The the Art of B o o k

The consensus of opinion is that watermarking began in the Italian town of Fabriano – one of the earliest European centres of paper production – in the 13th century. A watermark served as an indication of origin and, especially for the top rank of producers such as those in Fabriano, an assurance of quality. A clear parallel with modern commercial and marketing practices is to think of it as a logo.

A watermark is made by twisting a length of wire into an ornamental design and stitching it to the mesh of the paper mould. The wire causes fewer fibres of pulped linen to form along its contours, creating a thinner area that shows as lighter than the rest of the sheet.

The design of a watermark was generally chosen by the company that made the paper, and would sometimes incorporate their initials or settle on a variation of various emblems such as a pot, a shield, grapes, or a fool’s cap (the latter now enshrined in the lexicon as foolscap, also denoting a size of paper).

A mark could also express something about the paper’s intended destination: in the later 17th century, Dutch firms making paper specifically for the British market would combine Dutch marks with the monograms of British monarchs and other elements invoking their target consumers. This exporting of their product to Britain continued throughout the 18th century, even as paper production in England, having been hitherto fitful at best, became more established with mills such as James Whatman’s in Kent and the Portal family’s in Hampshire led a boom in fine English paper-making.

The selection and use of a watermark was not subject to approval by any authority, making it common for watermarks to be used by different makers and for different markets. It also led to unsanctioned imitation, for example of Dutch watermarks by mills in France, Württemberg and Bavaria. Such an unregulated state of affairs has posed challenges for historians working in this area; the benchmark for filigranology (the study of watermarks) was set in the early 1900s by Charles-Moïse Briquet, who attempted to systematise marks by appearance and assigned a descriptor to each. He then matched these with dated examples to provide a reliable four-volume reference work – a method adopted by Edward Haewood to produce his handy singlevolume book which concentrates on the 17th and 18th centuries. From an overview perspective, W.A. Churchill produced a historical survey that takes in the international developments in printing and the movement of the watermarks across continents.

The presence of watermarks in early-modern paper is a key part of the material history of books and manuscripts. A watermark can tell you that a manuscript was written within a certain date range: from the date the paper was produced to a relatively short time after that. We can establish this with a degree of confidence because it is unlikely that paper would have been left unused for long after being made. So, while a watermark can only tell you with certainty that a manuscript was not produced before a certain date, it does provide a useful ‘time window’, which when taken as part of the constellation of tools for dating documents can be extremely valuable to the codicologist.

Bibliography and other reference sources

Briquet, Charles-Moise. Les Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600. Hacker. 1985.

Churchill, W.A. Watermarks in paper in Holland, England, France, etc. in the XVII and XVIII centuries and their interconnection. Amsterdam: M. Hertzberger, 1935.

Haewood, Edward, 1863-1949, Watermarks, mainly of the 17th and 18th centuries. Krown & Spellman [2003]

Müller, Leonie. Understanding Paper: Structures, Watermarks, and a Conservator’s Passion https://harvardartmuseums.org/article/ understanding-paper-structures-watermarks-and-a-conservator-s-passion

www.memoryofpaper.eu/BernsteinPortal/appl_start.disp

https://memoryofpaper.eu/gravell/

www.paperhistory.org/Standards/IPHN2.1.1_en.pdf

www.paperhistory.org/Watermark-catalogues/

www.cdh.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/digital-approaches-to-the-capture-and-analysis-of-watermarks/

https://digitalcollections.folger.edu/bib244378-309586?=&sort_order=ASC&sort_by=field_collection_sort_order

[HOUSEHOLD RECIPES]. English manuscript containing recipes and remedies entitled ‘Booke of Receipts’. [England. Circa 1670-1791]. Folio (300 x 190 x 14 mm). A total 113 text pages on 92 leaves. Text in the earlier hand, mostly to rectos. Binding contemporary limp vellum, using an old deed. Heavily used condition, page edges frayed with loss of text to first 30 or so leaves.

Watermark: Horn (see Haewood 2666-2690 – dated circa 1650-1690 – for similar, but not exact match).

Provenance: old Sotheby's catalogue description loosely inserted.

¶ There were at least four contributors to the manuscript at one end and its earliest scribe (circa 1670) has also “flipped” the volume to create a section devoted to remedies at the opposite end.

Hand I (17th recipes and remedies over 39 pages.

Hand II (17 or so recipes and remedies to 9 pages.

Hand III (mid 23 pages.

Hand IV (late 18

At the opposite end:

Hand I (17th century): approximately 75 remedies on 27 pages.

¶ This homemade household book of recipes and remedies has been constructed in perhaps the cheapest way possible: the text block is formed from two stacks of paper stab-stitched and then stitched together as one volume, with a binding fashioned from an old vellum deed. Yet for all its parsimonious construction, it has been made with care, as hinted at by the title to the front cover: “Booke of Receipts 1670 [heart]”. The earlier leaves at each end have been damaged as a direct result of the unrobust binding, but such signs of use only add to the appeal of the artefact.

There are no straightforward clues to the identity of our scribes or their household. A pen trial to f.6r, which reads “Will White”, is the only inscription to the text. The vellum document that serves as the binding features numerous names including “Nicholas Dawkins”, “Katherine Cole”, “Thomas Mark Cuthbert” and “Margaret and John Piggott”, and further research may connect some of these to the text. There are several ascriptions in the section 1670-1700 (Hands I and II), including “Sr Tho: Millington” and “The D. of Newcastle” who each supply a “Diet drink”, “Lady Dorrell”, has a medicine “for the drying up of all the humers in the body”, “Dr. Burges”, other remedies are given by “Dr Stevens”, and “Dr Butler of Caimbrid[ge]”, but the conspicuous honorifics lead us to suspect these were attributed recipes circulated in manuscript rather than by individuals known to the scribes. More promising, at least as potential acquaintances, are a “Mrs Joha: Gard” and “John Gard”. Other clues are scattered throughout the recipes, as we shall see.

While its physical appearance might suggest a humble household, the ingredients tell a more nuanced story. The family are obviously affluent enough to afford a varied diet which, particularly in the early, fruit-heavy section (Hand I), includes sugar (“refined sugar”, “double refyned sugar”, “suger if you like itt”, “Clarified sugar”). They even have a “Candy Pan”, which in one recipe you should employ “with wyres Lay the Least of you wyres Lay 4 in the bottome of your Pan”. “To make Jelly of Pippins Amber Colour” also presupposes a healthy array of equipment: “Bagg it into a silver or earthen vessell upon a Chaffing dish of Coales& while itt is warme fill your moulds or box them [...] remembring always that your boxes or mouldes be aforehand Layd in water & then the Jelly will not cleave to them” (f.19r.).

The recipes feature a range of herbs and spices including “Gillyflowers”, “violetts”, “Cowslipps”, “peece of whole Cinamon” (or a “Thimble full of beaten Cinamon”), “sarsaparilla”, and “Carrott seed” – but appearing in remedies alongside such harmless ingredients is “crude Antimony in powder”, an ingredient no longer used in medicine, because although it can kill such things as parasites, it can also have the same effect on the patient!

Some recipes are quite particular about where to source ingredients (“Take Pippins whilst they be very greene those that especially grow upon the water boughs in the shadow”) and others about methods and materials for preparation. For example, when making “Past of Geneva ye true way as they doe beyond seas”, you must be sure to keep “stirring itt until you see it come from ye bottome of ye skillett then ffashion upon a pye plate or sheet of glasse some Like Leaves & some like halfe fruites & some you may prynt out wth mould then putt them into a warme oven” (f.8r). One’s choice of implement is also to be carefully considered, as in the recipe for preserved lemons, which advises the use of an “earthen Pipkine for Brass is not soe good” (f.11v). A simpler and frequently mentioned piece of equipment is paper: the recipe “To make marmalade of Quinces”, for example, directs: “take it of the fire Lay it on a sheete of white paper” (f.14r).

Of the recipes for fruit that predominate in the earlier sections of the manuscript (Hand I), there are over 20 varieties of marmalade, which, as well as the fairly common recipes using oranges and lemons, also include “Pomcittrons”, “Peare Plumes”, “Malecetones”, “Goosberrys”, “Quinces called Lumpe Marmalade yt shall Looke as red as Rubye”, “wardens a most Cordiall Marmalett”, and “Pippins yt shall Looke verry Orient”. Oranges, pippins and cherries are used to make jellies, in either “Quaking” or “Crystall” forms.

There are also more than 30 ways to “p[re]serve”, among other things, “Malacatoones”, “Rasberryes”, “Pippins” (of various colours: “greene”, “white”, “amber”, “Red”), “Barberryes”, “Pear Plumes”, “Lemmons”, “Apricockes”, “Cittrons”,

shellee” and the more unusual “Lettice Staulkes”

Some fruits are boiled into pulps called “Tartstuffe”, ranging from the nonspecific “white” or “yellow Tartstuffe” to damsons, prunes, hipps, and “Excelent Tartstuffe of Rasberrye or English Currants to serve all the yeare of a most delicate Tast & Colour” (f.17r).

This saccharine onslaught does eventually give way to a couple of savoury dishes including “How to pott a Swann” (f27v.) (and if you don’t have a swan, “you may pott a bustard butt you must not fflea ye bustard”) and directions to “bake Ducks or Teale” (f.28r.). The large grouping of fruit dishes proves the exception when it comes to organising: “Plague Water”, with its usual plethora of herbs, sits fairly contiguously next to a remedy “for sore in the eyes of what kind soever” (f.29r.), but these are immediately followed by “Harts horne jelly” and “To pickle Oysters” (f.29r.) and on the following page, “eye water” is followed by “Sause for a pig”. Similarly, the remedial trio of “To make Dr Stevens water”, “To make Balme Water”, and “To make Angellica Water” (f.22r.) is jarringly succeeded by “To make Marmaled of Cherryes Mrs Joha Gard” and “To Candy Goosberryes”.

This miscellaneous order continues as the book passes from its first user in the 1670s to Hand II who was writing in the late 17th or early 18th century. The final entries by Hand II are “The D. of Newcastle’s Diet Drink”, “Dr. Burges’s drink against ye Plague, Purples, spotted ffever. Meazles, or ye like sudden sicknesses”, and “To make Ginger bread” (f.32v). Opposite these (f33r), Hand III has left a similarly disparate arrangement, in which “To destroy Buggs” (f.33r), “To make Pancakes” and “Mrs Huntchinsons searcloth for a Strain or Bruise” follow in quick succession

A note beneath the remedy “To destroy Buggs” reads “The Mix Vomica to be had at the Golden Ball in Burleigh Street near Exeter Exchange in the Strand 1746 at 1s 6d ye Ounce Vial”. Whether this gives a location for our manuscript is a moot point because the address would have been sufficient for a postal transaction (although “Dr. Burges’s drink” on the opposite page does include “London”, but again, this was surely portable). The date “1746”, too, leaves room for ambiguity as there may have been a hiatus of several years before Hand III picked up the manuscript and continued adding recipes and remedies in the spirit of melange inherited from its earlier users. That said, small clusters continue to occur: for example “Duke of Norfolk’s Punch” is grouped with “Sack Mead”, “Small Mead” and “Cowslip wine”, but they are immediately followed by that ubiquitous panacea “Daffy’s Elixar” and “An excellent Cordial”, then a hotchpotch of eels and veal, oranges, lemons, fish, and a remedy for “the Itch”

After an undefined period, Hand IV (and possibly another) adds a few recipes. Several are attributed to “M. M.” and one is annotated at the end: “N.B. This is the best possible raisin wine if it is made with perfectly fresh Malaga raisins. They arrive at Nott. in the months of February, March & April. The wine should be made as early as possible in April. The raisins in 1791 were 1:8:0 an hundred” (f.50 r). The mention of “Nott[ingham]” perhaps gives us a location, and the date a time period, for our final contributor.

As is frequently the case in early modern household manuscripts, the volume is “flipped”, with remedies arranged by Hand I at the opposite end (although as we have already noted, remedies are liberally sprinkled throughout the recipes). Several use the apothecary’s abbreviation “Rx ”, but the manuscript does not appear to be the work of a professional.

