BEYOND CARBON NEUTRALITY

DEPARTMENT

DEPARTMENT

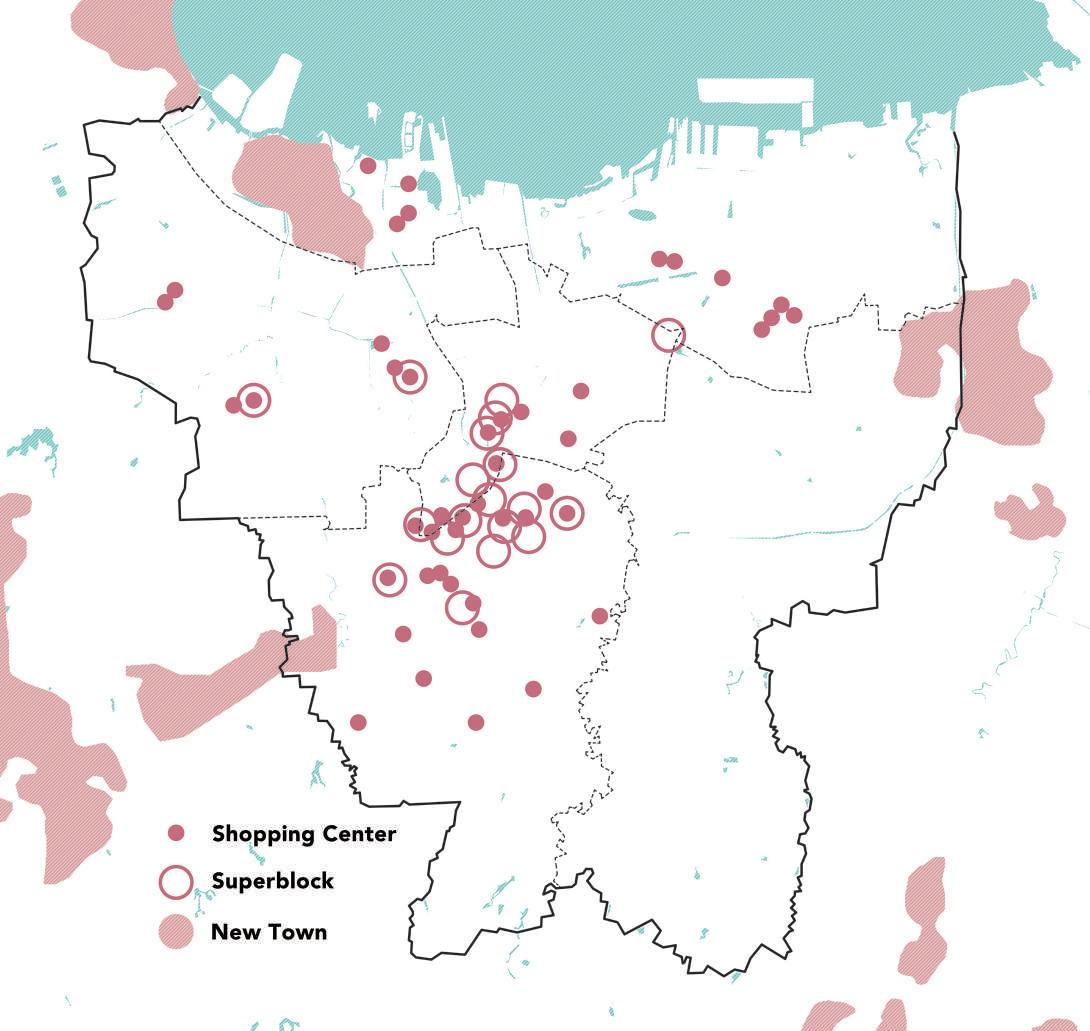

Jakarta is now one of the fastest-growing cities in Southeast Asia. Since the neoliberal urban rescaling in 2006, many superblocks have been built in urban and suburban areas. Superblocks tend to be in the middle of Kampungs because the land is most efficiently acquired here. This creates a unique scene with huge differences in scale with a great visual impact. As energy-intensive buildings, huge-scale superblocks embody architectural forms shaped by the contemporary fossil fuel resource system (Iturbe, 2019).

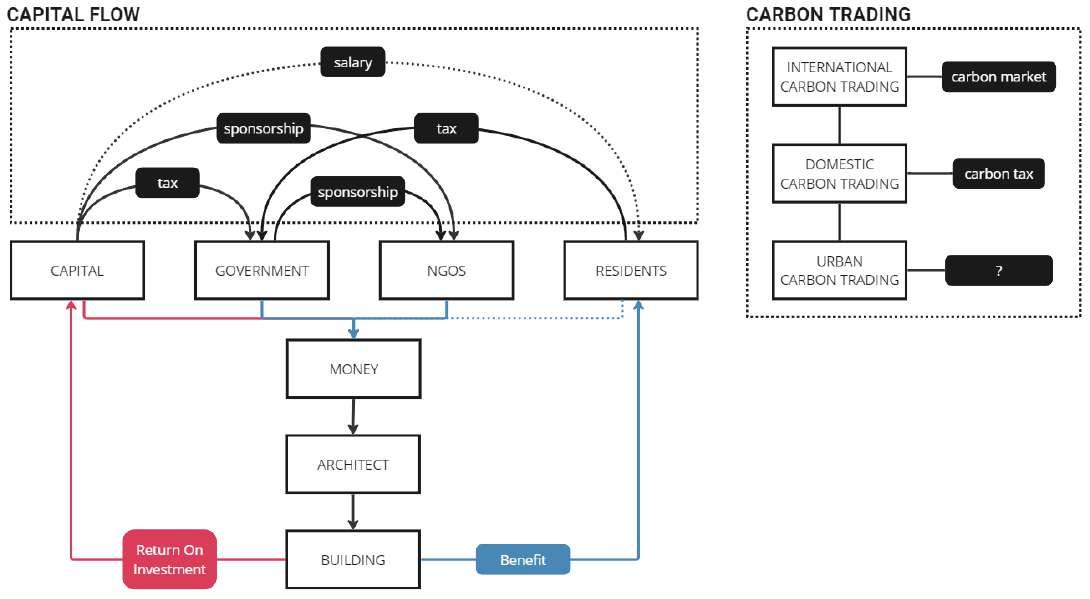

While the middle class living in superblocks owns more property, they also have the power and ability to emit more carbon. There is a highly bound positive relationship between capital and carbon emissions. This shows that aside from the contemporary background of globalization and neoliberalism, there is a deeper and long-term reason for this segregation, which is capital. To some extent, carbon is capital. Therefore, ordinary green buildings are no longer effectively solving Jakarta’s environmental and social problems.

This thesis report focuses on how green buildings can intervene in Jakarta’s urban space. It digs into the spatial and social fabric at a deeper level through a contemporary summary of the collective forms of the Superblock and Kampung. This paper utilizes Kampung’s decarbonization potential and carbon differentiation to drive capital flows to help residents. Architects, in turn, can use this capital to design green buildings to provide spaces and functions. Furthermore, through the energy production and carbon absorption of the buildings, the system can be made sustainable. Over time, the original split between Superblock and Kampung could be alleviated. Architecture goes beyond carbon neutrality to assume a larger role in Jakarta’s urban space.

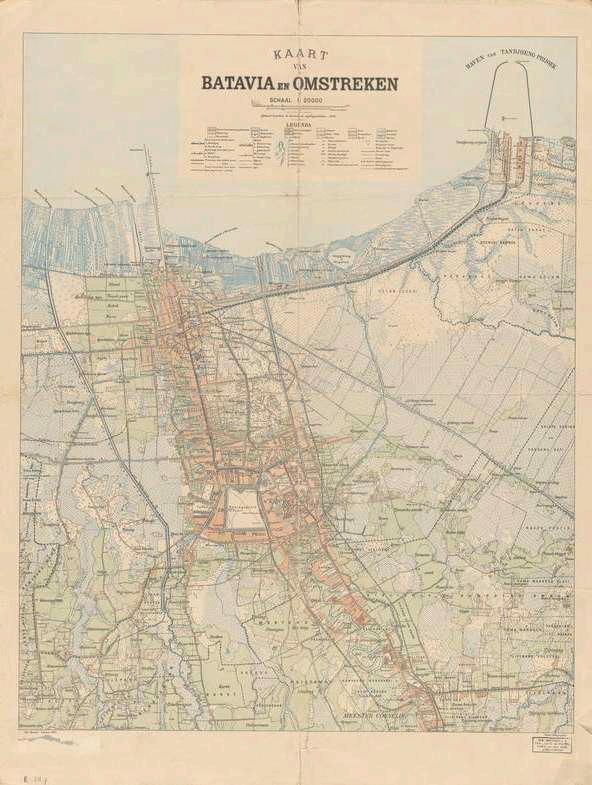

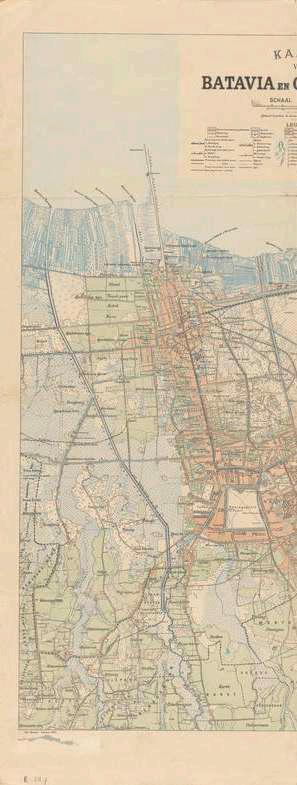

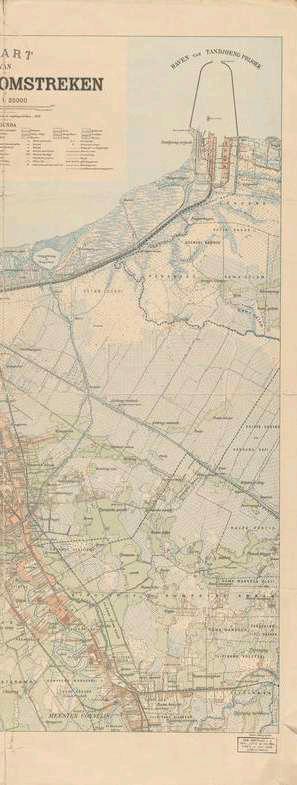

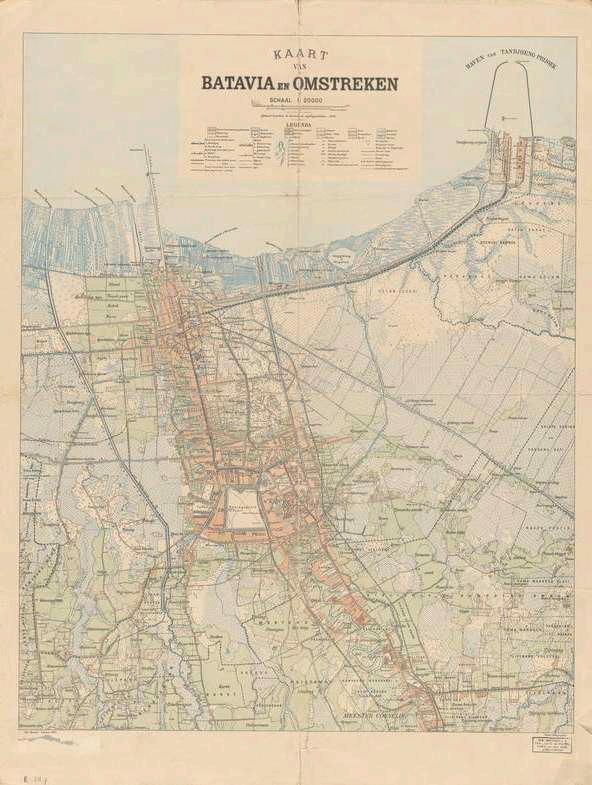

The history of Jakarta can be divided into pre-colonial period, colonial period, and post-colonial period. Although the land of modern Jakarta became a population center as early as the fifth century AD, urban emerged after the Dutch colonization. The governance system of Batavia (the predecessor of Jakarta) was zoning and subcontracting power, so Kampung in “niet bebouwde-kom” (non-built-up area) outside the “bebouwede-kom” (built-up area) maintained their autonomy(Kusno, 2015). Although Kampung’s development around the city was not greatly restricted, this colonial dualism set the tone for the city’s segregation feature, now known as “formal” and “informal”(Leaf, 1993).

After Indonesia’s independence, Sukarno pinned the glory and image of the post-colonial country on Jakarta. As a result, boulevards, memorial squares, and commercial high-rise buildings rose from the ground(Kusno, 2014). After Suharto took over, the power of private capital began to intervene and influence Jakarta’s urban development. People from surrounding areas poured into Jakarta to find better jobs and live in urban Kampung. In the 1970s and 1980s, the government’s permission to develop informal communities on the state’s informal land exacerbated the transformation of urban Kampung into slums.

The arrival of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 not only ended Suharto’s rule but also ended the era of rapid development of suburban new towns. Urban lands were sold off in large quantities under the International Monetary Fund’s leadership, and the Jakarta real estate market was significantly liberalized after the democratic transition. After 2006, many huge living complexes (also known as superblocks) emerged in urban areas, such as Mega Kuningan, which is now the center of Jakarta’s CBD.

Due to the informality of the land, residents in urban kampungs are the most manageable targets to be evicted, so many superblocks were built in urban kampungs. Throughout Indonesia’s history, division has been its feature, whether geographical, ethnic, cultural, or class. From the fortress-like architecture of the Dutch colonial period to the upscale gated communities surrounding Jakarta in the 1980s and 1990s to today’s superblocks, it is this legacy of urban segregation that has given rise to the present-day urban spectacle that resembles the descent of an alien spacecraft.

Jakarta map in 1897

Jakarta map

Jakarta map in 1897

Jakarta map

map in 1919

Jakarta map in 1938

Source:https://www.oldmapsonline.org/en/Jakarta

Jakarta Kampung Mapping

Source: Map by Prakoso,

by author

Saputra, and Dewangga, 2018, modified

Source: Herlambang et al., 2019, modified by author

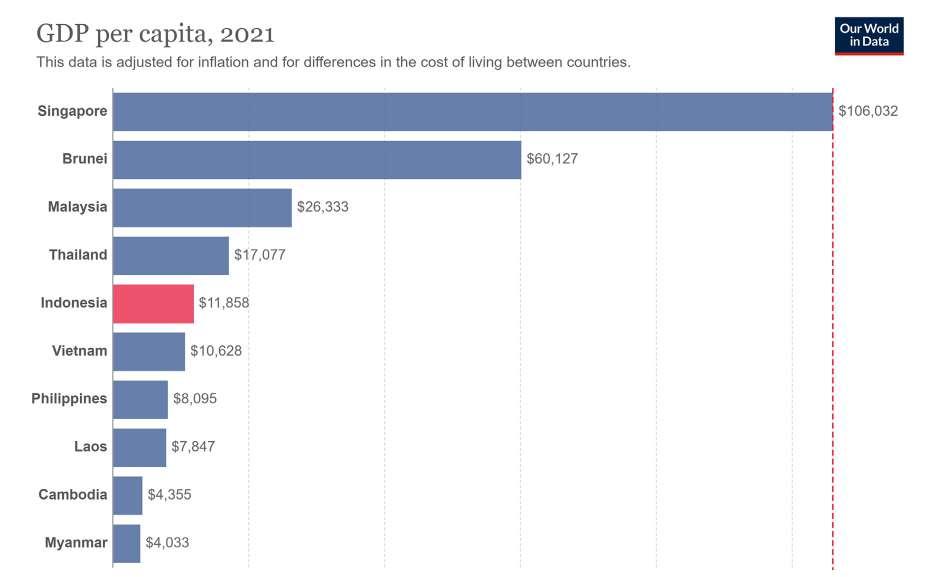

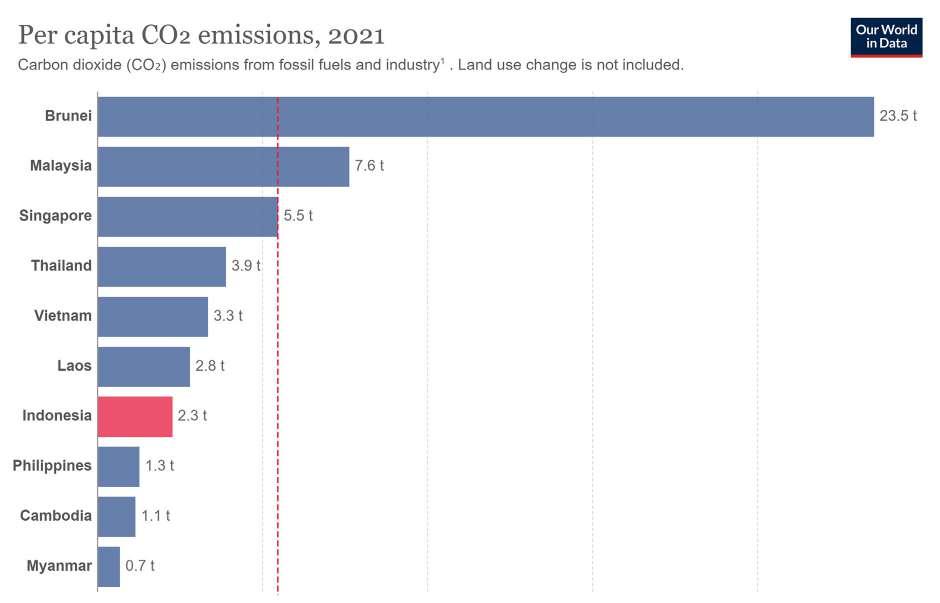

Jakarta Superblock MappingDue to rising sea levels caused by greenhouse gas emissions, Jakarta has become one of the cities that most severely affected by the climate crisis. Indonesia’s carbon emissions in 2021 were 619.28 million t, ranking first in Southeast Asia. However, Indonesia’s per capita carbon emissions in 2021 were 2.3t, ranking only 7th in Southeast Asia. By comparing with GDP per capita, there is a correlation between the two data.

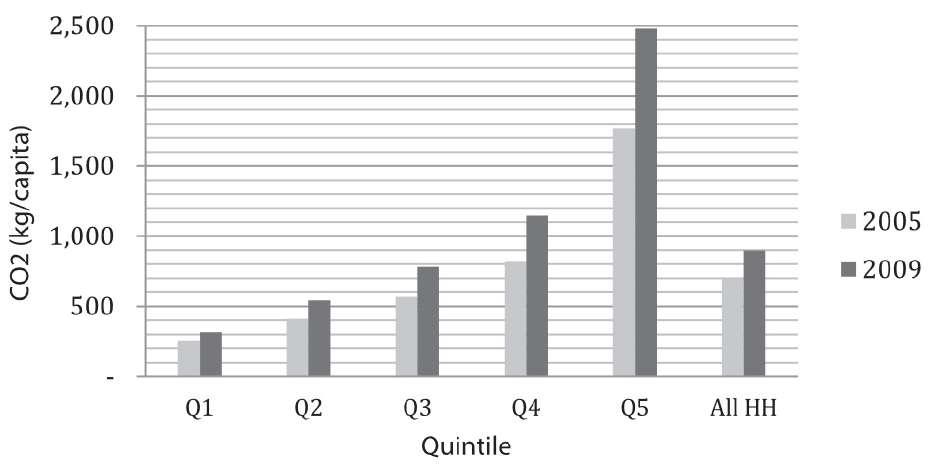

Moreover, the relationship between economic growth and carbon emissions also exists on a smaller scale. Rusiawan (2014) used Jakarta as a case to establish a system dynamic model to show the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions, energy consumption, population, and gross domestic regional product (GDRP), then found a strong correlation.

Irfany (2017) calculated the carbon emission intensity of each industry based on the Indonesian economic IO and each industry’s carbon emission values, then calculated the household carbon footprint by combining the various household expenditure values. The carbon emission per capita of the wealthiest group is 8.3 times that of the poorest group. Moreover, between 2005 and 2009, the former’s increase was 14 times that of the latter. During this period, superblocks began to be constructed on a large scale in Jakarta, emitting considerable amounts of carbon dioxide.

