www.delamed.org | www.djph.org www.delamed.org | www.djph.org

Volu me 8 | Issue 5 December 2022 A publication of th eD el aw ar e Ac adem y of Me di ci ne / Del aw ar eP ublic He alth Associatio n

Delawa

Jour

Fo cus on Delaware’s Healthcare Workforce

Public Health

re

na l of

Delaware Academy of Medicine

OFFICERS

S. John Swanson, M.D. President

Lynn Jones, FACHE President-Elect

Professor Rita Landgraf Vice President

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A. Treasurer

Stephen C. Eppes, M.D. Secretary

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Immediate Past President

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director, Ex-officio

DIRECTORS

David M. Bercaw, M.D.

Lee P. Dresser, M.D.

Eric T. Johnson, M.D.

Erin M. Kavanaugh, M.D.

Joseph Kelly, D.D.S.

Joseph F. Kestner, Jr., M.D.

Brian W. Little, M.D., Ph.D.

Arun V. Malhotra, M.D.

Daniel J. Meara, M.D., D.M.D.

Ann Painter, M.S.N., R.N.

John P. Piper, M.D.

Charmaine Wright, M.D., M.S.H.P. EMERITUS

Barry S. Kayne, D.D.S.

Delaware Public Health Association

Advisory Council:

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Co-Chair

Professor Rita Landgraf Co-Chair

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director

Louis E. Bartoshesky, M.D., M.P.H.

Gerard Gallucci, M.D., M.H.S.

Melissa K. Melby, Ph.D.

Mia A. Papas, Ph.D.

Karyl T. Rattay, M.D., M.S.

William J. Swiatek, M.A., A.I.C.P.

Delaware Journal of Public Health

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Publisher

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief

Liz Healy, M.P.H.

Managing Editor

Kate Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Copy Editor

Suzanne Fields Image Director

ISSN 2639-6378

Public Health

In This Issue

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S.

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

4 | Executive Summary

Richard J. Geisenberger

Nicholas A. Moriello, R.H.U.

5 | Delaware Department of Health and Social Services

Molly Magarik, M.S.

6 | U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration

Michelle M. Washko, Ph.D.

7 | Delaware Healthcare Commission Workforce Subcommittee

Richard J. Geisenberger

Nicholas A. Moriello, R.H.U.

8 | From the Delaware Academy of Medicine/ Delaware Public Health Association

S. John Swanson, M.D.

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

10 | Welcome from the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Pamela Gardner

11 | Delaware Division of Professional Regulation

Geoffry Christ, R.Ph., J.D.

12 | Delaware Nurses Association

Christopher E. Otto, M.S.N., R.N., C.H.F.N., P.C.C.N., C.C.R.N.

13 | Medical Society of Delaware

Mark B. Thompson, M.H.S.A.

18 | Origins of the PCP Shortage

Sharon Folkenroth Hess, M.A. 20 | Delaware Healthcare Workforce Vital Statistics 22 | Board of Chiropractic

| Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene

| Board of Dietetics / Nutrition

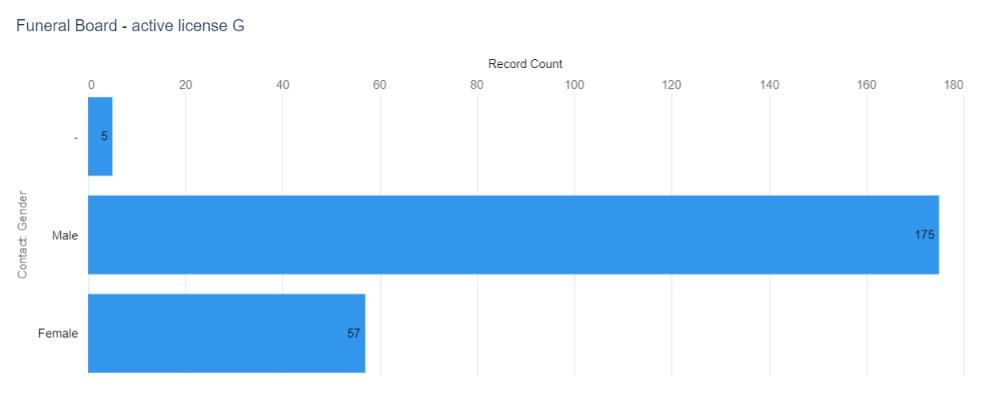

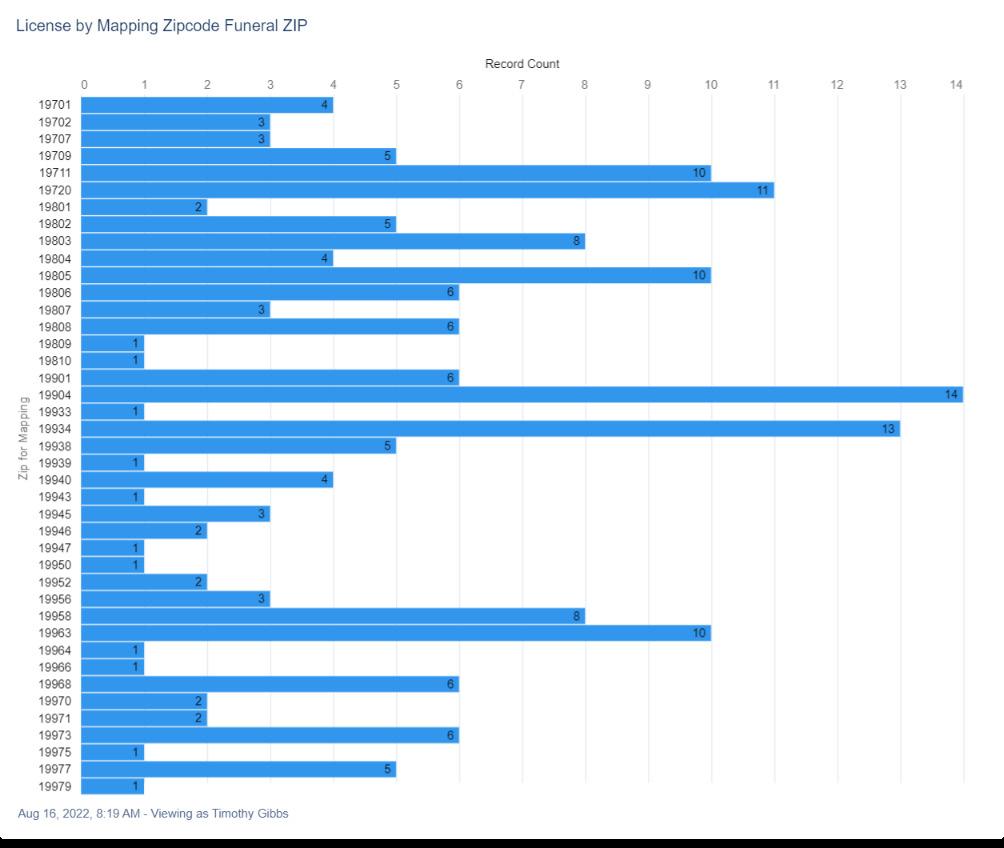

Board of Funeral Services

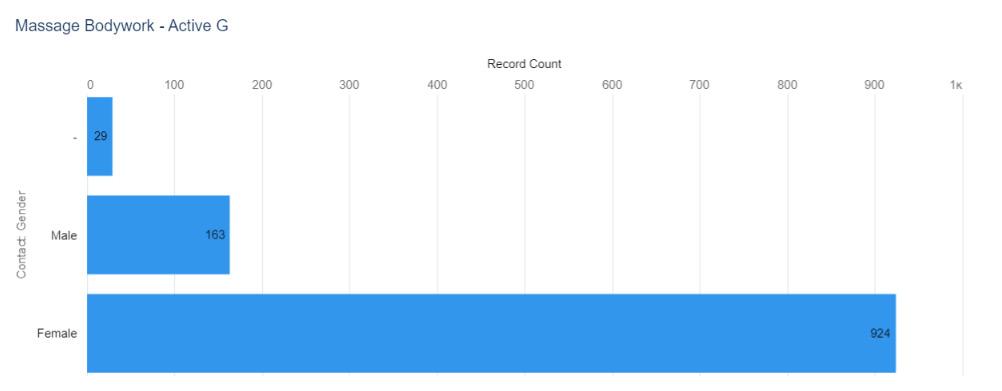

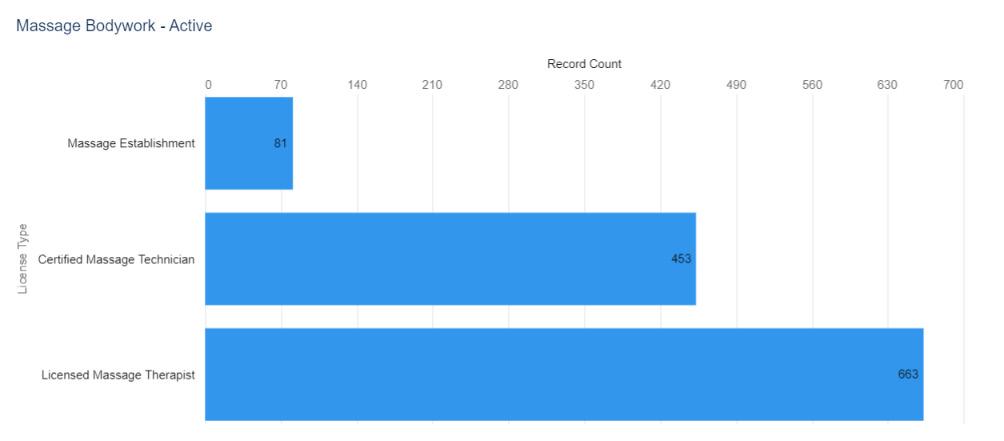

Board of Massage and Body

Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline

Board of Nursing

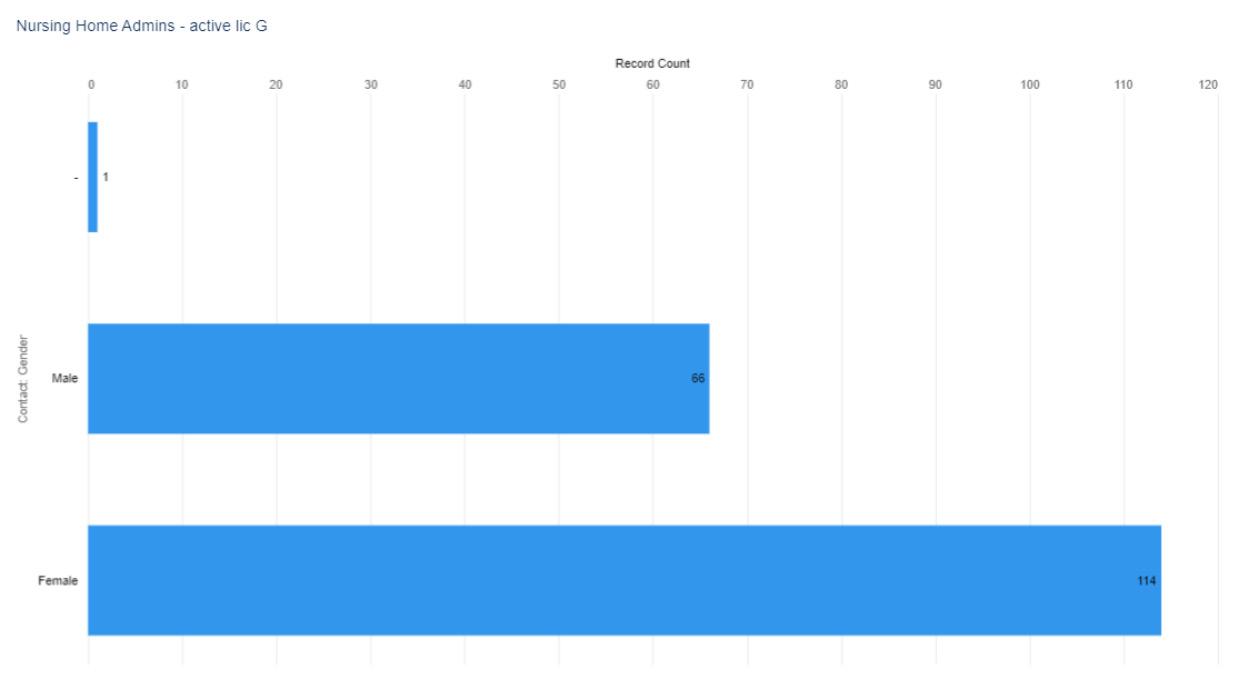

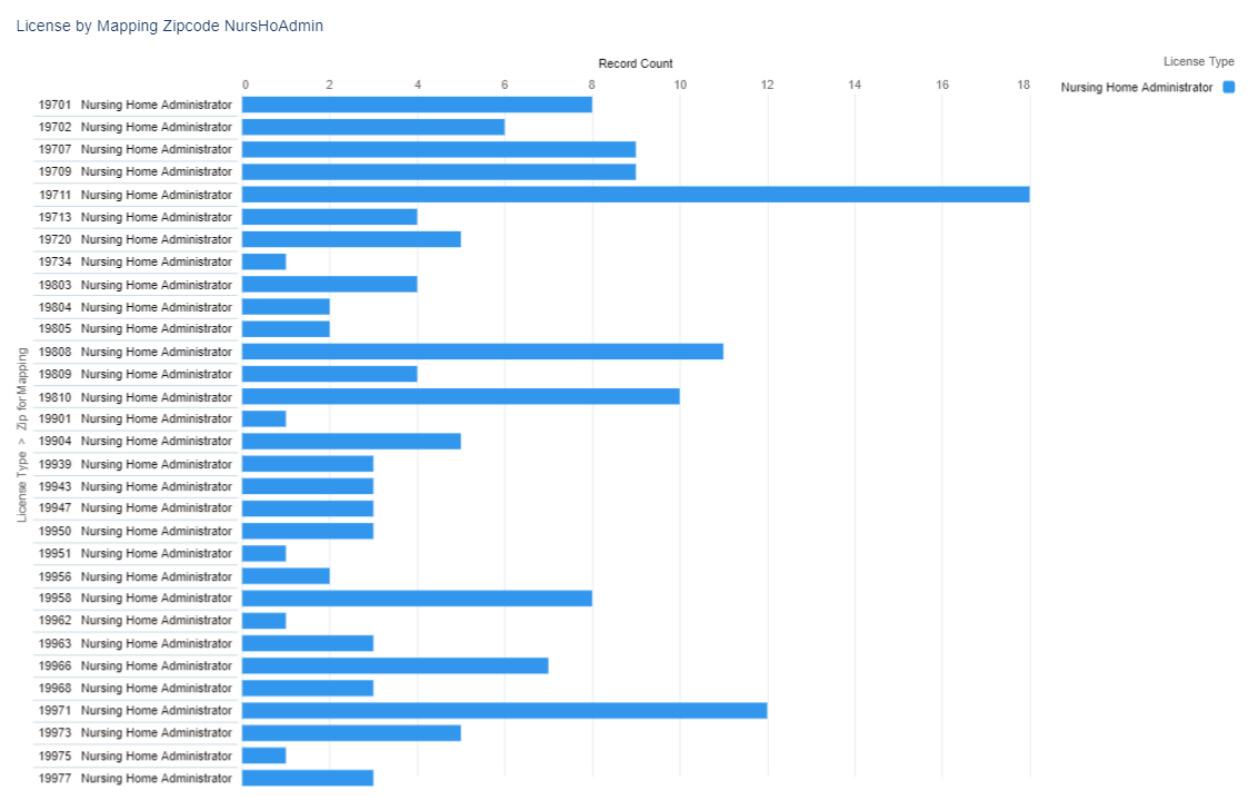

Board of Examiners of Nursing Home Administrators

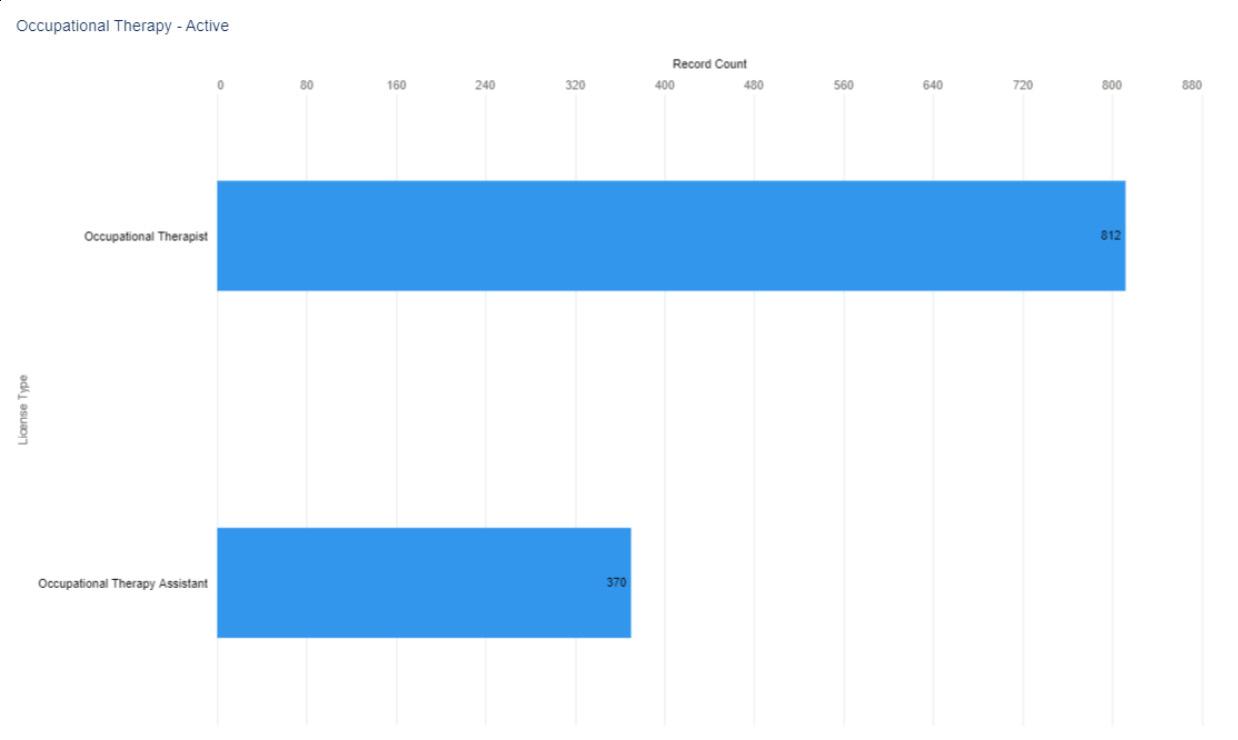

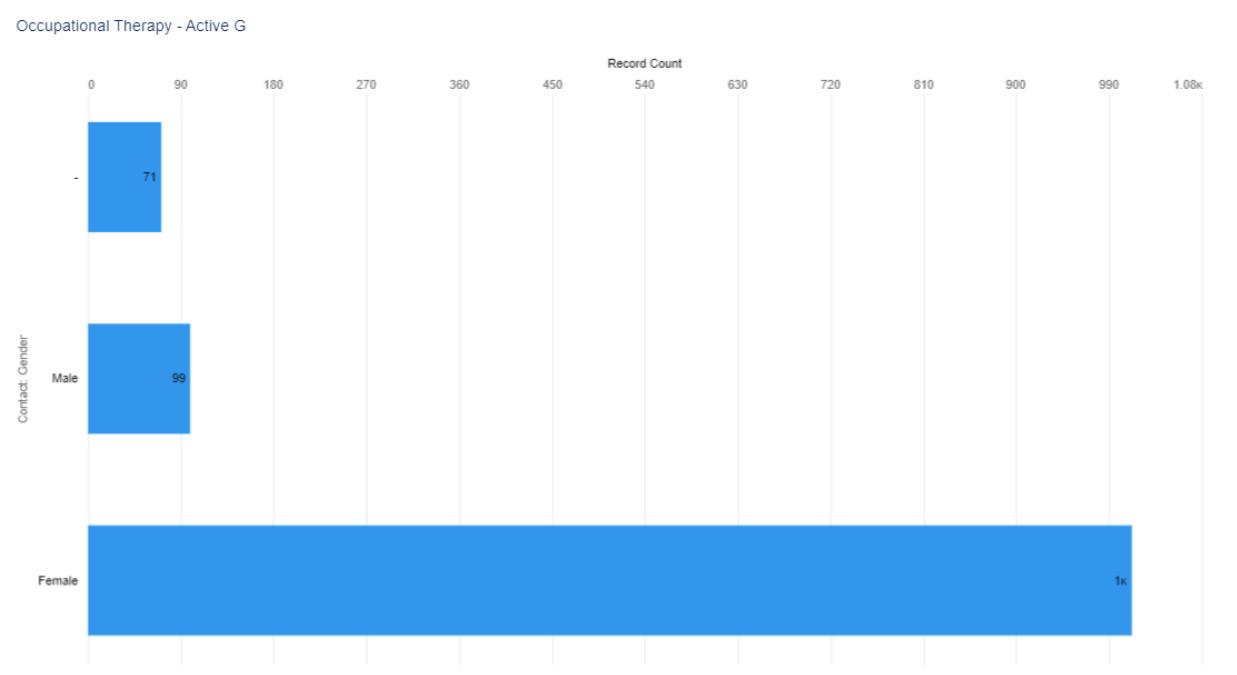

Board of Occupational Therapy Practice

Board of Examiners in Optometry

COVER

It is estimated that 20%, or more, of the social determinants of health are influenced by healthcare access and quality. While that number seems small, a lack of access through workforce shortages or weakness can disproportionately impact the provision of care to those who need it.

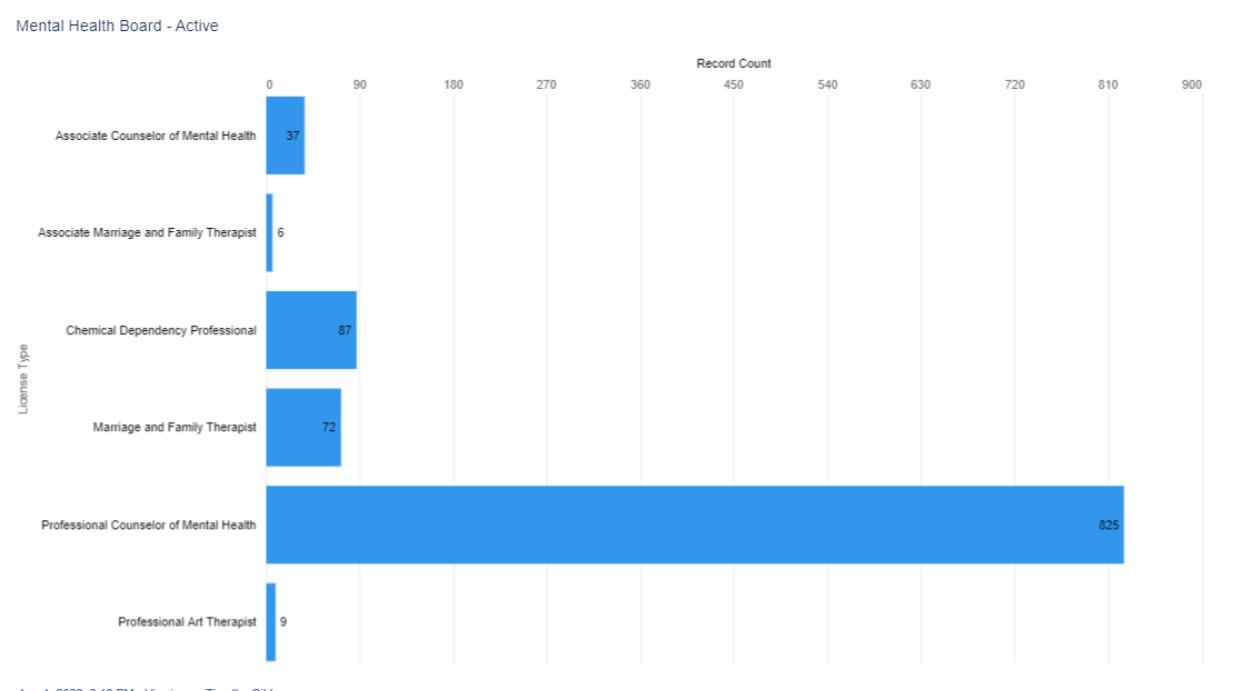

96 | Board of Pharmacy

102 | Board of Physical Therapists and Athletic Trainers 108 | Board of Podiatry 112 | Board of Mental Health and Chemical Dependency Professionals 118 | Board of Examiners of Psychologists 124 | Board of Social Work Examiners 128 | Board of Speech Pathologists, Audiologists, and Hearing Aid Dispersers 132 | Board of Veterinary Medicine 136 | Controlled Substance Advisory Committee 144 | Long Term Care and Skilled Nursing Facilities 150 | Composition of An Ideal Medical Care Team 154 | Considerations for Patient Panel Size 158 | Scope and Specialization in Dental Care 160 | Composition of Ideal Dental Team 162 | Delaware Health Provider Shortage Areas 164 | Extraordinary Impacts on the Healthcare Workforce:COVID-19 and Aging 168 | Addressing Health Disparities in Delaware by Diversifying the Next Generation of Delaware’s Physicians 172 | Physician and Dentist Basic Demographics: Race and Ethnicity

173 | Physician Statistics based on Allopathic (M.D.) and Osteopathic (D.O.) Education 174 | Physician and Dentist Basic Demographics Age 176 | Chronic Disease Management and the Healthcare Workforce 198 | Global Health Matters November/December 2022 210 | Methodology 212 | Health Care Database Comparisons by State 216 | Workforce In Training 221 | 2021 Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research (DIMER) Annual Report: Abridged Executive Summary

222|AnEnvironmentalScanofHealthcarePathways ProgramsinDelaware 236|IndexofAdvertisers

The Delaware Journal of Public Health (DJPH), first published in 2015, is the official journal of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA).

Submissions: Contributions of original unpublished research, social science analysis, scholarly essays, critical commentaries, departments, and letters to the editor are welcome. Questions? Write ehealy@delamed.org or call Liz Healy at 302-733-3989

Advertising: Please write to ehealy@delamed.org or call 302-733-3989 for other advertising opportunities. Ask about special exhibit packages and sponsorships. Acceptance of advertising by the Journal does not imply endorsement of products.

Copyright © 2022 by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association. Opinions expressed by authors of articles summarized, quoted, or published in full in this journal represent

only the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Delaware Public Health Association or the institution with which the author(s) is (are) affiliated, unless so specified.

Any report, article, or paper prepared by employees of the U.S. government as part of their official duties is, under Copyright Act, a “work of United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the U.S. Code is not available. However, the journal format is copyrighted and pages June not be photocopied, except in limited quantities, or posted online, without permission of the Academy/ DPHA. Copying done for other than personal or internal reference use-such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale- without the expressed permission of the Academy/DPHA is prohibited. Requests for special permission should be sent to ehealy@delamed.org

w.delamed.org w.djph.org

of Focus on Delaware’s Healthcare Workforce

pu Public Health Delaware Journal

3 |

28

34

40 |

46 |

52 |

70 |

82 |

86 |

90 |

Delaware Journal

of

December 2022 Volume 8 | Issue 5

A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association

IN THIS ISSUE

Dear Reader,

This issue of the Delaware Journal of Public Health is a bit different from any issue published to date. As always, we share a lot of information we think you will find useful; however, this issue expands the idea of ‘a lot of content.’ Second, it links to a specific website for additional information. Finally, it is based upon research done by various colleagues and institutions in Delaware who have worked on healthcare workforce concerns.

Why have an issue dedicated to healthcare and healthcare access? Simply stated, it is one of the social determinants of health, and depending where you look, it is ranked as being accountable for 10%1 to over 27% 2 within the larger framework including genetic predisposition, behavioral patterns, social circumstances, and environment.3

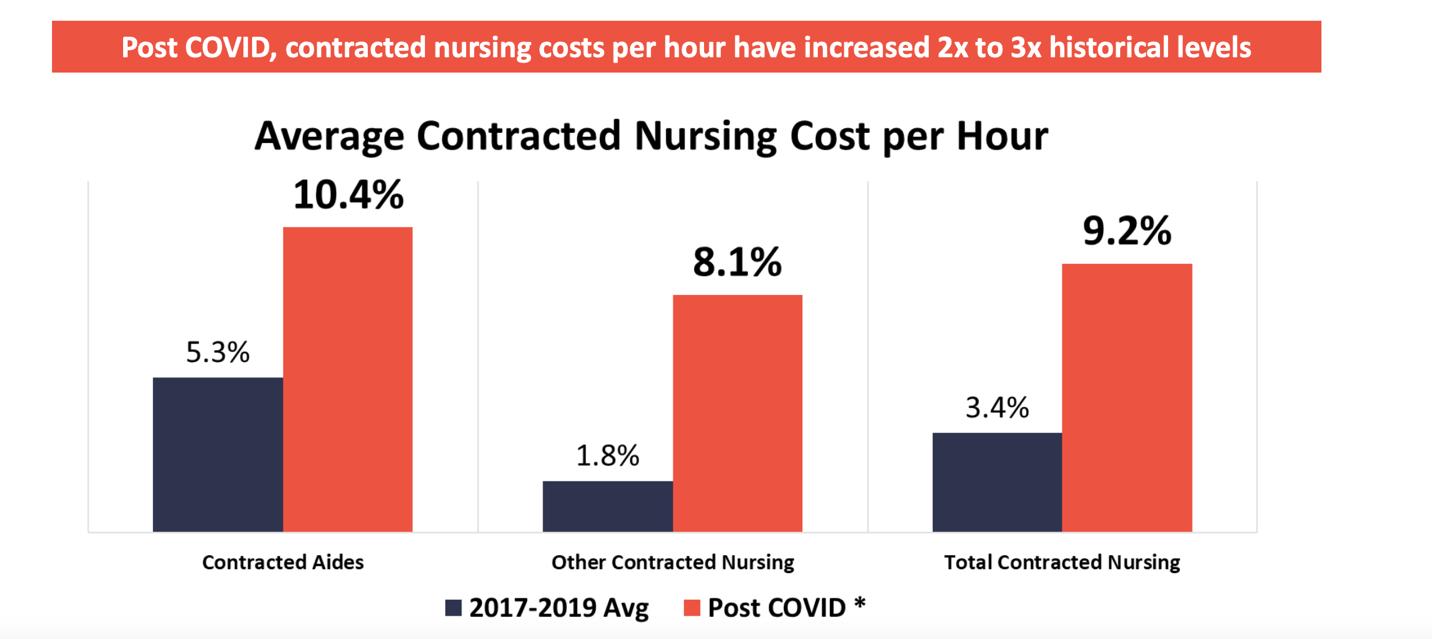

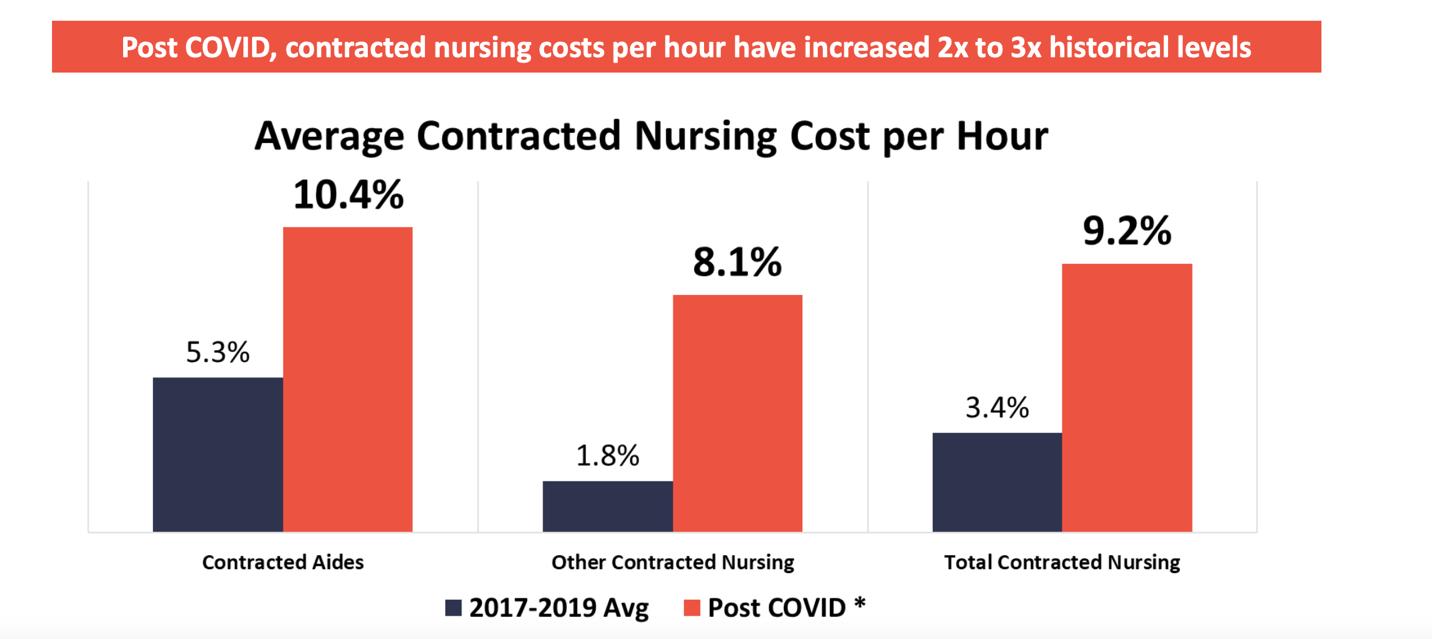

Those percentages, while informative, became even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic based upon the dramatic increase in need for services, the exodus of front line healthcare workers from the workforce, and the exacerbation of existing healthcare provider shortages and their impact on the provision of care, especially with respect to routine primary care and chronic disease management.

With startup funding from the Delaware Health Care Commission and American Rescue Plan Act funding from the United States Department of Treasury through the State of Delaware, we and our partners are engaged in a wide-ranging initiative. There are four components to the initiative:

1) To quantify the healthcare workforce in Delaware;

2) To expand pathways programs to encourage Delaware youth to pursue a career in healthcare;

3) To expand the graduate medical education capacity in Delaware for key practitioner disciplines; and

4) To expand our existing student financial aid program to include loans to nursing and physician assistant students, medical and dental technicians, and behavioral health providers who are residents of the State of Delaware, attend Delaware schools, and are willing to commit to practice in Delaware after graduation.

This issue of the Delaware Journal of Public Health focuses on our initial healthcare workforce analysis, based upon data from the Delaware Division of Professional Licensing and on data provided from the Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN) regarding healthcare utilization in Delaware and reflected in claims data. Numerous other sources of data have been brought to bear on this subject as well, which are too numerous to list here.

A website, https://dehealthforce.org has been built. You can find the complete (406 page!) 2022 Workforce Report there, and over time we will be enhancing the capacity of that website to bring you a series of dashboards and widgets to access additional, up-to-date workforce data.

Future issues of the DJPH will continue this dialog. We hope you enjoy this issue, and as always, we appreciate your input and suggestions on this and other public health topics.

REFERENCES

1. The Center for Health Affairs. (2017, May). Social determinants of health and their influence on health.

Retrieved from: https://www.neohospitals.org/healthcare-blog/2017/March/Social-Determinants-of-Health

2. Health Intelligence Network. (2017, Apr). What are the leading social determinants of health needs?

Retrieved from: http://www.hin.com/chartoftheweek/SDOH_domains_with_greatest_needs_printable.html#.Y5I5rnbMJPa

3. Schroeder, S. A. (2007, September 20). Shattuck Lecture. We can do better—Improving the health of the American people. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(12), 1221–1228. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa073350 PubMed

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.001

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H Publisher, Delaware Journal of Public Health

3

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Executive Summary

Richard J. Geisenberger

Secretary of Finance, State of Delaware; Co-Chair, Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission

Nicholas A. Moriello, R.H.U.

President, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield of Delaware; Co-Chair, Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission

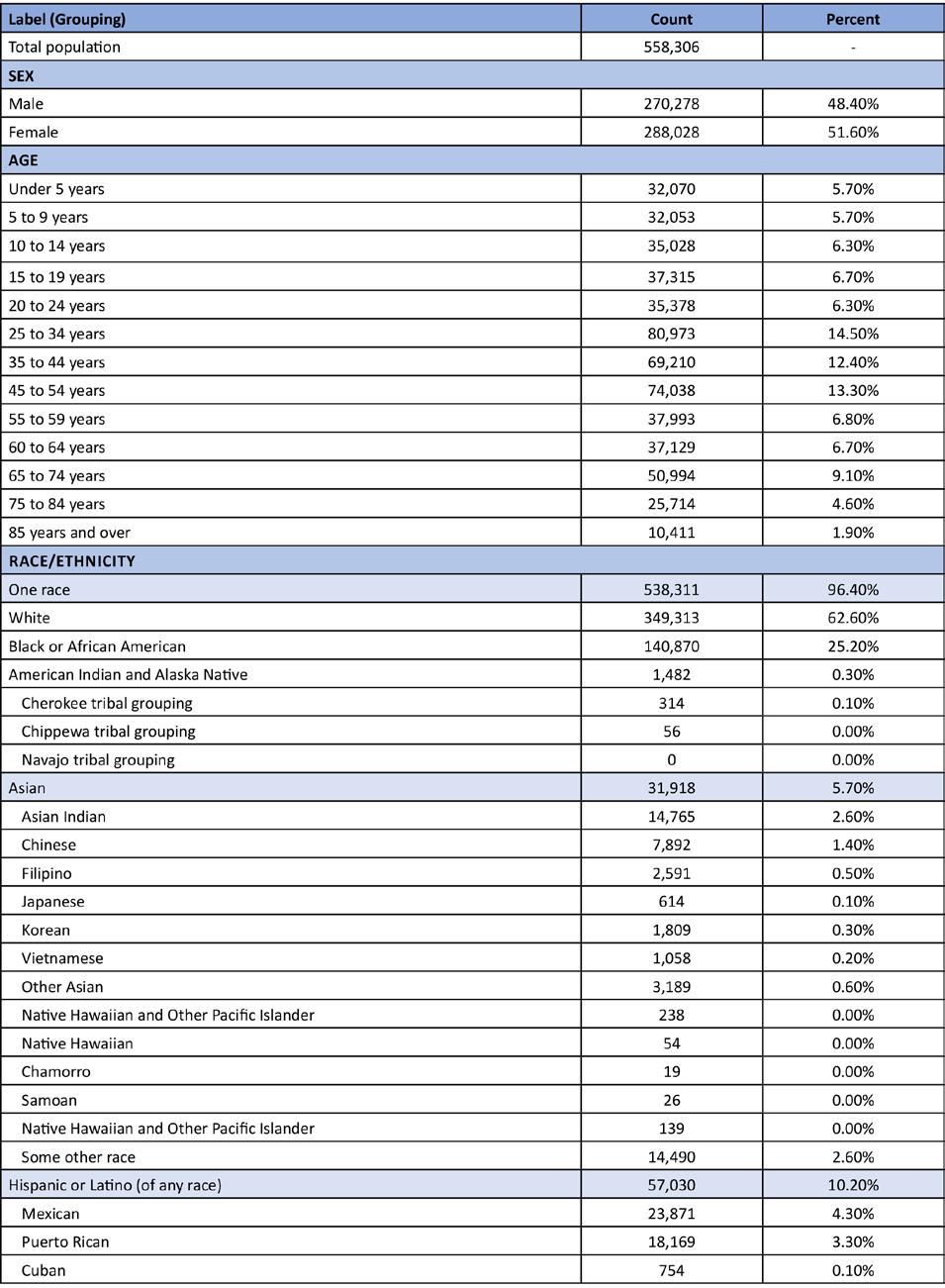

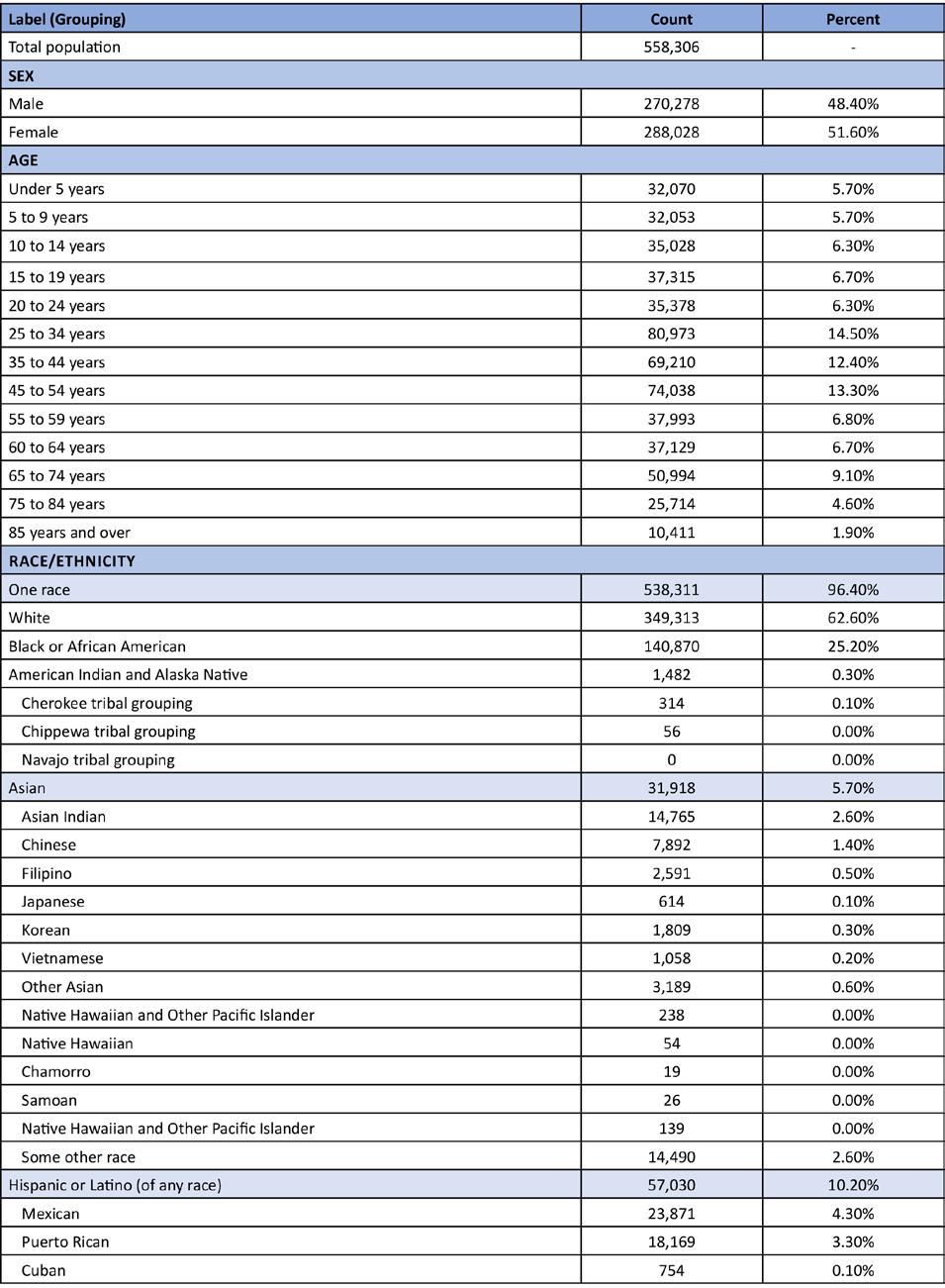

The purpose of this report is to provide an initial census of Delaware’s healthcare workforce contained in the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation (DPR) licensing database known as DELPROS and provide demographic and geographic information not readily available through DELPROS. The report also highlights key public health challenges related to common chronic disease states compiled from Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN) data on insurance claims. Finally, the report provides information on primary care, dental health, and behavioral health shortage areas as reported from Delaware’s Office of Primary Care and Rural Health. Based upon June 2022 DELPROS data, this report contains information from the 19 distinct boards and commissions of practice within DPR which provide regulatory oversight of a majority of Delaware’s healthcare workforce personnel and some types of institutional licensing (which is not a focus of this report). These 19 boards and commissions in turn oversee about 200 types of professional and institutional licenses. This report does not contain information on Certified Nursing Assistants and Direct Service Providers as they are not licensed by DPR nor Community Health Workers that are not registered or licensed in Delaware. Information on these professions is beyond the scope of this census data and report at this time.

