Com um universo imaginativo único e uma produção refinada, Antônio José de Barros Carvalho e Mello Mourão (1952-2016), o Tunga, é um artista emblemático e relevante das artes visuais do país. Para celebrar sua obra, o Itaú Cultural (IC), em parce ria com o Instituto Tunga e o Instituto Tomie Ohtake, realizou a exposição retrospectiva Tunga: conjunções magnéticas.

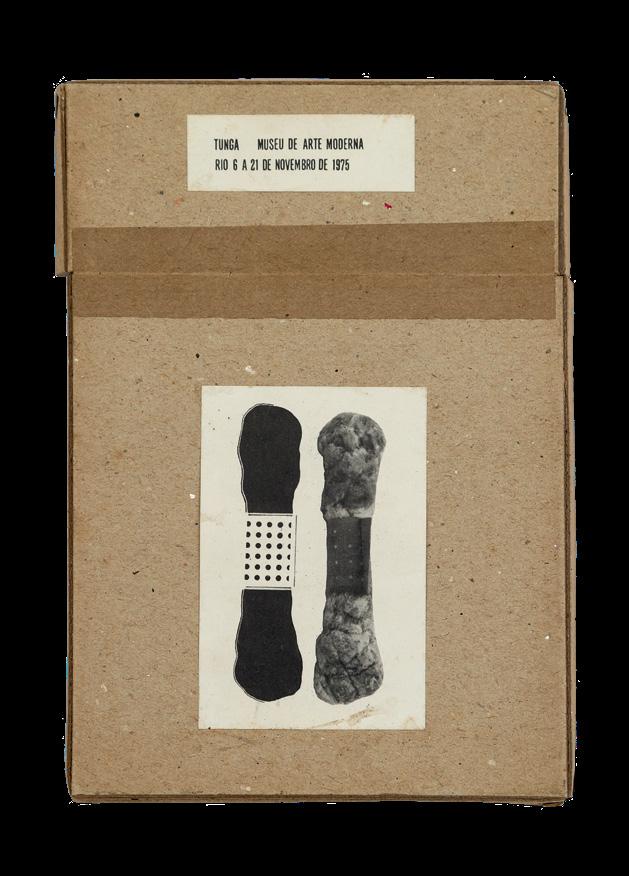

Tunga se formou em arquitetura e urbanismo em 1974, mesmo ano em que realizou sua primeira exposição indivi dual, no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio). No efervescente final dos anos 1970, conviveu e dialo gou intensamente com grandes nomes das artes contemporâ neas, como José Resende, Waltercio Caldas, Cildo Meireles, Sergio Camargo e Lygia Clark – os três últimos já tema de exposições no IC.

Desenhos, esculturas, objetos, instalações, vídeos e performan ces. A diversidade de suportes revela os múltiplos interesses de Tunga, que percorria diferentes áreas do conhecimento, como literatura, matemática, arte e filosofia. A pluralidade também se fez presente no uso de materiais. De maneira notável, Tunga explorou ímãs, vidro, feltro, borracha, dentes e ossos. Sua obra ganhou simbologia e presença, aproximando-o da produção artística em evidência no panorama internacional.

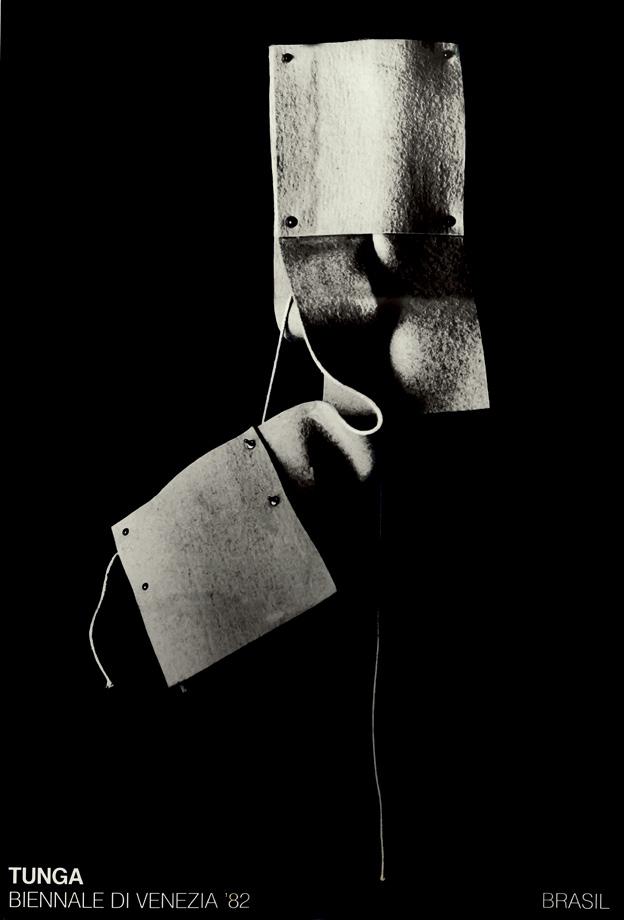

A partir da década de 1980, o artista participou da Bienal de Veneza, teve quatro passagens pela Bienal de São Paulo e expôs em mostras no Museu de Arte Moderna (MoMA), em Nova

York, e na Whitechapel Gallery, em Londres. No Instituto Inhotim, em Minas Gerais, dois espaços destacam sua obra, a Galeria True Rouge (2002) e a Galeria Psicoativa (2012). Tunga é o primeiro artista contemporâneo e o primeiro brasi leiro a expor no Museu do Louvre, em Paris – com a obra À la Lumière des Deux Mondes (2005).

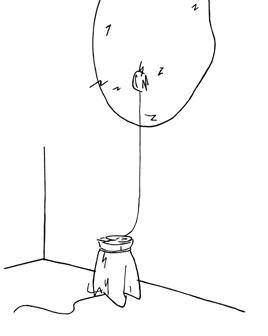

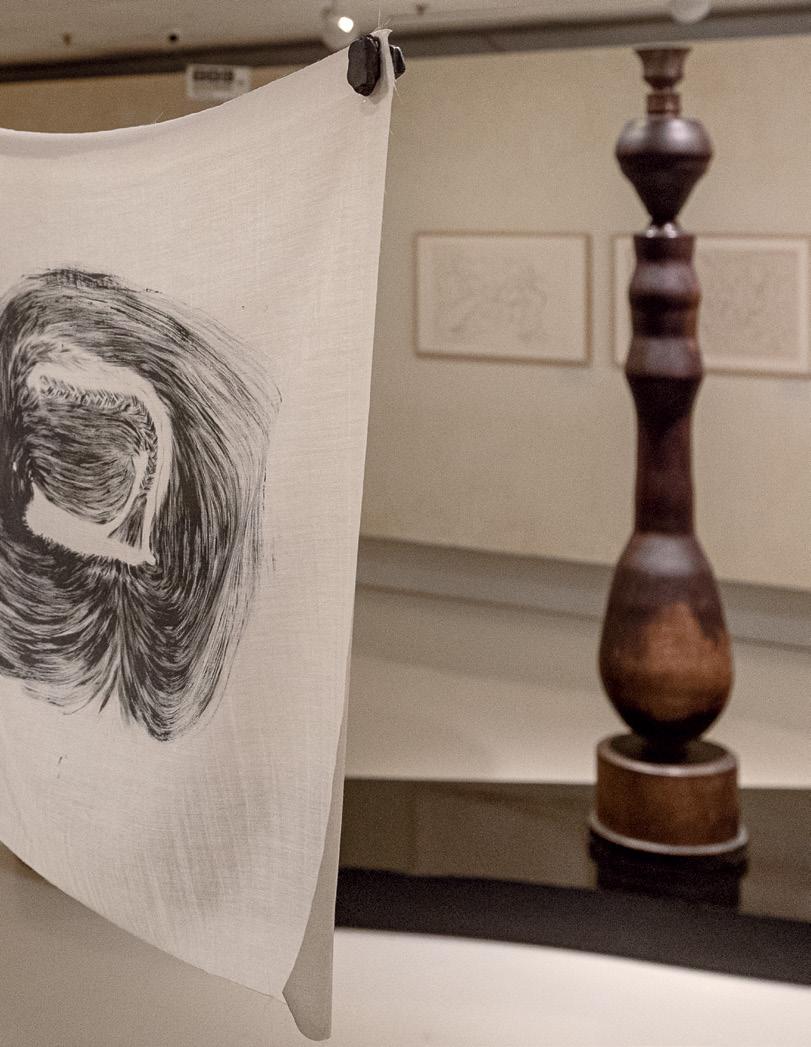

Parte dessa extensa produção está em Tunga: conjunções magnéticas. Além do IC, a mostra estende-se para o espaço do Instituto Tomie Ohtake, que recebe a escultura Gravitação Magnética (1987) – cujos esboços ocupam ambos os espaços culturais – e o filme-instalação Ão (1981).

Este catálogo traz as obras em exposição e um texto que apresenta a mostra, assinado pelo diretor do Instituto Tunga, Antônio Mourão, e pelo curador, Paulo Venancio Filho, que também contribui com um ensaio propondo uma reflexão aprofundada sobre as obras do artista. O IC e o Banco Itaú apoiam o projeto de um catálogo raisonné, que está sendo organizado pelo Instituto Tunga e deve ser lançado em 2024.

Desde 2010, o IC revisita, em mostras individuais, o acervo de artistas fundamentais para as artes visuais brasileiras. Esse conteúdo se expande no site itaucultural.org.br e na Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileira.

Conheça conteúdos exclusivos desenvolvidos para a exposição Tunga: conjunções magnéticas

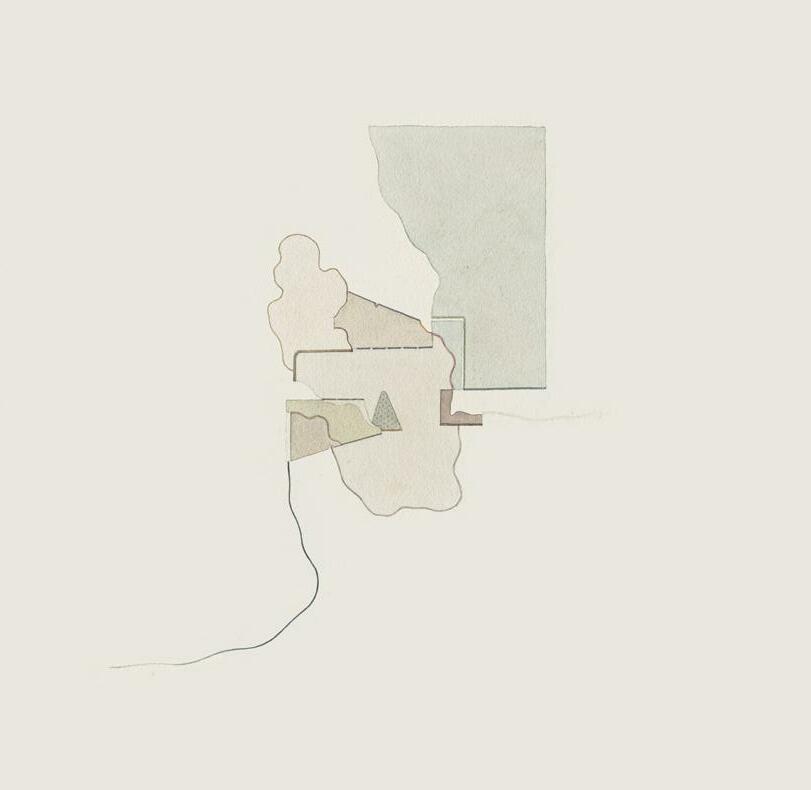

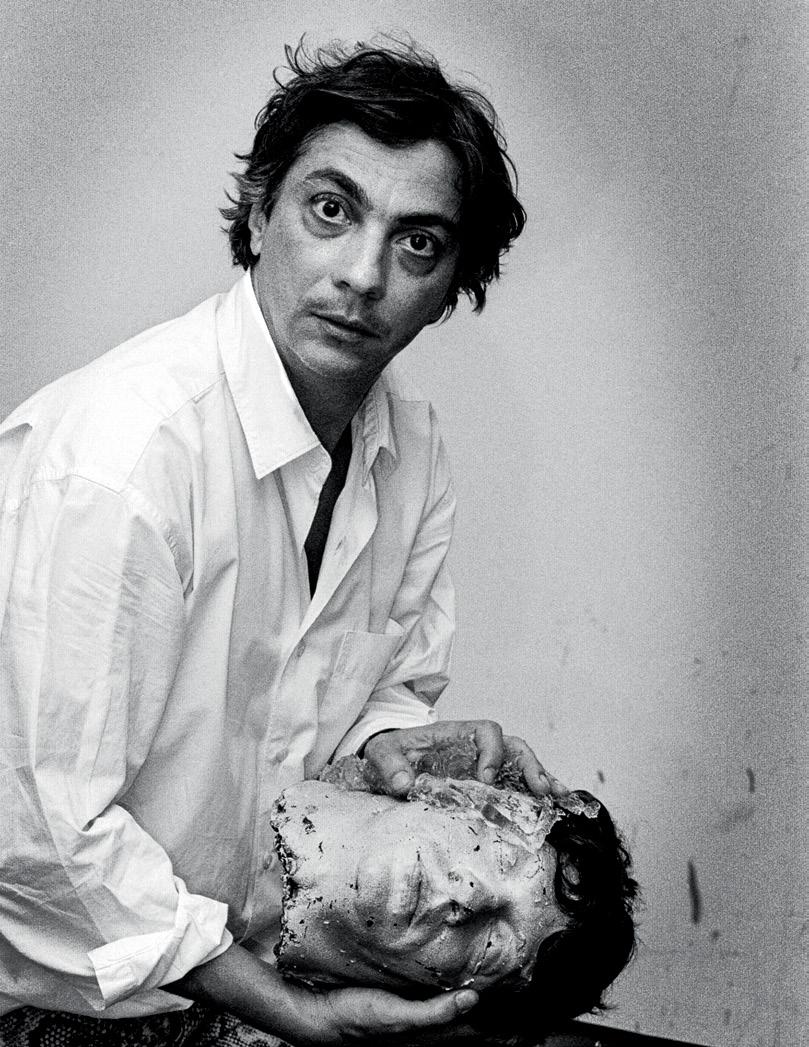

Apresentar a obra de Tunga em sua extensão, profundidade e integridade foi o que norteou a realização de Tunga: conjunções magnéticas. Com mais de 300 trabalhos em exi bição, muitos deles inéditos, a exposição é uma retrospectiva com as relações e os desdobramentos que se metamorfo seiam desde a década de 1970 – sua primeira individual foi em 1974, no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio) – até pouco antes do seu falecimento, em 2016.

Além do desenho, a inquietude artística de Antônio José de Barros Carvalho e Mello Mourão (1952-2016) o levou a outras práticas: esculturas, objetos, instalações, vídeos e performances . Esse conjunto de trabalhos revela a dimensão de seus múltiplos interesses, que transitavam livremente por diversas áreas do conhecimento, como arte, litera tura, ciência e filosofia. Grande parte da obra do artista se encontra sob a guarda do Instituto Tunga, que tem a res ponsabilidade de manter, divulgar e resguardar seu legado.

O espaço expositivo traz de maneira abrangente os momen tos mais significativos da trajetória do artista, sem qualquer tipo de hierarquia ou cronologia, fiel ao seu pensamento contínuo e circular, sempre se ampliando mais e mais. Ao apresentar a amplitude da obra em consonância com sua poética plástica, inspirada no conceito de “instauração” por ele proposto para as suas “instalações performáticas”, Tunga: conjunções magnéticas é uma exposição que

fisicamente se “instaura”, se é possível dizer, como uma verdadeira “obra”.