Modern high-rise buildings are a consequence of capital and the accumulation of substantial carbon deposits stemming from energy-intensive lifestyles. The coexistence of superblocks and urban Kampung in Jakarta visually represents the significant wealth gap within the city. Moreover, it is physical evidence of the modern carbon injustice under capitalism.

Southeast Asia’s CO2 Emissions Per Capita in 2021

Southeast Asia’s GDP Per Capita in 2021

There is a high degree of similarity in the ranking of GDP per capita and CO2 emissions per capita among the countries in Southeast Asia.

Source: Our World

Southeast Asia’s CO2 Emissions Per Capita in 2021

Source: Wawan Rusiawana, Prijono Tjiptoherijantob, Emirhadi Sugandac, Linda Darmajanti

Southeast Asia’s GDP Per Capita in 2021

Source: Mohammad Iqbal Irfany, 2017

There is a high degree of similarity in the ranking of GDP per capita and CO2 emissions per capita among the countries in Southeast Asia.

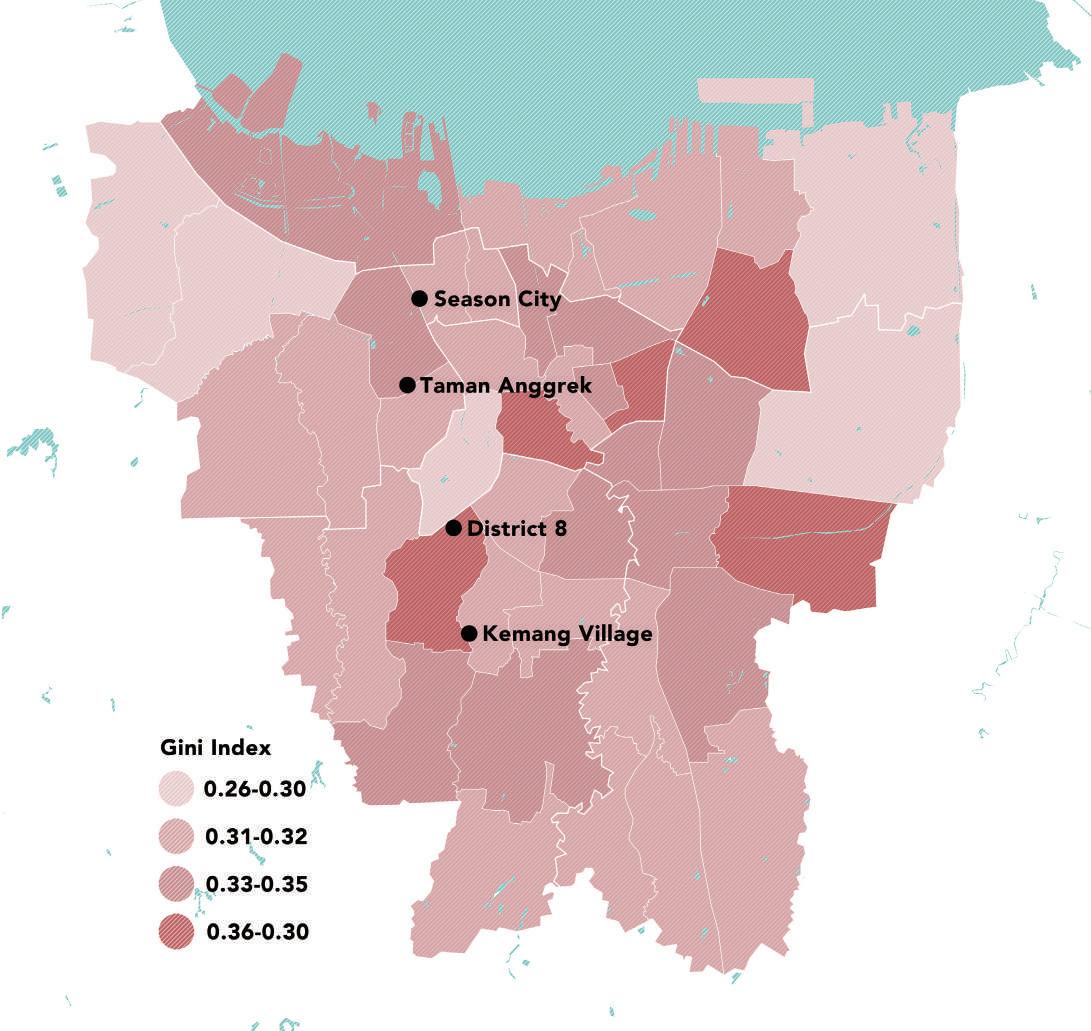

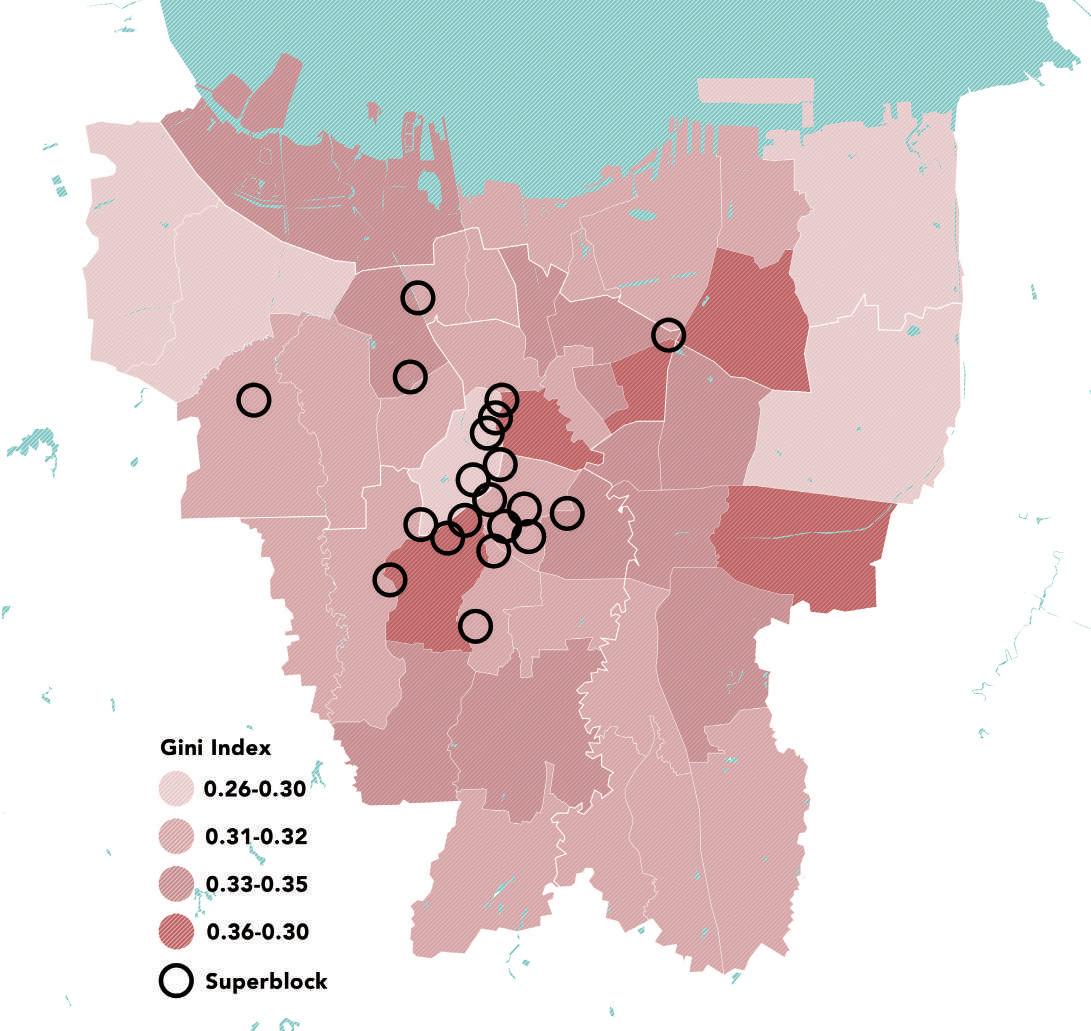

The four Sites chosen in Jakarta are Season City, Taman Anggrek (Orchid Garden), District 8, and Kemang Village. Interestingly, two superblocks use the super-scale words (city and district) as their names, while the other two use village and garden. This discrepancy is ironic and exclusive when expressing the developer’s vision (Wiryomartono, 2020).

Source: Autor

The location of the four sites are all at the districts’ boundaries. On the one hand, this is caused by Jakarta’s zoning method, using main roads, elevated highways, and waterways as boundaries. Another aspect is that the poorest people in cities tend to build their residences on marginal public land(Leitner & Sheppard, 2018), which is the easiest to purchase and demolish.

Source: Rukmana & Ramadhani, 2021, modified by author

Another aspect is that the poorest people in cities tend to build their residences on marginal public land(Leitner & Sheppard, 2018), which is the easiest to purchase and demolish. These geographical, economic, and social factors led to the distribution of superblocks today. These junctions are more accessible and attract developers. economic, and social factors led to the distribution of superblocks today.

Source: Rukmana & Ramadhani, 2021, modified by author

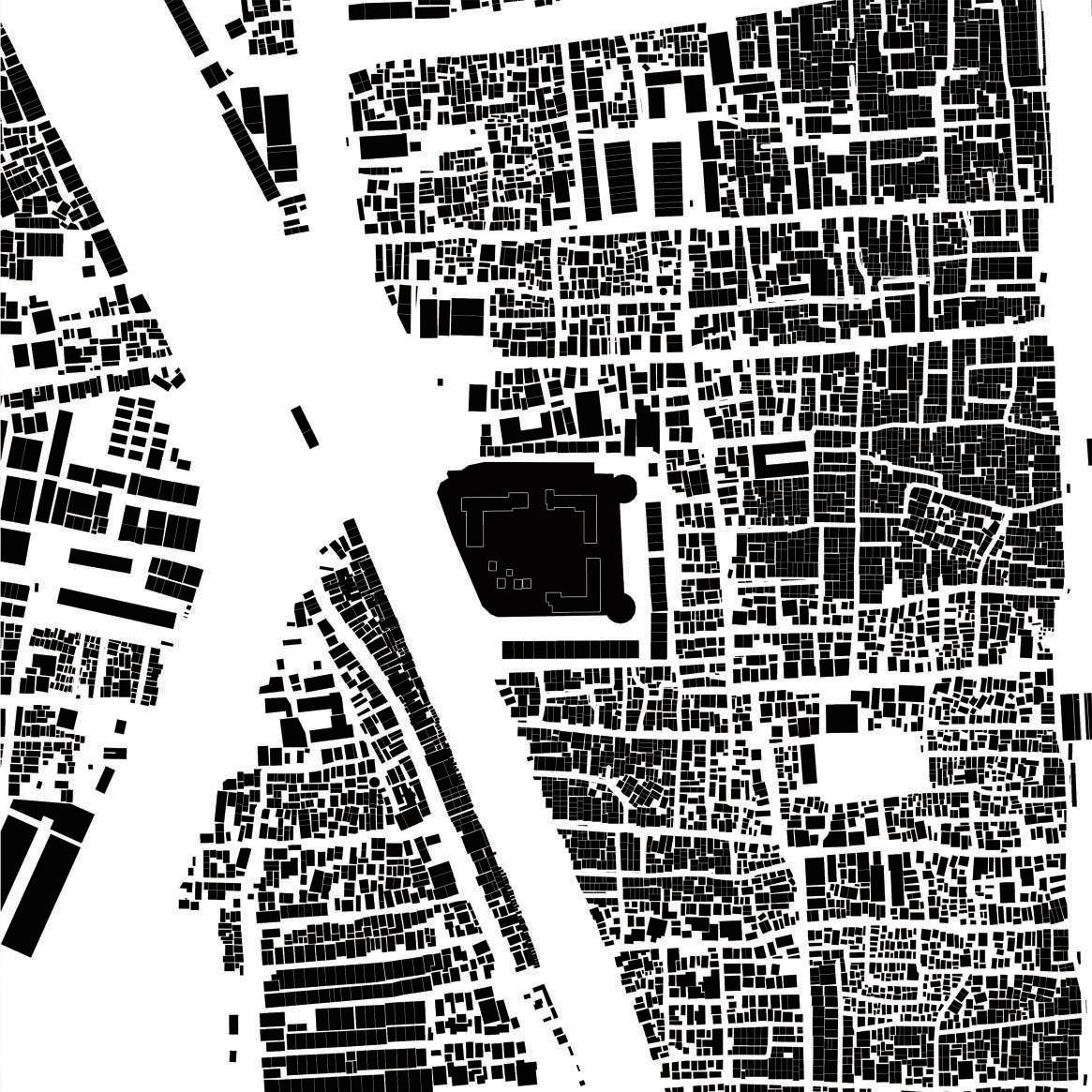

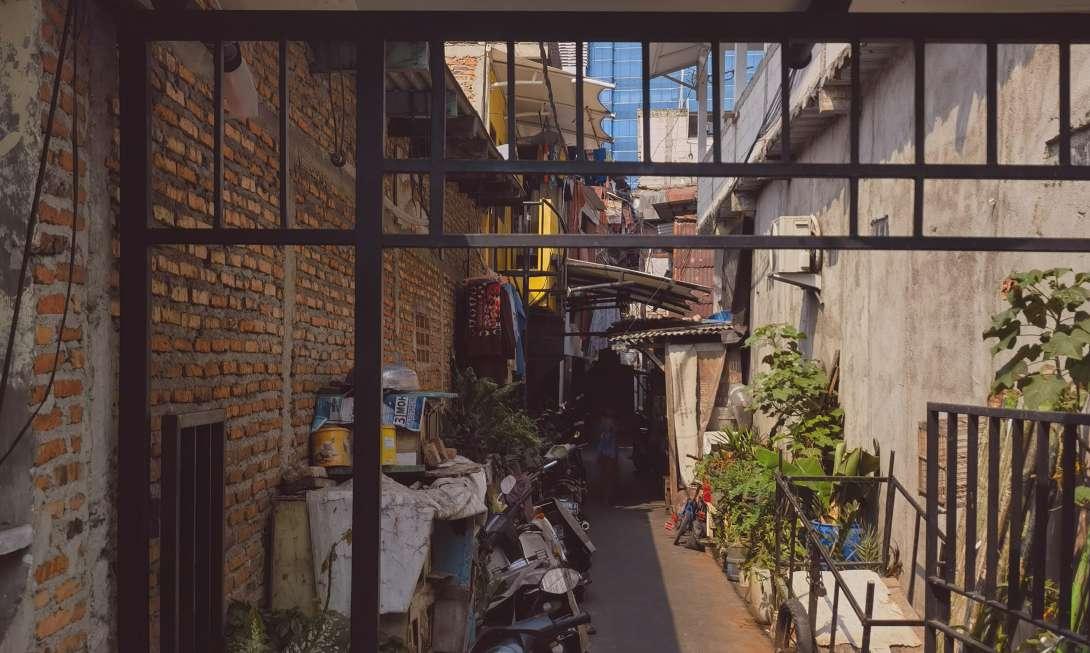

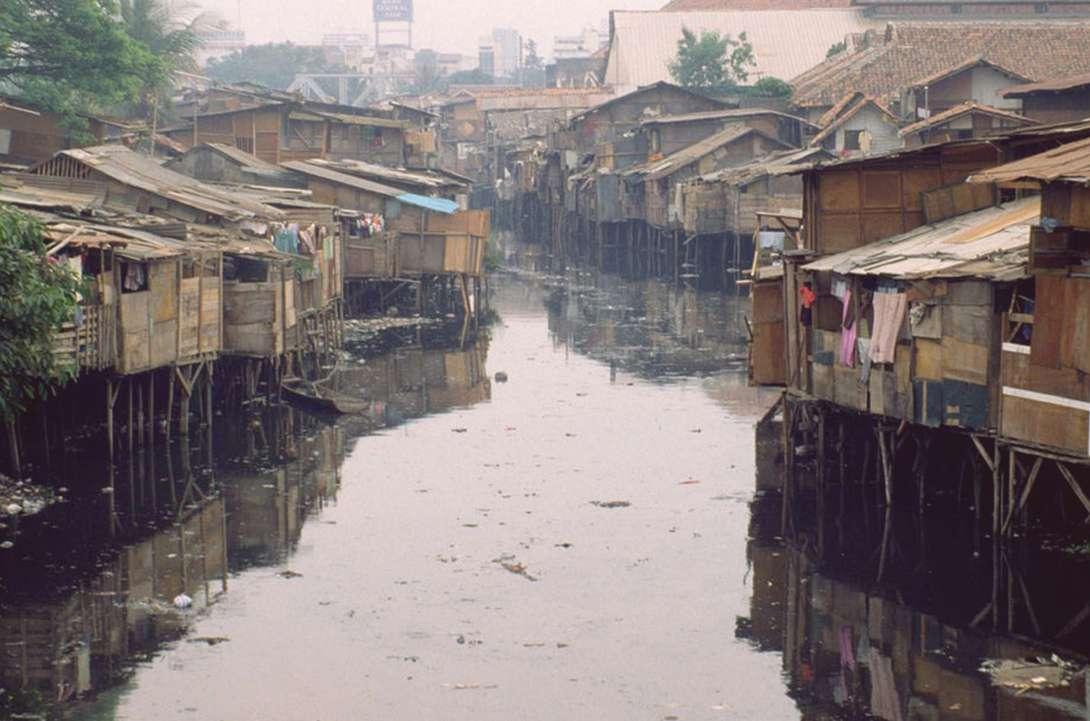

Season City is in Jembatan Besi at the junction of the Grogol Petamburan and Tambora districts, adjacent to the Ciliwung River. Low-income families along the river live in narrow alleys about 0.5m wide. To compete for more space, many of the alleys have been covered by additions, which results in a very tight urban fabric and high housing density.

Despite not being well off, residents refused to move to subsidized apartments in 2015. In the local Kampung community, their sources of income, education, and living needs are within a comfortable distance(Desiyana, 2018). The ground floors along the streets are primarily for commercial use, which includes restaurants, convenience stores, and laundry shops. And those residents living in narrow alleys move to the street using carts to sell poor-quality snacks and drinks. There is a tremendous economic gap between the households living along the streets and in the alleys.

The indoor playgrounds, hotels, parking lots, elevators, and security guards are barriers to separate high-income residents from the Kampung. Due to the large low-income community, the ground floor of Season City is mainly commercialized with low-end stores. At night, residents of Kampung take over the street to sing, eat, and cool off in a lively atmosphere that seems to be two worlds away from the high-rise residences.

Satellite Image of Season City and Kampung

Satellite Image of Season City and Kampung

Urban Fabric of Season City and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Urban Fabric of Season City and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

0.5m Wide Alley

1m Wide

0.5m Wide Alley

1m Wide

The wider the alley, the more items there are. The function changes from private to public, and the space transforms from informal to formal.

Source: Author

Wide Alley 2m Wide Alley Laundry Shop

Laundry Shop

Streets are different from alleys, with more open space, more commerce along the streets, and better economic conditions.

Source: Author

Snack Bar and Carts

Residents can pick up deliveries, eat, and shop for groceries on the parking lot level for their daily needs. When going out, they can just drive away. Residents’ lives do not intersect much with the ground floor.

Shops on the Parking Floor

At night, the inhabitants of Kampung begin to occupy the streets for recreation.

Source: Author

Drink Bar on the StreetTaman Anggrek lies in Tanjung Duren Selatan at the junction of Grogol Petamburan and Palmerah districts, a prestigious commercial area that has long been developed. There are three main superblocks in the eastern part of the site: Mall Taman Anggrek (1996), Central Park Mall (2009), and Taman Anggrek Residence (2019). Low-rise residences occupy the western part of the site. Urban Kampung is sandwiched between the two areas, radiating from west to east.

According to statistics, the local housing land area from 2009 to 2010 was 1.34 km2; in 2015, the value grew to 1.66 km2. At the same time, the area of land for service and trade grew from 0.026 km2 to 0.11 km2. The disparity between the two increase figures suggests that more people are attracted to urban Kampung as new superblocks are built(Aditantri et al., 2019).

