ENCLAVE US ALL

I S E A R C H

The inquiry of the thesis begins with a probe into Johor Bahru coastal zone, identifying the trends and ambitions of the new waterfront development which is noticed to grow along the edge of the state under Iskandar Malaysia Development Plan.

J O H O R B A H R U

Standing firmly across the rapidly growing Singapore, a series of new development is noticed to grow along the edge of Johor State. Orientated to overlook toward the neighboring Island State, this new development zone is the site of a new economic zone in the southern part of Malaysia – Iskandar Malaysia; an alternative urban model to the congested and polluted urban centre (Hangzo and Cook 2014).

Accompanied by this new development zone are numerous massive land reclamation projects along the straits, expanding out from the coastal line and pushing the state’s boundary closer to Singapore’s national border. Among the myriad land reclamation developments, the Forest City project near Singapore’s Second link stands out from the rest, due to its enormous size and scale – four linked islands featuring hybrid projects of residential and commercial developments that stretch across 1,386 hectares man-made land off the coast of Johor; a plot size that is equivalent to three Singapore Sentosa Island (Reme 2015).

Straddling in the middle of narrow straits between Malaysia Johor State and Singapore, these waterfront developments and its backstory assume an emblematic issue of transnational order (Comaroff 2014). The mega development with its large scale reclamation work has seemingly widened the cross-border rival as if it has effectively closed the gap between the two contiguous borders. Since the beginning of industrialization sand has become an essential substance in all aspects of our lives – in glass, building materials, vehicles, electronics and even cosmetics; it has been labeled as an “unappreciated hero” (Welland 2009). Above all, sand is the key ingredient in the construction industry. The unprecedented, enormous landfilling development has gathered attention on the flow of territory across the globe – more specifically, the flow of sand, which has been called the “most wanted raw material

on the planet” (Comaroff 2014; Dupont 2013).

Land reclamation is no longer confined to small territories to safeguard its right to urban development (Glaser, Haberzettl and Walsh 1991). Under the model of public-private partnership, urban development in Johor has been dominated by large-scale private property owners playing a decisive role in laying out urban models that varies in sizes and socio-economic influences (Rogerson 2003). While it has been the phenomenon that seeks to specify the process of postindustrial place making, these privately driven, distended urban models have reached new heights with the increasing visionary plans to construct mega-cities on the urban periphery, and more inexplicably, on large parcel of reclaimed land.

By rhetorically positioning these mega-cities as models of sustainable development and proponents of water-orientated urban form, large urban agglomerations have ambitiously proposed design with unique manifestations to secure a foothold in the competitive new economic zone. Although these artificial sites are in their early stages of development, they have brought together an urgent discourse on the process of land extraction and land reclamation that are taking place in an unprecedented scale and pace. As the increasing demand of sand become noticeable in any of the fast growing nations, access to sand has seemingly become a matter of national security (Comaroff 2014).

“We live in an era of completions, not new beginnings.”

“The world is running out of places where it can start over.”

(Koolhaas

2007)Johor Bahru, capital city of the State of Johor, Malaysia has a long and rich history that dates as early as the 16th century. The thriving city, which was originally a fishing settlement named Tanjung Putri began its urbanization in 1855 under the ruling of the Temenggong Lineage, followed by the 21st Sultan of Johor - Sultan Abu Bakar (1862 - 1895) laying the foundation to develop the inhabited city into a modern capital, later renamed Johor Bahru (Trocki 1979). Today the capital city reflects a blend of activities which large part of the core is devoted to state administration buildings and skyscrapers clustered within the centre houses banks, regional offices and large corporations.

The high-density central core is surrounded by rings of commuter-dependent lowdense residential fringes that spread out over a radius up to approximately 20 miles, all linked by wide transportation corridors. The metropolitan is also an industrial and commercial hotspot, especially in the east side of the city. Since its independence, the development in Johor has been lagging behind big cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Penang despite its geographical closeness to the global business hub, Singapore. The streets in the city are often marked by high rates of traffic congestion and crimes scenes, pedestrian-unfriendly and lack of planned public infrastructures.

As a transitional zone between the two city capitals – Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, the developing state has received much attention in negotiating the transnational integration between the contiguous borders. Although Iskandar Malaysia development plan is placed under the country’s Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) to reestablish the national position in the competitive global economy, Johor – as the focal point of this master plan and with its close geographical proximity to the regional hub has nonetheless turned and orientated its urban development facing toward the neighbor’s business core than its national capital. The emergence of large-scale developments and transformations along the Straits of Johor are the evidences. In this view, the massive land reclamation project can be described as a twofold underlying force – on one hand it encompasses a sense of exasperation toward the rapidity territorial expansion across the straits in the Republic Island; on the other hand it symbolizes a new venture to impose and construct new city portrait in juxtaposition to the regional hub.

