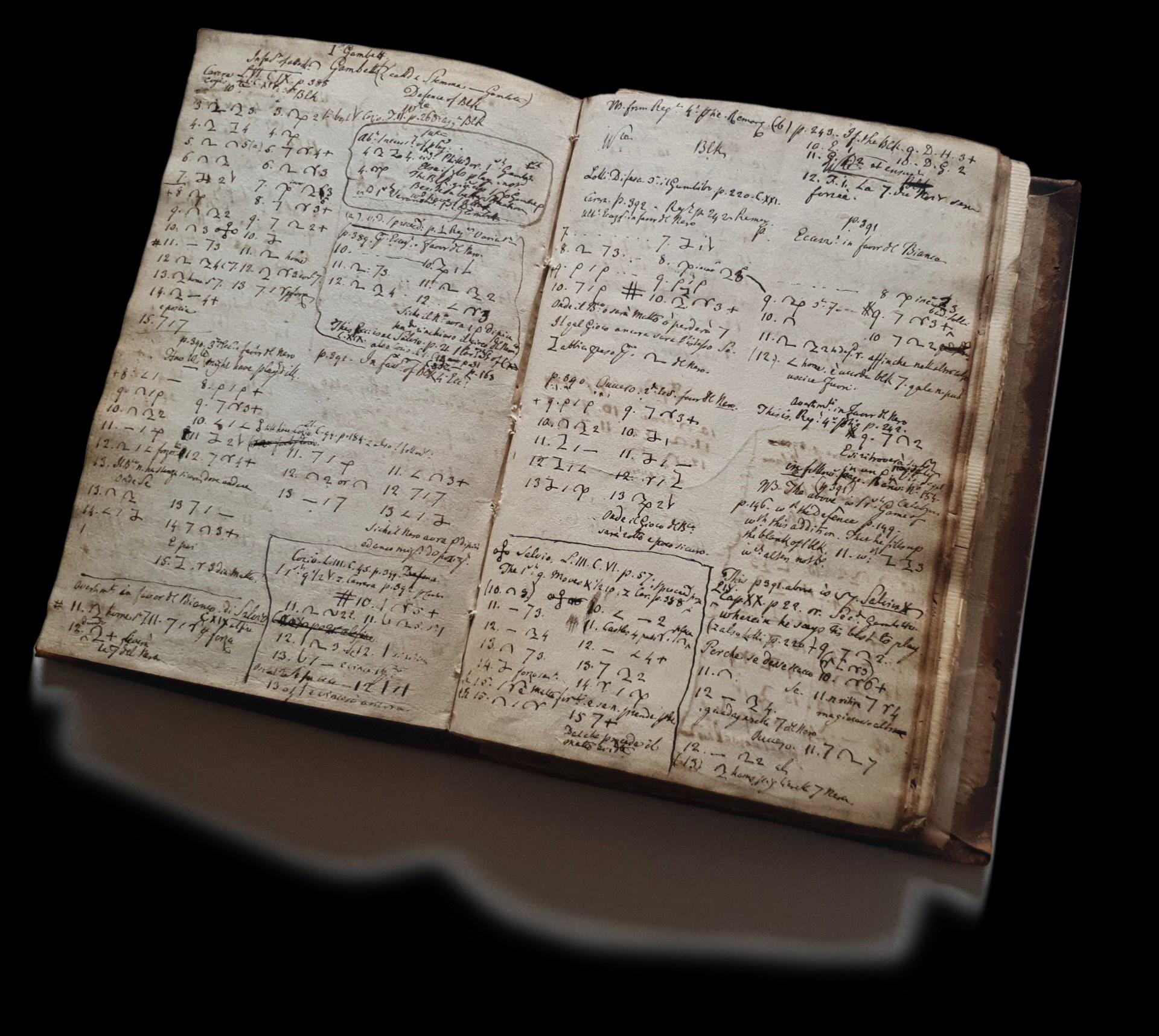

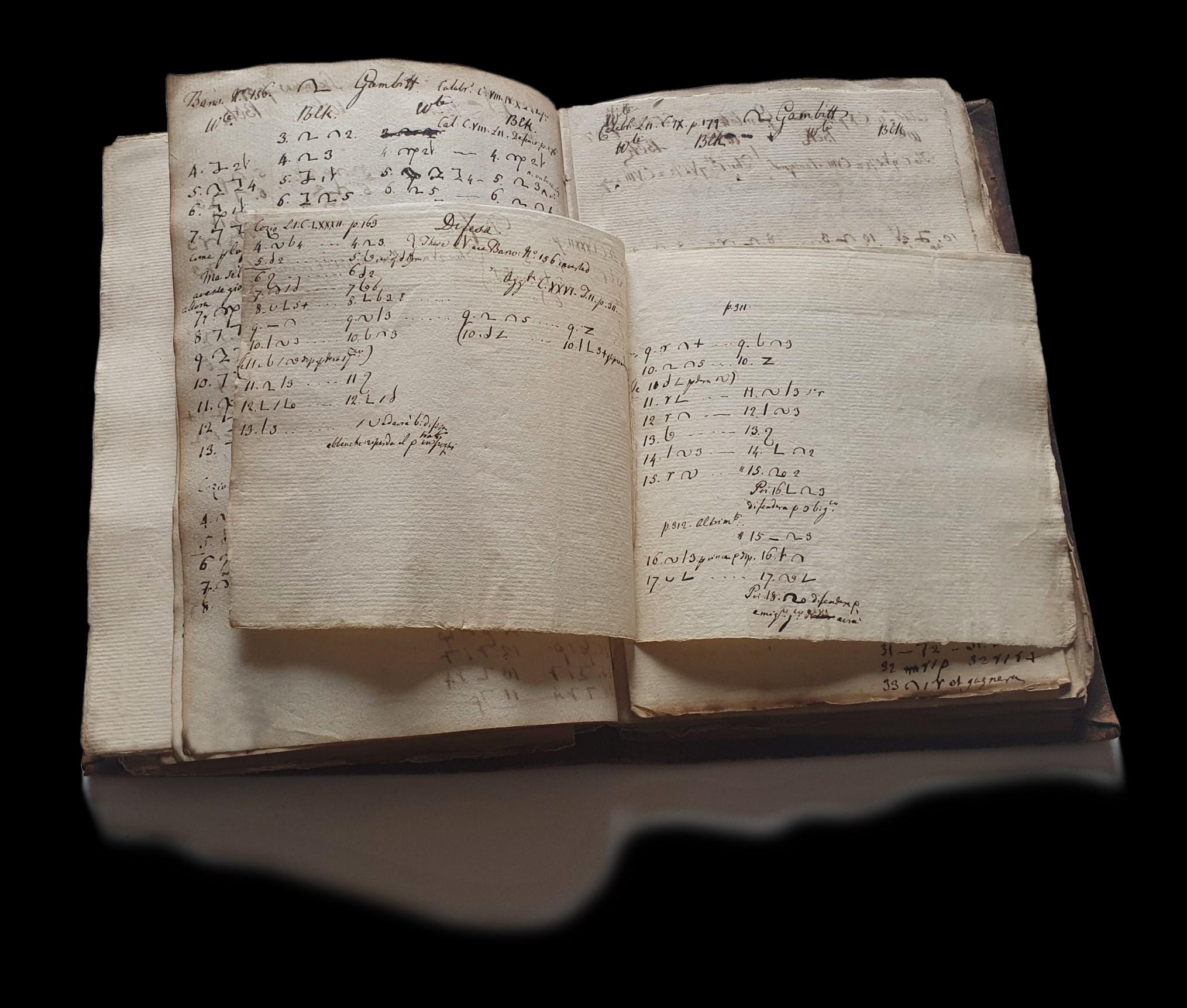

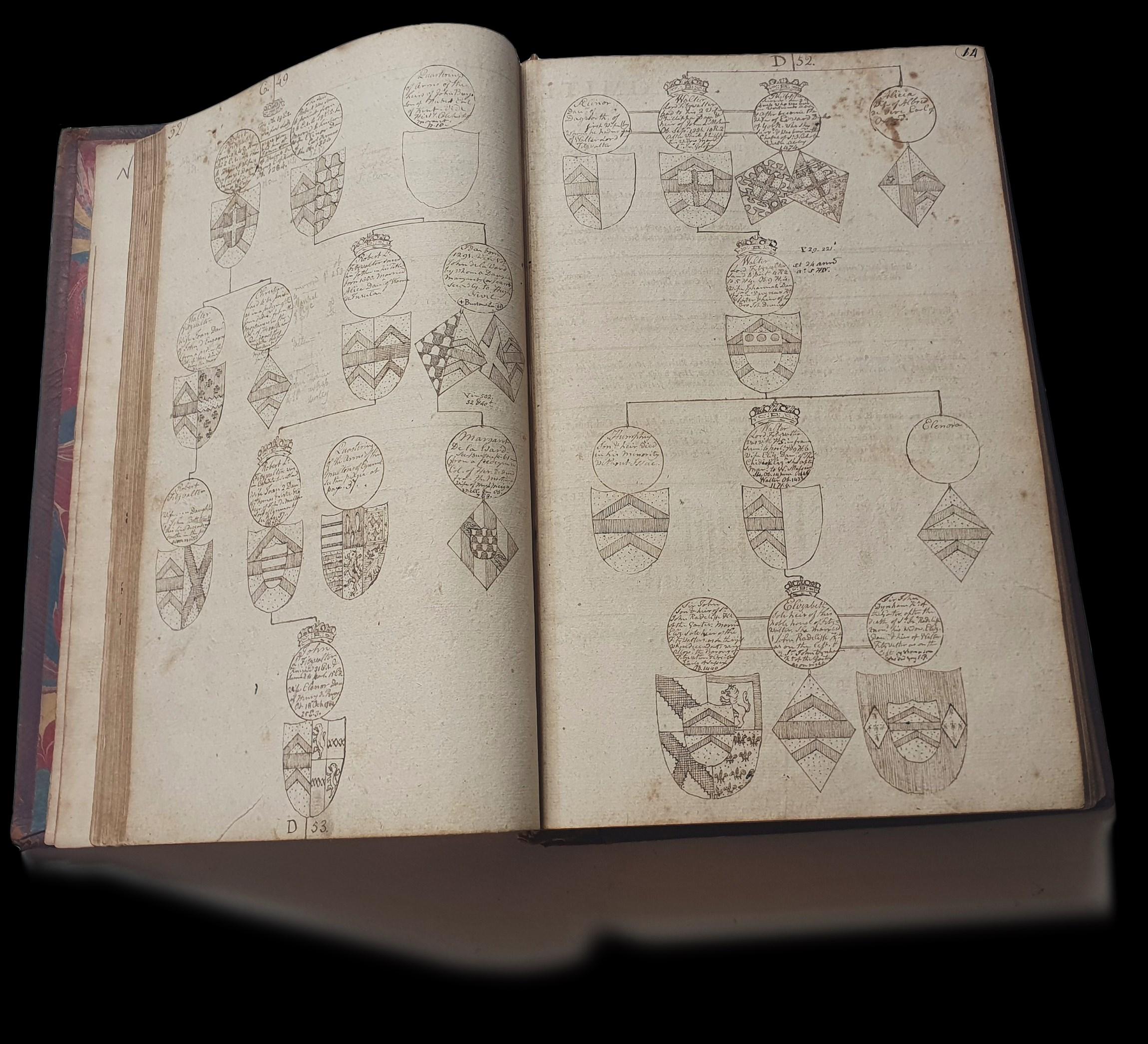

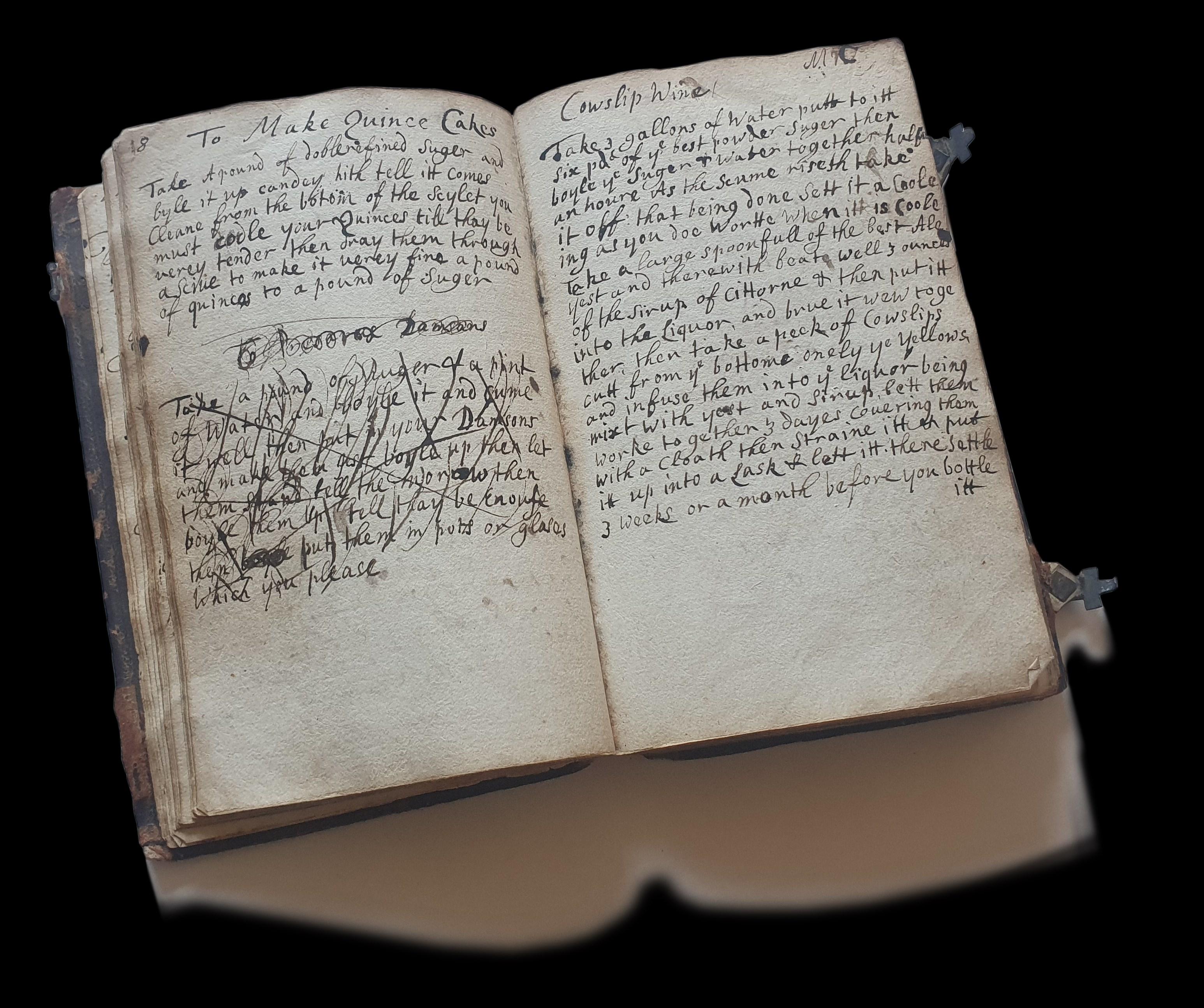

Extracts from Sir Richard Hoare’s (1648-1719) commonplace book. (pp19-22)

Manuscripts and annotated books do not always yield to straightforward categorisation – not because they lack some of the usual bibliographic features of printed books, but because they so often cross boundaries and include idiosyncrasies. But this resistance to easy codification is not something to be ironed out; the multidimensional forms of some artefacts can be key to understanding the context of their creation and crucial to determining their significance. Nonetheless, some modalities are necessary to gain any kind of useful interpretation. But too loose and we risk saying nothing; too tight and we lose vital individuating factors. Aristotle’s precept offers a useful approach by allowing for overlapping modalities:

“One way of classifying things is to distinguish different questions which may be asked about something and to notice that only a limited range of answers can appropriately be given to any particular question.”1

The early modern period introduced new ways of thinking about the world and new questions to ask, which in turn called for new ways of organising things. This catalogue, rather than attempting to provide exact definitions, considers some of the ways in which the early modern manuscript makers organised knowledge themselves – either from a pre-existing model or in an attempt to create something new.

Even a blank sheet is not a neutral tabula rasa: the context, form and framing of a blank space guide the forms and framings of thought articulated by the scribe on the manuscript’s surface. Various scholars have explored ideas around this: Julie Park’s work discusses how different forms can influence scribes and their readers, guiding their thoughts towards certain kinds of narrative and expression including graphic ones such as grids, tables, and other strategic arrangements of lines.2 Ian Hacking distinguishes between things (usually substances) which are not affected by categorisation but can still aid an understanding of them (eg carbon as arranged in the periodic table does not change carbon itself, but does change our understanding of it) and things (usually humans) that are affected by how they are categorised which causes modifications in their behaviour and approach to the world, creating what he calls a “looping” effect on the person.3

The interleaves in early modern almanacs begat certain kinds of narrative (brief, practical, chronological). Almanacs distil the unruly sprawl of life into reassuringly neat, predictable forms easily carried in the pocket. They were often interleaved with blanks, encouraging users to interact with them, but their format and written style fostered a particular kind of annotation: practical, often quantitative information conveyed concisely. The resulting narratives can seem blankly inscrutable and sometimes devoid of feeling, but, as Adam Smyth has demonstrated, they often formed part of a network of texts: the likes of Evelyn, Dugdale, and Wood used almanacs as “an early, although not necessarily initial, site of recording” for their diaries and other forms of life-writing. Evelyn, for example, revisited his brief almanac notes years later and expanded them into a fuller, more rounded picture of his life, raising questions about the veracity of remembered experience and the supposed spontaneity of such texts. 4 As modern-day readers of almanacs and other historical forms, we do something similar: for example, in presenting a long run of almanacs annotated by Francis Drewe (pp1-8), we have, in a sense, re-expanded his collection into a fuller, more rounded account, without the benefit of having lived the life in question, but with – we hope – the benefit of an impartial assessment of the material evidence.

The physical arrangement of manuscript volumes may speak to the attitudes and intentions of scribes towards their contents. Early modern receipt books often arranged culinary recipes at one end and remedies at the other to form different but equal parts of an integrated picture of human health. Such volumes are often referred to as dos-a-dos, but this term more accurately refers to a binding method with a board between the texts; a form suited to binding up texts such as the Old and New Testaments, so that each is opened at its beginning. Following the lead of the Folger Library and others, we have opted for the term tête-bêche (see pp93-98), which translates as “head-to-tail”. Since it’s a way of organising an already bound blank book, têtebêche does not call for a dividing central board.

