TWO NATIONS

ONE REMARKABLE ARCHIVE

SPECIAL RELATIONSHIPS: THREE BROTHERS

SPECIAL RELATIONSHIPS:

Three Brothers . Two Nations

One Remarkable Archive .

Dean Cooke Rare Books

& Julia Krysiak

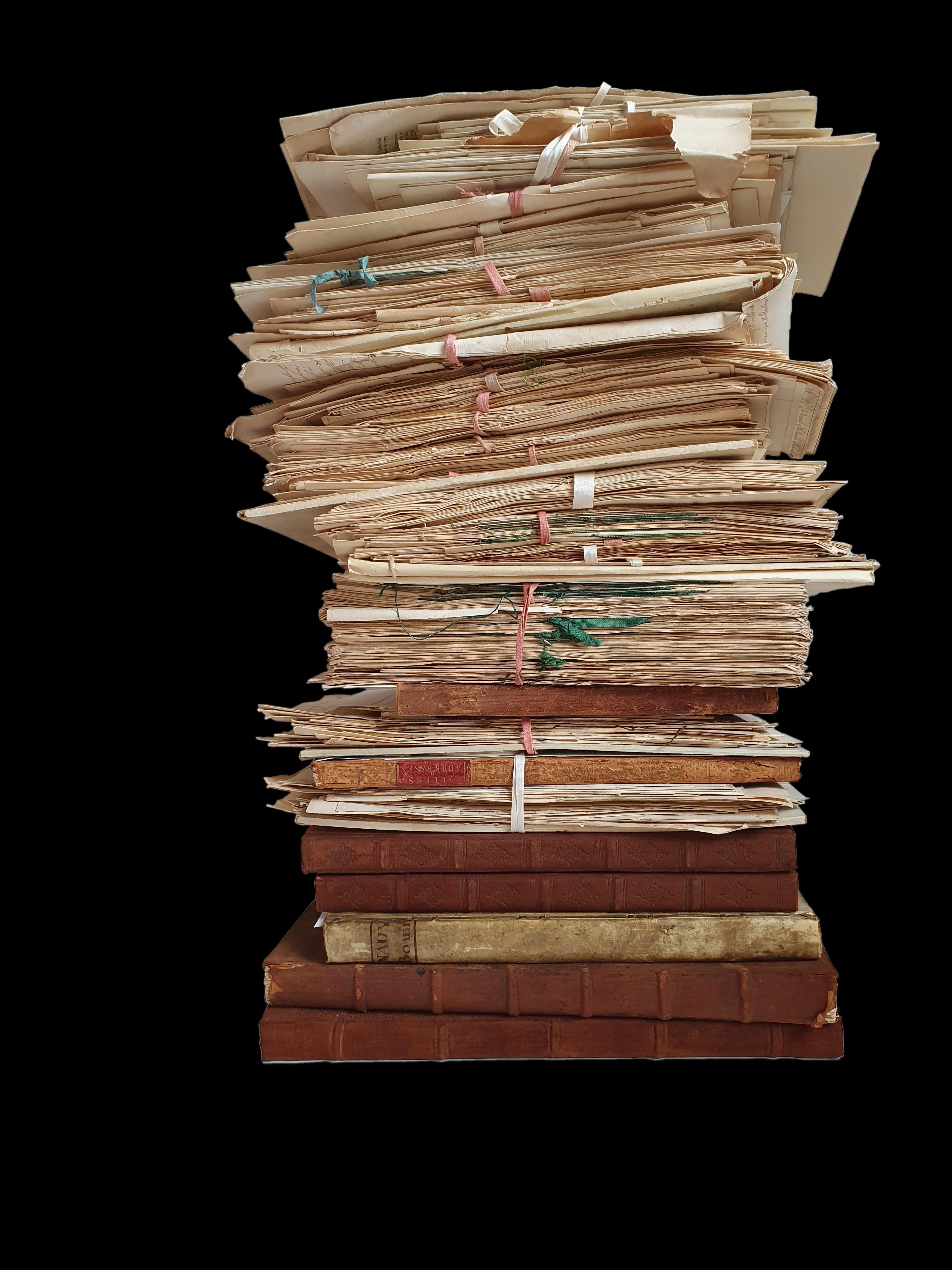

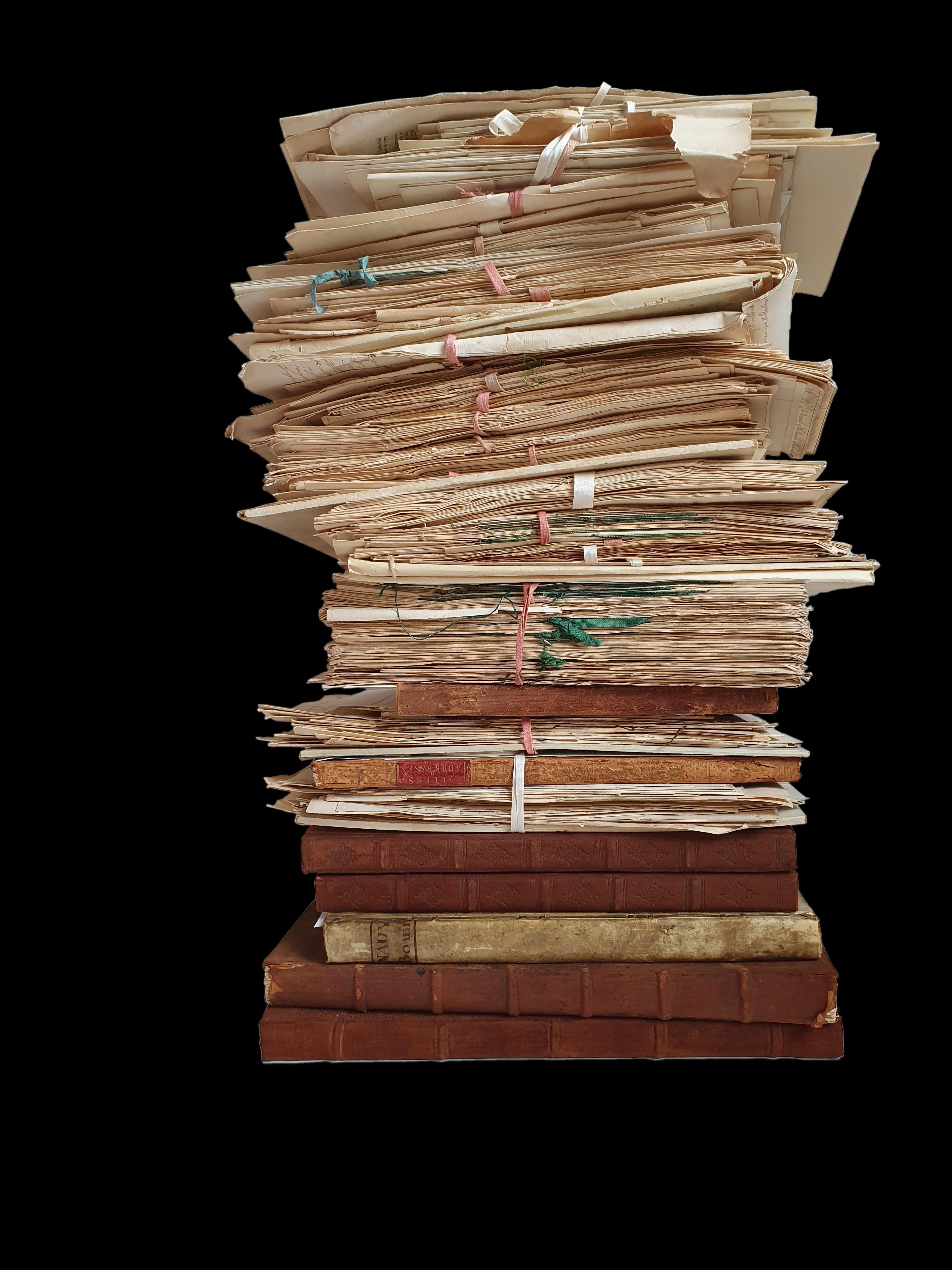

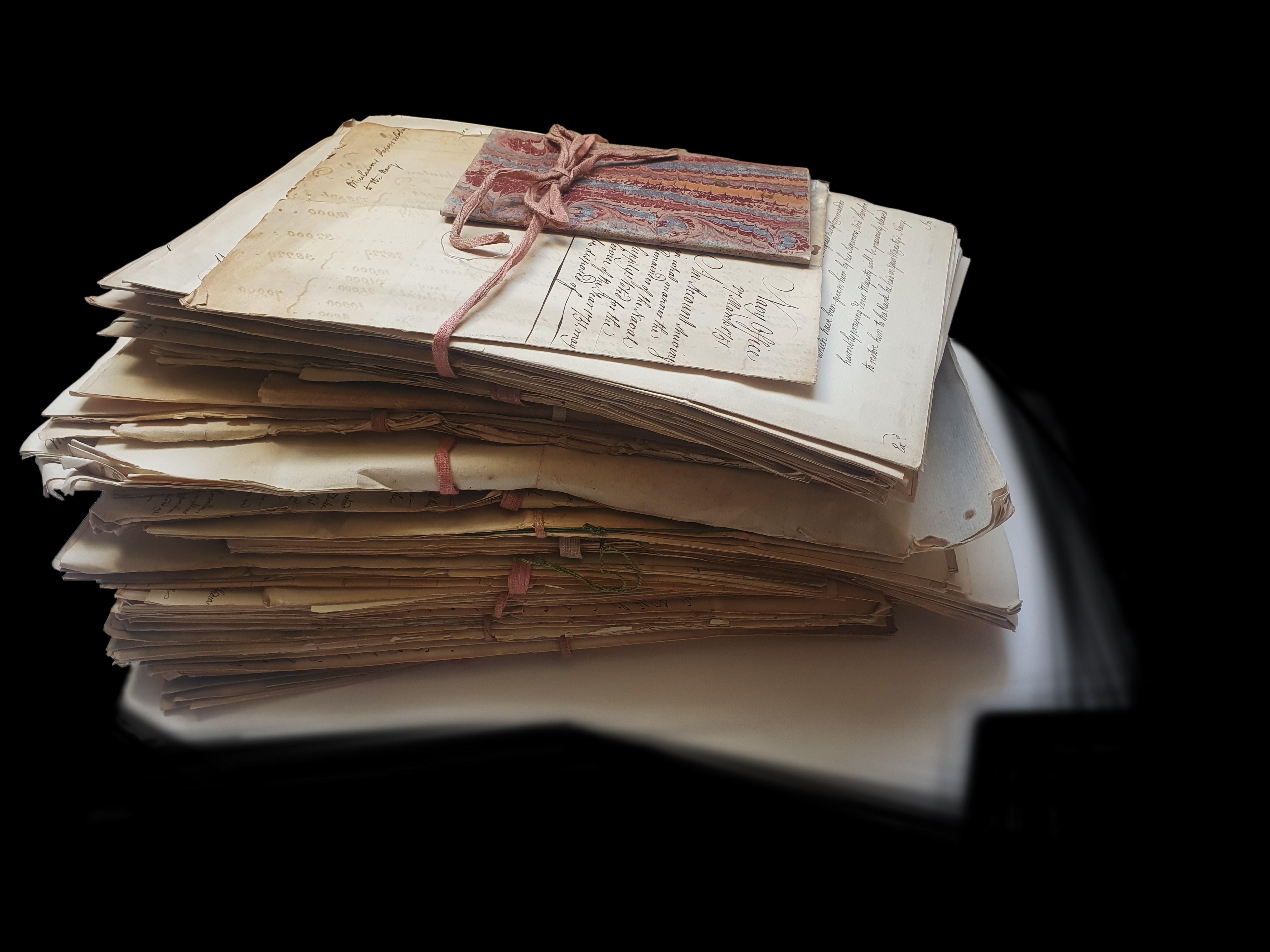

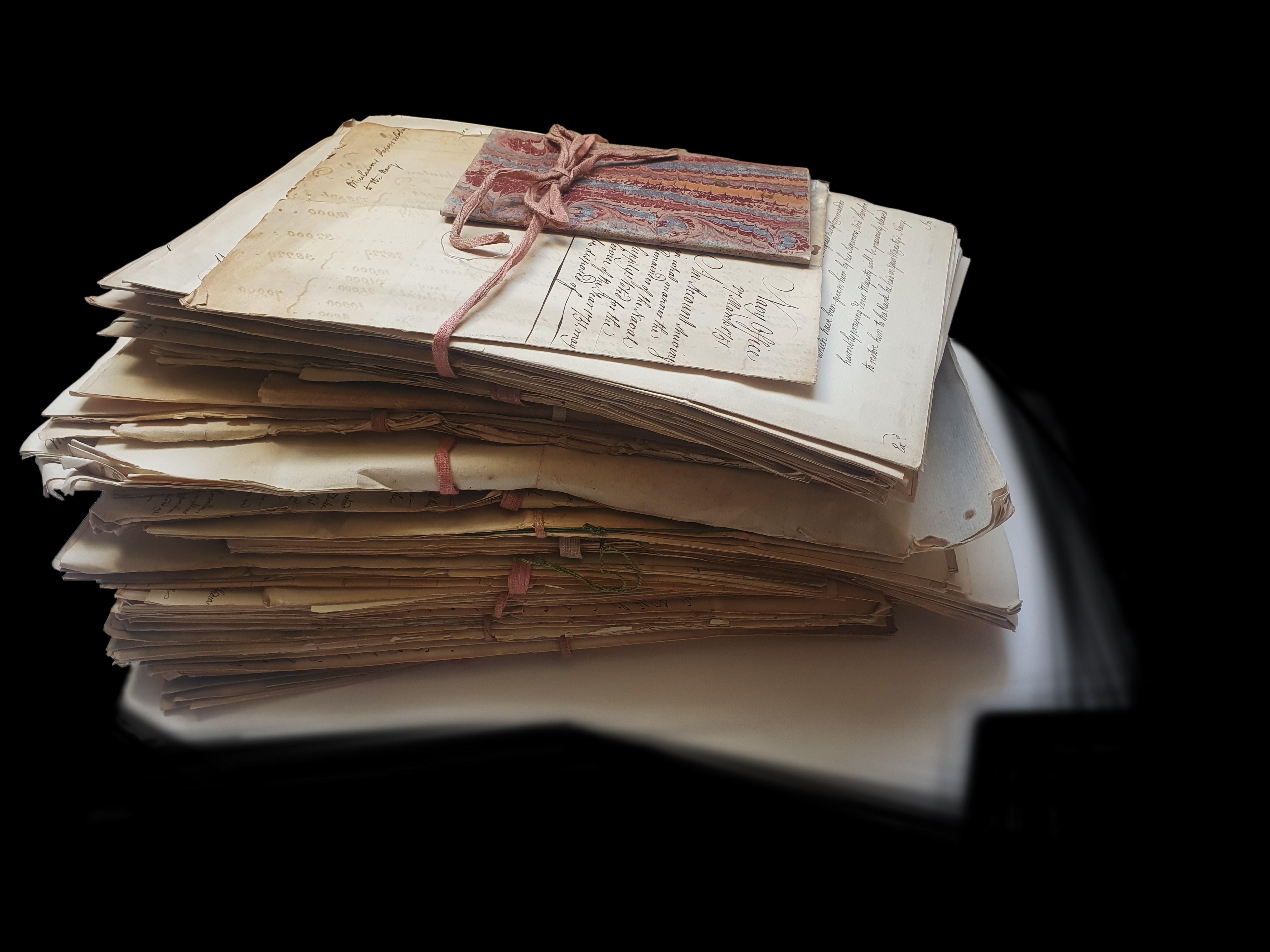

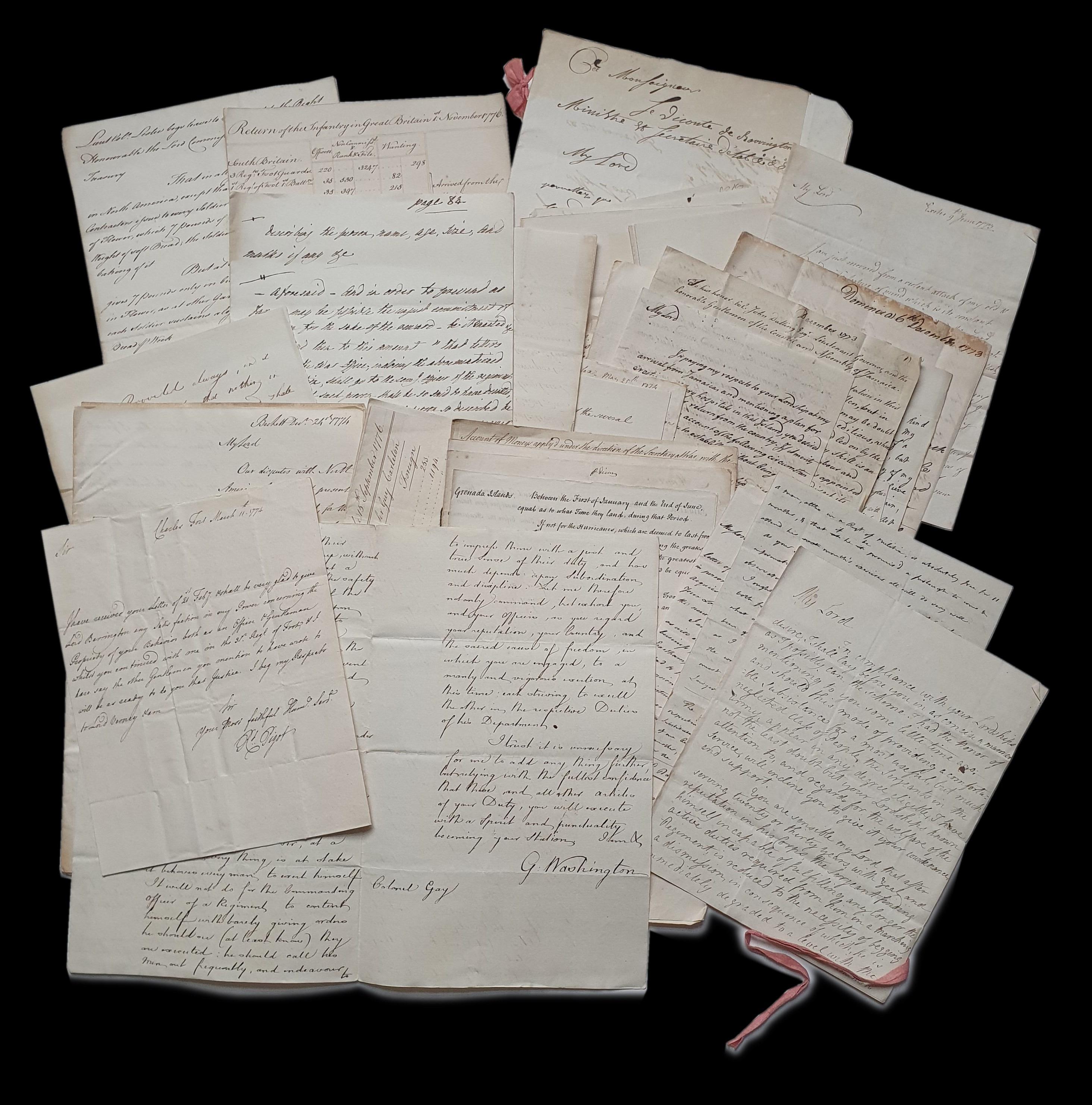

This hugely important archive comprises 7 folio letterbooks and journals, over 40 stitched pamphlets and booklets, and in excess of 600 letters and documents.

£65,000

Highlights include:

American War of Independence

Large group of letters and documents including correspondence and battle plans. 1770-1778.

George Washington

Copy of an intercepted letter from 1776.

The Stamp Act

Substantial group of letters and documents relating to the notorious Stamp Act. 1761-1778.

Capture of Guadeloupe

West Indies letterbook containing over 170 retained letters; complemented by a group of loose-leaf letters. 1759.

The Seven Years’ War

Two journals covering the period 1756-1766.

Correspondence between Barrington and disgraced Duke of Cumberland. 1756-1757.

Journal with detailed insights into a seminal period of British naval action against both France and Spain.

Capture of St. Lucia

Bound collection of original letters relating to St. Lucia and Barbados. 1778-1782..

Trial of Admiral Byng

Collection of original documents and letters relating to Byng’s Court Martial. 1746-1757.

INTRODUCTION

¶ Few families have meaningfully impacted the course of British and American history to the extent that brothers William, John and Samuel Barrington did. A politician, an army officer, and a naval officer respectively, each played a unique part in Britain’s development as a global power, and did so at a pivotal moment in the creation of the United States. This exhaustive, varied, highly detailed and fascinating archive offers both strategic and very personal insights into the trials and costs (political, economic, and human) of navigating a country through half a century of successive wars.

Covering four distinct historical periods, this remarkable archive focuses on Britain’s conflicts with its longstanding enemies – France and Spain – for European territories, and the escalating international contest for the West Indies and North America.

THE WAR OF AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION (1740-1748)

The disputed right of the Habsburgs to the Austrian crown - which involved all the great European powers including Prussia and the Dutch Republic – marked the opening struggle between Britain and France for colonial empire in North America, the Caribbean and India, and for maritime supremacy at large. At a time when the Barrington brothers were taking up their first significant posts (William as Lord of the Admiralty, John as captainlieutenant, Samuel as a naval captain), our archive shows Britain finely examining the state and manpower of its fleets and bolstering its overseas territories. In what comes to bear greater consequence in the trial of Admiral Byng nearly a decade later, we also see proposals for stricter British naval discipline and the key 1749 Courts Martial Act.

INTERIM PEACE — PREPARATION FOR WAR (1748-1756)

Anglo-French relations continued to deteriorate despite the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which ended the Austrian war. Here, at a point when William Barrington took up his first post as Secretary at War (1755-61), our archive shows Britain gathering enemy intelligence, refining official navy procedures, and improving navigation of the Thames to make valuable overseas trade more efficient. During a period of ostensibly peaceful relations between countries, our archive abounds with evidence of a government and its armed forces readying themselves from every angle for the major global conflict that was to come.

THE SEVEN YEARS’ WAR (1756-1765)

A great and interestingly varied bulk of our archive covers what may be considered the first ‘global war’. Despite Britain’s many successes, the immense financial repercussions of this period, which had already begun to accumulate in earlier wars, tipped Britain’s colonies into the American Revolution.

During the Seven Years’ War, we see all three of the Barrington brothers fighting their own campaigns – on land, at sea, and at Whitehall. William Barrington’s War Office collection opens the door to the interim ministry of William Cavendish and William Pitt the Elder as they reprioritised America (1756-57).

The archive includes a substantial and detailed examination of the trial and ultimate fate of Britain’s first and last Admiral to be executed, John Byng, after Britain’s loss of Minorca in May 1756 – the root of his infamous court martial.

The crowning but desperately hard-earned battle of John Barrington’s career, the capture of Guadeloupe during the 1759 Annus Mirabilis, or ‘Year of Victories’, is powerfully related in both his personal journal and his brother William’s papers – the brutal realities of war versus their triumphantly reported victories being a theme running throughout the archive. As we inch towards the end of the war, we see William in the role of Treasurer of the Navy (1762-65), and the diverting cases of John Wilkes’ satirical North Briton and Major Nicolas Dunbar’s extortion attempts that Barrington had to deal with alongside his more bureaucratic duties.

THE STAMP ACT & THE AMERICAN WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE (1765-1783)

The inflection point for the American Revolution – the infamous Stamp Act of 1765 – opens this final period with a rich and distinctive collection of papers. This controversial act sought to raise money to pay for the British Army in its American colonies through a tax on all legal and official papers and publications circulating there. Violent protests erupted in America and the colonists famously argued that there should be “no taxation without representation”.

William Barrington’s detailed records from his second stint as Secretary at War (1765-78) show Britain and America preparing themselves for one of the biggest battles in their shared history. This archive includes numerous documents exploring British policy in America, Canada and the Caribbean, including General William Howe’s executed plans at the Battle of Long Island, the war’s first major conflict (August 1776).

A notable item in the collection is a scribal copy of an intercepted letter by George Washington from 1776 demanding better discipline of troops. This kind of intelligence provided vital information on morale and other details for guiding Barrington’s formation of battle plans.

