a catalogue of recent acquisitions & selections from stock, to be exhibited

3-6 april 2025 booth e10 at the park avenue armory ny

¶ The remarkable provenance of this book traces its journey through a series of owners, whose hands record their different responses to this richly diverse and engrossing text. From ecology to antiquarianism to pilchards, the annotators display their particular interests through their manuscript interactions.

The Elizabethan antiquary and poet Richard Carew (1555–1620), is best known for his Survey of Cornwall. (1602). A pioneering work, it is above all a representation of Cornwall as its author saw it, in terms of the landscape and climate, and of the occupations of men and women whose lives these shaped. Such matters as the local tin mines, the fishing industry, and the games people played, including hurling, all come within the compass of his lively pen.

Carew includes an early account of the use of sign language by two deaf people, reflecting his lifelong interest in languages: he taught himself Greek, Italian, German, Spanish, and French, and his panegyric, The excellencie of the English tongue (1614), entangled him in a dispute which involved (among others) Richard Verstegan, Thomas Nashe, Edmund Spenser, and William Shakespeare.1 This feel for language may account for one of the pleasures of the Survey of Cornwall: Carew’s exuberant style. This, according to Halliday, 2 is perfectly encapsulated in his remarks on Cornish rats: “alike cumbersome through their crying and rattling, while they dance their gallop galliards in the roof at night”.

This passage attracted the attention of our earliest annotator, who has written “good store” beside the printed marginalia “rats”. The following paragraph concerning lice, or “slowe sixe-legged walkers” as Carew dubs them, has been marked out with a very neat manuscript manicule pointing directly to “Lice”.

¶ CAREW, Richard (1555-1620).

The Survey of Cornwall. Written by Richard Carew of Antonie, Esquire.

London: Printed by S. S[tafford] for Iohn Iaggard, and are to bee sold neere Temple-barre, at the signe of the Hand and Starre. 1602. FIRST EDITION.

Quarto. Foliation: [4], 159, [5] leaves. Collated and complete with the initial blank leaf. [STC 4615]. 18th or early 19th century half calf, gilt panelled spine, red morocco label.

Judging from their annotations, this anonymous reader seems interested in the Cornish landscape and its uses, picking out such matters as the denudation of land by the tin mining industry whose practices, Carew declares, “yeeldeth a speedie and gainful recompense” at the expense of the soil quality, or as our annotator says, “spoil much grownd” (a striking early modern instance of ecological concern). They make further scattered remarks upon

inclyned to furze & broome”. They also make occasional note on property rights, especially regarding the complicated operations of land management, ownership, leasing, and enclosures (“fines for .3. lyves”, “al imp[ro] vem[en]t in fine not in rent”, “they take for lyves not for yeares”).

The other important economic industry in Cornwall was sardine fishing - the subject that most occupies our first scribe’s attention, especially its consumption and export to Spain. They have underlined the words “The trayne is well solde” and noted in the margin “15li a tune” (presumably the current market rate); and they estimate the

quantity of pilchards and the markup on the original price paid to fishermen when the fish reach their destination in Spain: “i000 of pilchardes are sold for, 3s ther, & in Spayne for 8s”. But, as Carew notes, the fish must not only be caught, but also prepared for export – work which benefits “almost an infinite number of women and children” who carry out the “bulking, washing, and packing”. These words are numbered one to three in manuscript, and a note to the margins elaborates on each task: “1. Laying by ye walls in order / 2. After making them on stikes & washing the silt & [ smudged] of / 3. puting in barels to presse them”.

Our piscine-preoccupied annotator also weighs in on how sardines are to be eaten. The best way is to present “the pilchard for service at the table is drest thus taken out of the barell, & scrape of the skine & take out the bone, & then mince them & then put them in a platter, shred (?) with spanich onyons, & oil and bringe also minced / this dish the Spaniard eates to relish a / cup of wine without once [–shaved] it in [any?] fire” [last six words shaved].

The next reader, and the first to claim ownership, was the herald and antiquary Peter Le Neve, (1661-1729), who has inscribed the front blank A1 “Liber Petri Le Neve Rouge Crois [Pursuivant] 1695”, to which position he was appointed in January 1689/90, and advanced to Norroy King of Arms in 1704. Le Neve was fellow of the Royal Society and helped found the Antiquarian Society, becoming its first President. He was an active transcriber of early manuscripts and a voracious book and manuscript collector; it has been said that he was miserly in many things, but would “give more for a Book than it was worth, grudging no expence of that sort”.3 At a sale of Le Neve’s library over 12 days from 22 February 1731, over 2,000 printed books and 1,252 manuscript lots were sold, the latter including 584 heraldic manuscripts from Sir Thomas St George's collection, 72 pedigree rolls, 22 portfolios of pedigrees, and 28 boxes of charters.

Our book passed from one herald to another; its subsequent reader was the arms painter and herald painter, Josiah Jones (d. 1764) (not William Burton as a note to the endpaper claims). Although he has not inscribed the volume with his name, Jones has a distinctive hand which has something of a “modern” appearance about it. Were it not for the fact that he signed and dated some of his work, it might easily be taken for later in the 18th century or even into the next.4

Jones’s focus of attention in this book was the genealogical section. Although Carew was interested in the affairs of armigerous Cornish families, his Survey of Cornwall is unencumbered by the heraldry that bulks so large in other chorographies. Jones seems to have considered this an oversight, and has augmented the volume with no fewer than 74 heraldic shields in the margins, mostly annotated with names and tricked. Nonetheless, his method of augmentation was quite parsimonious and does not interrupt the flow of Carew’s narrative.

manuscripts through marriage. But there is no evidence that he did; instead he likely acquired some from le Neve, who had in turn received some from Morgan’s daughter. Among other material that Jones acquired from le Neve is the genealogical section of the volume commonly known as le Neve’s ‘Equestion Book’ [BL Add. Ms 62541]. Sir Anthony Wagner thought that Jones bought the whole volume, but close inspection reveals that it was only later and for some unknown reason that the genealogical and hippological sections were bound together to create the volume. As is the case in our book, Jones was only interested in genealogy.

Jones lived in Vauxhall and Lambeth and is known to have transcribed manuscripts at Lambeth Palace Library, which would have been within easy walking distance. His transcriptions include copies of manuscripts such as

Monumental Inscriptions, Arms & Co: which he has signed “Jos. Jones” and added the introductory note “These things were gather’d whilst the work was doing at Palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury 1749”. Later records show Jones was still working there in 1758, which overlaps with Andrew Coltée Ducarel’s time as keeper of the library. We know that Ducarel was aware of Jones: Thomas Thrope’s “Catalogue for 1840 of a Most Choise and Truly Valuable Collection of Autograph Letters” includes a letter dated 1762, from Sir Peter Thompson to Ducarel, informing the latter that he “knew Mr Jones near forty years back; he was then painter to Drury Lane play-house”.5

¶ References:

1. Carew’s The excellencie of the English tongue, was first published in the second edition of William Camden’s Remaines (1614).Quoted in ODNB, S. Mendyk.

2. Richard Carew of Antony: The Survey of Cornwall. Halliday, F.E. (Ed. and Intro.) (1969).

3. Thomas Woodcock in the ODNB.

4. We are very grateful to Dr Robert Colley for identifying the hand.

5. The biography and the complicated story of the dispersal of Morgan’s library is the subject of a forthcoming publication by Dr Robert Colley, who has been extremely generous in sharing his scholarship prior to publication.

6. Alston, R. C. Inventory of Sale catalogues… 1676-1800. (2010).

7. Robin Myers in the ODNB.

8. Ibid. Alston.

books of prints and drawings; library of books and manuscripts, of Mr. Josiah Jones, painter: including the valuable collection of heraldical manuscripts of the late Sylvanus Morgan. [Sale catalogue, Samuel Paterson, 3 December 1759]. We do not know exactly why Jones sold so much of his library, especially the valuable Sylvanus Morgan manuscripts, but he may have been quite old (we have been unable to establish his date of birth) and starting to divest himself of his bibliographic assets. Whatever the case, the sale catalogue following his death in September 1764 still featured around 400 books (including some of his manuscript transcriptions). Paterson’s services were again called upon, and in December of the same year, he issued A catalogue of the genuine collection of prints and drawings, books, and heraldical manuscripts, of Mr. Josiah Jones, late of Vaux-Hall, painter, deceased. 6

The next record of ownership is by the abovementioned Andrew Coltée Ducarel (1713-1785), a French-English antiquary, librarian, archivist, and lawyer who fled to England with his Huguenot family in 1722. He was educated at Oxford, was elected FSA at the age of twenty-four, and served as librarian (1754-7) and as treasurer (1757-61) of Doctors’ Commons, also writing a valuable reference work entitled A summary account of Doctors Commons.

In 1757, he took the position of librarian at Lambeth Palace Library – its first lay librarian and the longest serving, He put a great deal of effort into ordering the library’s collections by greatly improving the catalogues both of the printed books and of the manuscripts.

He has affixed his engraved armorial bookplate “Andrew Colteè Ducarel / L.L.D. / Doctor’s Commons”, to the paste-down, and inscribed the front blank “A Ducarel 1770” to the blank endpaper. A three-page manuscript index of surnames (“Index Cognominum”), bound in at the end, also appears to be by him. It is written on 18th-century paper, and the hand is very similar to examples of Ducarel’s held at Lambeth Palace Library [MS958f6; MS958f12; dedication to: MS5194a].

Our volume was included in the sale of Ducarel’s library, entitled A catalogue of the very valuable library of books, manuscripts, and prints, of the late Andrew Coltee Ducarel. [Sale catalogue, Leigh and Sotheby, 3 April 1786],8 where it was described laconically: Lot “361 Carew’s Survey of Cornwall 1602”. A year after this auction, the book came into the possession of “John (inscription to title page). A pencil note to the front endpaper claims that it is in the hand of the philanthropist and prison reformer, John Howard (1726?-1790) – an entirely plausible contention, but unsubstantiated. The most recent ownership record takes the book back to its Cornish roots: the armorial bookplate to the front endpaper reads “CLC / Treverben Vean” i.e. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Lygon Somers Cocks (1821-1885) of Treverben in Cornwall.

Charting the provenance in this copy amounts to its own chorographical study. The connections traced, especially those concerning the connecting paths in the libraries of Peter le Neve, Josiah Jones, and Ducarel have yet to be clearly mapped, but they offer an extra dimension of appeal to an already hugely engaging volume.

