State of the Delaware Healthcare Workforce Report 2022 ACTION AND OPPORTUNITY

The purpose of this report is to provide an initial census of Delaware’s healthcare workforce contained in the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation (DPR) licensing database known as DELPROS and provide demographic and geographic information not readily available through DELPROS. The report also highlights key public health challenges related to common chronic disease states compiled from Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN) data on insurance claims. Finally, the report provides infor- mation on primary care, dental health, and behavioral health shortage areas as reported from Delaware’s Office of Primary Care and Rural Health.

Based upon June 2022 DELPROS data, this report contains information from the 19 distinct boards and commissions of practice within DPR which provide regulatory oversight of a majority of Delaware’s healthcare workforce personnel and some types of institutional licensing (which is not a focus of this report). These 19 boards and commissions in turn oversee about 200 types of professional and institutional licenses. This report does not contain information on Certified Nursing Assistants and Direct Service Pro- viders as they are not licensed by DPR nor Community Health Workers that are not registered or licensed in Delaware. Information on these professions is beyond the scope of this census data and report at this time.

As of June 2022, there were 63,123 active healthcare licenses in DELPROS. This number includes 3,529 institutional licenses (e.g., pharmacies and funeral establishments). There are also 7,760 additional licenses issued for prescribing controlled substances which are issued to both individuals and facilities. After accounting for institutions and certain duplications, there are 56,469 individual healthcare providers in DELPROS. This count includes: approximately 26,000 nursing licenses; 9,900 medical practice licenses, (e.g., physicians and physician assistants); 2,600 pharmacist licenses; 2,700 social work-related licenses; and 1,700 dentistry licenses (e.g., dentists and dental hygienists). The remaining boards each account for 1,100 or fewer licensees per board and are covered in detail in this report.

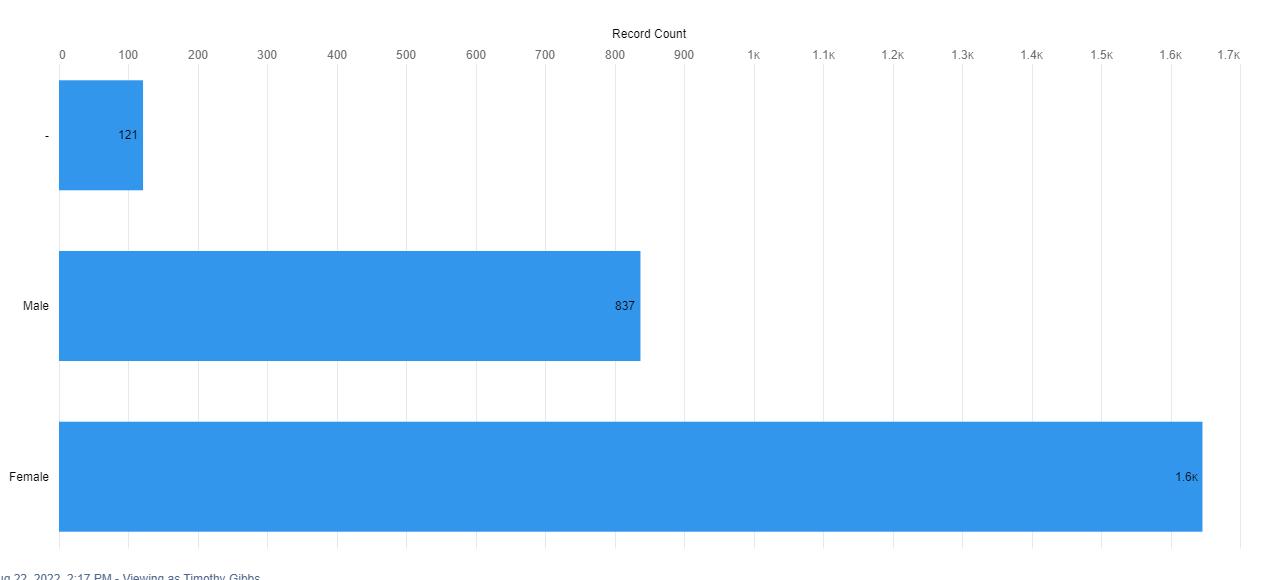

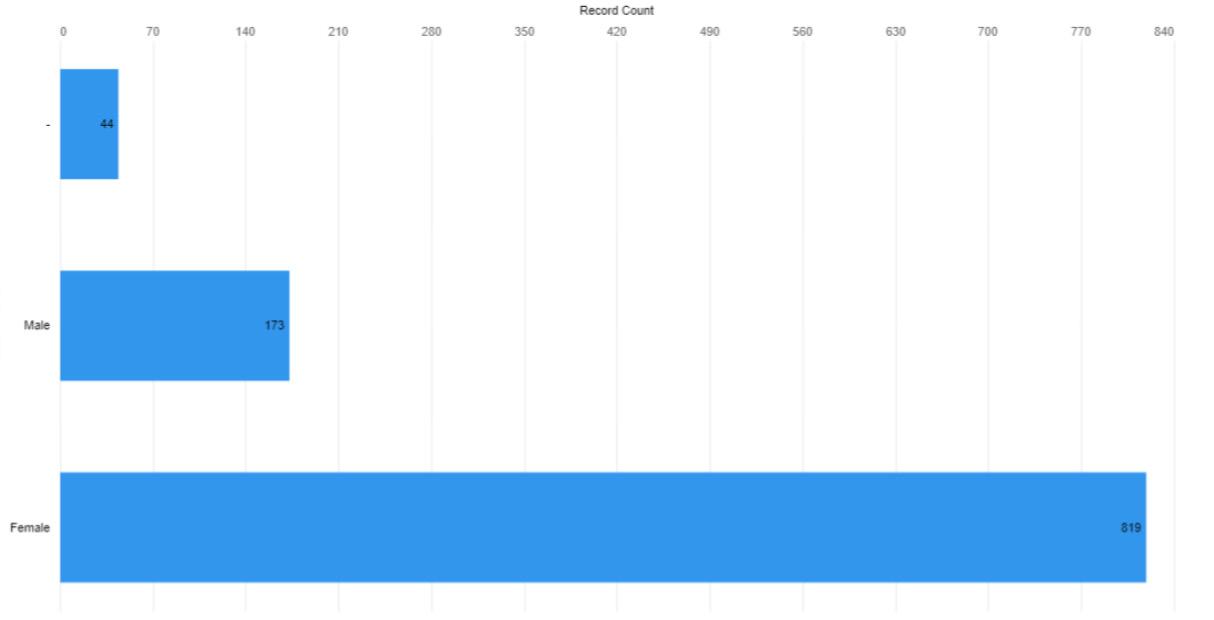

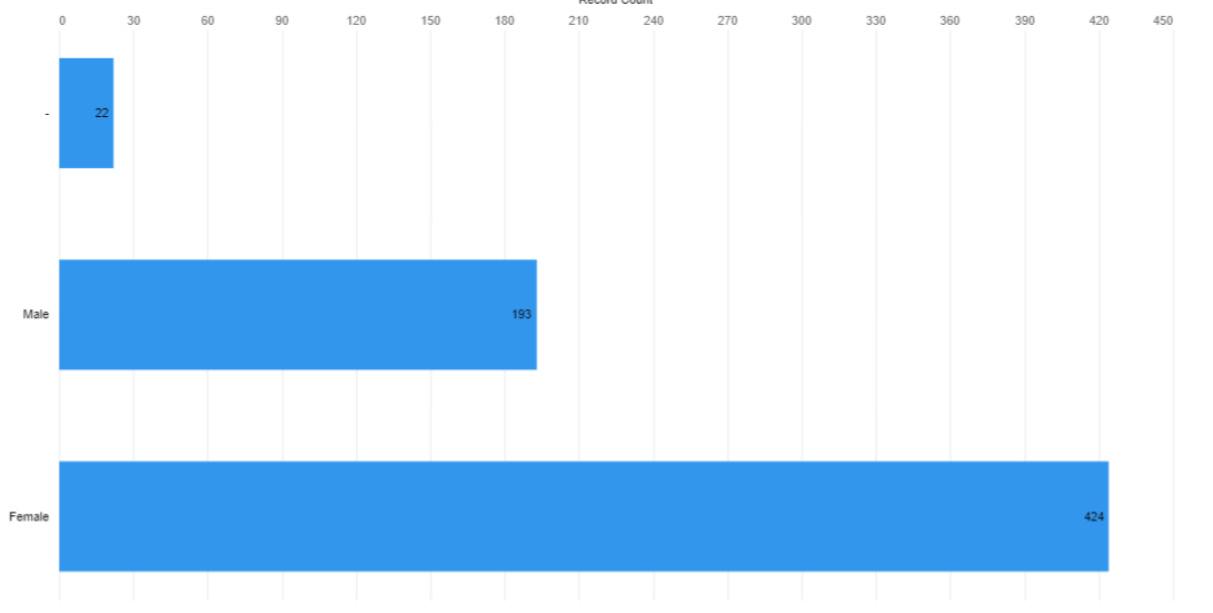

Overall, the licensed healthcare workforce in DELPROS is about 43,000 female (74%) and 15,000 male (26%). Gender is not reported for 4,566 licensees either because individuals did not disclose their gender or because the licensing database contains institutions which do not have a gender demographic. Based on year of birth (where individuals born in 1954 – 1955 are deemed by Social Security as age eligible for full Social Security benefits, we find that no less than 4,600 active licensed individuals are of full retirement age.

The purpose of this first report is not to provide recommendations. Rather this report provides the data and quantitative data analysis capacity to answer additional questions for policy makers and to begin to assess resource allocation to address health care workforce needs in our community. We thank the many institutions mentioned in this report, especially DPR, and look forward to further collaboration which will provide additional, robust information for future reports and a website dedicated to ongoing tracking of this critically important data.

Welcome Statements 6-13

Delaware Healthcare Workforce Vital Statistics 14

Boards and Commissions of the Division of Professional Regulation and notes 15

Board of Chiropractic 16-19

Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene 20-27

Board of Dietetics / Nutrition 28-33 Board of Funeral Services 34-39

Board of Massage and Bodywork 40-45

Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline Overview 46-53

ACGME Training 52-53

Acupuncture Detoxification Specialists 54-55

Eastern Medicine Practitioner 56-57

Genetic Counselors 58-59

Paramedics 60-61 Physician Assistants 62-63 Physicians – DO 64-65 Physicians – MD 66-67

Respiratory Practitioners 68-69

Acupuncture Practitioners 70-71 Administrative Medical 72-73 Polysomnographers 74-75

Certified Professional Midwife 76-77

Physician Licenses by Association of American Medical Colleges Specialty Overview 78-79 Association of American Medical Colleges Specialty Pathways Taxonomy 80-81

Addiction Medicine 82-83

Allergy and Immunology 84-85

Anesthesiology 86-87

Colon and Rectal Surgery 88-89

Dermatology 90-91 Diagnostic Radiology 92-93 Emergency Medicine 94-95 Family Medicine 96-97 General Surgery 98-99 Hospice and Palliative Care 100-101 Integrated Plastic Surgery 102-103 Integrated Thoracic Surgery 104-105 Integrated Vascular Surgery 106-107 Internal Medicine 108-109

Internal Medicine – Emergency Medicine 110-111 Internal Medicine – Pediatrics 112-113 Medical Genetics and Genomics 114-115

Neurological Surgery 116-117 Neurology 118-119 Nuclear Medicine 120-121 Obstetrics and Gynecology 122-123

Ophthalmology 124-125

Orthopaedic Surgery 126-127

Osteopathic Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine 128-129

Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 130-131 Pathology 132-133 Pediatric 134-135 Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 136-137 Plastic Surgery 138-139

Preventive Medicine 140-141 Psychiatry 142-143 Sleep Medicine 144-145

Thoracic Surgery/Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery 146-147 Urology 148-149