Satellite Image of Taman Anggrek and Kampung

Satellite Image of Taman Anggrek and Kampung

Urban Fabric of Taman Anggrek and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Urban Fabric of Taman Anggrek and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Kampung Street Commercial

Kampung Street Commercial

Kampung here is more commercially developed due to its location, and the houses are more formal.

Source: Author

Kampung Street CommercialDistrict 8 is a newly built high-end superblock in Senayan at the southwest end of Jakarta’s CBD. To the north is the Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex, and to the south is an upscale, low-rise, villa neighborhood. Only a tiny part of the east side is the urban Kampung.

From 2003 to 2022, the Kampung area decreased from 35,000 m2 to 13,000 m2. The land encroached is not high-rise buildings but private open space under security guards. The entire Kampung is isolated by walls, and some houses have been abandoned. On the contrary, walls protect the high-end villa. As a tool of spatial violence, the wall has completely different meanings for the two classes.

Satellite Image of District 8 and Kampung

Satellite Image of District 8 and Kampung

Urban Fabric of District 8 and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Urban Fabric of District 8 and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Satellite Image of Kampung in 2003

Satellite Image of Kampung

Satellite Image of Kampung in 2003

Satellite Image of Kampung

As the most central area in Jakarta, Kampung here has been heavily occupied by urban development and has lost community vitality.

Source: Google Earth, Author

Kampung in 2010 Satellite Image of Kampung in 2022

Fence of Private Open Space House for

Fence of Private Open Space House for

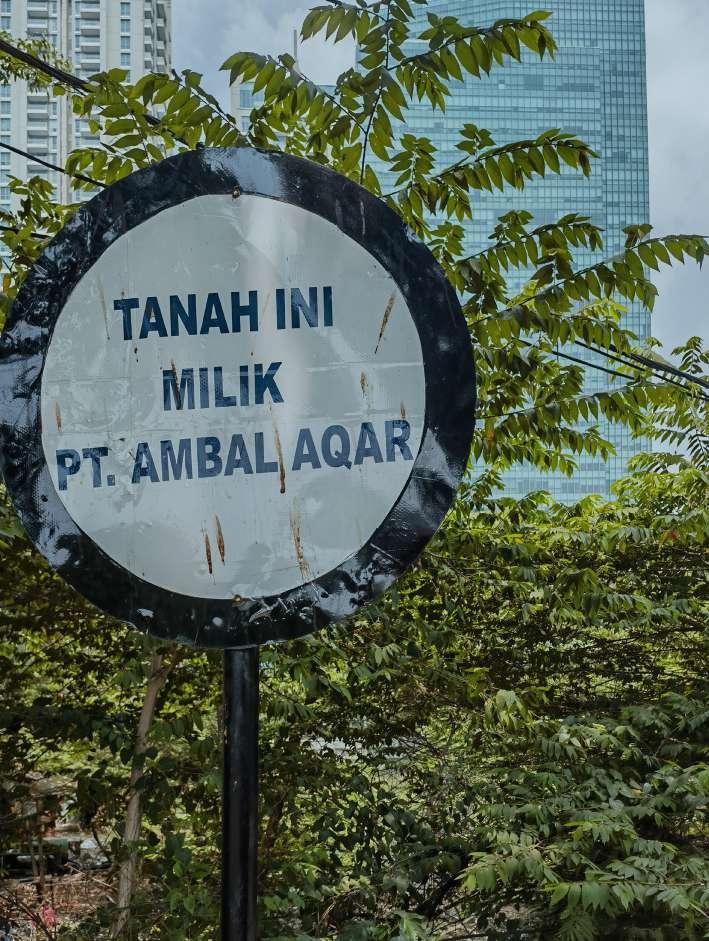

High-value land has long been bought by capital, and walls and slogans can be seen everywhere. Some Kampung residents have had to sell their houses.

Source: Author

Private Land Board

Private Land Board

Source: Author

Dog for Security Wall of Kampung (spikes facing inwards)

Wall of Kampung (spikes facing inwards)

The orientation of the spikes on the fences already hints at the purpose of the wall in each area.

Source: Author

Wall of Villa (spikes facing out)Kemang Village is in the Bangka area on the west side of Mampang Prapatan District. Bangka, known as Kemang, is a residential and commercial area for foreign elites.

Kampung on the east side is adjacent to the superblock and villa area but is surrounded by high walls, forming a long and narrow residential belt. Most of the housing is formal. However, the largest green area is isolated from the community and only serves as an external motorcycle parking lot. For a living, residents cut apertures on the walls facing the superblock and run shops and restaurants. The Grab riders and shopping mall staff eat and rest here. It is like two worlds above and below the superblock’s viaduct system. The top is for high-income groups, while low-income groups occupy the bottom.

On the west side of Kemang Village is the Krukut River. Due to flooding problems(Daniel Mangasi, 2023), green belts are on both sides of the river as a buffer zone, which has also become a natural obstacle between the superblock and Kampung in North Cipete. Informal housings are marginalized, close to the river. Here, the poorest fringes are closest to the wealthiest superblock.

Satellite Image of Kemang Village and Kampung

Satellite Image of Kemang Village and Kampung

Urban Fabric of Kemang Village and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

Urban Fabric of Kemang Village and Kampung

Source: Google Earth, Author

The Prison-like Walls around Kampung

The Prison-like Walls around Kampung

High walls and barbed wire surround Kampung, restricting residents’ space. But to survive, some residents on the border have to cut holes in the wall to serve meals to those working in the superblock.

Source: Author

Green Area from Above

Green Area’s True Function – Parking Lot

Green Area from Above

Green Area’s True Function – Parking Lot

Fence along the Riverbank

High-quality public green space is separated from Kampung by a barrier. For residents living in superblocks, some spaces are simply for infrastructure.

Source: Author

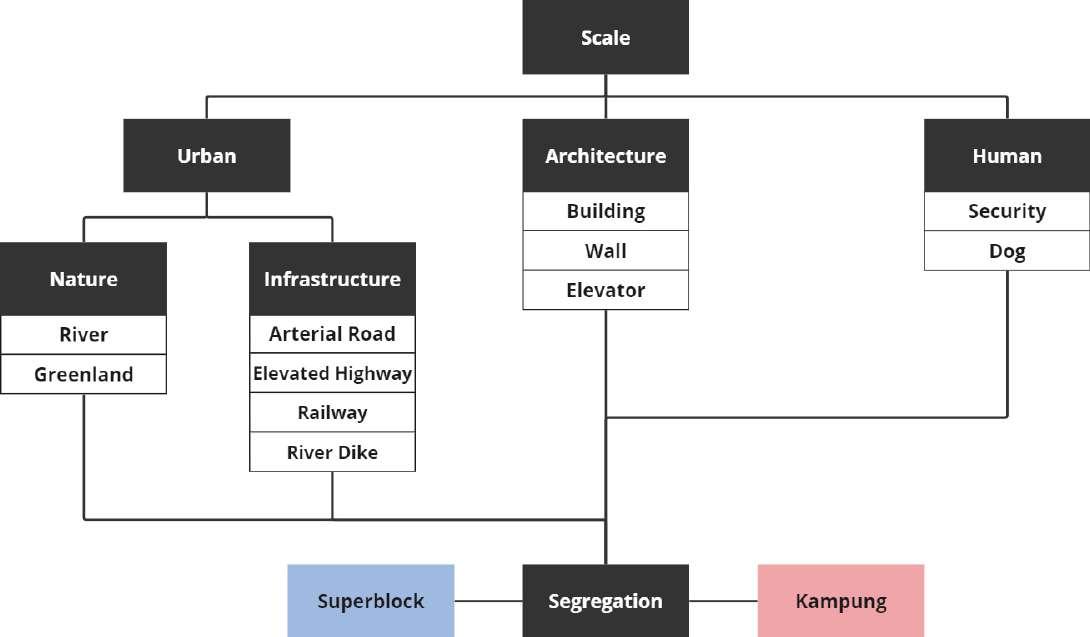

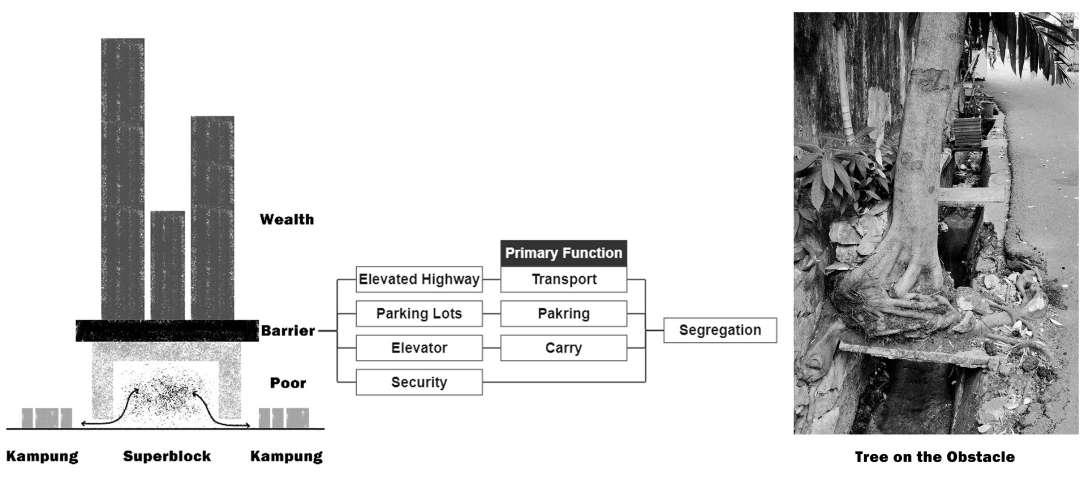

The relationship between superblock and the urban Kampung is symbiotic and segregated. The separation between the two classes can be categorized in terms of scale as urban scale, architectural scale, and human scale.

Urban-scale barriers include natural elements and urban infrastructures. Horizontally, they initially cut Kampung. When superblocks arise along streets, those infrastructures become barriers.

Architectural scale barriers mainly include buildings, walls, and elevators. Buildings are a relatively mild form of segregation that can provide a place for activities while blocking. On the other hand, the isolation effect can also be enhanced by changing the function of the buildings or layers (such as parking).

Walls have been the quintessential representation of spatial violence because their only function is segregation. Moreover, walls are often accompanied by graffiti. Since the 1970s, graffiti has been considered a voice of grassroots resistance(Hasan & Bleibleh, 2023). Therefore, graffiti on the walls also shows kampung residents’ feelings of defiance.

Human-scale barriers mainly refer to security and watchdogs. They are mainly complementary to the above methods, but their proactivity makes them more effective than the passive approaches of the two scales above.

Source: Autor

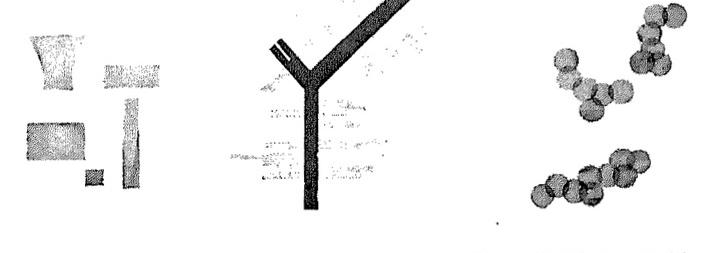

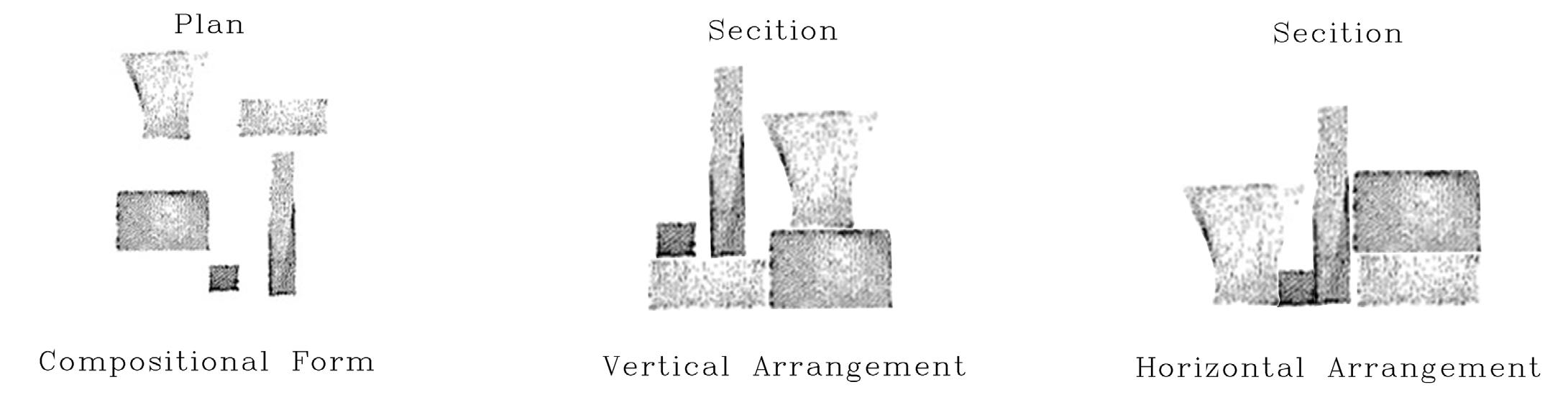

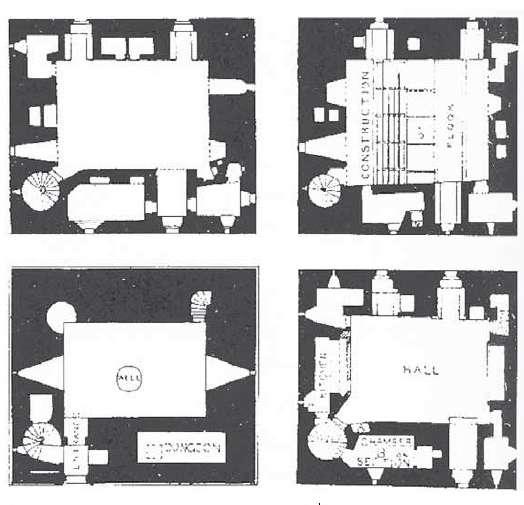

Fumihiko Maki proposed research on collective form in the 1960s. He argued that we must focus on collective forms and then find a way to understand and design cities during rapid development in the 1960s (Maki, 1964). Fumihiko Maki summarized three collective forms: Compositional Form, Megastructure (Form), and Group Form.

Each element in the compositional form is designed independently and then arranged in the site based on space or sight relationships. Compositional form is the most common collective form and is a static design approach.

The Megastructure Form is an artificial giant frame that contains some or all of the city’s functions. This new centralized large-scale space combination has attracted widespread attention as soon as it was proposed.

Group Form evolved from space-generated elements. The housing elements in the system are consistent in materials and construction methods. They are arranged on a human scale using the terrain wisely, such as traditional villages built along the river.

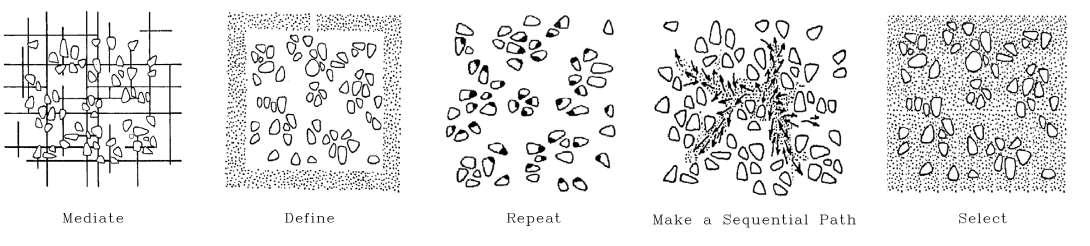

The Research on collective forms led Fumihiko Maki to reexamine architectural elements, such as wall, floor or roof, column, unit, and link. Among these elements, he focused on linkage in collective forms and summarized them into five categories: Mediate, Define, Repeat, Make a Sequential Path, and Select.

1. TO MEDIATE: Connect with intermediate elements or imply connection by spaces that demonstrate the cohesion of masses around them.

2. TO DEFINE: To surround a site with a wall, or any physical barrier, and thus set it off from its environs.

3. TO REPEAT: Give each element a feature common to all in the group so each is identified as part of the same order.

4. TO MAKE A SEQUENTIAL PATH: Place activities that are done sequence in identifiable spatial relation to one another.

5. TO SELECT: To establish unity in advance of the design process by choice of site.

(Maki,1964)

Collective Forms: Compositional Form, Megaform, Group Form (from left to right)

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964

Five Categories

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964

Superblocks can easily be regarded as Megastructure Form, which is large and contains multiple functions. But is it truly a Megastructure Form?

Although architects in 19070s tried their best to rationalize Megastructure through structural design, it is undeniable that Megastructure itself has an idealistic attribute. Many architects expected Megastructures to be a utopia without disparity between the economy and humans. The image of the superblock is different from this. Instead, he is a representative of the gap between rich and poor.

Another main reasons why Megastructure excites architects is that it provides a new framework of combining functions. As seen from famous projects such as Plug-in City and The Marine City project, the combination of units is very innovative and manifold. In comparison, the spatial combination of superblocks is quite traditional and rigid, which can be summarized into two types: vertical arrangement and horizontal arrangement. By contrast, superblocks are closer to compositional form.

Vertically arranged superblocks are mostly mid-end. The commercial area at the bottom has stronger connections with the surrounding community. The upper residential areas are isolated by being raised in height. The below area is usually a parking lot, and residents drive in and out directly on this floor.

The horizontally arranged superblocks are high-end. The kampung around them are either almost demolished or isolated. Since the entrances of residential areas are on the ground, isolation mainly relies on walls and security.

