Woods, and the Griswold GTD Conservation Area all contribute significantly to the city’s beauty and natural abundance.

i-Tree, a software tool developed by the USDA Forest Service, Davey Tree and other partners, estimates the quantitative values of ecosystem services provided by trees in any given location. According to i-Tree’s “OurTree Benefits” assessment, Greenfield’s forested acreage currently sequesters approximately 355,281 tons of carbon or 1,302,697 tons of “CO2 equivalent” with an annual uptake of 6,262 tons of carbon or 22,960 tons of “CO2 equivalent.”