t h i n g s w o r d s

t h i n g s w o r d s

w o r d s

t h i n g s

f i v e n o

¶ This hand-coloured and annotated first edition of Leanard Fuchs’ De historia stirpium tracks the evolving influence of what has been called “perhaps the most celebrated and most beautiful herbal ever published” 1. Its treatment over the subsequent two centuries, with annotations in the hands of several early modern owners, demonstrates its enduring relevance and usefulness as a practical and scientific resource.

Leonhard Fuchs (1501-66), a botanist and professor of medicine at Tübingen in Germany, in 1542 published De historia stirpium, an exhaustive and profusely illustrated herbal which “transform[ed] botany, medicine, and natural history in general” 2 –an achievement recognised in several forms including the naming of the fuchsia after him. Among Fuchs’ innovations was his inclusion of a glossary of botanical terms and the first published images of several plants from America such as maize and pumpkins.

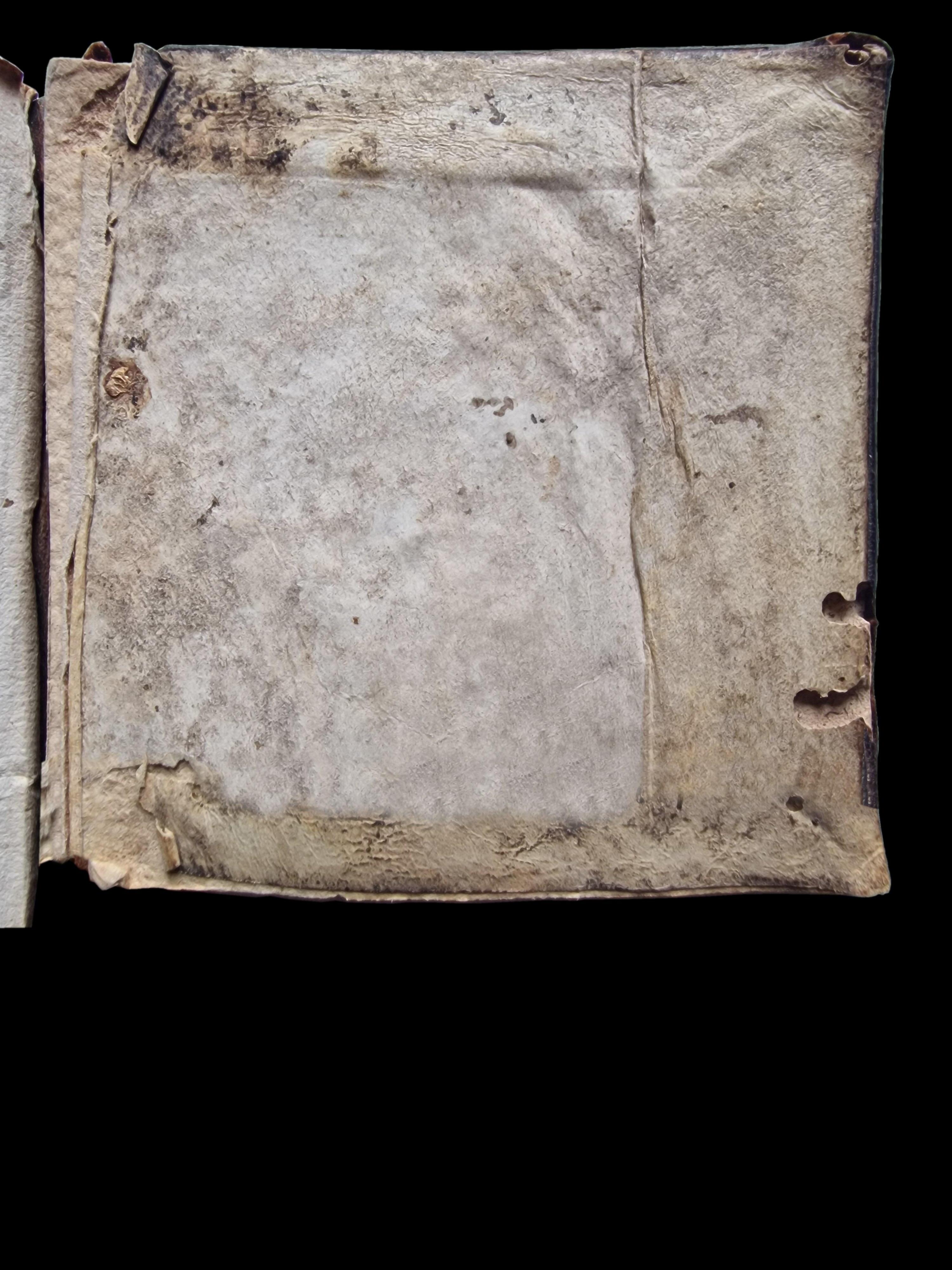

¶ FUCHS, Leonard [De historia stirpium commentarii insignes].

[Basel, 1542]. Folio (357 x 231 x 48 mm).

Pagination [8 (of 28)], 33, 35-60, [1], 61-884 (of 896). Lacks the following leaves: title and 13 prelims; 227-230 (inserted leaf, 2 woodcuts); 347 -350, (2 inserted leaves, 3 woodcuts); 373-4 (inserted leaf, 1 woodcut); 877-8, 885-896, [4]. Eight additional plates from the 1545, octavo edition of Fuchs’ De historia stirpium. window mounted and inserted to replace some missing leaves. Bound in 18th century half calf, rubbed, upper board becoming detached, tears and marks to text, some losses. [Horblit 33b; Hunt 48; Nissen BBI 658; PMM 69; Stafleu TL2 1909; VD16 F 3242; USTC 602520].

It is in the images that, in the words of PMM, “the air of modernity is clearest”: rather than being copied from previous renditions, the woodcuts were “based on a first-hand observation of the living plant and establishing a standard of plant illustration which has been followed until our own day” 3, and each image is in effect “a time-lapse composite, depicting all the stages of a plant’s blooming process, including flowers on one side, seeds on another”, to present “an image of a plant that you will never find in nature, but one very useful for botanical education” 4 .

The book’s material history clearly reflects this emphasis: its owners have made annotations, adaptations, and handcolouring that assist its usefulness, while any increase in its (already considerable) aesthetic appeal was probably incidental.

The earliest annotations, in Latin and sometimes several lines in length, are in a small, neat 16th-century hand, to over 130 pages (usually accompanying images) and indicate that this scribe put their newly acquired volume to use fairly soon after its publication.

Provenance: Samuel Ewer, soap-boiler of Bishopsgate Street, London; gifted by Ewer in 1787 to his son-in-law William Beeston Coyte (1740-1810): “W.B. C[oyt]e ex dono S. Ewer 1787” inscribed to preliminary blank, armorial bookplate (actually, a collage of two clippings of paper with his armorial and name) of William Beeston Coyte ( Coyte”); thence by family descent.

“Hec planta orbent habet frondes subtileter dentatas / ut auctor maiore vulider epinxit / et sumuletes flores in midia Intras / circum circa albis frondibus urtuti maior habet depinxit (This plant has delicately toothed leaves / as the author has depicted with greater vigor / and the flowers are gathered in the middle Enters / around the white leaves he has depicted a greater nettle)

Several shorter, more sporadic annotations, in a 16th- or early-17th-century English hand, strike a more parochial note. This scribe adds English names for a handful of specimens, sometimes giving folk names (e.g. “Jack by the hedg” for Garlic Mustard), but proves to be less than infallible, at one point mis-identifying an Iris as a “Daffadil” (p. 12). A hand from the same period strays into dangerous territory, annotating an illustration of “Aconitum” (wolf’s bane) (H2r) with the note: “Herba Paris or one berrye An excellent Alexiterium” – that is, a preservative against poisons and infectious diseases, which is ironic given that wolf’s bane is itself highly poisonous.

the 17th-century hands are perhaps more concerned with the medicinal applications of the plants. One reader notes, for instance, that the “Nymphaea Candida” (White Water Lily) (y3v) “remedieth lascivious dreames, beinge dronken. But the frequencie of it weakeneth the genitalles”. On the following page, next to the illustration of this plant (y4r), the same reader remarks that “the roote dronke with wine is excellente for those that are troubled with griping of the bellie & a desire to go to the stoole”, and that the plant “helpeth the paines of the stomache, and the bladder. It taketh of morphewe [i.e. a discoloured lesion] from the skinne”.

Other such annotations are more concise, as in the case of “Cynaus”, to which the note has been appended: “Blewbottle. This Herb is very good for inflammations of the eyes or any other parts” (n4v). This scribe, however, elsewhere indulges in longer disquisitions, such as the annotation to Rosemarinus”: “This Rosemary burnt in an House in time of Pestilence, will preserve it free from infection, for its burnt savour expell’s the deadly stench from the infected air. / It strengthens the Brain, the Heart & the memory. It Ks Evill ^Jaundice^. Recovers speech” (R5v). The sense of many hands with no agenda save to add what they deem useful – or simply what they happen to know – is evident everywhere, from the annotation for “Stratiotes” (“Millfoil / This herb is good for all Wounds made with Iron. / it swimons about ye Water having no fixt Root” (pp4r)) to that for “De Amni” which reads: “Herb so called haueing [l]eaves like the Wild marjora[m]. Of some it is called Pipcula” (F3v) (A woodcut on this page has manuscript Latin notes crossed out and the name “Bishops weed” added) – and onwards to the “Larix”, tree”, whose annotation strays into hyperbole: “This trees timber is apt for building and will not perish by rotting or eating of worms, not burn flame nor be brough to coles, but by long span consum’d” (t2v).

Some annotations point to ‘companion’ notes elsewhere in the volume. One of our 17th-century scribes, while paying particular attention to nettles, observes of “Ballote” (N5v): “[H]orehound. Or Archangell or Dead Nettle haveing red flower which answers to the Dead Nettle [w]h a while flower Page 469”. This corresponds to the note on p.469 (r1r) for “Lamium”: “Dead Nettle. vid 194 or rather,” (page shaved). Similarly, the woodcut for “Galeopsis” is annotated “Water-betony, Hungry, dead, oft blind Nettle. Archangel. vid 468”, which points to the text section for “Lamium” and a marginal note reading: “[ ?] Swellings Cankers, Wens. Impost[-] Boils. Gangreens”.

Adding to the overall diversity of interests and material is the frequent presence of more than one hand on a single page, sometimes from different eras. The illustration of “Adiantum” (Maidenhair fern) is annotated in two hands. A 17th-century scribe has written: “Polytrichum. Capil Veneris negro. Mayden-haire”, beneath which a second, 18th-century hand has added: “Instead of this herb Physicians use to put Rue of the wall in all their medicines / It is also called Sempervice”. (G5v).

