ISBN 978-88-6242-583-4

First edition

Italian market June 2021

International market October 2022

© LetteraVentidue Edizioni

© Francesco Santoro

© William J.R. Curtis. Foreword: Memories, dreams, reflections: the universe of Frank Lloyd Wright

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or educational use. Italian legislation only allows reproduction for personal use and provided it does not damage the author. Therefore, reproduction is illegal when it replaces the actual purchase of a book as it threatens the survival of a way of transmitting knowledge. Photocopying a book, providing the means to photocopy, or facilitating this practice by any means is like committing theft and damaging culture.

If any mistakes or omissions have been made concerning the copyrights of the illustrations, they will be corrected in the next reprint.

Printed in Italy by The Factory srl, Via Tiburtina 912, Rome

Book design: Gaetano Salemi

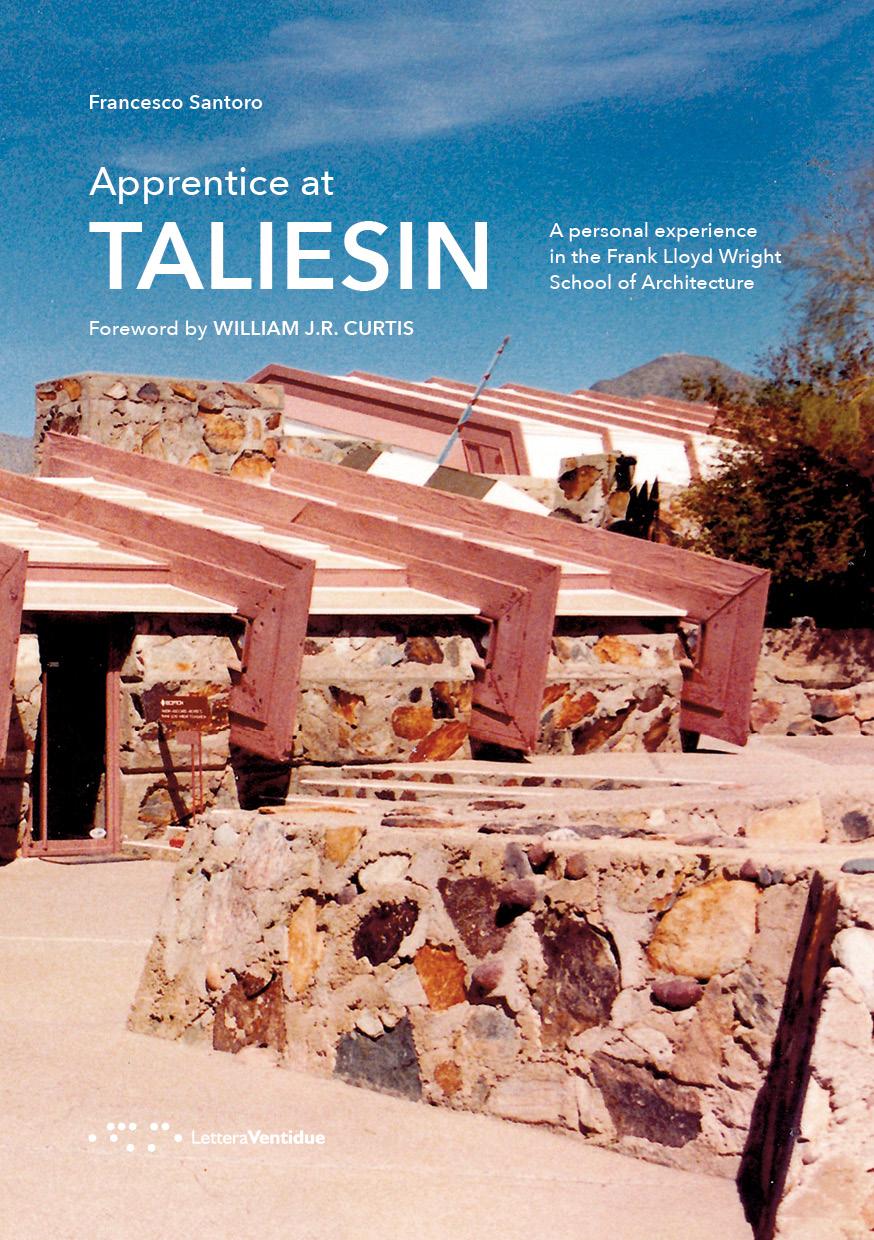

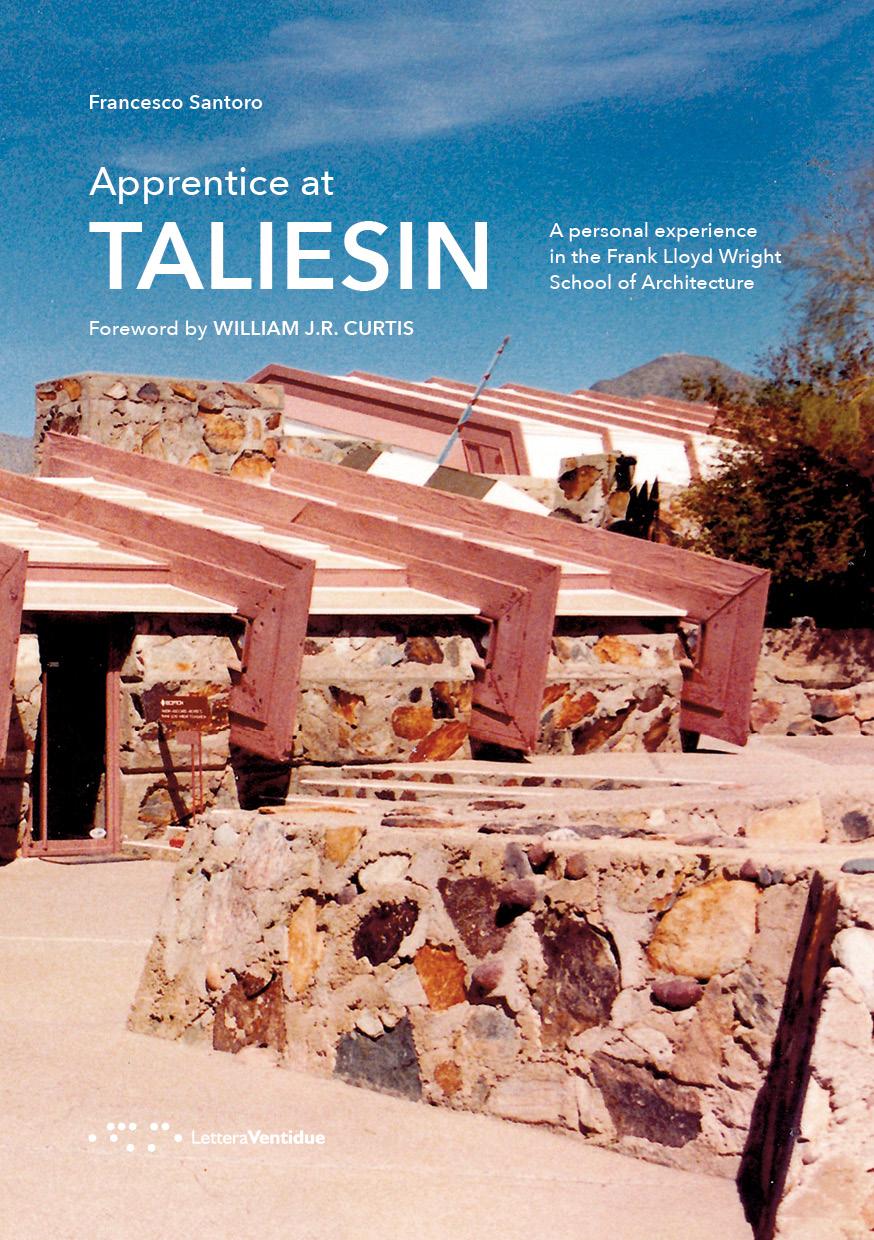

Front cover: Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Office, view from the south, winter 1989 (© Francesco Santoro).

Flap: Redesigned by Carlos Ortega Belando based on an author’s sketch.

LetteraVentidue Edizioni Srl

Via Luigi Spagna 50 P 96100 Siracusa, Italy

www.letteraventidue.com

A personal experience in the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture

Francesco Santoro

Verses of a Navajo song

Everything you have seen, remember because everything you forget blows back in the wind.1

FOREWORD William J.R. Curtis PREFACE INTRODUCTION Taliesin Arizona FROM ARIZONA TO WISCONSIN Wisconsin FROM WISCONSIN TO ARIZONA Taliesin West CONCLUSION POSTSCRIPT NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST OF MEMBERS AND APPRENTICES OF THE TALIESIN FELLOWSHIP SELECTION OF DESERT SHELTERS OF THE TALIESIN FELLOWSHIP APPRENTICES LIST OF PLACES, NAMES AND PROJECTS ICONOGRAPHIC SOURCES AND PHOTO CREDITS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8 17 19 25 37 99 119 167 195 217 226 228 242 246 259 262 271 272 CONTENTS

1. Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona (1938), view to the south along the diagonal platform from Frank Lloyd Wright’s office to the drafting studio inclined wooden trusses, October 2018.

1. Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona (1938), view to the south along the diagonal platform from Frank Lloyd Wright’s office to the drafting studio inclined wooden trusses, October 2018.

FOREWORD

William J.R. Curtis

Memories, dreams, reflections: the universe of Frank Lloyd Wright

“The past reappears because it is a hidden present”.2

This book was written in a wooden cabin in a grove of trees on the northwestern coast of Sicily, a magical place that provided the author with inspiring views across the Gulf of Cofano, a landscape haunted by Antiquity. As the ocean breezes rustled the carob trees and palms surrounding his rural retreat, the writer cast his mind back to another landscape, that of the parched desert of Arizona with its saguaro cacti, sandy arroyos, and vast mountain horizons where he had spent a key period of his youth three decades before. Francesco Santoro used the enforced confinement of 2020 to recreate events and places that he had experienced when he had left behind Italy and set out on a voyage of discovery and self-discovery in early 1989, enrolling for a year and a half in the Frank Lloyd Wright Taliesin Fellowship. This was housed in Taliesin West, the architect’s desert masterpiece, designed and constructed from 1938 onwards at Scottsdale not far from Phoenix. With its rocky platforms, crude stone and concrete walls, and leaning tent-like roofs held up on timber trusses, this extraordinary work was like a mythical landscape full of archetypal resonances. It was Wright’s hymn to the southwestern desert, its overwhelming natural features, and its ancestral Indian memories.3

Fed up with the sterility of Italian architectural education, and prompted by the Wrightian champion Bruno Zevi, the twenty-year-old Italian

8 APPRENTICE AT TALIESIN

Octavio Paz

student made a leap into the unknown. This is the adventure recaptured in this book which charts a youthful search for architectural knowledge. The text itself has the character of a personal journey back through space and time. But Apprentice at Taliesin. A personal experience in the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture is more than just an autobiographical recollection. It is reinforced by solid historical research on the evolution and personalities of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Foundation since its creation in the 1930s. Santoro’s account of daily life at Taliesin offers insights into the inheritance of the original value system (“learning by doing” “an organic philosophy”) and of ways that it changed over time. He recounts the teaching methods used at the end of the 1980s and the communal activities, whether for work or for leisure. Then there are the personalities: William Wesley Peters one of the old generation, and above all Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the guardian of collective memories and of the archive of drawings kept in a secure vault.

There is probably no better way of learning the fundamentals of architecture than to experience a great work firsthand, gradually penetrating beyond appearances to the guiding principles and philosophy which lie behind the forms. Even better if one can inhabit such a world over a long period of time, absorbing the spaces, materials, and atmospheres as these reveal themselves throughout the day, the night, and the changing seasons. Architecture communicates in silence, touching the mind and all of the senses, gradually revealing itself and its pervasive aura to the inhabitant. If in addition one can somehow be integrated with the way of life and social vision for which the structure was first envisaged, then the lessons to be absorbed take on new dimensions of meaning altogether. In effect, one lives the building and the site from day to day while reliving the intentions and imagination that created the work in the first place.

Santoro’s account is full of acute observations about the architecture of Taliesin West, especially the relationship to the surrounding landscape. He grasped the primary intentions, including the orchestration of views of key mountains in the distance. The plan of Taliesin West is like a map of human relationships charting the ebb and flow between different functions, such as the airy studios, the dining hall, or the introverted Kiva, a closed room at the heart of the plan resembling a lodge of secret knowledge. The plan combines orthogonal and diagonal geometries and the terraces engage with the horizon. Santoro began to understand the underlying geometry, especially the square spiral focussed on the Indian rock

9

FOREWORD

TALIESIN

IIt all began with a letter. A letter written during the first months of the Architecture course at the University of Palermo.

Driven by a moment of discouragement it was a protest destined to remain unheard, in the late ’80s static atmosphere of an Italian university trying to look for new directions, constrained between the exhausted modern tradition of rationalism and the useless outsized projects of postmodern.

