Technology, Trust, & Governance

Eric Gordon / Helena Rong

Eric Gordon / Helena Rong

Eric Gordon / Helena Rong

Eric Gordon / Helena Rong

This Open Project collaboration concentrates on the transformation of democratic institutions and the novel mechanisms of trust building that governments are exploring to address the problem of distrust. Models of governance where institutions respond to a singular public are no longer sufficient as diverse constituents or publics increasingly demand from institutions individualized responsiveness and the explicit articulation of shared values. As a response, democratic institutions are seeking better ways (often through technology) to deeply listen and to respond to the needs of multiple publics, especially those who have been historically excluded.

Students will examine trends in technologyaugmented listening and decision-making, including “web3” technologies such as blockchain, as well as novel data practices, and artificial intelligence. Students will imagine designs for governance that are inclusive, creative, functional, and sustainable. Research Trajectories include Governance as Medium, Design for Institutional Trust, Activism in Digital Culture, Responsive Media, Play and Experience Design.

Studio Instructors

Eric Gordon, Helena Rong

Teaching Associate

Ethica Burt

Aishwarya Sreenivas (Sreeni)

Students

Harshika Bisht, Ethica Burt, Kim Cordova, Quoc Dang Minh, Alejandra Fernandez, Tian Wei Li, Clair Ryu, Aishwarya Sreenivas, Alan Tebuev, Sharon Welch, Li Zhou

Critics

Amritha Jayanti, Carlos Centeno, Stephen Larrick, Nigel Jacob, Ceasar McDowell, Stephen Gray, Elizabeth Christoforetti, Yue (Will) Wu

10

Introduction

Introduction

Eric Gordon & Helena Rong

Material Infrastructure

15 Systems Under Pressure: Spaghetti Utilities in a Cluttered Subsurface

Ethica Burt

19 Community-based Sustainability Practice: Decentralizing Built Environment Standards

Quoc Dang

23 Equitable Built Emissions Reduction in Boston’s Neighborhoods

Harshika Bisht

Economic Infrastructure

31 From Gentrification to Redistribution: Designing Rental Platforms that Repair

Sharon Welch & Alejandra Fernandez

Social Infrastructure

39 Mapping Place Identity: The Physical and Psychological Contours of Boston’s Chinatown

Clair Ryu

Information Infrastructure

45 Thrive: A Community Driven Platform Connecting and Advocating for Immigrant Resources Through Public Libraries

Tian Wei Li

51 Empowering the Underrepresented: Participation in Overseeing Surveillance Data Collection

Li Zhou

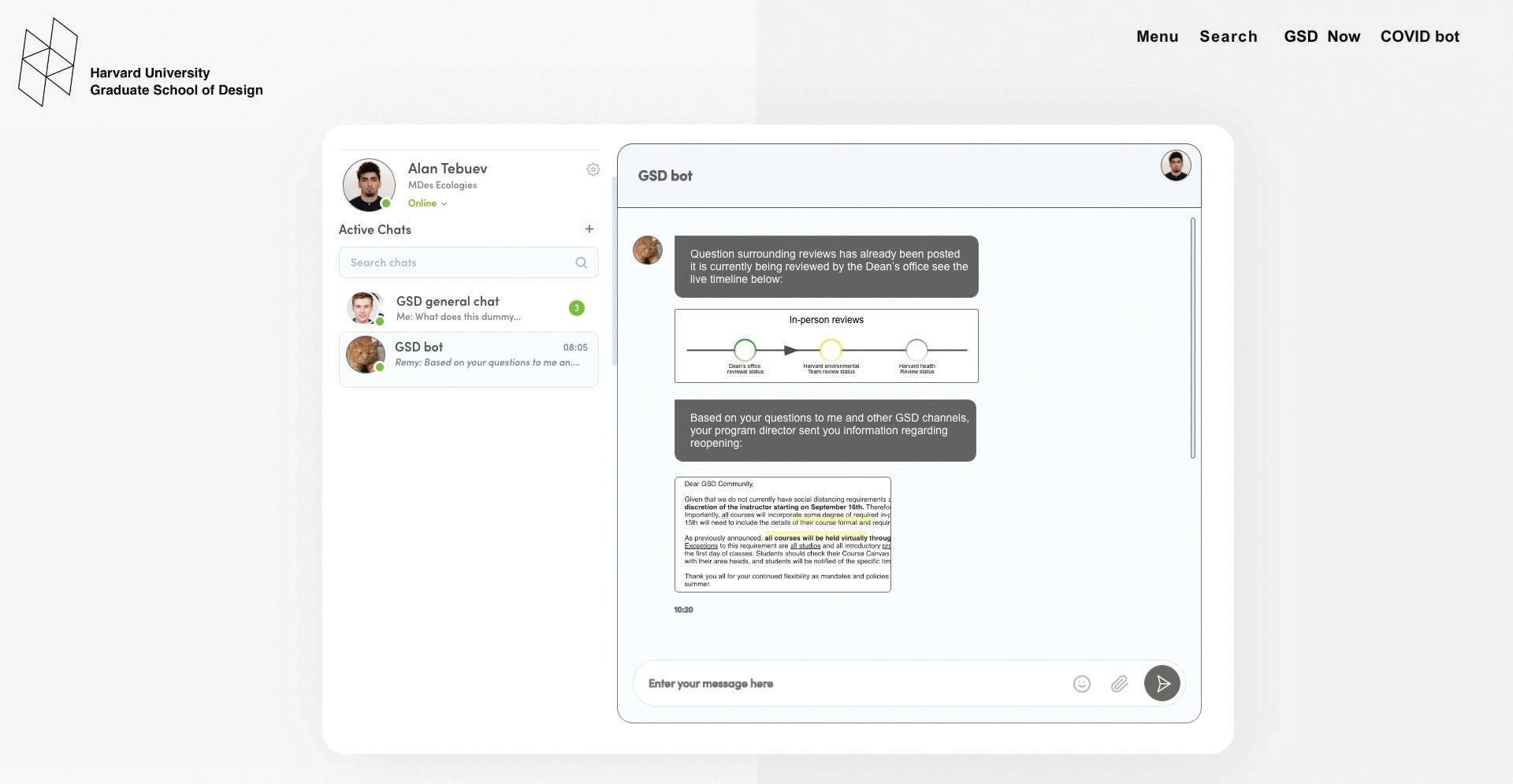

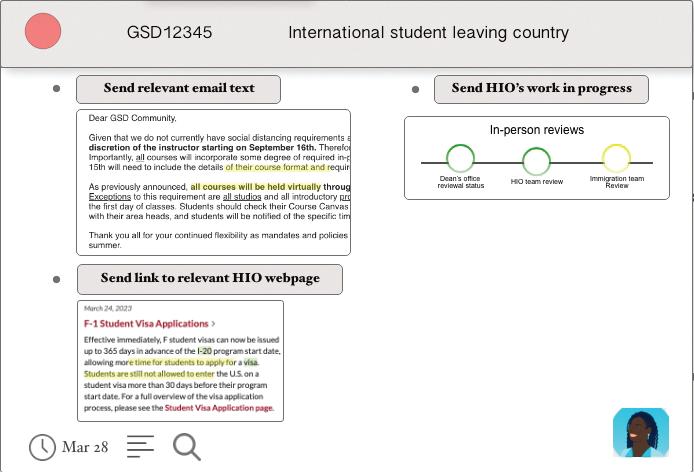

55 Reimagining Public Health Crisis Communication in Universities with Artificial Intelligence

Alan Tebuev

59 Building for Billions: Digital Infrastructure for Healthcare in Rural India

Aishwarya Sreenivas (Sreeni)

65 Contributors, Critics, and Guests

73 Syllabus

Eric Gordon Helena Rong

Eric Gordon Helena Rong

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What

Functional democracy describes a system of governance wherein the power of decision-making is equitably distributed to the people who make up the system. In small groups, this might look like a tacit agreement among participants to listen to each other and decide with the majority opinion. It works as long as each person trusts that the others will hold to the agreement. As groups get larger, from associations to societies, tacit rules are made explicit, and organizations are created to distribute resources and hold people accountable. Once this happens, decision-making requires not only lateral trust between individuals and groups, but also vertical trust in facilitating organizations.

In this studio, we have focused on the increasingly complex, and largely invisible, matrix of trust in systems of democratic governance. Designing democratic governance can feel like a fish designing water. It’s everywhere and impossible to see, and yet we couldn’t live without it. Too often it’s ignored by architects, planners, designers, and engineers or considered just a byproduct of other systems. We design buildings, service delivery systems, public engagement procedures, and we take for granted how individuals and groups come to use what we design, come to trust its integrity, and steward it over the long term. By not centering governance in our designs, the management of the intricate interactions between people and institutions defaults to market logics or top down bureacracies. Ultimately, good governance is a matter of trust.

Globally, trust in nearly every institution is down, from the media to NGOs to the government. Government institutions, in particular, are struggling to meet their mandate to govern when there are seemingly irreconcilable fissures in the social contract. A glut of information

creates slippery truths and foments distrust; extremist politics have been given oxygen by an over eager media ecosystem; social media creates expectations of constant and immediate responsiveness. As a result, government organizations are exploring how to build and/or maintain legitimacy in an exceedingly low trust environment. They are, sometimes thoughtfully, but more often hastily, deploying new digital tools to allocate resources, make decisions, represent processes, and build consensus. After all, there is urgency. Emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic and the racial reckoning spurred by the murder of George Floyd in the United States, there is growing recognition globally, illuminated by crisis, that our democratic institutions have failed in their promise to equitably distribute decision-making power.

What does it take for people to trust institutions? More importantly, what does it take for institutions to be trustworthy? How might novel digital tools or procedures reshape trust relationships between people and institutions? And, how do questions of trust in local governance intersect with the built environment, and the myriad ways in which people experience it. This is the crux of our studio: to uncover how and why people trust in the mediating organizations that facilitate public life.

The studio outcomes represented here compose a collage of possibilities in the democratic governance of public life. Each uncovers challenges, and proposes solutions that are grounded in lived experience, and yet deeply hopeful for an experience not yet lived. Taken together, they should be read as a call to action to practitioners, technologists, designers, and policymakers, to center questions of trust and governance in the infrastructures of democratic public life.

the hell is water?”

– David Foster Wallace (2005)

We have organized our collage into four intermingling infrastructures: material, economic, informational, and social. There are nine projects represented here, each is labeled with at least one infrastructure, some with secondary and tertiary labels.

Material infrastructure refers to the tangible or physical systems of the built environment. Projects defined by this label evaluate and/ or intervene in the decision-making practices that shape these systems.

Economic infrastructure refers to the ways in which activities and interactions produce welfare through the distribution of wealth and capital. Projects defined by this label facilitate the creation of networks between stakeholders through imagining services and strategies that promote alternative, more equitable, allocation of resources.

Informational infrastructure refers to the tools and procedures used to collect, manage, and disseminate information. Projects defined by this label seek to reimagine how data is shared with those who are typically excluded from accessing it, and how alternative modes of communicating data can lead to different and better decisions by those most impacted.

Social infrastructure refers to the procedures of sourcing shared narratives and values in geographically collocated communities. This includes narratives about physical space, spiritual life, and cultural bonds that fortify sense of place. Projects in this category explore the narratives that bind people and institutions together.

The specter of digital technology is present in every one of the projects. This is not to say that all challenges of governance have technological solutions. We have been very careful to avoid the traps of technological determinism. However, we believe that technology represents an important lens through which we can examine and address challenges in governance. Technology shapes the interface between people and institutions by shaping what we know, how we know it, and what we do with that knowledge. To that end, our studio has rigorously explored novel tools such as blockchains, and artificial intelligence as “objects to think with.” By introducing a new variable into stable state systems, we have had the opportunity to reimagine the logics that make up the systems we are part of. For example, how might AI impact constituent services? How might blockchain, or distributed ledger technology, provide a decentralized mechanism for the equitable distribution of resources in low trust environments? And while these “objects to think with” have not entered into all the final projects

you see here, they have unlocked our imagination to see the often invisible challenges right in front of us.

The governance of public life will always exist in intermingling infrastructures, meaning that solutions created will sometimes cohere for the individual, and sometimes contradict. There is no single system that works across all layers of infrastructure. Any promise of such a thing is thinly veiled autocracy. This is precisely why the design of governance is so urgently important right now. As digital networks permeate nearly every aspect of public and private life, and as the legitimacy of governing institutions steadily erodes, it is how we imagine interoperable systems that are person-, not institution-, centered, and how we build and sustain new institutions that can support democracy.

Material infrastructure refers to the tangible or immobile systems of the built environment. Projects falling under this category evaluate and/or intervene in the current practices and gaps within these systems.

Forgotten and buried, the veins of our city push deeper underground, reminders paved over and spoken about with hushed voices that fade into the background hum of a bustling surface.