As their name implies, books of receipts (ie things received) often tell stories of social connections; of giving and receiving. We have several instances of these exchanges, but one in particular exemplifies this practice (pp75-80). It began as an account book (which also uses the tête-bêche format), and gradually morphed into a miscellany that incorporated several ways of receiving including advice, finance, and recipes. A culinary manuscript by Jane Coxhead (pp23-26) includes a group of recipes that precede their printed appearance, implying that she was a member of a social group connected with the author of the later printed work. In another section she juxtaposes culinary recipes from an earlier printed book with similar but untraced recipes, seemingly her own improved versions. She appears to have compiled the volume over a short period of time, with an eye for aesthetics and a purpose beyond simply keeping a running list of recipes.

In a similar vein (although without the element of “display”), the several anonymous compilers of a multilingual book of remedies (pp27-28) cite professional physicians as authorities, but still created the book for home use. Its more medicalised focus is perhaps symptomatic of the gradual separation of recipes and remedies into two distinct fields of interest. This slow parting of the ways was perhaps inevitable because scribes amended recipes based on their subjective experience of whether this or that recipe tasted good, whereas remedies are tested empirically by noting whether the evidence indicates a salutary effect on a patient.

It would go beyond the scope of this catalogue to draw a direct line from the education offered at grammar schools, private schools, and free schools to that of their modern-day equivalents. But it is interesting to observe the kind of scope available to those who could afford an education. Our 17th-century schoolboy’s rhetorical exercises (pp29-32) would have equipped him with ever-ready witty remarks for every occasion as he expanded his horizons; in contrast, later ciphering manuscripts with their narrow range tended to limit the horizons of pupils to the “trades”. Hacking’s notion of “looping” might come into play here, as such expectations, in whichever direction, may be easily internalised. As James Baldwin observed: “the standards of the civilization into which you are born are first outside of you, and by the time you get to be a man they’re inside of you [...] they’re real for you whether they’re real or not”.5

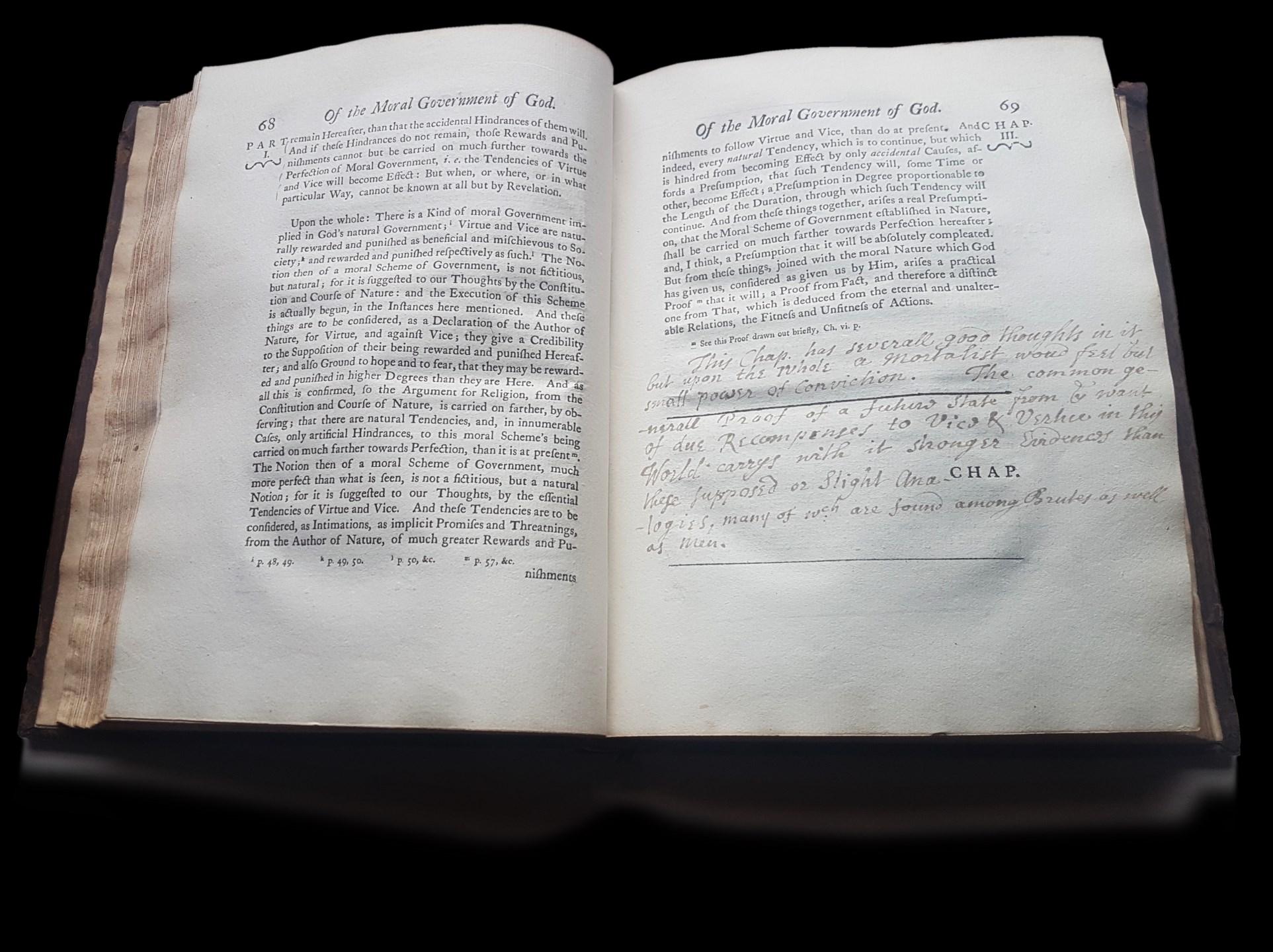

Annotations in printed books have long been rightly prized for the insights they bring to our understanding of the minds of other readers. The margins of a printed book afforded space enough for pithy remarks or terse objections, and they can create a kind of one-sided conversation, without the original author being present to answer back. Such is the case in one of the texts included in this catalogue (pp55-58). It was annotated by Isaac Watts and helps elucidate his thought and some of the crosscurrents of 18th-century Enlightenment philosophy. Other annotations are not so much a conversation as an extension of

another’s thought. In the 1650s, Joseph Clarke augmented Walter Blith’s already expanded edition with additional blank leaves bearing his personalised additions (pp9-12).

Explorations of the relationship between annotations and notebooks has led to insights into the luminaries of the early modern period. Such work demonstrates that marks and annotations in books were evidence of engaged, pen-in-hand reading and that notes in commonplace books were not simply copies of people’s thoughts, but part of an active process in which compilers sometimes ordered their volumes “spatially and materially as well as conceptually” juxtaposing ideas “to generate new examples, and thus in turn to produce new discourses and new knowledge”.6

Commonplace books, typically gleanings from other works arranged under subject headings, are sometimes conflated with other notebooks, especially miscellanies. While there is certainly overlap with other notebooks, Steven May cautions against conflating the forms: “literary anthologies are routinely termed commonplace books”, resulting in such works being overlooked by literary scholars.7

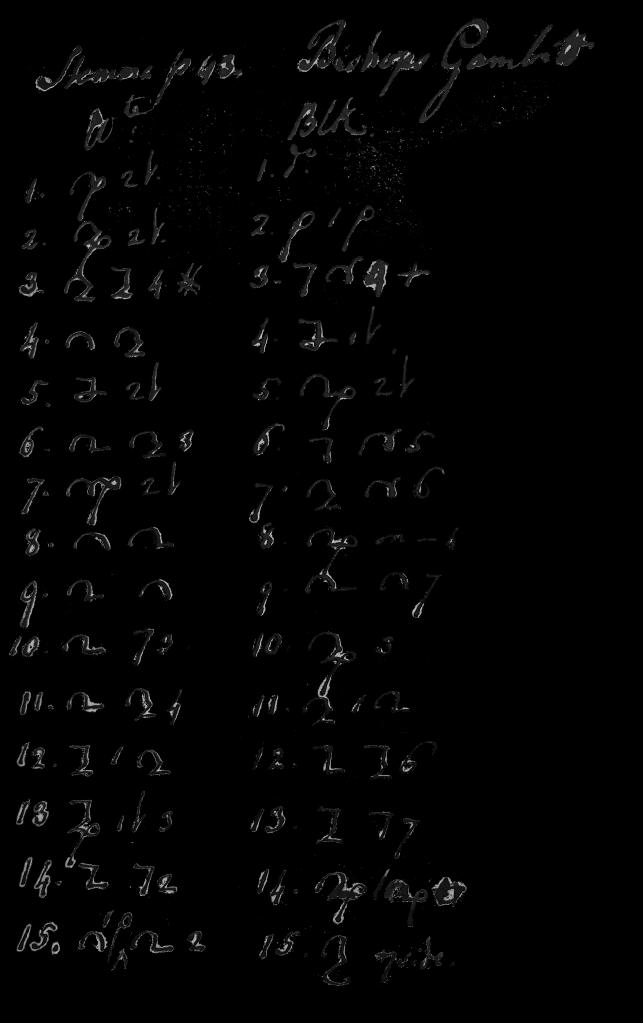

There is no neat line of progress from the early modern period, or the Renaissance as it is sometimes known, to the present day. Among the undoubted advances, there were faltering starts and dead ends which, in a parallel universe, could have become accepted conventions. Our chess manuscript (pp63-70) represents both an innovation and a cul-de-sac: some players perceived the need to develop a codified language – a realisation which in itself marks a great step forward in the systematisation of the chess moves themselves. While this particular method of recording did not catch on, it is part of the story of experimentation that led to the development of new forms of codification.

Ann Blair remarks that “many of our current ways of thinking about and handling information descend from patterns of thought and practices that extend back for centuries”.8 Some nascent patterns are evident in these manuscripts. Scribes often begin with a heuristic that is subsequently adapted or jettisoned in the face of new developments or needs, leading to a series of “rules of thumb” to help navigate an ongoing process of trial and error. In some cases, forms and arrangements are attempted, then changed or abandoned for no apparent reason, leaving a kind of testament to the scribe’s indecisiveness or fickleness. But out of these approaches emerged some of the ways in which we understand our world now. They might not be talking about the human condition in the way that a poem or a play does, but they can still be expressive of the human condition.

References:

1. ARISTOTLE. Categories and De Interpretatione. Translated with Notes by J. L. Ackrill. (1963).

2. PARK, Julie. The Self and It. (2010) Line-Making as Life Writing. (2023).

3. HACKING, Ian. The Social Construction of What? (2000)

4. SMYTH, Adam. Autobiography in Early Modern England. (2010).

5. GIOVANNI, Nikki. Conversations with Nikki Giovanni. Edited by Virginia C. Fowler. (1992).

6. VINE, Angus. Miscellaneous Order. (2019).

7. MAY, Steven. English Renaissance Manuscript Culture: The Paper Revolution. (2023).

8. BLAIR, Ann. Too Much to Know. (2010).

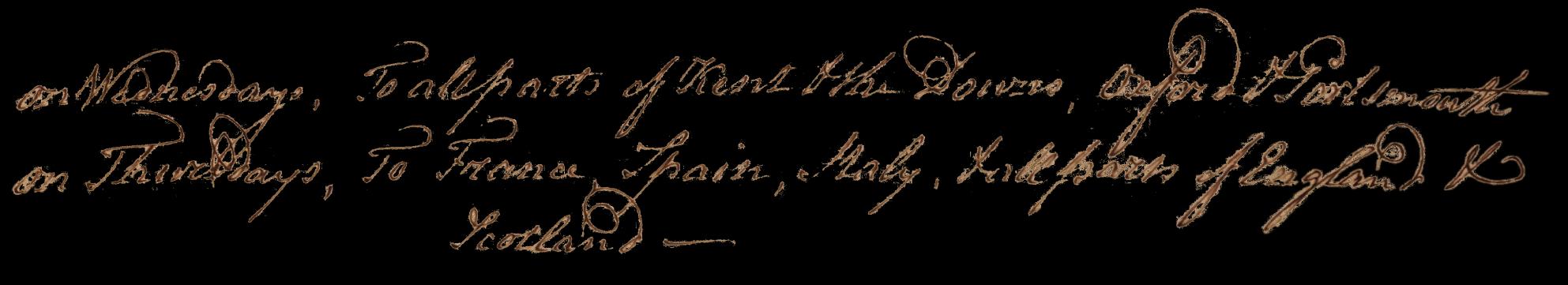

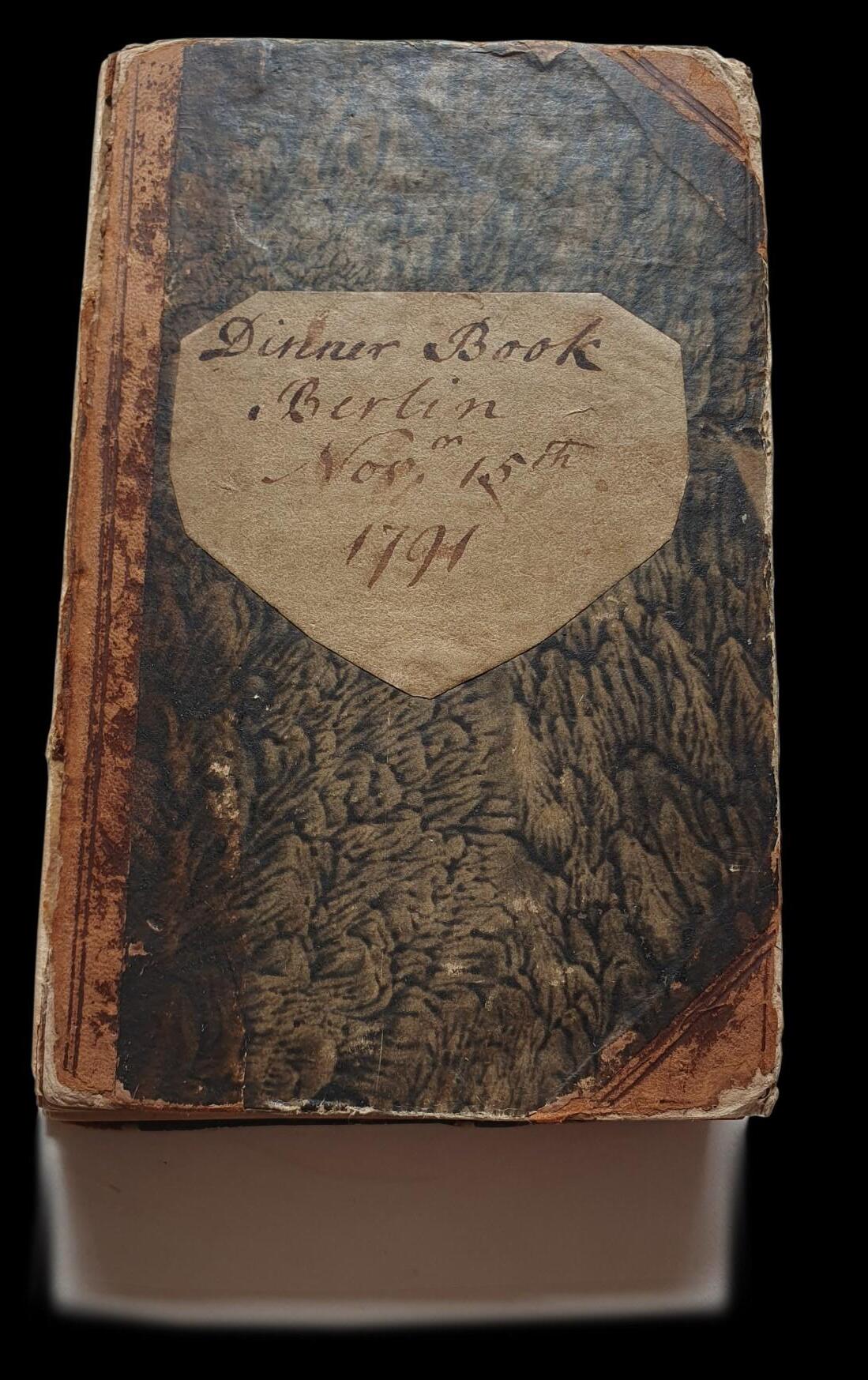

[DREWE, Francis (1673/4-1734)]; RIDER, Cardanus. A remarkable run of ‘Riders’s British Merlin’, interleaved and annotated by a single owner.

[The Grange, Broadhembury, Devon]. London: 1699-1733. 12mo. Pagination 48 p. All volumes are complete and interleaved with blank leaves, with annotations to front and rear leaves.

Provenance: ownership inscription of Francis Drewe to several volumes, then by descent to previous owner.

¶ Fact, fiction, and forecast all jostle for position in the little worlds created by almanacs. Time pulls in all directions: an entire millennium might be squeezed into a single page, improbable prognostications project the reader into possible futures, while a fleeting moment is captured in an annotator’s brief memo.

Almanacs guide the reader through a world of uncertainties by reducing the vicissitudes of life to neat, predictable forms easily carried in the pocket. They were often interleaved with blanks, encouraging users to interact with them, but their format and written style fostered a particular kind of annotation: practical, often quantitative information conveyed concisely. The effect may seem cold and distanced, but these narratives formed part of a network of texts and can give insights into often overlooked areas of people’s worlds.

This remarkable group of 17 annotated almanacs encapsulates many of these elements but is even more unusual for being annotated by a single user, one Francis Drewe, whose public, professional life is a matter of record, but whose private life is here partially revealed over a period of more than 30 years. Drewe’s memos capture his interactions with the world in a series of notes about the things that most concerned him: birth, people, money, death, and tree planting. And occasionally the pen reveals more than the writer intends.

The pseudonym “Cardanus Riders” was an anagram of the compiler, Richard Saunders, whose almanac first appeared in the 1650s and was so successful that the “brand” survived until the 19th century. The inverse law of print survival has reduced this once ubiquitous publication to a few surviving copies of the earlier editions, with some lost completely. This collection comprises extremely rare editions and one previously unrecorded copy.

Beneath the title’s predictive promises, the imprints tell their own story. The earliest edition of Riders’s almanac recorded in ESTC was printed by John Field in 1654 (one copy only, Folger). It came under the control of the Company of Stationers, and the right to publish it passed from Robert and William Leybourn to Samuel Griffin who each held the rights for around a decade. Next, it came to Thomas Newcombe who held onto this lucrative publication from the mid1670s until the late 1680s when his apprentice, Edward Jones, took command. Jones is the first of the printers credited in our collection, appearing in the imprints between 1699 and 1707. After he died in 1706, the rights passed to another Newcombe apprentice, John Nutt, whose name appears in our sequence from 1711 to 1715.