Moving evidence of the ardor of the youth, it reflected the initial and common infatuation for the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and a call for help in the continuation of the studies following an organic inspiration. The letter however was not sent. It would have remained a momentary breakout, set aside among the notes of the first-year courses, maybe remembered in the future with a smile, if I wouldn’t have found it by accident one year later.

Many things had happened, an entire year of studies had led to a new awareness of reality, a more conformist vision that had sadly smoothed down the impetus and the intolerance of the previous year. And therefore the decision, totally irrational, to send the letter anyway, revising it in its hardest parts and finally addressing it, a year later, to the same original recipient.

And the surprise to receive, after only a week, the answer that changes your life:

Dear Santoro, I have been very glad to receive your letter. Experiences come back and when I was your age, trapped in a fascist school, I felt the same way as you [...] I suggest you break with this atmosphere and go to Taliesin, to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona. If you really want, you will be accepted. Two or three years, maybe less, in Wright’s world, are wonderful. From there you can sail to other shores, or come back [...] If you are hearing the call and the message of organic architecture, you must head to Taliesin. Best wishes, greetings, and good work.

Bruno Zevi.12

25

15. Taliesin, Spring Green, view from the lake, summer 1989.

ARIZONA

1It was a wonderful sunny day in the warm Arizona winter.

I was walking through the camp like a child discovering the world, beginning to learn the buildings’ location and understanding their function and spatiality.

The famous living room with its labyrinth entryway, called Garden Room for its opening into a secret garden, the large drafting room enlightened by translucent roof panels, the kitchen, dining room, theatre, and Wright’s office, all connected by a series of pergolas, terraces, stairways, and walkways shaded or heated by the scorching desert sun, and then courtyards, gardens, pools, and fountains cooling the air, placed between water and bell towers.

Large stones engraved with Indian petroglyphs together with Chinese ceramic theatres embedded in masonry and concrete sculptures built by Alfonso Iannelli for the Midway Gardens project were punctuating the camp’s crucial points, marking a sort of ideal procession with continuous changes of direction and walking sequences throughout the campus.34

A couple of weeks after my arrival, on a visit to Taliesin West, LaVan Martineau, the Indian adopted cryptanalyst explained to us the meaning of the petroglyphs Wright had placed in the camp’s strategic points. After having studied the engravings on the stones with him, we walked at the base of the Maricopa Hill behind, where they were originally found and carried from by the first apprentices, and climbed afterward up the mountain to examine a few of them pointing west.35

The area on which Taliesin West was founded had been inhabited since prehistoric times by the Hohokam Indian tribes, followed by the Hopi and the Apache, who used the land for hunting and for ritual and ceremonial purposes, as indicated by the rock carvings found by Wright on site. The same existence of these ancient settlements at the base of the mountain had convinced Wright of the presence of water. Despite opposite indications by the State Land Office, a well of hot volcanic water was later discovered at a depth of 486 feet below ground.36

Wright arrived in Arizona in the spring of 1937 to establish there the Fellowship’s winter venue. After making different attempts looking for the best location, he finally purchased 600 acres of desert land at the base of

37

Taliesin West,. February 1989.

ocotillos with their scarlet red flowers, the staghorn and the dangerous jumping chollas, sticking to your legs due to desert static electricity, were just a few of my newest adventure companions. They were joined by the coyotes that I could hear howling at night, rabbits and wild javelinas running around in herds, lizards and small desert rodents, some random scorpion, and the countless quails gathering in the morning around the tent. The mild winter weather was interrupted by occasional sandstorms and tornadoes, occurring in the form of desert devils with the approaching of the warm season. There were also a few sporadic thunderstorms, during which the shallow dry washes, running through the desert surface around Taliesin West, were filled with water, performing their essential drainage function. Unforgettable was the sharp smell of the desert after the rain and the enchanting view of its sudden blooming, transforming the arid landscape into an ephemeral garden for just a few days. I would watch the desert sunsets every day from my privileged location, sitting below the Indian rock by the drafting room or on the prow of the triangular terrace, while the mountains around, the sky, the buildings, and the same people’s faces were colored by an infinity of shades, from red to orange to pink and purple.