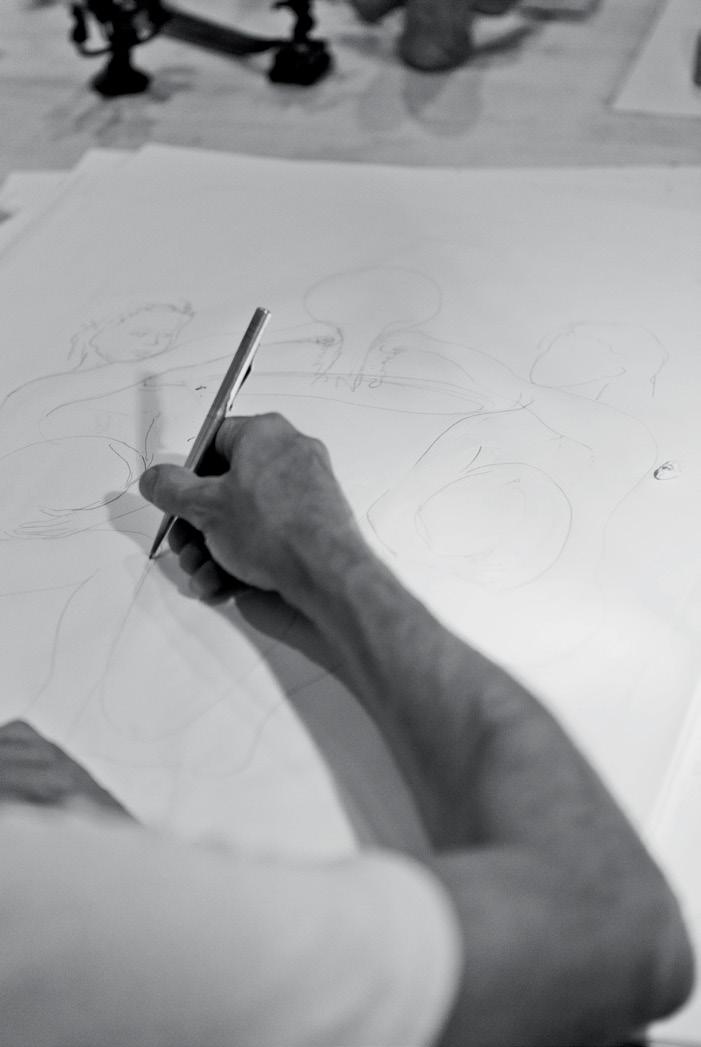

Tunga, como poucos artistas contemporâneos, explorou as mais diversas mídias e materiais como ímãs, vidro, feltro, borracha, dentes e ossos, impregnando-os de uma estranheza poética, não familiar. Por meio de sua peculiar prática metamórfica, propunha experiências artístico -poéticas díspares, heterogêneas e heterodoxas. Suas “instaurações”, instalações, esculturas e objetos buscam explorar tanto o apelo simbólico e físico dos materiais quanto sua articulação plástica e poética, e se encontram lado a lado com sua intensa obsessão pelo desenho. Esse, para Tunga, nunca foi apenas um esquema ou projeto, mas uma realização em si, indissociável e fundamental para a produção e a compreensão da totalidade do trabalho. Sendo assim, a prática do desenho como raciocínio e realização está presente na mostra em toda a sua extensão e relação com os trabalhos tridimensionais.

Tunga: conjunções magnéticas enfatiza a interação meta bólica, em constante dinâmica e mutação, entre mídias e materiais que se apresentam ao longo de quase meio século, característica fundamental de Tunga. E percorre sua exten são num conjunto de trabalhos que vão do início ao fim de sua obra e vice-versa, dobrando-se sobre si mesmo em cada um e em todos os seus momentos.

* As palavras em destaque ao longo do texto fazem parte de um glossário que agrega referências, termos e expressões próprias do artista. Confira nas páginas 45 a 54.

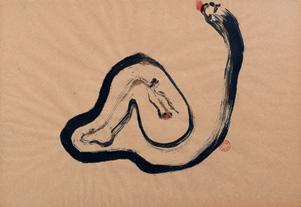

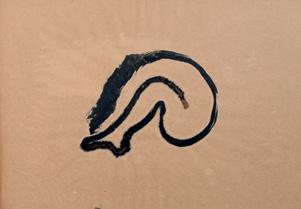

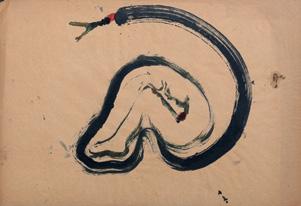

1. Tunga produzindo um desenho da série “From ‘La Voie Humide’” | Tunga producing a drawing of the series “From ‘La Voie Humide.’” Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera

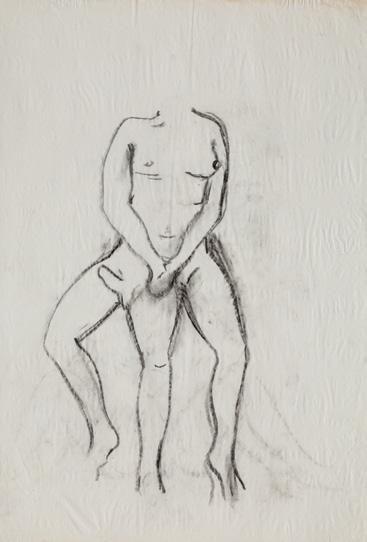

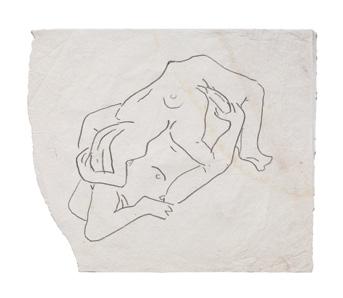

A obra toda de Tunga se desdobra em torno do corpo nu. Reversível, o corpo é, simultaneamente, o gerador e o gerado. É uma duplicidade que se multiplica, atrai tudo para si e repõe num plano mais elevado, refinado, magnificado. Desenhos, objetos, instalações, escul turas, “instaurações”* são os diversos resultados desse processo – o desenho em primeiro lugar.

Nota 1. Le grand verre, ou La mariée mise à nu par ses celibataires, même (O grande vidro, ou A noiva despida por seus celibatários, mesmo), pintura em vidro de Marcel Duchamp, é dividida em duas partes. Na metade superior, a Noiva e, na parte inferior, a Máquina celibatária, em que se encontram os Malic Moulds, ou Moldes machos, impossibilitados de entrar em contato direto com a Noiva. A cena se concentra nas atribulações eróticas entre a Noiva e os Moldes machos e representa a summa visual duchampiana que se estende por uma complexa e extensa narrativa.

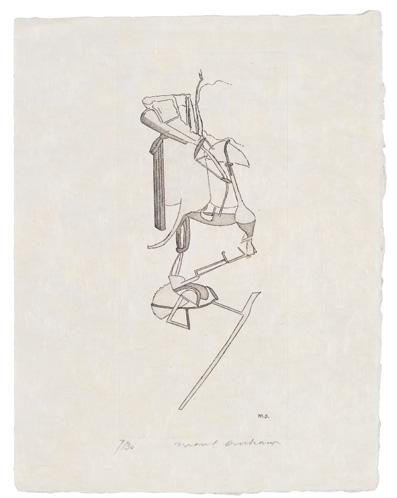

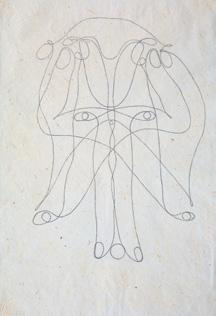

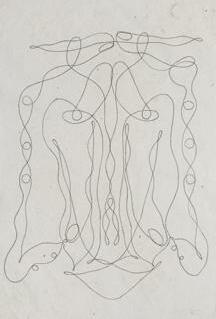

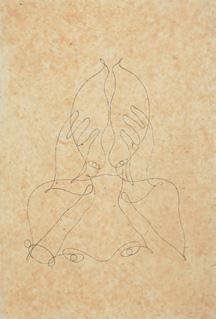

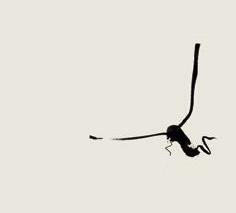

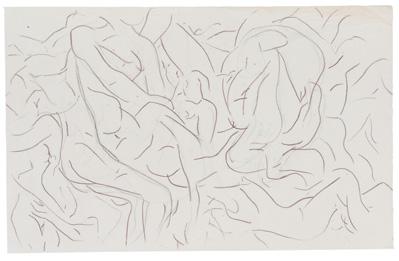

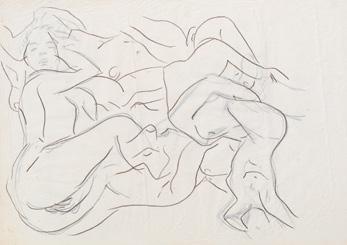

São eles que marcam o início da obra; inúmeros, resultado de uma prática constante, intensa, obsessiva, que vai prosseguir e determinar toda ela do começo ao fim. Sua primeira exposi ção – só de desenhos – ocorre em 1974, no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio), com o provo cante título de Museu da Masturbação Infantil . Ali se percebia claramente um desenhista em ação e uma vocação. Nos desenhos, que nada tinham de infantil ou de infantilizante, menos ainda de uma possível ingenuidade, aparecia, sobretudo, a manifesta ção de uma energia libidinal solta,

desinibida, indicada no sugestivo título da exposição – audacioso, provocante, intrigante para uma mostra de dese nhos abstratos tão intimistas, quase esboços inacabados do que propria mente desenhos. Alguns minúsculos, tendendo mais à invisibilidade do que a se dar a ver, como se nos obrigassem a nos aproximarmos com uma lupa para dar conta da sua frágil e delicada aparência, apenas imersa e diluída no papel, vindos de um fluxo ainda inominado, primeiras emanações de uma energia vital transbordante. Tão intrigantes figuras que recordam, por afinidade, La mariée da cena erótica de Le grand verre , ou La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même 1, de Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), tão admirada por Tunga. É para aí que se sentia atraído, para o “outro” Duchamp, aquele da imagérie erótica não literal, insinuada por figuras desprovidas de um apelo sensual do senso comum – cosa mentale , poderia se dizer. Portanto, são desenhos já informados de uma distinta genealogia

visual heterodoxa. Na mesma exposi ção, outro ritmo gestual diferenciava uma série de desenhos que se distin guiam enérgicos, nos quais o preto do nanquim predominava em rastros ejaculatórios de um movimento rápido dando vazão ao líquido e sua expansão livre pelo papel. Desenhos abstratos, sim, mas antes pulsações que encon tram seu termo último na afirmação da descarga gestual que percorre início e fim, sem adições ou correções, minuciosamente. Figuras ainda sem nome, embora exibidas sob títulos, não menos intrigantes: O Perverso, Pensamentos, Máquinas , Charles Fourier e Paisagens do Desejo . Entre eles, esse extravagantemente anacrônico, o que se refere a Charles Fourier (17721887), o socialista utópico das socieda des eróticas do século XVIII. Um nome que, como outros, indicava já o enre damento que a obra de Tunga manteria em toda a sua trajetória com aspectos radicais da cultura francesa, seja nas artes plásticas, na literatura ou na filo sofia. Fourier comparecia para nomear uma série de desenhos eminentemente contemporâneos e, naquele início, indicava uma afinidade eletiva que se reuniria a outras companhias ao longo de toda a sua obra.

Fourier era apenas um que o trabalho de Tunga trazia para si e, assim, expunha francamente aquilo cuja amplitude iria expandir incessantemente fazendo associações cada vez mais audaciosas e imaginativas, aproximando distâncias no tempo e no espaço. A vocação definida – desenhista em primeiro lugar e em toda a sua trajetória artística – colocava Tunga na geração dos artistas que emer giram nos anos 1970, quando o desenho

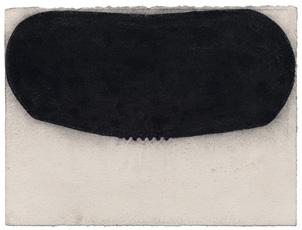

predominava, e que ascenderam a outro degrau de importância artística no Brasil. Entretanto, nessa geração ocupa um lugar bastante singular, singularís simo – é preciso aqui usar o superlativo. Seus primeiros desenhos abstratos levam a crer num anacronismo, quiçá deliberadamente deslocado do seu tempo e da sua geração. A gestualidade delicada, lenta ou rápida, econômica nas cores qualificava essas pequenas imagens sutilmente expressivas. O negro do nanquim, homogêneo e maleável, visualmente pesado, como que anteci pava a matéria escultórica que viria a seguir.

A exata indefinição conduzia ao informe ou disforme do improviso gestual, ora se aproximando, ora se afastando de uma improvável figura – entre mancha e figura –, oposições que teriam vida longa em toda a obra. Nessa dimensão reduzida de sua abstração, percebia-se que transitava por Henri Michaux (1899-1984), grande poeta, artista um tanto inclassificável, cujos desenhos mais famosos tinham sido feitos sob o efeito da mescalina; por André Masson (1896-1987), surrealista heterodoxo ligado a outro também um tanto à margem e eventual dissidente do movimento, o escritor Georges Bataille (1897-1962), leitura frequente de Tunga e a admiração de seus tempos de juven tude; por Roberto Magalhães (1940), que revitalizou o desenho no final dos anos 1960; e, por fim, pelo Duchamp desenhista eventual. De tais artistas veio, mais tarde, a possuir trabalhos, em reconhecimento à sua admiração e à sua dívida juvenil.

Nesses nomes percebem-se a escolha e o valor que ele dá a certa lateralidade

The Bride (Noiva),

1965-1966 gravura | print 26,7 × 11,9 cm Doação de | gift from Milton e | and Rosemary Okun Foto | photo: ©2022. Imagem digital do | digital image of Whitney Museum of American Art, licenciada por | licensed by Scala ©Association Marcel Duchamp/AUTVIS, Brasil, 2022