Nutt died in 1716, and his widow, Elizabeth Nutt, continued printing, becoming solely responsible for the years 1719-20. She was joined by their son Richard in 1722, and their names appear in our collection in 1725 and 1727. Elizabeth was prosecuted for libel in 1727 (apparently while bedridden), which probably accounts for her absence from that year’s printing (1728); but she rejoined Richard for printing almanacs until the 1740s. Our collection ends with the death of Francis Drewe, so Elizabeth’s name appears in this collection between 1725 and 1733.1

According to Capp, the “story of the eighteenth-century almanac is [...] one of evolution as well as stagnation and decay”2. Stagnation was well represented by the likes of Moore and Partridge, whose almanacs offered “an endlessly popular diet of jingoism, abuse of Catholics and predictions of the downfall of the pope and the French”. But the survival of Riders owed at least as much to its form as its content: it was “small and interleaved to make it suitable as a pocket-diary”.

The name “British Merlin” invoked the Arthurian magician’s legendary powers of foresight to promote the almanac’s mix of predictable astronomical information (“Eclipses this Year”) and general advice on husbandry (“the best times to fell Timber”). Some of the content was carried over from one year to the next (“Dimensions of England”, “Geographical Description of the World”), and regular events were updated each year (“Fairs in England and Wales”), interspersed with the occasional advert for products that relieved perennial problems: “Buckworth’s Lozinges”, say, or “Artificiall Teeth, set in so firm as to eat with them”.

Francis Drewe (c. 1674-1734) was a lawyer, and Member of Parliament for the City of Exeter (reportedly in the Tory interest) in four parliaments: 1713, 1715, 1722 and 1727. A member of the Drewe family of Broadhembury whose descendants still own The Grange today, Francis matriculated at Corpus Christi College, Oxford in 1690, aged 16, and entered the Middle Temple in 1691. In 1695 he married Mary Bidgood (died 1729/30), daughter of Humphrey Bidgood of Rockbeare, near Exeter. He was called to the bar in 1697 and appointed a bencher in 1723.3

Francis had two sisters: Susan (later Ayloff) and Elizabeth (later Mitchell), both of whom are mentioned in his annotations; other family references – births, deaths, etc – are also included.

In all 17 volumes, Drewe has often made annotations to the front and rear leaves, but rarely the additional blank interleaves. His coverage of these blanks varies with each almanac, from 45 pages (volume [6], 1705) to only three (volume [13], 1725); the rate of annotation fluctuates, until it declines in the final few years. The predominant topic is money, but family and related matters also feature strongly – and these entries are sometimes inadvertently moving, as Drewe’s outlook seems to shift, either with age or with grief.

The first few annotations in the earliest almanac concern hirings and payments: “Elizabeth ffary came to live with me on the 5th of December I bargained with her to give her for her wages p[er] an – 1816 / 1669 / 119”; and “Thomas Greet came to live with me on ye 23 of January 1698/9. I bargained with him to give him for his wages p[er] an -05-00-00”; then, “Elizabeth

Norman came to me on ye eleventh day of November 1699 I bargained with her to give her for her wages p[er] ann. 06-0000”. The crossings-out probably indicate that Drewe has copied these lines to another volume – illustrating the practice, identified by Adam Smyth, of annotators “shifting material from text to text”4. After further financial record-keeping, he reports: “My Grandmother Drewe dyed on ye 7th of September being Thursday”. A few pages later, he marks a professional milestone: “I was published in ye Temple Hall on ye 9th of feb: 1698/9 […] ye day after I took ye oathes at ye Kings bench”. Money matters soon reassert themselves, with “Expenses for this year”, a tally that self-referentially begins “Almanack – 00-00-10”, then continues with items including “Candles – 00-00-06 / Mending of Jones coat & breeches –00-05-00 [...] my Barristers gown – 06-15-00 [...] a silver headed cane – 01-03-00 / Chocolette 7 pd – 01-01-04” – and a few lines later, perhaps hinting at a sweet tooth, another “8 pd chocolette”.

The fourth volume takes a graver turn with the lines: “Mem: yt on March ye 20th about 6 o clock my daughter Elizabeth dyd of convulsions.” His terseness shows signs of strain when he continues: “Mem: also yt about an hour & half after ye same day evening my now daughter Betty Mary was born”. It is as if his grief breaks through, literally rupturing his carefully poised demeanour (the correction is written in lighter ink, so added sometime later) – and perhaps prompting another moment of discomposure when he concludes, also in lighter ink: “& xned ye Sunday monday […] after at ye cathedral Exon”.

The fifth volume includes another poignant example of brevity evoking the outlines of tragedy: “Mem: yt my son Thomas was born on Tuesday ye 26 day of September 1704 about 8 at night & christend ye Sunday sevenight after at St Peters Cathedral Exon 5th […] Mem: my son Thomas dyd on Tuesday ye 28th of Nov: & was buried at ye Cathedral Exon”. His child’s short life is thus compressed still further on the page.

Chronology is also manipulated in the first volume, to very different effect: what looks at first glance like a solemn marking of his father-in-law’s passing (“Humphry Bidgood Esq dy’d on ye 12th of May 1691”) is belied by the date (eight years before the printing of this almanac in 1699), indicating some other purpose. Sure enough, he continues: “ye interest of pxxx of my wives legacy from yt time to ye 12 of Aug: 1699 at 5 p[er] cent being 8 years & a quarter is 1443-00-00 / 350000-00 / 4943-00-00”. Drewe’s apparent memorial of a past death suddenly becomes an accounting of present finances.

Memos frequently include prominent public figures such as “Sr W Carew”, who “gave Mr John Bampfylde a guinea to give him 20 if ever he lost 50 shill. At play at cards or died at any one time”, and “Mr Manship”, whom Drewe paid “5d upon ye account of Mr Chishull wch money was lodged in my hands by Mr Chishull before he went to Smyrna”. Edmund Chishull (1671-1733) was a clergyman and antiquary who graduated from Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and was appointed chaplain to the factory of the Turkey Company at Smyrna, where he arrived in 1698. He published scholarly works including Antiquitates Asiaticæ (1728 -31), and his journals were posthumously published as Travels in Turkey (1747). The “Mr Manship” referred to above is Samuel Manship, who published several titles by Chishull from premises in Cornhill, London.

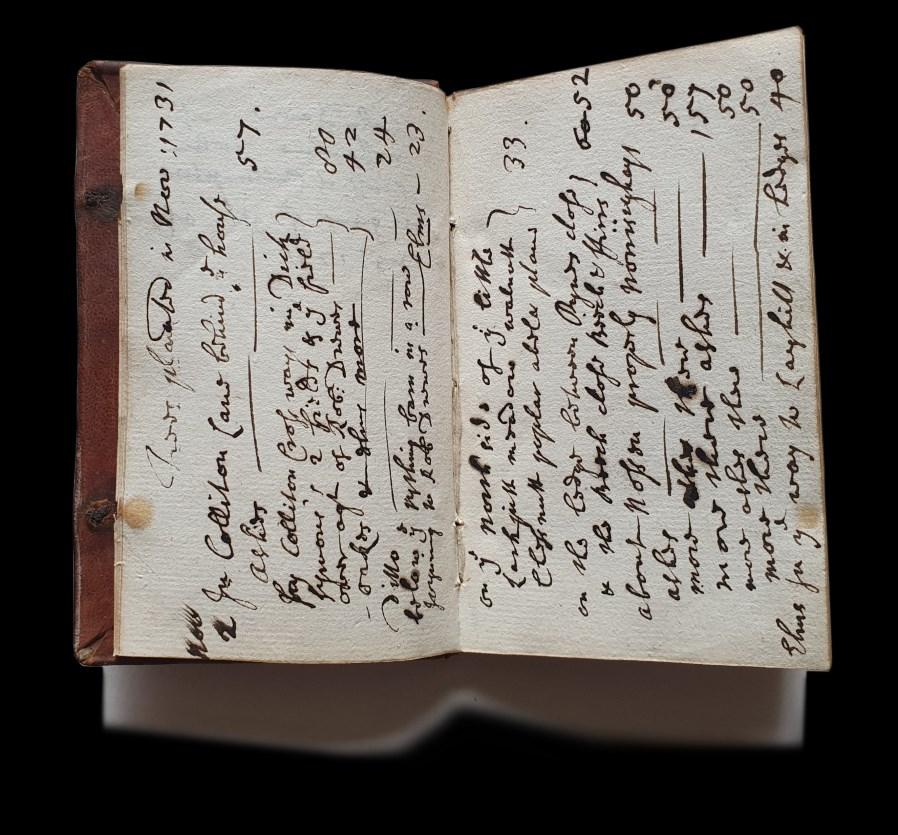

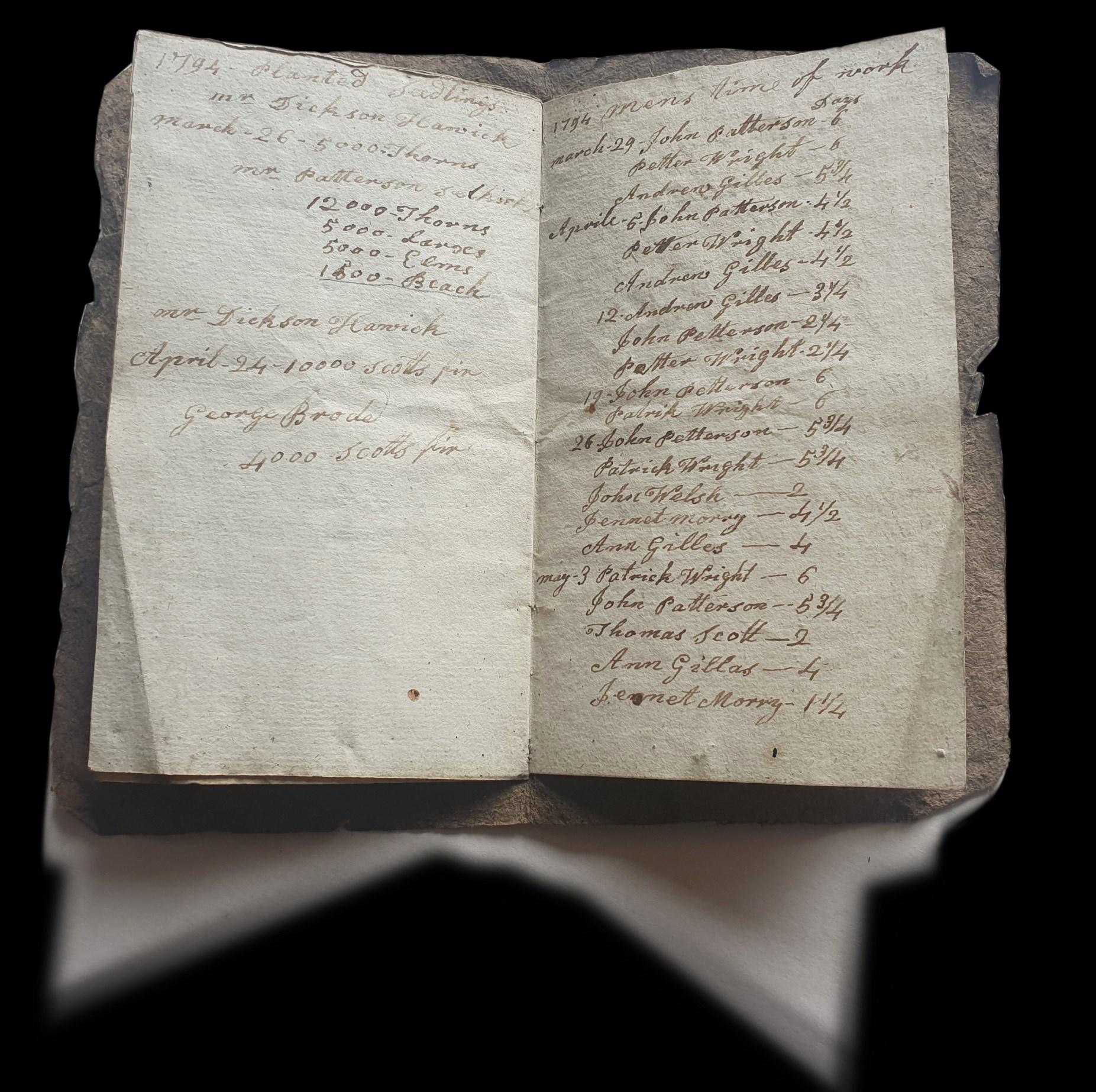

Back in rural Devonshire, Drewe’s entries at times reach into the future in the form of arboreal legacies frequently favoured by the aristocracy. On three occasions he records tree planting (in 1714 he records “Mr Cox ye gardners Catalogue of ye fruit Trees planted by him in ye year in Grange garden”; in 1731 he creates a woodland of indigenous trees; and in 1733, over 70 fruit trees, including many varieties of nectarines and peaches, are planned for “the best garden beginning from the study window”). The lists are so carefully laid out as to make physical, or at least mental reconstructions of the woodland and orchards possible.

Occasionally, Drewe’s characteristic straightforwardness becomes opaque – at least, for the reader. In the ninth volume, we find the note: “Charles begun his Reign 30 Janry 1649”. Which Charles? The date is that of Charles I’s execution, but his son was not recognised as king until the Restoration in 1660. Is Drewe quietly declaring himself a Royalist, 65 years too late? The fourth volume contains two notes written in 1703 whose intentions are less of a mystery, but whose context is now lost: “yr son hath been too forward in ye scandal of Mr B. but yn no wonder from a man I formerly told you tooke pains to shew he had no regard for churchmen […] as his ill nature & looseness in his principles reflect on you I must take notice of both”; and “say no more of this matter or of yr sons whome I shall be glad to doe all kindnesses to […] I wish now yn 2 of yr / letter were in ye fire”. These are clearly drafts of part of a letter, but to whom, and concerning what “scandal”, remains unknown to us.

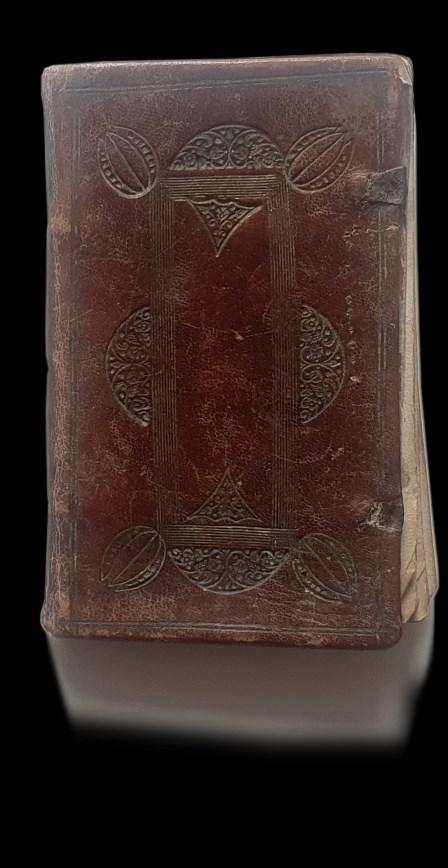

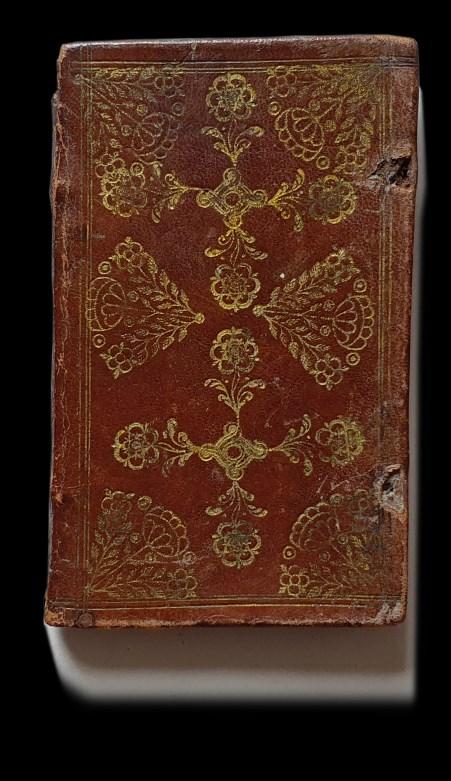

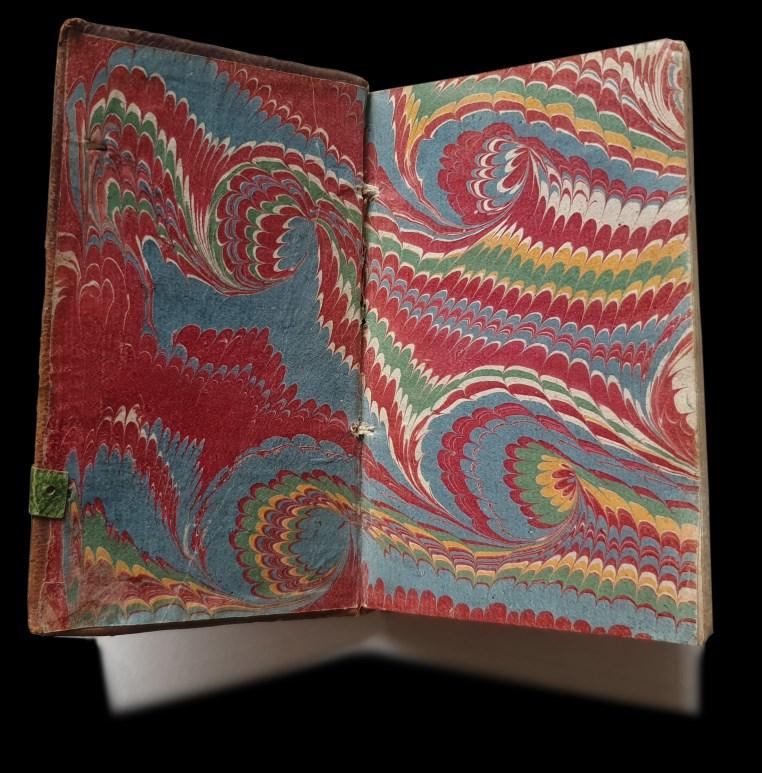

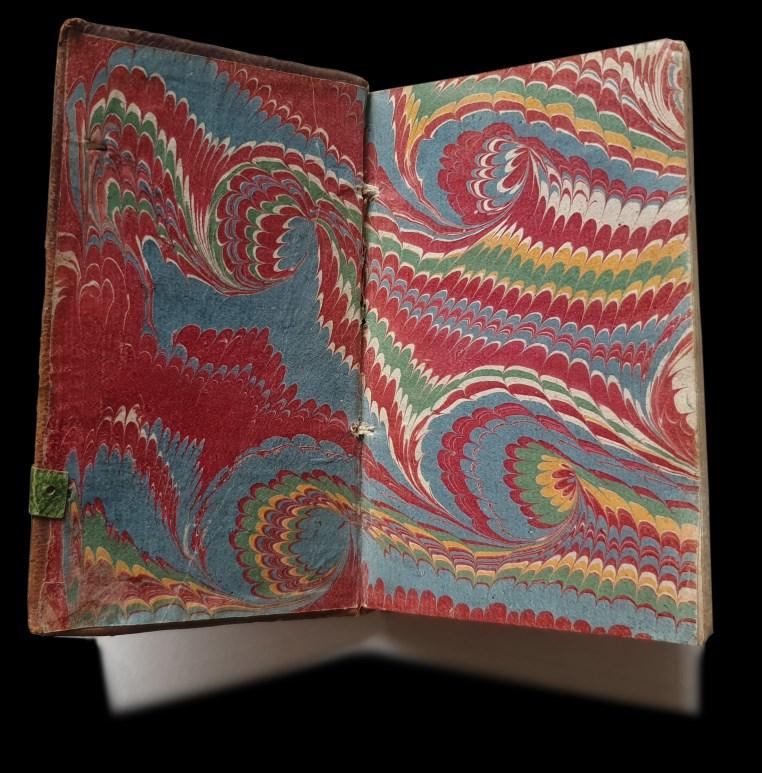

The contemporary gilt-tooled sheep bindings in this set are both unusual and intriguing, in that they diverge from the typical bindings – either very plain or elaborately tooled morocco – found on almanacs. All of these volumes are bound in contemporary light tan sheep (some with marbled endpapers), with gilt tooling typical of the later part of the 17th century: small tools, including drawer handles and floral shapes, and even the occasional bird, are combined into geometric designs. Each of these differs from the others, but all share what may be called a “family resemblance”; David Pearson has confirmed that they

“are all clearly from the same source, and were presumably issued sequentially year by year”, rather than being “all bound at the same time to those variant patterns”. The tooling is very aesthetically pleasing, and Pearson believes them to be “the work of a professional binder” but agrees that there is a certain “rusticity” to the workmanship, suggesting that these were done locally – that is, in Devonshire. Identifying the binder is no simple task, because, as Pearson remarks, there is “[s]o much work that could be done, and has not been, on provincial binding work” 5 .