£7,500 / $9,700 Ref: 8302

¶ A gender fluid spy, diplomat, and soldier, Chevalière d’Éon challenges our understanding of 18th-century attitudes to the politics of sex and gender. The story of their espionage in Britain and the ensuing public drama add further intrigue to an already compelling life. This rare broadside, written by his nemesis-turned-supporter, is at once the author’s confession and his defence of d’Éon, intended to restore their reputation.

Charlotte d’Éon de Beaumont or Charles d’Éon de Beaumont (1728-1810), usually known as the Chevalière d’Éon, lived openly as a man for the first part of their adult life, then as a woman until their death. Having entered diplomatic service in the 1750s, d’Éon spied for the French Russia and was appointed to Louis XV’s ‘secret service’. In 1762, they were posted to London to negotiate the Treaty of Paris; its successful signing the following year earned them the Order of Saint-Louis and the title ‘Chevalier’. During this period, however, and under the cover of their role as interim French ambassador, they collected information for a projected French invasion of Britain.

The arrival in London of the Comte de Guerchy, the new French ambassador, signalled a crisis for d’Éon, who lost their position and found themselves at odds, both politically and personally, with de Guerchy. After d’Éon published details in 1764 of the French government’s attempts to recall them – a serious violation of diplomatic protocol – de Guerchy engaged one Peter Henry Treyssac de Vergy to act against d’Éon.

[Chevalière d'Éon (1728-1810); Treyssac de Vergy, Pierre Henri (c.1740-1774)] A True Copy of the last Will and Testament of Peter Henry Treyssac de Vergy, deceased as proved at Doctors-Commons by his Executor, the 10th of October 1774.

London: W. Humphrey, Gerrard Street, Soho. 1775. [Publication details in plate]. Folio (460 x 280 mm). Single sheet, a little creased.

Only one copy located in the UK at the Guildhall Library [ESTC No: T197474]. No copies located in the USA.

Probably by virtue of having kept the more sensitive information about their spying activities close to their chest –with the implied threat of making it public – d’Éon apparently avoided serious censure from the French government. Their return to France was sanctioned on the strict condition that they lived openly as a woman –possibly to force them to the margins of political life. In any case, d’Éon spent the rest of their life as a woman, even after returning later to Britain, beyond the reach of the French authorities. De Vergy, though, soon had a change of heart about his shady assignment.

In this broadside, published in 1775 after de Vergy’s death, he explains his change of allegiance and issues a solemn apology to d’Éon for “the wrong which I have done to him, to his Fortune, to himself, and to all his Family” for his role in “Designs which were so hurtful to him; Designs, whose Blackness I was ignorant of, till the Moment when the Count de Guerchy thought that the Destruction of the Chevalier d’Eon ought not to be retarded any longer”. Indeed, it had been on de Vergy’s evidence that “the French ambassador was indicted in the court of common pleas of having incited [de Vergy] to kill D’Éon” (ODNB).

Contemporary accounts suggest that it was de Guerchy rather than D’Éon who needed rehabilitation. The latter’s popularity may have been largely due to speculation about their sexual identity (which in the 1770s was much discussed in London coffee houses and became the subject of a wager at the Stock Exchange), but Guerchy became something of a pariah, to judge by episodes as the stoning of his London residence by an angry mob (ODNB).

The top half of the broadside is taken up by a mezzotint of d’Éon, perhaps to help convey that the chief topic of de Vergy’s account is not himself but his former quarry (some descriptions have erroneously stated that the portrait depicts de Vergy himself). The question of d’Éon’s sexual identity, unsurprisingly, is not alluded to in this “last Will and Testament”, and the evidence suggests that, although some (including James Boswell) expressed distaste at their gender fluidity, just as common a contemporary reaction was fascination, or even admiration (Mary Wollstonecraft being one such admirer).

This broadside is an enthralling document from the final chapter in the remarkable story of Chevalière d’Éon; a story which raises questions about the changing views of gender in 18th-century Europe, and suggests that a more open attitude about gender and sexual politics long preceded our contemporary conversations about LGBTQ+ identities.

£1,750 / $2,260 Ref: 8298

¶ John Woodhouse had died long before this 1687 printing of his popular almanac, but so reliable was his “brand”, that the Stationers continued printing his almanacs into the 18th century. As is often the case with such widelycirculated books, the inverse law of print survival has reduced Woodhouse almanacs to a few surviving copies from various years. Only two copies of this 1687 edition are recorded (British Library and Yale).

This copy has been interleaved throughout with blanks. Its owner has annotated approximately 10 pages with notes, mostly payments (“Paid Jane Nancy’s maid her half years wage due ye 23d of December last past, being 02-00-00”, “Paid Jack in full of all notes to this day 00-6 -3”) in 1688, but is been picked up and used again in 1714 to add a couple of further pages of notes, one of which is so dense as to make transcription almost insurmountable.

¶ WOODHOUSE, John. Woodhouse 1687 a new almanack for the year of our Lord 1687 : being the third from the bissextile or leap-year, and from the worlds creation 5636 : wherein is contained a brief description of the four quarters of the year : excellent notes of husbandry and gardening for every month of the year : with the names of all the p[r]incipal fairs, and a description of the high-ways in England and Wales.

London: Printed by R.E. for the Company of Stationers. 1687. Octavo. Pagination 40 p. Second part (pp. [17-40]) has special title page: Woodhouse 1687 : a prognostication for the year of our Lord God 1687. [Wing, A2866; ESTC, R33053].

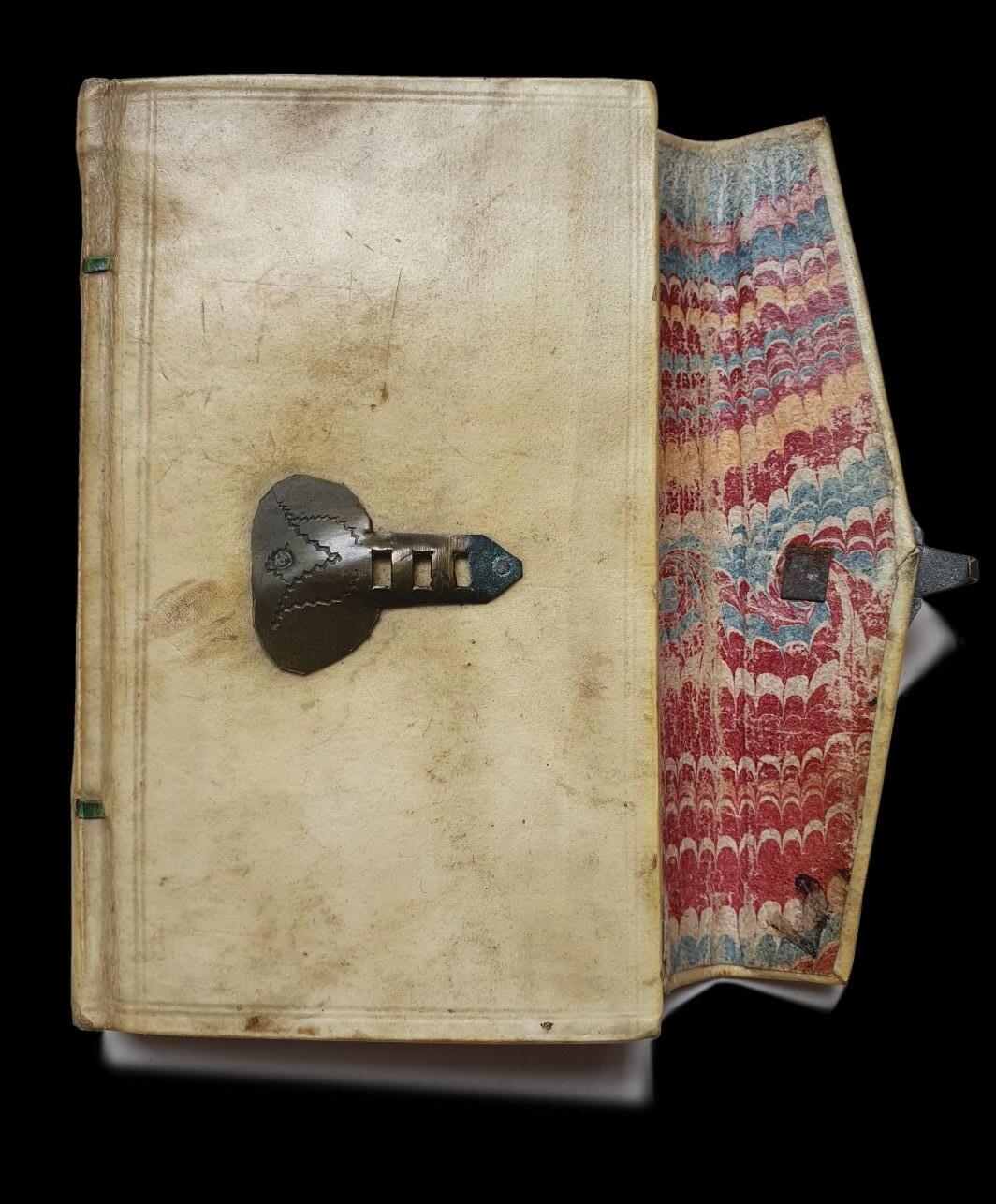

Contemporary full sheep, wallet style binding, rubbed, lacks tie.

£450 / $580 Ref: 8308

¶ The pseudonym “Cardanus Riders” was an anagram of the compiler, Richard Saunders, whose almanac first appeared in the 1650s and was so successful that the “brand” survived even longer than the likes of Dade and Woodhouse, with editions of Rider recorded in the 19th century.

Merlin: bedeckt with many delightful varieties and useful verities, fitting the longitude and latitude of all capacities within the islands of Great Britain's monarchy. With chronological observations of principal note to this year 1688.

London: printed by Tho. Newcomb, for the Company of Stationers, 1688. Octavo. 48 p. Interleaved with 39 blank leaves, of which 32 pages have annotations. Contemporary full sheep, wallet style binding, rubbed, tie intact. Title pages frayed with small area of loss

This copy has been interleaved and annotated with financial accounts from the late 1680s (“the 29 of September i689... for Doctor Johnston 2 closes” expenses incurred “i691 at my mothers funerall” through to 1705 (“ffeb 1704 took up ye Liquorice in ye 2 qu in Holden Garth next Hospitall... in Micklegate & above”, “Cutting of this Liquorice”, “Hay sold in ye year 1704”). On one of the pages, there is a short list of household goods taken in 1687, including ”the 10 of ffebruary 87: A table in ye house...” “A Little Chest”, “A Range in ye house”, and “Six shelfes”

The earliest edition of Riders’s almanac recorded in ESTC was printed by John Field in 1654 (one copy only, Folger). It came under the control of the Company of Stationers, and the right to publish it passed from Robert and William Leybourn to Samuel Griffin who each held the rights for around a decade.