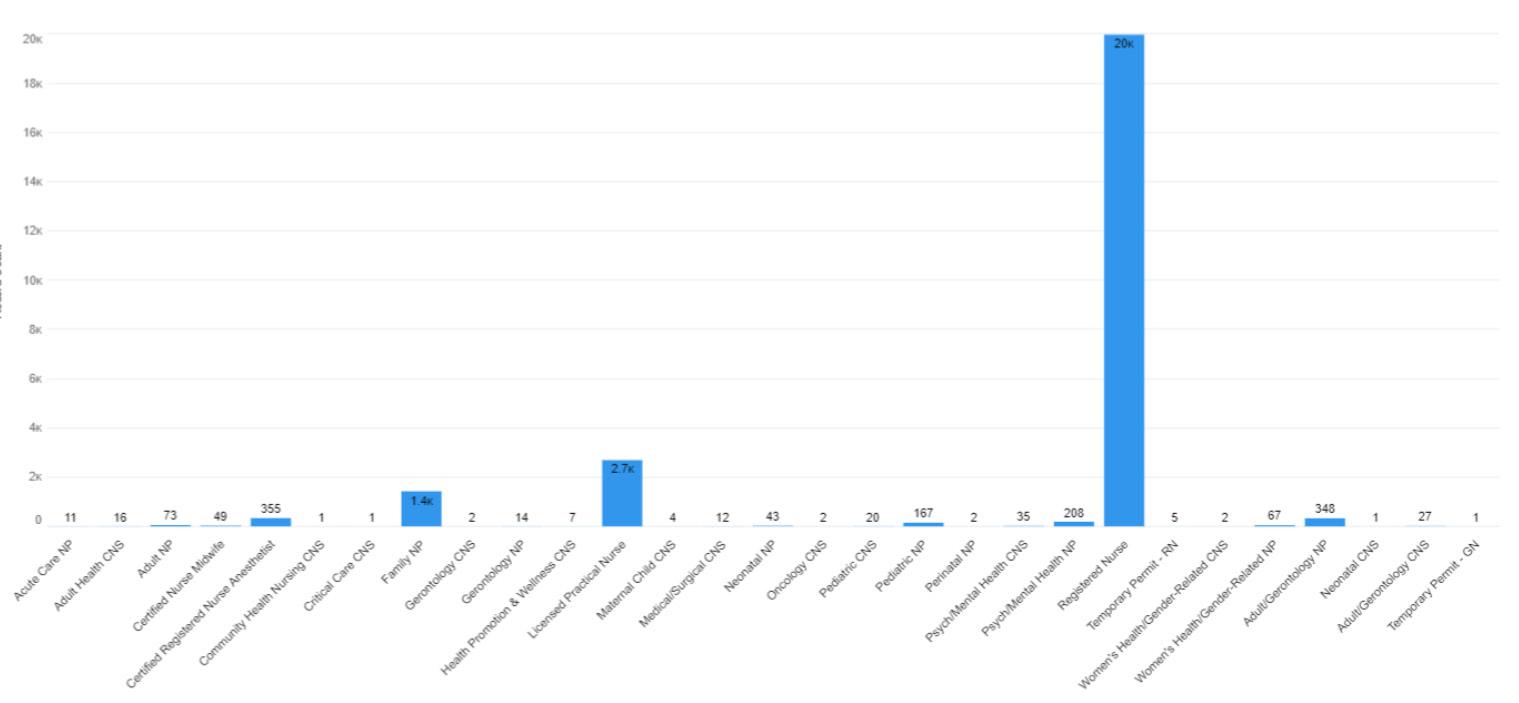

Board of Nursing Overview 150-155

Acute Care Nurse Practitioners 156-157

Acute Care Certified Nurse Specialist 158-159

Adult Health Certified Nurse Specialist 160-161

Adult Nurse Practitioners 162-163

Certified Nurse Midwives 164-165

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists 166-167

Community Health Nursing Certified Nurse Specialist 168-169

Critical Care Certified Nurse Specialists 170-171

Family Nurse Practitioners 172-173

Board of Nursing, Continued

Gerontology Certified Nurse Specialists 174-175

Gerontology Nurse Practitioners 176-177

Health Promotion & Wellness Certified Nurse Specialists 178-179

Licensed Practical Nurse 180-181

Maternal Child Certified Nurse Specialists 182-183

Medical/Surgical Certified Nurse Specialists 184-185

Neonatal Nurse Practitioners 186-187

Oncology Certified Nurse Specialists 188-189

Pediatric Certified Nurse Specialists 190-191

Pediatric Nurse Practitioners 192-193

Perinatal Nurse Practitioners 194-195

Psych/Mental Health Certified Nurse Specialists 196-197

Psych/Mental Health Nurse Practitioners 198-199

Registered Nurses 200-201

Temporary Permit Registered Nurse 202-203

Women’s Health/Gender-Related Certified Nurse Specialist 204-205

Women’s Health/Gender-Related Nurse Practitioner 206-207

Adult/Gerontology Nurse Practitioners 208-209

Neonatal Certified Nurse Specialists 210-211

Adult/Gerontology Certified Nurse Specialists 212-213

Temporary Permit Graduate Nursing 214-215

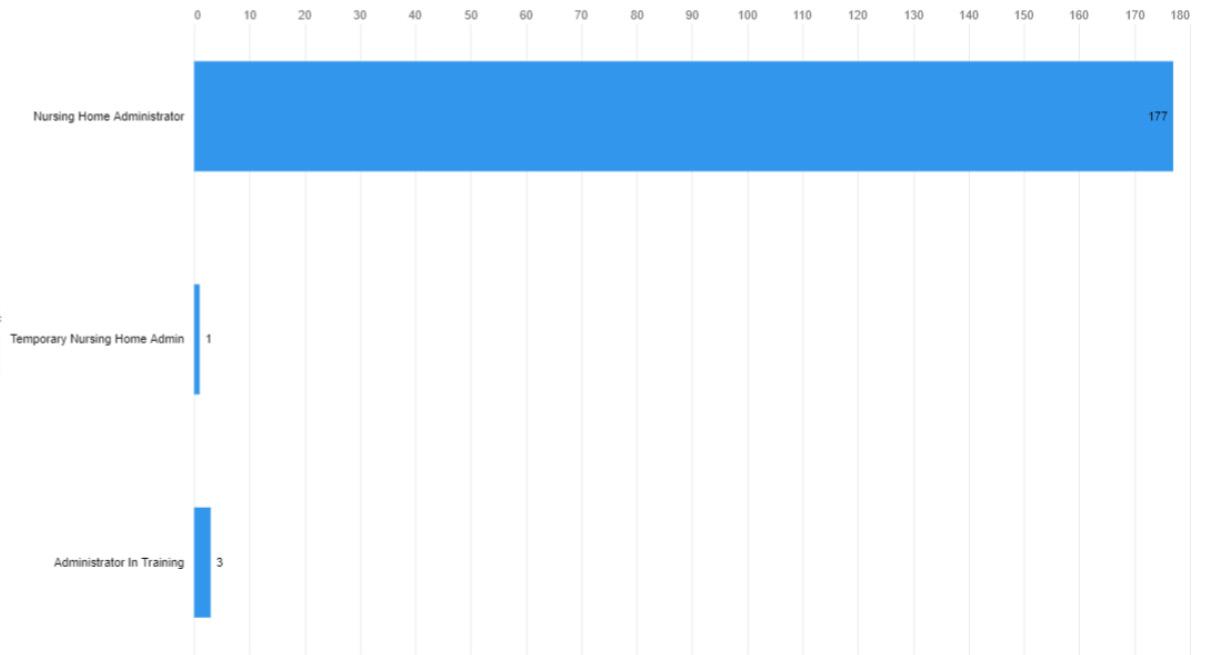

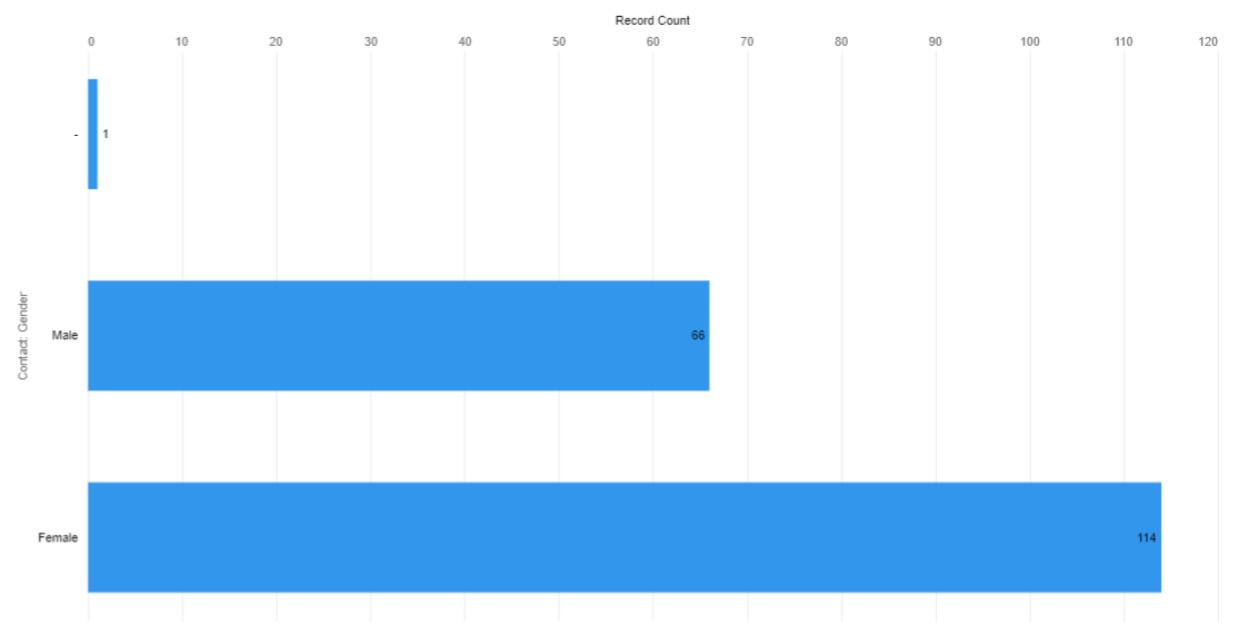

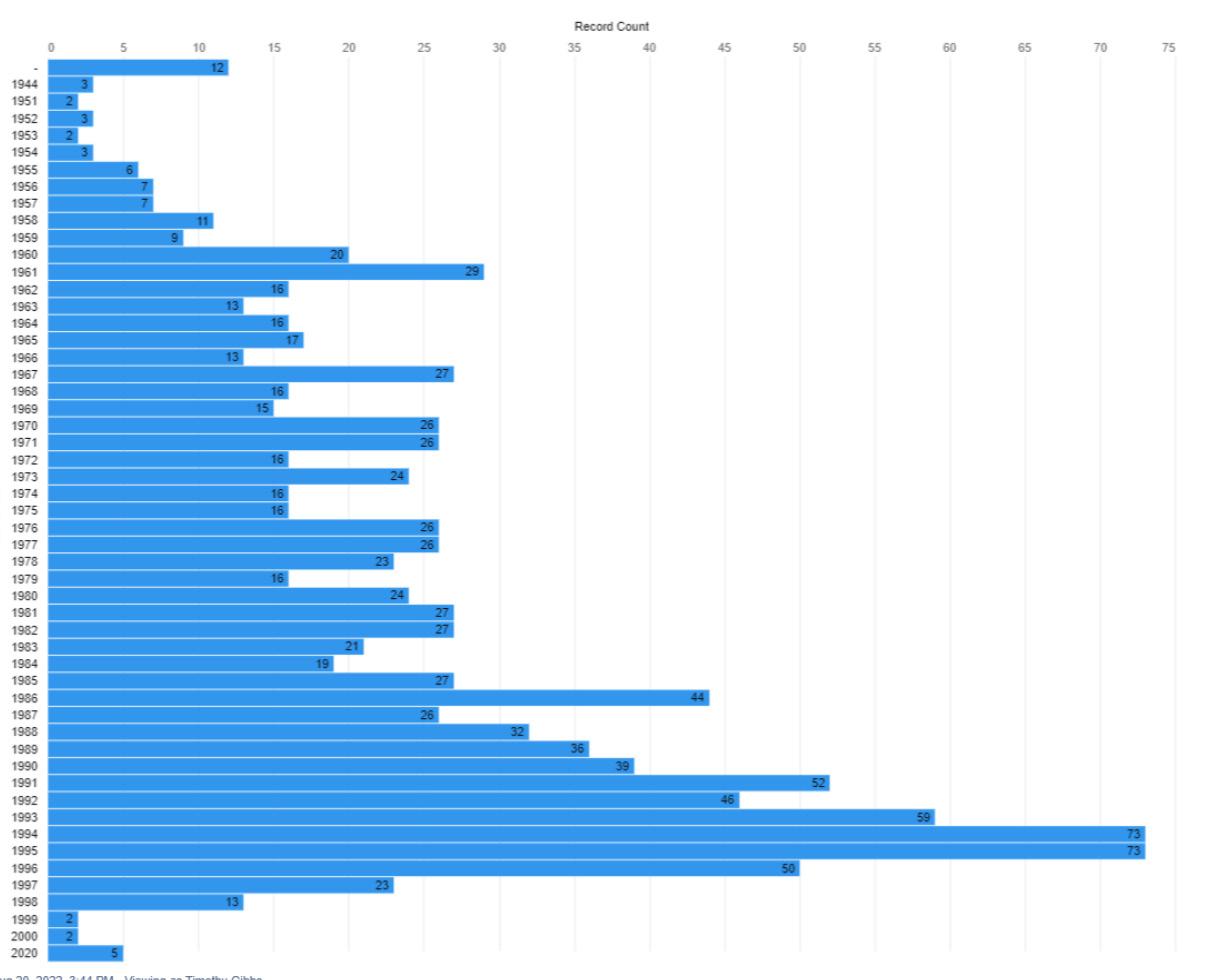

BoardofNursingHomeAdministrators 216-219

BoardofOccupationalTherapyPractice 220-225

BoardofExaminersinOptometry 226-229

BoardofPharmacy 230-233

BoardofPhysicalTherapistsandAthleticTrainers 234-241

BoardofPodiatry 242-245

BoardofMentalHealthandChemicalDependencyProfessionals 246-261

BoardofExaminersofPsychologists 262-267

BoardofSocialWorkExaminers 268-275

BoardofSpeechPathologists,Audiologists,andHearingAidDispesers 276-287

BoardofVeterinaryMedicine 288-293

ControlledSubstanceAdvisoryCommittee 294-297

LongTermCareandSkilledNursingFacilities 298-304

PageLeftIntentionallyBlank 305

CompositionofIdealMedical CareTeam 306-310

Considerations forPatientPanelSize 311-315

ScopeandSpecializationinDentalCare 316

CompositionofanIdealDentalTeam 317-319

Delaware Primary Care Office 320-321

ExtraordinaryImpactsontheHealthcareWorkforce:COVID-19andAging 322-326

REPRINT:AddressingHealthDisparitiesinDelawarebyDiversifyingtheNextGenerationofDelaware’sPhysicians 327-329

Physician and Dentist Basic Demographics: Race and Ethnicity 330 Physician Statistics based on Allopathic (M.D.) and Osteopathic (D.O.) Education 331 Physician and Dentist Basic Demographics Age 332-333 Chronic Disease Management and the Healthcare Workforce 334-335 New Castle County Demographics 336-337

Kent County Demographics 338-339

Sussex County Demographics 340-341

Alzheimer’s and Dementia Data 342

Arthritis and Deteriorative Bone Disease Data 343-344 Cancer Data - Breast, Colorectal, Endometrial, Lung, and Prostate 345-346

Cardiovascular Disease Data - Acute Myocardial Infarction, Atrial Fibrillation, Heart Failure, Ishemic Heart Disease 347-349 Depression and Suicide Data 350