Our scribe drifts into the realms of sympathetic magic “The Weapon Salve” (f.68v), which suggests that “When one is hurt take the same weapon & with a ffeather annoynt all over with the oyntmt & with Linnen wrap itt handsomely up & roll itt as you do the . Perhaps less magic-based but still evocatively named is “To make Unguente apostolorum” (“The Apostles’ Ointment”), “wch clenseth a ffistiloe & Clenseth all Cirrupt fflesh with paine & maketh itt to f.77v.).

More recognisable from modern herbals are a few other remedies, such as “An Unguent after hard f.66v.); “To make a drinke for the Collicke wch a woman may take If she be with Child”, which requires “handfulls” of various herbs (“Parsley”, “Burridge”, ) and “water Creses”, and directs that you “give the Patient every day 3 tymes” (f.83v.); and a concoction ]voke paines in Labour” (f.67v.). The “Powder for the Teeth” in Hand II’s section, begins with “a proportion of well burnt brick”, beaten very fine, then instructs that, to make this abrasive substance tolerable, you should add “fine sugar” (f.42r).

This handmade household resource has grown over the course of more than a century, by the end of which some of the earliest entries – particularly remedies such as “The Weapon Salve” – must have seemed decidedly quaint to its readers. Indeed, one of the draws of this artefact is its survival and development through time, despite its crude construction. Further research may establish connect the potential threads of provenance, but its usefulness to several generations seems beyond doubt.

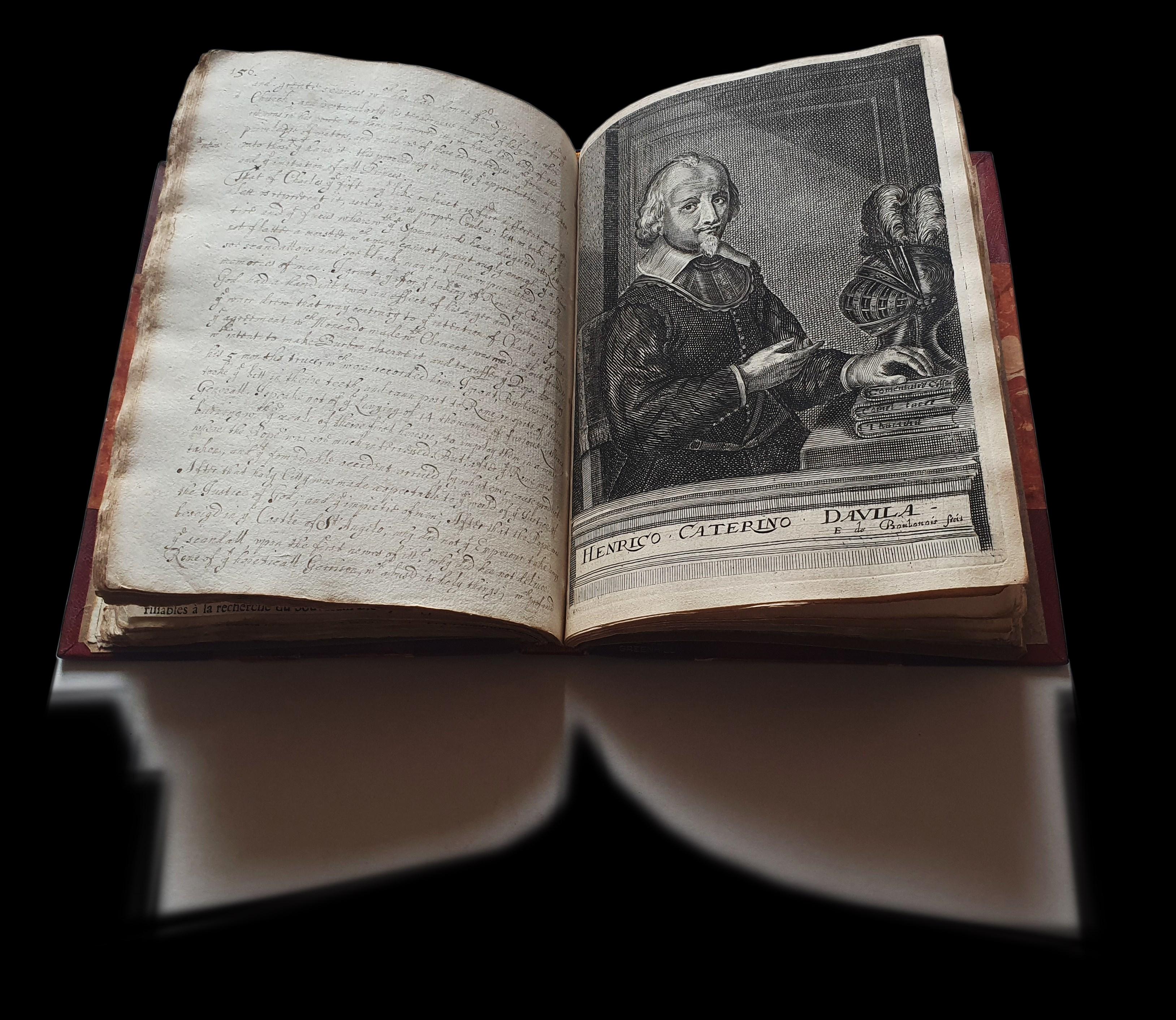

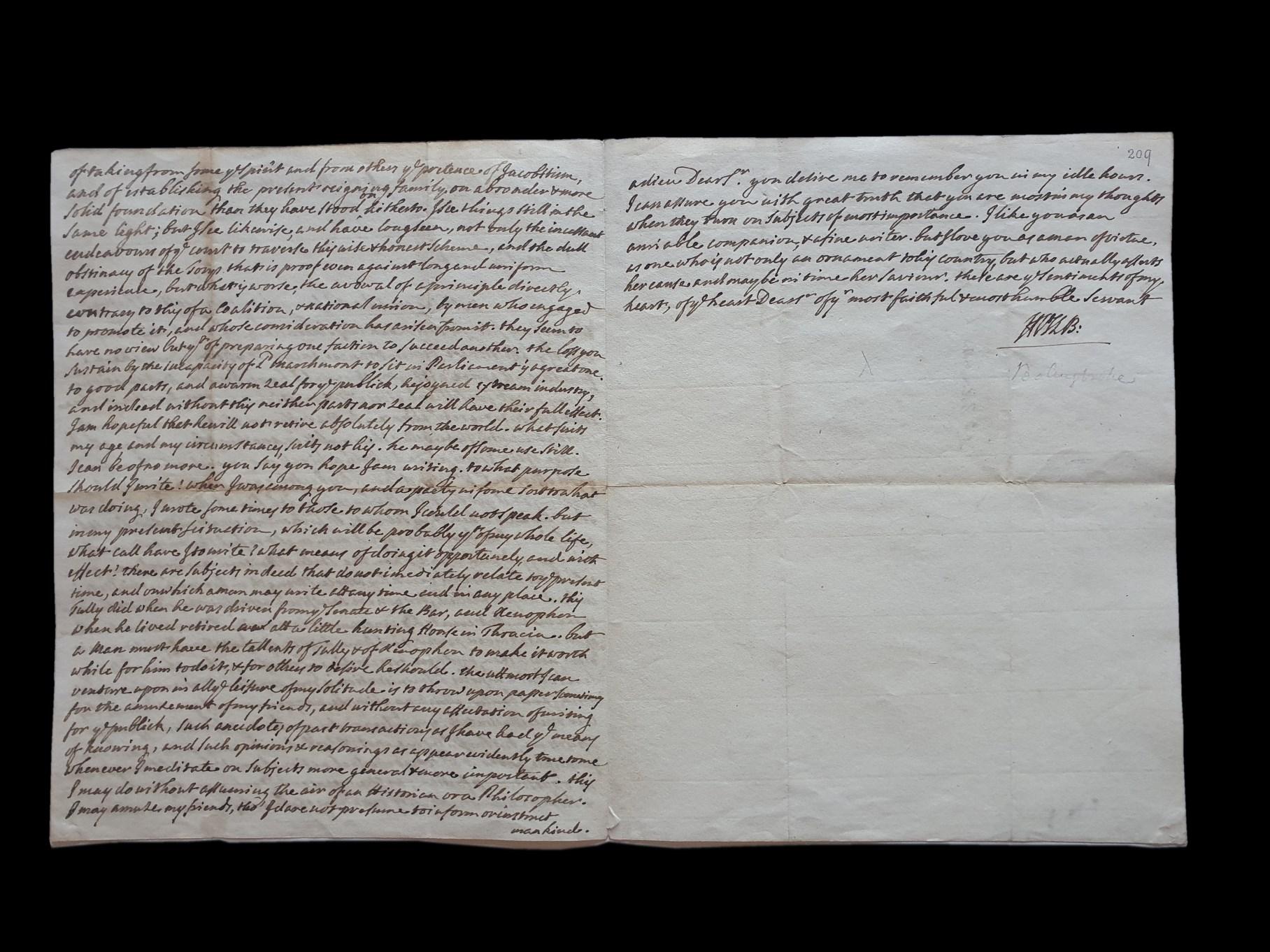

[SILHON, Jean de (1596-1667)] Manuscript scribal copy of ‘The State Minister’.

[Circa 1660]. Quarto (1196 x 145 x 18 mm). Pagination [4, blanks], [9, “to the Reader” and “Table”], [1, blank] 220 numbered pages. 20th-century burgundy half morocco gilt over marbled boards by Elizabeth Greenhill. Pencilled note to front endpaper, the hand-coloured frontispiece and six plates, were added in 1939.

The watermarks are split in the gutter, so exact matching is difficult. However, most sheets are identifiable to Post (similar to Haewood 3534); some later sheets are Pot. Both watermarks date from the mid-17th century.

Provenance: armorial bookplate of Charles Walmesley, Westwood; pencilled gift inscription to front endpaper, “Captain Samuel Lucas, York & Lanc. Regiment to A. J. Ellison of the same, 1925”; Sotheby’s, 20 June 1932, lot 213 (disbound); Bookplate to paste-down: W. A. Foyle, Beeleigh Abbey.

¶ Why would someone labour over translating a book from French into English if it had already been published in an English translation? The first part of Jean de Silhon’s Le ministre d’estat, avec le veritable usage de la politique moderne. Première partie (1631), is rendered in the contents pages of this manuscript as “Silhons State Minister”. This translation broadly similar (with many variations) to the first part by Henry Head, published by Thomas Dring in London in 1658 (a second part followed 1663). We can hazard a couple of theories concerning this apparent duplication of effort, but theories they must, for now, remain.

Jean de Silhon was born in 1596 at Sos in south-western France and became secretary to chief minister Cardinal Richelieu (who appointed him in 1634 to the nascent Académie française) and to Richelieu’s successor, Cardinal Mazarin. Silhon was closely acquainted with René Descartes and published several philosophical works including a refutation of scepticism that anticipated Descartes’ famous cogito, but Le ministre d’estat, as its title implies, is a political work – and de Silhon was a highly esteemed

political writer. Written at Richelieu’s behest, the book makes the case for raison d’état, or political realism, which, in essence, argues that the state has a right to diverge from accepted laws and ethical standards – for example, truthfulness – if political necessities require it.

Raison d’état has particular application to foreign policy, and developed as a doctrine during the 17th-century rise of what we now recognise as the modern nation state and the parallel evolution of international law. Its appearance in a printed English translation is an indication of how arguments were continuing to rage over the notion of what we would now call Realpolitik.

Our scribe, whose identity remains a mystery, was clearly highly engaged in these arguments; but what drove them to translate the first part of de Silhon’s treatise, if an English translation was already available?1 One possibility, given that this manuscript is difficult to date with any precision, is that it predates, or is contemporary with, the 1658 publication of Head’s translation; another would involve some kind of dissatisfaction our scribe felt with the published version, although this seems unlikely as a powerful enough spur to such an undertaking.

