Educating in the age of innovation

Creativity at school

PANORAMA Interview with Tony Wagner LEGACY Edward De Bono Leonie McIlvenny · Natalie Foster Robert Swartz · Sebastian Martin Coral Regí · Rosabel Rodríguez Maria Batet - Garbiñe Larralde

NOVEMBER 2022 VOL. 3 - NO. 2

editor's letter

When logic comes to a dead end, creativity comes to the rescue

Creativity within everyone's reach

Edward De Bono tells how Simon Batchelor, who was in charge of a mission in Cambodia to help the Khmer people fetch water, had failed in his attempts to get them involved in the project, when he decided to try something different and taught them the Six Thinking Hats method. The Khmer were so enthusiastic about the creative technique that they told Batchelor that learning to think was far more important than getting water. The Cambodians were right: those who learn to think are able not only to develop effective strategies to provide water to their people but also to make the progress of their people a reality under any circumstance, thanks to the potential of their thinking.

Ana Moreno Salvo Director of Impuls Educació

I remember in my university days in the Computer Science faculty, some professors enjoyed testing their students’ creativity, and they would give us exams that contained a single problem. It seems simple, right? Well, it wasn’t because the problem always had a ‘trick’, as we used to call it, and it could not be solved with our customary logical thinking; to find the way to solve it - which was always simple - a large dose of creativity was needed. I didn't understand it then and I thought I was being taken for a ride. Now I think it was a good way to encourage us to think differently and open our minds to the world of possibilities that a more creative way of thinking offers. We all admired everyone who had found the solution. Interestingly, they were not the most studious but those who had a natural tendency to be creative in their approaches. The rest of us were left with the hope of learning by trial and error.

The latest PISA test, which assesses the thinking of adolescents from almost all over the world, includes creative thinking. As Natalie Foster, developer of the test, says, ‘Creative thinking is important to help us adapt to a world that is constantly and rapidly changing, and to contribute to its development’. In the opinion of Tony Wagner, an education expert who has led the ‘Leadership for Change’ research group at Harvard University, innovation is what drives today's economy.

The school of the twenty-first century must prepare our children and youths to live in a world where it is harder and harder to survive without a large dose of creativity. As the discoverer of lateral thinking, Edward De Bono, said, ‘My aspiration is for there to be a few more young people in the world who can say: "I am a thinker," and I would be even more satisfied if they went further and said: "I am a thinker and I like to think”.’ Diàlegs shares this genius of thought’s intentions and hopes that this issue will serve to inspire new ideas to improve the way we teach thinking in both schools and the family.

While we were putting the finishing touches to this issue of Diàlegs we received the sad news of the death of Robert Swartz, whom we hold in high esteem and to whom we would like to dedicate this issue on creativity, where his last interview appears posthumously.

I hope you like it,

EDITORIAL 2

reader,

Dear

3

Manager

Ana Moreno

Publications

Jordi Viladrosa

Original Design

Guillem Batchellí

Design and Communication

Maria Font

Illustrations

Maria Yuling Martorell

Translation

Incyta Multilanguage

contents Creativity within everyone's reach 2 The only possible revolution in education stems from creativity 6 APURVA SAN JUAN & MIGUEL LUENGO project From theory to practice: A discussion on creativity and the curriculum 20 in depth LEONIE MCILVENNY panorama Schools must prepare for innovation INTERVIEW WITH TONY WAGNER 12

EDITORIAL BOARD

Montserrat Roig,

08195

Cugat del Vallès revista@impulseducacio.org https://impulseducacio.org/ ISSN 2696-5615 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License editor's letter

Editorial department and subscriptions Impuls Educació Avda.