70 APPRENTICE AT TALIESIN

48. Taliesin West, desert sunset, 1989.

49. Francesco Santoro, Taliesin West, desert shelter, side view, fall 1989.

50. Francesco Santoro, drawing of a desert stone, 1989.

51. Francesco Santoro, project of a desert shelter, 1989.

I remember that at night after dinner, at the end of the workday, I was hurrying back to my tent to write or read in the candlelight, leaving the canvas open or lighting a fire and lying down outside in the sleeping bag to look at the stars, under the flag-waving slowly in the desert breeze. The other apprentices’ tents around me, glowing with the light of their candles, looked like lanterns in the night, in that surviving plateau overlooking the valley below, lit by the myriad of lights shining over the endless spread of houses. I was starting to realize how these sensations would never leave me and that it would no longer be possible to return to a normal life, unlearning civilization and regaining the primitive sense of life, possibly losing contact with reality but achieving something unique forever.69

71 Arizona

FROM ARIZONA TO WISCONSIN

It was almost the end of May and time to migrate east. With the warm season approaching, following the Fellowship’s tradition, it was time to pack and leave Arizona to spend the summer in cooler Wisconsin. During the journey between the two Taliesins, a real road trip across the large North American country, the apprentices would split into small groups and plan the route in order to visit as many interesting places and architectural projects as possible, and then reunite in Wisconsin. The large convoy of the Taliesin Fellowship members was returning to the valley where it all began, following year after year the changing of the seasons in the nomadic spirit of its founder.

We started planning the trip.

In a small group of four apprentices, Todd, Bill and Eva, and myself, we decided to take turns driving a station wagon and a small truck across the vast territory of the United States, from the deserts of the Southwest to the plains of the Midwest, finally heading north and ending our trip at Taliesin. Shortly after arriving in Wisconsin, we would need to get back on the road again to reach Chicago in time for the inauguration of the great Wright exhibition scheduled for June 7th on the eve of the architect’s birthday. The plan included visiting afterward the splendid architecture of the “Windy City.”

99 1

Springfield ILLINOIS Taliesin WISCONSIN

Saint

MISSOURI

Taliesin West ARIZONA

Bartlesville OKLAHOMA

Louis

Cadillac Ranch TEXAS

76. Frank Lloyd Wright, Price Tower, Bartlesville, May 1989.

77. Route from Arizona to Wisconsin, May 1989.

178 APPRENTICE AT TALIESIN

COSANTI

1. ENTRANCE

2. NORTH STUDIO (COSANTI GALLERY)

3. NORTH APSE

4. CERAMIC STUDIO

5. DRAFTING ROOM

6. FOUNDRY APSE

7. METAL STUDIO

8. ANTIOCH BUILDING

9. PUMPKIN APSE (JACOB STUDIO)

10. SOUTH APSE

11. BARRELL VAULTS

12. EARTH HOUSE

13. CAT-CAST HOUSE

14. STUDENT APSE

15. SWIMMING POOL

1 2 8 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 13 15 16 14. 20 5 0 10 N

16. CANOPY

139. Cosanti, plan.

obtained from the glazed sections of a few recycled concrete pipes, echoing the astral geometry of a constellation. In front of the drafting room’s entry, Soleri had built the circular structure of the Ceramic Studio, under a decorated ribbed vault and a red skylight placed in the center of the complex recalling the sun.134

These first structures were built before the institution of the summer workshop programs and were followed by the North Apse with the Metal Studio used for the bronze bells, and the South Apse for the ceramic bells, both facing south. Additional structures were built later. The Cat-Cast House hosting the students, excavated with a Caterpillar supporting the roof with a series of recycled railway sleepers, and the Pool Canopy with a prefabricated reinforced concrete structure cast in place and hoisted upon a dozen of reused telephone poles. Moving along, I reached the Foundry Apse where the bronze bells were cast. Right in front of it the Pumpkin Apse looking like a large habitable pumpkin, and the Barrel Vaults, huge prefabricated recycled concrete pipes, cladded with glass and wood and converted into studios for the students. Right inside one of them I saw the panels and the brochures of the Minds for History symposiums and learned of the Cosanti Foundation’s cultural program, founded by Soleri in 1961, completing the workshops’ offer of ceramic and bronze windbells crafting courses. I finally walked to the Student Apse built by the pool, with the vaults decorated by the students and the huge plexiglass model of Arcosanti placed underneath. This was one of the last structures built at Cosanti together with the Antioch Building placed next to the Metal Studio. Walking back to the entrance I entered the breathtaking North Studio, used as a gallery and gift shop of the objects crafted at Cosanti, under the decorated vaults recalling the ribs of a prehistoric animal supported by concrete tilted columns.