The time-warping tendency of almanacs, so well exemplified here, culminates in a final, posthumous leap in the thirteenth volume, whose front endpaper bears a later inscription: “I have found 19 of these Pocket Books W D” – that is, presumably, William Drewe (1745-1821). The note suggests that two volumes have been lost from this collection and there is some perplexing manuscript numbering (see below), but it remains a tremendous run of almanacs covering a span of some 34 years of Francis Drewe’s life. The collection yields a rich series of glimpses of a life lived both publicly and privately. The unusual, perhaps provincial bindings throughout make for a very appealing external presentation worthy of further research.

The almanac’s format encouraged a focus on the perpetual concerns in the human life cycle (birth, death, relationships, money), and presented this material in a reassuringly orderly manner. But such concerns and events, for all their inevitability, are inherently unpredictable. Drewe’s collection shows the arbitrariness of life juxtaposed against the almanac’s fixed framework, and offers a rare opportunity to view these brief, scattered sketches as part of a connected whole.

SOLD Ref: 8179

1. http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

2. Capp, Bernard. English Almanacs, 1500–1800: Astrology and the Popular Press. (1979).

3. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/drewe-francis-1674-1734

4. Smyth, Adam. Autobiography in Early Modern England. (2010).

5. With thanks to David Pearson for his invaluable assistance and permission to quote from correspondence.

17 rare editions of Riders’BritishMerlin.

[1]. 1699. “No. 7” to endpaper. Annotations to approximately 26 pages.

2 UK. British Library, Northampton Record Office Central Library,

1 USA Yale University, Sterling Memorial

[2]. 1700. Annotations to approximately 16 pages.

2 UK. Northampton Record Office Central Library, Oxford University, Bodleian Library

1 USA Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery

[3]. 1701. “No. 8” to endpaper (apparently ignoring the 1700 almanac noted above). Annotations to approximately 11 pages.

3 UK locations. 2 at Northampton Record Office Central Library, 4 at Bodleian Library, 1 in the National Archives.

2 USA. New York Public Library, UCLA, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library.

[4]. 1703. “No. 15” to endpaper (apparently ignoring the almanacs noted above). Inscribed “Francis Drew / 1703”. Annotations to approximately 28 pages.

4 UK. Oxford University Queen’s College, Oxford

University, Bodleian Library, The John Rylands Library, The University of Manchester. USA no copies.

[5]. 1704. Inscribed to endpaper “Francis Drewe”

Annotations to approximately 19 pages.

2 UK locations. British Library, and 2 in Northampton Record Office Central Library. USA no copies.

[6]. 1705. Inscribed to endpaper “No 18. / Francis Drewe of ye middle Temple”. Annotations to approximately 45 pages. Worming to text.

2 UK. Cambridge University Library, The National Archives. USA no copies.

[7]. 1707. Annotations to approximately 20 pages.

2 UK locations. British Library, 2 in Northampton Record Office Central Library. USA no copies.

[8]. 1711. Annotations to approximately 10 pages.

2 UK. British Library, The National Archives.

1 USA. Folger Shakespeare.

[9]. 1714. Inscribed to endpaper “No 9”. Annotations to approximately 14 pages.

1 UK. Northampton Record Office Central Library.

1 USA. University of California, Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library.

[10]. 1715. Inscribed to endpaper “No 9”. Later inscriptions of “William Drewe” and “Ann Drewe”. Annotations to approximately 11 pages.

4 UK. British Library, Northampton Record Office Central Library, Senate House Library, University of London.

USA no copies.

[11]. 1719. Annotations to approximately 13 pages.

2 UK. British Library, Eton College Library.

USA no copies.

[12]. 1720. Annotations to approximately 20 pages. Worming to text and loose in binding.

2 UK. British Library, Royal College of Physicians of London.

USA no copies.

[13]. 1725. “No 9”. Annotations to approximately 3 pages. Spine broken, text block loose.

1 UK. British Library.

USA no copies.

[14]. 1727. Annotations to approximately 4 pages.

1 UK. British Library.

USA no copies.

[15]. 1728. Annotations to approximately 6 pages. Unrecorded. No copies in the UK or the USA.

[16]. 1731. Annotations to approximately 4 pages.

2 UK. British Library, The National Archives.

USA no copies.

[17]. 1733. Annotations to approximately 6 pages.

2 UK British Library, The National Archives .

1 Canada. University of Toronto, Library.

1 New Zealand. Alexander Turnbull Library.

USA no copies.

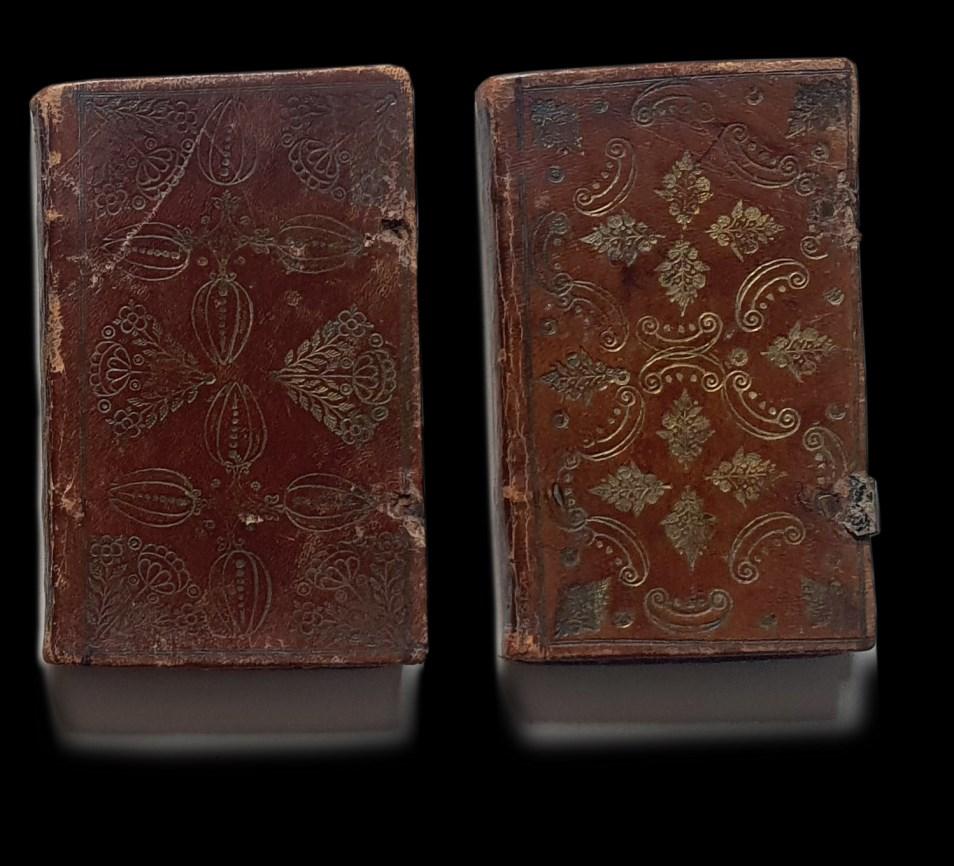

BLITH, Walter (1605-1654); annotated by CLARKE, Joseph. The English improuer improued or the survey of husbandry surueyed discovering the improueableness of all lands. With contemporary manuscript additions.

London: printed for John Wright, at the Kings-head in the Old-Bayley, 1652. [Manuscript additions dated 31 July 1652].

Quarto. [54], 230, 2], 231-248, [2], 249-256, [2], 261-264, [1], 258-262, [2 (blank)], [20] p., collated and complete with the 4 plates (2 full-page woodcuts, and 2 folded engraved plates). Additional leaves present. [Wing, B3195]. 18 blank leaves bound in at each end.

Manuscript notes to five full pages, seven part-pages, and occasional brief annotations to text. The watermarks front and rear differ: the front is difficult discern, but the rear is Pot (similar to Haewood 3637, but enclosing letters PDB).

Provenance: inscribed to a front free endpaper twice by “Joseph Clarke” and with his purchase note: “p. 0.3.4 / Julij 3i. i652”.

¶ The first user of this book, one Joseph Clarke, surely deserves the epithet of “Industrious READER”, whom Blith addresses in the preliminaries to this “much Augmented” edition of his English improuer improued or the survey of husbandry surueyed. For immediately upon buying his copy for “p. 0.3.4” on “Julij 3i” in the year it was published, Clarke has taken it straight to the binder to have it neatly bound in full reverse calf and enlarged with additional blank leaves at either end – and has augmented it still further with his manuscript additions.

Blith himself was a one-man hive of industry who, besides farming his own land, produced two books on husbandry which “surpass all others of their time for their practical good sense, their evidence of his own and others’ farming experience […] and the care given to describing new farming practices and making textual changes as time and improved knowledge permitted” (ODNB). Indeed, The English improuer improued, although presented as a third edition of the original volume, was so thoroughly revised that it can be considered a separate work.

Clarke – whom we have been unable to identify with certainty – was evidently a great reader of contemporary gardening and husbandry books, and follows Blith’s lead by “improuing” and expanding this copy. His first manuscript entry, “Of Bees”, “The best bees are small, round, light, & glistering like gold, & angry (which anger is appeased by dayly haunting among them”. This text is untraced, but it does bear some resemblance to passages from Thomas Hill’s Profitable Arte of Gardening (of

which there were several editions between 1563 and 1608), so we assume that he used the information from Hill’s book, perhaps mixed with details from other works or his personal experience.

brief recipes: “To make red or greene wax” and “To make wax White”, the first of which instructs the reader to “Take one pound of bee’s waxe, three ounces of cleare turpentine” (variations on this recipe can be found in many compilations of the period).

There are two pieces entitled “Of sheep”: the first is ascribed to “M. Conradus Heresbachius Pag. 138 &c to 144”, ie the German scholar Konrad Heresbach (1496-1576), whose Rei rusticae libri quatuor was translated into English in 1577 as Fovre bookes of husbandry. It was followed by four further editions (1578, 1586, 1596, 1601). It is clear from looking at Clarke’s page references that he has précised from the text rather than copied directly. The other, shorter text is ascribed to “Tho. Hill p.59”, and this, too is a précis.

Manuscript additions continue at the end of the printed text, with three short notes headed “A French experiment for the Multiplication of Wheat &c”, “Against ye Smuttiness of Wheat”, and “For planting or sowing wallnuts”, neatly written out on half a page. Overleaf, a half-page entry on “The Mulberry” is again sourced from “M. Conradus Heresbachius”.

The cross-pollination continues with a four-page section on growing from seed (“How to set & sow seeds, stones, kernells &c for plants”) and grafting trees (with five subheadings including “Ingrafting” and “Inoculating”), and “Of translating plants”. These have all been either copied verbatim or précised from A treatise of fruit-trees by Ralph Austen, whose book had only just appeared in 1653, so if, as seems likely, Clarke added his manuscript sections soon after purchasing and interleaving this volume, he took these notes immediately upon publication.

We get a brief glimpse from a note to the final text page of where he obtains at least some of his seed: “Mr James Long’s shop at ye Barge on Billings=gate, for Claver-seed &c” – a recommendation he may have come across from his perusal of Richard Weston’s A Discours of Husbandrie used in Brabant and Flanders (1652), the second edition of which included an advertisement for Long’s establishment.

Clarke’s addition of many blank leaves clearly signals his intention to expand Blith’s resource considerably more than he managed to. We have no way of knowing the reasons for his eagerness to begin annotating the book so soon after publication certainly indicates a high level of commitment, so perhaps some misfortune intervened. The additions he did make, however, show an impressively broad interest in husbandry – both animal and arable – and provide a superb example, in original condition, of how a 17th-century reader interacted with a printed publication by sowing further material from other contemporary works onto the leaves of his recently purchased book.

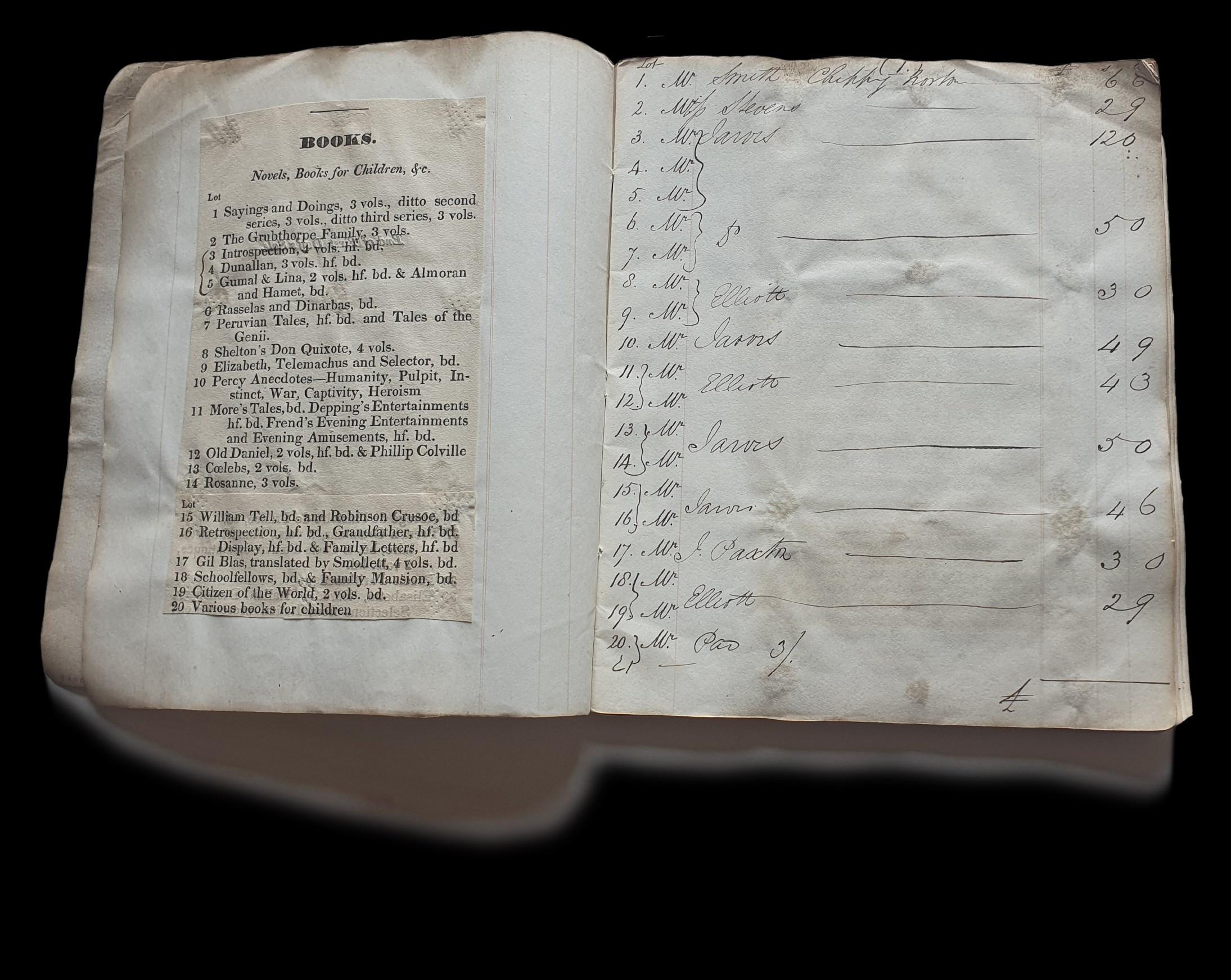

[WRIGHT, Rev. Thomas (c.1775-1841); PAXTON, Jonas] Claydon Rectory. Valuable and carefully selected library of upwards of 1,200 volumes, and other effects, of the late Rev. Thomas Wright, to be Sold by Auction, by Jonas Paxton. On the Premises, at Claydon aforesaid.

[Claydon Rectory, Buckinghamshire. Circa 1841]. Slim quarto (193 x 162 x 4 mm). There are 21 sheets (plus a sliver of one sheet) of two octavo printed catalogues. These sheets have been trimmed and pasted to the versos of quarto stationer’s book. The title of one of the catalogues has been trimmed and pasted to the front cover, with details of the date of the sale added in manuscript.

This unrecorded catalogue chronicles the sale of the books of a largely little-known country parson. As such, it nicely reflects the reading or at least collecting tastes of literate and once-important local figures whose profiles dwindled posthumously to near-anonymity, but who, through their acquisitive habits, contributed to the preservation and shaping of the wider culture and the formation of our collective memory.

Thomas Wright was born circa 1775, the eldest son of Thomas Wright, a London merchant. As so often for the period, his mother’s name is not recorded. He was educated St. Paul’s School, London before matriculating at Pembroke College, Cambridge in 1794 (B.A. 1798; M.A. 1801). He was ordained deacon in 1798 (London), subsequently becoming rector of Otton-Belchamp, Essex (1807-11), and of Little Henny (1811-20) before attaining the living as vicar of Middle and East Claydon, Buckinghamshire in 1820 until his death in 1841. Venn notes that he was the “Father of Thomas (1827)”. There are several possible matches for his marriage, but we have been unable to confirm the name of his wife or the date of their marriage with any degree of certainty. What we do know is that she predeceased him, since he requests in his will that he be “buried in the same grave as my beloved wife at Steeple Clayton”.

