LEARNINGS FROM S H I F T L A B 2 .0

Proudly supported by:

What is Shift Lab? ................................................................................................. 3 Thank-you............................................................................................................... 4 Shift Lab Bios......................................................................................................... 6 Our Context............................................................................................................10 Theory of Change and Methods...........................................................................12 Shift Lab 1.0 to Shift Lab 2.0.................................................................................16 Discovery Phase.................................................................................................... 20 Challenge Scope................................................................................................... 26 The Sleepy Middle................................................................................................. 28 Our Triple Helix......................................................................................................30 Indigenous Epistemologies............................................................................31 Design Thinking.............................................................................................. 32 Systems Thinking........................................................................................... 34 Going Deeper......................................................................................................... 36 The Shift Lab 2.0 Journey..................................................................................... 42 What Emerged from Shift Lab 2.0?................................................................... 44 Exploring Wahkohtowin ................................................................................46 Reflection Pool App........................................................................................50 You Need This Box.......................................................................................... 54 The De-Escalators........................................................................................... 58 Reflections on Centering Indigenous Knowledge............................................. 62 Tensions and Shared Key Stewardship Learning .............................................. 70 Shift Lab 2.0: Evaluation......................................................................................88 Now What, So What, What’s Next?................................................................... 106 Appendices:.......................................................................................................... 108 1. Core Shift Lab 2.0 Activities, Outputs, Outcomes..................................... 109 2. General Tools................................................................................................... 113 3. Behaviour Change Cards............................................................................... 114 4. Call to Join Shift Lab 2.0................................................................................ 119 5. Lab Challenge Briefs......................................................................................122 6. Shift Lab Innovation Manager Contract Description................................. 130

1

Our work is rooted in social innovation theory, where labs are the practice and process of uncovering promising solutions. But our work is also rooted in Indigenous worldviews. Social innovation is a lens we can look through to clearly see the systems that have harmed Indigenous peoples and continue to harm us. If we’re going to imagine solutions, co-creating ways to move forward to heal, to build successful economies and education systems, social innovation is a tool to leverage. It won’t do everything, it can’t do everything, but it certainly supports us in the big work we have ahead of us. Everything is rooted in relationships.

“ piko kîkway ehohcimahkak wâhkohtowinihk ohci”

Nothing is more important than our relationship with each other, with the land, with the animals and with the spirit beings; we must remember how to live in relation to one another.

“ namakîkway ayiwâk iteyihtakwan iyikohk kâhisiwâhkôhtoyahk, kâhisiwâhkôhtamahk askiy, asci pisiskiwak, ekwa nistameyimâkanak, piko kakiskiskiyahk ta’nsi kesi miyowâhkôhtoyahk”

Honour that peace and friendship Treaty and live as relatives.

2

“ kisteyihtetān ewako wehtaskewin ekwa miyo-otôtemitowin asotâmâkêwin ekwa wâhkôhtotân” - Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse

WHAT IS SHIFT LAB? The Edmonton Shift Lab is an action-oriented exploration of anti-racism in our city. The Lab is a partnership between the Edmonton Community Foundation and the Skills Society Action Lab. We build on great work focussed on anti-racism in Edmonton and elsewhere. We choose to approach this through a Social Innovation lab. A Social Innovation lab allows for community-based prototyping and testing of pathways that strive to enact behavioural change. As of April 2020, we have completed two cycles of the Shift Lab — what we affectionately call Shift Lab 1.0 and 2.0. To learn more about Shift Lab 1.0 please visit edmontonshiftlab.ca for the first-year report.

The Edmonton Shift Lab is based in amiskwaciwâskahikan on Treaty 6 territory, the traditional meeting grounds for the Cree, Saulteaux, Blackfoot, Dene, Nakota Sioux, Métis, and Inuit.

3

THANK-YOU The Edmonton Shift Lab is honoured to express our deep gratitude to all the folks that helped along the way. This includes those who have contributed over the years to social innovation and anti-racism work anonymously, unnamed and unheard. We see you, and are grateful for your help in getting us to where we are at today.

4

Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Researchers, Academics and Advisors • Grand Chief of Confederacy of Treaty Six Billy Morin • Charlie and Martha Letendre from Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation • Newday Letendre from Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation • Uncle Willard and Aunty Marilyn from Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation, for their hospitality and invitation to the lodge • Gilman Cardinal from Bigstone Cree Nation, for launching us in a good way when Shift Lab started • Jacquelyn Cardinal from Sucker Creek First Nation • Hunter Cardinal from Sucker Creek First Nation • Lewis Cardinal from Sucker Creek First Nation • Josh Littlechild from Ermineskin Cree Nation, Maskwacis • Colette Arcand from Alexander First Nation • Darcy Lindberg from Maskwacis and the Faculty of Law, at the University of Alberta • Ron Lameman, Bilateral Treaty Coordinator, Treaty 6 Confederacy • Elliot Young from Maskwacis, Indigenous Community Engagement Advisor Norquest College • Dorothy Thunder from Little Pine Cree Nation and the Faculty of Native Studies, at the University of Alberta • Sara Cardinal, Indigenous Career Advisor, Norquest College • Melissa Purcell Executive Staff Officer, Indigenous Education, Alberta Teachers Association • James Knibb-Lamouthe, Director of Innovation & Research, Indigenous Knowledge & Wisdom Centre • Tasha Power from Saddle Lake Cree Nation • Indigenous Knowledge and Wisdom Centre • Yellowhead Tribal Council • Confederacy of Treaty 6 • Yellowhead Indigenous Education Foundation

Partners & Funders: • Edmonton Community Foundation (funder) • Skills Society Action Lab Evaluators: • Mark Cabaj, Developmental Evaluation/ Guidance and Mentorship • Paige Reeves, Interviews, surveys and synthesis of evaluation Research: • Gladys Rowe, Behaviour Change • Naheyawin, Indigenous Research Methods and Praxis • Centre for Race and Culture, Anti-Racism Initiatives: A Rapid Review • Rhonda Gladue, Treaty and Aboriginal Resource Rights • Megan Auger, Researcher/Interviewer • Shayna Arcand, Researcher/Resource Developer • Cara Peacock, Researcher/Resource Developer • Roberta Taylor, Board Game Designer • More than 30 community members who provided live feedback on Shift Lab 2.0 questions

International Speakers: • Shelly Tochluk • Daryl Davis • Trevor Phillips • Antionette D Carroll Designers • Jaime Calayo • Melissa Bui • Alex Keays • Iwona Faferek Writing, Editing and Publishing Support • Tim Querengesser Consulting

Interviews with Social Innovation Practitioners and Friends: • Dianne Roussin, Winnipeg Boldness Project • Angela Pugh, Roller Strategies • Frances Westley, Waterloo Institute for Social Innovation and Resiliency • Gina Rembe, inSpiral • Joshua Cubista, Author • Lauren Morgan, Recent Business and Design grad • Nathan Heintz, Grove 3457 • David Prodan, e4c • Tad Hardgrave • Mark Holmgren, Edmonton Community Development Company • Lori Campbell, Norquest College • Zaid Hassan, Roller Strategies • Sam Rye, Social Labs Community • Alex Ryan, MaRs Solutions Lab

5

Shift Lab Stewards

SHIFT LAB BIOS Terms: Lab Stewards This term describes a group of five people (Jodi, Ashley, Ben, Sam, Aleeya) who were responsible for the development of lab design and the processes used, the coordinating activities, adapting and responding to feedback, and organizing the logistics of the lab. Terms: ‘Core Teams’ This term describes the Core Lab teams at the heart of the Shift Lab. These teams were the driving force behind developing the prototypes that emerged. Striving to be a diverse representation of the system being explored, the Core Lab teams did sense-making of the key challenge. They also did scrappy and rapid research, made sense of insights, came up with possibilities, as well as prototyped and tested solutions. In Shift Lab 2.0 there were four teams of around six to nine people each. The Core Team came from a variety of academic, nonprofit, and public sector backgrounds. Core Team members living directly in or near poverty also participated and contributed greatly to this work. While greater participation from all of these communities was possible, we were confident that the Core Team represented a true crosssection of Edmontonians affected by racism.

