w o r d s

& t h i n g s

S I X & t h i n g s w o r d s n u m b e r

ONE

¶ Early modern households were complex business operations which required careful management of health, finance, and social connections. The earliest contributor to this household manuscript was clearly equal to the task.

Elizabeth Preston was a shrewd 17th-century businesswoman who not only reversed the declining fortunes of her late father’s estates but, as is evident from our manuscript, passed her accumulated knowledge to her granddaughter, making this an heirloom manuscript, whereupon the latter enthusiastically added to the contents.

PROVENANCE AND CONNECTIONS

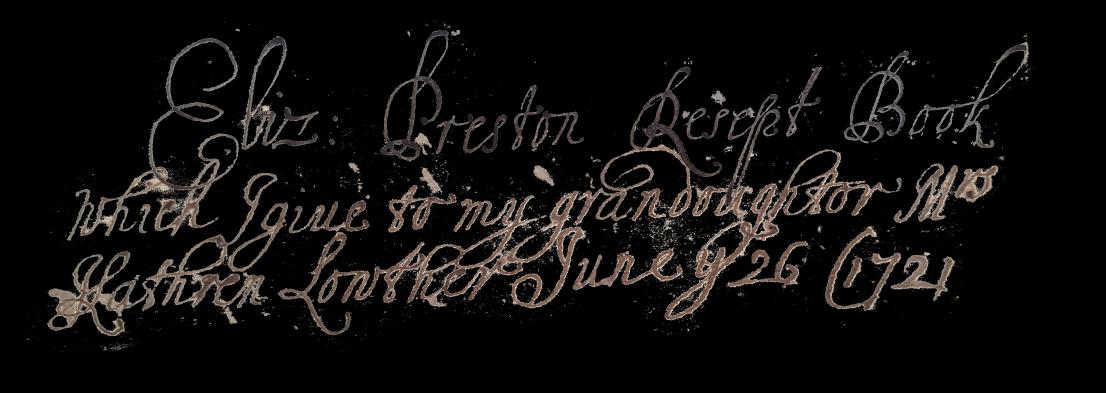

An inscription to front endpaper verso reads “Eliz: Preston Resept Book” in dark ink, with a note beneath in lighter ink: “which I giue to my grandoughtor Mrs Kathren Lowther June ye 26 (1721”. Other names – such as “Pennington”, which occurs several times in the manuscript – help us to triangulate these clues and establish our scribes.

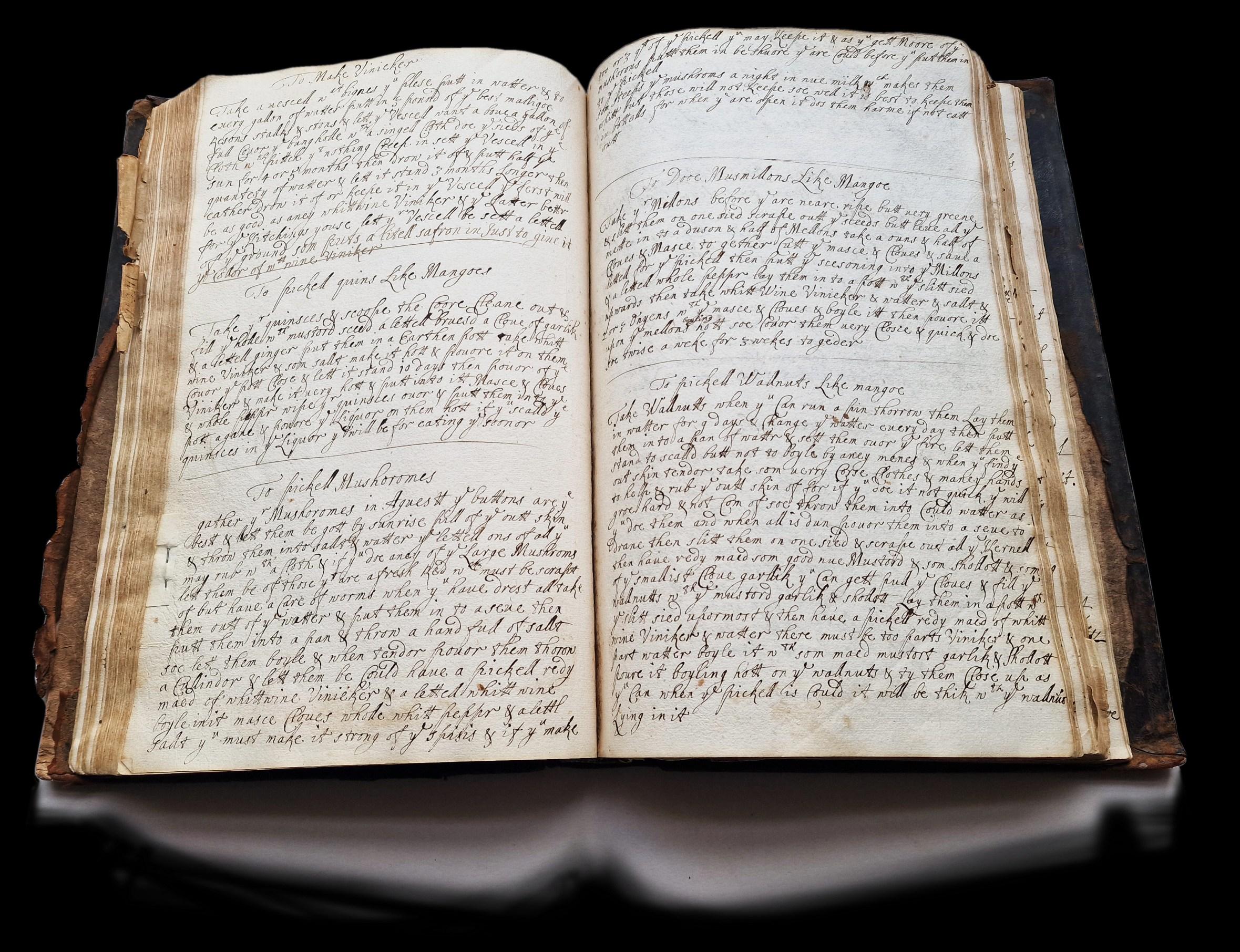

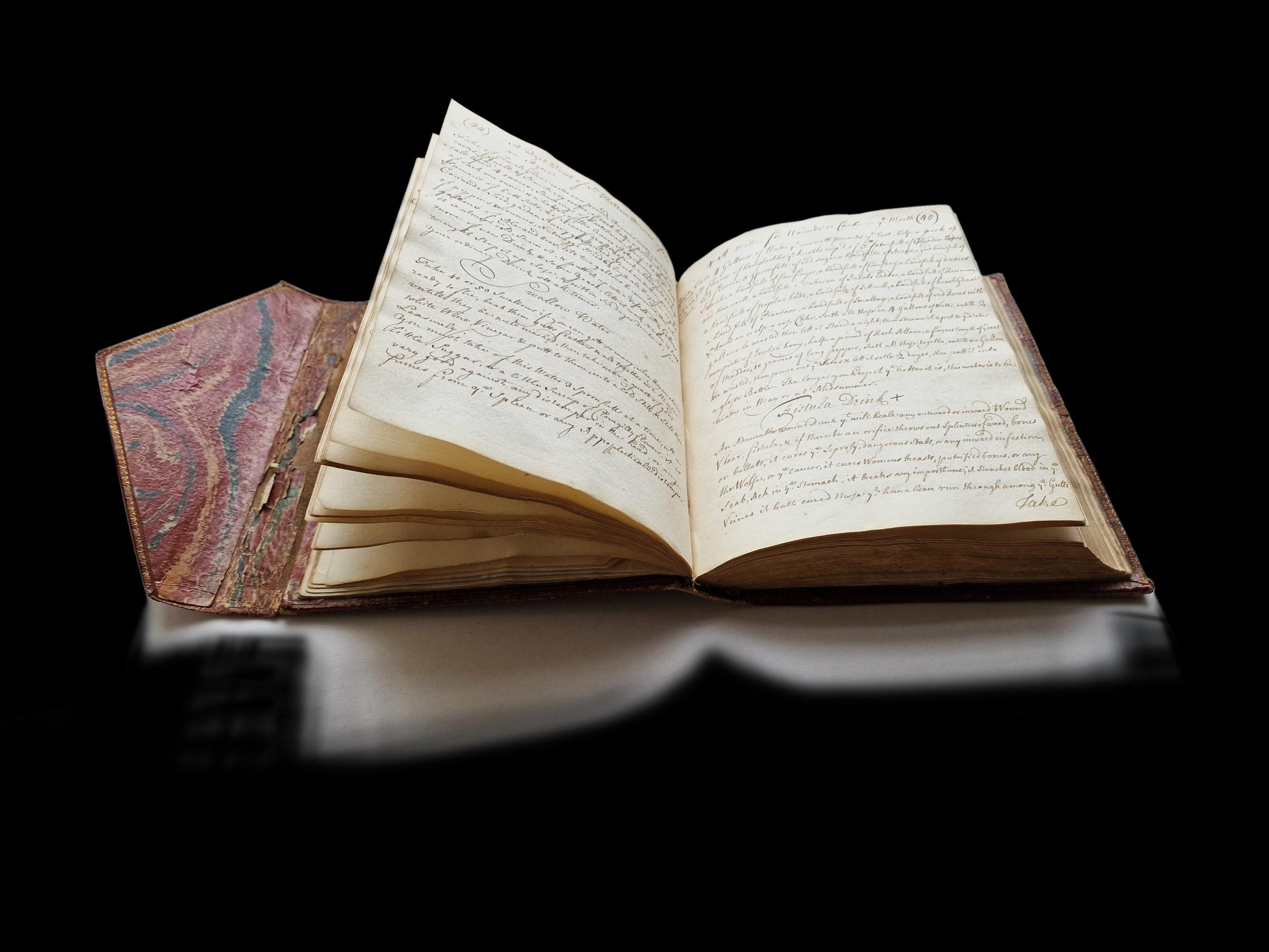

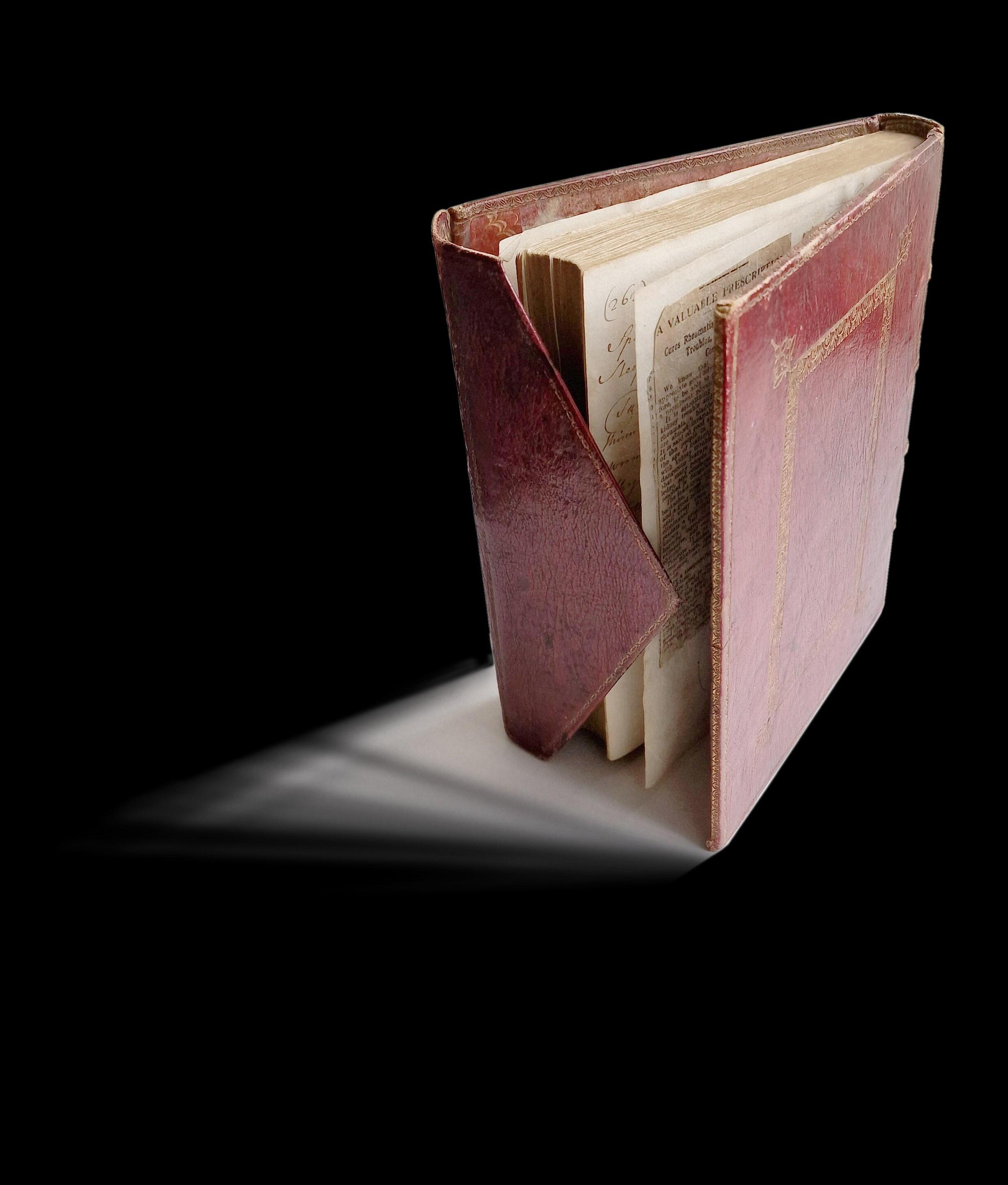

[PRESTON, Elizabeth (née Bradshaigh) (1650-1732); LOWTHER, Katherine (b.1698)]. English Late 17th-early 18th-Century Household Manuscript. [England. Holker Hall, Lancashire? Circa 16701730]. Folio (320 x 200 x 30 mm).

