ADDITIONS & SUBTRACTIONS STUDIES IN FORM

Published by the Department of Architecture

School of Design and Enviroment, National University of Singapore

4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566

Tel: +65 65163477

Email: akierik@nus.edu.sg

Grey Exhibition Community

Email: blackwhitegrey09@gmail.com

© Department of Architecture

School of Design and Enviroment, National University of Singapore

© Individual Contributors

All rights reserved; no part of this publication publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher.

The publisher does not warrant or assume any legal responsibility for the publication’s contents. All opinions expressed in the book are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National University of Singapore.

Grey Exhibition & Studio 4 Assistant Professor:

Erik G. L’Heureux AIA, LEED AP

Studio Four:

Chua Gong Yao

Huang Jun Cheng

Iyan Darmaja Mulyadi

Jiang Yiwei

Lee Rong Rong

Lee Wen Hui Jolene

Lim Li Wei Isaac

Lin Yanle Felicia

Teng Li Qin Ellyn

Teo Weiling

Yeo Hwee Ming Charlene

Accommodating Form

Form

c.1225, from O.Fr. forme, from L. forma “form, mold, shape, case,” origin unknown. One theory holds that it is from Gk. morphe “form, beauty, outward appearance” Sense of “behavior” is first recorded c.1386. The verb is attested from 1297

Noun:

1 visible shape or configuration.

2 a way in which a thing exists or appears.

Verb:

1 bring together parts to create.

2 go to make up.

3 establish or develop.

4 make or be made into a certain form.

Form is a dirty word in architecture. Yet form is everywhere. At the most basic level architecture is form itself, nothing less. Architecture is obviously more, though it is through form that we understand architectural intention. It is the voice of the architect. It speaks long after a design is completed. It is the delineator of space in a particular organization and arrangement. It is the spatial resolution of a multiplicity of complex relationships found in all human inhabitation. Like the foundation or a beam in a floor, the geometry of form is always within the architectural body.

The discussion on form is difficult. It is messy. It is not precise or clean. People do not like to talk about it, especially architects. Even more so with less talented ones. It is easier to speak of quantitative criteria rather than qualitative ones. Architects are also dreadfully afraid of the ubiquitous label “Formalist”. The formalist architect is reduced to a child making fantasy; the implication of playing with shapes. Robin Evans in his seminal text The Projective Cast states that “Geometry has an ambiguous reputation, associated as much with idiocy as with cleverness”.

Yet Guarino Guarini speaks of form and geometry. So does Sebastinao Serlio. Vitruvius notes in his treatise De Architectura, or Ten Books on Architecture “For without symmetry and proportion no temple can have a regular plan” in his prescription of a Classical strategy. Palladio designed with simple geometries incorporating rules of humanism and its proportion in form and space. However in the education of an architect today, the discussion on form either falls into the traps of humanism and its prescribed proportions: 1/3, 1/5, the golden section, perfect symmetries, and axial arrangements, or the modernist aesthetic vision of composition, triangulation, and dynamic appearances; or form suppressed by more “important” considerations of technology, utility, structure, urbanism, signification and atmosphere.

These more “important” considerations are always functional. Form must have utility for the functionalists for it to be valid. It must cool or heat for the environmentalists. It must be fabricated simply for the builders. It also must be refer to something else for the historians.

Yet, architecture maintains meaning and importance long after programs have been replaced, air conditioning brought in, color changed, and the context altered. What remains is form and its ability to interiorize all the functional necessities of building. Like an amazing jacket, form is the envelop of function – the very shape of the container of utility.

This fit between utility and form is not precise. Rather it operates as an accommodating system. Accommodation is fundamentally a spatial enterprise; “to have space for, to make space for, or to make fit, to incorporate, to include, and to integrate” the variety and multiplicities of forces into a formal logic. To accommodate is to allow for utility but to transcend it.

Three basic formal strategies are typically employed in design: 1) the collection of containers where each is employed calibrated to a particular function:“form follows function”. Often arranged in a collage strategy the approach allows individual expression for each function. 2) A single container filled with many small containers. The exterior container fulfills aesthetic criteria of the

exterior, think of the Home Insurance Building, Chicago’s first high rise building, while the interior containers are designed for each use as necessary irrespective of its larger envelop. 3) The single container is modified and mutated to accommodate all of the functional necessities of a project albeit in a loose calibration to function. The looseness allows for variation and flexibility. The gothic cathedral is an example of one such accommodating system where the envelop contains the church interior, displays biblical ideas, structures high vaults, and incorporates light and atmosphere in a single formal approach.

Architects typically begin with function (program) and as such, existing formal techniques are utilized rather than the invention of new ones. It is always easier to copy than to invent. Architecture is reduced to a rearrangement of pieces recycled project after project. However to have control over the container itself,-- to invent the container and its form and its geometry -- is to possess a tremendously powerful knowledge that only architects can muster. This is an autonomous knowledge interior to the discipline of architecture. The mastery of form and geometry is to control space, to control light, gravity, inhabitation, climate, function, use, and aesthetics. It is the control of the atmosphere around us. It is the architect’s specialty. Engineers can produce more comfortable air conditioning and more efficient structures. But only architects can invent and control the geometry of the container.

For architects, the knowledge of form, its geometries, its logic and its knowledge of itself is rarely spoken about on its own terms. The mathematical and geometrical complexities of intersections, adjacency, position and proportion are always present yet like the white elephant in the room. Form remains, regardless of function, efficiency, use, quantity. Sitting in the back of a conversation on architecture, form waits for problems to occur. Form waits for the functionalism to produce banality. Form waits for the environmentalists to solve their problems with technology. Form waits for geometry to collide in irreconcilable ways. And when all of the technical problems are resolved, architects start speaking about form; its clarity, its legibility, and its meaning.