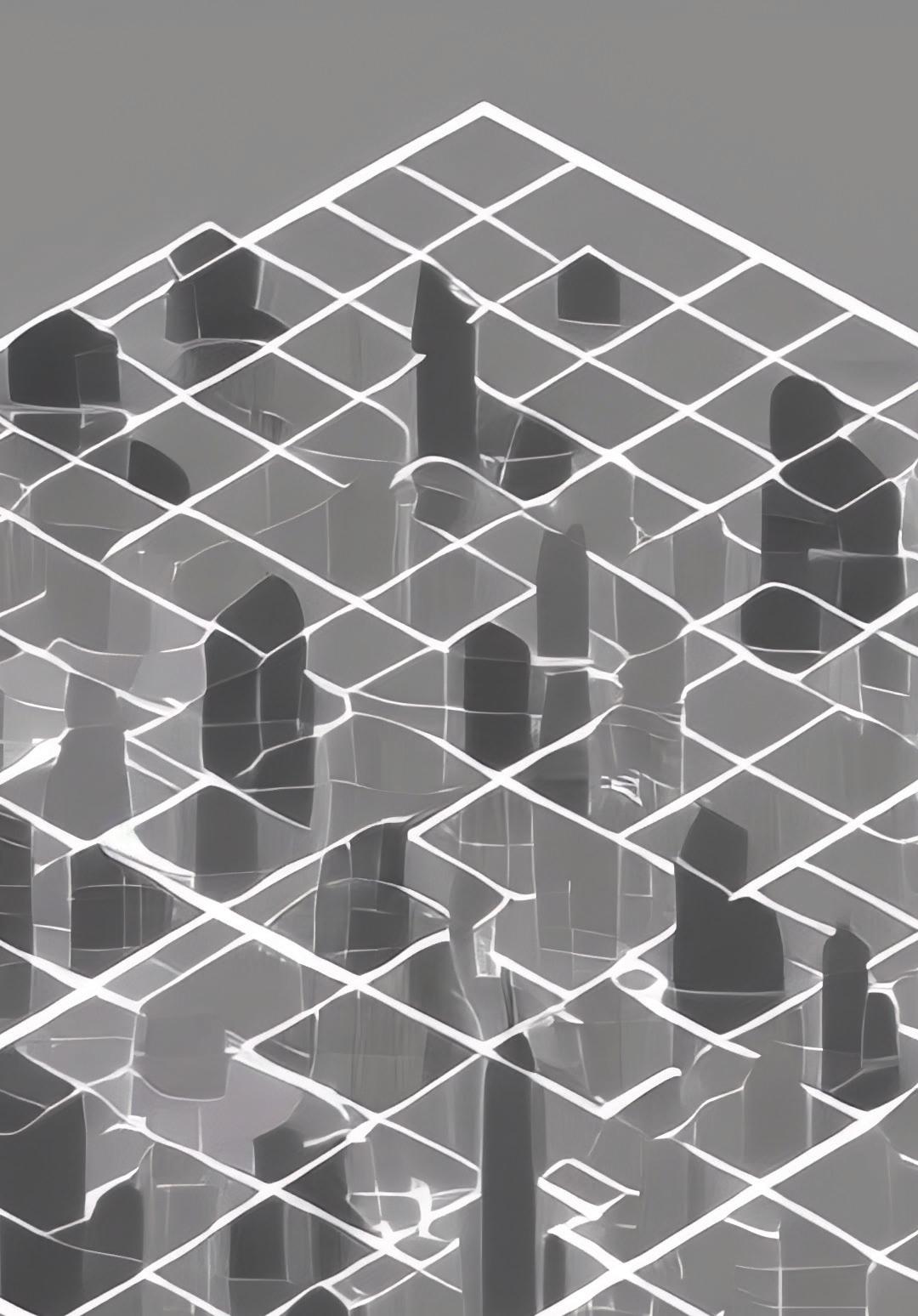

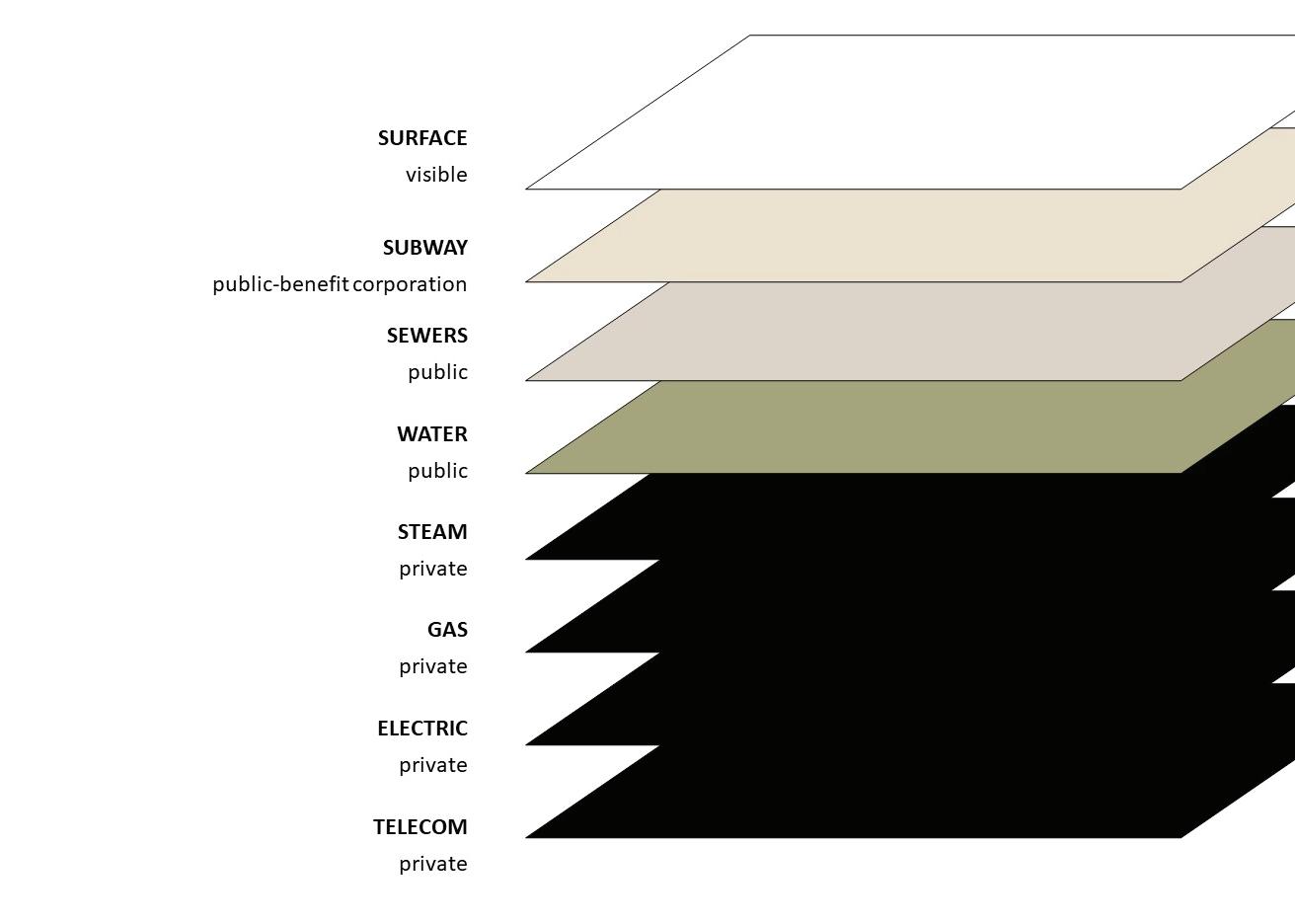

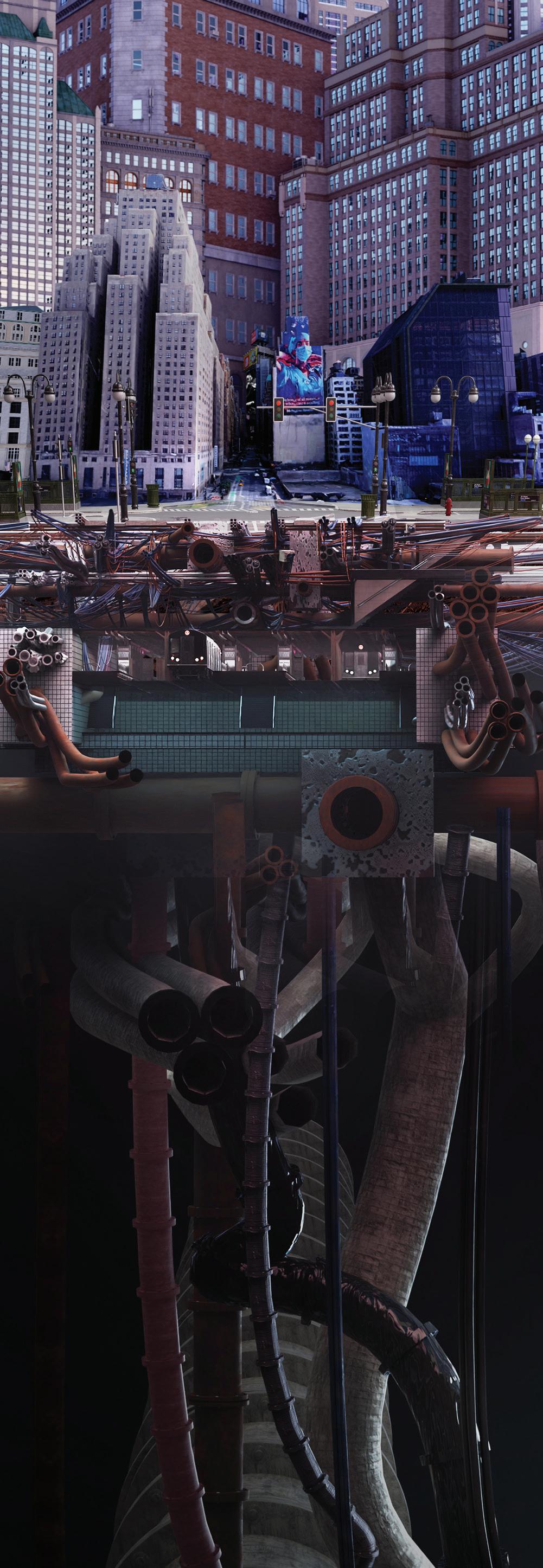

Beneath the vibrant streets of New York City lies a vast and intricate network of utility infrastructure. As time and unmitigated accumulation take a toll on these subterranean systems, challenges of reliability and safety become increasingly evident. Compounded by decentralized governance practices, the legibility of these utilities becomes obscured. Within the bowels of this underground labyrinth, entangled infrastructures reveal the collective beliefs, values, and aspirations that influence the decisions and actions of stakeholders involved in planning, maintaining, and expanding the underground, creating a social infrastructure that digs ever deeper. Amidst rising floods due to climate change, deteriorating infrastructure susceptible to natural degradation, ambitious plans for tripling the electricity grid, and the comprehensive OneNYC plan aiming for resource conservation and carbon neutrality which encourages momentum towards integrated smart city networks, there are a myriad of factors to contemplate. The recent passing of the two trillion dollar Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act further emphasizes the urgency for meaningful action that can improve both the reliability and legibility of the underground.

Exploring the interconnected realms of electricity, gas, water, sewer, telecoms, steam, and subway reveals an intricate tapestry of relationships between utility providers, government agencies, and stakeholders. This project aims to shed light on the underlying power structures and foster accountability among decision-makers, unveiling the dynamic essence of New York City’s utility networks by investigating the complex interplay of power and

time. Through visual representation, decisionmakers gain comprehensive insights into the interdependencies and interactions within this infrastructure. By visualizing these dynamics, decision-makers can be held accountable for their actions, facilitating measures that enhance infrastructure integrity, reduce repair costs, and minimize downtime. Armed with an understanding of these complexities, we can address the underground as a whole to ensure sustainable urban development beyond the surface.

This project amalgamates the experiences of over twenty professionals that interface with the underground - from the urban explorer, the borough commissioner, the author, the GIS mapper, the utility representative, the city science academic, the union representative, and various constituents in between. Within the historical records of the underground, a forgotten and abandoned multiplicity of explorations emerges, from pneumatic mail tubes to cow tunnels, burial sites, and pavedover trolley lines. These remnants create timelines that reflect a dynamic interplay, as ownership of utilities shifts between private and public domains. This intricate narrative reveals an ongoing interweaving of incentives for privatization and the pursuit of the public good. A cross-section of the city reveals a megalopolis that extends far below the surface. As we venture deeper into the depths of the earth, this intricate narrative guides us to the present day, a pivotal moment in the ever-evolving landscape of underground infrastructure.

Participants seize these separate and shared timeline threads and feel the weight of its governance, an intricate web of connections between public and private stakeholders. Conversations with and about this weight shape a new narrative, both further complicating and beginning to thread a collaborative path forward towards a more unified underground. How can stakeholders collaborate to think holistically about the past, present, and future

of the urban underground? This entails ensuring secure and accessible utility information, addressing challenges collectively, creating parallel timelines for work, organizing utility accumulation, prioritizing safety, and considering future scarcity. We must seize the opportunity to discuss the complexities of underground infrastructure, empowering decision-makers to make informed choices for an improved underground. By doing so, New York City can forge a path towards a resilient, efficient, and accountable utility infrastructure for future generations.

This project embraces a perspective that fosters accountability among decision-makers. Through data visualization, it unveils the roles and responsibilities of various actors, highlighting the interconnectedness that shapes the fate of the infrastructure. This heightened accountability encourages responsible decisionmaking, ensuring the alignment of interests, fostering collaboration, and enhancing the overall quality of the city’s infrastructure.

I approach the urban underground as a complex realm where diverse stakeholders hold distinct perspectives. Rather than imposing a singular solution, I facilitate a nuanced exploration of these perspectives, allowing participants to navigate and intertwine their views. This organic process fosters individual intersections and associations, leading to a dynamic and evolving understanding of the underground. Stakeholders navigate similar and opposing points of view within the context of an incident, entangling themselves in the process of disentanglement. Participants test associations, move on, and form new ones.