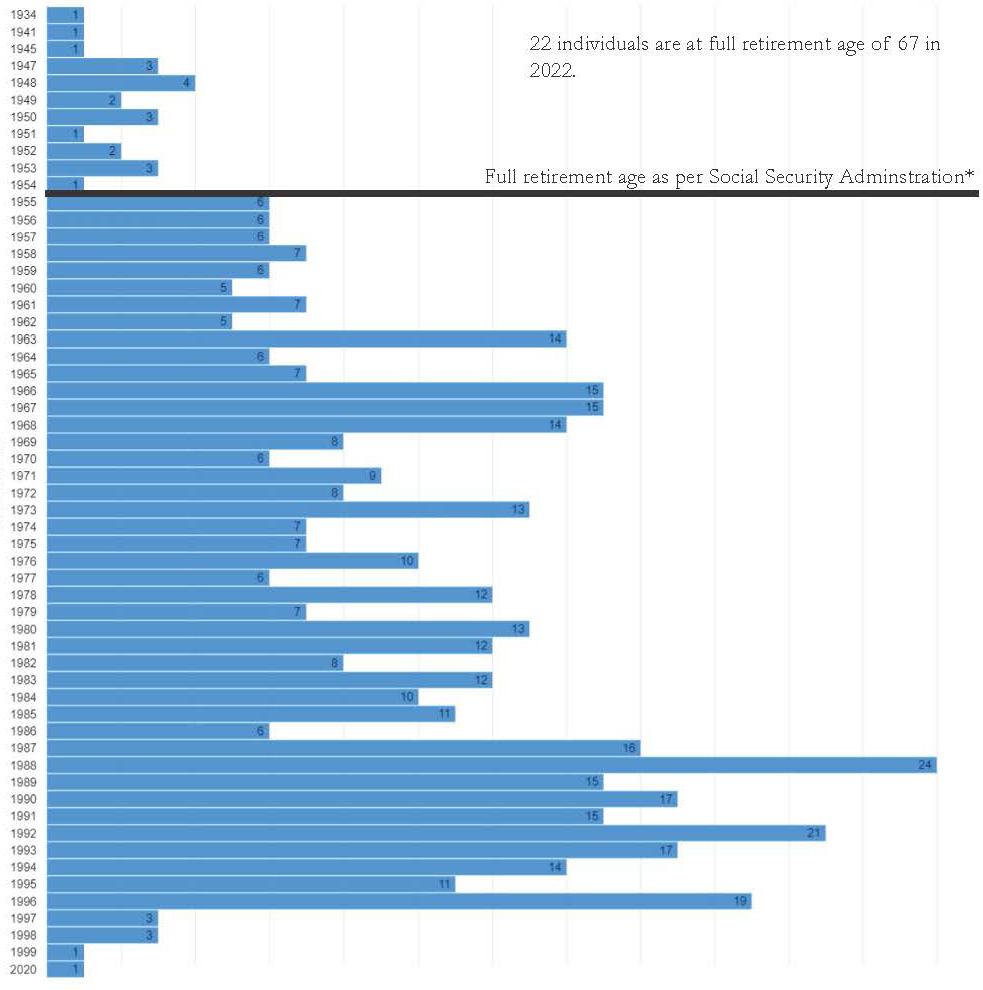

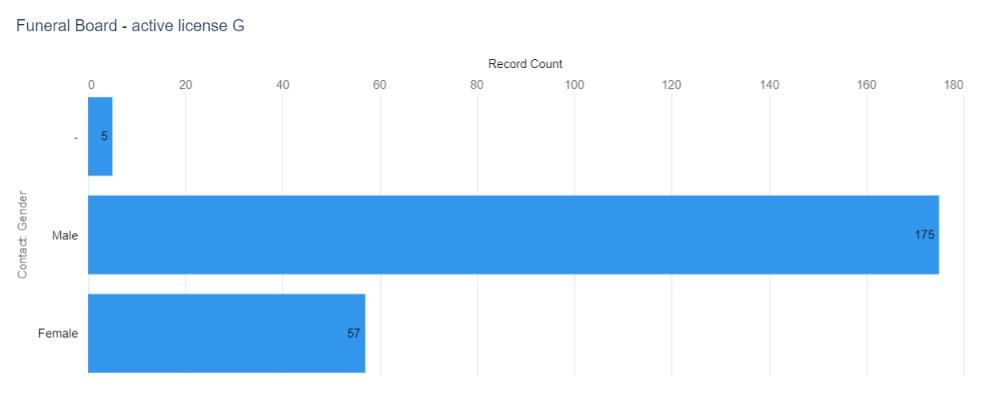

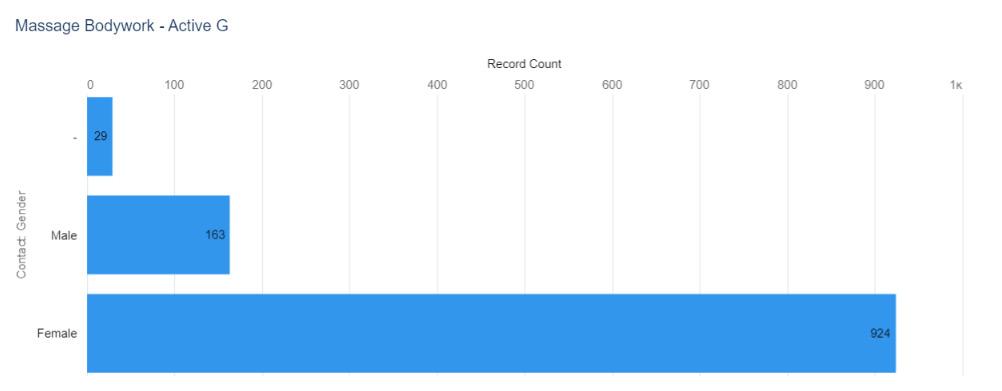

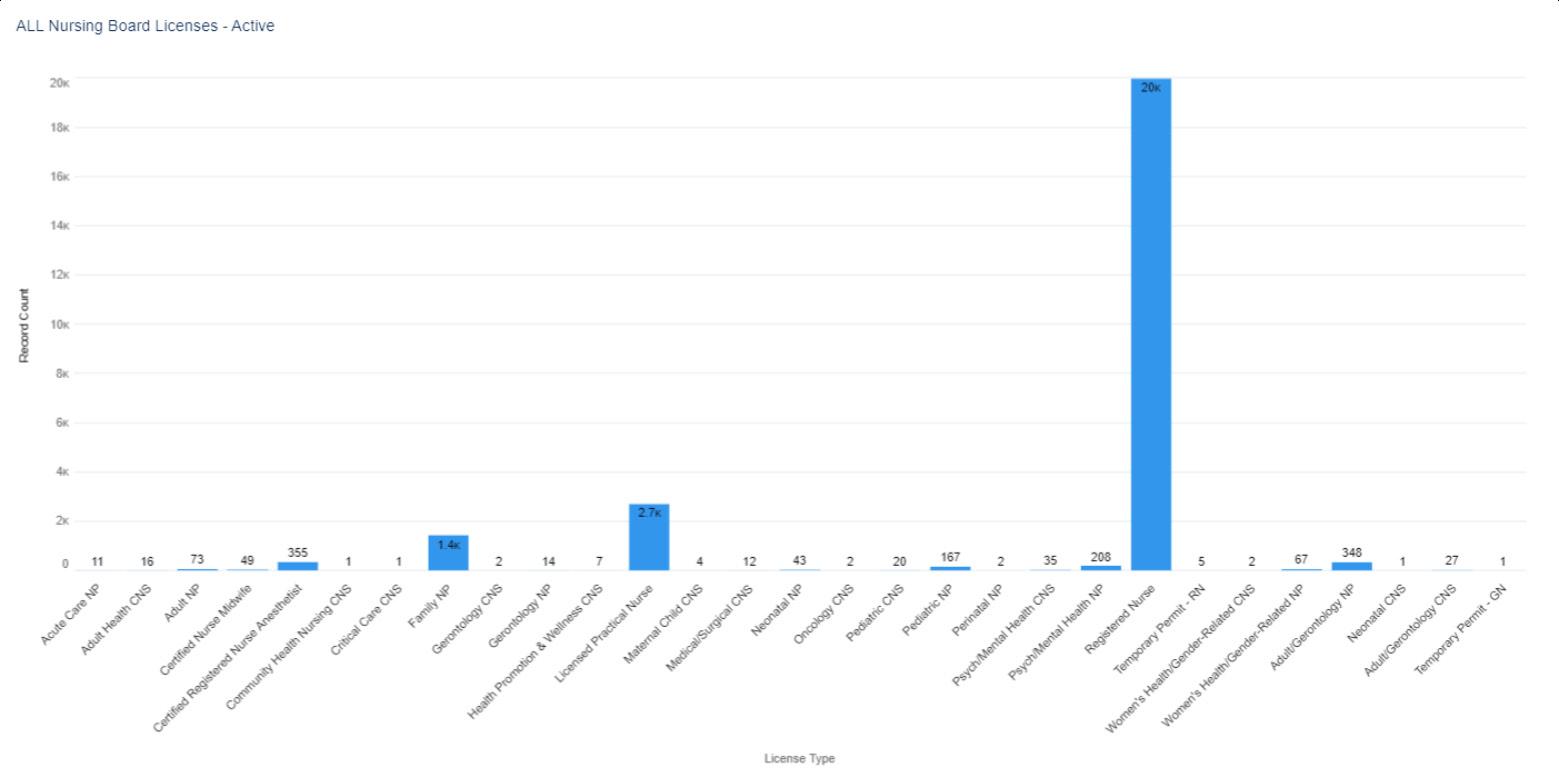

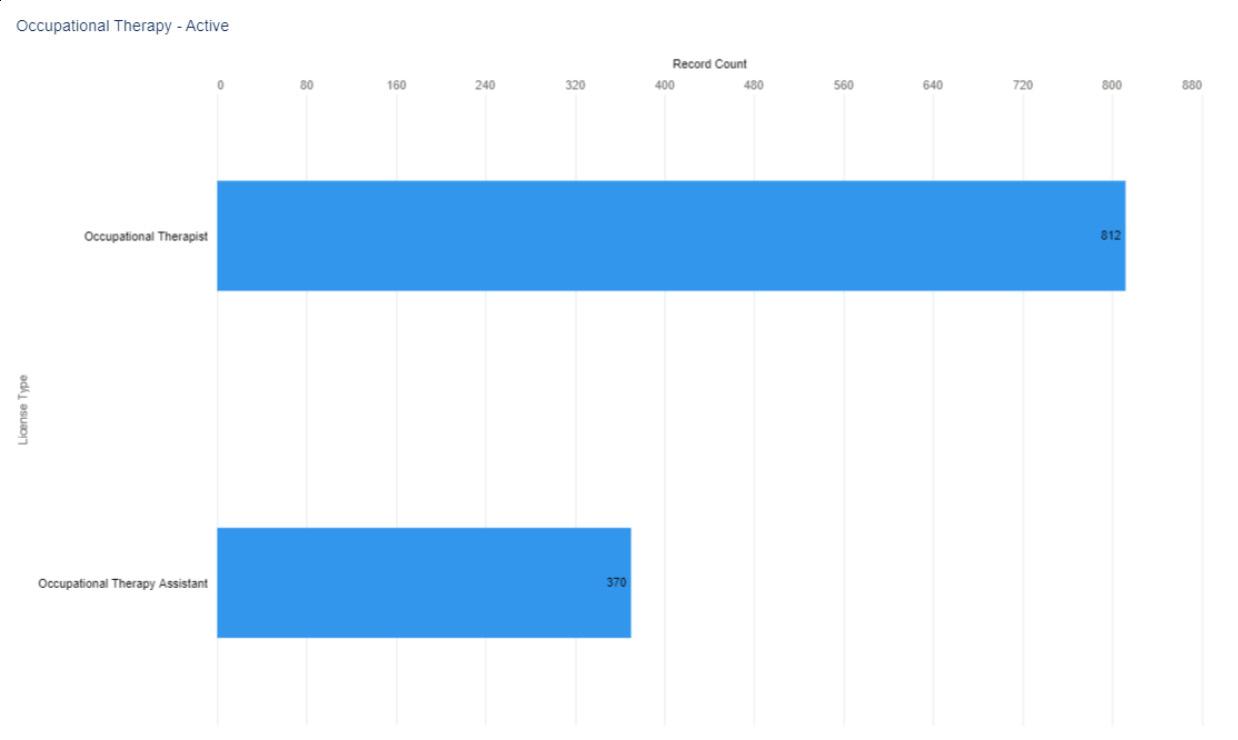

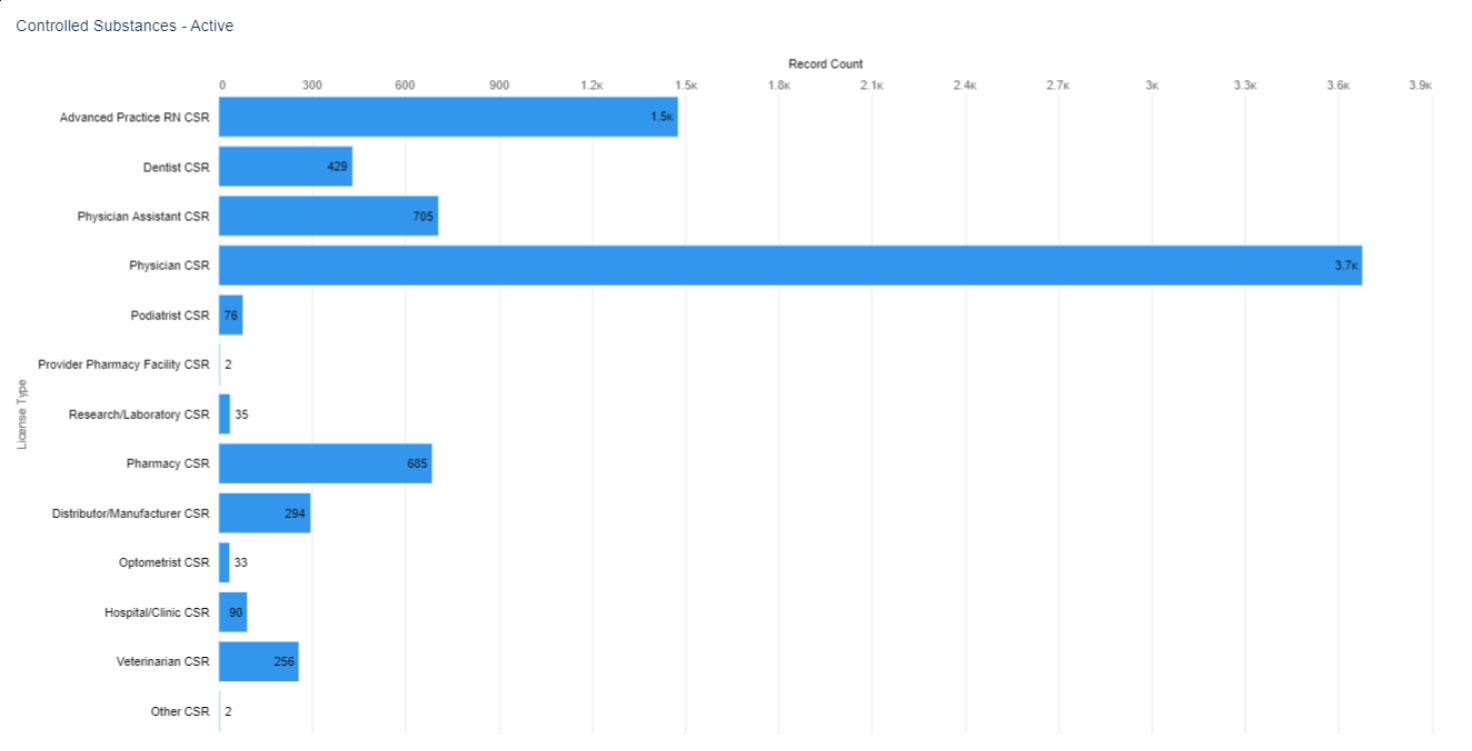

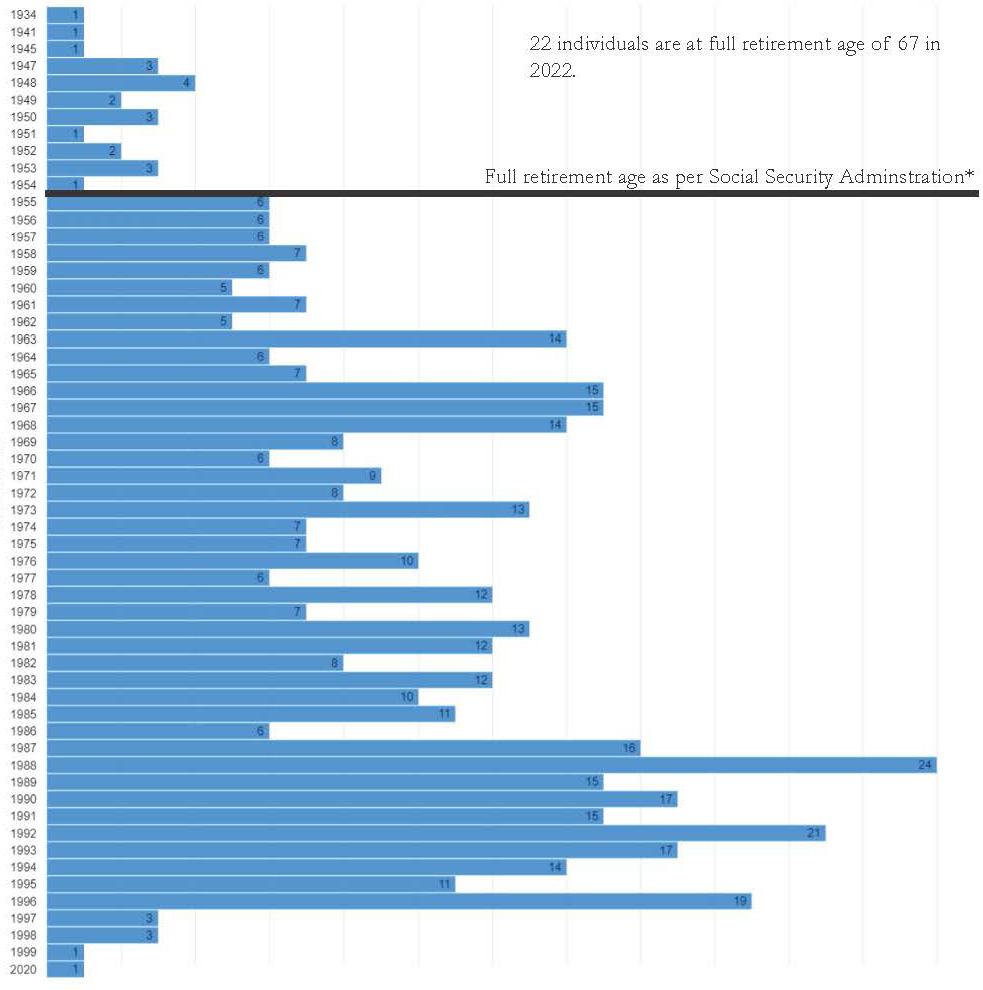

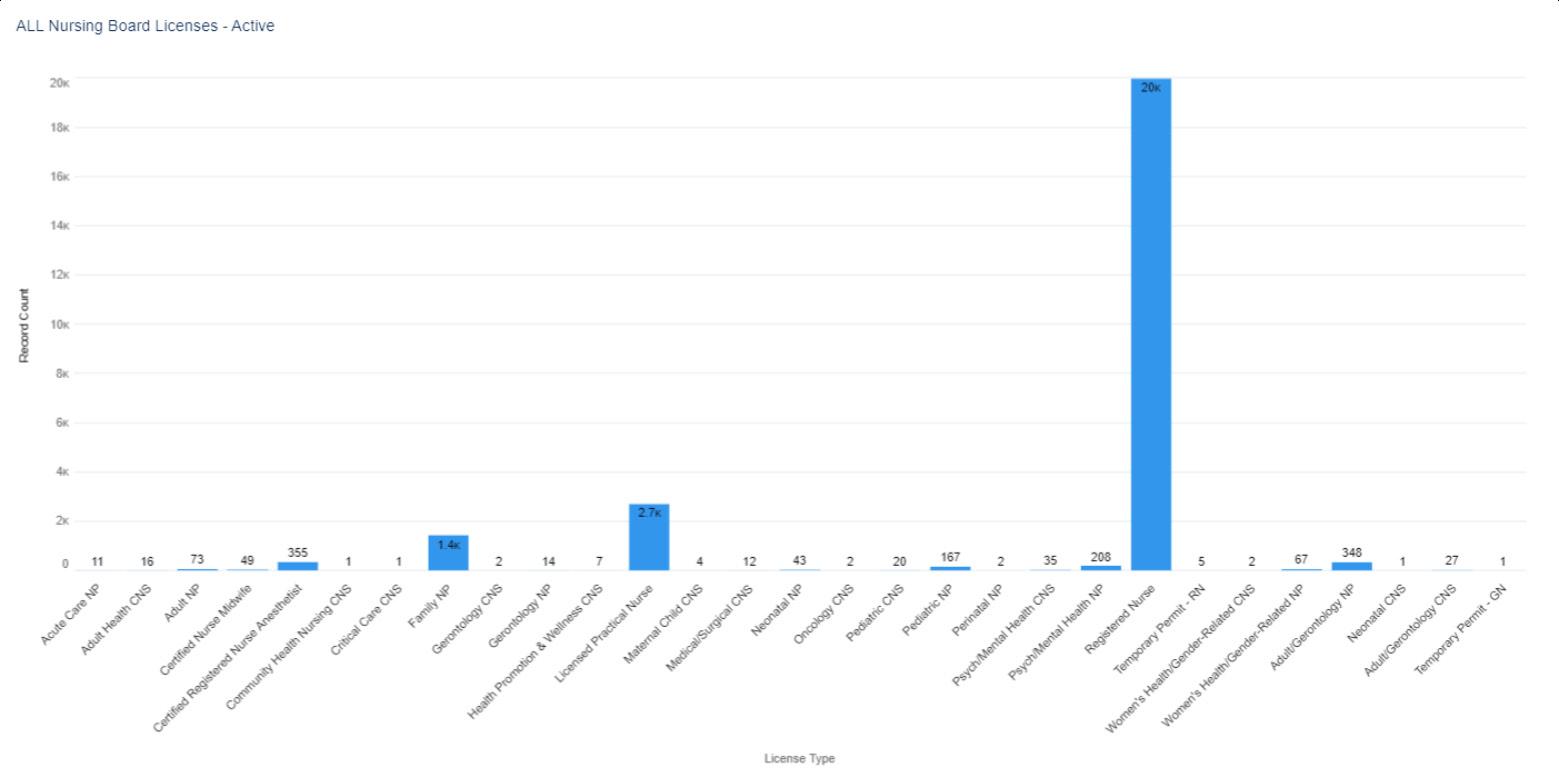

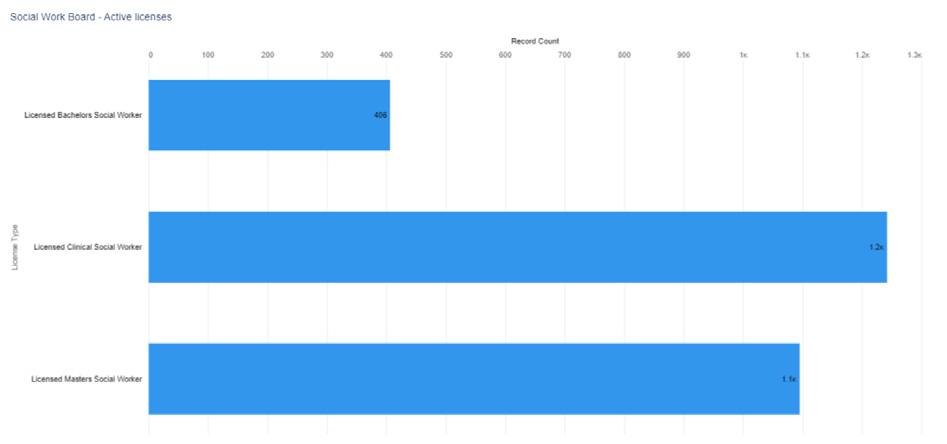

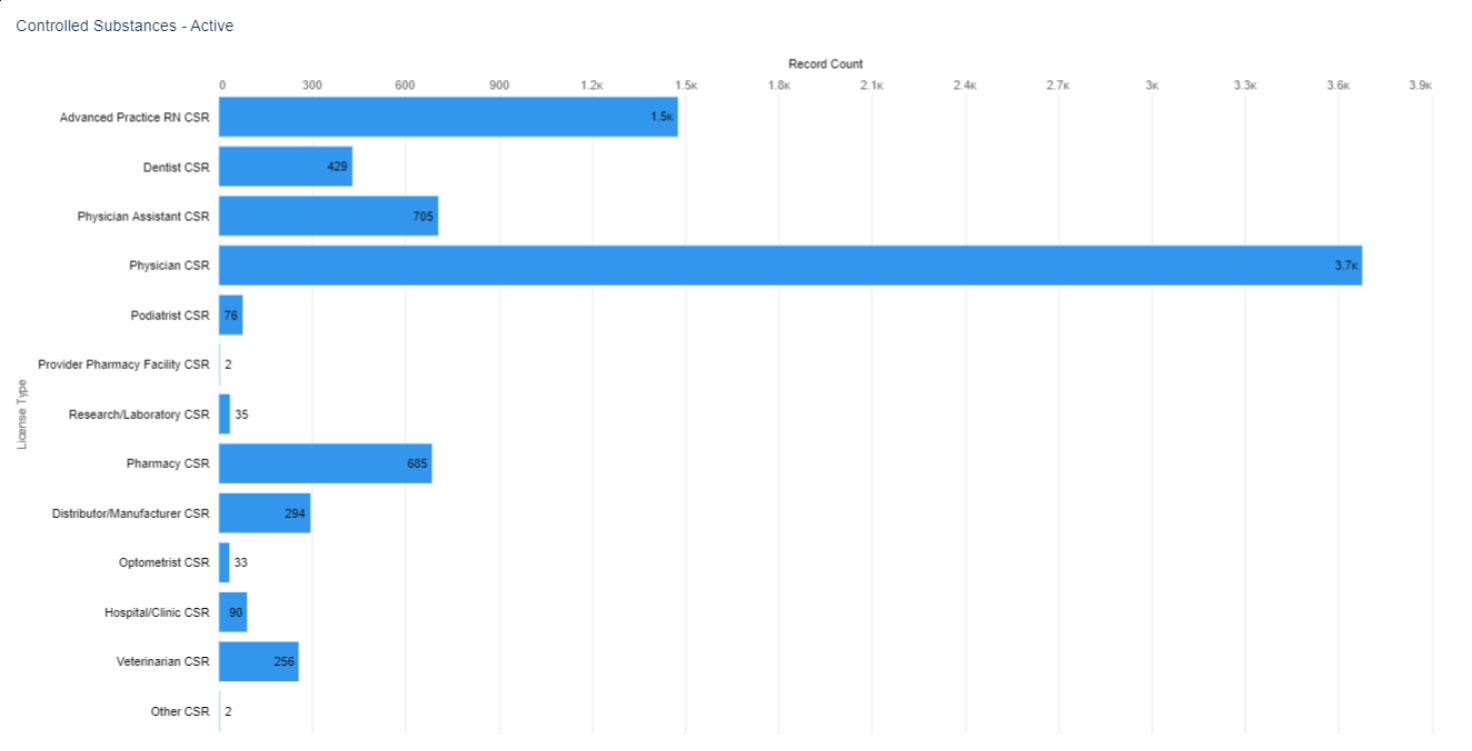

As of June 2022, there were 63,123 active healthcare licenses in DELPROS. This number includes 3,529 institutional licenses (e.g., pharmacies and funeral establishments). There are also 7,760 additional licenses issued for prescribing controlled substances which are issued to both individuals and facilities. After accounting for institutions and certain duplications, there are 56,469 individual healthcare providers in DELPROS. This count includes: approximately 26,000 nursing licenses; 9,900 medical practice licenses, (e.g., physicians and physician assistants); 2,600 pharmacist licenses; 2,700 social work-related licenses; and 1,700 dentistry licenses (e.g., dentists and dental hygienists). The remaining boards each account for 1,100 or fewer licensees per board and are covered in detail in this report.