Approximately 313 text pages on 220 leaves, including endpapers, including two leaves inserted (presumably sent as separates): f.130 folds and bearing Arms of London watermark; f.137 folds and bearing Pro Patria watermark. Fore-edges tabbed, torn with loss to original text, but “Distill’d W[aters]” and “Swett[s]” extant.

Contemporary blind-stamped full calf, rubbed and worn.

Elizabeth Preston (née Bradshaigh) was the daughter of Sir Roger Bradshaigh (1627/8-84) and Elizabeth (née Pennington) (1640-67), daughter of William Pennington of Muncaster. Elizabeth and Roger married in 1647 and had four sons and given her name she was probably the eldest of their three daughters. Elizabeth married Thomas Preston (1647-97) in 1675.

The Prestons lived at Holker Hall near Lancaster and at Marske, Yorkshire. They had one child, Catherine Preston (d. 1701), who was their sole heir, and was said to have brought a fortune of £30,000 to her husband, Sir William Lowther, 1st bart, of Marske (1676-1705). The Prestons and Lowthers were already linked in marriage prior to this: Mary Lowther, sister of Sir John Lowther of Lowther, married Thomas Preston’s (1647-97) elder brother George.1

Catherine and Sir William had two daughters, Katherine and Margaret. Katherine married Sir William Lowther (c.1699-1745), and they resided at Holker Hall. So we assume that the manuscript was given to Katherine, the younger daughter by her grandmother Elizabeth Preston, to continue the successful running of their estates.

Watermark: Foolscap with seven points; Countermark: LD (this combination not in Haewood, but see 1988-2087 for similar, which he dates to the second half of the 17th century).

Provenance: inscription to front endpaper verso reads “Eliz: Preston Resept Book” in dark ink, with a note beneath in lighter ink: “which I giue to my grandoughtor Mrs Kathren

Lowther June ye 26 (1721”. (certain sources –possibly including the family itself – have confused Catherine with her daughter Katherine, but we have adhered to the C / K distinction as above).

Elizabeth’s business acumen was conspicuous enough to merit a prominent place in at least one piece of published research that examines the Lowther family’s vicissitudes as an example of the experience of the English landowning class. Sir William died in 1705, four years after his wife, leaving their four children’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Preston, not only to act as their guardian but to address the parlous state of the family’s finances. The scale of Sir William’s debts made this a daunting undertaking; according to J. V. Beckett, “Elizabeth Preston had to redeem these debts and also meet the cost of an expensive Exchequer case relating to the manor of Furness. By careful management she not only redeemed the debts, but also managed to finance repairs at Holker Hall and buy a couple of small properties”.2 Elizabeth thus stands as an example of a 17th century female head of the family clearly a highly competent one.

The recipes are separated into sections, often demarcated by blank leaves. These sections have been tabulated with section titles pinned to fore-edges. These are, unsurprisingly, mostly lost, but two remain, and although torn with some loss, they retain some of their original text (“Distill’d W ” and “Sweet ”). However, despite this careful attempt at arrangement, the subjects as is often the case with receipt books have not been maintained, and the contributors overlap each other’s work, so no neat and easy separation is possible. Nonetheless, a brief summary might look something like this:

Hand I. Elizabeth Preston (1650-1732): (17th century): contributes around 400 recipes and around 34 remedies and miscellaneous household receipts on approximately 180 pages. Numerous attributions.

Hand II. Preston household member: (17th century): approximately 20 brief recipes to four pages.

Hand III. Katherine Lowther (b.1698): (early 18th century), adds another 285 or so recipes and 13 remedies to around 128 pages.

We can deduce from a note by Elizabeth that most entries were likely completed before 1701 (see below), and that after a hiatus, she passed it to “my grandoughtor Mrs Kathren Lowther June ye 26 (1721”, perhaps to mark a coming-of-age event such as her marriage.

Elizabeth’s contributions are the most straightforward: her inscription is written in a distinctive hand, which enables us to confidently attribute over 400 culinary recipes and more than 30 remedies to her. There are also some 20 brief remedies and culinary recipes written in another hand, which we presume was a contemporary member of her household – her husband, perhaps. Attributions are made throughout the volume and by all three hands, giving abundant evidence of Elizabeth’s family and social connections.

THE CONTENTS

The approach of all three scribes to arranging their material is erratic to varying degrees. Elizabeth (Hand I) often groups recipes by category – her addition of tabs, as we shall see, indicates at least an intention to do so – but not always; the anonymous household member (Hand II) is similarly inconsistent; and Katherine (Hand III) is perhaps the most hit-and-miss of all. We have chosen to follow the sequence of the manuscript itself, using the tabs (or their remaining pinholes) as waypoints, in order to elucidate the points at which order has been imposed and those where it has apparently been abandoned.

Hand I: ff.1-2v; Hand II: ff.2r-5v; Hand I: ff.5v-8v.

Elizabeth begins the volume with five entries, and immediately two characteristics of her approach are apparent: a concern with attributing her sources (“Derections from my Lord Duck Hambletons gardner for ye soing of ferr seeds” (f.1r)); and the aforementioned inconsistency in maintaining the order she often seems to bring to her contents (we jump from “ye soing of ferr seeds” to four remedies beginning with “my Unkell Dr Resept of a Jelly for strenktning ye back uerry good” (f.1v), the first of three consecutive remedies attributed to her maternal “Unkell Dr Pennington”, and of a number of entries that acknowledge family members).

Elizabeth concludes this brief selection with “A Receipt for the Wormes and may be giuen to Children: Dr Baynards”, after which Hand II takes over, initially continuing the theme of remedies – and doing so explicitly, since the first remedy is presented as “Anothr for the Wormes, wch is stronger and in some Cases more Effectuall, yet Safe. Dr Baynard” (f.2v). This hand records a further three remedies, including another vouchsafed by “Dr Baynard” and two from “Dr Kitson”, before going back to the kitchen for “A Receipt to make a Sacke Possett:, Mis ffleetwoodes” and a further eight recipes attributed to this same “Cosne fflett” (f.3v-f4v). Their final culinary handful, however, is interrupted halfway by the eructation of “A Gentle Purge. Mis Penningtons” (f.5r).

Elizabeth now resumes for a more substantial section (f.5v-f23v); and after a pair of recipes for a “bakt puding & uerry good” and “a good Jelly from my Lady Boyer” (f.5v), she begins a section entitled “Resepts to make Cremes”, consisting of eight recipes for the likes of “Sack”, “Cherry”, “hunney Come Creame”, and “a shugar lofe Creme”, attributed to “my Annt Rigby” (f.6r). There follows another lapse into miscellanea, albeit with some admirably detailed instructions (f.7v. “To pickell Cowcumbers ye best way I euer saw Mrs Bigland”; “Take Cowcumbers yt are gadred drye & lay them in water wth a lettell salt […] drye them in Clothes uerry well then take ye best whitt wine Vinieker as much a yu think will Couer them […] boyle it 3 seuerall times 3 days aftor one a nother”), or added remarks indicating use (“an Excellent Cordiel water Mrs Jolly”, annotated “I think Ale maks but a small water soe I always make is half wine” (f.7r)).

Tab at f.9 (text lost). Hand I: ff.9r-17v.

The categories stabilise somewhat with this first tab, as we find around 25 drinks recipes, mostly alcoholic (wine, cider, mead). First, a pair of recipes for “Couslop wine”, one from “Sistr Brads:”, the other from “Madm Standish” (and annotated “if yu make yr Couslop wine ye same way yu make yr Cloue gillyflowore wine it is best”) (f.10r). An air of conviviality prevails, as characters are acknowledged – and often commended – for their contributions: “Dr Lower” for “meaed […] & uerry good” (f.10v), “Excolent Sieder”, and “Sage wine” (f.11r); and “Mrs Mary Armstrong” for “Corren Wine”; and, traversing social classes, Elizabeth sets down directions “To Make Mead my Lady Lowedrs way” (f.11v), and shortly thereafter, “Coren wine for Keeping Long my maid Mulnixis way & uery good”. The latter’s exacting instructions, no doubt owing to familiarity with the recipe and proximity to the contributor, include the important final note to “put into each bottell a lettell suger yu must not fill ye botells too full this is too much suger”

Elizabeth sometimes adds a bit of context in her attributions, as in her entry “To make Elder bery wine my Lord Darbys way hee gaue mee it him selfe” (f.14r) – which can’t help but read a little like a social brag – or alludes to her own background, for example with “To make Wiggen Braggitt” (she grew up near Wigan where, according to this recipe, she would have drunk this “Liquor for Christmas & Lent”) (f.13r). She also adds herself to the attributees with “To make meaed my one way” (f.15r) – an unusual expression, probably a misspelling of “own”, but either way one subsequently used by her granddaughter Katherine.

Tab at f.20: “Distilled w[aters]”. Hand I: ff.20v-23v; Hand III: ff.24r-26v;

This second tab, labelled but with text partly lost, marks the beginning of half a dozen recipes for medicinal cordials and waters including “Red Cherry Watter” (“good in ye smalle pox & for fanting fiotts & may be geuen a womon in Labor” (f.21v)), “ye Milke watter good” (“You may leue outt ye Rue if yu Like it nott butt it is uery good for Children” (f.22r)), and “Rosemary Wattr to rub ye hed & make ye hare groe” (f.22v). Another physician gets his due here, in the directions “To still ye snalle Wattr Dr Askew gaue Mastr Lowther” (f.23v).

Katherine (Hand III) then makes her first appearance in the running order, immediately disrupting her grandmother’s category scheme by adding recipes for 11 varieties of wine (“Oringe”, “Sage”, “Damaseen”) (ff.2426) to blank pages left by Elizabeth.

Pinhole (tab lost) at f.27.

Hand I: ff.27r-43v.

Elizabeth begins a new set of entries, with a solid run of cake and biscuit recipes (a.k.a. “Kakes”, “Kaks” and “Keaks”), together with “Wafers”, “Biskitts”, “Puffes”, “Wiggs”, and “Mackaroons” (ff.26-44).

The menu here takes in puff pastry (“wch will allsoe make into pretty Keakes & Jumbells. Cosen Bradell good” (f.26v)), “Allmond Gingerbred” (f.27r), “Allmond Biskitts ye frensh way” (f.28r), “pastt of Apriecocks the

Italian Way or Whitt pare plums” (“uery good & when drye will be as Oriant as Ambor” (f.27v)), “Pistaches paestt” (f.27v), and a handful of recipes employing chocolate, such as “Chocolett Jumbells” (“Lay itt upon papers buttord thin & bake them in a Marchpane pan” (f.29r)), “Chocolette Allmonds” (f.29v), and “Jockellett Waffors” (f.28v). Attributions here are numerous, if not quite as plentiful as in some earlier sections: thus, we find “ye Countess of Arendells Oring biskitt” (f.28v), “Lettell Cakes my Lady Chumbleays way” (f.29v), “Mrs Leadbettors possit for breakefast uery good” (f.35v), and “my Cosen fflettwoods Chese Kakes” (f.39r). Other personages getting their due include “Mrs ffranklen” (or “Mrs ffran:”), “madm Leese”, “madm perepoynt”, “Mrs Kenyon”, “Mrs Harison”, more relatives such as “my Sistr Brad:” and “Cosen Bradell”, and a further smattering of titled ladies (“La: Denagall”, “Lad: Nut”).

Tab at f.44: “Swett[s]”. Hand I: ff.44-57; Hand III: ff.57-85.

The section title “Swett[s]” here signifies fruit, and accounts for 77 recipes, as Elizabeth (Hand I) records differing methods of preserving fruit (“plums”, “Apriecocks”, “Cherrys”, “pechis”, “pares”, “quins”, “Apells”, “Oringis”, “Swett Margrom”, “Sitterones” (f.44v – f.49r)). The section includes recipes for marmalades (“Marmalett of Cornelians”; “Marmorlett of Apriekocks Lady Nutton”; “Red Marmalett of quinsces”, which you should “bring to ye Collor of Clarritt”). Her final entry in this batch gives directions “To make swett baggs to Ly a mongst Linin”, featuring ingredients such as “a bushell of Damask Rosis […] beniamen & storix of each anouns & Amborgresce & Musk of each 4 graens”, to be powdered and, in a glass, placed in “an ouon aftr bred is drown & ye Ouen nott soe hott as to breake ye glass”. The final products, we are assured, “will keepe there sentt maney yeares” (f.48r).

Katherine (Hand III) again takes advantage of her grandmother’s blank pages to append a long section of 141 numbered recipes, none with attributions, all apparently copied out at one or two sittings. The “Sweets” theme is dropped in favour of a miscellany of recipes from puddings (“Apple”, “fine Lemon”, “Sweatmeat”, “Oringe”, “New College”) to sausages, collops and sauces (“Oister”, “Mushroom sauce for White Fowls”, “for Boild Rabbits”), pies (“Lamb”, “fish pyes”, “Artichocke”), pickles (“Walnuts”, “Colliflowers”, “Samphire”), soups (“Peases”, “Crayfish”), fish (“drest a Cods Head”, “Rost a Pike with a Pudding in its Belly”), and cakes (“Ginder Bread”, “Portugall”, “Plumb”).

Elizabeth has begun another section here, with 51 more recipes for creams, including two to make “Chocollat Creame” (“swetten it to yr taestt & soe whip it up & dish it or mill itt wth a Chocollatt mill” (f.86r)), another from a well-connected source (“To make Chocolate ye Duke of Boofords way” (f.92r)), and a “Spanish Creame” recipe garnished with comments that indicate this has been put to the test (“beate itt wth a spoone till it bee pretty thik but haue a Care it doth not tuorn to buttr soe putt it into yr Dish yu may lay it Like a rock or steepell […] please when yu send it to ye tabel yu may putt lettell Creame in ye bottom of ye dish but it is as well wthoutt” (f.87v)).