3

Sant

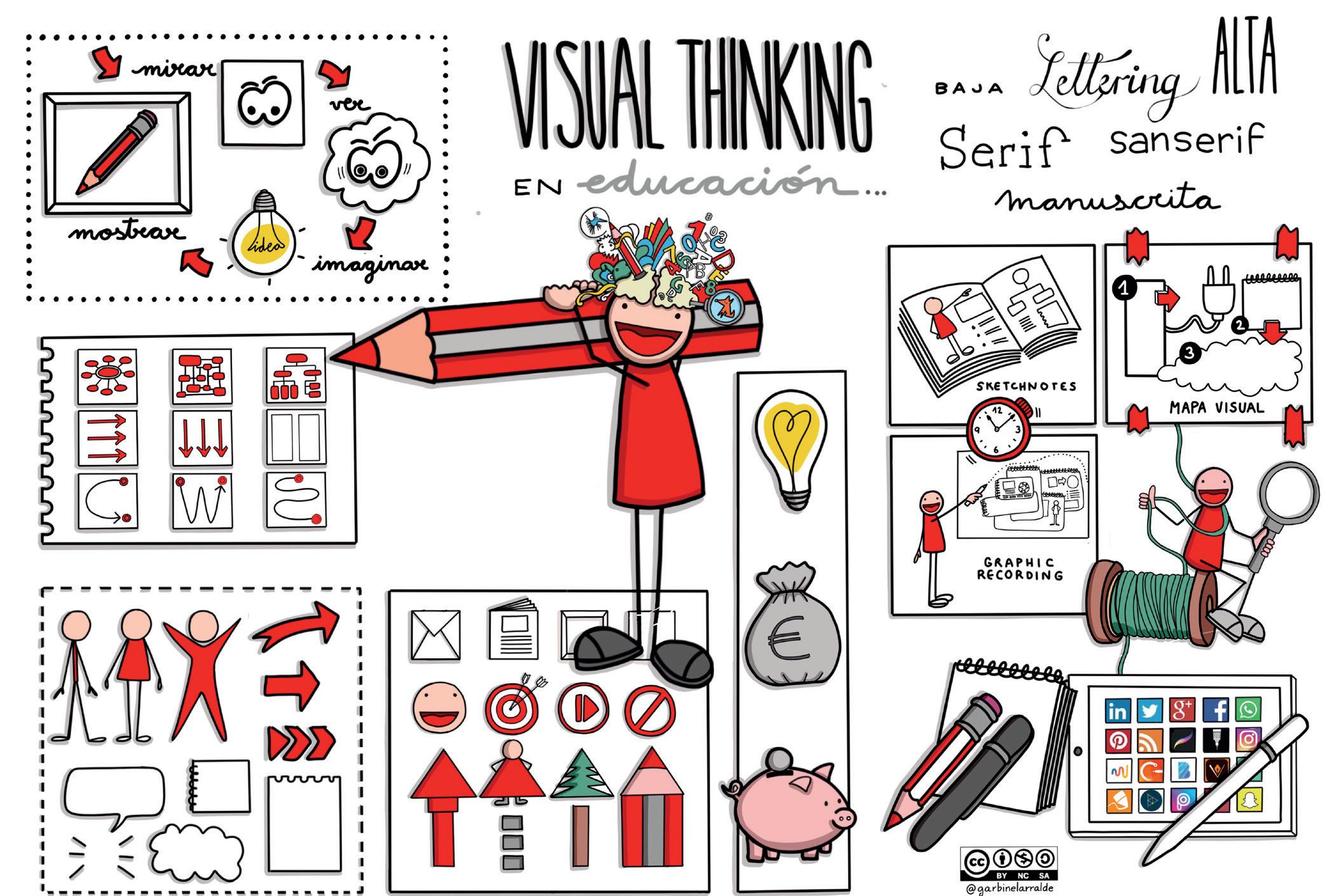

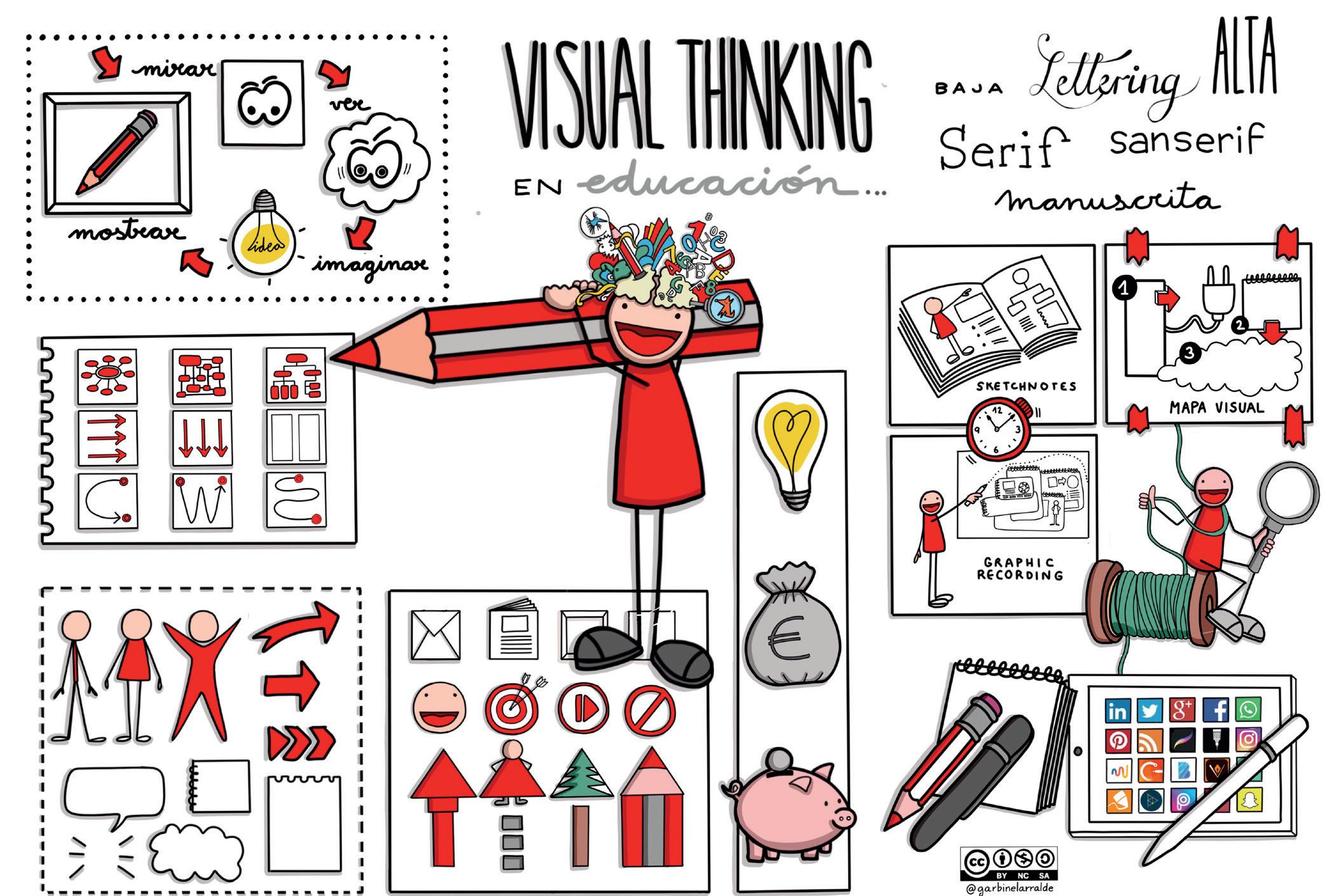

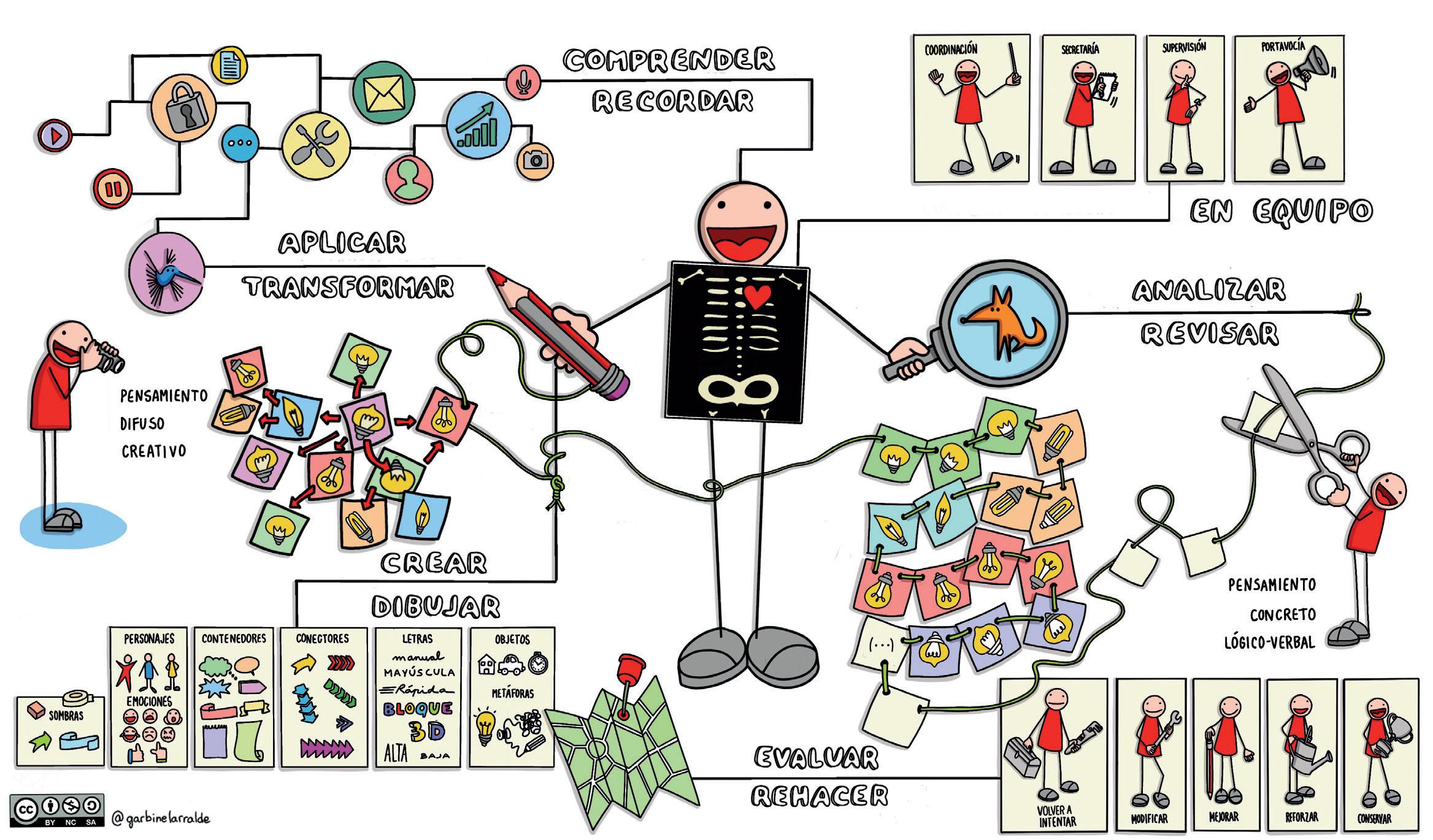

Thinking outside the box INTERVIEW WITH NATALIE FOSTER 28 Creativity, intelligence and high ability ROSABEL RODRÍGUEZ 34 Creativity and critical thinking in the classroom INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT SWARTZ 40 spotlight the report INTERVIEW WITH SEBASTIAN MARTIN 48 Tinkering Studio experiences 56 Thinking with your hands 64 Schools must promote creativity INTERVIEW WITH BEATRIZ REY CORAL REGÍ New books library 70 Visual Thinking, make what's in your mind visible author 72 A ‘palace of creativity’ would solve many of the world's problems 78 TRIBUTE TO EDWARD DE BONO legacy INTERVIEW WITH GARBIÑE LARRALDE

project

© Samuel Bregolin Design for Change

© Samuel Bregolin Design for Change

The only possible revolution in education stems from creativity

Design for Change brings design and creativity into the classroom

by Apurva San Juan Alonso & Miguel Luengo Pierrard

We have always been told that creativity, more specifically imagination,1 is a characteristic of children, artists or creators of large companies. But... have we really been told what creativity is?

In fact, one of the first premises to keep in mind is that creativity and imagination are not the same thing. Although the differences will be discussed in more detail throughout the article, there is one nuance that changes everything.

A BIT OF HISTORY ABOUT CREATIVITY

If we go back 200 years to the first industrial revolution, we find a historical juncture of great changes where new tools and ways of thinking were emerging. One of the great global breakthroughs was the invention and development of the steam engine. This concept revolutionised the previously known way of working. We moved away from the world of craftsmanship and manual labour to a faster and more efficient assembly-line manufacturing process.

People who were engaged in manual labour and handicrafts went to work in specialised factories. This required the implementation of a modern education system, in which the new generations were taught how to perform these tasks.

So what were the skills that this educational system sought to enhance? Those needed to efficiently perform tasks in a factory: memorisation, repetition, obedience, discipline and even competition among peers, in case they needed to vie for a promotion in the future. From our current perspective, it might sound like a kind of ‘education for robots’.

However, perhaps surprisingly, there are few differences between this educational system and the one we have known up to now: memorising facts, repeating them on a test, trying to be the best in class so as not to fail... and obeying. It seems that we are still being prepared to work in a factory like those of the first Industrial Revolution, although a study conducted by BBVA 2 determined that

PROJECT 7 6

only 36% of the jobs in Spain in 2018 fit this type. On the other hand, there has long been a machine, the computer, which is much better at performing these type of rote, repetitive tasks, leading to the automation of work.

Therefore, broadly speaking, the education system in recent years facilitates the development of skills that are needed in jobs that are doomed to disappear. Let's go back in time one last time: What skill did the creator of the steam engine, James Watt, use to develop his invention? Beyond the obvious ones, such as mathematics, there is an essential one: creativity.

IMAGINATION AND CREATIVITY

According to the official Spanish dictionary, imagination is the ‘ability to form new ideas and new projects’ and creativity is the ‘capacity to create’. Thus, creativity needs imagination to dream; imagination needs creativity to make those dreams come true. Imagination is inherent to human beings, but creativity has to be worked on.

Most of the progress that has been made so far has been achieved without the educational system training students in creativity. What if this skill had been encouraged in the past? What would today look like?

WE STILL HAVE TIME

According to IEBS Business School, one of the ten ‘soft’ skills that are the most in demand by companies in 2021 is creativity.3 At Design for Change (DFC) Spain, we have been working since 2011 with the conviction that children and young people are autonomous beings capable of taking action to change their environment. The DFC Methodology they use to achieve this allows them to develop creativity to provide solutions that they themselves implement. In addition, they strengthen their commitment to the environment, because from the outset they choose which problems they want to address. This characteristic makes the DFC Methodology an ideal complement for education professionals who already use other active methodologies such as Service-Learning or Project-Based Learning. With the implementation of the DFC Methodology based on ‘Design Thinking’ and entrepreneurship, which is simple, agile and effective, 100% practical and easily adaptable to different pedagogical models in both formal and nonformal education, children and young people are given the opportunity to design solutions to specific challenges.

Creativity needs imagination to dream and imagination needs creativity to make dreams come true

In addition, the DFC Methodology is recognised by the Complutense University of Madrid as a tool that facilitates the empowerment of children and youth. There is also scientific evidence of its benefits thanks to studies from universities such as Harvard and Stanford. 4

REVOLUTIONISING THE CLASSROOM WITH I CAN

Applying the DFC Methodology turns a place where children are educated into a meaningful learning space. Building this safe environment where young people are responsible for their own ideas and the way to carry them out is based on several premises:

1. We can all be creative. Not only children but also the teachers and educators who guide and mentor them must be aware of their (infinite) possibilities when creating. What ingredients are needed?

- An attitude: optimism, which is absolutely necessary to change the world.

- A method based on ‘Design Thinking’ : a succession of divergences, convergences and syntheses that avoids moving to the final solution too quickly. In this way, we go through the phases - of the DFC Methodology - that let

our ideas take flight.

- Simple techniques such as ‘crazy ideas’: use those ideas that are initially impossible but will not be judged, because they are valued as a starting point to help our imagination. Thus, they can be used as a trigger to achieve feasible ideas.

- Elements such as prototypes, whose rationale is ‘get it wrong quickly and cheaply’. If we start from mistakes to learn, the fear of creativity and value judgments fades away.