We (as collective stakeholders) must confront the challenges posed by decentralized governance practices that obscure the legibility of underground utilities. By unveiling the concealed cacophony of utility infrastructure, we aspire to lay the foundation for a comprehensive underground master plan that harmonizes functionality, sustainability, and resilience. By framing a holistic vision, we embrace the interconnectedness of these utilities and the weight each carries. By fostering a shared understanding of the underground’s complexities, we empower the development of an integrated plan that navigates the delicate balance between preservation and transformation, ensuring the longevity and adaptability of underground infrastructure in the

face of evolving urban challenges. Central to this visionary pursuit is a commitment to inclusivity and collaboration. We invite stakeholders from diverse disciplines, community representatives, and the public to actively participate in shaping the underground. Through dialogue, perspective sharing, and fostering a sense of ownership, we create a collective vision that resonates with the aspirations and values of the city’s constituents. The underground master plan emerges as a transformative force, breaking free from the limitations of surface-centric approaches, embracing the hidden depths, where the potential for innovation, efficiency, and sustainability lies untapped. As we bring clarity to the underground, we pave the way for a future where the subterranean landscape becomes an integral part of a vibrant and resilient urban tapestry.

Mary Soo Hoo Park, Boston

Ethica Burt

Representation of utilities under one intersection at 34th Street and 8th Avenue in Manhattan with available information and the entanglement of their respective governance timelines. Rendered in Blender, Wire Simulations created in Houdini

Mary Soo Hoo Park, Boston

Ethica Burt

Representation of utilities under one intersection at 34th Street and 8th Avenue in Manhattan with available information and the entanglement of their respective governance timelines. Rendered in Blender, Wire Simulations created in Houdini

When it comes to making sustainable design methods more accessible to communities and more locally based, decentralization and democratization are two of the most important factors. In the framework of green building standards, the LEED certification system has evolved into a universally acknowledged worldwide benchmark for environmentally responsible construction practices. On the other hand, it has been criticized for placing a higher priority on generality than on specificity, which might impair the responsiveness of sustainable design techniques to local factors such as climate, location, materials, and ways of life. The impact of Western-centered contemporary architecture makes this problem even worse. As a consequence, there is an increasing need to investigate ways to localize sustainable construction practices by decentralizing the framework under which building standards are now organized.

In sustainable design, striking a balance between international conventions and regional needs is one of the problems. While it is essential to have global standards for sustainable building practices, it is also critical to ensure that these standards are relevant to the community on a local level. For instance, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standard has been implemented in nations all over the globe, although it is not necessarily adapted to the specific requirements and conditions of each context. It is vital to establish a network of specialists that can convert global standards into local practices that are relevant to the local community in order to achieve the goal of bridging the gap that exists between global and local standards.

The economic incentive that drives the demand for sustainable building methods is another one of the challenges that comes along with sustainable design. There is a pattern where economic incentives are driven more by global demand than by the requirements of the local community. This might result in a

concentration of commercial structures rather than residential buildings, despite the fact that the latter are often more suited to meet the requirements of local communities. It is essential to place a priority on the requirements of individual homeowners and renters if one wants to encourage environmentally responsible construction practices beyond the financial benefit that they provide to companies and developers. This necessitates a change in the economic incentives that drive sustainable construction techniques, as well as a greater emphasis on the advantages that these practices may offer to people as well as communities. In sustainable design methods, there is a conflict between those who have specialist knowledge and those who have a shared understanding. On the one hand, specialty and expertise are needed to create novel and forward-thinking approaches to environmentally friendly design methods. On the other hand, there is a need for sustainable design methods that are easily accessible and widely adaptable so that they may be duplicated by local communities. Having a network of local specialists who can engage with the community to create new sustainable design techniques that are adapted to the demands of the local area is one method to overcome this problem. Having such a network is one way to address the issue. This may also assist in guaranteeing that invention is not privatized and monopolized, but instead shared with the larger community rather than being monopolized by a single company or individual.

This project utilizes various forms of technology that can help to achieve the goals of decentralization and democratization of sustainable design practices. Specifically, blockchain, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), smart contracts, and Web3 would help boost the accessibility, adoption, and application of sustainable design approaches. One potential use of blockchain technology is the development of a proof-ofstake system, which may be used to evaluate

and quantify green technological advancements or innovations. This may give a trustworthy assessment of the sustainability performance of a country, city, or neighborhood, which can attract investments and govern financial flows in a more environmentally responsible manner. The revenue that is produced by this method may be invested in the enhancement of critical infrastructure, such as sewage systems, which can contribute to the reduction of floods and the general improvement of the standard of living in the surrounding areas.

The establishment of a community-based sustainability practice that promotes the sharing of resources for the location in question as well as the environment in general, is yet another viable answer. By pooling their resources, local communities have the opportunity to collaborate on the development of sustainable design approaches that are adapted to meet the specific requirements of their environments. For instance, post-occupancy assessments may be used to evaluate the performance of sustainable building practices in real-time. Similarly, smart contracts can be used to withdraw badges or accreditation in real time if the performance of a building falls below the anticipated criteria. Both of these examples are ways in which real-time evaluations can be employed. In conclusion, the development of sustainable

design practices that are grounded in communities is essential to the decentralization and democratization of sustainable design practices. It is feasible to design sustainable solutions if one gives first consideration to the requirements of local communities and makes use of modern technologies to enhance accessibility.