6

Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse is the Executive Director of the Yellowhead Indigenous Education Foundation. She spent many years at the University of Alberta, serving in faculty development, advancement, recruitment, community relations, and as reconciliation advisor. During her time at the U of A she helped found the Wahkohtowin Law & Governance Lodge with the Faculty of Law. In 2021, Jodi was appointed to serve on Edmonton’s Police Commission. Jodi also worked with former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild in bringing the 2nd World Indigenous Nations Games to Edmonton in 2017. Jodi’s graduate research focused on Indigenous women’s experience of waterways downstream from the Alberta oil sands. Aside from academics, Jodi’s passion is media and community building. She has won multiple awards for her film productions and radio show production. Ashley Dryburgh is an anti-racist feminist who has committed her personal and professional development to learning and talking about racism, with a particular focus on engaging her fellow white folks. In previous work, Ashley pursued graduate research with a focus on whiteness in Canadian queer communities and was the Executive Director of the Facilitating Inclusion Cooperative, which provided community-based research training and services for immigrant and Indigenous women. In her role at ECF, she explored the development of targeted granting opportunities that will support the broader Edmonton community. Ben Weinlick is the Executive Director of Skills Society, a nonprofit that is one of the largest disability rights and service organizations in Edmonton. Ben helped create and launch the Skills Society Action Lab which stewards social innovation alongside community to tackle complex challenges and make systems change where it matters most. Aleeya Velji brings systems change to the policy space by designing labs and infusing new thinking into public sector organizations. She developed her understanding of complex systems by working as an educator, taking on a fellowship with ABSI connect, and by supporting systems change through various intrapreneurship roles within the municipal, provincial and federal levels of government. She is stellar to collaborate with as she brings a spirit of play and kindness to all the work she does. Sameer Singh melds journalism and design thinking with public engagement in Edmonton. He holds an MBA from the Rotman School of Business and an MJ from Carleton University. He is passionate about community development, stitching great ideas together, and getting projects off the ground.

Core Team Members Nicole Jones-Abad (she/her) is a community organizer doing work with Shades of Colour, a grassroots LGBTQ advocacy group in Edmonton. During the pre-lab research phase of Shift Lab 2.0, Nicole coordinated Shift Lab 2.0 and filmed the speaker’s series. Tamreen Arif, MPA, is a public-policy expert who worked on a range of issues from mining in South America to economic development in rural Alberta. Above all, she is passionate about creating meaningfully inclusive spaces and centring the voices of marginalised communities.

Iwona Faferek is an interdisciplinary designer who is passionate about engaging local communities in collaborative problem solving. She loves the challenge of turning complex ideas into a compelling story and strategy, adapting her approach to engage diverse audiences and stakeholder groups. Toni Fastlightning is the Director of Education of the Alexis Board of Education. She is currently on maternity leave raising her son, Sitoza Wapta, on Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation. Toni has a Bachelor of Native Studies and a Graduate Degree in Phys Ed and Recreation from the University of Alberta.

Jaime Calayo is a graduate of the Strategic Foresight and Innovation Master’s program at the Ontario College of Art and Design. His exploratory approach to strategic communications and public engagement pushes him to communicate socially complex issues in innovative and emotionally impactful ways.

Ilene Fleming is Director of Strategic Initiatives at United Way of the Alberta Capital Region. Her work focuses on breaking the cycle of poverty through early child development and making sure children and youth have the community support they need to succeed in school.

Rebecca Craver is a pastor who works with the Edmonton Moravian Church. She is active in interfaith work, has been an advocate for hotel and airport workers, and has a strong desire to engage in deep and transformative work in herself and in relationships with others.

Dr. Carla Hilario is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Alberta. Her area of research addresses youth mental health, including access to and experiences of care, protective factors for mental health, and youth-engaged research methods.

Darryl de Dios is a first-generation immigrant settler from the Philippines and works as a Youth Engagement Coordinator at Volunteer Alberta, where he co-designs the Youth @ the Table program, which matches youth to nonprofit boards across the province.

Alex Keays is a freelance graphic designer and design educator based in Edmonton. Her work focuses on research and participatory processes.

Kevin Drinkwater believes in bringing curiosity, creativity, and courage to the teams and projects he is privileged to be a part of. He is an entrepreneur and partner in J5, a design and innovation consultancy, and co-founder of The Social Impact Lab, a partnership between J5 and United Way. Eileen Edwards is driven by a love of learning and a vision of community where everyone has a place and value. These have led her to a PhD in Clinical and School Psychology, an MDiv, and a career that has encompassed psychology, teaching, ordination in the Moravian Church, starting a community cafe, and her current work serving in the Anglican Church.

Johnny Lee has been a social and environmental justice advocate for seven years and an off-the-wall social media presence. His work has evolved from reconciliation to decolonization to try and shift the conversation from symptoms, and management, to societal woes, to root causes and just, sustainable solutions. Avery Letendre is an administrator for the Indigenous Governance and Partnership Program and Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge at the University of Alberta. She is committed to working toward decolonization in Canada and is keen to join projects that build bridges, interconnections, stronger relationships, and knowledge toward those ends.

7

Derek Jagodzinsky is a designer/artist with Indigenous heritage whose works have been featured in the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and Canada’s Juno Awards. He obtained his Master’s degree in Industrial Design from the University of Alberta, researching how perceptions about Aboriginal culture can be positively impacted and redefined through design in a modern way. Naureen Mumtaz is an academic researcher and a design educator, whose work involves teaching and learning through participatory design thinking. Mumtaz’s interdisciplinary PhD at the University of Alberta explored participatory design-based research methods to inform intercultural understanding amongst marginalized youth. Rabia Naseer is currently working in public-sector research. She has contributed to discussions and initiatives in women leadership, anti-racism and human rights through working with various community organizations. Annand Ollivierre is a Strategic Foresight Analyst with the City of Edmonton. His experiences have shaped his capacity to be a bridge-builder and through his work, he uses a holistic perspective that encourages collaboration and empowers organizations to apply new frameworks, methods, and tools for greater impact. Paz Orellana-Fitzgerald is a design and user researcher who understands that a human-centred approach is the key to innovation and meaningful change. Paz’s research has informed and inspired projects in a wide range of industries and sectors — from the experience of buying eyewear to how nurses relate to technology in the workplace.

8

Helen Rusich is curious, passionate about community, and believes asking important questions is crucial to community development. Helen is a Project Manager with REACH Edmonton, working with newcomer communities in collaboration with organizations and systems to prevent family violence in a cultural context. Rosanne Tollenar has supported the capacity needs of organizations and the community throughout her career in the nonprofit/voluntary sector, working primarily with social service, health, education, and cultural organizations. She is with the Community Engagement Branch of the Ministry of Culture, Multiculturalism and Status of Women at the Government of Alberta . Essi Salokangas is a clinical pharmacist with a passion for improving health outcomes in vulnerable populations using evidence-based practice, empathy, and humor. Essi is a passionate advocate who believes in social equity, being trauma informed, and challenging systems to ensure they work for those who need them. Lisa Zhu supports newcomers at an immigration and settlement agency. She holds a degree from the University of Alberta in Education and a diploma in Digital Media and IT from NAIT. She is a strong believer in social equity and taking an active role in social issues.

Jodi CalahooStonehouse

Ashley Dryburgh

Ben Weinlick

Aleeya Velji

Sameer Singh

Nicole JonesAbad

Tamreen Arif

Jaime Calayo

Rebecca Craver

Darryl de Dios

Kevin Drinkwater

Eileen Edwards

Iwona Faferek

Toni Fastlightning

Ilene Fleming

Dr. Carla Hilario

Alex Keays

Johnny Lee

Avery Letendre

Derek Jagodzinsky

Naureen Mumtaz

Rabia Naseer

Annand Ollivierre

Paz OrellanaFitzgerald

Helen Rusich

Rosanne Tollenar

Essi Salokangas

Lisa Zhu

Keeping Power and Privilege In Check In creating teams for both Shift Lab 1.0 and 2.0, we aimed for diversity, lived experience, and expertise. With enthusiastic support from the Edmonton Community Foundation, our funder, we equitably compensated people for their time and expertise. Core Teams created their own charters of how to respect each other and keep power in check. Developmental evaluation helped Stewards ensure they were listening and adapting the process to the real-time feedback provided by individuals, teams, and the community. The power was really in the honest feedback community stakeholders offered. If there was positive feedback to keep moving forward with a prototype, then Core Teams would move towards piloting the intervention at a broader scale. No process can ever fully account for all the ways power and privilege manifest themselves in a collective effort. Still, we are confident that our processes respected and understood the privileges, perspectives, biases and limitations that we each bring to this work.