The variations between the two renditions are, as mentioned above, many but often slight, and mostly concern synonyms (“tempests” / “storms” in an example below), and syntax or punctuation. For example, the “Advertisement” to the reader in the printed version begins: “I Have some Considerations to represent unto thee concerning this Work, whereupon I beseech thee to cast thy eyes. The first is in relation to the Matter, which is composed of Reasonings and Examples.” Our scribe has arrived at something very similar: “I have some considerations, to represent unto thee, concerning this worke, uppon wch, I shall desire thee, to cast thy eyes, the first is, for the matter, wch is composed of Ratiocination, and of examples”. Later, “The seventh Discourse”, entitled “Of the disgrace of the Duke of Alva”, the Head translation begins: “Since we are upon the subject of Disgraces which happen at Court, and tempests which are there raised; Let us add the Duke of Alva’s to the former examples”; our scribe’s version (headed “Lib: 1. disc: 7: The disgrace of the Duke of Alva”) begins: “Since wee are upon ye subiect of y disgraces w arrive in Co , and y there arise, lett us add to y 2 preceading examples y of y

Published by Charles & Henry Baldwyn, Newgate Street. R. Cooper sculpt” (circa 1815-1836). This further complicates the artefact’s history, since vital clues to its early provenance may have been lost in the rebinding, but this act itself has now become part of its long history.

Whether or not our scribe accomplished their translation before Henry Head completed and published his own (which seems the most likely scenario), this is still an impressive piece of work that conveys some of the intensity with which the emerging issues of nation states and international relations were being considered in early modern England.

[SCOTTISH LAW]. 17th-century manuscript entitled ‘Syles of the most usual and Important Securities of and Concerning Rights personal & real, Redeemable & Irredeemable, used by and Conforme to the Laws & practique of The Kingdom of Scotland’.

[Scotland. Circa 1699]. Small quarto (205 x 163 x 19 mm). Pagination [18], 248 numbered pages. Ink on paper in a legible English mixed hand. Disbound, lacking covers. Water staining throughout, especially to the title page. Fore margins of pp.203248 charred with loss of text, but not of sense.

Provenance: 18th-century ownership inscription to final text page in a difficult hand: “Liber Davidson”(?).

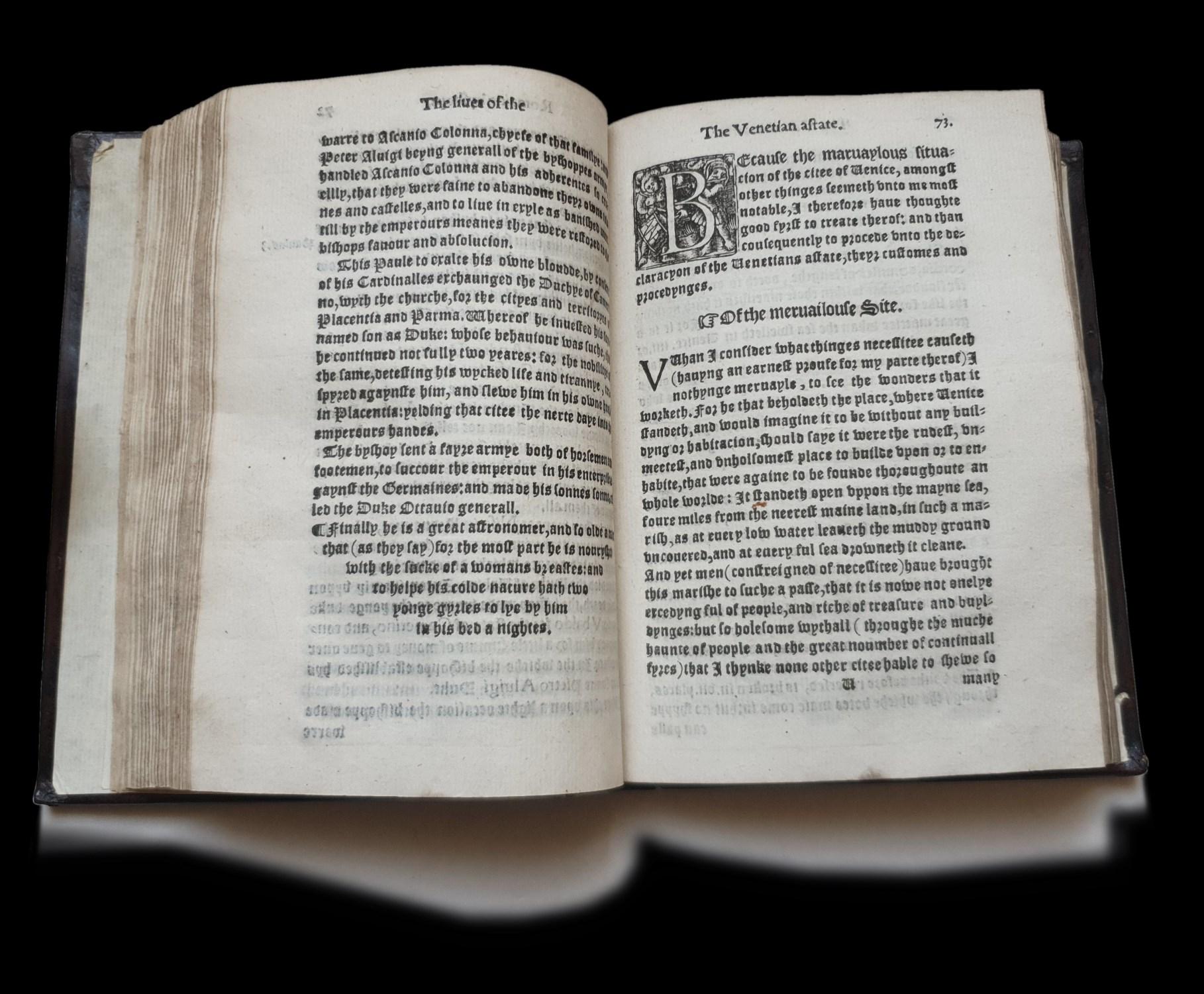

¶ The standard printed manual of legal stiles (or precedents) for the early modern Scottish lawyer was George Dallas’s System of Stiles (1697), a formidable folio of no fewer than 904 pages. Walter Ross referred to it as the “vast opake body” of the work, and described how the hearts of apprentices “failed within them, when presented, in the Writing-office, with such a frightful volume of arid, naked, unintelligible Forms”. (ODNB).

No wonder, then, that some legal professionals chose to compile their own books of precedents. This comprehensive but handy quarto volume, written in a clear and legible hand, could be easily consulted by any legal professional. Its general arrangement and mis-en-page resemble a printed book: the title page announces its intentions, varies the sizes of the lettering, and ends with a line aping an imprint; and all is neatly arranged within a decorative border. Single-line bordering is continued throughout the volume. The preliminary sections “The Writters Preface” and “An Table of the Styles and others Contained in the following Collection” are unnumbered, and the main body of the text is numbered in the upper margins. The “Dictionary” mentioned in the subtitle is arranged in double columns (pp201-218).

This volume was “Collated, digested and written Anno 1699” – two years after Dallas’s publication, which is reckoned the first Scottish book of precedents. But the anonymous scribe of this volume makes no reference to Dallas, which suggests that offices continued to compile their own reference works independent of printed publications. Instead, this scribe, in the “Preface”, identifies their antecedent in the very beginnings of written agreements: “In the first Ages of the World there appears to have been greater simplicity and ingenuity behind nations and amongst particular families and persons in the Commerce, and transmission of rights to Land and other goods from one to another then there is now”.

Our scribe reaches back through human history to establish a precedent for the very notion of written agreements. For all their supposed “simplicity”, people could not “trust one anothers bare words or verball promises”, and the Bible (“Genesis cap.23 v.16.17. and 20”) cites an early example of the art of conveyancing in the story of “Ephron with the Cave and trees in the field” in which his “Right to the field was transmitted [...] both by writ and other outward deeds”. The need for “some other outward art” beyond the spoken word was compounded “as nations and kingdoms grew more populous and polite, and their

Commerce and trading with others and amongst themselves did increase”, which further underscored the vital importance of legally binding agreements in the form of “written Evident, Chiro graphy, hand writting”.

For any such system to work it was of course vitally important that agreements be regulated and the forms agreed upon; and this manual was created to supply examples. But even where there is concord between people, there will be those who wish to subvert the system. As “nations and kingdoms grew more populous and polite”, societies became more sophisticated and so, too, did methods of subverting or evading the rules which support such societies. Indeed, according to our scribe, some of the very institutions which help sustain complex societies can also be used to subvert them for personal ends (“As also the progress the learning by the erecting of universities and schools and the Arts therein taught specially the logicke, whereby subtilty, deceit, and fraud full Contrivances did increase more and more, and yet under the collour of right and fair dealling”). But “Law givers” could offer some protection against such sophistries through the exercise of the written law: “these writtings and securities, that all these frauds, and deceits might be forseen, prevented and guarded against”. The models for such measures are provided here in “these writtings”.

The use of the word “styles” for precedents, together with numerous other Scottish words, indicates an ancestry which is confirmed in the sentence: “And now to come home to this our nation of Scotland”. The scribe goes on to describe a country where “before the Reformation in this kingdom from popery, As Churchmen did almost wholly, restrict Learning and the Liberall arts to themselves, and assumed the whole power in spirituall, so likewise they took upon themselves to be judges in Civill matters”. Their stranglehold on power was exercised in their capacity as “publick nottars and drawers of securities and instruments”. Furthermore, “nottars were admitted and had their dependence on Bishops and the pope, and therefore to this day, nottars usually design themselves of such a bishoprick or precinct”

Following the Reformation, “when Learning and the Liberall arts come to be more publick and free to all, secular as well as others”, power was wrested from the “Churchmen [who] were most rightly tyed up to matters Sprituall and Ecclesiasticall” and “affairs of Civill and wordly concerne left to the laity or secular men, bred up at schools and with those professing the Law, such as Judges, Advocates, propriators, writters to the signel Clerks and nottars”.

This process of Scottish secularisation created the need to educate professionals outside the spiritual realms; and while the author inveighs against some of the sophistries of university teaching, especially “logicke”, it is not learning itself that troubles him; rather it is what is being taught (“subtilty” and “deceit” rather than the firm ground of legal precedent).

Our scribe concludes by commending the volume’s contents, both as a corrective to this educational malpractice and as a reference tool that can stand comparison with its peers: “their styles seems to be as exact, new and formall, as well as methodicall in distinct titles and chapters as any extant”. It is certainly true that, although this manuscript was compiled shortly after Dallas’s publication, it is more concise and readily useable than its printed counterpart.

The contents are neatly summarised on the title page (detailed and indexed contents are also provided in the preliminary section):

1. A Collection of Speciall & Singular Clauses through all securities, Alphabetically digested.

2. Symbolls and Solemnities used for the perfecting and Consumating of these writs and rights.

3. The order of the Chancellary, and the styles of writs that are issued therefrom.

4. A Dictionary Latine and English of the most matteriall words in Charters, Leasing &c.

5. Clauses of writs and their import by the Decisions of the Lords of Session.

6. Also their Decisions as to the Solemnities & formalities Requisit in Law and by Municipal custome, for making writs and securities valid, binding and effectual.

With an Act of Parliament Concerning probative writs and instruments & an Act of Sederunt Anent Nottars.

The earliest extant style book is that by compiled by Oliver Colt (NAS RH13/2), circa 1600. Style books compiled before the Act of Union include one at Edinburgh University by William Lindesay of Culsh, circa 1685 (MS 3066/7); one at the University of Glasgow: circa 1695 (GB 247 MS Murray 554); and a circa 1685 at Yale University (Boswell Collection, Box 156, folder 2854), which belonged to James Boswell.

Style books continued to be compiled into the 19th century, but this manuscript was written during an interesting period in Scottish law. Eight years later, the Act of Union was declared, and although Scotland retained a different legal system from England, the English were the dominant party in the Union and exerted their influence upon Scots law.

The compiler and scribe of our manuscript demonstrates a passionate belief in the importance of codified laws and their correct practice, while also conveying a keen sense of the national – ie Scottish – context in which he is writing. His borrowing of the format of a printed work, with title page, preface and a list of contents, also suggests the need to “codify” these precedents into a framework that carries authority (hence, perhaps, the preface with its largely unnecessary apologia) and aligns in form and function with the printed resources being published around the same time.

