BACK TO CONTENTS

MAJOR PARTNER

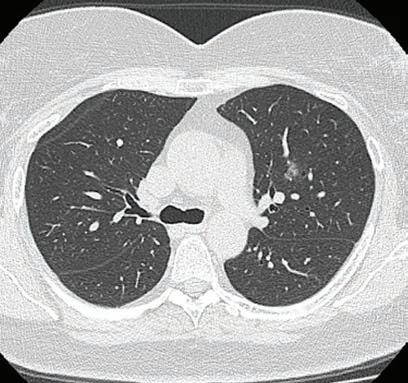

Infective exacerbations of COPD What is an exacerbation? The GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) report, updated in 2019, defines an exacerbation as “an acute event characterized by a worsening of the patient's respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations and leads to a change in medication.” Respiratory infections (predominantly viral), cause the majority of exacerbations. Other causes include pollution, heart failure or rarely pulmonary embolism or myocardial ischaemia. Role of antibiotics? Antibiotics have the greatest benefit (in morbidity and mortality) in more severe exacerbations (with the greatest evidence in the ICU population). The Anthonisen criteria, endorsed by the GOLD initiative, recommends antibiotics only for a severe exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation (non-invasive or invasive) or an exacerbation with increased sputum purulence plus either increased dyspnoea or increased sputum volume.

Reproduced with permission from: Shared decision making for antibiotic treatment in exacerbations of COPD in the community [published 2019 April, amended 2019 June]. In: eTG complete [digital]. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2020.

Even in hospitalised patients, the use of antibiotics has not been consistently

shown to demonstrate benefit. A meta-analysis in 2012 showed that antibiotics had no statistically significant effect on mortality and length of hospital stay in inpatients. In the community setting, the same meta-analysis showed low-quality evidence that antibiotics reduced the risk of treatment failure by 25% at one month. However, if the included trials were restricted to currently available drugs (they removed old studies that used chloramphenicol and oxytetracycline) there was no benefit shown. Viral causes should always be considered and empiric oseltamivir be prescribed in flu season. With the advent of COVID, it is likely that this virus will become one of the common causes of viral exacerbations. Hopefully we will have an effective treatment for this virus in the future. If used, antibiotics should be targeted against Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae species are rare, often occurring in patients with

Dr David New Consultant Specialist in Infectious Diseases in Microbiology

About the Author Infectious Diseases specialist Dr New has returned to Perth after training in Melbourne. He works at Armadale and RPH and privately at Clinipath Pathology.

underlying bronchiectasis. These patients tend to be sicker with pneumonia and require hospitalisation. Managing expectations: Talking to your patients about what to expect during an exacerbation is very important. The Box below is from the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines. Summary: Overall there is mixed evidence for the benefit of antibiotics in mild cases of COPD exacerbation. It is a difficult situation, and talking to your patients about the expected course of the illness is important. References on request

Shared decision making for exacerbations of COPD in the community To engage in shared decision making with patients and carers: • Ask about the patient or carer’s expectations for management of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). • Explain that the duration of a COPD exacerbation is related to the severity of underlying COPD. For patients with mild COPD, symptoms of the exacerbation can last 7 to 10 days. In patients with more severe COPD, symptoms can persist for weeks. • Explain that inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids are the standard treatment for exacerbations of COPD. Additional treatment with antibiotics should only be considered if all three of the following clinical features of a bacterial infection are present: • increased sputum volume

• sputum purulence or a change in sputum colour • fever. • Discuss the limited benefits of antibiotic therapy for nonsevere exacerbations of COPD, even when a bacterial cause is likely. • For patients managed in the community with less severe exacerbations, antibiotics do not consistently improve outcomes. Currently used antibiotics do not reduce the rate of treatment failure or prolong time to the next exacerbation. • Discuss the potential harms of antibiotic therapy. • Adverse effects of antibiotics include diarrhoea, rash or more serious hypersensitivity reactions. • Antibiotics disrupt the balance of bacteria in the body (the microbiome). While the consequences of this are not fully understood, it can cause problems

ranging from yeast infections (eg thrush) to more serious infections (eg Clostridium difficile infection). • Antibiotics can cause bacteria in the body to become resistant to antibiotics so that future infections are harder to treat. Multidrug resistant bacteria (known as ‘superbugs’) can be spread between people, affecting other family members and the community. • Ask about the preferences, values and concerns of the patient or carer, and answer any remaining questions. • Make a joint decision about whether to add antibiotics to standard care (inhaled bronchodilators and, where necessary, oral corticosteroids); if a decision is made to use antibiotic therapy, see eTG complete for treatment recommendations. • Discuss criteria for patient follow-up and reassessment.

Main Laboratory: 310 Selby St North, Osborne Park General Enquires: 9371 4200 Patient Results: 9371 4340 For information on our extensive network of Collection Centres, as well as other clinical information please visit our website at

www.clinipathpathology.com.au

MEDICAL FORUM | RESPIR ATORY HEALTH ISSUE

SEPTEMBER 2020 | 5