Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022 i Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Research methodology 1 3 Understanding Dharwad.................................................................................................................3 3.1 Regional setting.......................................................................................................................3 3.1.1 Location and climate 3 3.1.2 Natural setting ................................................................................................................3 3.1.3 Climate change trends ....................................................................................................4 3.2 Urban history and growth 4 3.2.1 Medieval history 4 3.2.2 Dharwad under the British rule ......................................................................................5 3.2.3 Dharwad- present growth trends ...................................................................................6 3.3 Urban Informality 8 3.4 Policies and plans 9 3.5 Climate change, urbanisation, and informality nexus- vulnerabilities and risks ..................10 4 Study area 13 4.1 Settlement selection 13 4.1.1 Stakeholder Workshop .................................................................................................15 4.1.2 Primary survey and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)...................................................16 4.2 Settlement Typology 18 5 Analysis and Findings ....................................................................................................................19 5.1 Analysis .................................................................................................................................19 5.1.1 Settlement and City-Settlement level...........................................................................19 5.2 Insights 25 5.2.1 Flooding: urbanisation and informality induced exacerbations ...................................25 5.2.2 Heat stress: Urbanisation and informality induced exacerbations...............................26 6 Potentials and possibilities: adaptation and mitigation measures 28 6.1.1 Settlement and city-settlement level 28 7 Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................35 References 36

ListofFigures

Figure 1: Research design 2

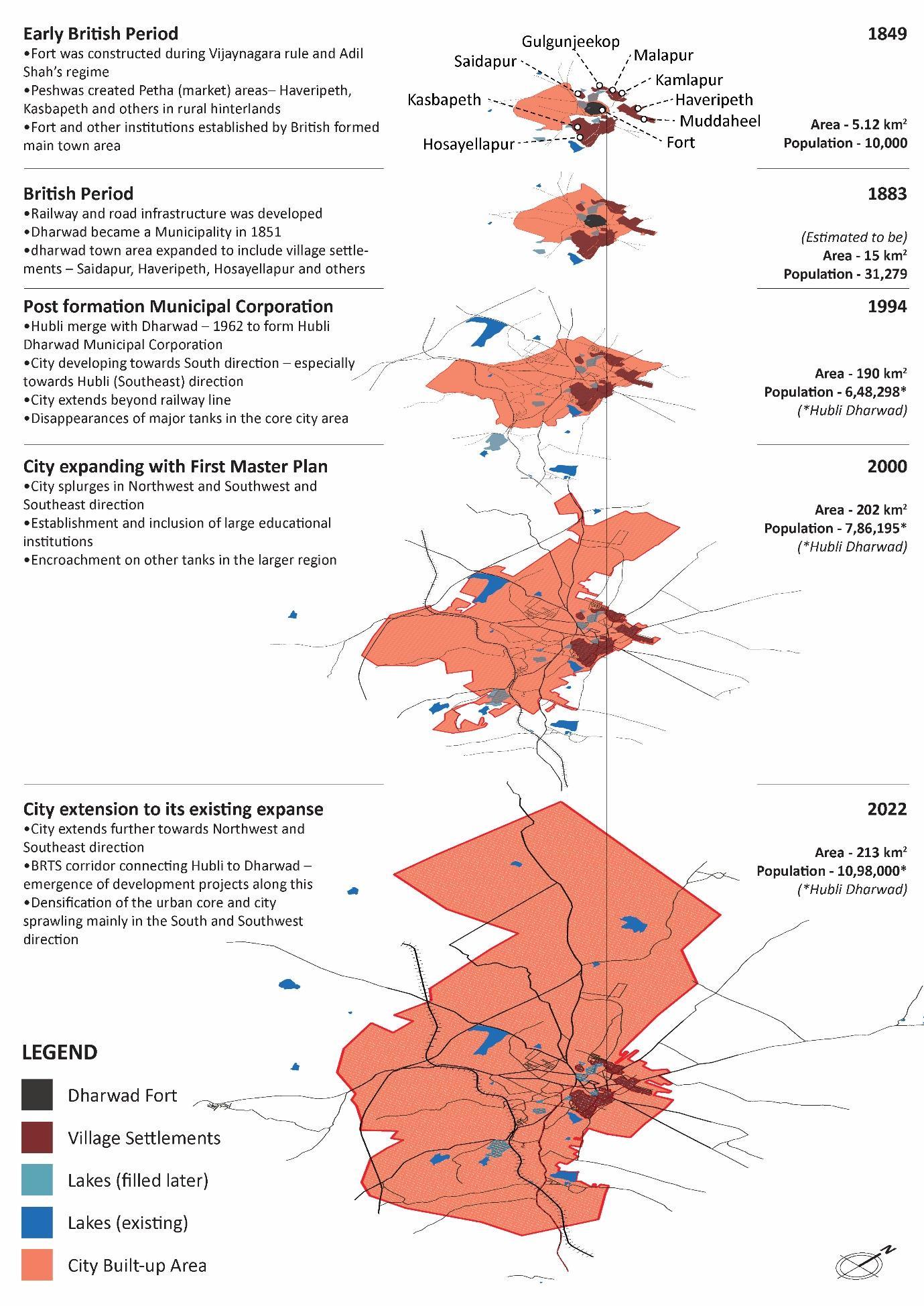

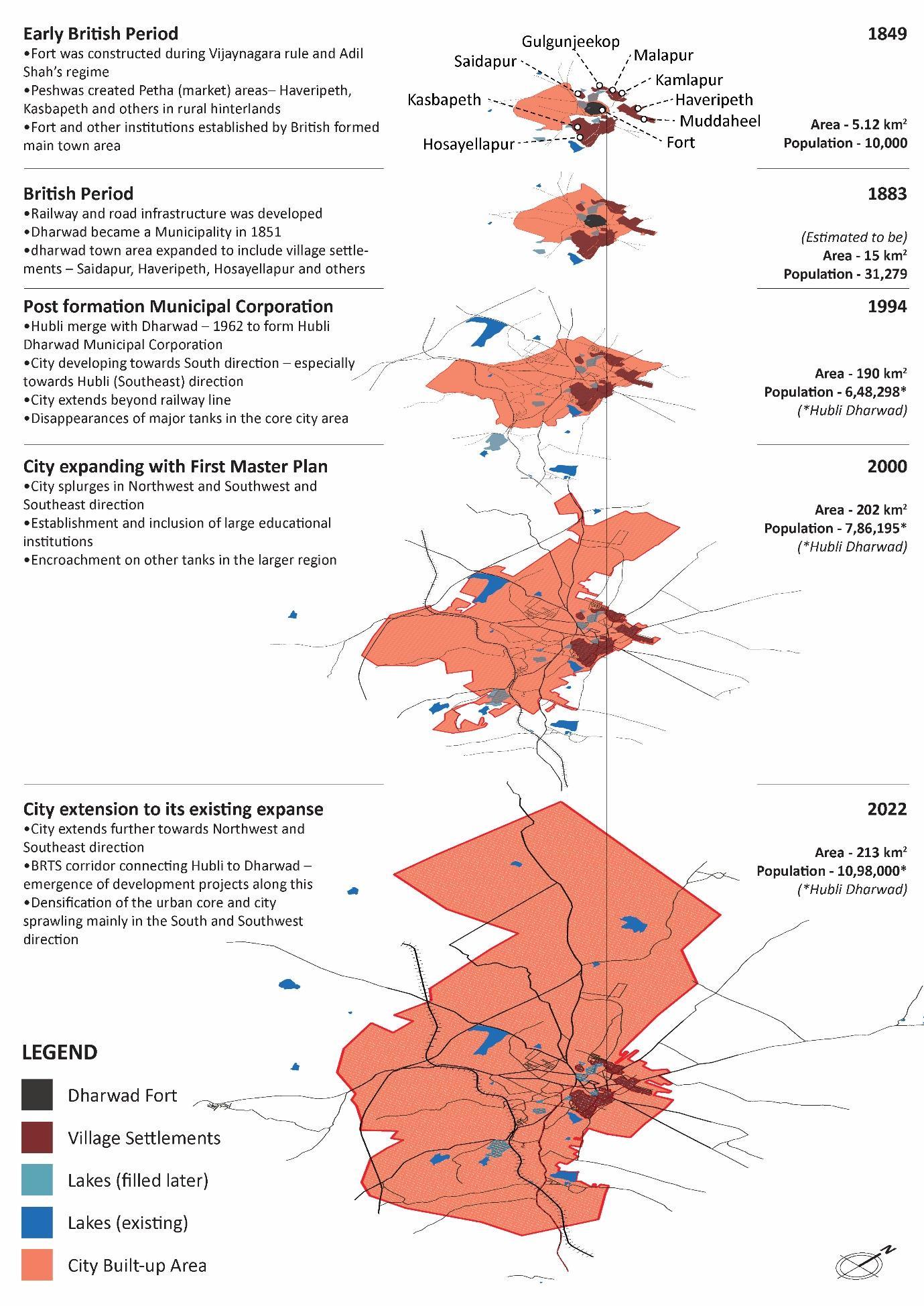

Figure 2: Evolution of Dharwad city........................................................................................................7