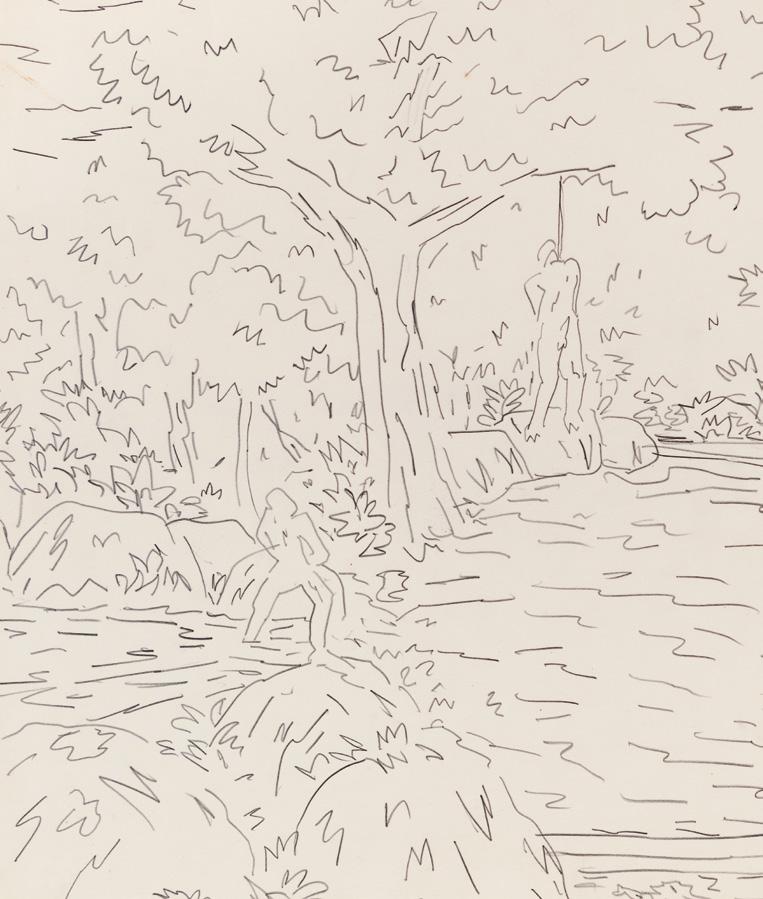

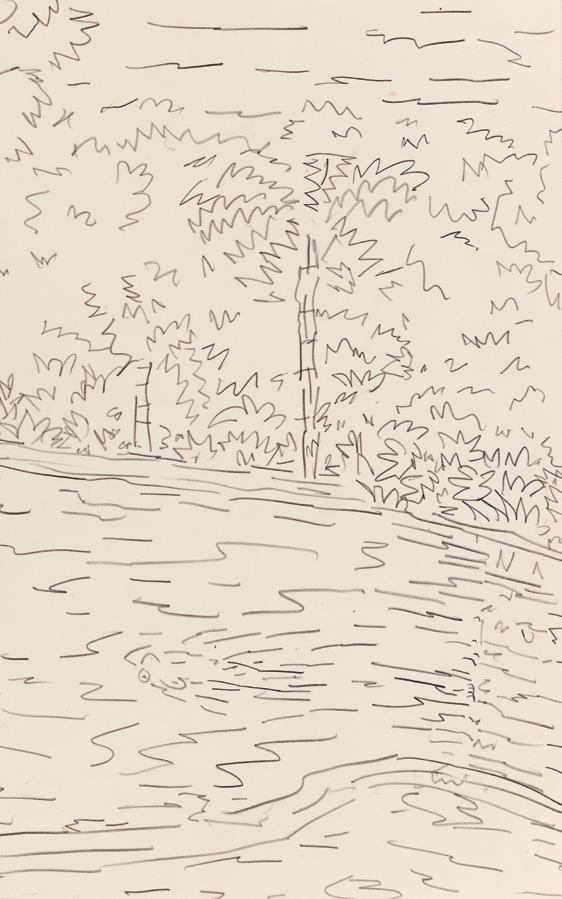

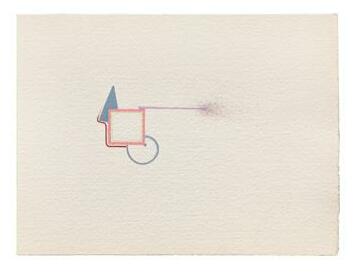

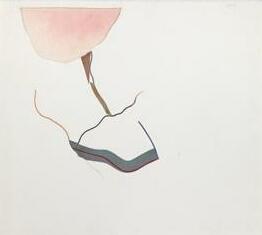

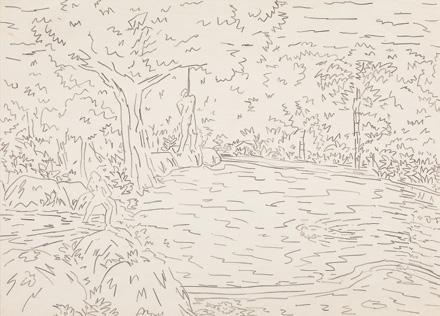

3. Sem título | Untitled, ca. 1970 aquarela sobre papel | watercolor on paper 34,5 x 34,8 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera

4.

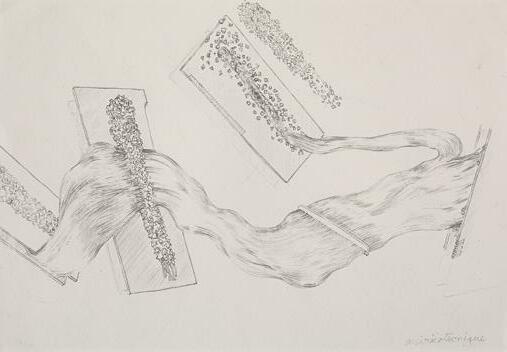

Sem título | Untitled, 1979-1983 grafite sobre papel | graphite on paper 48,5 x 66 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera Acervo Instituto Tunga

6

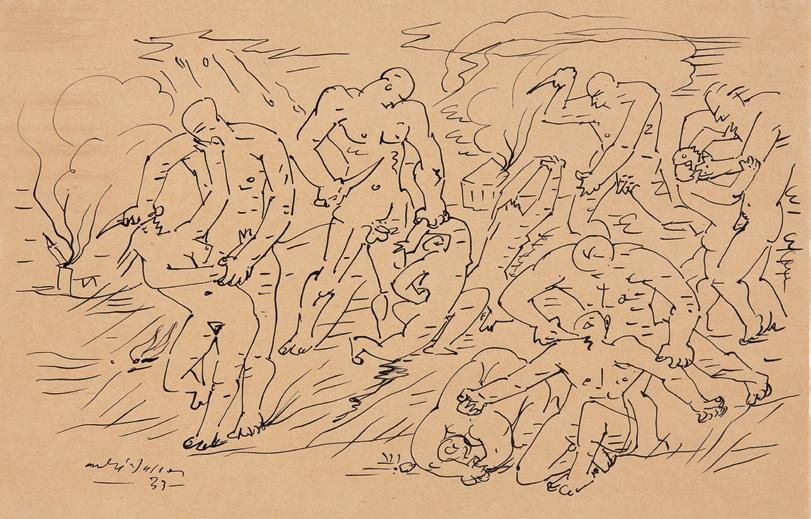

5. André Masson Massacre, 1933

nanquim sobre papel | Indian ink on paper

31 x 45 cm

Coleção | collection Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (depósito temporal coleção particular, Paris, 2012)

Foto | photo: Arquivo Fotográfico | photographic archive Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía ©MASSON, ANDRE/AUTVIS, Brasil, 2022

6. Da Pele, 1975

madeira, esponja natural, arame, aço inoxidável e termômetro | wood, natural sponge, wire, stainless steel, and thermometer

18 x 34 x 21,5 cm

Coleção | collection Thiago Gomide

Foto | photo: Renato Parada/Itaú Cultural

artística; opta por artistas que não ocupavam a centralidade da influência daqueles anos, o que é uma marca das admirações de Tunga, que viu proximi dade naqueles que o atraíam pela estra nheza e pela afinidade com seu mundo visual. Nessas escolhas, improváveis combinações, especialíssimas, encon tram-se os indícios que influenciaram a formação do jovem, ainda adoles cente, artista. Transcorriam nesses anos de 1970 a transição e mesmo a superposição entre a Pop art e a Arte Conceitual, da qual, estranhamente ou deliberadamente, não participava. Sua ligação transversal e idiossincrática com as margens do Surrealismo estru turava a poética que caracterizaria seu trabalho dali em diante.

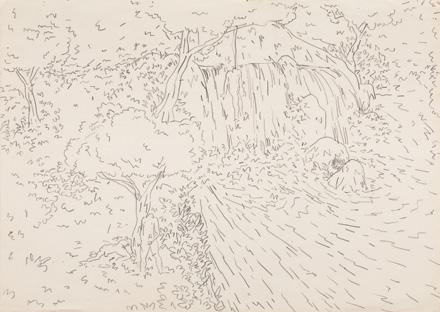

Não foi o Duchamp conceitual tão evidente na arte contemporânea que o atraiu, e sim aqueles trabalhos que constituem a “mitologia” ducham piana. A sua inclinação surrealista também se manifestaria em uma série de desenhos claramente inspirados em André Masson, da série Massacres .

Ali estava figurada a cena que cor respondia às suas obsessões: a com pulsão erótica e a presença da morte, essa última como o estágio final da primeira – cena que vai se repetir de formas diferentes em outros trabalhos. A figura enforcada aparecia só e camu flada, indistinta na natureza; tão invisí vel quanto “A carta roubada” do conto de Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849). Outra obra, Pintura Sedativa (1984), iria exemplificar o método que se iniciava; a contaminação metabólica entre matéria e título; para ser sedativa, a pintura tinha que ser na seda. Logo, seda/sedativa resume a transposição

poética da matéria para um estado mental – quem olha a seda é sedado por ela. A sedação se “cola” na seda e, por extensão, leva ao sono e ao sonho.

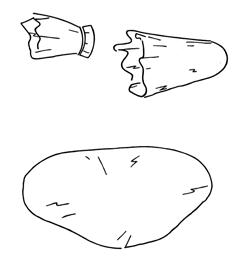

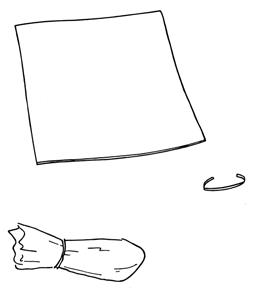

Não lhe interessava, ou interessava pouco, o tão influente na época ready -made , mas, sim, os trabalhos menores de Duchamp. Aqueles menos conheci dos, pequenos objetos “surrealistas” dos quais Tunga se aproximava e que, provavelmente, sugeririam a transição para a tridimensionalidade das obras apresentadas na sua segunda exposição individual, Ar do Corpo (no MAM Rio), na qual o título de uma delas, Objeto do Conhecimento Infantil (1974), poderia bem servir para todas as outras. Nessa exposição estamos um passo além dos fluxos inconscientes da primeira, no estágio posterior da apreensão da tridi mensionalidade dos objetos, que mais tarde o levaria à escultura. Agora a ação é tátil, da ordem da descoberta do objeto (do desejo); dos desenhos para esses insólitos “brinquedos” perversos – é o que sugere o título de um deles, Eros e o Pensamento Positivo (1974) –, estamos um grau acima e exterior da imaginação visual infantil. Objetos um tanto excêntricos, enigmáticos, plenos de possíveis descobertas reveladoras do mundo do erotismo polimórfico que, de agora em diante, vai se mani festar na escolha e no uso dos mate riais; inicialmente feltro e chumbo, ambos com uma decisiva importância ao longo da obra.

Uma ansiedade ambiciosa já se encon trava mesmo nas menores obras; uma grandiosidade íntima que, em alguns momentos mais tarde, atingiria a sun tuosidade – o grande e o pequeno são

variações homotéticas indistintas na obra de Tunga. Na seleção criteriosa dos materiais, brutos e refinados, na esme rada e meticulosa execução, acentua-se um programa deliberado que dá à obra autoridade, relevância material e o desejo de restaurar certa magnificência à arte contemporânea. Daí a recusa à unilateralidade conceitual e à banalidade decorrentes muitas vezes do ready-made; e, por outro lado, a busca de uma mitolo gia afim e da grandeza do Le grand verre duchampiano; a mesma vasta e intrin cada narrativa que vai ligar um trabalho ao outro, acrescentando a cada um deles uma nova e ampliada versão.

Sade, Fourier, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Lautréamont; a lista de nomes da litera tura francesa, e não só desta, comparece ao espírito do artista, como se fosse ele, e a partir deles, um revitalizador e trans formador dessas poéticas tão radicais, íntimas e precisamente escolhidas. Um peculiar caso mais de intoxicação do que de inspiração; delirante, mas consciente, rigorosamente operativo e calculado. Não se trata de meras apropriações, citações, transcrições; a validade desses nomes só se justifica quando mobilizam e penetram na obra, na sua mitologia poética, espécie de reencarnação da mística da soberania romântica própria do artista, que aqui se revela como poucas na arte contemporânea.

Exemplo de uma afinidade é o pequeno múltiplo de Jean Arp2 (1886-1966) adquirido num marché aux puces em Paris nos anos 1970, o qual revela não só uma escolha oportuna, mas uma proximidade não circunstancial. Frente e verso reversíveis, os dois buracos dos olhos da Masque Oiseaux podem ser

vistos como um indício germinal de elaborações posteriores que iriam com plexificar a simplicidade do objeto que é máscara e pássaro, ora um, ora outro, e também os dois simultaneamente. A reversibilidade implícita nessa dimi nuta escultura vai revigorar os impulsos já existentes no sentido de aproximar realidades distantes. Ocultas nessa máscara havia possibilidades que Tunga desvendou e retomou como se este fosse um objet trouvé particular, desti nado única e exclusivamente para ele.

Se a diversidade de seus interesses o levava para áreas remotas, divergentes, incongruentes – ciência, filosofia, lite ratura, ocultismo, religião –, todas eram reconduzidas como fontes de energia que se unificavam no trabalho e nele se metabolizavam. Essa erudição produtiva, fluida, inclassificável se expandia e se fixava em cada ideia a cada momento da transmutação plástica, imersa no fluxo de obra a obra. Esse domínio refinado de interesses deu à sua obra esse ar inconfundível de preciosidade longamente elaborada, destinada a durar e permanecer. Faltasse esse refinamento específico, seria falsa, inconsequente, artificial, insuficiente, sem a densidade do efeito que busca provocar, muitas vezes até em excesso; como é o caso das longas, exaustivas, encantatórias e exal tantes “instaurações”.

A ideia que perseguiu e da qual nunca se desvinculou estava já expressa em seu texto publicado no exemplar de número 3 da revista Malasartes , em 1976, intitulado “Prática de Claridade sobre o Nu” 3: lançar uma nova luz sobre um corpo e explorá-lo de todas as maneiras até a sua reaparição

Nota 2. Jean ou Hans Arp, um dos grandes artistas abstratos do século XX; iconoclasta, circulou pelo Dadaísmo e pelo Surrealismo. Foi um dos primeiros a privilegiar a participação do acaso em sua prática artística, mais especificamente nas colagens. Também poeta, suas esculturas representam um dos momentos altos da abstração moderna.

Nota 3. NE: “Os exemplos de objetos aqui apresentados são da classe do clássico tema do nu” é a primeira frase de “Prática de Claridade sobre o Nu”. Para ter acesso ao texto completo, acesse: https://issuu.com/tungaagnut/ docs/revista_malasarte

7. Lygia Clark

Almofada leve-pesada, 1976 areia, isopor e tecido de algodão | sand, Styrofoam, and cotton fabric

Fase | phase: Objetos Relacionais Número de edição: única | limited edition of one Coleção | collection Antônio Mourão

Foto | photo: Rafael Salim Agradecimento | Acknowledgement Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark”

8.

Sem título, da série |

Untitled, from the series Morfológicas, 2014 borracha | rubber edição 1/3 | edition 1/3 100 x 33 x 55 cm Acervo | collection

Instituto Tunga

Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera

reinventada; reinstaurar o corpo na escultura – o corpo é a escultura e vice-versa. Toda obra persegue a ideia obsessiva do nu, desdobrando-se a cada momento, a cada trabalho. Trata-se da cena erótica primordial de Tunga, resumida na frase de Georges Bataille: “A ação decisiva é o desnudamento”.

Suas primeiras esculturas já indica vam uma prática divergente, hete rodoxa, mas ainda assim próxima a outras da arte contemporânea. Não foi, por exemplo, o único a usar o feltro. Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) e Robert Morris (1931-2018), entre outros artis tas, também exploraram, de maneira diversa, o caráter tátil, flexível, anties cultural e orgânico desse material. Diferentemente deles, articulando a matéria mole do feltro a esquemas geométricos “duros”, Tunga realizou suas primeiras esculturas, os Albinos (1982) (p. 130 | img. 120 a 122), corpos recortados no feltro e remontados por meio de parafusos e cordões em diver sas variações. Neles a oposição entre a geometria estruturada das formas e a matéria flexível do feltro sugeria uma possível tensão e reação do inanimado em reivindicar-se como coisa viva –fenômeno semelhante aos Bichos de Lygia Clark (1920-1988). Era como se os cordões tensionassem a pureza geomé trica e o plano retorcido sugerisse um volume aprisionado em uma posição na qual o “corpo” tomava forma. Não é sugestivo que o branco do feltro recor dasse os nus das esculturas clássicas gregas? Aí se iniciava uma profunda ligação de Tunga com a matéria, ou as matérias; serão muitas aquelas que vão identificar, de agora em diante e à primeira vista, um trabalho seu.