Form has been around for a long time. The pyramids are a basic shape, as is the primitive hut, or the earth itself. It is a basic separator between the natural and constructed world. The world of the natural is of an intricacy beyond immediate comprehension. Natural form is seemingly infinitely complex. Constructed form, however, is of a comprehensible geometry even in its most sophisticated appearance. The geometrical world of form is applied to the natural world to produce order, control, and knowledge. The perspective grid organized the Renaissance city square. The axial centrality of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Paris controlled the city just as Louis XIV looked over his garden at Versailles. The shifting geometries of Le Corbusier organized the planning of Chandigarh. And today the computational algorithms push the fabrications and formal inventions of contemporary architects.

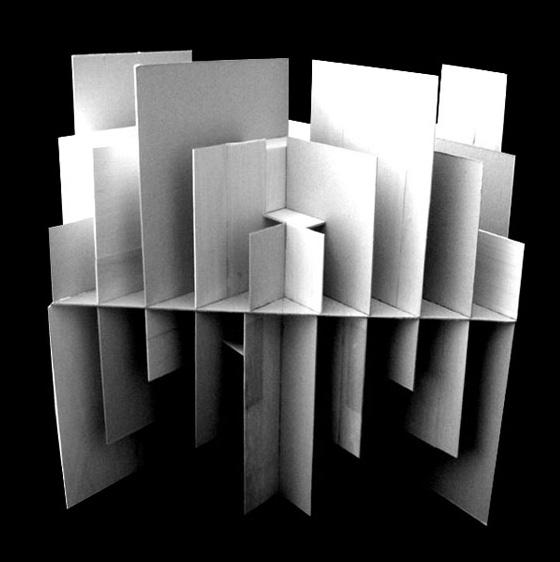

Architects do funny things to create form. They cut open spaces through drawing. They slice through buildings looking at them from weird angles. They draw obsessively and make many models some very simple, others with tremendous complexity. Yet in the drawing and model fabrication is a conversation legible to architects. No wonder architects have a difficult time talking to others outside the discipline. Unless it is related to function, utility, structure, etc: the basic logical components that can be quantified. It is the qualitative attributes that become a grey area where normative language fails. The drawings and models become the voice of architecture speaking in a manner that only architects understand; a language that only architects control. Form is under exclusive authorship of the architect.

The education of an architect often precludes education in form. Rather form is something that just happens in a student and later as professionals, as if by magic. The reality is that form is often copied, transcribed, sampled from projects floating in the current trends of the day. Normative forms become status quo operative devices to solve particular functional problems. Or theoretical or historical ideas are given basic formal strategies that are then repeated and recycled as the strategy of the season. Through the media, websites, and publications, students absorb these influences and regurgitate them back into their own work. It is no wonder that architecture could be described as the most plagiarized profession.