RECLAMATION PROJECT IN ISKANDAR MALAYSIA

(Source: Channel News Asia 2015, drawing adapted by author)

RECLAMATION PROJECT IN SINGAPORE

(Source: blogs@NTU 2014, drawing adapted by author)

Under the Ninth Malaysia Plan, the Government of Malaysia embarked on developing five economic corridors to promote balanced regional development and accelerate growth in designated geographic areas. Iskandar Malaysia, in one of the economic corridors is the manifestation of a plan to develop a world-class and dynamic metropolis in southern Johor that would be a key growth corridor for the country, by building upon the region’s strategic location, its vibrant population and strong logistical infrastructure.

With an area of 2,217 square kilometers, it is a massive development project, spread over a period of 20 years. Geographically, Iskandar Malaysia encompasses the Johor Bahru district as well several sub-districts in the neighbouring district of Pontian. The entire area is subdivided into five development nodes designated as Flagship Zones A to E, each focuses on different aspects of development.

The development of Iskandar Malaysia is guided by three key principles or foundations, namely, nation-building, growth and value creation, and equitable and fair distribution among stakeholders. These foundations serve to ensure that development is consistent in spirit with national and state-level plans and aspirations, while at the same time, aspires to drive further innovation and reform in the nation-building process. It should also emphasise growth, productivity and value creation, in line with globalization and increased competition. Most importantly, the development of Iskandar Malaysia must be consistent with the tenets of growth with equity, to ensure that the local and Bumiputera population in particular participate in its growth and progress in a meaningful manner.

The Iskandar Proposal Map can be translated into three development promotion areas namely the primary urban promotion areas, secondary urban promotion areas and the agriculture and tourism promotion areas. Particularly for the primary urban promotion areas which is designated at the southern periphery of Johor State, Johor straits has become the key anchor point of many catalyst developments.

As Singapore began to emerge as a dominant regional business hub, the focus of Johor’s urbanization started to shift from the old centre to the peripheries, consciously oriented and coordinated with Singapore’s dense development. Borrowing the idea from China’s opening and reform policy of “Hong Kong + ShenZhen Model”, Johor State’s close proximity to Singapore makes it a decisive factor in the construction of Waterfront Cities. As the second largest metropolitan area in Malaysia after Kuala Lumpur, Johor Bahru plays an important role in the ebb and flow of Malaysia’s bilateral relations with the Republic.

Johor-Singapore is a rapidly evolving transnational urban region in Southeast Asia. Under different rules governing, the contiguous states have embodied a distinctive urban image at either sides of the border where uneven economic dynamics across the borders have established as the prominent factor in encouraging cross-border integration between the island and the mainland. Being a small nation, Singapore has recognized its space constraint crisis could be overcome by expediting cooperative agreements with its neighboring territories. Johor with its abundance land banks has long emerged as the bi-national suburb of the Republic Island to accommodate the state’s desire for space and lower labor costs. The effect of cross-border has also put Johor as one of the biggest recipients of Singapore foreign direct investment, tourists and industries development.

On the other hand, thousands of Malaysians are crossing the Johor Straits during weekdays to enjoy better wages in Singapore, vice versa Singaporeans enjoy getaway for low cost goods and entertainments during the weekends. In this view, the dialectic centre-periphery transformation can be conceived as a result of two distinct cross-border dynamics: one, the growth pole-spillover phenomenon of Singapore from its core into surrounding hinterlands, particularly in the Southwest region of Johor, and two, the increasing daily transnational transit of commuters from Johor Bahru to Singapore via Second Link for better wages and education opportunities.

In the greater Johor Bahru metropolitan region, these edge cities has emblematized in the notion of an “escape from the negative aspects of civilization” (Garreau 1991), where homes and clusters of commerce are noticed to relocate from the densely developed downtowns to the outer rings and seamlessly integrated toward high-end development. It refers to an interweaving expansion that corresponds to the cycles of city economy and city life (Walker 1993) – a process to strive for a new and better restorative synthesis between the functions of the city (the machine) with the physical edge of the landscape (the frontier) (Garreau 1991). For all its newness, edge cities demonstrate a wave for new construction and new civilization in attempt to strike for a delicate balance between modernism and post-modernism cities, and furthermore, redefine a new mode of living on a rather flexible, unsettled nature on the edges.