“ A social innovation can be a product, process, or technology, but it can also be a principle, an idea, a piece of legislation, a social movement, an intervention, or some combination of them.” — Stanford Social Innovation Review

9

OUR CONTEXT The world changed in 2020. First, the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus brought most of the planet to a halt in the spring. Then, in May, the Minneapolis Police Department killed George Floyd, a Black man. This sparked a global wave of protests that brought Black Lives Matter and anti-racism issues to the forefront in a way that had never been seen before. The work of Shift Lab 2.0, including this report, took place during these events and was directly affected by both of them. For example, the Anti-Racism Subscription Box was launched two weeks after Floyd’s death. Subscriptions skyrocketed from the 30 we anticipated to more than 1,000, with another 500 people signed up on the waiting list. But rather than opportunistically scrambling to meet this newfound attention to fight racism, the Shift Lab continued its work— researching, developing, and testing the prototypes it has designed to combat racism and wake up the “Sleepy Middle” in the Treaty 6/Canadian context. As a result, our processes, perspectives, and conclusions may not satisfy everyone in the expanding anti-racism space. However, we hope you will read this report and strive to understand the work to combat racism that a diverse group of community leaders undertook from 2017 to 2020.

10

11

What is Social Innovation? A process that leads to relevant social innovation involves listening, learning, and co-creating promising solutions to complex problems that defy easy answers. We call these “wicked” problems. Wicked problems are full of tensions and defy simplistic answers. They are characterized by a low level of agreement on what the root of the problem is and often entail contradicting perspectives on what might be the best way to address it.

THEORY OF CHANGE AND METHODS

TYPOLOGY OF PROBLEMS HUMANS TEND TO TACKLE

Simple

Complicated

Complex

adapted from Cynefin Framework

Simple problem: baking a cake (follow the recipe and you’ll arrive at the same solution every time) Complicated problem: sending a rocket to the moon (work the problem long enough, break down the component parts, and complicated solutions can be found) Complex problem: raising a well-rounded human (no two babies are the same way, despite being raised the same). Recipes, equations, and formulas won’t cut it with a complex challenge.

12

Tackling wicked and complex problems is emotional, messy work. It defies definition and is filled with uncertainty. Once prototypes have been tested, a solution only becomes a true social innovation when it spreads and scales at a systemic level. This is a point of debate in the social innovation practitioner community. Often, local solutions won’t scale and their strength remains local. Tactically, social innovation solutions strive to tackle problems at their root. Social innovators are open to experimenting with new pathways and possibilities. Good social innovators don’t only go after the new; they look at traditions and what is already working, as well as question status-quo assumptions. As Canadian social innovator Al Etmanski says, “Innovation is a mix of the old and the new with a dash of surprise.”

What are Social Innovation Labs? If social innovation is the theory, labs are the practice and process of uncovering promising solutions. The central principle is that solutions are not known at the outset of the process but emerge through engaging multiple stakeholders, and therefore have potential for deeper systemic impact. Another key principle is not simply talking about ideas and possibilities, but making ideas tangible and testable. This helps uncover assumptions. By the time a prototype is ready for a pilot, it has been vetted and tested by people for whom a solution is meant to support or serve.

Is Social Innovation Just A Trendy New Fad? Nope. Social innovation may be new in some ways but it is also a form of problem solving that is deeply rooted in ancient traditions around the world. As it involves broadening the view of a current problem and what possible solutions may be, social innovation can be considered non-linear, holistic, and unconventional by traditional STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) problem-solving standards.

Social innovation recognizes that a single individual is not the cause of complex challenges nor the only source of a promising intervention. In many ways, collective problem solving in Indigenous communities has been around for thousands of years, striving to meet all the challenges that might affect the community. Indigenous communities think and act in systems, and recognize the interconnectedness of land, water, people, the winged and four-legged ones. The Shift Lab strove to ethically centre, and authentically engage, Indigenous knowledge and problem-solving systems with other social innovation ways of finding solutions. This “two-eyed-seeing” (a term brought forward by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall) approach helped inform all aspects of the process and prototypes.

The tools and methods of social innovation, such as design thinking and co-creation, are increasingly employed by the government and non-profit sectors in Canada. Social innovation often involves win-wins: for example, think of a recycling program which addresses littering, material waste, and income generation all in a single “blue box.” Social innovation can also involve remixing existing ideas to achieve new results. Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, for instance, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for pioneering the concept of “microcredit,” which helps impoverished entrepreneurs looking for financing. Social innovation can be used to convey emotional experiences as well. The Kairos Blanket Exercise is a powerful method to explain the broad strokes of Indigenous history in Canada through a unique exercise that involves shifting blankets and physical positions.

13

Shift Lab 2.0 Theory of Change 1. We wanted to create interactive processes that motivate people to change (covertly and overtly) racist behaviours that contribute to racialized outcomes. 2. We focused on the Sleepy Middle (see description on page 28): those who may exhibit unconscious or indirect racist ideas and behaviours, rather than overt and direct ones.

That leads to...

WELL-BEING

in order to...

Trying to increase...

3. We were committed to our approach of weaving together Indigenous processes, systems change, and design thinking to uncover promising pathways forward. We called this our Triple Helix approach (see page 30 for more).

REDUCE RACIST BEHAVIOURS

CAPACITY

MOTIVATION

OPPORTUNITY

How might we reimagine what it means to be a Treaty person?

Focussed on...

How might we create an interactive empathy experience that strives to reduce racist behaviour over time?

How might we create encouraging pathways that help potential allies for racial justice overcome white fragility?

How might we design intervention(s) that de-escalate public displays of overt racist behaviour?

Employing...

14

SYSTEMS THINKING

DESIGN THINKING

INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES

Shaped by political, economic, social and environmental factors

Tackling Racism in an Edmonton Context Through a Social Innovation Lab

Why Use Social Innovation Approaches to Address Racism?

If anything can be considered a wicked problem, it is racism. Can racism be “solved” in Canada? Perhaps — but the burden of racism carries with it political, economic, cultural, legal, and social dimensions, all of which require society-wide responses. The number of ways racism can manifest is only limited by how we as human beings choose to treat one another. These tensions revealed themselves early on in the Shift Lab as we moved to explore, understand, and unpack this topic.

As Stewards of the Shift Lab, we saw promise in a social innovation lab approach because it nudges participants to go beyond talking about ideas, policies and systems and into making ideas tangible and testable. Good social innovation labs are rooted in community, keep assumptions in check and engage in deeply participatory approaches to tackle tough challenges. We thought this approach would be promising to explore with a diverse group of Edmontonians living in Treaty 6 Territory. Our Core Team participants were all Edmonton residents but each had different roots here in amiskwaciwâskahikan (the original name for Edmonton, which translates as “Beaver Hills House” in Cree). They brought their various identities to this work and shared personal insights with one another during the lab sessions. While there is no prescriptive response to fight racism, having a diverse collective tackling the issue better ensured the complexity of the challenge was being worked on from many perspectives. From this experience, we surmise that scaling anti-racism work to influence systems and policy in other parts of Canada or beyond will likely require a deep understanding of the local context.

We acknowledge a long history of grassroots work that preceded us in Edmonton, as well as a slew of new voices contributing to this ongoing dialog. Combatting racism is hard work, and we are grateful for those who have sacrificed their time, energy, and lives for this cause. As best we can, we are attuned to feedback from these folks and from other communities. Because of the complexity with racism and anti-racism, we are skeptical of formulas, prescriptions and one-size-fitsall approaches. An approach that works for one particular community or for one complex system may not work in another. For example, anti-Black racism and anti-Indigenous racism in Canada can be seen in the over-representation of Black and Indigenous people in the criminal justice system, as noted by journalist Desmond Cole and others. Redress for both communities might take the form of similar measures (de-policing, restorative/alternative forms of justice etc.). However, if we look at another systemic issue, such as the achievement gaps in primary education for both communities, we would see different reasons for those gaps: the legacy of the Indian residential school system on Indigenous communities on the one hand, and underresourced urban schools serving primarily Black students on the other. We could conclude that different solutions, tailored to each community, would be required to close those gaps.