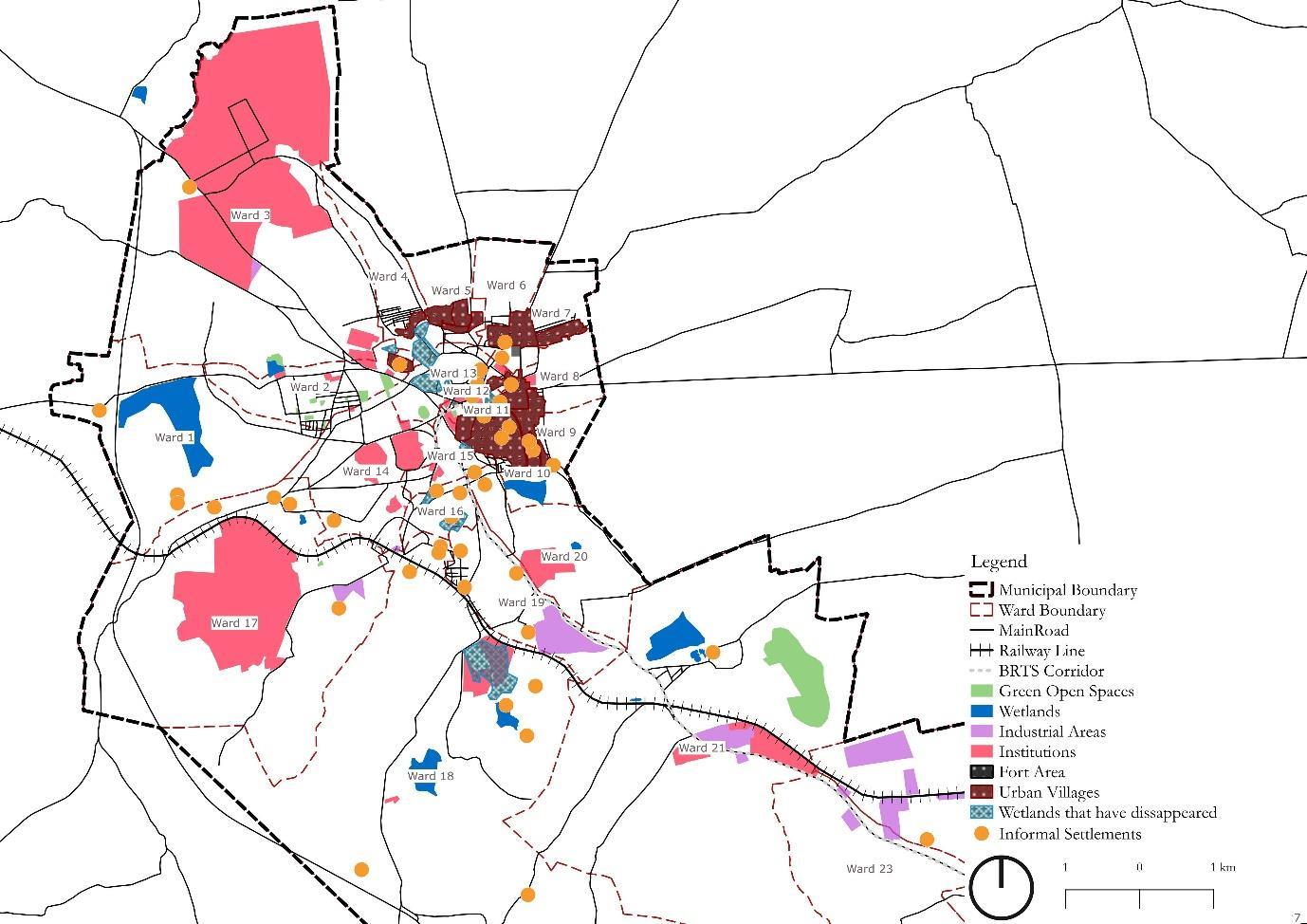

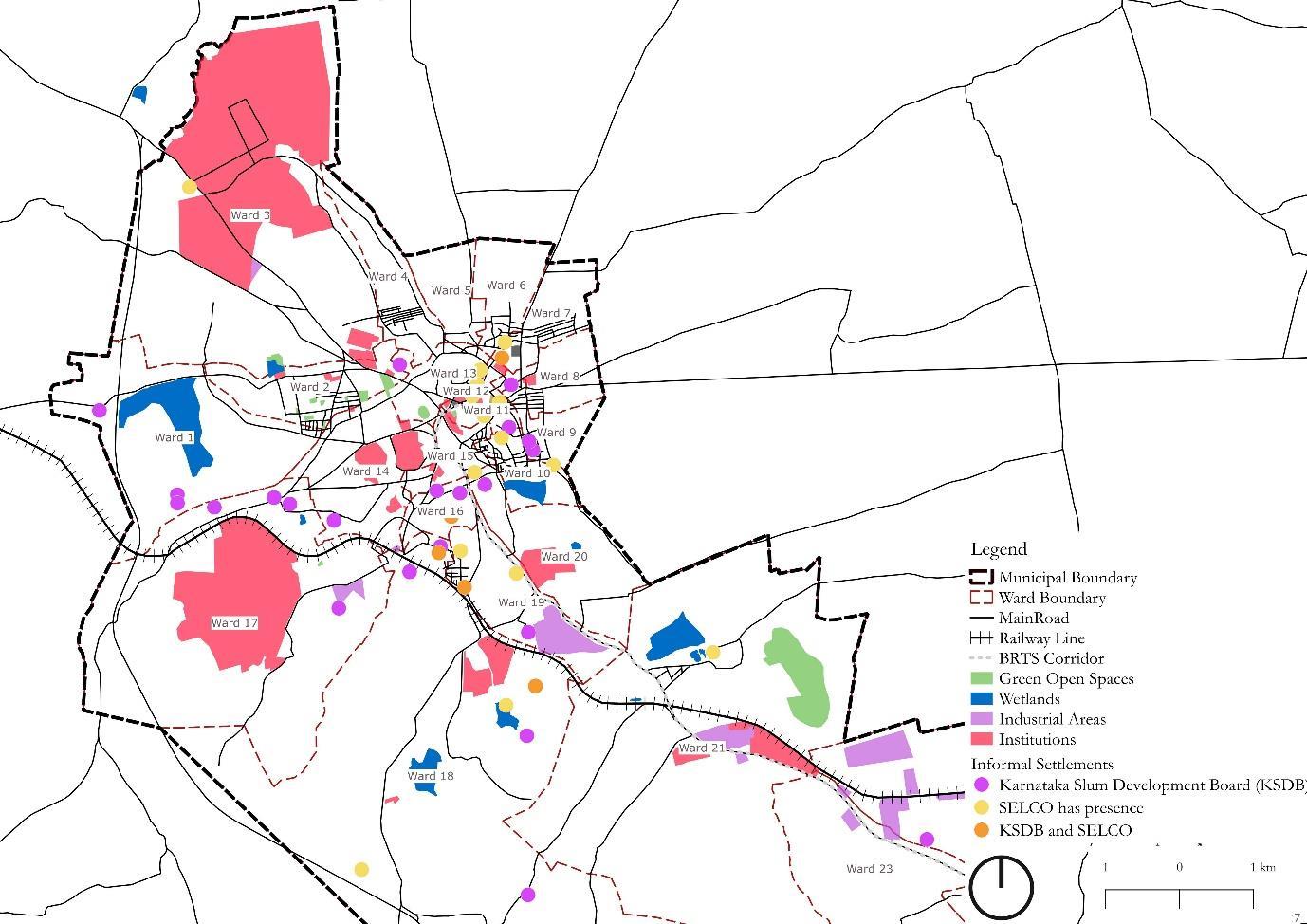

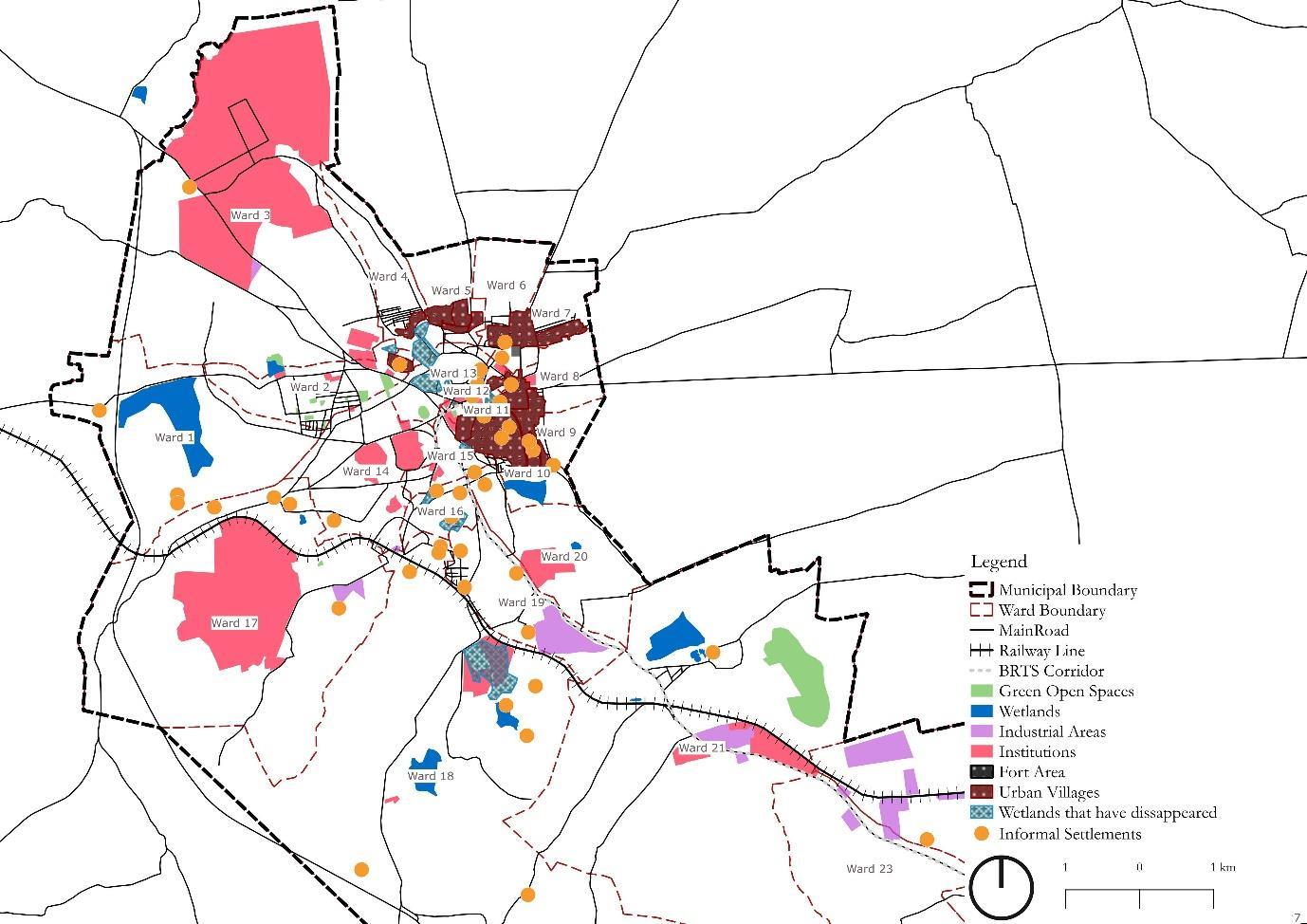

Figure 3: Informal settlements in Dharwad............................................................................................8

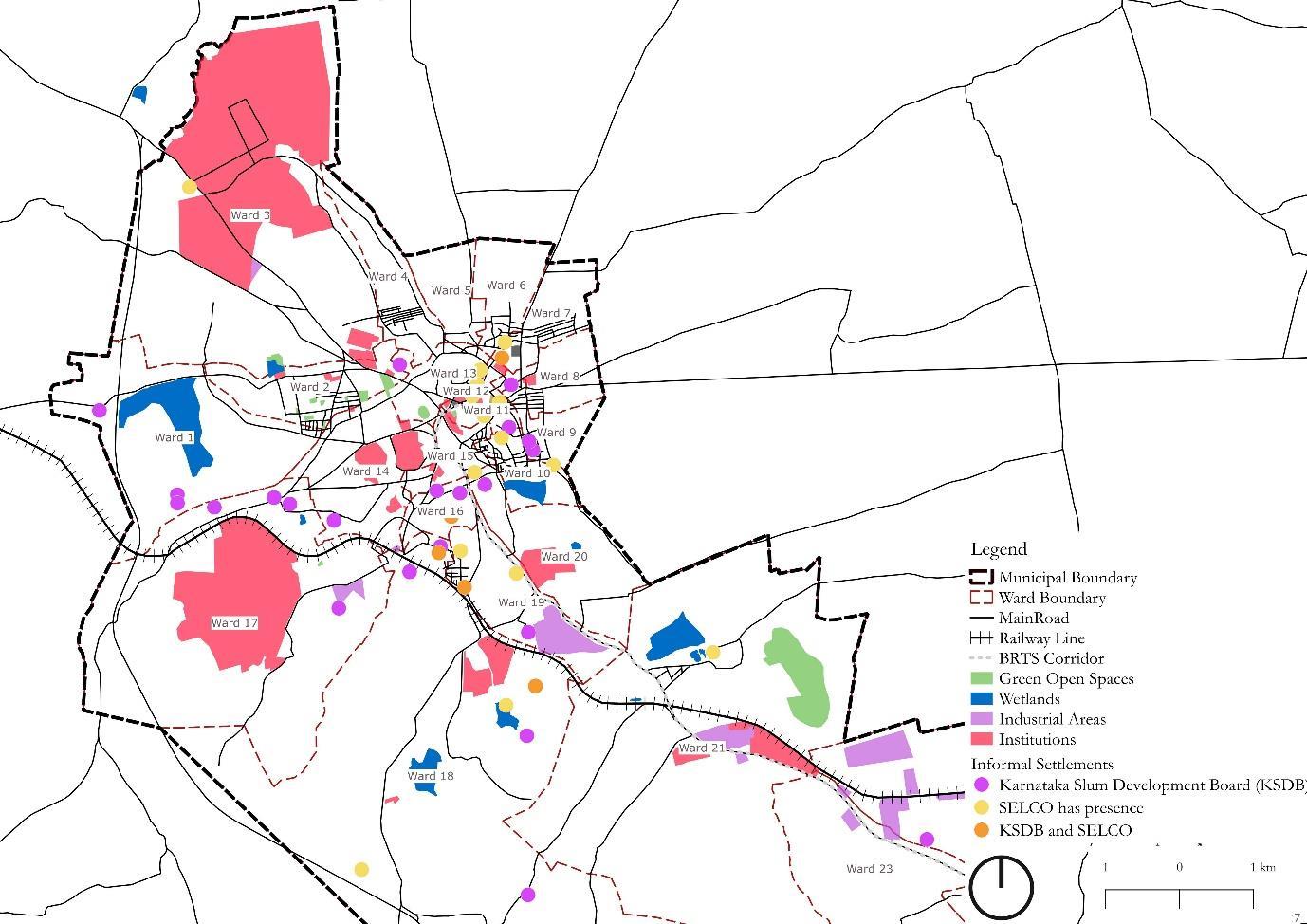

Figure 4: Existing and extinct water systems in Dharwad 12

Figure 5: Informal settlements in Dharwad (categorised)....................................................................13