Samuel Barrington’s moving letterbook and papers during his command of the Leeward Islands squadron in the Caribbean (1778-89) reveal the very real human struggles of conducting remote warfare in weather-battered conditions with little communication or aid. Samuel’s capture of the strategically crucial St Lucia on 30 December 1778 was one of Britain’s greatest naval achievements of the period, securing continued access to the valuable sugar -producing colonies of the eastern Caribbean. A final collection of papers from William’s archive, ending a year before his death, reveals the examination into Navy accounts by the nascent National Audit Office, which hung a supposedly unpaid sum of £22,500 over the former Navy Treasurer’s head for 11 long years.

BRITISH EXPANSION & AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

“How illustrious are honourable deeds” reads the motto of the Barrington family crest, expressing the values that, as our archive shows, brothers William, John and Samuel held in earnest. Its wide-ranging contents reveal the considerable personal and professional challenges that each of them grappled with during their services to the crown at a time of enormous change, both in Britain and abroad. It was during these decades that Britain rose from a small nation on the periphery of Europe to a global power with an international empire, and the Barringtons’ roles in Britain’s actions in America, the Caribbean and Europe affected the course of their nation’s history.

Domestically, the second half of the 18th century saw widespread reforms and professionalisation of British political, military, and naval life, but the Barrington brothers remained a constant throughout. The range of roles they occupied means that, taken together, their papers offer a variety of lenses – military, political, administrative, and personal – through which to view these events. The level of detail that characterises much of our archive brings alive the chaos and suffering underlying such apparent triumphs as the Annus Mirabilis, and the physical and psychological toll exacted as a result.

The Barrington brothers were significant actors in the world-changing events that led to Britain’s expanding influence in the North American colonies, then to the contraction of its power as America won its independence. This important archive is testament to the mark left by William, John, and Samuel Barrington, and a valuable asset to any archive interested in this transformative period in British and American history.

THREE BROTHERS

William, John, and Samuel Barrington were the first, third and fifth respectively of six sons of John Shute, first Viscount Barrington (1673-1734), politician and Christian apologist, and his wife, Anne Daines (d. 1763), the daughter of Sir William Daines. Their other children included Daines Barrington, a judge and natural philosopher, and Shute Barrington, Bishop of Durham, and three daughters, Sarah, Anne and Mary. John Shute had inherited two considerable estates, one of John Wildman of Beckett, Berkshire – the other, Tofts in Little Baddow, Essex, following the death of relative Francis Barrington. In accordance with the latter’s will, Shute assumed the name and arms of Barrington of Essex.

WILLIAM WILDMAN BARRINGTON (1717-1793)

William was born in Beckett, Berkshire he became the second Viscount Barrington in 1734. He went on the grand tour aged eighteen, and returned to England in 1738. In 1740 he was elected as a member for Berwick upon Tweed. The same year, he married Mary Grimston (d. 1764), the daughter of Henry Lovell and Mary Cole. The couple had no children. On entering parliament, in contrast to later years, William was in opposition to Walpole’s government. In 1746 he was appointed a lord of the Admiralty, embarking on his long and unbroken commitment to public service. He quickly gained a reputation as an effective administrator and, at George II’s request, he was appointed as master of the great wardrobe in 1754, a position of great political influence. That year William was also elected at Plymouth, a seat he held until his retirement over thirty years later. In 1755 he became secretary at war, an appointment that lasted, in two spells, for nineteen years. George II perceived him as a ‘faithful servant of the state’, not permitting William to retire at his first request in 1775. William Barrington’s political career was renowned for the fact he held continuous public office for over thirty years, witness to a wide breadth of ministerial changes. Modern opinion assesses him as “the quintessential politician – administrator in an age when the civil service had not yet separated from politics, and a man of principle who contributed much to the development of the administration of government in Britain” (ODNB). Throughout his career William relinquished any power struggles, prioritising efficient administration for an effective government above all. He inspired friendship and respect - including from his long-term enemy, Horace Walpole – helping many less privileged in the army. He died on 1 February 1793 in Cavendish Square, London, and was succeeded as viscount by his nephew, William Barrington, the son of his younger brother John Barrington.

JOHN BARRINGTON (1719-1764)

Third son of John Shute Barrington, John Barrington was baptised on 11 December in Little Baddow, Essex. He joined the 3rd regiment of the Scots guards in 1739 with the rank of lieutenant, and likely served in Flanders during the War of the Austrian Succession. He was senior lieutenant-colonel of the 2nd regiment of the Coldstream Guards in 1755 when his elder brother William was appointed secretary at war. Within a successive two-year period, John received several promotions, first serving as aide-de-camp to George II (12 June 1756). In October 1758, despite only a junior colonel, he was appointed second in command for the expedition against the French Leeward Islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe under Major-General

Peregrine Thomas Hopson. John returned to England in June 1759 victorious – having taking command and succeeded in Guadeloupe – but with his health severely affected by the harsh local climate. He was promoted to Major-General in recognition of his services, in September 1759. He died less than five years later, in Paris on 2 April 1764, survived by his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of wealthy plant owner and slave-owner in Jamaica, Florentius Vassall, and their four children, William, Richard, George and Louisa. Year later, his elder brother William wrote: “He returned from Guadeloupe as poor as he went thither… left at his death a very bare subsistence for his widow; and his four children have since the year 1764 been educated and maintained by me”1. After the second Viscount died childless in 1793, the title passed to John Barrington’s three sons in turn.