15

SHIFT LAB 1.0 TO SHIFT LAB 2.0: HOW THE LAB EVOLVED

Incorporating Indigenous epistemologies: land-based practices, ceremony, deep listening, asking elders for guidance, storytelling, relationship-building practices

Inspirations from other lab practitioners and gratitude towards them

Behaviour-change Science: relying on best practices and research across fields

16

There is no single way to design and lead a social innovation lab. A lab for us is less about beakers and Bunsen burners, and more about creating an experimental safe zone — a space to dig deep, build trust, remove fear, be bold, and find meaningful pathways forward as a collective. As there are many approaches, lab design and methodologies need to be tailored to the context of the particular lab. We drew on the following key approaches and practices.

Design thinking process: employing a “scrappy” humancentred design process to co-create solutions with community

Ethnography: searning and listening to people affected by the issue by hanging out with them in context, deep canvassing, capturing the environment with audio and visual tools

Whole-systems thinking: bridging experiences across public + private + non-profit + communitybased sectors

The story of Shift Lab is one of evolution. In Shift Lab 1.0 we learned early on that we had a tension around scope. The intersection of racism and poverty is massively complex, and within the context of Edmonton it manifests differently depending on culture, on neighbourhood, on what government happens to be in power, and a hundred other factors. A requirement of an effective social innovation lab is a decently focussed problem area that can be worked with. However, early community consultations in Shift Lab 1.0 told us that the focus couldn’t be developed by a diverse Stewardship team alone — it had to come from the community.

Terms: Anti-Racist, White Fragility The Edmonton Shift Lab does not use one term to describe its design efforts to combat racism. While “anti-racism” is an appropriate term, it is also one associated with a specific school of thought, best epitomized by Ibram X Kendi’s How To Be An AntiRacist. Similarly, while we use “white fragility” we are not directly referring to the book White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo. We consider “anti-racism” and “white fragility” as umbrella terms that are not limited to the way they are used in these and other books.

We listened and acted on that feedback. Once we recruited our first Core Team of diverse community members, their first task was to pick a focus area. Through a variety of methods, the Shift Lab 1.0 core team landed on housing as the intervention point to tackle racism. Some promising prototypes emerged — one of which is currently being piloted. After Shift Lab 1.0 was completed, the Stewardship team began reflecting on feedback, tensions and what had been learned.

Terms: Lab Sprints This term describes a practice in the work. Five weekend workshops with all Core Teams and Stewards were what we referred to as ‘sprints’. The sprints were where everyone from Shift Lab 2.0 got together, learned, built relationships and applied Indigenous, design- and systems-thinking approaches to tackling racism together.

A theme that emerged was the challenge around scope. This led to our first big “A-Ha!” moment that helped shape version 2.0. We realized that we needed to simplify and drop the intersecting part of the problem (in this case, poverty) and focus on addressing racism more specifically. To sharpen the focus and discover where there was demand for hard work around addressing racism, we initiated a research discovery phase that lasted about eight months.

Check out the tools section for more of the processes and tools we used in Shift Lab 1.0 and 2.0 https://www.edmontonshiftlab.ca/tools/ Read our Shift Lab 1.0 report here www.edmontonshiftlab.ca/learning-from-our-f irst-year/

17

SHIFT LAB 2.0 TIMELINE 2017

2018

November December Steward retreat: Evaluating feedback and Shift Lab 2.0 planning

January

February

Interviews with community embers and anti-racism and m social innovation experts

LAB SEASON

March

April

May

Expert Literature Review Indigenous Research Methods, Worldviews, and Praxis: Naheyawin Behavioural Insights: Gladys Rowe Anti-Racism Initiatives: Edmonton Centre for Race and Culture

In Shift Lab 2.0, the Core Lab team came together as a group over the course of four intensive weekend sprints and c oncluded with a Prototype Showcase. Individual prototype teams met between sprints to work on their projects.

2019

January

February

Core Lab team recruitment

March

April

May

Sprint 1 March 1 – 3 ECF/ Action Lab Opening feast. Building relationships and group agreements. Orientation to Shift Lab. Ethnographic research preparation.

Sprint 2 April 5 – 7 Action Lab Speaker Panel about Treaty, whiteness, and hate crimes. Ethnographic research share back. The shadow side of innovation.

Sprint 3: May 31 – June 2 Action Lab Elder circle. Behaviour change theory. Ideation. Developmental evaluation. Prototype pitches.

Ethnographic research

18

Ethnographic research deep dive

June

July Sprint 4: July 12 – 14 Yorath House Sharing circle. Learning from the land. Power, privilege, and antiracism insights. Perfecting the pitch.

Prototype development

June

July

August

Research synthesis. Development of principles, focus area, and guiding question

September

September

Prototype refinement and testing

October

November December

Design, design, design

September 27 Shelley Tochluk “Witnessing Whiteness: The Need to Talk about Race and How to Do It.”

August

October

October 17 Daryl Davis “Klan We Talk?”

November December

Prototype Showcase October 25 Norquest College Shared latest stages of prototypes with community and celebrated our journey.

A Shift Lab Special Presentation: October 7 Antionette D. Carroll “The Future of Leadership: The Roles of Identity, Power & Equity.”

November 27: Trevor Phillips “Equality & Integration: Why We Can’t Afford to Fail.”

2020 Hire three Prototype Managers to steward the further development and testing of the four prototypes. Evaluation. Continue to develop new tools, relationships, and insights.

October 8 Creative Reaction Lab “Leaders for Community Action & Equity” workshop.

19

DISCOVERY PHASE Literature Reviews and Expert Perspectives In the discovery phase of Shift Lab 2.0 we reviewed four literature areas: 1. 2. 3. 4.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing Racism Myths Anti-Racism Insights Behaviour-Change Science

IYINIW KISKEYIHTAMOWIN INDIGENOUS WAYS OF KNOWING

RACISM MYTHS

ewako iyiniw kiskinohamâkewitipahikestamâkewin/ nîkânîwin anita wîtatoskemitowak, omâmînomiwewak, ekwa mâmawinitowin owîtatoskemitowak kwayask kanisitohtahkik pakwâtitowin ôta amiskwacîwâskahikanihk/kihcihasotamâtowin nikotwâsik askiy.

“If only people would just _____.” This presumes people will act differently if they knew better. On the surface the sentiment is understandable. But it’s a tautology; people do as they are conditioned to and won’t “just” shift their behaviour at will.

We centred Indigenous scholarship/leadership in the stewardship team, advisors, and community core team members to better understand the context of racism in Edmonton/Treaty 6 Territory.

“Racism is a product of ignorance.” People who commit racist acts or hold racist beliefs are often highly educated. Today, nearly everyone has access to information to dispel ignorant beliefs, yet racism still persists. Knowledge and information alone do not prevent racism.

mihcet kîkwaya kâhisihayisinihkâtamak nehiyawihtwâwin ôta kitatoskewininaw namoya kwayask epimohtâtamihk, mâka înîsiwin kâhohcipayik ohci isihtwâwin kiskeyihtamowin namoya asime iteyihtahkwan. Many of the ways we centered Indigneous knowledge in the lab can’t be captured in steps and linear processes, but the wisdom that emerges is critical in informing how the Lab might engage with a) land-based practice b) ceremony and c) elder stories, all of which is essential to our triple helix methodology. We learned the importance of place and land-based practices and did our best to incorporate this into the Shift Lab. We centred Indigenous scholarship/leadership in the stewardship team, advisors, and community core team members to better understand the context of racism in Edmonton/Treaty 6 Territory. kikiskeyihtenaw ehispihteyihtakwak ayâwin êkwa askiy isihtwâwina ekwa kitahkameyihtenaw ôta kahastâyahk Shift Lab. We learned the importance of place and land-based practices and did our best to incorporate this into the Shift Lab.