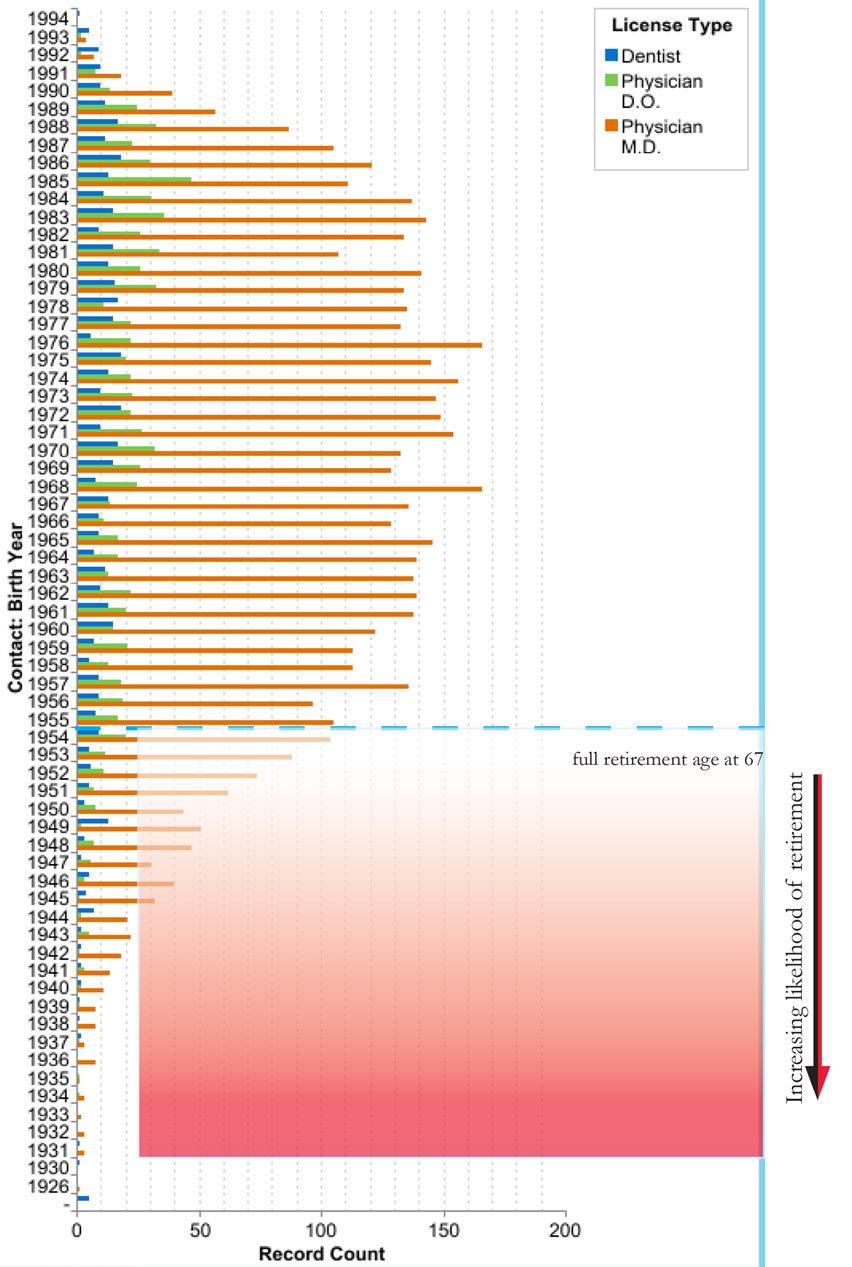

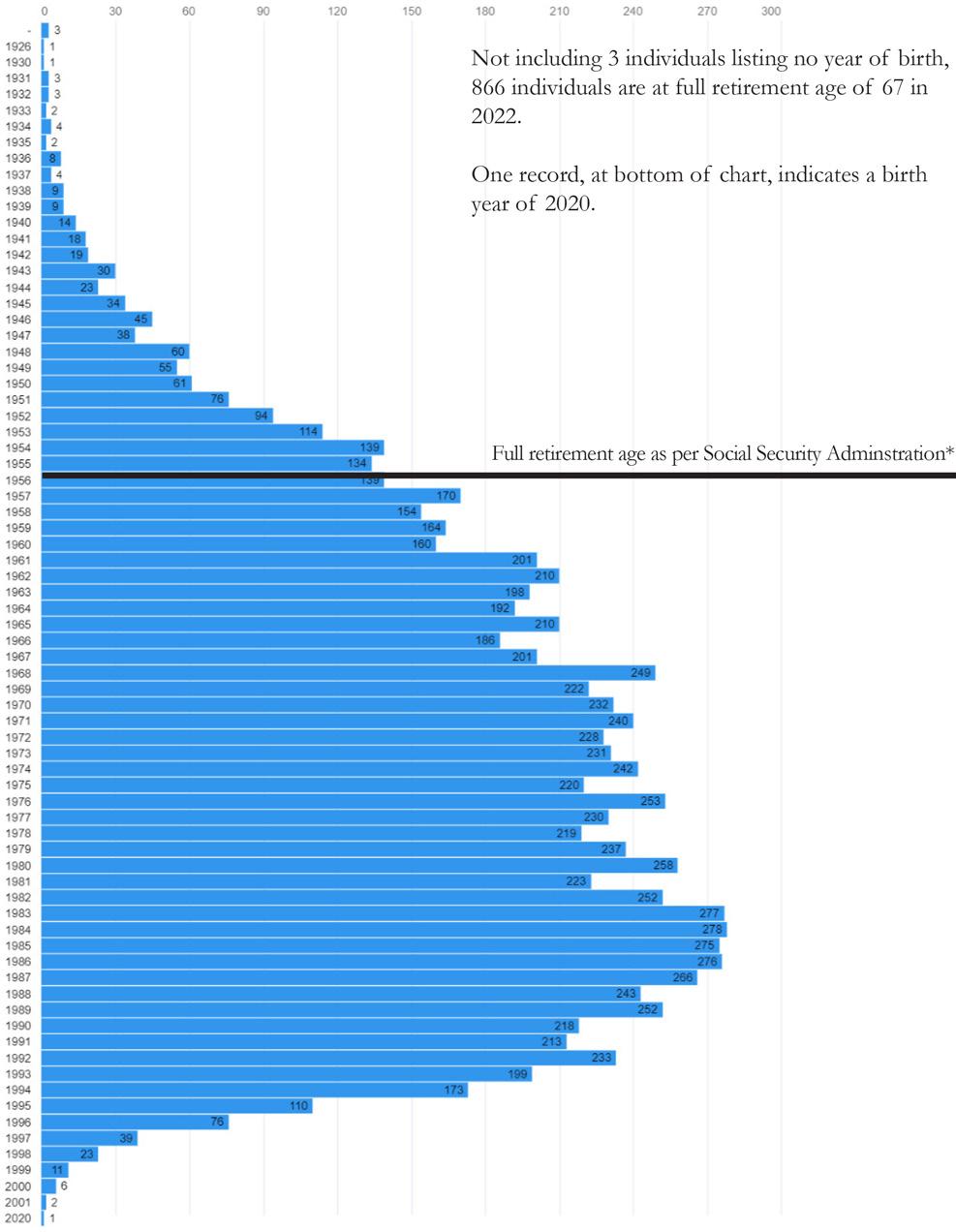

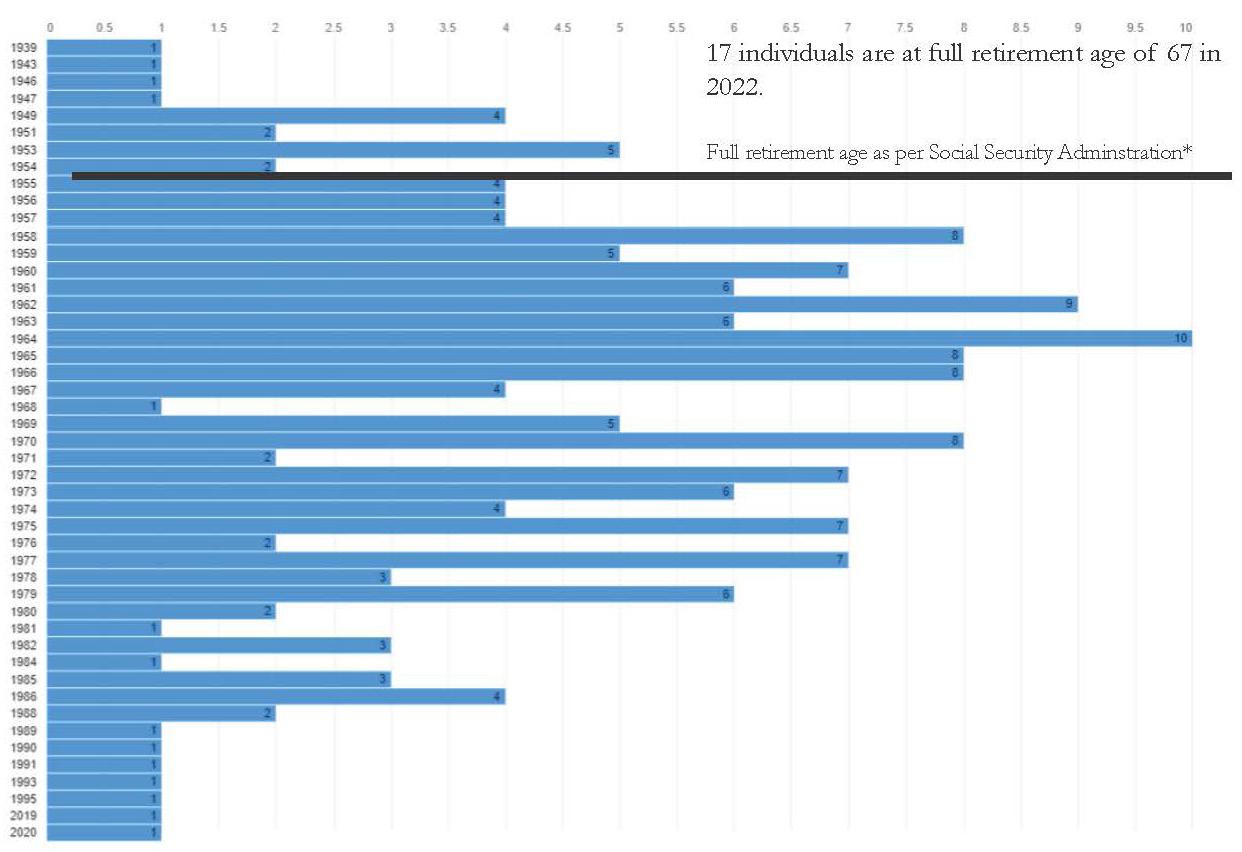

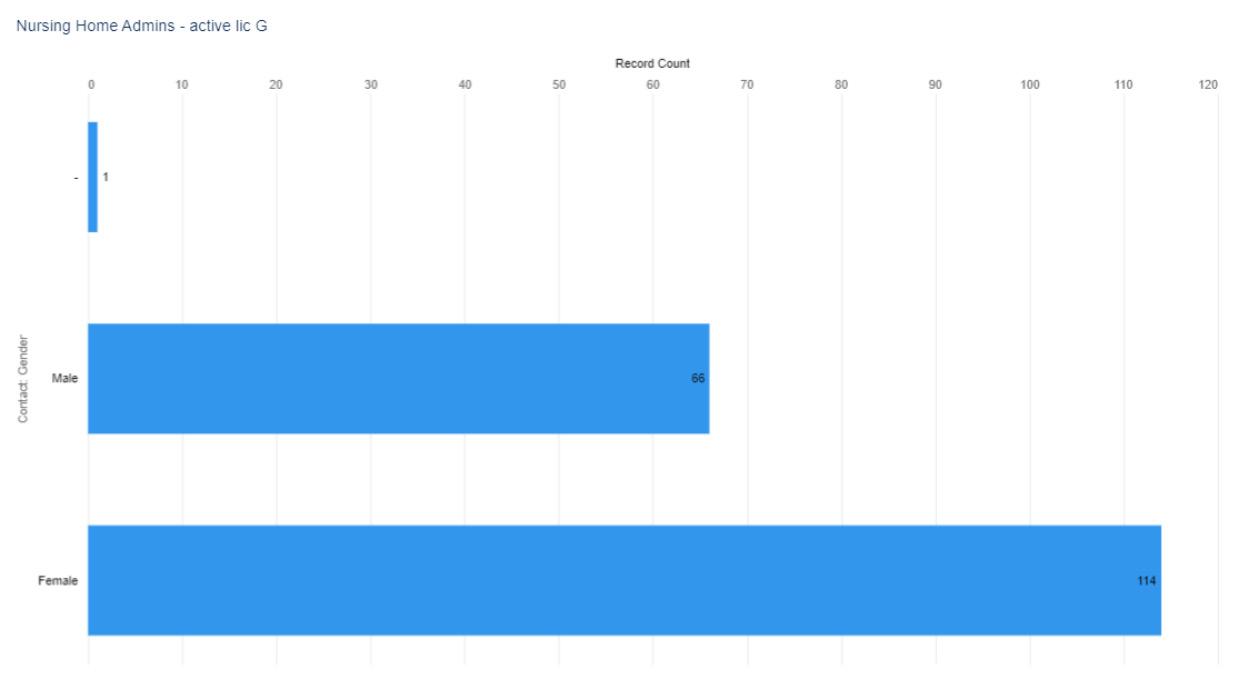

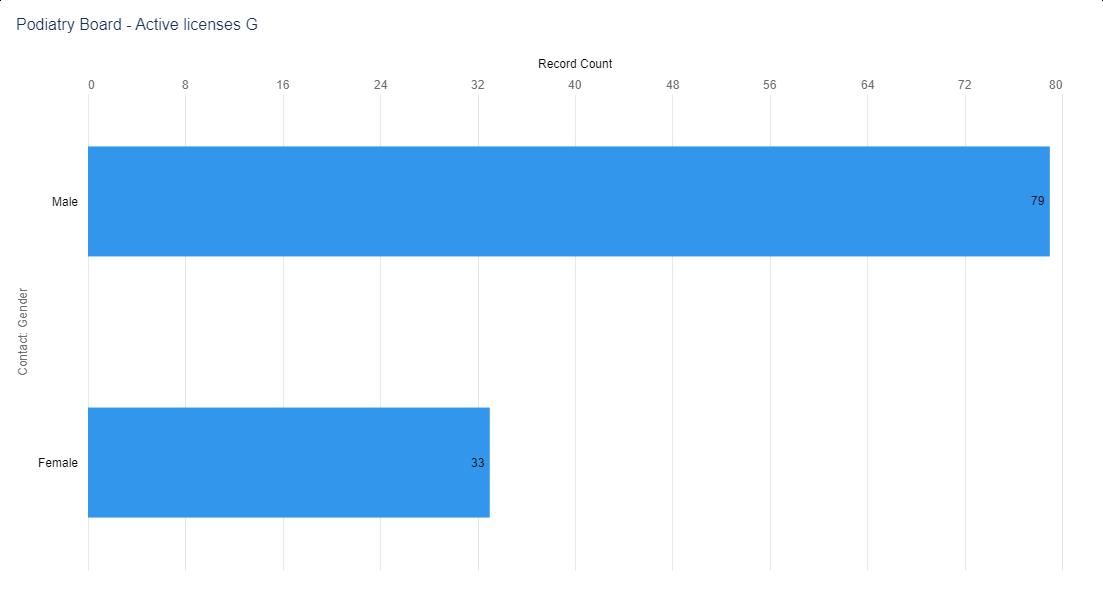

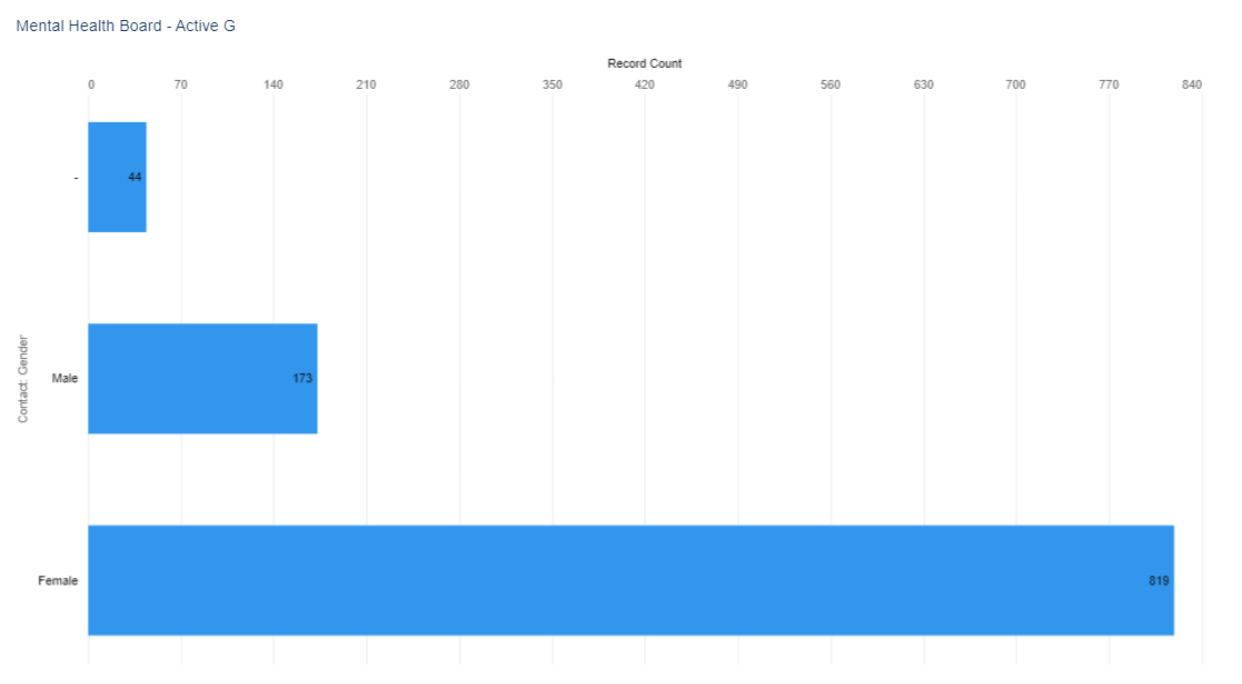

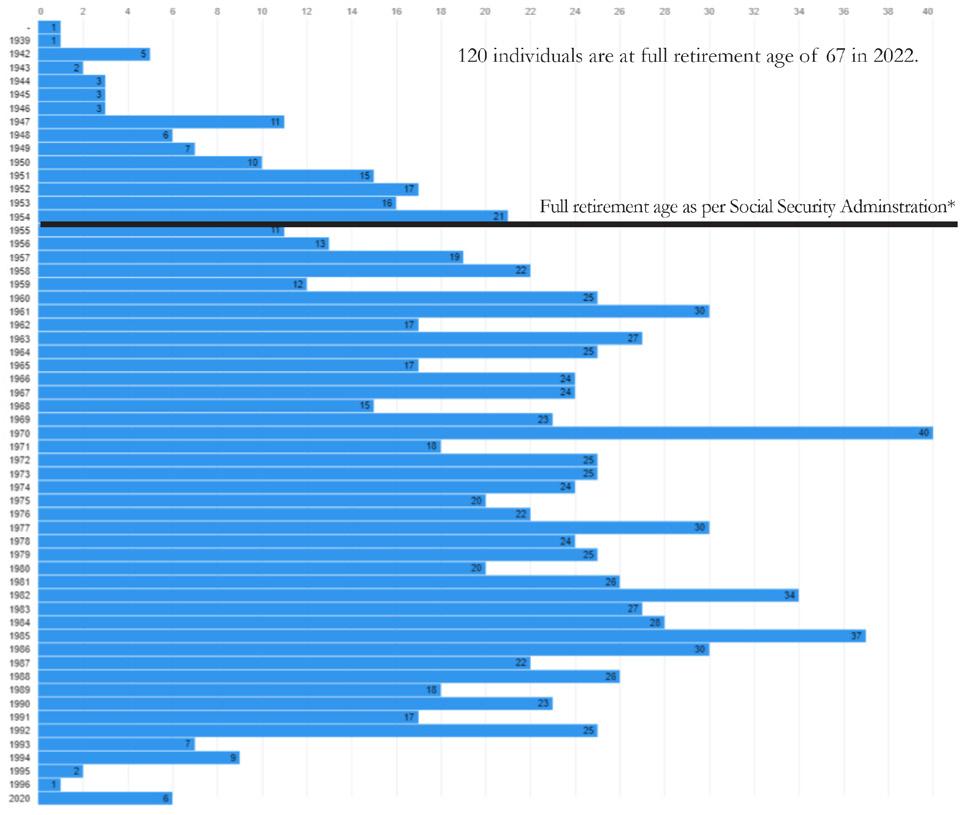

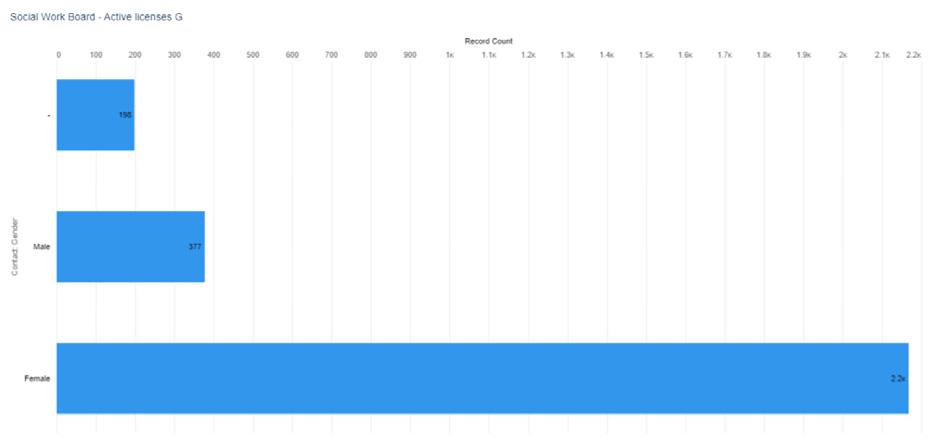

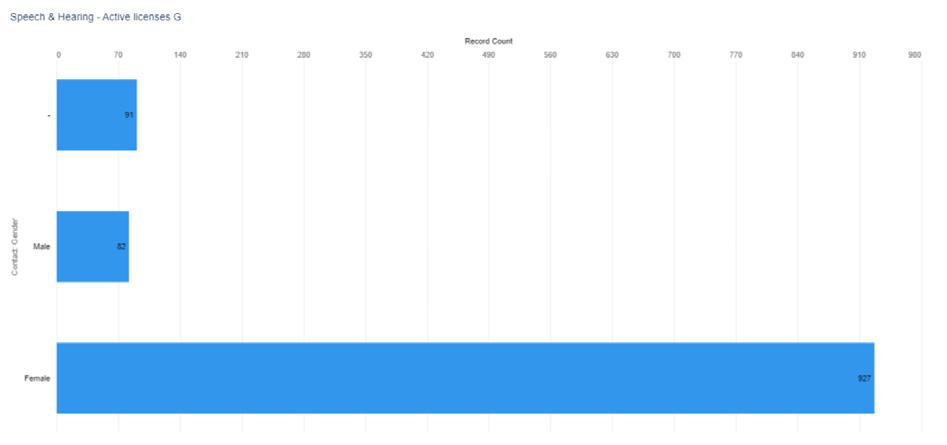

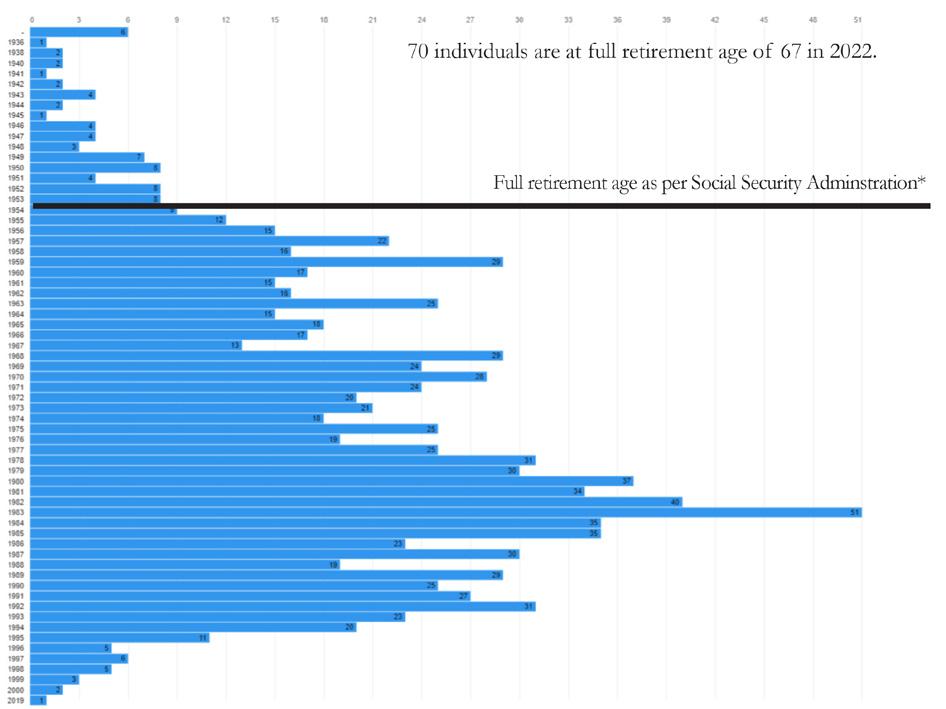

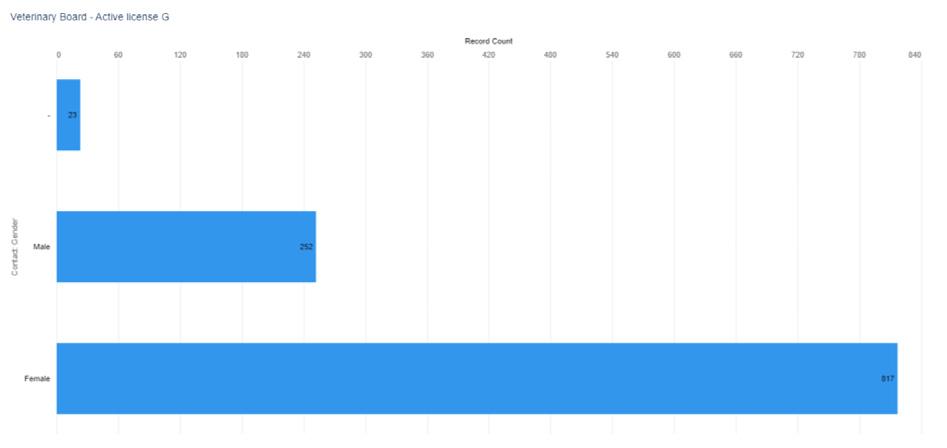

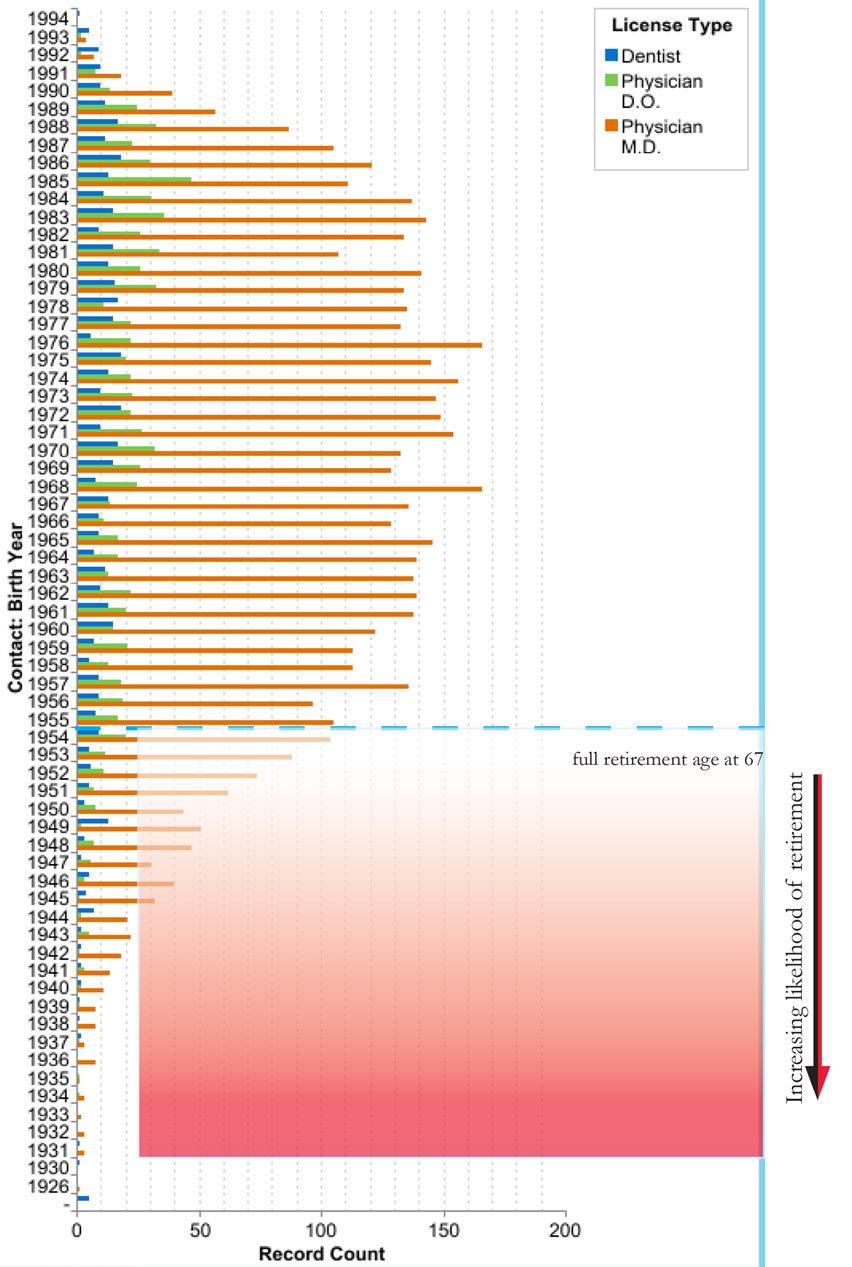

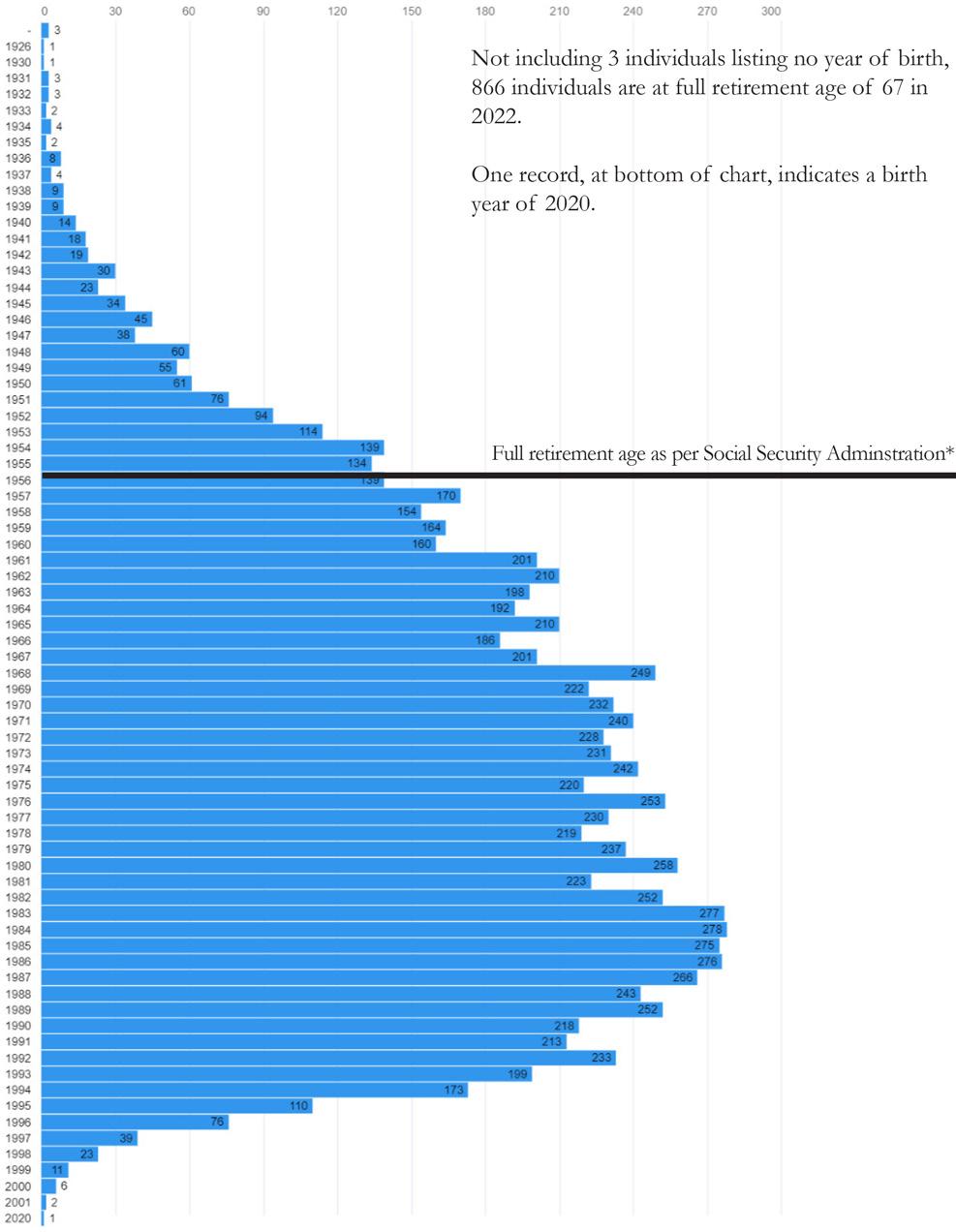

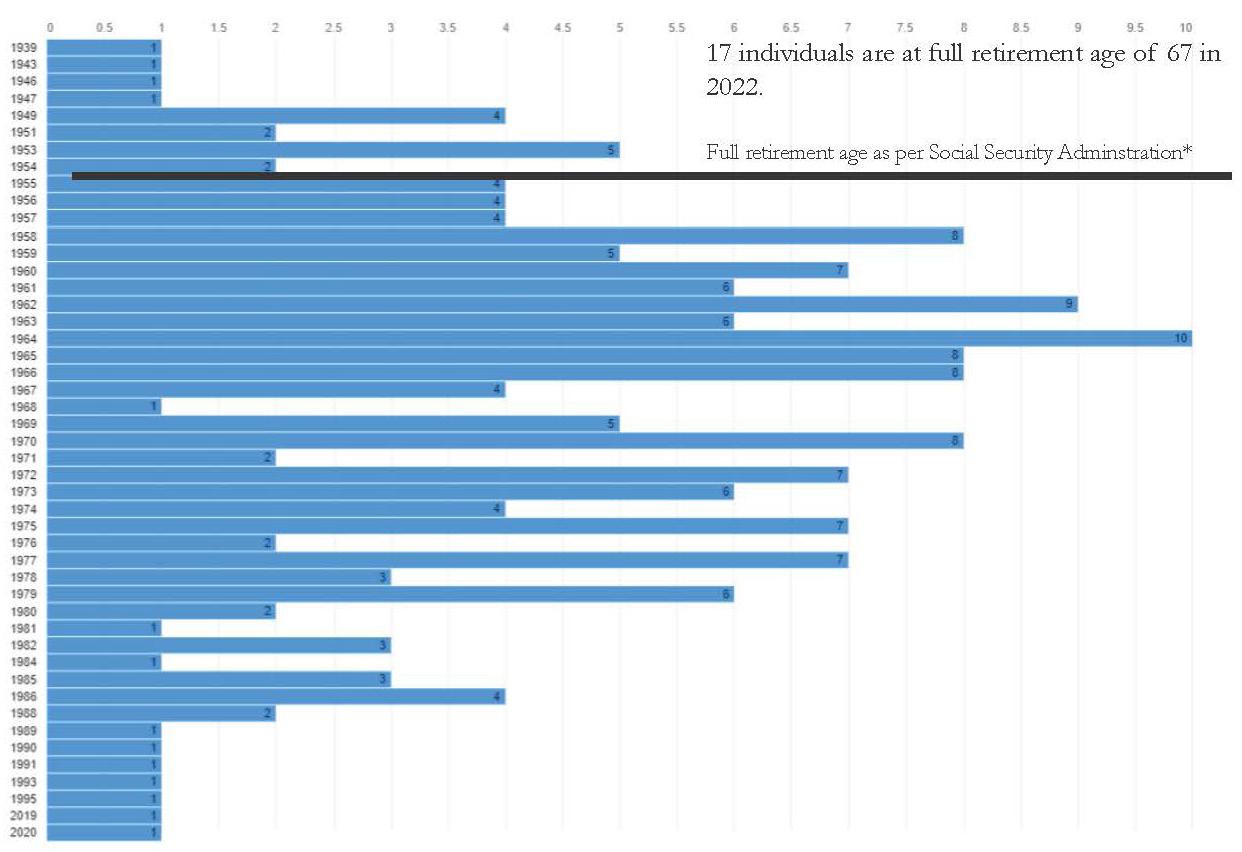

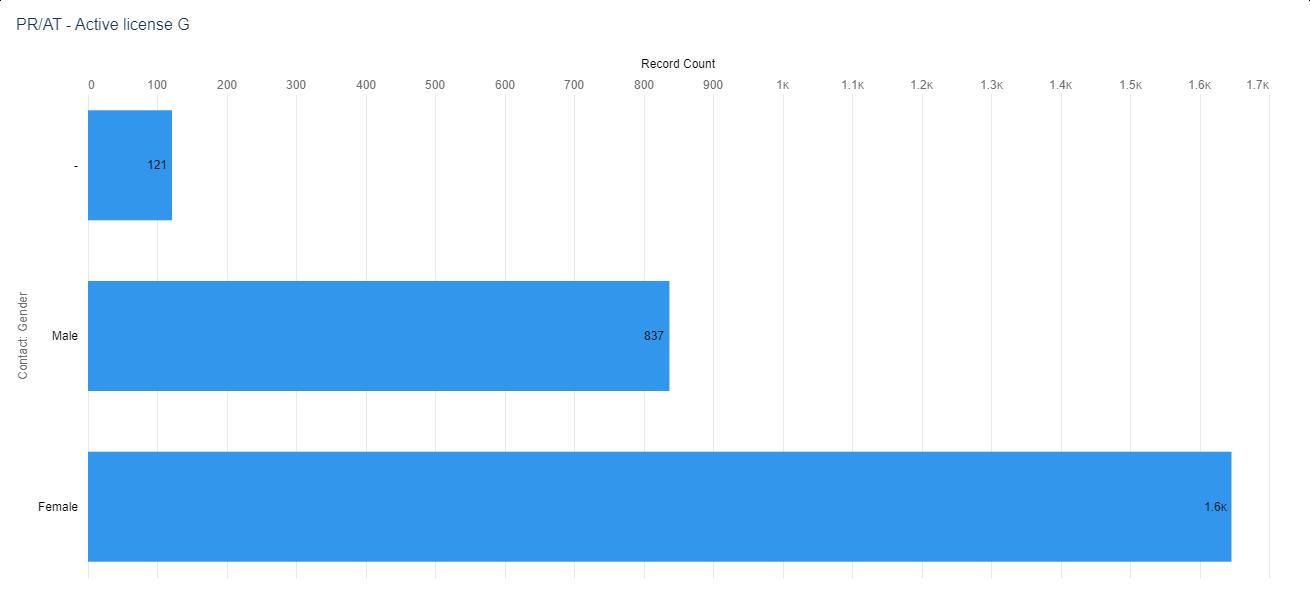

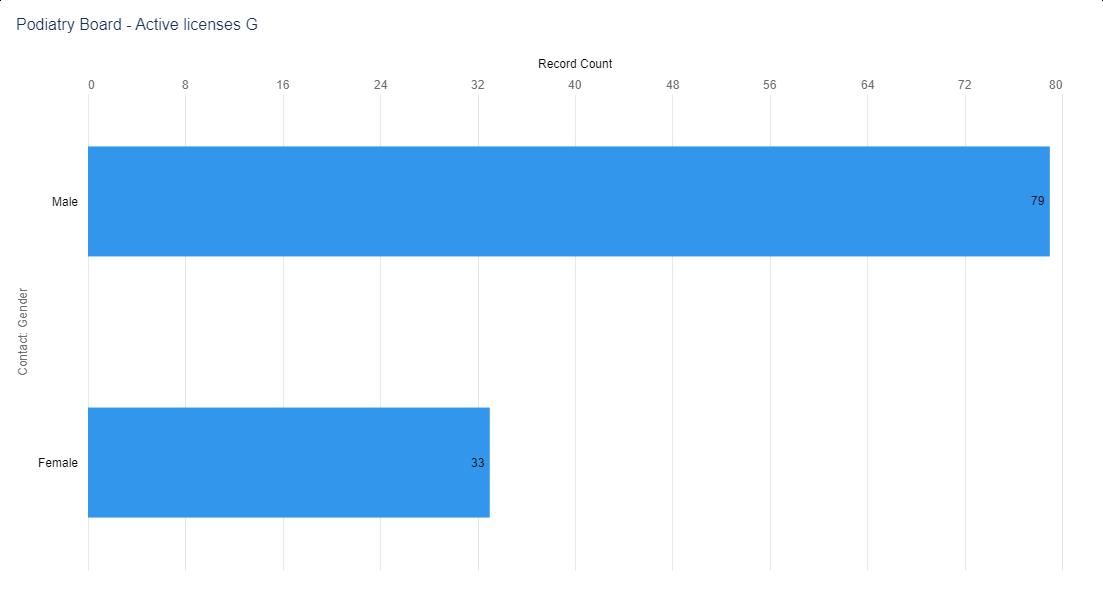

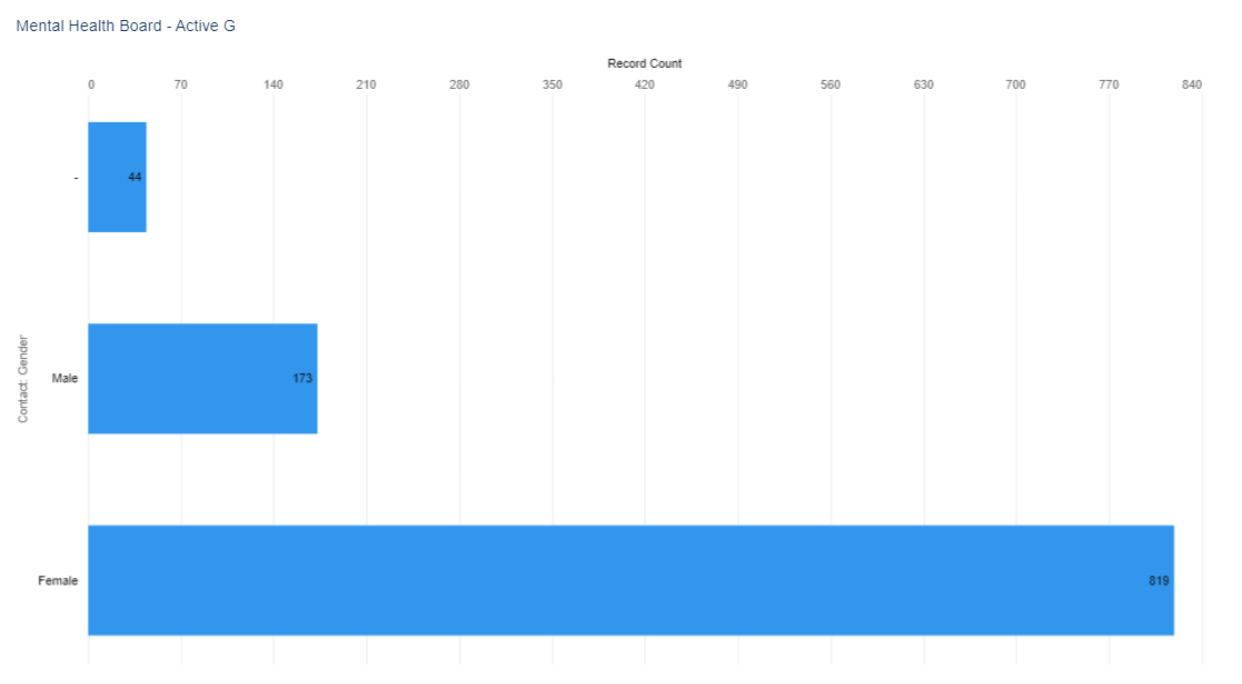

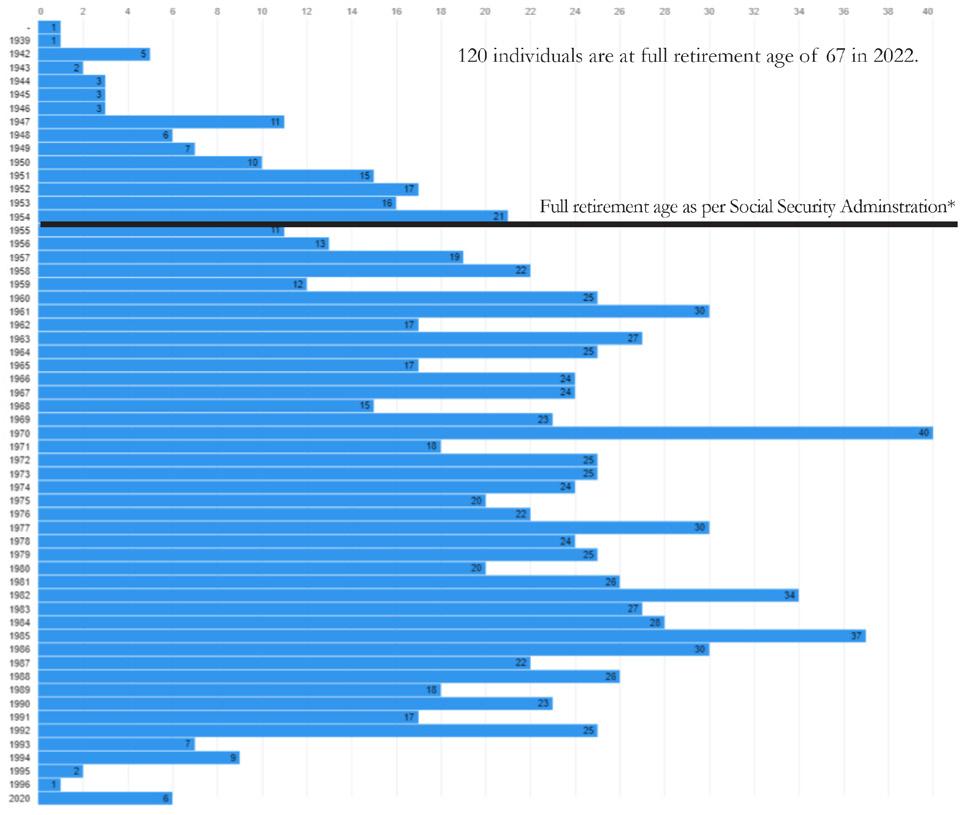

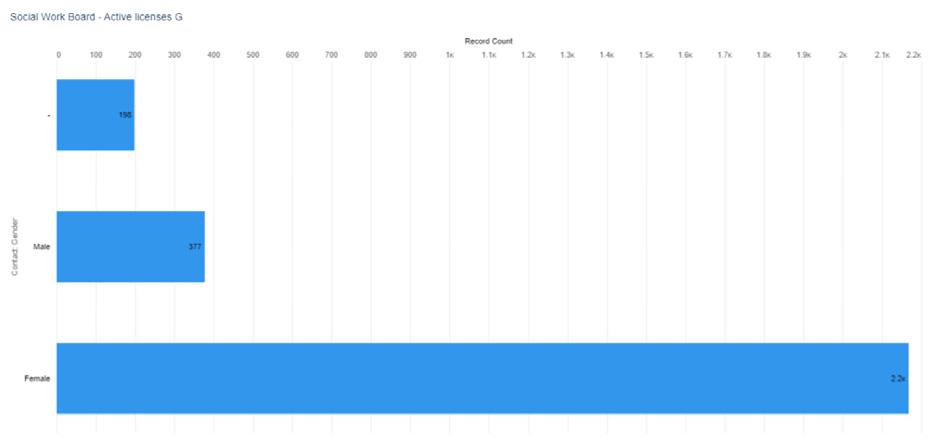

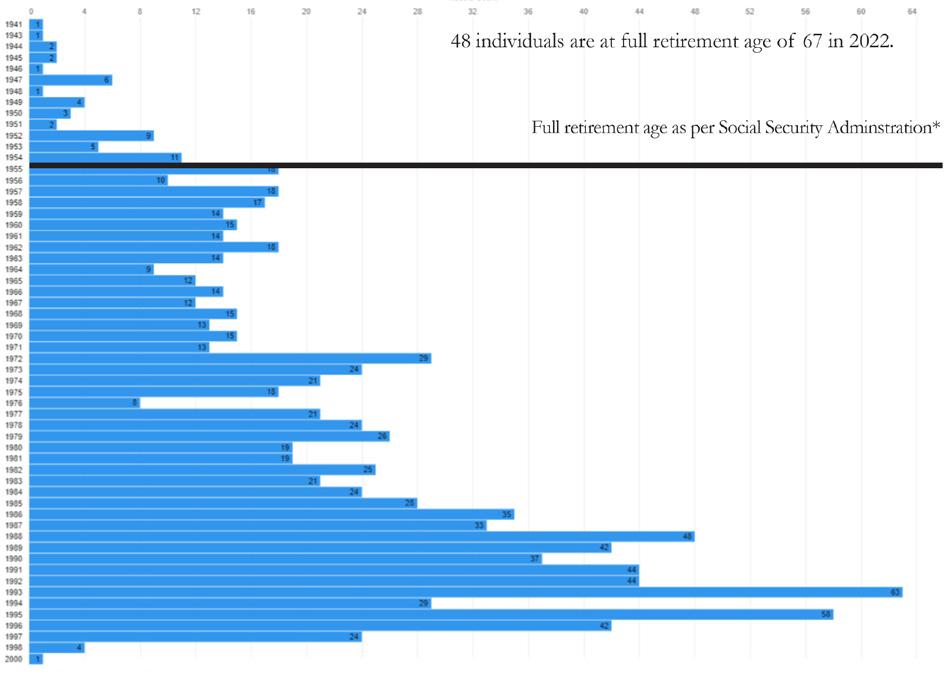

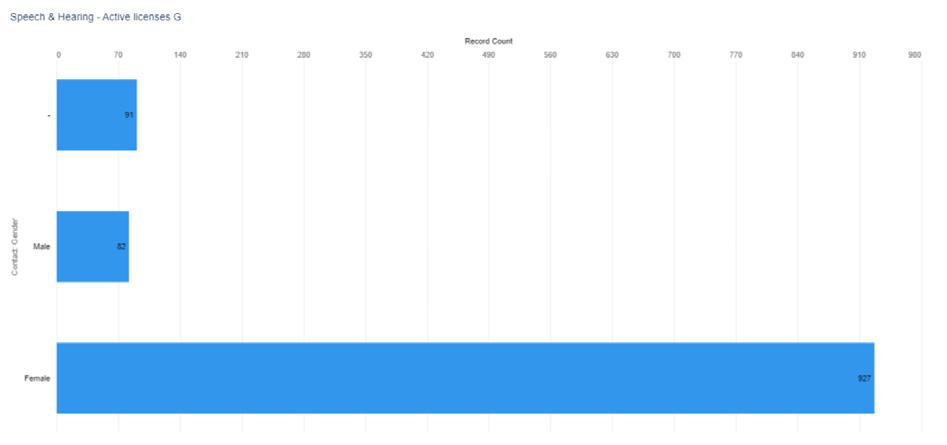

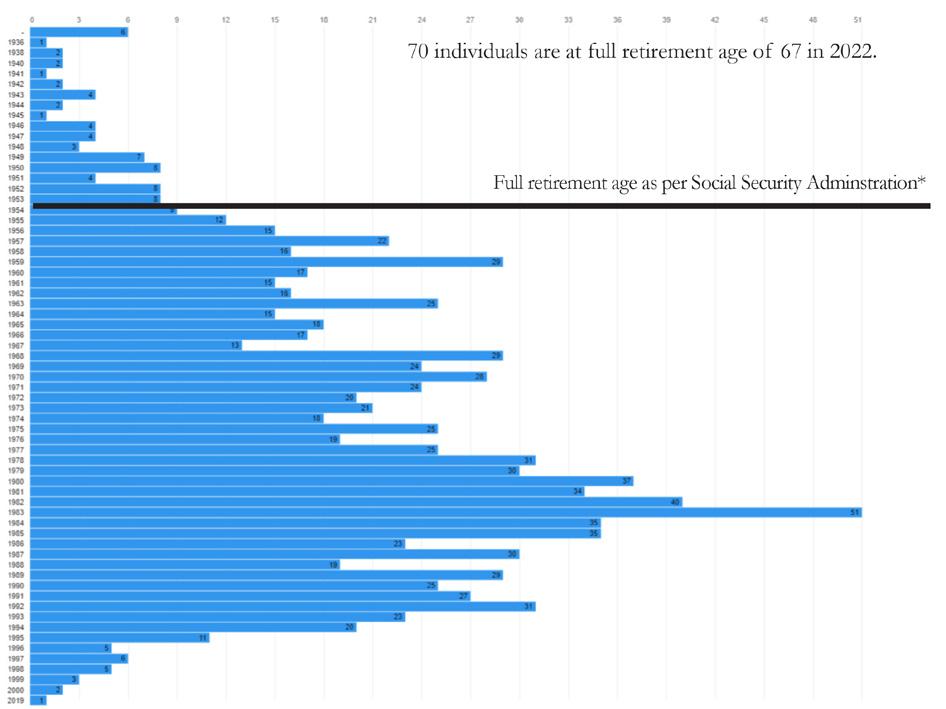

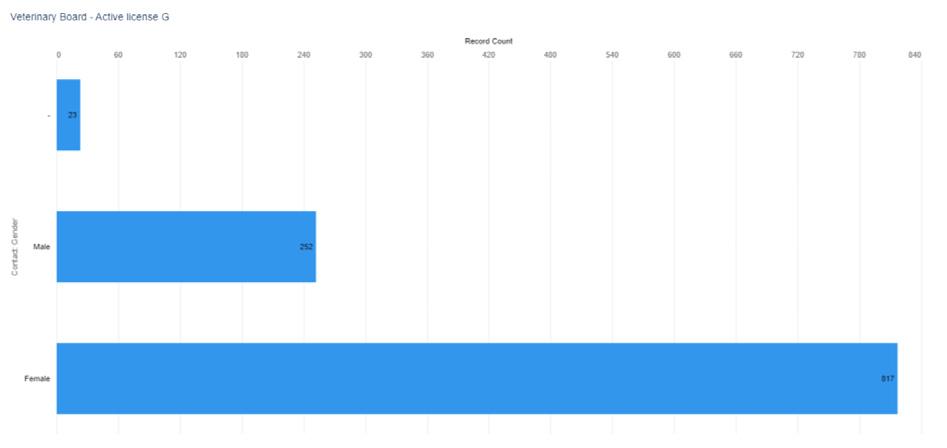

Overall, the licensed healthcare workforce in DELPROS is about 43,000 female (74%) and 15,000 male (26%). Gender is not reported for 4,566 licensees either because individuals did not disclose their gender or because the licensing database contains institutions which do not have a gender demographic. Based on year of birth (where individuals born in 1954 – 1955 are deemed by Social Security as age eligible for full Social Security benefits, we find that no less than 4,600 active licensed individuals are of full retirement age.

The purpose of this first report is not to provide recommendations. Rather this report provides the data and quantitative data analysis capacity to answer additional questions for policy makers and to begin to assess resource allocation to address health care workforce needs in our community. We thank the many institutions mentioned in this report, especially DPR, and look forward to further collaboration which will provide additional, robust information for future reports and a website dedicated to ongoing tracking of this critically important data.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.002

4 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Delaware Department of Health and Social Services

Molly Magarik, M.S. Secretary, Delaware Department of Health and Social Services

Out of every crisis is borne an opportunity for change. Think back to the natural disasters, human conflicts and tragedies, and economic crises that have befallen our country. Each time, when the after-action report is written, an elected body examines the response, or the business community embraces reforms, we benefit as a society from the lessons learned. The COVID-19 pandemic is no different.

During the past two-and-a-half years, we have seen healthcare providers in our state stretched beyond their limits, dealing not only with the impacts brought on by a new and deadly respiratory virus, but also forced to embrace new ways of managing the chronic and acute conditions of their patients, unrelated to COVID-19. We know that this massive disruption to our healthcare system – and to the health of Delawareans – has taken a tremendous toll on our healthcare workforce, with many providers deciding to retire or leave the profession entirely.

And yet, we also are experiencing the opportunity. During the worst of the pandemic, providers across our state embraced telehealth as a way to see their patients for routine medical exams, to diagnose injuries or illnesses, or to continue regular psychiatric sessions. Regulators changed the rules, allowing insurers to reimburse for these services. The federal and state government provided funding to help advance providers’ transition to telehealth services. Patients no longer had to wait in reception areas or exam rooms when they didn’t feel well, because now their provider would call them back – in the comfort of their own home – when they were ready to see them virtually. It all worked because the situation required it.

With the existing shortage of primary care providers exacerbated by the pandemic, patients, providers, employers and insurers all had to adapt to changes in primary care. Often, primary care was delivered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants practicing at the top of their license.

As practices and clinics evolve, we are likely to see this broadening of primary care and the use of telehealth increase. The state is investing in primary care practices, promoting person-centered care and advancing equity, and has embraced the new State Loan Repayment Program, all while continuing to support the Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research (DIMER) to help grow the next generation of primary care providers. We will continue to work with the General Assembly, healthcare providers, insurers and consumers to embrace additional changes that improve the patient and provider experience, improve overall health and help lower costs.

I am grateful to all of the Delaware stakeholders that are leaning into the workforce issue to help determine the best paths forward. In this context, I especially want to thank the Academy of Medicine/the Delaware Public Health Association, the Health Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission, the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance, and the Delaware Journal of Public Health for shining a light on the specific recommendations for Delaware’s workforce outlined in this report.

I look forward to joining stakeholders across our state in examining the recommendations in more detail, exploring the potential benefits, determining the policy changes that are needed, and embracing those changes that will have the most positive impact for the future of the healthcare system in our state – and the future health of Delawareans.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.003

5

U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration

Michelle M. Washko, Ph.D. Director, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

In 2019, the healthcare workforce was 22 million individuals strong. This sector was one of the largest and fastest-growing in the United States, accounting for 14% of all civilian, employed workers in the U.S. The majority worked in hospital settings—about 7 million healthcare workers to be exact. Another 4 million were in outpatient and physician offices, and 3.5 million were in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Home Care settings. All in all, the healthcare workforce was large, growing, and there was a steady amount of jobs that were open, making it a very employable sector overall.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged. As we now know, its impact on healthcare cannot be understated. It changed care delivery and clearly demonstrated the need for sufficiently-sized and well-trained public health, healthcare, and health support workforces. Easy-entry, easy-exit occupations—the lowest-wage earners in healthcare—were the same groups whose employment was the most adversely impacted by COVID. In 2020 alone, total injury and illness cases decreased or remained the same in all sectors except for healthcare, which saw a 4,000% increase in employer-reported respiratory illness.

The pandemic forced states to innovate to meet the needs of their populations, and at the center of that response was the workforce. A number of strategies were implemented in response. Many focused on creating state-level regulatory flexibilities, and engaging the public health workforce. Some states modified scope of practice rules for health professionals, allowing for more autonomous practice. Others allowed health professionals licensed in other states to practice in their state. Additionally, laws and regulations were changed to support greater use of telemedicine. As our nation entered the 3rd year of the pandemic, issues surrounding health workforce capacity, resilience, training, education, and scope of practice have become front and center to moving forward from this phase of our history. While the full impact on our health workforce will not be known for some time, a number of the resulting changes are likely to be long lasting.

Despite the effects of the pandemic, there are several large, persistent policy issues that existed in 2019 and are still present today. These include: sufficiency of the workforce, mal-distribution, quality of healthcare training, and barriers to accessing services. Additionally, there are population factors that have far reaching ramifications for our nation, impacting more than just the health workforce and employment in this sector. First and foremost is the aging of our population. The current cohort of individuals ages 65 and older will continue to generate the majority of demand for healthcare and health support services, and we will need a workforce of sufficient size and distribution to meet this demand. However, this is juxtaposed against the fact that the U.S. birth rate has fallen by 20% since 2007, due to overall lower childbearing rates of current generations. Our population has shown zero growth for several years now, primarily because deaths (attributed to the aging population) exceed births (due to people not having children). Of course, these are issues affecting more than just healthcare in the U.S.

In a nutshell, the health workforce is in flux. We are still understanding the impacts of the pandemic, while having to address previously existing problems. We know that addressing shortages and mal-distributions, continuing to try to improve access to services and train individuals in a way that improves the quality of patient and population outcomes needs to happen. But we must also harness the power of this moment to address pandemic-exacerbated issues like burnout and equity in the workforce.

While it may seem like chaos, there is opportunity in times like this. Despite a low birthrate, demand from our aging population and the after-effects of the pandemic will cause employment in healthcare to grow faster than for other industries. This still allows for great opportunity to tackle the persistent policy issues, and if we follow the data, to craft a better health workforce for the future.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.004

6 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Delaware Healthcare Commission Workforce Subcommittee

Richard J. Geisenberger, M.G.A. Nicholas A. Moriello, R.H.U.

As co-chairs of the Workforce Subcommittee of the Delaware Healthcare Commission, we are pleased to welcome you to the first “State of the Healthcare Workforce in Delaware: Action and Opportunity” Report.

This report focuses on select components of the healthcare workforce, including primary care, dentistry, behavioral health, and others. It seeks a broader view of the entire healthcare sector, composed of physicians, dentists, nurses, physician assistants, the allied therapies, dental hygienists, and a vast ecosystem of providers.

We acknowledge and appreciate the work of others in this space. Work on this initiative was started by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA) and the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance (DHSA) long before the COVID-19 pandemic changed our world, and the landscape of healthcare. As the reader knows, the pandemic directly and profoundly impacted both healthcare systems and individual providers.

Before the pandemic, there were tectonic workforce and demographic challenges facing almost every major industry in our State and our nation: the aging of our population, the related increase in the incidence and burden of chronic disease, and the concurrent aging of the healthcare workforce. And the financial impact is clear: the healthcare industry is rapidly approaching one-fifth of the United States Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The contents of this report are based upon an unprecedented collaboration between multiple components of State government including the Delaware Healthcare Commission, the Division of Professional Regulation, the Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research (DIMER), the Division of Public Health Primary Care Office, and the Departments of Finance and Labor. They are joined by the Academy/DPHA, DHSA, and the Delaware Health Information Network, and many other organizations playing essential smaller roles.

This public-private partnership has gathered data on the healthcare workforce and analyzed the needs—both current and future—of the State of Delaware. The strategies within this report are based on hard data and analysis and recommend support for polices that will strengthen the healthcare workforce for years to come.

During the past two-years of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have experienced stress and crisis. We now have an extraordinary, federally-funded opportunity to take meaningful action to address the opportunities in our healthcare sector for employment throughout the workforce, as well as novel models (including telehealth and nurse-led health clinics) leading the way.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.005

7

From the Delaware Academy of Medicine/ Delaware Public Health Association

S. John Swanson, M.D.

President, Board of Directors, Delaware Academy of Medicine/Delaware Public Health Association

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

Executive Director, Delaware Academy of Medicine/Delaware Public Health Association

On behalf of the board and advisory council of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/ DPHA), we are pleased to be the lead institution in the public/private partnership named Delaware Health Force, and the author of this report, which includes content from other experts in the field.

The Academy/DPHA started this initiative in early 2019, long before the COVID-19 Pandemic swept around the world and across our State. In the beginning, this effort focused on the State of Delaware’s DIMER (Delaware Institute for Medical Education and Research) program and its graduates for the 50th Anniversary Report of the program. As data was collected and analyzed, we realized we were pursing an important vein of data which, if related to other information, could supply policy makers and resource allocation alike.

We are informed by the Social Determinants of Health (see Figure 1), in particular the healthcare access and equity components (often overlooked due to their perceived to be relatively minor role in health outcomes). Many scholarly articles have been written citing healthcare as being responsible for ten to twenty percent of health outcomes,2 however if an individual or community is medically underserved or has acute shortages of a variety of healthcare facilities, that 10% can become the single largest barrier to care for those who seek or need it.2

We are also informed by the reality that the healthcare landscape is a complex one, and that simply looking at the physician component of the workforce, or the anchor institutions (hospitals) providing care, is not enough to truly understand the nature of opportunity for workforce enhancement. Today’s healthcare is a series of interlocking systems of care, and the better those connections, the stronger the fabric of the safety net of care for our fellow Delawareans.

Several methodologies were considered before we settled on the approach used to generate this report. Some of those methodologies are used to great success by other researchers analyzing specific parts of the healthcare landscape (e.g., voluntary surveys). This report does not replace the high value of that research. Instead, it expands upon that research with additional data and analysis. Our methodology is articulated in depth in a later section of this report. For now, we extend sincere thanks to our institutional and individual partners:

• Delaware Division of Professional Regulation and Division Director, Geoff Christ;

• Delaware Health Information Network, Executive Director, Jan Lee, MD and staff;

• Agile Cloud Consulting and President and CEO, Sharif Shaalan and staff;

• TechImpact and Delaware Innovation Lab Director of Strategy and Operations, Ryan Harrington, and Director, Research Development & Analytics Data Lab, Héc Maldonado-Reis, and staff;

•Delaware Nurses Association Executive Director, Chris Otto; and

• The team at the Academy/DPHA including Kate Smith, MD, MPH; Matt McNeill, BS; Nicole Sabine, BS; Caroline Harrington, MS, and members of the Board of Directors.

REFERENCES

1. Healthy People 2030. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

2. Artiga, S., & Hinton, E. (2018, May). Beyond health care: The role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. KFF.org.

https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

10.32481/djph.2022.12.006

DOI:

8 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Figure 1. The Social Determinants of Health1

9

Welcome from the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. President and CEO, Delaware Health Sciences Alliance

Pamela

Gardner, M.S.M. Program Manager, Delaware Health Sciences Alliance

The Delaware Health Sciences Alliance (DHSA) was established in 2009 with founding partners ChristianaCare, Nemours Children’s Health, Thomas Jefferson University, and the University of Delaware. Since then, additional partners have joined including the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Bayhealth Medical Center, and the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association.

The alliance enables partner organizations to collaborate and conduct cutting-edge research, to improve the health of Delawareans through access to services in the state and region, and to educate the next generation of healthcare professionals.

The DHSA’s unique, broad-based partnership focuses on establishing innovative collaborations among experts in medical education and practice, health economics and policy, population sciences, public health, and biomedical sciences and engineering.

This report, and the work behind it, is an example of the fruits of collaboration. In this case, through our partnership with the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA). In addition, the original work conducted by DHSA and the Academy/DPHA which was the basis for the DIMER 50th Anniversary Report and subsequent annual reports, continues in this report as reflected in key data as well as the recommendations section.

As mentioned elsewhere in this report, Delaware Health Force is comprised of four programmatic components: the core data and research initiative upon which this report is based, the expansion of Delaware Mini Medical School, the expansion of Student Financial Aid for Delawareans, and the expansion of key graduate education and fellowship programs. The DHSA is pleased to support all these programs, in particular those which directly address the pipeline of Delawareans pursuing a career in the health sciences generally, and in medicine and dentistry in particular.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.007

10 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Delaware Division of Professional Regulation

Geoffry Christ, R.Ph., J.D.

Director, Delaware Division of Professional Regulation

The mission of the Division of Professional Regulation (DPR) is to ensure protection of the public’s health, safety, and welfare. Our services benefit the citizens of Delaware, professional licensees, license applicants, other state and national agencies, and private organizations.

DPR provides regulatory oversight for 34 boards/commissions comprised of Governor-appointed public and professional members. Oversight activities include administrative, investigative, and fiscal support for 54 professions, trades and events with over 200 types of licenses and permits. License fees fund DPR and the expenditures related to each licensing board.

The following types of healthcare, and healthcare related services, are overseen by DPR:

Acupuncture

Acupuncture Detoxification

Art Therapy

Athletic Trainers

Audiology

Chemical Dependency Professionals

Chiropractic

Controlled Substances

Counselors of Mental Health

Dental

Dietitians

Eastern Medicine

Genetic Counselors

Hearing Aid Dispensers

Marriage and Family Therapy

Massage and Bodywork

Medical Practice

Mental Health

Midwife (Nursing)

Midwife (non-Nursing)

Nutritionist

Occupational Therapy

Optometry

Paramedic

Pharmacy

Physical Therapy

Physician

Physician Assistant

Podiatry

Polysomnographer

Psychology

Respiratory Care

Social Workers

Speech Pathology

Tamper-Resistant Prescriptions

Veterinary Medicine

The Division is pleased to collaborate on this important initiative through the sharing of publicly available information. The Division looks forward to the findings that result from the information it shares through collaboration.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.008

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

11

•

Delaware Nurses Association

Christopher E. Otto, M.S.N., R.N., C.H.F.N., P.C.C.N., C.C.R.N. Executive

Director, Delaware Nurses Association

The Delaware Nurses Association (DNA) was established in 1911 in Claymont, DE and has served to advance the profession of nursing and our collective mission to improve the health of all Delawareans. We are the only professional association in Delaware representing all Licensed Practical Nurses, Registered Nurses, and Advanced Practice Registered Nurses. We continue to advance health through the art and science of nursing supported by diverse members, advocacy, professional development, generation of new knowledge, effective communication, and community service.

In addition to our robust and inclusive membership, we also facilitate an organizational affiliate program. This program brings together state specialty nursing associations and health-related associations with nursing representation together. The goal of the organizational affiliate program is to strengthen nursing’s and healthcare advocate’s voices in the reformation of healthcare delivery in Delaware.

In addition to sharing physical space, DNA has a long history of collaboration with the Delaware Academy of Medicine/Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA). This includes interprofessional education, removing scope of practice barriers and advancing public health. Both organizations continue to partner with new endeavors. For example, the design and launch of Healthy Nurse Healthy Delaware, a program spearheaded by DNA to support Delaware nurses’ mental health and overall wellbeing.

The DNA is proud to partner with the Academy/DPHA on Delaware Health Force and further inform efforts to grow, strengthen and advance Delaware’s healthcare workforce. At DNA, we appreciate the importance of robust data and transparent reporting to further inform efforts that will support Delaware’s healthcare workforce and access to high-quality, equitable, affordable and convenient healthcare services for all Delawareans.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.009

12 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Mark B. Thompson, M.H.S.A.

Executive Director, Medical Society of Delaware

The Society is one of the oldest institutions of its kind in the United States and rich in history. It was founded in 1776 and incorporated on February 3, 1789, only 12 days after President Washington took his oath of office. The first official meeting of the Society was held in Dover on May 12, 1789.

Today, the Apollo Youth in Medicine program provides opportunities for high school students who are interested in a physician career path to shadow practicing physicians and further pursue their interests in the medical profession.

With the support of The Medical Society of Delaware (MSD) and Delaware Youth Leadership Network (DYLN), the Apollo: Youth in Medicine program (see Figure 1) was founded by Sean Holly and Arjan Kahlon in the summer of 2018, with John Kepley joining the leadership team shortly after. Since then, the Apollo leadership team has grown to be led by several focused & resourceful students who are firmly supported by MSD and DYLN.

Together this team supports and coordinates opportunities and activities for Apollo students and their high schools with participating Apollo Physician Mentors.

APOLLO: YOUTH IN MEDICINE

Apollo was founded on the idea that high school students interested in the medical field need an outlet to connect them to opportunities present in the medical community, and that clinical shadowing provides valuable first-hand insight allowing exploration. Apollo has expanded its physician network to allow students across Delaware expansive access to shadowing in 17 medical disciplines. The Apollo Program is Multistep

1.) Delaware high school juniors and seniors are invited to apply every fall through our application.

2.) New students representing multiple Delaware high schools attend a fall education session that covers specific topics such as different specialties in medicine, and the academic pathway to becoming a doctor. Here, Students receive HIPAA training through Apollo, enabling them to shadow in physicians’ offices appropriately.

3.) Apollo gives students access to several shadowing slots offered by dozens of Delaware physicians across various specialties through ‘The Match,’ which occurs multiple times per year. Students can choose as many or as few shadow slots as they’d like.

4.) In addition to shadowing opportunities, Apollo serves as a liaison to gain our students optional access to medical seminars and exclusive Apollo Enhanced Experiences.

Additional information can be found at their website, https://www.apolloprogram.org/

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.010

13

Figure 1. The Apollo Youth in Medicine Program Logo

Flu cases in Delaware soared to 1,404 laboratoryconfirmed cases as of November 12, according to the Division of Public Health (DPH). Of the total number of flu cases, 598 were reported between November 6 and 12

Slightly more than a quarter of the state’s population (26.2%) had received a flu vaccination as of November 12. DPH urges all Delawareans 6 months of age and older to get their annual flu vaccine as soon as possible to protect against flurelated illness, hospitalization, and death.

Flu vaccination also frees the state’s health care providers to address other respiratory viruses such as COVID-19 and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), which are especially dangerous to infants, young children under 2 and seniors

To find vaccine sites, use DPH’s Flu Vaccine Finder at flu.delaware.gov Uninsured and underinsured individuals can get flu vaccinations at Public Health Clinics and at community-based locations where DPH mobile units provide additional health services.

DPH launched its flu dashboard on My Healthy Community earlier this month.

The flu dashboard will share the state’s weekly and seasonal data on positive cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and for the first time, vaccinations. Updates will occur weekly on Thursdays for local data, and monthly for other geographies. Access the flu dashboard at https://myhealthycommunity.dhss.delaware.gov/home or click on the ‘Weekly Flu Data’ link at flu.delaware.gov.

flu.delaware.gov or call 1-800-282-8672.

Help Me Grow celebrates 10th anniversary

The Division of Public Health’s (DPH) Maternal Child Health (MCH) Bureau, Delaware 2-1-1, and other state and community organizations proudly recognized the 10th anniversary of the Help Me Grow Delaware program on November 9 at the Route 9 Library & Innovation Center in New Castle. Help Me Grow connects families with children at risk for developmental and behavioral challenges to community-based programs and services.

The MCH Bureau presented plaques to three individuals for their contributions to the program:

• Matthew Denn: During his tenure as Insurance Commissioner, Denn helped pass legislation that mandated insurance coverage of developmental screenings and provided funding to promote screenings in primary care, improving access across the state.

• Norma Everett: As the Early Childhood Comprehensive Systems Manager, Everett built community stakeholder relations to improve conditions for Delaware families and opened the door for collaboration that resulted in the passing of developmental screening legislation in 2009.

• Dr. Aguida Atkinson: She spent her career advocating for community health and, as Help Me Grow Physician Champion, continues to work toward improving Delaware's early childhood system through collaboration and innovation.

Of 19,693 calls to Delaware 2-1-1, a confidential, toll-free help hotline, 17,076 children were served. Learn more at DEThrives.com/Help-Me-Grow.

November 202

From the Delaware Division of Public Health

Delawareans urged to get vaccinated as 1,404 flu cases reported statewide

Three individuals were recognized for their contributions to the Help Me Grow program, now in its 10th year. From left: Paulina Gyan of the Division of Public Health’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Doug Tyan with Bryn Mawr Psychological Associates , and awardees Dr. Aguida Atkinson, Norma Everett, and Matthew Denn. Photos by Sharon Smith.

14 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Telehealth: a new public health tool

Telehealth is the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to provide longdistance health care. Live videoconferencing, remote patient monitoring, streaming media, and land and wireless communications are examples of telehealth technologies.

Telehealth is a service delivery option that enables physicians and practitioners to provide health care throughout Delaware. Patients may be able to avoid lost wages, travel expenses, and childcare costs; overcome transportation barriers; and access services privately without worrying about any perceived stigma.

In Delaware:

• Telehealth services can be accessed, provided there is an established physician-patient relationship. This relationship can be established through previous in-person visits or through an initial telehealth visit.

• Informed consent is required and must comply with current HIPAA requirements.

• Prescriptions may be prescribed through a telehealth visit once the physician-provider relationship is established.

• Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance carriers reimburse for telehealth services if those in-person services are covered.

• Telehealth appointments can occur through the use of audio-only technologies.

Visit the 2022 National Telehealth Conference Summary B and Telehealth.HHS.gov for how to use telehealth, prepare for a virtual visit, policies, reimbursement, and best practices.

Other sources are the Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resource Center (https://www.matrc.org/) and the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration’s Office for the Advancement of Telehealth: https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/topics/telehealth.

COVID-19 bivalent boosters advised

The Division of Public Health (DPH) recommends that all eligible Delawareans ages 5 years+ get vaccinated without delay for protection from severe COVID-19 disease, hospitalization, and death.

Individuals ages 5+ are eligible for the COVID-19 bivalent booster if they completed their primary series (gotten both doses of a two-dose vaccine) at least two months ago.

Bivalent boosters target both the original strain of COVID-19, and BA.4/BA.5 strains of the Omicron variant. They provide better and updated protection against the virus. The original boosters (monovalent) from Pfizer and Moderna are no longer available.

For bivalent booster information, visit de.gov/boosters. For vaccination sites, visit de.gov/getmyvaccine. For COVID-19 data, visit My Healthy Community. For COVID-19 information, visit https://coronavirus.delaware.gov/, email delaware211@uwde.org, or call Delaware 2-1-1. Individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing can text their ZIP code to 898-211 weekdays 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. and Saturdays 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus

Monkeypox cases gradually decline

Only two new monkeypox (MPX) cases were reported to the Division of Public Health (DPH) between October 14 and November 16. As of November 18, DPH received reports of 43 MPX cases: 29 in New Castle County, five in Kent County, and nine in Sussex County. In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 29,080 MPX cases as of November 18, with New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. each having between 522 and 855 cases.

Visit de.gov/monkeypox for more information about MPX vaccination for at-risk individuals and health care workers who provide direct patient care to confirmed or suspected MPX cases. Email questions to DPHCall@delaware.gov

The DPH Bulletin – November 2022 Page 2 of 4

Getty Images

15

Daily Monkeypox Cases Reported and 7-Day Daily Average, U.S., May 17, 2022 - November 16, 2022

Caregiver Resource Centers offer support

Whether caring for a parent diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a loved one who suffered a stroke, or a child with a disability, caregivers benefit from information, assistance, and support. They can find those things and more through the Delaware Caregiver Resource Center (CRC) Network.

CRCs in all three counties help caregivers navigate services systems, find solutions to individualized concerns, make appropriate referrals, conduct support groups, and provide specialized training to caregivers. Center coordinators understand the challenges that caregivers face. The CRCs are supported by the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services’ (DHSS) Division of Services for Aging and Adults with Physical Disabilities (DSAAPD)

The six CRC locations include: Easterseals Delaware & Maryland’s Eastern Shore (which operates a CRC in New Castle and Georgetown), the Wilmington Senior Center (with a Latino outreach specialist), Newark Senior Center, Modern Maturity Center in Dover, and the CHEER Community Center in Georgetown.

Caregivers seeking communication devices and modified items that support people with daily tasks, employment, and play can visit three assistive technology centers in person through the Delaware Assistive Technology Initiative’s (DATI) or in person and virtually at Easterseals’ demonstration center in New Castle. Caregivers can explore assistive devices such as medication reminders, adapted keyboards, smart devices, and other assistive technologies such as a smartphone application Search DATI’s lending inventory at www.dati.org/loan/search_inventory_new.php

For more information, visit Delaware's Aging and Disability Resource Center or call 1-800-223-9074.

November honors family caregivers

November is National Family Caregivers Month Caregiving is a physically and emotionally exhausting job According to National Today, most caregivers have additional jobs and most family caregiving is unpaid.

Easterseals’ respite voucher program, supported by the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services’ (DHSS) Division of Services for Aging and Adults with Physical Disabilities, gives family caregivers a much-needed temporary break. The DHSS Division of Developmental Disabilities Services, Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance, and hospice agencies also offer respite. Adult day care programs offer activities for seniors, veterans, and adults with physical disabilities and individuals with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. The DHSS Division of Health Care Quality provides a list of licensed adult day services

Caregiving resources

Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Services for Aging and Adults with Physical Disabilities (DSAAPD): Delaware's Aging and Disability Resource Center (ADRC), 1-800-223-9074, delawareadrc@delaware.gov. Caregiving information, including an Alzheimer’s toolkit and a legal handbook for relatives raising children

The Guide to Services for Older Delawareans and Persons with Disabilities

Assistive technology centers: The Resource and Technology Demonstration Center, 61 Corporate Circle, New Castle, Delaware 19720. Open Monday through Friday, 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.; or take a virtual tour at www.easterseals.com Contact them at 302-221-2087 or resources@esdel.org

Delaware Assistive Technology Initiative’s (DATI) lending libraries:

• University of Delaware Center for Disabilities Studies, 461 Wyoming Road, Newark, Delaware 19716-5901, Newcastle.atrc@dati.org, 302-831-0354

• Milford Wellness Village, 21 West Clarke Avenue, Suite 1200, Milford, Delaware, 19963, kent-sussex.atrc@dati.org, 302-739-6885.

The DPH Bulletin – November 2022 Page 3 of 4

16 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Getty Images

Display address numbers

correctly

Can first responders quickly find your residence or business during an emergency?

New Castle County, Kent County, and Sussex County require structures and mailboxes to have legible address numbers that are visible from the street or road fronting the property. Structures that sit back from the road and/or are hidden are required to display address numbers on a pole, sign, monument placed where the driveway meets the street or road.

New Castle County Code requires residences to have Arabic or alphabetical characters that are at least 4” tall and a half-inch wide. They must contrast with their background and not be spelled out. Reflective numbers are not required. For more information, visit the New Castle County Department of Land Use or call 302-395-5572.

Kent County Code requires address residential numbers to contrast with their background, be either Arabic numbers or alphabetical letters, and be at least 4” tall and three-quarters of an inch wide Reflective numbers are not required. For more information, including commercial requirements, visit the Kent County Department of Planning Services or call 302-744-2451.

Sussex County Code requires address numbers on residences, townhouses, and businesses to be reflective, in block style, contrast with their background, and be visible from both sides of the street or road during day and nighttime hours. Numbers should be at least 3” tall on mailboxes and 4” tall on the side of residences, townhouses, and businesses. Apartment buildings and high-rises must display 6” reflective numbers above or to the side of the main entrance and above or to the side of the doorway of each unit. For more information, including industrial and commercial requirements, visit the Sussex County Geographic Information Office or call 302-855-1176.

Smoke detectors save lives

Your family only has four minutes or less to escape a house fire. Working smoke detectors reduce house fire deaths by as much as 70 percent.

Del. Code Title 16, Chapter 66, Section 6631 requires that smoke detectors be installed at each level of the home, including the basement, and outside each bedroom or group of bedrooms. The Delaware State Fire Marshal’s Office explains the law and includes placement diagrams; visit https://statefiremarshal.delaware.gov/specialprograms/smoke-detectors/.

Occupied residences constructed before July 8, 1993, are required to have individual, single station, battery-powered smoke detectors. Owners of occupied residences constructed after July 8, 1993 are required to have a licensed electrician install hard-wired smoke detectors powered by household electricity. Multiple smoke detectors must be wired so that if one smoke detector sounds, they all will sound. Most experts recommend that homes have hard-wired smoke detectors with a battery backup to provide protection with or without power. In rented or leased units, tenants are responsible for maintaining the smoke detector battery.

The Delaware State Fire School recommends following these fire protection steps:

• Every month, test a smoke detector by pushing its test button. It should loudly beep or chirp. Dust it regularly.

• Replace batteries whenever the smoke detector chirps or beeps and when changing the clocks to daylight savings time. Ten-year 10-year lithium batteries are good for 10 years from the date of manufacture, not 10 years from installation. Mark the date of manufacture on the outside of the smoke alarm to remind you when to replace it.

• The blind and deaf can purchase smoke detectors with a strobe-light feature and a vibration appliance placed beneath your pillow.

• If you cannot afford to purchase a new smoke detector, ask your local fire company if they distribute them.

For more information, visit the Delaware State Fire Marshal’s Office, the Delaware State Fire School or the National Fire Protection Association, which has fire safety information in different languages

The DPH Bulletin – November 2022 Page 4 of 4

17

Getty Images

Origins of the PCP Shortage

Sharon Folkenroth Hess, M.A. Collections Manager and Archivist, Delaware Academy of Medicine/Delaware Public Health Association

In John Thomas Scharf ’s History of Delaware: 1609 to 1888, the chapter “Medicine and Medical Men” concludes with a directory of all physicians registered with the clerk of the peace. The detailed list starts on page 507 and ends halfway down page 508 after just 230 names. He does not mention other healthcare providers, such as barbers, nurses, or unregistered doctors. With a population of ~146,608, Delaware doctors were outnumbered 638 to one.1 Though when bleeding, blistering, and purging are used as curatives, this ratio of providers-to-patients likely benefited many nineteenth-century patients and increased their chances of survival. However, even as medical science improved and the population increased, the number of doctors in the state remained roughly the same. In 1910, the state had grown to 202,322 inhabitants but added only 17 physicians— approximately 820 people for every doctor.2 Today, the ratio of primary care providers to patients in the state remains alarmingly high at 1,418 to one. While the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, our state has grappled with a healthcare workforce deficit for over a century.

THE WAY IT WAS

For most of human existence, healthcare happened at home. Generations of the sick or injured relied on the wisdom and support of family and community. Extra medical care came as a house call. With tools in tow, the doctor arrived ready to perform any number of treatments in any setting. Hospitals were few and primarily provided charitable care for the friendless and destitute. Medical training for rural doctors, such as it was, often happened ‘on the job’ with an apprenticeship. City physicians or those caring for wealthy families went to for-profit, proprietary medical schools. The professional training they provided was not much better— in two 16-week terms, a medical student read the required materials, attended lectures, and passed their exams, sometimes without touching a human patient.

To provide some oversight of the field, Delaware created a Board of Medical Examiners in 1802. Chief among their duties was to establish a system for issuing medical licenses. The requirements included “the presentation of a diploma conferred by a reputable college of medicine” or an examination by the Board, a thesis on a medical subject, and a $10 fee.3 However, even this bare-bones process was compromised within a few decades when the state legislature exempted homeopaths— allowing them to administer a separate self-regulated assessment system instead. Unfortunately, these competing systems decreased the state’s medical community’s reputation, rendering Delaware-issued licenses valid within her borders only.4

THE TIMES, THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’

By the end of the nineteenth century, the theory and practice of medicine in America began to change. With the growing acceptance of germ theory, centuries-old humoral and miasmal theories fell aside. Medicine quickly became a science rather than an art, requiring greater accountability from its practitioners. Sanitation, vaccination, and education became top public health priorities. Delaware’s General Assembly created the State Board of Health in 1879 to enforce the growing number of laws regarding contagious diseases and the duties of physicians in reporting them. Hospitals, too, transformed, becoming centers for clinical research and treatment of acute ailments.

In April 1899, the trustees of Delaware College (now the University of Delaware) provided space in the main building for a fully equipped pathological-biological laboratory, the Delaware Public Health Laboratory (DPHL). The lab continues to serve as an adjunct in diagnosing and controlling diseases. Physicians began to develop expertise in specialized areas like microscopy and infectious diseases, expanding opportunities in medicine beyond primary care.

In the last decades of the century, the face of medicine began to change as well. Western medicine had been a White man’s game for centuries. However as the field expanded, it began to open to previously excluded groups. Women were training at co-educational medical schools and newly-established women’s colleges. By the early 1900s, multiple medical schools opened for Black students.

This period of rapid expansion would soon end. In 1904, the largest professional organization of its kind, the American Medical Association, created the Council on Medical Education (CME) to evaluate the quality of training available in the US and Canada. The first order of business was to agree on what counted as a “medical education.” In addition to setting the minimum prior education required for admission to a medical school, they defined proper medical education as two years of human anatomy and physiology training followed by two years of clinical work in a teaching hospital.

Next, with funding from the Carnegie Foundation, they hired Abraham Flexner to examine the curricula offered by North American schools. Using the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as his standard for comparison, Flexner visited over 150 institutions for his evaluation. He published his findings in 1910 as Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, generally referred to as the Flexner Report.5

Nearly half of American medical schools fell short of the report’s rubric. Flexner’s recommended reforms included increasing standards, partnering with hospitals for clinical training, and closing schools that could not afford to update and maintain facilities. He emphasized the need for curricula to adhere to the protocols of mainstream sciences in their teaching and research. Flexner additionally reported that too many medical schools were training too many doctors.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.011

18 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

While Flexner and the CME did not have the power to enforce their recommendations, state licensing boards did, and they moved quickly to mitigate the perceived public health threat. Not long after the report’s publication, medical schools were legally required to refine admission standards and follow stricter curriculum requirements.

Though proprietary schools were already struggling financially, Flexner’s report sounded the death knell. Many schools derided in the report either merged or closed soon after publication. By 1915, ninety-six schools were training physicians; fifteen years later, there were only seventy-six.

With a standardized comprehensive course of study and stricter entrance requirements, medical education was available only to those from economically privileged backgrounds.6 The constriction of medical education to an elite few raised the social status of those granted access to the field and the price for their services.

Furthermore, the culling of the field reinforced race and gender segregation within the profession. Women were excluded to accommodate White men competing for spots at the remaining universities. Some opportunities remained for women within hospitals as nurses, though their role was limited. Many schools that dissolved were smaller rural and Black colleges. When these colleges disappeared, so too did the already small pool of doctors serving poor, working-class, rural, and Black communities. Few who graduated from the surviving medical schools moved away from cities and more populated areas, expanding the already large healthcare deserts throughout the county.