SAMUEL BARRINGTON (1729-1800)

The fifth of six brothers, Samuel Barrington joined the navy aged just eleven, serving in the Lark, under Lord George Gordon in 1740. He passed his lieutenant’s examination on 25 September 1745, gaining command of the sloop Weasel in early 1747. He swiftly became captain of the frigate Bellona later that year, in which he captured the French East India ship Le Duc de Chatres –aged eighteen. Samuel saw extensive action in the Mediterranean, off the Guinea coast, off North America and as part of the Channel Fleet, in the run up to and during the Seven Years’ War. Unemployed during the five years of peace, Samuel was finally appointed flag captain to the duke of Cumberland aboard the 36-gun frigate Venus in 1768 and continued his service in the Channel Fleet for the years following. On 23 January 1778 he was promoted rear-admiral of the white – a senior rank of the Royal Navy. He sailed to the West Indies that year to take command of the Leeward Islands squadron – exactly twenty years after his brother John had seen action there in Guadeloupe. In December 1778 Samuel achieved his greatest naval victory, capturing and defending the strategic island of St Lucia against d’Estaing’s French squadron. He was to clash against D’Estaing several times more in the couple of years following. Samuel was promoted vice-admiral of the white on 16 September 1781 and raised his flag in the Britannia under Lord Howe in the Channel Fleet – with whom he was at the relief of Gibraltar in October 1782. He struck his flag on 20 February 1783 and was promoted to admiral on 24 September 1787, close to sixty years of age. When war broke out with France in 1793 Samuel did not return to active service. He died, unmarried, on 16 August 1800. He is remembered as a brave and capable officer in action, successful in tricky amphibious operations that were often hindered by bad relations between naval and military commanders.

1 Tony Hayter (ed.), ‘An Eighteenth Century Secretary at War: The Papers of William, Viscount Barrington’ (London: Bodley Head for Army Records Society, 1988), p. 328

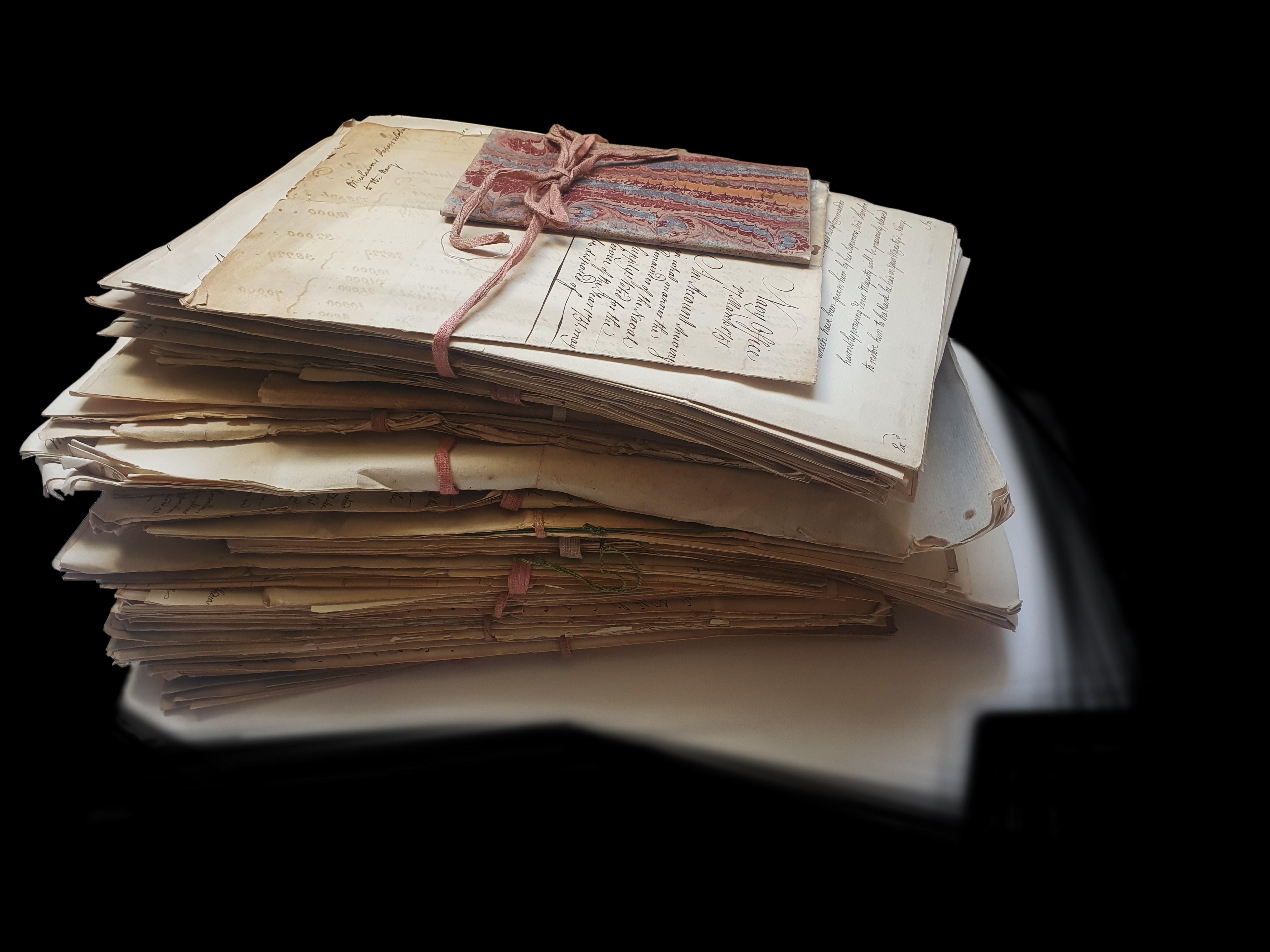

The archive was collated by a member of the Barrington family some time in the 20th century. They used a straightforward alphanumeric reference system. We have rearranged the material into a different order, but retained their codes in our catalogue.

THE A R C H I V E

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (WB 2, 3, 5, 7-10)]; [BARRINGTON, Admiral Samuel (1729-1800) (SB 2/1-8, SB 2/10 & SB 3)]; [Naval Office. (NO 6-10)]. Original, mostly unbound Documents and Letters.

[circa 1731-1755]

Approximately 220 items, made up of variously sized papers. Mostly 1-2 text pages per item, with some lengthier items up to 15 pages; a few longer stitched pamphlets; some broadsides; one slim pocket notebook; two printed Bills. Items grouped together by subject matter.

¶ The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), which saw Britain side with Austria, and France with Prussia, also involved colonial conflict between the British and French in India and Canada. The War was ended by the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, leaving all parties dissatisfied – and sowing the seeds of the Seven Years’ War (1756-63).

It was during this Austrian War that brothers William and Samuel Barrington were both embarking on their new services to the crown. In February 1746, William Barrington was appointed Lord of the Admiralty, quickly gaining a reputation as an effective administrator. A year earlier, his brother Samuel had gained the junior rank of lieutenant in the British Navy, and in 1747 was made captain. This group of documents spans these two key periods of Britain’s action on the world stage, and the hostile interval between, and its contents bear all the hallmarks of a naval power lining its battle ships in order. There are records of British ships across the globe and intelligencegathering on foreign fleets; details of key naval docks and improvements of waterways; earlier British naval action plans that were never executed; and lengthy accounts of mounting debts. Everything past and present is being considered and reconsidered in minute detail, as Britain prepares for its biggest battles yet.

WB9 & WB10. [1731-1755].

18 items, mostly 1-2 text pages per item, some up to 8 pages; one 33-page collection of letters.

These earliest papers present a range of unexecuted naval action plans in the 20 years before the Seven Years’ War. There are schemes to prepare warships for “Nova Scotia” [WB9/2-3] and for the “conquest of Canada” [WB9/8], as well as for attacking the enemy at major naval stations (Spanish ships at Cartagena [WB9/4]; French ships at Brest [WB9/7]). Also included are 1747 proposals to “seize and fortify the Isthmus of Darien” (present-day Panama), “the successful execution which would give the severest blow ever conceived to Great Britain’s rivals in power, trade and riches, and proportionally grandize hers” [WB9/9-10. Capt. Simcoe]. This plan – along with the others in the group – never reached fruition, with Panama remaining firmly part of the Spanish Empire until 1821. There are also several early papers regarding the Sixpenny Office, detailing the numbers of merchant seamen in America and elsewhere from 1716 to 1755 who had six pennies collected monthly from their wages to fund Greenwich Hospital’s provision of care for sick and aged seamen [WB10/1, 3-5]1 . NO7, NO10, NO12, WB2 & WB3. [circa 1744-1755].

49 items, mostly 1-2 text pages per item, several printed, some as broadsides, plus three pamphlets.

The working state of the Navy’s key shipyards and harbours are rigorously attended to during these years of action. Early in the War of the Austrian Succession, a small bundle of papers contains proposals for a new dock in Kinsale, a strategic British Royal Navy base in Ireland which was used as a rendezvous point for large squadrons during the 17th and 18th centuries2 [NO7/4-5. c. 1744-46]. There are also some 23 items relating to the naval dockyards of Deptford, Woolwich, Sheerness, Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth from around 1744 to 1753 [NO7/1, 3 & N10/2-20]. Included are accounts of vessels (e.g. “List and Condition of the Ships at Portsmouth” [NO10/15.

Undated]); a six-page pamphlet, “Observations necessary to be made in His Majesty’s Dock Yards”, regarding the various roles in place, with marginal annotations [NO10/1. Undated]; and a draft bill for enlisting and retaining able seamen [NO12/1]. Later, on the cusp of the Seven Years’ War, we see the strategic significance of Plymouth during this period3 in a collection of 10 papers relating to the lease of Sutton Pool harbour in 1755 [WB3. 1754-1755]. But harbours were not the only waterways of concern to the British Navy; and modernising interior navigation systems to improve trade is addressed in a group of seven papers [WB2]. These likely relate to the pioneering Thames Navigation Commission which managed the river from 1751 and improved its navigation from 1771 through measures such as building pound locks to make it a super-highway of its day4. There is a nine-page proposal by a “Brian Philpot” to prevent further “great loss of Trade to this City” [WB2/5. Undated], as well as a printed proposal for deepening the Thames to render it “the finest Inland Navigation in the Kingdom” [WB2/7. London, 6 February 1755].

SB2/1-8, 10. [1746-1748].

9 items, mostly 3-4 text pages per item, some up to 15 pages long; 1 printed Bill.

Here we see a still-uneasy Britain retaining a firm eye on its strategic overseas colonies, while Europe continued to simmer. A printed Bill seeks “the better Protecting and Securing the Trade and Navigation” in American settlements during the Austrian war [SB2/1]. Meanwhile the Admiralty proposes lists of “guard” ships and others to be kept in commission at “Jamaica”, “Leeward Islands and Barbardos”, “Plantations”, “Coast of Africa”, and “Newfoundland & Consoe”, amongst other destinations, despite a “time of Peace” after the Treaty at Aix-laChapelle [SB2/5-6. May 1748]. We also see an undated proposal for the registration and payment of seamen as reservists for “His Majesty’s Ships of War” [SB2/8].

NO6, NO8 & NO9 & SB3/1. [1745-1753].

58 items, mostly 1-3 text pages per item, some several pages long, one 33-page damp damaged report.

This collection of papers offers sober calculations of naval costs and accumulations of debts as one war merged into another. There are some 11 accounts of Navy debt and various comparative accounts, including “An Estimate of the Charge of Building & Completely Equipping a Ship of each Class” 1706-1745 [NO6/5]. A 33-page document (with recent transcription), William Barrington’s “Defence of the Admiralty” for the House of Commons, details three charges made against the Navy, including “that due regard has not been had to economy, by which, tho’ the annual Grants have been greater than was ever known in former Wars, the Navy Debt is also larger” [SB3/1. February 1747]. Two years later, an official copy of a letter from the Lords of the Admiralty grants “above £1,020,000 for the Sea Service of next year, a large allowance in time of Peace”, but warns the Navy Board to “take care that the expenses of next year […] do not exceed the Grants” [NO6/17. 15 December 1749]. There

are also papers comparing the actions and states of the English, French and Spanish fleets in the period (e.g. “State of the Marine of France, 27 April 1750”) as Britain assessed its strength against the enemy [NO8/21, NO9/10, 1213]. We see the British navy scattered across the world, from Nova Scotia, North America and the West Indies, across to the Mediterranean, Africa, and the East Indies (e.g. “Abstract[s] of Ships proposed to be kept in Commission” 1751-54 – including ships stationed at “Bahama Islands, So. Carolina, No. Carolina, Virginia, New York, New England” [NO8/15-19]). Interestingly, a letter from a notable and prosperous East London Jewish merchant, Jacob Buzaglos5, offers Lord Barrington a vessel for surveying “of Great Benefit to the Nation in Case a war Should Brake” [NO9/22. 22 May 1753]. All these papers point towards escalating plans of naval domination at increasingly heavier costs to Britain – their financial and political debts later tipping Britain’s own colonies against it, bringing about the American Revolution.

WB5, WB7 & WB8. [1732-1754].

66 items, mostly 1-2 text pages per item; some slightly longer and thread-bound; some broadsides; one half-filled slim pocket notebook; one seven-page printed bill.

Enemy fleets and overseas territories are the focus of this collection. The first part looks at the years preceding and during the Austrian War [WB7 & WB8. 1732-1754]. Materials include a printed Bill from 1739 encouraging “the Taking of Ships of War from the Enemy” [WB8/1]; comparative lists of British ships stationed in the Caribbean (“Jamaica”, “Barbados & Leeward Islands”, “Bahama Islands”), East Coast of America (“New England”, “South Carolina”, “Virginia”, “New York”), Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Africa, and the Mediterranean, 1724-1752 [3 items]; and accounts of foreign goods contracted in “Dantzick”, “Prussia” and “Norway” since the end of the Austrian War [WB7/17]. The second part moves onto the rapidly deteriorating relations between the French and British colonists in North America after the ineffective 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle [WB5. 1751-1752]. London had originally issued a policy to “let Americans fight Americans”6 for fear of renewed war after just six years of peace – but these papers show that Britain could no longer ignore French aggression in North America. Several letters and lists of French Naval details sent from Lord Albermarle, a high-ranked diplomatic minister regularly based in Paris during this time, reveal intelligence being gathered about the enemy. There are lists in French of workers in the Royal shipyard in Brest, as well as those in Rochefort and Toulon [WB5/8, 10]; and of naval manpower in various French departments [WB5/11]. One letter from Albermarle speaks of “intelligence” gathered from “three different Persons unknown to each other” [WB5/1. Compeigne, 10 July 1752] – while another requests “the French order of Battle in a Naval engagement” [WB5/4. Fontainebleau, 31 October 1752]. Within two years of the last date in this collection, the Seven Years’ War – the last major conflict before the French Revolution to involve all the great powers of Europe – began.