£2,250 Ref: 8205

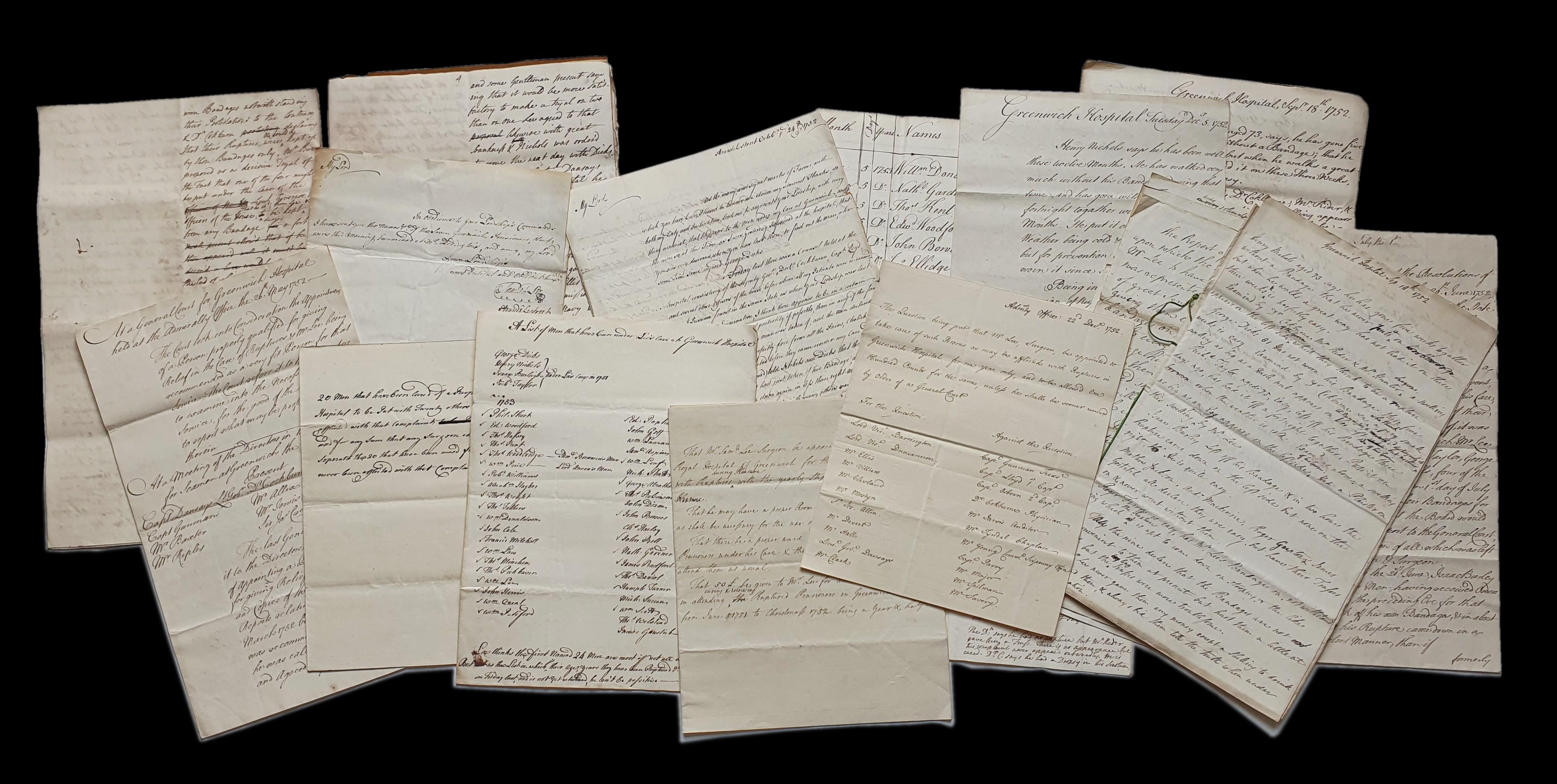

[RICH, Claudius James (1786/7-1821)] Correspondence related to Claudius Rich’s time in Baghdad.

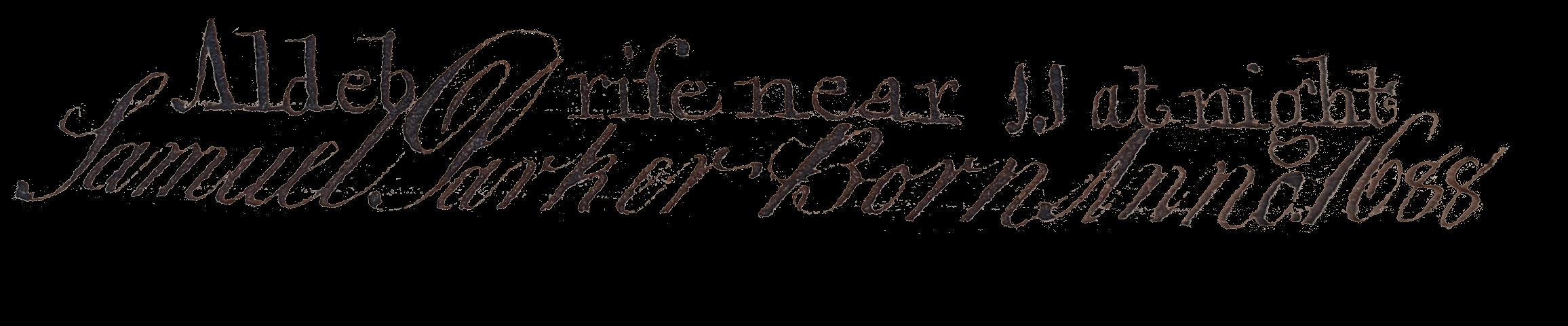

[Baghdad and Bombay. 1809-10]. A group of 20 letters. Folio and quarto. Various watermarks, including Horn (illustrated left) which shows a 19th century variation of a motif often found in much earlier papers (e.g. item one in this catalogue).

¶ As an account of ‘a little local difficulty’ encountered by a representative of the still 20 letters depicts, in miniature, its uneasy relations with a branch of the Ottoman Empire, largely through the eyes of a tra and collector of manuscripts and antiquities whose interest in oriental languages began in childhood.

Claudius Rich was born in Dijon, “probably the illegitimate son of Colonel Sir James Cockburn, fifth baronet (1723–1809), whose mother’s maiden name was Rich, and who lived in Bristol” (ODNB). Already something of a prodigy in ‘oriental’ languages before his adolescence, in 1803 he joined the East India Company as a cadet, and the next year his linguistic prowess earned him a transfer to the Company’s Bombay establishment on a writership. After a series of exploits that took him to Malta, Naples, Constantinople, Smyrna, Cairo (where he became assistant to the consulgeneral) and most of Syria and Palestine, he arrived in Bombay in 1807. Early in 1808 he married Mary, daughter of Bombay’s governor, Sir James Mackintosh, very shortly after being appointed the East India Company’s resident at Baghdad.

These letters show some of the more vexatious aspects of Rich’s interactions with local functionaries. Things begin pleasantly enough, with a letter to Rich in Persian from the King’s Grand Vizier extending cordial relations (accompanied here by a translation into English). But by early August 1809, he is writing apologetically to Robert Adair (who was based at the Constantinople embassy) with a request for aid in dealing with Ottoman officials. Rich opens with his credentials: “In the last five years I have made the manners & language of the Turks my particular study, I have travelled over almost every part of Turkey”; and experience has shown him that “the most positive firmness is requisite in all transactions with them, All submissions being by them invariably construed into an acknowledgment of inferiority, and consequently an encouragement to greater excesses” He contrasts the agreeable behaviour of “the Turks in their Capital”, where “the Politeness is in a great measure reciprocal”, with “the difficulties I have experienced at this provincial Court”. Rich continues with palpable frustration: “I have tried every means short of unbecoming concessions, but with no other effect, than that of occasionally carrying the immediate point, without stopping general current of opposition – which I perceive can only be effected by your means.”

Relations fail to improve throughout the autumn of 1809: both Rich and the Grand Vizier of Baghdad, Suleiman Pasha, write to Adair complaining of each other’s behaviour (Rich believes that Pasha’s enmity goes beyond the personal and signals the Grand Vizier’s bid to reduce British influence; Pasha complains to Adair that Rich plays fifes and drums at prayer time and asks for him to be replaced). Rich makes repeated requests for Adair to intervene in various matters, and on 23 October dispatches two letters to him from “Gherara Camp” near Baghdad – suggesting an enforced relocation outside the city – one speculating on the causes of recent antipathy (“the Pasha’s conduct was visibly altered since the Peace between Great Britain and the Porte was concluded […] during the War we had the government entirely at our mercy [...] the Pasha is now encouraged by the belief that we cannot annoy him from India”), the other announcing that, since Suleiman “seems inclined to refuse me a Tatar [ie a messenger] for the conveyance of this dispatch [...] I have therefore come to the resolution of

Further tensions arise in late November 1809, when Rich informs Adair that “the Messenger bearing my last dispatches to you, had been plundered near [Aleppo]”, which Rich considers “equivalent to a declaration of war against the British property both official and private”. He goes on to report that “after the Pasha had prohibited the entrance of any British subject into his town [...] I have discovered by means of my secret agents that the Pasha has so far forgotten himself as to write in the most unbecoming manner accusations or rather calumnies against me”. Suleiman has also “prohibited any Musselman from serving or having any connection with me under pain of a thousand strokes of the Batinade and banishment from the territory”, but Rich brags that “My people (though I advised them to quit my service) declared their resolution to suffer death rather than abandon me and my Camp has been more crowded with visitors than ever”.

A letter from Adair to Suleiman Pasha, dated 19 December and translated into French, concerning Rich’s treatment, may have contributed to a certain easing of the situation, since Rich, now back in Baghdad, writes on 28 January 1810 to Jonathan Duncan, Governor in Council, Bombay, to report that the “disputes between the Pasha and myself have been at length brought to a most honorable conclusion [...] the Pasha consented to acknowledge publickly my Resident, and to mention me as such in al his acts and letters”. In a similar update to Adair two days later, he announces that the Pasha “is now convinced of his Error” and, clearly emboldened by this successful resolution, relaxes into racist stereotypes: “The Turks, in common with most Orientals, are invariably presuming and insolent if countenanced, mean & submissive if checked”.

Rich’s final letter, dated 12 April 1810, serves as a kind of epilogue: he thanks Adair for his interventions “The Pasha’s present conduct to me is of the most gratifying nature He confesses to me to have been deceived, and takes every opportunity of doing away the unfavourable impressions”. Invoking a ‘higher authority’ than himself to signal the restoration of order, Rich reports: “General Malcolm has arrived at Abushehr (Bushehr) in Quality of Envoy from the Governor General to the Shah, to vindicate, as his Instructions express it, the insulted dignity of the Anglo-Indian Government. He will proceed to the Court of Persia”.

Rich drew on his time in Baghdad, and his travels to Babylon, Kurdistan and beyond until his death from cholera in 1821, for a handful of well-received memoirs and travel narratives. He remains a representative figure in the British Empire’s cast of characters: intrepid, deftly multilingual, culturally curious, highly acquisitive, and – as these letters compellingly demonstrate – chauvinistic, Anglocentric and exasperated by the behaviour of foreign antagonists who posed obstacles to the Empire’s expansion.

£2,500 Ref: 8242

[BRETT, Anne]. 18th-century miscellany book of poems. [England? Circa 1763]. Quarto (200 x 165 x 13 mm). 174 pages (numbered to 172), including five blank pages (four of which separate the main text from the two-page index). Written in a neat italic hand throughout. Contemporary sprinkled calf, rubbed and worn, front board nearly detached. Watermark: Pro Patria. Provenance: inscription to paste-down: “Anne Brett. 1763”.

¶ This neatly written compilation of poems captures an early-modern moment in the rise of women readers, women authors, and the integration of both into the mainstream of British culture and society. Its compiler, Anne Brett, who does not seem to have been part of “coterie culture”, has nonetheless created her own portable soiree in the material form of a literary miscellany.

According to Carly Watson, “Conversation was regarded by many in eighteenth-century Britain as the lifeblood of society and culture [and] was seen as the engine driving the circulation of knowledge and opinion”. This culture was embedded in the compilation of “miscellanies of various kinds modelled and facilitated forms of conversation and sociability” and that “conversation played a key part in defining the character of the miscellany as a literary form in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries” 1 .

The dramatic increase in women’s literacy during that century meant that miscellanies found a ready readership in this growing demographic; for the same reason, some of the ideas expressed in these and other works were attentively received by women readers, as demonstrated by the practice of compiling their own selections in manuscript. Meanwhile, conversations grew and evolved, giving rise to new coteries and circles: among the most famous of were the bluestockings (originating in the “literary breakfasts” held by Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey, and Frances Boscawen) and the Scriblerians (whose focal points were Swift and Pope), but dozens more proliferated, in the provinces or in less exalted seams of literary culture.