Diabetes Data 351

Endocrine Disease and Disorders Data 352

Systemic Illness Data - Anemia, Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension 353-354 Neurologic Disorders and Injury (Including Stroke) Data 355

Renal Disease Data 356

Respiratory Disease Data 357-358

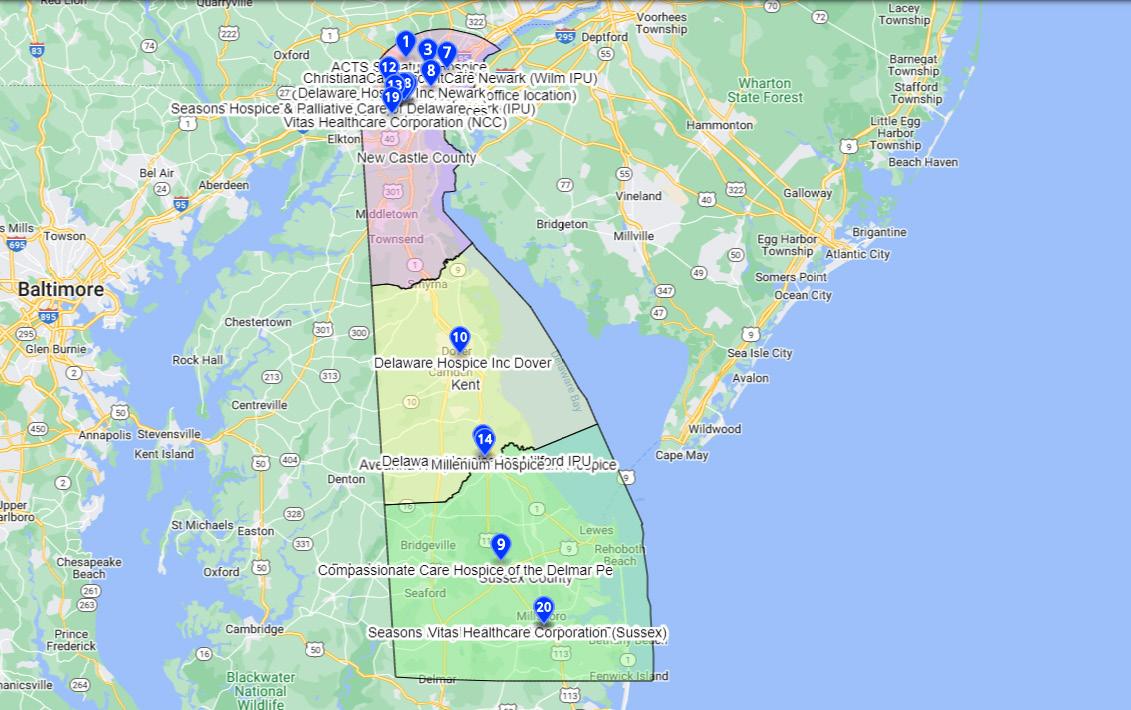

Male Urology - Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Prostate Cancer 359 Vision Data - Cataract and Glaucoma 360 Appendices including Facility Maps 361

Methodology 362-363 Residency and Fellows as a Part of the Healthcare Workforce 364 Delaware Institutions Who Have OR Host Residents in Their Facilities 365 National and Delaware Fellowship Programs 366-367

Nursing Career Path 368-369

DELPROS License Types and Counts 370

Abbreviations 371

Select Facilities – Adult Day Care 372-373

Select Facilities – Dialysis 374-375

Select Facilities – Free-Standing Birthing Center 376-377

Select Facilities – Free Standing Surgical Care 378-379

Select Facilities – Home Healthcare Agencies 380-381

Select Facilities – Home Healthcare, Skilled 382-383

Select Facilities – Hospice 384-385

Select Facilities – Hospitals 386-38

Select Facilities – Personal Assistant Staffing Agencies 388-389

Select Facilities – Prescribed Pediatric Extended Care 390-391

Out of every crisis is borne an opportunity for change. Think back to the natural disasters, human conflicts and tragedies, and economic crises that have befallen our country. Each time, when the after-action report is written, an elected body examines the response, or the business community embraces reforms, we benefit as a society from the lessons learned. The COVID-19 pandemic is no different.

During the past two-and-a-half years, we have seen healthcare providers in our state stretched beyond their limits, dealing not only with the impacts brought on by a new and deadly respiratory virus, but also forced to embrace new ways of managing the chronic and acute conditions of their patients, unrelated to COVID-19. We know that this massive disruption to our healthcare system – and to the health of Delawareans – has taken a tremendous toll on our healthcare workforce, with many providers deciding to retire or leave the profession entirely.

And yet, we also are experiencing the opportunity. During the worst of the pandemic, providers across our state embraced telehealth as a way to see their patients for routine medical exams, to diagnose injuries or illnesses, or to continue regular psychiatric sessions. Regulators changed the rules, allowing insurers to reimburse for these services. The federal and state government provided funding to help advance providers’ transition to telehealth services. Patients no longer had to wait in reception areas or exam rooms when they didn’t feel well, because now their provider would call them back – in the comfort of their own home – when they were ready to see them virtually It all worked because the situation required it.

With the existing shortage of primary care providers exacerbated by the pandemic, patients, providers, employers and insurers all had to adapt to changes in primary care Often, primary care was delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants practicing at the top of their license

As practices and clinics evolve, we are likely to see this broadening of primary care and the use of telehealth increase. The state is investing in primary care practices, promoting person-centered care and advancing equity, and has embraced the new State Loan Repayment Program, all while continuing to support the Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research (DIMER) to help grow the next generation of primary care providers We will continue to work with the General Assembly, healthcare providers, insurers and consumers to embrace additional changes that improve the patient and provider experience, improve overall health and help lower costs.

I am grateful to all of the Delaware stakeholders that are leaning into the workforce issue to help determine the best paths forward In this context, I especially want to thank the Academy of Medicine/the Delaware Public Health Association, the Health Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission, the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance, and the Delaware Journal of Public Health for shining a light on the specific recommendations for Delaware’s workforce outlined in this report.

I look forward to joining stakeholders across our state in examining the recommendations in more detail, exploring the potential benefits, deter mining the policy changes that are needed, and embracing those changes that will have the most positive impact for the future of the healthcare system in our state – and the future health of Delawareans

Magarik, MS Secretary, Delaware Department of Health and Social ServicesIn 2019, the healthcare workforce was 22 million individuals strong. This sector was one of the largest and fastest-growing in the United States, accounting for 14% of all civilian, employed workers in the U.S. The majority worked in hospital settings—about 7 million healthcare workers to be exact. Another 4 million were in outpatient and physician offices, and 3.5 million were in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Home Care settings. All in all, the healthcare workforce was large, growing, and there was a steady amount of jobs that were open, making it a very employable sector overall

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged As we now know, its impact on healthcare cannot be understated It changed care delivery and clearly demonstrated the need for sufficiently-sized and well-trained public health, healthcare, and health support workforces. Easy-entry, easy-exit occupations - the lowest-wage earners in healthcare - were the same groups whose employment was the most adversely impacted by COVID In 2020 alone, total injury and illness cases decreased or remained the same in all sectors except for healthcare, which saw a 4,000% increase in employer-reported respiratory illness.

The pandemic forced states to innovate to meet the needs of their populations, and at the center of that response was the workforce A number of strategies were implemented in response Many focused on creating state-level regulatory flexibilities, and engaging the public health workforce. Some states modified scope of practice r ules for health professionals, allowing for more autonomous practice. Others allowed health professionals licensed in other states to practice in their state Additionally, laws and regulations were changed to support greater use of telemedicine As our nation entered the 3rd year of the pandemic, issues surrounding health workforce capacity, resilience, training, education, and scope of practice have become front and center to moving forward from this phase of our history While the full impact on our health workforce will not be known for some time, a number of the resulting changes are likely to be long lasting

Despite the effects of the pandemic, there are several large, persistent policy issues that existed in 2019 and are still present today. These include: sufficiency of the workforce, mal-distribution, quality of healthcare training, and barriers to accessing ser vices. Additionally, there are population factors that have far reaching ramifications for our nation, impacting more than just the health workforce and employment in this sector First and foremost is the aging of our population. The current cohort of individuals ages 65 and older will continue to generate the majority of demand for healthcare and health support ser vices, and we will need a workforce of sufficient size and distribution to meet this demand However, this is juxtaposed against the fact that the U S birth rate has fallen by 20% since 2007, due to overall lower childbearing rates of current generations. Our population has shown zero growth for several years now, primarily because deaths (attributed to the aging population) exceed births (due to people not having children). Of course, these are issues affecting more than just healthcare in the U S

In a nutshell, the health workforce is in flux We are still understanding the impacts of the pandemic, while having to address previously existing problems. We know that addressing shortages and mal-distributions, continuing to try to improve access to services and train individuals in a way that improves the quality of patient and population outcomes needs to happen But we must also harness the power of this moment to address pandemic-exacerbated issues like burnout and equity in the workforce.

While it may seem like chaos, there is opportunity in times like this. Despite a low birthrate, demand from our aging population and the after-effects of the pandemic will cause employment in healthcare to grow faster than for other industries. This still allows for great opportunity to tackle the persistent policy issues, and if we follow the data, to craft a better health workforce for the future.

Michelle M Washko, PhD DirectorNational Center for Health Workforce Analysis Health Resources and Services Administration

As co-chairs of the Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission, we are pleased to welcome you to the first “State of the Healthcare Workforce in Delaware: Action and Opportunity” Report. This report focuses on select components of the healthcare workforce, including primary care, dentistry, behavioral health, and others. It seeks a broader view of the entire healthcare sector, composed of physicians, dentists, nurses, physician assistants, the allied therapies, dental hygienists, and a vast ecosystem of providers.

We acknowledge and appreciate the work of others in this space. Work on this initiative was started by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA) and the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance (DHSA) long before the COVID-19 pandemic changed our world, and the landscape of healthcare. As the reader knows, the pandemic directly and profoundly impacted both healthcare systems and individual providers.

Before the pandemic, there were tectonic workforce and demographic challenges facing almost every major industry in our State and our nation: the aging of our population, the related increase in the incidence and burden of chronic disease, and the concurrent aging of the healthcare workforce. And the financial impact is clear: the healthcare industry is rapidly approaching one-fifth of the United States Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The contents of this report are based upon an unprecedented collaboration between multiple components of State government including the Delaware Healthcare Commission, the Division of Professional Regulation, the Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research (DIMER), the Division of Public Health Primary Care Office, and the Departments of Finance and Labor. They are joined by the Academy/DPHA, DHSA, and the Delaware Health Information Network, and many other organizations playing essential smaller roles. This public-private partnership has gathered data on the healthcare workforce and analyzed the needs—both current and future—of the State of Delaware. The strategies within this report are based on hard data and analysis and recommend support for polices that will strengthen the healthcare workforce for years to come.

During the past two-years of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have experienced stress and crisis. We now have an extraordinary, federally-funded opportunity to take meaningful action to address the opportunities in our healthcare sector for employment throughout the workforce, as well as novel models (including telehealth and nurse-led health clinics) leading the way.

J. Geisenberger Nicholas A. Moriello, R.H.U.On behalf of the board and advisory council of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA), we are pleased to be the lead institution in the public/private partnership named Delaware Health Force and the author of this report, which includes content from other experts in the field.

The Academy/DPHA started this initiative in early 2019, long before the COVID-19 Pandemic swept around the world and across our State. In the beginning, this effort focused on the State of Delaware’s DIMER (Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research) program and its graduates for the 50th Anniversary Report of the program. As data was collected and analyzed, we realized we were pursing an important vein of data which, if related to other information, could supply policy makers and resource allocation alike.

We are informed by the Social Determinants of Health - in particular healthcare access and equity, components of the SDoH often overlooked due to their perceived, relatively minor role in health outcomes. Many scholarly articles have been written citing healthcare as only being responsible for 10-20% of health outcomes, however if an individual or community is medically underserved or has acute shortages of a variety of healthcare facilities, that 10% can become the single largest barrier to care for those who seek or need it.

We are also informed by the reality that the healthcare landscape is a complex one, and that simply looking at the physician component of the workforce, or the anchor institutions (hospitals) providing care, is not enough to truly understand the nature of opportunity for workforce enhancement. Today’s healthcare is a series of interlocking systems of care, and the better those connections, the strong the fabric of the safety net of care for our fellow Delawareans.

Several methodologies were considered before we settled on the approach used to generate this report. Some of those methodologies are used to great success by other researchers analyzing specific parts of the healthcare landscape, for instance, voluntary surveys. This report does not replace the high value of that research. Instead, it expands upon that research with additional data and analysis.

In a later section of this report our methodology is articulated in depth. For now, we extend sincere thanks to our institutional and individual partners: Delaware Division of Professional Regulation and Division Director, Geoff Christ; Delaware Health Information Network and executive director, Jan Lee, MD and staff; Agile Cloud Consulting and President and CEO, Sharif Shaalan and staff; TechImpact and Delaware Innovation Lab Director of Strategy and Operations, Ryan Harrington, and Director, Research Development & Analytics Data Lab, Héc Maldonado-Reis, and staff; Delaware Nurses Association Executive Director, Chris Otto; and the team at the Academy/DPHA including Kate Smith, MD, MPH; Matt McNeill, BS; Nicole Sabine, BS; and Caroline Harrington, M.S. and members of the board of directors.

S. John Swanson, MD President of the Board of Directors Timothy E. Gibbs, MPH Executive DirectorThe Delaware Health Sciences Alliance (DHSA) was established in 2009 with founding partners ChristianaCare, Nemours Children's Health, Thomas Jefferson University, and the University of Delaware. Since then, additional partners have joined including the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Bayhealth Medical Center, and the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association.

The alliance enables partner organizations to collaborate and conduct cutting-edge research, to improve the health of Delawareans through access to services in the state and region, and to educate the next generation of healthcare professionals.

The DHSA’s unique, broad-based partnership focuses on establishing innovative collaborations among experts in medical education and practice, health economics and policy, population sciences, public health, and biomedical sciences and engineering.