NO9/1-9, 11, 14-21, 23-25 [1743-1753].

21 items, mostly 2-3 pages per item, some several pages long.

This is a miscellany of various sea affairs from the period: accounts and correspondence related to the affairs of the “Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich” [NO9/1-5. 1747-51]; “State of the Newfoundland Fishery in 1749” including a list of “quintals of fish”, “seal oyl” and “fishing skallops” caught in its waters to be traded in “Portugal, Spain & Italy” [NO9/7]; two lists of “Necessaries for a Boy going to Sea”, including “A Great Coat, Two Hatts [and] A Pewter Spoon” [NO9/8. Undated]; two Court Martial reports, one regarding the “Assault, Battery, Wounding and False Imprisonment” of Lieutenant Frye by Sir Chalover Ogle [NO9/11. 25 February 1742]; and an account of the quality of Lownd’s meat and fish curing salt on Newfoundland [NO9/15. Undated].

The strong appeal of this substantial group of material lies in the variety and detail with which it portrays British naval affairs at the tipping point of the Seven Years’ War, and the decisions that ultimately fed into the American War of Independence.

1 ‘Cobbett’s Parliamentary Debattes’, Vol. 3, (Cox & Baylis, 1812), pp. 947, 955

2 www.thejournal.ie/charles-fort-cork-heywood-gardens-laois-heritage-ireland-2132908-May2015

3 www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-13391

4 www.nationaltrail.co.uk/en_GB/trails/thames-path/25-years/

5 Roth, Cecil, ‘The Amazing Clan of Buzaglo’, Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England), Vol. 23 (1969-1970), pp. 11-21 [www.jstor.org/stable/29778782]

6 Thomas Pelham-Holles, www.britannica.com/event/French-and-Indian-War

7 Walpole, Horace, Memoirs, 2.115)

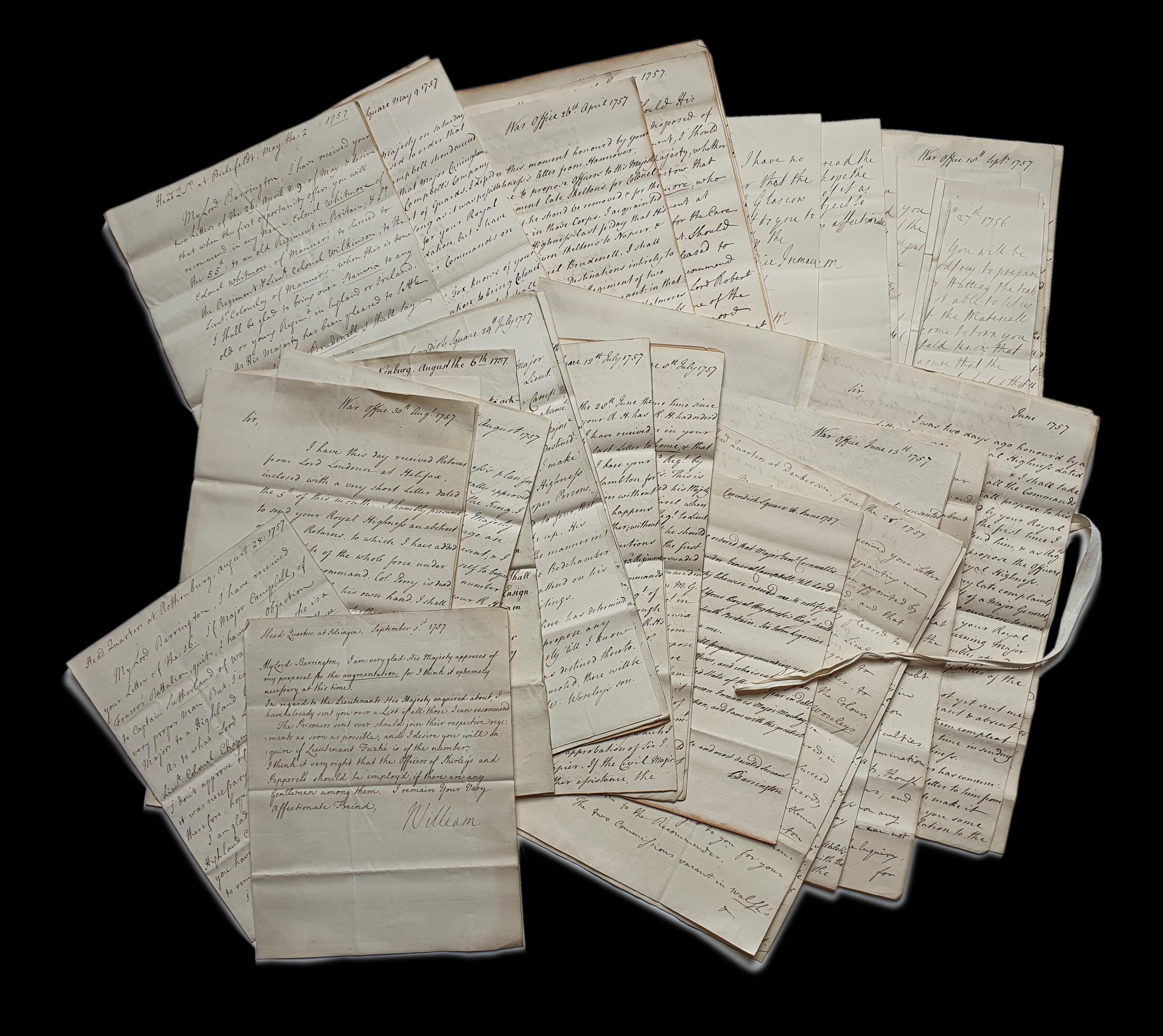

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (WOB 1, 2, 3, & 6)]. Unbound War Office Papers mainly concerning the Seven Years’ War.

[Circa 1746-1757].

Approximately 57 items, made up of variously sized papers, including thread-stitched pamphlets, and others bound with

of British military action in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). The conflict began badly for the British, with an invasion scare, a series of embarrassing defeats, failed plans, and reversals of alliances. Military action in both America and Europe had experienced little success. This rather dismal opening – during a time when William Barrington had just taken up his first appointment as secretary at war – frames these papers.

We witness William Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire, and William Pitt the Elder trying to refocus a collapsed government through new foreign policies; the British fleet scattered to every corner of the globe; and the aftermath of the two great early failures of the Seven Years’ War – the Battle of Minorca in 1756 (see Byng selection) and the Raid on Rochefort in 1757 – both of which ended with courts martial for the leading officers. There is also a curiously comic insight into the solemn court etiquette of kissing a king’s hand.

WOB1 & WOB6 [c. 1756-1757].

48 items, mostly 1-3 text pages per item, a few longer and stitched with thread.

These papers shine a light on the short political marriage of the Duke of Devonshire and William Pitt, appointed to lead the interim ministry after Newcastle’s administration failed at the end of 1756. Early papers in our collection show the previous government’s almost scattershot approach to foreign policy as the Seven Years’ War commenced. The British fleet is hastily being sent across the breadth of the globe in April 1756: “one to Convoy the Trade going to the Leeward Islands, one to Convoy the Trade going to Jamaica, one to the Coast of Africa, & one to north America being in all 13, the Complements of which amounted to 6120 men” [WOB6/25]. There are also some 15 lists of British ships, frigates, sloops and their men, in “Jamaica & Leewards Islands”, “North America”, “St Helena”, “East Indies”, “Coast of Africa”, “Nova Scotia” and Europe [WOB6/7-19]. Devonshire, the “great engine, on whom the whole turns at present”1, and ‘patriotic’ Pitt as secretary of state, refocused Britain’s strategies. They prioritised America, established a militia for home defence, assembled a continental army and organised naval warfare against the French coast. Over 19 papers, we see the government hastily preparing a “decisive Expedition” of troops from Ireland to North America [WOB1/1-19]. Devonshire asks Barrington to send “a Compleat Set of Camp Equipage for Each of the Seven Battalions” [WOB1/2. 5 February 1757], while Pitt admits to the secretary at war that he “can hardly sleep” from worrying about anything that might “retard the Expedition” [WOB1/11. 5 February 1757]. The final, six-page paper from May 1757 attempts to resolve the longstanding political problems between Pitt and Newcastle –draft plans which were never executed, after the two men came to an agreement. [WOB1/20].

WOB2. [c. 1757].

4 items, between 3 and 11 text pages per item.

The trials of Sir John Mordaunt, Major General Henry Seymour Conway and Major General Edward Cornwallis, who led the failed British raid on the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757, are the focus of this collection. The collapse of the amphibious attempt, which had been part of Pitt’s pioneering new tactic against the French coast and had cost upwards of a million pounds, was received with fury by Pitt. Our collection details formal hearings for the three men who, from the outset, had doubted the success of the attack. Mordaunt’s lengthy, ribbon-bound court defence shows the commander was confident in his reasons for calling off the operation, stating he “understood that unless proper place for the Landing and safe retreat of the Troops was discovered… the attempt cou’d not be made” [WOB2/2]. Major General Conway’s court defence reflects Mordaunt’s opinion that to “attack Rochefort directly […] was neither advisable nor practicable” [WOB2/3]. Major General Cornwallis too stated that “there appeared to him no security for Landing the Troops, nor any retreat secured” and so “cou’d not answer to himself risk giving the whole” [WOB2/4]. Despite his unanimous acquittal at the time, Mordaunt joined Conway and Cornwallis in being struck from the staff by George II the following July.

WOB3. [c. 1758].

5 items, 1-2 text pages per item.

An urgent concern with reinforcing proper procedures for kissing the King’s hand on receipt of miliary promotion fills this interesting – and resolutely outraged – correspondence between Barrington and senior army officer Lord John Ligonier. In one letter, Ligonier writes to Barrington of a “Mr Charles Townsend”, who needs to be acquainted “with how improper a thing it is that an Officer should kiss the King’s hand for a Preferment before it is notify’d from the War Office” – surmising that the King “must think this premature Rape of his hand very extraordinary” [WOB3/1. 1 February 1758]. In another, Barrington, equally appalled by the ill-mannered actions of a “Lord Blandford”, begs Ligonier’s “assistance in putting an End to a very irregular method lately crept onto the Army”, certain it will otherwise cause “Essential mischiefs & inconveniences” in the future [WOB3/4. 1 April 1758].

1. www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-4949? rskey=KpMHOB&result=2

2. Yonge, Charles D., ‘The History of the British Navy: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time’, (R. Bentley, 1866) Vol. 1, p. 246

3. The 1749 Naval Act, Anno 22° Georgii II c.33. CAP. XXXIII.

4. ODNB

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (WOB4, WOB5 & SB2/9, 11)];

[BARRINGTON, Admiral Samuel (1729-1800) (SB2/9, 11)]. A substantial collection of papers concerning the trial and execution of Admiral John Byng. [circa 1746-1757].

37 items in total ranging from letters and slim pamphlets of 3 to 10 text pages through to lengthier items (the longest being 136 pages) most of which have been bound with ribbon.

¶ The “cruel and unjust execution”1 by firing squad of Admiral John Byng on 14 March 1757, the first and last admiral to be sentenced to death, is at the heart of this substantial group of papers.

The 1756 Battle of Minorca was one of Britain’s early failures in the Seven Years’ War. The defeated British withdrew to Gibraltar and handed France a strategic victory which led directly to the Fall of Minorca. Byng was charged with the imprecise “failure to do his utmost” to relieve the siege of the British garrison on Minorca.

The most fascinating papers in this archive give context to the brutal execution of Admiral John Byng after the Minorca defeat: not only can we see early reforms of naval courts martial and the breadth of official evidence gathered for the Admiral’s polarising trial, but we learn the long-term impact Byng’s execution had on successive courts martial law.

Two early documents from circa 1746-8, show proposals for court martial reform (with marginal annotations, probably by William Barrington) after the poor performance of the Royal Navy in the battle of Toulon in 1744, during the War of the Austrian Succession [SB2/9, 11]. The resulting 1749 act established the powers and independence of naval courts martial but offered little flexibility in the severe penalties of the Articles of War. It is within this key legal context that Admiral Byng was arrested and tried by court martial for his “cowardice, negligence [and] disaffection”, after the British loss of Minorca under his command in May 1756 at the start of the Seven Years’ War3 .

A substantial group of documents include the official evidence gathered for Byng’s court martial, contextualising the Admiral’s actions in Minorca [WOB5]. There are two official copies of Byng’s Admiralty orders, one with instructions for “transporting a Batallion from Gibraltar to Minorca” on 31 March 1757 [WOB5/4]. There follow 18 official “Intelligence” papers, some six of which specifically report details of the French fleet. These include “No. 8” (2 pages), surveying “French Armaments by Land and Sea” [WOB5/8]; “No. 7” (59 pages), detailing the “Preparations at Toulon and Design against the Island of Minorca” in the six months before the battle [WOB5/7]’ and “No. 9”, the longest report (136 pages), concerning “Intelligence relating to the Preparations and Designs of the French in the Mediterranean and the Siege of Minorca, received after the 6th of April 1756” [WOB5/11] (relevant since Byng was then sailing for Minorca via Gibraltar). Reports “No. 11” to “No. 14” focus on the British fleet, and include a first-person account from Commodore Keppel, who had unsuccessfully advocated clemency for Byng at his court martial4 [WOB5/17].

The trial took place on board the St George in Portsmouth Harbour from 27 December 1756 to 27 January 1757. Six weeks later, despite appeals and the refusal of two vice-admirals to sign the sentence, Byng was executed under the inflexible 12th Article of War. The second part of our group of documents shows evidence gathered for courts martial reform in the wake of Byng’s draconian punishment, “there being several Defects in the present Laws and Customs” [WOB4/5-7. Undated]. Within this, a 10-page report regarding the position of the British Navy in 1755 also reflects on “the disgrace of our Arms and loss of Minorca”. It argues: “If our professions and Our Commerce encrease, Our Cases and Our difficulties are encreased likewise” –and concludes: “If Our Fleets had been kept in Port, when they were able to be at sea, timidity & weakness might be justly charged on the ministry; but […] no ship has ever remained in Port which could go to sea” [WOB4/10. Undated]. This is an evident nod to overly harsh judgements of officers like Byng, who “fell, to the astonishment of all Europe… rashly condemned, cruelly sacrificed to vile political intrigues”5. It took 22 years for the Articles of War slowly to be amended, until in 1779 courts martial were allowed some measure of discretion.