Katherine yet again abandons her grandmother’s scheme, adding a miscellany of fruit recipes (“Preserve Oringe Flowers”, “Golden Pippins”, “Quince Marmalade”) and meat dishes (“Sausages”, “Savoury Patties”, “To hash a Calfs head”) (ff.93v-96v).

Pin hole (tab lost) at f.97.

Hand I: ff.98r-102r.

Elizabeth’s next section begins here, with a group of 22 fish and meat recipes (ff.97r-102r), opening with “To make a good boyld blud puding” (“Take sheeps blud or wat blud yu Like best make it thin by stering it”) (f.97r) before switching to fish. Details abound, whether “To ffrigosce Sallmon” (“when ye Liquor is allmost gin take a lettl whitt wine or Aelle & put it in to ye pan”) (f.98r), “To dres a Carpe” (f.98v), or “To pickell Oysters ye Very Best Way”, a page-long recipe – but worth it, as “itt will keep a boue a yeare” (f.102r).

Stub (with pin, text lost) at f.111. Hand I: ff.111v-114r.

After several blank pages, this stub signals a batch of recipes for “Pickels” (ff.111v-114r), beginning with “Vinicker” (“for ye Kitchings youse lett yr Vescell be sett a lettell of ye ground”, with a note added in lighter ink: “som puts a litell safron in Just to giue it ye Collor of wtt wine Viniker”). Elizabeth commends this for use with the likes of “To Dooe Musmillons Like Mangoe”, “quins to Keepe all ye yeare”, and “Sparlings”.

Katherine then anticipates Elizabeth’s upcoming large group of remedies with a trio of her own: “The Rhumatick Tinture by Doctor Boerhaven” (f.123v) and two remedies for piles (“Plane hiera=piera” and “A medicine for an Ague by Doctor Mead” (f.124r.)). The addition of “Dutch Blamangee” here – not a euphemistic name for some nasty condition, but a dessert recipe – is one of her more anomalous choices.

Pin hole (tab lost) at f.125. Hand III: ff.123v-124r; Hand I: 124v-136r; Hand III: 136v; one tipped-in leaf.

The subsequent group of 67 remedies is mostly by Elizabeth but also features seven from Katherine and two in another 18th-century hand. Heading the roster of cures, salves and nostrums is a 17th-century panacea, in the form of Woond drink”, requiring an impressive 23 different herbs, among them “Southerenwood”, Singellfoile”, “stroberey leaues”, and “Villitt Leaues”. These are to be gathered month of may”, dried “in a Closce Roome from y and turned “ons a day till ye bee drye”. After instructions for the making and applying of the liquor, a final note declares: “This drink will Cuore all soors Ould & nue & soore brests putriefied bones Achies in ye stumak Impostumes fistaleays & it will stop bleding aplying a scere Cloth” (f.125r).

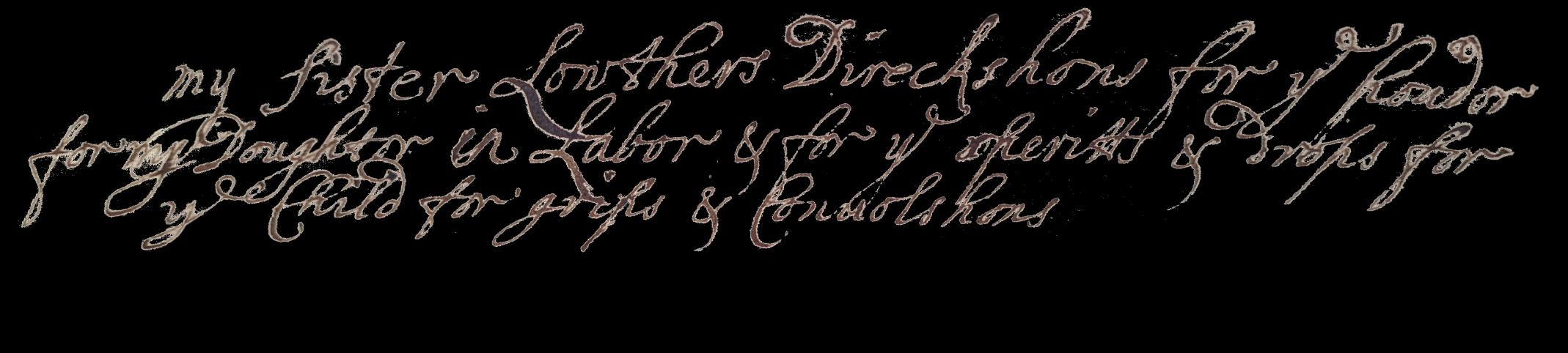

There are several remedies related to childbirth, each illuminating in their own way. A tipped-in leaf headed “My Sister Lowthers Directshons for ye pouder for my Doughter in Labor & for ye Speritts & drops for ye Child for grips & Conuolshons” helps us date this remedy – and presumably many of the others by Elizabeth – to between 1698, when her “Doughter” Catherine bore her first child (Katherine, our Hand III), and 1701, when Catherine died. The “watter” serves double duty, being both “for ye Child if ocasion bee” and for the mother “if shee should be trubelled wth Vapers upon ye tuorn of her milk” (f.130r).

The mythology that breeding creates a ‘finer sort’ is evident in “My Lord Chesterfields Resept for Labor pouder” (“take halfe an anouns of graynes of parides wch yu may haue at ye Apoteycareys of Safron

Dayttes stons Comine sceeds & of Whitt Ambor of Eache half anouns […] 24 graens for persons of a fine quality & for Ordnorey persons 32 or 34 granes” (f.131v); and one of the after-effects of childbirth is addressed with “ye Batth I Cuord Will: Berrys wife whoe Could not hould her water of half a yeare aftor her Lying (f.125v).

Other remedies treat conditions such as “greene woonds goutt Sceatticall or Rumatism” (thanks to “Cosen Shakrleay”) 126r), “a Coff” (“an Excolent Sceroup”) (f.129r), “ye Saiatikay” (from “ye Lady Dalyuall”) (f.129v), “Sore Eays or headache” (relieved by “Mrs Dorethy Bellinghams Snuf”) (f.134v), and “an Ague” (to be eased by “Mr Booshers medson”) (f.136r). Some entries supply a little more commentary: the remedy “for ye Bludy fluocks” appeals to the power of the ‘exotic’ in its addendum “& found out in the West Inde to bee ye Onley Cuore for it” (f.134v); closer to hand, a family connection graces “To make a pouder for Stone wch will Desolue it soe yt it comes a way in Grauell as my Cosen Heber found by taking itt” (f.135r); and both medic and patient are cited in “Dr Askews Direckshons for eating ye dead flesh out of Tom: Robinsons finger yt was Stung” (f.136r). Another response to an encounter with hostile fauna has a sting in its tail: “For ye Bitting of a Mad Doggs tooth” has, apparently, “neuer falled nether Christion nor Dum Beasst” – presumably lumping in the unbaptised with the rest of the animal kingdom (f.133r).

Katherine bookends her grandmother’s sizeable collection of remedies with a few more: “To Cause Sleep” (f.136r), and four formulations for teeth and gums, including “Excellent Medicine to fasten ye Teeth in Scorbutick Gums” (f.136v).

Tab at f.182 (text lost). Hand I: ff.182v-192v; Hand III; 192v-218v.

This final tab marks the beginning of a series of miscellaneous recipes set down by Elizabeth (ff.182-192). The mostly savoury dishes range from “stued Ollieues” (f.185r) to “a Hagouos puding” and “a fastingday potaedge” (both f.186v) to “my Lad: Monmorths Sosingis” (f.187v) and “pankeaks my Lady Lonsdells way” (f.185v). Katherine this time outdoes her grandmother by adding some 24 recipes, continuing the miscellany with the likes of “A Crayfish Pottage”, “Portugall Cakes” (both f.193r), “Oyster Sausages” (f.193v), “a HedgeHog” (f.194v), “Usgebaugh” (f.196r), “Oringe Puding” (f.196v), “Crème Bruille” (f.200r), and “Ice-Cream” (f.194r) – all of these acknowledged as “my Sisters” – this, one assumes, being her younger sister Margaret.

Katherine credits a gamut of sources for other recipes, from the ‘middling sort’ (“To Make a Plumb-Cake. Mrs Wills way” (f.195v); another “Oringe Pudding”, this time “Mrs Gowlands way”, likewise “To Make A Cake” (both f.200r)) to the more exalted (“To Pickle Hams. Lady Catherine Taylors way” (f.194v)) or their staff (“To Make Bombards of whole Apples By the Queens Cook” (f.194r)). These social strata collapse briefly with “To Make Ragoo of Oysters. King Williams way and Mrs Scott” (f.196r). Katherine rounds off her culinary selections with five recipes – covering meat, fowl, fish and pudding – all appended “my one way”, in apparent imitation of her grandmother’s earlier, insistent sounding phrase.

The last section, though lacking any visible surviving tab or pinhole, shifts to general household matters, and again Katherine has inserted a couple of her own entries before Elizabeth’s: “To do Lace After ye Manner it is don in Holland” (f.219r), and “To Make Veal or Cake Soup to carry in they Pocket” (f.211r). Her grandmother, though writing earlier, has been allowed the last word, with a brace of household hints concerning the care of pictures (“To Make A Varnish to Ly on picktours” (f.219r); “Mr Bonifellds way to take spotts out of picktours wch Lookes like mould” (f.220r.)), linen (“To make ye best pastt to Ly Lasse on beds wch ye London Abholsters yousis” (f.219r)), rockeries (“To Make Correll to putt in Rockworck” (f.219v)), odours (“To porffume Rose budds”; “To make a Swett Porfume” (both f.220r), and lips (“To Make ye Red Lip Salue” (f.220v)).

Of particular note is a set of directions “To Mak ye best putty to fasten Glass in Sassh Windows” (f.220r), reflecting a growing taste among the aristocracy for sash windows, after early adopters in England set the trend at places like Hampton Court and Trinity College, Oxford in the early 1690s.3

CONCLUSION

Elizabeth Preston’s formidable management of the family finances would have been of a piece with her running of the household. To judge by this impressive volume, her initial ordering served its function as a heuristic to be adapted or replaced as context or needs changed. Her inscription at the beginning signals the handing of the now successful family business to the succeeding generation in the person of Katherine Lowther. Katherine’s contributions amount to an act of consolidation, which takes the work of the greater authority and adopts Elizabeth’s pragmatic attitude. Katherine’s significant expansion of the contents expresses her ascendancy to a position that merits her having an authoritative household book of her own.

£15,000 Ref: 8280

References:

1. < https://www.ancestry.co.uk/genealogy/records/elizabeth-bradshaigh-preston-24-4t0t3r? geo_a=r&o_iid=41013&o_lid=41013&o_sch=Web+Property>

2. Becket, J. V. ‘The Lowthers at Holker’. Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1978. pp. 47-64.

3. A. P. Baggs, ‘The Earliest Sash-Window in Britain?’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. VII, 1997, pp. 168–171

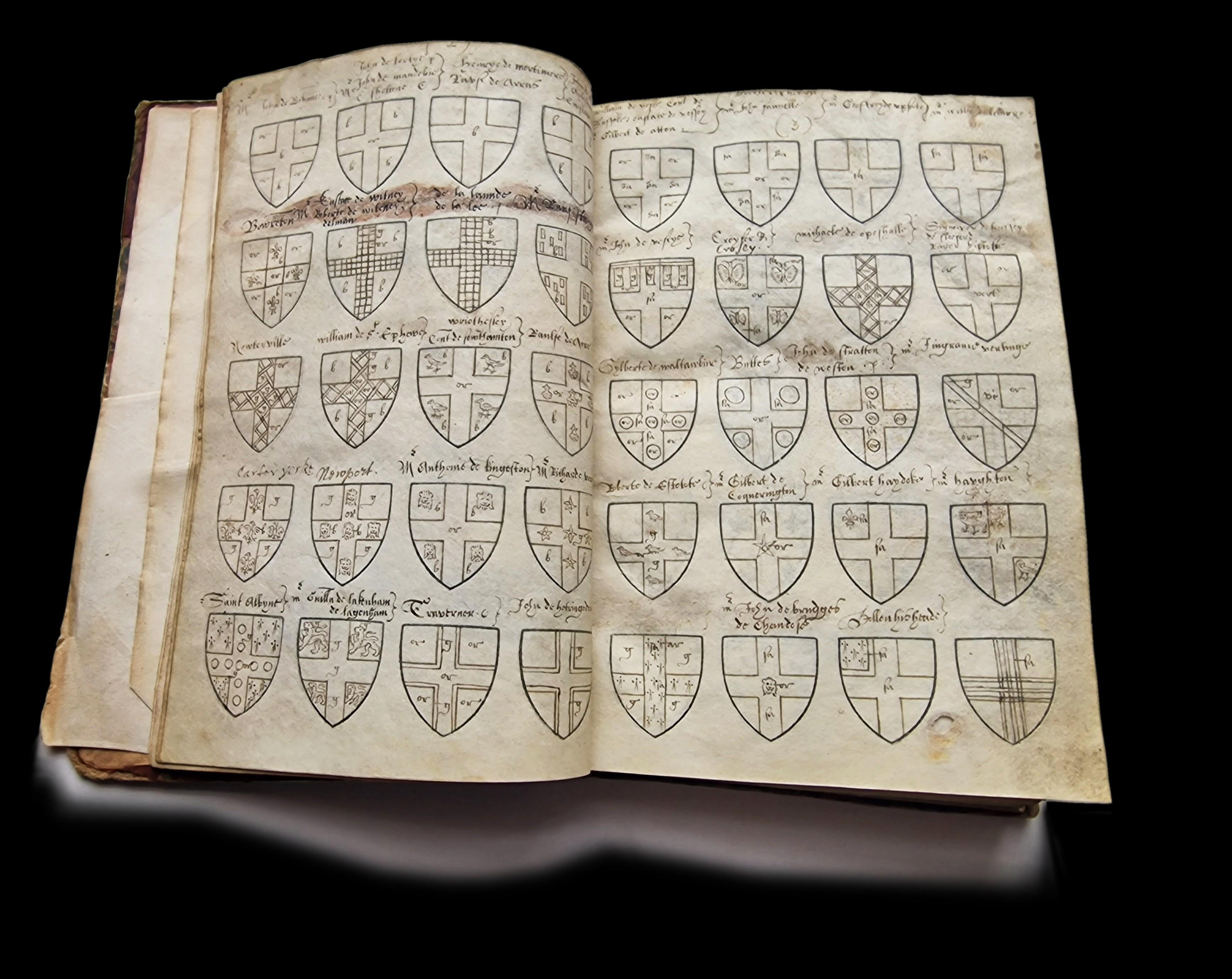

TWO

¶ The anonymous author of this epistolary manuscript combines travelogue with amateur anthropology, occasionally grisly sightseeing and at least one sighting of a famous literary figure. He conveys his impressions with a lively eye, strong opinions (especially concerning architecture and landscaping) and a good deal of snobbery. His particular focus is on Scotland, where he travels at a time when the country’s infrastructure for transport and tourism was at an early stage of development; and the principal genre within which he operates here is the picturesque tour.

