Getting to the heart of cardiovascular diseases Vast amounts of genomic data are available today, and analysing it can help researchers pinpoint the genetic factors involved in the development of disease. We spoke to Dr Nabila Bouatia-Naji about her research into the genetic causes of conditions associated with cardiovascular diseases, and its wider importance to diagnosis and treatment. There is a

relatively small degree of variability in genetic profile across the human population, and any two individuals have very similar DNA sequences in their genomes. However, there are variations, and analysing minor differences across the population could help researchers identify which are associated with cardiovascular diseases, a topic central to the ROSALIND project. “We look at the specific differences in the genomes of different individuals, and compare patients with certain cardiovascular diseases with people who don’t have these conditions. By comparing them we can then identify, in the genome, the important differences,” explains Dr Nabila Bouatia-Naji, the project’s Principal Investigator. Based at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm) in Paris, Dr BouatiaNaji is working to identify differences in the genome that are associated with certain types of cardiovascular disease. “It could be that because there is a little bit less of a protein, certain cells are more likely to be unstable, and then this will affect the structure of the arteries,” she outlines.

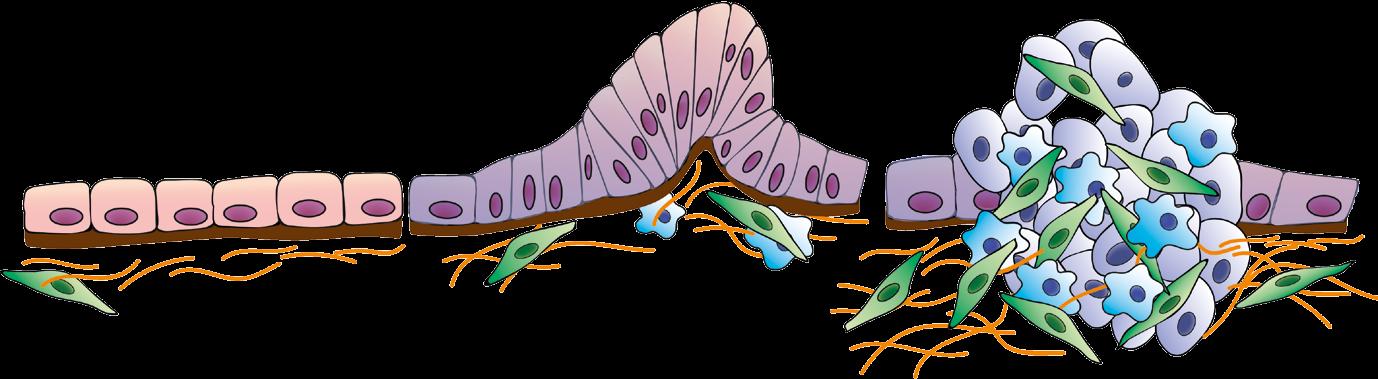

Cardiovascular diseases The coronary arteries play an important role in the transport of oxygenated blood to the heart, so they need to function correctly. The function of the coronary arteries is underpinned by many different biological events and processes, and problems here can have serious consequences, even a myocardial infarction. “A myocardial infarction can be due to many different reasons, not just the accumulation of cholesterol. When we look at

the genetic causes of cardiovascular diseases, we may find different genetic causes, many different events happening at the cellular level that in the long-term may leave individuals more prone to arterial disease,” says Dr Bouatia-Naji. The aim now is to build a deeper picture of the genetic factors associated with cardiovascular diseases such as fibromuscular dysplasia, and spontaneous coronary artery dissection, two conditions that affect blood vessels “We have data on around 3,000

one of our projects we’re studying the genetic determinants in the genome, that influence an individual’s levels of testosterone or oestrogen in order to identify if patients with naturally higher or lower levels of these hormones are more prone to these diseases” says Dr Bouatia-Naji. “The strength of a genetics-based approach is that genetic information doesn’t change over time, while hormone levels in women change almost from day-to-day during an individual’s lifetime.”

We look at the specific differences in the genomes of different individuals, and compare patients with certain cardiovascular diseases with people who don’t have these conditions. By comparing them we can then identify, in the genome, the important differences. patients with one or both of these diseases, as well as data on more than 6,000 individuals who don’t,” continues Dr Bouatia-Naji. This provides solid foundations for researchers to investigate the underlying genetic factors behind the diseases, which affects the structure of arteries. One striking point is that the vast majority of patients affected are women, an issue Dr Bouatia-Naji is exploring in the project. “Maybe it’s because women’s hormone levels fluctuate every month. So, these repeated increases and decreases in hormone levels may affect the stability of the arteries,” she suggests. Researchers in the project are able to look at the genetic determinants of these fluctuating hormone levels, from which deeper insights into cardiovascular diseases can then be drawn. “In

The samples from both healthy controls and patients with specific cardiovascular diseases are sent to specific genomic centres, which house specialist machines to analyse DNA. The results are then sent back to Dr Bouatia-Naji and her colleagues for further investigation. “We use computational biology and statistical methods to analyse this data. We try to compare, for instance, all the differences that were categorised in our cases and in the controls. Then we apply statistical tests, to see if these differences are meaningful, and where they are localised in the genome,” she outlines. This approach has already yielded results; a variant of interest on the gene called PHACTR1 has been incriminated. “We found an allele, a version of this specific position in

Names of members of my team are from left to right: Delia Dupré, Nabila Bouatia-Naji, Adrien Georges, Mengyao YU, Romain Glandier, Sergiy Kyryachenko, Lu LIU, Dana Federici, and Takiy Berrandou.

18

EU Research