1. Yonge, Charles D., The History of the British Navy: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, (R. Bentley, 1866) Vol. 1, p. 246

2. The 1749 Naval Act, Anno 22° Georgii II c.33. CAP. XXXIII.

3. ODNB

4. Admiral Byng, ‘The Newgate Calendar’, Part II (1741-1799)

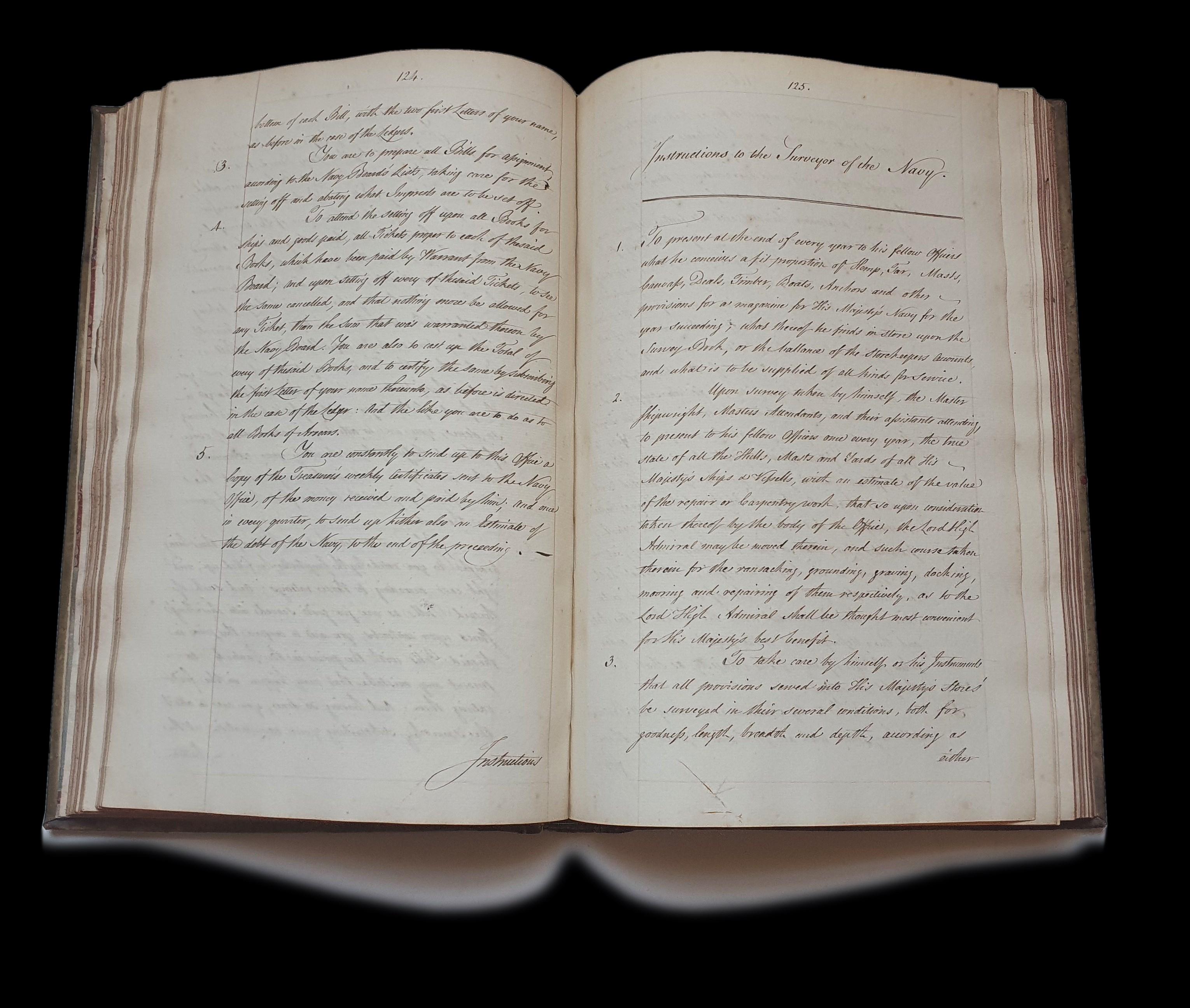

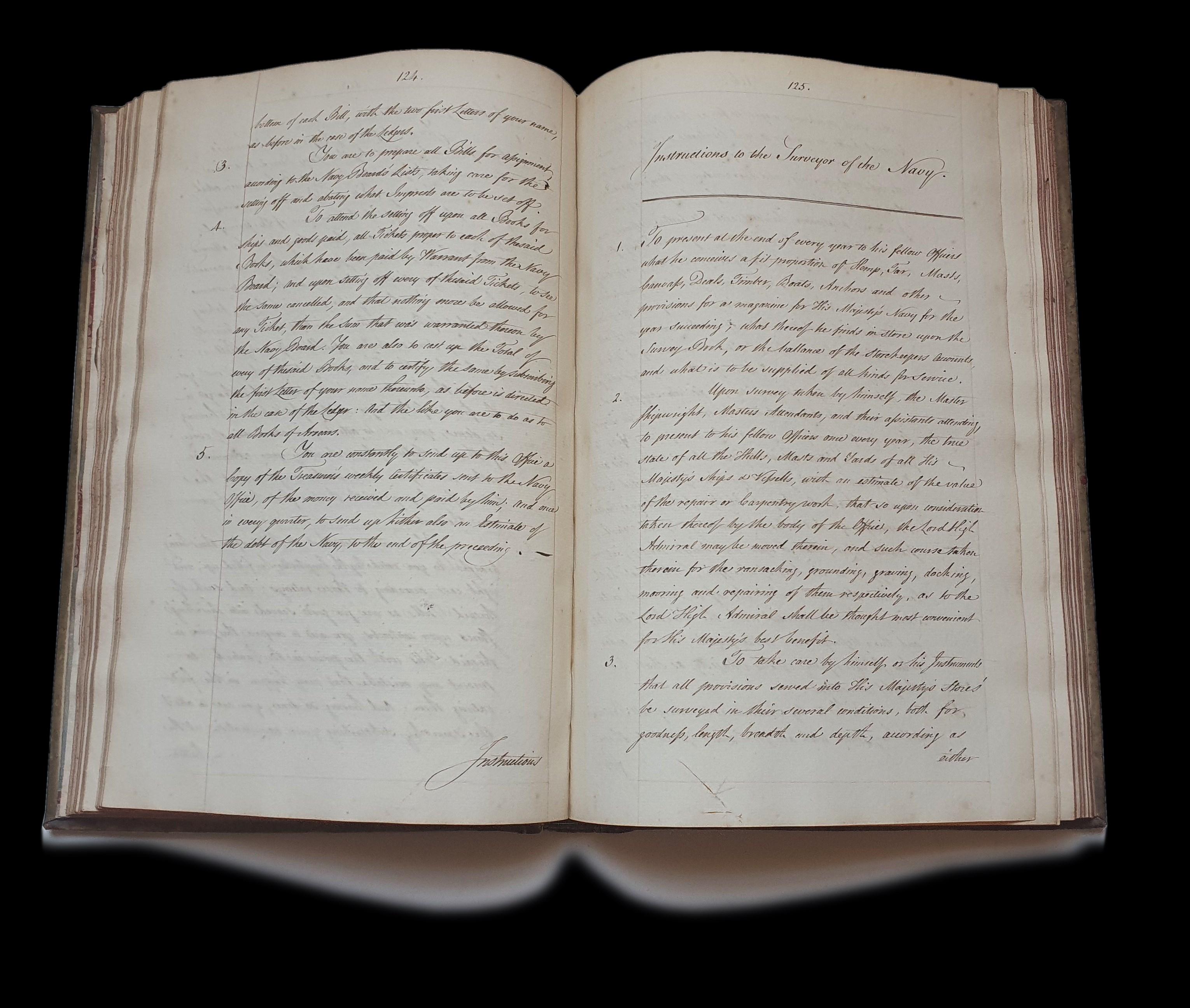

[NAVY BOARD] An 18th-century book of Precedents and Procedures. [Circa 1755]. Folio (315 x 200 x 25 mm). Foliation, 305 numbered pages on 151 leaves (including a 4-page index at the back).

Bound in contemporary vellum, manuscript titled spine “Nauy Board”

Watermark: Lion; countermark: Crown above GR (this combination similar to Heawood 3149, which he dates circa 1753).

¶ Books of ‘Precedents and Procedures’ were essential guides for naval officers; they recorded cases and administrative procedures in a number of naval departments and branches. The principal officers were chiefly made up of a Treasurer, Controller, Surveyor, and a Clerk of Ships. During the 18th century they acted largely independently of the Board of Admiralty, issuing orders directly from the Secretary of State.

The Navy Board existed from 1546 until 1832 (when it was abolished and taken over by the Board of Admiralty) and assigned responsibility to a group of officers, under the Lord High Admiral, for the civil administration of the British Navy.

This manuscript was probably transcribed by a Navy Board clerk. It offers a detailed index, which separates the contents neatly between “The Old Instructions” (pp. 1-144, offering precedents as far back as 1660) and “New Instructions” (pp. 145-301). The book opens with a historical overview of “The Navy Board” and goes on to detail duties of various departments and instructions to the principal officers. The second half commences with a “Council Order for Constituting a New Board” as called by “His Royal Highness James Duke of York Lord High Admiral of England” (Whitehall, 4 July 1660). From here follow the newly relayed duties of the principal officers, and of others, such as the Storekeeper, Purser, Gunner and Boatswains, as well as of the Lord High Admiral (Whitehall, 16 June 1673). The final entry sets out the orders from the Admiralty Lords for instructions to the Commanders of the Navy, including provisions for “Sick and Hurt Seamen” (Admiralty Office, 6 May 1715).

The volume offers an interesting view on the evolution of the Navy Board, and the past and prevailing duties and instructions given to its principal officers and other notable commanders. It thus represents the ‘ideal’ from which the rather messier reality of operations at sea so often diverges – as shown in so many of the other manuscripts in this archive.

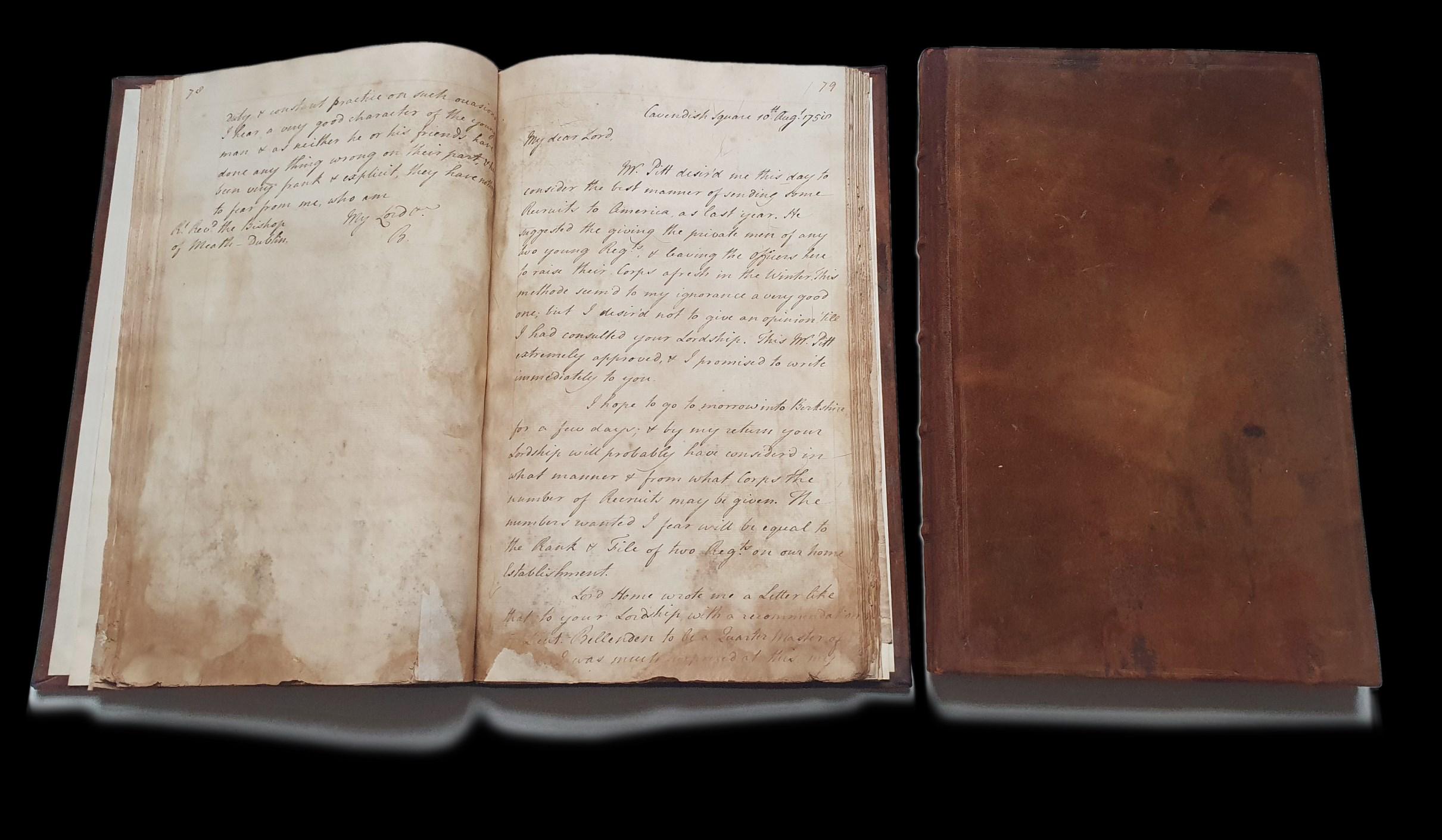

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (LEB/4/1-155; LEB/5/1-130)]. Two folio letterbooks contain copies of letters spanning a period of approximately ten years.

[Volume 1: 1756-60; Volume 2: 1760-1766].

Folio (322 x 200 x 20 mm each). Foliation [21, index], 195 numbered pages on 98 leaves; foliation [21, index], 200 numbered pages on 100 leaves.