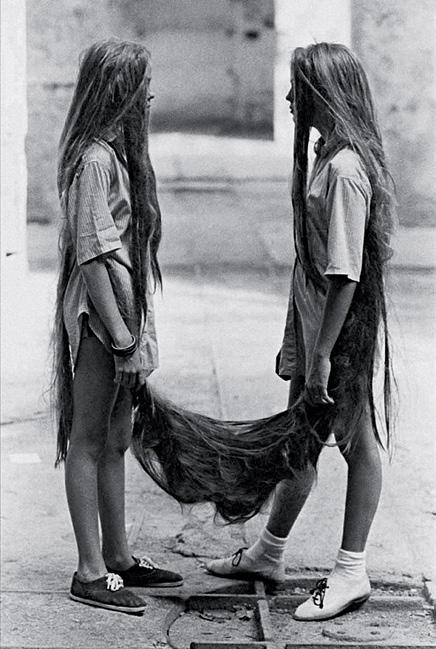

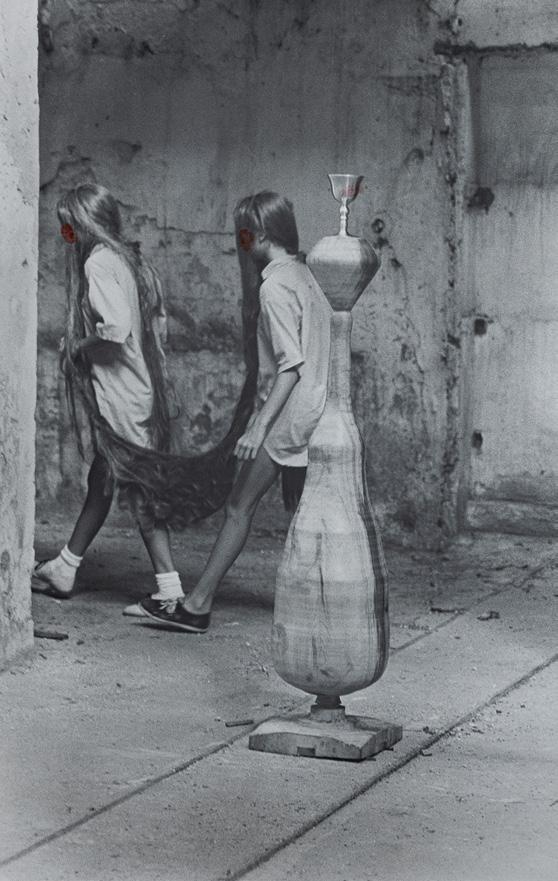

9. Jacqueline Silva e seu Eixo Exógeno, 1986 | Jacqueline Silva and her Eixo Exógeno, 1986. Foto realizada durante as filmagens de O Nervo de Prata, de Arthur Omar | photo taken during the filming of O Nervo de Prata, by Arthur Omar. Foto | photo: ©Wilton Montenegro

10. Performance Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós, 1986. Foto realizada durante as filmagens de O Nervo de Prata, de Arthur Omar. | Performance Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós, 1986. Photo taken during the filming of O Nervo de Prata, directed by Arthur Omar.

Foto | photo: ©Wilton Montenegro

A Vênus que surge pela primeira vez na pré-história do trabalho de Tunga tinha que ser pré-histórica: a Vênus de Laussel , estatueta paleolítica desco berta na França em 1909, aparece na fotografia que faz parte de uma obra, hoje perdida, Piscina (1975), publicada na revista Malasartes junto com o texto “Prática de Claridade sobre o Nu”. Nota-se que essa Vênus já é o “nu”, um dos primeiros da história. A Vênus vai se tornar Vê-Nus (1976); ao separar e ligar a sua nudez ao voyeur por um hífen, Tunga indica que sem um não há o outro. Algo semelhante ocorre com os Eixos Exógenos . Eixos x Exógenos – o “x” que se repete nas duas palavras é como a representação gráfica de um eixo –, há uma proximidade entre esses termos, um está ligado ao outro, umbi licalmente, como as Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós (1984), por um “x”, incógnita que nos fascina e desconhecemos. Cariátides contemporâneas – assim poderíamos denominar os Exógenos, corpos eretos e hieráticos gerados pela circunvolução de um corpo de mulher em torno de um eixo; o “x” que lhe dá corpo ao se retirar quando a ausência se torna presença. Portanto, cariátides negativas; simultaneamente clássicas e contemporâneas. Essa volubilidade do imaginário da obra leva o corpo às intermináveis aventuras da forma; aliás, aqui, forma deve ser compreen dida apenas como um estágio, um momento de passagem que se presen tifica em um e noutro trabalho. Forma é um fluido entre mental e material, ideado e materializado, portanto indis tinto, uno; a “substância” da poética. Ora é a corporificação de uma expe riência planar, como nos Albinos , ora o corpo se materializa como “vazio”

11

e perfaz uma ocupação que é também uma “desocupação do espaço”, para usar o conceito escultórico de Jorge de Oteiza 4 (1908-2003).

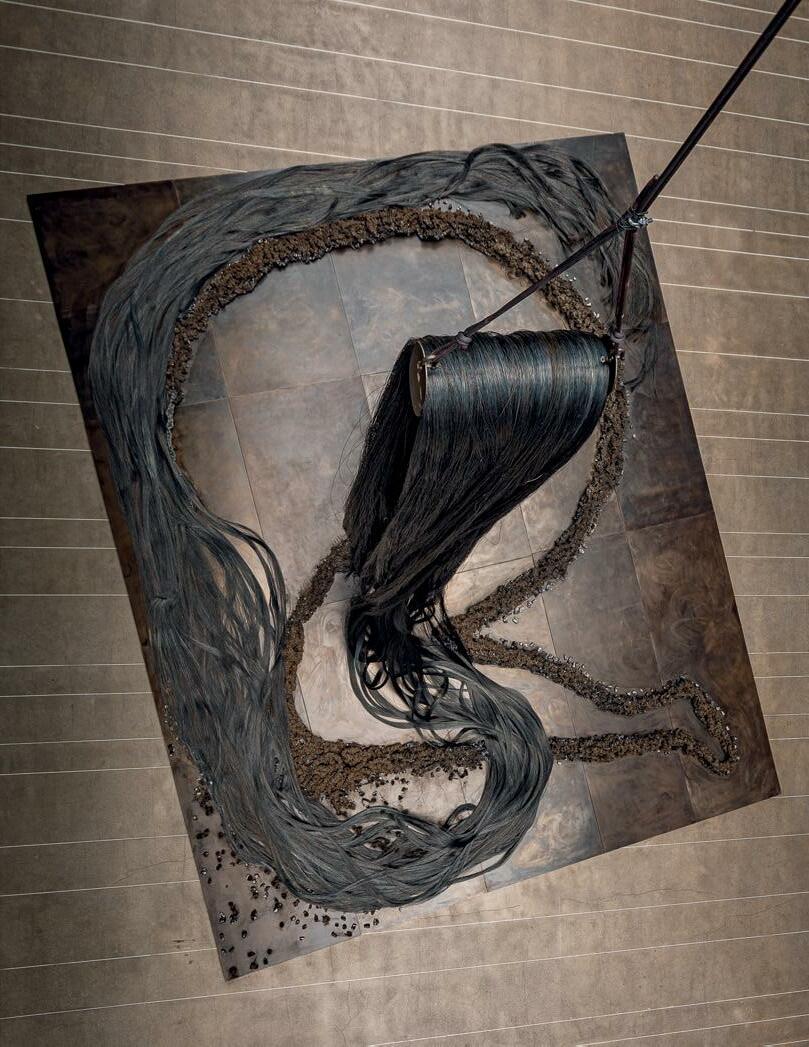

Fixações peculiares vão estabelecer uma família de fetiches; cabelos, por exemplo, são um dos mais notáveis. Ao torná-los matéria escultórica, o que em certa medida já o são poten cialmente, o trabalho entrelaça, como sempre, corpo e escultura. Portanto, as gêmeas xifópagas só poderiam estar unidas pelos cabelos, sendo os fios os condutores da “energia de conjunção” que as envolve numa atmosfera lírica, musical, encantatória, tal uma mesma melodia repetida e repetida. Uma ode à puberdade, pois se supõe que só nessa idade os cabelos manifestam sua pura sensualidade nascente. E aí o “x”, a incógnita, é um palíndromo capilar:

os cabelos crescem em uma e terminam na outra ou vice-versa? Nessa cabe leira- “palíndromo” , assim como as gêmeas, é tão indiferente quanto igual o sentido que as une. Ambas se encon tram envoltas num halo de liberdade e fraternidade que só a elas é dado e só elas conhecem e vivenciam – seria a revisitação da infância que as fanta siaria unidas pelos cabelos, sua mãe e tia, irmãs gêmeas?5 Estaria Tunga aí ressignificando na sua imaginação, num mito pessoal ou fábula imemo rial? Essa, entre outras, é uma de suas construções míticas; o horizonte que elas buscam articular abrange origens desde as mais arcaicas até as mani festações contemporâneas, tempo e espaço se confundem. Essa dualidade estranha, heterodoxa, não familiar, vai percorrer toda a sua obra, assumindo formas variadas em seus fascinantes

11. Alberto da Veiga Guignard

Léa e Maura, ca. 1940

óleo sobre tela | oil on canvas 86 x 104 cm

Coleção | collection Museu Nacional de Belas Artes/ IBRAM / MINC Foto | photo: Vicente de Mello

Nota 4. Jorge de Oteiza, escultor basco, recebeu o Prêmio para Escultor Estrangeiro na V bienal de São Paulo, em 1957. Intitulou sua participação na mostra de “propósito experimental”. Seu construtivismo idiossincrático o levou a indagar sobre a presença do vazio na escultura e àquilo que chamou “desocupação do espaço”.

Nota 5. Léa, mãe, e Maura, tia de Tunga, irmãs gêmeas, foram retratadas, lado a lado, vestidas idênticas, em um famoso quadro de Alberto da Veiga Guignard (1896-1962) pintado em 1940.

12. Esquema da construção de São João Batista | plans for the construction of São João Batista Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Rafael Adorján/Itaú Cultural

amálgamas heteróclitos. Tal é a cele bração da “monstruosidade” juvenil purificada das gêmeas. Exalam uma verdadeira joie de vivre , esculturas vivas da liberdade, vivacidade e luminosi dade que só vão reaparecer na série “From ‘La Voie Humide’” , mais de 30 anos depois.

Os cabelos continuam, perseguem o imaginário, pressionam com a força e a insistência do fetiche. Tal processo intrincado de comunicação entre as coisas, o trabalho apresenta literal mente muitas vezes e, em primeiro lugar, como Trança (1981). O entrelaça mento se repete de tranças em tranças, de dimensões e formatos diferentes, tal como a variação dos penteados, estes também – e por que não – escul turas. Tranças que supõem um escalpo, o corte violento do objeto-fetiche.

Uma escultura metálica, mas flexível, sinuosa, muitas vezes amarrada – num toque final – com um irônico, gracioso e perverso laço de seda colorido.

Já Troféu (1981) (p. 120 | img. 108), enorme cabeleira, assume, pela dimen são, a condição de objeto de sacrifício, subjugação e veneração, significados possíveis que as tranças encerram. Despojo de um corte que tantas vezes vai reaparecer no trabalho de Tunga como um gesto material e simbólico de uma separação radical e irremediá vel – e também a ser rearticulada. O corte dá origem a algo que é parte e se soma ao todo e, se ele se refere à decapitação, invoca o desígnio de um santo que lhe dá o nome: São João Batista (2 a.C.-27). Uma parte no chão, outra na parede, como uma espécie de troféu à vista de todos; a

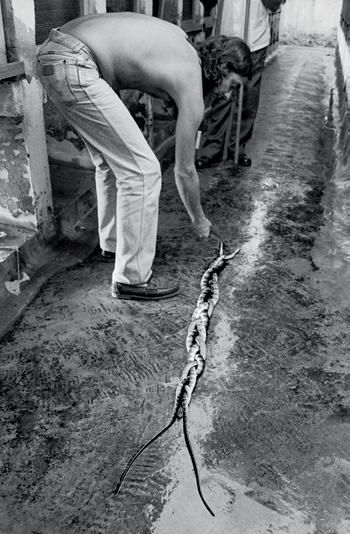

13.

A Vanguarda Viperina, 1985 fotografia em papel metalizado | photograph on metalized paper 102 x 76 cm

Foto | photo: Lucia Helena Zaremba

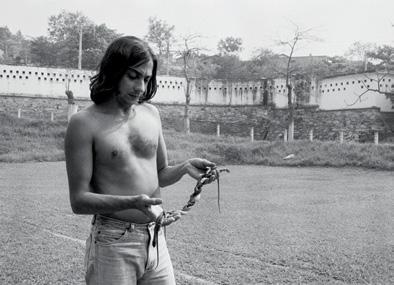

14, 15.

Tunga segura as cobras que fazem parte de A Vanguarda Viperina, 1985, no Instituto Vital Brasil, em Niterói, Rio de Janeiro. |

Tunga holding snakes that are part of A Vanguarda Viperina, 1985, at Instituto Vital Brasil, in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro.

Foto | photo: Lucia Helena Zaremba

Nota

O

cabeça decapitada do santo apresen tada em uma bandeja. Em Vênus, ou Vê-Nus (p. 121 | img. 109), também se entrelaçam, como em São João Batista (1977) (p. 132| img. 123), o arcaico e o contemporâneo. O jogo de pala vras Vênus e/ou Vê-Nus expressa as múltiplas implicações que ampliam e abrem novas dimensões a um sentido inicial, aparentemente fechado. Os nomes, palavras e conceitos deslizam em direções diferentes, como por um impulso insatisfeito, inquieto, gerador e ampliador – o desejo permanente de trazer para si, não importa o que estiver próximo ou distante. Tal é o espírito daquilo que Tunga chamava de “energia de conjunção”, aproximar realidades distantes, físicas e mentais e amalgamá -las na matéria e substância dos traba lhos. Como revela Georges Bataille, “o sentido último do erotismo é a fusão, a supressão dos limites”6 .

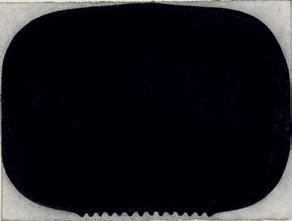

metabolizada, embora ainda “clássica”. Vê-Nus é um trabalho de borracha, flexível e pesado, maciçamente negro, recorte de um plano ao qual perma nece atado, o “outro”, o rejeitado fica abaixo, suspenso no jogo visual vazio e cheio, dentro e fora, como peça de um quebra-cabeça que antes se comuni cava pelas bordas. Limites, fronteiras, tudo a ultrapassar, afinal nada mais do que a pele que nos separa do mundo exterior e esconde o que somos por dentro. A fluência da continuidade/des continuidade entre os materiais desfaz a fronteira – a borda – entre orgânico e inorgânico, liga o chumbo das tranças às cobras de A Vanguarda Viperina (1985).

Editores,

A Vê-Nus, antes Vênus, se inscreve na “Prática de Claridade sobre o Nu”. Estamos, então, dentro de uma linha gem histórica que o trabalho quer inter rogar ou nela se inscrever. De tal modo que aquilo a que Tunga se propõe vai sugerir outra dimensão do nu físico; da mera aparência externa. O nu, a Vênus, primeiramente, se manifesta nos dese nhos como uma figura negra, mancha com pequenas ondulações na borda inferior. Um nu em repouso, clássico, poderíamos dizer. Não o clima ligei ramente sádico da Vê-Nus. Esse corpo recém-operado, destacado, separado ou talvez recém-nascido – nascimento (ou morte) da Vênus –, preso às cor rentes, jaz sem forças sob a tênue iluminação das lâmpadas. A Vênus está aí contemporaneamente transmutada,

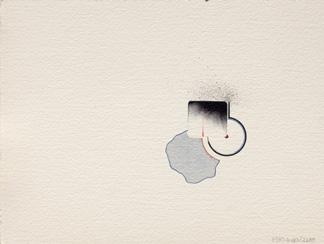

Tunga faz o ateliê se transmutar em laboratório; um e outro contaminam-se, experimentando e sedimentando a volatilidade dos impulsos e das ideias. Nele a figura topológica do toro pode ser tanto um objeto de metal, um túnel, como um círculo de fumaça expirada de um cigarro. E a infini tude da circularidade em Ão (1981) é também o infinito entrelaçamento de uma trança escultórica e verticali zada modernamente por Constantin Brâncusi (1876-1957) na sua Coluna infinita (1937). Já o desejo de Tunga é incorporar à Trança a sinuosidade orgânica e corpórea da serpente e estendê-la como algo simplesmente jogado ao chão, o oposto de Lezart (1989), vertical, sua primeira grande escultura de ímãs.

Antes a matéria era cortada, trançada, amarrada, e então ocorre a “descoberta” do ímã, a matéria por excelência da prática de Tunga. Nenhum outro mate rial resume tão bem o fundamento

de seu trabalho; unir, conectar, ligar, transmitir, conjugar etc.; o ímã como a matéria última, o próprio pensamento materializado, a pedra filosofal da sua prática artística. Deve-se conceder a Tunga o título de “inventor” do ímã na escultura contemporânea – pela des coberta, pela constância e pela intensi dade do uso. Só esse material “avesso” à escultura poderia chamar sua atenção, magnetizá-lo; a matéria ready-made que “in-corpora” à sua escultura. Com ele torna-se desnecessário qualquer ele mento que ligue as partes, o ímã já é a parte e o todo; ele próprio a “cola” que dispensa qualquer intermediário.