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964 and modified by author

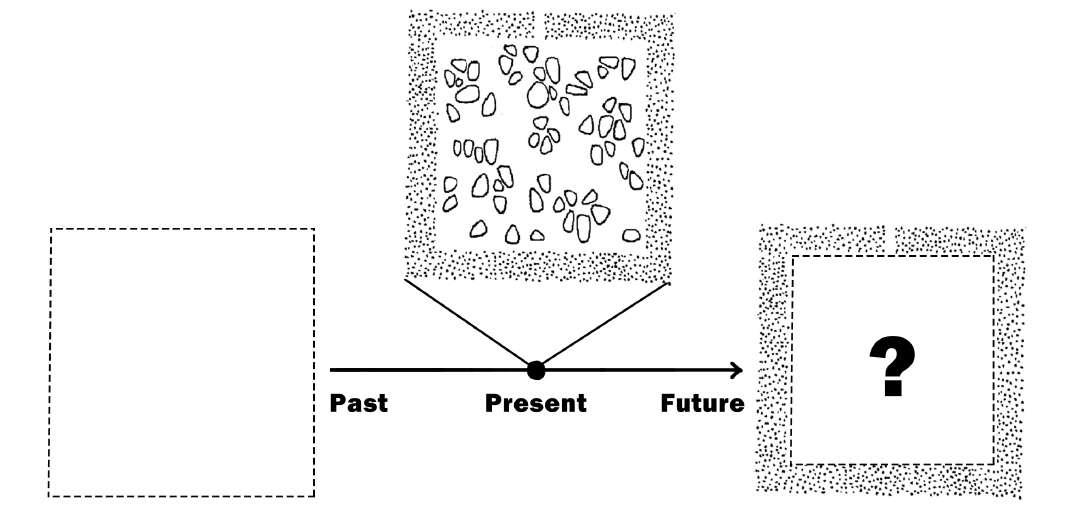

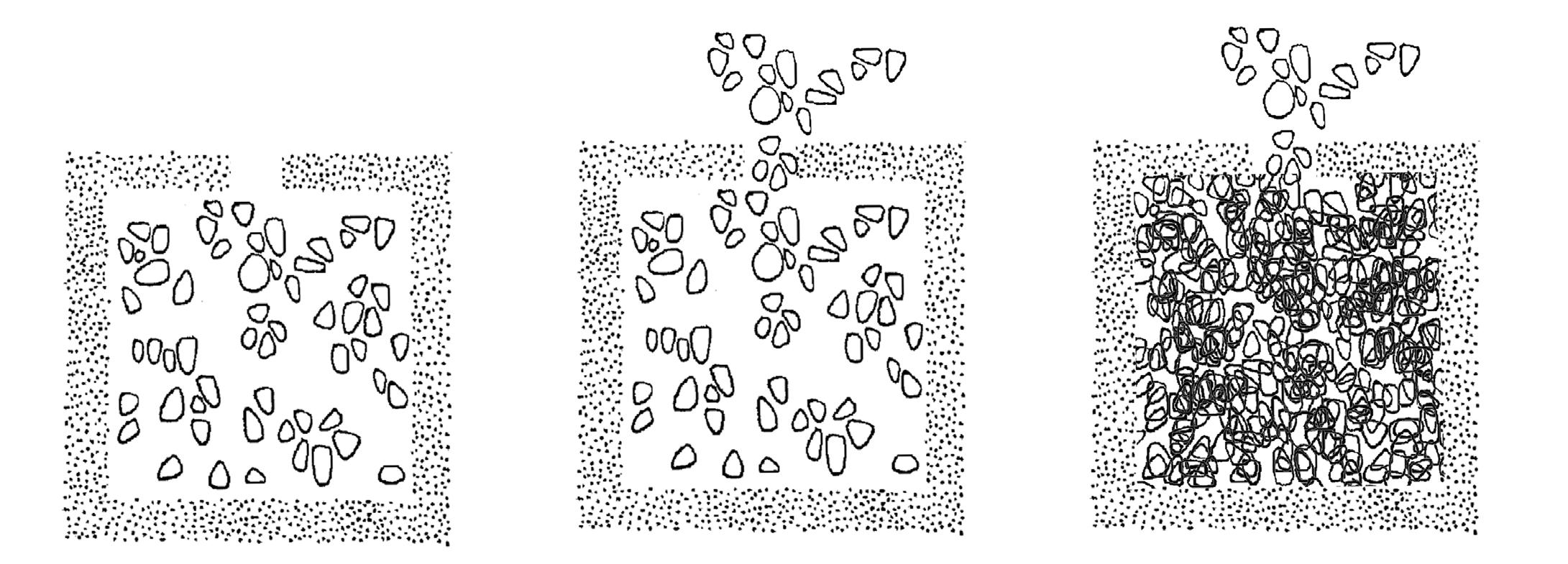

Kampung, as a type of village, is a Group form. However, compared with ordinary villages, Kampung is more chaotic. Maki mentioned walls in Defined Form, which can be many things, such as parking lots and railways. It can be repressive or protective (Maki, 1964). However, Maki did not draw the form from a developmental standpoint. He argued that Group Form is the consequence of evolvement, but his diagram only stayed in the static state. Over time, Group Form will continue to evolve or over-evolve. Kampung’s clutter is the result of residents’ competition for space. The form of Kampung is a squeezed group form. As more people live in an area restricted by barriers, the arrangement of houses will naturally become chaotic.

However, this evolution is not haphazard. In fact, there are patterns in the arrangement of Kampong communities. As the population increased, houses occupied the original vacant land. Kampung started to get denser but not cluttered. When the population reached saturation, to compete for space, the shapes of houses began to diversify. Houses began to overlap, and some alleys were covered with shelters. However, along the streets, the houses still maintained their original order. Streets mean more foot traffic and foot traffic leads to income, so residents along the streets are much better off financially. As a result, Kampung’s houses gradually became cluttered from street to edge.

Timeline of the defined group form

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964 and modified by author

Chaotic Group Form with more units

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964 and modified by author

Evolvement of Kampung

Source: Author

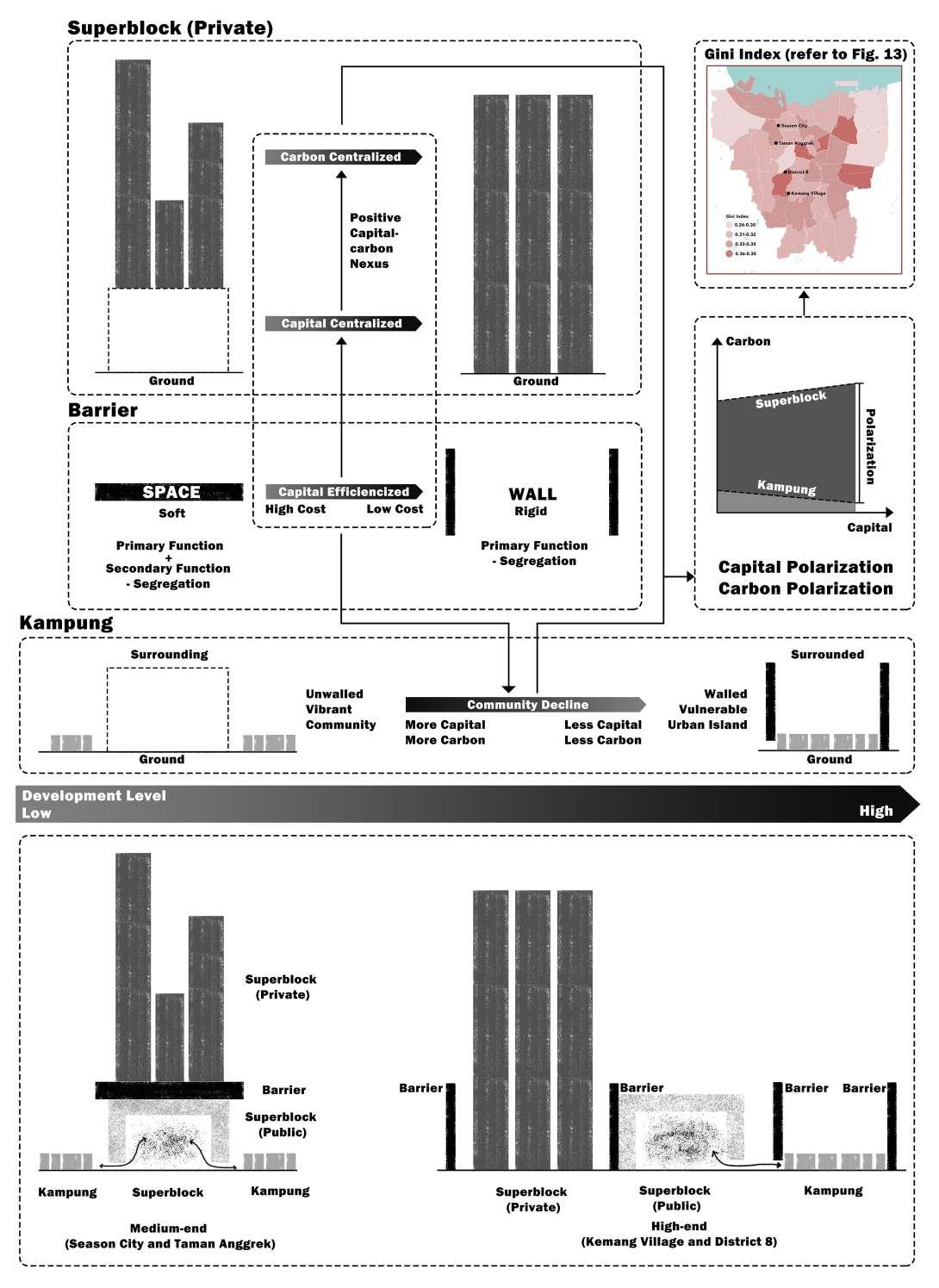

Although the site research findings focus on the segregation in the four sites, the superblock and Kampung are also symbiotic with each other. “The immense pool of cheap surplus labour provided by the kampung sustains the economy of the formal sector of the city”(Kusno, 2014). There is a strange, bamboo-like relationship that is articulatory yet connected. Therefore, to understand the city of Jakarta, it is necessary to study the Collective Form between superblocks and Kampung.

The first one is the tree form. Typically, the bottom of the superblock is a mall, and the upper part is the high-end residence with a rigid barrier between them. There is a link between Kampung and the bottom of the superblock. Residents can enter but cannot reach the upper residential areas. In Norse mythology, the branches and roots of the “Yggdrasill” (world tree) connect the nine worlds on three levels. The combination of Superblock and Kampung is like a tree, divided into three parts: the aboveground world, the surface, and the underground world. The roots of the underground trees represent the people at the bottom supporting the entire system.

The second type is the Multiple Defined Form. In this form, the bottom of each section connects to the ground. Superblock residential areas are surrounded by tight security and gate controls, which is the Defined Compositional Form. Walls surround the Kampung community, which makes it a Defined Group Form. The two residential areas of Kampung and Superblock have almost no connection, while the commercial area is a public area for the general masses. The barrier no longer has other functions but only serves for isolation.

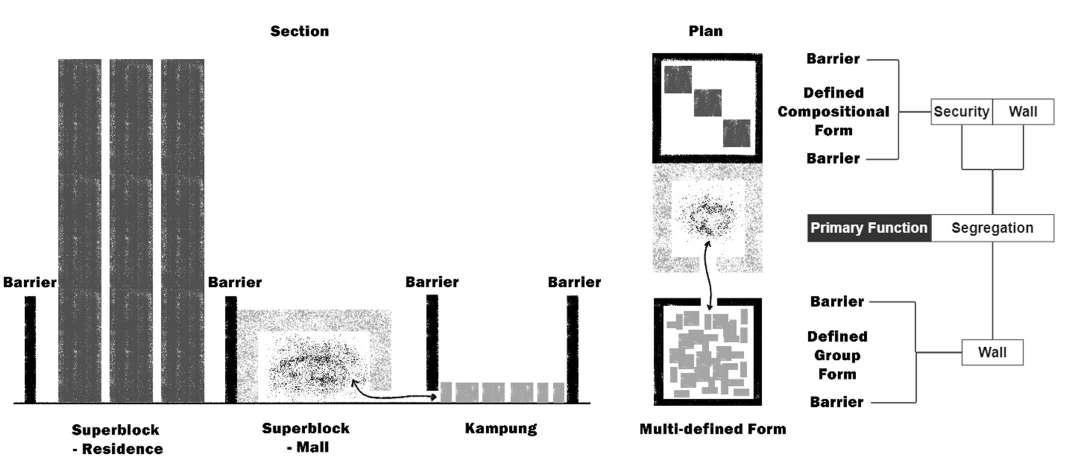

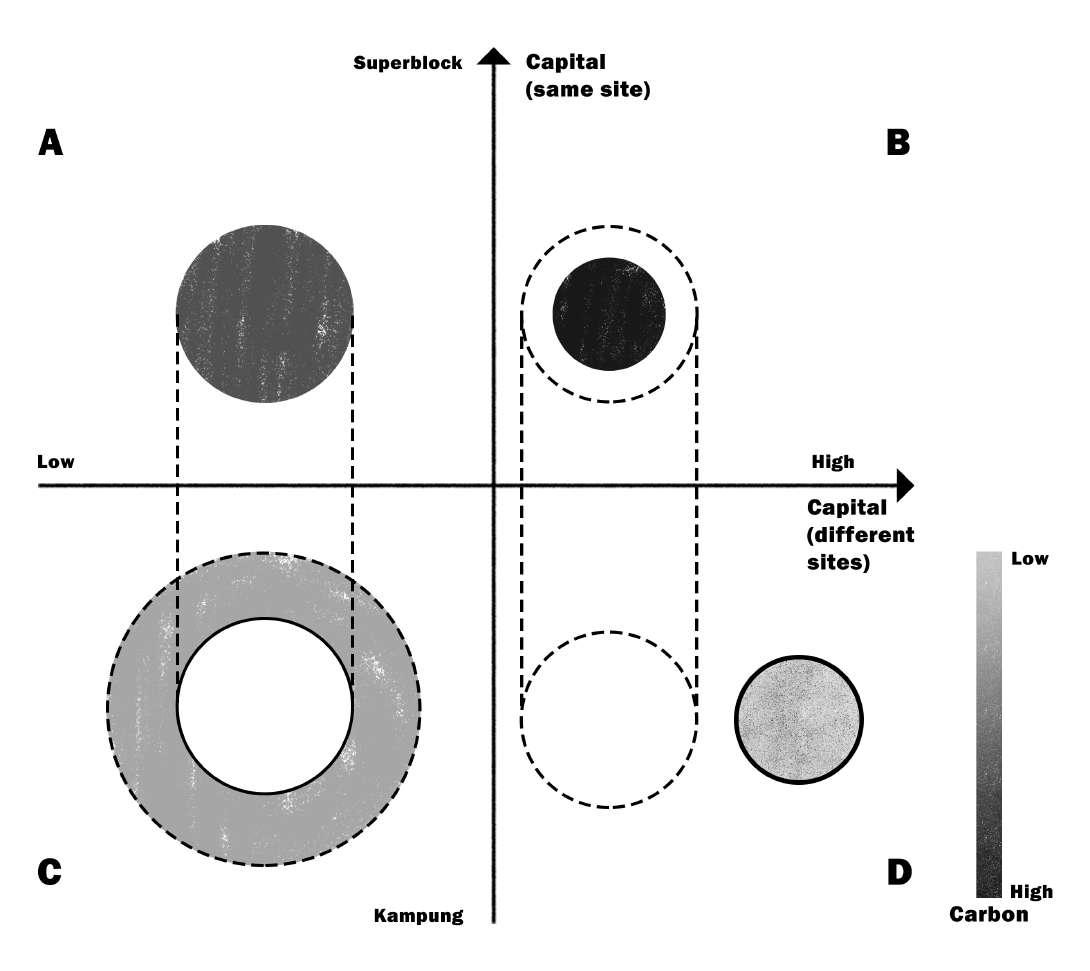

The above two Collective Forms are in different socio-economic environments. Tree Form is mainly located in low-development areas, where many Kampungs surround the superblock. Multiple Defined Form is mainly located in high-developed areas. Kampung is minor and isolated by walls. Through capital efficiency, the original space is simplified to walls. Capital is centralized, and residents of superblocks directly occupy a piece of land. According to the relationship between capital and carbon mentioned above, carbon is also centralized in highly developed areas. In contrast, the Kampung community gradually declined because high walls isolated it. Therefore, driven by capital, the carbon emission gap between superblocks and Kampung has widened. In Jakarta, it is unrealistic to eliminate such differences. The main issue discussed in the next chapter is how to capitalize on it.

Tree Form

Author

Multiple Defined Form

Source: Author

Source: Hedwig Schlender, 1903 and

Capital/Carbon Polarization in Two Collective Forms

Source: Author

Carbon Form in Capital Axis

A and C /B and D are Superblock and Kampung on the same site.

Source: Author

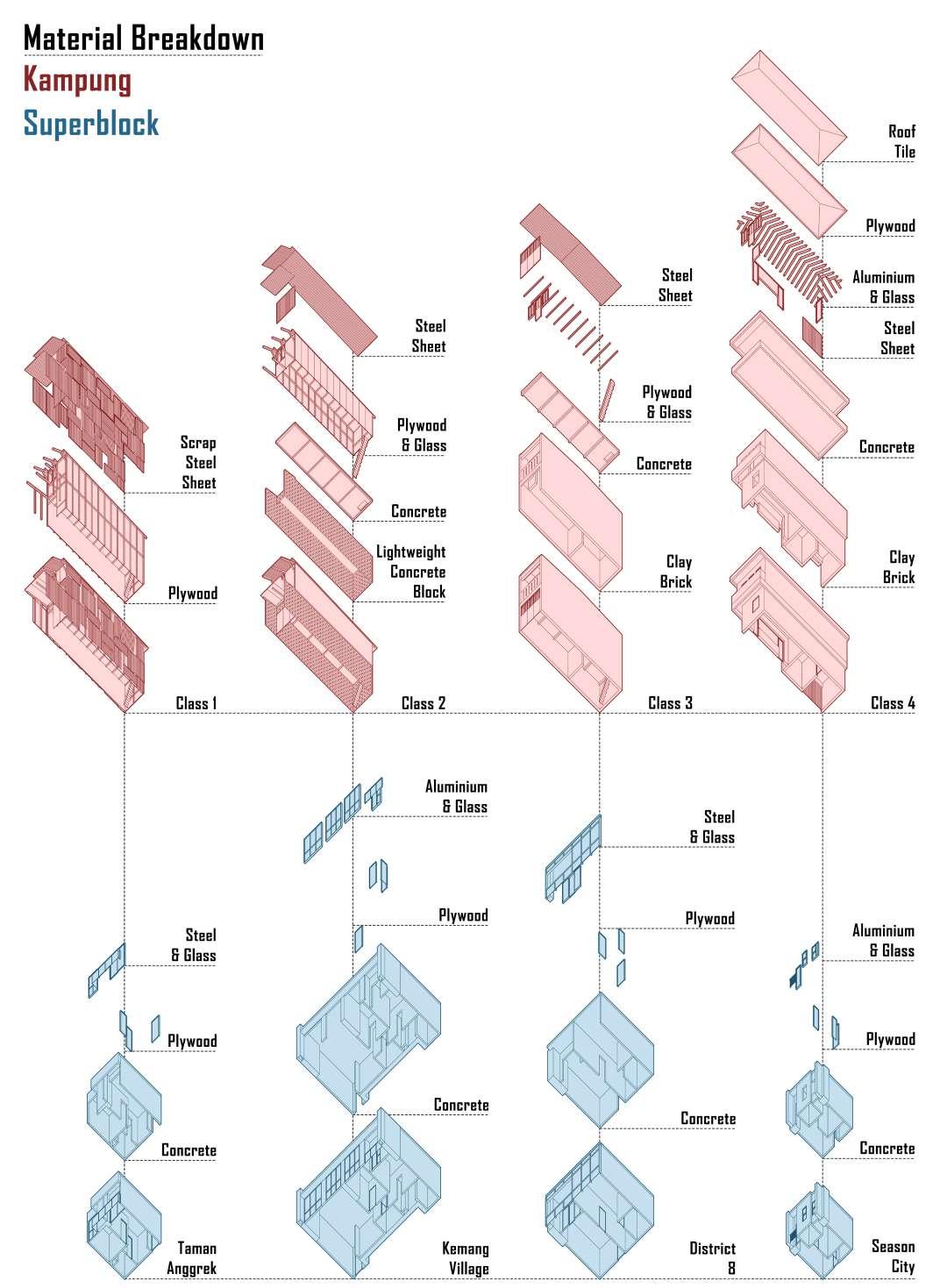

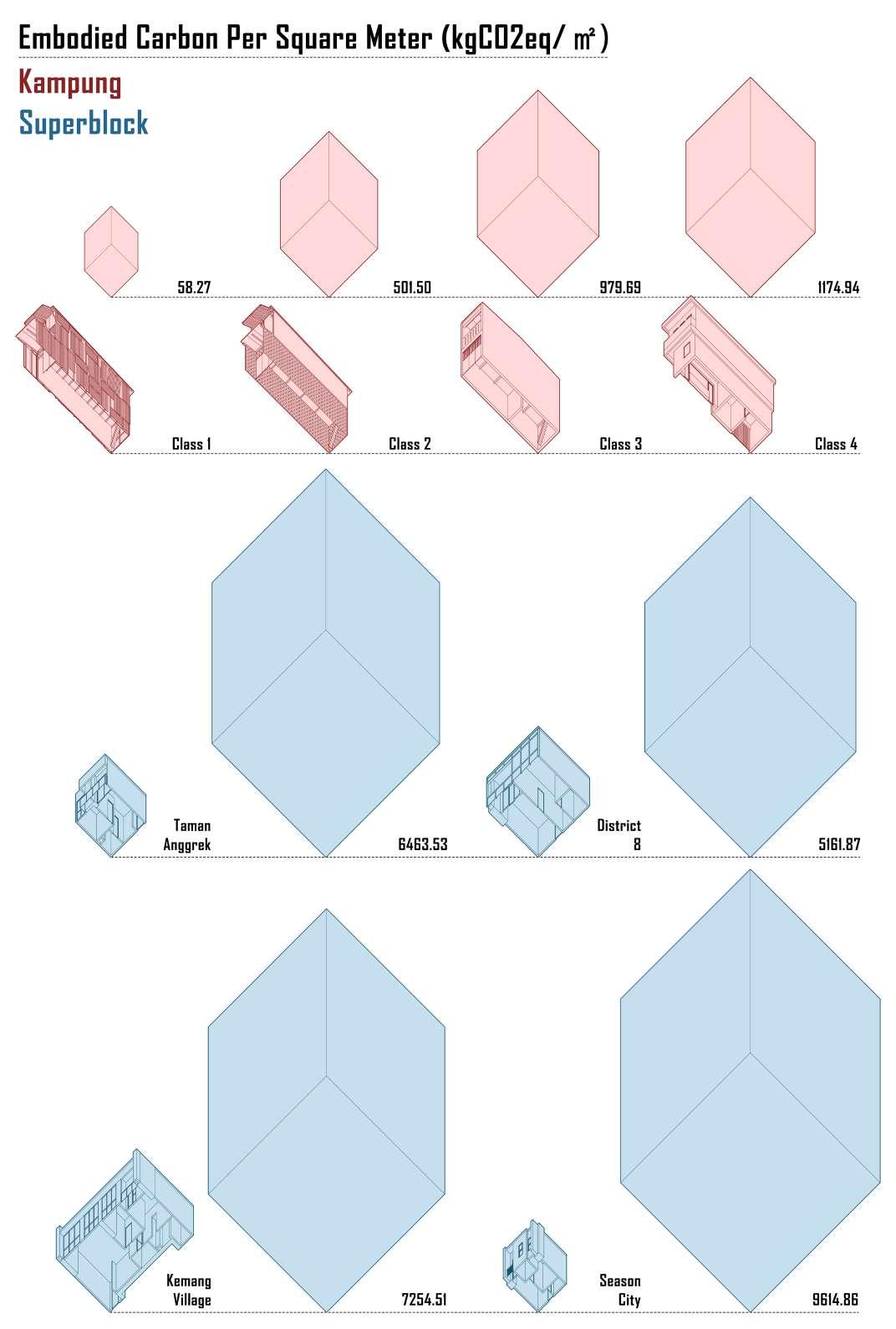

The variety of housing in the Kampungs makes it difficult to calculate specific embodied carbon. Therefore, the buildings are divided into four classes based on materials.