Bound in contemporary reverse calf, both recently re-backed with new endpapers. Text in poor condition, very badly dampstained, with some text obscured. Several modern paper repairs, especially to manuscript tabulated indexes and final leaves.

¶ These two folio volumes comprise copies of letters from the time of William Barrington’s appointment as Secretary at War (1755-1761; 1765-1778) through to his serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer (1761-1762) and Treasurer of the Navy (176265). They record his exchanges with cabinet ministers and army officials during his administration of Britain’s forces, in particular during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63).

The 1756-60 volume, (around 155 letters) shows Barrington writing frequently to British Army officers and officials including the Duke of Argyll (7 letters); Lord George Beauclerck (10 letters); Lieutenant General Bligh (3 letters); the Marquis of Granby (6 letters); and Sir John Louis Ligonier (10 letters). He also addresses politicians, including William Pitt (5 letters) and the Duke of Newcastle (4 letters). The letters, which begin just before the opening sea battle of the Seven Years’ War at Minorca (May 1756), include discussions about provisioning, movement and payment of troops; recruitment problems (“His Royal Highness wou’d not have any officers left in Scotland to recruit the bad men who shall be discharged” [LEB/4/18. To Lord Geo. Beauclerck, 31 March 1757]); appointments and promotions (“Don’t be displeased […] that I send you over a Brevet of Colonel for America only: It may lead here after to better things” [LEB/4/43. To Colonel Gage, 27 December 1757]); and conditions in military hospitals (“Doctor Brockley […] is apprehensive of very bad consequences from the men lying so crowded” [LEB/4/83. To Frederick Charles, 16 December 1758]).

In the second letterbook (some 130 letters, 1760-1766), Barrington’s most frequent correspondents are Major General Amherst (7 letters); Major General Gage (5 letters); the Marquis of Granby (19 letters); and a ‘Monsieur Feronce’ (10 letters in French). Matters include finance; troop recruitment; and appeals for assistance (“It is the duty of every Gentleman, to assist a Lady who is struggling” [LEB/5/17. The Marquis of Granby, 10 September 1760]). Other letters discuss the appointment of Ensigns (“I have issued so many King’s Letters lately, that I fear it will be a long time before I can grant any more” [LEB/5/33. To Sir Charles Howard, 11 January 1761]); and the contested election for Essex (“I have been disappointed in my hopes that some means would be found to preserve the peace and good humour of the County” [LEB/5/87. To Isaac Pledger, 21st July 1763]).

These two volumes are in very poor condition, but nonetheless, they offer rich insights into the breadth of British affairs local and overseas, and notably in relation to war in the West Indies.

[BARRINGTON, Admiral Samuel] Journal of Admiral Samuel Barrington, 1759-1771. [Circa 1759-1771].

Folio (370 x 250 x 25 mm). Approximately 250 text pages on 129 leaves. Bound in reverse panel calf, manuscript titled front board “ORDERS”.

Watermark: Fleur-de-Lis, IV over LVG; Countermark: IV (similar but not an exact match to Haewood 1839, circa 1750-1760).

¶ Samuel Barrington’s formal daily journal records navigation, weather, battle orders, signals, in and out letters, and other business pertaining to four ships under his command in the Channel Fleet, between 22 July 1759 and 16 October 1771 – a key period of British engagement with France and Spain (Seven Years’ War, 1756-63; The Falklands Crisis, 1770). The book relates

Barrington’s captaincy of the Achilles 1757-1761; his move to the Hero in 1762; and his appointment to the Venus in 1768 under the Duke of Cumberland and to the Albion in 1771.

The journal begins just after the Achilles successfully destroyed the flat-bottomed boats at Le Havre, with Barrington under Sir Edward Hawke (4 July 1759). Various “Lines of Battle” occupy the months following, as the Fleet again prepares to attack the French: “You are hereby required and directed, when I shall hoist a Blue Flag with a Red Cross […], to fire twenty one guns” [Hawke to Barrington, 27 August 1759]. In September, the Achilles grounded heavily while attempting to cut out French ships in Quiberon Bay, and orders were given “to send her immediately to England, and it being hazardous to let her go to sea without ships in Company” (Robert Duff to Barrington, 18 October 1759).

A good deal of material between March and December 1761 records correspondence between Barrington and Commodore Keppel (commanding the Valiant) as they lead operations against Belle Îsle. It also includes an order “to have twenty one guns fir’d” to celebrate the marriage and Coronation of King George III and Queen Charlotte (Keppel to Barrington, 4 October 1761).

In 1762, on Barrington’s transfer to the Hero, much of the correspondence focuses on detailed “Signal” and “Fighting” instructions from Lord Howe, including schematic diagrams (“Anchoring Stations of the Squadron”) showing battle positions between ships [Basque Road, March-April 1762].

After the Treaty of Paris (1763) Barrington was unemployed until his appointment in 1768 to the Venus as flag captain to the Duke of Cumberland, and the journal mostly records in- and out-letters between the two. From October 1770, we find Barrington on the Albion, as disputes with Spain begin over the Falkland Islands. Countless letters between Barrington, Admiralty Secretary Philip Stephens, Commander-in-Chief Francis Geary and Admiral Matthew Buckle are recorded as Britain teeters on the edge of war – with final entries from October 1771, ten months after the crisis was resolved.

The journal covers almost a decade of Samuel Barrington’s command in the Channel Fleet and offers detailed insights into a seminal period of British naval action against both France and Spain.

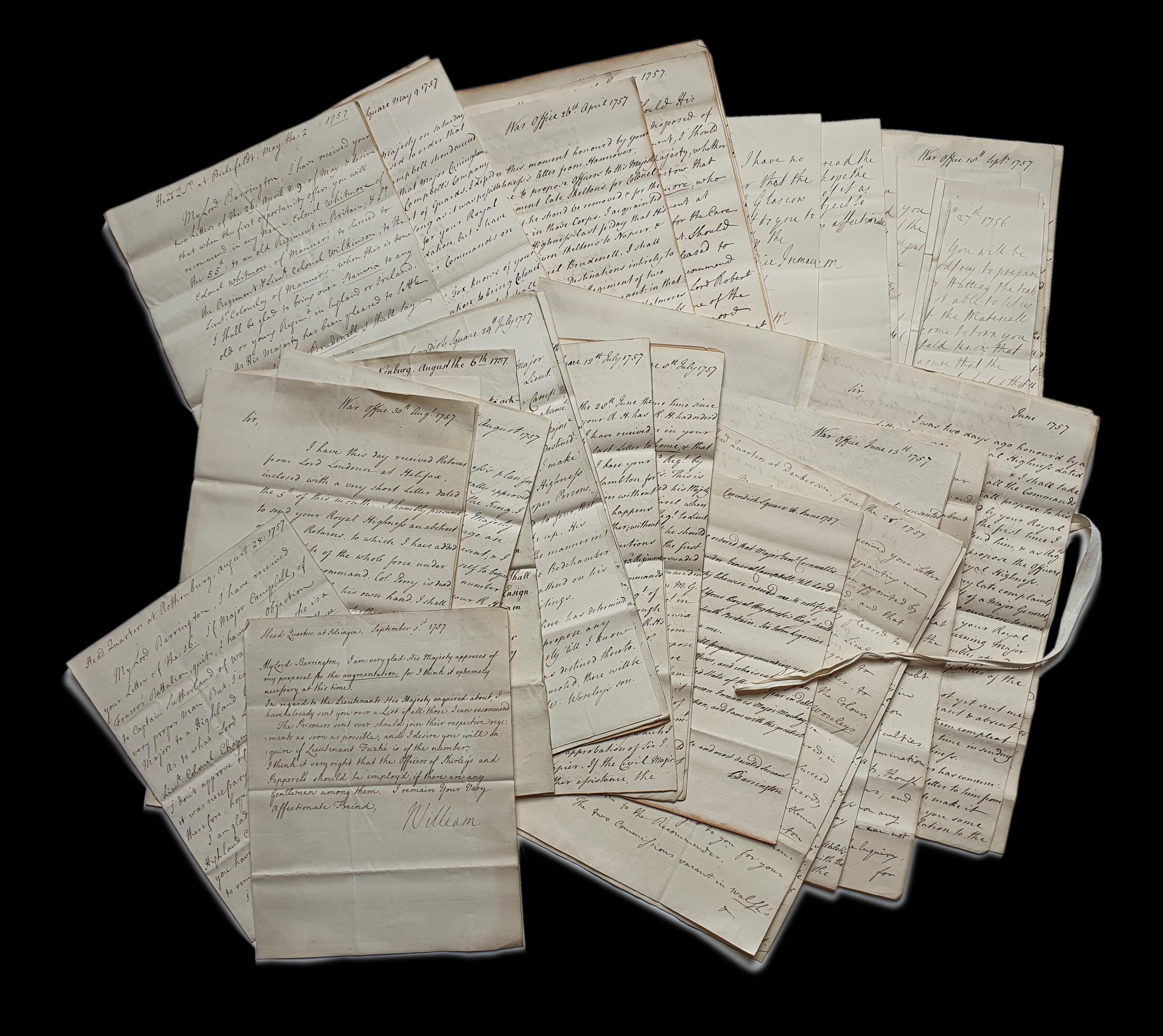

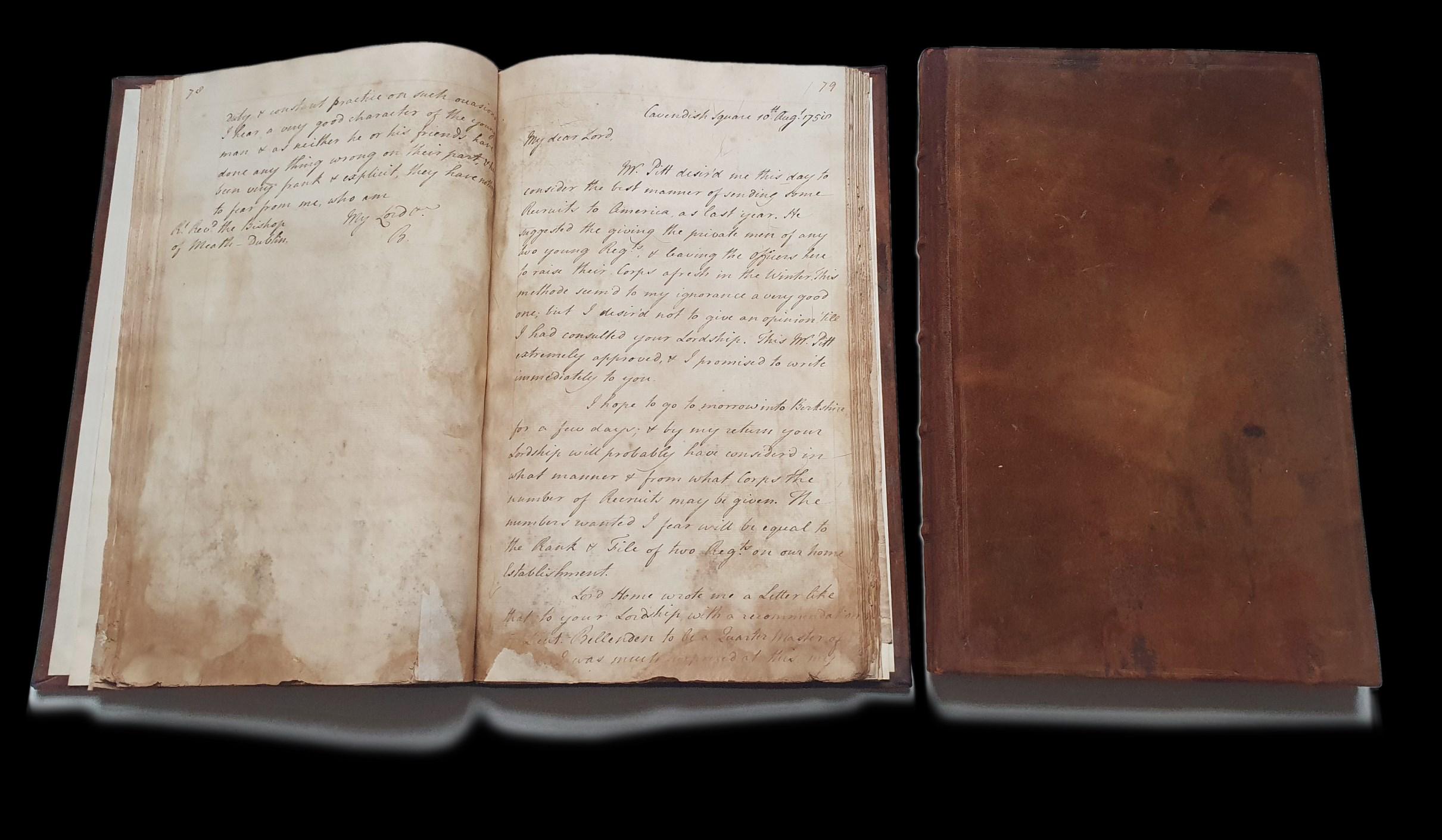

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (LB5/1-44 )]. 44 letters between Barrington and the disgraced Duke of Cumberland, including original correspondence. [1756-1757].

44 items, mostly 1-2 text pages.

¶ Celebrated military leader; both “Sweet William” and “Butcher Cumberland”1; honoured by Handel as “the Conqu’ring Hero”; disgraced royal offspring… The titles and reputations earned by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1721-1765), British General and erstwhile favourite son to George II, were many and varied. This rich group of letters comprises correspondence between Cumberland and William Wildman Barrington, Secretary at War, between 1756 and 1757, as the Seven Years’ War was getting under way. The letters, many of which are written in the duke’s own hand, offer a mostly administrative view of Cumberland’s command of British and allied forces.

The opening European sea battle of the Seven Years’ War saw Britain and France fighting for Minorca. A letter from March 1756 – two months before this disastrous engagement – notes troops sent “for Gibraltar & for a detachment equall to a Battallion being sent thence to Minorca” [LB5/38]. The battle was an inauspicious start for Britain, with France quickly seizing victory. By December of that year, our archive shows Cumberland seeking renewed recruitment for the Mediterranean fleet, “as great a number of men forward compleating the three Battallions” [LB5/34], and “men to be raised be sent fully equipped & cloathed” to increase Irish Battalion numbers, a month later [LB5/33]. The remainder mostly comprises some 20 letters discussing various appointments between April and August 1757, including postings to regiments at Gibraltar [2 letters] and America [7 letters].