É o elemento material da “energia de conjunção”, da “cola poética” –o ímã como metáfora, assim podería mos chamar o processo escultórico de Tunga. E é esse fenômeno magnético

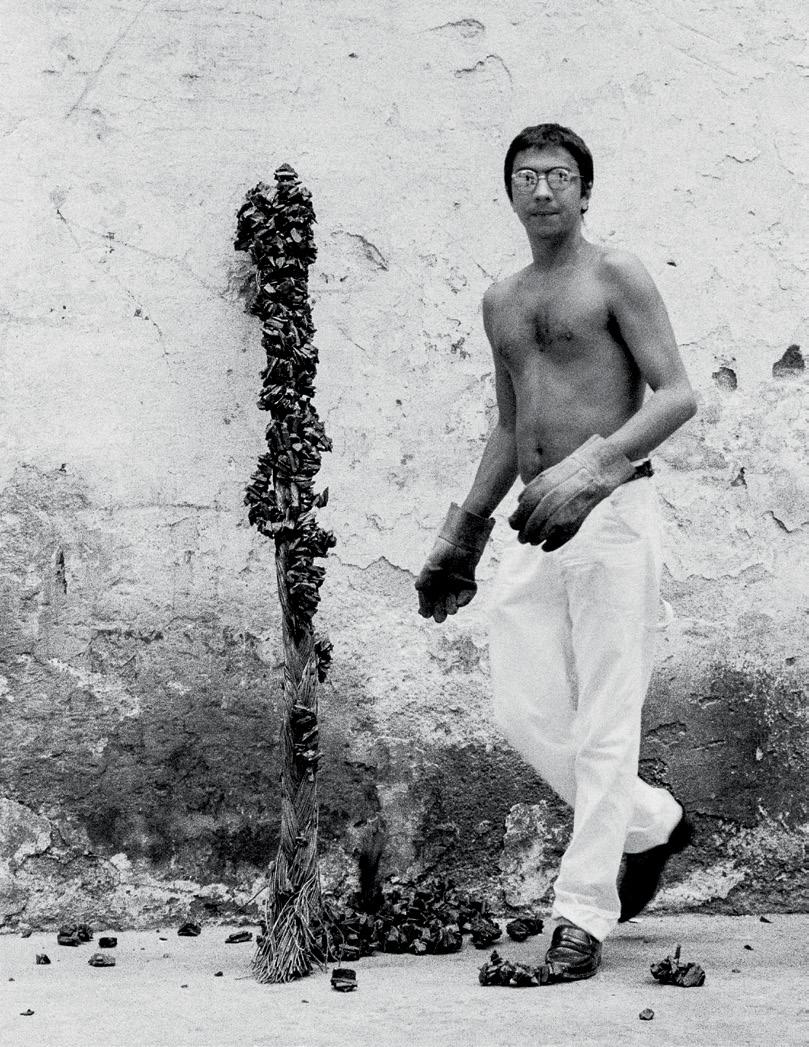

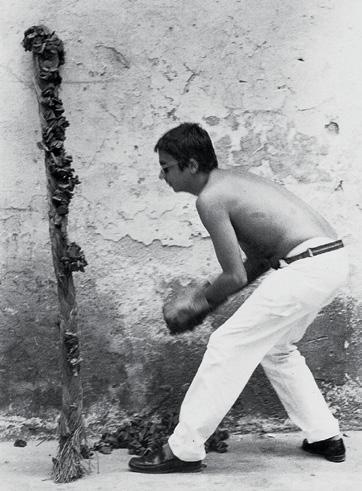

que vai dar “corpo” e tudo colar. Tal descoberta surge pela primeira vez em TaCaPe (1986). Tunga dividiu a palavra, separando cada sílaba por uma maiús cula, que também é ligação; ímã. TaCaPe é feito de ímãs “tacados”, um a um, numa haste metálica vertical, formando a figura de um tacape, cuja aspereza rugosa ressoa uma escultura de Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) às avessas.

TaCaPe (p. 137 | img. 130) é uma nova escultura; não por adição nem por subtra ção, como a escultura clássica; tampouco o “desenhar no espaço” moderno inau gurado por Julio González7 (1876-1942), mas uma escultura por “magnetização”. A introdução do ímã pode muito bem representar um passo além da construção da escultura moderna; não mais a solda ou qualquer outro artifício, mas a energia da própria matéria como agregador das

16.

Tunga montando TaCaPe para o filme O Nervo de Prata, dirigido por Arthur Omar, 1986. | Tunga setting up TaCaPe for the video O Nervo de Prata, directed by Arthur Omar, 1986.

Foto | photo:

©Wilton Montenegro

Nota 7. Julio González é um dos pioneiros da escultura moderna, junto com Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Desenvolveu sua prática de escultura em ferro por meio da solda, método inédito na época, ao qual chamou de “desenhar no espaço”.

partes e da fluência incongruente da construção. A presença dos ímãs como elemento da “energia de conjunção” expressa fisicamente o processo mental. Uma matéria que produz “energia” que se metaboliza, por assim dizer, teria que ter vida longa na obra e, como tal, é uma manifestação poética da natureza; está em tudo e todos, por ela estamos indis sociavelmente ligados, unidos, em troca constante, dando e recebendo.

Enquanto os artistas da arte minimalista estavam presos à geometria clássica, Tunga enveredou pela topologia, daí o Toro (p. 104 | img. 86) e suas variações. E não apenas isso; toda a exuberância que daí resulta transcende o ascetismo minimalista. Ainda assim, o trabalho não poderia se limitar a uma só determina ção; sua tendência é sempre transbordar para outras associações, afinidades, relações; ultrapassar as bordas; “trans -bordar”. Só assim poderia surgir Ão –o toro é uma figura que por definição não tem bordas –, como uma penetração sob a pele do toro; o rompimento imagi nário de uma borda.

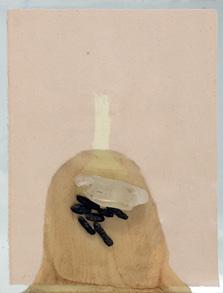

Os elementos da escultura – uma cate goria um tanto limitada para definir essa obra, como a de outros, a de Beuys, por exemplo – eram já entendidos como relíquias, troféus, fetiches. Dentes, ossos, cabelos são elevados ao grau mais alto da preciosidade; o de verda deiras joias. Uma delas, diz o título, é de uma possuidora particular, Madame de Sade – uma invenção de Tunga ou ela teria existido? Como o próprio nome indica, introduz uma figura da literatura afim da obra e merecedora de uma homenagem envolta em um véu de sugestões possíveis – esposa do

famoso marquês? Les Bijoux de Madame de Sade (1983) (p. 109 | img. 95) é criado como uma relíquia contemporânea – uma joia atual do século XVIII? –, outro de muitos paradoxos que a obra postula. Essas joias, os bijoux, são ossos curvados como um círculo, anel ou tiara, e não são os ossos a matéria real mente escultural do corpo?

Os materiais “duros” irão entrar em cena; a escultura se volta para a solidez metálica. O chumbo, metal “mole”, maleável, pesado, em fios, retorna após longo tempo, desde O Objeto do Conhecimento Infantil. Retorna como tranças, a parte do corpo feminino ostensivamente nua, que só o pudor implícito na trança pode dissimular. As tranças trazem rememorações do conhe cimento infantil, contêm sua possível reinstauração imaginária, e ocorrem em diversos formatos e tamanhos. As qua lidades metálicas são exploradas como poucas vezes antes. É como se ressur gissem com a potência de uma matéria única em sua dureza, brilho, peso, maleabilidade, volume, formas.

A sinuosidade plástica do metal desliza para sua tradução e extensão biológica em A Vanguarda Viperina, nada menos que uma escultura viva, que não é senão a simulação da cópula ofídica, o abraço sensual de duas cobras, uma refletida na outra como gêmeas incestuosas –Palíndromo Incesto (1990) (p. 71 | img. 32) não é o título de outro trabalho? Está aí uma entre outras analogias, metáforas, alegorias e paradoxos que transitam incessantemente de um trabalho para outro, seguindo uma lógica voraz e sem limites, cuja ação, em última instân cia, é “des-bordar”; ir além das bordas,

romper com os limites da lógica e da razão. Amante dos paradoxos, Tunga certamente assinaria o paradoxo de Epimênides, poeta e filósofo grego que viveu no século VI ou VII a.C.: “Todos os cretenses são mentirosos” e que foi parafraseada assim: “A frase a seguir é falsa. A frase anterior é verdadeira”. E a traduziria assim: “O trabalho a seguir é falso. O trabalho anterior é verdadeiro”.

Lezart (p. 138 | img. 131 e 132) é o primeiro indício de uma aspiração à monumentalidade, a uma expan são da escala que não só é física, mas também insiste na construção de uma mitologia, uma narrativa que se desenvolve como o movimento de uma espiral envolvendo elementos anterio res, etapas autofágicas da obra que se desdobram. Trabalhos anteriores são resgatados em outro plano, rearticu lados e ampliados, conectando-se uns ao outros, formando um todo do que antes estava separado, desmembrado, e que se volta a reunir em observação à seletividade intrínseca da obra – não seria descabido aqui usar o termo hegeliano aufheben (superação dialé tica). A cada etapa, o corpo – o corpo é escultura e escultura é corpo – retorna como uma unidade final e provisória; à espera de uma nova realização adiante. Diríamos que o verbo “imantar” é aquele que designa e simboliza a junção dos elementos dispersos, o processo da energia agregadora da qual o ímã é apenas a matéria física, uma das partes – a outra é a “cola poética” da livre imaginação. Uma se enreda na outra, penetrando, desdobrando-se na outra, obedecendo à lógica da magnetização que, como exemplo, faz de Lezart um

complexo escultural sustentado por placas metálicas verticais fixadas por ímãs e atravessadas por fios, lembrando um gigantesco e anacrônico arcaico gerador de energia ou, combinação tão frequente, a plena nudez de uma mons truosa máquina erótica.

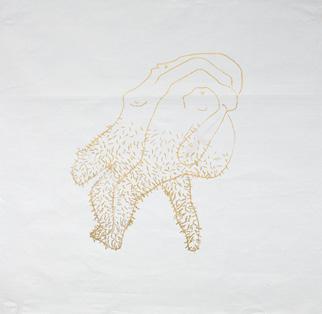

Bordas (1983) é um desenho impor tante não só pelo título, mas pelas implicações que sugere; limites, fron teiras, passagens de uma coisa para outra; via de transmutação entre con tinuidade e descontinuidade. Bordas se manifesta na ordem do palíndromo, de um lado um significado, de outro lado, outro, ultrapassamos de uma coisa para outra imediatamente ao transbordar. Nesse desenho transicio nal, primeiro surgimento de figuras, a cabeleira se metaboliza em tacape.

A borda é o limite e também a junção de uma coisa e outra. Explica bem o processo do trabalho e exige o plural; bordas que se desdobram e fazem, por exemplo, de um dente uma escultura.

O mesmo fenômeno ocorre, em outro plano, quando os pequenos Objetos do Conhecimento Infantil assumem uma condição escultórica, mais uma revi ravolta, transbordamento em direção a uma monumentalidade, a uma nova escala, em que a presença do corpo se insinua insistente mais uma vez. A obra se impõe na nossa escala, altiva, frente a frente, exibindo sua extrava gante majestade. Mais uma etapa do intrincado raciocínio de Tunga em que as associações se ampliam como uma espiral sem fim.

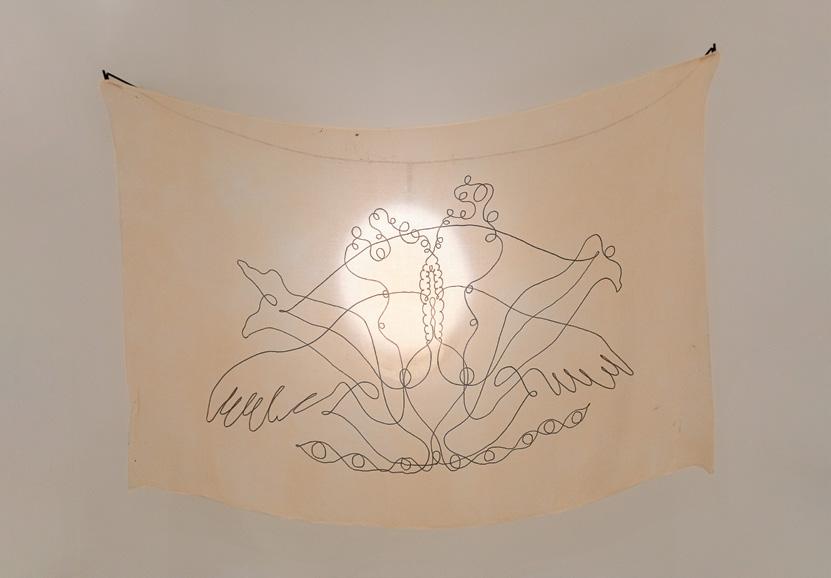

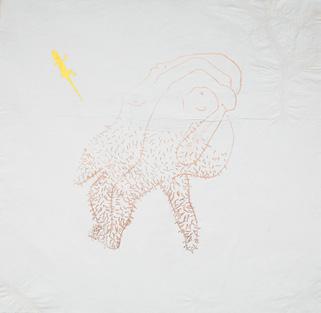

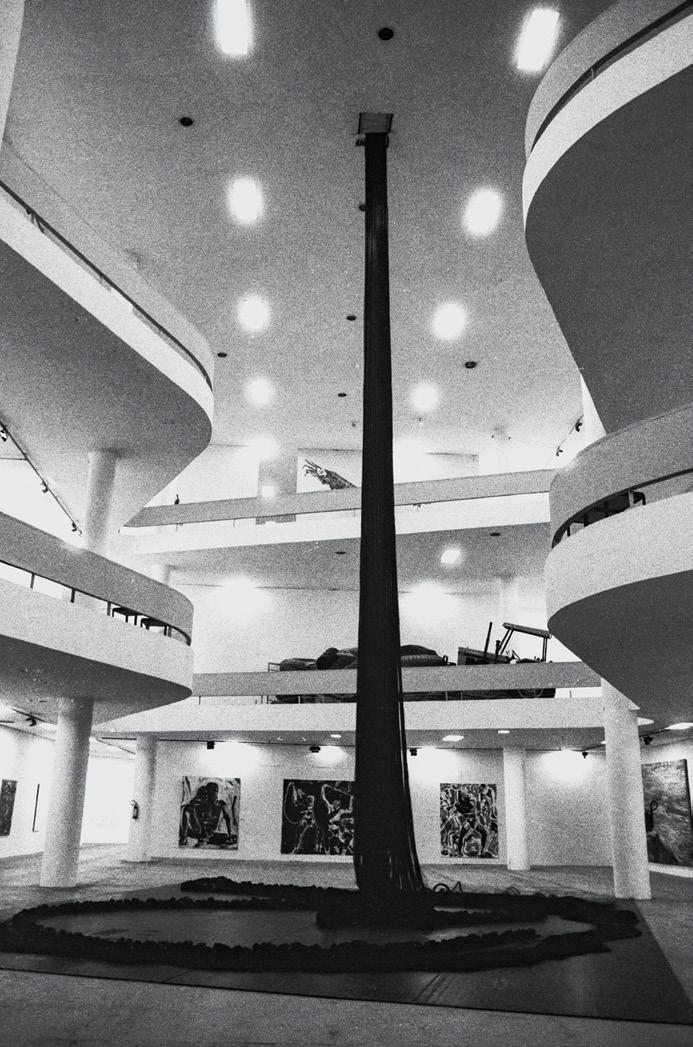

Com Gravitação Magnética (1987), o trabalho atinge uma dimensão ambi ciosa e inédita. Gravitação Magnética ,

17.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series Bordas, 1983 impressão dourada e serigrafia sobre papel | golden print and silkscreen on paper 63 x 63 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera

Magnética na 19a bienal de São Paulo, 1987. | The work Gravitação Magnética at the 19th Bienal de São Paulo, 1987. Foto | photo: Romulo Fialdini/Tempo Composto

19.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series Gravitação Magnética, ca. 1980

aguada sobre papel | ink wash on paper 32,9 x 47,9 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Renato Parada/ Itaú Cultural

Nota 8. NE: A obra ganha nova montagem em 2021 –em virtude da exposição Tunga: conjunções magnéticas – no espaço do Instituto Tomie Ohtake (pp. 144 e 145).

ou Enquanto Flora a Borda Tomba Magnética de Acúleos Zumbidos a Trilha Atapetara Aérea Ataraxia Pendular Arrepio Marsupial que Mesmo Hominídeo Cabia Fenoso Pêlos ao Lóbulo Rastreara Assistência Fractal Hesita-o Animal de Níquel Vêm o Vôo Entomológico Fêmea Asculta Cabeça Genomas Penetrarás ; aí está um título proporcional à grandeza do trabalho; desenho gigantesco que se transmuta em escultura e a escultura em desenho, reversão tão característica de toda a obra de Tunga. É o primeiro grande salto de escala; a ocupação, do teto ao chão, do vão central do prédio da Bienal de São Paulo em sua 19 a edição. Como num único gesto, o desenho de fios metálicos se eleva, desce do teto do edifício e se espar rama pelo chão; a monstruosa cabeleira termina na cabeça decepada do artista – novamente o “corte” reaparece – e

se une a um corpo desenhado por ímãs no chão. Só a dimensão espacial da Bienal possibilitou esse acontecimento único. Totem imprevisto, surpreen dente, Gravitação Magnética 8 impunha ao ambiente sua presença imponente, intimidante, quase ameaçadora.