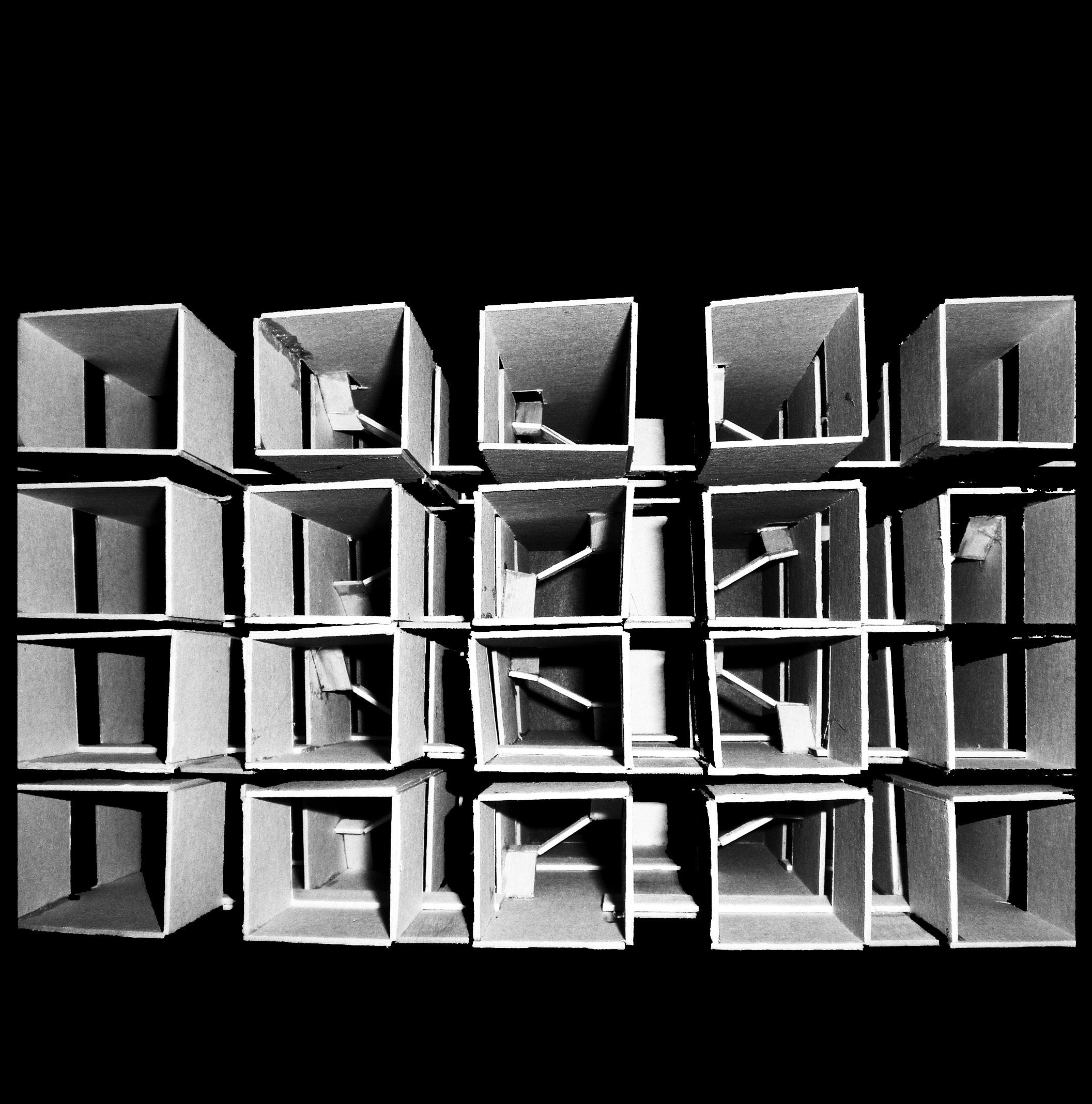

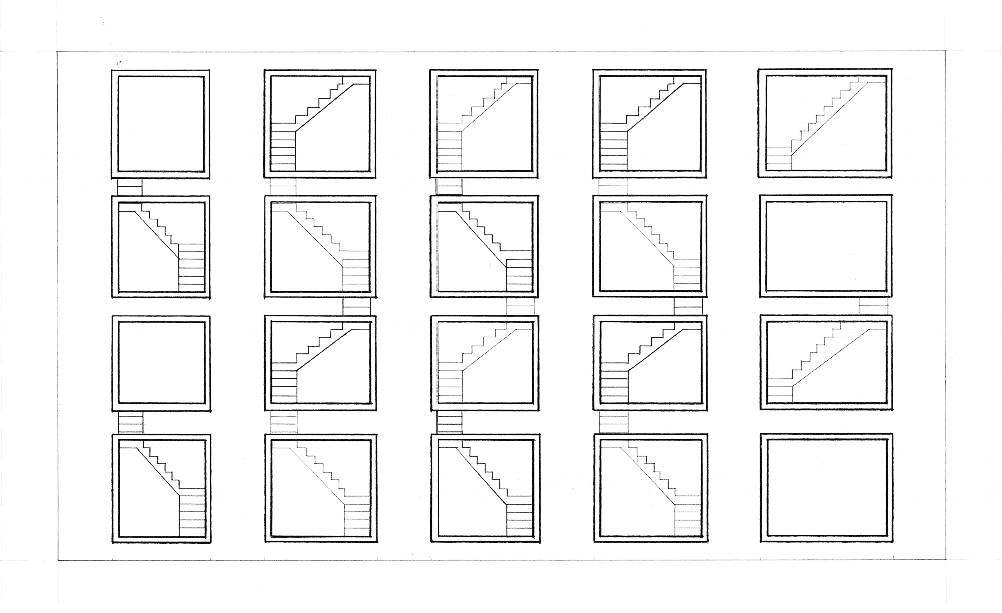

The works in this book are of pedagogical approach to create knowledge, expertise, and ability through geometry and form exclusively. Textual readings are not prescribed. Students rarely if ever go to the site. Culture and economies are discussed in a very limited manner. Students are not required to look at precedents or historical ideas. They operate almost exclusively in the confines of the studio environment. The studio trusts that the other classes, readings, and intellectual curiosity will inform their work accordingly. It is actually very simple. Reductive, yes. Basic even. Yet it is empowering. It is based on simple geometries and focused ideas. But for students in their second year of an architectural education handling the very geometries of form is fundamental.

Manfredo Tafuri wrote about the problems of this approach in the late 1970s. In his text “Architecture and Utopia Design and Capitalist Development”, Tafuri notes that architecture had returned to “pure architecture” – to a form devoid of its utopian aspirations. It was a reading that architecture had become of “sublime uselessness”. It is the problem of a reductive formal approach where form is all there is. I counter this reading. The work in the book is proof in the power of understanding form and its operative potential in the design process. Without knowledge of form itself, architects are always working deficiently in another discipline be that politics, economy, or engineering. To operate in form as a material itself Students learn approaches in creating and handling form. And more importantly how form can be utilized to engage structure, function, material, and atmosphere.