Anne Brett, the compiler of our manuscript miscellany, has included work by several poets associated with coteries – including Elizabeth Carter (1717-1806), a bluestocking member, and Elizabeth Pennington (1732-1759), who belonged to the literary circle frequented by Samuel Richardson and Frances Sheridan. These and other women writers featured here were also publicly acclaimed in panegyric works such as John Duncombe’s The Feminiad (1754) and the anonymous Biographium faemineum (1766). Many poems were available in print editions by the time Anne made her selections: several by Elizabeth Carter were published in Poems on particular occasions (1738), and three anonymous poems (“An Ode to Adversity”, “Hymn to the Evening”, and “Resignation”) appeared in The court magazine; or, royal chronicle of news, politics, and literature between 1756 and 1762. A handful of others, however, she set down before the published versions, suggesting that these circulated in manuscript.

For example, “An Ode to the Morning” is one of only a small handful of surviving poems by Elizabeth Pennington. Her poems circulated in manuscript and three of her poems were posthumously published in collections such as Specimens of British Poetesses (1798) and Poems of Eminent Ladies (1780); Anne’s manuscript copy, however, predates the published versions. Similarly,

“To Prosperity. By Miss Sally Carter” seems not to have appeared in print until 1781/2 (in The lady's poetical magazine, or Beauties of British poetry “An Ode to Solitude” by Maria Susanna Cooper (1737-1807) appeared in her epistolary novel Letters between Emilia and Harriet (1762), published anonymously but here attributed to her under her birthname “Miss Bransby”, suggesting that Anne had access to this information via another source, perhaps in manuscript.

Another poem, the anonymous “To Melinda on her dancing a minuet”, sits on the cusp of its print publication: it appeared in The Scot’s Magazine and Gentleman’s Magazine in 1764 and The British magazine: or, monthly repository in 1765, variously entitled a young lady, on seeing her dance, Advice to a young lady, on seeing her dance, On seeing Miss Parrot dance. Brett’s dating of her compilation to 1763 means that she may easily have scooped it up on first reading it in print, but the variant titles might signify that several manuscript copies were already circulating.

She certainly nurtured no exclusively female agenda for her collection: the likes of John Campbell (1708-1775), Nathaniel Cotton (1705-1788), Andrew Kippis (1725-1795) and James Merrick (1720-1769) are represented in abundance. But her inclusion of pieces by Martha Ferrar (1729-1805) (“An Address to the Moon”, published in The works of Anacreon, Sappho, Bion, Moschus and Musaeus (1760)), Fanny Greville (c. 1724-1789) (“Ode to Indifference”, which also seems only to have circulated in manuscript), and Anne Ingram (c.1696–1764) (“An Epistle to Mr. Pope, Occasion’d by his Characters of Women”, her

famous riposte to Pope’s “Epistle 2. To a Lady” published in Gentleman’s Magazine, (1736)) indicates a lively interest in the work and discourse of the rising cohort of women writers. Her selection by Laetitia Pilkington (1709-1750), whose response to her unhappy marriage made her the subject of infamy, leads one to conclude that Anne was, despite her inclusion of a few hymns, no piously unthinking moralist. She seems, rather, to have had a broad palate, and her collection is highly suggestive of how women’s writing became a component, rather than an anomaly, in the British literary diet.

It would be tempting to infer from the presence of several pre print or never-printed poems that Anne had access to, or membership of, some coterie or other. But it is equally possible that the work and ideas of these pioneering women writers were already circulating far and wide, and that Anne’s ‘conversation’ was with herself. In either case, our manuscript miscellany could prove fertile ground for an examination of how print and manuscript transmission interacted with “conversation and sociability” to drive social change.

£1,500 Ref: 8231

1. Carly Watson, Miscellanies, Poetry, and Authorship, 16801800 (Palgrave Macmillan 2021)

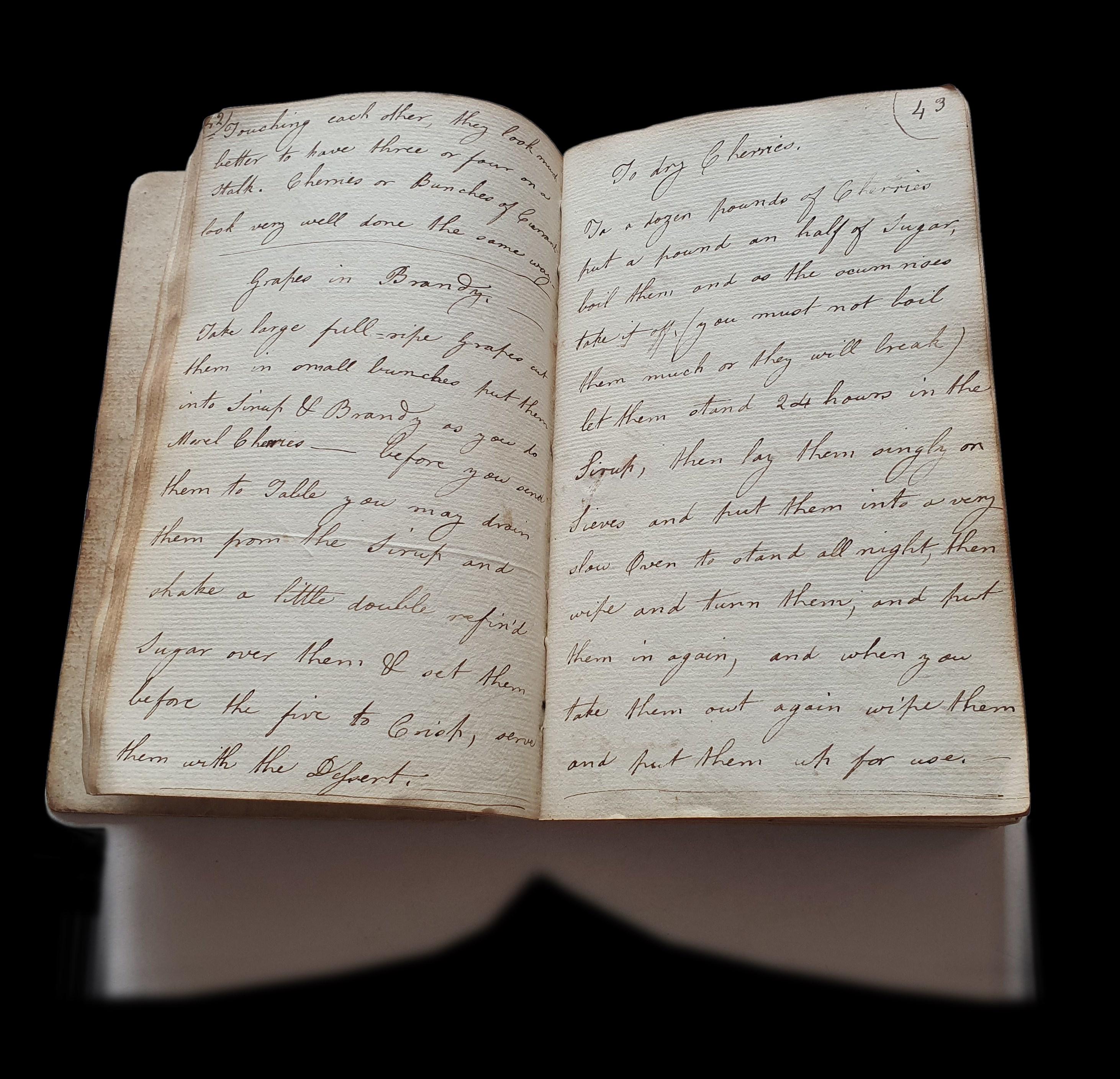

Household manuscript entitled ‘A Most Valuable Collection of Curious Receipts in Cookery in all It’s (sic) Branches Also Confectionary, of all sorts, of Picklings Flesh, Fish, Greens, Stalks, Budds, and Whatsoever is Profitable and Usefull or has as Yet been known to be Pickled. & Kettchups And How to Pot all sorts of Flesh

Fowls and Fish How to make Meads, Wines of all Sorts that are made of Our English Produce. To Make the Best Elixars and Cordills And Curious

Physical and Chyrurgical Receipts Carefully

Collected by Charles Collins. G.’

[England. Kensington? Circa 1720-30].

Contemporary sheep, rubbed and worn, joints split, hinges holding. Pagination [4, (title and blanks)], [277 (numbered to 274)], several leaves excised, but this appears to have been done deliberately by the scribe to create sections (see pagination below). Watermark: Pro Patria; countermark: GR.

The compiler of this folio manuscript styles himself “Charles the initial, we assume, standing for “Gentleman”. Was he a little too modest to describe himself in full, or doubtful that he was fully a gentleman? Regardless, Collins has created an impressive, densely filled household book of the

While its selection of recipes may be the result of its compiler’s experience, the volume itself does not appear to have been anywhere near a kitchen. Rather, it is an anthology of the choicest dishes from the table, much as one might compile recipes for a printed cookery book. Indeed, Collins’ ostentatious volume employs many of the conventions of a printed publication, and he has devoted great attention to its appearance. It opens with an elaborate, verbose title page characteristic of the early modern period; recipes and remedies are organised into sections with running titles; each recipe is separated by double-ruled red lines; and the pages are bordered in double-lines throughout and numbered to the upper corners. All of this contributes to a very pleasing “display” manuscript, but with detailed instructions which could easily be followed.

The sections’ running titles begin with “Soops”, (1-10); “Catchup” (13); and “Fricasseys” (with subsections “and Suchlike” and “Ragoos Harshes and the Like”) (16-36). Pages 37-42 have been excised, before the next run of sections picks up with “Fish and their Proper Sauces” (including “Divers Dressings” and “Pickling & Sousing”) (43-58); “Ragoo’s, Balls, Forc’d-Meats, and Harshes” (61-98); “Some General Rules in Cookery to be Observ’d” (94); “Of Collaring” (100-105); “Of Potting” (108-110); “Of Pastes, Pies, Pasties, Puddings, Tansies, Cakes, Jellies, &c” (later entries also include “Creams Confectionaries &c”) (114207); “Of Pickling” (208-221); “Meads Made Wines and Cordials” (222-231); and “Cordials and Physical and Chirurgical Receipts” (232-277).

Collins appears to have done his curation while compiling rather than in advance, to judge by the excised pages (see pagination jumps above). These may seem at first glance to be damage, but on closer inspection they turn out to have been deliberately removed in order to create sections that segue from one subject to the next. The excised pages are all preceded by either a blank page or a blank lower margin, suggesting that Collins was deliberately removing the pages to give order to his manuscript. It looks as if he has begun several sections in the earlier stages, but has found that he allowed for too much space between them and has removed the extraneous leaves. This excising continues for around the first half of the volume, but in the second half there are no removals, and each topic moves seamlessly to the next.

It is not uncommon for household compilations to gather material from a wide range of sources, whether printed publications or recipes circulated in manuscript. Examining these sources can yield vital clues to the reading habits and social connections of the scribe.

Of the 30 or so attributed recipes, some 23 occur in the “Cordials Physical and Chyrurchical Receipts”. Several of these contributors provide more than one remedy, and a couple also supply entries for the culinary sections. “Madam Granville” (also “Granvil”) is a case in point: she is credited with the culinary recipe “To Make Cheese Cake Madam Granvils Way” and two recipes for “Elder Wine” (one made from “Malaga Raisins” and “Elder Blossoms”, the other featuring only “Elder Berries” distilled in an “Alembeck”) as well as “Surfeit Water”, although one wonders whether “a Gallon of Brandy” mixed with “two Pecks or more of Poppys”, various spices (“Cinnamon”, “Ginger”, “Cloves” “Nutmegs”), “Figgs” and “Raisins of ye Sun ston’d” will really do much for the effects of overindulgence.