20

We hired research experts in each area to gather insights from relevant literature and data to find leverage points. This evidence helped us design Shift Lab 2.0 and identify features required to tackle racism. We recognized the need to synthesize insights from the literature review into digestible chunks so future Core Teams could use them.

“Reverse racism is real.” Not really. Racism is predicated on power relations within a society. While white people can be individually discriminated against, as a group, white people in Canada generally do not suffer the repercussions of decades of policies, actions, attitudes, systems, and media portrayals that disrespect their humanity. That said, anti-racist policies should avoid privileging racialized Canadians at the expense of white Canadians. “Anti-racism is a “zero-sum game.” Here, the idea is that one person’s benefit is to another’s detriment. Racial quotas in hiring are often raised as evidence of this. Anti-racism praxis is, ideally, based on equity and human rights, and sees the elimination of “race” (and related factors such as ethnicity, skin colour) as any kind of determinant in a person’s fortune.

ANTI-RACISM INSIGHTS

BEHAVIOUR-CHANGE SCIENCE

A clear working definition of racism is difficult to land on, and there are many valid definitions in use today. For example, author Shelly Tochluk’s framework addresses four levels of racism (internal, interpersonal, structural, systemic) but there is less agreement about what distinguishes the latter two.

Understanding that individuals respond differently to cues and incentives, we learned that people are more likely to change behaviour if they have agency to identify what they want to change within themselves.

Indicators of what a reduction in racist behaviour at multiple levels of scale looks like is hard to agree upon. Blanket approaches that treat all communities the same are ineffective compared to more specific, targeted approaches. Opposing racism is not easy or comfortable — nor is it meant to be! Undoing the legacy of racism embedded in systems is a process that sometimes involves overcoming paradoxes and recognizing tensions. It leaves us vulnerable and open to criticism. And that’s okay.

Intensive one-off workshops or training (known as “shower” campaigns) are less effective than “drip” campaigns, where engagement and information is dispersed periodically over time. We learned that Western societies typically focus on three main approaches to effecting social change. They involve some level of: 1) incentives; 2) threats; or 3) reasoned debate. Social psychologist Kurt Lewin (founder of what is now known as sensitivity training) asked a different question that intrigued us: “Why aren’t people going to the right change on their own?” That motivated us to ask, “How can we remove barriers for people to adopt the change that we want to see in the world?”

Existing diversity training and other corporate-based approaches to reducing racism have been proven to be of limited use and can even be counterproductive.

21

Discovery Through Interviews and Community Consultation Workshops To go deep or broad? During the eight month Discovery Phase, we explored whether Shift Lab 2.0 should focus more deeply on a system/ sector/organization that wanted to make progress on racism, or whether to go broad to tackle racism as it exists and shows up in Edmonton. Some lab theories believe that going deeper in a specific system (for example, education or healthcare) can help uncover more powerful insights and lead to richer interventions. The challenge of going down this route is that the possible solutions generated for a specific system may only work in that context and cannot be scaled to other domains or sectors. On the other hand, the drawback to tackling racism more broadly is that it increases complexity and it is just as challenging to have multiple systems adopt the interventions that emerge from a lab process. To explore whether Shift Lab 2.0 needed to go deep into one system or stay more broad, the Stewards interviewed leaders in various systems to see if there was appetite for working with a community-based team to tackle a specific racismrelated challenge. We also held two community workshops to explore what community members, anti-racism experts, and systems-change leaders thought might be the best approach for Shift Lab 2.0. Interestingly, from the quantitative and qualitative information that came from these interviews and workshops, we could see that community members were torn. Half wanted a deeper approach and half wanted a broad approach, despite its limitations.

22

Essence of what we learned from this part of the Discovery Phase • People in organizations want to progress and reduce racism in the organization’s practices and structures. However, this requires a very delicate approach; these same organizations are sensitive to risk and bad publicity if something goes awry, and therefore leery of engaging. • There was a divide between anti-racism experts wanting to tackle deep racism in systems and community members wanting to stop racial harassment happening on the street.

Discovery Through International Speaker Series Research While we were in the eight month pre-lab phase, we simultaneously ran an international speaker’s series to share with Edmontonians expert insights and ideas on racism. The series was called “How to Have Difficult Conversations About Race” and brought four speakers that had tackled racism in unique and transformative ways in the United States and the United Kingdom. These speakers were chosen not because they had “solved” racism, but because they could bring outside ideas on challenging and eliminating racism that could work in Edmonton. So far, the series has only featured White and Black speakers. They were chosen partially based on the perspectives they could bring to our audience as well as expediency. While the series has not yet featured Indigenous speakers, we are planning to include these perspectives in future iterations. The series was open to the community. It attracted people working in this space and people who were curious from around the city. During the series we also surveyed attendees before and after the talks to get their sense of racism and asked what they felt was important to focus on. The views of the experts on practices that were working outside of Canada and survey results from lecture participants also contributed to help us formulate our direction for Shift Lab 2.0.

Thanks to local documentary filmmaker and Shift Lab 2.0 coordinator Nicole Jones-Abad, you can view videos of each lecture at https://www.edmontonshiftlab.ca/tools/

23

Key Insights from the Speaker Series: • The need to meet people where they are at: Not everyone will become an anti-racist activist overnight. Shelly Tochluk’s analogy of the ‘Racial Justice Freeway,’ in her book, Witnessing Whiteness, and in her lecture, was intriguing. It recognized different approaches can lead to the same destination. According to this analogy, a onesize-fits-all approach is not useful and may create further polarization. People rarely go from ignorant to anti-racist based on a single interaction, call out, or diversity training workshop. • The uniquely personal and relational nature of racism: Addressing racism through calm conversations, deep listening, and relationship building at an interpersonal level is hard. But people are less likely to “other” and hurt one another if they know a person in a relational way. Deep relationship building, as musician Daryl Davis demonstrates with members of the Ku Klux Klan, may be the quickest way to stop racism even in extreme contexts. It can be deeply draining to many racialized persons, however, and is difficult to grow these interactions to a public scale.

• Conventional anti-racist practises may backfire even with the best of intentions, as we learned from Trevor Phillips. Some messaging may not work the way it is intended to, and may in fact create polarization and intolerance. Additionally, the consensus agreement on what racism is and isn’t is fracturing, calling into question the efficacy of public responses such as “naming and shaming” as a corrective to racial discrimination. • Narratives depend on the language used to construct and frame them. As Antionette D. Carroll with the Creative Reaction Lab explains, creativity, humility, and even humour can become powerful tools for marginalized communities mobilizing to fight for equity and against racism. Agreement on language-setting is a key step towards establishing goals for anti-racist actions.

The graphic above was part of an anti-racism campaign in the UK for the Commission for Racial Equality. Trevor Phillips shared in the speaker series that the graphic actually backfired when tested and may have contributed to more racist views being developed.

24

Posters for the speaker series

25

CHALLENGE SCOPE After eight months of head scratching, going out on to the land, and holding paradoxes — as well as learning from the multiple research modalities listed above and the community feedback we received in the pre-lab phase — we landed on the scope and direction for Shift Lab 2.0. The research showed we needed a grounding question that linked everyone involved. The overarching question was:

How might we create anti-racism interventions that acknowledge everyone’s humanity and create behaviour change? We further narrowed the scope based on consultation with lab mentors and Indigenous elders, and landed on four questions that our teams assembled around: • How might we reimagine what it means to be a Treaty person? • How might we create an interactive empathy experience that strives to reduce racist behaviour over time? • How might we create encouraging pathways that help potential allies for racial justice overcome white fragility? • How might we design intervention(s) that de-escalate public displays of overt racist behaviour?

26

Our Working Definition of Racism Conventional wisdom frames racism as a product of ignorance. According to this framing, the solution is education. While this may be true in some cases, it has been the experience of the Shift Lab participants that this is incomplete and frames the problem as a personal one, rather than as an issue with historic, systemic, cultural, and institutional roots. Additionally, at a time when Canadians are more highly-educated than ever before, racism has metastasized rather than faded away. We define racism as the individual and systemic manifestation of the uneven distribution of power and prejudice related to culturally-defined ideas of “race,” which is itself a social construction with no grounding in science or biology. We acknowledge that racism is a hotly debated topic — one that is highly political, emotional, deeply individual, but also systemic, anecdotal, and historic. One of the confounding things about racism is that widespread agreement on what it is may differ from how it looked in a particular place and time or how it will look tomorrow. Within Edmonton, the nature of racism is broadly illustrative of racism in Canada and other Western settler-colonial societies generally.