Our scribe records seven journeys, written on different papers and bound out of chronological sequence. But, this appears to be either an oversight or eccentricity, as the binding is almost certainly contemporary with their composition.

1. 1771: Newcastle to Scotland. 111 pages. Watermark: Pro Patria.

2. 1778: London to Portsmouth, then to Oxford, Stratford, Kedlestone, Matlock, Sheffield, Wakefield. 42 pages. Watermark: Britannia; Countermark: S. Lay.

3. 1780: Scotland, a third tour (out of sequence – bound in before the second Scottish journey): Cairngorms, Inverness. 70 pages (page numbering continues from Journey 2, so this begins at p.43). Watermark: Britannia; Countermark: S. Lay. Later pages watermarked: Pro Patria.

4. 1781: “a little Tour”. London to “Godalmin”, Waltham Cross, Burleigh. 18 pages (page numbering still continues from Journey 2, so this begins at p.95). Watermark: Pro Patria.

5. 1777: Scotland, a second Scottish expedition. 32 pages, numbering restarts from 1. Watermark: Britannia; Countermark: W A.

6. 1783: “Devonshire”, (18 pages) a tour “which I recollect without much Pleasure or Spirit” (p.18).Watermark: Crown M D; Countermark: F Cap.

7. Undated: Peterborough (starts p.19, 5 pages). Watermark: Crown M D; Countermark: F Cap.

THE PICTURESQUE TOUR

The Grand Tour, which gained popularity during the Restoration, required two conditions in order for it to flourish: a steady supply of moneyed, aristocratic young Englishmen in search of cultural enlightenment; and relative peace in those areas of the Continent – chiefly France, Switzerland, Italy and Germany – so that this leisured but studious travel could be safely undertaken. The less elevated had an option closer to home, and one increasingly adopted by their ‘betters’ after the French Revolution and its lengthy repercussions made European travel inadvisable: the Picturesque Tour.

¶ [PICTURESQUE TOUR]. Manuscript

Account of Seven Tours In England & Scotland.

[England & Scotland. Circa 1771-1783].

The notion of domestic travel as a cheaper, safer route to self-education took hold following the publication of William Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty (1782). Gilpin’s conceit was to present scenes, using both prose and illustration, that promoted their suitability as subjects for painting by the amateur traveller – thereby providing “a new object of pursuit”, as he put it in this first of his series of books on the subject. The notion of picturesque tourism caught on – some of the most popular areas included the Scottish Highlands, the Lake District, and Snowdonia in Wales.

Folio (328 x 220 x 28 mm). Pagination 111, [5, blanks], 113, [19, blanks], 33, [35, blanks], 23, [25, blanks], plus 4 loosely inserted at end. Contemporary half calf, heavily rubbed and worn, front board detached.

Watermarks: the sections are written on different papers (see notes opposite).

Our anonymous author makes seven ‘tours’ of varying lengths, taking in the Midlands, the West Country, northern England and – in three separate tours –Scotland, to which he evidently takes an especial liking. He writes his accounts in epistolary form, explaining in his first letter that he is undertaking this “as you seem desirous of learning a more particular account of our late Journey than I could write you from the road” (p.1). Over one hundred pages later he concludes this first letter: “I write from memory, & […] I may have made some mistakes, but I hope not many, I have described things as they appear’d to me, I have always been particularly delighted with the great works of Nature” (p.110).

SCOTLAND

Our scribe is an observant, oftentimes critical author, clearly keen to demonstrate his cultural capital and confident – or wishing to seem so – of his opinions on matters of taste and judgement. For this first journey, he takes up his narrative in Northumberland, and immediately establishes a practice of orienting his path by referring to the owners of the estates he passes: “Sir Matthew Ridleys House” near Morpeth “seems a pretty place, Morpeth is in a Romantic agreeable situation on the woody Banks of a River”; from there to Alnwick “is nineteen miles of improved Country, & abounding with Gentlemens Houses … the most pleasing situation was Felton Bridge (Mrs Riddalls) it stands near a Small River & is well wooded. Mr Grieves’s is also a pretty looking Place” (pp.1-2).

A few pages later, they have reached Edinburgh, where our scribe relates the proceedings at “a Ball” attended by “a great deal of good company who deserv’d a better Room”. Ever the curious observer of local customs, he describes the interactions of those present and the quality of the entertainment, noting: “the managers always send a medal to some Lady of Fashion who is call’d Lady Directress for the time […] when the twelve Couples have danced they call one Country Dance […] they have a very good Band at the Concert & generally some Italian singer is engaged for the season” (pp.9-10). He is favourably impressed, too, by some of the shops, which are “plaister’d on the outside yellow, white red or some other Colour & then painted all over with figures of what they sell, the Bakers are particularly ingenious in this way, Cakes & Bread of all kinds covering all the front”

He finds himself less taken with the trappings of poverty, pronouncing extremely dirty”, while delivering an implied criticism of “the better ^sort”, observing of “their under maids” that many “go without shoes or stockings & generally wear Linen Gowns, Tuck’d through the Pocket Hole, which ^gives^ them a trolloping look” (pp.11-12). A richer environment, in every sense, greets him in “the Law Library” and nearby rooms where “they show you a Mummy & some other curiosities”, including “some manuscripts, some Drawings, & the Engravings of the Antiquities of Herculaneum in four volumes which the King of Naples sent them”. To complete the scene, we witness the fleeting appearance of “Mr Boswell […] who has made himself known by writing an account of Paoli, the brave but unfortunate General of the Corsicans” (pp.16-17) – this being, of course, James Boswell, whose book An account of Corsica, the journal of a tour to that island and memoirs of Pascal Paoli (1768) is among the earliest of Boswell’s travel writing.

Having encountered a few sights that score low against the criteria for the picturesque (including, “in the Anatomy School”, several “skeletons hanging over the seats” and “a muscular body, & several Limbs &c preserv’d in Spirits, which are really a sight to turn ones Stomach” (p.17), our guide brings his critical faculties to bear on Amisfield House, which Francis Charteris had had rebuilt in the Palladian style to a design by the English architect Isaac Ware. The exterior, however, fails to impress, being “a very Clumsy Building of Red stone with a Portico the same, & two white stone wings, all this does not prepossess you in its favour”. Inside is another story: he declares it “one of the best habitable Houses I ever saw […] I did

not see one Room that any body need scruple lying in, so perfectly well is the whole furnish’d, even the Garrets are Paper’d the drawing Room is hung with Brussels Tapestry” (p.21). At Hopeton House, he again makes a show of his discriminating eye, allowing that “there are some exceedingly fine Pictures”, but “some modern Portraits that are abominable” (p.23).

Thus our scribe proceeds, weighing the attractions of various locales with disdain (Dundee “seems very little to deserve the name of Bonny Dundee” (p.31)), and taking a supercilious view of certain landed types (“a Baronet who lives in the Old Town [of Aberdeen], insisted on showing us his Place, as he told us it was in a new taste which few People in that Country had done much in […] he seem’d so very much delighted with it himself, that I believe he had not time to find out that we were rather impatient to get out of it to see something much better worth our while” (pp.34-5)), but also noting points of interest beyond the purely scenic. Near Falkirk, he relates that they “stay’d a night to view the Iron there, which are the most extensive in great Britain, the cast Cannon for some foreign Potentates, & send great quantities of Vessels Sugar Plantations, the method of casting those Vessels is very curious, […] they burn all their Coals to Cinders, before they use them in the Foundary” (p.25).

OUR TRAVELLER

Our scribe gives away next to nothing about himself or the recipient of his letters, and it is only in the odd aside that we infer some very general background: he is travelling in company and is attended by at least a couple of servants (whose diet while near “Linlithgow Loch” includes “the largest & finest Perch I ever saw”, of which “our Servants had a great many dress’d for their Dinners” (p.44)). He delights in comparing one place with another (Warwick Castle “puts me in mind of Alnwick” (p.37)), and is clearly very taken with Scotland, as his return visits indicate: his comparisons of particular locations there over time are evocative of the ‘opening up’ of the Highlands to tourism, as we shall see.

As for his correspondent, they are certainly familiar with at least some of the places he visits; on his second journey (1778, 42 pages), an “intended Tour to Portsmouth &c” (which continues to Oxford, Stratford-onAvon, the Midlands and Wakefield), he tells his reader: “we went to Matlock & Buxton the Romantic Beauties of the former, & the dreary situation of the latter you know, so I will only mention that the Duke of Devonshire has a liberal Plan for the improvement of the latter” (p.41).

TOURISM ASCENDANT

After the living apparition of James Boswell in Edinburgh, our scribe encounters in Portsmouth the displayed remains of a famous saboteur executed the year before: “we saw John the Painter on a Gibbet on the shore between Portsmouth & Gosport, he was carried in a Cart before his execution to all the Places he had been the means of destroying”. (James Aitken (1752-1777), aka John the Painter, mounted an arson campaign in Royal Navy dockyards during the American Revolutionary War.) History, both recent and ancient, is a frequent ingredient in these narratives, no doubt as a consequence of being promoted by local guides – a key feature of what we have come to know as modern tourism. Thus, in Oxford, our scribe reports “a fine prospect” from the top of “Bodleian & Ratcliffe Libraries”, where “they pointed out to us the Spot, where the two Bishops, Cranmer & Ridley were burnt” (p.30). His three sections on Scotland make frequent reference to that century’s Jacobite rebellions, which, as historians such as R.W. Butler have pointed out, “indirectly helped to open the Highlands to visitors”, thanks to the government’s “attempts to improve communications and make it more possible to establish control in Scotland”.

Soon afterwards, he gives his impressions of Stratford, and particularly of Shakespeare’s house, where souvenirhunters and at least one famous champion of the Bard’s legacy have demonstrated other faces of tourism: having met the house’s current owner, “I observed that her Floors were almost dangerous to walk upon, she said it was true, but that Mr Garrick charged them to make no Alterations, she complain’d that People cut away Pieces of his ancient Chair that stands in the Chimney Corner” pp.35-36.

Our volume is as valuable for these contemporary observations of human behaviour as it is for the more Gilpinesque qualities of our scribe’s travelogue. Indeed, he exhibits certain traits of his era in many of his own scenic assessments: “prospects” and “views” are usually more valuable to him than practical function, and on his second journey he writes approvingly of measures at “Kedlestone” near Derby, where a village next to the estate has been “entirely taken away, which must be a great improvement for the Place […] the situation was not a good one till the alterations were made” (p.40).

IMPROVING EXPERIENCE

Our scribe’s two return journeys to Scotland (for some reason bound into the volume out of sequence) build a kind of narrative of their own, as he revisits places and sees signs of development and improvement. On his shorter “second expedition” in 1777, he pronounces himself “more pleas’d with Alnewick this year than I was six years ago […] partly from the situation being really improv’d, by the view of the new Bridge […] & by the Pains that has been taken to give the Lawn an uncommon fine verdure” (p.1).

1. Quoted in Hagglund, Betty, Tourists and Travellers: Women’s Non-fictional Writing about Scotland, 1770-1830. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Channel View Publications, 2010. pp16-17.

His third Scottish journey abounds with both ruggedness and the presence of the modern landowners who are subduing the wilderness by degrees into something more picturesque and accessible. He describes a walk above the river Spey “surrounded with mountains of the most uncouth Shapes imaginable” (p.63), and some nearby woods “from thence to Inverdruie, are wild and romantic” (p.65); soon afterwards, he observes: “the Glen is so narrow that it has the apperance of a Rock divided by an Earthquake” (pp.66 -67), and the landscape around Loch Moy is “inexpressibly wild” (p.67). His view of the northward spread of ‘civilisation’ is sometimes ambiguous: he notes that “the Superstitions of the Highlanders are innumerable, but are wearing out by degrees as the more frequent communication with other Countries gives their ideas a different turn” (p.66) –whether with an undertone of regret is hard to determine.

The upgrades to access and aesthetics, however, are mostly reported approvingly: “the Duke of Athole has built a Bridge over the Rocks”, as well as “a little Temple on one of the neighbouring Mountains which makes a good object from this walk” (p.51); and “some arches have been thrown over Roads to make a communication between different parts of the Pleasure Grounds” (p.52). Inverness, meanwhile, “had a much better appearance than when I saw it before, there are really some improvements in it for travellers, the Gentlemen of the Town having built a very large & handsome Inn, it is not yet quite furnish’d, when it is, it will be the finest in the Country, it is also to serve for the Free Masons Lodge, of which there is one in almost every large Town”( p.68).

CONCLUSION

As the extracts above indicate, the picturesque is not our traveller’s sole concern – history, politics and human behaviour often pique his interest – but it serves as the chief motivation for his travels. The beginnings of mass tourism in the UK (especially Scotland) are glimpsed in this manuscript, whose author is by turns curious, intrepid, patronising, complacent and entertaining – in short, an early-modern forebear of a recognisable kind of modern tourist.