Next, it came to Thomas Newcombe who held onto this lucrative publication from the mid-1670s until the late 1680s when his apprentice, Edward Jones, took command. Indeed, the 1688 was the last to appear with

¶ This poignant English Civil War pocketbook from a little-documented parish, reminds us of the number of individuals from the early modern period who have left little or no trace in the historical record.

When first produced, this would have been an attractive artefact comprising over a hundred blank leaves with a 1641 book of Psalms bound at the end. The contemporary sheep binding is rubbed and the boards have indentations, from having been carried around as a notebook. Our scribe has added learned and pious notes over a period of time, most likely whenever such thoughts occurred to them.

Two names are inscribed partway through the “Barnabas Atkins / 1648” (f.11v); then “Barnabus Atkins is my name” and “God is good and grasiouse / Hester Atkins / 1648” (f.12r). These answer to records at St. Martins, Tipton (or Tibberton) in Staffordshire: Hester Atkins (Bap. 25 March 1633) and Barnabas Atkins (Bap. 21 September 1634). The manuscript notes are fairly sophisticated, and since Hester and Barnabus would have been 15 and 14 respectively at the time of the inscriptions, we attribute most of these notes to their father, Robert Atkins, “clerk, lately of Tibbington alias Tipton, parish clerk of the parish church of Tibbington”.1

¶ [ATKINS, Robert]. 17th Century

Manuscript Pocketbook [bound with]

Sternhold & Hopkins, The Whole Book of Psalmes, 1641.

[Tipton, Staffordshire. Circa 1641-1648].

Octavo (170 x 112 x 20 mm).

Manuscript: Approximately 181 text pages on 100 leaves (several leaves excised).

The Whole Book of Psalmes: [10], 91, [3], p. Collated and complete. [Wing, B2381].

Despite Atkins père’s evident knowledge of Ancient Greek and Hebrew, he does not appear in the alumni lists of Oxford or Cambridge universities, but must surely have attended a grammar school. John Parkes reports that “the name of ‘Robert Atkins, minister of Tipton’” appears “in the Protestant List of Tipton residents in the Library of the Palace of Westminster”.2 Stebbing Shaw, writing his History & Antiquities Of Staffordshire at the end of the 18th century, complained of the poverty of extant material relating to Tipton, a state of affairs further illustrated in a printing of the Tipton Parish Register which lists Atkins’ name only as “occurring” between 1621 and 1634.3

Given the date of the Psalms bound into the end, we suggest the book was begun around 1642, which may coincide with the beginning of Robert Atkins’ Tipton ministry. The text, in a small, neat hand, is mostly in English, with numerous abbreviations and contractions, as well as some Ancient Greek and Hebrew. Various changes in the ink support the notion that Atkins has returned at different times to correct, amend, and expand on his thoughts. Atkins uses an aphoristic style (e.g. “D. It is a grevious sinne to omitt duties / privatine sinnes provoke aswel as positive sinnes of omiss: aswell &c” (f.30v.), apparently more for his own reflection and recollection than for use in

sermons or homilies. On occasion, however, he alights upon an image or phrase that may have found its way to the pulpit, for example: “Those yt oppose or fight against ye truth are like the fluds beating against strong rocks being ye more miser: dashed in peeces though fire & sword assault it yet will it not die” (f.31v.)).

A short time after their father’s use of the manuscript, Barnabus and Hester have claimed the book. At first their additions are juvenile, but they become more sophisticated (e.g. “ye the law of moses my seruant which I commanded … the heat of the fathers to the children to there fathers & lest I comme & smite the earth with a curse”).

Bound in contemporary sheep, blindstamped rules, rubbed, corners bumped, spine worn with traces of worming.

Provenance: inscriptions to ff. 11-12r of “Barnabas Atkins / 1648” and “Hester Atkins / 1648” (see details below). 20th century bookplate of Essex & Chelmsford Museum, manuscript label dated 1843 front board.

Whether or not the upheavals of the Civil War affected the Atkins family, Robert chose not to record such matters here, perhaps preferring the abstract realm of eternal truths such as “knowledg of God. Is a virtue whereby wee doe not only conceive there is a God but so know him exper yt wee may worsh: him. to know him is as to prize him love him &c.” (f.34r.). Primary sources from this conflagration-heavy period of English history are notoriously scarce and piecemeal, but this notebook survives to speak eloquently of its primary owner’s earnest piety, illuminating the work and beliefs of a provincial clergyman whose existence is barely represented elsewhere.

References:

1. Ancestry.com

2. John Parkes, History of Tipton (1915).

3. Tipton Parish Register.

£3,000 / $3,880 Ref: 8261

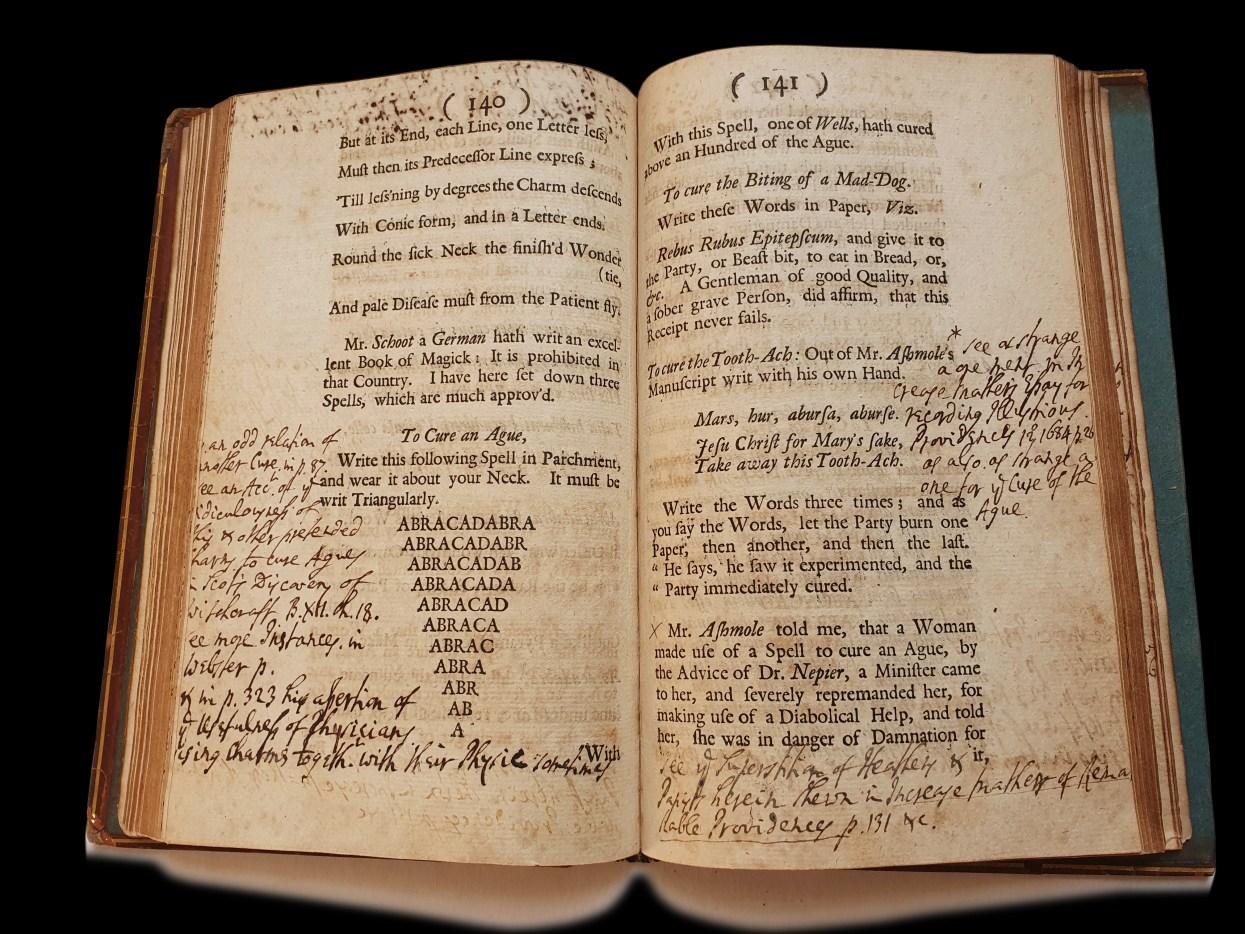

¶ An apothecary’s shop provides the setting for our unusual volume. The scribe, one “R. H.”, was, according to a note to the endpaper, “a Quaker and very curious Chymist who kept a large shop in London”. The copious annotations of this “Chymist” record his own experiments together his thoughts on those by Kenelm Digby, open a window into the workshop practices of a late 17th century apothecary and alchemist.

The importance of apothecaries and alchemists in the history of science and medicine should not be underestimated. Isaac Newton, for example, was himself an alchemist whose earliest encounters with its theories were at the apothecary’s shop where he boarded at the age of twelve, and where he was inspired by John Bate’s Mysteries of Nature and Art (1634), which he borrowed from the apothecary.

The English natural philosopher and courtier, Sir Kenelm Digby (1603-1665), developed an interest in scientific experiments early in his life, was one of the Founder Fellows of the Royal Society, and according to John Aubrey, “retired into Gresham College at London, where he diverted himself with his chemistry and the professors’ good conversation”. After Digby’s death, his records of experiments were published as Collection of Rare Secrets reissued as Chymical Secrets

ODNB remarks: “some of his research, especially in embryology, made positive contributions to scientific progress. All in all, Digby was one of the most remarkable thinkers and scientific enquirers of his day.”

¶ DIGBY, Kenelm, Sir (1603-1665); annotated by “R. H.”. Chymical Secrets, and Rare Experiments in Physick published since his death by George Hartman, 2 parts in 1 vol.