Types of Racism Author, activist and educator Shelly Tochluk has written extensively about how racism is framed for a majority-white audience. This includes defining racism in four discrete but sometimes overlapping frameworks:

INTERNALIZED RACISM

INTERPERSONAL RACISM

• Lies within individuals, can result in self-hatred or selfabnegation.

• O ccurs between individuals, can be random and anecdotal in nature.

• Private beliefs and biases about race and racism, influenced by culture.

• B iases that occur when individuals interact with others and their private racial beliefs affect their public interactions.

• May be unconscious or psychologically rooted. Often reflects historic, intergenerational trauma.

• M ost “visible” form of racism that gets noticed.

• Example: self-loathing or hatred of one’s own culture.

• E xample: one stranger saying or doing something racist to another.

INSTITUTIONAL RACISM

STRUCTURAL RACISM

• Occurs within organizations, institutions and systems of power.

• R acial bias among institutions and across society.

• Unfair policies and discriminatory practices of institutions and systems (schools, workplaces, the criminal justice system, etc.) that routinely produce racially inequitable outcomes for people of color and advantages for white people.

• C umulative and compounding effects of an array of societal factors including the history, culture, ideology, and interactions of institutions and policies. • Examples: The Indian Act. “Redlining.”

• Example: Segregated workplaces.

Adapted from Shelly Tochluk

27

THE SLEEPY MIDDLE

The “Sleepy Middle” is an archetype that emerged in the research development of Shift Lab 2.0. Picture a continuum of racism: On one end are the tiki torch-carrying, KKKsupporting racists who care only for people who look like them; on the other are Critical Race Theory activists, who seek equity through direct, sometimes polarizing methods. The Sleepy Middle is somewhere between these two poles. People in this middle may think of themselves as good people who “don’t see colour.” They disapprove of racist jokes but are also unaware of what residential schools were, or think that police brutality is the result of a few “bad apples.” They have varying levels of understanding of what racism is, whether it still exists, and why it’s important to work to end it. Determining skillful ways to engage the Sleepy Middle and create within them allies for positive change was identified as a powerful leverage point for systems change.

Why the Sleepy Middle? The reason we focussed on the Sleepy Middle was not to coddle or shelter the privileged. What emerged from our research was that if the Sleepy Middle could become better allies for racial justice, then they could become powerful systems-change agents — because the Sleepy Middle is connected with and even commands many systems. What Shift Lab 2.0 had to explore was what approaches and interventions could truly shift the Sleepy Middle to change, become allies and avoid further polarization. We recognized from the outset that this was experimental and unconventional compared to some current practices. Additionally, a key learning was that it is not appropriate to default to racialized persons to explain to the Sleepy Middle that racism still exists, how it manifests, and why it’s so painful. Our intention was to be strategic, question any and all practices presumed to be working to reduce racism, and do our best to carve out effective pathways forward that make a difference.

28

“Who is the sleep middle? From my perspective, the sleepy middle could be defined as the so-called helpers, whether they are government officials, doctors, lawyers, nurses, teachers, social workers, etc. They all come with their own belief systems, their own ideas on how to ‘fix the Indian problem’ and it is often these folks with good intentions who embody systemic racism; they are the gears that move systemic racism. They are the sleepy middle.” — Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse

Top: Core Team in action Bottom: Tool used in the lab showcase behaviour change principles

29

OUR TRIPLE HELIX IND

IGE

NOU

S EP

DES

S YS

IND

IGE

30

THI

IST

IGN

TEM

EMO

NKI

S TH

S EP

DES

S YS

IGN

TEM

NOU

IST

INK

NKI

S TH

IES

NG

EMO

THI

LO G

ING

LO G

NG

INK

ING

IES

Addressing a wicked problem like racism requires thinking and acting in creative ways. It means drawing on what’s already working, questioning assumptions, and experimenting with pathways to move forward. The design and facilitation of a lab allows people to deeply think about and understand the problem. In Shift Lab 1.0, the process mainly adopted Human Centred Design (HCD), and Systems Thinking. Along the way, we recognized that Indigenous methodologies have startling similarities with design and systems thinking. In Shift Lab 2.0, guided by Indigenous thought leaders, we tried to weave these three processes into a ‘Triple Helix’. We modelled our process as an example of what working together as good treaty people looks like in action. We believe it demonstrates respect for traditions, viewpoints, and approaches without privileging one worldview over another.

WHY INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGIES? Why Indigenous Epistemologies? Our worldviews influence our belief systems, our decision making, and our modes of problem solving. A worldview helps determine an epistemology. An epistemology, simple stated, is how a culture generates knowledge. How one creates knowledge determines morals, values, and ethics. For example, dominant Western epistemologies are based on linear, hierarchical, and discrete modes of thinking. These modes of thinking are the roots of such problems like scientific racism and colonization and leads to worldviews based in domination and competition. On the other hand, many Indigenous epistemologies are based on holistic, universal, and de-centralized modes of thinking. Indigenous world views have been rooted in systems perspectives for thousands of years. For example, in the Cree worldview, the human is not the centre of the system; the Cree recognize the interconnection of the four-legged beings, the winged ones, the water, the air, the cosmos, and the land with us, the two-legged.

What Indigenous epistemologies look like in action

While the Indigenous epistemological theory we engaged with was primarily Cree, it was not exclusively so. Edmonton is an urban centre with a long history of multiple nations co-existing. Our theory is rooted in Cree perspectives and our lab practical application explored Nakota Sioux practices and relationships, creating a rich engagement with multiple Indigenous worldviews. Therefore, our exploration is based on mutual shared knowledge and relationships. This knowledge is not owned by us, it cannot be replicated, and it most certainly is not meant to be applied wholesale to any other context. Engaging in multiple Indigenous epistemologies was enabled by relationships and as a consequence our methodology was grounded in relational accountability. For Indigenous worldviews, this means being accountable to all our relations and for the Shift Lab, this was a deep dive into discovering the relationship of being treaty relatives.

Indigenous epistemologies are based in: • Story-telling • Land-based practices • Customary law • Ceremonies • Languages • Connections to land, water, and cosmos Questions Indigenous epistemologies ask: • What relationships are existing here? • What are my obligations and responsibilities? • How is this problem connected to the world around us? • What legal traditions provide precedent here? • Whose territory am I on? • What languages are spoken here? • Who are all my relatives in this territory (two-leggeds, four-leggeds, winged ones) • What are the existing treaties in this territory?

31

DESIGN THINKING We are all designers. When we try to figure out solutions to challenges that pop up personally, at an organizational level, or at the community level, we enter a mode of problemsolving where we design solutions. But we too often design solutions based on our own experiences. This is a problem when we are trying to find solutions for other people who live on the margins or experience a system differently. Human-Centred Design (HCD) or Design Thinking is a creative process to problem solving that starts with striving to deeply listen, see and empathize with what people/systems need. It is a highly experimental, thought-provoking, and action orientated approach.

* tâpiskohc aya, iyiniw kesiwâpahtahk, ayisiyiniw anima namoy wiya tâwâyihk ehapit nehiyaw nistaweyihtam ehisiwâhkomâcik newikâtêw ayisiyin, kâpimihâcik, nipiy. kâyehyehtamihk, ekwa askiy ohci nîsokâtak (ayisiyiniwak).

What Design Thinking Looks Like in Action Design thinkers: • take “deep dives” into what motivates people to use a product or service • use ethnography or field studies of people using the product or service • brainstorm ideas that may be unconventional, unorthodox and radical • make sense from personal and sometimes emotional insights • react quickly and use a rapid iteration process to develop prototypes rather than get bogged down in details

Why Design Thinking? Design Thinking emphasizes the good over the perfect and allows for rapid iterations of a prototype to be possible through quick edits and changes on the fly. From different ways of listening and learning, sense-making insights are generated that identify these needs as well as challenges, and key things to consider when designing a potential solution. A design approach strives to co-create tangible prototypes that can be tested by its users to ensure the proposed solutions will actually work in the real world.