There, at every successive visit, I compulsively purchased a large quantity of copper and ceramic windbells after having tested their tone, starting from the first one, the smallest I bought for my shelter at Taliesin West. Their tinkling was going to accompany my life since thereafter, traveling with me in the various parts of the world where I would live, warning me of the breath of a morning breeze or the arriving mistral, turning out to be a wonderful system to bring me back to the awareness of the present and the sacrality of every instant.

Soleri’s first activity on his return to Arizona was the handicraft production of windbells called Cosanti Originals, together with the design of textile

179

FROM WISCONSIN TO ARIZONA

My readings and the collected testimonies confirmed that during Wright’s last years the presence of Olgivanna and the strong influence of Gurdjieff’s philosophy had increased in the Fellowship’s life. Already in the early ’50s, an annual festival of music and dance was organized, involving various apprentices in the preparation and execution of the movements of the Oriental sacred dances. They were based on the musical compositions of Olgivanna and the choreographies of her daughter Iovanna, returning from Gurdjieff’s Institute in Fontainebleau where she had gone to study. Among the different apprentices engaged in the festival’s activities had excelled the Egyptian Kamal Amin and the same Heloise, who besides participating as a dancer, had designed the costumes inspired by the original ones from the Gurdjieff's Institute. But there were other aspects of the Armenian mystic’s philosophy, embraced by Olgivanna, which had made the Fellowship’s life particularly problematic, especially after Wright’s death. The manipulatory control system on the apprentices’ lives and the limitations to their privacy was determining an almost total subjugation of the will, dangerously transforming the devotion to an alternative Fellowship’s ideal into a religious cult’s fanaticism. The studio work carried on under the guidance of the same Olgivanna and her son-in-law Wes Peters was becoming antagonistic to the various Fellowship’s activities, losing inspiration with the passing away of his main

204 APPRENTICE AT TALIESIN

156. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Italian apprentice Franco d’Ayala Valva at Taliesin West, 1954.

actor. The disbandment caused by Wright’s death had also led many of his best apprentices to abandon the Fellowship, leaving the survivors orphans of their most important interlocutor. Their blind devotion would constitute the main limit to the development of an original architecture following their master’s ideas, not being able to go beyond the imitation of his projects. Wright himself had indeed predicted its fate: Given the eclecticism of our educational system, imitation is still inevitable. People will take my ideas and my principles, will exploit them, or will give an academic formulation, to create a “style” where it is required; in fact, they are already creating it [...] at Taliesin, we put daily into practice the organic principles, in contact with life and nature. Nevertheless, we have a wing that goes too far to the right, and one too far to the left. The left-wing has taken the appearance of the things we love and, with the spirit of the painter, has drawn a superficial style from it; in other words, the left escapes from reality with the usual method of aestheticism, without understanding that buildings can be built scientifically, that science, art, and religion can find unity of expression. The right-wing sees the way we work and knows something of the tools but exaggerates both. Unfortunately, traditional education had produced young people only able to create by election and selection, not from the inside out of a creative impulse, by instinct guided by proven principles.160

205

Taliesin West

157. Taliesin Fellowship apprentices during a formal event, 1954.

Postscript

Palermo, March 30, 2021

169. Taliesin West, view of the complex from the south-west, winter 1990.

169. Taliesin West, view of the complex from the south-west, winter 1990.

Before going to press, right after the passing of John Rattenbury, who had contributed to establishing the firm Taliesin Associated Architects, I receive the news that the studio of H&S International, founded by my fellow apprentices Bing Hu and his wife WenChin Shi, has reached an agreement with the Foundation to move a branch of their office in the currently empty drafting rooms of Taliesin and Taliesin West. Bing Hu, who succeeded in the past months in the acquisition of the David Wright House in Phoenix, for a long time in the sights of speculators and at risk of demolition, was more recently engaged in rescuing the Taliesin school of architecture, relocating its headquarters and students in the campuses of Paolo Soleri at Cosanti and Arcosanti. From the Foundation’s official statement, H&S International is accepting applications for its summer “Learning by Doing” internship at Taliesin West.

Taliesin lives …

1. Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona (1938), view to the south along the diagonal platform from Frank Lloyd Wright’s office to the drafting studio inclined wooden trusses, October 2018.

1. Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona (1938), view to the south along the diagonal platform from Frank Lloyd Wright’s office to the drafting studio inclined wooden trusses, October 2018.

169. Taliesin West, view of the complex from the south-west, winter 1990.

169. Taliesin West, view of the complex from the south-west, winter 1990.