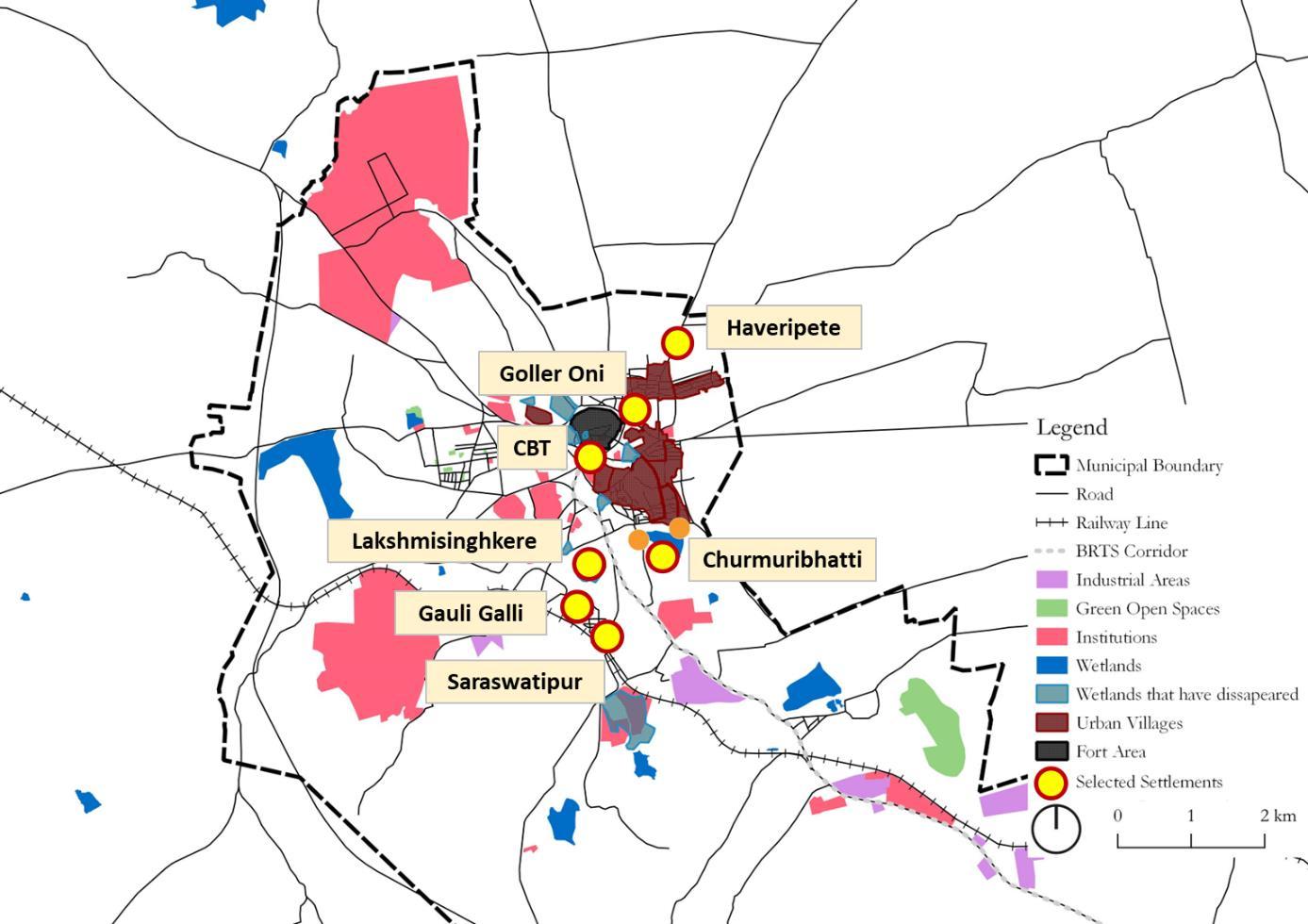

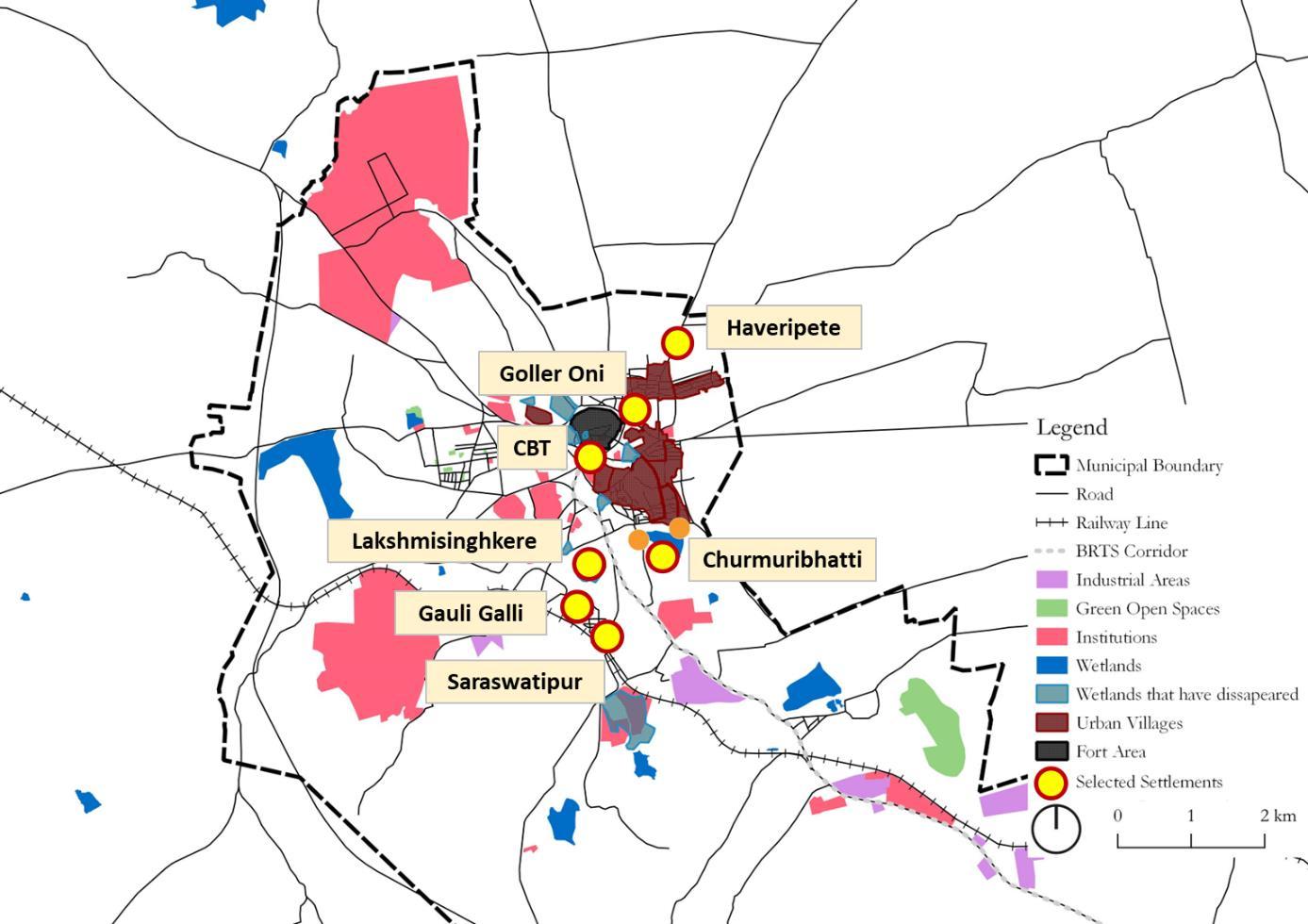

Figure 6: Location of settlements selected for the study 15

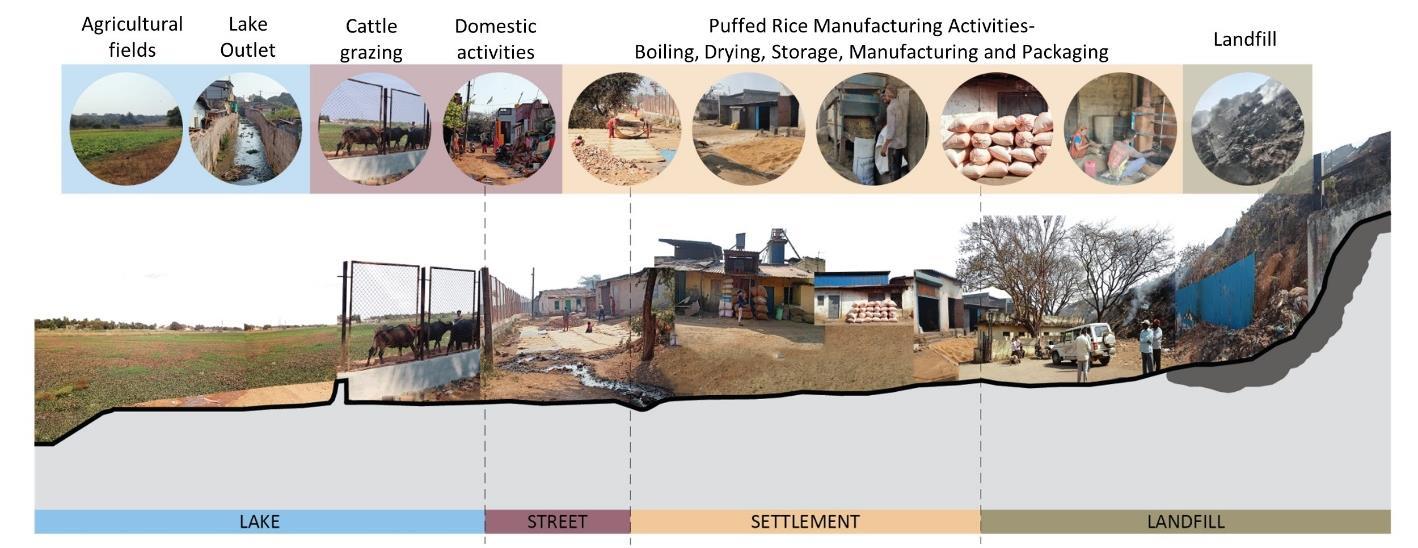

Figure 7: Stakeholder consultation workshop in progress 16

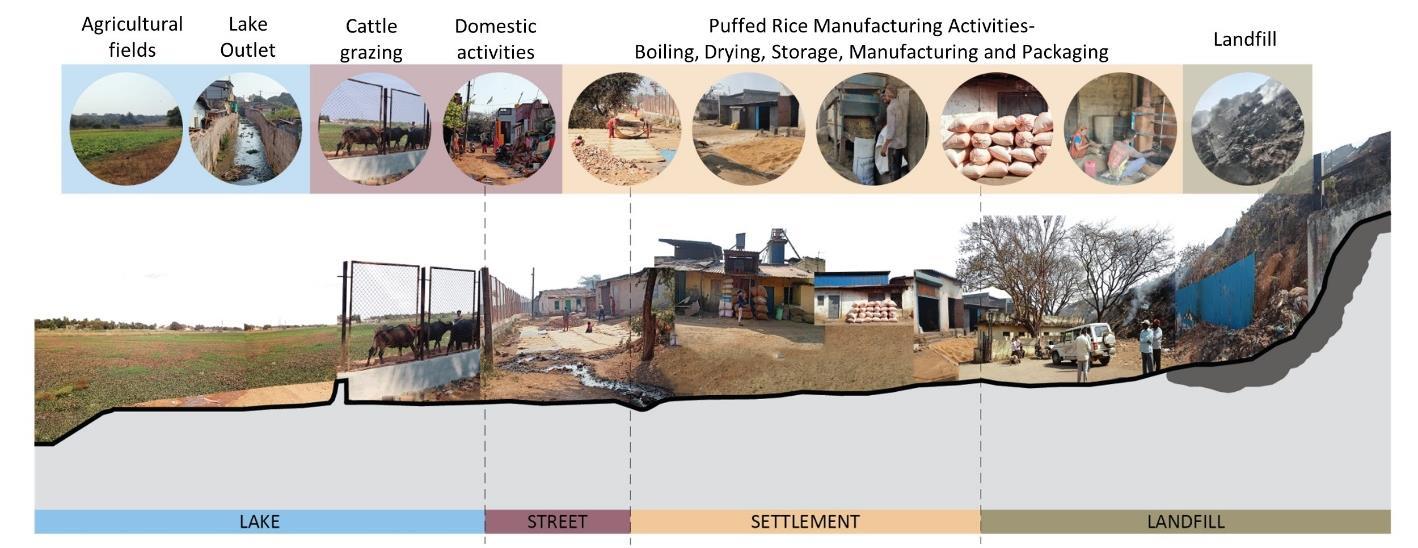

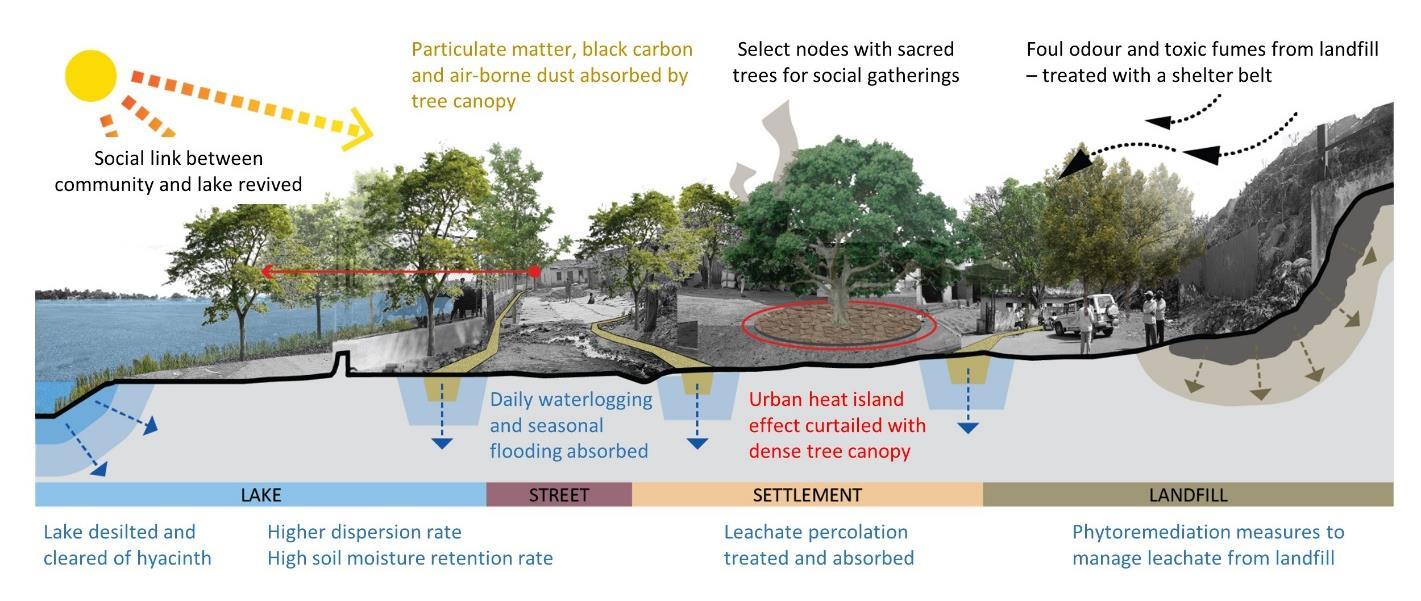

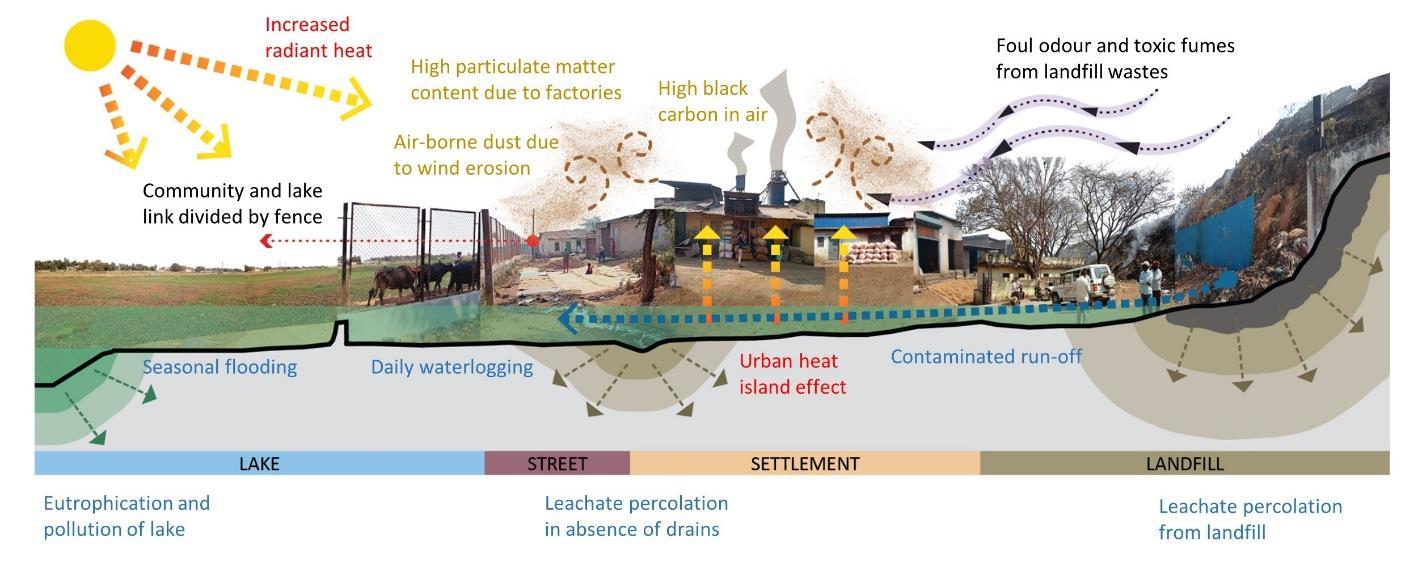

Figure 8: Activities carried out in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad................................................................30

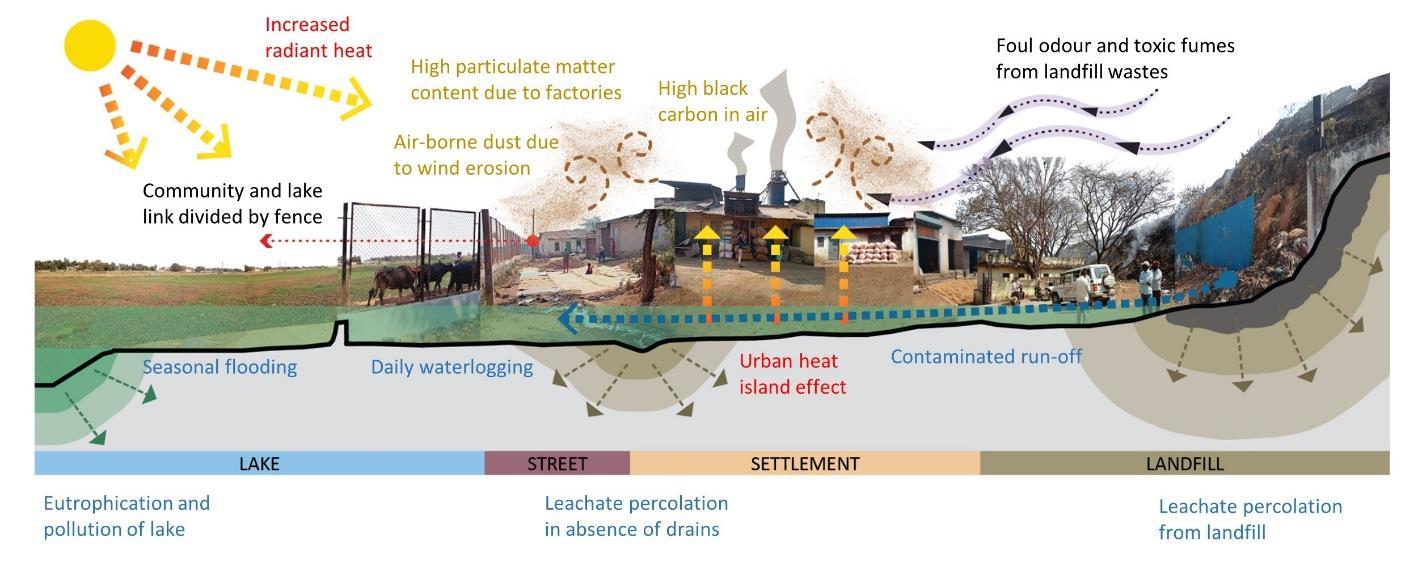

Figure 9: Vulnerabilities in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad 30