His books, however, seem to have left more of a trace in the “valuable and carefully selected library of upwards of 1,200 volumes” which lists 414 lots. The majority are individually lotted books, which usually include author’s name, title, date and very brief details (“Dryden’s Juvenal, 1713”, “Donne’s ditto [i.e. ‘LXXX Sermons’], folio, 1640”), while some lowervalue items are grouped into titles of two or three (e.g. “27 Levizac’s French Grammar, hf. bd., Clef de Levizac’s 2 copies, and Boyer’s Dictionary, bd.”), and others of apparently nominal value do not justify naming (“School books”, “Ditto”).

The collection has been grouped into nine categories arranged in the following order: “Novels, Books for Children, &c.” (1-25); “Works in Modern Languages Grammars, &c.” (26-43, plus one added in manuscript: “*43 Cobbetts Grammar”); “Works on Gardening, Botany, &c” (44-50); “Classics, School Books, &c” (51-104, although 54 is recorded as “no lot”); “Hebrew Works” (105); “Works on Law” (106-121); “Works on Divinity, Sermons, &c” (122-254*; this latter and six other extra lots are marked with an * or added in manuscript); “Miscellaneous” (255-410); and “Odd Volumes or Imperfect Books” (411-414). The numbering is continued in manuscript to 431. These sundry lots include “Odd Books” (415-6), and five lots (427-31) of “Miscellaneous books” which were all bought by a “Mr Road” for “1.3.0”, and the others (417-26) are left blank.

As the above list indicates, pride of place is given to novels and children’s books, although it is not certain that this reflects a value judgment by the auctioneer: of these first 25 lots, several are bundled up together (e.g. “5 Gumal & Lina, 2 vols. hf. bd. & Almoran and Hamet, bd.”, “11 More’s Tales, bd. Depping’s Entertainments hf. bd. Frend’s Evening Entertainments and Evening Amusements, hf. bd.”); lot 20 is generalized “Various books for children” and 21-25 follow simply with “Ditto”. Books which warrant a single-entry name include “6 Rasselas and Dinarbas, bd”, “Shelton’s Don Quixote, 4 vols”, and “17 Gil Blas, translated by Smollett, 4 vols. bd.”

Wright kept several books on languages including Welsh, Italian, and French. The last of these is reflected in some of his books, but to judge from his collection, he preferred works in Latin or English. Unsurprisingly for a man of the cloth, there are many theological books. These range from influential 17th-century works like “Pearson on the Creed” in “2 vols. hf. bd”, “Butler’s Analogy” and “Taylor’s Holy Living and Dying, bd., and Pilgrim’s Progress, bd” (these latter lotted together), and important works from the 18th century like Paley’s “View of Christianity” and “Natural Theology” and “Wilberforce’s View”, through to contemporary authors such as Hannah More (here represented by “on St. Paul”, “Christian Morals”, “Moral Sketches”, and “Bible Rhymes”).

The “Miscellaneous” books encompass works of literature (including “293 Pope’s Odyssey, 5vs. bd. Ditto Iliad, 6 vols. bd. Ditto Works, 9 vols bound”, “294 Shakespeare, with notes, 8 vols. bd.”, and “329 Works of Rabelais, 1694”), travel books (“267 Maundrell’s Journey, Bingley’s Voyagers and ditto Travellers”, “283 Salame’s Algiers, bd”, “286 Voyage to China, by M’Leod, hf. bd”), and scientific works (“280 Plurality of Worlds, Fontenelle”, “325 Treatise in the Globes, 1639”, “358 Lavoisier’s Chemistry”). And Wright would have taken his place in the pantheon of the great and good recorded in “327 Graduati Canatbridgienses ab anno 1639 ad 1824”.

We are confident that this was the auctioneer’s retained copy. As noted in the physical details above, it was collaged together from at least two printed copies of the catalogue and then mounted into a book to allow the scribe to record in manuscript the buyer’s names, the prices paid, and several other crucial details. These include manuscript notes such as “5 Lots of Miscellaneous works to be inserted as Lots 427, 428, 429, 430 & 431” – and the “clincher” is the record of several instances of the buyer having settled their invoice (several lots are marked “Paid” or “Pd” next to the purchaser’s name).

Jonas Paxton was an auctioneer based in Bicester, Buckinghamshire. From this rural market town, he held sales of farms and farmland as well as household dwellings and contents. The earliest record of his name as an auctioneer was in 1838, with the announcement in Jackson’s Oxford Journal of a sale to be held in Bicester. However, the earliest record for Paxton in library holdings is a catalogue for a sale held in 1849 (Particulars & conditions of sale of freehold and copyhold estates at Blackthorn and Fritwell in the County of Oxford). His son appears to have joined the firm around 1854, and Paxton senior sometimes worked in partnership with George Castle (library holdings record various combinations of Jonas, his son, and Castle). The early catalogues were often printed by “E. Smith and Son, printers and booksellers”.

As noted above, the earliest library holding for a Paxton sale catalogue is 1849. Although he travelled as far as Cambridgeshire on occasion, all his other sales were for land, dwellings, or house contents; this sale, therefore, not only marks his earliest recorded sale catalogue, but suggests a remarkably intrepid debut, involving as it did the taking on and cataloguing of a library as a stand-alone sale and conducting it in situ at Claydon Rectory.

The most voracious buyer was a “Mr Elliott”, who secured 107 lots – over a quarter of the total sale. Given the sheer quantity and range of his purchasing, we would assume he was a dealer. “Mr Rowsell” picked up 36 lots (again wideranging), and several buyers bought in the high teens to early twenties. A cluster of bidders secured around a dozen lots each, including a “Mr Child” who bought John Donne’s sermons for “7s”, along with several other books. After that, the purchases tail off into small amounts or even single books. Whether they were unsuccessful or highly focused in their buying is difficult to say at this distance, but a few are certainly worth drawing attention to. Paxton himself appears to have bought

bought nine lots, including “297 Dictionary of “15s” as well as Hind’s Arithmetic, Moore’s Juvenal, Edinburgh Dispensatory (342-344), and several others, so was perhaps selling books from his premises in Bicester as well as printing, among other things, Paxton’s sale catalogues. The scribe has prewritten “Mr” before each entry, but lot 35 (“Italian Pocket Dictionary and Zotti’s Italian Grammar”) has been amended to “Miss” followed by “Elliston” who paid “4s 6d” – an unusual early record of a woman purchasing at auction.

The 1,200-plus volumes recorded in this sale catalogue offer a window onto the rich cultural and literary landscape of a rural clergyman in the early 19th century. Wright’s vocation may (or may not) have secured him eternal glory, but in the temporal realm, it was his passion for books that has left the clearest traces of his earthly existence.

£2,650 Ref: 8152

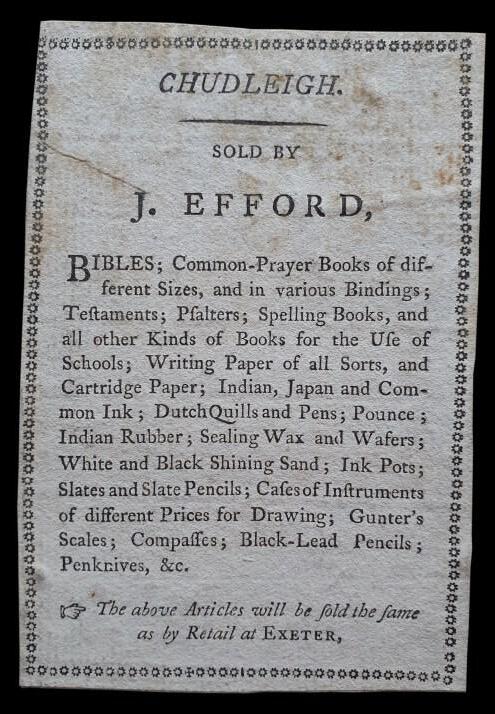

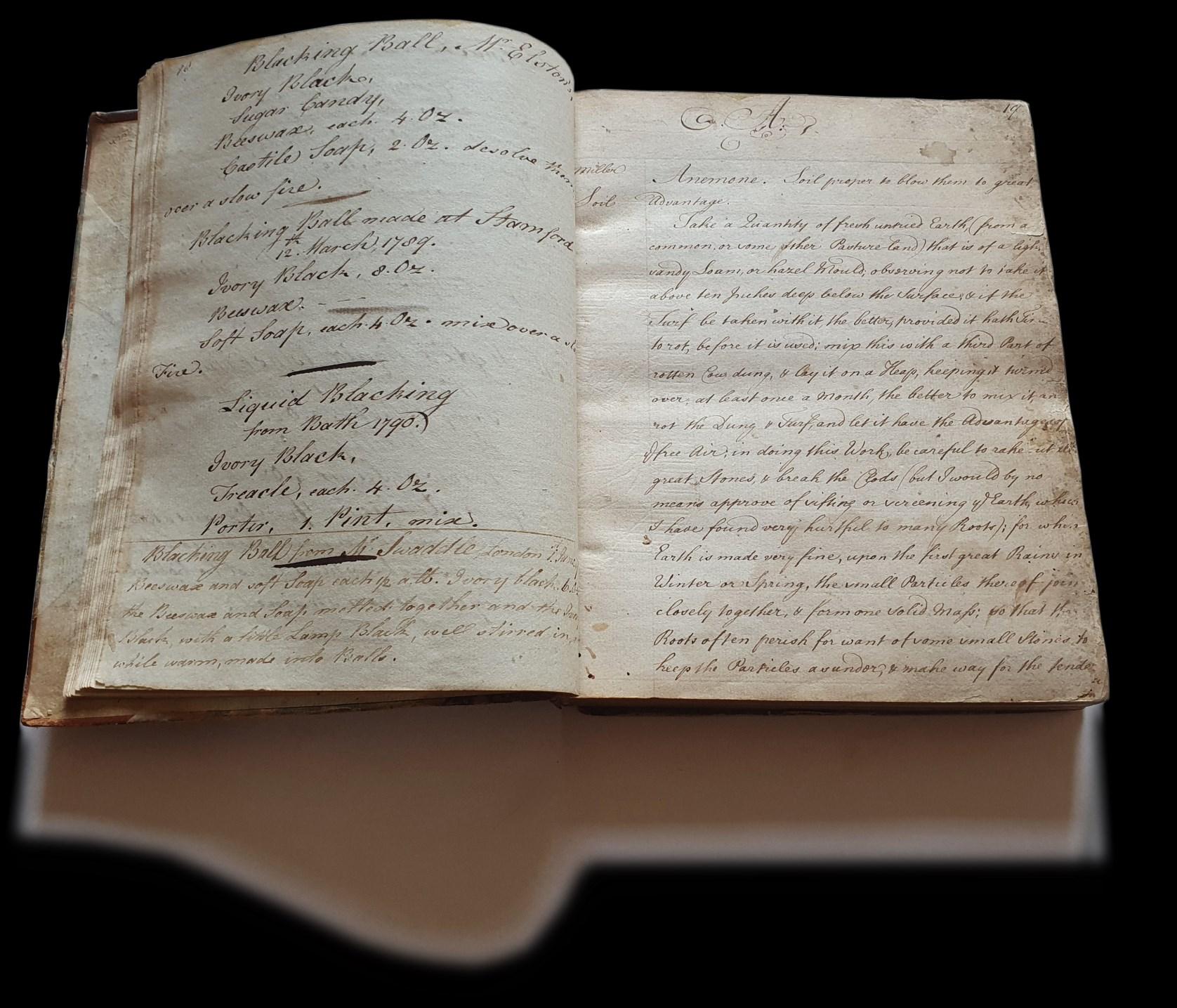

[THOMPSON, Dr.] Manuscript commonplace book on farming and gardening.

[Chudleigh, Devon. Circa 1800-1825]. Quarto 207 x 160 x 30 mm). Pagination [2, index], [3, unnumbered remedies], 367 numbered pages, several illustrations. Original half sheep, rubbed and worn, joints splitting, spine worn. Engraved bookseller’s advertisement “Chudleigh” to front paste-down. Loosely inserted letter addressed to “Dr Thompson, Chudleigh”.

¶ This manuscript compilation of agricultural and horticultural observations began as a series of remedies jotted down randomly for approximately 20 pages, before the compiler decided to systematise the collection by arranging subjects in the traditional alphabetical form of a commonplace book. But after about 180 pages the system breaks down and it once again becomes a place for random jottings of medical as well as horticultural notes. Order is partially restored by the creation of an index to two leaves at the beginning of the volume which presumably had previously been left blank.

The volume appears to be the work of one Dr Thompson of Chudleigh, Devon. The two pieces of evidence for this attribution are a loosely inserted letter addressed to “Dr Thompson, Chudleigh”, and the stationer’s label to the front pastedown of J. Efford, also of Chudleigh in Devon. Efford advertises “Bibles; Common-Prayer Books of different Sizes, and in various Binding” as well as “Spelling Books [...] Writing Paper of all Sorts [...] Indian, Japan and Common Ink; Dutch Quills”, etc.

Thompson collects material on horticulture, agriculture and veterinary matters (from growing “Apricots” and “Cyder Apples” to the economics of animal husbandry and treating “the Scab” in sheep), with diversions into cheesemaking, viticulture, apiary (including “A Caution” on the swarming of bees), maintenance of regalia (receipts for “regimental blacking Balls” and “regimental Colouring for the belts”), and a few remedies (“Mistletoe of the Oak” for “Use in Epilepsy”). The text is variously dated between 1753 and 1825 but appears to have been compiled in the early 19th century. Attributions, which occur throughout, take in a wide array of sources, including periodicals (“Gent Mag”, “Bath Papers”), books (“An Invitation to the Inhabitants of England, to the Manufacture of Wines, from the Fruits of Their Own Country […] By R. Worthington […] 1812”), and individuals (“Capt Farquarson”).