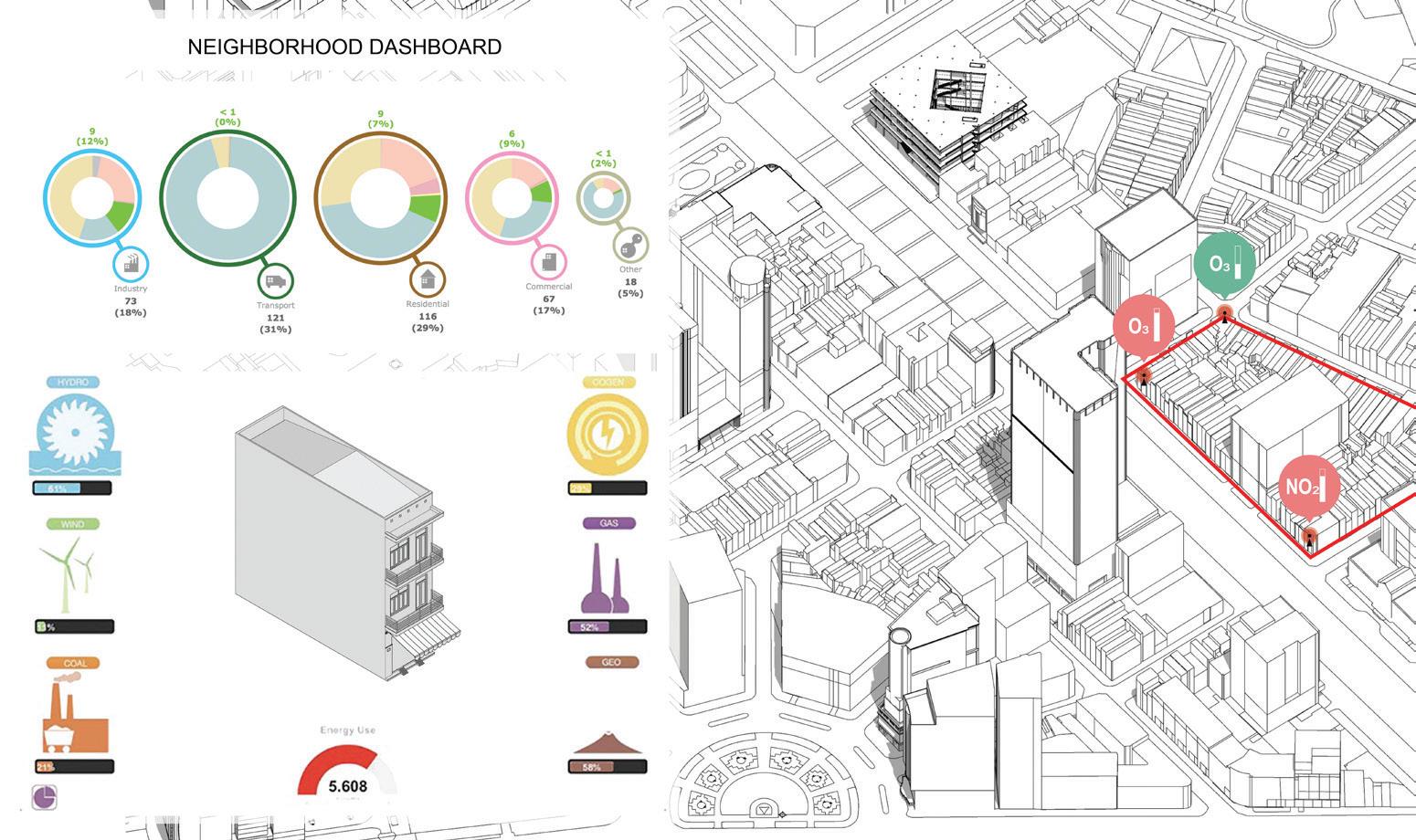

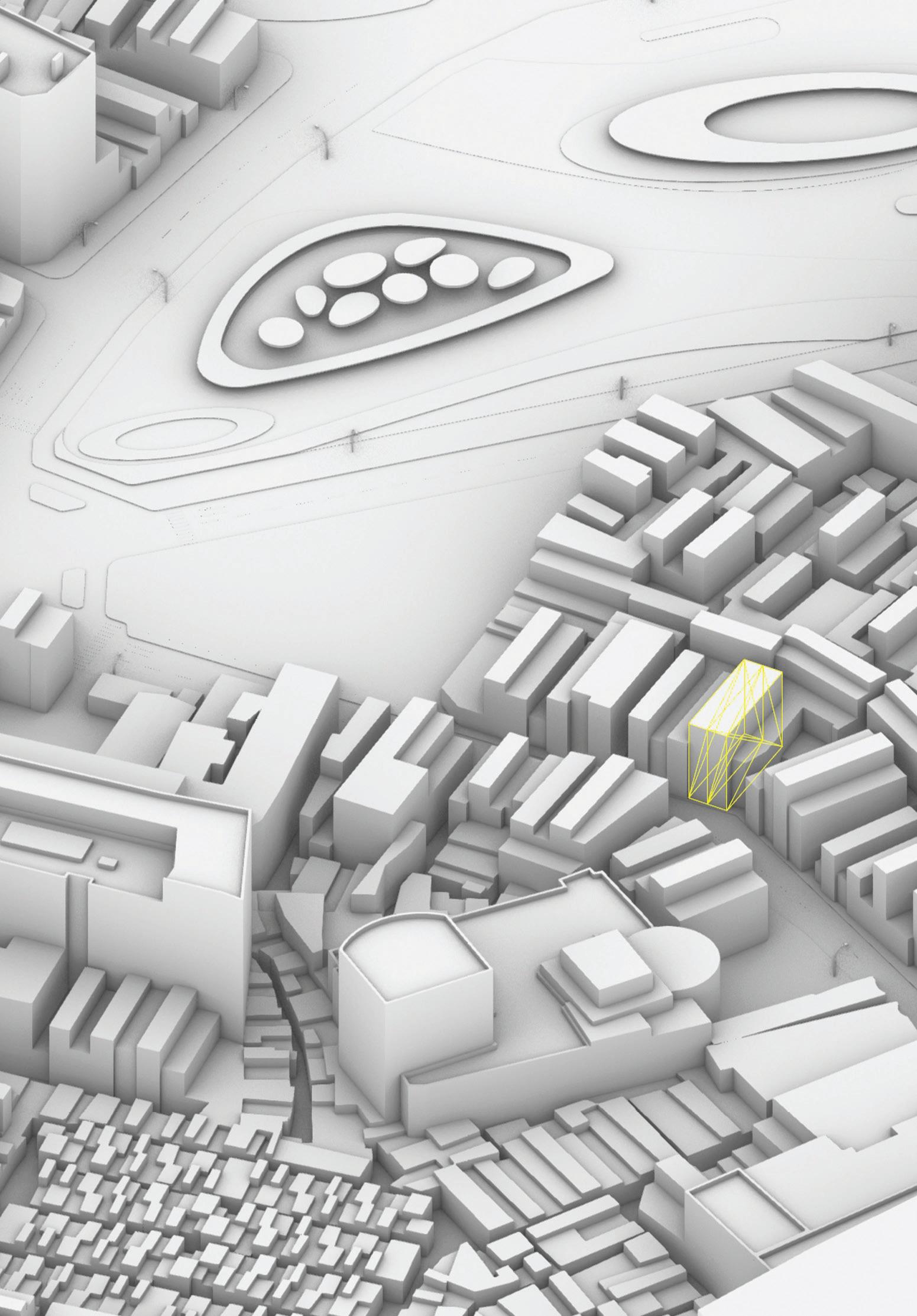

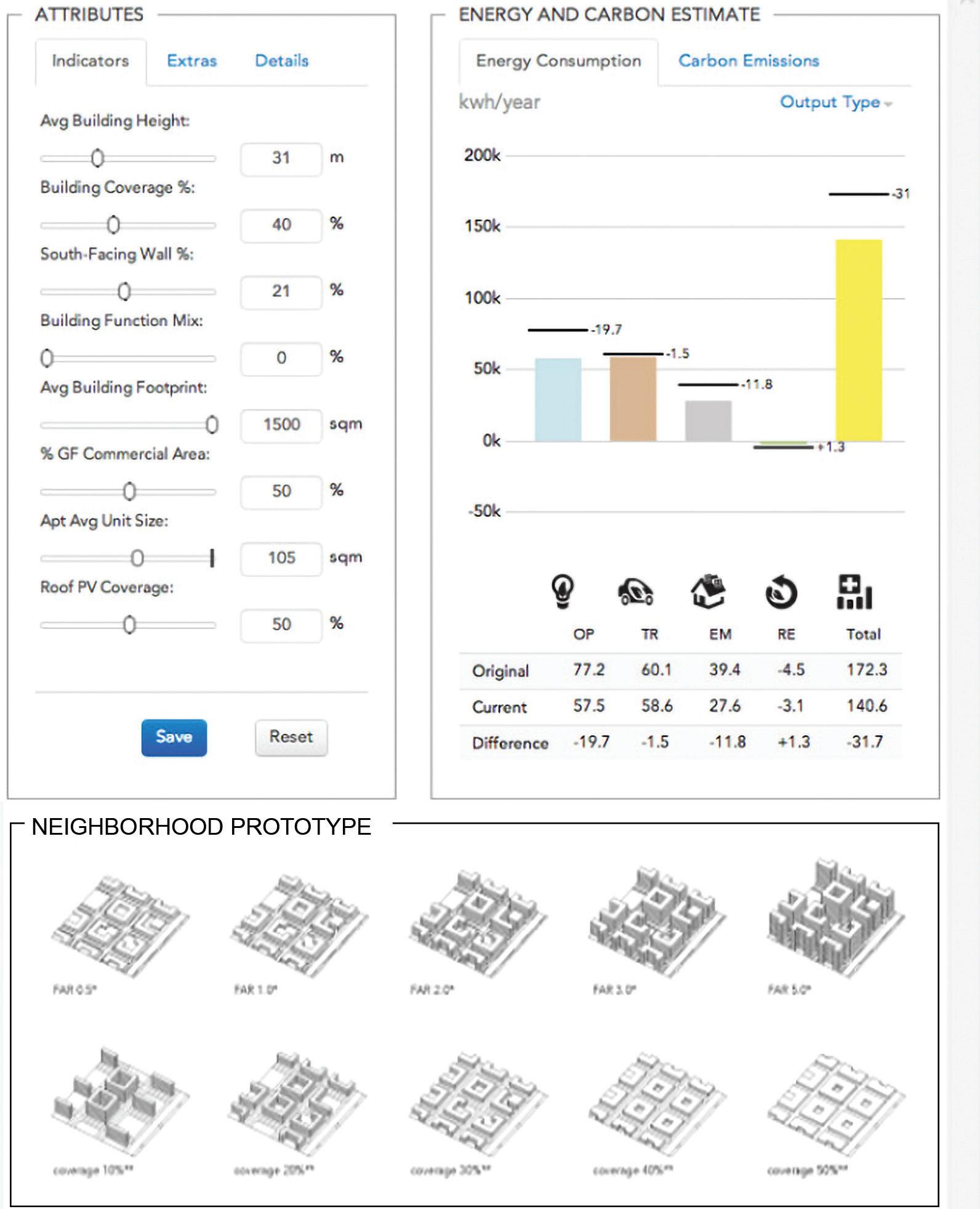

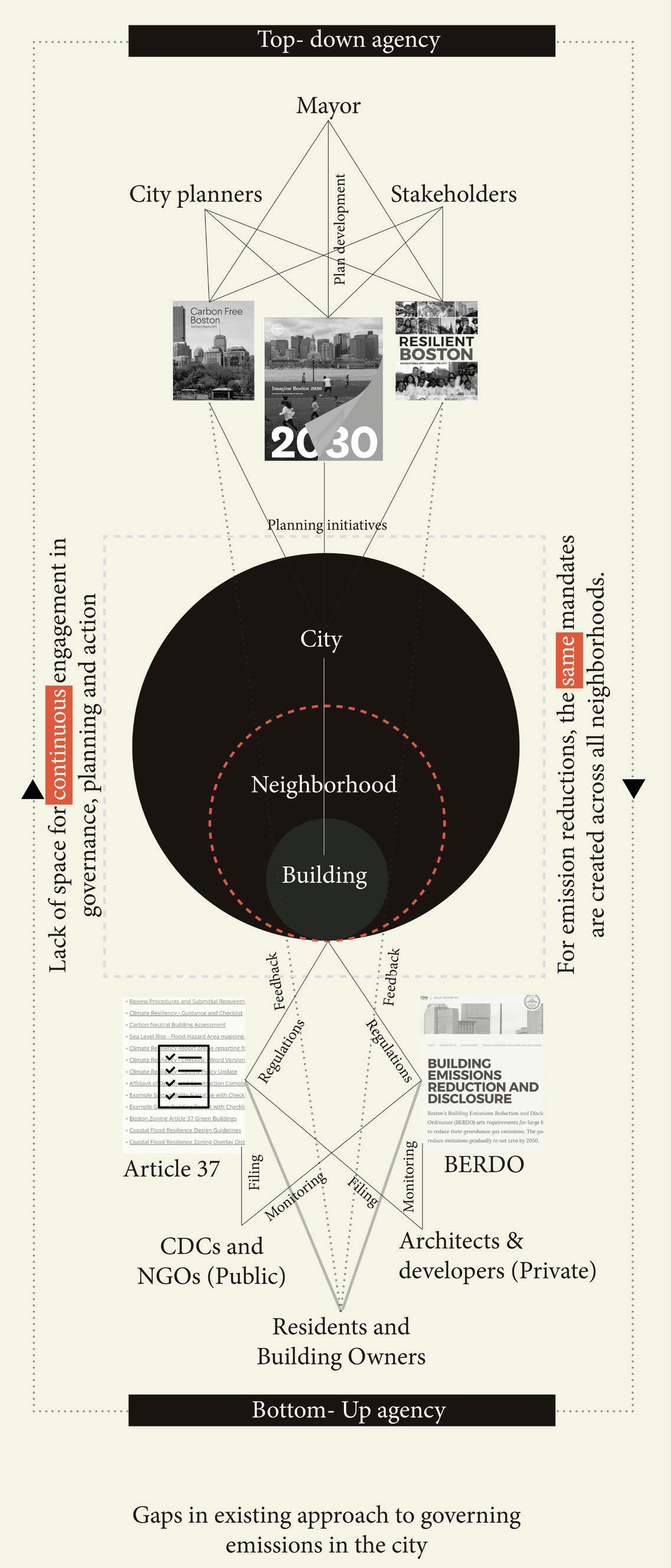

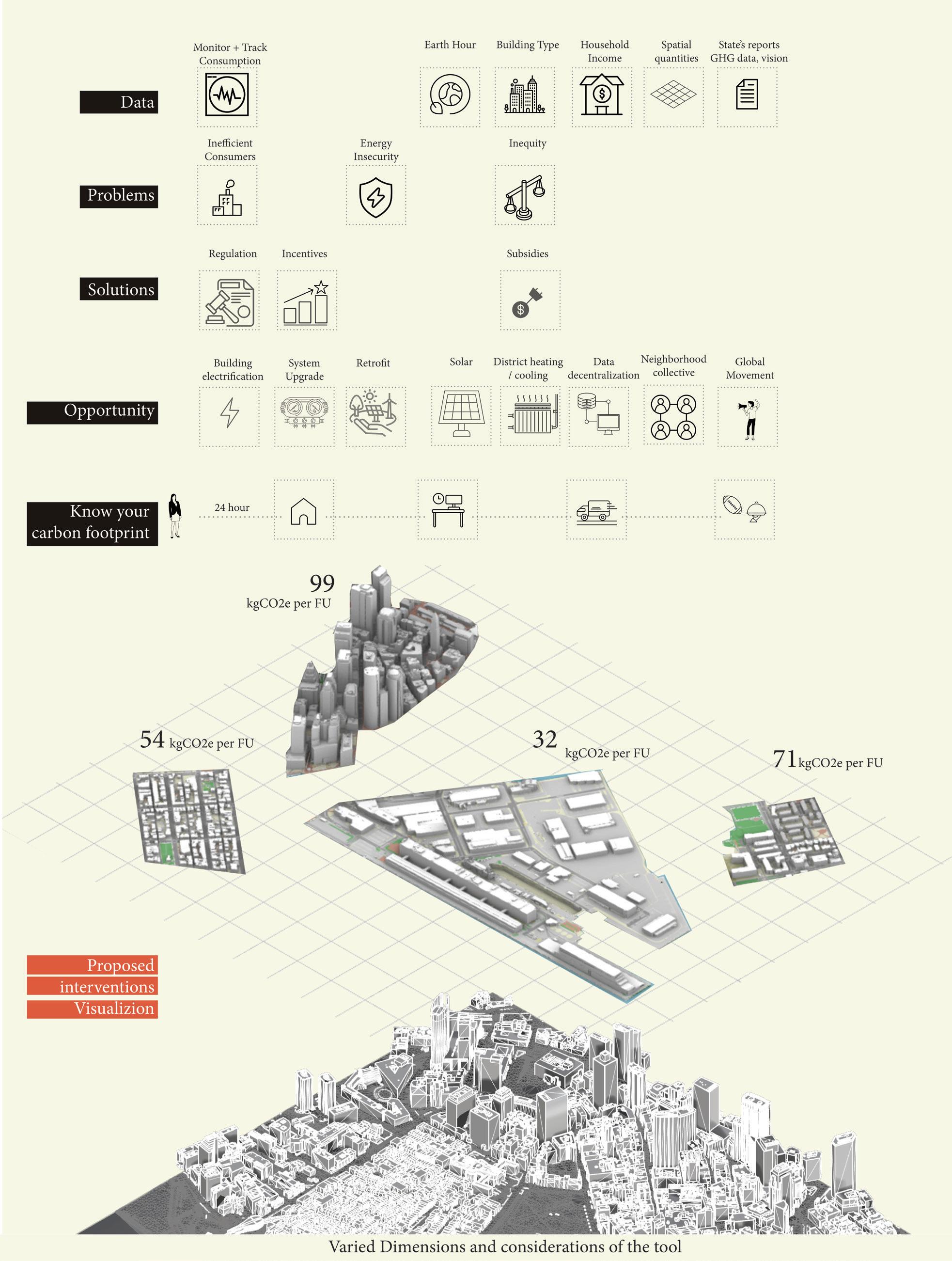

Reducing emissions is a pressing global issue. Boston’s Imagine 2030 plan is a city-wide initiative to address the problem, but it fails to address neighborhood scale solutions. The focus of this project is on creating an emission-based public-facing tool for building owners, intending to increase awareness among citizens and create informed decision-makers.

One of the primary challenges in reducing emissions is the question of scale. Existing policies, pilots, and regulations assess energy and carbon emissions aggregate data from individual buildings for cities, creating the same mandates across all neighborhoods in the process. However, the planning objectives for the City are set at a neighborhood scale. This discrepancy creates a gap in neighborhood-level governance from a bottom-up approach, which this project aims to fill.

Equity and accessibility are also significant considerations. This project seeks to move away from top-down agencies of territorial enforcement and policing through regulations and instead encourages community participation in shaping reduction goals in governance, planning, and action. To achieve this, the project aims to create a two-sided virtual tool for continuous engagement in governance, planning, and action.

The tool will allow planners to easily differentiate between optimal and excessive consumers and correlate emissions data with demographic data. It will also provide visualizations of neighborhoods’ performance over the years, monitoring and tracking retrofitting strategies’ effectiveness and creating neighborhood-specific strategies for retrofitting. On the citizen user side, the tool will provide future compliance checks based on BERDO emission standards and visualizations of energy retrofit scenarios.

The tool development will involve layering data such as demographic data, income, and

property taxes, land use, energy consumption, wealth, lived versus floating population, opento-built ratio, and climate awareness. Process improvement will involve interactions on the application, data flow from both sides, networks of users inside neighborhoods, and a nested system of local governance. Financial assistance such as loans, carbon trading, subsidies, and federal or state aid will also be incorporated. Social acceptance will be promoted through awareness campaigns and engagement in new project suggestions, and public perception will be measured through acceptance rates of pilot projects.

The tool will have a simplified interface to make it accessible to non-experts and it will be gamified to encourage public participation. Additionally, use by community development corporations and other nonprofit developers will be explored in order to create an inclusive methodology that can be embraced by a multiplicity of stakeholders.

In conclusion, reducing emissions is a critical challenge that requires a neighborhoodlevel approach. This project seeks to fill the gap in neighborhood-level governance by creating a two-sided virtual tool that allows for continuous engagement in governance, planning, and action. By incorporating data layers such as demographic data, income, and property taxes, land use, energy consumption, wealth, lived versus floating population, open-to-built ratio, and climate awareness, the tool will provide a comprehensive approach to reducing emissions. Financial assistance and social acceptance will also be incorporated, making the tool accessible to a wide range of users.

By gamifying the experience and promoting engagement, the tool has the potential to create informed decision-makers and increase awareness among citizens, ultimately leading to a reduction in emissions in Boston’s neighborhoods.

Economic infrastructure refers to the ways in which activities and interactions produce welfare through the distribution of wealth and capital. Interventions in this category facilitate the creation of networks between stakeholders through the design of services and strategies that promote the allocation of resources among different sectors.