City building in Johor Bahru has increasingly been left to the facilitation of public-private corporate in sponsoring strategic interventions in urban development. The privatization programme established by the national development agenda has resulted in the private sector undertaking large investments, particularly in transportation, telecommunications and energy. Unlike the small metropolitan Singapore where it is implemented with effective planning and executive strategies, Johor’s urban development reflects a form of spontaneity than planned and regulated growth. The absence of efficient public transport networks has composed the city into a car-based fragmented metropolitan area (Graham and Marvin 2001) with wide roads and system of highways serve as the main network.

With the launch of Iskandar Malaysia special development zone, the uneven patchwork of high-density clusters and low-density suburbs has appeared dominantly across the metropolitan urban fabric at the start of the twenty-first century. Stretching along the periphery, within the new economic zone are the rapidly urbanizing landscapes that have attracted increased concentrations of private capital investment on luxury real estate and commercial developments. These new urban models share some distinctive features – they are self-contained properties with exclusive landscaping and privatized common spaces; sequestered urban typologies that sealed off from surrounding by perimeter of high walls, formidable gates and security checkpoints.

FOREST

AreaL 11. 405.44 ha

Coverage: 27.9%

AGRICULTURE

Area: 13,691.69 ha

Coverage: 33.5%

BUILT-UP AREA

Area: 9267.53ha

Coverage: 14.2%

INDUSTRY & PORT

Area: 1442.89 ha

Coverage: 3.5%

MANGROVE FORESTS BUILT-UP AREAS

AGRICULTURE LANDS INDUSTRY & PORT

RAMSAR WETLANDS VILLAGES

UNDEVELOPED LAND

Coverage: 77% VACANT LAND

Area: 5837.22 ha

Coverage: 15.6%

DEVELOPED LAND

Coverage: 23% VACANT LAND

Area: 1500 ha

Coverage: 3.6%

II C O N S T R U C T S

The launch of Iskandar Malaysia Development has revealed a new form of urban fragmetation and collision in the suburban Johor Bahru, leading to the research on the meaning of walls as deplyoed as the dividing element; to explore the significance of the walls and their boudary functions rather than the simple physical form they take.

The tile of the project alludes to the fast walling city Johor Bahru – a congested city with fortified cells of affluent society and places of terror encircled by layers of forbidding walls and barriers, building walls on the perimeter in perceived fear of crime and as a response to the extreme rejection of violence in the public sphere. These militarized wall structures reveal a new pattern of urban discrimination that articulates socioeconomic segregation, class distinction, and spatial exclusion, walling itself in and out by the nature of activities and the social structure differences on the opposite sides of the boundaries.

In this era of network and mobility, city has undergone a revolutionary state which the pattern of metropolitan development produced by various economic and political powers are becoming agglomerations of unequal, fragmented districts in the dense urban centres (Angotti 2013). These isolated settlements can be seen as the product of twenty-first century metropolis free-market ideology which advocates limited government and state intervention in the use and development of urban land (Angotti 2013). Under free-market model, individual developers and investors gained individual freedom to develop the acquired space, thus consciously separated the private land away from the surrounding urban environment, and subsequently led to the formation of ‘enclave’ – a distinct territorial, cultural, or social unit enclosed within or as if within foreign territory (Merriam-Webster 2015).

Nevertheless, the fragmentation of the land into parcels is not something new. Modernist city in the early twentieth century first started to propose new forms of urban landscape where city is divided into a rational order of zones and activities. Initially, these new form of settlements are developed to serve the separation of functions constitute in the city (Lossifova 2015) that result from an evolving prod-

uct of the everyday lives and needs. As powerful individuals began to be involved in urban development, these spaces which were originally accessible to all are seen consciously separated from the commons, defined by boundaries where the people of selected group and resources are under surveillance (Angotti 2013). They are typically inward-looking, physically isolated, and consist of homogenous social that are controlled with enforced rules of inclusion and exclusion; they are defined by differences and distinctions.

“Any city, however small, is divided by two, one of the city of the poor, the other of the rich; these are at war with one another.“

- Plato Greek Philosopher (427-347 B.C.)