LASTING EFFECTS

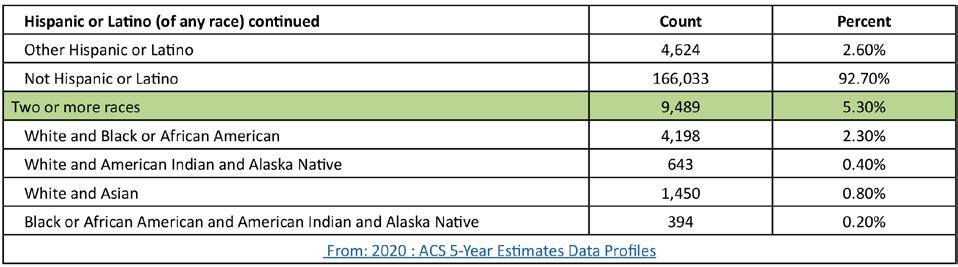

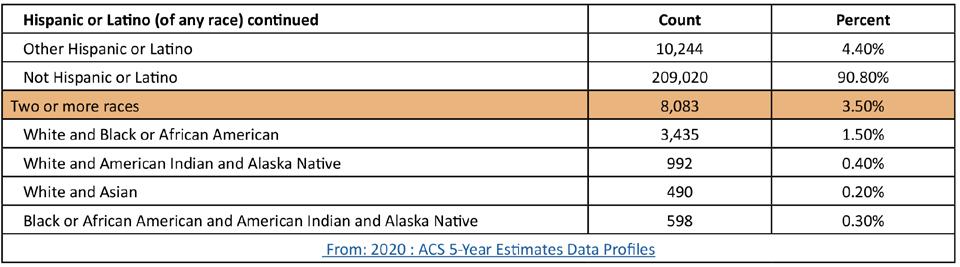

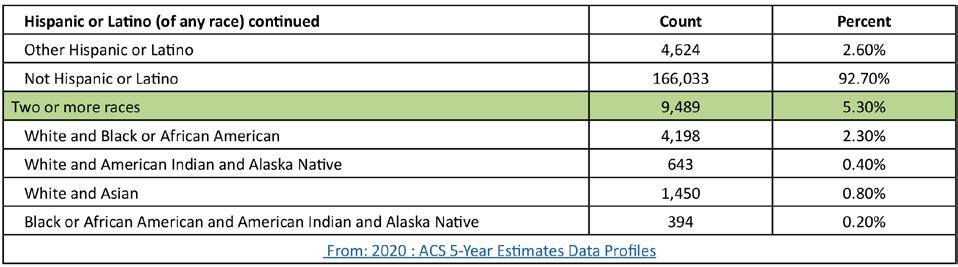

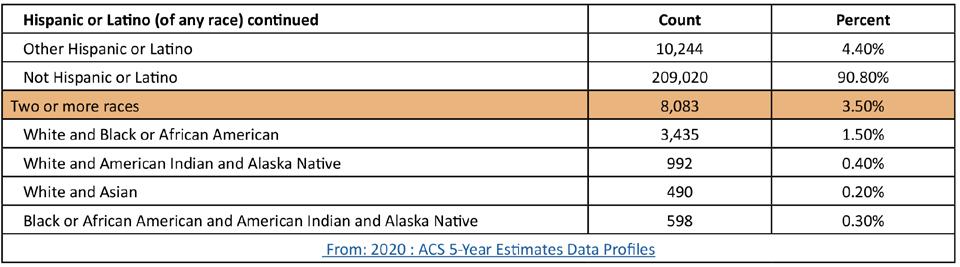

Black Delawareans comprise 23% of the population but only 6.6% of its doctors. In comparison, 66.7% of Delaware’s doctors are white, representing only 61.9% of the population. A 2020 study estimated that if all of the medical schools that educated Black physicians in the early 20th century remained open, there would have been an additional 35,315 Black physicians in the workforce between the 1910s and today.7

In 1900, six percent of practicing physicians were women, yet by 1940, they made up only four percent. Women started to raise that percentage in the 1960s, though they have yet to catch up to men in compensation, leadership positions, and research publications.8

Although Delaware has suffered from a lack of primary healthcare providers since the 1880s, racism and sexism have exacerbated the problem. The reforms ushered by the Flexner Report and the CME continue reverberating throughout the profession today.

REFERENCES

1. Scharf, J. T. (1888). History of Delaware: 1609 to 1888 (Vol. I). L.J. Richards.

2. Department of Health and Social Services. (1911). Annual Report. Department of Health and Social Services. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/Ll9LAQAAMAAJ

3. Medical Society of Delaware. (n.d.). History of the Medical Society of Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.medicalsocietyofdelaware.org/DELAWARE/assets/files/History%20of%20the%20Medical%20Society%20of%20Delaware.pdf

4. Conrad, H. C. (1908). History of the State of Delaware, from the Earliest Settlements to the Year 1907. Henry C. Conrad.

5. Duffy, T. P. (2011, September). The Flexner Report—100 years later. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 84(3), 269–276. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178858/

6. Beck, A. H. (2004, May 5). STUDENTJAMA. The Flexner report and the standardization of American medical education. JAMA, 291(17), 2139–2140. Retrieved from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/198677 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.17.2139

7. Campbell, K. M., Corral, I., Infante Linares, J. L., & Tumin, D. (2020, August 3). Projected estimates of African American medical graduates of closed historically black medical schools. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), e2015220. Retrieved from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2769573 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15220

8. Redford, G. (2020, November 17). AAMC renames prestigious Abraham Flexner award in light of racist and sexist writings. AAMC. Retrieved from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/aamc-renames-prestigious-abraham-flexner-award-light-racist-and-sexist-writings

19

Delaware Healthcare Workforce Vital Statistics

DATA

This section’s data contains workforce vital statistics as collected in the DELPROS system. It is important to note that it does NOT cover the entire healthcare workforce, some of which is not licensed through this system, and others who are not directly licensed by any entity at this time. For instance, Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) are not licensed by DELPROS, nor are Community Health Workers (CHWs) or Direct Service Providers (DSPs).

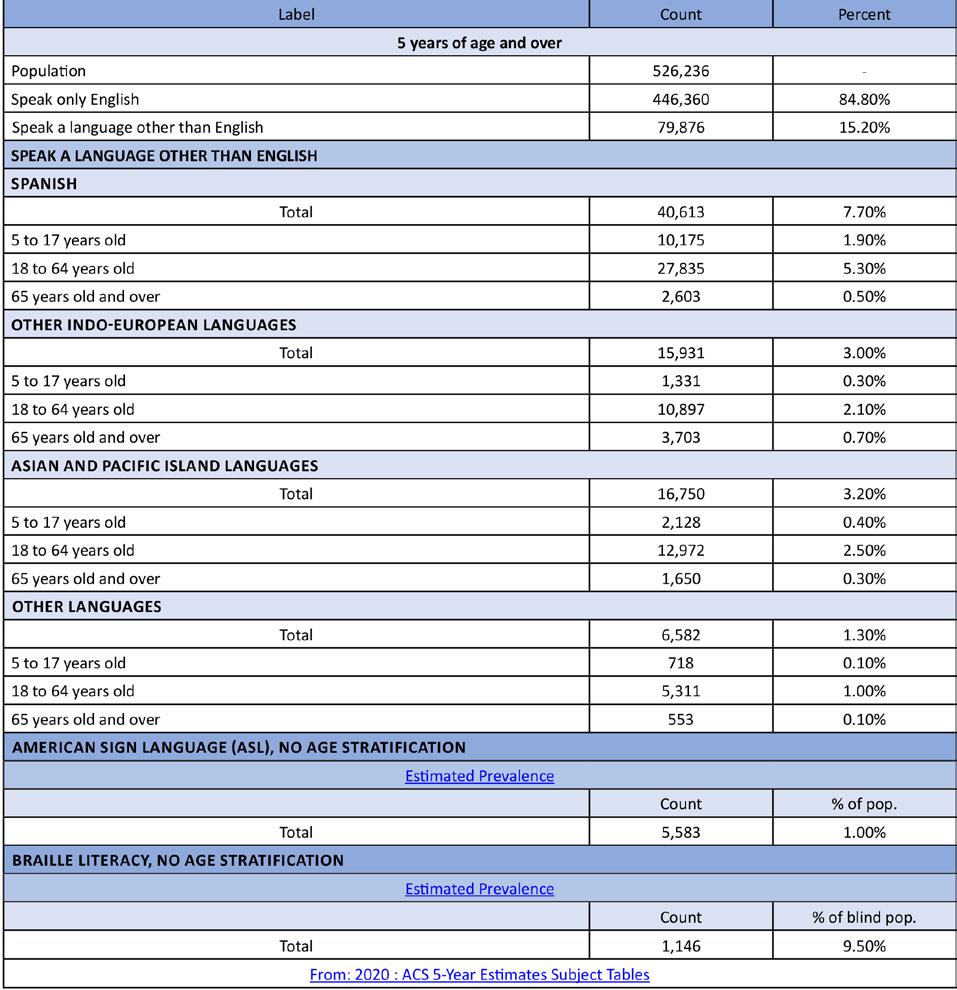

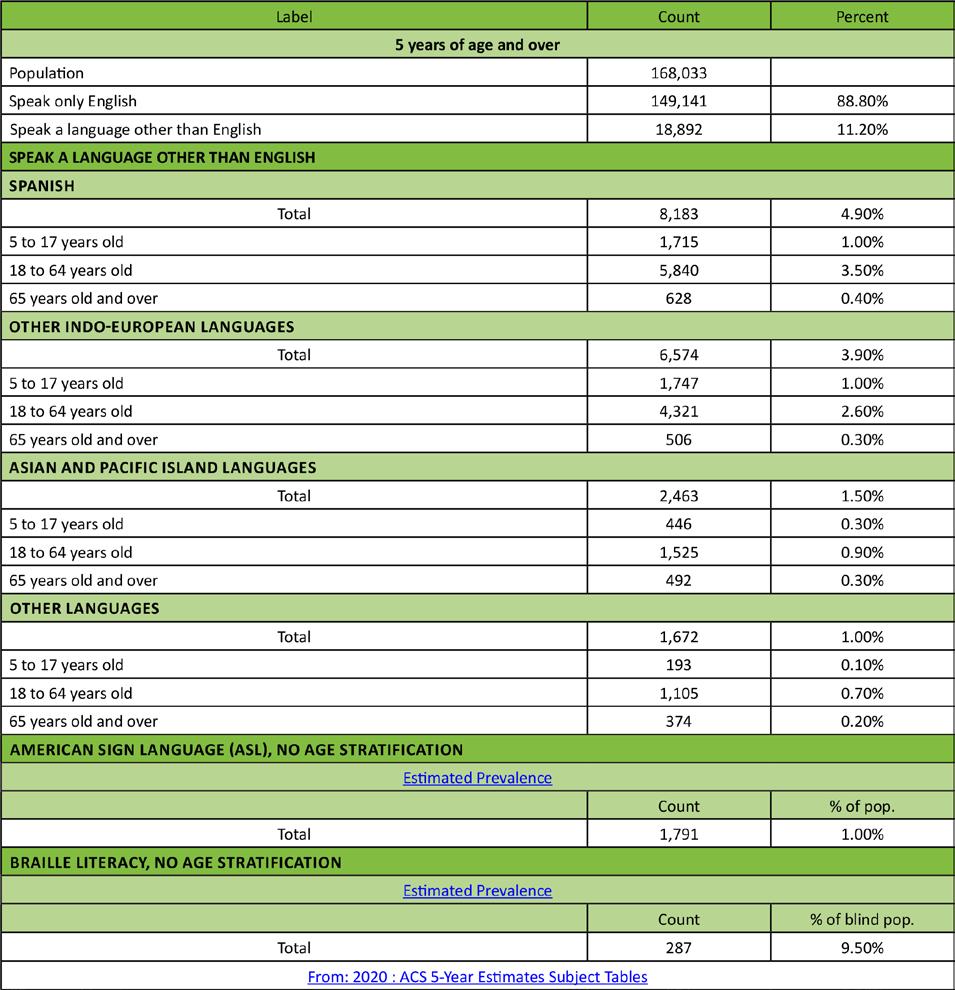

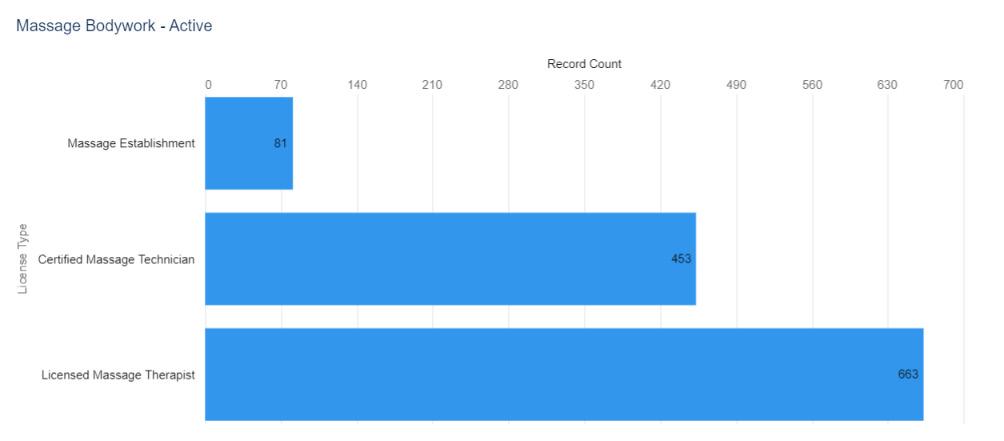

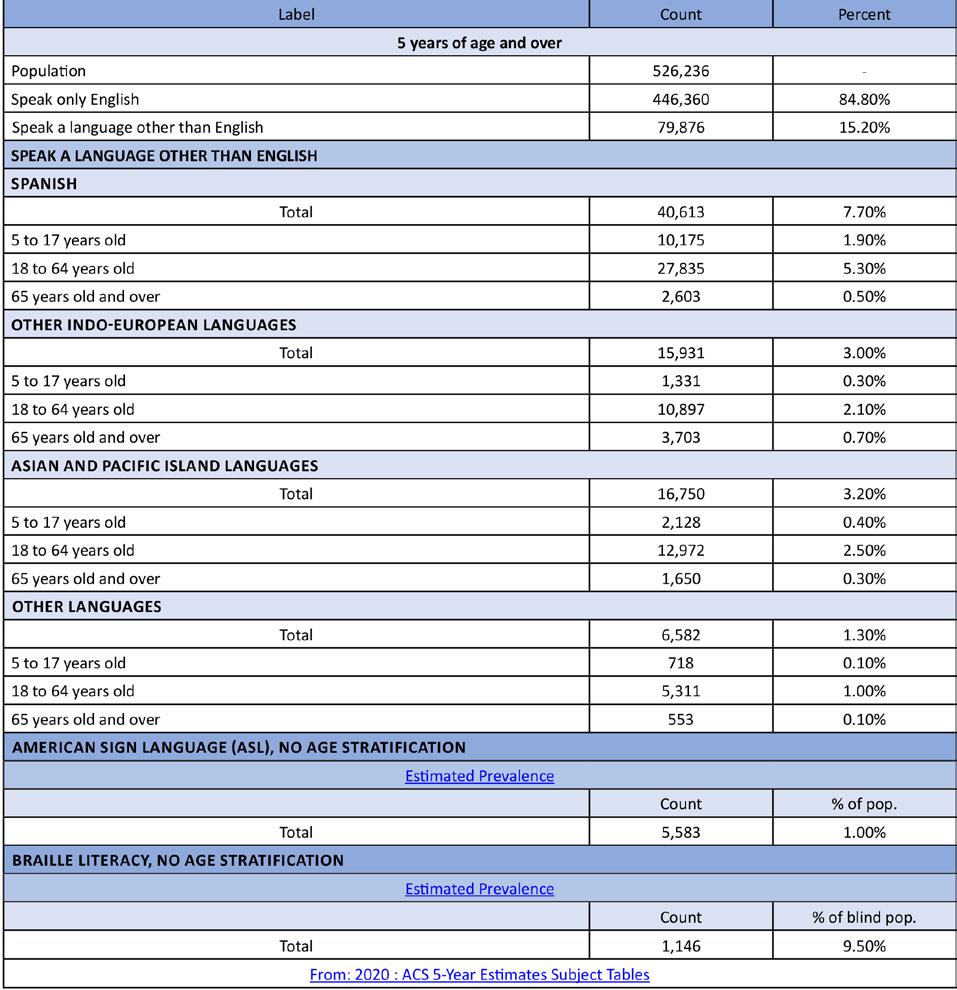

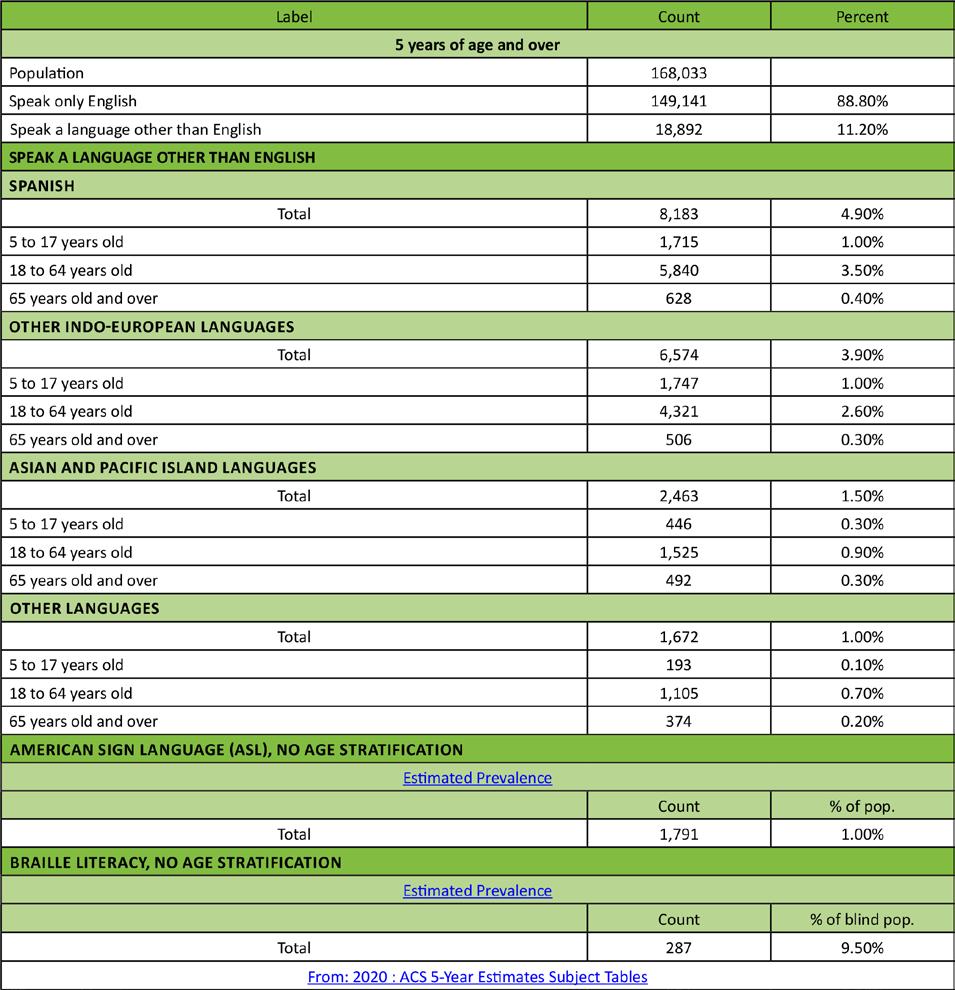

Some types of facilities are licensed through DELPROS, while others are licensed through the Department of Health and Social Services Office Division of Healthcare Quality, Office of Health Facilities Licensing and Certification. We credit that office for providing a significant portion of facilities data found in this report. The following is entirely based on the data contained within the DELPROS system, and therefore we make no claims to its accuracy or completeness except where noted. For instance, DELPROS does ask about gender when an individual registers, however it is not a required field, and therefore most sections will show a percent of persons who did not state their gender. DELPROS itself does not collect information regarding race and ethnicity, therefore this report does not contain that information. DELPROS does ask for date of birth, and we were supplied with year of birth only so provide a level of privacy to the licensees of the State licensing system. DELPROS does not collect information on languages spoken, therefore we do not report on that information. That said, race, ethnicity, languages spoken, and a variety of other characterizes of the healthcare workforce are essential data points to be considered in future reports as that information is collected.

The section is alphabetical by Division of Professional Regulation board name, which is then followed by information from the Office of Health Facilities Licensing and Certification. All information and tables contained in the following section is based on data from June 2022. Each section starts with objective of the Board which oversees a given area of licenses. Sometimes, but not always, this is followed by additional detail on the types of licensure granted under that board.