£500 Ref: 8142

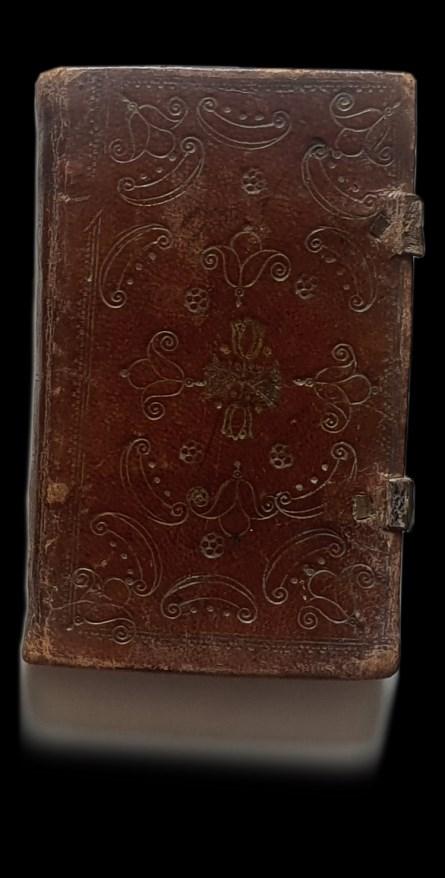

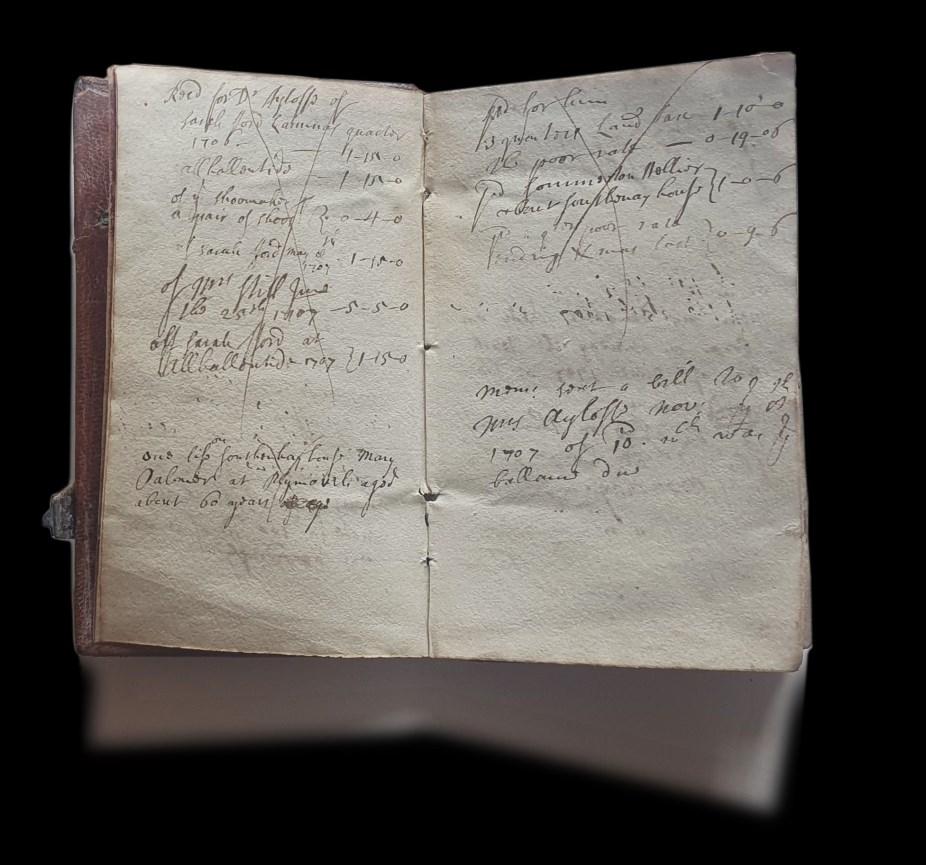

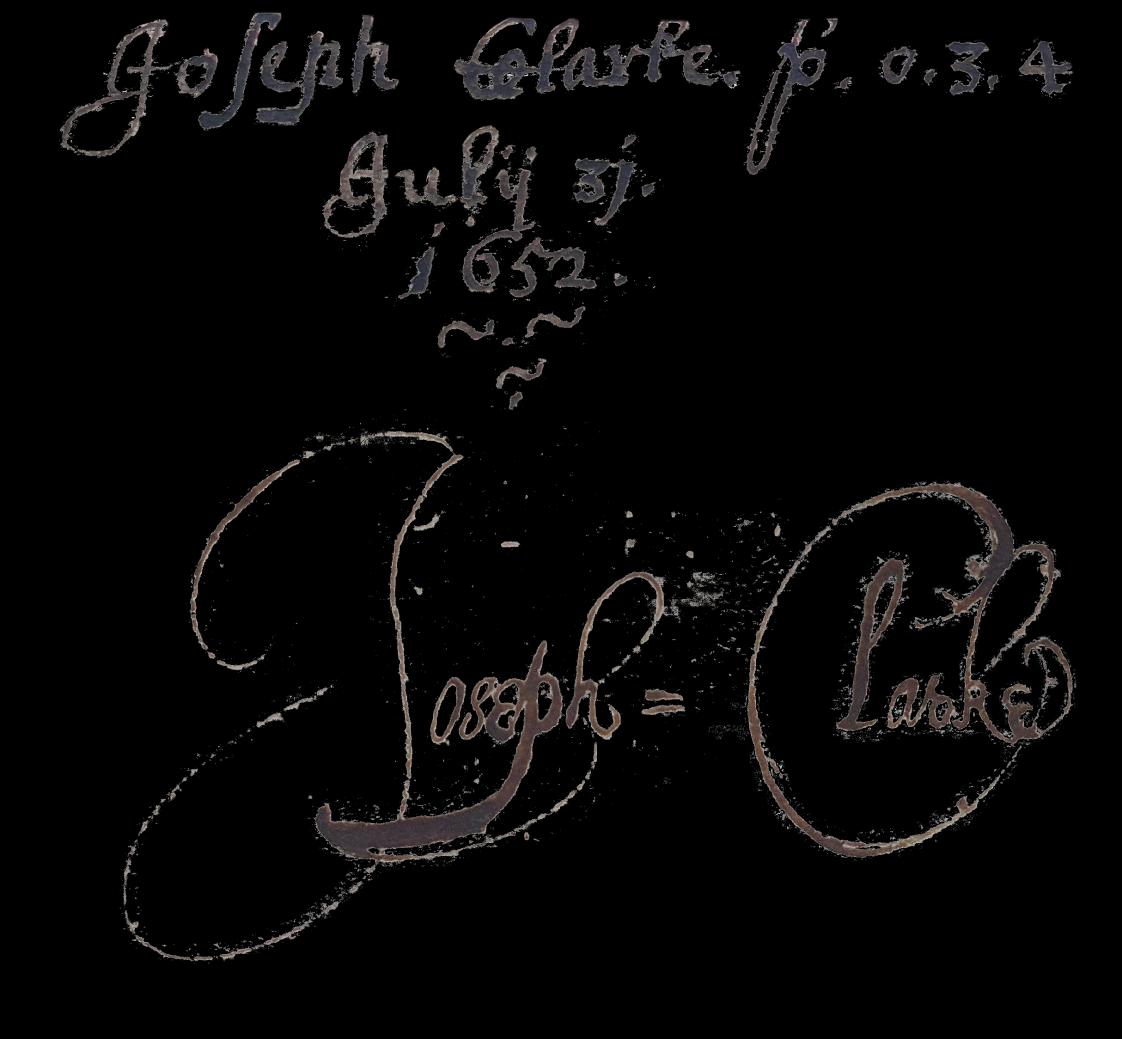

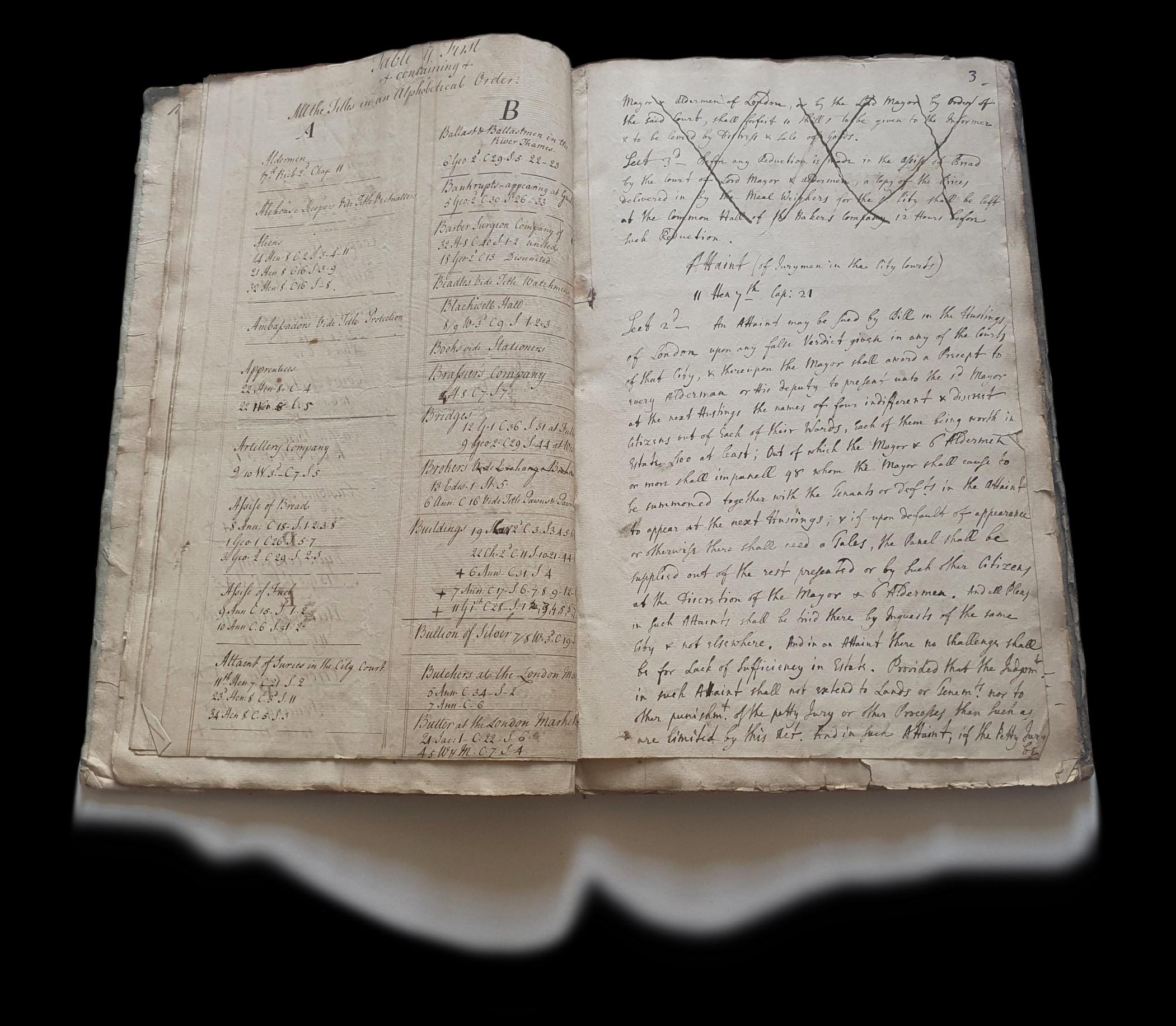

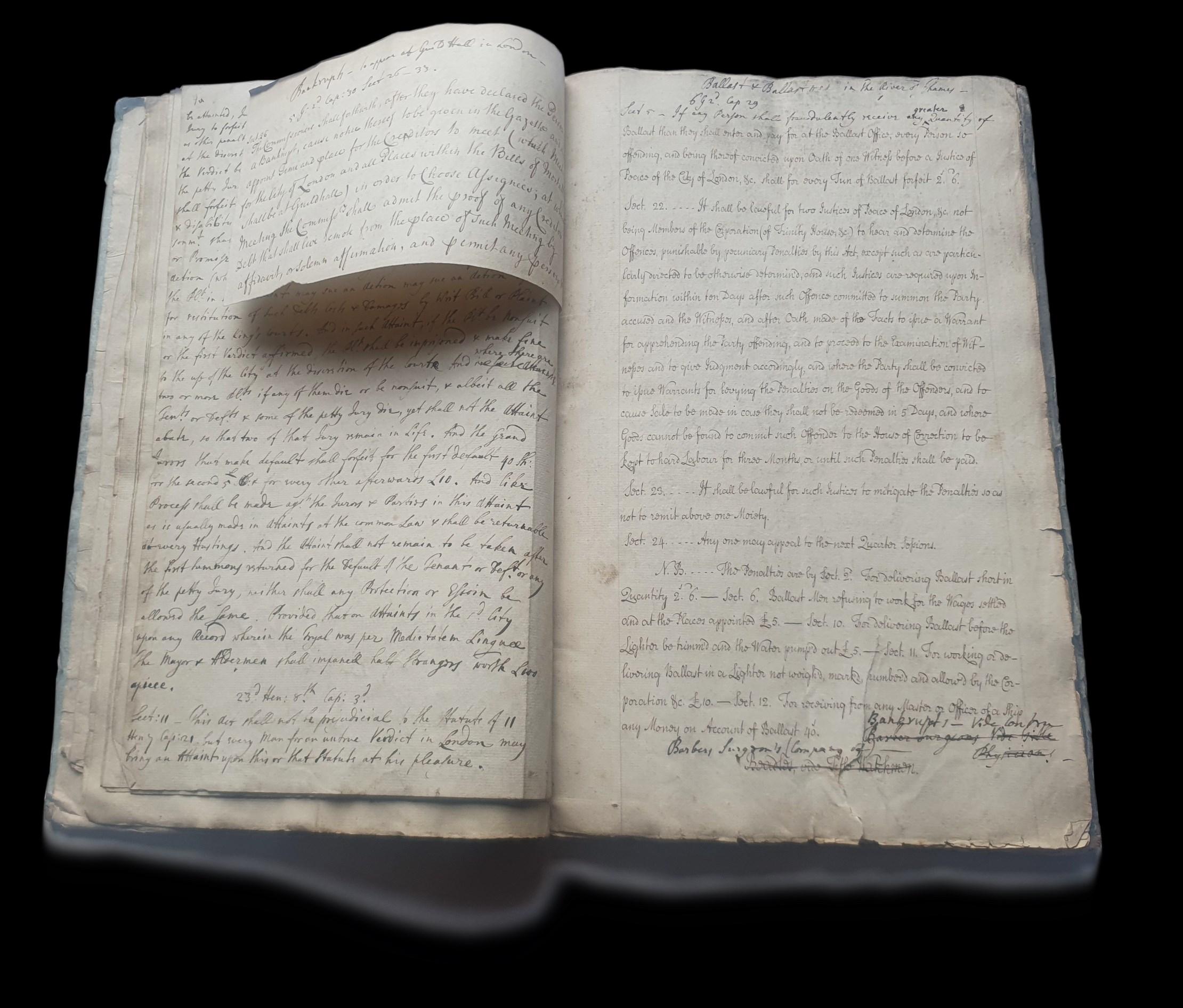

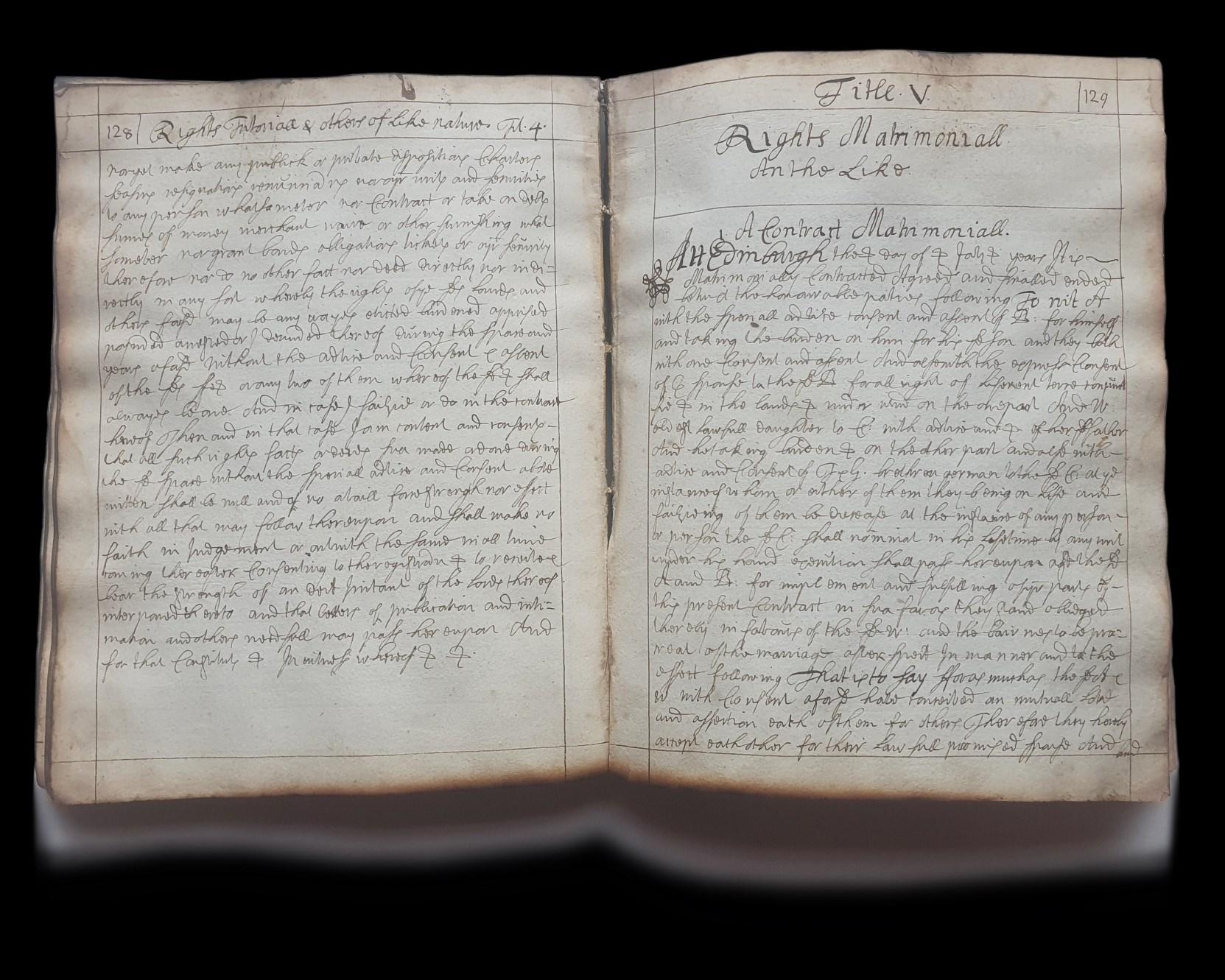

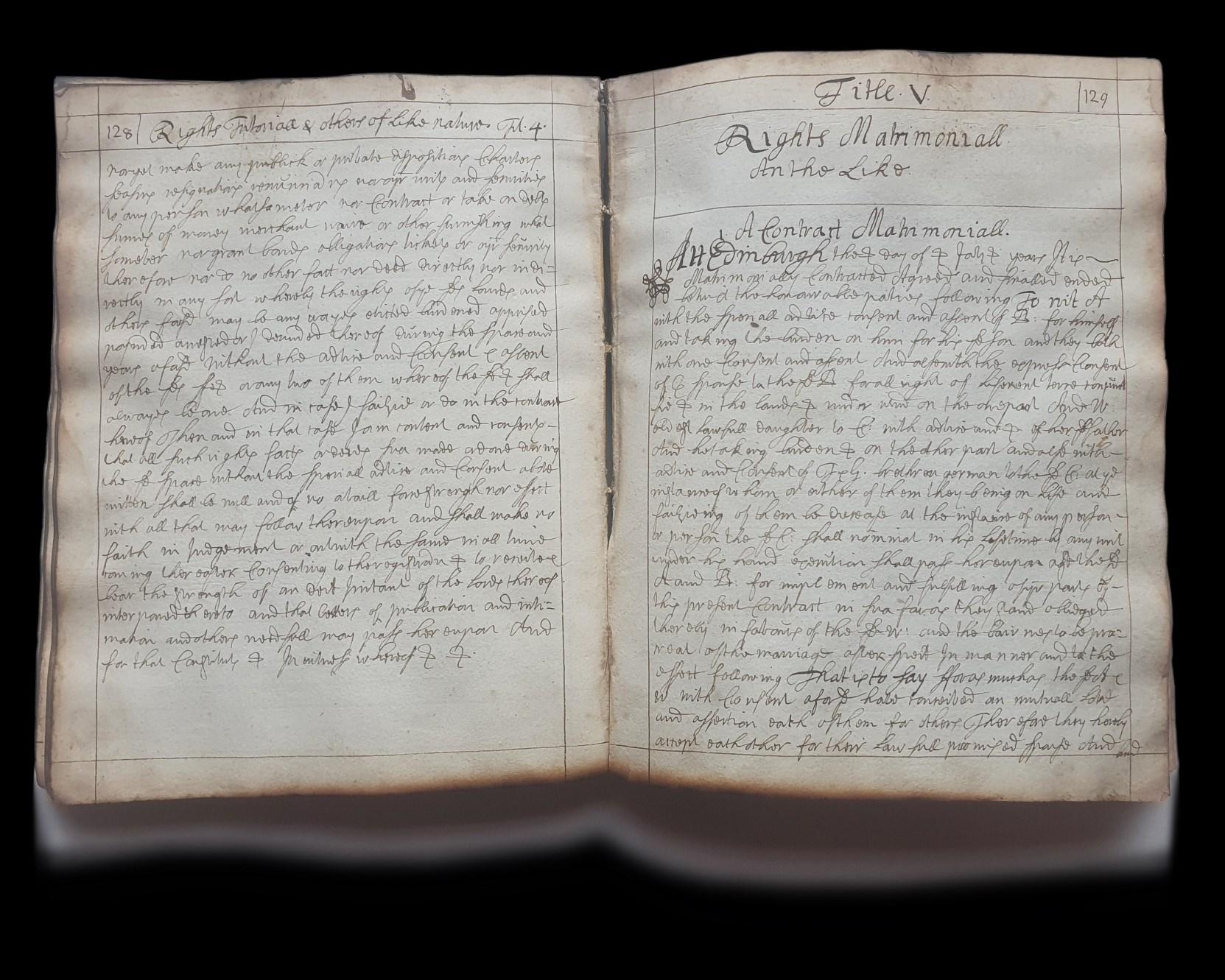

[HOARE, Sir Richard (1648-1719); DEARDS, William (d.1761)]. Early 18th-century legal commonplace book.

[London. Circa 1712]. Folio (340 x 210 x 10 mm). Approximately 108 text pages on 60 leaves and a tipped-in slip. Text in at least three neat, legible hands. The pages are numbered erratically, and volume appears to have been bound from loose sheets of slightly different sizes, however they all share the same watermark: Pro-Patria with a GR countermark.

Contemporary plain grey boards, calf, spine, very heavily rubbed with loss, remnant of paper spine label which appears to have read “PRIVILEDGES”.

Provenance: note in pencil at the end of the preface attributes the text to “R. Hoare, Lord Mayor of London 1713”, and an ownership inscription to f4r reads “William Deards”. The volume apparently passed by descent to the previous owners via Henry Merrick Hoare (1770-1856), the husband of Sophia Thrale (1771-1824).

¶ This legal commonplace book appears to have been compiled with a specific purpose in mind. Its compiler was, according to a pencilled note to the preface, “R. Hoare, Lord Mayor of London 1713”. This attribution of the text to Sir Richard Hoare is extremely plausible: Hoare was appointed Lord Mayor of London in 1712, and an easily consulted reference work such as this would have been extremely useful in such an important role.