2. The job of education professionals is to ‘facilitate’ This means listening, identifying what the students or group of young people need and offering them tools and suggestions. Sometimes facilitating also means doing nothing, just observing and being amazed at what they are capable of doing if given the right techniques and space. It consists of ‘really

The DFC Methodology gives children and young people the opportunity to design solutions to specific challenges

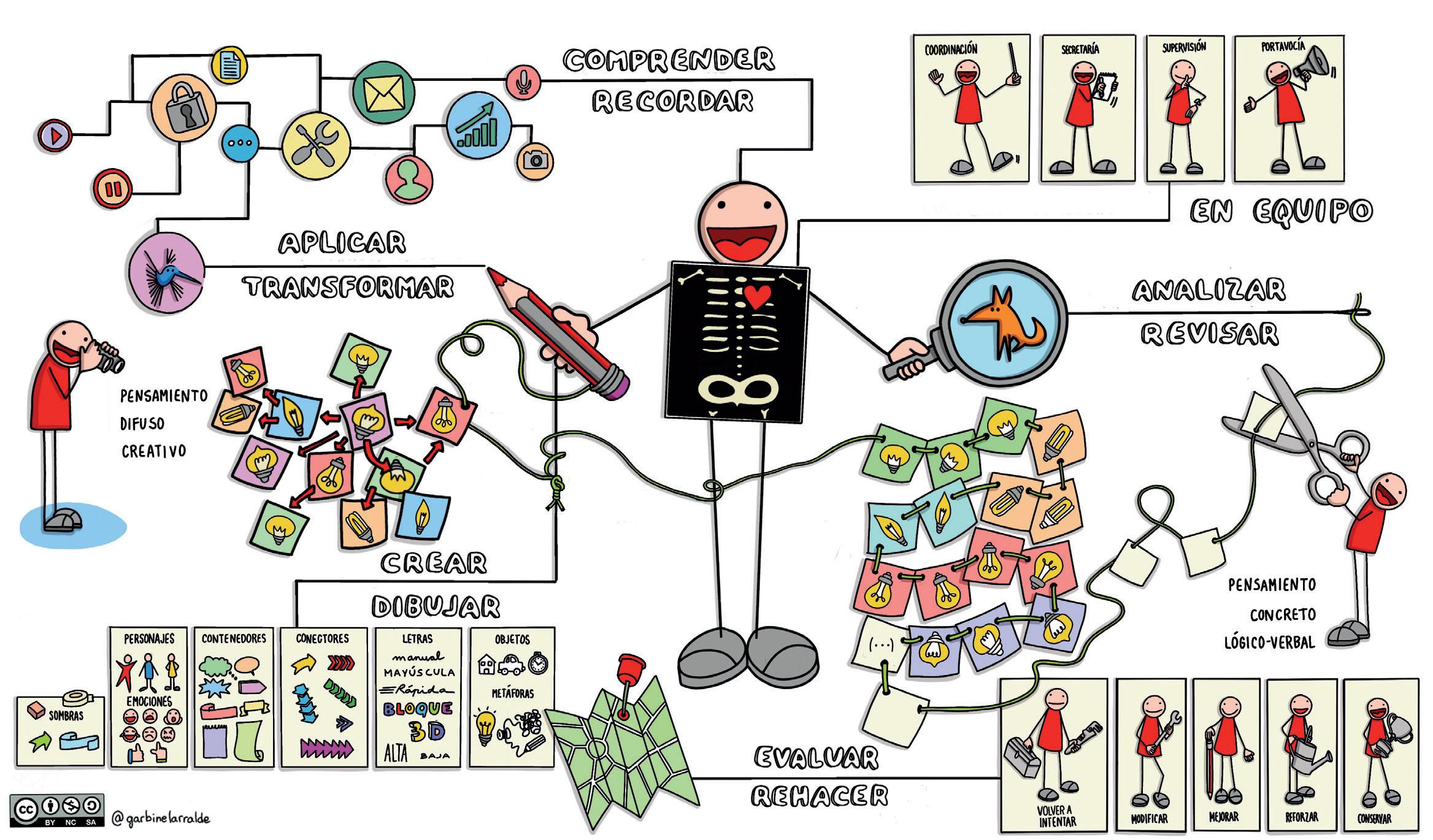

© Samuel Bregolin Design for Change

seeing’ the students in front of us; not the image of a passive student who in the future will be able to do something but right now only listens.

3. The importance of the process. If we focus on the result - which we take for granted has to ‘turn out well’- we strip the students of freedom with the belief that adults have more experience and, therefore, know better what to do. Thus, creativity is reduced to copying. However, this premise does not mean that the result does not matter, 5 but rather that the adult guide has to learn how to determine when his or her involvements adds and when it subtracts.

4. Ethics as a key factor. In the Imagine Phase of the DFC Methodology, where creativity stands out as the main skill, it is important to be aware of the effect of the ideas we are putting forward.

By experiencing the DFC methodological process, the young people begin to discover their own potential and how it is magnified in a group. They discover that they have the real ability to change the world, their world. This helps develop the ‘I CAN Mindset’: a way of thinking that allows them to rise to challenges flexibly in any field, that invites them to be active agents of change and that happens ‘Not by chance, by design’. At Design for Change Spain, we know that we are responsible for making change happen, for educating students to learn competencies to develop the skills that the job market is already demanding.

We need a change, a revolution in the way we teach. We need to stop creating memorisation machines and start teaching young people to foster creativity to change their world within the framework of the 2030 Agenda, furthering the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),6 choosing where they want to act, choosing where and how they can contribute (fight) in the education revolution.

We at Design for Change Spain invite you to join the revolution, to be bold and to dare to make creativity a fundamental part of your daily life. We encourage you to try the DFC Methodology 7 with your children, with your nieces and nephews, with your students. We encourage you to give them the opportunity to use their imagination and equip them with the tools to be creative. In our organisation, we have been putting creativity at

the service of young people for more than ten years, not only to prepare them for the future, but also so that they can provide solutions and change the rules of the game today. Because they are not the future, they are the present. And we have to listen to them. The most necessary revolution is the revolution in education, because it is the only basis for change, where everything begins. Let's be the education revolution we want to see in the world!

Apurva San Juan is the general director of Design for Change Spain. Trained in leadership, entrepreneurship and innovation at the University of Mondragon. At the age of 22, she has been CEO of Design for Change Spain since 2022 and co-founder of a cooperative that develops products to make reading easier for people with poor vision.

Miguel Luengo Pierrard is the president of Design for Change Spain. A ‘dream awakener’ who loves working with people. He has a degree in Industrial Engineering from ETSII Madrid and worked for 13 years as a consultant in an international company, until he found his true passion with Design for Change in 2011.

Notes

1 According to the theory of Guzmán López, author of several books on the subject, girls and boys are actually imaginative, which does not mean that they are creative.

2 https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Cuanvulnerable-es-el-empleo-en-Espana-a-la-revolucion-digital.pdf

3 https://www.iebschool.com/saladeprensa/2021/02/04/las-10-soft-skills-masdemandadas-por-las-empresas-en-2021/

4 https://dfcspain.org/

5 The DFC Philosophy is born with the objective of fostering the will, commitment and HumanE™ values based on the 5 ‘E's’: Empathy, Ethics, Excellence, Elevation and Evolution. We encourage this third ‘E’, ‘Excellence’, as a result of the process and the repetition of the process to master the technique, which involves focusing more and more attention on the result in a natural way. More information: https://dfcspain.org/nuestro-metodo/ 6 Design for Change is recognised by the United Nations as an organisation that promotes the SDGs. Each DFC project works on one or more SDGs.

7 To use the DFC Methodology, you can download the Project Facilitation Guide at this link https://dfcspain.org/guia-para-facilitar-proyectos-dfc/

We need to start teaching young people how to foster creativity to change their world within the framework of the 2030 Agenda

The most necessary revolution is the revolution in education, because it is the only basis for change, where everything begins