Class 1: The house has a wooden frame with internal walls made of plywood boards, and the exterior is covered with scrapped steel sheets.

Class 2: The first floor of the house is made of lightweight concrete blocks but placed vertically to save material. The second floor is a wooden frame covered by plywood boards. The floor slab is concrete with a low proportion of rebar, while the roof is corrugated steel sheets.

Class 3: The walls are clay bricks. The floor slab is concrete, and the roof is corrugated steel sheets. From this level, the house is formalized.

Class 4: The walls are clay bricks. The floor slab is concrete, and the roof is tiles. The frame and window profiles in the house are aluminum.

In this section, the calculation of embodied carbon only includes part of the life cycle of the building (the carbon emissions generated by material production). Whether it is material transportation or building construction and maintenance, the carbon emissions of superblocks are higher than those of Kampung. Therefore, the actual carbon emissions differences are more extreme than the data in this section.

For superblocks, there are many types of units. Therefore, the embodied carbon calculations for each superblock include only one house type. Since the calculation is based on the mass of materials, the area of the house has a significant impact on the value of embodied carbon. To reduce the impact, the final data uses embodied carbon per square meter (ECPSM).

In the Kampung community, the ECPSM of informal housing and formal housing differs enormously, which is mainly related to the source of materials (waste materials or purchased materials). Within the superblock, Season City, the lowest end, has the highest value, while District 8, the highest end, has the lowest value. On the one hand, the larger the area, the smaller the wall volume allocated per square meter. Therefore, the ECPSM of a smaller room is higher than the actual figure. On the other hand, Season City has a denser grid of columns and enclosed facades. The results show a significant difference (maximum of 165 times) between the embodied carbon per unit area of dwellings in Kampung and superblocks.

Source: Fumihiko Maki, 1964 and modified by author

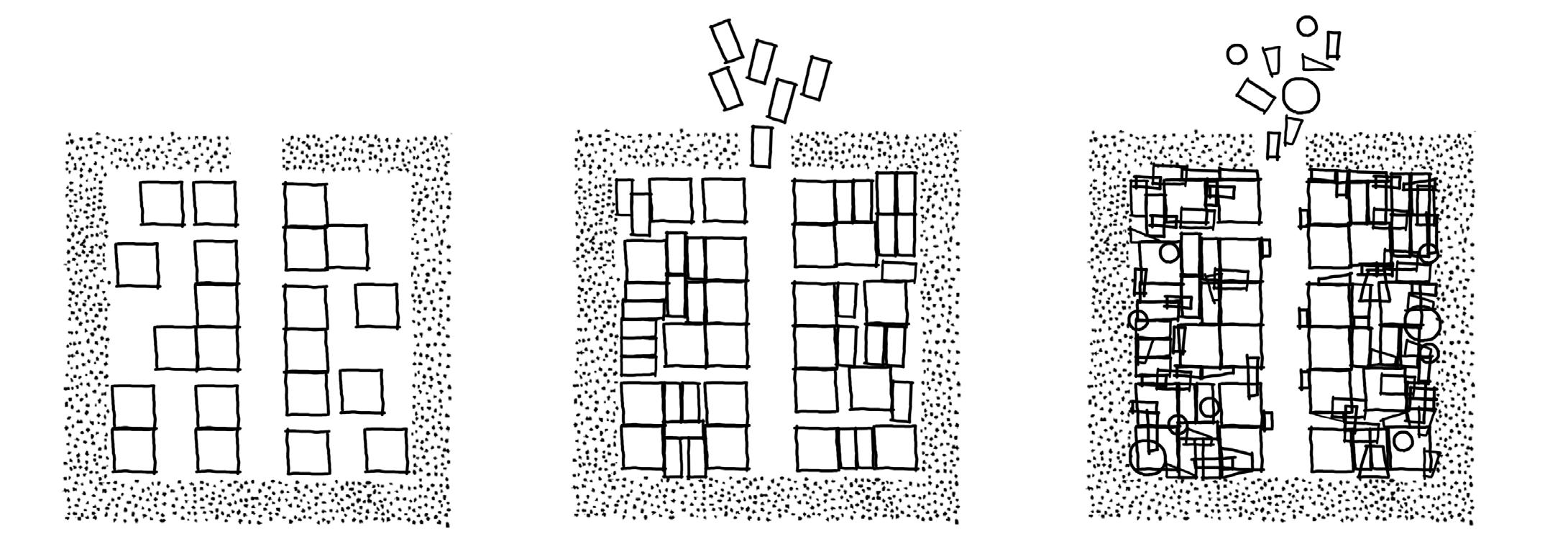

Scope Of An Architect

Site Selection - Season City

Incremental Kampung

Architectural Consequence

Previous chapters have shown Jakarta’s many problems, such as the wealth gap, the carbon gap, and environmental issues. However, architects can’t solve everything. In the physical world, building anything requires resources and finances. Therefore, decarbonization potential and carbon disparity can drive capital flows to finance building construction. Architects can design high-performance buildings to serve the citizens. The absorption of carbon and energy production maintains the decarbonization to sustain the capital flow system. Therefore, the scope of an architect is to design a good architecture, which is also the scope of this thesis project.

Workflow of a Building and Carbon Trading in Different Scale

Source: Author

Capital Flow and the Scope of an Architect

Source: Author

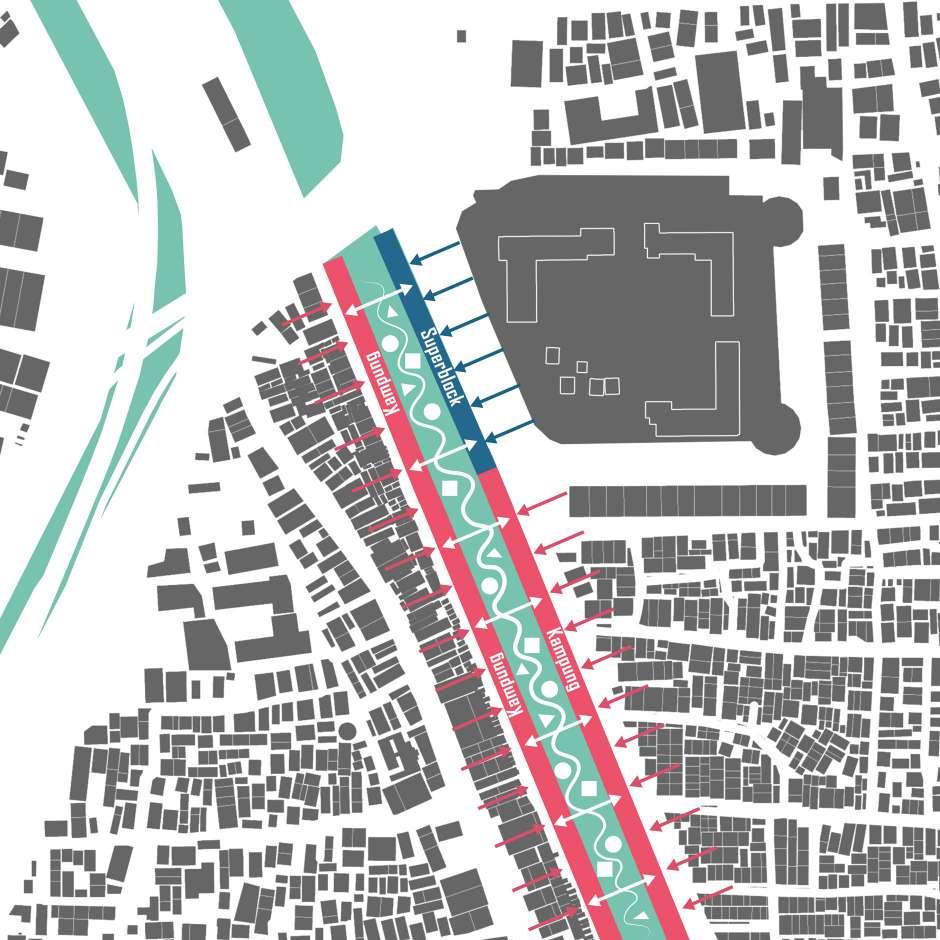

The site chosen for the project is around Season City, which has the largest area of Kampung among the four sites. The heavily polluted Ciliwung River bisects the entire site. There are abundant activities along the river, but space is limited.

This project will not transform the superblock and Kampung community. On the one hand, for superblocks, the carbon footprint is minimized by maintaining the status quo ante. On the other hand, the Kampung community is in a subtle dynamic balance, and the texture and environment are very complex.

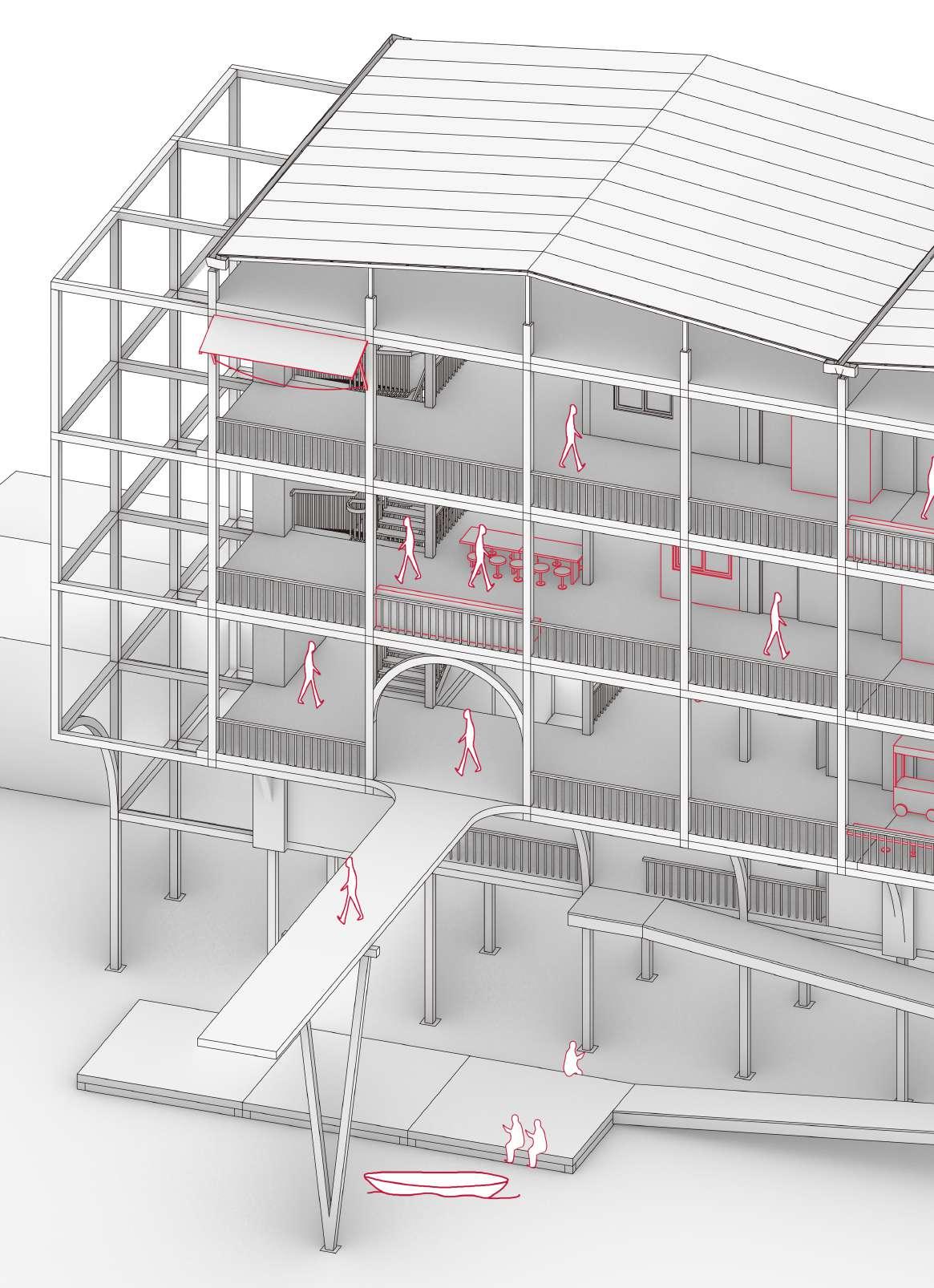

This site is on the Ciliwung River, which is in the center of the area, cutting off the connection between the superblock and Kampung on the other side. The river itself is seriously polluted and in urgent need of treatment. Currently, the Jakarta government uses barrier strips to block garbage and fish it out, which is inefficient and cannot solve the pollution problem.