Com À la Lumière des Deux Mondes (2005), Tunga elevou o “balangandã” à monumentalidade ao instalar a obra sob a pirâmide do Museu do Louvre, como anos antes tinha feito com Gravitação Magnética no vão central da Bienal de São Paulo . À la Lumière des Deux Mondes é o retorno antropofágico do nativo ao seu locus de admiração; o provocante totem da reverência e da emancipação; regresso audacioso do filho pródigo. Tal efeito só poderia ser consequente na França, em Paris, no Louvre, nada menos que no primeiro

grande museu da cultura do Ocidente. Toda arte ali acumulada estava pre sente, revirada e reposta naquele magnificado objeto originário da escra vidão colonial, no tipiti e na rede da cultura indígena. Tal como Gravitação Magnética , a obra surge como um monumento estranho, irônico e lúgubre, majestoso e decadente, con temporâneo e anacrônico, luminoso e subterrâneo – todos os antípodas que a obra unifica. Certamente o trabalho mais “intencional” de Tunga; apoiado, apenas, na coluna originariamente projetada para sustentar a Vitória de Samotrácia 9. E ali parece interro gar exatamente esse lugar “vazio”, e preenchê-lo. Com suas caveiras e seu esqueleto, À la Lumière des Deux Mondes é, por assim dizer, a summa e o cadáver da escultura em metal de Tunga. A partir daí, sua obra vai se voltar cada vez mais para a incorpora ção de outros materiais e elementos e para a expansão cada vez maior das suas “instaurações”.

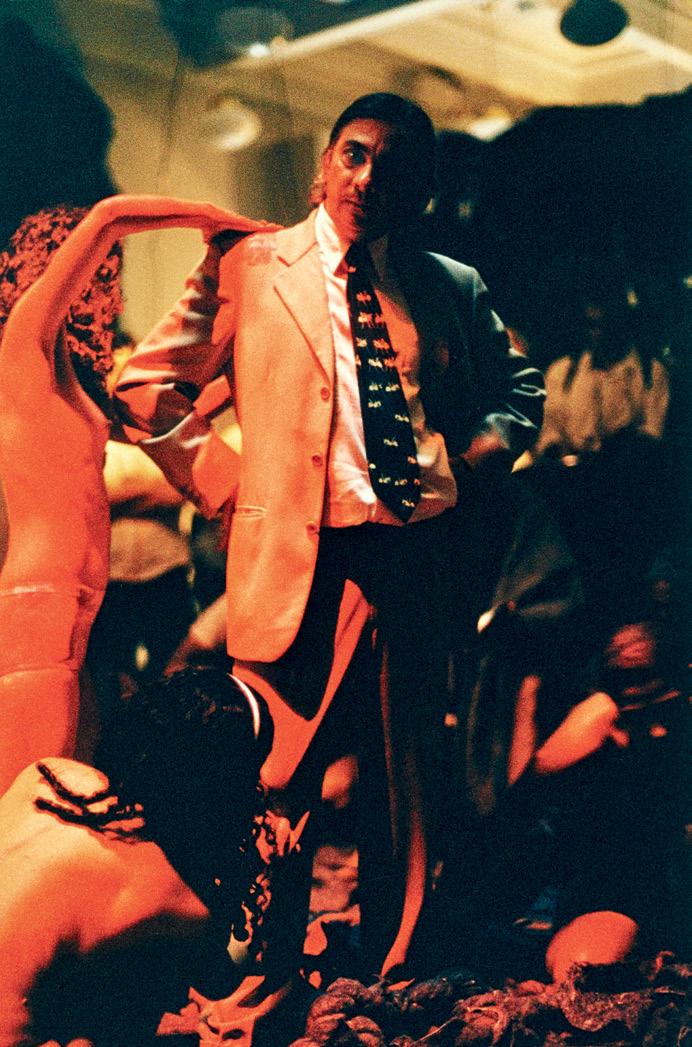

As “instaurações” derivam de uma genealogia artística contemporânea, das modalidades efêmeras de arte, abertas à intervenção do acaso e à participação do público; os happe nings e as performances configuravam a radical desmaterialização do objeto artístico e buscavam erradicar as fronteiras entre arte e vida, na intera ção efêmera, ocasional, sem espaço ou temporalidade próprios. À improvisa ção do happening e ao “programa” da performance os acionistas vienenses 10 acrescentaram a ritualística de suas ações de sanguinolência “teatral” junto aos participantes, numa exalta ção da corporeidade como sujeito da

experiência; exaltação que é modulada, por outro lado, nas ações “aristocráti cas” 11 de Yves Klein (1928-1962) e nas “proposições” coletivas de Lygia Clark. São esses os precedentes parciais das “instaurações” – a Gesamtkunstwerke de Tunga –, a “obra total” tantas vezes perseguida encontra nelas um possível exemplar. Evento por vezes íntimo, mas também público, de exposição e contato corpóreos, em que as ações se desenvolvem na imersão dos elemen tos na obra, para celebrar a vivência sensorial e sensual.

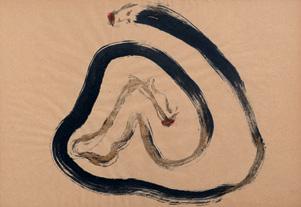

Quanto mais se intensificam as “instau rações”, mais os desenhos se tornam explicitamente figurativos. A cena agora é outra, dominada pela ampla presença de corpos nus, que se introduzem mais e mais na apresentação do trabalho; é a matéria viva do “nu” que se impõe de forma explícita, comunal, orgástica. Aí também o corpo se manifesta como ímã, catalisador magnético de outros corpos, multiplicando e expandindo sua energia para o todo e para todos.

É notável como a palavra “poética” aparece tão frequente e insistente na ideação, descrição e qualificação que Tunga faz de seus trabalhos. As “ins taurações”, mais que todos, propõem a “cola poética” como prática artística. É a colagem moderna elevada a outro plano plástico, discursivo, espacial e simbólico. Tudo, a princípio, pode ser “colado”. Em tudo há “cola”, e a “poesia” é o agente universal dessa “cola”. Nota-se então novamente uma atitude anticonceitual, antiminimalista, mais próxima das articulações da arte povera12, porém de um requinte e refinamento peculiares, retornando

Nota 9. Vitória de Samotrácia é uma escultura do período helenístico que representa uma mulher alada, a deusa grega Nice, sem cabeça e braços, de pé na proa de um navio; provavelmente ligada à comemoração de uma vitória naval. Criada por volta de 190 a.C. em mármore branco, com 3,28 metros de altura, a obra teria sido construída para o Santuário dos Grandes Deuses, na ilha de Samotrácia, na Grécia, onde foi descoberta em 1863. Está hoje localizada no Museu do Louvre.

Nota 10. Os acionistas vienenses eram um grupo de artistas austríacos, entre eles Otto Müehl (1925-2013), Günther Brus (1938-) e Hermann Nitsch (1938-), que, na década de 1960, ficaram conhecidos por suas performances ritualísticas, escatológicas, sanguinolentas e obscenas, realizadas muitas vezes com a participação do público.

Nota 11. Na mais famosa de suas ações aristocráticas, Anthropométrie de l’époque bleue, realizada em 1960, Yves Klein, vestido de fraque e gravata-borboleta, rege músicos que tocam sua peça, Symphonie monotone, e comanda três mulheres nuas cobertas de tinta azul que esfregam o corpo em telas em branco.

Nota 12. Cunhado pelo historiador da arte italiano Germano Celant (19402020), o termo arte povera se refere ao movimento de vanguarda que surgiu na Itália em meados dos anos 1960. Também chamada de “arte pobre”, sobretudo como crítica ao consumismo e à comercialização da arte, foi desenvolvida na pintura, escultura, instalação e performance com obras compostas de materiais orgânicos, efêmeros e diversos, como madeira, terra, folhas de árvores, areia, tecidos e sucata.

20

e ampliando as intenções plurais do Surrealismo; tudo que determina, como poucas, a prática heterodoxa de Tunga no ambiente artístico contemporâneo.

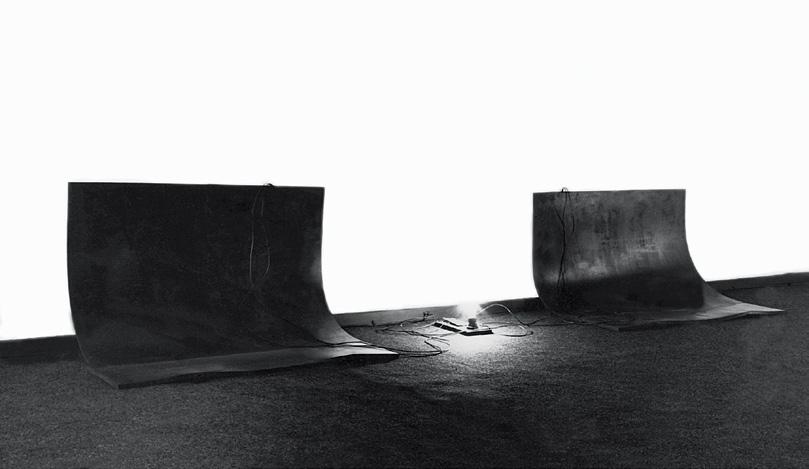

20.

Vista da obra Pálpebras, 1979, primeira instalação de Tunga | view of the work Pálpebras, 1979, the first installation by Tunga Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga Foto | photo: Pedro Oswaldo Cruz

Lembremos então de Pálpebras (1979), a primeira “instauração” – embora o termo ainda não fosse usado – de Tunga: uma caixinha de música – distra ção infantil – toca sem parar a canção “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” na semiobs curidade de uma sala, enquanto uma aranha sobe e desce entre duas placas de borracha, num movimento intermi nável, hipnótico, misterioso. Aqui, pela primeira vez, o trabalho quer provocar a situação indutora do estado de indis tinção entre sonho e realidade, fazer sentir o cansaço do peso das pálpebras, dormir e sonhar, e que vai ter continui dade anos mais tarde na circularidade infinita de Ão.

Em Ão, noite e dia, simultâneos, “gêmeos xifópagos”; na fusão de um pelo outro se encontra o infindável e inescapável trajeto pelo interior de um toro. Deveria conter um aviso: sem saída! Ouve-se “Night and Day” na voz moderna por excelência de Frank Sinatra, e ela se torna uma espécie de canção de ninar, sedativa, embalando uma viagem que não tem fim nem começo e que só existe em um túnel no qual também só se pode entrar sonhando; sedado pela canção – a viagem por dentro de uma escultura, uma escultura “nua”. Em Ão, “escultura visual”, dois movimentos se interpene tram; o da película que circula inces santemente pela sala e o da imagem na tela – um a tradução do outro. Nesses dois movimentos que se cruzam encon tramos mais uma vez, e não será a última, o método da “trança” em ação;

a peculiar versão espacial de Tunga da fita de Möbius13.

Ão é a infindável diuturna circulação dentro de um túnel; “Night and Day”, onde não se sabe se é dia ou noite. O movimento incessante que parece levar a algum lugar e leva a lugar nenhum. Voltas e voltas, incalculáveis, inumeráveis, mesméricas, intoxicantes. Percurso estranhamente monótono e excitante. Nesse experimento fílmico, delirante, só a película que circula pela galeria dá a dimensão da reali dade. Somos lançados no interior de um carrossel fantástico vindo de um laboratório de outros tempos. Ão é um palíndromo espaçovisual, sem letras, palavras, vazio, nu – o toro despido. Um “outro” Nu descendo uma escada, no 2 (1912), de Duchamp, vertido em um processador topológico.

A aventura do corpo persiste ainda na série Morfológicas e no parentesco que possuem com os Objetos relacionais, de Lygia Clark – não é por acaso que Tunga possuía um deles, presenteado por Lygia. Os Objetos relacionais eram aqueles que Lygia colocava no corpo do paciente nas suas sessões de terapia e que, segundo ela, compensavam e preen chiam um “buraco”, vazio corpóreo imaginário. A origem das Morfológicas é semelhante, moldam-se a partir do corpo, provocando fantasias táteis como se este fosse submetido a uma sessão de distor ção da imagem corporal, partes do corpo diminuem, outras se agigantam, outras desaparecem, formando uma sequência de figuras inquietantes, uma verdadeira família contaminada pela anamorfose. Assim, as Morfológicas devolvem, de uma maneira alucinada a carnalidade aos Bichos, a organicidade do plano ao corpo.

“From ‘La Voie Humide’” no espaço de trabalho que Tunga chamava de Pensatorium. | Drawings from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’” in the workspace that Tunga referred to as his Pensatorium.

Foto | photo: Gabi Carrera Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

Nota 13. Criada pelo matemático e astrônomo alemão August Ferdinand Möbius, em 1858, a fita de Möbius consiste em um espaço topológico onde uma linha perpendicular ao plano não possui a mesma direção em todos os pontos da superfície. É uma forma não orientável, na qual não é possível determinar a parte superior ou inferior, interna ou externa.

Nota 14. Mathesis universalis é a ciência do conhecimento em geral voltada para todos os objetos passíveis de conhecimento, inclusive metafísicos, a partir da ordem e da medida. Desenvolvida ao longo dos séculos, por exemplo, pelos filósofos e matemáticos Pitágoras, Descartes e Husserl, sua universalidade consiste em sua aplicabilidade em toda e qualquer problematização das naturezas, em que a razão humana e a matemática provêm um caminho universal para o conhecimento.