JB, HOME OF MALAYSIA’S VERY OWN LEGOLAND Mural Artwork of Lithuanian-Born Ernest Zacharevic

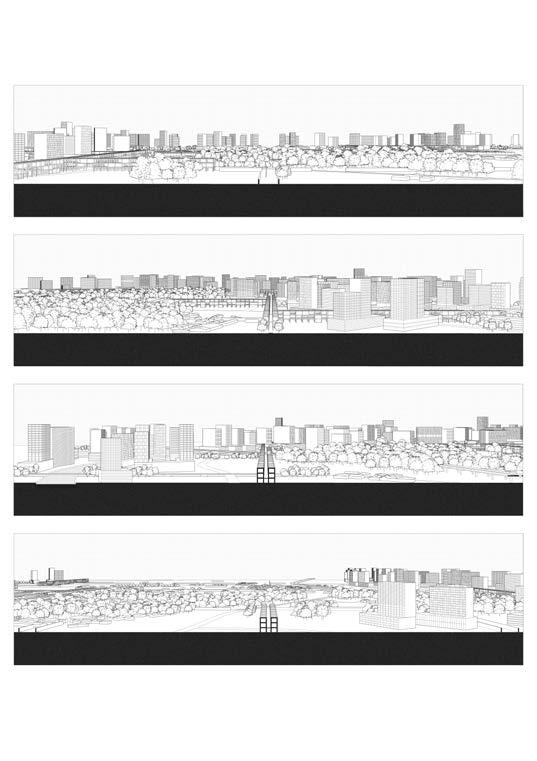

Johor Bahru - a metropolitan city that moves entirely sideward, is divided into two parts. Once part is the Protected Half, the other part the Unprotected Half. The Protected Half settled within the walls, romanticized through a mythical narrative dramatizing what separates the inhabitants from the otherness, demonstrated a superior lifestyle enclave glazed with seductive images of exclusivity, conspicuous consumption and social prestige. The Unprotected Half hindered outside the walls, decolorized as the residual of the contructed ‘dreamworld’, endangered by the risk of urban relocation and replacement.

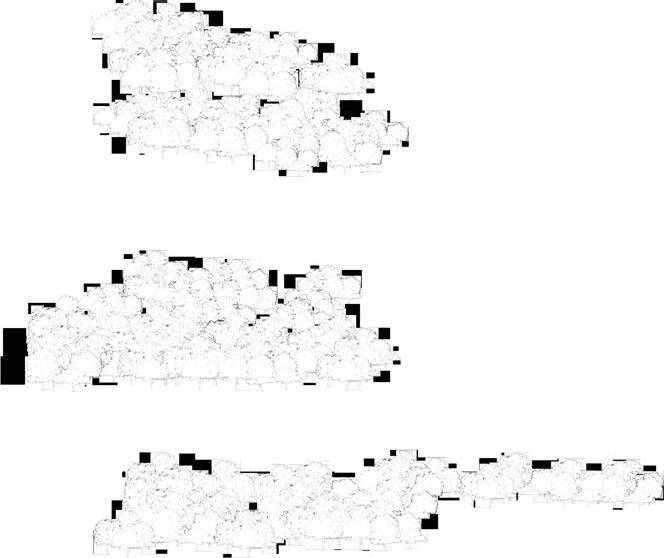

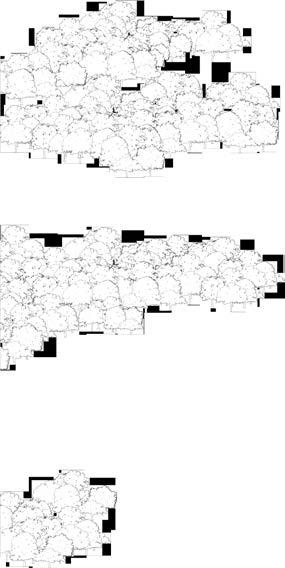

These fortified enclaves are privatized and monitored spaces for residence, consumption, leisure and work, enclosing themselves in from the public sphere through a series of techniques,

1. Modes: Encasement of the city with hierarchal road system: highways > ring roads > local streets > privatized inner streets

2. Topographies: vegetation and waterways enclosure

3. Surveillance systems and arms: barrier gates, security guards, surveillance camera, road hums, electronic access card, intercom systems

4. Physical boundary: walls, fences, landscapes, empty plots

While they are embedded in a list of codes set by the state authority to obscure the structural separation of the walling phenomena, the actualization of the walling element mutates and amplifies the codes through additional devices, reveal the desire of the city to enclose and insulate itself in from the common ground. The additional devices include:

1. Horizontal exemplification of gates/entrances with prominent roof structures

2. Optical obscuring of the ground floor

3. Layering of enclosure that create thickness and spatial distance around the perimeter

4. Falsifying opacity of fences through the devices of landscapes

Beyond the defensive utility of the element of wall, these barriers also represent the status and independence of the enclave they embraced. The territorial ownership of a fortified enclave can be read in 3 scales:

1. Compound Communities

A social unit of any size that shares common values and characteristics, , often characterized by a close perimeter walls and fences.

2. Precinct

A space enclosed by walls or other boundaries of a particular place, or an arbitary line drawn around it.