London: Printed for will. Cooper, at the Pelican in Little Britain. 1683 [Part. 2 dated 1682]. Octavo. Pagination [16], 272, with 4 engraved plates. The second part has a separate titlepage on L1r; register and

Our 17th-century scribe remains anonymous, except for the initials “R. H.” after a note on p.56; but a later note –probably 18th-century – to the front endpaper reads “This book belonged to Mr –xx a Quaker and very curious Chymist who kept a large shop in London a Lover of Natural Truths and that by Labour and Experience [attd] - he attain’d – The Notes are worthy the consideration of ye Lovers of this Art. S. Mann”. Harris’s Eighteenth Century Medics, lists a Samuel Mann who in 1762 was apprenticed to John Beck, Apothecary of Armsley, York – a plausible match with our “S. Mann”, if not quite conclusive. But it is surprising that an apothecary working at so late a date counted himself among “ye Lovers of this Art”, when the “Art” had already begun its decline by the time of the book’s publication a century earlier.

Collated and complete. [Wing, D1421A (a reissue, with cancel title, of Wing D1426A)]. Underlining and manuscript notes in Latin and English to approximately 90 pages.

Contemporary panelled calf, worn and broken, spotting to text. 19th century bookplate to pastedown “Supreme Council” and the Masonic slogan “deus meumque jus”.

The 17th-century annotations show a high degree of active engagement. Some 31 pages have printed text underlined, 29 pages have marginalia (mostly with manicules), and six have interlinear notes. Our scribe has also made nine additions to the index, for example inserting “Acetum Radicat” before the first printed entry under “A” (and similarly annotating the given page, “171”, apparently assigning this Latin name to the preparation described by Digby as “The Dissolvent” – perhaps to mark a significant correlation with their own learning). Their confident additions are no doubt connected with their own, evidently extensive, practical experiments in alchemy, as we shall see.

“R. H.” is well read in the core alchemical texts and liberally cross-references authors and works. The Augustinian canon and alchemist George Ripley (d.1490) makes frequent appearances (“vide G: Riplea in pa et etiam Bassilius valentius” (p.152), the latter signifying the pseudonymous 15th-century alchemist Basilius Valentinus; “vide G Riplei in Medulla Alchimiae folio 127 et folio 157” (pp.63). So, too does the Majorcan philosopher and theologian Ramon Lull (c.1232-c.1316), whose coverage includes extensive marginal notes on p.114 (where “Milius”, i.e. the alchemical writer and composer Johann Daniel Mylius (c.1583-1642), is also acknowledged) and a citation on p.68 of Llull’s Testamentum and his other major work Liber de secretis: “Talem aquam [spirit] in venenies [recte invenies] in Testamento novissimo R. Luly pa 64. 66. Et in lib[ro] experimentorum pa 184”. Also invoked in the annotations are the polymath / theologian Roger Bacon (c.1220 – c.1292) (“vide Rogerum Baconem in sua Arte Chimica passim et precipue (in) pa[gina] 339 et in pa” (p.125.)), and the German alchemist Johann Glauber (1604-1670), whose eponymous salt our annotator traces to a process outlined on p.194 for “a wonderful Salt, that is exceeding fusible” (“NB Hoc est [salt] Enixum Glauberi”).

Sometimes our scribe sweeps up several such names in one sentence, as in the vertical note next to “Elixir ex vina & sole”: “NB This is a very excellent and true process, if well don: see Bas: Valentius his manu and R. Lullij and G. Ripleai but note yt when yr [gold] is dissolved to draw yr spirit often, and at last to a very thick oyle wch yw must fix gradually in a Gentel heate” (p.153). This sense of someone completely immersed in their materials is also evident on pages 55-56, where the recipe for ‘‘Tincture of Mars’’ has copious marginal notes that combine several modes of commentary: the cross-reference to other works (“Vide Bassilium Valentinum in particularibus or is pa 19 set pa 192”); endorsement of methods described (“I believe this process of ox. is a very good and true one”); and the mention of another practitioner (“This calcination of [gold] and the ox. is the best of all other I euer met wth I doe believe it was Docr Antony’s way”).

This devoted familiarity is also reflected in a comment on p.175 referring to a rare manuscript they either own or have access to: “Vide mea manuscripta Italia etatis R Lullium in expositione 13 excellentissimus modus calcinandi [gold]”. This suggests a late-13th or early-14th-century manuscript, written in Italian, by or about Ramon Lull – no trifling possession for an 17th-century “Chymist”, even a “very curious” one.

Our scribe is, however, a ‘hands-on’ commentator, with considerable practical experience of many of the experiments described by Digby. Sometimes they let their expertise speak for itself, as on pages 252 where marginal annotations include a recommendation to use a “Glass retort”, especially if it is “well coated”, as it will be “better than an Earthen one” (they also suggest an ‘improvement’ to Digby’s instructions by offering an alternative method “To make the true spirit of [tartar]”, directing the reader to distil it Glauber teacheth”).

In other instances, they make a direct address to the reader, professing a firm belief in their own informed judgement and asking that we, too, share that belief. To a printed recipe outlining “An Operation with [gold] and [spirit] of [antimony]” (pp.65-68), they have added annotations in Latin and English: “Hic processus est notandus quia verus et optimus” (This process is to be noted because it is true and the best); and “I looke uppon this process to be true and the best of all others either in this or any other booke” – and a further note commends the recipe to future readers: “My friend who ever thou art that shalt have this Booke hearafter trust to this process above all others”.

Their desire for the reader’s faith in them is even more plainly expressed on pp.250 Laxative and Emetick Cream of Tartar”) when he appends the printed remedy: “NB when yw draw of yr spiritt mix alittel sirupp of Gilij flours wth it give it to ye patient it will revive him if he has any life left in him” – and

beseechingly adds: “believe me (as experience’d)”. On the following page, after detailing an alternative to the printed text (“Instead of quicklime, take slackt lime, and then you may doe it in a Retort without feare of heate to Break yr Glass and the spirit will be the same”), they again implore the reader: “believe me”. The Latin notes, too, feature similar sentiments: a long marginal note to “Concerning May Dew” includes the phrase “confide dictis meis et hanc meam assertionem serva tibi ipsi” (Trust my words and keep this statement of mine to yourself) (p.116); and near the end of the volume, after recommending “Good Cerule Roman vitriol” (p.270) for staunching blood, by “beating it into powder put it into a spoon then lett 2 or 3 drops of the Blood fall uppon it &c”, they command the reader: “experto crede” (Believe in experience).

Our annotator’s use of Latin includes a tendency to translate some of Digby’s printed English into Latin, for example on p.18. This is in striking contrast to the practice of his contemporary, Nicholas Culpeper, who in 1649 famously translated the Royal College of Physicians’ Pharmacopoeia into English, thus demystifying a work closely guarded by the College and creating a medical handbook for the lay reader. Is our scribe engaged in a bid to remystify their field?

An unusual confluence of philosophies has coalesced into this small medical artefact: a profusely annotated copy of Digby’s Chymical Secrets which illuminates the importance of alchemical thought in the world of 17th-century

emerges as a fascinating figure: a Quaker apothecary steeped in the works of his alchemist forebears and committed to experimentation, keen to insert himself into the waning alchemical tradition and tempering his apparent confidence with appeals to his readers’ faith in his expertise. Perhaps the final word should be given to him as he commends his work to future readers: “My friend who ever thou art that shalt have this Booke hearafter trust to this process above all others”.

£4,500 / $5,800 Ref: 8293

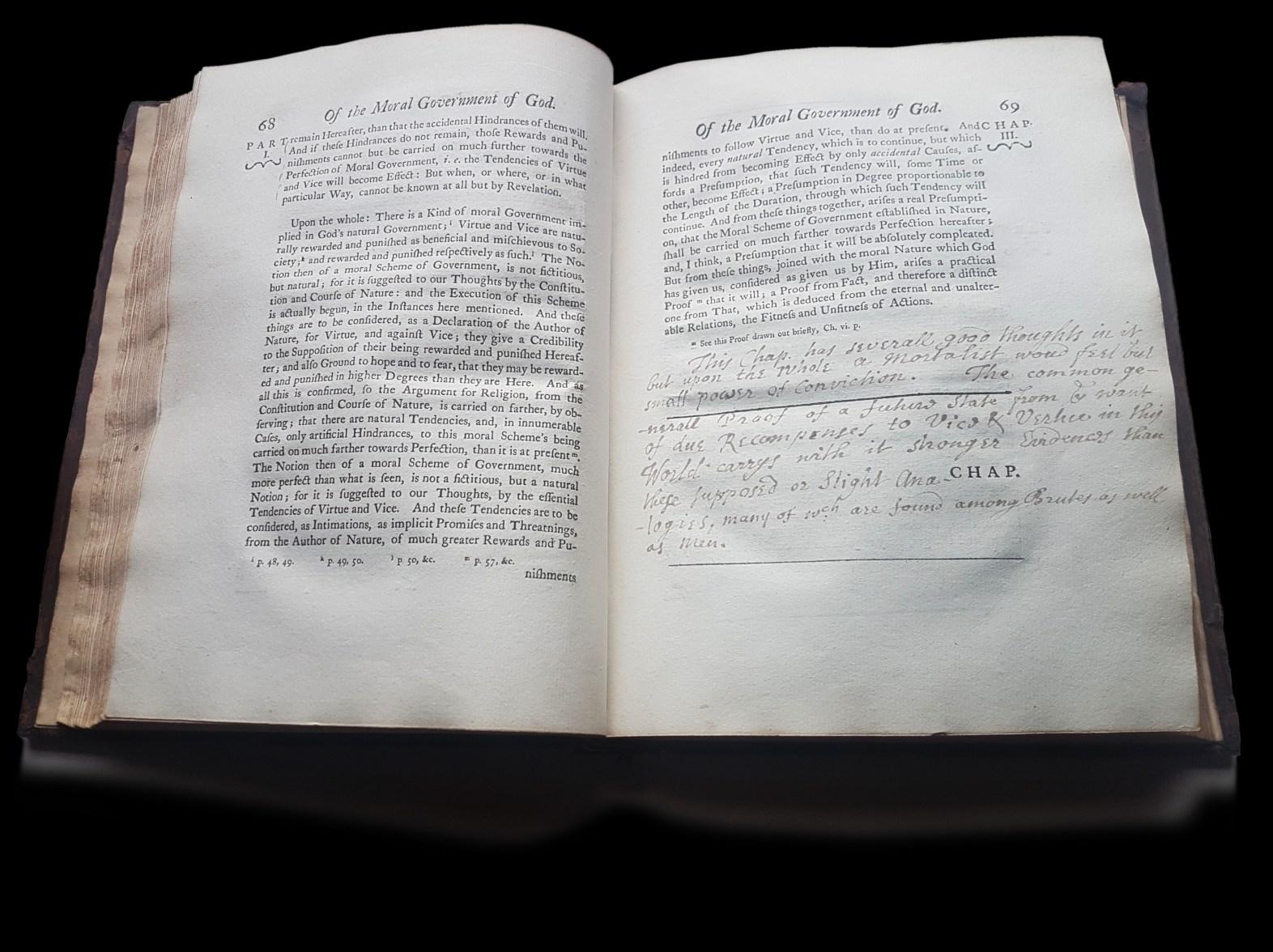

¶ This rare Scottish Enlightenment manuscript deals with an abiding theme throughout the period: how to reconcile the torrent of new scientific and medical discoveries with the tenets of theology that still presided over every sphere of existence?