Around the end of the 17th century, another form of interaction with the book seems to have taken place. A number of illustrations on leaves that were presumably missing or badly damaged have been replaced by windowmounted plates taken from the 1545, octavo edition of Fuchs’ book. These plates were mounted on watermarked paper which closely matches Haewood 1786 (which he dates circa 1680). The mounting is rather crude but perfectly serviceable, adding to the sense of a practical resource being repaired rather than an aesthetic object receiving restoration work. The replacement plates have not been coloured, whereas the original folio plates have, suggesting that the colouring of the illustrations was carried out in the 16 (more likely) the 17

Fuchs’ volume moves into its second century of active use with the addition of at least two 18 make some tentative identification of their owners, despite their contributions to the book being far less numerous than those of their predecessors.

One of these annotators uses a hand that closely resembles the ownership inscription of William Beeston Coyte (1740 Cambridge alumnus, and subsequently a fellow of the Linnaean Society who, after inheriting the Ipswich Botanic Gardens, diligently catalogued its specimens for publication in Hortus botanicus Gippoviciensis certainly indicate an erudite reader proficient in Classical Greek. Beside the text on Chamomile, for example, is the note “so called from Kαμας & Μηλον interest the therapeutic application of plants, observing of Southernwood that it is accounted good to destroy worms in Children. vide Miller”. The citation here refers to Miller’s Gardener's Dictionary, a popular 18th-century treatise on plants grown in England.

Beeston Coyte could well have used this copy of Fuchs to aid identification of plants for his physic garden, or even in his research at the Ipswich gardens that yielded his botanicus Gippoviciensis: some of the illustrations are captioned with the plants’ binomial nomenclature, indicating a scholarly as well as a practical bent.

As to how he obtained his copy, an inscription on the preliminary blank page reads: “W.B. C[oyt]e ex dono S. Ewer 1787”, matching the name of Coyte’s father-in-law Samuel Ewer, a soap-boiler of Bishopsgate Street, London (Coyte married Hester Ewer on 4 January 1779 at Saint Ethelburga in Bishopsgate).

We can assume that the book was lacking pages when Ewer first acquired it because he has inscribed the front free endpaper “Leonharti Fuchsii M.D. } Historia StirpiumBasilea 1542. Regno Henrici viii” with his ownership inscription, “S. Ewer” to the upper right corner, so it was obviously lacking its title page at that point (and presumably others too). Ewer clearly interacted with the book himself before making a gift of it, to judge by his addition of a few English plant names (“Lambs-Tongue”, “St Peters Wort”, “Wolfs bane”) – but these laconic notes scattered throughout the text are the only traces of his interactions. Coyte’s own interaction with Ewer’s earlier ownership inscription – grafting his initials and other details onto it to produce “W B C ex dono S. Ewer 1787” – nicely conveys the volume’s development with this change of owner.

This aspect of the book’s provenance also adds a further point of interest: the well-to-do Coyte having married his daughter, Ewer – though lower down the social scale – presented his son-in-law with this impressive first edition of Fuchs, perhaps in an attempt to impress him, to demonstrate a shared interest, or for some other reason.

This illustration of social mobility is only one of a host of attractions to be found in our volume, which shows several hands at work on the cultivation and dissemination of knowledge. It is both a striking copy of a classic 16thcentury herbal and an eloquent document recording its own use over two centuries.

1. Carter, John and Muir, Henry. Printing and the Mind of Man (69).

2. https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/leonhart-fuchs/

3. Carter, John and Muir, Henry. Printing and the Mind of Man (69).

4. https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/leonhart-fuchs/

£15,000 Ref: 8263

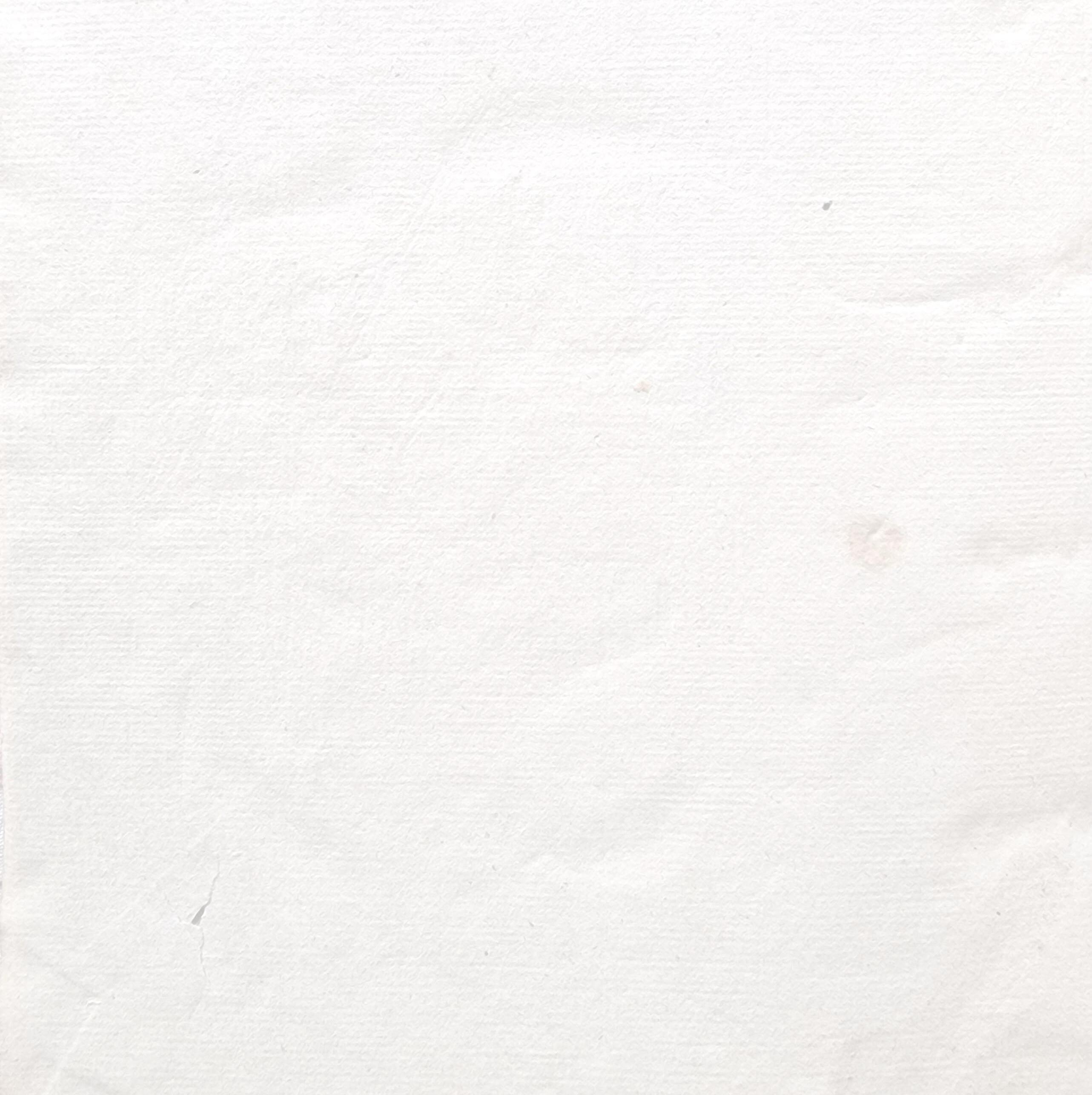

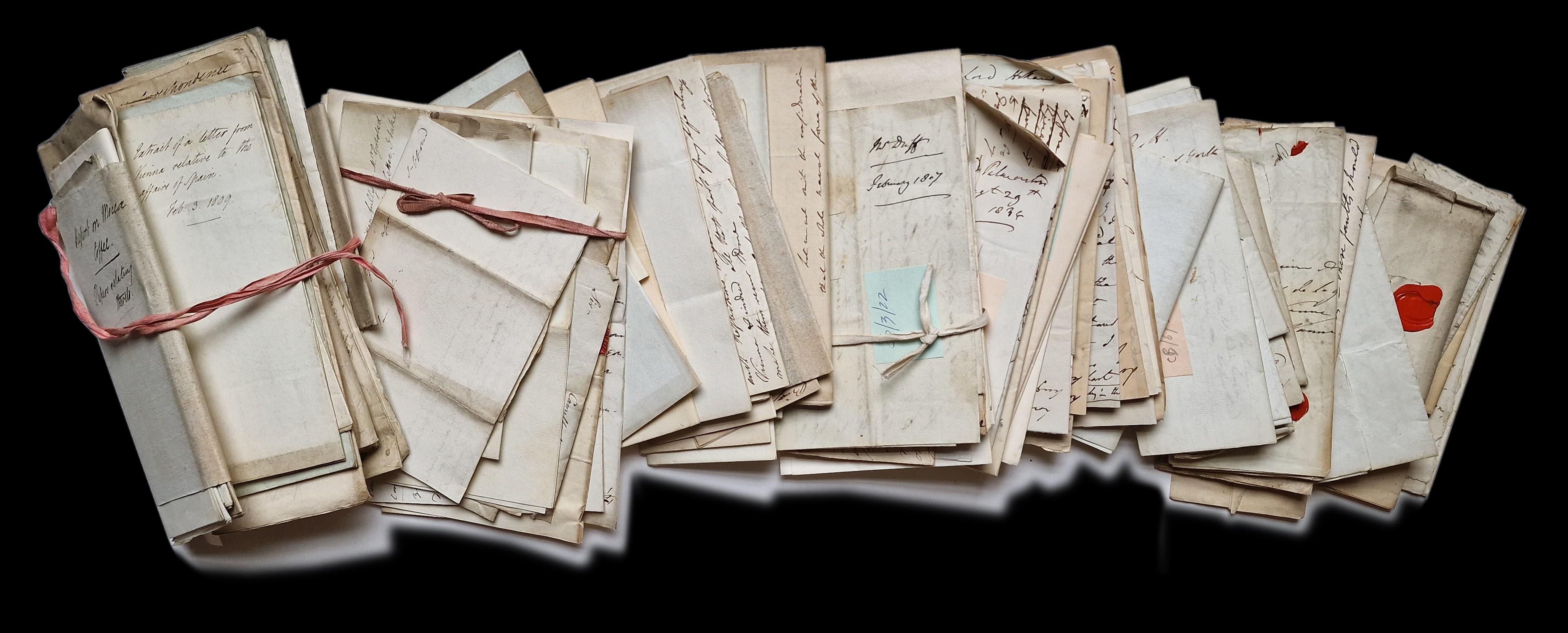

¶ It’s a common fate of rank-and-file individuals – especially women – from centuries past to disappear from view, having lacked the socio-economic weight to make an impression on the historical record. One of the handful of ways in which the ‘middling sort’ can become exceptions to this tendency is through the connections they make, whether through marriage, friendship, employment, business, or some legal matter that enters the public domain. Indeed, the principal owner of this manuscript becomes partially visible to us through such indirect sources.