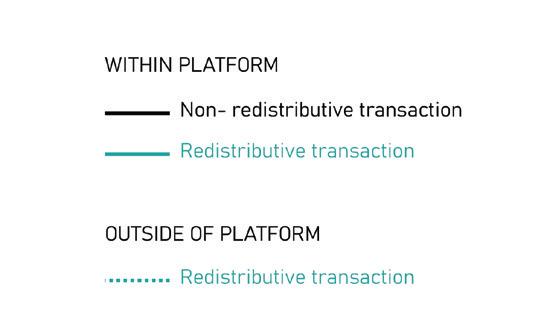

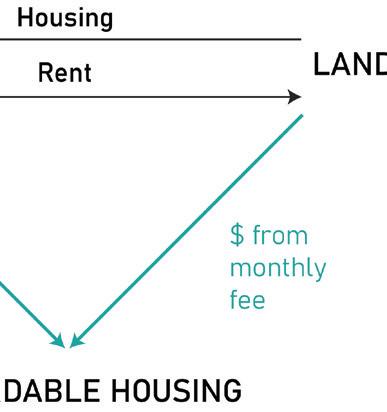

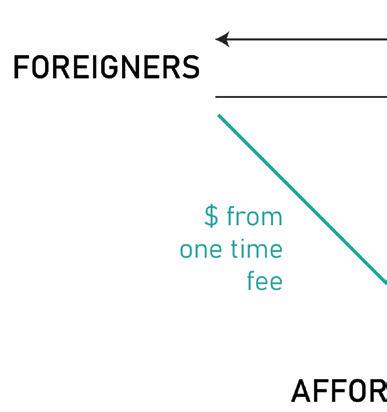

Transnational gentrification is a phenomenon driven by the mobile middle class citizens of the Global North visiting lower income areas of the Global South (as tourists, or short or long term visitors) for leisure, experiencing heritage zones of cities, and/or to benefit from the high value of American, Canadian, or Western European money in comparison to much of the Global South. This “touristification” is defined by a concentration of housing and services for visitors, which dominate the uses of public space and often cause both physical and emotional displacement of long time residents. The neoliberal policies and development practices that catalyze these changes in the economic and housing landscapes and that are promoted by municipal governments are rooted in antiquated beliefs around planning: that economic development of any kind necessarily benefits all citizens.

Mexico City is one such area that has seen a rise in transnational tourism and is currently struggling to figure out how to regulate short term rental platforms like Airbnb while also benefiting from the revenue brought in by tourism. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the city became a popular destination for foreigners from the US to live while working online. In two neighborhoods in particular, Condesa and Roma, Airbnb is a primary way that foreigners find housing, as is shown by a 30% rise in the use of Airbnb for long term rentals (over 90 days). The economic benefits from the presence of foreigners tend to stay concentrated in neighborhoods like Roma and Condesa where they live and spend money.

The continued development and rise in prices in Roma and Condesa are rooted in policies that began in the 1980s, when the city provided incentives to real estate developers to build in the area as well as other central neighborhoods in the city. We believe that the increase in foreigners living in Condesa and Roma, while not the primary cause or starting

point for gentrification in these neighborhoods, deepens already existing spatial, economic, and cultural divides in the city, primarily through contributing to an increase in cost of living. As such, we ask: How can we leverage technology to funnel wealth from accommodations for foreigners directly into affordable housing projects?

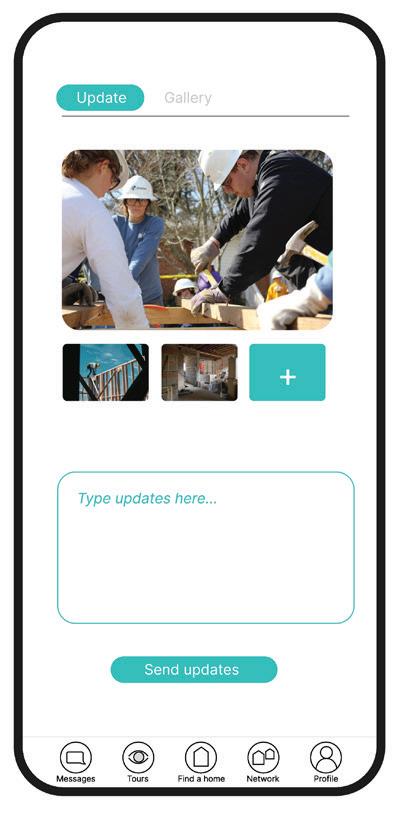

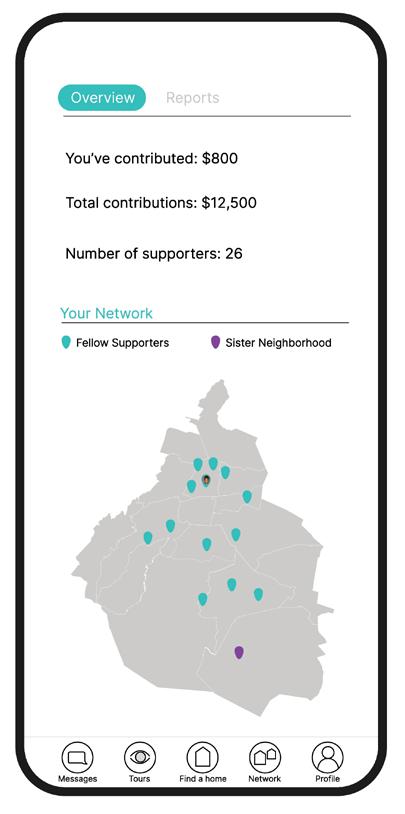

Our project imagines what redistribution of wealth could look like in the context of transnational gentrification in Mexico City. We think about technology as a mediator between the city, foreigners, landlords, and local organizations and residents, for whom accelerated gentrification following Covid has led to new dynamics and levels of mistrust/trust. Technology is a tool that can move resources across regions, and in doing so alter the physical, social, cultural, and economic fabric of the city. We propose a long term rental platform that channels resources to housing projects throughout the city.

Our design intervention seeks to leverage technology to move wealth around the city to contribute to minimizing these divides through a strategy of redistribution. We use Ravallion’s definition of redistribution as the “deliberate and systematic transfer of wealth, income, or other resources from one group or individual to another”. 3

Our design intervention proposes a long term housing rental platform that seeks to repair urban divides through a model of redistribution. It approaches this through:

1. A business model that funnels wealth from foreigners and landlords to housing organizations working with communities

2. Creating a user experience for foreigners, landlords, and housing organizations that emphasizes their app use as the creation of a network of support across the city.

In interviews, foreigners seeking long term housing expressed that they do not know who to trust and feel they are being taken advantage of by being overcharged, given unreasonable terms in contracts, lied to by landlords and real estate agents about what a typical’ contract is in Mexico, and/or asked to meet excessive requirements to rent. Landlords–those subletting spaces they live in and renting out full apartments–feared unreliable tenants who did not pay rent. Both parties recognized their role in gentrification, rising housing prices, while also feeling inevitability in development and a lack of viable alternatives. Our point of entry to collect capital to redistribute is to solve issues of mistrust between foreigners seeking long-term rental housing and landlords. We provide an easier documentsharing process and secure payment platform for foreigners and landlords.

Simultaneously, integrated into the platform is a model of redistribution of wealth from foreigners and landlords to organizations working on improving housing in the city. Foreigners and landlords pay to use the platform, and a portion of their fees is channeled to housing organizations.

Our user experience aims to make foreigners, landlords, and NGOs feel like part of a community that is working together to improve housing in the city. The design of the platform situates the users inside a network, enabling them to visualize themselves as part of a system, creating positivity around participating in a redistributive model within systems that are normally capitalistic.

We believe that redistribution can be a method of repairing existing economic, social, and political divisions in cities.

In an economy centered on redistribution, designers of sharing economy technologies would

1. Develop technologies that are situated within the larger economic, cultural, political and physical systems of the city.

2. Leverage the technology and the talent and assets it gathers to repair divisions in the city created by unequal access to resources.

3. Use the technology to connect and serve stakeholders beyond those who channel capital into the platform.

4. Create networks of support that span the city through using the platform to share resources among paying and no paying users of the technology.

5. Make visible for users of the technology their connections to redistributive networks that span the city.

1. Cocola-Gant, Agustín. “Apartamentos Turísticos, COVID-19 e Capitalismo de Plataformas.” Finisterra 55, no. 115 (2020): 211–16. https://doi.org/10.18055/finis20187.

2. Navarrete Escobedo, David. “Foreigners as Gentrifiers and Tourists in a Mexican Historic District.” Urban Studies 57, no. 15 (November 2020): 3151–68. https://doi. org/10.1177/0042098019896532.

3. Ravallion, M. (2019). Inequality, globalization, and redistribution. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 35(3), 491-508.

Social infrastructure is composed of the shared imaginaries that connect and build communities through narratives and values. These imaginaries reflect the physical, spiritual, and psychological geographies that fortify sense of place. Imaginaries bind people to people, people to communities, communities to societies, societies to states, and even states to states.

The gate to Chinatown in Boston

The gate to Chinatown in Boston

According to the French poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, borders, while they are often viewed as markers of exclusion or protection, can also be seen as facilitators of passage, communication, and relations. Boundary, which can at times exert a more prominent presence within the mind than as a physical object in space, is subject to continual change, fluctuating according to one’s sense of belonging. What can border conditions, tangible and intangible, reveal about the history of a place and its people? How can the erosion of physical borders impact the less definable, more visceral impressions of a place?

I apply these questions to examine the physical and psychological contours of Boston’s Chinatown in the minds of residents, visitors, and Boston’s Chinese American community. As a historically disinvested neighborhood undergoing gentrification, Chinatown is shrinking with the development of institutions, highways, and luxury condominiums. This destabilization not only reduces the neighborhood’s footprint, but it also contributes to the erasure of personal and historical narratives.

How might we fortify Chinatown’s significance as a historic district and a symbol of a thriving Chinese American community in the Boston metropolitan area by documenting its place identity? Through visual representation informed by observations and interviews, this project captures Chinatown’s sense of place in order to project it as an integral part of Boston.

Boston’s Chinatown is a historic neighborhood with a rich culture that has been the home to Chinese immigrants since the 1860s. In the past few decades, Boston’s development, including highway construction, institutional expansions, and urban renewal efforts, has turned the previously undesired space into an area of interest. Given its proximity to downtown and Tufts Medical Center, the neighborhood has

become a hotspot for new businesses, tourists, and working professionals. Today, the lack of affordable housing and the emergence of Airbnb and short-term rentals displaces Chinese American residents who have lived in Chinatown for generations.

This issue is exacerbated by the fact that there is limited availability of land to build more affordable housing as the district is hemmed in by highways I-90 in the south and I-93 in the east. Furthermore, Chinatown is undergoing a steady demographic shift as a new wave of working professionals in their mid-20s to late 30s are replacing working-class Chinese American families as the new residents of Chinatown.

How do these rapid changes impact how Chinatown lives in the hearts and minds of Boston residents? How can we preserve its sense of place and ensure its resiliency through inevitable future developments?

We might examine the psychological contours of Chinatown by first looking at what a “sense of place” entails. “Place” is a state of being that is difficult to pin down on a map yet is undeniably enmeshed with location. The notion of “place” encompasses qualitative aspects of experiencing space through all five senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, and the memories and impressions they evoke. Place is invisible yet hyper-present as it exists beyond any physical boundary and lives inside the mind as a form of visceral knowledge.

In order to understand Chinatown’s sense of place, I went to speak to locals and visitors about their impressions of the area. Through an interactive activity where I gave each of my interviewees a map and asked them to draw a border around where they think Chinatown begins and ends, I examined how impressions of a locale can represent itself through cartographic means. This exercise revealed how the boundaries of Chinatown fluctuated

wildly for Chinese Americans who lived in or frequented Chinatown and visitors from outside the district. Visitors and those who only visit Chinatown for restaurants and shops mostly circled Chinatown’s commercial area above Tufts Medical Center. In contrast, Chinatown residents or visitors with relatives in Chinatown circled a much larger portion extending further south. Each interviewee applied different criteria to determine whether or not an area could be identified as part of the district. Some people pointed to the presence of Asian supermarkets, such as C-mart, to guide their pen, whereas others recounted seeing Asian Americans in a particular area to justify their boundaries. The criteria applied, consciously or unconsciously, reveal different perspectives on what constitutes Chinatown’s “sense of place.” Collated, the maps start unveiling Chinatown’s multifaceted identity and significance in the context of Boston’s metropolitan area.

After several rounds of interviews, I realized that Chinatown is significant not only for Bostonians but also for the greater network of Chinese Americans in the Greater Boston Area. According to Barry Wellman, a Canadian American sociologist whose work focuses on social networks, far from the assumption that a sense of community decays with the decline of locally organized behavior, communities exist as a “spatially knit, spatially dispersed, ramifying structure instead of being bound up within a single densely knit solidarity.” Even though its physical boundaries are evolving, Chinatown is still an enduring symbol of community across the diaspora of Chinese Americans in Greater Boston. There is something powerful about the ability to point to a map and locate the cultural center and heart of a community.

Through the collection of personal narratives, this project maps the imaginaries of Chinatown held in the hearts and minds of Boston’s Chinese American community in order to represent the unique psychological and physical landscape of Chinatown. Exploring the relationship between space and place, the defined and the undefined, the official and the unofficial, this project documents the place identity of Chinatown and projects it as an integral part of Boston.

1 Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation. Directed by Diawara, M., Featuring Édouard Glissant, Third World Newsreel, 2010.

2 Wellman, Barry. “The Community Question: The Intimate Networks of East Yorkers,” American Journal of Sociology, Mar. 1979, pp. 1201-1231.

Mapping Place Identity: The Physical and Psychological Contours of Boston’s Chinatown

Mary Soo Hoo Park, Boston

Mary Soo Hoo Park, Boston

Information infrastructure refers to the underlying foundation of systems, processes, and technologies used to collect, manage, and disseminate information and their social impact on privacy and civil liberties. It includes the various databases and networks that are used to store, process, and share information between different institutions and constituents. The information infrastructure serves as the backbone for facilitating communication, collaboration, and decision-making among these stakeholders, and plays a critical role in ensuring transparency, accountability, and protection of civil liberties in the use of surveillance technologies. It is central to how society communicates and learns.