PROJECT 10 11

© Samuel Bregolin Design for Change

panorama

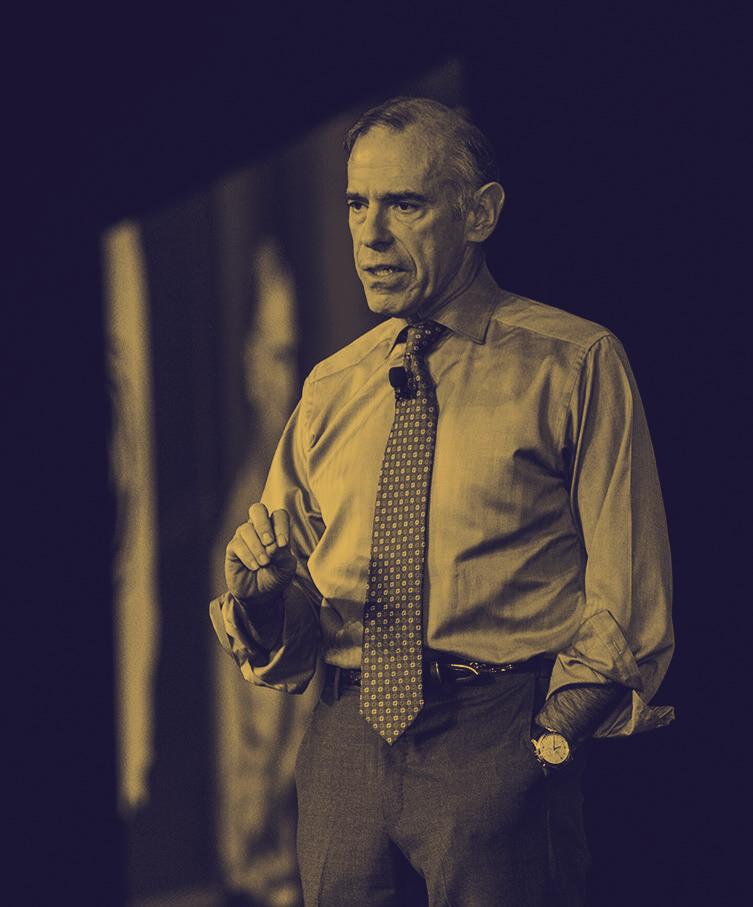

Schools must prepare for innovation

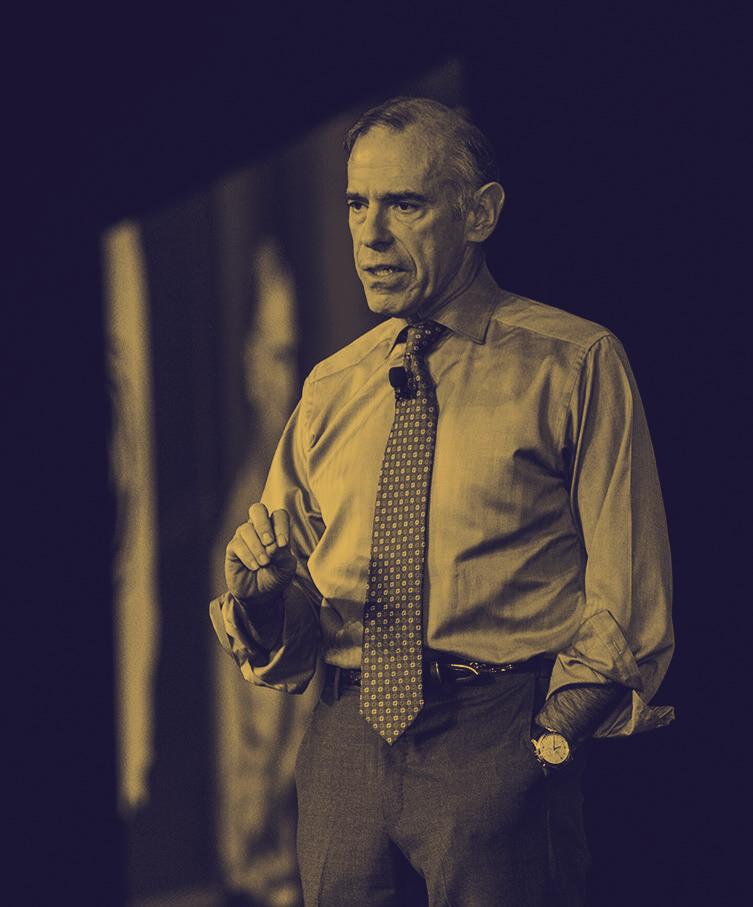

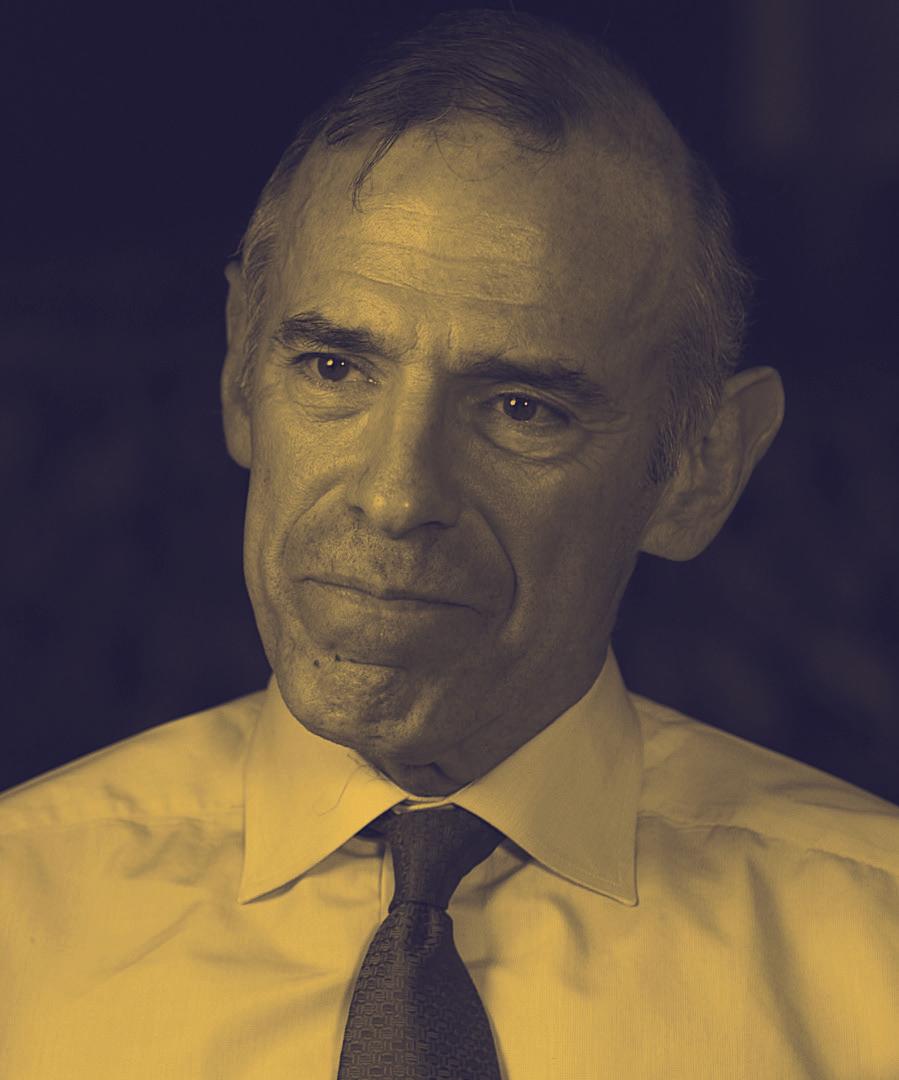

Tony Wagner is a senior fellow at the Learning Policy Institute in the United States. He participates in international conferences as an educational communicator and is a successful author in the field of educational innovation. He has been a school teacher, school principal and university professor. He holds a PhD in Education and was the founder and co-director of the Leadership for Change group at Harvard University's Graduate School of Education, as well as an expert advisor at Harvard University's Innovation Lab. His books include educational ‘bestsellers’ such as "The Global Achievement Gap" (2008), "Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World" (2012) and "Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing our Kids for the Innovation Era" (2016).

by Ana Moreno Salvo

by Ana Moreno Salvo

INTERVIEW WITH TONY WAGNER

You have dedicated your entire life to improving education. In you book, "The Global Achievement Gap", you argue that the current education system has become obsolete and does not need to be reformed but reinvented. Could you tell us what you mean by that?

When I became aware of the concern of employers and others about young people’s lack of skills, I wanted to try to understand what skills were important in different work environments, and for citizenship. I began interviewing a wide variety of executives, from Apple to Unilever, along with the military, civic leaders and university educators. And I realised that even students graduating from our best schools lack the skills that these people were telling me were critical. The global achievement gap is the gap between what our best schools teach and assess and what students need in order to work, learn and be citizens.

What are the ‘survival skills’ for the twenty-first century that you identified 12 years ago? Are they still valid today?

The seven survival skills emerged from the interviews. I heard the same kinds of things in all of them: the ability to ask good questions, the critical thinking needed to be able to ask them, the ability to communicate effectively, the ability to take initiative, etc. Some were intended to educate a large number of people with a few basic skills. Others were supposedly for young people going to university who are supposed to have some sort of higher knowledge. But the problem is that none of these skills are taught to children at

either the most basic or advanced levels. The fact that assessment takes place with multiple-choice, computer-scored questions means that the skills that matter the most are not assessed. You can't assess critical thinking or creativity or imagination or initiative or good character, for example. It simply does not prepare all students for twenty-first-century work, learning and citizenship.

Just last year, an article was published in the journal of the World Economic Forum on these seven ‘survival skills’, their relevance and importance. Would you do anything differently now if you were to write it again? I didn't talk much about character qualities at the time, because I assumed they were nothing new. For thousands of years, we have been teaching the importance of certain character qualities, whether through philosophical, religious or ethical systems; the importance of empathy, of thinking carefully about

It is necessary to teach the skills of an active, informed citizenry that is prepared for lifelong learning

Achievement gap: difference between what is taught at school and what students need

the consequences of our actions on other people, and so on. If I had to rewrite the book, I would certainly talk about character education or civics education, because it is becoming increasingly clear to me that some children are growing up without any moral grounding, and more and more young people are not going to any church or synagogue. So I think schools have to talk about those universal ethical principles that are common to all major religions and philosophical systems, to expect children to behave at a higher level and to teach them to solve conflicts peacefully. You can call them life skills if you want, but they are the things I would write more about.

Could you tell us how to educate for innovation, why it is so important and what we need to change in schools to do it effectively?

After writing the book, I continued to talk to leaders in many different

settings and realised that there has been a swift evolution in what has been called a knowledge economy. Peter Drucker coined the term in 1969, more than 50 years ago. The idea of the knowledge economy is that you have a competitive edge if you know more than the person next to you. And the more you know, the greater your competitive edge. Knowledge has become a commodity. However, the world simply doesn't care anymore how much our children know, because Google knows everything. What matters to the world is what our children can do with what they know. And that's a profound change, because we actually don't know how to do it. Well, we know how to do it, but we are not teaching the skills of creativity or creative problem-solving, just to cite two of them.

When I started to see that we really had an innovation economy, I needed to understand what innovation was. And I discovered that there are actually two very different

types of innovation: one is about bringing new possibilities to life. Take the iPhone, for example. That's the kind of high tech that people talk about a lot. But there is another type of innovation that is perhaps less glamorous but just as important as these technical advances, if not more so. And it is the ability to solve local and global problems creatively, whether in government, for-profit or non-profit organisations, developing countries or in developed countries. All of these things really create spheres of opportunity for young people who are properly prepared to make meaningful contributions and earn a very good living. So the upshot is that there are more and

What matters to the world is what our children can do with what they know, and that's a change

more employers who don't care whether or not a young person goes to college. When Google started, they said, okay, let's find the smartest people in the world. How are we going to do it? We’ll choose those with the highest test scores and the best grades, and we will interview them with intelligent questions. They did it for years, over the long term. A decade ago, Laszlo Boch, Senior Vice President of People Operations at Google, Inc. tried to analyse whether this strategy was appropriate. And he realised that what they had been doing to select, hire or promote people was worthless. He saw that the skills you need to succeed in a competitive academic environment, that is, a university, are totally different from the skills you need to succeed in the innovation economy. So what is Google doing right now? Google is using structured interviews, where it asks questions such as: tell me about a situation

where you tried to solve a complex problem, tell me about a time when you worked with a team to solve a problem, tell me about a time when you failed. A growing number of companies are moving in the same direction.