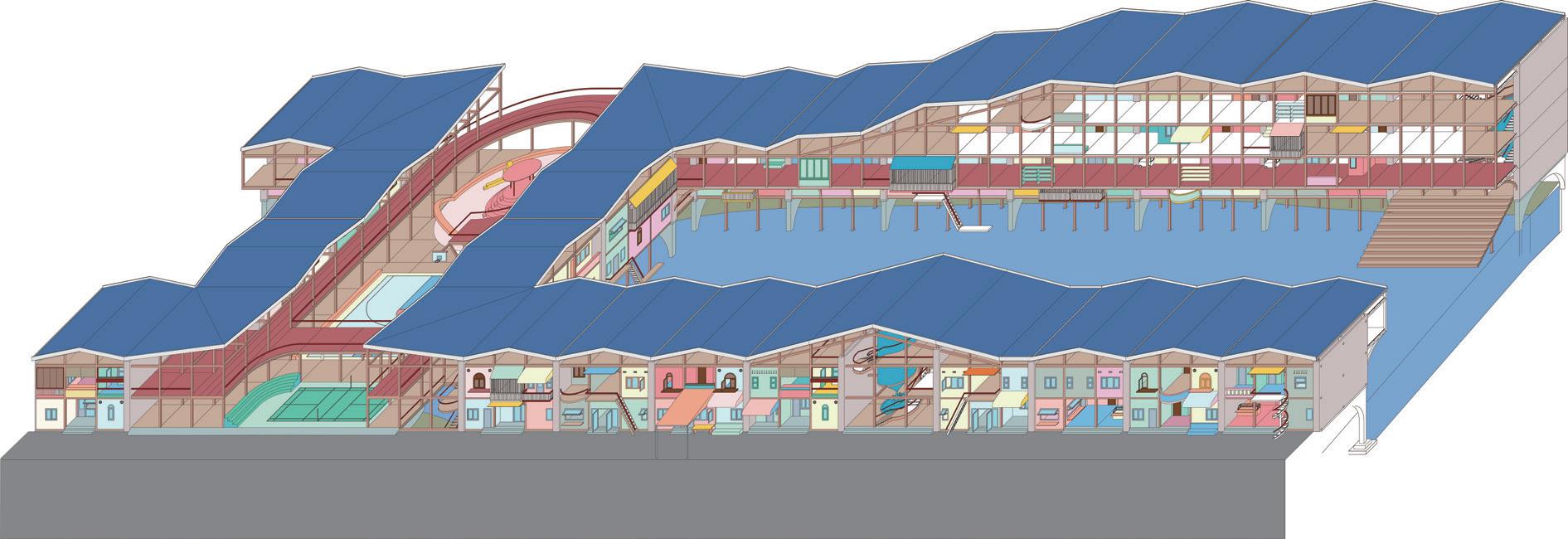

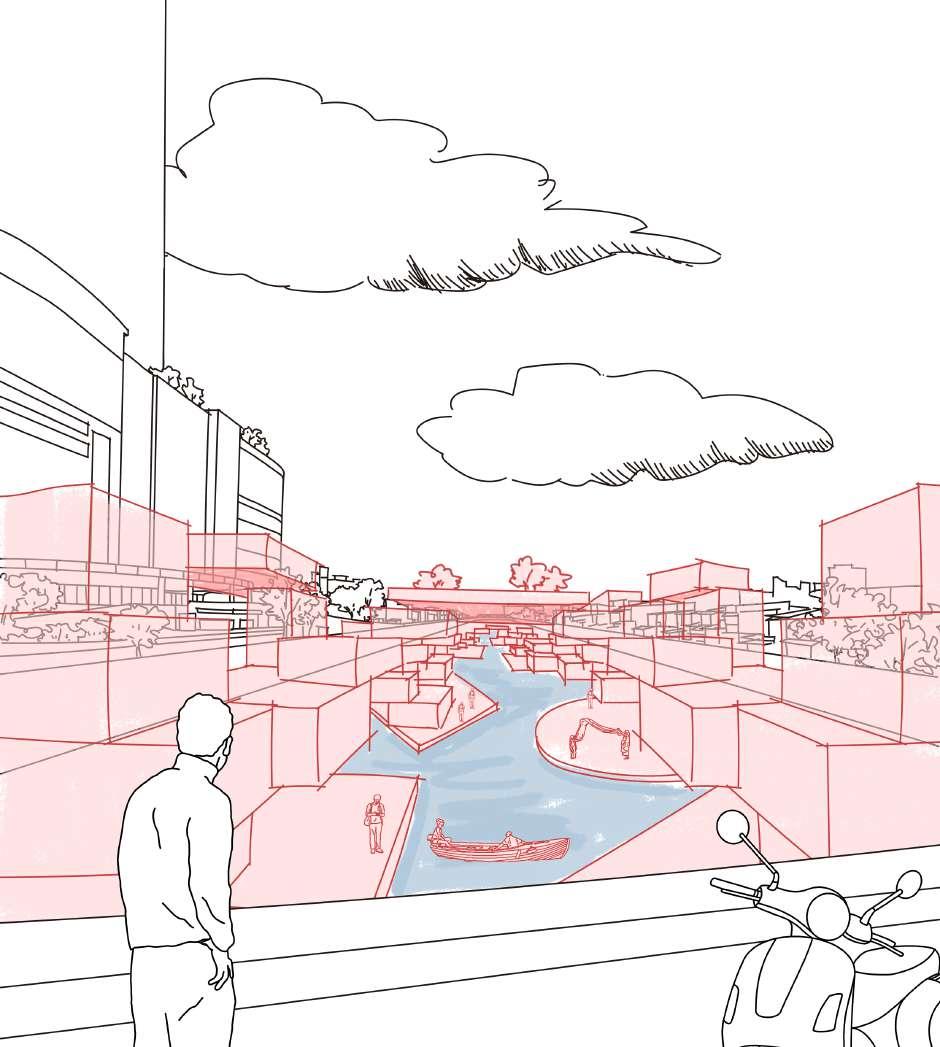

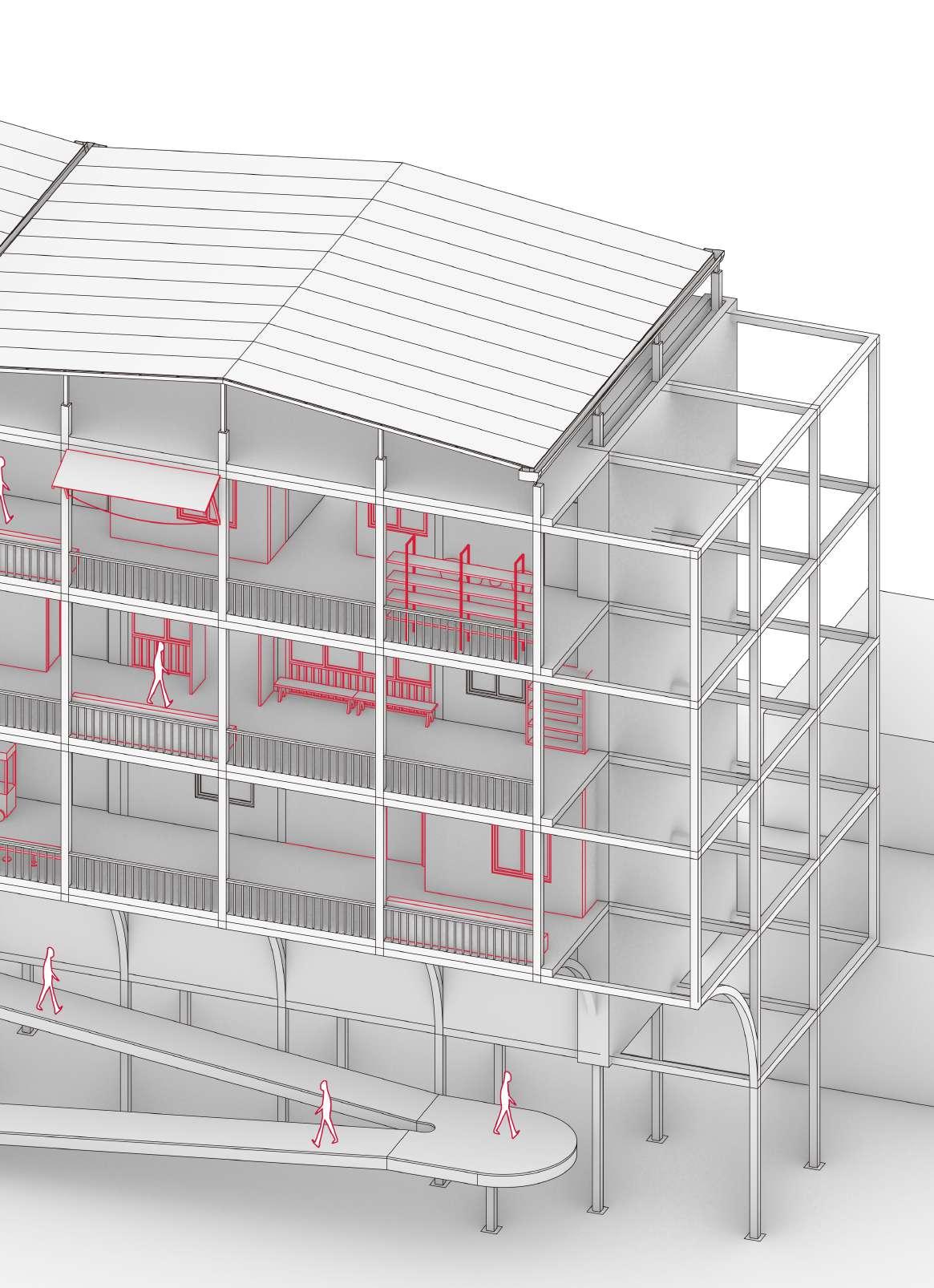

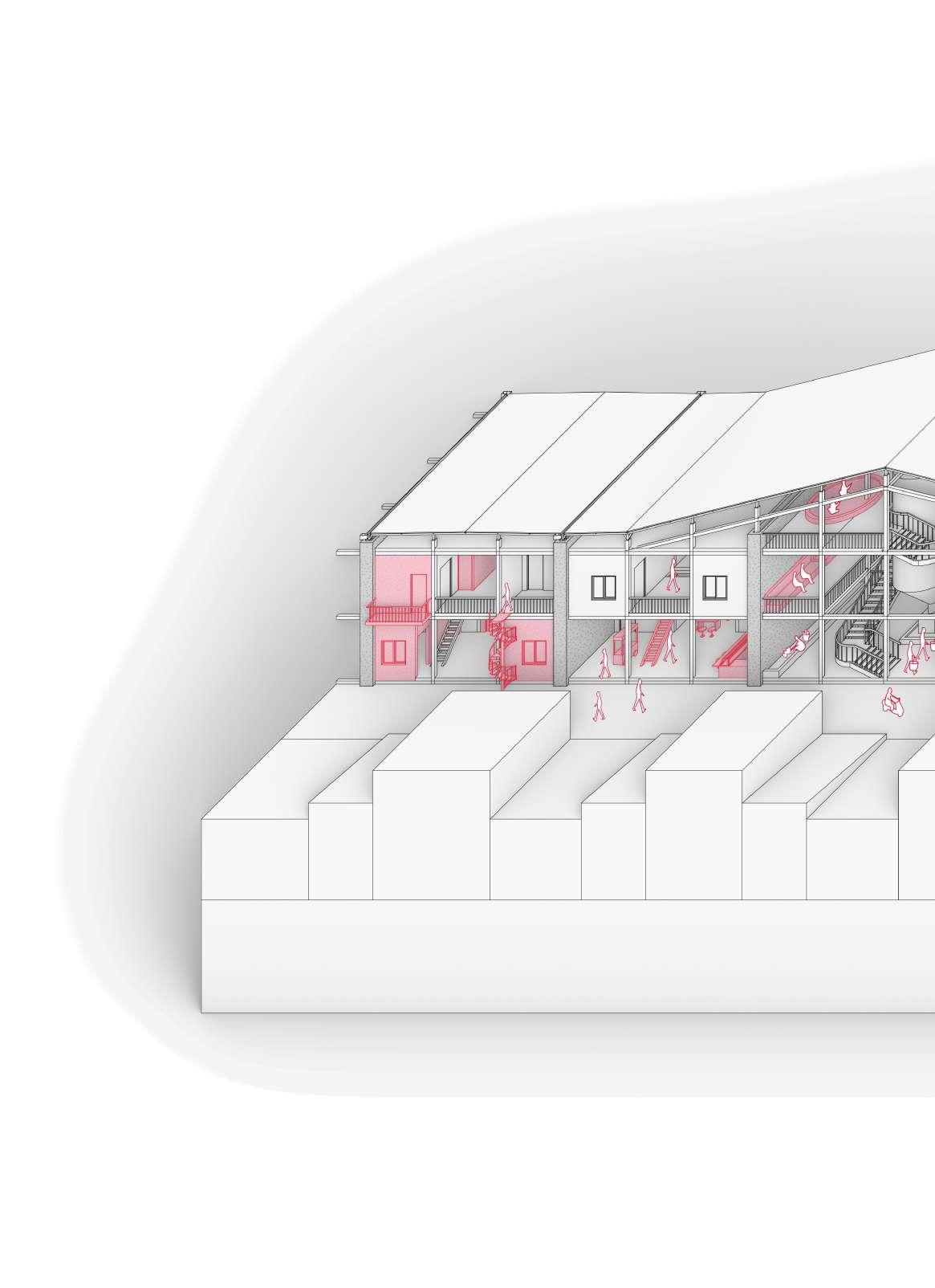

This project expects to place a kind of architectural form on the site and intervene in this area as a third party. A new zero-carbon building will sit above the river, countering the towering superblocks with a horizontal stance as a megastructure form. As a complex, it can provide public space, manage environmental issues, and provide jobs and new housing for residents. Going beyond carbon neutrality doesn’t just mean that buildings must absorb more carbon, but that architects need to move away from a decarbon-centric architectural mindset to help people have better lives.

Source: Unequal Scenes, Jakarta

Main Road

Garbage Barrier

Main Road

Garbage Barrier

There are four bridges on the site that separate the river and serve as important nodes providing transportation functions and public space for the community.

Source: Author

Footbridge Railway

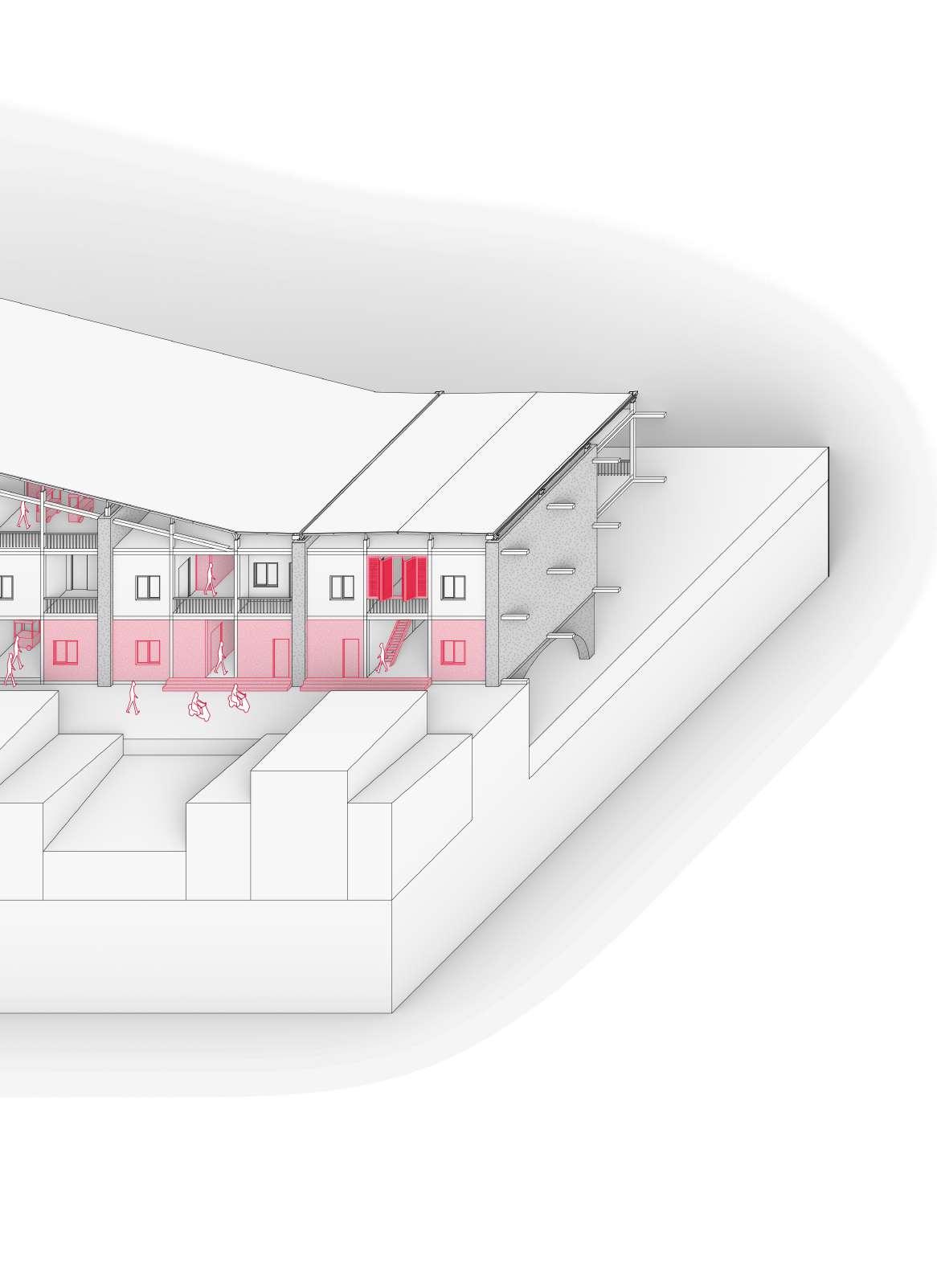

The spatial relationship between Kampung and river dikes on both sides of the river is different. However, the function of river dikes is to resist river water, and at the same time, it also limits the addition of communities.

River Dike Road(South Side) River Dike Road(North Side)

Kampung on the south side is closer to the river dike and the houses are more informal. There is a road between Kampung on the north side and the river dike, and the community is more formalized.

Source: Author

View from Kampung to River Dike Road (South Side) View from Kampung to River Dike Road (North Side)

Playing with Pigeon

Fishing

Playing with Pigeon

Fishing

Kampung residents use as much space as possible around the river dikes, which reflects the residents’ desire for more public space and the reality of being oppressed by limited space.

Source: Author

There are two methods of kampung renovation in Jakarta today, KIP and social housing. But social housing is mostly located in suburban and industrial areas. The remote location, inadequate facilities and housing size restrictions cut off residents’ original source of income. So we need a better way to provide housing.

In addition to modernist slab-sided buildings, there is another architectural form, incremental housing. Incremental housing is an approach to housing development that focuses on providing residents with the opportunity to gradually improve and expand their homes over time, in response to their changing needs and financial capabilities. Instead of constructing fully finished houses all at once, incremental housing projects typically begin with the provision of basic infrastructure and a starter unit, which residents can then incrementally upgrade and expand according to their preferences and resources.

Incremental housing has been implemented in various contexts around the world, particularly in informal settlements and low-income urban areas where access to adequate housing is limited. In fact, kampung is the result of self-increment, only under the condition of being squeezed. Due to the instability of residents’ income, the layout of their houses largely depends on their jobs. The flexibility of incremental housing can better help residents obtain income.

Social Housings in Jakarta

Social Housings in Jakarta

Source: Andrean Kristianto

Source: Ian Wilson

Social Housings in Jakarta

Social Housings in Jakarta

Source: Andrean Kristianto

Source: Ian Wilson

Kampung - Colors & Incrementality

Kampung - Colors & Incrementality

Kampung - Colors & Incrementality

Kampung is colorful, which is a reflection of the increment of the community. Due to the restrictions of the street, the addition of the facade along the street was not excessive.