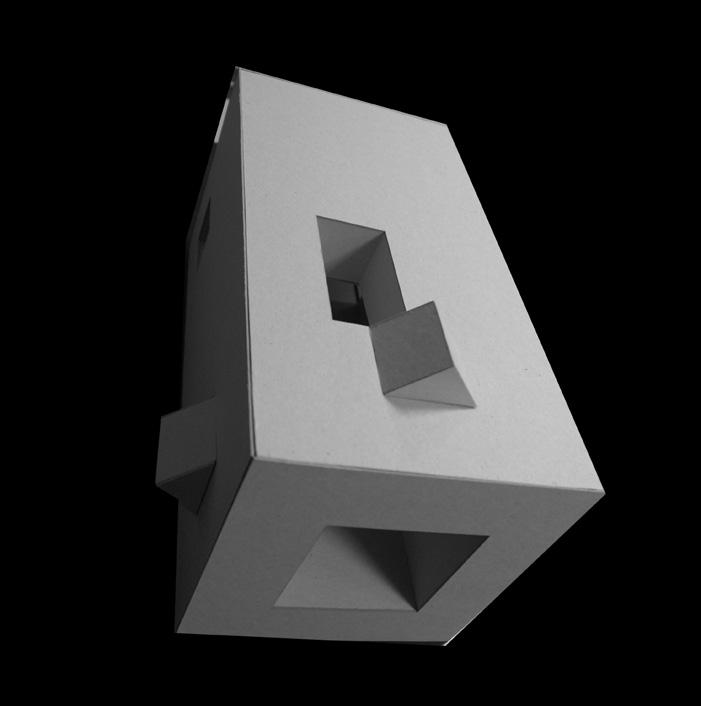

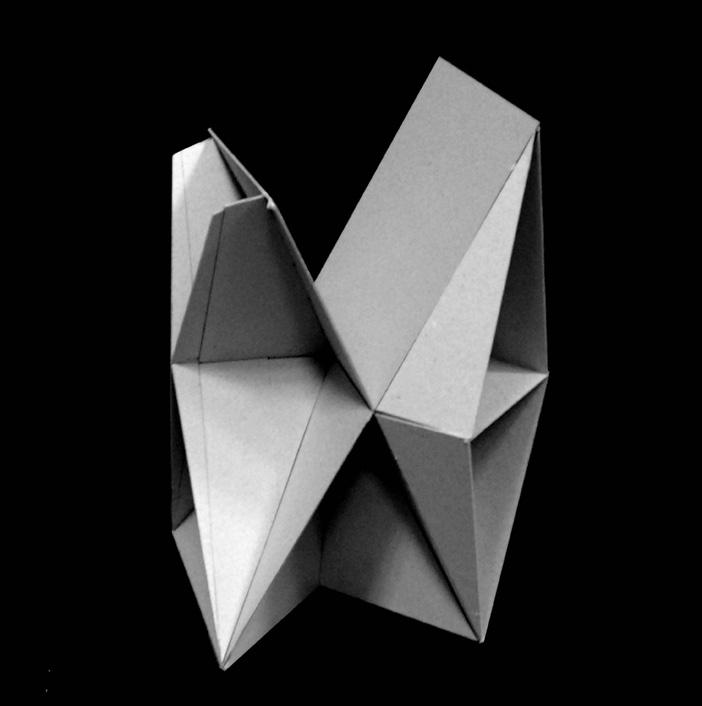

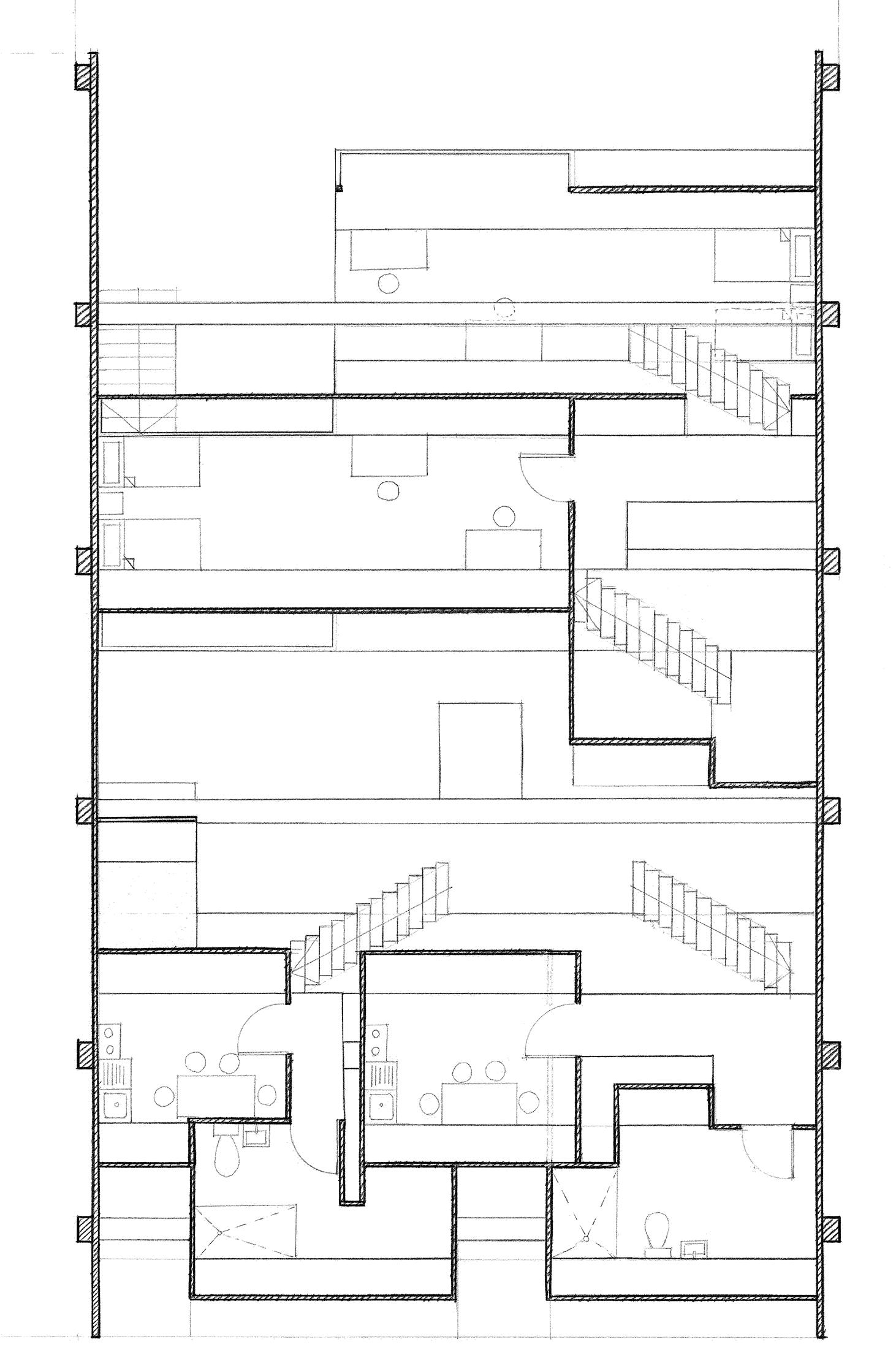

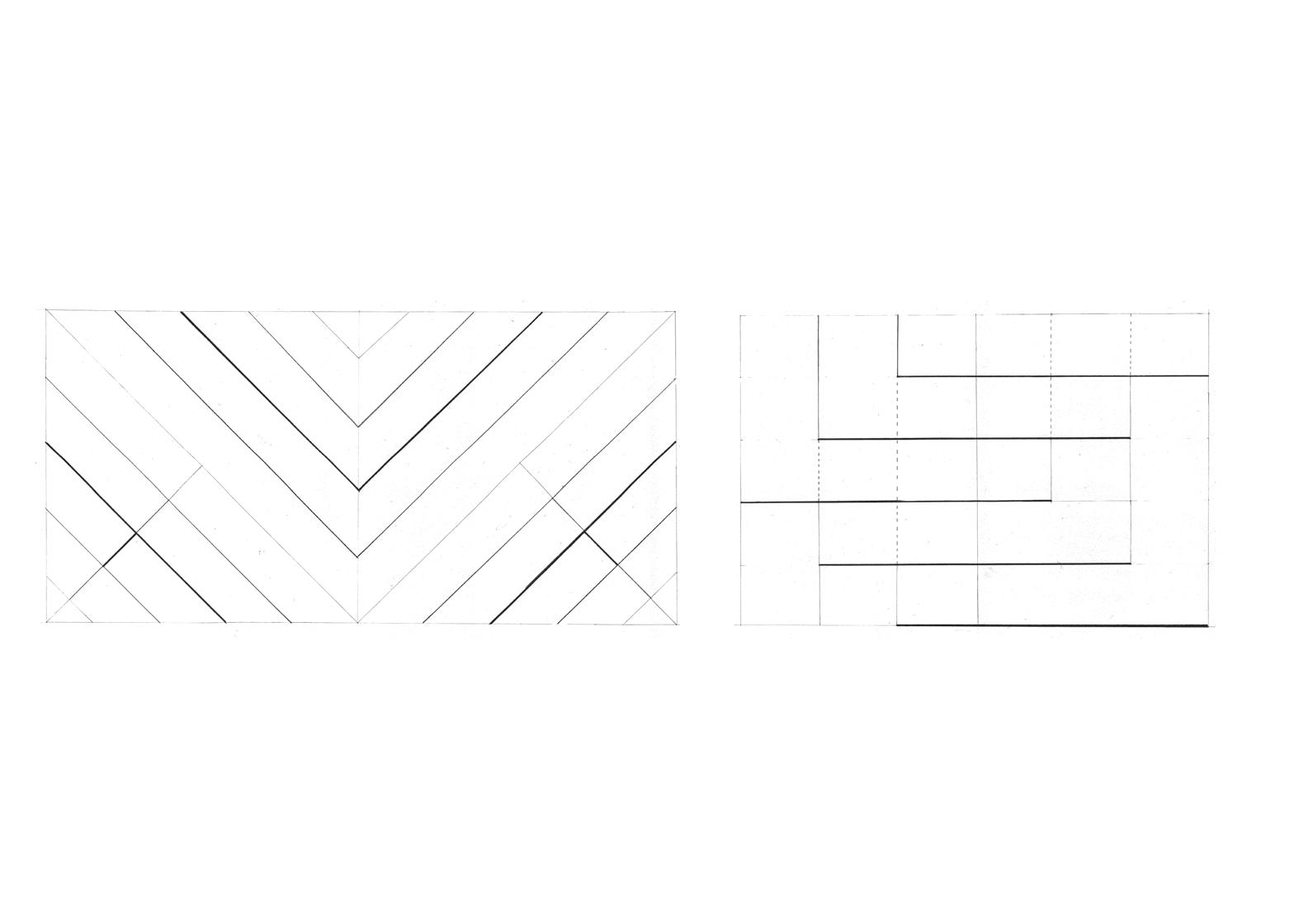

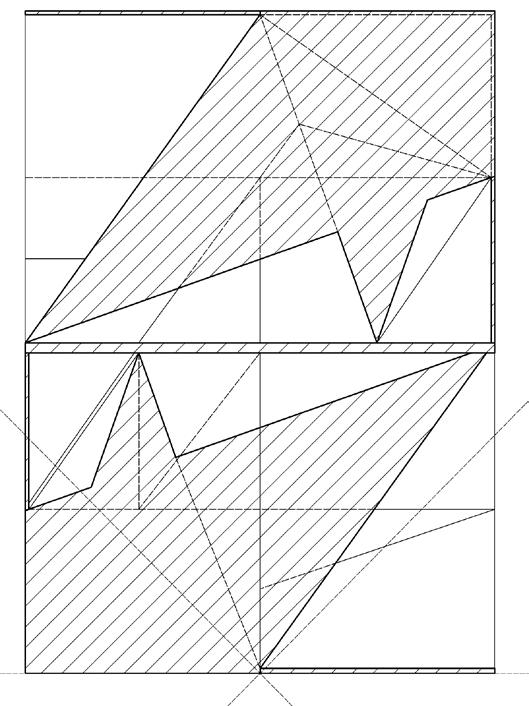

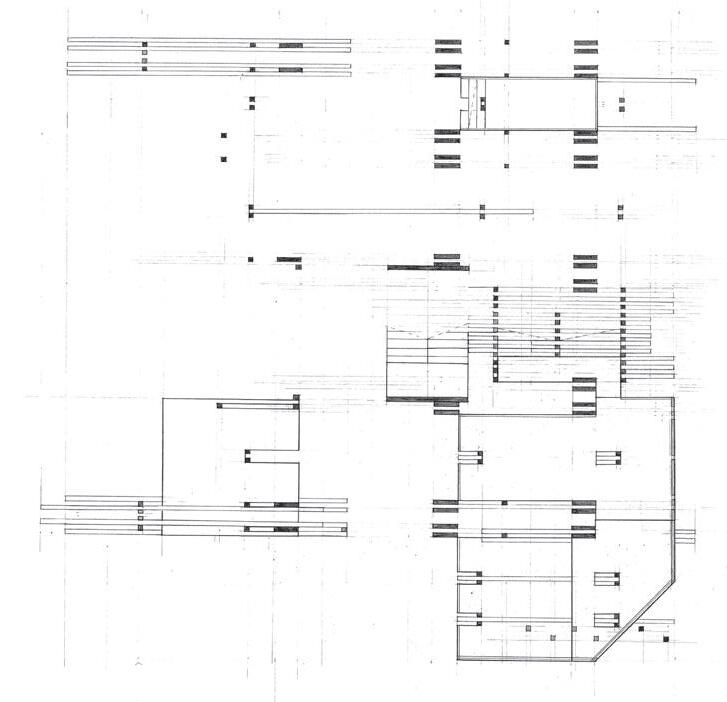

The drawings, models and images in the book are the product of a series of basic probes. The probes are predicated on Euclidean geometry for the ease of manipulation. Models can simply be constructed. Drawings are relatively basic. Digital technology is present though usually not the driver. Complex algorithms are left to upper level studios. Basic operative techniques are taught: addition, subtraction, duplication, displacement, repetition, deformation, mutation, warping, folding, shearing, stretching, compression, expansion. These are

verbs. They are applied to basic geometries: A cube, a plane, a line, a screen, a mesh. Worlds of inhabitation are created between the noun and the verb. Further complexity is added after formal logics are developed; new materials, limited functions, possible sites create additional demands on the form.