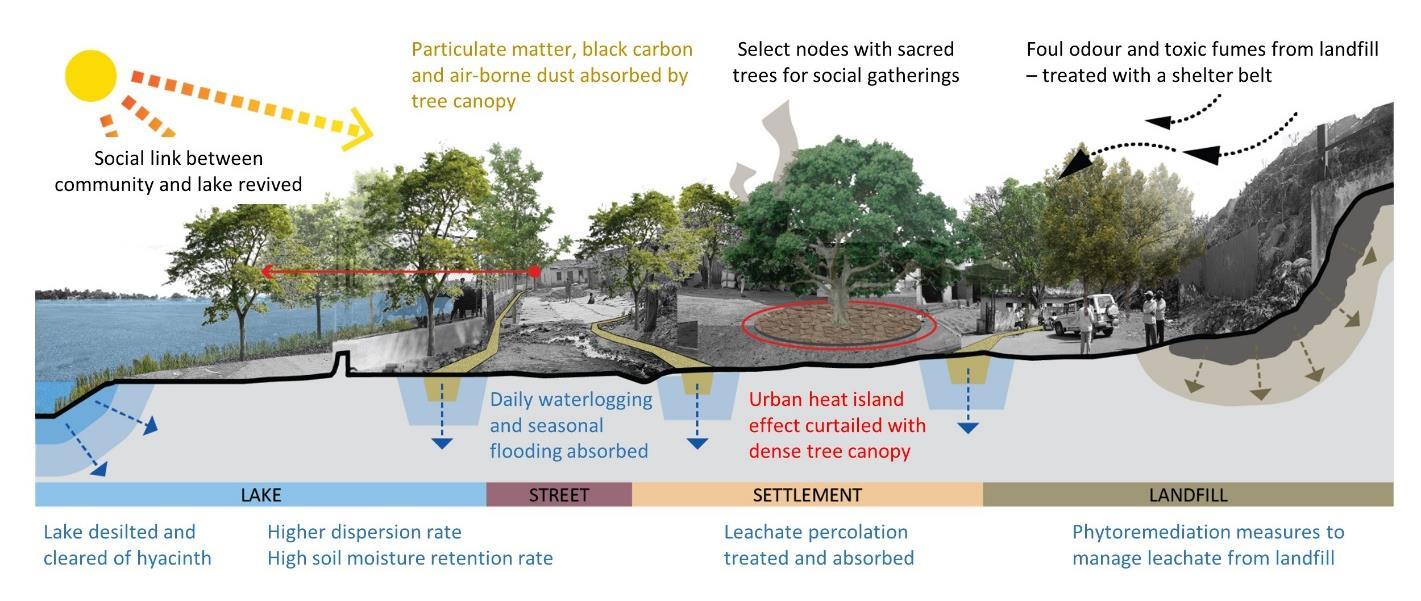

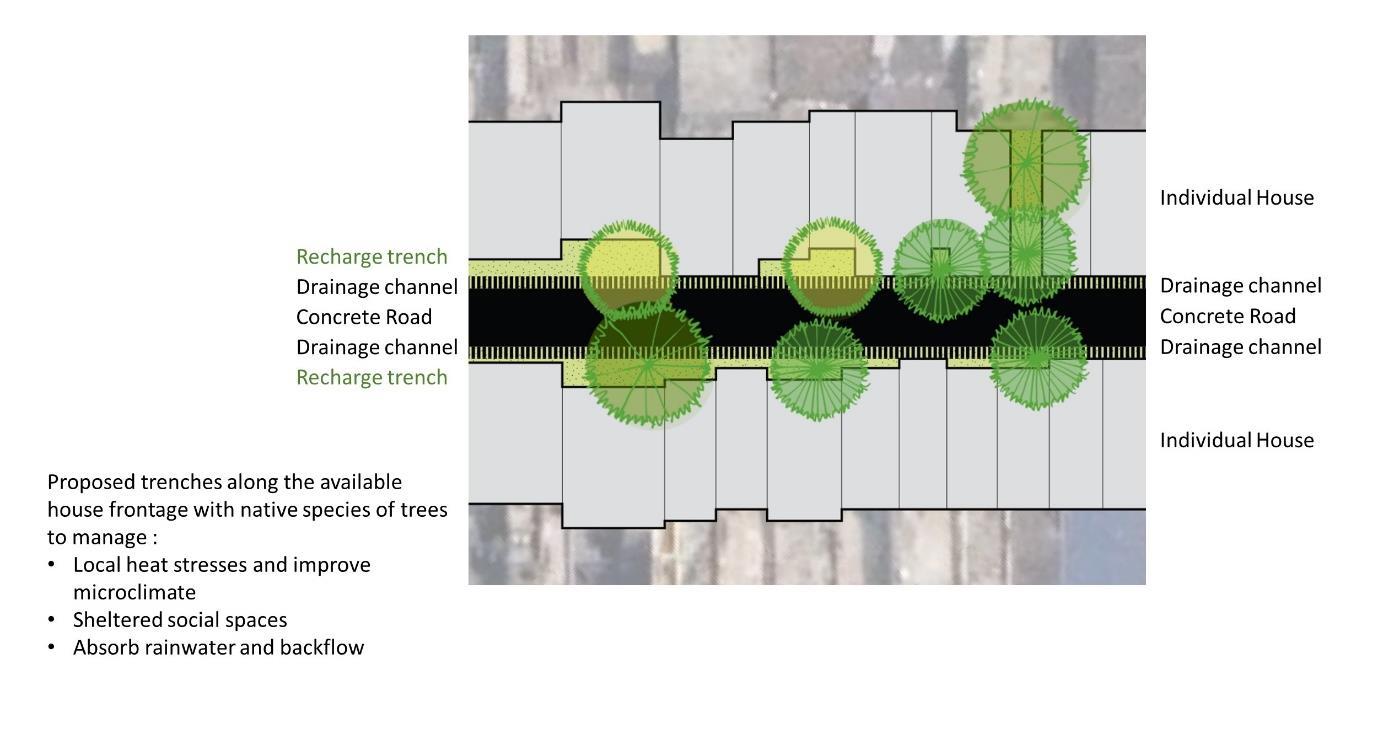

Figure 10: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad (a) 30

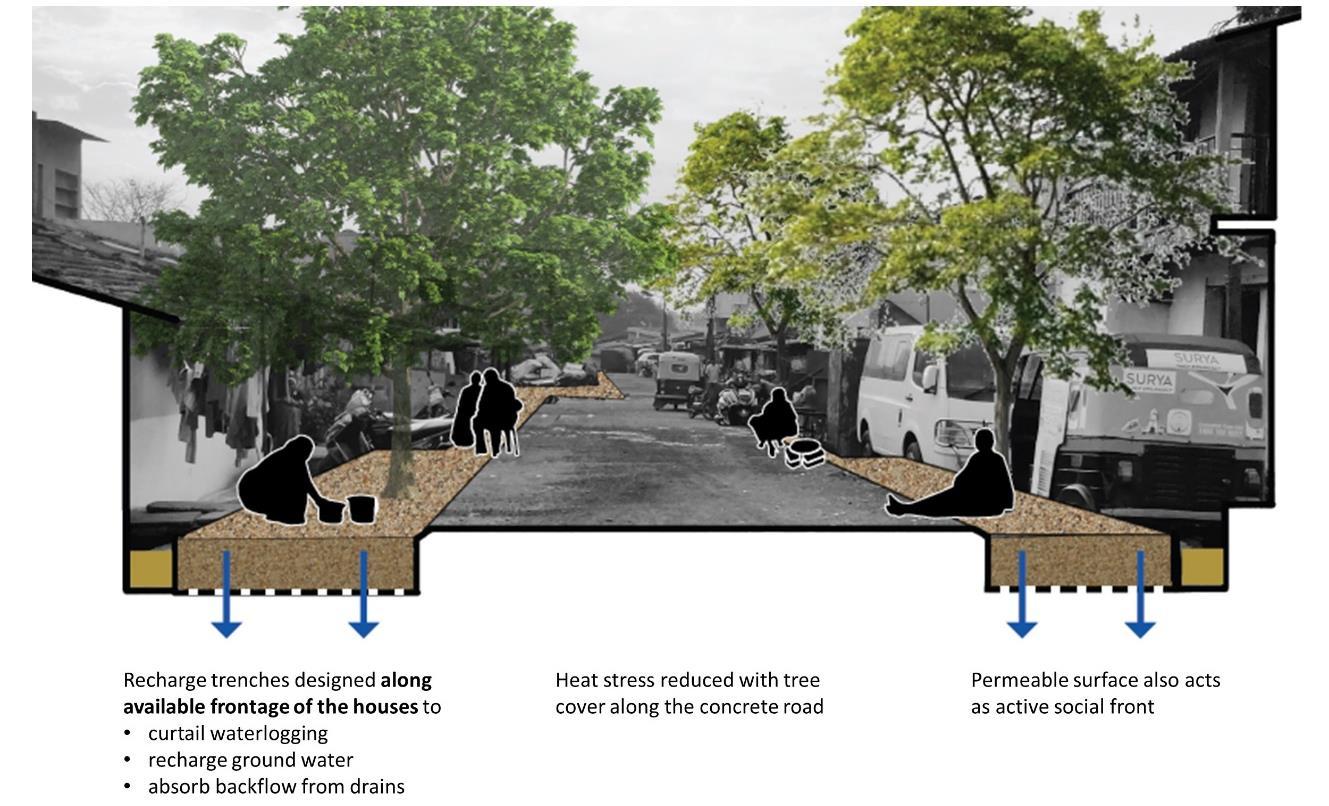

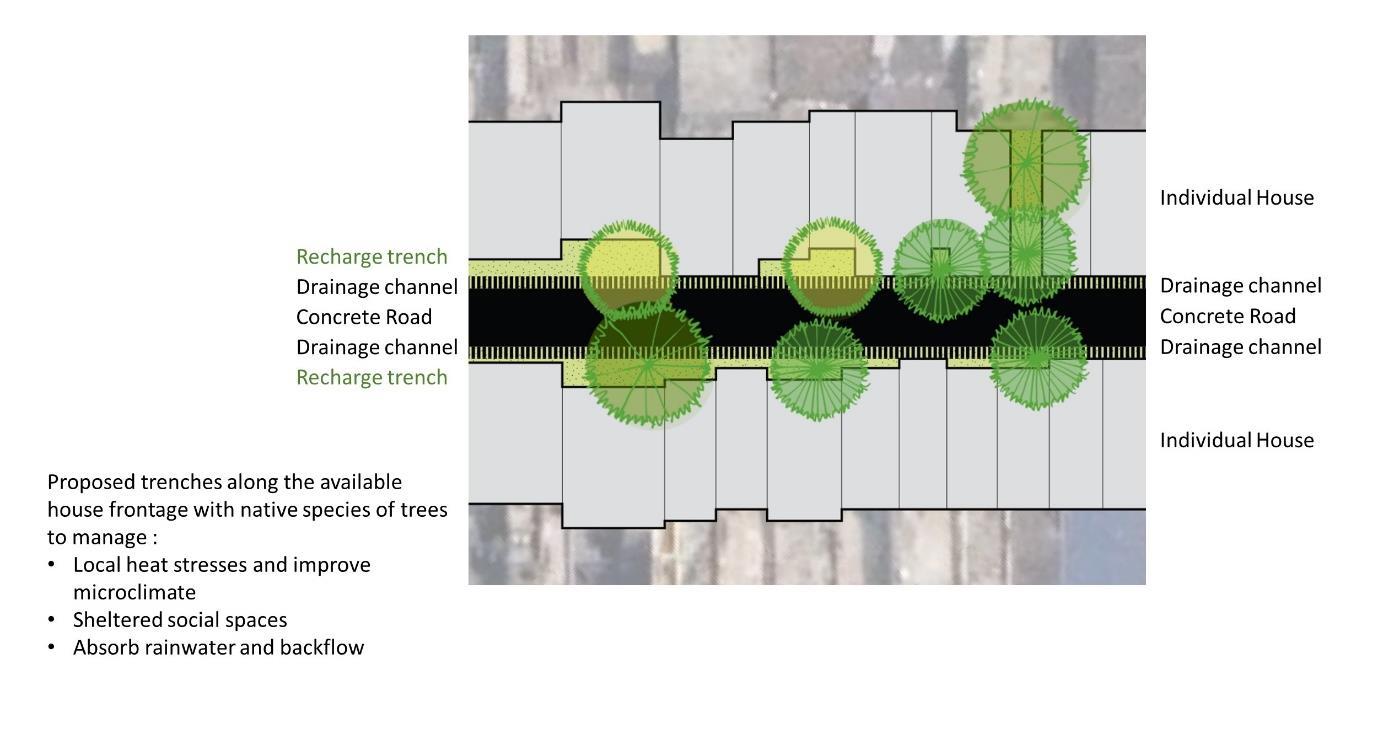

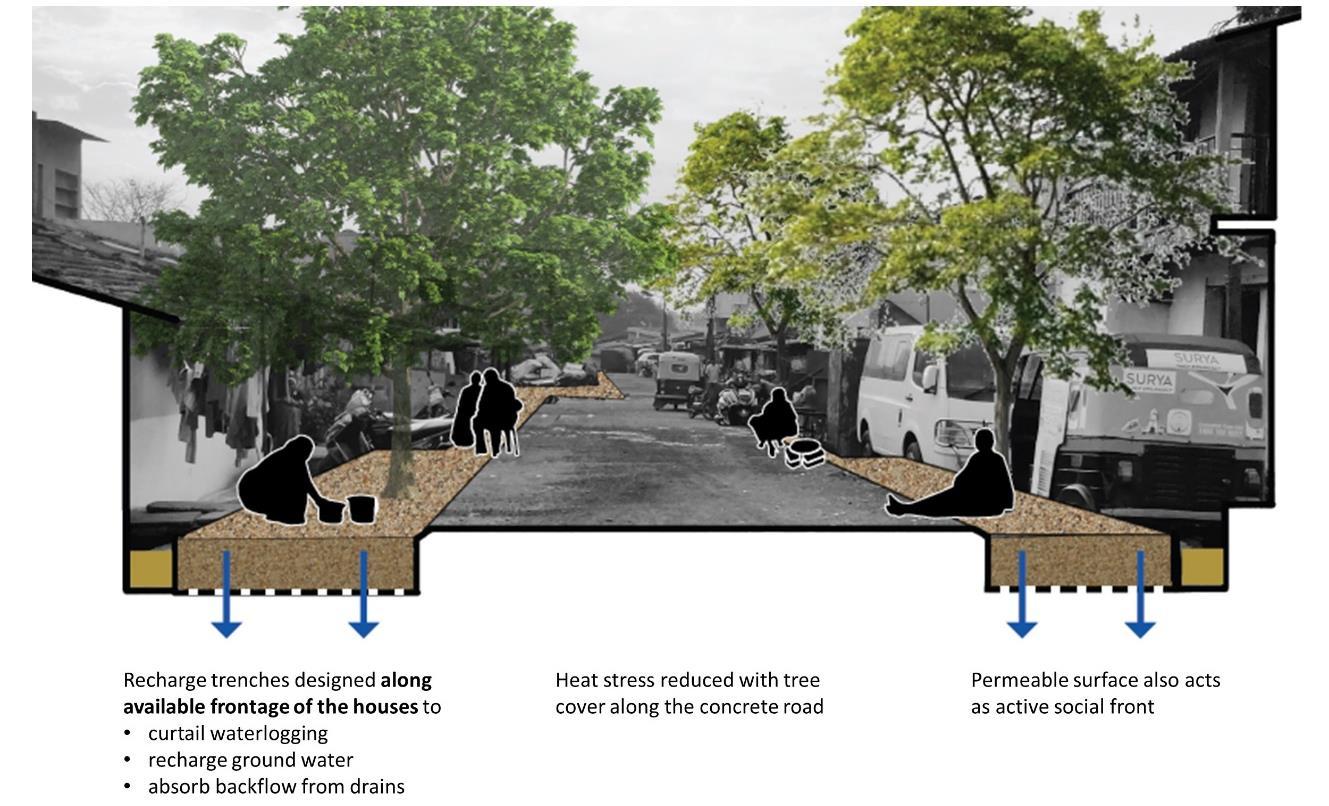

Figure 11: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad (b).....................31