Source: Author

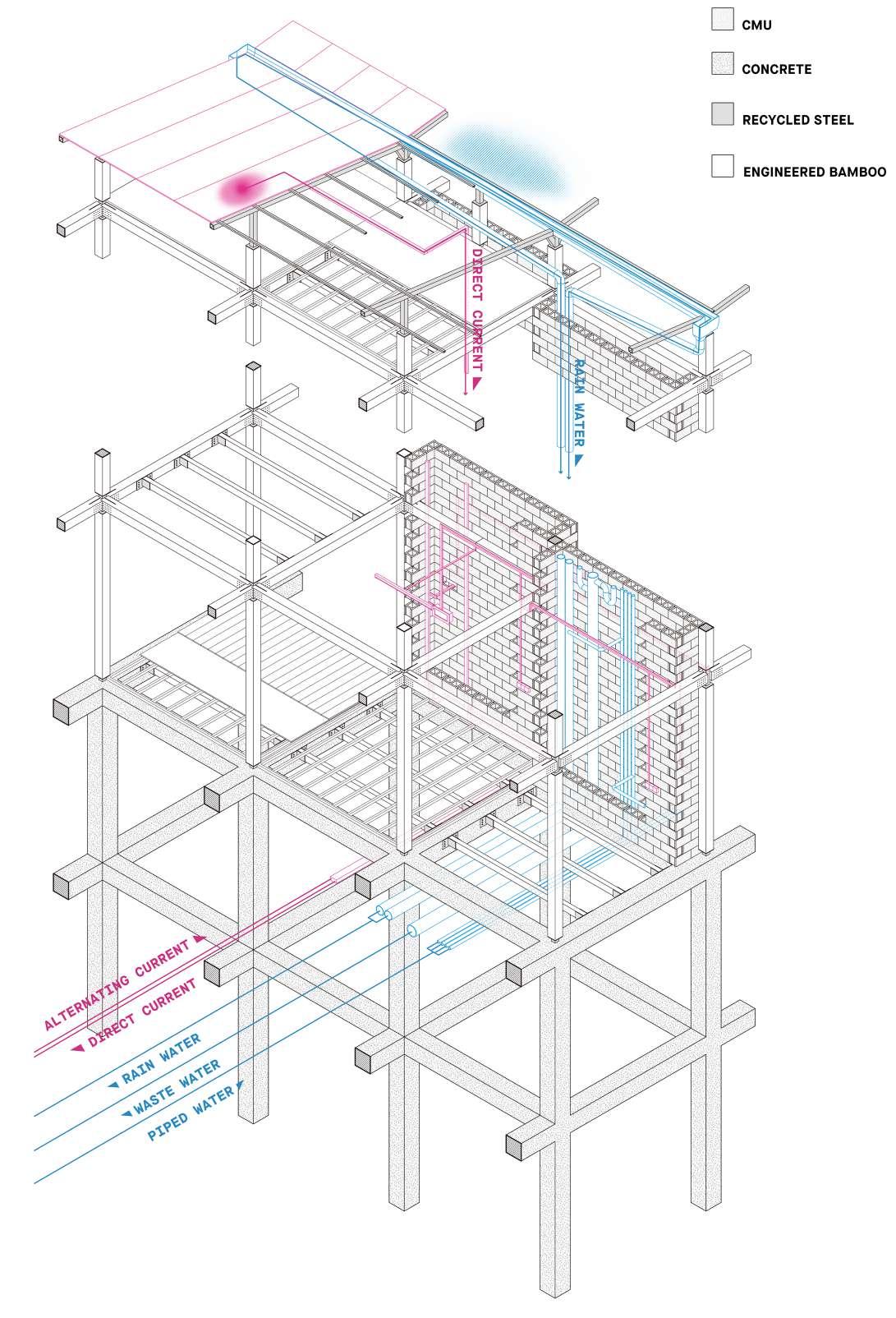

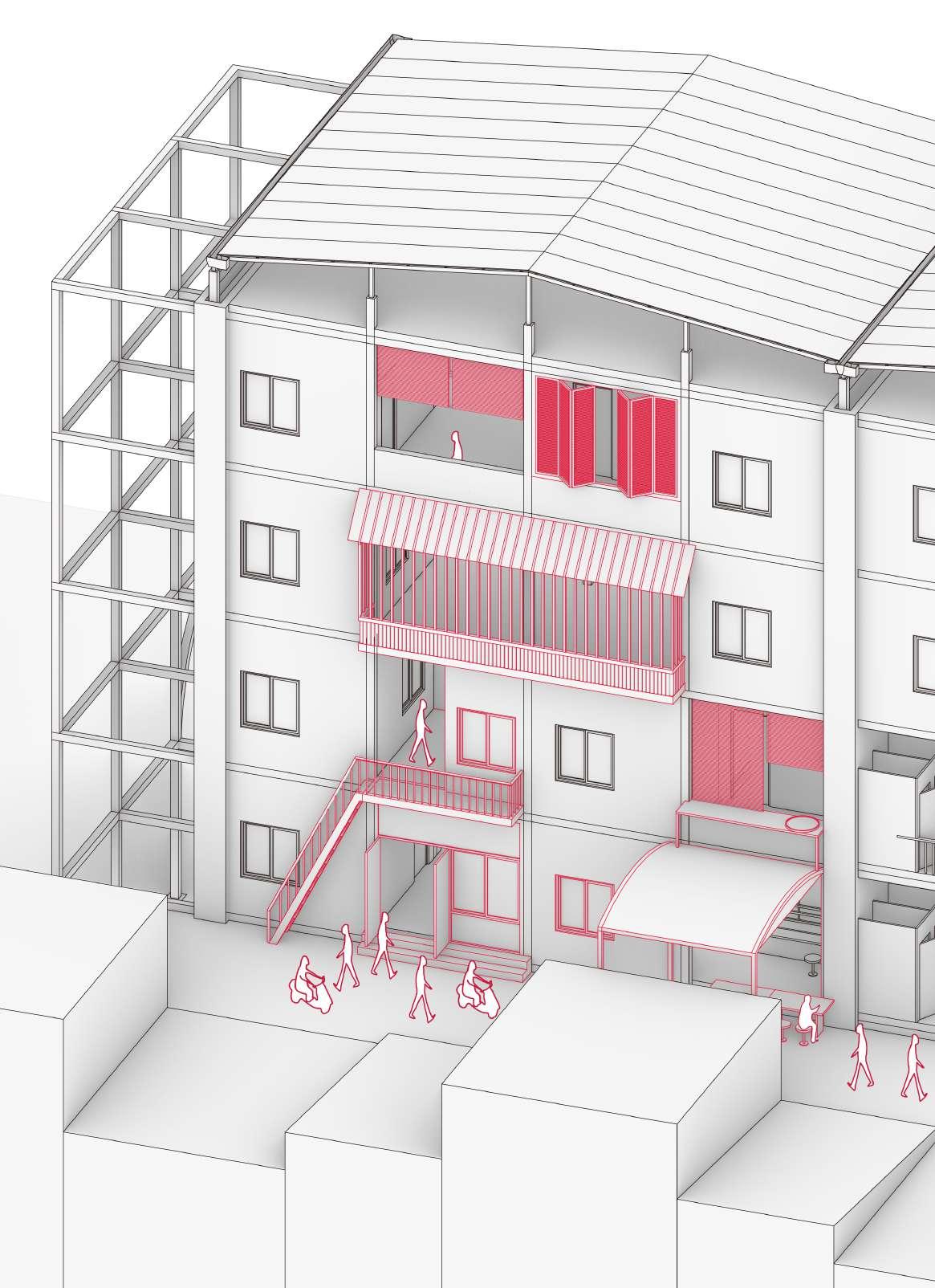

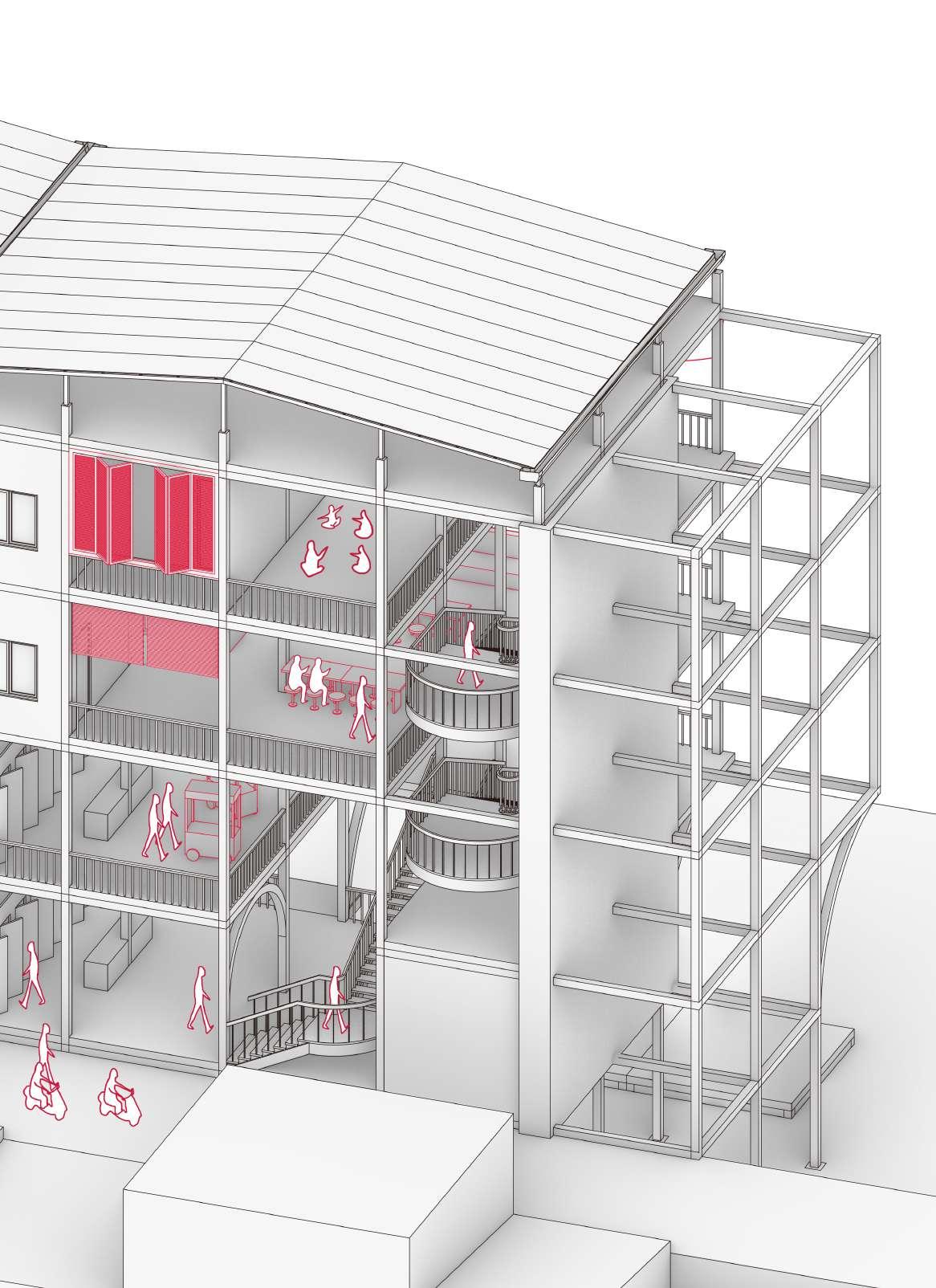

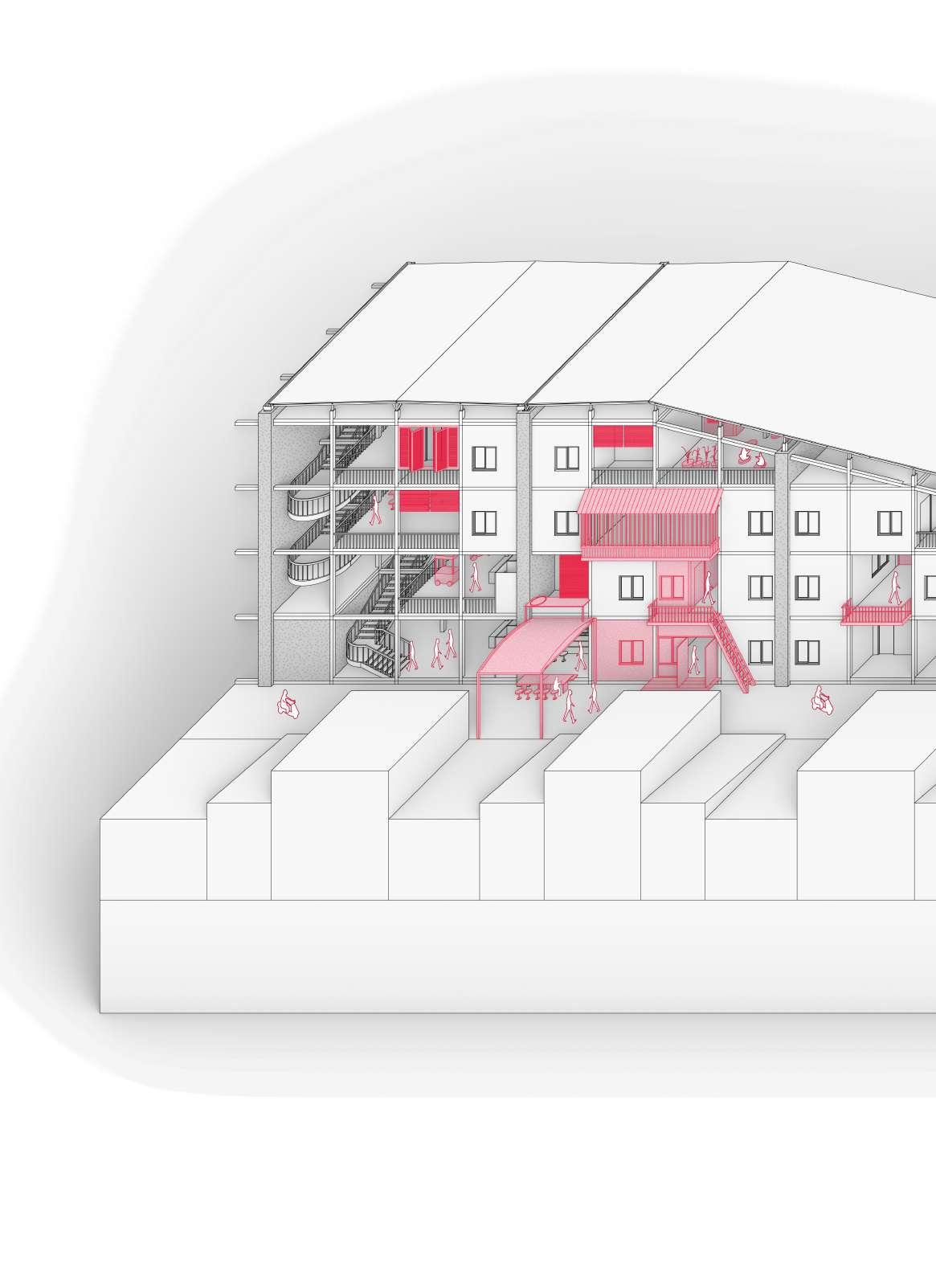

The disadvantage of incremental housing is that additions are difficult to control. To limit excessive increments, the project has four rules. With rivers and roads on both sides, the building is restricted by soft barriers. The pre-built walls in the building serve as hard barriers to divide several units. Secondly, social factors also have a huge impact on public housing. With the cooperation of residents and rigid regulations, increment can be further limited.

Servant Space and Served Space

Castle Sketches Source: Louis Kahn Source: Louis KahnLouis Kahn divided architecture into “servant” space and “served” space. For incremental houses, the construction part can be divided into three levels according to the difficulty of construction. The most difficult thing to build is the structure, pipes and other “servant” spaces. The parts being served are easier to build, such as wall, door, and etc. Therefore, the architect can be responsible for the “servant” space, and the residents can be responsible for the “served” space for self-incremental construction.

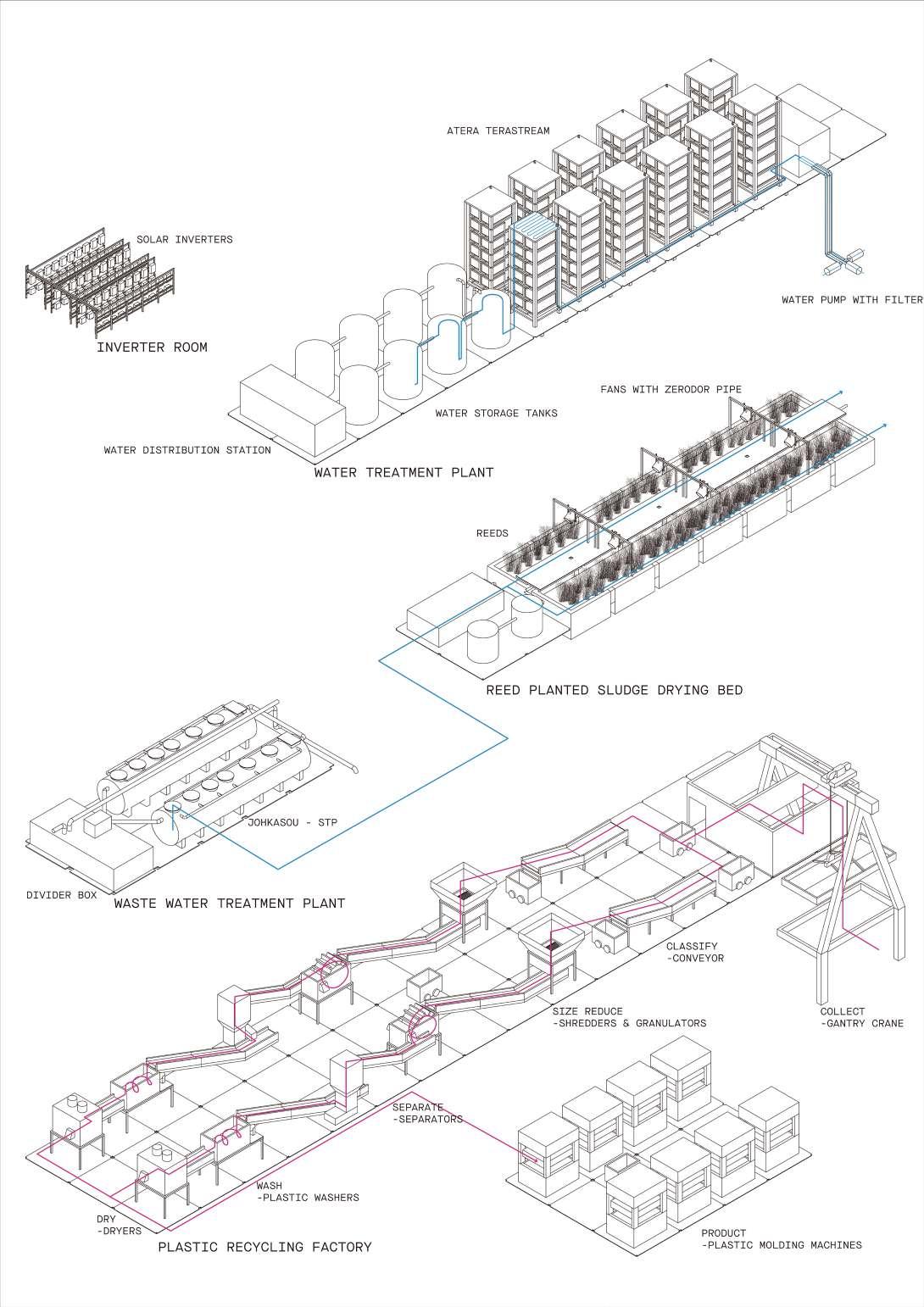

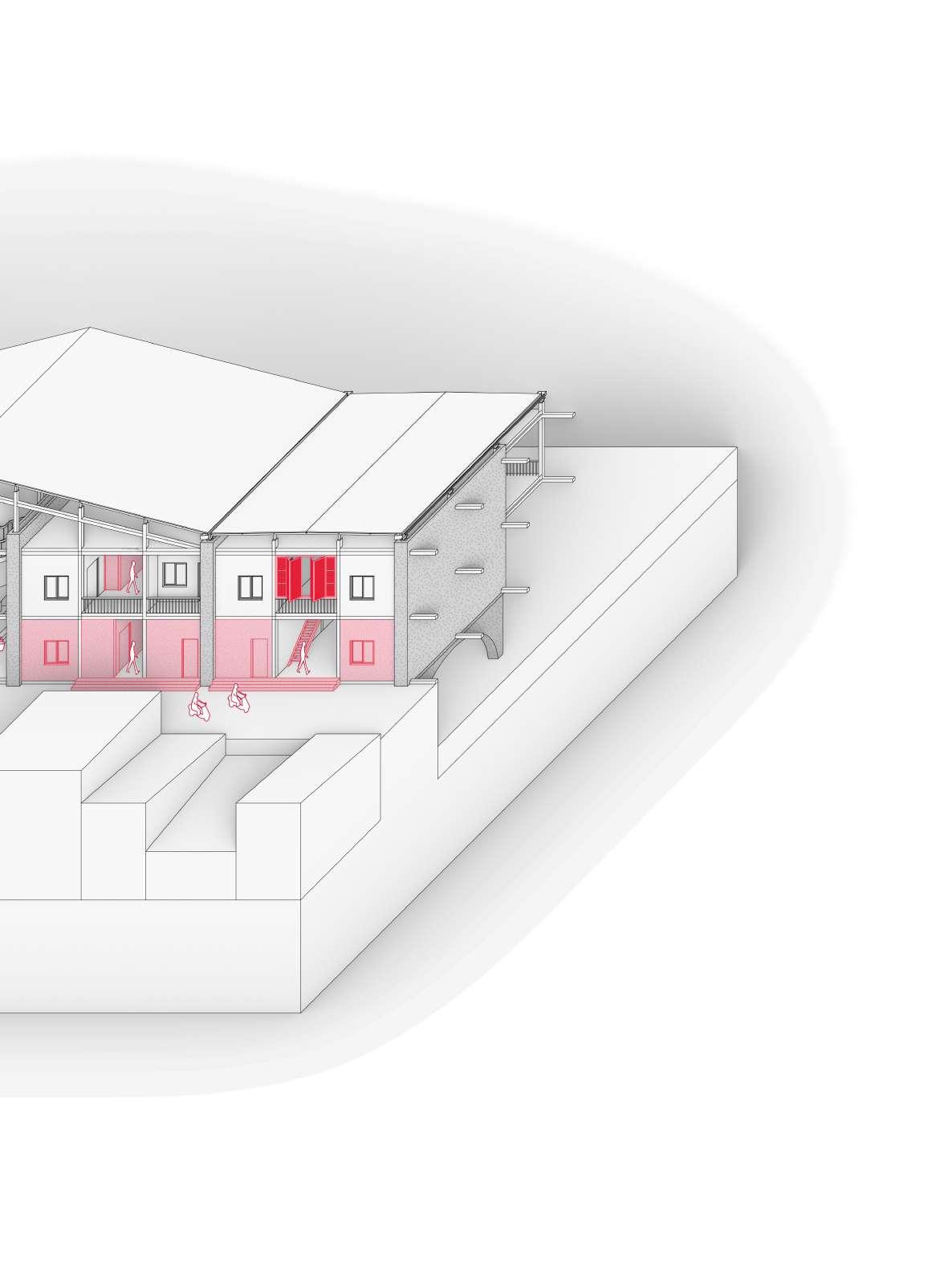

Incremental PyramidIndonesia, the largest carbon emitter in Southeast Asia, has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. The site is Season City in West Jakarta. The extreme size gap between Superblock and Kampung is a physical manifestation of the difference in carbon emission and capital. Kampung residents face challenges due to limited living space and poor sanitation. Usual carbon-neutral methods won’t improve their lives and may even cut off their unstable income. Therefore, this project proposes a collective form different from Superblock and Kampung. In the context of carbon neutrality, the difference in carbon emission is used to drive capital flows to provide more housing for low-income groups.

The Jakarta government has constructed numerous social housing units, but the remote location and insufficient facilities cut off residents’ income. As the result of increment under a squeezed condition, Kampung is a physical reflection of the residents’ lives. Would it be better to excavate enough space from the city to provide housing and allow incremental construction?