In recent years, the way humans compile, disseminate, and access information has advanced significantly with the rise of digital devices, the Internet, big data, and machine learning. Mobile devices have made it easier for people to access information from virtually anywhere, at any time. Search engines and online databases have made it possible to find information quickly and easily, and social media platforms have enabled people to share information with a wide audience.

Despite the many advantages of modern information infrastructure, it presents significant challenges and disadvantages when it comes to accessibility, understandability, and trustworthiness, particularly for new immigrants. The sheer volume of available information can make it difficult for new immigrants to find relevant information. Moreover, information can be both redundant and scattered across numerous platforms, making the search process time-intensive for their often already busy lives. Accessing information is made more challenging for those who face language barriers or are not tech-savvy. These difficulties create significant barriers to accessing vital information and resources, hindering new immigrants’ ability to trust and use the information to integrate into their communities, access services, and find help. Because new immigrants face a considerable disadvantage in navigating modern information systems, they may feel excluded and unsupported that further prevents them from integrating into their new surroundings.

Libraries have historically been viewed as places of knowledge, information, and learning, and as such, they have the potential to serve as a hub for informational and social exchange. They offer physical spaces and resources that are often free and open to all members of the community. Libraries also have a reputation for being trusted sources of information and inclusive spaces; however, these benefits may not be readily accessible to immigrants due to a lack of funding

and staffing. Understanding the limitations and strengths of the public library, can we leverage the trust people have of libraries and use it as a bridge to connect resources in and beyond the library? Can the digital public library take on a different form for new immigrants that not only pool information and resources but also create new knowledge? Can the digital library be more community-driven and allow for better public processes to help new immigrants integrate into their communities?

I interviewed immigrant adults from China through my personal network as well as residents of Boston’s Chinatown; I also interviewed a library learning program instructor and library coordinator from the Boston Public Library to have a clearer perspective. From the conversations, it became clear that there are four user pain points involved with information:(1) lack of trust for information on the web; (2) the scattered nature of information and lack of personalized content to help expedite the search process; (3)absence of certain resources; and (4) lack of language options. It also became apparent that immigrants naturally trust the library, yet at the same time, public libraries do not have the capacity to offer enough support to them. Although partner organizations do offer a wide variety of services, they are very disconnected from the library, so these resources are scattered for immigrants. Lastly, there were no options for these institutions and organizations to gain feedback from the users to improve their offerings. Understanding these challenges and opportunities, my project investigates: How might we give more agency to new immigrants to take charge of their integration into their new communities through more accessible and trustworthy information creation and sharing?

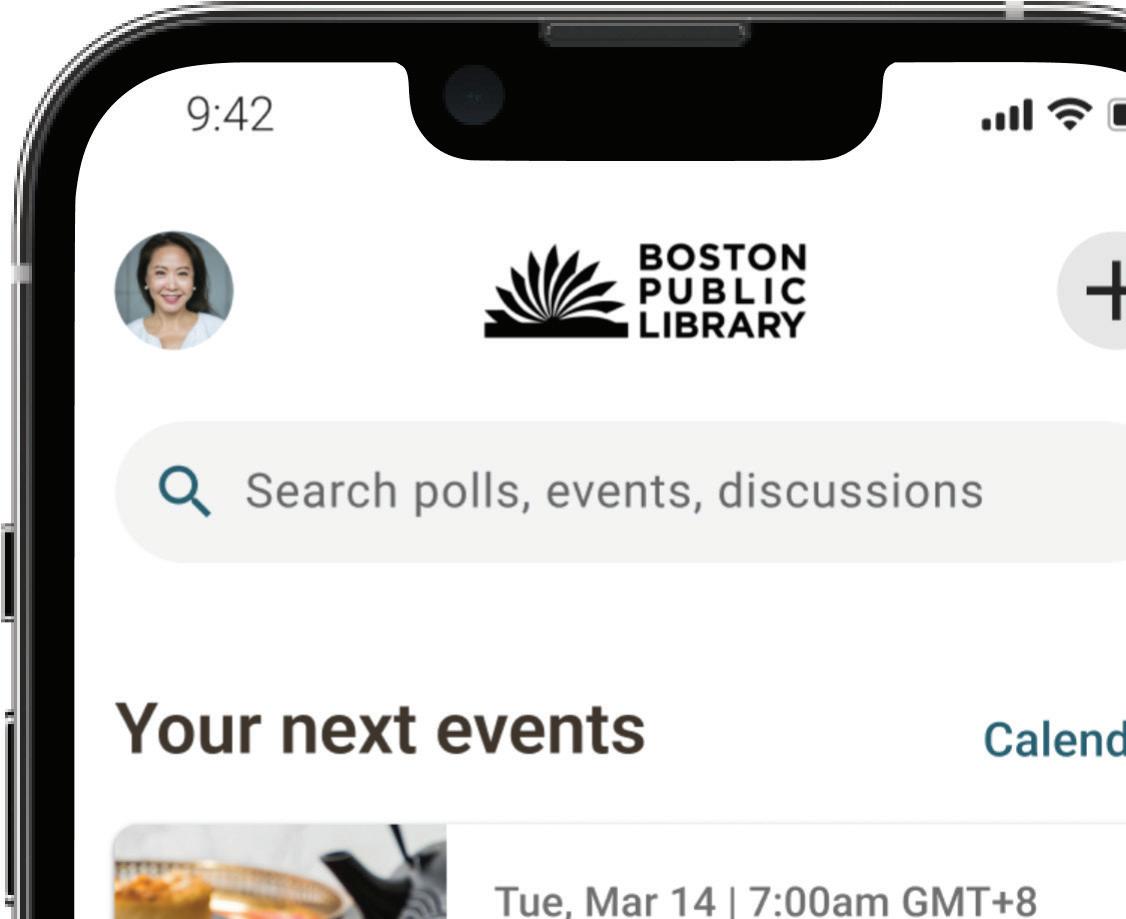

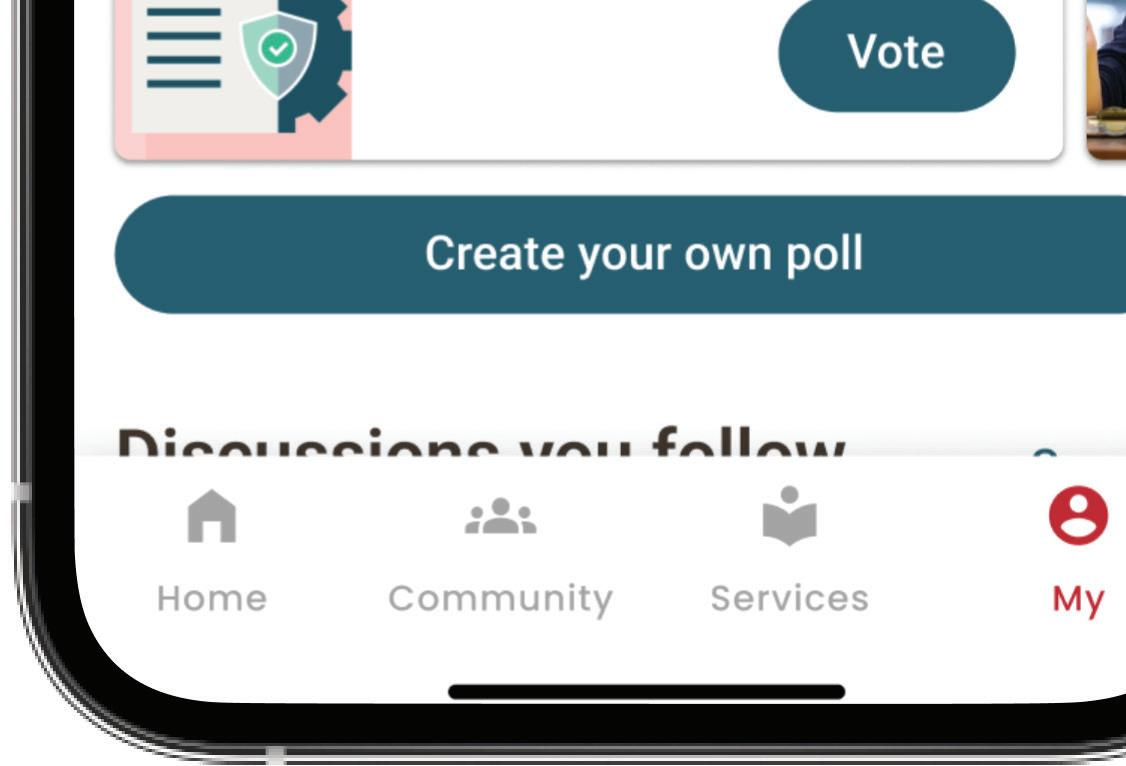

This project aims to promote inclusion, agency, and social cohesion for immigrant adults by leveraging the library as a resource and trust bridge. The proposed solution is an

online platform in the form of a mobile app that is accessible through the Boston Public Library’s website, specifically targeting new immigrants. After rounds of user testing and associated design iterations, the application has four main functions:

1. Resource Hub and Trust Bridge: The platform acts as a user-friendly central hub for resources, bridging the trust that immigrants have in public libraries with other organizations and services that provide resources to immigrants.

2. Knowledge Creation: The platform’s community feature enables users to form groups, create discussions, and upvote information that they find most relevant, thereby creating a system of collective knowledge sharing. This feature helps to address the challenges posed by scattered and difficult-to-trust information by allowing communities to collaborate and share their experiences, insights, and expertise. By promoting knowledge sharing, the platform facilitates the creation of new knowledge and fosters a sense of community among users. Democratic Public Processes: The platform enables democratic processes by allowing immigrants to advocate for their needs through creating polls and voting for resources and services that the libraries and partner organizations can provide. This feature empowers immigrants to take

control of their own learning. By allowing immigrants to have a say in the resources and services they need, the platform promotes a sense of agency and autonomy, helping immigrants to feel more connected and supported in their new environment.

3. Personalization: The platform’s onboarding process enables the application to learn about users’ specific needs, allowing it to push personalized resources to them based on their preferences. Additionally, the app’s customizable language and display settings allow users to access content intuitively in ways that are most comfortable for them.

The platform addresses the issue of scattered and difficult-to-trust information by creating a centralized platform that compiles resources in one place and offers personalized resources to the user through the library and its partner organizations. It tackles the lack of funding and staffing for adult learning programs by leveraging technology to create collective knowledge sharing among communities of immigrants. Finally, it addresses the issue of social exclusion by creating a democratic process that empowers immigrants to advocate for their needs and take agency in their own learning and integration. The platform’s ability to personalize resources for each user through the library and partner organizations offers a more efficient way for new immigrants to access relevant and reliable information at their fingertips.

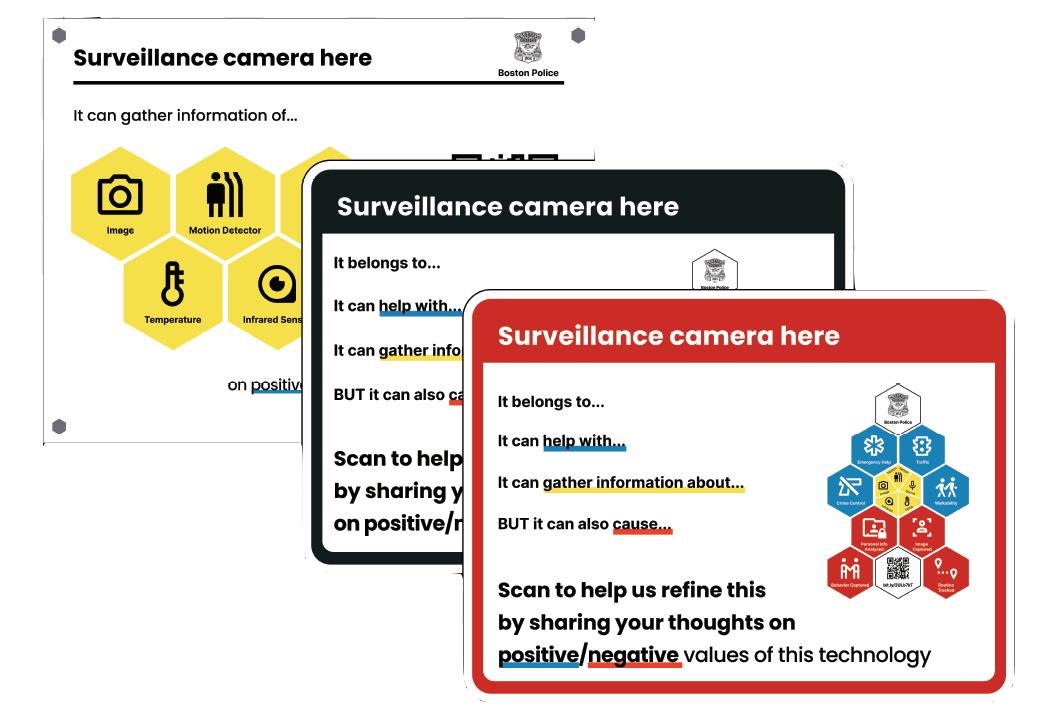

Have you ever noticed the surveillance cameras as you walk down the street? Do you know what kind of information is being collected - public or private - and how it can impact individuals and the city? Does the presence of more surveillance cameras make you feel safer or, conversely, less secure? In areas like Boston’s Chinatown, where there is a high level of surveillance, these are important questions to ask. But surprisingly, many residents, business owners, and visitors are unaware of the abundance of surveillance cameras in the area, let alone have a say in their deployment and current usage.