•Board of Chiropractic

• Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene

• Board of Dietetics/Nutrition

• Board of Funeral Services

• Board of Massage and Bodywork

• Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline

• Board of Nursing

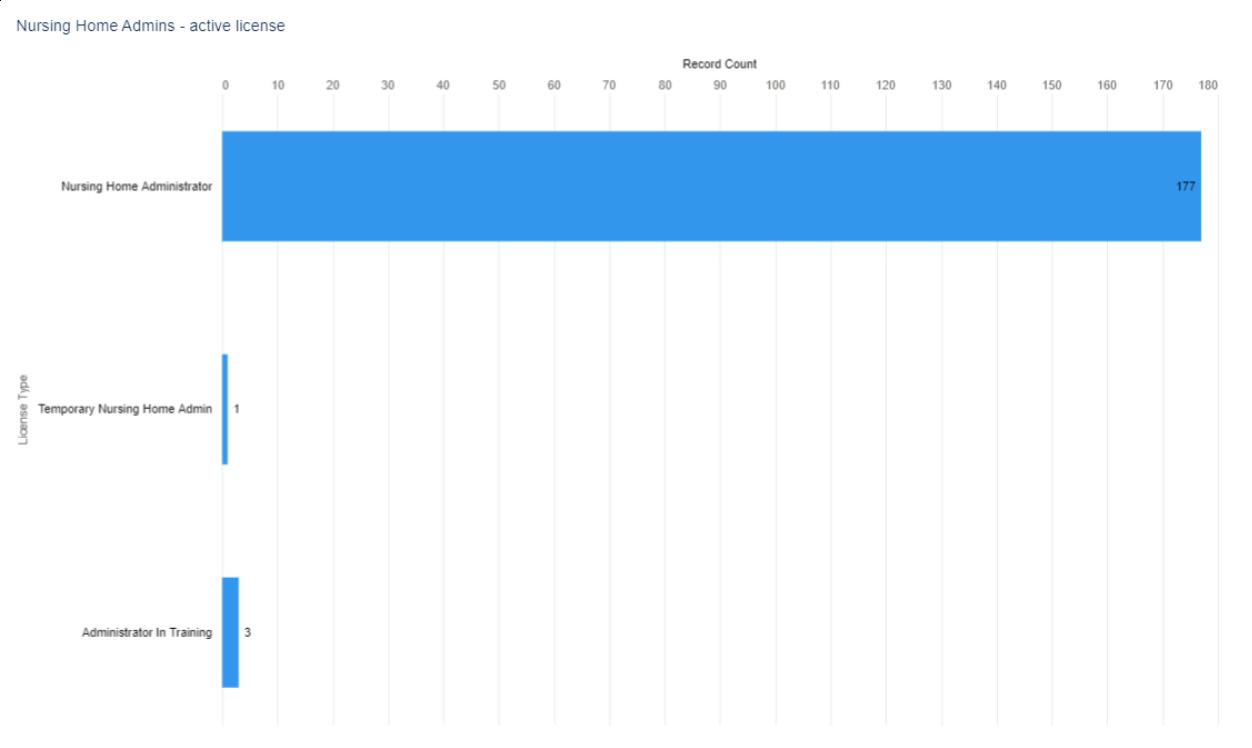

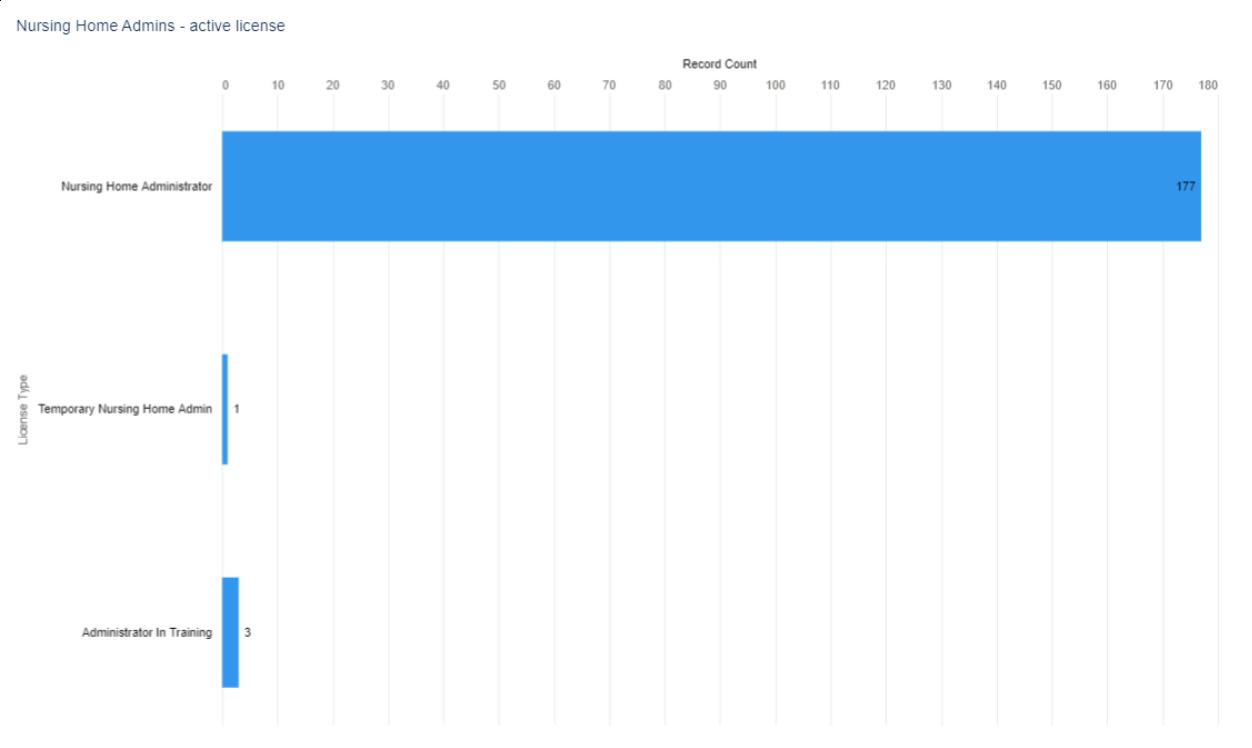

• Board of Examiners of Nursing Home Administrators

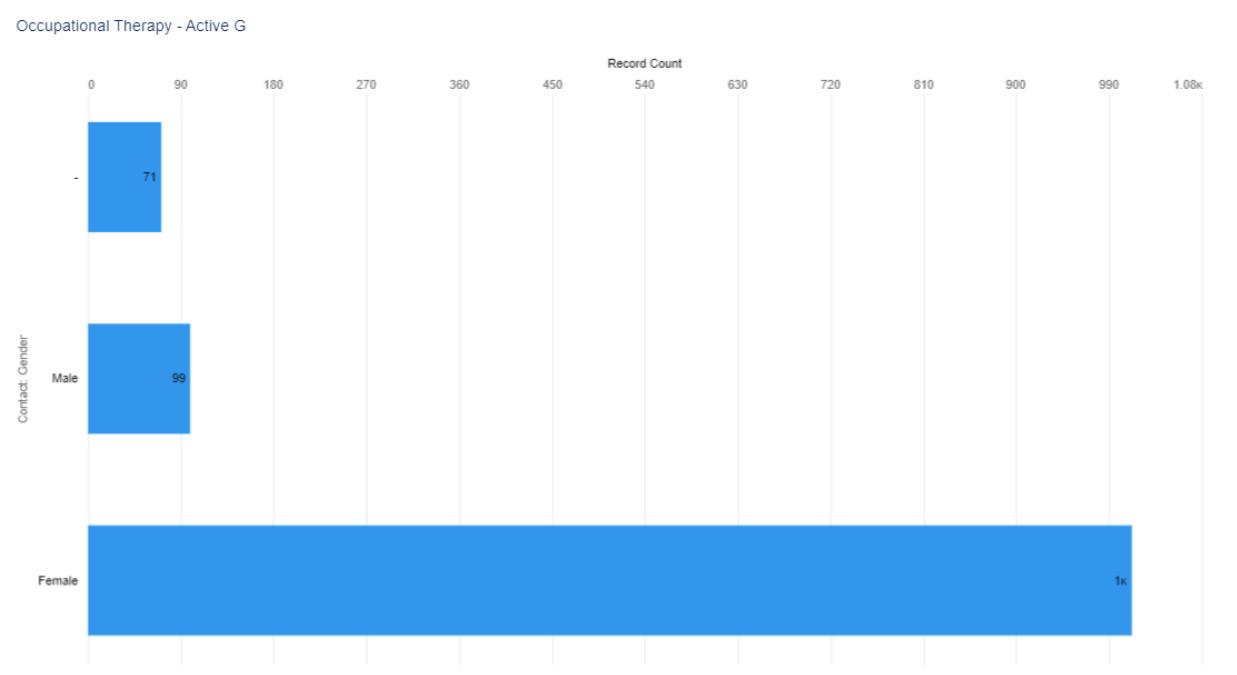

• Board of Occupational Therapy Practice

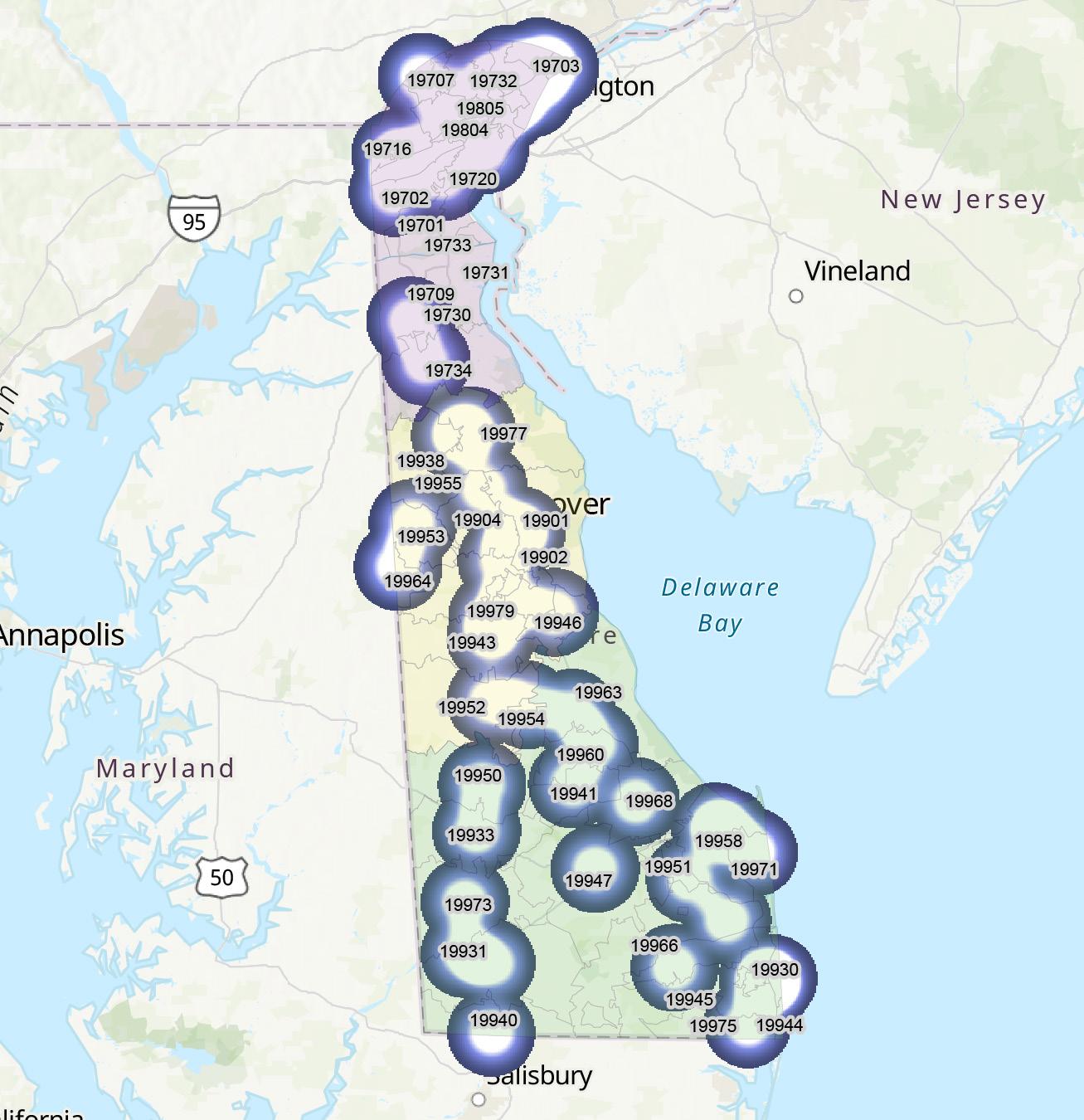

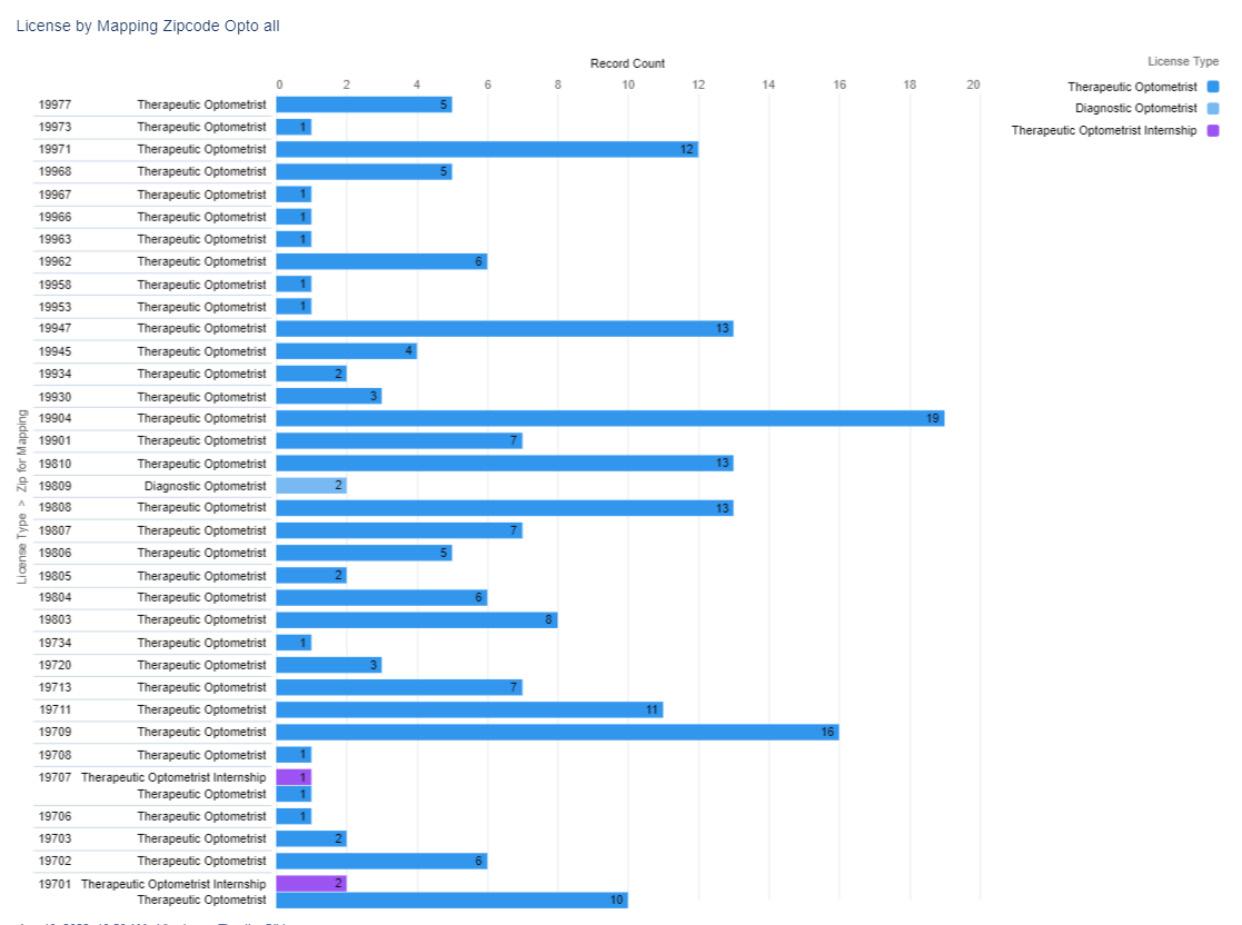

• Board of Examiners in Optometry

METHODS

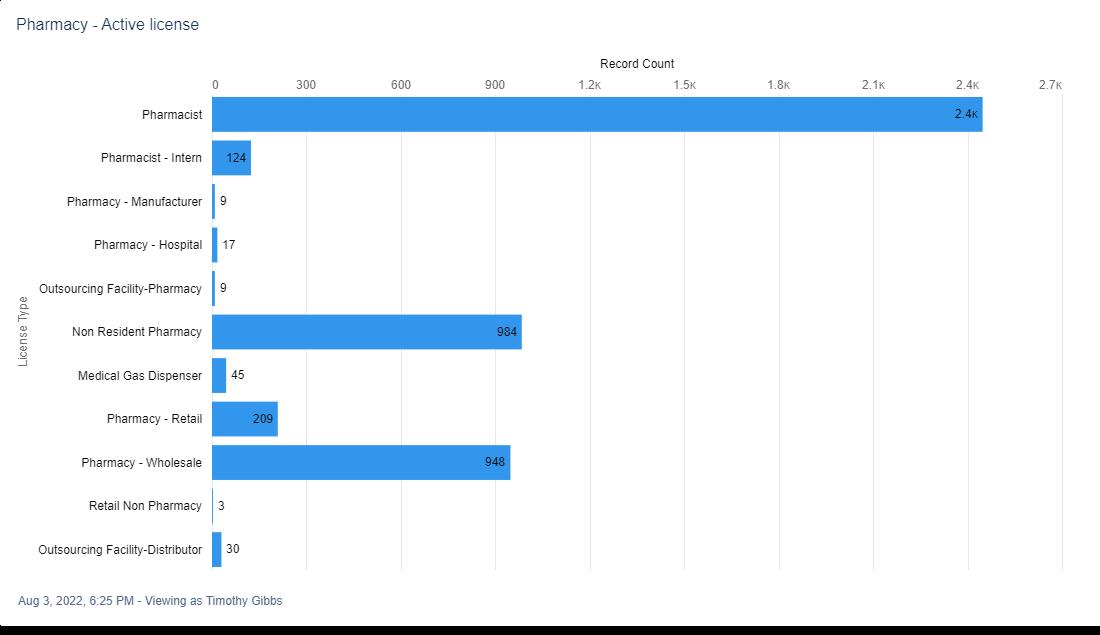

• Board of Pharmacy

• Board of Physical Therapists and Athletic Trainers

• Board of Podiatry

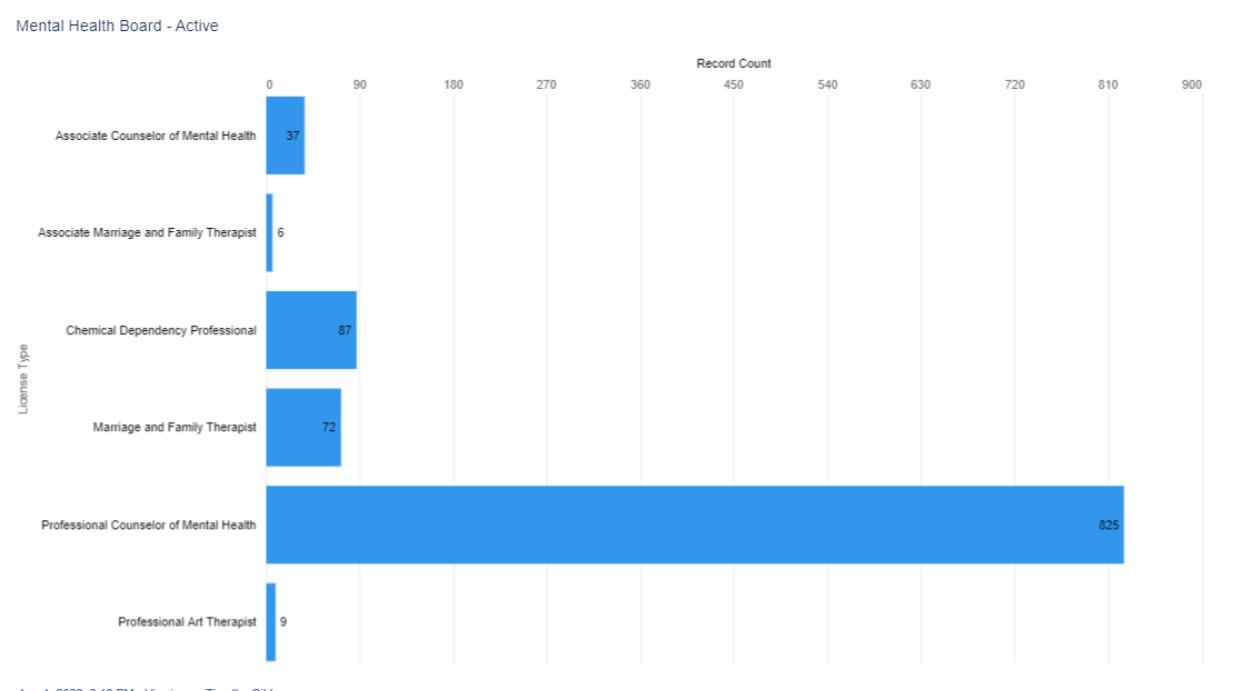

• Board of Mental Health and Chemical Dependency Professionals

• Board of Examiners of Psychologists

• Board of Social Work Examiners

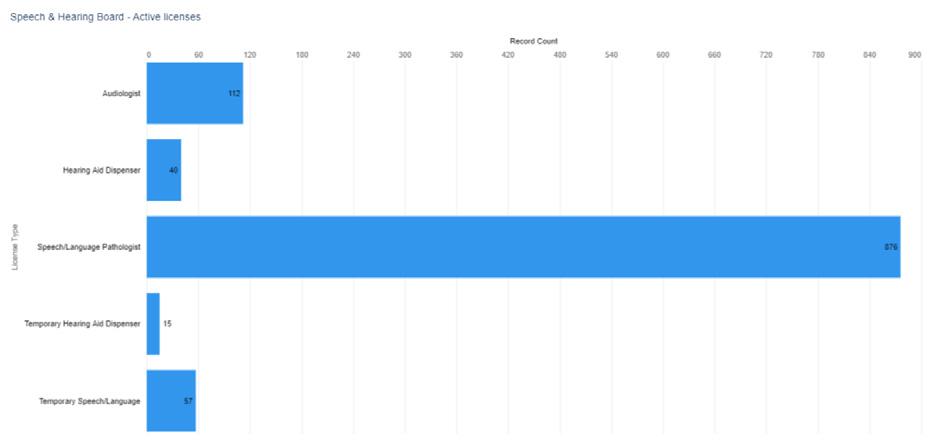

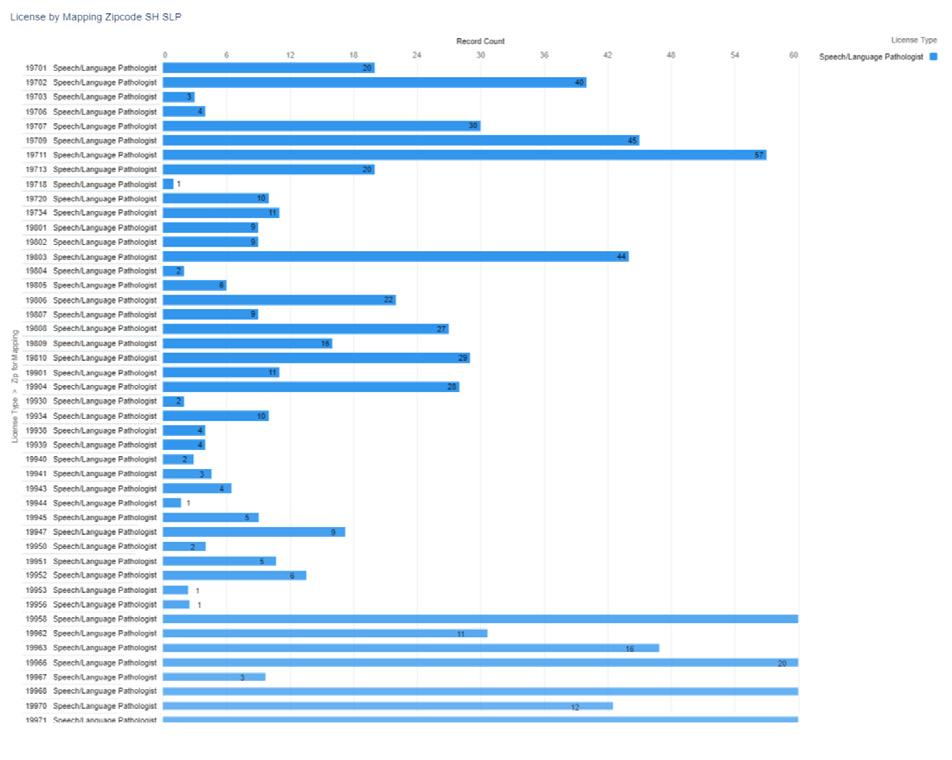

• Board of Speech Pathologists, Audiologists, and Hearing Aid Dispensers

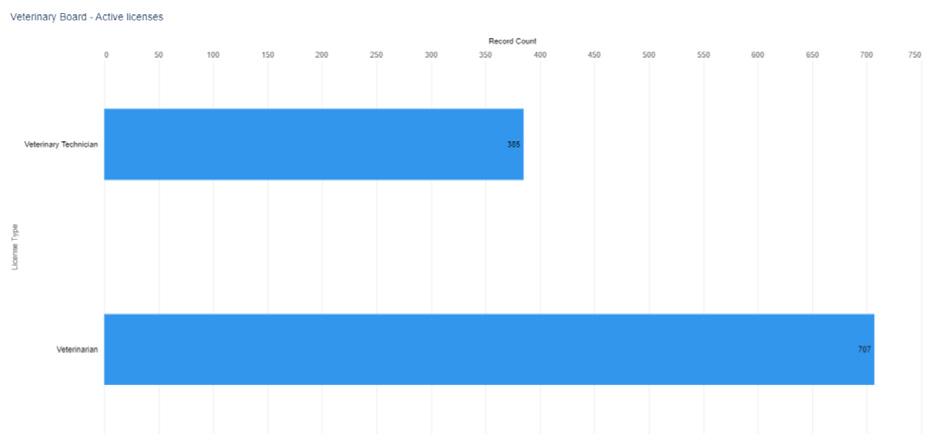

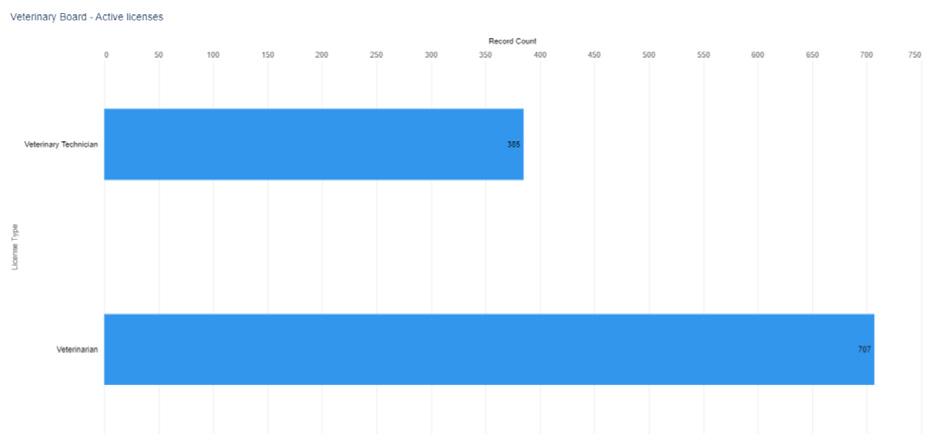

• Board of Veterinary Medicine

• Controlled Substance Advisory Committee

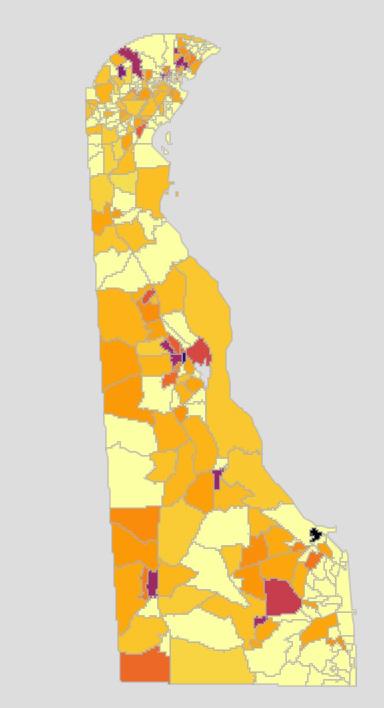

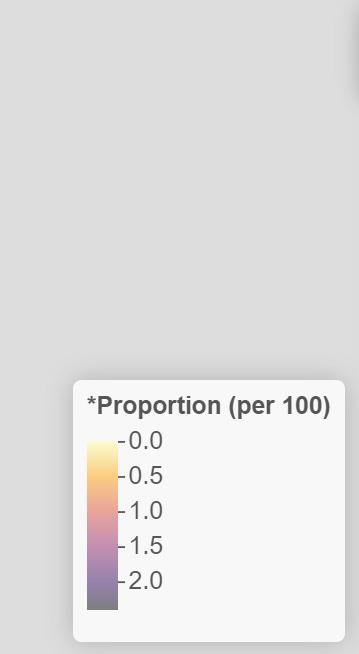

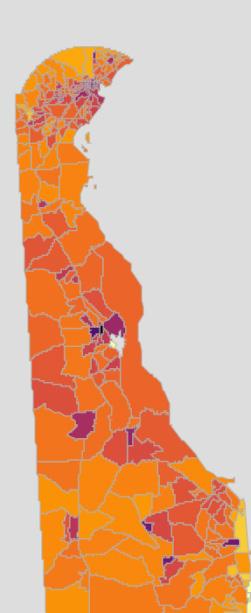

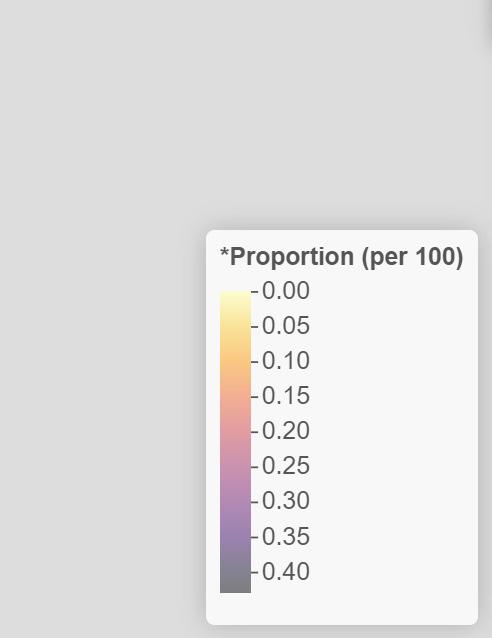

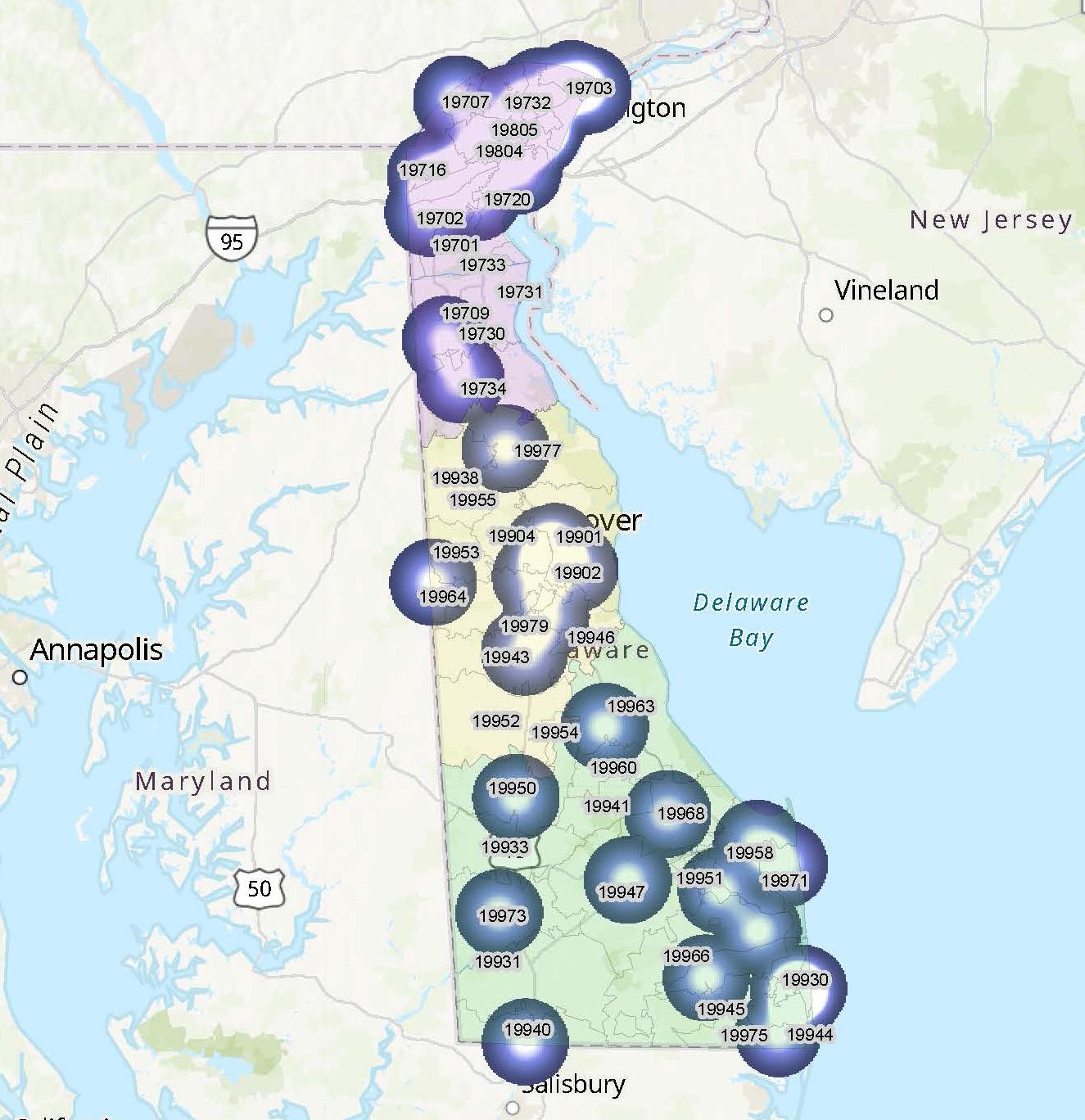

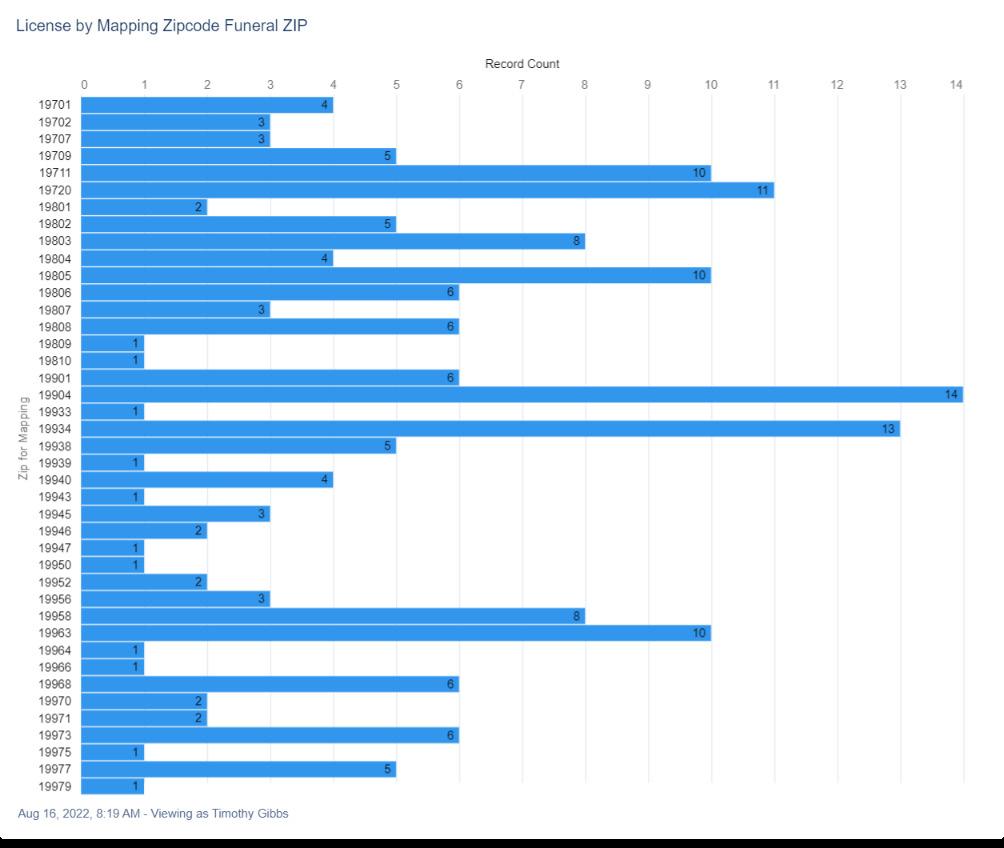

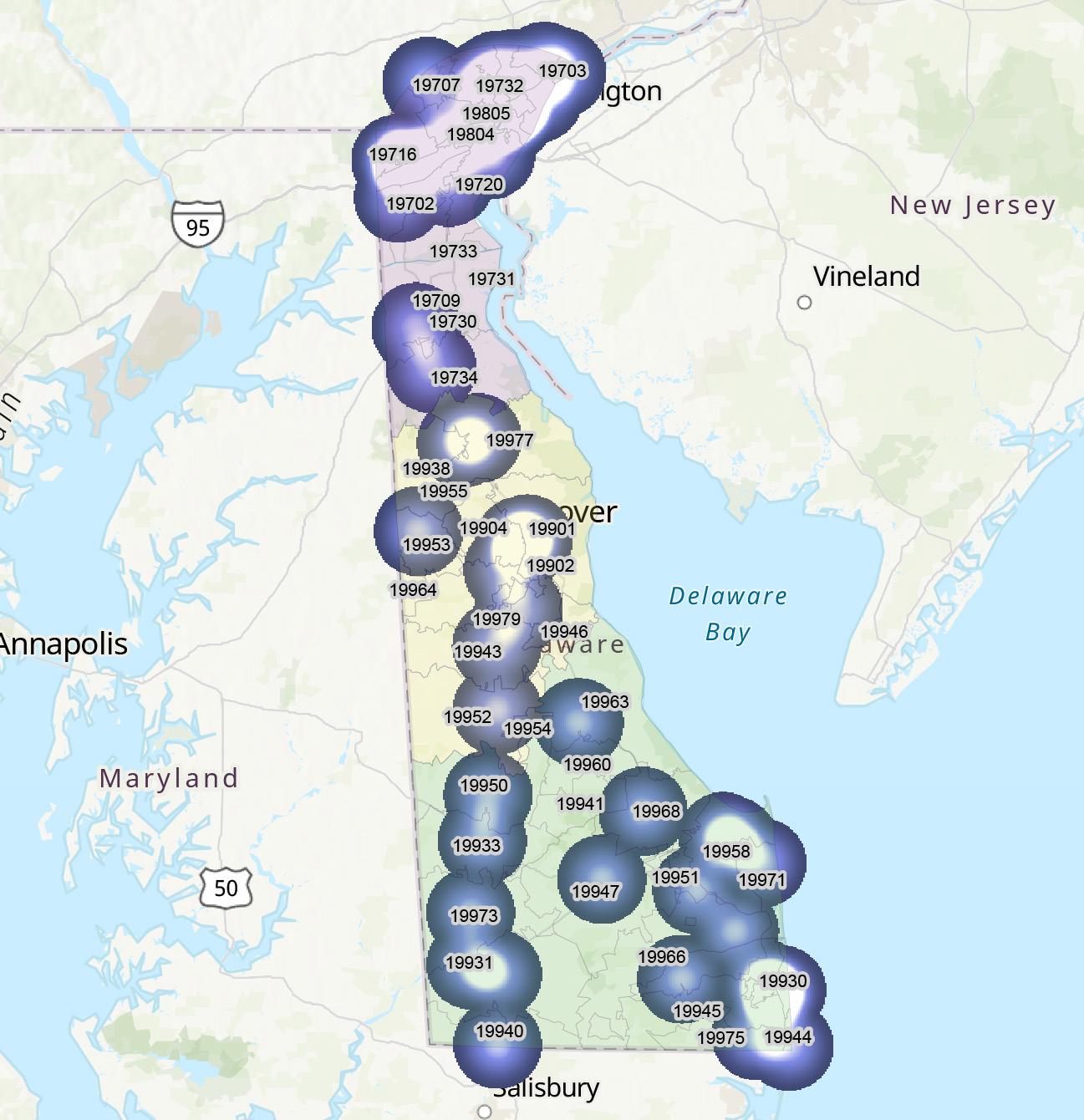

