It’s not all childsplay Playing with their peers helps children develop their social and cognitive skills, but should adults get involved? And if so then how? We spoke to Professor Sonja Perren and AnnKathrin Jaggy about their work in evaluating the impact of specific interventions on the quality of play, and whether these interventions could be more widely adopted in future. Many important developmental steps take place between the ages of 3-4, as children start to spend more time with peers and experience longer separations from their parents. A lot of this time is spent playing with peers and developing imaginary scenarios, yet there are big differences in the quality of children’s pretend play, a topic at the core of Professor Sonja Perren and Ann-Kathrin Jaggy’s research. “We recently published a paper about how to assess social pretend play competence in young children. We identified five important features of pretend play,” says Jaggy, a researcher at Thurgau University of Teacher Education. These five features are decentration, decontextualization, roletaking, planning and sequencing.

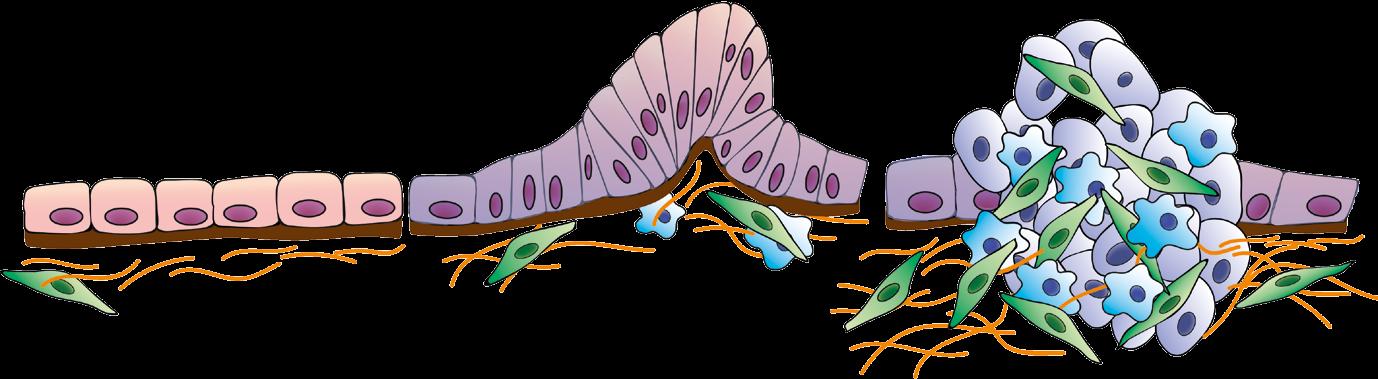

Social pretend play “Children typically start playing on their own, then progress to engaging in pretend play with others, which characterises the decentration of the play. Decontextualization describes the point when children start pretending with real objects, then bring in more fantasy and use their imaginations.” explains Jaggy.

68

The role-taking feature relates to children’s ability to project themselves into a particular role that might be involved in an imaginary scenario, like a firefighter for example. Children may start with simple actions, then Jaggy says they often move on to do more complex planning. “They negotiate about the roles, who will be the firefighter, who will be the doctor and so on - it’s a higher level of pretend play. The last feature is the sequencing. High levels of sequencing mean that the children know that when there is a fire there is an alarm, they have to start at the fire station, then they have to drive to the fire, and so on,” she outlines. One aim in the study is to investigate the impact of providing play material and adult support on the quality of social pretend play, with researchers evaluating the effectiveness of different interventions. “We have three different groups, and one group has an intervention where a research assistant goes into the group, plays with them and tutors them,” says Professor Perren, who is based at the University of Konstanz.

In the first group a research assistant provides role-play material, models the play and suggests ideas, so provides a fairly high level of support to the children. In the second group, children were given the roleplay material, but were not supported by the involvement of an external research assistant, while there was no intervention at all with the third group. “They participated in their normal pre-school activities, which mostly involved play,” outlines Professor Perren. These different approaches to promoting children’s quality of social pretend play will then be evaluated regarding their impact on children’s social competence. “We test how well they can play, their pretend-play competence,” continues Professor Perren. “We also test them regarding their social-cognitive skills, so their emotional understanding, perspectivetaking ability, and also their language. Then we also ask the educators and the parents about children’s social skills.” A large part of the project’s research centres around testing causal mechanisms, and looking at whether it is possible to promote the quality of pretend play. While an outside

EU Research