The recipe “to Make Plague Water Mdm Granville” (p.238) mixes “Wines Lees sider or Brandy” with over 30 herbs, flowers and roots including “Angelica”, “Dragon Baum”, “Featherfew”, “Orange flowers” and “Virginea Snake Root” (the latter recently imported, one presumes). Should this cosmopolitan concoction prove ineffective, Collins also includes on the facing page “A most Excellent Medicine for ye Plague”, in which alcohol (“Muscadine Wine”) is again a key ingredient, this time mixed with “Pepper, Ginger and Nutmeg”, some “Treacle” and the non-specific and quasi-mythical cure-all “Methridate”. The last great wave of plague in England was some 40 years before the compilation of this manuscript, but outbreaks were recorded in Continental Europe in the 18th century and fears of its recurrence clearly lingered on, as Collins adds another six cures. These include one by “Lord Rich”, who likewise recommends alcohol (“Malmsey Wine”), herbs and “Methridate”, and we are told that “there was never Man, Woman or Child, that this drink Deceived, if the heart Were not already clean Mortified and drown’d with the Disease Long before”. But if any were “Deceived” after all, a crack team of dignitaries and medical professionals combined to recommend “A remedy for the Plague sent ye Lord Mayor of London by King Henry the 8th and approved by Dr Burgess and all ye Eminent Physitians of London” (p.251).

Slightly lesser authority seems to have been accorded to certain other medics, as in the case of “Dr Purslows Water who at 125 Years of Age read without Spectacles” and the (no longer) “Famous Dr Double of Chichester’s Plaister for ye Eyes” (both on p.250), together with “Dr Ratcliffs Receipt to make Salutifera” (p.251); and they are listed alongside the likes of “The Burnt Oyntment Mtrs Hall’s” and “Madam Waintworth’s Excellent Medicine for any Ach”.

The movement of recipes from manuscript to print and vice versa is exemplified over several pages: “two receipts for ye Cure of ye Bite of a Mad Dog” are prefaced: “ye first was attended to ye Publisher for a General good by a Reverend Prelate of Our Church the following taken out of Church in Lincolnshire” (p.271-2); and the reverse movement occurs on the following page: “This Receipt was Inserted in Mist’s Journal Saturday December the 2d – 1727 as an Approved Remedy for Cure of a Violent Cold”. Similarly, an entry treating “Of Mushrooms and how to raise them” is credited as “Translated out of the French” by “John Evelyn Fellow of the Royal Society” – presumably referring to Evelyn’s 1693 translation of La Quintinie’s The compleat gard’ner (but Collins’ text appears to be a detailed summary rather than a verbatim copy).

Evidence of manuscript circulation occurs in several recipes, some of which is helpful in locating our scribe. One for “The Lady Katherine Windhams powder for Convulsion fits” (p.237) likely refers to Katherine Windham (fl 1669-1729) of Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk, whose ‘A Book of Cookery and Housekeeping’ (dated 1707) is held at the Norfolk Record Office (NRO, WKC 6/457). Unlike the abovementioned Madam Granville’s five recipes, Lady Katherine appears only once, so it seems probable that any connection Collins had to her socially or geographically was fairly distant. A much closer connection is recorded in “An Inward Cure for deafness wch cured a person above seventy and had been deaf 40 years and used a speaking Trumpet and cured the Clark of St Clement’s Danes of whom I had the Receipt ye Clarks name Cox” (p.272). The church of “St Clement’s Danes”, completed in 1682 by Sir Christopher Wren, is situated in Westminster. Another remedy which seems to have been

obtained directly is “Chymichal Drops never known to fail in Rheumatism. So safe are they that a Sucking Infant may take them and any one without any Inconvenience are sold only at Jacobs Coffee House against the Angel and Crown Tavern in Threadneedle Street behind ye Royal Exchange, at 3s & 6d the Bottle, with Directions” (p.273).

Such references usefully narrow down the area in which Collins lived and possibly worked. On p.258 he provides a very exact reference that brings us even closer: “Mr Fox of Kensington’s Receipt for ye Gravel and Stone” has the distinction that it “brought away several stones at several Times and gave present ease to Mr Newlin of Kensington tho’ a Wreck”; and on p.275

“Sr John Busby’s Most admirable Black Plaister” came not from Sir John, but “ye Receit was given me by Madam Tempest of Kensington”. Another remedy both confirms his location and points to a likely family connection: “A Receipt to pickle Mango Melons or Pickle ym Mango Fashion” carries the addendum: “N:B: This receipt I have tried […] Famous Christopher Johnsons Receipt that Presented several Crro Crown’d Heads with a Melon on Christmas Day as fresh and good as in the Summer cut fresh out of the Garden and has imparted ye Secret to None but his own Family, though tempted with much Money. is now living at Kensington this present 22 Day of October 1724” (p.213). From this it appears Collins was either related to Christopher Johnson or acquainted with a family member. Either way, having obtained this closely guarded recipe, he has secreted it in the pages of this volume for private use. Given the exact local references, we conclude that Collins lived in the fashionable suburb of Kensington.

The arrangement of Collins’ volume mirrors that of a full-course dinner, with dishes taken from printed and manuscript sources.

For the first course: “soups”, some 29 recipes from various sources, including “A good Herb Soop for the Spring” (which appeared in several 18th-century recipe books, including Robert Smith’s Court cookery (1723)), “A good English Soop”, “CrayFish Soop”, and “Muscle Soop”

Multiple savoury dishes follow, including “Fricasseys” (“Chickens”, “Rabbets”, “Surpriz’d Fowls”); some are copied from Smith’s Court Cookery, while others appear to be from manuscript exchange. These include “Another way to Make Ketchup Mrs Cutliffs” (p.13) and “The Lady Lansdons Sauce for Pidgeons or Chickens” (p.27), which includes the unusual analogy: “Take one Anchovie, the bigness of a Pidgeons Egg in Capers”.

Recipes for “Fish”, “Ragoos, Balls, Forc’d-Meats”, and “Potting” include some copied from Smith’s book, including “An Admirable Way to Roast a Pike”, “Scotch Collops”, mixed with others which are untraced, and presumably taken from manuscript sources – for instance “To Dress a Pike a Nother Way” (p.47), “to Pickle Scallops” (which notes that “Slimy Skirt lyes between the two had finns with the Black Eye and Red Tail must needs be left”, and is to be done “Mrs Blunt’s Way” (p.48)), and “The Lord Lovelace’s way to Fry Mutton” (p.69).

If sheer quantity of recipes is an indication of Collins’ preferences, then from the almost 100 pages of “Pastes, Pies, Pasties, Puddings, Tansies, Cakes, Jellies, &c” (including “Creams Confectionaries &c”), we now know why the abovementioned “Surfeit Water” was required!

The section begins with basic recipes for pastry (“Puff Paste”, “Paste for Pasty”), one for a “Caudle”, and two for “A Lear” (a kind of liquor for the pies). A partiality to encasing animals in pastry emerges in several recipes including “Swan Pie to be

Eaten Cold”, “Lobster Pie”, “Carp Pie”, “Venison Pasty”, “Lamprey Pie”, and “Neats Tongue Pie”. Somewhat easier on the digestion are “Lady Saundersons Biscakes” (“bake them in such Pans as they do Naples Bisket”) (p.126), “Portugal Cake” (“strow in the Flower and Currans by degrees; still keeping them beating till tis little Past and bake them in Tin pans or with Paper Hoops round them”) (p.134), and a range of fruit-centred recipes such as “Light Plumb Cakes for Breakfast” (p.125), “Little Plumb Cakes” (p.126), and “Orange Cheese-Cakes” (“beat the Peels in a Mortar till as tender as Marmalade, without any Knots”) (p.135). Also present are recipes for “Spanish Butter” (p.149), “Trout Cream” (p.150), “Rock Sugar” (p.177), and the ambiguously named “Doncaster Sick Wife’s Cakes” (p.125).

Some of the recipes include instructions on how to cook and recommendations on how to prepare food with notes on the best utensils and other paraphernalia, from simple home-made “Butter’d Paper moulds long or square” for “Ratifea Bisket” (p.130) to preparing “Spanish Butter” (“beat it with a Silver Ladle or Wooden beater, till it is stiff enough to lie as high as you would have it, be sure to beat it all one way and not change your hand”) (p.149) and “Chocolate Almonds” (“Take two pound of fine sifted sugar, half a pound of Chocolate grated and sifted thro’ a hair sieve, a grain of Musk, a grain of Amber, twos spoonfulls of Benn”) (p.181). Others have notes on presentation: for “Trout Cream”, we are directed “when you send it up turn the Baskets on a plate and give it a knock with your hand, they will come out like a fish, Whip Cream and lay about them, they will look well in any little Basket that is shallow, if you have no long ones” (p.150). Some have very specific instructions: the “Red earthen pot that will hold about four Quarts those potts that are something less at the top and bottom then in y e Middle” is exactly what is required “To Make Rock Sugar” (p.177).

All the above dishes may be washed down or followed by dinner drinks, including “Lady Litchfield’s Mead”, various wines (“Quince”, “Cowslip”, “Birch”, the abovementioned “Elder Wine Madam Granville’s”), and an incongruous recipe to “Make Ketchup with Mushrooms ye Lady Foxs’s way”.

Having attended to their sustenance, the volume ends with over 40 pages of remedies (“Physical and Chirurgical Receipts”) which tell us something about the health complaints of the Collins household (besides a keen anxiety about a resurgent plague). One or more of them may have been experiencing fluid retention (“Dr Shore of Chichesters Receipt to Cure a Dropsie”), kidney stones (“Mr Fox of Kensington’s Receipt for ye Gravel and Stone”), hearing and vision problems (“Mr Rideout’s Receipt to help ye hearing or cure Deafness”, “An Admirable receipt to help ye Hearing Dr Halsey’s”, “Famous Dr Double of Chichester’s Plaister for ye Eyes”), and possibly a speech impediment (“A cure for Stuttering”, p.247).

From its specific local connections to its Transatlantic references, Charles Collins’ lively and comprehensive folio household book epitomises the crosscurrents of the early modern period. It gathers material from printed works and manuscript recipe exchange, and the results of copying, swapping, approving and discussing, and brings together some of the domestic and social interactions of an early 18th-century Kensington gentleman.

£8,500 Ref: 8228

AUBREY, John (1626-1697); POPE, Alexander (1688 subjects. I. Day-Fatality. II. Local-Fatality. III. Ostenta. IV. Omens. V. Dreams. VI. Apparitions. Vii. Voices. Viii. Impulses. IX. Knockings. X. Blows Invisible. XI. Prophesies. XII. Marvels. XIII. Magick. XIV. Transportation in the Air. XV. Visions in a Beril, or Glass. XVI. Converse with Angels and Spirits, XVII Corps-Candles in Wales. XVIII. Oracles. XIX. Exstasie. XX. Glances of Love and Envy. XXI. Second-Sighted-Persons. XXII. The discovery of two murders by an apparition. Collected by John Aubrey, Esq; F.R.S. The second edition, with large additions. To which is prefixed, some account of his life.

London: printed for A. Bettesworth, and J. Battley in Pater Row, J. Pemberton in Fleetstreet, and E. Curll in the Strand, M.D.CC.XXI. [1721].

Octavo. Pagination [4], x, [6], 236, [2], p. Collated and complete with the engraved plate and first and final blank leaves. With two engraved portraits of Pope tipped in at the front; a manuscript page with a clipped signature of Pope affixed is tipped in (see below). Annotations to 63 pages which range from a few words to profuse marginalia.

Binding: 19th-century diced Russia gilt, a.e.g. Front cover detached; lower portion of backstrip missing; some spots and marks; collector’s notes in ink to two preliminary leaves; extensive marginal ink annotations throughout, some trimmed by the binder.

A certain ambiguity attends the history of this copy of Aubrey’s . According to a manuscript note to the front free “This book belonged to Alexander Pope: of with whose hand writing this Book Abounds”. We do not know whether this note was written by an optimistic bookseller or by the book’s erstwhile owner, Sir Mark Masterman-Sykes (see below). Either way, the ink annotations, which run throughout the volume, continued to be attributed to Pope until relatively recently. A letter with Pope’s signature pasted on (“Odd Observations on St Pauls Cathedral

London Journal of Sat Feb. 15. 1723/24” with a slip signed Friend & Sert A. Pope Aug. 16. 1732”) were probably added for comparison with the annotations. But are the annotations really by him? This is a vexed question: many of the distinguishing features of Pope’s hand changed markedly over his lifetime, and even comparison with manuscripts in library collections that are known to be his hand often do not resemble each other. We will try to weigh up the evidence of provenance, palaeography, and

The book has the gilt arms of Sir Mark Masterman-Sykes (17711823) to the front and rear boards and his shelf-mark, initials and address, “Sledmere”, to the front endpaper. MastermanSykes, a baronet and member of parliament for York, was well known in his time as a bibliophile who amassed an impressive

Sykes’s collection was auctioned by Robert Harding Evans in 1824, as detailed in the Catalogue of the splendid, curious, and extensive library of the late Sir Mark Masterman Sykes, Bart 1. The first part of the sale began on 11 May and continued for ten days; the second part ran from 28 May to the five following days; and the third part was on 3 June 21 and continued on seven following days (in all sales, Sundays were excepted). There were some 3,700 lots in total, which brought nearly £18,000.