£3,750 Ref: 8281

THREE

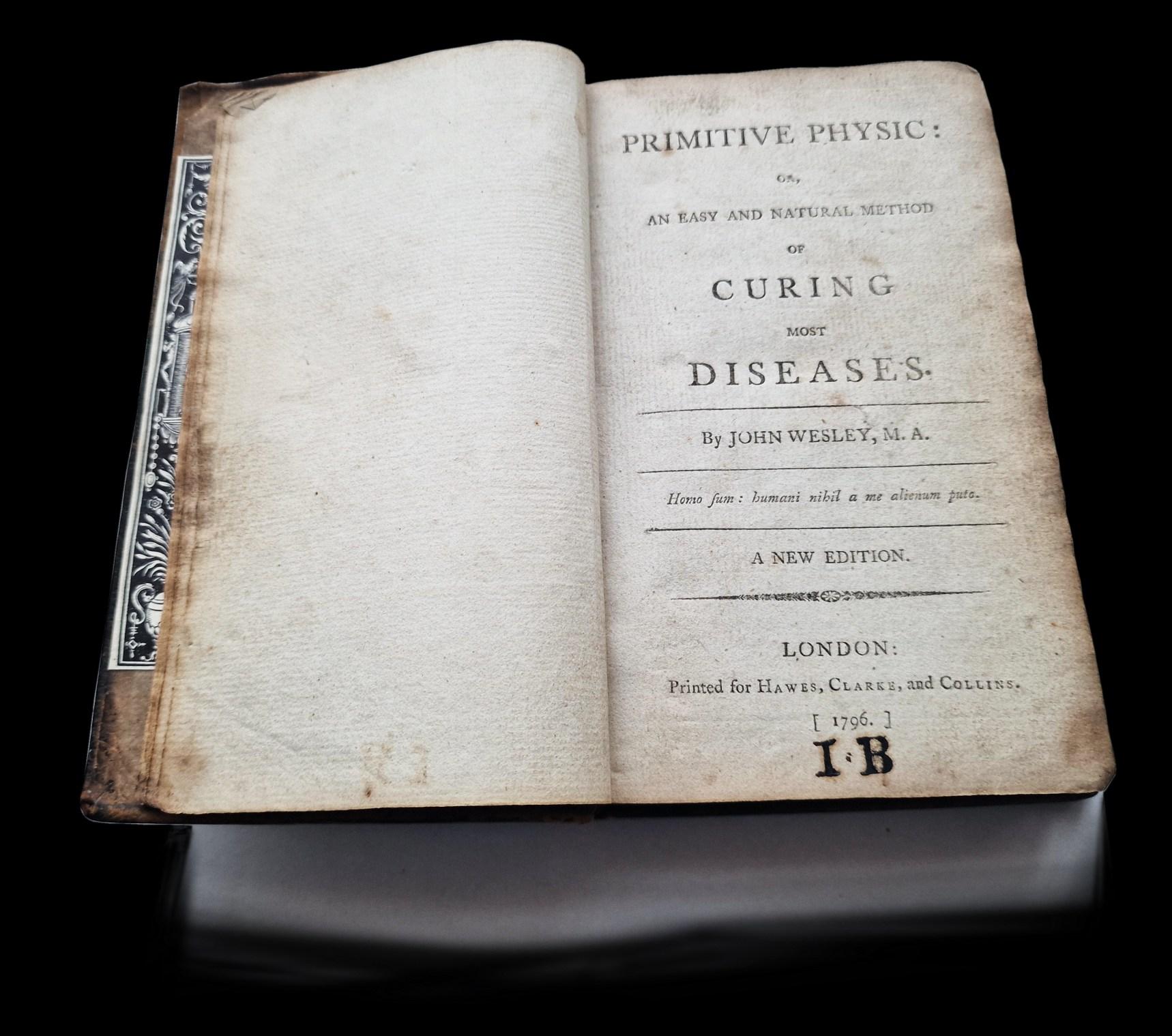

¶ Magic, medicine, print, and manuscript are uniquely combined in this volume. Around the time of its publication, the purchaser – with a clear purpose in mind – had their new book bound up with additional leaves on which to extend Wesley’s already comprehensive text. They have added a 22-page index at the end which treats the printed and manuscript remedies as one continuous text, creating a unified medical resource.

Wesley published the first edition of his Primitive Physick in 1747. He included over 800 remedies to treat nearly 300 disorders, and our industrious scribe has more than doubled this. As with Wesley’s material, most conditions merit only one or two remedies, but exceptions include “Jaundice”, “Menses obstructed”, and “Worms”, which have four each; and no fewer than nine each for “Rheumatism” and “Venereal Disease”.

There are panaceas such as “Canada Balsam” (p.256) and “Scots Pills” (p.258), and the even more general “Balsam of Life”, a concoction comprising “Gum Benjamin”, “Camphire”, “Storax”, “Balsom Peru”, and “Dragans Blood” of which they claim “I know none like it for aither Man or beast” (p.239). More specific treatments include one for “Women Rupter’d or a Bearing down” (p.266); remedies for scurvy (“Roasted Eggs ^the yock fresh Butter made into an Ointment Anoint the Head with this once a Day without ever washing it” (p.336)) and a “cure” for “A shittering Cow” (p.273).

¶ WESLEY, John (1703-1791). Primitive Physic: or, an easy and natural method of curing most diseases [bound with] contemporary manuscript book of remedies.

London: Printed for Hawes, Clarke, and Collins. 1796. Manuscript: Circa 1796.

Duodecimo (158 x 90 x 18 mm). 120 p., with 139 manuscript pages on 72 additional leaves bound at the end. Some errors in the page numbering.

Contemporary sheep, rubbed but sound, text heavily used, soiled and dusty, some tears and repairs, one manuscript leaf torn, with loss to lower half of page.

Provenance: ownership stamped initials “I B” to lower margin of title, 20th century bookplate of Terence H. Aldridge to paste-down.

Attributions are few, but some remedies have apparently been tested (“Probatom”) and even deemed “Infalible”. A “Dr Cook”’s cure for “Blindness” (p.271), requires the patient to “Shave the top of the Head size of a Crown Piece and beat the Yock of an Egg with Salt to a stiff past bind it on the top of the Head 1 Day the 2d Day repeat the same atop of the other and also the 3d Day after which take of the whole and dress it as a Blister”. This is improbably annotated: “Probatom”.

There are eccentric or plain inadvisable remedies, such as one of several for “Venerial Desease” which prescribes a “Solution of Mercury” (p.294) but recommends avoiding “Asids”. A concoction “To make Hair grow” supposedly works “in any part of the Body even the Palm of the hand” (p.278). Afflictions such as “Outward Piles” can be discharged with a mixture of “Gun powder” and “Hogs Lard” (p.284); and “Pulvis Fulminans or Thundering Powder” (p.259) seems not to relieve any condition, but “great will be the explotion”.

Unusually for a text from this period, a belief in magic seems to persist. Among several incantations, one invokes the symbolic power of blood in Christianity: “Blood to stop –When Adam die’d his Blood run chill. when Christ die’d his Blood was spilt A. B. J. Adjure thee in the name of Fathar Son and Holy Ghost to flow no more. repeat 3 times” (p.279); and sympathetic magic is invoked in “Bleeding at the Nose to stop –With the same blood Write the following word on their forehead Conxumatumes” (p.245). The material and the magical combine in “Blood to stop” (p.284): “Bruse Vitriol grease sise of a Nut put it in a Clout let the Pati[ent] (smudged) Bleed a drop or 2 into in it then burn it in the fire”. For burns, rather than cold water, the patient should instead repeat the following mantra: “Two Angils came from the East the one brought Fire the other Frost” three times “with your Hand on the place” (p.280).

Witches, too, apparently persisted as a problem in the late 18th century. For “Witchcraft evil speaking &c Charms” you must “Put in your Hat […] a little Earth thrown up by a Mouldwarp, this is a certain cure” (p.245). “Cattle Witched” requires something more complicated: you should “Take 7 Sprigs of Rice 9 Sprigs of a Wickin that does not bear berries ge the Wicken before the Sun rise […] say the Lords prayer while getting the wickin & boiling &c a friday morning is best to give the Cow”.

Wesley believed that only physical and spiritual health combined could make for healthy people, and our scribe clearly also subscribed to this view, although the distinction between the spiritual and the magical – never entirely cleared up to everyone’s satisfaction – is especially blurry in some of these remedies. Our hybrid volume is both impressive in its comprehensiveness and illuminating in its suggestion that magical belief co-existed with the new orthodoxies of medicine for longer than we sometimes assume.

£1,650 Ref: 8279

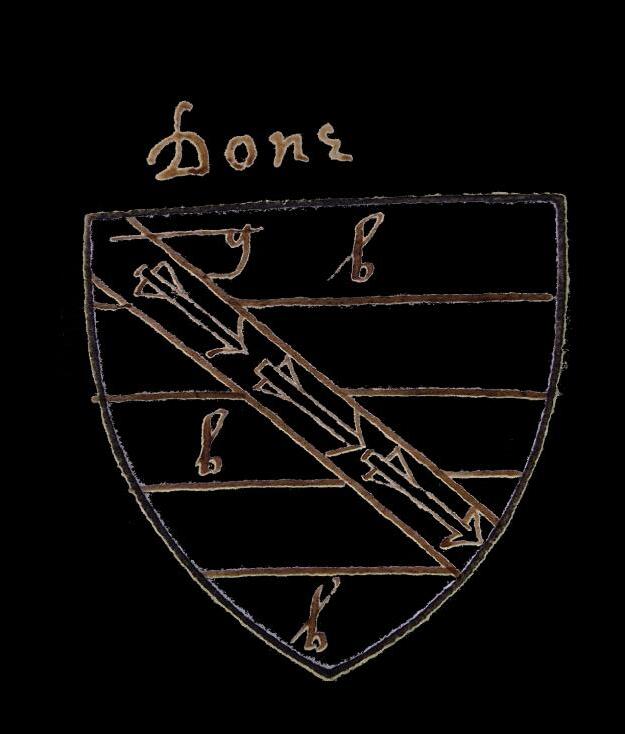

¶ A clandestine child marriage, abduction at pistol point, bribery, bigamy, political corruption, royal debts, a wastrel aristocrat, and an extended court case the affair of Bridget Hyde combined these and other elements to produce a remarkable 17 showed the darker side of the English Restoration. It was, according to the poet Andrew Marvell, “a detestable and most ignominious story”.

This voluminous manuscript work belonged to the family whose son found himself in the dock. It gives a detailed contemporary account of the Bridget Hyde case, which speaks volumes about attitudes to women in early modern English society. The woman at the centre of this vortex was one of the inspirations for (1682), a play by Hyde’s contemporary Aphra Behn.2

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

Mis Bridget Hyde, A young, wealthy heiress, married at the age of 12 in a clandestine marriage with John Emerton, is involved in a protracted legal case, is kidnapped at gun point, becomes pregnant by Viscount Dunblane, elopes to a secret wedding, dies in poverty.

Lady Mary Hyde, Bridget’s mother. Dies when Bridget is 12 years old, gives posthumous testimony (mediated by the Emertons) of her wishes for her daughter.

Sir Robert Vyner, Bridget’s stepfather. Goldsmith and banker; Lord Mayor of London. Motivated by financial self-interest, he mishandles his stepdaughter’s legal case.

John Emerton At age 15, he marries his cousin, Bridget Hyde, in a clandestine ceremony, a marriage contested by Sir Robert and the Earl of Danby, vehemently defends his marital rights in court, exits following financial settlement.

Sara Emerton Lady Mary’s sister, Bridget’s aunt, and mother of John. Together with her husband, William, choreographs the wedding of 12-year-old Bridget to her son John.

Susan Emerton Lady Mary’s sister, Bridget’s aunt. Together with her husband, Richard, choreographs the wedding of 12-year-old Bridget to her son John.

Viscount Dunblane Second son of Danby, marries Bridget in secret, enjoys marital bliss, becomes a rake, squanders Bridget’s fortune.

Earl of Danby Lord Treasurer, father of Viscount Dunblane, while locked in the Tower on charges of impeachment, takes control of Bridget’s legal case after Sir Robert’s mishandling.

SCENE, The Court of Delegates, London, and Swakeleys, Hertfordshire.

AN EXTRAORDINARY CASE

Some of the details of this extraordinary case are still disputed, particularly where the agency of its main subject –and that of her mother – are concerned. We present an outline here, before illustrating some of the ways in which our manuscript offers points of departure from the generally rendered version of events.

Bridget Hyde (1662-1734) was the daughter of Lady Mary (d. 1674) and Sir Thomas Hyde (c. 1597-1665). They lived at Swakeleys, Hertfordshire. Lady Mary’s two sisters, Sara and Susan, were not as socially successful; they married the brothers William and Richard Emerton (respectively) who worked as bailiffs on the Hyde estate.

As an only child, Bridget was to become heiress to a large fortune, and consequently a pawn in the machinations of her adult relatives. Soon after the death of her father, Bridget acquired a stepfather in the form of Mary’s second husband, Sir Robert Vyner.

¶ [HYDE, Bridget (1662-1734); later Duchess of Leeds] Manuscript Record of a Remarkable 17th-Century Legal Case.

[London. Circa 1677]. Folio (357 x 220 x 85 mm). Pagination [4, blanks], 306 [4 inserted pages, each numbered 306], 307-696 [4 inserted pages, each numbered 696], 697-935, [9, blanks], [4, index], [1, blank], [1, table of contents].

Vyner was a goldsmith and chief banker to Charles II. He lent large sums of money to the Crown, but the King had frozen repayments, and as a result, Vyner had to secure debts against monies owed to him. Fortune seemed to have smiled when Vyner was approached by Lord Danby, seeking a match for his second son, Viscount Dunblane. Vyner’s stepdaughter Bridget was heir to a substantial estate, and Dunblane had a title. This quid pro quo manoeuvre was especially appealing to Vyner, who hoped Lord Danby would use his influence to speed up the monarch’s debt repayments.