But even when people try to become involved, it’s undeniable and unfortunate that the communication channel is blocked. Currently, the conversation around the use of data surveillance technology is happening primarily at the municipal level, between the government and private technology companies. This conversation excludes the voices of the public, which means that decisions around surveillance technology are often made without consulting the community’s values or opinions. This exclusion can lead to a lack of transparency and accountability, eroding trust between the government and its people. When individuals feel that their voices are not being heard, it can lead to feelings of alienation and distrust in the authorities. This lack of trust can be particularly detrimental in areas like Boston’s Chinatown, where a strong sense of community is essential.

The issue of surveillance technology is more pressing now than ever before, as it rapidly expands in use. It’s crucial that we understand how it affects us, particularly in areas like Boston’s Chinatown where awareness of the surveillance cameras is worryingly low. So I ask: How might we increase the participation of underrepresented populations in the governance of surveillance technologies in Boston’s Chinatown?

Due to low levels of awareness and participation in the area, the first step is to start thinking and talking about it. But where do

we begin? Let’s start by looking at how people receive information about these technologies. Often, the only information people receive is from small, ominous signs saying “You are under CCTV 24/7,” “Smile, you are under surveillance,” or “Trespassers will be prosecuted.” But what do these signs actually tell us, besides the fact that there is a camera in use?

The reality is that these signs do very little to inform the public about the values and implications of surveillance technology. Instead, they leave people with a mix of emotions, including concern, suspicion, threat, safety, security, monitoring, watchfulness, privacy, intrusion, paranoia, reassurance, indifference, apathy, and normalcy. This mixed response reflects the complexity of the issue and the need for greater understanding and dialogue.

So, how might we raise more awareness and understanding of surveillance technology in Boston’s Chinatown? We need to understand the implications of surveillance technology. People’s concerns go beyond the mere technical specifications of the cameras or other devices in use. Rather, they care about the values and implications surrounding its use that relates to their daily lives. In Boston’s Chinatown, residents might ask: Can surveillance technology make our neighborhood safer from crime? Can it help us track traffic flow and reduce congestion? Can it contribute to cleaner streets with fewer pests and litter? These questions are invaluable because comprehending the technology from the perspective of people is the key to the goal of this project.

The aim of this project is to address the pressing issue of the use of surveillance technology by designing a solution that raises awareness, conveys information, and enables people to comprehend these technologies for themselves. I seek to understand the pain points experienced by people in their daily lives, and to design a set of easily understandable materials that effectively communicate the functions and values of these technologies.

This design intervention proposes the utilization of multiple mediums, including signs, videos, a physical game, and interactive app platform, to effectively present information and activate participation in a clear, accessible, and engaging manner.

The video component showcases what a common surveillance camera can capture when placed in public areas and everyday locations, thus providing a visual representation of the surveillance technology in action. This approach aims to introduce people to what is actually being captured by the camera, thereby increasing their understanding of the technology.

created by others, reflecting their understanding of the values associated with a particular surveillance device. Participants can then create their own value map, a process that encourages reflection and a deeper understanding of the technology.

Overall, the proposed design intervention aims to empower individuals by enabling them to comprehend surveillance technology for themselves. By utilizing a range of mediums to present information, this project seeks to make the technology more accessible and engaging for individuals.

The physical game is an interactive element of the intervention that is designed to engage individuals in the Chinatown area. Participants are invited to play the game on a physical whiteboard by moving magnetic icons around while considering the trade-offs of specific surveillance devices and their key values. This activity is intended to encourage critical thinking around the technology for people themselves. The activity can be conducted as a workshop or as a casual group session, providing an opportunity for participants to engage with the topic in a relaxed and engaging setting.

For the long term, the interactive app platform will enable individuals to scan a newly designed sign mounted next to a specific surveillance device, which conveys information about the type of information gathered by the device. Participants can see the value maps

In conclusion, this design intervention is not the only solution to the issue of surveillance technology, but rather the first step towards raising awareness and promoting understanding among the public. By presenting information in an accessible and engaging manner, my aim is to inspire individuals to become more concerned and actively involved in considering the implications of surveillance technology for themselves. The value maps created by participants through the physical game and interactive app can provide valuable insights to help inform government decisions and policy-making. Ultimately, this project aims to promote a more transparent and equitable use of surveillance technology.

Communication and information sharing have been an integral part of human history, evolving from ancient civilizations like Egypt and Greece, where hieroglyphics were used to record important events, to modern technologies like telephones, radios, and telegraphs. However, each evolution of information sharing has come with its own set of disadvantages. Hieroglyphics, for instance, required specialized knowledge and were limited in accessibility. Similarly, radios and telephones in their early stages were inefficient and inflexible modes of communication. Even though today’s society is equipped with such sophisticated modes of communication, we are facing an unprecedented informational challenge.

Recent technological innovation has completely rocked the global information infrastructure. The foundation of systems and processes has undergone a complete overhaul, presenting both positive and negative implications. On the one hand, technology has bridged gaps between individuals from different backgrounds, countries, and social statuses. Social media platforms, for instance, have enabled individuals to connect with people in advantageous positions, unlocking economic opportunities and improving their lives. However, this universal access has resulted in a problem of volume, where the sheer amount of people who can contact a single person can be overwhelming and difficult to manage.

The issue described above is a natural occurrence that is a result of the design inadequacy of new technology. Unfortunately, ease of communication has also exposed the incorrectness of information to a wider audience, leading to a rise in misinformation and a proliferation of false narratives. The malicious use of technology to promote damaging narratives is one of the most significant challenges we face today. Regrettably, technology has not proven to be very good at countering this problem, even the most recent advances in artificial intelligence has come up short in this.

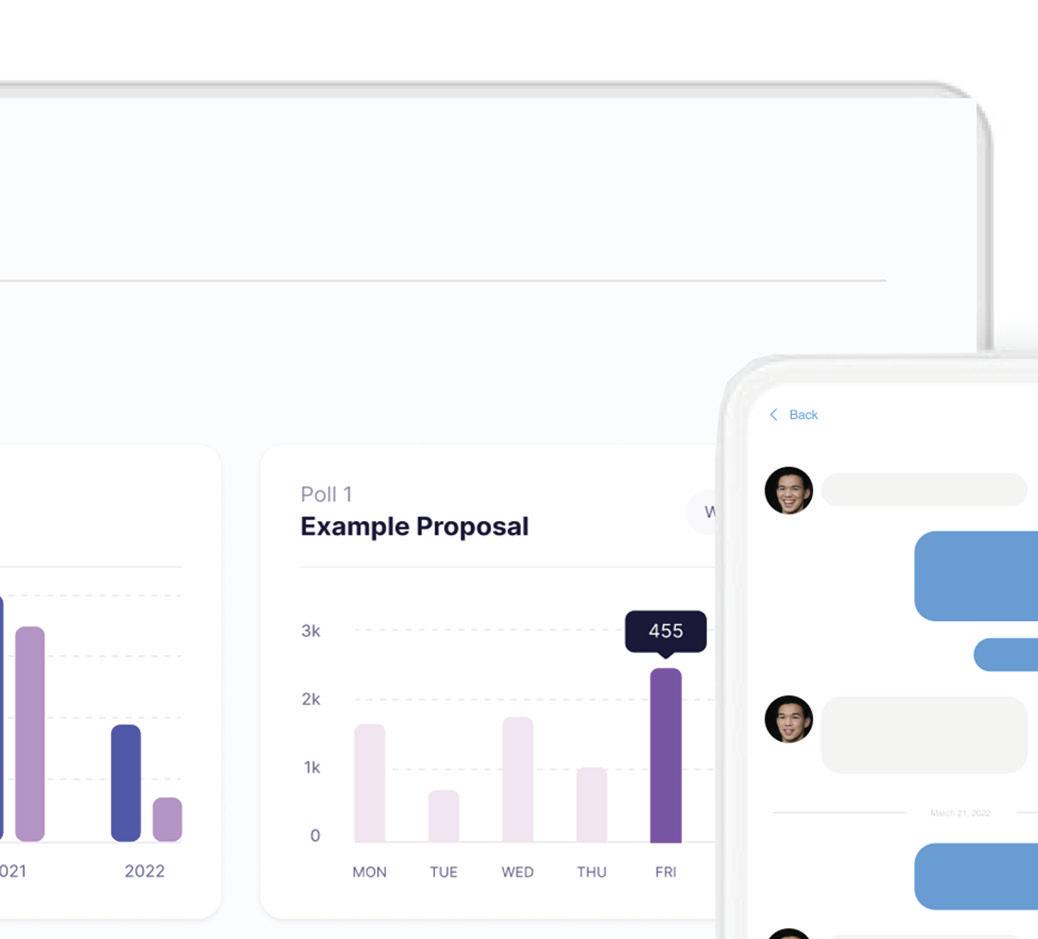

Artificial intelligence does, however, present an interesting case study to resolving certain problems that the earliest stages of the pandemic have brought to the information space.

The pandemic was a global crisis that quickly overwhelmed our informational systems. The crisis revealed the limitations of our communication channels and decisionmaking processes. Individuals from all over the world were grappling with a multitude of questions that were sometimes unique, but oftentimes identical. This flood of inquiries was predominantly directed at a limited number of people who were responsible for communicating and making crucial decisions within various institutions. The sheer volume of communication made it difficult for those who were tasked with responding to queries to effectively sort through them. As a result, information seekers were left feeling frustrated and confused because decision-makers were unable to answer their questions in a timely manner due to their busy schedules.

The difficulties brought by the pandemic globally were present in the microcosm of Harvard University. To gain insight into the students’ experiences, I conducted interviews across five Harvard schools, which highlighted three major themes: transparency, infrequency of communication, and ancillary problems. Students expressed concerns about the lack of information regarding ongoing developments, whether the faculty was working to address their concerns and by the fact that communication updates were issued infrequently. Ancillary problems were unforeseeable problems that were an indirect result of the disruption caused by the pandemic. For example, students on a leave of absence were unable to participate in student clubs because they were technically no longer a student, this resulted in some students losing leadership positions that they were in line to receive.

To gain a broader perspective, interviews with members of faculty and administrators

were also conducted. One persistent issue was the difficulty in managing the influx of emails during select moments. This issue was strongly related to challenges of transparency and infrequency of communication that was faced by the students.

While predicting ancillary problems is challenging, AI is well-positioned to address the other issues identified. The strength of AI lies in its ability to recognize patterns, which could have been leveraged by decisionmakers to address similar questions that were asked by many individuals. AI can bridge the missing informational layer between faculty, administrators, and students.

The final design of the project will consist of an AI-powered messenger that allows students to discuss the effects of the next public health crisis with each other. This will help build up valuable data that faculty can use to better understand the issues that students are most concerned about. Additionally, the messenger will feature an AI assistant that can provide more direct interaction with students. This means that students will be able to ask specific questions, and the AI bot will direct them to the specific parts of Harvard’s web pages that contain the answers they need. The AI bot will also show the stage at which particular requests are, so students can see if their questions have been received by the relevant

However, there are several prerequisites to the successful adoption of AI, one of which was a central discussion throughout my project: how to gain access to data. Tracking emails and calendars of faculty and administrators could provide the necessary information for the AI to understand what is being discussed and worked on, but it may be infeasible due to privacy violations.

An alternative approach is to create a dedicated email address or chatbot that would be used only during crises and would be tracked. For the AI to provide updates of meetings and different decisions, faculty and administrators would still need to record the contents of meetings and make them available to the AI. This could be achieved through maintenance of detailed meeting minutes.

decision makers, and to see how departments have responded to their requests. While this project shows promising potential for positive change in the context of universities, it is important to acknowledge the potential negative implications of using AI in similar ways at other institutions. AI models require access to data, and in the context of a public health crisis, this data may include sensitive information. The need for data can act as a precedent for institutions, especially governments, around the world to push their jurisdictional boundaries to gain access to more data than they need.

Throughout history, technology has demonstrated its ability to improve various aspects of daily life, including healthcare, finance, business, and navigation, among other areas. These technological platforms are used by people worldwide. However, the benefits of these systems are not evenly distributed, as their effects are felt more significantly by people in wealthier regions of the world. Governments in emerging markets are in the active process of attempting to build out digital infrastructure as a method to access millions worldwide with their services but are unable to reach the levels of penetration they hoped to achieve. This project asks how digital infrastructure and front-end design principles can be re-architected to build trust and increase access for emerging markets, looking specifically at healthcare platforms in rural India.

Digital Health is one of the most important initiatives undertaken by the Indian government. The government-led digital effort aims to use technology to enhance healthcare outcomes and delivery across the nation. The program is built on three main tenets: (1) building a digital health infrastructure; (2) establishing privacy and data-sharing norms; and (3) empowering patients through digital health literacy. It is attempting to do the following:

1. Digital Health Ecosystem: To promote smooth data interchange between various stakeholders and healthcare providers.

2. Electronic Records: Encouraging healthcare professionals to use electronic health records (EHRs) to enhance clinical results and patient care.

3. Telehealth: Promoting the application of telemedicine and mobile health (mHealth) technology to broaden access to healthcare services, particularly in isolated and underserved regions.

In order to accomplish this, it uses India

Stack, a digital infrastructure that includes a set of open APIs for developers to build digital services for identity, payments, and authentication in India. It enables faster and more secure transactions, simplified onboarding, and improved credit and government services access.