This book was lot 98 in the Sykes catalogue, where it was laconically described as “Aubrey’s Miscellanies with manuscript Notes by Pope, and his Autograph”. This surely refers to our added manuscript page and Pope’s signature, so it seems these were added at an early stage. A pencil note to the front endpaper reads “Sykes Sale 1824 Lot 98 £3.15.0.” The book was acquired by the celebrated collector Richard Heber (1773-1833); a note of the cost of this book at the Sykes sale and commission of 11 shillings to the London bookseller, 1851) is written at the upper left corner of the endpaper.

The book reappeared on the market just over a decade later in the famous sale of Bibliotheca Heberiana 2. Once again, the annotations were ascribed to Pope: “101 Aubrey’s (John) Miscellanies with numerous Manuscript Notes by Pope, and his Autograph, russia, portraits inserted, 1721”.

So, in the Sykes and Heber catalogues the annotations were attributed to Pope. However, an early 20th-century bookseller’s catalogue entry (clipped and loosely inserted) is more equivocal: “THE FAMOUS SYKES COPY, long supposed to be Alexander Pope’s, with a profusion of manuscript annotations said to be in his hand (according to a contemporary note on flyleaf). A genuine signature of Pope is bound in for comparison.”

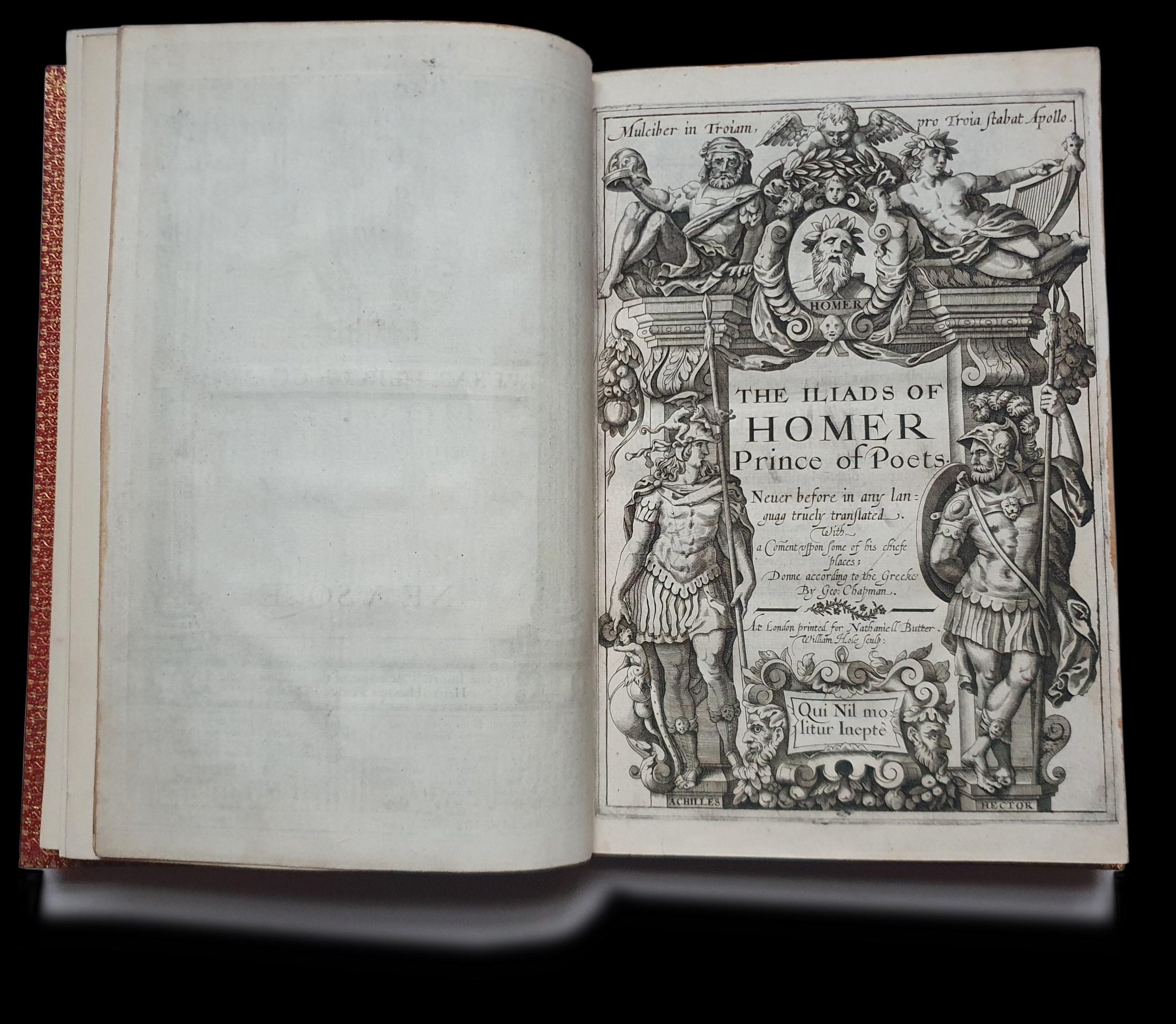

When the book was sold at Sotheby’s (1970), they gave no attribution, and opted instead for “extensive annotations through the book in a contemporary hand including an inserted leaf with Pope’s signature pasted on to it”. The Sotheby’s catalogue also describes a further autograph item, namely a receipt to John Fownes, signed by Pope, for a subscription to Pope’s translation of Homer. There are remnants of paper where this item was probably attached. This seems to be the earliest mention of a receipt, so we assume it was added in the 20th century. Either way, it became separated from the book at some point and later turned up inserted into to a set of Pope’s Homer sold by Bauman Rare Books in New York.

In 1976, the book was sold at Swann Galleries with the Sykes provenance noted, but they seem to have simply elided the issue of Pope’s hand, instead making no mention of annotations despite their profusion. The book then went into a private collection before reappearing on the market recently.

Any comparison of our annotations with those known to be in Pope’s hand is contentious because his hand differs depending upon time and context.

Joseph Hone charts these changes in Alexander Pope in the Making (2023). In his early years, Pope carefully prepared his manuscripts and “precisely imitates the swashes, serifs, and ligatures of printed type”.3 Hone also cites Pope’s literary executor, who observed that Pope’s manuscripts were so beautifully written, “one can hardly believe they are not really from the press”. But over time Pope became less concerned with appearance and his later manuscripts and annotations were in a “less careful hand”. Similarly, the young Alexander Pope inscribed his books “Alexandri Popei” in imitation roman and swash italic, whereas our book has no inscription. However, as Hone observes in ‘Pope and the Blounts’ (2023), “It is important to note that although as a young man Pope habitually inscribed his books, with age he became increasingly lax” 4 .

Perhaps the early manuscripts, with their attempts to imitate printed books, reflected the pretensions of a young man creating his idea of a ‘great author’, but once he acquired an indisputable greatness, he had no need for youthful affectations.

If our annotator is indeed Pope, then it is most certainly a later example. The book itself tells us that much: it was printed in 1721, so the annotations are obviously after that date. But how long after? Hone is again helpful, noting that by the 1730s, Pope’s handwriting had deteriorated considerably. There are no dates in the annotations, but an array of books are cited and none date from after Pope’s death, so we can be reasonably confident that, even if our annotator is not Pope, it is nonetheless one of his contemporaries.

We used three examples of Pope’s hand as our comparators: British Library Add MS 4807, f. 87v and Add MS 4808; and Beinecke GEN MSS 270 (an album formally owned by John Murray, which includes “original proof of two pages from Pope’s Epistles, pages 69 and 70, with the author’s corrections”).

To avoid excessive ‘cherry-picking’, we present examples from only the last of these (GEN MSS 270) and compare them with our annotated Aubrey.

On the right are two sample annotations in GEN MSS 270 (upper and lower sections of margin):

…and these are examples of pages from our book:

When we look at individual words, there are as many matches as there are misses.

For example, the words Hear, years, tears from GEN MSS 270:

… and from our annotated Aubrey: Years, year, years:

The word Dead in GEN MSS 270: ... and Dead in our annotated Aubrey:

GEN MSS 270: fortune

GEN MSS 270: husband

Annotated Aubrey: unfortunate

Annotated Aubrey: Husbands

Given the differences as well as the similarities, this exercise illustrates how palaeographic evidence, at least when comparing Pope’s hand, is an uncertain business, and that any argument that hangs on it alone is insufficient.

One aspect of the annotations which is consistent with known examples of Pope’s style lies in the numerous little crosses throughout the book. However, this was not unique to Pope, and can be found in other annotated books of the period, so taken alone it is insufficient evidence evidence, it becomes more compelling.

A counterweight to this arises from the same restraint that characterises his use of little crosses: Pope did not usually indulge in annotating as profusely as the hand here has done, and Aubrey’s Miscellanies (notwithstanding that the miscellany was a form Pope himself favoured) seems a strange choice upon which to lavish his intellectual gifts.

A further argument against the attribution of Pope as scribe needs to be addressed: is his Catholicism consonant with notes such as the one to the upper margin of I5r that reads: [P]opish Tale of S Teresias Knocking after he[ Cells of her Votaries”; and, on K7r. against an annotation “see ye Superstition of Heathens & Papists”; in the index: “Prejudices of ye Wild Irish Papists ag 45” (Q6v)? (If we follow the reference to page 45 there is an “x” against the section of printed text referring to “the Popish Irish”). Would a Catholic use a pejorative term like “Papists”? In fact, Pope used the word frequently in his correspondence and often in a hostile manner: “I resolve to take any opportunity of declaring (even upon Oath) how different I am from what a reputed Papist is. I could almost wish, I were askd if I am not a Papist? Would it be proper, in such case, to reply, That I dont perfectly know the Import of the word, & would not answer any thing that might for ought I know, be prejudicial to me, during the Bill against such, which is depending. But that if to be a Papist be to profess & hold many such Tenets of faith as are ascribd to Papists, I am not a Papist. And if to be a Papist, be to hold any that are averse to, or destructive of, the present Government, King, or Constitution; I am no Papist” (Pope to Harcourt, 6 May 1723, in Corr., ii. 171-2). 5

The evidence for Pope as scribe, then, although certainly not to be dismissed, is inconclusive. What seems certain is that the annotator was at least a contemporary of Pope’s, if not the man himself; and Aubrey’s Miscellanies is itself a work of great interest. ODNB describes it as “an investigation into a variety of psychic and supernatural phenomena such as omens and prophecies, dreams and apparitions, day fatality and second sight, all of which he was concerned to explore and explain, verify or discredit”.

Our annotator follows Aubrey’s lead by taking a mostly detached approach to the subject matter; and while they are not afraid of giving an opinion, they mainly cite other books and authors. Among the most “Mr Wood” i.e. Anthony à Wood (1632-1695), whose great Athenae Oxonienses (“Athenae Ath. Oxon”, “A. O.”) (1691-2) and are referenced; also well represented are “Increase Mathers recording of Illustrious Providence. 12o 1684”, and “Mr Baxter’s Certainty of the World of Spirits”, with single references to the likes of “Tho: Widdowes ad ann. 1655 & from thence by Dr Plot in his Natural Hist. of Oxfordshire”, “Camden in his Hist. of Qu. Eliz. Sub. An. 1570”, “Bovets Pandæmonium”, and “Stows Survey of London”. Such sources are drawn upon to furnish additional information pertinent to the tales cited by Aubrey, so that the annotator is in effect ‘conversing’ with the printed text and its

To take a few examples among many: our scribe augments Aubrey’s accounts of superstition, omens and so on with an abundance of further incidents gleaned from their reading. Thus, we read: “N.B. Mr Str. In his Eccl. Mem. Vol 3 p286. modestly seems to ascribe […] ye great Death that happened in 1555 or 1556 to the appearance of the Blazing star there mention’d” (D1v); and on occasion, they hitch a couple of links to the chain of association, for example describing how “Deacon Eachard has in his Hist. of Eng. Vol 3 observ’d Kings of Eng. Nam’d Seconds [h]ave been unfortunate as Edw ii Rich ii & James ii”, then recounting that “Eachard” was “wittily censur’d” for this “by Mr Salmon in his Examinat. Of Bp. Burnets Hist. of his own Times. P.1065” (C7v).