Parts are subtracted, ideas eliminated. Nothing is given priority yet the container of form drives the research. Basic addition and subtraction take on new meaning. Geometry, material, structure, program, atmosphere, become mutational components in architecture brought together in form. Programs, functions and utility are designed just as geometry is designed. A loose fit is encouraged. The intent is to push the formal strategy to the breaking point where form reaches the limit of its accommodating potential. It is to find where the geometrical logic has a limit.

Amazing creations happen in this crucible of production. Invention irrupts. Ideas are created that we haven’t seen before. Some strategies may be familiar yet they are new to the students’ eyes. A few ideas are old, yet given a new lease on life. Students develop an ability to express themselves in geometry, in drawings, and in models. Words are purposely left off the drawings. Students can speak all they want. But ultimately, it is the drawings and models, like buildings themselves that speak after the architect is gone.

In the context of Southeast Asia, functionalism remains prevalent in the discourse of architecture. In Singapore, where this work is produced, its entire territory is functionalized for quantifiable results. The architecture of the nation suffers in its monotony. An environment where eighty three percent of the population lives in a uniform landscape of Government sponsored housing (HDB), formal variety is repressed supplanted by uniform construction expediency.

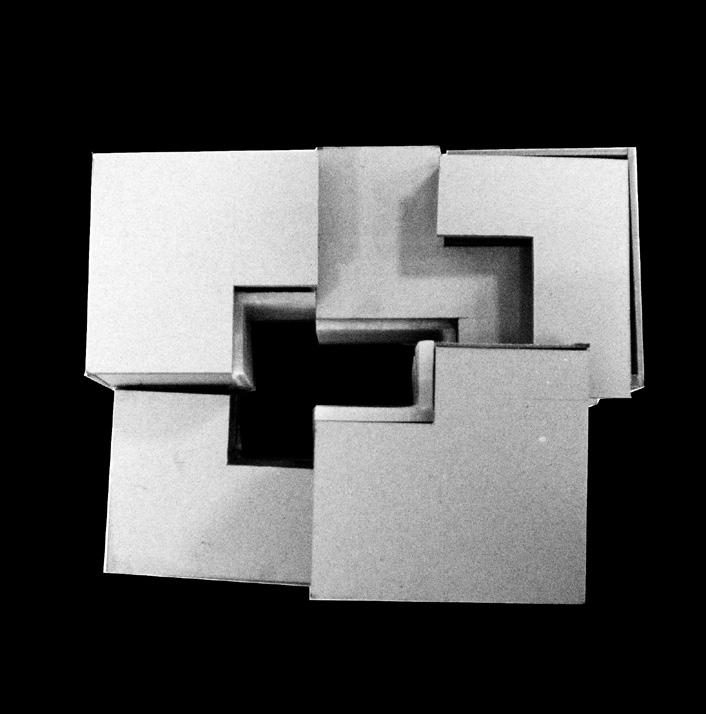

Yet in this landscape of geometric simplicity, in a school of the slab block studio, 11 students, starting with a basic 200x200x400 mm volume and through a series of transformational processes, create 11 amazingly diverse and provocative projects where atmosphere, material, function, structure, program, urbanism, site, environment are all contained within their own container of

formal logic. Projects individually deal with the burdens of the grid, the dynamics of the diagonal, repetition of objects, symmetry/asymmetry, and section vs. plan organizations among many others. Students speak with confidence in their geometric research. They take on the white elephant directly.