¶ [BURZIO, Madam]. English 18th-Century Culinary Manuscript.

[London, Charles Street, Grosvenor Square. Circa 1780-1830]. Quarto (195 x 166 x 20 m).

Approximately 240 text pages on 122 leaves. 18thcentury stationer’s vellum binding, oval bookplate to paste-down of “Richard Cust / Stationer / Parliament Street / Westminster”, text waterstained.

Provenance: ownership inscriptions to front endpaper: “Madme Barzio / Charles St / Grosvenor Sqr” and “John Simpson Cookery Book” . Watermark: Britannia; countermark: Crown GR.

The front endpaper of this book of recipes is inscribed “Madme Burzio” – and a woman with even such an unusual surname has barely a trace in the records. Fortunately, one Marie Jeanne Sophie Burzio, a “Fancy Dress ma[ke]r”, is recorded in January 1808 as Master to an apprentice named Rebecca Giles, and her address tallies with the rest of the inscription: “Charles St / Grosvenor Sqr” . 1

Marie Burzio is also outlined by another connection: Ferdinand Burzio, a jeweller recorded at the same address –her husband, we assume – who was called to testify in the trial in 1810 of Joseph Sellis, accused of attempting to assassinate the Duke of Cumberland (one of Burzio’s customers). Burzio provided a character witness statement concerning Sellis, who supposedly committed suicide after the failed attempt. Suspicions surrounded the case, especially after the husband of one of Cumberland’s lovers died in a similar manner to Sellis, adding grist to the rumour mill. 2

The pastedown has a stationer’s label: “Richard Cust / Stationer / Parliament Street / Westminster”. Cust had premises at several addresses in Parliament Street between 1779 and 1802, 3 so we can reasonably assume that Marie bought the book from his shop in the late 18th century.

Marie’s hand predominates for approximately the first 60 pages of the manuscript, and the context above helps us to conclude that these entries date from the late 18th century. Another hand, also 18th-century, takes over for some 30-40 pages, followed by a mixture of hands for the remainder, which takes us into the 19th century. It remains unclear whether the arrival of the second hand signals a change of ownership; no dates are given in the text until the mixed-hand section some 118 pages in, when “To make Apoplectic Jelly” is annotated at the end: “The above Receipt was written by Joseph Jekyll, Esq. M:. P. 1805”. Since we know that Marie lived until at least 1808 (the date of the apprenticeship), we might hazard that some of the subsequent hands belonged to other members of her household (one of whom may have been responsible for the endpaper’s second inscription: “John Simpson Cookery Book”), but this remains speculation.

Marie refrains from making any attributions, but the second hand records several: “To make Pease Soup. Lady Wright” begins a run of 17 recipes (the rest marked “ditto”) evidently copied out from Lady Wright’s manuscript at a single sitting. Likewise, “To make puff Paste. Mrs Spooner” is followed by three recipes again marked “ditto”. Meanwhile, “Mrs G Smith” is credited with the recipes “To make Gooseberry Biscuits”, “To make White Soup”, “Browning”, “Spanish Puffs”, and “To dress Hams”. One-off contributions include the likes of “Mrs Sourbys Spunge Cake”, “To make Buns. Mrs Lee”, and “To make Italian Cheese. Mrs Arrowsmith”; and two recipes – “To make Goffer” and “Potatoe Pudding” – acknowledge “Mr Sloane”.

References:

1. https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/ view/342643:1851?tid=&pid=&queryId=157ba243-ae044017-8fb1-

4c228f1c8666&_phsrc=wUb187&_phstart=successSource.

2. A Minute Detail of the Attempt to Assassinate His Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland. 1810.

3. http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/details/?traderid=18054

A couple of the attributions are easy to identify, since their rank positions them comfortably above the ‘middling sort’. The aforementioned “To make Apoplectic Jelly” is attributed to “Joseph Jekyll, Esq. M:. P.” – that is, Joseph Jekyll (1754-1837), MP for Calne, Wiltshire and author of an anonymous “Memoir” of the life of the enslaved man Ignatius Sancho; and the recipes for “Breakfast Cakes” and “To Make a Baked Apple of Goosebury Pudding” are the work of “Mrs Bosanquet” of “Forest House”, referring to Eleanor Bosanquet (née Hunter) (1737-1820), wife of Samuel Bosanquet (1744-1806), merchant and governor of the Bank of England, whose main residence was Forest House, Leyton.

There is no overarching order to the volume. “Madme Burzio” began her compilation with predominantly culinary recipes (“To Pickle Walnuts”, “Italian Cheese”, “To Pott Shrimps”, “Almond Cheescakes”, “Orange Pudding”) with a sprinkling of remedies to treat common conditions such as “Ague” and a recipe “To make Saffron Cakes” which are “good against infection”. The food is varied and nourishing, but not elaborate – qualities perhaps to be expected from someone whose “Fancy” dresses were made for others to wear. When the second hand takes over, they continue this focus on wholesome, basic food for another 40 pages or so; and the appearance of the mixed hands around the turn of the century signals the manuscript’s evolution into a more general household book, with recipes and remedies contributed in ad hoc fashion by various contributors.

Although the grandly named Marie Jeanne Sophie Burzio makes only a brief appearance in the historical records, the survival of her manuscript augments this fleeting presence with insights into her domestic life. The stationer’s label allows us to conjure a picture of Marie travelling the short distance to Richard Cust’s bookshop in Parliament Street to buy her new, vellum-bound, blank book to fill with recipes, the contents of which trace a household’s connections and interactions with people of various ranks – and help to give a flavour of the lives of working people in Georgian London.

¶ A rare and vivid embroidered depiction of Georgian pantomime favourites, Harlequin and Colombina, juxtaposed with the reverent verse and imagery of the earliest lovers in biblical literature.

The first stitches in the sampler immediately herald our young needleworker’s moral and religious teachings, with two lines from John Milton’s Paradise Lost: “Adam and Eve whilst innocent in Paradiſe were placd / But soon the serpent By his wiles the happy Pair disgracd”. Such extracts from Milton’s epic were frequently incorporated into 18th- and 19th-century domestic arts by educated readers. Next to this we find the name and date of its maker, likely aged between 9 and 12 years of age, “Mary Saunde/rs 1763”; and below the quotation is a typical embroidering of the English alphabet – but with one accidentally missed letter somewhat comically restored at its conclusion, “& J”

¶ [SAUNDERS, Mary] An early George III needlework sampler by Mary Saunders, dated 1763. [Circa 1763]. (420 x 310 mm). Finely worked in coloured silks, faded, especially to text. Neatly mounted on board.

Below this solemn opening, there spills out a magnificent sweep of decorative motifs, pictorial designs and colourfully elaborate details. The Tree of Life stands prominently, flanked by fig-leaf-covered Adam and Eve, as the ‘wily serpent’ coils around the tree trunk, holding out the fated apple to the First Woman. Surrounding them are majestically horned deer, squirrels, tropical birds, owls, swans, butterflies and other creatures. Their garden blossoms with fruit trees, tropical plants and winding blooms. Two cherubs fly at the very centre, a heart emblazoned between them. And there, amidst all this fantastical biblical imagery, we see two more figures: Harlequin and Colombina, the two lovers of the Italian Commedia dell’Arte. Harlequin, is bedecked in his distinctively colourful chequered costume topped by a yellow hat, and holds a wooden batte (or ‘slapstick’) in his left hand – an instrument used to change the scenery of the play – these elements collectively evoking the multifaceted character of the Medieval Masque tradition.

But why did the young embroiderer incorporate these two theatrical characters into her, otherwise overtly religious, sampler? The British pantomime tradition first took root in the Georgian period, thanks to English theatre manager and actor John Rich, who founded Covent Garden Theatre in 1732. It was there that Rich staged the earliest slapstick pantomimes – a blend of classical fable and Italian grotesque, featuring Harlequin and his beloved Columbine. But the black mask worn by the Harlequin of the period had undeniable racial connotations against the backdrop of 18th-century Britain, with its colonies built on enslaved labour. There is no doubt that Georgian

theatregoers would have associated the black-masked Harlequin with an African identity: some pantomimes, such as Harlequin Negro (1807), made that connection explicitly, and the figure laid the foundations for the racist tradition of blackface minstrels that later developed in Britain and North America.

Our embroiderer may well have witnessed a pantomime with Harlequin in a black mask, but she has depicted Harlequin as a Black person, whose face, hands, and feet are woven in black silk. Samplers depicting Black people are incredibly rare, and a sampler showing a Black harlequin figure is rarer still. The extensive collection of samplers at Colonial Williamsburg contains one example featuring a Black harlequin figure, dated 1803 (object number: 1995-208, A); the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Centre at Vassar College, holds just one more from 1800 (object number: 1960.9.32). Our sampler, which dates from 1763, is an early piece of pantomime theatre history and perhaps the earliest extant example of a sampler depicting Harlequin not in a mask or blackface, but as a Black person.

£3,500 Ref: 8247

¶ [SCOTTISH LAW; RESTORATION]. Manuscript entitled ‘The Acts of Sederunt of The Lords of Session/ Beginning the 5th of June 1661[-1694]’.

[Circa 1661-1694]. Quarto (182 x 142 x 15 mm). Watermark: earlier leaves are Fleur-de-lis; later leaves are Arms of Amsterdam. Pagination 171 (numbered pages), [18, index], [1, blank]. Contemporary plain calf, rubbed but sound.

¶ A Restoration Scottish manuscript legal compilation, containing “Acts of Sederunt of the Lords of Session”. The Scottish Courts define an Act of Sederunt as “the legal name given to the procedural rules regulating various civil legal procedures in Scotland”.

The notebook covers the period from the Restoration up until shortly before the death of Queen Mary. The first comprehensive printing of these acts was not to appear until Illay Campbell's edition of 1811, although Lord Stair had included a set, running from 5 June 1661 to 22 February 1681, with his Decisions of the Lords of Council & Session of 1683. But even where our volume overlaps with Stair’s it differs from the version given by him and is clearly not derivative. For example, the first entry in our volume, “Act for Continuing Summonds & Wryteing in Latine as formerly”, is dated 5 June 1661, whereas Stair opens on this date with an “Act uniformity of Habit by the ordinary Lords” – which in our manuscript appears on 6 June. Likewise, Stair’s text for the latter act opens: “The Lords taking to their serious consideration, of how dangerous consequence the alteration of Formes and Customes is...”, in contrast with ours, which begins: “Which day the Lords taking to their serious Consideration of how dangerous consequence the alteration of forms & customs is...”.