This report, and the work behind it, is an example of the fruits of collaboration. In this case, through our partnership with the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA). In addition, the original work conducted by DHSA and the Academy/DPHA which was the basis for the DIMER 50th Anniversary Report and subsequent annual reports, continues in this report as reflected in key data as well as the recommendations section.

As mentioned elsewhere in this report, Delaware Health Source is comprised of four programmatic components; the core data and research initiative upon which this report is based, the expansion of Delaware Mini Medical School, the expansion of Student Financial Aid for Delawareans, and the expansion of key graduate education and fellowship programs. The DHSA is pleased to support all these programs, in particular those who directly address the pipeline of Delawareans pursuing a career in the health sciences generally, and in medicine and dentistry in particular.

Omar A. Khan, MD, MHS President and CEO Pamela Gardener Program ManagerThe mission of the Division of Professional Regulation (DPR) is to ensure protection of the public’s health, safety, and welfare. Our services benefit the citizens of Delaware, professional licensees, license applicants, other state and national agencies, and private organizations.

DPR provides regulatory oversight for 34 boards/commissions comprised of Governor-appointed public and professional members. Oversight activities include administrative, investigative, and fiscal support for 54 professions, trades and events with over 200 types of licenses and permits. License fees fund DPR and the expenditures related to each licensing board.

The following types of healthcare, and healthcare related services, are overseen by DPR:

- Acupuncture - Acupuncture Detoxification - Art Therapy - Athletic Trainers - Audiology - Chemical Dependency Professionals - Chiropractic - Controlled Substances - Counselors of Mental Health - Dental - Dietitians - Eastern Medicine - Genetic Counselors - Hearing Aid Dispensers - Marriage and Family Therapy - Massage and Bodywork - Medical Practice - Mental Health - Midwife (non-Nursing)

- Nursing - Nursing Home Administrators - Nutritionist - Occupational Therapy - Optometry - Paramedic - Pharmacy - Physical Therapy - Physician - Physician Assistant - Podiatry - Polysomnographer - Psychology - Respiratory Care - Social Workers - Speech Pathology - Tamper-Resistant Prescriptions - Veterinary Medicine

The Division is pleased to collaborate on this important initiative through the sharing of publicly available information. The Division looks forward to the findings that result from the information it shares through collaboration.

Geoffry Christ, RPh, J.D. DirectorThe Delaware Nurses Association (DNA) was established in 1911 in Claymont, DE and has served to advance the profession of nursing and our collective mission to improve the health of all Delawareans. We are the only professional association in Delaware representing all Licensed Practical Nurses, Registered Nurses, and Advanced Practice Registered Nurses We continue to advance health through the art and science of nursing supported by diverse members, advocacy, professional development, generation of new knowledge, effective communication, and community service.

In addition to our robust and inclusive membership , we also facilitate an organizational affiliate program . This program brings together state specialty nursing associations and health - related associations with nursing representation together The goal of the organizational affiliate program is to strengthen nursing ’ s and healthcare advocate’s voices in the reformation of healthcare delivery in Delaware.

In addition to sharing physical space, DNA has a long history of collaboration with the Delaware Academy of Medicine/Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA). This includes interprofessional education, removing scope of practice barriers and advancing public health Both organizations continue to partner with new endeavors. For example, the design and launch of Healthy Nurse Healthy Delaware, a program spearheaded by DNA to sup- port Delaware nurses’ mental health and overall wellbeing.

The DNA is proud to partner with the Academy/DPHA on Delaware Health Force and further inform efforts to grow, strengthen and advance Delaware ’ s healthcare workforce At DNA, we appreciate the importance of robust data and transparent reporting to further inform efforts that will support Delaware ’ s healthcare workforce and access to high-quality, equitable, affordable and convenient healthcare services for all Delawareans.

Christopher E. Otto, MSN, RN, CHFN, PCCN, CCRN Executive DirectorDelaware Nurses Association

The Society is one of the oldest institutions of its kind in the United States and rich in history. It was founded in 1776 and incorporated on February 3, 1789, only 12 days after President Washington took his oath of office. The first official meeting of the Society was held in Dover on May 12, 1789.

Today, the Apollo Youth in Medicine program provides opportunities for high school students who are interested in a physician career path to shadow practicing physicians and further pursue their interests in the medical profession. Please find below a summary for the Apollo Youth in Medicine Program, and the program logo attached.

With the support of The Medical Society of Delaware (MSD) and Delaware Youth Leadership Network (DYLN), the Apollo: Youth in Medicine program was founded by Sean Holly and Arjan Kahlon in the summer of 2018 with John Kepley joining the leadership team shortly after. Since then, the Apollo leadership team has grown to be led by several focused & resourceful students who are firmly supported by MSD and DYLN.

Together this team supports and coordinates opportunities and activities for Apollo students and their high schools with participating Apollo Physician Mentors.

Apollo was founded on the idea that high school students interested in the medical field need an outlet to connect them to opportunities present in the medical community, and that clinical shadowing provides valuable first-hand insight allowing exploration. Apollo has expanded its physician network to allow students across Delaware expansive access to shadowing in 17 medical disciplines.

The Apollo Program is Multistep

1.) Interested Delaware high school juniors and seniors are invited to apply every fall through our application.

2.) New students representing multiple Delaware high schools attend a fall education session that covers specific topics such as different specialties in medicine, and the academic pathway to becoming a doctor. Here, Students receive HIPAA training through Apollo, enabling them to shadow in physicians’ offices appropriately.

3.) Apollo gives students access to several shadowing slots offered by dozens of Delaware physicians across various specialties through ‘The Match’, which occurs multiple times per year. Students can choose as many or as few shadow slots as they’d like.

4.) In addition to shadowing opportunities, Apollo serves as a liaison to gain our students optional access to medical seminars and exclusive Apollo Enhanced Experiences.

Additional information can be found at their website, https://www.apolloprogram.org/.

Mark B. Thompson, MHSA Executive Director Medical Society of DelawareThis section’s data contains this vital statistics as collected in the DELPROS system. It is important to note that it does NOT cover the entire healthcare workforce, some of which is not licensed through this system, and others who are not directly licensed by any entity at this time. For instance, Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) are not licensed by DELPROS, nor are Community Health Workers (CHWs) or Direct Service Providers (DSPs).

Some types of facilities are licensed through DELPROS, while others are licensed through the Department of Health and Social Services Office Division of Healthcare Quality, Office of Health Facilities Licensing and Certification. We credit that office for providing a significant portion of facilities data found in this report.

The following is entirely based on the data contained within the DELPROS system, and therefore we make no claims to its accuracy or completeness except where noted. For instance, DELPROS does ask about gender when an individual registers, however it is not a required field, and therefore most sections will show a percent of persons who did not state their gender. DELPROS itself does not collect information regarding race and ethnicity - therefore this report does not contain that information. DELPROS does ask for date of birth, and we were supplied with year of birth only so provide a level of privacy to the licensees of the State licensing system. DELPROS does not collect information on languages spoken, therefore we do not report on that information. That said, race, ethnicity, languages spoken, and a variety of other characteristics of the healthcare workforce ARE essential data points to be considered in future reports as that information is collected.

The section is alphabetical by Division of Professional Regulation board name, which is then followed by information from the Office of Health Facilities Licensing and Certification. All information and tables contained in the following section is based on data from June 2022. Each section starts with objective of the Board which oversees a given area of licenses. Sometimes, but not always, this is followed by additional detail on the types of licensure granted under that board.

There will be a chart on active licenses; gender; year of birth and related conjecture one when individuals of a certain age may retire; and facing pages with numerical and visual distributions of providers by ZIP code. We use the primary license application ZIP code as the best available proxy for approximate location within Delaware, and acknowledge that a margin of error is inherent in this method. There are also a small number of providers who provided a ZIP code outside of the State of Delaware, which further compounds the absolute accuracy of our methodology.

Most of this report focuses on the healthcare workforce overseen by the following boards.