Figure 12: Activities carried out in Goller oni, Dharwad 32

Figure 13: Vulnerabilities in Goller oni, Dharwad (a) 32

Figure 14: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Goller oni, Dharwad (a) ..............................33

Figure 15: Vulnerabilities in Goller oni, Dharwad (b) 34

Figure 16: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Goller oni, Dharwad (b) 34

ListofTables

Table 1: Urban Growth of the Dharwad urban area 6

Table 3: Selected settlements and their profile....................................................................................14

Table 4: Guide for site observation and FGDs 16

Table 5: Pilot settlements 18

Table 6: Common spaces impacted by climate stress, urbanisation, and informality. ........................21

ii Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

1 Introduction

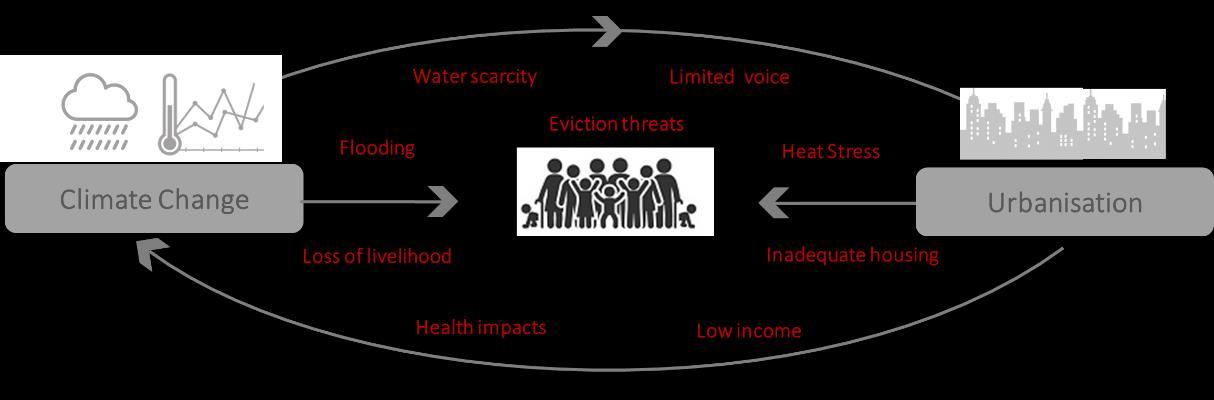

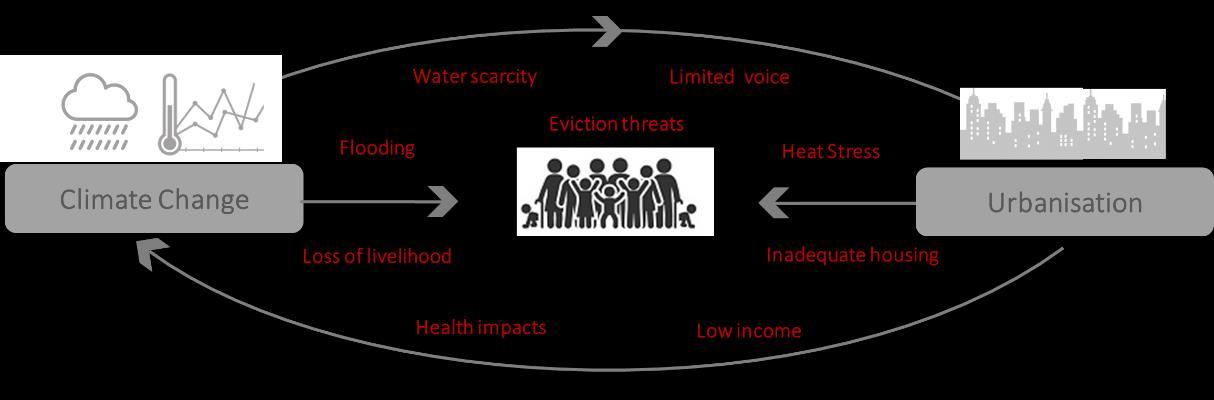

Climate change is intensifying poverty and socio-economic inequality- especially in urban areas which are at the forefront of climate change impacts (Burzyński et al., 2019; Dodman et al., 2019). The situation is particularly alarming in the global South which is facing unprecedented urbanisation, extreme levels of inequality, and is also highly under prepared to face the impacts of climate change (Onodugo & Ezeadichie, 2019; Roy, 2018). The urban informal settlements of the global South, with its perilous socio-economic and spatial placement, face some of the harshest impacts of climate change.

These vulnerable city pockets are also rapidly growing owing to the unprecedented urbanisation trend in the South (IPCC, 2014) . As climate change induced risks intersect with unprecedented urbanization, the implications on livelihoods and health of urban poor are immense. Residents of informal settlements have low incomes, inadequate housing, and limited voice in governance which leaves them vulnerable to climate risks (Sverdlik et al., 2019). Increasingly, cities need solutions that address both climate change and inequality together. In these contexts, hazards can take form of disasters because of the lack of adaptation capacity. At the same time, an understanding of what the urban poor need and undertake to deal with disasters and risk, yield important insights for the restructuring of planning and programming efforts (Wamsler, 2007)

In this background, the present study, taking the case of Dharwad (a city in Karnataka, India), explored the intersectional impacts of climate change, inequality, and urbanisation in informal geographies, and explored potential solutions and programs that can make cities equitable and climate resilient. The study also explored existing adaptation strategies employed by the urban poor, and how it can be improved through measures that are equitable and sustainable. The study explored the impacts, adaptive capacity, gaps and intervention areas at the individual unit level, settlement level, and at the settlement-city interface, and the need for these to come together to allow for improved adaptation capacity.

2 Researchmethodology

The detailed methodology followed in the study is illustrated in Figure 1 The initial phase of the study focused on understanding Dharwad (through secondary research) with respect to its location, climate, ecological setting, climate change trends etc. The study also traced the historical evolution of the city through an intersectional lens of urbanisation, ecology, and informality The insights gathered through

1 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

this secondary research aided in mapping and profiling the informal settlements across Dharwad. A stakeholder consultation workshop was also conducted to glean insights from different city stakeholders working on the themes relevant to this study (urbanisation, informal settlements, climate change, gender). Anchoring on the secondary research and the perceptions gathered through the workshop, a few pilot settlements were selected for further exploration. This led to a deeper understanding of the urbanisation, climate change, and informality nexus in urban poor settlements, the ensuing vulnerabilities of this nexus, and the existing grass root efforts that respond to these vulnerabilities. These findings were collated at the household, settlement, and settlement-city scales, which revealed entry points to possible adaptation/ mitigation measures in these scales.

Figure 1: Research design

The study also developed illustrative examples of adaptation strategies for two of the pilot settlements.

2 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

3 UnderstandingDharwad

The present chapter discusses the focus geography of the study- the Dharwad city. The chapter begins with an introduction on Dharwad’s location, climate, and ecological setting, followed by an exploration of the climate change trends that the city-region has been experiencing over the years. The subsequent two sections of the chapter trace the city’s history and growth followed by an examination of the informality in the city. The chapter also studies the policies, plans and institutional structure governing the city growth, particularly through a climate change and informality lens. It concludes by bringing forth the climate change, urbanisation and informality links in the city and the vulnerabilities and risks associated with this complex nexus.

3.1 Regional setting

3.1.1

Location and climate

Dharwad city is in the north –western region of the Indian state of Karnataka and forms a contiguous urban area with the city of Hubballi located 20 km to its south-east. The twin-cities of HubballiDharwad lies 430km north-west of Bengaluru on NH-48. While the focus geography of this study is limited to the Dharwad city, the socio-ecological and political linkages with its twin Hubballi necessitates its inclusion in this chapter’s discourse.

The region experiences tropical and semi-arid climate with distinct summer, rainy and winter seasons. Dharwad is in the leeward side of the Western Ghats due to which it receives lesser rains during SW monsoon with an average of 657mm/yr. The region recorded an average of 59 rainy days during 1901 to 1970. There has been a 55% reduction in the annual rainfall received during SW monsoon (JuneSeptember) in the Dharwad region in the same period. Low to moderate annual rainfall results in frequent drought conditions Summers are hot and dry, lasting from late February to early June with whirlwinds commonly seen during April. The microclimate of Dharwad city is cooler than Hubballi due to its elevation, tree cover ratio and proximity to Western Ghats. Winds are generally light with some increase during late summer and monsoon seasons (Karnataka Gazetteer Department, 2002)

3.1.2 Natural setting

Dharwad is located in the Western Ghats at an altitude of roughly 750 m from the mean sea level. The twin city region is located at the frontier of the eastern plains and the Western Ghats and is positioned on a geological formation called the ‘Dharwar system’1 formed by lava, dust and other particles of volcanic origin made up of sedimentary rocks (C.Manikyamba & RobertKerrich, 2012)

The eastern half of the city area is covered with black cotton soil2, the western and southern rolling terrain of the city is dominated by lateritic red to red gravelly clay soil3 (prone to wind and water erosion), and loamy to kankary soil are seen along the banks of river/stream courses.

Dry and moist deciduous forests with tall trees and large trunk diameter are the main carbon sinks in the region. The main food crops are jowar, paddy and wheat. Among the non-food crops, cotton, groundnut, chillies, sugarcane, and safflower are predominant (Gazeteer Department, 2002)

1 Bruce Foote gave the name 'Dharwar System' to the 'Lower Transition' rocks occurring near Dharwar in Mysore State, when he first separated these schistose rocks from the 'great granitoid gneiss system'

2 BCS having 2-5m thickness, are high humus and low phosphate content, with normal pH-value and very low infiltration characteristic 3 19.62 to 3.6 cm/hour rate of infiltration characteristic

3 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

The Dharwad city sits at the ridge of two watersheds, one sloping in north and north-east direction feeding the Krishna upper basin, and the other sloping in the north and south-west direction feeding the Vasishti basin. The region has a network of seasonal streams feeding into keres/ tanks/ lakes of various sizes. The micro watersheds within Dharwad City limits feed in to Tuprinala watershed of Krishna River basin (Central Ground Water Board, 2008). As per the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB, 2013), ground water is available at a depth of 10 to 20 metres below ground level (mbgl) in the city region. Rainfall is the main source of ground water recharge in the region.

3.1.3 Climate change trends

Climate change research carried out based on agronomic, climatic and demographic indicators show that Dharwad district has moderate vulnerability to climate change (Kumar et al., 2016). A climate change analysis and projection study (based on historical data from 1990-2019) carried out at a district level for Karnataka lays down the following findings for Dharwad district:

• Temperature increase: The temperature in Dharwad is projected to increase by 1.30C in summer and by 1.80C in winter during 2021-2050 compared to 1990-2019 (CSTEP, 2022).

• Rainfall Increase: Rainfall is projected to increase by 8% by 2050 compared to 2019. The number of rainy days (>2.5 cm/day) is also projected to increase from 886 days (1990-2019) to 1044 days (2021-2050) (CSTEP, 2022).

• Extreme rainfall events: Extreme rainfall events (days with either high- or very high-intensity rainfall over a 30-year period) is projected to increase from 34 days (1990-2019) to 129 days (2021-2050) (CSTEP, 2022)

• Heat waves: An analysis carried out by KSDMA (2020) also notes Dharwad district as vulnerable to heat wave like conditions.

3.2 Urban history and growth

3.2.1 Medieval history

Historical research traces the genesis of Dharwad as a prominent city back to the 12th century. The city finds mention in multiple inscriptions found in nearby locations- one found in the Durga Devi temple in the city belonging to the Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI of 1117 A.D, two found at Narendra (8 km from present Dharwad) dated 1125 A.D. and 1126 A.D., and multiple others at Mangudi, Hombal, Katnur all dated around 12th century. Some of these mention the city as the headquarters of a large administrative unit (Savant,1991).

There are various theories describing the origin of the city’s name, though none have been confirmed for lack of epigraphic evidence. Its original Sanskrit name is thought to be ‘Dara-vata’ meaning gateway town. Some inscriptions indicate that Dharwad served as a door or gate- way (dara) for the movement of goods between Malenaadu (Western mountains) and Bayaluseeme (Plains) area. Some also say that the city was named after an official ‘Dhara Rao’ who was appointed by King Rama Raya who built a fort here is 1403 A.D (Savant,1991).

Historical records indicate that Dharwad was a part of the Vijayanagara dynasty from 1336 AD to 1565 AD. After the fall of the dynasty, Dharwad passed onto the hands of the Bijapur Sultanate from 1573

4 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

AD to 1686 AD when Adil Shah I captured the city. He built a fort here named Manna Killa4 , remnants of which can still be seen in the city (Savant,1991).

Being in a strategic location, the city has witnessed multiple sieges and conquests over the years. In 1686, the Mughals led by Aurangzeb’s son took over Hubballi and Dharwad. It came under the Peshwa rule in 1753 AD when the fort was surrendered to Nana Saheb by the Mughal commandant Prithwiraj. Hyder Ali of Mysore occupied the city in 1764 AD and Tipu Sultan captured the city in 1784 AD. It was later recaptured by the Marathas in 1790 AD who ruled the city till 1818 AD (Savant,1991). In this period, Peshwas created Petha (market) areas near the fort and the neighbouring areas – Kasabapeth (Hosayellapur), Mangalvarpeth, Ravivarpeth, Haveripeth and other areas came up as thriving markets during this time (Gazeteer Department, 2002)

The Peshwas were later defeated by British and Dharwad and its neighboring region5 were subsumed into Bombay presidency6. The British received a lot of resistance from the local rulers7 , and as a counter measure the British started establishing educational and medical institutions in the city. The extent of the town in 1849 was limited to the fort and the various institutions that were established at the time. Settlements such as Hosayellapur, Saidapur, Haveripeth and (shown in Figure 2) were revenue villages outside the town extent.

3.2.2 Dharwad under the British rule

Dharwad became a Municipality on 15th August 1855 under the Government of India Act 1850. At the time, the city was limited to the fort and the institutional areas established by the British. The municipality in 1856 was about 5.12 sq. km in area with a population of 10,000 (Census of India, 1951).

In 1883, the extent of the Dharwad City Municipality included the neighbouring village settlements of Saidapur, Lakamanhalli, Haveripeth,Hosayellapur and others8 Over time the markets in the area flourished as cotton and chilly 9 became widely cultivated in the district’s hinterland. Hubli (Rayara Hubli or Old Hubli) emerged as a major industrial centre that transported the produce through land routes to major ports. The American Civil War (1862-66) expedited the cotton boom in the area10 and various ginning units11 were set up here. This necessitated the improvement of transport through both road and rail 12 As a result, Hubli and Gadag were developed as railway junctions, and the Administrative Office of the Railways was setup at Dharwad in 1888. Economic, commercial, educational and cultural activities grew in the Dharwad town (Gazeteer Department, 2002; Census of India, 1951) By 1901, the town was home to several cotton gins, a cotton mill, and two high schools, one maintained by the government and the other by the Basel German Mission. Between 1901 and 1951, Dharwad Municipality expanded to include the old fort area, Kasbapeth, extensions near the railways and the suburban areas.