It was this kind of conscientiousness that would have enabled the only child of Henry Hoare (d. 1699), a horse-dealer of Smithfield, and his wife, Cicely (d. 1679), to rise through the social ranks, beginning as an apprentice goldsmith in 1665. By 1673, having been granted the freedom of the Goldsmiths’ Company the previous year, he was able to buy the business of his lately deceased employer; and in a shift of focus, he began acting as a banker to his customers, earning a reputation for sound judgement and assiduous client relations. He entered politics through his election as an alderman in 1703, became Sheriff of London in 1708 and, after several setbacks, finally became Lord Mayor in 1712 (the same year in which he became a founding director of the South Sea Company). Ill health forced him into retirement, and he died in 1719. C. Hoare & Co still operates, as the oldest surviving bank in the UK.

It seems highly likely that Hoare compiled this volume – or supervised its creation – around the time of his becoming Lord Mayor of London (although he had already made several foiled bids for the position, so it is possible that he had begun preparing it earlier, in optimistic anticipation). Its title page reads: “Powers, Jurisdiction, Rights, Privileges & Functions of of [sic] the Mayor’s Commonalty of Citizens of the City of London” (f1r); and in an accompanying, two-page “Preface”, Hoare (or an assistant under his direction) explains the purpose behind the book. He describes several changes of approach, as he began to suspect that his initial criteria would generate too short a work, then that his revised parameters take the project “as much beyond the compass of my design, as the other was short of it”; and having settled on a third way, he painstakingly sets out this more satisfactory methodology, which encompasses only “the Clauses of such Statutes which relate to the Citizens of London, as Citizens & Inhabitants therein”.

Having decided the scope of his requirements, he has arranged the text alphabetically in just over 90 pages. The first 33 pages have been filled by a neat scribal hand and cover subjects from “Aliens” to “Juries” and the beginning of an entry for “Lamps”, via the likes of “Brokers”, “Cloth Workers”, “Gun-Powder” and “Inn-Keepers”. A section headed “Gold and Silver” (which would have had personal significance for both Hoare and Deards, the latter of whom was a very highly regarded silversmith), has been partly crossed out and amended in a loose but easily legible italic hand to read “Goldsmiths”

It is this latter editor (again, we assume either Hoare or a clerk under his guidance) who seems to have been responsible for organising the volume into a user-friendly reference book. They have added the title page and preface mentioned above, extended the text by approximately 61 pages and edited the previous scribe’s work with numerous crossingsout, amendments, and annotations. A section comprising may also be in the same hand, but it is much neater, so we remain uncertain. A second table listing the statutes is mentioned in the preface, but does not appear to have been executed. This “Table” forms part of a group of six slightly shorter leaves (but with the same watermark) which are inscribed by “William Deards” and comprise “The Clauses of the Acts of Parliament relating to the Powers Jurisdictions Rights Priviledges & Franchises granted to the Mayor Alderman & Commonalty & Citizens of London” arranged as “Table ye First containing All the Titles in an Alphabetical Order” and two pages of notes on “Attain”

Having edited the previous scribe’s work, the second scribe has restarted and completed the entry on “Lamps” and continued the text through to “Workhouse of London” (with one insert by the first scribe entitled “Physician, Apothecaries and Surgeons”). Their contributions include “Misdemeanors”, “Nonconformists”, “Orphan’s Fund”, “Pavement of the Streets Scavengers & Sewers”, “Prisons”, “Victuallers, “Watermen”, and the perennially persecuted “Papists & Popish Recusants”. They have also subjected these sections to correction and amendment.

Hoare’s evident reputation as a diligent, detail-conscious businessman is reflected in his careful, twice-revised approach to creating this ready reference for his duties as Lord Mayor of London. A major point of interest is his highlighting in the “Preface” of the heuristic that changed alongside his evolving notions of a format would answer his needs. Untidy though its appearance may be, it was still an efficient tool for its sedulous creator.

£2,500 Ref: 8206

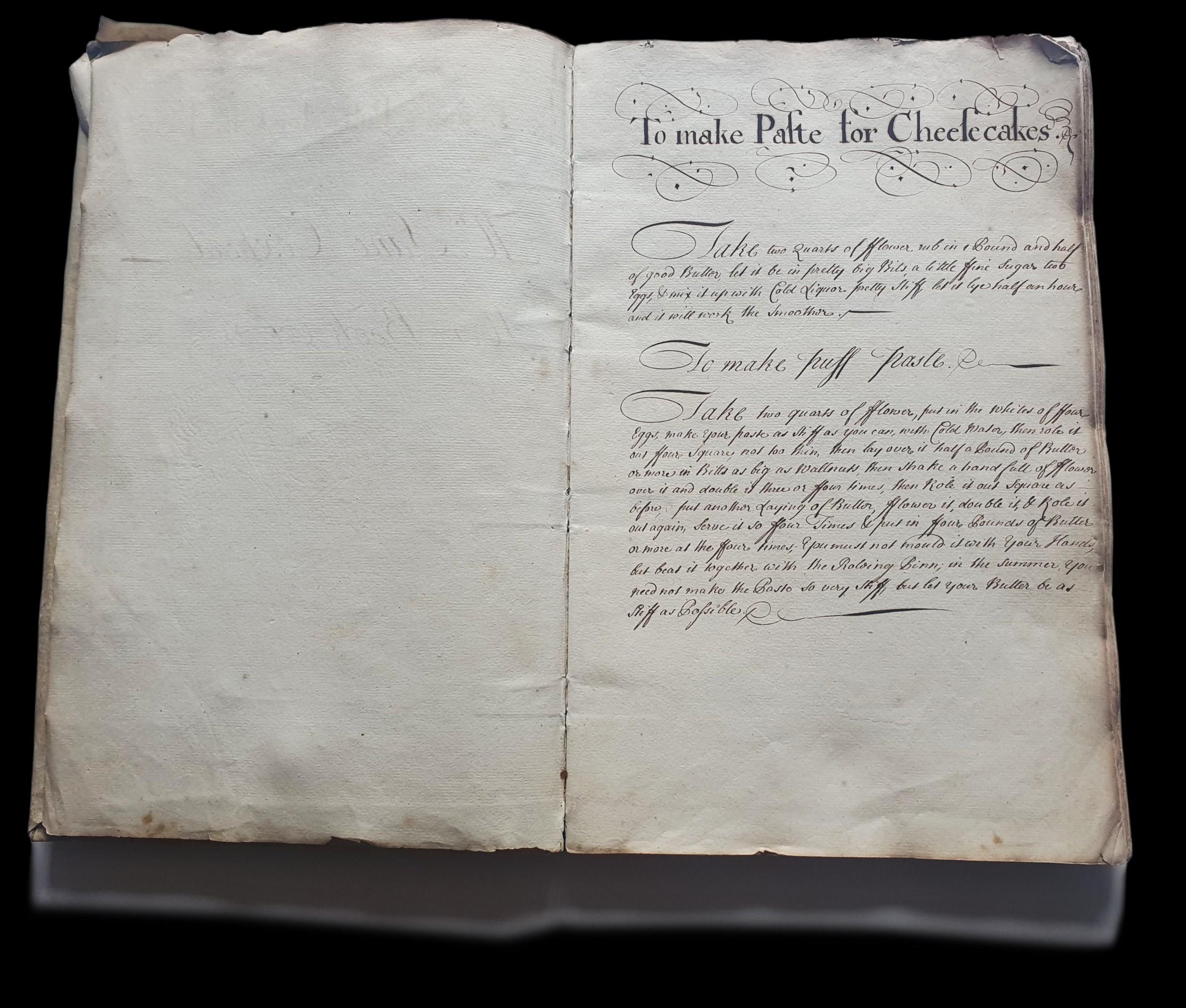

COXHEAD, Jane Early 18th-century Culinary Manuscript.

[Circa 1721]. Folio (320 x 200 x 15 mm). 70 leaves. Ink on paper. Written in a neat hand to rectos only and numbered to 69 at upper right corner throughout. A few recipes with calligraphic headings. Contemporary vellum, some soiling, title page dusty, thereafter clean.

Provenance: inscription to first leaf reads “Mrs. Jane Coxhead / Her Book, Octr. 21st: 1721.”

Watermark: Pro Patria; countermark: IV.

¶ Selecting, adapting, copying, and converting are among the myriad ways in which recipe books were created as part of an ongoing process in which recipes merged and changed as they passed through manuscript, printed publications, and of course, kitchens.

Just as printed books might use manuscripts as their sources, household manuscripts took some of their material from printed works or other manuscripts. So it is with this volume, in which its compiler, Jane Coxhead, has taken recipes from printed sources some copied verbatim, others adapted to suit her needs and mixed these with manuscript sources, some of which later made their way into print.

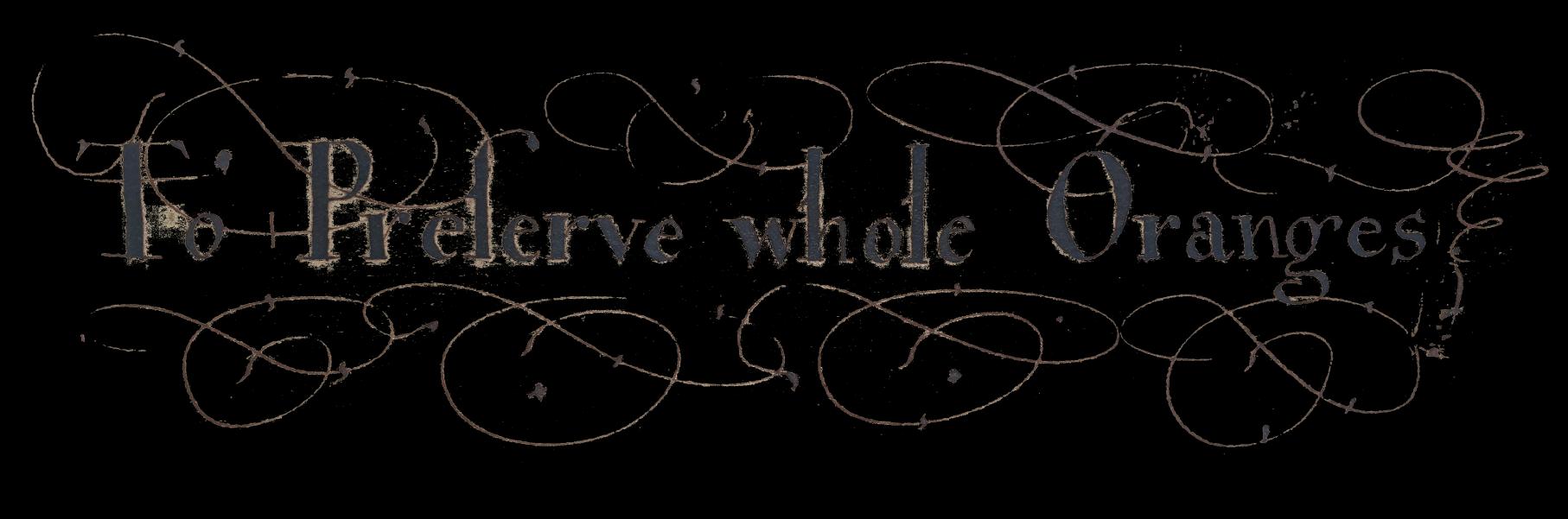

The volume comprises 92 recipes on 70 leaves. It begins with half a dozen kinds of pastry (or “Paste”) – for “Cheescakes”, “High Pies”, “Hare Pye” and so on – then move to a handful of sweet dishes (“Orange Tarts”, “a Rich Cake”), before alternating between clusters of savouries (“a Lumber pye”, and seasoning for the likes of “a pigeon Pye”, “a Goose or Turkey pye”, and “a Chicken Pye”) and sweeter fare (“Allmond Pudding”, “Lemon Cream without Cream”, etc). After a brace of meat and fish recipes and several kinds of pickling, Coxhead devotes the second half of her volume to fruit.

Many of these fruit recipes can be traced to the anonymous The True way of preserving and candying, first published in 1681 and reprinted in 1695 (Wing T3126A and T3126B). This provides a good example of the kind of journey a recipe undergoes: among those taken from The True way is “To dry Pears with Sugar, to keep all the Year” (p58). A similar recipe was later published in Eliza Smith’s Compleat Housewife (first published in 1727), but with small variations in quantities and method, suggesting that Smith either adapted her recipe from another printed book (perhaps the above) or found a recipe filtered through manuscript usage.

Variations on this practice occur throughout Coxhead’s manuscript – for instance, the first of the main group of fruit recipes, which bears its own calligraphic title: “To Preserve whole Oranges” (p.32). Again, this has been copied from The true way (and is the first recipe in that book), but the recipe on the following page of the manuscript, also entitled “To Preserve whole Oranges” (p.34), is untraced, and Coxhead has juxtaposed it without comment, so it may represent her own improvements on the preceding recipe, or it could be something taken from a now-lost publication or perhaps another manuscript. Whichever is the case, it contributes to the endless process of variation through reading and practical use.

One particular recipe has the extra ingredient of notoriety mixed in: “The Dutchess of Cleavlands Pan=Cakes” (p.14) refers to Barbara Palmer (née Villiers) (1640-1709), Countess of Castlemaine and 1st Duchess of Cleveland, “the first acknowledged royal mistress in Britain for some centuries” (ODNB), who bore several children sired by King Charles II, merited multiple mentions in the diaries of Samuel Pepys, and wielded considerable influence at court. Her eponymous recipe appears not to have been published in print, although as we see from this volume, it was clearly circulating in manuscript. There is a degree of chronological teasing-out to be done on this mélange of dishes, with some entries apparently predating their printed debuts: for example, several recipes (“To make Paste for Cheescakes”, “To make Puff Paste” (p.1); “To make Paste for tarts or Mince Pies” p.2; “To preserve Pippins in Jelly” (p.69)) were included in The young lady’s companion in cookery, an anonymous collection ublished in just one edition in 1734, over a decade later than the given date of this manuscript. Coxhead’s arrangement of certain recipes compounds this sense of a porous divide between print and

manuscript, as when she pairs “To preserve and Dry Wallnuts” (p.67) (which she has copied verbatim from The true way), with “To preserve Wallnuts when they are Green” which, while it has similarities to its predecessor, also appeared later in the abovementioned The young lady’s companion in cookery.

“It is Use that makes Perfectness; and no person can do that with a pen”, declares the anonymous author in their preface to The True way of preserving and candying; there are indications, though small, that Coxhead has employed her volume in the kitchen. Though lacking “clinchers” such as “probatum est”, her text includes cross-references to other pages: in “To preserve green Apricocks” (p.39), she adds “If you please you may make it a New Jelly with Double refined Sugar & Pippin Water as Directed before in the Receipt for doing whole Oranges”; and for the directions “To Dry Apricocks Green” (p.40), she instructs: “you must Preserve them ffirst as before Directed” (on the previous page). Similarly, her recipe for “Quiddeny of Rasberries” (p.46) specifies that one “Make a Decoction of Rasberries as you do of Currants (See Page 43)”.

We found two possible matches in the records for a Jane Coxhead: the first is Jane Lloyd (birth details unknown), who married Richard Coxhead on 2 December 1697 at Saint James Dukes Place in London; the second is Jane Sanders (again no details), who married William Coxhead on 3 May 1715 at St Lawrence, Hungerford in Berkshire. We have found no corroborating evidence for either attribution, but we suggest that the latter is more likely since the date is closer to that of the manuscript.

As to evidence for the background to its composition, it is worth noting that the “Advertisement” to The young lady’s companion in cookery declares: “The following Receipts were Collected by a Gentlewoman who formerly kept a Boarding School; her often being Importun’d by her Friends for Copies of them, has occasioned their being published” – a statement raising the distinct possibility that Jane Coxhead was one such friend who diligently copied some of the recipes into her book several years before they appeared in print, and contributing to a manuscript compilation that, with further research, promises to yield insights into how manuscript and print culture met and mingled in the kitchen.

£6,000 Ref: 8169

[HEALTH & REMEDIES] 18th-century manuscript book of remedies and notes on health.

[Circa 1770-80]. 16mo (127 x 100 x 5mm). 82 text pages on 48 leaves. Stitched marbled wrappers.

¶ This small, home-made, square booklet mixes material from different continents and languages united by their subject matter: health, its preservation, and the treatment of illness.

Instead of the more usual neat vellum stationer’s book found in early British manuscripts, six quires have been crudely but effectively hand-stitched into marbled covers; a style more often found in America. The resulting notebook has been almost filled (save for a few blank leaves) with text written in Italian and English by at least three scribes. One of these contributes a section in Italian; another is evidently bilingual, and switches between the two languages with ease but, curiously, without any obvious reason.

The notebook begins with “Precetti per Conservare La Sanita, del Sigr Mackensie Medico d’Edinburgo” (“Precepts for Preserving Health, by Mr Mackenzie Physician of Edinburgh”). This is untraced but appears to be a commentary on James Mackenzie’s The history of health, published in Edinburgh in 1760; it begins “L’Aria sana dev’esser pura, secca & temperata” (“Healthy air must be pure, dry & temperate”), and some 26 pages later, concludes: “Mackenzie non crede, che queste rimedi posso estendere la vita olere l’ordinario termine che non s’e cangiato dal tempo di davidde sino a noi” (“Mackenzie does not believe that these remedies can extend life beyond the ordinary term that has not changed from the time of David to us”).

At this point, a second scribe chips in with two remedies written in English over three pages: “Lord Blakeneys Cure for the Yellow Jaundice” and “A Tinea, or Scald Head &c &c”, attributed to “J. Cook. M.D.” (“Tinea” being a fungal infection better known as ringworm). The latter recommends boiling “4 Ounces of pure Quicksilver in 2 Quarts of Water in a glazed pipkin” and suggests that the patient drink it “freely as a diet drink, as much and as often as you please”.

The hand changes again, as a third scribe signals a new section with the full-page title “Dr Sutherland on Health”, set in a nest of ornamentation. The subsequent 21 pages are copied from Alexander Sutherland’s (1710-1773) The nature and qualities of Bristol -water: illustrated by experiments and observations, with practical reflections on Bath-waters, occasionally interspersed (1st edition 1758, 2nd edition 1764), although the material, presented under three headings (“Of Aliment”, “Of Exercise”, “Of Sleep”, also given some modest embellishment), only occasionally refers to mineral or spa water. Sutherland, who practised in Bath, is best known for being allegedly the first physician to use placebos in a medical context.