• Board of Chiropractic

• Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene

• Board of Dietetics/Nutrition

• Board of Funeral Services

• Board of Massage and Bodywork

• Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline

• Board of Nursing

• Board of Examiners of Nursing Home Administrators

• Board of Occupational Therapy Practice

• Board of Examiners in Optometry

• Board of Pharmacy

• Board of Physical Therapists and Athletic Trainers

• Board of Podiatry

• Board of Mental Health and Chemical Dependency Professionals

• Board of Examiners of Psychologists

• Board of Social Work Examiners

• Board of Speech Pathologists, Audiologists, and Hearing Aid Dispensers

• Board of Veterinary Medicine

• Controlled Substance Advisory Committee

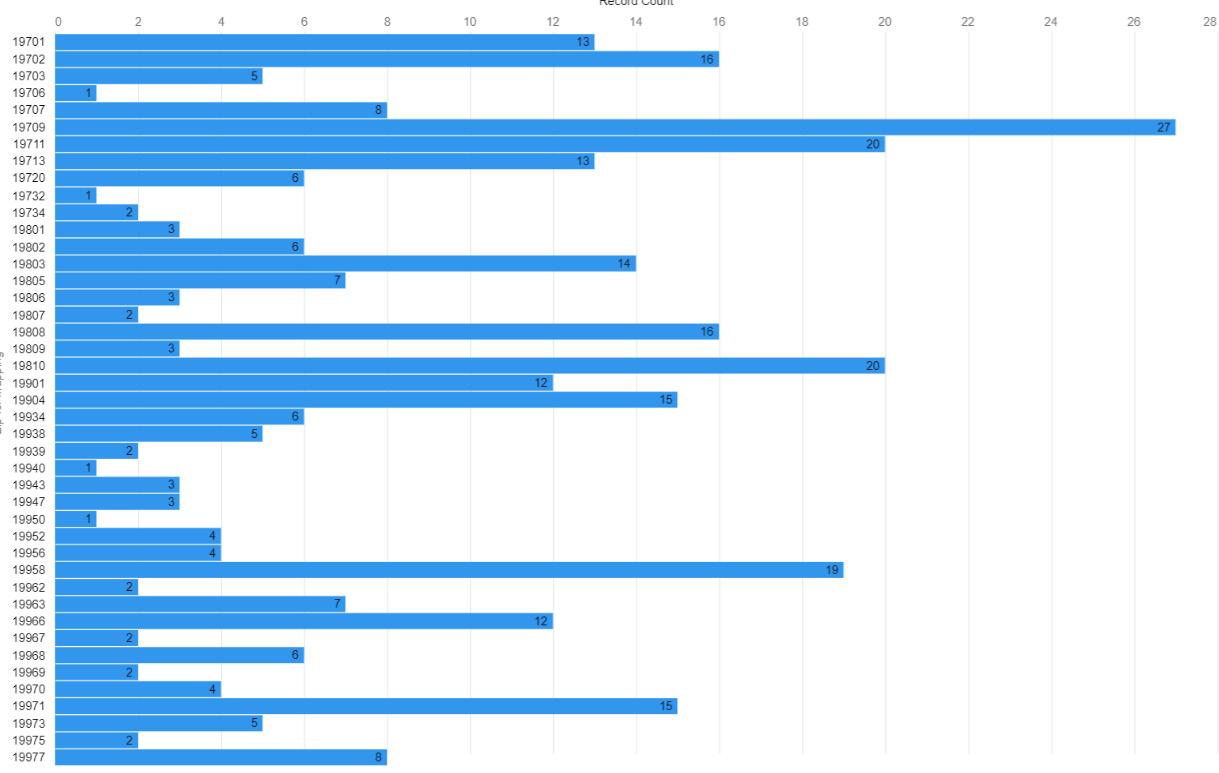

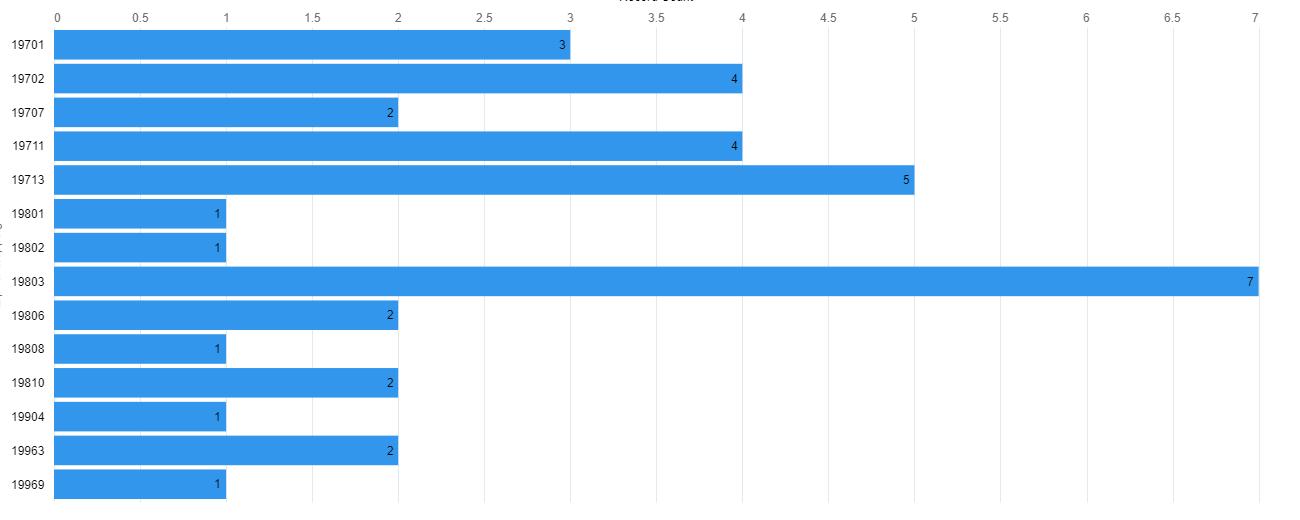

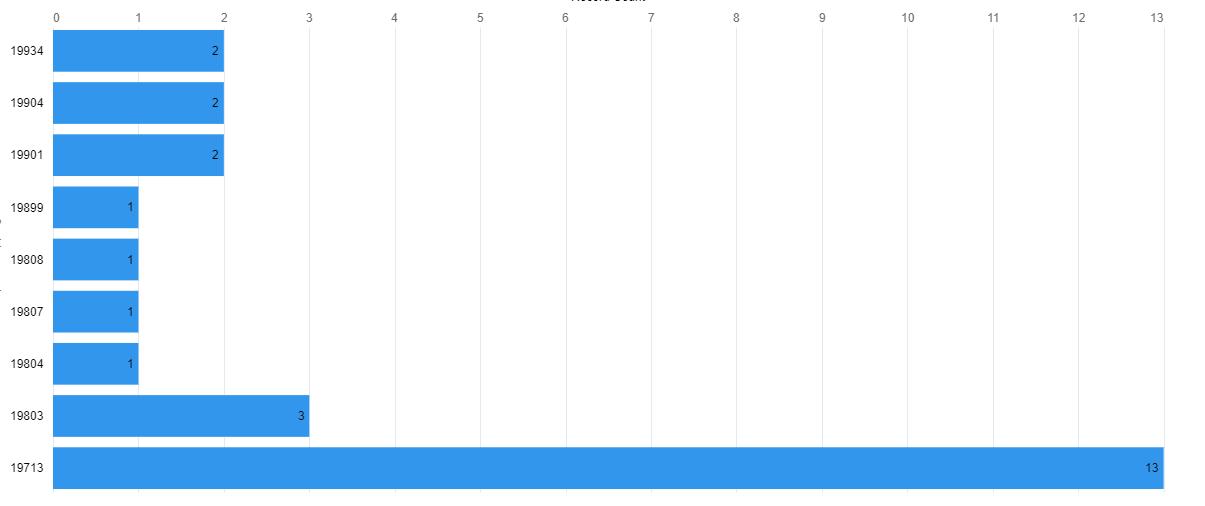

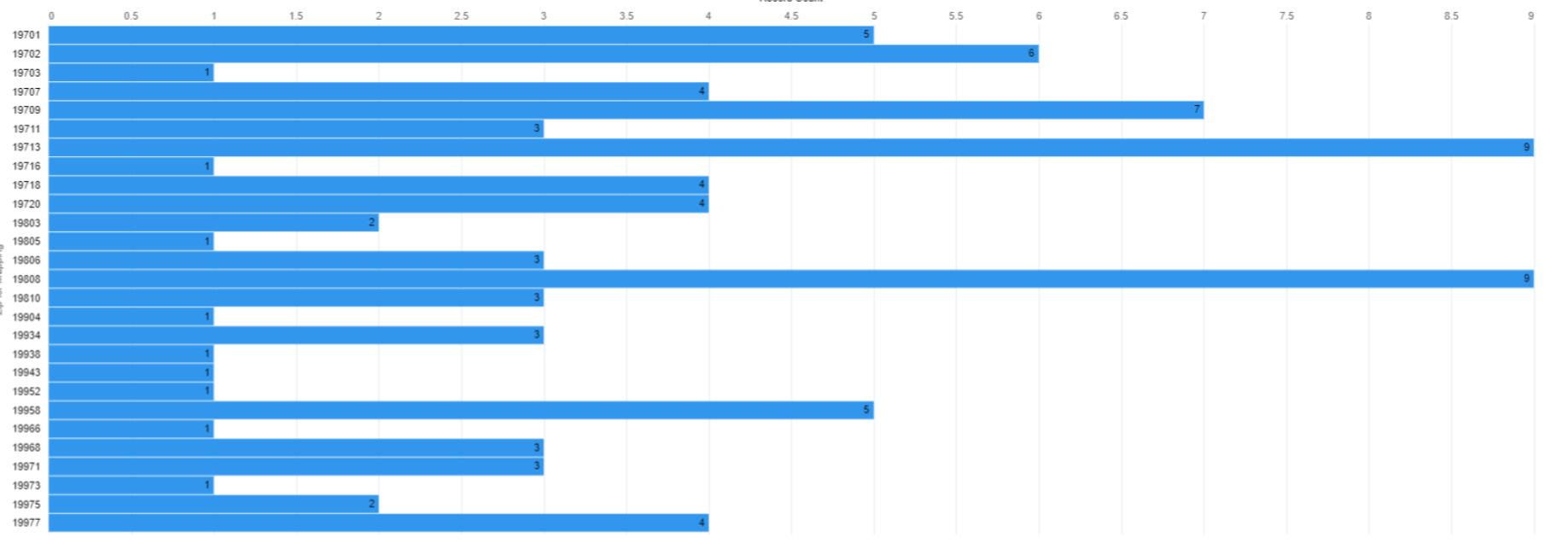

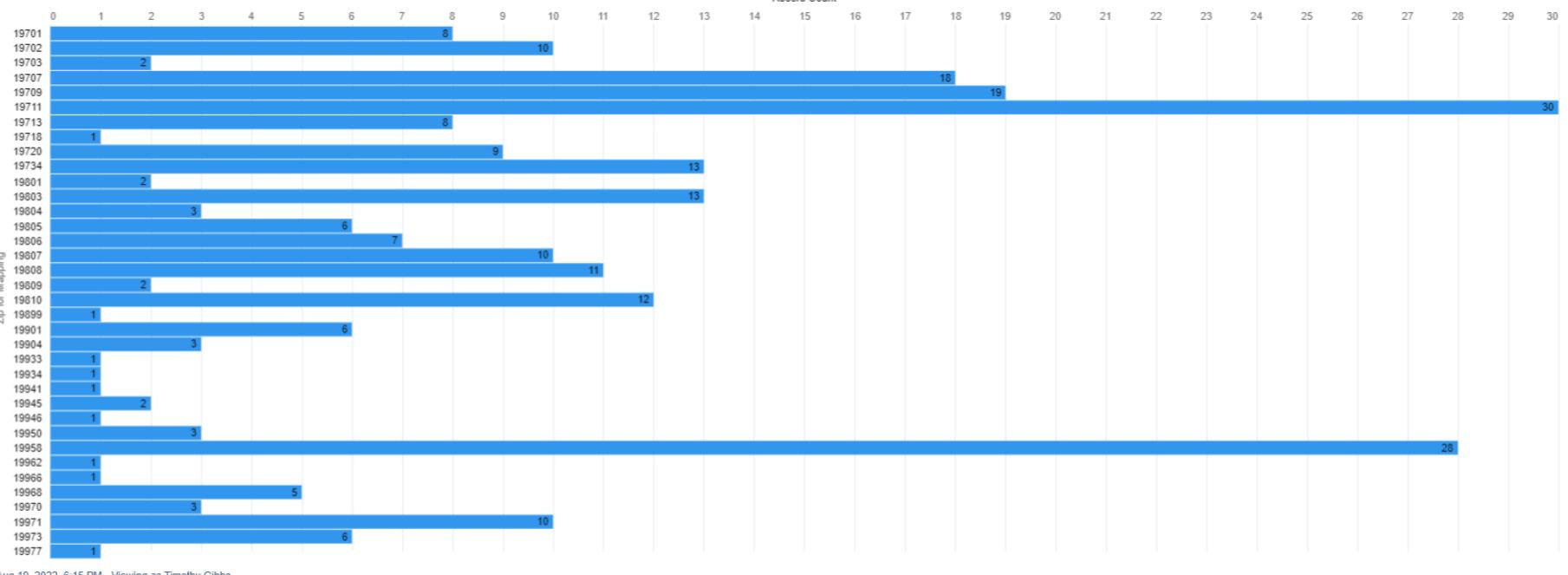

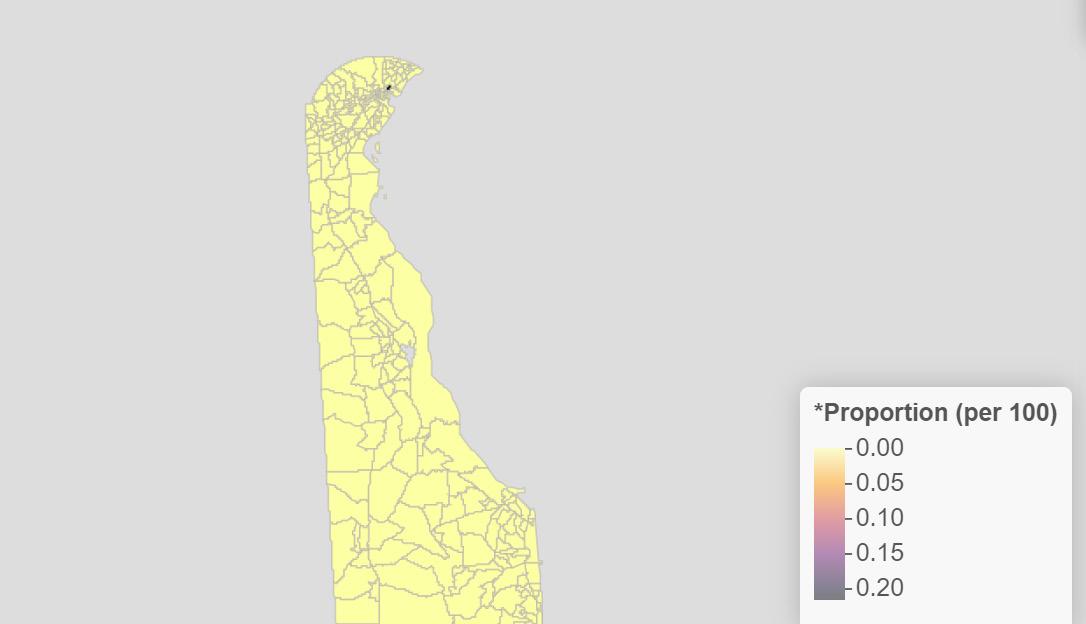

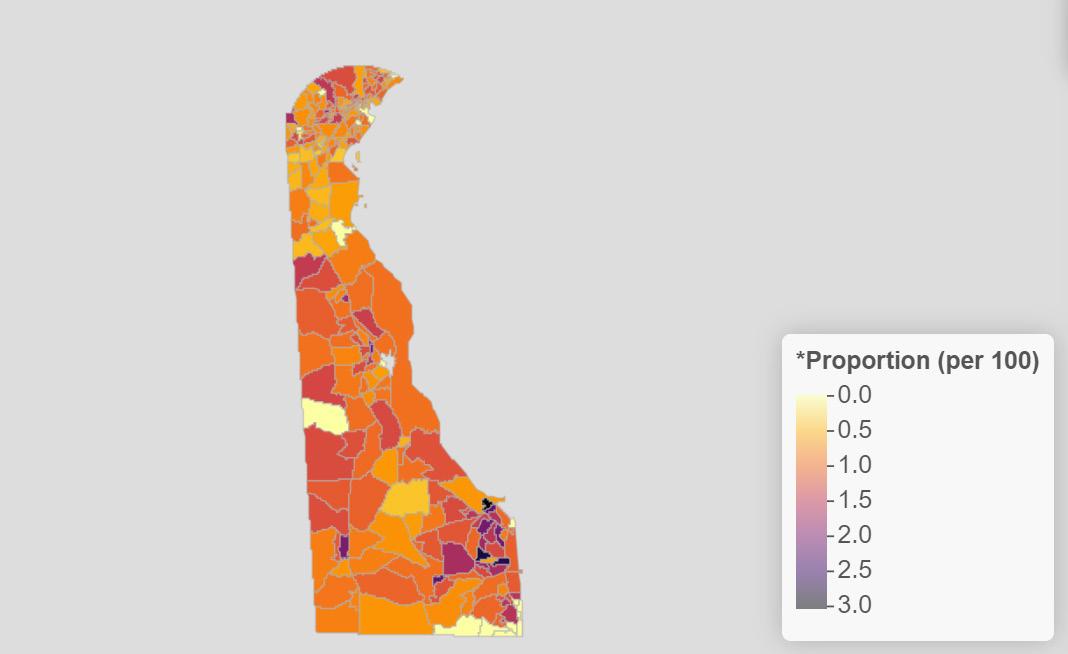

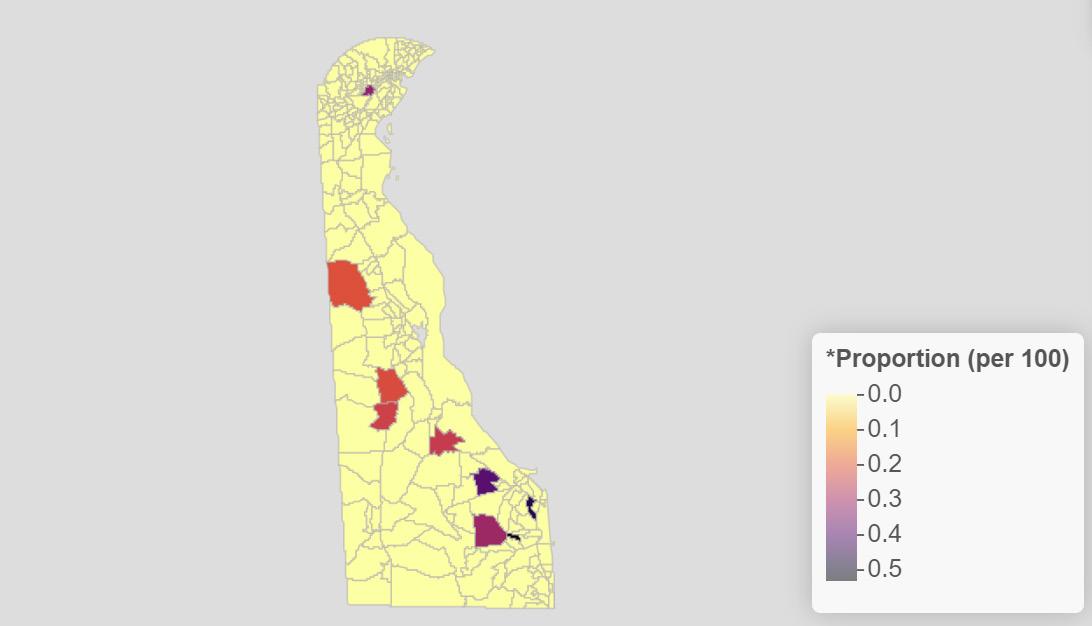

From page 16 to 271 we use charts created in Salesforce and maps created in ArcGIS. Please read the following so that you understand why they are configured as they are, and how to interpret them.