3. Strata Titles

A form of ownership devised for multi-level apartment blocks and horizontal subdivisions with shared areas.

To obscure the structural segregation of gating phenomena, the militarized structures are embedded in a list of codes which aims to give a sense of security to the communities that settle within the walls, while reducing the visibility of the defensive boundary structures. The codes can be categorized into four components:

1. Entrance & Accessway

Minimum 20m wide entrance road, with 2 separate access roads – one for residences and one for visitors.

2. Guardhouse

Size not exceeding 1.8m x 2.4m to keep its visibility minimal, and the location of the guardhouse should be at least 6m from the main public road to provide smooth traffic.

3. Perimeter Wall

Maximum 2.75m high, with a minimum 50% visibility from outside to allow interaction between the inside and outside, at the same time allow motoring and surveillance work to be carried out from the outside.

4. Landscape

Mandatory to design landscape element around the perimeter of the development to create a more appealing environment. However, the planting should not interrupt the permeability and visibility at the perimeter and for shrubs planting it should not be higher than the perimeter fencing.

III E X O D U S

The proliferation of the fortified enclaves has created a new model of spatial segregation and transformed the quality of public life in many cities around the world. Upper and middle classes have abandoned the detached house – the dominant housing form in Malaysia, for secure apartment complexes in the city centre and gated communities on the periphery. The rich and poor are no longer entirely separated by urban distance; they are instead increasingly separated by high walls and elaborated security systems.

The site of the proposal is in the heart of Johor Bahru New Iskandar Waterfront Development Zone – a highly gentrified territory where the fringe zone is terrorized by new high-end growth centres and financial hubs anchored with riverine and marina features, encroached upon the agricultural ground where the small settlements lie. This new outer ring heightens the profound social polarization in the city, threatening the unprotected groups with the risk of urban relocation and replacement.

Historically, the public space of the modern city was idealized as anonymous, open and egalitarian space where differences could be ignored. In cities fragmented by fortified enclaves, the principles of openness and free circulation has diminished; public space are enclosed and emphasized with boundaries and socioeconomic differences through the building of walls. Particularly in the New Iskandar Waterfront Development site, the land bank is parcelized and owned by a confluence of developer holdings, each with enormous development size and scale dominating the waterfront periphery.

In the context of Danga Bay, the new development is stitched in in such as way that it creates layers of ring enclosure, each insulate itself in and out from one and the other. The outer ring -- the anticipated waterfront city is encapsulated by riverine and waterway, is also in itself encircle and isolate the middle ring -- the small settlement away from the waterfront. The passive ring-shaped urban morphology is leading to a new pattern of geographical stratification that fragmentized the territory into “onion” profile, each ring running in parallel and clearly segregated by walls. The dialouge of settling within and outside of the wall is blurred, one find himself constantly being included in a space and excluded from another spatial structure.

Danga Bay Waterfront Development Land Bank Holding

IWH total land bank: 1618.7 ha

Danga Bay total land bank: 809.37 ha

IWH: 161.9 ha land reclamation

Singapore’s Temasek Holdings Pte Ltd, Capital Land Malaysia Pte Ltd,

IWSB: 28.33ha man-made island

Hao Yuan Pte Ltd: 15 ha

Country Garden: 22.26 ha

Greenland: 60 ha

Australia’s Walker Group: 81.75 ha

Tropicana: 14.97 ha

Brunsfield: 10.12 ha

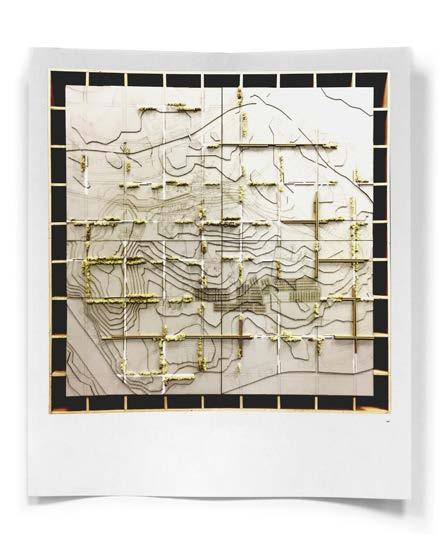

EXISTING & NEW ROADS

Iskandar Waterfront Development

WATERWAYS

Iskandar Waterfront Development

FOREST & VEGETATION

Iskandar Waterfront Development

WALLS & ENTRNCES

Iskandar Waterfront Development

COMMON FACILITIES

Iskandar Waterfront Development PRIMARY

Iskandar Waterfront Development