In 1674, Lady Mary became seriously ill and moved to their London home, leaving Bridget at Swakeleys in the care of her aunts Sara and Susan. With Lady Mary indisposed and Bridget in their care, her aunts arranged for Bridget to marry her to one of her Emerton cousins, thereby keeping the Hyde fortune in the family.

Contemporary blind-ruled vellum, rubbed and wear to corners, some soiling, occasional minor marks to text, overall very good original condition.

Provenance: By indirect descent from the Emerton family, via the Byron and later the Seymour families, at Thrumpton Hall, Nottinghamshire.

There are conflicting accounts of exactly what happened next. It was asserted during the court case that Bridget’s aunts tricked her into a kind of marriage (“this p[re]tended marriage” as Sir Robert Vyner called it), or that she was intimidated by her aunts and felt coerced into agreeing to a ceremony whose significance was beyond the 12-year-old girl.

But, as we note below, the Emertons swore under oath that both Lady Mary and Bridget were party to their plans; indeed, in their evidence recorded in this manuscript, they even assert that Bridget insisted not on a match with her elder cousin William supposedly the more eligible but with the younger John, who had neither money nor property.

Lady Mary died in December 1674, so whether or not she knew of her daughter’s marriage is a secret she took to her grave. But her husband was soon apprised of the information and received the news of the marriage with fury. Bridget, now in London, was returned to her stepfather’s care, and the case went to court.

The Emertons in their testimony attempted to prove two things: the validity of the marriage; and John Emerton’s right to her property. Jean Davis, in her pamphlet entitled The Pretended Marriage, sums up the proofs submitted on behalf of John Emerton at the King’s Bench as resting “on three salient points: that both Lady Vyner and her daughter Bridget were determined upon a marriage between Bridget and John Emerton; that the girl was of marriageable age; and that the ceremony was suitably performed, witnessed and consummated.”3

Marriageable she may have been, but it was apparently felt necessary to supplement this simple legal fact with evidence of the involvement of Bridget’s mother, most likely to circumvent any arrangements subsequently made between Vyner and Danby. Perhaps this is why the Emertons in their statements emphasised that the Lady Mary had devised the whole plan to be carried out in her absence.

The case went first to the Court of Delegates, which declared in favour of Bridget’s marriage to Emerton and awarded him temporary possession of her property while the morality of the case was being tested in the Court of Arches. Bridget immediately lodged an appeal and the case dragged on for some eight years, becoming first a cause célèbre and then a full-blown scandal with elements of farce.

RUCTIONS AND ABDUCTIONS

While the legality of her marriage was being debated, several attempts were made to kidnap Bridget. The most notorious bid was carried out in 1678 while she was as Swakeleys, when Vyner’s supper guest, Cornet Henry Wroth, kidnapped her at gunpoint. She was soon found and returned safely, but Wroth’s motives remain a mystery: he had no known connection to the Emertons, and was apparently pardoned by the king.

The marriage ceremony was said to have been conducted by the minister John Brandly (or Brandling). Lord Danby subsequently had Brandly abducted and tried to bribe him into denying that he had conducted Bridget’s marriage ceremony. Danby had a reputation for bribery or simply riding roughshod over opponents; in this instance, his actions formed part of charges of impeachment, and in 1679 he was locked in the Tower.4 With time on his hands, and despairing of Vyner’s efforts, he took command of the case, and probed the credibility of Emerton’s witnesses. The Emertons were said to be Anabaptists, as was one of their prime witnesses, Anne Glasscock, who had been promised a promotion if the case went in favour of the Emertons.5 Danby also questioned the validity of a marriage of such close relations, especially as there were rumours that John Emerton’s mother, Sarah, was once Sir Thomas Hyde’s mistress.

Despite his efforts, in July 1680 the Court of Delegates, which consisted of many of Danby’s enemies, upheld the marriage of Bridget with Emerton. Nonetheless, Lord Danby was still determined that Bridget should marry his son, Viscount Dunblane. However, in April 1682, Dunblane took matters into his own hands and eloped with Bridget, this time willing (and now aged around 20) to St Marylebone Church for a clandestine marriage.

Abduction and bigamy transformed a cause célèbre into a full-blown scandal. In an act of face-saving, Danby offered the Emertons 20,000 guineas to withdraw their claim, and April 1683, the Court of Delegates reversed its decision and declared the Hyde-Emerton marriage null and void.

17th-CENTURY LITERATURE AND GOSSIP

As these events played out in the public realm, they were bound to attract attention, whether considered, prurient or satirical. Bridget’s familial and social connections, and her importance as a ‘prize’ in the contemporary marriage market (being an heiress of both land and capital reputedly worth £100,000) made her a focus of fascination, all the more because of her being a woman – and an aristocrat to boot.

Andrew Marvell was among those to mention the case in his letters; longer treatments included an anonymous account of her abduction entitled A relation from the Old-Bayly, of the tryal and condemnation of the persons who the 21th day of July last, made that barbarous attempt upon Mrs. Bridget Hyde, near Uxbridge (1678), and a pamphlet by the lawyer, Thomas Hunt (1627?-1688), Mr. Emmertons marriage with Mrs. Bridget Hyde considered (1682). The Hyde case, and similar ones during this period that ensued as a familiar result of inheritance and the lack of a male heir, were topically satirised in Aphra Behn’s drama The City-Heiress (1682).6 According to Robert Markley “In The City Heiress,

Behn brilliantly stages the comic struggles of her characters to come to terms with their cynical participation in social rituals that mirror those of fashionable Restoration society: her heroes and heroines recognize that they, like the audience, are complicit in the very practices and beliefs that frustrate their desires.”7 The topical references to Hyde’s protracted case, which ended the year Behn’s play was performed, would not have been lost on

EXTANT MANUSCRIPTS

In contrast to these very public events, Bridget Hyde’s household manuscript of recipes and remedies compiled between 1676 and 1690 is preserved at the Wellcome Library (MS.2990). It is, according to the catalogue description, a folio volume of around 240 pages: “The first part is mainly concerned with cookery receipts, in the second there are many medical receipts, household remedies, cordial waters, etc”.8

Records of the legal proceedings are extant in different forms: Lambeth Palace holds a copy of the case notes for the Court of Arches (Arches Eee 5 ff. 713-757. Microfilm: Lambeth Palace Library. MS Film 150); the British Library holds letters and documents (Egerton MS 3384, 3390; Add MS 28050, 28051, 28072), as well as records of the Court of Delegates at the National Archives, Kew (DEL 1/146 and DEL 8/76). Our manuscript volume is similar to the documents at the National Archives. However, their records contain sections of the case written at different times, and in varying degrees of completion, whereas our volume collects and collates the relevant material into a single volume and includes substantial material that does not appear to be in the other extant manuscripts. It also has the distinction of being the Emerton family’s own copy.

OUR MANUSCRIPT

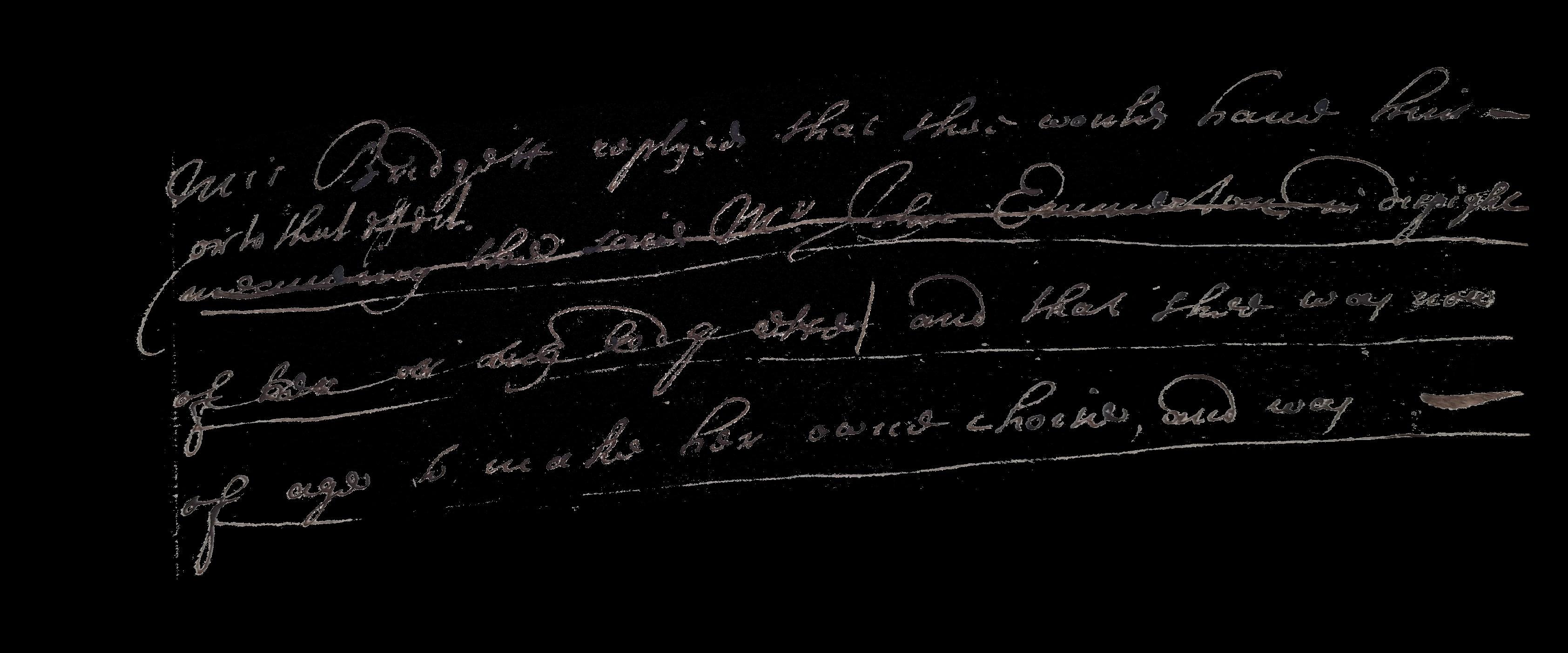

This material was drawn together by a contemporary (aided by several legal scribes) into a large folio volume which runs to well over 900 pages, including an index. The transcripts that form part of it ostensibly confound the notion that Bridget’s mother was ignorant of the wedding. The testimonies offered by the Emertons suggest that she was herself enmeshed in a marriage plan hatched by her aunts – but they needed to show that the marriage had the consent of daughter and mother alike. Since the latter was now dead, she was unable to refute their story.

In laying out the case, the Emertons’ counsel asserted that “Mr Wm Emerton and Mis Sarah Emerton his wife” were aware of “the constant desires of the said Sister to have a marryage completed betweene her sayd daughter and one of their ^said^ sonns” (p.18). There was supposedly even a discussion as to “how much a Younger brother was beneath such a Match as the said Mis Bridgett ^Hyde^ would be”, but the account restates that the Emertons noted “that the sayd Lady Vyner and her sayd daughter were both willing and desirous” (p.18). Mary Vyner is also cited as having wished to “putt another Coachman and other servants to attend upon her sayd daughter that the sayd businesse might bee the lesse Suspected for shee did much desire to keepe it Secret as long as shee could from her sayd husband Sr Robert” (p.21). Her parting words to Bridget before returning to London are reported to have been “Farewell Bride goe along with your Aunte and bee marryed and then come to London as soone as you will or words to that effect” (p.21).

Despite their young age, Bridget and John were “both Sufficiently capable of the Lawes of this nation to contract and give their consent in marriage” (p.28). But there is no escaping the suspicion that this rendition of the deceased Lady Mary’s actions and utterances might amount to posthumous ventriloquism on the part of the Emertons, who were keen to establish that the now silent mother had not just willingly given her consent, but even encouraged a match between the two young people.

Furthermore, the ceremony itself was conducted in subterfuge: it was determined that “the sayd marryage should bee solemnized in the passage betweene Swakeley and Albury and that some person should carry the Coachman and Servants to some house thereabouts to drinke, dureing the time of ye Solemnizacon, that soe they might have ye Lesse opportunity to observe or suspect what was doeing” (p.22). This seems at odds with the assertions that Bridget was “willing and desirous”, and that these nuptials were all above board.

Our manuscript relates that the secret union was kept from Bridget’s stepfather for several months: Bridget is reported to have visited her mother on her deathbed, and after the latter’s passing, “the said Sr Robert Vyner hath been informed & heard of the marriage aforesaid”, at which he “very seriously Examined and asked the said Mis Bridgett his daughter in Law whether shee was really marryed to the said Mr John Emerton and shee the said Mis Bridgett did absolutely declare and acknowledge unto him shee was marryed”. In response, “Sr Robert Vyner … told her shee had ruined ^or undone^ her selfe in her fortunes and p[re]ferments unlesse this p[re]tended marriage could bee made void and null” (p.38-9).

The Emertons took the case to the Court of Delegates in 1674, but despite Sir Robert’s fury, he did not offer any defence at the original trial, apparently believing that nothing would be decided until it had passed through the Court of Arches. He was wrong: the judgement was almost unanimously in favour of the marriage. A retrial was obtained in 1676, and as Davis writes, “In all, five Commissions were to be granted, for each of which new Delegates were appointed”.9 This may account for certain differences detectable in the extant accounts.