4The fort near the city centre 5 Areas that fall under Bijapur, Belgaum and Solapur districts. These together with Dharward formed the District or Zilla in 1830 6 Bombay and not Madras Presidency as all these areas were previously administered by Maratha rulers

7 Baba Saheb of Nargund, Bhimarao of Mundarg1 and Kenchangauda of Shirhatti 8Bagtalan, Madihal, Galaganjikop, Malapur, Kamalapur, Narayanpur, Saptapur, Atti kolla 9Introduced by the Portugese 10 cotton that was exported from the America to England stopped 11 In Dharwad district itself, four steam operated ginning units were setup 12Boom helped the completion of the railway line (1887) reaching Pune (and Bombay) and Dharwad -Vasco (Goa) line was also completed in 1889.

5 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

3.2.3 Dharwad- present growth trends

In 1962 Dharwad and Hubballi municipalities were merged to form a single Mahanagara Palike (Municipal Corporation). Around 21 villages of Dharwad and 24 villages of Hubli taluk were merged13 with the Corporation (Census of India, 1981).

The Hubli Dharwad Urban Development Authority was established14in 1988 to manage the expansion of the twin cities. Under its jurisdiction, Hubli, Dharwad and 6 border villages of Hubli taluk and 11 of Dharwad taluk were included in the planning authority area. The city witnessed rapid growth in the last 30 years during which the city has expanded towards the northwest and southwest (Brook & Dávila, 2000) Hubballi-Dharwad is currently the second largest city in the state after the capital city Bengaluru. Dharwad has emerged as an important educational hub in North Karnataka, while its twin Hubballi is the commercial and industrial hub of the region (Hubballi-Dharwad Master Plan 2031).

AMRUT, Smart Cities Mission, and others urban programmes are further moulding the city’s growth trajectory. While Hubballi is spreading towards south, west and along NH 4 (towards Dharwad), Dharwad is expanding in all directions except north (since this area is not suitable for construction). Government offices and industries have come up between the two cities as well (L.T.Nayak & Priyadarshani, 2014)

As per the Census 2011, Hubballi-Dharwad city has a population of 9,43,788 and an area of 213 sq. km. The city experienced population growth spurts post-independence -during 1950s (due to State reorganisation) and between 1971 and 1981 (due to increased migration). Urban population growth rate has been declining post 1981- this has been attributed to the lack of new economic activities. The density in the twin cities has increased from 1947 persons per sq km to 4667 persons per sq. km (in 2011). The density for Dharwad city alone is however relatively lower at 2464 persons per sq. km as per Census 2011. However, the core and old city areas in Dharwad are particularly dense (HubballiDharwad Master Plan 2031).

Table 1: Urban Growth of the Dharwad urban area Year Population Area (sq. km) 1901 31,279 NA 1921 34,220 NA 1931 40,904 NA 1941 47,992 NA 1951 66,571 36.3 1961 77,163 36.8 1971*15 3,79,166 190.9 1981 5,27,108 190.9 199116 6,48,298 190.9 2001 7,86,195 202 2011 9,43,788 202

Source: District Census Handbook

13 Off which 18 villages are in the outskirt of the City Corporation 14 Under 1987 Act 15 Dharwad and Hubli merged under one Municipal Corporation 16 The Mahanagara Palike during 1992-93 was spread across 181.77 sq.km populating 6,48,298 in 1,10,700 houses.

6 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 2: Evolution of Dharwad city

7 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Sources: Gazetteer and District Census Handbook

3.3 Urban Informality

The figures on informality in the city varies across different data sources. The Karnataka Slum Development Board (KSDB) Annual Report (2019-20) lists 130 slums in Hubli-Dharwad district with a population of 78,790. The data available with KSDB in 2020 is however for 86 slums (population 1,02, 845). Of this, 36 slums with a population of 50,163 are in Dharwad city. Figure 3 shows the location of these 36 slums.

Other data sources indicate that nearly 13.6% (1,07,000) of the total population in Hubballi-Dharwad (HDMC) live in slums (CLIP report quoted in Hubballi-Dharwad Master Plan, 2018). The Master Plan also mentions a total slum population of 1,75,465 (22% of total population) in HDMC As per the data published by Hubballi-Dharwad Smart City Limited (HDSCL) in 2019, there are a total of 99 slums in the HDMC limits with a total population of 1,56,016. Of these 34 slums with a population of 60,077 are in Dharwad city alone.

The slums IN HDMC are located on both private and government lands (Hubli Dharwad Urban Development Authority, 2011).Presently almost all the informal households are supplied with piped water supply, but a large section of the slum dwellers still lack sanitation services (HDPA, 2016) Centre for Multidisciplinary Development Research (CMDR)’s report of 2006 states that about 48% of the house structures are kutcha in nature

Figure 3: Informal settlements in Dharwad

8 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

3.4 Policies and plans

This section explores the policies and plans shaping Dharwad’s growth through a climate change and informality lens.

A perusal of projects proposed for Dharwad under the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) indicate that these could play a subsidiary role in addressing the larger climate change effects on the city region. The Smart City Plan (SCP) primarily focusses on improving the connectivity of the city to garner more investment in the Northern Karnataka region. It also focusses on improving the internal connectivity within the municipal limits. The proposal foresees potential in improving the liveability in the city through place making initiatives. The existing gardens, parks, nallah, and wetlands are seen as spaces that can be enhanced for community engagement. The city aims to shift to the use of renewable energy through the implementation of solar roof tops and solar streetlights. These are proposed to be implemented in convergence with Solar City Programme17 and PPP schemes. Additionally, they are making efforts to increase the efficiency of MSME through the adoption of better technological inputs to lower carbon emissions. A large majority of the projects proposed in the SCP are however concentrated in Hubballi. Hardly any projects cater to the needs of the informal settlements in Dharwad.

Regarding planning for informal settlements in the city, the master plan 2031 (revised version) for Hubballi-Dharwad has stipulated guidelines for slum redevelopment that need to be undertaken by KSDB/Local Authority/HDUDA/KHB or any other Government agency. Among the re-development specifications, 10% of the community area is required to be designated for parks and 5% as common areas (HDPA, 2016). With respect to improving the city environment, the master plan designates areas around the water bodies as “no development zone” where only activities associated with the lake are allowed and development of parks can be considered. The buffer zone demarcation is based on the size of the water bodies. The BRTS corridor along the national highway connecting Dharwad with Hubli has transit-oriented development zone of 500m on both the sides where compact high-rise development is proposed. There are also provisions to create public spaces in these zones

Over the years, multiple schemes and programmes have been launched to improve the living conditions of slums dwellers. These include the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) launched in 2005 which included provisions to offer civic amenities to the urban poor, the Rajiv Awas Yojana launched in 2009 which envisioned a slum free country, and the latest being the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana Urban (PMAY-U) launched in 2015 with a goal to provide housing for all by 2024. However, ground realities reveal that many slum dwellers are yet to reap the benefits of such schemes. Some cite the inability of slum dwellers to pay the Rs.50000 required from the beneficiary’s end for the PMAY scheme18. Systemic delays in implementation are also cited as issues inherent in these schemes. At present Karnataka has completed just 29% of the sanctioned projects under the PMAY, and Dharwad is one of the worst performing districts with just 16% of the projects completed. The lack of basic infrastructure also goes unaddressed in many of the redeveloped housing projects (DH, 2022) PMAY is implemented in convergence with other housing schemes in the state including Ashraya Vajpayee Housing Scheme, Ambedkar Housing Scheme, Special Housing Scheme, etc. The

17financing of renewable energy projects / systems as per provisions of various schemes of MNRE

18 Under PMAY scheme, the Government has to provide houses worth Rs 5 lakh each to the EWS from which Rs1.5 lakh is sponsored by the central government, Rs 1.5 lakh is contributed by state government, Rs 1.5 lakh is taken as loan by the beneficiary while the remaining sum of Rs 50,000 is also contributed by them.

9 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

implementing agencies of these schemes include Karnataka Slum Development Board, Karnataka Housing Board, Urban Development Authorities, Urban Local Bodies, etc. (MoHUA,202019).

3.5 Climate change, urbanisation, and informality nexus- vulnerabilities and risks

Evidence from across the globe over the past years have shown how cities will be at the forefront of climate change impacts (Dodman et al., 2019). While urban areas are the major contributors of climate change with economic activities in cities accounting for 76 % of the carbon emissions, a high concentration of population, financial and infrastructure assets make these areas highly vulnerable to climate change impacts (UN Habitat). These impacts will intensify manifold for slum dwellers, vulnerable settlements, and informal traders with inherent socio-economic deprivations. This section elucidates the vulnerabilities and risks associated with the urbanisation, climate change, and informality nexus in Dharwad.

As an outcome of unprecedented urbanisation, the land use in Hubballi-Dharwad has undergone tremendous change over the past few decades. The agricultural area in the city region has more than halved (from nearly 5000 Ha to 2320 Ha), and the built-up area has more than tripled (1080 Ha to 3850 Ha) from 1975 to 2011. The area covered by water bodies in the city has also reduced by 10% (L.T.Nayak & Priyadarshani, 2014). The expansion of Dharwad town over the years has led to densification and overcrowding of the older clusters in the city such as Haveripeth, Hosayellapur, Saidapur, and Fort Area. Some of these areas have been redeveloped and have access to basic services, while the rest have remained as informal clusters.

This urban transformation, which is not cohesively planned, has been accompanied by temperature rise, pollution, water depletion, urban floods, etc. which is further exacerbated by climate change impacts like heat waves, extreme rainfall events, and droughts. A few of these layered vulnerabilities in Dharwad are evidenced in the following sections.

Temperature rise and air pollution

The temperature variation between the city and neighbouring hinterland20 is 1.90C (L.T.Nayak & Priyadarshani, 2014) The city is warmer than the surrounding rural areas due to the heat island effect caused by urban emissions, high density of buildings and road network, and heat generated directly from human activities. A reduction in the number of water tanks in the city, from nearly 100 in 1975 to barely a few in 2011, has also contributed to this rise in temperature (L.T.Nayak & Priyadarshani, 2014)

A study carried out in 2018 indicate that the average PM2.5 concentration for the twin cities has increased from 15 μg/m3 in 1998 to 28.0 ± 13.4 μg/m3 in 2018 While the 2018 value is within the national standard (40), it is nearly three times the WHO guideline (10) (urban emissions, 2018)21 The main sources contributing towards PM2.5 in 2018 was transport emissions, followed by dust emissions from road re-suspension and construction activities Industrial emissions and open waste burning are also major contributors. There is also a variation in PM 2.5 concentration over the months, with the levels dipping usually during monsoons (between June to September) (urban emissions, 19 https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/2-%20Karnataka.pdf 20The study doesn’t specify the exact location where temperature measurements were undertaken 21 https://urbanemissions.info/india-apna/dharwad-india/

10 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

2018)22 Urbanization along with the Dharwad wind pattern can also induce phenomena such as the urban dryness island -referring to conditions where lower humidity values are observed in cities relative to more rural locations, and slower wind speed compared to adjacent suburbs and countryside

The impacts of increase in temperature and air pollution are intensified for urban poor communities in the city. Many of these settlements live near busy roads and are prone to pollution and dust related health issues This coupled with high density, low vegetation, burning of waste, and cooking outdoors with firewood amplifies the impacts. Increase in temperature also increases fire risks within the settlements because of increased use of inflammable materials like tarpaulin for housing Increased temperature associated with occupations (like working in rice puff industries), is already leading to health impacts among informal settlement dwellers. Many of these workers are unable to work beyond 45 years of age due to deteriorated health conditions. This occupational hazard together with projected increase in temperature will lead to further aggravation of heat related health issues for the vulnerable (inference based on site study).

Water depletion

As per a WRI analysis, the water risk is extremely high for the Dharwad city region. Presently Karnataka Urban Water Supply and Drainage Board (KUWSDB) relies on surface water sources23 , borewells and tanks/reservoirs in the city limits for sourcing the water demand of the city Maintaining these thus become crucial in this water stressed region (HDPA, 2016). The leakage in the water supply network in the city is estimated to be around 40%. Further as per WRI’s water risk atlas, the city area is predicted to face high water stress (40-80%) with medium to high water depletion levels by 2031 (based on business-as-usual scenario climate projection). In the core areas of the Dharwad city, the ground water level has depleted, and the over-extraction has turned groundwater brackish along with high nitrate concentration

Dharwad city lies in a region that is prone to heat waves and heat stress according to Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC) (Karnataka State Health System Resource Center, 2018) which puts pressure on the water sources. The risk of water stress is worsened due to increased surface water run-off (because of decreased permeability exacerbated by the soil type in the region).

The North Karnataka arid region traditionally supported water demands through series of interconnected manmade tanks. These artificial systems were used for domestic 24 and irrigation purpose and formed a larger ecosystem and were maintained and improved by communities. In 1884 there were 2,979 tanks in Dharwad district but by 1901 the number of tanks reduced to 2,404. (Gazeteer Department, 2002). Within Dharwad area tanks such as Kempagere tank, Yemmikere tank, Sadankere tank, Koppadakere tank, Kolikere tank, Laxmisinghakere tank, Attikollaand others (I.T. & S.G., 2002; Gazeteer Department, 2002) have been filled and the area has been used for commercial and residential development In the ones that remain, privatisation and fencing has disrupted the socio-ecological relationship that the communities had with these water systems (Hazareesingh,

11 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

22 https://urbanemissions.info/india-apna/dharwad-india/ 23Renukasagar Reservoir on Malprabha River and Neerasagar Reservoir 24 Herekeri,

Koppadakeri and Halakeri along with some stepwells were sourcing water to households in Dharwad town area in early eighteenth century

2013). Presently the tanks that remain are heavily polluted and prone to eutrophication (Kudari & Kanamadi, 2013), there are few which form part of restoration plan of AMRUT25 and other schemes.

An example of Kolikere lake further elucidates these disruptions. Kolikere located on the eastern periphery of the city is a highly polluted wetland (in the present date26) (Comptroller and Auditor General of India, 2015) It has been enlisted as a wetland to be restored under the AMRUT mission since 2016. The tank was called Bagh Talab and attracted tigers, wild boars, and panthers along with various migrating birds during earlier days An IISC study notes that around 800- 1000 open wells and 100 -120 bore wells in the area were fed by the Kolikere lake system (I.T. & S.G., 2002). Apart from supporting rich biodiversity and recharging the groundwater table in the area, 50-60 years back the tank supported the livelihood of a dhobi community residing at edge of the tank The water level quality in the tank and the surrounding wells degraded over time, and the dhobi and other communities residing near the lake transitioned to other water sources These wells were earlier used for household purpose, cattle grazing and for irrigating nearby fields (located in eastern part of the city). The decrease in the wetland coverage area, pressure on the existing groundwater resource, and degradation of the existing water systems necessitate the need to enquire into possible measures to counter these effects in the city. Figure 4 shows the city terrain overlaid with the existing as well as extinct lakes and lake systems in the city.

Figure 4: Existing and extinct water systems in Dharwad

25 PHYTORID wastewater treatment plant is proposed to be installed for Kolikere and Kelgere A lake park is also proposed at Kolikere 26Based on the field work as part of the study, the team observed the tank is polluted, covered with water hyacinth and has become a breeding place for mosquitoes.

12 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Urban floods and associated risks

The parts of the city which are located on the undulating plains in the northeast covered with black cotton soil (BCS) are more vulnerable to flooding. This is because of their high clay content and ironrich granular structure that makes the area impermeable.