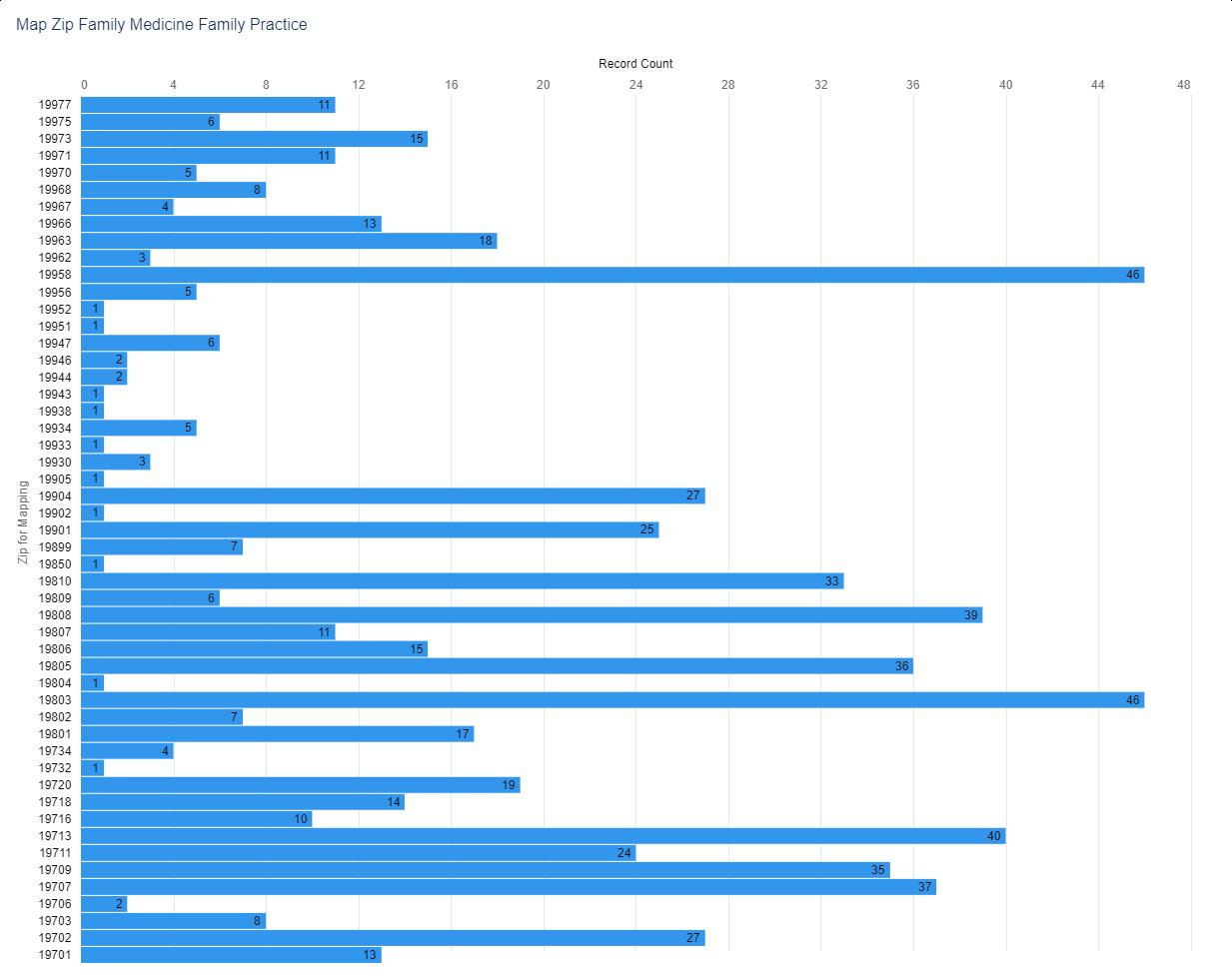

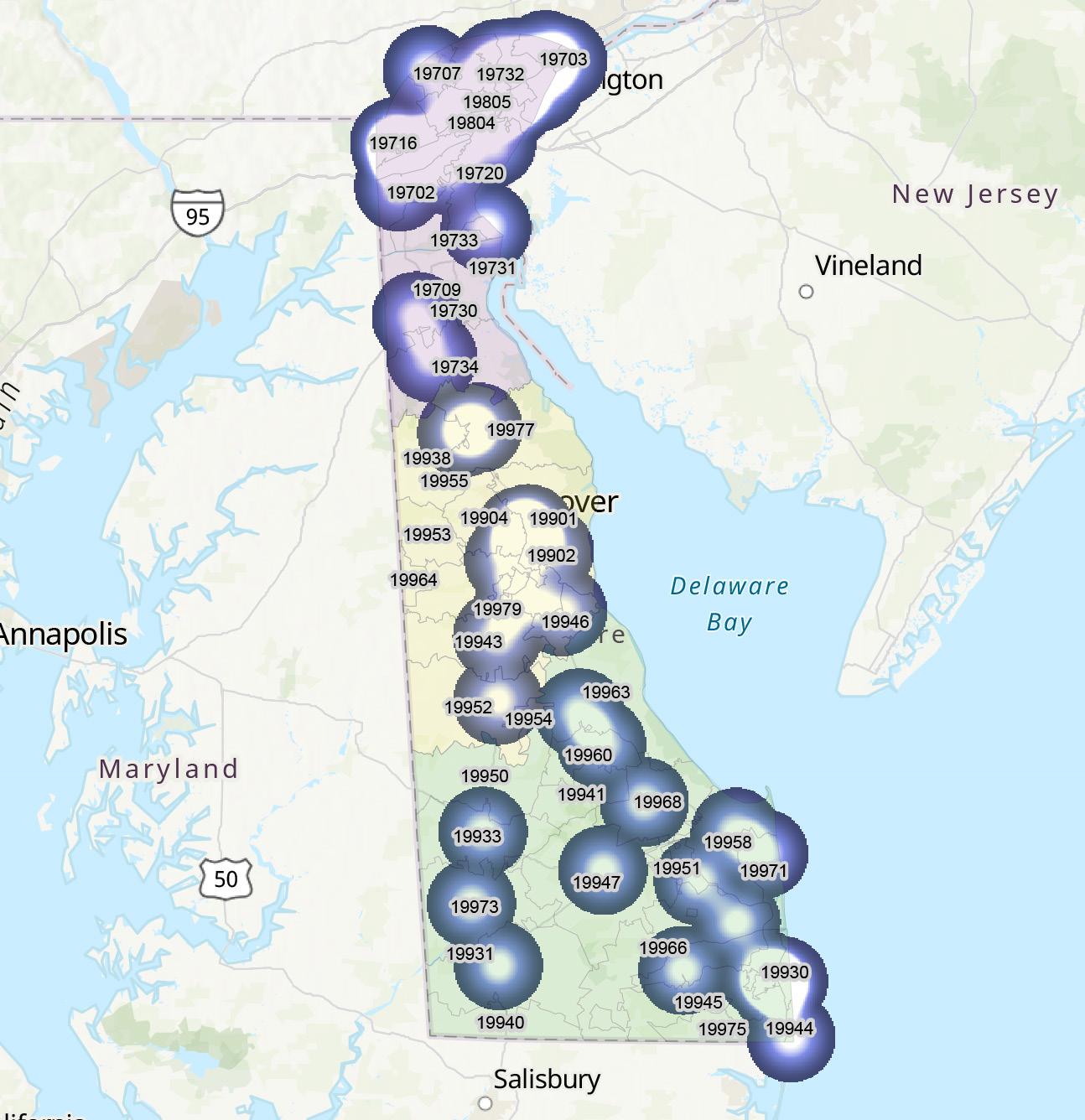

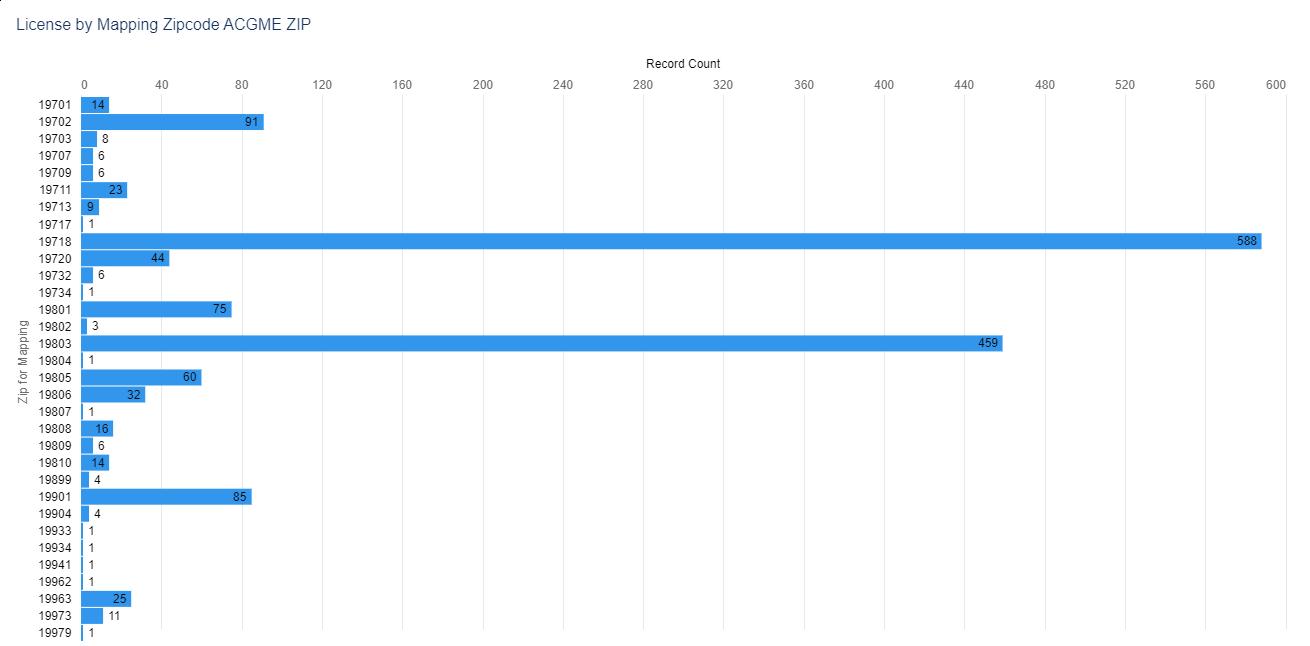

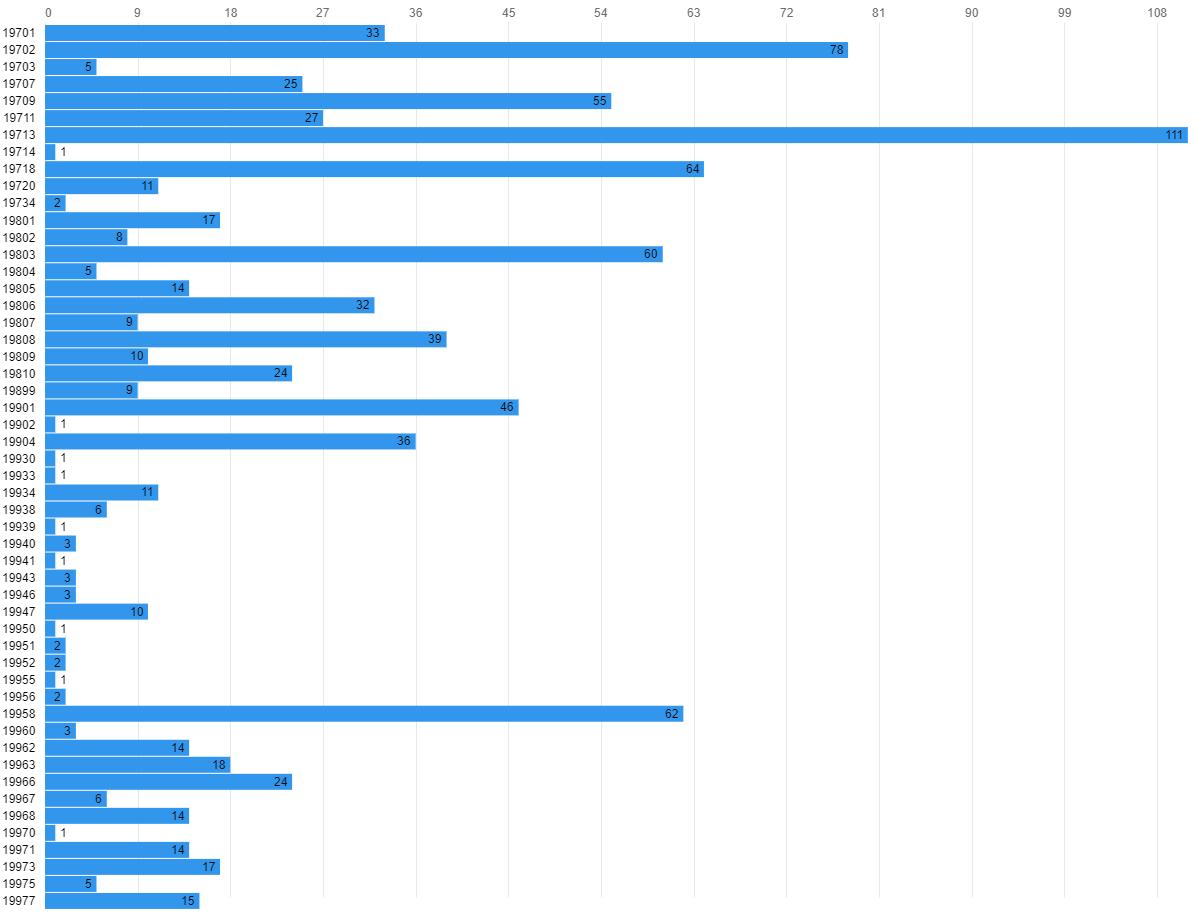

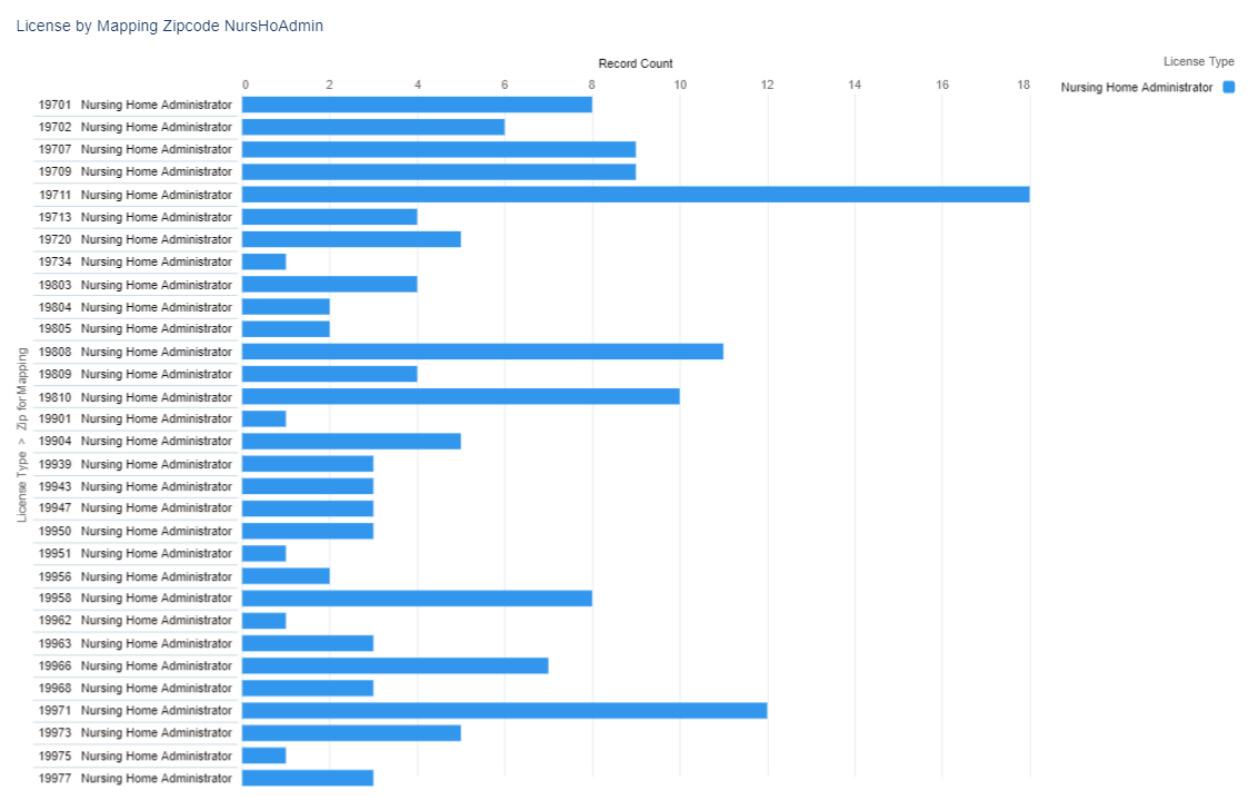

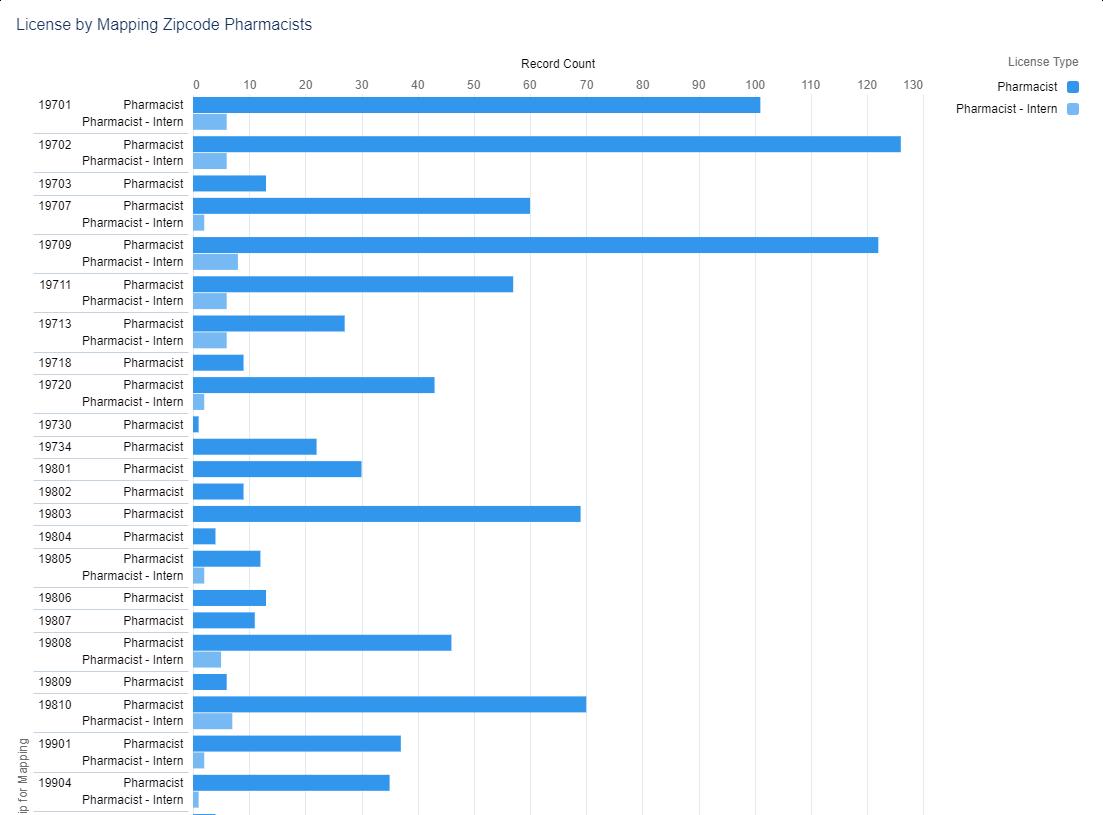

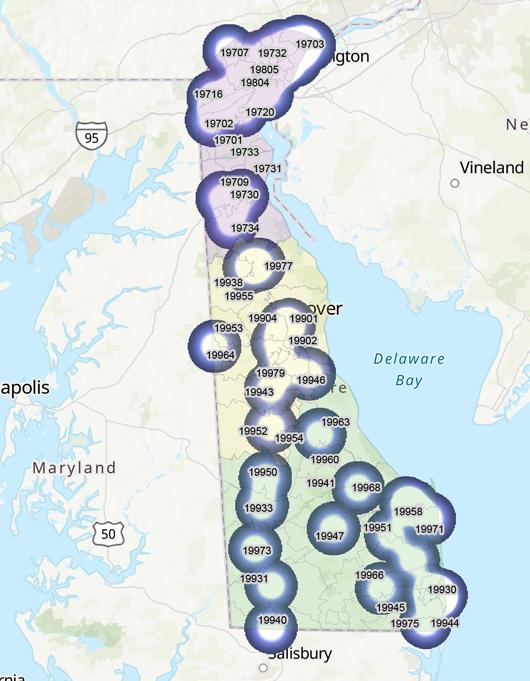

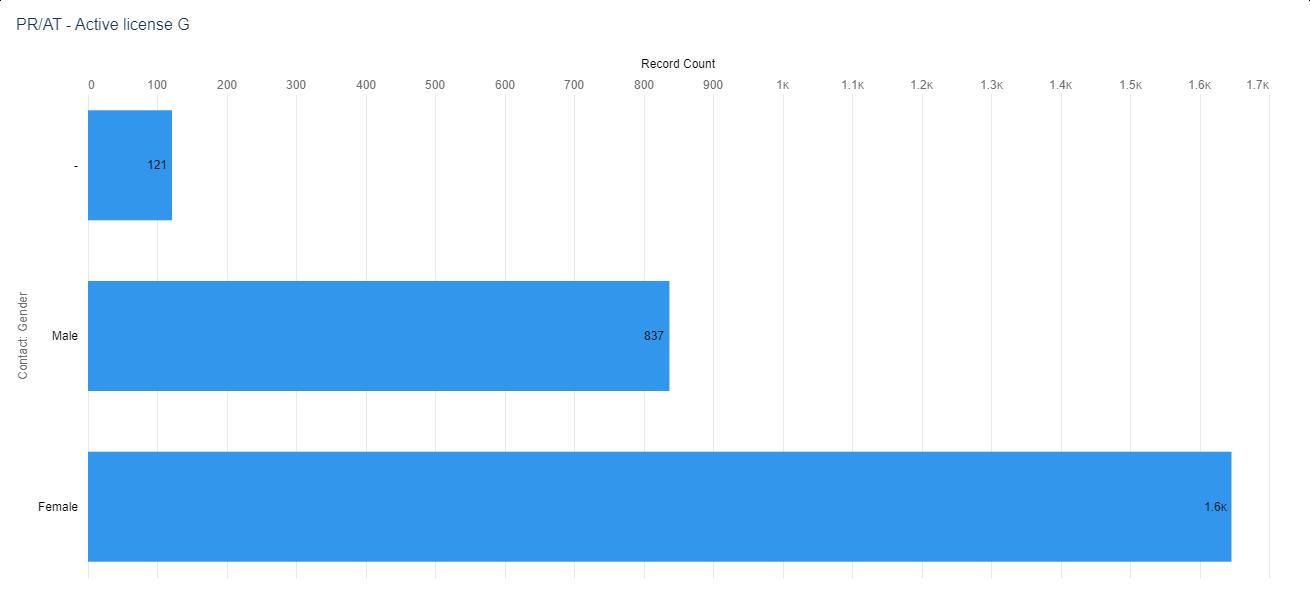

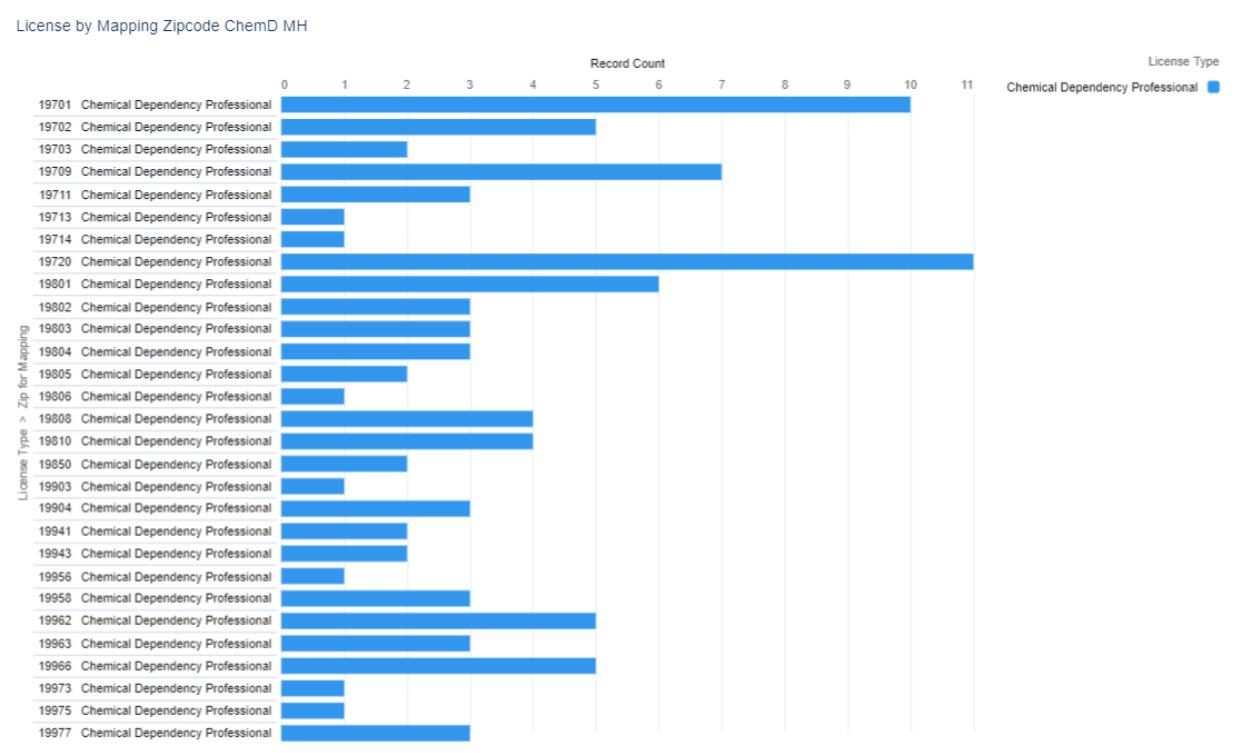

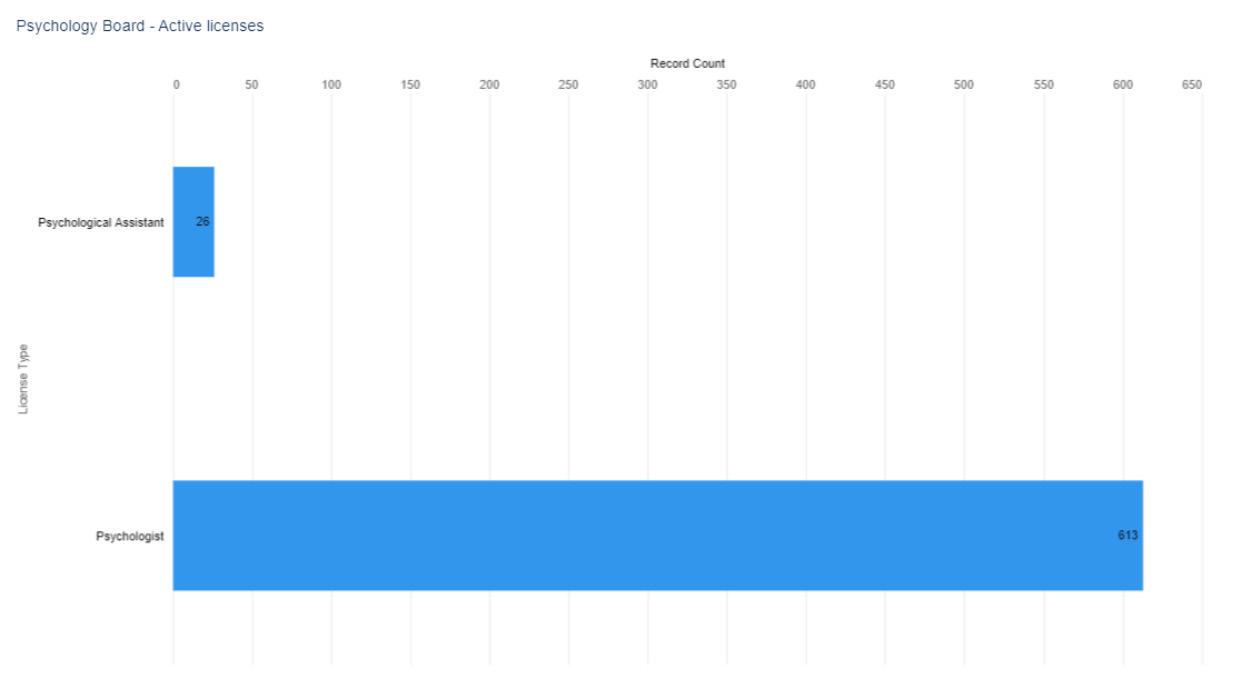

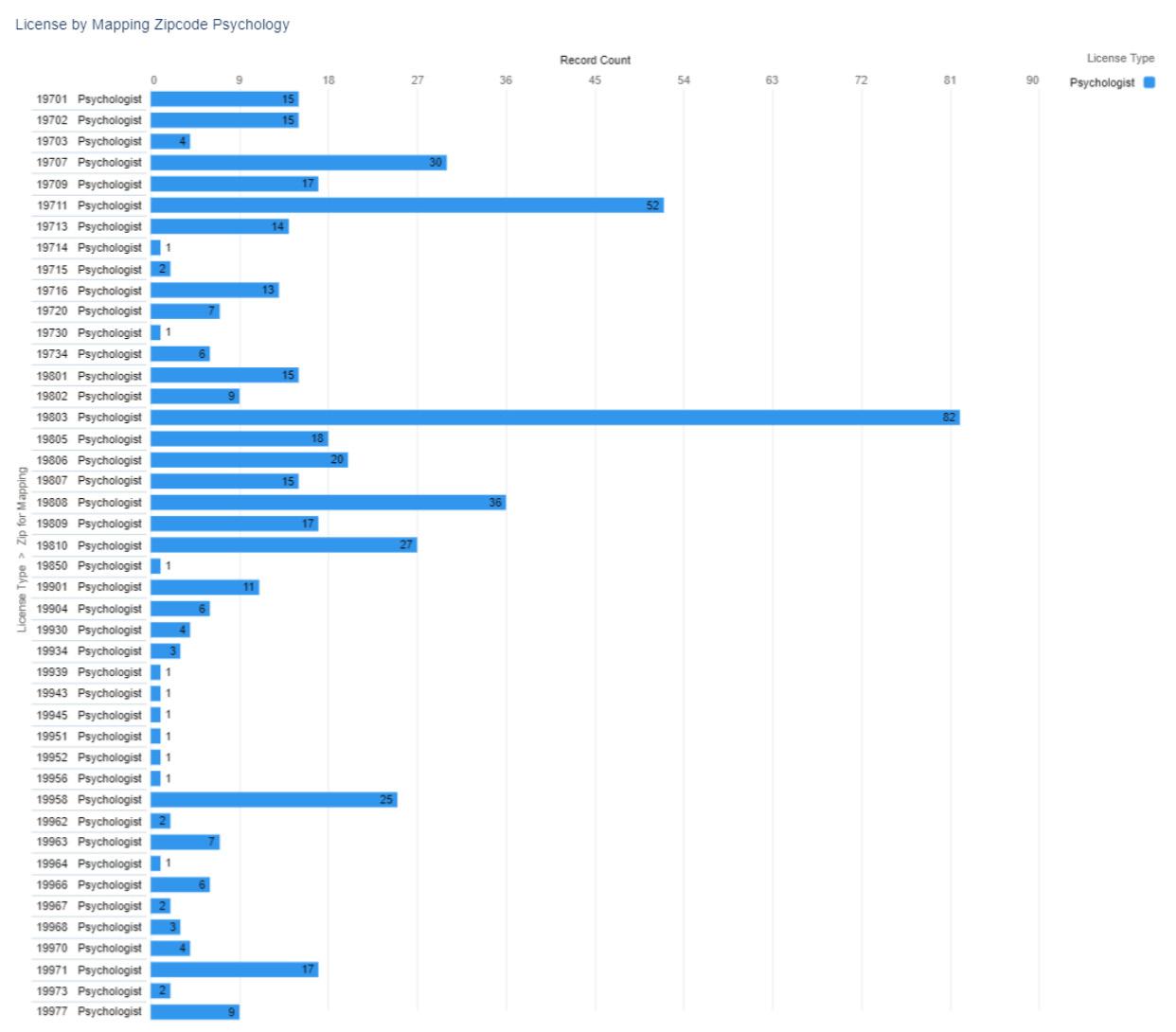

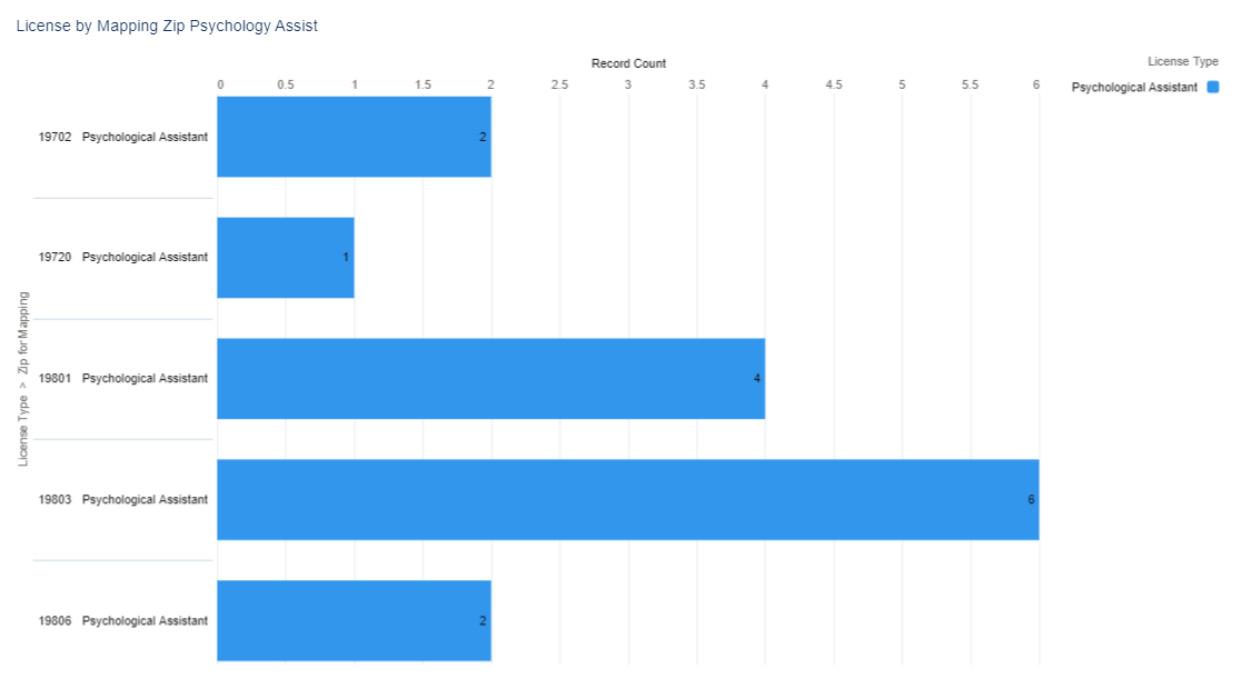

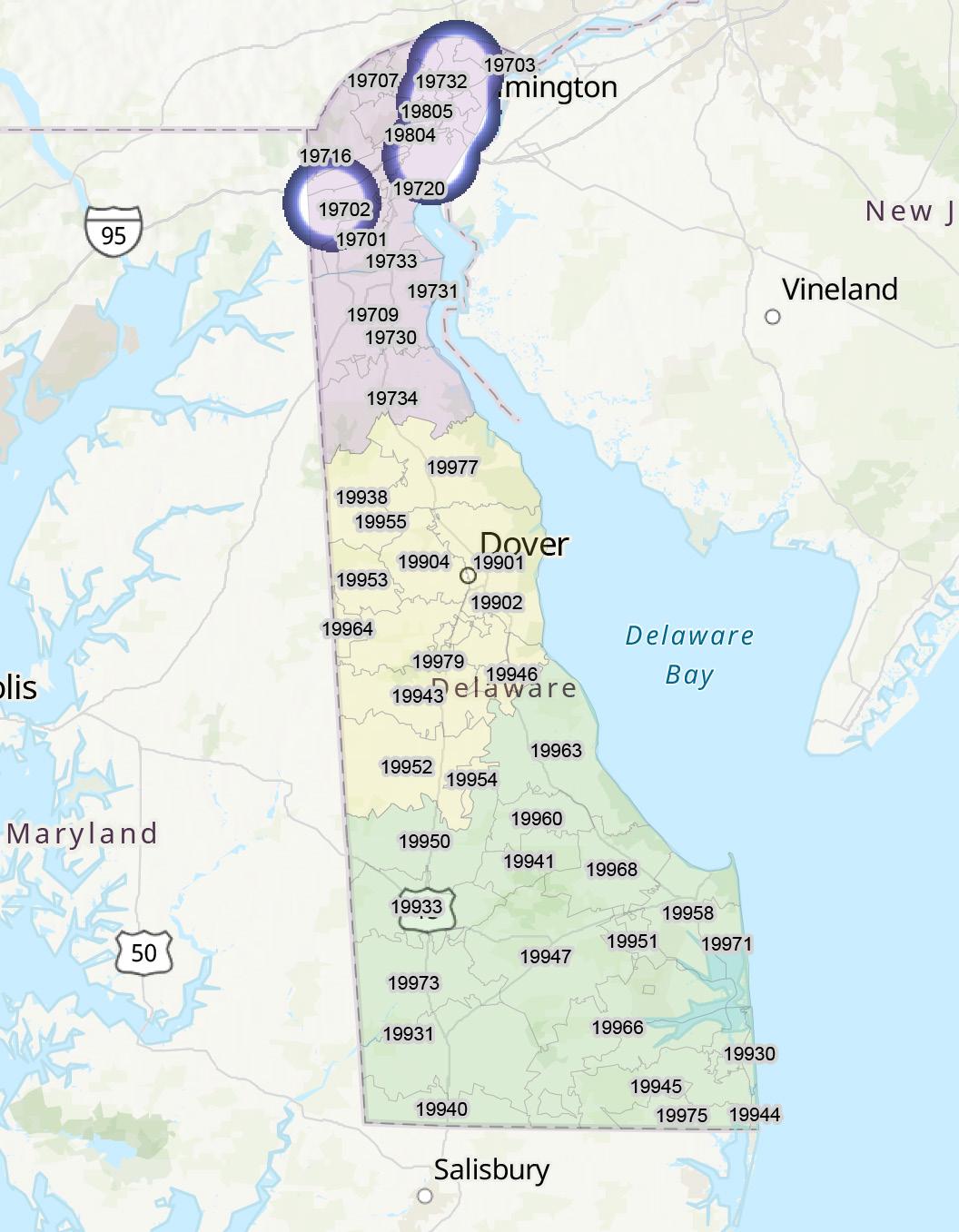

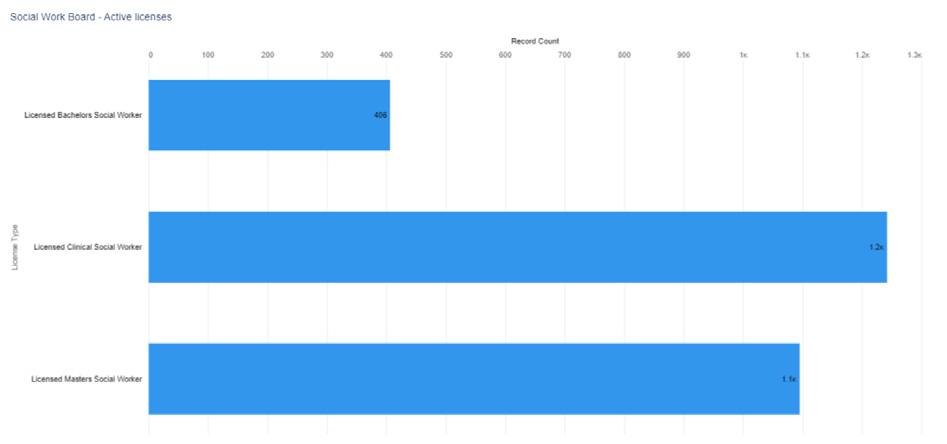

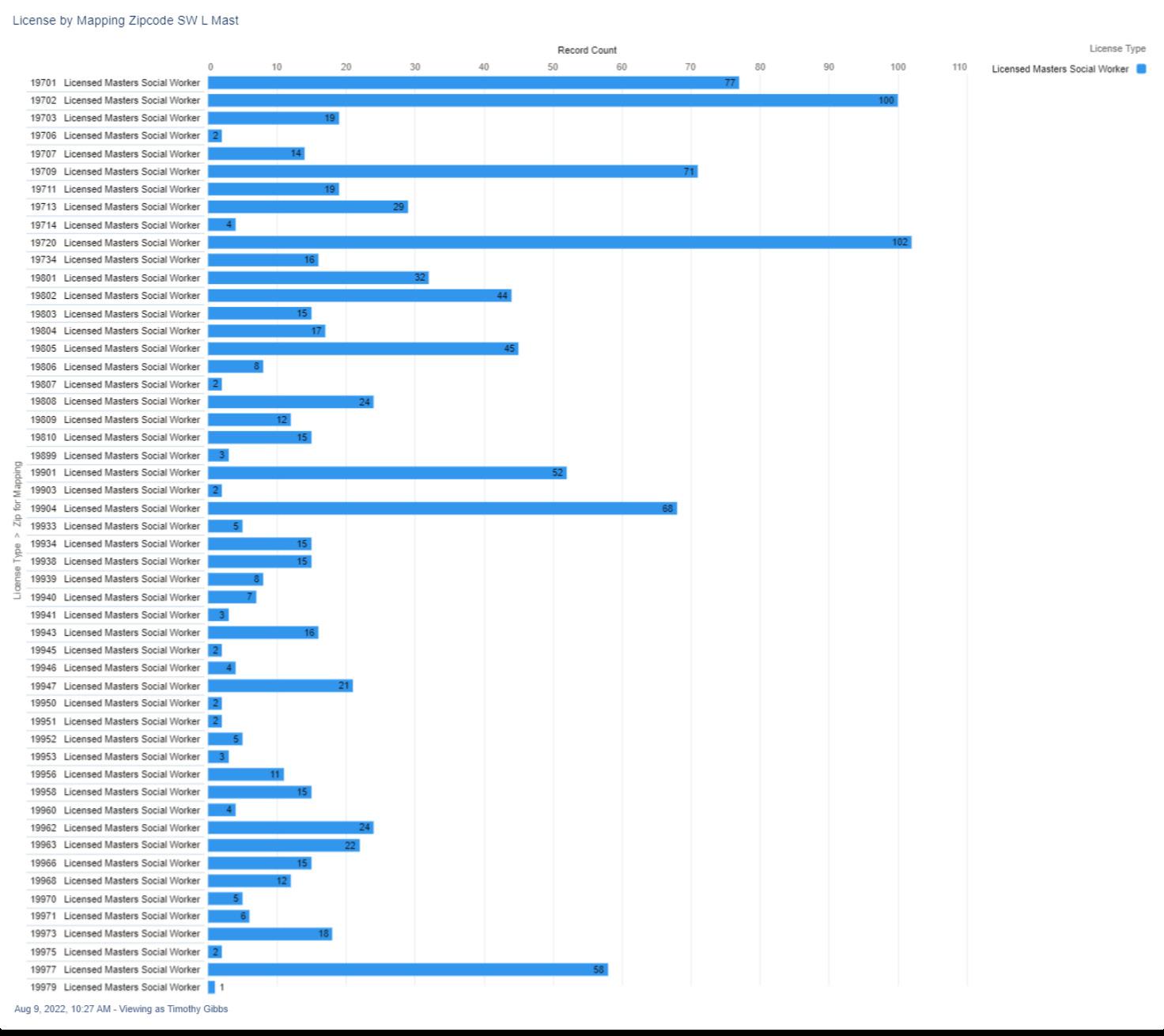

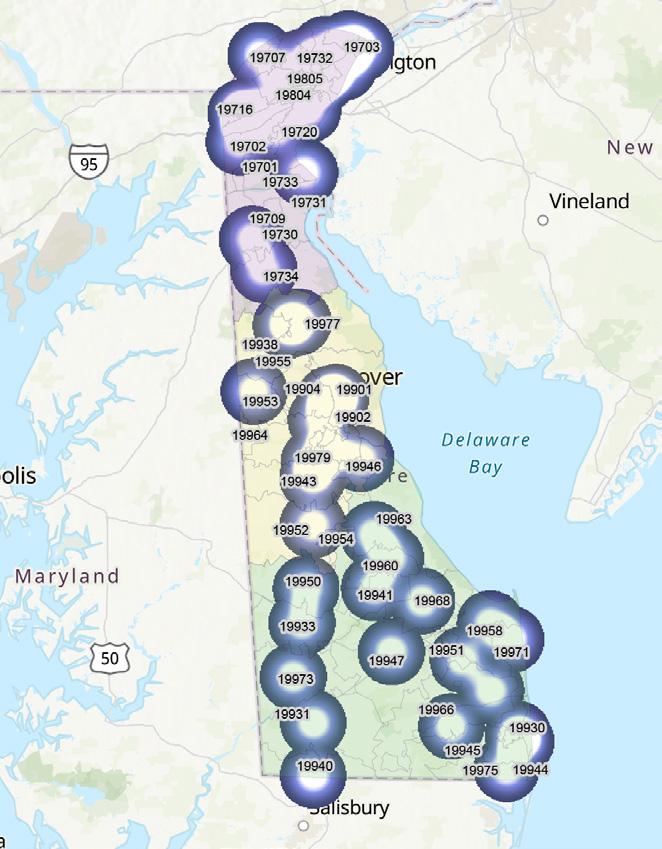

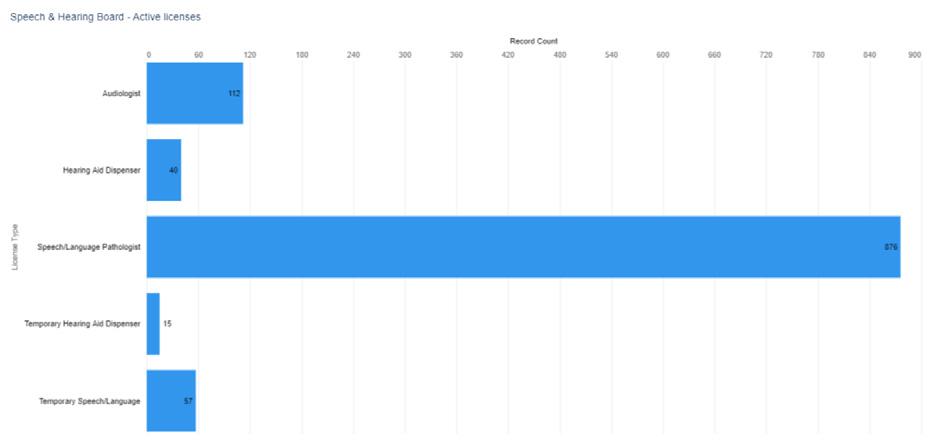

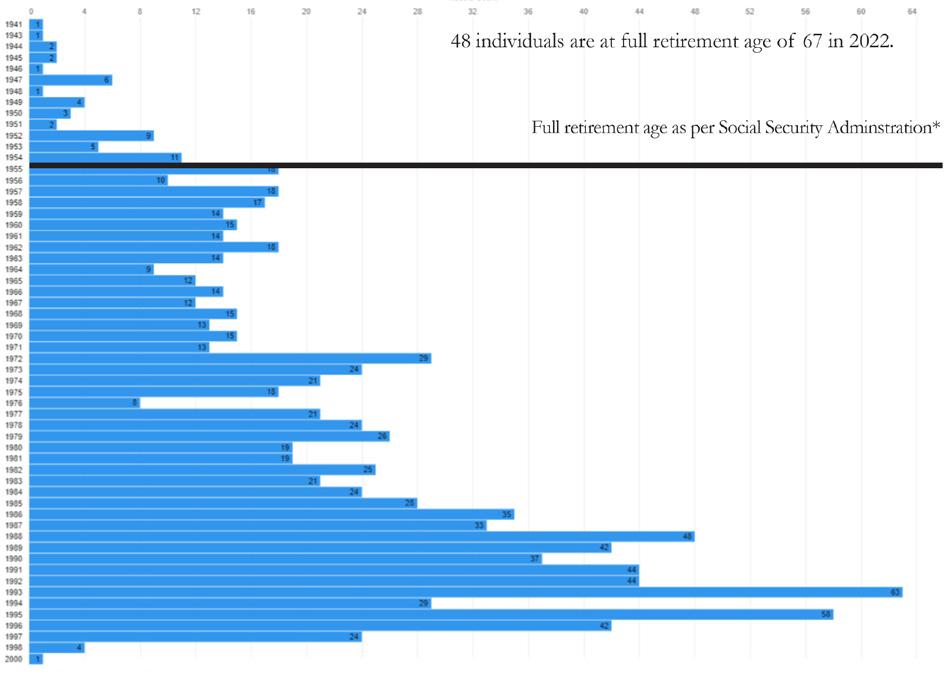

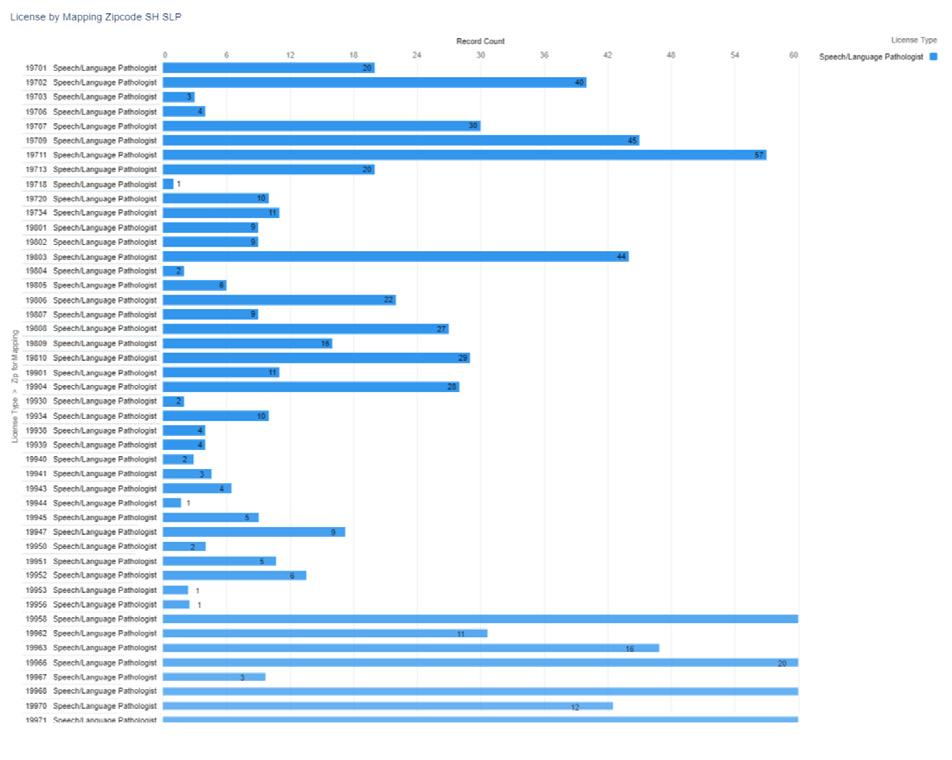

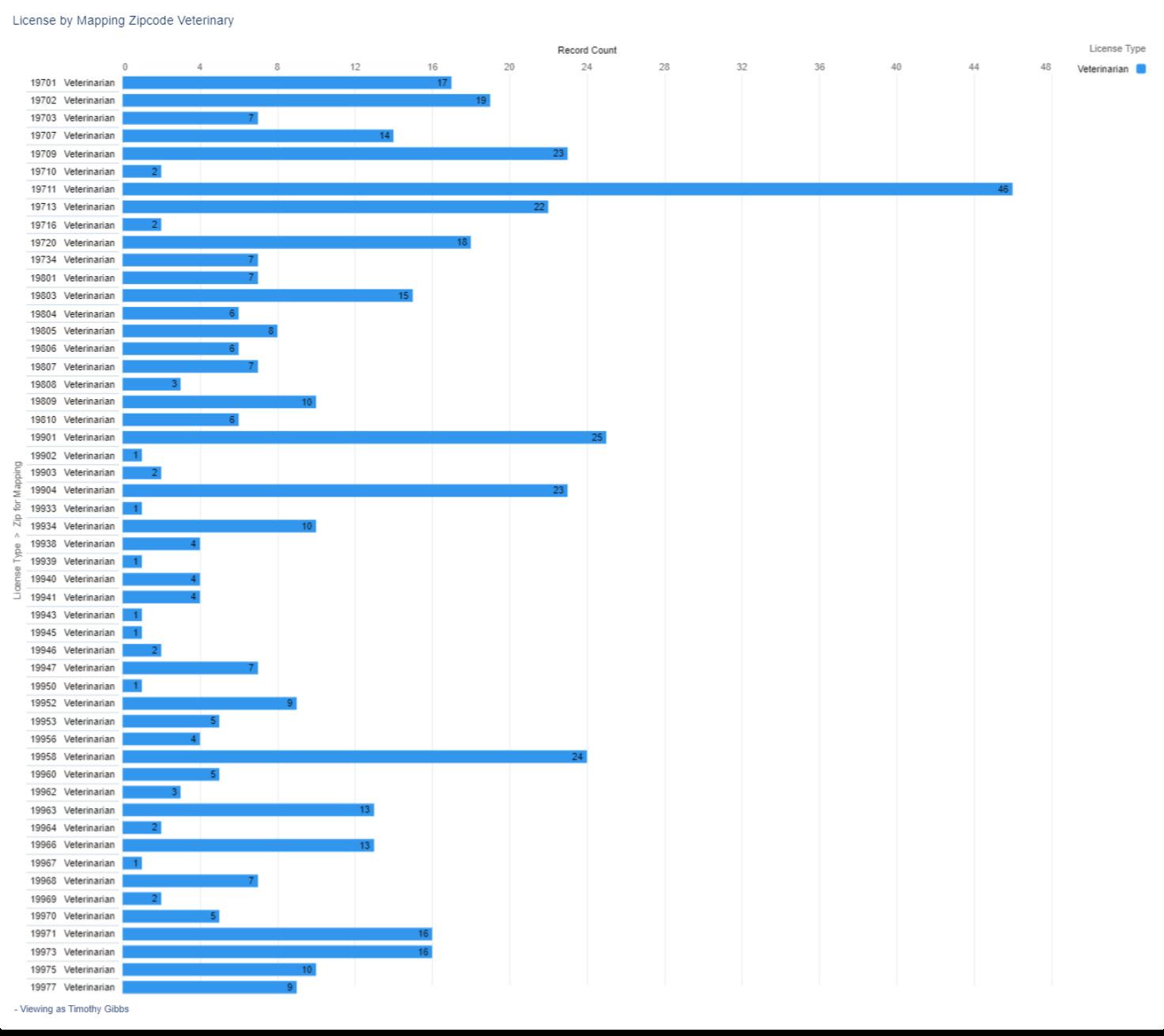

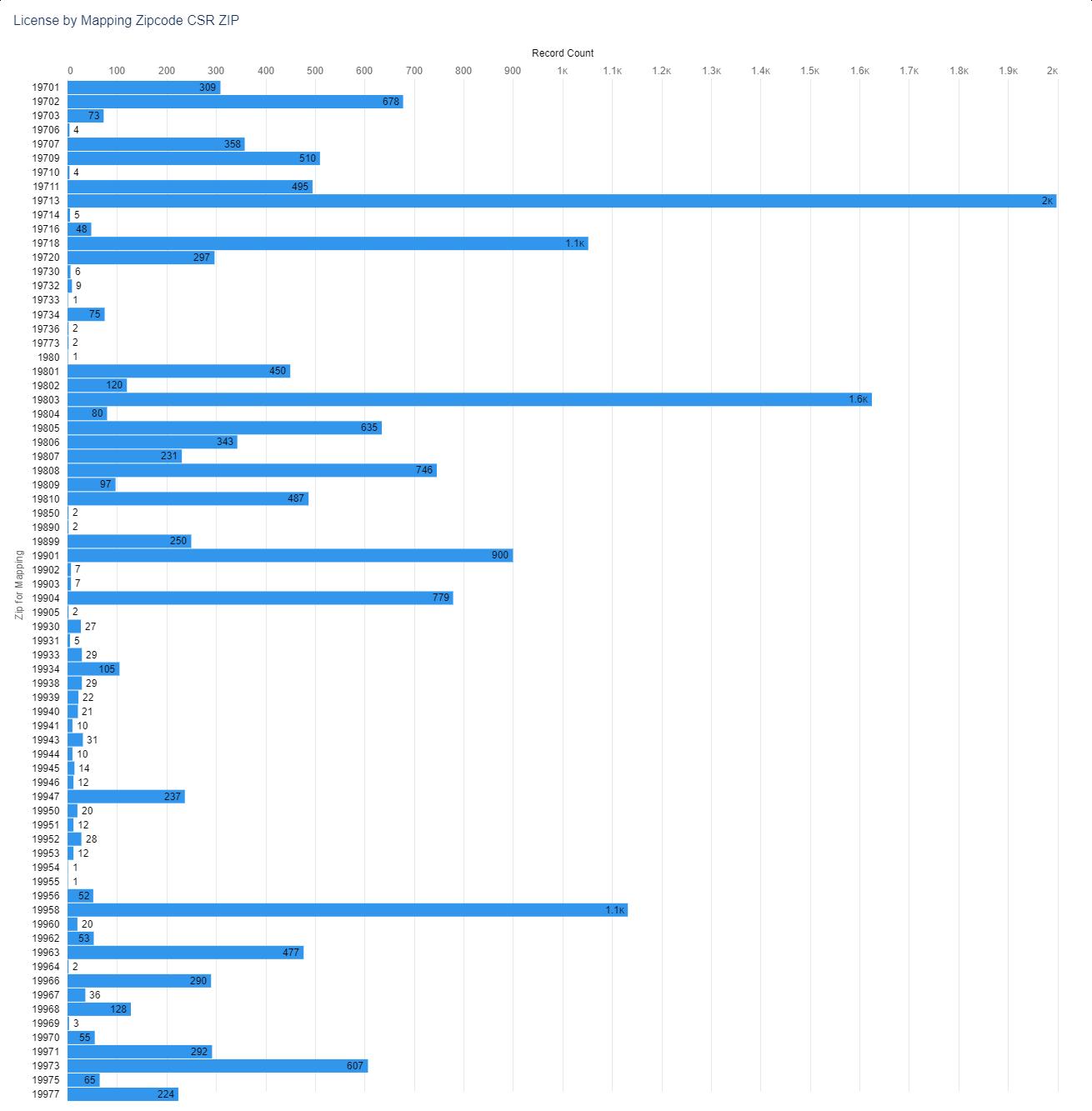

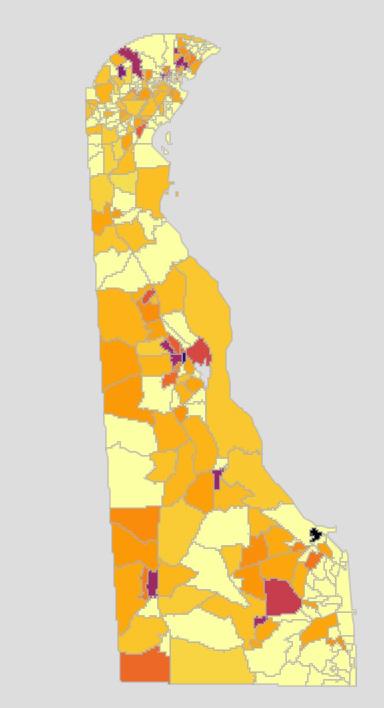

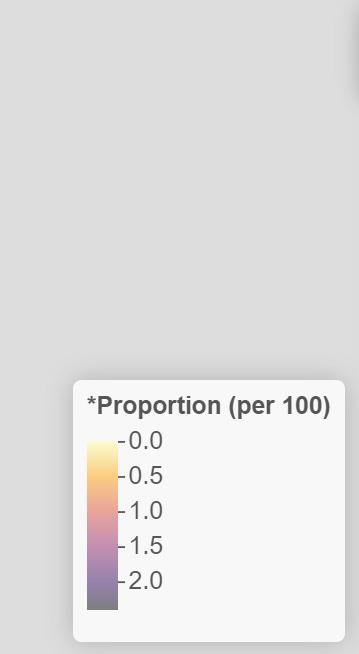

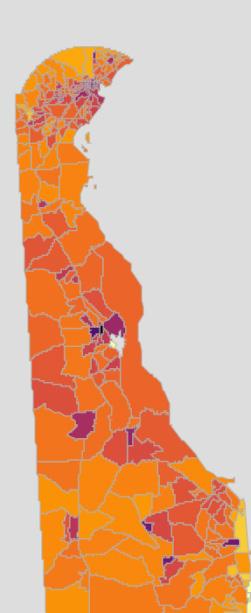

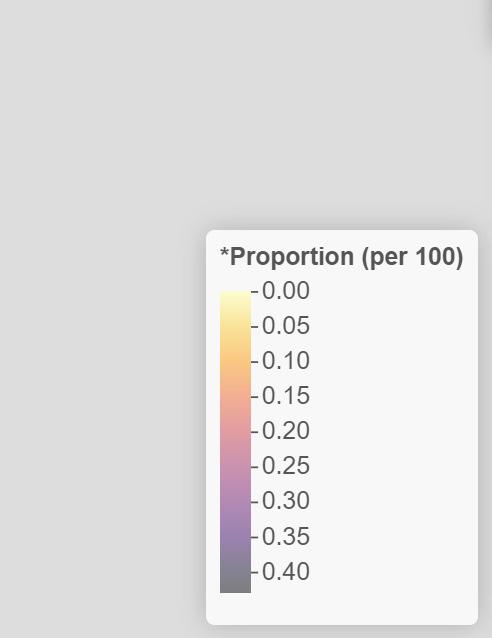

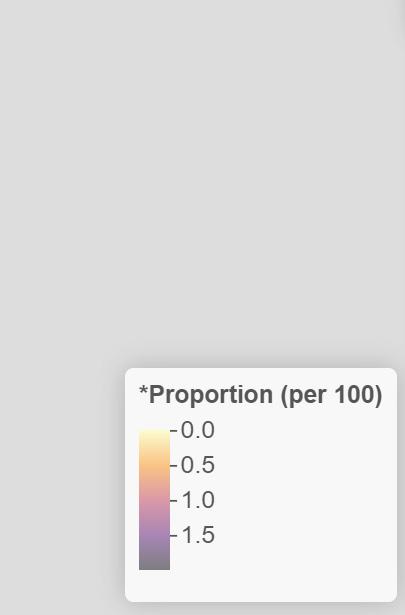

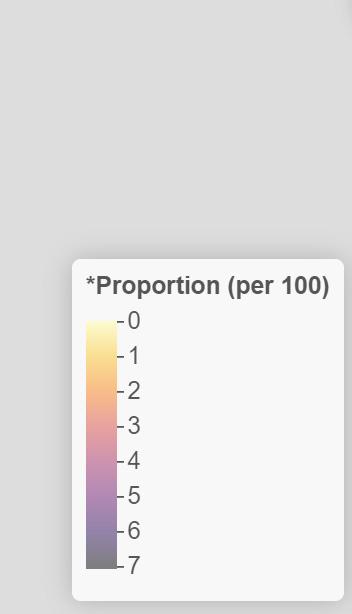

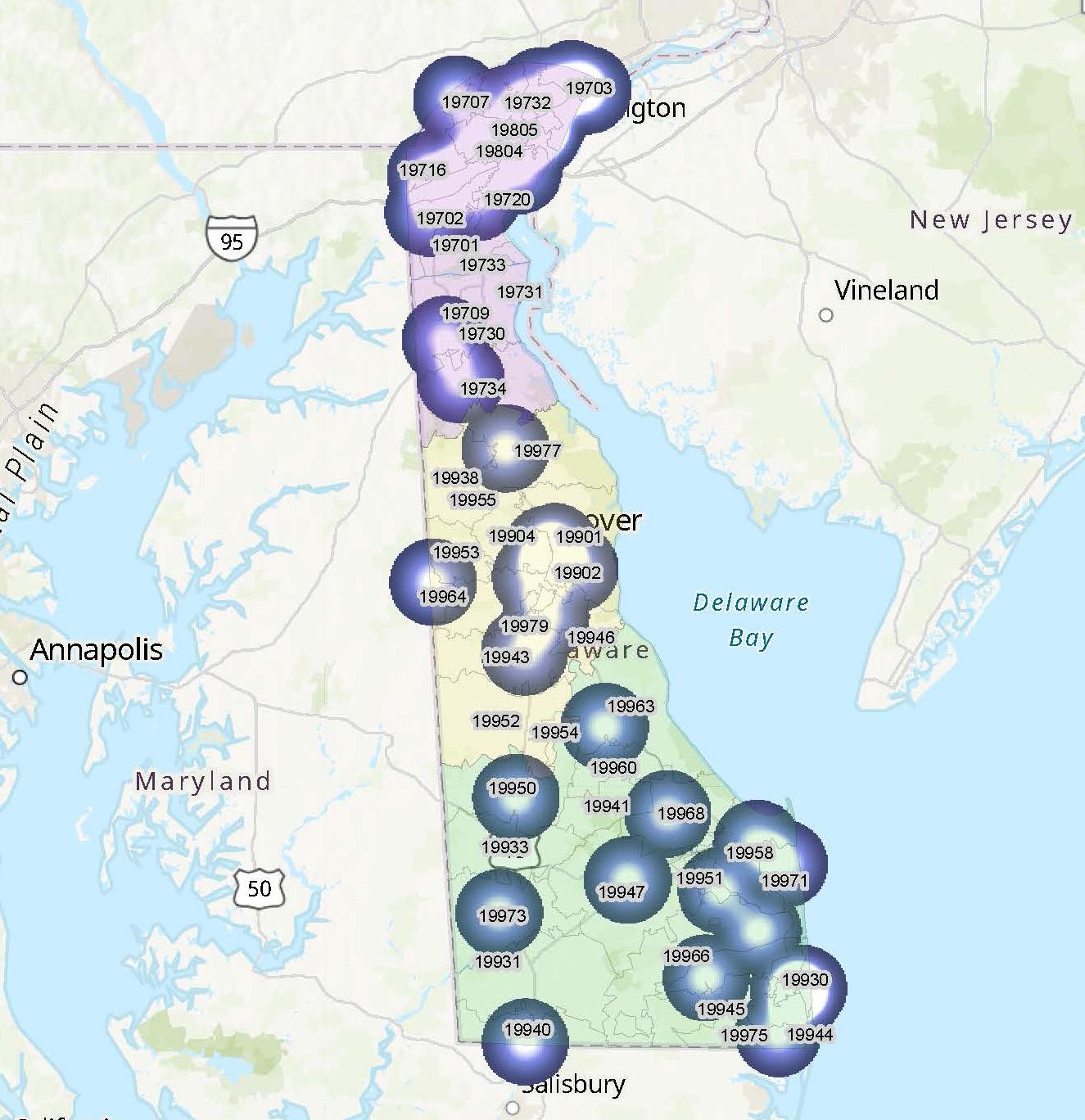

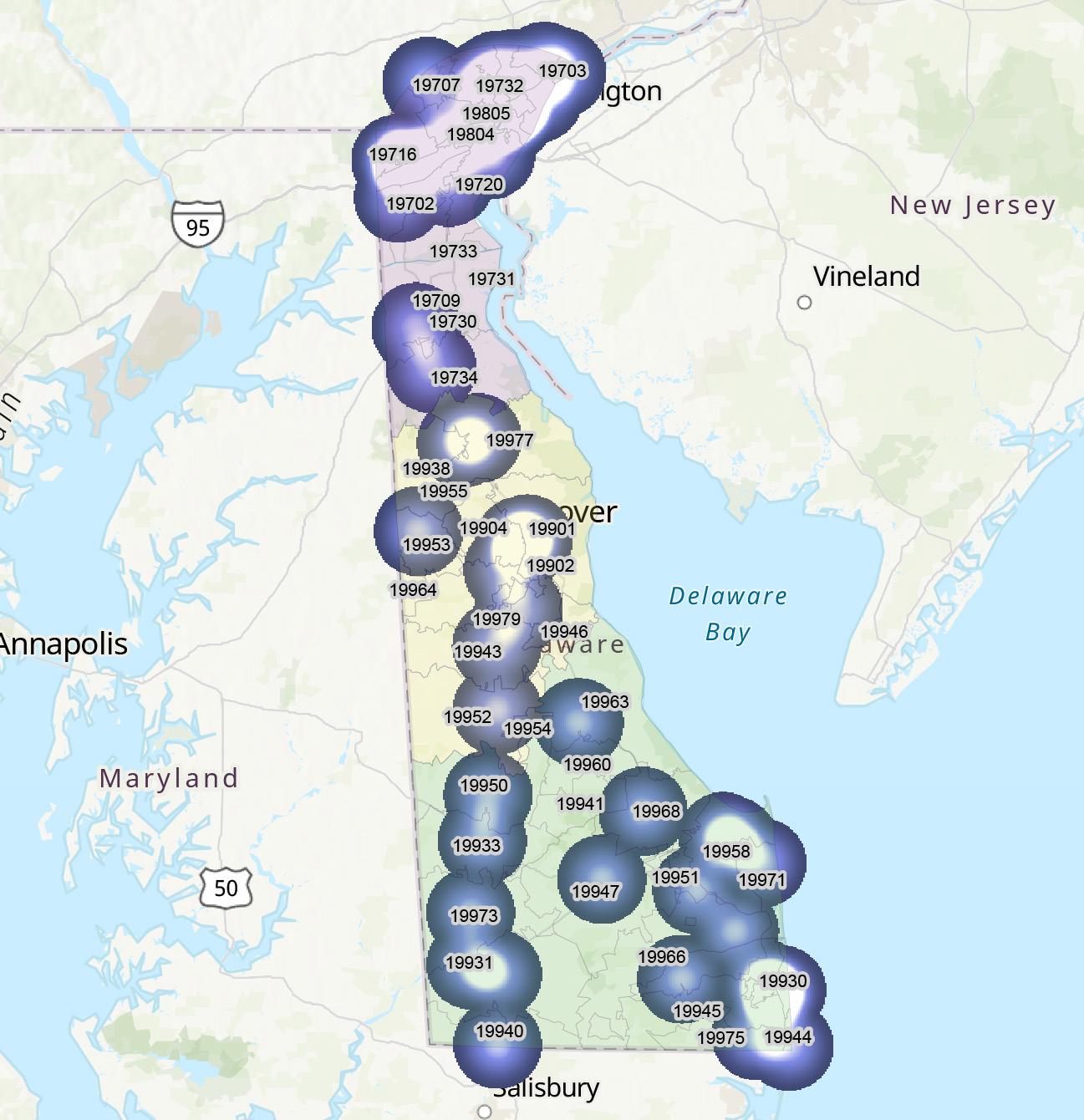

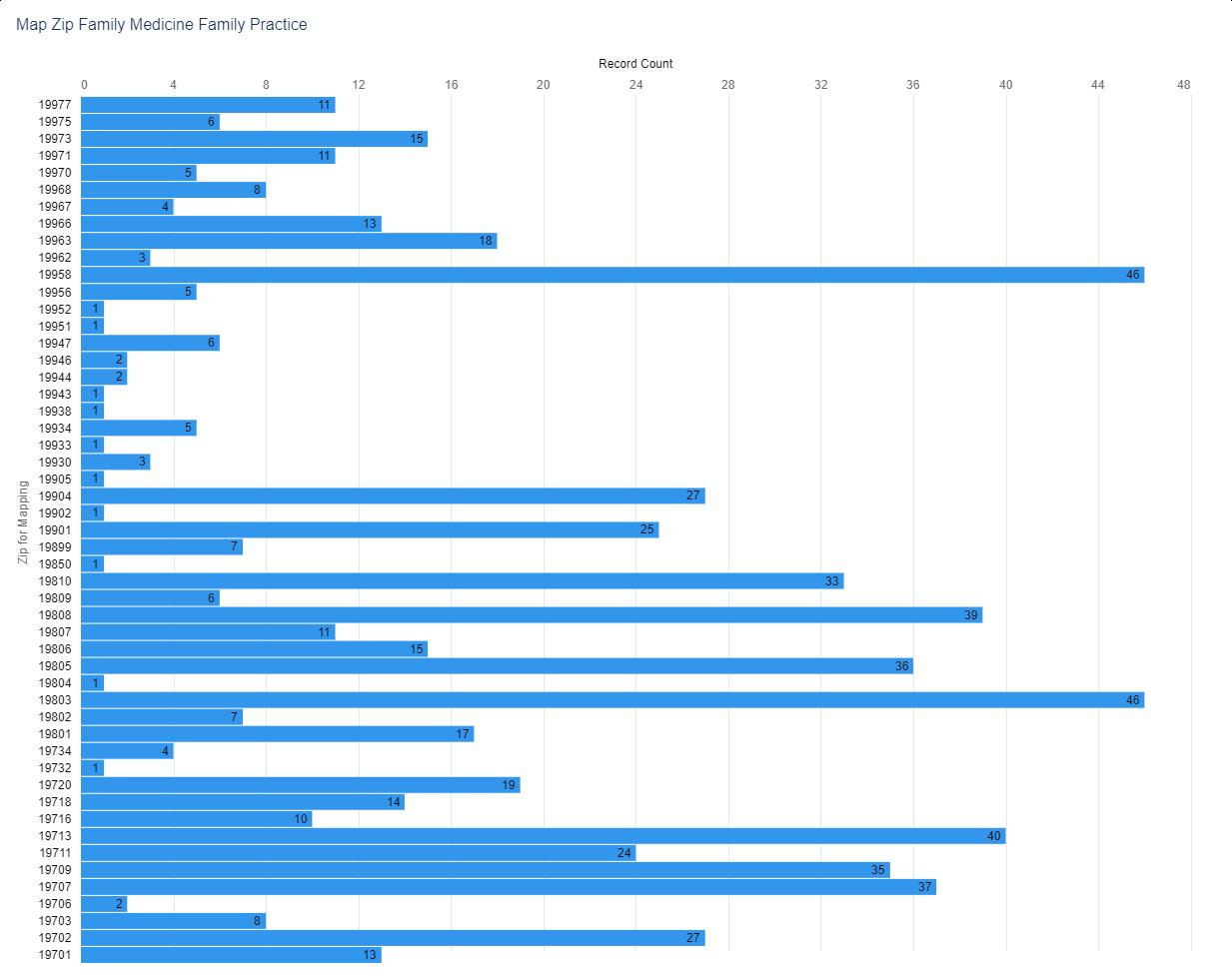

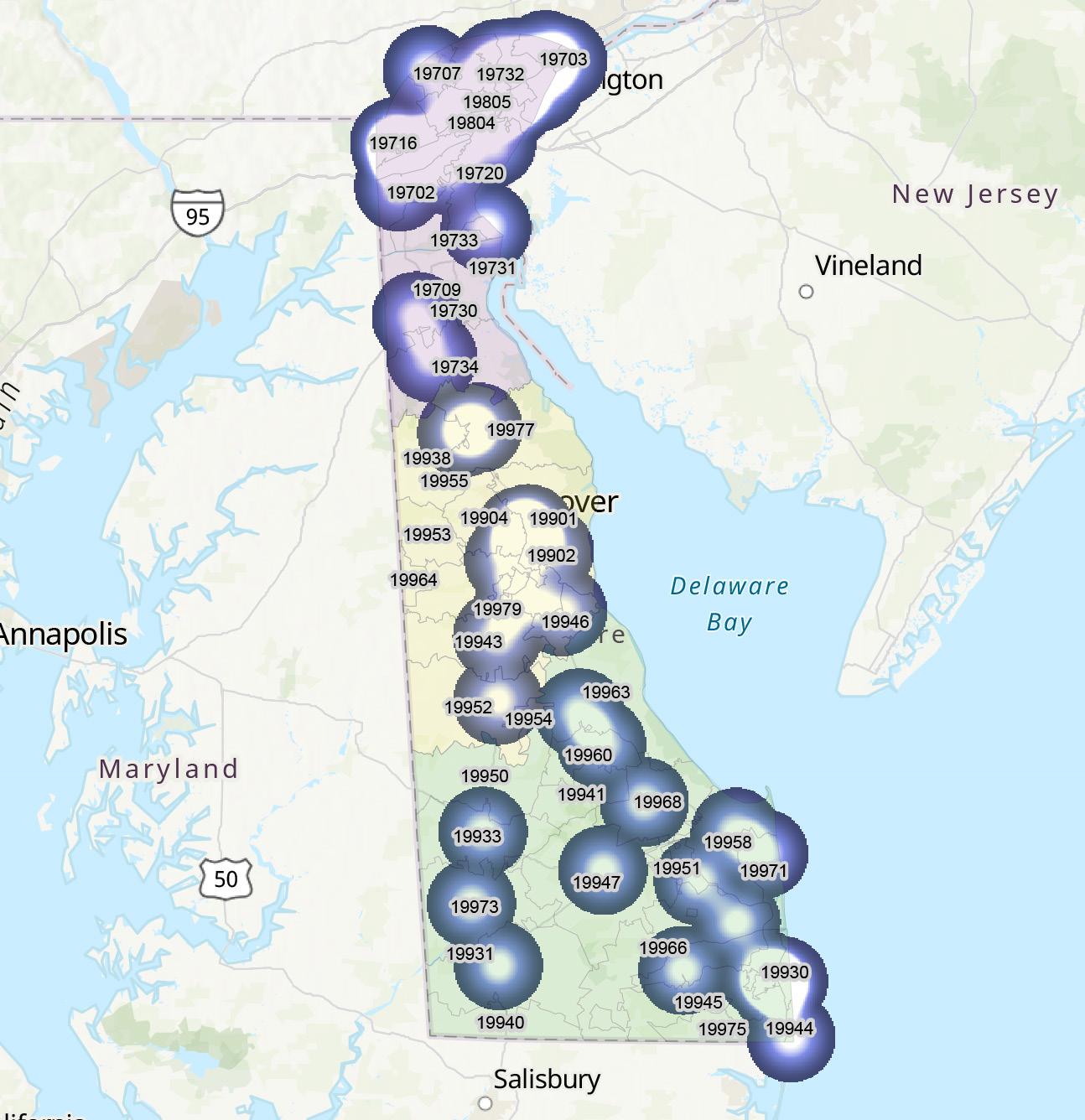

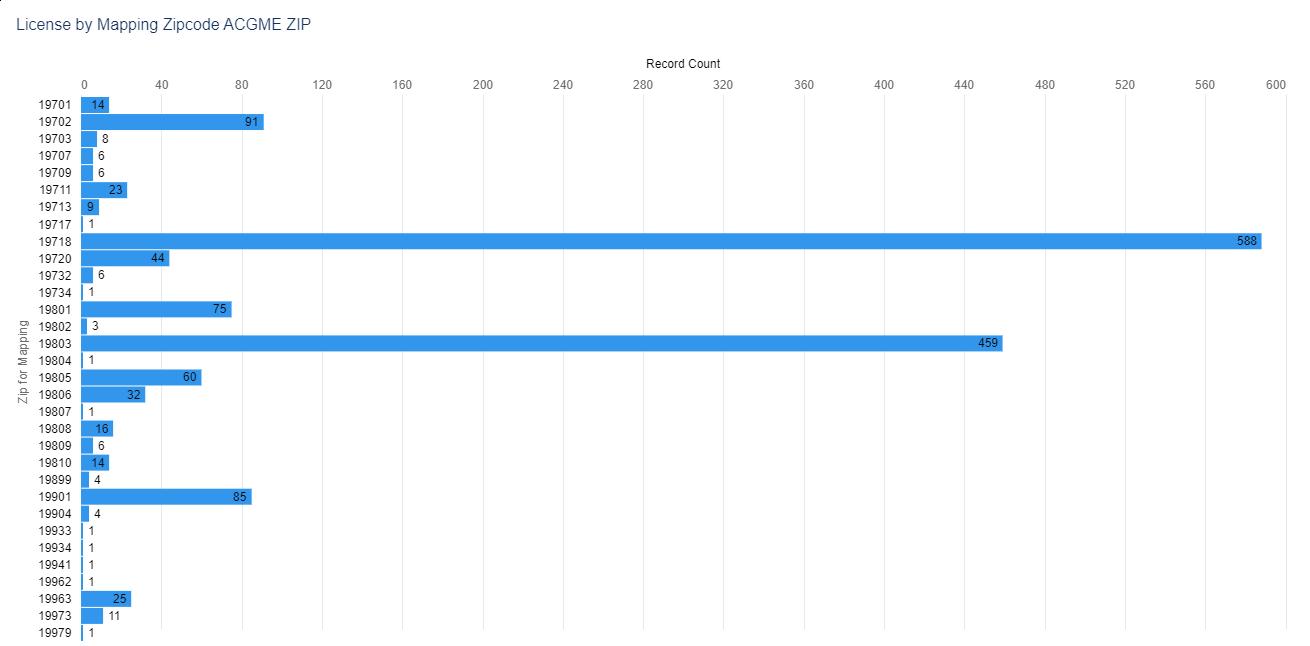

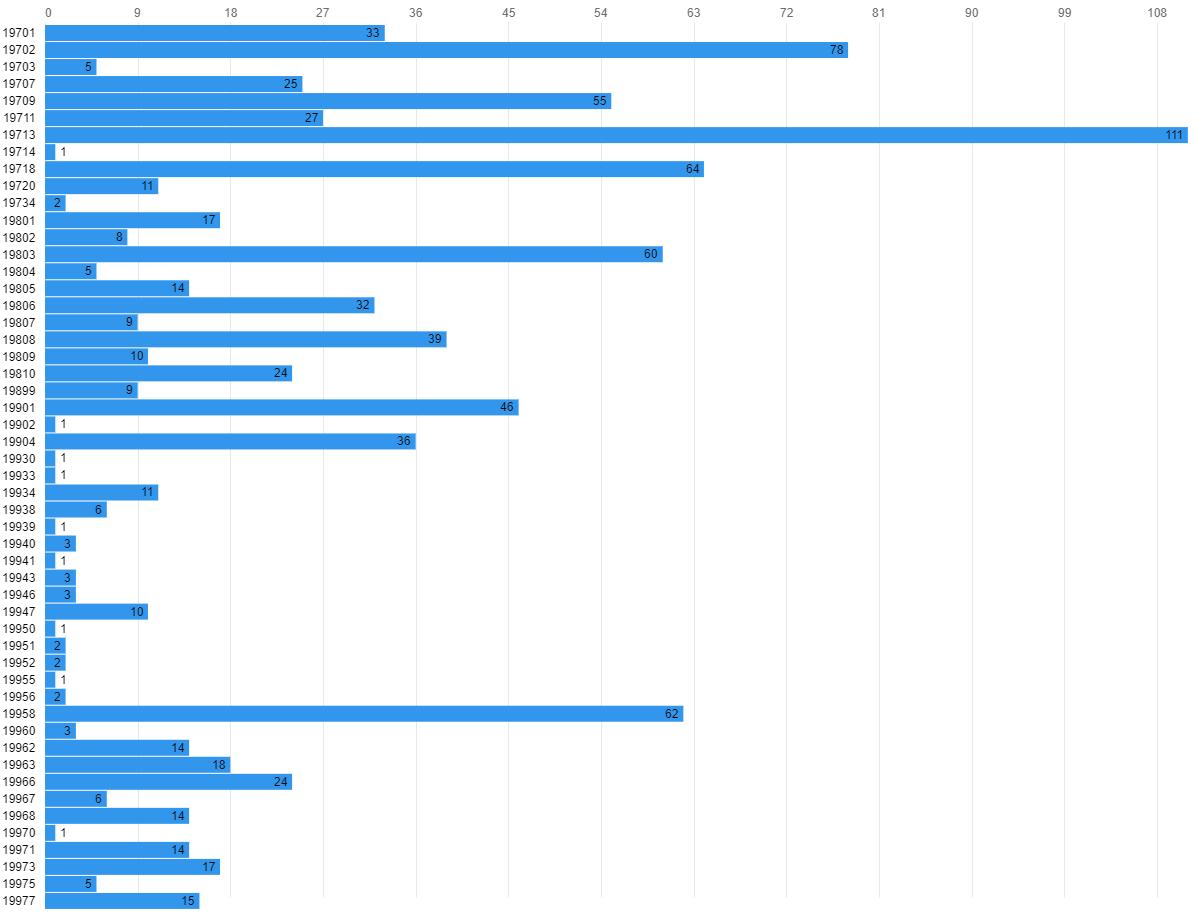

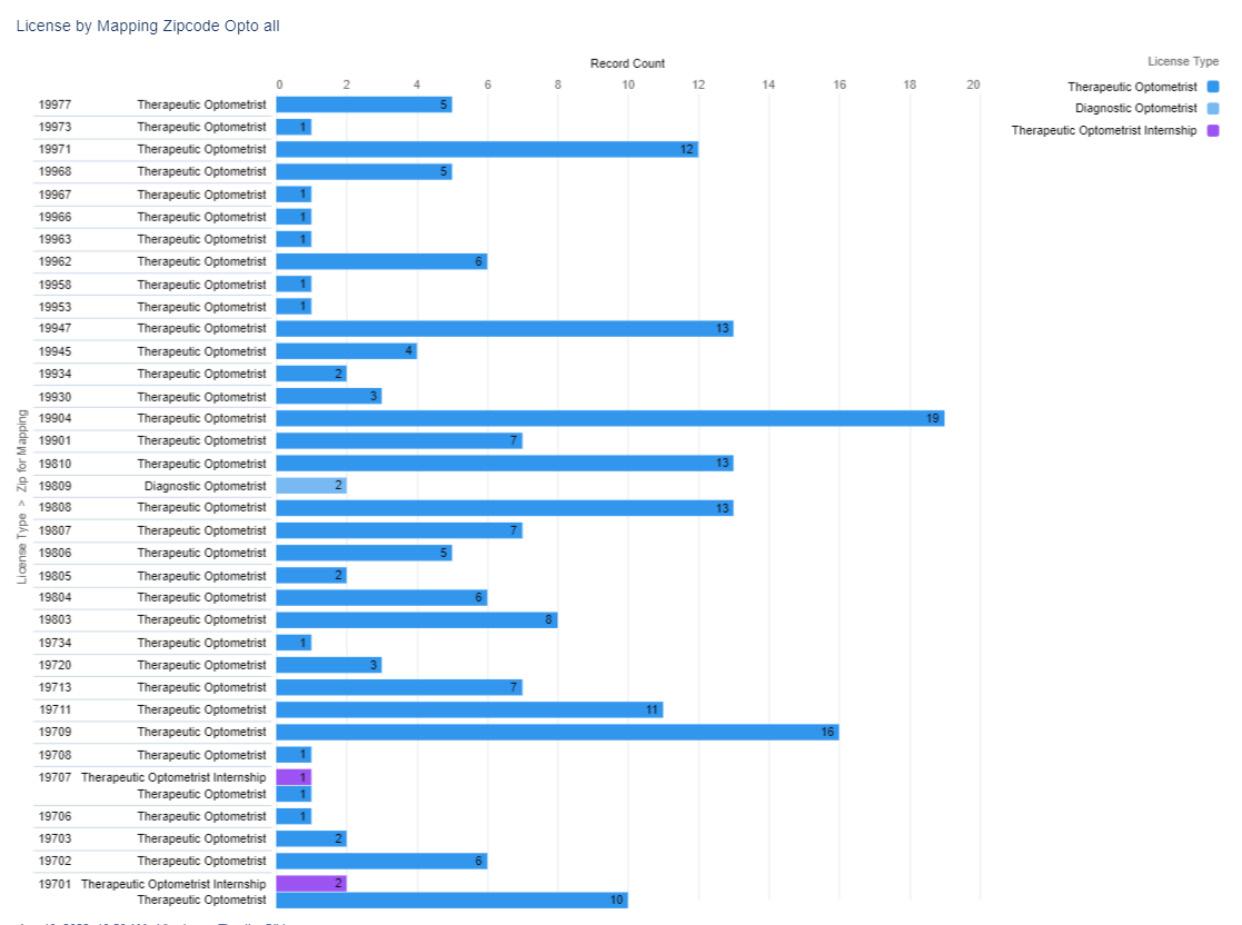

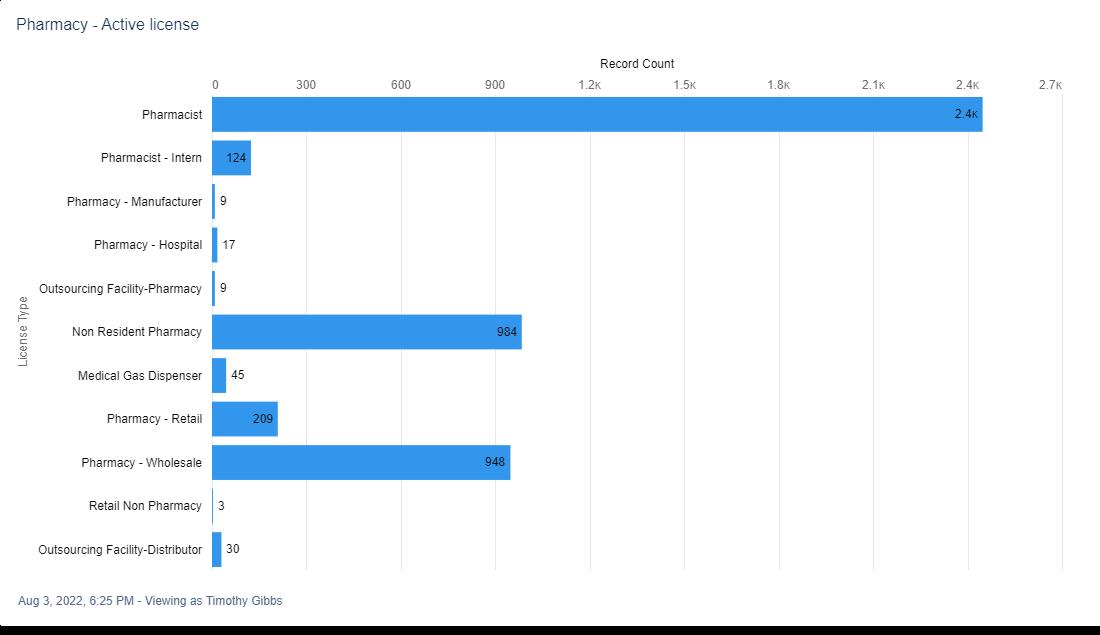

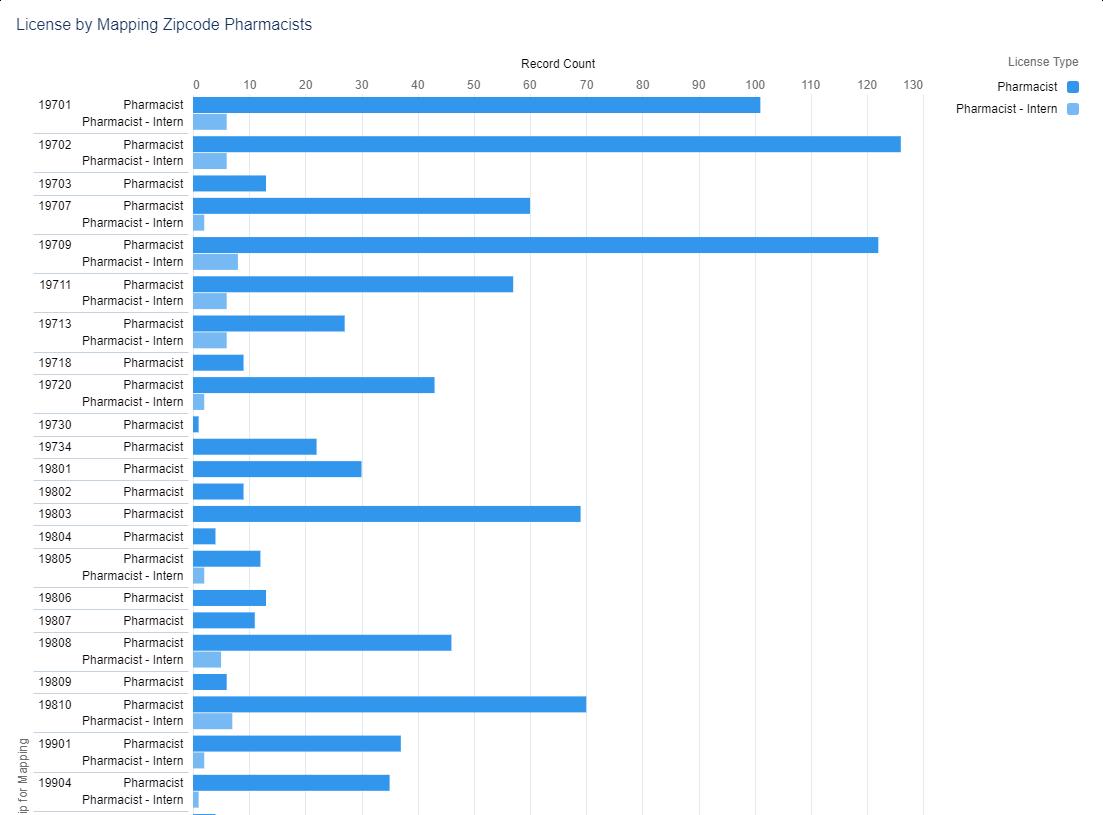