The records in the National Archive are contained in DEL 1/146 (a small folio of written-up records, in a 19thcentury binding), and DEL 8/76 (two volumes bound in contemporary limp vellum, folded). These documents are in a quite different order to our volume, and Bridget’s responses seem to conflate her four replies into a single answer, whereas our slightly later volume offers a much fuller rendering of her four answers:

“Mis Bridgetts Answer to Mr John Emertons first Allegac[on] – 847”

“Mis Bridgett Answer to his Second Allegation – 847”

“Mis Bridgetts answer to his 3d All[egati]on – 855”

“Mis Bridgetts answer to his 4th All[egati]on – 858”

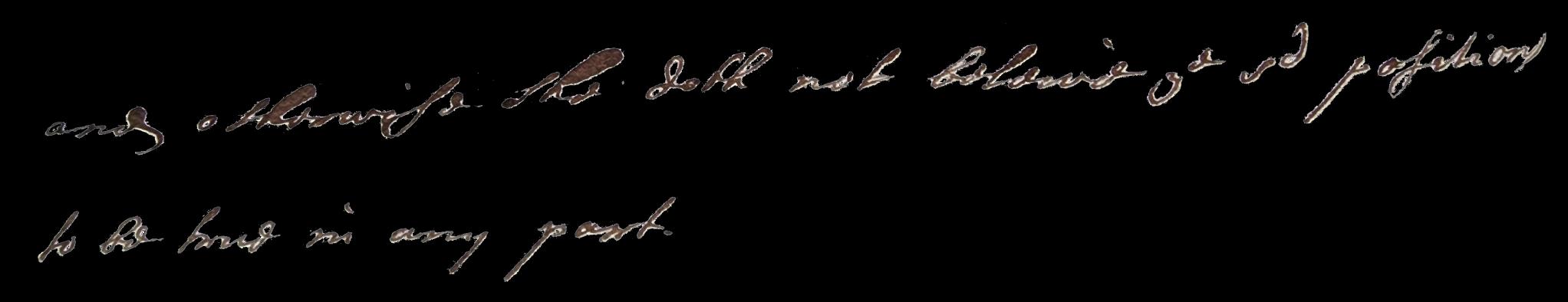

She refutes the notion that there was ever any intimacy between herself and her cousins, insisting that her interactions with the Emerton brothers were solely cordial, and when she “did sevlly converse wth either of them at such times as she was in ye company of either of them in the Matter of ordinary conversation but not concerning any Love or affection nor anything tending thereunto or otherwise” (p.848). In this, as in most of her replies to the Emertons’ allegations, she closes with a phrase along the lines that “she doth not believe this p[re]tensed position to be true”.

As to the ceremony itself (annotated in the margin “ye Mock marriage”), she swears that she was deceived: “Sara Emerton haveing a Booke in her hand did abt some short time happening before ye first of octobr 1674 speaking ye p[re]sence of this R[esp]ondents footboy & one of her Aunt Emertons Maydes say ye words”. On the next page (annotated the margin “Bridgett told at Swakeley yt she was to be Married yt day”) she recounts a series of events, suggesting she was coerced into “ye p[re]tensed Marriage in question” as she “was in & under the power of her Aunt Sara & Susan Emerton who told her she must goe to be Married to her Cousen John [but] this R[es]pondent trying & refusing it they urged & told her she must goe or else her Mother would not abide her and upon their urgeing & importunity she tho much agt her will yeilded to goe wth them not dareing to gainsay them who carried a sharp & seveere hand over her & used to terryfie her”.

EPILOGUE

Dunblane’s squandering of Bridget’s inheritance makes for a sorry postscript to the whole affair. His military exploits – which included “pursuing a naval career with flamboyance” – seem to have gone hand in hand with his “riotous living and wanton extravagance” in both France and England; and after his debts mounted beyond the estate’s ability to settle them, Danby “sent £100 to his daughter-in-law and apologised for his son’s behaviour”.10 Further costly legal trouble arose when a mistress of Dunblane’s claimed that he had bigamously married her, and Danby, again showing solicitude, “sent her instructions on how to act if the bailiffs seized her property”.11 Dunblane continued his downward trajectory, styling himself the first Duke of Leeds but missing out on his father’s inheritance owing to estrangement and instead becoming reliant on his son, Peregrine Hyde Osborne, for support.

Bridget died penniless in 1733, four years after her husband; her final title of dowager Duchess of Leeds was likely cold comfort indeed.

As to our manuscript – multi-faceted enough to qualify as a virtual character in its own right – it has been in the possession of the Emertons’ descendants at Thrumpton Hall, Nottinghamshire. John Emerton (1685-1745) acquired Thrumpton Hall in the 1690s, and presumably brought this manuscript with him. The house was inherited by a nephew, John Wescomb Emerton, who resided at Thrumpton until his death in 1823, then by Lucy Wescomb (1822–1912), who married George Byron, 8th Baron Byron (1818-1870). It passed to the 9th– and then to the 10th – Baron Byron, who married into the Fitzroy family, who in turn married into the Seymour family in whose possession the house still remains.

References:

1. Marvell, Andrew (1621-1678). The Prose Works of Andrew Marvell: 1672-1673. Edited by Annabel M. Patterson, Martin Dzelzainis. (2003). p.463.

2. Behn, Aphra (1640-1689). The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Aphra Behn. Volume IV. Plays 1682-1696. Edited by Rachel Adcock. (2021). p.10.

3. Davis, Jean. The Pretended Marriage. (1976). p.18.

4. Allen, David. “Bridget Hyde and Lord Treasurer Danby’s Alliance with Lord Mayor Vyner”. Guildhall Studies in London History. Volume 2. (1972).

5. Davis. Ibid. (p.26).

6. Behn. Ibid. (p.10).

7. Markley, Robert. “Aphra Behn’s “The City Heiress”: Feminism and the Dynamics of Popular Success on the Late Seventeenth-Century Stage”. Comparative Drama. Volume 47. No. 2. (2007).

8. <https://wellcomecollection.org/works/jsy2hhm6>

9. Davis. Ibid. (p.19).

10. Davis. Ibid. (p35).

11. Davis. Ibid. (p36).

12. Adcock. Ibid. (p.1).

The Emerton family’s image fares poorly in these pages. But as noted above, the ruling went in their favour, and they received a handsome financial settlement to withdraw from the legal proceedings. Hence the manuscript, with all its dramatic contents, could rest quietly on the shelves of their fine Jacobean house.

CONCLUSION

Despite the undoubted importance of this case, no full-length study has yet been attempted. In the brief written accounts, several points of ambiguity remain; in view of this, our manuscript offers perhaps the most detailed and comprehensive contemporary account, complete with its ambiguities and competing claims to truth.

Rachel Adcock remarks that Aphra Behn’s The City Heiress raises “questions about such politically contentious issues” as “arbitrary rule, force, and consent”.12 Her words could also serve as a summary of our manuscript formerly the property of the Emerton family which captures the complex interplay of vested interests, class tensions, misogyny, deception and underhandedness that characterises the Hyde and Emerton case.

£27,500 Ref: 8273

¶ The embittered blackmailing of a rejected Queen; the scandal that ‘threatened to blow the roof off the Nunnery’ by revealing the secret, lascivious goings-on of George III’s locked-up daughters; disastrous royal marriages; incendiary writings from secret sources; hush money and century-long political cover-ups as panic swept through the corridors of power… It all sounds like ripe fodder for a sensationalist, bestselling story. And that is exactly what Captain Thomas Ashe produced, in two forms: a hefty novel, and this extraordinary manuscript poem.

Ashe’s two very different versions of The Claustral Palace are among several gleefully prurient revelatory pieces he wrote about the Hanoverian royals over half a decade, as the nation keenly followed the conflicts between George, Prince of Wales, and his wife, Caroline of Brunswick. But where many of Ashe’s other sordidly detailed (often epistolary) writings ran to several editions by dint of their popularity (for example, The Spirit of the Book (1812) and its abridgement, The Spirit of the Spirit)1, this early verse rendition of The Claustral Palace Ashe’s was, like its subsequent ‘novelisation’, quickly seized by government agents, suppressed and remained unpublished.

Our manuscript is literary testament to a powerful union between Ashe, an Irish army officer and writer, and Caroline Amelia Elizabeth of Brunswick-Wolfenbuettel – the estranged wife of King George IV – to whom Ashe became a ghostwriter2. Not long after the ‘ideal’ match between the two royal first cousins was forged in 1795, the marriage deteriorated, and the king’s supporters made Caroline a political scapegoat. A growing sense of powerlessness, of being used, and of ignominy at being officially investigated, pushed “the injured Queen of England” (as the inscription on her coffin described her) to use the only weapon at her disposal: access to the royal family’s greatest and dirtiest of secrets.

Ashe, similarly, deployed his high-society connections and interactions to feed his penchant for writing blackmailing novels and satirical journalism. Through his relationship with Queen Caroline, he recognised a monarchy in decline, a state of affairs that offered ample storytelling material – not to mention financial opportunity through a bit of wellwritten blackmail.

Britain was in a vulnerable position thanks to a perfect political storm created by the French Revolution, an unfair Royal Marriages Act challenging the succession, and the King’s escalating mental illness. As an anxious George III confined Queen Charlotte and their six unmarried daughters at Frogmore House, scandalous rumours began to fly about their reclused lives. There were whiffs of politically unacceptable romantic dalliances, violent disagreements, fatal attractions and even venereal diseases – a goldmine of outrages from which Ashe forged the contents of The Claustral Palace.

Ashe’s verse manuscript is an intriguing companion piece to his novel. From the very outset, there are several marked differences between this earlier poetic version of The Claustral Palace (written circa 1811) and the 1812 manuscript of the same name. The latter is a three-volume “political romance” set in Denmark, and narrated via the epistolary form (Ashe’s preferred device for evoking the power and vulnerability of letters when used as blackmail),3 whereas our manuscript is a 64-page poetic piece; the novel bears Ashe’s name on the title page, along with an epigram about “Wedlock forced” (from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I), but the title page of our

This verse work invokes one of the greats of classical literature in its subtitle: “An Ovidian & Political Poem”. Below it are reproduced the lines “Dicique beautus / Ante obitum memo, supremaque funera debet” (“True happiness or fortune cannot be determined until a person’s life is fully complete”) – a sentiment found in the works of Herodotus and in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The manuscript is dedicated to Princess Charlotte, the only child of King George IV and Caroline of Brunswick, who in turn is acclaimed as “her Royal Highness’s most persecuted & most Illustrious Mother” – a more personalised opening than that to the novel. As the poem begins, we find ourselves not in Denmark but in England, near “proud Windsora”, our eyes (and ears) quickly drawn to “A stately Palace [that] rises to the sight… From this, from that, from ev’ry quarter rise / Loud shouts, and sullen groans, & dreadful doleful sighs; / Heartrending plaints demand the pitying ear, / And tales of hideous portent shock the ear”.

References:

1. Travers, James, A Blackmailer at Frogmore: The Adventures of Queen Charlotte’s Ghost, Amberley Publishing (2022), p. 13.

2. Ibid., p. 13.

3. Ibid,. p. 117

4. Although Ashe claimed four volumes for his novel, only three have come down to us (TNA TS 17/1388) and there is no sign it is not complete. Volume three ends with the death of Amelia which must have been only months before the novel was written and there is a flourished ‘Finis’ on the final page which does not appear on the final page of the other volumes. (James Travers, email correspondence.)

5. Ashe, Thomas, Memoirs and Confessions of Captain Ashe, Vol. III (1815) pp. 147-148.

6. Redding, Cyrus, Fifty Years’ Recollections, Literary and Personal, Vol. III, London (1858), pp. 63-64.

It is with these mock-classical – if not downright melodramatic – tones that the two texts (novel and poem) begin to align, as both quickly dive into the sinister gothic undertones of popular sensationalist literature of the period. In the earlier part of our poetic manuscript, “Mad” King George appears as “A Shiv’ring Monarch [who] keeps his awful Court”; his wife, Queen Charlotte, “a Witch to Avarice assign’d”. The melodrama ripens, as “fragrant sighs”, “plaintive cooings”, and “swelling breasts” pervade the poem, and Ashe contemplates the princesses behind the walls. His sympathy towards “the blest Nymphs, whom rural graves confine” reaches exclamatory heights in the third part, echoing Homeric invocations of the Muse: “Oh, World! Oh, Fortune! Vainly ‘tis your charm, / Against the Conqueror, Death, there’s none can charm”. But beneath this overblown and brutal imagery lies reference to the very real and pitiless Royal Marriages Act (which Ashe’s novel also uses explicitly to lend coherence and topicality to his narrative), trapping the princesses in both texts and making a gothic horror show of their fate. On this grave note, Ashe offers his final thought in the poem: “As / None happy call, in this uncertain state / Death only sits us safe beyond the reach of fate”. The predicament of the royal children is clear. Ashe’s Memoirs and Confessions (1815) speak frankly of his “most deplorable state of poverty” and the “spirit of avarice and ambition” that led him to write his salacious literature: “I had no treasure but my talents; no instrument

but my pen… I sat down, and, in the course of three months, composed a large work in four volumes,4 entitled, ‘The Claustral Palace; or Memoirs of the Family’.” He goes on: “I received several proposals respecting it, and was visited by several violent characters from London… I closed with the offer of a Mr. C , and sold half of my copyright for the sum of seven hundred pounds. Mr. C was to print and publish at his cost, and give me half the profits, clear of all demands.” 5 Did Ashe ever intend, as with his suppressed novel version of The Claustral Palace, to publish the earlier poem? The 18th-century journalist, Cyrus Redding, wrote of Ashe as “a notorious scoundrel” who “wrote false memoirs of living people, to get paid for their suppression. One of these, I remember, was ‘Memoirs of the Countess of Berkeley’; another was called ‘The Claustral Palace’” 6. Perhaps our poetic manuscript, which has been folded as though for posting, or for just carrying around, had only ever been meant as a handedover warning? Perhaps the desperate Ashe, spurred on by the success of The Spirit of the Book, decided to put aside this earlier poetic version and exercise his ‘talent’ further by extending it into another Hanoverian hit novel? Neither possibility necessarily accounts for the contemporary morocco binding.

Ashe knew its power to rock the already unstable royal politics of the period – a power confirmed by the government’s actions taken upon its discovery. Its suppression, and the small ink stamp to the title page (possibly that of Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, second son of George III), marked its value as a work for safe keeping and not to be taken lightly.

Our manuscript complements not only its later novel version but Thomas Ashe’s related papers in the National Archives at Kew. The poem abounds with fantastical Gothic imagery and intrigue, but its impression of blackmail dressed up as literature is all too real, and gives a flavour of the kind of unsavoury profiteering that attended the crisis-ridden Hanoverian dynasty.