However, users in rural India have shown extremely low penetration for these healthcare platforms, even given the fact that a large percentage of them are willing to travel to urban areas to access care. This primarily stems from four major issues:

1. Lack of usability: Users in emerging markets cannot interact effectively with the products currently built for them due to the lack of natural and contextualized patterns and the heavy usage of standardized libraries (like Material Design). It is also not optimized to their environments.

2. Lack of trust: Beyond the interaction design of a platform, users need to trust that the information they receive from the healthcare platform is accurate and trustworthy. There is a need to overcome issues like trusting a human more than a machine, cultural contexts, and a lack of understanding of complex technology.

3. High levels of friction: The backend incentive model of India stack has the ability to do a lot of heavy lifting for healthcare platforms, removing a lot of the friction for the user experience. However, only a few companies have power over how the stack is architected.

4. Lack of focus on contextual issues: Every country has unique issues in digital healthcare delivery. In the United States, there is significant concern about data privacy. In India, the concern is around safety. This cultural need ought to be accounted for when building healthcare platforms.

In order to serve these needs, this project proposes a re-architecture of commonly used design principles that will adequately serve emerging market users. Additionally, there is a need for a platform to assist with the re-architecture of backend infrastructure so many companies can have influence over the incentive models that will reduce friction in healthcare platforms.

While access to healthcare technology is available, these platforms in rural India typically face 60% more churn within the first 60 days of a user onboarding than their counterparts in urban areas. This stems from the fact that these systems were initially designed with a particular user in mind, one who is from the Western world. Indian healthcare platforms require new models and workflows to serve as the foundation for building tech that users can intuitively navigate without instructions, especially with the exchange of sensitive healthcare information. These frameworks rely heavily on the social and cultural context and natural mental models of the user. This can be divided into two:

1. Interface (Visual Design): Elements your consumers immediately interact with on the platform - language, colors, Image, iconography, navigation, motion design, UI localization, etc.

2. Interaction: Feature discovery, user flows, in-product education strategies. Generative AI will play a significant role in changing user flow strategies.

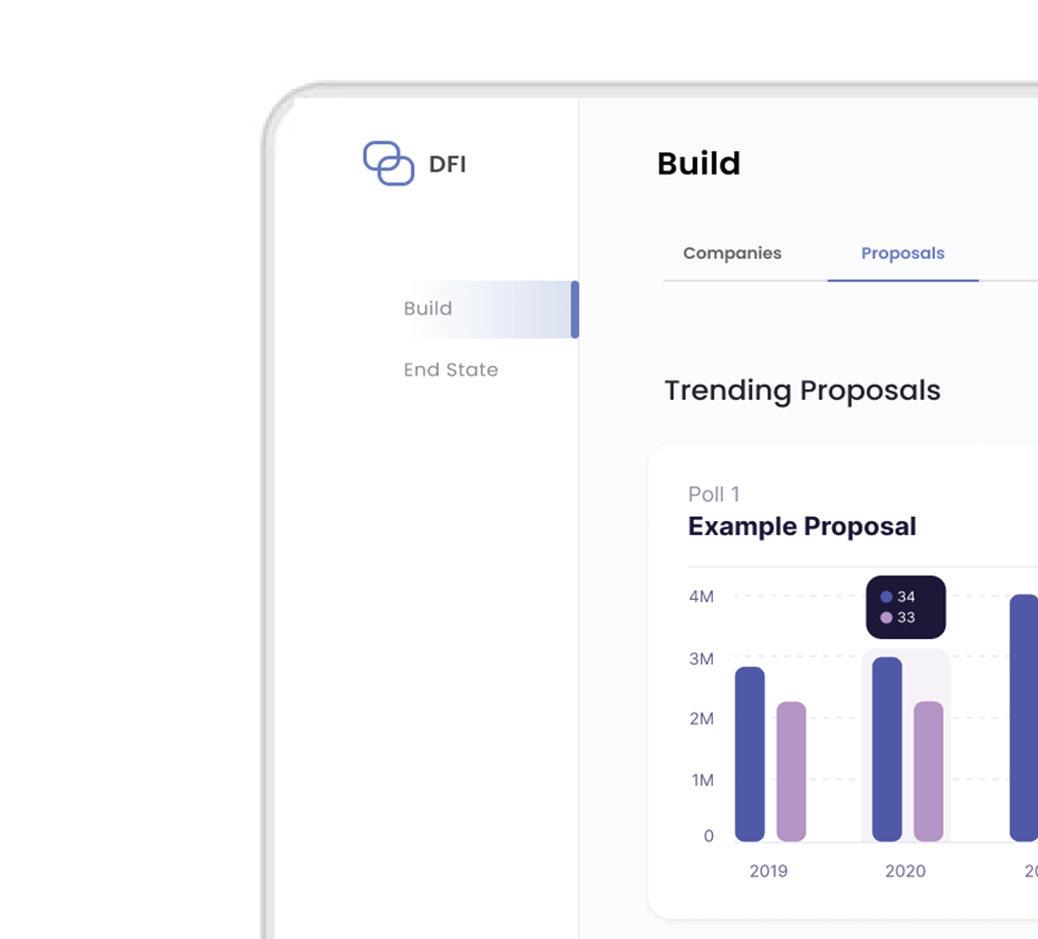

In order to improve the usability of healthcare apps, a platform needs to be built at the lowest layer of the India Stack to accomplish the following:

1. Build: Allow companies to collaborate on what features and incentives need to be built into the stack. This will allow companies to remove friction points in usual app flows and focus on the core values of delivering healthcare to users. The platform allows companies to post what features they think will be required to improve access and reduce areas of churn. It additionally has safety and ethics filters.

2. Test: The rearchitected design principles can also be accessed here. Once the health stack is built, companies can then test their apps on the tool. Using AI, the tool will predict areas of churn or friction and propose solutions based on the new principles.

Building for Billions: Digital Infrastructure for Healthcare in Rural India

Experiments conducted using edited Figma community designs

Experiments conducted using edited Figma community designs

Eric Gordon is a professor of civic media and director of the Engagement Lab at Emerson College in Boston. His research focuses on transforming public life and governance in digital culture, particularly in equitable “smart cities.” With expertise in play and creativity, he advises governments and NGOs worldwide, designing inclusive processes and creating games for civic participation. Author of influential books, including “Meaningful Inefficiencies,” he explores innovative approaches that prioritize play and care over efficiency.

Helena Rong is an interdisciplinary urbanist and researcher investigating the intersection of digital technology and urban planning. As a Technology and Public Purpose (TAPP) Fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center and a PhD Candidate in Urban Planning at Columbia University, her research focuses on the intersection of digital technology, collective intelligence, and urban planning. She explores disruptive technologies like blockchain for collective decision-making in urban governance. As the founder of CIVIS Design, she engages in diverse architectural and urban projects globally, focusing on innovative approaches.

Harshika Bisht is a Master of

Ecologies student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. She is interested in finding solutions to the contemporary issues that lie in the intersection of building design, energy sustainability, and occupant health through research in emergent technologies. Her interests have expanded to Boston’s building emission policies and regulations and the inequity challenges in the city’s vision to net zero.

Ethica Burt is a cross-disciplinary sustainability professional with a background in the solar and civil infrastructure industries. She leverages her expertise to create climate-focused solutions in the built environment. Her experience includes business operations, corporate sustainability management, and proposal development. Ethica is currently pursuing a Master in Design Studies, Ecologies at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Quoc Dang is a Master in Design Studies candidate at Harvard Graduate School of Design, focusing on building performance and sustainable design. With experience as an architectural designer and sustainability analyst, he has contributed to projects achieving industry-leading certification standards like Passive House and LEED. His research explores innovative techniques for positive impacts on the built environment and communities.

Alejandra Fernandez

Alejandra Fernández is a Costa Rican architect with experience in the public and private sector. She is the main editor of an award winning research platform that focuses on projects that promote spatial justice in Latin America. She is interested in exploring the intersection of design and public policy, with special emphasis on the Latin American region.

Tian Wei Li

Tian Wei Li is a product designer and a master’s student at Harvard GSD pursuing a dual degree in Design Studies Mediums domain and Landscape Architecture. Her research focuses on education technologies, equity-based design, and tech for environmental sustainability. Recently, she is having fun designing biomaterials and learning games for children.

Clair Ryu

Clair Ryu is an architectural designer and writer driven by a passion for exploring the relationship between people, processes, and places. Previously, she practiced architecture and lighting design in California, where she designed branded environments and experimented with storytelling strategies. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Southern California and is currently pursuing a Master in Design Studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Design with a focus on Narrative studies.

Aishwarya Sreenivas (Sreeni)

Aishwarya Sreenivas (Sreeni) is an MDes

Mediums candidate at Harvard GSD. She is interested in the intersection of design and technology, particularly in emerging markets. Previously, she worked with the Next Billion Users team at Google and is currently a researcher at the Tech for All Lab at Harvard Business School.

Alan Tebuev

Alan Tebuev is a student in the Master of Design Studies Ecologies domain who is very interested in exploring the role that artificial intelligence can play to aid governance during public health crises. His specific focus is on how AI can be used to improve information exchange at universities during public health crises.

Sharon Welch

Sharon Welch is a current Masters in Design Studies candidate at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Her work focuses on the intersections of design and policy, with a particular interest in how participatory design processes can create more just built environments and shift public policy to encompass all citizens’ needs. Her research on housing in tribal and rural contexts in both the US and Mexico has been supported by the Joint Center for Housing Studies and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Li Zhou

Li Zhou is a Master of Design Studies candidate in the Publics domain at Harvard GSD with a Bachelor’s degree in architecture and experience in user-centered design. Her research focuses on privacy and discrimination, with a particular emphasis on issues affecting underrepresented communities, such as the Asian and LGBTQAI+ communities.

Amritha Jayanti

Associate Director of the Technology and Public Purpose Project at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Amritha Jayanti is the Associate Director of the Technology and Public Purpose (TAPP) Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center. With expertise in emerging technology and international security, she conducted AI governance research at Cambridge and contributed to the Brookings Institution. Amritha co-founded Technica, promoting gender diversity in STEM.

Carlos Centeno

Associate Director of Innovation at MIT Governance Lab

Carlos Centeno is the Associate Director of Innovation at MIT Governance Lab [GOV/ LAB], co-developing tech-enabled governance solutions by merging design, technology, and political science. He is also a Research Affiliate at MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, prioritizing constituents’ needs. Carlos has contributed to the United Nations World Food Programme, leveraging data and community-driven approaches in humanitarian interventions. His ALIA prototype was a WFP Innovation Accelerator finalist.

Stephen Larrick

Digital Services Manager at MAPC

Stephen Larrick is an urbanist and open government advocate with a decade of experience in community planning, municipal governance, and data & technology. As Manager of the Digital Group at MAPC Data Services, he develops civic tech products and plans for digital equity in Boston. Previously, as a Technology and Public Purpose Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School, he researched local government access to platform data and promoted data transparency through the Sunlight Foundation and an urban-tech startup.

Nigel Jacob

Managing Director of Innovation at Boston Society of Architects

Nigel Jacob is the Co-founder of the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, a civic innovation incubator and R&D Lab in Boston’s City Hall. He now brings the New Urban Mechanics model to other cities through Northeastern University’s Burnes Center for Social Change and Innovation. Nigel uses technology and design to improve urban life and is recognized for his work including the White House Champion of Change, serving on boards like Code For America and coUrbanize.

Ceasar McDowell, Professor of the Practice of Civic Design at MIT, is an expert in civic engagement and social technology. He serves as Associate Head of the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Associate Director of the MIT Center for Constructive Communication, and Chair of the Master in City Planning Program. Ceasar focuses on designing civic infrastructures and processes to connect diverse communities. He co-hosts the WeWhoEngage podcast and is dedicated to building just and equitable communities for a better future.

Stephen Gray is an Associate Professor of Urban Design at Harvard University and founder of Grayscale Collaborative. His work explores the intersection of race, class, and spatial production, addressing design’s role in structural racism. He develops interventions to tackle inequality and social injustice, including co-leading an Equitable Impacts Framework pilot advancing racial equity in infrastructure reuse projects across North America.

Elizabeth Christoforetti leads Supernormal, a Cambridge-based design studio focusing on architecture, urbanism, technology, and culture. Her work in practice, research, and teaching reflects her perspective that the future of design embraces collective creativity, humanmachine collaboration, and scalable systems. With a vision for meaningful change through the intersection of architecture, urbanism, technology, and contemporary culture, Supernormal designs housing, institutional, and cultural projects for both public and private sectors, embracing the world as it is.

Yue Wu is an interdisciplinary designer and urbanist, currently serving as a Design Director and Engagement Manager at McKinsey & Company. With expertise in user-centric design, technology, and entrepreneurship, he helps healthcare, consumer, energy, telecom, and insurance industries develop business strategies based on deep user insights. Yue holds an MS degree in Architecture Studies and Urbanism from MIT and has received recognition for his design work internationally.

Peter Levine

Associate Dean, Tufts University, Author

Peter Levine is the Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Lincoln Filene Professor of Citizenship & Public Affairs at Tufts University. His work focuses on civic life in the United States, including civic education, voting rights, public deliberation, and social movements. He is dedicated to promoting civic engagement, democratic values, and equitable participation in the political process.

Erika Mouynes

Former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Panama

Erika Mouynes is the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Panama and Fulbright scholar, with a background in public service and the private sector. She played a key role in negotiating trade agreements and investment partnerships in various sectors. As Minister, she led the country’s successful vaccine procurement and is now focused on regional political dialogue, addressing the climate crisis, and migration.

Nigel Jacob

Managing Director of Innovation, Boston Society for Architects