32

Questions design thinkers ask: • How does this idea make people feel and think? • What is deeply needed and why? • Is there an analogous situation that we can learn from? • How would this work if we changed a key assumption about the people who might use it? • How will this impact users on the margins of this service? • Are people reacting differently to this solution than what they are telling us? • What if we work backwards from the solution to the problem?

Stories Ethnographic Research Sense Making System Mapping

1

empathy Checking the prototypes with community/with user groups the prototypes are for

5

2

test

Choosing ideas that could meet needs Making prototypes of what a service, policy innovation could look like

define

HUMAN CENTRED LAB PROCESS

4

3

prototype

ideate

Making sense of needs and insights from stories “How Might We� Questions

Brainstorming Getting ideas from other fields Co-designing with community Building on ideas of others

33

SYSTEMS THINKING Why Systems Thinking? Systems thinking is a holistic way to step back and look at the parts that make up a complex challenge and explore what biases, assumptions, and structures that might be keeping a system operating the way it does.

“A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something (function or purpose).” — Donella Meadows

34

There is a tricky tension to navigate when trying to enact deep, positive change around a complex issue. It’s the tension between focusing too much on helping make change at an individual level versus the need to step back and look at the big picture. It’s a bit like an out-of-control patch of poison ivy at a children’s playground: you can cut the leaves back to prevent children from being stung, or you can attack the roots so it doesn’t come back. Systems thinking helps people to look at things that have happened, structures, and assumptions that might be causing a problem like racism to continue to exist.

What Systems Thinking Looks Like in Action System thinkers: • Strive to be keenly aware of their biases and assumptions • Seek to acknowledge that an improvement in one area of a system can adversely affect another area of the system • Look at what root causes might be contributing to a problem • Ask questions and wonder why something happens • See the interconnections within the physical environment of the land, water, beings, values Questions systems thinkers ask: • Has this problem occurred in the past? • What structures may be causing this problem? • What change is needed? • Why is this change needed? • How will this change affect other parts of the system? • How do we increase people’s understanding of the issue in a way that integrates the richness of diverse perspectives with the simplicity required to act?

hat structures W may be causing this problem?

Adapted from: Systems Thinking For Social Change, by David Peter Stroh

35

GOING DEEPER In Shift Lab 1.0 we learned from feedback that we might have fostered too much of a polite atmosphere, which hindered going deeper and sparking personal transformation. In Shift Lab 2.0 there were a number of tools we used to go deeper.

Indigenous Traditions iyiniw ihtwâwina One of the important ways for going deeper was through Shift Lab steward Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse sharing Indigenous traditions. This included sitting together, listening more deeply to each other, feasting together and strengthening relationships. There was no set tool or method to follow for this, but we made space and centred these moments throughout the lab. Jodi also introduced the lab participants to going out on the land to recognize the interconnections in systems, pick berries together and carry questions together.

i spihteyihtakwan kakiskisihk ekwa kahâhkameyihtamihk kâkînakatamakoyahkik aniki kitaniskotapaninawak. *It is important to remember and practice the ways

of our ancestors.

36

Theory U Another way we explored supporting teams going deeper was through the Theory U framework, developed by Otto Scharmer. This framework describes the journey of changemakers as working through multiple phases of discovery, beginning with “downloading� their own mental models of a complex situation and then gaining increasing insight through conversations, experiences and research with others. This (ideally) results in an openness to the emergence of new ideas about how to address the challenge.

Downloading Past Patterns

Performing Scaling and Internalizing

Seeing with Fresh Eyes

Prototyping Experimenting with the New

OPEN MIND Sensing from the Field

Letting Go

O P E N H E A RT

OPEN WILL

Presencing

Crystallizing Vision and Intention

Letting Come

2.0 Lab t f i Sh

connecting to source

Adapted from Otto Scharmer

37

4 Types of Conversations Tool We utilized Otto Scharmer’s four types of conversations that support how we talk together to create deeper understanding and cultivate richer insights. The four types of conversations framework creates the conditions for this by structuring dialogue accordingly. We endeavored to weave these ways of going deeper throughout the process.

We Sought Behaviour Change, Not Nice Transformational Experiences

How might we create anti-racism interventions that acknowledge everyone’s humanity and create behaviour change?

38

Generative Dialogue • presencing, flow • time: slowing down • space: boundaries collapse • listening from one’s Future Self • rule-generating

Reflexive Dialogue • inquiry • I can change my view • empathic listening (from within the other self) • other = you • rule-reflecting

Talking Nice

Talking Tough

• downloading • polite, cautious • listening = projecting • rule-reenacting

• debate, clash • I am my point of view • listening = reloading • other = target • rule-revealing

From our overarching question, you can see that we wanted to move the needle to making an actual impact. Ideally, we all want system behaviours to change at the root. But along the way we at least wanted to work towards ways people, groups, and organizations could more easily learn how they can change behaviours to be less racist. A common thing we heard in our early research was that one-off transformational diversity or anti-racism training is great, but too often people snap back to their “normal” modes and don’t shift behaviour over the long term. We wondered and wanted to experiment with how we might improve that, or at least uncover principles that can improve lasting behaviour change.

BIL

C APA

Au to m

ati c

Physical

MO en

t

T I V AT I O N Training

on

em

Incentivisat ion

cal

UNIT Y

Env

RT

ysi

n asio rsu Pe

OP

Y

PO

Restironm ruc en tur ta ing l

Educa tion

Ph

bl

a

Motivation is defined as all those brain processes that energize and direct behaviour, not just goals and conscious decision-making. It includes habitual processes, emotional responding as well as analytical decision-making. The Behaviour Change Wheel breaks motivation down into reflective and automatic categories.

IT

Psychological

En

Capability is defined as the individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned. It includes having the necessary knowledge and skills to act.

M o d e lli n g

We used the COM-B model of behaviour change, which is based on a synthesis of 19+ public health behaviour change models summarized by Michie, Atkins and West in the book, The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. This UK-based approach proposes that the direction, depth and pace of any kind of behaviour change — whether it’s quitting smoking, wearing seatbelts or recycling more — is shaped by three factors: capability, motivation and opportunity.

tions stric e R

So cia l

The COM-B Model of Behaviour Change

C

r oe

ci

Mayne, John. 2018. The COM-B Theory of Change Model. A Working Paper.

Opportunity is defined as all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it. It is primarily broken down into physical and social categories. The participants of Shift Lab 2.0 were introduced to this framework, and then asked to consider how all three factors might be integrated into their behaviour-change interventions. Many also used it to manage expectations about the direction, depth and pace of behaviour change and the extent to which we are able to effectively address all three factors (e.g., an intervention that focuses only on capability will only be useful in situations where motivation and opportunity already exist).

39

Behaviour-Change Nudging We also explored how we might remix behaviour-change nudging into the prototypes to help with positive behaviour change. In the process, we created a deck of prompt cards (called our Shift Lab Behaviour Change card deck) with principles from behaviour change science. Teams used the cards to see how they might design ethical behaviour-change nudging into possible prototypes. Types of nudges “Nudges� are small changes in the environment or interactions that are easy and inexpensive to implement. These nudges are gleaned from the worlds of social psychology and marketing. Several different techniques exist for nudging, including defaults, social proof heuristics, and increasing the salience of the desired option. A default option is the option an individual automatically receives if he or she does nothing. People are more likely to choose a particular option if it is the default option. For example, Daniel Pichert & Konstantinos Katsikopoulos noted in the Journal of Environmental Psychology that a greater number of people chose the renewable energy option for electricity when it was offered as the default option. Steward Sameer Singh sharing insights on behaviour change science

40

A social proof heuristic refers to the tendency for individuals to look at the behaviour of other people to help guide their own behaviour. Studies have found some success in using social proof heuristics to nudge individuals to make healthier food choices. When an individual’s attention is drawn towards a particular option, that option will become more salient to the individual, and he or she will be more likely to choose that option. As an example, in snack shops at train stations in the Netherlands, consumers purchased more fruit and healthy snack options when they were relocated next to the cash register.