Of particular interest is a longer letter from William Barrington to the duke in July 1757, relating the need for “a large number of Recruits […] wanting in America before the next Campaign” as “5000 might in all probability be wanted, a number much to great to be got in America” [LB5/13] – clearly reflecting a war cabinet girding itself for more action as the Seven Years’ War accelerated.

After a series of military defeats and blunders shortly thereafter that same year, including a French defeat at Hastenbeck and almost losing George II’s authority over Hanover, the duke returned to England in disgrace having “ruined his country and his army,” and “hurt, or lost, his own reputation” 2, never to command again.

1 www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/scottish-history-and-archaeology/the-jacobite-challenge/the-jacobitechallenge/portrait-of-the-duke-of-cumberland/

2 Walpole, Memoirs, 1.158, via www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb9780198614128-e-29455?rskey=oVxGqA&result=1

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (LB4)]. Nine letters and documents concerning the capture of Guadeloupe and the ‘Annus Mirabilis’ of 1759. [1759]. 9 items, mostly 1-2 text pages, including a personal 10-page journal bound with ribbon.

[BARRINGTON, Major-General John (c. 1719-1764) (LEB6)]. West Indies Letterbook.

[Circa 1759]. Folio (365 x 242 x 12 mm). 176 numbered pages (50-51 excised) including two blank leaves.

Reverse calf wallet style binding, locking clasp broken, manuscript title to spine

“Genl Barrington Commander in Chief”.

¶ “Our bells are worn threadbare with ringing for victories”, remarked Horace Walpole, as he summarised the Annus Mirabilis of 1759 1. The British capture of Guadeloupe, the richest of the French islands in the Caribbean, on 1 May – which this group contextualises – was the second of the successive military victories that together decisively shifted the momentum of the Seven Years’ War against the French. John Barrington was appointed second in command to Major General Peregrine Hopson and Commodore John Moore 2. Despite being one of the most important actions of that historic year, Guadeloupe was not a neat and tidy tale of British military success, as our archive amply demonstrates.

A vivid newspaper account elatedly describes the first British success on the island on 23 January, as the capital, Basseterre, went up in flames: “The Bombs, which had been ordered to play on the Town, having set in on Fire, occasioned, from the Quantity of Rum and Sugar, which was in it, great Destruction of Houses, with Goods and Treasure to a very great Value” [LB4/1. The London Gazette Extraordinary, 7 March 1759].

But, as so often in war, the headlines elide the exhausting drudgery of military success – and the details of these travails, at times very personal, are movingly revealed in our assemblage. From the outset we see that the campaign to capture the Leeward Islands was riddled with obstacles. When first landing on Martinique, the 6,000 British troops and naval escort quickly realised the island’s rugged environment was impenetrable: “we were obliged to pass a Ravine which this Country is full of an Immense Depth, and only by a Foot path which was so narrow […] the small Remaining twilight that we had the Army must have been in Great Confusion” [LB4/5. John Barrington. January 1759].

After several days of struggling to make any advance, the British diverted to Guadeloupe. Launching their attack there “with great bravery & success”, they were surprised to find the island’s main point of defence, Fort Royal, abandoned by the French: “a mistake in the Governor’s Aide de Camp delivering a wrong message to the Commanding Officer, but be that as it will, it was a lucky circumstance for us, because it could not be taken without a regular siege” [LB4/4. Capt. Haldane, HMS Panther. 23 and 24 January 1759]. Their swift success, however, was quickly overshadowed by a military stalemate and relentless French raids, causing the British troops – mostly bottled up in the fort – to deteriorate quickly. An unusually emotional letter for a military archive, opening “Dear Brother”, expresses the reflections of John Barrington to William back in London: “possibly Mr Hopson will be hanged for not taking Fort Royal […] however I feel my Conscience tells me I have acted like a soldier and an honest man which makes one sleep sound” [LB4/6. Basseterre, Guadeloupe. 29 January 1759]. Another letter that same day from Captain Haldane (written in a much more erratic hand than in his journals a few days earlier), makes plain to the Secretary at War the extent of his men’s struggles (“we are in a melancholy state and growing worse every day”), and tells of growing discord between those in charge: “I am sure the Chief Ingeneer Mr Cunningham blames our retreat from Fort Royall, and I believe has wrote so to some great men in England” [LB4/7].

After a short but serious illness during the French raids, Hopson died on 27 February – and command was transferred to John Barrington. It was on this day that Barrington began keeping his letterbook, assuming control in a situation that “would have challenged the most senior and experienced of commanding officers” – hunger, poor drinking water, and inadequate reinforcements – “nevertheless, he moved rapidly to restore the initiative” 3. Barrington’s letterbook brings a dose of realism to this impression of military decisiveness, with matters large and small claiming his attention. In the second letter he complains to his French counterpart, “Monsieur le Roy de Lapotherije”, concerning “the many Barbarities exercised by the Negroes under your Command”, and citing an incident in which “not contented with Murdering a White Man whom they had in their power, but (notwithstanding his entreating upon his knees for mercy) they cooley and deliberately Butchered”, until “the

appearance of a detached party” who “rescued his mangled Body from the hand of the Barbarians”. A racist outburst, certainly, only slightly tempered by his laying responsibility for these actions on de Lapotherie for having offered reward for “every head they shall bring in”. Barrington demands that he should not offer incentives to “the Slaves in Your Army to commit any Cruelties whatever”.

Despite the norm in this period for “White Men” and “Negroes” to receive different treatment and rewards, he later assures a correspondent that everyone is treated equally: “The Negroes were under my Inspection the greatest part of the time; were much better fed than in their own Island, having the same allowance of Provisions and Spirits as the Kings Troops”. However, it seems clear that he considers this equality undeserved: “There is great reason to suppose them the very Dregs of the whole Island, and such as were Thieves, Idlers, and an Incumbrance to the Estates”.

The British takeover of Guadeloupe was a remarkable achievement given the circumstances. During the three months of fighting, the troops were severely weakened by bad weather, sickness on a vast scale, and lack of military support. Barrington had launched counter-offensives against the French with an uncanny knack for working in severely constrained circumstances, not to mention a ruthless, scorched-earth approach to attacking French settlements along the coast and river valleys of Grande -Terre. It is said that his assumption of command following Hopson’s death was critical to the eventual success of the expedition 4 – but again, underlying this ostensibly triumphant outcome was a chaotic and desperate series of tribulations, as Barrington’s own letterbook from the campaign confirms. This Annus Mirabilis proved otherwise for the 800 troops who died of illness, the scores more killed or injured, and Barrington himself, who had his previously sound health ruined by the effects of the local climate and the stresses of command.

1 Letter to George Montagu, Esq. Strawberry Hill, 21 October 1759, ‘The Letters of Horace Walpole’, Volume II (1749-1759)

2 https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-65499#odnb9780198614128-e-65499

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

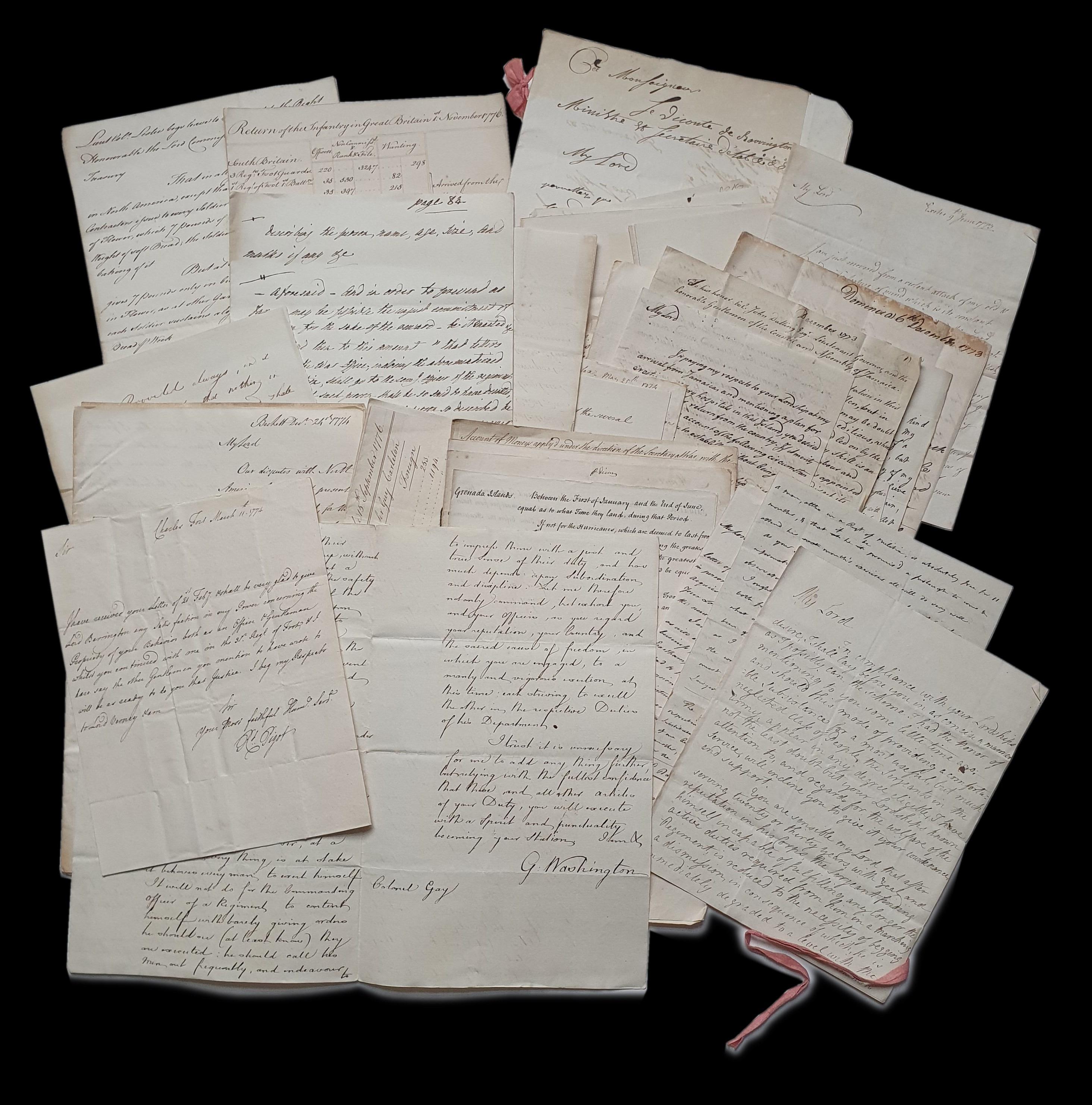

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (LB2/1-25; LB3/1-4; LB6/4; WB4/5)]. A collection of letters and documents relating to the Stamp Act.

[1761-1778]. 57 items, mostly 1-2 text pages, some significantly longer, including one 52-page report bound with ribbon.

¶ One of the most controversial laws ever passed by Parliament – the Stamp Act of 1765 – is given context by the colourful, varied and fascinating papers in this collection. The British government was heavily in debt after its long-fought victory over the French in the Seven Years’ War, and was concerned that the growing disquiet in its new colonies required firm action to secure its new North American stronghold.

The Empire’s unequivocally war-drained finances are detailed in an official copy of former Chancellor of the Exchequer Henry Legge’s four-page paper, “The State of Great Britain at the End of 1762” [LB2/4]. Having played a key part in Britain’s success in the Seven Years’ War, Legge maintained his interest in finances by compiling for the Duke of Newcastle a set of analyses of government debt and revenues and by speaking on financial affairs in the Commons. His paper shows British debt at “130,707,586” – with almost half that amount attributed to “the War” He concludes with grave and palpable concern: “I leave it to any sober man, to say, how it is possible to raise money for a further campaign, after the supplies of 1762 are exhausted”

An absorbing bundle of letters and proposals between Lord Barrington and a charismatic active Jewish leader and London merchant, Joseph Salvador, opens the archive’s earliest (and most desperate) discussions about raising money for the Navy in 1761 [some 12 items, LB3/1-4]. Salvador was an “articulate, able, and ambitious merchant”, a ship-owner and a major importer of rough diamonds and bullion1 who rose to become an expert on public finance, a key advisor to the Treasury, and an important underwriter of government issues during Newcastle’s final reign as Prime Minister, 1757-1762. In September 1761, he provided Newcastle with “a lengthy discourse on finance together with suggestions for ways and means of raising money”, including proposing a lottery to aid market instability2. Our own archive shows Salvador making several financial recommendations to Barrington, including renewed British trade in silver “to thwart the French having that advantage so openly” [undated], and a staggering proposal that he make a loan of £4 million to cover Navy debt, on which Salvador “should decline interest […] as matter of honour” [Tooting. 27 September 1761]. It is not known whether the loan was ever taken up. Despite Salvador’s deep and long engagement in government finance, he never received any direct payment for his considerable services.

Further detailed accounts [some 12 items] show incomes from public revenues and Stamp Duties between 1759 and 1764, for goods including “Wine” and “Ale”, and for “Cards & Dice” licences “for one year ending 2 August 1763” [LB2/2] – six months after Britain had acquired the province of Quebec from the defeated French and relations between American colonists and the British government had come to a head. Also included are “Charges” on “National Debt” versus the “Payments” towards clearing it in 1763 [LB2/3]. Later accounts compare increases and decreases in national debt “from Christmas 1739, to Christmas 1766” [LB2/6], while others list savings deposited 1757-61 [LB2/8]. Together, the archive lays out scrupulous investigations into British accounts as the government readied itself for the Stamp Act of 1765 to raise funds to station a large army in North America.

The colonies reacted strongly as soon as the Stamp Act was passed in March 1765, and violence repeatedly erupted against Britain’s attempts at control and raising finances from afar. It is during this time that our archive shows Secretary at War, William Barrington, attempting to reinstate the careful and frugal management of British coffers, as well as pursuing the type of reforming procedures and regulations that he was known for. A neatly-laid-out, 10-page document detailing the “Regulations

made in favor of the Public, and of the Army, between June 1765 and December 1778” opens by highlighting “a surplus of near £5,000” to be called “out of the hands of the [stamp] Agents” for “public uses” [LB6/4]. Having asked to resign two years earlier, describing himself as “a baker in a famine, his shop crowded with customers, and very little bread to give them”4 , Barrington was granted retirement by the king in December 1778, the very same month as our document concludes – making this a kind of valedictory statement.