In the age of innovation, knowledge is necessary but not enough. And in fact, due to the changing nature of knowledge, it is quite often better if you acquire the knowledge you need to solve a problem at that particular moment. That is, if you are working on a problem, you have to try to understand it, and that's when you

acquire that knowledge, rather than acquiring it in advance just in case. The age of innovation demands a radically different preparation for young people to thrive and succeed, and not just in the workplace. The skills needed for work today are those needed for active, informed citizenship and lifelong learning. Competencies are converging for the first time in human history. All too often, we only talk about job skills, but when we look around at the world today, we very clearly see the problem entailed by not thinking enough about how we are preparing young people for citizenship, for civic life.

Could you describe what a young innovator should be like and give us some examples?

In my book "Creating Innovators", I made in-depth profiles of eight young people, an equal number of women and men. Some were

Job skills are the same skills needed for active, informed citizenship and lifelong learning

first-generation immigrants, while others had families that had been here for many generations. One of the young people I interviewed was the project manager of the first iPhone and had dropped out of college. Others were innovators in the arts, and yet others were innovators as social entrepreneurs trying to solve social problems. They were curious about the world around them. They asked very good questions, were thoughtful, had the ability to take initiative and, perhaps most importantly, had the ability to bounce back from what seemed like failure. In schools, on the other hand, the more mistakes you make, the lower your grade. Mistakes are penalised. Whereas in the world of innovation, if you make a smart mistake, you are rewarded because you will learn from it. All of these young people I interviewed had that ability. They were willing to take the initiative, and when something

didn't work, they learned from it and kept moving forward. Another thing I would add is that they were very intrinsically motivated. They really wanted to stand out in the world, to make their mark on it in the sense that Steve Jobs put it. And when I went back to try to understand what their parents and teachers had done to create these kinds of character traits, I came to the conclusion that one pattern that both teachers and parents had encouraged was play. The goal is to explore new interests in the hope that a young person will discover a passion, because that's the real

driver of innovation. They evolve, but they all do so with a deeper meaning, a purpose. Play, passion and purpose were common elements in the way these young people had been educated by their parents and teachers, which had made a difference in their lives.

What would you say to teachers who want to start educating students for innovation? do you think they need special training to do so?

I think universities do a very good job preparing teachers almost everywhere, but there are notable differences. Teachers teach the way they have been taught. So if you sit in a master class for most teacher training programmes and are graded in a conventional way, that's all you know and can do, because you haven't learned anything different. Today we have many tests or standardised tests of knowledge and

16 PANORAMA 17

Playfulness, passion and purpose are elements that make a difference in young innovators

skills which tell us absolutely nothing about work, citizenship or readiness for learning. This is another reason why educators and business leaders need to work together, because together they can help policymakers understand that very different types of assessment are needed. Teaching for the test, especially if they are poorly written, is a downward spiral for education everywhere. The first step is to clarify which results matter. It's not about test scores, or getting into the most prestigious universities. Let's ask ourselves, what is our education R&D budget? I advocate creating funds, either at the school level or by regions, so that teams of teachers can apply for money to develop new curricula or new forms of assessment, visit other schools or learn good practices.

Currently, what we find in schools is what I call ‘random acts of excellence’. These are individual teachers who go off in a corner and maybe do really good things, but they hide them because it doesn't pay for them to share it, or they don't have the time to. We need to reward educators who take initiative, who are willing to experiment and accommodate mistakes.

When you create those conditions for innovation in schools, based on teams and constant learning, you see rapid improvement, real change. Instead of being a culture of rewards and punishments, a culture of compliance, a culture of passivity, it becomes a culture of innovation, so that the school is the incubator of the skills that are needed in the world at large. That's part of the reason I talk about

‘reimagining schools’ or reinventing schools rather than reforming them, because the traditional scheduled egg-box structure where kids change classrooms every 45 minutes and teachers don't have time to innovate, create or collaborate makes for schools that will always be stuck in the past.

In the United States and Great Britain, teachers spend about 1,200 hours a year in front of students. They collaborate, learn, develop assessments and grade together to find out how students are doing, rather than relying on computerscored tests. And at the core, it's about thinking differently about what makes a good educator and what conditions are needed to support high-quality learning for both educators and children.

Finally, in another of your successful books, "Most Likely to Succeed", you lay out the keys to creating an education system that meets the needs of the twentyfirst century. Could you give us some key points and why you consider them so important? We need to see that no matter what classes students take, they are progressing toward developing real skills: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creative problem-solving, developing a capacity for civic life. In fact, I am working on a new book with colleagues on a mastery-based approach to learning, because I believe it is also the solution to the traditional achievement gap between underserved and middle- or uppermiddle-class youth. Disadvantaged youth start two to three years behind in school, especially if they have not received early childhood education, but they are expected to catch up and be in the same place 12 years later. We need to understand that each young person needs his or her own individual educational plan and needs to be

treated as a unique individual, and that progress should be measured in terms of increasing competence or mastery. Every student should have a digital portfolio that follows them through school. All students should have a time to present and defend their work on a regular basis, with performance standards as indicators of proficiency. Students' work is simply incomplete until they meet that standard. Some may need more time, and others may need a little more help. But all students can meet that standard, and some can far exceed it.

I would end with one last easy thing that every educator reading this article can put into practice tomorrow: have every child keep a question journal, a curiosity journal, in which they periodically write down a question they find interesting, or an interest they want to explore or a concern they have about the world. An interest, a concern, a question: write them down in a sentence and then periodically sit down with that child. Parents and teachers can ask the child to circle the question, interest or concern and then give the child time and space to pursue that interest or try to answer that question or explore that concern. What we are trying to do with this type of exercise is to keep curiosity alive. So curiosity is at the core of what I think we need to cultivate and develop with our young people. Not just because of the things that happen in front of them, but because of the world around them.

Student progress should be measured in terms of increasing competence or mastery

Curiosity is at the core of what I believe we need to cultivate and develop in our young people

18 PANORAMA 19

in depth

From theory to practice: A discussion on creativity and the curriculum

by Leonie McIlvenny

by Leonie McIlvenny

The importance of creativity as an essential twenty-first century skill has gained momentum since the European Parliament and Council identified it as a ‘key competence for lifelong learning’.1 As indicated in the report on ‘transversal competencies in education policy and practice’, 2 it has been introduced in the curriculum documents of many countries, such as in Scotland 3 and Australia.4 Creativity also features prominently in several global initiatives, such as the Partnership for Twenty-First Century Skills,5 which identifies ‘creativity’ as one of its 4Cs; the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), which identifies ‘creativity and innovation’ as one of the six domains of its NETS-S (US National Standards in Technology) for students; 6 and the 2021 Delphi Expert Report on ‘critical thinking and creativity’, which puts the spotlight on the importance of creativity in an educational environment. 7 To consolidate the importance of creativity development, the OECD programs for international student assessment (PISA)

‘2021 Creating Thinking Framework, 2022 Creating Thinking Assessment’,8 and the 2012 ‘Creative Problem Solving Assessment Framework’ highlight the growing

importance being given to creativity in education systems internationally.

WHAT IS CREATIVITY?

Definitions of creativity abound. Ken Robinson 9 defines it as ‘imaginative processes with original and valuable results’. The OECD Strategic Advisory Group 10 states that it is ‘the process by which we generate new ideas that require specific knowledge, skills and attitudes’.

Regardless of the definition, some common themes around creativity are as follows:

– It is a complex and dynamic process.

– It involves generating original ideas.

– It is often triggered by the need to find a solution to something.

– It is an interaction between nature and nurture, in which innate dispositions are nurtured through structured opportunities to engage in creative activities.

– It can occur either spontaneously (unconsciously) or strategically (consciously).

‘We all have the potential creativity to contribute, individually or collectively, to the survival, advancement and wellbeing of our society of human beings’ Lederach (2005)

IN DEPTH 20 21

THE CREATIVITY QUADRANT

Much of the thinking on creativity derives from the work of Craft,11 who suggested two contrasting ways of viewing creativity: one as an individual or collective phenomenon, and the other as domain-specific versus domain-free. Craft also describes creativity as ‘little c’ or ‘big C’, depending on the context and purpose of the creative exercise or activity. ‘Little c’ creativity could be considered more spontaneous, individual efforts compared to the ‘big C’, which combines creative thinking with key disciplines such as science and the humanities for a more conscious and reflective process. 12 The Creativity Quadrant attempts to merge these ideas graphically.

BARRIERS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF CREATIVITY IN SCHOOLS

Even with the growing body of literature promoting creativity as an essential twenty-first-century skill, there are still significant barriers to its implementation within the school curriculum. The UNESCO report on ‘transversal competencies in educational policies and practices’13 identifies three key areas that hinder their implementation. The challenge of a definition, which stems from the difficulty in determining what creativity is and what it looks like in an educational setting. In other words, how do we turn an abstract concept into assessable behaviours? Operational challenges, which focus on its place in the curriculum and on the mechanisms put in place to assess it. In an education

system that continues to separate subjects, the responsibility for developing the ‘soft’ skill of creativity has traditionally been relegated to the creative arts. As the imperative to develop a collective creative disposition gains momentum, there is a shift toward a more strategic, expansive view of the role of creativity across a broader range of disciplines (‘big C’). This trend also highlights the need to shift the responsibility for teaching these skills from a single learning area to a more multidisciplinary approach, which requires the revitalisation and transformation of traditional curricular frameworks, pedagogies and assessment practices. Systemic challenges include aspects such as an overloaded curriculum, pressure to achieve academic success and a teacher-centred approach to learning.

TEACHERS ARE THE KEY

Improving teachers' beliefs and attitudes about the value of creativity and developing their competence and confidence to carry out creative activities in a pedagogical way is essential to ensure that creativity becomes ubiquitous in the learning process. Gonski 14 suggests that teaching and assessing creativity, particularly in an integrated fashion, is a very complex task that requires teachers to have a solid understanding of how to integrate it into their teaching. Teachers need to understand the circumstances that foster it, how they can effectively guide students to be more creative in their thinking and how creative thinking can be recognised.

Creativity Quadrant (Craft, 2008)

This transformation process requires extensive professional development and systemic support, as well as a reassessment of what education systems really value.