For the charts, to save space – a premium for many charts dense with information – we removed secondary labeling on the y-axis. For instance, on charts with ZIP codes, we removed the secondary label stating “ZIP code.” In doing so we freed up significant space to make some charts larger and more legible. The x-axis on all charts is always the number of licensed individuals or entities.

The bars on the charts are proportional to the number they represent, and therefore to each other. The Workforce Subcommittee Chairs and report writers reviewed a number of options for the maps used to represent where types of licensed individuals and facilities are located. By consensus we arrived at the decision to use a non-weighted heatmap.

The heatmaps are an exact representation of the data provided on the facing page. The maps are also subdivided by ZIP codes rather than census tracts to broaden they accessibility to a wide audience who many not be as familiar with census tract information. Counties are demarcated by different background colors. In all cases maps only look at the ZIP code level except later in the facilities section of the report. The location of the center of any ZIP code is solely determined by ArcGIS defaults, and in no manner implies actual location of any one (or more) individuals or facilities.

The size of the area representing licenses has no relation to the number of licenses or to their “reach” in that area. They only bring attention to the map and areas with, or without, licensed individuals or institutions. To restate, these maps are presented to give a sense, based on the primary ZIP code listed for each DELPROS license, of where licensed individuals and institutions are physically located.

IMPORTANT: ZIP codes are a proxy for provider or institution location and should not be considered definitive. For instance, while an institution can have one license per location, a provider (and especially physicians and nurses) may have multiple locations associated with their license. This was a limitation of the data provided for this first report which we hope to address in future reports as we become more granular in licensing information.

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Chiropractic is to protect the public from unsafe chiropractic practice and practices which tend to reduce competition or fix prices for services. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board:

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to chiropractic practitioners and approves preceptors.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 7.

Chiropractors focus on patients’ overall health. Chiropractors believe that malfunctioning spinal joints and other somatic tissues interfere with a person’s neuromuscular system and can result in poor health.

Some chiropractors use procedures such as massage therapy, rehabilitative exercise, and ultrasound in addition to spinal adjustments and manipulation. They also may apply supports, such as braces or shoe inserts, to treat patients and relieve pain.1

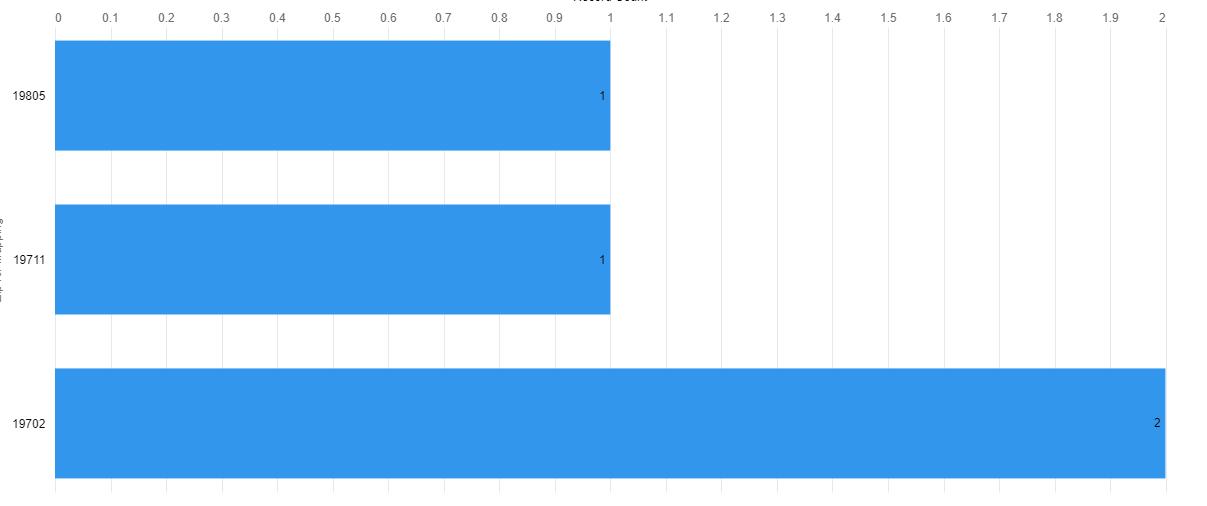

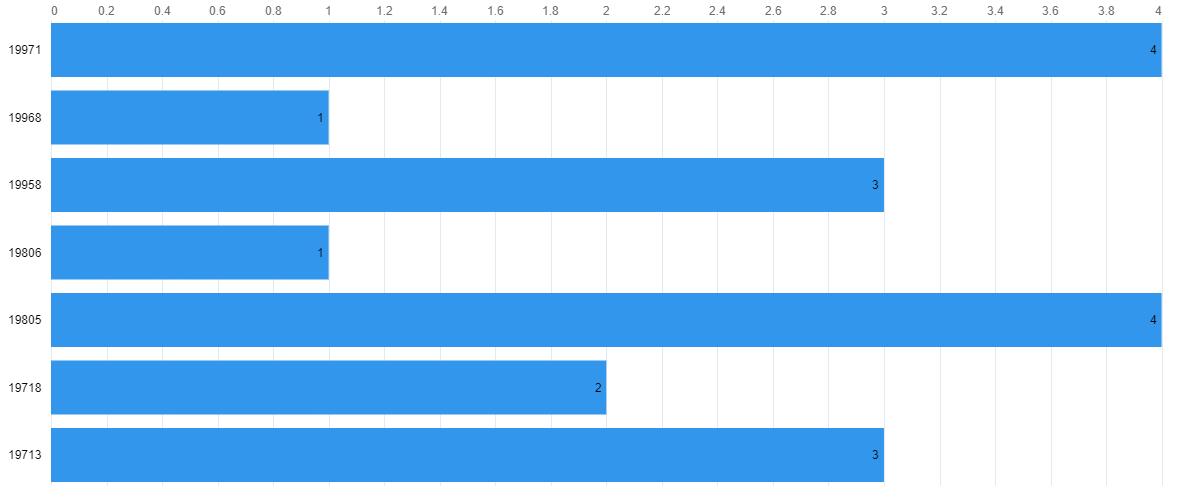

Figure 1

Active Chiropractic Licenses, N= 383

Figure 2

Active Chiropractic Licenses by Gender (when reported)

Note. An active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Note. 18 individuals did not provide a year of birth

38 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022

age

per Social Security

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene is to protect the general public from unsafe and unprofessional practices. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to dentists, dentist academics, dental hygienists and dental residents. The Board also issues three types of permits to dentists and dentist academics who administer anesthesia.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 11.

The dental profession is the branch of healthcare devoted to maintaining the health of the teeth, gums and other tissues in and around the mouth.

A dentist is a doctor, scientist and clinician dedicated to the highest standards of health through prevention, diagnosis and treatment of oral diseases and conditions.

Dentists play a key role in the early detection of oral cancer and other systemic conditions of the body that manifest themselves in the mouth. They often identify other health conditions, illnesses, and other problems that sometimes show up in the oral cavity before they are identified in other parts of the body.

• Evaluates the overall health of their patients while advising them about oral health and disease prevention;

• Performs clinical procedures, such as exams, fillings, crowns, implants, extractions and corrective surgeries;

• Identifies, diagnoses and treats oral conditions; and

• Performs general dentistry or practices in one of nine dental specialties.

• Advances in dental research, including genetic engineering, the discovery of links between oral and systemic diseases, the development of salivary diagnostics and the continued development of new materials and techniques, make dentistry an exciting, challenging and rewarding profession.

Dental hygienists are preventive oral health professionals who have graduated from an accredited dental hygiene program in an institution of higher education, licensed in dental hygiene to provide educational, clinical, research, administrative and therapeutic services supporting total health through the promotion of optimum oral health.

In performing the dental hygiene process of care, the dental hygienist assesses the patient’s oral tissues and overall health determining the presence or absence of disease, other abnormalities and disease risks; develops a dental hygiene diagnosis based on clinical findings; formulates evidence-based, patient-centered treatment care plans; performs the clinical procedures outlined in the treatment care plan; educates patients regarding oral hygiene and preventive oral care; and evaluates the outcomes of educational strategies and clinical procedures provided.

Dental hygienists are preventive oral health professionals who have graduated from an accredited dental hygiene program in an institution of higher education, licensed in dental hygiene to provide educational, clinical, research, administrative and therapeutic services supporting total health through the promotion of optimum oral health.

In performing the dental hygiene process of care, the dental hygienist assesses the patient’s oral tissues and overall health determining the presence or absence of disease, other abnormalities and disease risks; develops a dental hygiene diagnosis based on clinical findings; formulates evidence-based, patient-centered treatment care plans; performs the clinical procedures outlined in the treatment care plan; educates patients regarding oral hygiene and preventive oral care; and evaluates the outcomes of educational strategies and clinical procedures provided.

Dental hygienists provide clinical services in a variety of settings such as private dental practice, community health settings, nursing homes, hospitals, prisons, schools, faculty practice clinics, state and federal government facilities and Indian reservations.

In addition to clinical practice, there are career opportunities in education, research, sales and marketing, public

health, administration and government. Some hygienists combine positions in different settings and career paths for professional variety. Working in education and clinical practice is an example.

A Delaware Dentist Academic license is given to practioners who are full-time directors, chairpersons, or attending faculty members of a hospital-based dental, oral and maxillofacial surgery or other dental specialty residency program. The program must be:

• based in Delaware, and

• accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation of the American Dental Association (CODA) for the purposes of teaching, has received initial CODA accreditation or is in the process of establishing CODA accreditation

The academic license allows a practitioner to practice dentistry or oral and maxillofacial surgery only in the institution designated on the license and only on patients in an academic setting for teaching purposes.

What are Restricted Permits ?

Restricted Permit I

A Restricted Permit I allows a practitioner to induce only conscious sedation by parenteral, enteral, or rectal routes, as well as nitrous oxide inhalation, at a specific location. (This does not prohibit the usual and customary preoperative oral sedation.)

A Restricted Permit I does not allow induction using:

• deep sedation

• general anesthesia

Restricted Permit II

A Restricted Permit II allows induction of conscious sedation by nitrous oxide inhalation.

It does not allow:

• deep sedation

• general anesthesia

Unrestricted Permit

An Unrestricted Permit applies only to one office location where anesthesia is administered. The two types of Unrestricted Permits are Individual and Facility. The type of permit selected determines who is allowed to administer anesthesia at that location:

An Unrestricted Permit-Individual allows the dentist to administer conscious sedation, general anesthesia and deep sedation, as defined by the Board’s Rules and Regulations governing anesthesia, at the location. If a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) is employed for deep sedation or general anesthesia at an office location, the facility must also have at least one individual with an Unrestricted Permit-Individual.

This type of dental licensure is specific to dentists contracted to practice at a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Delaware. The Dentist-FQHC Provisional license allows the practice of dentistry in Delaware…

• before the three examinations required for full Dentist licensure have been passed,

• only at the FQHC named on the license, and

• only under the general supervision of a Delaware-licensed dentist.

A Dental Resident is a license for dentists who will be starting a residency program in Delaware.

Figure 6

Active Dental Licenses by Type*, N=1,740

Note. An active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Figure 7

Active Dental Licenses by Gender, all types (when reported)

80 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022.

Full retirement age as per Social Security Adminstration*

Note. Three individuals did not provide a year of birth

* According to the Social Security Administration “Full retirement age is the age when you can start receiving your full retirement benefit amount. The full retirement age is 66 if you were born from 1943 to 1954. The full retirement age increases gradually if you were born from 1955 to 1960, until it reaches 67. For anyone born 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67.”

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Dietetics/Nutrition is to protect the health of the public by broadening access to appropriate dietetic and nutrition therapy. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board

• evaluates the credentials of persons applying for licensure, • promulgates rules and regulations, • adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to dietitian/nutritionists.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 38

What is the difference between a dietician and a nutritionist?

Although dietitians and nutritionists both help people find the best diets and foods to meet their health needs, they have different qualifications.

In the United States, dietitians are certified to treat clinical conditions, whereas nutritionists are not always certified. In the U.S., dietitians must receive certification from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in order to practice. Dietitians can treat specific health conditions, such as eating disorders, by providing food recommendations.

Some organizations also certify nutritionists, such as the Board for Certification of Nutrition Specialists (BCNS), however, nutritionist training can vary. Some states do not require certification, so it is possible for anyone in those states to offer nutrition advice.

Nutritionists may also have different areas of focus to dietitians. For example, nutritionists can pursue advanced qualifications in specific health areas, such as sports nutrition, digestive disorders, and autoimmune conditions. The BCNS also offer Certified Ketogenic Nutrition Specialist qualifications for those who want to understand the keto diet in more detail.

However, some nutritionists provide more general advice on healthful eating, weight loss, and reducing tiredness.1

Nutrition is a key element of good health. Registered dietitian nutritionists are the experts on good nutrition and the food choices that can make us healthy, whether it’s a proper diet or eating to manage the symptoms of a disease or chronic condition. Registered dietitian nutritionists design nutrition programs to protect health, prevent allergic reactions and alleviate the symptoms of many types of disease.

Clinical dietitians provide medical nutrition therapy for patients in institutions such as hospitals and nursing care facilities. They assess patients’ nutritional needs, develop and implement nutrition programs and evaluate and report the results. They confer with doctors and other healthcare professionals in order to coordinate medical and dietary needs. Some clinical dietitians specialize in the management of overweight and critically ill patients, such as those with renal (kidney) disease and diabetes. In addition, clinical dietitians in nursing care facilities, small hospitals, or correctional facilities may manage the food service department.