Other acts in this volume include “Discharging Letters to be Signed to wryters who have not taken the oath of allegiance” [30 July 1661]; “Reference Anent Impositions at the Ports” [6 November 1686]; and “Anent the Death bed” [29 February 1692].

The manuscript is written in a very neat and legible contemporary scribal hand throughout. This hand is fairly consistent, but there are variations, especially in ink, and the index at the end is in a much looser hand. All of this leads us to conclude that it was compiled over time, and most likely written as the acts were issued.

£1,250 Ref: 8258

¶ Poised somewhere between memoir and fiction, this lively digressive manuscript seems to be the work of an unreliable narrator. The title page suggests a sober discussion of national debt, but the text presents a story of calamity, intrigue, insurrection and misadventure, mostly in Portugal and then in England, before concluding with some thoughts on English politics and foreign policy between the Jacobite rising of 1745 and the 1784 India Bill. In that sense, it partly answers the description of the title’s final clause, being indeed “some account of the author by

“editor” (“Mr Benjamin Farmer”) are clearly both one and the same, Benjamin Farmer, and the pseudonymous “Timothy Quidnunc” is an allusion to the satirical “Thomas Quidnunc” character invented by Joseph Addison in the Tatler – and the source of a certain mystery as to Farmer’s intention.

FARMER, Benjamin]. Manuscript entitled ‘An enquiry into the rise, progress, and consequences of the National Debt, with the means by which it may be liquidated. By Timothy Quidnunc. With some account of the author by the editor.’

[Circa1785?]. Slim quarto (195 x 232 x 6 mm). Paper wrappers, 28 leaves, and six inserted leaves. Approximately 64 text pages: Title to inner front wrapper, text numbered to 51, and 12 unnumbered pages.

Stab-stitched paper wrappers, stained and with loss to lower of rear wrapper. Written in a neat legible hand throughout, and ascribed to the front wrapper “By Mr. Benjamin Farmer” in the same hand.

Benjamin Farmer, son of Thomas, came from a Quaker family who intermarried several times with the Galtons, who became gun manufacturers in the Birmingham area in the 18th century. Samuel Galton (1720-99), having married into the Farmer family, formed a business partnership with the Farmers; Farmer & Galton supplied the government with guns, exploited the growing market in India and equipped slave traders in Africa. In the summer of 1755, Benjamin Farmer arrived in Lisbon with a letter of introduction to Abraham Castres, the English Envoy Extraordinary, from Secretary of State Sir Thomas Robinson.

Even before the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, which almost ruined the Farmers, things had not been plain sailing for the family. Benjamin had been trying to recover a schooner confiscated by the Portuguese in the Cape Verde islands; and his gunmaker cousin James Farmer was fighting off insolvency after a partner in Lisbon had left him with huge losses. 1

The manuscript takes up the (perhaps lightly fictionalised) Lisbon story eight pages in; first, by way of introduction, there is a kind of apologia for the “Quidnuncs”: writing in the third person, Farmer begins: “Timothy values himself much on the Antiquity of his Family, and insists upon it, it is as old as the Origin of Common-Wealths, of which the Quidnunc’s have been the principal Founders”. He goes on to admit that “there has always been a sort of Extravagancy in their Character which has subjected ^them to the Ridicule and Contempt of the moderate and prudent part of the Community”, and that their overriding focus on “the Common-Good” has led them to act “so differently from the common practice of mankind as to be accounted a little mad”.

The “Quidnunc” epithet, coined by Richard Steele, was a reaction to the rise of political coverage in newspapers. The Latin construction, which translates as something like “What news?” or “What now?” described a certain breed of newspaper-reader: “the news addict hooked on the latest dispatches” to use Stuart Sherman’s phrase 2 –or, in Joseph Addison’s words, “wrong-headed politicians who live more in the coffeehouse than in their own shops, and whose thoughts are so taken up with the affairs of the continent that they forget their customers.” It can be interpreted now as an attempt to exclude the ‘tradesman’ and the ‘middling sort’ from serious political discourse, at a time when such debates were opening up to the literate masses.

References

1. Pearson, Karl. The Life and Letters of Francis Galton. 1914-1930.

2. Sherman, Stuart: “The General Entertainment of My Life”: The Tatler, the Spectator, and the Quidnunc’s Cure, in Eighteenth-Century Fiction, (UTP, Toronto), Volume 27 Issue 3–4, 2015, pp. 343-371.

Is Farmer’s apologia in earnest, or is he, à la Tatler, attempting a satire? Or is it a form of gentle self-deprecation, a modest throat-clearing? Farmer is, after all, a kind of ‘tradesman’, a manufacturer from the Midlands whose family came close to bankruptcy. Interestingly, Steele commented in the Tatler that “the News-Papers of this Island are as pernicious to weak Heads in England as ever Books of Chivalry to Spain” – an idea that seems to be echoed in Farmer’s “a little mad” remark. Timothy Quidnunc is certainly depicted as an innocent, gulled by the “crafty Designs of his more cunning Acquaintance” (p.6); perhaps his “Quidnunc” conceit is intended to frame the narrative that follows as a Quixotic tale (it unfolds, after all, in a Hispanic-adjacent context)?

3. Maslen and Lancaster. Bowyer ledgers, 4441. ‘A view of the internal policy of Great Britain’. In two parts. For A. Millar. 1764. LEDGER: P1185, 1202, 1208. Perhaps written by Farmer, but ESTC queries ‘by Robert Wallace’.

Paice, Edward. Wrath of God: The Great Lisbon Earthquakes of 1755. 2008.

After the apologia’s romp through Quidnunc’s background and early life, the main narrative drops our knight-errant in Lisbon. After being “rob^bed and treated with great cruelty” by the Portuguese (p.8) and being drawn into a quarrel with “one Gentleman, of a name now famous in the Annals of France” that escalates into a duel (p.9), Farmer/Quidnunc relates his experiences in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the subsequent “conspiracy of the Nobillity to destroy the King” (p.17). He gives a long account of the unrest and the reprisals against the nobility that followed, including the execution of Duke D’Averso (p.27), before claiming that “Timothy, unwilling to be shocked at such a Scene, spent the Day at Home”.

£2,500 Ref: 7988

Sundry other incidents are recounted, including an awkward meeting with the King; then, on a batch of six inserted leaves, he relates “a very singular Adventure” which “shews the Simplicity & unguardedness of his Character”. The anecdote involves Timothy being accused of stealing a mule outside a village and undergoing a makeshift trial, only to be acquitted and escorted, for a fee, to safety.

The manuscript’s final section recounts the return of Timothy to England and his attempts at a new enterprise distilling turpentine (apparently curtailed by a fire). There are further anecdotes and reflections – on the politics of the American Settlements, taxation of the colonies and other events in America, where Farmer’s own business lost trade through the War of Independence – before Timothy concludes with his thoughts on the balance of power in England between Crown and Parliament, political corruption, the death of Rockingham, the rise of Fox and North and the advent of the Pitt ministry, and the 1784 India Bill.

Among the misadventures and tribulations is a passage that unexpectedly appears to resolve an issue of authorship: “He found at last to his great surprise,” writes Farmer, “that he had written a Book, and believing his Observations might be usefull, # published it. Dedicating it to his brother Quidnunc’s, and recommending Men of Letters to pursue the Idea, which the Author of the Wealth of Nations has done, much to his Honour, and Timothy hopes, his Profitt.” (p.35) His footnote gives the title as “# Internal Policy of Great Britain, in two parts Millar, Strand 1764” – a book which has for some time been tentatively ascribed to Rev. Robert Wallace (1697-1771), author of Characteristics of the Present Political State of Great Britain (1758), but with no confirmation in the limited biographical accounts of Wallace. Farmer’s stray remark supports the tentative attribution in the Bowyer Ledgers. 3

An ostensibly more reliable attribution may be found in the first eye-witness report of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake: Two very circumstantial accounts of the late dreadful earthquake at Lisbon, Exeter 1755 (reprinted Boston, 1756). The title goes on to claim that the first account was “drawn up by Mr. Farmer, a merchant, of undoubted veracity”. The name, profession, and date all correlate with our author, and we leave open the question of his veracity.

A manuscript held at the Folger Library (Call No.: N.a.14) bears strong resemblance to ours. It too purports to be a work on economics: Considerations on the national debt written by “Timothy Quidnunc” (ca. 1800). According to the catalogue entry, a “bookseller’s note in front cover and the binder's title attribute the work to one Farmer, i.e., Benjamin Farmer, merchant in Portugal”. The hand is a very close match for our manuscript, and the subject and authorship (pseudonymous and ascribed) support the attribution to Benjamin Farmer. But why did the manuscript end up at the Folger? The explanation seems to be that in the 1950s a bookseller muddled Benjamin Farmer with the Shakespearean scholar Rev. Richard Farmer and the manuscript has remained at the library ever since.

This strange, fascinating manuscript provides a firsthand account of an English businessman’s personal experience of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and fire, and adds substantially to mercantile history and Anglo-Portuguese trading relations. It also offers evidence that Farmer, not Robert Wallace, was the likely author of A View of the Internal Policy of Great Britain and links to another, similar manuscript whose playful approach to title, authorship, and narrative have led to it taking an unusual journey into the archives.

This manuscript’s mixture of vivid autobiography and anecdotes, political commentary and mischievously ambiguous approach to presentation deserves closer attention, in order to ascertain how reliable our narrator really is and what his purpose may have been.