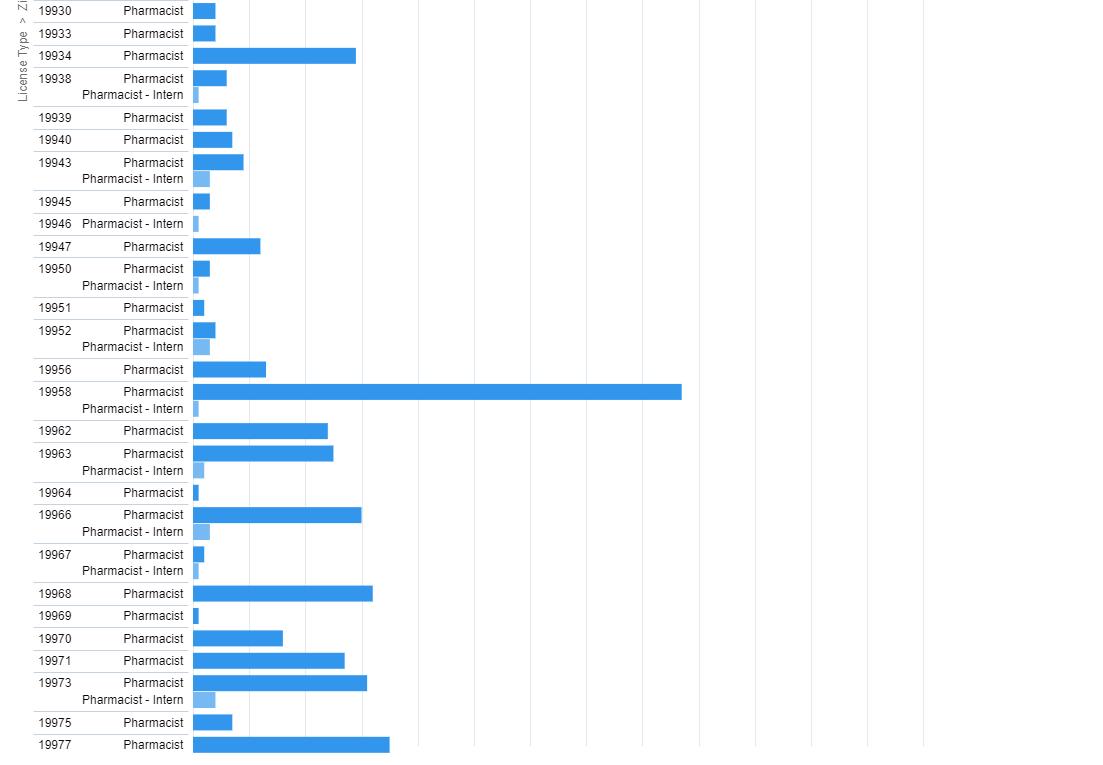

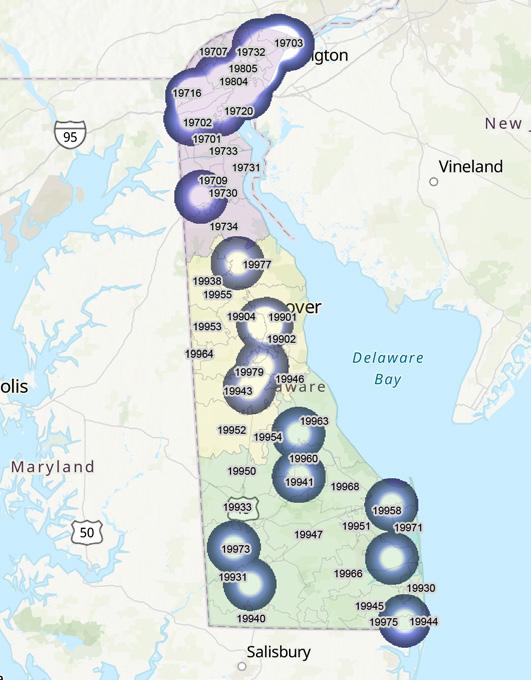

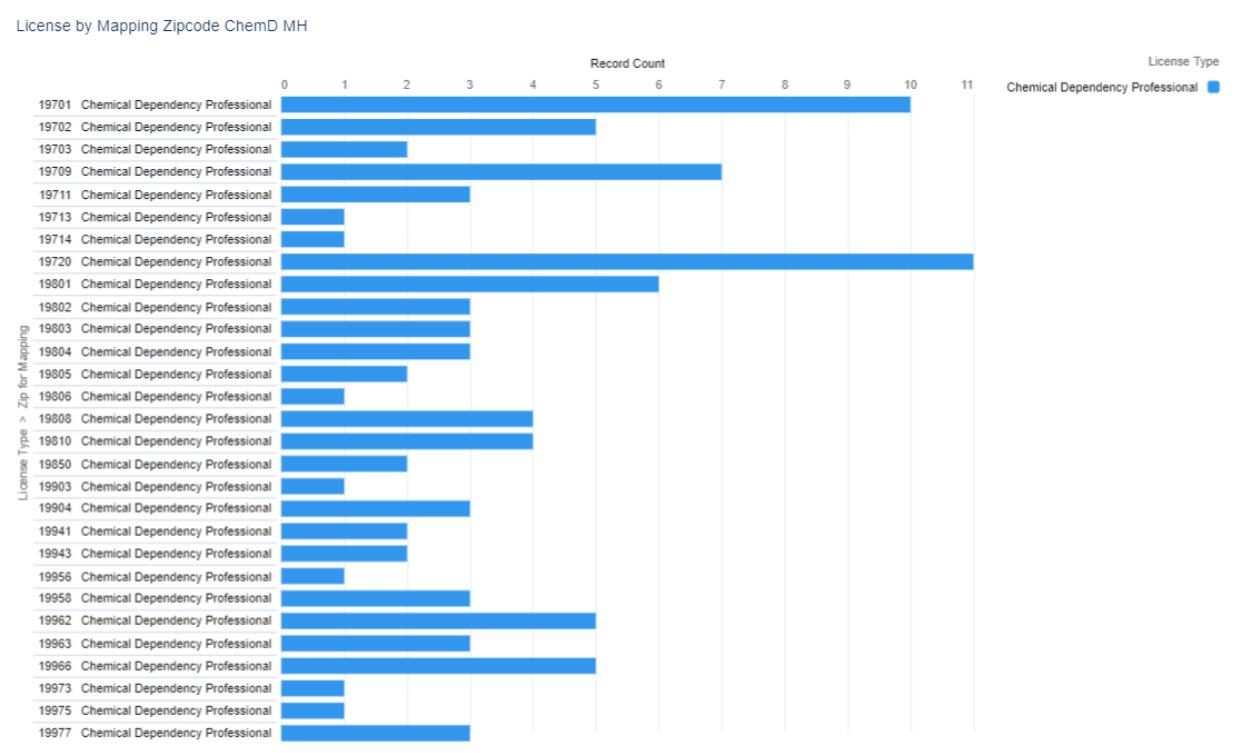

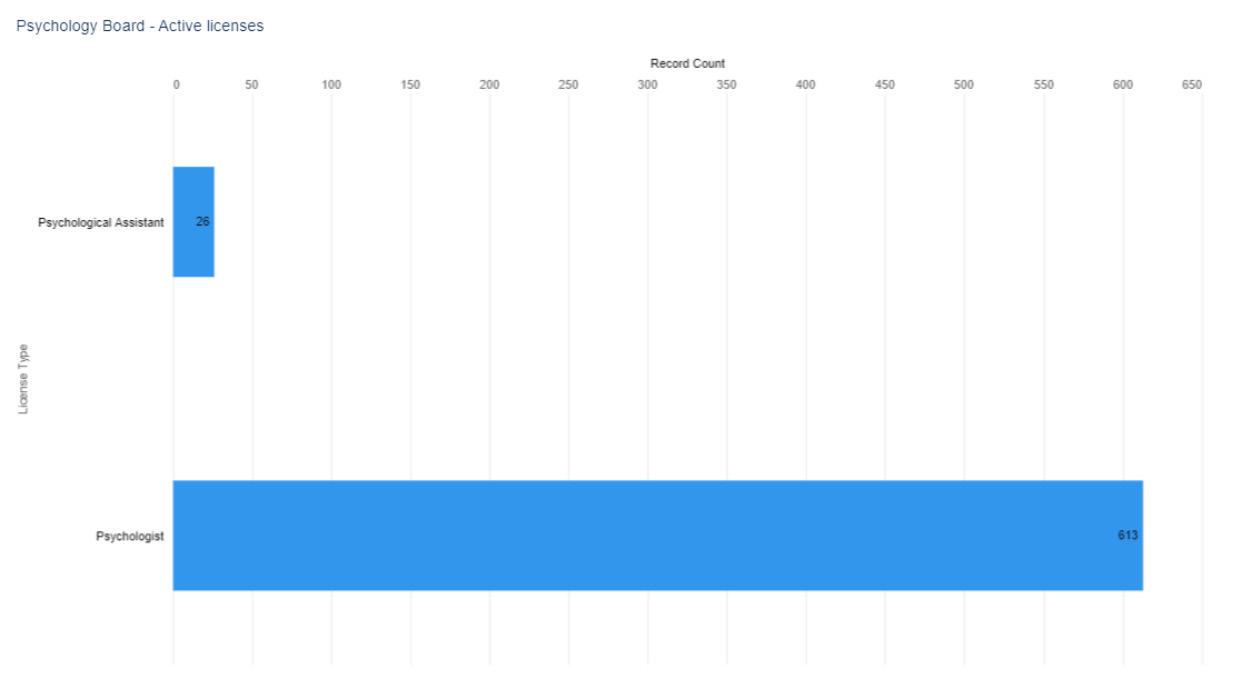

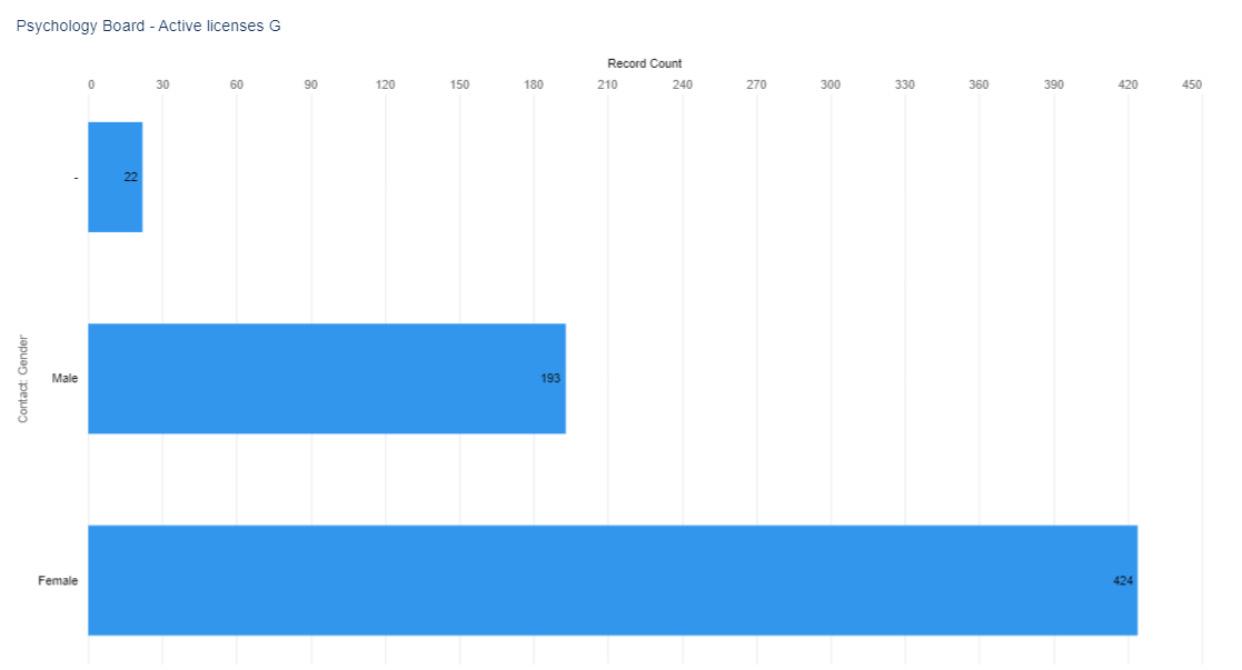

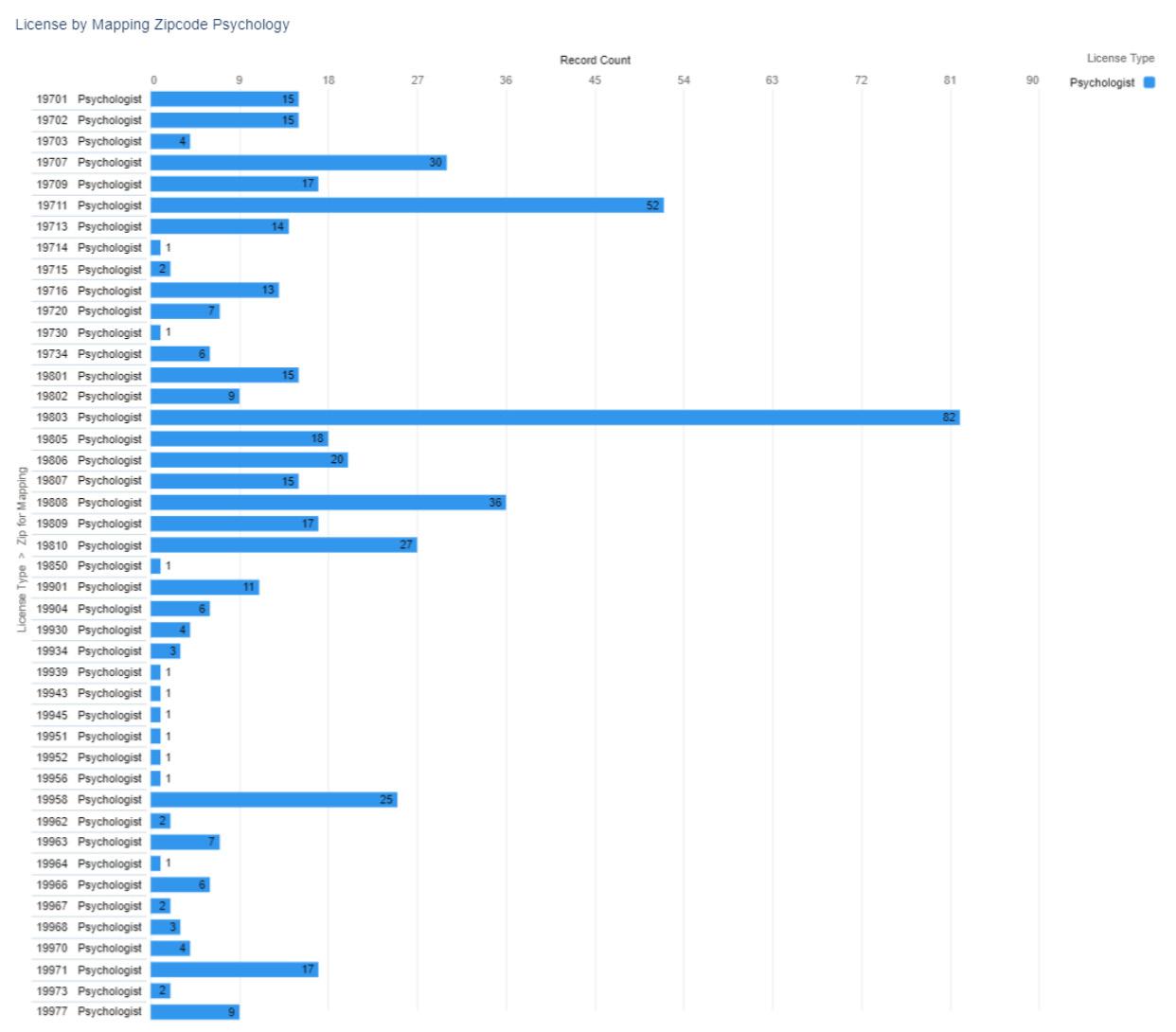

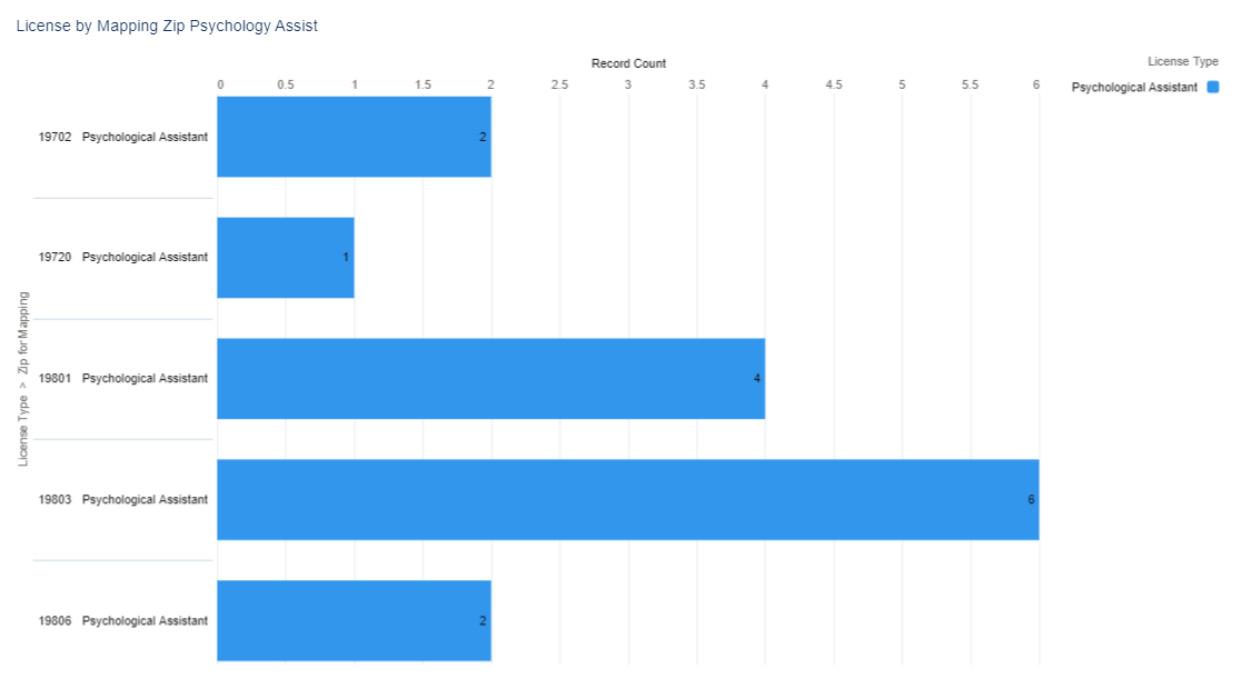

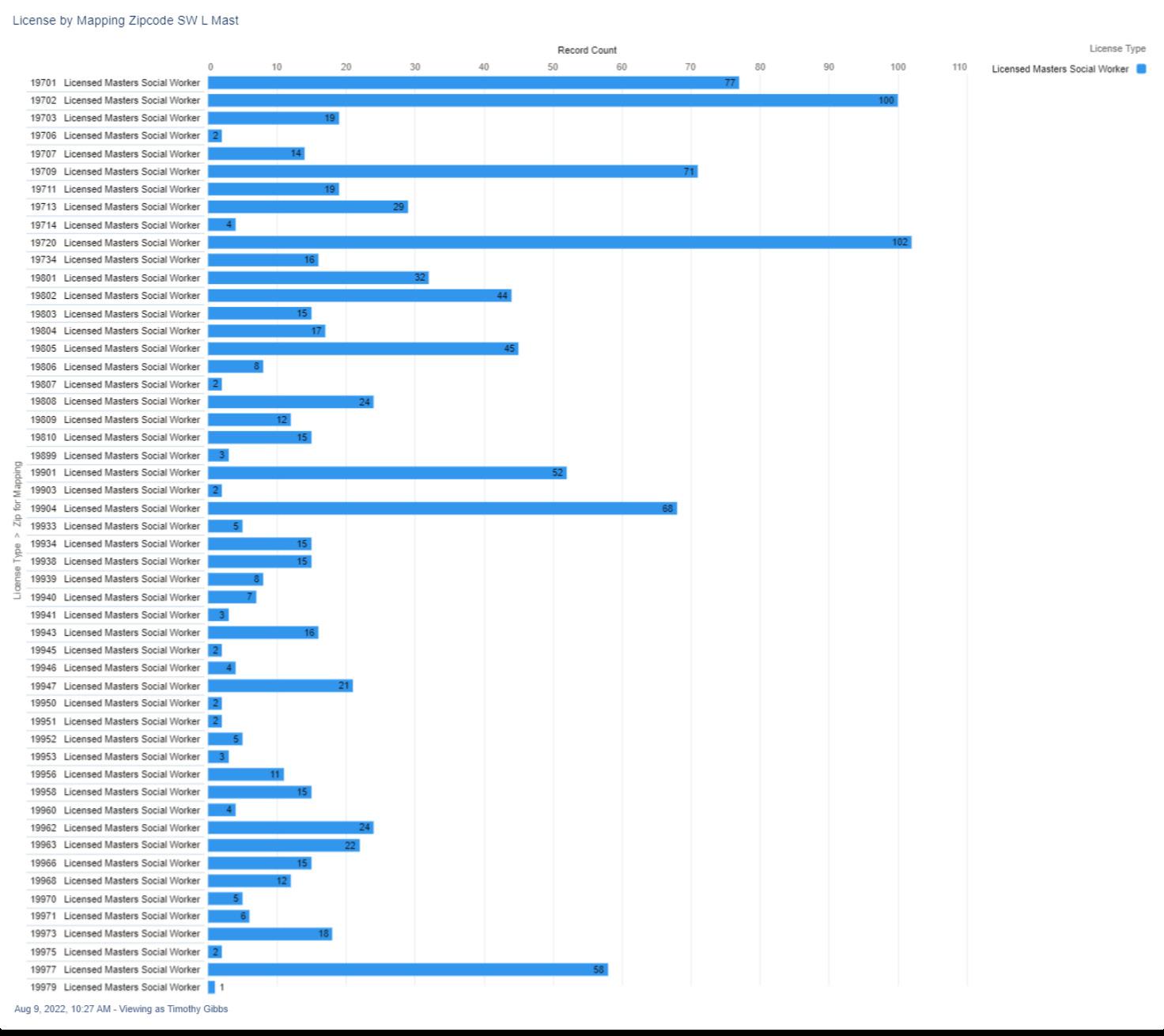

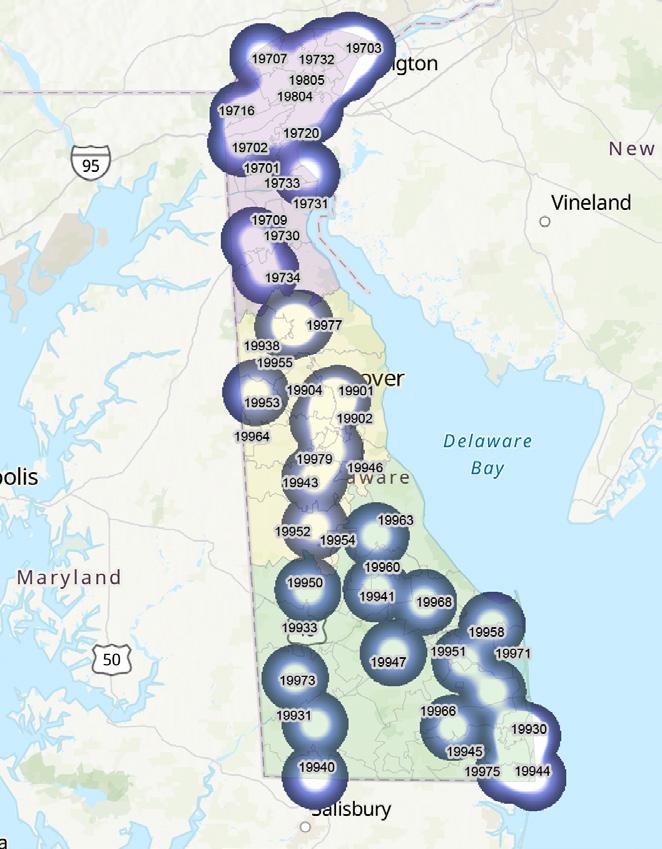

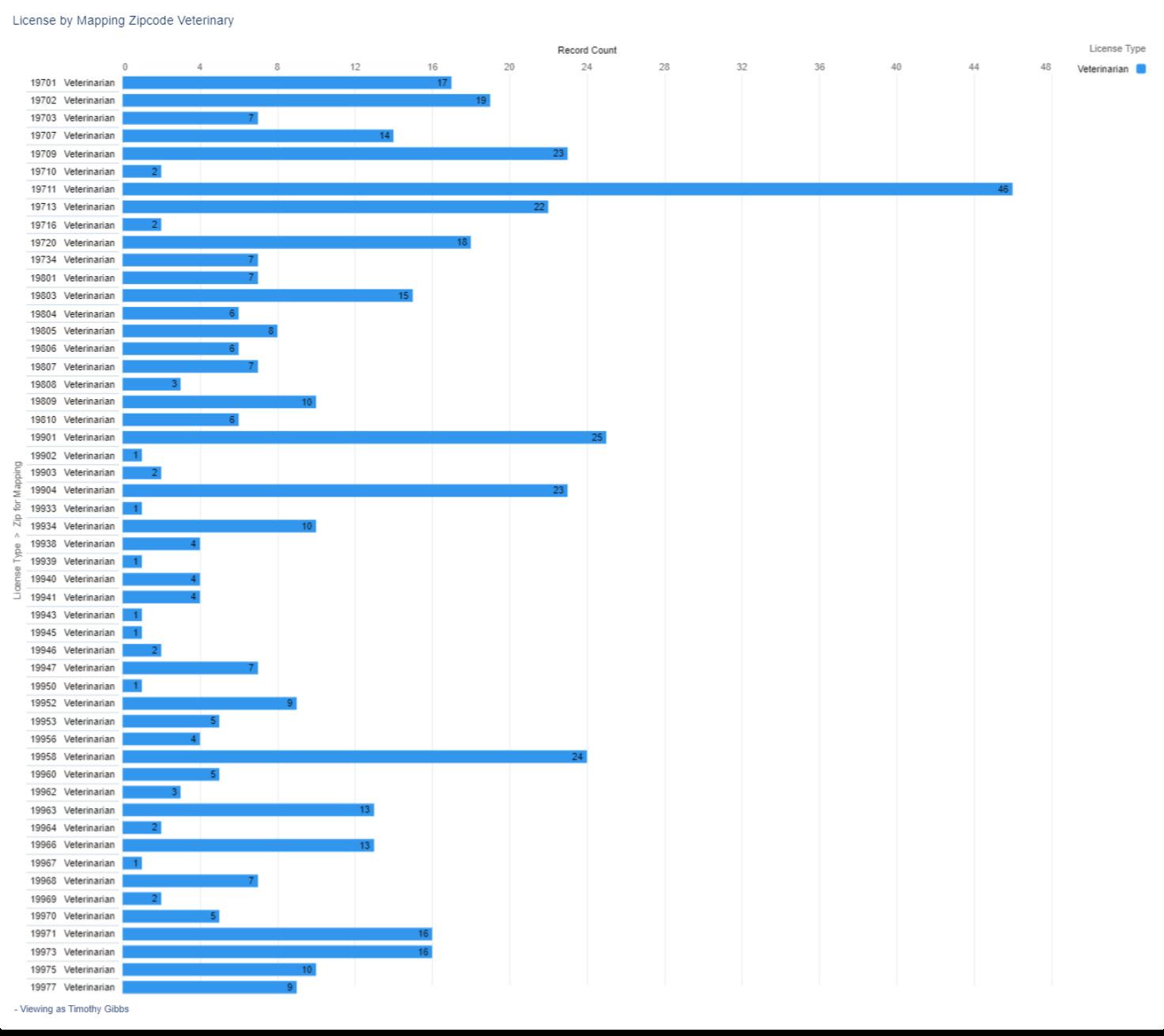

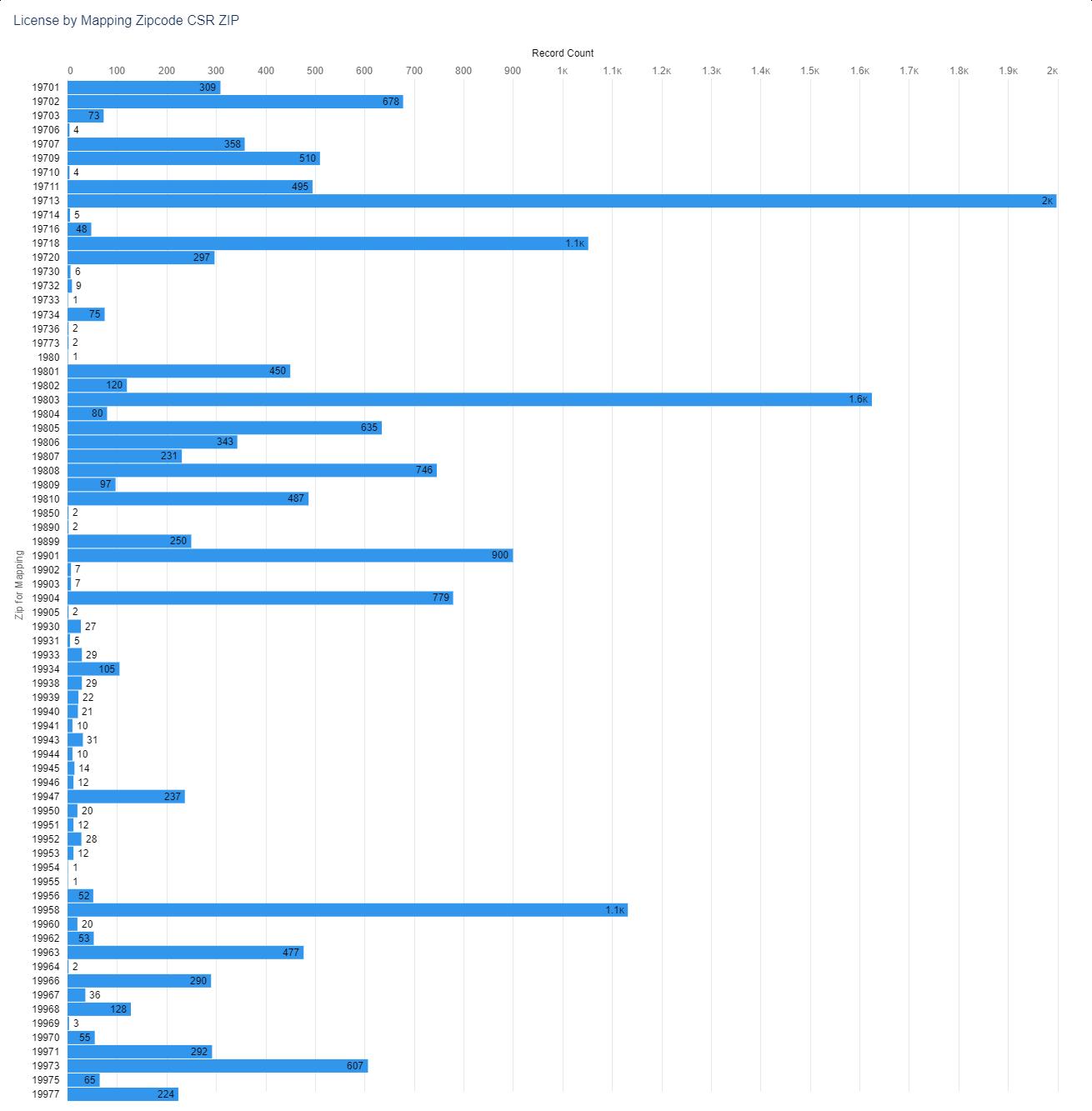

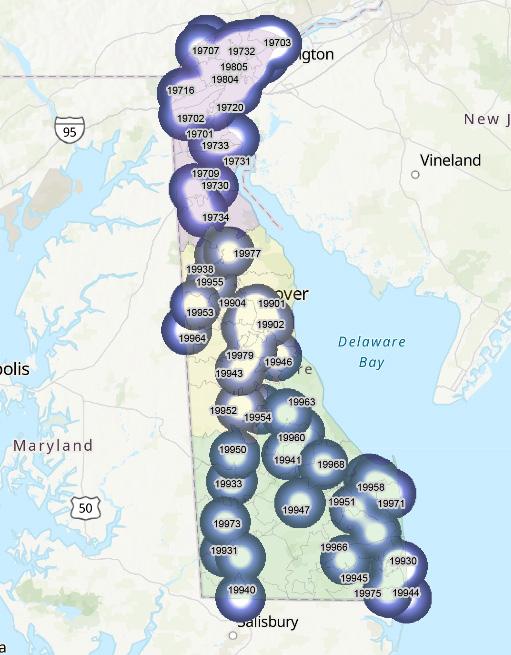

There are charts on active licenses, gender, year of birth and related conjecture one when individuals of a certain age may retire, and facing pages with numerical and visual distributions of providers by ZIP code. We use the primary license application ZIP code as the best available proxy for approximate location within Delaware, and acknowledge that a margin of error is inherent in this method. There are also a small number of providers who provided a ZIP code outside of the State of Delaware, which further compounds the absolute accuracy of our methodology.

Charts were created in Salesforce and maps created in ArcGIS.

CHARTS

To save space, we removed secondary labeling on the y-axis (i.e., “ZIP code”). In so doing, we freed up significant space to make some charts larger and more legible. The x-axis on all charts is always the number of licensed individuals or entities. The bars on the charts are proportional to the number they represent, and therefore to each other.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.012