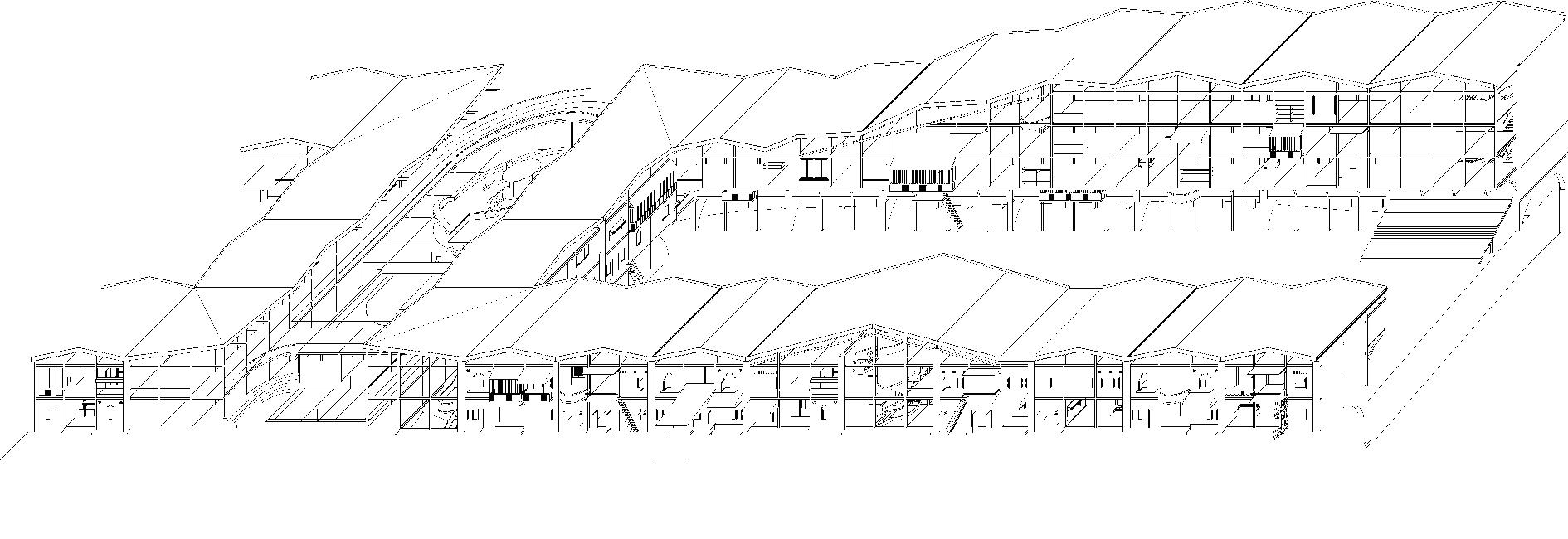

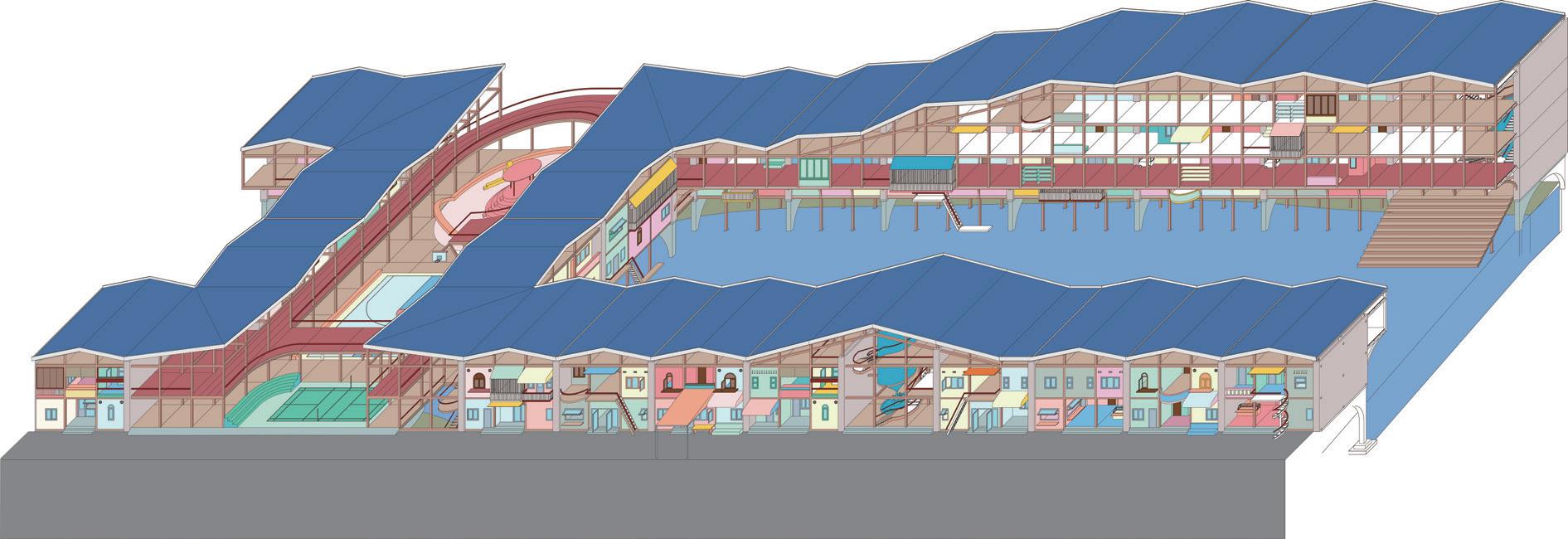

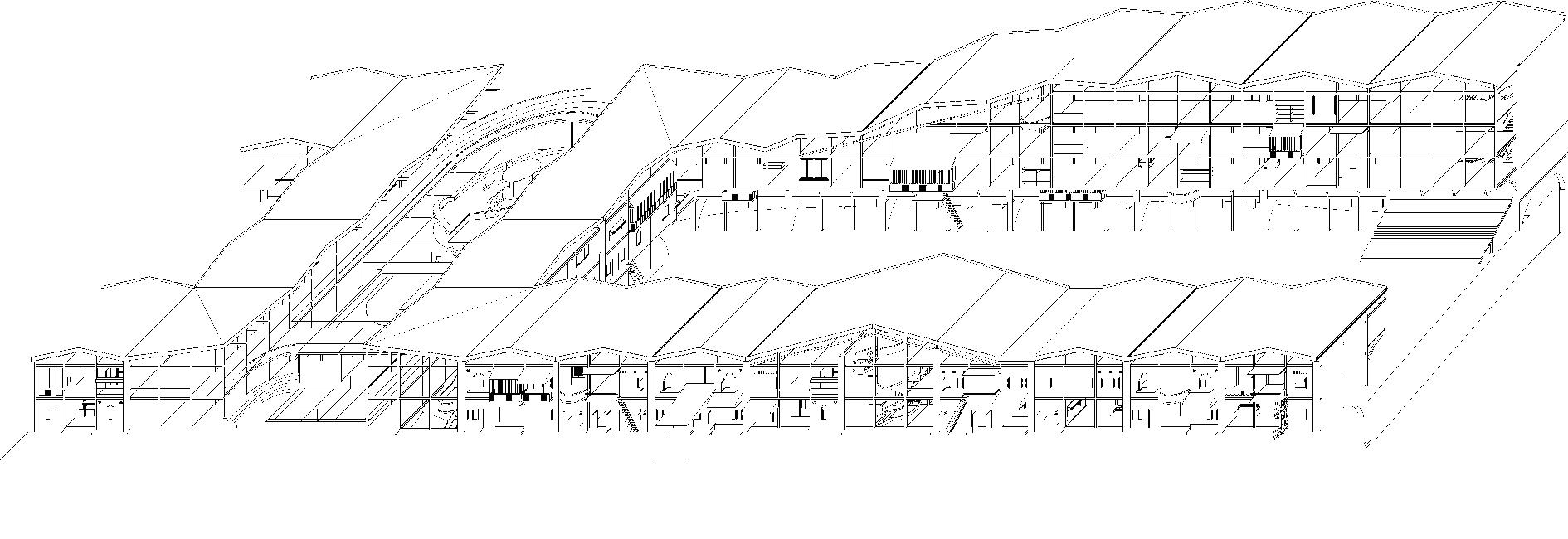

The river is one of the few unoccupied areas in such a high-density area. Housings are arranged along both sides of the Ciliwung River, and the main public spaces are built across the river as bridges to provide more connections. However, incremental housing is uncontrollable, and communities often develop beyond the scope of architects. Therefore, the project begins by identifying the architect’s and residents’ portions. The engineered bamboo structural frame and infrastructure are put in first, with a continuous solar panel roof providing sufficient energy for the building. The CMU partition walls integrate the functions of electricity, water, and sewage and serve as the boundary of the unit to inhibit excessive addition. Through residents’ cooperation or arguments, the community slowly fills in flesh and blood incrementally and eventually integrates into the site. At this point, green building is no longer a cold numbers game; it goes beyond carbon neutrality and provides more regional housing solutions for Kampung residents.

Street interfaces and residential layouts are developed incrementally by residents. The traffic function of the street limits the excessive construction of the house to some extent.

Give functional properties to public Spaces, such as vertical traffic and water stations, to prevent over-occupancy.

While the water tower serves residents, it also welcomes Kampung residents from outside, and the activities of the two are integrated.

Engineered Bamboo Volume: 8143.8m3

Embodied Carbon:

2057529.9kgCO2e

Biomass Offset: 2178791.1kgCO2e

Concrete (40% Recycled)

Volume: 1894.7m3

Embodied Carbon: 544455.4.9kgCO2e

Aluminum (100% Recycled) Volume: 171.4m3

Embodied Carbon: 971689.0kgCO2e

CMU (Wood Fibre Filling) Unit: 296615

Embodied Carbon: 548737.8kgCO2e Biomass Offset: 222461.3kgCO2e

PV Panel Area: 20842.0m2

Embodied Carbon: 5239897.3kgCO2e

Rebar (100% Recycled)

Volume: 78.9m3

Embodied Carbon: 260290.8kgCO2e

Total Embodied Carbon: 9622600.2kgCO2e

(Biomass offset): 7221347.9kgCO2e

Household Operational Carbon: 1595404.7kgCO2e

Indonesian Emission Factor (2020): 0.82924kgCO2e/kWh

Facilities Operational Carbon: 1257003.8kgCO2e Total Operational Carbon: 2852408.5kgCO2e

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aditantri, R., Krisnaputri, N., & Oktaviyani, A. (2019). Morphological Study of Planned Human Settlement Affected by Service Trade Activities. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 328, 012073. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/328/1/012073

Alzamil, W. S. (2018). Evaluating Urban Status of Informal Settlements in Indonesia: A Comparative Analysis of Three Case Studies in North Jakarta. Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(4), 148. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n4p148

Cuff, D. (n.d.). Architectures of Spatial Justice. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14505.001.0001

Daniel Mangasi, K. (2023). Study of The Impact of The Incompatibility of Space Utilization In The Krukut River. Smart City, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.56940/sc.v3.i1.3

Desiyana, I. (2018). INTERROGATING SOCIO-SPATIAL SUSTAINABILITY IN DENSE CITY: CASE STUDIES IN KALIANYAR AND JEMBATAN BESI.

Grima, J. (2021). Non-Extractive Architecture. Sternberg Press.

Heriyanto, D. (2019). One in Five Indonesians Don’t Believe Human Activity Causes Climate Change. Jakarta: The Jakarta Post.

Hasan, D., & Bleibleh, S. (2023). The everyday art of resistance: Interpreting “resistancescapes” against urban violence in Palestine. Political Geography, 101, 102833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. polgeo.2023.102833

Irfany, M. I., & Klasen, S. (2017). Affluence and emission tradeoffs: Evidence from Indonesian households’ carbon footprint. Environment and Development Economics, 22(5), 546–570. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X17000262

Iturbe, E. (2019). Architecture And the Death of Carbon Modernity. Log, 47, 10–23. JSTOR.

Kusno, A. (2014). Behind the Postcolonial (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315011370

Kusno, A. (2015). Power and time turning: The capital, the state and the kampung in Jakarta. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 19(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2014 .992938

Laksana, E. P., Prabowo, Y., Sujono, S., Sirait, R., Fath, N., Priyadi, A., & Purnomo, M. H. (2021). Potential Usage of Solar Energy as a Renewable Energy Source in Petukangan Utara, South Jakarta. Jurnal Rekayasa Elektrika, 17(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.17529/jre.v17i4.22538

Leaf, M. (1993). Land Rights for Residential Development in Jakarta, Indonesia: The Colonial Roots of Contemporary Urban Dualism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 17(4), 477–491. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1993. tb00236.x

Leitner, H., & Sheppard, E. (2018). From Kampungs to Condos? Contested accumulations through displacement in Jakarta. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(2), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17709279

Mulligan, M. (Ed.). (2008). Investigations in Collective Form. In F. Maki, Nurturing Dreams. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7596.003.0008

Rukmana, D., & Ramadhani, D. (2021). Income Inequality and Socioeconomic Segregation in Jakarta. In M. van Ham, T. Tammaru, R. Ubarevičien, & H. Janssen (Eds.), Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality: A Global Perspective (pp. 135–152). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_7

Rusiawan, W., Tjiptoherijanto, P., Suganda, E., & Darmajanti, L. (2015). System Dynamics Modeling for Urban Economic Growth and CO2 Emission: A Case Study of Jakarta, Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 28, 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2015.07.042

Salsabila, S., Amir, S., & Nastiti, A. (2023). Cooling as social practice: Heat mitigation and the making of communal space in Jakarta’s informal settlements. Habitat International, 140, 102924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102924

Teismann, M. (2018). An Ideological City: Koolhaas’ Exodus in the Second Ecumene. Joelho Revista de Cultura Arquitectonica, 8, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8681_8_3

Wiryomartono, B. (2020). Urbanism and Superblock Mixed-Use Development in Jakarta: Politics of Gentrification of Post-Suharto Indonesia. In B. Wiryomartono (Ed.), Traditions and Transformations of Habitation in Indonesia: Power, Architecture, and Urbanism (pp. 201–221). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3405-8_10

In Exodus, Rem Koolhaas inserted a mega architecture surrounded by high walls across London. Within a divided urban environment, he wanted to create a “hedonistic science of designing collective facilities that fully accommodate individual desires “(Koolhaas, 1972). The residents are voluntary prisoners. However, its ideological purpose is exclusion(Teismann, 2018). Due to the high walls, it keeps capital, goods, and politics out and creates a utopian collective society inside. Today, scenes of division are also general in Jakarta now. Rather than transforming Kampung or Superblock, implanting a new architecture between or on top of the two with a new perspective is worthy of discussion.

Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture

Source: Rem Koolhaas, 1972

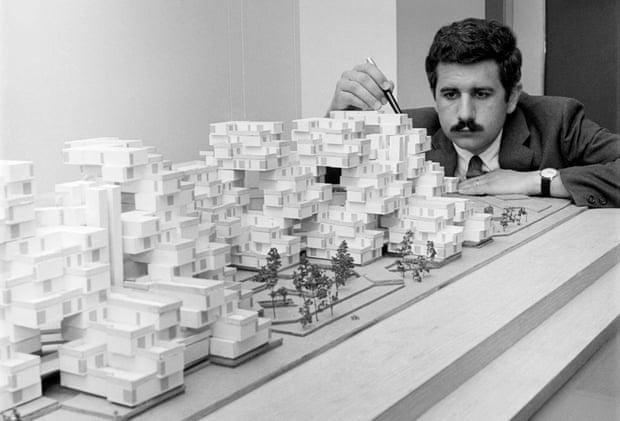

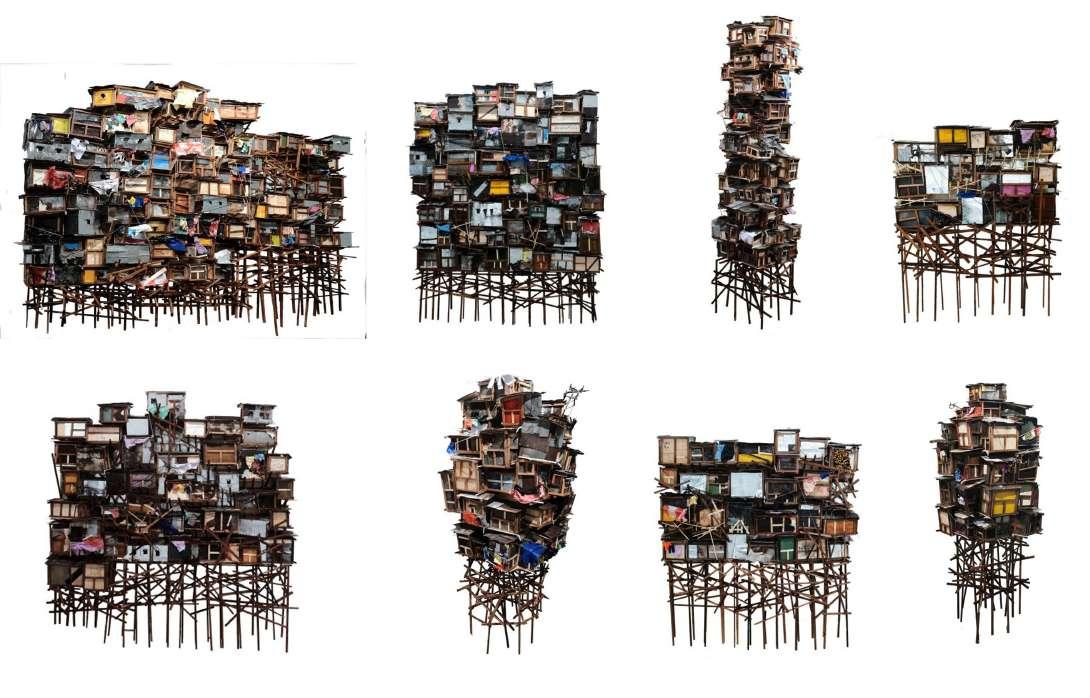

Habitat 67

Habitat 67 was unveiled during the 1967 World Expo. Safdie described it as a prototype based on the mass production system. Habitat 67 creates a Megastructure through the organic stacking of numerous prefabricated modules. The art installation “Di Balik Kampung Itu” (Behind the Village), designed by artist Asmo Adji, was exhibited at the Jakarta Architecture Festival 2023. By stacking Kampung buildings, he wanted to show an authentic portrayal of Jakarta residents’ lives. Interestingly, these installations bear a striking visual resemblance to Habitat 67. This three-dimensional building system could provide a future direction for Jakarta.

Moshe Safdie and Habitat 67

Di Balik Kampung Itu

Source: Bettmann Corbis

Source: Asmo Adji

Moshe Safdie and Habitat 67

Di Balik Kampung Itu

Source: Bettmann Corbis

Source: Asmo Adji

Architectures of Spatial Justice

Source: Dana Cuff

Architecture Volume 1

Source: Space Caviar Supports

Source: John Habraken

The residents of the second floor and the ground floor invest in the shops together, and the living and working Spaces of the two are integrated.

The common area between the two homes was converted into a kindergarten.

Embodied Carbon

Total Pre-constructed Part

9622600.181kgCO2e

Embodied Carbon/sqm 153.1960237kgCO2e/sqm

Pre-constructed Part (Biomass Offset) 7221347.877kgCO2e

Embodied Carbon/sqm 115.5011603kgCO2e/sqm

Breakdown

Materials

Engineered Bamboo

Engineered Bamboo Biomass Offset

Concrete (40% Recycled)

Aluminum (100% Recycled)

CMU (Wood Fibre Filling)

CMU Biomass Offset (Wood Fibre Filling)

PV Panel

Rebar (100% Recycled)

Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e) Volume/Unit /Area (m3) (m2)

GWP (kgCO2e/m3) (kgCO2e/unit) (kgCO2e/m2)

8143.795521m3 252.65kgCO2e/m3

8143.795521m3

267.54kgCO2e/m3

287.35kgCO2e/m3

5670kgCO2e/m3

1.85kgCO2e/unit

0.75kgCO2e/unit

251.41kgCO2e/m2 32971kgCO2e/m3

2057529.938kgCO2e

2178791.054kgCO2e

544455.4424kgCO2e

971688.9811kgCO2e

548737.75kgCO2e

222461.25kgCO2e

5239897.251kgCO2e

260290.8175kgCO2e

Operational Carbon

Indonesian Emission Factor (2020): 0.82924kgCO2e/kWh

Average Electricity Consumption Per Household in Jakarta: 5726kWh

Household Electricity Consumption: 1923936kWh

Household Operational Carbon: 1595404.689kgCO2e

Facilities Electricity Consumption: 1515850.458kWh

Facilities Operational Carbon: 1257003.834kgCO2e

Breakdown

Plastic Recycling Line

Water Filters (18)

Water Pumps (13)

Ventilation Fans (12)

Offsets

Electricity Consumption (kWh)

Operational Carbon (kgCO2e)

61438.7716kgCO2e

414620kgCO2e

392263.69kgCO2e

377735.405kgCO2e

10945.968kgCO2e