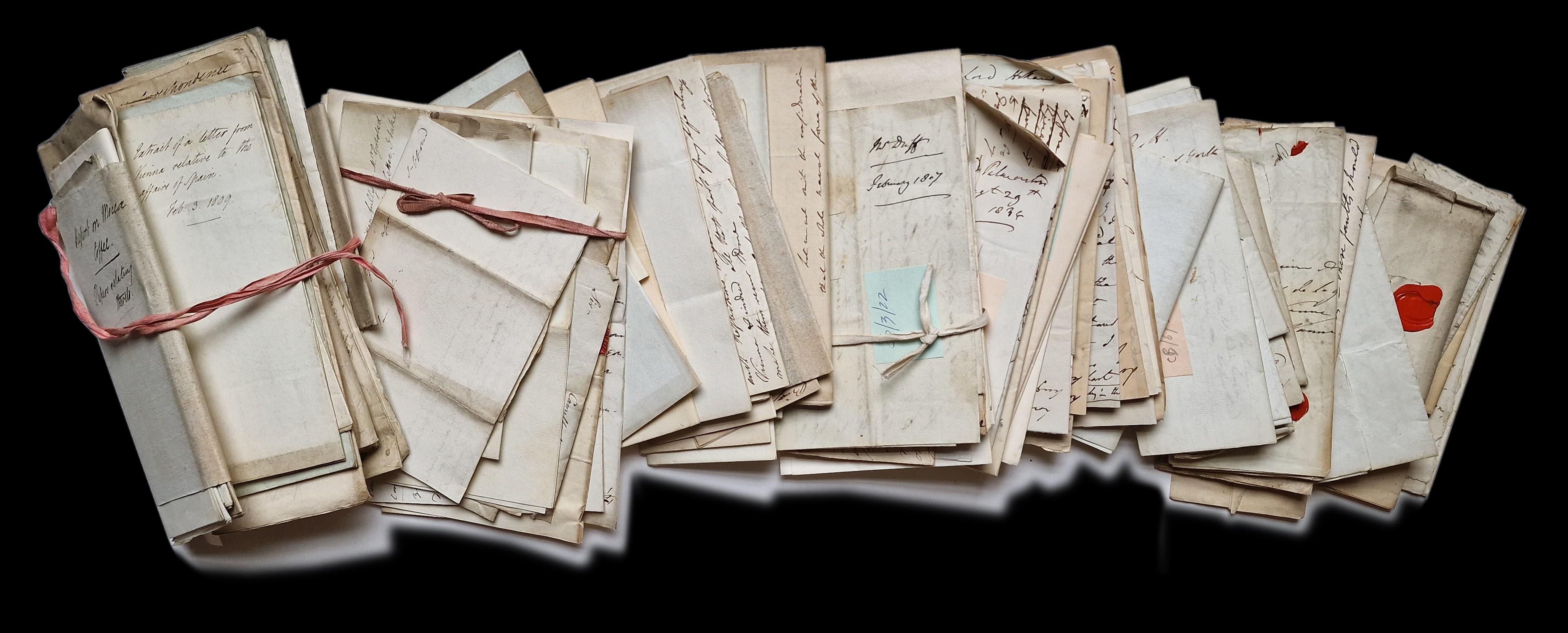

PROVENANCE

¶ TERENCE, Publius Terentius Afer (c.195/185c.159? BCE) Comedie: cum famatissimorum oratorum commentis [With commentaries of Donatus and Guido Juvenalis, edited by Jodocus Badius Ascensius].

[Lyon], [Impresse Lugduni, per Joannem de La Place M. CCCCC. XX]. [Jean de La Place & Martin Boillon], [8 April, 1520].

Quarto in eights. Collation: a-v8 x4 y8, title printed in red and black and woodcut vignette of Badius presenting book to dedicatee within composite woodcut border of portraits of religious figures, woodcut decorative initials, woodcut printer's device to final verso, woodcut illustrations to the first act of each play. [Adams T315].

¶ The early annotators of this rare edition of Terence offer remarkable evidence of the kind of learning that a Tudor pupil would have received at school, and of how schoolboys of the period studied Terence (and the classics more generally). Subsequent inscriptions trace the book’s evolution from wellused classroom resource to object of antiquarian contemplation. Terence’s ‘Comedies’, besides strongly influencing Chaucer, Dante, and later Shakespeare, were deployed as classroom material in English schools from the 16th century onwards. A great many young scholars thus learned the structure and style of Latin through getting to grips with the works of Terence; and this profusely annotated copy of his Comoediae provides us with a striking illustration of this scholarly engagement.

Contemporary English blind-stamped panelled calf, spine in compartments and with modern red morocco label and gilt date), covers with arabesque centrepieces, joints splitting, but holding firm, backstrip with original piece crudely reattached at head and lifting, corners worn, rubbed.

There are several inscriptions to the title page, giving the researcher a range of threads to follow. Though no specific dates are given, the hands enable us to establish an approximate timeline: starting in the 16th century, we have “Thom[as] Pyke of Kingsley”, “ferdinando Calestone”, and “Edward Witt of Bradford”; late-16th to early-17th-century hands have inscribed the names “Thomas Sutton Gent” (and an annotation to b3v reads: “Thom Sutton is a good fellowe and a knave so beyt”), “Edward Euleston” (as well as a cipher to b1: “EE”, an inscription to x6: “Edward Euleston Clarke of ffrodsham Church” and his name to y1.

Inscriptions adorn the title page at different angles, suggesting the kind of unceremonious practices common to many a classroom, which we think the likely setting for this volume’s early life. Indeed, the rest of the class (or a succession of classes) seem to have pitched in at the other end: the colophon leaf fairly bristles with further names, marks and pen trials, also 16thcentury. Here, the printer’s device is hemmed in by dozens of inscriptions including those of “Sampsone Daviden”, “Robert Haryson”, and “Rychard Denteth” (who for a while “ownes this Booke”). This was clearly a communal resource, and any distinction between the inscribers of the title page and those filling up the colophon becomes hard to make.

Small piece from blank upper corner of title, d1 short tear within text without loss at upper inner corner, i5 small hole within text with loss, a little marginal worming at start, water-stained, some spotting and staining (including ink), lightly browned.

Provenance: various inscriptions to title page, colophon and within to text margins; armorial bookplate of Johnstone of Lathrisk, county Fife.

Similarly, the point at which the book graduated from the classroom to the outside world – perhaps via “Thomas Sutton Gent” “Edward Euleston Clarke of ffrodsham Church” –is difficult to determine.

Frodsham and Kingsley are only a few miles from one another in Cheshire, so the volume

at least seems to have stayed in one area for a period of time). Another inscription to the title page, almost certainly 17th-century, reads “Thomas Davenport”, and an annotation in the outer margin of s8v (late 16th- or early 17thcentury) bears the signature “Hugh Haxley” – thus muddying the picture further.

The works of the African Roman playwright Publius Terentius Afer, or Terence, had an enormous and many-faceted influence on early modern English drama: long before Shakespeare and many others adopted his use of the five-act structure, Terence’s drama was, says Martine van Elk, “fairly frequently put on in grammar schools, at universities, and at Inns of Court” 1; indeed, she cites the earliest surviving record of an ancient drama being staged in England (in King’s Hall, Cambridge around 1510), which features a play by Terence.

But van Elk argues that he also influenced writing in general: Terence’s work was pressed into “pervasive use in the school curriculum, making his work important not only as a model of playwriting but also as a way of looking at the world that had been inculcated into grammar school boys from a relatively early age” 2 .

This was despite the fact that most of Terence’s plays remained unpublished in English translation until the late 16th century, leaving readers in England to “rely on imported books in order to gain access to many important classical works” 3. Our copy of Comoediae is a case in point, and the woodcut images (in two variations) to the first act of each play depicting a tutor handing a book to a pupil also neatly conveys not only the principle of transmission between teacher and student but, for our copy in particular, the continuation of these exchanges between subsequent owners.

“When thou art in prosperitie, think on adversitie, and in Adversitie, hope for prosperity,” runs Hugh Haxley’s inscription (s8v); “for it is but a small thing wth god, soddenly – To make a poore man rich. In all thy glory, memento mori”. This is a rare occurrence of annotation with a signature, and it ranks among one of the more legible: some 200 pages of the volume are annotated in ink, ranging from underlining, single word notes, and manicules, through to interlinear translations in a minuscule hand and marginalia in a larger hand. Almost all of the work appears to date from the 16th century.

The annotations, in many different hands, show the book’s young users getting to grips with Terence’s language. Marginal notes on c5r present the translated phrases “I do not resent me of yt. I die” and “That yt was acceptable so you I prefer you hautye thanke”. On the same page, interlinear notes include a rendering of the printed “dictum puta nempe curentur recte hec” as “I knowe what you will say”. Fleeting phrases occur in the same manner throughout, whether as marginal notes (“his owne mynde to do his owne pleasure” (d1r); “shall youe fynd many spewde and knavish wordes” (e4v); (“3 who seme I to you or what mann[er] of man do I seem to you to bee?” (one of several on e5r)) or interlinear translations (“is this a thinge credible to be spoken” (e4r); “the matter came not wel to passe this waye but soe says and offer ways [...] yt chance not weltorwarde” (e5r); “yt is the selfe same thynge” (d5v)).

It is perhaps appropriate that most of the annotations cannot be confidently ascribed to any particular hands that have left their inscription; as a survival from a Tudor classroom, it bears the marks of the pupils’ engagement en masse, before it became a distinctive historical artefact for later owners such as Johnstone of Lathrisk. As a material illustration of several aspects of early modern schooling including the key role played by Terence, the apparent deployment of shared or exchanged resources, and the suggestions of scattershot youthful energy in the sometimes-chaotic inscriptions – this copy of Comoediae speaks volumes.

£13,500 Ref: 8235

References

1. Elk, Martine van ‘“Thou shalt present me as an eunuch to him”: Terence in early modern England’ in A Companion to Terence. Edited by Antony Augoustakis and Ariana Traill. (2013). p.416

2. ibid. p.410.

3. https://shakespeare.lib.uiowa.edu/exhibit

¶ Happenstance seems to have played as great a role as design in this rare survival from early modern England and Ireland. The volume was clearly designed to be carried around: its slim dimensions and wallet-style binding meant it could be slipped into the pocket, and brought out as occasion required. It functions as a register of chance moments of life: an address, a song or poem recited, a remedy required, all juxtaposed with the ever-present need to record financial transactions, among whose seemingly dry contents little nuggets of personality reveal themselves.

While we do not know who compiled this book, we gain a good picture of him through his interactions, the journeys he took, the kind of clothes he wore, the songs he sang, and the ailments he suffered. There are some clues to his profession, which seems to have involved knowing where certain personages were at certain times.

“Heare followeth all the dismal and perilous dayes in the yeare”, begins the section entitled “Curse Dayes” in the opening two pages at one end of the volume. This was probably the beginning of the book as it would have provided a strict guide to when –and when not – to carry out certain activities: there are, for example, certain days “In wch if any man, or woman be lett blood of wound or vein they shall dye 20 dayes following”,

English and Irish 17th-Century Miscellany of household expenses, songs, and remedies.

[County Cork, and London. Circa 1688-91 (dated in text)]. Tall quarto (181 x 75 x 9 mm). Text to both ends. 88 text pages on 44 leaves, some leaves excised and one torn vertically with loss (not included in page count). Text in two 17th-century hands, both neat and legible.