The manuscript itself bears no inscription that explicitly identifies its author (although the titles “West Street Chapel 1780” and “New Road Chapel” may have a significance, as we shall see); however, the contents include a section laying out instructions on the publication of the scribe’s works. From these, we can confidently attribute the notebook to Andrew Wilson (1718-1792).

Wilson was born in Maxton, Roxburghshire in Scotland and graduated in medicine from the University of Edinburgh, in 1749. After receiving a practitioner’s licence and a fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1764, he established a practice in Newcastle and later (1775 or ‘76) in London, where he was appointed to the Medical Asylum. A proponent of natural philosophy, Wilson published many medical treatises and works that integrated his wide-ranging interests in science, medicine, theology and philosophy.

¶ [WILSON, Andrew (1718-1792)].

Original manuscript philosophical notebook.

[Circa 1780]. Oblong notebook (190 x 80 x 6 mm). Contemporary stitched paper wrappers with titles in ink manuscript

“West Street Chapel 1780” and “New Road Chapel”. Approximately 44 text pages on 40 leaves. Written in a small, neat hand (approximately 10,000 words).

Contemporary plain brown-paper wrappers, minor ink splashes to text.

Watermark: Horn, GR.

References:

1. Telford (ed.), The Letters of the Rev. John Wesley, Vol. 5, p.205.

2. John P. Wright in the ODNB.

The cover’s “West Street Chapel” inscription may signal a link with the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, who founded West Street Chapel in the West End of London and used it in the second half of the 18th century. Wesley knew of Wilson and his work: in a 1770 letter to one of his itinerant preachers, he writes: “I am glad you have Dr. Wilson near. A more skilful man, I suppose, is not in England”.1

Our manuscript appears to be a working notebook, albeit a neat one with relatively few crossings-out. Its unusual format – a tall oblong with fragile paper covers and a simple stitched binding – may indicate that it was homemade. The majority of the contents comprise Wilson’s detailed arguments in natural philosophy; he opposed the Newtonian idea that the deity needs to intervene in the creation, arguing instead that all natural phenomena, including gravitation, are to be explained purely mechanically. The natural philosopher must then uncover these underlying laws of nature and reveal the work of the creator 2 .

Of particular interest is the section, mentioned above, in which Wilson gives instructions regarding the publication of his manuscripts. He begins: “It is my will and desire that after necessary correction of the language & distinct paragraphing my MSS be published in the following order”. What follows are titles and subjects that clearly allude to a number of Wilson’s already (as of “1780”) published works, organised into three categories: “These on Natural Science” (four works, beginning with “1. My observations of the Newtonian principles of philosophy” – probably his Short observations on the principles and moving powers assumed by the present system of philosophy (1764)); “These Publications and Writings relative to Physiology or the Theory & the Practice of Medicine” (five, including “2. Aphorisms on the Diseases of Infants” – a close match for his Aphorisms on the Constitution and Diseases of Children (1783)); and “Theological” (three, including “Revelation the Language of Nature” – possibly his Human Nature surveyed by Philosophy and Revelation (1758)).

Although Wilson’s printed works are well represented in library collections, this appears to be his sole surviving manuscript, especially as any similarly constructed examples probably disintegrated long ago. Here he gives the clear impression of someone organising and curating their legacy, and strikingly brings to bear on his own works a kind of categorisation that reflects the emerging field of taxonomy.

This unusual homemade artefact by a key figure in the Scottish Enlightenment is a remarkably well-preserved example of the many complex intersections of science, religion and philosophy during this period. It provides a window onto the intellectual life of its owner, as well as demonstrating that the drive to synthesise science, medicine and theology extended – naturally enough – to how the likes of Andrew Wilson wished to organise their own published work.

£3,250 / $4,200 Ref: 8272

¶ The most well-defined figure in this archive is Susanna Harrison, whose notebook [1] is the chief draw. Her entries represent the attempts of an intelligent woman from a well-to-do family to find an outlet for her energies –especially creative – in a constrained social existence.

The Harrisons lived in Lincolnshire, to judge by the placenames sprinkled throughout. Susanna Harrison (d.1775), subject of a note in item [1]; Thomas Harrison (1748-1804?), whose name appears on the back of a business card; Rachel Harrison (1748-?), also referenced on the business card; and Bridgit Harrison (d.1733) and Bridgit Harrison the younger (d.1737), both mentioned in item [2].

¶ HARRISON, Susanna (d.1775)

Small family archive of notebooks.

[Circa 1770-1810]. All items in original (some homemade) bindings and generally good original condition.

[1]. 18th-century notebook. Octavo (152 x 92 x 15mm). Approximately 22 text pages and 20 pages of designs (three pencil; 17 in ink), on 103 leaves with four embroidery samples loosely inserted and piece of folded paper containing red pigment stashed into the pocket of the binding. Original vellum wallet-style stationer’s book. Slightly soiled but very good original condition with functioning clasp.

The first section gives a series of instructions for 25 dances ranging from the well-known (“Flowers of Edenborough”, “Hunting the Squeril”) to the apparently hitherto lost (“Rolling on the Grass”, “The Ladies Setifficat Rant”, and “Wainfleet Boys” – probably a local dance, since Wainfleet is a Lincolnshire town).

There are some eight pages of religious verse, one of which is written in a simple code (“Wh28 459 siv459C172 t4 th2 C94ss[...]”). Further on, another hand has recorded several family deaths, including that of “my Sister Susannah” – our main scribe, we assume, for this volume. At the rear are 20 pages of designs in pencil and ink, closely resembling the original samples loosely inserted. Tucked into the rear pocket is a sample of powdered red pigment, folded inside a scrap of paper.

[2]. 18th-century receipt book. Octavo (153 x 95 x 2mm). Approximately 7 text pages on 5 leaves. Homemade notebook made from a few folded sheets of paper stitched into a crudely cut piece of vellum.

Receipts for land rentals e.g. “Nouember ye 20th 1735 ye 22 shillings Receiued of Richard Smith ye Sum of Ten Pounds of a House In attaerbe dew may Day Last”.

[3]. 18th-century manuscript terrier. Octavo (165 x 90 x 5mm). Approximately 35 text pages on 43 leaves. Some leaves excised, one cut with loss of upper half. Crudely made notebook , quires stitched into vellum-covered paste-board.

Entitled: “A Terrier of the Carr meadows belonging to wadington Snitterby and atterby”. The text includes names, quantities and some notes to the versos.

[4]. Hellaby’s Town and Country Lady’s Repository; or, Memorandum Book for the Year 1807. Boston. Printed by and for J [ames]. Hellaby. and sold by Lackington, Allen and Co. and Champante and Whitrow, London. [1807]. Octavo (165 x 90 x 5mm). Pagination 132 (lacking 90-91) engraved title page and folded frontispiece. Green wallet-style binding.

No other copies are recorded in library collections. Pennsylvania State University Libraries have a similar publication under the slightly different title of Hellaby's pocket repository [1806] which is included in a sammelband of five Georgian women’s pocketbooks. Our copy has a handful of manuscript notes.

[5]. Advertisement for ‘Joseph Goodyger Weaver, Wheatley. Single sheet (205 x 170 mm). Folded, upper left corner torn.

Brief manuscript accounts to upper margin . Docketed on the reverse “Mr Storey of heapam Lincoln[shire].

[6]. Sundry items including a business card for “Clulow & Unett, Manufacturers of Eartheware”, a bill, a remedy, a letter dated 1792 referring to their land at Atterby, and a few letters from later in the 19th century. All items relate either to the Harrisons or the Storeys.

The supporting documents [2] to [6], with their comparatively pedestrian concerns, set Sarah Harrison’s notebook usefully in a context that allows her creative pursuits to stand out against their background. These sections, nevertheless, are unified by their prescriptiveness: they establish patterns –terpsichorial, moral or lacy –that must be followed, echoing the confinement of expression so adroitly explored by the likes of Fanny Burney and Jane Austen that Georgian women had to live within.

£3,750 / $4,850 Ref: 8211

¶ Several hands in this well-used manuscript volume keep track of the general flow of work and business, life and death: inventories are recorded, cattle branded, taxes, rents and expenditure accounted for, and so on. And among these notes and accounts are some 10 recipes and remedies.

Thus, at one end of the tete-beche arrangement, an inventory “of ye good & Chattls of Aron Wright distrained by me Walter Stanhope” is followed by a small clutch of recipes in a different hand. First, four brief equine remedies, including “A good purge for a horse” (“halfe a dram or a dram cream of tarter two drams anni seeds […] in a pint of warme ale about four in ye afternoone”) and “ffor stratches or scabed heels”.

On the opposite page is a recipe “To make Birtch Wine”, which specifies “two pounds of Best powder shugar” to “every wine gallon of Birtch juce” sanctuary of each a handful / Gentian an ounce sena”, slise all in a gallon of old Beer w ruste iron”. The entries at this end then revert to business matters, mainly comprising rents, land tax payments and other expenses from 1706 to 1730.

At the opposite end, our scribe begins on “Aprill ye last day 1711” when he “Accounted w Mother Baron & payd her for Rich Table” as well as “four paire of new

¶ [STANHOPE, Walter (?)]. 18thcentury manuscript Accounts and Recipes.

[Bolton, Bradford, Yorkshire. Circa 1706-58]. Quarto (202 x 167 x 22 mm).

Approximately 100 pages of accounts and sundry notes arranged tete beche (roughly 40; 60) on 134 leaves.

shoes” and “worstett wool for stockings”, followed by a similar set of accounts for 1712 (although they then unsystematically revert to 1708-9 and 1706). Most of these detail leases, bonds, and mortgages, alongside costs of building repairs and maintenance (“Wright for sageing bords”, “for glaseing ye windows”).