This book purposefully leaves out notations of program, site, function, utility, temperature, and color. In fact it indicates little of the functional complexity of each project. Trust me, it is all there. You will need to look closely. And this repression is by design. The arrangement of projects is not linear or typological though similarities between approaches may be compared. What this book does show is probes into formal logic. The reader can project his or her functional imagination into each project’s strategy of accommodation. The promise is that the architect is always in control, always probing into the specific knowledge autonomous to the discipline of architecture.

“Geometry used to be called the science of space” as noted by Robin Evans. I like this saying. The science of geometry -- the science of form -- sounds a little less dirty and definitely more empowering.

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP Assistant Professor Department of Architecture School of Design and EnvironmentA single sheet of paper, with words donning a familiar font.

Grey board, basswood, wax, and lines on paper.

Every week.

We all started the same way - with the same parameters, with the same materials, trying to interpret the black and white of the probes and translate those words into something we could present (or, try to) in the next studio session.

We began, all the same.

We ended, different. Each of us vastly so from the adjacent person sharing (or, fighting for) the space on the cutting mat next to him/her.

We ended up with more models than our humble studio space could accommodate; with thick stacks of drawings too overwhelming to count; as well as an entire stack of post-it stickers upon submission.

Which is, perhaps the reason why we decided to hold this exhibition? Not.

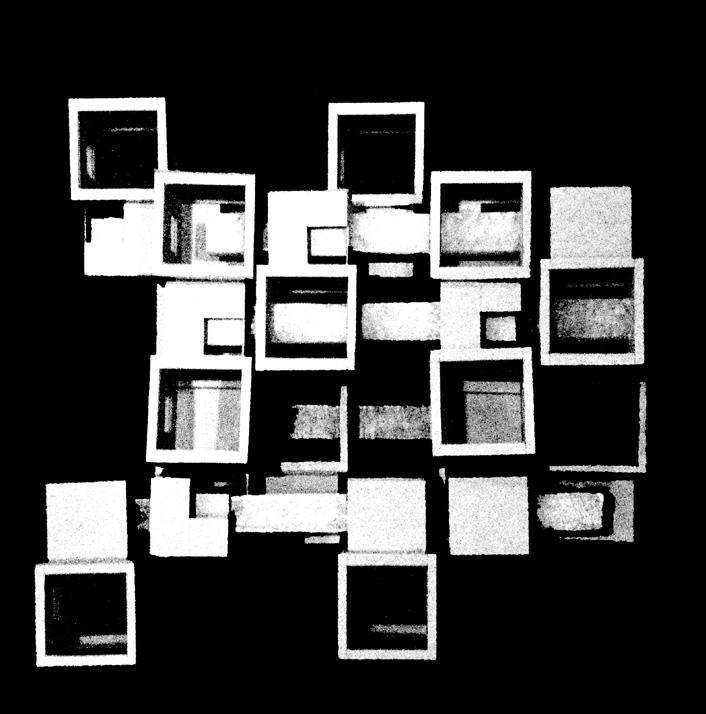

We want to show how black and white can become grey, how differences and diversity can emerge from singularity and homogeneity. We want to showcase our studio direction and how it has allowed for eleven individuals to come up with vastly different projects based on the same parameters set in text every single week.

A singular volume, with fixed dimensions. Every single one of us. That’s how it all started.

But it was not how it ended. And we present to you, not the conclusion, for there is no conclusion, but the process of our work.

This is studioFOUR’s one semester.

Lee Wen Hui, Jolene Studio 4 RepresentativeLooking back at the semester that has passed, it has been a truly rewarding experience. Throughout both projects, a bold and consistent method was used to guide us along the process – a method which was followed religiously, yet, it produced a myriad of results.