APPLICATION OF A CREATIVE THINKING CURRICULUM

There are many approaches that can be taken to ensure that creativity is strategically placed in the curriculum. Here are four approaches: 1) The individual teacher championing the teaching of thinking skills in their own classroom; 2) Agreed-upon frameworks and tools that are used school-wide to create a common (but not necessarily scripted or assessed) language; 3) The use of an explicit programme ‘outside’ the subject-based curriculum; or 4) A school-wide approach where skills are strategically embedded in the curriculum, written into programmes and formally assessed (an example of this model is the general critical and creative thinking skills in the Australian curriculum 15).

FRAMEWORKS AND THINKING MODELS

Regardless of the approach taken, there is no dearth of

frameworks or ‘thinking tools’ that can be used. The P21 Framework16 describes creativity in three domains:

– Thinking creatively, using thinking tools and strategies to create new and valuable ideas.

– Working creatively with others to develop, apply and communicate new ideas to others.

– Implementing the innovation to make a tangible and useful contribution to the field in which the innovation will occur.

Other approaches explore thinking habits. Some models of this approach are: The Five Dimensions of Creativity Model 17 (be inquisitive, be imaginative, persevere, collaborate and be disciplined); Arthur Costa’s Habits of Mind,18 four of which relate to creativity (Create, imagine and innovate; Question and problem pose;

Teaching creativity is a highly complex task that requires a grasp of how to integrate it

Think interdependently; and Think flexibly); Bloom’s Taxonomy,19 which provides a hierarchy of six levels of thinking skills, the highest being Create; Tony Ryan's Keys to Thinking,20 which promote creative thinking through different creative keys (Challenge, Inventions, Improve, Brainstorm, and Question); and finally, De Bono's ‘Green Thinking Hat’,21 which addresses creativity.

One could argue that these models are an artificial representation of a very complex and dynamic process, but for educators who are new to or struggling with this complex process, they provide a bridge between the abstract and the operational, allowing creativity to be seen and applied in the classroom.

ASSESSING CREATIVITY

Conducting international assessments that seek to assess and, perhaps more importantly, understand the place of creativity in the curriculum adds status and visibility

to this skill to ensure that it is integrated into curricular documents in a strategic, transparent way. The OECD22 suggests the following potential advantages of assessing creativity in schools:

– Creative thinking is taken seriously as an important part of formal school curricula.

– Emphasis is placed on developing curricula and teaching activities that foster creativity.

– Teachers are supported in developing their capacity to be creative and facilitate creative practices in their teaching-learning programmes.

– The status of creativity as an essential life skill is growing.

? 1 2 3

Creativity assessment in schools enhances curricula and syllabi and adds status and visibility

Although we still have a long way to go to put fair and valid educational assessment practices around creativity into practice, progress continues to be made.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

Whatever steps a teacher, school or system takes to make creativity more important, it first must be defined and its purpose specified. Educators have to reconcile conflicting agendas that see an institutional imperative to collect evidence of a child's learning efforts with the idea that the very act of formalising and quantifying the creative process can clip the creator’s wings and the potentiality of what he or she might create and become if left free. Is the full potential of that creativity really being captured? Or only what is determined by the limited (controlled) parameters of the learning task? Is one more important than the other, and if so, what should the objective be? The challenge, perhaps, is to do both: to help illuminate, or bring to light, the creative spark in every child and to pave alternative ways for this creativity to unfold, not only to help students become self-actualised but also to enable them to be valuable contributors to a much greater collective challenge: to make our world a better place.

‘You can't just give someone a creativity injection. You have to create an environment for curiosity and a way to encourage people and get the best out of them.’

Sir Ken

Robinson

Leonie McIlvenny is a professor at Curtin University specialising in information literacy and digital technology. She is the author of "Teaching 21st Century Skills in a STEM Makerspace", a contributor to the Delphi Report on critical thinking and creativity and judge of the 2021 ‘QS Reimagine Education Awards’.

References

1 European Commission (2018). ‘Proposal for a Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning’. Brussels, 17.1.2018 SWD(2018) 14 final

2 UNESCO (2015), ‘Asia-Pacific Education Research Institutes Network (ERI-Net) regional study on: transversal competencies in education policy and practice (Phase I): regional synthesis report’. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/ pf0000231907

3 Education Scotland. (2013). ‘Creativity across learning 3–18’. Edinburgh: Education Scotland. http:// www.educationscotland.gov.uk/Images/Creativity3to18_tcm4814361.pdf

4 Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2009). ‘Melbourne declaration on educational goals’. Melbourne, Australia. http://www. curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/national_ declaration_on_the_educational_goals_for_young_australians.pdf

5 Battelle for Kids. (2019). ‘Framework for 21st Century Learning’. https://static.battelleforkids.org/documents/p21/P21_Framework_Brief.pdf

6 International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). (2000) ‘ISTE Standards: Students’. https://www.iste.org/standards/iste-standards-for-students

7 Impuls Educació. (2021). ‘Delphi Expert Report: Critical thinking and creativity. Two key lessons for the knowledge society in the age of innovation’. Impuls Educació. Barcelona.

8 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. (2019). ‘PISA 2021 Creating Thinking Framework’. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/ PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf

9 Robinson, K (2001). "Out of our Minds: Learning to be Creative". P. 118. Capstone Publishing.

10 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD] (2017). ‘PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Strategic Advisory Group Report’. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, https://one.oecd.org/document/EDU/PISA/GB(2017)19/en/pdf

11 Craft, A. (2008). ‘Approaches to assessing creativity in fostering personalisation’. Paper prepared for discussion at DCSF Seminar, October 3, Wallacespace, London, UK.

12 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. (2019). ‘PISA 2021 Creating Thinking Framework’. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/ PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf

13 UNESCO (2015), ‘Asia-Pacific Education Research Institutes Network (ERI-Net) regional study on: transversal competencies in education policy and practice (Phase I): regional synthesis report’. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/ pf0000231907

14 Gonski, D et al. (2018), ‘Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools’, March 2018, Commonwealth of Australia.

15 Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] (2018) ‘Australian Curriculum General Capabilities’. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu. au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/

16 Battelle for Kids. (2019). ‘Framework for 21st Century Learning’. https://static.battelleforkids.org/documents/p21/P21_Framework_Brief.pdf

17 Lucas, B. and E. Spencer (2017). ‘Teaching Creative Thinking: Developing Learners Who Generate Ideas and Can Think Critically’, Crown House Publishing, https:// bookshop.canterbury.ac.uk/Teaching-Creative-Thinking-Developing-learners-whogenerate-ideas-and-can-think-critically_9781785832369

18 Costa, AL & Kallick, B 2000–2001b, ‘Habits of Mind’, Search Models Unlimited, Highlands Ranch, Colorado. http://www.instituteforhabitsofmind. com/

19 Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). ‘Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals’. Vol. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

20 Ryan, T. (n.d) Thinker’s Keys. https://www.thinkerskeys.com

21 Kivunja, C. (2015) ‘Using De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats Model to Teach Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills Essential for Success in the 21st Century Economy’. "Creative Education", 6, 380-391. doi: 10.4236/ce.2015.63037.

22 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD] (2020). ‘PISA 2022 Creative Thinking’. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/creative-thinking/

IN DEPTH 24

25

In order for creativity to become more important, it first must be defined and its purpose specified

creative thinking spotlight

INTERVIEW WITH NATALIE FOSTER

Thinking outside the box

p. 28

ROSABEL RODRÍGUEZ

Creativity, intelligence and high ability

p. 34

INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT SWARTZ

Creativity and critical thinking in the classroom

p. 40

Natalie Foster has worked with Mario Piacentini to develop the framework for assessing creative thinking for PISA 2022. She joined the OECD in November 2017 to work on research and development of the PISA innovative domain assessments. She holds a BA in French and Spanish from the University of Nottingham and completed her MA in European Studies (Politics, Policy and Society) at the University of Bath, Charles University (Prague) and Sciences Po (Paris).

Thinking outside the box

PISA assesses students' creative thinking in 2022

by Ana Moreno Salvo

Every year, PISA evaluates some of what are known as the innovation competencies. Why creative thinking now? What impact does creativity have on a person's daily life in the twentyfirst century?

PISA's innovative competencies assessment aims to measure important learning beyond the ‘traditional’ ones in each PISA cycle: reading, mathematics and science. It seeks to offer a more complete perspective of the participating students’ ‘preparation for life’. PISA already ventured into this area in 2012 with the assessment of creative problem-solving. That time, the main focus was on the success of the problem-solving process. The question was: Are the students able

to solve the problem? The creative aspect depended on how students explored the context of the problem. This time, the focus is on the students' ability to generate creative ideas.

For many years, the international community has considered creativity and creative thinking some of the most important skills for young people to develop in the twenty-first century. The innovation assessment for each PISA cycle is determined through a collaborative consultation process involving OECD countries and economies. The decision to

assess creative thinking in PISA reflects this international interest.

In our daily lives, we all think creatively in some situations, whether it is solving a traffic problem, preparing a meal or sketching a drawing, but we are not aware that they involve creative thinking. More generally, creative thinking is important to help us adapt to a world that is constantly and rapidly changing and to contribute to its development. Organisations and societies are increasingly dependent on innovation and knowledge creation to address emerging and

SPOTLIGHT 29

Creative thinking can have a positive effect on students' interest, academic performance and social-emotional development

INTERVIEW WITH NATALIE FOSTER

28

complex challenges, especially since the digital era allows access to existing knowledge within seconds. In the case of students, research has shown that creative thinking can have a positive impact on their academic interest and performance, their identity and their socioemotional development.

On what vision or conceptual framework on creative thinking is the PISA assessment based? What data do you expect to obtain? What will be done with that data?

As in all PISA assessments, the OECD convenes a group of experts to define the construct and guide the drafting of the assessment framework. In our case, it is based on a very rich existing literature on creativity. The PISA framework identifies and focuses on creative thinking factors that are adaptable and relevant to education systems.