Most of the roads laid in and around the informal settlements are at a higher level than the settlements abutting the road This coupled with an inefficient drainage network along the main roads leads to flow of water inside the settlements and in many cases the hutments itself. Drains provided along the roads are not efficient given the poor maintenance and abuse. Reverse flow from the sanitary pipes and drains is reported in all the studied communities. As the intensity of the rain increases (with climate change), these issues will further exacerbate for the urban poor. Water borne diseases, which are already widespread during floods (due to limited access to clean water during these times), will also increase with these climate change and urbanisation impacts.

4 Studyarea

4.1 Settlement selection

As a first step to understand the informality in the city, the informal settlements were profiled and mapped. The 36 slums (as available from the KSDB data) have been mapped (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Informal settlements in Dharwad (categorised)

One of the criteria for selection of pilot settlements was the presence of intervention efforts by project partners. To this end, a list of 19 settlements where renewable energy interventions like installation of solar panels (by SELCO) were also mapped. These 19 settlements (marked in orange in the map

13 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

below) were mapped along with the KSDB list (marked in purple in the map below). There were some settlements which overlapped across the two lists (marked in blue in the map below).

The map shows location of the informal settlements in the city along with other locations like– fort, nearby villages, railway lines, encroached wetlands, etc. From the map we see that a large share of the informal settlements is in the older city area near the fort. Many settlements are also located along the railway line and main road connecting Dharwad and Hubballi. The criterion chosen to select the pilot settlements for the study were:

1. Location of the settlement with respect to a. the larger city context, b. proximity to ecological setting (lake, hill, agricultural fields), c. presence of socio-cultural and economic institutions (market, schools, health centres, parks, and others) and d. infrastructure (bus terminal, railway track, highway, and others)

2. Size of the settlement in terms of number of households

3. Typology of the settlement determined by the land use around the settlement and the main livelihood activities in the settlement.

4. Presence of SELCO or partner organisations in the area that allowed building a community connect

5. Age of the settlement

6. Status of the settlement (notified/non-notified)

7. Presence in KSDB list

Based on the above criteria, the following settlements were shortlisted for the study. Insights from the workshop co-organized with SELCO were also considered to finalise the settlements.

Table 2: Selected settlements and their profile No . Settlements Locational factors No. HHs Land use and Livelihood Mapping

1

Churmuribhatti

2 CBT

3

4

Lakshmisingha Kere

Eastern periphery of the city and is close to the old fabric of the city 20-25

Sarasvatipur

5 Goller Oni

6

Rajeevgandhi Nagar

Tentative age of the settlement (Years)

Presence of SELCO

Micro Informal Industrial – Rice Puff Units At least 15 Yes

Main market centre and TOD 3 CommercialMain market area At least 30 Yes

Old slum near hill, lies in between Railway line and BRTS lane 1,500

Old slum on top of a hill, lies in between Railway line and BRTS lane 500600

ResidentialOdd jobs, Iron smiths At least 60 Yes

Residential –Hair collectors, Masala and Agarbatti makers

At least 50 Yes

Main market centre near the oldest and biggest market - Lower Market 300350 ResidentialScrap collectors At least 70 Yes

Southern periphery of the city, near a lake and agricultural fields 7001,000

ResidentialGarment work At least 40 Yes

14 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

7 Haveripete

One of the old fabrics of the city, densely packed and large cluster. Located near the main market - Lower Market

8 Gauli Galli

Located on top of a hill, near Lakshmi Singh Keri and Saraswatipur. The three settlements are interconnected

2,000 Mix Use At least 100 Yes

150200 Residentialcattle based livelihood Atleast100 No/ Partner present

The following map shows the location of the settlements listed above.

Figure 6: Location of settlements selected for the study

4.1.1 Stakeholder Workshop

A consultation workshop was conducted with a diverse range of city stakeholders working on informal settlements in the city. The stakeholders ranged from organisations carrying out training and capacity building programs, gender-based support programs, SHGs, micro finance institutions, etc. The stakeholder workshop helped in gaining insights on the evolution of the city informality over the years, issues, and challenges they face, innovations and programs that have been successful, etc. A list of stakeholder organisations that were a part of the workshop is given in Annexure A

15 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 7: Stakeholder consultation workshop in progress

4.1.2 Primary survey and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

Settlement and city-settlement level

To understand the settlement vulnerabilities in the context of climate change and urbanisation, a primary survey of the settlement and the city-settlement interface was carried out. The survey entailed an exploration of community spaces, its uses and potential in the context of climate change, settlement level climate change and urbanisation induced vulnerabilities, and existing coping strategies prevalent to address these. The survey was largely observational and was interspersed with small FGDs with community members to garner deeper insights. The following table acted as a guide for the observation and discussions.

Table 3: Guide for site observation and FGDs Parameters Objective

Discussion and observation points General

To get a general understanding of the settlement.

Types of Common spaces

To identify different types of community spaces in urban poor settlements and their usage.

• History and evolution of the settlement (social/spatial/economic)

• Cases of eviction

• What are the different types of common spaces in the settlements and how are these used?

o Streets/lanes

o House frontage

o Verandahs

o Water bodies/tanks/ wells

o Drain/ network (roads, footpaths, railline edges

o Shops/stalls

o Open space / maidans

o Temples, places of worship

o Platforms (ashwathkatte)

o Others: please specify

Function and performance of commons

To comprehend what makes them (the spaces identified) community spaces or commons.

• What are the different types of commoning activities in the settlement?

o Livelihood (buying and selling, trading)

o Recreation

o Service delivery

16 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Climate change impacts To understand community commons in the context of climate change impacts.

o Care work

o Social gatherings

o Daily HH chores (washing, bathing

o Others: please specify

• What are the different types of spaces where commoning happens in the settlement? Are they limited to common public spaces?

o Streets/lanes

o Water bodies/tanks/drains

o Shops/stalls

o Open space o Others: Please specify

• What factors determine the use of common spaces (reasons for use/ reasons for preference?) Could be o Proximity

o Economies of scale

o Safety

o Climate related

o Others: please specify

• How does the use of community commons change over

o Time of the day

o Day of the week

o Seasons/festivals (Economic/social/cultural criteria determining the daily, weekly, and yearly use of the space)

• Does the user base also change during these time frames?

• Any abuse of community commons/common spaces?

• Who is responsible for these spaces: ownership, maintenance, operation?

• Any general consensus on what the commons can be used for?

• Are these common spaces accessible to all? If not, which are the groups that are unable to access and reasons for the same.

• What are the predominant climate change manifestations in the settlements?

o Water logging o Increased heat stress o Water scarcity

o Health and everyday living –disease prevalence

o Dust/air pollution

o Noise pollution

o Others: please specify

• Which areas in the settlements are most impacted by these manifestations?

• Any future risks that the community perceives?

Adaptive responses To understand community commons as adaptive spaces.

• How are common spaces used for responding to these impacts?

• Has the use of the common spaces changed due to increase in heat/water logging/high rainfall?

o New spaces have been identified/evolved

o Space have been lost/not used anymore

o Others: please specify

17 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Settlement- City Interface To understand the network and hierarchy of community commons.

4.2 Settlement Typology

• Does the city-settlement interface evolve into community commons due to economic/social/cultural factors? (Possibly linking it to a network/hierarchy of commons within the settlement)

The selected pilot settlements have varying genesis and pathways to informality which played an important role in the character, scale, and use of spaces in these settlements. Based on the genesis, the settlements were organised into three broad categories:

• Traditional turned informal settlements: These were originally traditional villages Urbanisation has led to densification and squatting in these settlements. They have organically formed common open spaces (like wide street junctions and shaded open spaces) owing mainly to its organic spatial fabric. These are however increasingly being lost due to urbanisation and attendant densification.

• Squatter turned informal settlements: These were originally formed as squatters mainly by migrants who settled in the city for better economic opportunities.

• Clusters with occupational vulnerabilities: These also have a genesis as squatters but currently face occupational vulnerabilities.

The names of the settlements under each of these categories are listed in the table below.

Table

4: Pilot settlements

City Traditional turned informal settlement Squatter turned informal Clusters with occupational vulnerabilities

• Haveripete

• Gauli galli

• Goller oni

• Saraswatipur

• Lakshmi singh kere

• CBT

• Churmuribhatti

18 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Dharwad

5 AnalysisandFindings

Studying informal settlements and enabling them to adapt to climate change impacts has emerged as one of the key priorities in cities and climate change research in recent years (Bai et al., 2018) Contributing to this end, the present study through the following sections, attempts to understand the urbanisation, climate change, and informality nexus in selected urban poor settlements in Dharwad, the ensuing vulnerabilities of this nexus, and the existing grass root efforts that respond to these vulnerabilities.

Climate resilience for informal settlements needs to be enhanced at different scales – at households, neighbourhoods, settlements, settlement-city links, and settlement-city-regional links (Satterthwaite, 2020). The following sections of this report collate and analyse the findings from the previous sections at the settlement, and settlement-city scales, which will potentially reveal entry points to possible adaptation/ mitigation measures in these scales.

5.1 Analysis

5.1.1 Settlement and City-Settlement level

The analysis at the settlement and city-settlement level started with the exploration of spaces (located in each of these 2 scales) along the following three lines of enquiry.

What are the different types of common spaces at the settlement and the city-settlement levels?

In line with this first point of enquiry, different types of common spaces in the settlements were identified and were then organised into three broad categories depending on the spatial location of these spaces as below:

• Category A: City-settlement interface (these included spaces like pavements, garbage dumps, open spaces, etc.)

• Category B: Settlement (like street junctions, religious structures, and attendant spaces, etc.)

• Category C: Settlement- private interface (like house frontages)

A categorisation along this line was carried out to understand the variations/fluidity/linkages in the use of these spaces (if any), which would aid in evolving suitable adaptation/mitigation measures.

What are the different activities that are performed in these common spaces?

The elements of diversity and density make common spaces in an urban setting much more than a mere tangible space (Waliuzzaman, 2020). The social processes that produce and organise these spaces are equally important to explore the potential and significance of these spaces in informal settlements. To this end, following the identification of spaces in the settlements, different activities that were performed within these spaces were observed (like cooking, washing, socialising, vending, etc.). These were then classified into relevant groups like livelihood, domestic, religious, recreational, socio-cultural, and livestock related (refer Annexure B for complete list of spaces and activities).

19 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

How do climate change, urbanisation, and informality affect these spaces and attendant activities? What are the coping strategies (if any) adopted to respond to these impacts?

The spaces organised into spatial and activity-based categories were then analysed through an intersectional lens of climate change, urbanisation, and informality. A comprehensive analysis along these lines foregrounded the various dimensions of vulnerability, its manifestations, and implications on the urban poor and potential entry points to comprehensive solutions.

The existing coping strategies adopted to respond to the intersectional vulnerabilities were also investigated during the analysis. Growing research indicate that acknowledging and comprehending the existing coping strategies used by informal settlements can become a linchpin in developing contextually suited adaptation strategies, and to generate community ownership and commitment to these (Jabeen, Johnson, & Allen, 2010) An understanding of the coping strategies in the selected pilot settlements became pertinent in this regard.

Table 5 is an outcome of the analysis carried out pursuant to the above three key points of enquiry. A detailed description of each settlement is available in Annexure C. The classification of spaces and the activities carried out in each of these spaces in each settlement is available in Annexure D.

20 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Table 5: Common spaces impacted by climate stress, urbanisation, and informality.

Settlement Typology Settlement Space and Category Activities Climate Stress

Informal Pavement along settlement boundary (A)

Informal Landfill (A)

Urbanisation trends that can aggravate climate stress

Informality associated factors that can aggravate climate stress

Coping Strategy (if any)

Crematorium (A)

• Livelihood

• Domestic Flooding during rainfall events Backflow of flood water due to level difference between the road and house and clogged city drainage network

Intersectional vulnerability

Dumping of SW in internal drains due to limited access to SWM services

Flooding issue exacerbated by disconnected urban development initiatives between the city and settlement. These locations at the settlement periphery are usually the first to be affected.

Heat stress and dust Concretisation as a part of development initiatives within and around settlement accompanied by loss of vegetation and green cover

Use of materials like corrugated sheets and tarpaulin as roofs

Household level intervention: Construction of small platforms near house entrance

• Livelihood

• Livestock

Intersectional vulnerability

Location at the settlement periphery increases the heat stress and dust issue due proximity to external main roads. Stress is compounded by use of materials that increase internal heat.

Flooding during rainfall events

Location of city level infrastructure near settlement without measures to reduce risks

Locational disadvantage leads to leachate and waste flowing into settlement area during rains

Intervention by members of one household, but impacts settlement area: Some of the trees were forcefully retained by a household citing its necessity in bringing down heat stress

No coping strategy observed

• Socio-cultural Related

• Religious Related

Flooding during rainfall events

Location of city level infrastructure near settlement without measures to reduce risks

Locational disadvantage leads to increased pollution in the

No coping strategy observed

21

Adaptation 2022

Strengthening Cities for Inclusive

Climate

Traditional Lakes or Tank (A) • Livestock (cattle grazing)

• Livelihood (animal husbandry)

Informal Lakes or Tank (A) • Livestock (cattle grazing)

• Livelihood (animal husbandry)

• Livelihood (washer men)

• Domestic

Traditional Railway Track (A) • Domestic (open defecation, dumping solid waste)

Traditional Public Chowk (A) • Socio-cultural Related

• Livestock Related

Informal Open ground –fenced (A)

Informal

• Domestic (dumping solid waste)

settlement from the crematorium

- Lake encroached for development - Have started commuting to other lakes/tanks in the city area which are further away from their settlement, gradual change in livelihood pattern

- Fencing the lake as a part of urban development initiatives which prevents access for livelihood and other needs

- Pollution due to dumping of untreated sewage These tanks recharge the neighbouring wells and bore wells

Informal status preventing access to lake and surrounding

Moving into the lake area through small gaps in the fencing

- Gradual change in livelihood pattern. Rely on other water sources for their use.

- - Lack of access to toilets leading to vector borne diseases. Dumping of SW in due to limited access to SWM services

Heat Stress Concretisation of the common space associated loss of vegetation

- Fencing limits possibility of use by community for social/livelihood/domestic activities

No coping strategy observed

- No coping strategy observed

Dumping of SW in due to limited access to SWM services

No coping strategy observed

• Livelihood Flooding Location of city level infrastructure (landfill) Critical spaces for carrying out all activities Activities are limited to private spaces

22

2022

Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation

Pockets of open spaces between the built structures (B)

• Livestock

• Recreational

• Daily household

• Religious and spiritual

• Socio-Cultural

proximity to settlement without measures to reduce risks and other health issues

are affected due to locational disadvantage. Lack of drainage system worsens situation.

Intersectionality: Locational disadvantage leads to leachate and waste from landfill flowing into settlement area during rains. The situation is exacerbated due to lack of efficient drains. Existing drains channels are mostly clogged worsening the situation. This often leads adverse health impacts due to vector borne diseases.

during flooding events. Production in manual units (rice puff) is reduced. Automatic unit uses dryer which consumes more energy thus adding on to their operating cost.

Traditional Small shrines under trees (B)

• Religious • Socio-Cultural

Heat stress Urbanisation leading to densification and concretisation of settlement and surrounding; accompanied loss of green space

- Green spaces associated with religious structures are often retained which are used as spaces for socialising during evenings.