Community dietitians develop nutrition programs designed to prevent disease and promote health, targeting particular groups of people. Dietitians in this practice area may work in settings such as public health clinics, fitness centers, corporate wellness programs or home health agencies.

Corporate dietitians work in food manufacturing, advertising and marketing. In these areas, dietitians analyze foods, prepare literature for distribution, or report on issues such as the nutritional content of recipes, dietary fiber or vitamin supplements.

Management dietitians oversee large-scale meal planning and preparation in healthcare facilities, company cafeterias, prisons and schools. They hire, train and direct other dietitians and food service workers; budget for and purchase food, equipment, and supplies; enforce sanitary and safety regulations; and prepare records and reports.

Consultant dietitians work under contract with healthcare facilities or in their own private practice. They perform nutrition assessments for their clients and advise them about diet-related concerns, such as weight loss or cholesterol reduction. Some work for wellness programs, sports teams, supermarkets and other nutrition-related businesses. They consult with food service managers, providing expertise in sanitation, safety procedures, menu development, budgeting and planning.2

1. Medical News Today. (2020, Aug). What is the difference between nutritionists and dietitians? Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/ articles/nutritionist-vs-dietician#training

2. Explore Healthcareers. (n.d.). Dietitian nutritionist. Retrieved from: https://explorehealthcareers.org/career/nutrition-dietetics/dietitian-nutritionist/

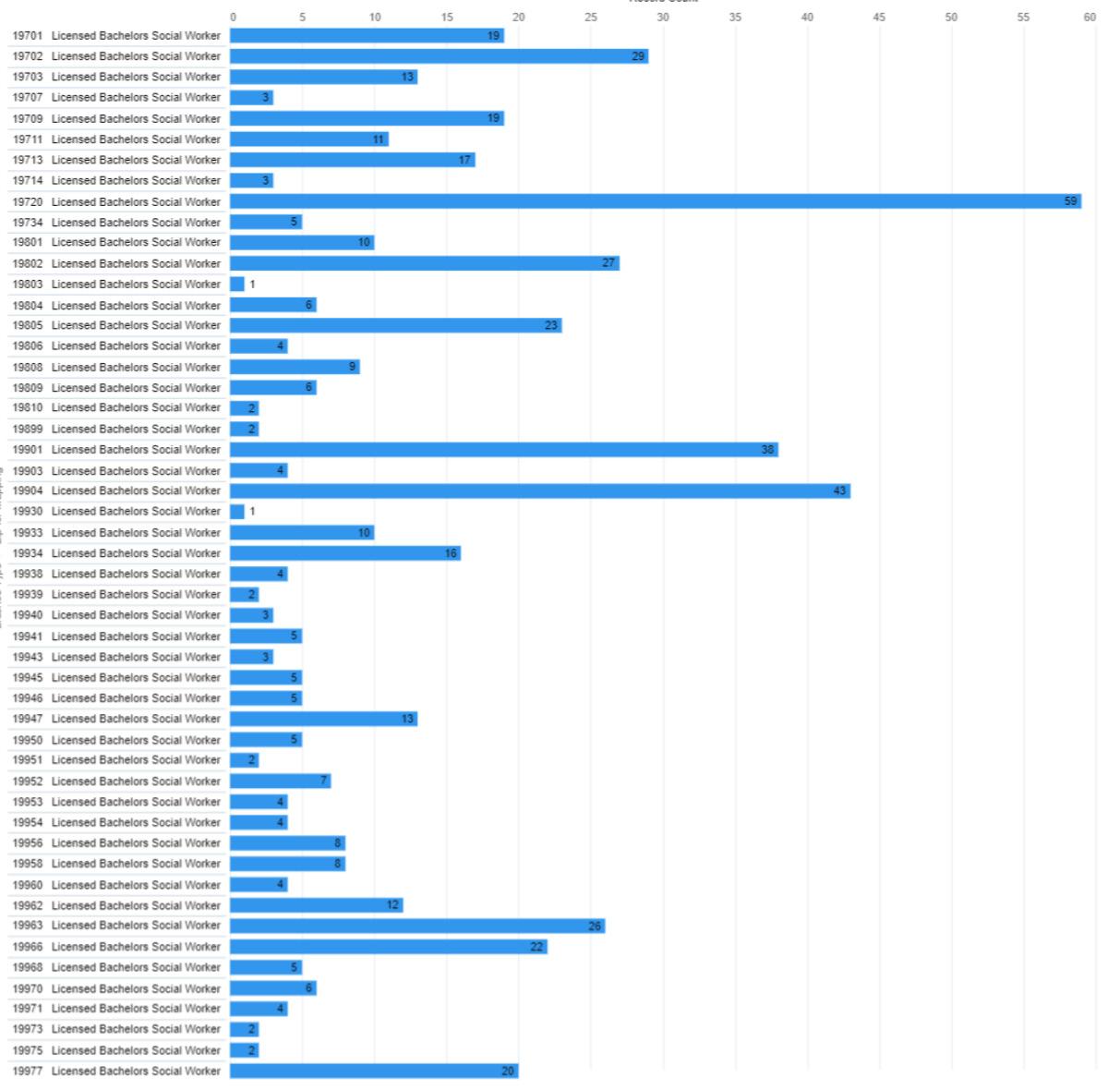

Figure 13

Active Dietician Licenses*, N=483

* an active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Figure 14

Active Dietician Licenses by Gender (when reported)

22 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022.

* According to the Social Security Administration “Full retirement age is the age when you can start receiving your full retirement benefit amount. The full retirement age is 66 if you were born from 1943 to 1954. The full retirement age increases gradually if you were born from 1955 to 1960, until it reaches 67. For anyone born 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67.”

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Funeral Services is to protect the public from unsafe practices and practices which tend to reduce competition or fix prices for services. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to funeral directors, interns, funeral establishments and crematory establishments. It also issues funeral director limited licenses to Maryland- or Pennsylvania-licensed funeral directors.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 31.

The Board of Funeral Services licenses both individuals and facilities which is somewhat different from many other board of the Division of Professional Regulation. Information on facilities is contained in the facilities section of this report.

All applicants, with the exception of the applicants who meet the experience requirement below to apply by reciprocity, must apply for a Funeral Resident Intern license and serve a one-year internship in Delaware, with the intention of later applying for Delaware licensure as a Funeral Director. A Delaware resident internship is required if a practitioner:

• does not hold a current Funeral Director license in any jurisdiction (state, U.S. territory or District of Columbia)

• holds a current Funeral Director license in another jurisdiction but has not practiced as a funeral director at least three of the past five years.

If a current Funeral Director license is current in another jurisdiction and an individual has practiced as a funeral director at least three of the past five years, they may submit the Funeral Director application.

The Funeral Director oversees, directs, and coordinates all aspects of funeral services including body preparation, visitation, services, burials, and cremations, while providing caring support and advice to families and friends of the deceased.1

Funeral Director Limited licensure is available only to funeral directors validly licensed by another jurisdiction (U.S. state, possession, territory or District of Columbia) provided that the jurisdiction where he or she is licensed grants a similar privilege to Delaware-licensed funeral directors (24 Del. C. §3108). Currently, Delaware only has limited licensure agreements with the States of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Funeral Director Limited licensure allows a practitioner to:

• make a removal of a dead human body in Delaware,

• return the body to another state or country,

• return dead bodies from another state or country to Delaware for final disposition,

• complete the family history portion of the death certificate,

• sign the death certificate in the capacity of a licensed funeral director, and

• execute any other procedures necessary to arrange for the final disposition of a dead human body.

A valid Funeral Establishment Permit issued by the Board of Funeral Services is required to open or operate a funeral establishment in Delaware. This permit is required in addition to any business license issued by the Division of Revenue.

Please see the facilities section of this report for additional information.

A valid Crematory Establishment Permit issued by the Board of Funeral Services is required to open or operate a crematory in Delaware when crematory is not part of a Delaware-licensed Funeral Establishment’s operation. Section 13.2.13 of the Board’s Rules and Regulations more fully explains when a crematory does not need a permit.

Please see facilities section of this report for additional information.

1. Society for Human Resource Management. (2022). Funeral directors. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/tools-and-samples/ job-descriptions/Pages/Funeral-Director.aspx

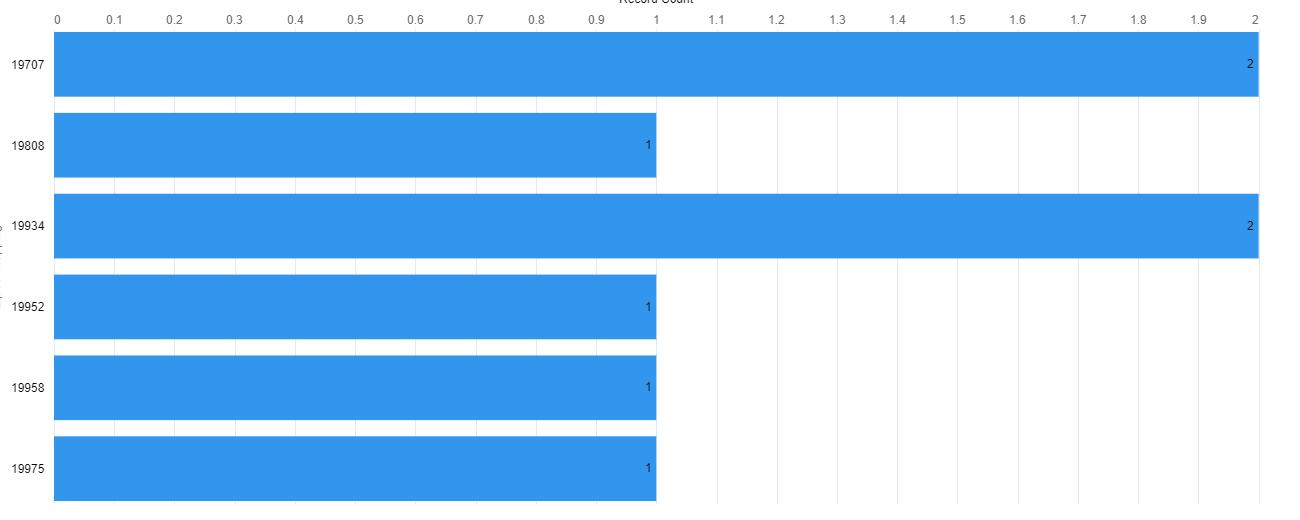

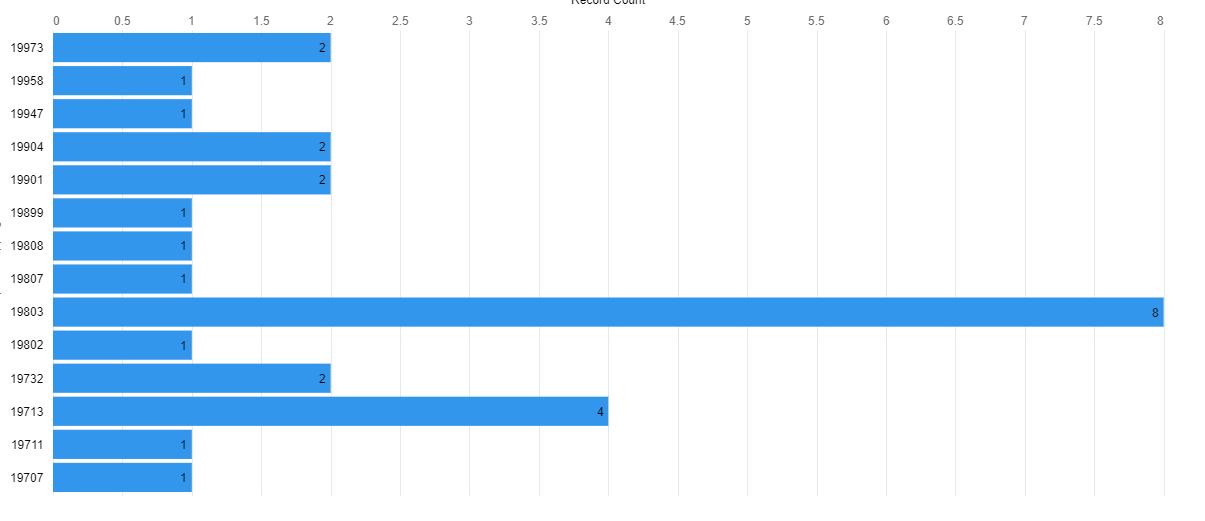

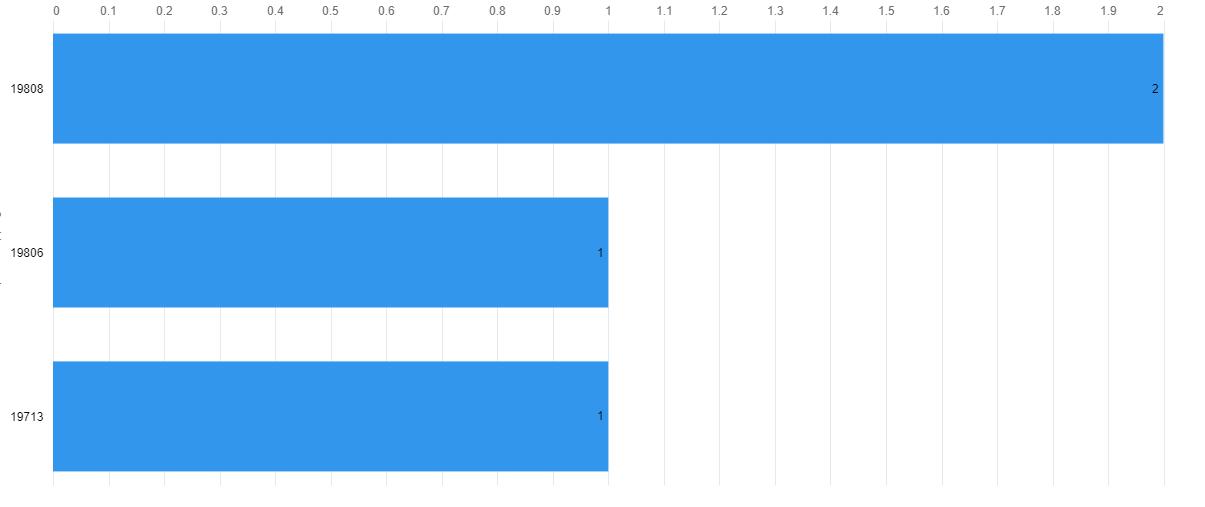

Figure 18

Active Funeral Services Licenses by Type*, N=3

* an active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Figure 19

Active Funeral Services Licenses by Gender, select license types (when reported)

* an active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing clients.