Sandwiched between “Repairs att Bolton” and a “Field Book” (two pages of acreage measurements for various closes and “Leays”) are a pair of related recipes in another hand: “To make a Rich frute Cake” and “The Eiseing of it”. The evident size of the cake (“three pounds & a halfe of fine flower”, the same of “currants”) makes the “quart of cream”, “one pound of butter” and “ye yolke of twelfe eggs” seem a little less sclerosis-inducing, but “rich” it certainly is, especially with the “Eiseing”, which contains “a pound of double loafe loa lofe shugar”.

A further ten pages of accounts are recorded, including “Monthly Assessment for ye poor according to ye pound

Rent” and annual land taxes. Again, business is interrupted by recipes, this time three of them: “To make Cowslop wine” (“six gallons of water”, “twelfe pounds of fine powder sugar”, “30 quarts of Cowslops & six Lemons slised”) has a helpful footnote that adjusts the recipe’s quantities for each of three sizes of pot (“great”, “red” and “little”) in the household (with the further information that “great pot will hold 14 quarts of water […] little pot will hold 11 quarts of water & 13 quarts & 3 gills of fflowers”). On the next page is another “To make Birtch Wine”, then “Mrs Buck receipt to make salve” (involving “bees wax”, “ffine Rosin”, “ffrankinsence”, “white pitch”, “camphor”, “venus turpentine”, “sweet oyle or oyle of Ollives”, and a handful each of “Bishup leaves plantine self-heal St John Grass Winter Cherry Smaleige Loveige Arkangle Bettoney”; all these to be combined “with May Butter unsalted”).

In the 1740s, another scribe adds to the volume, concerned more with sartorial refinement than bodily health or sustenance. From “Will: Rawson” they buy “3 yrds: Super fine Cloath for Coat & Britches”, “4½ yrds Shallown”, “Swan Skin 1.yrd”, and for the finishing touches “Silk half ounce”, “Gold thread buttons” and “Buttons what please”.

As to authorship, there are several mentions of the name Stanhope, including the reflexive reference in the inventory mentioned above, but elsewhere the scribes refer to “me Mother Baron”; and, in the 1770s, another scribe records a series of payments to “my Bror Geo: Greene”. All of this is complicated by the early modern penchant for colloquial monikers.

This early modern miscellany, with its clear signs of use, conveys the ebb and flow of life in an early 18th-century household, as finance, property and livelihood intermingle with health, husbandry, and the necessities and pleasures of food and drink. Nowhere is this better illustrated than the presence – after pages of accounts concerning coal, linen and clothing – of “House keeping meat” expenditure between 1772 and 1786, the considerable fluctuations of which tell a story all their own.

£1,250 / $1,600 Ref: 8269

¶ The spirit of Scotland suffuses this manuscript, which features several recipes for preserves and remedies from a famous 17th-century Scottish woman medical practitioner – possibly an acquaintance of our anonymous scribes.

Only 29 of the available 80 pages of this slim volume have been used, but the presence of at least three hands, who between them have contributed some 60 recipes and remedies, indicate it was used in a very busy household (that it saw regular use is confirmed by the marking of several recipes as “Approved” and a few instances of crossing out). The receipts have been arranged tête-bêche (often referred to as dos-a-dos), with culinary at one end and remedies at the other (although, as is often the case in household receipt books, order is never entirely adhered to).

¶ [SCOTTISH RECEIPTS] 17th-Century Household Manuscript of Recipes and Remedies.

[Scotland? Circa 1690]. Folio (305 x 190 x 10 mm). A total of approximately 29 text pages (19 culinary; 10 medical) on 40 leaves. Contemporary mottled calf, the text block appears to have come loose at some point, and then stitched back in.

Watermark: Arms of Amsterdam.

The culinary recipes include around 20 fruit preserves, one of which is a general recipe “To keep frute all the year long for tarts”, for which you’ll need “a new pipkin that will hold 3 quartes and a pound of sugar”; you are then instructed to “frute then sugar a layer of each” until the pipkin is filled, and cook “in the oven after the household bread is drawn”. More specific recipes include “syrop of Mullberries”, “syrop of Gillieflowers” (both of which are “approved”), and how to preserve cherries, “Apricocks”, “quaddliongs”, and “figges”. Oranges can be preserved whole (“scrape them with a peece of glass”) and made into a “past” (“the best way” requires “Civill orenges”), “Marmalet”, “Sirope”, or “chips” (these last two can also be used to preserve lemons). There are also recipes for cakes (“plume”, “portugall”) and jellies (“Goosberries”, “Raspberries”, “plumes”), as well as six for wine (including “Cherry”, “Currant”, “Goosbery” or “any sort of ffuite”). Sugar of course features throughout this section (“lump”, “Loafe”, “fyne white”), which includes a recipe “To clarefie suger”.

At the opposite end of the volume, the overlapping hands have written 21 remedies on five leaves. There are several interesting attributions within this section, the first of which is recorded on p.1: “Recept of my Lady Kincairdens Pills”. This probably refers to Veronica (nee Sommelsdyk) Bruce (c.1640-1700), who married Edward Bruce, 2nd Earl of Kincardine FRS (1629-1681), a Scottish inventor, politician, judge, and co-developer (with Christiaan Huygens) of a marine pendulum clock. Also acknowledged is “Doctor Pitcairne”, whose “ordinary Jentell Purg” calls for “sclised reubarb” and “Senna”, to which should be added “a much kin of ordenery tabell Eall”. This should be applied “6 or 7 tim’s, & after 4 hours if it do’s not work you nay give 3 spoonfull’s more, you may mark in the fution of less quantity”.

The most notable attribution accompanies a group of five receipts by Margaret Hamilton, Lady Belhaven and Stenton (bef. 1625–c.1695), a Scottish medical practitioner of the period known for her knowledge of herbal remedies who achieved further notoriety for her part in faking her husband’s death.

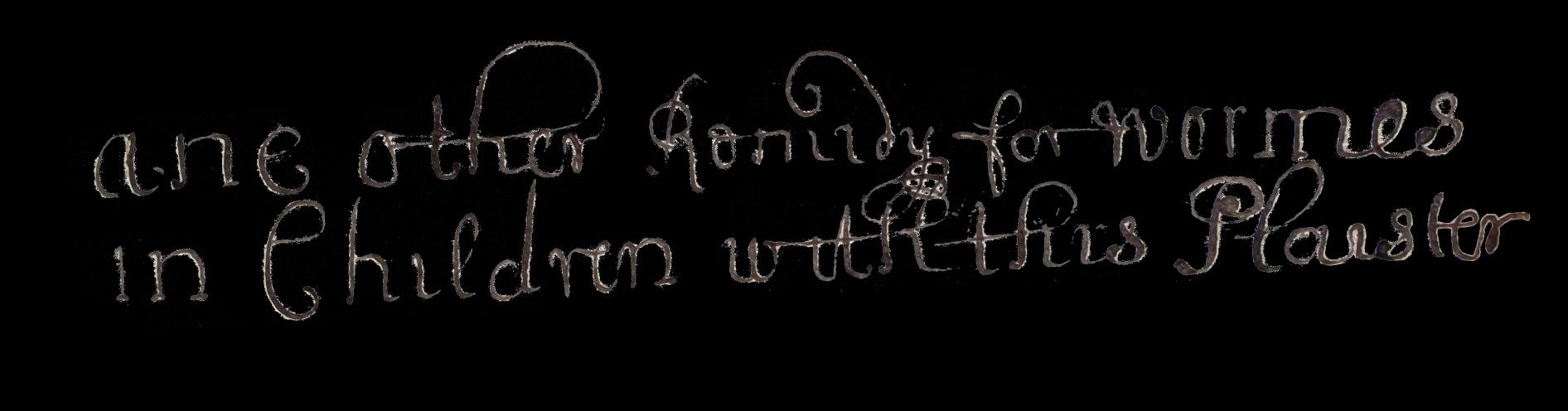

On pp.3-5 of this manuscript, she supplies remedies for “A Plaister for Wormes in Children” and “ane other Remidy for wormes in Children with this

. The latter calls for such things as wormwood, gentian and currants, beaten together, and this mixture to be steeped “in a pint of Muskadine”; then, after “two or thrie dayes at the face of the moon lett the Child eat a good quantitie”, followed by periods of fasting. Among Hamilton’s other remedies are treatments for “The ffalling fundament” and “itch or breacking out of Children” (which “may be used without hurt Ether to young or old”), and the generically named “The ointment”, with ingredients such as “fumatarie ground jvie English tabacco” mixed with numerous herbs. Despite its detailed instructions (“anoint the places where the spotts are with a little thereof”), there is no indication as to the condition it treats.

More specific is a receipt “For a tetter or ringworme”, which directs the reader to “anoint the place” with a mixture of such things as “white wyne vinegar”, “juice of a Lemon”, and “a litle honey”. All of these remedies have apparently been “Aproved by my Lady Belhaven (also spelt “Balheaven”, and “Balhaven”), but, as we have not identified the scribe, we do not know if she received these directly from Lady Belhaven or whether they were circulated among Scottish households.

Outwith the Belhaven selection, the remedies continue with the likes of “Tablets for coughs”, which call for readymade “distolled water” of “red roses Scabious sweet Margoram Hysop Coultsfoor Maiden hair”, mixed in a pan with “Burage”, “Buglas” and other herbs. “When all is boylled”, add “white suggar Candie fynly beaten or refyned Suggar”, together with “liquorish”, “Oyll of Cinamon”, “Anniseseeds” and other ingredients. To make the mixture into pill shape, “work your tablet past with a litle of the Suggar”, being careful not to add too much, for “if you mix much at once you will make it Dry too fast”. Once they have been prepared, strew “some of the Suggar upon papers” and dry them “before a ffyre” ensuring the heat is only “very moderate”. But “Iff yow have not the distolled water you boyle the herbs of those that are mentioned in spring watter”.

The attributions locate the household firmly in Scotland: Kincardine and Belhaven are roughly 30 miles west and east of Edinburgh respectively. This is a well-to-do family, to judge from the prominent use of sugar and fruit, not to mention the aristocratic name-dropping. Despite its slightness, our manuscript shows clearly the traces of a social network, providing several coordinates for the wider transmission in Scotland of various remedies, notably including several attributed to the renowned medic, Margaret Hamilton, Lady Belhaven.