“The words ‘If people would just…’ are never a part of an effective social innovation. If your goal is to create social change through behaviour change, strong arguments will rarely suffice. You must also understand people’s behaviour and design solutions that disrupt their habits.” — Ben Weinlick on the MyCompass Planning Social Innovation

“A nudge, as we will use the term, is something that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.” — Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness_ by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein

41

THE SHIFT LAB 2.0 JOURNEY We chose to conduct the lab over several weekend intervals, known as sprints, for a number of reasons, including feasibility, participation, and logistics. Transportation and childcare were also factored in to enable broader participation.

Sprints were structured as three-day intensive working sessions, starting on Friday evenings with relationship building activities and a shared meal and finishing by Sunday afternoon with a debriefing session to allow participants to close the weekend.

The Triple Helix In Action: The Sprints Each design sprint started with a grounding activity, typically Indigenous focussed, to intellectually and emotionally centre the participants. The opportunity to Indigenize the design sprints was essential to their effectiveness. Indeed, it’s what grounds the work of the Shift Lab in Edmonton and Treaty 6 Territory. Under Jodi’s tutelage, each sprint featured Indigenous-themed activities, foods and speakers, including local/regional elders and wisdom keepers, political representatives, educators, activists, drummers and business people. This was followed by sharing food and relationship building. A participant observer (witness) was invited to provide feedback on group dynamics throughout each weekend, and invited to share anonymous feedback with the team. Feedback from each sprint was considered and iterated into each successive sprint.

42

While no sprint is identical, each followed a similar structure, combining three elements from Shift Lab 1.0: Grounding Days, Workshops and Campfires (see below). As much as possible, each design sprint embodied our Triple Helix of Design Thinking, Systems Thinking and Indigenous Epistemologies. • Grounding Days made space to think deeply about the topic at hand, usually started by an Indigenous custom, practice or observation as assisted by Jodi and Elders. • Workshops reflecting an exploration of the humancentred design process from a solutions-oriented narrative. • Campfire exercises provided emotional on- and offramps into the topic, with often deeply emotional experiences shared alongside problem-oriented analyses.

Sprint 1: March 1-3, 2019

ECF and Skills Action Lab

Getting to know one another; relationship building; Indigenous practices of locating ourselves, which includes the sharing of where we come from, who our ancestors are, and our purpose; setting up the team for ethnographic research to explore their Challenge Briefs.

Sprint 2: April 5-7, 2019

Skills Action Lab

Indigenous speaker panel about Treaty; ethnographic research shareback; adaptive cycle/nemesis; open space for team members to share their skills and insights to support our work together.

Sprint 3: May 31-June 2, 2019

Skills Action Lab

Elder circle; cultural teachings and medicine wheel; COM-B; evaluation; ideation; landing on prototype ideas.

Sprint 4: July 12-14, 2019

Yorath House

Berry picking; land-based practices; circle work exploring power relations; getting ready for field testing; prototype presentations/pitches.

September 15-16, 2019

Banff Centre

Stewards sifted through Core Team feedback, envisioned how prototypes could be launched and determined future aspects of the Lab. Started to develop an indigenous evaluation tool.

October 25, 2019

Norquest

Each team presented their prototypes to potential partners and funders from the community.

43

WHAT EMERGED FROM SHIFT LAB 2.0? PROTOTYPES, TRANSFORMATION, ACTION

Prototyping can be the most exciting part of the social innovation process, but also the messiest. Prototyping involves taking knowledge, observations, and insights from the field, and translating them into actionable ideas that can be replicated and scaled to other users or communities. It is a highly creative, physical, and non-linear process. It frequently challenges status-quo assumptions. The “a-ha!” moments are only limited by the duration and resources of the lab. In addition to the above, prototyping to fight racism brings a mix of experiences, perspectives, histories and learnings to bear onto a “wicked problem.” Responding to racism as it manifests at the institutional and social level can invoke painful, powerful emotions. Tears were shed during prototyping sessions. This is particularly true for racialized participants, who were asked to draw on their own experiences of discrimination at the hands of another person, organization or system. In contrast to prototyping a mobile app, or a new flavour of toothpaste, this is unfiltered, uncomfortable work. But it is only through an intense visioning of what the future could look like that we can arrive there.

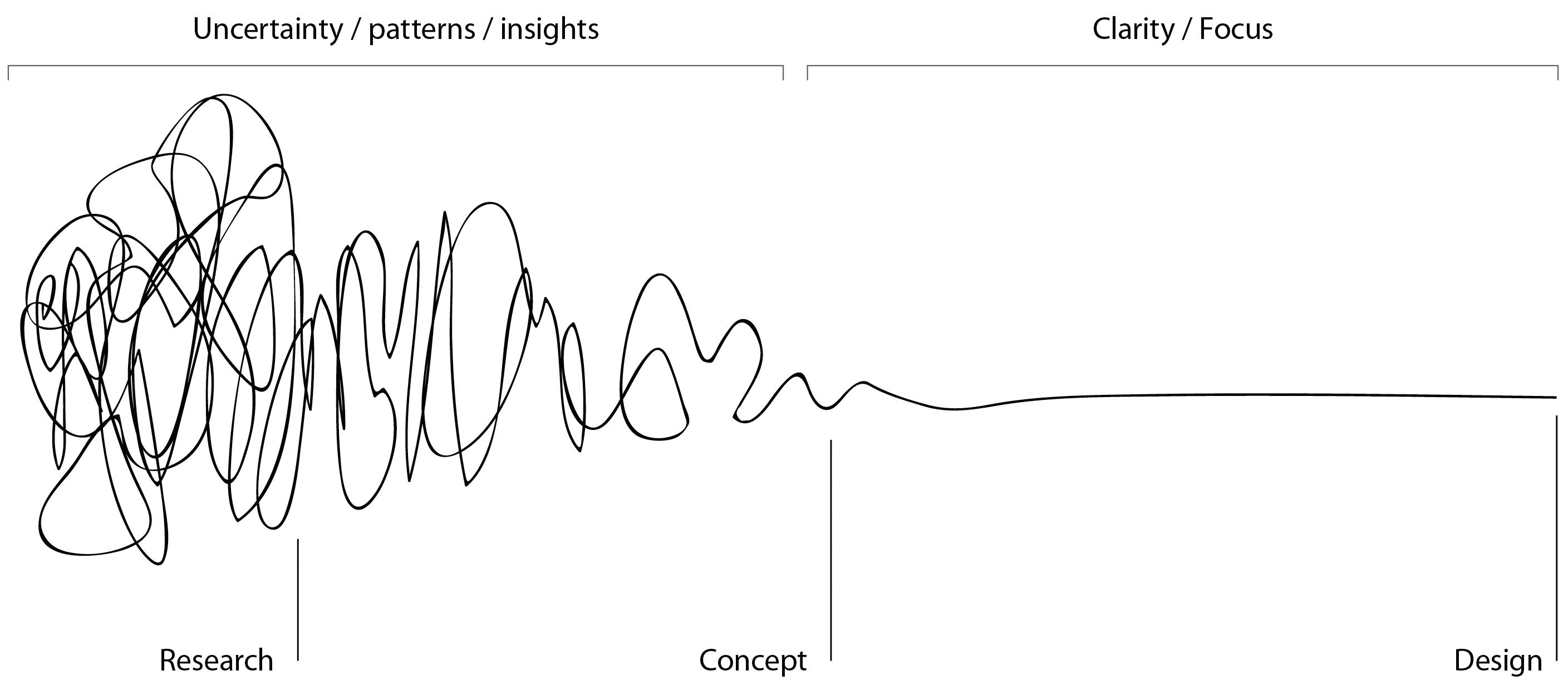

Uncertainty / Patterns / Insights

Research

Clarity / Focus

Concept

The Process of Design Squiggle by Damien Newman

44

Core Team members practicing pitching prototypes

45

Exploring Wahkohtowin The Challenge How might we reimagine what it means to be a Treaty person? Derek Jagodzinsky

Carla Hilario

Rebecca Craver

Avery Letendre

Iwona Faferek

Eileen Edwards

Rabia Naseer