Figure

Birth

37 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022.

Note. Six individuals did not provide a year of birth

Full retirement age as per Social Security Adminstration*

(when reported) * According to the Social Security Administration “Full retirement age is the age when you can start receiving your full retirement benefit amount. The full retirement age is 66 if you were born from 1943 to 1954. The full retirement age increases gradually if you were born from 1955 to 1960, until it reaches 67. For anyone born 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67.”

Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Massage and Bodywork is to protect the public from unsafe practices and practices which tend to reduce competition or fix prices for services. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board:

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to massage therapists, certifications to massage technicians and Massage Establishment licenses. It also issues temporary certifications to massage technicians.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 53.

The Board of Massage and bodywork licenses both individuals and facilities which is somewhat different from many other board of the Division of Professional Regulation. Information on facilities is contained in the facilities section of this report.

Massage therapists treat clients by using touch to manipulate the muscles and other soft tissues of the body. 1

Individuals holding a Delaware Massage Therapist license must be 18 years old, pass the National Certification Board for Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork (NCBTMB) exam and:

• not licensed by any other jurisdiction (state, District of Columbia, or U.S. territory), OR

• licensed by another jurisdiction but have not practiced continuously in that jurisdiction for at least two years, OR

• currently licensed as a Certified Massage Technician or Temporary Massage Technician in Delaware.

A “reciprocity” agreement can be made if a therapist is are currently licensed in another jurisdiction AND has practiced continuously in that jurisdiction for at least two years, AND has passed the NCBTMB exam.

Delaware Certified Massage Technicians must be 18 years old and:

• not licensed by any other jurisdiction (state, District of Columbia, or U.S. territory), OR

• licensed by another jurisdiction but have not practiced continuously in that jurisdiction for at least two years.

A “reciprocity” agreement can be made if a technician is currently licensed in another jurisdication AND has practiced continuously in that jurisdication for at least two years.

The purpose of a Temporary Massage Technician Certification is to allow an individual to practice while completing the educational requirements. They must be at least 18 years old, and have not yet completed the educational requirements for Massage Technician Certification.

The temporary certification is valid for one year only. It cannot be renewed, reissued or changed to inactive status.

An establishment license from the Board of Massage and Bodywork is required for each location operating as a

Massage Establishment as defined by 24 Del. C. §5302 and Section 12.0 of the Board’s Rules and Regulations. If any of the following occurs, a new application for licensure must be approved:

• An existing unlicensed massage/bodywork business with a first application for establishment licensure,

• Opening a new establishment,

• The ownership of an existing establishment is changing (regardless of whether the name is changing),

• The name of an existing establishment is changing (regardless of whether the owner is changing),

• The location of an existing establishment is changing.

The establishment may need other licenses and permits (such as a business license from the Division of Revenue or permit from the town/city where the establishment operates).

Please see facilities section of this report for additional information.

1. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Aug). Massage therapists. Occupational outlook handbook. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/massage-therapists.htm

Figure 23

Active Massage and Bodywork Licenses by Type*, N=1,197

* an active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Figure 24

Active Certified Massage Technician & Massage Therapist Licenses by Gender (when reported)

Figure 25

55 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022.

Note. One individual did not provide a year of birth

Full retirement age as per Social Security Adminstration*

reported) * According to the Social Security Administration “Full retirement age is the age when you can start receiving your full retirement benefit amount. The full retirement age is 66 if you were born from 1943 to 1954. The full retirement age increases gradually if you were born from 1955 to 1960, until it reaches 67. For anyone born 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67.”

Figure 26

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

The primary objectives of the Delaware Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline are to promote public health, safety and welfare and to protect the public from the unprofessional, improper, unauthorized, or unqualified practice of medicine and certain other healthcare professions. To meet these objectives, the Board:

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues physician (M.D. and D.O.) licenses and physician training licenses to residents, interns, fellows and house physicians.

The Board also issues for licenses these additional healthcare professions: physician assistants, respiratory care practitioners, acupuncture practitioners, acupuncture detoxification specialists, eastern medicine practitioners, genetic counselors, polysomnographers, midwifery practitioners and administrative medical. A Council for each of these healthcare professions advises and assists the Board on licensure and regulatory matters pertaining to its profession.

The Board also issues certifications to and has other responsibilities in regard to emergency medical technicians/ paramedics in collaboration with the Office of Emergency Medical Services.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 17. Additional statutory provisions on the Board’s responsibilities in connection with emergency medical technicians/paramedics are in 16 Del. C., Chapter 97 and Chapter 98.

Physicians and surgeons diagnose and treat injuries or illnesses and address health maintenance.

Physicians and surgeons work in both clinical and nonclinical settings. Clinical settings include physicians’ offices and hospitals; nonclinical settings include government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and insurance companies.1

There are two terminal degrees for physicians, Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.) and Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) from the Latin Medicinae Doctor.

MDs are allopathic doctors. That means they treat and diagnose conditions using conventional medical tools like x-rays, prescription drugs, and surgery. Allopathic medicine is also called conventional or mainstream medicine.

MDs can choose to be broad practitioners and work as family medicine or primary care doctors. They can also specialize in several different areas requiring further education including:

• Surgery,

• Organ System Specific Specialty,

• Psychiatry,

• Geriatric Medicine, and

• Pediatrics

DO stands for doctor of osteopathic medicine. They use the same conventional medical techniques as MDs but with a few other methods. DOs tend to focus more on holistic health and prevention. In holistic health, all parts of a person, including their mind, body, and emotions, are considered during the treatment. They also use a system of physical manipulations and adjustments to diagnose and treat people.

Over half of DOs choose to work in primary care, but they can also choose to specialize in another area, just like MDs. DOs have all the same responsibilities and rights as MDs, including the abilities to perform surgery with proper training and prescribe medicine.

MDs and DOs follow similar educational routes. They must first earn a four-year undergraduate degree, and most will take pre-medicine courses during this time. After getting an undergraduate degree, they will attend either medical school or a college of osteopathic medicine.

After finishing four years of medical education, MDs and DOs must complete an internship and a residency. A residency is on-the-job training under the supervision of more experienced doctors. Some MDs and DOs will also go on to do fellowships to learn more about a specialty.

MDs and DOs often train side by side in residencies and internships, despite going to different types of schools.

Both MDs and DOs must also take a licensing exam in order to practice medicine professionally.2

An ACGME training license is required for that part of the education which all physicians, regardless of degree type (D.O. or M.D.), go through after medical school to prepare them for fully independent practice. Another section of this report examines these types of trainings and the Delaware institutions at which they are offered..

Physicians are employed in an ACGME-approved institution located in Delaware and are:

• a Resident, Intern or Fellow registered in a training program outside of Delaware who will rotate through a program in Delaware for over one month, or

• employed as a House Physician.

For more information about Training licensure, see Section 4.0 of the Board’s Rules and Regulations.

Physician assistants practice medicine on teams with physicians, surgeons, and other healthcare workers.

Physician assistants work in physicians’ offices, hospitals, outpatient clinics, and other healthcare settings. Most work full time.3

An Administrative Medical license allows physicians to use their medical and clinical knowledge, skill, and judgment only in an administrative capacity. These licensed cover physicians practicing administrative medicine and who do not provide any of the following medical or clinical services:

• examine, care for or treat patients;

• prescribe medications including controlled substances; or

• delegate medical acts or prescriptive authority to others

Respiratory therapists care for patients who have trouble breathing—for example, because of a chronic condition such as asthma.

Most respiratory therapists work full time. Because they may work in medical facilities that are always open, such as hospitals, they may have shifts that include nights, weekends, or holidays.4

• Acupuncture Practitioners have earned a Diplomate in Acupuncture from the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) or an equivalent organization.

• Eastern Medicine Practitioners have earned a Diplomate in Oriental Medicine from the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) or an equivalent organization. The Acupuncture Advisory Council may waive this Diplomate requirement under specific circumstances as outlined in 24 Del. C. §1798 (c)

Acupuncture/Oriental medicine (AOM) is an ancient and empirical system of medicine based on the concept of qi (pronounced “chee”), which is usually translated as energy.

AOM treatments identify a pattern of energetic imbalance within a patient and redress that disharmony through a variety of therapies that may include acupuncture needling, cupping, acupressure, exercises such as tai ji and qi gong and Chinese herbal preparations.

AOM is virtually free of the side effects that accompany many modern medical procedures. As a relatively inexpensive form of treatment, it is especially appropriate for reducing healthcare costs. The success of acupuncture today is due to its efficacy, remarkable safety record, cost-effectiveness and significant public demand.5

Individuals that have a current license or certificate, are in good standing in a healthcare related profession, are approved by the Acupuncture Advisory Council and the Medical Board are eligible for this additional level of specialization.6

The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) protocol is a unique form of acupuncture. It specifically targets behavioral health, including addictions and co-occurring disorders. The protocol involves the bilateral insertion of 1Y5 needles into predetermined points on each ear (auricle).7

Genetic counselors assess individual or family risk for a variety of inherited conditions, such as genetic disorders and birth defects.

Genetic counselors work in university medical centers, private and public hospitals, diagnostic laboratories, and physicians’ offices. They work with families, patients, and other medical professionals. Most genetic counselors work full time.

Genetic counseling requires an original or provisional license from the American Board of Genetic Counselors or the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genetic counselors typically need a master’s degree in genetic counseling or genetics, along with board certification.8

A Polysomnographer is an allied health professional who performs overnight sleep assessments used to diagnose various sleep disorders. In the evening the patient will arrive at a sleep laboratory in a hospital, medical facility, or hotel. Increasingly, physicians are prescribing at-home sleep tests to ensure the patient’s comfort and to reduce cost. The polysomnographer will attach various electrodes used to record the patient’s brain activity and will then monitor the patient throughout the night.

Work environments include:9

• Hospitals

• Medical facilities

• Hotels

• Patients’ homes

Midwifery encompasses the independent provision of care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period; sexual and reproductive health; gynecologic health; and family planning services, including preconception care. 10

• Certified Professional Midwifes (CPM) receive certification by the North American Registry of Midwives (NARM) or its equivalent or successor.

• Certified Midwifes (CM) receive certification by the American Midwifery Certification Board (AMCB) or its equivalent or successor.

1. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Aug). Physicians and surgeons. Occupational Outlook handbook. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/physicians-and-surgeons.htm

2. Web MD. (2021, Apr). Difference between MD and DO. Retrieved from: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/difference-between-md-and-do

3. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Aug). Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook handbook. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

4. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Aug). Respiratory therapists. Occupational Outlook handbook. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/respiratory-therapists.htm

5. Explore Healthcareers. (n.d.). Acupuncture/oriental medicine practitioner. Retrieved from: https://explorehealthcareers.org/career/complementary-and-integrative-medicine/acupuncture-oriental-medicine-practitioner/

6. National Acupuncture Detoxification Association. (n.d.). Regulations. Retrieved from: https://acudetox.com/resources/regulations/

7. Carter, K., Olshan-Perlmutter, M. (2014). NADA protocol. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 25(4), 182-187. https://alliedhealth.ceconnection.com/files/ NADAProtocolIntegrativeAcupunctureinAddictions-1419263411853.pdf

8. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Aug). Genetic counselors. Occupational Outlook handbook. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/genetic-counselors.htm

9. Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Polysomnographer. Retrieved from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/departments/health-sciences-education/careers/career-options/polysomnographer

10. American College of Nurse-Midwives. (n.d.). About the midwifery profession. Retrieved from: https://www.midwife.org/About-the-Midwifery-Profession

Figure 28

Active Medical Board Licenses by Type*, N=9,895 records across licenses

* an active license does not guarantee an individual is actively seeing patients.

Figure 29

Active Medical Board Licenses by Gender, select license types (when reported)

Not including 3 individuals listing no year of birth, 866 individuals are at full retirement age of 67 in 2022.

One record, at bottom of chart, indicates a birth year of 2020.

Full retirement age as per Social Security Adminstration*

Note. Three individuals did not provide a year of birth

* According to the Social Security Administration “Full retirement age is the age when you can start receiving your full retirement benefit amount. The full retirement age is 66 if you were born from 1943 to 1954. The full retirement age increases gradually if you were born from 1955 to 1960, until it reaches 67. For anyone born 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67.”

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

19805

19703 19702

19964

19720

19707 19732 19804 19730

19716 19731 19709 19734

19733

19977 19902

19938 19946

19955 19901 19943

19904

19953 19979 19954 19952

19950 19960 19941 19973 19940

19931

19963 19966

19933 19971

19951 19947

19968 19975

19958 19930

Philadelphia 19944 19945

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

19805

19703 19702

19964

19720

19707 19732 19804 19730

19716 19731 19709 19734

19733

19977 19902

19938 19946

19955 19901 19943

19904

19953 19979 19954 19952

19950 19960 19941 19973 19940

19931

19963 19966

19933 19971

19951 19947

19968 19975

19958 19930

Philadelphia 19944 19945

Note. Map on facing page shows most, but not all, ZIP codes due to scaling limitations. Hot spots are employed to bring perspective to viewing the overall map and distribution of healthcare professionals and should not be interpreted has valuing value without referring to the numbers listed in the chart above.

19805