One of the most engaging and surprising pieces in the collection is an official copy of a letter from the first British governor of Quebec, James Murray, to Lord Shelburne, the secretary of state responsible for America [LB2/13. 1766]. It reveals a man conflicted by the state of affairs in the new colony, with greater sympathy for the agrarian “poor Canadians” who “cheerfully comply’d with the Stamp Act” than with the newly arrived English-speaking traders (“the most immoral collection of men I ever knew”). Faced with pressures from London, including directives made in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 barring Catholic Canadians from public positions and giving the British monarch the power to buy and sell Indigenous land, Murray was left in discord with British settlers and officials alike. After submitting this report on “the nature and causes of the disorders” of the 1764 civil unrest in Montreal, and unable to form a viable system of government for “that Brave hardy People”, Murray was recalled from Canada to London in June 1766.

A likely case of attempted extortion is the highlight of this collection. “Major Nicolas Dunbar” makes ten intriguing desperate personal appeals to William Barrington between November 1764 and May 1765 [WB4/5]. Writing from “Young Wills Coffee House, Buckingham Court”, Dunbar explains he writes due to “his Interest hurt, and himself, and family, injured and ruined” Stating he had been appointed Deputy Governor of St Helena under the East India Company in 1759 – conveniently Britain’s most remote overseas territory – Dunbar seeks help from Barrington with financial compensation after being prevented from selling his purported military commission. Floridly obsequious addresses (“No man, more respectfully reveres your Lordship, than I do”) and deeply personal turns of phrase (“were he be alive, Your Own brother, should be my Umpire”) fill the insistent letters, as Dunbar implores the Secretary at War to “support the friendless and the unsupported”. He even quotes the motto of the Barrington Family Crest, “Honesta quam splendida!” (‘How illustrious are honourable deeds’)3 in urging Barrington’s justice. Over six months, Dunbar’s unanswered letters escalate in their desperation, boldly including a bill calculating his “misfortune and disappointment” at “£1000” – reaching a hysterical climax “Think My Lord! for God’s Sake Think! […] Do as you would wish to be done by, My Lord!”. Barrington’s one short response rejects Dunbar’s appeals, finishing in post scriptum “Mr Wood never mentioned you or your employment to me” [8 January 1764]. What is the real truth of these curious letters? We could find no records linking Dunbar to St Helena. However, a 1763 entry in the Journals of the House of Commons, lists a complaint of embezzlement by a “Major Nicolas Dunbar”, based at “Young Will’s Coffee House, Buckingham Court” against a “Mr Fitter”, seeking recompense for sums as high as “£6,621”. The House concluded that Nicolas Dunbar’s petition was “frivolous, groundless, vexatious, and scandalous” – and he was “taken into the Custody of the Serjeant at Arms”4. Evidently, Dunbar’s sentence had not deterred him, and the serial swindler had decided to take his act up the ranks to the secretary at war.

This group also includes a very colourful 52-page report of House of Lords proceedings, in which William Barrington took part, regarding the expulsion of the MP John Wilkes from the Commons on grounds of seditious and obscene libels for his political satire. Wilkes gained notoriety for issue 45 of The North Briton, which criticized a royal speech in which King George III praised the Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years’ War. [LB2/1. 16 December 1768]. Barrington’s performances in the Commons caused Horace Walpole to place him in a 1755 list of the 28 best speakers in the house, overcoming “a lisp and a tedious precision”.

1 https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-40772? rskey=ApDhsT&result=1

2 Woolf, Maurice. “Joseph Salvador 1716 1786.” Transactions (Jewish Historical Society of England), vol. 21, 1962, pp. 104–37. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29777993.

3 Ibid.

4 www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1535?rskey=522WZl&result=2

[BARRINGTON, Admiral Samuel (1729-1800) (LEB1/1-25)]. St. Lucia and Barbados Bound Original Letters. [Circa 1778-1782].

Folio (325 x 205 x 10 mm). Approximately 65 unnumbered text pages, letters of various sizes bound into one volume, some separated by blanks or original address leaf (not included in page count). Contemporary calf, rubbed.

[BARRINGTON, Admiral Samuel (1729-1800) (SB1/1 – 44)]. Unbound Original Papers. [Circa 1779-1789].

Approximately 44 items, made up of variously sized papers, including printed articles. Mostly 2-3 text pages per item.

¶ After France declared war and allied itself with American rebels in 1778, during the American Revolution, Britain briefly turned its focus from North America to the Caribbean, the lucrative sugar-producing colonies that produced important sources of revenue. The French had captured the British-controlled island of Dominica in a surprise invasion in September 1778. The British in turn reinforced Barbados, their main base in the Windward Islands, with some 5,000 troops from Henry Clinton’s army in New York. And Rear-Admiral Samuel Barrington moved swiftly against the French island of St Lucia. Despite the ultimate British win on 28 December, the St Lucia campaign seriously compromised Britain’s war for America. This archive collection – made up of Barrington’s letterbook and several complementary unbound papers – focuses mostly on Barrington’s actions commanding the Leeward Islands squadron in the Caribbean (1778-89), as well as British action in America of the same period. There are also papers related to Barrington’s service in the English Channel (1782) and the relief of Gibraltar (1783).

The letterbook opens with copies of “Articles of Capitulation” in both French and English, relaying the successful English takeover of St Lucia from the French on 30 December 1778 [LEB1/1]. But, as we’ve seen in other collections, the reported resounding successes of wars ever omits the reality. Despite Barrington’s swift initial securing of the island on 15December, the conquest coincided with the sudden arrival of the French West Indies fleet, as related in a letter from Barrington to his “Dear Brother”, Daines: “D’Estaigne appear’d off the harbour with 11 ships of the line & some frigates. He is said also to have had 5000 troops on board destin’d for St Vincents or Barbados” [SB1/6. 22 February 1779]. An account from the St Vincent Gazette, Extraordinary, speaks of D’Estaing’s heavy losses in failing to storm the higher British positions: “Seventy of the French were killed in our Intrenchments, and their whole loss, in killed, wounded and prisoners, is estimated about 1600. On our side we had 60 killed and 100 wounded” [26 December 1778]. Impeded by bad weather and unable to make a successful attack twelve days later, D’Estaing quit the island and surrendered on 30 December. Despite the British win, a letter that same day from an “Edward Otto Bayer” expresses his anxieties to Barrington about further attacks: “you are surrounded on all sides by a superior force of the enemy” – promising to send “many very fast sailing Armed Vessels” to assist him [LEB1/4. Antigua.].

At this point, the letterbook goes on to celebrate Barrington’s victory at St Lucia. Letters in the days and weeks that follow offer congratulations for “the Services rendered to this Country” [LEB1/7. John Gaye Alleyne, Barbados, 3 January 1779], noting Barrington’s “judicious and Spirited Conduct in opposing and defeating the sophisticated Attacks of a French Naval Force” [LEB1/10. Assembly of Nevis, Nevis, 3 February 1779]. They detail the Admiralty’s recognition of Barrington as one who “rescued a considerable and very valuable part of the Kings dominions from imminent destruction”, and the acclaim expressed by other naval and military commanders: “how much your conduct is approved by your Royal Master, & by all ranks of people in this kingdom” [LEB/1/15. Lord Sandwich, Admiralty, 14 March 1779].

But it seems the news was only travelling one way – at least successfully. The sheer distance between Britain and its West Indian colonies, as well as North America, meant that communication across the Atlantic Ocean was sluggish and problematic. “I have been frustrated in any attempts to send an account of our success at St Lucia”, Samuel writes to his brother and secretary at war, William, over a month after the battle was won [SB1/5. 5 February 1779]. A letter sent by the Admiral later that same month, requesting “a large squadron constantly here [if] they can be spar’d” to support him, is only marked as being received as late as June [SB1/15]. In another from August, Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, expresses “it has been very difficult to supply you properly till now, as we did not know at first where to send to you as your motions were uncertain, depending entirely upon your adversary: for this reason we were obliged to send the stores first by America” [LEB1/16].

The battles that played out thousands of miles from home, were riddled with significant natural challenges that shaped the course of the war. Hurricanes and Trade Winds blew and devastated fleets1. On land, the foreign American terrain was often swampy and difficult to navigate. At the same time as Barrington was fighting in the West Indies, the severely weakened British troops in America led by Henry Clinton, (whose portion had been relocated to Barrington’s cause in St Lucia), were moving up from Florida to capture Savannah, Georgia. Three printed newspapers from 23 February 1779 report the very different environmental challenges of British action on the ground [SB1/10-13. The London Gazette.]. At one point the troops are grounded at “a narrow Causeway 600 Yards in length, with a Ditch on each Side, led through a Rice Swamp directly for Gerridoe’s House, which stood upon a Bluff of 30 Feet in Height, above the Level of the Rice Swamps” [SB1/9]. The same year, the heavy loss of Britain’s richest sugar-producing colony, Grenada, on 4 July 1779, was also marked by the harsh changeable environment and difficulties of communication in remote sea warfare2. Yet our papers show the acknowledged bravery of Barrington’s part in the battle against d’Estaing – during which he was wounded – expressed by the Admiralty as “the very spirited example, and gallant behaviour of Vice Admiral Barrington” [SB1/25. 30 October 1779].

Barrington’s 1778 capture and defence of the small but strategically located island of St Lucia is considered his greatest achievement. With the success, Barrington managed to secure access to the eastern Caribbean, ensuring the continuation of British trade between its most valuable sugar plantations. This collection of letters sheds light on British action in the Leeward Islands, as well as that in North America, during the early years of the American Revolution, and offers the untold truths and lesser glories of 18th-century warfare far from home soil.

1 www.militaryhistoryonline.com/Century18th/Caribbean

2 https://grenadanationalarchives.wordpress.com/2009/07/06/heritage-the-french-battle-of-grenada-and-the-comte-desta/

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (WB6)]. Letters and Documents. [1781-1792].

Approximately 51 items, mostly 1-2 text pages.

¶ This group of papers reveals William Barrington’s personal – and undoubtedly highly stressful – wrangles with the nascent National Audit Office, which tried to reclaim a balance of “£2,914.13.5¾” (almost £22,500 in today’s money) from his time as Navy Treasurer, despite Barrington’s having repaid it ten years earlier.

The crucible of modern Westminster constitutional audit, as developed in the final decades of the 18th century, lies at the heart of this lengthy 11-year collection. By 1780, Britain was left overstretched and woefully enfeebled by the American War of Independence (1775-83). The strains of war were being felt by the government, and the resulting political and economic crisis increased pressure for more detailed parliamentary scrutiny of military expenditures. In a series of key accounting and audit reforms, led chiefly by Edmund Burke, Parliament appointed seven Commissioners of Audit in 1780 to “examine, take and state the Public Accounts of the Kingdom”6 – working as the early National Audit Office.

Various papers from 1781 to 1788 between the Navy Pay Office, the Office for Auditing and William Barrington show the Navy’s finances being inspected in this manner. We see Auditors of the Imprest requesting records of the former Treasurer of the Navy, only to find them in “great Arrear” and regularly “incomplete” [WB6/3-7]. Despite sending the “Tally” for Navy Treasury monies owed to the Exchequer early in 1781, Barrington is swept up in the disorder of the new Audit Office, suddenly facing “Sheriffs” knocking at his door with “Proceedings against your Lordship” [WB6/13. 4 April 1788] and a letter stating that his “Final Account as Treasurer of the Navy from 1 January to 9 August 1765, was this day declared by the Chancellor of His Majesty’s Exchequer, with a Balance due to the Public of £2,914.13.5¾” [WB6/14. Office for Auditing the Public Accounts, 9 July 1788].

Barrington responds immediately that he has “paid every farthing which the Officers of the Parliament requested of me”, and conducts urgent correspondence with various individuals over the next days, seeking assistance and an “affidavit” of cleared debts from the Navy Office clerks [WB6/15-23]. It is not until 9 June 1792 – over ten years after Barrington paid his Tally –that he receives a receipt from the Auditing Office confirming “the payment of the Sum of £2,914.13.5¾ into the Receipt of His Majesty’s Exchequer” [WB6/24]. The 11-year affair – described in a letter to Barrington as “the most absurd thing in the World” [WB6/21. J. Slade. Hammersmith, 24 August 1788] – must have taken a great toll on the retired politician, who was 72 years old by the time the case was closed. Indeed, William Barrington died only eight months later.

[BARRINGTON, William Wildman (1717-1793) (LB1/1-52)]. Letters to Barrington, including a copy of an intercepted letter by George Washington. [1770-1778]. 52 items, mostly 2-3 text pages per item, a few up to 8-10 pages.

¶ Britain’s steady march into the American Revolution (1774-83) frames this utterly engrossing and detailed archive. In it we can vividly see Britain and America deliberating, readying themselves for and engaging in one of the most notable wars in their histories. The majority of Viscount Barrington’s ‘in’ and ‘out’ correspondence between 1770 and 1778, which the archive comprises, focuses on America specifically (roughly 18 items), Grenada (2 items), Jamaica (3 items), Canada (roughly 9 items), as well as the Mediterranean (France, Minorca, Gibraltar (4 items in total)). Also included is a fascinating official copy of intercepted orders from George Washington to Colonel Gay from 1776, of which the original is held in the Library of Congress.

Some of the earliest items in the collection reveal concerns about British troops already stationed for lengthy periods in the Americas well before the War of Independence. Two letters from Daniel Magenise to Barrington in December 1773 discuss the need for military hospitals in Jamaica: one empathetically recounts the struggles of British seamen “altogether abandoned to drinking new Rum”, suggesting they be sent home to recover “on account of the climate and the difficulty of weaning them from that liquor” [LB1/20]. Letters from Lord Dartmouth, a key colonial statesman, and his half-brother and then Prime Minister, Lord North, debate Britain’s future American policy in December 1774 (both docketed as ‘copies’ on their backs). North expresses his concerns about the numbers of British troops overseas impacting domestic matters [LB1/52]; while Lord Dartmouth warns “the contest [with North America] will cost us more than we can ever gain by our success” and emphasises how important it is that “the Colonies will feel we are their Masters, and will be less provoking for the future” [LB1/50].

By the early years of the conflict, some 12 abstracts detail British troops stationed abroad. A document titled “Strength and Disposition of the Land Forces” reveals that, in 1776, over half the entire British army (“96,314”) was stationed in North America (“54,364”) [LB1/14], and that in 1777, Britain had almost ten times the total number of ranked officers stationed in North America compared with any other colony [LB1/10]. An undated letter from a “Mr Smith” offers advice on the best and worst times of the year for landing British troops in the West Indies: arrival to Antigua, he writes, is “improper in October” [LB1/32]. Also included are striking details of war strategy: for example, an “Order of Battle” dated 15 August 1776 clearly lays out plans for General Howe’s Army in North America – 12 days before 20,000 British troops attacked Long Island in the war’s first major battle, causing the Americans to retreat1 [LB1/42]. Another, from 25 January 1777, lists the names of Officers of Foot Guards ordered to America, not long after Washington had captured the British garrison at Princeton, New Jersey [LB1/48].