The PISA assessment consists of

two parts: a test and a questionnaire. The data we expect to collect from the test are similar to those of the other PISA domains, that is, information on the degree to which students are able to produce creative ideas. The test unit is placed in a different domain context; we are interested in whether students' creative abilities in certain domains (e.g., creative expression in writing or visual design) are different from those in problem-solving domains. For each country, we aim to produce an overall score that summarises student performance in this realm. In the questionnaire, we ask students about a number of topics that primarily help us interpret their test performance data, including general information about their background and more specific questions related to their attitudes and beliefs about creativity or the types of

activities they engage in inside and outside of school.

It must not be easy to assess creativity. What aspects are you trying to assess? Why these and not others? What type of questions or activities do the tests contain?

Assessing creativity as a broad construct is challenging. Creativity is defined in part by a given social context. Therefore, we focus on the cognitive processes associated with the performance of the creative task. This is more appropriate in the context of PISA, which assesses 15-year-olds from all over the world, as it is an individual ability that can be developed through practice and does not take into account the social value of the final result.

PISA defines creative thinking as ‘the capacity to engage productively in the generation, evaluation and improvement of ideas that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge, and impactful expressions of imagination’. The definition describes

Context is important. The tasks are in the areas of: writing, visual design, social and scientific problem-solving

all the cognitive processes involved in creative thinking (generating, evaluating and improving ideas) and the different manifestations that 15-year-olds can perform and produce.

In each section of the test, students are presented with a brief scenario or stimulus and asked to do one of three things: think of an original idea, think of many different ideas for the same given situation or improve on a given idea in an original way. The tasks are in four different domains: writing, visual design, social problem-solving and scientific problem-solving. For example, in the course of the test, a student may be asked to write an idea for a short story with two characters, design several logos for an event, improve a given solution to a community problem and propose two hypotheses that can explain a scientific problem. It should be noted that students are not scored on how ‘correct’ or practically feasible their ideas are but on whether they are able to come up with qualitatively different or original ideas.

What do you consider to be the keys to developing creativity at school? How should it be integrated into the curriculum?

First, I think it is important to overcome the perception that devoting time or effort to developing creative thinking is detrimental to learning important content or developing other skills. They are in no way mutually exclusive; in fact, they can be complementary. If you have to think creatively about something in particular, why not focus on relevant and meaningful content? In fact, research has also shown that creative thinking promotes learning by presenting information in an engaging and personally meaningful way, even within the context of formal learning objectives. Learning in more creative, exploratory

and inquiry-based ways can also increase students' motivation and interest in learning, especially for those who struggle with rote learning and other teacher-centred school methods.

As a general principle, creative thinking can be developed through the application of more learner-centred pedagogies (such as problem- or project-based learning), in which students have the opportunity to engage in more open-ended, iterative and personally meaningful activities, while teachers act as facilitators of the process. Of course, this type of pedagogy can be more difficult for teachers. Another key factor in developing creativity in schools is to train teachers to be able to apply these pedagogies. This relates to cultivating attitudes about developing creative thinking in teachers, which is important and achievable. It also has to do with relieving some of the

31 30

SPOTLIGHT

Another key factor in developing creativity in schools is to train teachers to be able to apply these pedagogies

pressure on teachers that might go against the development of creative thinking. They include pressure to cover all the curriculum content, a lack of autonomy or excessive pressure on students to perform on standardised tests that focus primarily on recall of facts. Schools and school systems therefore have an important role to play in combating this pressure and could consider implementing policies and practices aimed at increasing the opportunities and benefits for students to practice creative thinking and decreasing the costs associated with it.

There is a lot of talk that creative thinking must also be cooperative to go far. Why is that? How should we work at school to develop creative thinking in all students? Both the rationale for why the development of creative thinking in general is important and the body of literature focused on ‘knowledge creation’ as a particular type of creative thinking highlight that innovation is often a collaborative effort which is needed to find solutions to complex, global problems and advance our collective knowledge and understanding. That's why we also focus part of the PISA assessment on evaluating and improving others’ ideas, on the fact that creative thinking is not just about having a brilliant idea but about being able to draw inspiration from existing ideas and move them forward in new and original ways to achieve something better collectively.

The learner-centred pedagogy I mentioned earlier --project-based and problem-based learning-- lends itself well to collaborative work. Integrating knowledge creation

intentionally into classroom life encourages students to contribute new ideas to their peers and the community and to work to continually improve them. This can happen by encouraging ‘wonder questions’, in which students are encouraged to try to express their curiosity, ask questions about the world and share their ideas about different phenomena that their peers can take advantage of.

What can teachers do to find out the degree to which their students have developed this competency?

I think one of the keys is to provide meaningful opportunities for them to participate and demonstrate their competency, such as by asking them to participate in open-ended tasks for which there is no one correct answer. Without that, it will always be very difficult if not impossible for teachers to get a sense of students' creative thinking abilities.

It is important to clarify the fact that although we assess creativity in PISA, this does not necessarily mean that we are advocating that schools or countries should assess creative thinking similarly. In our framework, we emphasise that creative thinking is a skill that can be used in all disciplines and that what characterises the competency of creative thinking is students’ ability to generate original ideas and think of many different possibilities.

Related to this, another aspect to keep in mind is that, for twentyfirst-century skills like creative

thinking, the process is as important as the end result. Even if a student ultimately develops an idea that is not the most original, has he or she engaged in an idea generation process in which he or she has considered multiple ideas and evaluated those ideas for relevance, appropriateness and quality? Do students consider multiple possibilities? Do they follow the most obvious problem-solving path or do they attempt to question their own or others’ ideas? And once they have a solution, do they consider whether and how it can be improved?

Finally, how can the community and the family be involved in creativity education?

The PISA framework recognises several individual factors that can influence creative thinking, including students' attitudes and beliefs about creativity. One of the ways that family and society can help foster creative thinking is by cultivating positive attitudes about the value of creativity and supporting the idea that it is a competency that can be developed through intentional practice.

For example, play is something that children do every day, and it’s a great opportunity to exercise and develop creative thinking. Rather than thinking of play as an activity that detracts from learning, it can actually be a highly motivating, autonomous and interactive process that facilitates the development of a range of skills related to creative thinking, such as improvisation, risk-taking, imagination, cognitive flexibility and perspectivetaking. And the great thing about creative play is that it can be easily replicated in diverse cultures, different age groups and abilities and high - and low-resource settings.

Creative thinking: is inspiration from existing ideas, moving them forward in an original way and achieving something better collectively

Play facilitates the development of skills related to creative thinking, such as improvisation and cognitive flexibility

Creativity, intelligence and high ability

Some people stand out for their creative talent, whether or not they have a high intellectual ability

by Rosabel Rodríguez Rodríguez

The relationship between creativity, intelligence and high intellectual ability (HIA), and more specifically with giftedness, has always been a complex issue to address. Many authors have suggested that high intelligence is a necessary but insufficient component to activate creativity, and the reality is that many people with a high intellectual capacity are not creative. So what is creativity and how can we foster it?

THE EVOLUTION OF A CONCEPT: CREATIVITY

Views about creativity have evolved over several decades of research and the application of creative thinking strategies. Although it is still often claimed that there is no universally agreed upon definition of creativity, the reality is that there is now a fairly consistent conception. 1

For more than six decades2 most creativity researchers have consistently focused on two key concepts: 3

1. Creativity must represent something different, new or innovative.

2. Creativity must also be appropriate to the task at hand. It must be useful and relevant.

Both "’new’ and ‘appropriate’ are absolutely necessary. Having an original, novel or different idea is not enough to be creative, because creativity is described as a multiplicative all-or-nothing game: 4

Creativity = Originality x Appropriateness

Thus, if originality or appropriateness is zero, then we will get a zero in creativity.

The traditional approach to creativity can be characterized as the four P's approach, that is, the study of the person, the process, the product and the productive conditions. In addition, there are a number

of confluence theories of creativity, such as Robert Sternberg y Todd Lubart’s investment theory5 and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s systems theory 6 In them, a person's general intelligence (g) is a necessary but not sufficient component for Creativity (C) to manifest itself. In other words, a person with high intellectual ability is not necessarily creative. Here, Creativity (‘Big C’) is understood as domain-specific, and a creative product is one that causes significant change within that specialised domain of knowledge, as opposed to the idea of everyday creativity (‘little c’), which is used to describe activities such as improvising a recipe. 7

Psychometric approaches, such as those used to measure intelligence, have also been used to measure creativity. This involves quantifying the notion of creativity with the help of paper-and-pencil tasks. One example is the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking developed by E. Paul Torrance,8 which are frequently used to identify students with High Intellectual Ability (HIA).

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CREATIVITY, INTELLIGENCE AND HIGH ABILITY

As creativity and intelligence became better known, the inherent relationship between the two concepts became clear, but it was not so easy to elucidate what it was: Is intelligence part of creativity? Or is creativity part of intelligence?

Different theories offer different answers. For example, threshold theory suggests that intelligence is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creativity; 9

SPOTLIGHT 35 34

Creativity must represent something new or innovative and must be useful, relevant and appropriate to the task at hand

certification theory focuses on the environmental factors that enable people to show creativity and intelligence; 10 while the interference hypothesis suggests that very high levels of intelligence can interfere with creativity.11 All these proposals are supported by very high quality work, so it is easy to read them and end up thinking: how is this possible?

Currently, the most widely accepted perspective suggests that although there is a certain positive relationship between intelligence and creativity, this relationship is minimal and is therefore understood that intelligence and creativity are two independent though complementary factors.

At this point, we can also ask ourselves: Is there a direct relationship between creativity and high ability? And if so, what type of relationship is it? In view of the above, it is probably easy to anticipate that there is no simple or consensual answer.

On the one hand, we can find authors such as E. Paul

Torrance,12 who was a staunch defender of the idea that giftedness cannot be understood without creativity. For him, high intelligence is not enough for a person to be gifted; however, his position is not widely shared. In fact, generally speaking, high IQ is more often sought after than high creativity. Thus, for example, in countries such as the United States, where there is a long tradition of studying HIA, each state has its own definition (mostly variations of Maryland's 1972 definition). 13 In 2012, a study by McClain and Pfeiffer14 revealed that only 27 states included creativity in the definition of HIA.

On the other hand, Renzulli's proposal 15 is probably one of the most widely accepted today. According to this author, there are two types of giftedness: high-achieving (academic or ‘school’) giftedness and creative-productive giftedness. The former is more analytical in nature, while the creative-productive type emphasises generation and production.