Traditional and Informal

Inner streets and lanes (B)

• Daily household

• Recreational

• Livelihood

• Socio-cultural

Heat stress Concretisation as a part of development initiatives within and around settlement accompanied by loss of vegetation and green cover

Floods Backflow of flood water due to level difference between the road and house and clogged city drainage network

Lack of open spaces due to dense fabric Streets and lanes used for socialising and relaxing during evenings due to lack of other open spaces.

Dumping of SW in internal drains due to limited access to SWM services

Assets are usually covered in plastic bags and stored on higher racks and cupboards.

Traditional Junctions of internal lanes (B)

• Recreation Related Heat stress Concretisation as a part of development initiatives within and around settlement accompanied by

- -

23

Adaptation 2022

Strengthening Cities for Inclusive

Climate

Informal House Frontage (C)

• Livelihood Related

loss of vegetation and green cover

Floods Backflow of flood water due flawed city drainage network

• Daily household

• Recreational

• Religious

• Livelihood

Heat stress Cutting down of trees in the area which is resulting lesser shaded spaces within the settlement

• Floods Backflow of flood water due flawed city drainage network

- Complain to higher authorities

Sleeping outside during summer nights is a common coping strategy.

In the rainy season they have limited space to carry out domestic and livelihood activities.

Assets are usually covered in plastic bags and stored on higher racks and cupboards.

24

2022

Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation

5.2 Insights

While Table 5 maps the settlement spaces, associated activities, intersectional vulnerabilities and coping strategies, the following sections highlight the key insights gathered through this mapping. These insights also reveal potential directions for adaptation/mitigation actions.

Research across cities, especially in the global south, elucidate the intersectional risks that urban poor face in the context of rapid and unplanned urbanisation and climate change. The present research study corroborates this elucidation through the following findings:

5.2.1 Flooding: urbanisation and informality induced exacerbations

Manifestations

Many climate-change impacts within informal settlements depend on city-wide infrastructure (e.g., flood management is related to city-wide drainage infrastructure and land use management), which is why settlement-city-region links are especially important (Satterthwaite, 2020). This is true in the case of Dharwad settlements as well Nearly all the informal settlements studied in Dharwad face issues of flooding during rainfall events. While the frequency and intensity of rainfall have increased over the years, flooding incidents in these settlements intensify due to flaws in the urban development initiatives at the city level. For example, development of new roads at a higher level along the settlement periphery lead to easy flow of storm water inside the settlement and dwellings. Improper drainage networks along peripheral roads and within settlements further worsen the situation. Location of city level infrastructure (like landfills and crematoriums) adjacent to these settlements (without effective measures to reduce associated risks) further pollutes the flood water.

While these issues indicate the limitations in possible adaptation measures within informal settlements, it also points to the pertinence of settlement-city-region linkage in urban development initiatives.

Lack of space often forces informal settlers to build over drains, as was seen in many of the settlements in Dharwad. This coupled with dumping of solid waste in settlement drains (often due to limited access to solid waste collection service) further exacerbates flooding. The location of informal settlements (usually selected to avoid eviction threats) is another cause of flooding. For example, settlements that came up on areas like extinct lake beds experience increased flooding. This locational disadvantage layered over exogenous urbanisation trends described above, and lack of/ inefficiency of endogenous drainage systems leads to increased flooding events.

Increased intensity and frequency of extreme rainfall events (as pointed by climate change predictions) and a status quo in the urbanisation and informality induced deprivations will push informal settlements into deeper cycles of intersectional vulnerabilities.

Implications

Domestic impacts: Limited availability of private space within informal settlements often necessitates domestic activities to spill over onto common spaces like streets and house frontages. Heavy rainfall and associated flooding events often render these common spaces unusable forcing them to drastically curtail many activities and carry out the unavoidable ones within the limited private spaces. This further reduces their already subpar quality of life.

25 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Dilapidated housing which are unable to withstand heavy rains add another layer of vulnerability. Rebuilding after a flooding event also drains their finances in turn affecting other aspects like health and education.

Livelihood impacts: Common spaces (at settlement and settlement- private interface) become important spaces for livelihood activities within most informal settlements- be it for rice puff industries, scrap work, agriculture related storage, livestock rearing, or for small scale vending. Flooding accompanied by pollution make these spaces unusable for carrying out these activities and leads to loss of livelihood related belongings leading to economic impacts. Lack of financial cushions during these situations often pushes them into a vicious poverty cycle.

Health impacts: Flooding coupled with clogged drains and improper solid waste management, and limited access to clean drinking water during these times impact the health of informal settlement dwellers, especially children.

Coping strategies

Since flooding incidents are a result of the larger urbanisation narrative and the inherent deprivations of informality, coping strategies that most of these settlements follow is limited to quick-fix measures. These include covering valuable and domestic paraphernalia with plastic sheets and storing them on higher racks within the dwelling unit. In some cases, a few shanties were upgraded into pucca houses (with private efforts) which were jointly used by severely affected neighbours (especially women and children) during flooding events. Their inability to move out of these settlements even during flooding events (due to financial constraints) is a further revelation of their vulnerability.

5.2.2

Heat stress: Urbanisation and informality induced exacerbations

Manifestations

Rapid urbanisation in the city is leading to densification inside informal settlements as well. This is especially true for settlements that have evolved from traditional villages into informal slums. Common spaces between buildings are increasingly being occupied by new construction. Conversion of traditional buildings (built of materials which are relatively better accustomed to providing relief during summers) are progressively being replaced by concrete houses- often to increase private space. Decrease in commons space (associated with loss of vegetation), increased densification, and concretisation of internal streets as a part of redevelopment efforts has increased the heat stress in most of the informal settlements.

Some of the settlement dwellers already face increased heat stress associated with their occupations. A projected increase in temperature due to climate change, along with loss of vegetation and common space, coupled with existing occupational vulnerabilities will further exacerbate heat stress.

Implications

Health impacts: While continuous exposure to heat leads to a presumed improvement in tolerance levels, the long-term impacts of such exposure on health are often dire and not well understood. For instance, the urban poor working in puffed rice industries mentioned that heat (associated with their livelihood and increase in temperature over the years) is often tolerable for them as compared to the cold weather. However, the increased heat stress drastically cut shorts their working years- most of them are unable to work beyond 45 years of age

26 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Coping strategies

Urban poor in the informal settlements in Dharwad use a variety of seemingly simple strategies to cope with climate change impacts. One such strategy is to sleep outside their house/hutment at night during summer, which was common across most of the urban poor settlements that was studied. However, it is interesting to note that there are also cases of reversal of such coping strategies when the community perceives other issues as a higher threat than heat. For example, in a settlement which has come up on a now extinct lakebed, a shoddy drainage network has resulted in a major issue of rodents and pests at night. This has forced the community to reverse their coping strategy of sleeping outside during summers, since they perceive health issues as a much higher threat than summer heat.

Using settlement level common spaces for socialising and carrying out domestic activities during summer evenings was also seen in most of the settlements.

27 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

6 Potentials and possibilities: adaptation and mitigationmeasures

As mentioned earlier, building on the existing coping strategies at the settlement, and city-settlement scales is an essential pillar for effective adaptation. Some of the potential adaptation strategies emerging from the above analysis are discussed in the following sections.

6.1.1 Settlement and city-settlement level

The analysis carried out in the previous chapter brings forth the significance of settlement level common spaces in urban informal settlements. Limited availability of private space makes these areas multi-functional and dynamic. However increased impacts of climate change – in the form of floods, and heat stress- are threatening these spaces. This calls for an urgent need to look at potential solutions to protect and enhance these. Ecosystem based adaptation (EbA) is one of the emerging approaches that are increasingly being acknowledged to hold a lot of potential for climate change adaptation and mitigation for the urban poor (Reid, 2020).

Ecosystem based adaptive solutions

EbA is an approach that uses nature-based solutions (NbS) to enhance resilience and reduce vulnerability of human communities and natural systems to climate change. It focuses on restoring and rehabilitating urban ecosystems that support climate change adaptation like the reduction of heat island effect, increasing the buffer capabilities for flooding or reduce pollution, along with creating significant co-benefits for communities. An established set of seven guiding social principles further strengthen its implementation. These include- participation and inclusiveness, capacity building, fairness and equitability, gender consideration, livelihood improvement, appropriateness of scale, and integration of indigenous and local knowledge (FEBA, 2021).

Potential for urban poor

Enhanced vulnerability to urban floods (due to where they live) and increased heat stress (due to their inability to control the temperature of where they live and work) in urban informal settlements necessitates cost-effective sustainable adaptive solutions which can provide potential co-benefits. A few examples of potential ways in which EbA and NbS can be useful for urban informal settlements are:

• Increasing tree cover, green roofs or walls, wetlands, and natural water reservoirs are solutions that can be used to combat heat stress in the settlements.

Co-benefits: Potential co-benefits could include improved scenery and recreation opportunities which can lead to a multitude of physical well-being, and mental health benefits. Urban greens also have a direct role in climate mitigation by sequestering carbon.

• Green permeable spaces (like urban gardens, agriculture) and permeable pavements, tree cover, wetlands, and vegetative storm water channels (bio swales) can play an important role in complementing existing drainage infrastructure, reducing surface water run-off, increasing ground water recharge, all of which can greatly reduce the intensity of flooding events.

28 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Co-benefits: Vegetative channels or those with aggregates could play a role in trapping contaminants and pollutants and reduce the pollution of groundwater. Agriculture in urban gardens could lead to food security and increase in income for the urban poor.

• Vegetation buffers can act as a wind barrier, which can to a certain extent protect from toxic fumes and smoke (Reid,2020).

Co-benefits: Potential co-benefits could include climate mitigation by sequestering carbon.

• However, it is extremely critical that EbA approaches be considerate of the local and traditional knowledge, and needs of community members, for its successful adoption in urban poor communities (IUCN, 2017)

Co-benefit: Increased community involvement in governance and monitoring of infrastructure produced through EbA can facilitate social cohesion and social justice for the urban poor.

Illustrative Examples

Based on the above understanding, two of the studied settlements were selected to showcase a few illustrative examples of how EbA and NbS solutions could be embedded in these settlements to address their contextual vulnerabilities.

Example 1: Churmuribhatti

This is a settlement that is primarily engaged in the production of puffed rice. Currently open spaces are used by the factory units to dry their rice and husks. The settlement lacks an efficient proper drainage system which leads to residential and industrial wastewater flooding the common spaces. The lack of green cover, proximity to a landfill, and crematorium, exacerbates the vulnerability of the settlement to climate change impacts. While the fumes from the landfill and crematorium, and dusty pavements greatly impact the air quality and increases heat stress, leachate from the landfill during heavy rains impacts the areas used for livelihood and the lake water quality as well. There is a possibility of the groundwater in the area to also get affected due to the same. Figure 8 illustrates the various activities carried out in the settlement, and Figure 9 illustrates the issues discussed above.

Some of the suggested measures to address these issues include:

Green spaces:

• Buffer vegetation along the lake edge to revive lake ecology and to provide shaded areas that can be used for domestic, livelihood and social community activities.

• Buffer vegetation near the landfill to block toxic fumes and improve air quality in the settlement.

• Green cover along the edge of selected lanes to combat heat island effect due to industries.

Elements to increase surface permeability:

• Percolation trenches (with aggregate layers) to decrease surface run-off and filter it before it percolates

• Permeable pavements to allow recharge of run-off water. Pavement of selected stretches to bring down the issue of dust.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the location of these measures in the settlement.

29 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 8: Activities carried out in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad

Figure 9: Vulnerabilities in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad

30 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 10: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad (a)

Example 2: Goller Oni

The main livelihood of the settlement dwellers is scrap work. Organised along the five main lanes, there are no organically formed common (open) spaces within the settlement. In the absence of such spaces, the five streets evolve into common spaces for the community. These become multi-functional dynamic spaces, with potential adaptive capacity. An existing large open space is currently used for garbage dumping. Heat stress and flooding emerged as important issues affecting the quality of life in the community. Figure 12 illustrates the various activities carried out in the settlement, and Figure 13 and Figure 15 illustrate the key issues.

Some of the suggested measures to address these issues include:

Blue-Green spaces:

• Green spaces along the streets to reduce heat island effects and create spaces suitable for recreation, social, and livelihood activities.

• Conversion of the derelict open space into an active usable community space which can be multi-functional (usable for social, recreational, livelihood activities). A water retention pond within this open space will play the dual role of bringing down the heat island effect further and also act as a retention pond to hold and recharge excess run-off storm water.

Elements to increase surface permeability

• Percolation trenches (with aggregate layers) to decrease surface run-off and filter it before it percolates

Figure 14 and Figure 16 illustrate the suggested measures listed above.

31 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 11: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Churmuribhatti, Dharwad (b)

32 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 12: Activities carried out in Goller oni, Dharwad

Figure 13: Vulnerabilities in Goller oni, Dharwad (a)

Figure 14: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Goller oni, Dharwad (a)

33 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

34 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

Figure 15: Vulnerabilities in Goller oni, Dharwad (b)

Figure 16: Proposed adaptation/mitigation measures in Goller oni, Dharwad (b)

7 Conclusion

Climate change is intensifying the existing urbanisation and informality induced vulnerabilities of the urban poor. Unplanned urbanisation and lack of recognition by the State coupled with occupational hazards and location on ecologically fragile areas are already impacting the health and livelihood of the urban poor. Climate change will only exacerbate these impacts.

The analysis carried out in this report foregrounds the significance of settlement level common spaces, and spaces located in the city-settlement interface in urban informal settlements. Limited availability of private space makes these areas multi-functional and dynamic. However increased impacts of climate change – in the form of floods, and heat stress- are threatening these spaces. The solutions put forth in this report, though passive in nature, stem from the existing coping strategies used by the urban poor in facing climate change and urbanisation induced challenges. Since the communities recognise and relate to such solutions, it helps in ensuring better community ownership.

Finally, since many climate-change impacts within the informal settlements depend on city-wide infrastructure, settlement-city-region links are especially important There is an urgent need to link climate action at various scales to ensure on-ground impacts that are inclusive, sustainable, and just.

35 Strengthening Cities for Inclusive Climate Adaptation 2022

References

Brook, R. M., & Dávila, J. (2000). The Peri-Urban Interface: a Tale of two cities. London: School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, University of College of London .

Burzyński, M., Deuster, C., Docquier, F., & de Melo, J. (2019). Climate Change, Inequality, and Human Migration (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3464525). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3464525

C.Manikyamba, & RobertKerrich. (2012). Eastern Dharwar Craton, India: Continental lithosphere growth by accretion of diverse plume and arc terranes. Geoscience Frontiers, 225-240.

Census of India. (1951). District Census Handbook. Ministry of Home Affairs.

Census of India. (1981). District Census Handbook 1981. Ministry of Home Affairs.

Central Ground Water Board. (2008). Groundwater Information Booklet. Bangalore: Karnataka State Government .

Comptroller and Auditor General of India. (2015). Performance audit on Conservation and Ecological restoration of Lakes under the jurisdiction of Lake Development Authority and Urban Local Bodies. Government of Karnataka.

Dodman, D., Archer, D., & Satterthwaite, D. (2019). Editorial: Responding to climate change in contexts of urban poverty and informality. Environment and Urbanization, 31(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247819830004