The scribe often adds a ‘run-on’ clause to continue Aubrey’s printed text: the line “The Romans counted Febr. 13. an Unlucky Day” has acquired a note that extends this thought: “as also the month of May an unlucky month to marry in according to Ovid in his Fasti” (B2r); and Aubrey’s anecdote “The picture of Arch-Bishop Laud in his Closet fell down (the String brake) the Day of the sitting of that Parliament” has the manuscript addendum: “so did ye D. of Bucks on June 13. 1688 at Lambeth wch was look[ed] on also as ominous as it sa[ys] in ye Compl. Hist of Eng. Vol.3. p48” (D4r).

In keeping with Aubrey’s even-handedness, the annotator acknowledges different sides of the debate on witchcraft, mentioning the sceptical “Scots Discovery of Witchcraft” four times, while the rational “Websters Display of Witchcraft” and its spiritually motivated response “Glanvil’s Sadd. Triumph” receive equal billing with five mentions each. At the same time, one might choose to detect a certain

such as this one on the ominous quirks of the calendar: “N.B. In bp. Burnets Hist Ref pt.11. p.316. tis said yt at ye beginning of Qu. Marys Reign twas observ’d as a wonderful thing yt K. Edw. VI. shd die on ye same day of ye year yt Sr Tho: More was beheaded”. Furthermore, “it was said that the great Duke of Florence lay sick as many days as had reigned years” (B1v).

This mention of “bp. Burnet”, incidentally, is one of several, and lest it be seized upon as the clincher that Pope is not our scribe – since he would be unlikely to include an approbatory reference to Thomas Burnet (1694-1753), with whom he had a vicious and public rivalry – “bp Burnet” is, of course, Gilbert Burnet (1643-1715), whose History of the Reformation (referred to in the annotations) was a standard work on the subject for a century.

Our book’s journey and strong provenance convey an absorbing mixture of hopes, desires and disappointments of dealers, auctions, and collectors. It has a letter and Alexander Pope signature bound in for comparison. But as to Pope’s ascription as annotator, the consensus seems to have developed in relation to distance, so that the further it has travelled from its original source, the fainter the claim to Pope has become. The palaeographic evidence, though bringing us to a resounding “maybe”, is helpful in reminding us that time and context are essential features of any assessment, especially when those factors are brought to bear upon a character as complex as Pope. As to the content of the annotations themselves, we can at least be confident that, whether or not the ‘great author’ created them, they provide an engrossing window into the world of Pope’s contemporary readers.

Conversations abound in this profusely annotated book, and if we remain uncertain as to the identity of one of its chief interlocutors, the sheer quantity of discursive threads, references and additions makes it a hugely appealing showcase for the high levels of engagement and the emerging concerns with objective verification (albeit of the occult and superstition in this case) that characterised the period.

£11,500 Ref: 8203

1. Evans, Robert Harding (1778-1857). Catalogue of the splendid, curious, and extensive library of the late Sir Mark Masterman Sykes, Bart., parts 1-3: ... which will be sold by auction, by Mr. Evans, at His House, No. 93, Pall-Mall. (London: Printed by W. Nicol 1824).

2. Heber, Richard (1773-1833). Bibliotheca Heberiana. Catalogue of the library of ... R. Heber ... which will be sold by ... Messrs. Sotheby and Son [R.H. Evans and B. Wheatley] ... 1834[-1837]. [London]: [1834-1837], part 6, 23 March 1835.

3. Hone, Joseph. Alexander Pope in the Making (2023).

4. In The Library, 7th series, vol. 24, no. 3 (September 2023). p.352

5. We are extremely grateful to Joseph Hone for pointing this out to us and for numerous other valuable insights.

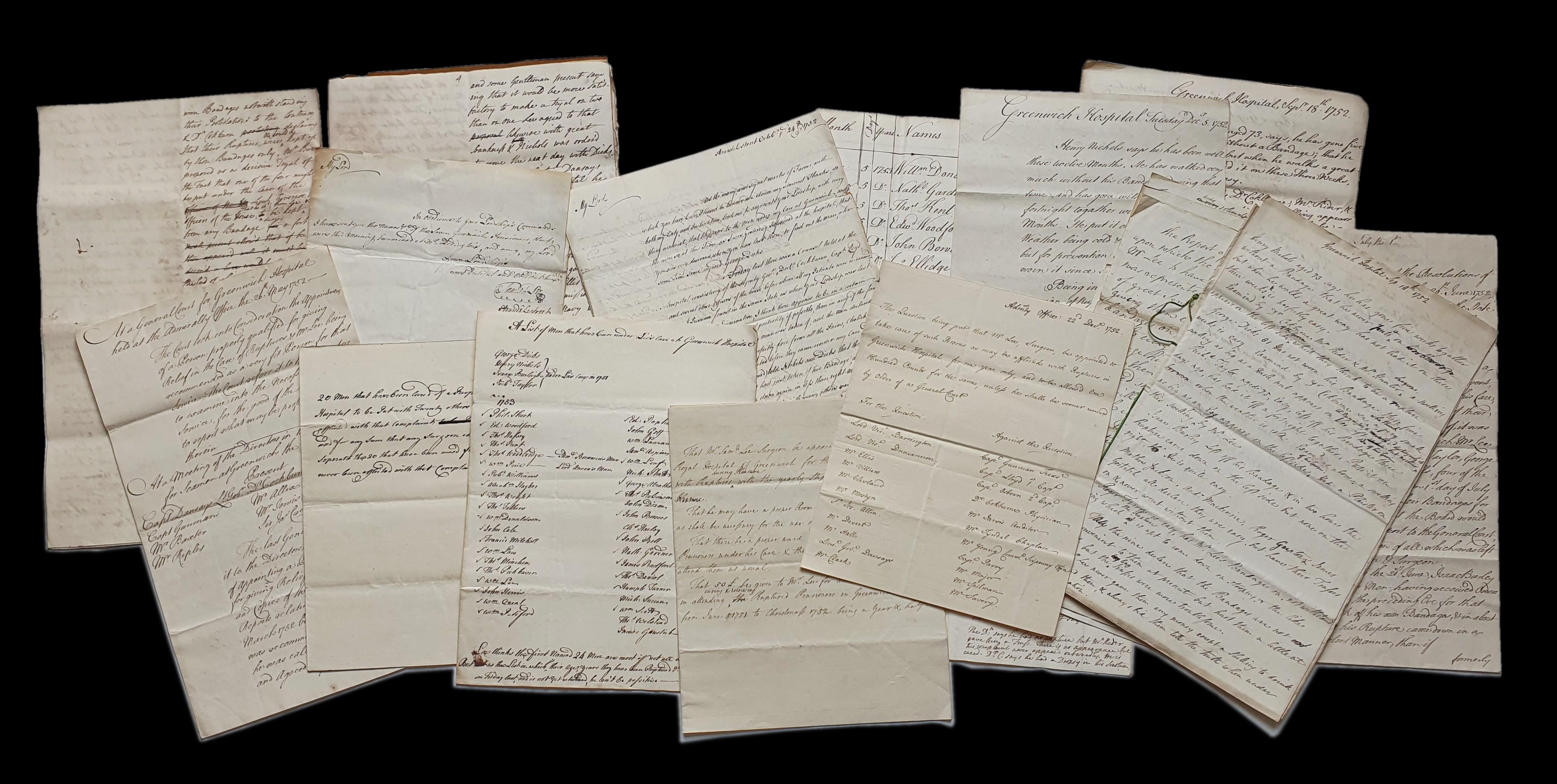

Two manuscript accounts books recording administration of poor law. [Weston & Wixhill, Shropshire. Circa 1676-1737]. Two volumes.

Manuscript Records by Overseers of the Poor. Circa 1676-1737. Small quarto (180 x 150 x 10 mm). 82 pages of accounts on 41 leaves. Vellum binding. Paper softened and fragile, frayed at edges, some leaves loose, and some presumably lost. Watermark: Pot (Haewood 3677-9, but with central letters NM).

Manuscript ledger recording debits and credits. Circa 1702-1721. Tabulated index on 12 leaves, approximately 75 pages of accounts (varying from sparse to full), plus numerous blanks leaves. Narrow folio (394 x 152 x 15 mm). Vellum binding retaining original ties. Unusually, all of the sheets have been arranged into a single gathering and stitched through the centre. Watermark: Coat of Arms (Haewood 456-73).

¶ The issue of ‘what to do with the poor’ has taxed rulers and governments for centuries. The origins of Poor Laws in England are generally traced back to the reign of Richard II in the late 14th century, but Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries (and the consequent confiscation of the assets from which they disbursed relief for the poor), and the expropriation of common land, or “enclosures” (which continued into the 19th century) compounded matters, leading to a series of parliamentary acts throughout the 16th century. The Poor Relief Act of 1597 created the role of Overseers of the Poor, appointed for every parish and supervised by a local Justice of the Peace, and a 1601 act formalised and refined previous measures, making assessment for the relief of the poor compulsory.

Acts and legislation came and went; meanwhile, this manuscript shows life at the sharp end, as the overseers in “Weston and Wixill” (some 14 miles north of Shrewsbury) assess local need, collect the poor rate from landowners, and distribute food or money as they deem appropriate. These accounts are kept by a series of overseers, beginning in 1676 with “Thomas Hoden”, who records amounts “Recd”, presumably from landowners, then lists disbursements to “widow Baly” (ranging from “00-0300” to “00-06-00”) and others. On the next page, his accounts are signed as “Seen & allowed” by two worthies – perhaps Justices of the Peace “Ch: Maynwaringe” and “Th: Hitt”. Subsequent entries follow

the same pattern over several decades, with overseers for the parish (including “Robert Longdon”, “Robert Peate”, and “Thomas Massey”) itemising their receipts and recording payouts and expenses, often with a specific purpose added “Rent”, “3 yards of peats”, “for a blankit”, “a paire of shooes tinkers Child”, “pd William Ridgway for 5 days and a halfe for thatching Thoms Gitttens house”, “Elizabeth: Haries when her husband was sick”).

The pages also disclose the unusual presence of a female overseer: “Elizabeth Berry”, who sets down her accounts for 56”. A late entry here concerns her payment to “Thomas Griffis for wrighting and going with me to gather some part of my Lowne”, followed by a separate payment for “puting them in the book”

The second book is a ledger recording debits and credits by individuals mostly in the same region (Hodnet, Whitchurch, Hawkestone, and so on), beginning in the late 1690s. A few of the names in the first book appear here (“Bayley”, “Fletcher”), and they are joined by the likes of “Sr Orlando Bridgman” for such things as “money lent in a Mortgage in Lands in Droit witch” and several amounts “Recd of Mr Fletcher”. The infamous Sir Orlando Bridgeman, 2nd Baronet (1678-1746) a British landowner and Whig politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1707 and 1738. In order to build an impressive mansion, he took on too much debt, and was pursued by creditors. He faked his own death in 1738 and went into hiding, but was soon caught and spent the rest of his life in prison.

Both manuscripts retain their original bindings, and, while the earlier of the two is in poor condition, it is an unusual survivor which provides rare first-hand evidence of the administration of poor law; of who decided who “deserved” financial assistance in small, rural communities of early modern England.

£2,000 Ref: 8216

[HARRISON, Susanna (d.1773) et al]. Small family archive of notebooks and related manuscripts. [Circa 1770-1810]. All items in original (some homemade) bindings and good original condition.

¶ The most well-defined figure in this archive is Susanna Harrison, whose notebook Her entries, as we shall see, represent the attempts of an intelligent woman from a clearly well do family to find an outlet for her energies – especially creative – in an existence constrained by the social conventions of her age.