Journey”, and while they do not specify the duration, they do state that they “Shall be in danger to dye ere he come whome again”. Neither should a wedding be held on “Curse Dayes”, for “who soe weddeth a wife […] they shall soone be parted or else they shall liue together wth much sorrow” nor should “great worke” be undertaken, because “it shall neuer come to good”. In all there are 29 such days listed on which you should curtail your actions, but “there are allsoe 3 – Ill moon dayes” to worry about.

Contemporary wallet-style calf binding, lacks tie. The text is arranged tête-bêche. This is a term borrowed from philately. And although some prefer to use dos-a-dos, such a volume is usually understood to have a central board so we have opted for the former as it more accurately describes the composition, furthermore it indicates that it was probably bought as a stationer’s blank book rather than bound after writing.

At the opposite end of the volume to “Curse Dayes”, after a dozen pages of accounts and memoranda, our scribe records three poems or songs. The first is a rendering of a poem by Thomas D’Urfey which appeared under several titles including ‘The crafty mistress’s resolution’, ‘Excuse me’ and, as here, simply ‘Song’. Although the poem was published in two contemporaneous collections (A compleat collection of Mr. D'Urfey's songs and odes, 1687, and The theatre of complements, 1689), our version is arranged into seven stanzas, and begins “All ye town soe lieud is grown”. There are differences to the wording of the printed version in several places, which strongly suggests that our scribe’s rendering came via the oral tradition or from another manuscript. Curiously, for such a popular author the First Line Index records only one other manuscript version, namely Bod: Rawl. poet. 196.

On the opposite page, he has rendered “Ise oftne for ^my Jenny Strove”, which appeared in several printed versions, but none of which seem to match ours. As with the previous poem it is recorded in only one other manuscript volume the very same manuscript: ‘Bod: Rawl. poet. 196’ (‘I've often for my Jenny strove’) whose last line “Joined to none but only thee” closely matches ours: “Joyn’d wth none but onely thee”.

Further confirmation of the theory that our scribe was collecting material from either oral or manuscript sources comes from the third song in this group: “As he lay on the plaine wth his arms undr his head”, which circulated only in manuscript (until 1713, when it was published in The Guardian). The First Line Index records only two copies of this poem: ‘Bod: Montagu e. 13’ and ‘U. Chicago: MS f553’.

In one section, across nine pages, our scribe has grouped together the musical notation to 12 “Irish Crye”, “Capt. Pursels delight”, “The Antick dance”, “Shack boots”, “The Duke of Munmoths Jigg”, “Prithy dearest doe not “A Tune from These are immediately followed by another clutch of three poems, the first of which is “Ah Chloris! that I now could sit” by Sir Charles Sedley, which appeared as a song in his 1668 The mulberry-garden and was included in collections such as The academy of complements (1639, and later editions) and (1672). We have

located three manuscript copies: ‘Folger: V.a.308’, ‘Yale Osborn A0721’, and ‘BL Harley 3991’. The next two entries are variations of ‘I've often for my Jenny strove’, the first of which has been struck through.

One exception to these verse groupings, nestled alone between notes of financial payments, is “Out upon this fooeling for shame” – a rendering of a “manuscript-circulated piece about a woman’s having covert sex on a fashionable social occasion”.1 CELM records a 29-line version ascribed to Sir Philip Sidney, beginning ‘Naye, phewe nay pishe? nay faythe, and will ye, flye’. A shorter version, beginning ‘Nay pish, nay pew, nay faith, and will you, fie’, was first published, as ‘A Maids Denyall’, in Richard Chamberlain’s The Harmony of the Muses (London, 1654). We have also found a yet shorter version, entitled ‘Love’s Folly’, in drollery, or a collection of jovial poems the first part rendition begins: “Nay, out upon this fooling for shame”.

Our manuscript, which shortens it to 16 lines, often takes a more assertive or accusatory turn, so that “Nay pish, nay fie, in faith you are to blame” becomes you’r to blame” faith I dare not do’t” is rendered upon't, I faith I’ll not doe it” couplet in the 1654 Sidney version reads:

Your buttons scratch (O God) what a coil is here You make me sweat, infaith here’s goodly geere

Whereas the 1668-73 renders this:

Your Buttons scratch me, you ruffle my band, You hurt my thighs, pray take away your hand; And our manuscript has the equally earthy variation: You tumble my head, you Ruffle my band, You Squeeze my breast Pray take ^away^ yor hand

The 1654 and 1668-73 versions show significant variations: the final line of the former reads “After at Cards we better will agree”, while in the latter it becomes “Since it’s no more pray tickle me”, and in ours “Then Pray good Sr come tickle me”. Although closest in length and content to the 1668-73 version, our poem displays different characteristics to the heroine – and like the other poems in this volume, it has come from either the oral or manuscript tradition.

Aside from this single instance, our scribe has grouped the poems into two batches, one of which is juxtaposed with musical notation (albeit not directly related) and suggests that either he was copying from another manuscript or he heard them one evening and jotted them down in his (apparently ever-present) pocketbook.

A large proportion of the financial accounts recording in-and-out monies from rents and loans are rarely as workaday and colourless as they might at first appear: locations and connections are inadvertently revealed (see below), we learn his gender through monies paid to his wife, and we also glean some sense of his priorities. Clothes, of course, must be bought, including such items as “1 shirt 4 sleeues 4 stockins 2 Caruats 1 Cap & 1 handkerchiue”, but our scribe also requires “trimming for ye Rideing coate, coate – Britches & Beste Brits 00=13=09=1”. When it comes to shoes, he seems to have some obligation to his sister, but apparently only after he has the best and the second-best pairs:

It – for a payre of Shoose for my selfe 00=04=00=0 It – for a payre for same 00=03=06=0 It – for a payre for my sister Jane 00=02=10=0

Scattered throughout the volume again, seemingly on the hoof are short remedies (usually half a page) such as one “For the Jaundice”, which requires a little “Cyrup” and “Conserve” of “Barbaryes” together with spices such as “Saffron” and “Turmarick”; one then mingles “all ye Victualls” into a drink “& then put the same behind ye fyer back for 3 dayes”. There are two other half-page remedies: “For a Cough”, and “for a Sore Eye”; and a two-page recipe “for usquebah”. This word derives from the Gaelic for ‘water of life’ and is usually a recipe for whiskey (whisky if Scotch), but ours bears a closer resemblance to a kind of medicinal punch, calling as it does for “4 Gallons of spirrits or Good Brandy (being ye best)” and various spices including “Annis seed”, “Carraway”, “Colliander

Seeds”, “Nuttmeggs”, “Green Liquorice”. We are instructed to “Lett them Infuse 12 houers, or more ye better – then Distill them”. Following the addition of “Raysons solis” and more “Nuttmeggs” the mixture is infused for a further “six Dayes or till yor Liquor is high enough Collour’d pouer it of very fine & cleane & keep it for your use”.

Adding to the pocketbook’s sense of miscellaneity are seven pages of theological notes on the Epistles and “The 3 Lamentations”, an 11-line Latin poem (“Song. Amarila Ama me - Super modum amo te”) with a translation into English of the first stanza (“Amarila tould his swain …”), various memoranda and an inventory of household goods; this appears not to be an executors’ inventory as it omits finances, so it was perhaps a list of goods destined for removal. Either way, it makes for interesting reading and includes items such as “3 Beds &c” (valued at “45:00:00”), the usual chairs, tables, kitchen utensils and so on, but also unusual items like a “Settle bed”, “Spice Box”, and “3 Lookinglasses” (valued at “01:10:00”, “00:06:06”, and

“05:00:00” respectively) which, in an age of spartan possessions, indicate that he was fairly affluent.

The bulk of the manuscript entries relate to Ireland, but our scribe also spends some time in London, where, for example, he should “Inquire for Mr H. Strong att Margretts Coffy House”, and if this person is not to be found there, “att his House next Doare to ye Mercers Chappell or at Mr Goodwin ye Stationers neere ye Royall Exchange”. Beneath this he adds: “at ye Cloysters faceing Smith feild-at ye Indian Queene” .

Since all of these are crossed out, and a final note suggests he try “in St John Streete by ye Sessions House”, it may be that he finally found “Mr H. Strong” here, in an early example of a purpose-built sessions house for justices of the peace: Hicks Hall, or Hickes’ Hall, was a courthouse at the southern end of St John Street, Clerkenwell, London.

A “mdm” mentions one “Mrs Mary Orsby att Sr Edwd Wards att Generall In Essex Street, London”. While we have not traced Mary Orsby, we can be certain that she was at the house of Sir Edward Ward (1638-1714), who was a lawyer, judge, and chief baron of the exchequer, and is best known as the judge in the state trial for piracy of Captain Kidd. He died at his house in Essex Street, The Strand in 1714. Other London references include “Doctor Pack at ye Signe of ye Pack in Moone” and “Mr ffermin liueth att the Signe of ye 3 Courts” coupled with notes such as “The Ld Cidney hath a grant for ye office of ye Clkes of ye markets of England & that Commr: will be appointed to Inspec & Receue all mony that hath been leuid upon Diseuers”.

References:

Marotti, Arthur F. The Circulation of Poetry in Manuscript in Early Modern England. (2021). Vine, Angus. Miscellaneous Order. (2019). https://celm.folger.edu/repositories/bodleianrawlinson-50.html#bodleian-rawlinson-50_id497129 https://firstlines.folger.edu/

Our pocketbook owner does not give his exact location in Ireland (there are general references to the likes of “Sr Joseph Fredeman concern’d in cheife of ye Irish Committee”), he mentions a number of locations in County Cork (Castelyons, Youghal, Connagh Castle), and records the costs incurred for places further afield (Limerick, Kerry, Dublin, Munster), so it seems reasonable to assume that he lived in County Cork, probably the city itself. For instance, he travelled “to Castlelyons in ordr to receiue the monney”, but does not mention travel expenses, whereas “wn I went to Lymerick” the costs came to “00=11=06=0”; the exact same amount was incurred “wn I went to Kerry 00=11=06=0”, although when “Harry […] went to Dublin” it cost only “00=02=06=0”, which suggests that either Harry lived close to that city or travel to it was cheaper. A note recording travel by boat: “Saturday the 6th of Apr 1689 about 5 of the Clock in the after noone I saild from yeoughall & arriu’d att Mytehead on Munday the 8th following”, situates him in or near Youghal, which lies east of Cork and was an important harbour town in the early modern period. In the year our scribe took his trip, King James II issued an order that colonisers with a “zealous attachment to the Protestant religion” were to be rounded up and detained in castles in Youghal where they were held for 12 months before being released to flee back to England.