The reality is that the most creative students may be perceived as ‘weird’ in schools, rather than smart.

Creativity exists as a talent, that is, as an outstanding aptitude in some people, and that it is part of high ability.

We currently understand that intelligence and creativity are two independent though complementary factors

Predictability is often valued in classrooms, and these children defy the monotony by doing unexpected things. This way of acting may increase their popularity among other students,16 but not their attractiveness to teachers.

So what do we really know about the relationship between these concepts? Although there are still many issues to be resolved, progress has gradually been made and certain consensuses have been reached. In general we can agree that:

1. For there to be creativity there must be a certain intellectual capacity, although this is not a guarantee that they will grow together progressively.

2. Similarly, it seems clear that having high intelligence does not guarantee high creativity, nor vice-versa.

3. We also know that creativity exists as a talent, that is, as an outstanding aptitude in some people, and that it is part of high ability. Creative talent does not depend exclusively on a high IQ but also on other social and personality factors that facilitate creative production.

4. Finally, it has been proven that in any situation, the convergence of intelligence and creativity produces a synergistic effect where both benefit each other.

Therefore, creativity must always be present when we talk about high ability, both during assessment, as an indispensable element of it, and in classroom programmes, where it should occupy a prominent place in the curriculum.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CREATIVITY

Pedagogical practice is very important in enhancing creative potential or its achievement in childhood. In fact, schools should provide an environment that specifically values creative thinking, recognises it in students, and promotes it through teacher behaviours in the classroom.

Given our understanding of the phenomenon, what can teachers and schools do to promote students' creative abilities?

SPOTLIGHT 37 36

Schools should provide an environment that specifically values creative thinking and recognises it in students

It has been proven that the convergence of intelligence and creativity has a positive effect on both

There are six goals we can focus on to promote these behaviours:17

1. Develop intellectual risk-taking through the expression and appreciation of differences and the choice of activities of interest.

2. Develop high-level convergent and divergent skills through the use of educational models that require and promote these skills.

3. Encourage deep learning in those who have an interest and aptitude in a given domain so they can develop quality knowledge in it.

4. Develop strong communication skills in written and oral contexts, providing feedback on the effectiveness of the work.

5. Develop personal motivation and passion.

6. Encourage creative habits of mind through reading and perspective-taking and introducing novelty.

Teachers are often informed and aware of these principles, but applying them can be difficult. 18 Therefore, teachers and professors must be educated to understand creative development and the ways creativity can be fostered or inhibited by school practices.

The suggested goals should be systematically applied to each learning area to maximise student engagement and learning, and applied to current ideas and problems in the world that are encountered in real life.

Rosabel Rodríguez Rodríguez holds a PhD in Educational Psychology (UIB) and is a psychologist and university professor in the field of Developmental Psychology and Education (UIB). She specialises in the field of high intellectual ability (giftedness and talent), creativity and teacher training.

References

1 Cropley, D. H. (2015). ‘Enseñar a los ingenieros a pensar de forma creativa’. In: R. Wegerif, L. Li, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.). "The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Teaching Thinking" (pp. 402–410). Routledge.

2 Guilford, J. P. (1950). ‘Creativity’. "American Psychologist", 5, 444–454

3 Stein, M. (1953). ‘Creativity and culture’. "Journal of Psychology", 36, 311–322.

4 Simonton, D. K. (2012). Criterios de la Oficina de Patentes de EE.UU.: ‘Una definición cuantitativa de creatividad de tres criterios y sus implicaciones’. "Creativity Research Journal", 24, 97–106.

5 Sternberg, R., & Lubart, T.I. (1995). ‘Desafiando a la multitud: Cultivar la creatividad en una cultura de la conformidad’. Free Press.

6 Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). ‘La creatividad: El flujo y la psicología del descubrimiento y la invención’. HarperCollins.

7 Richards, R. (2007). ‘Creatividad cotidiana y nuevas visiones de la naturaleza humana’. American Psychological Association.

8 Torrance, E.P. (1976). ‘Pruebas de pensamiento creativo’. Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée.

9 Barron, F. (1963). ‘Creatividad y salud psicológica’. D. Van Nostrand Company.

10 Hayes, J. R. (1989). ‘Procesos cognitivos en la creatividad’. In: J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning, & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), Handbook of Creativity. Plenum Press.

11 Sternberg, R. J. (1996). ‘La inteligencia del éxito: Cómo la inteligencia práctica y la creativa determinan el éxito en la vida’. Simon & Schuster.

12 Grantham, T. (2013). ‘Creatividad y equidad: El legado de E. Paul Torrance como defensor de los varones negros superdotados’. "The Urban Review", 45, 518–538.

13 Marland, S. (1972). ‘Educación de los superdotados y con talento’ (Informe al Congreso de los Estados Unidos por el Comisionado de Educación de los Estados Unidos). U.S. Government Printing Office.

14 McClain, M. C., & Pfeiffer, S. (2012). ‘La identificación de los alumnos superdotados en los Estados Unidos en la actualidad: Una mirada a las definiciones, políticas y prácticas estatales’. "Journal of Applied School Psychology", 28, 59–88.

15 Renzulli, J. S. (1978). ‘¿En qué consiste la superdotación? Reexaminando la definición’. Phi Delta Kappan, 60, 180–184.

16 Kaufman, J. C. (2009). "Creativity 101". Springer.

17 VanTassel-Baska, J. (2004). ‘La creatividad como factor elusivo de la superdotación’. https://www.davidsongifted.org/gifted-blog/creativity-as-an-elusive-factor-ingiftedness/

18 Sak, U. (2004). ‘Creatividad, superdotación y enseñanza de los superdotados de la creatividad en el aula’. Roeper Review, 26(4), 216-222.

Teachers need to understand creative development and the ways it can be fostered or inhibited in school practices

SPOTLIGHT 39 38 C reative Logical Adventure r Strategi c Passionate

Creativity and critical thinking in the classroom

by Ana Moreno Salvo

INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT SWARTZ

Some time ago, David Perkins and you wrote some ideas about the need to teach ‘good thinking’. What, to you, is a good thinker? David and I met at Harvard when I was a graduate student. We were both very sensitive to the fact that most people don't think well. They make quick decisions, snap judgments and mistakes. For example, in an ad for breakfast cereal, it says ‘this is a delicious cereal’ or ‘it is as beneficial to eat a spoonful of this cereal as it is to

eat an apple’ next to a picture of an apple that looks delicious. The message is designed to make me decide that it is a good idea to buy this cereal. Now research has been done that shows that if you eat a certain type of cereal every day, after 20 years there is a chance that you will develop cancer. What David and I realised is that most people make decisions this way. They think good things, but don't ask themselves, are there any disadvantages? We realised that this was true of most types of thinking and decided that it

would be a good idea to help them develop the habit of asking not only if there is any good, but also if there is any negative consequence, that is, to learn how to think better. It was about figuring out how to teach students so that they learn early in their schooling how to really think more carefully when making decisions, when solving problems, when thinking about how something works and so on.

Could you give us a definition of creative thinking? How does it relate to critical thinking, if at all? Thinking creatively is one of the different types of thinking that we need to learn to do well in different circumstances. It implies having new, original, creative and different ideas.

Many people do not think well, because they don't ask about disadvantages. They make quick decisions, snap judgments and mistakes

‘Productive creativity’ arises when we apply critical thinking to creative thinking

Robert Swartz(†1936- †2022), held a PhD in Philosophy from Harvard University, was a professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and the creator, along with Sandra Parks, of the Thinking-Based Learning (TBL) methodology, which replaces teaching based on memory with teaching based on active thinking. He founded and directed the Center for Teaching Thinking (CTT), dedicated to promoting this methodology in the United States, Spain and countries around the world. For the past 30 years, he worked with teachers, schools and universities internationally on projects in teacher development, curriculum reorganisation and education through the infusion of critical and creative thinking into the teaching of content.

The mere fact that you come up with these creative ideas is the practice of creativity. Critical thinking, on the other hand, consists of trying to think about ideas and asking ourselves if they are right, if what we are saying is true or true. In creative thinking, we try to come up with something new, original and interesting, and in critical thinking we ask ourselves, are these creative ideas good ideas?

I like to work on creative thinking in what I call ‘productive creativity’, which is coming up with new and original ideas that work, that move our lives forward. And that means applying critical thinking to the creative thinking we have practised. For example, you have a problem that no one has been able to solve, or it’s a new problem that has just

arisen and needs to be solved, so you have to use creative thinking to try to come up with some original ways to solve that situation. Critical thinking then has to be applied to determine whether the proposed solutions will work.

I think it is important to emphasise the idea of ‘productive creativity’ when we are trying to come up with new ways of doing something. We have tried every possible way we know of and it doesn't seem to work. So we try to exercise creativity, but we want to make sure that the creative ideas we come up with are productive.

He is one of the world's leading experts in the teaching of thinking, and his books are very popular in schools. His dedication to teacher training on five continents has given him a privileged knowledge and experience on how thinking is taught in schools. What do you think are the keys to teaching thinking?

When I started in the United States, in Massachusetts, I was a faculty member at a university, and that limited me. I wanted to go to schools all over the world, work with their

Thinking creatively implies having new, original, creative and different ideas. These creative ideas is the practice of creativity

SPOTLIGHT 43 42

teachers, and show them everything I had discovered and what I had learned from other teachers to make it all work. I aimed to help them put this into practice in their classrooms, to help teachers learn how to teach children to be better thinkers. So I got permission from my university and started traveling and turned the schools into what I

call ‘Thinking Schools’. I created the ‘Center for Teaching Thinking’ and a certificate to certify that these schools taught not only content but also how to think. Eighty to 90% of the teachers in these schools teach all their content through thinking. We have developed a technique, TBL (Thinking-Based Learning), for teachers and their students to learn

how to do this, and it really works. The approach starts with thinking about what real learning is. I then ask them to pass the challenge on to the students and ask them: How are you going to learn this? What questions do you need to know how to answer to think about it well and come to an acceptable conclusion? Teachers work together and find the technique of learning to think that will allow them to transform learning into thinking to learn. They should not provide the thinking strategy to the students, but instead they should challenge them to find the