20 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

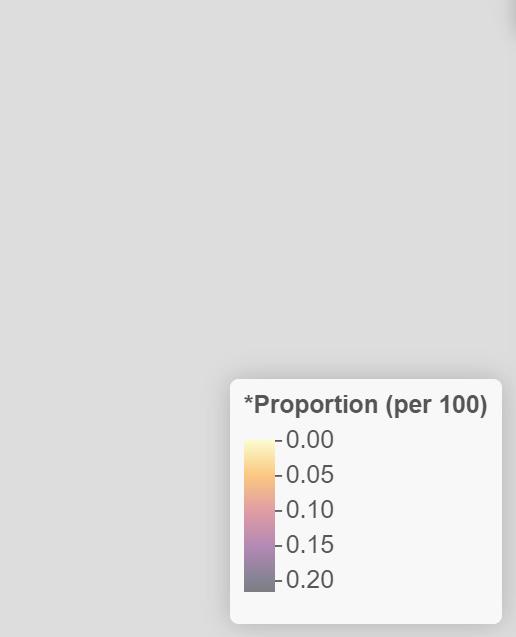

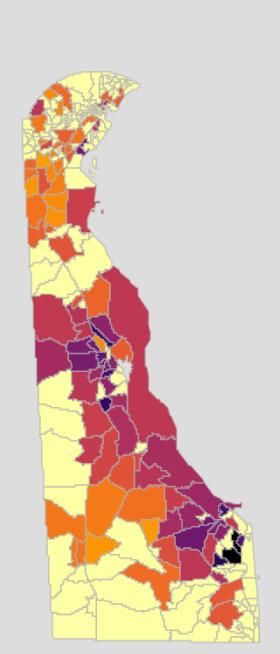

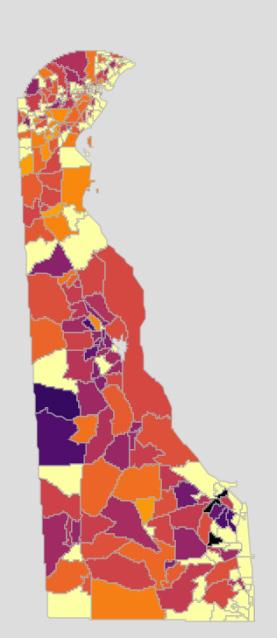

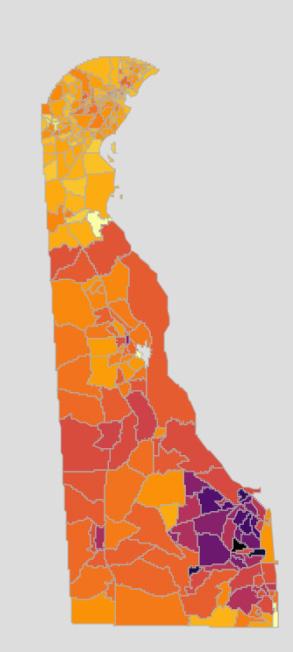

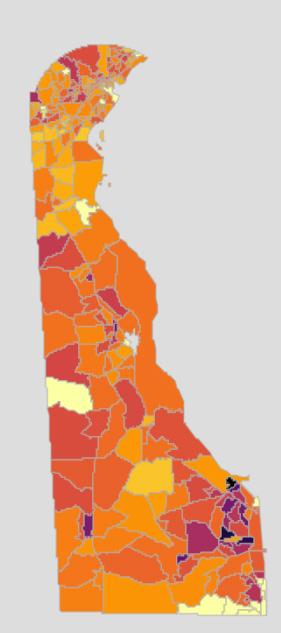

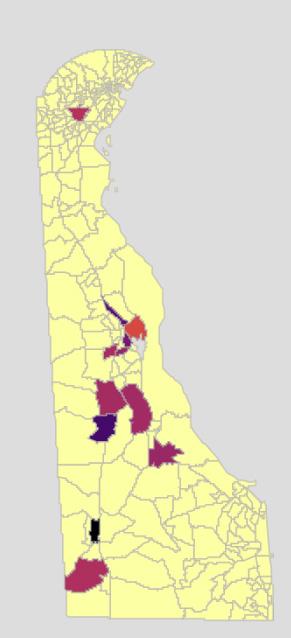

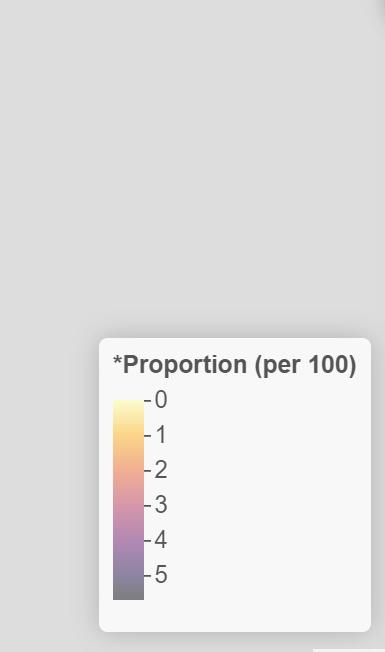

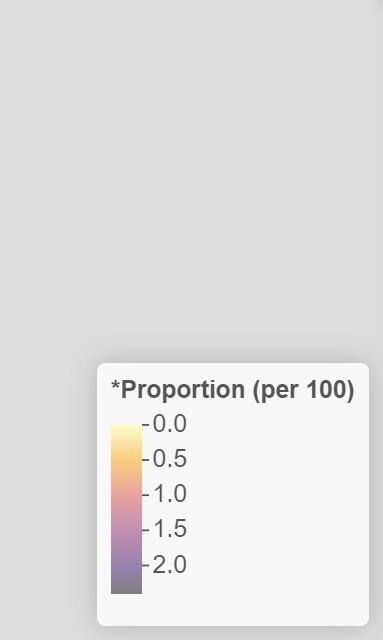

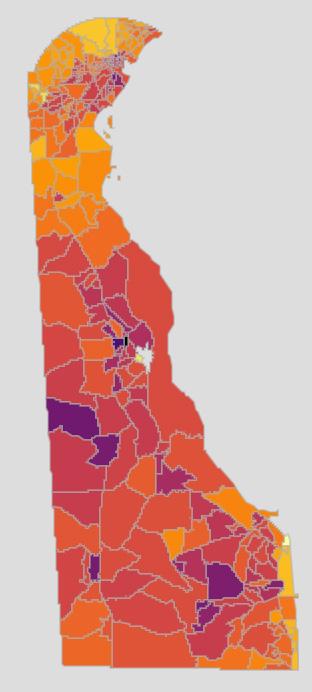

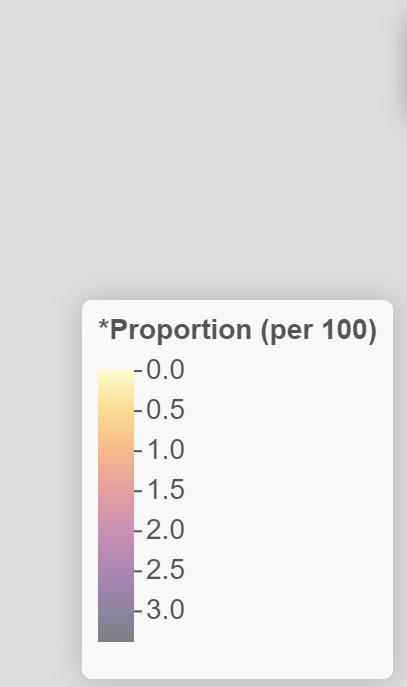

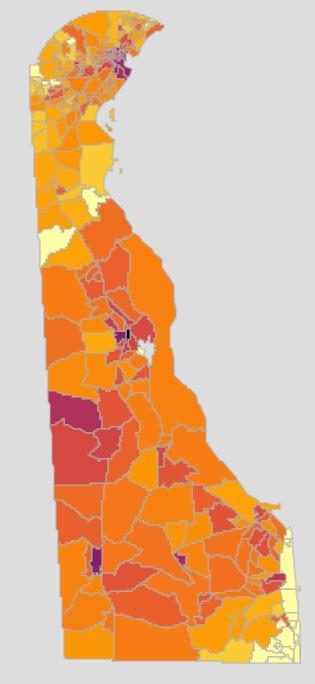

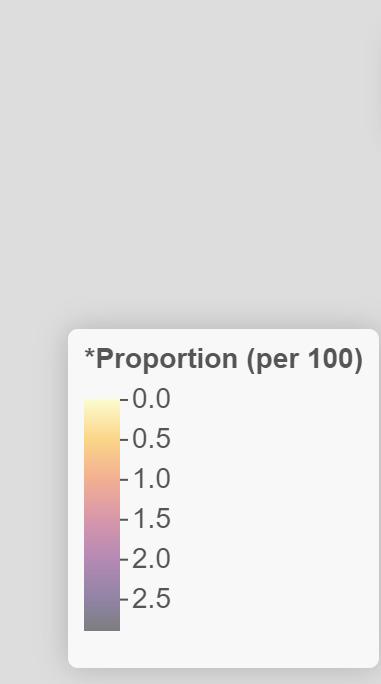

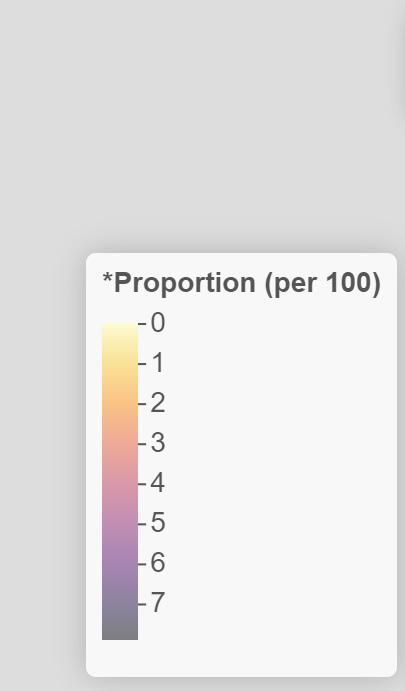

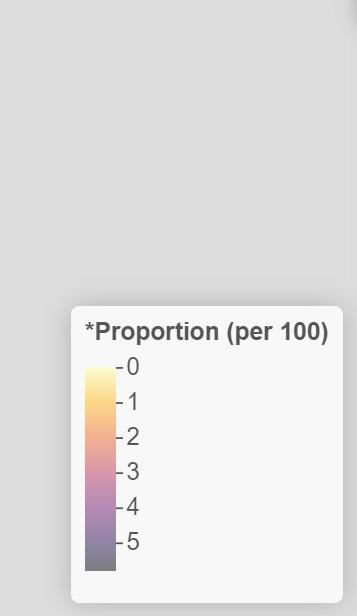

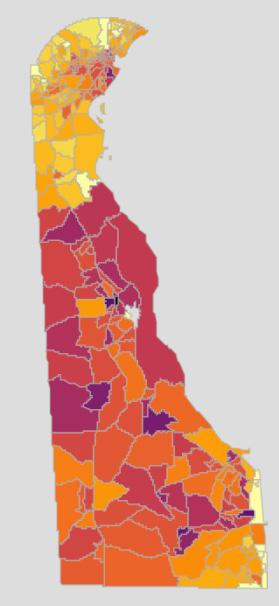

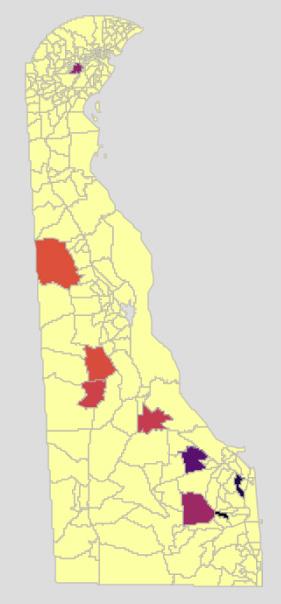

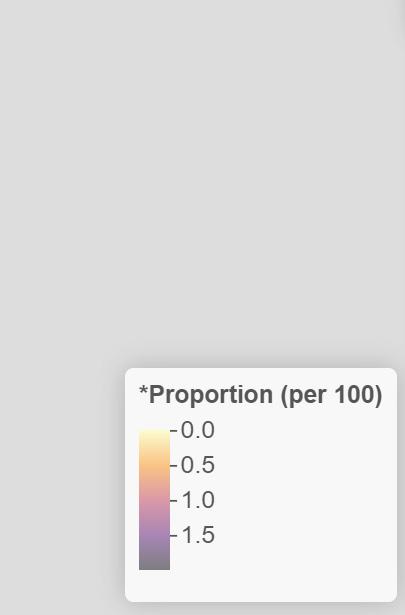

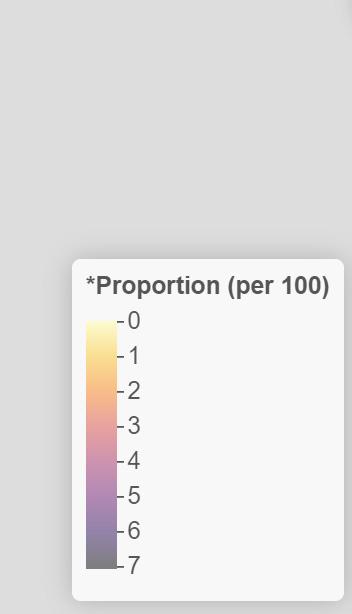

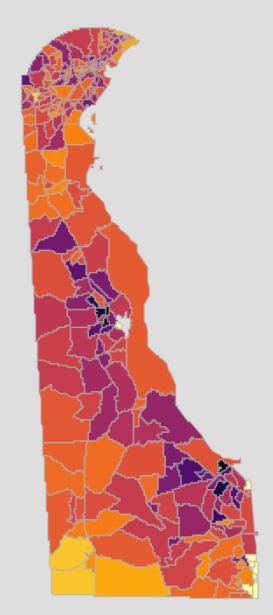

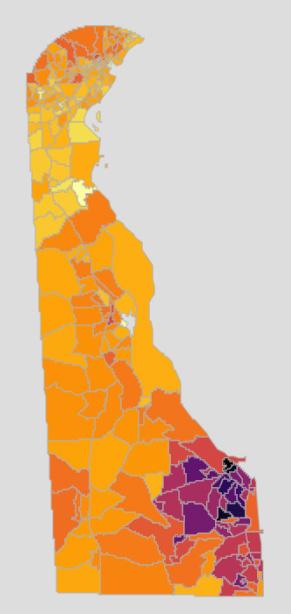

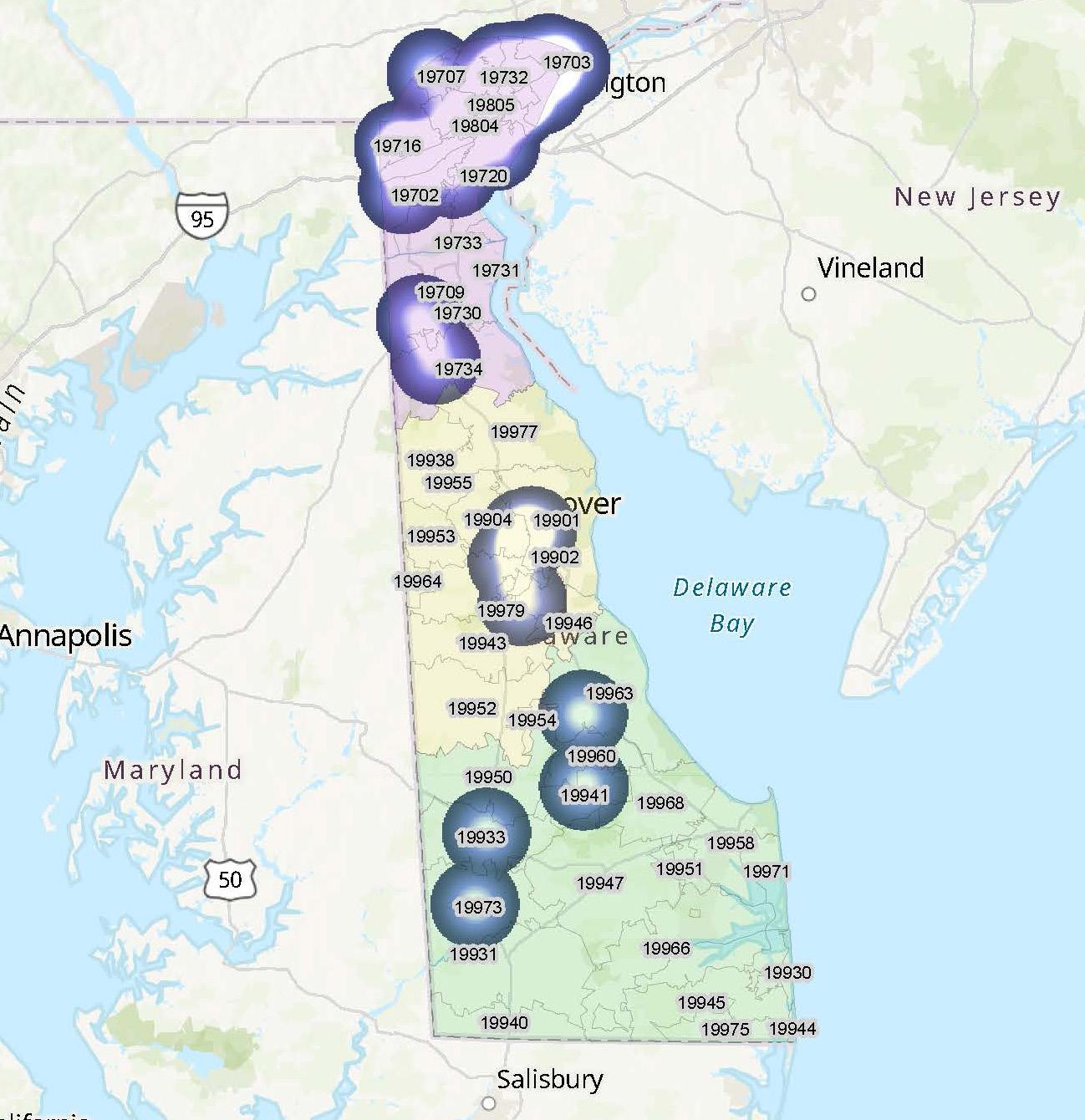

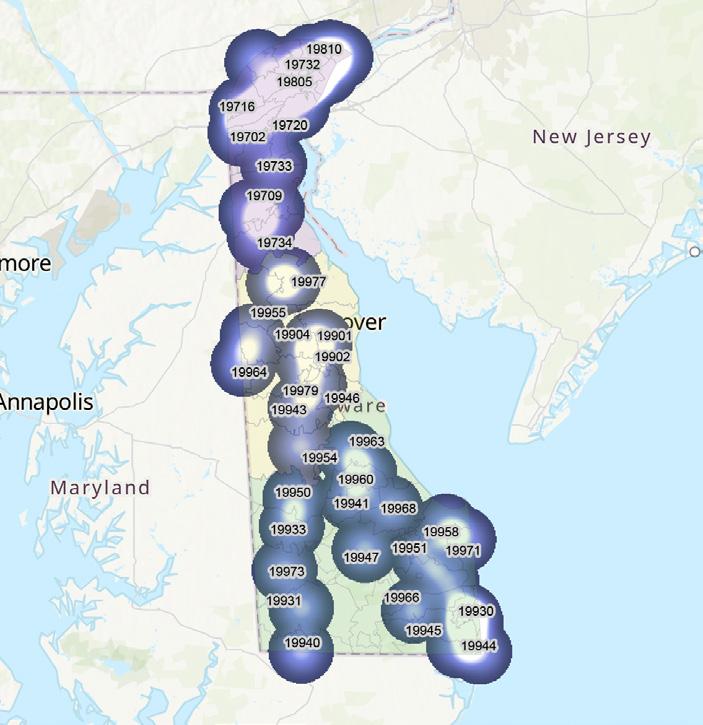

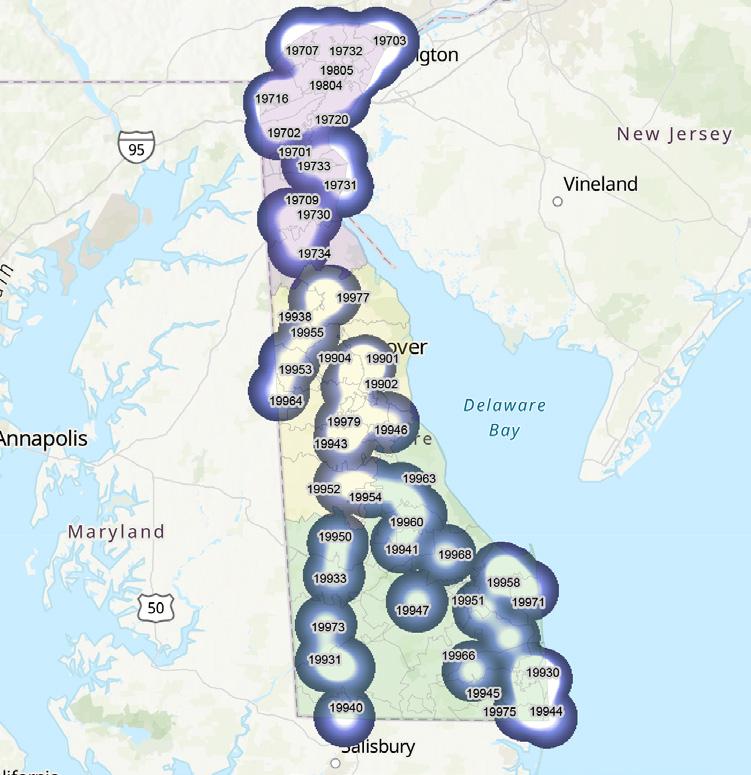

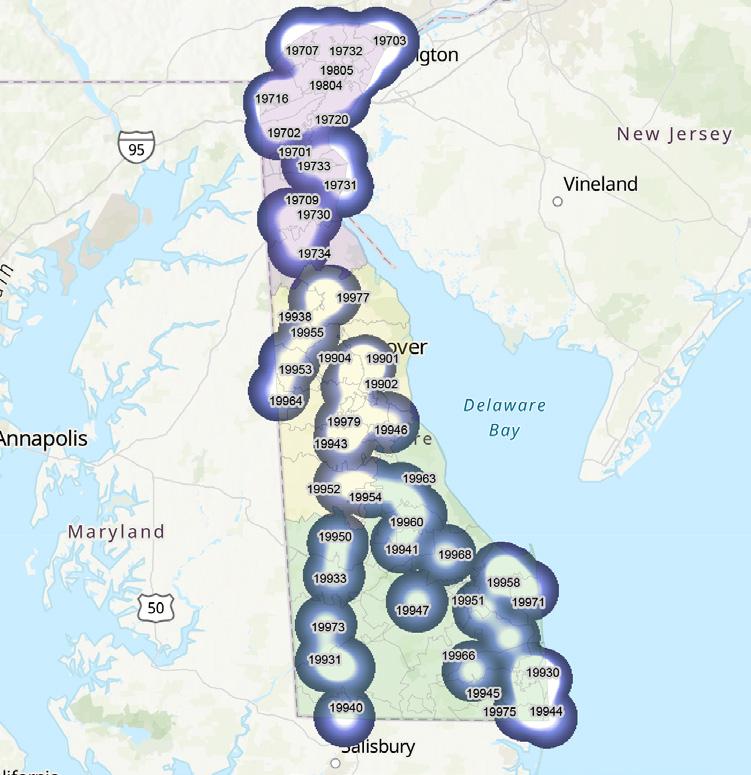

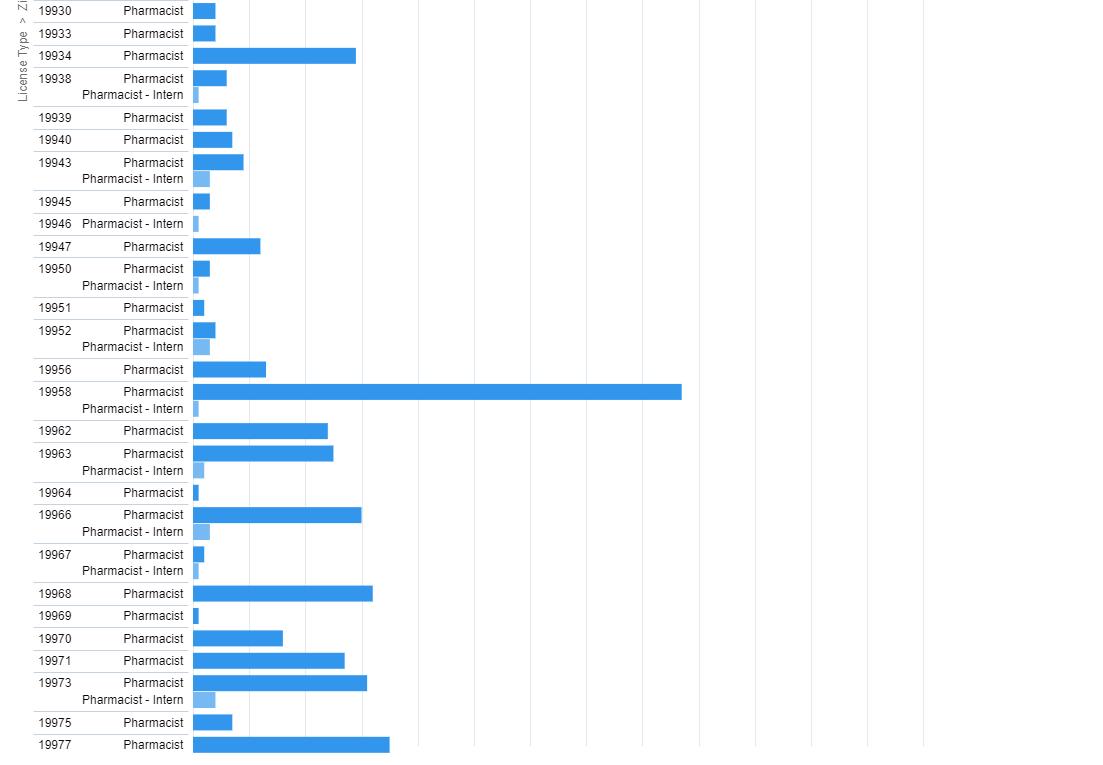

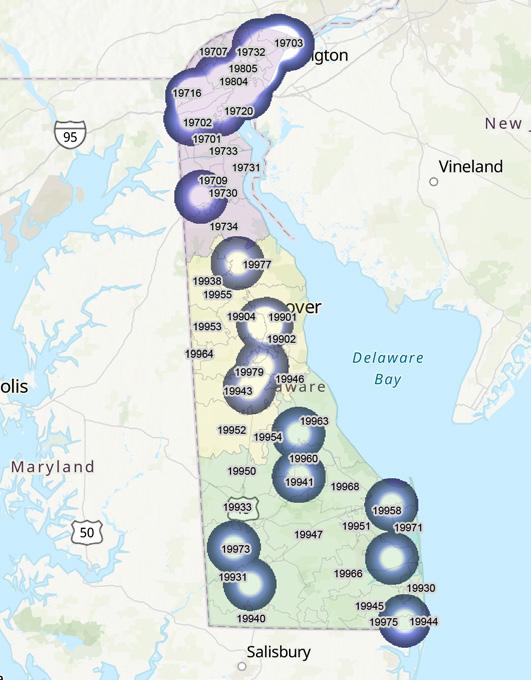

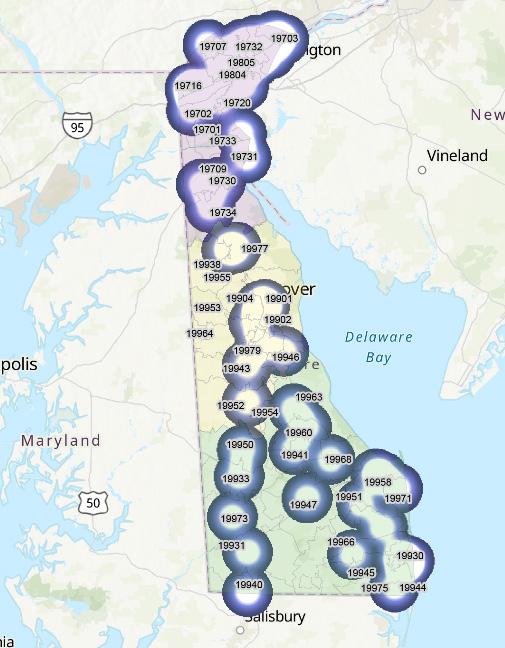

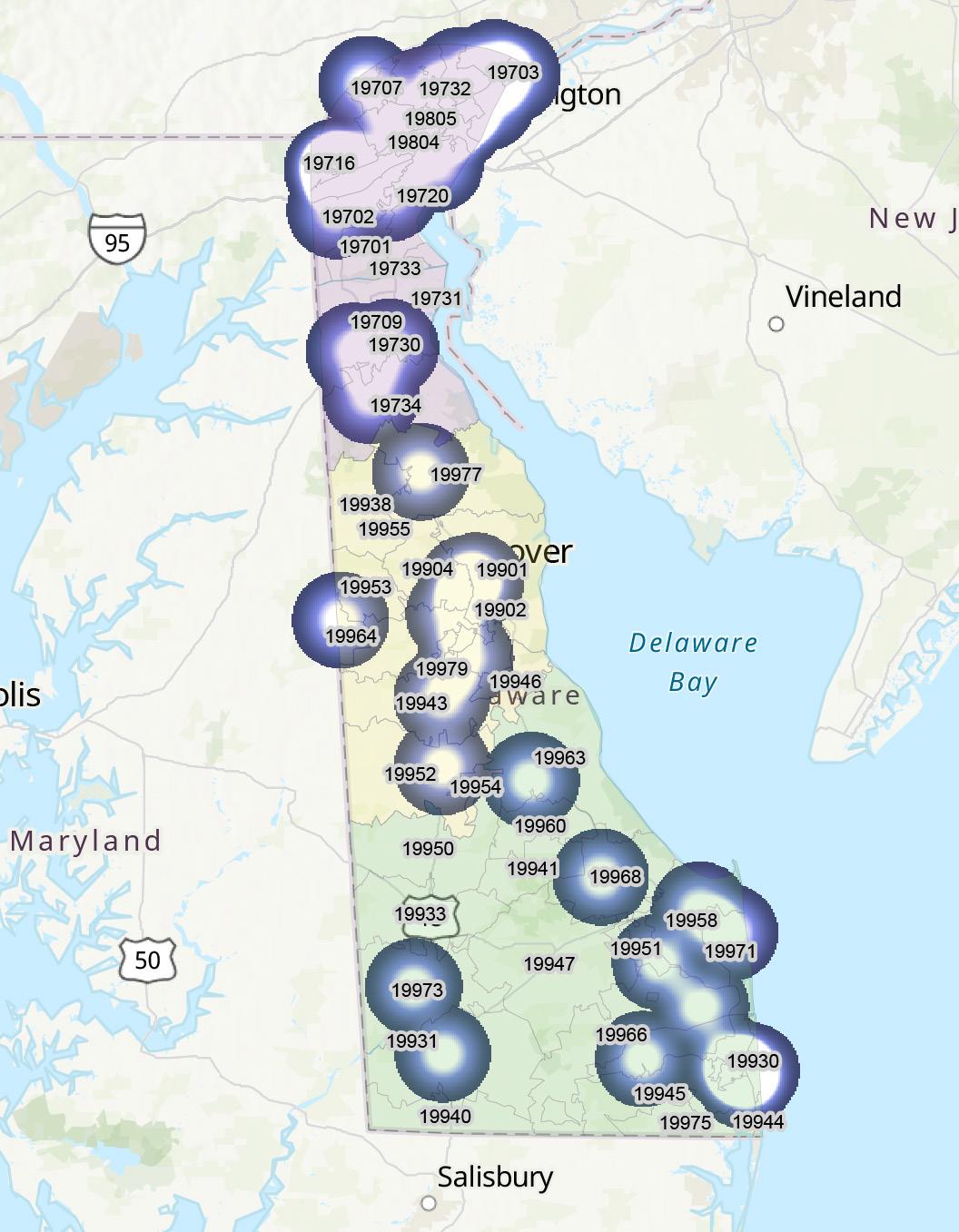

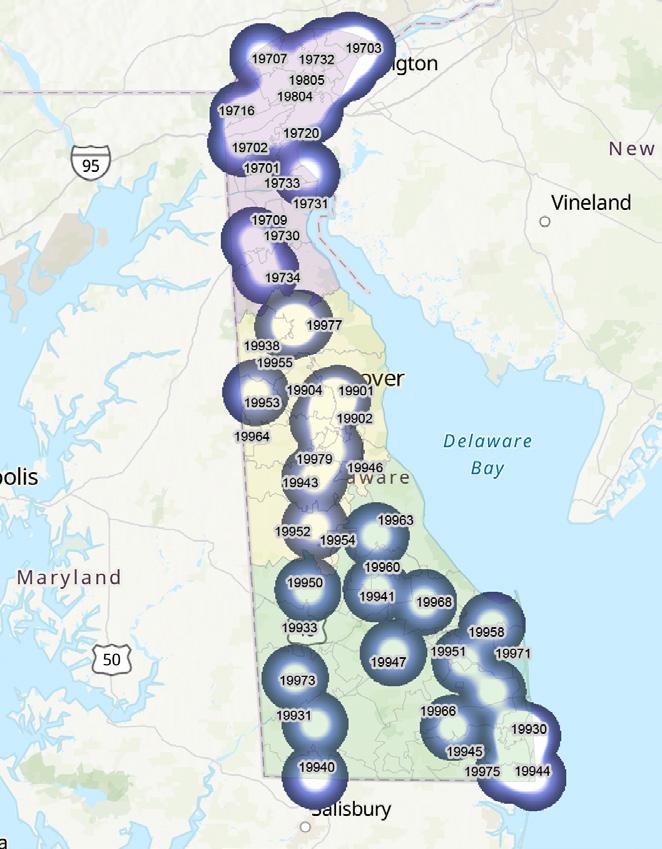

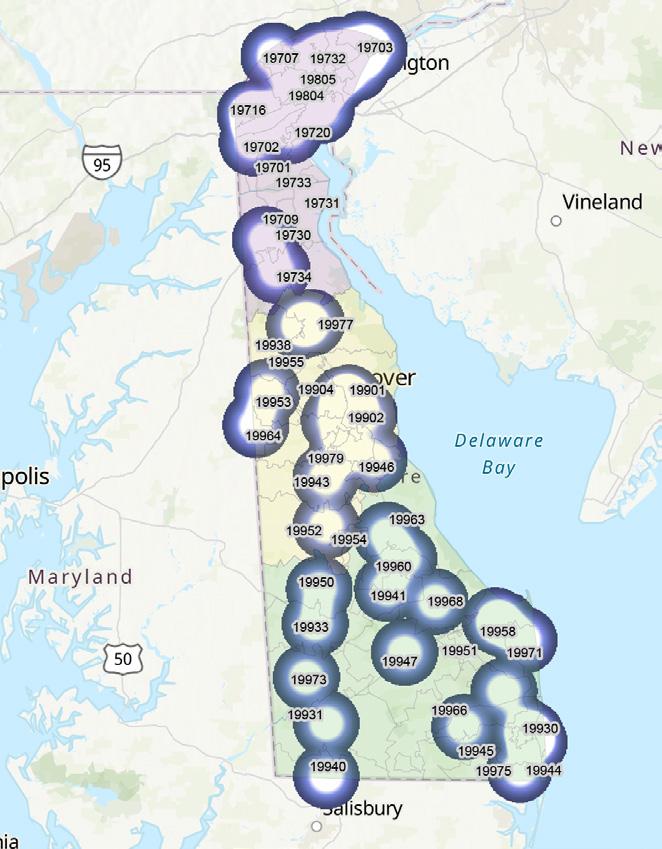

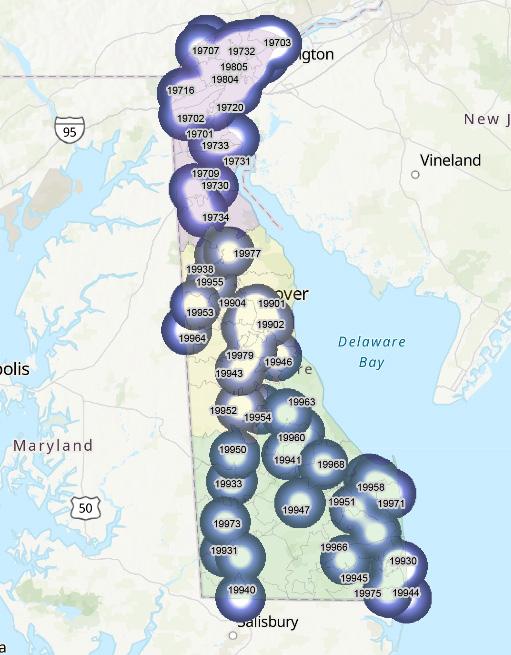

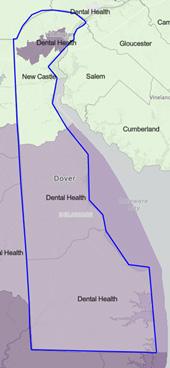

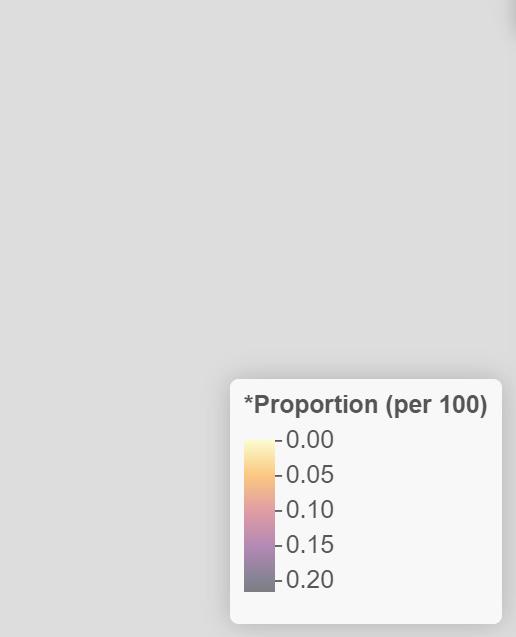

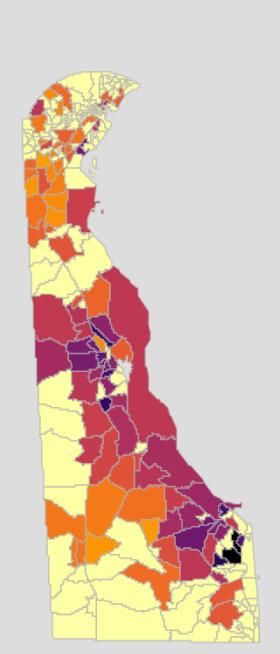

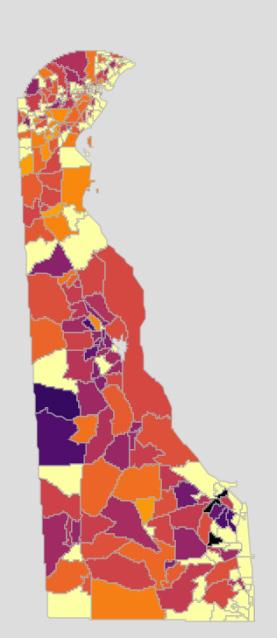

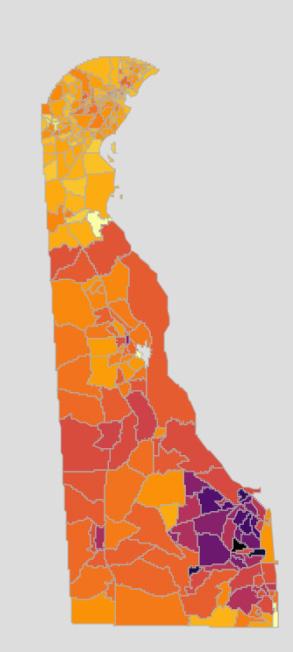

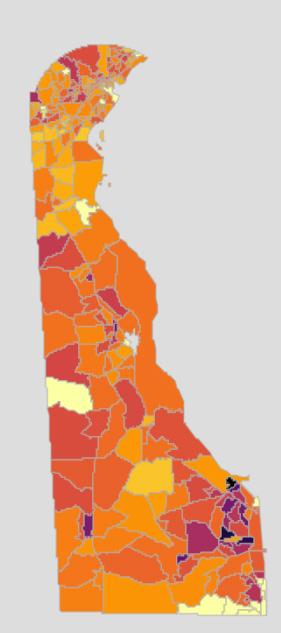

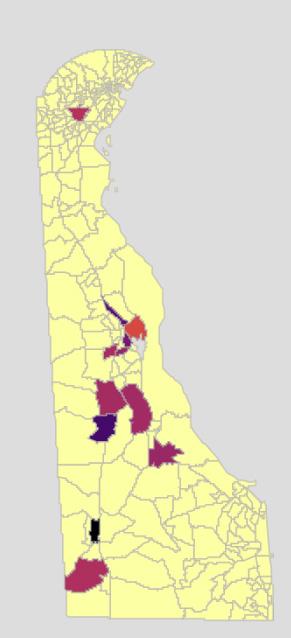

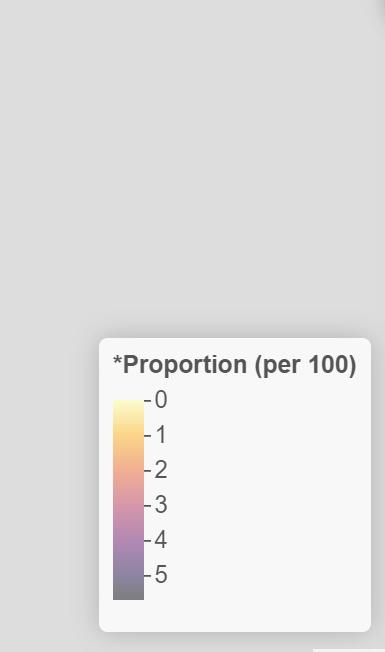

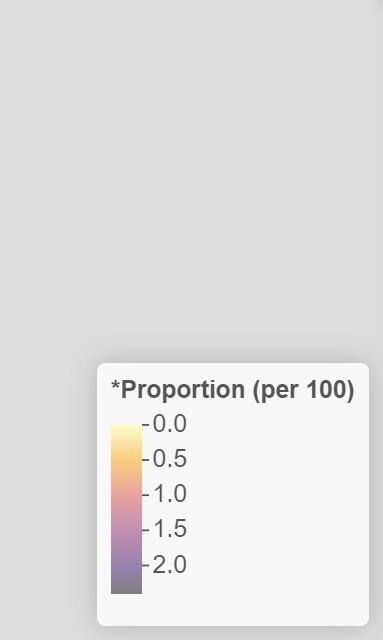

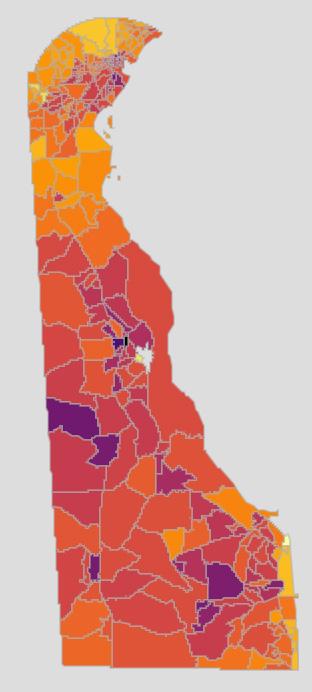

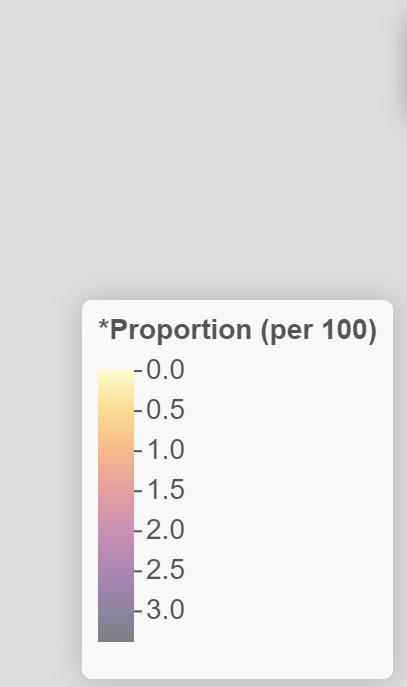

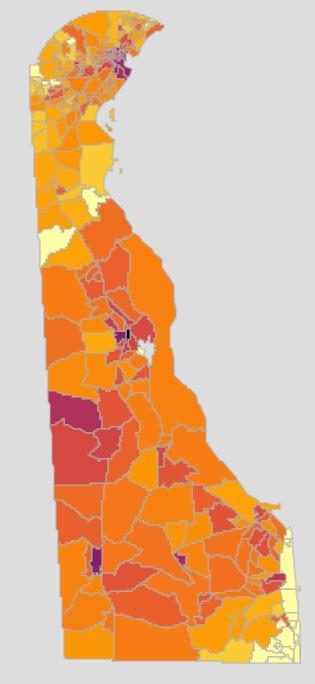

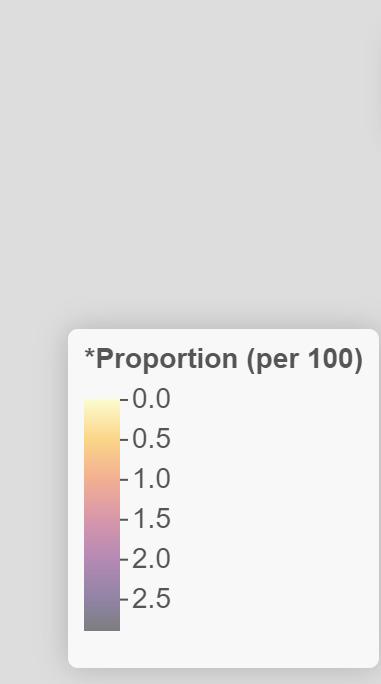

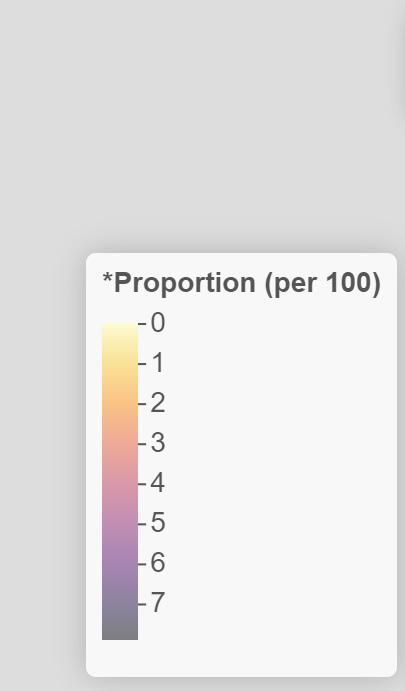

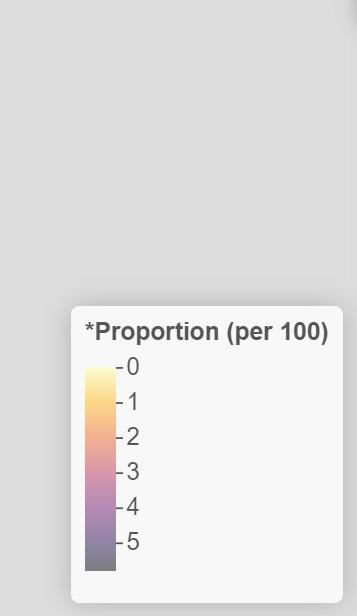

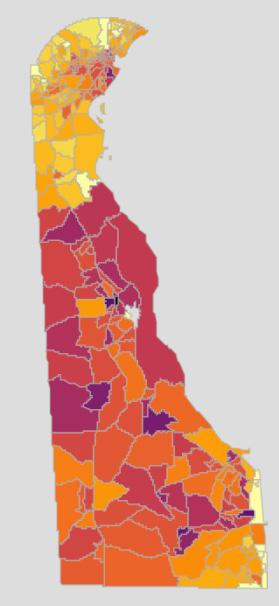

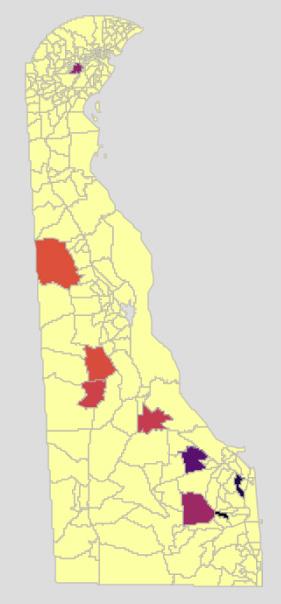

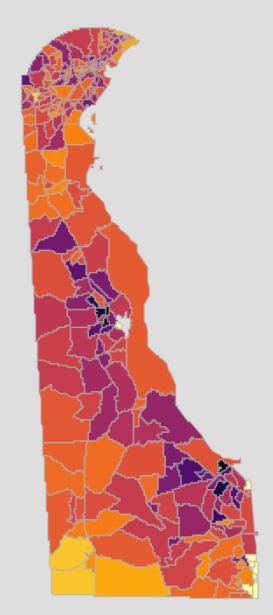

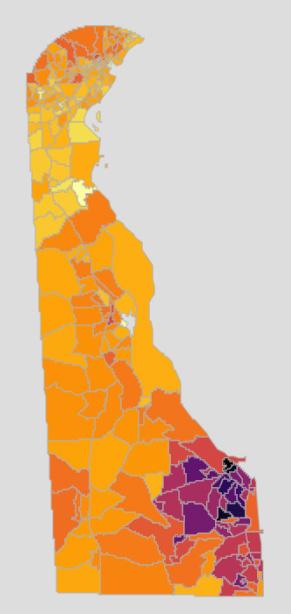

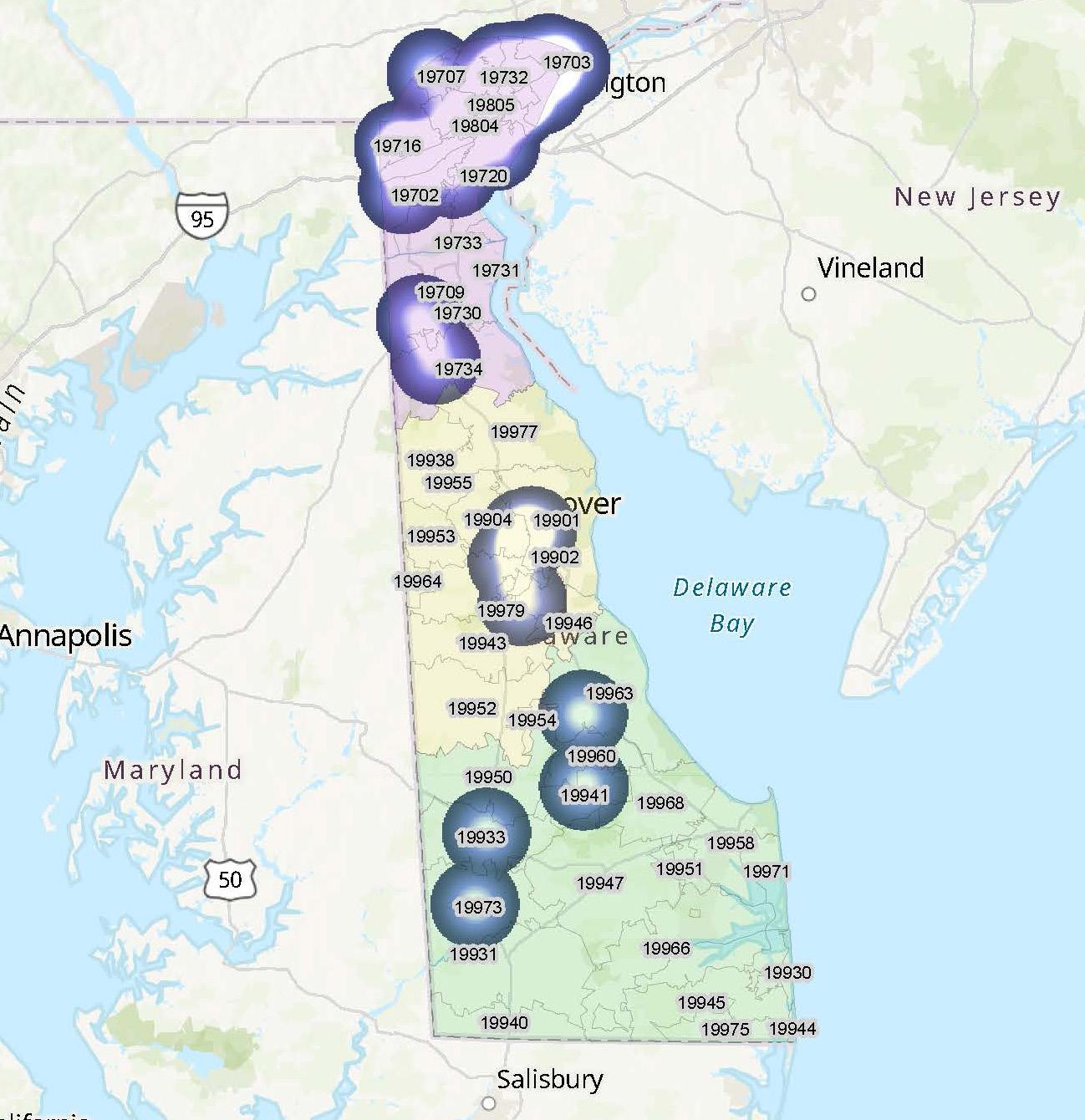

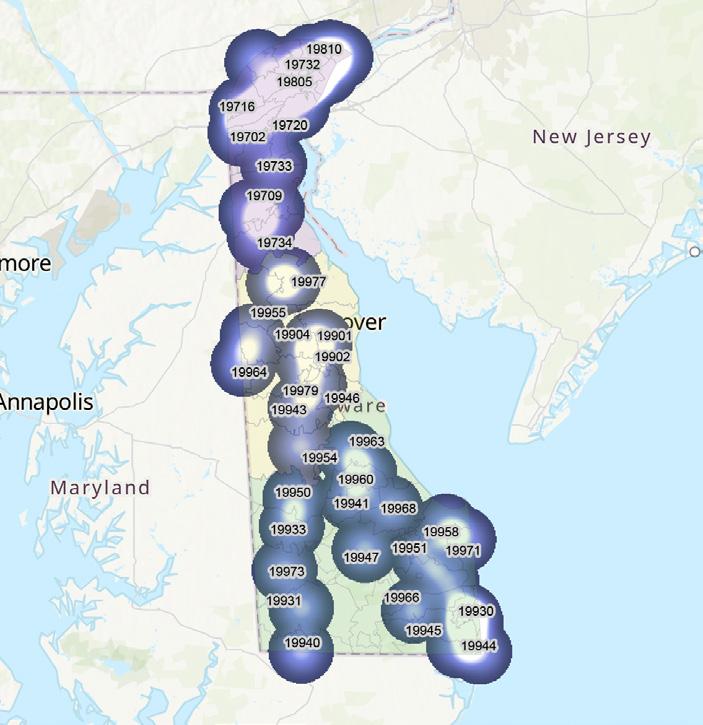

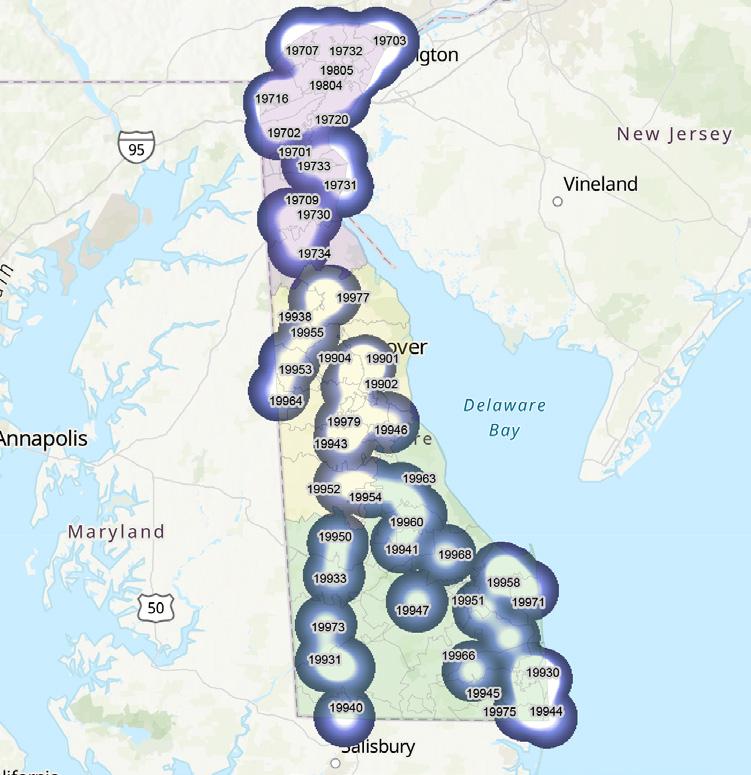

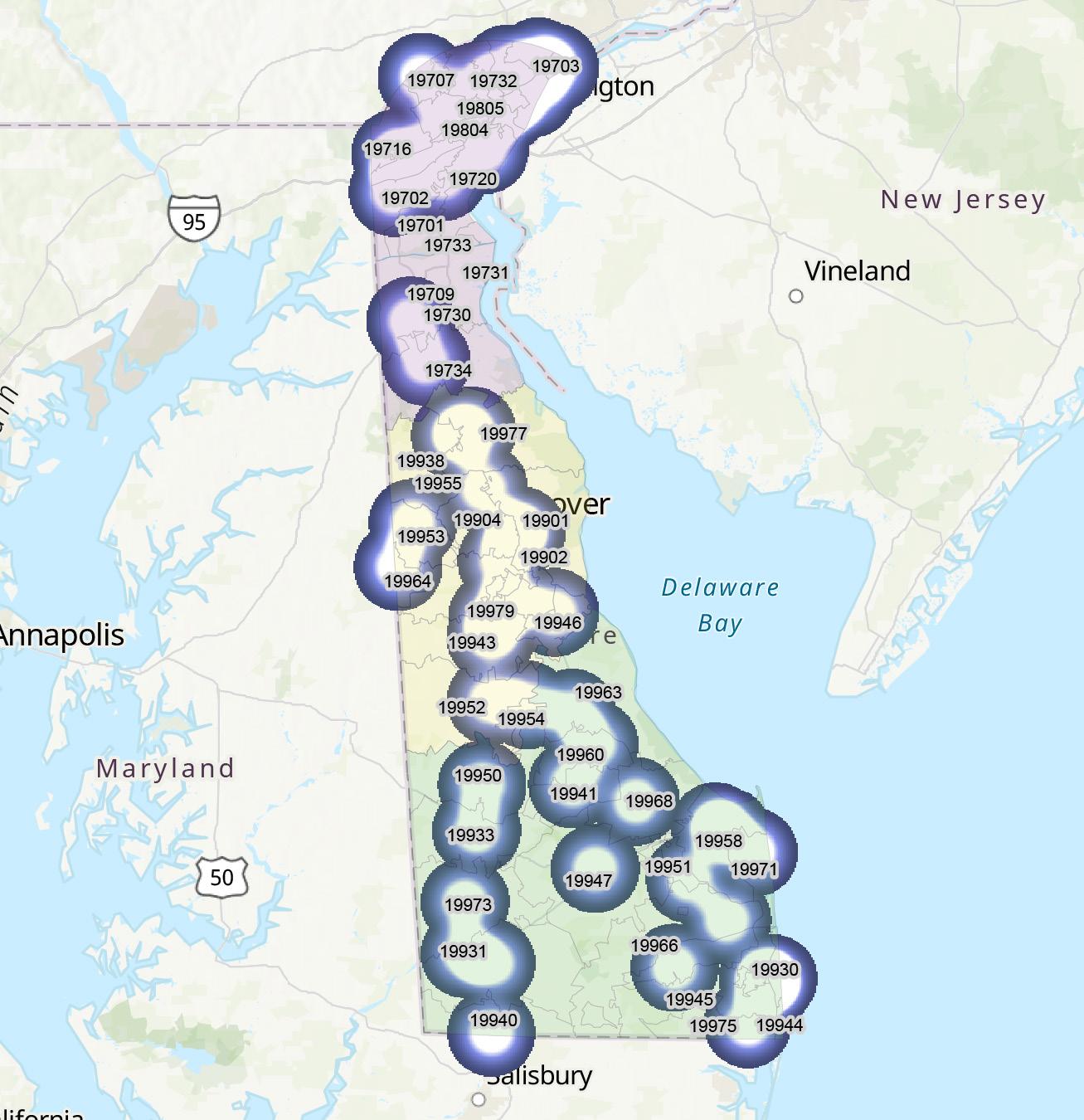

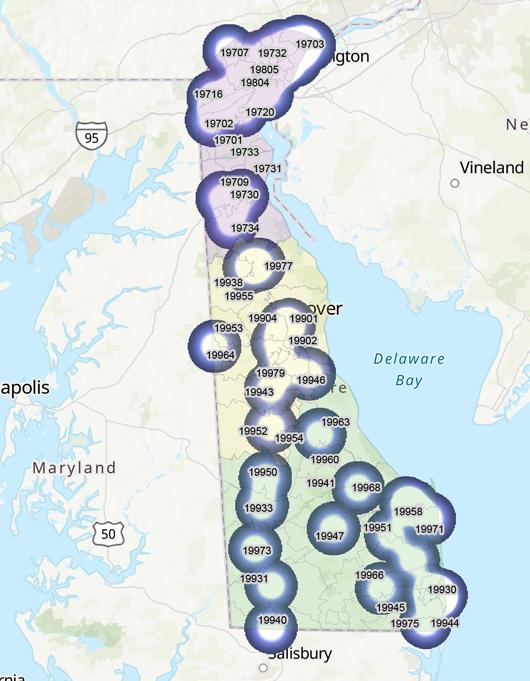

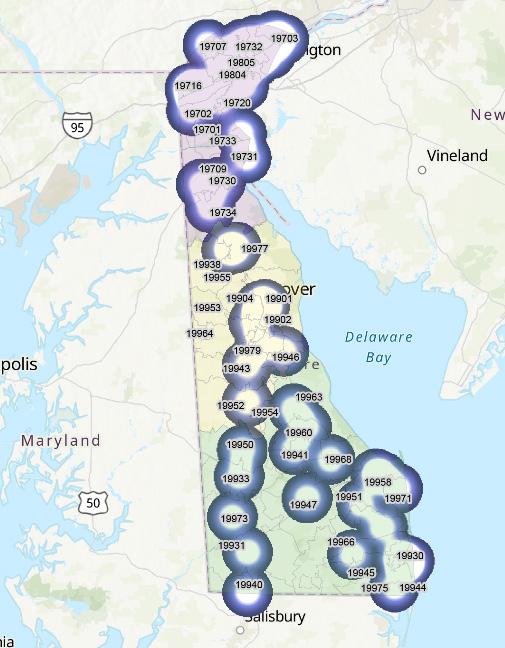

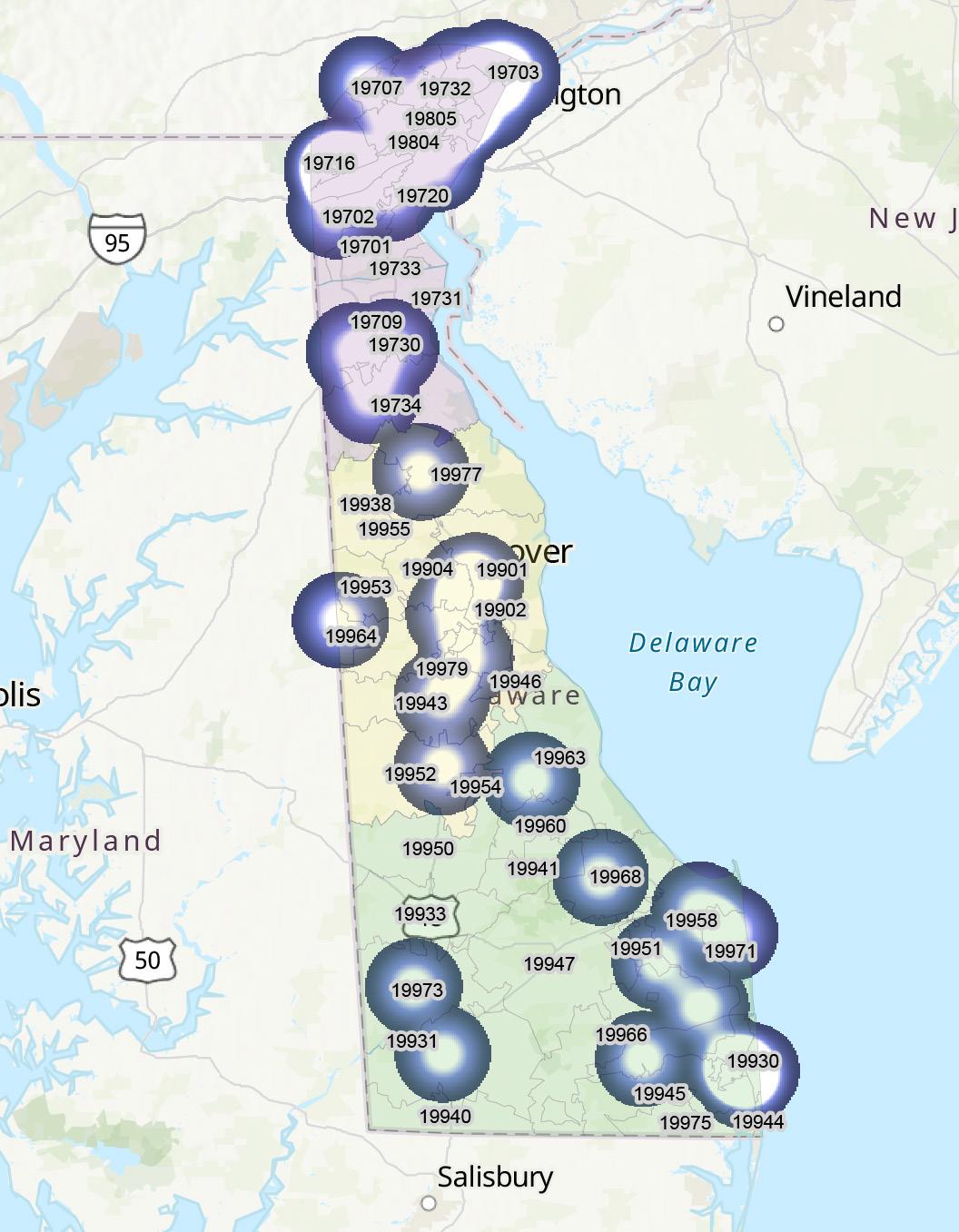

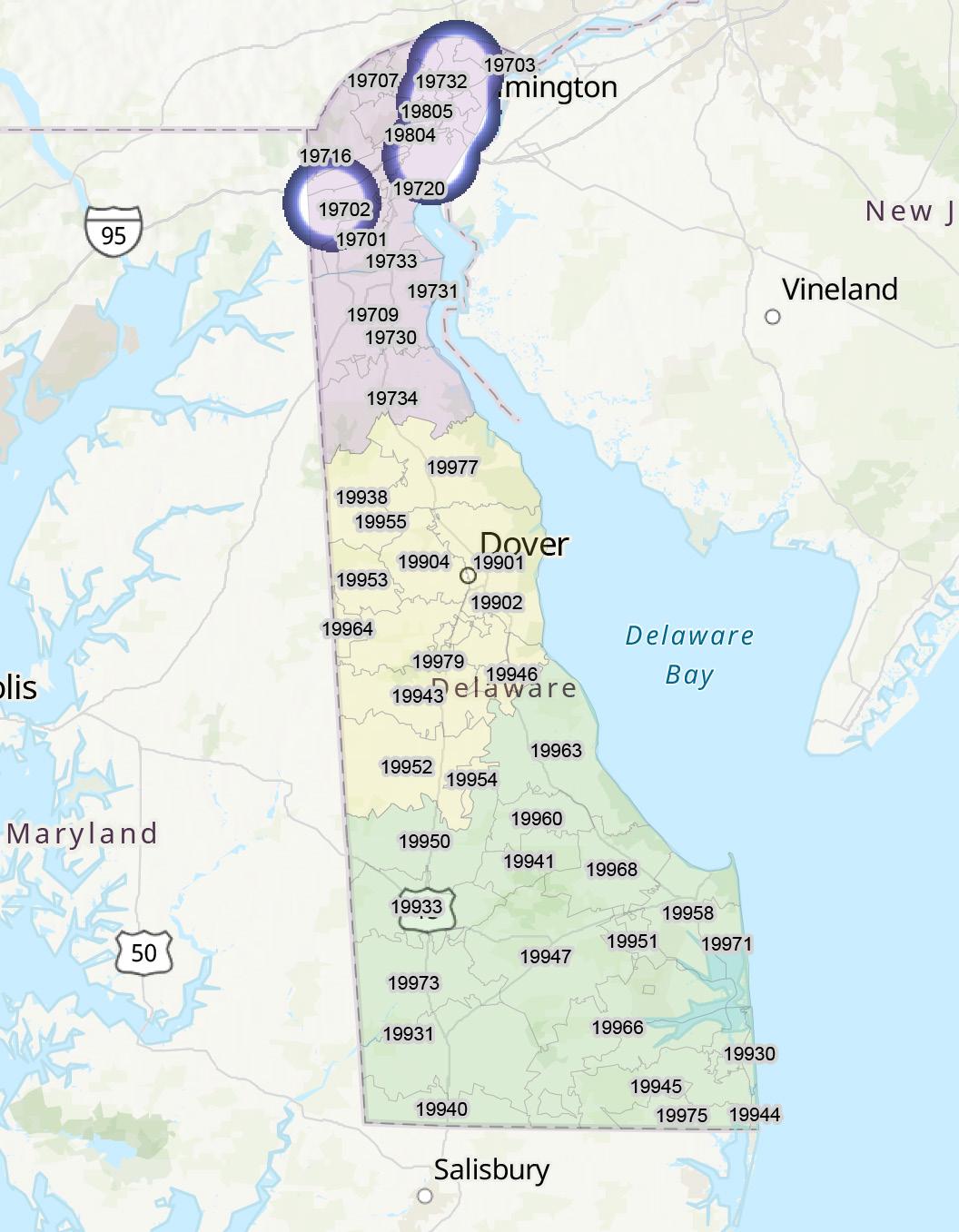

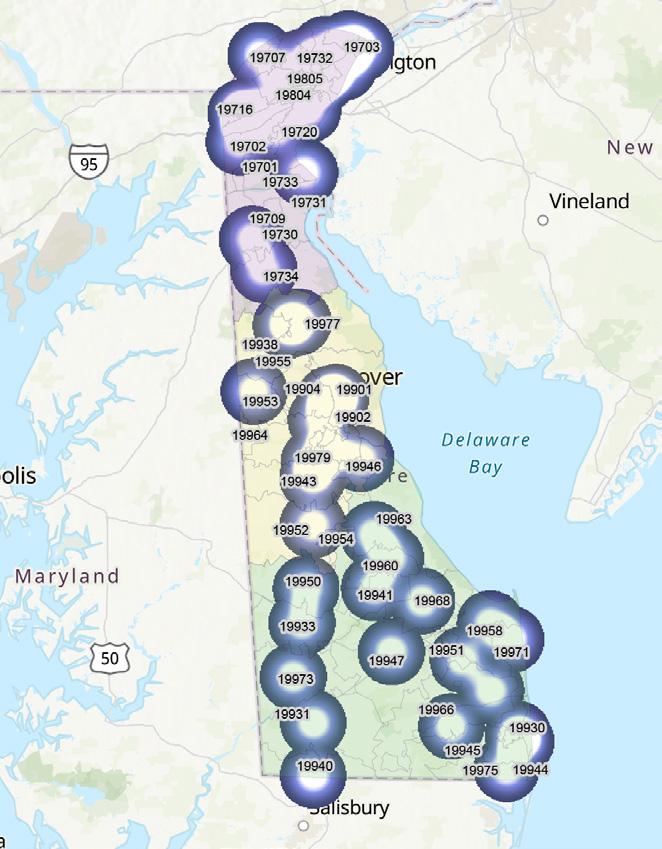

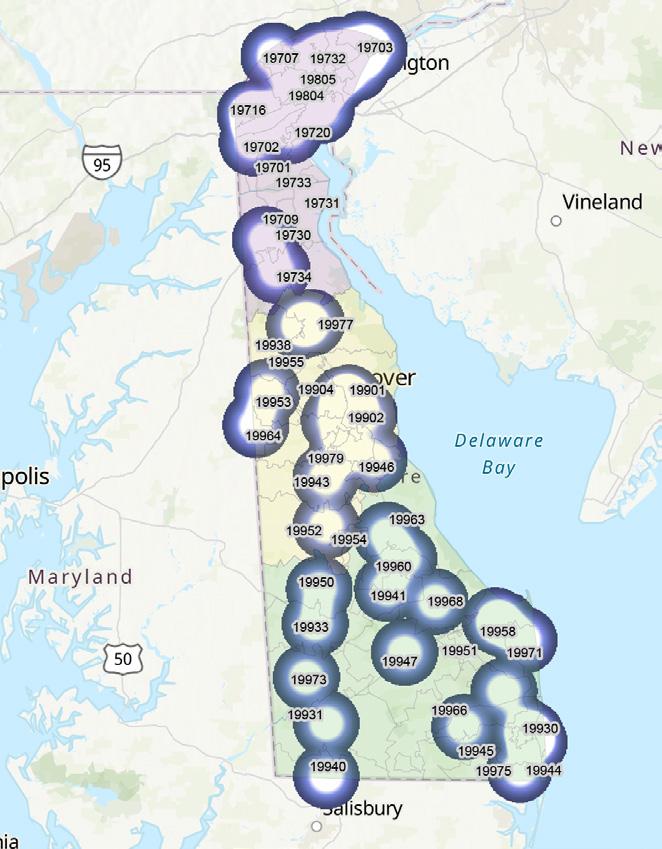

MAPS

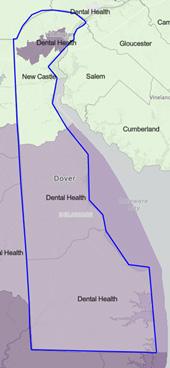

The Workforce Subcommittee Chairs and report writers reviewed a number of options for the images used to represent where types of licensed individuals and facilities are located. By consensus we arrived at the decision to use a non-weighted heatmap. The heatmaps are an exact representation of the data provided on the facing page. The maps are also subdivided by ZIP codes rather than census tracts to broaden they accessibility to a wide audience who many not be as familiar with census tract information. Counties are demarcated by different background colors.

In all cases, maps only look at the ZIP code level (the exception is the facilities section of the report). The location of the center of any ZIP code is solely determined by ArcGIS defaults, and in no manner implies actual location of any one (or more) individuals or facilities. The size of the area representing licenses has no relation to the number of licenses or to their “reach” in that area. They only bring attention to the map and areas with, or without, licensed individuals or institutions.

These maps are presented to give a sense, based on the primary ZIP code listed for each DELPROS license, of where licensed individuals and institutions are physically located.

Please note that ZIP codes are being used as a proxy for provider or institution location and should not be considered definitive. For instance, while an institution can have one license per location, a provider (and especially physicians and nurses) may have multiple locations associated with their license. This was a limitation of the data provided for this first report which we hope to address in future reports as we become more granular in licensing information.

21

Board of Chiropractic

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Chiropractic is to protect the public from unsafe chiropractic practice and practices which tend to reduce competition or fix prices for services. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board:

• develops standards for professional competency, • promulgates rules and regulations, • adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to chiropractic practitioners and approves preceptors. The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 7.

CHIROPRACTOR

Chiropractors focus on patients’ overall health (see Figures 1-5). Chiropractors believe that malfunctioning spinal joints and other somatic tissues interfere with a person’s neuromuscular system and can result in poor health. Some chiropractors use procedures such as massage therapy, rehabilitative exercise, and ultrasound in addition to spinal adjustments and manipulation. They also may apply supports, such as braces or shoe inserts, to treat patients and relieve pain.1

Figure 1. Active Chiropractic Licenses, N= 383

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.013

22 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Figure 2. Active

(when reported) 23

Chiropractic Licenses by Gender

Figure 3.

24 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

Active Chiropractic Licenses by Birth Year (when reported)

25

Figure 4. Numerical Distribution of Active Chiropractors by ZIP code

REFERENCES

1. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, Apr 18). What chiropractors do. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/chiropractors.htm#tab-2

Figure 5. Visual Distribution of Active Chiropractors by ZIP code

26 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

HIGHLIGHTS FROM

HEALTH

December 2022

Online-only news from The Nation’s Health newspaper

Pandemic takeaways being applied to broader public health practice: Pressures of pandemic spur innovation Mark Barna

Growing number of state, local measures undermining public health authority: Temple University researchers tracking laws, policies that limit public health protections Eeshika Dadheech

TGIF: How to make it a happy, healthy weekend Teddi Nicolaus

Climate change increasingly harming mental health: Resource-poor communities in US, across globe at high risk Teddi Nicolaus

Wanted: Advocates who speak up for climate justice, vulnerable people Kim Krisberg

In their own words: Advice from and for youth climate activists

APHA 2022 to rally around health equity, mark 150 years of progress

27

The NATION’S

A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION

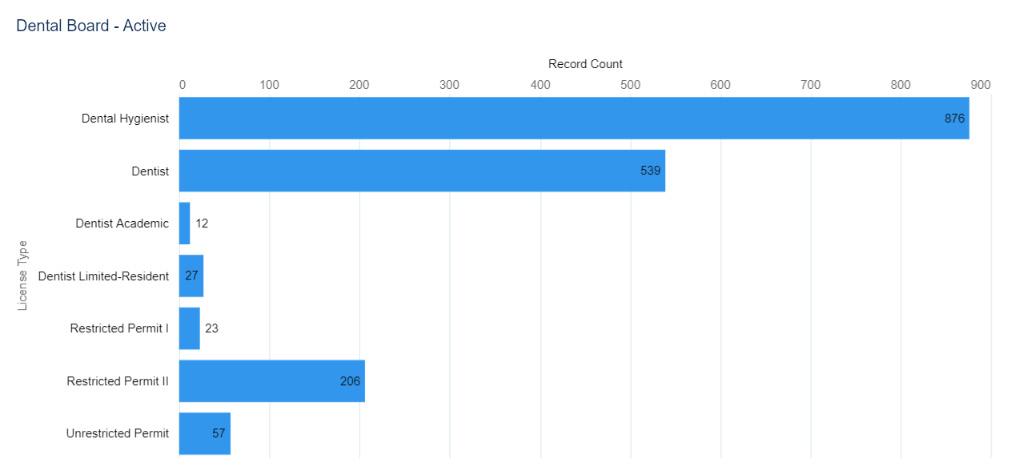

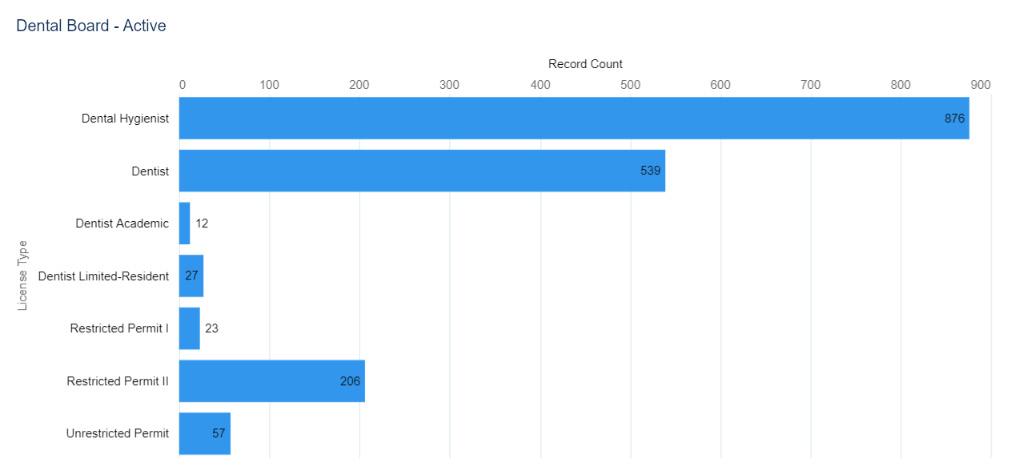

Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene

The primary objective of the Delaware Board of Dentistry and Dental Hygiene is to protect the general public from unsafe and unprofessional practices. The Board must also maintain standards of professional competence and service delivery. To meet these objectives, the Board

• develops standards for professional competency,

• promulgates rules and regulations,

• adjudicates complaints against professionals and, when necessary, imposes disciplinary sanctions.

The Board issues licenses to dentists, dentist academics, dental hygienists and dental residents. The Board also issues three types of permits to dentists and dentist academics who administer anesthesia.

The Board’s statutory authority is in 24 Del. C., Chapter 11.

The dental profession is the branch of healthcare devoted to maintaining the health of the teeth, gums and other tissues in and around the mouth.

WHAT IS A DENTIST?1

A dentist is a doctor, scientist and clinician dedicated to the highest standards of health through prevention, diagnosis and treatment of oral diseases and conditions (see Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Dentists play a key role in the early detection of oral cancer and other systemic conditions of the body that manifest themselves in the mouth. They often identify other health conditions, illnesses, and other problems that sometimes show up in the oral cavity before they are identified in other parts of the body.

What does a Dentist do?

• Evaluates the overall health of their patients while advising them about oral health and disease prevention;

• Performs clinical procedures, such as exams, fillings, crowns, implants, extractions and corrective surgeries;

• Identifies, diagnoses and treats oral conditions; and

• Performs general dentistry or practices in one of nine dental specialties.

• Advances in dental research, including genetic engineering, the discovery of links between oral and systemic diseases, the development of salivary diagnostics and the continued development of new materials and techniques, make dentistry an exciting, challenging and rewarding profession.

WHAT IS A DENTAL HYGIENIST?2

Dental hygienists are preventive oral health professionals who have graduated from an accredited dental hygiene program in an institution of higher education, licensed in dental hygiene to provide educational, clinical, research, administrative and therapeutic services supporting total health through the promotion of optimum oral health.

In performing the dental hygiene process of care, the dental hygienist assesses the patient’s oral tissues and overall health determining the presence or absence of disease, other abnormalities and disease risks; develops a dental hygiene diagnosis based on clinical findings; formulates evidence-based, patient-centered treatment care plans; performs the clinical procedures outlined in the treatment care plan; educates patients regarding oral hygiene and preventive oral care; and evaluates the outcomes of educational strategies and clinical procedures provided.

Dental hygienists are preventive oral health professionals who have graduated from an accredited dental hygiene program in an institution of higher education, licensed in dental hygiene to provide educational, clinical, research, administrative and therapeutic services supporting total health through the promotion of optimum oral health.

In performing the dental hygiene process of care, the dental hygienist assesses the patient’s oral tissues and overall health determining the presence or absence of disease, other abnormalities and disease risks; develops a dental hygiene diagnosis based on clinical findings; formulates evidence-based, patient-centered treatment care plans; performs the clinical procedures outlined in the treatment care plan; educates patients regarding oral hygiene and preventive oral care; and evaluates the outcomes of educational strategies and clinical procedures provided.

Dental hygienists provide clinical services in a variety of settings such as private dental practice, community health settings, nursing homes, hospitals, prisons, schools, faculty practice clinics, state and federal government facilities and Indian reservations. In addition to clinical practice, there are career opportunities in education, research, sales and marketing, public health, administration and government. Some hygienists combine positions in different settings and career paths for professional variety. Working in education and clinical practice is an example.

DOI: 10.32481/djph.2022.12.014

28 Delaware Journal of Public Health - December 2022

WHAT IS A DENTIST ACADEMIC LICENSE?

A Delaware Dentist Academic license is given to practitioners who are full-time directors, chairpersons, or attending faculty members of a hospital-based dental, oral and maxillofacial surgery or other dental specialty residency program. The program must be:

• based in Delaware, and

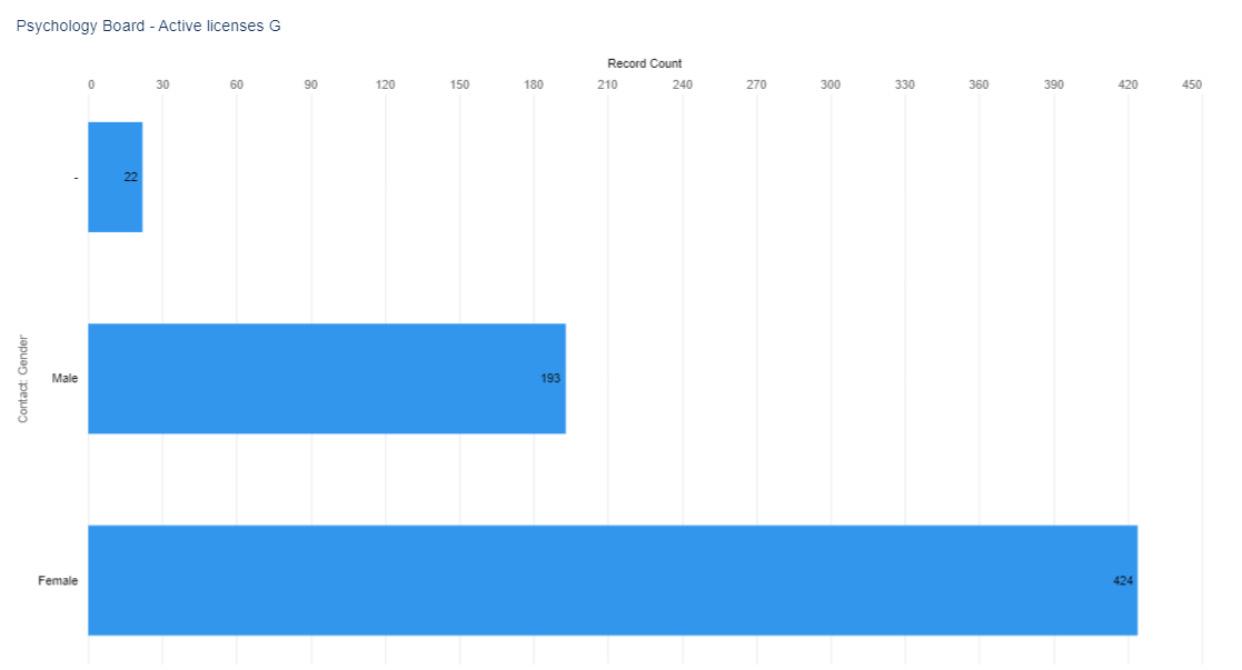

• accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation of the American Dental Association (CODA) for the purposes of teaching, has received initial CODA accreditation or is in the process of establishing CODA accreditation