Among the financial accounts our scribe mentions an “Ante Rayners” who lived in Limerick, but more compelling are the numerous members of the Jerman family who appear in different contexts including in Ireland and in London, so it is plausible that he shared this name. One entry recounts “Edwd Jerman Senr of Connagh Castle in ye County of Corke & Prouinces of Munster in Ireland wth 5 sonns & 1 Daughter & not able to helpe himself being Sick ^& yet in Ireland but his edler sonne now in England being forc’d to make his escape to prserve his life”. This pitiable tale culminates in a valuation of “His Losses in Ireland” which include “90 Cows & Bullocks vallue 120 – Corn in Hayyard 12 – Corne in Ground” - totalling the eye-watering sum of “£4365”. One page later he writes “Enquire for Mr James Jerman att the Signe of the Bell in Wood Street”.

Other references are scattered throughout the book: on one page he lists the names and addresses of members of the family with different surname spellings and differing social ranks ranging from “Mr Wm Jarman a Distiller of Strongwaters” who lives “Neere Newmarket in London” to “The Lord Thomas Jermyn Barron of Berry & Gouernour of ye Isle of Jersy” and “John Jerman of Shelton in Norfolk” who is simply “A Person”.

A few pages later, after the recipe “for usquebah”, he adds the note: “March ye 5th 1695 betwixt ye Houers of Nine & tenn of ye Clock att Night our Daughter was born ye wind North: North East” (again displaying a concern for auguries). If our extrapolation that his interest in members of the Jerman family is genealogical, then possible candidates for a girl born that date bearing the name Jerman (or a variation) include the following: Susanna Jerman, the daughter of Edward and Mariae, was baptised 8 March 1695 (her exact date of birth is not given) at Glemsford, Suffolk, England; Catherine Jarman, the daughter of Samuel Jarman, was baptised on 5 March 1695 at St. Mary's, Ely, Cambridge (again the date of birth is not stated, but given our scribe’s references to County Cork and London, neither Glemsford or Ely, while not impossible, seem unlikely). More promising, but requiring a wider variation in spelling, is Margaret Germain, the daughter of Edward and Margaret Germain, born 5 March 1695 and baptised on 18 March 1695 at Saint Martin in the Fields, Westminster, London. The dates and location make her the most likely candidate, which would make our scribe Edward Germain. However, this conclusion requires several leaps, so we leave it there inconclusively for future researchers.

The diversity of 17th-century life and culture is neatly encapsulated in this manuscript notebook, with its miscellaneous contents: recipes, a household inventory, songs, musical notation, and memoranda jostle among financial accounts. Our scribe’s wallet-style pocketbook has the characteristics of a volume carried around to record things ad hoc, and in its transcriptions of popular songs and poems it conveys the protean qualities of oral and manuscript culture. Above all we get a sense, among the transactional notes, of what caught the attention of this eclectic compiler who captures early modern life in all its variety as he travels between England and Ireland.

£6,500 Ref: 8264

¶ This volume captures a transitional stage in the physical and textual development of the notebook format. Its tall oblong orientation is descended from the accountant’s daybook, whose columnal arrangement helped shape the compositional conventions of the commonplace book and the miscellany – two similar-but-different formats that organised information in such a way as to allow sometimes disparate elements to co-exist in a unified space.

The manuscript appears to have been compiled by Alexander Evesham, who has inscribed f.21 “p[er] Alexander Evesham Anno Elizabethe

Regina 19 Anno[que] domini 1577”. Alexander was the son (one of 14) of William Evesham (1518/19–1584) and his wife, Jane (d. 1570), daughter of Alexander Howarth (or Howorth) of Burghill.

There are three recorded manuscripts associated with Alexander Evesham:

1. Harley MS. 615 “A Book in fol. fairly written”. “Genealogyes of Gentlemen of Hereford, Wooster, Gloster, & Shropshere At the Chardge of me Alexander Evesham”.

2. Harley MS. 214. “A Book in long 8vo”. “Proterologos, or the Nobilitie described... are plainlie set down by me Alexander Evesham”.

3. College of Arms MS. A.9. Arms of Nobility. 1585. (322 x 210 mm).

¶ [EVESHAM, Alexander (d. 1592)] English

16th Century Manuscript Alphabet of Arms and Armorials.

[Circa 1577]. Tall oblong octavo (380 x 125 x 15 mm). Manuscript text and illustrations to approximately 100 pages on 54 leaves. The manuscript is lacking some leaves, exactly how many is difficult to say but almost certainly a substantial portion, as the text commences with section M-W of an alphabet of arms. Some leaves repaired to edges, lined with tissue and few lined to verso on paper. Bound in old (but later) limp vellum covers.

Provenance: inscription of Alexander Evesham dated 1577. W. A. Foyle, Beeleigh Abbey.

Our volume now adds a fourth to the list of extant manuscripts by Alexander Evesham. It appears to be the predecessor of MS. A.9., which is described as “a heraldic and historical commonplace book containing painted arms ... begun in 1583 an finished in 1585 in London”. Both are probably more accurately described as miscellanies rather than commonplace books, since neither of them group information under subject headings but instead collect a mixture of related material in no particular order.

Alexander’s brother Epiphanius (fl. 1570-c.1623), a sculptor, painter, and metal-engraver who has left more traces than his sibling in the historical record, is quoted in the 1886 edition of Robert Cooke’s The visitation of Herefordshire, edited by Frederic William Weaver, giving an account of Alexander’s death in the following note by his brother Epiphanius: “The transcript [of Harley MS 615] was made at the charge of Alexander Evesham, of whose death there is an account on folio 1. ... “In the year of our Lord God 1592 dyed Alexander Evesham and in 28th day of descember he dyed in the house of the Lady Stafford at Westminster and was buryed on the South Syde of the Church of Saint Margrett his hed lyeth just agaiynst the end of the pew of the left hand; he was the son of William Evesham of Wellington in the County of Hereford ... Thys wrytten by me Epiphanyius Evesham in the yeure of our Lord god 1592 whos soule Resteth with Gode. Amen.”

Our volume begins with letters M-W of an alphabet of arms (ff. 1-19, 21), followed by sketches of armorial shields (ff. 20, 22-24) and blank pen-and-ink shields, approximately 99 to a page (ff. 24v-33). After some blank leaves (ff. 34-37), there is a contemporary copy of a grant of arms to William Haynes dated 1578 by Robert Cooke (f. 38) and notes on the nobility, possibly copied from Robert Cooke’s work (f. 39r).

There follows a drawing of a shield to f.39v: Stury arms is Argent a lion rampant crowned queue forchee double nowed Purpure, annotated above “Stury”. This leaf has been cut down with significant loss, but preserving at the top a short poem in its entirety:

To old men or childrene few giftes geve and eke to wemen kynde

The old man dyes, the child forgetes and wemen chainge their myndes

Beneath is the same text in Latin:

Munera pauca seni puero des et mulieri

Hic moritur puer immemor est cor femine mutuat

References:

A Catalogue of the Harleian Manuscripts. 1808.

A Catalogue of Manuscripts in the College of Arms. 1988.

Cooke, Robert The visitation of Herefordshire, edited by Frederic William Weaver. 1886.

We are extremely grateful to Dr Robert Colley and Christopher Whittick for their invaluable assistance.

£1,750 Ref: 8251

After another set of pen-and-ink sketches of armorial shields, these numbered 150-233 (ff.40-42), and some blank pen-and-ink shields (ff 41-43), another alphabet of arms begins, but only covers A-B (ff. 44-47v). Its format is different to that of the M-W section with which the volume begins: in the A-B section each entry is numbered, whereas M-W is unnumbered; and while both give family names along with their blazon, in A-B some are illustrated with small inset shields. The numbering here seems not to correspond to the M-W illustrations, so it is unclear whether Evesham was experimenting with the format using two different alphabets of arms or whether he simply abandoned the numbering system partway. A notable feature of the manuscript is that the shields are not tricked and blazoned sufficiently to identify arms, so any user would have had to be among the heraldic cognoscenti.

On f.48v Evesham has copied another grant of arms, this one to Henry Brodbridge dated 1577 by Sir Gilbert Dethick (unfortunately with the shield excised); and folios 49-54 comprise part of a baronage, unattributed but probably originally prepared by Robert Cooke.

As is often the case with early modern manuscripts, some of its interest lies in the extra details – and these are especially notable as Evesham renders them as addenda to each section. For example, in the M-W section at the end of P we learn that “John Passwater first steward to Sr tho cheyney knight after steward to Sr henry Sidney knight Lord deputy in Ireland wch John died ye 24. aprill 1555”, that one “Wm Phillipp of London [was] customer or Recever of the custom for wooll & clothe wthn the porte of London”, and, tragically, that “John Osbourne one of the auditors ... in Q.E. tyme ended his life ye 21. may. 1577” (although we do not learn how or why, as the text reverts to a description in blazon of his arms).

Evesham’s Elizabethan miscellany is the very definition of a working document: it shows him in the act of assembling and ordering information, including parts of an alphabet of arms, sketches of armorial shields and copies of grants of arms by Cooke and Dethick. Its material history has been complicated by loss, damage and restoration, adding to its air of untidiness, but it retains its character as an on-the-fly workbook and a work in progress.

¶ A profusely annotated Plantin Bible, with 16th century annotations in secretary and italic hands with underlining throughout. It was owned first by the prominent 16th-century physician Thomas Moundeford – and annotated in either his hand or a contemporary – then by the influential 18th-century Scottish moral philosopher Frances Hutcheson.

Thomas Moundeford (1550-1630) was president of the College of Physicians and author of a slim volume entitled Vir bonus (1622) (dedicated to several worthies including James I, the Bishop of Lincoln, and a batch of judges) in which he “praises the king, denounces smoking, alludes to the Basilicon doron, and shows that he was well read in Cicero, Tertullian, the Greek Testament, and the Latin Bible” (ODNB).

¶ [MOUNDEFORD, Thomas (1550-1630); HUTCHESON, Francis (1694-1746)] Biblia, Ad vetustissima exemplaria castigata, 2 parts in 1, Antwerp, Christopher Plantin, 1567. Octavo. Foliation [8], 303, [1, blank], 74, [4]. Woodcut architectural title border, I7 verso printed correction slip pasted in. [D&M 6150].

18th century speckled calf, spine gilt in compartments with tulip decoration. Front board detached, small hole in lower margin of title, margins cropped affecting manuscript notes.