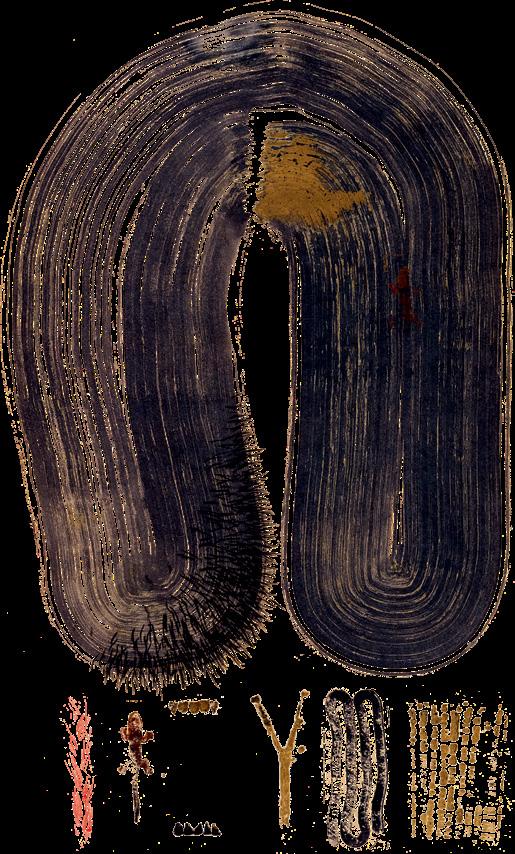

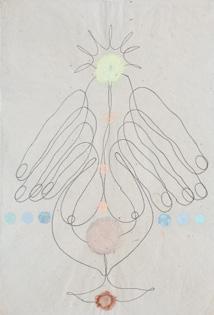

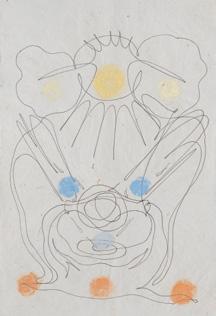

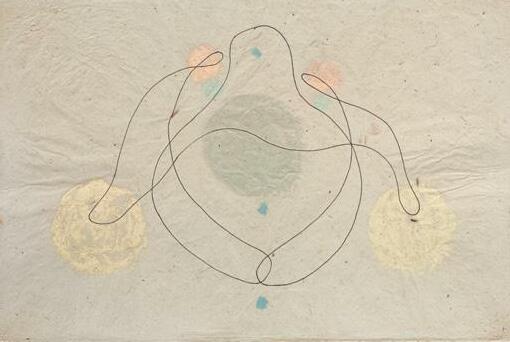

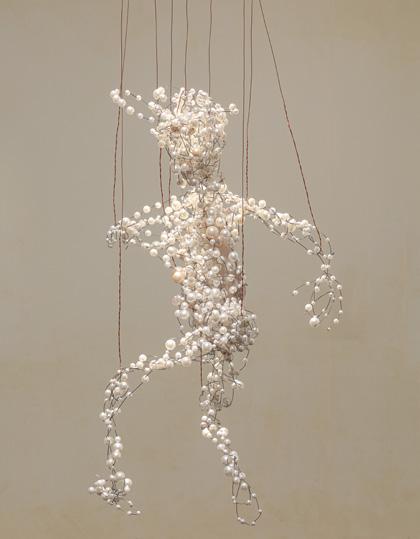

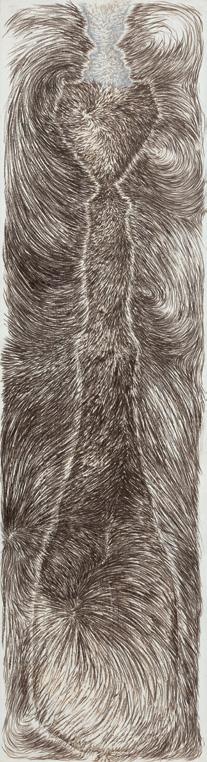

Na série “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, voltam a se revelar as tonalidades dos primeiros desenhos, azuis, verdes, laranja; cores que engendram uma deli cada ordenação espacial, quase em sus pensão, obras no ar; líricas, luminosas, totens contemporâneos. Neles o tripé, também pertencente a um trabalho do início, Piscina, sugere o trípode oracular da antiguidade pagã, consagrando não mais aos deuses, mas aos olhos contem porâneos ávidos e carentes, uma beleza autêntica e verdadeira. Variante vertical e gigante dos balangandãs, de materiais e formas e cores diferentes, em que o tripé é o sustentáculo dos elementos conectados a ele; suporte e ligação – a “brutalidade” do ímã dá lugar a uma delicada justaposição das partes. São corpos abertos com seus diversos órgãos à mostra, ou ainda órgãos sem corpo; restos de um massacre, esquar tejamento; o exemplo último de uma escultura por “conjunção”; nenhuma outra antes continha tamanha varie dade de elementos na sua ficha técnica – um mix de cerâmica, resina, metal, cristais, pérolas... A “conjunção” na sua maior extensão.

Já os desenhos de “From ‘La Voie Humide’” são resultado do percurso de uma só linha, cujo fim volta a se encon trar com o começo não sabemos onde; assim como em Ão, desconhecemos onde começa e onde termina, e seguimos seu percurso como que hipnotizados pelo mesmo efeito sedativo, espécie de calma interior, de um exercício espiri tual vindo de alguma inspiração medi tativa do Oriente. O desenho contínuo produz aquele efeito mesmerizante, hipnótico, ficamos seguindo a linha e nos desligamos da figura para um infinito,

interminável sedação pacificadora do olhar; desenhos que parecem também nos fixar, nos atrair pela avidez de um olhar convidativo, extático e enigmá tico. A transversalidade de referências e materiais na obra de Tunga manifesta esse contágio metamórfico, toda matéria contém uma simbologia, toda simbolo gia se manifesta nas matérias. Nenhum material se esgota nele mesmo, no seu silêncio e na imobilidade. Cada um deles é evocado para outro plano e se revela, renovado e ampliado, a cada trabalho. Tal é a natureza deslizante da obra, do desenho para o objeto, do objeto para a escultura, da escultura para as instala ções, das instalações para as instaurações, das instaurações para o desenho... Nada menos do que fazer da arte uma rigorosa e delirante mathesis universalis14 poética.

Ao final, toda a obra são “tranças”, “palíndromos”, “xifópagas” “bordas”, imantadas pela “energia de conjunção” –o “ímã” universal da obra que tudo atrai, reúne e articula. É a energia que faz a conjunção do estranho, do incongruente, do improvável, e os reverte para uni-los no trabalho, o qual Tunga reivindicava chamar, legitimamente, de “poesia”.

Paulo Venancio Filho é professor titular na Escola de Belas Artes da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), curador e crítico de arte. Publicou A pre sença da arte (2013), pela editora Cosac & Naify. Realizou curadorias em diver sas instituições, como Tate Modern, Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Moderna Museet, Kunsthaus Zürich, Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM/SP), Wexner Center for the Arts e Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB).

Ato de instaurar, de dar início a algo que não existia; processo ou consequência da ação de criar alguma coisa. Associado ao filósofo norte-americano Nelson Goodman (1906-1998), o termo inseriu-se em dis cussões sobre estética, teoria e filosofia da arte, difundindo-se nesse campo. Atribui-se a Tunga a introdução de “instauração” no contexto artístico, já desde o seu trabalho Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós (1984). A partir dos anos 1990, por meio de Tunga, a palavra tornou-se um dos conceitos seminais para a arte contemporânea.

Tunga atribui à “instauração” o instante em que um objeto se torna trabalho de arte, ou seja, o momento de implementação e ativação da obra, que, por sua vez, ocorre a partir das conexões de significados em determinado contexto. Nas suas palavras, “o trabalho é um conjunto de trabalhos; um sempre leva ao outro, como se entre eles existisse um ímã [...] trata-se de repotencia lizar uma obra em relação às outras”.

Artista francês, Marcel Duchamp (18871968) iniciou ainda jovem sua carreira como pintor e escultor, tornando-se posteriormente um antecipador da arte conceitual, sobretudo por introduzir o conceito de ready-made , a apropriação de objetos de uso cotidiano e sua elevação à categoria de obra de arte. Sua pintura Nu descendo uma escada nº 2 (1912) é, por sua proposta irônica, mal recebida e recu sada pelo Salão dos Independentes . Nos anos seguintes, Duchamp produz seus primei ros ready-mades , Roda de bicicleta (1913) e Porta-garrafas (1914).

Em 1915, inicia sua obra O grande vidro, ou A noiva despida por seus celibatários, mesmo (1915-1923). Em 1917, cria A fonte – nada mais do que um mictório assinado com o pseudônimo “R. Mutt” –, que se torna sua obra mais polêmica, responsável pela repercussão de seu nome. Dois anos depois, produz a também provocativa L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), em que manipula uma cópia da obra Mona Lisa, acrescentando-lhe bigode e cava nhaque. Nos anos 1920 e 1930, dedica-se ao jogo de xadrez, cria o alter ego feminino Rrose Sélavy e une-se ao movimento sur realista. Por meio dos seus trabalhos e da noção de ready-made, Duchamp tornou-se um dos artistas mais influentes do século XX e da arte contemporânea.

Representante da tradição hedonista, Charles Fourier (1772-1837) foi um filó sofo francês do século XIX famoso por suas teses sobre libertação sexual. Com duras críticas à religião e à moral cristã, à hierarquia social, à burguesia, à família tradicional, à monogamia, ao matrimônio, às estruturas econômicas do capitalismo e a muitos outros aspectos da sociedade, Fourier identificava na restrição do desejo e do prazer a origem da dor e dos conflitos que assolam a humanidade.

Segundo o filósofo, a sociedade pauta-se pela hipocrisia, uma vez que, ao mesmo tempo que busca a realização de seus desejos, os reprime recorrendo à moral.

A saída dessa contradição se daria com a satisfação dos desejos e o livre exercício das paixões, princípios divinos e partes fun damentais da natureza humana. Somente por meios desses a sociedade alcança ria um estado de equilíbrio e harmonia.

Para Fourier, a vivência com as mesmas pessoas durante toda a vida, seja em relações amorosas e sexuais ou não, traz uma condenação à monotonia e ao tédio, o que, por sua vez, impede o desenvolvi mento da personalidade. Relações diversas e por períodos diversos são necessárias ao desenvolvimento da personalidade e toda atividade criativa surge, imprescindivel mente, da libertação da paixão.

Escritor e pintor belga, em 1920, Henri Michaux (1899-1984) dá início a inúmeras viagens e passa, ao longo de sua vida, por diversos países da América do Norte, da América do Sul, da Europa, da África e da Ásia. Nesse período começa seu processo de escrita, sobretudo de textos poéticos e de cadernos de viagens. Ecuador (1929) foi seu primeiro livro a obter sucesso, resultado de uma viagem que ele definiu como fracassada e precária. Nos anos 1930 muda-se para Paris, começa a pintar e a participar de exposições, influenciado principalmente pelas obras surrealistas, mantendo assíduo contato com artistas e escritores.

Próximo da antropologia, em suas narra tivas, cria culturas e países imaginários, projeções etnográficas que se desdobram em mitos, lendas, ficções e fábulas. Sua escrita é marcada por fúria, angústia, desespero, ansiedade e descontentamento do mundo e do humano, de maneira que sua atenção se direciona para o interior de si mesmo.

Com a morte de sua esposa, em 1948, Michaux concentra-se em sua pintura e escrita a partir de outro nível de evasão, explorando os efeitos da mescalina e do haxixe. As experiências alucinógenas, com a alteração dos estados de consciência e da percepção do tempo, deram início a uma série de livros e desenhos. Em uma de suas entrevistas, Tunga cita a seguinte frase de Henri Michaux: “Même si c’est vrai c’est faux” [Mesmo se for verdadeiro, é falso]. Complementa dizendo que o inverso também é válido: mesmo se for falso, é verdadeiro.

Pintor francês, André Masson (1896-1987) começa bastante jovem seus estudos na Academia Real de Belas-Artes de Bruxelas, dando continuidade a eles em Paris. Com interesse inicial pelo Cubismo, mais tarde associou-se ao Surrealismo e, em suas obras, explorou uma questão fundamental para os surrealistas: o inconsciente. Entre as várias técnicas de libertação do incons ciente, o desenho automático, também conhecido como automatismo, apontava um modo de minimizar o controle consciente no processo artístico. Masson foi um dos surrealistas que mais explorou a técnica, em seus dessins automatiques. Realizados a partir de atos independentes da vontade do sujeito, com aleatoriedade dos movi mentos e espontaneidade do gesto, revelam ou sugerem aspectos do subconsciente; ausente o controle racional, o resultado são desenhos eróticos, sonhos e combinações inesperadas próprias do Surrealismo, em que atua a mente inconsciente.

Com vínculos de parentesco com o escritor Georges Bataille (1897-1962) e com o psica nalista Jacques Lacan (1901-1981), Masson estava imerso em um meio proveniente da acentuada relação entre a arte e a psica nálise, de modo que seu trabalho buscou o que vem diretamente do inconsciente, sem intermédio da razão, da moral ou das convenções estabelecidas, exprimindo o desconhecido do humano.

Escritor francês, Georges Bataille (18971962) é autor de poemas, ensaios, romances e conferências; sua obra abrange filosofia, antropologia, sociologia, economia, arte, erotismo e misticismo. Foi convertido ao catolicismo em 1914 e frequentou o semi nário em Reims, no entanto, renunciou ao cristianismo na década de 1920 e, dois anos depois, graduou-se na École Nationale des Chartes, em Paris. Durante sua juventude, foi influenciado pelas leituras de Marcel Mauss (1872-1950), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) e Marquês de Sade (1740-1814), estudou psicanálise, aproximou-se do movimento surrealista e fundou grupos lite rários, como o Acéphale (1936), com André Masson (1896-1987), Michel Leiris (19011990) e Roger Caillois (1913-1978).

Bataille trabalhou a vida toda como arqui vista da Biblioteca Nacional da França e fundou importantes jornais e revistas, como o influente Critique (1951). Com uma obra permeada por profundidade filosófica, sugestões autobiográficas e uso de pseudô nimos, estão entre os principais aspectos de seu trabalho: a ruptura com a morali dade e a racionalidade burguesa, conflitos íntimos, o sagrado, transgressões, a morte, o inumano, o mal, o sacrifício, a sexuali dade, a transcendência e o erotismo. Entre suas últimas produções estão os ensaios “O erotismo” e “A literatura e o mal”, ambos de 1957.

Artista plástico brasileiro, Roberto Magalhães (1940), ao longo de sua carreira, sob inspira ção de seus estudos de alquimia, ocultismo e esoterismo e de experiências místicas, desenvolveu em seus desenhos, pinturas e gravuras sobretudo deformações e antro pomorfizações, que levaram a um universo temático próprio. Em 1961, frequentou cursos na Escola Nacional de Belas-Artes (Enba), no Rio de Janeiro, e, em 1965, tornou-se um dos principais integrantes do grupo de jovens pintores da exposição Opinião 65, no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio). Nessa fase, recebeu prêmios por seus trabalhos e mudou-se para Paris, onde permaneceu por dois anos. A partir de 1969, com seus estudos sobre ocultismo e teosofia e sua aproximação com o budismo, interrom peu suas atividades artísticas, retomando-as somente em 1975, quando participa de expo sições individuais e coletivas.

Do latim venus, a palavra é atribuída ao segundo planeta do sistema solar, com órbita entre Mercúrio e a Terra, também chamado de estrela vespertina; à deusa do amor e da beleza na mitologia romana; e à deusa Afrodite na mitologia grega. Inúmeras foram as representações de Vênus ao longo da história da arte, desde as estatuetas de mulheres com corpos avan tajados esculpidas no período Paleolítico em pedras, ossos ou marfim, associadas à fertilidade – sendo a mais famosa a Vênus de Willendorf –, até inúmeras representações de jovens nuas com medidas equilibradas a partir da Antiguidade, representando ideais de beleza – sendo a mais conhecida pintada por Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510).

Seja na Pré-História, na Antiguidade, na Idade Média, nos séculos XVIII e XIX, na arte moderna ou na contemporânea, Vênus sempre esteve presente. Das estatuetas pré -históricas às esculturas em mármore e às incontáveis pinturas, emergindo das águas a partir de uma concha ou em situa ções diversas, a nudez de Vênus atravessa os séculos, refletindo as transformações e as mudanças próprias da sociedade que a representa e caracteriza. É, a cada momento, reformulada e adaptada de acordo com as novas questões que se apresentam.

Os Eixos Exógenos de Tunga geram a per cepção visual do antagonismo simultâneo entre figura e fundo. Neste processo em que o aspecto ilusório interfere na apreensão do objeto observado, ocorre uma espécie de desorientação na percepção da figura e do fundo, de modo que há mais de uma interpretação para o que é visto e ambas as formas observadas se destacam conjunta mente. Assim, ao se tentar observar figura e fundo simultaneamente, a percepção é organizada de maneira a uma impedir a outra: figura torna-se fundo; fundo torna-se figura, ininterruptamente.