The same scribe, after signalling the end of the Sutherland transcriptions with some hasty curlicues, goes on to set down a number of remedies, beginning with “To make the Balsom called Turlington’s Balsom of Life” – famously one of the first patented medicines (in 1744). Other remedies follow, including “Three easy Rules to preserve health in hot climates”, ascribed to “Dr Hallis”; “A Receipt for a Cold”; “An infallible Receipt to destroy Buggs”; and “For the Nightmare, Low Spirits,

Melancholy, & disturbed Sleep”, ascribed to “Dr Whytt’s Obsns on Nerv: disordrs” (and consisting of the instruction to drink “a dram of Brandy”). Dropped in among these, but not sequentially, are two further items in Italian, which also differ from the majority in their non-medical topic: “Ricetta per fare inchiosto nero” (“Recipe for making black ink”) and “Segreto per Levare dalli Abiti agni Sorte di Macchie senza alternarne I Colori” (“Secret for removing all sorts of stains from clothes without affecting the colours”).

Having so far represented Britain and Italy, the selections include two from the American colonies: “The famous American Receipt for the Rhumatism”; and “For the Yaws, Venerial Complaint, Dropsy &c. discver’d by a Negro in Virginia & rewarded with a pension of £30 per annum for life”. A similar recipe was included in Sarah Harrison’s House-keeper's pocketbook (1764), but the wording is slightly different, especially the accreditation, which concludes “This is esteem’d in Virginia a Valuable Discovery”

£1,250 Ref: 8204

[CLARKE, John]. Mid-17th-century English manuscript schoolbook and notes on gardening.

[Circa 1670]. 16mo (123 x 91 x 20 mm). 144 leaves (including endpapers), some leaves excised. Pencil guidelines. Ink on paper. Contemporary sheep, rubbed, edges worn and spine chipped at head, upper joint cracked. Provenance: 17th-century ownership inscription of “John Clarke”, which is a close match for the manuscript text. later inscription of “Arthur Hutchins” dated 4 December 1811. Watermark: Horn.

¶ Before one even opens this volume, the inscription to the top edge of the text block (in a 17th- or 18th-century hand) announces that its title is “Garden of Eden”; a later hand has repeated the title on the other two block edges. But that is not the whole story: inside the book begins and ends like a 17th-century grammar schoolbook, with notes on Ovid and parallel-text Latin and English phrases. Sandwiched between these sections are passages copied from the 1653 edition of Sir Hugh Plat’s Garden of Eden, a horticultural work whose relevance to the concerns of a school pupil is far less obvious than that of the Latin texts and exercises that surround it.

The titling to the page edges suggests that the contemporary hand (probably that of the book’s first owner) and the later hand both consider the Plat transcriptions to be the chief draw of this artefact. So why do these prized extracts sprout incongruously from the middle of this grammar book? We can offer a few speculations for this unusual juxtaposition of text, but none of

Judging from the style of the hand, the paper and at least one of the sources used (i.e. Helwig – see below), the manuscript appears to have been written during the Restoration. The young “John Clarke” has a clear, legible hand (in line with Hoole’s direction that young scholars should be able to “write a fair hand before ever he dream of his grammar” 1). Clearly a precocious pupil, he begins with brief notes (apparently his own) on characters from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (“pentheus fuid filius echionis & agaves qui arrifit verba praesage & tenebras Tiresice, etiam contempsit bacchum”, “bacchus fiut filius jovis ex semele et deus vini”). He then tackles one of the staples of English grammar school education: Christoph Helwig’s (1581-1617) Familiaria colloquia, operâ Christophori Helvici D. & Proffesoris Giessensis olim; ex Erasmo

Roterodamo, Ludovico Vive, & Schottenio Hasso selecta. Helwig was “professor at Giessen from 1605, and reputed a good grammarian and skilful teacher”; his Familiaria colloquia, containing selections in Latin from Erasmus, Ludovicus Vives and Shottenius, was first published in England in 1652, with further editions into the 1720s. Watson confirms the popularity in the mid-to-late 17th century of Helwig’s work, which enabled “frequent perusal of vocabularies for common words and colloquies for familiar phrases” 2

Clarke’s Latin text conforms to that found in Familiaria colloquia, but the English translations are untraced: they may have been provided by the teacher to learn by rote or produced by Clarke himself. They may, alternatively, have been the outcome of classwork. Watson suggests that this period saw a collaborative form of learning in which the teacher “may appoint one or two of the best boys in each form to have in hand the grammatical translation” 3 – a method that would have been especially useful in light of evidence that many of the teachers were not themselves first-rate Latinists, this in turn being a legacy of “a catastrophic collapse of elementary education in the period of the civil war and its aftermath”. The situation was compounded during the Commonwealth when “proponents of mass literacy were never more vocal than in the revolutionary era, and never less effectual” 4, resulting in the training of new teachers being neglected. Much of this assumes that Clarke was a school pupil rather than taught at home, but the book offers no concrete evidence for either – and, as we shall see, positing a home-learning environment would offer a possible explanation for the intrusion of horticulture into Latin grammar.

Clarke’s diversion may interrupt the classical flow, but it seems at least partly planned: the preceding section concludes with a firm “FINIS”. His transcriptions from Sir Hugh Plat’s Garden of Eden are the only material in this manuscript to be given a date (“1653”); this was actually the second edition of Plat’s Floraes Paradise (1608), reissued in 1653 “with some omissions and rearrangements, by Charles Bellingham” 5. Clarke has followed Bellingham’s lead and made further and greater omissions and rearrangements. The passages are copied verbatim or very close to the text, but Clarke has selected only certain sections, omitted others, and sometimes changed the sequence from that of the printed text.

The extracts begin at with “Tempering ye Ground. Break up your Ground & dung it at Michmas, In Janry turn yr Ground 3 or 4 times, to mingle yor Dung & Earth ye better […] Proved by Mr T” before getting into specifics such as how “To keep Artichocks from Frost”, “Carrots Parsneps & Turneps kept long” and “To have Early fruit”. Later, he sets down methods “To kill Worms”, and “Of grafting one plant upon another or upon a Tree”, both on the same page. He records practical tips on how to “Sow seeds yt are not above one year old” and the advice that “If herbs be nipt wth fingers or clipt they will head well. They will grow to have good heads”, ending with notes on “Apples without Wrinkles” and “Sap choaked, to make barren trees bear” before returning to his translation work on the very next page.

What drove Clarke – who to judge by his Latin studies was aged around 15 – to select and plant this assortment of extracts from a gardening book into the middle of his grammar exercises? He has evidently arranged certain pieces in an order that suits his needs – but what those needs are remains unclear. It’s possible that, although the Latin texts and translations are commensurate with a grammar school education, Clarke may have been tutored at home, leaving him freer to indulge his broader interests away from the potentially constraining forces of peer pressure or a master’s disapproval of his distinctly personal use of a schoolbook.

Clarke completes his manuscript volume with translations “Out of the 3d book of Ovid” and further advanced studies along the lines laid by Watson (“More forward and keener boys should be encouraged to provide themselves with Gerard’s Meditations, Thomas a Kempis”; although he has diverged from those particular models, apparently having instead acquired a book containing “Roman Phrases”, which he has translated into English. We have been unable to identify the book in question; perhaps, again following Watson, “[t]he explanation is to be found in the fact that foreign scholarship and foreign books found their way into English schools” 6 .

That an early-modern adolescent had a keen interest in gardening and in curating these passages from Plat is not impossible, merely unusual; and it’s this aspect of the book’s content that is highlighted on each side of the page edges (“Garden of Eden”), initially apparently by Clarke and then almost certainly by its later owner, “Arthur Hutchins”. Perhaps Clarke’s interpolation of this material, thus creating such an idiosyncratic arrangement, ultimately reminds us that the early modern period was often messy, and the principles which categorise and create genres were still being written.

£6,500 Ref: 8195

1. Hoole, Charles. A New Discovery of the old Art of Teaching (1660). Quoted in Watson, Foster. The English Grammar Schools to 1660. (1908).

2. Watson, Foster. The English Grammar Schools to 1660. (1908).

3. ibid.

4. Cressy, David. Literacy & the Social Order. (1980).

5. ODNB.

6. Watson, Foster. The English Grammar Schools to 1660. (1908).

JEAMSON, Thomas (d.1674). Artificiall embellishments. Or Arts best directions how to preserve beauty or procure it.

Oxford: printed by William Hall, ann. D. 1665. ONLY EDITION.

Octavo. Pagination [16], 192 p. Collated and complete. [Wing J503; Madan III, 2705]. Contemporary calf, rebacked, head of spine chipped, front hinge cracking, endpapers renewed, marginal worming (not affecting text), corner of L8 torn away, just touching edge of catchword, but without loss, paper flaw in L3 with loss of one letter.

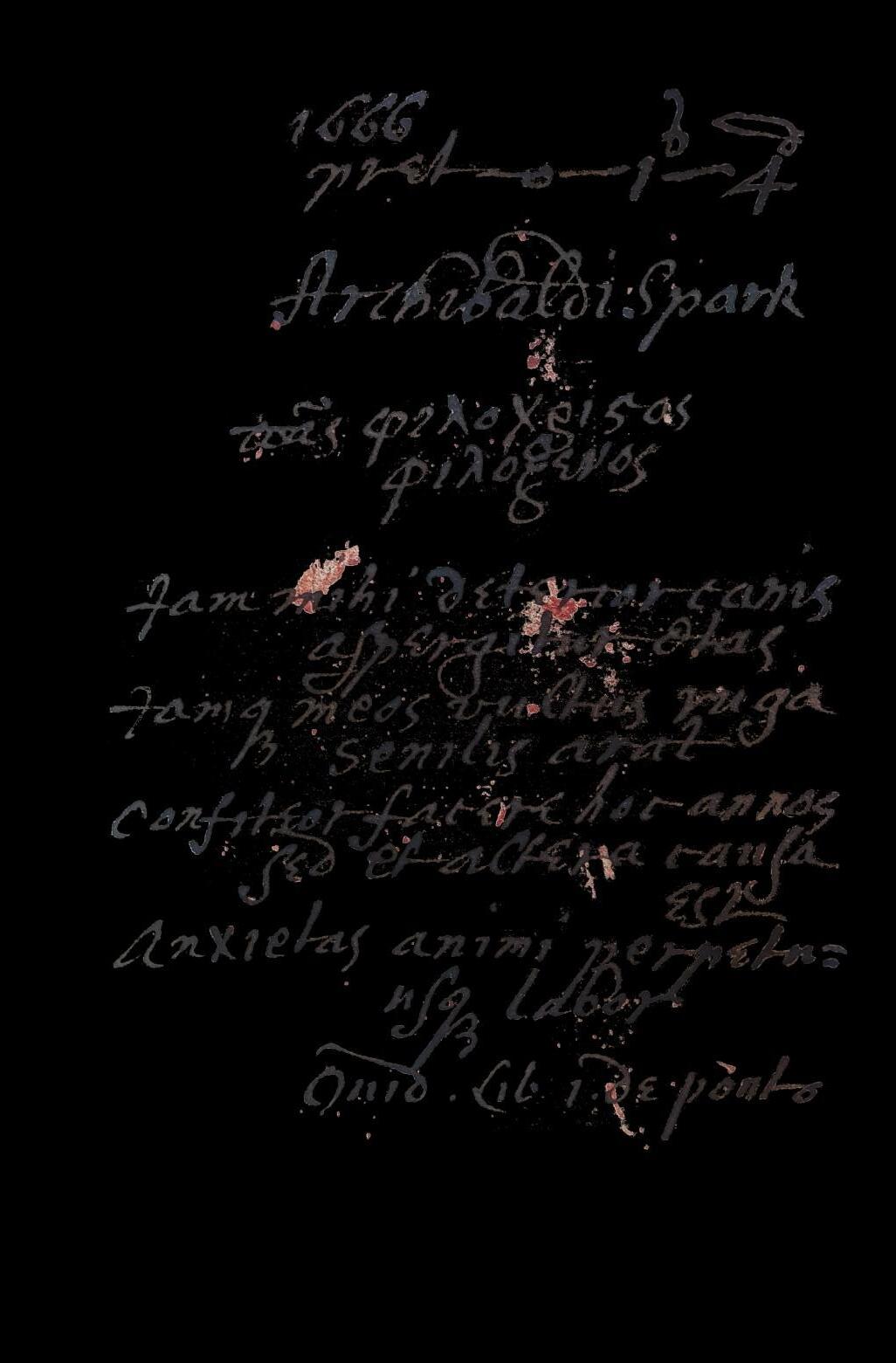

Provenance: inscriptions “Archibaldi Spark” (dated “1666”), “John Lloyd” dated “1706” and “Catherine Lloyd”. (See notes below).

¶ Emulsions, emollients, creams, and other concoctions were often included among the various recipes in English printed and manuscript compilations. But around the middle of the 17th century, some writers began to collate and arrange preparations exclusively concerned with personal appearance, and in doing so, created a new genre: the beauty manual 1 .

Outward appearance was thought to reflect one’s inner morality and balance of humours, so any attempt to hide the “true” inner identity by face-painting – which had been in vogue during the previous century – was considered immoral and might be condemned from the pulpit or whispered about behind the backs of those who practiced such acts of deceit. In contrast to face-painting, cosmetics were considered by some more acceptable because, rather than completely covering the face, they merely enhanced a person’s natural attributes.

When Thomas Jeamson published Artificiall embellishments in 1665, there were very few antecedents for a book devoted solely to cosmetics, and all of them were nearcontemporary. Sir Hugh Plat’s Delights for ladies, to adorne their persons, tables, closets, and distillatories with beauties, banquets, perfumes, and waters first appeared in 1600, and included cosmetics alongside culinary and household recipes. John Gauden’s A discourse of auxiliary beauty. Or artificiall hansomenesse. In point of conscience between two ladies (1656) and Johann Jacob Wecker’s Arts master-piece: or, The beautifying part of physick (1660) only just predated Jeamson’s book; but taken together, these works signalled a shift in attitudes: layers of paint and paste were out; more subtle enhancements were in.

Jeamson’s book, according to more than one account, did nothing to enhance his reputation. As a physician, he was, according to William Munk, “much ridiculed”, presumably for writing something considered superficial and infra dig (Artificiall embellishments was published anonymously, but Munk blames “the indiscretion of his publisher” for the leaking of the author’s identity). How much damage this really inflicted is unclear: Jeamson published the book in the year after his graduation from Wadham College, Oxford (Bachelor of Medicine, 1664), and went on to become a Doctor of Medicine in 1668, before being admitted to the College of Physicians in 1671 – hardly a downward spiral (although he died only three years later, in 1674).

This copy of Jeamson’s book was bought shortly after its publication. An inscription to the front endpaper reads “Archibaldi Spark”, beneath the date “1666”, and the purchase price of the book (pret-0-1s-4d”), followed by an inscription in the same hand in ancient Greek and lines of verse taken from Ovid (to which we shall return). There are two further inscriptions: one to the front free endpaper by “John Lloyd” dated “1706” and the other, that of “Catherine Lloyd” (with two further inscriptions of her forename) to the rear endpaper. Historical records offer up an Archibald Spark who was born in Scotland and attended Jesus College, Cambridge, where he earned an MA in 1634 and a BD in 1637. Among his posts as a clergyman were several in Merionethshire, Montgomeryshire and Flintshire, in the latter of which he was buried in 1669/70 2 .

But why did a clergyman in rural Wales acquire a book on cosmetics almost immediately after its publication? The evolution, noted above, from artificial face-painting, with its moral connotations of “whited sepulchres”, to supposedly more complementary and healthier “Cosmeticks”, arguably made the practice more acceptable to many in the church: external beauty, subtly enhanced, could express inner virtue. More pointedly, Spark’s inscription of lines from Ovid’s Ex Ponto are quite endearingly suggestive of something deeply felt in him:

“Iam mihi deterior canis aspergitur aetas

Iamque meos vultus ruga senilis arat

Confiteor facere hoc annos sed et altera causa est

Anxietas animi continuusque labor”

(“Now is the worse period of life upon me with its sprinkling of white hairs / now the wrinkles of age are furrowing my face […] I admit that this is the work of the years, but there is yet another cause anguish and constant suffering.” 3)

Whether he pontificated from the pulpit or perhaps took subtle tips from Jeamson’s book on hiding the “sprinkling of white hairs” and the furrowed “wrinkles of age”, we cannot say for certain. He died three or four years after buying this book, but it appears to have stayed in Flintshire where it came into the possession of John and Catherine Lloyd. There were two couples in the area by those names: a John Lloyd who married Catherine Pierce on 30 November 1715 at Nannerch, Flintshire4; and a John Lloyd who married Catherine Roberts on 3 September 1719 at Northope, Flintshire5. Although we have not found any connection between the Spark and Lloyd families, this volume does seem to have remained in Flintshire for some time.

In the introductory “Epistle”, Jeamson takes up the inner/outer theme that so concerned 17th-century moralists. But although he fleetingly mentions the soul and evokes “a Hell of misery”, he largely elides the question of morality, and opts instead for a simple appeal to vanity (especially under the male gaze). He promises “to save you Ladies from the loathsome embraces of this hideous Hagge” with “these Cosmeticks”, and to improve their chances of marriageability (while also indulging in class snobbery): “none save Grooms or Oastlers think those worth their courtship, who are rusted over with ill-inticing looks”. He sets out his scheme at the end of the “Proeme”: “it is regularly methodiz’d into a quaternion of parts. The first whereof treats of Embellishing the Body in generall; the Next of the Head, neck and breast; the Third of the Hands, Armes, Leggs and Feet; and the Last supplies you with Sents, Perfumes and Pouders”.

Jeamson begins this tour of the female body with a few words on pregnancy – that is, “How Women with Child are to order themselves that they may be delivered of fair and handsom Children”, so that the new arrival will be “not a misshapen or monstrous lump, but a sparkling luminary”. Some fairly sensible advice, such as taking “moderate and frequent exercise”, coexists with passages that hammer home the importance of “regulating the phantasie, or imagination of the Mother”; for this “phantasie”, or “Phancie”, has a life of its own: “finding the soft and plyant Fœtus pinion’d in a membranious mantle […] it freely without resistance makes impression as the Mother directs it. So that she by the help of this invisible Agent usually works & adorns the Infant with those features which her mind most runs upon”.

He dwells on this idea, laying it on thick by recounting a series of improbable tales: of a woman “big with Child” who witnessed a duel “twixt two Soldiers, one whereof lost his hand”, was “frighted with the sight” into labour and “was delivered of a Daughter with one hand”, the other having been “cut off at the same place with the maimed Soldier”; and of several cases of pregnant women who, “by often looking on a Black-a-moores picture, have been delivered of a Child clouded with Natures sooty mask”. One wonders whether Jeamson himself took the stories at face value or was simply employing them to embellish his argument for the more credulous of his readers.

After these preambles, he begins to supply the many recipes, which include methods to “alter the ill colour of the eyes and how to make them bigger or less”, “To make the Lip ruddie”, “To make Haire what colour you please”, “To whiten a tan’d visage and to keep the face from Sunburn”, “To Sweeten the Breath”, and “to keep the Breasts from growing too big, and to make them plumpe and round”, along with formulations to make “Pouders for the Hair”, “Sents and Perfumes”, and other nostrums.