If the hand is indeed Moundeford’s (his inscription (see opposite page) is too elaborate to bear comparison with the annotations), we can see him engaging thoroughly with this copy of the Latin Bible: some 465 individual pages have been copiously underlined and annotated (circa 385 in the Old Testament, and circa 80 in the New). Notes range from single-word memos with relevant printed text underlined (“Ebrietas”, “sapientia”, etc) to longer marginalia running over several lines (e.g. “Angeli lenarates ne flarent mali & qui spirit verbi dei impe anter pro omibus posint repugnant verbi dei” f.70v NT). In his inscription to the rear, he states “praetiu vs . anno 1569 . Ætatis 18”, so if the annotations are his, he may well have made them as a callow 18-year-old eager simply to mark, learn and inwardly digest the contents.

£3,500 Ref: 8237

Provenance: Thomas Moundeford’s copy with his ink ownership inscription at head of title (“T. Moundefords”) and colophon at end

“Thomas Moundeford. praetiu v Ætatis 18”.

Francis Hutcheson’s inscription to *2r Hutcheson 1720”

bookplate of F. Hutcheson M.D. to front pastedown. A slip inserted into the back of the book reads “This book belongs to E.H. Leslie”, with an embossed address in Donaghadee, County Down. Hutcheson was born in near Saintfield in Country Down, Ireland.

Francis Hutcheson (1694Hutcheson 1720”), was Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow and author of several treatises on beauty and virtue, morality, and the emotions, as well as the posthumously published, multi-volume

David Hume, Adam Smith and other Enlightenment thinkers, and several of his works “were widely used in Scottish and American universities in the eighteenth century” (ODNB). Hutcheson’s library was passed to his son Francis Hutcheson M.D. (1721 front pastedown.

Moundeford’s facility with Biblical Latin, noted by the ODNB, could have originated in his labours with this text; at the very least, the annotations, show the scribe in the process of developing their skills through copiously and studiously annotating this book.

¶ [BAYFIELD (née RISEBROW), Elizabeth (1722

Provincial Woman.

[North Walsham, Norfolk. Circa. 1743

The seven items in the archive are arranged in approximately chronological order

century women are often recorded in scant detail, much of which relates to their husbands. The 1790), whose material this is, is a case in point. Following the usual format, we might say that she was the daughter of Samuel Risebrow, surgeon, of North Walsham, Norfolk, (d. 1727 aged 32)

Elizabeth, however, gives a good account of herself in this rich and varied archive. Her writing style is fluid, accomplished, and often observant or witty, and she is clearly well read and sufficiently aware of the era’s coterie culture to partake in some of its conventions. Three of the volumes in turn show her engaged in the activities of writing, travelling, and reading. The archive is given further breadth and context through complementary material including a book of recipes and remedies and evidence of books

¶ [1]. Elizabeth’s opening inscriptions date these poems to her early-to-mid-twenties and suggest that her earnest versification ended the same year as her marriage began (1747); indeed, they could represent her ‘farewell’ to her younger, unmarried self. The first poem, “My Wish 1744/5”, acquires some poignancy in this light, as she beseeches “yea Gods” to grant her wish to “enjoy a house […] Near to a wood near water”, with a small menagerie, two servants and “two Hundred pounds a year”. The second poem, “My Epitaph”, seems of a piece with the first, with its introverted, idealistic air and its exhortation to “Contemn all Riches look for Peace above”. And the place of women in society is touched upon, in a poem in which the death of an infant is felt:

“Without Doubt the more as this was a Boy, As Girls are esteem’d no more than a Toy”.

In her volume’s original poems, Elizabeth engages in a culture of exchange which she reinforces through classical allusions (“Juno”, “Cupid”, “Leander”) and coterie names (some of her poems are signed “E. Risebrow” or “ER”, while in others she uses the sobriquets “Rosalinda” or “Belinda”).

¶ [1]. Manuscript notebook entitled “Verses on several subjects” [Circa 1743-47].

Slim quarto (185 x 155 mm). Approximately 34 text pages on 31 leaves, plus two loose leaves. Contemporary stationer’s booklet with wrappers made using an old engraving by De Poilly.

Damp damaged, text block loose in binding, binding and text torn and edges frayed.

Inscription to front wrapper reads “Verses made by me E Risebrow began in ye Year 1744 / October ye 31 1745 1745:” and inscribed to inner wrapper “Verses on several subjects made by me E: Risebrow 1743 1744 1745 1746 1747”.

“Miss Kitty Cooper” (also referred to as “Dearest Sister”), who actively encourages exchanges (“To Miss Cooper who Bid me write to her in Verse”), and at other times is admonished for remissness (“write a Long Letter, or else you Receive / no more Letters from me”). Other figures include the Berneys who lived at Westwick House, a short “Horse Chaise” ride away from Elizabeth’s home in North Walsham. We encounter family members such as “Miss Julia Berney”, but it is William Berney who is elevated with the coterie moniker “Thirses” (presumably a reference to the shepherd Thyrsis, in Virgil's seventh Eclogue), in numerous poems where they exchange such things as “Paper of Ashes in a Glove” and “a Receipt to Cure Love”.

¶ [2]. A year before her marriage, Elizabeth took a trip to Yorkshire with three friends (“Captain Cooper, Miss Peggy & Miss Kitty”), which she commemorates in a narrative dedicated to “Miss Kitty Battely, Suffield” (probably Catherine Battely (circa 1717-1787) of Suffield, Norfolk). Like her poems, this story seems to be part of a gift economy (although it is not certain it was ever sent): it is offered to “to you, and you alone, I dare Attempt to send it”.

Elizabeth relates her journey in lively prose and with a keen eye for details. Along the way, she remarks upon the places she stayed (“The Market is an Extream good one, well supply’d with all sorts of Provisions Especially Salmon the River abounds with Plenty of Soles Smelts & other fine Fish in great Perfection” (p.2)), while avoiding others (“We did not stop at this Town [Leeds] the small pox being allmost in Every House” (p.17)).

¶ [2]. Manuscript notebook entitled “Travells of a Month into Yorkshire in 1746”. [Circa 1746]. Slim quarto (195 x 160 mm). Approximately 30 text pages on 17 leaves. Contemporary stationer’s booklet, marbled wrappers.

She comments on architecture (“The East Window is all of A Bright Colour’d Blew Glass both odd & Prett” (p.3); “nothing of any Curiosity worthy Attention except three Alablaster Monuments of Sr Edward Carr his Lady & two Sons” (p.5)) and includes historical notes – for example at York, she reflects on the fate of prisoners taken there for execution following the Battle of Culloden in April 1746: “In this Castle were two Hundred of the Scoth Rebels Poor Despicable Wretches, in their Highland Dress, four of whom where women, We staid but little time at this Melancholly, tho’ strong & well defended Place.” (p.15). A few days into their expedition, they are accosted by “four Rude Disorderly Fellows who Oblig’d the Gentlemen in their own Defence to Draw their Swords & take their Pistols they had A Skirmish about ten Minutes with no great Harm on either Sides, only we where much frighted”. After about an hour “they Gallop’d full speed past us, saying to the footman we shall meet you in A Better place By & By”; they did not meet with the ruffians again, but “we can’t help thinking them to be either Highwaymen or Smuglers, they had no Armes but where bold Desperate Fellows & extremely well mounted.” (pp.4 -5).

After this unpleasant incident, she relaxes into her journey through the countryside, making notes on agriculture and landscapes and shifting seamlessly from geological observations (“having many great Quarrys of stone some Veins of Iron Lead, & Coal” (p.8)) to poetic reveries (“I think nothing can come up to the Beauty of Unbounded Prospects on some of the Hills […] Which Strikes the Attentive mind with great Surprise, To see the Hills in Natural order Rise” (pp.8-9)).

She closes her account with another apology for “the faults I fear in this Journal” and a reaffirmation of their bond, hoping Kitty will cast “A Gentle Eye of Friendship and be always as much my Friend as I am Yours ER”.

¶ [3]. In this volume Elizabeth has mixed, and sometimes juxtaposed, diverse material from her reading with her own original verse. For example, “The search for Happiness or the Vision Universal Magazine March 1774” (pp.27 -31) is followed by two verse meditations on the close relationship between sleep and death by Elizabeth: “To sleep” and “Thoughts on sleep Ocr. 1785” (pp.32-33), annotated “*Don Quixote says Heaven bless the Man who first invented Sleep: it covers one all over like a cloak”, and concluded with a bittersweet reflection on the sight of a transient visitor: “Ode to the Swallow 1787”, whose migratory habit allows the bird to enjoy “summer all the year”

Some of the extracts are from contemporary novels, including thoughts on friendship from

¶ [3]. Manuscript notebook of “Sentimental Memorandums and Observations from the different books I have Read since the year 1766: Eliza: Bayfield”.

[Circa 1766-88]. Demi quarto (208 x 80 x 13 mm). Approximately 67 text pages (numbered in manuscript) on 68 leaves. Vellum stationer’s book, lacking clasps.

The Fool of Quality (1765-1770); The Mutability of Human Life; or, Memoirs of Adelaide, Marchioness of Melville” (1777); and The History of Emily Montague by Frances Brooke (1769), often considered the first Canadian novel. Elizabeth’s rendering of the text is very similar to printed text, but some of the wording differs, which implies she is absorbing the meaning rather than simply copying. Elizabeth’s thoughts are often mirrored in the books she read: on page 40 she comments on a melancholy written-out passage from George Crabbe’s “The Village” (published 1782), “a picture of my self at 64: E Bayfield 1787” – a year before her death.

¶ [4]. Written in different hands from the late 18th to the early 19th century. The volume was possibly begun by Elizabeth; the first two remedies (“For a sore Throat Mrs Coleman, Hembsby” (i.e. Hemsby) and a receipt for removing ink) have some resemblance to her hand. Thereafter, the volume is added to by several scribes, with a later contribution dated 1809.

¶ [4]. Manuscript book of recipes and household remedies.

[Circa 1780-1810]. Small oblong notebook

Manuscript recipes include the amusingly titled “Milk of Roses For Ladies Noses as well as Toeses” by a “Mr Randall”, and the more straightforward “For a Cough”, which is attributed to “Mrs Clarke and considered very good”. These are interspersed with printed clippings to “make a never-failing Mouse Trap, by which forty or fifty Mice may be caught in a night” and the “celebrated Pomade Divine” by “Dr. Beddoes” i.e. Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808).

(115 x 88 x 11 mm). Approximately 66 pages of text and pasted-in clippings on 42 leaves.

Bound in limp-calf, rear cover missing, but retaining original tie.

Watermark: Fleur-de-lis.

Whether begun by Elizabeth or not, it certainly appears to have stayed in the family: a recipe “For Chilblains” and “Plum or seed cake” is attributed to “Miss Bayfield, London”.

¶ [5]. Elizabeth does not display evidence of being Latinate in this archive, and she has not inscribed this book, so we do not know if it was hers. However, as noted above, she does make numerous classical allusions in her coterie writing.