£4,500 / $5,800 Ref: 8289

¶ Remedies to treat horses, cows, dogs and the occasional “Christian” are to be found in this cheaply made but beautifully presented manuscript book. The high incidence of equine remedies, as well as the presence at the back of a “Table Of the Price Value & Virtue of most of the principal Drugs belonging to Farrying as they are Frequently Sold at ye Druggests in London”, lead us to assume that our anonymous scribe was most likely a farrier – that is, someone practising both blacksmithing and veterinary care – with an evident sideline in treating humans.

The volume was clearly intended to be a reference book containing its owner’s best tried-and-tested remedies, rather than an “on the hoof” notebook. The remedies have all been numbered, although a few have been left blank for the intended remedy, and two unnumbered remedies have been added at the end. It has been written in a very neat cursive hand, probably in one or two sittings, and several loose-leaf additions confirm the notion that this is a compilation of trusted remedies: one of them, “for a Cow or horse”, is annotated “Entered in ye Book 219”, and indeed the same receipt has been squeezed in under “219” as an alternative remedy for “A Lax or Looseness”.

The remedies include cures for conditions such as “a Moon Blind Horse” (no. 19), “a Canker in ye Tongue” (no. 118), “Pox in a Horse” (no. 70), and “Strangullion” (treated with “Juniper Berries and a Handful of Beef Brine” (no. 190)).

¶ [FARRIERY]. 18th-Century Manuscript Book of Remedies.

[Cambridgeshire?, England. Circa 1788].

Quarto (210 x 175 x 8 mm). Approximately 75 unnumbered text pages (including a nine-page at the end) on 48 leaves. A tiny fragment of what would have been plain grey wrappers remains, but stitching intact.

Watermark: Britannia; countermark: CM in italics.

There are recommendations for perennial pests like gadflies (“For Warbles under a Saddle” (no. 57)) and overenthusiastic riders (“For a Horse yt is over Rode” (no. 107)), as well as formulations “To make a Horse Piss & Dung” (no. 115) and the more fragrant “Perfume for a Horses Head” (no. 218); and one cross-species concoction claims to be effective for “A Strain in a Horse or Christian” (no. 105).

The two unnumbered receipts both address forms of derangement: “Insanity”, which “a respectable author attended with uncommon success”; and in prophylactic mode, “Canine Madness”, the entry for which considers how the disease passes between dogs and humans (“It is generally allowed by Physicians, that ye spittle of a mad animal, infused into a wound is the only cause hereto known”), and assures the reader that, even if this does occur, it likely “does no sudden mischief”, so a thorough and prolonged dousing with warm and cold water alternately should prevent the bitten human from contracting the disease.

identify the subject of two loose-leaf remedies (“For a Nervous Disorder or a great Shaking” and “The Piles”), which are intended “For Alice Murphet” and “For Alice Murphy”. We assume the second is an error, as they are both dated 21 August 1788 and have been annotated in the same hand, but in slightly different ink: “by order of Mr Levitt”. While “Mr Levitt” remains elusive, the patient was probably Alice Murfit (1757-1842), who was born at Stretham, Cambridgeshire, and died in nearby Ely.

Our scribe shows themselves to be well organised and practical in their use of simple, inexpensive materials to create a handy reference work that evokes the conditions encountered and measures required in the field of husbandry (both animal and human) in the late 18th century.

£950 /$1,230 Ref: 8282

¶ This unrecorded set of 18th-century cards contains a range of morally and philosophically instructive information, including ‘On Cruelty to Animals’, ‘Benevolence and Humility’, and ‘On Negroes’, presented across a range of parsimoniously printed cards in their original slipcase. This is apparently the sole surviving set, and it raises many questions, several of which remain unanswered.

The presentation of information in ‘bitesize’ chunks and the material’s instructional tone might suggest a pedagogical function, perhaps for a younger audience; however, other factors may confute this reading.

¶ [LEWIS, M. and LEWIS, Caroline Amelia (owners)]. Educational Cards entitled ‘Literary Present’.

[England. Circa 1785]. Each card measures approximately 126 x 80 mm. 12 cards, printed to one side only. Contained in, what appears to be the original slip case, with engraved label (cut from larger title piece), pasted to one side, early repairs.

Provenance: Each card is inscribed to the blank side “M Lewis” and the slip case is inscribed “Lewis / Caroline Amelia Lewis”.

The notion of a younger intended audience is at first glance borne out by the choice of material, which includes three entries from Thomas Percival’s A Father's Instructions to his Children (1775): ‘The Folly and Odiousness of Affectation’; ‘Tenderness to Mothers’; ‘A Generous Return for an Injury’. But a further examination of the range of content reveals a syllabus of relative intellectual maturity. For example, questions of moral philosophy are addressed in four extracts from Blair’s Sermons (1777): ‘Temperance in Pleasure Recommended’; ‘Benevolence and Humanity’; ‘Religion not to be treated with Levity’ (‘The spirit of true Religion breathes gentleness and affability’); and ‘Content’, which advises that ‘the principal materials of our comforts, or uneasiness, lie within ourselves’.

Further philosophical discourse can be found in ‘Sensibility’, drawn from Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey (1768) (‘Sensibility! Source inexhausted of all that’s precious in our joys, or costly in our sorrows!’); as well as in ‘The Character of a True Friend’, from William Enfield’s The Speaker (1774); and in ‘Creation’, from Goethe’s ‘Sorrows of Werter’ (1779), which adopts a more poetic style of contemplation (‘Weak mortal! all things appear little to thee for thou art little thyself’).

Moreover, one can infer a relatively progressive attitude from two particular entries: ‘On Negroes’, from Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, which is the ‘tender tale’ mentioned by Sterne in his correspondence with Ignatius Sancho; and ‘On Cruelty to Animals’, from Soame Jenyns’s Disquisitions on several subjects, advocating animal rights by attributing personhood (‘the majestic bull is tortured by every mode which malice can invent for no offence, but that he is unwilling to assail his diabolical tormentors’) and positing their intrinsic right to life, since ‘We are unable to give life, and therefore ought not wantonly to take it away’.

The excerpts amount to a kind of ‘cheat sheet’ for moral philosophy, enabling the reader to make an intelligent contribution to discourse within a social setting. But who is our budding moral philosopher? All 12 cards have been inscribed “M Lewis” on the back, suggesting a concern that these may be lost or mixed with other, similar cards in the course of a social event. They have also inscribed the slipcase, and beneath is a slightly later inscription of “Caroline Amelia Lewis”. This may well be the Caroline Amelia Lewis whose baptism is listed on ancestry.com as being in Manchester on 8 April 1810 – and whose parents’ names are Mary and Maurice. This doubly tantalising lead may well point to the cards’ original owners.

Who published the cards? Their source material derives from a handful of 18th-century A Father’s Instructions to his Children); Dodsley (Sorrows of Werter, Disquisitions on several subjects, and Tristram Shandy – for which he was joined by T. Becket and P. A. De Hondt for Vol. 4., and they in turn published Sterne’s Sentimental Journey) and a syndicate of William Creech, W. Strahan, and T. Cadell (Blair’s Sermons). Given the close typographical match of the printed cards to their original sources, and that all these texts appeared in the 1770s, any of them could have produced the cards cheaply and simply, generating a potentially lucrative product from already available material. It’s also possible that the cards were ‘pirahttps://www.msn.com/ en-gb/news/uknews/labour-s-jess-phillips-reveals-she-was-told-to-not-apply-for-a-job-because-she-was-pregnant/ ar-AA1AuWeJted’ and their printer concealed by anonymity.

Regardless of which publisher it was, they would have been confident, given the recent proven track record of the texts in book form, that the cards would find a readership with an appetite for these progressive ideas and their dissemination in social spaces of Georgian Britain. As such, these thrifty cards offer insights into the intellectual and social concerns of their 18th-century owner, although a more detailed study of those concerns requires the resolution of questions around the identity of both publisher and reader.

£2,750 / $3,350 Ref: 8238

¶ The standard manual of legal stiles (or precedents) for the early-modern Scottish lawyer was George Dallas’s System of Stiles (1697), a formidable folio of no fewer than 904 pages. Walter Ross referred to it as the ‘vast opake body’ of the work, and described how the hearts of apprentices ‘failed within them, when presented, in the Writing -office, with such a frightful volume of arid, naked, unintelligible Forms’. (ODNB).

No wonder, then, that some legal professional chose to compile their own books of precedents. This folio volume, written in a clear and legible hand, could be easily consulted by any legal professional, and precedes Dallas’s work.

The volume is entitled “Stylorum Veterum ac Recentiorum Collectio A me

Guilielmo Granteo Juniore de Creichie Fideliter Conscripta Anno Salutis Humana Millesimo Sexcentesimo Nonagesimo Quinto”.

William Grant was laird of Creichie. Based on a 1696 Poll record of the “Paroch of Fyvie”, he was married to Katherine Grant (nee Gordon): “William Grant of Criechie should pay of the proportion of the hundreth part of the valued rent of 1 pound 10 shillings Scots, effeirand to the duty of the said land in his own labouring, its absorbet in the highest, in which he is raited being 12 pounds Scots inde with generall poll Katherin Gordon, his spouse William, James, and Loodwick Grants, his sons”.

¶ [GRANT, William]. Late 17th-Century Manuscript Book of Legal Stiles. [Fyvie, Aberdeenshire. Circa 1695]. Folio (325 x 200 x 20mm). Pagination 90, [2, blanks], 179, [1, blank].

Contemporary sheep, rubbed and scuffed, worm damage to final leaf (no loss of text) and rear board.

Provenance: 18th century ownership of “Theodor Morison”, and bookplate of Thomas Fraser Duff to paste-down

William next appears in 1700, as a tutor to Elizabeth Barclay Lady Towie’s son, “Patrick Barclay Being only of Eleven years of age of therby is in the custody and Keeping and under the Education of William Grant of Creichie his Tutor Testamentar”.

This volume is divided into two sections: the first section comprises 90 pages, beginning with “A Moveable Bond”, and moves through examples such as “Form off Ane Bill off Captione”, “off Letters off Poynding”, “Sumonds of Generall Declarator”. “Form off Ane Inhibitione”. The second, much longer section, is separately paginated and runs to page 179. It includes examples of “Form off Ane Discharge”, “Suspensione”, “Letters of Apprizing”, “Acts of Court”, “The next thing Proposed is Personall & Reall Executione”.

The earliest extant style book is that by compiled by Oliver Colt (NAS RH13/2), circa 1600. Style books compiled before the Act of Union include one at Edinburgh University by William Lindesay of Culsh, c.1685 (MS 3066/7); one at the University of Glasgow: one circa 1695 (GB 247 MS Murray 554); and a circa 1685 at Yale University (Boswell Collection, Box 156, folder 2854), which belonged to James Bowell.