£2,000 Ref: 8241

¶ These letters were written during the American Revolutionary War by a key figure in the British government: the fourth Earl of Sandwich, a highly gifted and industrious figure who, as first lord of the Admiralty, helped to transform the British Navy during this important period of Anglo-American history. The correspondence brims with the day-by-day business – large and small – of managing a maritime fleet that had yet to reach the strength required of a nation with a growing empire. The recipient of these letters shared with their author both a friendship and a bruising experience of the political machinations of their era.

The politician and statesman John Montagu, fourth earl of Sandwich, began his ministerial career in 1744 as a member of the Admiralty board under the patronage of the Duke of Bedford, where he was instrumental in reforming many aspects of the navy, from training and discipline to ship design and dockyard management. His debut as a diplomat at the Breda peace talks in 1746, and his deft manoeuvres during the framing of the resulting treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, left his more seasoned contemporaries impressed.

Almost concurrently, he became first lord of the Admiralty, but his determination to intensify the reform of the navy, particularly its management practices, proved unpopular and led to his dismissal in 1751. He briefly returned to the post in 1763, then began a third stint in 1771, this time meeting with greater success in reforming the dockyards and increasing the navy’s shipbuilding capacity. Our collection of letters dates from this third term, which coincided with the British response to the American Revolution, and all of the correspondence is concerned with naval matters – the greater portion of it relating to the American colonies.

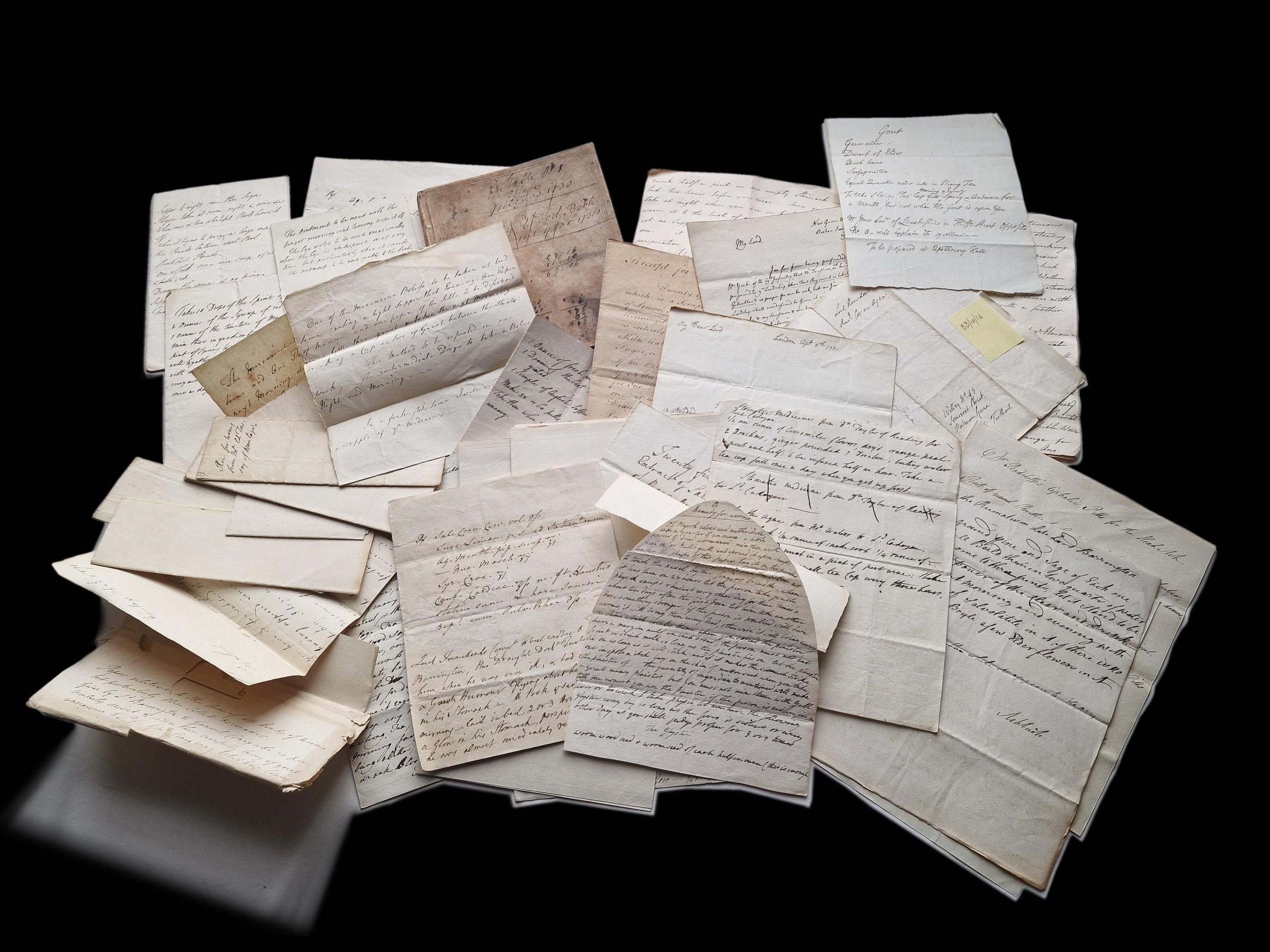

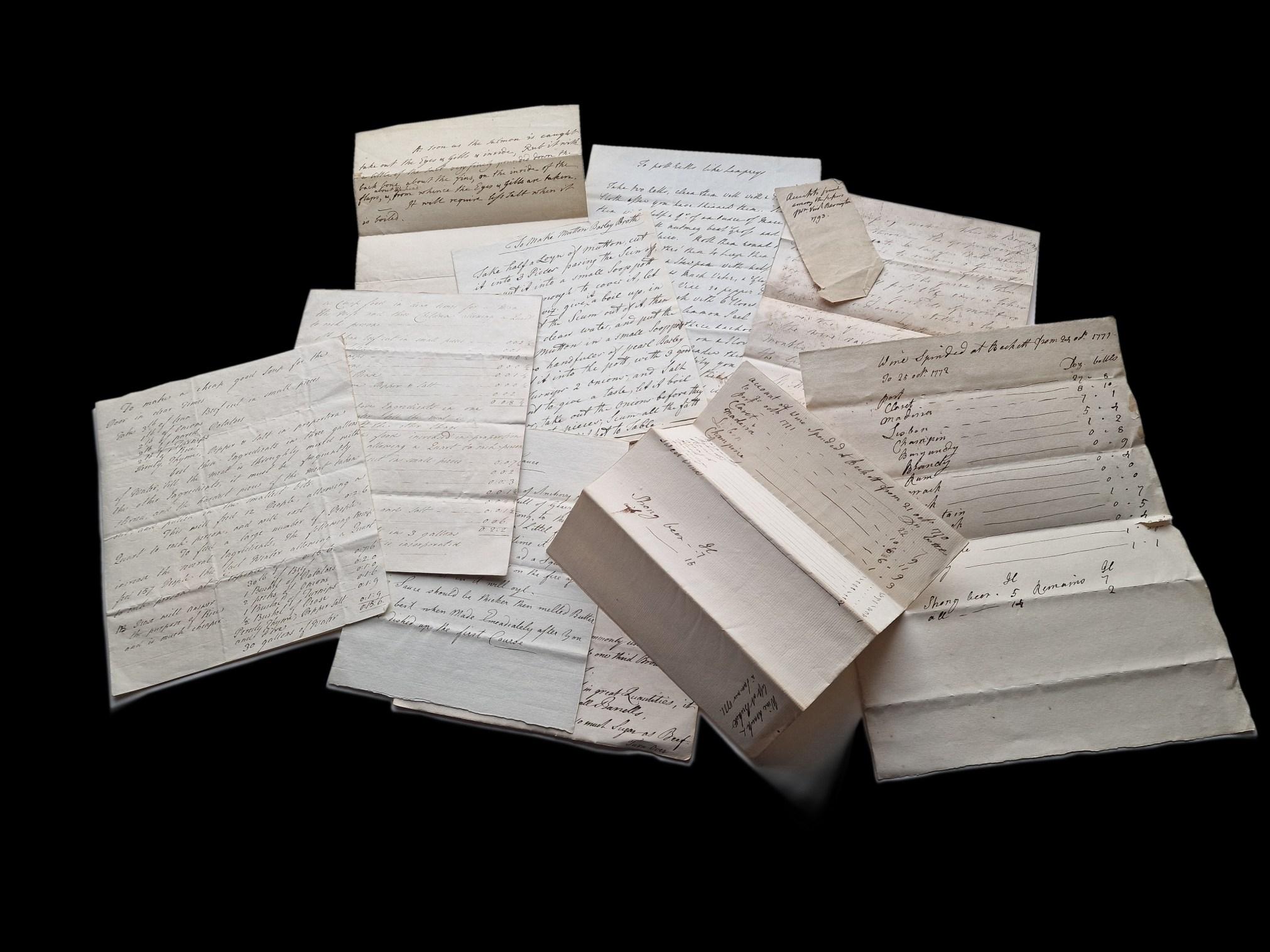

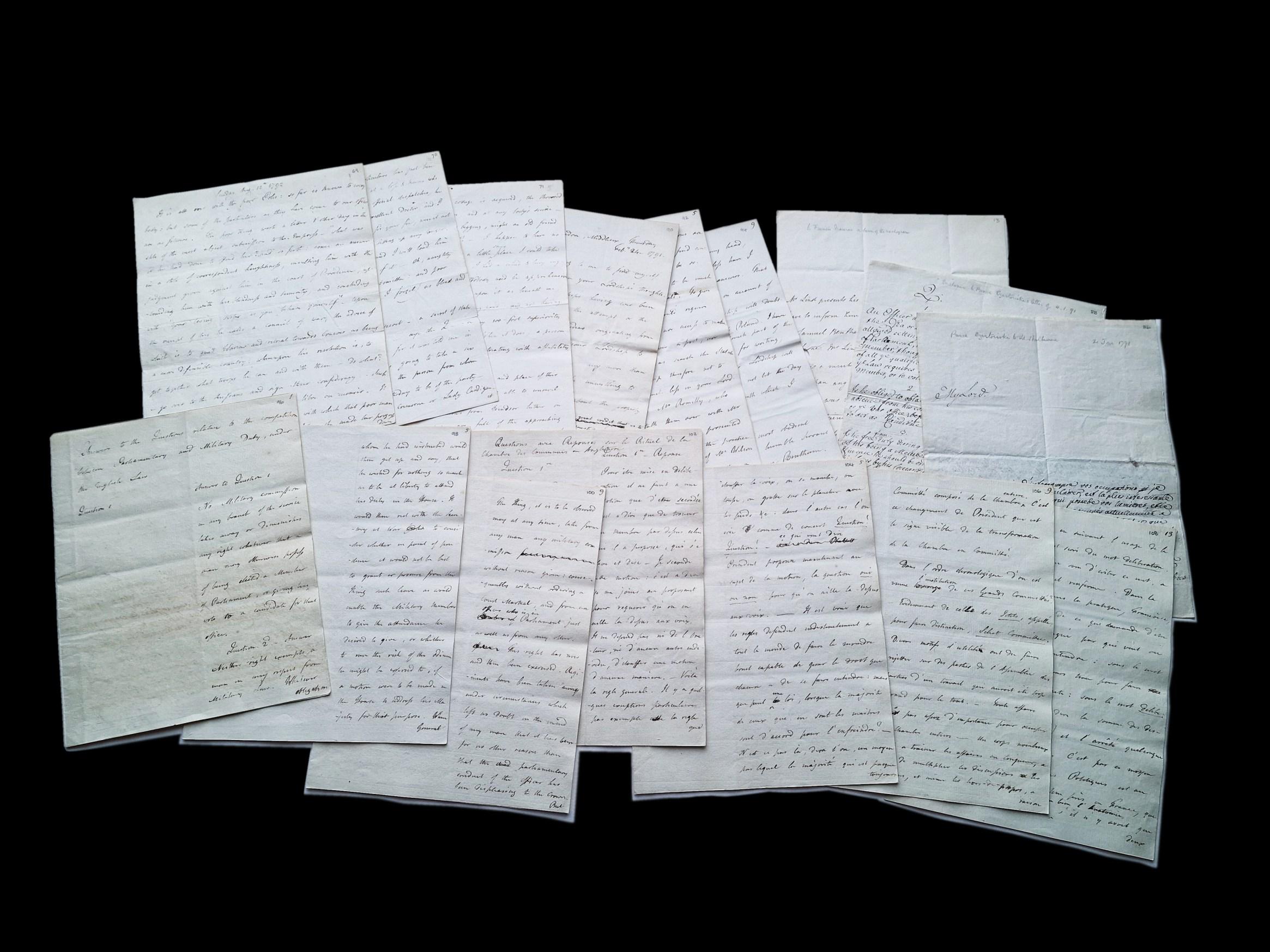

¶ [SANDWICH, John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich (1718-1792)]. Twenty-four Autograph Letters and Notes.

[Circa 1774-81]. Folded for posting (240 x 375 mm unfolded). Address panels, some seals intact. 23 letters, each signed “Sandwich”; all but one headed “Hinchingbrook” (i.e. Hinchingbrooke House, Huntingdon, formerly the home of the Earls of Sandwich), and one letter signed by Captain Hugh Dalrymple.

Watermarks: Fleur-de-lis in shield, surmounted by crown, GR, over a bell, (Strasbourg lily), lettered “JUBB” in bell, others lettered “LVG”.

NB: despite writing over 20 years after the introduction of the new calendar style, Sandwich rather eccentrically dates his letters according to the pre-1750 calendar; Jackson, however, when

Two of the letters have an integral address panel addressed to “George Jackson Esqr.”; this, we assume, is Sir George Jackson, 1st Baronet. (1725-1822), deputy secretary of Admiralty and first clerk of the marine department between 1766 and 1782 – and a friend of Montagu’s.