Conceitualmente, os Eixos se aproximam da noção proposta por Edgar Rubin (18861951) na imagem conhecida como vaso de Rubin. Se observados em comparação com ela ou como variações dela, formal mente, os Eixos Exógenos se assemelham a uma espécie de distensão ou alongamento vertical do vaso, com adaptações em suas formas. Se no vaso de Rubin há a percep ção da silhueta de um vaso ou do perfil de duas faces humanas, nos Eixos Exógenos percebe-se a silhueta de um eixo ou o perfil de dois corpos femininos. Em ambos os casos, a duplicação das formas laterais parte da forma e de reentrâncias do seu eixo central. Ora se percebe vaso, ora se percebem faces; ora se percebe eixo, ora se percebem corpos. Assim, a analogia do eixo e do vaso se dá pelas premissas gestálticas presentes em ambos.

Criada por Tunga, a ideia de energia de con junção surgiu a partir da vontade de trazer um conceito que fosse capaz de explicar o que ele fazia. Definiu como “[...] a capacidade de colocar o heterogêneo junto e achar no heterogêneo duas coisas que não têm nada a ver uma com a outra: uma terceira coisa que é produzida por esse encontro”. E acrescen tou: “Energia de conjunção é, por excelência, a energia do amor” – ou seja, Eros. Assim, com base na fala de Tunga, o conceito pode ser analisado a partir de três sentidos que, juntos, definem sua ideia central: a conjunção de heterogêneos; o novo gerado a partir da conjunção; a energia como Eros.

Em diversas entrevistas, o artista refere-se à energia de conjunção como sua “cola poética”. Segundo ele, significa a ligação de duas coisas que não seriam comumente ligadas, isto é, a conexão de coisas diversas para a criação de sentidos – e, nesse processo, ter como resul tado o desconhecido. Desvelar, revelar, tornar presente, fazer aparecer, fazer surgir, ou, ligar coisas que nunca foram ligadas antes para trazer à presença o que não está presente.

Uma das principais definições do conceito de “instauração” – a construção de mundos a partir das conexões de significados em determinado contexto – possui bastante apro ximação com a noção de energia de conjunção explorada por Tunga, no sentido de trazer em si o estabelecimento de relações e as pos sibilidades de criação e revelação que delas provêm, assim instaurando mundos. Isso o faz afirmar que “talvez a vocação da arte seja o uso da energia de conjunção”. Esta é imedia tamente relacionada à “cola poética” que liga dois elementos díspares, criando um terceiro. Tunga acreditava que essa cola era única e exclusiva de cada artista. Cada poeta, músico etc. cria a sua própria cola poética e, portanto, produz arte.

Do grego palíndromos, a palavra é com posta da junção dos termos palin (de novo, de volta) e dromos (corrida), remetendo a “repetição, volta, de novo, novamente”. Assim, palíndromo está associado a palavras, números (capicua) e frases (anacíclica) que podem ser lidos da esquerda para a direita e vice-versa mantendo o mesmo significado.

O uso e a retomada do palíndromo ao longo da história sugerem um aspecto próprio dele, sua volta e repetição constantes, desde as incisões de letras em colunas de pedra no período do Império Romano. De certo modo, individualmente, cada palín dromo traz em si um aspecto topológico, no sentido de que, mesmo na mudança, permanece algo que não se altera – a orien tação e a direção da leitura não interferem no seu significado –, não importa sua forma, o significado é preservado.

Pregador judeu, João Batista (2 a.C.-27) nasceu em Aim Karim, cidade de Israel, filho de Santa Isabel (prima de Maria, que viria a ser mãe de Jesus) e do sacerdote Zacarias, que ficou mudo após duvidar do que o anjo Gabriel lhe disse: que Isabel, idosa e estéril, teria um filho e ele deveria se chamar João. Pouco tempo depois, ela deu à luz, como Gabriel havia anunciado.

Adulto, João Batista foi viver como um nômade no deserto da Judeia, em uma vida de penitência e pregação, anunciando a chegada do Messias. Passa, então, a ser chamado de profeta. Em sua missão, pregava a conversão e o arrependimento dos pecados por meio do batismo, por isso o seu nome, que significa “aquele que batiza”. Entre tantos outros, João foi responsável pelo batismo também de Jesus, seu primo. Nas pregações, denunciava injustiças, abusos de poder, imoralida des e, sobretudo, a vida adúltera do rei Herodes, que tinha se unido a Herodíades, sua própria cunhada. A oposição acabou levando à prisão de João. São Marcos, em seu Evangelho, narra que Salomé, filha de Herodíades, dançou para Herodes, que ficou deslumbrado e disse que daria a ela tudo o que pedisse. Salomé então pede a cabeça de João Batista numa bandeja, ao que o rei atende, ordenando a decapitação do profeta.

Do latim torus, toro é um espaço topoló gico, homeomorfo e não euclidiano gerado a partir da rotação de um círculo em torno de uma reta do mesmo plano, sem ponto de contato entre reta e círculo. Em sua mor fologia, por meio do diagrama plano, seu formato circular e seus atributos curvilíneos surgem, no entanto, de um retângulo. Isto é, é uma forma simples, porém de construção complexa pela perspectiva matemática.

O toro é uma das figuras topológicas mais básicas na qual uma deformação é homeo morfa; semelhante a um cilindro, fechado e orientável, construído a partir de uma dupla rotação, horizontal e vertical, assim como outras figuras topológicas, preserva pro priedades qualitativas intrínsecas mesmo sob deformações.

Das palavras gregas topos (lugar) e logos (estudo), a topologia volta-se às proprieda des geométricas de um corpo, as quais não se alteram em função de sua deformação. É oriunda de uma geometria não euclidiana. Um espaço topológico, seja um objeto, um corpo, uma figura ou uma forma, quando manipulado de modo semelhante a uma borracha em um processo de deformação, mantém suas propriedades qualitativas inalteradas; ou seja, não há diferença entre uma esfera e um cubo, ambos podem se transformar um no outro, mantendo suas propriedades topológicas.

O nó de Borromeu, como aparece em Les Bijoux de Madame de Sade (1983), possui uma topologia constituída por três anéis entrelaçados de modo que a remoção de qualquer um deles desata todos. Essas propriedades foram utilizadas também na teoria psicanalítica de Lacan, que propõe uma topologia de três registros presentes em todo sujeito: o real, o simbólico e o ima ginário, sendo que o nó de cada indivíduo, em analogia ao nó de Borromeu, representa a consistência de sua realidade.

A palavra surge do som que objetos pendura dos fazem ao ser movimentados, tratando-se de uma onomatopeia cuja raiz advém de “balançar” ou “um pedaço pendurado”. De origem africana – possivelmente bantu –, surgida por volta dos séculos XVIII e XIX, a palavra balangandã está relacionada às primeiras manifestações artísticas afrodes cendentes; mais diretamente, a acessórios de metal de variados tipos e formatos, como figas, frutos e animais, presos em pencas para decoração ou uso devocional.

O termo possui variações, como baran gandãs (atribuídos a objetos de devoção particular), balangandãs, balangangãs e berenguendéns (referentes a joias, enfeites ou decoração). Assim, como objetos votivos ou de adorno, amuletos ou ornamentos, dispostos como penduricalhos ou em pencas, os balangandãs carregam inúmeros sentidos, significados e aspectos simbóli cos associados a quem os produz ou à sua origem, de modo que, por suas inúmeras possibilidades simbólicas, têm seu uso continuamente retomado na contempora neidade para finalidades distintas.

Do tupi tepití, a palavra define um artefato indígena destinado à prensagem de man dioca ralada para a extração de seu líquido e, em certos casos, também do veneno. Elaborado em bambu ou palha trançada e de diferentes formas e tamanhos, o tipiti é um tubo esguio composto de um orifício em cada extremidade; uma espécie de cesto no qual um dos orifícios é pendurado a uma árvore e o outro é segurado por uma pessoa para o processo de torção. Cilindro elaborado a partir de tranças e nós, topolo gicamente, o tipiti aproxima-se do formato de um bitoro distendido, cuja conforma ção é ideal à torção. Assim, seu formato alongado e sua confecção a partir da trança não só propiciam a maleabilidade e a flexibilidade necessárias à torcedura pelas mãos como também tornam sua aparência semelhante a uma cobra ou a um tacape.

Das palavras gregas morphe (forma) e logos (estudo), a morfologia volta-se ao aspecto, à forma e à aparência externa da matéria. É aplicada em diversas áreas, como a lin guagem e a biologia, no estudo da forma e da estrutura do objeto que lhes diz respeito. No campo da matemática, a morfologia está relacionada mais diretamente a estruturas espaciais presentes na ordenação geomé trica das imagens e, por sua vez, à análise das formas nela identificáveis.

Inicialmente estudada nos anos 1960, a partir da teoria dos conjuntos, e original mente desenvolvida para imagens binárias, a morfologia concentra-se na extração de características, componentes e informações em imagens digitais relativos à geometria e à topologia de um conjunto desconhecido, em busca da representação e da descrição das formas que delas advêm. Ou seja, as propriedades geométricas identificadas na imagem indicam as características e a aparência da forma, possibilitando, a partir do seu processamento em imagem, a com preensão de sua estrutura espacial. Desse modo, a morfologia amplia, por exemplo, as possibilidades de estudo da topologia, iden tificando por meio da imagem os processos de seus homeomorfismos e demais caracte rísticas e aspectos dos espaços topológicos.

Do grego anamórfosis, cujo significado remete a “nova formação, transformação”, o termo está associado à imagem deformada de um objeto dada por um espelho curvo ou por um sistema óptico não esférico. Essa representação ou imagem aparentemente irreconhecível se apresenta mais regular ou perceptível a partir de determinado ângulo ou posição, assim como por meio de lente ou espelho não plano, tornando-se, dessa forma, uma imagem reconhecível, não mais deformada. Assim, anamorfose é um efeito óptico criado a partir de uma modificação intencional da imagem que consiste em deformar aquilo que, visto sob certo ângulo, retoma seu aspecto verdadeiro.

O exemplo mais conhecido é a caveira pre sente no quadro Os embaixadores (1533), de Hans Holbein (1497-1543). Quando observada frontalmente, é uma imagem imprecisa e desconectada do restante da obra; no entanto, quando observada late ralmente, torna-se precisa, sendo possível reconhecê-la como caveira. Portanto, diante de uma anamorfose, a perspectiva, o ângulo, a distância, a orientação e a direção do olhar devem estar sob um exato ponto de vista, o único a partir do qual o elemento recu pera uma forma proporcionada e clara em que o irreconhecível e deformado pode ser identificado; caso o observador se coloque em qualquer outra posição, a imagem se torna novamente incompreensível.

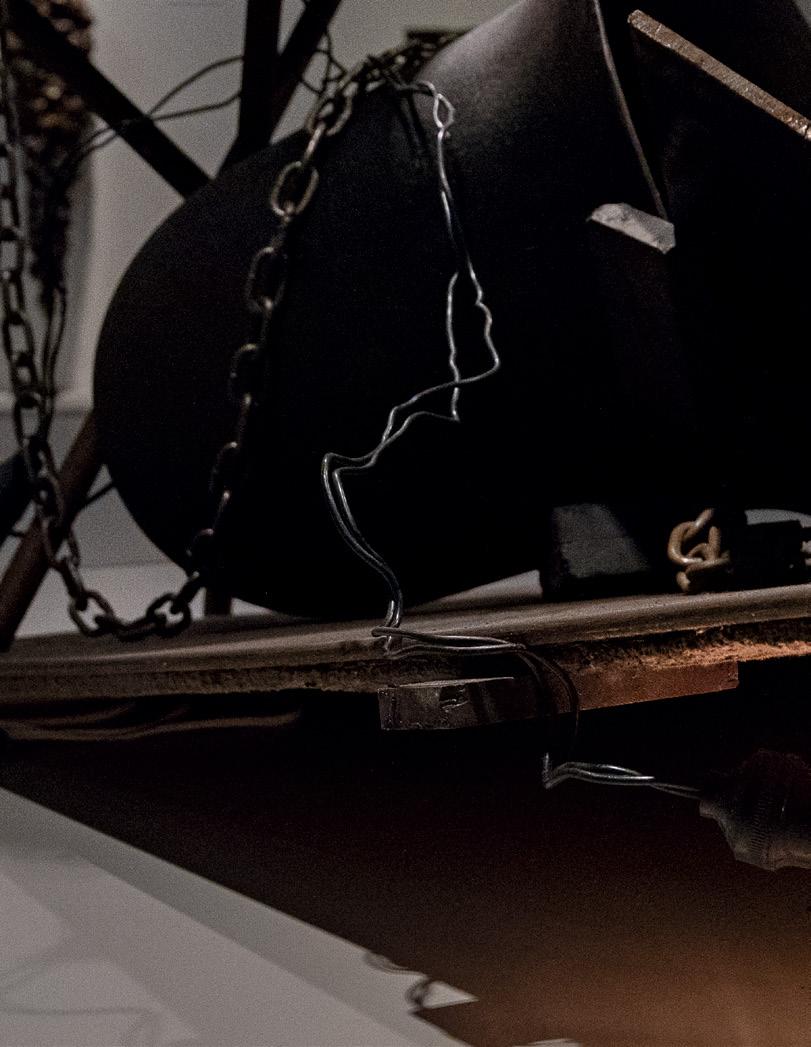

22, 23.

Sem título, da série |

Untitled, from the series Marionettes, 2010 aço-carbono, aço inoxidável, água cromatizada, cabo de aço, cristal de quartzo, ferro, ímã, resina epóxi, silicone e vidro | carbon steel, chromatized water, epoxy resin, glass, iron, magnet, quartz crystal, silicone, stainless steel, and steel cable dimensões variáveis | variable dimensions (150 x 180 x 300 cm) Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

24.

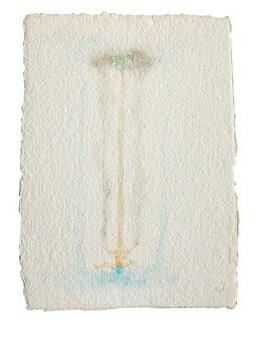

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, ca. 2014 pastel seco e tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | dry pastel and calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75 x 50,5 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

25.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, ca. 2014 pastel seco e tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | dry pastel and calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75,5 x 50,5 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

26.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, 2011 tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75 x 50 cm

Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

27.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, 2012 tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75 x 50 cm

Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

28.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, 2011 tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75 x 50 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

29.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, 2014 tinta caligráfica sobre papel Nepal | calligraphic ink on Nepal paper 75 x 50 cm

Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

30.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series Portal, 2010 aço inoxidável, cristal de quartzo, ferro e ímã | stainless steel, quartz crystal, iron, and magnet 60 x 74 x 300 cm

Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

31.

, 1977 bronze, couro, ferro e dente | bronze, leather, iron, and tooth

x

x

cm

Coleção | collection

Chateaubriand

MAM/RJ

32. Palíndromo Incesto, 1989-1992 cobre, ferro, fio de cobre, ímã e limalha de ferro | copper, iron, copper wire, magnet, and iron filings dimensões variáveis | variable dimensions (65 x 150 x 245 cm) Acervo | collection

Banco Itaú

33.

Sem título, da série | Untitled, from the series “From ‘La Voie Humide’”, 2014 espelho, ferro e impressão sobre tecido | mirror, iron, and print on fabric 170 x 140 x 220 cm Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

34.

Desenho Protuberante 2, 2010 cristal de quartzo, espelho, ferro, resina epóxi, têmpera sobre papel algodão e vidro | quartz crystal, mirror, iron, epoxy resin, tempera on cotton paper, and glass

75 x 59,1 x 7 cm

Acervo | collection Instituto Tunga

35.

Desenho Protuberante 6, 2010 cristal de quartzo, coprólitos, espelho, resina epóxi, têmpera sobre papel e vidro | quartz crystal, coprolites, mirror, epoxy resin, tempera on cotton paper, and glass

75,3 x 59 x 8,5 cm

Acervo | collection

Instituto Tunga

36.

Desenho Protuberante 3, 2010 cristal de quartzo, espelho, ferro, resina epóxi, têmpera sobre papel algodão e vidro | quartz crystal, mirror, iron, epoxy resin, tempera on paper, and glass

75 x 59,4 x 9 cm