Style books continued to be compiled into the 19th century, but this manuscript was written in an interesting period in Scottish law. Twelve years later after it was written, the Act of Union was declared, and although Scotland retained a different legal system from England, the English were the dominant party in the Union and exerted their

The manuscript is written in a very neat and legible hand, with pages laid out clearly. It was intended as a reference work, but Grant has included numerous decorative flourishes throughout the volume. His creativity makes for a visually appealing volume, which offers a comprehensive overview of late 17th century Scottish law.

£1,750 / $2,260 Ref: 8305

Thomas (1588-1679, trans.) Eight bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre written by Thucydides the sonne of Olorus. Interpreted with faith and diligence immediately out of the Greeke.

London: imprinted [at Eliot’s Court Press] for Hen: Seile, and are to be sold at the Tigres Head in Paules Churchyard. 1629. FIRST EDITION, FIRST ISSUE. Pagination [34], 536 [i.e. 535], [13] p. complete with 5 engraved plates (3 folded).

-century half calf, marbled boards, rebacked and recornered. Small, marginal tears, section torn from upper margin of title, paper flaw to (b2), scattered spotting and occasional light damp staining, closed tear to map, repaired to reverse.

In this rare first edition, first issue of this classic work, two giants of European literature are brought together across two millennia: the founder of political realism, Thucydides (c.460 –400 BC), and one of its most famous adherents, Thomas Hobbes, who developed his arguments under the strong influence of his ancient Greek forerunner, whom he named as his favourite ancient historian.

Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) and other political works were years away when he began translating Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War; and by his own account in the book’s preface, “After I had finished it, it lay long by me”. His hesitancy has been puzzled over, but when it finally appeared in 1629 as his first published book, it was recognised as a significant achievement: the first complete translation of Thucydides directly from the Greek (the only previous English edition of the History having been based on a French translation of a Latin translation – “traduced, rather than translated”, as Hobbes himself puts it). What drew him to the book appears to have been “the cool dissection of political motivation and the ‘realist’ approach to power, together with the peculiarly Thucydidean analysis of the role of rhetoric in political debate”; but regardless of his motivation, this translation established him “at a stroke as one of the leading Grecianists of his day” (ODNB).

Hobbes’ translation of Thucydides was, many scholars suggest, in tune with his age: the 16th-century insistence on reading ancient Greek and Roman works “for their ethical values” had worked against the popularity of a writer famous for his “reluctance to point a moral and his scepticism about the influence of ethical principles on human behavior”. By Hobbes’ time, “scepticism in the realm of faith and morals and a belief in self-interest as the dominant motive in human affairs were growing stronger” – a change in attitudes also detectable in the work of early Jacobean contemporaries such as Francis Bacon.1

Hobbes frames his rendering of Thucydides in four prefatory sections. The “Epistle Dedicatorie” consists of a eulogy of his late patron, the Earl of Devonshire, via an address to his son, whom he assures, using an apt metaphor, that “never was a man more exactly coppied out, then he in you” (that Hobbes was angling for a renewal of his employment with the Earl’s family is obvious, but in this he was unsuccessful). In an introduction entitled “To the Readers”, he turns his eulogising towards his ancient Greek model, of whom he writes: “as Plutarch saith, he maketh his Auditor a Spectator. For he settteh [sic] his Reader in the Assemblies of the People, and in the Senates, at their debating; in the Streets, at their Seditions; and in the Field at their Battels”.

Then, in an account “Of the Life and History of Thucydides”, Hobbes, after recounting what can be known or inferred about the ancient historian’s career and fate, commends his approach (he “wrote not his History to win present applause, as was the use of that Age, but for a Monument to instruct the Ages to come”), and defends his work against criticism, for example unfavourable comparisons with that of Herodotus. Finally, Hobbes diligently presents an index of the “names of the places of Greece occurring in Thucydides, or in the Mappe of Greece, briefly noted out of divers Authors, for the better manifesting of their scituation, and enlightning of the History”.

All this conscientious throat-clearing before the translated work itself is an effective bit of scene-setting for Hobbes’ first published book – a masterly act of cultural transmission that looks back to a key influence on his thought and forward to some of the ideas that became central to his later political philosophy.

£12,500 / $16,100 Ref: 8197

¶ The lives of 18th-century women are often recorded in scant detail. Elizabeth Risebrow (1722-1790) is a case in point: she was the daughter of Samuel Risebrow, surgeon, of North Walsham, Norfolk, and his wife Anna. In 1747 she married Robert Bayfield, gentleman, of Antingham. Elizabeth, however, gives a good account of herself in this rich and varied archive. Her writing style is fluid and often observant or witty, and she is clearly well read and aware of the era’s coterie culture.

Elizabeth’s inscriptions in [1] date these poems to her early-tomid-twenties, suggesting that her versification ended the same year as her marriage began. The first poem poignantly expresses her wish to “enjoy a house […] Near to a wood near water”, with a menagerie and “two Hundred pounds a year”. Elsewhere, she touches on the place of women in society, remarking that grief over the death of an infant was “Without Doubt the more as this was a Boy / As Girls are esteem’d no more than a Toy”.

Elizabeth engages in a culture of exchange which she reinforces through classical allusions (“Juno”, “Cupid”, “Leander”) and coterie names (some poems are signed “E. Risebrow” or “ER”, while in others she uses the sobriquets “Rosalinda” or “Belinda”). One of the central figures is a “Miss Kitty Cooper”, who is sometimes admonished for remissness (“write a Long Letter, or else you Receive / no more Letters from me”). Other figures include the Berneys who lived at nearby Westwick House.

In [2], Elizabeth relates in lively prose a trip with three friends. She comments on the places she stayed (“the River abounds with Plenty of Soles Smelts & other fine Fish in great Perfection” (p.2)) and their architecture (“The East Window is all of A Bright Colour’d Blew Glass both odd & Prett” (p.3)), and adds historical notes and reflections. Early on, they are accosted by “four Rude Disorderly Fellows who Oblig’d the Gentlemen in their own Defence to Draw their Swords & take their Pistols” (pp.4-5), but after an ineffectual skirmish, the ruffians depart; and soon Elizabeth is making calmer notes on agriculture and landscapes.

¶ [BAYFIELD (née RISEBROW), Elizabeth (1722-1790)] 18th-century archive of manuscripts.

[North Walsham, Norfolk. Circa. 1743-1810?].

The archive comprises:

[1]. Manuscript notebook entitled “Verses on several subjects” [Circa 1743-47]. Slim quarto (185 x 155 mm). 34 text pages on 31 leaves, plus two loose leaves. Contemporary stationer’s wrappers.

[2]. Manuscript notebook entitled “Travells of a Month into Yorkshire in 1746”. Slim quarto (195 x 160 mm). Approximately 30 text pages on 17 leaves. Contemporary stationer’s, marbled wrappers.

[3]. Manuscript notebook of “Sentimental Memorandums and Observations from the different books I have Read since the year 1766: Eliza: Bayfield”. [Circa 1766-88]. Demi quarto (208 x 80 x 13 mm). Approximately 67 text pages on 68 leaves. Vellum stationer’s book, lacking clasps.

[4]. Manuscript book of recipes and household remedies. [Circa 1780-1810]. Small oblong notebook (115 x 88 x 11 mm). 66 pages of text and pasted-in clippings. Limp-calf, rear cover missing.

[5-7]. Two 17th century books from her library (QUARLES,Francis(1592-1644). Emblemes. 1676, and SALLUST (86-34 B.C). C Crispus Sallustius. 1621), and a Manuscript Travel Journal, which we assume was written by a descendent as it is dated 1839.

Elizabeth may have begun [4] – the first two (“For a sore Throat Mrs Coleman, Hembsby” and a receipt for removing ink) resemble her hand – but different hands have continued it from the late 18th to the early 19th century. Interspersed among the recipes (including the amusingly titled “Milk of Roses For Ladies Noses as well as Toeses” by a “Mr Randall”) are printed clippings (e.g. “make a never-failing Mouse Trap, by which forty or fifty Mice may be caught in a night”.

Elizabeth Risebrow’s archive offers a valuable panoply, from her literary diet and self-reflective responses to observations of the world around her and musings on history, to original verse and engagement with coterie culture. Taken together, her manuscripts arc across her single and married life and offer rare first-hand insight into the world of an 18th-century provincial writer and reader.

£9,500 / $12,200 Ref: 8248

¶ A remarkable mid-18th century almanac, with two writing tables, both of which shows traces of use. The almanac has been interleaved with 41 blank leaves. The two writing tables, which appear to be gesso coated, have been used to record written notes and calculations.

There are annotations to approximately seven pages with notes such as “frances Harise gave me warning house Maid Octb 26/1742 the same day I gave Letty Coast Warning My London Cook” and “Lord Anson was Maried to Miss York Eldest Daughter to Ld Chanceler Hardwick they was Maryd of Mundy Marks day Aprill 25/1748”

¶ SAUNDERS, Richard Rider’s British Merlin: For the year of Our Lord God 1742. Being the bissextile or leap-year. Adorn’d with many delightful and useful verities, fitting all capacities. in the islands of Great Britain’s Monarchy. With notes of husbandry, fairs, marts, and tables for many necessary uses. Compiled for his country’s benefit by Cardanus Rider.

London: Printed by R. Nutt for the Company of Stationers. [1741]. Duodecimo. Pagination 48, text complete, interleaved with blanks and two gesso coated writing tables.

Contemporary red morocco, elaborately gilt tooled, edges gilt, Dutch floral endpapers, metal slots for stylus (missing) with decorative floral bosses.

£850 / $1,100 Ref: 8306

¶ Rare first edition of the first book by Mary Matilda Betham, an English poet, diarist, and portrait miniature painter whose unconventional outlook exacted a heavy price on her livelihood and mental health.

¶ BETHAM, Mary Matilda (1776-1852). Elegies, and Other Smaller Poems.

Ipswich: W. Burrell. [1797]. Only Edition.

Octavo. Pagination xii, [1], 128, errata present, but lacking half-title and final advert leaf. Contemporary half calf.

She championed women’s rights, calling for the greater participation of women in parliamentary affairs and writing Challenge to Women (1821). Poverty and troubled relations with her family exacerbated her mental health, leading to her incarceration in an asylum, but by the 1830s she returned to writing poetry, and in her old age became a popular figure with both her peers and the upcoming literary generation.

£1,750 / $2,260