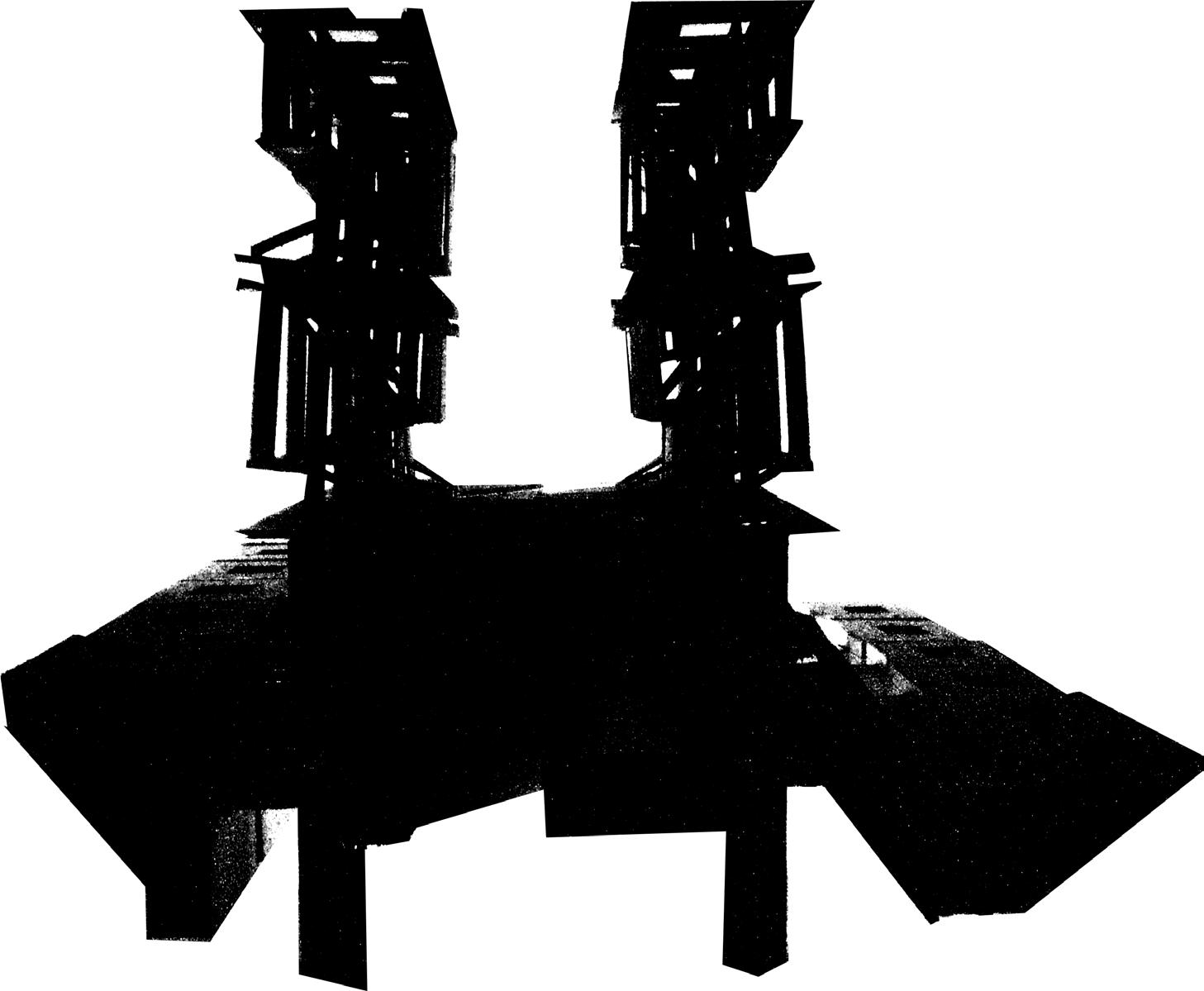

The process was unusual from the start. With few written instructions and specific dimensions to follow, we were to come up with modifications and interventions to a cuboid.

After a mere couple of weeks, the cuboid began to morph, evolving into something strange and compelling. No one could even come close to predicting what resulting schemes would transpire. Often, drawings and words helped to make sense of what it was, attempting to keep the dynamic “creature” under control.

Then came the time when we had to assign function to our unconventional composition. Further transformations were executed to appropriately fit our creation into its site and context. Finally, we rounded off the project with a poetic narrative to further enrich the architecture’s meaning and elegance.

We learnt the importance of the process of model making, drawings and writings, and, of the ability to look at our models and read them formally.

Most importantly, we realise the significance of having our models formally legible; That is, to communicate effectively, a compelling idea to our audience.

Lim Li Wei, Isaac

Acknowledgements

In design, there is hardly any right or wrong. There is no such thing as perfection when beauty can be found in flaws; Like the texture of cracked cement inspiring the beauty of raw simplicity. The physics of construction holds rules written in black and white. The creative imagination of the mind holds none of such limitations.

The symbiotic blend between the technicalities of construction and the limitless reach of the mind is arguably the very definition of architecture. It is a grey area. It is always, a thing of potential; And the same can be said about these eleven students from NUS Faculty of Architecture as they set out to venture into the far reaches of architectural possibilities. They arrived at a myriad of findings over a course of one semester as they embarked on two very challenging projects.

As such, we show our gratitude to these students who had the courage to challenge themselves and just as significant, the people who supported them and allowed them to share their discoveries with the public.

Their tutor for the semester, Professor Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP, whose guidance and motivation are certain to have been a great impact on the students and their works, is to be congratulated for having aided in the process of producing such great results. Similarly the guidance and critique of the other tutors and the student’s peers should be shown the same gratitude and appreciation.

Finally, a special thanks to Daiya Engineering Pte Ltd, DCA Architects Pte Ltd, Zenecon Pte Ltd, LAUD Architects, Vento Systems, Stone Element, Axis Architects Planners and Fancy Papers Supplier for their sponsorship and support, without which, this exhibition could never have been possible.

In appreciation to the Black and White and everything that comes in between; Grey.

We knew Erik L’Heureux’s studio approach prior to checking the box beside his name during the online bidding exercise for our studios, taking into full account the consequences of our actions.

The experience was nothing short of the stories we heard from his previous studios - grueling, intense, relentless, and most importantly of all, extremely rewarding.

This challenge allowed us to emerge with a large collection of impeccable works, as well as, a new found vigour towards the pursuit of design.

Erik believed that the rest of the architecture modules we were simultaneously juggling would be sufficient in informing our design decisions. This maximized the time he had with us, by forcing us to be significantly focused on our formal approaches.

His timely guidance, invaluable expertise, as well as constant support and motivation throughout the two projects have benefitted us immensely.

He was always delighted to hear about our eccentric ideas about design and even shared a few of his own, pushing us forward, ensuing unpredictable results and radical new forms.

For these, we thank him for his unfailing faith in us all.

On behalf of the NUS GREY _Exhibition ‘09 team, we would like to take this opportunity to express our heartfelt gratitude and many thanks towards Daiya Engineering & Construction Pte. Ltd. for their generous sponsorship and contribution to GREY_Exhibition ‘09.

This publication and the exhibition would not have been possible without their generosity.

With their kind donation, they provided the GREY Exhibition team with the platform to share our design approach and architectural beliefs to a large audience.

As a result, the GREY_Exhibition ’09 team was able to gain the invaluable experience of realizing an exhibition from scratch, as well as, of designing and publishing a book.

Thus, we would like to sincerely thank the company for their industrious undertaking in aiding the design students in an effort to bridge the gap between the design students and the public.

We wish the company affluence and success in their business endeavours.